Title: Account of the Skerryvore lighthouse

with notes on the illumination of lighthouses

Author: Alan Stevenson

Release date: January 26, 2025 [eBook #75213]

Language: English

Original publication: Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1848

Credits: deaurider, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

Larger versions of illustrations and plates are available by opening them in a new tab or window.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

SKERRYVORE LIGHTHOUSE.

BY

ALAN STEVENSON, LL.B., F.R.S.E., M.I.C.E.,

ENGINEER TO THE NORTHERN LIGHTHOUSE BOARD.

“ΥΠΕΡ · ΤΩΝ · ΠΛΩΙΖΟΜΕΝΩΝ”

Inscription on the Ancient Pharos of Alexandria.

BY ORDER OF THE COMMISSIONERS OF NORTHERN LIGHTHOUSES.

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK, NORTH BRIDGE, EDINBURGH.

LONGMAN AND CO., LONDON.

MDCCCXLVIII.

PRINTED BY NEILL AND COMPANY, EDINBURGH.

[iii]

I am unwilling to dismiss the following pages from my hands without saying a few words in extenuation of the defects which they contain. My chief plea in defence is, that the preparation of this Account of the Skerryvore Lighthouse, and the Notes on the Illumination of Lighthouses which follow it, was not chosen or assumed by me, but was a task imposed by the express desire of the Lighthouse Board, to whose enlightened and liberal views the Mariner owes the erection of the Lighthouse itself. My labours were also continually interrupted by the urgent calls of my official duties; and, on several occasions, I was forced to dismiss unfinished chapters from my mind for a period of several months—circumstances which, I hope, will in some measure account for the desultory character of the performance, the disproportion of some of its parts, and more especially for repetitions and perhaps omissions which would otherwise have been quite unpardonable.

Having said thus much by way of apology for this Volume, I must acknowledge my many and great obligations to my Father who preceded me as Engineer to the Board of Northern Lighthouses, and of whose experience, as the Architect of no fewer than twenty-five Lighthouses, including that of the Bell Rock, I had[iv] the full benefit during the erection of the Skerryvore Lighthouse. To the generosity of my esteemed friend, M. Leonor Fresnel, I owe all that I know of the Dioptric System of Illumination, invented by his late illustrious Brother; but this general acknowledgment will not supersede the necessity of frequent repetitions of my obligations to him, as occasion offers, in the course of these pages. I have also derived much assistance, as a careful reader will easily trace, from the valuable little work of M. Peclet, entitled Traité de l’Eclairage. There are, besides, many other obligations, which I cannot attempt to acknowledge individually, but which those, who kindly conferred them, well know how much I value.

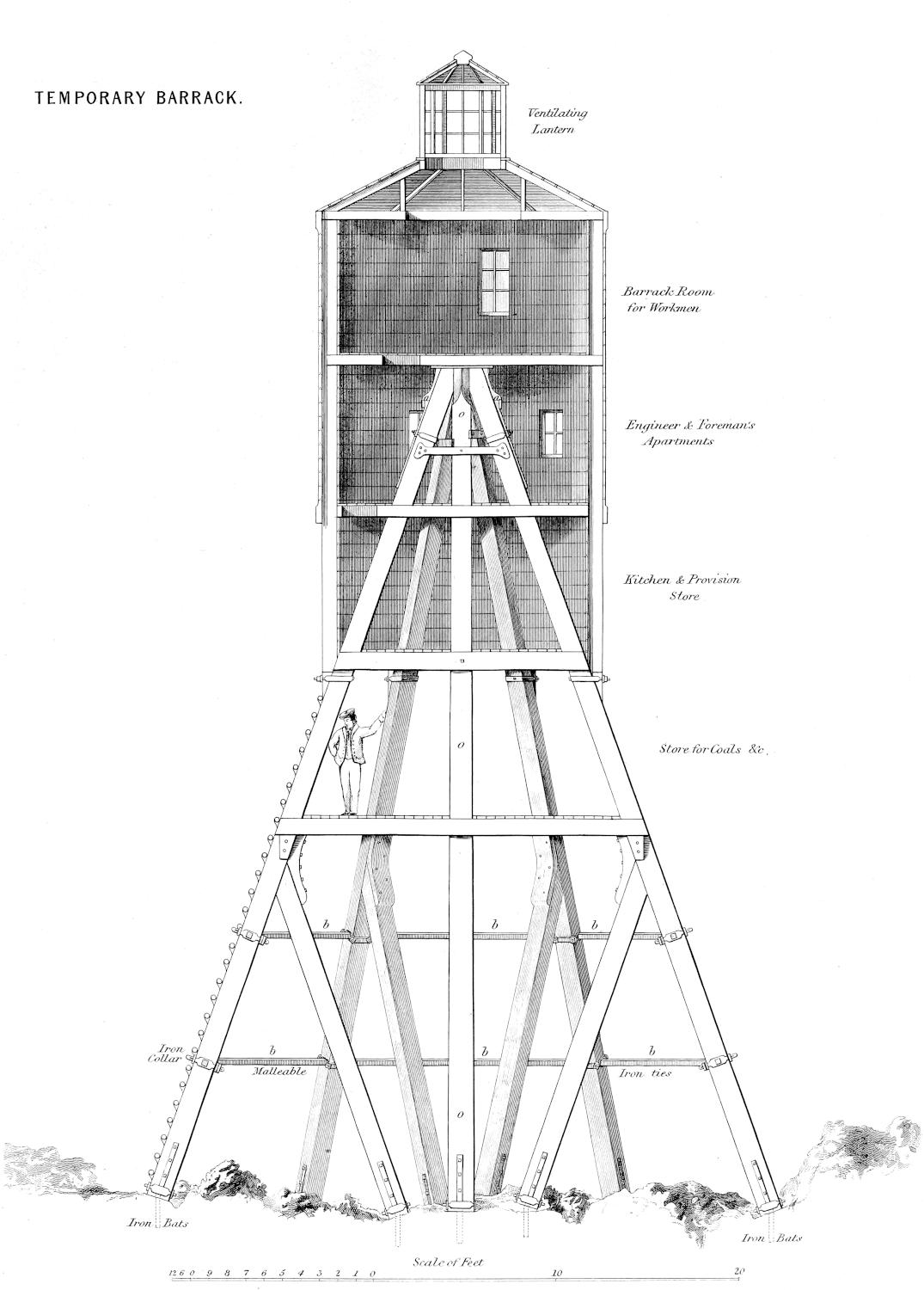

In the Account of the Skerryvore Lighthouse, which forms the first part of this Volume, there is an important omission; and, in this short prefatory notice, I gladly embrace the only opportunity, which now remains, of supplying the defect. Although, in the course of the Narrative, I have occasionally noticed some special deliverances from danger, I have altogether neglected to record the remarkable fact, that, amidst our almost daily perils, during six seasons on the Skerryvore Rock, there was no loss of either life or limb amongst us. Those who best know the nature of the service in which we were engaged,—the daily jeopardy connected with landing weighty materials in a heavy surf and transporting the workmen in boats through a boisterous sea, the risks to so many men, involved in mining the foundations of the Tower in a space so limited, and above all, the destruction, in a single night by the violence of the waves, of our temporary barrack on the Rock,[v] which had cost the toils of a whole season, will not wonder that I am anxious to express, what I know to have been a general feeling amongst those engaged in the work—that of heartfelt thankfulness to Almighty God for merciful preservation in danger, and for the final success which terminated our arduous and protracted labours.

Edinburgh, March 25, 1848.

| PART I. | |

| ACCOUNT OF SKERRYVORE LIGHTHOUSE. | |

| Page | |

| Introduction — Constitution of the Lighthouse Board — Lights established since 1821 — Improvements in the mode of illumination — Dioptric Lights — Beacons and Buoys, | 9 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Topographic notice of the Skerryvore Rock, | 19 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Preliminary arrangements and works, including survey of the rocks, and opening of quarries from 1834 to 1837 — Survey of the Skerryvore rocks — Disadvantages of Tyree — Pier and workyard at Hynish, Tyree — Quarries at Hynish — Skerryvore Committee appointed, | 37 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

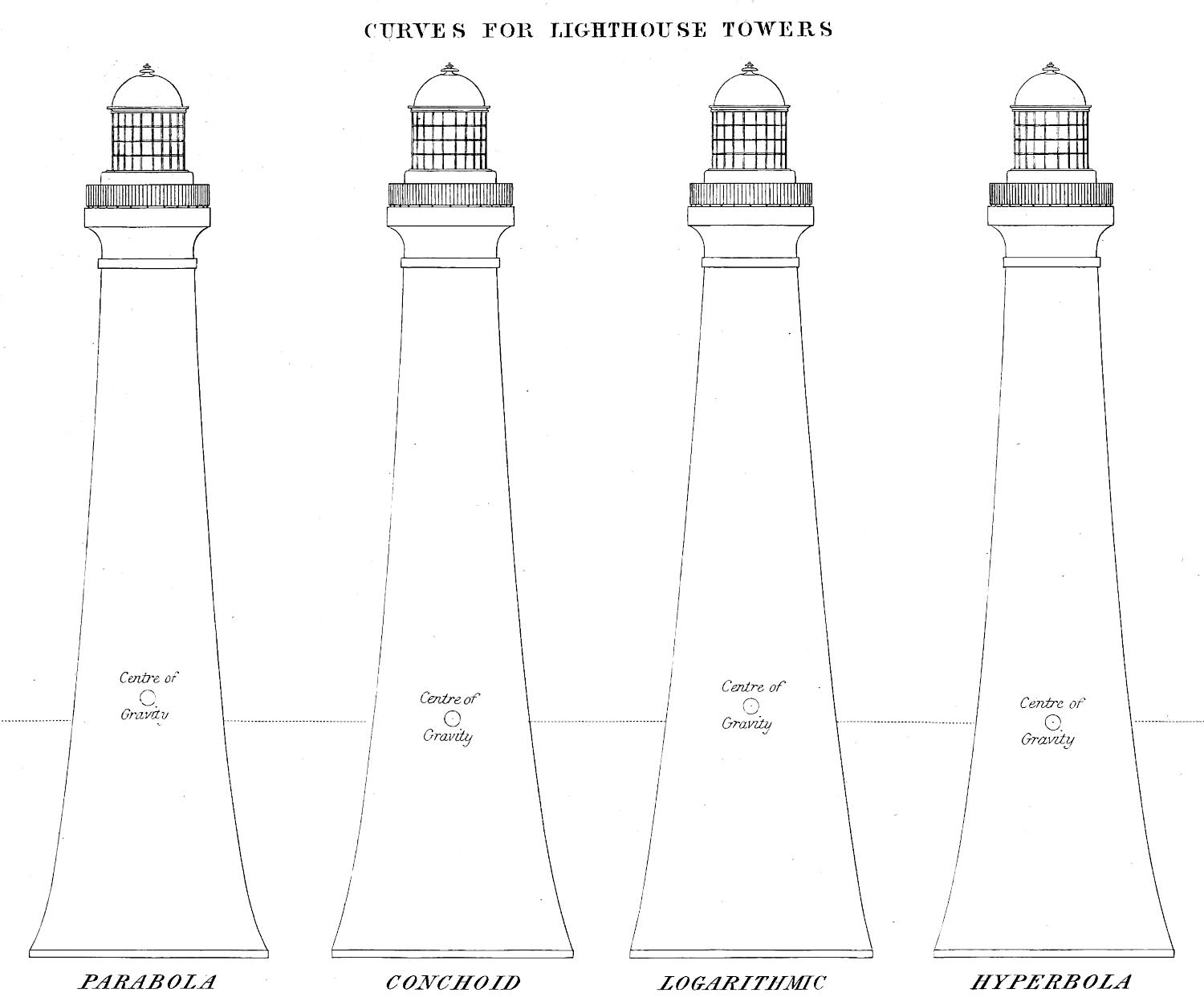

| On the construction of Lighthouse Towers, | 45 |

| CHAPTER IV. OPERATIONS OF 1838. |

|

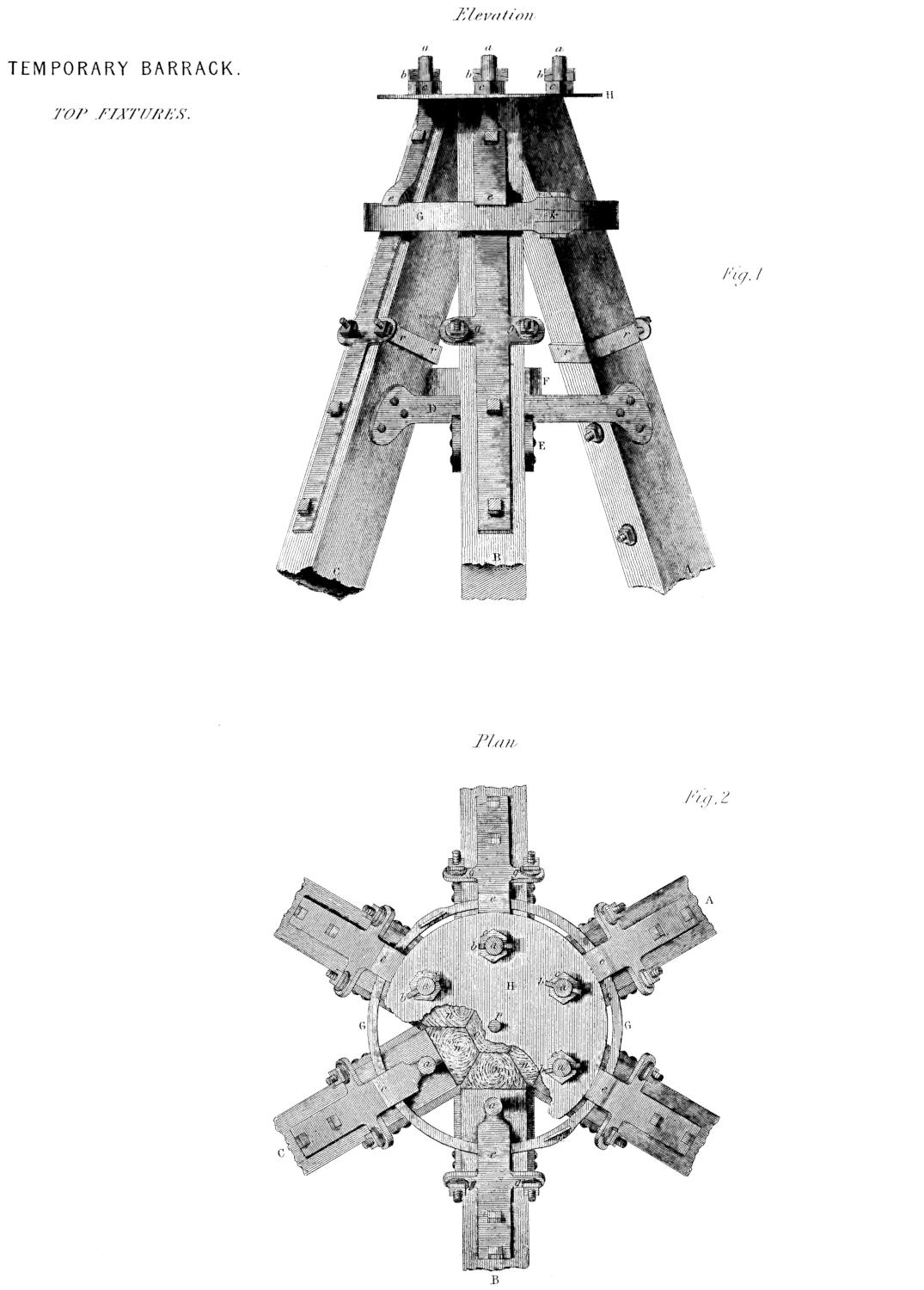

| Temporary Barrack on Rock — Tools and machinery — Steam Tender for the works — Employment and wages of workmen — Progress of the outfit for the season’s operations — Embark for Skerryvore — Lay down moorings, and try to land on the Rock — Driven to Mull — First day’s work on the Rock — Shipment of materials at Glasgow and Greenock — Reach Tyree — Driven to Mull — Return to Tyree — First good day’s work on the Rock — Sudden gale and great peril to the vessels — Reach Hynish in safety — Detained by bad weather four days at Hynish — Return to the Rock and have six days of good weather — Erection of the pyramid of the wooden barrack — Mode of determining the length of the beams, and the sites for their fixtures — Pyramid completed — Mode of living while erecting the barrack — Shoals of Medusæ seen — Driven by a gale to Mull — Return to Hynish and are driven to Coll — Return to the Rock — Driven to Tyree — Return to the Rock — Horizontal braces fixed — Driven to Mull — Heavy gale — Timber[viii] cast on Tyree — Return to Rock and further progress of barrack — Last day’s work on Rock this season — Precaution for the benefit of shipwrecked seamen — View from top of pyramid — Destruction of the barrack during a gale — Letter from Mr Hogben — Proceed to Skerryvore — State in which the Rock was found — Cause of the destruction of the barrack — Preparations for a new barrack — Works at Hynish — Hynish quarries, | 71 |

| CHAPTER V. OPERATIONS OF 1839. |

|

| Shipping station and pier at Hynish — Granite quarries in Mull — Observations on the quarrying of granite — Dressing of the Lighthouse blocks — Excavation of foundation for the Lighthouse Tower on the Skerryvore Rock — Fitting up of the second barrack on the Rock — Sudden death of George Middlemiss — Wharf and landing-place on the Rock — Ring-bolts, water-tanks, and railways — Incidents of the season — Effects of a gale from the south-west — Mutiny of the crew — Near approach of the vessels to the Rock, and other circumstances shewing the importance of a Light on the Skerryvore, | 107 |

| CHAPTER VI. OPERATIONS OF 1840. |

|

| Hynish workyard — Hynish pier — The Rock — Life in the barrack — Foundation-pit — Landing of the materials on the Rock — Laying the first stone, | 140 |

| CHAPTER VII. OPERATIONS OF 1841. |

|

| Hynish workyard — The Rock — The waves — Colours of the breaking waves — The seals, | 151 |

| CHAPTER VIII. OPERATIONS OF 1842. |

|

| State of the Rock in Spring of 1842 — Commencement of Rock operations — Last stone — The Lantern, | 163 |

| CHAPTER IX. CONCLUDING OPERATIONS AND EXHIBITION OF THE LIGHT. |

|

| Harbour works — Bo Pheg beacon — Light-keepers’ and seamen’s houses — Concluding works on the Rock, such as pointing, &c. — Interior fittings of the Tower — Light-room apparatus, and first exhibition of the Light — Removal of the barrack from the Rock — Expense, | 169[ix] |

| PART II. | |

| NOTES ON THE ILLUMINATION OF LIGHTHOUSES, WITH SHORT NOTICES OF THEIR HISTORY, 181. | |

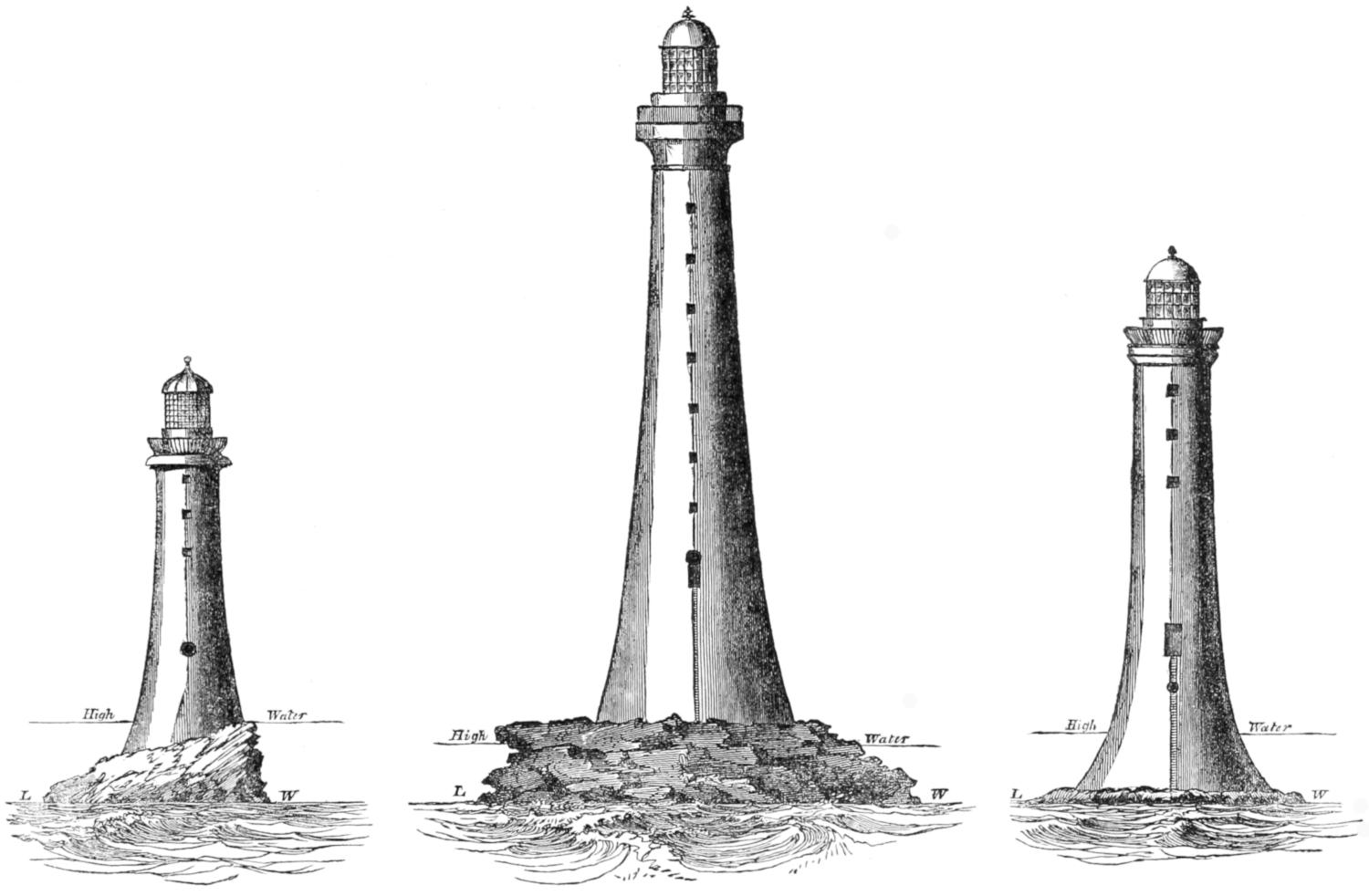

| Early history, 181 — Colossus of Rhodes, 182 — Pharos of Alexandria, 183 — Coruna Tower, 187 — Lighthouse at the mouth of the Quadalquivir, 188 — Ancient Phari in Britain, 188 — Tour de Corduan, 189 — Eddystone, 189 — Bell Rock, 192 — Carlingford, 194 — Iron lighthouses, 194 — Early modes of illumination, 195 — Flame, 196 — Drummond and Voltaic Lights, 199 — Mr Gurney’s Lamp, 200 — Argand Burners, 200. | |

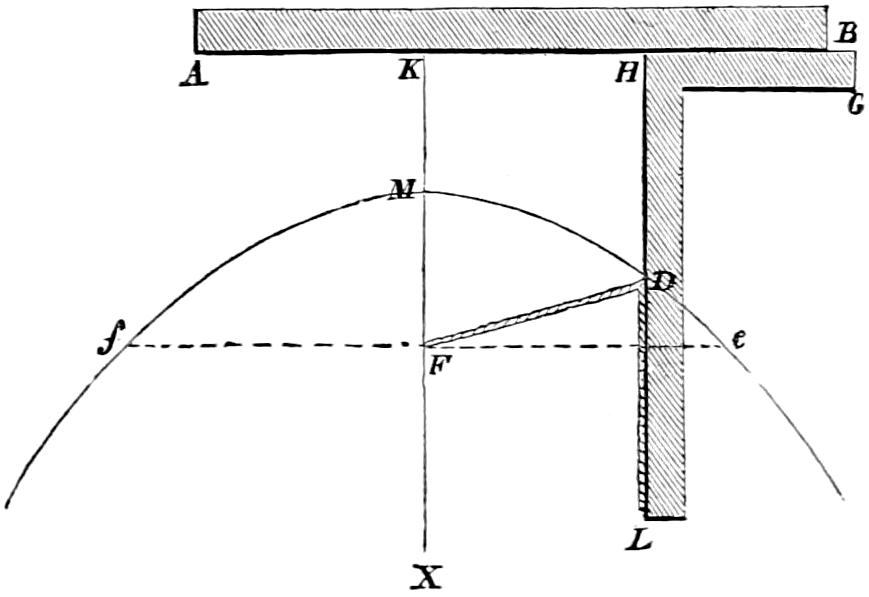

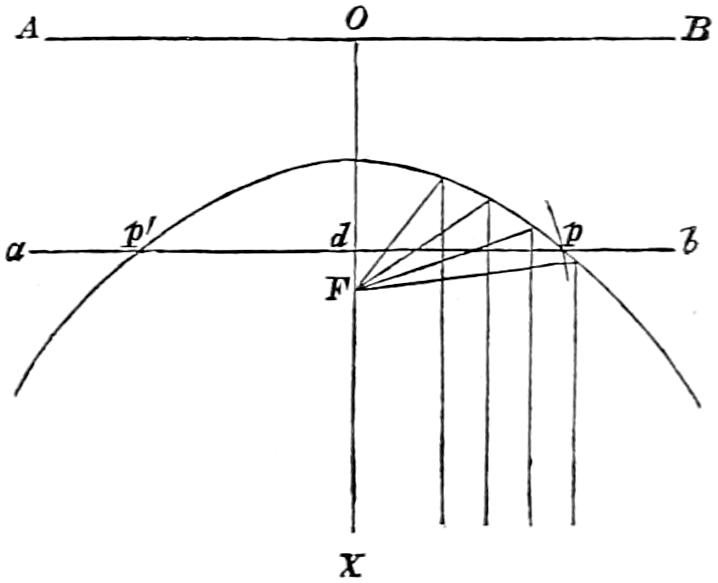

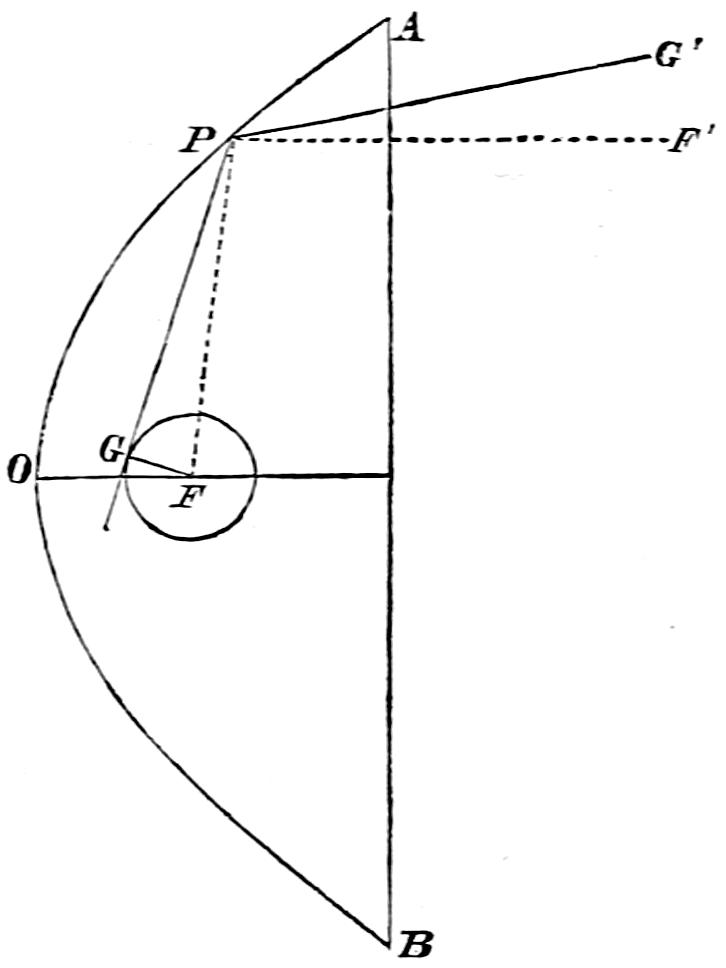

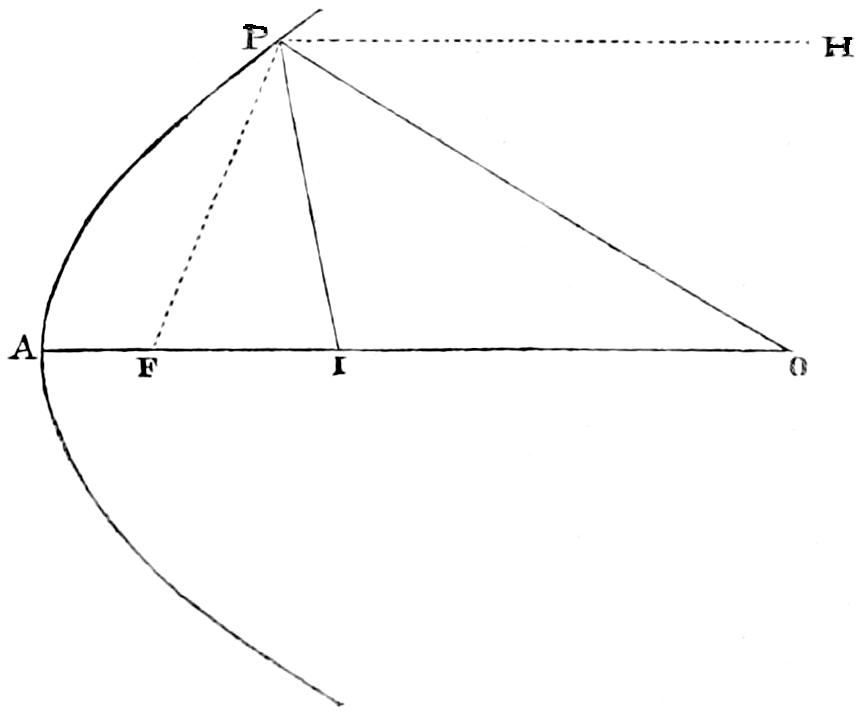

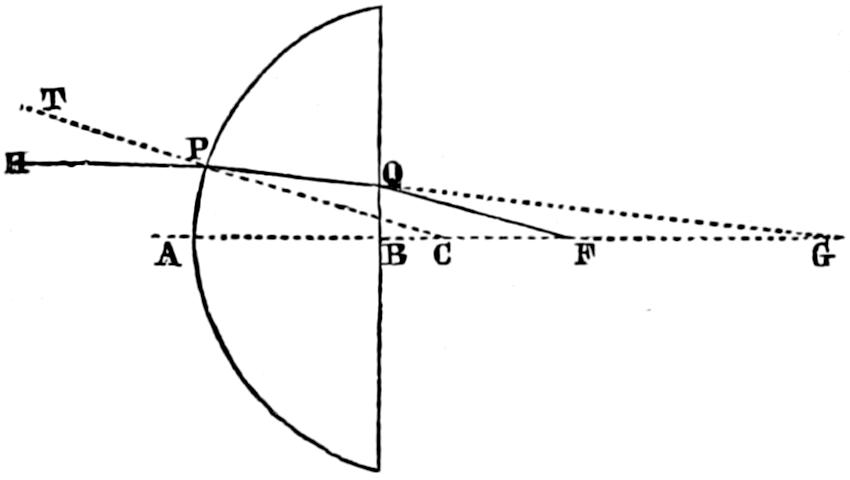

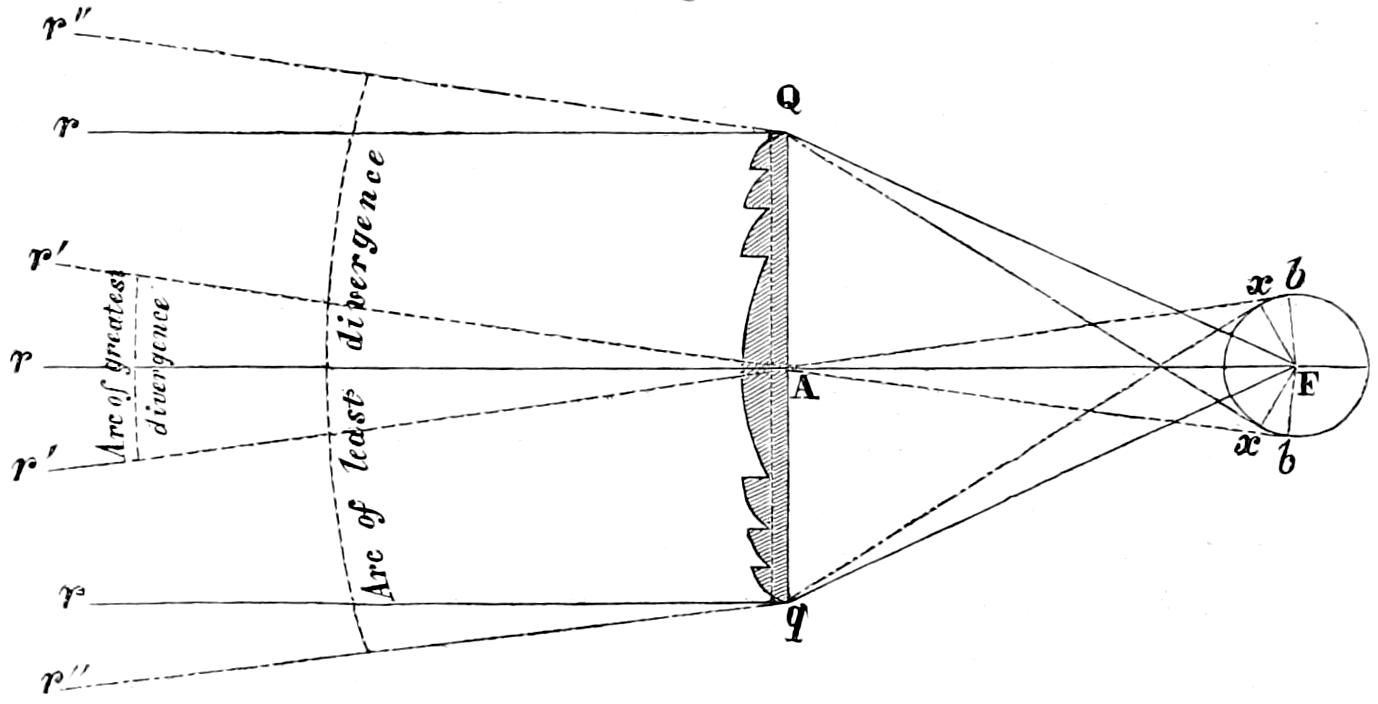

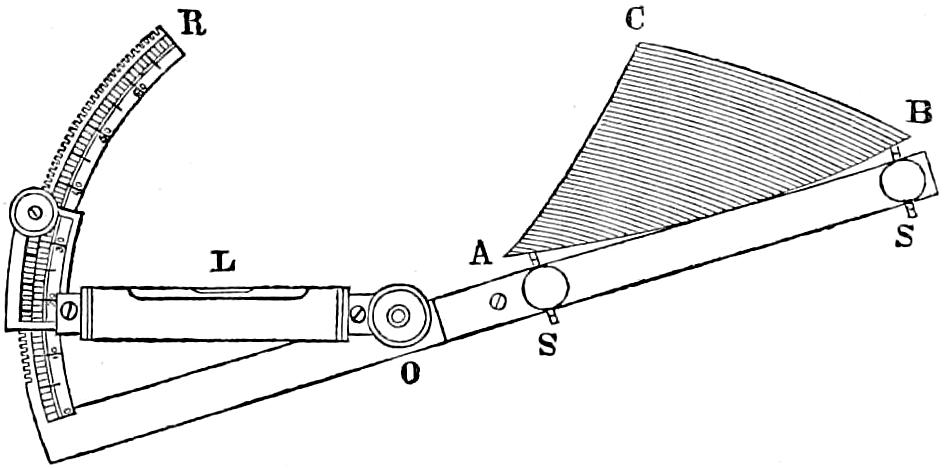

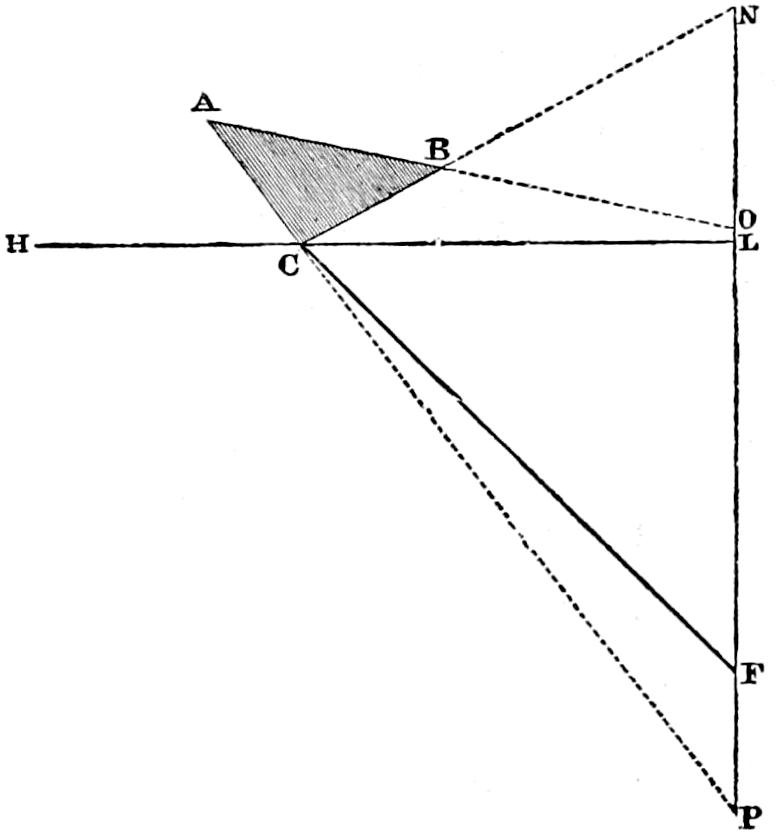

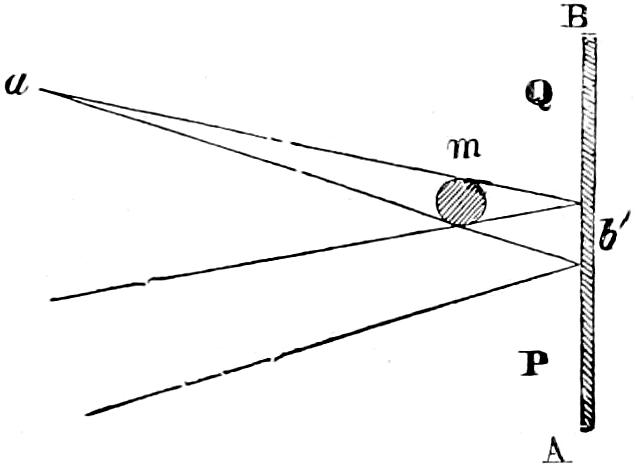

| CATOPTRIC SYSTEM OF LIGHTS, 204. | |

| Application of Paraboloidal Mirrors, 205 — Reflection, 207 — Paraboloidal Mirrors, 209 — Divergence of Paraboloidal Mirrors, 212 — Effect of Paraboloidal Mirrors, 217 — Power of ditto, 218 — Manufacture of reflectors, 218 — Testing of mirrors, 219 — Argand Lamps used in reflectors, 220 — Arrangements for raising or lowering the Argand wick, 222 — Flowing of the lamp, 223 — Placing the lamp in the focus, 226 — Distinctions of Catoptric Lights, 227 — Colour as a distinction for lights, 229 — Arrangement of reflectors on the frame, 230 — Bordier Marcet’s reflectors, 232 — Fanal sidéral, 232 — Fanal à double effet, 234 — Fanal à double face, 236 — Mr Barlow’s spherical mirrors, 237 — Captain Smith’s mirrors in the form of a parabolic spindle, 238. | |

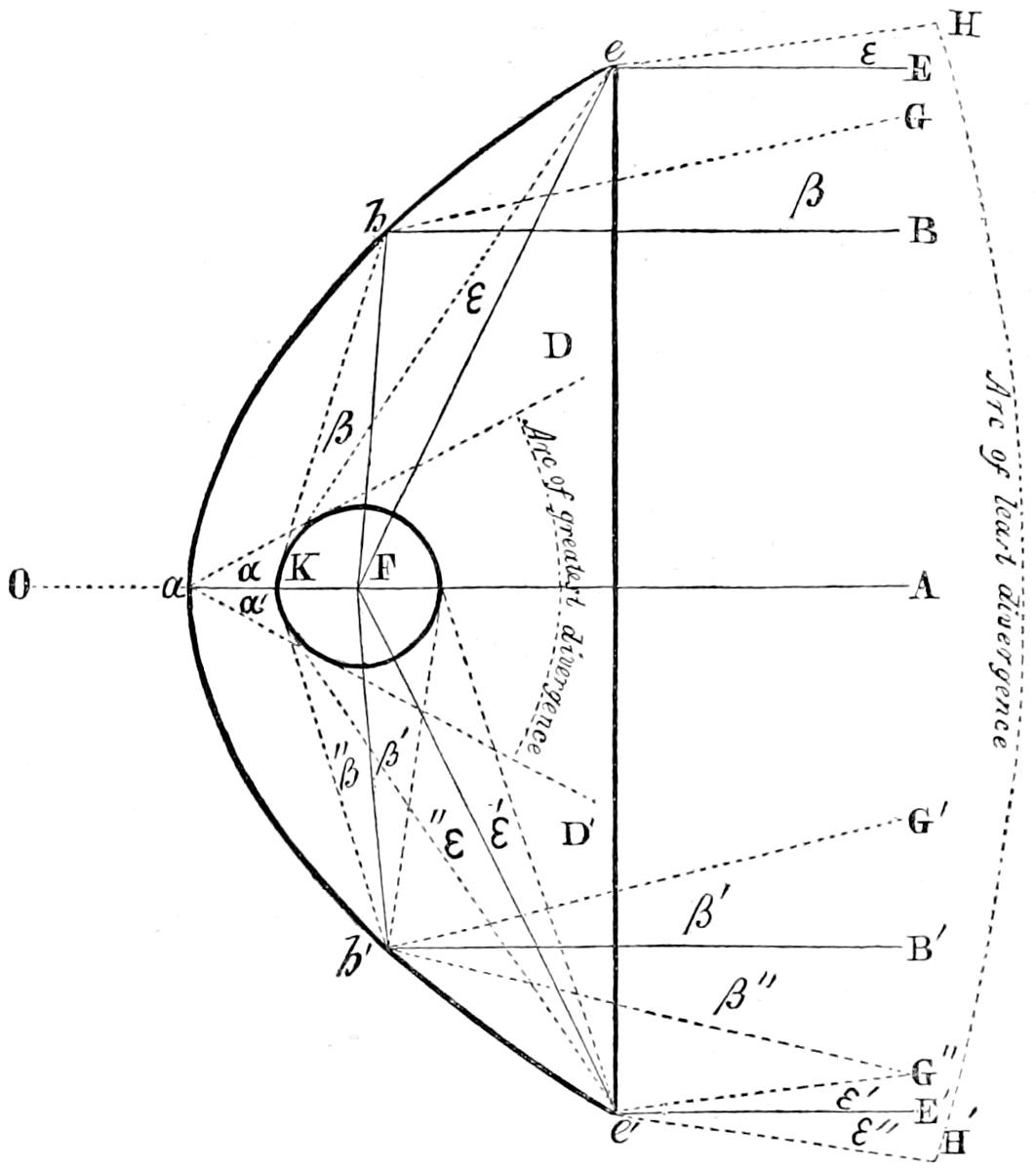

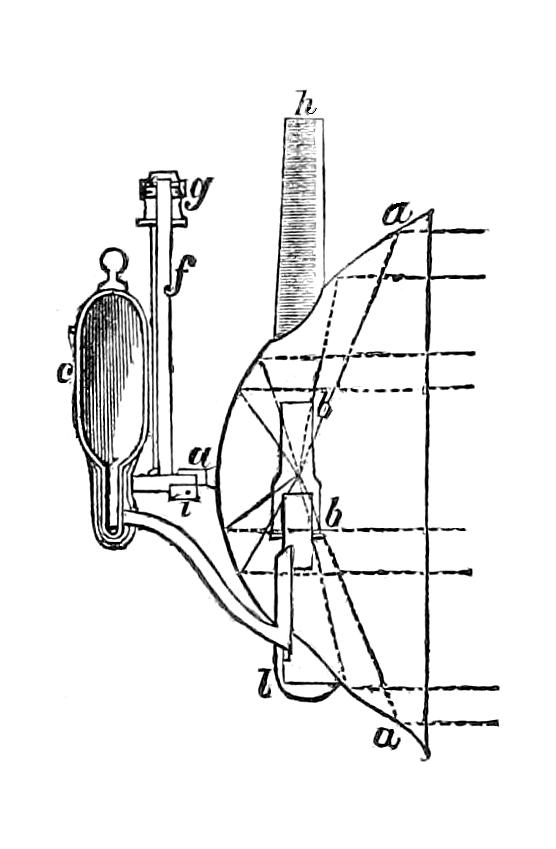

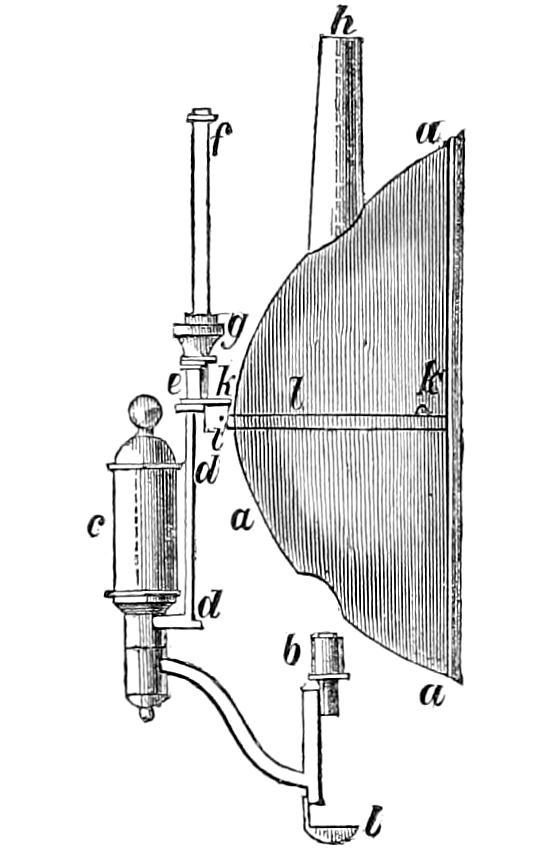

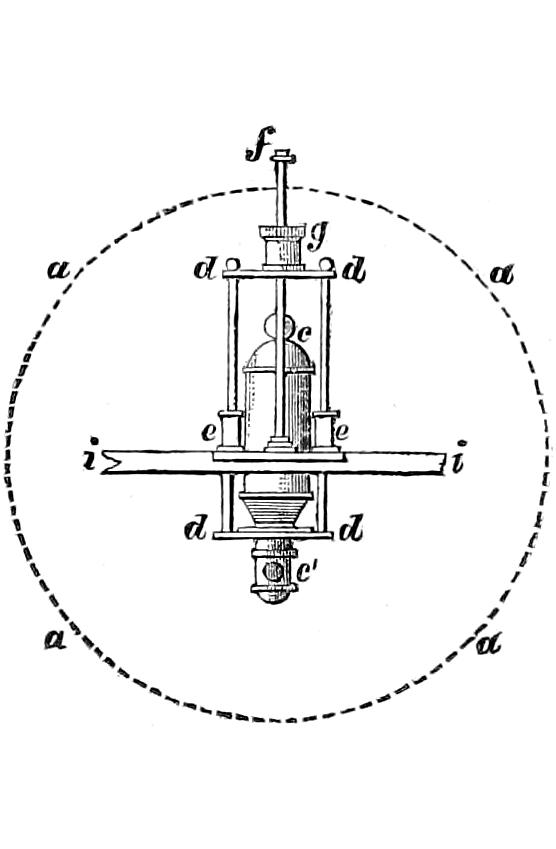

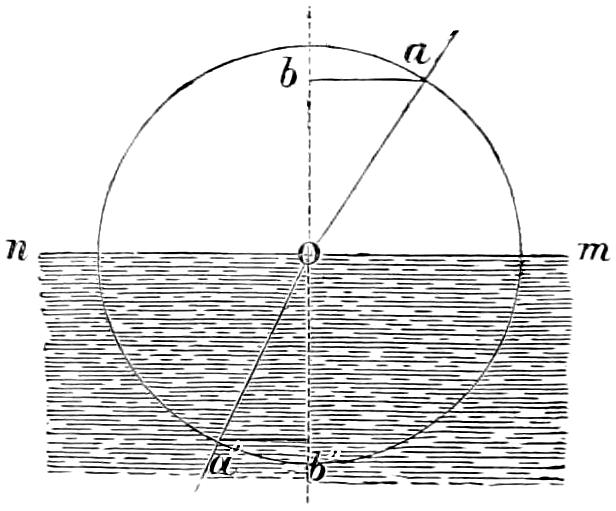

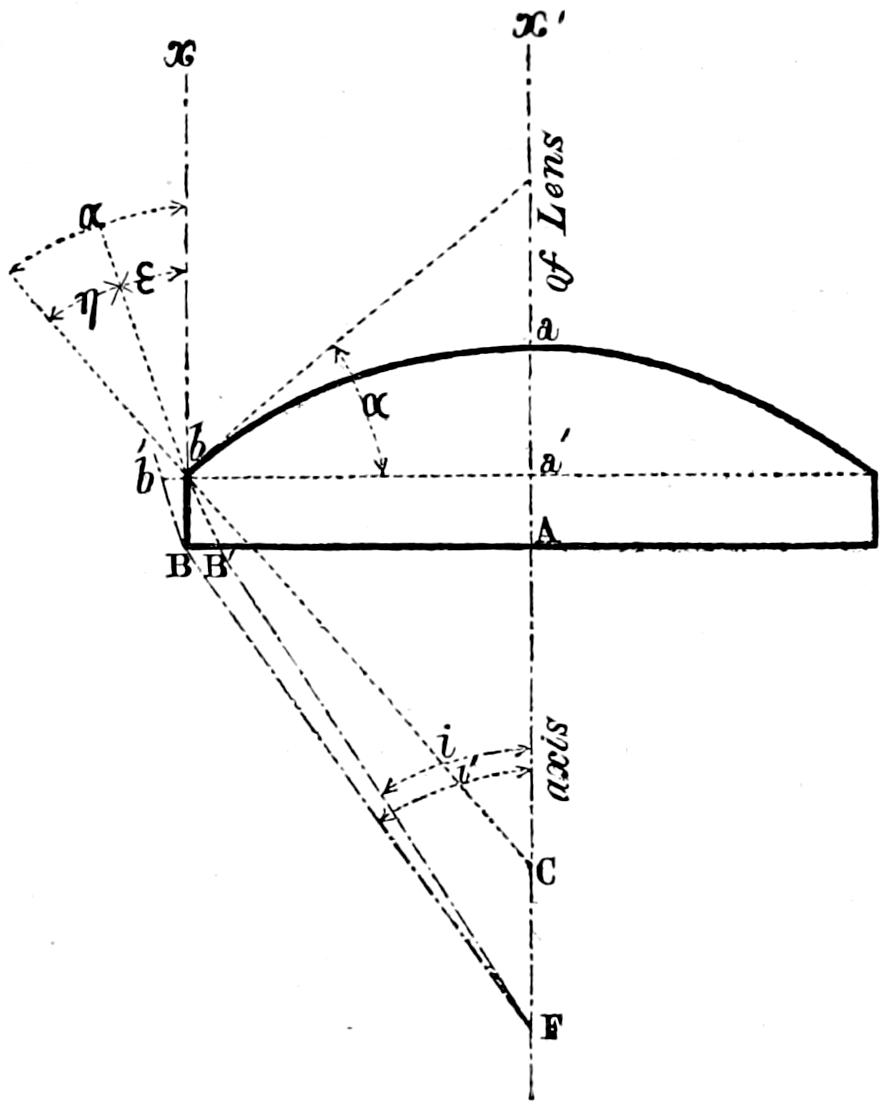

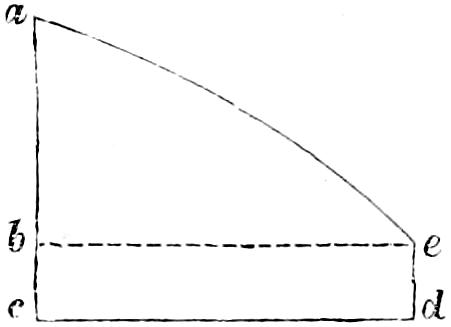

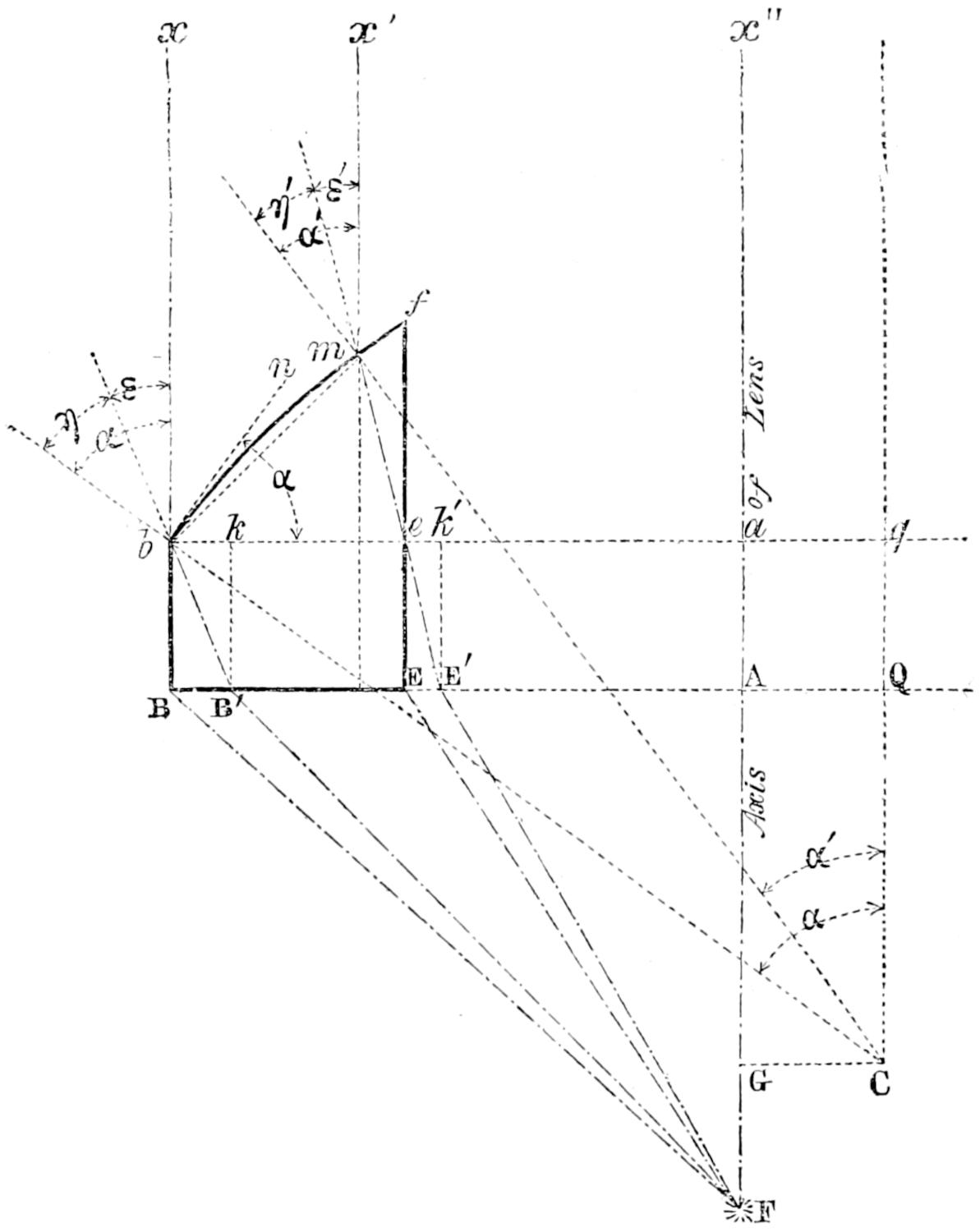

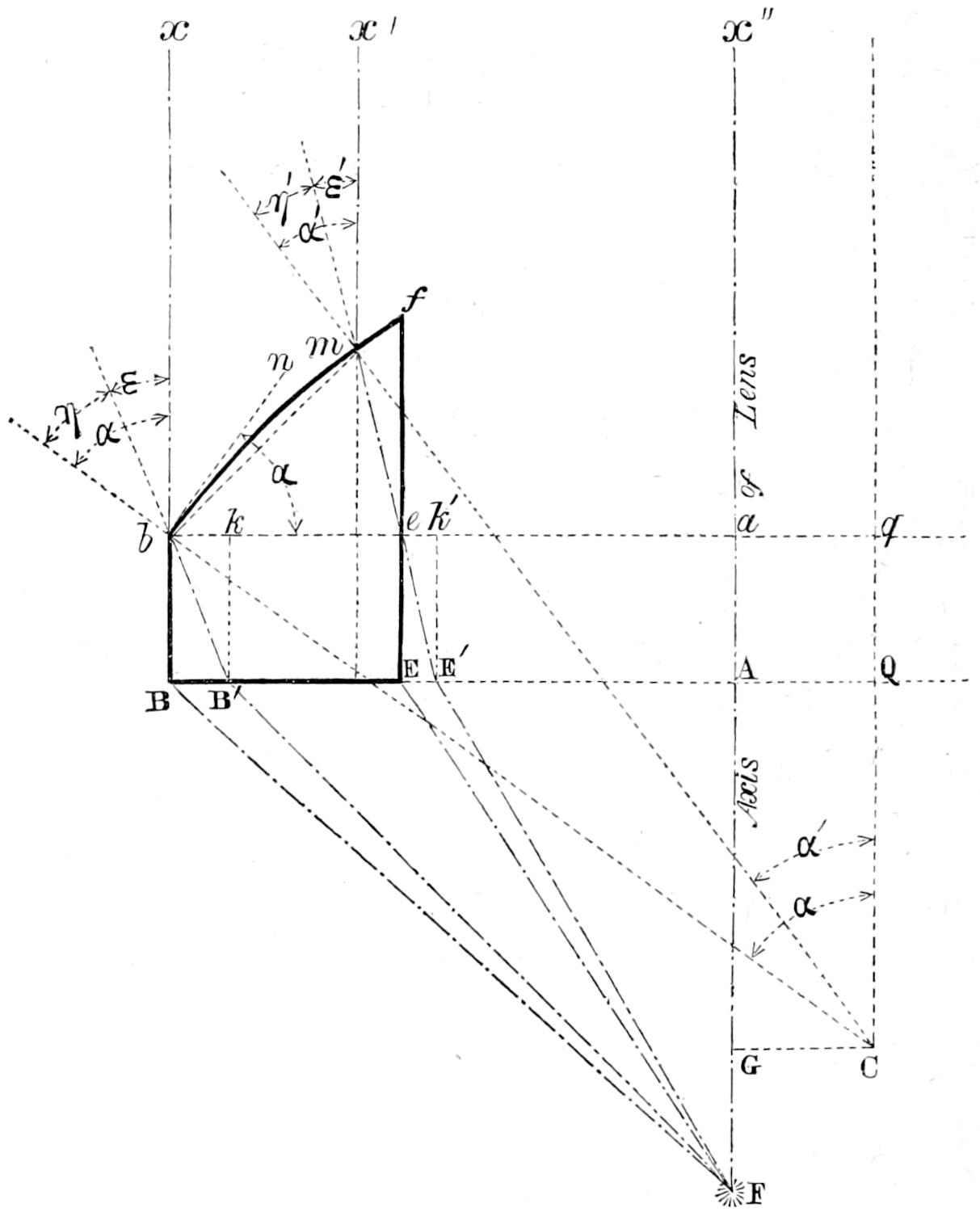

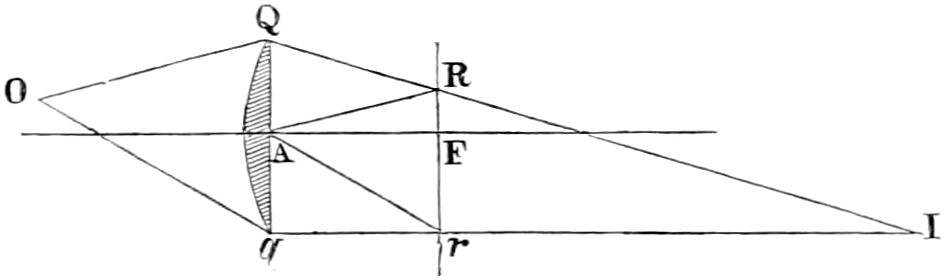

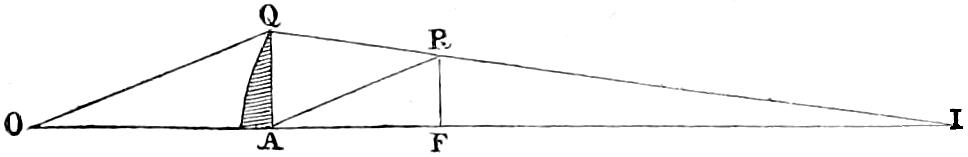

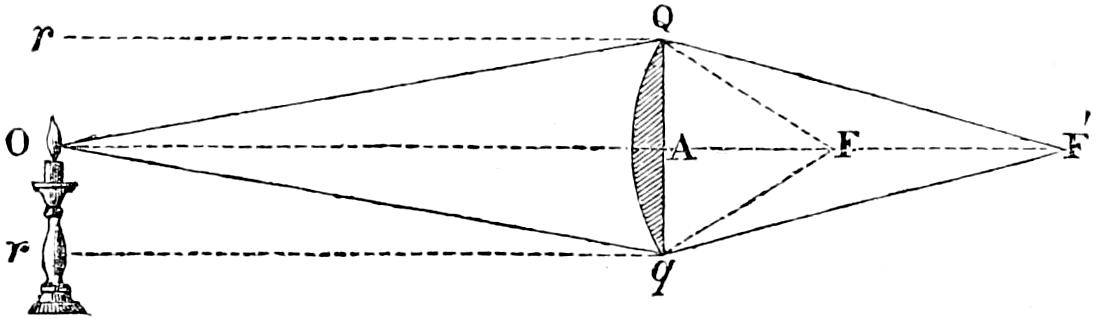

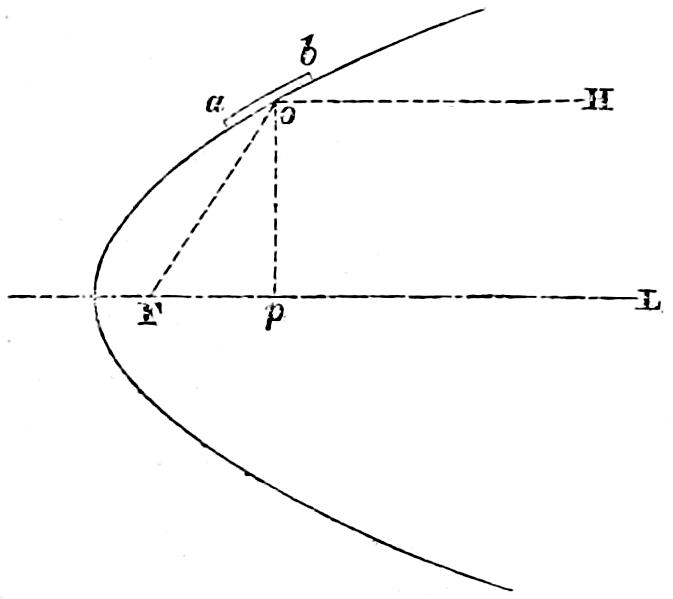

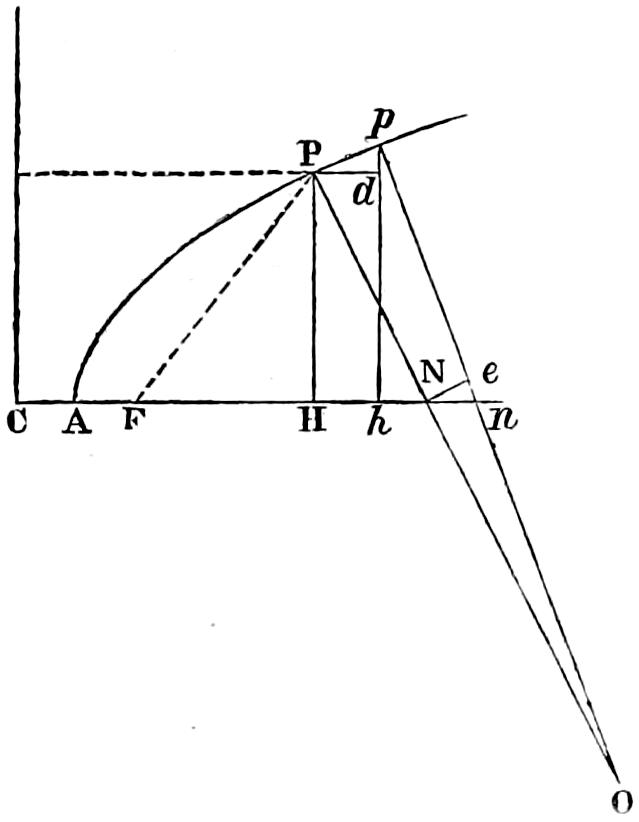

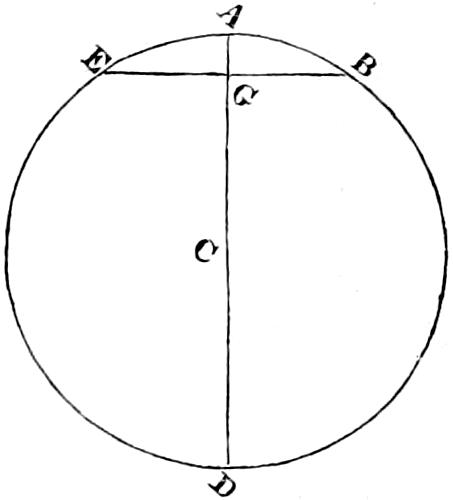

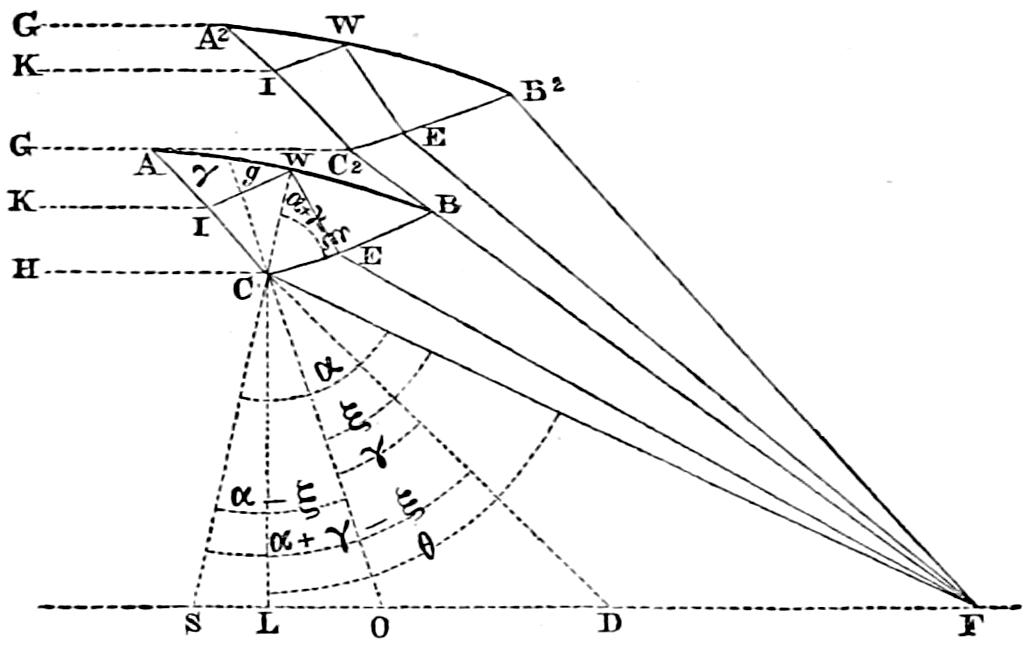

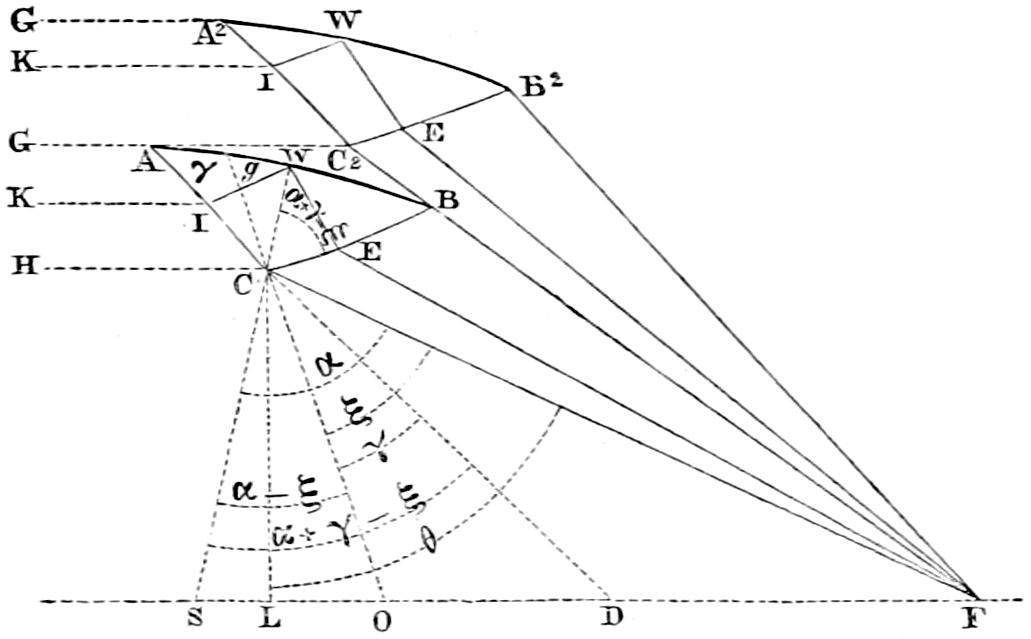

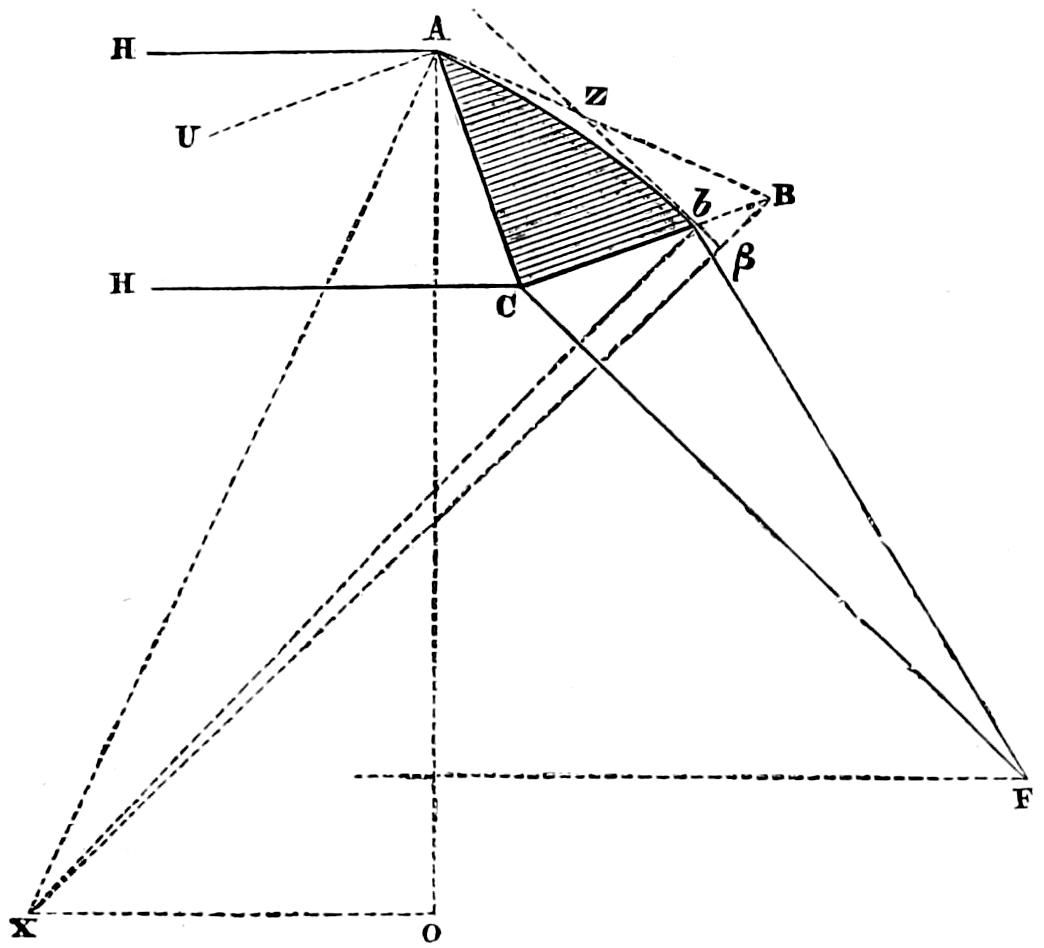

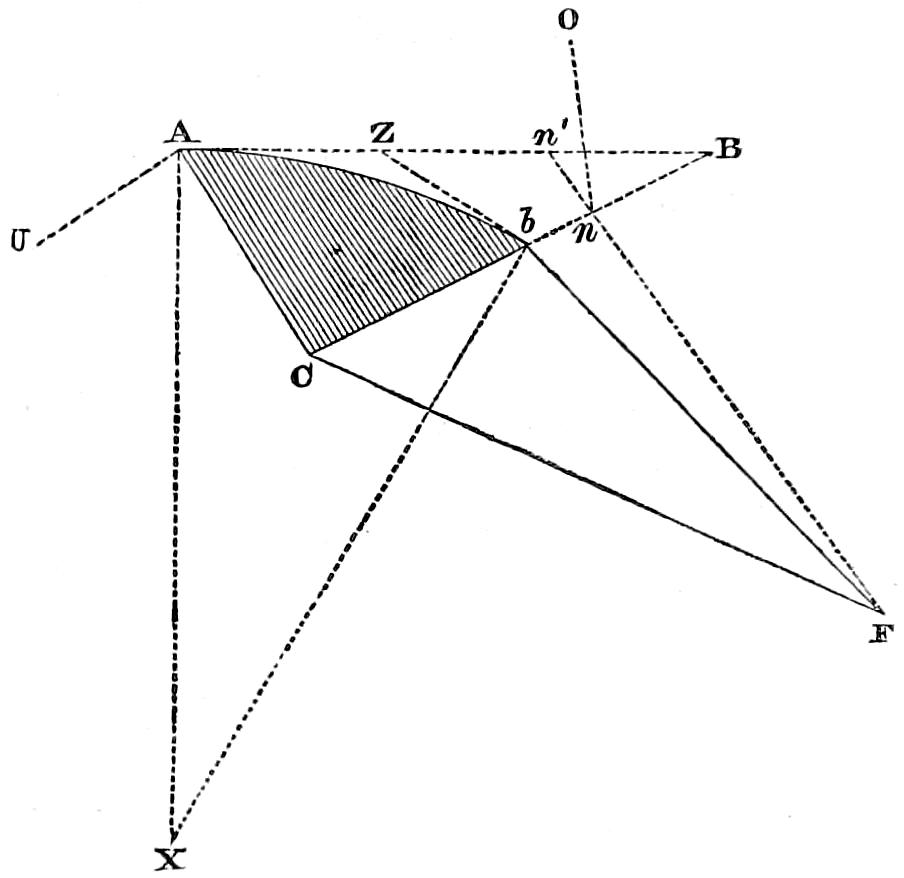

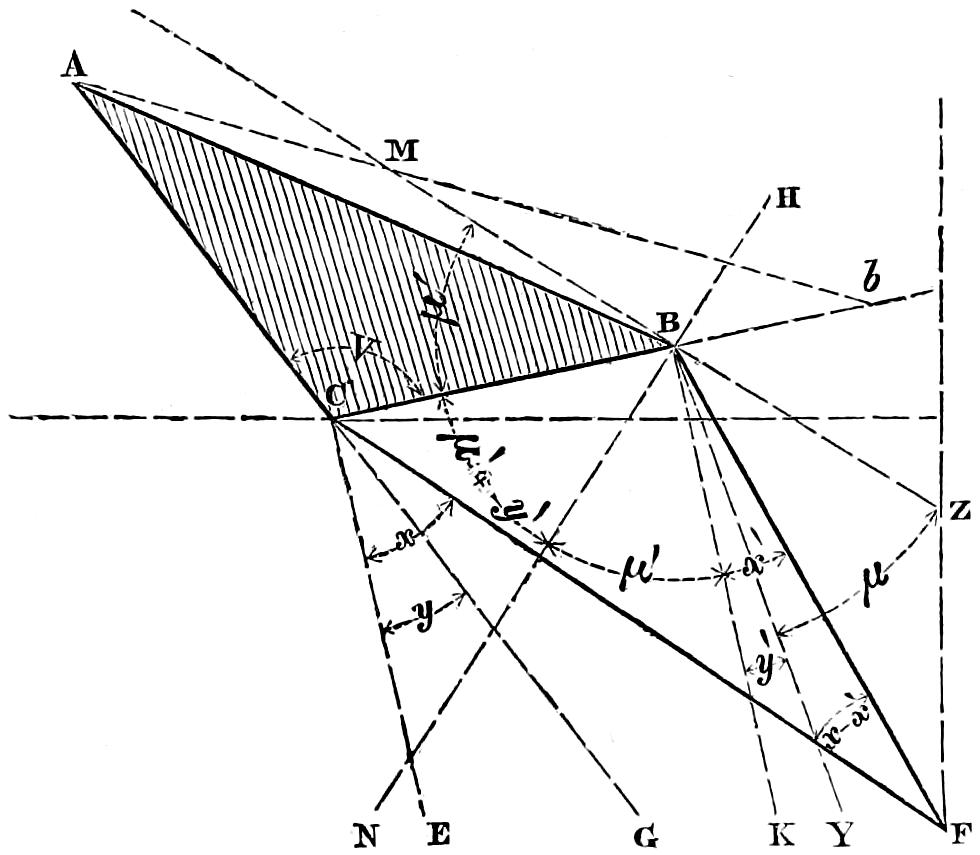

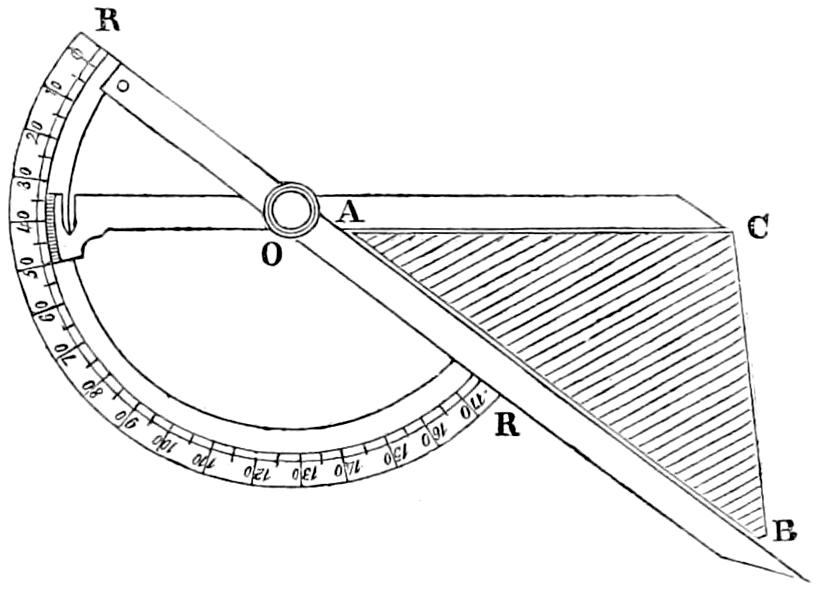

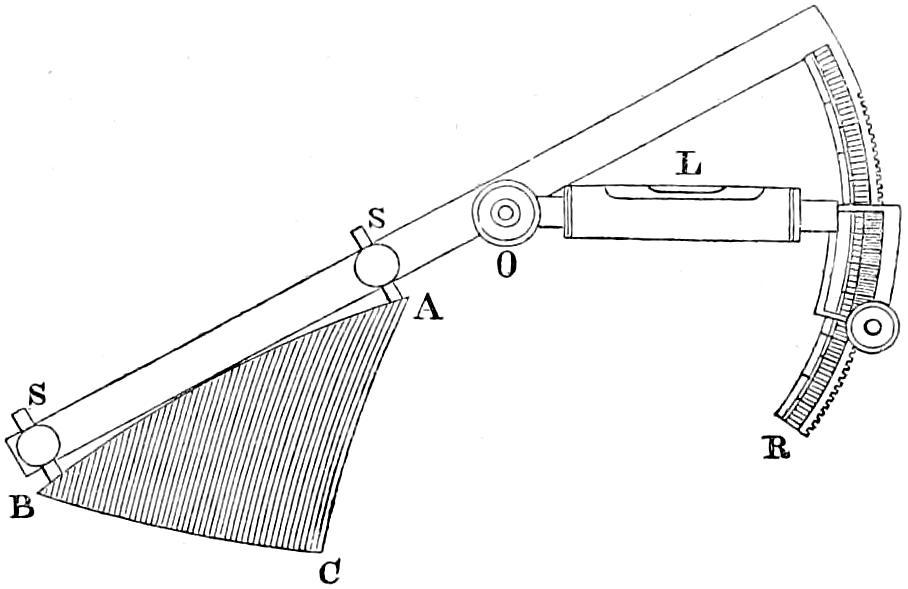

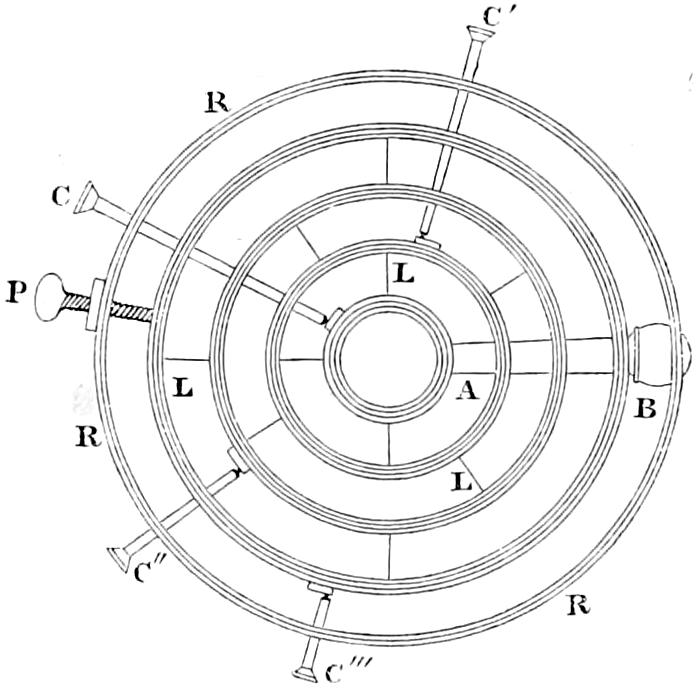

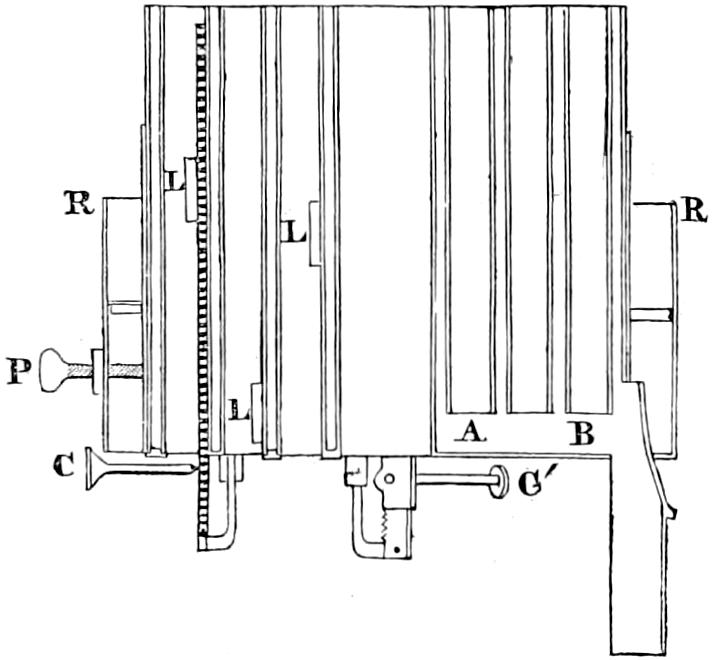

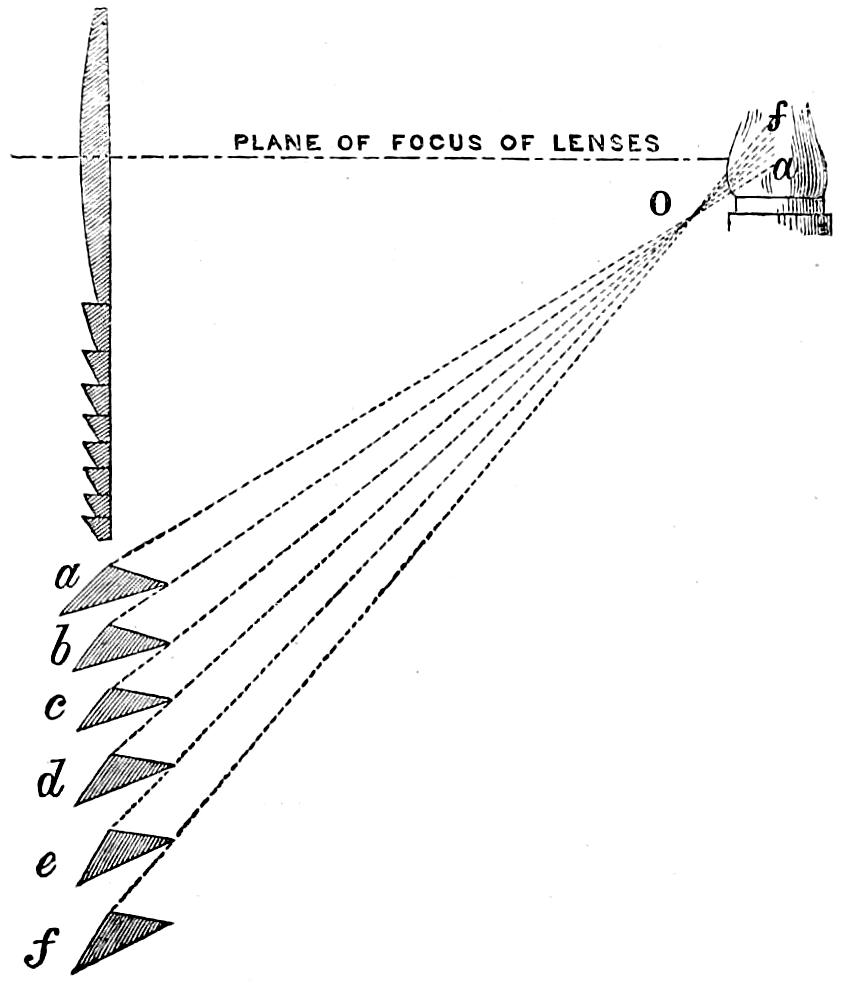

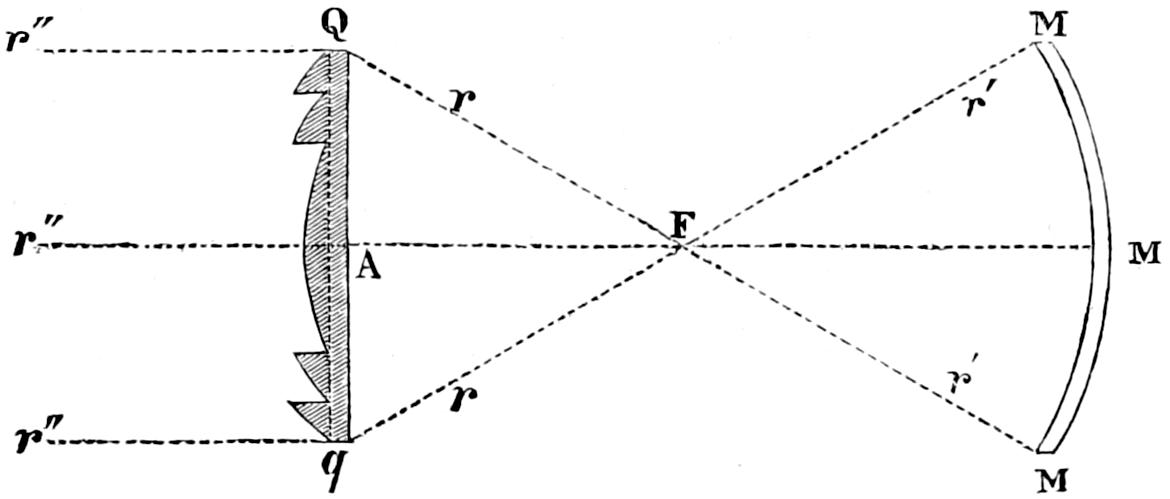

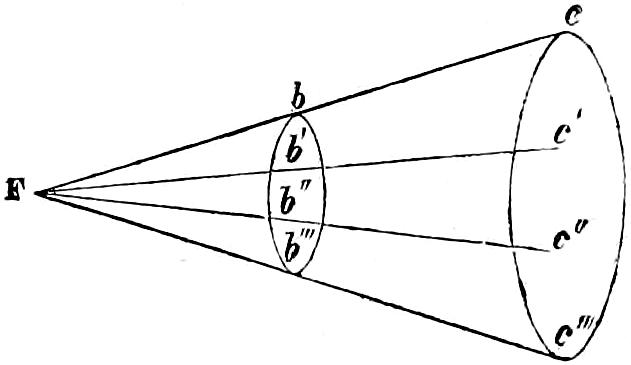

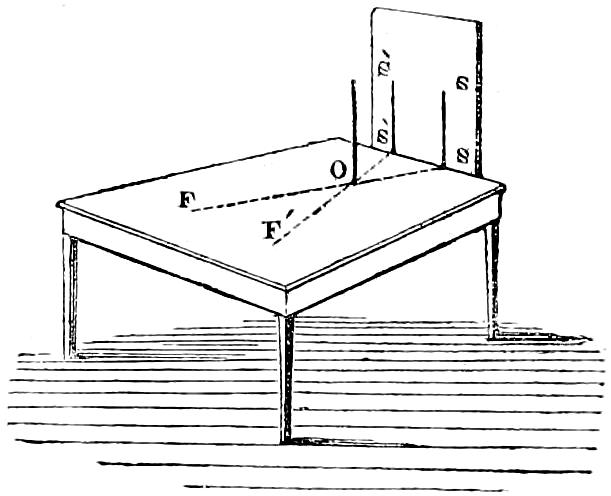

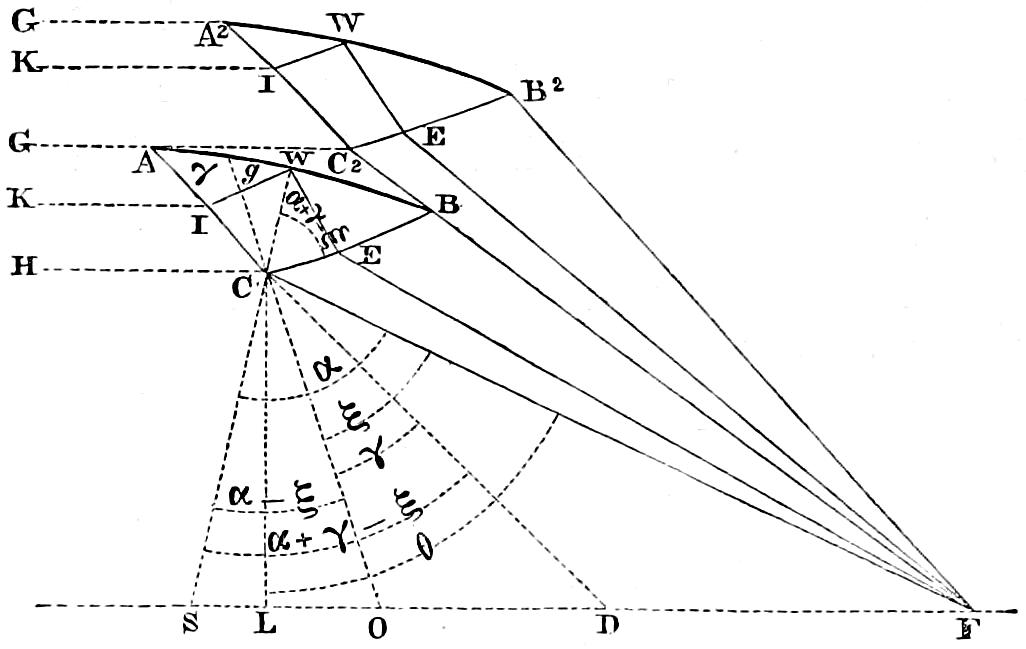

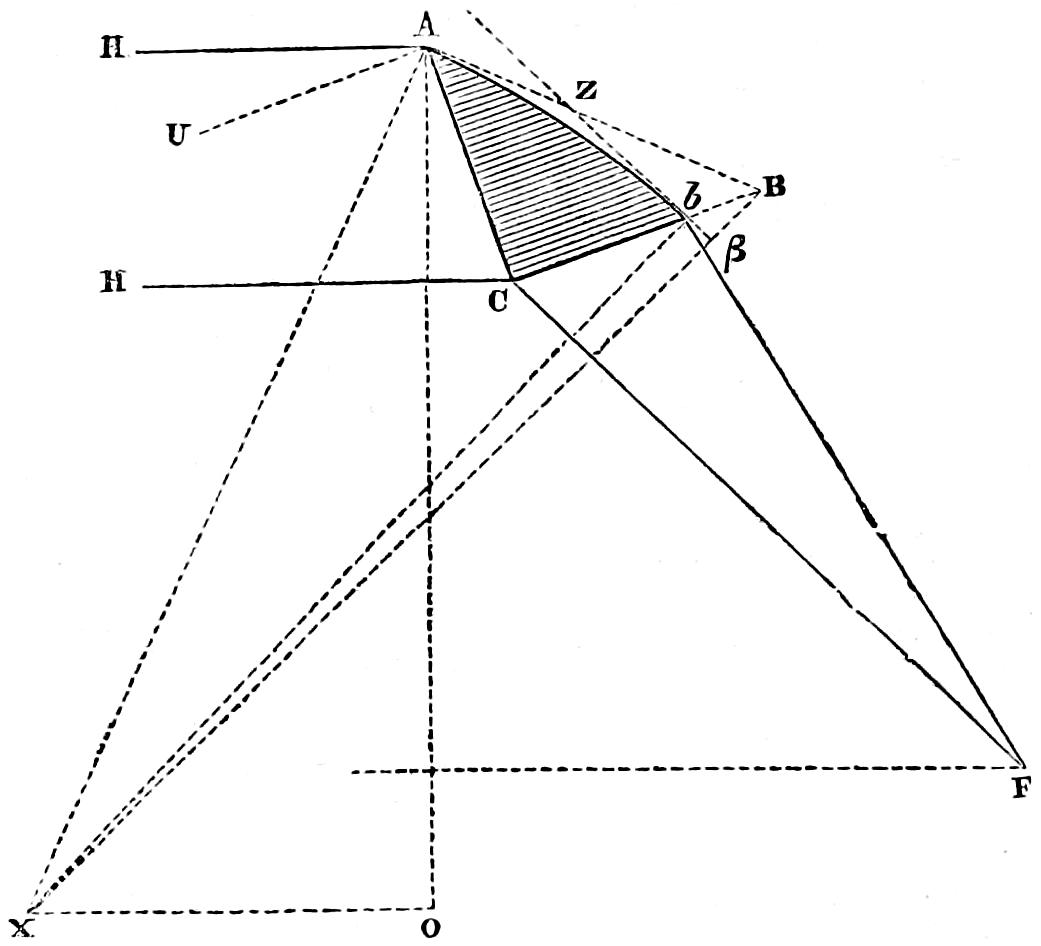

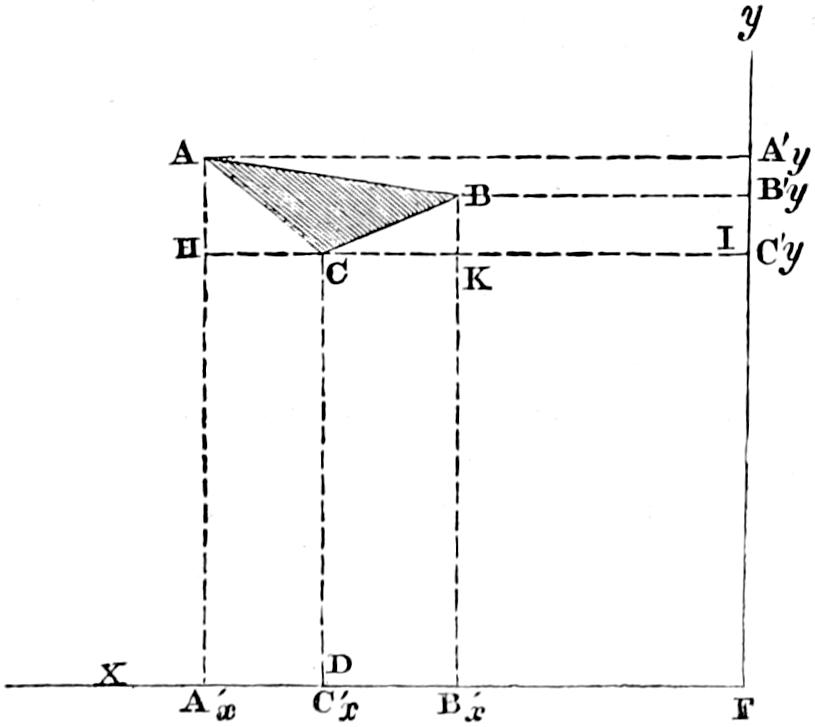

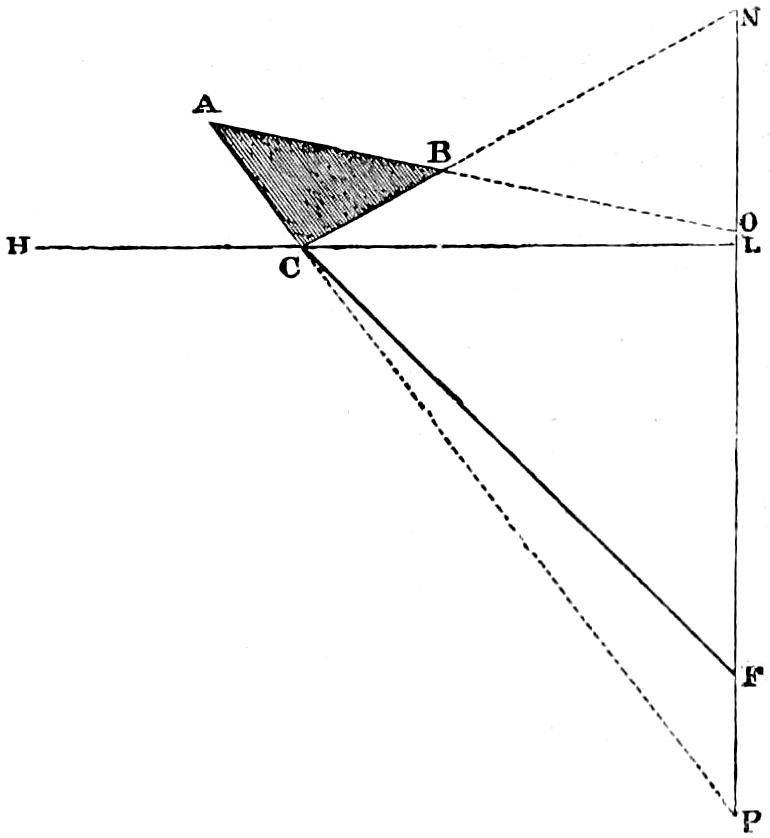

| DIOPTRIC SYSTEM OF LIGHTS, 239. | |

| Early history of Lighthouse lenses, Condorcet, Buffon, Brewster, Fresnel, 239 — Refraction, 242 — Lenses, 245 — Spherical aberration, 248 — Fresnel’s formulæ for annular lenses, 249 — Testing lenses, 255 — Divergence of lenses, 256 — Illuminating power of lenses, 257 — Arrangement of lenses in a Lighthouse, 258 — Pyramidal lenses and mirrors, 259 — Curved mirrors, 260 — Cylindric refractors of fixed Lights, 263 — Application of crossed prisms to cause flashes, 264 — True cylindric form given to refractors, and other improvements in their construction, 264 — Catadioptric zones, the mode of computing their elements, &c., 267 — Testing of zones, 282 — Framing of zones, 286 — Mechanical lamp, 286 — Height of flame of mechanical lamp, 289 — Position of flame in reference to focus, 290 — Working of the pumps, 291 — Choice of focal point for various parts of apparatus, 292 — Choice of a focal point for zones, 292 — Application of spherical mirrors to fixed Dioptric Lights, 293 — Arrangement of Dioptric apparatus, 293 — Arrangement of Dioptric apparatus in Lightroom, 294 — Power of Dioptric instruments, 298 — Orders of French Lights, 298 — Distinctions of Dioptric Lights, 299 — Comparison of Dioptric and Catoptric apparatus for revolving lights, 301 — Comparison for fixed lights, 303 — Summary[x] of views as to two systems for revolving lights, 306 — Summary of views as to two systems for fixed lights, 306 — Advantages and disadvantages of both systems under certain circumstances, 308 — Distinctions of the Dioptric Lights and the application of coloured media, 311 — Captain Basil Hall’s proposal for fixed lights, 313 — Effects of rapid motion on the power of lights, 315 — Connection of experiments with irradiation, 320. | |

| VARIOUS GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS CONNECTED WITH LIGHTHOUSES, 320. | |

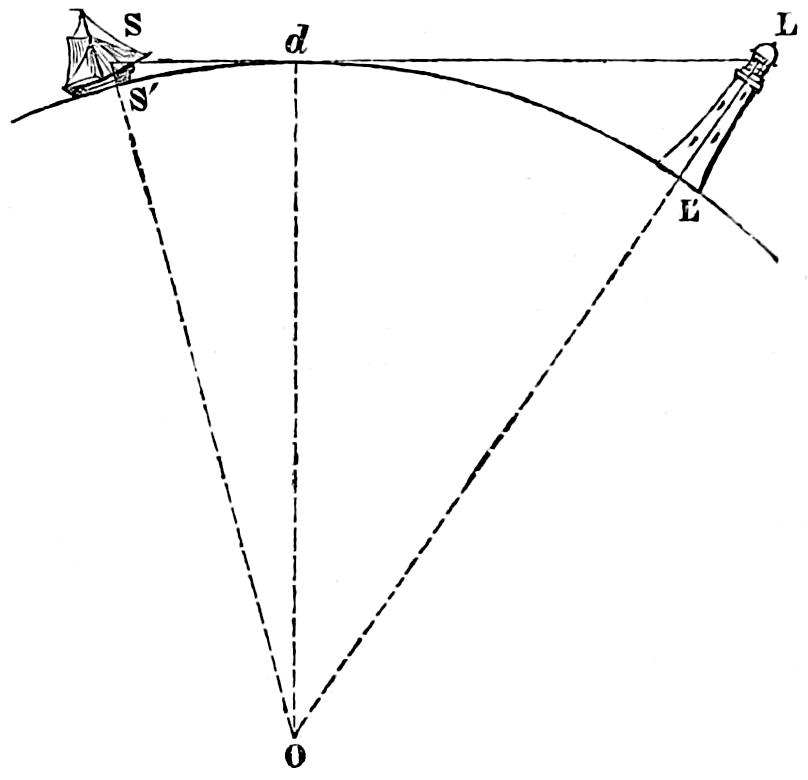

| Masking Lights, 320 — Double Lights, 322 — Leading Lights, 323 — Distribution of Lights on a coast, 325 — Height of Lighthouse Tower, and its relation to range of light, 328 — Diagonal Lantern, 330 — Glazing of Lantern, 331 — Ventilation of Lanterns, 331 — Arrangements and Management of a Lighthouse, 334 — Cleansing of apparatus, 335 — Mode of measuring relative power of lights, 336 — More accurate comparison of intensity of lights, 338 — Floating Lights, 346 — Beacons and Buoys, 347. | |

| 1. | Table of Co-ordinates of Hyperbolic Column. |

| 2. | Notes on the Making of Paraboloïdal Mirrors. |

| 3. | Notes on the Grinding and Polishing of Dioptric Instruments for Lighthouses. |

| 4. | Table of the Elements of the Catadioptric Zones for Lights of the first order in the system of Augustin Fresnel. |

| 5. | Notice to Mariners of the Exhibition of the Skerryvore Light. |

| 6. | Detailed Account of the Expense of the Skerryvore Lighthouse. |

| 7. | Excerpts from Account of Experiments on the Force of the Waves of the Atlantic and German Oceans, by Thomas Stevenson, F.R.S.E., Civil Engineer. |

| 8. | Annual List for 1848 of Lighthouses, Beacons, and Buoys, in the District of the Northern Lights Board. |

| 9. | Annual Report by the Secretary as to the Income and Expenditure of the Northern Lights Board for 1846. |

| 10. | Instructions to the Light-keepers in the Service of the Commissioners of the Northern Lighthouses. |

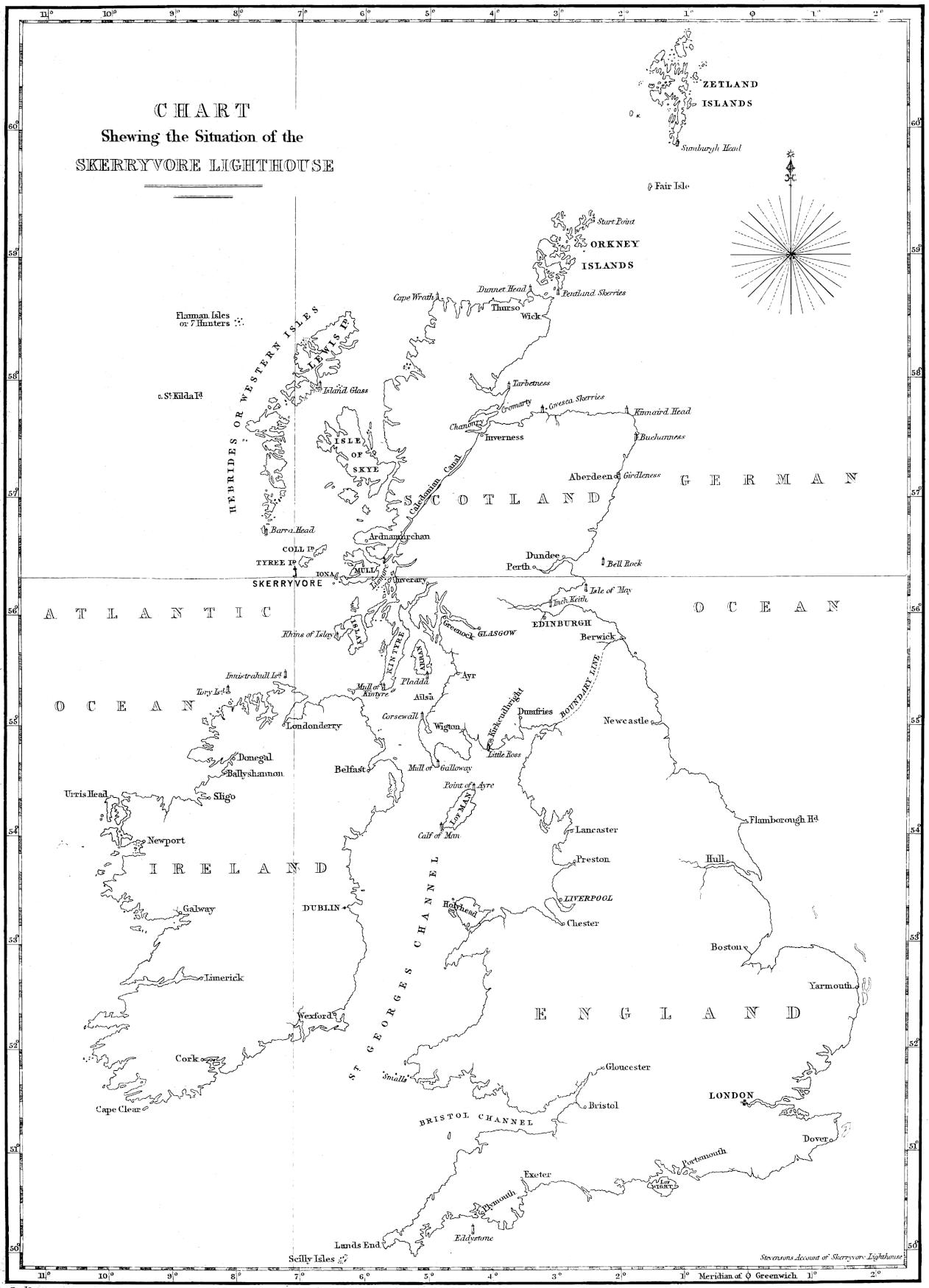

| I. | Chart shewing the situation of the Skerryvore Lighthouse. |

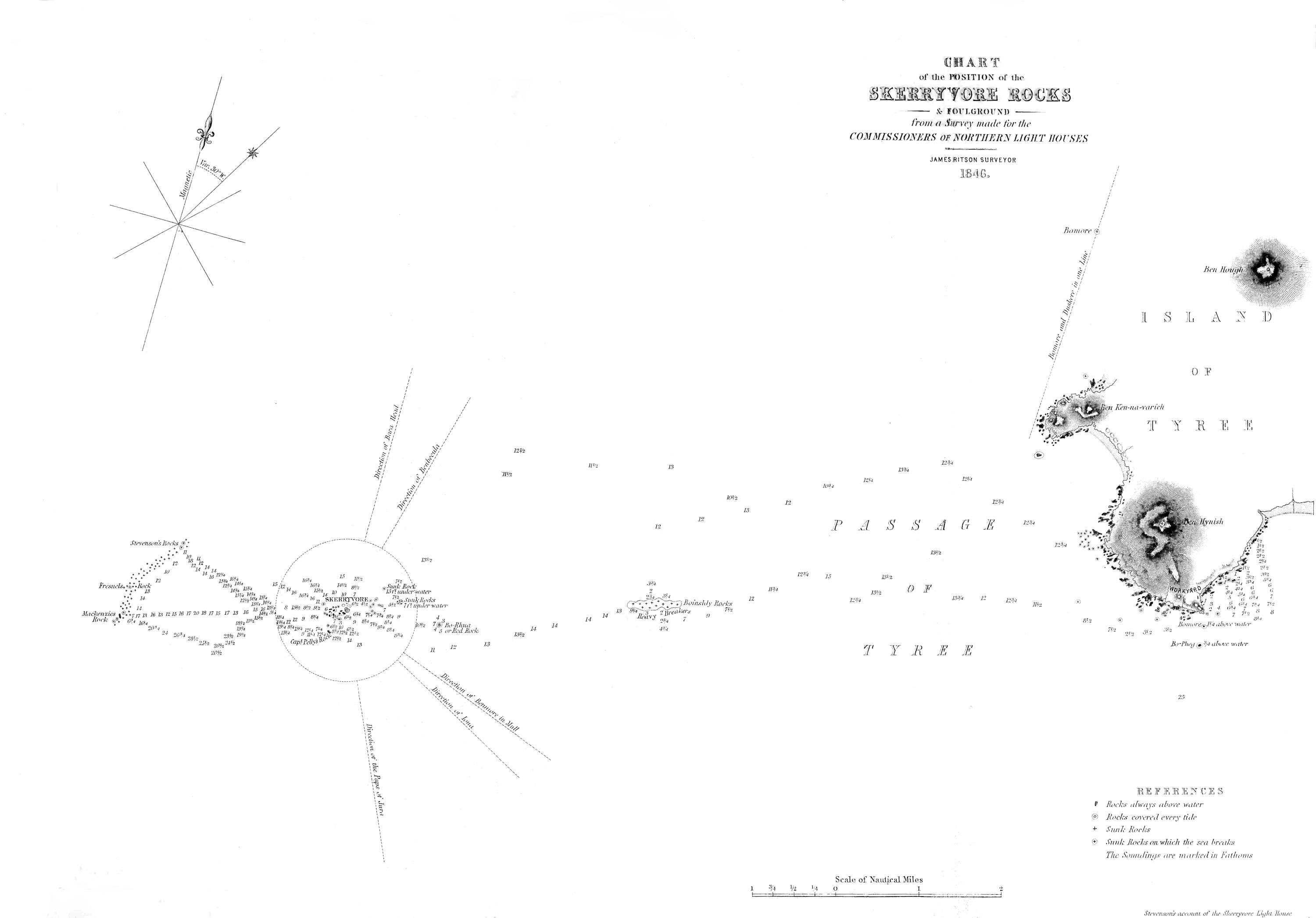

| II. | Chart shewing the position of the Skerryvore Rocks and foul ground. |

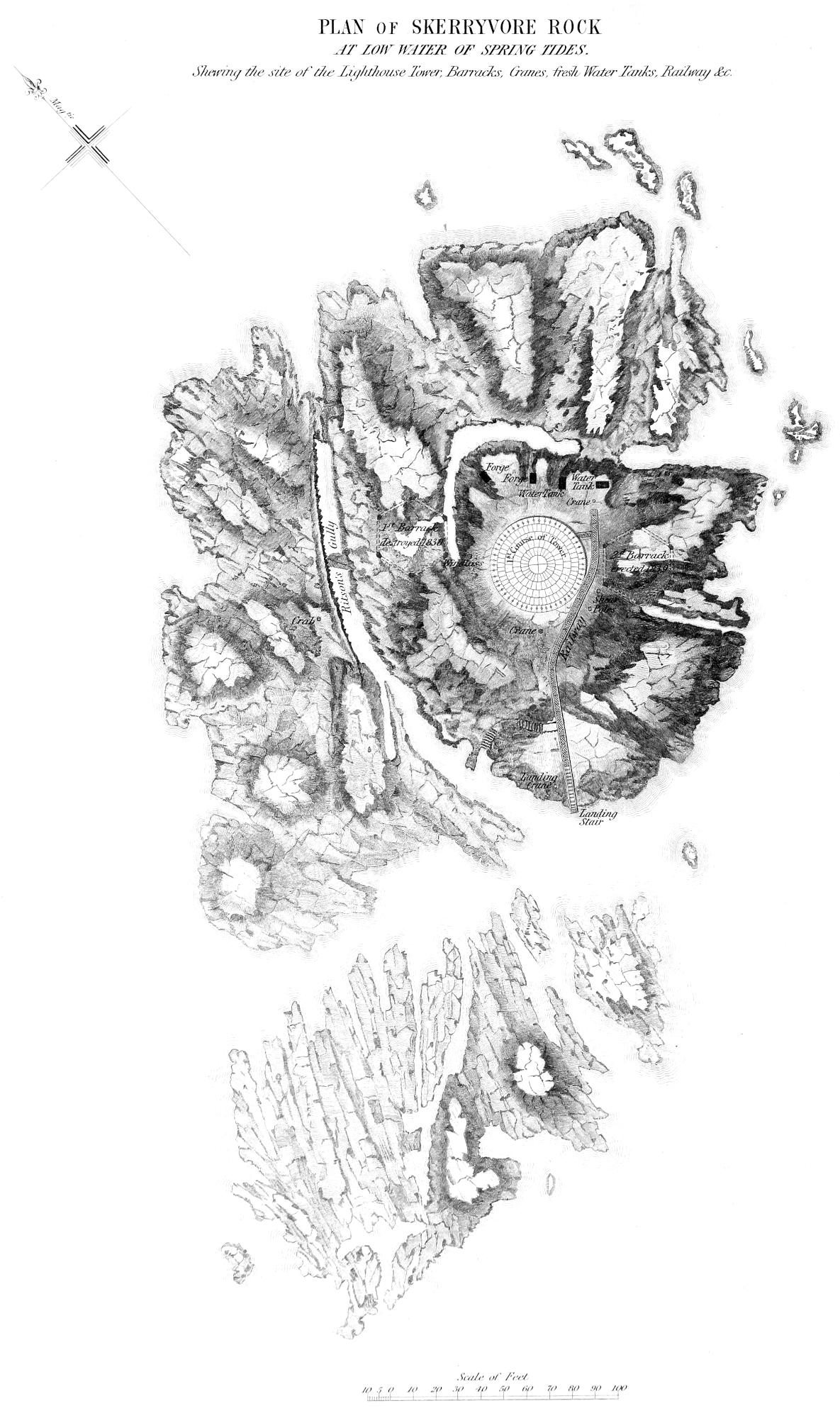

| III. | Plans of the Skerryvore Rock at high and low water of spring tides. |

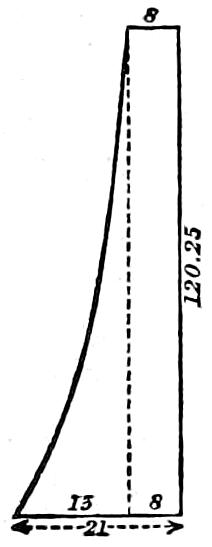

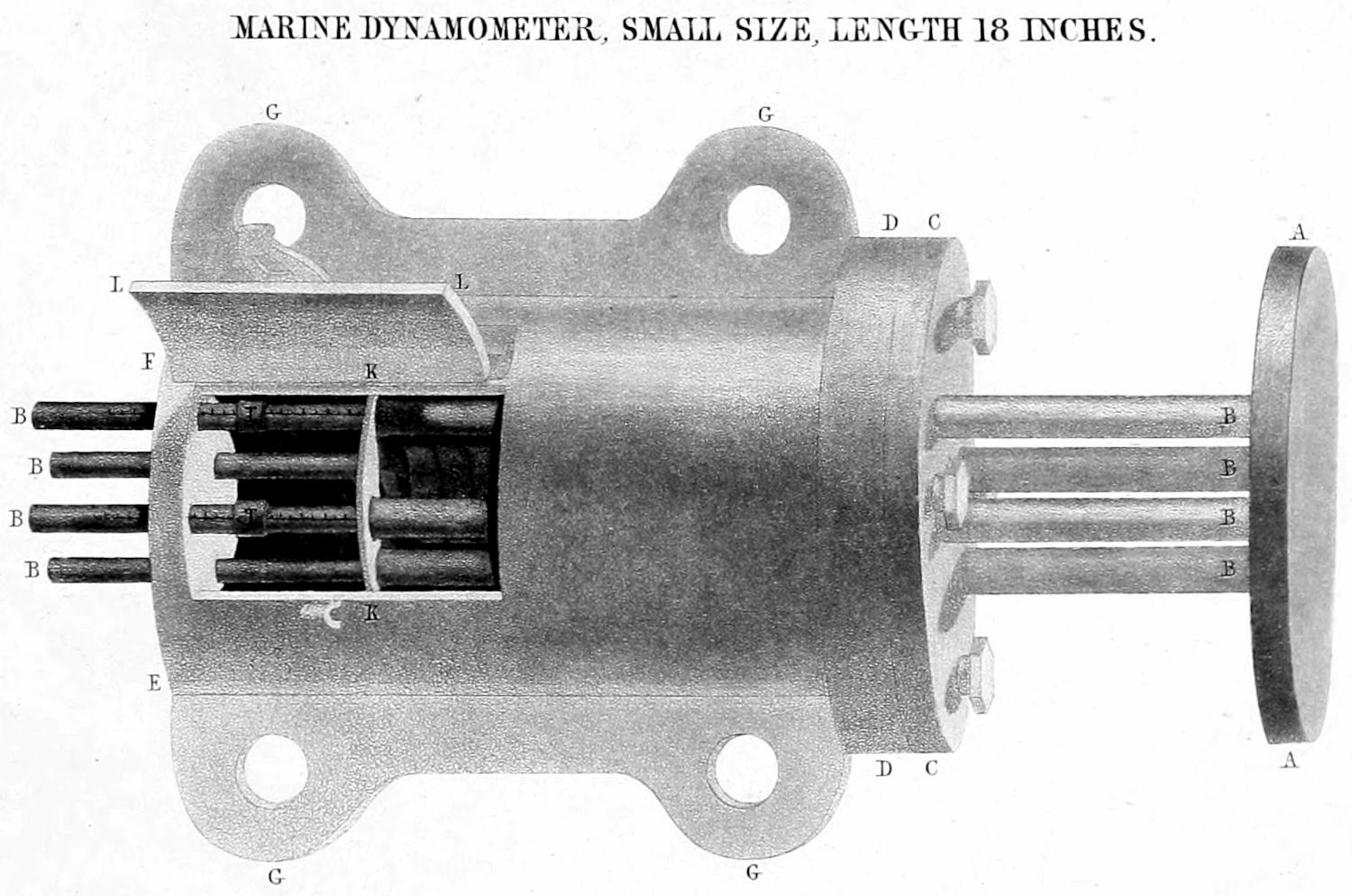

| IV. | Curves for Lighthouse Towers — Marine Dynamometer. |

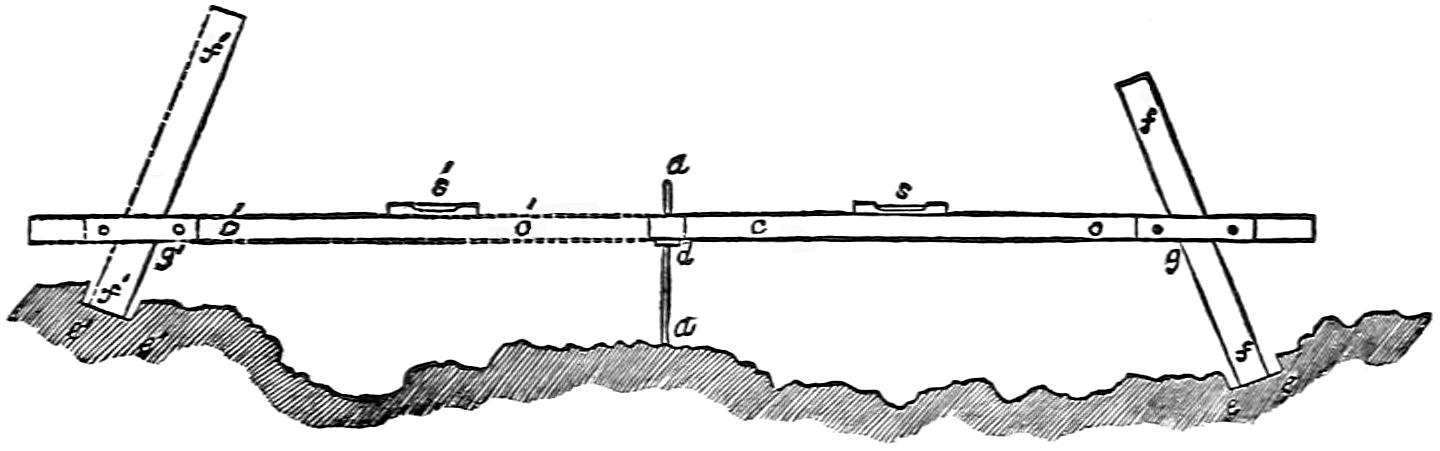

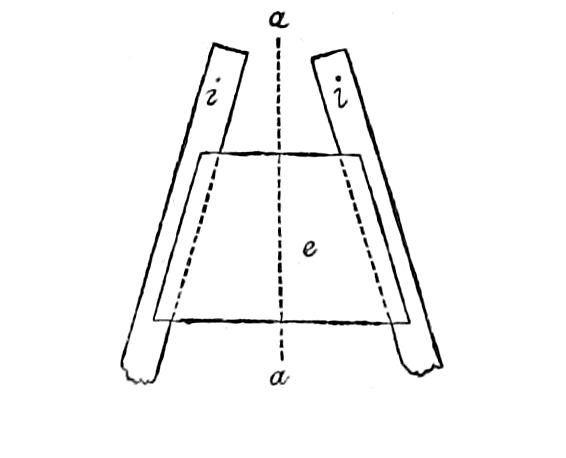

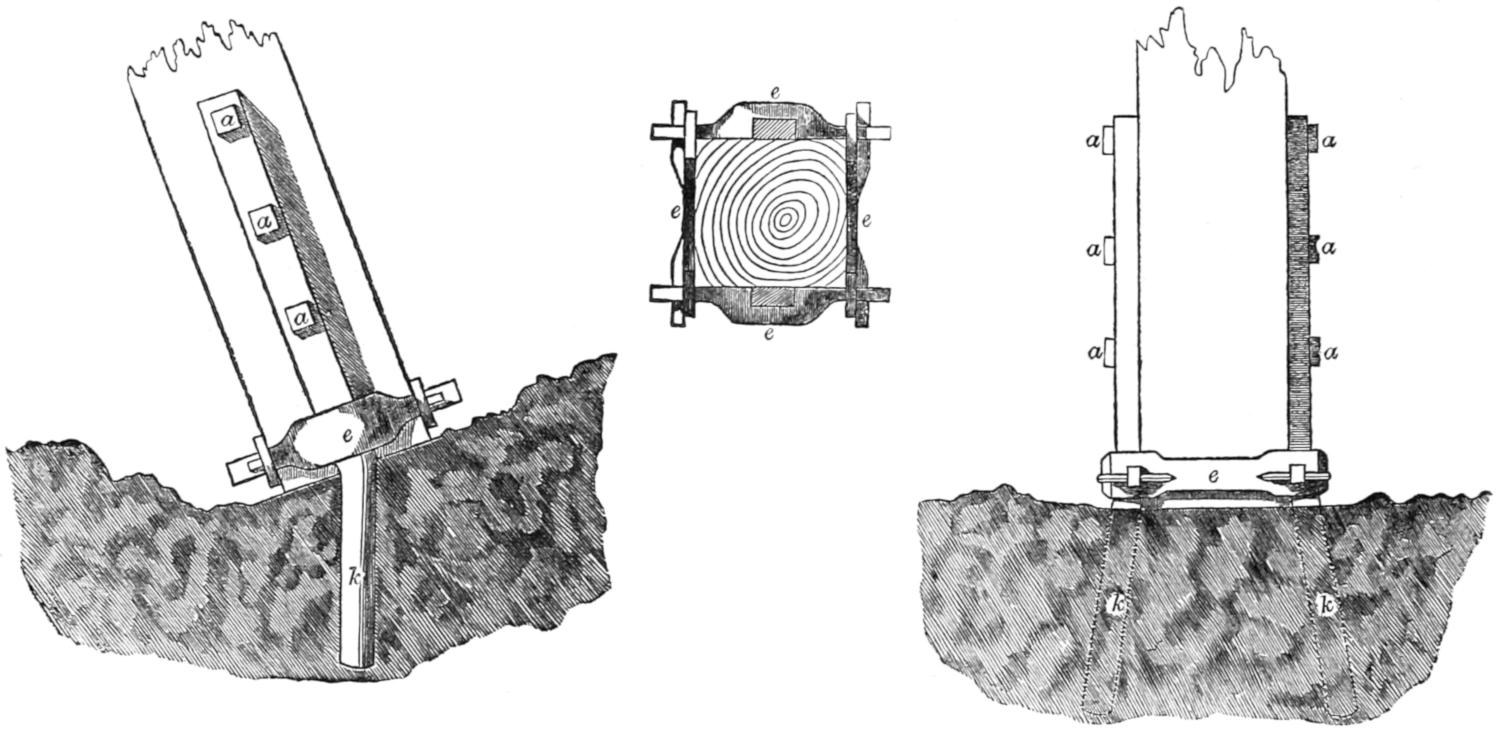

| V. | Barrack of timber on the Skerryvore Rock. |

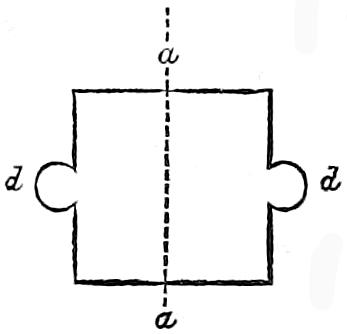

| VI. | Details of fixtures of timbers at the top of the Timber Barrack. |

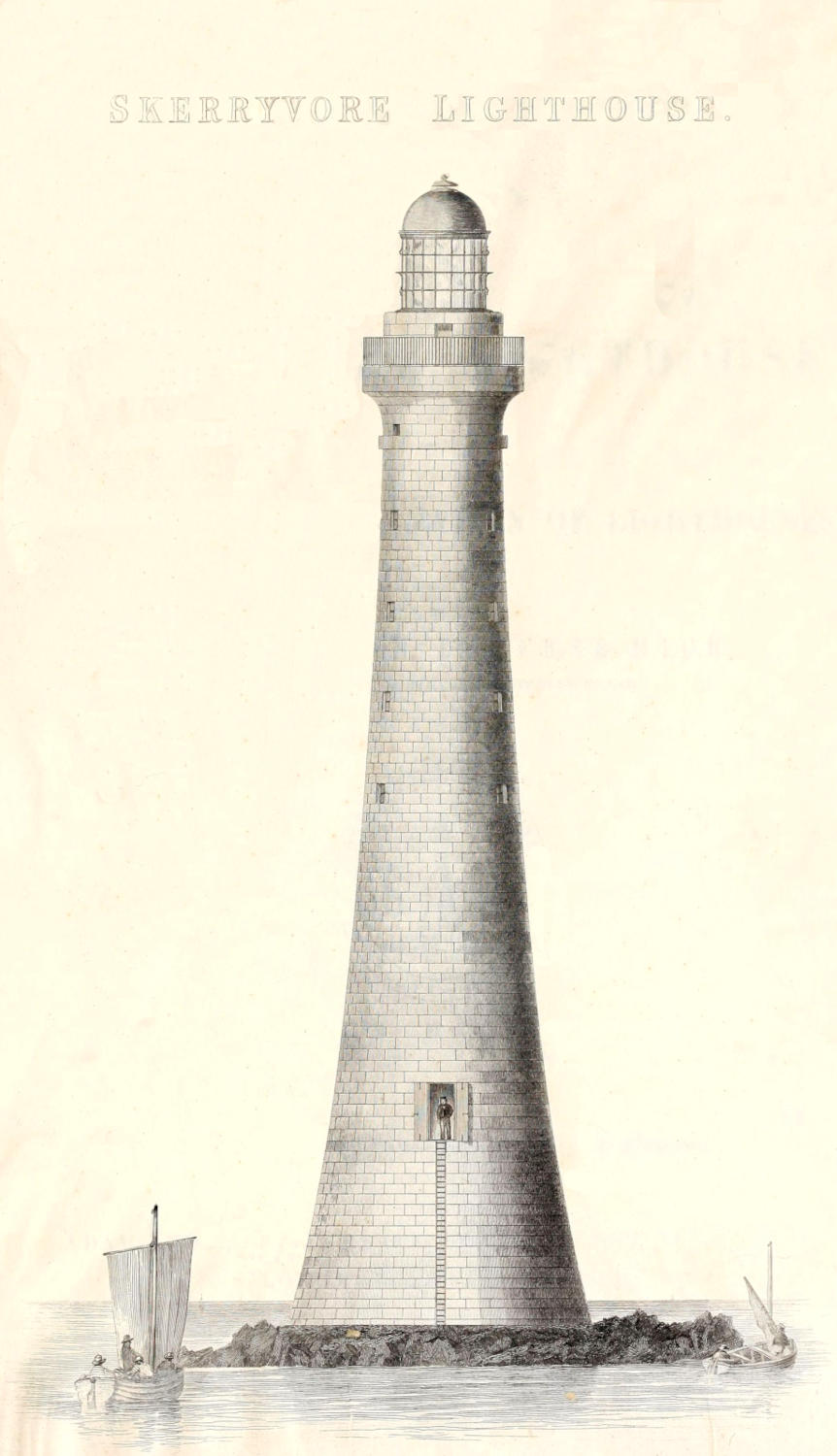

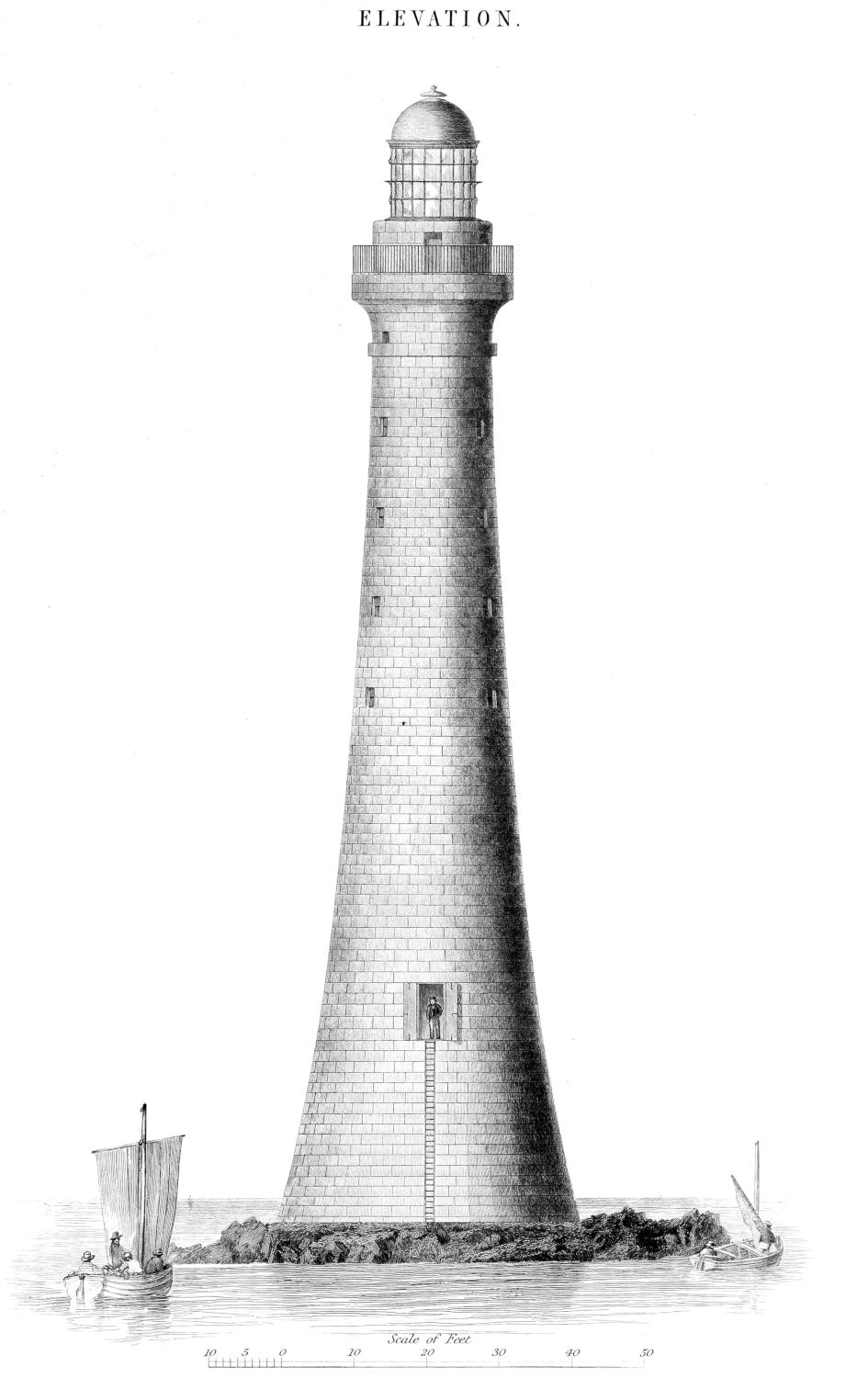

| VII. | Elevation of Skerryvore Lighthouse. |

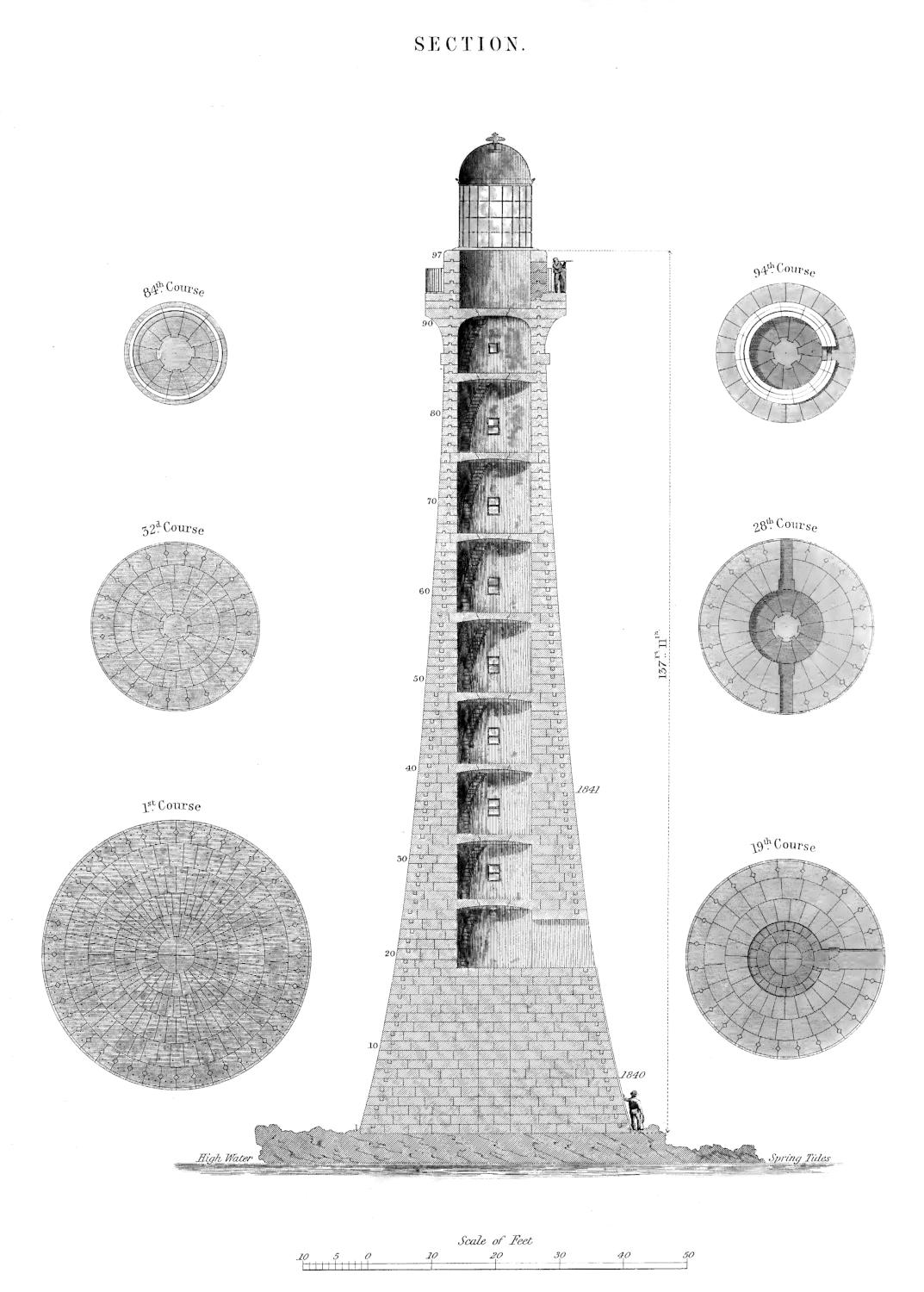

| VIII. | Section of Skerryvore Lighthouse. |

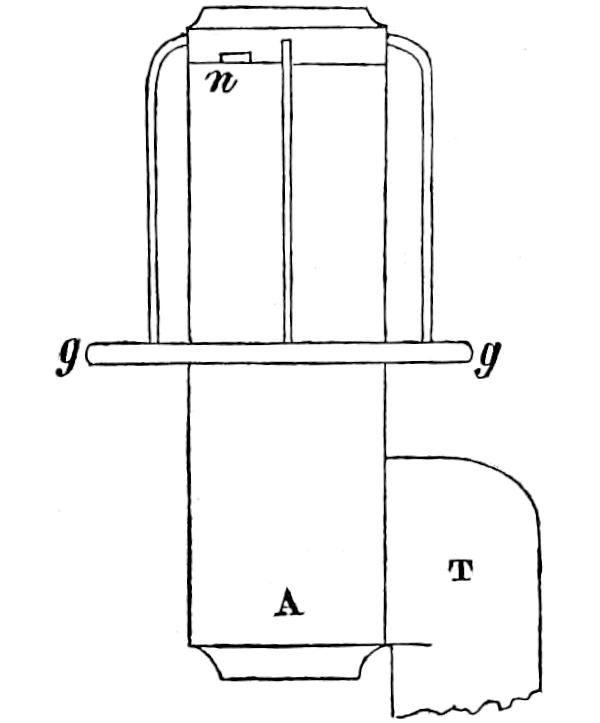

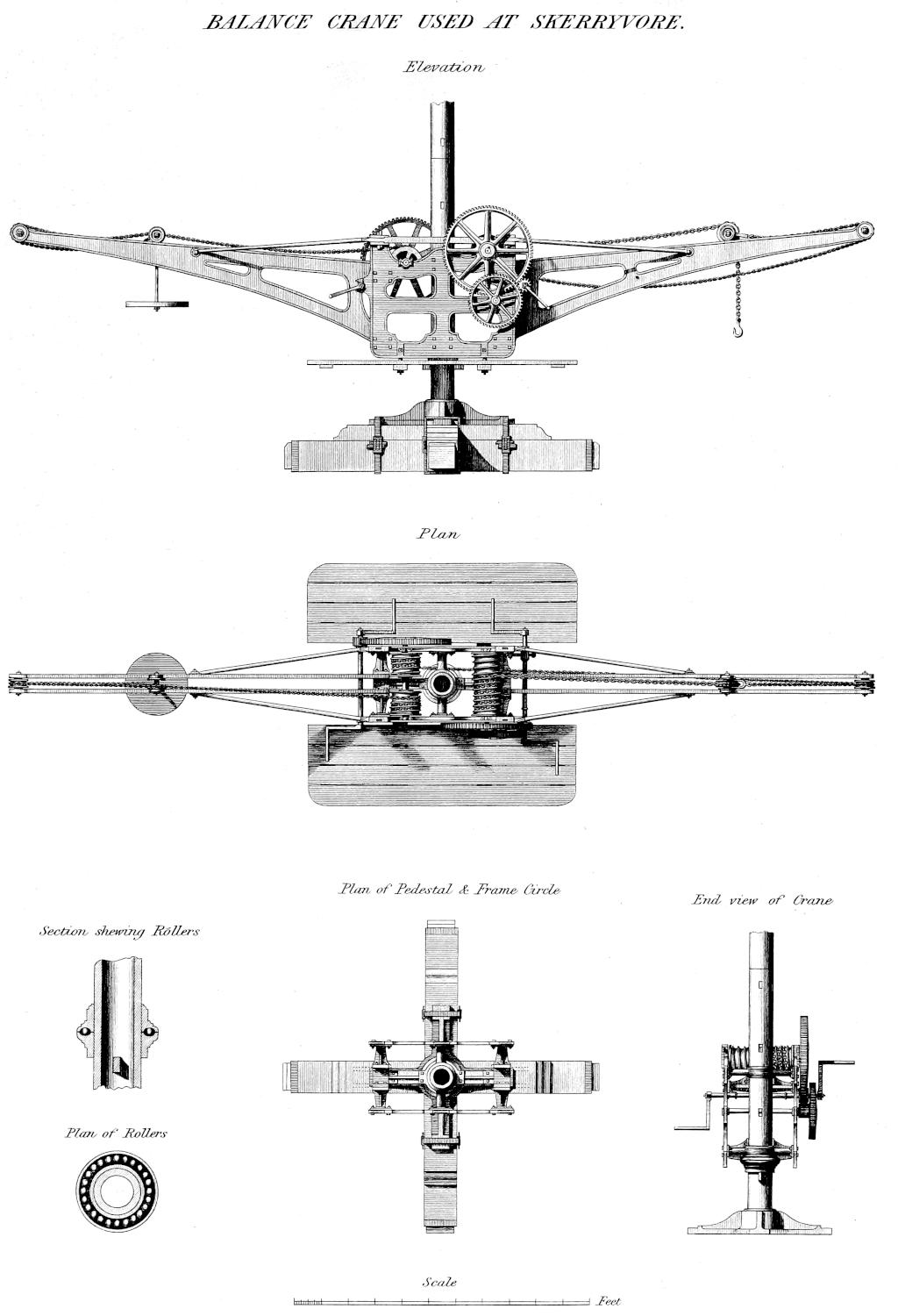

| IX. | Balance Crane used at Skerryvore. |

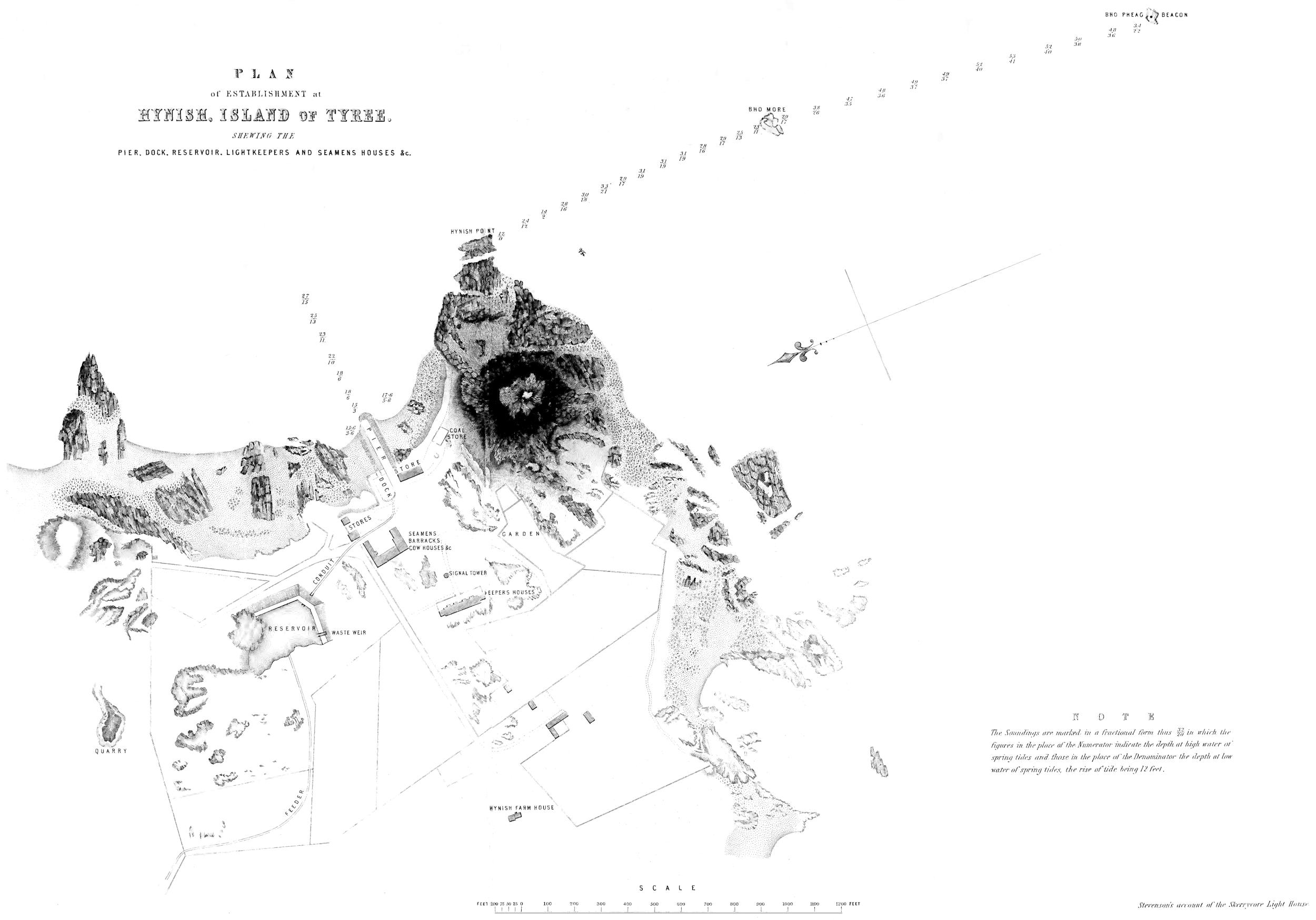

| X. | Plan shewing the Lighthouse Establishment of Barracks, Harbour, &c., at Hynish, in the Island of Tyree. |

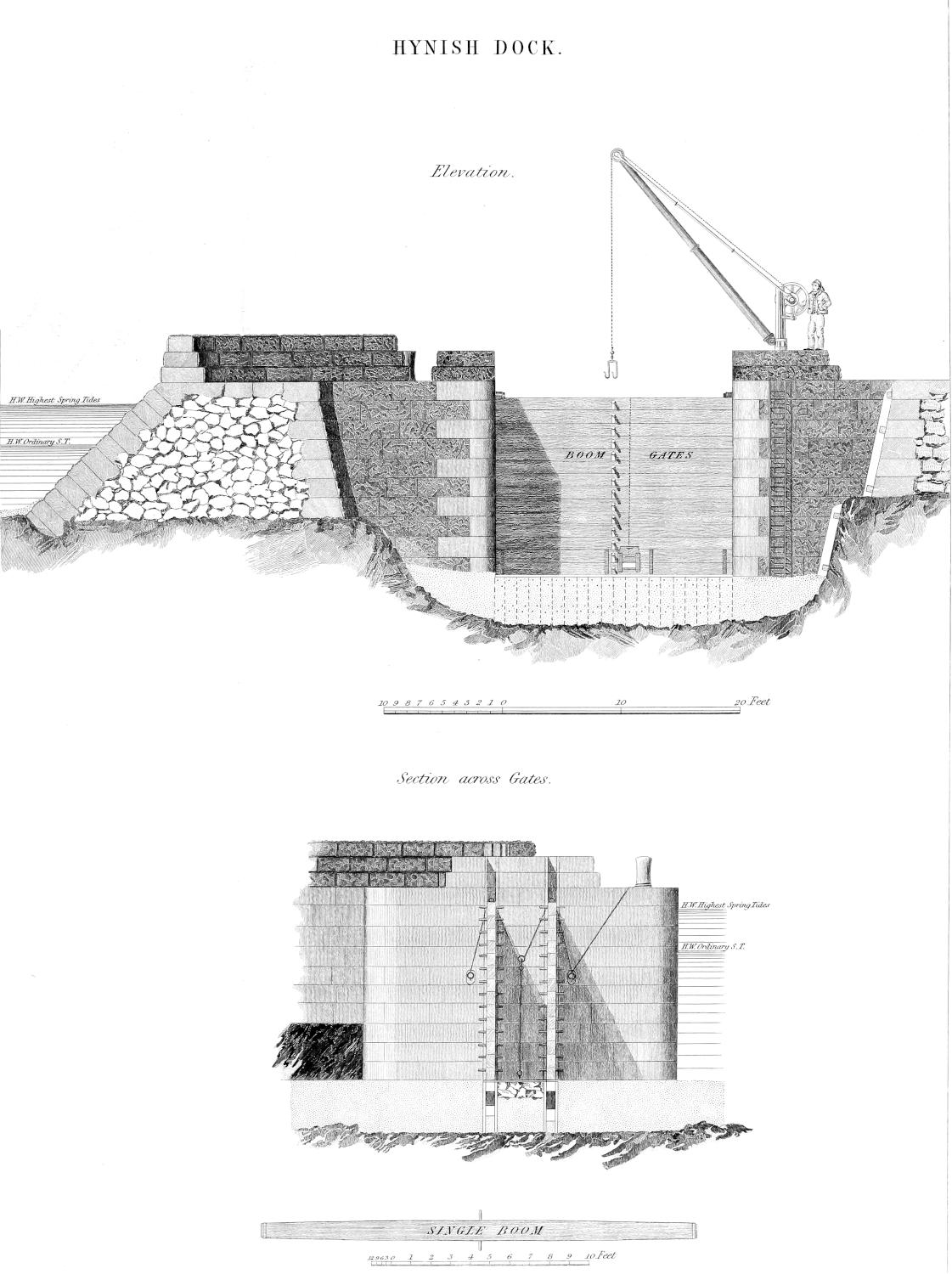

| XI. | Elevation and Section entrance to Dock at Hynish. |

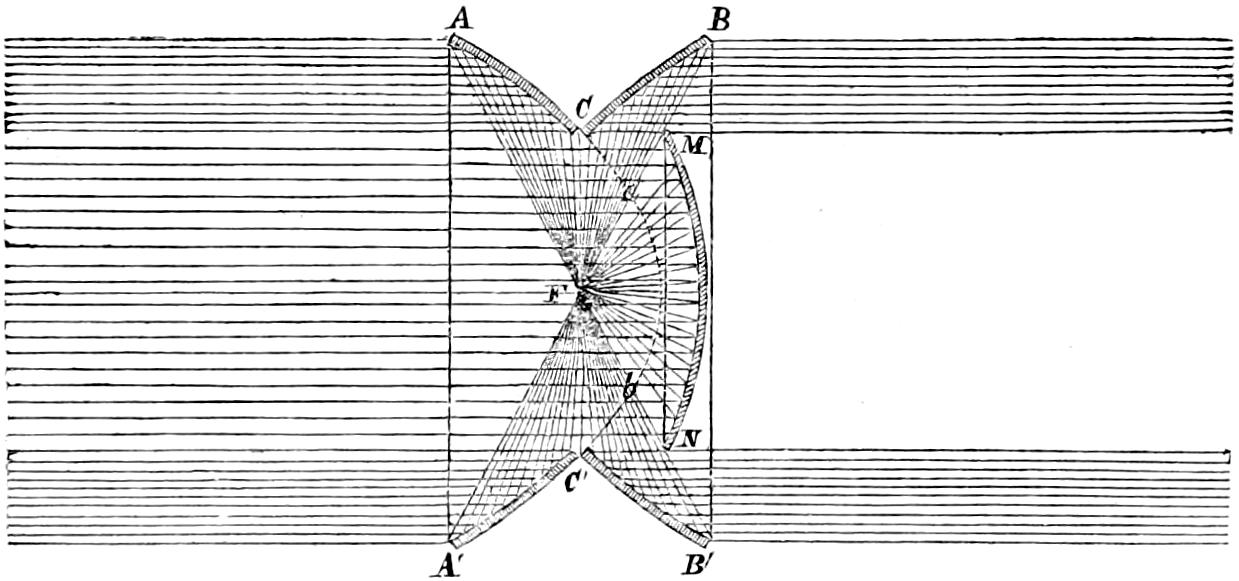

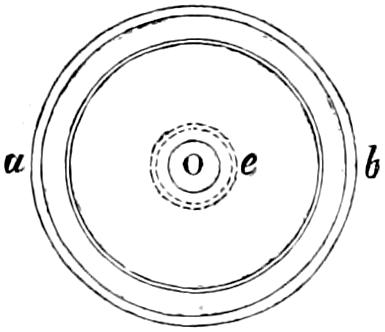

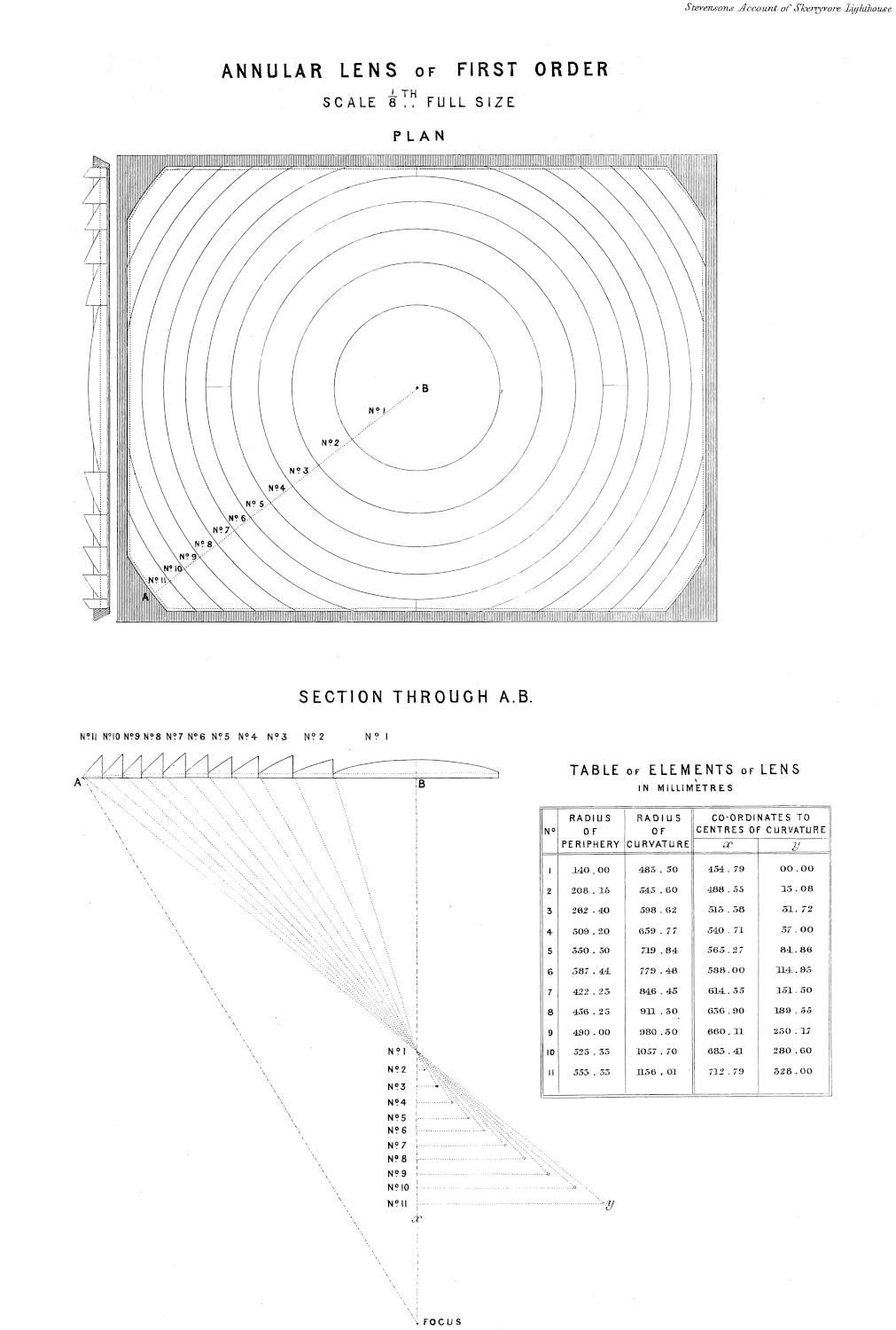

| XII. | Plan and Section of Annular Lens. |

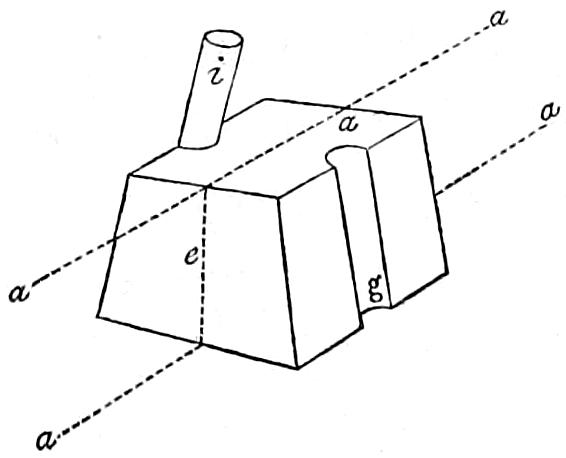

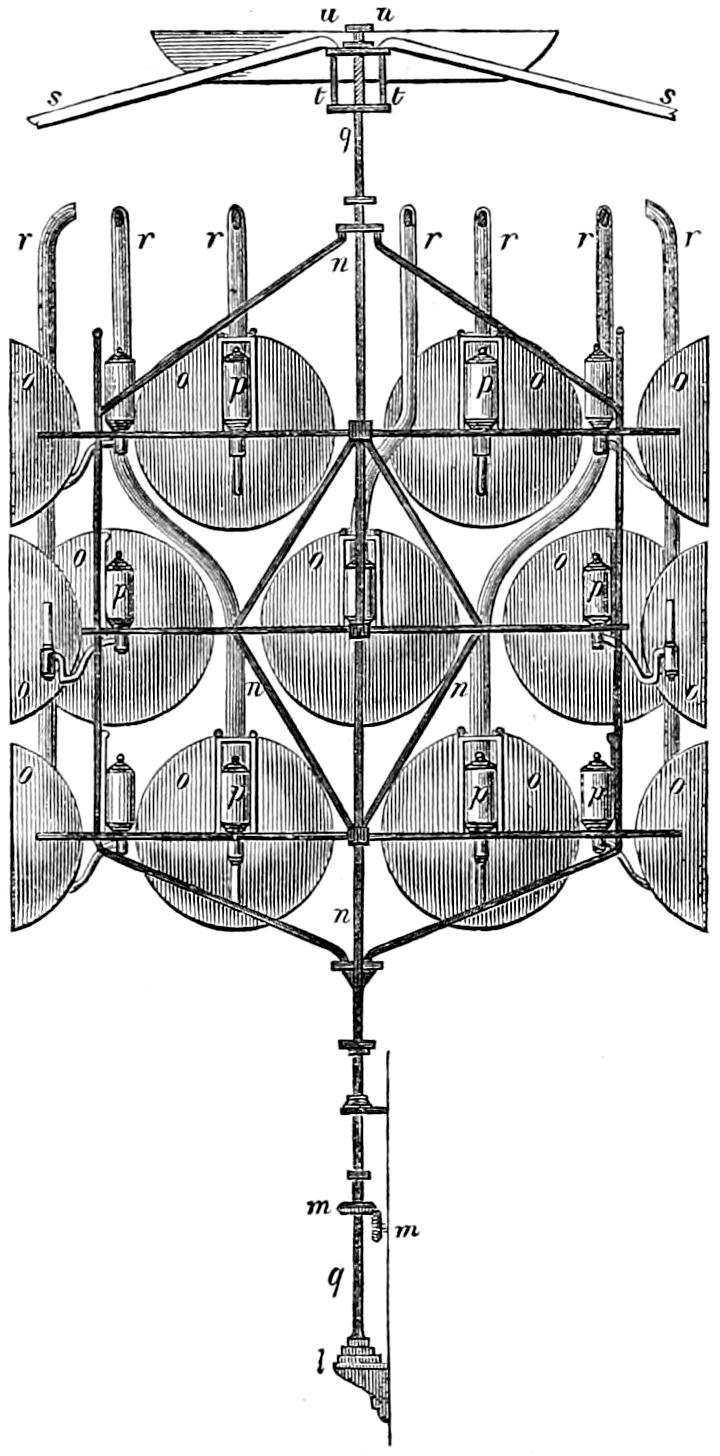

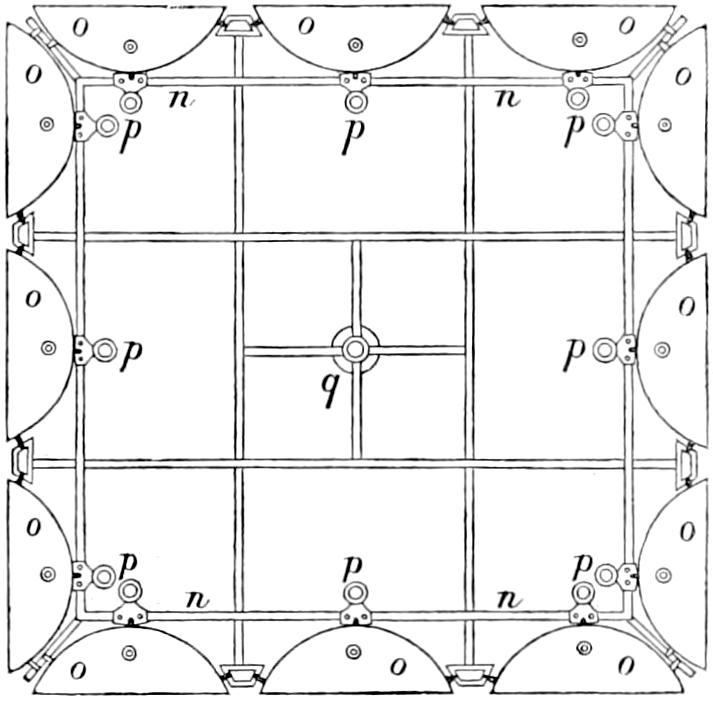

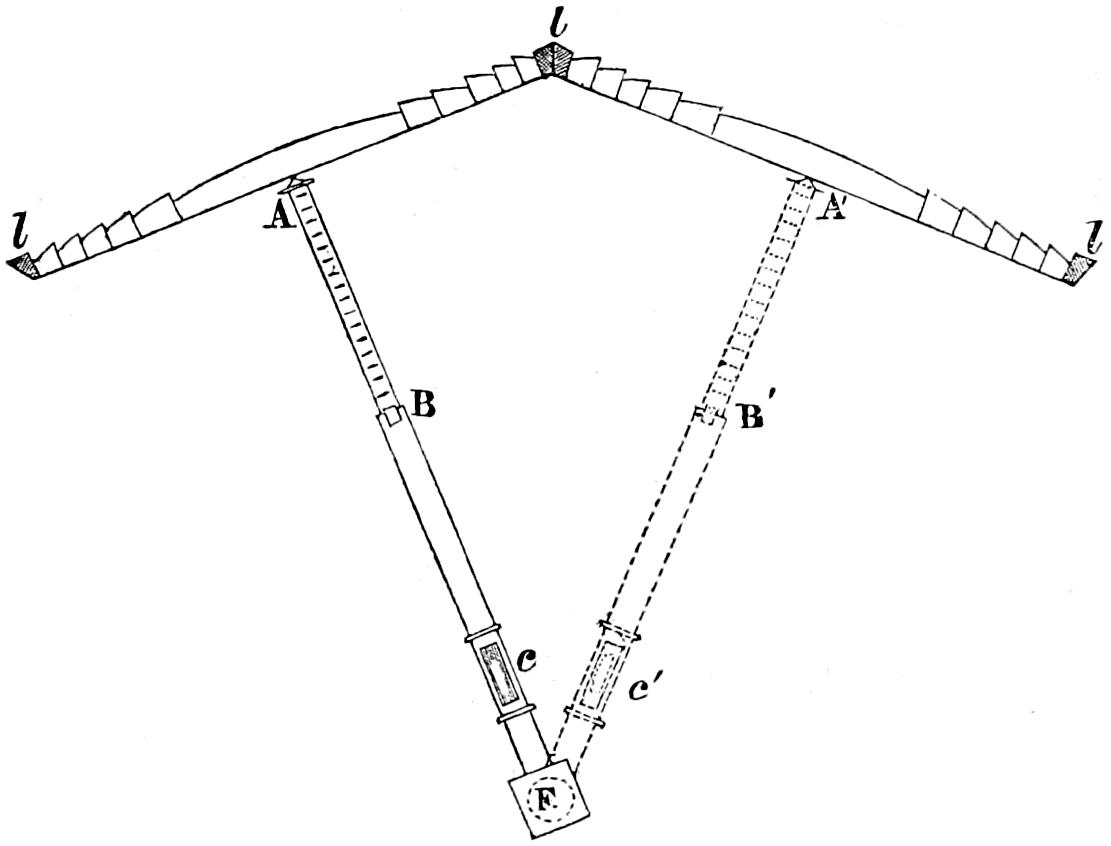

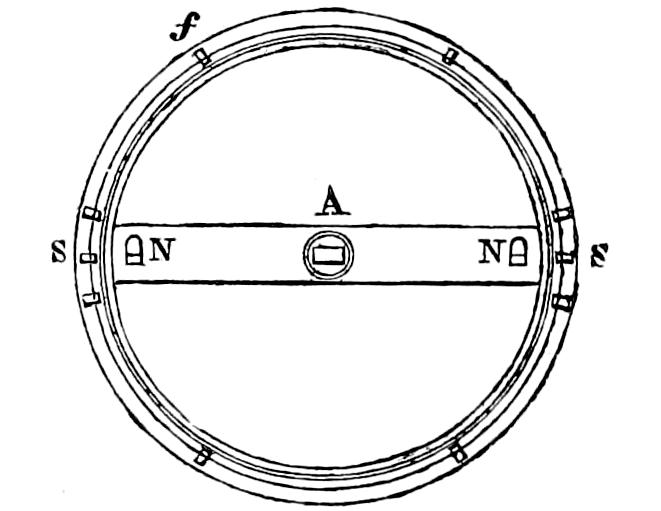

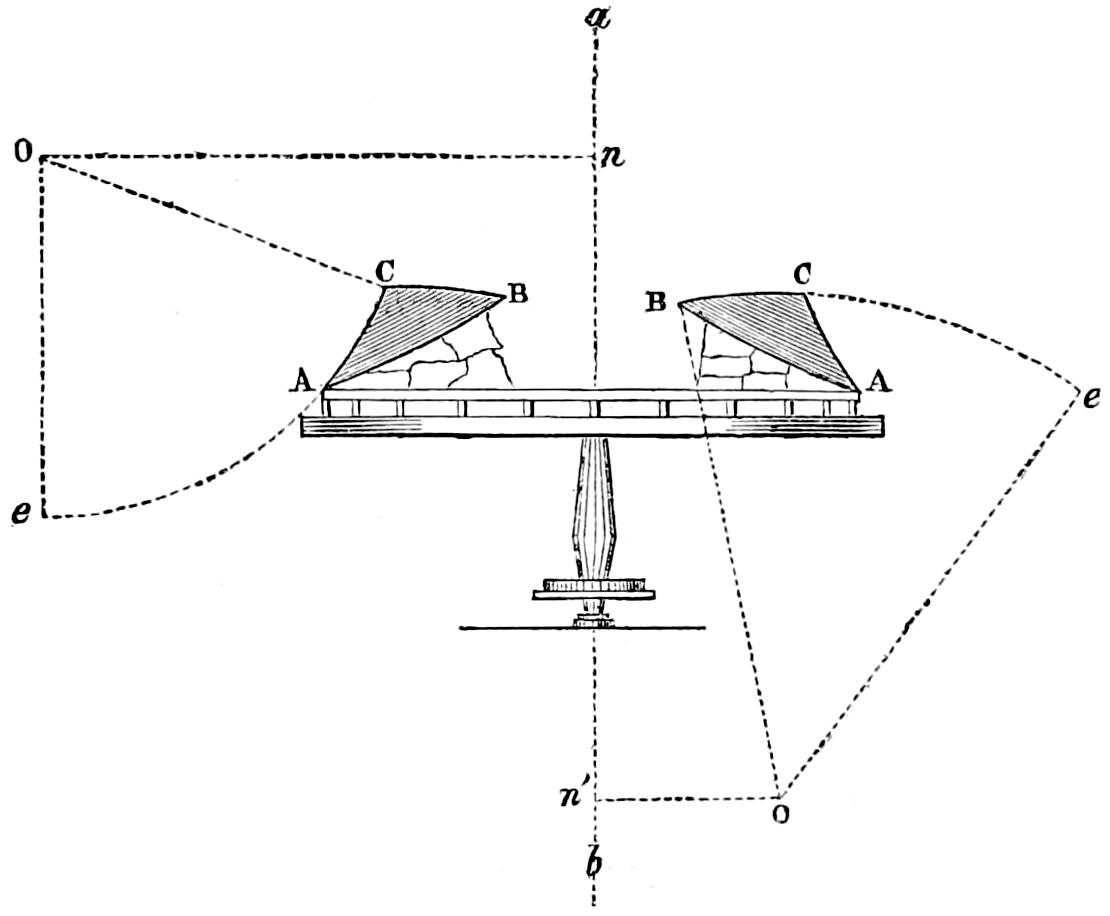

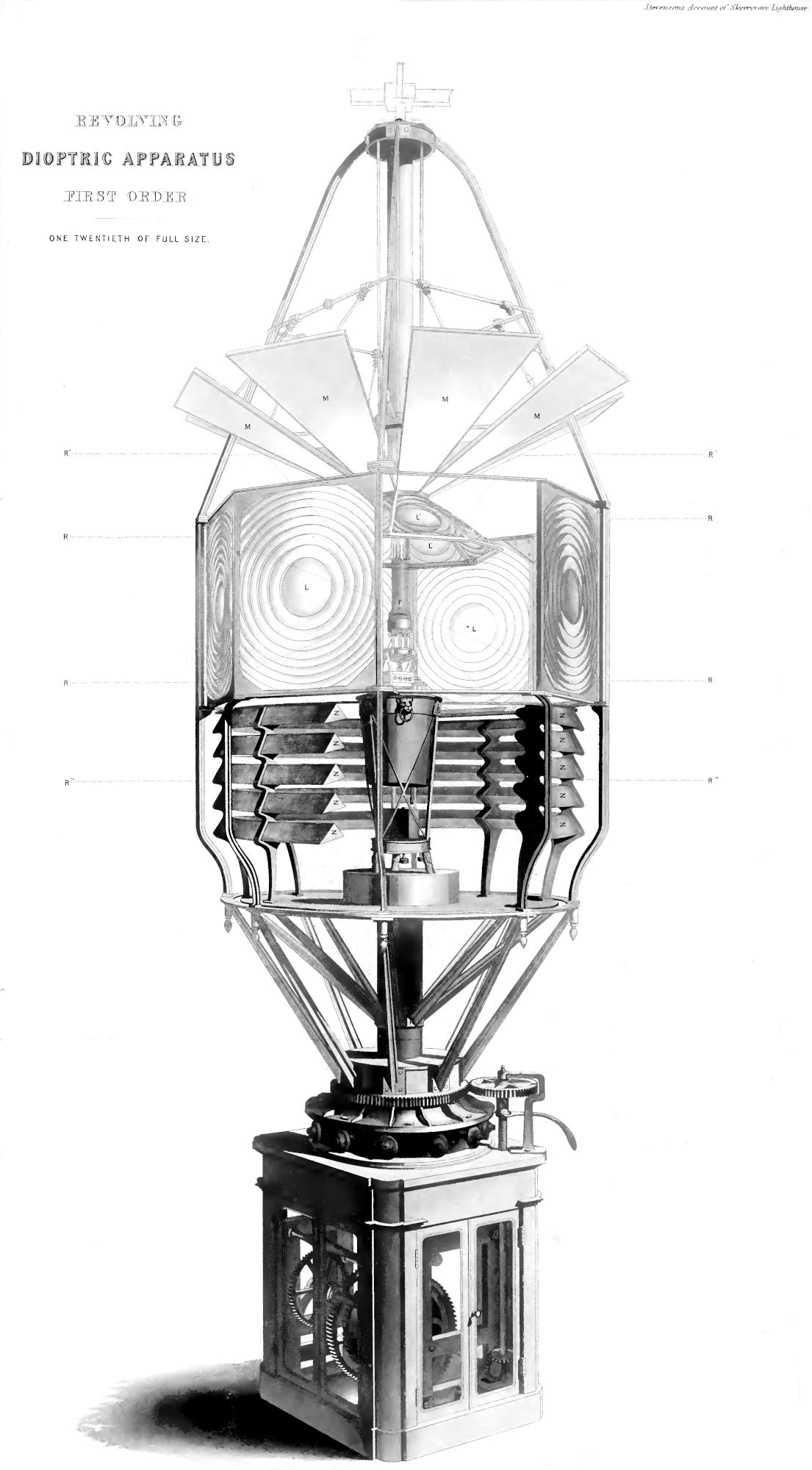

| XIII. | Perspective Elevation of Revolving Dioptric Apparatus of First Order. |

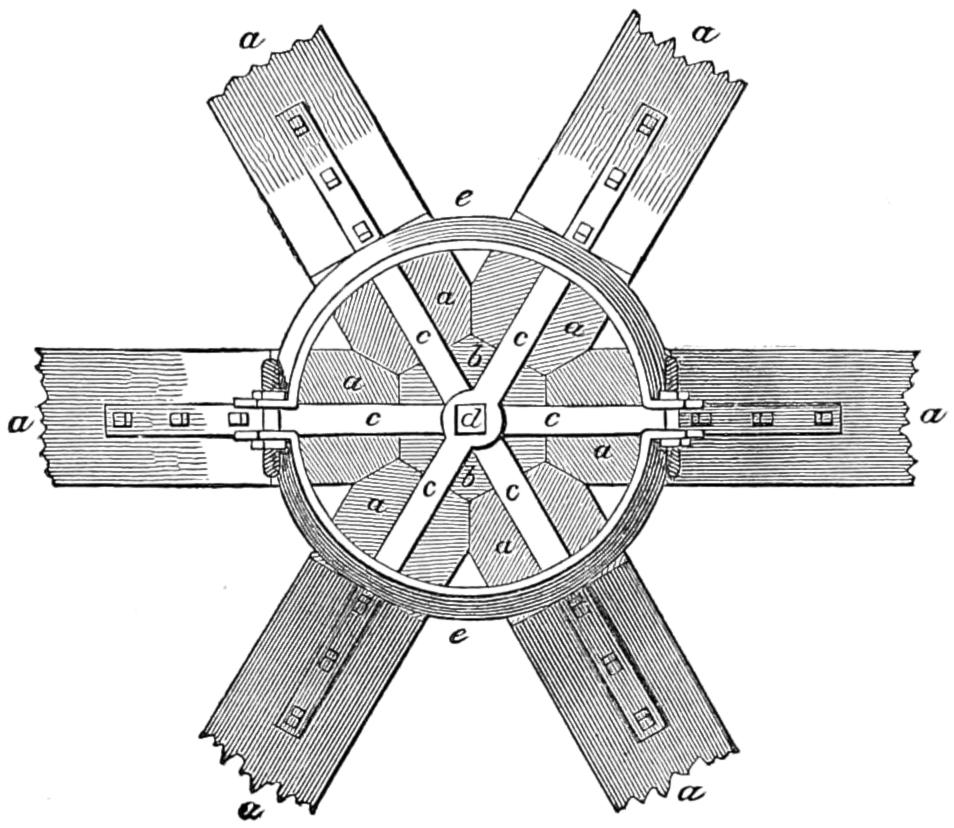

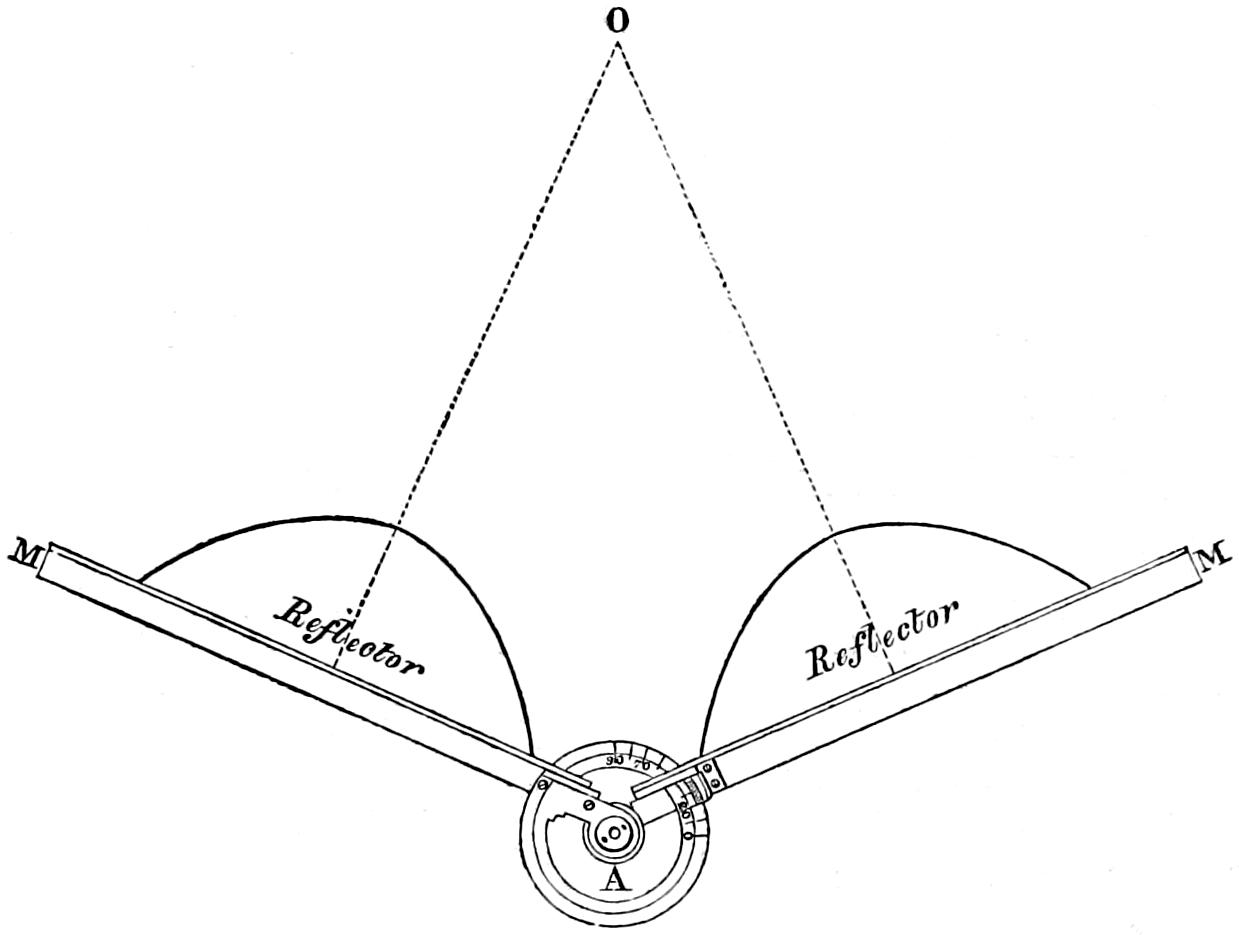

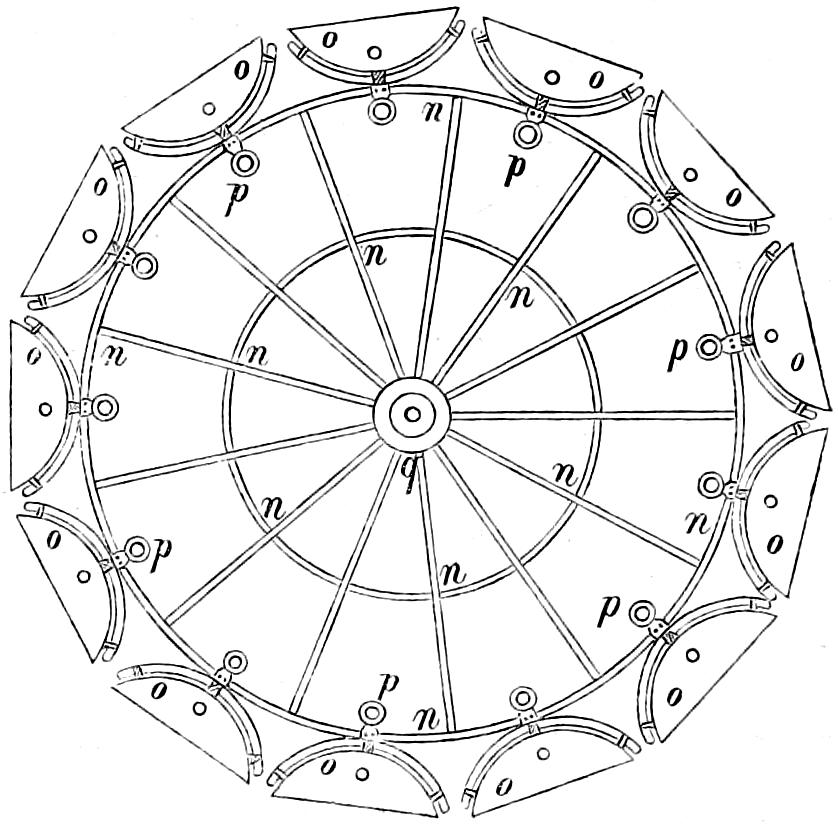

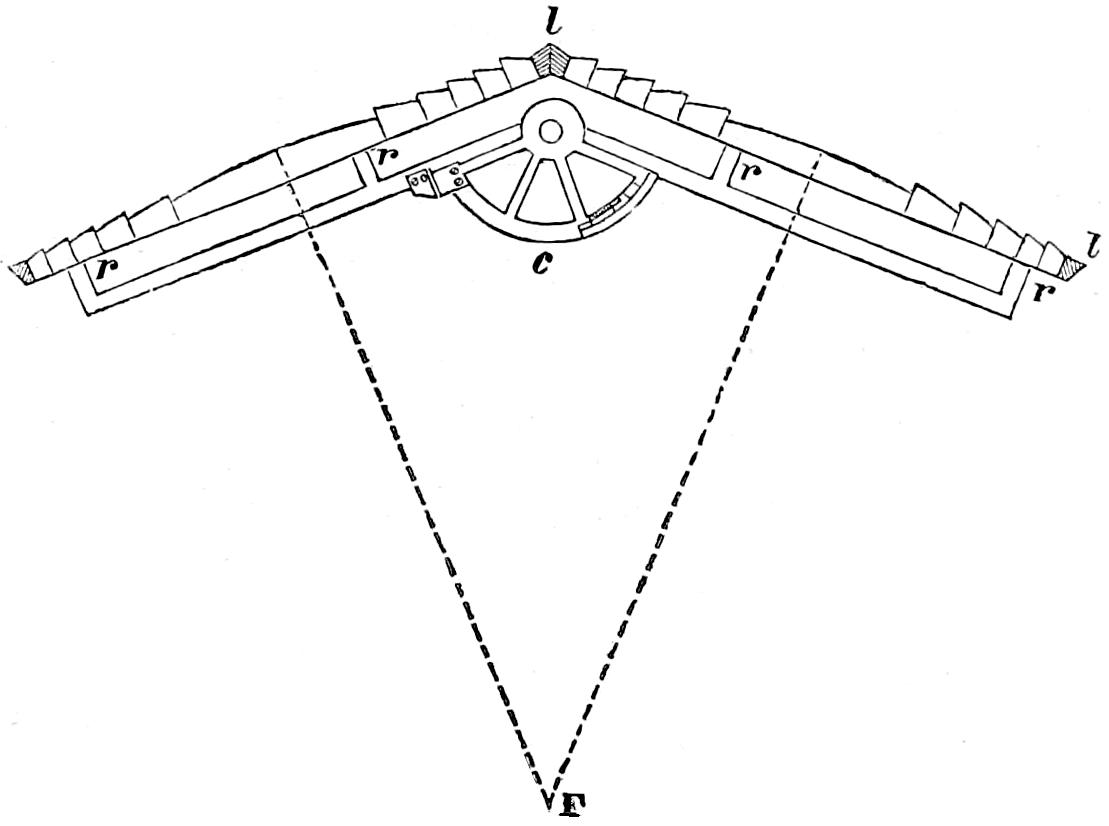

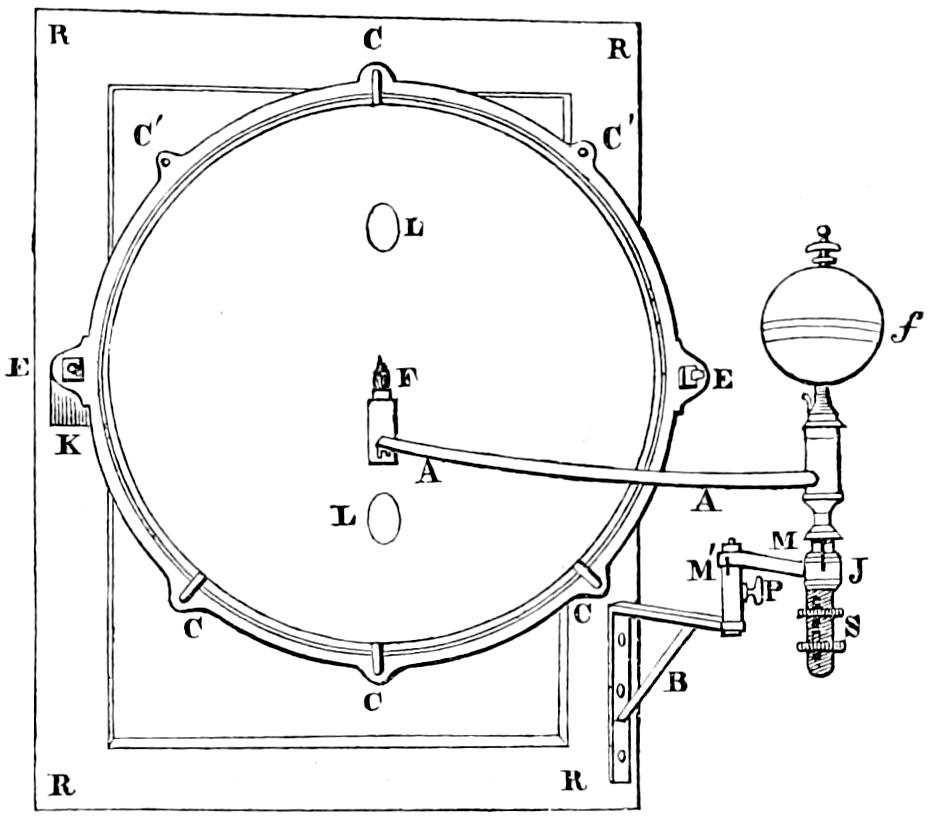

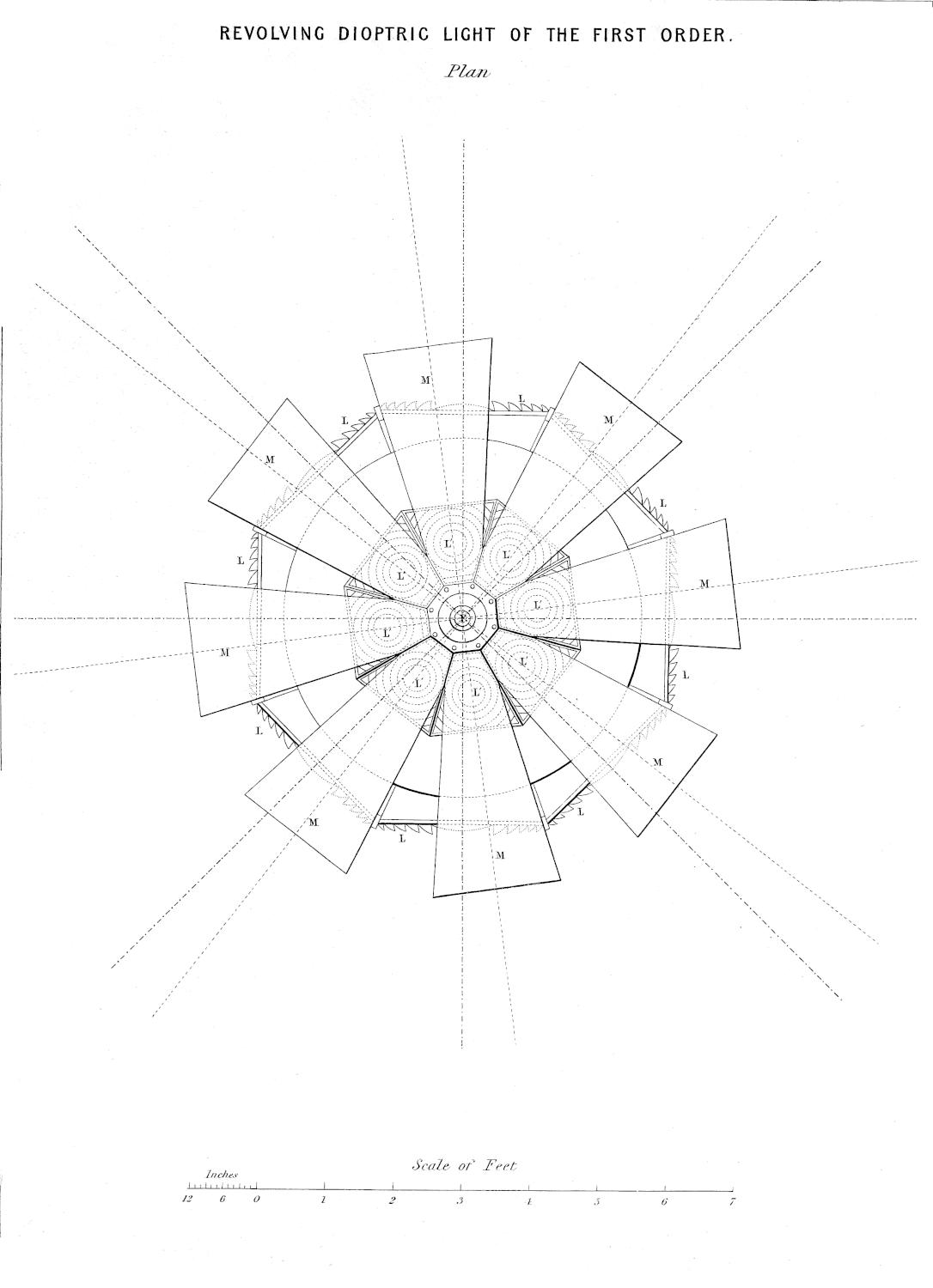

| XIV. | Plan of Revolving Dioptric Light of First Order, with Mirrors. |

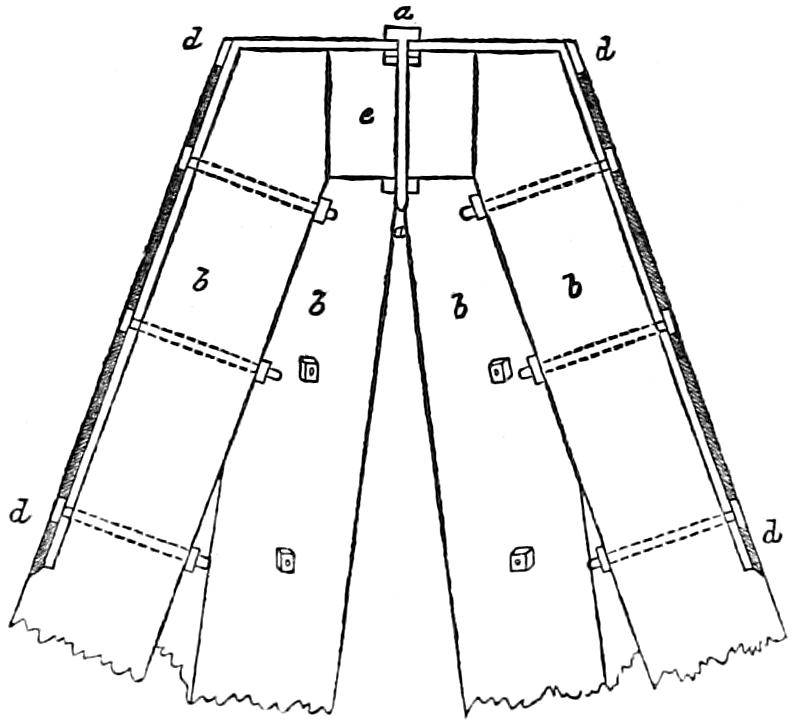

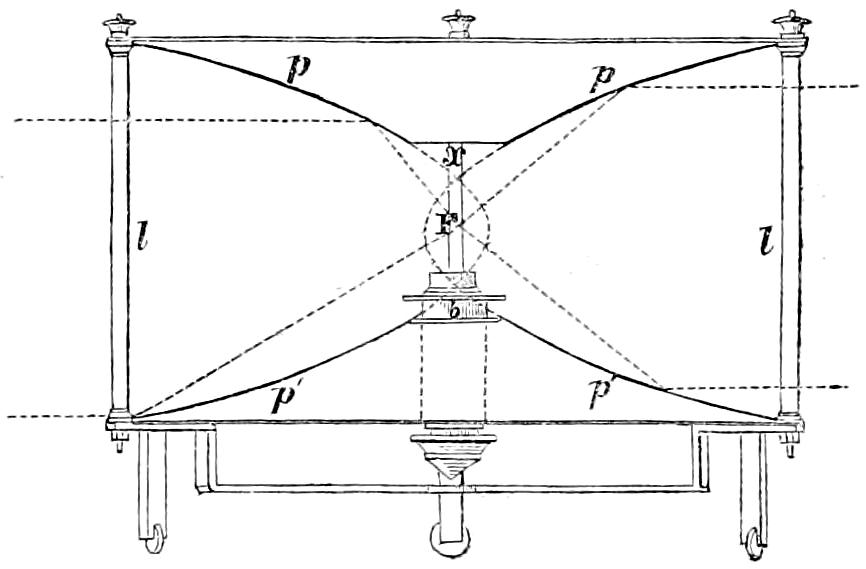

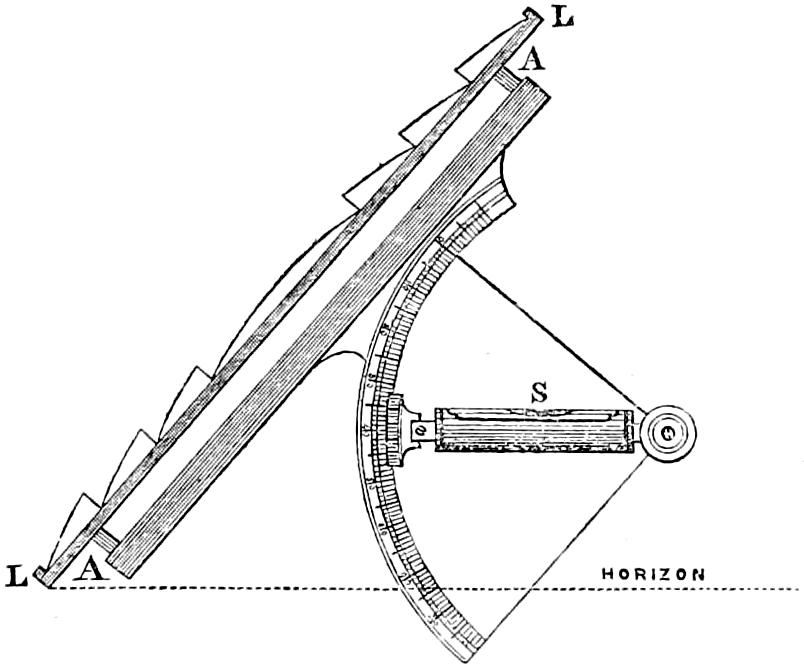

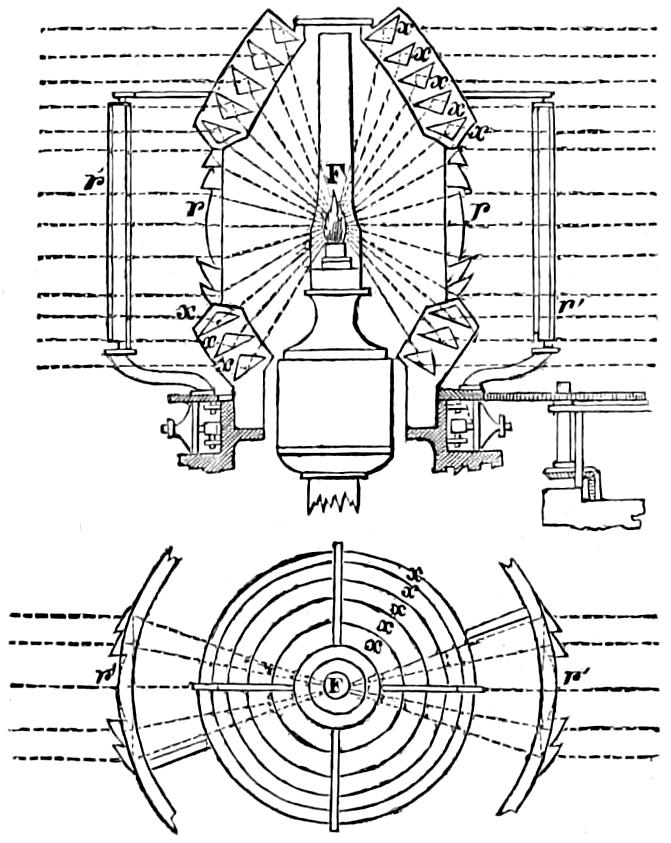

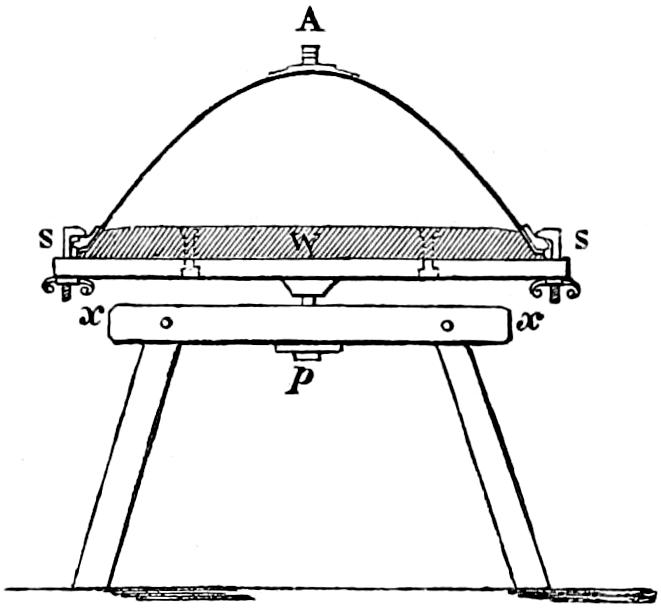

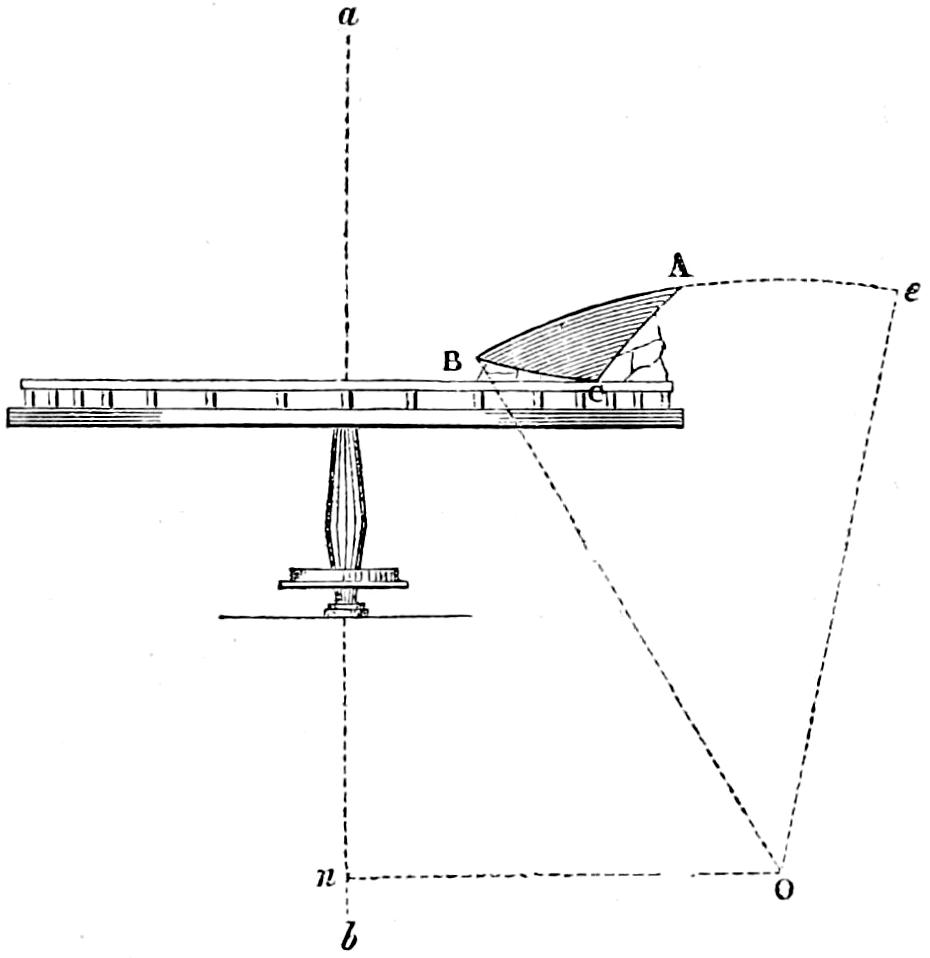

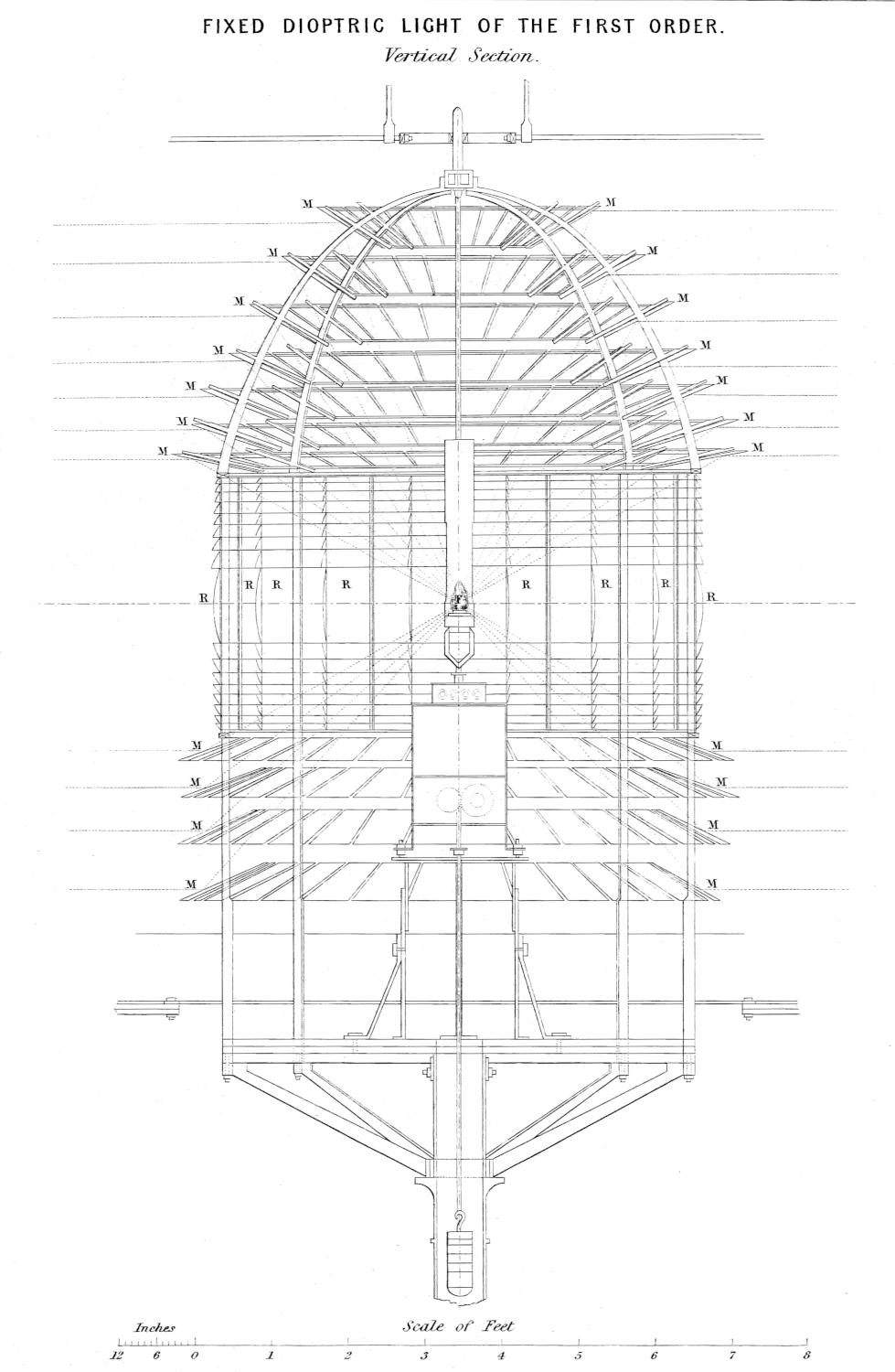

| XV. | Vertical Section of fixed Dioptric Lights of First Order, with Mirrors. |

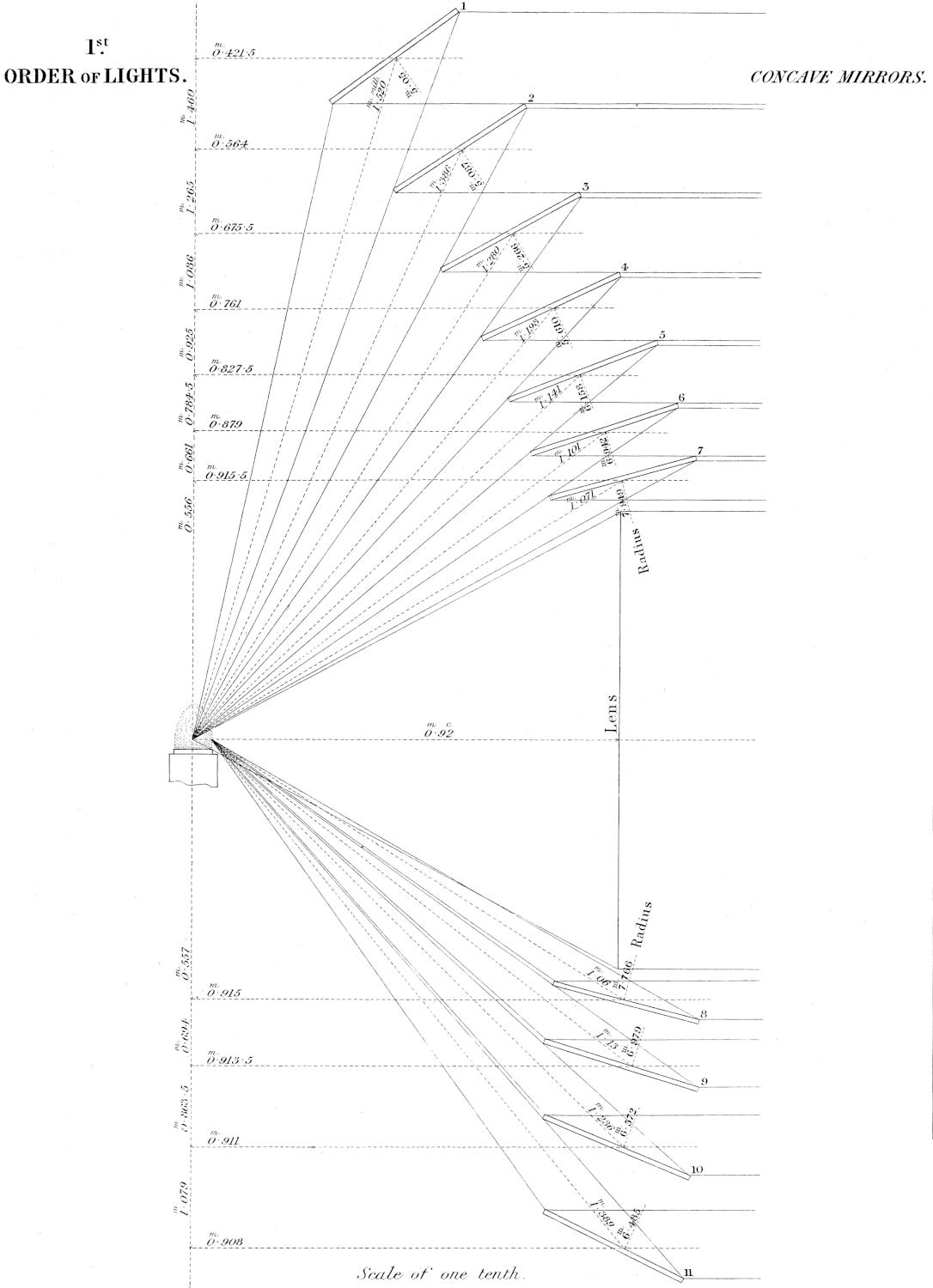

| XVI. | Elements of Concave Mirrors for Dioptric Lights of First Order, and arrangement on the Frame. |

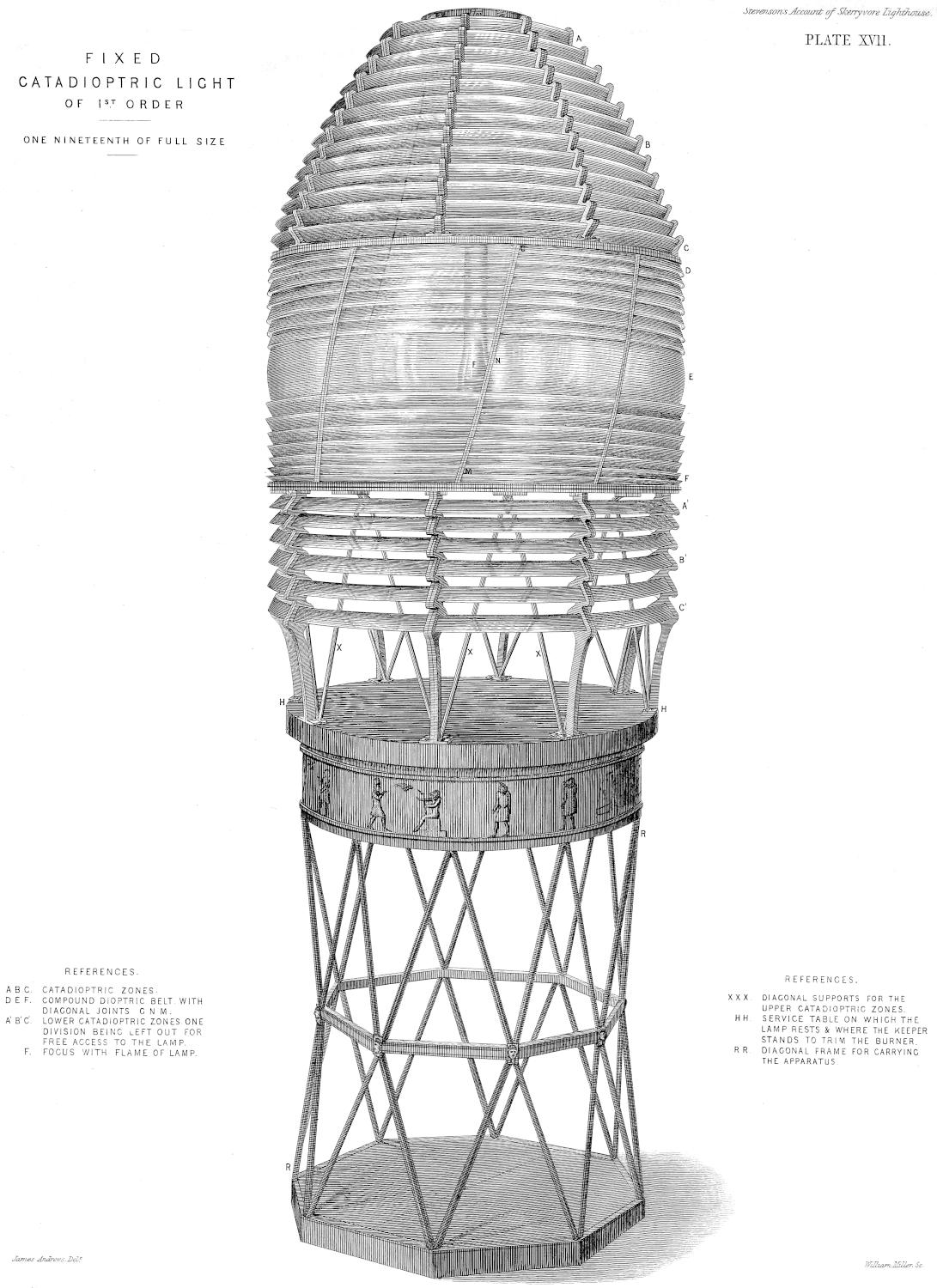

| XVII. | Perspective View of Fixed Dioptric Light of First Order, with Catadioptric Zones. |

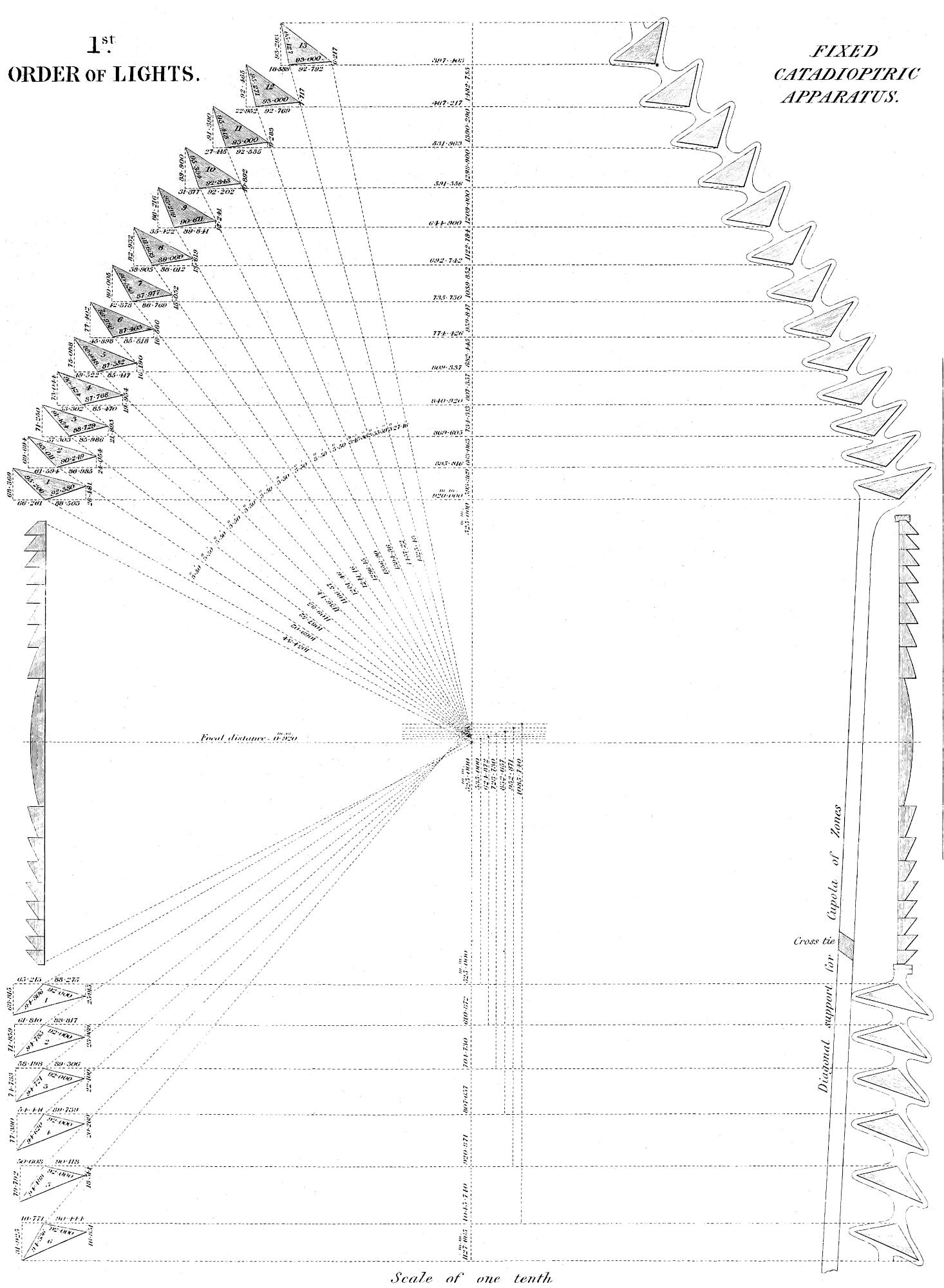

| XVIII. | Vertical Section of Fixed Dioptric Light of First Order, with Catadioptric Zones. |

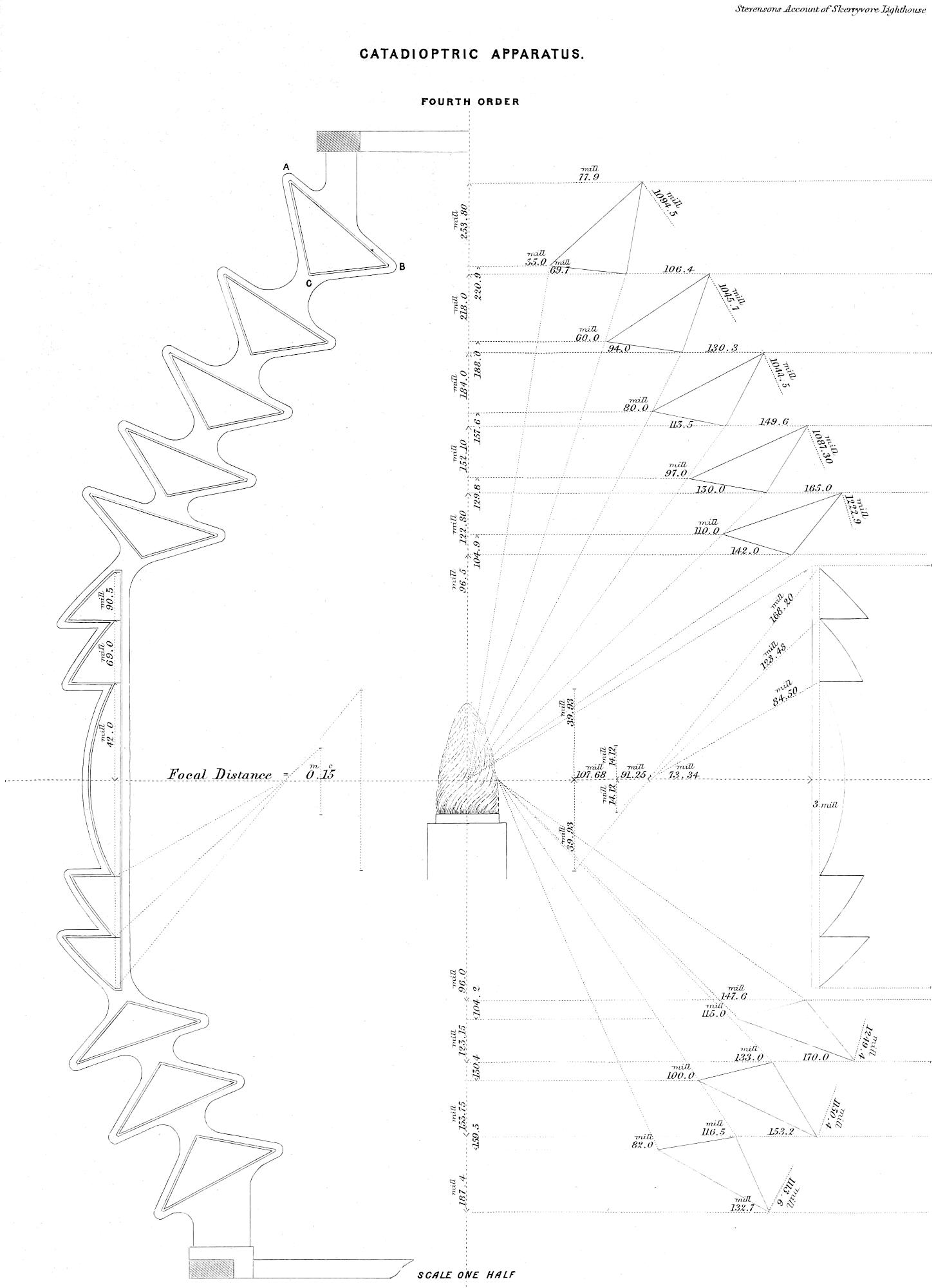

| XIX. | Vertical Section of Catadioptric Light of Fourth Order, with Framing. |

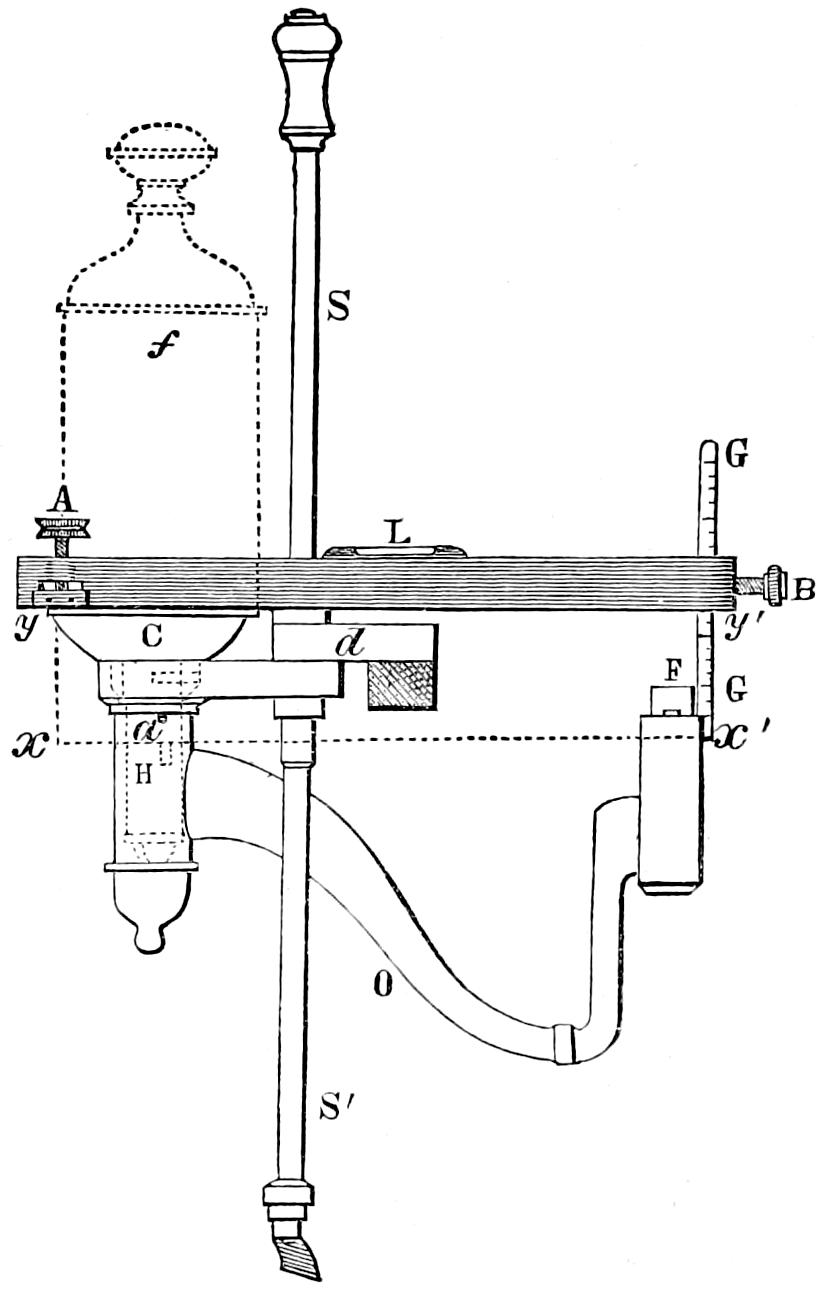

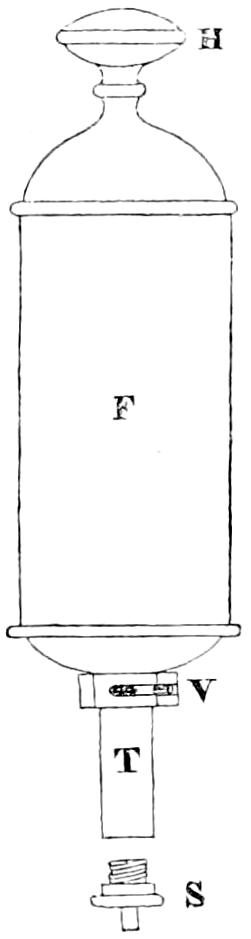

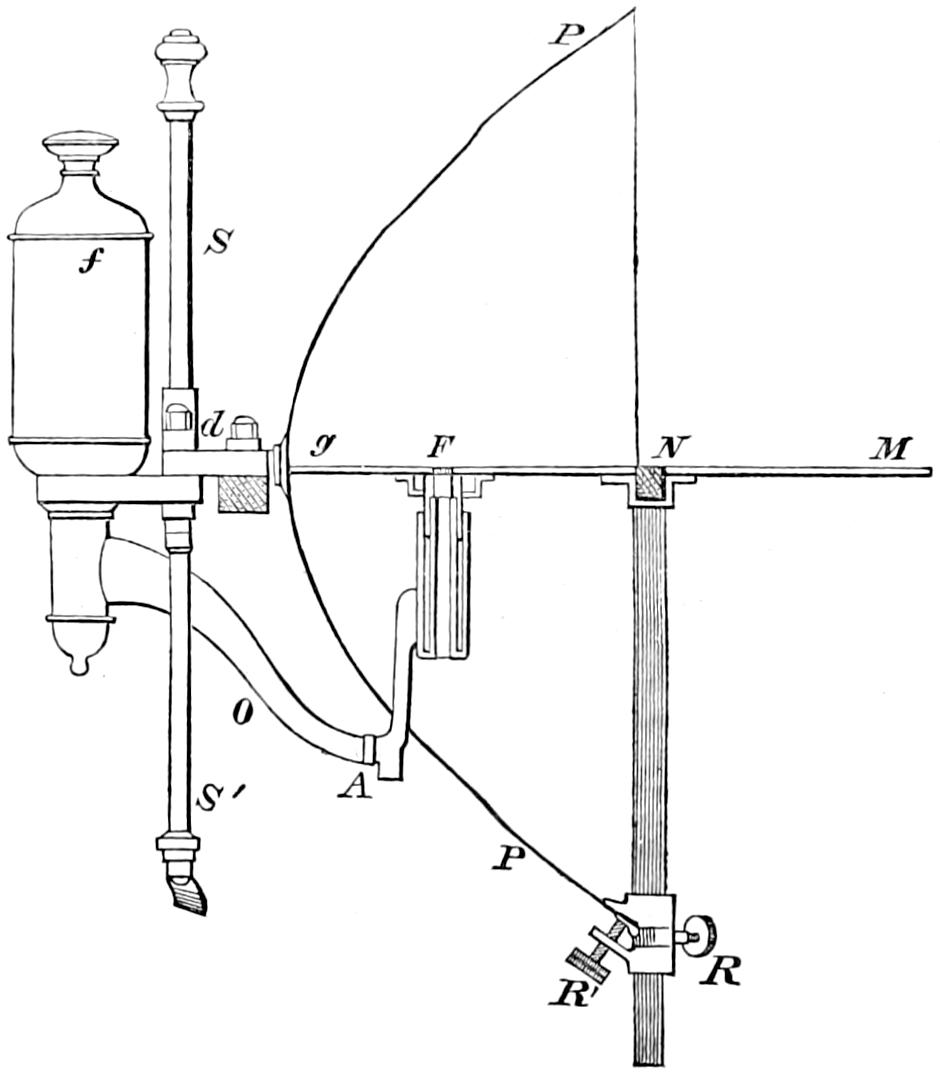

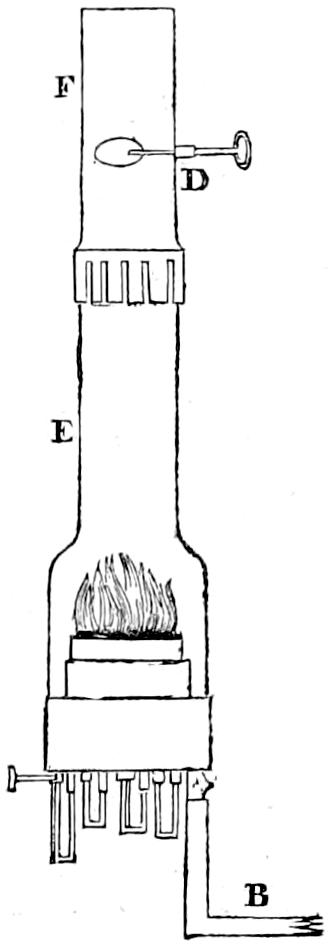

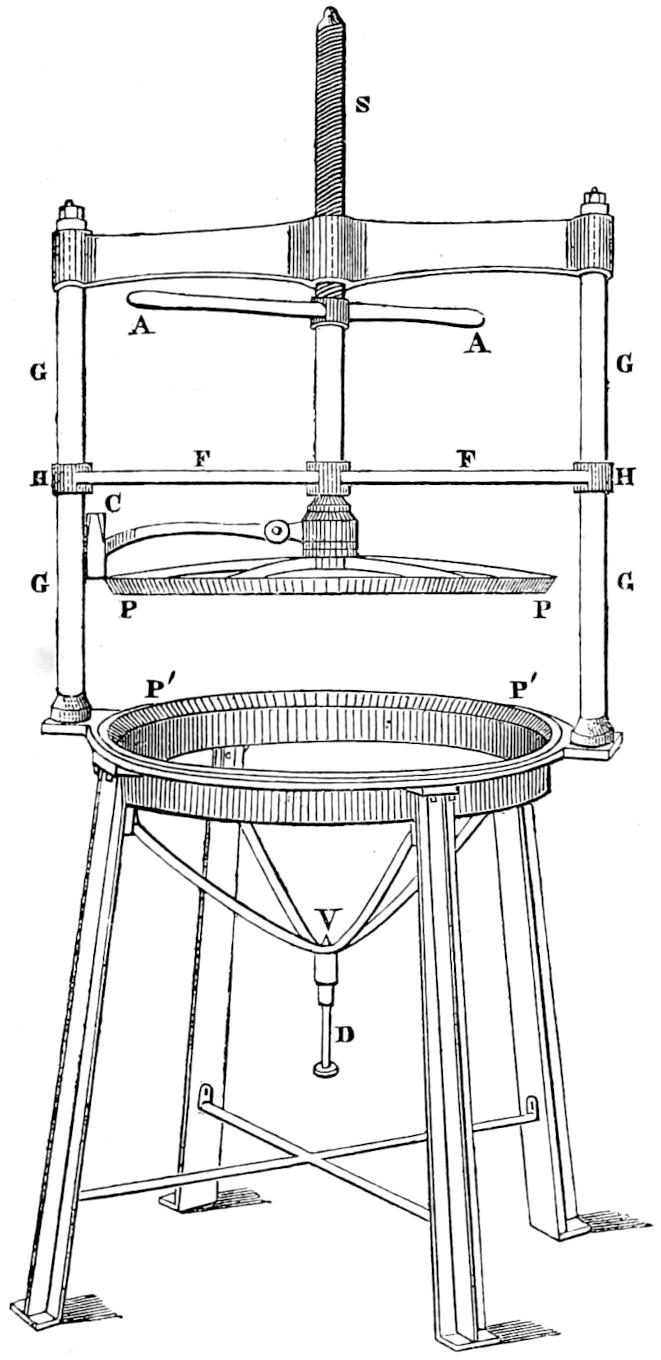

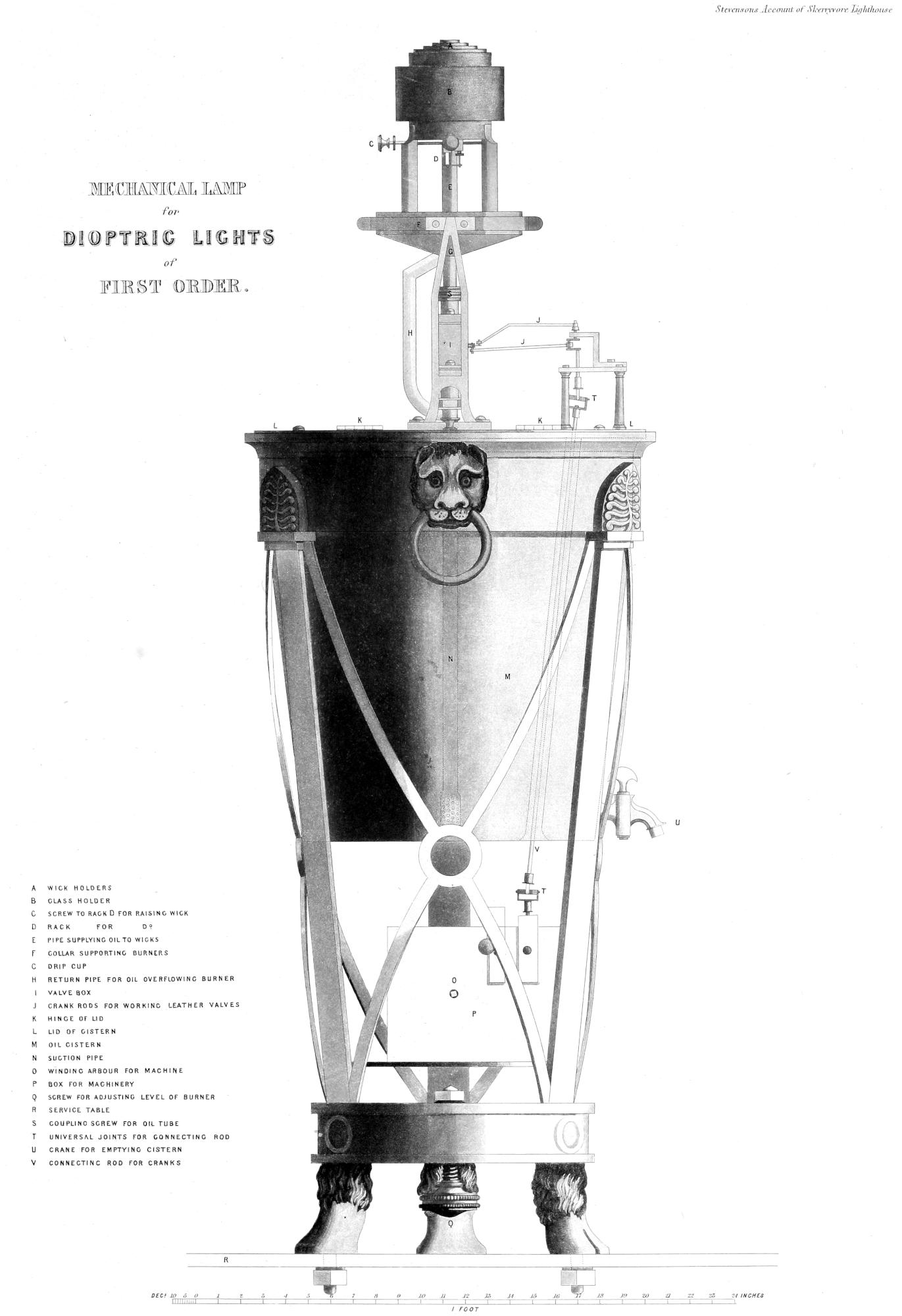

| XX. | Elevation of Mechanical Lamp for Dioptric Lights of First Order. |

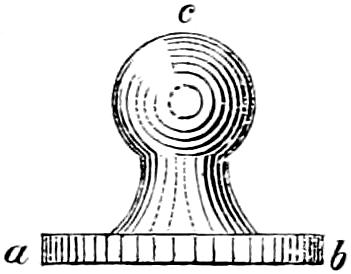

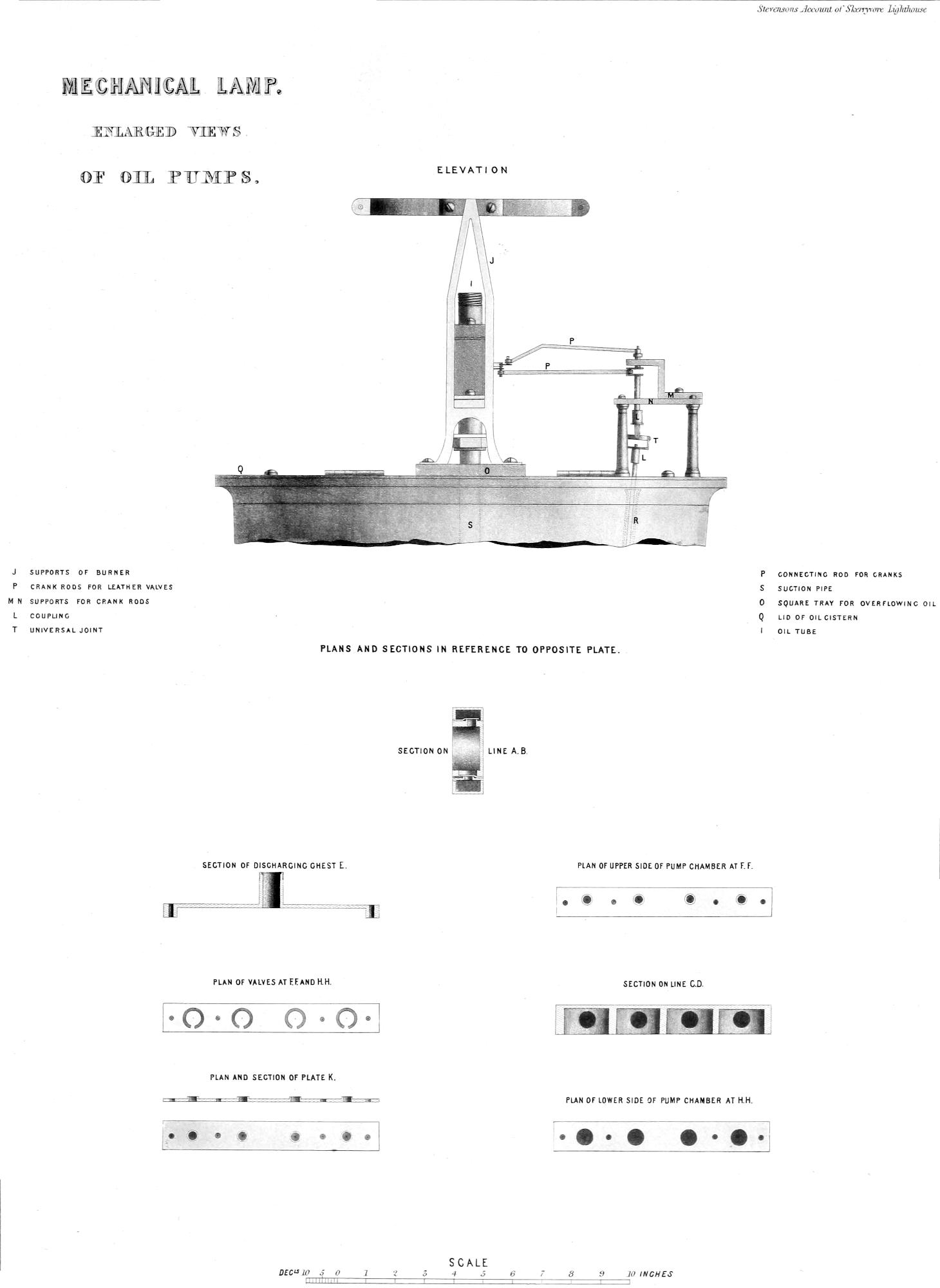

| XXI. | Enlarged Views of Oil-Pumps of Mechanical Lamp. |

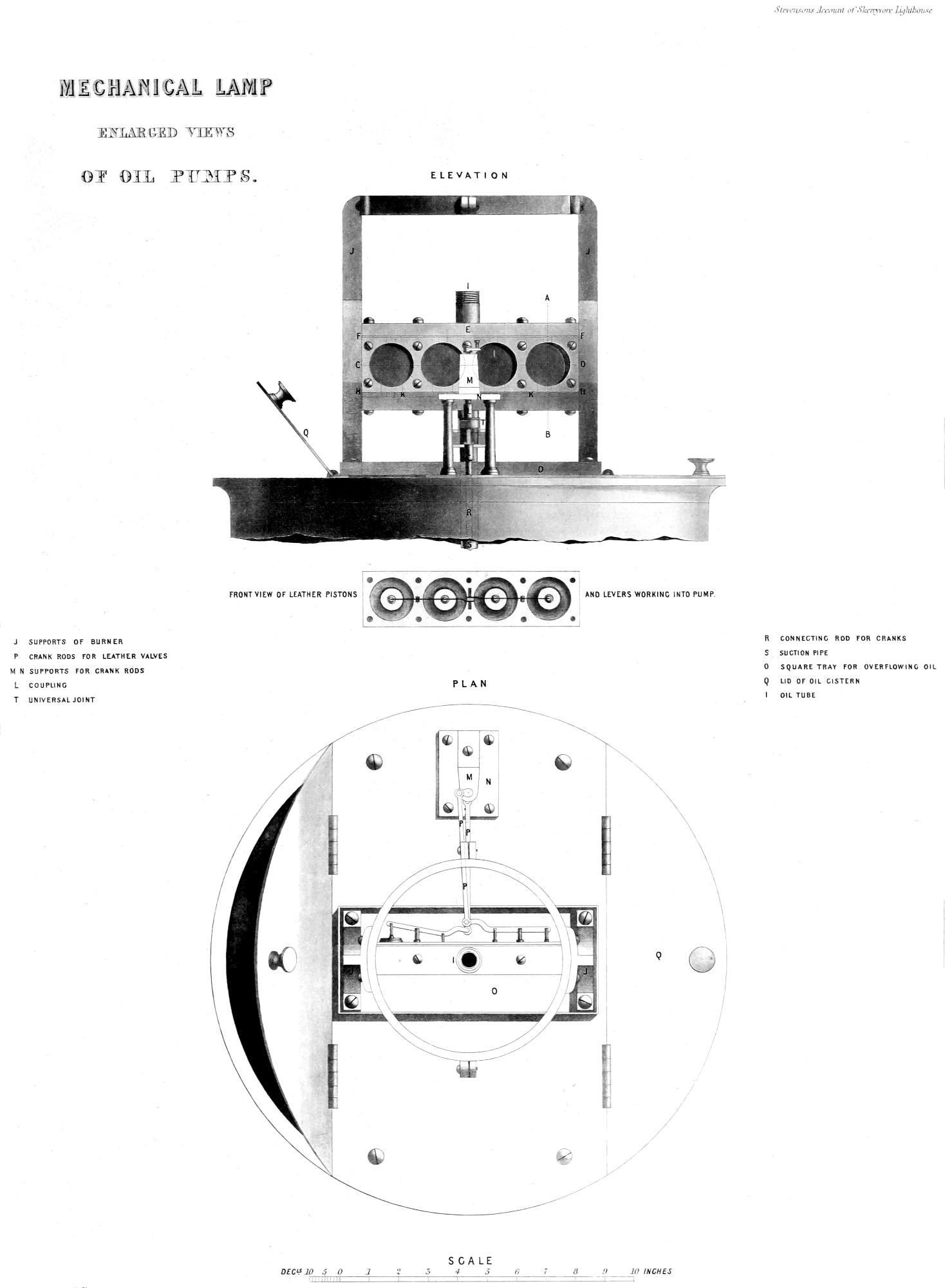

| XXII. | Enlarged Views of Oil-Pumps of Mechanical Lamp. |

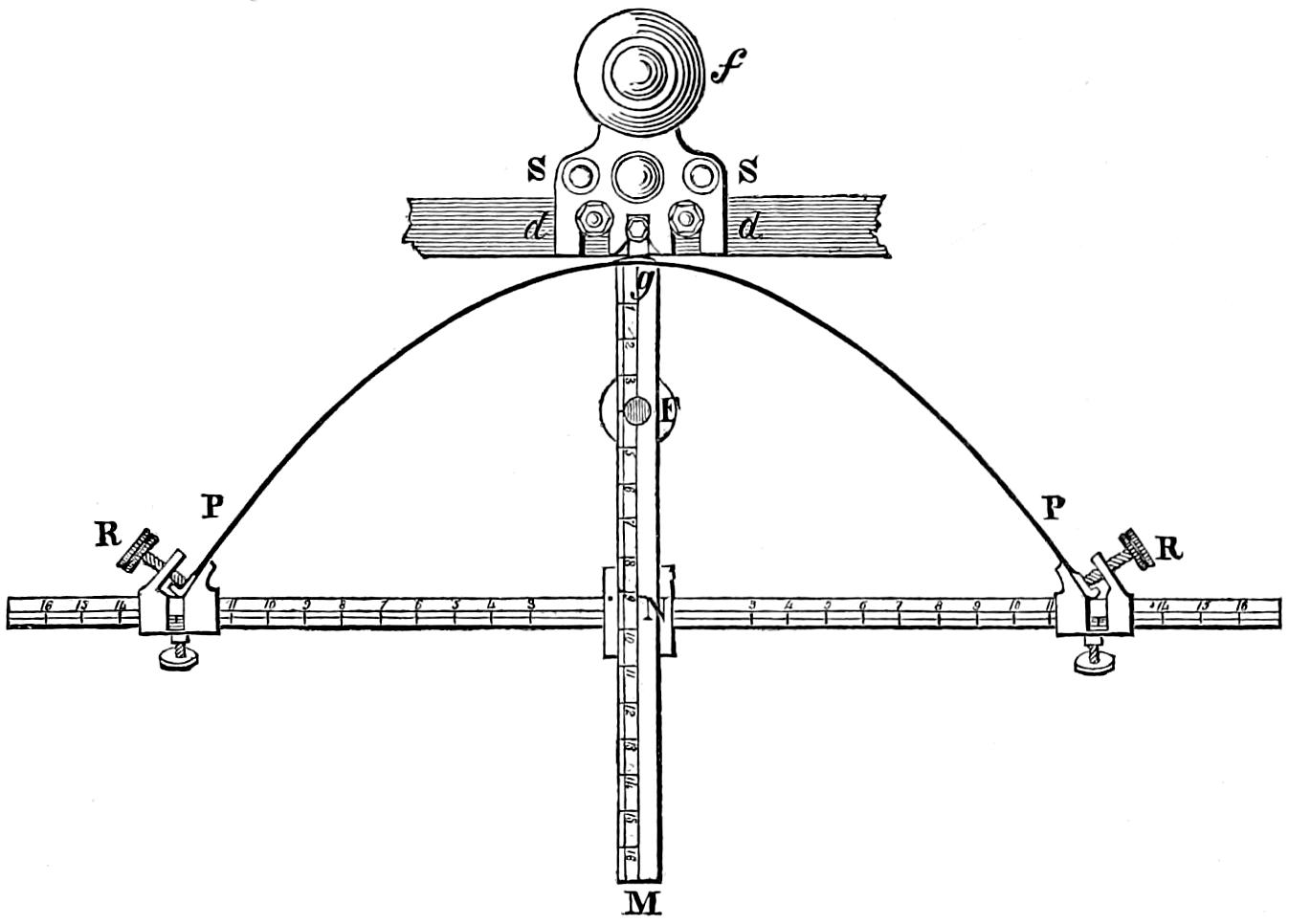

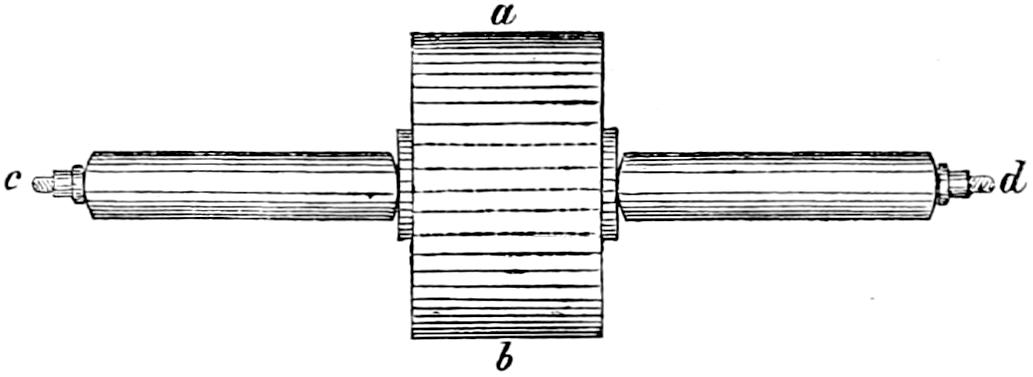

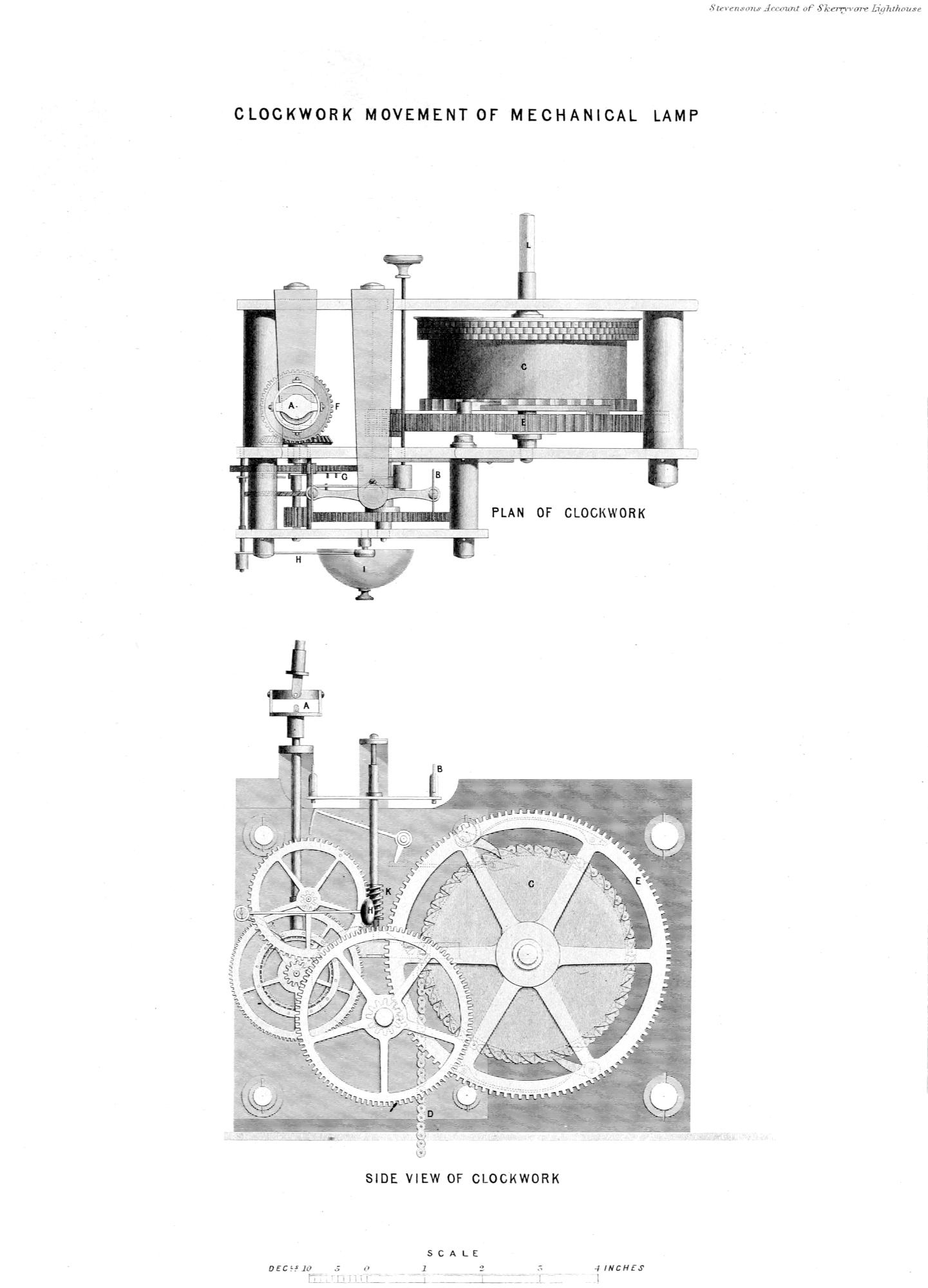

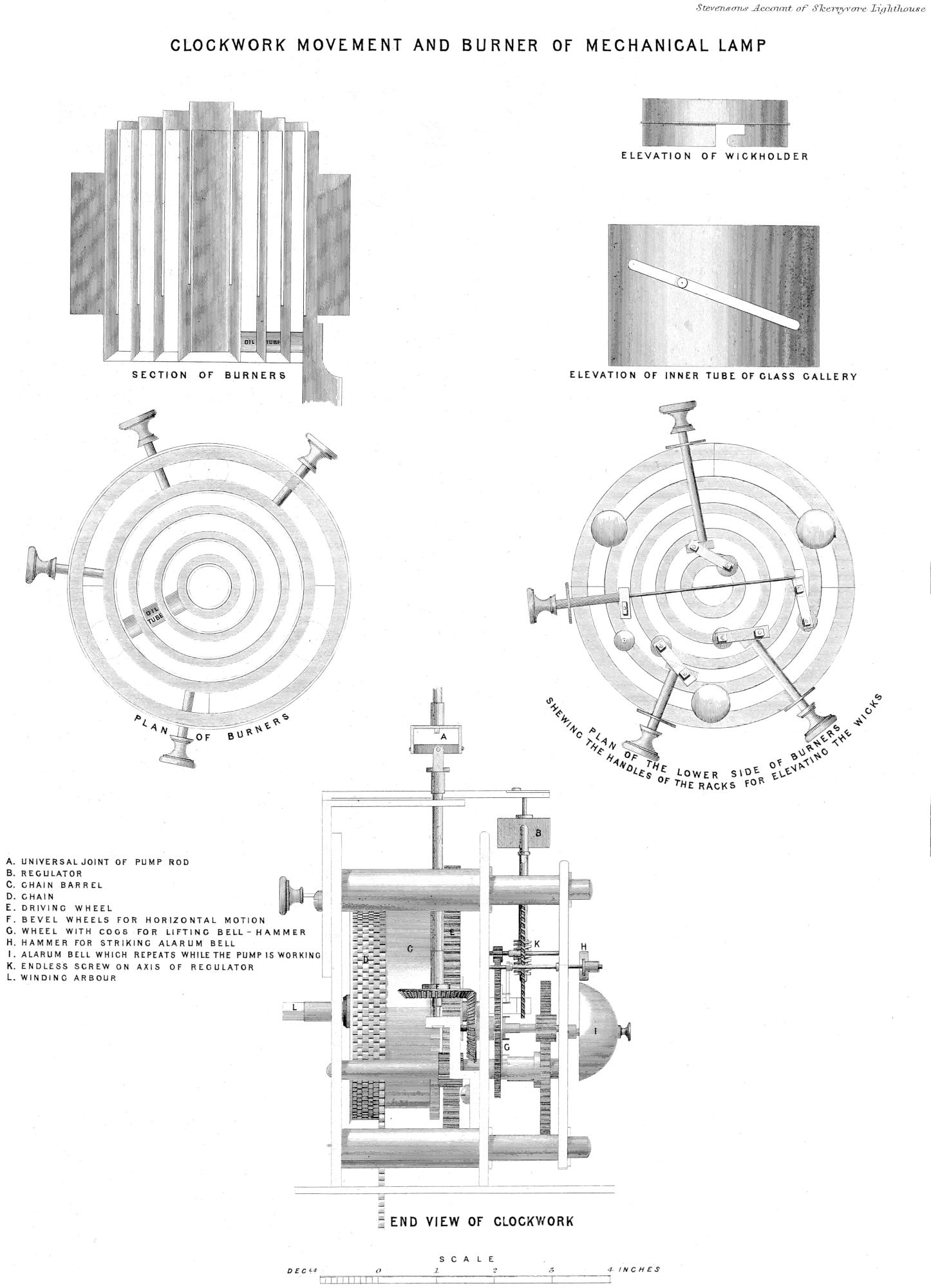

| XXIII. | Details of Clock-work of Mechanical Lamp. |

| XXIV. | Details of Clock-work of Mechanical Lamp. |

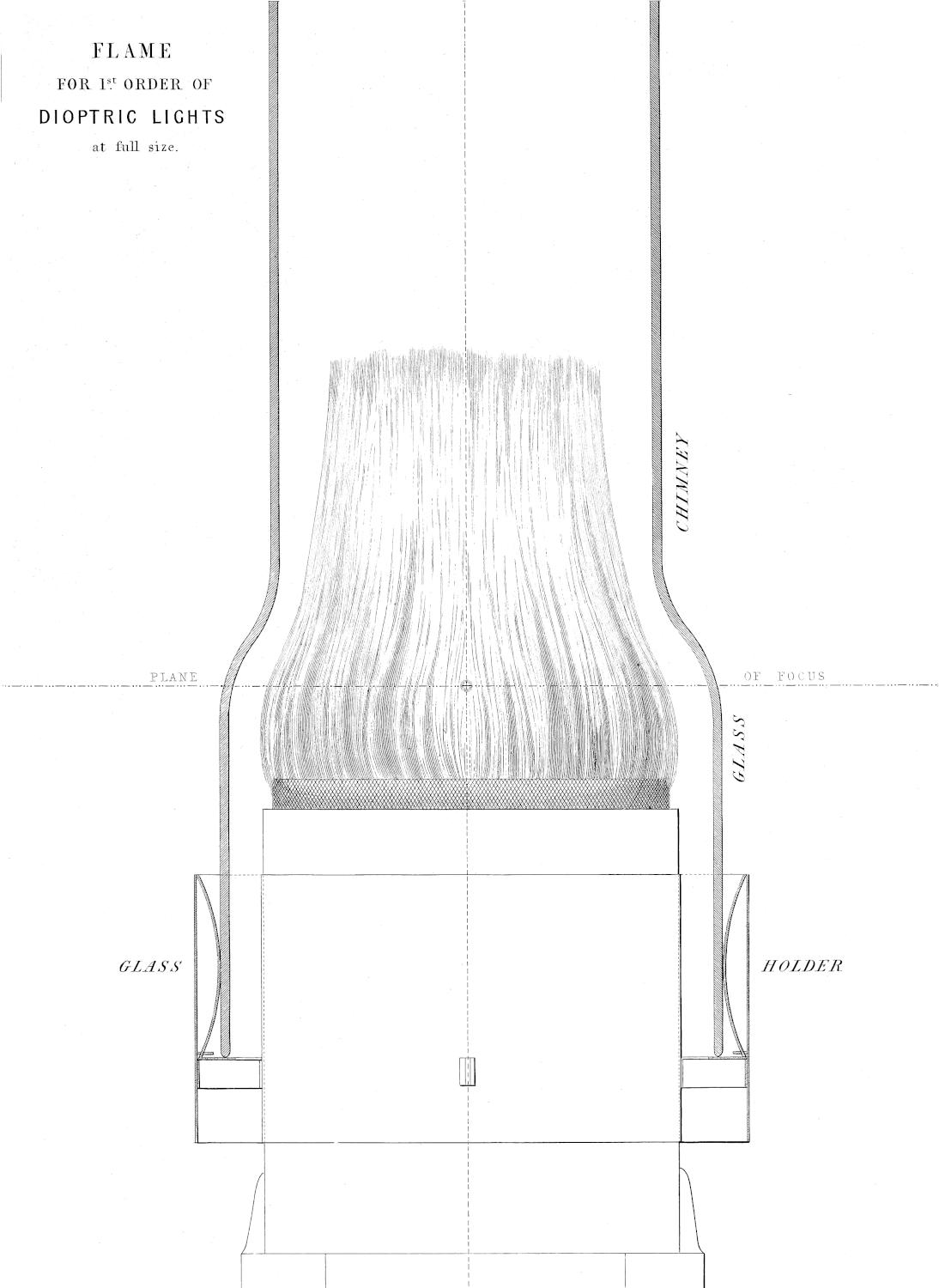

| XXV. | Flame of Mechanical Lamp of First Order at full size. |

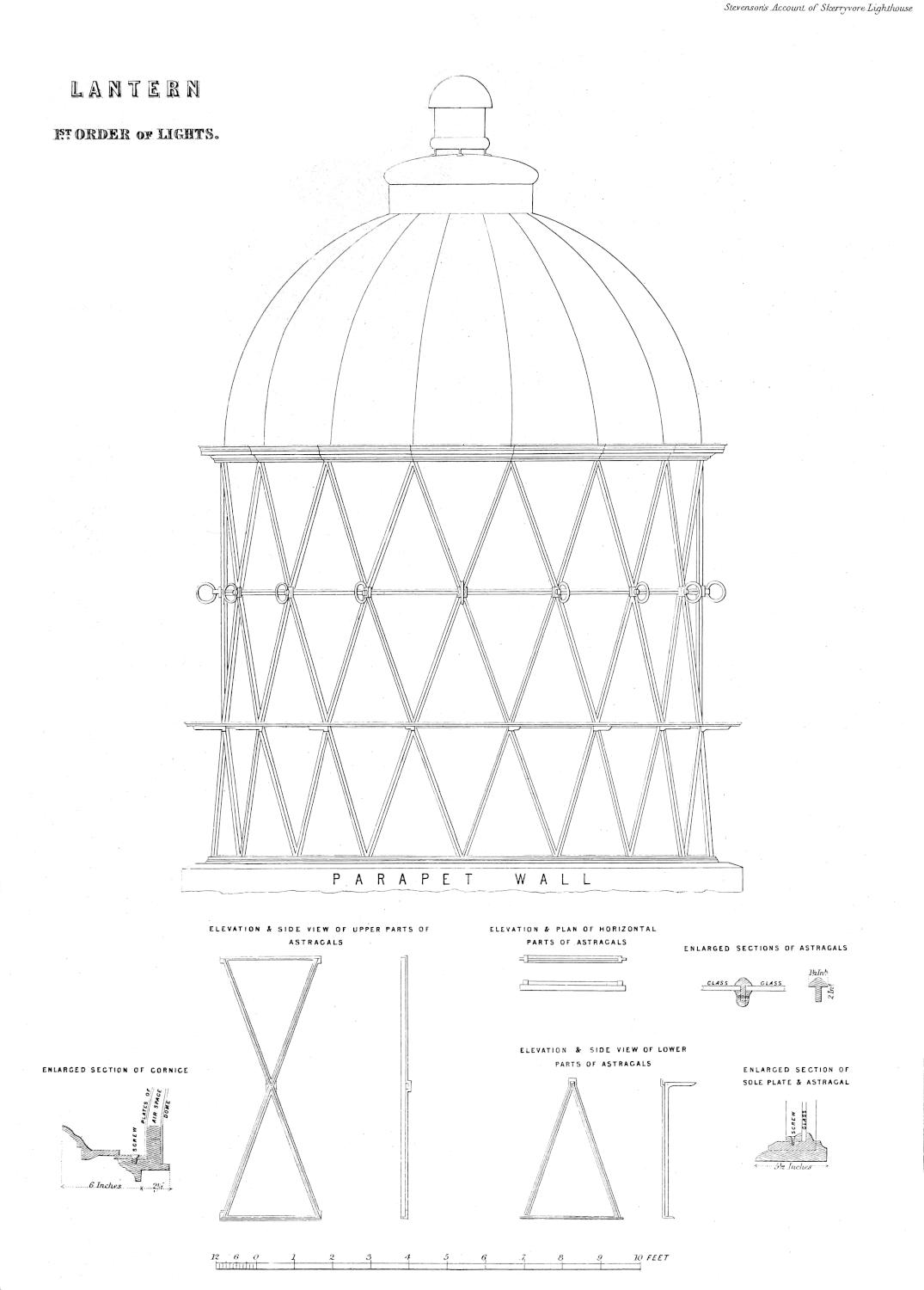

| XXVI. | Elevation of Diagonal Lantern, and details of Astragals. |

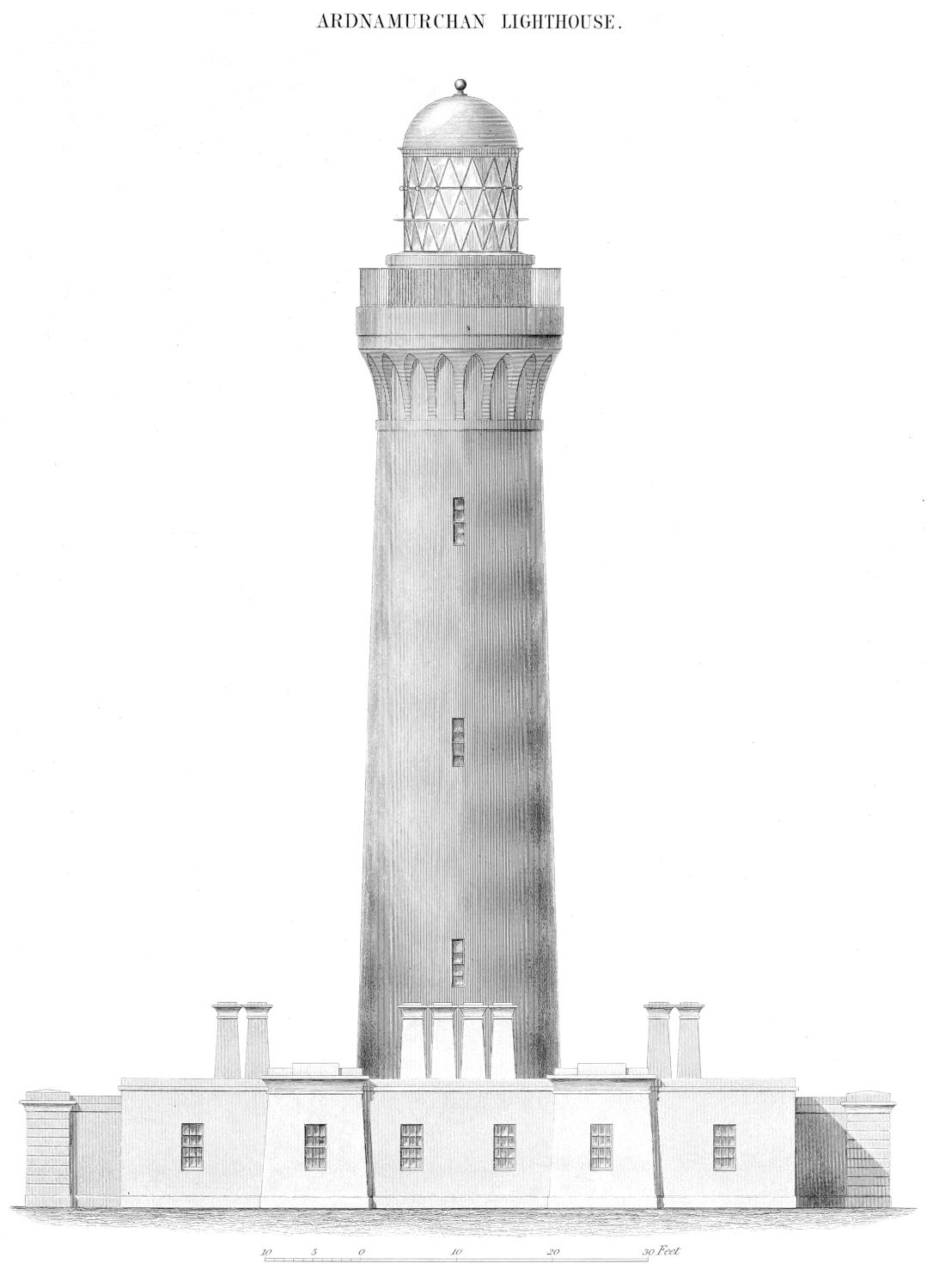

| XXVII. | Elevation of Ardnamurchan Lighthouse. |

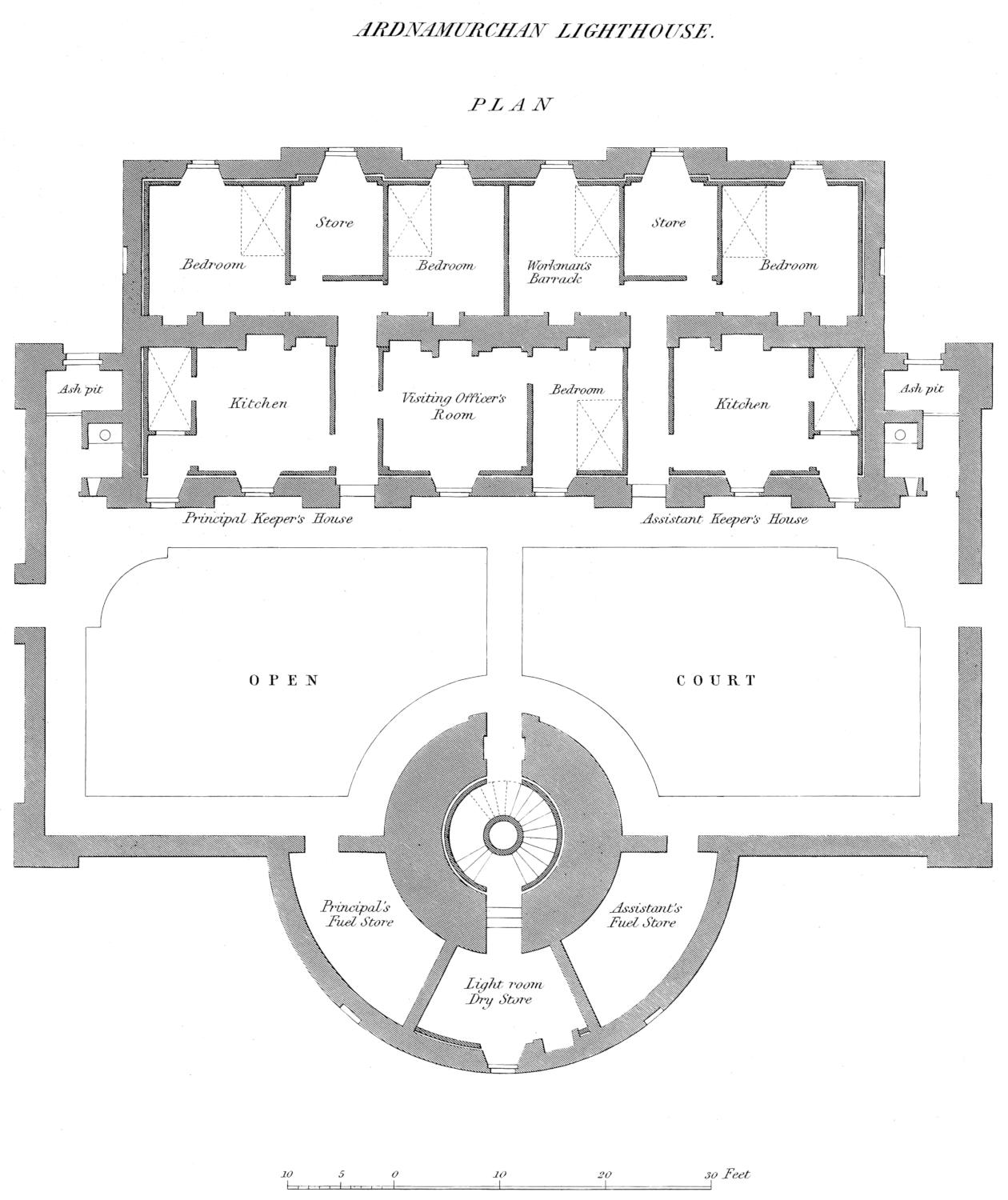

| XXVIII. | Plan of Ardnamurchan Lighthouse. |

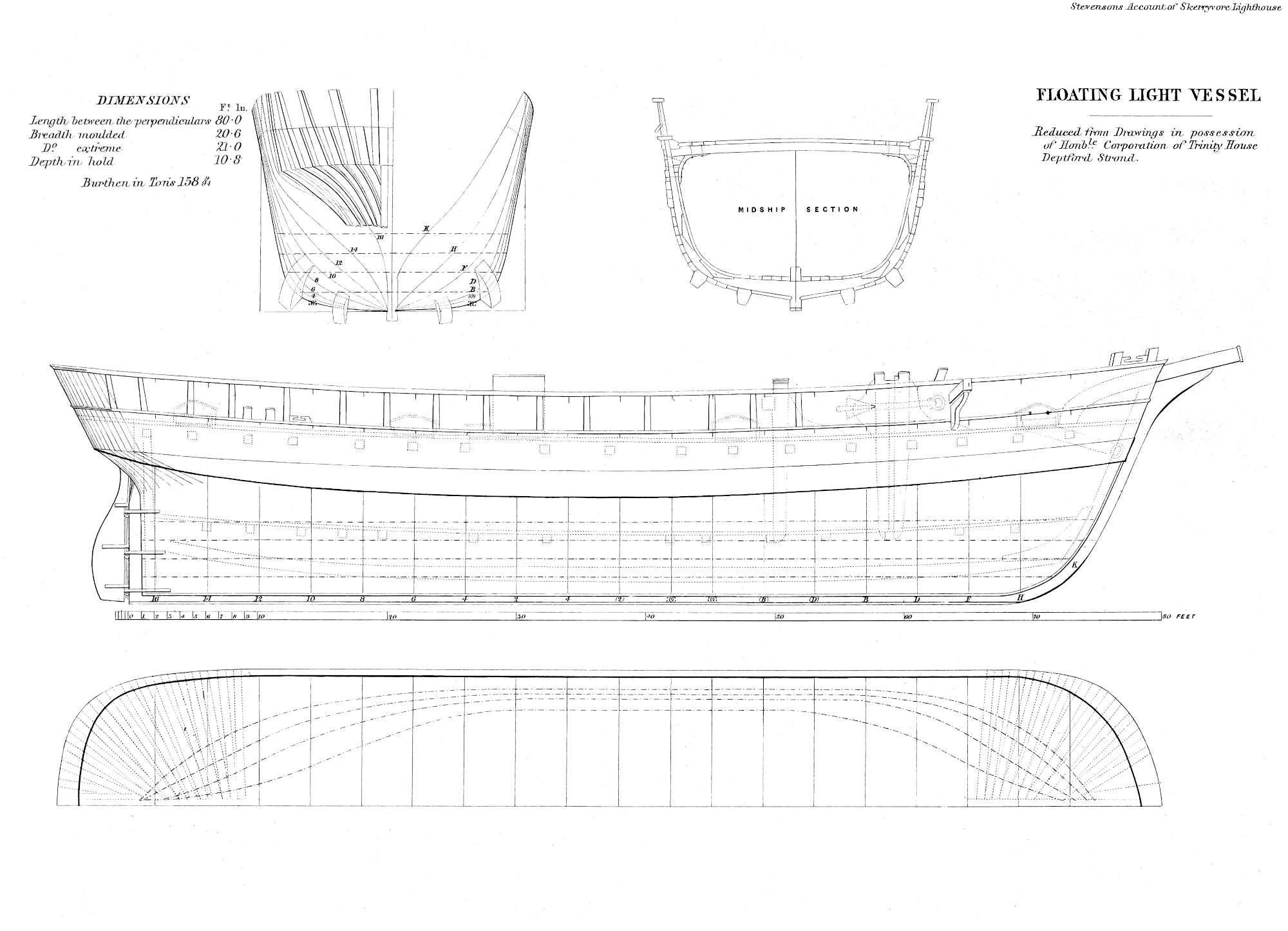

| XXIX. | Lines of a Floating Light Vessel belonging to the Corporation of Trinity House of Deptford Strond. |

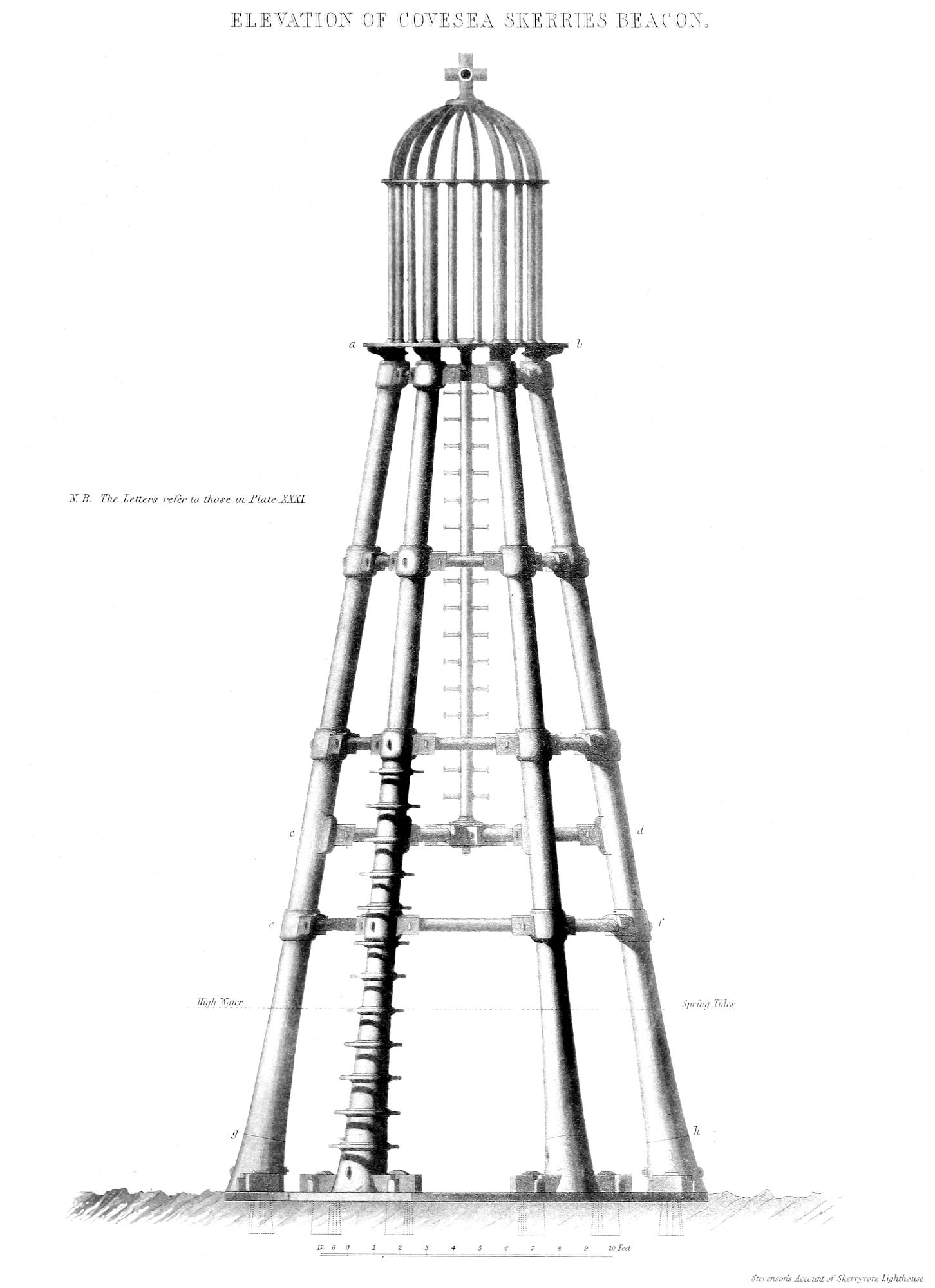

| XXX. | Elevation of Covesea Skerries Beacon. |

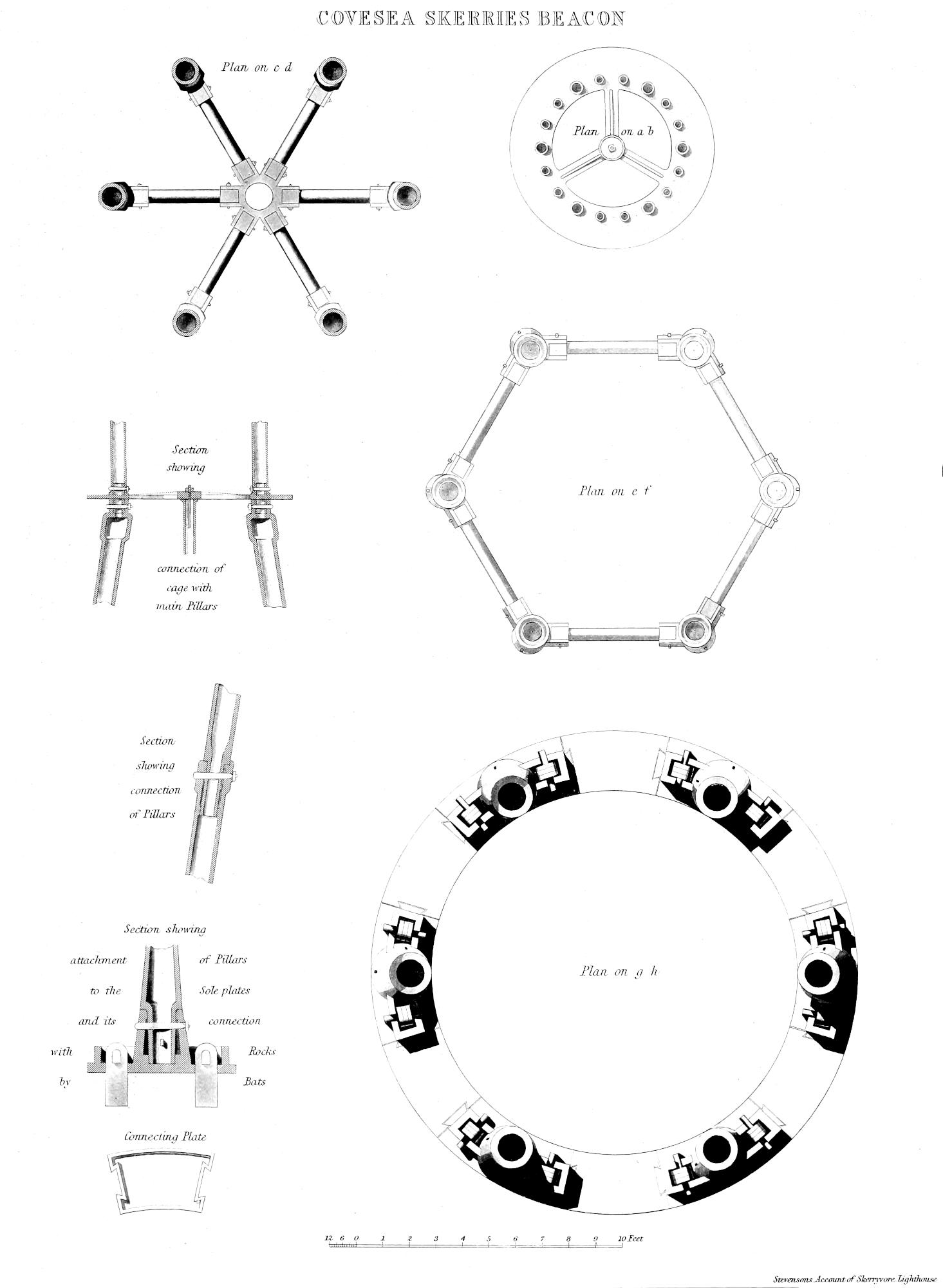

| XXXI. | Details of Covesea Skerries Beacon. |

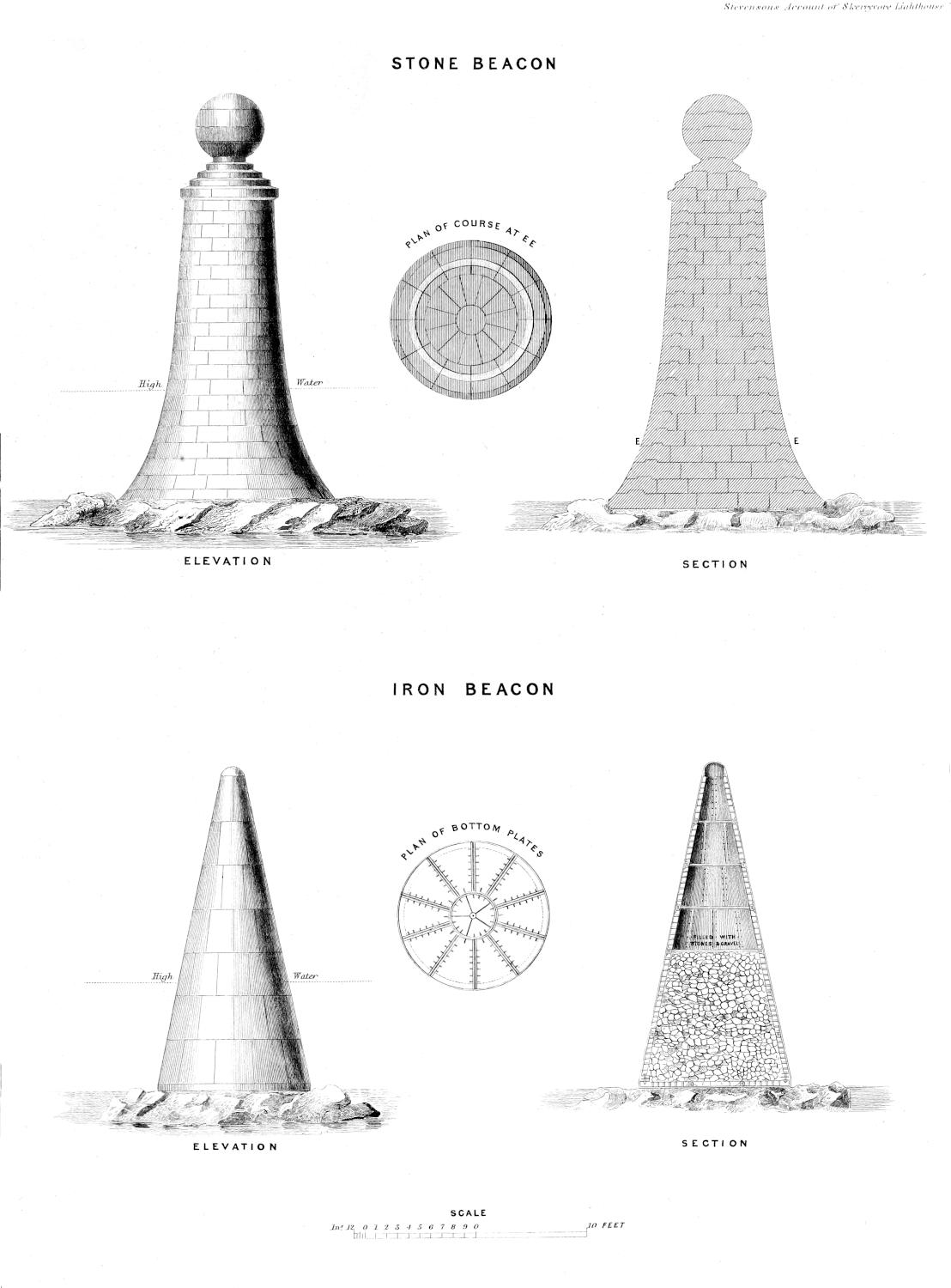

| XXXII. | Elevations and Sections of Stone and Iron Beacons. |

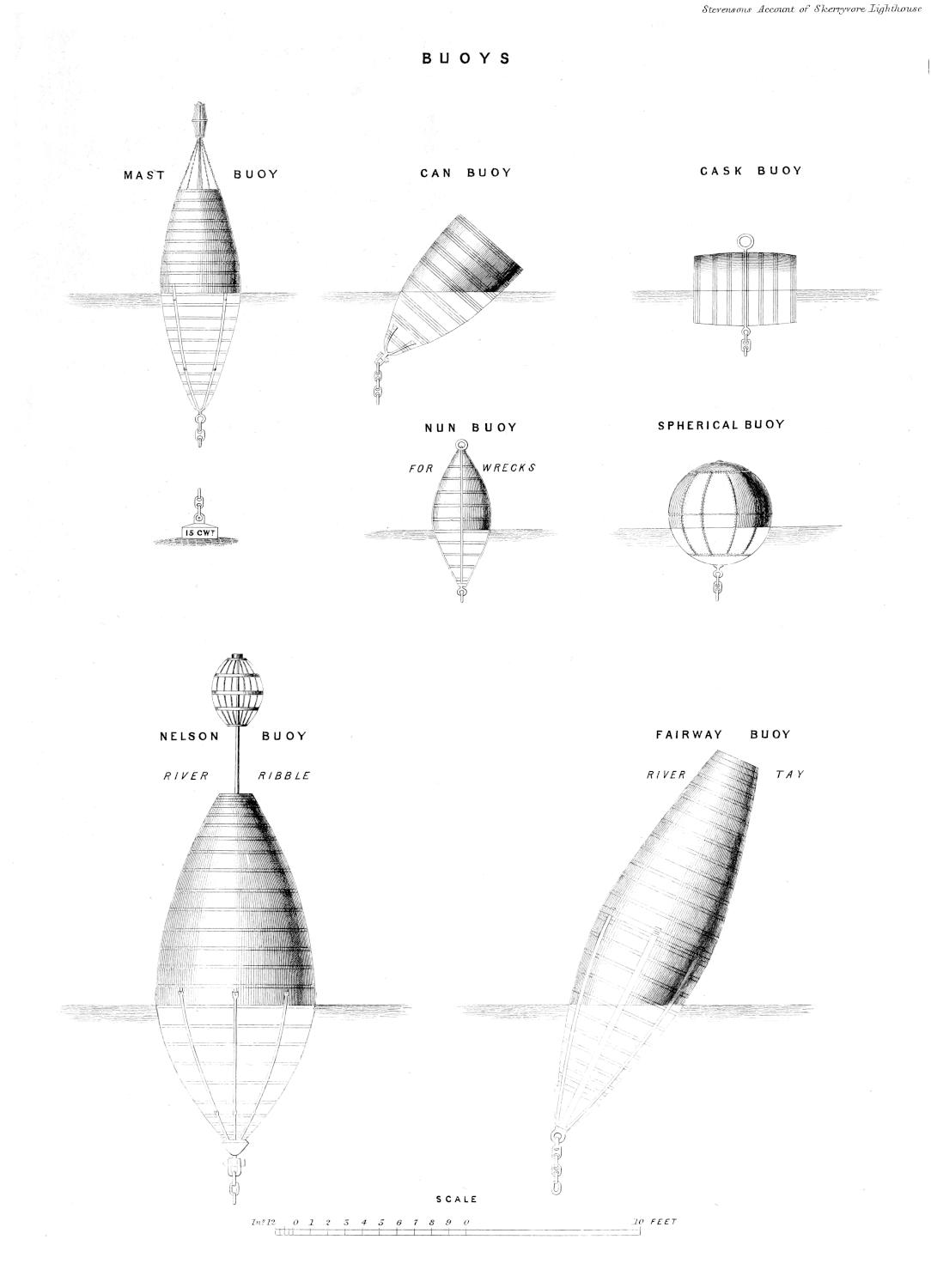

| XXXIII. | Elevations of Buoys. |

| Page | 52, | line 8, for Redelet read Rondelet |

| ... | 178, | line 6, for L.93,306:8:10 read L.86,977:17:7 |

| ... | 292, | line 30, for radius rector read radius vector |

| ... | 294, | line 13, for give read gives |

| ... | 329, | line 3, for earth read sea |

| ... | 347, | line 29, for Plate XXXII., read Plate XXX., |

[7]

In the course of preparing the account of the building of the Skerryvore Lighthouse, it occurred to me, that a short Introduction should be prefixed, embracing a concise view of the constitution and acts of the Board of Commissioners of Northern Lights, more especially from 1824, when my Father’s work on the Bell Rock Lighthouse was published, up to the present time. This object will be best accomplished, by presenting to the reader, in the first place, an account of the constitution and powers of the Lighthouse Board, chiefly drawn from the “Introduction to the Bye-Laws, Rules, and Regulations of the Commissioners of Northern Lighthouses,” prepared by a Committee of their number; and by afterwards briefly noticing the principal works of the Board since 1824, and stating generally the nature of the changes and improvements made within that period on the mode of illumination, of which I propose, in a subsequent part of this volume, to give a somewhat detailed account.

The trade of Scotland had begun to increase very soon after the settlement of the civil war in 1745; but it was not till the year Constitution of the Lighthouse Board. 1784 that the general establishment of Sea Lights upon the Coast appears to have been brought under the notice of the Legislature. In that year, the subject was first mentioned at a meeting of the Convention of the Royal Burghs of Scotland, by Mr Dempster of Dunichen, M.P., the Provost of the burgh of Forfar; and, in the year 1786, that gentleman brought a bill into Parliament, and an Act was obtained establishing the present Board of Northern Lights.

[10]

This Act sets forth, that “it would conduce greatly to the security of navigation and the fisheries, if four Lighthouses were erected in the Northern parts of Great Britain, one on Kinnaird’s Head, Aberdeenshire, one in the North Isles of Orkney, one on the point of Scalpa, in the Island of Harris, and a fourth on the Mull of Kintyre, Argyllshire;” and it accordingly authorises the erection of those four Lighthouses. The Commissioners appointed for carrying this Act into execution were, the Lord Advocate and Solicitor-General of Scotland, the Lord Provost and first Bailie of Edinburgh, the Lord Provost and first Bailie of Glasgow, the Provosts of Aberdeen, Inverness, and Campbeltown, the Sheriffs of the counties of Edinburgh, Lanark, Renfrew, Bute, Argyll, Inverness, Ross, Orkney and Zetland, Caithness, and Aberdeen. An Act was subsequently passed, which authorised the Commissioners, when any new Lighthouse was established on any part of the coast of Scotland, to add to their number the Provost or Chief Magistrate of the nearest Royal Burgh, and also the Sheriff-Depute of the nearest county; and, by the exercise of this power of assumption, the board now includes the Sheriffs of the counties of Ayr, Fife, Forfar, Wigtown, Sutherland, Kincardine, and Kirkcudbright. To enable the Board to carry on the intended works and to provide the means of maintaining the Lights, those Acts gave power to the Commissioners to levy a duty of 1d. per ton on British vessels, and 2d. per ton on foreign vessels; and liability to pay this duty was incurred by all vessels passing any of the Lighthouses in the course of a voyage; but this single payment freed them from any farther exaction, although they should pass more than one Lighthouse in the course of the voyage. The Board held its first meeting at Edinburgh on 1st August 1786. A Secretary and Engineer were appointed, and a resolution was adopted to borrow L.1200. For this sum the Magistrates of the five Royal Burghs named in the Act interposed their security; and, at the same time, assigned, in farther security, the duties under the Act of Parliament. After appointing a Committee to prepare matters for a general[11] meeting, they adjourned till the 23d of January 1787. Some inconvenience having been felt in conducting the business of the Board, particularly in the holding of stock and other property, by reason of its not being an incorporated body, an Act was obtained for erecting the Commissioners into a body politic, by the name of the “Commissioners of the Northern Lighthouses.” Several Acts have been subsequently passed, in order to facilitate the erection of particular Lighthouses, and for the purpose of granting duties for their support. All those duties, however, are now abolished, and others have been substituted, the collection of which is regulated by an Act, 6th and 7th William IV., cap. 79, intituled, “An Act for vesting Lighthouses, Lights, and Sea-marks on the Coasts of England, in the Corporation of Trinity-House of Deptford Strond, and for making provision respecting Lighthouses, Lights, Buoys, Beacons, and Sea-marks, and the Tolls and Duties payable in respect thereof.” This Act declares, “That from the first day of January one thousand eight hundred and thirty-seven, the tolls now payable by or in respect of vessels for or towards the maintenance of the several lighthouses at present under the management of the Commissioners of Northern Lighthouses shall cease to be payable, and that, in lieu thereof, there shall thenceforth for ever be paid to the said Commissioners of the Northern Lighthouses, for every vessel belonging to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (the same not belonging to his Majesty, his heirs or successors, or being navigated wholly in ballast), and for every foreign vessel which, by any Act of Parliament, order in Council, convention, or treaty, shall be privileged to enter the ports of the said United Kingdom, upon paying the same duties of tonnage as are paid by British vessels (the same not being vessels navigated wholly in ballast), which shall pass any of the said lighthouses, or derive benefit thereby, the toll of one halfpenny per ton of the burden of every such vessel for each time of passing every such lighthouse, or deriving benefit thereby, and of one penny per ton for each time of passing the Bell Rock Lighthouse,[12] and double the said tolls for every foreign vessel not so privileged.” And with regard to any new Lighthouses to be hereafter erected, it is provided, that there “shall be paid to the Commissioners by the owner, or other person having the command of any vessel not belonging to His Majesty, which shall pass such lighthouse, or derive benefit thereby, such reasonable toll as shall have been first approved in that behalf by His Majesty in Council.” Before the passing of this Act, the Commissioners had been uncontrolled in the selection of stations for Lighthouses, or in choosing the characteristic appearance for the Lights; but it being considered desirable to have a systematic arrangement in the three kingdoms, the Irish Lighthouse Board, as well as the Commissioners, are now required to give notice to the Corporation of the Trinity-House of Deptford Strond, before altering the character of any Light, or erecting any new Lighthouse; and that Corporation must, within the period of six months after receiving such notice, signify their opinion as to the propriety of the change, or the utility of any new Lighthouses submitted for their consideration. The Act, however, provides, that, if the Commissioners are dissatisfied with the opinion of the Trinity-House, they may appeal to the Privy Council, whose determination is final. By this Act, also, an important power is given to the Commissioners to control the exhibition of all harbour and local Lights, or other sea-marks, and to prevent the exhibition of any Lights or fires on the sea-coast, which might be mistaken for the regular Lights exhibited by the Board. In the Appendix I have given a copy of the Annual Statement of the Income and Expenditure of the Board for the year 1846, prepared by Mr Alexander Cuningham, the Secretary to the Commissioners.

Since the Sumburghhead Lighthouse in Zetland was lighted in the year Lights established since 1821. 1821, with a notice of which the account of the Bell Rock Lighthouse concludes, the Commissioners have been engaged in the establishment of seventeen new Lighthouses, and the remodelling of several old ones; and they have, more particularly,[13] effected important changes in the mode of illumination, and have begun to place Beacons and Buoys on the coast. They have, besides, executed several considerable improvements, for the purpose of facilitating the communication with the Lighthouses at Kintyre in Argyllshire, Cape Wrath in Sutherlandshire, and Dunnethead in the county of Caithness, by the establishment of landing-piers and the formation of roads, varying in length from three to ten miles, in connection with those Stations. Of those works, many interesting details might be given, were it not desirable that the introduction to an account of a single Lighthouse should be restricted within a very moderate compass; and I have, therefore, thought it sufficient to lay before the reader the most important circumstances of each Lighthouse Station belonging to the Board in a tabular form in the Appendix.

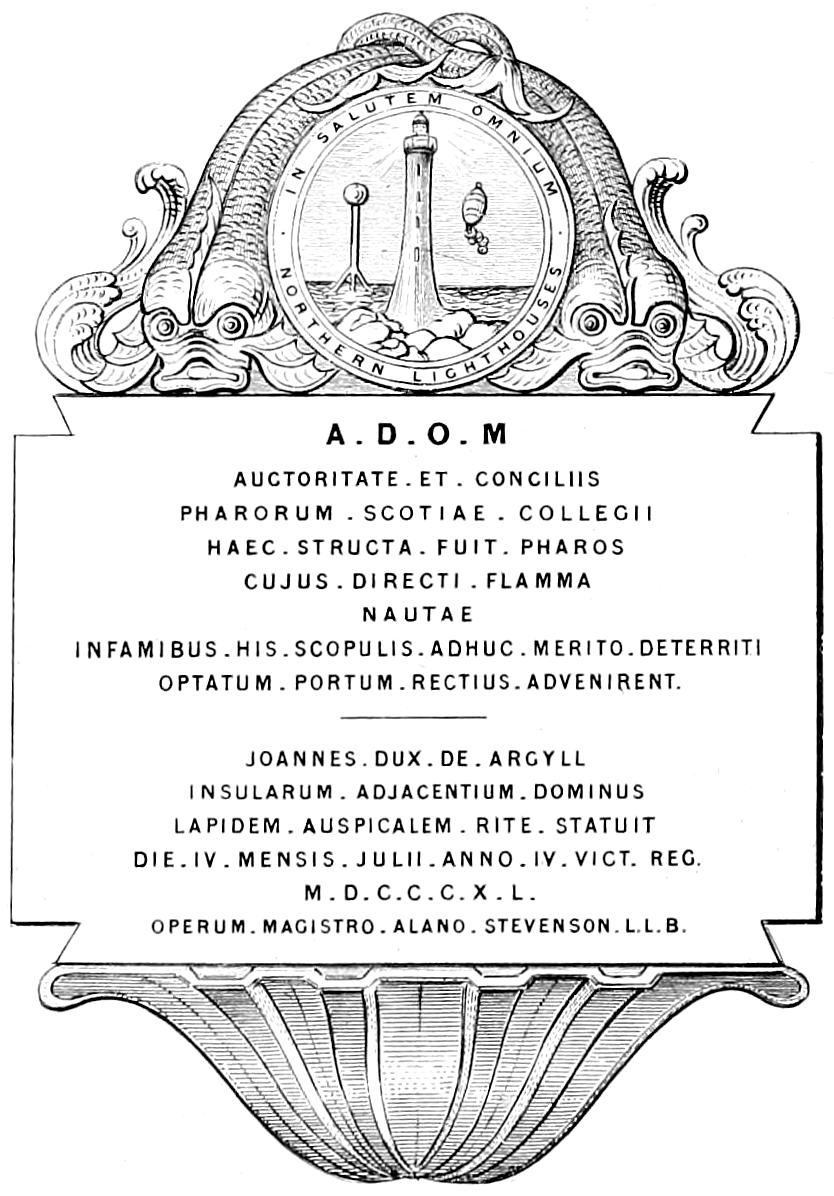

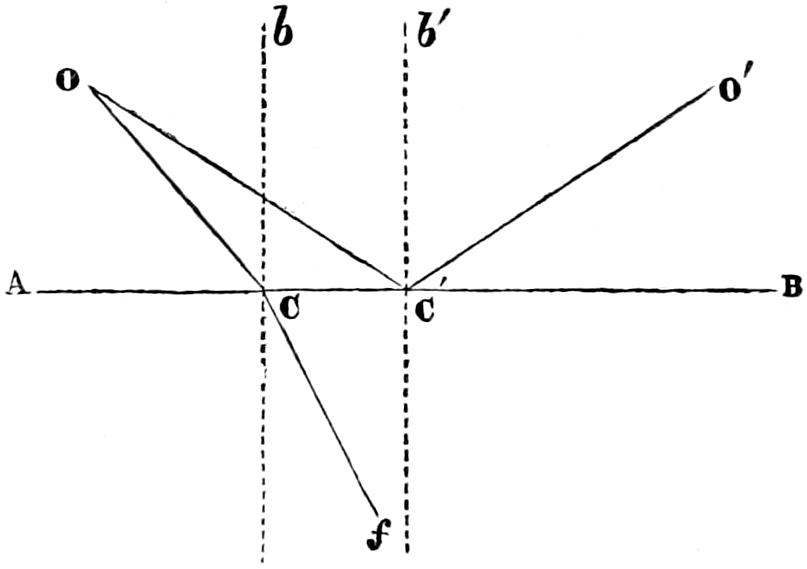

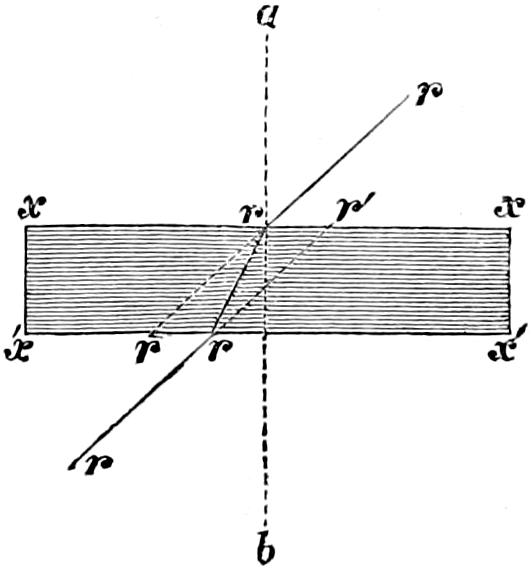

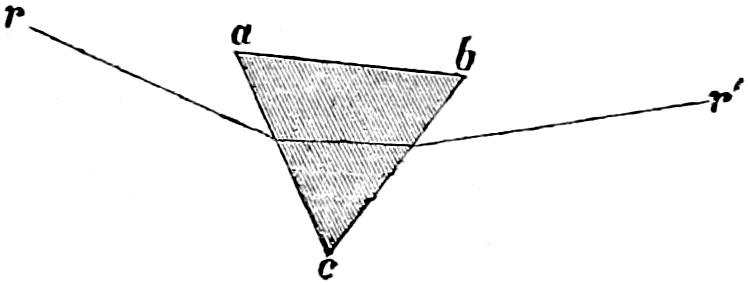

I shall not, in this place, enter on any exposition of the general principles which regulate the illumination of Lighthouses, and still less will it be proper to discuss the advantages of the different methods of illumination by Reflection and Refraction, as I shall, in the sequel, find a more convenient opportunity for speaking somewhat in detail on those subjects. It will be enough to present a very brief notice of the Improvements in the mode of illumination.improvements in the mode of illuminating Lighthouses, which the Northern Lights Board have introduced since 1824, up to which time, as already mentioned, a sketch of their works is already before the public. One of the most important changes in Lighthouse apparatus was, unquestionably, the introduction of Revolving Lights at the Tour de Corduan about the year 1780, by which the means of distinguishing one light from another were greatly extended, and a marked difference in the appearance of contiguous lights was at once simply obtained. The mere variation of the velocity of the revolution is so simple as to afford an obvious source of distinction among lights; and yet it is remarkable, that it was only lately that one of its principal advantages was perceived by my Father, who first applied it in the year 1827 as a means of distinction for the Light of Buchanness. This distinction consists in giving the frame a greater number of sides or[14] faces, and a more rapid revolution, so as to cause a flash in every five seconds of time, which produces an effect so marked and characteristic as to afford by far the most effective distinction which has been exhibited since the introduction of Revolving Lights. Under the auspices of the Board, this distinction has been since applied at the Rhinns of Islay Lighthouse, and has given much satisfaction wherever it has been tried. The late King of the Netherlands, a great patron of the useful arts, was so much pleased with this device that he presented the author of it with a splendid gold medal, in token of his approbation. The only other improvement on the Reflecting Lights, which I shall notice in this place, is that called the intermittent light, which is due to the same officer, and was by him introduced at the stations of Mull of Galloway, Tarbetness, and Barrahead. It consists of the apparatus of a fixed Light, in front of which two cylindric shades are alternately shut and opened by a vertical movement, so as to produce a sudden extinction and exhibition of the light, in a manner very difference from the gradual decline and growth of the flash, which is produced in revolving Lights by the attenuating effects of divergence on the penumbral portions of the light reflected from the mirror.

Dioptric Lights. The introduction of lenticular apparatus into Lighthouses has been the last great improvement effected in their illumination. So far back as the year 1823, the attention of the Commissioners was first called by their Engineer to the invention of the late Augustin Fresnel, who had succeeded in building polyzonal lenses of large dimensions, and in adapting to them a lamp of great power, having four concentric wicks supplied with oil by a clock-work movement like that of the Carcel lamp. A committee was appointed to consider this subject; and under its direction a long train of experiments was made with those instruments and with the paraboloidal mirrors which are generally used in British Lighthouses. The results of the experiments led the Board, in the summer of 1834, to send me on a mission to France, with instructions to report my opinion as to the comparative merits of the dioptric and catoptric[15] apparatus for the illumination of Lighthouses. Through the kindness of my friend M. Leonor Fresnel, Secretary of the Commission des Phares, who in the most liberal manner put me in possession of all the information which I required, and afforded me an opportunity of visiting the most important Lighthouses on the French coast, I was enabled on my return to report very fully my views on the various topics whose investigation had been committed to me by the Lighthouse Board.

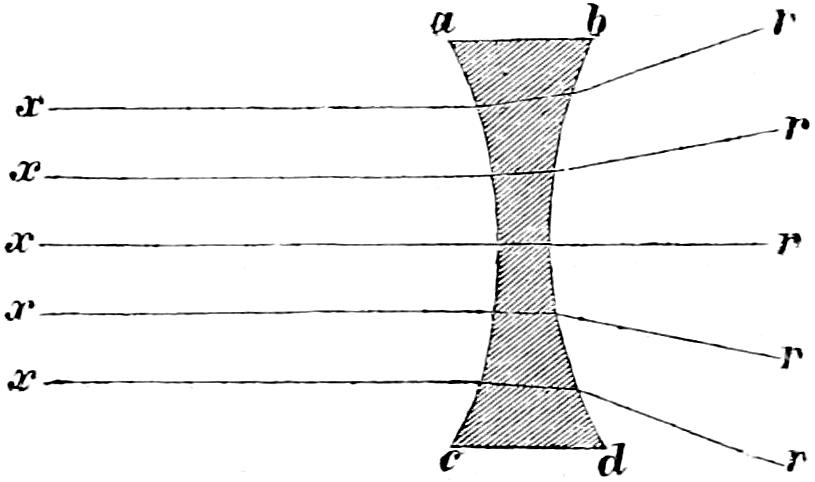

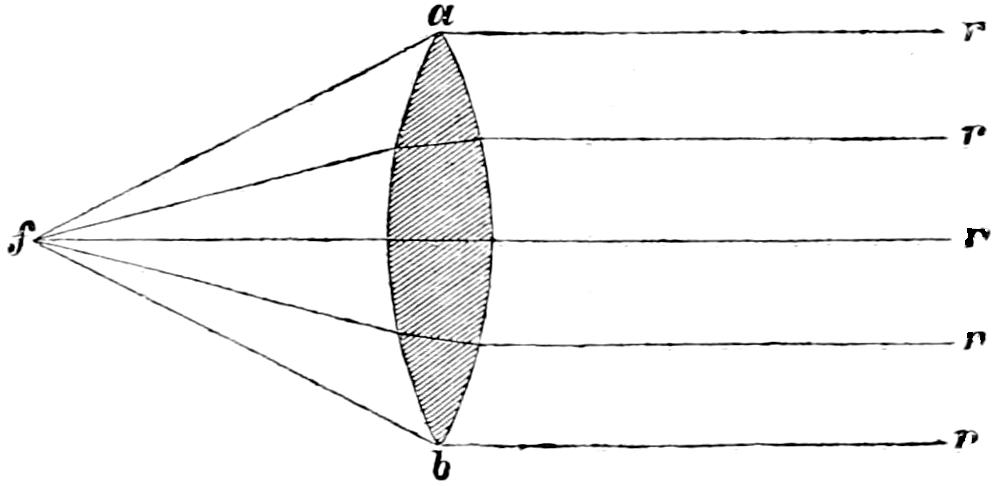

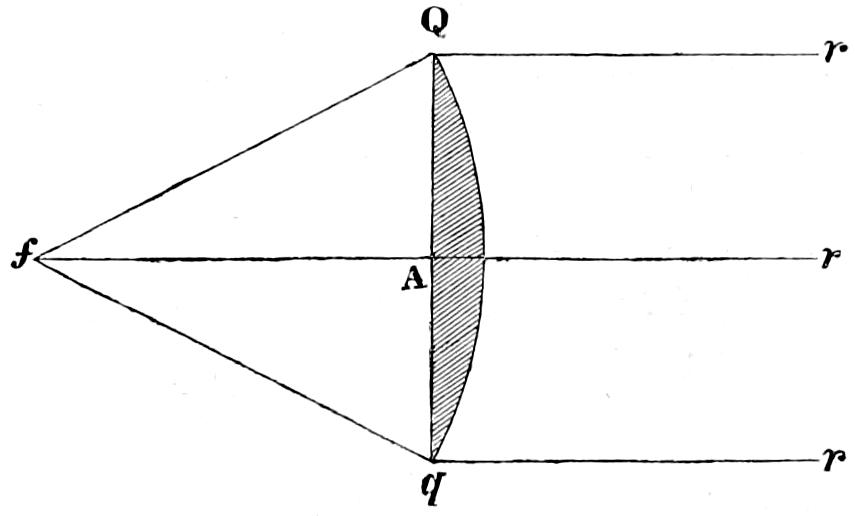

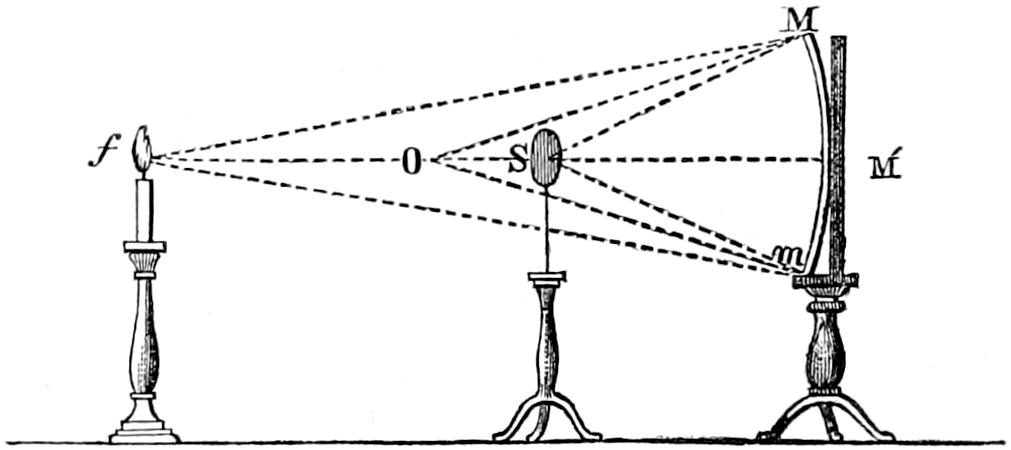

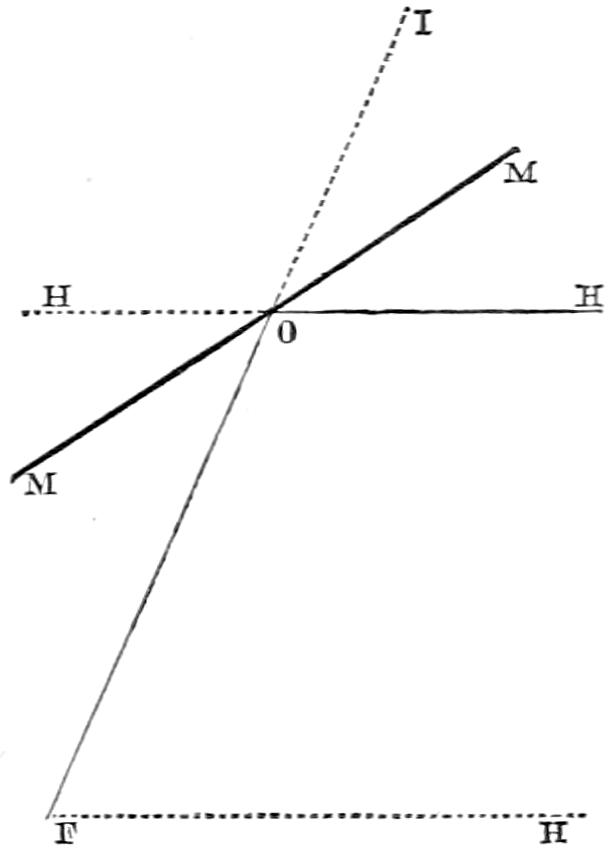

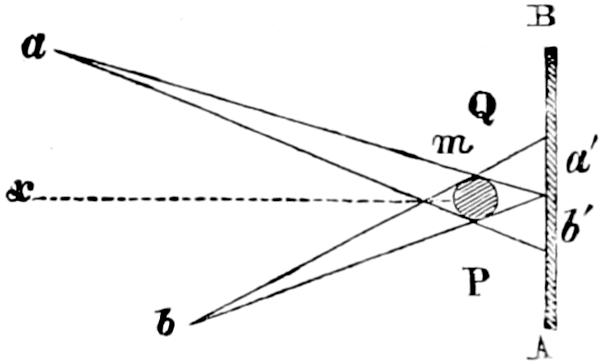

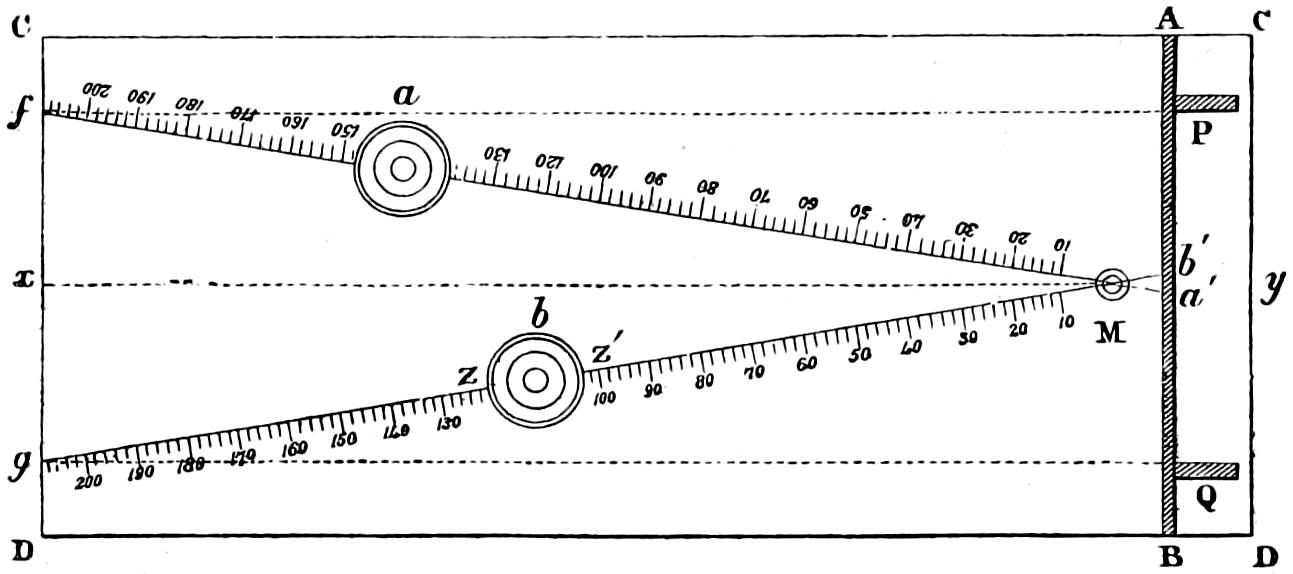

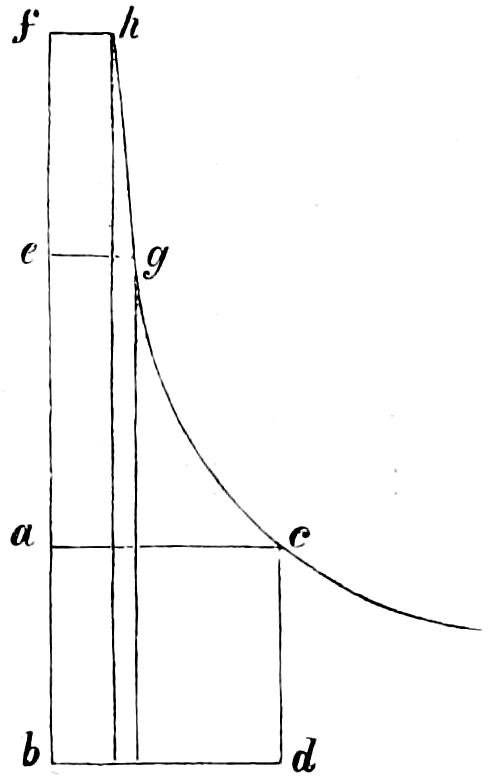

The characteristics of the two systems of illumination by Reflection and Refraction may be briefly described as follows: In the reflecting apparatus, the lamp is placed in front of the mirror, whose surface is so formed that the rays which fall upon it, and are reflected from it, must afterwards move in lines parallel to the axis of the mirror; while in using Refracting instruments, the flame is placed behind the lens, whose action is simply to bend the rays in their passage through it, in such a manner that they come out from its face parallel to a line drawn from the focus to the centre of the lens. In Revolving Lights, on the reflecting principle, the mirrors containing the lamps are placed on a frame which revolves on its centre, and carries them round in succession to the different points of the horizon, so that each mirror produces a bright flash when it crosses the line drawn from an observer’s eye to the centre of the Lighthouse; but in Refracting Lights, a single lamp of great power is fixed in the centre of the lightroom, while the lenses, placed on a revolving frame, intercept and modify the rays which fall upon them from the Lamp, as they pass in front of it, and thus produce successive flashes whenever the centre of the lens crosses the imaginary line already noticed, as joining the observer’s eye and the lightroom.

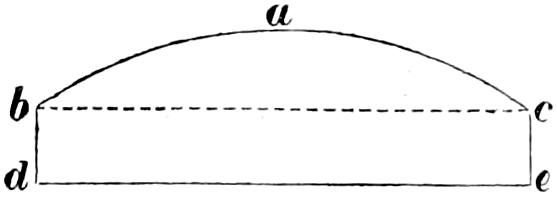

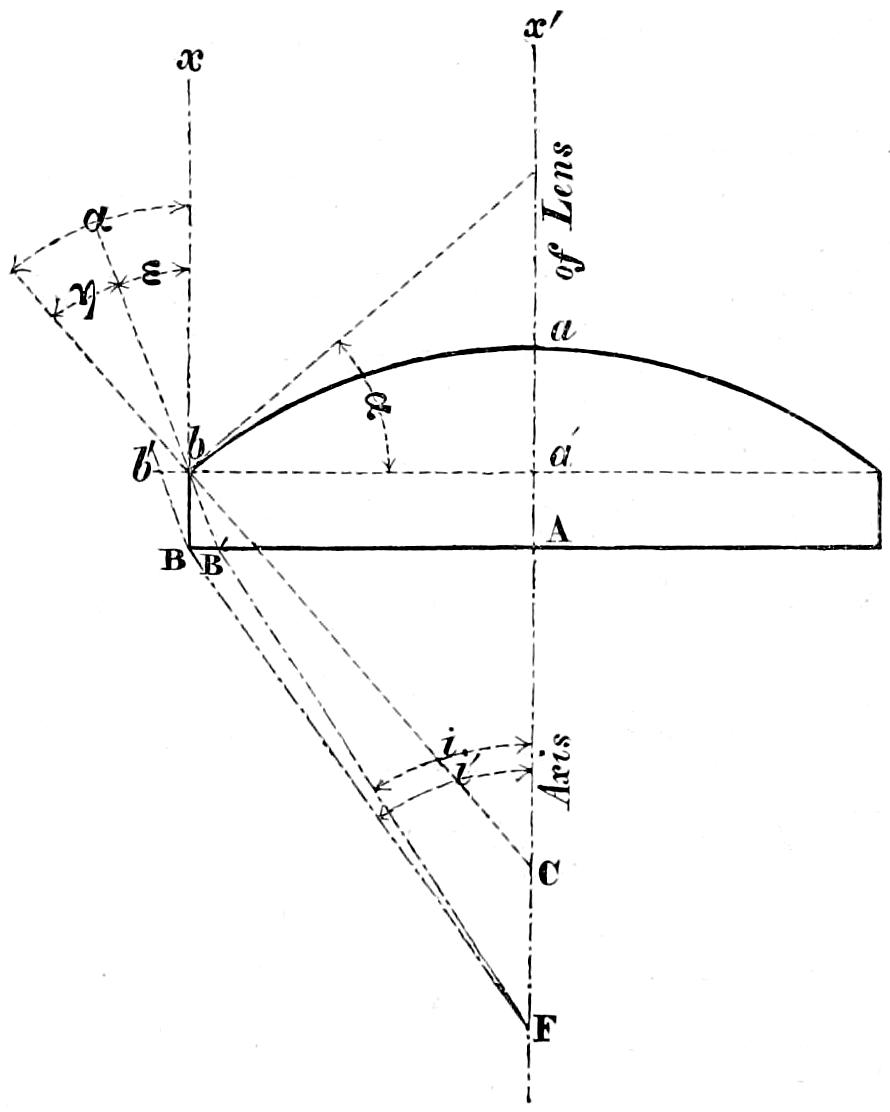

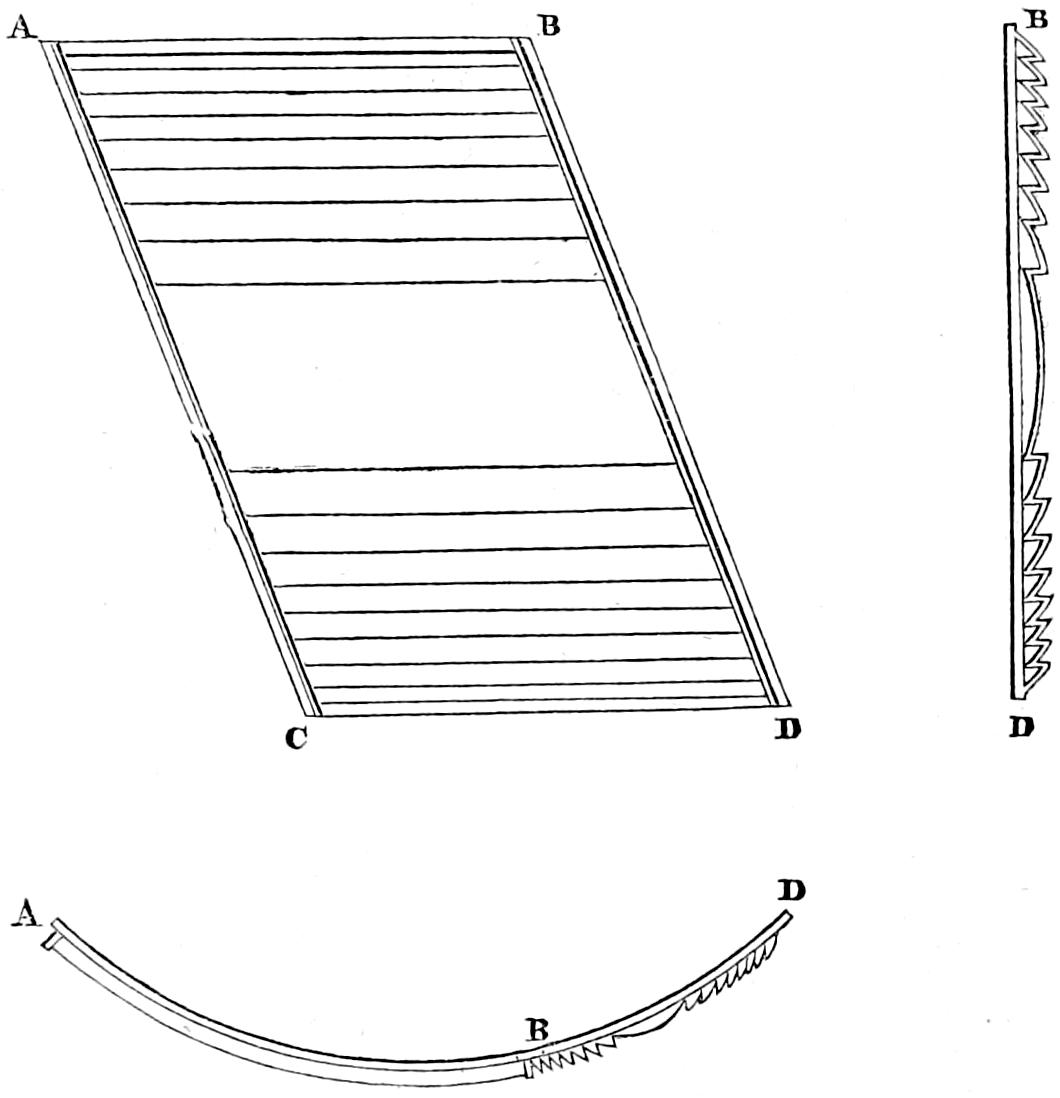

In Fixed Lights, on the Reflecting plan, the mirrors are ranged around a fixed chandelier in tiers, one above another, their centres being placed in spiral lines, so that each shall subtend an equal arc of the horizon, and thus distribute the light with as little inequality as is consistent with the application of such an instrument as the[16] paraboloidal mirror to this purpose. This object of distributing the light equally over the horizon, which, next to intensity, is the main object of a fixed light, and ought, indeed, to be strictly co-ordinate with it, is much better effected by using dioptric instruments. That apparatus consists of successive rings or bent prisms arranged in the form of a hoop or belt, which may be described as a cylinder, generated by the revolution of the central section of a polyzonal lens about its focus as a vertical axis, and which consequently acts only in a vertical direction, leaving the natural horizontal divergence of the light unchanged, and thus distributing it with perfect equality in every direction.

Those two systems of illumination possess advantages and defects peculiar to each. The lenticular instruments insure greater intensity when applied to revolving lights; but this advantage is in part counterbalanced by the greater duration of the flash caused by the reflectors, whose divergence is greater; while in fixed lights, the refracting instruments not only produce at least an equal intensity of light, but, what is of the greatest importance, afford the same quantity of light in all directions, a property which fixed Lights on the reflecting principle employed in Britain cannot possess.

On my return from France I made a Report, which was printed by order of the Commissioners; and the views which I gave of the superiority of the refracting apparatus, led the Board to adopt the resolution of at once converting the revolving light of Inchkeith from the catoptric to the dioptric system, as its nearness to Edinburgh offered good opportunity of observation as to the effect of the change. In October 1835, the new light was exhibited to the public, and I was forthwith instructed to make a similar change on the fixed light of the Isle of May; but in carrying this into effect, I introduced an important modification of the form of the refracting part of the apparatus, with the view of obtaining a still nearer approach to the equal distribution of the light. The only other considerable change in the lightroom apparatus which has[17] since been effected, is the substitution of catadioptric zones in room of the mirrors hitherto used in the subsidiary parts of the larger French lights, which, as will appear in the sequel, was suggested by me in 1841, and finally carried into effect in 1843, agreeably to the computations of M. Leonor Fresnel. A Table of the Elements of those zones computed by myself, and closely verifying M. Fresnel’s results, will be found in the Appendix. The lenticular apparatus has been applied at the new Lighthouse stations of the Little Ross and the Skerryvore, and, still more recently, at Covesea Skerries, Cromarty Point, Chanonry Point, Loch Ryan, and Girdleness.

The establishment of a system of Beacons and Buoys. Beacons and Buoys on the coast of Scotland for the purpose of affording additional facilities to navigation, had long been looked upon as a desirable extension of the operations of the Northern Lights Board; and the increase of the trade and shipping of the kingdom having, some years ago, directed particular attention to the subject, a committee was named, on the 12th January 1839, to take special superintendence of that department. In 1840, the Engineer reported to the committee upwards of fifty stations for Beacons, and nearly a hundred for Buoys, as auxiliaries to the navigation in situations where the establishment of a Lighthouse was either too expensive or not warranted by the wants of the district; and means were immediately taken for erecting three Beacons in the Frith of Forth, two in the Clyde, one in Loch Ryan, and two in Cambeltown Loch. Beacons were also erected on the Iron Rock or Skervuile in the Sound of Jura, and on the Covesea Skerries in Morayshire, in connection with the Lighthouse of that name. Those works, notwithstanding many obstacles arising from doubts as to the powers of the Board, have been carried on with great vigour. In the Appendix, I have given drawings of three of those Beacons, one being of masonry, and the other two of iron; and also Tables which shew the positions of the various Beacons and Buoys at present belonging to the Board.

From the great difficulty of access to the inhospitable rock of Skerryvore, which is exposed to the full fury of the Atlantic, and is surrounded by an almost perpetual surf, the erection of a Light Tower on its small and rugged surface has always been regarded as an undertaking of the most formidable kind. So discouraging was the consideration of expense, and the uncertainty of the final success of such a work, that the Commissioners of the Northern Lighthouses, after successfully completing the arduous and somewhat similar work on the Bell Rock, were induced to proceed with other operations of less magnitude, but probably, in some respects, of no less utility; and to delay the construction of the Skerryvore Lighthouse till the present time, although the Act of Parliament authorising its erection was obtained so long ago as 1814.

The cluster of Rocks, of which that called the Skerryvore is the largest, has ever been a just cause of terror to the mariner. Its dangers have long been known, and the means of removing these dangers, by converting its dark horrors into a cheering guide for the benighted mariner, have often occupied the attention of the Lighthouse Board, and especially of my predecessor in the office of their Engineer, with whom it was a constant subject of interest, from its similarity to his own work on the Bell Rock.

The first landing that my Father, in the course of his annual voyages round the coast, as Engineer of the Northern Lighthouse Board, effected on Skerryvore, was in the year 1804. In 1814, he visited it a second time, while accompanying a committee of the Commissioners on a tour of inspection to the Lighthouses[20] all round the coast, from the Frith of Forth to the Clyde. On that occasion, Sir Walter Scott was of the party, and we find in his diary the following record of his impressions at the time, expressed in the terse and humorous language by which this interesting relic of the poet is characterised; and as the hasty observations of that great man seem worthy of a place in a work descriptive of the means which have been taken to obviate the dangers to which he refers, no apology seems necessary for introducing it in this place.

“Having crept upon deck about four in the morning,” says Sir Walter, “I find we are beating to windward off the Isle of Tyree, with the determination, on the part of Mr Stevenson, that his constituents should visit a reef of rocks called Skerry Vhor, where he thought it would be essential to have a Lighthouse. Loud remonstrances, on the part of the Commissioners, who, one and all, declare they will subscribe to his opinion, whatever it may be, rather than continue the infernal buffeting. Quiet perseverance on the part of Mr S., and great kicking, bouncing, and squabbling, upon that of the yacht, who seems to like the idea of Skerryvore as little as the Commissioners. At length, by dint of exertion, come in sight of this long ridge of rocks (chiefly under water) on which the tide breaks in a most tremendous style. There appear a few low broad rocks at one end of the reef, which is about a mile in length. These are never entirely under water, though the surf dashes over them. To go through all the forms, Hamilton, Duff,[1] and I, resolve to land upon these bare rocks, in company with Mr Stevenson. Pull through a very heavy swell with great difficulty, and approach a tremendous surf dashing over black pointed rocks. Our rowers, however, get the boat into a quiet creek between two rocks, where we contrive to land well wetted. I saw nothing remarkable in my way excepting several seals, which[21] we might have shot, but, in the doubtful circumstances of the landing, we did not care to bring guns. We took possession of the rock in name of the Commissioners, and generously bestowed our own great names on its crags and creeks. The rock was carefully measured by Mr S. It will be a most desolate position for a Lighthouse—the Bell Rock and Eddystone a joke to it, for the nearest land is the wild island of Tyree, at fourteen miles distance. So much for the Skerry Vhor.”

[1] The Sheriffs-Depute of Lanark and Edinburgh.

Notwithstanding those occasional visits, however, it was not till the year 1834, that the Commissioners directed their Engineer to make a survey of the whole of this extensive reef, preparatory to taking measures for the erection of a Lighthouse on that part of it which might be found, after careful inspection, to afford the most suitable site; and, at the same time, the shores of part of the Island of Tyree were surveyed, with the view of establishing a Signal Tower for communicating with the Lighthouse, and of forming a small harbour, of shelter for the vessels to be employed in attending it. From these surveys the general view of the Reef which is given in Plate II., and the enlarged plan shewn in Plate III. of the Skerryvore or principal Rock, on which the Lighthouse has been built, were constructed.

The Skerryvore or principal Rock of this remarkable group, is situated in North Lat. 56° 19′ 22″, and West Long. 7° 6′ 32″.[2] It is about 11 Nautic miles W.S.W ¹⁄₄ W. of the island of Tyree, which is the nearest land, 20 miles W.N.W ³⁄₄ N. of the island of Iona, 33 miles S. ¹⁄₄ E. of the Lighthouse of Barrahead, the most southern of the Hebrides, and 53¹⁄₂ miles N.E. by N. of Mallinhead, in the county of Donegal in Ireland. It may also be added, that the principal rock is about 50 miles from the nearest point of[22] the main land of Scotland. The extent of the Reef, and its situation in reference to the general position of the coast, will be best understood by referring to Plate I., which is a small Map of the British Isles. From this it will be seen that it lies in an irregular semicircular sea, inclosed by the southern extremity of the Hebrides, the rugged shores of Argyllshire, and the northern coast of Ireland on the one side, but open on the other to the Atlantic.

[2] According to information for which I am indebted to Captain Yolland, R.E., of the Ordnance Survey.

The importance of the Skerryvore as a station for a Lighthouse is so evident as to require but little comment. Although the smaller class of coasting vessels almost invariably sail through the sheltered Sounds of Mull, Loing, and Islay, to avoid the difficulties and dangers (Skerryvore among the number) of the rough navigation of the outward passage, yet these rocks lie much in the track of the larger vessels bound over seas round the North of Ireland from the Clyde and the Mersey. Government Cruisers and Ships of War are also necessarily often within a short distance of its dangers. But for homeward-bound vessels sailing for the Clyde, or for any of the Ports in the Irish sea, and directing their course for the North Irish Channel, the establishment of a light at this place is of the last importance. When such vessels happened to encounter bad weather before making land, and so had difficulty in ascertaining their true position in relation to the coast, they often, in the event of being driven so far north from their course, as to miss the lights of Ireland or that of Barrahead, continued their progress onwards in the direction of the Skerryvore Rocks; and thus, while running in apparent safety, and probably, from the state of the weather, not within sight of Tyree, which it is often difficult to see, they were very liable to encounter some of the many detached rocks and shoals which form this broken reef of nearly seven miles in extent.

In estimating the risks to which vessels were exposed from this cause, the peculiarly insidious nature of the danger must be[23] kept in view. A headland, or line of coast, which rises to some height above the surface of the sea can be seen in most states of the weather, at a sufficient distance, even during the night, to enable the seaman to avoid danger; but, in approaching a sunken reef or a low rock, in the dark, there is no object to warn the crew of their position, until their vessel gets unexpectedly among breakers, after which it is generally too late to bring her round again. And even the very knowledge of the existence of a reef, such as this, often causes the seaman, in ignorance of its exact position, to give it too wide a berth; in which case his ship is liable to be carried away by the force of tides or winds, perhaps on a lee shore, where, although the crew may be saved, the vessel generally goes to pieces.

The exhibition of a Light, however, altogether changes the case. Instead of shunning as a danger those dreaded rocks, vessels will steer boldly on their course, until checked by the Light, availing themselves of which they will be enabled to lie off-and-on during the night, and so wait the return of daylight, in perfect confidence as to their position, and without the necessity of endeavouring to avoid hidden dangers. Thus, that which was formerly an obstruction and a danger, is rendered an aid and a safety, to the navigation of the western coasts of our country.

That this source of danger to shipping was by no means imaginary, and the consequent terror of mariners far from being ill founded, there is a too melancholy proof in the following list of disasters caused by the Skerryvore Rock, and the neighbouring dangers off the coast of Tyree:—

| In | 1790. | The Ship Rebecca of 700 tons lost; crew saved. |

| 1804. | Ship Brigand of Nova Scotia, Wright, master, of 600 tons, lost off Hough, in Tyree; crew saved. | |

| 1804. | A Brig, M‘Iver, master, lost off Hough; crew saved.[24] | |

| 1806. | Ellen of Bath, Paterson, master, of 90 tons, lost off Balaphuil, in Tyree; one man drowned. | |

| 1809. | Brig Mary, Sanders, master, lost off Balaphuil; crew saved. | |

| 1813. | Sloop, Penelope of Wick, 60 tons, lost at Gott Bay, Tyree; crew saved. | |

| 1810. | A Brig from New York, Greenlees, master, lost off Hynish Point, Tyree; crew all drowned. | |

| 1813. | A Sloop, Eugene M‘Intyre, master, lost off Balaphuil; one man drowned. | |

| 1814. | Brig, Betsey of Leith, Ross, master, lost off Hough; crew saved. | |

| 1817. | A Brig, of 400 tons, foundered off Kennavarah, Tyree; crew all drowned. Numerous casks of butter came ashore. | |

| 1818. | Sloop, Benlomond of Greenock, M‘Lauchlan, master, lost off Balaphuil; crew all drowned. | |

| 1819. | Sloop, Bee, Coice, master, of 60 tons, lost off Hough; crew saved. | |

| 1820. | A Sloop, M‘Donald, master, of 50 tons, lost in Reef Bay, Tyree; crew saved. | |

| 1820. | Ship, Masters, of Port-Glasgow, Martin, master, of 700 tons, foundered off Skerryvore Rocks, and came ashore at Clate Hynish, in Tyree; crew saved. | |

| 1821. | Sloop, Catharine, M‘Rae, master lost; crew saved. | |

| 1821. | A Sloop, of 60 tons, lost off Hough; master and three men drowned. | |

| 1825. | Sloop, Dan of Campbelltown, M‘Innes, master, of 50 tons, lost; crew saved. | |

| 1828. | Sloop, Delight, of 70 tons, Stevenson, Master, lost. | |

| 1828. | An Irish Schooner of 100 tons, Montgomery, master, lost off Hough; crew saved. | |

| 1828. | Jane of Sligo, Collins, master, lost off Balaphuil. | |

| 1829. | Van Scapan of Stockholm, Fisherton, master, of 700 tons, lost off Hough; fourteen people drowned.[25] | |

| 1834. | Confidence of Dundee, Wesley, master, lost off Hough; crew saved. | |

| 1834. | A Schooner of 70 tons, lost; three men drowned. | |

| 1835. | Peggy, Bitters, master, of 500 tons, lost off Beist, Tyree; crew saved. | |

| 1841. | April 2. Majestic of North Shields, Tait, master, of 400 tons, foundered by a sea off Boinshly Rock, and came ashore at Gott Bay; captain and four men washed overboard and drowned, and the mate and one seaman had their legs broken when the vessel was struck by the sea. | |

| 1842. | Fleurs of Liverpool, Thomson, master, of 300 tons, lost off Kennavarah; crew saved. | |

| 1842. | March 14. Two deck beams, a knee, and some pieces of deck-plank of a North American built vessel, came ashore at Clate Hynish. | |

| 1842. | A Barra Boat wrecked, and four corpses washed ashore; two men, a woman and a child. | |

| 1842. | Pieces of wreck were seen in the Sound of Coll, and at the same time the shores of Tyree were strewed with candles, mostly of wax, supposed to be altar candles for the West Indies. | |

| 1843. | September 2. The Prussian Barque Formosa, of 326 tons, P. R. Reick, master, lost off Hough; two seamen drowned. | |

| 1844. | December 1. The Hull of a Sloop of about 70 tons, was washed ashore off Clate Hynish. The Hull was very much broken up by being in contact with the rocks; and one of the planks, apparently off the taffrail, had the words “Port of Dundee” lettered upon it; the crew supposed to be all drowned. |

This list is made up chiefly from data kindly furnished to me by the Rev. Neil Maclean, the Minister of Tyree and Coll, whose long residence on the former island has afforded him ample opportunity[26] for making observations on the subject. It is not to be imagined, however, that Mr Maclean’s list, which is made up from recollection, contains a full catalogue of the disasters caused by the Skerryvore, within the dates which it cites. Very many vessels were wrecked on this dangerous reef whose names could never be learned, and of which nothing but portions of the drift wood or cargo came ashore; and there have, no doubt, been many shipwrecks of which not a single trace has been left. Nothing, indeed, is more probable than that many of the foreign vessels whose course lay through the North Irish Channel, and whose fate has been briefly and vaguely described, as “foundered at sea,” have met their fate on the infames scopuli of the Skerryvore. It is also well known that the Tyree Fishermen were in the constant practice of visiting the Skerryvore, after gales, in quest of wrecks and their produce, in finding which they were but too often successful.

The natives of Tyree have many traditions of vessels having struck on the Skerryvore and gone to pieces; but, as might have been anticipated, few traces of this were to be found on the Rocks themselves, the breach of sea which sweeps over them during storms being sufficient to remove any heavy bodies which might be left there after a shipwreck. Some relics, however, were found during the progress of the works, and among the rest an anchor which was fished up close to the Rock, and which appeared to have belonged to a vessel of about 150 tons burden. It had been wasted to a perfect shadow by the action of the sea, and was covered with a thick coating of seaweed and barnacles. Although, however, the Rocks themselves do not retain the proofs of the disasters of which they have been the cause, the shores of the neighbouring Islands, during the progress of the works, were frequently strewed with drift wreck in such a manner as clearly to indicate what had taken place on the shoals round the Skerryvore.

On examining Plate II., it will be seen that what I have hitherto denominated the Skerryvore Reef, is a tract of foul ground,[27] consisting of various small rocks, some always above the level of the sea, others covered at high water, and exposed only at low water, and others, again, constantly under the surface, but on which the sea is often seen to break after heavy gales from the westward. This cluster of rocks extends from Tyree in a south-westerly direction, leaving, however, between that island and the rock called Boinshly, the first of the great Skerryvore cluster, a passage of about five miles in breadth, and having a depth of thirteen fathoms at low water of spring tides, but not without hidden dangers, which line the rugged shores of Tyree from Kennavarah to Ben Hynish, and some of which lie farther off than might be expected. This passage is called the passage of Tyree; but it is by no means safe during strong and long continued gales, as the sea which rises between Tyree and Skerryvore, is such that no vessel can live in it. I have myself often seen it one field of white broken water, the whole way from Tyree to the Rock; and we know that the wreck of the Majestic, which occurred in 1841, during the progress of the works, was entirely caused by the heavy seas which she encountered off Boinshly.

The principal rocks of the group, are called Boinshly, Bo-rhua, and Skerryvore, while those lying to the westward, which have been more recently laid down, have received the names of Mackenzie, Fresnel, and Stevenson.

The rock called Boinshly lies about 3³⁄₄ miles from Skerryvore, and is of considerable extent. The origin of the names of the different rocks in the vicinity of Tyree is by no means clear, and very little assistance or information is to be obtained in this matter from the natives. The name of Boinshly is probably derived from the Gaelic words boun, signifying bottom, and slighe, deceitful, as indicative of the dangers of the place; but other interpretations have been put on it, and that which has been now given is by no means certain. In the course of the survey, several soundings were[28] at considerable risk obtained, both upon this Rock itself, and in its immediate vicinity. The sea in that exposed situation is seldom so tranquil as to warrant an attempt to approach very near this Rock. The swell, which, in a greater or less degree, almost constantly prevails, is apt to impel, or seemingly draw the boat as by a kind of suction, upon the rock; and sometimes such accidents cannot be prevented, even although the greatest caution is used. Sudden lifts of the sea, during an apparent calm, are common in all the more exposed parts of the coast, more especially in the Orkney and Zetland Isles, and on the shores of the most western of the Hebrides; and any one much accustomed to the use of boats on these shores, must have experienced the hazard of encountering such unexpected risings of the sea, more especially near shelving rocks, or in rapid tide-ways. In some places the boatmen apply the name of lumps to these sudden waves. This effect is not felt to the same extent in attempting to reach a rock which is partially uncovered at low water, as a landing can, in such a case, often be effected on one side, at a time when the same rock on the opposite side, or a sunk rock just topping with the water, would, on every side, be quite unapproachable. From the soundings marked on the plan, it will be seen that shoal water extends all round Boinshly to distances varying from a quarter to half a mile. The sea breaks on the rock with great violence, and its position can easily be discovered from the island of Tyree by the white foam with which it is almost constantly surrounded, and which, in the heavy swells which sometimes accompany a dead calm, before or after a heavy gale of wind, rises to a prodigious height in a column or jet, resembling, at a distance, the play of a gigantic fountain. So high, indeed, does the sea rise on this shoal after heavy gales, that it often quite obscures the larger and more distant object of the Rock and Tower of the Skerryvore, even when viewed from the top of Ben Hynish in Tyree. The wooden barrack erected on the Skerryvore for the use of the workmen during the progress of the operations,[29] although about sixty feet in height, was often lost sight of at Tyree by the uprising of the sea on Boinshly, and could be seen only during the calm that intervenes between returning waves.

The next Rock that occurs is Bo-rhua, a name derived from the Celtic, and signifying, according to the natives, Red Rock. It lies about 2³⁄₄ miles from Boinshly, and about one mile from the Skerryvore. The passage between it and Boinshly is clear, and has a depth of about fourteen fathoms; but it is too narrow to be safely navigated except by daylight, even under the most favourable circumstances, and then no mariner would run the risk of taking such a passage, but would prefer, even at some sacrifice of time, the fairway of the passage of Tyree. Bo-rhua is completely covered at high, but is dry at low water. The extent of rock uncovered is about forty feet by twenty feet, and the highest point of it is about six feet above low water level of spring tides. A small outlying pinnacle, about ten feet square, is also uncovered at low water. The depth immediately round Bo-rhua is considerable, from three to seven fathoms being found within fifty feet of it; and in this respect it differs from Boinshly, which, as already mentioned, is surrounded by shoal water for some distance. Between Bo-rhua and Skerryvore, however, which is a distance of about a mile, there cannot properly be said to be any clear navigable channel, as will be distinctly seen by referring to the plan. The whole of this tract may, in fact, be termed foul ground.

The Skerryvore or chief rock, and the detached rocks immediately surrounding it, were surveyed with greater minuteness than the others, as it was at once apparent, that on this part of the reef alone could a suitable site for a lighthouse be found. The name is derived from the Gaelic, and signifies the Great Rock. It is very much wasted and cut up; the number of detached rocks, sunk and exposed, in its immediate neighbourhood, whose positions were determined during the survey, amounting to no fewer than 130. The[30] depth of water between those different detached fragments, which extend over a surface of about a mile in length, by half a mile in breadth, is considerable, varying from 2¹⁄₂ to 8¹⁄₂ fathoms at low water of spring tides.

The surface of the main or principal rock, on which the Lighthouse has been placed, measures, at the lowest tides, about 280 feet square. It is extremely irregular, and is intersected by many gullies or fissures, of considerable breadth, and of unlooked for depth, and which leave it solid only to the extent of 160 feet by 70 feet. The extremity of one of these gullies, at the south-east corner of the rock, forms the landing-creek, which is a narrow track of 30 feet wide, having deep water; and, with the help of some artificial clearing and dressing, which was executed with much difficulty, by blasting under water, while the other works were in progress, its sides and bottom are now comparatively smooth. At this place a landing can often be effected when the rock is unapproachable from any other quarter, although great inconvenience is felt from the surge, which finds its way from the opposite side of the rock, through the westward opening of the gulley in which the landing-place is situated.

Another of the gullies, immediately to the south-east of the Lighthouse, was found, on examination, to undermine the rock to the extent of eight or ten feet, and to terminate in a hollow submarine chamber, which threw up a spout or jet of water about twenty feet high, resembling in appearance the Geyser of Iceland, and accompanied by a loud sound like the snorting of some sea monster. The effect of this marine jet d’eau was at times extremely beautiful, the water being so much broken as to form a snow-white and opaque pillar, surrounded by a fine vapour, in which, during sunshine, beautiful rainbows were observed. But its beauties by no means reconciled us to the inconvenience and discomfort it occasioned, by drenching us whenever our work carried[31] us near it. One calm day I contrived, at a very low tide, by means of ropes and a ladder, to explore the interior of the cavern, from which this fountain rose, and found it to terminate in a polished spherical chamber, about seven feet in diameter, its floor filled with boulders, whose incessant play had hollowed it out of the veined rock, and rendered its interior beautifully smooth and glassy. As I considered that this curious cavern penetrated too far, and came too close to what I had selected as the best foundation, I changed the site of the tower, so as to avoid any chance of its being undermined. I also deemed it prudent to fill up the cavity, to prevent its further extension, and at the same time to rid ourselves of the discomfort of being drenched by the column of water which spouted up from it, even during fine weather, when the sea was apparently calm. This gulley affords a good example of the power of pebbles kept constantly in play by the waves to wear down the hardest rock, and shews what extensive effects so insignificant an agent may effect in the course of time.

Before the excavation for the foundation of the tower was made, a single conical loaf of rock, about five feet in diameter, rose to the height of eighteen feet above the level of high water, the greater part of the rest of its surface being about six feet above the tide mark.

In addition to its shattered and disjointed appearance, the Skerryvore Rock presents, in another respect, a striking example of the action of the sea, which no one, on first landing on the rock, can fail to perceive. I allude to the glassy smoothness of its surface, a feature that existed to so remarkable an extent as to have proved throughout the whole duration of the work, but more especially at its commencement, a serious obstacle and hindrance to the operations. It may, at first sight, appear strange that this grievance should have been so much felt; but, when I mention that the landings[32] were often made in very bad weather, it will be obvious that there was considerable danger in springing ashore from a boat in a heavy surf upon an irregular mass of rock as smooth and slippery as ice. The workmen were, in that respect, often sorely tried, and many inconvenient accidents occurred from falls. It was after one of these trials of patience, that the foreman of the masons was heard very graphically to describe a landing on the rock as “like climbing up the side of a bottle.” Instead of a weather-beaten rock, whitened by the dung of sea-fowls, and with marine crustacea adhering to it, the surface of the Skerryvore is smoothly polished by the action of the waves, every projecting angle or point is worn down, and the whole presents more the appearance of a mass of dark-coloured glass than a reef of gneiss-rock. Excepting in some of the more sheltered crevices, no marine crustacea find shelter; but different kinds of sea-plants grow upon it, in great abundance, at and below the low water mark. These plants are, doubtless, enabled to resist the action of the waves in the same way as the sapling, yielding to the blast, is preserved during the storm that uproots the aged and more stubborn oak.

The rocks of Skerryvore have the same characteristics as those of the neighbourhood of Tyree, being what we may, perhaps, call a syenitic gneiss, as it consists of quartz, felspar, hornblende, and also mica. It will be seen, from the narrative of the progress of the works, that this rock was, from its hardness, exceedingly difficult and tedious to excavate. The only variation in the geology of the Skerryvore, is the presence of a trap rock, in the form of a dyke of basalt, which intersects the strata, and exhibits a fine specimen of the intrusion of igneous rocks. It is shewn in Plate, No. III., by a thick black line.

Connected with this general view of the appearance and geology of the rock, it may be interesting also to notice, that a considerable mass of foreign matter, somewhat resembling, in its[33] structure, a deposit of lime, was found in different places resting in horizontal layers of various thickness and size. This substance was found in pools or sheltered parts of the rock, about the level of high water mark, and, in some cases, even a little below it. It was so hard as to admit of a pretty high degree of polish; and emitted an offensive odour on being burned in the fire, or rubbed on a stone with water. It gave other clear indications of containing animal matter, and in other respects resembled the bergmeal and guano. To account for its presence in such a situation, seems rather a difficult problem. On sending a specimen of this material to my friend the Rev. Dr Fleming, Professor of Natural Philosophy in King’s College, Aberdeen, I received from him an analysis of the substance, and a concurrence in the opinion I had formed as to its containing animal matter; and Dr Fleming, indeed, expressed his belief that the matter in question is the indurated soil of birds, and had been deposited when the reef was more extensive, and the resort, and probably the breeding-place of sea-fowls.[3] How this singular formation should be found on the verge of the ocean, and even within the high water mark, in spite of winds and waves, or how it should have assumed the stratified structure which seems to indicate the depositation of successive layers in still water, are matters very difficult to be explained, without coming to the conclusion, that the uncovered surface of Skerryvore Rock must at some distant period have been much more extensive than at present, so as to permit the deposit to go on in an interior basin or lagoon, sheltered from the waves, and somewhat similar to those which Dr Darwin has described as characteristic of the Coral Isles of the Pacific. This supposition seems not at all improbable, as it does not require a great stretch of fancy to conceive, that at some period, the whole of the rocks in the immediate vicinity of Skerryvore, and extending perhaps even so far as Bo-rhua, may have been connected by a matrix of softer materials, which have[34] gradually yielded to the action of the sea, leaving the harder portions to be smoothed and polished by the waves, and to assume the characteristic features of permanent rocks and sunk reefs which they now possess. There is also some countenance to such a view to be derived from the features of the neighbouring Island of Tyree, which contains numerous small lagoons, in which such deposits might be formed by the flocks of sea fowl which frequent them. Some of these pools are so near the shore, as to make it no difficult matter to conceive that their walls might be broken by the sea, and that they might eventually become part of it, and thus exhibit the phenomenon of deposits apparently lacustrine within the verge of the ocean.

[3] Dr Fleming has since obtained from Ichaboe indurated bird-soil or guano, closely resembling that from the Skerryvore.

Another remarkable feature which I observed in the Skerryvore Rock, was a deposit of gravel in the narrow crevices of the rock, which run nearly from north-east to south-west, dipping at an angle of 80° to the westward. In almost all of the fissures we found great quantities of small water worn boulders, less in size than a horsebean, and generally of the same materials as the rock itself. The boulders bore the appearance of having been forced into the fissures of the rock by some very powerful pressure, and were wedged hard into the crevices. In some cases a considerable quantity of softer matter containing iron was found, and in it the pebbles were imbedded. In the upper parts of the rock the crevices swarmed with centipedes of a reddish-brown colour. The rock was covered with sea fowl when first visited, and during heavy gales seals resorted to it.

About three miles to the westward of Skerryvore lie Mackenzie’s Rock, Fresnel’s Rock, and Stevenson’s Rock, which, as will be seen from Plate II., are connected by a tract of foul ground of about a mile and a quarter in length. Those rocks are the western limit of what we have already denominated the Skerryvore Reef. The passage between them and the Skerryvore or main rock is clear,[35] and has a depth of water varying from eleven to twenty-eight fathoms.

Mackenzie’s Rock, which derives its name from the celebrated Marine Surveyor, is uncovered, at low water, to the extent of about forty yards, and consists of scattered patches of rock, one of which, at its highest part, rises about ten feet above high water mark of spring-tides. Fresnel’s and Stevenson’s Rocks are always under water; but the sea is often seen to break violently over them, as well as over the whole stretch of the sunken reefs which extend between them. The first of those rocks is indebted for its name to the great optical philosopher, who so greatly improved lighthouses; and the second bears the name of the surveyor who first laid down the rock,—the late Engineer of the Northern Lights Board.

During the progress of the survey, a register of the rise and fall of the tides was regularly kept at Hynish on the neighbouring Island of Tyree; and from those observations it was determined, that the rise at that place is between twelve and thirteen feet at high spring tides, and three feet at dead low neap tides; and observations subsequently made while the works were in progress, gave the same results at the Rock of Skerryvore. It is high water at the Rock at full and change of the moon, at five hours and twenty-five minutes. The tides round the Skerryvore are not remarkable for their rapidity. In spring-tides the velocity is between four and five miles, and in neap-tides between two and three miles an hour. The flood sets to the N.N.E., and the ebb to the S.S.W.

In this chapter I shall very briefly notice those preliminary arrangements which may be said to have been in a great measure preparatory to the commencement of the work itself. It has been already stated, that the erection of the Lighthouse was provided for in the Act of 1814; but so formidable did this work appear, that although it was repeatedly under consideration, it was not until the General Meeting of the Board, on the 8th July 1834, that any measures were taken to carry into effect the provisions of the Act. On that occasion it was moved by the late Mr Maconochie, Sheriff of Orkney and Zetland, that the Engineer should be instructed to make the Survey of the Skerryvore Rocks. necessary survey, and to report as to the expense of erecting the Lighthouse. In terms of this remit, the survey of the Rocks was commenced in the autumn of 1834; but from the broken state of the weather, little was effected at that time beyond making the triangulation; and it was not until the summer of 1835 that the survey was completed from which the Chart, Plate No. II. was constructed. This survey was attended with much more labour than its extent would lead one to suppose, in consequence of its embracing the entire range of operations required in a more extensive nautical survey, and combining with the ordinary details required for a Chart, the minute accuracy in regard to surface and levels, which are always necessary for the purposes of the Engineer.

[38]

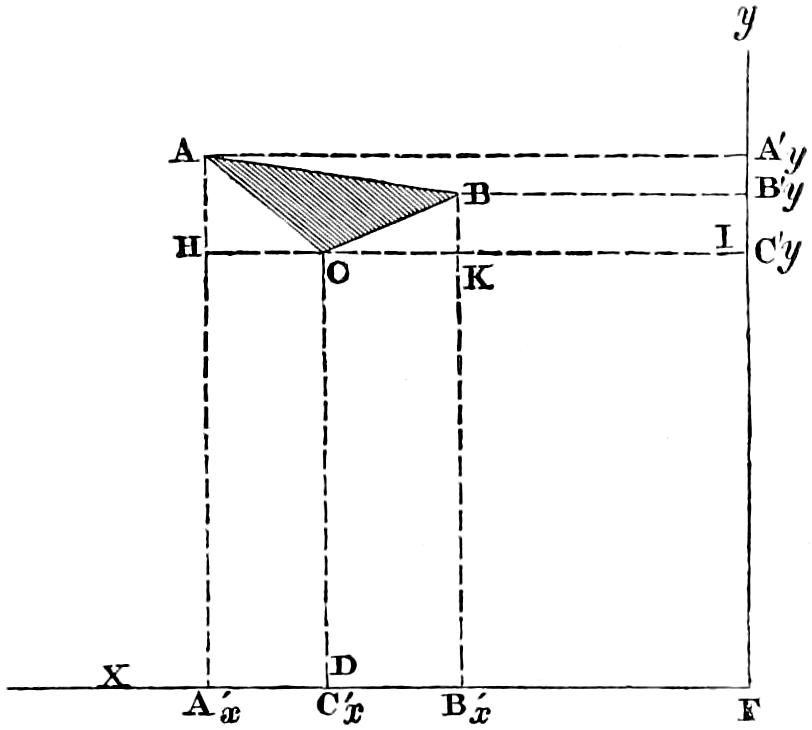

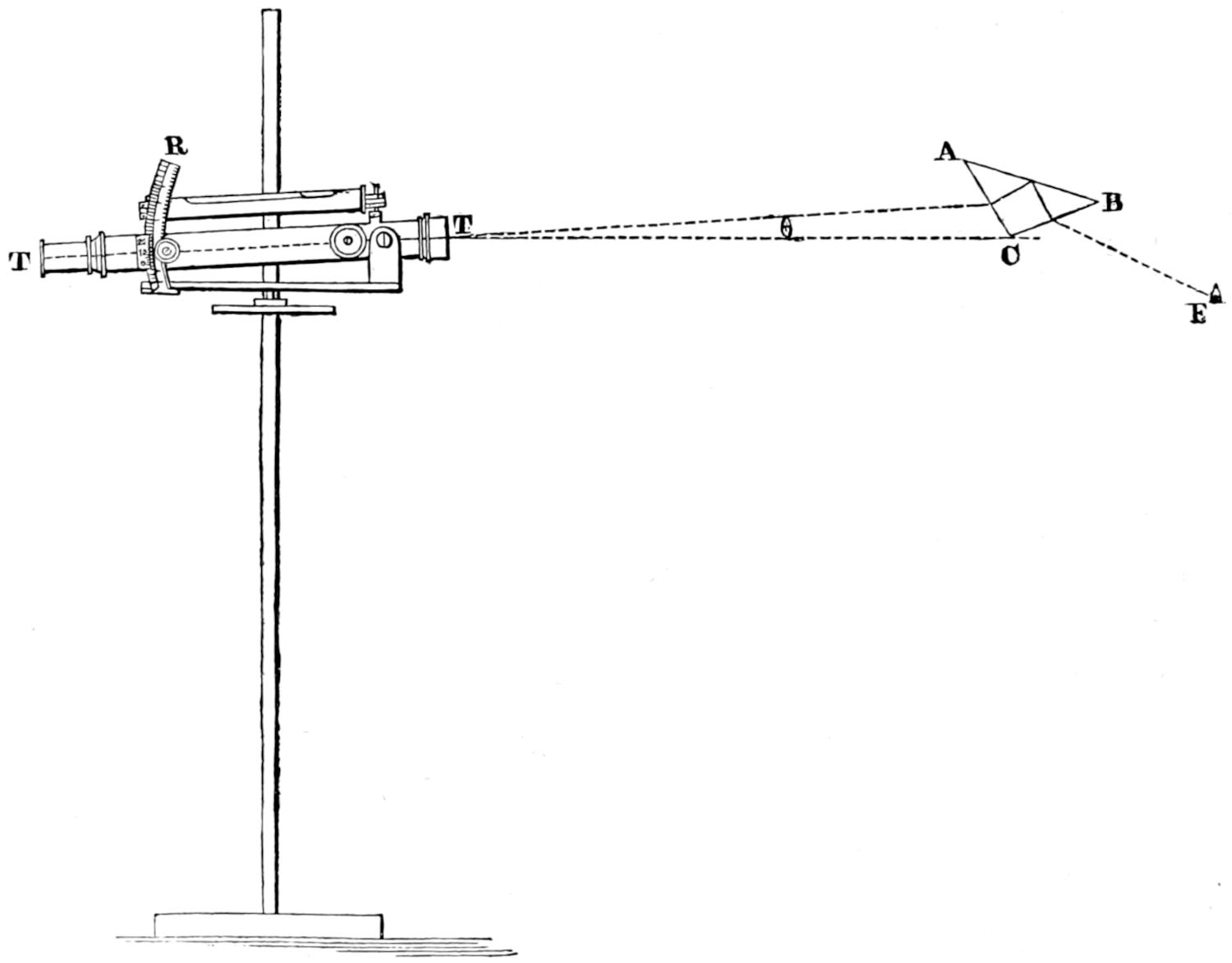

The first step was the measurement of a base line in the low lands of the adjoining Island of Tyree, which, owing to the distance and disadvantageous position of that island, could not be satisfactorily extended to the Rock without fixing stations in some of the more distant islands; and in the course of the work not fewer than twenty land triangles were measured. The calculations of the distances founded on this triangulation agreed with those afterwards obtained from the data of the Trigonometrical Survey, which were kindly furnished to me by Captain Yolland of the Royal Engineers, in 1843. For the purpose of making the soundings and laying down the sunken rocks, an entirely separate triangulation, based upon and connected with that which has already been noticed, became necessary, as the land objects were too distant, and their relative positions were such as to render it difficult by observations from them alone to determine any stations on the sea. Buoys were therefore moored at convenient points, and their positions determined by a subsidiary triangulation, so as to form a net-work of triangles between the shore and the Skerryvore Rock. The distances between these buoys were afterwards used as the bases of imaginary triangles, having points of sounding or shoals in their apex; and the angles subtended by those distances being measured by the sextant, the positions of the shoals or soundings were thence easily deduced and protracted on the Chart.[4] In connection also with the soundings whose positions were determined in the way above described, a complete set of tide observations was made, extending over a period of about six weeks. Those tide observations were connected in point of time, with the soundings, and were employed as the means of correcting the observed depths taken with the sounding-line, so as to give the true depth in reference to the high or low water of a given tide. Accurate measurements, and minute sections, were also made of the rocks in reference to the tide-level, and more especially of the main rock, on which[39] alone it was obvious, from the first inspection, that the Lighthouse Tower could be erected. In the course of this survey, the positions of upwards of 140 rocks were determined, and laid down on the Chart, and 500 soundings were taken, and their positions protracted. An interesting fact was also noticed regarding the mean level of all the tides which had been watched during the period of about six weeks, as above noticed, viz., that the point half way between the high and low water of every tide is on one and the same level. This fact regarding the tides was, it is believed, first detected by my Father, in the course of some tidal observations which he made in the Dornoch Frith in 1830, and has since been observed in the Frith of Forth in 1833, and again on the shores of the Isle of Man, and at Liverpool. The agreement of so many observations by various persons at places on the opposite shores of the Kingdom, seems to imply the universality of this phenomenon in the British Seas; and the position of Skerryvore would lead to the belief, that it is not confined to narrow seas, but that it exists in the ocean. I cannot dismiss the subject of the survey, without mentioning the late Mr James Ritson, who acted as principal assistant surveyor, and to whose zeal and intelligence so much of its accuracy is to be attributed. The deep gulley which intersects the main Rock from N.E. to S.W., and across which he one day sprang while it was filled with a breaking wave, bears his name, as a memorial of his activity and perseverance. At the close of the survey in 1835, the station-pole was left wedged and batted into one of the fissures or crevices of the Rock, and a cask of water was firmly lashed to ring-bolts in a cleft of the highest part of the Rock, in the hope that it might possibly prove useful to some shipwrecked seamen.

[4] Vide Stevenson’s Marine Surveying and Hydrometry. Edinburgh, 1842, p. 144.

For the purposes of navigation generally, a survey merely indicating the position and extent of the foul ground would have been sufficient. But in connection with the work which was about to be commenced, it was particularly desirable to have exact details of the depths, rocks, and shallows of the surrounding sea, with the[40] nature of the bottom, accurately laid down; and our experience during the course of the work, more than once shewed how essential was the possession of minute topographic information to the safety of the shipping attending the works; more especially as some of the vessels lay very near the rocks, and were frequently driven, by a sudden change of wind, to seek shelter, during the darkest nights, among the neighbouring islands.

Until this time the greatest ignorance prevailed amongst seamen as to the extent of the Reef, which had never before been minutely surveyed. Of this some proofs occurred even during the progress of the survey; for several vessels came so near the Rocks as to cause, in the minds of the surveyors, who witnessed their temerity, serious fears for their safety. On one occasion, in particular, a large vessel belonging to Yarmouth, with a cargo of timber, was actually boarded between Mackenzie’s Rock and the main Rock of Skerryvore by the surveyors, who warned the master of his danger in having so nearly approached these rocks, of the existence of which his chart gave no indication. On another occasion, a vessel belonging to Newcastle was boarded while passing between Bo-Rhua and the main Rock; and so little, indeed, had the master (whose chart terminated with the main Rock, and shewed nothing of Bo-Rhua) been dreaming of danger, or fancying that he was within a cable’s length of the reef, that he was found lying at ease on the companion, enjoying his pipe, with his wife sitting beside him knitting stockings.

Much preliminary investigation was necessarily occasioned by the difficulties and disadvantages arising from the remote situation of the island in which a great part of the works was to be carried on. Not only is the Rock itself often inaccessible and dangerous, being surrounded by numerous shoals, and visited by the heaviest seas of the Atlantic; but what gave rise to no small part of the difficulties which attended this work, was the nature of the neighbouring Island of Tyree. Disadvantages of Tyree. This island is unhappily destitute of any[41] shelter for shipping, a fact which was noticed as a hinderance to its improvement, upwards of 140 years ago, by Martin, in his well-known description of the Western Islands.[5] Nor is its interior more attractive; for although some parts of the soil when cultivated are excellent, the greater part of its surface is composed of sand. It was therefore obvious, at a glance, that Tyree was one of those places to which every thing must be brought; and this is not much to be wondered at, as the population, who, on a surface not exceeding 27 square miles, amounted in 1841 to 4687 souls, labour under all the disadvantages of remoteness from markets, inaccessible shores and stormy seas, and the oft-recurring toil of seeking fuel (of which Tyree itself is destitute) from the Island of Mull, nearly 30 miles distant, through a stormy sea. It is said that this total absence of fuel in Tyree is the result of the reckless manner in which it was wasted, in former days, in the preparation of whisky; but, however this may be, certain it is that the want of fuel greatly depresses the condition of the people. For our works, therefore, craftsmen of every sort were to be transported, houses were to be built for their reception, provisions and fuel were to be imported, and tools and implements of every kind were to be made.

[5] A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland, &c., by M. Martin, Gent. London, 1703. Vide 2d Edition of 1716, p. 267.

In the course of the survey, much attention had been bestowed upon the selection of a convenient place for a workyard in Tyree for the preparation of materials, and in examining its rugged shores in quest of the best site for a Harbour, for the shipment of the building materials for the Rock, and for the all-important purpose of enabling the future attending vessel to lie in safety within sight of signals from the Rock, when the Light should come to be exhibited to the public. The point chosen for this establishment was Pier and workyard at Hynish Tyree. Hynish, which, though twelve miles distant, is, nevertheless, the nearest creek to the Skerryvore Rock, and which,[42] however exposed it may be, if compared with creeks elsewhere dignified with the name of Harbour, certainly affords as good prospect of shelter as any other part of the Island of Tyree, and is, in this respect, greatly to be preferred to any other place within sight of the Rock. A deputation of the Commissioners visited the Skerryvore in the month of July 1836, and concurred with the Engineer in regard to his choice of Hynish as a site for the Harbour and establishment.