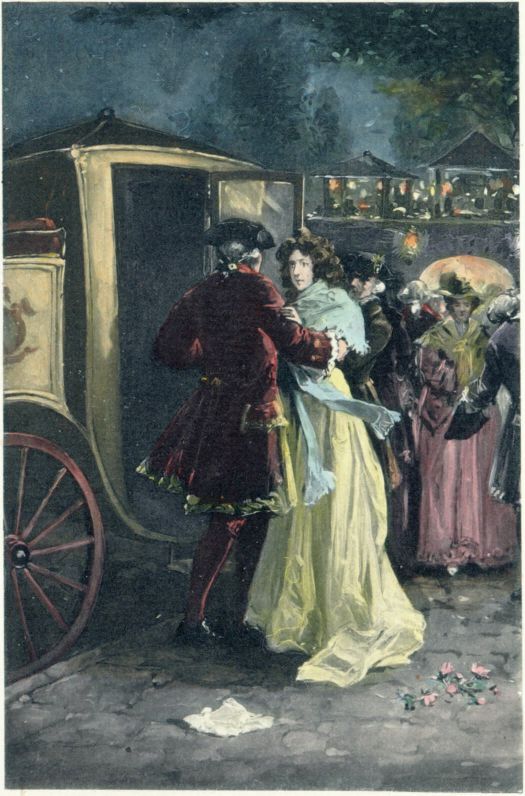

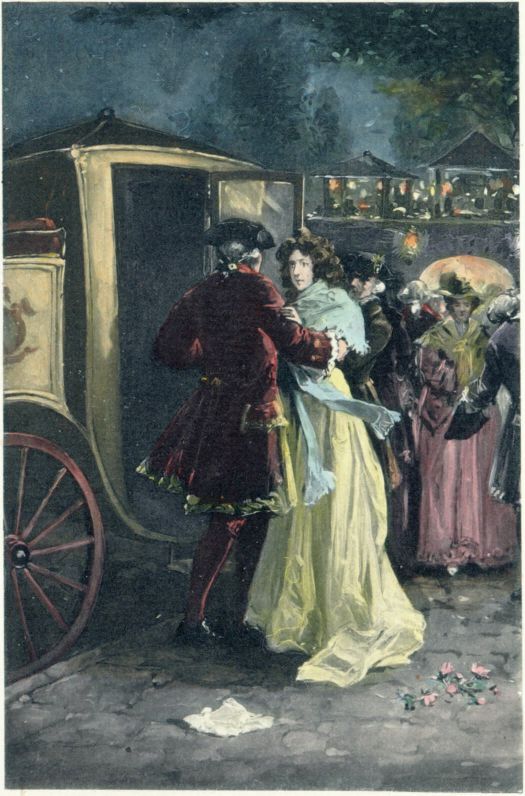

The Attempted Abduction, Original painting by B. Wesley Rand

Title: Mrs. Mary Robinson, Written by Herself,

Author: Mary Robinson

Mrs. A. T. Thomson

Philip Wharton

Release date: February 1, 2006 [eBook #9822]

Most recently updated: December 26, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stan Goodman and PG Distributed Proofreaders

Written by Herself

With the Lives of the Duchesses of Gordon and Devonshire by Grace and Philip Wharton

London, EDITION DE LUXE

INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL EDITION

GEORGIANA, DUCHESS OF DEVONSHIRE

The following brief memoirs of a beautiful, engaging, and, in many respects, highly gifted woman require little in the way of introduction. While we may trace same little negative disingenuousness in the writer, in regard to a due admission of her own failings, sufficient of uncoloured matter of fact remains to show the exposed situation of an unprotected beauty—or, what is worse, of a female of great personal and natural attraction, exposed to the gaze of libertine rank and fashion, under the mere nominal guardianship of a neglectful and profligate husband. Autobiography of this class is sometimes dangerous; not so that of Mrs. Robinson, who conceals not the thorns inherent in the paths along which vice externally scatters roses; For the rest, the arrangement of princely establishments in the way of amour is pleasantly portrayed in this brief volume, which in many respects is not without its moral. One at least is sufficiently obvious, and it will be found in the cold-hearted neglect which a woman of the most fascinating mental and personal attractions may encounter from those whose homage is merely sensual, and whose admiration is but a snare.

The author of these memoirs, Mary Robinson, was one of the most prominent and eminently beautiful women of her day. From the description she furnishes of her personal appearance, we gather that her complexion was dark, her eyes large, her features expressive of melancholy; and this verbal sketch corresponds with her portrait, which presents a face at once grave, refined, and charming. Her beauty, indeed, was such as to attract, amongst others, the attentions of Lords Lyttelton and Northington, Fighting Fitzgerald, Captain Ayscough, and finally the Prince of Wales; whilst her talents and conversation secured her the friendship and interest of David Garrick, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Charles James Fox, Joshua Reynolds, Arthur Murphy, the dramatist, and various other men of distinguished talent.

Though her memoirs are briefly sketched, they are sufficiently vivid to present us with various pictures of the social life of the period of which she was the centre. Now we find her at the Pantheon, with its coloured lamps and brilliant music, moving amidst a fashionable crowd, where large hoops and high feathers abounded, she herself dressed in a habit of pale pink satin trimmed with sable, attracting the attention of men of fashion. Again she is surrounded by friends at Vauxhall Gardens, and barely escapes from a cunning plot to abduct her,—a plot in which loaded pistols and a waiting coach prominently figure; whilst on another occasion she is at Ranelagh, where, in the course of the evening, half a dozen gallants "evinced their attentions;" and ultimately she makes her first appearance as an actress on the stage of Drury Lane, before a brilliant house, David Garrick, now retired, watching her from the orchestra, whilst she played Juliet in pink satin richly spangled with silver, her head ornamented with white feathers.

The fact of her becoming an actress brought about the turning-point in her life; it being whilst she played Perdita in "The Winter's Tale" before royalty that she attracted the Prince of Wales, afterward George IV., who was then in his eighteenth year. The incidents which follow are so briefly treated in the memoirs that explanations are necessary to those who would follow the story of her life.

The performance of the play in which the prince saw her, probably for the first time, took place on the 3d of December, 1779. It was not until some months later, during which the prince and Perdita corresponded, that she consented to meet him at Kew, where his education was being continued and strict guard kept upon his conduct. During 1780 he urged his father to give him a commission in the army, but, dreading the liberty which would result from such a step, the king refused the request. It was, however, considered advisable to provide the prince with a small separate establishment in a wing of Buckingham House; this arrangement taking place On the 1st of January, 1781.

Being now his own master, the prince became a man about town, attended routs, masquerades, horse-races, identified himself with politicians detested by the king, set up an establishment for Mrs. Robinson, gambled, drank, and in a single year spent ten thousand pounds on clothes. He now openly appeared in the company of Perdita at places of public resort and amusement; she, magnificently dressed, driving a splendid equipage which had cost him nine hundred guineas, and surrounded by his friends. We read that: "To-day she was a paysanne, with her straw hat tied at the back of her head. Yesterday she perhaps had been the dressed belle of Hyde Park, trimmed, powdered, patched, painted to the utmost power of rouge and white lead; to-morrow she would be the cravated Amazon of the riding-house; but, be she what she might, the hats of the fashionable promenaders swept the ground as she passed."

This life lasted about two years, when, just as the prince, on his coming of age, was about to take possession of Carlton House, to receive £30,000 from the nation toward paying his debts, and an annuity of £63,000, he absented himself from Perdita, leaving her in ignorance of the cause of his change, which was none other than an interest in Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott.

In the early fervour of his fancy, he had assured Mrs. Robinson his love would remain unchangeable till death, and that he would prove unalterable to his Perdita through life. Moreover, his generosity being heated by passion, he gave her a bond promising to pay her £20,000 on his coming of age.

On the prince separating from her, Perdita found herself some £7,000 in debt to tradespeople, who became clamorous for their money, whereon she wrote to her royal lover, who paid her no heed; but presently she was visited by his friend, Charles James Fox, when she agreed to give up her bond in consideration of receiving an annuity of £500 a year.

She would now gladly have gone back to the stage, but that she feared the hostility of public opinion. Shortly after, she went to Paris, and on her return to England devoted herself to literature. It was about this time she entered into relations with Colonel—afterward Sir Banastre—Tarleton, who was born in the same year as herself, and had served in the American army from 1776 until the surrender of Yorktown, on which he returned to England. For many years he sat in Parliament as the representative of Liverpool, his native town; and in 1817 he gained the grade of lieutenant-general, and was created a baronet. His friendship with Mrs. Robinson lasted some sixteen years.

It was whilst undertaking a journey on his behalf, at a time when he was in pecuniary difficulties, that she contracted the illness that resulted in her losing the active use of her lower limbs. This did not prevent her from working, and she poured out novels, poems, essays on the condition of women, and plays. A communication written by her to John Taylor, the proprietor of the Sun newspaper and author of various epilogues, prologues, songs, etc., gives a view of her life. This letter, now published for the first time, is contained in the famous Morrison collection of autograph letters, and is dated the 5th of October, 1794.

"I was really happy to receive your letter. Your silence gave me no small degree of uneasiness, and I began to think some demon had broken the links of that chain which I trust has united us in friendship for ever. Life is such a scene of trouble and disappointment that the sensible mind can ill endure the loss of any consolation that renders it supportable. How, then, can it be possible that we should resign, without a severe pang, the first of all human blessings, the friend we love? Never give me reason again, I conjure you, to suppose you have wholly forgot me.

"Now I will impart to you a secret, which must not be revealed. I think that before the 10th of December next I shall quit England for ever. My dear and valuable brother, who is now in Lancashire, wishes to persuade me, and the unkindness of the world tends not a little to forward his hopes. I have no relations in England except my darling girl, and, I fear, few friends. Yet, my dear Juan, I shall feel a very severe struggle in quitting those paths of fancy I have been childish enough to admire,—false prospects. They have led me into the vain expectation that fame would attend my labours, and my country be my pride. How have I been treated? I need only refer you to the critiques of last month, and you will acquit me of unreasonable instability. When I leave England,—adieu to the muse for ever,—I will never publish another line while I exist, and even those manuscripts now finished I will destroy.

"Perhaps this will be no loss to the world, yet I may regret the many fruitless hours I have employed to furnish occasions for malevolence and persecution.

"In every walk of life I have been equally unfortunate, but here shall end my complaints.

"I shall return to St. James's Place for a few days this month to meet my brother, who then goes to York for a very short time, and after his return (the end of November), I depart. This must be secret, for to my other misfortunes pecuniary derangement is not the least. Let common sense judge how I can subsist upon £500 a year, when my carriage (a necessary expense) alone costs me £200. My mental labours have failed through the dishonest conduct of my publishers. My works have sold handsomely, but the profits have been theirs.

"Have I not reason to be disgusted when I see him to whom I ought to look for better fortune lavishing favours on unworthy objects, gratifying the avarice of ignorance and dulness, while I, who sacrificed reputation, an advantageous profession, friends, patronage, the brilliant hours of youth, and the conscious delight of correct conduct, am condemned to the scanty pittance bestowed on every indifferent page who holds up his ermined train of ceremony?

"You will say, 'Why trouble me with all this?' I answer, 'Because when I am at peace, you may be in possession of my real sentiments and defend my cause when I shall not have the power of doing it.'

"My comedy has been long in the hands of a manager, but whether it will ever be brought forward time must decide. You know, my dear friend, what sort of authors have lately been patronised by managers; their pieces ushered to public view, with all the advantages of splendour; yet I am obliged to wait two long years without a single hope that a trial would be granted. Oh, I am tired of the world and all its mortifications. I promise you this shall close my chapters of complaints. Keep them, and remember how ill I have been treated."

Eight days later she wrote to the same friend:

"In wretched spirits I wrote you last week a most melancholy letter. Your kind answer consoled me. The balsam of pure and disinterested friendship never fails to cure the mind's sickness, particularly when it proceeds from disgust at the ingratitude of the world."

The play to which she referred was probably that mentioned in the sequel to her memoirs, which was unhappily a failure. It is notable that the principal character in the farce was played by Mrs. Jordan, who was later to become the victim of a royal prince, who left her to die in poverty and exile.

The letter of another great actress, Sarah Siddons, written to John Taylor, shows kindness and compassion toward Perdita.

"I am very much obliged to Mrs. Robinson," says Mrs. Siddons, "for her polite attention in sending me her poems. Pray tell her so with my compliments. I hope the poor, charming woman has quite recovered from her fall. If she is half as amiable as her writings, I shall long for the possibility of being acquainted with her. I say the possibility, because one's whole life is one continual sacrifice of inclinations, which to indulge, however laudable or innocent, would draw down the malice and reproach of those prudent people who never do ill, 'but feed and sleep and do observances to the stale ritual of quaint ceremony.' The charming and beautiful Mrs. Robinson: I pity her from the bottom of my soul."

Almost to the last she retained her beauty, and delighted in receiving her friends and learning from them news of the world in which she could no longer move. Reclining on her sofa in the little drawing-room of her house in St. James's Place, she was the centre of a circle which comprised many of those who had surrounded her in the days of her brilliancy, amongst them being the Prince of Wales and his brother the Duke of York.

Possibly, for the former, memory lent her a charm which years had not utterly failed to dispel.

J. Fitzgerald Molloy.

William Brereton in the Character of Douglas

The First Meeting of Mrs. Robinson and the Prince of Wales

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire

At the period when the ancient city of Bristol was besieged by Fairfax's army, the troops being stationed on a rising ground in the vicinity of the suburbs, a great part of the venerable minster was destroyed by the cannonading before Prince Rupert surrendered to the enemy; and the beautiful Gothic structure, which at this moment fills the contemplative mind with melancholy awe, was reduced to but little more than one-half of the original fabric. Adjoining to the consecrated hill, whose antique tower resists the ravages of time, once stood a monastery of monks of the order of St. Augustine. This building formed a part of the spacious boundaries which fell before the attacks of the enemy, and became a part of the ruin, which never was repaired or re-raised to its former Gothic splendours.

On this spot was built a private house, partly of simple, and partly of modern architecture. The front faced a small garden, the gates of which opened to the Minster Green (now called the College Green); the west side was bounded by the cathedral, and the back was supported by the ancient cloisters of St. Augustine's monastery. A spot more calculated to inspire the soul with mournful meditation can scarcely be found amidst the monuments of antiquity.

In this venerable mansion there was one chamber whose dismal and singular constructure left no doubt of its having been a part of the original monastery. It was supported by the mouldering arches of the cloisters, dark, Gothic, and opening on the minster sanctuary, not only by casement windows that shed a dim midday gloom, but by a narrow winding staircase, at the foot of which an iron-spiked door led to the long gloomy path of cloistered solitude. This place remained in the situation in which I describe it in the year 1776, and probably may, in a more ruined state, continue so to this hour.

In this awe-inspiring habitation, which I shall henceforth denominate the Minster House, during a tempestuous night, on the 27th of November, 1758, I first opened my eyes to this world of duplicity and sorrow. I have often heard my mother say that a mare stormy hour she never remembered. The wind whistled round the dark pinnacles of the minster tower, and the rain beat in torrents against the casements of her chamber. Through life the tempest has followed my footsteps, and I have in vain looked for a short interval of repose from the perseverance of sorrow.

In the male line I am descended from a respectable family in Ireland, the original name of which was MacDermott. From an Irish estate, my great-grandfather changed it to that of Darby. My father, who was born in America, was a man of strong mind, high spirit, and great personal intrepidity. Many anecdotes, well authenticated, and which, being irrefragable, are recorded as just tributes to his fame and memory, shall, in the course of these memoirs, confirm this assertion.

My mother was the grandchild of Catherine Seys, one of the daughters and co-heiresses of Richard Sey's, Esq., of Boverton Castle, in Glamorganshire. The sister of my great-grandmother, named Anne, married Peter, Lord King, who was nephew, in the female line, to the learned and truly illustrious John Locke—a name that has acquired celebrity which admits of no augmented panegyric.

Catherine Seys was a woman of great piety and virtue—a character which she transferred to her daughter, and which has also been acknowledged as justly due to her sister, Lady King.[1] She quitted this life when my grandmother was yet a child, leaving an only daughter, whose father also died while she was in her infancy. By this privation of paternal care my grandmother became the élève of her mother's father, and passed the early part of her life at the family castle in Glamorganshire. From this period till the marriage of my mother, I can give but a brief account. All I know is, that my grandmother, though wedded unhappily, to the latest period of her existence was a woman of amiable and simple manners, unaffected piety, and exemplary virtue. I remember her well; and I speak not only from report, but from my own knowledge. She died in the year 1780.

My grandmother Elizabeth, whom I may, without the vanity of consanguinity, term a truly good woman, in the early part of her life devoted much of her time to botanic study. She frequently passed many successive months with Lady Tynt, of Haswell, in Somersetshire, who was her godmother, and who was the Lady Bountiful of the surrounding villages. Animated by so distinguished an example, the young Elizabeth, who was remarkably handsome,[2] took particular delight in visiting the old, the indigent, and the infirm, resident within many miles of Haswell, and in preparing such medicines as were useful to the maladies of the peasantry. She was the village doctress, and, with her worthy godmother, seldom passed a day without exemplifying the benevolence of her nature.

My mother was born at Bridgwater, in Somersetshire, in the house near the bridge, which is now occupied by Jonathan Chub, Esq., a relation of my beloved and lamented parent, and a gentleman who, to acknowledged worth and a powerful understanding, adds a superior claim to attention by all the acquirements of a scholar and a philosopher.

My mother, who never was what may be called a handsome woman, had nevertheless, in her youth, a peculiarly neat figure, and a vivacity of manner which obtained her many suitors. Among others, a young gentleman of good family, of the name of Storr, paid his addresses. My father was the object of my mother's choice, though her relations rather wished her to form a matrimonial alliance with Mr. S. The conflict between affection and duty was at length decided in favour of my father, and the rejected lover set out in despair for Bristol. From thence, in a few days after his arrival, he took his passage in a merchantman for a distant part of the globe; and from that hour no intelligence ever arrived of his fate or fortune. I have often heard my mother speak of this gentleman with regret and sorrow.

My mother was between twenty and thirty years of age at the period of her marriage. The ceremony was performed at Dunyatt, in the county of Somerset. My father was shortly after settled at Bristol, and during the second year after their union a son was born to bless and honour them.[3]

Three years after my mother gave birth to a daughter, named Elizabeth, who died of the smallpox at the age of two years and ten months. In the second winter following this event, which deeply afflicted the most affectionate of parents, I was born. She had afterward two sons: William, who died at the age of six years; and George, who is now a respectable merchant at Leghorn, in Tuscany.

All the offspring of my parents were, in their infancy, uncommonly handsome, excepting myself. The boys were fair and lusty, with auburn hair, light blue eyes, and countenances peculiarly animated and lovely, I was swarthy; my eyes were singularly large in proportion to my face, which was small and round, exhibiting features peculiarly marked with the most pensive and melancholy cast.

The great difference betwixt my brothers and myself, in point of personal beauty, tended much to endear me to my parents, particularly to my father, whom I strongly resembled. The early propensities of my life were tinctured with romantic and singular characteristics; some of which I shall here mention, as proofs that the mind is never to be diverted from its original bent, and that every event of my life has more or less been marked by the progressive evils of a too acute sensibility.

The nursery in which I passed my hours of infancy was so near the great aisle of the minster that the organ, which reechoed its deep tones, accompanied by the chanting of the choristers, was distinctly heard both at morning and evening service. I remember with what pleasure I used to listen, and how much I was delighted whenever I was permitted to sit on the winding steps which led from the aisle to the cloisters. I can at this moment recall to memory the sensations I then experienced—the tones that seemed to thrill through my heart, the longing which I felt to unite my feeble voice to the full anthem, and the awful though sublime impression which the church service never failed to make upon my feelings. While my brothers were playing on the green before the minster, the servant who attended us has often, by my earnest entreaties, suffered me to remain beneath the great eagle which stood in the centre of the aisle, to support the book from which the clergyman read the lessons of the day; and nothing could keep me away, even in the coldest seasons, but the stern looks of an old man, whom I named Black John from the colour of his beard and complexion, and whose occupations within the sacred precincts were those of a bell-ringer and sexton.

As soon as I had learned to read, my great delight was that of learning epitaphs and monumental inscriptions. A story of melancholy import never failed to excite my attention; and before I was seven years old I could correctly repeat Pope's "Lines to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady;" Mason's "Elegy on the Death of the Beautiful Countess of Coventry," and many smaller poems on similar subjects. I had then been attended two years by various masters. Mr. Edmund Broadrip taught me music, my father having presented me with one of Kirkman's finest harpsichords, as an incitement to emulation. Even there my natural bent of mind evinced itself. The only melody which pleased me was that of the mournful and touching kind. Two of my earliest favourites were the celebrated ballad by Gay, beginning, "'Twas when the sea was roaring," and the simple pathetic stanzas of "The Heavy Hours," by the poet Lord Lyttelton. These, though nature had given me but little voice, I could at seven years of age sing so pathetically that my mother, to the latest hour of her life,' never could bear to hear the latter of them repeated. They reminded her of sorrows in which I have since painfully learned to sympathise.

The early hours of boarding-school study I passed under the tuition of the Misses More, sisters to the lady of that name whose talents have been so often celebrated.[4] The education of their young pupils was undertaken by the five sisters. "In my mind's eye," I see them now before me; while every circumstance of those early days is minutely and indelibly impressed upon my memory.

I remember the first time I ever was present at a dramatic representation: it was the benefit of that great actor[5] who was proceeding rapidly toward the highest paths of fame, when death, dropped the oblivious curtain, and closed the scene for ever. The part which he performed was King Lear; his wife, afterward Mrs. Fisher, played Cordelia, but not with sufficient éclat to render the profession an object for her future exertions. The whole school attended, Mr. Powel's two daughters being then pupils of the Misses More. Mrs. John Kemble, then Miss P. Hopkins, was also one of my schoolfellows, as was the daughter of Mrs. Palmer, formerly Miss Pritchard, and afterward Mrs. Lloyd. I mention these circumstances merely to prove that memory does not deceive me.

In my early days my father was prosperous, and my mother was the happiest of wives. She adored her children; she devoted her thoughts and divided her affections between them and the tenderest of husbands. Their spirits now, I trust, are in happier regions, blest, and reunited for ever.

If there could be found a fault in the conduct of my mother toward her children, it was that of a too unlimited indulgence, a too tender care, which but little served to arm their breast against the perpetual arrows of mortal vicissitude. My father's commercial concerns were crowned with prosperity. His house was opened by hospitality, and his generosity was only equalled by the liberality of fortune: every day augmented his successes; every hour seemed to increase his domestic felicity, till I attained my ninth year, when a change took place as sudden as it was unfortunate, at a moment when every luxury, every happiness, not only brightened the present, but gave promise of future felicity. A scheme was suggested to my father, as wild and romantic as it was perilous to hazard, which was no less than that of establishing a whale fishery on the coast of Labrador, and of civilising the Esquimaux Indians, in order to employ them in the extensive undertaking. During two years this eccentric plan occupied his thoughts by day, his dreams by night: all the smiles of prosperity could not tranquillise the restless spirit, and while he anticipated an acquirement of fame, he little considered the perils that would attend his fortune.

My mother (who, content with affluence and happy in beholding the prosperity of her children, trembled at the fear of endangering either), in vain endeavoured to dissuade my father from putting his favourite scheme in practice. In the early part of his youth he had been accustomed to a sea life, and, being born an American, his restless spirit was ever busied in plans for the increase of wealth and honour to his native country, whose fame and interest were then united to those of Britain. After many dreams of success and many conflicts betwixt prudence and ambition, he resolved on putting his scheme in practice; the potent witchery possessed his brain, and all the persuasive powers of reason shrunk before its magic.

Full of the important business, my misguided parent repaired to the metropolis, and on his arrival laid the plan before the late Earl of Hilsborough, Sir Hugh Palliser, the late Earl of Bristol, Lord Chatham (father to the present Mr. William Pitt), the chancellor Lord Northington, who was my godfather, and several other equally distinguished personages; who all not only approved the plan, but commended the laudable and public spirit which induced my father to suggest it. The prospect appeared full of promise, and the Labrador whale fishery was expected to be equally productive with that of Greenland. My parent's commercial connections were of the highest respectability, while his own name for worth and integrity gave a powerful sanction to the eccentric undertaking.

In order to facilitate this plan, my father deemed it absolutely necessary to reside at least two years in America. My mother, who felt an invincible antipathy to the sea, heard his determination with grief and horror. All the persuasive powers of affection failed to detain him; all the pleadings of reason, prudence, a fond wife, and an infant family, proved ineffectual. My father was determined on departing, and my mother's unconquerable timidity prevented her being the companion of his voyage. From this epocha I date the sorrows of my family.

He sailed for America. His eldest son, John, was previously placed in a mercantile house at Leghorn. My younger brothers and myself remained with my mother at Bristol. Two years was the limited time of his absence, and, on his departure, the sorrow of my parents was reciprocal. My mother's heart was almost bursting with anguish; but even death would to her have been preferable to the horrors of crossing a tempestuous ocean and quitting her children, my father having resolved on leaving my brothers and myself in England for education.

Still the comforts, and even the luxuries of life distinguished our habitation. The tenderness of my mother's affection made her lavish of every elegance; and the darlings of her bosom were dressed, waited on, watched, and indulged with a degree of fondness bordering on folly. My clothes were sent for from London; my fancy was indulged to the extent of its caprices; I was flattered and praised into a belief that I was a being of superior order. To sing, to play a lesson on the harpsichord, to recite an elegy, and to make doggerel verses, made the extent of my occupations, while my person improved, and my mother's indulgence was almost unexampled.

My father, several years before his departure for America, had removed from the Minster House, and resided in one larger and more convenient for his increased family. This habitation was elegantly arranged; all the luxuries of plate, silk furniture, foreign wines, etc., evinced his knowledge of what was worth enjoying, and displayed that warm hospitality which is often the characteristic of a British merchant. This disposition for the good things of the world influenced even the disposal of his children's comforts. The bed in which I slept was of the richest crimson damask; the dresses which we wore were of the finest cambric; during the summer months we were sent to Clifton Hill for the advantages of a purer air; and I never was permitted to board at school, or to pass a night of separation from the fondest of mothers.

Many months elapsed, and my mother continued to receive the kindest letters from that husband whose rash scheme filled her bosom with regret and apprehension. At length the intervals became more frequent and protracted. The professions of regard, no longer flowing from the heart, assumed a laboured style, and seemed rather the efforts of honourable feeling than the involuntary language of confidential affection. My mother felt the change, and her affliction was infinite.

At length a total silence of several months awoke her mind to the sorrows of neglect, the torture of compunction; she now lamented the timidity which had divided her from a husband's bosom, the natural fondness which had bound her to her children; for while her heart bled with sorrow and palpitated with apprehension, the dreadful secret was unfolded, and the cause of my father's silence was discovered to be a new attachment—a mistress, whose resisting nerves could brave the stormy ocean, and who had consented to remain two years with him in the frozen wilds of America.

This intelligence nearly annihilated my mother, whose mind, though not strongly organised, was tenderly susceptible. She resigned herself to grief. I was then at an age to feel and to participate in her sorrows. I often wept to see her weep; I tried all my little skill to soothe her, but in vain; the first shock was followed by calamities of a different nature. The scheme in which my father had embarked his fortune failed, the Indians rose in a body, burnt his settlement, murdered many of his people, and turned the produce of their toil adrift on the wide and merciless ocean. The noble patrons of his plan deceived him in their assurances of marine protection, and the island of promise presented a scene of barbarous desolation. This misfortune was rapidly followed by other commercial losses; and to complete the vexations which pressed heavily on my mother, her rash husband gave a bill of sale of his whole property, by the authority of which we were obliged to quit our home, and to endure those accumulated vicissitudes for which there appeared no remedy.

It was at this period of trial that my mother was enabled to prove, by that unerring touchstone, adversity, who were her real and disinterested friends. Many, with affected commiseration, dropped a tear—or rather seemed to drop one—on the disappointments of our family; while others, with a malignant triumph, condemned the expensive style in which my father had reared his children, the studied elegance which had characterised my mother's dress and habitation, and the hospitality, which was now marked by the ungrateful epithet of prodigal luxuriance, but which had evinced the open liberality of my father's heart.

At this period my brother William died. He was only six years of age, but a promising and most lovely infant. His sudden death, in consequence of the measles, nearly deprived my mother of her senses. She was deeply affected; but she found, after a period of time, that consolation which, springing from the bosom of an amiable friend, doubly solaced her afflictions. This female was one of the most estimable of her sex; she had been the widow of Sir Charles Erskine, and was then the wife of a respectable medical man who resided at Bristol.

In the society of Lady Erskine my mother gradually recovered her serenity of mind, or rather found it soften into a religious resignation. But the event of her domestic loss by death was less painful than that which she felt in the alienation of my father's affections. She frequently heard that he resided in America with his mistress, till, at the expiration of another year, she received a summons to meet him in London.

Language would but feebly describe the varying emotions which struggled in her bosom. At this interesting era she was preparing to encounter the freezing scorn, or the contrite glances, of either an estranged or a repentant husband; in either case her situation was replete with anticipated chagrin, for she loved him too tenderly not to participate even in the anguish of his compunction. His letter, which was coldly civil, requested particularly that the children might be the companions of her journey. We departed for the metropolis.

I was not then quite ten years old, though so tall and formed in my person that I might have passed for twelve or thirteen. My brother George was a few years younger. On our arrival in London we repaired to my father's lodgings in Spring Gardens. He received us, after three years' absence, with a mixture of pain and pleasure; he embraced us with tears, and his voice was scarcely articulate. My mother's agitation was indescribable; she received a cold embrace at their meeting—it was the last she ever received from her alienated husband.

As soon as the first conflicts seemed to subside, my father informed my mother that he was determined to place my brother and myself at a school in the vicinity of London; that he purposed very shortly returning to America, and that he would readily pay for my mother's board in any private and respectable family. This information seemed like a death-blow to their domestic hopes. A freezing, formal, premeditated separation from a wife who was guiltless of any crime, who was as innocent as an angel, seemed the very extent of decided misery. It was in vain that my mother essayed to change his resolution, and influence his heart in pronouncing a milder judgment: my father was held by a fatal fascination; he was the slave of a young and artful woman, who had availed herself of his American solitude, to undermine his affections for his wife and the felicity of his family.

This deviation from domestic faith was the only dark shade that marked my father's character. He possessed a soul brave, liberal, enlightened, and ingenuous. He felt the impropriety of his conduct. Yet, though his mind was strongly organised, though his understanding was capacious, and his sense of honour delicate even to fastidiousness, he was still the dupe of his passions, the victim of unfortunate attachment.

Within a few days of our arrival in London we were placed for education in a school at Chelsea. The mistress of this seminary was perhaps one of the most extraordinary women that ever graced, or disgraced, society; her name was Meribah Lorrington. She was the most extensively accomplished female that I ever remember to have met with; her mental powers were no less capable of cultivation than superiorly cultivated. Her father, whose name was Hull, had from her infancy been the master of an academy at Earl's Court, near Fulham; and early after his marriage losing his wife, he resolved on giving his daughter a masculine education. Meribah was early instructed in all the modern accomplishments, as well as in classical knowledge. She was mistress of the Latin, French, and Italian languages; she was said to be a perfect arithmetician and astronomer, and possessed the art of painting on silk to a degree of exquisite perfection. But, alas! with all these advantages, she was addicted to one vice, which at times so completely absorbed her faculties as to deprive her of every power, either mental or corporeal. Thus, daily and hourly, her superior acquirements, her enlightened understanding, yielded to the intemperance of her ruling infatuation, and every power of reflection seemed lost in the unfeminine propensity.

All that I ever learned I acquired from this extraordinary woman. In those hours when her senses were not intoxicated, she would delight in the task of instructing me. She had only five or six pupils, and it was my lot to be her particular favourite. She always, out of school, called me her little friend, and made no scruple of conversing with me (sometimes half the night, for I slept in her chamber), on domestic and confidential affairs. I felt for her a very sincere affection, and I listened with peculiar attention to all the lessons she inculcated. Once I recollect her mentioning the particular failing which disgraced so intelligent a being. She pleaded, in excuse of it, the immitigable regret of a widowed heart, and with compunction declared that she flew to intoxication as the only refuge from the pang of prevailing sorrow. I continued more than twelve months under the care of Mrs. Lorrington, during which period my mother boarded in a clergyman's family at Chelsea. I applied rigidly to study, and acquired a taste for books, which has never, from that time, deserted me. Mrs. Lorrington frequently read to me after school hours, and I to her. I sometimes indulged my fancy in writing verses, or composing rebuses, and my governess never failed to applaud the juvenile compositions I presented to her. Some of them, which I preserved and printed in a small volume shortly after my marriage, were written when I was between twelve and thirteen years of age; but as love was the theme of my poetical fantasies, I never showed them to my mother till I was about to publish them.

It was my custom, every Sunday evening, to drink tea with my mother. During one of those visits a captain in the British navy, a friend of my father's, became so partial to my person and manners that a proposal of marriage shortly after followed. My mother was astonished when she heard it, and, as soon as she recovered from her surprise, inquired of my suitor how old he thought me; his reply was, "About sixteen." My mother smiled, and informed him that I was then not quite thirteen. He appeared to be skeptical on the subject, till he was again assured of the fact, when he took his leave with evident chagrin, but not without expressing his hopes that, on his return to England,—for he was going on a two years' expedition,—I should be still disengaged. His ship foundered at sea a few months after, and this amiable gallant officer perished.

I had remained a year and two months with Mrs. Lorrington, when pecuniary derangements obliged her to give up her school. Her father's manners were singularly disgusting, as was his appearance; for he wore a silvery beard which reached to his breast; and a kind of Persian robe which gave him the external appearance of a necromancer. He was of the Anabaptist persuasion, and so stern in his conversation that the young pupils were exposed to perpetual terror. Added to these circumstances, the failing of his daughter became so evident, that even during school hours she was frequently in a state of confirmed intoxication. These events conspired to break up the establishment, and I was shortly after removed to a boarding-school at Battersea.

The mistress of this seminary, Mrs. Leigh, was a lively, sensible, and accomplished woman; her daughter was only a few years older than myself, and extremely amiable as well as lovely. Here I might have been happy, but my father's remissness in sending pecuniary supplies, and my mother's dread of pecuniary inconvenience, induced her to remove me; my brother, nevertheless, still remained under the care of the Reverend Mr. Gore, at Chelsea.

Several months elapsed, and no remittance arrived from my father. I was now near fourteen years old, and my mother began to foresee the vicissitudes to which my youth might be exposed, unprotected, tenderly educated, and without the advantages of fortune. My father's impracticable scheme had impoverished his fortune, and deprived his children of that affluence which, in their in fancy, they had been taught to hope for. I cannot speak of my own person, but my partial friends were too apt to flatter me. I was naturally of a pensive and melancholy character; my reflections on the changes of fortune frequently gave me an air of dejection which perhaps etched an interest beyond what might have been awakened by the vivacity or bloom of juvenility.

I adored my mother. She was the mildest, the most unoffending of existing mortals; her temper was cheerful, as her heart was innocent; she beheld her children as it seemed fatherless, and she resolved, by honourable means, to support them. For this purpose a convenient house was hired at Little Chelsea, and furnished, for a ladies' boarding-school. Assistants of every kind were engaged, and I was deemed worthy of an occupation that flattered my self-love and impressed my mind with a sort of domestic consequence. The English language was my department in the seminary, and I was permitted to select passages both in prose and verse for the studies of my infant pupils. It was also my occupation to superintend their wardrobes, to see them dressed and undressed by the servants or half-boarders, and to read sacred and moral lessons on saints' days and Sunday evenings.

Shortly after my mother had established herself at Chelsea, on a summer's evening, as I was sitting at the window, I heard a deep sigh, or rather a groan of anguish, which suddenly attracted my attention. The night was approaching rapidly, and I looked toward the gate before the house, where I observed a woman evidently labouring under excessive affliction; I instantly descended and approached her. She, bursting into tears, asked whether I did not know her. Her dress was torn and filthy; she was almost naked; and an old bonnet, which nearly hid her face, so completely disfigured her features that I had not the smallest idea of the person who was then almost sinking before me. I gave her a small sum of money, and inquired the cause of her apparent agony. She took my hand and pressed it to her lips. "Sweet girl," said she, "you are still the angel I ever knew you!" I was astonished. She raised her bonnet—her fine dark eyes met mine. It was Mrs. Lorrington. I led her into the house; my mother was not at home. I took her to my chamber, and, with the assistance of a lady who was our French teacher, I clothed and comforted her. She refused to say how she came to be in so deplorable a situation, and took her leave. It was in vain that I entreated, that I conjured her to let me know where I might send to her. She refused to give me her address, but promised that in a few days she would call on me again. It is impossible to describe the wretched appearance of this accomplished woman! The failing to which she had now yielded, as to a monster that would destroy her, was evident even at the moment when she was speaking to me. I saw no more of her; but to my infinite regret, I was informed some years after that she had died, the martyr of a premature decay, brought on by the indulgence of her propensity to intoxication, in the workhouse of Chelsea!

The number of my mother's pupils in a few months amounted to ten or twelve, and just at a period when an honourable independence promised to cheer the days of an unexampled parent, my father unexpectedly returned from America. The pride of his soul was deeply wounded by the step which my mother had taken; he was offended even beyond the bounds of reason: he considered his name as disgraced, his conjugal reputation tarnished, by the public mode which his wife had adopted of revealing to the world her unprotected situation. A prouder heart never palpitated in the breast of man than that of my father: tenacious of fame, ardent in the pursuit of visionary schemes, he could not endure the exposure of his altered fortune; while Hope still beguiled him with her flattering promise that time would favour his projects, and fortune, at some future period, reward him with success.

At the expiration of eight months my mother, by my father's positive command, broke up her establishment and returned to London. She engaged lodgings in the neighbourhood of Marylebone. My father then resided in Green Street, Grosvenor Square. His provision for his family was scanty, his visits few. He had a new scheme on foot respecting the Labrador coast, the particulars of which I do not remember, and all his zeal, united with all his interest, was employed in promoting its accomplishment. My mother, knowing that my father publicly resided with his mistress, did not even hope for his returning affection. She devoted herself to her children, and endured her sorrows with the patience of conscious rectitude.

At this period my father frequently called upon us, and often attended me while we walked in the fields near Marylebone. His conversation was generally of a domestic nature, and he always lamented that fatal attachment, which was now too strongly cemented by time and obligations ever to be dissolved without an ample provision for Elenor, which was the name of my father's mistress. In one of our morning walks we called upon the Earl of Northington, my father having some commercial business to communicate to his lordship. Lord Northington then resided in Berkeley Square, two doors from Hill Street, in the house which is now occupied by Lord Robert Spencer. We were received with the most marked attention and politeness (I was presented as the goddaughter of the late Chancellor Lord Northington), and my father was requested to dine with his lordship a few days after. From this period I frequently saw Lord Northington, and always experienced from him the most flattering and gratifying civility. I was then a child, not more than fourteen years of age.

The finishing points of my education I received at Oxford House, Marylebone. I was at this period within a few months of fifteen years of age, tall, and nearly such as my partial friends, the few whose affection has followed me from childhood, remember me. My early love for lyric harmony had led me to a fondness for the more sublime scenes of dramatic poetry. I embraced every leisure moment to write verses; I even fancied that I could compose a tragedy, and more than once unsuccessfully attempted the arduous undertaking.

The dancing-master at Oxford House, Mr. Hussey, was then ballet-master at Covent Garden Theatre. Mrs. Hervey, the governess, mentioned me to him as possessing an extraordinary genius for dramatic exhibitions. My figure was commanding for my age, and (my father's pecuniary embarrassments augmenting by the failure of another American project) my mother was consulted as to the propriety of my making the stage my profession. Many cited examples of females who, even in that perilous and arduous situation, preserved an unspotted fame, inclined her to listen to the suggestion, and to allow of my consulting some master of the art as to my capability of becoming an ornament to the theatre.

Previous to this idea my father had again quitted England. He left his wife with assurances of good-will, his children with all the agonies of parental regret. When he took leave of my mother, his emphatic words were these,—I never shall forget them—"Take care that no dishonour falls upon my daughter. If she is not safe at my return, I will annihilate you!" My mother heard the stern injunction, and trembled while he repeated it.

I was, in consequence of my wish to appear on the stage, introduced to Mr. Hull,[6] of Covent Garden Theatre; he then resided in King Street, Soho. He heard me recite some passages of the character of Jane Shore, and seemed delighted with my attempt. I was shortly after presented by a friend of my mother's, to Mr. Garrick;[7] Mr. Murphy,[8] the celebrated dramatic poet, was one of the party, and we passed the evening at the house of the British Roscius in the Adelphi. This was during the last year that he dignified the profession by his public appearance. Mr. Garrick's encomiums were of the most gratifying kind. He determined that he would appear in the same play with me on the first night's trial; but what part to choose for my début was a difficult question. I was too young for anything beyond the girlish character, and the dignity of tragedy afforded but few opportunities for the display of such juvenile talents. After some hesitation my tutor fixed on the part of Cordelia. His own Lear can never be forgotten.

It was not till the period when everything was arranged for my appearance that the last solemn injunction, so emphatically uttered by my father, nearly palsied my mother's resolution. She dreaded the perils, the temptations to which an unprotected girl would be exposed in so public a situation; while my ardent fancy was busied in contemplating a thousand triumphs in which my vanity would be publicly gratified without the smallest sacrifice of my private character.

While this plan was in agitation, I was one evening at Drury Lane Theatre with my mother and a small party of her friends, when an officer entered the box. His eyes were fixed on me, and his persevering attention at length nearly overwhelmed me with confusion. The entertainment being finished, we departed. The stranger followed us. At that period my mother resided in Southampton Buildings, Chancery Lane, for the protection which a venerable and respectable friend offered at a moment when it was so necessary. This friend was the late Samuel Cox, Esq., the intimate friend of Mr. Garrick, and an honour to those laws of which he was a distinguished professor.

It was Mr. Garrick's particular request that I would frequent the theatre as much as possible till the period fixed on for my appearance on the stage. I had now just completed my fifteenth year, and my little heart throbbed with impatience for the hour of trial. My tutor was most sanguine in his expectations of my success, and every rehearsal seemed to strengthen his flattering opinion.

It happened that, several evenings following, the stranger officer, whose name, for motives of delicacy toward his family, I forbear to mention, followed me to and from the theatre. It was in vain that he offered his attentions in the box; my mother's frown and assiduous care repulsed them effectually. But the perseverance of a bad mind in the accomplishment of a bad action is not to be subdued. A letter was written and conveyed to me through the hands of a female servant; I opened it; I read a declaration of the most ardent love. The writer avowed himself the son of Lady——, and offered marriage; he was graceful and handsome. I instantly delivered the letter to my mother, and, shortly after, he was, by an acquaintance, presented with decorous ceremony.

The idea of my appearing on the stage seemed to distract this accomplished suitor. My mother, who but half approved a dramatic life, was more than half inclined to favour the addresses of Captain ——. The injunction of my father every hour became more indelibly impressed on her memory; she knew his stern and invincible sense of honour too well to hazard the thought of awakening it to vengeance.

After a short period, the friend who had presented Captain——, alarmed for my safety, and actuated by a liberal wish to defend me from the artifice of his associate, waited on my mother, and, after some hesitation, informed her that my lover was already married; that he had a young and amiable wife in a sister kingdom, and that he apprehended some diabolical stratagem for the enthralment of my honour. My mother's consternation was infinite. The important secret was communicated to me, and I felt little regret in the loss of a husband when I reflected that a matrimonial alliance would have compelled me to relinquish my theatrical profession.

I had, also, at this period, another professed admirer, a man of splendid fortune, but nearly old enough to be my grandfather. This suit I never would listen to; and the drama, the delightful drama, seemed the very criterion of all human happiness.

I now found myself an object of attention whenever I appeared at the theatre. I had been too often in public not to be observed, and it was buzzed about that I was the juvenile pupil of Garrick,—the promised Cordelia. My person improved daily; yet a sort of dignified air, which from a child I had acquired, effectually shielded me from the attacks of impertinence or curiosity. Garrick was delighted with everything I did. He would sometimes dance a minuet with me, sometimes request me to sing the favourite ballads of the day; but the circumstance which most pleased him was my tone of voice, which he frequently told me closely resembled that of his favourite Cibber.[9]

Never shall I forget the enchanting hours which I passed in Mr. Garrick's society; he appeared to me as one who possessed more power, both to awe and to attract, than any man I ever met with. His smile was fascinating, but he had at times a restless peevishness of tone which excessively affected his hearers; at least it affected me so that I never shall forget it.

Opposite to the house in which I resided lived John Vernon, Esq., an eminent solicitor. I observed a young inmate of his habitation frequently watching me with more than ordinary attention. He was handsome in person, and his countenance was overcast by a sort of languor, the effect of sickness, which rendered it peculiarly interesting. Frequently, when I approached the window of our drawing-room, this young observer would bow or turn away with evident emotion. I related the circumstance to my mother, and from that time the lower shutters of our windows were perpetually closed. The young lawyer often excited my mirth, and my mother's indignation; and the injunction of my father was frequently repeated by her, with the addition of her wish, that I was "once well married."

Every attention which was now paid to me augmented my dear mother's apprehensions. She fancied every man a seducer, and every hour an hour of accumulating peril! I know what she was doomed to feel, for that Being who formed my sensitive and perpetually aching heart knows that I have since felt it.

Among other friends who were in the habit of visiting my mother there was one, a Mr. Wayman, an attorney of whom she entertained the highest opinion. He was distinguished by the patronage of Mr. Cox, and his reputation required no other voucher. One evening a party of six was proposed for the following Sunday; with much persuasion my mother consented to go, and to allow that I should also attend her. Greenwich was the place fixed on for the dinner, and we prepared for the day of recreation. It was then the fashion to wear silks. I remember that I wore a nightgown of pale blue lustring, with a chip hat trimmed with ribands of the same colour. Never was I dressed so perfectly to my own satisfaction; I anticipated a day of admiration. Heaven can bear witness that to me it was a day of fatal victory!

On our stopping at the "Star and Garter," at Greenwich, the person who came to hand me from the carriage was our opposite neighbour in Southampton Buildings. I was confused, but my mother was indignant. Mr. Wayman presented his young friend,—that friend who was ordained to be my husband!

Our party dined, and early in the evening we returned to London. Mr. Robinson remained at Greenwich for the benefit of the air, being recently recovered from a fit of sickness. During the remainder of the evening Mr. Wayman expatiated on the many good qualities of his friend Mr. Robinson: spoke of his future expectations a rich old uncle; of his probable advancement in his profession; and, more than all, of his enthusiastic admiration of me.

A few days after, Mr. Robinson paid my mother a visit. We had now removed to Villars Street, York Buildings. My mother's fondness for books of a moral and religious character was not lost upon my new lover, and elegantly bound editions of Hervey's "Meditations," with some others of a similar description, were presented as small tokens of admiration and respect. My mother was beguiled by these little interesting attentions, and soon began to feel a strong predilection in favour of Mr. Robinson.

Every day some new mark of respect augmented my mother's favourable opinion; till Mr. Robinson became so great a favourite that he seemed to her the most perfect of existing beings. Just at this period my brother George sickened for the smallpox; my mother idolised him; he was dangerously ill. Mr. Robinson was indefatigable in his attentions, and my appearance on the stage was postponed till the period of his perfect recovery. Day and night Mr. Robinson devoted himself to the task of consoling my mother, and of attending to her darling boy; hourly, and indeed momentarily, Mr. Robinson's praises were reiterated with enthusiasm by my mother. He was "the kindest, the best of mortals!" the least addicted to worldly follies, and the man, of all others, whom she should adore as a son-in-law.

My brother recovered at the period when I sickened from the infection of his disease. I felt little terror at the approaches of a dangerous and deforming malady; for, I know not why, but personal beauty has never been to me an object of material solicitude. It was now that Mr. Robinson exerted all his assiduity to win my affections; it was when a destructive disorder menaced my features and the few graces that nature had lent them, that he professed a disinterested fondness; every day he attended with the zeal of a brother, and that zeal made an impression of gratitude upon my heart, which was the source of all my succeeding sorrows.

During my illness Mr. Robinson so powerfully wrought upon the feelings of my mother, that she prevailed on me to promise, in case I should recover, to give him my hand in marriage. The words of my father were frequently repeated, not without some innuendoes that I refused my ready consent to a union with Mr. Robinson from a blind partiality to the libertine Captain——. Repeatedly urged and hourly reminded of my father's vow, I at last consented, and the banns were published while I was yet lying on a bed of sickness. I was then only a few months advanced in my sixteenth year.

My mother, whose affection for me was boundless, notwithstanding her hopes of my forming an alliance that would be productive of felicity, still felt the most severe pain at the thought of our approaching separation. She was estranged from her husband's affections; she had treasured up all her fondest hopes in the society of an only daughter; she knew that no earthly pleasure can compensate for the loss of that sweet sympathy which is the bond of union betwixt child and parent. Her regrets were infinite as they were evident, and Mr. Robinson, in order to remove any obstacle which this consideration might throw in the way of our marriage, voluntarily proposed that she should reside with us. He represented me as too young and inexperienced to superintend domestic concerns; and while he flattered my mother's armour propre, he rather requested her aid as a sacrifice to his interest than as an obligation conferred on her.

The banns were published three successive Sundays at St. Martin's Church, and the day was fixed for our marriage,—the twelfth of April. It was not till all preliminaries were adjusted that Mr. Robinson, with much apparent agitation, suggested the necessity of keeping our union a secret. I was astonished at the proposal; but two reasons were given for his having made it, both of which seemed plausible; the first was, that Mr. Robinson had still three months to serve before his articles to Messrs. Vernon and Elderton expired; and the second was, the hope which a young lady entertained of forming a matrimonial union with Mr. Robinson as soon as that period should arrive. The latter reason alarmed me, but I was most solemnly assured that all the affection was cherished on the lady's part; that Mr. Robinson was particularly averse to the idea of such a marriage, and that as soon as he should become of age his independence would place him beyond the control of any person whatsoever.

I now proposed deferring our wedding-day till that period. I pleaded that I thought myself too young to encounter the cares and important duties of domestic life; I shrunk from the idea of everything clandestine, and anticipated a thousand ill consequences that might attend on a concealed marriage. My scruples only seemed to increase Mr. Robinson's impatience for that ceremony which should make me his for ever. He represented to my mother the disapprobation which my father would not fail to evince at my adopting a theatrical life in preference to engaging in an honourable and prosperous connection. He so powerfully worked upon the credulity of my beloved parent that she became a decided convert to his opinions. My youth, my person, he represented as the destined snares for my honour on a public stage, where all the attractions of the mimic scene would combine to render me a fascinating object. He also persuaded her that my health would suffer by the fatigues and exertions of the profession, and that probably I might be induced to marry some man who would not approve of a mother's forming a part in our domestic establishment.

These circumstances were repeatedly urged in favour of the union. Still I felt an almost instinctive repugnance at the thought of a clandestine marriage. My mother, whose parental fondness was ever watchful for my safety, now imagined that my objections proceeded from a fixed partiality toward the libertine Captain——, who, though he had not the temerity to present himself before my mother, persisted in writing to me, and in following me whenever I appeared in public. I never spoke to him after the story of his marriage was repeated to my mother; I never corresponded with him, but felt a decided and proud indignation whenever his name was mentioned in my presence.

My appearance on the stage had been put off from time to time, till Mr. Garrick became impatient, and desired my mother to allow of his fixing the night of important trial. It was now that Mr. Robinson and my mother united in persuading me to relinquish my project; and so perpetually, during three days, was I tormented on the subject, so ridiculed for having permitted the banns to be published, and afterward hesitating to fulfil my contract, that I consented—and was married.

As soon as the day of my wedding was fixed, it was deemed necessary that a total revolution should take place in my external appearance. I had till that period worn the habit of a child, and the dress of a woman, so suddenly assumed, sat rather awkwardly upon me. Still, so juvenile was my appearance, that, even two years after my union with Mr. Robinson, I was always accosted with the appellation of "Miss" whenever I entered a shop or was in company with strangers. My manners were no less childish than my appearance; only three months before I became a wife I had dressed a doll, and such was my dislike to the idea of a matrimonial alliance that the only circumstance which induced me to marry was that of being still permitted to reside with my mother, and to live separated, at least for some time, from my husband.

My heart, even when I knelt at the altar, was as free from any tender impression as it had been at the moment of my birth. I knew not the sensation of any sentiment beyond that of esteem; love was still a stranger to my bosom. I had never, then, seen the being who was destined to inspire a thought which might influence my fancy or excite an interest in my mind, and I well remember that, even while I was pronouncing the marriage vow, my fancy involuntarily wandered to that scene where I had hoped to support myself with éclat and reputation.

The ceremony was performed by Doctor Saunders, the venerable vicar of St. Martin's, who, at the conclusion of the ceremony, declared that he had never before performed the office for so young a bride. The clerk officiated as father; my mother and the woman who opened the pews were the only witnesses to the union. I was dressed in the habit of a Quaker,—a society to which, in early youth, I was particularly partial. From the church we repaired to the house of a female friend, where a splendid breakfast was waiting; I changed my dress to one of white muslin, a chip hat adorned with white ribbons, a white sarsnet scarf-cloak, and slippers of white satin embroidered with silver. I mention these trifling circumstances because they lead to some others of more importance.

From the house of my mother's friend we set out for the inn at Maidenhead Bridge, Mr. Robinson and myself in a phaeton, my mother in a post-chaise; we were also accompanied by a gentleman by the name of Balack, a very intimate acquaintance and schoolfellow of my husband, who was not apprised of our wedding, but who nevertheless considered Mr. Robinson as my avowed suitor.

On his first seeing me, he remarked that I was "dressed like a bride." The observation overwhelmed me with confusion. During the day I was more than pensive,—I was melancholy; I considered all that had passed as a vision, and would scarcely persuade myself that the union which I had permitted to be solemnised was indissoluble. My mother frequently remarked my evident chagrin; and in the evening, while we strolled together in the garden which was opposite the inn, I told her, with a torrent of tears, the vouchers of my sincerity, that I was the most wretched of mortals! that I felt the most perfect esteem for Mr. Robinson, but that, according to my ideas of domestic happiness, there should be a warm and powerful union of soul, to which I was yet totally a stranger.

During my absence from town, a letter was written to Mr. Garrick, informing him that an advantageous marriage (for my mother considered Mr. Robinson as the legal heir to a handsome fortune, together with an estate in South Wales) had induced me to relinquish my theatrical prospects; and a few weeks after, meeting Mr. Garrick in the street, he congratulated me on my union, and expressed the warmest wishes for my future happiness.

The day after our marriage, Mr. Robinson proposed dining at Henley-upon-Thames. My mother would not venture in the phaeton, and Mr. Balack occupied the place which was declined by her. On taking his seat between Robinson and myself, he remarked, "Were you married, I should think of the holy anathema,—Cursed is he that parteth man and wife." My countenance was suddenly suffused with the deepest scarlet; I cautiously concealed the effect which his remarks had produced, and we proceeded on our journey.

Descending a steep hill, betwixt Maidenhead Thicket and Henley, we met a drove of oxen. The comic opera of the "Padlock" was then in high celebrity, and our facetious little friend a second time disconcerted me by saying, in the words of Don Diego, "I don't like oxen, I wish they had been a flock of sheep!" I now began to discover the variety of unpleasant sensations which, even undesignedly, must arise from conversation, in the presence of those who were clandestinely married. I also trembled with apprehension, lest anything disgraceful should attach itself to my fame, by being seen under doubtful circumstances in the society of Mr. Robinson.

On our return to London, after ten days' absence, a house was hired in Great Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields. It was a large, old-fashioned mansion, and stood on the spot where the Freemasons' Tavern has been since erected. This house was the property of a lady, an acquaintance of my mother, the widow of Mr. Worlidge, an artist of considerable celebrity. It was handsomely furnished, and contained many valuable pictures by various masters. I resided with my mother; Mr. Robinson continued at the house of Messrs. Vernon and Elderton, in Southampton Buildings.

The stated time of concealment elapsed, and still my husband was perpetually at chambers in Lincoln's Inn. Still he was evidently under the control of his articles, and still desirous that our marriage should be kept a secret. My mother began to feel a considerable degree of inquietude upon the subject; particularly as she was informed that Mr. Robinson was not exactly in that state of expectation which he had represented. She found that he was already of age, and that he had still some months to serve of his clerkship. She also heard that he was not the nephew and heir, but the illegitimate son of the man from whom he expected a handsome fortune; though he had an elder brother, now Commodore William Robinson, who was then in India, reaping the fruits of industry under the patronage of Lord Clive.

It was now for the first time that my mother repented the influence she had used in promoting our union. She informed Mr. Robinson that she apprehended some gross deception on his part, and that she would no longer consent to our marriage being kept a secret. The reputation of a darling child, she alleged, was at stake; and though during a few weeks the world might have been kept in ignorance of my marriage, some circumstances that had transpired, now rendered an immediate disclosure absolutely necessary.

Mr. Robinson, finding my mother inexorable, resolved on setting out for Wales, in order to avow our marriage, and to present me to his "uncle," for such he still obstinately denominated his father. My mother wished to avail herself of this opportunity to visit her friends at Bristol, and accordingly we set out on the journey. We passed through Oxford; visited the different colleges; proceeded to Blenheim, and made the tour a tour of pleasure, with the hope of soothing my mother's resentment, and exhilarating my spirits, which were now perpetually dejected. I cannot help mentioning that, shortly after my marriage, I formed an acquaintance with a young lady, whose mind was no less romantic than my own, and while Mr. Robinson was occupied at chambers, we almost daily passed our morning hours in Westminster Abbey. It was to me a soothing and a gratifying scene of meditation. I have often remained in the gloomy chapels of that sublime fabric till I became, as it were, an inhabitant of another world. The dim light of the Gothic windows, the vibration of my footsteps along the lofty aisles, the train of reflections that the scene inspired, were all suited to the temper of my soul; and the melancholy propensities of my earliest infancy seemed to revive with an instinctive energy, which rendered them the leading characteristics of my existence. Indeed, the world has mistaken the character of my mind; I have ever been the reverse of volatile and dissipated. I mean not to write my own eulogy, though with the candid and sensitive mind I shall, I trust, succeed in my vindication.

On our arrival at Bristol, Mr. Robinson thought it most advisable to proceed toward Tregunter, the seat of his "uncle," alone, in order to prepare him for my cordial reception, or to avoid the mortification I should experience, should he refuse to sanction our union. Mr. Robinson left me a few guineas, and promised that his absence should be short, and his affection increasing.

I had now been married near four months; and, though love was not the basis of my fidelity, honour, and a refined sense of feminine rectitude, attached me to the interest as well as to the person of my husband. I considered chastity as the brightest ornament that could embellish the female mind, and I regulated my conduct to that tenor which has principle more than affection to strengthen its progress.

At Bristol my mother experienced the most gratifying reception; all her former friends rejoiced to see her; I was invited daily to feasts of hospitality, and I found that fortune was to common minds a never failing passport. Mr. Robinson was represented as a young man of considerable expectations, and his wife was consequently again received as the daughter of Mr. Darby. The house in which I first opened my eyes to this world of sorrow, the minster, its green, the schoolhouse where I had passed many days, the tomb of my lost relatives in the church of St. Augustine, were all visited by me with a sweet and melancholy interest. But the cathedral, the brass eagle in the middle aisle, under which, when an infant, I used to sit and join in the loud anthem, or chant the morning service, most sensibly attached me. I longed again to occupy my place beneath its expanding wings, and once I went before the service began to gratify my inclination.

Language cannot describe the sort of sensation which I felt when I heard the well-known, long-remembered organ flinging its loud peal through the Gothic structure. I hastened to the cloisters. The nursery windows were dim and shattered; the house was sinking to decay. The mouldering walk was gloomy, and my spirits were depressed beyond description: I stood alone, rapt in meditation, "Here," said I, "did my infant feet pace to and fro; here did I climb the long stone bench, and swiftly measure it at the peril of my safety. On those dark and winding steps did I sit and listen to the full-toned organ, the loud anthem, the bell which called the parishioners to prayer." I entered the cathedral once more; I read and re-read the monumental inscriptions; I paused upon the grave of Powell; I dropped a tear on the small square ground tablet which bore the name of Evelyn. Ah! how little has the misjudging world known of what has passed in my mind, even in the apparently gayest moments of my existence! How much have I regretted that ever I was born, even when I have been surrounded with all that could gratify the vanity of woman!

Mr. Robinson, on his arrival at Tregunter, despatched a letter informing me that his "uncle" seemed disposed to act handsomely, but that he had only ventured to avow an intention to marry, fearful of abruptly declaring that he had been already some months a husband. Mr. Harris, for that was the name of my father-in-law, replied that "he hoped the object of his choice was not too young!" At this question Mr. Robinson was somewhat disconcerted. "A young wife," continued Mr. Harris, "cannot mend a man's fortune. How old is the girl you have chosen?"

"She is nearly seventeen!"

I was then only fifteen and a few months.[10]

"I hope she is not handsome," was the second observation. "You say she is not rich; and beauty without money is but a dangerous sort of portion."

"Will you see her?"

"I have no objection," said Mr. Harris.

"She is now with her mother at Bristol,—for," continued Mr. Robinson, with some hesitation, "she is my wife."

Mr. Harris paused, and then replied, "Well! stay with me only a few days, and then you shall fetch her. If the thing is done, it cannot be undone. She is a gentlewoman, you say, and I can have no reason to refuse seeing her."

The same letter which contained this intelligence also requested me to prepare for my journey, and desired me to write to a person whom Mr. Robinson named in London, and whom I had seen in his company, for a sum of money which would be necessary for our journey. This person was Mr. John King, then a money-broker in Goodman's Fields; but I was an entire stranger to the transaction which rendered him the temporary source of my husband's finances.

One or two letters passed on this subject, and I waited anxiously for my presentation at Tregunter. At length the period of Mr. Robinson's return arrived, and we set out together, while my mother remained with her friends at Bristol. Crossing the old passage to Chepstow in an open boat, a distance, though not extended, extremely perilous, we found the tide so strong and the night so boisterous that we were apprehensive of much danger. The rain poured and the wind blew tempestuously. The boat was full of passengers, and at one end of it were placed a drove of oxen. My terror was infinite; I considered this storm as an ill omen, but little thought that at future periods of my life I should have cause to regret that I had not perished!

During our journey Robinson entreated me to overlook anything harsh that might appear in the manners of his "uncle,"—for he still denied that Mr. Harris was his father. But above all things he conjured me to conceal my real age, and to say that I was some years older than he knew me to be. To this proposal I readily consented, and I felt myself firm in courage at the moment when we came within sight of Tregunter.

Mr. Harris was then building the family mansion, and resided in a pretty little decorated cottage which was afterward converted into domestic offices. We passed through a thick wood, the mountains at every break meeting our eyes, covered with thin clouds, and rising in a sublime altitude above the valley. A more romantic space of scenery never met the human eye! I felt my mind inspired with a pensive melancholy, and was only awakened from my reverie by the postboy stopping at the mansion of Tregunter.