Title: The other Miller girl

Author: Joslyn Gray

Illustrator: Beryl Boughton

Release date: June 6, 2024 [eBook #73780]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Chas. Scribners Sons

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

BY JOSLYN GRAY

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

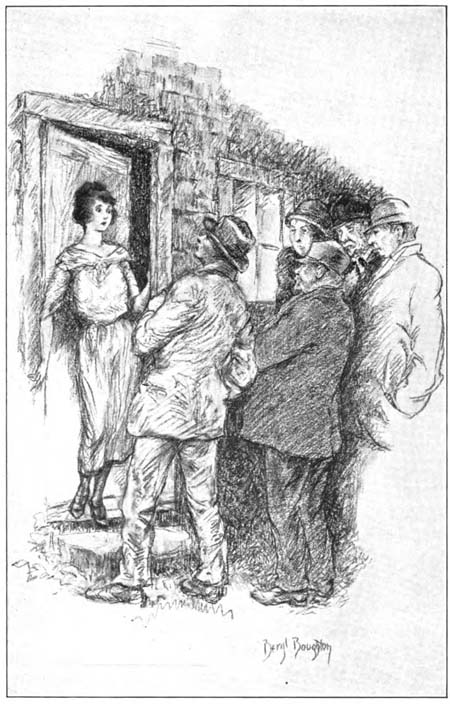

“I am so sorry ... but we don’t have company, you know.”

[Page 53

THE

OTHER MILLER GIRL

BY

JOSLYN GRAY

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1922

Copyright, 1922, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Printed in the United States of America

TO

FLORENCE TEMPLETON GRAY

JANUARY 31, 1922

IN MEMORY OF TODDIE

AND THE DAYS BEFORE THE BIRTHDAY

ON WHICH SHE WAS BANISHED

| “I am so sorry—but we don’t have company, you know” | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| “Please, may I come in? I want to—tell you something” | 26 |

| Anna took pride and pleasure in ironing the frills and laces of his little frocks | 124 |

| The echoes of the thundering knocks had hardly died away ... when Alice Lorraine appeared | 216 |

THE OTHER MILLER GIRL

ON a pleasant Saturday afternoon of the latter part of the September following the awarding of the Wadsworth prize, Mr. Langley received three distinct shocks. The first was occasioned by hearing Miss Penny referred to as an old lady, and the second, which was almost simultaneous, by learning that Anna Miller was commonly known as the ‘other Miller girl.’ The third, which was more subtle, was also more personal and might have wrought real havoc but for the slip of a yellow-haired girl who was characterised thus negatively. Her discovery of this third shock to Mr. Langley and the action she took led to such consequences that if it were the fashion now-a-days to invoke the muse, this history must needs begin by bidding the goddess sing of the uncommon sense of the other Miller girl.

The church at Farleigh was a really beautiful building. It was only an old-fashioned New England meeting-house, but its proportions were perfect for its style and its pillared portico was almost as appropriate to its structure and environment as the chaste[2] marble columns of Greece to their more artistic and romantic setting. It stood on an height truncated by natural forces to form a plateau and was surrounded by broad lawns shaded by great English elms and a single oak-tree.

The greensward was as rich and velvety as if the season had been midsummer and the foliage of the trees as luxuriant and almost as bright, on this Saturday afternoon of the third week of September when the minister sauntered slowly up the broad walk leading to the porch. For the summer had been wet: more than one week had disproved the old saying that there will always be one fair day in the six to dry the parson’s shirt. It had been favourable for grass and trees and uncultivated vegetation but too rainy for crops. The September sunshine was, however, making amends; and as he glanced at the picturesque regularity of the fenced and walled fields of a farm across the river, Mr. Langley said to himself that the harvest would be bountiful after all if the frosts held off a bare fortnight.

The choir had been rehearsing for the morrow and the women members were lingering in the porch to chat. The minister had just noticed that Miss Garland, a member who had been away on a visit in the West for three months or more, had returned, when he heard her ask who was staying with old Miss Penny this winter. It gave him a start to hear Miss Penny called old, though she hadn’t been a young woman when he had come to the two villages straight[3] from theological school, and if he had stopped to reckon the years he must have realised that she was well beyond three score and ten. But he did not stop, for Miss Harriman’s reply gave him another start.

“The other Miller girl,” she said in her high, strong voice which fortunately lost its nasal twang when she sang. “Rusty has gone to college, you know, even though she didn’t get the Wadsworth prize. But this girl goes to the academy and it seems to me that Miss Penny ought to have more help than she can give her outside of school hours, for she has rheumatism so bad now that she’s almost a cripple.”

Glancing up, the speaker saw that the minister was upon them and smilingly apprised him of the obvious fact that Miss Garland had got back. He shook hands with Miss Garland and with the other three, questioned the former about her summer and declared that he should call upon her next week for a fuller account. Then he turned to Miss Merriman.

“What was that I overheard you saying, Miss Merriman?” he asked with his slow smile. “Did I hear you speak of the other Miller girl? And does that mean Anna?”

“Yes, Mr. Langley, Anna Miller. But that is what everybody in the South Hollow, and for that matter, in Farleigh, too, I guess, calls her. But she was away so long that people forgot there was such a person—such as knew of the family at all—and anyhow, she seems so different from Rusty. Of course she’s pretty,—she looks for all the world like a doll,—and[4] everybody says she’s good-natured to a fault. And there’s something droll about her. And yet——”

The expression of Mr. Langley’s face made her pause.

“Do you know, Miss Merriman,” he said whimsically but at the same time rather wistfully, “at this moment it seems to me that to be supremely good-natured and somewhat droll is a triumph in itself.”

He smiled and sighed.

“Nevertheless, life in the two villages will seem different without Rusty,” he owned. “It will be quieter, but doubtless far less exciting.”

He went into the church to fetch a book, then overtook Miss Garland and walked with her as far as the post office. And as they went, he asked her why she thought of Miss Penny as old; and they occupied the time recollecting dates and computing the passing of the years. And both felt older at parting, and one of them strangely depressed.

Just as Miss Penny had long realised that people called her an old lady so Anna Miller was quite aware that she was known as the ‘other Miller girl.’ But the younger resented the fact as little as the older. Anna adored her sister, looked up to her in many ways, and never dreamed of disputing or questioning her title as virtual head of the family. The girl knew, too, that she was pretty and in doll-fashion, though she didn’t herself consider doll-fashion bad. If the question had come up, she would have acknowledged promptly, too, that she was good-humored, and[5] she couldn’t help realising that people thought her droll. Nevertheless, vain as she undoubtedly was, Anna Miller did not attach undue weight to any of these qualities, and otherwise would have been likely to rate her own powers lower than anyone else would have done. Enjoying life thoroughly, and perhaps more consciously than is usual at her years, she was quite content to be the ‘other Miller girl’ and to endeavor to stop any portion she might of the gap left in hearts and households by Rusty’s absence.

But the girl was herself quite unconscious and others quite unaware of her most valuable characteristic. Young as she was, Anna Miller had one quality seldom gained before middle age, and rare even then,—a truly humourous outlook upon the world. The girl viewed life and her fellow human beings almost in the detached manner of a philosopher, yet warmly and sympathetically withal. She enjoyed oddities and idiosyncrasies which annoyed or vexed others and made allowance for larger faults with a singularly mature tolerance. She was one of the few who habitually demand less than they are willing to proffer,—simply and naturally and quite without any sense of superiority.

Experience had made Anna Miller prematurely middle-aged in her grasp of reality,—experience acting upon that endowment of good nature which everyone granted her. Running away as a child from the dreary, shiftless household that had been her home, for five years the girl had supported herself in the[6] great city to which she had fled, to the extent of keeping soul and body together, successively as errand girl to a dressmaker, as bundle and cash-girl, and finally as sales-girl in a department store. But all the while something within her—perhaps the adventurous instinct that had hurtled her forth—had responded to the clarion which is within the din of every struggle. She had known the extremes of heat and cold, of loneliness and hunger, but she had made light of them. She had clung to her shred of vanity, masquerading on an empty stomach, and cheering long hours in her cramped, dreary hall-bedroom arranging her tangle of pale yellow hair in various fashions before her tiny cracked mirror, trying on scraps of finery, and coquetting with the reflection which was always picturesque no matter how absurdly arrayed. She had ‘bluffed’ her way through the lean, meagre years, her shockingly slangy expression being a veritable gospel of cheer to her fellow clerks and lodgers, and the snatches of ugly popular songs on her lips, real melody which echoed in her own heart as well as in theirs. And she had ‘won out’ triumphantly with her natural sweetness of disposition not only unimpaired but strengthened and enriched, with a keenness of mind which is one of the ends of education, and with that curiously mature and humourous outlook instead of the bitterness which might have been expected.

On the day following that on which Mr. Langley had first heard her referred to as the other Miller girl,[7] Anna was in her usual place in Miss Penny’s pew at the opening of the Sunday morning service. She was rather preoccupied by her new suit. Rusty had had to have a new one when she went to college, and she had insisted upon Anna’s having one at the same time. Rusty’s was brown, the peculiar russet shade that matched her hair exactly and was peculiarly Rusty’s, loose in the jacket, and plain. Anna’s was green, more elaborate than Rusty’s and not in nearly so good taste, as Anna knew well. But it was exceedingly smart and very becoming and the girl was, as she declared, ‘crazy over it.’ Clever with her fingers, she had made a green velvet hat to match the suit, a three-cornered affair which did not fall far short of being utterly absurd, but which, set jauntily upon her riotous yellow hair, certainly made her little doll-face bewitching.

Anna had a very sweet voice and had been asked to join the choir, and during the anthem, she fixed her long-lashed blue eyes seriously upon the women members, studying, not their voices nor their manner of using their vocal organs, but their attitude and demeanour. As she saw herself in fancy standing behind the low railing in her new green suit and ‘nifty’ hat, she wondered if it wouldn’t be an exceedingly pleasant change for the congregation to have a younger person to gaze upon and one who had more regard for the current fashions. And dear me! Every blooming member of the present choir had hair of the same colour, something between brown and drab. Anna[8] said to herself that when she should stand up among them to sing, if her long yellow braid with the curl at the end did not of its own accord flop over her shoulder, she would flop it,—it stood out so picturesquely against the green. Here in the pew, of course, it was just as well to let it hang down her back, for Miss Penny sat very near the pulpit.

So near, indeed, that she was directly in front of Mr. Langley,—which reflection induced another that when she should sit with the choir, Mr. Langley couldn’t see her at all. That seemed a pity, and yet—Anna wondered if he saw her now,—saw her, that is, not as a soul but as a young girl in a new suit, with yellow hair shining like pale gold against it. He might possibly notice the latter, for his beloved little Ella May, who had died before the Millers had come to Farleigh, had had long golden curls.

Suddenly the girl recalled her roving gaze. Mr. Langley was preaching, and Anna hadn’t even heard the text! It was right down mean, she said to herself, when anyone worked as hard as he did to write such beautiful sermons for people not to listen to every single word. He didn’t write absolutely new sermons, indeed, he had so many on hand after preaching here for years and years and years; but they were new to the greater part of the congregation and practically so to all of them, for he worked over them, added new matter and quoted from new poems whose authors had been at school or in their cradles when[9] the sermons were first composed. Moreover they were quite fresh to Anna.

Though her mental equipment was haphazard, Anna Miller had a certain power of concentration. To-day, however, she had no sooner fixed her eyes resolutely upon the minister than her thoughts began to wander again. For it came to the girl suddenly and startlingly that Mr. Langley was changed—yes, greatly changed. He looked tired, but it was worse than that: he looked as if he had lost something. There seemed no longer to be any springiness about him. He was like a jack-in-the-box that has been so mishandled that when you open the lid he doesn’t jump out at you but only flaps feebly. Mr. Langley was too young to have his springs go flat. He had only a few grey hairs. He was tall and slim and straight and graceful and really much handsomer than that floor-walker at Martin and Mason’s that had been so stuck on himself.

Glancing hurriedly back over his life as she knew it by hearsay, Anna felt it to have been unusually placid and untroubled. Of course it had been a terrible grief to him losing his little girl, that golden-haired little Ella May who had gone about through the two villages scattering sunshine. But that had happened years ago and he had seemed happy and young until now. Then it came to her that this was, perhaps, Ella May’s birthday. Perhaps he had it all to go through again every year as the day came round?

Early in the afternoon, Anna appeared suddenly in[10] the parlour, which was seldom used excepting on Sunday, briskly polishing a goblet with a cross-barred dish towel.

“O Miss Penny, tell me, when did Ella May die?” she asked. “Was it the twenty-second day of September?”

“O no, Anna, she died on the twenty-eighth day of December,” Miss Penny returned promptly and in some surprise. And although the storms of more than a score of winters had yellowed the tiny marble lamb upon the little grave in the cemetery on the hillside where the minister’s baby had been laid, probably every adult person in the parish could have given the date as readily.

Anna returned to the kitchen. Passing the mirror, she paused and gazed at her own image. She shook her head ruefully. Even with her festive blouse and smart skirt covered by her checked gingham overall, she was a picture, and after all, her hair looked as pale golden against this dull ground. Hastily gathering an handful of wet silver, she returned to the parlour.

“She had golden curls, didn’t she, Miss Penny—little Ella May?” she asked.

“Long, golden ringlets and deep blue eyes,” asseverated Miss Penny in the tone she used only in speaking of the dead.

“Well, was her birthday in September?”

“Why Anna Miller! She was born on Christmas-day—O my dear child, it must have been twenty-five[11] years ago this next Christmas day, for I was fifty myself at the time and I am seventy-five now. That was the year I had my plum-coloured moreen—you remember the under side of the cushion in grandma’s old chair up in Reuben’s room? Sarah Pettingill made it, and I wore it to the Christmas tree for the first time and word came while we were there that Mr. Langley had the finest gift in the world—a little daughter. Some of the ladies wanted him to call her Christmas and he said he’d like to have her named Carol, but she was called for his wife after all. Her maiden name was May.”

Mrs. Langley was so little a personality in the mind of the girl that it seemed incongruous in her to have had a maiden name. As she would have asked a careless question in regard to her, however, she looked up to see Miss Penny’s face drawn with dismay.

“Dear me, I know I am old, but I didn’t think I was losing my memory,” Miss Penny cried. “It comes to me all of a sudden that I wore that plum-coloured dress to the child’s funeral. I remember distinctly my mother’s telling me that plum-colour was next door to purple and that purple was light mourning and quite suitable for a young person’s funeral.”

“But you could have worn it to both,” declared Anna. “You keep your clothes so well that it probably looked new for the funeral.”

“But Anna, my aunt Penny died the February after that dress was made and mother and I coloured it[12] black for the funeral. And she died twenty-five years ago the tenth of February.”

“Then it couldn’t be the Christmas that Ella May was born that you had it, but the one before her death. I’m glad it wasn’t, for I don’t like her to be so old.”

“But if the little thing wasn’t born that year, I’m sure I don’t know when she was born,” remarked Miss Penny plaintively.

“We’ll have to find out,” said Anna cheerfully. “Anyhow, I’m glad it wasn’t the twenty-second of September. I got to thinking of it at church and it sort of—got on my nerves.”

Returning to her work, she couldn’t get Mr. Langley and the mysterious, lamentable alteration in him off her mind. Ella May might have nothing to do with it—and then again she might. In any event, the first thing to be done was to learn the age of the child at the time of her death. She was just wondering whether she had time to go over to the cemetery that afternoon, when Miss Penny called her. Going into the parlour, she found Mrs. Phelps, their next-door neighbour.

“O Anna, what do you think?” cried Miss Penny in great excitement. “Mrs. Phelps says that Ella May Langley was only three days old when she died. She can prove it!”

ANNA MILLER gasped. But she recovered herself immediately.

“Well then, you were right about the plum-coloured moreen, Miss Penny. It served for the christening and the funeral just like the baked meats in Hamlet that coldly furnished forth the wedding-feast,” she commented. “Only—this is what gets me. How about those golden ringlets?”

“Dear me, dear me! I cannot understand!” cried Miss Penny in dismay. “Even now I seem to see that little thing as plain as day, toddling along beside Mr. Langley, in her fine white dress with the lace frill at the neck pressed down by those lovely long curls. I suppose I dreamed it.”

“The fact is, Miss Penny, most everybody in the church feels just about so,” remarked her neighbour.

She turned to Anna. “As I said to Miss Penny, the reason I am so sure about it all is because the marble lamb on their lot in the cemetery on Ella May’s grave was the last thing my cousin Alfred ever did. Mrs. Langley was so particular that it should be copied from life from a lamb that was just three days old same as the baby was when she passed away that Albert had to wait until spring to do it. He went off[14] on a farm up in the hills beyond Marsden and stayed over two nights to make his sketches. He took to his bed that spring and never did another stroke of marble work. Mrs. Langley was more than satisfied with the monument and had it photographed and framed. The last I heard—which wasn’t very lately—the photograph stood on the marble-topped stand in her room close to her bed.”

Anna’s eyes grew round. It seemed strange to hear Mrs. Phelps speak of Mrs. Langley as a person. Until to-day she had been hardly so much as a dim vision, a mere word, this woman who had been an invalid for more years than Anna had lived. She seemed far less a person than Ella May. And now to think of her—or to try to stretch her mind to think of her as Ella May’s mother and Mr. Langley’s wife gave the girl an uncanny feeling. And she couldn’t mention her in the present tense.

“What was she like, Mrs. Phelps?” she asked in an hushed manner.

“Mrs. Langley? O Anna, don’t ask me!” protested Mrs. Phelps. “She was pretty with soft dark eyes and fine brown hair the last time I saw her, but that was twenty-odd years ago.”

“My goodness! Hasn’t anyone seen her since?” asked Anna.

“It has been years and years, I don’t know just how many, since the last outsider saw her. She had neuralagy in her face and headache. The last I knew she had had one headache for ten years. I don’t[15] know whether that one is still going on or whether she had begun on another.”

“I wonder if Mr. Langley sees her?” Anna asked.

“I believe he goes in once a day—he used to. But Bell Adams that keeps house for him takes care of Mrs. Langley and I guess she’s the only one that ever really sees her.”

Anna betook herself to the porch. Understanding had come to her. Poor Mr. Langley! He, too, had played with the vision of the golden-haired little daughter; all these years he had kept himself young with the image of his little girl in his heart. Most likely he hadn’t thought of her as of any particular age—just a darling little girl. But now, since last Sunday,—since Wednesday, indeed, some idiot had reminded him that she would have been a grown-up young lady at this time. Anna could fairly see him shrinking, cowering before the appalling fact. Then he had taken a great leap headlong to overtake a daughter twenty-five years old!

What a pity! What a calamity, indeed! How would he ever get through the remainder of his life with his poor heart all flattened out and his vision forever shattered? But no one could bring the baby back nor could anyone halt or turn back the revolving years. Everything moved relentlessly on towards old age excepting that little marble lamb that would remain just three days old to the end of time.

But the marble lamb recalled Mrs. Langley, and suddenly Anna seemed to see a ray of light. Mrs.[16] Langley had been dead to the minister almost as long as the baby, and yet she wasn’t hopelessly dead. Suppose she were to be restored to him? There must have been something very dear about one who had insisted upon the little symbolic image’s being copied from a baby lamb just three days old, and if she still kept the photograph beside her in her loneliness and pain, she must herself be a lovely creature with the added saintliness of the years of patient suffering. If she could be restored to Mr. Langley, a sweet girl-wife, would not the weight of years that had suddenly pounced down upon him take instant flight? One was always hearing of people who had been bed-ridden for years getting well, and Mrs. Langley wasn’t so bad as bed-ridden. ‘Neuralagy’ and sleeplessness and headache and the like were what ailed her, and youth saw no reason why these should not be speedily banished. Quite likely it might have been put through long since had anyone taken the matter in hand.

Anna grinned as she said to herself she would now be Charley on-the-spot. Mr. Langley had been goodness itself to Rusty and their father—to all the family, indeed. He was putting Rusty through college. Her mother and the boys worshipped him; and Anna herself really owed him most of all. For she had deserted her family for five years, coming back to find a quite different and to her ideal home, a changed father and mother and a wonderful sister—and all through Mr. Langley. In any case, Anna said to herself she would have wanted to do what she was[17] going to do (she didn’t know how or even exactly what as yet); but as it was, she simply had to do it.

That evening when she and Miss Penny were having their tea, Miss Penny asked her how she happened to be thinking of Ella May that day.

“I noticed that Mr. Langley looked sort of sad this morning at church, and I was trying to scare up a reason,” Anna returned.

“Sad!” cried Miss Penny in real distress. “O Anna!”

“Well, tired, perhaps,” the girl amended.

“Do you suppose, Anna, that it can be because of his lifting me in and out of the phaeton every Sunday?” Miss Penny asked almost tragically. “If I thought it was that, I wouldn’t go to meeting at all—though I should miss it—I don’t know how I should get along without it. And then he might be hurt. Or—I suppose I could get that Luke Thompson—not his brother, you know—to help me. He isn’t very bright, and yet—I hardly know whether I could offer him money. And yet how could I ask him unless I did? And I should have to explain to Mr. Langley—but so I should if I stayed at home. Only——”

“I could lift you myself. I could run three times round the house with you in my arms,” Anna assured her. “It’s nothing at all to Mr. Langley. He’s got muscle to burn. I didn’t mean that. I meant—I don’t know exactly, but I believe he’s tired at heart after all these years of well-doing. I’ll tell you what his expression this morning makes me think of—pa’s[18] Aunt Marthy he’s always telling of who was taken with her last sickness in the dead of winter and had a terrible hankering for dandelion greens. She said she knew she’d get well if she could have just one mess of ’em—and the snow three feet deep on the ground. And when it came to the end and they asked her if she had any last wishes, she said: ‘Thank you kindly, I could relish a mess of dandelions.’ And while she was waiting for them, she died.”

“We’re all more or less like that, wanting something or other beyond our reach,” commented Miss Penny with a smile and a sigh, “But I shouldn’t think it of Mr. Langley.”

“Do you know, Miss Penny, I believe I’ll run in to see Mrs. Langley some day soon,” Anna remarked.

Miss Penny looked as if she believed Anna had suddenly gone mad.

“She might take to me where she didn’t to other people—some do, you know,” the girl went on coolly. “And some people like just to look at me—on account of my hair, I dare say, for otherwise I’m not much to look at. It’s a yard long, you know, if I pull it out perfectly straight.”

“Anna, dear, there are moments when I almost think you are vain,” said Miss Penny smiling. “But listen to me, child. Reuben stayed at the parsonage for weeks after his father passed away, and Mrs. Langley would never see him even once. And he was the sweetest little fellow! Mr. Langley would have liked to keep him, but of course he couldn’t under[19] the circumstances. And so—you know how it all came about that he came here, don’t you, Anna?”

“I have heard it many a time. It’s one of pa’s favourite yarn. But it’s a good story and worth repeating just the same,” Anna returned.

The girl’s last waking thought was of standing by the invalid’s couch bathing her aching brow with cologne-water. But in the course of the following week she learned that Mrs. Langley had acquired the reputation of being extremely formidable. Big Bell, as Bell Adams, the tall, large-boned, hard-featured but good-natured housekeeper was called, cherished considerable affection for her mistress but gave Anna no encouragement whatever. When she hinted that it might be well for her to see someone, Bell was horrified and aghast. It was as much as ever, she declared, that Mrs. Langley would see her own husband for two minutes a day.

Admitting that visiting Mrs. Langley would be no cinch, the girl was nevertheless undaunted. It wasn’t natural for her to live in that way. If she weren’t lonely, she ought to be; if she were not wretched, it was because there were no extremes in her life—only one dead level of headache and neuralagy. And constantly Anna came back to the realisation that there was something to appeal to in a woman who had thought of having the three days old lamb carved and who had cherished the picture of it all these years.

Finally she decided to see the image itself and receive, it might be, some inspiration or suggestion[20] for making a beginning. She learned the location of the minister’s lot and set off secretly early Saturday afternoon.

The cemetery, which overlooked the whole valley of the river, was a retired, lonely place, hedged in by evergreen, yet not without beauty. Anna had been vaguely perplexed and anxious, but the serenity of the place soothed her, and she made straight for the minister’s lot with a subdued eagerness of expectation that was almost adventurous.

Suddenly she saw it from a distance, the tiny baby lamb with its feet folded neatly beneath it. So little and quaint and homely it was, that the girl stilled a cry, a little motherly murmur of pity, as if the tiny creature were alive and had been left here lonely through all the long years. And running, she dropped down on her knees beside it to fondle it.

Then she shrank back and caught her breath sharply, almost in a sob. It was as if, believing it to be alive, she had found it dead. One side of the marble was sadly discoloured. It was so blackened indeed as to be quite defaced and ugly, to have lost all its symbolism and significance and to have become an hideous caricature. Suddenly the other Miller girl, who seldom shed tears, covered her face and wept.

MR. LANGLEY was nearer fifty than forty, though only by a little. He was, in a way, ‘settled’ in his habits. He liked and affected, on all days save the Sabbath, old clothes and old shoes, though both were always scrupulously neat, and his shabbiness was never otherwise than picturesque and attractive. Though he went about constantly among his people, he led a lonely, pensive life in the big, empty, shabby parsonage, almost as little aware, it would seem, of the existence of his invalid wife as were his parishioners who practically thought of him as a bachelor. And truly, since his wife had taken to her room upwards of twenty years ago, and shut herself out from everyone, he had been almost as literally widowed as if she, too, lay in the enclosure marked by the little marble lamb in the cemetery on the hillside.

For all that, Russell Langley had still somehow kept intact through all the years the heart of youth—almost of boyhood. Not that his parishioners were aware of it, except indirectly. Most of them regarded their beloved pastor and bore themselves towards him as if he had something like three score years to his credit—or debit. The boys and girls, it is true, the children and even the babies found him singularly[22] companionable,—but so did the very oldest. The greybeards of the congregation and those who were contemporaries of Russell Langley’s grandparents talked to him as they would have talked to the latter had they been living and had their lines been cast in Farleigh instead of in Albany, New York. His youthful appearance impressed them only in the sense that he was a fine figure in the pulpit and a graceful presiding officer in the town hall whenever the services of such an one were required. His tall, slim, indolently erect figure was attributed to the fact that he had played base-ball at college, and the lack of lines in his face to freedom from family cares. For, when all is said, an invalid wife whom a clergyman sees no more frequently than an invalid parishioner and with whom he holds no conversation whatever is scarcely to be classed among family cares.

It was only the other Miller girl who recognised the elusive quality that made up a large part of the charm which everyone felt in the man. Likewise when this quality had taken flight, temporarily or irretrievably, it was Anna Miller who guessed the secret of its loss. Everyone knew that the minister had never forgotten his little daughter who had died. Ella May’s name was constantly upon his lips. But Anna said to herself that the light of enthusiasm in his eye and the buoyancy of his step had been largely due to the thought of a child toddling or tripping along beside him.

Then suddenly he had lost her, had lost his child-companion[23] and with her the spirit of youth. Someone must have said to him—some idiot, some gump, some galoot, the girl reflected indignantly—that Ella May would have been—was it possible that she would have been twenty-five if she had lived? Twenty-five! Poor Mr. Langley! He couldn’t tote a person of twenty-five around with him leading her by the hand. It must have been a terrible shock to him to reach out for the golden-haired child and see a tall young lady with her hair put up and a college education! No wonder that he had grown old overnight, that his youth had fallen from him as if it had been something material, a mantle of slippery silk that had dropped from his shoulders at the loosing of a clasp.

Ah! but he should have it back. He should recapture it, the Reverend Russell Langley should, before it was beyond recall. He would renew his youth in the companionship of his youthful wife. Mrs. Langley was nearly forty-five, but she wouldn’t look over thirty at the most—probably not over twenty-five. And twenty-five in a wife is quite another thing than in a daughter. It was work and care and fuss and bother that made people grow old, and she hadn’t done a thing or had a care for nearly twenty-five years. Mrs. Langley had, as it were, lain upon rose leaves, gazed at the little pictured lamb (that was, alas! so much fairer than the marble image) and thought of all sorts of sweet and lovely things. She had suffered pain, of course, but that is refining and would only[24] add a pensive, perhaps mournful charm to her flower-like beauty.

A week from the day of her visit to the minister’s lot in the cemetery, Mr. Langley passed the Miller house, bound for a conference at the academy, and the other Miller girl set forth for Farleigh, of which village the South Hollow was one end. As she drew near the parsonage, she saw a blue haze of smoke coming from the chimney of the summer kitchen. That meant that Big Bell was at work in that remote part of the house, and Anna’s feet flew.

As she came to a lane which extended a few rods from the avenue which was the main street of the village to a pine grove which was originally the western boundary of a large farm, she glanced up absently. The one house in the lane had been vacant during the summer, but within a few weeks a mother and daughter, a rather mysterious pair, had moved into it. Now she saw a young girl, who was dark and looked handsome in an haughty fashion, on the steps. Anna waved her hand in a friendly way. The girl inclined her small head proudly, rose and went into the cottage.

“I do believe she’s mad because I haven’t been in to see her,” Anna said to herself in dismay. “She’s about my age and I’m the one who would naturally do it. Of course, they wouldn’t let Mr. Langley in, but I’m different. Nobody would mind a little thing like me.”

She was tempted to run up the lane and tap at the[25] door. But this afternoon was pledged to Mr. Langley and his girl-wife, and Anna regretfully left the lane behind her.

She opened the parsonage gate softly. If she could elude Bell the way was clear, for the front door stood open, and of course the screen door wouldn’t be fastened. Creeping up the walk, she tried it gently. It did not yield. Peeping in, she could just make out that it was hooked.

As she stood irresolute, she noticed a loose place where the wire netting was tacked to the wooden frame of door. It was too late for June-bugs, but the season was still like summer and if there were any chance, moth millers would fly in by the score as soon as the lamps were lighted and commit suicide in their harrowing way. Poor things! It seemed wicked to entice them to destruction.

But there was no other way. Boldly the girl poked her finger through the aperture, tearing the netting ruthlessly until she could reach the hook and raise it. Then, withdrawing her scratched and bleeding hand, she opened the door softly and stole in, only to be immediately seized and oppressed by a sensation of guilt and even of fright. Pausing only a moment, however, she made her way noiselessly down the passage to the door of the room she knew to be that of the minister’s wife. It was ajar and she knocked timidly.

Absolute silence save for the loud ticking of the[26] clock and the yet louder beating of her heart. Screwing her courage, Anna knocked again.

“Bell?” called out a strange, hoarse voice that accorded ill with the vision of the girl-wife.

“No’m. It’s me—Anna. It’s the other Miller girl—Rusty’s sister, you know,” murmured Anna faintly. “Please may I come in? I want to—tell you something.”

Without waiting for an answer, she pushed the door wide and entered a large, bare, gloomy looking chamber, darkened and musty-smelling though one window was open a few inches. For a minute she stood motionless, unable to make out anything clearly in the dimness. Then, as suddenly as if a blind had been raised or a match struck she saw the dark figure of the minister’s wife dimly silhouetted against the dun background.

Mrs. Langley—if indeed it were Mrs. Langley?—had raised herself from the cushions of a padded arm chair and was staring at the intruder in mingled amazement and horror. And the girl, her heart in her mouth, stood as if transfixed and stared back. It was as if she had heard a tremendous explosion or witnessed a silent one (as one does in a dream) and found herself standing in the midst of a mass of wreckage—which might have been the shattered fragments of the bottle of cologne-water with which she had in fancy bathed the white brow of the pale, romantic invalid she had pictured.

“Please, may I come in? I want to—tell you something.”

This woman’s figure, outlined against the lowered[27] blind, was that of a witch, the shoulders being curved almost in an hump and the emaciated profile resembling the terrible nutcracker contour commonly associated with the broomstick. Her dark hair, streaked with yellowish grey, was strained back from her yellow face into a tight little wad on the back of her head. Her lips were colourless, her cheeks appallingly hollow. Her sunken eyes, set in deep, greenish cavities, burned fiercely beneath her frowning brow. She looked as old and ugly as a sybil and to Anna as wicked.

It was she who first recovered sufficiently to speak.

“Who are you and WHAT are you doing in my room?” she demanded in a voice that made the girl say to herself ‘Hark from the tomb!’ and gain thereby a bit of audacity.

“I’m the other Miller girl, Rusty’s sister,” she faltered. “I just thought—I’d come——”

But she could not go on.

“Are you mad? Are you stark, staring crazy?” challenged the old woman whom Anna couldn’t believe to be the minister’s wife. As she spoke, large gaps on either side of her front teeth explained the unnatural hollows in her cheeks.

“N-no, I guess not. I’m only—sort of fresh,” the girl gasped.

“Did Bell let you in?”—still more fiercely.

“O no, I let myself in,” Anna returned, and as the fierce dark eyes bored into her she seemed forced to confess the whole enormity of her action as if she[28] had been a naughty child. “I poked my finger in and made a hole in the screen, but I don’t believe it’ll matter—it’s so late,—the season, I mean.”

“If you are not crazy, what do you mean by breaking into people’s houses and disturbing the sick?” demanded the old woman. “Don’t you know that I haven’t seen anyone except the doctor for twenty-three years?”

“Twenty-three—that’s skidoo,” murmured Anna under her breath and caught another bit of spirit. Withdrawing her gaze, not without difficulty, from the face before her, she glanced about her, half fearfully, half boldly. A marble-topped table next the chair in which the invalid huddled was covered with bottles, apothecaries’ boxes and medicine glasses. In their midst, a photograph in a velvet frame stood upright by means of a support at the back. As the girl’s eye encountered this, on a sudden she knew it was the little lamb, and her fear took wings. Quite bold now, she went straight up to Mrs. Langley, held out her hand—which was ignored—and smiled ingratiatingly.

“The little marble lamb up in the cemetery,” she murmured softly, “I went to see it. I thought you would like to know—that is, I thought you would want to know that it’s all turned black and yellow and mildewed, and——”

“What!” the woman almost shrieked.

“The little lamb—the cunning little marble lamb on Ella May’s grave with its little legs tucked under it like a baby kitten,—it’s all black and—slimy!”

[29]Mrs. Langley fell back among the cushions.

“My baby! My baby!” she cried, and the genuine pain in the harsh voice awaked the girl’s pity. “Has no one looked after it? O, I might have known! I might have known!”

As she looked beseechingly at Anna, she seemed to see her for the first time.

“Sit down, little girl,” she said, and her voice though not pleasant was less harsh.

Pity contending with shrinking, Anna fetched a chair and seated herself beside the table bearing the bottles and the photograph. As she fixed her eyes on the latter, the woman in the chair gazed at her. She had had no glimpse of youth, of young life, for more than twenty years, and it might not have been strange if this slip of a girl with her long-lashed demure blue eyes, her charming, peaked little face and her riotous yellow hair that almost seemed to light up the dark chamber, had appeared a supernatural visitant. She made an apparent effort to collect herself, to marshal forces that had been dormant for so many years as almost to have become non-existent.

“It was—good of you to tell me,” she croaked. “Is it—ruined?”

“O no, indeed, one side of it is as good as ever, or nearly. A marble man could mend it up slick, I’m sure. But Mrs. Phelps’ cousin Alfred isn’t Charley-on-the-spot any longer because he cashed in right after he made it.”

The invalid grasped only the first sentence. “I[30] should hate to have it—scraped,” she said in a low voice.

“I get you. So should I,” the girl responded eagerly. “Of course you know that it isn’t alive, but you can’t help feeling all the time just as if it were—those darling little sticks of legs tucked in under so naturally and all that. I shouldn’t want it scraped, either. Promise not to let on if I tell you something?”

The invalid looked as if she would have smiled if she hadn’t long since forgotten how.

“I promise,” she said in a voice which indicated the weary while since she had relaxed her terrible grimness.

“Well, when I saw it, so little and cunning and helpless, and then saw—what had happened to it, out there all alone, I just cried. I couldn’t help it, honestly.”

As she looked at the girl, tears came to the invalid’s eyes. The hand which held her pocket handkerchief to them was like a yellow claw, but they were less sharp when she removed it.

“O, don’t you feel badly about it, please, please,” Anna begged. “I’ll tell you what—I’ll clean it all up slick. I can use sand soap and all sorts of lightning cleaners. I’ll get someone to put me wise about cleaning marble without letting on what it’s for.”

“O, if you only would!” cried the invalid looking and speaking more like Red-Riding-Hood’s wolf than like the girl-wife Anna had dreamed of restoring to[31] her husband (who might be this woman’s son or grandson).

“I hope—I didn’t frighten you?”

“I was a bit fazed, but I shouldn’t be again,” Anna admitted as she rose. Then she caught her breath sharply at the thought of there being an again. And after all, why should there be? Though she couldn’t help being sorry for her, there was nothing she could do with that sort of person. Surely she couldn’t wish that sort of wife upon poor Mr. Langley!

“And you will tell me how you get along?” the other asked.

“Come here, you mean?”

“Of course,” Mrs. Langley responded so promptly that Anna couldn’t help feeling how elated she must have been if the invalid had been the invalid of her fancy. She felt a bit indignant as she asked herself why, with absolutely nothing to do for twenty years and no real illness, this woman couldn’t at least have kept her figure and her complexion. “How soon can you do it, little girl?” Mrs. Langley added.

“Not before next Saturday, for I’m in school—the academy. So you see I’m not what you’d call a little girl. Well—so long.”

She held out her hand. The hand of the invalid was cold and clammy, besides being like a claw, and as she let herself out, on a sudden Anna shivered. The yellow face with its cavernous eyes, the sunken mouth, the gaping teeth, the claw-like grasp of her hand,—the[32] girl made a wild dash to get away from it all only to ran violently into Mr. Langley, who was coming slowly up the walk with bent head.

Apologising in profound distress, as if it had been his fault, he asked Anna if she had been looking for him, that being the sole reason that anyone but the doctor ever came to the parsonage.

“No, sir,” faltered the girl oppressed by a sudden and awful sense of guilt towards him, “I came to see—your wife.”

“What’s that, Anna?” he demanded looking at her as if he doubted her sanity or his own sense of hearing.

“I’ve been—visiting with your wife,” the girl said and laughed hysterically.

With a startled face, he pushed by her into the house. And only then Anna realised the whole force of the situation, the ugly, naked fact. She—that terrible old woman who was really an old hag, was Mr. Langley’s wife!

She began to run, wildly, blindly, pursued by the terrible vision. She did not see the girl who lived in the lane come forth into the avenue on an errand, and ran directly into her arms.

REUBEN CARTWRIGHT’S father had built the house in the lane at Farleigh, and one who had known Dick Cartwright well would have said the cottage was like him. There was something odd and unusual about it which gave it a peculiar charm without making it startling or bizarre; and something of his whimsicality seemed to have crept into the arrangement of nooks and corners and cupboards and bookcases. Oddest of all was the living-room, which was disproportionately large and contained a good-sized platform, raised three feet or more above the floor, which was to have held the pipe organ which the years were to have brought. But the years, instead of bringing the pipe organ, fame and other desiderata, material and otherwise, had taken away from Dick Cartwright his greatest blessing, his wife and sweet-heart whose presence and companionship had been the necessary conditions of fulfilling and enjoying his dreams. And after her death, the quaint cottage with the platform for the organ and the odd bits of furniture he had made and carved were only a mockery to Dick Cartwright. He had his little boy, it is true, who was very like his mother, and he had Mr. Langley as an intimate friend; but he could not forget[34] Jessie and he took to drink to ease the torture remembrance was. Whereupon he forgot not only Jessie but their child and his duty as well. He lost his place as organist at Farleigh church and as book-keeper at one of the banks at Wenham. And when presently, three years after the death of his wife, he disappeared, it was found that he had lost his house also and all his possessions.

When news of his death in a railway wreck near Chicago came to Mr. Langley, who had meanwhile sheltered Reuben, he made enquiries and found that the cottage had been mortgaged to its full value. The bank at Wenham which held the mortgage offered the cottage for sale, then, when no purchaser appeared, for rent. Soon after, an elderly couple whose married daughter lived in the South Hollow took it and occupied it for six years until early in the preceding summer when their daughter had been widowed and they had gone to live with her. The cottage stood idle all summer but early in September a new family moved in, a mother and daughter, the first strangers to come to the village for years. No one knew whence they came nor who they were. They moved in so quietly that scarcely anyone knew the house was occupied until they saw smoke coming from the squat, picturesque chimney.

No one had seen the mother; but the daughter, who had answered the door or gone out on errands, was said to be as handsome as she was haughty. They responded to no friendly overtures, refusing entrance[35] even to Mr. Langley, and seemed to feel themselves superior to the place and the people and to the cottage where they lived which was, indeed, a simple dwelling when compared with the simplest summer homes of the wealthy. For they were said to have been enormously wealthy and suddenly to have found themselves penniless at the death of the husband and father who had gambled or speculated until he had come to his last farthing. It was understood that they were relatives or connections of the president of the bank at Wenham, who had offered them the shelter of the cottage in the lane.

Anna Miller attributed their desire for seclusion to grief over the death of the husband and father rather than to pride. She couldn’t help fearing what had evidently occurred to none other that he might have died by his own hand, and she felt that such a shock might well leave them too sore and sick at heart to wish to see any human being. Nevertheless she said to herself, with an assurance that was made up of humility and warm-heartedness as well as of vanity, that she would somehow effect an entrance where others failed.

When she ran straight into the strange girl’s arms on the day she was fleeing from the parsonage and the spectre she had elicited, the one shock counteracted the other. Controlling her hysterical shuddering, she murmured an earnest apology.

“Dear me! I might have knocked you down, butting[36] into you that way. You are sure I didn’t hurt you?”

“Not at all,” the girl repeated quietly, and Anna liked her voice as much as her dark, pretty face. “But what was it?” she asked. “Was someone or something chasing you?”

Anna smiled rather wanly as she moved back to get the support of the stone wall which fenced the lane. “Not exactly, unless it was a ghost,” she said in her usual droll way. “Sit down here, won’t you, and I’ll tell you about it.”

“I mustn’t stop,” the girl said nervously. “I only thought—you needed help.”

“So I do, the worst way. Honest, I’m like a rag. My knees shake and——”

The stranger sat down on the wall beside her and put her arm about her shelteringly. Anna leaned against her gratefully and closed her eyes for a few moments. The older girl gazed at her wonderingly. An hungry, almost a starved look came into the dark eyes and the arm which supported Anna clasped her almost fiercely.

Anna opened her eyes and smiled without moving.

“You’ll think I’m a perfect baby,” she declared, “but truly I have had a queer sort of shock.”

She sat erect and slipped down, then seated herself again. “I’m too wobbly to walk just yet. I’ll wait a bit until I feel better or see a waggon. I wish you felt like waiting with me?”

[37]The other girl’s brow puckered in a slight frown. Anna introduced herself.

“I am Anna Miller. I have wanted awfully to get acquainted with you, though truly I didn’t mean to break in the way I did.”

The dark girl smiled vaguely and rose slowly from the wall. Anna sprang up also.

“You mind—waiting alone?” the stranger asked hesitatingly.

“I’m not afraid, only I don’t seem to feel like facing my thoughts at this moment. I guess I’ll hike along if you’re leaving me.”

As she breathed a deep sigh, the dark girl looked at her in troubled fashion.

“Come up to our cottage and have a cup of tea first,” she asked in a constrained manner. Anna said afterwards to Miss Penny that if she had talked Latin she would have used the form of interrogation that expects the answer no.

“I’d like to, first rate, if it wouldn’t be too much bother for you,” she said frankly. And when the other assured her that it would be no trouble, she put her hand on her arm and they went up the lane together.

The outer door led straight into the living-room. As they entered, a tall, handsome, dark-eyed woman with a proud, forbidding countenance rose from a chair and confronted them.

“Mother, this is Miss Miller,” the girl said deprecatingly.[38] “She doesn’t feel well—she’s faint and I want to make her a cup of tea.”

“Not Miss Miller,—Anna, please. No one calls me anything else,” the girl asked in her sweet young voice. But the woman, who bowed stiffly without extending her hand, asked Miss Miller stiffly to be seated. Anna dropped limply into a chair. The other girl went out of the room.

“I—I didn’t catch your name,” murmured Anna.

“Lorraine,” said the woman coldly and yet with a certain fierce warmth.

“Somehow that name sounds very familiar to me,” Anna observed, only to perceive by the woman’s face that she had made an extremely mal àpropos remark. “I suppose it’s the city—or province in France I am thinking of,” she added lamely.

“Quite likely,” returned Mrs. Lorraine frigidly, and taking up a piece of embroidery began sternly to set fine stitches in it. Anna glanced at her timidly.

“How pretty your fancy-work is,” she remarked, politely deprecatory. She told Miss Penny afterwards that she wondered the stuff weren’t all eyelet-holes, for Mrs. Lorraine’s eyes, black as they were, reminded her of burning coals. And she declared that hereafter she would believe in the tamarisk or basilisk or whatever the bird was whose gaze turned one to stone.

“It could hardly be called fancy-work,” Mrs. Lorraine rejoined, and her voice was the more cutting in that it was naturally good and had the modulations of one who has lived among educated people in society.[39] “I make my living and that of my daughter—or try to—doing this work.”

Anna felt she should have run from this house also had not the daughter appeared at this moment with a tray containing a cup of tea and a plate of biscuit. She took it gratefully and in her nervousness scalded her throat so that tears came to her eyes. It would have been easy to burst into tears, and the girl resolutely studied the pattern of the napkin. So doing, she noticed that it was of the finest damask she had ever seen but was apparently old for it was darned and patched. Somehow, she had never heard of patching napkins. But she felt Mrs. Lorraine’s piercing eyes upon her and transferred her attention to the silver spoon which was also old, very thin and exceedingly fine.

“They were my grandmother’s, and I kept the dozen. They were too thin and worn to be worth anything,” Mrs. Lorraine declared in the manner of challenge. And Anna felt that she could endure no longer. Gulping down the tea, she rose to her feet.

“I must be going,” she said and turning to the daughter thanked her for the refreshment.

“I feel so much better,” she said. “I——”

Pausing, she gazed wistfully at the girl who seemed sweeter and gentler in contrast with her mother’s haughtiness, and to whom Anna’s heart went out warmly. It seemed as if she couldn’t leave her without pledge of another meeting. But when she asked if she might call for her on the morrow to go to[40] church, Mrs. Lorraine said that she and her daughter did not go out.

“Just the same, I am sure there were tears in that sweet girl’s eyes,” Anna told Miss Penny that evening. “She is all ready to be friendly, but what can she do with that terrible old woman. And yet—I’m sorry for her, too, poor thing!”

“I suppose she doesn’t like to appear out after being so rich, though they must have some of their fine clothes left,” returned Miss Penny. “But it may be their carriage, you know, though for that matter I don’t know why even people with a coachman and footmen should care to drive to church when it’s only across the way—that is, it’s cross-wise from the parsonage and there’s only one house between the parsonage and the lane, and Reuben’s father didn’t have to start until the last minute, though he was always there, of course, to begin to play before the opening of service. And there’s no barn for the carriage and where would they put the coachman?”

“They could make a nice little coop for him by putting hinges on the floor of the pipe organ platform and making a lid of it,” remarked Anna lightly. She had decided on the way home that she would not mention her visit to the parsonage to anyone. She would fulfill her promise, clean the little marble lamb and then forget all about it and about Mrs. Langley and go back to thinking of Mr. Langley as if he were a bachelor. She would make no further ill-advised efforts to bring back his youthfulness; she would be[41] thankful if she hadn’t added ten years to his age. If he didn’t appear to-morrow in the pulpit with snow-white hair she would thank her lucky stars and never meddle with his affairs again.

“I forgot there’s a shop on the place,—it went with the old house that was torn down,” Miss Penny remarked and went on to try to fit the coachman and at least one footman in there, though she could not recollect whether there was a second story or loft or not. And Anna listened absently and thought of Mrs. Langley.

Fortunately the third Saturday was also fair. Anna set out early with a basket that might have been intended for autumn wild flowers but really contained cloths, a cake of sand soap, a bottle of ammonia and a tiny vial containing acid. As she followed the winding foot-path leading up the hill, and all the while she was working on the stone with patient skilful fingers, she seemed to hear over and over in her mind, she seemed to scrub to the rhythm of the warning Let sleeping dogs lie, Let sleeping dogs lie. Mr. Langley wouldn’t have thanked her for arousing that old woman to life,—but fortunately she hadn’t done any such thing. It was only temporary—a flare-up of interest that would die down as soon as she should be satisfied concerning the stone. She would report her success—for she was succeeding—on her way home and would thereafter leave her in the condition in which she had found her and wherein she seemed perfectly content.

[42]When she had done, the little image was so white and sweet and appealing that Anna was loth to leave it. And when she bent to kiss the meek little head in long farewell she couldn’t help thinking pityingly of Mrs. Langley. Poor thing! Poor forlorn creature! If only someone had gotten at her earlier before she had become a petrified mummy! It was too late now, but Anna wished with all her heart she could see the little lamb in its new freshness. She was sorry for her, more than sorry. Nevertheless as she descended the hill the girl simply could not face the thought of that darkened, musty room with the wild eyes glaring through the dimness. She decided to write a note and took a bypath which avoided the parsonage.

That night she wrote a note which her brother Frank delivered after Sunday school next day:

“Dear Mrs. Langley, the little lamb is white as snow again, a perfect darling,—fleckless as the books would say. I had to kiss its little head when I had finished, it was such a cutey. As I ought really to be studying up to my ears to keep up with the little cash-girls of the ABC class, I will send this note by my brother instead of disturbing you. I will keep my eye on the image from this time on.

Yours faithfully,

Anna.”

As she finished the letter, Mrs. Phelps came in. Anna knew by her face that she had some exciting or shocking bit of news to relate, and her heart sank.[43] Quite likely the report of her visit to the parsonage was all over the place!

“Have you heard about the Lorraines?” she asked.

“The Lorraines?” repeated Anna.

“Yes, Anna. Do you happen to know where Mr. Lorraine is?” Mrs. Phelps asked eagerly.

“In heaven I trust,” Anna murmured with charitable intent.

“Not at all and never will be unless he mends his ways. He’s behind the bars. He is serving a sentence of ten years in prison for embezzlement!” cried Mrs. Phelps almost triumphantly.

“O ANNA,” cried her mother as soon as the girl had seated herself, “have you heard about the people who have moved in where the Converses moved out?”

“Why, Jenny, that’s the house where Reuben was born and brought up,” observed Seth Miller. “It was before we knew Reuben or had any suspicion there was such a person, and we get in the way of thinking he always lived at Miss Penny’s; but I mistrust he had a good home and indulgent parents until his ma died, and his pa, who was one of them musical geniuses, took to drink.”

“Yes, ma, I heard about the Lorraines. Mrs. Phelps told Miss Penny last night,” returned Anna who always spent Sunday afternoon at her own home, which was diagonally across the way from Miss Penny’s. The girl was pale to-day and leaned listlessly back in her chair in a way that was foreign to her wonted lively self. Her mother had noticed in church that Anna, who was always thin, had grown intensely so within the last fortnight and had hastened to get the dinner dishes out of the way before her daughter should rush in and take the task off her hands.

[45]“It was all in the papers last spring,” said Miller. “They was chock full of it for a spell, and the queer part of it was that the denouncement of the hull thing came right at the same time Wat Graham was arrested over at Wenham. If it hadn’t ’a been for Wat’s brother-in-law, Mudge, going bail for him and helping settle with the creditors, why Wat himself might ’a been in the cell next to Mr. Lorraine.”

“Why, Pa Miller! Wat Graham’s in another class altogether,” protested Anna.

“I know they called Lorraine an embezzler, but I supposed that was only a polite name for thief,” her father rejoined. “Anyhow, it looked from the papers and from what was said over to Spicer’s last night as if he was a particularly mean kind of thief—sort of specialized on widders and orphans, you might say.”

Anna uttered a little cry of protest. Mrs. Phelps had said that the story was that Lorraine’s crookedness had involved thousands of small investors who had lost their all through him. She had added that more than one of those ruined thus had committed suicide. As Anna had lain awake thinking of it, she had tried to convince herself that the latter statement was false, and the rest exaggerated. She hadn’t succeeded, but it was not until now that she realized that she had utterly failed. Poor Miss Lorraine! And no wonder Mrs. Lorraine protected herself with the bristles and spikes of a porcupine!

“Reuben will most likely feel cut up to have such[46] people living in his old house,” Mrs. Miller opined sadly.

“O ma, they can’t help it, and they aren’t that sort themselves at all!” cried Anna.

“And my patience, Jenny, Reuben would be the last one in the world to object to anybody because they was down; the quickest way to reach Reuben’s heart is to be in trouble,” declared Seth Miller loyally. “He started out as a little shaver by rescuing a poor, forlorn tramp cat, and he’s been like a shepherd seeking for lost sheep ever since. By the by, Anna, did I ever tell you that story—how Reuben clumb the highest tree in the county and like as not in the state?”

“You certainly did, pa, the very day after I got back, and many’s the time you have offered to tell it to me again,” retorted the girl. “Miss Penny told me the same story the second time she laid eyes on me and this very week she refreshed my memory with all the fine points of it. But all the same, it’s a first rate yarn, and Reuben’s a brick.”

“That was the beginning of his going to Miss Penny’s,” Seth Miller went on as if he could not leave the fascinating subject. Then suddenly he opened his eyes wide to see Mr. Langley drive up to the gate.

As Mr. Langley stepped on the porch, Anna was seized with a sudden and almost unaccountable sense of guilt. She felt as if she must make her escape. But there was no stairway except that in the front passage, and here was her mother beamingly ushering the minister in upon her. But as she glanced up—even[47] indeed, as she heard his step, the girl was reassured. Somehow, it seemed as if Mr. Langley had recaptured his springiness. He looked his old young self again, and as he took her hand he smiled in a way that made her feel as if she had had a benediction all to herself.

“O Anna, my dear child, Mrs. Langley wishes very much to see you,” he said eagerly and with a certain largeness that would have been amusing if it hadn’t been pathetic. For it seemed to indicate that he was the bearer of a mandate from royalty.

“She expected you yesterday, it seems, and to-day she was so disappointed to get a note instead of a call that I volunteered to come up at once and fetch you.”

Thus far no one outside the parsonage had known of that audacious visit of Anna’s. Seth Miller’s face wore an expression half-jaunty, half proud. No man had such extraordinary daughters as he, and sometimes it seemed as if Anna were quite as remarkable as Rusty. But Mrs. Miller looked frightened.

Mr. Langley turned to her with his charming smile.

“What do you think, Mrs. Miller! This is the first time that Mrs. Langley has felt any interest whatever in anyone or anything since we lost our little Ella May,” he said in a sort of hushed wonderment. “You will spare Anna for a little while, won’t you? I’ll bring her back shortly safe and sound.”

When Anna returned to Miss Penny’s at tea time, she found her in a state of almost wild excitement.

“O Anna, do sit down and tell me all about it,” she[48] cried. “For the first time in my life I was glad—no, I can’t say I was glad, but I wasn’t really disappointed that Mr. Langley didn’t come in. Not that he thinks it wrong, being Sunday, and anyhow I really am an old lady and won’t be getting out to service many years more. But he had the Smith’s horse, you know. It was nice of him to bring you home, but of course he would. He thought you were here—that was why he stopped. And to think of Mrs. Langley’s asking for you all of her own accord. Dear me, dear me, what does she look like and did you have a nice time?”

“Not exactly what you would call slick,” replied Anna in her droll way that cloaked her weariness even for herself. “There was nothing lively enough about it to break the Sabbath. Our conversation was confined to the subject of tombstones.”

“O Anna, my dear!” said Miss Penny in mild reproof as if it were sacrilegious to speak lightly of such things.

Anna related briefly the occasion of her first visit and described the restoration of the marble image in the cemetery.

“Bless its little heart!” cried Miss Penny who was as enthusiastic as Anna in her love of animals. “It must be sweet. I wonder I never thought of going to look at it on Memorial day. I used to go to the cemetery regularly every year until I got so lame.”

“We’ll drive the pony up there some day. It’s not far to walk from the gate,” Anna said.

She dropped into a rocking chair, let her yellow head[49] fall wearily back against the cushion and closed her eyes.

“I had to tell her of it over and over and over,” she said presently, raising her lashes pensively.

“Anna, you are very tired!” cried Miss Penny.

“Only a wee bit and it isn’t exactly tired, then,” declared the girl. “But you know how it is when you go into a painty room or pass by that awful-smelling tannery place beyond Wenham? You don’t draw a long breath all the while and yet you don’t realise that you’re holding your breath. Well, there’s something about Mrs. Langley and her room that makes you feel as if you were sitting on the edge of your chair waiting until you can get out where you see sunshine and people that talk and smile. Her eyes, you know, like coals of fire in the Bible, and great hollows in her cheeks and a voice that seems to come from a cave or a tomb. The blinds are drawn down almost to the window sills and there are medicine bottles to burn. There’s air enough, I suppose, but not the kind that’s sweetened by sunshine. It seems musty and makes you feel as if there were spiders in all the dark corners—huge black spiders with bodies big as this and crooked legs!”

“O Anna!”

“Sure thing! And what do you think? She wants me to come to see her every Saturday,—every blooming Saturday afternoon, Miss Penny.”

“Anna dear, I wouldn’t do it. You really must[50] not,” said Miss Penny gravely. “It would be too great a strain upon you.”

Anna threw herself on the hassock at Miss Penny’s feet leaning her head upon the knee that was not lame.

“Really, Miss Penny, I am glad to go again and every Saturday,” she said softly. “Mr. Langley almost had tears in his eyes when he spoke of it. I didn’t dare look at him again to make sure, because after I had come out of that creepy place it wouldn’t have taken much to set me to crying.”

“I understand,” murmured Miss Penny stroking the girl’s yellow hair. “And to tell the truth, Anna, I almost envy you in being able to do something for Mr. Langley. Ever since he came to be our preacher, I have longed to do something for him to express my appreciation and affection for him, but it always seems impossible. It has always been the other way—his doing for me. And the best things in my life have come to me through him, Reuben and Rusty and now you, Anna.”

“Miss Penny,” said Anna quickly, “you know he visits her every day. Do you suppose he kisses her?”

“Dear me, Anna! what a question! I’m sure I have no idea. I suppose he does.”

“But how can he! But you haven’t seen her as she is now, and you never could imagine how she looks. He certainly seems to think a heap of her all the same, and as he can see as well as I can in the dark, he can’t help seeing that she looks old enough to be his great aunt. Well, I’m sorry for her but I[51] wouldn’t be related to her for a gold mine. However, I can stand it once a week all right.”

In the following days, they recurred to the matter frequently. A dozen times, Miss Penny suggested suddenly a new topic of conversation that had popped into her head as appropriate for Anna to introduce as an alternative to that of tombstones; but each one being only more utterly absurd than the foregoing, Anna would laugh until she cried, Miss Penny joining her merrily. None the less, when she returned late Saturday afternoon, she announced that she had gotten away from the little lamb, though not perhaps very far.

The girl had proposed one subject after another, receiving no response. And it had presently been borne in upon her there could hardly be a response in the nature of the case. Mrs. Langley was really living, so far as she was alive at all, in another generation, so that trying to converse with her was like shouting to someone miles behind one on the highway and only visible because of curves in the course of it. The years she had lived in retirement had counted for little more than nothing. Her mind was twenty years younger than the village she dwelt in.

“When I realised that, I tried to get back, and after a bit she was glad to talk about Ella May,” Anna said to Miss Penny as she dried the china after tea. “Only you would hardly know it was Ella May. Mr. Langley’s Ella May has been growing all these years until she went to college with Rusty and jumped ahead and graduated and—O dear me! Hers is still a teeny baby[52] three days old. Now, Miss Penny, when those two get to heaven one of them is going to have the surprise of their lives.”

“Why Anna,” murmured Miss Penny reproachfully.

“Meantime, things are at sixes and sevens with both of them. What she needs is another baby, and what he needs is a full grown wife. Both of ’em need it frightfully. But how in the world is it ever going to be brought about, and who is to do it? I may think I am Charley-on-the-spot for ordinary cases, but a sticker like this stumps me flat. It would take someone a heap smarter than me to haul her over all the years she has missed and bring her up to date. And while that’s being done to her mind, her face, her looks ought to be stretched the other way until she looks somewhere near as young as her husband.”

The girl sighed. “It’s like the North-west Passage. It ought to be done, and I suppose it could be, but not by yours truly. And the worst is, she refuses to see anybody else. She hardly pays any more attention to Mr. Langley than she did before—just sends him orders about me through Big Bell. O Miss Penny, did you ever hear the proverb ‘Let sleeping dogs lie’?”

MEANTIME the other Miller girl had made a second call at the house in the lane which Reuben’s father had built. When her rat-a-tat at the door sounded drearily as from an empty house, the girl said to herself that it was too much. Most likely the ogress had slain her lovely daughter and then fallen dead herself and their corpses lay stretched upon the organ platform in the room which would never be a living-room thereafter. But the lovely daughter came to the door. The cold, haughty expression on her face changed to eagerness as she saw Anna and she smiled sweetly and rather touchingly.

“O Miss Miller, I am so glad—to see you,” she said. But with the last words enthusiasm had become dismay. She paled and looked appealingly at Anna.

“Don’t call me Miss Miller, please. Nobody does. And—may I come in?” asked Anna.

“I am so sorry, Miss—Anna, but mother—we don’t have company, you know.”

“But I’m not company. And anyhow, I’ve got to come in this once for I’ve got something for you,” Anna declared.

As the proud look returned to the older girl’s face and she started to say something in regard to her[54] mother, Anna drew forth from the covert of her jacket a tiny ball of a maltese kitten with a white parting between its baby blue eyes, a line of white waistcoat, and four white paws, two of which had extra toes. Nothing could have been rounder or silkier or more altogether appealing than this baby kitten with its round, innocent eyes and its bit of pink tongue visible, and as Anna held it out, the other girl took it ecstatically and held it close to her face. Then she cried out impulsively to her mother and ran with it to her. Anna followed her in, closing the door behind her.

Anna’s purpose had been deliberate. Still, it was almost unbelievable to see Mrs. Lorraine’s grimness melt before that absurd mite of kitten. As her daughter passed it over to her, she, too, hid her face against its softness. Then she put it in her lap and gazed at it in a sort of fascination, her daughter hanging over her and quite unnecessarily calling attention to the little thing’s charms. As a matter of fact, Mrs. Lorraine hadn’t handled—hadn’t even seen—a baby kitten of the ordinary, harmless, necessary cat-kind since she had been a child in a New England farmhouse and had worshipped the successive litters of a three-coloured Tabby that had lived at one of the barns. They had left the farm for the city before she was twelve; but though she had had pets in the elegant home her parents had fallen heirs to and in the magnificent residences of the millionaire she had married, they had been the expensive, pedigreed sophisticated[55] pets of the rich and hadn’t appealed to her as Tabby and her kittens and the mongrel shepherd dog of the farm had done. And not even the latter had so appealed to her as this tiny plebeian offspring of a too prolific Tabby mother who kept the tender-hearted Anna busy in finding homes for her numerous kittens. Her sore heart could reach out to its innocence without injury to her wounded pride.

“It is a love, isn’t it?” remarked Anna presently, partly to call attention to herself and partly because she couldn’t help it. For she was herself ‘crazy over’ the kitten, as she put it. And joining the little group, she pointed out its double paws and the white tip of its tail which were the only details the daughter hadn’t exclaimed over.

“I started out right after school to find a home for it. There were three of them but the grocer at the Hollow took the yellow twins—I suppose he’ll call ’em the Gold-Dust Twins. It looks as if I needn’t go further. Are you willing to take him in, Mrs. Lorraine?”

“I don’t know that we ought to,” returned Mrs. Lorraine, trying to speak stiffly. But somehow, even the thought that perhaps it would be wrong for the family of a criminal to indulge themselves even so little was ineffectual to stiffen her with that soft little ball in her lap.

“Mother!” cried the girl beseechingly.

“You will need a cat, you know. Every household does,” said Anna sagely. “This one will make a[56] fine one, too. All of Tabby’s kittens do. Never a one has failed to give satisfaction in the households in which I have placed them. Ma’s never had any mice in our house since I brought the mother-cat home. I found her on a lonely road a mile or more from any house. Just think, someone had abandoned her. It must have been someone in Wenham that came over to drop poor Tabby, for before there wasn’t a three-coloured cat in all Farleigh.”

“We had a tortoise-shell cat on the farm when I was a little girl,” remarked Mrs. Lorraine quietly with a gentler look in her eyes than Anna would have believed possible. “Alice, perhaps the kitten would like some milk,” she added.

Alice fetched a saucer and put it on the hearth. Mrs. Lorraine placed the kitten beside it as gently as if it had been a fragile egg shell and the three hung over it eagerly. The kitten put his nose in so far that he spluttered amusingly and once he dipped a paw in; but it was too light to overturn the dish and he drank enough to prove himself of sufficient age to be taken from his mother.

“Now he’d like a nap,” remarked Anna, picking him up. She wanted to give him to Alice (sweet name, Alice Lorraine!) who hadn’t had a chance at him at all; but she put him into Mrs. Lorraine’s lap and he curled into a yet rounder ball and was asleep at once.

“Speaking of tramp cats,” Anna remarked, though as a matter of fact the subject hadn’t come up, “you[57] probably know that Reuben Cartright once lived in this house?”

“Reuben Cartright—is he a musician?” asked Mrs. Lorraine.

“Dear me, no. His father was a musician, though he wasn’t noted. He was organist at the church for a long time. He built this house, though not with his own hands. Did you ever wonder what that platform was for?”

“I thought this was a very old house and that perhaps that was a trundle bed,” said Alice. Anna laughed and Mrs. Lorraine had to smile.

“Mr. Cartright had the floor raised so that when he got rich he could have a pipe organ put in,” Anna explained. “I believe the clothes-press in the chamber above is right over the platform and the same size and they say he planned to tear out the floor of that so that the space would go way up to the roof. But it never came to that. His wife died and he took to booze and that was the last of him as well as of the pipe organ.”

“Is the son musical?” asked Mrs. Lorraine, speaking softly as if the sleeping kitten were a baby.