Title: Everybody's business

Author: Agnes Giberne

Release date: October 22, 2024 [eBook #74626]

Language: English

Original publication: London: John F. Shaw & Co., Ltd

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

"You haven't been to see us for ever so long."

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

AUTHOR OF

"OLD COMRADES," "LIFE-TANGLES," "WON AT LAST,"

ETC. ETC.

NEW EDITION

John F. Shaw & Co., Ltd.

Publishers

3, Pilgrim Street, London, E.C.

CONTENTS

CHAP.

XII. WHAT LIFE LOOKED LIKE TO MILDRED

XIII. SOMETHING FOR MILDRED TO DO

XVIII. WHO COULD HAVE SENT IT?

EVERYBODY'S BUSINESS

THE VILLAGE OF OLD MAXHAM

"IT'S getting to be a regular storm! What a lot of storms we have had lately, to be sure! Just hark to the wind," said Jessie Perkins. "And I do believe I can hear the waves down at the Point. I do believe I can."

Miss Perkins sewed on solemnly. She was seated at the round deal table, with her shoulder towards the light.

"Aunt Barbara, you just listen. . . Can't you hear the waves? I can! . . . Mrs. Mokes will have it that nobody's ever heard them as far off as this; but I know better. I've heard them many a time at night, when it's rough; and I declare I can now. You just hark!"

"There isn't over much chance of anybody hearing anything, except your clapper, when you're in the room," Miss Perkins observed with severity.

"But I stopped talking twice on purpose, and you wouldn't try to listen. There it is again—a regular boom!—as clear as can be. And it's getting so dark. I can't think how ever you can manage to see at all, away there at the table. It's all I can do to thread my needle here."

"I'm not so desperate fond of staring out o' windows as some folks," snapped Miss Perkins.

Jessie sighed audibly, and took another peep through the clustering plants which intercepted her view of the outside world. It was not easy to see anything clearly, with so substantial a screen in the way. She had, however, a distinct glimpse of the shop opposite, beyond the wide and irregular village street, also of a group standing on the flagged pathway in front of the said shop.

"Something is the matter. I am sure something is the matter," she murmured, deeply interested.

Jessie allowed her work to fall upon her knees, whence it slid to the ground. Her pretty little short face, neatly rounded and rosily coloured, became altogether absorbed in what was going on across the road.

"I'll have that window blocked up some day,—see if I don't,—the bottom half of it," burst out Miss Perkins. "That's what I'll do."

Jessie had perhaps heard the threat before. "But where's the hurry?" she asked. "I've heaps of time, aunt Barbara. You said yourself I shouldn't need those night-dresses till next winter; and March isn't out yet. Just hear the wind! What a howl! I wish I was out in it . . . Something has happened somewhere, I'm quite sure. Mr. Mokes is all in a taking. And there's Mr. Gilbert, and a sailor,—I think it's Robins,—and—and there's Ben too."

Jessie's face grew more pink. Not that she cared a brass farthing for Ben Mokes; but he was one of her admirers, and she did care for admiration.

"Ben Mokes is as idle and useless a young spendthrift as ever lived," commented Miss Perkins. "I wonder at his parents for letting him go on as he does. I wouldn't! I'd make him work, or I'd send him about his business. Old Mokes just slaves, and Alice Mokes like another; and Ben don't do a single hand's turn that he isn't obliged. But there! They've spoilt him all through, and they've got to reap as they've sowed. He'll come to no good, nor nobody else that he has to do with."

This outburst seemed to amuse Jessie immensely. She had to bite her lips to keep in laughter.

"Poor Ben! Oh, he's well enough, aunt Barbara. He isn't handsome, and he's awfully lazy and rather stupid, but I don't see how he can help that. People can't help being stupid when they are made so. Can they?"

Miss Perkins did not feel herself competent to answer this question. It involved too much. She sewed in a persistent and combative fashion, the droop at the end of her thin pinched nose very near indeed to her needle. Perhaps her sight had begun to fail a little, for she was well over fifty; besides, it was uncommonly dark and dull for only half-past four o'clock on an afternoon in the end of March. Twice she looked round with indignant protest at the window, as if somehow it were to blame.

"I can't possibly see to work any more. I couldn't if you paid me for it," Jessie observed. "I'll wait till we have lights, or till it gets clearer. It's hours too early for lights yet. I don't see the good of sitting here doing nothing . . . Aunt Barbara, there is something wrong, and I'm going to see what it is. Don't hinder me. I must go."

Miss Perkins gazed in grim disapproval after the girl's retreating figure, and said nothing. She pretty well knew the extent of her own restraining power, and she did not often risk a battle where she could not be secure of victory. But, oh, the ways of these giddy young folks! Miss Perkins shook her head over them all, including Jessie.

Even while Jessie chattered the wind had been audible enough, and now nothing hindered her from listening. It came in rushes, with a roar each time as of a great gun, swirling round the cottages, bending trees like reeds, shrieking in the chimney, and making Jessie's light figure stagger as she struggled across the road. She had caught up a small woollen shawl, wrapping it round head and shoulders. Though Jessie wanted greatly to know what was wrong, she was not in the least alarmed or anxious. It only formed a nice excuse for getting away from the needlework which she abhorred.

But other people viewed the matter after a more serious fashion, and Jessie speedily found herself close to a troubled and intent group; far too much troubled and far too intent to pay any attention to her little self.

The village shop, outside which they were gathered, stood back, country-wise, in its own garden, where in summer stray ramblers from the neighbourhood were wont to sit and have their tea. On the front flagged pathway, between door and gate, stood Mokes himself, a man of elderly middle age, bareheaded and aproned. His manners were marked by mild suavity and by an air of proper dignity. His face was all over of a reddish tan, the nose thickish, but well-shaped; the light-tinted eyes, under bushy brows, keen and benevolent; the grey hair brushed upwards, converging to a point. Gusts of wind creeping round a corner of the house blew his apron to and fro in vehement jerks; but Mr. Mokes stood with an unruffled air and an expression of solemn concern.

Mrs. Mokes, having no customers on hand, was peering out of the front door; and Ben Mokes, her hopeful youngest, a limp lanky youth, lounged in his father's rear. Only Alice remained within. Somebody had to see to things, and Alice, as a matter of course, was that somebody.

Before Mokes stood a weather-beaten sailor, or rather fisherman, in blue jersey and sou'-wester; and beside him was a boyish-looking smooth-shaven individual, in black coat and white necktie, the new Vicar of Old Maxham. Judging from appearances, he might have been under one-and-twenty; but since he had already filled two Curacies, remaining in each about two years, and since no man can be ordained under the age of twenty-three, it is obvious that in his case looks were deceptive. The youthful features of the Vicar showed excitement.

"And you actually mean, Mr. Mokes, that there is no lifeboat nearer than twelve miles off!" Mr. Gilbert gave vent to these words, just as Jessie arrived on the scene, in an extraordinarily deep voice, which no one would have expected from his boyish appearance. "Twelve miles off, with such a coast, such rocks, such currents, as yours!" He had not been in the place a fortnight, and the pronoun "our" did not yet come readily.

"That's so, sir," admitted Mokes, with an air of regret. "It hadn't ought to be; and times and again we've talked over what could be done. But there's a lot of difficulties in the way."

"Talked! Ah, I see! Every time a ship goes to pieces on your rocks, you talk about a lifeboat. And then, when the storm is over, you forget it all,—till next time! That's it: eh?"

Mokes shook his head mildly. He "supposed it had ought to be seen to, but he didn't know; it didn't seem to be nobody's business in particular."

"It's everybody's business," declared Mr. Gilbert. "And it's a disgrace to Maxham to have no lifeboat. I don't care who hears me say it. A disgrace to Maxham!" The speaker's fair boyish face flushed, while his deep tones rolled down the street. "See now, if, instead of talking, you had all clubbed together and bought a boat, those poor fellows who are coming to their death upon the rocks might have been saved, one and all of them. Do you think the people of Maxham won't be reckoned accountable for the untimely death of those poor men? I tell you it's everybody's business, and everybody has a share in the responsibility."

Mokes could have been offended; but he remembered that it was the Vicar who spoke, and also that the Vicar was young.

"At all events, that reproach shall not lie upon Maxham much longer. I'll start a subscription for the boat next Sunday." Mr. Gilbert came from a large town, and, as everybody knows, a subscription list in a town is the panacea for all evils. "Why it hasn't been done before passes my comprehension. Well, but look here—what's to be done now? We can't leave those poor fellows to rush on their death without an effort to save them. Women on board, too, you say."

"Adams was sure he see'd one, sir, through his glass. But he doubted no boat could live in this sea, without it was a lifeboat."

"We can try; always possible to try. Better to die doing our duty than to live with the duty left undone!" The "our" came naturally enough here. "Out of the question that the lifeboat should arrive in time. She'll be on the rocks in less than an hour, and it will be short work then. Whose is the best boat? And who can row?"

Mokes gently rubbed the side of his head, surveying the speaker with dubious eyes.

"Come! Whose boat shall it be? And who will man it? I'm the first volunteer."

"Then I'm the second," added Robins. "I'll never be the one to hold back, though I doubt it'll be no good. They're doomed, poor chaps."

"No man is doomed while life remains—at all events, so far as our knowledge is concerned. Here are two of us ready, and we may count upon Adams. He is old, but he knows every inch of the rocks, and he must steer. Adams will be the third, I don't doubt. Who's fourth?"

"Here's your fourth, sir," a voice said behind; and at the sound Jessie clasped her hands under the shawl which she wore. A lithe well-built young fellow stood outside the gate. At sight of him Mokes' face fell, and on the younger Mokes' brow might be noted an unpleasant scowl.

"Right, my lad! And your name?"

"Jack Groates."

"Good at an oar?"

"Yes, sir."

"You know what it's for? A work of danger."

"Yes, sir, a barque drifting on to the rocks."

"She's disabled, and she'll be on them in less than an hour. If she doesn't break up with the first crash, we may get off the crew. But it will be a ticklish job. Ready?"

Jack Groates nodded.

"Then the sooner the better. Any more volunteers?" Mr. Gilbert looked towards young Mokes. "Are you good at rowing in rough weather?"

Ben Mokes knew himself to be probably as good as Jack Groates, but he said nothing, and a shrill voice sounded in his rear,—

"Not our Ben! Ben's not to go. You hear, Ben! You ain't going!"

Ben shuffled sheepishly from one foot to the other. Jessie's eyes sparkled, as the three started off at a swinging pace, and Mrs. Mokes came out with a red face of indignation.

"I never heard of such a thing in all my born days! To be wanting our Ben, the only boy we've got! Why, they'll all be drowned, as sure as fate."

"It's as bad for others, I s'pose, if they are," burst out Jessie. "Jack Groates has a mother too."

"He's one of seven; that's all the difference," retorted Mrs. Mokes. "You go home, Jessie, and don't be talking of things you can't understand. And you just tell your aunt—"

"Not yet. I'm going to take a look at the shore first and see what's doing."

"Of all idle girls—" began Mrs. Mokes. "Well, I'm sure Miss Perkins has a handful of her, and no mistake."

Jessie did not wait to hear the latter half of this utterance. The wind was cold as well as boisterous but she folded her shawl more closely round her, and set off at full speed for the nearest part of the distant shore—that jutting rock which was known among them as "Reef Point." Many and many a good vessel had come to grief on those rocks.

A BRAVE VENTURE

THE fishermen's cottages near Reef Point were strictly an outlying part of Maxham, possibly a more ancient part than even the village; but they were commonly distinguished as being simply "down at the Point."

Despite the perilous nature of the coast, these very rocks would, when the wind was westerly, make something of a sheltered semi-harbour between themselves and the shore. In fair weather it was no such bad place for fishing; and when rough weather came on from the east, the boats which were out made no attempt to get back to Maxham. They would take refuge in the next fishing village, and await a favourable change. The fishermen of Maxham were a hardy race; and their wives had grown used to a life of suspense. If a storm broke, they were well pleased not to see their husbands' boats near land.

An unwonted stir was created when the young clergyman, with his two companions, dashed into the hamlet, demanding volunteers. Attention was already, of course, wide awake on the subject of the unhappy barque; though nobody supposed that much could be done. The men at first held back, and the women threw their influence into the safe side of the scale. But when it dawned upon them who was the first volunteer, when they looked into Mr. Gilbert's face, and heard his deep eager indignant voice, opposition wavered. How could they continue to hold back, when a clergyman and a shopman were willing to go?

It might be just possible that a boat could approach near enough, when the barque drifted on the rocks, to save any men who threw themselves overboard, or who could be hauled in with a line. All agreed that to attempt to get beyond the reef, through one of the narrow openings in it, would, in such a sea, be worse than madness. But at least it was worth making the venture of doing what they could. In a very short time the crew was complete, and the chosen boat was down at the water's edge in readiness.

By this stage Jessie had arrived on the spot, cold and blue-lipped, despite her run, with a chill at her little heart. She stood somewhat apart, looking on forlornly; and there Jack Groates caught sight of her.

He dropped a rope, and sprang to her side. The attention of everybody else was bent upon the tossing helpless barque, dimly seen at intervals in the offing. In Mokes' garden Jack Groates had barely acknowledged Jessie's presence, partly because his mind was full of another matter, partly because he knew what the Mokes family felt about his family, and he did not wish to draw blame upon Jessie. Now, however, there was not the same restraint.

"Jessie! You here! Whatever did you come for?"

"I wanted to see—" Words failed, and she clutched a corner of her shawl between two chilly hands.

"Don't stay. Go back straight home. It isn't fit for you to be here. You're like ice."

"You won't—won't—" she struggled to say, "won't get into danger?"

"I'll do my duty, I hope. Danger may take care of itself."

"I don't want you to get hurt."

He just caught the words.

"Now look here, Jessie, you're to go back home directly. It's no good your staying, not one scrap. I've got to be off; and you can do something for me. Go and tell mother about it. Tell her I'm come because it's right, and I hadn't a moment to look in and see her. If she'd a boy on board, she'd want folks to try and save him; and there's some mothers have got boys on board. Tell her to think of that. Promise me you'll go."

"Yes," faltered Jessie.

"This very minute?"

"Yes."

"And you won't look back?"

"I'll—try not."

"Groates!" shouted a voice.

"Mind! You've promised!" And he was gone.

Jessie kept her word. She turned her back upon them all, and went swiftly up the rugged road, with furze bushes on either side, never pausing till a higher spot was reached, whence she knew she could command a good view of the sea she had left. Jessie hesitated then; and the temptation proved too strong. She had not actually promised to give no backward glance.

One look, and she stood rooted to the spot. At that instant the boat, just launched and not two strokes from the beach, was caught in the grasp of a huge swell, which turned her round broadside to the land, and flung her back, bottom up. Her crew was scattered right and left.

No sound left Jessie's lips. She only stood like an image, staring, till one and another swam or struggled to shore. All were there, safe so far and apparently unhurt. Another trial would be made; Jessie saw so much. Then, remembering her promise, she once more turned away and went on along the lonely road, with a weight pulling at her heart. Who could say whether she would ever again look Jack Groates in the face?

It seemed, oh, such a pity for Jack to risk his life. Not that she would have liked Jack to be willing to hold back. Jessie thought with scorn of Ben Mokes, lazily safe at home. And yet it did seem such a pity!

Jessie had hardly known till to-day how much she cared for Jack. Barely nine months had elapsed since first the elder Groates had set up his shop in Old Maxham, and Jessie had learnt very gradually to know the family. She knew them now well, and she liked them all, unless the father were to be excepted; but certainly Jack stood first in her estimation.

And perhaps he would be dashed to pieces on those cruel rocks. Jessie was aware that just such an attempt had been made before, with a common boat, some three or four years earlier; and she remembered too well the result. Not a man of the little crew had come back alive. Then she tried to comfort herself by murmuring that that storm was worse than this.

Jack's message had to be taken to his mother the first thing. So she made her way to the western end of the main village street, and was soon standing outside the rival establishment, which was distinguished from Mokes' "shop" by the more Yankee name of "store." Jessie waited a moment. Then she slipped softly in, passing without a pause to the room behind. Business being slack that afternoon, Mr. Groates stood alone at the counter, and since he was occupied in lifting down a big canister from a high shelf, he did not even see Jessie's entrance.

In the back room was Mrs. Groates, a plump genial blue-eyed little body, with a smile like Jack's own and a motherly tenderness which had quickly won Jessie's heart. Of the seven children, six were still at home. The boy next after Jack had gone to sea. Then came Mimy, a girl of fifteen, three more boys, and one little girl. The four youngest were at school when Jessie stumbled into the room. A sudden realization of what she had to say almost overcame her.

"Why, Jessie, so it's you!" exclaimed Mrs. Groates. "We haven't seen you for days. Dear me, what an afternoon it is, to be sure! Come along and sit down by the fire, and tell us all the news. How is Miss Perkins? Why, child, you're as cold as anything. What's come to you, and where have you been?"

Jessie could not utter a word. She could only shiver. Mrs. Groates pulled her closer to the fire, and set a kettle on the glowing coals.

"I'll make you a cup of tea as sharp as can be. Just to think of you walking out in this bitter wind, and nothing on but a little thin shawl! You don't half take care of yourself, child."

She began rubbing the girl's chilled fingers between her own plump cushion-like palms; and Jessie had difficulty in checking a sob. It was dreadful to think of bringing a cloud upon that cheery face.

"I shouldn't wonder but Miss Perkins has been scolding her for something or other," thought Mrs. Groates. "It's too bad, though folks do say that her bark is worse than her bite; and she's really fond of Jessie." Aloud, Mrs. Groates asked, "Nothing gone wrong, I hope! Eh, dear?"

Jessie faltered and had a struggle to get out the words. "It's a barque," she said. "It's got dismasted; and its coming right upon the rocks."

"Dear, dear! That is bad! I don't wonder you're upset. And in this storm I s'pose there's scarce a chance for any of them. Poor things!"

"The lifeboat has been sent for; but they say it can't be here soon enough to do any good. And a boat's gone off from down at the point."

"Well, now, that's plucky, ain't it? Right enough, too! But it must be an uncommon rough sea. I hope no harm 'll come to any of them. You don't know which of the sailors is gone?"

"Adams—and Mr. Gilbert—and—"

Jessie turned her face away, and an anxious look crept into the other's eyes.

"Poor little dear!" she said, and she kissed Jessie's cheek. "You're quite upset with it all. Now, now, I wouldn't cry; there's no need, and I dare say it'll all come right. Mimy, that kettle's on the boil; it hasn't been long took off. Get out the teapot quick. Jessie will be a deal better when she has had a hot drink. Don't you fret, dearie! Things often aren't half so bad as we expect, you know. Come, cheer up! Now you shan't say another word till you've had your tea."

After a few sips Jessie was able to master the inclination to cry whenever she tried to speak. "I oughtn't to have been so silly," she said; "but I didn't know how to say it. I'm so very very sorry for—" and a break—"for you."

"Finish that cup first, Jessie . . . That's it! Now you'll be better . . . Sorry for me, are you? Then it's something to do with Jack. What has he been doing? Nothing wrong, I know."

"Oh no, nothing wrong! Only Mr. Gilbert persuaded them to try having the boat out; and he asked for volunteers. And—Jack—"

"Jack was one of the first, wasn't he? Why, of course he was! Of course he was! He wouldn't be my Jack, if he was one to hold back!" Mrs. Groates spoke bravely, though her lips twitched.

"He's a brave boy; he always was; and always ready to help other people, specially if it's a woman or child. Perhaps there's women on board."

"Yes, there is one," said Jessie, "and Jack knew. And he told me—he told me to tell you—" Jessie could not get on.

"Yes; he told you to tell me—You must tell me, Jessie. I've waited patiently till now; and I can't wait any more." The little plump woman spoke almost sternly. "Tell me, dear; you can cry afterwards."

"He said—said—" sobbed Jessie, "he was going—going—because it was right. And he said, if—if you had a boy on board, you'd want him to go. And he said some mothers had got boys on board."

"He's right, too."

Then Mrs. Groates took down her bonnet from inside a cupboard, where it hung on a nail.

"Mimy, you'll have to keep shop. I'm going, and I shouldn't wonder but father 'll want to go too. Whatever happens to Jack, I'll be there to see, and you must stop here. Maybe Jessie 'll keep you company for a while. There won't be many come in to buy. Folks' heads will be full of this. Jack's a dear brave boy; that's what he is."

"And you don't mind?" sobbed Jessie. "I didn't know how to tell you."

"Mind! Is that all you understand? I'd mind if my boy was afraid to do his duty! But—all the same—Jack's the apple of my eye—and if anything was to go wrong with him—"

Mrs. Groates for a moment hid her face in both hands, and her whole frame heaved and shook.

"Don't, please," entreated Jessie.

"I'm not going to,—not now! There's time enough by-and-by. I've got to see what they're doing now, first. Anyway, I know one thing: my Jack 'll be doing his duty."

Mrs. Groates smiled with the words, though it was a smile nearer akin to tears than to laughter; and by this time her face was quite white all over. Then she walked off, folding her shawl around her; and the girls could hear her voice in the shop, saying firmly,—

"There's a vessel drifting down upon the rocks, Jim, and a boat has gone out to help the sailors; and our Jack's gone in the boat."

Something in Groates' hand fell clattering to the ground.

"Jack!"

"Yes, our Jack. Why, of course he'd be the first to go, if he had a chance. And he's as good as anybody with his oar. I'm off straight to the Point. And if you want to come too, Mimy 'll keep shop."

"Jane, you'd best stop here. I'll go!"

"I'm not going to stay, not for anybody," was the resolute answer. Then there was silence.

"Jessie, I do hope nothing 'll happen to Jack," sighed Mimy. "I don't know how ever mother would bear it."

UPON THE ROCKY REEF

ADAMS had been in the right when he thought he saw a woman on board the barque "Sunlight." There was a woman, the Captain's sister; and there was also a little baby girl, the Captain's child.

They had come in for very bad weather this voyage. A heavy gale, lasting two days, had carried away the masts and gear. Jury-masts had been rigged, but another terrible storm carried these also by the board, and washed away a great portion of the gunwale. Somewhat later both the rudder and the boats were swept clean away, and three of the crew went with them. After this the disabled barque could do little more than drift whither wind or current should bear her. A brief lull succeeded: but before any other vessel could be sighted and summoned to her aid, the weather again changed for the worse, a fresh gale coming on. The damaged ship was now steadily nearing the shore, and a long white gleam of breakers ahead spoke of hidden rocks.

On the deck stood a young woman, probably under thirty, her serious eyes bent landward, and one hand resting on the head of a large powerful Newfoundland dog, while the other held fast to a rope, as she swayed to and fro with the heaving of the ship. She looked both grave and sad. A dark ulster clothed her from head to foot, and she wore a round sailor hat, with a black ribbon.

Mildred Pattison had lost both her parents in one week, shortly before starting on this voyage with her brother and his wife; and only two weeks before this date her brother's wife had been left below the deep Atlantic waters. No near relative remained to her on earth save her brother and his little one. Now death stared them all in the face. Captain Pattison, a bronzed and kind-faced man, many years older than herself, made his way to her side. He too looked sad and anxious.

"It's a bad look-out, Millie."

"If we go on like this, we shall soon be on those rocks," she replied. It was not easy to make him hear, though she had a penetrating voice.

"We're setting for them straight. The wind and tide are carrying us fast to leeward."

"And nothing can be done?"

He made a negative sign. "They see us from the shore. Perhaps they'll try something or other. But look at those breakers. Not much chance for us when we get among them!"

"I'll bring Louey on deck. She was sound asleep, and I left her for ten minutes. Poor little dear!"

The Captain sighed. "I'm glad to think Lucy passed away as she did—so peacefully. Do you remember what a still day it was, just before all our troubles began?"

Millie nodded, with moist eyes.

"She wasn't frightened to go, but she'd have been frightened at this. Louey's too young to understand, and that's a mercy. Well, going Home early means being spared a lot of trouble."

His strong voice, well used to making itself heard against boisterous winds, reached Millie more easily than hers reached him.

"I wonder if Lucy sees us now," she murmured.

"I shouldn't wonder if we're all together again this evening—you and me and Lucy and little Lou—up there." For an instant the Captain half bared his head, despite the bitter blast, with a reverent upward glance, and a light of hope sprang into the bronzed features. "So long as One is aboard, it don't much matter which way we get into port."

"Is HE aboard?" questioned Millie to herself. Then aloud, "I don't seem to feel anything much, Phil, good or bad. I'm stupefied with all I've gone through this last year."

The Captain's hand came on her shoulder. "Poor Millie! Poor old girl! But HE knows what's best for us, Millie."

"Hadn't I better get Louey on deck?"

"Don't wake the child. If she's asleep, let her sleep."

"Yes, but, Phil, I can't stay down there any longer, boxed up." Millie shuddered. "I must see what's coming. And, Phil, listen to me. Phil, remember one thing: you are to look to Lou. If anybody can do anything for me, Hero will do it. You've got to save little Lou, for Lucy's sake."

"God bless you, Millie. You're a brave woman."

"Am I?" A smile flickered, as she thought how little he could guess at the deadly heart-sinking below. "I hope I know what is right, at all events."

Perhaps he failed to catch her words. His eyes were strained shoreward as the barque swayed and lurched under their feet, tossed to and fro by the surging billows, which again and again broke over the deck. It was marvellous how Millie managed to stand at all.

Each minute the broad irregular line of breakers seemed to draw nearer; each minute their angry crests seemed to leap higher. The very terror of the sight was fascinating, for in a short time they would themselves be in the grip of those furious waters. The rudderless vessel could not be guided, a makeshift attempt at a rudder having proved valueless; and in any case she could not, without masts, have escaped from the clutch of the strong current which dragged her onwards to her fate. But whatever Mildred Pattison felt below the surface, she remained outwardly composed. She was not one of the shrieking and hysterical kind.

Apathetic indifference seemed to have settled down for a while upon the crew, only seven of whom remained. Nothing further could be done. Not even a boat was left to them, or they would no doubt have tried launching it, however hopelessly.

Nearer, and nearer, and yet nearer, they drew to the rocks. It was worse, waiting thus for the final crash, than if the crash had come unexpectedly; worse in some respects. The end was so sure, yet so gradual.

True, time was given them for thought and prayer, and for this they might well be grateful. But Millie felt herself unable either to think or to pray. This may have been a mistake. She did think unconsciously; and while definite words or sentences of petition were impossible, the whole attitude of her heart was a despairing cry for help. She had not, perhaps, sufficiently practised habits of steady prayer in happier hours, and during late months she had yielded herself too much of a victim to a spirit of heavy repining. Now, in dire danger, she could not shake herself free from the clog which she had hung round her own neck. She seemed to be dulled, wordless, helpless.

Was Christ indeed on board this barque, as He had been on board the boat which crossed Galilee's waters, not in Bodily Form, but none the less absolutely present? To Captain Pattison, a man of childlike trust, it was so undoubtedly. But to Millie Pattison? If things spiritual are verily to us "according to our faith," then, according to Millie's lack of trust, she had not that Divine Presence to bear her through the bitter hour, not consciously and comfortingly at all events.

The Captain would not let her go down below. He had noted her shudder at the thought, and crossing the deck was no easy or safe matter. He went himself, and brought the fair-haired child of two, still half asleep, wrapped warmly in a thick shawl and folded in his arms.

"Shall I take her?" asked Millie.

"No, no; you keep yourself free. I've told Bill Jonson to mind and see if he can do anything for you, and he will. They're trying on shore to launch a boat."

"It's been thrown back twice. And how can they get to us, with those rocks between?"

"They won't try. There's a break in the line of rocks some way off: But in this sea—no, they won't try. They'll just keep near, if they can, and pick up some of us. That's the one chance. Time for your lifebelt!"

She put it on obediently, only murmuring, "What is the use? It may just mean longer torture."

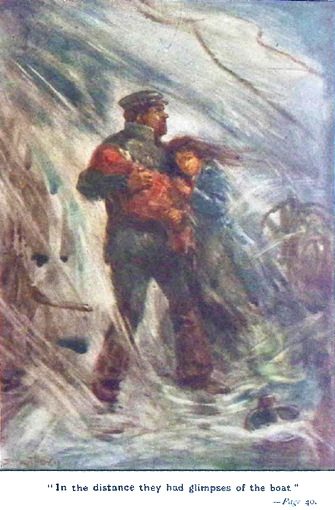

In the distance they had glimpses of the boat, which, after two failures, was at length fairly off. It seemed a mere cockle-shell, tossed from billow to billow, and its advance in the teeth of the rising tide was of necessity slow. Millie saw it, and lost it, and saw it, and lost it anew. Was it afloat still, or had it gone down?

In the distance they had glimpses of the boat.

Then she found that the shore was blotted out as by a veil, the air around having grown thick with flying spray; and the thundering crash of breakers was suddenly close at hand. She had not known that they were quite so near. The barque seemed for a moment to pause, almost to draw back, and to plunge forward with a fearful crash.

Millie was dashed flat on her face by the concussion, and when she slowly struggled to her knees, clinging for support to rope and bulwark, she found the deck so slanting that to stand upright was no longer possible. The barque was lying over almost on her side, and Millie was alone. Even Hero had vanished, and through the masses of flying spray, which half blinded and half stifled her, she could catch no glimpse of her brother or the child.

For one instant the veil of spray was flung aside by the wind, and she saw two of the crew, clinging to the vessel as she herself clung; but the Captain was not there. A faint whining next became audible, and Hero struggled, dripping, to her side, to seize her dress in his jaws, with an evident determination that they two should not be again separated.

The barque seemed to be settling slowly over, and every plank quivered with the shock of those heavy seas, which swept her from stem to stern. Millie held on determinately; but she knew that it would not be possible to hold on long. Breath and strength were fast failing.

Yet somehow she no longer felt afraid. In the booming rush of billows and the blinding dash of spray, a vision had come to her eyes of a distant lull and a Cross thereupon, and ONE whom she knew hanging patiently on the Cross; and her whole soul leapt up in a passionate prayer for pardon, because she had doubted His love.

"I shall never doubt Him again. He will take me now Home," she thought.

And when another momentary break allowed her to see something swept to and fro in the surge below, which she recognised as her brother, almost a smile came.

"It is over for him! It will soon be over for me too."

Then her hand went to the dog's rough coat. "Dear old Hero! You can't do any more for me. Poor old fellow! It's nearly over!"

A mountainous wave rushed past, and Millie was all but torn away. She held on, gasping, and knew that she could not withstand such another. The return rush of water swept a small bundle to her very feet, and Millie quitted her hold to grasp it. As she saw, close to her own, the white still face of Louey, fixed in eternal peace, it was torn away by the next giant billow, which came crashing up from behind.

On Millie's part there was a momentary sense of helplessness, of whirling noise and darkness and bewilderment, and then she remembered no more. When the great green mass of water had passed by, neither Millie nor Hero remained on the deck. They had together been lifted clean over the rocky reef, and swept far into the troubled waters beyond. With this last shock the barque parted amidships.

The Maxham boat, in imminent danger each moment of being capsized, was drawing slowly nearer, and old Adams, at the stern, witnessed what had happened. He said nothing at first, till Mr. Gilbert, glancing round, exclaimed,—

"She's gone!"

"Ay, she be gone, sir. Broke up like a bit of matchwood. And I'm afeared them aboard be gone with her."

"The tide is coming in. Some of them may be carried this way. We'll not give up yet," shouted Gilbert.

"No, sir."

Again they bent to their oars, rising and falling as one big wave after another swept under them. But for the practised skill of Adams, they would soon have found themselves struggling in the water.

Another shout from Gilbert. "See there: something yonder!" And soon to one and another became apparent a small dark object, half swimming, half borne along, and a larger object, floating or dragged with it.

"A dog, and he's got hold of something. Steady, boys, steady! Ease a bit! Now then!"

Another minute, and they were beside the almost exhausted Hero, whose teeth held firmly still a portion of Millie's dress. With difficulty they hauled her in—a dripping senseless figure, perhaps past recovery—and Hero was helped to climb in after.

Millie was laid in the bottom of the boat, and for a few minutes still they lingered, but in vain. No other body could be seen. Longer delay might mean the certainty of death for the one whom they had rescued; and soon they turned towards the shore.

This was quicker work, for now the incoming tide was in their favour, and wave after wave carried them on. The worst was, or seemed to be, over, when, near the land, a heavy swell caught the boat, carried it forward, turned it as before broadside to the beach, then, as if with a last expiring effort dashed it, bottom up, upon the shingle.

OLD MAXHAM

MR. MOKES' shop was the general and long-established shop of Old Maxham, a shop which had existed when Old Maxham was Maxham whole and entire, with no brisk young growing town of the same name to cast it into the shade, and when no other shop of any kind was to be found for nearly a couple of miles in any direction.

Things now were different. New Maxham, hardly a mile distant, possessed shops in plenty; but Old Maxham, though no longer a place of one shop, was still a primitive village, very much behind the age.

How much longer it could remain so was doubtful. Already lengthening arms of red houses in rows stretched affectionately outwards from the younger town, threatening by-and-by to engulf in their embrace the whole parent village. However, this consummation lay yet in the future; and the shop of Old Maxham, while partly supplanted by young aspirants, still held its own, as an institution venerable through antiquity and altogether reliable after generations of honesty.

It was only to be expected that, as the place grew, fresh shops should be started. Mr. Mokes was a reasonable man in most respects; and he viewed the question on the whole reasonably.

He did not expect his family—ancestors and descendants, inclusive of himself—to retain through ages a complete monopoly of Old Maxham trade. That a butcher should start his little shop was only to be looked for; he never had taken to that branch of trade, and people had gone to a neighbouring village or to New Maxham for their meat. A fishmonger was equally right; and a greengrocer, a small ironmonger, even a draper, came one and all in the natural course of events.

But when a man from New Maxham, Groates by name, chose to set up in the same street with himself a rival house to his own—a second "general," following in almost every respect his own particular lines, with the one exception of the Post-office—then Mr. Mokes, mild-tempered though he might be, did "turn" like the proverbial worm. He could not stand with patience such barefaced competition—grocery on one side and everything else on the other side; and outside shady seats among trees, with little tables for tea and fruit! The whole thing was a careful imitation, with improvements, which made the matter worse.

Flesh and blood could not be expected to endure such conduct. Mr. Mokes objected strongly, and his indignant dislike to the man extended to the man's whole family. When Groates was so impudent as to rent a pew in Church exactly in front of the Mokes' pew, Mr. Mokes actually quitted the pew of his forefathers, and went to another as far removed as possible.

By this means he lost one of his Sunday pleasures: the attentive perusal of a long and wordy inscription upon a certain stone slab, detailing all the virtues of his deceased Mokes' grandfather, who apparently had been a benefit to the neighbourhood, a blessing to his acquaintances, a model man, and an ideal tradesman. Mr. Mokes had always rejoiced in the reflected glory of that esteemed monument. But to sit and see just below it the row of Groateses, big and little, was too much for his equanimity. He couldn't do it, he avowed, and "feel like a Christian."

Of course Jessie Perkins knew all the ins and outs of Old Maxham society and politics. She had lived at Periwinkle Cottage ever since she became an orphan, at the age of four. Miss Perkins had adopted and brought her up. Miss Perkins was practically very good to Jessie, and no doubt was sincerely fond of her. Unhappily, the fondness was not apparent, and the goodness was far from attractive in its manifestations. And Jessie was not very fond of her aunt.

It was the same thing over again as with Jessie's father—Miss Perkins' only brother. Miss Perkins would have worked her fingers to the bone to serve him, but somehow she had not managed to keep his love. She had too many angles and corners, too testy and jealous a temper, to be lovable. Two or three friends or cronies she did possess, but then they had never lived under the same roof with Miss Perkins. There were many who pitied Jessie; and while she tried to be patient and dutiful to her aunt, her affections turned elsewhere.

Among the girl's oldest friends, after a sort, were the Mokeses opposite; among her newest were the Groateses, down the same main village street to the west.

Miss Perkins just knew the Groateses civilly, and no more. She did not like them or care to know them better. Jessie, on the contrary, had somehow slipped into a fast-growing intimacy, and, after the frequent fashion of young people, she gave much more ardent love to the new friends than to the old.

Perhaps this was not altogether surprising, since she had chosen the new friends for herself, while the others had been chosen for her. But she seldom spoke of the Groateses to the Mokeses or even to her aunt: not from any wish for secrecy, but simply because such speaking was apt to produce a snubbing. The growth of her new friendship was not fully understood therefore by others.

Mokes' shop was a genuine country concern, of a mixed and heterogeneous nature. Country shops are like country doctors: they go in for all round treatment. Specialists are a growth of town necessities.

The droll little old-fashioned windows—Groates' plate-glass panes were no copy of these—showed an astonishing assortment of articles within. On one side were groceries, using the word in its most elastic sense; on the other side were drapery goods, fancy articles, toys, wools, stationery. At the back was the Post-office. So Mokes had a good deal to attend to in his calling,—even with the help of his wife, of one very capable daughter, and of one most incompetent son. He had only two children, not seven like Groates.

Exactly opposite Groates' Store was a creeper-grown cottage, much after the model of Periwinkle Cottage, which stood in like manner just opposite Mokes' shop; and on the little gate of the tiny front garden, a more slip of bed and gravel, was a plate intimating that here resided "The Misses Coxen, Dressmakers."

On this particular afternoon the two sisters sat, as indeed was their usual habit, close to the prim little bay-window, one on either side, occasionally moving their respective needles, but on the whole more intent upon the outer than upon the inner world.

They were a well-meaning pair of little women; and they took an enormous interest in their neighbours' concerns,—not an unkind interest, though at times a degree meddlesome in kind.

It was no doubt natural that they should take this interest, since they really had no concerns of their own, beyond the new dress for the butcher's wife, or the latest frock for the linen-draper's little girl, or the question of how many darns were needed in the household linen each week, or the fluctuating health of their dearly beloved tabby cat, of Persian breed, the pride of the whole village.

TWO LITTLE DRESSMAKERS

IT was whispered that the Misses Coxen, or at least the Miss Coxens' parents, had seen better days, and that they themselves had been by no means originally intended for dressmakers.

If it were so, they had, like a wise pair of little women, settled down cheerily into the position where they found themselves; and after thirty years of dressmaking in Old Maxham, they had probably ceased to wish very keenly for anything more distinguished in the way of a career. A small annuity, left to each of them by a thoughtful relative, had lately placed them both, after years of struggling, in a position of comparative ease. Dressmaking was still to some extent necessary, or at least desirable; but they now sewed for butter and jam to their bread, not for the bread itself, which makes all the difference in the world. They might safely indulge in many a peep out of the front window, or even in an occasional whole holiday, instead of having to toil with might and main to hold soul and body together.

"It seems such a Providence, you know," Miss Coxen would remark to her friends, "such a Providence, the money coming just when it did, when my sight had begun to fail a little—only just a little, of course—and when poor dear Sophy getting so rheumaticky in her hands. It really seemed quite a special Providence to us both; I am sure I hope we are properly grateful. I am sure we try to be."

The pair talked much of their legacy, and always carefully avoided stating the amount which they had received. Reports therefore varied much, Mrs. Mokes setting down the annual sum-total as £40 or £50, while Miss Perkins believed it to be at least £60 or £70.

"Of course we shouldn't like not to work, you know," Miss Sophy would chime in mildly. "It would be so bad for us to be idle, and such an example, too, to the neighbourhood! And then dresses have got to be made, and there isn't a single person here who knows how to do it properly, except sister and me. I suppose if her sight quite went, and my hands too,—I mean if they got so rheumaticky that I couldn't work,—why, then I suppose Providence would send another dressmaker to Old Maxham. Things generally come when they are wanted, you know,—" which axiom would, perhaps, not be fully endorsed by everybody.

The two sisters were good little women after their kind; but they had odd impersonal ideas on the subject of "Providence," as of some hidden machine, which kept matters going, and supplied people's needs.

"And that will not be yet, I hope," Miss Coxen would add. "At present we get along pretty well—on the whole pretty well—though somehow we don't seem able to work so hard as we used to do."

On this particular afternoon they did not work hard at all. It became evident that something unwonted was stirring the air of the village, over and above the gale that had hitherto kept the sisters prisoners in fear of possible chills.

Nobody had happened to call and to tell them what had befallen the place. They saw Jessie Perkins arrive, breathless and troubled, to vanish inside the opposite door. And they saw Mrs. Groates, resolved and pale, come out; and a minute later they saw Mr. Groates himself hasten away in rear of his wife. At this, the Miss Coxens exchanged glances full of meaning.

The elder sister, who was bony and thin, with corkscrew curls and blank eyes, murmured, "Dear me! Dear me! What can it mean?"

And Miss Sophy, who was plump and loose-lipped, with thicker and larger curls, began to wax restless.

"It's a strong wind, to be sure," she remarked, "and rather boisterous—at least, it sounds so—but not so very cold, sister. March isn't so cold as January; and I generally get out even in January. I haven't been outside the door once to-day."

"No, Sophy; you haven't."

"I almost think I should like to get just a breath. It's so refreshing. You mustn't, because of your eyes; but for me it is different. I can wrap up warmly. There's Mimy taking a look down the street. And Jessie is there still: because we haven't seen her go away. They are nice girls. I always do like Mimy, and her mother too, though it doesn't do to say so to Mrs. Mokes."

"I wonder what Jessie Perkins has got to do with the matter," debated Miss Coxen, letting her work lie on her knee. "Seems to me she's a great deal with the Groateses, slipping in and out. I don't believe Miss Perkins half knows how often. It's no business of yours or mine, of course; but still I do wonder if Miss Perkins knows."

"She's a funny woman, Miss Perkins, though it wouldn't do to say so to everybody."

"And she's done a lot for Jessie. Why, if it wasn't for her, Jessie might just have gone into the Union. The girl ought to be grateful. But young people in these days don't trouble their heads to be grateful. They only want to have their owns way. And Jessie's like the rest of them."

"Well, well!" sighed Miss Sophy, in deprecating tones. She was burning to get out, but did not see her way to doing so, unless Miss Coxen should take up her suggestion.

"I don't believe it ever so much as comes into that girl's mind how much she owes to her aunt. She takes it all as a matter of course. That's the way. I don't say,—" and Miss Coxen shook her little ringlets,—"I don't say Miss Perkins is one to make a young girl fond of her. She's sort of cold in her ways, you know. But there's duty to be thought of."

"And really, sister, I can't, for my part, see that Jessie is wanting in her duty to Miss Perkins. I really can't! I'm sure she's as steady and nice a girl as you could wish; and she always does as her aunt tells her. And if she does find her home a little dull, and makes friends outside, isn't it natural? And that young Groates is as nice a young fellow as anybody can come across; as good to his mother as a daughter."

"He's not bad," murmured Miss Coxen.

"I don't say much for Mr. Groates. It wasn't pretty of him to come and set up an opposition shop to Mr. Mokes, after all these years and years that Mokes has had everything his own way. But I suppose Mr. Groates has got to make his way in life; and seven children aren't so easily provided for as two. And I know one thing,—though I wouldn't say it to everybody,—I know Groates' cotton is ever so much better than Mokes'. I've done nothing but snap my cotton every other minute. It's that reel from Mokes, you know."

Miss Coxen slowly swallowed the bait. She looked up at Miss Sophy, then at the shop opposite. "Well, I don't mind," she said. "If you want a breath of air, Sophy, and don't feel afraid of the wind, I shouldn't mind a reel of No. 36 and a reel of No. 30 from opposite. It's uncommonly good cotton Groates supplies, almost as good as we get from London. And Mr. Mokes couldn't expect us to go so far as to his shop in such a wind."

At this moment, as if to lend additional weight to her words, the small and not very tidy girl, who acted as their maid-of-all-work, burst into the room.

"O mum!—" with eyes and mouth equally wide—"O mum! Only to think!"

"Do you know what is the matter, Susanna?" asked Miss Coxen, retaining her self-control, while Miss Sophy gasped audibly.

"O mum, it's a ship on the rocks, and the sailors all drownded—every one of 'em drownded. And the boat what went out 's got turned top side down, and every man jack of 'em's drownded too. And young Groates is one of 'em."

"You shouldn't say 'every man jack,' Susanna. It's a foolish expression." Then Miss Coxen looked at Miss Sophy. "Dear me, how melancholy."

"You are quite sure, Susanna?" panted Miss Sophy.

"The doctor's been sent for all of a hurry, mum; and he 've gone down to the Point. But Tim, he says it's no manner of good. And all the bodies is laid in a row like, and every one of 'em dead, every man jack of 'em, Tim says."

"Tim Robins isn't always a perfectly truthful boy," remarked Miss Sophy.

This was a mild way of stating the fact that Tim was known far and wide to be an arrant liar.

"How came you to see Tim, Susanna?"

"Oh, please, mum, I was only just a-peeping out, and he went by, and he told me, and he'd been for the doctor, and all of 'em was drownded, he says."

"I'm afraid it must really be true," sighed Miss Coxen. "Well, you may go, Susanna; and mind, you are not to peep out any more."

Whereat Susanna vanished.

There could be no further question as to the propriety of Miss Sophy dressing with all speed and hastening across the road. Not only were the two reels of cotton found to be an urgent necessity, but also "that poor dear girl Mimy" would need comforting for her brother's death.

So the little woman bustled herself as fast as possible into a superabundance of wraps, and then pitter-pattered over to the opposite door, being vary nearly blown clean away by the blast which assailed her half-way. However, she just managed to keep her equilibrium, and in two or three more seconds she was under shelter.

"I've come for some reels of cotton, Mimy; No. 30 and No. 36, the best make."

Mimy had appeared at the sound of the bell.

"We like your cotton so much, sister and I. But, oh dear, isn't this bad news! I'm so sorry for you all; I am really."

Miss Sophy had no intention of being unkind; but she never could resist talking, and it did not so much as occur to her that silence would be the kinder course, until at least she was sure of her facts. There was no need to say anything yet.

Mimy's rather stolid face looked straight at her, with a blunt "What?"

"About the ship on the rocks, you know. Of course you've heard all that. And a boat went out to save the sailors, and they're all drowned; and I'm told your brother was in the boat."

A reel slipped through Mimy's fingers. "Who told you?"

"Tim Robins was sent for the doctor, and he says so—every one of them, he says. Poor things! It's too dreadful."

"I don't believe it," Mimy responded, turning scared eyes to the door of the back room, whence came a hoarse murmur,—

"Jack drowned!"

Mimy forgot her duties as saleswoman. Leaving the cotton reels to take care of themselves, she went towards Jessie.

"I don't believe it," she repeated. "Tim isn't to be trusted. I don't believe a word of it."

"Jack drowned!"

The words seemed to be forced from Jessie's white lips. Then she turned her back, went gropingly into the room once more, and crouched down in the big arm-chair, with her face hidden. They could see her through the open door.

"Dear me, poor girl! Who ever would have thought she'd mind it like that?"

Mimy flashed out upon the visitor. "Mind it! Who wouldn't mind it that knows our Jack? You don't know him, and Jessie does! And if Jack is dead, it'll kill mother; I know it will. And you to come and tell it in such a way, as if it was just nothing at all! Our Jack to be drowned! I don't believe it, and I won't believe it. If you'd just go away and leave us! Cotton! Oh, I'll see to the cotton. Make haste, please, and don't go near Jessie. You don't know anything about it."

"Really, Mimy!" faltered Miss Sophy. She hardly knew whether to be offended or unhappy. To receive such a rebuke, especially from a young girl, was not what she was accustomed to. Resentment strove with regret; and when she turned her back upon the shop, she was very nearly in tears.

Mimy hurried into the room behind, where Jessie still crouched in a silent heap.

"Jessie!" she whispered.

No answer came. Mimy put her arms round the other girl.

"Poor Jessie! Don't mind. I don't believe it's true. That Tim is a regular story-teller. It isn't likely, you know,—all of them to be drowned."

"I don't see why not," moaned Jessie.

Then she pulled herself together, and sat up.

"I can't think why I'm so silly. Isn't it silly of me! I'm cold, I think,—all of a shiver! It's you that ought to cry, not me. There's nobody belonging to me in danger."

Mimy said nothing. She only hold Jessie fast.

"And you mustn't say anything to anybody, not one word, about how stupid I've been. Promise me, Mimy—not one single word to anybody. I've no business to be so silly."

"No, I won't," Mimy answered. She would not remind Jessie of what was evidently forgotten,—the presence of the little dressmaker.

"I ought to go home. Aunt Barbara will wonder what ever has become of me."

"But mother asked you to stop here, just till somebody comes. It won't be long now."

Nor was it long. As the two girls clung together, each hiding her face from the other, approaching footsteps became audible. Another moment, and the shop-bell rang sharply with the opening of the door. That was no customer, however; and Mimy did not stir. Mrs. Groates walked in, her face agitated, yet joyous. A variety of feelings seemed to be striving for the mastery.

"Mother, is it true?"

"Poor boy! Yes. But it might have been worse; it might have been a deal worse, Mimy."

"Then Jack isn't drowned!"

"Drowned! No. What's put that into your head? Not but what he might have been. I did think—one minute—but he isn't killed. He's got a broken leg, and that's all."

"Miss Sophy came and told us that Tim said they were all drowned, every one of them."

"Miss Sophy needn't have been in such a mighty hurry with her news!" It was seldom that Mrs. Groates gave utterance to so tart a remark; but her eyes had fallen upon Jessie's woe-begone visage. "There's some folks can't be happy without they can make other folks miserable. No, it isn't true, Mimy. But it might have been. They got back close to shore, and then a big wave caught the boat and threw it on the beach upside down. And Jack's leg is broken; and Mr. Gilbert's arm is crushed; and old Adams was stunned."

"And nobody killed?"

"The ship broke up, and all the sailors were lost. Poor fellows! Not a single one saved except a woman! And she was kept afloat by a big dog, till the boat picked them both up. She hasn't come round, but they say she's alive, and maybe she'll do well yet." Mrs. Groates collapsed into a chair, and into a flood of tears. "I didn't think when I got there that we'd have any of them back alive; that I didn't! It was a sight! O dear me!" Then she jumped up again. "And now we must get things ready for Jack. They are bringing him on a shutter; and Dr. Bateson 'll come to set the bone. Poor Jack! He's a brave boy; isn't he, Jessie?"

Jessie had not spoken a word, simply because she lacked the power to do so. When Mrs. Groates looked her in the face, with wet proud eyes, Jessie just stooped to kiss her, and ran away.

"Poor dear Jessie!" murmured Mrs. Groates.

Mimy began impulsively to tell about Jessie's distress on hearing that Jack was drowned. Then came a recollection of her own promise; and she pulled herself up sharply. Mrs. Groates was too much occupied to notice what had or had not been said.

"Yes, she's a nice girl, Mimy. I always do like Jessie Perkins. And so feeling, too! Only think, there was Miss Perkins herself down at the beach. And when everybody was wondering what to do with the poor woman from the wreck, if Miss Perkins didn't up and say, 'I've got a bedroom as she can have!' I wouldn't have expected it of Miss Perkins, and that's a fact. But there, nobody ever knows. Folks has got their good and their bad sides, and the very tiresomest people has mostly got some soft spot or other, I do believe, if only it can be got at. Now, Mimy, we've got to brisk up and make things ready. Jack 'll soon be here."

WHAT WOULD BE SAID?

"WELL, I never!" uttered Miss Perkins as Jessie stepped in. "So that's what you call just going across the road, is it?"

Jessie had not the faintest recollection of any such words as coming from herself; but she seemed to have lived through a small lifetime of feeling since last crossing the threshold, and memory was confused.

"I couldn't help it," she made answer meekly.

Miss Perkins still sat in the self-same chair where Jessie had seen her last, with the self-same piece of work in her hands, exactly as if she had been glued there throughout the time of Jessie's absence. Only her sewing had made scant advance; and a bonnet and shawl lay near, where they had not been earlier.

Jessie observed neither fact, being painfully conscious of the scrutiny which she was herself undergoing. The colour in her face came and went. Miss Perkins gave vent to a sniff, which Jessie supposed to intimate displeasure, though possibly it may have meant concern.

"I couldn't help myself, aunt Barbara—I mean partly. Mrs. Groates asked me to stay with Mimy."

"Oh, it's the Groateses, is it?" with unmitigated disdain. "I might have guessed you were after the Groateses. And how ever came you to see Mrs. Groates at all, I wonder?"

Jessie dropped upon a chair, with her back to the window, and murmured, "I went there."

"What for?"

"Jack Groates asked me. He hadn't time to see his mother. And he wanted me to tell her he was gone in the boat."

"What boat?"

"The boat that tried—tried—" Jessie could not finish her sentence.

"Jack Groates didn't speak to you over the way at Mr. Mokes'. I know he didn't, for I could see quite well from here. He didn't say a word to you."

"No."

"When did he?"

"I—ran to the shore; I wanted to see. Jack sent me back. He wouldn't let me stay."

"That's one sensible thing he's done, anyway." Miss Perkins continued to sew, with lowered eyes, as if her existence depended on getting the seam done within a given time. "And I s'pose you wanted to catch your death o' cold. Done your best, anyhow, running all that way to the beach, in this wind, with nothing but a cobweb of a shawl! I wonder at you, Jessie! At your age."

Jessie was silent.

"Mrs. Mokes told me you'd gone. 'Silly girl, too!' says she. As if you could ha' done a scrap o' good to anybody by all your going! Why, they might have been all drowned before your eyes; and I s'pose you'd just ha' sat and cried. Much use that would have been."

Jessie tried to speak, and produced only a clatter of shaking teeth.

Miss Perkins glanced up in astonishment. "Eh?" she said.

The girl was clinging to her chair, white as a table-cloth. She met her aunt's eyes, and tried to laugh; but the chair shook beneath her.

"That's the sort of thing, is it?" quoth Miss Perkins, with a certain grim satisfaction. "Didn't I say you'd catch your death o' cold? Shouldn't wonder but you've done it now. You'll just come straight upstairs this minute, and get into bed, and have a basin of gruel, and not stir till I give you leave. I'm not going to have you ill on my hands too, if I can help it."

"Please—" protested Jessie.

But she was in no state for effective resistance; and Miss Perkins hauled rather than helped her up the two flights.

Midway, as they passed the open door of the spare room on the first landing, Jessie exclaimed, "Why, there's a fire!"

"Well, why not?"

Jessie stared in bewilderment.

"The room wanted airing," Miss Perkins condescended to explain. "And I thought of a fire,—all of a sudden. Come, make haste. I've got a lot to see to."

"If only I needn't go to bed—And then I could see to something too."

"You see to things,—a quaky piece of goods like you! You're best out of the way. Leave other folks more room."

Jessie noted suddenly the creaking of her aunt's walking boots, and remembered the words, "Mrs. Mokes told me." She exclaimed again, in her surprise, "Why, aunt, you've been out."

"And if I have, what then? And if I choose to go out again, what's that to anybody? Some who ain't quite so spry as others in running after other folks' business maybe do as much in the world. I shouldn't wonder if my going out had been a deal more use than yours."

This was crushing; for Jessie could not honestly feel that she had done much good to anybody by her going. She drooped her head, and was mute, offering no further resistance.

Ten minutes later saw her tucked up in her little white bed, in the front attic, a cosy small bedroom with sloping roof, scrupulously clean.

The "spare room," so called, which in summer was often let to a single lady, desirous of some few days or weeks by the sea, lay under this attic, and over the front sitting-room. Behind the said sitting-room was the kitchen; over the kitchen was Miss Perkins' bedroom; and over Miss Perkins' bedroom was an attic box-room. Miss Perkins, being an indefatigable worker, kept no servant-girl, but only had a woman in for two or three hours twice a week, to "scrub down."

The warmth and rest were comfortable, and Jessie's shivering fit soon subsided. She turned her face from the light, and felt very thankful for Jack's escape, as well as somewhat ashamed of having been betrayed into showing what she felt about him. For who could say with certainty whether Jack cared for Jessie?

"But Mimy promised; Mimy won't tell anybody how silly I was. I'm sure Mimy will take care."

Then in a moment she remembered the little dressmaker, forgotten hitherto. A rush of hot blood suffused Jessie's face. Miss Sophy Coxen had seen, and Miss Sophy Coxen would talk. Not a man, woman, or child in Old Maxham would fail to receive from Miss Sophy a full and detailed description of precisely how Jessie Perkins had looked, had spoken, had acted, upon that notable occasion when she was informed that Jack Groates had met his end.

Jessie could easily picture to herself what would be said. "That poor dear girl Jessie!" Miss Sophy Coxen would remark. "Now would you have thought it? I shouldn't! I didn't know she cared for young Groates any more than for anybody else. But she does! O yes, it is quite certain. I can answer for that. You see, I was told that poor young Groates had been drowned, and when Jessie heard it, why, the poor dear was like a thing demented. She kept saying, 'Jack Groates drowned!' over and over again and she hid her face, and didn't seem half to know where she was. And of course anybody can guess what that sort of thing means!" And so on, and so on.

"It's horrid! Horrid! How could I be so foolish?" cried Jessie. One burning blush followed upon another. "Oh dear, oh dear, what ever shall I do? What can I say? How can I put things right? And if it should come to Jack's ears! Oh! And it will; I know it will! Everybody tells everything to everybody in this horrid place."

Jessie groaned aloud, and another rush of crimson came.

Miss Perkins chose this instant to enter with the promised "basin" of steaming gruel. A dubious expression crept into her long narrow visage as she surveyed Jessie's face. Had she been anything of an experienced nurse, she would have known quickly that the heat was moist in kind, not fever heat. As it was, she took alarm.

"I declare you're as feverish as can be. You weren't that colour downstairs."

"I'm not a scrap feverish." Jessie accentuated the assertion by an added glow. "It's nothing of the sort. I'm not ill one bit, only just nicely warm."

"If I was you, I'd speak the truth another time, and not go along making believe. Your face is es hot as fire; and if that isn't fever, my name isn't Barbara Perkins." A rather rash assertion, since she possessed no other name.

Jessie broke into a nervous giggle.

"It's a chill you've got; and you'll just lay quiet in bed till it's gone. I'll have no more rampaging about, without I give you leave."

"Aunt Barbara, do you know who's hurt?" asked Jessie.

Since blushing was to be taken for fever, and since she was already about as crimson as it was possible to be, the question might be ventured upon.

Miss Perkins offered no response.

"Because the boat was thrown up on the beach, and all of them were tossed out. And some were hurt, I know—poor Mr. Gilbert, and old Adams, oh, yes, and Jack Groates too. Was there anybody else? I do want to know how they're all getting on. And the poor woman off the wreck—was she killed?"

"She wasn't dead an hour ago. That's about all I know. And Adams was come to; and Mr. Gilbert's arm was enough to make a body sick to look at it. And Jack Groates is a silly fellow."

"Oh-h!"

"A silly fellow! That's what he is. He ought to have thought of his family." Miss Perkins always took a peculiar pleasure in saying exactly the opposite to what was expected of her. "A nice expense for them it'll be, to have him laid by with a broken leg for nobody knows how long. Shouldn't wonder if he never was able to walk straight again."

Jessie giggled anew faintly, as a picture arose in her mind of Jack sidling along, crab fashion.

"Well, I shouldn't. It's what they call a compound fracture. The bone was sticking right out," pursued Miss Perkins, with the relish of one who loved to deal in horrors. "Right out! And the setting of it 'ud be awful, they say. Serve him right, too! What must he meddle for? If he was a sailor—but he isn't! Ben Mokes is a deal more sensible."

"Ben Mokes is a horrid lazy selfish creature, and I can't bear him," Jessie cried, with almost a sob. "And Jack has behaved like a man; and you know he has, aunt Barbara."

Miss Perkins sniffed. "If he isn't a man, I don't know what else he is. Folks has their different sorts of ways of thinking, though; and my way of thinking isn't yours by a long chalk."

Then she quitted the room, and Jessie, pushing aside the basin of gruel, tossed restlessly to and fro for a long while, divided between distress at Jack's sufferings and poignant regrets for her own betrayal of feeling. She ended by dropping sound asleep.

When, two hours later, she woke up, things did not look quite so desperate. Flushes and shivering had departed; and Jessie felt altogether more like her ordinary self. After all, everybody knew the ways of little Miss Sophy Coxen; and people would allow for probable exaggerations; and nobody could wonder at a certain amount of feeling shown at such a moment; and besides all this, Jessie herself could do much to set matters right, by assuming on air of high-and-mighty indifference whenever Jack was named.

Having arrived at these conclusions and consoled herself therewith, Jessie began to debate whether she might not get up and dress. She decided, however, that this would be venturing too far, in the face of her aunt's prohibition. The act might draw unpleasant consequences.

Something of a mysterious nature seemed to be going on below. Was Miss Perkins airing the room still? And why should she take to airing it thus abruptly, without any especial reason, in the middle of an afternoon? Jessie listened intently, and presently made out subdued voices—a man's voice, she was sure. Curiosity rose high.

MISS PERKINS' NEW INMATE

MILDRED PATTISON'S coming to, out of her long unconsciousness, was a slow and tedious affair. Not only had she been three-fourths drowned before the brave crew of rescuers dragged her into their boat, but also, when the rising tide, with a final effort, dashed the boat bottom up on the shingles, smashing Mr. Gilbert's right arm, stunning Adams, and breaking Jack Groates' leg, Millie received a blow upon her head, sufficient to have rendered her senseless, apart from other calamities.

She was taken first to old Adams' cottage, the most roomy of all the small cottages "down at the Corner." Every effort was there made to bring her to, and enough success rewarded the efforts to show that she was living. But though more than once Millie opened her eyes and gazed vaguely about, it could scarcely be called "consciousness." In after-days she had no recollection of this time, or of being conveyed to Old Maxham.

The question soon arose: What was to be done with her? Adams' family had enough to do in looking after himself; and they were very poor; and space was scanty. But for Mr. Gilbert's severe injuries, he would doubtless have had her taken to the Vicarage, and placed under the care of his old housekeeper. That plan now was impossible; at all events, he was too ill to think of it, and the old housekeeper counted that her hands were sufficiently full.

For a while no one else came forward. Few indeed were in a position to do so. Most of the Old Maxham people were more or less poor; and not many could boast the possession of an unused room,—the doctor least of all, since he had not only six small children, but one or two permanent invalids as patients.

Then it was that Miss Perkins astonished everybody by stepping into the breach. She had been present for a short time, had heard everything, had listened to what everybody had to say. And when the world in general, as represented down at the Point, had reached the end of its wits, Miss Perkins spoke.

She had a spare room, she said; and she didn't suppose any lodgers would be likely to come yet awhile. The poor woman might come and sleep in that room just for a few days, till she was well enough to go on her journey to her home. Of course she'd got a home somewhere, and friends expecting her. Yes, it meant a lot of trouble, of course. Folks had got to take trouble sometimes. Miss Perkins didn't know as she was one who minded trouble particular. Anyway, if the woman hadn't got nowhere else to go to, why, there was the bedroom ready.

"That's splendid of you, Miss Perkins!" the village doctor said impulsively.

Miss Perkins twitched the end of her long nose, and sniffed. She didn't know as there was anything out of the common, she said, in letting a room be used, when it wasn't wanted, by a poor thing as hadn't got anywhere else to go.

"Only, it may mean—Well, of course I can't tell you exactly how soon she'll be fit to move," suggested the doctor. "That blow on the head might mean mischief; and if fever set in—"

Miss Perkins didn't see as she had any call to be expecting evils.

"No, no; I only thought it right to warn you about possibilities. But at the worst she could be taken to the hospital. I'm afraid so long a drive in her present state would be a serious risk." The doctor might well fear this, since the nearest hospital was fifteen miles off. "Well, I can only say you're a splendid woman, Miss Perkins."

Miss Perkins might have been inwardly gratified; but she received the praise with outward disdain. And when one or two minor arrangements had been made, she set off to make things ready at home.

She would have found it difficult to explain why she had offered her room: still more why, having offered it, she should feel positively ashamed of her own generosity, and should shrink from telling her niece. Something in the pale face of the unconscious half-drowned woman, friendless and forlorn, had appealed to the softer side of her nature, and to some extent she had acted on impulse. Certainly, no one would have expected Miss Perkins so to rise to the needs of another; and perhaps it was this very knowledge of having done the unexpected which made her feel bashful.

More than once, while hurrying along the rough road, she regretted her own precipitation, wondering whether she might not find herself to be "in for" a good deal more than she had calculated on. It was a positive relief to her mind to find Jessie absent, and not at once to have to confess what she had done. Not that she supposed Jessie to be likely to object, or that she would have cared if Jessie had objected, but only that she shrank oddly from appearing in a more benevolent character than her wont.

She threw off bonnet and shawl, lighted a fire in the spare room, made the bed, which was always kept well aired, and put a hot bottle between the sheets. Then, under a queer sense of shyness, she resumed her seat and her work, to be found by Jessie, as already described. And there can be no question that Miss Perkins was charmed to seize upon an excuse for putting her niece to bed out of the way, and so deferring for a time the need to tell her news.

Mildred Pattison's arrival happened opportunely, when Jessie was sound asleep. Still secrecy could not be long preserved; and when Miss Perkins, after long delay, made her appearance anew in the attic bedroom, it was to find Jessie sitting up in bed, listening with all her ears.

"Aunt Barbara, I'm positive there's somebody in the room below."

"You didn't eat that gruel, Jessie."

"Oh, I couldn't. It was so horrid. And I'm not ill,—not in the least ill. Is there somebody in the spare room? Why mayn't I know?"

"There's no reason why you mayn't, I suppose."

"Then who is it? Do tell me."

"Nobody of consequence to make a fuss about. It's just the poor creature off the wreck."

"Oh-h-h!" Jessie's eyes and mouth widened in sympathy.

"She hadn't got any place to go to . . . So they've just brought her here for a day or two. Lodgers ain't likely to turn up yet . . . And if they do, they'll have to wait, I s'pose."

Jessie did what she had not done for at least ten years past. She sprang up on her knees in the bed, and clutched Miss Perkins round the neck in a hearty hug.

"Aunt Barbara! O how kind! How very very good of you!"

"There's no call to rumple my capstrings."

Jessie released her, but wore a look of delight.

"How lovely of you! I never should have thought you'd be the one to do anything of the sort."

Yes, that was it. Nobody expected good deeds from Miss Perkins. Anybody, rather than Miss Perkins. The fact caused a sense of injury. Why might not she do a kindness naturally and simply, like other people, without uplifted hands and amazed eyes to follow? If Mr. Gilbert had taken the poor woman to the Vicarage, no one would have been in the least degree surprised.

"Never!" repeated Jessie, without the smallest intention of hurting Miss Perkins' feelings. "That poor thing! How glad she must be!"

"She isn't. She doesn't know anything."

"Hasn't she come round yet?"