Title: Little Metacomet

or, The Indian playmate

Author: Hezekiah Butterworth

Illustrator: Frank T. Merrill

Release date: March 8, 2025 [eBook #75556]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co, 1904

Credits: Mary Meehan and The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

OR

THE INDIAN PLAYMATE

BY HEZEKIAH BUTTERWORTH

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL & CO.

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1904,

By Thomas Y. Crowell & Company.

Published September, 1904.

The author's purpose in writing this book for young people is to picture life in the New England woods in old Indian days, when barbarism was passing under the influence of civilization. His mother passed a part of her girlhood at Mt. Hope, and he was born near the Mt. Hope Lands, at Warren, R. I., the Sowams of Massasoit, who protected the Pilgrims and sheltered Roger Williams when the latter was forming his views of liberty of conscience, or soul freedom, which have entered into the constitution of every republic in the world. He used to roam in the green groves of Swansea, has often met the last of the Wampanoags at Lakeville, and as often pictured in his own mind the charming life of an Indian boy in the green woods around the Mt. Hope and Narragansett Bays in the days of the forest kings.

This little nature book is an attempt to portray such a life. In it the author has endeavored to picture, by much fact and a slight framework of fiction, the life of Little Metacomet, the son of King Philip, or Pometacom, or Metacomet, who followed his father, the great chieftain, and his mother, the beautiful forest queen, before the Indian war, and his mother during the war, and who was deported to the Palm Islands after this last event. He has used Little Metacomet to picture an Indian boy's life in the woods among the birds, animals, and native races, and to tell the tale of what was most merciful in Philip's war.

TIMID SUSAN AND HER NEIGHBORS

During the early settlement days of this country, before the great Indian war of 1675, when the pioneers and the savages shared the land on Mt. Hope Bay and the Narragansett Bay between them, there was a little woman named Susan Barley who was much afraid lest she should "see something." We may not wonder that she was so much afraid, for she lived in the green groves of Swansea, which bordered on the Mt. Hope lands, and the Assowamset pond country, at the time that the Indians of Pokonoket began to be hostile towards the white people.

Near her little cabin in the Swansea groves lived a very odd hermit named William Blackstone, or, as he was generally called, Blaxton. He founded Boston in apple orchards, and English roses, and then went away to live all alone at a place which he called "Study Hill," near Pawtucket Falls. He was a graduate of Oxford, England, but he loved little birds and animals, and wished to live by himself that he might study the soul. He made the birds and animals his brothers, and tamed the forests around him, and the jays talked with him, and squirrels lived with him, and hunted deer ran to him for protection. A bear and her cubs would visit him among his apple trees, and the deer feed around him like so many Jersey cows at the present time. At Study Hill he wrote some ten volumes, probably of philosophy, which were burned in the Indian wars.

He used to travel about on a white ox, which he guided by a cord running through a ring in the animal's nose. It was in the witchcraft times, and some people may have thought that the white ox and his rider were ghosts. Blackstone used to visit Roger Williams at Providence, riding on this white ox. He probably did his courting at Boston in a like way. We are giving here some of the curious incidents of a real character.

After his apple orchards had grown at Study Hill, now Lonsdale, R.I.—where you may see his tomb in a yard of an immense cotton mill, under the cornerstone of which he was finally buried, with the bones of an ox, or an animal,—he would sometimes take a basket of the new fruit to a place where Roger Williams preached, on the hill, probably near Brown University, and when the good man of liberty of conscience had ended a sermon, would say—

"Ho, ho! And here are refreshments from the trees of the Lord."

He would then toss about his apples to the people who had assembled to worship,—Quakers, Baptists, outcasts, Indians and all.

"Ho, ho!"—they would sit down and eat the apples.

All the forest people loved Blackstone, and the very birds seemed to sing his praise.

Near Blackstone and his orchards lived John Eliot, the Indian Apostle, at Natick, where he preached to the Indians and had gathered an Indian church. He was the minister of Roxbury Fields, and his grave may be seen in Roxbury, in the Washington and Eustis Street Burying Ground, where probably rests Anne Bradstreet, the first American poetess, in the Dudley tomb. Eliot preached in many places near Natick, among them on the high rock at the present Brook Farm, at West Roxbury; the memorials of his Indian work are to be seen at Natick. Had all white men been like him, there probably would have been no Indian war.

What noble men were these—Blackstone, Roger Williams, and John Eliot! The latter failed to convert the Indian tribes, but his influence saved New England. King Philip told him in a friendly way that he cared no more for his religion than for the bright button on his coat, and yet the chieftain at one time was very much interested in Eliot's teaching. King Philip had a good heart at times—but it was a double heart.

The New England woods were like a menagerie in those days, full of animals and birds. Turkeys and partridges scurried everywhere among the white birches and green savins, and fat geese filled the coverts about the ponds in the fall. On the open fields the Indians grew corn, which they parched and pounded, and ate with clams and fish.

Savages, though they were, the Indians led a charming life in the woods, and the Indian boy had a lively wonder age in his youth, when he was learning the secrets of the forests. Little Metacomet, King Philip's or Metacomet's son, was a small naturalist of these forests and waterways before the great war. He met the great pioneers, Blackstone, Williams, and Eliot, he followed his father in the last days of peace, and he hunted and fished and enjoyed the Indian clambakes and autumn festivals. So let us take the little brown hand of the boy Metacomet, and go forth into our story, when every covert had an animal, and every tree a bird, and the Indians thought that this abundant life would last forever.

One day timid Susan said to her son Roger, a lad of some ten years—

"Let's go over to the hermit's and see what the world is about. I will be careful not to touch anything."

So the two went over to Study Hill to visit Blackstone, and the little woman from the green groves of Swansea came timidly to the hermit's door; for she had heard the strange tales of a phantom white ox in the forest.

The hermit came out to welcome her.

"I'm proper glad I got here," said she. "I was afraid I might see something. I came all the way from the green groves of Swansea."

"What were you afraid you might see, good mother?"

"The dead that wander; I'm never afraid of no living human, but I am scary of the dead—they know all."

"But the dead do not wander, little woman, to scare innocent people like you. There are no ghosts outside of us—ships do not sail on the land, nor cattle pasture in the sea."

"You must be an infidel. Are you?"

"No."

"Sure—perfectly sure?"

"Sure!"

"And you've been to college?" She shook her head and added:

"But Boston folks believe such things!"

"They are led by a blind spirit of superstition."

"Have you ever seen the rider on the white ox?"

"Yes."

"You don't tell me!—I'd fly right out of my head were I to see that. Where did you see it?"

"Here."

The little mother's eyes grew.

"There is no spirit rider of any white ox," said the hermit. "But, my good woman, King Philip, John Eliot, and Roger Williams are coming here to-morrow, and you and Roger must stay and see the great chieftain. Perhaps the Indian chief will bring the Princess and Little Metacomet with him."

"But Joe, my husband, what will he do? He would think that the white ox had got me."

"I will send young John Quitumug to Swansea to tell your husband where you are, and you will not see anything 'scary'."

"Then I will stay."

And in the morning came Roger Williams, sturdy, with an open face, beautiful with the inner light. His spirit was full of loveliness, but his language seemed strange.

"Brother Blaxton, the Inward Voice said 'Come'—and I am here. Thee surprises me; who is this little woman and her boy? What may thy name be, woman?"

"Susan, Joe's wife, of Swansea—they call him 'Onery Joe'—they say his head was put on wrong—but he is good to me, ain't he, Roger?"

A sudden sound rose in the air—"Netop!" (friend), said an Indian runner, peeping out of the thick wood. Philip, the Forest King, was coming. There was heard a breaking of dry twigs beneath mocassined feet, behind the thick curtains of leaves. Wood birds flew up into the air with notes of alarm. Presently the glimmering hazels opened like a wicker gate, and King Philip and his family, with some grave and stately warriors, came into view, and approached the place.

With Philip came his wife, known as the Beautiful Princess, and Little Metacomet, their son. The princess wore royal robes woven of river grasses, and around her neck was a copper chain. The Pilgrim Fathers had given two copper chains to Massasoit the lord of Lakonoket as a pledge of eternal friendship.

It was to be a peace day; the princess had come as a kind of rural goddess of Peace: King Philip extended his hand to Blackstone, and the world seemed filled with gladness.

Presently the red bushes opened and the witch hazels that bloom in the fall shook, at a place near the brook. A grave man appeared, and Blackstone said—

"Thou art welcome, Father Eliot. I feared that thou wouldst not be able to leave thy flock in Natick fields."

Then Blackstone, Williams, and Eliot shook hands with each other and with Philip, while the Indians looked on in wonder.

More Indians came, and among them some praying Indians. They shook hands with the three white men, but when they greeted King Philip's men they followed the Indian custom of greeting.

Blackstone made an Indian clambake that day near the Falls of the Pawtucket, to King Philip, John Eliot and Roger Williams. Some Indian children were there, and they gathered in the cool to play.

It was October and the woods seemed to be on fire, they were so bright in color.

The princess, the wife of King Philip, whose name was Wootoneshanuske, hung her papoose in a cradle on a tree near by and began to sing to it, shaking the copper chain.

The Indian cradle song of "Rock-a-bye, baby, upon the tree-top," though of American origin, pictures the Indian cradle swinging in the woods. The birds came to talk to the baby, the squirrels ran past it, and stopped to chipper to it. The dogwood bloomed near it, and the early leaves fell around it.

When the Indian boy, Metacomet, began to run about, his dog went with him. They played tag, and hid, and made hide-and-seek surprises of the game. Then he flew a kite. The Indian boys flew kites that were made in a peculiar way of fish bladders. It was a charm to them to see these light boats rise and sail away in the air.

At Indian clambakes Indian boys played "shinny" and games of skill with the bow and arrow, and entered into long races. Eliot said of the Indian children—"They play sly tricks upon dogs, and are much given to singing."

The grave white men on this serene day sang or repeated Psalms, after which the Indians made music and sang, and with them sang the beautiful Princess of the Copper Chain.

The Indian music was simple; drums, rattles, and reeds or whistles.

The princess stood apart from the rest, and sang as if to her baby in the trees.

The calling of birds by imitating the bird-call was amusement and music with Little Metacomet. The birds whistled, and piped and drummed. So did the boy. The black wild geese honked; so did the Indian. The dove cooed; so did the mother to the baby, and so did the baby to the mother.

There were singing forests then; a thousand birds sang together; in the pearl red morning; before the shower; on the long evenings of June in the still light. The Indian mother and her children had quick ears for vocal nature.

The winds of the seasons had their differing tones, and it was a joy to hear the coming of the south wind, and a sadness to catch the first piping of the north wind in the fall.

The beautiful season of the year was the red part of November called the Indian summer. The leaves seemed to burn; the walnuts and acorns fell. The purple gentians bloomed. The moonrise blended with the sunset.

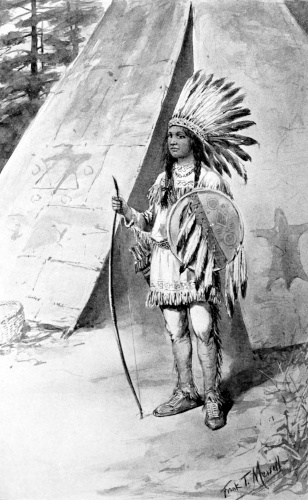

LITTLE METACOMET

Little Metacomet, the prince, was an usually bright Indian boy. His quickness of feeling and of ear and eye pleased the royal Indians, for it was expected that he would succeed his father in the sachemship. The boy followed his parents at times from Mt. Hope, the royal seat, to Kickemuit, Sowams, and the Assowamset Hill, near the great and beautiful lake. He was the grandson of Massasoit, and like that great monarch seems to have liked the English well.

He had learned a little English very early in life from John Sassamon, the interpreter to Philip, who had studied under John Eliot, and became a teacher and preacher in the towns of the praying Indians. It was Sassamon who later informed the English at Plymouth of the secret purpose of Philip to unite the tribes for war against the English, which caused Philip to demand his death. He was killed at Assowamset Lake, near Philip's seat. The English arrested his executioners, which Philip regarded as an interference with his own government, and this fact was the direct cause of the great war.

In the days when Sassamon was in the favor of the Indian court, Little Metacomet met many of the English people to whom his father was friendly, and heard the Indian teacher interpret for his father. So English words were impressed upon his mind when he was very young. He also had an uncle who had been to school in Cambridge. He loved nature, and he came to be interested in nature lovers like Blackstone.

There was one little animal with whom he became very friendly—the chipmunk, or ground squirrel, sometimes called the painted or striped squirrel.

The ground squirrel was very industrious in the fall. He gathered corn, grain, chestnuts, walnuts, acorns, and the like, and stored them away in his little house under ground. He filled the inside of his cheeks, which could be made a kind of pouch, with his foods, and he looked like a squirrel with a toothache when he carried these down cellar. He came up from his warm house looking very thin after putting these storages on the shelves and in his chests, which may have been crevices in hard earth, or hollows of rocks.

Little Metacomet would whistle to him, or blow a shell, and he would stand upon his feet, and seem to say—

"What now?"

"Chipper, chipper, chipper," would say the Indian prince, and his little companion of the woods would answer—

"Chipper, chipper, chipper," and then would be gone.

Metacomet was often followed by his dog. When the dog spoke to the ground squirrel, the latter had nothing more to say. He went.

Metacomet and Roger liked each other as soon as they looked into each other's face. We know our heart friends when we first see them. The prince from the Mt. Hope Lands, warmed toward the boy from the green groves of Swansea and wished to rub noses with him at once, after the queer Indian fashion.

"I wish I could have the Indian boy for a playmate," said Roger to his mother.

"What for?"

"O, think what things he might show me in the woods: animals, birds, flowers; he knows them all."

Roger watched Little Metacomet. The prince was scarcely ten years old, or about that age, but he seemed to see clearly into everything in nature, and he was friendly to every one. He inherited the keenness and sharpness of the Indian instinct.

"I find that the boy has an eye for what is wonderful," said timid Susan to Roger towards the end of the day. "We might ask him over to the green groves of Swansea."

The sun sprinkled the groves with long shadows. A little quail whistled. Little Metacomet listened to the quail. He loved this bird of the wild fields of the woods. There was something about the bird that kindled his imagination and went to his heart.

Presently he went over to his father and listened gravely to the speech of his address. King Philip was beginning to distrust the English, but he still desired to maintain peace.

He was talking with Eliot when Little Metacomet came and stood by him.

"I am true to my race," said the king, "but I can forgive. I forgave a man who spoke evil of the dead. I can be merciful. Hawks are in the sky. Suppose war should come and I were to fall, would you pity my family? Here is Little Metacomet, would you be merciful to him?"

"I would, as God is merciful to me," said Eliot.

He desired the welfare of the Indian Prince.

At first Little Metacomet walked apart from Roger, but he gradually drew nearer to him. There was something in his heart that he wished to express.

He whistled and called a blue jay to him from the trees. He looked towards Roger and smiled in a friendly way. Indian children do not often smile.

Then he went to Roger, and the latter put out his hand for him to shake, but Little Metacomet drew back his hand. Instead, he lifted his own hand and touched Roger on the nose.

"You do not understand, my boy," said Father Eliot to Roger. "He wishes to rub noses with you. It is the Indian custom. He will do it if you will always be his friend."

"I will be his friend," said Roger.

"And I," said Father Eliot, "for his grandfather's sake, and the copper chain of peace. I will always be a friend to Little Metacomet."

The two boys walked apart again, and the heart of Eliot followed the Indian, with a deeper interest.

It was a glorious day. The world was still; nature blazed; the maples were red; the oaks yellow; the gentians blue. Did a breeze move? It brought down showers of leaves of crimson and yellow.

The walls were purple with grapes; the swale meadows red with cranberries. The jays talked in the trees. The migrating birds gathered in flocks. The wild geese honked on high. The witch hazels bloomed amid the falling leaves.

Winter was delaying; a spell was on the earth, the waters, and in the air. "The trumpets of the north," as the Indians call the cold winds, were about to blow, but week by week they waited. Color was everywhere. Then was the charmed spell of the ripened year; the harvest calm; the rest of the spent forces of nature; all things in the silence were parables of life.

Night fell and the pine knots were lighted.

Then a great supper was spread—samp, succotash, game, no-cake, nuts, apples and oranges from over the sea, which Philip may never have seen before.

Susan was "scary of these great folks," but helped to wait on the table. Roger shrank away into the dark corner of the room, and Little Metacomet followed him there. The two boys sat down silently, but they began to feel friendly towards each other, as before. At last Roger touched the hand of Metacomet and then his small white hand grasped the brown hand of the Indian boy.

They did not speak.

Metacomet's black eyes were turned upon the yellow-globed oranges and red apples on the table.

Presently the hermit sent Roger an orange and an apple. He did not notice the Indian boy, for he was hidden behind Roger.

Roger handed his orange to Little Metacomet. The Indian grasped it eagerly. Roger then gave him the apple, which was seized as quickly.

The two sat in silence. Then the Indian boy began to draw nearer to Roger, nearer and nearer, and pushed his head slowly forward, and rubbed his brown nose against Roger's nose many times.

"I will be a king," said he.

Father Eliot saw that the better heart of Massasoit was in the little prince, the heart of the old sachem who had once worn the copper chain.

Roger's heart went out to this child of the forest. The two were friends for life after the pledge.

After the feast there was a talk by the great fire.

"If the two races would only come together like the hearts of these two children, the Indians would be saved to civilization," said Eliot.

"They might be made to come together by the same means; is that not so, brother Eliot?" said Williams.

"Will Little Metacomet here ever come to the throne of the forest kings?" asked Blackstone.

There was a silence. The Indian boy was standing by the red hickory fire. What would be his destiny?

Before the company lay down upon their mats in their rooms and lodges, another queer thing happened.

The little prince came to timid Susan, and put up his red hand to her kerchief.

"What would you have?"

He shook his nose kindly, and she bent down her face.

The two rubbed noses.

"And now you must come over to the green groves of Swansea and see us all some day," she said, her heart warming to the child.

There was a light step behind her. It was that of the princess. They too rubbed noses and parted. John Eliot prayed. Then all went to their beds and mats, and the whip-poor-wills sang outside in the woods, and the Indians crooned themselves to sleep.

HAYSTACK FRIENDSHIP

The next morning the little mother and Roger went away. She said she was terribly afraid that she would "see something" on the trail.

"Do not fear," said the hermit. "It is I who ride the white ox, and I will accompany you part of the way, and Father Eliot shall ride the ox."

So they went into the forest trail, and Metacomet followed.

They parted at last on the borders of the green groves of Swansea.

"Little Prince," said timid Susan, "you love the oaks. I see that you do. The squirrels love the oaks, too, and I see that you and the squirrels which live under ground are friends. There are great oaks and green mosses in Swansea. There are white birches there, and green savins, and all around are mossy places where one can rest, and hear the birds sing, and pick berries. The wild geese stop there in their flight—oh, it is a lovely place, and my husband, Joe, he is a good man, a wood-chopper. Won't you come over to our cabin some day, and see Roger, and help him find things in the woods?—you know all about the wonders of the woods, and we are near to them."

The Indian lad turned to Roger and said, "I will come."

"That will be fine!" said Roger clapping his hands at the prospect of a playmate.

"If anything should happen," said timid Susan, "we will not forsake each other. We will always be true to each other, whatever may happen."

So the timid woman and Roger and the Indian prince made a treaty of peace. And they were very sincere.

As they parted Little Metacomet said, "My heart will never forget."

The very next day he came up from the river bend at Sowams to see Roger. Timid Susan made some pancakes for him, and he said—

"Me will never forget; me will come two times mo' (again and again) and will bring you things out of the woods."

He now began to look for things in the woods that would cause Susan to wonder. He liked to see her wonder "two times mo'"—again and again.

There were great open places in the woods then full of tall grasses and berry bushes. The redberry grew in them, the black alders, the wild rose bushes and barberry bushes from whose berries candles were made. The barberries lined the uplands. There lived the meadow birds of windward ways. The snipe hid there, and the bobolink made the air ring in summer when singing to his nesting mate. These meadowy places were all bloom and song, and the little prince roamed among them, the feathers on his head scarcely higher than last year's pussy-willows, and the red-winged blackbirds following him in alarm and wonder.

Susan was a simple woman, with a faithful heart. She lacked strong sense or the expression of it, but she loved everybody. In the old country she had been called "queer," a "little off," "touched in mind." But she tried to make every one happy.

When her husband, the woodman, bought of King Philip a piece of land, he and Susan and Roger went there to live. It was summer, and the air was all fragrance and song. There was a large flat stack of swale meadow grass on the land. The family took shelter under it for a few nights, while the woodman was building his cabin.

Susan used to go out to the stack to rest often during the summer. Many of the early New Englanders used to pray in the woods, and it was thought that Susan used a hollow in the stack for this purpose.

Some Indians frequently saw her sheltered by the stack. They came to call her "The Lady of the Haystack," in Indian words.

She used to give pancakes to the Indians who sat down to rest under the great trees by her door.

The Indians brought her corn husks and meal from the tribal mill, which was near. She would make cornmeal cakes and roast them in the husks, which she would share with the wayfarers under the trees.

Little Metacomet began to come often and loiter about the cabin or stack until he was seen. Susan would go out to invite him in, at first very cautiously.

"You hav'n't got no war-whoop in ye," she would sometimes say.

The little prince would bow his head, as if it dropped from a pivot.

"Then don't let it come out," she would say. "Follow me, now."

Susan every day feared more and more that she would hear the war-whoop notwithstanding that she was so friendly with the little prince. When the loon cried in the night, she would say, "Never mind: I have the little prince's heart. He will always be true to me."

There were three things that Susan was afraid she would see or hear. One was a ghost, after the old New England superstition, another, an Indian conjurer, or medicine man, and the last was the war-whoop.

"Why, I would be that scart," she used to say, "if I were to hear it, I would go right out of my head, and never would come back."

"Where would you go?" asked Roger one day, "if you should hear it skittering along the air?"

"I would fly to the old haystack, and hide in the hay, and put my fingers on both ears and pray."

She had a tame blue jay that used to scream after her in the trees as if to frighten her. The roguish bird seemed to know that he could alarm her, and to delight in it. He would make a sound like the turning of a crank, after he had yelled his war-whoop.

Poor Susan, when she was in trouble she resorted to the haystack, in which was a cavern, where she said the Lord "covered her with his wings." The little prince used to find her there when she was not in the cabin, and he would take her surprises there, as wild strawberries, flowers, birds and little animals. He once carried her there the rose of birds, the red bird of the deep woods, whose disposition was as shy as her own.

"I must let him go," she said, while holding it in wonder.

"Why?" asked the little prince.

"Because his heart beats so fast. The Golden Rule was meant for birds, too."

"What is the Golden Rule?"

And Susan let the red bird go, and taught Metacomet the Golden Rule in the shadow of the haystack.

There was one charm of the woods that is little valued to-day. It is almost a lost art among us. It was the odors of the flowers and the trees. The Indian women knew, or thought they knew, the value of all roots and herbs as medicines, but they also found delight in the odors of vegetation, like the nature-loving children of the Eastern world. It was not the pungent rose, the sassafras and pennyroyal that most attracted them, but the violet, the arbutus, the locust, the wild honeysuckle, the spearmint, the bruised checkerberry, the musk plants, and the sweet brier. The last exceeded all other plants in the subtlety of its perfume.

The faculty of scent of the Indian to enjoy all these fragrances was highly developed. Nature to the wild man was more than to the pioneer; the former lived in a fragrance which the man of towns knew but little.

The Indian loved his own world. The rocks bloomed for him, the streams filled their banks with flowers for him, the forests were his parks, and he could see and hear more clearly and smell more keenly than the toilers from over the sea.

The Indian boy brought Susan the nosegays that had not the most showy colors, but the sweetest odors. Among his surprises for her was a "clear horn." There were certain horns that grew white towards the end and were pointed with a clear substance like amber. The point of these horns shone in the sunlight like gold. This clear horn was an emblem of dignity and royalty. Suggestions of the use of the emblem of the clear horn are to be found in the Hebrew Scriptures, and ancient art.

"It shines," said Little Metacomet.

"What shines?" asked Roger, who stood by admiring it.

"The horn—let me hold it up to the sun."

He held the top of the horn in a way that the sun might strike it. It seemed to turn into fire; to burn; to send forth rays as from a flame of gold.

"It is like a king, with a crown on his head," said Susan. "May you wear white robes and a crown of gold that will shine."

The little prince did not quite comprehend this figure of speech.

He stood in the sun for a long time, holding up the clear horn to the sun to see the rays reflected from the top of it. The clear horn was a kind of parable of life to the Indian priests, after the ancient Hebrew thought, and even the prince saw a meaning in it.

ANOTHER VISIT TO THE HERMIT

Little Metacomet liked to look into nature; his small mind probably did not know that the hidden force and wisdom of the universe was there. Blackstone, the hermit, studied nature in this broad way; he studied animals to discover the human nature in them.

As often as Little Metacomet went to timid Susan with one of his surprises, she took him and Roger over to Study Hill to see the hermit.

"He knows near upon everything," she would say. "There are few things in heaven and earth that he don't know; we must go over and ask him."

So the three would wander along the flowery ways of the green groves of Swansea toward Pawtucket Falls where the hermit lived.

Little Metacomet brought to Susan, one day, a fat woodchuck almost as big as himself. The lazy animal struggled to get away, but the boy held it fast.

LITTLE METACOMET BROUGHT A FAT WOODCHUCK ALMOST AS BIG AS HIMSELF.

He put it down on the split wood of the house, shut the door, and said:

"He fats himself for winter, and he lives on his own fat all the winter long. Why do not we do so?"

Timid Susan could not answer.

"The ground squirrel lays up two winters' stores of food," said the little prince. "He no fats himself. The woodchuck he is lean and hungry in the spring; the ground squirrel he is no lean and hungry. He come out of the ground all chipper, chipper. Why does the woodchuck fat himself, and sleep, and the ground squirrel and crow lay up food for themselves?"

Timid Susan lifted her hands, and rolled her eyes.

"The Lord only knows," she said, "except Mr. Blaxton. We will have to go to Study Hill, and ask the hermit all about these things. I will put on my slat sunbonnet, and we will go."

They went, and timid Susan propounded to the hermit these simple questions.

"You know everything," said she, "you and the Lord. I am a poor, simple creature, and I couldn't tell anyone how it is I think, and how I know my own thoughts, nor even how it is that I raise my hand to my head. How is it that you lift your hand to your head, Mr. Blaxton?"

The hermit lifted his hand to his head and said nothing.

"Wonderful, wonderful," said timid Susan, "now I know."

She then put to him the questions of Little Metacomet: why did the woodchuck fat himself for the winter and the crow make cribs in the trees, and the ground squirrel cellars under ground?

There was a blank look on the hermit's face.

"Come with me," he said.

He took them out to the stream which now bears his name. Some badgers were building a dam there. They were felling a tree, sawing it with their teeth in such a way that it would fall upon the half built dam.

"Do you see," said he, "that they are sawing more on this side of the tree than that, so that it will fall this way across the river? What taught them to do that? If you will answer me, I will answer you."

"Nature," said the little prince.

"No, it is the wisdom unseen in nature," said the hermit. "The spirit of the Eternal."

"But what makes the ground squirrel make cellars?"

"I can answer that," said timid Susan. "The ground squirrel is all hands—his feet are little hands—and he's just like some of the rest of us—he is afore-handed."

She lifted her hands, and counted four. The hermit dropped his head and laughed, as also did Roger; but Metacomet stood puzzled. He could not comprehend the four.

Having learned so much about nature, timid Susan and Roger returned to the green groves of Swansea, and Little Metacomet to Sowams where were bearded oaks and wild roses by the bright waterways.

The woodman, Mr. Barley, often came home from the forests worn with work.

"Susan," he would say, putting down his ax by his couch of hides, "the wood-choppers do say that war is coming."

"Never you mind," said Susan, "I have the heart of the little prince. If the war-whoop comes it will pass us by. Philip is true to his own."

There is a beautiful pond near Taunton called Winnecunett. This was one of King Philip's country resorts. Its borders are rocks, like an ancient ruin, but one interested in Indian lore ought to visit it, for it shows the love that King Philip had for what was lovely in nature. The wild geese flocked there. There grew the wild honeysuckle. There, the pond lilies. King Philip had poetry in his nature, or he would not have so loved the castle-like pond.

Roger took his mother to this beautiful pond one day. It was summer time.

"The king, if he loves such places as these," said she, "will not harm you and me, Roger. He has a better heart."

HOW THE HERMIT TAMED BIRDS

William Blackstone, as we have said, was a keen lover of nature. It made him happy to have a wild animal begin to follow him; to have the birds come to him for protection and shelter, and for food in the winter. This feeling grew. The ospreys used to build their great nests near his house and to repair them by sticks of wood and new sea-weed every year. If an animal climbed one of the trees where these nests were, when the birds were rearing their young, the parent birds would wheel over his house on Study Hill and scream for help. This touched the heart of the hermit. He told the incident to Roger, and asked him to bring any strange animals or birds that he could find to him.

One summer day, bright Little Metacomet came again to timid Susan with a new surprise. It was a nest with the most beautiful bird sitting upon it that the boy had ever seen. The bird was rare and was called the swamp robin. It was of a fiery crimson color, and had the reputation of being a very shy bird.

Timid Susan held up her hands, and rolled up her eyes.

"Do my eyes dazzle me?" said she. "That is a mighty strange bird, all fiery red; it might have come down from the sun. Why doesn't it fly?"

"It can't," said Little Metacomet.

"Why?"

"It has eggs under her. She is going to hatch," meaning that the eggs were about to hatch.

"And she would rather die than leave her eggs, is that it? You darling bird; you are bound by the cords of a mother's love."

A bird of the same kind, the mate, had been following Little Metacomet in the top of the trees. It flashed like a red flame of fire above the nest, and rose into the air. The mother bird rose up from the nest a little and uttered a cry. There were four eggs under her.

"I wonder what kind of a bird that can be," said timid Susan.

"Let's take it over to the hermit," said Roger, "and ask him all about it. He knows almost everything."

So again the three took the forest trail to the Falls of the Pawtucket carrying the bird and nest. The other bird followed them in the trees.

"Look!" said the Indian boy to the hermit, pointing to his treasure.

"A redbird," said the hermit. "See how faithful her little heart is to her nest. I love things that are faithful to their own."

"I did not know but that you might find a cage for her," said Roger.

"There is no need of cages," said the hermit. "Does it need any string to tie that bird to her nest?"

"But she would fly away when her eggs hatch, and we would lose her. That would be a pity. She is the handsomest thing that flies."

"I will not lose her," said the hermit. "Let me have her, and I will keep her for you."

"What makes her so red?" asked Little Metacomet.

"You must ask the sun, the sky, the woods, and the hidden wisdom there," said the hermit.

He took the nest and went to a ladder that led up to a loft where was a window with a shutter. He placed the nest before the open window and left it there, and they all went out into the orchard, and talked together merrily on the goodness of everything. To them everything appeared good. Only the good see what is good.

Mr. Barley was away in the wood at the charcoal pits, and would not return that day, so the hermit persuaded them to stay over night, as the princess was coming to see him the next morning.

During the day the parent redbird came to the eaves of the house and fed his little wife on her nest.

The hermit and Metacomet and Roger slept in the loft that night where the nest was.

When the hermit blew out the candle, he said—

"We will be very still and not disturb the bird. Still, still."

The night was hushed. There were fireflies in the air. The whip-poor-wills sang in far trees. The moon rose high, and everything seemed to swim in her rays as in a sea. The air was a sea of moonlight.

There was heard a queer sound—it was a living sound—tick, tick.

"What is that?" asked Roger.

"Still, still," said the hermit. "That is the clock of life. Listen—still, still."

Pick—peck—peck.

"That is the little bird in the egg," said the hermit. "Listen, still, still."

Pick, peck, peck.

"What makes him do it?" said Roger. "How does he know that there is a world outside the shell?"

"Ask God that," said the hermit. "Still, still."

They listened. Timid Susan came part way up the ladder and listened.

"The little birds are pecking against the shells of their eggs," said the hermit. "They are about to hatch."

In the morning they found four egg shells outside of the nest. They did not disturb the bird.

When the princess came they showed her the four egg shells, and told her the story.

Little animals came out of the woods to the door. Some blue jays flew into the house. A white goose with many goslings came up from the pond, and even the wild crows cawed as if laughing in the near tree-tops.

"I have no need of any cages," said the hermit to the princess. "The birds and animals all love me, and therein I am content."

THE FEATHERED CAT

The New England woods were full of wonders to the pioneer. Little Metacomet delighted more and more to bring to Susan Barley things that would most surprise her. Susan's way of lifting her hands and staring upward as in amazement greatly delighted the Indian boy. It pleased Roger as much as himself.

He once brought her a bunch of yellow mocassins, or yellow lady's-slippers, which so surprised her that she said that these "new parts" must be near to heaven, and caused her to kiss the boy's hand. He brought her once a bouquet of fringed gentian which so pleased her that she rubbed noses with him, greatly to his delight. He brought her also the "ghost flower," or the Indian-pipe, which she was almost afraid to touch lest something should happen. The Indians claimed that the Indian-pipe would cure fits. It grew everywhere in the marshy woods. He brought her honeysuckles from the gray rocks.

Susan Barley had a cat which was a wonder to the little boy. It was Roger's playmate brought from over sea.

The cat would nestle up to Metacomet, and purr, and purr, and purr.

"The Indians have cats," said he. "They are feathered. Me find one for you!"

Roger laughed, while Susan raised her hands and uplifted her eyes in wonder.

"A feathered cat?" said she. "What do you think of that? I would shut my eyes."

"Me go bring you one," said Metacomet.

He went out into the trails and forest ways.

Then, the day after, he came back again, holding something to his breast.

He put this feathered something into Susan's hand. She held it out. It was alive and seemed all eyes.

"It has big eyes," said Roger, "but somehow it don't seem to see."

"It sees in the night," said Little Metacomet.

"Then it must be bewitched," said Susan. She laid it down on a mat and it lay there as if it had lost all power of motion.

The cat went to wonder at it.

It snapped and spit.

The cat started away.

"What is it?" asked Roger. "What funny thing of the forest can that be?"

"It is a feathered cat."

"It is an owl," said Susan. "It does see in the night. It is all feathers. Look, look."

She ruffled the bird's feathers.

"It has no body to speak of," said she. "Roger, go get a cage for the feathered cat, and we will tame it. What does it eat?"

"Mice," said Metacomet.

"Then the kitten shall catch mice for it," said Roger.

"The kitten might catch the owl," said Metacomet.

The owl began to swell its feathers, and looked as big as an eagle.

"Or the owl might catch the kitten," said Susan. "I am going to get a mouse when the dark comes, and let the fur kitten and the feathered kitten eat together."

So Susan in this land of wonders brought up the owl and the kitten together.

But one day the owl was gone. The feathered cat had flown away, and it never came back again.

LITTLE METACOMET'S QUAIL

One morning Little Metacomet heard a quail piping in the open wood, where were rocks and partridge berries. That music of the woods always caused him to turn his quick ear.

The quail was the Indian's true bird. Did the flock not sit around in a circle at night on the brown and mottled leaves, their own color, so that each one could fly away rapidly, and scatter, and did they not all come back again after such a flight, at the call of their leader, or little brown chief? Who elected the quail that called the flock a leader, and how did he know that he was to act as leader in his kingdom?

Oh, he was a shy, true-hearted bird, the quail of the white birch woods. He loved nature, and he knew when the rain was gathering, though the sun shone bright. He liked the bushes near the open meadows, the banks near the ponds where the cranberries grew, and the fringed gentians in the Indian summer. He loved to scoot, and to pipe, and to lift his velvet head high, and draw it back again.

Roger joined the Indian boy.

"He is calling for you," said Little Metacomet, "What does he say?"

"Ah, Bob-White," said Roger, repeating the Puritan interpretation.

"Is your name Bob-White?" asked Little Metacomet. "It calls you Bob White. The quail knows."

He leaped, and lifted his hand.

"Still, still."

A brown bird was darting to and fro under the bushes—two of them. They were carrying away something under their wings.

"Still, still," said Little Metacomet, "they are moving their nest."

The quails came to a heap of straw near the trail, and darted away to a huge trunk of a tree where had gathered a pile of brown leaves.

The way from their nest to this tree was brown; it was covered with brown leaves of the last fall. The birds tried to spread themselves out, so that the color might protect them. They came and went in this swift but cautious way many times.

"Let's go look," said Little Metacomet.

There were two eggs left in the nest.

"Let's go far, and see if they will come after them, now that we have looked," said Little Metacomet.

They went away some rods. The quails were true to their nest and to all of the eggs. They came scurrying back and then they came no more. They thought that they had moved their eggs from danger.

Little Metacomet now called Roger "Bob-White," as he thought the quail had named him so.

The next day, Little Metacomet said—

"Bob-White, let us go to the nest, and see how many eggs are there. Still, still."

They went very softly back to the nest. There were shells of eggs to be seen, scattered about, but no mother bird, nor any eggs. The mother quail had hatched her brood, and hurried with them away farther from danger.

"Bob-White!" The whistle came from the far woods.

"The quail is calling you," said Little Metacomet.

"Bob-White!" The tone was pure, honest, and clear.

"The quail is my bird," said Little Metacomet. "He calls you by name. I like him for that. Let us both cover the quail from harm. He is my bird—he is yours, he calls you by name. He is a little chief—I am a little chief."

LITTLE METACOMET VISITS THE WHITE-WINGED BLACKBIRD

"I know a bird," said Little Metacomet to Roger one day. "Let's go and visit him." Sassamon was with him. They traveled down to the Assowomset Lakes.

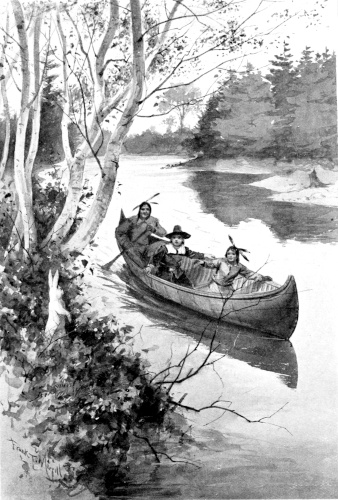

It was June. The wild roses were in bloom. Little Metacomet with Sassamon led Roger, or "Bob-White," to a great pond surrounded by black alders. It was nearly noon and the sun seemed to hang over the middle of the pond. The Indian boy found a birch canoe on the border of the pond.

They went out on the water, under the shadows of some great trees, Sassamon paddling. Small animals ran hither and thither as they passed along. Suddenly Little Metacomet said—

"Hold, I see my baby brother."

He pointed. A white rabbit was standing up on his haunches, like a little child, or a baby made of white wool.

"I no draw the bow," said he. "Good-morning, little brother of the wood."

"GOOD-MORNING, LITTLE BROTHER."

The white rabbit said nothing. The paddle struck a branch of a tree under water which caused the boat to curve. They all turned their eyes on the snag, and when they lifted them again "little brother" was gone. He understood his opportunity.

They glided along. The ospreys were wheeling and screaming overhead in the blue sky, and the red robins flamed in a colonnade of tall trees, which were bearded with green moss.

They came to a covert of dark alders and leadlike hazels. Here seemed to be a colony of blackbirds. They rose from the bushes into the sun. The male birds had red spots on their wings.

Sassamon ceased paddling that Roger might see the red wings which were in alarm, and fluttered here and there in the sun.

"That is not he," said Little Metacomet. "Wait and see my bird. I know the nest. My bird is a wonder-wonder."

He stepped on shore, and made his way through some tall grasses where were clusters of the yellow lady's-slippers, the most beautiful flower of the New England woods. He plucked one in full bloom, and cried—

"Ho, ho!"

He shook a tall black alder. There was a nest in it, from which rose a bird in great alarm.

"Ho, ho—see the wonder-wonder!"

The bird cried as if to nature for help.

It was not a red-winged blackbird—the downy spots on its wings were white.

"Bob-White—here is a brother bird of the wood. I bring you to see a brother bird of the wood. Shall I bring him down, Bob-White?"

Roger admired the beautiful white-winged blackbird, and pitied his distress.

"Has he a nest?"

"Yes, yes; come and see your brother bird, Bob-White."

But the bird flew down to the lake, its wings quivering.

"I see," said Roger. "No, you need not bring him down if he has a nest."

"You have a heart," said Little Metacomet, returning. "Never I strike a bird with a nest. Niquentum. See, he is going home."

What did he mean by "Niquentum"?

It was a law among the Indians that no one should stop or delay a traveler who uttered that word, which spoke to the heart—"I am going home." As a rule, when a traveler said that, he was going to his family who needed him: home to a wedding; home to one sick or in distress; home to help some one in misfortune; home to a funeral, to dig a grave, or to bury the dead,—it was a sacred word.

The Indian boy saw the white-winged blackbird going back to his nest.

He showed Roger, or "Bob-White," his brother with the white sign on his wing.

They pushed on to a great pond,—there were three hundred and sixty-five ponds in all this place, called the Assowomset Country,—and sailed free into the lake. Here were many geese, and among them some white geese which the Indian boy thought would delight Roger. Purple water-lilies lined the shore. The berry bushes were in bloom, and they landed and rested on some great shelves of rock under an osprey's nest, which contained possibly a half cord of wood.

While resting here and eating some powdered parched corn, they saw a fat rattlesnake on a flat shelf of rock near by.

Little Metacomet took up his bow.

"I will show you something," said Sassamon. "Wait."

He took from his pouch a pinch of tobacco, cut down a tall alder, put the tobacco on the top end of it and reached it slowly towards the reptile.

The snake coiled, rattled, lifted its head in fiery anger, and displayed its fangs.

Sassamon with a steady arm dropped the tobacco into the serpent's open mouth. The reptile uncoiled, rolled over, quivered, and was soon dead.

Little Metacomet leaped up, and sang something that sounded odd to Roger, and then began to dance.

Late in the day the great pond seemed to turn to gold in the declining light. Then they journeyed home.

It was a time of superstitions. People believed in signs and wonders. Roger found his father, the wood-chopper, very much depressed at home.

"Don't tell her," he said, referring to Susan. "But what do you think the Plymouth people have seen?"

Roger could not answer.

"An Indian scalp in the sky."

"Where?"

"On the moon."

"I am afraid you have heard some bad news," said Susan, later. But the wood-chopper did not reply. He only spread out his hands before the fire.

LITTLE METACOMET'S BLUE ROBIN

The blue jay was the bird companion of the Indian.

He could laugh, mock, and pilfer, but he did the latter in such a comical way as to cause even a red-face to smile. Very wild by nature he could be made very tame, as tame as a kitten, if brought up from the nest. Moreover, he could be called. A blue jay brought up from the nest in the house would always live near a lodge or house, and return at the whistle of its mistress.

But the joy of the woods in the early spring was the blue robin, or bluebird. The wild winter passed, ending in tempests, through which spring broke; the cowslips began to line the still frozen streams and soon to bloom amid the breaking ice; the maple buds turned red and swelled. Then out of the woods came the blue robin, and notes as lovely as the changing air announced the coming of spring.

The blue pairs breasted some hard belated winds for a time. Then the air was bloom and song, and they began to make their nests in some hollow arm of a tree, near a lodge or house often, for the blue robin was a home bird.

Little Metacomet came up to the groves one day, and discovered on the way some blue robins flying about the hollow of an oak, as in great distress. He climbed up the tree, saw a hollow in a crotch, and ran his hand down into the hollow, the blue robins flying and crying around his head.

Suddenly he found his arm in a coil as if a rope had been wound around it. The coil was cold. It tightened. He drew his arm out of the hollow and found that a black snake had coiled itself around it. The snake had gone into the hollow probably to destroy the blue robins' nest.

The black snake is not poisonous, and Little Metacomet was not frightened. He was angered that the snake should have intruded upon the blue robins. He seized it by his free hand, leaped down to the ground, and ran for timid Susan's, saying—

"Now I will give her a surprise!"

He did.

He called—"Mother Susan, Mother Susan!" as he came to the door.

Timid Susan opened the door, and shrieked—

"Roger, Roger, a snake has got Little Metacomet!"

Little Metacomet rushed in to the cabin and shook off the snake, and Susan pounded the reptile's head, and threw its body outside the door.

"Where did it get you?" asked timid Susan.

"I tore it out of the blue robins' nest. He went into a hole of the tree to destroy the blue robins' eggs, or young."

"Oh, oh!" said Susan. "The beautiful blue robins that bring the sky on their wings."

"The blue robins that paint themselves in the sky," said Little Metacomet. "I am going to defend that nest."

He went back to the tree, the others following him. He put his arm into the hollow again, and took out a blue robin, the mother bird.

"She has young," he called to Susan.

"Take care," said Susan, "there may be another snake."

He let the bird fly away, but she circled near, crying.

"I will keep the bird from harm until her young have grown," said Little Metacomet.

"So you shall, and I will help you," said timid Susan. "And the bird shall be ours. How many things we do own—we folks who live in the forest."

"I will help you, too," said Roger.

Little Metacomet looked after the safety of the blue robin daily. The parent birds came to know him. He did not need any cage for them.

THE CAT IN A BAG—THE FROG RACE

In the summer, when the cloud of war was gathering, the last beautiful season of the Indian race of the bays, the visits of Little Metacomet to the Barley cabin in the green groves of Swansea were frequent. He became more than ever a playmate of Roger, and the two searched the groves as they then were, for the wonders of nature.

The animals are gone now that then inhabited the woods of beautiful oaks, green savins, white birches, and bright waters. The moose came down from the north then, and there were bears and wolves and many foxes. Buzzards' Bay was full of buzzards, and the coves, of waterfowl.

But there were no cats, except wild cats, and when Little Metacomet found a domestic cat, all gentleness and lovingness, at timid Susan's, he thought the purring animal to be a wonder indeed. He himself had a little fox dog, or a red dog that resembled a fox. It was quite tame and followed him, and slept beside him in the lodge.

One day, when a great tempest and downpour kept the boys indoors in the green groves, the Indian playmate said to Roger—

"Let's trade."

"What shall we trade?"

"I will give you my dog for your cat. I like pussy; she purrs in my arms. You need a little dog like mine. His nose is sharp."

Timid Susan did not like the idea.

"I would be afraid that his teeth would be sharp, too sharp for me. And the cat is the only thing we have got that came from England. She seems like one of the family. But there is little that we would not do for you, Metacomet."

Metacomet sat on the floor silent for a time.

"Would you lend kitty to me? I will lend you my dog."

"Yes, yes," said Susan. "I will give her to you, and you can keep her here."

"No, no. I want my mother to see her, and the papooses and all. Let me take her to the lodges."

"But how would you carry her? She would come back. Cats come back. They see by scent. They see in the night. In the old country they carry them in bags. I will make a bag for you to carry her in, and Roger shall go with you to the oaks of Sowams when the bag is ready."

"I will send back the dog with Roger, if he will follow him."

So the trade was made, and timid Susan prepared a bag, hugged and kissed the cat many times, until she purred, and then put her into the bag and drew the string.

The two boys with the bag, which seemed greatly agitated, went together to Sowams and the little prince took the cat to his mother, who welcomed her with wonder.

When Roger was about to return, he called the dog after him, and Metacomet said to the animal—"Go!" but he would not follow. So he put a collar around his neck, and attached a long leather cord to it, and Roger, pulling the animal along, compelled him to follow him. But the dog did not seem at home in the cabin in the groves. He turned around and around as if looking for his tail, and whined. He would not eat. He seemed to be longing for the little prince, and the bountiful and lively lodges.

The next morning timid Susan let the dog out into the yard. In a moment he was gone. "He went like a streak," said Susan.

Just then they heard a sharp, glad "mew" in the road. Susan ran out in surprise. The cat was coming as fast as her legs could bring her.

"Wonder of wonders!" said Susan. "And what are we to do now? We will have to go over to Study Hill and ask the hermit what it was that made the dog go home and the cat come back. When Little Metacomet comes, I will take my slat sunbonnet and we will go over there, and ask him about these things."

They went, on a long sunny day. They asked the hermit, and he looked wonderfully wise.

"The heart follows its own gravitations," said he.

Timid Susan did not know any more what that meant than the little prince himself. But they knew that was the true answer, and Susan courtesied, and the prince's eyes blinked, and they were pleased to hear the hermit add—

"The home is in the heart; the animal's is in the lair, and the bird's in her nest, and all in their own country. Little animals love their own, and they are good people whom animals will not leave. The cat was true to Susan, and the dog to Metacomet, and you have all promised to be true to each other."

"Then we will not trade," said the Indian boy "and we will all be true to each other—I to Roger, he to me, and both to his mother, and she to us, and mother to you all."

"How many will that be?" asked Susan. "Mr. Blaxton can tell. I seem to lose my count."

So as the cat and dog did not wish to trade homes, but were allowed to stay with their own keepers.

On their road home, that day, the three paused to rest upon a moss-covered log, when they saw a toad leaping quickly along.

"What hurries him?" asked Roger.

"A snake is following him," said Metacomet.

And sure enough a snake came swiftly after the toad and struck him, evidently poisoning him.

Little Metacomet struck the snake with a stick, breaking his back.

There was a bed of plantain leaves in the moss under the trees.

The toad turned and went to the plantain leaves, and seemed to suck them, and to rub against them, and to spread himself out upon them.

"They will cure him," said Metacomet. "Had he not found the plantain he would have died. How did he know that the plantain would cure him?"

But the others shook their heads.

"They say," said Susan, "that the witch-hazels cure people of poisons. How wonderfully nature works, and I, a poor, simple soul, don't understand it as the hermit does. He knows what we don't know—there are not many like him."

Roger brushed the toad with a stalk of green leaves, gently. He leaped away; he had evidently been cured by the plantain leaves. In what school did he learn of the right doctor?

"He seems to be running all right," said Roger's mother.

The Indian boy grunted. "I could outrun him," he said.

"Outrun him?" said timid Susan. "I would think that you might with your nimble feet. I could."

"No, no, mother Susan, not if I gave him a start; there is something in him that you do not know about. Do you know how long a bullfrog's legs are when he gets to going?"

The little prince spread out his hands.

"Let me take that big frog out of the water, and tickle him by a hazel stick so that he will think it is a snake. Then when he begins to run, you run with him, and if you outrun him, I will give you a string of wampum."

So Metacomet captured a big green frog. He cut down a hazel stick, which did indeed look like a snake.

Susan dropped the sticks that she had gathered and prepared to run with the frog. Little Metacomet tickled the frog, and the frog made one leap, and timid Susan kept pace with him.

But he made another leap, more rapid than before, and another farther and more rapid still. The Indian boy tried to wiggle the hazel after him, but he was left behind.

Then the frog got to going; leap, leap! he brought all the arts of animal electricity into motion. He leaped quicker and quicker, higher and higher, farther and farther. Susan ran, but she did not know how to use electricity like the frog. At last the frog seemed to fly.

Metacomet sat down by the way and laughed in the suppressed Indian manner, while Roger rolled over and over in delight.

The frog soon left timid Susan far behind, and came to a ferny brook and dove into it from a high leap into the air.

Poor Susan threw up her hands and sat down on a fern bank by the way, saying—

"I am all tuckered out. I never would have believed it. I shut my eyes to think of it. What surprising things do happen, if you stop to look. How that frog did go! He could outrun a horse!"

Yes, Susan, and some of the arts of the twentieth century were illustrated in those long, high leaps.

THE SCHOOL OF THE WOODS

In the green groves of Swansea was an Indian national mill which may still be seen on the main road from Warren to Barneyville, about half-way between the two towns. A stone wall runs over it. It is worn smooth with the grindings of the corn, and was probably used by generations of aborigines.

Here gathered the native Indian races, and here it is probable the arts and crafts of these races were taught before the great sickness, when the Wampanoags were in their glory.

The mill was not far from the simple cabin of timid Susan, and here the sharp, hard stone probably furnished material for arrows.

Little Metacomet was educated by the grinders and the arrow-makers in places like these. On the shores he was taught to make spears and arrows in the lodges, or saw how this work was done. In places like the Indian mill he saw how mortars and pestles for pounding corn and meals were made. At Mt. Hope Lands he saw how it was that the Indian women painted their fabrics with pigeon-berry and how fruit was dried for winter use. The great cloaks of the chieftains and sagamores were probably painted there, for there were the royal lodges.

His instructor may have been his mother, or his father's brother, who died early in the Indian war, and who is said to have studied at the Indian school at Cambridge. Though he was only a little boy, princes were trained young in the Indian arts.

The first thing that was taught such children was picture making, on white birch bark. The books of the Indians were pictures on bark, and these represented the sun, moon, stars and the manitous, or gods.

The Indian boys were early taught to run. The Indian runners were almost electric in their motions, and made quick journeys from Mt. Hope or Sowams to Plymouth, or to the Narragansett country.

Little Metacomet was probably taught to use the sassafras bow and to feather his arrows from osprey-wings. The ospreys or fishing hawks were very peaceable, dwelling among the great rugged oaks. They never quarreled among themselves. But the great eagle sometimes attacked them, and then they would gather for war against him.

Little Metacomet was taught to attack the great eagle, and to help the peaceable ospreys. When his arrow brought down the eagle with its wings broken and torn, he received the applause of the arrow-makers, spear-makers, mortar-makers, and basket-makers.

In the winter canoes were hollowed from logs, and he was taught the arts of fishing. He was told of the Great Spirit who dwelt in the happy hunting-grounds in the regions of the sun. These places of departed souls were said to be in the south. The Indians sang themselves to sleep, by thoughts of the happy hunting-ground.

The making of wampum was one of the arts of the Indian schools. Wampum was made of shells, and was the Indian money.

It was reckoned by "fathoms," or the length of the string. The making of beads and ornaments of fur, feathers, and shells was also among their arts.

When the children of the braves began to grow rapidly, they were put into the hardening process, or what might be termed physical education. They were cast out into the cold in winter that they might endure cold; they were tortured that they might learn never to complain. An old song tells this story—

How to become stolid was one of the arts of this forest education.

As the months passed on, the hostility of the Indians toward the white people grew, and Susan every day talked with Roger about what would happen if hostile Indians were to "come diving down the road, right past her door."

"Mother," Roger used to say, "they would remember what the little prince has said of us. An Indian never harms a friend. The women all know how we have treated Metacomet."

A FLYING MOUSE

It was a lovely summer day. The long mornings in New England in June are almost days of themselves. Wild roses reddened the woods; there were water-lilies on the ponds, that filled the air with fragrance; the forest was all odor and song. It was glorious to live in days like these.

Little Metacomet had found a flying squirrel, and he hurried away from Sowams to the green groves of Swansea with the leathery little animal that performed such wonders among the tree-tops.

He showed his prize to Roger and his mother.

"This squirrel flies," said he. "He spreads himself out so—then he makes wings of himself, and he goes through the air so-o-o. He has far wings."

Timid Susan thought the flying squirrel a most extraordinary kind of a bird, and said—

"Let him go and run up the tall maple tree and see if he will fly."

Little Metacomet gave the "squirrel bird," as he called him, his liberty to run up the maple that was not connected with any other tree. A great oak stood near it, on the edge of the wood. The squirrel ran nimbly up the maple, and presently sailed away as on wings for the oak.

"That beats the cow that jumped over the moon," said Roger. "Did you ever know a rabbit to fly, or a deer or a moose?"

The prince laughed and shook his head.

"But I will bring you a flying mouse."

Timid Susan's eyes grew round.

"Wonder of wonders! a flying mouse. I have heard of singing mice, but never one that flew. How high can he fly?"

"All around the limb of a tree, and hang under the limb, and pick worms with his back toward the ground."

Metacomet went to the door.

"There is one now, look, look!"

He pointed to a witching little titmouse.

"That is not a mouse, but a bird," said Roger.

"No, no—he gets his living by his feet—see, see!"

The bird whirled around a dead limb, clinging to it with his feet. As he did this, picking grubs, he looked wonderfully like a mouse.

"Well, well," said Susan, wonderingly, "we will have to go to the hermit, and ask him what makes some squirrels fly, and some birds run about trees and under the limbs like mice. He knows everything, almost. Let me get my slat bonnet and we will go."

So once more they went to Blackstone's home, and asked him questions, after telling him the story of the bird squirrel and the mouse bird.

"What makes these creatures do such things?" asked timid Susan. "There seem to be a great many wonders in the world this year. What makes some squirrels fly?"

"Instinct," said the hermit.

"And now won't you tell us what is instinct—I don't seem to be gifted with much sense. You must know all these things."

"Instinct is instinct," said the hermit.

"How wonderful! I knew that you would know. 'Instinct is instinct.' Where did it come from?"

"From the divine wisdom in everything. Everything that lives has its own gift. It is Little Metacomet's gift to see into nature."

"What is my gift?"

"To have a good, true heart; that is the greatest of all gifts."

"Then you take me to be gifted woman. I will tell Joseph, my husband, the wood-chopper, of what you say. He will be proud of me then, and say—'What a wife I have got!' I will go home slowly, and get Little Metacomet to gather me some water-lilies, flying squirrels and mousing birds. Nature is proper interesting, if you only have eyes like Little Metacomet. He sees into things that we don't know about at all."

As she went out of the hermit's cabin, she looked up and said,

"There are hawks in the air."

Little Metacomet laid hold of her apron.

"There are hawks in the air," he said. "I can see. I'll keep them away for you; I will always keep you and Roger from harm. Hawks, hawks; there are hawks in the heart."

What did he mean, this boy of ten, this small philosopher?

Timid Susan caught Little Metacomet's meaning. There were hawks in the red man's heart, and there were Indians who were hostile to the white people. They were becoming more and more numerous, and his father the king sometimes found it difficult to restrain them from open violence.

"I hope I will never live to hear the war-whoop," said Susan, and Metacomet answered gravely,

"I hope you never will."

LITTLE METACOMET SEES HIMSELF IN A LOOKING-GLASS

Among many wonderful playthings of wood, metal and shell that Little Metacomet had in his lodge were a bundle of notch-sticks, by which he numbered the changes of the moon, and rising of the tide. His mother had shown him how to make these calculations, and she had been taught by a paniese, or Indian prophet. He came out to the groves one day, and brought his notch-sticks with him, and he told timid Susan that he could tell her when the moon was going to change.

"Are you sure?" said she. "I'm powerful uncertain about the planets. Suppose to-morrow night should be the full moon instead of the new moon?"

"No, no," said the little prince, "the paniese, he knows."

"How does he know?"

"Because things are always so. The Great Spirit he never changes his notch-sticks."

Timid Susan raised her hands.

She had a looking-glass. She kept it covered for fear of the dust and flies, and when the little prince was explaining to her how the Great Spirit never changed his notch-sticks, a happy thought came to her. She would show Little Metacomet his own face in the looking-glass.

A tame blue jay came into the door, and lighted upon Little Metacomet's crown of feathers, and the cat ran toward them with her back up to drive the audacious bird away.

Just here timid Susan took the curtain from the glass and lowered it, so that the prince could see his face, and the bird with her pretty head with its raised crown, and the cat with her humped back and resentful eyes.

The prince had never seen a looking-glass before. He had seen his face in the clear water among the lilies, the water glass. But when he saw himself now with his crown feathers, and the blue jay with her crown feathers raised, and the resentful cat, he thought that all had changed into two. He rolled over in surprise, the bird screamed, and the cat drew back.

The bird flew up to one of the beams under the roof, and expressed her surprise in a series of shrieks that sounded like the turning of a rusty crank.

The cat ran down toward the glass, and found what seemed to be another cat rushing towards her. She drew back and spit, and the other cat seemed to do the same.

Metacomet leaped up and went toward the other little Indian in the glass, which seemed to mock him.

"I am two to-day," said he, gazing into the glass. "Where did you get the water face? I came here to surprise you and you surprised me. I have a sun glass in the lodge that the English gave to my father. It draws down the fire from the sun. Don't you think it is all great conjuring? The notch-sticks they be always the same. Why are the notch-sticks always the same over and over, why the moon full out and be sharp again? It was so in the moons ago. Why?"

Susan shook her head.

"It is so because it was always so."

And they knew as much as anybody knew about it—even the hermit.

ROGER GOES TO THE INDIAN RACES

One day Little Metacomet came to timid Susan with a message that caused her to stand long silent, with lifted hands and open mouth.

"My father has sent for Roger."

"But you scare me; I can't spare him; he is all I've got. What does the king want him for?"

"To see the races. He wants to be good to Roger because you have been good to me—you give me pancakes."

"What are the races?"

"The races of the Indian boys at Mt. Hope. The boys race, jump over a rock into the water, and swim, swim, swim, and he who runs and swims the fastest and farthest, is given moccasins, and is made a runner."

"And what is a runner?"

"He carries words from one part of the country to another."

"Roger, I will have to let you go. It will be better for us to do as Philip wishes."

So Roger went with Little Metacomet to Mt. Hope.

It was a land of brightness, beauty, and history. Here the forest lords may have reigned for a thousand years.

The throne of Philip was a tall cliff, at whose foot ran a natural spring. The cliff and spring are still to be seen. It faced the sea, and over-looked the far forests, the Indian villages of Kickemuit and Sowams, both of which were at natural springs near the sea.

Here he lighted his council fires. Here he gathered his warriors to national dances. Here he prepared to make his last hunt with a thousand warriors, which he believed would end the dominion of the English race.

Wetamoo, the warrior queen of his dead brother Alexander, reigned at the sunny highlands of Pocasset, across the bay from the throne cliff of Mt. Hope.

Philip made Mt. Hope the place of his royal residence. Here were the shell villages, the national cornfields, and the ancient burying-ground of the Indian race. There were other royal places, but this was the favored resort.

What a beautiful elevation about the seas, these rocks were! The shores were shaded by great oaks, and the rocks were green with savins. Here the ospreys or fishing eagles made their nests and wheeled screaming in the purple sky at noon. Here were the great river meadows where the night heron wandered. Over the bay, where Fall River now is, were the woods of Pocasset, grand with ancient trees and tangling vines. The wild grape grew there, its vines purpling in the fall. There was sumac. There the arbutus bloomed in the snow of early spring, the laurel blazed in early summer and the wild aster and purple gentian fringed the meadows.

To the west from the great boulders on the summit of the Sugar Loaf Mountain lay the cerulean expanse of the Narragansett, into which the sail of Verazzumi had ventured, and found the shores a vineland. At the foot of the mountain were shelving rocks where the Northmen are thought to have landed in 1001. After the tradition, the first white child in America was born there, near the place where now is the Sanitarium. To the north ran the Kickemuit through cornfields, and sea meadows—where grew the giant thatch of which cabin roofs were made. There were the shell villages around the natural springs.

It was a bright day in early spring, that of the races. Across the bay came the skiff of Queen Wetamoo, seeming as light as air. The queen was plumed, and bedecked with red robes and glittering pearl shells. She was to crown the winner of the race.

Her sister, Philip's wife, who was called the beautiful princess, received her. Then the drums were beaten, and the tribe formed a semicircle, with Philip on a black horse in the front, and the signal was given, and the race began.

Twelve or more youths started from the top of the hill and seemed to fly over the ground and through the air. They wheeled down to a rock on the borders of the bay, leaped the rock, and went swimming out into the tide. The Indian warriors shouted and the women cried out and waved their hands.

An Indian boy, shorter but more nimble than the rest, won the race, and came swimming back to receive the moccasins from Queen Wetamoo.

Then Philip spread out his hands. The tribe formed a circle, and the princess brought forward a pair of moccasins, decorated with pearl.

The Indians' eyes were all fixed upon Roger.

The princess came up to Roger, and laid one hand on his shoulder.

"These are for you," she said. "You have a good mother. We have all heard of the good woman of the haystack, who fries pancakes for the young chief. Put up your foot."

The princess put the shoes on Roger's feet, and said—

"Now carry my heart to your mother."

A shout went up that seemed to pierce the sky, and Roger went home to his mother, his heart almost bursting with pride and joy.

THE THUNDER BIRD

The Indian's mind was full of poetry, and nature was like a book of poems to it! The seasons published the poems year by year.

Little Metacomet thought the cabin in the groves the most delightful of the hiding-places of nature, for the lands of the rivers and bays were to him the open world. He, too, liked the old haystack and the green haystack meadows.