Title: The Grand Old Man

Author: Richard B. Cook

Release date: February 1, 2006 [eBook #9900]

Most recently updated: December 27, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Charlie Kirschner, Tom

Allen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

William E. Gladstone was cosmopolitan. The Premier of the British Empire is ever a prominent personage, but he has stood above them all. For more than half a century he has been the active advocate of liberty, morality and religion, and of movements that had for their object the prosperity, advancement and happiness of men. In all this he has been upright, disinterested and conscientious in word and deed. He has proved himself to be the world's champion of human rights. For these reasons he has endeared himself to all men wherever civilization has advanced to enlighten and to elevate in this wide world.

With the closing of the 19th century the world is approaching a crisis in which every nation is involved. For a time the map of the world might as well be rolled up. Great questions that have agitated one or more nations have convulsed the whole earth because steam and electricity have annihilated time and space. Questions that have sprung up between England and Africa, France and Prussia, China and Japan, Russia and China, Turkey and Armenia, Greece and Turkey, Spain and America have proved international and have moved all nations. The daily proceedings of Congress at Washington are discussed in Japan.

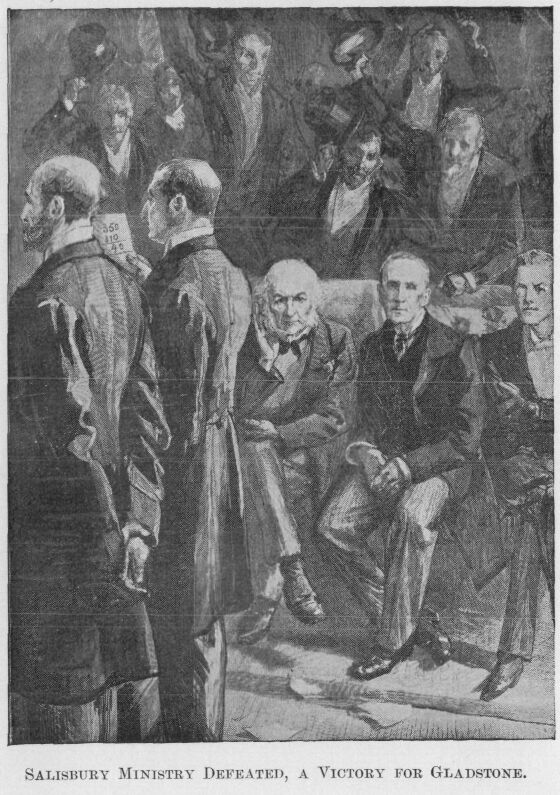

In these times of turning and overturning, of discontent and unrest, of greed and war, when the needs of the nations most demand men of world-wide renown, of great experience in government and diplomacy, and of firm hold upon the confidence of the people; such men as, for example, Gladstone, Salisbury, Bismark, Crispi and Li Hung Chang, who have led the mighty advance of civilization, are passing away. Upon younger men falls the heavy burden of the world, and the solution of the mighty problems of this climax of the most momentous of all centuries.

However, the Record of these illustrious lives remains to us for guidance and inspiration. History is the biography of great men. The lamp of history is the beacon light of many lives. The biography of William E. Gladstone is the history, not only of the English Parliament, but of the progress of civilization in the earth for the whole period of his public life. With the life of Mr. Gladstone in his hand, the student of history or the young statesman has a light to guide him and to help him solve those intricate problems now perplexing the nations, and upon the right solution of which depends Christian civilization—the liberties, progress, prosperity and happiness of the human race.

Hence, the life and public services of the Grand Old Man cannot fail to be of intense interest to all, particularly to the English, because he has repeatedly occupied the highest position under the sovereign of England, to the Irish whether Protestant or Catholic, north or south, because of his advocacy of (Reforms) for Ireland; to the Scotch because of his Scottish descent; to the German because he reminds them of their own great chancellor, the Unifier of Germany, Prince Bismarck; and to the American because he was ever the champion of freedom; and as there has been erected in Westminster Abbey a tablet to the memory of Lord Howe, so will the American people enshrine in their hearts, among the greatest of the great, the memory of William Ewart Gladstone.

|

"In youth a student and in eld a sage; |

| CHAPTER I | ANCESTRY AND BIRTH |

| CHAPTER II | AT ETON AND OXFORD |

| CHAPTER III | EARLY PARLIAMENTARY EXPERIENCES |

| CHAPTER IV | BOOK ON CHURCH AND STATE |

| CHAPTER V | TRAVELS AND MARRIAGE |

| CHAPTER VI | ENTERS THE CABINET |

| CHAPTER VII | MEMBER FOR OXFORD |

| CHAPTER VIII | THE NEAPOLITAN PRISONS |

| CHAPTER IX | THE FIRST BUDGET |

| CHAPTER X | THE CRIMEAN WAR |

| CHAPTER XI | IN OPPOSITION TO THE GOVERNMENT |

| CHAPTER XII | HOMERIC STUDIES |

| CHAPTER XIII | GREAT BUDGETS |

| CHAPTER XIV | LIBERAL REFORMER AND PRIME MINISTER |

| CHAPTER XV | THE GOLDEN AGE OF LIBERALISM |

| CHAPTER XVI | THE EASTERN QUESTION |

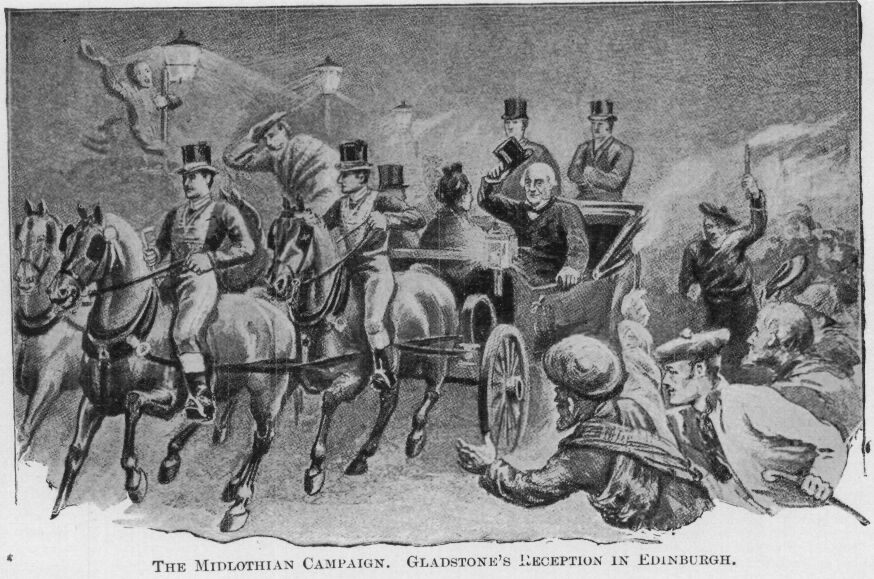

| CHAPTER XVII | MIDLOTHIAN AND THE SECOND PREMIERSHIP |

| CHAPTER XVIII | THIRD ADMINISTRATION AND HOME RULE |

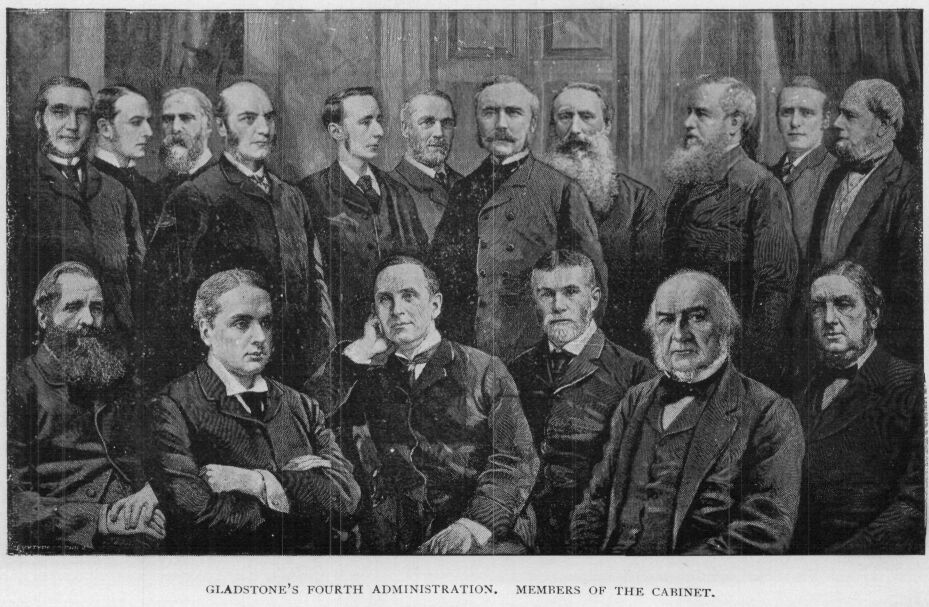

| CHAPTER XIX | PRIME MINISTER THE FOURTH TIME |

| CHAPTER XX | IN PRIVATE LIFE |

| CHAPTER XXI | CLOSING SCENES |

|

"In thought, word and deed, |

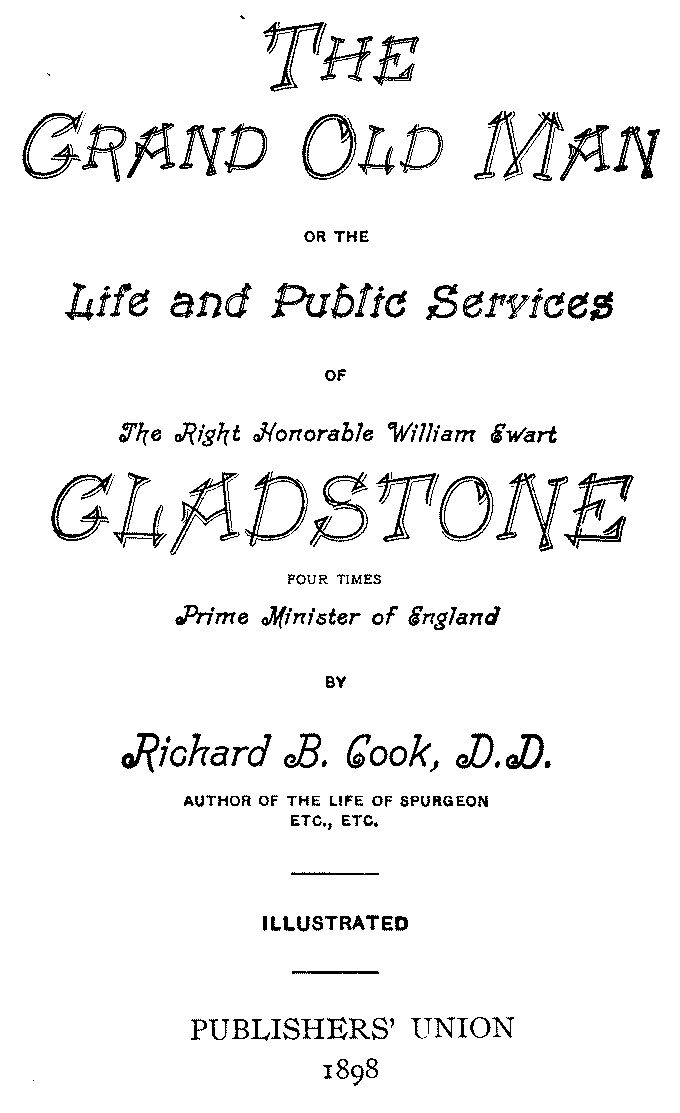

WILLIAM E. GLADSTONE (Frontispiece)

GLADSTONE ENTERING PALACE YARD, WESTMINSTER

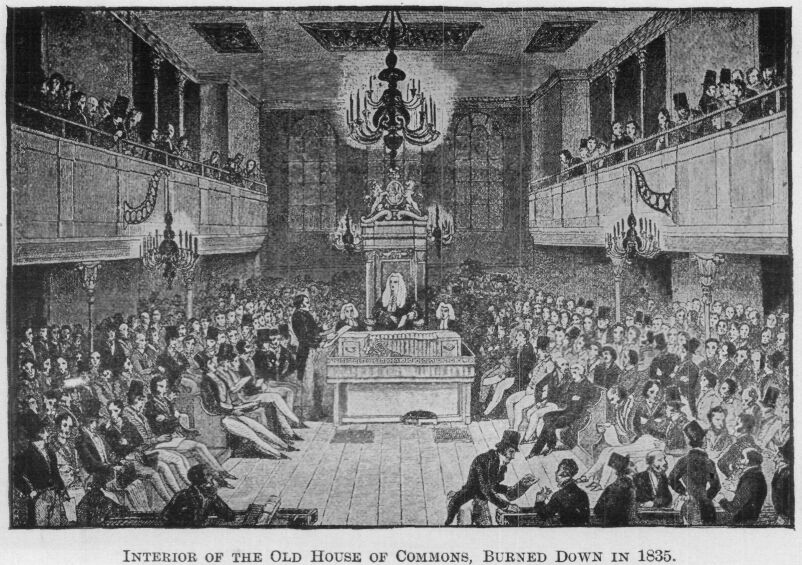

INTERIOR OF THE OLD HOUSE OF COMMONS

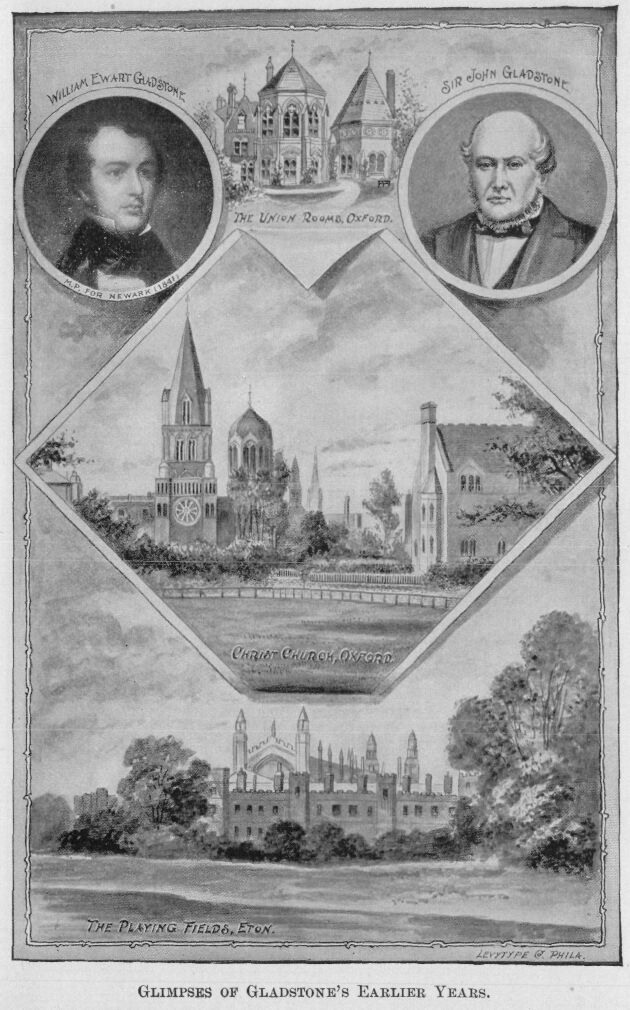

GLIMPSES OF GLADSTONE'S EARLIER YEARS

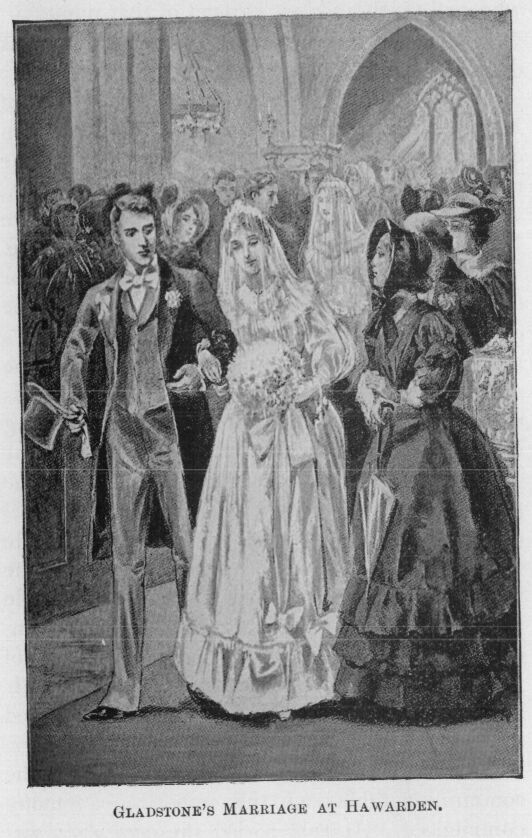

GLADSTONE'S MARRIAGE AT HAWARDEN

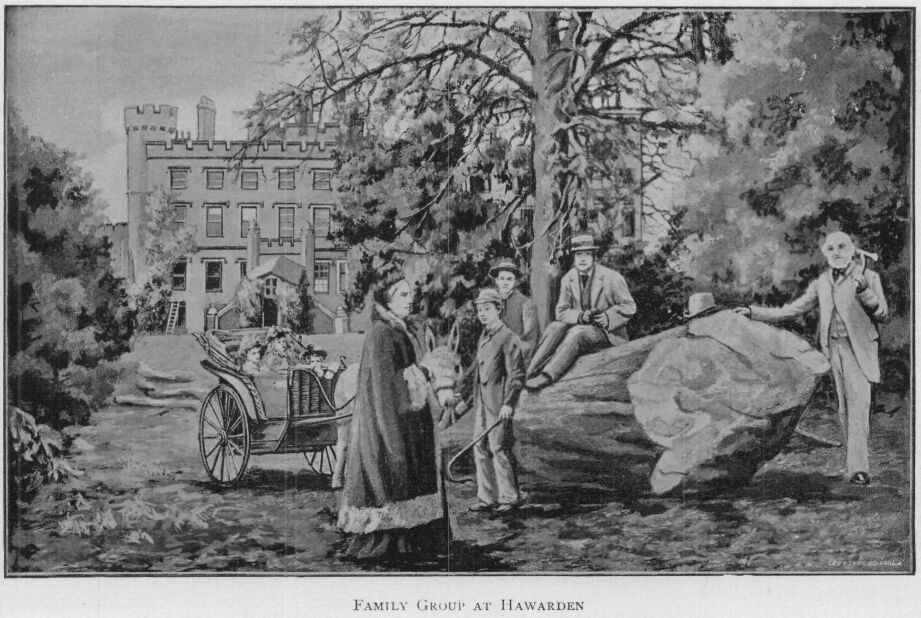

HAWARDEN CASTLE, FROM THE PARK

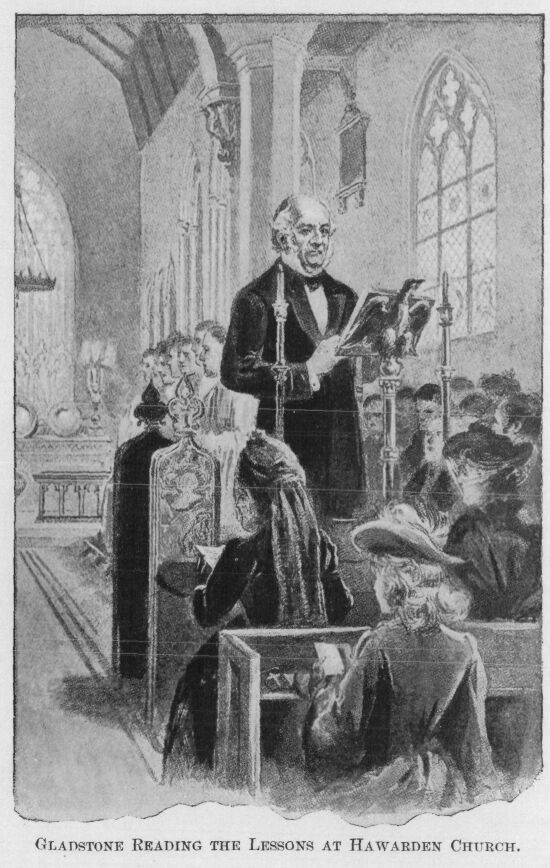

GLADSTONE READING THE LESSONS AT HAWARDEN CHURCH

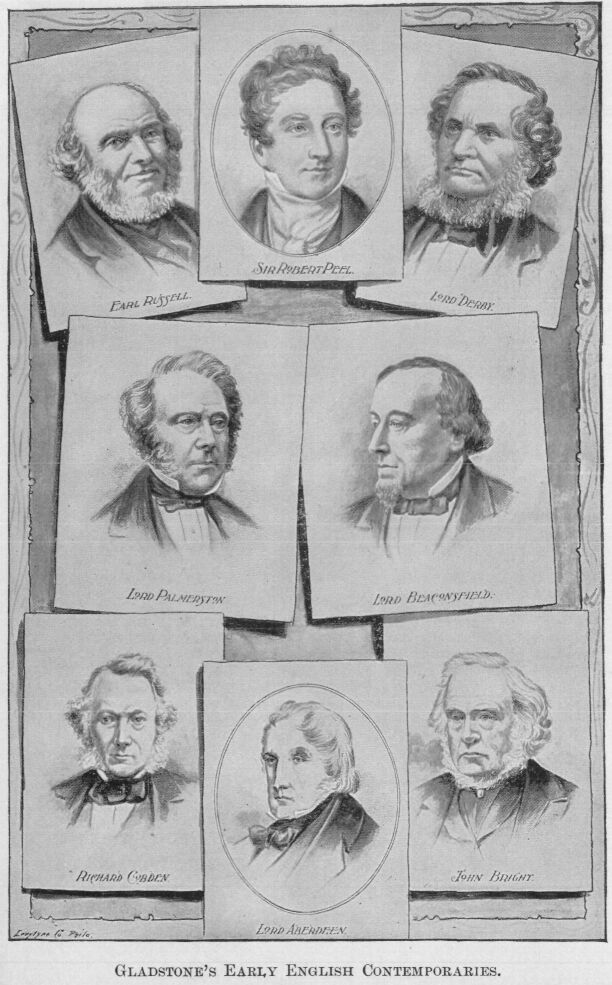

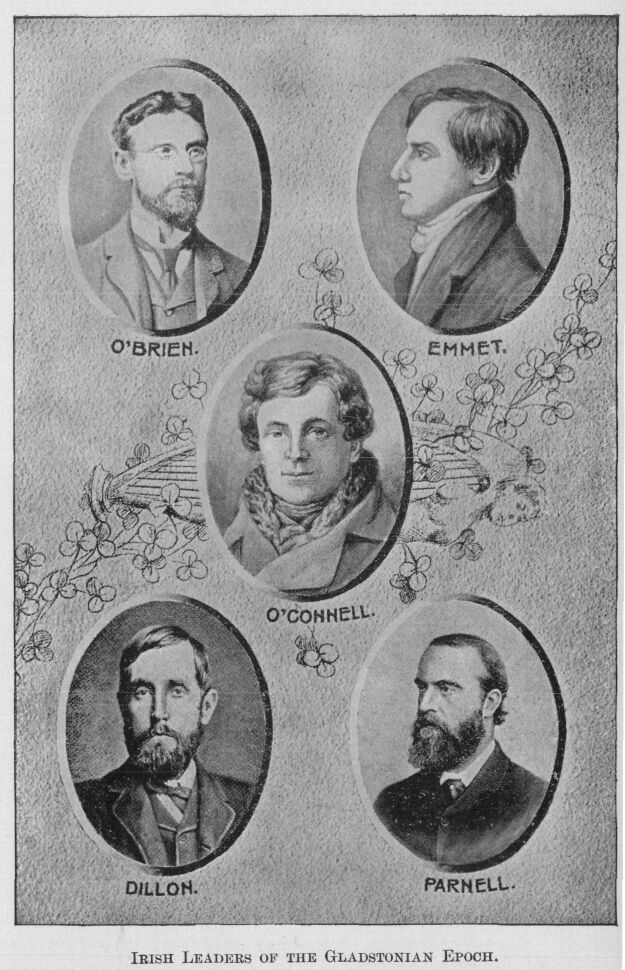

GLADSTONE'S EARLY ENGLISH CONTEMPORARIES

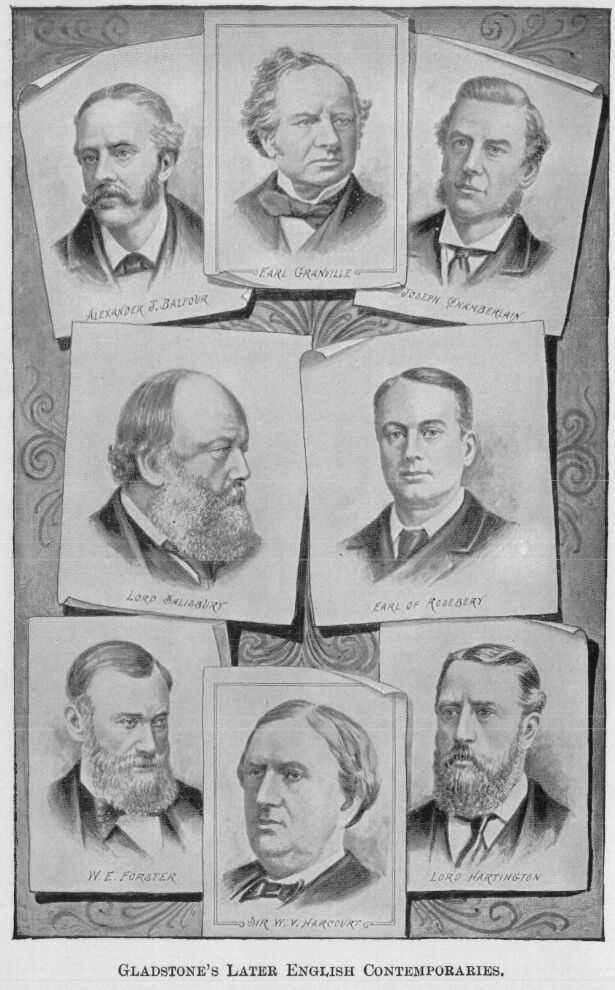

GLADSTONE'S LATER ENGLISH CONTEMPORARIES

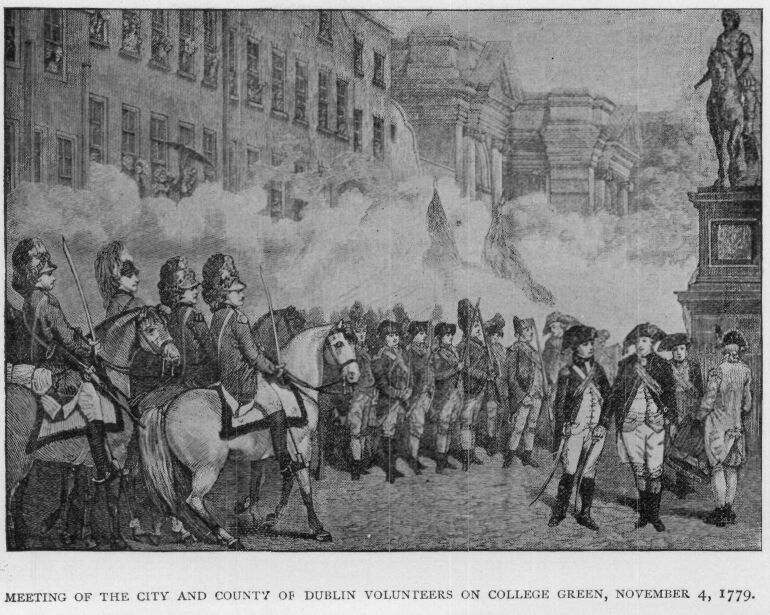

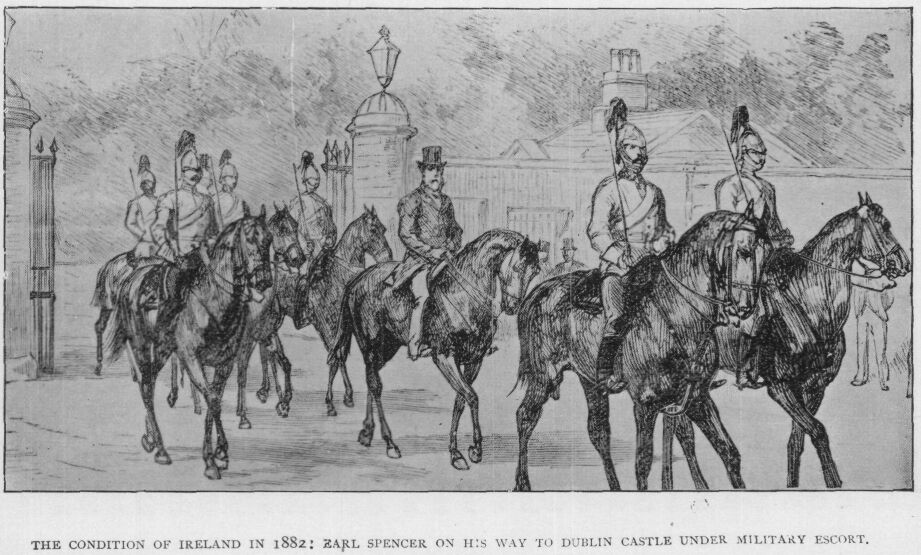

CITY AND COUNTY VOLUNTEERS OF DUBLIN

GLADSTONE VISITING NEAPOLITAN PRISONS

GLADSTONE INTRODUCING HIS FIRST BUDGET

THE SUNDERLAND SHIPOWNER SURPRISED

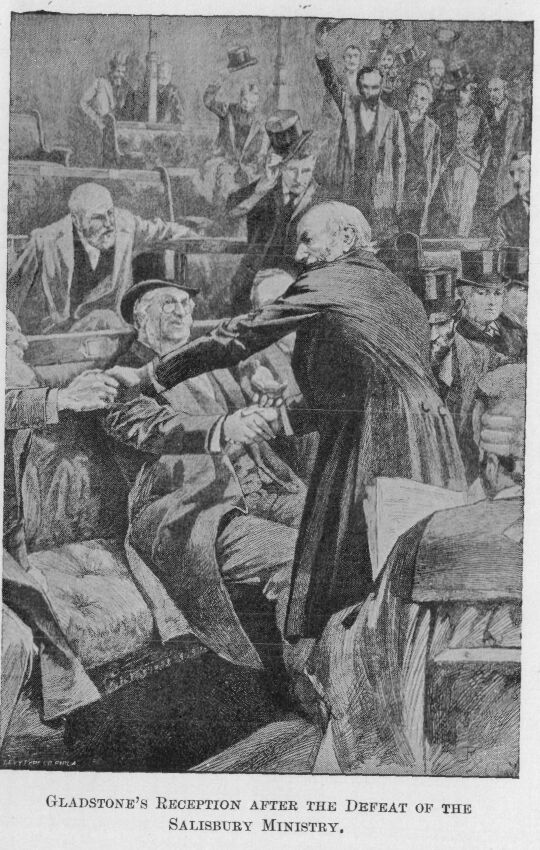

GLADSTONE'S RECEPTION IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS

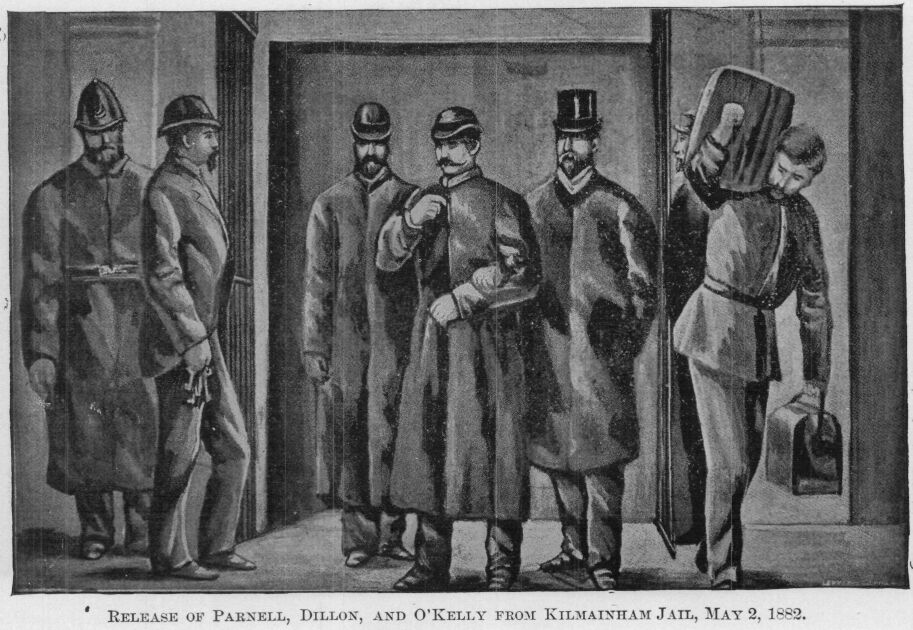

RELEASE OF PARNELL, DILLON AND O'KELLY

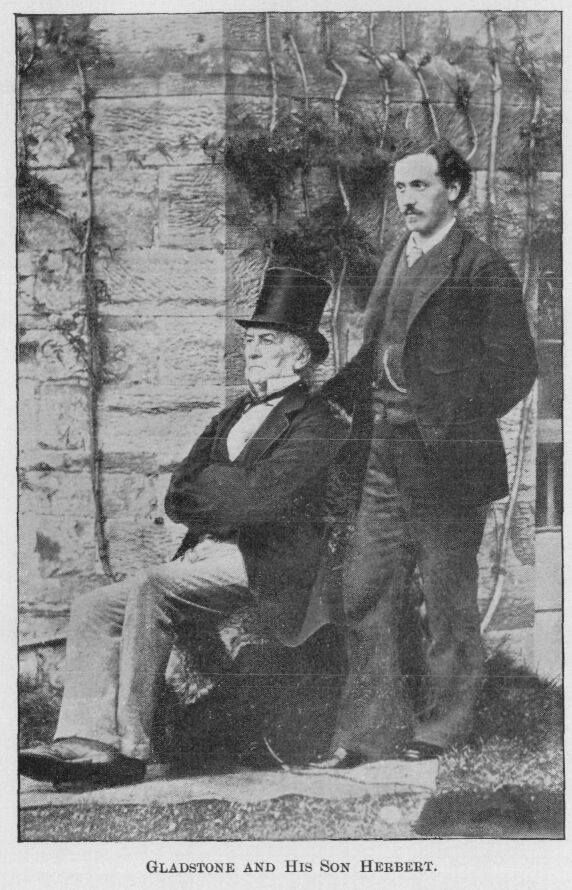

GLADSTONE AND HIS SON, HERBERT

GALLERY OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS

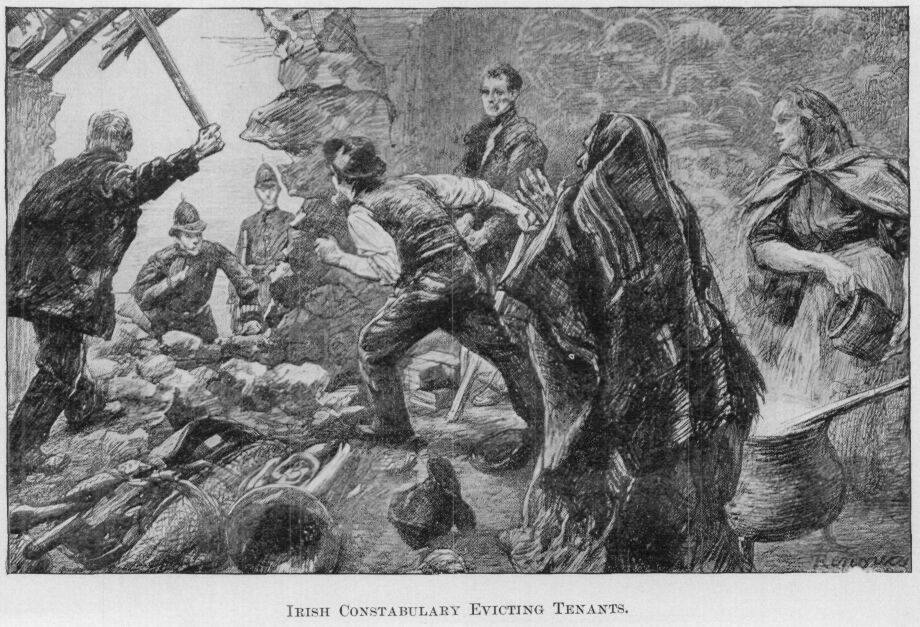

IRISH CONSTABULARY EVICTING TENANTS

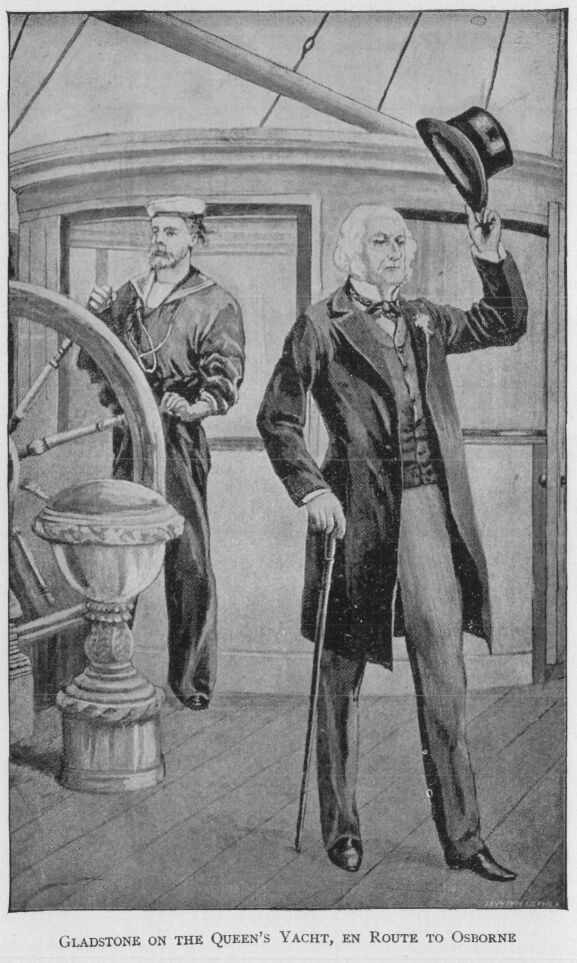

GLADSTONE ON THE QUEEN'S YACHT

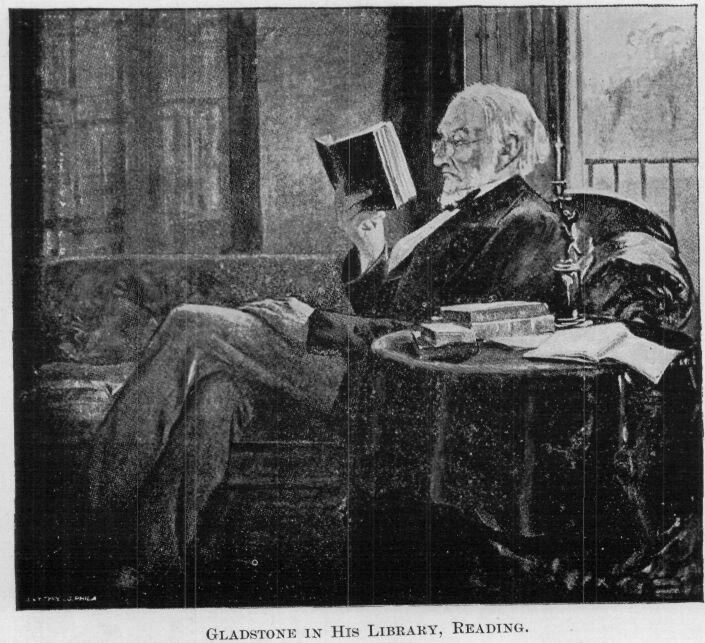

GLADSTONE IN HIS STUDY, READING

FUNERAL PROCESSION HAWARDEN VILLAGE

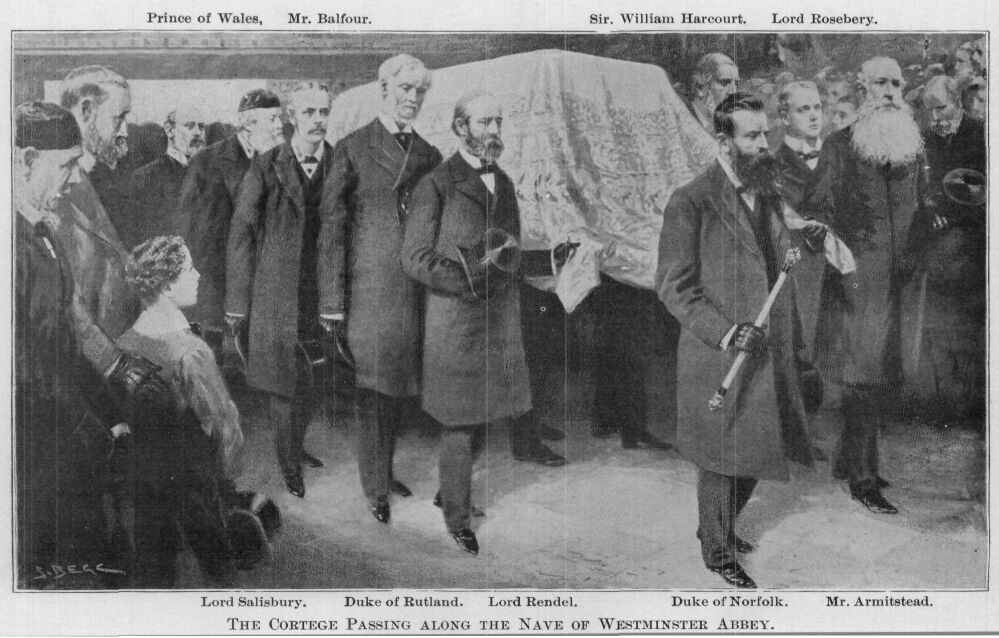

CORTEGE IN NAVE OF WESTMINSTER ABBEY

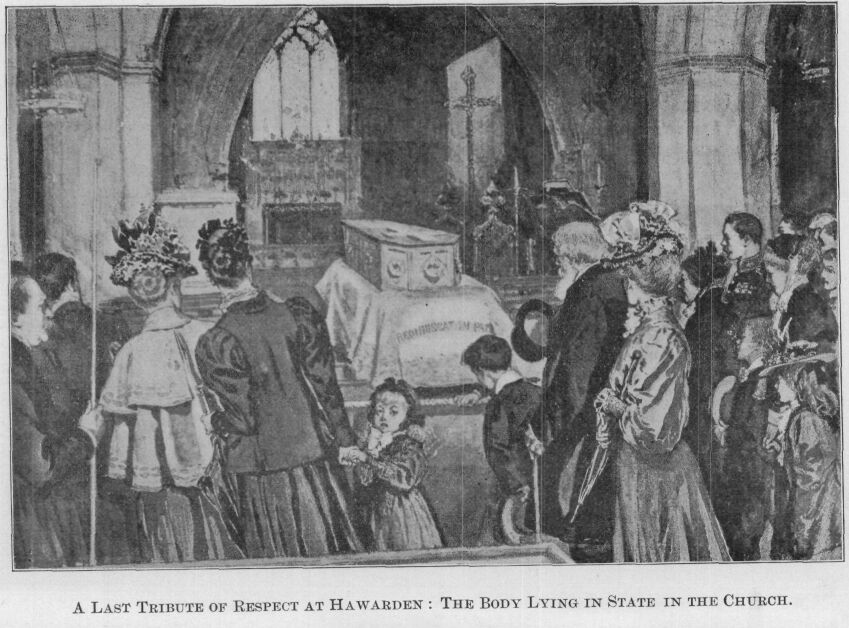

LAST TRIBUTE OF RESPECT AT HAWARDEN

There are few, even among those who differed from him, who would deny to Mr. Gladstone the title of a great statesman: and in order to appreciate his wonderful career, it is necessary to realize the condition of the world of thought, manners and works at the time when he entered public life.

In medicine there was no chloroform; in art the sun had not been enlisted in portraiture; railways were just struggling into existence; the electric telegraph was unknown; gas was an unfashionable light; postage was dear, and newspapers were taxed.

In literature, Scott had just died; Carlyle was awaiting the publication of his first characteristic book; Tennyson was regarded as worthy of hope because of his juvenile poems; Macaulay was simply a brilliant young man who had written some stirring verse and splendid prose; the Brontës were schoolgirls; Thackeray was dreaming of becoming an artist; Dickens had not written a line of fiction; Browning and George Eliot were yet to come.

In theology, Newman was just emerging from evangelicalism; Pusey was an Oxford tutor; Samuel Wilberforce a village curate; Henry Manning a young graduate; and Darwin was commencing that series of investigations which revolutionized the popular conception of created things.

Princess, afterwards Queen Victoria, was a girl of thirteen; Cobden a young calico printer; Bright a younger cotton spinner; Palmerston was regarded as a man-about-town, and Disraeli as a brilliant and eccentric novelist with parliamentary ambition. The future Marquis of Salisbury and Prime Minister of Great Britain was an infant scarcely out of arms; Lord Rosebery, (Mr. Gladstone's successor in the Liberal Premiership), Lord Spencer, Lord Herschell, Mr. John Morley, Mr. Campbell-Bannerman, Mr. Asquith, Mr. Brice, Mr. Acland and Mr. Arnold Morley, or more than half the members of his latest cabinet remained to be born; as did also the Duke of Devonshire, Mr. Balfour and Mr. Chamberlain, among those who were his keenest opponents toward the end of his public career.

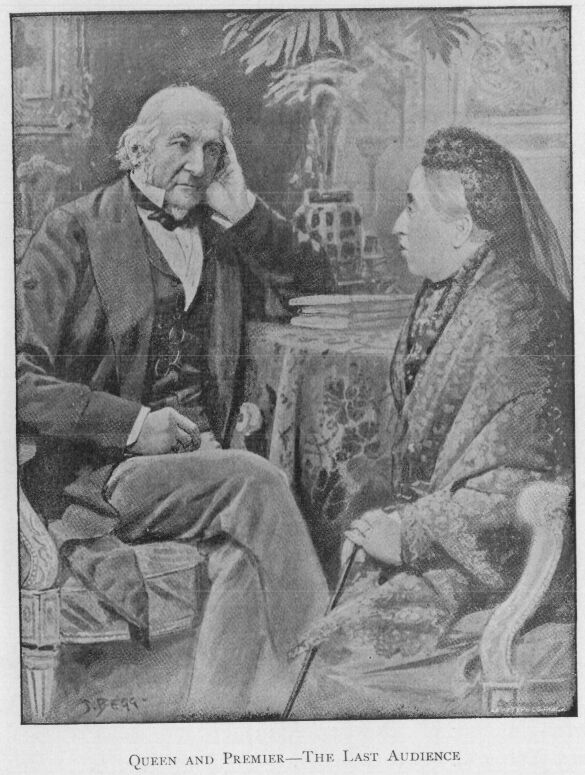

At last the end of Mr. Gladstone's public life arrived, but it had been extended to an age greater than that at which any English statesman had ever conducted the government of his country.

Of the significance of the life of this great man, it would be superfluous to speak. The story will signally fail of its purpose if it does not carry its own moral with it. We can best conclude these introductory remarks by applying to the subject of the following pages, some words which he applied a generation ago to others:

In the sphere of common experience we see some human beings live and die, and furnish by their life no special lessons visible to man, but only that general teaching in elementary and simple forms which is derivable from every particle of human histories. Others there have been, who, from the times when their young lives first, as it were, peeped over the horizon, seemed at once to—

|

"'Flame in the forehead of the evening sky,'" |

All history, says Emerson, "resolves itself into the biographies of a few stout and earnest persons." These remarks find exemplification in the life of William Ewart Gladstone, of whom they are pre-eminently true. His recorded life, from the early period of his graduation to his fourth premiership, would embrace in every important respect not only the history of the British Empire, but very largely the international events of every nation of the world for more than half a century.

William Ewart Gladstone, M.P., D.C.L., statesman, orator and scholar, was born December 27, 1809, in Liverpool, England. The house in which he was born, number 62 Rodney Street, a commodious and imposing "double-fronted" dwelling of red brick, is still standing. In the neighborhood of the Rodney Street house, and a few years before or after the birth of William E. Gladstone, a number of distinguished persons were born, among them William Roscoe, the writer and philanthropist, John Gibson, the sculptor, Doctor Bickersteth, the late Bishop of Ripon, Mrs. Hemans, the poetess, and Doctor James Martineau, Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy in Manchester New College, and the brother of Harriet Martineau, the authoress.

The Gladstone family, or Gledstanes, which was the original family name, was of Scottish origin. The derivation of the name is obvious enough to any one familiar with the ancestral home. A gled is a hawk, and that fierce and beautiful bird would have found its natural refuge among the stanes, or rocks, of the craggy moorlands which surround the "fortalice of gledstanes." As far back as 1296 Herbert de Gledstane figures in the Ragman Roll as one of the lairds who swore fealty to Edward I. His descendants for generations held knightly rank, and bore their part in the adventurous life of the Border. The chief stock was settled at Liberton, in the upper part of Clydesdale. It was a family of Scottish lairds, holding large estates in the sixteenth century. The estate dwindled, and in the beginning of the seventeenth century passed out of their hands, except the adjacent property of Authurshiel, which remained in their possession for a hundred years longer. A younger branch of the family—the son of the last of the Gledstanes of Arthurshiel—after many generations, came to dwell at Biggar, in Lanarkshire, where he conducted the business of a "maltster," or grain merchant.

Here, and at about this time, the name was changed to Gladstones, and a grandson of the maltster of Biggar, Thomas Gladstones, settled in Leith and there became a "corn-merchant." He was born at Mid Toftcombs, in 1732, and married Helen Neilson, of Springfield. His aptitude for business was so great that he was enabled to make ample provision for a large family of sixteen children. His son, John Gladstone, was the father of William E. Gladstone, the subject of our sketch.

Some have ascribed to Mr. Gladstone an illustrious, even a royal ancestry, through his father's marriage. He met and married a lovely, cultured and pious woman of Dingwall, in Orkney, the daughter of Andrew Robertson, Provost of Dingwall, named Ann Robertson, whom the unimpeachable Sir Bernard Burke supplied with a pedigree from Henry III, king of England, and Robert Bruce, of Bannockburn, king of Scotland, so that it is royal English and Scottish blood that runs in the veins of Mr. Gladstone.

"This alleged illustrious pedigree," says E.B. Smith, in his elaborate work on William E. Gladstone, "is thus traced: Lady Jane Beaufort, who was a descendant of Henry III, married James I, of Scotland, who was a descendant of Bruce. From this alliance it is said that the steps can be followed clearly down to the father of Miss Robertson. A Scottish writer upon genealogy, also referring to this matter, states that Mr. Gladstone is descended on the mother's side from the ancient Mackenzie of Kintail, through whom is introduced the blood of the Bruce, of the ancient Kings of Man, and of the Lords of the Isles and Earls of Ross; also from the Munros of Fowlis, and the Robertsons of Strowan and Athole. What was of more consequence to the Gladstones of recent generations, however, than royal blood, was the fact that by their energy and honorable enterprise they carved their own fortunes, and rose to positions of public esteem and eminence." It has been their pride that they sprang from the ranks of the middle classes, from which have come so many of the great men of England eminent in political and military life.

In an address delivered at the Liverpool Collegiate Institute, December 21, 1872, Sir John Gladstone said; "I know not why the commerce of England should not have its old families rejoicing to be connected with commerce from generation to generation. It has been so in other countries; I trust it may be so in this country. I think it is a subject of sorrow, and almost of scandal, when those families who have either acquired or recovered wealth and station through commerce, turn their backs upon it and seem to be ashamed of it. It certainly is not so with my brother or with me. His sons are treading in his steps, and one of my sons, I rejoice to say, is treading in the steps of my father and my brother."

George W.E. Russell, in his admirable biography of Mr. William E. Gladstone, says, "Sir John Gladstone was a pure Scotchman, a lowlander by birth and descent. Provost Robertson belonged to the Clan Donachie, and by this marriage the robust and business-like qualities of the Lowlander were blended with the poetic imagination, the sensibility and fire of the Gael."

An interesting story is told, showing how Sir John Gladstone, the father of William E. Gladstone, came to live in Liverpool, and enter upon his great business career, and where he became a merchant prince. Born at Leith in 1763, he in due time entered his father's business, where he served until he was twenty-one years old. At that time his father sent him to Liverpool to dispose of a cargo of grain, belonging to him, which had arrived at that port. His demeanor and business qualities so impressed Mr. Corrie, a grain merchant of that place, that he urged his father to let him settle there. Consent was obtained and young Gladstone entered the house of Corrie & Company as a clerk. His tact and shrewdness were soon manifest, and he was eventually taken into the firm as a partner, and the name of the house became Corrie, Gladstone & Bradshaw.

John Gladstone on one occasion proved the temporary preserver of the firm of which he had become a member. He was sent to America to buy grain for the firm, in a time of great scarcity in Europe, owing to the failure of the crops, but he found the condition of things the same in America. There was no grain to be had. While in great perplexity as to what to do he received advices from Liverpool that twenty-four vessels had been dispatched for the grain he was expected to purchase, to bring it to Europe. The prospect was that these vessels would have to return to Europe empty as they had come, and the house of Corrie & Company be involved thereby in ruin. It was then that John Gladstone rose to the emergency of the occasion, and by his enterprise and energy saved himself and partners from financial failure, to the great surprise and admiration of the merchants of Liverpool. It was in this way: He made a thorough examination of the American markets for articles of commerce that could be sold in Europe to advantage, and filling his vessels with them sent them home. This sagacious movement not only saved his house, but gave him a name and place among the foremost merchants of his day. His name was also a synonym for push and integrity, not only on the Liverpool exchange, but in London and throughout all England. The business of the firm became very great and the wealth of its members very large.

During the war with Napoleon, on the continent, and the war of 1812 with the United States, the commerce of England, as mistress of the seas, was injured, and the Gladstone firm suffered greatly and was among the first to seek peace, for its own sake and in the interests of trade. In one year the commerce of Liverpool declined to the amount of 140,000 tons, which was about one-fourth of the entire trade, and there was a decrease of more than $100,000 in the dock-dues of that port. John Gladstone was among those who successfully petitioned the British government for a change of its suicidal policy towards the American States.

After sixteen years of successful operations, during a part of which time it had been government agent, the firm was dissolved and its business was continued by John Gladstone. His six brothers having followed him from Leith to Liverpool, he took into partnership with him his brother Robert. Their business became very extensive, having a large trade with Russia, and as sugar importers and West India merchants. John Gladstone was the chairman of the West India Association and took an active part in the improvement and enlargement of the docks of Liverpool. In 1814, when the monopoly of the East India Company was broken and the trade of India and China thrown open to competition, the firm of John Gladstone & Company was the first to send a private vessel to Calcutta.

John Gladstone was a public-spirited man and took great interest in the welfare of his adopted city. He was ever ready to labor for its prosperity, and consequently endeared himself to the people of all classes and conditions, and of every shade of political opinion.

The high estimation in which he was held by the citizens of Liverpool was especially manifest October 18, 1824, when they presented him with a testimonial, consisting of a magnificent service of plate, of twenty-eight pieces, and bearing the following inscription: "To John Gladstone, Esq., M.P., this service of plate was presented MDCCCXXIV, by his fellow townsmen and friends, to mark their high sense of his successful exertions for the promotion of trade and commerce, and in acknowledgment of his most important services rendered to the town of Liverpool."

John Gladstone, though devoted to commerce, had time for literary pursuits. He wrote a pamphlet, "On the Present State of Slavery in the British West Indies and in the United States of America; and on the Importation of Sugar from British Settlements in India." He also published, in 1830, another pamphlet, containing a statement of facts connected with the same general subject, "in a letter addressed to Sir Robert Peel." In 1846 he published a pamphlet, entitled "Plain facts intimately connected with the intended Repeal of the Corn Laws; or Probable Effects on the Public Revenue and the Prosperity of the Country."

From the subject discussed it can be readily and truly imagined that John Gladstone had given thought to political subjects. He was in favor of a qualified reform which, while affording a greater enfranchisement of the people, looked also to the interests of all. Having an opinion, and not being afraid to express it, he was frequently called upon to address public meetings. The matters discussed by him were, however, rather national than municipal, rather humane than partisan. He was a strong advocate for certain reforms at home in 1818, and in 1823 on the seas, and for Greek independence in 1824. "On the 14th of February, 1824, a public meeting was held in Liverpool Town Hall, 'for the purpose of considering the best means of assisting the Greeks in their present important struggle for independence.' Mr. Gladstone spoke impressively in favor of the cause which had already evoked great enthusiasm amongst the people, and enlisted the sympathies and support of Lord Byron and other distinguished friends of freedom."

It was in 1818 that he addressed a meeting called "to consider the propriety of petitioning Parliament to take into consideration the progressive and alarming increase in the crimes of forging and uttering forged Bank of England notes." The penalties for these crimes were already heavy, but their infliction did not deter men from committing them, and these crimes increased at an enormous rate. Resolutions were passed at the Liverpool meeting, recommending the revision and amendment of existing laws.

Then again, so late as the year 1823, the navigation between Liverpool and Dublin was in a lamentable condition, and human life was recklessly imperiled, and no one seemed willing to interfere and to interest himself in the interests of humanity. It was then that he again came to the front to advocate a just cause. To illustrate the dangers to vessels and passengers, the case of the sloop Alert may be cited. It was wrecked off the Welsh coast, with between 100 and 140 persons on board, of whom only seventeen were saved. For the safety and rescue of all those souls on board this packet-boat there was only one small shallop, twelve feet long. Mr. Gladstone was impressed with the terrible nature of the existing evil, and obtained an amendment to the Steamboat Act, requiring imperatively that every passenger vessel should be provided with boats sufficient for every passenger it was licensed to carry. By this wise and humane provision thousands of lives were doubtless saved that would otherwise have been lost—the victims of reckless seamanship and commercial greed.

John Gladstone, either through the influence of Mr. Canning, or from having imbibed some political taste, sat in the House of Commons nine years, representing Lancaster in 1819, Woodstock from 1821 to 1826, and Berwick in 1827; but he never would consent to sit in Parliament for the city of Liverpool, for he thought that so large and important a constituency required peculiar representation such as he was unqualified to give.

He was the warm supporter and intimate friend of the celebrated Canning. At first he was a Whig, but finally came to support Mr. Canning, and became a Liberal Conservative. In 1812 he presided over a meeting at Liverpool, which was called to invite Mr. Canning to represent the borough in Parliament. After the election the successful candidates were claimed and carried in procession through the streets. The procession finally halted at Mr. Gladstone's house, in Rodney Street, from the balcony of which Mr. Canning addressed the populace. His election laid the foundation of a deep and lasting friendship between Mr. Canning and Mr. Gladstone. "At this time the son of the latter was but three years of age. Shortly afterwards—that is, as soon as he was able to understand anything of public men, and public movements and events"—says G.B. Smith, "the name of Canning began to exercise that strange fascination over the mind of William Ewart Gladstone which has never wholly passed away," and Mr. Gladstone himself acknowledged that he was brought up "under the shadow of the great name of Canning."

John Gladstone presided at a farewell dinner given by the Liverpool Canning Club, in August, 1822, in honor of Mr. Canning, who had been Governor-General of India. But Mr. Canning, instead of going to India, entered the British Cabinet, and in 1827 became Prime Minister, and John Gladstone moved a congratulatory address to the king upon the formation of the Canning Ministry.

In 1845 John Gladstone was created a baronet by Sir Robert Peel, but he lived to enjoy his deserved honors but a short time, for he died in 1851, at the advanced age of eighty-eight. His motto had ever been, "Diligent in business." His enormous wealth enabled him to provide handsomely for his family, not only after death, but during his lifetime.

At the time of his father's death, William E. Gladstone was still an adherent of the Tory party, yet his steps indicated that he was advancing towards Liberalism; and he had already reached distinction as a statesman, both in Parliament and in the Cabinet, while as yet he was but 42 years old, which was about half of his age when called for the fourth time to be Prime Minister of England.

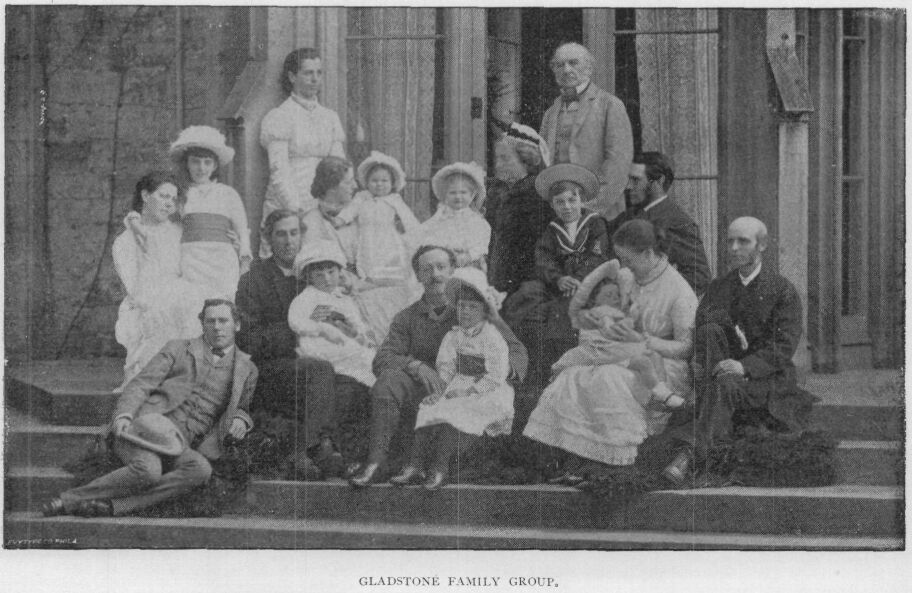

Sir John Gladstone and his wife had six children—four sons, Thomas Gladstone, afterwards baronet; John Gladstone, who became a captain, and died in 1863; Robert Gladstone, brought up a merchant, who died in 1875, and two daughters, Annie McKenzie Gladstone, who died years ago, and Helen Jane Gladstone. William E. Gladstone was the fourth son. The following is from the pen of the son, who says of his aged father, Sir John Gladstone: "His eye was not dim, nor his natural force abated; he was full of bodily and mental vigor; whatsoever his hand found to do he did it with his might; he could not understand or tolerate those who, perceiving an object to be good, did not at once and actively pursue it; and with all this energy he gained a corresponding warmth, and, so to speak, eagerness of affection, a keen appreciation of humor, in which he found a rest, and an indescribable frankness and simplicity of character, which, crowning his other qualities, made him, I think, and I strive to think impartially, nearly or quite the most interesting old man I ever knew."

Personally, Sir John Gladstone was a man of much intelligence and of sterling principle, of high moral and religious character, and his house consequently was a model home. "His house was by all accounts a home pre-eminently calculated to mould the thoughts and direct the course of an intelligent and receptive nature. There was a father's masterful will and keen perception, the sweetness and piety of the mother, wealth with all its substantial advantages and few of its mischiefs, a strong sense of the value of money, a rigid avoidance of extravagance and excesses; everywhere a strenuous purpose in life, constant employment, and concentrated ambition."

Mrs. John Gladstone, the wife and mother, is described by one who knew her intimately as "a lady of very great accomplishments; of fascinating manners, of commanding presence and high intellect; one to grace any home and endear any heart."

The following picture of the everyday life of the family is interesting and instructive, on account of Sir John Gladstone, as well as on that of his more distinguished son, and is from the pen of an eye-witness: "Nothing was ever taken for granted between him and his sons. A succession of arguments on great topics and small topics alike—arguments conducted with perfect good humor, but also with the most implicable logic—formed the staple of the family conversation. The children and their parents argued upon everything. They would debate as to whether a window should be opened, and whether it was likely to be fair or wet the next day. It was all perfectly good-humored, but curious to a stranger, because of the evident care which all the disputants took to advance no proposition, even as to the prospect of rain, rashly."

In such a home as this was William E. Gladstone in training as the great Parliamentary debater and leader, and for the highest office under the British crown. This reminds us of a story of Burke. The king one day, unexpectedly entering the office of his minister, found the elder Burke sitting at his desk, with his eyes fixed upon his young son, who was standing on his father's desk in the attitude of speaking. "What are you doing?" asked the astonished king. "I am making the greatest minister England ever saw," was the reply. And so in fact, and yet all unconsciously, was Sir John doing for his son, William.

William E. Gladstone "was born," says his biographer, G.W.E. Russell, "at a critical moment in the fortunes of England and of Europe. Abroad the greatest genius that the world has ever seen was wading through slaughter to a universal throne, and no effectual resistance had as yet been offered to a progress which menaced the liberty of Europe and the existence of its States. At home, a crazy king and a profligate heir-apparent presided over a social system in which all civil evils were harmoniously combined. A despotic administration was supported by a parliamentary representation as corrupt as illusory; a church, in which spiritual religion was all but extinct, had sold herself as a bondslave to the governing classes. Rank and wealth and territorial ascendency were divorced from public duty, and even learning had become the handmaid of tyranny. The sacred name of justice was prostituted to sanction a system of legal murder. Commercial enterprise was paralyzed by prohibitive legislation; public credit was shaken to its base; the prime necessaries of life were ruinously dear. The pangs of poverty were aggravated by the concurrent evils of war and famine, and the common people, fast bound in misery and iron, were powerless to make their sufferings known or to seek redress, except by the desperate methods of conspiracy and insurrection. None of the elements of revolution were wanting, and the fates seemed to be hurrying England to the brink of a civil catastrophe.

"The general sense of insecurity and apprehension, inseparable from such a condition of affairs, produced its effect upon even the robust minds. Sir John Gladstone was not a likely victim of panic, but he was a man with a large stake in the country, the more precious because acquired by his own exertion; he believed that the safeguards of property and order were imperilled by foreign arms and domestic sedition; and he had seen with indignation and disgust the excesses of a factious Whiggery, which was not ashamed to exult in the triumph of the French over the English Government. Under the pressure of these influences Sir John Gladstone gradually separated himself from the Whigs, with whom in earlier life he had acted, and became the close ally of Canning, whose return for Liverpool he actually promoted."

With such surroundings it is not to be wondered at that William E. Gladstone entered political life a Tory, contending against the principles he afterwards espoused. His original bent, however, was not towards politics, but the church; and it was only at the earnest desire of his father that he ultimately decided to enter Parliament, and serve his country in the Legislature.

His subsequent life proved the wisdom of the choice. In the Legislature of his country was begun, carried on and consummated grandly, one of the most remarkable careers in the annals of history for versatility, brilliancy, solidity and long continuance. Rarely has there been exhibited so complete a combination of qualities in statesmanship. His intellectual endowments were almost without a parallel, and his achievements without a precedent. In him seemed to be centered a rich collection of the highest gifts of genius, great learning and readiness in debate and discourse in the House of Commons, and extraordinary wisdom in the administration of the affairs of the nation. His financial talent, his business aptitude, his classical attainments, and above all his moral fervor, and religious spirit were conspicuous. Some men would have been contented with political power, or classical learning, or literary distinction, but he excelled in all these—not only as a statesman, but as a man of letters and a classical scholar. Neither has held him exclusively as its own—he belongs to all, or rather they belong to him—for he explored and conquered them. His literary productions equal in merit his papers of State, while his knowledge of the classics would do credit to any scholar.

He possessed the unusual quality of throwing the light of his own mind on the greatest questions of national and international importance, of bringing them down to the understanding and appreciation of the masses of the people, of infusing, by his earnestness, the fire of his own soul in the people, and of arousing in them the greatest enthusiasm.

In the biography of this wonderful person we propose to set before the reader the man himself—his words and his deeds. This method enables him to speak for himself, and thus the reader may study him and know him, and because thereof be lifted into a higher plane of nobler and better being. The acts and utterances of such a character are his best biography, and especially for one differing so largely from all other men as to have none to be compared with him.

In this record we simply spread before the reader his private life and public services, connected together through many startling changes, from home to school, from university to Parliament, from Tory follower to Liberal leader, from the early start in his political course to the grand consummation of the statesman's success in his attainment to the fourth Premiership of this Grand Old Man, and the glorious end of an eventful life.

We could not do better, in closing this chapter, than to reproduce a part of the character sketch of William E. Gladstone, from the pen of William T. Stead, and published in the "Review of Reviews:"

"So much has been written about Mr. Gladstone that it was with some sinking of heart I ventured to select him as a subject for my next character sketch. But I took heart of grace when I remembered that the object of these sketches is to describe their subject as he appears to himself at his best, and his countrymen. There are plenty of other people ready to fill in the shadows. This paper claims in no way to be a critical estimate or a judicial summing up of the merits and demerits of the most remarkable of all living Englishmen. It is merely an attempt to catch, as it were, the outline of the heroic figure which has dominated English politics for the lifetime of this generation, and thereby to explain something of the fascination which his personality has exercised and still exercises over the men and women of his time. If his enemies, and they are many, say that I have idealized a wily old opportunist out of all recognition, I answer that to the majority of his fellow-subjects my portrait is not overdrawn. The real Gladstone may be other than this, but this is probably more like the Gladstone for whom the electors believe they are voting, than a picture of Gladstone, 'warts and all,' would be. And when I am abused, as I know I shall be, for printing such a sketch, I shall reply that there is at least one thing to be said in its favor. To those who know him best, in his own household, and to those who only know him as a great name in history, my sketch will only appear faulty because it does not do full justice to the character and genius of this extraordinary man."

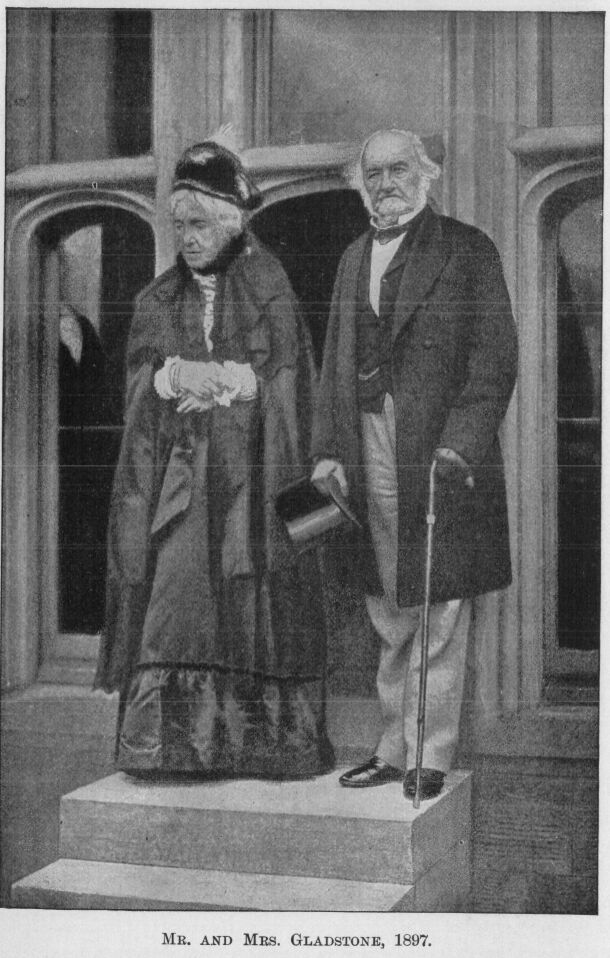

Mr. Gladstone appeals to the men of to-day from the vantage point of extreme old age. Age is so frequently dotage, that when a veteran appears who preserves the heart of a boy and the happy audacity of youth, under the 'lyart haffets wearing thin and bare' of aged manhood, it seems as if there is something supernatural about it, and all men feel the fascination and the charm. Mr. Gladstone, as he gleefully remarked the other day, has broken the record. He has outlived Lord Palmerston, who died when eighty-one, and Thiers, who only lived to be eighty. The blind old Dandolo in Byron's familiar verse—

The octogenarian chief, Byzantium's conquering foe,

had not more energy than the Liberal leader, who, now in his eighty-third year, has more nerve and spring and go than any of his lieutenants, not excluding the youngest recruit. There is something imposing and even sublime in the long procession of years which bridge as with eighty-two arches the abyss of past time, and carry us back to the days of Canning, and of Castlereagh, of Napoleon, and of Wellington. His parliamentary career extends over sixty years—the lifetime of two generations. He is the custodian of all the traditions, the hero of the experience of successive administrations, from a time dating back longer than most of his colleagues can remember. For nearly forty years he has had a leading part in making or unmaking of Cabinets; he has served his Queen and his country in almost every capacity in office and in opposition, and yet to-day, despite his prolonged sojourn in the malaria of political wire-pulling, his heart seems to be as the heart of a little child. If some who remember 'the old Parliamentary hand' should whisper that innocence of the dove is sometimes compatible with the wisdom of the serpent, I make no dissent. It is easy to be a dove, and to be as silly as a dove. It is easy to be as wise as a serpent, and as wicked, let us say, as Mr. Governor Hill or Lord Beaconsfield. But it is the combination that is difficult, and in Mr. Gladstone the combination is almost ideally complete.

"Mr. Gladstone is old enough to be the grandfather of the younger race of politicians, but still his courage, his faith, his versatility, put the youngest of them to shame. It is this ebullience of youthful energy, this inexhaustible vitality, which is the admiration and despair of his contemporaries. Surely when a schoolboy at Eton he must somewhere have discovered the elixir of life, or have been bathed by some beneficent fairy in the well of perpetual youth. Gladly would many a man of fifty exchange physique with this hale and hearty octogenarian. Only in one respect does he show any trace of advancing years. His hearing is not quite so good as it was, but still it is far better than that of Cardinal Manning, who became very deaf in his closing years. Otherwise Mr. Gladstone is hale and hearty. His eye is not dim, neither is his natural force abated. A splendid physical frame, carefully preserved, gives every promise of a continuance of his green old age.

"His political opponents, who began this Parliament by confidently calculating upon his death before the dissolution, are now beginning to admit that it is by no means improbable that Mr. Gladstone may survive the century. Nor was it quite so fantastic as it appears at first sight, when an ingenious disciple told him the other day that by the fitness of things he ought to live for twenty years yet. 'For,' said this political arithmetician, 'you have been twenty-six years a Tory, twenty-six years a Whig Liberal, and you have been only six years a Radical Home Ruler. To make the balance even you have twenty years still to serve.'

"Sir Provo Wallis, the Admiral of the Fleet, who died the other day at the age of one hundred, had not a better constitution than Mr. Gladstone, nor had it been more carefully preserved in the rough and tumble of our naval war. If the man who smelt powder in the famous fight between the Chesapeake and the Shannon lived to read the reports of the preparations for the exhibition at Chicago, it is not so incredible that Mr. Gladstone may at least be in the foretop of the State at the dawn of the twentieth century.

"The thought is enough to turn the Tories green with sickening despair, that the chances of his life, from a life insurance office point of view, are probably much better than Lord Salisbury's. But that is one of the attributes of Mr. Gladstone which endear him so much to his party. He is always making his enemies sick with despairing jealousy. He is the great political evergreen, who seems, even in his political life, to have borrowed something of immortality from the fame which he has won. He has long been the Grand Old Man. If he lives much longer he bids fair to be known as the immortal old man in more senses than one."

There is very little recorded of the boyhood of some great men, and this is true of the childhood of William E. Gladstone, until he leaves the parental home for school, which he does in 1821, at the early age of eleven. He was fortunate in his parentage, but no less so in his early associations, both in and out of school. We refer particularly to his private preceptors, two of whom, the venerable Archdeacon Jones and the Rev. William Rawson, first Vicar of Seaforth, a watering-place near Liverpool, were both men of high character and great ability. Mr. Gladstone always highly esteemed Mr. Rawson, his earliest preceptor, and visited him on his death-bed. Dr. Turner, afterwards Bishop of Calcutta, was for two years young Gladstone's private tutor, beginning his instruction when his pupil left Eton in 1827.

Besides these associations of his early life there were Canning, a frequent visitor, as has been mentioned, at his father's house, and Hannah More—"Holy Hannah," as Horace Walpole called her. She singled out "Billy" Gladstone for her especial pet out of the group of eleven children in whom her warm heart delighted, and it has been asked wonderingly if Miss More could preternaturally have lengthened her days until William E. Gladstone's present glory, whether she would have gone on dubbing him "Billy" in undignified brevity until the end.

William E. Gladstone, when very young, gave such evidence of uncommon intellectual ability and promise of future greatness that his father resolved upon educating him in the best schools of England. There are four or five great schools in England in which the English youth are prepared in four or five years for Cambridge or Oxford. "Eton, the largest and the most celebrated of the public schools of England, ranks as the second in point of antiquity, Winchester alone being older." After the preparation at home, under private teachers, to which we have referred, William E. Gladstone was sent to Eton, in September, 1821. His biographer, George W.E. Russell, writes, "From a provincial town, from mercantile surroundings, from an atmosphere of money-making, from a strictly regulated life, the impressible boy was transplanted, at the age of eleven, to the shadow of Windsor and the banks of the Thames, to an institution which belongs to history, to scenes haunted by the memory of the most illustrious Englishmen, to a free and independent existence among companions who were the very flower of English boyhood. A transition so violent and yet so delightful was bound to produce an impression which lapse of time was powerless to efface, and no one who knows the man and the school can wonder that for seventy years Mr. Gladstone has been the most enthusiastic of Etonians."

Eton of to-day is not in all respects the Eton of three-quarters of a century ago, and yet in some particulars it is as it was when young "Billy" Gladstone studied within its walls. The system of education and discipline pursued has undergone some modifications in recent years—notably during the provostship of the Rev. Francis Hodgson; but radical defects are still alleged against it. It is not remarkable, however, that every Eton boy becomes deeply attached to the school, notwithstanding the apprenticeship to hardships he may have been compelled to undergo.

The "hardships" there must have been particularly great when young Gladstone entered Eton, at the close of the summer holidays of 1821. The school was under the head-mastership of "the terrific Dr. Keate." He was not the man to spare even the scholar who, upon the emphatic testimony of Sir Roderick Murchison, was "the prettiest boy that ever went to Eton," and who was as studious and well-behaved as he was good-looking.

The town of Eton, in which the school is located, about 22 miles from London, in Berkshire, is beautifully situated on the banks of the river Thames, opposite Windsor Castle, the residence of the Queen of England.

Eton College is one of the most famous and best endowed educational institutions of learning in England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI. The king was very solicitous that the work should be of a durable kind, and he provided for free scholarships. Eton of Mr. Gladstone's day, according to a critic, was divided into two schools—the upper and the lower. It also had two kinds of scholars, namely, seventy called king's scholars or "collegers," who are maintained gratuitously, sleep in the college, and wear a peculiar dress; and another class—the majority—called "oppidans," who live in the town. Between these two classes of students there prevails perpetual hostility. At Cambridge, there was founded, in connection with Eton, what is called King's College, to receive as fellows students from Eton, and to give them gratuitously an education. The ground on which students of Eton were promoted to King's College and these fellowships was, strangely to say, upon that of seniority, or long residence, and not of merit. Because there was no competition, scholars who were deficient in education at Eton were promoted to Cambridge, where they had no incentive to work, being exempt from the ordinary university examination.

At Eton "no instruction was given in any branch of mathematical, physical, metaphysical or moral science, nor in the evidences of Christianity. The only subjects which it professed to impart a knowledge of were the Greek and Latin languages; as much divinity as can be gained from construing the Greek Testament, and reading a portion of Tomline on the Thirty-nine Articles, and a little ancient and modern geography." So much for the instruction imparted. As regards the hours of tuition, there seems to have been fault there, in that they were too few and insufficient, there being in all only eleven hours a week study. Then as to the manner of study, no time was given the scholar to study the style of an author; he was "hurried from Herodotus to Thucydides, from Thucydides to Xenophon, from Xenophon to Lucian, without being habituated to the style of any one author—without gaining an interest in the history, or even catching the thread of the narrative; and when the whole book is finished he has probably collected only a few vague ideas about Darius crying over a great army, Abydos and Nicias and Demosthenes being routed with a great army near Syracuse, mixed up with a recollection of the death of Cyrus and Socrates, some moral precept from Socrates, and some jokes against false philosophers and heathen gods." Hence the Eton student who goes to Cambridge finds he has done but a little desultory reading, and that he must begin again. It was charged that the system of education at Eton failed in every point. The moral discipline of the school was also called in question. The number of scholars was so great that the proper control of them seemed impossible under the management. Great laxity prevailed among the larger boys, while the younger and weaker students were exposed to the tyranny of the older and stronger ones without hope of redress. The result was that the system of "fagging," or the acting of some boys as drudges for the others, flourished. "The right" of fagging depended upon the place in the school; all boys in the sixth and fifth forms had the power of ordering—all below the latter form being bound to obey. This system of fagging has a very injurious effect upon most of the boys; "it finds them slaves and leaves them despots. A boy who has suffered himself, insensibly learns to see no harm in making others suffer in turn. The whole thing is wrong in principle, and engenders passions which should be stifled and not encouraged." Why free and enlightened England should tolerate, even then, such barbarous slavery cannot be understood and yet there are outrageous customs prevailing among college students of our day in every civilized land that should be suppressed.

Flogging was in vogue, too, at Eton, with all its degrading and demoralizing effects, and was performed by the Head-Master himself. In 1820, the year before Mr. Gladstone entered Eton, there were 280 upper students and 319 lower, a total of 612, and none were exempt.

Some curious stories are told of flogging, which has ever existed at Eton, and from which even the largest boys were not exempt. Mr. Lewis relates how a young man of twenty, just upon the point of leaving school, and engaged to be married to a lady at Windsor, was well and soundly whipped by Dr. Goodford, for arriving one evening at his tutor's house after the specified time. And it is related that Arthur Wellesley, afterwards the Iron Duke of Wellington, was flogged at Eton for having been "barred out." At the same time there were eighty boys who were whipped.

And the Eton of twenty years later was very little improved over its condition in Mr. Gladstone's time there, or in 1845. John D. Lewis, speaking of this period, says that after the boys reached the fifth form, then began "some of the greatest anomalies and absurdities of the then Etonian system." The student was now safe from the ordeal of examinations, and that the higher classes, including ten senior collegers and ten senior oppidans, contained some of the very worst scholars. "A boy's place on the general roll was no more a criterion of his acquirements and his industry than would be the 'year' of a young man at Oxford or Cambridge." The collegers, however, were required to pass some kind of examination, in accordance with which their place on the list for the King's college was fixed. But the evils regarding the hours of study and the nature of the studies were as bad. "The regular holidays and Saints' days, two whole holidays in a week, and two half-holidays, were a matter of common occurrence."

Lord Morley, in his examination before the Commission on Public Schools, was asked whether a boy would be looked down upon at Eton for being industrious in his studies, replied, "Not if he could do something else well." And this seems to be the spirit of the Eton boy with whom a lack of scholarship is more than made up by skill in river or field sports.

This is true to-day; for a recent writer in the Forum, upon "The Training of Boys at Eton," says: "Athletic prominence is in English public schools almost synonymous with social prominence; many a boy whose capacity and character commanded both respect and liking at the universities and in after life, is almost a nobody at a public school, because he has no special athletic gifts.... Great athletic capacity may co-exist with low moral and intellectual character."

There were few inducements to study and to excel in scholarship, and plenty to idleness and neglect, hence he who did so must study in hours and out of hours, in season and out of season. The curriculum is still strictly classical, but French, German and mathematics are taught. The collegers of recent years have done very fair work and carried off many distinctions at Cambridge. With all these odds against them, and these difficulties to surmount, yet there were Eton boys whose attainments were deep and solid, and who became famous men, and one of these was William E. Gladstone.

When young Gladstone entered Eton his brothers, Thomas and Robertson Gladstone, were already there, and the three boys boarded at Mrs. Shurey's, whose house "at the south end of the broad walk in front of the schools and facing the chapel," was rather nearer the famous "Christopher Inn" than would be thought desirable nowadays. On the wall opposite the house the name of "Gladstone" is carved. Thomas Gladstone was in the fifth form, and William was placed in the middle remove of the fourth form, and became his eldest brother's "fag." This doubtlessly saved him much annoyance and suffering, and allowed him better to pursue the studious bent of his indications.

William E. Gladstone was what Etonians called a "sap"—in other words, a student faithful in the discharge of every duty devolving upon him at school—one who studied his lessons and was prepared for his recitations in the classroom. This agreeable fact has been immortalized in a famous line in Lord Lytton's "New Timon." He worked hard at his classical studies, as required by the rules of the school, and applied himself diligently to the study of mathematics during the holidays.

It is said that his interest in the work of the school was first aroused by Mr. Hawtrey, who afterwards became Head-Master, who commended some of his Latin verses, and "sent him up for good." This led the young man to associate intellectual work with the ideas of ambition and success. While he did not seem to be especially an apt scholar in the restricted sense for original versification in the classical languages, or for turning English into Greek or Latin, yet he seemed to seize the precise meaning of the authors and to give the sense. "His composition was stiff," but yet, says a classmate, "when there were thrilling passages of Virgil or Homer, or difficult passages in 'Scriptores Graeci' to translate, he or Lord Arthur Hervey was generally called up to edify the class with quotations or translations."

He had no prizes at Eton except what is called being sent up for good, on account of verses, and he was honored on several occasions. Besides he took deep interest in starting a college periodical, and with some of the most intellectual of the students sustained it with his pen. The more studious of Eton boys have on several occasions in the present century been in the habit of establishing periodicals for the purpose of ventilating their opinions. In 1786 Mr. Canning and Mr. Hookham Frere established the Microcosm, whose essays and jeux d'esprit, while having reference primarily to Eton, demonstrated that the writers were not insensible to what was going on in the great world without. It was for this college paper that Canning wrote his "Essay on the Epic of the Queen of Hearts," which, as a burlesque criticism, has been awarded a high place in English literature. Lord Henry Spencer, Hookham Frere, Capel Lofft, and Mr. Millish, were also contributors to the columns of the Microcosm. In the year 1820 W. Mackworth Praed set on foot a manuscript journal, entitled Apis Matina. This was in turn succeeded by the Etonian, to which Praed contributed some of his most brilliant productions. John Moultrie, Henry Nelson Coleridge, Walter Blunt, and Chauncy Hare Townshend were also among the writers for its papers, who helped to make it of exceptional excellence. Its articles are of no ordinary interest even now.

In the last year of William E. Gladstone's stay at Eton, in 1827, and seven years after Praed's venture, he was largely instrumental in launching the Eton Miscellany, professedly edited by Bartholomew Bouverie, and Mr. Gladstone became a most frequent, voluminous and valuable contributor to its pages. He wrote articles of every kind—prologues, epilogues, leaders, historical essays, satirical sketches, classical translations, humorous productions, poetry and prose. And among the principal contributors with him were Sir Francis Doyle, George Selwyn, James Colville, Arthur Hallam, John Haumer and James Milnes-Gaskell. The introduction, written by and signed "William Ewart Gladstone" for this magazine, contained the following interesting and singular passage, which probably fairly sets forth the hopes and fears that beset statesmen in maturer years, as well as Eton boys of only seventeen years of age:

"In my present undertaking there is one gulf in which I fear to sink, and that gulf is Lethe. There is one stream which I dread my inability to stem—it is the tide of Popular Opinion. I have ventured, and no doubt rashly ventured—

|

Like little wanton boys that swim on bladders, |

At present it is hope alone that buoys me up; for more substantial support I must be indebted to my own exertions, well knowing that in this land of literature merit never wants its reward. That such merit is mine I dare not presume to think; but still there is something within me that bids me hope that I may be able to glide prosperously down the stream of public estimation; or, in the words of Virgil,

'—Celerare viam rumore secundo.'

"I was surprised even to see some works with the names of Shakespeare and Milton on them sharing the common destiny, but on examination I found that those of the latter were some political rhapsodies, which richly deserved their fate; and that the former consisted of some editions of his works which had been burdened with notes and mangled with emendations by his merciless commentators. In other places I perceived authors worked up into frenzy by seeing their own compositions descending like the rest. Often did the infuriated scribes extend their hands, and make a plunge to endeavor to save their beloved offspring, but in vain; I pitied the anguish of their disappointment, but with feelings of the same commiseration as that which one feels for a malefactor on beholding his death, being at the same time fully conscious how well he has deserved it."

Little did this diffident and youthful editor imagine that he was forecasting the future for himself by the aid of youth's most ardent desires, and that he would live to become the Primate of all England and the foremost statesman of his day.

There were two volumes of the Miscellany, dated June-July and October-November, respectively, and Mr. Gladstone contributed thirteen articles to the first volume. Among the contributions were an "Ode to the Shade of Watt Tyler," a vigorous rendering of a chorus from the Hucuba of Euripides, and a letter under the name of "Philophantasm," detailing an encounter he had with the poet Virgil, in which the great poet appeared muttering something which did not sound like Latin to an Eton boy, and complaining that he knew he was hated by the Eton boys because he was difficult to learn, and pleading to be as well received henceforth as Horace.

We give a quotation from a poem, consisting of some two hundred and fifty lines, from his pen, which, appeared also in the Miscellany:

|

"Who foremost now the deadly spear to dart, |

Among other writers who contributed to the first volume of the Miscellany were Arthur Henry Hallam and Doyle, also G.A. Selwyn, afterwards Bishop Selwyn, the friend of Mr. Gladstone, and to whom he recently paid the following tribute: "Connected as tutor with families of rank and influence, universally popular from his frank, manly, and engaging character—and scarcely less so from his extraordinary rigor as an athlete—he was attached to Eton, where he resided, with a love surpassing the love of Etonians. In himself he formed a large part of the life of Eton, and Eton formed a large part of his life. To him is due no small share of the beneficial movement in the direction of religious earnestness which marked the Eton of forty years back, and which was not, in my opinion, sensibly affected by any influence extraneous to the place itself. At a moment's notice, upon the call of duty, he tore up the singularly deep roots which his life had struck deep into the soil of England."

Both Mr. Gladstone and the future Bishop of Selwyn contributed humorous letters to "The Postman," the correspondence department of the Eton Miscellany.

In the second volume of the Eton Miscellany are articles of equal interest to those that appeared in the first. Doyle, Jelf, Selwyn, Shadwell and Arthur Henry Hallam were contributors, the latter having written "The Battle of the Boyne," a parody upon Campbell's "Hohenlinden." But here again Mr. Gladstone was the principal contributor, having contributed to this even more largely than to the first, having written seventeen articles, besides the introductions to the various numbers of the volume. Indeed one would think from his devotion to these literary pursuits during his last year at Eton, that he had very little leisure for those ordinary sports so necessary to Eton boys. He seems to have begun his great literary activity. Among them may be mentioned an "Ode to the Shade of Watt Tyler," mentioned before, which is an example of his humorous style:

|

"Shade of him whose valiant tongue "Still may thy spirit flap its wings "I hymn the gallant and the good "Shades, that soft Sedition woo, |

In a paper on "Eloquence," in the same volume, he shows that even then his young mind was impressed by the fame attached to successful oratory in Parliament. Visions of glory and honor open before the enraptured sight of those devoted to oratorical pursuits, and whose ardent and aspiring minds are directed to the House of Commons. Evidently the young writer himself "had visions of parliamentary oratory, and of a successful debut in the House of Commons, with perhaps an offer from the Minister, a Secretaryship of State, and even the Premiership itself in the distance." But then there are barriers to pass and ordeals to undergo. "There are roars of coughing, as well as roars of cheering" from the members of the House, "and maiden speeches sometimes act more forcibly on the lungs of hearers than the most violent or most cutting of all the breezes which AEOLUS can boast." But the writer draws comfort from the fact that Lord Morfeth, Edward Geoffrey, Stanley and Lord Castlereagh who were all members of the Eton college debating society were then among the most successful young speakers in Parliament. This sounds more like prophecy than dreams, for within a very few years after writing this article the writer himself had passed the dreaded barrier and endured the ordeal, and had not only made his appearance in the House of Commons, but had been invited to fill an honorable place in the Cabinet of the Ministry then in power.

Another contribution of Mr. Gladstone's to the Miscellany, and perhaps the most meritorious of the youthful writer's productions, was entitled, "Ancient and Modern Genius Compared," in which the young Etonian editor ardently and affectionately apostrophized the memory of Canning, his father's great friend and his own ideal man and statesman, who had just then perished untimely and amid universal regret. In this article he first takes the part of the moderns as against the ancients, though he by no means deprecates the genius of the latter, and then eloquently apostrophizes the object of his youthful hero-worship, the immortal Canning, whose death he compares to that of the lamented Pitt. The following are extracts from this production:

"It is for those who revered him in the plenitude of his meridian glory to mourn over him in the darkness of his premature extinction: to mourn over the hopes that are buried in his grave, and the evils that arise from his withdrawing from the scene of life. Surely if eloquence never excelled and seldom equalled—if an expanded mind and judgment whose vigor was paralleled only by its soundness—if brilliant wit—if a glowing imagination—if a warm heart, and an unbending firmness—could have strengthened the frail tenure, and prolonged the momentary duration of human existence, that man had been immortal! But nature could endure no longer. Thus has Providence ordained that inasmuch as the intellect is more brilliant, it shall be more short-lived; as its sphere is more expanded, more swiftly is it summoned away. Lest we should give to man the honor due to God—lest we should exalt the object of our admiration into a divinity for our worship—He who calls the weary and the mourner to eternal rest hath been pleased to remove him from our eyes.

"The degrees of inscrutable wisdom are unknown to us; but if ever there was a man for whose sake it was meet to indulge the kindly though frail feelings of our nature—for whom the tear of sorrow was to us both prompted by affection and dictated by duty—that man was George Canning."

After Hallam, Selwyn and other contributors to the Miscellany left Eton, at midsummer, 1827, Mr. Gladstone still remained and became the mainstay of the magazine. "Mr. Gladstone and I remained behind as its main supporters," writes Sir Francis Doyle, "or rather it would be more like the truth if I said that Mr. Gladstone supported the whole burden upon his own shoulders. I was unpunctual and unmethodical, so were his other vassals; and the 'Miscellany' would have fallen to the ground but for Mr. Gladstone's untiring energy, pertinacity and tact."

Although Mr. Gladstone labored in editorial work upon the Miscellany, yet he took time to bestow attention upon his duties in the Eton Society of the College, learnedly called "The Literati," and vulgarly called "Pop," and took a leading part in the debates and in the private business of the Society. The Eton Society of Gladstone's day was a brilliant group of boys. He introduced desirable new members, moved for more readable and instructive newspapers, proposing new rules for better order and more decorous conduct, moving fines on those guilty of disorder or breaches of the rules, and paying a fine imposed upon himself for putting down an illegal question. "In debate he champions the claims of metaphysics against those of mathematics, and defends aristocracy against democracy;" confesses innate feelings of dislike to the French; protests against disarmament of the Highlanders as inexpedient and unjust; deplores the fate of Strafford and the action of the House of Commons, which he claimed they should be able to "revere as our glory and confide in as our protection." The meetings of the Eton Society were held over Miss Hatton's "sock-shop."

In politics its members were Tory—intensely so, and although current politics were forbidden subjects, yet, political opinions were disclosed in discussions of historical or academical questions. "The execution of Strafford and Charles I, the characters of Oliver Cromwell and Milton, the 'Central Social' of Rousseau, and the events of the French Revolution, laid bare the speakers' political tendencies as effectually as if the conduct of Queen Caroline, the foreign policy of Lord Castlereagh, or the repeal of the Test and Corporation Act had been the subject of debate."

It was October 15, 1825, when Gladstone was elected a member of the Eton Society, and on the 29th of the same month made his maiden speech on the question "Is the education of the poor on the whole beneficial?" It is recorded in the minutes of the meeting that "Mr. Gladstone rose and eloquently addressed the house." He spoke in favor of education; and one who heard him says that his opening words were, "Sir, in this age of increased and increasing civilization." Says an eminent writer, by way of comment upon these words, "It almost oppresses the imagination to picture the shoreless sea of eloquence which rolls between that exordium and the oratory to which we still are listening and hope to listen for years to come."

"The peroration of his speech on the question whether Queen Anne's Ministers, in the last four years of her reign, deserved well of their country, is so characteristic, both in substance and in form," that we reproduce it here from Dr, Russell's work on Gladstone:

"Thus much, sir, I have said, as conceiving myself bound in fairness not to regard the names under which men have hidden their designs so much as the designs themselves. I am well aware that my prejudices and my predilections have long been enlisted on the side of Toryism (cheers) and that in a cause like this I am not likely to be influenced unfairly against men bearing that name and professing to act on the principles which I have always been accustomed to revere. But the good of my country must stand on a higher ground than distinctions like these. In common fairness and in common candor, I feel myself compelled to give my decisive verdict against the conduct of men whose measures I firmly believe to have been hostile to British interests, destructive of British glory, and subversive of the splendid and, I trust, lasting fabric of the British constitution."

The following extracts from the diary of William Cowper, afterwards Lord Mount-Temple, we also reproduce from the same author: "On Saturday, October 27, 1827, the subject for debate was:

"'Whether the deposition of Richard II was justifiable or not.' Jelf opened; not a good speech. Doyle spoke extempore, made several mistakes, which were corrected by Jelf. Gladstone spoke well. The Whigs were regularly floored; only four Whigs to eleven Tories, but they very nearly kept up with them in coughing and 'hear, hears,' Adjourned to Monday after 4.

"Monday, 29.—Gladstone finished his speech, and ended with a great deal of flattery of Doyle, saying that he was sure he would have courage enough to own that he was wrong. It succeeded. Doyle rose amidst reiterated cheers to own that he was convinced by the arguments of the other side. He had determined before to answer them and cut up Gladstone!

"December 1.—Debate, 'Whether the Peerage Bill of 1719 was calculated to be beneficial or not.' Thanks voted to Doyle and Gladstone; the latter spoke well; will be a great loss to the Society."

There were many boys at Eton—schoolfellows of Mr. Gladstone—who became men of note in after days. Among them the Hallams, Charles Canning, afterwards Lord Canning and Governor-General of India; Walter Hamilton, Bishop of Salisbury; Edward Hamilton, his brother, of Charters; James Hope, afterwards Hope-Scott; James Bruce, afterwards Lord Elgin; James Milnes-Gaskell, M.P. for Wenlock; Henry Denison; Sir Francis Doyle; Alexander Kinglake; George Selwyn, Bishop of New Zealand and of Litchfield; Lord Arthur Hervey, Bishop of Bath and Wells; William Cavendish, Duke of Devonshire; George Cornwallis Lewis; Frederic Tennyson; Gerald Wellesley, Dean of Windsor; Spencer Walpole, Home Secretary; Frederic Rogers, Lord Blachford; James Colvile, Chief Justice at Calcutta, and others.

By universal acknowledgment the most remarkable youth at Eton in that day was Arthur Hallam, "in mind and character not unworthy of the magnificent eulogy of 'In Memoriam.'" He was the most intimate friend of young Gladstone. They always took breakfast together, although they boarded apart in different houses, and during the separation of vacations they were diligent correspondents.

The father of William E. Gladstone, as we have seen, discovered premonitions of future greatness in his son, and we may well ask the question what impression was made by him upon his fellow school-mates at Eton. Arthur Hallam wrote: "Whatever may be our lot, I am confident that he is a bud that will bloom with a richer fragrance than almost any whose early promise I have witnessed."

James Milnes-Gaskell says: "Gladstone is no ordinary individual; and perhaps if I were called on to select the individual I am intimate with to whom I should first turn in an emergency, and whom I thought in every way pre-eminently distinguished for high excellence, I think I should turn to Gladstone. If you finally decide in favor of Cambridge, my separation from Gladstone will be a source of great sorrow to me." And the explanation of this latter remark is that the writer's mother wanted him to go to Cambridge, while he wished to go to Oxford, because Gladstone was going there.

Sir Francis Doyle writes: "I may as well remark that my father, a man of great ability, as well as of great experience of life, predicted Gladstone's future eminence from the manner in which he handled this somewhat tiresome business. [The editorial work and management of the Eton Miscellany.] 'It is not' he remarked, 'that I think his papers better than yours or Hallam's—that is not my meaning at all; but the force of character he has shown in managing his subordinates, and the combination of ability and power that he has made evident, convince me that such a young man cannot fail to distinguish himself hereafter.'"

The recreations of young Gladstone were not in all respects like his school-mates. He took no part in games, for he had no taste in that direction, and while his companions were at play he was studiously employed in his room. One of the boys afterwards declared, "without challenge or contradiction, that he was never seen to run." Yet he had his diversions and was fond of sculling, and kept a "lock-up," or private boat, for his own use. He liked walking for exercise, and walked fast and far. His chief amusement when not writing, reading or debating, was to ramble among the delights of Windsor with a few intimate friends; and he had only a few whom he admitted to his inner circle. To others beyond he was not known and was not generally popular. Gladstone, Charles Canning, Handley, Bruce, Hodgson, Lord Bruce and Milnes-Gaskell set up a Salt Hill Club. They met every whole holiday or half-holiday, as was convenient, after twelve, "and went up to Salt Hill to bully the fat waiter, eat toasted cheese, and drink egg-wine." It is startling to hear from such an authority as James Milnes-Gaskell that "in all our meetings, as well as at almost every time, Gladstone went by the name of Mr. Tipple."

The strongest testimony is borne to the moral character of young Gladstone while at Eton. By common consent he was pre-eminently God-fearing, orderly and conscientious. Bishop Hamilton, of Salisbury, writes: "At Eton I was a thoroughly idle boy; but I was saved from some worse things by getting to know Gladstone." This is the strong testimony of one school-boy after he has reached maturity and distinction for another. "To have exercised, while still a school-boy, an influence for good upon one of the greatest of contemporary saints, is surely such a distinction as few Prime Ministers ever attain."

Two stories are told of him while at Eton that go to show the moral determination of the boy to do right. On one occasion he turned his glass upside down and refused to drink a coarse toast proposed, according to annual custom, at an election dinner at the "Christopher Inn." This shows the purity of his mind, but there is another illustrating the humane feeling in his heart. He came forth as the champion of some miserable pigs which it was the inhumane custom to torture at Eton Fair on Ash Wednesday, and when he was bantered by his school-fellows for his humanity, he offered to write his reply "in good round hand upon their faces."

At Christmas, 1827, Gladstone left Eton, and after that studied six months under private tutors, Dr. Turner, afterwards Bishop of Calcutta, being one. Of this Mr. Gladstone writes: "I resided with Dr. Turner at Wilmslow (in Cheshire) from January till a few months later. My residence with him was cut off by his appointment to the Bishopric of Calcutta.... My companions were the present (1877) Bishop of Sodor and Man, and Sir C.A. Wood, Deputy-Chairman of the G.W. Railway. We employed our spare time in gymnastics, in turning, and in rambles. I remember paying a visit to Macclesfield. In a silk factory the owner showed us his silk handkerchiefs, and complained much of Mr. Huskisson for having removed the prohibition of the foreign article. The thought passed through my mind at the time: Why make laws to enable people to produce articles of such hideous pattern and indifferent quality as this? Alderly Edge was a favorite place of resort. We dined with Sir John Stanley (at Alderly) on the day when the king's speech was received; and I recollect that he ridiculed (I think very justly) the epithet untoward, which was applied in it to the Battle of Navarino."

In 1828, and after two years as a private pupil of Dr. Turner, Mr. Gladstone entered Christ Church College, Oxford and in the following year was nominated to a studentship on the foundation. Although he had no prizes at Oxford of the highest class, unless honors in the schools be so called—and in this respect he achieved a success which falls to the lot of but few students. In the year 1831, when he went up for his final examination, he completed his academical education by attaining the highest honors in the university—graduating double-first-class.

Of the city of Oxford, where Oxford University is situated, Matthew Arnold writes: "Beautiful city! So venerable, so lovely, so unravaged by the fierce intellectual life of our century, so serene! And yet, steeped in sentiment as she lies, spreading her gardens to the moonlight, or whispering from her towers the last enchantments of the Middle Age, who will deny that Oxford, by her ineffable charm, keeps ever calling us near to the true goal of all of us, to the ideal, to perfection—to beauty, in a word, which is only truth seen from another side."

Describing Christ Church College, a writer has said that there is no other College where a man has so great a choice of society, or a man entire freedom in choosing it.

As to the studies required, a greater stress was laid upon a knowledge of the Bible and of the evidences of Christianity than upon classical literature; some proficiency was required also, either in mathematics or the science of reasoning. The system of education accommodated itself to the capacity and wants of the students, but the man of talent was at no loss as to a field for his exertions, or a reward for his industry. The honors of the ministry were all within his reach. In the cultivation of taste and general information Oxford afforded every opportunity, but the modern languages were not taught.

An interesting fact is related of young Gladstone when he entered Oxford, as to his studies at the university. He wrote his father that he disliked mathematics, and that he intended to concentrate his time and attention upon the classics. This was a great blow to his father, who replied that he did not think a man was a man unless he knew mathematics. The dutiful son yielded to his father's wishes, abandoned his own plan, and applied himself with energy and success to the study of mathematics. But for this change of study he might not have become the greatest of Chancellors of the Exchequer.

Gladstone's instructors at Oxford were men of reputation. Rev. Robert Biscoe, whose lectures on Aristotle attracted some of the best men to the university, was his tutor; he attended the lectures of Dr. Burton on Divinity, and of Dr. Pusey on Hebrew, and read classics privately with Bishop Wordsworth. He read steadily but not laboriously. Nothing was ever allowed to interfere with his morning's work. He read for four hours, and then took a walk. Though not averse to company and suppers, yet he always read for two or three hours before bedtime.

Among the undergraduates at Oxford then, who became conspicuous, were Henry Edward Manning, afterwards Cardinal Archbishop; Archibald Campbell Tait, Archbishop of Canterbury; Sidney Herbert, Robert Lowe, Lord Sherbrooke, and Lord Selborne. "The man who took me most," says a visitor to Oxford in 1829, "was the youngest Gladstone of Liverpool—I am sure a very superior person."

Gladstone's chosen friends were all steady and industrious men, and many of them were more distinctively religious than is generally found in the life of undergraduates. And his choice of associates in this respect was the subject of criticism on the part of a more secularly minded student who wrote, "Gladstone has mixed himself up with the St. Mary Hall and Oriel set, who are really, for the most part, only fit to live with maiden aunts and keep tame rabbits." And the question, Which was right—Gladstone or the student? may be answered by another, Which one became Prime Minister of England?