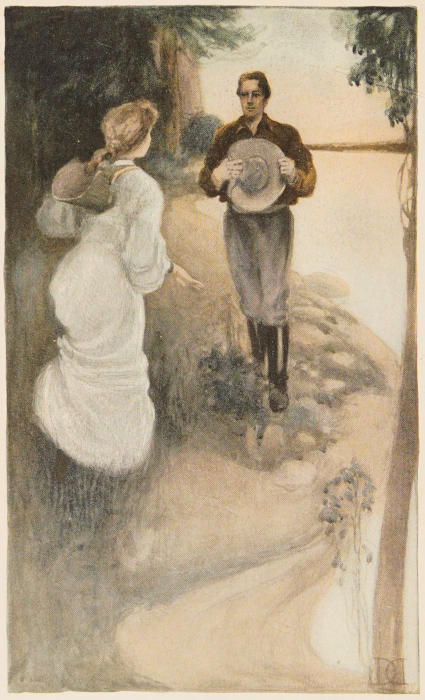

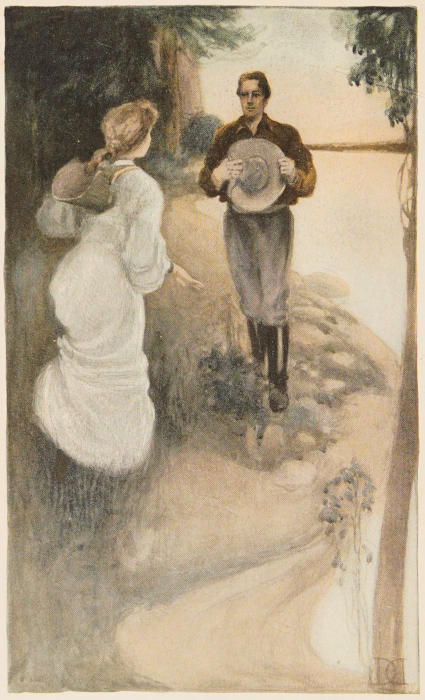

Jean beheld a tall, sunburned young man.—Page 185

Title: From the West to the West

Across the plains to Oregon

Author: Abigail Scott Duniway

Release date: January 17, 2025 [eBook #75131]

Language: English

Original publication: Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co, 1905

Credits: The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Jean beheld a tall, sunburned young man.—Page 185

FROM THE WEST

TO THE WEST

Across the Plains to

Oregon

BY

ABIGAIL SCOTT DUNIWAY

With Frontispiece in Color

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1905

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1905

Published April 7, 1905

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

To

THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF OREGON

AND HER RISEN AND REMAINING PIONEERS

I affectionately Dedicate

This Book

ABIGAIL SCOTT DUNIWAY

Not from any desire for augmented fame, or for further notoriety than has long been mine (at least within the chosen bailiwick of my farthest and best beloved West), have I consented to indite these pages.

The events of pioneer life, which form the groundwork of this story, are woven into a composite whole by memory and imagination. But they are not personal, nor do they present the reader, except in a fragmentary and romantic sense, with the actual, individual lives of borderers I have known. The story, nevertheless, is true to life and border history; and, no matter what may be the fate of the book, the facts it delineates will never die.

Fifty years ago, as an illiterate, inexperienced settler, a busy, overworked child-mother and housewife, an impulse to write was born within me, inherited from my Scottish ancestry, which no lack of education or opportunity could allay. So I wrote a little book which I called “Captain Gray’s Company, or Crossing the Plains and Living in Oregon.”

Measured by time and distance as now computed, that was ages ago. The iron horse and the telegraph had not crossed the Mississippi; the telephone and the electric light were not; and there were no cables under the sea.

Life’s twilight’s shadows are around me now. The good husband who shaped my destiny in childhood has passed to the skies; my beloved, beautiful, and only daughter has also risen; my faithful sons have founded homes and[x] families of their own. Sitting alone in my deserted but not lonely home, I have yielded to a demand that for several years has been reaching me by person, post, and telephone, requesting the republication of my first little story, which passed rapidly through two editions, and for forty years has been out of print. In its stead I have written this historical novel.

Among the relics of the border times that abound in the rooms of the Oregon Historical Society may be seen an immigrant wagon, a battered ox-yoke, a clumsy, home-made hand-loom, an old-fashioned spinning-wheel, and a rusty Dutch oven. Such articles are valuable as relics, but they would not sell in paying quantities in this utilitarian age if duplicated and placed upon the market. Just so with “Captain Gray’s Company.” It accomplished its mission in its day and way. By its aid its struggling author stumbled forward to higher aims. Let it rest, and let the world go marching on.

A. S. D.

Portland, Oregon,

January 15, 1905.

| Page | ||

| I. | A Removal is Planned | 15 |

| II. | Early Life in the Middle West | 22 |

| III. | Marrying and Giving in Marriage | 28 |

| IV. | Old Blood and New | 35 |

| V. | Sally O’Dowd | 43 |

| VI. | The Beginning of a Journey | 50 |

| VII. | Scotty’s First Romance | 55 |

| VIII. | A Border Incident | 62 |

| IX. | The Captain defends the Law | 68 |

| X. | The Captain makes a Distinction | 76 |

| XI. | Mrs. McAlpin seeks Advice | 84 |

| XII. | Jean becomes a Witness | 92 |

| XIII. | An Approaching Storm | 99 |

| XIV. | A Camp in Consternation | 106 |

| XV. | Cholera Rages | 113 |

| XVI. | Jean’s Visit beyond the Veil | 121 |

| XVII. | Father and Daughter | 128 |

| XVIII. | The Little Doctor | 134 |

| XIX. | A Brief Message for Mrs. Benson | 142 |

| XX. | The Teamsters Desert | 148 |

| XXI. | An Unexpected Encounter | 156 |

| XXII. | The Squaw Man | 163 |

| XXIII. | The Squaw asserts her Rights | 170[xii] |

| XXIV. | A Mormon Woman | 177 |

| XXV. | Jean loses her Way | 184 |

| XXVI. | Le-Le, the Indian Girl | 191 |

| XXVII. | Jean transformed | 197 |

| XXVIII. | The Stampede | 203 |

| XXIX. | In the Land of Drouth | 209 |

| XXX. | Bobbie goes to his Mother | 217 |

| XXXI. | Through the Oregon Mountains | 223 |

| XXXII. | Letters from Home | 229 |

| XXXIII. | Love finds a Way | 238 |

| XXXIV. | Happy Jack introduces Himself | 246 |

| XXXV. | Ashleigh makes New Plans | 253 |

| XXXVI. | Happy Jack is Surprised | 258 |

| XXXVII. | News for Jean | 264 |

| XXXVIII. | The Brothers journey Homeward Together | 271 |

| XXXIX. | The Old Homestead | 283 |

| XL. | The Unexpected Happens | 290 |

| XLI. | “In Prison and Ye Visited Me” | 299 |

| XLII. | Too Busy to be Miserable | 303 |

| XLIII. | Jean is Happy—and Another Person | 307 |

On the front veranda of a rectangular farmhouse, somewhat pretentious for its time and place, stood a woman in expectant attitude. The bleak wind of a spent March day played rudely with the straying ends of her bright, abundant red-brown hair, which she brushed frequently from her careworn face as she peered through the thickening shadows of approaching night. The ice-laden branches of a leafless locust swept the latticed corner behind which she had retreated for protection from the wind. A great white-and-yellow watch-dog crouched expectantly at her feet, whining and wagging his tail.

Indoors, the big living-room echoed with the laughter and prattle of many voices. At one end of a long table, littered with books and slates and dimly lighted by flickering tallow dips, sat the older children of the household, busy with their lessons for the morrow’s recitations. A big fire of maple logs roared on the hearth in harmony with the roaring of the wind outside.

“Yes, Rover, he’s coming,” exclaimed the watcher on the veranda, as the dog sprang to his feet with a noisy proclamation of welcome.

A shaggy-bearded horseman, muffled to the ears in a tawny fur coat, tossed his bridle to a stable-boy and, rushing up the icy steps, caught the gentle woman in his[16] arms. “It’s all settled, mother. I’ve made terms with Lije. He’s to take my farm and pay me as he can. I’ve made a liberal discount for the keep of the old folks; and we’ll sell off the stock, the farming implements, the household stuff, and the sawmill, and be off in less than a month for the Territory of Oregon.”

Mrs. Ranger shrank and shivered. “Oregon is a long way off, John,” she said, nestling closer to his side and half suppressing a sob. “There’s the danger and the hardships of the journey to be considered, you know.”

“I will always protect you and the children under all circumstances, Annie. Can’t you trust me?”

“Haven’t I always trusted you, John? But—”

“What is it, Annie? Don’t be afraid to speak your mind.”

“I was thinking, dear,—you know we’ve always lived on the frontier, and civilization is just now beginning to catch up with us,—mightn’t it be better for us to stay here and enjoy it? Illinois is still a new country, you know. We’ve never had any advantages to speak of, and none of the children, nor I, have ever seen a railroad.”

“Don’t be foolish, Annie! We’ll take civilization with us wherever we go, railroads or no railroads.”

“But we’ll be compelled to leave our parents behind, John. They’re old and infirm now, and we’ll be going so far away that we’ll never see them again. At least, I sha’n’t.”

The husband cleared his throat, but did not reply. The wife continued her protest.

“Just think of the sorrow we’ll bring upon ’em in their closing days, dear! Then there’s that awful journey for us and the children through more than two thousand miles of unsettled country, among wild beasts and wilder Indians. Hadn’t we better let well-enough alone, and remain where we are comfortable?”

“A six months’ journey across the untracked continent,[17] with ox teams and dead-ax wagons, won’t be a summer picnic; I’ll admit that. But the experience will come only one day at a time, and we can stand it. It will be like a whipping,—it will feel good when it is over and quits hurting.”

“You are well and strong, John, but you know I have never been like myself since that awful time when your brother Joe got into that trouble. It was at the time of Harry’s birth, you know. You didn’t mean to neglect me, dear, but you had to do it.”

“There, there, little wife!” placing his hand over her mouth. “Let the dead past bury its dead. Never mention Joe to me again. And never fear for a minute that you and the children won’t be taken care of.”

“I beg your pardon, John!” and the wife shrank back against the lattice and shivered. The protruding thorn of a naked locust bough scratched her cheek, and the red blood trickled down.

“I need your encouragement, in this time of all times, Annie. You mustn’t fail me now,” he said, speaking in an injured tone.

“Have I ever failed you yet, my husband?”

“I can’t say that you have, Annie. But you worry too much; you bore a fellow so. Just brace up; don’t anticipate trouble. It’ll come soon enough without your meeting it halfway. You ought to consider the welfare of the children.”

“Have I ever lived for myself, John?”

“No, no; but you fret too much. I suppose it’s a woman’s way, though, and I must stand it. There’s the chance of a lifetime before us, Annie.” He added after a pause, “The Oregon Donation Land Law that was passed by Congress nearly two years ago won’t be a law always. United States Senators in the farthest East are already urging its repeal. We’ve barely time, even by going now, to get in on the ground-floor. Then we’ll get, in our own right, to have and to hold, in fee simple,[18] as the lawyers say, a big square mile of the finest land that ever rolled out o’ doors.”

“Will there be no mortgage to eat us up with interest, and no malaria to shake us to pieces, John? And will you keep the woodpile away from the front gate, and make an out-of-the-way lane for the cows, so they won’t come home at night through the front avenue?”

“There’ll be no mortgage and no malaria. One-half of the claim will belong to you absolutely; and you can order the improvements to suit yourself. Only think of it! A square mile o’ land is six hundred and forty acres, and six hundred and forty acres is a whole square mile! We wouldn’t be dealing justly by our children if we let the opportunity slip. We’ll get plenty o’ land to make a good-sized farm for every child on the plantation, and it won’t cost us a red cent to have and to hold it!”

“That was the plan our parents had in view when they came here from Kentucky, John. They wanted land for their children, you know. They wanted us all to settle close around ’em, and be the stay and comfort of their old age.” And Mrs. Ranger laughed hysterically.

“You shiver, Annie. You oughtn’t to be out in this bleak March wind. Let’s go inside.”

“I’m not minding the wind, dear. I was thinking of the way people’s plans so often miscarry. Children do their own thinking and planning nowadays, as they always did, regardless of what their parents wish. Look at us! We’re planning to leave your parents and mine, for good and all, after they’ve worn themselves out in our service; and we needn’t expect different treatment from our children when we get old and decrepit.”

“But I’ve already arranged for our parents’ keep with Lije and Mary,” said the husband, petulantly. “Didn’t I tell you so?”

“But suppose Lije fails in business; or suppose he gets the far Western fever too; or suppose he tires of his bargain and quits?”

A black cloud scudded away before the wind, uncovering the face of the moon. The silver light burst suddenly upon the pair.

“What’s the matter, Annie?” cried the husband, in alarm. “Are you sick?” Her upturned face was like ashes.

“No; it’s nothing. I was only thinking.”

They entered the house together, their brains busy with unuttered thoughts. The baby of less than a year extended her chubby hands to her father, and the older babies clamored for recognition in roistering glee.

“Take my coat and hat, Hal; and get my slippers, somebody. Don’t all jump at once! Gals, put down your books, and go to the kitchen and help your mother. Don’t sit around like so many cash boarders! You oughtn’t to let your mother do a stroke of work at anything.”

“You couldn’t help it unless you caged her, or bound her hand and foot,” answered Jean, who strongly resembled her father in disposition, voice, and speech. But the command was obeyed; and the pale-faced mother, escorted from the kitchen amid much laughter by Mary, Marjorie, and Jean, was soon seated before the roaring fire beside her husband, enjoying with him the frolics of the babies, and banishing for the nonce the subject which had so engrossed their thoughts outside. The delayed meal was soon steaming on the long table in the low, lean-to kitchen, and was despatched with avidity by the healthy and ravenous brood which constituted the good old-fashioned household of John Ranger and Annie Robinson, his wife.

“Children,” said Mrs. Ranger, as an interval of silence gave her a chance to be heard, “did you know your father had sold the farm?”

A thunderbolt from a clear sky would hardly have created greater astonishment. True, John Ranger had been talking “new country” ever since the older children could remember anything; the theme was an old story,[20] invoking no comment. But now there was an ominous pause, followed with exclamations of mingled dissent and approval, to which the parents gave unrestricted liberty.

“I’m not going a single step; so there!” exclaimed Mary, a gentle girl of seventeen, who did not look her years, but who had a reason of her own for this unexpected avowal.

“My decision will depend on where we’re going,” cried Jean.

“Maybe your mother and I can be consulted,—just a little bit,” said the father, laughing.

“We’re going to Oregon; that’s what,” exclaimed Harry, who was as impulsive as he was noisy.

“How did you come to know so much?” asked Marjorie, the youngest of John Ranger’s “Three Graces,” as he was wont to style his trio of eldest daughters, who had persisted in coming into his household—much to his discomfort—before the advent of Harry, the fourth in his catalogue of seven, of whom only two were boys.

“I get my learning by studying o’ nights!” answered Hal, in playful allusion to his success as a sound sleeper, especially during study hours.

“Of course you don’t want to emigrate, Miss Mame,” cried Jean, “but you can’t help yourself, unless you run away and get married; and then you’ll have to help everybody else through the rest of your life and take what’s left for yourself,-if there’s anything left to take! At least, that is mother’s and Aunt Mary’s lot.”

“Jean speaks from the depths of long experience,” laughed Mary, blushing to the roots of her hair.

“I’m sick to death of this cold kitchen,” cried Jean, snapping her tea-towel in the frosty air of the unplastered lean-to. “Hurrah for Oregon! Hurrah for a warmer climate, and a snug cabin home among the evergreen trees!”

“Good for Jean!” exclaimed her father. “The[21] weather’ll be so mild in Oregon we shall not need a tight kitchen.”

“Is Oregon a tight house?” asked three-year-old Bobbie, whose brief life had many a time been clouded by the complaints of his mother and sisters,—complaints such as are often heard to this day from women in the country homes of the frontier and middle West, where more than one-half of their waking hours are spent in the unfinished and uncomfortable kitchens peculiar to the slave era, in which—as almost any makeshift was considered “good enough for niggers”—the unfinished kitchen came to stay.

The vigorous barking of Rover announced the approach of visitors; and the circle around the fireside was enlarged, amid the clatter of moving chairs and tables, to make room for Elijah Robinson and his wife,—the former a brother of Annie Ranger, and the latter a sister of John. The meeting between the sisters-in-law was expectant, anxious, and embarrassing.

“How did you like the news?” asked Mrs. Robinson, after an awkward silence.

“How did you like it?” was the evasive reply, as the twain withdrew to a distant corner, where they could exchange confidences undisturbed.

“I haven’t had time to think it over yet,” said Mrs. Ranger. “My greatest trouble is about leaving our parents. It seems as if I could not bear to break the news to them.”

“Don’t worry, Annie; they know already. When Lije told his mother that John was going to Oregon, she fainted dead away. When she revived and sat up, she wanted to come right over to see you, in spite of the storm.”

“Just listen! How the wind does roar!”

“I don’t see how your mother can live without you, Annie. I tried very hard to persuade Lije to refuse to buy John’s farm; but he would have his way, as he[22] always does. Of course, we’ll do all we can for the old folks, but Lije is heavily in debt again, with the ever-recurring interest staring us all in the face. John will want his money, with interest,—they all do,—and we know how rapidly it accumulates, from our own dearly bought experience, the result of poor Joe’s troubles!”

“I hope my dear father and mother won’t live very long,” sighed Mrs. Ranger. “If John would only let me make them a deed to my little ten-acre farm! But I can’t get him to talk about it.”

The surroundings of the budding daughters of the Ranger and Robinson families had thus far been limited, outside of their respective homes, to attendance at the district school on winter week-days when weather permitted, and on Sundays at the primitive church services held by itinerant clergymen in the same rude edifice.

Oh, that never-to-be-forgotten schoolhouse of the borderland and the olden time! Modelled everywhere after the same one-roomed, quadrangular pattern,—and often the only seat of learning yet to be seen in school districts of the far frontier,—the building in which the children of these chronicles received the rudimentary education which led to the future weal of most of them was built of logs unhewn, and roofed with “shakes” unshaven. One rough horizontal log was omitted from the western wall when the structure was raised by the men of the district, who purposely left the space for the admission of a long line of little window-panes above the rows of desks. A huge open fireplace occupied the whole northern[23] end of the room; rude benches rocked on the uneven puncheon floor and creaked as the students turned upon them to face the long desks beneath the little window-panes, or to confront the centre of the room. The children’s feet generally swung to and fro in a sort of rhythmic consonance with the audible whispers in which they studied their lessons,—when not holding sly conversation, amid much suppressed giggling, with their neighbors at elbow, if the teacher’s back was turned.

The busy agricultural seasons of springtime and summer, and often extending far into the autumn, prevented the regular attendance at school of the older children of the district, who were usually employed early and late, indoors and out, with the ever-exacting labors of the farm.

Up to the time of the departure of the Ranger family for the Pacific coast and for a brief time thereafter, the most of the summer and all of the winter clothing worn in the country districts of the middle West was the product of the individual housewife’s skill in the use of the spinning-wheel, dye-kettle, and clumsy, home-made hand-loom.

But, few and far between as were the schoolhouses and schooldays of the border times, of which the present-day grandparent loves to boast, there was a rigorous course of primitive study then in vogue which justifies their boasting. Oh, that old-fashioned pedagogue! What resident of the border can fail to remember—if his early lot was cast anywhere west of the Alleghanies, at any time antedating the era of railroads—the austere piety and stately dignity of that mighty master of the rod and the rule, who never by any chance forgot to use the rod, lest by so doing he should spoil the child!

The terror of those days lingers now only as an amusing memory. The pain of which the rod and the rule were the instruments has long since lost its sting; but the sound morals inculcated by the teacher (whose[24] example never strayed from his precept) have proved the ballast needed to hold a level head on many a pair of shoulders otherwise prone to push their way into forbidden places.

And the old-fashioned singing-school! How tenderly the memory of the time-dulled ear recalls the doubtful harmony of many youthful voices, as they ran the gamut in a jangling merry-go-round! Did any other musical entertainment ever equal it? Then, when the exercises were over, and the stars hung high and glittering above the frosty branches of the naked treetops, and the crisp white snow crunched musically beneath the feet of fancy-smitten swains, hurrying homeward with ruddy-visaged sweethearts on their pulsing arms, did any other joy ever equal the stolen kisses of the youthful lovers at the parting doorstep,—the one to return to the parental home with an exultant throbbing at his heart, and the other to creep noiselessly to her cold, dark bedroom to blush unseen over her first little secret from her mother.

And there is yet another memory.

Can anybody who has enjoyed it ever forget the school of metrical geography which sometimes alternated, on winter evenings, with the singing-school? What could have been more enchanting, or more instructive withal, than those exercises wherein the States and their capitals were chanted over and over to a sort of rhymeless rhythm, so often repeated that to this day the old-time student finds it only necessary to mention the name of any State then in the Union to call to mind the name of its capital. After the States and their capitals, the boundaries came next in order, chanted in the same rhythmic way, until the youngest pupil had conquered all the names by sound, and localities on the map by sight, of all the continents, islands, capes, promontories, peninsulas, mountains, kingdoms, republics, oceans, seas, rivers, lakes, harbors, and cities then known upon the planet.

In its season, beginning with the New Year, came the[25] regular religious revival. No chronicles like these would be complete without its mention, since no rural life on the border exists without it. Much to the regret of doting parents who failed to get all their dear ones “saved”—especially the boys—before the sap began to run in the sugar maples, the revival season was sometimes cut short by the advent of an early spring. The meetings were then brought to a halt, notwithstanding the fervent prayers of the righteous, who in vain besought the Lord of the harvest to delay the necessary seed-time, so that the work of saving souls might not be interrupted by the sports and labors of the sugar camp, which called young people together for collecting fagots, rolling logs, and gathering and boiling down the sap.

Many were the matches made at these rural gatherings, as the lads and lasses sat together on frosty nights and replenished the open fires under the silent stars.

To depict one revival season is to give a general outline of all. The itinerant preacher was generally a young man and a bachelor. In his annual returns to the scenes of his emotional endeavors to save the unconverted, he would find that many had backslidden; and the first week was usually spent in getting those who had not “held out faithful” up to the mourners’ bench for re-conversion.

Agnostics, of whom John Ranger was an example, were many, who took a humorous or good-naturedly critical view of the situation. But the preacher’s efforts to arouse the emotional nature, especially of the women, began to bear fruit generally after the first week’s praying, singing, and exhorting; and the excitement, once begun, went on without interruption as long as temporal affairs permitted. The rankest infidel in the district kept open house, in his turn, for the preacher and exhorter; and once, when the schoolhouse was partly destroyed by fire, John Ranger permitted the meetings to be held in his house till the damage was repaired by the tax-payers of the district.

The kindly preacher who most frequently visited the Ranger district as a revivalist would not knowingly have given needless pain to a fly. But, when wrought up to great tension by religious frenzy, he seemed to find delight in holding the frightened penitent spellbound, while he led him to the very brink of perdition, where he would hang him suspended, mentally, as by a hair, over a liquid lake of fire and brimstone, with the blue blazes shooting, like tongues of forked lightning, beneath his writhing body; while overhead, looking on, sat his Heavenly Father, as a benignant and affectionate Deity, pictured to the speaker’s imagination, nevertheless, as waiting with scythe in hand to snip that hair.

“I can’t see a bit of logic in any of it!” exclaimed Jean Ranger, as she and Mary, accompanied by Hal, were returning home one night from such a meeting.

“God’s ways are not our ways,” sighed Mary, as she tripped over the frozen path under the denuded maple-trees, where night owls hooted and wild turkeys slept.

Harry laughed immoderately. “Jean, you’re right,” he exclaimed. “I’m going to get religion myself some day before I die, but I’ve got first to find a Heavenly Father who’s better’n I am. There’s no preacher on top o’ dirt can make me believe that the great Author of all Creation deserves the awful character they’re giving Him at the schoolhouse!”

“Don’t blaspheme, Hal. It’s wicked!” said Mary.

“I’m not blaspheming; I’m defending God!” retorted Hal.

“You used to be a sensible girl, Mame,” said Jean; “and you could then see the ridiculous side of all this excitement just as Hal and I now see it. But you’re in love with the preacher now, and that has turned your head.”

Jean was cold and sleepy and cross; but she did not mean to be unkind, and on reflection added, “Forgive me, sister dear. I was only in fun. I have no right to[27] meddle with your love affairs or your religious feelings, and neither has Hal. S’pose we talk about maple sugar.”

Mary did not reply, but her thoughts went toward heaven in silent, self-satisfying prayer.

The Reverend Thomas Rogers—so he must be designated in these pages, because he yet lives—was the avowed suitor for the hand and heart of Mary Ranger; and the winsome girl, with whose prematurely aroused affections her parents had no patience,—and with reason, for she was but a child,—was the envy of all the older girls of the district, any one of whom, while censuring her for her folly in encouraging the poverty-stricken preacher’s suit, would gladly have found like favor in his eyes, if the opportunity had been given her.

But while romantic maidens were going into rhapsodies over their hero, and many of the dowager mothers echoed their sentiments, most of the unmarried men of the district remained aloof from his persuasions and unmoved by his fiery eloquence. But they took him out “sniping” one off-night in true schoolboy fashion; and while Mary Ranger dreamed of him in the seclusion of her snug chamber, the poor fellow stood half frozen at the end of a gulch, holding a bag to catch the snipes that never came.

“If I were not too poor in worldly goods to pay my way in your father’s train, I’d go to Oregon,” he said, a few nights after the “sniping” episode, as he walked homeward with Mary after coaxing Jean and Hal to keep the little episode a secret from their parents,—a promise they made after due hesitation, but with much sly chuckling, as they munched the red-and-white-striped sugar sticks with which they had been bribed.

The destinies of the Ranger and Robinson families had been linked together by the double ties of affinity and consanguinity in the first third of the nineteenth century. Their broad and fertile lands, to which they held the original title-deeds direct from the government, bore the signature and seal of Andrew Jackson, seventh President of the United States; and their children and children’s children, though scattered now in the farthest West, from Alaska and the Hawaiian Islands to the Philippine Archipelago, treasure to this day among their most valued heirlooms the historic parchments. For these were signed by Old Hickory when the original West was bounded on its outermost verge by the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, and when the new West, though discovered in the infancy of the century by Lewis and Clark (aided by Sacajawea, their one woman ally and pathfinder), was to the average American citizen an unknown country, quite as obscure to his understanding as was the Dark Continent of Africa in the days antedating Sir Samuel Baker, Oom Paul, and Cecil Rhodes.

The elder Rangers, who claimed Knickerbocker blood, and the Robinsons, who boasted of Scotch ancestry, though living in adjoining counties in Kentucky in their earlier years, had never met until, as if by accident,—if accident it might be called through which there seems to have been an original, interwoven design,—the fates of the two families became interlinked through their settlement upon adjoining lands, situated some fifty miles south of old Fort Dearborn, in the days when Chicago was a mosquito-beleaguered swamp, and Portland, Oregon, an unbroken forest of pointed firs.

There was a double wedding on the memorable day when John Ranger, Junior, and pretty Annie Robinson, the belle of Pleasant Prairie, linked their destinies together in marriage; and when, without previous notice to the assembled multitude or any other parties but their parents, the preacher, and the necessary legal authorities, Elijah Robinson and Mary Ranger took their allotted places beside their brother and sister, as candidates for matrimony, the festivities were doubled in interest and rejoicing.

“It seems but yesterday since our bonnie bairns were babes in arms,” said the elder Mrs. Robinson, as she advanced with Mrs. Ranger mère to give a tearful greeting to each newly wedded pair. And there was scarcely a dry eye in the assembled multitude when the mother’s voice arose in a shrill treble as she sang, in the ears of the startled listeners, from an old Scottish ballad the words,—

Her voice, which at first was as clear as the tones of a silver bell, quavered at the close of the first stanza and then ceased altogether. But by this time old Mrs. Ranger had caught the spirit of the ballad, and though her voice was husky, she cleared her throat and added, in a low contralto, the impressive lines, paraphrased somewhat to suit the occasion,—

At the close of this stanza, Mrs. Ranger’s voice broke also; and the good circuit rider, parson of many a scattered flock, who had pronounced the double ceremony, caught the tune and, in a mellow barytone that rose upon the air like an inspired benediction, added most impressively another stanza:

“It’s high time there was a little change o’ sentiment in all this!” cried a bachelor uncle, whose eyes were suspiciously red notwithstanding his affected gayety. “I move that we march in a solid phalanx on the victuals!”

The primitive cabin homes of the borderers of no Western settlement were large enough to hold the crowds that were invariably bidden to a neighborhood merrymaking. The ceremonies of this occasion, including a most sumptuous feast, were held on the sloping green beneath an overtopping elm, which, rising high above its fellows, made a noted landmark for a circumference of many miles.

People who live apart from markets, in fertile regions where the very forests drop richness, subsist literally on the fat of the land. Having no sale for their surplus products, they feast upon them in the most prodigal way. Although through gormandizing they beget malaria, not to say dyspepsia and rheumatic ails, they boast of “living well”; and the sympathy they bestow upon the city denizen who in his wanderings sometimes feasts at their hospitable boards, and praises without stint their prodigal display of viands, is often more sincere than wise.

The lands of the early settlers, with whom these chronicles have to deal, had been surrounded, as soon as possible after occupancy, with substantial rail fences, laid in zigzag fashion along dividing lines, marking the boundaries between neighbors who lived at peace with each other and with all the world. These fences, built to a sufficient height to discourage all attempts at trespass by man or beast, were securely staked at the corners, and weighted with heavy top rails, or “riders,” so stanchly placed that many miles of such enclosures remain to this day, long surviving the brawny hands that felled the trees and split the rails. In their mute eloquence they reveal the lasting qualities of the hardwood timber that abounded in the many and beautiful groves which flourished in the prairie States in the early part of the nineteenth century, when Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri comprised all that was generally known as the West.

Much of the primitive glory of these diversified landscapes departed long ago with the trees. The “Hook-and-Eye Dutch,” as the thrifty followers of ancient Ohm are called by their American neighbors (with whom they do not assimilate), are rapidly replacing the old-time maple and black walnut fences with the modern barbed-wire horror; they are selling off the historical rails, stakes and riders and all, to the equally thrifty and not a whit more sentimental timber-dealers of Chicago, Milwaukee, and Grand Rapids, to be manufactured into high-grade lumber, which is destined to find lodgment as costly furniture in the palatial homes, gilded churches, great club-houses, and mammoth modern hostelries that abound on the shores of Lake Michigan, Massachusetts Bay, Manhattan Island, and Long Island Sound. But no vandalism yet invented by man can wholly despoil the rolling lands of the middle West of their beauty, nor rob Mother Nature of her power to rehabilitate them with the living green of cultivated loveliness.

Original settlers of the border-lands had little time and[32] less opportunity for the observation of the beautiful in art or nature. Their lives were spent in toil, which blunted many of the finer sensibilities of a more leisurely existence. The hardy huntsman who spent his only hours of relaxation in chasing the wild game, and the weary mother who scarcely ever left her wheel or loom and shuttle by the light of day, except to bake her brain before a great open fire while preparing food, or to nurse to sleep the future lawmakers of a coming world-round republic, were alike too busy to ponder deeply the far-reaching possibilities of the lives they led.

Such men of renown as Lincoln, Douglas, Baker, Grant, Logan, and Oglesby were evolved from environments similar to these, as were also the numerous adventurous borderers not known to fame (many of whom are yet living) who crossed the continent with ox teams, and whose patient and enduring wives nursed the future statesmen of a coming West in fear and trembling, as they protected their camps from the depredations of the wily Indian or the frenzy of the desert’s storms.

Rail-making in the middle West was long a diversion and an art. The destruction of the hardwood timber, which if spared till to-day would be almost priceless, could not have been prevented, even if this commercial fact had been foreseen. The urgent need of fuel, shelter, bridges, public buildings, and fences allowed no consideration for future values to intervene and save the trees.

In times of a temporary lull in a season’s activities, when, for a wonder, there were days together that the stroke of the woodman’s ax was not heard and the music of the cross-cut saw had ceased, the settler would take advantage of the interim to draw a bead with unerring aim upon the eye of a squirrel in a treetop, or bring down a wild turkey from its covert in the lower branches; or, if favored by a fall of virgin snow, it would be his delight to track the wild deer, and drag it home as a[33] trophy of his marksmanship,—an earnest of the feast in which all his neighbors were invited to partake.

Then, too, there were the merrymakings of the border. What modern banquet can equal the festive board at which a genial hostess, in a homespun cotton or linsey-woolsey gown, presided over her own stuffed turkey, huge corn-pone, and wild paw-paw preserves? What array of glittering china, gleaming cut-glass, or burnished silver, can give the jaded appetite of the blasé reveller of to-day the enjoyment of a home-set table, laden with the best and sweetest “salt-rising” bread spread thick with golden butter, fresh from the old-fashioned churn? The freshest of meats and fish regularly graced the well-laden board, in localities where the modern chef was unknown, where ice-cream was unheard of, and terrapin sauce and lobster salad found no place. House-raisings, log-rollings, barn-raisings, quilting bees, weddings, christenings, and even funerals, were times of feasting, though these last were divested of the gayety, but not of the gossip, that at other times abounded; and the sympathetic aid of an entire neighborhood was always voluntarily extended to any house of mourning. There were few if any wage-earners, the accommodating method of exchanging work among neighbors being generally in vogue.

Such, in brief, were the daily customs of the early settlers of the middle West, whose children wandered still farther westward in the forties and fifties, carrying with them the habits in which they had been reared to the distant Territory afterwards known as the “Whole of Oregon,” which originally comprised the great Northwest Territory, where now flourish massive blocks of mighty States.

Prior to the time of the departure of the subjects of these chronicles for the goal of John Ranger’s ambition, but one unusual occurrence had marred the lives and[34] prosperity of the rising generation of Rangers and Robinsons. To the progenitors of the two families the mutations of time had brought problems serious and difficult, not the least of which was the infirmity of advancing years. This they had made doubly annoying through having assigned to their children, when they themselves needed it most, everything of value which they had struggled to accumulate during their years of vigorous effort to raise and educate their families.

In the two households under review, all dependent upon the energies and bounty of the second generation of Rangers and Robinsons, there were besides the great-grandmother (a universal favorite) two sexagenarian bachelor uncles and two elderly spinsters, the latter remote cousins of uncertain age, uncertain health, and still more uncertain temper, who had long outlived their usefulness, after having missed, in their young and vigorous years, the duties and responsibilities that accompany the founding of families and homes of their own. It was little wonder that drones like these were out of place in the overcrowded households of their more provident kinspeople, to whom the modern “Home of the Friendless” was unknown. What plan to pursue in making necessary provision for these outside incumbents, even John Ranger, the optimistic leader of the related hosts, could not conjecture.

“We’ve fixed it,—Mame and I,” said Jean, one evening, after an anxious discussion of the question had been carried on with some warmth between the two family heads, in which no conclusion had been reached except a flat refusal on the part of Elijah Robinson to quadruple the quota of dependants in his own household.

“And how have you fixed it?” asked her father, who often called Jean his “Heart’s Delight.”

“Our bachelor uncles and cousins are just rusting out with irresponsibility!” she cried with characteristic Ranger vehemence. “They ought to have a home of[35] their own and be compelled to take care of it. There’s that house and garden where you board and lodge the mill-hands. Why not give ’em that and let ’em keep boarders? The boarders, the four acres of ground, and the cow and garden ought to keep them in modest comfort. This would make them free and independent, as everybody ought to be.”

“But the boarding-house belongs with the farm. I’ve sold it to your uncle.”

“Then let Uncle Lije lease or sell it to them, share and share alike.”

“What is it worth?” asked Mary.

“Only about three hundred dollars, the way property sells now,” said her uncle.

“Then let ’em pay you rent. The place ought to support them and pay interest and taxes.”

“Yes,” cried Mary; “the old bachelor contingent, that worry you all so much because you keep ’em dependent on your bounty, can take care of themselves for twenty years to come, if you’ll only let ’em.”

“The proposition is worth considering, certainly,” said their father, smiling admiringly upon his daughters.

“And we’ll consider it, too,” said the uncle. “That much is settled.”

“I can’t see why old folks like us will persist in living after we’ve outgrown our usefulness,” exclaimed Grandfather Ranger, one sloppy March evening, as he entered the little kitchen and placed a pail of foaming milk upon the clean white table. The severely cold weather had given way to a springtime thaw; but a wet snow had begun falling at sundown, and a soft,[36] muddy liquid made dirty pools wherever his feet pressed the polished floor.

“You’re right, father; we’ve lived long enough,” sighed the feeble mother of many children, following her husband’s footprints with mop and broom.

“If you and John think you’ve lived long enough, what do you think of me?” cried the great-grandmother, who had passed her fourscore years and ten, but who still amply supported herself (if only she and the rest of the family had thought so) as she sat from early morning till late at night in her corner, knitting, always knitting.

“Never mind, grannie,” said her son, swallowing a lump that rose unbidden in his throat. “You’ve as good a right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as any fellow that ever put his name to a Declaration of Independence! There’ll be room for you in the cosiest corner of this little house as long as there’s a corner for anybody. Don’t worry.”

“But this state of things isn’t just or fair!” exclaimed the wife, folding her last bit of mending and dropping back into her chair. “It seems to me that we, as parents, deserve a better fate in our old days than any set of bachelor hangers-on on earth, who’ve never had anybody but themselves to provide for. If Joseph would only come back, or the good Lord would let us know his fate, I could endure the rest.”

“There, there, mother! Not another word. Haven’t I forbidden the mention of his name?”

“But he was our darling, father. I can’t dismiss him from my thoughts as you say you can.”

“We must keep the grandchildren in ignorance of his existence, wife. It’s bad enough in all conscience for the stain of his misguided life to rest on older heads. We must forget our unfortunate son.”

“I can never forget my bonnie boy,—not even to obey you, father!”

The back door, which had been unintentionally left ajar, flew open, and Jean, who had for the first time in her life heard a word of complaint from her grandparents, or a word from them concerning her mysterious Uncle Joe, burst suddenly into the room and knelt at the feet of her grandmother, her whole frame convulsed with sobs.

“Forgive us, darlings, do!” she cried as soon as she could control her voice to speak. “You’ve borne so much sorrow, and we never knew it! We never meant to be thoughtless or unkind, but I see now how ungrateful we have been. We must have hurt your feelings often.”

“Don’t cry, Jean,” and the thin hand of the grandmother stroked the girl’s bright hair. “We don’t often repine at our lot. I am sorry you overheard a word.”

“But I am not sorry a single bit, grandma. We children have been thoughtless and impudent. I can see it all now. We didn’t ever mean to complain, though, about you, or grandpa, or you either, grannie dear. We only meant to draw the line at bachelor great-uncles and meddlesome second and third cousins, who ought to have provided themselves in their youth with homes of their own, as our parents did.”

“Do you think they can help themselves hereafter, Jean?”

“Why, of course! The feeling of self-dependence will make ’em young and strong again,—though they don’t deserve good treatment, for they ought to have had homes and families of their own in their youth, as you did.”

“It’s too late to lodge a complaint of that kind against them now, Jean,” said the grandmother, with a smile.

“Did you overhear all we were talking about?” asked the grandfather, his head bowed upon his cane.

“I am afraid I did, grandpa. I was cleaning the slush from my shoes, and I couldn’t help overhearing,[38] though I hate eavesdroppers, on general principles. They never hear any good of themselves. But, say, grandpa, what about our Uncle Joe, whom I heard you denounce so bitterly? You haven’t said I mustn’t speak his name, you know.”

“Don’t talk about him, child, to us or anybody else. He’s an outlaw. Dismiss him from your thoughts, just as I have.”

“Your uncle may not be living now, Jean; if he is alive, I hope he’ll find a better friend than his father,” exclaimed the great-grandmother, speaking in a tone of reproach that surprised none more than herself.

“Tell me all about it, grand-daddie darling! Do! I know there’s a sad secret somewhere in the family. Something unusual must have happened a long time ago to bring us all under the ban of poverty. I have heard hints of it now and then all my life; and now I must hear the whole story. The schoolmaster will tell me if you don’t.”

“No, no, Jean,” exclaimed her grandfather, anxiously. “Don’t speak of family affairs outside. It is never seemly.”

“Neither is it seemly or just to keep members of the family in ignorance of family affairs when all the rest of the neighborhood knows all about ’em! We ought to know all, grandma darling. The reason children are so often unreasonable is that they don’t understand.”

“‘I have been young and now am old, yet have I not seen the righteous forsaken nor his seed begging bread,’” said the grandfather, his head still bowed low upon his staff and his white locks falling over his stooping shoulders. “Let us not repine, mother.”

“I am not repining, father, but I do feel so—so disappointed with the outcome of all our hard struggles that I can’t always be cheerful.”

“We’d just begun to get our heads above water when it happened, Jean,” said the old man. “We’d been[39] making a new farm. You see, we’d manumitted our slaves before we left Kaintuck, and we had to begin with our bare hands in this new country and work our way from the ground up. We’d only got a part o’ the children raised when the older ones began to get it in their heads to get married. But our second son took to book-learning, and we sent him off to Tennessee to finish his schooling. That cost a pile o’ money. Then we had to set out the married ones. We’d got things going in tol’ble shape and was beginning to get on our feet again, when Joseph—”

“Do stop, husband. Don’t tell any more; please don’t,” cried the grandmother, nervously stroking the bright young head that nestled in her lap. “I cannot bear to hear it, though I thought I could.”

“Let him go on, grandmother dear! I don’t want to be driven to the schoolmaster for the information that I am bound to get someway. When I have grandchildren of my own, I’ll tell ’em everything they ought to know about the family, and then they won’t be teased by the school-children, as we are.”

“We had to mortgage the farm,” continued the grandfather; “and then there came a financial panic. The wild-cat banks of the country all went to pieces, and the bottom kind o’ fell out o’ things.”

“But why did you borrow money, grandpa? Why was it necessary to mortgage the farms?”

“We did it because we had to stand by Joe in his trouble.”

“What did you hear at school, darling?” asked the grandmother.

“Oh, nothing much. But one day Jim Danover got mad at me because I went head in the class; and he said I needn’t be puttin’ on airs, for everybody knew that my uncle had been hung.”

“Good Lord! has it come to that?” cried the great-grandmother, dropping her knitting to the floor and[40] clasping her withered hands over her knees. “I’ve always told you that you’d better tell the older children about it yourself, John.”

“No, Jean; your uncle wasn’t hung,” said the old man; “but he got into trouble, and we all believe he is dead. He was the pride and joy of us all. He was so promising that we gave him all the education that ought to have been distributed evenly through the family.”

“But John and Mollie took a notion to get married young, and you know that ended their chances,” interposed the mother.

“Your uncle’s trouble would never have come upon him and us if he had stayed out o’ that college,” exclaimed the great-grandmother, who did not approve of the course the family had taken with Joseph at the beginning of his college days.

“That’s true, grannie,” replied the father; “but he ought to have kept out o’ the scrape, college or no college.”

“Do go on,” cried Jean.

“Your Uncle Joe got mixed up in a hazing frolic, or something o’ that sort,” resumed the grandfather. “One or two of the students got hurt, one of ’em so bad that he died,—or it was given out that he died,—and the blame fell on Joe. He declared he wasn’t guilty, but the college authorities had to fix the blame somewhere, though the case was uncertain. They never proved that the boy was dead, but we raised the money and bailed Joe out o’ jail. When the story was started that the fellow had died, Joe skipped his bail and left us all in a hole. That was what made and has kept us poor.”

“Did you never hear of the other man, grandpa?”

“Oh, yes; he turned up, but too late to do Joe or the rest of us any good.”

“Poor dear Uncle Joe!”

“You’d better say poor dear all the rest of us,” cried[41] the great-grandmother, who had staked and lost her little all in the great calamity.

“But Uncle Joe was sinned against, grannie dear. How he must have suffered!”

“Them that’s sinned against are often greater sufferers than them that sins,” was the sad reply.

“When the bail was jumped, the hard times set in with all of us,” resumed the grandfather. “The banks, as I was saying, went broke, the interest on the mortgages piled up, and the notes fell due. The crops got the rust and the weevil, and everything else went wrong. You see, Jean, when a man starts down hill, everybody tries to give him a kick. The long and the short of it is that mother, here, and grannie and I have been the same as paupers for more than a dozen years.”

“I must be going, though you must first tell me how you two and dear old grannie are going to live when we are away in Oregon. Your way seems very uncertain,” said Jean.

“Your father has made some kind of a bargain for our support with your Uncle Lije. But he’s sort o’ visionary, and he never has much luck. If he loses the property, we can go to the poorhouse.”

“Are you to be allowed no stated sum to live on? Will you have no means of your own to gratify your individual wishes or tastes?”

“No, child; not a picayune.”

“What’s a picayune?”

“A six-and-a-quarter-cent piece.”

“I’m just as wise as I was before.”

“They’re wellnigh out o’ circulation nowadays, though I used to come across ’em frequently when I was sheriff,” said the old man.

Jean covered her face with her hands and burst into tears.

“Don’t worry about us, dearie,” said the old man. “There is One above us who heareth even the young[42] ravens when they cry. There is not a sparrow that falleth to the ground without His knowledge. Your Uncle Lije will move into the old homestead when you are all gone. Your father built this cottage for us when he assumed the mortgage, as you know. We won’t be entirely alone, but we’ll miss you all; and we’ll try to remember that we are of more value than many sparrows.”

“I’ve heard such talk as that all my life, grandpa. But I can’t help thinking that it would have been better to keep the ravens from having anything to cry about in the first place, and to save the sparrows from falling.”

“If none o’ God’s creatures ever had any hard experiences, they’d never know enough to enjoy their blessings, Jean. A child has to stumble and hurt itself many times before it learns to walk steady. We’ve all got to be purified and saved, as by fire, before we are fit to stand in the presence of the awful God.”

“The God I love and worship isn’t an awful God,” cried Jean. “I couldn’t love Him if He were awful. My earthly daddie whipped me once. No doubt I deserved the punishment, but I couldn’t love him for a whole month afterwards. And I’d have hated him for the rest of my life if I hadn’t deserved the whipping.”

“Didn’t it do you any good?”

Jean confronted her grandfather, her eyes flashing. “No, sir!” she cried. “I ought not to have been whipped, and I wasn’t a bit repentant after the punishment. I was sorry beforehand, though, and said so.”

“What was your offence, Jean?”

“I dropped a pan full of dishes and broke more than half o’ the lot. They fell to the floor with a crash, and scared me half to death.”

“Didn’t the whipping make you more careful afterwards?”.

“Not at all; it only made me mad and afraid and nervous, so I broke more dishes. But the next time it[43] happened, I hid the broken pieces in the ash hopper, and when they were found, I saved myself a whipping by telling my first lie.”

“The Lord chasteneth whom He loveth, my child.”

“I once saw a mill-hand strike his wife,” retorted Jean, “and he said, as she rubbed her bruises, ‘I love you, Mollie. Take another kick!’ But I must go now. Be of good cheer. And remember, when I get to Oregon and get to making money, you shall have every cent that I can spare.”

Great excitement prevailed in the rural neighborhood when it became generally known that John Ranger, Junior, had sold the farm and was preparing to dispose of his sawmill and all his personal belongings, with the intention of departing to the new and far-away West in an ox-wagon train with his family,—an undertaking that seemed to his friends as foolhardy as would have been an attempt to reach the North Pole with his wife and children in a balloon.

Of more than ordinary ability, enterprise, and daring, John Ranger had long been a man of note in his bailiwick. Twice he had represented his county in the State Legislative Assembly; but when the Old Line Whigs of his district offered to nominate him for Congress,—“No, gentlemen!” he exclaimed. “I started out early in life to assist my good wife in rearing and educating a big family of young Americans. I frankly admit that we’ve got a bigger job on hand than either of us imagined it would be when we made the bargain; but that doesn’t lessen our mutual responsibility. There is always a regiment, more or less, of unencumbered men[44] in waiting in every locality, ready and willing to wear the toga of office; so, with thanks for the proffered honor, I must beg to be excused.”

But there was one office, that of justice of the peace, which he never refused, and to which he had been so often re-elected that the appellation of “Squire” had grown to belong to him as a matter of course. One room of the great barnlike farmhouse had long been set apart as his office; and many were the litigants who remained after office hours to be entertained at his hospitable board.

“It’s a lot of trouble, having so much extra company on account of your office being in the house,” his wife said at times; “but it’s better than having you away two-thirds of your time down town, so it is all right.”

“There’s a woman going round the corner to the office,” exclaimed Mary, one evening, just as her father had settled himself before the fire to enjoy a frolic with the little ones.

“It’s that grass widow, Sally O’Dowd,” said Mrs. Ranger.

“She’s booked for a solid hour,” snapped Marjorie, “and we’ll have to delay supper till nine o’clock.”

The Squire had barely time to reach his office by an inner passage and seat himself before the fire, when Mrs. O’Dowd—an oversized, plainly dressed, intelligent-looking woman, who was remarkably handsome, notwithstanding the expression of pain upon her face—entered the office and stood silent before the open fire.

“Well,” exclaimed the Squire, impatiently, motioning her to a chair, “what can I do for you now?”

“Oh, Squire!” she cried, ignoring the proffered chair and dropping on her knees at his feet, her wealth of rippling hair falling about her face and over her shapely shoulders like a deluge of gold, “I want you to take me with you to Oregon.”

“What! And leave your children to the care of others? I didn’t think that of you, Mrs. O’Dowd.”

“But what else can I do? You know the court has assigned the custody of all three of my babies to Sam.”

“Yes, Sally; but you can see them once in a while if you stay here.”

“The court gave them to Samuel and his mother absolutely, you know.”

“Yes, yes, child; and while in one way it is hard, if you look at it in a practical light, you will see that it was best for the children. You couldn’t keep them with you and go out as hired help in anybody’s kitchen; and you have no other means of support any more.”

“If I stay here, I cannot have even the poor privilege of caring for them, except when they’re sick. I must get entirely away from their vicinity, or lose my senses altogether.”

“I thought that was what was the matter when you married the fellow, Sally. You certainly had lost your senses then.”

“But love is blind, Squire—till it gets its eyes open; and then it is generally too late to see to any advantage. Little did my dear father think, when he made a will leaving his homestead, his bank account, and all his belongings to me, that he was reducing my dear mother and me to beggary.”

“But that wouldn’t have happened if you hadn’t married that worthless fellow, Sally.”

“But the if exists, Squire. I married the fellow. It was an awful blunder,—I’ll admit that. But it wasn’t a crime. It should have been no reason for robbing me. And yet this marriage was made the legal pretext for permitting the robbery. Oh, I was so glad when my dear mother died! I couldn’t have shed a tear at her grave if I’d been hung for my seeming heartlessness. Poor mother! I was made an unwilling party to a robbery[46] that beggared her and myself. Then, when I could no longer endure the presence of the robber and his accomplice, and live, I was doubly, yes, trebly robbed, by being deprived of my children.”

The Squire cleared his throat and spoke huskily.

“That will was a sad mistake of your father’s, Sally. He should have left his property to your mother. It was wrong to put her means of livelihood in jeopardy by leaving all to you. He ought to have known you’d marry, and that the property would accrue to your husband.”

“But mother insisted that all should be left to me. She even waived her right of dower, in my interest—as she thought.”

“Well, Sally, you can’t say that I didn’t warn you.”

The woman laughed hysterically. “Much good that warning can do me now!” she cried, rising to her feet and unconsciously assuming a dramatic pose. “We hadn’t been married a week when he ordered my mother out of my house. And then he installed his own mother in my home, and expected me to be silent. Oh, I am so glad my dear mother is dead! I would rejoice if my poor, defrauded children were all dead also.”

The Squire cleared his throat again and leaned forward on his hands. “The law recognizes the husband and wife as one, and the husband as that one, Mrs. O’Dowd.”

“Yes, yes, I know that, to my bitter sorrow,” she said with a meaning smile, her white teeth shining through her parted lips and her eyes flashing. The woman sank upon the hearth, looking strangely white and calm.

John Ranger sighed helplessly. “I worked the underground railroad last night for all it was worth, in the interest of some runaway niggers,” he said under his breath; then audibly, “The laws of the land must be obeyed, my child.”

“The law is a fiend,” cried Jean, who had entered the[47] room unobserved and had stood listening in the shadow of the chimney jamb. “I’ll never rest till this awful one-sided power is broken. You know yourself that it’s a monster, daddie. I know you know it, or you’d never help a run—”

He put his finger on his lips, and the girl changed the subject. The underground railroad was a forbidden topic in the Ranger household.

“Because Sally Danover knew no better than to become the wife of an unworthy man,—who knew what he was about, though she didn’t,—the law declares that all the benefits resulting from the fraudulent transaction must accrue to the villain in the case, and all the penalties must be borne by his victim. What would you do to such a fellow, daddie, if I should marry him?”

John Ranger did not answer, but gazed steadily into the fire, his brow contracted and his thoughts gloomy.

“Sally, cheer up!” cried Jean, shaking the woman by the shoulder. “Daddie’s a whole lot better man than he thinks he is. I’ve seen him tested. You’re as good as a nigger, if you are white, and he’ll help you.”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about, my daughter. It’s a crime to break the law, and crime must be followed by fitting punishment.”

“If you get caught, you get punished,” cried Jean, laughing in her father’s face. “To break such a law would be an act of heroism for which I should be glad to be arrested and sent to jail! It would be an act of heroism beside which the defence of the Stars and Stripes would be cowardice!” she cried in a transport of fury.

“Come, Jean,” said her father, rising, “we must go to supper. Won’t you join us, Mrs. O’Dowd?”

“Food would choke me,” said the visitor, bowing herself out.

“Hang the luck!” said the Squire, as the door slammed behind her.

“What are you going to do to help the poor woman, John?” asked Mrs. Ranger, as the family sat at the belated meal.

“Ask Jean.”

“What do you know about the case, daughter?”

“She thinks she knows a lot,” interrupted her father. “She’d ’a’ made a plaguy good lawyer if she’d only been born a boy.”

“Who knew best what I ought to be,—you or God?” asked Jean, her eyes glowing like stars.

“I give it up,” replied her father, smiling.

“I was reading to-day,” said Mrs. Ranger, “of a man down East who lured his runaway wife back home by stealing the babies and then warning everybody through the papers, and by posters, not to trust or harbor her, under penalty of the law. The woman held out quite a spell, but cold and hunger got the better of her at last; and when the stolen children fell sick, she went back to her lawful protector and stayed till she died, as meek as any lamb.”

“Sally Danover won’t go back to Sam O’Dowd; she’ll die first,” cried Mary; “and I glory in her grit.”

“You haven’t answered my question, John,” said Mrs. Ranger. “What do you propose to do with Sally O’Dowd?”

“I s’pose I’ll have to take her to Oregon and let her take a new start. She says she must get away from here, or go insane.”

“I’d go crazy if I had to leave my children, John.”

“You can boast, Annie; you can afford to. But if you were in Sally’s shoes, you’d sing a different song.”

Mrs. Ranger shrugged her shoulders.

“I can’t see why women with good husbands and happy homes are so ready to censure less fortunate women for breaking bonds that are unbearable,” said her husband. “Women are women’s worst enemies.”

“Sam O’Dowd’s no woman,” exclaimed Jean.[49] “There’s not a woman on top o’ dirt that’d treat any man as he’s treated Sally.”

“I guess it’s about an even stand-off,” rejoined her mother.

“No,” cried Jean. “The conditions are not equal. No woman has the power to turn her husband out of doors. Even if it is her own house, he is its lawful master. Women don’t stand any show at all compared with men.”

“Jean is going to-morrow to see Sam O’Dowd’s mother. She can make matters smooth for Sally if anybody can,” said the Squire.

“The sale of our effects is only two weeks off, John,” said his wife, when they were alone. “I want to reserve a few things that are sacred. There’s Baby Jamie’s cradle, that you made from the hollow section of that old gum-tree that stood in the back pasture. Do you remember how nicely I lined it with the back breadths of my wedding dress?”

“Could I forget it, Annie?”

“Then there’s my mother’s little old spinning-wheel. It was my grandmother’s and great-grandmother’s. May I keep it for Mary?”

“It won’t pay to haul such things over the plains, Annie. Better let your mother keep ’em here till there’s a transcontinental railroad.”

“But that won’t come in my time, John.”

The sale of Squire Ranger’s effects proceeded without unnecessary delay. The sawmill, the first portable structure of its kind ever seen west of the Wabash River, was eagerly purchased on credit by a waiting customer, and work at the mill went on without interruption. What a primitive affair it was! And how like a pygmy it seems as the resident on the North Pacific’s border recalls its littleness, and contrasts it with the mammoth mills of Oregon, the lower Columbia, and Puget Sound, which grasp in their giant arms the dead leviathans of the primeval forest, and set their teeth to work tearing to pieces the patient upbuilding of the ages gone!

The motive power of John Ranger’s sawmill consisted of about a dozen superannuated horses, some spavined, some ringboned, some wind-broken, all more or less disabled in some way; these were regularly harnessed, each in his turn, to a set of horizontal radiating shafts attached to a rotating centre, above which, on a little platform, stood the driver, with a whip.

“I know it’s wicked to kill the trees and cut them up into boards; it’s just as wicked as it is to kill pigs and cattle,” was Mary Ranger’s comment when she first beheld the frantic work of the raging saw, which, screaming like a demon, ate its way through hearts of oak and hickory, or tore the slabs from the sides of the black-walnut and sugar-maple patriarchs with ever unsated ferocity.

But this sawmill had long been a boon to the entire country, as was evidenced by the multiplication, since its advent, of framed houses, barns, bridges, schoolhouses,[51] and churches, which suddenly sprang into vogue, not to mention the many miles of planked highways that rushed into fashion before the railroad era in the days when “good roads conventions” were unheard of.

Children born and reared in cities—subject, if of the tenant class, to frequent changes of habitation, or, if their homes are permanent, to frequent intervals of travel—can have little idea of the love which children of the country cherish for the farms and homes to which they are born, and in which their brief lives are spent. The very soil on which they have trodden is dear to them, and seems instinct with sentience. They make a boon companion of everything with which they come in contact, whether pertaining to the earth, the water, or the air. Their little gardens are familiar friends; the flowers of the wildwood are loving entities; the brook that sings in summer through the tangled grass and sleeps in winter under a bed of ice is always a communing spirit. The sighing winds chant rhythmic lullabies in the treetops, and the language of every insect, bird, and beast has, to them, a distinctive meaning. The blue heavens are their delight, and the passing clouds their friends. The sun, the moon, and the stars hold converse with them, and the changing seasons bring to them, each in its turn, peculiar joy.

But, dearly as they loved the old home and its surroundings, the Ranger children, who had never crossed the boundary of township number twelve, range three west, in which they were born, looked forward eagerly to the forthcoming journey. Once only had Mrs. Ranger ventured beyond the township limits since leaving the Kentucky home of her childhood; and that was many years before, when she went with her husband to the county seat to attach her mark to the fateful mortgage, upon which the accruing interest seemed always to be maturing at the time when she or the children were the most in need of books or shoes or clothing.

“I wasn’t allowed to learn to write in my childhood,” she falteringly explained to the notary, when, after affixing her mark, she watched him as he attached his seal to the document which was to be as a millstone about her neck forever after. “My father always thought that education was bad for girls,” she added. “He said if they knew how to write they’d be forging their husbands’ names and getting their money out of the bank. And he said, too, that if girls learned to write, they’d be sending love letters to the boys.”

“It’s never too late to learn,” was the notary’s reply. “If I were you, I would learn to write when the children learn. You can do it if you try.”

“I’d be glad to, if I could find the time; but it’s hard to learn anything for one’s own especial benefit with a baby always in one’s arms. When the children get big enough to learn to write, I’ll try, though.”

And she did; with such success that she never after signed her name with a cross.

“I’m glad we’ve got that mortgage off our hands at last, Annie,” said her husband as they counted up the somewhat disappointing returns after the sale of their personal effects was over.

“But you’re not morally free from it, John, or even legally so. If the purchaser should fail, the load would then revert to Lije, you know. Say, John, can’t I deed my little ten-acre farm to my father and mother? It never cost you anything. I took care of old man Eustis for six long years; and you know he gave the little farm to me as pay for my services, absolutely.”

“Haven’t I paid its taxes all along, Annie?”

“And have I earned nothing all this time, my husband?”

“Oh, yes, you’ve earned a living; and you’ve got it as you went along, haven’t you?”

Mrs. Ranger made no reply, but being silenced was not being convinced.

“Be patient,” said Jean, aside. “I’ll manage it.”

Several pairs of great brown-eyed oxen, with which the children had become familiar in their days of logging about the sawmill, were easily trained for the long journey; but others, untamed and terrified, as if pre-sensing the trials awaiting them through untracked deserts, submitted to the yoke only under the cruelest compulsion. New wagons, stanchly built and covered with white canvas hoods, stretched tightly over hickory bows, were ranged on the lawn, under the naked, creaking branches of the big elm-tree. Provisions, resembling in quantity the supplies for a small army, were carted to the front veranda, awaiting shipment down the Illinois and Mississippi rivers to St. Louis, to be reshipped up the Missouri to the final point of loading into wagons for crossing the Great American Desert, as the Great Plains were then known.

Visitors, including friends and relatives from far and near, came to the dismantled house in great relays, and the business of Squire Ranger’s office as justice of the peace increased a dozen fold. All this commotion involved increasing labor for Mrs. Ranger, who faded visibly as she silently counted the intervening days before the hour of final separation from her sorrowing parents. If the Squire suffered at the thought of parting with anybody, he made no sign except to complain of a “pesky cold” that made his eyes water, which he attributed to the “beastly climate.”

“The spirit of adventure that inspires my husband to emigrate does not permit him to foresee danger,” was Mrs. Ranger’s ever-ready reply to the numerous prophets of evil who came to condole, but got only their labor for their pains. “I will not try to interfere with his plans. I started out as a bride to walk the road of life beside him, and I mean to do as I agreed.”

But the good wife grew thinner and whiter as the days sped on; and when at last the wagons were all ranged in line, with every yoke of oxen in place; when the last farewell had been spoken; when the last audible prayer had ascended heavenward, and the command to move on had been given,—she sank on her feather bed in the great family wagon and closed her eyes with a feeling of thankfulness akin to that of the sufferer from a fatal malady who realizes that his last hour has come.

“‘He giveth His beloved sleep,’” said Mary, softly, as she covered her mother with a heavy shawl.

It was now the first of April, a fitful, gray, and misty day. A soft breeze was stirring from the south, and straggling rays of sunlight struggled through occasional rifts in the straying clouds. The spring thaw had at last set in. The sticky soil adhered to the feet of man and beast, and clung in heavy masses to the wheels of wagons.

The dog, Rover, who had always willingly remained at home on watch during the family’s absence at church or elsewhere, had hidden himself at starting-time; but he was found waiting in the road when the party was several miles out on the way, and, when discovered, approached his master with drooping tail and piteous whine.

There were tears in the eyes of the strong man, of which he was not ashamed, as he dismounted from the back of Sukie, his favorite mare, and, stooping, patted the dog affectionately on the head.

“They didn’t fool ’oo, did ’ey, Rovie?” said Bobbie, as he hugged the dog, unmindful of his muddy coat.

“Come to me, Rover,” exclaimed Mrs. Ranger, who had been refreshed by her nap. The dog obeyed, and, wet and dirty as he was, attempted to hide himself among the baggage. But his hopes were blasted by a peremptory command from his master: “Go back home and stay with grandfather!” The poor brute jumped, whining, to the ground and affected to obey; but he reappeared[55] a dozen miles farther on, at the Illinois River’s edge; and when the ferry-boat, which he was forbidden to enter, was out of reach of either command or missile, he sat on his haunches on the river-bank and howled dismally.

“Don’t you think a dog has a soul, daddie?” asked Jean, through her tears.

“How should I know, daughter?” was the husky response. “I’m not yet certain that a man has a soul.”

The home that was to be the abode of the Ranger family during the journey was an over-jutting wagon-box,—Harry called it a “hurricane deck,”—made to fit over the running gear of a substantial wagon, in which a dozen or more persons might be stowed away at night in crosswise fashion. It was named “the saloon” by the teamsters, in jocose recognition of its owner’s well-known teetotal habits, and was assigned to the women and children as their especial domicile.

“It will be your duty to keep a daily record of our journey, Jean.”

This was the first official order issued by Captain Ranger after he had been formally elected as commander of the expedition, and was given under the thickly falling snow, amid the bustle and confusion of making the first camp.

“What sort of a record?”

“A daily write-up of current events. Here is a brand-new blank-book I have bought for the purpose. And here’s a portable inkstand, with some lead pencils, a[56] pocket knife, and a box of pens. I’ve selected you as scribe because you won the prize in that competitive contest over the doings of Bismarck.”

“But that was a different proposition, daddie.”

“It’s all in the same line, Jean. You have a record to preserve now. You must keep your credit good. Look to your laurels, and don’t forget!”

And Jean, partly from innate ambition, but chiefly because she was under orders from which she knew there could be no appeal, kept, through all the tedious journey, a diary, from which the chronicler of these pages proposes to cull such fragments as may fit into the narrative, without strict regard to chronology, though with due regard to facts.

“We made camp last night in the discomfort of a driving snowstorm,” wrote the scribe under date of April 2. “But in spite of our sorrow over our departure from home and loved ones, the most of us were jolly, and we made the best we could of the situation. To-night, after a day’s disagreeable wheeling through mud that freezes at night and thaws by day, making travel nasty, sticky, and tedious, we stopped for camp near an isolated farmhouse, where the goodwife is disheartened and sick, and the children are ragged, dirty, and frightened.

“The storm has abated, and the sky is clear. Our teamsters are kneeling on the ground around our mess-boxes, which are used for tables at mealtime, and stored in the ends of the wagons when we are moving ahead.”

“There, I can’t think of another word to write.” She closed the book with a bang.

For many minutes after gathering around the tables, all were too busy with the supper to make any attempt at conversation.

Beans and bacon, coffee and crackers, and great heaps of stewed fruits, were reinforced by mountains of steaming[57] flapjacks, which Mary and Marjorie took turns at baking, their eyes watery from the smoke of the open fire, and their cheeks reddened by the wind.

“Wonder what’s become o’ Scotty,” said Captain Ranger, as he knelt in the absent teamster’s place at table and helped himself bountifully.

“He filled our water-buckets and was off like a shot,” said Hal. “He ought to show up at mealtime. Ah, there he comes.”

“Where’ve you been, Scotty?” asked the Captain. “Here’s plenty of room. Kneel, and give an account of yourself.”

“So you’re in love, eh, Scotty? and with that pretty widow in the next camp?”