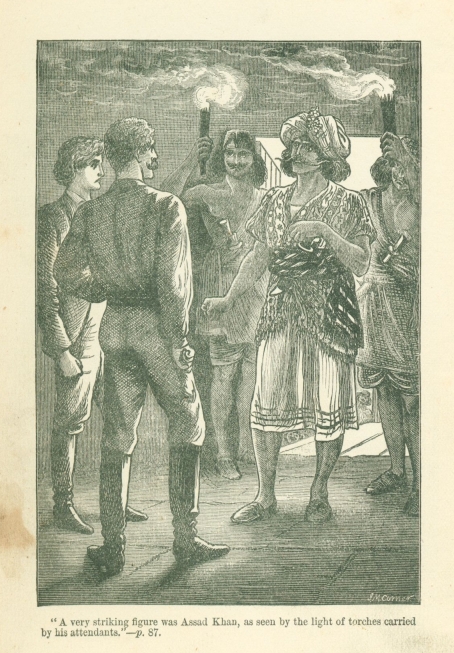

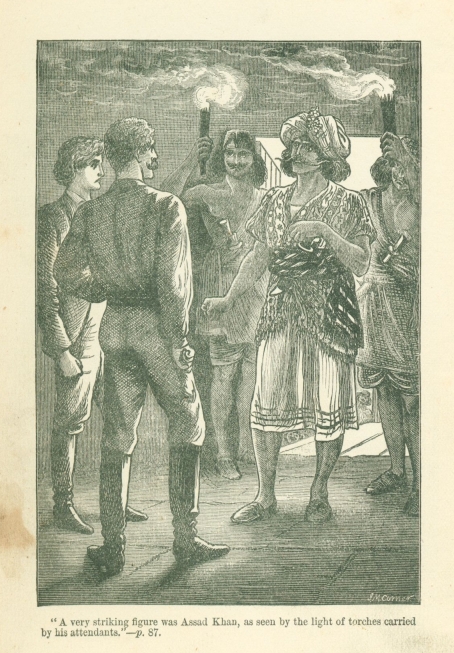

"A very striking figure was Assad Khan, as seen by the light

of torches carried by his attendants."—p. 87.

Title: Life in the Eagle's Nest

A tale of Afghanistan

Author: A. L. O. E.

Engraver: James Mackenzie Corner

Release date: August 23, 2024 [eBook #74306]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Gall & Inglis

Credits: Al Haines

"A very striking figure was Assad Khan, as seen by the light

of torches carried by his attendants."—p. 87.

A Tale of Afghanistan.

BY

A. L O. E.,

(Charlotte Maria Tucker)

AUTHORESS OF "THE CLAREMONT TALES," "NED FRANKS," "SHEER OFF,"

"THE WHITE BEAR'S DEN," ETC.

London:

GALL & INGLIS, 25 PATERNOSTER SQUARE;

AND EDINBURGH.

PREFACE.

The Authoress of the following tale has often said that she has devoted her pen to her adopted country, India. Has she then changed her purpose in again writing a story for British readers? No; though in a different way, she is still seeking to serve the Missionary cause. A.L.O.E. wants money for her "Mission Plough," a School for Mohammedan and heathen boys in Batala, and it occurred to her that hours, not taken from her city work, might be given to earning something by literary effort.

The School which A.L.O.E. thus attempts to prop up by her quill, sprang out of a felt want. Native boys were willing to hear the Gospel, and in the Government School were taught no religion at all. The Missionary Society to which A.L.O.E. belongs, restricts its attention to women and girls; of course not a penny could be taken from its funds for boys, though teaching them indirectly helps the Zenana work—the seed of truth being sometimes carried by them to the very strongholds of feminine bigotry.

Thus the "Mission Plough" is supported by no society; the expenses are to be met by personal effort, or the assistance of those who sympathise with its object. A.L.O.E most gratefully acknowledges the great liberality with which kind friends have come to her aid. May the Lord reward them a thousandfold for what they have done!

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

I. NEWS FROM ENGLAND

II. A SUDDEN CHANGE

III. GILDING RUBS OFF

IV. FAIRLY STARTED

V. A ROUGH WAY

VI. THE MOUNTAIN CHILD

VII. THE STRUGGLE COMES

VIII. PRISON LIFE

IX. THE AFGHAN CHIEF

X. CONSCIENCE AWAKENED

XI. REPENTANCE AND REPARATION

XII. THE HOUR OF PERIL

XIII. A DARING ATTEMPT

XIV. SPEAK OR DIE!

XV. THE KNOTTED ROPE

XVI. AFTER SEVEN YEARS

XVII. A RICH REWARD

XVIII. NOONTIDE GLARE

XIX. DECISION

XX. A POST OF PERIL

XXI. THE ATTACK

XXII. WHERE THE PILLAR RESTED

LIFE IN THE EAGLE'S NEST.

"The post-dák at last!" exclaimed Walter Gurney, springing to his feet, as, encompassed by a cloud of dust, the vehicle for which he had been watching appeared in the distance, the flourish of a horn announcing its approach. The youth had been reclining under the shade of a peepul tree, at the side of the road which led to a frontier station on the border line which divides India from the land of the Afghans. The post had always to be met at this point by Walter, as the horses were never turned down the rude road which led to a missionary's bungalow, situated about two miles off, almost close to a native village. The Rev. William Gurney, till his death, which had occurred about two months ere my story opens, had always dwelt amongst his poor flock, "the world forgetting, by the world forgot." The missionary's sole companion had been Walter, his only son, whom he had himself educated in India, the neighbourhood of mountains preventing the absolute necessity of his sending his motherless boy to England.

This was the third time that Walter had anxiously gone to meet the home mail. By his dying father's desire he had remained at Santgunge till he should receive a letter from his grandmother in London, in answer to the announcement of the missionary's death. Walter could not form any plans for his own future till he should hear from the nearest relative now left to him upon earth.

The expected letter was handed down by the coachman to Walter, and with another blast of the horn the dák-gári* rattled on its way. Walter returned to the peepul tree, and, leaning against its trunk, examined the envelope of the letter before opening it to read the contents.

* Post-cart or carriage.

"Black-edged, but not written in my grandmother's hand. She must have been ill, which would account for her not writing before. The news which I sent must have grieved her sorely."

Walter broke open the letter and glanced at the signature at the end; it was that of his uncle, whose handwriting was strange to the youth. Augustus Gurney, the wealthy banker, had never cared to keep up intercourse with a brother who had demeaned himself, as he thought, by becoming a humble missionary. The stiff, formal, business-like writing was characteristic of him who had penned it. The letter was dated from Eaton Square, 1871.

"DEAR WALTER,—The melancholy announcement of your father's decease never reached your grandmother; it arrived on the day of her funeral. I have delayed writing till all affairs were settled. You asked for directions for your future course, and whether there were any means of your finishing your education in some college in England. You shall receive a frank reply. My mother's income being only a life annuity, ceased at her death; she had no property to leave. There are no funds available to pay your passage home or start you in life. Every profession here is overcrowded. You must not look to me, as I have three sous to provide for, and I never approved of the course which your father chose to take. You had better try to find some employment in India. Doubtless you have there plenty of friends; here you would be amongst strangers.—Your affectionate uncle,

AUGUSTUS GURNEY."

"Strangers indeed," muttered Walter between his clenched teeth. "Can this man, I will not call him uncle, actually receive the news of the death of his only brother, a brother whom he always neglected, a brother of whom he should have been proud, without so much as a feeling of remorse, or one word of sympathy to his orphan? He does not wish to be burdened with a poor relation! He shall certainly never be troubled by me!" Walter crushed up the letter in his bands, and with long rapid strides took his way along the rough, weed-overgrown path which led to his desolate home. Bitter were the orphan youth's reflections.

"'Doubtless you have plenty of friends,'" he writes. "Did my uncle know nothing of the isolated life of self-denial led by my father amongst our ignorant peasants? I have seen nothing of the world; know no one to take me by the hand. Though I have a passion for study, I have not received the educational advantages that would fit me for Government employment. I have led a kind of Robinson Crusoe life; I can shoot, can turn a straight furrow, ride, plant trees, and do a little carpenter's work; talk to natives of India or Afghanistan in half-a-dozen jargons; but I know little of mathematics, am only self-taught in Latin; I could pass no examination,—at least I doubt that I could,—and I have no funds to support me till I could study up for one. I changed my last rupee to-day."

It may be little to the credit of Walter that indignation towards his uncle and anxiety about his own future were the first thoughts that came into his mind on learning of the death of his aged relative in England. But Walter, brought up in the wilds of Santgunge, had never seen his grandmother nor received any letter from her. Once a-month an epistle from the old lady had regularly reached her missionary son, with a brief message to his boy at the end. Before Walter reached his home, more gentle feelings prevailed. He could feel thankful that parent and son had both been spared the pang of bereavement which had wrung his own heart. Walter thought of the joyful surprise of the meeting above of those who for twenty years had been severed on earth.

"Yes, a time will come when we shall care little whether our path was rough or smooth on earth; whether it led upwards to distinction, or downwards to poverty and trouble," said Walter to himself, as he entered the little bungalow in which he had dwelt from his birth. It was a most unadorned dwelling, built chiefly of sun-dried bricks, and by no means in good repair, for the rains had injured the walls, and white ants eaten into the timber. The interior matched the outside; a few prints and texts, with an old brown map, were the only ornaments; the rough mat on the brick floor had been worn into holes by the tread of many bare feet. A few chairs and a table, a bookcase and its contents, chiefly religious books, reports, and Urdu pamphlets, summed up the furniture of the room which Walter entered. The youth's own appearance was in character with his surroundings. His clothes, originally of common material, were worn almost threadbare. Walter was tall and slight, and the first impression which a stranger would receive was that he was overgrown and underfed. Though his age was barely seventeen, there were signs of care on his countenance, and a sunken look under his eyes that told of months of night watching and daily hardship. Yet a second glance at his form, and the broad expansive brow from which the weary lad now pushed back the wavy auburn hair, might suggest a presage that after a few years the figure might be remarkably fine, the countenance singularly intellectual.

Walter threw himself on a chair. Raising his eyes, their glance rested on a picture with time-stained margin, which had been familiar to him from his earliest childhood. The youth's almost sole recollection of his mother was her explaining the meaning of the print to her little boy, then young enough to be raised in her arms. The print represented the Israelites encamped at night in the desert, their tents made visible by the light streaming from the pillar of fire before them. That print had been, as it were, the text of the last exhortation which Walter had heard from his father, which vividly now recurred to the mind of the desolate youth.

"God may lead us into the desert, my boy, but it is a blessed way if His presence go with us. The eye of faith still sees the pillar of cloud and fire to guide us wherever God wills we should go, and we are safe—ay, and happy—as long as we follow the path marked out by Him who is all wisdom and love."

"The pillar has for me long rested over this place," said Walter to himself; "I would not have left my father, with his broken health, to struggle on alone. But now the pillar will move on,—I wonder whither! I had hoped to England—and Cambridge—with future honour and usefulness beyond. That letter has dashed down all my air-built castles! The desert around me looks very bare; but O my God!—my father's God! do Thou guide me, and give me grace and courage to follow on, nor turn aside to the right or the left."

Walter knelt down in his desolate home, and in a short but fervent prayer commended himself to the guardian care of a Saviour God. He arose from his knees cheered and refreshed. Walter then applied himself to the homely care of preparing his evening meal, for, soon after his father's death, he had dismissed his only servant. Some of the native flock would willingly have worked for the missionary's son, without hope of payment beyond that of a kind look and word, but their offers had been declined with grateful thanks by the orphan.

Walter's gun had on this day supplied him with a more sumptuous repast than usually fell to his lot; but he had emptied his powder-flask for the charge which had brought down his pheasant, and had no means of filling it again. The youth, as he plucked off the beautiful feathers of his prize, saw in their loveliness a pledge that He who had so clothed the bird of the jungle would not leave His child uncared for. Walter had to light his fire, and cook his food, as well as provide it. His kitchen was the open air; his oven—native fashion—was formed of dried mud, and was of the simplest construction. The apparatus comprised merely a few brass vessels, and an iron plate for cooking chapatties.* While the pheasant was being stewed, Walter proceeded to prepare this simple substitute for the bread, which was a rare luxury in Santgunge. Skilled as he was by practice, round balls of dough in Walter's hand were successively patted out and flattened, then spread on the heated iron and turned, till a nicely browned chapattie was ready. Walter, engaged in his humble occupation, and absorbed in thoughts quite unconnected with chapatties, did not notice the sound of a horse's hoofs, and was rather startled by the loud voice of its rider, which suddenly broke on the silence.

* Flat unleavened cakes.

"Koi hai? any one there?" the usual summons to a servant in India, brought Walter to his feet. Turning, he saw in the horseman, splendidly mounted, who appeared before him, a gentleman whom he had only once met before, about three months previously, but whom he instantly recognised. Walter would have done so had thrice as many years intervened since the meeting.

For Dermot Denis was not one to be quickly forgotten. He was upwards of six feet in height, and with form graceful as well as powerfully built. A quantity of thick curly hair, of a tint that might be called golden, surmounted an intelligent face, both handsome and pleasant, whose grey eyes sparkled with life and fun. Walter had, as has been mentioned, seen Denis but once before; but it was under circumstances that had made a deep impression on his mind.

It had been a time of great trouble amongst the native Christians of Santgunge. Their crops had utterly failed. Their missionary was sinking under a slow and painful disease. Mr. Gurney, who felt the trials of his people more than his own, desired Walter to pay a visit to an official at the nearest station, which was fifteen miles away, to try to induce him to give some relief. It was a commission distasteful to the youth. He disliked playing the beggar, and had no faith in his own powers of persuasion. It was shyly that he told his father's message to the official, whom he found entertaining the handsome Irishman.

"I wish I could do more for your people," said the official, placing five rupees on the table; then, as if changing the subject, he turned and said, "Let me introduce you to Mr. Dermot Denis, an Irish gentleman, who, having more time and money on his hands than he knows what to make of, has come to India in search of adventures. Mr. Denis, this is the son of a missionary who, for twenty years, in a desolate jungle, has devoted his life to attempts to convert the natives."

The cordial shake of the young Irishman's hand which followed this introduction was gratifying to Walter, and still more so was the currency note for a hundred rupees which was frankly and pleasantly given. Walter could hardly utter a word of thanks, but his heart felt deeply grateful. Joyfully he bore back the large contribution, which his sick father received almost with tears, as a gift from heaven.

"God bless the generous donor!" he faltered.

"O father! I wish that you could have seen him!" exclaimed Walter, with the enthusiasm of youth. "I never met with any one like him, he looked so bright and brave! How noble he must be in whom wealth and position have raised no pride, one who gives without being asked, and in a manner so frank and kind!"

The parting words of Denis to Walter had been, "I'll some day invade you in your jungle, and see the fruits of your good father's attempts to manufacture monkeys into men."

And now the Irishman had kept his promise. Walter eagerly went forward to meet him, wrung his hand warmly, and in few words told him of the heavy loss which he himself had sustained.

"And you're here all alone!" exclaimed Denis, as he dismounted; "just call your sais (groom); my man has fallen desperately ill on the road—I had to leave him behind."

"I am my own sais, and will be yours," said Walter, laying his hand on the horse's bridle to lead it away.

"Groom and cook too? you're a clever fellow!" cried Denis, gaily. "I'm glad that I've caught you just at dinner-time, for I'm desperately hungry. Just returned from a long expedition, riding day and night from dawn to sunset. I'll just turn into the house and have a smoke, whilst you look after the bay."

Even had Walter had no reason to feel grateful towards Denis, he was much too hospitable to grudge the stranger a share of the dinner which was to have lasted himself for two meals, though he had had nothing but chapatties on the previous day, and it was doubtful when he would again be able to procure anything more substantial.

When Walter re-entered the dwelling, carrying with him the stewed pheasant and chapatties, he found his guest seated at his ease on a chair, with his feet on the table, smoking. Denis threw away his cigar, put down his feet, and applied himself with vigour to the occupation of eating his dinner, demolishing more than two-thirds of the pheasant, whilst talking all the time.

"A most unlucky chance for me, my fellow's falling ill!" he exclaimed. "He was a regular brick; could jabber several languages, was clever at everything—of course cheating his master included. I daresay that he shammed sickness, because he had no fancy to go where I am going. How to supply his place I know not. By-the-by, do you happen to know anything of Pushtoo?"*

* The language of the Afghans.

"I know it pretty well," replied Walter, who was a very good linguist; "Afghans frequently pass this way; we have had one here for weeks who has just recovered from a troublesome illness, and is going back to his home. He is a Kandahar man."

"A Kandahar man!" exclaimed Denis eagerly. "That's just what I wanted. Do you think that he would act as my guide into Afghanistan?"

"You do not mean that you think of crossing the border?" said Walter in surprise.

"Cross it? yes, and go a great way beyond it—as far as Kandahar, possibly to Kabul; I have a great object before me," said Denis, mysteriously lowering his voice.

"You are hardly aware of the danger——"

"Danger!" interrupted Denis, "I revel in danger. I know that the Afghans, every mother's son of them, are thieves and cut-throats; they slice off your head, and then——"

"And then?" said Walter, smiling.

"You have something to put into a book."

Walter could not help laughing at the Hibernian's bull; but resuming his grave expression he observed, "I do not think that you fully know what you would undertake."

"I know everything!" cried Denis, a little impatiently; "I've had it all dunned into me by every one whom I've met, but all I've heard only strengthens my resolution to go. I'm sick of travelling about in a place like India, where every black fellow salams you, and vows he's your slave. I've done India thoroughly all round; seen all that's to be seen, and much more. I've visited no end of Hindu mosques and Mohammedan temples, have dined with the Viceroy, and taken pot-luck with the Brahmins. Now I want something new and exciting. Besides, as I told you, I've an object in view. I'm going, if all the world should cry 'stay.'" And with a look of stern determination, Denis finished off the last bit of the pheasant.

Then followed a few seconds of silence. It was broken by Denis exclaiming, with the joyousness inspired by a happy thought: "I say, Walter, you will come with me! You know the language, you have made friends with the Afghans; having you with me would increase a thousandfold my chance of getting back with a whole skin. You're a good shot, I suppose?"—he glanced at a gun in a corner.

"Fair," replied Walter Gurney, who hardly ever missed his aim.

"You have a horse, I suppose?"

"A hill-pony,—not much of a mount."

"But, doubtless, he can keep his legs on the mountains; you're not such a weight as I am, though pretty nearly as tall. Yes, yes, you're just the companion I wanted; a jovial young chap, sticking at nothing, who can ride, shoot, cook, groom a horse, and I daresay shoe it at a pinch, and who will think no more of danger than I do."

The blood mantled on Walter's cheek; he was young, and his heart beat high at the thought of adventures; besides, he knew that it was true that his knowledge of Afghan character, customs, and language, might possibly be the means of even saving the life of his imprudent friend, who scarcely opened his lips without making a blunder. Denis saw Walter's look of hesitation, and eagerly pushed his advantage.

"We'll strike a fair bargain!" the Irishman cried. "You go with me for one or two months, and I'll take you back with me to England. You're poor—there's no disgrace in that; I happen to have a full purse; I'll share with you as if you were my brother. I'll see to your education, and start you in life; you shall never know a want whilst Dermot Denis has a sovereign left. It's a bargain! Give me your hand on it, old boy!" And Denis stretched out his own.

How rapidly thoughts fly through the mind—more rapidly than fingers can trace them! "Is not this an answer to my prayer?" thought Walter. "A few minutes ago I felt, as regards earth, friendless, penniless, desolate! At once, how unexpectedly a friend and the means of future independence are given me! If I risk something, is it not for a hero, a benefactor, one who has shown me kindness unsought! Then the journey itself may be an opening for good. My father often expressed hopes that a day might come when mission-work might be pushed on beyond the frontier—the Afghans were frequently in his prayers. May I not hope to carry the Gospel to some of the wild people of the mountains, several of whom have enjoyed the hospitality of my parent, and received some instruction from his lips. I believe that my 'fiery cloudy pillar' is moving towards the hills."

"How long will you keep me with my hand stretched out like a sign-post, waiting till you come to a decision which I see that you have jumped at already?" the Irishman cried.

Walter grasped the strong, sun-burnt hand. The silent bargain was concluded; no signed and sealed bond could have made it more firm, at least as regarded the missionary's son.

An interruption now occurred in the arrival of two large heavily-laden mules with their drivers.

"Ah, there comes my luggage at last!" exclaimed Denis, jumping up from his seat, and going forth to meet them. "I hope, Walter, that your goods and chattels will pack into the very smallest dimensions, for as my beasts have as much as they can bear, they can't well carry very much more."

"A case of 'The last feather breaks the camel's back,'" observed Walter.

"I never could make out the sense of that proverb," said the Irishman. "I'd put the last feather first, and the camel would not so much as feel it."

Walter glanced at the speaker to see if he were in jest or earnest; but Denis's handsome face betrayed no consciousness that he had been talking nonsense.

"My pony," said young Gurney, "can carry the few things which I shall require; I shall walk, and lead it."

Dermot Denis was busy with one of his trunks which had been removed from the mule and placed on the ground. He extracted from it a corkscrew and a bottle of brandy, and with these returned to the house, followed by Walter.

"I'm glad that the rascals brought the mules in time," said the Irishman, seating himself, and applying the screw to the cork. "You and I must finish our dinner with a 'dhrop of the cratur,' as my countrymen say."

"Thanks; but I never taste wine or spirits."

"Oh, nonsense; if you've never done it yet, you must do it now, if only for good fellowship. You've not been ass enough to take the pledge, I suppose?" Denis had the bottle between his knees, and out came the cork.

"Excuse me for two minutes," said Walter, and he went hastily into the inner apartment. There on a table lay his Bible, his desk, and a few scattered papers and books.

"Here is a new danger," said Walter to himself. "I had better do at once what I have often thought of doing." He opened his Bible, dipped his pen, and in a firm bold hand wrote on the fly-leaf, "I declare that I will never, except by medical advice or at communion, let a drop of alcohol pass my lips." Walter signed the declaration, added the date, and returned to the room where Denis was mixing his brandy and water. The Irishman pushed the bottle towards him. "I have taken a pledge," said Walter.

"When did you take it?"

"I took it just now."

Denis gave a little whistle of surprise. Walter had made up his mind that his friend would be angry at opposition from one so much his inferior in age and position; but the frank face of Denis did not look angry, it had only an expression of half-contemptuous pity, which was to Walter harder to bear. No man, especially a very young one, likes to be thought weak-minded by the companion to whom he looks up. It was the doubt how he himself could bear perpetually to oppose himself to the wishes of his benefactor that had made Walter take the decided step of signing the pledge. "Well, you're the loser, I'm the gainer, for my liquor will last the longer," said Denis, raising his glass to his lips. "But," he observed, as he set it down empty, "if you fancy that you will curry favour with the Mohammedans by giving way to their nonsensical prejudices regarding wines, you'll find that you are greatly mistaken. They don't follow their Vedas* at all." (Denis, it appears, did not know any difference between the Vedas and the Koran.) "The Mohammedan drinks on the sly. He sits on his carpet spread on the floor, with his brandy-bottle in one hand and his hookah in the other, and drinks till he rolls under the table." Denis spoke authoritatively, as one who knows a great deal more about Eastern habits than a youth who had spent all his years in India. Walter did not care to contradict him. Half-an-hour before Denis had been a hero in his eyes; the gilded image of a chivalrous knight was already losing a little of its brightness.

* Hindu Scriptures.

"Now, take me to your Kandahar man; I'll strike my bargain at once. He shall guide us through the Afghan passes."

Walter led the way into the native village, which was not many steps distant from what had been the home of the pastor. It was much like other villages in India—a congregation of mud-huts, with not a pane of glass to be seen, but was somewhat cleaner than those of the heathen. One small, neat building of brick, with a bell hung aloft, showed that it possessed a place for Christian worship. Swarthy natives came out of what Denis called their ant-hill; women stood in the doorways, to stare at the unwonted sight of a European stranger. There were swarms of children of both sexes and all ages, who received many a kind word from Walter as they stood smiling and salaming.

"Fancy passing all one's life among such as these!" exclaimed Denis, shrugging his shoulders. "Do you dignify these bare-footed blackies by the name of Christians?"

"My father has baptised more than forty," replied Walter, "but the majority——"

"Where's the Kandahar fellow?" asked Denis, who had no taste for anything like a missionary report.

Walter led the way into a mud-built dwelling. The Irishman did not stoop his tall form sufficiently to avoid knocking his head as he entered, and in the semi-darkness stumbled over a recumbent calf which shared the dwelling. Hanif, the Afghan, wrapped in a blanket, was lying on his charpai.*

* Native bedstead.

Conversation was at once entered upon by Denis, Walter acting as his interpreter. The Afghan looked astonished at the opening sentences, and burst forth into rapid, excited utterances.

"What on earth is the fellow saying?" asked Denis with impatience.

"He is vowing by his Prophet's beard that he will not undertake to guide you; that the Feringhee* must be mad to think of crossing the frontier. Hanif declares that if you did reach Kandahar by his means, he would be bastinadoed, or lose his hand or his head; and that if you were murdered on the way, the Feringhees would insist on his being hanged, however innocent he might be. Really," said Walter, in a tone of expostulation, "I think that there is some reason in what the man says. I wish that you would turn your thoughts in some other direction."

* Natives call Europeans Feringhees.

"Give your advice when it's asked for," said Denis, pettishly. "If you're afraid to accompany me, I let you off your agreement. You may stay and vegetate here amongst your niggers."

"I am not afraid," commenced Walter, who was a good deal nettled; "but——"

His new friend cut him short: "Tell the fellow I'll pay him treble what he could fairly demand. Afghans would do anything for gold."

And so it proved. Hanif's eyes glistened at the thought of the large payment offered; and as the bard sahib (great gentleman) was evidently so rich, perhaps an idea of helping to relieve him of some of his goods by the way made the Pathan less reluctant to run some risk. Was he not accustomed to hazard his life for loot (plunder)? So the bargain was struck; the party were to start early on the following morning.

Denis returned to the house. Walter remained to make arrangements with a respectable Christian native employed as a catechist as to the care of his own trifling property during his absence. He gave him the keys of the dwelling, to which some missionary might perhaps be sent before long.

The little church-bell was rung—such was the custom at Santgunge—to gather the native Christians for devotions before they retired to rest. As, surrounded by simple worshippers, Walter joined in the praise and the prayer, again he solemnly devoted himself to his God, before proceeding on what might prove to be a dangerous journey. Then, after exchanging kind words and good wishes with those who loved him for his father's sake as well as his own, the missionary's son returned to his dwelling.

Denis, having had his own way, had quite recovered his temper, and was in exuberant spirits when Walter joined him.

"I wondered how long you were going to leave me to my own meditations, with no light but that of my cigar, while you enjoyed the intellectual conversation of your niggers, so soon to be exchanged for company so insipid as mine!" he said, laughing, as Walter entered the room.

Young Gurney, by lighting a lamp, soon dispelled the darkness. In the gaiety of his heart Denis drew his chair closer to Walter's, and was inclined to be quite confidential.

"I don't mind telling you, old boy—for I know you'll be silent as the grave—what is my great object in pushing on beyond the border. You'll not breathe a word to a soul alive."

"Mr. Denis," said Walter, "we are going amongst Afghans, one of whose characteristics is intense curiosity. We shall be questioned and cross-questioned on every point, and often silence is in itself a reply."

"Oh, I'm a match for Afghans!" cried Denis lightly; "I can lie like a Persian—only, unluckily, I don't know the language they lie in!"

"I do know the language, and I cannot lie," observed Walter; "therefore I had better be in ignorance of anything that you wish to remain concealed."

"You mean that ignorance would be bliss to you, and safety to me!" cried Denis. "You would not wilfully let the cat out of the bag, but you could not help her mewing in it. Well, be it as you wish; I will not reveal to you my great object. But—oh here's just what I want, a supply of paper; I've a bottle of ink, and pens, but I quite forgot the paper!" Denis's hand was upon about a quire of letter-sized paper, on the first six or seven pages of which something had been written, which he was about to tear off in order to throw them away.

"Hold!" exclaimed Walter hastily, laying his hand on the Irishman's arm. "That's valuable; that's my father's writing,—a translation of the Gospel into Pushtoo which he began but never lived to finish. You shall have other paper. I mean to take this with me," and he put the manuscript into his bosom.

"Now there's one thing I want to say to you, Walter Gurney," began Dermot Denis, looking his companion full in the face; "you've been brought up in the midst of a great deal of religious talk with all sort of puritanical notions, till I daresay you think it a deadly sin to look at a bottle, or dance a polka, or shuffle a pack of cards. You're welcome to your thoughts if you keep them to yourself. But we're going amongst a pack of rabid Moslems, and if they come on the subject of religion, the least contradiction on your part will make them fly at our throats. I'm not going to wave a red flag in the face of a bull. If the bigots question me I'll say I'm a philosopher, with no particular notions; that will save me from all the troublesome arguments on ticklish subjects that I don't understand. And I desire you'll do just the same."

Walter coloured to the roots of his hair, but he returned with steady firmness the gaze of his comrade. "I'll never deny my faith," he said, laying his clenched hand on the table; "in religious matters I will be in bondage to no man, and if God gives me an opportunity of speaking a word for Him, I can never engage to be silent. If you do not accept this condition, sir, it will be impossible for me to remain your companion."

Denis tried to laugh off his annoyance, but there was more of irony than of mirth in his laugh. "Hear how the young cock crows!" he cried, "when hardly out of the shell. He'll sing a different note when his feathers are grown. Good-night, my puritanical friend, I'm going to bed; as we start to-morrow, I hope that you'll awake in the morning a wiser and a merrier man." And taking up the solitary lamp, Denis retreated into the inner room, leaving Walter Gurney to darkness and his own reflections.

These reflections were by no means agreeable. If the gilded image of a knightly man had before appeared dimmed to Walter, it was now as if fragments dropping off from what had seemed like armour had betrayed the plaster of Paris beneath. When Walter had grasped the hand of Denis as a pledge that he would, if needful, follow him to the death, the Irishman had appeared to him in the light of a hero, generous, gallant, and noble—a Cœur de Lion, Bayard, Sir Philip Sidney in one. Walter, with boyish enthusiasm,—for he was little more than a boy,—had imagined his handsome young benefactor, protector, and friend, all that he desired him to be. They had now been but a few hours together, and the youth had already seen folly, vanity, selfishness, and a want of principle in his companion. Walter would fain have recalled the feelings with which he had welcomed his friend, and accused himself of ingratitude, fickleness, and presumption for so quickly altering his opinion of one whom he still desired to honour, for he still felt strongly disposed to love him.

But Walter's judgment was not now in fault. He was simply beginning to see Denis as he actually was. Not that the bold, dashing traveller was what the world would regard as a bad man; on the contrary, he was made to be its favourite. Brought up in the atmosphere of a pleasant home, Denis was addicted to no particular vice. He was said to bear a high character, and to be liberal almost to a fault. Yes, Denis was liberal when to be so cost him no sacrifice of self-love. He could throw a sovereign to a beggar, but he would not have parted with his last cigar even to his dearest friend. But Denis had no very dear friend. As his judgment was shallow, so his affections were weak. He was almost an exemplification of the witty description of a man whose heart is the exact size of his coffin—it can hold nothing but himself. Denis's ruling passions were vanity, selfishness, and an intense thirst for admiration. He had had too much of the last-mentioned sweet poison already, and to imbibe it seemed a necessity of his nature. It was this, and love of excitement which made the young Irishman undertake dashing adventures. He would rather have been talked about for his faults and follies than not be talked about at all.

The two companions shared the single sleeping apartment in the small house. Thus Walter could not but observe that Denis commenced the day on which a dangerous journey would be begun without anything like prayer. It was no small effort to Walter to bow the knee when he felt that Denis's eyes were watching his movements, and that the gay adventurer would be likely to despise the spirit of devotion which he did not himself possess. Walter was much disposed to go out into the jungle, and there—alone with his God—pour out his supplications for his friend as well as himself. But conscience told Walter that it was chiefly moral cowardice that prompted the love of solitude. He remembered, that thrown closely together as he and Denis must be for a considerable length of time, it was far better to meet the difficulty at once, and openly show his colours. After Walter's usual reading of the Scriptures, he therefore knelt down, and in silent but earnest supplication committed himself to his Heavenly Guide. The youth confessed his own weakness, and asked for strength, for grace never to be ashamed of his religion, whether in the presence of those who might mock, or those who might threaten. The missionary's son rose with a spirit refreshed. Denis had left the apartment. Walter knew not how his comrade regarded his conduct. If he could have read the mind of Denis he would have seen there a feeling of slight annoyance, for if anything can make a worldly man's conscience uneasy, it is the contrast between his own carelessness and the earnestness of another. But Denis had not at all a troublesome conscience—it scarcely ever gave token of its existence. The Hibernian thought exceedingly well of himself. One thing on which he prided himself was his tolerance; he extended it so widely that it embraced every form of spiritual error, and made him yield a little indulgence even to the devotion of what he would call a narrow-minded puritan like Walter Gurney.

When Walter went forth, he found his companion giving directions in most imperfect Urdu to the mule-drivers.

"Oh, come here and make these stupid fellows understand me," cried Denis; "they've no more brains than the beasts that they lead."

A few intelligible words from Walter soon made matters clear. "Are we to start at once, Mr. Denis?" he inquired.

"Oh, don't 'Mister' me, as Rob Roy said," cried the Hibernian, in his frank, pleasant tone. "We're sworn brothers in the field; you're Walter, and I Dermot Denis."

When Walter saw the young Irishman again, mounted on his beautiful steed, in the pride of his manly strength, the breeze playing with the golden locks which curled beneath his white helmet-shaped topi* and the picturesque folds of muslin which enwreathed it, again the feeling of admiration came back to the heart of the youth like a tide that had but ebbed for a while. Denis, fearless in heart and buoyant in spirit, appeared again as the preux chevalier, the bravest of the brave.

* A kind of hat specially constructed to protect the bead from the sun.

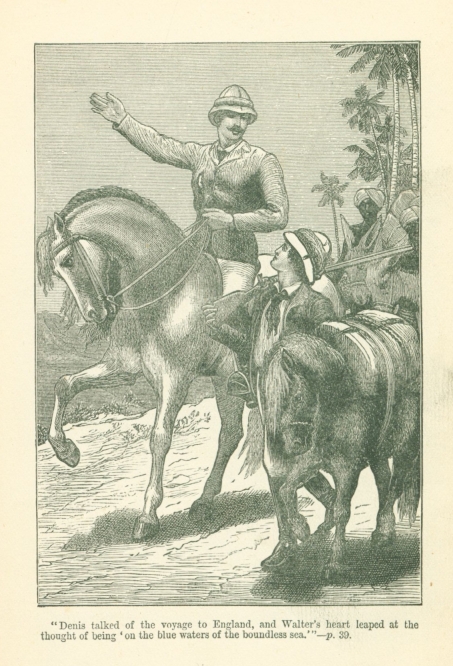

"Denis talked of the voyage to England, and Walter's heart leaped

at the thought of being 'on the blue waters of the boundless sea.'"

Walter felt leaving his childhood's home, with its dear though mournful recollections, and the native friends who had known him from his birth. With simple affection they crowded around to bid him farewell, and invoke blessings on the missionary's son. It was not till he had left the villagers behind that sadness in Walter's breast gave place to emotions more natural to youth. Then came a rebound from the long depressing influence of sorrow and care—a sense of freedom, a joyousness of hope. Few but have known the keen enjoyment of starting on a journey with a lively, amusing companion, and some have experienced the added zest which a little difficulty or even peril bestows. There are those to whom

"If a path be dangerous known,

The danger's self is lure alone."

This was eminently the case with the light-hearted Hibernian; and Walter shared the pleasant excitement. Then the future, which had been so dark before, shone out glittering before him like the snow-capped mountains in front. Denis talked of the voyage to England, and Walter's heart leaped at the thought of being, for the first time in his life, "on the blue waters of the boundless sea." He had often longed to hear the dash of the ocean waves, and inhale the briny breezes. England, too, was in prospect. The youth intensely desired to behold the mother-land. He had often pictured to himself the white cliffs of Albion, and awoke with a sigh from' day-dreams of success in a college career. Now things that, not twenty-four hours before, had seemed well-nigh impossible of attainment, appeared to eager hope to have come almost within reach of his grasp.

The grand scenery through which Walter was passing, the lively conversation of Denis when he could sufficiently curb his own patience and that of his horse to accommodate its pace to a walk, combined to make that morning march one of the bright spots in the life of young Gurney. When, on passing the frontier, Denis put spurs to his steed, and waving his right arm, shouted "Afghanistan at last!" his companion caught the infection of his exultation, and nothing for the time seemed more enjoyable than this wild foray into a dangerous land. A noonday halt was needed, both on account of the heat and the weariness of men and beasts. Denis selected a charming spot under the shadow of a high rock for the travellers' bivouac. A sparkling streamlet, dancing over pebbles, supplied the means of both bathing and relieving thirst. The tired mules were unloaded, saddles and bridles were removed from horse and pony; the animals were tethered and allowed to crop the herbage around them, after their thirst had been slaked.

One of the trunks was opened, and gave ample proof of Denis's skill in providing for travelling comfort. There was a store of small tin canisters containing a variety of articles of food, some of them unknown even by name to the missionary's son. Truffles, turtles, oysters, anchovies, potted game, tongues, and pickles, gave a choice of delicacies to Walter, only perplexing by its abundance. He quickly prepared a meal, while Denis, stretched on the ground, amused himself by writing notes of his journey, or refreshed himself with a cigar.

"I say, who are these advancing?" he playfully cried, as a party of Afghan women carrying baskets of fruit appeared descending the road; "not very formidable opponents, I guess, nor carrying very terrible weapons. Walter, are you prepared for a charge!"

The women stopped to stare at the Feringhee strangers. Denis hardly needed an interpreter; he held up a bag and jingled rupees, then signed to the women to put down their baskets, and pointed significantly towards his own mouth.

"I'm getting on with the language bravely!" Denis gaily cried. "Walter, these women understand my questions without my speaking a word."

The baskets were quickly emptied of the fruit for which Kabul is famous. Denis, notwithstanding his companion's remonstrances, paid for his purchases a price which astonished the Afghans.

"Some great Feringhee lord!" they remarked to each other.

The dinner was by this time ready. "Let's set to!" cried Denis, whose appetite was keen.

Again recurred the difficulty which, trifling as it may appear, is one that so often meets the Christian on his first mingling with the world, that to sensitive minds it becomes a real cross. Walter had always been accustomed to return thanks before meals from the time when his mother had first put his little hands together, and he had lisped after her the words which his lips could hardly frame. So strong had the habit become, that before dinner on the previous evening Walter had said grace as a matter of course at his own board, without even thinking whether his guest could object. He knew Denis better now; he had met the supercilious glance which had been to him like a sting. Was there any need to obtrude his religion on one who could not understand it? Was not faith a private matter between a man and his God? So whispered the ever-ready Tempter. But a few Scripture words recurred to the mind of the youth—Let your light shine before men; and with an effort which cost Walter more than it would have done to face a real danger, in a low, but audible voice he said, "Thanks to God for all His mercies bestowed through Christ our Lord."

"He who prepares the meal considers, I suppose, that he should finish off by saying the grace," observed Denis lightly. "As for me, I never pretend to be one of your saints."

It is remarkable how many men seem to plume themselves on making no profession of religion, as if hypocrisy were the only vice to be shunned. We do not admire a beggar for parading his rags, and declaring that he does not profess to be rich; and who is so destitute as he who has no portion in the world to come! We do not think the debt of gratitude to a bountiful father repaid by his son's openly declaring that he neither loves nor honours his parent! Surely those who with self-complacency avow that they make no profession of religion, and never pretend to be saints, may be reckoned amongst such as "glory in their shame."

After a long halt, partly passed in sleep, the march was resumed. Progress was necessarily slow, as the mules could not travel fast, and it was desirable that the party should keep together. The pass was wild and desolate; little appeared to denote that travellers ever passed that way, save here and there the skeleton of bullock or mule. As the shadows of evening fell, the travellers noticed that Hanif seemed to be more on the qui vive. The eyes of Denis and Walter naturally followed the direction of the Afghan's, as he glanced upwards towards the high cliffs which on either hand bordered the way.

"I say, Walter, I'm sure that I caught sight of two or three heads up yonder—not those of deer!" said Denis, bending from his saddle. "Don't you see something—just above the bush yonder?"

"I see," replied Walter. "Don't you know that it is the nature of vultures to swoop down on their prey?" As he spoke about a score of the powerful birds, napping their huge wings, rose from the carcase of some animal on which they had been gorging, disturbed by the travellers' approach.

"I have two double-barrelled guns and a brace of revolvers; I could give account of fourteen Afghans," said Denis. "I'll adorn my belt with the pistols, and a gun would be better in my hand than on the back of the mule. You look to the priming of yours. We're no dead sheep for the vultures to prey on."

Perhaps on account of the precautions taken, or the fact that the wild tribes of the mountain were at the time too much engaged in their internecine quarrels, to trouble armed travellers, the place for the night-halt was reached without any interruption, though not without several alarms. All the party were tired, with the exception, perhaps, of Denis, who had ridden when others had walked. A fire was kindled by Hanif; another, at a short distance, by the muleteers, who were soon engaged in cooking. Walter, on whom all travelling arrangements devolved, lighted a lamp, and looked after the horse and pony. None of the beasts were allowed to stray away from the little encampment. Grain for the horse had been brought with them by the travellers.

"We'll make Hanif our watchman to-night," said Denis, glancing towards the spot where he and the muleteers, smoking hookahs by their own little fire, formed a picturesque group.

"Never trust an Afghan," replied Walter. "You and I must play sentinel by turns."

"All right," said Denis, taking out his costly gold watch. "From ten to four, that will be six hours between us. I never care to sit up late when there's no dancing or fun to keep me alive, so you'll take the first turn—and mind you awake me at one."

Walter, who had walked during the greater part of the day, was exceedingly weary when he began his night-watch, and, long ere it was ended, found it almost impossible to keep his eyes open. He fed the fire, stick by stick, with the wood which he had made the muleteers collect. But it had not been easy to find much fuel, and before midnight no light was left but that of the small hurricane-lamp below, and the brilliant stars above. Walter thought of the pillar of glory over the camp of Israel, under whose calm radiance the multitudes had slept in calm security. That pillar was but the visible emblem of the power which was watching above him now. In present, as in olden times, He that keepeth Israel doth not slumber or sleep. With the thought came calm and restful assurance. Walter spent much of his time of watch in silent prayer.

At length the hand of the old watch which Mr. Gurney the missionary had left to his son, pointed to one. Walter went to the spot where lay the tall form of Denis, wrapped in a large luxurious cloak lined with costly fur. The youth stooped down, and tried to rouse the sleeper, first by his voice, then by his hand.

"It is one o'clock; rise, it is your turn now!" said Walter.

The only sound heard in reply was the heavy breathing of the sleeper.

"Come, come, I can't keep awake longer," said Walter, shaking the Irishman by the shoulder.

"Just leave me in peace, will you?" was the growled-out expostulation of the drowsy Denis.

"I am too sleepy to play sentinel any longer," said Walter.

"Another hour—just another hour; you roused me from such a delicious dream!" said Denis, turning on his side.

"He rode all day while I trudged on foot," thought Walter, as he resumed his weary watch; "but as I am maintained by his bounty, I suppose that I must be content to take the lion's—or rather the mule's share of the burden."

Again and again the youth caught himself nodding. Never, it seemed to him, had watch-hands moved so slowly. The instant that the point of two was reached, Walter was again at the side of Denis.

"Hold off, or I'll blow your brains out!" exclaimed Denis, suddenly starting up to a sitting position, and looking wildly around him. "Oh, Walter, is it only you? I dreamed that I had half-a-dozen Afghans upon me!—why, what is that horrible noise?"

"Only the jackals," said Walter drowsily, coiling himself up in his rug.

"Dismal noise—worse than the screeching of owls! One would think that some venerable grandfather jackal had departed this life, and that all his descendants had collected together to howl at his wake."

Walter made no observation; he was already asleep.

He was roused at daybreak to prepare for the morning's journey. The Europeans did not find it easy to start. The muleteers were unwilling to go forwards, and demanded bakhshish,* and leave to return. They refused to reload the mules, though Denis used very strong Hibernian language, which Walter did not care to translate. The fiery young Irishman then used the argument of the stick, which was for the time more effectual.

* A present.

The mules were laden at last; but scarcely had the party started before one of the beasts of burden was found to be lame. The slowness of progress had sorely tried the philosophy of Denis on the previous day; he now became fiercely impatient at having to curb in his steed to suit a lame mule's halting pace.

"I'd bet anything that sneaking fellow had something to do with the beast's lameness!" he exclaimed. "I'll give him another taste of my cane."

"Mr. Denis—Dermot! nothing is gained, everything hazarded by making enemies of these men!" cried Walter. "That poor creature cannot limp on with its burden; we shall have to leave something behind."

"Put the boxes on your pony," suggested Denis; "your gun, rug, and other light chattels we'll heap on the top of the other mule's burden, and then turn this wretched brute adrift."

"That arrangement will never do," said Walter, who had a good deal more common sense than his older companion. "My pony could not carry a mule's burden, and the other animal is overladen already. It is absolutely needful to leave something behind. We must part with the least important part of the luggage."

Dermot Denis was reluctant to part with anything. His weapons, of course, must be kept; his ammunition and provision for man and horse by the way, his cooking-vessels and cash—all were necessaries not to be left behind. But his choice cigars, his yellow-backed novels, crockery, glass, and plate, his looking-glass, dressing-case, brandy and champagne,—Denis made a fight for each article, was pathetic over his eau-de-cologne, and grudged his box of fine soap. A great deal of time was consumed in opening, unpacking, arranging, rearranging, and trying to force down lids on overflowing trunks that obstinately refused to be shut. It was long before the luggage was so readjusted, that one mule, with some help from the pony, could carry the needful part of what had been heavy burdens for two. More than one trunk had to be left behind, and a quantity of most heterogeneous articles strewed the ground—objects of great interest to curious spectators.

For, by twos and threes, a little crowd of most inquisitive Afghans had arrived on the spot. Bejewelled women appeared who had been carrying burdens—one, in addition, with a child seated on her hip, and another led by the hand. Most picturesque men, swathed in striped blankets, with long black hair hanging wildly over Jewish features, each with a gun in his hand, or a formidable knife stuck in the scarf which he wore as a belt. All looked as if they had never been washed in their lives, but would have made fine subjects for an artist. The articles on the ground were freely handled; an embroidered smoking-cap found its place on the head of a little urchin who had no clothing besides; the silver-topped bottles of the dressing-case were speedily appropriated, and vanished somewhere under the blankets. Denis was indignant at seeing his property disappearing under the very eyes of its owner.

"Walter, I say, drive these harpies away!" he exclaimed in an angry tone.

"We could not do so without using our weapons," replied Walter; "and were blood once shed, our lives would not be worth a day's purchase. In Afghanistan revenge is reckoned as a virtue."

"The Sahib had much better return," said one of the muleteers, who had been from the first most reluctant to advance.

"The Sahib is a great hero,—the Sahib never retreats," observed Hanif the Pathan, with a grin.

"Don't trust that man—he's an Afghan; he would urge you to go on," said Walter, as Denis looked to him for an explanation of words which, he could not understand.

"I need no urging—I'm resolved to go on; do you think me a weak girl to want to go back now? No, not if I had to go alone."

The Afghans not only used their eyes and their fingers, but they poured forth a volley of questions. "Who were the travellers? whence had they come? whither were they going? Were they merchants? were their camels behind them? why did they go without an escort of armed men?" Such, and many more, were the interrogations made on all sides. Walter had not time to translate half to his comrade.

"Tell them I'm a Feringhee nobleman," cried Denis, "a great friend of their Khan; that he expects me, that I bring him rich presents; that he'll hang any man, woman, or child that dares to lay a finger on my goods!"—he snatched his umbrella from the hand of a boy, and sent him spinning and howling. "Tell them that I've lots of powder and shot, and could bring down a sparrow half-a-mile off, to say nothing of a thief of an Afghan!"

Walter did not think it necessary to give a literal translation of the words of his angry companion; what he did say could hardly be heard amidst the Babel of voices, for Hanif and the muleteers were all taking on themselves to answer the questions, which they did, in true Oriental style, with wildest exaggerations.

Some of the tin cases of luxuries were on the ground, glittering in the sun. An Afghan seized on one, perhaps in hopes that the metal was silver, wrenched it open, then flung it from him with an exclamation of disgust, and a curse.

"Dogs of Kafirs! (unbelievers); they eat the unclean beast!" he cried, surveying the Europeans with a look of intense hatred.

"If we are to proceed, we had better go at once," said Walter to Denis. The Irishman's quick temper was as a lighted cigar, and Gurney saw that those around him were as gunpowder ready for explosion.

"I'm ready to go!" cried Denis fiercely; "but I should like to kick those fellows all round first."

"It is well that they do not understand you," observed Walter Gurney.

Denis mounted his horse, which had attracted many admiring and covetous looks from the Afghans. He shouldered his gun with a very determined expression, and glanced down significantly at the pistols stuck in his belt.

The party then moved on, the unladed mule with difficulty managing to keep up with the rest. For at least a mile the travellers were accompanied by a most unwelcome escort of Afghans; more would have come but for the temptation afforded by the loot which the strangers had left behind. Denis had insisted on Hanif's carrying for him his valuable fur-lined cloak. At the point where the Europeans at last parted company with the Afghans, Denis looked round for Hanif, but neither the guide nor the cloak were anywhere to be seen!

"The villain has robbed me!" Denis exclaimed.

"One could hardly have expected anything else," thought Walter. Indeed it was rather a matter of surprise to young Gurney that the remainder of the day passed without any attempt at attack. The road had grown steeper, the cliffs higher; it was at least impossible here to miss the way, as there was no visible opening on either side. Walter felt as if walking, with his eyes open, into a trap; but even if retreat were possible, he would not for an instant entertain the thought of deserting his friend. The march took longer than that of the previous day, but much less ground had been passed over. Before sunset men and beasts were thoroughly tired out (always excepting Denis and his high-mettled steed), notwithstanding the mid-day rest.

Again the party bivouacked, and Walter prepared the meal, which was eaten almost in silence. The mishaps of the day had greatly damped the high spirits of Denis.

"I don't care to lie on the bare earth," he said, "with nothing to keep off the night dews. Just lend me your rug."

Walter complied at once with the request, and parted with the only warm wrap in his possession.

The day had been a trying one to the missionary's son; but he had more steel in his composition than had his more excitable friend; Walter was less easily elated than Denis, was less impetuous in action, but had greater power to endure.

Yet Walter felt the need of a brief period of perfect solitude to compose his troubled mind, and hold communion for a-while with the invisible world. No trace of an Afghan was in sight. The rich red glow of the setting sun was bathing cliff and stream, and lighting up with beauty a copse to the right, a little oasis of green in the wild and sterile mountain landscape. This copse formed a tempting place of retreat; Walter would be within call of his travelling companion, yet be completely screened from observation. He made his way over some stones and tangled brushwood to the spot, buried himself in the copse, and then, in a half-reclining posture, gave himself up to thought.

"How mysterious are the dealings of Providence! When, led by gratitude for past kindness, and hope of future independence, I linked my fortunes to those of the only being on earth who seemed willing and able to help me, I thought that I was following the guidance of the heavenly pillar. Yet into what a desert has it led me! It were childish folly to close my eyes to the fact that it is more than probable that I may never return from this mad expedition; it is more than possible that my blood may stain an Afghan dagger, my body feed the mountain eagles. What then would become of all my cherished hopes of following in my father's steps with (such was my vain presumption) a wider field for missionary enterprise than was given to him upon earth. I would not, I thought, lead so dull, so monotonous a life; I would acquire knowledge, distinction, eloquence, that I might devote every gift to my Master's work, lay every talent at His feet. I hoped to become a sharp and polished instrument to be used for the welfare of men, and I find myself a kind of travelling servant to a man who cannot sympathise in my views, cannot understand my aspirations—a man whom I seem to have no power to influence for good!

"Shall I then doubt the wisdom of Him whose guidance I have sought in prayer; shall I think myself forgotten by my Master even if He let me perish here? No!" and Walter raised his eyes to a light cloud floating above, flushed with the rosy light of the sun, which was itself hidden from view by the tall cliff behind which it had set. "No! though He slay me, yet will I trust in Him! I have seen the child of fortune stripped of some of the things which he valued; gradually he and I may have to part with all—perhaps liberty, possibly life. But there is that of which no power either of earth or hell can deprive the Christian; nor life, nor death, nor things present, nor things to come, can separate him from the love of Christ Jesus our Lord. Let what will come, my best treasure is safe; the Lord is the strength of my heart and my portion for ever."

Walter was startled from his meditations by a sudden rustling in the bushes, followed by a cry of pain or terror, not many yards from the spot where he was reclining. In an instant he was on his feet; and turning towards the point whence the sound came, Walter saw a very large cheetah (leopard), that had sprung from its covert on an Afghan child, and was trying to carry her off. The little girl was struggling and resisting with all her might, striking at the savage beast with her small clenched hand, while she loudly cried out for help. It was well that help was near, or the struggle would have been short, and its fatal issue certain. Walter had no weapon in his hand; but unarmed as he was, he dashed through the brushwood to the rescue of the poor child. His short and sudden rush was enough to alarm the cheetah, which seldom, if ever, attacks a man. The wild beast dropped its hold of its prey, and bounding off, escaped by some unseen outlet from the copse.

Walter went up to the child, and beheld the most beautiful girl on whom his eyes had ever rested. Excitement and the effort of the struggle had added a deeper crimson to her cheeks; her face was scarcely darker than that of a European. Large blue eyes, dilated with fear, fringed with long soft dark lashes, were raised towards her preserver with an eager wistful gaze. The girl's hair, in long rich plaits, fell over her bright red hurta, and was adorned with many a silver ornament. Walter was too well accustomed to Oriental taste to think the child's loveliness lessened by the numerous rings which weighed down her little ears, or even the jewel on one side of the delicately formed nose. The child was evidently no poor man's daughter.

The girl did not appear to be seriously injured; her loose sleeve was very much torn, and a few drops of blood fell from one of her arms. The attack and rescue had been the work of but a few seconds.

"You are wounded, my poor lamb!" cried Walter in the Pushtoo tongue, and drawing out his handkerchief he tore it into shreds to bind up the bleeding arm.

"Not a lamb—for I fought it; I struck it! If I'd had a dagger I would have killed it!" cried the girl with a fierceness which seemed strange in one so young and fair. "I'm an eagle, for I live in the Eagle's Nest!"

With childlike confidence the little Afghan let Walter bind up her arm, looking at him with a curiosity which seemed to overpower every other emotion.

"They say you're a Kafir," she observed; "you're not a dog of a Kafir, you are brave and you are kind."

"How came you to be in the jungle, my child?" asked Walter; "I never saw you till you cried out."

The child smiled as she answered: "You did not see me, nor did you see the cheetah. Wild beasts know how to hide, and so does the wild Afghan."

"Why did you hide?" asked Walter.

"I crept down to see what Kafirs are like. They told me that rich white Feringhees were going through the pass, one riding on a beautiful horse. I hope that the horse is not yours?" she added in a tone of inquiry.

"No, the horse is not mine," replied Walter.

"I am glad of that," said the girl.

"And why?" inquired the Englishman.

"Because I should not like to loot you."

"Ha! a secret let out!" thought Walter. "Do you think that poor travellers ought to be looted?" he said aloud.

"No, but rich ones should," was the naive reply. "My father says there are big boxes all filled with treasure. He promised to change my silver bracelets for gold ones from the Feringhee's spoils."

Walter was almost as much amused by the frankness of the child, as alarmed by the information which she gave.

"What is your name?" he inquired.

"Sultána," replied the child, whose queenly manner suited her name. "Sometimes my father calls me his little eagle."

"And who is your father, Sultána?"

"My father is a bold chief, a bara bahadar (great hero)," replied the girl proudly. "His foes all dread Assad Khan. When last he came back to the Eagle's Nest from a foray, I saw that two heads hung from his saddle-bow."

"You did not like to see those ghastly heads? you turned away?" said the English youth, his soul revolting from the idea of that beautiful child being connected with scenes of slaughter.

"Why should I turn away? Afghans like to see dead foes. I wish, when I'm old enough, that I could ride about and fight like the Turkystan women!"

"Now, Sultána, you say that your father is a chief. If we travellers came to his fort and asked for food and shelter, would he not give them?" asked Walter, who had almost finished his surgical task."

"Yes, Assad Khan would kill a sheep; he would feast the strangers; Afghans are kind to strangers," replied the girl.

"And your father would send them on their way in safety?" inquired Walter, who had a personal interest in the reply to the question.

"Yes, they would be safe, till they had gone a little distance," said Sultána, a smile rising to her rose-bud lips.

"And then?"

"Then, if they were rich, he would follow and loot them; if they fought—he would kill them."

"Oh, what fearful darkness broods over this land!" thought Walter, "when the very children are trained to delight in deeds of rapine and blood;" and he sighed.

"Why do you sigh?" said Sultána, more gently, laying her little hand upon Walter's. "My father would not cut off your head. You saved his little Eagle. I like you—I thank you!" and soft moisture rose in her large blue eyes as she uttered the words.

"Sultána, you have not thanked Him who sent me to save you," said Walter, gently caressing the small, sun-burnt hand.

"Who sent you?" exclaimed Sultána, glancing suspiciously around.

"The great God,—He whom you call Allah."

"Did He send you,—did He speak to you? when? how?" exclaimed Sultána, in great surprise, withdrawing her hand as she spoke.

"I did not hear His voice with my mortal ears; and yet, Sultána, I feel sure, quite sure, that He sent me here to save you. I came into this jungle thinking to be quite alone, that I might talk with God."

"How can you talk with Allah?" cried Sultána, the mystery exciting her curiosity, almost her fear.

"I tell him all my troubles," replied Walter; "I have had many troubles of late, and I thank Allah for helping me through them. I shall thank Him to-night for saving you from the cheetah."

"And does Allah answer?" inquired Sultána, her large eyes fixed inquiringly on the speaker.

"Yes, but in a way that you cannot understand. O Sultána, I am so glad that the Lord both hears me and loves me. I wish that you too would talk with God."

"The Moullahs don't teach us anything like that," observed Sultána; "they teach us to say 'There is one God, and Mohammed is His prophet.'" She repeated this moslem confession of faith with the enthusiasm with which its very sound seems to inspire the followers of Islam. "Is that what you want me to say?"

"No, my child," said Walter, very gently; "I want you to say such words as these: 'Allah! teach me to know Thee! Allah! teach me to love Thee!'"

"Love!" repeated the young Afghan, as if her mind could scarcely take in an idea so new. "We must obey Allah, and fast in the Ramazan (though my father doesn't), and those who want to be saints should go and walk round the black stone at Mecca. But love! why should I love Allah?"

"Because He loves you," replied Walter; "I can tell you, for I know it, what your Moullahs never have told you, that God is love."

At this moment, a peculiar sound, something like a whistle, was heard from the height above. Sultána started at the sound.

"They've missed me—they're seeking me!" she exclaimed, and with the rapidity of a fawn she sprang away, and disappeared as the cheetah had done, by some unperceived outlet.

It was useless to attempt to follow the child, especially as the sunset glow had given place to deepening twilight. With rapid steps Walter returned to Denis, whom he found smoking by the fire.

"What on earth were those strange noises that I heard a little while ago?" asked Denis, taking the cigar from his lips; "I heard something like a scramble and a cry, and you shouted from the thicket yonder, and there was, I think, a crashing of bushes. I'd half a mind to come and see what you were after. Did you rouse some wild beast from his lair?"

Walter gave a short account of Sultána's adventure, to which Denis listened with keen interest, bursting into laughter when he heard of the little maiden's intended appropriation of his horse; it was a very brief laugh, however, and by no means one of unmingled mirth.

"And now, Dermot, you see that we are watched, waylaid, that we shall certainly be attacked and robbed by these fierce mountaineers; you must resolve at once on what course to pursue."

"Sell my life as dearly as I can," muttered Denis, grasping one of his pistols.

"No; mount your horse, your good fleet horse, and make your way back with all speed, under the cover of night. Your animal is not knocked up like ours. He may at least bear you far enough to place you beyond immediate pursuit. You must of course abandon your property, and it may serve to satisfy for a time the rapacity of these wolves. I do not think that the muleteers, who will not attempt to fight, run any serious risk; they will merely lose the beasts. But you—you must not delay for an hour your escape back to India."

"Escape back to India!" exclaimed Denis, indignantly starting to his feet. "What do you take me for, boy? Do you think that I, Dermot Denis, am the man to run off from the shadow of danger like a cur that flies yelping away if you do but lift up a stone. Do you think that I am the man to endure being twitted with having begun an enterprise which I had not the spirit to carry out, a man to save his own neck by leaving his comrade to be murdered by these brutal Afghans!"

"My danger is less then yours," observed Walter. "In the first place I have the protection of poverty; in the second I have made friends with the child of a chief."

"What a bit of luck for us!" exclaimed Denis, in a completely altered tone, throwing himself again on the ground beside the glowing embers of the fire. "I certainly was born under some auspicious star! No sooner do I lose my rogue of a guide, than up starts a powerful chief to act both as guide and protector. Of course I'll be hand and glove with this Assad Khan; he'll introduce me at Kandahar as his most particular friend. Of course I'll make him no end of promises,—one must never be sparing of them. I'll tell the chief that when I get back to India, I'll send him my horse—a free gift—and half-a-dozen others loaded with jewels for pretty Sultána. I'll make it the chief's interest to stand my friend. I'll see more of Afghan life than any being in the world ever saw before. Stay, stay, I must write up my journal; where have I put my ink-bottle?"

Denis, now in wild spirits, wrote for about five minutes as if writing for life; he then threw down his pen, and pushed the paper from him. "That's enough for to-night, I shall have plenty of time to-morrow to write up my story."

"Will he have plenty of time?" thought Walter to himself. "Is not my gay, bold comrade beset with dangers not the less real because he chooses to shut his eyes as he takes the leap which may land him—one shrinks from asking where! I am the only Christian near him, the only being who can speak to him of that soul which may so soon be required. And yet, coward and faithless friend that I am, I sit, as it were, with lips sealed, watching his career towards the precipice over which he so soon may plunge with a laugh on his lips!"

"Dermot," said Walter, aloud; "even you must own that our lives are uncertain."

"Yes; it's a toss up whether you and I ever see old Ireland again."

"Is it not well to be prepared for whatever may happen?"

"Yes; I've looked both to my guns and pistols," was Denis's reply.

"It was not that which I meant. I was thinking of what follows death."

"You don't want me surely to set about making my will?" exclaimed Denis. "It is not needed; if I die my estate must go to my brother."

"I am not speaking of worldly property. I was thinking that you—that we both—need to know more of God's will, that we may be ready, should He please to call us suddenly." Walter took his small pocket Testament from his bosom. "I am going to read my evening chapter; would you have any objection to my reading aloud?"

"None in the world," replied Denis, lightly; "but I can't promise to listen."

Walter selected his chapter, and selected well. Never before had he so realised the force of the expression, "Preaching as a dying man to dying men." Walter knew that at that moment stealthy foes might be creeping towards them under the cover of darkness, or that his reading might be interrupted by a sudden volley from the thicket or the heights above it. But the feeling of peril which solemnised the young Englishman did not at all un-nerve him; Walter drank in the meaning of each life-giving verse which he read. His companion's perfect silence encouraged Walter, till—when he closed the book—he turned to look at Dermot Denis, and saw him sunk in a deep slumber.

Walter's strange interview with the child of the Eagle's Nest had strengthened the missionary spirit in the young man's breast. He went over in thought every circumstance of their brief meeting during the long hours of his night-watch. On this occasion Walter felt no disposition to sleep; physical discomfort, combined with mental anxiety to take away all desire for repose. The wind had arisen, and, rushing through the pass as through a funnel, extinguished the fire, put out even the hurricane-lamp, and chilled the frame of the young sentinel. Dermot Denis, with characteristic thoughtlessness, had appropriated the rug of his friend. Though the day had been hot, there was sharp keenness in the night wind, and young Gurney missed his usual protection. It was only by motion that he could keep up any degree of warmth. As Walter paced up and down, now facing the furious blast, now almost swept down by its violence, watching the wild lightning-illumined clouds above him, as they seemed in their rapid course to blot out star after star, Walter's spirit yearned over the Afghan child in the power of the king of darkness.

"One wearing almost the form of an angel is developing the instincts of a tigress," muttered Walter to himself. "Eyes that can express so much of feminine tenderness can look complacently at what a Christian girl would turn from with sickening horror! A heart made to reverence what is holy and love what is good, a kindly—yes, I am sure of it—a kindly affectionate heart, is filled with bigotry and pride, and a debasing hunger after plunder won by red-handed violence! Oh, what hath not Satan wrought in this miserable land; and not only here, but over the widest tracks of this fallen but beautiful earth! Millions of victims are lying in worse than Egyptian bondage, whilst those who could carry to them the message of deliverance are, as it were, quietly pasturing their sheep amongst the comforts of civilised life. Oh for the voice from the burning bush that gave His commission to Moses! Oh for the power to say to the murderer of souls—Let My people go that they may serve Me. Lord! how long, how long shall Thy servants rest in selfish indifference whilst generation after generation perishes in darkness and sin! If it please Thee to prolong my life, let it be the one object of that life to glorify Thee by rescuing souls through the power of Thy spirit; it is the object best worth living for—the object best worth dying for! Where does the fiery pillar lead the believer but along the path consecrated by the track of the Saviour's own footsteps. He came to seek and to save the lost."

Very fervently did Walter Gurney plead on that tempestuous night for Sultána and her guilt-stained race. The sense of personal danger was almost lost in the intense realisation of the spiritual peril of others. In wrestling supplication on that wild, stormy night the hours wore away. Walter felt himself in the immediate presence of One who could say to the wilder storm of human passion, the sweeping blast of satanic power, Peace, be still! Whatever outward circumstances may be, these are blessed hours that are spent alone with God; they are hours whose result will be seen through countless ages, when corresponding to the fervour of prayer will be the rapture of praise!

Walter had no difficulty on this night in arousing Dermot Denis. Partly on account of the boisterous weather, partly from anticipation of a possible attack, the young Irishman's sleep had been broken and disturbed. Ever and anon he would start, as if his mind were still on the watch.