GLEANINGS

FROM CHINESE FOLKLORE

Nellie N. Russell.

Gleanings

From Chinese Folklore

Fleming H. Revell Company

London and Edinburgh

Copyright, 1915, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue

Chicago: 125 N. Wabash Ave.

Toronto: 25 Richmond St., W.

London: 21 Paternoster Square

Edinburgh: 100 Princes Street

[5]

To Miss Russell’s fellow-workers, who still have the joy of service in the great old-new land which she loved; and who tread the unfamiliar ways with more strength and courage, because in many of them she was the Pathfinder, this little volume is affectionately dedicated by

M. H. P.

La Mesa, California,

January, 1915.

[7]

FOREWORD

It was in the autumn of 1890 that I sat one evening looking into the face of a young woman who was passing through Tung-chow on her way to her new field of work in Peking. A few words about her work in the past explained the sadness of the brown eyes which had already seen many life tragedies in her five years of city mission work, but their merry sparkle when she entered into the happy flow of talk about her showed that her sympathies were as full and rich for joy as for sorrow. Hers was one of those rare natures in which all the lives about them are relived. Such lives are intense, but their earth span is short.

Before many years Miss Russell knew the life histories of most of the thousand Christians connected with the Peking Congregational churches and outstations, knew them with her heart as well as her head. The timepiece was never made which could tell her that the night hours were passing when she sat in a humble, dirty home in a far-off outstation beside some toil-worn, heartsore woman, listening to the details of the sordid daily life, and the wrecked hopes, then resurrecting hope, and [8]ennobling life by linking it with the Divine life. She took no note of the lapse either of time or strength when, in her city home, she entertained guests of high or low degree with equal courtesy and charm. Hers was the gift of making even the brief, formal call an opportunity for speaking the word which might lead to an upward look or an outward vision.

The Chinese pastor came to Miss Russell with his problems, also the child with her new toy. She loved flowers, animals, and children, the latter with the passionate love of a mother-heart. One who watched her taking a little dead goldfish out of the water said, “Don’t keep goldfish any more, it hurts you so when they die.” But the things which hurt could no more be put outside of that wide-embracing life than could the things which gave a thrill of joy, or enraptured her with a sense of the beautiful.

The tragedy of 1900 brought to one of such wideness and depth of friendship and intimate knowledge a sorrow whose outward tokens were whitening hair and a physically weakened constitution. The first massacres in the country brought refugees to Peking, to whom she ministered day and night. In the British Legation she went to the hospital to nurse wounded soldiers when she needed herself to [9]be carried there on a stretcher. Naturally sensitive not only to pain but to danger and to all that was unsightly or repulsive, her sufferings during those two months cannot be measured. The year that followed was a drawn-out agony, as she heard the stories of martyrdoms, listened with tense sympathy to the tales of returned refugees, gathered orphans and widows into schools, and with a faith that never faltered planned to build up the waste places. She might indeed have said, with Paul, “I die daily.”

Miss Russell was large in her plans as well as in her feelings. The past could not chain her, the present could not bind her. A Bible school for women rose in her future, and after it became a fact, and others were doing most of the routine work, she passed on to work into a reality dreams of a school for women of the higher classes, with lecture courses, mothers’ clubs, and training for social service, a work which for many years to come cannot reach the proportions of her vision. There could be no more fitting memorial for Miss Russell than buildings which would help to make her dreams come true. If Mark Hopkins, one student, and a log made a college, Miss Russell, a Chinese woman, and a tiny Chinese room made a Social Settlement. [10]

Miss Russell was not always logical and judicial. Her virtues carried their dear earthly defects with them. From those who disappointed her hope after long patience of love she might recoil into an attitude which seemed like prejudice. Sometimes she walked so far with others into the Valley of Baca that no strength was left to make it a well.

It might seem that the outpouring of her life was too lavish, and so injudicious. But who knows? The impulse which went upward in prayer and outward in loving service had its fruition in a clearer vision of the earth mission of the Master, a vision for herself, and a vision for the thousands with whom she came in touch. And China needs nothing more than she needs this vision.

For those who find their richest fruition in deeds accomplished, we crave the threescore years and ten, crowded with achievement. Those whose gifts lie in loving and befriending may sooner rest from their labours, for their works do follow them, and love and friendship are deathless. Those of us in Peking who walk where Miss Russell’s feet have trod still see the spiritual blossoming of that beautiful life.

Luella Miner. [11]

CONTENTS

| An Appreciation of Nellie N. Russell

By Charles Frederic Goss, her pastor in Chicago. |

13 | |

| Nellie N. Russell (Historical) | 16 | |

| Miss Nellie N. Russell’s Unique Work

An Appreciation—Mrs. Chauncey Goodrich. |

31 | |

| Miss Russell’s Funeral Service | 41 | |

| A Tartar Joan of Arc | 47 | |

| A Daughter of the Orient | 52 | |

| The Wild Goose and the Sparrow | 56 | |

| A Chinese Hero

Han Hsin. |

61 | |

| A Chinese Tea-House Story

Chi Hsiao Tang. |

71 | |

| The Jade Treasure | 82 | |

| Chinese Heroism | 88 | |

| Literary Glory | 92 | |

| How the Dog and Cat Came to Be Enemies | 98 | |

| A Daughter of the Present | 106 | |

| T’ang Sung’s Journey to Get the Buddhist Classics | 110 | |

| A Story of Old China | 124 | |

| Notes | 169 |

[13]

AN APPRECIATION OF NELLIE N. RUSSELL

By Charles Frederic Goss,

Her Pastor in Chicago

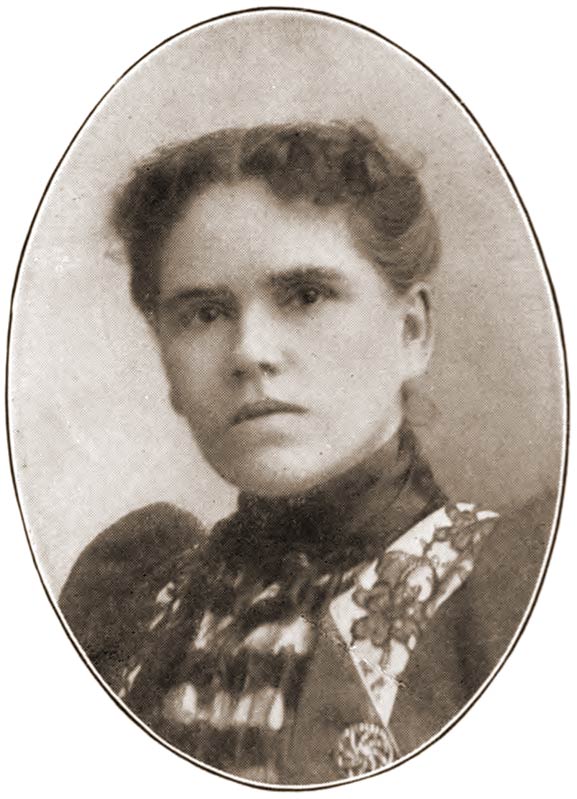

It is common enough to find persons endowed with one, two, or even three of those four great elemental qualities out of which the noblest souls are made—an inviolable conscience, profound intellect, irresistible will, and illimitable affections. But to meet a man or woman having all is as moving as it is uncommon. Our Nellie Russell had all. For four years she was an inmate of our home and, during all her remarkable career as a missionary in China, we kept in the closest possible touch with her and her work. As a result of this intimate acquaintance we learned to look upon her as an unique and even wonderful woman. Life took hold of her with tremendous power and so did she of life. To see all things clearly, to feel her solemn responsibility to every soul that crossed her path, to act with decision and determination in every emergency, was as natural for her as to breathe. [14]Her great dark eyes were at some times like deep wells at the bottom of which truth lay, at others like stars emitting a tender light, and at others like hot coals flashing fires of generous and righteous wrath.

Righteousness never went unpraised nor unrighteousness unrebuked or unscourged by Nellie Russell. She loved the good and she hated the evil of life with equal ardor. Her sympathy for those in trouble cost her a sort of agony, her love for her friends was an undying passion. When she went to China she took its great people into her very heart. All men, women, and children were brothers and sisters to her, and to spend and be spent for them was a spiritual hunger.

During a memorable week of one of her vacations spent in our summer cottage we were made to marvel at her insight into human nature and into the great problems of life. As we listened to her modest story of her experience in the siege of Peking, or heard her merry, ringing laugh whenever the ludicrous elements in social intercourse or surroundings appeared; when, in our little motor-boat, we saw her great eyes beam with delight at some fresh form of nature’s loveliness and heard her exclaim with irrepressible enthusiasm as we floated here and there among the islands, “Oh, [15]it is as beautiful as the Orient!” we seemed to be in contact with the very soul of the universe in some peculiar manner.

And when we heard of her death! oh, that was hard indeed! Again and again we had written her that there was a room in our home reserved for her perpetual use. It was a cherished hope to have her with us when her work was done, but it was too good and great a hope for realization here.

If this seems like overpraise to you, just let it go at that. You did not know her, or you did not appreciate her. We never heard her overpraised! She has ever been and ever more must be a pure, inspiring presence in our lives. [16]

NELLIE N. RUSSELL

Historical

The enduring charm of a rich personality is ever found to be in devotion to a chosen cause. Such a personality is here presented in a brief study of an earnest life of effort and high purpose.

Nellie Naomi Russell was born in Ontonagon, Michigan, March 31, 1862. The family removed to Wisconsin when she was very young, and there her father died when she was about eight years of age. She was the second of four children whom the widowed mother took to Vermont to live with one of their uncles. He also was soon taken away, and the family removed to Ludlow, in that state. Nellie, however, spent much of her time at West Rutland. Here she united with the church, and attended school, until her mother’s death in 1877. At this time the eldest sister, Janet, was in Michigan, and the following spring Nellie, with her brother William, joined her there, while the younger sister remained with their guardian, Dr. D. F. Coolidge, in Ludlow. [17]

Nellie attended school in Ontonagon, but she longed to return to New England. Dr. Coolidge, at her earnest request, advanced the money for her travelling expenses from the funds of a small legacy left her by her uncle, on condition that it should be returned to the fund from her first earnings.

In the autumn of the year 1879, Nellie, although so young, taught a country school, boarding around from house to house, as was the custom at that time. The sum advanced to her was returned from her first earnings with the scrupulous integrity which, throughout her life, marked all her business dealings. She won the admiration of the school district by her industry and capacity for work and service both in school and out.

At the close of the session she went to North Bennington, Vermont, where she spent two years in the family of Mrs. Coolidge’s sister, Mrs. H. W. Spafford.

All this time her great desire had been to prepare herself for missionary service. In order that she might get the education requisite for it she toiled and saved until she was able to enter Northfield Seminary, which had just been founded by Mr. D. L. Moody. After the first year she was given a scholarship. With this as a help she was able to meet all other [18]expenses by what she earned during vacations. All she had received from the scholarship she later returned to the institution she had learned to love. At Northfield she spent four years in study and congenial work. During the last two years she roomed with Lila Peabody, now Mrs. Edward F. Cragin of Brooklyn, New York, with whom she formed a friendship, one of the most intimate and strongest of her life. It is to this friendship that we are indebted for the few details of the years between her entrance into the seminary and going to China. She was an eager, enthusiastic student and was recognized at once by her companions as a leader, was made president of her class, and of the first missionary society formed among the pupils of the Northfield Seminary.

Mrs. Cragin says of her, “She was of a deeply spiritual nature.” I remember her telling me that from her early childhood she loved no stories so well as those of foreign missionaries, and that she hoped, even when a little girl, that some day she might become one.

One June morning, just before graduation, Mr. Moody took us for an early drive. He told us of a plan he had for us to go together to Chicago, to be pastor’s assistants and Sunday-school workers in Mr. Moody’s, the Chicago Avenue Church. The Rev. Charles F. Goss [19]was the pastor at that time. It seemed a large undertaking for two inexperienced young women to go from the little village of Northfield to the great city of Chicago, and to engage in such a work. But Mr. Moody felt confident of the results and assured us that we could do it, and so we made the venture.

Our experiences the first winter were strangely new and varied. We worked under Dr. Goss’s directions, calling upon church members and others who we thought might be influenced to attend the services. We also visited the sick and helped such as were in need in the neighbourhood.

Our Sunday-school work was among the very poor, and in localities where we went with not a little trepidation. Our custom was to select a street and to call from house to house, from family to family. We asked the children of those visited to come to the Sunday-school, and gave them cards telling them when and where to go. In many cases the parents could not understand English, but, as the children practically lived on the streets and so picked up its language, they understood us when we asked them to come and to bring others with them. In this way we gathered the children into Sunday-school, the boys into Miss Russell’s class and the girls into mine. Miss Russell [20]soon had a class of one hundred and fifty or more boys. In connection with this there were organized evening classes. The help of young men, who taught the boys carpentry and other kinds of manual work, was secured, and they were encouraged to seek other vocations than those of newspaper venders and boot-blacks. Some showed unusual talent, but had no opportunity for study or advancement. Miss Russell wrote to Mr. Moody with regard to them and asked if an arrangement could be made by which the most promising could be admitted to Mt. Hermon. He gladly entered into the plan and carried out her wishes. A number of these boys thus entered Mt. Hermon school and afterward took college courses. They were accompanied all the way upward by the sympathy, advice, and assistance of Miss Russell. She kept in touch with many of them all her life, corresponding with them after going to China, and hunting them up during her furloughs in this country.

Miss Russell’s great characteristics were, I think, the giving of herself unsparingly for others, and doing this with sympathy, tenderness, and love. One incident, among many which I recall, strikingly illustrates this. During the anarchist riots in Chicago, when even men did not dare go into the disturbed neighbourhood, [21]Miss Russell went without fear, and without protection, to the anarchist headquarters to comfort the little old mother of one of the condemned men.

After five years of earnest, successful work in Chicago, Miss Russell, well fitted by such training, felt that the time had come for her to go to the distant field, which she always had kept in view. The way was opened for her to enter the work in China under the Woman’s Board of the Interior in connection with the American Board of Foreign Missions. She accepted the opportunity as the fruition of the hope and desire of childhood, girlhood, and young womanhood, and in twenty-one years of devoted service made “good proof of her ministry.”

The record of the rare life of Miss Russell is in the hearts of many to whom she was very dear. It is suggestive of some of her loveliest qualities that it has been difficult to secure anything beyond the bare historical facts with regard to her early years.

The brief outline, given by the only sister who survives her, Mrs. J. R. Branaman, and a lifelong friend, Mrs. D. F. Coolidge of Ludlow, Vermont, show how heavy were the burdens of her youth and explain, in a measure, her peculiar and yearning sympathy for toilers [22]struggling under difficulties for an entrance into a larger intellectual and social life; for widowed mothers, caring for groups of children, and for young students making their way with little aid through courses of study. Of her own early experiences she rarely spoke. In years of close companionship I learned little of them beyond the ever-recurring suggestion of her rich inheritance from a father of deep religious faith and a mother brave and tender, with the highest standards of duty. These so impressed her daughter that, in incidental ways, they were often implied in the reasons given for her choice of lines of conduct.

Her warmth of affection for her own was apparent in every mention of them, and knowing this, one can realize what separation from them, even in childhood, meant to her. She truly “Bore the yoke in her youth” and learned to carry it so buoyantly, and walk under it with such elasticity of spirit, that one’s memory of her is always that of largeness and joy rather than of mere patience or resignation. She knew better than most of God’s children how to delight in all the beautiful things her Heavenly Father had placed in the earthly environment, and it was not until disease and sorrow had wasted her reserves of strength that she began to speak often of the life beyond. [23]To that she looked and for it she longed, not as rest from service but as larger opportunity and wider vision. The springs of her life deepened as the physical resources were depleted, and we who were much with her during the last years often realized that she drank from celestial fountains and in weakness found courage and power among the Hills of God. In the long night watches when pain was her companion, and the burdens of those about her who claimed her never-failing sympathy pressed heavily upon her loving spirit, she would often light the candle at the head of her bed and read from some author of insight a poem or other glowing page, ponder it for relief, and bring to us at the breakfast table the result of her thought upon it, in a radiant face and a gentle aloofness from everything petty and trivial, which banished mere gossip or small talk and sent us refreshed to our tasks. She, worn with sleeplessness and anxiety, was yet the inspirer and comforter, and all with a self-effacing sweetness which sought no recognition of what she gave! Indeed, in her quiet dignity, she made any allusion to, or expressed gratitude for, such obligation difficult.

So it was with her intercourse with the Chinese. She came from interviews with individuals or groups of women with the most [24]delightful stories of those she had met. There were almost always among them “Such a charming” or “Such a bright and lovely lady.” She set their striking characteristics before us in racy, sympathetic stories to which we, in the Ladies’ Home, listened with delight, and went from the recital to our routine duties with a sense of having been introduced to a fresh circle of attractive friends from day to day. But of herself and what she had done for them, rarely a word! She who gave herself so lavishly, who had by her wonderful tact and charm won from each their best, had nothing to tell of how she had come to learn so much of these strangers. One of her sentences was rarely introduced by “I said” or “I told her.” Yet we, who sometimes caught a glimpse of the inner life, knew that she made a constant study of methods of approach and went with prayerful preparation to meet the various calls.

She, more than any other missionary whom I have known, held herself conscientiously free from the restrictions of fixed hours and a teaching schedule, that she might be at liberty for large social and individual service. It was her aim to come into intimate touch with many and to order her days so that she might be ready to respond to every call which came. [25]In this, as in everything to which she really set herself, she was singularly successful.

It was beautiful to see her welcome a group of curious visitors and make them feel that their interests were hers and, for the time, the thing of most importance. In a little while she knew something of their personal history and, before most hostesses could have gotten beyond the merest conventionalities, she was touching, tenderly, the sore spot in some life, with words of help and healing.

From the very beginning of her life in China Miss Russell realized the importance of the country work. For years she spent more than half her time in the outstations connected with the Peking church as a centre. This work involved long and trying journeys and great physical fatigue. On these trips she established herself whenever practicable in a room or rooms of which she could have control. Here she could receive guests and give, by the attractiveness of her surroundings, object lessons in home-making. To any who desired to follow her example she gave advice and help so unobtrusively that it never seemed like criticism or an assumption of being wiser or better than they, but just ordinary neighbourliness. She knew so well that “It is more blessed,” and also more comfortable, “to give than to [26]receive,” that in the happiest ways she made herself debtor to those about her. She learned from the Christian women many Chinese household arts and liked to show her missionary associates of less dexterity that she could feed a fire under a native kettle with as little waste of fuel and as large result in the boiling of porridge as those to the manner born.

The stories published in this volume were gathered in long evenings when she wanted relief from the constant giving out from mind and heart, and were sought also that those who had treasured them in memory might, by imparting, feel themselves her aids and instructors. In those days the kerosene lamp was a luxury almost unknown outside the large cities; never seen anywhere in the homes of the poor. Even foreign candles gave so much clearer light than the smoky open lamps, filled with the native bean or cottonseed oil, that her room seemed brilliantly illuminated even though she had only a tiny lamp or a candle on its table. It was sure to be daintily clean, for, whatever her surroundings, she was a lady always and everywhere and tidiness was a part of herself. So was her love of beauty, and one can never think of her without some flower or picture to attract the eye and give a touch of brightness to the room in which she sat. On these country [27]trips she wore the native dress and her dark eyes and hair made her seem more at home in it than many Western women. She was careful so to select and combine colours as to be attractive to Chinese tastes. As she had advisers on every hand, in this also she seized her opportunity to rely upon them, and let them feel their importance to her as counsellors.

As I have read over the tales I could well imagine the scene in her little temporary home; the small room with its brick kang—the brick platform—on which her folded bedding was piled; her books on the table, and her guest or guests in the seats of comfort, if such there were, certainly in the seats of honour, for in all such matters of Chinese etiquette she was punctilious; she, sitting with eager attention, listening to the one who told the story as it had been handed down in the home or the village for generations. Perhaps she had been off for a long drive over bad roads during the day, had spoken to a restless crowd in a court, or by the roadside to a group of women gathered on the river bank, each with her bundle of clothes to be washed on the stones in the flowing stream. She was very weary and how tempting a quiet evening by herself, or with only her dear Bible woman helper as companion, [28]must have seemed, but she had the engagement with this teacher or that Christian brother to listen to his tale. She asked many questions as he went on and her pencil jotted down names and a point here and there, that when he was gone she might write out a skeleton, with the hope of using the material some time to help friends in America to a better understanding of these neighbours of ours on the other side of “The Great Eastern Sea” for “Eastern” the Pacific is to China and so her people name it.

These manuscripts she had put into shape roughly in summer vacation days and so we found them after she had gone.

It had been her cherished plan to edit them carefully, add to them other stories of Chinese life as she had seen it, and make a volume which should be the contribution of her leisure, after retirement from active work, to the new understanding of the people whom she loved by those of her own land.

She had come to realize, as the later years brought increased physical suffering, that the time might be short and said many times in the last few months, “I must get my stories together on my next furlough, whether I come back to China or not.”

The furlough never came, but instead, the [29]call to “Come up higher.” During the brief final illness she seemed to have no thought that it might be the end. There were no farewells, no last expressions of a wish that this or that should be done, before she passed into the unconsciousness from which she never wakened here. Her friends, knowing the purpose and desire of the years, have felt the fulfilling of it by the issue of this little volume, a sacred trust. The first thought was to do the editing which she planned, but every attempt seemed to take from the stories that which made them hers. Characteristic phrases and little turns of expression were her very own. The pages have, therefore, been left with only such alterations as were necessary to complete sentences or make meaning clear, with no attempt at such improvement of literary style as she herself would have given them.

They are issued for the sake of the many who loved her and who will prize them as coming from her hands, and as representing one of the activities of her many-sided life. As the expense of publication is borne by friends, whatever money returns come from their sale will go directly to the work to which Miss Russell gave her latest strength, “The Hall of Enlightenment,” or Ming Lung Tang in Peking, which is a growing social centre and the [30]point from which radiate lines of influence which touch the lives of the women of that city in a variety of ways. She was its originator and her memory is still its inspiration.

Mrs. Goodrich’s appreciation, on page 31, gives the story of these later years and presents forcibly many of the especially striking characteristics of Miss Russell. To this has been added Mrs. Ament’s account of the funeral services in Peking. Miss Russell died at the summer resting-place, Pei Tai Ho; from thence the casket was taken by rail to the city, an eight-hour journey. The desire of the women, that the monument at her grave should have a Chinese as well as English inscription, has been carried out. Every spring a company of those who loved her, and looked upon her as their leader, meet at her grave to sing Christian hymns, place flowers upon the mound, and recall the beautiful life from which they learned how full of fruitfulness and blessing fifty years of Christian discipleship could be made. [31]

MISS NELLIE N. RUSSELL’S UNIQUE WORK

By Mrs. Chauncey Goodrich

An Appreciation

The twenty-second day of August the cable flashed across the Pacific the news that Miss Nellie N. Russell of Peking had succumbed to illness and was no more.

Those who had not known Miss Russell intimately can little guess the grief that came to every heart which knew her in China, whether belonging to the missionary body, American or British, the Legation circles of these countries, or the countless hundreds of Chinese who had felt the beautiful uplift of her personality. While at school at Northfield, Dwight L. Moody came to know her, and this reader of men at once saw her rarely winsome gifts. I, who have known and loved her for these twenty-one years, would like to write of her life in China, hoping perchance that some whiff of that beautiful fragrance may enter the hearts of those who read and make them more beautiful for God. [32]

It was in 1890 Miss Russell came to Peking. One never could think of her as being a bachelor maid, she was so womanly. How we revelled in her pretty clothes, so dainty and becoming—so fit. The home-making instinct was so strong that she was not content, as others had been, to live in the families of married missionaries, but just as soon as possible secured a house, that she might have a home. It was simplicity itself, but every nook and corner breathed the woman,—home-maker,—and it was always open to her friends, Chinese and Western.

Very early in her missionary life she felt the call of the country village work. Dressed most carefully in Chinese garments, for many years she spent months at a time away from Peking, living at some branch station, making trips to nearby villages, holding classes for women or visiting them in their homes. She purchased a cart and mule, and with a young serving-man from the better class who respected her every whim, consenting to be carter, cook, protector, whatever Miss Russell wished, she went everywhere.

And how wonderfully she entered into every one’s life, whether of the evangelist, his wife, the Christian school teacher, the wife of the richest man in the region roundabout, the old [33]lady tottering to her grave, or the young daughter-in-law, the bride, or the little mischievous boy. “With heart at leisure from itself,” she drew out from each one his story. She never went in the spirit, “Now-I-am-holier,-more-civilized-than-thou,-therefore-hear-ye-me,” but rather in the spirit of one who sought to find out the interest or the hunger of each one’s life, and so somehow bring it in touch with the Lover of all. Such discoveries as she made of possibilities in the lives of this one and that!

On returning to Peking for work in the city, she again wore the European dress. There was something in her nature that compelled her to have things suitable if possible, and she at once felt the dress that other foreigners wore would meet with greater acceptance in Peking.

When the Boxer storm began to gather, being so much in the country in the winter of 1899 and 1900, she saw, as few did, the blackening clouds. The persecution of each Christian took a mighty hold on her sympathetic heart. Ah! no one who was out of China can ever realize the strain of the months preceding that awful cataclysm, the agony of those months in the siege itself, not because of self, but because of missionary friends, and because of the children [34]begotten of the Lord, who were out unsheltered in the fury of that wild and awful storm.

At its close, with no reserve, Miss Russell poured out her love and sympathy on the one hand, and on the other sought to regather the church in city and country, and to find work and help for men, women, and children. The situation was all abnormal, and Satan slew many with the poisoned darts of revenge and greed, whom he could not slay otherwise. Oh! but these things almost broke her tender heart. Her hair grew grey and the power to resist disease and overweariness lessened, yet the spirit of our friend rallied, and she entered into the joy of the Conquering Christ.

When she saw that she could not take as long country trips and endure the same fatigue as formerly, she set all her energies to work in bringing the Bible school for training women workers into being, and in reaching city women. This did not mean giving up her country work, only less prolonged visits.

Following the sudden but prolonged sickness and the death of Dr. Ament, no one knew as did Miss Russell the work of the pastors, evangelists, teachers, and chapel-keepers, in the city and in the large country field, which reached into a few walled cities and many [35]market towns and villages. It was she who gave her days and nights for many weeks, and even months, to helping Dr. Charles Young, the only gentleman then in the Peking station, settle and rearrange the work. More than once the midnight hour found her still in conference with Chinese workers, strengthening those who were strong, exhorting the weak, and in some cases reporting and removing those who were proving inefficient, and even unworthy of their trust.

The pastor of the North Congregational Church, after the Hague Conference, invited a Chinese friend who had been on the commission to come to the church and tell about the meetings. This meeting he advertised widely, and it was enthusiastically attended by many non-Christians. Miss Russell, seeing the opportunity, began both at this and the First Church to have simple lectures for women on the great Fair days, three times a month.

These lectures were given sometimes by Chinese, sometimes by Westerners, and covered every kind of subject. She invited noted ladies to come and address these meetings. In this way she and her associates made hundreds of friends among women of every rank in society. Her associates helped receive and entertain, sometimes for hours afterward, the many [36]guests who came, showing school, kindergarten, museums, etc.

With rare tact Miss Russell showed her appreciation of all things in Chinese life that were really beautiful. She read the papers, learned the newest phrases, found out what Chinese women loved, the motive of their acts, and, best of all, helped every one to be her best.

How they confided in her! The wealthy, aristocratic sisters, whose brother, drawn away by the skilful efforts of some European gambler, was gradually losing all their property; the ardent Confucian lady teacher, who was using her property for the establishment of a school for girls, and who so longed to bring to Chinese and Manchu women the teaching of Confucius to make them forceful in their lives; the high official’s wife, who would learn from her how best to work to banish polygamy; the princess who in Mongolia would establish a school for Mongol girls; or the wives and sisters of high officials who would open schools or work against the evils of the cigarette or of opium. Chinese youth and Chinese women are in that sensitive state—the state of real life and growth—when they long to originate and execute for themselves. It is the sign of independence, and while it leads to mistakes, in the end it will lead to more vigorous thinking and action. [37]No one unassociated with Miss Russell can understand the tactful way in which she made suggestions.

This past winter (1911) Miss Russell and Mrs. Ament opened rooms in a court directly opening from a gate on the main street, where they received their lady guests, held classes and small lectures, etc. Nowhere in Peking was there a daintier, prettier reception-room. It was a joy of every Chinese heart. There were always flowers, the flowers they loved, and tea served in the daintiest manner. The Chinese, in the desire to be “enlightened” and like Europeans, which has temporarily seized them, have too often banished their beautiful furniture from their reception-rooms, substituting an inferior European article. In this room there was a beautiful blending of European and Chinese furnishings, with Chinese largely predominating.

Some of the ladies, when they found they would be free to have meetings here, said, “So often we want to meet together, we who are interested in the progress of our women, and plan and talk over matters. It is not easy. We come from different ranks in society. We are not free to open our homes, as we do not control them, but we are so grateful that we may come here. You do not laugh at us. We are new [38]to all this and we know are often bungling.”

Another said, and she a lady of high rank and highest breeding, “One thing I have discovered. If ever Miss Russell encourages any movement for our betterment, I am always sure I can indorse it. Some of the suggestions of the Chinese ladies I cannot favour, but Miss Russell is so wise, so careful, so good a friend of the Chinese, I can always trust her.”

Our friend, not content in keeping this means—the lecture and class courses—of reaching women confined to our Mission, one day a year ago invited the representatives of all the Missions in Peking to her study. There she unfolded a plan by which these might be repeated in every Mission and each of its centres of work in the city. This eventuated in a plan for fifty lectures, often a missionary and a Chinese lady speaking on the same subject, and thus reinforcing each other.

Seeing, too, the great result following the union evangelistic meetings for men during fairs held in the spring and early summer at the temples, her fertile brain conceived a plan for a union effort on the part of all the various Christian workers for women. Tents were erected, seats rented, tea served, and there large and small groups of women heard the Gospel message for the first time. The result has been [39]that several of the Missions have opened new centres of work in the city, near city gates, or in the suburbs.

The tireless brain is still—the living heart has ceased its beating. The loss to our work in Peking only those who knew and saw what she was able to do and to inspire done can fathom. Miss Russell always carried with her the dignity of her womanhood, yet with never a sense of independence. She sought the help of men and in some way drew out all their manhood and chivalry by her belief and trust in it. Her nature never was distorted by her work, but her power to love and enter into others’ lives increased with every passing year.

Her love for little children—the new-born babe, the toddling child, the merry boy or girl, was peculiarly reverent and beautiful. Her face often expressed an abandonment of joy as she watched the children play, or laughed at their wise and witty sayings. She took time for friendships, of which she had a few very close and dear. She never failed a friend in time of need.

She loved, too, the social life, being always most punctilious about her calls at the Legations and Customs, and on her Chinese friends of official families. She went not from a sense of duty, but from real pleasure. She heartily [40]enjoyed intercourse with the cultured ladies and gentlemen of these circles and was often able to bring them into touch with her Manchu and Chinese friends with real advantage to both sides.

“And was she perfect?” you ask. Ah, no! She had her strong likes and dislikes. She had her battles to fight, but each year, as her thoughts dwelt more and more upon the Lord and Master of us all, His power to uplift and to save, she grew in likeness to Him, and now she sits radiant in the Heavenlies, enjoying Him who was her life, and who can doubt but that He whom she loved and lifted up will draw the souls she knew and loved, up and up, even to Himself. [41]

MISS RUSSELL’S FUNERAL SERVICE

Mrs. Mary P. Ament, who has been closely associated with Miss Russell during the past year, sends the following account of the last loving services rendered to our beloved missionary:

Many friends had roamed the hills and meadows, bringing a variety of flowers—wild pinks, fine everlastings peculiar to Pei Tai Ho, also a feathery foliage, and had massed them on piano and organ before the pulpit with beautiful effect.

Intimate friends went slowly down from the service to Ivy Lodge, the Stanleys’ pleasant home, where Miss Russell had been spending the vacation days and where she died. As we entered the room and saw our friend of many years, she seemed asleep, yet in repose one felt the power of her personality, her high purpose, her dignity. The casket was covered with heavy pongee and lined with cream-white crêpe. She wore a white embroidered dress, and about her lay sprays of cypress vine. Her beautiful silvery hair made her look so queenly!

The long journey to Peking accomplished, [42]a large number of friends, foreign and Chinese, awaited us, and next morning followed the flower-laden bier to the cemetery.

There, as one listened to the discriminating words of Pastor Li in his address, and Pastor Wang in his prayer, it brought keen satisfaction to think that the fragrance, the real essence of such a life, was perceived by those for whose welfare she had laboured. Rev. Mr. Stelle, speaking in Chinese, emphasized our opportunity to show our respect for her by seeking the things which she valued. In English, he told us of the comfort sought by the dear friend in the Twenty-third Psalm, which she asked to have read to her the day before she left us. He read the Psalm and offered a prayer in English.

At early dawn the messenger came and, taking her by the hand, ascended the heavenly heights. “And there shall be no night there, and they need no candle, neither light of the sun, for the Lord God giveth them light, and they shall reign for ever and ever.”

These words are full of comfort, but as yet we feel the need of her ministry so keenly that only the knowledge that the same God who strengthened her is with us still enables us to move forward and conserve what we may of her lifework. [43]

With severe limitations of health she yet wrought with delicate touch and a beautiful fabric was merging from beneath her hands.

I must allude briefly to the beauty of the day, with its clear shining after rain, the deep sorrow of the devoted friends who followed the bier on foot over miles of roadless distance from Ch’ienmen to the cemetery, that quiet, ivy-walled inclosure in which stands the chapel where the service was held—a tender, impressive service.

We had thought that few American or English friends could be present at this time of year, when the foreign residents are away from the city, but we were mistaken. Two secretaries of Legation, physicians of the Union Medical College, fellow-workers, and old-time friends were there; native pastors, Bible women, and church friends, servants and guards of honour sent by the military governor of the city and by the chief of the civil administration. The chapel had as many people standing as there were sitting. The casket with its covering of beautiful vines and white flowers, roses, day lilies, tuberoses, spirea, stood in front of the altar and was carried by the friends to the grave, where loving hands had arranged the beautiful wild date branches and vines as a lining. There, a short service with Pastor Jen and [44]Teacher Ch’uan taking part, and a prayer and a hymn.

The mound as we left it was beautiful with the sides covered with the green vines and date branches, and on top the lovely floral pieces and coloured flowers, two great wreaths of the long palm leaves and roses, and at the head a floral cross. There in the quiet and peace among the trees we left it. Some of the Chinese are already saying, “When a stone is erected, let it have one Chinese word upon it, just her name, then we can find her grave and every spring at the ‘Ch’ing Ming’—feast of all souls—we will go out and honour her memory.”

There is a hush upon us all. God has come very near and taken our Great Missionary from us. We shall not look upon her like again. [45]