Title: Tide marks

being some records of a journey to the beaches of the Moluccas and the forest of Malaya in 1923

Author: H. M. Tomlinson

Illustrator: Kerr Eby

Release date: December 6, 2024 [eBook #74847]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Harper & brothers

Credits: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

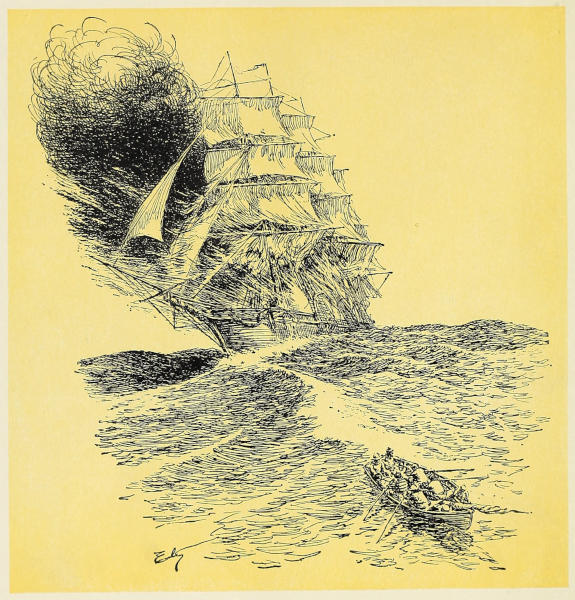

“All Was Quiet Again, Except for the Flames”

TIDE MARKS

BEING SOME RECORDS OF A JOURNEY

TO THE BEACHES OF THE MOLUCCAS

AND THE FOREST OF MALAYA IN 1923

By

H. M. Tomlinson

AUTHOR OF “THE SEA AND THE JUNGLE”

With Illustrations from Drawings by

KERR EBY

Harper & Brothers Publishers

New York and London MCMXXIV

TIDE MARKS

Copyright, 1924

By Harper & Brothers

Printed in the U. S. A.

K-Y

To

Richard Durning Holt

| “All Was Quiet Again, Except for the Flames” | Frontispiece | |

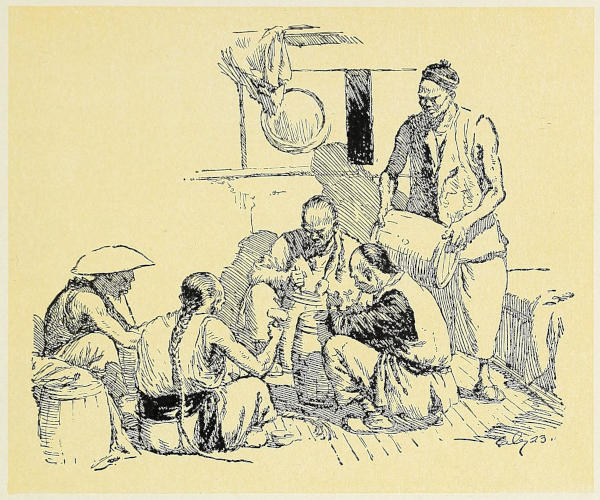

| A Group of Chinese Firemen | Facing p. | 22 |

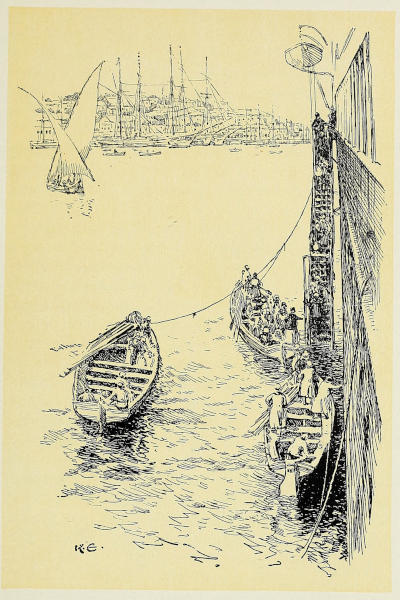

| Port Said Is More West than East | ” | 42 |

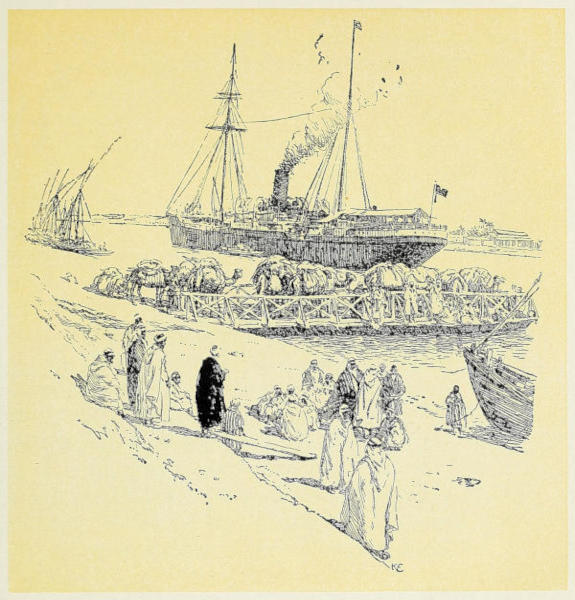

| Old and New on the Suez Canal | ” | 62 |

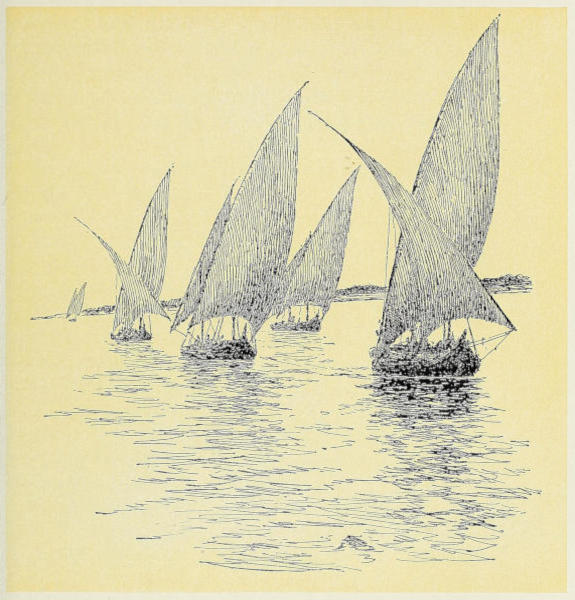

| This Sea Was Plainly the Setting for Legend and Fable | ” | 84 |

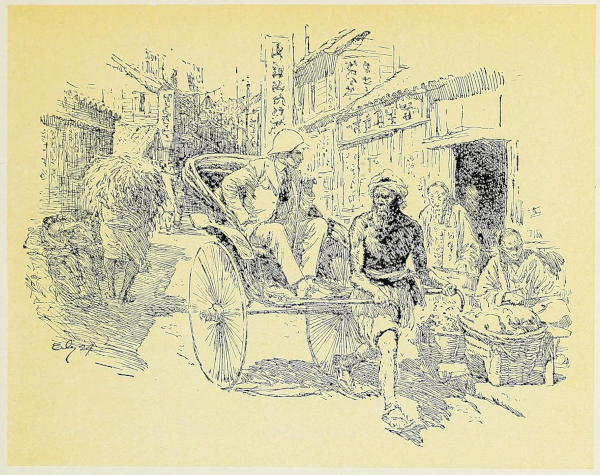

| He Had Skimmed About Singapore in a Jinrickshaw All the Morning | ” | 100 |

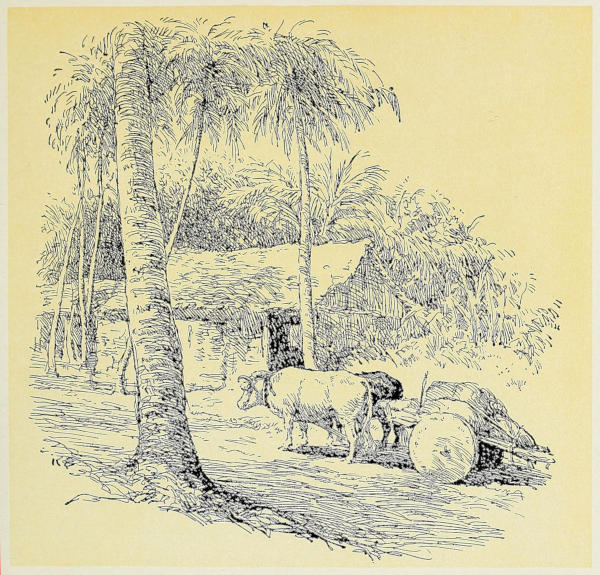

| The Road Was Empty, Except for a Bullock Cart | ” | 122 |

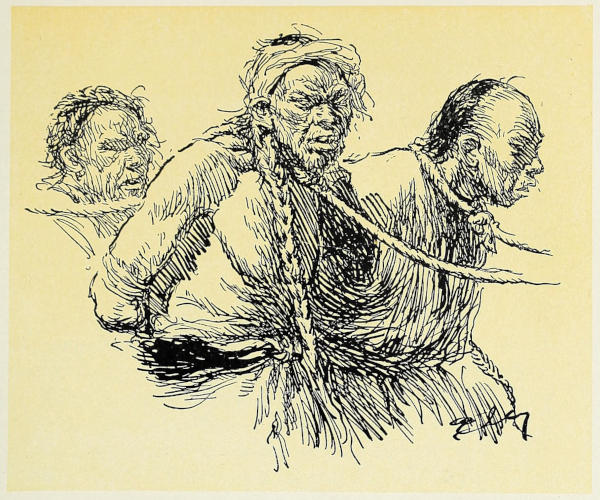

| “One of ’Em Looked at Me as He Came Aboard” | ” | 140 |

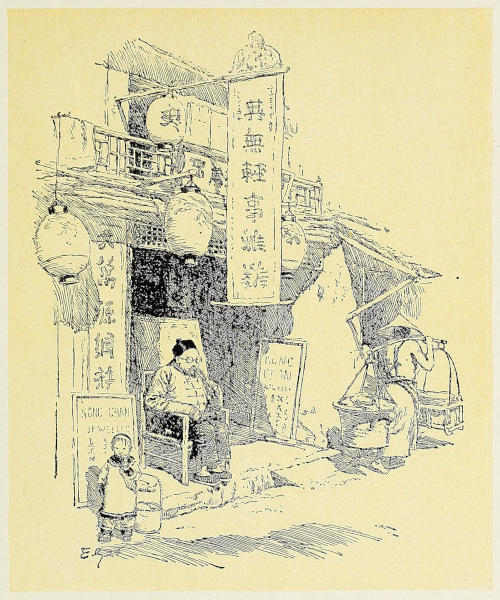

| He Sits in Front of His Shop in Macassar | ” | 160 |

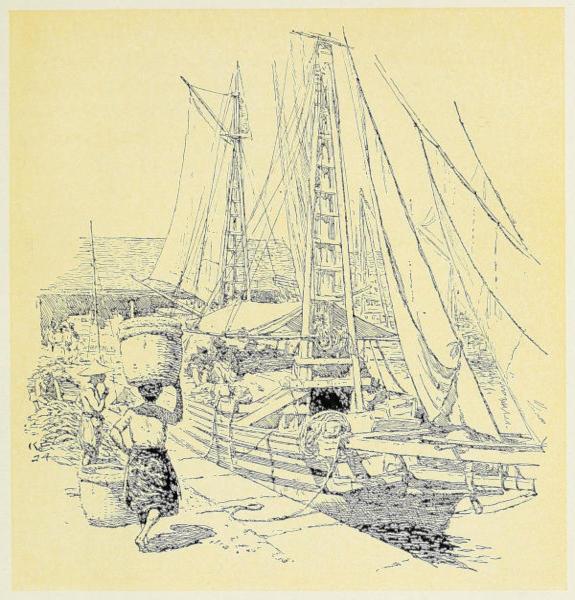

| The Malays Sit on Their Decks, Cooking Breakfast | ” | 180 |

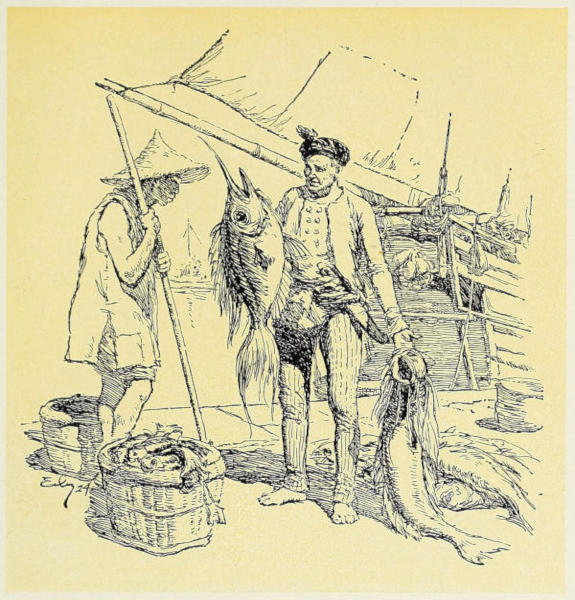

| Gathered from the Submarine Gardens of the Tropics | ” | 200 |

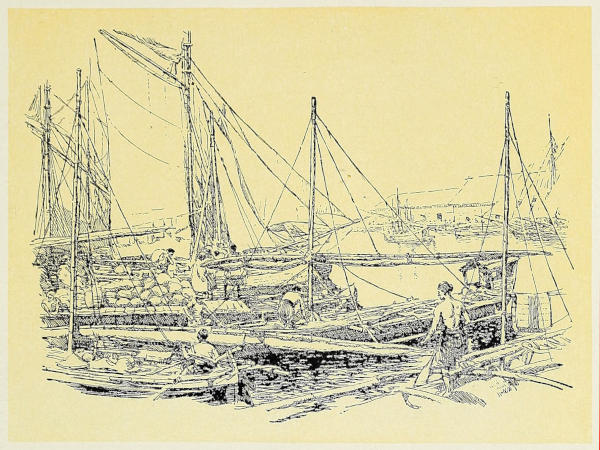

| Macassar Is a Convenient Meeting Place for Traders | ” | 220 |

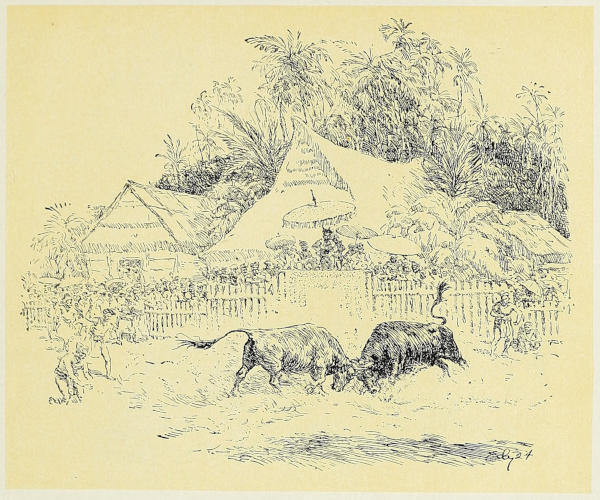

| The Fighters Stood with Horns Interlocked, Waiting for Each Other to Move | ” | 232 |

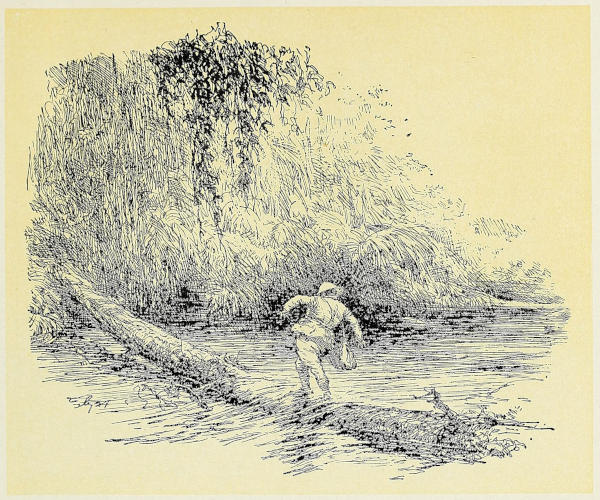

| He Began to Treat His Foothold Too Punctiliously | ” | 252 |

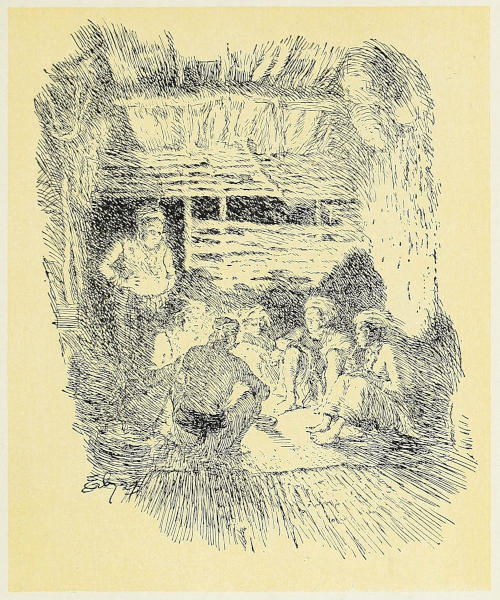

| The Heavy Shadows Were Hardly Disturbed by a Little Oil Lamp | ” | 264 |

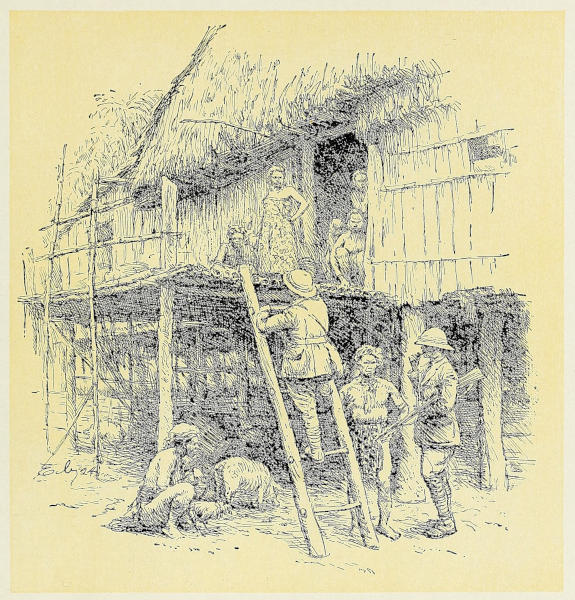

| It Was a Larger House than the Rest, with an Unusual Length of Irregular Ladder to Its Veranda | ” | 282 |

From his high window he could see where the Thames, once upon a time, was crossed by Charing Cross Bridge. But not on that winter afternoon. The bridge was a shadow in a murk. It did not cross the Thames. There was no Thames. It was suspended in a void which it did not span; there was no reason to cross, because the other side had gone. The bridge ended midway in space. It was but a spectral relic, the ghost of something already half forgotten above a dim gulf into which London was dissolving in the twilight and silence at the end of an epoch. For the twilight did not seem merely of a day at the end of another year, but the useless residue, in which no more could be accomplished, of a period of human history, long and remarkable, that had all but closed.

He wondered whether he would ever cross that bridge again, outward bound. What, a broken bridge? And is there any escape from your own time, even though its end seems so close that you feel you could take one step and be over in the new era? No. There is nothing to do but to put up with the disappearance of the[2] everlasting hills and safe landmarks, and grope about in this fog at the latter end of things, like everybody else. The bridge that day went but halfway across. Once it carried men over to France. It was not wanted for that now. The rocket which he heard burst above it to announce the long-desired arrival of a lovely dove was welcomed four years ago; and the dove either did not stay long or else it had turned into a crow.

A postman burst in with a parcel, and went, leaving the door open. Another book! He cut the string, in his right as guardian of literature in that newspaper office. The volume disclosed had a colored wrapper with the seductive picture of a perfect little lady smiling so fatuously that St. Anthony would have laughed miserably at the temptation. Again a novel! He dropped it on the heap behind him—a detritus of beautiful fiction piled in a slope against the wall, a deposit of a variety of glad eyes and simpers. What a market for green gooseberries this world must be! That deposit slithered over a wider area whenever the energetic editor in the next room was trampling to and fro in another attack on the Prime Minister. Then some of it had to be kicked back. But kicking never made that deposit of literature better or different, any more than it did the Premier. Only the cleansing junk-shop man with his periodical cart for the removal of refuse ever did that. And the same trouble sprouted again next day. Trouble generally does. A literary editor, he thought, might be better employed peddling bootlaces, for all the traffic he has with literature; yet it was plain that if he began to edit bootlaces instead, then most likely people would take to wearing buttoned boots, or even jemimas. For,[3] in spite of the Sermon on the Mount, crystal-gazing, spiritualism, Plato, wireless telegraphy, Buddha, and Old Moore’s Almanac, there is no telling what the world will be doing next. The barbarian of ancient Europe who trusted to his reading of the entrails of a fowl when looking for the hidden truth was quite as reasonable as the editor in the next room frowning at the signs of the times through his spectacles. Moreover, at the moment, the editor was not doing even that. He was on a journey to interview the proprietor, to learn whether he should continue to hold up a lamp in a dark and naughty world, or blow it out. Oil costs money.

The open door let in a draught, and with the draught blew in a figure which might have been a poet, but was certainly not an advertising agent. It was a bundle of clothes which looked as though it had been abandoned under the seat of a railway carriage and had crawled out because nobody had troubled to remove it. But its face was still new. It had diffident eyes and a grayish beard. Most likely it was another poet. The lines of that thin face had come of contemplating the glory of the world, and had been deepened by lack of bread. The figure hesitated, knowing that it ought to have remained where it had been thrown. It did not speak. It took off a matured cloth cap and offered for sale some Christmas cards. It had a difficulty in getting them out of its pocket, because one sleeve of its jacket was limp, being empty. But the literary editor was patient; for this visitor had a rare and attractive virtue. He was modest; more modest even than the veiled ladies who brought secret information from Poland, or an[4] editor with a new idea. He seemed uncertain of his rights, unlike the publisher who had called because his important work had been overlooked, and the politician who was cruelly wronged because the reward he had earned in bolting his principles had gone elsewhere. What had purified this human wreck? He seemed to be unaware of what in justice should be done to him, and was in enjoyable relief from the reviewer who could have handled the job so much better than the fool who did, the inventor of the machine for converting offal into prime cuts, and the superior mystic who knew it long before Einstein. In what school had he learned to be a gentleman?

The man of letters examined the Christmas cards, and read on most of them, “Love One Another.” This spiritual injunction was made authoritative with realistic sprays of mistletoe.

“Where,” asked the literary editor, rising and pointing to the place where his visitor’s right arm used to be—“where did you stop your packet?”

The visitor became very embarrassed. “Well,” he said, in doubt—“well, if you were a nice lady, I’d say it was cut off by a German on the Somme, if you understand me. But it was an army mule at Arras. It bit me. And heroes ain’t bitten by their own mules. Not in war, sir. Not for home consumption, as you might say.”

“But there must be accidents in war.”

The visitor rubbed his nose briskly with a dark white handkerchief. “No, sir. Believe me, no. I saw a pal o’ mine drowned in a mud hole, but he had to be killed in action, being a gunner, for his friends’ sake, like.[5] In war, heroes are either shot through the heart at the moment of victory or else they gets their arms in slings. Don’t you believe nothing else.”

“You’ve come to the wrong office. Everybody here knows that mules are ugly brutes, and never rise to Christian feelings even when war ennobles them.”

“Not at all, if I may say so. You don’t understand, sir. If I tell people that our mules kicked the enemy, that’s all right. But if I tell ’em one of our gun mules bit me, why, I don’t know but what they’d think the artful patriotic swine saw through me, if you know what I mean. Got to be careful. Besides, that’s nothing now.”

“What, nothing to lose your arm?”

The shabby figure stared over the literary table to the shadow of the bridge beyond. He spoke with the quiet confidence of a man whose rich uncle had unexpectedly left a fortune to him. “Nothing at all, sir. I’ve found God. I’ve found God.” Then he looked at the journalist. “Do you believe in God? You don’t begin to live until you do.”

The journalist rose in alarm. Not in all his life had another fellow creature asked him whether he believed in God. In that office it was assumed that the name of God should never be used except rhetorically.

“Of all the swindling rogues! You talk to me like that, after telling me you’d have lied, if I’d been an old woman!”

“Sorry, sir, but you were not an old lady, so I give it to you straight. I give people what they can take, just to make the world go around, you understand.[6] What does it matter? People who can’t see the light—well, you can’t blame ’em.”

“So you think there’s a chance I may see it? I wish I knew how to tell whether you are only another hypocrite or not. Here, I’m living in darkness, too, but I’ll buy your stock of cards if you’ll tell me whether you’d have mentioned God to me if I’d been a nice old lady. What about it?”

“Not a word about God to the old lady, sir. Not a word. On my oath. And for the same reason. She wouldn’t have known what I meant. She wouldn’t understand that a hero nearly lost his life in a righteous war through the bite of an allied bastard, if you understand me, sir, but if I said I’d found God she’d take it for granted I was all right, like herself. Why get her mixed up, the old dear?”

“So you’re all right, are you?” said the envious man of letters, mournfully, who had no God to whom he could give a name. He pointed to the vision of the dissolution of London in the murk. “How do you feel about being at the fag end of everything in that?”

The peddler looked puzzled. “Me? Do you mean the fog? What’s that to do with me?” He had accepted a coin, and now he eyed it on his palm and graciously spat upon it before putting it in his pocket. He sidled to the door, and from there he said: “Gov’nor, I’ll tell you something. Do you know what we’re told?...” But the oracle was not revealed, for the fellow turned as though he knew of an interrupter outside, closed the door respectfully, and was gone.

The eye of the bookman wandered to the bridge again. Where did it go to now? That was a rum fellow who[7] had just gone. Had he really seen a light which could shine clear through the fog and confusion of the earth? But what was the good of trying to see such a light because another man said it was there? Besides, to distinguish between shell shock and God wanted a bit of doing nowadays. Damn that bridge! Why wasn’t it blotted out altogether? What was the good of half of it? It used to go to France. Now it projected over a bottomless gulf of time, and was lost midway. It was broken. Where were the fellows who once crossed it? Now they could never get back. It ought not to be looked at. One’s thoughts got on to it, fell into the emptiness beyond, and were lost. Yet it was hard to keep the eyes from it. The printer’s proofs were the same dust and ashes as ever. No light or humor in them except the places where the compositor had happily blundered. And there the blessed relic still floated in the outer fog, an instant road for vagrant thoughts. And odd visitors, like poets with messages from a world not this or from no world at all, or like the armless man with his seasonable message to love one another, kept blowing in with the cold draught when the careless door was ajar. Perhaps a ghostly traffic moved on that spectral relic. That bridge should be either abolished or adventured upon again. What was the good of sitting and staring at it, while fiction not fit for dogs accumulated against the wall behind? Life was standing still.

At that very instant some of the fiction shot fanwise abruptly over the floor. Was the editor back in the next room? Literary editors might be at the dead end of things, but was life? He went to interview his chief.

But the great man—all editors are that, naturally—was not at his desk. He stood at the window, looking out, though not as if he saw anything there worth having. He turned to his assistant, and began to unwind his muffler.

“Well?”

“Not at all,” said the editor, cheerfully, “by no means. We blow out the lamp of our vestal, and the chaste darling is to be sold as a slave.”

They stood regarding each other.

“What about us?”

The editor smiled and poked his finger at the bridge in the fog. “We get a move on. Out into the snow, my child, out into the snow.”

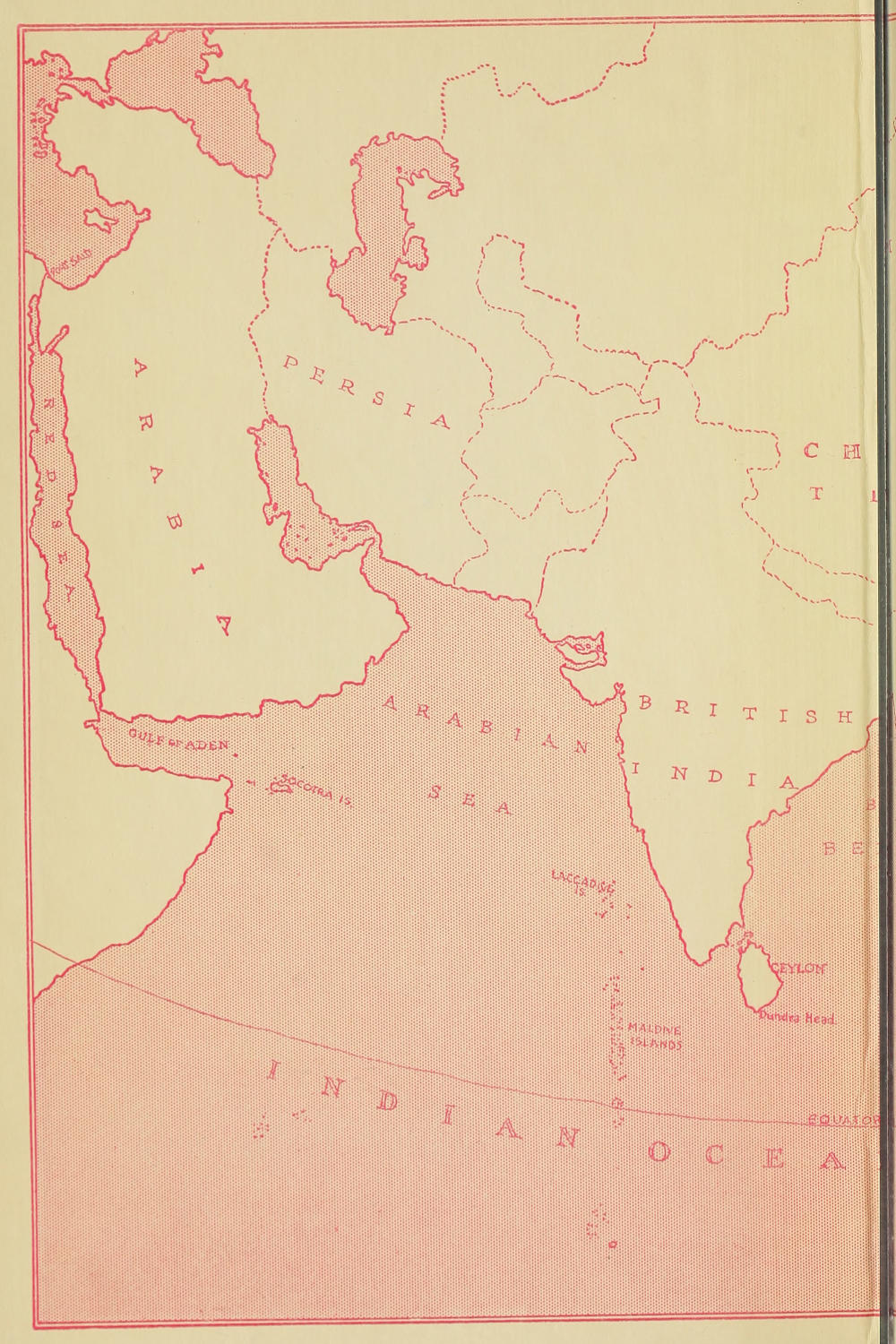

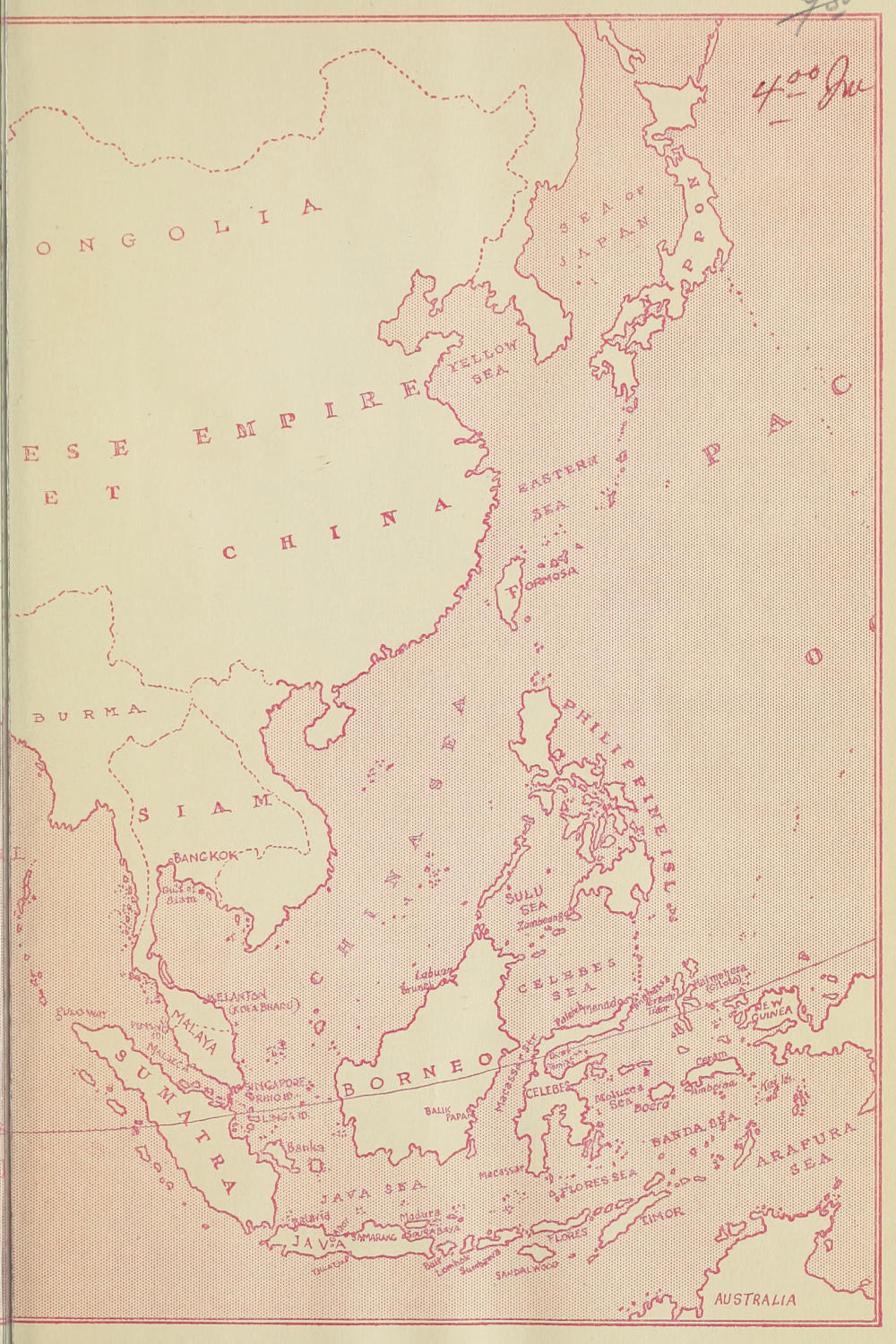

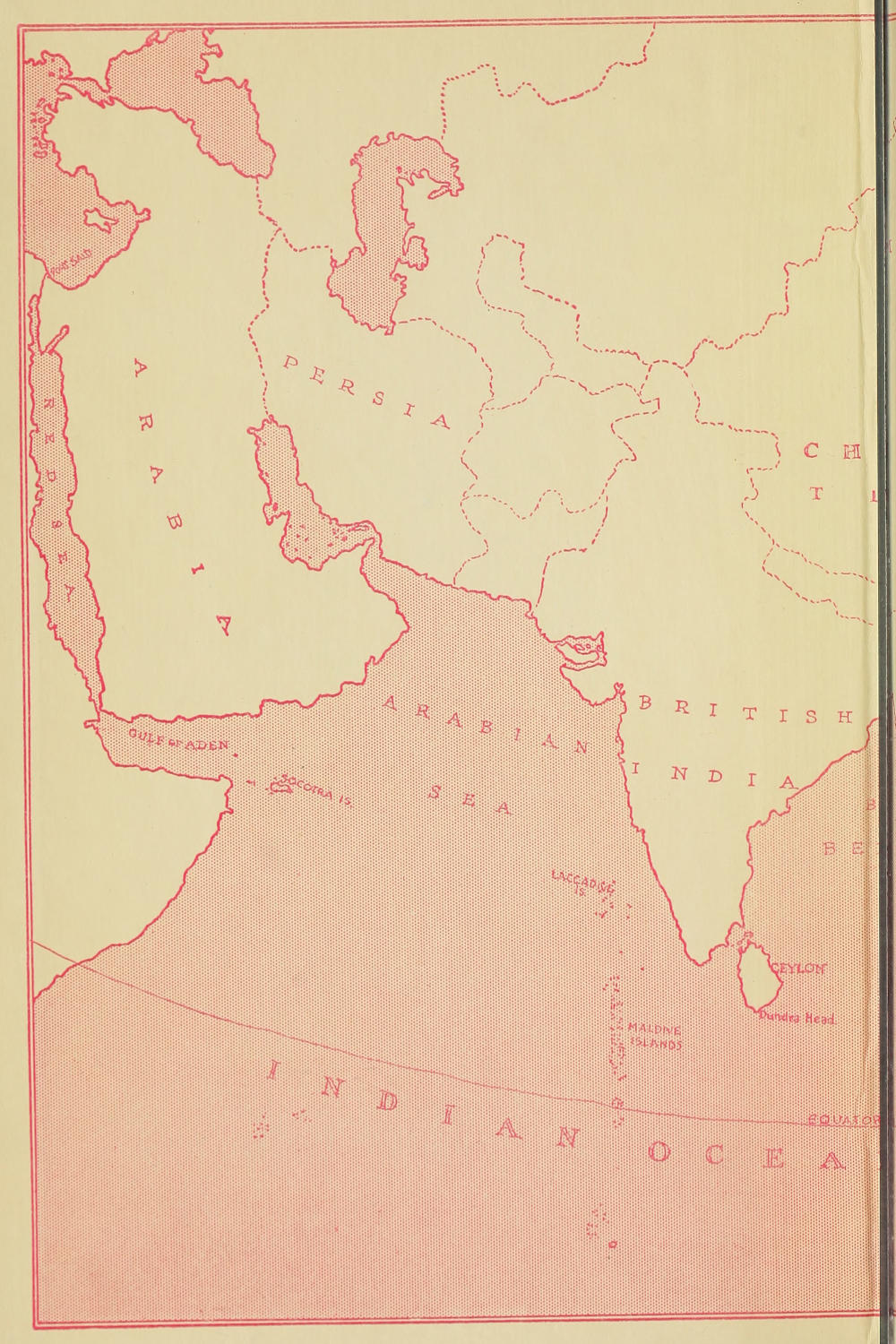

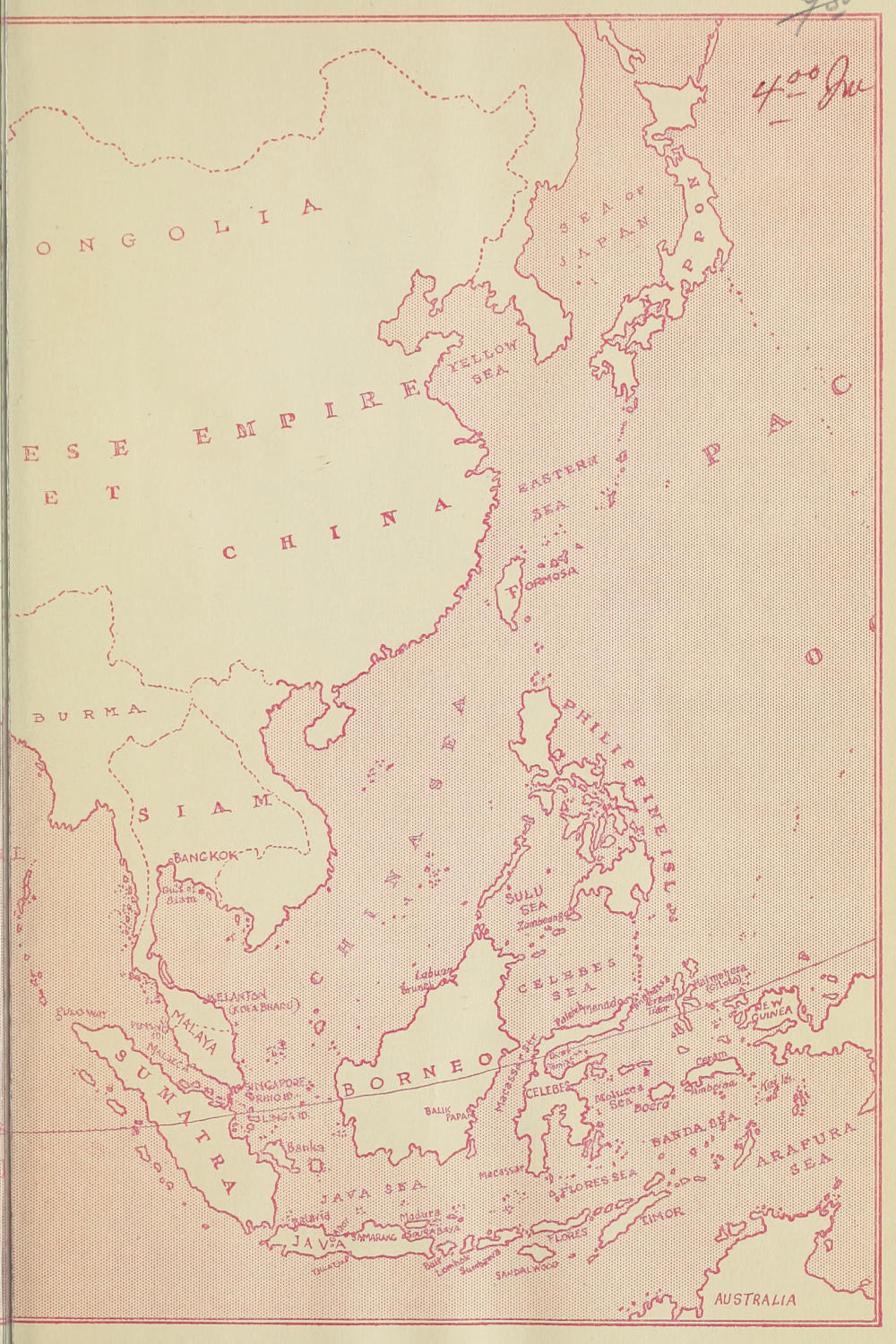

The letter, there could be no doubt, was addressed to me. This fact, apparently so doubtful, I was careful to verify at once. And so far as English can be plain it told me to go to the Moluccas. Nor was its purpose merely abusive and figurative, as would be the letter of a friend. The letter was typewritten on a commercial form; it was direct and curt; it gave telephone and reference numbers in case I wished to answer back. The letter advised me to pack up, and the place it told me to go to lies—as anyone may see who uses a magnifying glass—between Celebes and New Guinea. But it would take more than a business letter, however formal, to compel us into a belief that we are to travel to a place with a name which can be spelled out only with a strong glass. You experiment with such news on your friends. They will not contradict you; they will be too polite. They will merely stare for an instant, and perhaps nod as though they saw good reason for hoping that you would soon get over this little trouble. Curious things happen to people after war, of course, but time works wonders. That was how they took it from me. It was no good trying to persuade them that this sudden revelation which had come to me by post, this wild dream disguised as a business letter (in exactly the silly way of a dream), suggested anything more than the need of[10] rest and quiet in a room with primrose walls and windows opening south.

Of course. What else could a man expect of the straightforward, practical minds of his friends? In my best moments I myself laughed at the letter. Though I admit that I played with the pleasing dream the letter had aroused. I used the lens on the chart secretly. I stopped work now and then to think it over. I asked one or two sailors whether they knew the Moluccas; but they appeared to wish to avoid such a subject, as though this sort of talk was childish. Nevertheless, it became plain that so extraordinary a portent as that letter could not be treated lightly. Sometimes, when alone—for it was natural that I did not wish the puerile act to be witnessed in such earnest days of reconstruction as these—I took down the Malay Archipelago. Then I found, despite the urgency of our times, it was natural to drop at once on the very place where Wallace becomes, for a man of science, almost lyrical from his boat over the sea meadows of Amboina. And yet that chanting prose passage appeared to settle it. By artificial light in an English winter it was ridiculous. When we know the world to be what it is, who is going to find faith in an open boat afloat in a transparency where sponges and corals are on the floor, and fishes as bright as parrots dart among fronds in the sunlight far below the keel?

It was no good. Ternate and Banda faded away toward the days of Henry the Navigator. The Portuguese, English, Dutch, and Spanish navigators of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries knew how to find them; but not one of my friends who, for whatever privileged[11] reason, might advise me to go to Hades or anywhere, could also readily separate the Moluccas from the Pleiades. The Spice Islands are forgotten. So I was unable to take that business instruction seriously. Wallace, with his outburst over his sea meadows, canceled the letter for me. The mirage dissolved, in the way of dreams that are fair—dissolved reluctantly, like one’s faith in a Golden Age—vanished! What to us in Europe are islands poised in a visionary sea, a sea vast and mute, Paradise set in Eternity? Well, we know what they are. Beauty of that kind is merely a stock of sensational stuff, which is safe and easy for the use of hearty novelists and short-story writers who require, to make their books move at all, pirates, trepang, beach-combers, copra, head-hunters, schooners full of rice, and similar matter which easily takes coal-tar dyes in the rapid output of bright and lusty fudge. Otherwise they do not exist. Nor did the conquest of space, as it is called, by flying and wireless telegraphy, give me any heart. Those wonders of human progress brought such islands no nearer to me than they were to Plymouth in Drake’s time. Do we imagine we are gods, and may order the world to be re-created superiorly to a geometrical design of petrol tanks and telephone stations? We forget that gods would never do anything of the kind. The gods may be, and perhaps are, anything we choose to make them, but they should be allowed more sense than that. Are we able, with all our aids to progress, to conjure apparitions like those sea meadows any nearer to us? They are where they were, if ever they were anywhere. They are in the same world as the Hesperides. We see them only in idleness, as we see mankind[12] at peace, and the star again over Bethlehem. No flying machine will ever reach the Hesperides. You will never, even in the quiet of midnight when hopefully listening in, hear a whisper from that seclusion. How it is some lucky men become assured, and sometimes quite suddenly and without the aid of wireless, the encyclopedias, or any help of ours, of such islands, of such sanctuary from the deadening uproar of error and folly, and so are immune from fogs of every kind, the lessons of the war, the gravest of political disclosures, revolutions, signs of the times, mysticism, and anything the public seems urgently to want, is a wonder to me; but there are such men, and I wish I knew whether they are really mad, or whether their bright serenity is only madness when compared with our practical cynicism and our sane motives of enlightened self-interest.

Yet even we ourselves at times—and there is no serene brightness of madness about us—are startled now and then by a hint of easy escape, as though an unknown door somewhere had opened on light and music which we do not know. Where did that come from? The door closes before we can be sure so curious a light and strange a sound were more than our own hope deceiving itself. And dreary experience has taught us that it is wasting time to look for that door. Either it does not exist or we cannot find it. So that letter was a release, though in a way far inferior to the momentary escape of celestial music. It pretended there was a door. I could fancy a decision had been made in my favor in that invisible sphere where our circumstances are devised, those little incidents which move us this way and that without our ever knowing why. And other[13] hints continued to drop through my letter box, all at the same angle of incidence. The last one was more than a hint. It named a ship, a place of embarkation, and a day. The day was not far off, either.

This began to make me feel acutely nervous. There could be hardly a doubt that I myself was designated. But could I really accept this mysterious decree? I could not, and I did not. Man never accepts his fate. He has a faith, which nothing ever shakes, that his habits are stronger than destiny. He believes that from the fortress of his daily routine, within which he feels secure, the urgent messengers from the gods will recoil, baffled. Nevertheless, I felt certain by now that one of those dangerous messengers had assaulted my citadel again, so I arranged about me a few mascots, for luck. If that messenger forced his way in, then I was ready for him.

A final imperative knock came at last. No doubt about it. It was on the very day, I noticed, which fate had indicated. Others in that room stood up at the sound, and looked at me. I could see they knew for whom the messenger had come. Apparently the hour had struck. My routine had fallen down. It was a cab-driver who had knocked. And not till I saw some of my mascots, which were traveling bags, already on his chariot, did I look back at my porch and understand that that cab was to take me over the first stage to the Moluccas. Was I exalted at that moment? I shall not say. But what the deuce, I said to myself, as I climbed into the cab, do the blessed sponges of the Pacific matter to me? Have the presiding gods, I silently exclaimed,[14] ever heard me complain about my pleasing suburb? What have I done? But the cabman had a face like the shutter of an empty house. He was clearly in the conspiracy to get me out of it. He drove on.

The lethargy of soul is proof against all the facts we do not care to look at. No immortal soldier ever accepted the nature of his destiny in France till the moment when he saw his pal drop. And therefore I still thought there was a chance that this cab was a misdirection. I had been mistaken for another man. But promptly to the minute I was left at Euston. Still, Euston was real enough to be not at all ominous. There can be nothing in all this world less fay than the London and North Western Railway and its officials. There is little in them to make anyone suspect the subtle and transforming art of what is faery. So I fell asleep in moderate confidence, and the wheels went around.

I don’t know how long they had been revolving, with many a jolt and bump through the night, but I woke with a conviction of the need that day to give attention to those old volumes in the cupboard ... if the mice were really nesting there, as I was told.... Where was I? Odd! I could see through a window the dark waste of a railway siding. By the look of it this was the dead end of all railway tracks. Beyond this no man could go. The dawn had barely glanced at it, because, I suppose, it was not going to spoil good sunshine on such a place as that. It was littered with old newspapers with dates that would be in the week before last. Nothing else could be seen, except a wall the color of soot,[16] which was high enough to screen us from all that was lovely and of good report. Now, I thought, my misdirection has been discovered. Here I am, shoved into a celestial pigeonhole for lost souls, till there is time to find my right label and post me back to my old volumes. It was then that a familiar appeared, in a gold-braided uniform, and whispered craftily that this was Birkenhead. How I got there I don’t know.

Outside it was drizzling. I was dubious about that, for I have noticed that an ominous sign that I have been uprooted and am drifting again is that I am in a strange place and that it is raining there.

A man came out of a dank wall and begged for the privilege of carrying my two heavy bags. He could only have been evolved by the progressive lines of a highly complex civilization. His mouth was a little open, and perhaps it had not been shut since his last meal, some days before. It was open and waiting for the next, and to save time in coughing. As he was the only visible agent in the strange scheme which had got me to Birkenhead, I invited him to try the luggage. At the word, he took off the belt of his trousers. Why his trousers remained in their place is known only to the powers which were getting me to the Moluccas because, so far as I could see, the man had no stomach; which was lucky for him, as it turned out, because he explained that his average fortune was seven shillings a week, and that, take it by and large, Ypres was as good as the commercial facilities of that fine port. We halved the weight, and trudged off. I saw no signs anywhere of the Far East. All the streets were alike; yet this fellow with me, who never looked up, but stared at the pavement[17] and breathed hard, seemed to have prior advice as to what to do with me. He knew; for, turning a corner, I saw above dingy roofs a tall funnel of a ship. It was the color of a genuine sky, though its top was black, like the sky we had. From the mainmast head of that hidden steamer the blue peter was flying. “Your ship,” coughed the wraith shambling beside me. I was sure he knew. The whole affair was foreordained.

Carefully observe what happened next! That ship had a name out of the Iliad. I had never seen her before. The way to her was cumbered with packages marked for Singapore, and places beyond which we forget after we leave school. Nor could I make out what she was like, from the quay. She was a mass in which white boats were mixed, and a length of black wall, a blue smokestack, two men looking down from a rail, a flag, some round windows with brass rims, a shout or two, a roar that stopped when some cases checked in midair and swung on a pack-thread; a height topped by brown derricks and ventilators. She could not be seen. There was no beginning to her and no end. I went through a door in the upper works of the structure, expecting to be thrown out. That place was nothing to do with me. I could see and smell that. But a man whose smile indicated that he had known me all my life met me in a passage, knew my name, and invited me to follow him. What else could I do? I followed in resignation. He took me to a room. It had been prepared for me. He went to a drawer and handed me some letters whose senders clearly knew where next I would be found. “If you want anything,” he said, “touch that button”; and vanished.

Thereupon I surrendered. I sat on the couch and wondered who I was, why all this had happened, how long it would last, what I should do about it, and whether any man since the world began ever knew for certain why and by what means his affairs were shaped for him. I found no answer to this, though the ship hooted once in an insistent way. I took no notice of that till, looking through my round window, I noticed that the shed just outside—a shed which, after all, represented England—was stealing away from me. The shed disappeared. Nothing could be seen then but two ropes, and they were blithely dancing a hornpipe over some hidden joy.

I went outside to see what made them so gay. But the sky was still drizzling. Those dancing ropes were aware of something hidden from me, and I determined to find it. Our ship, which I have reported was a hero of the Iliad, was athwart a great rectangle of water and in the midst of her peers. They stood about her—and here I will declare that though a ship is named after a warrior in a bronze helmet I am not going to call her him—she was, then, in the midst of her peers: Shires, Clans, White Stars, Halls, and her family Blue Funnels. It seemed to me she knew her family tradition and her worth. There was such a stateliness about her, so easy a dignity, and her commands were so peremptory and haughty, that it was clear she had the idea that nothing afloat could deny her house flag.

By the Bar Lightship some steamers we passed were making a fuss about the weather. But our Trojan took no notice of it. I will even confess that off the Isle of Man roast pork was conspicuous on the lunch card, and[19] that I knew of no reason why it should not be. With the dark obstinacy of its northern character the spring pursued us south. The northwest wind was bleak and sullen. The sun hid his face. We were alone in the Western ocean on the second day. We had the wind and the desolation to ourselves, except for a dozen lesser black-back gulls which were following us because, perhaps, those waters were the same as all the seas of the north, and so it did not matter to them where they were. The surge mourned aloud, sometimes rising to a concluding and despairing diapason. The blue jeans of the sailors busy on the exposed parts of the ship quivered violently in the perishing cold. Once, I remembered, some dauntless men pulled galleys westward through the Pillars for the first time, and then turned northward toward the top of the world. How did they find in that ocean the spirit to maintain a determined course? I do not know. They must have been good men, and hard sailors. I will never believe that the thought of more and easier shekels kept them facing the gloom of those sweeping ranges of water and the bitter heartless wind. It is a lie that men are never moved except by the hope of gain. It is a miserable lie of the money-changers, and it is time to kick their tables outside once more. Why, fellows even as stout as those earliest navigators must have seen in dismay that their gods to whom they had sacrificed would be helpless in seas that were beyond all known things, where they could guess they had entered the realm of the powers of darkness, and that the warmth of human and friendly hearts would go to leeward with the spindrift, and hope could be abandoned. It was while I was seeing this so plainly that a[20] youth in uniform caught hold of a stanchion and flung himself into the wind toward me. He handed me a familiar yellow telegram. It was from home, praying a good voyage for us. The sightless message had just been picked out of that gale and that sky. I glanced beyond the telegraph messenger, and wondered if he had left his bicycle round the corner.

The English spring gave up the hunt just beyond Finisterre. The sun, glad of the chance, came out to look at us, and made a habit of a magnificent appearance each day at the due hour. We found another wind. It allowed me to loaf on the exposed forecastle head, watch the flying fish glance away from the noisy snow of our bow wash, and listen to the lookout, standing at the stem, answer the bridge when its bell gave the ship’s hour. But Ternate seemed no nearer than it did at Birkenhead. It was still an incredible fable, a jest by an old traveler which he tries on the foolish. All the East I had seen so far was no more than three Chinamen squatting on their hams on our after deck, chanting together while one punched a hole in a paint keg and the others admired it; that, and a smell of curry. Anyhow, it was a strong smell of curry.

One morning the lookout signaled land. It was a thin shadow over the port bow. There was no other cloud in the sky. That shadow grew in height, darkened, and closed in on us. Then the shadow of Africa approached our other beam. Toward evening we passed between the Pillars. We may have been no nearer to the Moluccas, but we had escaped from the darkness of the north. That was certain at sunset, when we might have sailed off the waters of earth and were elevated[21] to a sea where there were no soundings, and logs would be profane. We were not alone there. A felucca was in the vacancy between us and the phantom of a high coast. Our own yellow masts were columns of light. The foam at the bows was flushed with hues never seen in water. And ahead of us, that sea we were to enter was the smooth expanse of an unknown and lustrous element. It was brighter than the sky. From the lower wall of a vault of saffron a purple veil dropped to the rim of a vast mirror. I do not know what was hidden by that veil. It was a dusky curtain circling the brightness and its folds rested on the mirror. Down on a hatch below me some of our fellows started a gramophone with a fox trot.

We had seen the shadow of Crete in the north, and the next noon our ship was somewhere off the Nile. Despite its antiquity the sky was still in its first bloom, and the sea was its perfect reflection. It was easy to feel older than the sky and the sea, for our ship was solitary in the very waters where, out of the traffic in ideas and commodities between Knossos and Memphis, had grown the Athens of Pericles, and Rome and Paris, London and New York. If there is anything to be said of that awful thought, perhaps it would never do to say it here. It may be altogether too late in the day to brood with fond and kindling eye upon the cradle of that particular deep which rocked our childhood into the beginnings of Chicago and Manchester. Let us say nothing about it.

The next sunrise it was the skipper himself who called me. This was a genuinely surprising event. His white figure was even startling, for to me then he had become a senior master mariner in a service so august as our blue funnel, the house flag of which is, I suspect, east of Suez, more potent than the emblems of not a few proud states. The honor was unusual enough to cause me to strike my forehead against the opened port as I sat up respectfully. Our master has been at sea for forty years, so his appearance of weariness and of ironic understanding may mean that his experience of men has been extensive, or it may mean nothing. “We are entering[23] Egypt,” was all he said, while his lean hands rested on the edge of the bunk; he then turned away as if he supposed this sort of thing would never end. But possibly he had been up all night.

A Group of Chinese Firemen

There was an apparition of a city over the sea ahead of us. It was so delicate that the primrose of sunrise, deepened in inclosed and quiet waters, might in that place have conspired to produce a mirage of one’s bright expectations. That was the gate to all that romantic folk with a meaning eager but scarcely articulate call the Orient. Yet which of us is not romantic when we see it for the first time? I watched that gate heighten and become material as our ship insensibly approached it, till I could read on the seaward brow of this entrance to romance the famous legends, “Topman’s Tea” and “Macgregor’s Whisky.” Port Said, you soon discover, is just like that.

If it is anything at all it is more West than East. A somber flotilla of barges manned by a multitude of dark fiends was waiting for us, and our ship hardly had way off her before she became Tophet with coal dust, unholy activity, and frightful jubilation. It is the privilege of civilized men to give their appetites and repulsions the sanction of reason with its logic, and therefore I did not accept Port Said because I did not like it. It is certainly not the Orient, and I hoped it was not even its gate. Its address and its manners are as abrupt and threatening as is the Stock Exchange to a timid stranger who has misadventured within its sacred precincts. I went ashore, but soon returned to the ship, for I fancied that our Chinamen might be closer to a simple heart than the oblique calculation of that port.

For what are the significant things in travel? Let travelers candidly own up. He is a wise traveler who has few doubts about that, and such a man would be silent, of course, being wise. Who would believe him if he spoke? There was, for example, the French mail steamer close to us at Port Said, homeward bound. Her saloon passengers, the ultimate Parisian reflection of the grandeur that was Rome, surveyed in aloof elegance and in static hauteur the barbaric coarseness of Port Said. But for a chance hint I would most certainly have saluted, as is the Anglo-Saxon habit, the refinement and pride of the folk on the Frenchman’s promenade deck as the very luster—which is so hard to attain—of Western civilization’s most exquisite stuff. But my glance drew away to the Frenchman’s forward deck, and there I saw something which tumbled down my hitherto unquestioned convictions about those qualities which make, as we should put it, the right folk. That deck was loaded with passengers from Cambodia and Cochin China, people of quite another culture—or of no culture. They did not seem to be travelers by deliberation or decision, like ourselves. It was easy to guess they had merely obeyed, like little children, the stern directing finger of fate. They showed no curiosity in us, or in Port Said. They were as still, and as watchful or as indifferent, as delightful images. They stayed where they had been placed. Yet if the French ladies were beautiful, then what shall we say of those little figures? By what means, by what habitual, tranquil, and happy thoughts, did they attain without wish or effort to a countenance which made the refinement and haughty demeanor of the first-class passengers[25] above them identical with the barbaric challenge and insolence of Port Said? It did not surprise me that for our exhibition of Western enterprise and energy those children of another clime had but shy and mild astonishment. One of them, who might have been an attractive piece of craftsmanship in ivory and ebony, did give to the busy and heated scene the faintest of smiles. A doubt as to what made him smile blurred for me later the enduring testimony to Western skill and activity in the Suez Canal, and even the still more remarkable evidence of our energy at Kantara, a wilderness of abandoned railways and earthworks, with square miles of abandoned airdromes and rusting and sand-blown wreckage, where Anglo-Saxon genius for scientific organization, and British wealth, had built the camp and engines for the last conquest of the Holy Land. It is most disquieting to get a hint that the established way of life of one’s kin may be foolish after all, and that there are other ways.

Why should a Cambodian smile have so haunted me that my hope and endurance in travel were not rewarded with the satisfaction I had a right to expect, when witnessing the marvels in foreign lands created there by the superior culture of my dominant race? Did I go to sea for that? Nothing like it. And next morning, when I looked out from my cabin port, there still was the mere canal. Beyond it was the desert, and over that gray and vacant plain was an announcement of the coming sun. The sky was empty, like the desert. Nothing unusual was expected, evidently. But it was only with the first half-awakened glance that I guessed it was the common sun which was to come. In another[26] instant I was aware that that hushed and obscure land was humbly awaiting its lord. The majestic presence suddenly blazed, and ascended to overlook his dominion. A terrifying spectacle! It would have frightened even a poet in the mood to hail the beneficence of one of man’s earliest gods. The glances of that celestial incandescence were as direct as white blades.

In the south, to which we were headed, a high range of Africa’s stark limestone crags stood over a burnished sea. The sun looked straight at them. And just above them, parted from their yellow metallic sheen by a narrow band of sky, was the full globe of the declining moon; and the moon herself was no more distant and no more spectral than earth’s bright rocks beneath her. It was not surprising that that scene was motionless and constant. There was no wind, there was no air, or all would have vanished like a vision of what has departed. Those luminous bergs shone like copper. Their markings were as clear and fine as the far landscape of a newly risen harvest moon. Suez was not far away, and its lilac shadows were as unearthly as the desert. But there was substance alongside our ship. Some villas were immediately below, arbored in tamarisk and cassia. A few trees in that green mass were in crimson flower. I could smell the burning ashore of aromatic wood. A child in a cerise gown stood under a tree, but she was so still that, like the polished water, like the hills of brass and the city built of tinted shades, she might have been the deceit of an enchantment.

A tugboat rounded a point, shattered the glass of the sea, and the child, released from the spell, moved from under the tree. Men in our ship were shouting. Mail[27] bags for Singapore, Hongkong, Shanghai, and other places as well defined were thrown aboard. Life began to circulate. These men gave no attention to dead hills and the tyrant in the heavens. I am prepared to believe they would have been incredulous concerning any town about there built of lilac shadows. Our ship rounded away into the Gulf of Suez, the northern corner of the Red Sea.

We are aware—though we hardly dare to whisper our knowledge—that even our street at home will, at rare times, give us the sensational idea that we really do not know it. Can it exist in a dimension beyond our common experience? We think we glimpse it occasionally on another plane. This sense, luckily, is but fleeting. We could not support a continued apprehension of a state of being so remarkable. We come down to our beans and bacon, and are even glad to answer the bell to that and the coffee. Well, it is more remarkable of the Gulf of Suez that it permits no certain return to common sense. The coast of Africa, and its Asian opposite, remained within a few miles of our ship all day, as pellucid as things in a vacuum, but as unapproachable as what is abstract and unworldly—the memory of a dead land, though as plain as the noonday sun. There can be no shores in other seas anything like the coast of that gulf. The panorama of heights silently opened and went astern, monotonous, brilliant, and fascinating. In all those long miles there was not a tree, not a shrub, not a cloud, not a habitation. The sky was silver, the sea was pewter, and the high bergs were of graven gold or bronze. The chart informed us of Moses’ well, and of Badiat Ettih, or the Wilderness of the Wanderings, and Mount Sinai. “Moses, sir,” said the bo’sun to me, “he had enough rock for his[29] tablets, but that was a hot job he had getting them down.” But since those early days and tribulations the land has been left to mankind but as a reminder of things gone. Nobody to-day ever lands on those beaches, on those arid islands. How could they? That we could see the contortions of the exposed strata, and the dark stains thrown by the sun from yellow bowlders on immaculate sands, was nothing. We see, in the same way, the clear magnification of another planet through a glass, but that is as near as we can get to it. There were numerous small islands between us and the shore. They were always glowing satellites of bare ore, without surf, fixed in a sea of lava, and blanched by the direct and ceaseless blaze in the heavens. Unshielded by air and cloud from that fire, they perished long ago.

Our smoke rose straight over the ship’s funnel, then curled forward, showering grits. If the hand was placed carelessly on a piece of exposed metal work one knew it. Our bo’sun, who has no expression but a disapproving stare, who never sleeps, who has the frame of a gorilla, and whose long hairy arms, bowed inward and pendent as he walks the deck, are clearly made for balance and dreadful prehensility, admitted to me that it was “warm.” Yes. The sprightly fourth engineer appeared from below as I loafed along an alleyway which had the fierce radiation of a nether corridor, and he drooped on the engine-room grating with the air of a fainting girl; he did not call it warm, but that is what he meant.

Night came, and the cabin had to be faced. The hour was made as late as possible, but it came. Reading was not easy. It would not have been easy then for a young novelist to enjoy the press cuttings assuring him[30] of those original features of his work which distinguished it from that of Thomas Hardy. But the cabin made it no easier to do nothing, for how can one lie sleepless in a bunk and merely look at time standing still because the thermometer has frightened it? Beside me was a book the skipper had lent to me, with a hearty commendation of its merits. “Facts,” he had said to me significantly, looking at me very hard. “Facts, my dear sir!”

So it looked. It looked like nothing but facts. Who wants them? What are they for? And the coarse red cover of the book betrayed its assurance in its uncontaminated usefulness. A copy of it will never be found in any boudoir. (This is probably the first reference to it by a critic.) I lifted the weighty thing, took another look at my watch—no hope!—summoned so much of my will as had not melted, and began.

When I awoke the sun was pouring heat again. The decks were being drenched. But my cabin light was burning foolishly and the book was beside me. If already you know something of that special sort of literature which is published exclusively for use in the chart houses of ships, you will understand. And you will know, too, where R. L. Stevenson got much of the actuality which in places lights the ships and islands of The Wrecker and The Ebb Tide into startling distinction. The pilotage directions for the Pacific were volumes into which Stevenson must have often pushed off, like a happy boy in a boat, to lose himself in that bright wilderness. Yes, and if only the writers of other kinds of books but knew their work as well, could keep as close to the matter in hand, and could show their knowledge,[31] or admit their want of it, with the brief candor and unconscious modesty of the compilers of the works published for mariners by a Mr. Potter, of the Minories, London! I hope that some day I may be able to enter Mr. Potter’s shop, where books are published in so unlikely a place as Aldgate, which is Whitechapel way, and press Mr. Potter’s hand in silent gratitude, for I am sure there is no phenomenon in nature, not even an exhibition of human gratitude, which would astonish him, or move him indeed to anything more than a perfectly just comment in words not exceeding two syllables each.

I will make no secret of the book which put away the heat for me, and abolished time—for I do not remember looking at the time after 1.30 A.M., when I was still far from sleep, and had been reading steadily for hours. Yet this book no more resembled a best-seller than a chronometer resembles the lovely object out of a prize packet. Its name is The Red Sea and Gulf of Aden Pilot—the seventh edition, we may gladly learn of so respectable an exhibition of prose. Its price, I noticed, proved that the truth—or as near to the truth as one should expect to attain—is no more, is really no more, than the price of more doubtful commodities. And let us remember that it is all very well for wise pilots in other and darker seas to assume they may teach young voyagers the right ways in the deceptive and fog-bound coasts of philosophy. Philosophy? That is easy. We may make our charts, then, according to inspiration or desire. But when it comes to advising a mariner where he may venture with a valuable ship, according to her draught, then it is essential that words should be chosen[32] with care, and the student warned to note with unusual caution every qualitative parenthesis. There can be no casual and friendly agreement to differ about the truth when the question concerned is a coral reef in five fathoms and a ship drawing thirty feet. One must be able to assure a sailor either that his ship can do it, or he must be told that he may not try. Yet with what confidence each of us will venture to pilot others in the more dangerous, the more alluring, and the supremely frustrating elements of morality and æsthetics!

My bed book made no attempt to beguile me. It opened with the simple statement that its purpose was to give “Directions for the navigation of the Suez Canal, the Gulf of Suez, and the central track for steam vessels through the Red Sea, Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb, and the Gulf of Aden; also descriptions of the Gulf of Akaba, the African and Arabian shores of the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden, and the southeastern coast of Arabia to Ras-al-Hadd, the coast of Africa from Siyan to Ras Asir, including the Gulf of Tajura, then to Ras Hafun, Abd-al-Kuri, the Brothers, and Socotra Island.”

And Socotra Island! We know the South Pole better than that island, although from prehistoric times every maker of specifics has depended on Socotran aloes. After this simple avowal the book informs its reader that “all its bearings are true, and in degrees measured clockwise from 0° to 360°.” Dare we ever ask for more than that? Here was a book which actually declared that its bearings were true and were not magnetic. No work could be more frank. It relied entirely on its reader being a man of honor, of common sense, of skill in his craft, and of a desire so simple that his only care[33] was the safety of the lives and the property of others. Yet such is the force of habit, which sends us to a book to look, not for the life we know, but for the glory of its falsification, that at first I was inclined to put the captain’s volume aside and trust to boredom and the whirring of the electric fan to send me to sleep. But something prevented that.

Here I was, in these very waters; and their uninhabited islands, beaches, and reefs, which had been passing us all that day, were altogether too insistent. These Arabian and African gulfs have more coral to the square mile than any other seas in the world, so, although their shores, during all a day’s run, may be rainless and dead, the waters are more alive than the most fertile of earth’s fields. Sometimes, when listlessly gazing overside, one was shocked by the sight of a monstrous shape dim in the fathoms. And one evening when the very waves, as though subdued by the heat, moved languidly in hyaline mounds, several black fins began to score their polish. A few dark bodies then partly emerged, gliding and progressing in long, leisurely arcs. As soon as those dolphins saw us they woke up. They began leaping eagerly toward us in the direction of our bows, as though the sight of our ship had overjoyed them. They behaved deliriously, like excited children released from school at that moment. Now, we were used to a small family of these creatures so greeting us. They would amuse themselves for ten minutes by revolving round one another immediately before the ship’s stem, weaving intricate evolutions in the clear water so close to our iron nose that one looked for them to be sheared apart. They were so plain that it was[34] easy to see the crescent-shaped valve of the nose, or blowhole, open whenever a head cleared the water. But the exhibition this evening was phenomenal. Thousands of them—yes, thousands, for I will imitate the Pilot—as though they had had word of us, appeared at once, throwing themselves in parabolas toward us, and when alongside breaching straight up, perhaps because their usual curved leap did not take them high enough, and they intended at all costs to get a view of our amusing deck. The level sun signaled from the varnish of their bodies. One of these little whales moved for some time below me, turning up an eye now and then in the way of a swimmer who converses with his friend in the boat. He rolled over lazily, went down, and dissolved in the mystery under us. When I looked up the sea was vacant. Dolphins might never have been created.

This sea was so plainly the setting for legend and fable. Crusoe and Sinbad both would be at home here. I should guess, however, from what we saw of the coast and the islands, that this was more the world of Sinbad than of any level-headed adventurer. Djinns might be looked for in those desolate gorges into which we had glimpses. It would be wrong to pretend that the Pilot ever mentioned such things by name, but now and then I suspected in the text fair substitutes for such infernal and maleficent powers. The Pilot would check the reader going easily through its pages with an unexpected caution: “The coast from Ras Mingi northwards to Ras Jibeh, a distance of 330 miles, is mainly inhabited by the Jemeba tribe, who generally have a bad character.”

But the faithful Pilot would allow no harsh judgment on the Jemebas. We ourselves might develop a similar[35] bearing toward visitors who appeared to be unduly prosperous if we were as poor as the Jemebas, had no boats, and had to “depend on inflated sheepskins” for our “fishing operations.” Of certain channels we were advised not to attempt them “unless the sun is astern of the ship and a good lookout is kept.” The reefs in this sea do not behave like reefs. They are numberless, but they are rarely marked by so much as a ripple; and that, I can vouch, is true. Their fatal presence may be revealed on a lucky day by a change in the color of the water. For those seamen who are not fortunate when watching for the water to change color the Pilot gives advice on what may happen when boats must be beached and help sought. The beach “was formerly inhabited, and remains of dwellings are still to be seen.”

I was leaning on the rail of the bridge with the master, watching the brown scum, peculiar to the Red Sea, pass alongside with its not really pleasant smell, for it hints that the very deep itself is stagnant and decomposing; and I was foolish enough to tell him that to me the bearings of his excellent book of sailing directions were not only true, but magnetic. He half turned to me sharply, considered this remark and myself for a moment, and then made the noise of impatience in his throat. It was at the hour when we were passing into the Red Sea proper. The Ashrafi Islands were abeam, with Shadwán Island, the greatest of the group, the very picture in little of what this earth will be when its ichor will all have evaporated. Behind the barrier of outer islands is a labyrinth of reefs and coral patches where the signs of danger may be mistaken for the usual mirage, or an innocent and fortuitous shadow may have the obvious face of a genuine reef and thus scare a ship away on a safer course till she runs full upon the real and unannounced rocks. I mentioned to our captain that his book occasionally whispered of a few inexplicable tents to be seen on these uninhabited islands.

“Oh, tents! That’s right. A man I know got aground here,” he said, “and in half an hour his ship was surrounded by little boats. He never saw the coming of them. There they were. A year or two before the war[37] a steamer got aground here one night, and at daybreak she was boarded by a big mob. The crew were stripped of their clothes. The Arabs were in a hurry to get the chief engineer’s ring, so they cut his finger off. Then they tried to shift a copper steam pipe. Steam was still on, and they took an ax to it. The engineer told me it did his finger a lot of good when the Arabs got down to the steam. The pressure was all right.”

Even a deep-water channel of the Red Sea may commit the crime which some think worse than murder—the betrayal and mockery of a confiding trust, of a simple faith in the pledged word, of repose in the moral order of things. A steamer, the Avocet, where the chart, the Admiralty chart, and Mr. Potter’s Pilot allowed her master to rest on the comforting knowledge of deep water, struck a rock. “Naturally the Court of Enquiry,” commented my captain, bitterly, “as much as told that man he was a liar about that rock.” Our own master exhibited the sort of displeasure which good craftsmen reserve for theorists and experts—the learned men who would debate such a subject as the Red Sea in the Law Courts of London. But even then he did not begrudge them a fair word. “But they didn’t suspend his certificate.” They sent a gunboat from Aden to search for the rock. The gunboat cruised and dragged for it for three weeks, but the rock had gone. “Got tired,” suggested my captain, “of waiting for another ship, I suppose. Went down below for a rest. The gunboat said there was no rock. And there you are, sir. That proved the Avocet’s skipper was a liar. Couldn’t be plainer. Ten months later another ship found it, though she wasn’t looking for it. It don’t do for a sailor to say[38] a thing isn’t there because he can’t see it and has never heard of it before. Give it a margin.”

The Red Sea, I suppose, will never be a popular resort. No pleasure, as it is commonly defined, may be found where the shade temperature may rise to 110°, where rain rarely falls, where there is either no wind or a malicious stern wind, where the inclosing shores have no rivers, but only beaches of radiant sand and precipices of glowing metal, and where you are not likely to meet any folk except an occasional tribe with a bad reputation and so poor that it goes fishing on inflated sheepskins. At the lower end of that sea there are a few ports, used mainly by the pilgrims to the holy places Mecca and Medina. And indeed the Pilot does not attempt any attractive testimony. Even of such a choice subject as a small island secluded within an unfrequented gulf it is but terse, even exasperatingly brief. It will merely report of it that it “produces no vegetables, except two or three date palms and a few pumpkins. There are a few jackals, gazelles, and wild asses here. Cephalopods are abundant in the surrounding waters, and sperm whales are common.”

But is not that enough? Could you get that at Monte Carlo? What more could a traveler wish for as he looks overside at such a coast? What more does he deserve in a world which has become patterned with airdromes and oil tanks? These coasts are no more placable and are little better known than they were to the early navigators. There are large and even populous islands which great ships must pass almost every day that are still as they were when the insatiable curiosity of Marco Polo drew him to so many first views of the[39] earth’s entertaining wonders. For there on our starboard beam, immense on a sea which moved in smooth mounds so languidly that the surface of the waters might have been filmed with silk, rose the battlements of Socotra. I think the last we heard from that island was dated 1848. Yet, the Pilot informs us, “it is said to enjoy a remarkably temperate and cool climate.” Its capital, Tamrida, is less frequently visited by Christians than Mecca. It should be worth a visit, if one had the heart for it. The town is “pleasantly situated” and its people are mixed of Arab, Indian, Negro, and Portuguese blood. The natives have an unwritten language peculiar to themselves. But we are kept out of so attractive an island because, for one thing, though it is a British possession, both monsoons appear unfeeling about that important fact concerning a land which has no harbors and no safe holding-ground for ships; in addition there is the “unfavorable character of its natives.” Is it then surprising that the literature made by tourists in these seas is mainly devoted to arabesques of places like Port Said? A day in Socotra would be worth a year with the Pyramids. And, as it happened, the southwest monsoon was waiting for us. When we had cleared the easterly point of the island it caught us, filled our decks, smashed the crockery, and at night set the mast-heads describing arcs amid the stars.

June 5.—To look down a lane in our village you might suppose that literature was about as likely there as the harpsichord. The narrow pathway (when two of us meet in it we must go sideways) is of wood, and it has white walls and a roof of steel. There are doors all along its length, and it ends at a ladder descending to the afterdeck. The doors are generally open in a friendly way, as though we had no doubt about our neighbors. Some of these doors give on comfortable little sanctuaries in white and mahogany, with blue and orange bunk curtains, electric lamps, and settles on which—should you call on a friend when he is off duty—you may hear enough to keep your own improving knowledge modest and dumb.

There are sections of surprising warmth in that steel passage. You feel no astonishment, therefore, when you come to other doors which do not admit to mahogany and bright curtains, but to the noises and dark business of the pit; you may see, down below, little figures most intent on whatever duties have to be performed about eternal fires and boilers.

Therefore literature? No, nor flower boxes. Besides, this ship and its men are as good as some books, and better than others. In the early days of the voyage I felt no desire to read. Yet one night the initial interest in the novelty of my new home wavered. There was[41] no sound but the creaking of a piece of unseen gear and the monody of the waters. There was nothing to do, and the last word had been said. That was the time when a book would have helped. But I knew it would be useless to look for aid to the kind of books which go to sea. I recalled other voyages and their chance volumes. Easy reading! Yet to take to sea what has the comical name of “light literature,” because that is the stuff to read there, is an insult to one’s circumstances, where ignorance and light-mindedness are ever in jeopardy and may be severely handled. Anyhow, I do know that the sea converts that kind of confectionery into sodden, dismal, and unappetizing stuff.

There was nothing for it but patience. Mine had been rather a hurried departure, and, except a few geographical and other reference works, I had nothing with me but a Malay grammar, and so far the grammar had too easily repulsed my polite and insinuating advances upon it. Our ship is an extensive and busy place, managed in a way which shows an exclusive attention for the job, and so I did not betray my interest in literature till one day I saw a cadet with a likely volume. It turned out to be the Iliad, in Derby’s translation. I was so impressed that I mentioned this curious adventure to the captain.

He thought nothing of it. “Our ship has plenty of books—part of our gear. Come with me.” He showed me a bookcase for the boys—I had passed the place where it stood scores of times and would never have guessed so much was secreted there. Excepting for some transient volumes of fiction, changed whenever the ship is home again, the books in that case would have[42] shown a country parsonage to have an horizon strangely beyond the parochial confines.

There was the Odyssey, the Oxford Book of English Verse, Milton, Wordsworth, Tennyson, Know Your Own Ship, Lubbock’s China Clippers, Green’s Short History, a history of China, Japanese and Malay grammars, volumes on engineering and navigation. Ball’s Wonders of the Heavens, the Oxford Dictionary, Wallace’s Malay Archipelago, books on sea birds, books on marine zoölogy, books enough to keep one hunting along their backs for something else unexpected and good. And in this very place where I had imagined that I was cut off from letters, the captain, casually at breakfast one morning, gave a frank judgment on a recent novel, and his reasons for his opinion were so sparkling and original that I saw at once what is the matter with the professional reviewing of books. In the place where I had guessed that letters were nothing, the significance of the popular reading is such that it would break the heart of a sensational novelist to see it, and might drive him to seek his meat in the more useful mysteries of crochet work.

Port Said Is More West Than East

June 6.—The southwest monsoon has broken. The heat and languor of the Red Sea are being washed from us by the Gulf of Arabia. The decks have been wet and lively to-day. The ship is rolled by quick and abrupt waves heaping along our starboard side. The waters recoil from our bulk, and the sun shining through their translucent summits gives the tumult brief pyramids of beryl. There are acres of noisy snow, and clouds of apple-green foundered deep within inclines of dark glass. Spectra are constant over the forward deck,[43] where the spray towers between us and the sun, and drives inboard. After a nasty lurch I hear more crockery smash below. One of the other two passengers, the young Scots farmer who has left his Ayrshire oats to see whether rubber trees are better, and who had fancied at the first trial that he was a proved sailor, now seems to miss the placidity of his cows. He groans. At first I was a little doubtful about myself, but bluffed the Gulf of Arabia into supposing that it was a mistake to take me for a longshoreman; yet for a mysterious reason, so uncertain is the soul and its uninvited thoughts, I have had “Tipperary” running through my head all this day—music, one would think, which had nothing to do with monsoons; and thoughts of Paris, and the look of the English soldiers of the Mons retreat I met long ago. Why? How are we made? For here I am, with nothing to remind me of Crépy-en-Valois, climbing companion ladders where ascent and descent are checked at times by an invisible force, which holds me firm to the reality of a ship at sea. And yet “Tipperary,” that fond and foolish air, will not leave me. I wish I had the clew to this. After sunset, in a brief wild light, it was a test of the firmness of the mind to be on deck. The clouds, the sea, the horizon, were a great world displaced. The universe with its stars swayed giddily at bonds that threatened to burst at any moment, and away then we should have gone into space. It is darksome to see very heaven itself behaving as though it were working loose from its eternal laws. An anarchic firmament?

June 7.—Bracing myself last night in my cot, from which the ship tried to eject me, I read Kidd’s Science[44] of Power. The captain had commended it to me, saying it was one of the best books he had ever read. Now, would it have been possible before 1914 for a book which describes the theory of mankind’s inborn and unalterable nature as blasphemous nonsense, and condemns civilization based on force, to win so handsome a tribute from such a tough character as our skipper? Kidd declares that it is the psychic condition of a people which matters, and that their outlook on life can be changed in a generation. He says the collective emotion can be charged for war or for peace. That our captain, who had his share of war, should have been moved by such an idea, need not surprise us to-day. Kidd’s theory is proved by our skipper’s own eagerness in this new hope. But the prophets and all the artists who have never served in the House of Rimmon have always held that faith, and have worked in its light. Otherwise they would have cursed God and then have cleared out of this world by a short cut. All the material manifestations of our civilization, which are thought to be from everlasting to everlasting, are nothing but the reflections of our commonest thoughts, and may be changed like lantern slides. The better world will be here as soon as we really want it. It depends on how we look at things. I recall a school anniversary, and a brigadier as the central light to shine on assembled youth. He advised the boys to take no notice of the talk about the brotherhood of man; man always had been a fighting animal; war was a fine training for our most manly qualities; with God’s help we had to prepare for the next war, which was sure to come; all this peace nonsense was eye-wash. It was plain that[45] brigadier felt he was the very man to scrawl upon the virgin minds of children, as indeed our applause assured him he was. But suppose we pose the problem of the education of boys on the same plane of intelligence, though from another angle. Let us imagine the governors of that school had invited a painted lady to address the boys, and that she had assured them that they should laugh at this nonsense of the virtue of man, for man is a lecherous animal and concupiscence brings out all his lusty qualities, and therefore they should prepare for riotous nights because all the talk of honor and a fastidious mind is just eye-wash. What would careful parents think of that? But would the outrage be worse than the brigadier’s?

We have four cadets, and they make the best-looking group of our company. They move about lightly in shorts and singlets as though they were enjoying life in a delightful world. I stand where I can see them unobserved. They reconcile me to great statesmen, brigadiers, Bottomley, and the strong silent men. It is dreadful to think that soon they may lose their jolly life and become serious lumber in the councils of the world, and very highly respected.

June 8.—Rain came like the collapse of the sky at six o’clock this morning. Numerous waterfalls roared from the upper works as the ship rolled. The weather cleared at breakfast time, and immense clouds walled the sea, vague and still, and inclosed us in a glittering clammy heat. Perhaps it was the heat that did it, but certainly the ship’s master revealed himself in another character. Our captain has the bearing and the look of a scholarly cleric. He is an elderly man, with a lean, grave face,[46] though his gray eyes, when they meet yours, have a playful interrogatory irony. Luckily he is clean shaven, so that I may admire a mouth and chin which would become a prelate. His thin nose points downward in gentle deprecation. A few men, under the bo’sun, were at some job this morning on the captain’s bridge, where we have our few staterooms. The bo’sun is a short fellow, with the build of a higher anthropoid. If he began to strangle me I should not resist. I should commend my soul to God. I have not seen him bend iron bars in those paws of his, but I am sure that if a straight bar ever displeases him he will put a crook in it. And he knows his job. He is always waddling about rapidly, glancing right and left with scowling dissatisfaction. There he was this morning on our bridge, where I was enjoying early morning at sea in the tropics while trying to keep clear of the men at work. Our captain stood near me, indifferent to my existence, and apparently oblivious even of the ship and its place in the sun. The bo’sun, growling in his throat, and lifting in indication a brown and hairy paw, was keeping the men active and silent. I don’t know what happened. But the captain turned; he regarded for several seconds in silent disfavor the bo’sun, the men, and their job; then there was a sudden blast from him which made all the figures of those seamen appear to wilt and bend as in a cruel wind. The captain did not raise his voice, but with that deep and sonorous tone which in the peroration from a pulpit shakes the secret fastnesses of wicked souls he stated how things looked to him in similes and with other decorations that increased the heat and my perspiration till I looked around for the nearest ladder out of it.

June 9.—I met the chief engineer in an alleyway of the main deck. We stopped to yarn, for we have become no more intimate yet than is possible across the mess-room table. One of his Chinese firemen squeezed past us as we were talking, and the chief’s eyes followed him. Then he chuckled. “I found that man below last week with a bit of spun yarn round his throat. He was pretending suicide, and kept up the joke to amuse me. The Chink said, ‘Me all same Jesus Clist.’ I told him he was wrong. Christ did not commit suicide. Christ was topside man, not a devil. That Chink was quite surprised. He shook his head. I could see he did not believe me. Nothing that I explained to him convinced him that Jesus was not a devil. ‘Clist no devil? Velly good.’” The fellow smiled bitterly and shook his head at the joke. It took me some minutes to get at his idea, and from what I could make out that Chink thought it was incredible we should go to any trouble about a good man. Good spirits would do us no harm. People only kow-tow to devils they are afraid of.

June 10.—We are nearing the Laccadives. A dragonfly passed over the ship on the wind. The wind is southwest, and the nearest land in that direction is Africa, over one thousand miles away. Some day a sailor who has a taste for natural history will give us the records of his voyages, and his notes may surprise the ornithologists, at least. Our men caught a merlin in the Red Sea, which was quite friendly, and took its own time to depart when it was released. Another day, while in the same waters, I was looking at a group of Chinese, firemen sprawled on the after hatch and was wondering where in England a chance group of workers could be[48] found to match those models, when a ray of colored light flashed over them and focused on a davit. It was an unfamiliar bird, and I began to stalk it with binoculars while it changed its perches about the poop, till it was made out to be a bee-eater. Then I found the chief mate was behind me, intent also with his binoculars. We had some bickering about it. He said the bird was a roller; but I told him he should stick to his chipping hammer and leave the birds to better men. He said he would soon show me who was the better man, and escorted me the length of the ship to his cabin, where he produced a bird book, which was a log of several long voyages to the Far East. Like so many sailors to-day he is versed in several matters which we landsmen think are certainly not the business of sailors at all. He has been keeping a log of the land birds which he has recognized at sea, and his record suggested what an excellent book a sailor, who is also a naturalist, may write for us some day.

This sailor had observed for himself, what naturalists know well enough, that the gulls are not sea birds at all in the sense that are albatrosses and petrels, and the frigate and bo’sun birds of the tropics. When you see gulls, then land is near, though dirty weather may hide it. The herring gulls, kittiwakes, and black-backs never follow a ship to blue water. When, outward bound, land dissolves astern, then they, too, leave you. You may meet their fellows again off Ushant or Finisterre if your ship passes not too far from the land; but should you be well to the westward, then the ship’s next visitors will be land birds when approaching Gibraltar.

Several pairs of noddies kept about the ship at the[49] lower end of the Red Sea, and not because of anything we could give them except our society. They did not beg astern, like hungry gulls, for scraps, but wheeled about the bows, or maneuvered close abeam like swallows at play. As a fact, I think they were tired and wanted to rest. Once or twice they alighted on our bulwarks and went through some astonishing aërial acrobatics while their tiny webbed feet sought the awkward perch.

After sundown one actually tried to alight on my head, while I stood in the dusk on the captain’s bridge watching its evolutions. It swerved and stooped so unexpectedly that I ducked, as one used to at the sound of a shell going over. But soon it alighted behind me, and it made no more fuss about being picked up than though it were a rag. It was only a little sick, but got over that, and settled down on the palm of my hand. A group of shipmates were overworking a gramophone below on a hatch, where lamps made the deck bright. Down went the noddy and I to them. Our visitor cocked an eye at the gramophone and took quiet stock of the men who came round to stroke it. It accepted us all as quietly as though it had known us for years, and this was the usual routine. It heard its mate later, or else our musical records were not to its taste, for it shook itself disconsolately, waddled a little, and projected itself into the night.

Last night the surgeon brought to my cabin another visitor. It was a petrel, about the size of a blackbird, and of a uniform dark chocolate color. We judged it was uncommon, and there was a brief hint of chloroform, which was immediately dismissed, for our captain[50] might have objected to any modern version of the Ancient Mariner’s crime on his ship, even in the name of science. We enjoyed our guest in life till it was pleased to leave us.[1]

June 11.—The south end of Ceylon was in sight twenty miles distant on the port bow at 2 P.M. I did not notice any spicy breeze, but the water had changed to an olive green. The coast was dim as we drew abreast of Dondra Head, but the white stalk of its beacon was distinct and the pulsing light of the combers. We seem to have been at sea for an age. The exposed forecastle with its rusty gear, where I feel most at home, has become friendly and comforting. You are secluded there. You are elevated from the sea and outside the ship. The great red links of the cable, the ochraceous stains on the plates, the squat black winches like crouched and faithful familiars, the rush and gurgle of fountains in the hawse pipes when the ship’s head dips, the glow of the deck and the rails, like the grateful warmth of a living body, and the ancient smell, as if you could sniff the antiquity of the sea and the sweat of a deathless ship on a voyage beyond the counting of mere days, give me a deeper conviction of immortality than all the eager arguments from welcome surmises. I am in eternity. There is no time. There is no death. This is not only the Indian Ocean. Those leisurely white caps diminishing to infinity, the serene heaven,[51] the silence except for the sonority of the waters, are Bideford Bay, too, on a summer long past, and the Gulf Stream on a voyage which ended I forget when, and what Magellan saw in the Pacific, and is the Channel on our first passage across, and they are the lure and hope of all the voyagers who ever stood at a ship’s head and looked to the unknown. They are all the seas under the sun, and I am not myself, but the yearning eyes of Man. To-day, when so disembodied and universal, leaning on the rail over the stem, both the confident interrogation and the answer to the mystery of the world, a little flying fish appeared in the heaving glass beneath me, was bewildered by our approaching mass, and got up too late. He emerged from a wave at the wrong angle, and the water and draught flung him against our iron.

[1] Later, Mr. Moulton, of the Raffles Museum at Singapore, showed me a rarity, one of the six specimens taken of Swinhoe’s fork-tailed petrel. Our little friend of the Indian Ocean was at once recognized and named, and his visit to our liner added something new to our knowledge of his kind, for it was unknown that he was likely to be found so far to the westward.