Title: Kathleen in Ireland

Author: Etta Blaisdell McDonald

Julia Dalrymple

Release date: May 21, 2024 [eBook #73665]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Little, Brown & Company

Credits: Fiona Holmes, Andrew Sly and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

In the Vocabulary section on the last 4 pages of the project there are many diacritical characters that won't render properly on many ereaders. end of the book.

Hence the following explanation:a᷵ = the letter 'a' with an uptack above.

Double vowels ee, aa, oo, show extended macron above.

Joining two letters such as oi, ow, ou shows the extended breve below.

The use of =L= around a word indicates bold lettering.

Hyphenations have been standardised.

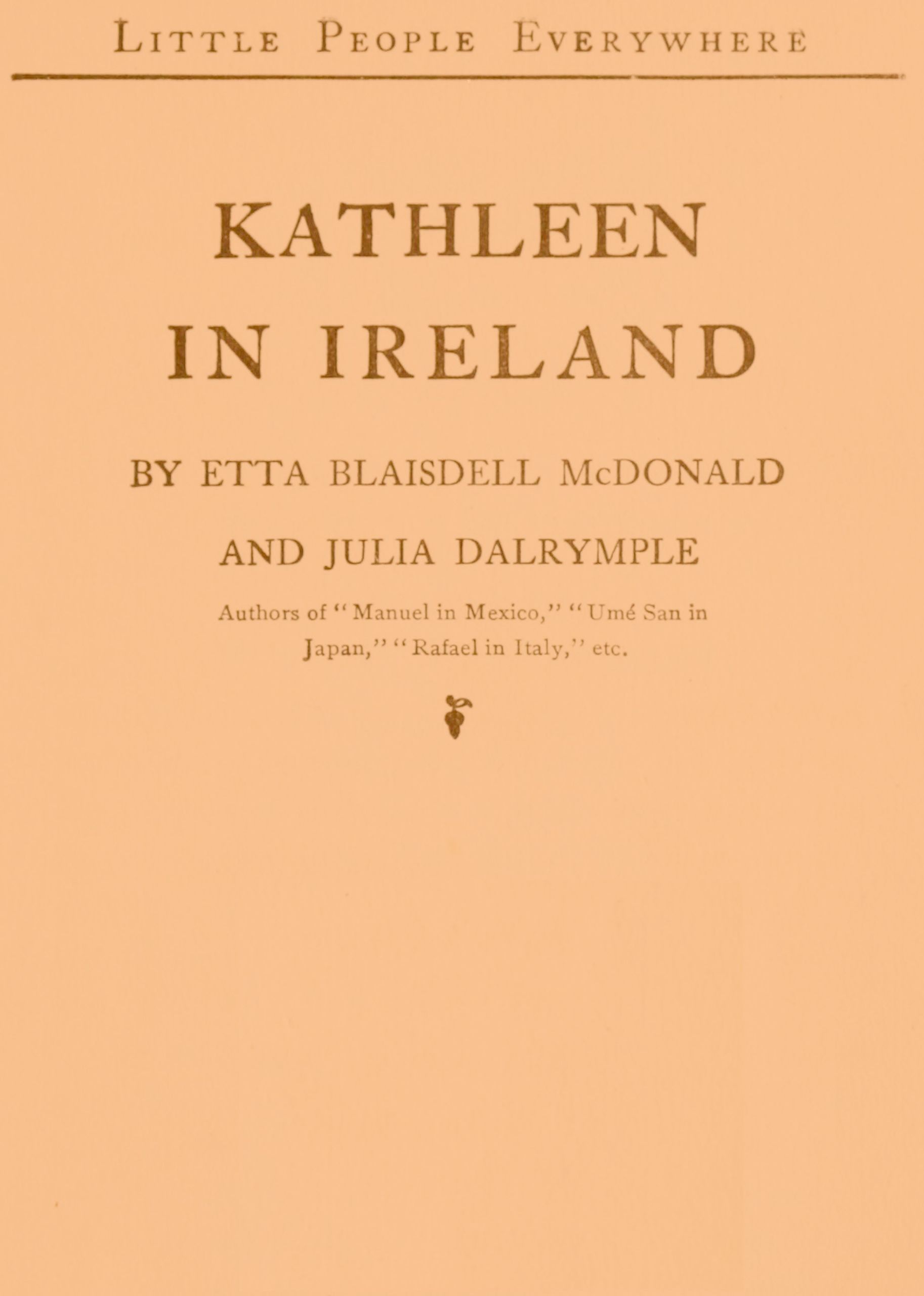

KATHLEEN AT HOME

Little People Everywhere

BY ETTA BLAISDELL McDONALD AND JULIA DALRYMPLE

Authors of “Manuel in Mexico,” “Umé San in

Japan,” “Rafael in Italy,” etc.

Illustrated

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1912

Copyright, 1909, By Little, Brown, and Company

All rights reserved

Printers S. J. Parkhill & Co., Boston, U. S. A.

[v]

There is surely no country in the world where hearts so thinly covered beat so warmly as in the Emerald Isle. Wherever one travels,—over the bare mountains of Donegal and the rocks and cliffs of the northern coast, or among the blue lakes and green fields of the South,—he will always find a merry greeting and a hearty Irish welcome. The boys and girls have a smile and a cheerful word for every wind that blows; and that day is a rare one, indeed, which is not sunny with laughter and singing, even while clouds hide the blue sky and Irish rains are falling.

The wonder is that Irish boys and girls can find it in their hearts to leave their beautiful, loving land of the shamrock. So many fairy lakes were never found in any other country. Green meadows never offered sweeter resting places than those of the Emerald Isle; yet its young people turn their backs to it, and their blue eyes toward the more barren worlds beyond the seas.

[vi]

This story of Irish Kathleen gives glimpses of ancient Ireland, as well as pictures of the life of to-day with its tales of wee folk and giants, its picnics and turf-cutting, its dancing and sheep-shearing, its hunting and farming.

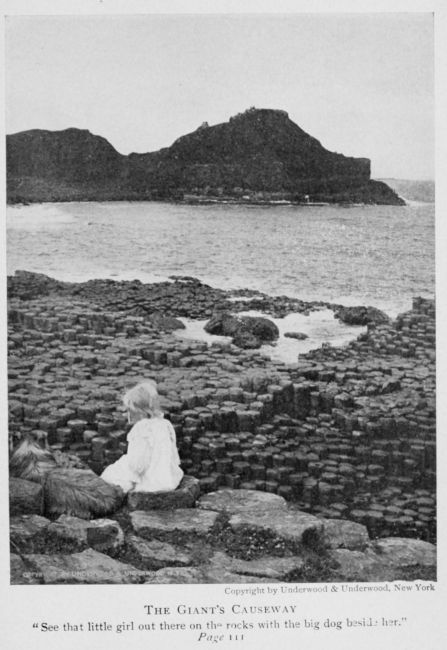

Kathleen lives first with her father up among the mountains of lonely Donegal; she goes with her little sister to spend a summer in County Sligo, and she lives a year with her ten cousins, the Malones of old Kilkenny, and a jolly, rollicking brood she finds them. She learns something of the history of Ireland from her father, and hears the story of the life of the good Saint Patrick; but she enjoys also the Gaelic tales which her grandmother tells her about the fairies, and the story of Finn MacCool, which she hears when she goes with her uncle to see the Giant’s Causeway.

[vii]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The Shoemaker of Donegal | 1 |

| II. | In the Fairy Rath | 9 |

| III. | The Old Woman in Red | 13 |

| IV. | Erin’s Harp | 19 |

| V. | The Little Green Shamrock | 26 |

| VI. | Good Saint Patrick | 31 |

| VII. | A Ride with the Postman | 39 |

| VIII. | Cousin Bee’s Farm in Tonroe | 46 |

| IX. | May-Day on Lough Gara | 56 |

| X. | A Bank of Turf | 64 |

| XI. | Kathleen Earns a Pound | 71 |

| XII. | The Young Malones | 78 |

| XIII. | Kathleen’s Composition | 85 |

| XIV. | The Wishing Spring | 91 |

| XV. | Good News from Cousin Bee | 99 |

| XVI. | The Giant’s Causeway | 104 |

[viii]

| Page | |

| Kathleen at Home | Frontispiece in Color |

| “The old grandmother was spinning at the door” | 2 |

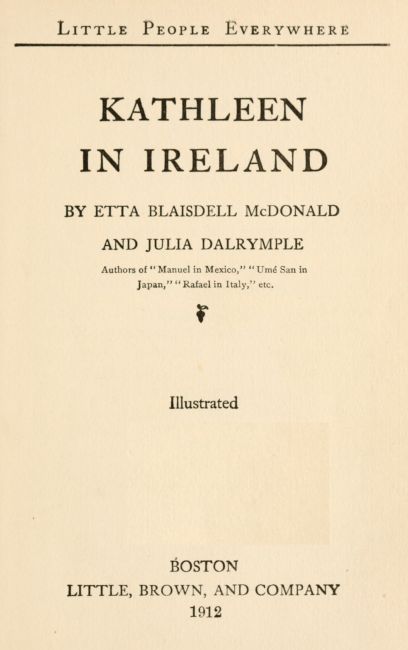

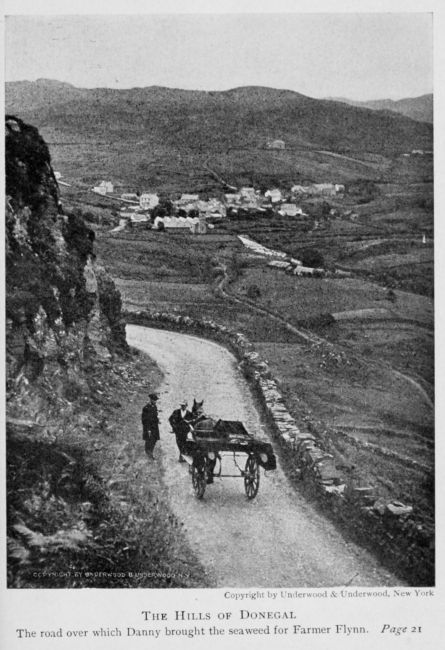

| The Hills of Donegal | 21 |

| “They are playing ‘Green grow the rushes-O’” | 42 |

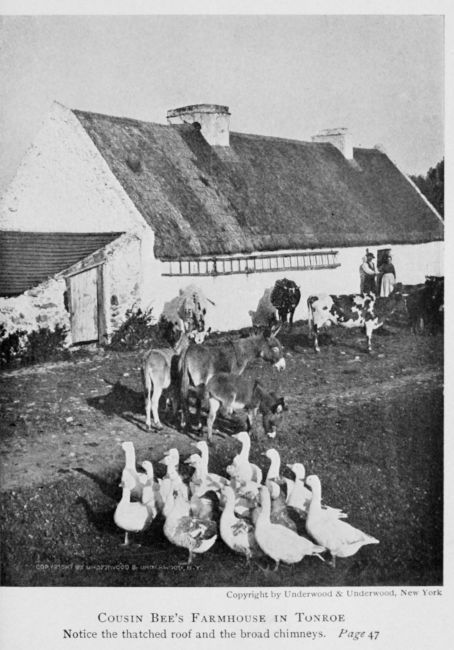

| Cousin Bee’s Farmhouse in Tonroe | 47 |

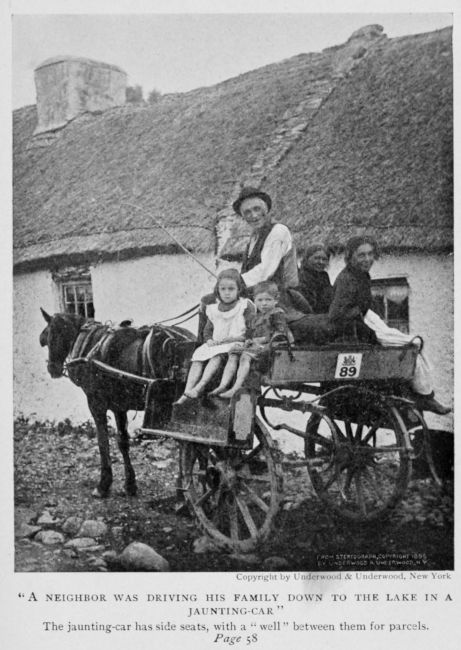

| “A neighbor was driving his family down to the lake in a jaunting-car” |

58 |

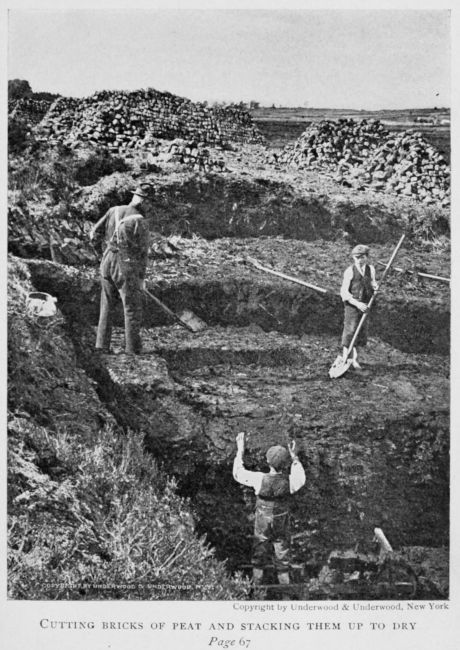

| Cutting bricks of peat and stacking them up to dry | 67 |

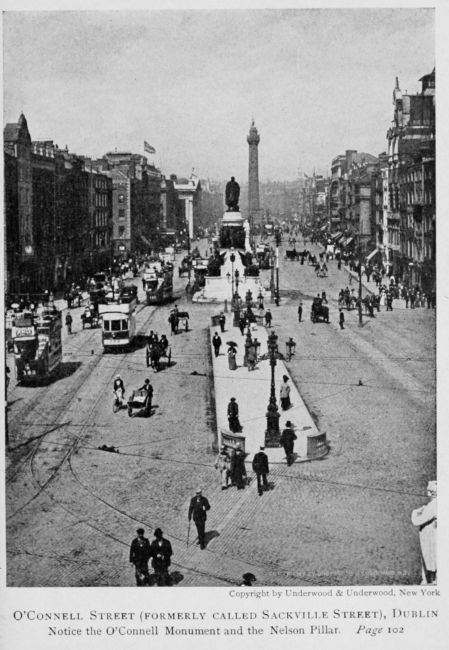

| O’Connell Street, Dublin | 102 |

| The Giant’s Causeway | 111 |

[1]

THE SHOEMAKER OF DONEGAL

“Tell me the story again, Kathleen.”

“I can’t tell it to you here, Mary Ellen,” whispered her sister. “Sure, he might be under the hedge this minute and hear me talking about him. Come to the top of the hill and I’ll tell you.”

Mary Ellen slipped her hand into Kathleen’s, and the two children stole softly away from the door-stone where they had been playing. Their bare feet made no sound on the green grass, and the old grandmother, who was spinning at the door of the cottage, did not even look up as they passed.

A thick fuchsia hedge bordered the plot of green grass that surrounded the cottage, shutting out the barren field behind the house. Slipping through the hedge, the little girls followed the narrow foot-path that led across the field to the top of the hill.

“I’m thinkin’ of a riddle Danny gave me the morn,” said Kathleen, as they ran along the path.

[2]

“Give it to me,” said Mary Ellen eagerly, and Kathleen laughed merrily as she repeated:

“I’ll never guess it; tell it to me now, alanna,” begged her sister.

“If your blue eyes could see the little path under your feet you would see the answer,” replied Kathleen, as she led the blind child carefully over the steep pathway to the long stone slab where they loved to play. “We’ll sit here a bit,” she added, and drew Mary Ellen down beside her on the stone.

“Now tell me why you put the dish of stirabout under the hawthorn bush last night, and what became of it,” asked the child, who could wait no longer for the story.

“It was for the leprecaun,” Kathleen told her. “He is the fairy shoemaker, and he sits under the hedge all day tapping away on an old shoe. He wears a scarlet cap and a green coat, and there are two rows of buttons on his coat, with seven buttons in each row. He has a fairy purse which is filled with gold, and he puts it down beside him on the grass while he works; but he is always watching it. If I could just see him once and hold his eye for a minute, I could snatch the purse of gold and run away with it.”

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood, New York

“The old grandmother was spinning at the door”

The cottage is of stone, plastered and whitewashed Page 1

[3]

“Did you ever see him?” whispered Mary Ellen.

“No,” replied her sister; “but I have heard him tapping on his shoe many a time. Once I saw his scarlet cap under the hedge, but when I knelt down to look closer he threw sand in my eyes, as he always does, and was gone in a winkin’.”

“Belike it was a humming-bird,” said Mary Ellen. “Danny says the hedge is full of their nests. But what would you do with the purse, Kathleen dear?”

Kathleen’s eyes filled with tears and she looked at her sister with a sad face. “Oh, darlin’, it’s for you,” she said, “to give you the sight in your pretty blue eyes. I’m thinkin’ of it all the time, and faith, some day I’ll find a way. That’s why I took the dish of oaten stirabout and put it under the hawthorn bush last night, and why I put the bowl of milk on the window ledge. It’s for the ‘good people,’ so that they’ll know we take thought of them.”

“Did the ‘good people’ drink the milk?” asked the blind child eagerly.

“No, Mary Ellen,” said her sister, “but, listen! The stirabout was gone this morning, dish and all. The leprecaun must have taken it. I shall watch for him the night, and if I do catch the old shoemaker’s eye, I’ll hold it till he gives me his purse.”

“I’m thinkin’ that no one has ever held it yet,"[4] said Mary Ellen, snuggling against Kathleen’s shoulder, as if there might be some danger in holding a fairy dwarf spellbound with the look of one’s eye.

Kathleen lowered her voice and asked mysteriously, “Whist, Mary Ellen, do you mind old Granny Connor?”

“She that lives beyond the bog?” questioned Mary Ellen.

“Yes,” said Kathleen.

“I mind that she lives all alone, and that the father tells us not to go near her,” answered her sister. “She’s too friendly with the fairies.”

“Last night,” said Kathleen, taking her sister’s hand, and looking into her blue eyes while her own grew big and dark, “when I was driving the little cow home across the bog, who should I meet under the old oak tree but Granny Connor herself.

“I picked a bit of shamrock and held it tight in my hand, but she stopped me and made me talk to her, and she told me that it is our own father, himself, that has a purse from the leprecaun.”

“I’ll not believe it,” said her sister quickly. “If he had, he’d not be making shoes all day by himself.”

But Kathleen shook her head. “Granny Connor told me,” she confided, “that he has made a bargain with the fairy dwarf, and must make shoes[5] all day long, or go wandering over the mountains a-tinkerin’.”

“What’s that you’re saying, Kathleen?” a voice behind them asked suddenly, and the children jumped up in surprise.

A man with a leather apron tied round his waist was standing beside the stone slab. It was hard to tell where he had come from so quickly, for there had been no sign of any one near when Kathleen climbed to the top of the hill.

“It is the father himself,” said Mary Ellen.

The shoemaker seated himself on the big stone and drew his little daughters down beside him; but it was such an unusual thing for him to spare any time from his work that they sat awkwardly within the shelter of his arms, waiting for him to speak.

Kathleen wondered how much of their talk he had heard, and whether he would scold her for listening to old Granny Connor, and repeating the tales to her little sister. She hung her head in silence, and Mary Ellen felt as if the sunshine had been darkened by a cloud; but the father’s arms were around both little girls to hold them, although he did not speak for some time.

“So you have been listening to old Granny Connor,” he said at last.

Kathleen stole a look into his face, which always had a kindly smile for everyone. “I did not mean[6] any wrong,” she said timidly. “I was only wanting to find some way to help Mary Ellen.”

“What would you be doing for Mary Ellen?” he asked.

“I’d like to find some way to get money so that she might go to Dublin and have a doctor cure her eyes,” said the child simply.

“And so you put a dish of stirabout where the little old shoemaker might see it?” asked her father.

Both the children nodded their heads.

“How did you find out about the fairy dwarf?”

“Great-grandmother Connell and Grandmother Barry talk about him in Gaelic. Sometimes Grandmother Barry tells us what they are saying,” answered Kathleen. “And last night I asked old Granny Connor to tell me more.”

“What did she say?” asked her father.

“She said that people call you the leprecaun of Donegal, because of the two rows of buttons in sevens on your green frieze coat.”

The shoemaker laughed. “And where do they think I keep my money?” he asked.

“They say you have it hidden in a purse that can never grow empty, and that you keep it in the place where you mend your shoes,” the child replied, looking away from her father and off across the bog to the purple mountains. “And no one knows where[7] it is that you have your work-bench,” she added with a sigh.

“Look at me, Kathleen,” said her father.

The child turned her gray eyes up to his, gray and honest like her own.

“Did you think when you put the dish of stirabout under the hawthorn bush last night, that you would see me take it up?”

“Oh, no, no!” cried Kathleen. “Sure, I thought it would be the tiny man, himself, who would find it.”

“But it was myself who found it and took it away, when you were sound asleep in your bed,” said her father.

Kathleen jumped up in surprise, but Mary Ellen nodded her curly head, as if she knew all the time that it was not the fairy.

“I saw Granny Connor’s red cloak bobbing across the bog last night, as I stood at my bench mending an old shoe,” her father continued, “and I watched you stop under the oak tree to talk with her. When I found the dish of stirabout under the hawthorn bush I knew it was time for me to put an end to these foolish notions about the good people, and tell you the true words about Ireland’s brave men and women. You should be learning about Brian Boru, who drove the Danes out of Ireland, and Daniel O’Connell, the greatest orator ever born on Irish[8] soil. Those are the men for you to be thinking of, instead of the leprecaun.”

Kathleen looked at him earnestly. “It’s not one word I’m believin’ of all they say about you, Father,” she said.

“It is what they say about the fairy people that’s not for you to believe,” he answered, and rising from the stone slab, he took a hand of each of the children and led them across the top of the hill to a grassy mound which was encircled by a ring of jagged rocks.

[9]

IN THE FAIRY RATH

“Oh, Mary Ellen, it’s the fairy rath,” said Kathleen under her breath, and she clasped her father’s hand more tightly.

Grandmother Barry, who talked often in Gaelic about the fairies with Great-grandmother Connell, had told the children many times not to play too near the fairy rath.

“There be many such mounds scattered over the hills and glens of ould Ireland,” she said. “The good people live in them and may do harm to childer that make too bold with their haunts.”

“They must be bad people if they would do harm to little Mary Ellen,” Kathleen replied.

“Hush, child!” her grandmother reproved her. “They are like all men and women, liker to do good if they be called good.”

Now, as they drew near the fairy rath, Kathleen tiptoed over the rocky path, thinking every moment to see a fairy slip behind a pebble or a blade of grass. She felt sure that when they stepped within the rocky ring, a door would open in the grassy[10] mound and show to her eager eyes long rooms glittering with jewelled walls, leading one after another into the depths of the earth.

What was her surprise then, when they entered the enclosure, to find, not a magic door leading to fairyland but a single tiny room dug out of the mound, sheltered from wind and rain by sods and stones, with just room enough for a man to work at his bench, and no more.

Her father pointed out to the child’s disappointed eyes a leather pouch lying among the tools on the work-bench.

“That is the only purse I’ve got, Kathleen,” he said, “and my fingers have never seen the magic day when they could fill it with silver.”

Poor Mary Ellen’s blind eyes could see nothing of the shoemaker’s bench and the empty purse, but her heart felt all the loving thought that moved her sister to ask, “Then why did you not leave the dish of stirabout under the hawthorn bush? The little elf shoemaker sits there every night mending his shoe, with his purse of gold beside him. Belike you might snatch it yourself.”

“Oh, Kathleen, it’s myself will be the only shoemaker in these parts,” her father answered. “Put the foolish fancies out of your head now. No good ever came of such thoughts.”

It was not the first time he had told Kathleen to[11] forget the fairy lore, and he had often checked Grandmother Barry when her unruly tongue touched upon the forbidden subject. “The childer’s heads should not be filled with such nonsense,” he said.

But it was not easy to check Great-grandmother Connell. She had lived ninety long years among a fairy-loving people, and liked to tell the Gaelic stories of old Ireland over and over again.

She it was who believed that Ireland was first inhabited by a race of giants. “They lived here with the birds and beasts before ever a man rode through the green forests,” she told Grandmother Barry.

“What became of them, then?” inquired her daughter.

“Sure, they turned themselves into the wee folk when men came here from over the seas, and they live under the rocks and trees and in the fairy mounds.”

“True it is,” agreed Grandmother Barry, and she told Kathleen what the great-grandmother had been saying in Gaelic about the giants and fairies.

That was how Kathleen came to know so many of the tales of old Ireland, and why she was always thinking of the wee folk.

“How can I put the thoughts out of my head?” she asked her father. “Sure, the fairies are putting them in again all the time, with their doings.”

[Pg 12]

“What are they doing, the day, to make you think of them?” asked the shoemaker.

“There’s the ring of green grass beyond the hawthorn bush,” she said timidly. “Danny borrowed the plow from Farmer Flynn and plowed through it over and over, but it came up again as round and green as ever. What else could make it but the fairies with their dancing feet?”

The shoemaker shook his head hopelessly at the child’s simple faith in her old grandmother’s stories. “It’s not like you, with your sense and handy ways about the house, to believe the fairy nonsense,” he said. “It must be because you have never learned the reading. After this you must come up here when your work in the house is done, and I’ll teach you the words. If you don’t believe it from my telling, you will from the books, that there are no fairies in Ireland.”

So it came about that on sunny afternoons through the winter two little girls played on the top of the hill near a fairy rath in far Donegal, in the north of Ireland. And often the shoemaker put his work down on the bench and called the children to his side, where he told them true stories of Irish history, and taught Kathleen to read from the pages of an old Irish book.

[13]

THE OLD WOMAN IN RED

With the last words the two little girls clasped hands and ran round and round the great stone slab, not hearing their father’s voice calling to them from his bench.

As the children dropped upon the stone he called more sharply, “Kathleen! Do you hear me?”

“I hear you, but I do not fear you,” answered Kathleen, leading Mary Ellen to her father’s side. She put her arm around his neck and kissed his patient face, then seated herself on his knee.

“I used to fear you,” she said with a laugh, “after Granny Connor told me you had made a bargain with the leprecaun, and that you had a secret hiding-place.”

“And now it’s no secret at all, at all,” her father said. “The grandmother has learned it, too, and[14] will be calling you down to run errands the minute she lays eyes on you here.”

“We were both helping her, the morn,” said Mary Ellen.

“What were you doing, jewel?” asked the father of the little blind child.

“Oh, reddin’ up the house,” replied Mary Ellen. “Kathleen swept the floor, and I wiped the dishes, and then I held the yarn for Grandma Connell. She is knitting you some stockings.”

“Yes,” added Kathleen, “and I drove the little dun cow to the pasture beyond the bog; and on my way home I pulled some rushes to make a new brush for the hearth.”

“I helped Grandma Barry with the churning, too,” said Mary Ellen. “We churned and churned, but not a bit of butter did we get till Kathleen came home and put a sod of burning peat under the churn. Then the butter came soon enough, and Kathleen said the good people had put a spell upon the cream.”

“Faith, you’re always thinking of the fairies,” exclaimed her father. “Do you like old Granny Connor’s witch tales better than the stories I tell you of brave Irish men, like Brian Boru and Conn of the Hundred Battles?”

Kathleen looked at him quickly. “You tell us that Conn lived many hundred years ago, and Brian[15] Boru has been dead these eight hundred years; but Granny Connor says that the fairies are living now. They have a council hall in a cave between here and Letterkenny. The cave is under the great Rock of Doon, and—”

“I like not to hear you speak so much of old Granny Connor and her tales,” her father interrupted her. “It’s her and her red cloak have put sorrow and shame on me these many years.

“Do you mind how green the grass is already, down there in front of the door, Kathleen, child?” he added.

“Yes,” she said. “I’m fond of the feeling of it to my bare feet.”

“You might travel over the whole of Donegal without seeing another yard so green,” he said sadly, “and it’s a shame to me to have it so.”

“Why?” asked Mary Ellen, who thought the soft grass the best playground in the whole world.

“Because no stranger ever stops before our door to beg a bite or a night’s shelter from us,” he replied.

“True it is,” said the child, “but Grandma Barry says it is lonely here and no one cares to come.”

“I mind it is because Granny Connor put the curse upon me years ago, when first I came here,” her father repeated. “She said, ‘May the grass be always green before your door,’ and green it has been ever since.”

[16]

“But why should that be a curse?” asked Kathleen.

“Because Ireland is the kindest country under the sun,” he answered. “Open house and open heart is our motto, and if a yard is green, ’tis because no friendly foot has worn it bare.”

Kathleen’s cheeks flushed. “Danny and I will dig up every blade of grass before we sleep the night,” she declared.

“Whist,” said her father. “It is as it is. But it might have been different if I had said the kind word to the old woman in red when I brought your mother to these parts years gone.”

“What did she do?” asked Mary Ellen, taking her father’s big hand in her two little ones and holding it fast.

“We were just after lighting the first sod of peat on the hearth, when Granny Connor stood at the door, dressed all in her red cloak, and so still that no one had heard her step. ‘’Tis a haunted country that you’ve come to,’ she said, and it frightened your mother to hear her.

“There were the three of you children, and Mary Ellen but a wee baby. Your mother was ailing, and I was angered at the old woman’s tongue. ‘Be off with your crazy talk!’ I said, seeing that your mother was scared, and Granny went away across the bog, but first she said the curse.”

[17]

“I wouldn’t have bided here after that,” said Kathleen, but her father shook his head.

“I had worked a long time to build the little cottage and get it dry-thatched,” he said, “and I had a fine flock of sheep to pasture on the hillside. But the mother was lonely and fearsome after Granny Connor’s visit, and she pined away and died.”

The children nestled closer to his side to comfort him, and he put a hand on each little head,—Kathleen’s dark and straight-haired, Mary Ellen’s yellow and curly.

“Then I sent into County Sligo for your two grandmothers to come and bide,” he went on, “and soon I had to do something else to earn a living, because the sheep fell sick and died in the pasture.”

“What did you do?” questioned Mary Ellen.

“I went over the mountains a-tinkering,” replied her father. “But your mother used to say that bad luck follows those that have no steady biding-place, and so it was for me. Wherever I went there was a whisper that I was like to have trouble for company, and faith, in those days he seemed my best friend.”

“Grandma Barry says to look trouble in the eye and he’ll turn away,” said Kathleen.

“Sure I’ve seen no more of him since Danny got big enough to lend a hand,” said her father.[18] “Danny’s the good lad and will do a hand’s turn of work with the best of them.”

“’Tis Danny that keeps the house dry-thatched,” said Kathleen, looking down at the brown-thatched, white-walled cottage at the foot of the hill.

“’Tis Kathleen that reds up the house and helps the two grandmothers,” suggested Mary Ellen.

“She’s a fine slip of a girl,” replied her father heartily, “and you too, Molly jewel; there’s a pair of ye.”

[19]

ERIN’S HARP

March winds blew across the valley and ruffled Mary Ellen’s yellow curls as she sat in the ring of green grass made by the fairies’ dancing feet, and played with some sea-shells and pebbles Danny had found in the seaweed he gathered for Farmer Flynn.

She had been playing contentedly for a long time when she suddenly jumped up, scattering a handful of pebbles from her lap. “Kathleen,” she called, “I hear the peddler’s cart. Sure, he’s comin’ across the bridge this minute.”

Kathleen rushed out of the house, clasped her sister’s hand tightly in her own, and ran up the little path to the top of the hill as fast as she could go.

“Oh, Mary Ellen!” she panted; “I made sure I’d finish the stockings before the peddler came this way again; but here he is now and only one done. The blue dress will be worn out before the other stocking’s finished.”

The peddler drew up his cart before the door of the little cottage, and Grandmother Barry went out[20] to bargain with him for a piece of linen in exchange for her butter and eggs. Great-grandmother Connell hobbled out to see that the bargain was well made, and the three laughed heartily over Kathleen’s hurried flight.

In the winter the peddler had given the child a piece of blue homespun for a dress, and she had promised to knit a pair of stockings for him in payment; but there were so many more interesting things to do every day that the knitting proved slow work, and Kathleen had often wished the blue dress back in the peddler’s cart.

“Faith, Kathleen makes it harder work to keep out of my sight than to do the knitting,” the peddler said, as he opened his cart and took out the linen.

Grandmother Barry laughed as she answered, “I’m thinkin’ it will teach the child a good lesson. It’s best to keep well out of debt, and a dress is better paid for before it is worn. But she shall finish the stockings this day week, or I’ll knit them myself.”

She went into the house to fetch her butter and eggs, and after much weighing and measuring and talking, they were exchanged for a piece of coarse linen and a pound of good honey.

In the meantime the two little girls hid behind the fairy rath and whispered together about the stockings.

[21]

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood, New York

The Hills of Donegal

The road over which Danny brought the seaweed for Farmer Flynn. Page 21

“The minute the peddler drives down the road I’ll go and get the knitting, and I’ll keep the needles clickin’ while I’m out of my bed till it’s done,” Kathleen declared.

Mary Ellen held up her hand. “Whist, alanna,” she said softly, “’tis fairy music I hear.”

Kathleen listened eagerly for a moment. “True for you,” she said. “I hear it myself. Belike it’s the sea-gods over at Horn Head. There was a big storm last night, and Grandmother Barry says that after a big storm thousands of the sea-gods ride over the waves on their white-maned steeds winding their battle horns.”

It is ten miles across the country to Horn Head, which is one of the rocky headlands on the north coast of Ireland, where the waves of the Atlantic Ocean beat against the dark cliffs. Highland lakes and mountain rivers lie between, and the road over which Danny brought the seaweed for Farmer Flynn leads across purple hills that would surely deaden the sound of surf miles away.

“It’s nearer than Horn Head,” said Mary Ellen. “There may be fairies in the rath after all.”

“Let’s go and see,” Kathleen suggested, and the two children tiptoed carefully around the circle of rocks, forgetting all about the peddler, and the stockings, and Kathleen’s good resolution.

As they crept softly up to the open door of the[22] grassy mound the sweet notes became a little tune, and a voice began singing the familiar words of an old Irish song.

Kathleen stood still, hardly daring to breathe, but Mary Ellen stepped boldly into the tiny room. “It’s the father himself,” she said, and Kathleen followed her sister, astonished indeed to find her father sitting on his work-bench and gently touching the strings of a small harp.

“I’m glad it wasn’t the fairy music we heard,” she said, after the surprise was over. “Grandma Barry says a spell is cast over him that hears it, and after the spell is taken off he pines away and dies in a year and a day.”

“Is it your own harp, Father?” asked Mary Ellen, thinking he might perhaps have borrowed it from the fairies.

“It was your mother’s,” he answered. “It was in her family from the days of the old Irish chiefs, and she showed me how to pick the strings.”

Mary Ellen touched it softly with her fingers. “It almost seems alive,” she said, as the strings gave out their sweet sounds.

“There was once a god in Ireland who owned a harp that was alive,” her father said with a smile. “He used to be called the ‘Mighty Father of Ireland,’ and his harp could do strange things when it had a mind. Sometimes he would go to the top[23] of the mountain and play the whole procession of the seasons—spring, summer, autumn, winter—out of the strings of the harp.

“Once the god was captured by the giants, and was taken away to their castle, but he called to his harp for help, and it heard and answered. It flew through the air straight to its master, and killed nine of the giants as it flew.”

“Listen to him, telling us tales of the giants,” whispered Kathleen, but Mary Ellen was thinking of the harp and paid no attention to her sister.

“Danny says there is a harp on the green flag of Ireland,” she said.

“Yes,” said her father, “it was an Irish god who made the harp and played upon its strings.”

“Tell us about it,” begged Kathleen, who loved the gods and giants as well as she did the fairies.

“The god’s name was Dagda,” her father told her, “and once when he was walking beside a blue lake he saw a beautiful maiden and wished to have her for his wife. But the maiden feared him and ran away through the forest.

“Dagda followed her and she went on running away; and so at last they came to a beautiful curving beach, with the waves washing the yellow sands.

“As the maiden fled swiftly across the wet sands she heard a strange, mournful sound, and stopped to listen to the music.

[24]

“The bones of a fish lay on the sand at her feet, and the dry skin, stretched from rib to rib, made a harp for the wind to play upon.

“When Dagda saw that the sweet sounds pleased the maiden, he took a piece of wood and made a harp after the same pattern, playing upon the strings with his fingers as the wind had taught him to do. After that the maiden followed him gladly for love of the music.

“It was the first music ever heard in all Ireland, but since that day we have had harpers from one end of the land to the other. ’Tis a wonderful country for music, and we put the harp on our green flag to show that we’re proud of the sweet songs of Erin.”

Kathleen sighed when the story was finished. “I wish it were the days of gods and giants and beautiful maidens now,” she said.

“I’d wish for the days of the harpers and story-tellers,” said Mary Ellen wistfully.

“Right you are, Molly jewel,” said her father, putting the harp carefully away in its case. “The giants were just plain men like myself, but with no learning at all, at all. Faith, they could neither read nor write, and but for the harpers we’d know nothing about them.”

“How do we know from the harpers?” asked Kathleen.

[25]

“Sure, the harpers and story-tellers made up grand songs and stories about the gods and the giants of old Ireland, and travelled up and down the length and breadth of the land singing their songs and telling their stories wherever they went. It was the only way of learning that people had in the days when there were no books.”

“The people must have been glad to see the harpers coming,” said Mary Ellen, thinking how much she would like to hear their songs.

“That they were,” replied her father. “Even the kings made them welcome, and gave great feasts in their honor. The feasts were held in a long banquet hall with rows of tables up and down the sides, and there were sometimes more than a hundred men at the tables. The king sat at the head of the hall, with a harper on one side and a story-teller on the other, and there was merry-making through half the night.”

“Those old kings of Ireland must have been great men,” said Kathleen.

“That they were,” replied her father, “and Brian Boru was the best of them all.”

“The grandmother is callin’,” interrupted Mary Ellen. “I hear the sound of her bell.”

“She’s always callin’,” Kathleen complained, but she took her sister’s hand and hurried obediently down the hill.

[26]

THE LITTLE GREEN SHAMROCK

“Look, Kathleen,” said Grandmother Barry, as the two children reached the cottage door, “there’s not another sod of peat in the house. Run down to Farmer Flynn’s to meet Danny, and tell him to bring some home with him.”

“I’ll get the small creel Danny made for me, and bring some home myself,” said Kathleen, running into the cottage.

She was out again in a moment with two light wicker baskets. “Here’s your creel, too, Mary Ellen,” she said, and hung it carefully over her sister’s shoulders.

Farmer Flynn lived a mile away on a big sheep farm, and Kathleen was glad to be sent there for peat. She liked the work and bustle of the farm life and always saw something new and interesting. Sometimes there were baby lambs in the sheepfold, sometimes she saw a calf or a pair of young donkeys, and then, best of all, there was the big flock of white geese that belonged to the farmer’s wife.

Kathleen loved to watch the geese, and she often[27] told Mary Ellen funny stories about them and their strange ways. “I’m going to ask Mrs. Flynn to let me tend them for her next summer,” she had confided to her sister. “That will be one way to earn pennies for your eyes, darlin’.”

Danny had worked for the farmer ever since the winter his father had brought them all to live in Donegal. He had been a pale, shy little lad at first, but now he was grown strong and sturdy, “able to do a day’s work with the best of them,” he said proudly.

Farmer Flynn was proud of him, too, and often said, “I made of Dan Barry the man that he is. He can thatch a roof or shear a sheep to-day as well as I can myself.”

And whenever little Kathleen caught the farmer’s eye she would stand straighter to hear him say, “There’s a fine slip of a lass. She’ll be a good woman and a pride to you, Danny my boy.”

The two children, with their creels on their backs, ran down the little lane behind the house, followed the brook which chattered over the rocks at the foot of the heather glen, crossed the bog and climbed the hill, and then, at a quick turn of the path, there they were at the peat-shed, and there was Danny standing at the door.

He was talking with a strange man who carried a bundle of blackthorn sticks on his back; but just[28] as the little girls came around the corner Danny shook his head and turned to go into the shed.

“Oh, Mary Ellen,” said Kathleen, “there’s a peddler and he’s trying to sell Danny a shillalah.”

“He’ll not do it,” said Mary Ellen. “Sure, Danny’s saving every odd shilling he earns. He has them in an old stocking, and he shook them out and let me count them. He has near a pound.”

“The peddler has a bundle of fine big sticks,” said Kathleen, “but not one of them is as thick and strong as the blackthorn Father has from Great-grandfather Connell. I’m thinkin’ Danny will have that some day.”

The peddler smiled pleasantly at the two little girls as they drew nearer, and put his hand so gently on Mary Ellen’s curly head that Kathleen took a liking to him at once.

“Where’s your bit of green ribbon?” he asked with a laugh, looking at the blue homespun dresses as if he thought they ought to be trimmed with green.

Kathleen looked up into her brother’s face to see if he knew what the stranger meant by the question.

Before Danny could tell her the peddler added, “Mayhap you never heard of our good St. Patrick in these parts,” and he laughed again as if he thought this question a better joke than the other.

[29]

“We know St. Patrick well,” said Kathleen. “It’s not more than a day’s journey from here to his mountain in County Mayo, where he drove all the snakes out of Ireland into the sea.”

“Then you should be wearing the green for him this day,” said the peddler, and he showed proudly a big knot of green ribbon on one of the black-thorn sticks he carried, and a smaller knot on his worn coat. “Tell the truth now, that you clean forgot this is the seventeenth of March and St. Patrick’s Day in the morning.”

“Go away with you!” exclaimed Danny. “Where are your eyes, man? Don’t you see the green in my cap?”

Ireland is often called the Emerald Isle because of its setting of green fields and hills, and the national color, which is green, is seen everywhere. The English flag floats over the public buildings, but on holidays and feast-days the green flag of Erin decorates the houses, and on St. Patrick’s Day every one wears a bit of green in memory of the patron saint, and in honor of Ireland.

Danny, who had no green ribbon to wear to show his love for his country, had tucked a sprig of green shamrock into his cap, but now the tender leaves were wilted and hung drooping from their slender stems.

“It’s St. Patrick’s own little plant, and it was[30] fresh and green enough when I found it beside the brook this morning,” he said, taking off his cap and touching the withered leaves tenderly as if he loved them.

“Come home with us now,” he added, turning to the peddler, “and we’ll give you a good Irish welcome and a bite and a sup.”

“I’ll gladly go with you and the childer here,” said the peddler heartily. So he helped the little girls fill their creels with the sods of dry peat and fastened a bit of shamrock on their dresses “for St. Patrick and old Ireland.” Danny finished up his work in a hurry, and soon they were all on their way back along the lonely path. But it was lonely no longer, for they sang as they marched along:

[31]

GOOD ST. PATRICK

Grandmother Barry heard the song, and went to the door to see who was singing it so heartily. When she saw the peddler with the children she hurried to put an extra bowl and plate on the table, and bustled about the room setting out the simple meal.

The potatoes were baking in the embers, the kettle was boiling cheerfully over the burning peat, and a big dish of oaten stirabout was already steaming on the table.

“I’ll make a good cup of tay, and well have a supper fit for the king,” Grandmother Barry said aloud to herself, as she measured out the tea carefully and poured the boiling water over it. Then she went again to the door to give the stranger a hearty welcome.

Kathleen rang the bell to call her father down from his work-bench, Danny milked the little cow, and “in just no time at all” they were ready for supper.

[32]

“’Tis a sin and a shame that Kathleen is not wearing her green dress for St. Patrick,” said Grandmother Barry, as she saw the knot of green ribbon in the peddler’s coat. “I put it on her to wear to Mass, but ’tis her best and not to be worn common when she’s here at home. ’Twas a grand morning, and Father Burke gave the children a good talk about St. Patrick.”

“A fine morning it was, woman dear,” said the peddler, “and a grand day for the best saint that ever lived in ould Ireland.

“Tell us what Father Burke said about him,” he added, turning to Kathleen.

Poor Kathleen flushed and hung her head. “Sure, I know he stood on Croagh Patrick, over in County Mayo, and drove all the snakes out of the whole country into the sea,” she said, wishing she could remember some of the stories the good priest had told them.

“I’m not so sure about that,” said the peddler; “but it is true that there is not one to be found in the whole island. Some say there was never a snake here, and some say the good saint drove them all out with one stroke of his big stick. However it is, he is the best saint that ever lived, and a glory to Ireland, praise be to him!”

“Father Burke says he was only a lad when he was stolen away from his father and mother in[33] Scotland, and brought to Ireland to tend swine for one of the chiefs,” said Mary Ellen shyly.

“He was sixteen years old, and as straight and handsome a lad as ever lived,” said the peddler.

“Was he a saint then?” asked Kathleen.

“Whist, child,” exclaimed Grandmother Barry, “would a saint tend wild pigs on the mountains for any man, chief or no chief?”

“He was a brave lad,” repeated the peddler. “It should be told oftener how he served one of the chiefs for six long years, and served him well. He set a good example to the flighty gossoons nowadays that can’t stick to one thing for as long as a month at a time.”

“Danny has worked for Farmer Flynn ten years,” said Mary Ellen, fearing the peddler might think her brother a “flighty gossoon.”

“Father Burke said that St. Patrick went all over Ireland, ringing his bell and preaching to the people,” said Kathleen, beginning to remember some of the story.

“So he did; he was a wonderful preacher,” said Grandmother Barry, “and he was Bishop of all Ireland for many years.”

“Was that when Great-grandmother Connell was a little girl?” asked Mary Ellen, who thought her great-grandmother very old.

“Whist, jewel; it was nearly fifteen hundred[34] years ago that St. Patrick died,” her father told her, “and your great-grandmother’s only ninety.”

“Tell us the story of St. Patrick,” begged Kathleen. “I’ll remember it this time, for sure.”

“Well, now,” the peddler began, “when Patrick was a lad of sixteen he was brought to Ireland and sold as a slave to one of the rich chiefs, who sent him to tend swine on the mountains. At first he was no doubt sad and lonely, but he bore his troubles bravely and thought often of the good Father in Heaven.”

Kathleen’s father rose quickly, and going to a box in the corner of the room, he took out a book and brought it back to the fire.

“This is what the good saint himself wrote about those lonely days in the mountains,” he said, and turning the page he began to read slowly: “I was daily employed tending flocks; and I prayed frequently during the day, and the love of God was more and more enkindled in my heart, my fear and faith were increased, and my spirit was stirred; so much so that in a single day I poured out my prayers a hundred times and nearly as often in the night. Nay, even in the woods and mountains I remained, and rose before the dawn to my prayer, in frost and snow and rain; neither did I suffer any injury from it; for the spirit of the Lord was fervent within me.”

[35]

“He was a good lad,” said Grandmother Barry, wiping a tear from her wrinkled cheek, and taking up her knitting again.

“That he was, praise be to him,” the peddler agreed. “He tended the swine for six years, and then he escaped and made his way back to his home in Scotland; but he could not forget the Irish people and he longed to go back and teach them to be Christians. He studied for many years in France and other countries, but all the time his thoughts turned back to Ireland and he had dreams and visions about it.

“At last the Pope gave his permission, and Patrick set out for Ireland, landing on the north coast, in what is now County Down. Dicho, the chief of the district, thought that Patrick and his companions were pirates, and went to meet them and drive them out of the country; but when he saw their calm and peaceful ways he saluted them and invited them to his castle.

“Here Patrick told the chief his story and explained his belief in God, and Dicho and his whole family became Christians and were baptized.”

“He was a wonderful preacher,” repeated Grandmother Barry, with a nod of her head.

“Father Burke says that no missionary, since the time of the apostles, ever preached the gospel with more success than St. Patrick,” said Danny.

[36]

“That was because he cared nothing for riches and honor,” said the peddler. “He loved the people of Ireland and longed to make them all good Christians.

“After living with Dicho for some time and converting all the people roundabout, he bade good-bye to his friends and sailed down to the mouth of the river Boyne. From there he walked to the Hill of Tara, where the high-king of all Ireland lived in a great palace.

“He arrived at the palace on Easter morning, and presented himself before the king and his court. Patrick was robed in white, as were also his companions, and he wore his mitre and carried his crosier in his hand. He converted many of the king’s followers, and preached to the people throughout all the king’s dominions.

“’Twas so all over Ireland,—wherever Patrick went he turned pagans to Christians and built churches.

“He died in the very place where he first preached to Dicho, on the seventeenth day of March, about the year 465.”

“Is that why we call the seventeenth of March St. Patrick’s Day?” asked Mary Ellen.

“Yes,” replied her father, “it is the day that he died. We don’t rightly know just what day he was born.”

[37]

“How do you know so many things about St. Patrick, then, if he lived so many hundred years ago?” asked Kathleen.

“The old books tell us,” her father said. “Patrick, himself, wrote about his wanderings, and the monks copied these books and many others, painting pictures on the pages to illustrate them. It is from these ancient Gaelic books that we learn much about the life and customs of the people.”

“There were books of laws for the kings and the people, too,” said the peddler.

“Did the kings have to obey laws?” asked Kathleen, who supposed kings did just as they chose.

“That they did,” replied the peddler. “There was a law that no man could rule at Tara who was not perfect in his looks; so when Cormac mac Art lost an eye he had to give up being king.”

“’Twas a shame, too, for he was a good king,” said the father.

“It was also against the law for the sun to rise while the king was lying in bed at Tara,” said the peddler.

The children laughed merrily, and Danny asked, “How could they keep the sun from rising till the king was out of his bed?”

“Faith, they made the king get up before the sun did,” the peddler answered.

While the children were laughing over his joke,[38] Grandmother Barry put down her knitting and went to the cupboard for a plate of oat-cakes and her precious pound of honey.

Everyone was quiet for a few minutes over the feast, and little Mary Ellen was the first to break the silence. “Father told us a story about St. Columbkille one day,” she said. “He was born here in our own Donegal and he had little cakes baked for him with the letters of the alphabet on them. I’m thinkin’ if I had cakes like that I could learn the letters with my fingers.”

“Faith, he must have had a fine time picnicking on his letters,” said the peddler.

“There was St. Bridget, too,” said Grandmother Barry; “she was a fine woman and took great pride in learning and teaching. And I doubt not her fingers had magic in them to turn wool into yarn and yarn into stockings, like any colleen of Donegal,” she added, with a look at Kathleen.

But Kathleen was sound asleep in her chair and had forgotten all about the stocking she was going to finish knitting that very day.

“The child is tired out with our stories,” said her father.

“I mind we should all be in our beds,” said Grandmother Barry, and soon they were tucked away comfortably for the night.

[39]

A RIDE WITH THE POSTMAN

It was Mary Ellen’s sweet Irish way of saying good-bye to the peddler when he went away the next day; and he replied heartily, “If I should travel over the whole of Ireland between sun-up and sun-down, I’d hear no better word.”

At the cross-roads he met the postman in his red jaunting-car, riding toward the thatched cottage at the foot of the hill, and he stopped to pass the time of day with him.

“Give the two little girls a ride,” said the peddler. “If ’tis to the National School you are going, with a letter for the teacher, this way is as short as the other, and ’tis a lonely life the two children lead,—a mile from any other house, and never another child to play with.”

“’Tis a letter for Jerry, himself, that I have, and ’twill take me by the cottage, anyway,” answered the postman; and looked the letter over,[40] thinking that it was probably from Grandmother Barry’s daughter, Hannah Malone, as the postmark was “Kilkenny.”

He found the great-grandmother crooning an old Gaelic milking tune over her wheel, instead of the spinning song which she usually sang; and Grandmother Barry greeted him with, “Ah, Larry O’Day, this is just such a morning as the one when you and I went with the rest on the pilgrimage to ‘Tobar N’alt,’ the holy well in County Sligo, to cure us of our rheumatism.”

The postman laughed. “That was forty years ago, and I’d forgot all about it,” he said, throwing out a letter from the pack. “It’s a dozen pilgrimages to holy wells that I’ve made since then,” he went on, “and there’s not a heartier man for his age, than myself, in all Ireland.”

Then he called to the children and asked if they cared to ride with him as far as the National School, four miles back of the hill, to carry a letter to the teacher.

“Oh, Molly darlin’, a ride!” gasped Kathleen, hardly believing her ears; while Mary Ellen was so excited that she climbed over the seat and would have tumbled into the well of the jaunting-car if Kathleen had not held her back.

“Steady, there, steady!” said Larry O’Day. “There be all sorts of wells in holy Ireland, from[41] the blessed ones filled with the water that cures all ailments, to the empty one between the seats of a jaunting-car; but not a one is there built to hold little girls in red dresses.”

Both children laughed merrily, and held tight to each other as the old horse jogged up hill and down dale toward the far-away schoolhouse.

The blue waters of a lake glistened afar off among the heather, and the postman said, “I mind me that somewhere in these parts there is a long flat stone that marks the place where the good Saint Columba was born. I’ve heard that if a body sleeps on it for one night before leaving dear old Ireland, he’ll never be homesick.”

“Perhaps ’tis the same flat stone by Father’s bench, where we play betimes,” said Kathleen. “I’ll tell Danny about it. He’s thinking of going to find his fortune in America.”

Then the children asked about the schoolhouse and the children who went to school in it. “How old are they?” asked Kathleen. “Are there any as little as Mary Ellen?”

“There are some smaller than Mary Ellen and some bigger than you,” answered the postman. “There are both boys and girls.”

“What do they learn?” she asked again, while Mary Ellen asked, “What do they play?”

“I’ve seen them playing some kind of a game[42] where they hold hands in a circle,” he told Mary Ellen, and both little girls cried at once, “That’s ‘Green grow the rushes-o.’”

“Belike it is,” he said cheerfully, and went on, “they learn reading, and writing, and the church catechism.”

“Don’t they learn about the grand places there are in the other parts of the world?” asked Kathleen wistfully. One of her few great pleasures was to get out an old geography-book belonging to her father, and study the pictures in it.

“Perhaps there’s something of the sort for the older ones,” said the postman, “but if a body can’t travel the world over, to see such places, I’m doubtful if there’s any good in learning about them.”

“Oh, no, no!” cried Kathleen, aghast at such a thought; while Mary Ellen said softly, “If I could see just one little green shamrock, I’d walk to the end of the world.”

Then they turned into another road and saw the children playing in the school-yard, and a sudden shyness fell upon Kathleen at the sight of so many children.

After the teacher had taken her letter and the red cart was jogging back over the road, there was no end to the questions Larry O’Day had to answer.

“Would those little girls feed the chickens and pigs, and drive the cow to pasture, as Kathleen did? [43]Would the boys plant potatoes and work in the bog just the same as Danny? Was that the very school where Danny himself walked eight miles a day, one winter, to learn to figure?”

Before they reached the thatched cottage again, the postman had talked more than he had for many a day before, and Kathleen helped her little sister down from the car in a great hurry to run to Grandmother Barry and ask still other questions.

But Grandmother Barry had questions of her own to ask. “Sure, Kathleen alanna,” she began, “and how would you like to go down to Kilkenny and live with your Aunt Hannah?”

“When?” asked Kathleen breathlessly.

“As soon as the plans can be made,” answered her grandmother. “Your Aunt Hannah has sent the word in the letter the postman left; and your father has gone to fetch Danny and talk it over with him.”

“There they are now,” said Mary Ellen, her quick ear catching the sound of their footsteps, and the next moment Danny and his father were turning into the yard.

Then Mary Ellen held the wonderful letter while Kathleen looked it over and Father Jerry told what it said.

“Himself has been doing well in his business, praise be!” Aunt Hannah wrote, “and I’d like to[44] do something for a child of my youngest brother, though he did take up with the tinker’s trade against my wishes; and him with the schooling.”

“That’s true,” said the shoemaker, looking up at the circle of faces. “Hannah begged me to take up teaching for a living. I had the learning for it, and it is an honorable calling in Ireland, and always has been. But I longed to see the whole of the green island, so I took on a trade that gave me a chance to travel over it.”

“’Tis of the chair in the chimney-corner at Barney’s house in Sligo, I’ve been thinking all the morn,” said Great-grandmother Connell. “Do you believe Barney has kept it waiting for me these ten years as he said he would?”

“I doubt not there’s a chair each side of the chimney, one for you and one for Mother Barry,” said Father Jerry gently.

“’Tis Ireland that never forgets the old mother,” said the older woman, “and my heart is crying out for the dear old home where I lived for eighty years.”

“Why shouldn’t we all go?” asked Danny boldly. “I’ve money enough for my passage to America, and I’d like to try my fortune in the world.”

“But what will become of me?” asked little Mary Ellen.

“’Tis you and I will buy a great dog to keep[45] us company, and we’ll go travelling together up north to listen to the waves beating around the Giant’s Causeway, Molly darling,” her father told her.

But Danny had to give a month’s warning to Farmer Flynn, and before the time was up, a letter had reached them from Tonroe. It said that Cousin Bee, Uncle Barney’s daughter who had married a Donovan, would be glad to have Mary Ellen bide with her for a while, at her home in Roscommon County.

“So you and the doggie must travel alone to the North,” whispered Mary Ellen to her father.

And that was the way of it.

[46]

COUSIN BEE’S FARM IN TONROE

It was an April morning at Cousin Bee’s little farm-house in Tonroe. The kettle was bubbling cheerfully over the burning peat in the fireplace; the cement floor of the kitchen was spotlessly clean; and Patrick, Bee’s husband, was making the children feel quite at home as he talked with them about Donegal and laughed heartily over their little stories.

Danny, Kathleen and Mary Ellen had arrived at the station with the two grandmothers the night before, and nothing would do but they must all leave the train together.

“Sure, we’ve room and to spare for a strong lad like you,” Patrick had told Danny; and Bee had said, “’Twould be a shame for Mary Ellen and Kathleen to be separated so sudden-like.”

So Uncle Barney took the two grandmothers home with him to Killaraght, while Danny and Kathleen went with Mary Ellen to visit Cousin Bee before going on with their journey,—Kathleen to Kilkenny, and Danny to Queenstown, where he was to take the steamer for America.

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood, New York

Cousin Bee’s Farmhouse in Tonroe

Notice the thatched roof and the broad chimneys.

Their first morning in Tonroe opened bright and[47] cheery, outside as well as in, and Kathleen was so excited over all the new sights that she could hardly wait to eat her breakfast. Of course everything had to be described to Mary Ellen, and Patrick’s hearty laugh filled the kitchen when Kathleen told her sister that the village looked as if a giant had taken a great creel filled with houses, and dropped them from a high ladder to the plain below.

“Kathleen never saw so many houses together before, till she went to Letterkenny yesterday to take the train away from Donegal,” Danny explained.

“Then she’ll like to ride over to Boyle with Bee on market days,” said Patrick kindly; “there’s houses a-plenty there. But the plains of Boyle will look flat enough to her after the mountains of her own county.”

“Oh, Mary Ellen, come here!” cried Kathleen, who had gone to the back door for another look at the village. “There’s a church steeple far away beyond a hilleen, and there’s the fine National School building that Grandma Barry used to tell us about. It’s on the little hill, and I can see it every time I look out at the door. But the mountains are far away. There’s not one to be seen near by.”

“Perhaps they have put on a cloak of darkness,”[48] suggested Mary Ellen. “Is there nothing at all where the mountains rightly belong?”

“It’s better than mountains,” said Kathleen decidedly, to Patrick’s delight. “There’s another hilleen of trees just beyond the hedge, and it looks like a picnic garden, for the trees are all covered with creels and creels of pink and white blossoms.”

“She means the rath, and the hawthorn trees,” exclaimed Patrick.

“It is an old fort, darlin’,” Bee explained, “and it was built by a great chief hundreds of years ago; but it looks like a little hill now. There’s another just forninst the church steeple; and one off to the side of the house that you’d best not go too near.”

“Why not?” asked Kathleen curiously.

“An old chief was buried there hundreds of years ago,” answered Bee, “and now the fairies live in it.”

“Oh, Mary Ellen,” whispered Kathleen, “there are fairies here after all, and we were thinkin’ we had left them behind us in Donegal.”

Then she said aloud to Cousin Bee, “It would be a fine place for the fairies to dance under the pink and white trees in the rath beyond the garden. Did the old chiefs have their picnics there?”

“Whist, jewel, the Irish chiefs had other things to do,” said her cousin. “They had to be fighting with other chiefs, and killing the wild beasts; and sometimes they went off hunting foxes and deer[49] through the green forests, but I’m thinking they had no time for picnics.”

Mary Ellen was standing by Kathleen’s side, her sightless eyes looking beyond the green hedge toward the beautiful mound of trees that scented the air with thousands of blossoms.

“What did the chiefs do with the forts?” she asked.

“They lived in them,” answered Bee. “First they built a great circular wall of earth or stone to keep out wild beasts and robbers; and then inside the wall they built their house. Sometimes there were two or three walls, one outside the other. The forts were called raths, and if a king lived in them his house was called a dun.”

“That rath looks like a grove of trees now,” said Kathleen.

“The trees have grown up on the walls, and the houses are all gone hundreds of years ago,” Bee replied.

“What did the houses look like?” asked Mary Ellen.

“The darlin’! she wants to know how it all looked just as if she had the sight,” said Bee, putting her arm around the child.

“Well,” she went on, “the houses were shaped like bee-hives. They were built of poles all woven in and out with twigs, like wicker baskets, so the[50] books say. Many a town in Ireland to-day is built where a chief’s rath or a king’s dun once stood, and it gets its name by that token. There’s Dundalk and Dunglow and Dunmore, Rathmelton, Rathdrum and Rathcormack. There are duns and raths all over the country.”

“There are ‘Kils,’ too,” said Mary Ellen. “Kathleen found them in our old geography, and Father made a little verse about them. He says that ‘Kil’ means church, and that St. Patrick built some of the churches. I don’t remember the verse, though. Do you, Kathleen?”

“That I do,” said her sister, and she sang to an odd little tune:

“Good enough,” said Patrick, clapping his hands and laughing so heartily that everyone else laughed.

“There are dozens of ‘ballys,’ too,” said Mary Ellen, when the laughter was over. “Kathleen made a list of them, and Father said they would make a whole string of verses, but he didn’t get time for it yet. ‘Bally means town,’ he said.”

“Did the chiefs ever have any sports besides[51] hunting?” asked Danny, who was fond of sports and had tried many a running race with the boys at Farmer Flynn’s.

“To be sure,” Patrick replied. “Over in Leinster they held a great fair once in every three years, and they had games and chariot races and horse races. People went to the fair from miles around, and the harpers and story-tellers always planned their wanderings so as to be there for the three days.”

“It must have been something like market day,” said Kathleen, who could not forget the crowd she saw at the Letterkenny market.

“There was marketing, too,” said Patrick. “It wouldn’t be Ireland without marketing. There was selling and buying of horses, sheep, and pigs, and all sorts of hand-made gold and bronze ornaments. The country was famous for her hand-crafts then; and she will be so again some day, praise be!”

“There couldn’t have been such pig markets as the one we saw yesterday,” said Danny, laughing at the thought of the hundreds of squealing pigs in the Letterkenny streets.

“I don’t know about that,” said Bee. “It took them two years to get ready for the Leinster fairs, and we go to market in Boyle twice a week.”

“I should be on my way there now, instead of sitting here talking as if I’d nothing to do,” said[52] Patrick. “I want to see Tim Keefe about buying the heifer come Saturday. Have you any eggs to send, Bridget mavourneen? And will you go with me, Danny, my boy?”

Danny went out to help Patrick harness the mule, Mary Ellen held the creel while Kathleen counted out five score of eggs, and Bee packed ten pounds of beautiful, golden butter into the market basket.

“There, Patrick avic,” she said, as she followed him to the barn and put the basket into the trap, “bring me back a good bit of silver for my work, and a ribbon apiece for the children. I’ll have them watching for you when you come home.”

“This is the best day to sell the butter,” she said to Kathleen, as the trap disappeared down the boreen toward the road. “There’ll be people buying everything you can name, from butter and eggs to needles and pins and imitation gold chains, at the Wednesday market.”

“What will they buy in the Saturday market?” asked the child.

“Pigs, calves, sheep and wool, hay, potatoes, and every kind of vegetable that grows,” was the answer. “I’m raising a little pig that I’m going to take to the Saturday market myself some day; and Patrick’s heifer is the best in Boyle for its age. Tim Keefe ought to give him a good price for it.”

Then she took Kathleen into the barn and showed[53] her the heifer and the little pig, the two baby donkeys, the hens and the geese.

“If we get everything well started in the garden we will go on a picnic to Lough Gara come May-day, and you shall stay and go with us,” she said, leading Kathleen into the garden.

Such a pretty garden it was, too! Paths bordered with box led through beds of lilies and roses; and there were beds of cowslips and hollyhocks and many another sweet, old-fashioned flower.

After they had walked up and down the little paths and looked at all the buds and blossoms, they went back into the kitchen, where Kathleen washed the dishes while Bee put the bread to bake in the Irish baking-oven. This oven looks like a kettle and it stands on four feet among the burning peat with more peat heaped on the cover.

“If Mary Ellen could see, and I was going to live here always, and Father could come back and live here, too, and Danny need never go to America, this would be the prettiest farm and the best place in the whole world,” Kathleen said to herself with a long sigh.

Bee heard the sigh and asked what it meant.

“I’m wishing I could find some way to bring Mary Ellen’s eyesight back,” Kathleen told her.

“Was she born blind?” questioned Bee.

[54]

“No,” said Kathleen, “but her eyes were weak when she born, and when Grandma Barry came to live with us she said it was the smoke of the peat that had taken the sight away altogether. That was how it came about that Father made a chimney for the cottage, so that the smoke could go out instead of spreading through the room.”

“There has been a good deal of blindness in Ireland from the smoke of burning peat in the houses,” said Bee, looking thankfully at her own broad chimney and deep fireplace.

“Hark!” said Kathleen suddenly, “there’s the child calling this minute,” and she ran out into the garden to see what was the matter.

Mary Ellen had been exploring the little farm for herself. She had found her way through the garden to the old fort and was catching the pink and white petals as they drifted down to her from the trees. An old magpie had built his nest in the tree over her head and he was scolding so angrily that the child was afraid of him.

“Was it only a bird, Kathleen dear?” she asked, when her sister tried to quiet her by telling her just how funny he looked, sitting up there in the tree and opening and shutting his big bill. “Faith, I thought it was an ogre!”

“That’s the very magpie that steals my young turkeys,” said Bee, who had run out after Kathleen.[55] “If you children will find a way to drive him off I will give you a shilling.”

Then she left the little girls to play by themselves, and Mary Ellen lay on the grass among the spring blossoms while Kathleen sat down beside her to tell her a long story.

“This is a truly fairy rath,” she began, “and Cousin Bee’s farm is the fortune fairy’s palace.”

And Cousin Bee, putting her cream into the churn, said to herself, “Sure, the farm is big enough to keep both the children for awhile. I’ll let Kathleen stay on with Mary Ellen till her Aunt Hannah sends for her again.”

[56]

MAY-DAY ON LOUGH GARA

“It’s the cute way nature has with her!” exclaimed Kathleen, holding up her face for the white-thorn petals to blow down upon it. She and Mary Ellen had been to the old rath after flowers for the May-baskets, and were returning to the cottage, where Cousin Bee was waiting to take them to Lough Gara for the May-day picnic. A breeze was scattering the petals from the trees, which were “as white with bloom as the snow of one night,” and Mary Ellen turned her face to the sky so that she, too, might feel the soft shower.

“Sure, nature has a cute way,” Kathleen repeated. “When a cloud hides the bright sun and you’d think an Irish rain was going to fall the next minute, the wind gives a laugh and sends a snowstorm instead; and here it is the first day of May, and the blackbirds are singing in the meadow.”

“Can you see the snow on the mountains far away?” asked Mary Ellen.

“No, but the white chalk cliffs shine like snow,” replied Kathleen. “It seems as if we must forget,[57] here in Tonroe, about the mountains and the cold, snowy winter. When I wake up in the morning and hear the lark singing his way up into the sky, and smell the May-bloom through the window, I almost forget the gray stones and low clouds of purple Donegal.”

“Do you mind the old black crows that used to call over the hills all day long?” asked Mary Ellen.

“Of caws! Of caws!” croaked Kathleen, so much like an old crow that her sister made her do it again and again, “to remind her of home,” she said.

The children had been at Cousin Bee’s little farm in Tonroe for over two weeks, and Danny had made himself so useful that Patrick offered him good wages to stay and help him through the planting season.

“Sure, I care more for work than for anything else just now,” Danny made answer, and he rolled up his sleeves and went to work with a will.

“There’s no need for Kathleen to go to Kilkenny either, now that the school is near to closing for the summer,” Bee suggested.

So Kathleen washed the dishes and watched the young turkeys. She fed the hens and found their eggs when they stole nests in the little village of grain-stacks in the hay-haggard. And, best of all, she found an old cow-bell in the barn and set Mary[58] Ellen to ringing it every time the thieving magpie came back to his nest, until he was glad to take his family away to live in a quieter neighborhood and leave the young turkeys to wander through the old rath in safety.

In fact, she made herself so useful that Uncle Barney, over in Killaraght, nodded his head when he heard of it, and Grandmother Connell said in the old Gaelic, which looks in print as if it might be fairy speech, “Kathleen always had good sense and handy ways.”

And now it was May-day at last, and the little family had been busy all the morning getting ready for the picnic.

“Come, children,” called Bee from the house door, “here are Norah Higgins and Hannah Kelley waiting for us, and Patrick and Danny have gone on ahead for the boat.”

Then off they all went down the lane, between the hedges of pink hawthorn, purple lilac and gleaming golden gorse, across the fields, and along the green bank of the river.

A neighbor who was driving his family down to the lake in a jaunting-car stopped to ask them why they weren’t riding themselves, but Bee said she thought it was far more pleasant to walk, and they trudged along, talking and laughing merrily.

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood, New York

“A NEIGHBOR WAS DRIVING HIS FAMILY DOWN TO THE LAKE IN A JAUNTING-CAR.”

The jaunting-car has side seats, with a “well” between them for parcels.

Pink and white mayflowers, blue wall-flowers and yellow daffies grew under their feet, and the fields were full of blue-bells. Robins and thrushes sang over their heads, and in the distance they heard the sound of a hunting horn and the baying of the hounds.

Danny was waiting for them at the boat landing, and Patrick made haste to gather his party into a boat and row them out upon the blue water, so that they could watch the happy crowds coming and going along the shore. Kathleen looked back across the fields and saw hundreds of men, women, and children, all dressed in their very best, trooping toward the lake, carrying lunch-baskets for their May-day picnic on Lough Gara.

“Oh, Molly darling,” she whispered, “it’s better than anything we ever thought of in Donegal. It’s a wish come true.”

Mary Ellen clung to her sister’s hand, listening to the happy voices calling from boat to boat, and from water to shore. “It must be the place Grandma Barry used to tell us about,” she said,—“the place where happiness is so common you can buy it for a ha’penny.”

Kathleen’s eyes were fixed on the green island toward which Danny was rowing them. “It looks more like the home of the fairies than does the Rock of Doon,” she told Bee.

“They do say that the fairies haunt Lough Gara,”[60] her cousin answered. “At night, when there’s no one to see them, they gallop round and round the lake, winding their hunting horns and following the fairy hounds just as the ladies and gentlemen do at the meets on the big estate at French Park.”

Just then the boat touched the shore of the little island and there was no more time to talk of fairies. Pretty Mary Hever and her brother John were waiting for them under the trees, and every one was ready to help in the merry fun of setting out the lunch.

The girls plaited wreaths of flowers and oak leaves, and crowned Bee and Mary Ellen; John Hever found a spring of clear water and filled the cups; and Bee set out the sandwiches and cheese and some of her delicious cookies which were the best in all Tonroe.

“There’ll be just time enough for the lunch before we go to Kingsland for the sports,” Patrick said, as he sat down on the grass between Kathleen and Mary Ellen and began to help them to cookies the very first thing.

“Be off with your joking,” said Bee. “We can’t hurry the picnic like that. Half the fun of the lunch is the blarney that goes with it.”

“Faith, John Hever will do the eating while we take care of the blarney,” replied her husband, laughing at the boy’s first mouthful.

[61]

“Tell us about Donegal,” Hannah Kelley said to Kathleen.

“There’s nothing to tell,” replied Kathleen. “There are just purple mountains and rocky hills and bogs, and Mary Ellen and I had no one to play with at all.”

“You should see the great cliffs over at Horn Head,” said Danny proudly. “That’s something to tell about! When there has been a storm, the waves pound against them and the spray dashes up so that it is a grand sight.”

“I’m thinking it was up there that the giant used to step from cliff to cliff when he was walking round the island to be sure everything was all right for the night,” said Bee, who seemed to know stories of all the giants and fairies.

John Hever looked down at his own short legs with a sigh. “Sure, he must have been a big giant,” he said, “to walk around all Ireland every night of his life.”

“That he was,” replied Patrick with a laugh. “Were you thinking you’d catch up with him on his next round?”

“I was not,” answered John, “but I’ll soon be beating you in a race to Dublin town.”

“It’s ten years and more since I played that game with fifty other boys and girls; and that, too, around the policeman’s legs in the streets of Cork!”[62] exclaimed Patrick. “But come on then, and we’ll see how it seems to go doubling among these tree-trunks.”

He seized Bee’s hand and they began singing “How many miles to Dublin Town?” just as Kathleen and Mary Ellen had sung it so often in far Donegal. But now there were many to join in the game, and one after another the children caught hold of hands and ran in and out among the trees, singing and shouting.

When Patrick thought they had had enough of the game he led them all down to the boat and pushed off for the sports at the Kingsland shore.

Never before, Kathleen thought, had so many things happened in one day. There were bicycle-races, hurdle-races, foot-races, sack-races and a tug-of-war. There was leaping, and jumping, and running, and it seemed as if Danny was in everything.

Such shouting and cheering she had never even dreamed of! And when Danny won the long-distance run, she found herself jumping up and down and shouting as loudly as any one.

“I could have won that first dash, too, if Tim Keefe hadn’t stolen the start,” said Danny wrathfully, as he brought up his prize to show to his cousins.

“The prize for that race was a mirror, anyway,”[63] said Patrick consolingly, “and you’ve little use for one now. But as for Tim Keefe, with his old pipe in his mouth, he needs it to see himself for a spalpeen.”

After the fun was all over they went home together across the fields, filling their arms with great branches of the pink and white hawthorn blossoms; but at the boreen they had to start running, for a sudden shower fell to drive them into the house the quicker.

Just as the children were going off to bed that night, Kathleen went softly up to Bee and put her arm shyly around her cousin’s plump waist. “It’s thankful I am to you and Patrick for the happy day,” she whispered.

Bee gave her a good hug and a hearty kiss as she answered, “’Tis you and little Mary Ellen that make all the days happy for me.”

[64]

A BANK OF TURF

“Mary Ellen, dear, did you ever think it would be so fine to live out of Donegal?”

“No,” answered the little sister, “I’ve been thinking of the market ever since Saturday; and yesterday was the walk to Lough Gara again, and to-day is the sheep-shearing. Belike by Friday they will begin to cut the turf. It is better than Donegal, even if Father is not with us.”

“Oh, Mary Ellen, I doubt they’ll begin cutting out peat on a Friday. It will bring them bad luck.”

“Perhaps they will begin on Thursday, then,” suggested her sister. “Is there any ill luck in that day?”

It was a beautiful morning toward the end of May, and the two little girls were watching the shearing of the sheep at Uncle Barney’s farm. More than a hundred bleating sheep and lambs were collected near the house, where they were guarded by a trained shepherd dog and watched over by Kathleen.

[65]

“Kathleen is the colleen that’s good at everything,” Patrick said one day after the picnic at Lough Gara. “She’ll milk a cow as well as ever her great-grandmother Connell did. She’s got the firm hand for it, and the sweet voice.”

“She can bake as fine a loaf of bread as I can, and that is saying a good deal, too,” said Bee proudly.

“I’ll see what kind of a shepherd lass she will make, come shearing-time,” said Uncle Barney, who had come over from Killaraght to get Danny to help him. “We’ll need some one to keep the sheep from straying away after they have been washed.”

So Kathleen was watching the sheep for her uncle, and talking over the Saturday market with her sister.

“Sure, I thought Bee’s little pig would squeal himself black in the face before she got him sold,” said Mary Ellen.

“I mind Bee did better with her little pig than Patrick did with his big heifer,” Kathleen replied with a laugh.

“Why?” asked Mary Ellen.

“Hasn’t Patrick been trying to sell his heifer to Tim Keefe ever since we came to Tonroe?” Kathleen answered. “Faith, he only finished the bargain last Saturday; and it was Uncle Barney that brought it about then, else they’d still be a-higgling.”

[66]

“What’s this you are saying?” asked Patrick, who was selecting another sheep to shear.

“We’re saying that Bee makes a better bargain than you,” Kathleen told him.