Title: Opening the iron trail

or, Terry as a "U. Pay." man (a semi-centennial story)

Author: Edwin L. Sabin

Release date: May 3, 2024 [eBook #73521]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Thomas Crowell and Company

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BOOKS BY EDWIN L. SABIN

Wild Men of the Wild West

“Old” Jim Bridger on the Moccasin Trail

Pluck on the Long Trail; or, Boy Scouts in the Rockies

GREAT WEST SERIES

“The Great Pike’s Peak Rush”; or, Terry in the New Gold Fields

On the Overland Stage; or, Terry as a King Whip Cub

Opening the Iron Trail

RANGE AND TRAIL SERIES

Bar B Boys; or, The Young Cow-Punchers

Range and Trail; or, the Bar B’s Great Drive

Old Four-Toes; or, Hunters of the Peaks

Treasure Mountain; or, The Young Prospectors

Scarface Ranch; or, The Young Homesteaders

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

NEW YORK

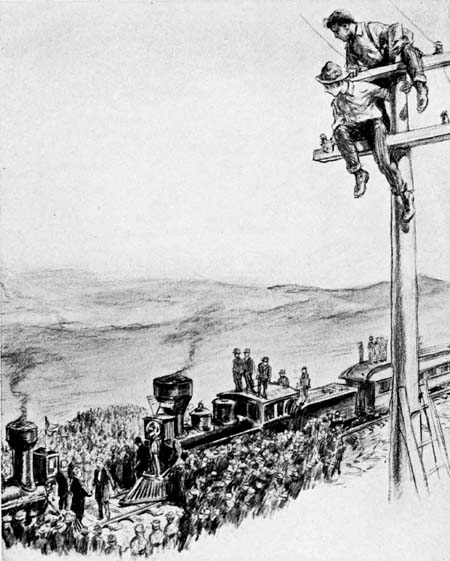

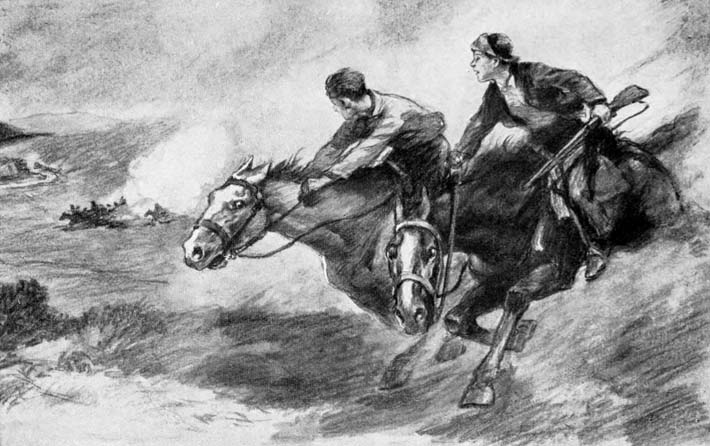

Frontis.

THE WEDDING OF THE RAILS

OR

TERRY AS A “U. PAY.” MAN

(A Semi-Centennial Story)

BY

EDWIN L. SABIN

AUTHOR OF “THE BOY SETTLER,” “THE GREAT PIKES

PEAK RUSH,” “ON THE OVERLAND STAGE,” ETC.

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1919, by

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

Fourth Printing

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

It is fifty years ago, this year 1919, that the first of the iron trails across the United States, between the East and the West, was finally completed. At noon of May 10, 1869, the last four rails in the new Pacific Railway were laid, and upon Promontory Point, Utah, about fifty miles westward from Ogden, the locomotive of the Union Pacific and the locomotive of the Central Pacific touched noses. That was indeed a great event.

The Union Pacific, coming from Omaha at the Missouri River, had built over one thousand miles of track in three years; the Central Pacific, coming from Sacramento at the Pacific Ocean, had built over six hundred miles in the same space. Altogether, in seven years there had been built one thousand, seven hundred and seventy-five miles of main track, and the side-tracks, stations, water-tanks, and so forth.

In one year the Union Pacific had laid four hundred and twenty-five miles of track; in the same year the Central Pacific had laid three hundred and sixty-three miles. In one day the Union Pacific had laid seven and three-quarters miles; in one day the Central Pacific had laid a full ten miles. These records have never been beaten.

The whole thing was a feat equaled again only[iv] when America speeded up in the war against Germany; for when they once get started, Americans astonish the world.

Twenty-five thousand men, including boys, were working at one time, on the twain roads. This book tells of the experiences of Terry Richards and George Stanton, who were two out of the twenty-five thousand; and of their friends.

The Author.

AT THE UNION PACIFIC END

| Terry Richards | On the Job | |

| George Stanton | Likewise on the Job | |

| Terry’s Father | } | The Crew of No. 119 |

| Stoker Bill Sweeny | ||

| George’s Father | Out on Survey | |

| Mother Richards | } | Heroines of the U. P. |

| Mother Stanton | ||

| Virgie Stanton | First Passenger Across | |

| Harry Revere | Expert Lightning Shooter | |

| Jenny the Yellow Mule | Dead in Line of Duty | |

| Shep the Black Dog | “Killed in Action” | |

| Jimmie Muldoon | Who “Stays Wid the Irish” | |

| Major-General Greenville M. Dodge | The Big Chief | |

| Colonel Silas Seymour | His New York Assistant | |

| Paddy Miles | Boss of the Track “Tarriers” | |

| General “Jack” Casement | The Scrappy Hustler | |

| Mr. Sam Reed | Construction Superintendent | |

| Major Frank M. North | White Chief of the Pawnees | |

| Lineman William Thompson | Who Rescues his own Scalp | |

General Grant, General Sherman, U. P. Vice-President Thomas C. Durant, Director Sidney Dillon, and other distinguished visitors; Major Marshall Hurd, John Evans, Tom Bates, Francis Appleton, and other daring survey engineers; General John A. Rawlins, young Mr. Duff, Mr. John Corwith, tourists; Mr. David Van Lennep, geologist; Sol Judy and old Jim Bridger, scouts; Chief Petalesharo’s Pawnees; United States soldiers; the Irish “tarriers” who built the road; Jack Slade’s “roaring town” toughs; and bad Injuns.

AT THE CENTRAL PACIFIC END

| Governor Leland Stanford | A President in Broadcloth |

| Vice-President Collis P. Huntington | Who Raises the Money |

| Mr. Charles Crocker | Commanding “Crocker’s Pets” |

| Mr. Sam S. Montague | Chief Engineer |

| Mr. J. H. Strowbridge | Construction Superintendent |

| Mr. Hi Minkler | Who Opens Paddy Miles’ Eyes |

Mike Shay, Pat Joyce, Tom Dailey, Mike Kennedy, Fred McNamara, Ed Killeen, George Wyatt, Mike Sullivan, the ten-miles-a-day “cracks”; and the 10,000 Chinks who saved the Central.

Time and Place: 1867-1869, upon the great plains, through the deserts and over the mountains, during the famous railroad-building race to cross the continent.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Terry Richards on the Job | 1 |

| II. | A Little Interruption | 12 |

| III. | “Track’s Clear” | 24 |

| IV. | Down the Line—and Back | 39 |

| V. | The Cheyennes Have Some Fun | 60 |

| VI. | Moving Day Along the Line | 74 |

| VII. | Out Into the Survey Country | 83 |

| VIII. | General Dodge Shows the Way | 99 |

| IX. | More Bad News | 111 |

| X. | A Meeting in the Desert | 122 |

| XI. | Major Hurd in a Fix | 138 |

| XII. | Two on the Scout Trail | 148 |

| XIII. | Set for the Great Race | 166 |

| XIV. | The “Tarriers” Make a Record | 178 |

| XV. | A Fight for a Finish | 197 |

| XVI. | Fast Time Down Echo Canyon | 207 |

| XVII. | The Last Stretch | 217 |

| XVIII. | The U. P. Breasts the Tape | 229 |

| XIX. | The C. P. Show Their Mettle | 238 |

| XX. | The Wedding of the Rails | 251 |

OPENING THE IRON TRAIL

The rousing chant rang gaily upon the thin air of Western spring. Sitting Jenny, the old yellow mule, for a moment’s breather while the load of rails was being swept from his flat-car truck, Terry Richards had to smile.

Nobody knew who invented that song. Some said Paddy Miles, the track-laying boss—and it did sound like Pat. At any rate, the lines had made a hit, until already their words were echoing from the Omaha yards, the beginning of track, past end o’ track and on through the grading-camps clear to the mountains where the surveying parties were spying out the trail, for this new Union Pacific Railroad across continent.

Time, early in May, 1867. Place, end o’ track, on the Great Plains just north of the Platte River, between North Platte Station of west central Nebraska and Julesburg, the old Overland Stage Station, of[2] northeastern Colorado. Scene, track-laying—a bevy of sweaty, flannel-shirted, cowhide-booted men working like beavers, but with spades, picks, sledges, wrenches and hands, while far before were the graders, keeping ahead, and behind were the boarding-train and the construction-train, puffing back and forth.

Aye, this was a bustling scene, here where a few weeks ago there had been open country traveled by only the emigrant wagons, the stages and the Indians.

And yonder, farther than the graders and out of sight in the northwest, there were still more workers on the big job: the location surveyors, the path-finding surveyors, the—but Terry’s breather was cut short.

“All right!” yelped the command, from the front.

Terry’s empty truck was tipped sideways from the single track. A second little flat-car, hauled by a galloping white horse ridden by small red-headed Jimmie Muldoon, passed full speed, bound to the fray with more rails. Terry’s own car was tipped back upon the track again, one-legged Dennis, its “conductor,” hopped aboard, to the brakes, and uttering a whoop Terry started, to get another load, himself.

Old Jenny headed down track, by the path that she had worn; the fifty feet of rope tautened; with the truck rumbling after and Shep, Terry’s shaggy black dog, romping alongside, they tore for the fresh supplies. Sitting bareback, Terry rode like an Indian.

At the waiting pile of rails dumped from the construction-train he swerved Jenny out, and halted. The light flat-car rolled on until Dennis (who had been crippled in the war) stopped it with the brake. Instantly[3] the rail-slingers there began to load it. And presently Terry was launched once more for end o’ track, with his cargo of forty rails to be placed, lightning quick, upon the ties.

Jimmie’s emptied truck was tipped aside, to give clearance. Then Jimmie pelted rearward, for iron ammunition, and Terry had another breather.

That was a great system by which at the rate of a mile and a half to two miles and a half and sometimes three miles a day the rails for the Iron Horse were being laid to the land of the setting sun.

Beyond end o’ track the graded roadbed stretched straight into the west as far as eye could see, with a graders’ camp of sodded dug-outs and dingy tents breaking the distance. At the tapering-off place the ploughs and scrapers were busy, building the roadbed. Next there came the shovel and pick squads, leveling the roadbed. Next, between end o’ track and shovel squads, there were the tie-layers—seizing the ties from the piles, throwing them upon the roadbed, tamping them and straightening them and constantly asking for more, while six-horse and six-mule wagons toiled up and down, hauling all kinds of material to the “front.”

Already the row of ties laid yesterday and this very morning extended like a rippling stream for three miles, inviting the rails.

At end o’ track itself there were the track-builders—the rail-layers, the gaugers, the spikers, the bolters, the ballasters. And upon the new track there were the boarding-train and the construction-train.

[4]The boarding-train, for the track-gang, held the advance. It was a long train of box-cars fitted up with bunks and dining tables and kitchen—with hammocks slung underneath to the cross-rods and beds made up on top, for the over-flow; and with one car used as an office by General “Jack” Casement and his brother, Dan Casement, who were building the road for the U. P.

The construction-train of flat-cars and caboose plied back and forth between end o’ track and the last supply depot, twenty miles back. These supply depots, linked by construction-trains, were located every twenty miles, on the plains beside the track, back to North Platte, the supply base.

From its depot the train for end o’ track brought up rails, ties, spikes, fish-plate joints—everything. It backed in until its caboose almost touched the rear car of the boarding-train. Overboard went the loads from the flat-cars; with a shrill whistle, away for another outfit of track stuff puffed the construction-train; with answering whistle the boarding-train (Terry’s father at the throttle) followed, a short distance, to clear the path for the rail-trucks.

The rail-truck, Terry’s or Jimmie Muldoon’s, according to whose turn, loaded at the farthest pile. Then up track it scampered, to the very end, where two lines of track-layers, five on a side, were waiting. Each squad grabbed a rail, man after man, and hustled it forward at a run; dropped it so skillfully that the rear end fell into the last fish-plate. They forced the end down, and held the rail straight.

[5]“Down!” signaled the squad bosses. The gaugers had measured the width between the pair of rails: four feet eight and one-half inches. The spikers and bolters sprang with spikes and bolts and sledges. “Whang! Whang! Whangity-whang!” pealed the sledges—a rhythmic chorus. By the time that the first spikes had been driven two more rails were in position. Now and again the little car was shoved forward a few yards, on the new track, to keep up with the work.

A pair of rails were laid—“Down! Down!”—every thirty seconds! Two hundred pairs of rails were reckoned to the mile; there were ten spikes to each rail, three sledge blows to each spike. A pair of rails were laid and spiked fast every minute, which meant a mile of track in three hours and a third—or say three and a half. In fifteen minutes the fish-plate joints had been bolted and everything made taut.

It was a clock-work job, at top speed, with maybe 1,000 miles yet to go in this race to beat the Central Pacific.

The Central Pacific was the road being built eastward from Sacramento of California. The Government had ordered the Union Pacific to meet it and join end o’ track with it, somewhere west of the Rocky Mountains. That would make a railroad clear across continent between the Missouri River and the Pacific Ocean!

The Union Pacific had much the longer trail: 1,000 miles across the plains and the Rockies and as much farther as it could get. The Central Pacific had[6] started in to build only about 150 miles, and then as much farther as it could get, east from the California border.

The C. P. had commenced first. By the time the U. P. had built eleven miles of track, the C. P. had completed over fifty. But while the Central was completing 100 miles, the Union Pacific had completed 300.

Now the Central was still fighting the snowy Sierra Nevada Mountains of eastern California, and the U. P. had open going on the plains. The C. P. had plenty of timber for ties and culverts and bridges, and plenty of cheap Chinese labor; the U. P. had no timber, all its ties were cut up and down the Missouri River or as far east as Wisconsin, and hauled to end o’ track from Omaha, and by the time that they were laid they cost two dollars apiece. Its workmen were mainly Irish, gathered from everywhere and pretty hard to manage.

The C. P. began at Sacramento on the Sacramento River, up from San Francisco, but its rails and locomotives had to be shipped clear around Cape Horn, from the Pennsylvania factories—or else across the Isthmus of Panama. The U. P. began at Omaha, on the Missouri River, but Omaha was 100 miles from any eastern railroad and all the iron and other supplies had to be shipped by steamboat up from St. Louis or by wagon from central Iowa.

It was nip and tuck. Just the same, General G. M. Dodge, the Union Pacific chief engineer (and a mighty fine man), was bound to reach Salt Lake of Utah first,[7] where big business from the Mormons only waited for a railroad. This year he had set out to build 288 more miles of track between April 1 and November 1. That would take the U. P. to the Black Hills of the Rocky Mountains. The C. P. had still forty miles to go, before it was out of its mountains and down into the Nevada desert; and this looked like a year’s work, also.

Then the U. P. would be tackling the mountains, while the C. P. had the desert, with Salt Lake as the prize for both.

But 288 miles, this year, against the Central’s forty! Phew! No matter. General Dodge was the man to do it, and the U. P. gangs believed that they could beat the C. P. gangs to a frazzle.

“B’ gorry, ’tis the Paddies ag’in the Chinks, it is?” growled Pat Miles, the track-laying boss. “Ould Ireland foriver! Shall the like of us let a lot o’ pig-tailed, rice-’atin’ haythen wid shovels an’ picks hoist the yaller above the grane? Niver! Not whilst we have a man who can spit on his hands. Away yonder on that desert over ferninst Californy won’t there be a shindig, though, when the shillaly meets the chop-stick! For ’tis not at Salt Lake we’ll stop; we’ll kape right on into Nevady, glory be!”

So——

[8]And—“Down! Down!” “Whang! Whang! Whangity-whang!”

The track-laying and the grading gangs were red-shirted, blue-shirted, gray-shirted; with trousers tucked into heavy boots—and many of the trousers were the army blue. For though the men were mainly Irish, they were Americans and two-thirds had fought in the Union armies during the Civil War. Some also had fought in the Confederate armies.

There were ex-sergeants, ex-corporals, and ex-privates by the scores, working shoulder to shoulder. In fact, the whole U. P. corps was like an army corps. Chief Engineer Dodge had been a major-general in the East and on the Plains; Chief Contractor “Jack” Casement had been brigadier general; about all the way-up men had been generals, colonels, majors, what-not; while the workers under them were ready at a moment to drop picks and shovels and sledges and transits, and grabbing guns “fall in” as regular soldiers.

This meant a great deal, when the Indians were fighting the road. This past winter the engineers doing advance survey work had been told by Chief Red Cloud of the Sioux that they must get out and stay out of the country—but there they were there again. Nobody could bluff those surveyors: fellows like “Major” Marshall Hurd who had served as a private of engineers through the war, and Tom Bates, and young Percy Browne, and their parties.

All the survey parties—some of them 500 miles in the lead—moved and worked, carrying guns; the[9] graders’ camps were little forts; the track-builders marched to their jobs, and stacked their rifles while they plied their tools. At night the guns were arranged in racks in the boarding-cars, to be handy. The construction-trains’ cabooses were padded with sand between double walls, and loop-holed, and even the passenger trains were supplied with rifles and revolvers, in cars and cabs. General Dodge called his private car, in which he shuttled up and down the line, his “traveling arsenal.”

This was the arrangement, from the end o’ track back to beginning, 360 miles, and on ahead to the last survey camp. The Central Pacific was not having such trouble.

“An’ lucky for it, too,” as said Paddy Miles. “For betwixt the yaller an’ the red, sure I’d bet on the red. Wan Injun could lick all the Chinymen on this side the Paycific. But there’s niver an Injun who can lick an Irishman, b’ gosh!”

However, today everything seemed peaceful. Usually a detachment of soldiers, or a company of the Pawnee Indian scouts under Major Frank M. North, their white-scout commander, were camped near by, guarding the track-laying. But the soldiers were elsewhere, on a short cross-country trip, and the Pawnees (Company A) were up at Fort Sedgwick, near old Julesburg, fifteen or twenty miles west.

The air was very clear. The graders working on the roadbed five miles away might be seen. The long trains of huge wagons, hauling supplies, wended slowly out to refit them. On this section there were 100 teams[10] and 2,000 men, scattered along; on the next section there were another thousand men, doing the first grading according to the stakes set by the engineers. And eastward there were the trains and the stations, all manned, and other gangs fixing the rough places in the track.

Of all this Terry felt himself to be rather a small part—just riding old Jenny back and forth, with the little rail-truck, while his father imitated with the engine of the boarding-train. Of course, his father had a bad knee (which the war had made worse), and driving an engine was important; but he himself envied his chum, George Stanton. George was out with his father on railroad survey under Mr. Tom Bates—probably fighting Injuns and shooting buffalo and bear, too. That also was man’s work, while riding an old yellow mule over the track was boy’s work.

Every truck-load of forty rails carried the track forward about 560 feet. To that steady “Down! Down!” and “Whangity-whang!” end o’ track reached out farther and farther from the piles of iron thrown off by the construction-train, and from the boarding-train that waited for the construction-train to back in with another supply.

So while cleaning up the piles, Terry and little Jimmie Muldoon had to travel farther and farther with their loads. Then in due time the construction-train would come puffing up, the boarding-train, with Terry’s father leaning from the cab, would move on as close to end o’ track as it dared, the construction-train would follow and with a great noise dump its[11] cargo of jangling iron, and retreat again; the boarding-train would back out, to clear the track for the trucks; and Terry and Jimmie would start in on short hauls, for a spell.

The supply of iron at the last dump was almost exhausted. The construction-train was hurrying in, with more. Engine Driver Ralph Richards and his stoker, Bill Sweeny, were climbing lazily into the cab of old No. 119, ready to pull on up as soon as Jimmie Muldoon’s truck left with the final load. Terry had his eye upon the track, to see it emptied——

Hark! A sudden spatter of shots sounded—a series of shouts and whoops—the whistle of the boarding-train was wide open—up the grade the graders were diving to cover like frightened prairie-dogs—and out from the sandhills not a quarter of a mile to the right there boiled a bevy of wild horsemen, charging full tilt to join with another bevy who tore down diagonally past the graders themselves.

Sioux? Or Cheyennes? The war had begun, for 1867!

The Indians had chosen exactly the right time, for them. They had awaited the moment when the main body of track-layers were farthest separated from the boarding-train and the stacks of arms; they had seen that there were no soldiers on guard; and here they came, with a rush, at least 500 of them.

“Fall in, men! Lay down! Down wid yez!”

Terry tumbled off his yellow mule in a jiffy. Dropping spade and sledge, ducking and lunging, the men were scurrying along the roadbed, seeking shelter. Only the squad of tampers and ballasters following end o’ track to settle the ties were near the first gun stacks; Terry joined their flat line. The Springfield carbines were passed rapidly, but there were not enough.

“Stiddy, boys!” bawled Pat. He had been a top sergeant in the regular army before the war. “Hug the ground. The word from headquarters is ‘Niver retrate.’ Sure, if we haven’t guns we can foight wid picks. Wait for orders, now.”

Down dashed the Indians, at reckless speed: one party straight from the north, one party obliquing from the west. The engines of both trains were shrieking furiously. All up the grade the wagons were bunching, at a gallop, with military precision; the laborers[13] were rushing in squads to corral in them and in the low dug-outs beside the roadbed.

The party of Indians from the westward split; one half veered in, and racing back and forth there, pelted the road embankment with a storm of bullets and arrows. The graders replied, but it was hard to land on those weaving, scudding figures.

The other half of the party tore on, heading to unite with the second party and cut off the boarding-train. That was it! The Indians wanted the boarding-train and supplies.

Hurrah! The boarding-train was coming on, regardless. It was manned by only Engine Driver Richards and Fireman Sweeny, a brakeman and the cooks; but no matter. Like a great demon it was coming on, whistling long shrieks and belching pitchy smoke.

The Sioux (some Cheyennes, too) were close upon it. They began to race it, whooping and shooting. The windows of dining-car and caboose replied with jets of white, as the cook and the brakeman bravely defended. Stoker Bill shot from his side of the cab. The train gathered way slowly; the ponies easily kept up with it—their riders, swerving in, flung themselves free of the saddles, clung to the steps and ladders and vaulted the couplings; clung like ants and dragged and writhed, as if they could hold it back!

They charged the engine; even cast their ropes at the smoke-stack; swarmed to the tender and from there shot into the cab. Terry’s heart welled into his mouth, with fear for his father. Suddenly there was a great[14] gush of white steam—Engineer Richards had opened the cylinder cocks, and the cloud of scalding vapor surged back, sweeping the tender. Out popped sprawly brown figures, to land head over heels upon the right-of-way, and blindly scramble for safety.

Hurrah! Bully for Engineer Richards! And the construction-train was coming too. No! Look at it! From Terry’s neighbors a groan of disgust issued.

“The dirty cowards! Bad cess to ’em! Turnin’ tail, they are!”

For the construction-train was standing still, on the track, and the engine was making off, back across the wide plains, leaving a trail of smoke and a good-by shriek.

“Niver mind! We’ve a train of our own. Yis, an’ hearts to match it.”

“’Tis all right, boys. He’s only goin’ to the tiligraph,” Pat shouted. “It’s word to the troops at Sidgwick he has up his sleeve. The Pawnees’ll be wid us in a jiffy—an’ then watch them red rascals skedaddle. ’Asy, ’asy,” continued Pat, “till the train’s widin reach of us. Stiddy. We mustn’t get scattered, like.”

The boarding-train was jolting and swaying on the newly laid rails; but what ailed it, besides? Aha!

“Settin’ the brakes! Settin’ the brakes, they are!”

And sure enough. These Cheyennes and Sioux were wise. For a year and a half they had been watching the white man’s iron horses and big thunder wagons advancing onward into the buffalo country; and they had learned a number of new wrinkles. They[15] were no longer afraid of the strange “medicine.” For here they were, boldly tackling the cars, laying hands upon them, climbing aboard—and setting the brakes!

Their almost naked figures, outlined against the sky, atop the cars, tugged and hauled at the brake wheels. The brake-shoes ground harshly; fumy smoke floated from underneath, as the locked car-wheels slid on the rails; the engine, with throttle open, roared vainly. Out from the cab darted Fireman Bill Sweeny, mounted the tender and, skipping to the first car, revolver in hand, hung to the ladder while he raked the tops beyond.

“Sharp-shooters give it to ’em!” Pat yelped. The carbines of the track-layer gang banged hopefully.

The Indians ducked and swung off to the farther side. The brakeman was out of the caboose. He lay flat upon one end of the train, the fireman lay flat upon the other end; and hitching along they began to kick the brakes free. The galloping Indians peppered at them, but failed to hit them.

“Be ready, lads,” Pat ordered. “Skirmishes wid the guns, first. The rist of us wid the picks. We’ll run for it, and meet the train. Jist a minute, now.” And—“Oh, the divils!” he added. “Charge!”

A squad of the Indians, dismounted, had thrown a tie across the track. A wild volley from the carbines had not stayed them. Engineer Richards, plunged in his own steam cloud, evidently did not see the tie; he came on, pushing Jimmie Muldoon’s loaded truck before him; the white horse tried to bolt and fell with a broken neck just as the rope parted; the smoke-stack[16] was atilt, and spitting smoke and steam from a dozen bullet-holes; but twitched by the roaring engine, the train moved faster and faster.

Up sprang the men, with a yell. The line of skirmishers, carbines poised, charged—charged in splendid order, like soldiers, aiming, firing, running. With picks and sledges and even spades the other men also charged, behind the skirmishers; bending low and shouting, yes, laughing in their excitement.

“The tie! Look out for the tie on the track!” they hallooed.

Terry had nothing to carry, and he was fast on his feet. Never had he sprinted so, before. The first thing he knew, he was through the skirmishers and legging on by himself, while the bullets hummed by him and every instant the distance between tie and truck was lessening. All his eyes and thoughts were on that tie. If the engine—his father’s engine—rammed it with the rail-loaded truck—wow!

He lost his hat—he heard whoops and shouts and excited Shep’s wild barking—the Indians on his side were swerving off, before the carbine bullets—but the engine was thundering down upon him, he saw his father’s astonished grimy face peering from the cab and he glimpsed the cars behind spewing naked figures. Then he dived for the tie. He barely had time to lift one end when the truck struck the tie, hurled it to the left and him to the right; but they both fell clear, for as he picked himself up the box-cars were rumbling by, jerking to the sharply braked engine.

All was hurly-burly with the Indians scooting and[17] screeching, the men scrambling and cheering, catching at the steps and braces, running alongside until the train stopped, and clutching the guns passed out from doors and windows.

The dining-car door slid back; the sweaty faces of the cook and cookee grinned down; the brakeman leaped off——

“Fall in, now! Fall in wid yez!” were Pat’s orders. “Take your distances ben’ath—two men to each pair o’ wheels. An’ them that hasn’t guns lay flat inside.”

Terry had no notion of lying flat inside. He plunged like a rabbit under the dining-car (bewildered Shep at his heels), for a place between the rails; found none, and dodged on, trying not to step on anybody or be in the way. He arrived at the tender, and had to come out.

“Get in here! Quick!” It was his father, sighting him. Terry hoisted himself into the engine, while several bullets rang upon the metal grasped by his hands. He lurched to the fireman’s seat and huddled there, to gain breath and grin. With a running leap Shep followed, to curl close in a corner, safe, he believed, from all that racket.

“Well, where were you going?” his father demanded.

“Just looking for a good place,” Terry panted.

“You’ve found it, and you’d better stick. ’Tisn’t healthy, outside. What were you doing on the track ahead of me? Didn’t I hit something?”

“A tie, dad. They’d laid a tie across the track.”

“Oho! Good for you. But you took a big chance. Did you reach it?”

[18]“I got one end up.”

“If I’d hit it plumb, reckon some of those rails would have been driven into the boiler. I couldn’t see plain, on account the steam and the truck. The crooked stack bothered me, too. Anyhow, here’s one train they don’t capture.”

“They can’t take it, can they, dad?”

“Not on your life, Terry. Not while there’s a cartridge for a gun or an Irishman to swing a pick, or an ounce of steam in the boiler of old 119. If worst comes to worst we can run back and forth, ’twixt here and that construction-train.”

Terry jumped down and crawled to peek out between engine and tender.

“No, we can’t, dad. They’re piling ties on the track ’way behind!”

“I declare! They’re too smart. They even set the brakes on me, and tried to rope the engine stack, like they would a horse’s neck! So they think they have us corralled, do they?”

That was so. The pesky Indian had daringly charged to the farthest pile of ties—a spare pile—tied ropes, and at a gallop dragging the ties to safer distance were erecting a barricade upon the track.

Evidently they meant business, this time. It was to be a fight to a finish. All up the graded roadbed the U. P. men were fighting off the red bandits—fighting from the dug-outs and the embankment and the wagon corrals; they had no chance to sally to the boarding-train. And here at the boarding-train Paddy Miles’ track-layers were fighting.

[19]Part of the Indians dashed around and around in a great circle, whooping gleefully and shooting at long distance. “Blamed if they haven’t got better guns than we have,” remarked Terry’s father, as now and then a bullet pinged viciously against the boiler-iron of engine or tank. Others, dismounted, crept steadily forward, like snakes, firing from little hollows and clumps of brush.

The Paddy Miles sharp-shooters, snug beneath the cars, and protected by the rails and the car-wheels, stanchly replied. The heavy Springfield balls kicked up long spurts of sand and ’dobe dust; once in a while a pony rider darted in, for closer shot—sometimes he got away with it, and sometimes his horse lunged headlong, to lie floundering while the rider himself ran hunched, for shelter. Then the men cheered and volleyed at him; maybe bowled him over, but not always.

Terry’s father had lighted his pipe; and there he sat, on his seat, with his gun poked out of the window, to get a shot when he might. He was as cool as a cucumber, and ready for any kind of business. This was not his first scrape, by any means. He had been a gold-seeker in the rush of Fifty-nine, to the Pike’s Peak diggin’s of Colorado; and he had served in the Union Army of the Civil War. Only his crippled knee had put him into the cab—but brave men were needed here, the same as elsewhere, these days.

“Where did the other engine go, dad?” Terry asked.

“To the nearest wire. There’s a spur station and[20] operator ten miles back, you know. Sedgwick has the word, by now; and so has North Platte. Pretty soon we’ll see the Pawnees coming from the one direction and the general himself from the other; and that’ll put an end to this fracas.”

Terry exclaimed.

“They’re shooting fire arrows!”

Cleverly worming along, several of the Indians had posted themselves near enough to use their bows. They launched arrow after arrow, with bunches of flaming dried grass and greasy rags—yes, as like as not old waste—tied to the heads; and these plumped into car top and car side.

“The confounded rascals!” growled Engineer Richards.

Fireman Bill Sweeny hurdled from the first car down to the tender. He was sweat-streaked and grim, and bleeding at the shoulder. He grabbed a bucket, soused it into the tank, and away he staggered.

“Train’s afire, Ralph,” he yelled back. “Don’t shove out——” and he was gone.

Forward bustled other men, with buckets; dipped into the tank and sped for the rear again. Matters were getting serious. The Springfields seemed unable to ferret out the bow-wielders. There was a cheer, and Pat Miles led a charge. Out from beneath the cars there rushed a line of skirmishers, while behind them the carbines barked, supporting them. Up from their coverts sprang the fire-arrow Indians, and bolted. Giving them a volley the skirmish dropped and dug in.

[21]A line was thrown out on the other side of the train, also. This made the Indians furious; their horsemen raced madly up and down, showing only an arm and a leg, or suddenly firing from the saddle and hanging low again. At the best they were difficult marks. They had plenty of ammunition, and rifles that outranged the stubby carbines.

“Fire’s squelched except the last car; that’s a-burnin’,” gasped Stoker Bill, lurching in and sinking breathless upon his seat. “Don’t back up. Say, kid, help me tie this shoulder, will you?”

“Hurt bad, Bill?” Engineer Richards queried, keenly.

“Nope. Just perforated a trifle.”

“Anybody else hurt?”

“None particular. But I sure thought this kid was a goner, though. Did you see him?”

“Where?”

“When he reached for that tie?”

“Didn’t see him or the tie either, till too late. I knew I hit something.”

“Well, I happened to be squinting up this way, and I saw him just as he heaved an end clear of the track. Next thing, you sent him one way and the tie the other. He’s an all-right boy.”

“Guess he is,” laughed Terry’s father. “He’ll get promoted off that old yellow mule, first thing we know.”

“Wish General Dodge would let me go out on a survey,” Terry blurted. “Like George Stanton.”

“I’ll speak to the general about it,” said Fireman Bill, with a wink at his cab partner.

[22]But Engineer Richards did not notice. He was peering behind, out of his window.

“Hi! Here comes the other engine,” he uttered. “Yes, and the headquarters car for a trailer! The old man (that was Major-General Dodge, of course) is inside it, I’ll bet a hat!”

They all looked. Far down the track an engine, twitching a single car, was approaching. By her trail of dense wood smoke and the way she bounced on the little curves and bumps, she was making good time, too.

“Chief boss is on the job, sure,” quoth Bill.

“Usually is,” added Terry’s father. “Always has been. Nothing happens from one end of line to t’other, but he’s there.”

The fighting track-layers had seen, and began to cheer afresh. Away galloped a portion of the enemy, to pester the reinforcements. But the engine came right on, until it halted at the end of the construction-train. Out from the headquarters car issued man after man—springing to the ground, guns in their hands, until they numbered some twenty.

The first was a straight, well-knit figure in broad-brimmed black slouch hat and ordinary civilian clothes. There appeared to be two or three men in regular city clothes with him; the rest were dressed more rough and ready, like trainmen and workmen.

The Indians were circling and yelling and shooting, at long distance. The slouch hat led forward at a run. From the construction-train the handful of train crew leaped out; they had been housed, waiting, on defense,[23] but helpless to do much. All ran forward. The slouch hat man pointed and gave orders; the train crew jumped at the pile of ties, while the other men rapidly deployed, in accurate line—advancing as if in uniform, and yielding not an inch.

The ties were scattered in a twinkling; the engine pushed—the train moved slowly up track, with the slouch hat’s men clearing either side of the track, at a trot, fire, and trot again. The train crew closed the rear. The engine whistled triumphantly; Terry’s father yanked the whistle cord of No. 119, and by blast after blast welcomed the new-comers.

In spite of the frantic Indians the trains joined. But the fighting was not over. It had only been extended into a longer line. Terry could stay quiet no more. He simply had to be out into the midst of things. With General Dodge, the chief engineer and noted army man, on deck, there would be a change of program.

“I’m going, dad,” he announced. Not waiting for answer, out he tumbled, so quickly that Shep did not know it. For Shep was sound asleep.

The few carbine barrels jutting here and there from behind the car-wheels were silent, as hugging the side of the train Terry boldly stepped over them; the skirmish lines were doing the shooting. Half way down the train a knot of men were holding a council.

They were Chief Engineer Dodge (the figure in the black slouch hat) and three men in city clothes, and Pat Miles. But before Terry might steal nearer, fresh cheers arose.

“The Pawnees! Here they come! Hooray for the Pawnees!”

The men underneath the cars began to squirm out, and stand, to yell. Over a swale up the graded right-of-way there appeared a mounted force—looked like soldiers—cavalry—one company, two companies, deploying in broad front; and how they did come!

The graders yonder were waving hats, and cheering; the Cheyennes and Sioux hemming them in dug their heels into their ponies and bending low fled before the charge. The General Dodge council had moved out a few paces, to watch. The general swung his hat, also.

“Now for it!” he shouted. “Form your men, Pat. Blair, you wanted to see some fighting. Take one[25] company and advance to the left. Simpson, you take another detachment and advance to the right. White, you and I and Pat will guard the train with the train crews and the reserve. We’ll put those rascals between two fires.”

“Fall in! Fall in wid yez!” Pat bawled, running. The words were repeated. “Yez’ve thray gin’rals, a major an’ meself to lead yez,” bawled Pat.

“Come on, men,” cried the general named Blair, to his detachment; he climbed through between the cars; his men followed him and away they went, in extended order, picking up the skirmishers as they proceeded.

In the other direction ran General Simpson’s detachment, and out across the plain. But the Indians did not stand. With answering yells they scattered, and occasionally firing backward at the Pawnees they scoured away—the Pawnees, separating into their two companies, pursuing madly.

And a funny sight it was, too; for as the Pawnees rode, they kept throwing off their uniforms, until pretty soon they were riding in only their trousers.

“B’ gorry!” Pat panted, as he and the general halted near Terry. “The only thing I have ag’in them Pawnees is, that when they come there’s nothin’ left for the Irish.” He turned on the general, and saluted—coming to a carry arms, with his left arm stiffly across his red-shirted chest. “Track’s clear, gin’ral.”

“So it seems,” laughed General Dodge. “Simpson and Blair might as well come in. Now let’s see what the damage is.” His sharp eyes fell on Terry, standing[26] fascinated. “What’s this boy doing out here? He ought to be under cover.”

“Sure, he’s bigger’n he looks,” apologized Pat. “If ye could have seen him lift at a tie when the engine was jest onto it——! He earned a brevet—but I thought he was under the wheels entoirely.”

“That’s the kind of work that counts—but I’ll have to hear about it later,” answered the general. “Now let’s check up the damage, and get the men out again. Where’s General Casement?”

“He’s on up at Julesburg, sorr; him and Mr. Reed, too. But I’m thinkin’ they’ll both be back in a jiffy.”

General “Jack” Casement was the chief contractor—the head boss of the whole construction. Mr. S. B. Reed was the general superintendent of building. Yes, they doubtless would arrive on the jump.

The two companies of the construction gang were brought in, for the Pawnees had chased the Sioux and Cheyennes out of sight. Before they came in, themselves, General Dodge and Foreman Pat had made their inspection. Three men badly wounded, here; several slightly wounded; one car burned, other cars, and the engine, riddled and scarred.

But within half an hour all the unhurt men had stacked their guns, had resumed their tools, and were out on the grade, ready to start in, just as though there had been no fight.

Jenny the yellow mule had a bullet hole through her ear; Jimmie Muldoon’s white horse was dead; but speedily he and Terry were mounted again, waiting for the construction-train to finish unloading, and for the boarding-train to back out and clear.

[27]That was the system of the U. P., building across the plains into the Far West.

“Hey, Jimmie! Where were you?” hailed Terry.

“I got behind the cook’s stove,” piped little Jimmie, blushing as red as his hair. “But I came out and handed ca’tridges. Weren’t you afraid?”

“I dunno. I guess I was too excited.”

“You done well, anyhow,” praised Jimmie, with disregard of grammar.

General Dodge went on up the grade, inspecting. The three men in city clothes, with him, were General J. H. Simpson, of the United States Engineer Corps; General Frank P. Blair, who had been one of the youngest major-generals in the Civil War; and Congressman H. M. White, who was called “Major” and “Doctor.” They formed a board of inspectors, or commissioners, sent out by the Government to examine every twenty or forty miles of the road, when finished, and accept it.

The United States was lending money for the building of the first railroad across continent, and naturally wished to see that the money was being well spent.

The commissioners traveled in a special coach, called the “Lincoln” coach because it had been made for President Abraham Lincoln, during the War. The railroad had bought it, for the use of officials.

Now it was back at North Platte, the terminus. When the commissioners heard of the fight, they had volunteered to come along with General Dodge and help out.

[28]

The construction-train had dumped its iron, the boarding-train had backed out, and Jimmie and Terry again plied back and forth, with the rails.

The Pawnees returned, in high feather like a lot of boys themselves. They certainly were fighters. Major Frank M. North, a white man, was their commander. He had lived among them, and spoke their language, and they’d follow him to the death. He had enlisted four companies—drilled them as regular cavalry, according to army regulations; they were sworn into the United States Army as scouts, and were deadly enemies to the Sioux and the Cheyennes. The Sioux and Cheyennes feared them so, that it was said a company of North’s Pawnees was worth more than a regiment of regular soldiers. When these Pawnees sighted an enemy, they simply threw off their clothes and waded right in.

The two companies, A and B, made camp on the plains, a little distance off, near the Platte River. Major North and Chief Petalesharo—who was the war-chief and son of old Petalesharo, known as “bravest of the braves”—cantered forward to the track. The major wore buckskin and long hair, like a frontiersman. Petalesharo wore army pants with the seat cut out, and the legs sewed tight, same as leggins.

“Take any hair, major?” was the call.

[29]“Yes; there are three or four fresh scalps in the camp yonder. But most of the beggars got away too fast.”

“Say, Pete! Heap fight, what?”

Petalesharo smiled and grunted, with wave of hand.

“He says the Sioux ponies have long legs,” called Major North. “Where’s the general? He was here, wasn’t he?”

“Yes; he’s up ahead, with the graders.”

The major—young and daring and very popular—rode on with Chief “Pete,” as if to report to General Dodge.

They all came back together, after a time—and the newly laid track was advancing to meet them. Already the boarding-train had moved up a notch. The Pawnees from the camp were scattered along, watching the progress. The way with which the white man’s road grew, before their eyes, seemed to be a constant marvel to them.

“Faith, we’ll build our two miles this day in spite o’ the Injuns,” cheered the sweaty Pat, everywhere at once and urging on the toiling men.

The three commissioners were as interested as the Pawnees; they hung around, while Chief Engineer Dodge, General Jack Casement and Supervising Engineer Reed (who had arrived horseback) conferred in the headquarters car.

General Simpson and Dr. White had seen the track-laying gang at work last year, but this was young General Blair’s first trip out. Now while he was here, three-quarters of a mile of track was laid before the[30] call for supper sounded; and as the men rushed to meet the train, Engineer Richards unhooked and gave the three commissioners a ride on the cow-catcher to the very end o’ track, to show them how well the rails had been put down.

In honor of the commissioners, after supper there was a parade of the Pawnees, under Major North and the white captains Lute North and Mr. Morse, Lieutenants Beecher and Matthews, and Chief Petalesharo.

A great parade it was, too—“Might call it a dress p’rade, and ag’in ye might call it an undress p’rade,” as Foreman Pat remarked. The Pawnees were in all kinds of costume: some wore cavalry blouses and left their legs naked; some wore cavalry trousers with the seats cut out, and left their bodies naked; some wore large black campaign hats of Civil War time, with brass bugles and crossed muskets and crossed cannon, on the front; some wore nothing but breech clouts, and brass spurs on their naked heels; but they kept excellent line and wheeled and trotted at word of command.

They broke up with a wild yell, and away they went, careening over the plain, whooping and prancing and shooting, and taking scalps—chasing the “Sioux.”

“The gin’ral wants to see you,” ordered Pat, of Terry. “Ye’ll find him in his car yon. Now stand on your feet an’ take off your hat an’ do the polite, an’ mebbe it’s promoted you’ll be.”

So Terry, with Shep close following, trudged down the line of box-cars, to the Chief Engineer’s “traveling[31] arsenal.” He was curious to see the inside of it. This was the general’s home, in which he toured up and down the line, from Omaha to the end o’ track, caring not a whit for the Indians.

It was fitted up inside with bunks and a desk and racked guns, and a forward compartment which was dining-room and kitchen, ruled by a darky cook. When the general was not traveling in his car, he was out overseeing the surveys far beyond the railroad; he had explored through the plains and mountains to Salt Lake long before the railroad had started at Omaha.

The whole party were in the car; the three commissioners (General Simpson was a famous explorer, too), and General Casement, and Superintendent Reed, sitting with General Dodge. Terry removed his dusty hat, and stood in the doorway. Shep stuck his black nose past his legs, to gaze and sniff.

“Hello, my boy,” General Dodge greeted.

“Pat Miles said you wanted to see me, sir.”

“That’s right. Come in, dog and all. Gentlemen, this is Terry Richards. They tell me he risked his life to save the boarding-train from being wrecked during the Indian attack. I move that we all shake hands with him.”

Terry, considerably flustrated, had his hand shaken, all ’round.

“Well, what’s your job, Terry?” asked General Dodge. He was a handsome man, every inch a soldier, but with a very kind eye above a dark, trimmed beard. Nobody could feel afraid of General Dodge.

[32]“I help bring up the rails, on a truck. I ride a yellow mule, sir.”

“You’re rather a big boy to be doing that.”

“Yes, sir; but that’s my job. Somebody has to do it. The men have got to have rails.”

“Very necessary, in building a railroad,” laughed General Blair.

“We did almost two miles today,” informed Terry. “We’d have done two miles sure if the Injuns hadn’t tried to stop us.”

“That’s the right spirit,” approved General Simpson.

“General Casement is responsible for it,” quickly spoke Chief Engineer Dodge. “His men are trained to the minute, either to work or to fight. But the Union Pacific Company doesn’t overlook individual acts of bravery. What would you like to do instead of riding that yellow mule, Terry?”

“I’d like to be out in front, exploring with the engineers, sir.”

“Oh, you would!” General Dodge’s eyes kindled. Evidently he liked that kind of work, himself. “Why? It’s the most dangerous job of all—away out in the Indian country, with only a handful of men and maybe no help except your own guns.”

“I think I’d like it, though,” stammered Terry. “If I could be any use, George Stanton’s out there somewhere.”

“Who’s George Stanton?”

“He’s another boy. He’s my pardner. We were station hands on the Overland [that was the stage line] before we joined the railroad.”

[33]“Where is George?”

“I don’t know, exactly. He went out with his father in Mr. Bates’ survey party, as a sort of a cub to learn engineering. I guess he cuts stakes.”

“Oh, I see. The Bates party are bound from Utah, to run a line this way. But they’ll not be back before winter. Probably none of the survey parties will turn up before winter. I’m afraid it’s too late for a job with the engineers in the field, this year. Maybe you’ll have to stick to your old mule, and haul rails for General Casement.”

“Well, if there’s nothing better I can do,” agreed Terry. “It’s fun to help the track go forward, anyhow. We’ll beat the Central folks.”

“Yes, siree!” General Casement declared. He was a great little man, this General “Jack” Casement: a wiry, nervy, snappy little man, not much more than five feet tall, peaceful weight about 135 pounds and fighting weight about a ton—“an’ sure there’s sand enough in him to ballast the tracks clear to Californy,” Pat asserted. He had a brown beard and a bold blue eye and a voice like a whip-crack. His brother “Dan” Casement was smaller still, outside, but just as big inside. They two were commanders of the grading and track-laying outfits.

“There’s one more party to go out yet,” General Dodge suddenly said; “and that’s mine. If General Casement will lend you to me, maybe I’ll have a place for you. We’ll see if we can’t find the Bates party, and George Stanton.” And he added, with a smile, to the other men: “A fellow can always use a boy, around camp, you know, gentlemen.”

[34]“Golly! I’d sure like to go, sir,” Terry blurted.

“Were you ever farther west?”

“Yes, sir. I helped drive stage, when I was working for the Overland. And George and I had a pass to Salt Lake, but George broke his leg up on the divide, in the mountains, so we quit and came back.”

“How did you happen to get a pass?”

“Just for something we did. We brought a stage through, when the driver was near frozen. ’Twasn’t much, though. But we were glad to get a pass. We’d never been west over the line.”

“How far east have you been over this line?” asked the general, keenly.

“North Platte, is all. I joined at North Platte, this spring, when you began the big push to make 290 miles before stopping again.”

“Two hundred and eighty-eight,” the general corrected. “That will take us to Fort Sanders in the Laramie Plains. But I think you ought to inspect what’s been done in the two other years. It’s up to the Union Pacific to treat you as well as the Overland treated you. Did you ever ride on a railroad?”

“I guess I did when I was little, before we came out to Kansas. We drove out to Kansas from Ohio in 1858; but after that Harry Revere and I drove across to Denver.”

“Who’s Harry Revere?”

“He’s a friend of George and me. He was an Overland man, too—he was station-keeper at Beaver Creek station while George and I were hostlers. Then he rode Pony Express for a while, between Bijou[35] Junction and Denver. He’s a dandy; as spunky as a badger. He’s back east somewhere, on the railroad, doing telegraphing.”

“You build railroads, but you don’t travel on them, eh?” laughed General Blair.

“Yes, sir. All I do is haul rails and watch ’em being laid—but the graders don’t even see the rails. They just shovel dirt.”

“You’ll be out of sight of the rails and the dirt, too, if you go on that western trip with me,” General Dodge said, grimly. “So first, you’d better get acquainted with the finished end and see what those rails that you’ve helped lay are being used for. Suppose you stay right aboard this car and take a trip back, of a couple of hundred miles, if General Casement will spare you.”

“I’ll spare him if you’ll spare some of that 288 miles,” General Casement retorted. “You’re breaking up my army.”

Evidently even a boy was important, these days.

“Jimmie Muldoon’s brother will spell me, while I’m gone,” Terry proffered. “He can ride my mule. Her name’s Jenny. She’s smart. She’d do the hauling without anybody on her.”

“All right. You make your arrangements with Pat and Jimmie Muldoon, then,” said General Casement.

“And I guess I’ll ask my father.”

“Where’s he?”

“He’s the engine driver for the boarding-train. That’s his job, because he got crippled up in the war.”

[36]“Oh, Ralph Richards?” queried General Dodge. “He was one of my soldiers, in that same war. You’re his boy, are you? Any more of the family on the U. P.?”

“My mother’s down at Denver still, but here’s my dog. His name’s Shep. He’d fight Injuns, only today there was too much shooting, so he stayed in the engine.”

“Well,” spoke the general, “you see your father and Pat Miles and Jimmie Muldoon; then bring your dog and come along back to the car. We’re going down to North Platte tonight, and tomorrow I’ll take you as far as Kearney, anyhow. How’ll that suit you?”

“Fine, sir.” And Terry hustled out, his head in a whirl of excitement.

Matters were speedily fixed; but before he could return dusk had settled over the great expanse of lonely plains. The Pawnees were on guard. Far up the grade a few lights twinkled, from the graders’ camps. Already the track-layer gang were going to bed; some inside the boarding-train, some on top, some underneath—just as they all pleased.

Ordinarily Terry would have spread his blankets on top, where there was plenty of fresh air. However, this night he was to be a guest of the big chief, General Dodge himself, in the headquarters car, for a trip over the new U. P. Railroad, to see that the rails were O. K.

And so was Shep. Shep usually tried to go wherever Terry went—except, of course, when guns were banging too recklessly.

[37]The men were still up, in the rear or office end of the headquarters car, talking together.

“The rest of us won’t turn in till we’re back at North Platte,” the general explained. “I’ve had a bunk opened for you, up forward. Do you think you can sleep?”

“Yes, sir. I can always sleep,” Terry assured.

“All right. Good night. You won’t miss much. We’ll probably lie over at North Platte till morning.”

The bunk was a clever arrangement. During the day it was folded against the side of the car and nobody would know it was there. At night it was let down, and hung flat with a curtain in front of it. The car probably had several such bunks. They were something new, the invention of a Mr. Pullman; and when Terry climbed into his, he found it mighty comfortable. Shep curled underneath, between the seats.

Lying snug and warm, Terry prepared to calm himself, and sleep; but the future looked very bright. He caught his thoughts surging ahead, upon the survey trip half promised by the general: maybe clear to Utah, exploring and finding George and the Bates party. Hooray! Indians, bear and buffalo, new country—! Pshaw! He was getting wide awake. He ought to sleep. So he began to figure.

Over 300 miles, so far, by the Union Pacific, in the two years and a quarter; 700 miles yet to Salt Lake, and then as much farther as they could get before meeting the Central! The general had planned to lay nearly 300 miles more—288 anyway—this year! Whew! Forty car-loads of supplies to every mile;[38] 400 rails and 2,650 ties to every mile; ten spikes to each rail, three blows of the sledge to each spike—then how many rails, how many ties, how many sledge blows, how many galloping charges back and forth of Jenny and the little truck, to cross plains and deserts and mountains and win the race with the Central?

This tour by train was going to be nice enough, but it seemed tame compared with end o’ track work, and with surveying. And the laying of the track looked to be such a big job that perhaps General Casement couldn’t spare him again. Shucks!

While figuring and bothering, Terry fell asleep. He did not know that his trip east and back was not going to be as tame as it appeared in advance.

Sometime in the night he knew that they were in motion—the engine was pushing them along, over the track. But when he really woke up, they were standing still, in daylight. North Platte, as like as not; or maybe Kearney. No, it couldn’t be Kearney, could it, for Kearney was 100 miles and more, and that seemed a long way to go, in just one night. At any rate, they were standing in some town; there was a lot of noise outside, of shouting and engine-puffing and feet-scuffling. So he put on his clothes in a jiffy and jumped down through the curtains.

By the rattle of dishes and the smell of bacon the cook was getting breakfast, but the main part of the car was empty. Everybody had left. Seemed as though General Dodge didn’t take time to sleep, himself, for no other bunk was open. Here came old Shep, yawning, from his night’s quarters. Terry hastened to the platform, to find where they were.

North Platte, sure. They’d come only sixty or seventy miles, and must have been lying here quite a while. Yes, it was North Platte, on the south bank of the North Platte River just above where the North Platte joined the South Platte to help make the big Platte.

[40]North Platte was the end of the road, for traffic; the terminal point, that is. The freight and passenger trains from Omaha, 293 miles, stopped here and went back; only the construction-trains went on, with supplies for end o’ track. But North Platte was considerable of a place—and an awful tough place, too, plumb full of gambling joints and saloons.

It had started up in a hurry, last December, when the road had reached it and had made a terminal point and supply depot of it, for the winter. There hadn’t been a thing here, except a prairie-dog town—and in three weeks there had been a brick round-house to hold forty engines, and a station-house, and a water tank heated by a stove so it wouldn’t freeze, and a big hotel to cost $18,000, and a knock-down warehouse (the kind that could be taken apart and fitted together again) almost as large, for the Casement Brothers, and fifteen or sixteen other business buildings, and over a thousand people, including gamblers and saloon keepers, living in all kinds of board and sheet-iron and canvas shacks.

When Terry had joined the road, at the close of winter, North Platte boasted 2,000 people, counting the graders and track-layers, and was a “roaring” town. There was some talk of making it the headquarters of the Union Pacific, instead of Omaha.

It used to be livelier at night than in the day-time, even; but it certainly was lively enough this morning. A long freight-train was unloading ties and iron, to be added to the great collection of ties and iron already waiting for the haul onward to the next supply dump,[41] toward end o’ track. A passenger train had pulled in from Omaha. The passengers were trooping to the Railroad House (which was the name of the $18,000 hotel) or to the eating-room in the Casement Brothers’ portable warehouse, or bargaining to be taken by wagons across the South Platte ford, where the Overland Stage for Denver connected with the railroad.

As fast as the Union Pacific, on the north side of the Platte River, lengthened its passenger haul from Omaha, on the south side of the Platte River the Overland Stage shortened its haul to Denver and Salt Lake.

After a while there would be no stage haul needed, through this country. The stages would run only between Denver and wherever the railroad passed by, north of it; and people would go through from the Missouri River in two days instead of in six.

An engine and tender backed up and hooked on to the Dodge car; a fine-looking car, which must be the Lincoln car for the Government commissioners, had been coupled on, behind. While Terry gazed about, from his platform, trying to take in all the sights, here came General Dodge and Superintendent Reed, as if in a hurry.

“All aboard!” The general waved his arm at the engineer, as he sprang up the steps. To ring of bell and hiss of exhaust the little train started. There was no time lost.

“Hello, young man,” the general greeted, to Terry. “Ready for the day?”

[42]“Yes, sir.”

“I expect you’d like to begin with breakfast. So would Mr. Reed and I. We’ve made one beginning but we’ll make another. We all can eat and watch things go past at the same time.”

Decidedly, it was fun to sit at a table and eat while whirled along across country at a tremendous pace, with the landscape flitting by in plain sight just outside the windows.

“How fast are we going now, please?” Terry ventured.

The general looked at his watch a minute, and seemed to be listening.

“About twenty-five miles an hour, I should judge. Is that right, Sam?”

“Pretty nearly right,” agreed Superintendent Reed.

Whew! And when Ben Holladay, the King of the Overland Stage, had made fourteen miles in an hour with his special coach and a special team of fours, that had seemed like a lightning trip.

They had thundered over the long bridge above the North Platte River, and were scooting eastward, parallel with the main Platte. From across the river the emigrants who still stuck to their slow prairie schooners or covered wagons, waved at the train. At a safe distance some antelope fled, flashing their white rumps. Prairie-dogs sat up at the mouth of their burrows, to gaze.

Once in a while a ranch, with low adobe buildings, might be seen, south of the river; and an old stage station there, before or behind, was almost always[43] in sight. The Overland had quit running, east of Cottonwood station, near North Platte.

On this side of the river there was not much to see, except the railroad telegraph poles, and the prairie-dogs, and the line of rails that stretched clear to Omaha on the Missouri River, and a side-station of one little building which slipped by so quickly that Terry could not read the sign.

The general and Superintendent Reed went back into the Lincoln car, to talk with the commissioners there. They left the headquarters car to Terry, Shep and the black cook.

“How you like this sort o’ travel, boy?” queried the cook, as he tidied the car with a dust-rag.

“We’re sure moving,” Terry grinned. “It beats staging. How fast are we going now, do you think?”

“Oh, mebbe thirty miles an houah. Reckon we gotto meet ’nother train. This heah road is shy on meetin’ places yet. But, sho’, thirty miles ain’t nothin’, boy. When the gin’ral heahs somethin’ callin’ him, he jest tells this old cah to step on the injine’s tail, an’—woof! ’Way we go, fifty, mebbe fifty-five miles an houah! Yessuh. Sometimes the gin’ral he likes to show off a bit, too, when there’s gover’ment folks abohd. He shuah gives ’em a ride, so they’ll know this ain’t any play road, down today an’ up tomorrow. Where you from?”

“End o’ track,” answered Terry.

“What you do there?”

“Haul rails.”

“Was you up there yestuhday, when they fit the Injuns?”

[44]“You bet. They found we were bad medicine, too. They almost set the boarding-train on fire, though. That was a right smart fight, till the general and the Pawnees came and drove ’em off in a jiffy.”

“Hi yi!” the cook chuckled. “We-all had jest got into Nohth Platte when the gin’ral, he heard about it. He’s a powerful fightin’ man, the gin’ral is. He’s fit Injuns a lot o’ times befoh. An’ those commishners, they’re fightin’ men, too; they done fit in the wah. An’ there was a passel o’ seemed like white trash here, who was quittin’ work on the road because they’d got paid off. But the gin’ral, he calls out: ‘You boys, the Injuns are ’tackin’ our camps up the road. Pile in, if you want to go with me.’ An’ they shuah piled in, every last one of ’em, same as though they hadn’t quit the road at all. Yessuh! An’ when they piled in, this chile he piled out, t’other end. He guessed like he wasn’t needed. Hi yi! No, suh! He’s got too much scalp. His hair ain’t like white man’s hair; it’s same length all ovuh his haid.”

“Indians don’t scalp negroes. They can’t. And they think it’s bad medicine,” said Terry. “They call you buffalo soldiers.”

“I ain’t no buff’lo soldiers. I’m a cook, an’ I knowed they didn’t want no cook up yonduh,” the darky retorted. “Yessuh. An’ in case it come on night, Injuns might not make any diff’rence ’tween a white man an’ a black man. No, suh.”

“Not unless they felt your hair,” laughed Terry.

The cook seemed to turn a shade pale.

[45]“No Injun’s gwine to feel my hair. No, suh! Not unless he can outrun this heah train; an’ then when he reaches in he’s got to catch me, foh if I once get out the othuh end—oh, boy! I’d jest hit the ground twice between the train an’ Omaha. The Injuns’d be sayin’ ‘There he goes’ the same time Omaha was sayin’ ‘Heah he comes!’ Yessuh! I’m powerful scared o’ Injuns. It’s gwine to be a mighty bad yeah, foh Injuns, too.”

“How do you know?”

“’Cause I heard the gin’ral sayin’ so. I heard him say he’d asked foh moh soldiers, to guard the line cl’ar to the mountings. Yessuh. He’s asked Gin’ral Sherman. How far you gwine?”

“I dunno. To Omaha, maybe. Why?”

“Got some kin there?”

“No. I’m riding for fun.”

“You ridin’ foh fun?”

“Yes.”

“When you get to Omaha, then you gwine back where you come from?”

“Sure thing. I’ve got a job, at end o’ track.”

“Don’t you do it; don’t you do it, boy,” advised the cook, as darkly as his face. “Don’t you ride ’round these pahts foh fun. No, suh! An’ don’t you staht back from Omaha till Gin’ral Sherman’s soldiers have killed ev’ry one o’ them Injuns. Yessuh! You let Gin’ral Sherman an’ Gin’ral Dodge ’tend to one end o’ track, an’ you get a job at t’other end.”

Terry had to laugh, but the cook’s words struck home. Matters looked bad. The Indians had started[46] in, that was certain; and everybody appeared to think that this was an “Injun” year. Somehow, he felt that he was deserting his post. He was leaving Paddy Miles and the gang to their troubles, and was making for safety, himself.

“When do we stop next?” he asked.

“I dunno. Mebbe we’ll stop at Willow Island, foh ohduhs; an’ mebbe we’ll stop at Kearney. Jest depends on the gin’ral. We stop whenever we please, or whenever the injineer needs wood an’ watuh, or whenever we got to meet ’nothuh train.”

“How far is Kearney?”

“Hundred miles from Nohth Platte. We’ll get there befoh noon, an’ we’ll get to Omaha befoh dark. Yessuh, we’ll travel right along.”

The cook went on about his business, and Terry stared out at the flying country, which danced a reel in tune with the roaring wheels. This was great fun, of course, to be speeding over the new Union Pacific Railroad, in a private car, but——! And he wondered how Jenny and Jimmie Muldoon’s brother were holding down the job at end o’ track.

With a swoop and a whistle they rushed past a long freight-train, waiting on a siding. At every siding there was one of these long freights, plumb loaded and headed west, or partly empty and headed east.

They might get a glimpse of Fort McPherson, at Cottonwood Springs on the stage road along the other side of the river. Then they whirled right through Brady Island station of the railroad. But stop they did at Willow Island, which bore the same name as the old Overland station, across from it.

[47]The station buildings, except the station-house itself, were of sod, and loop-holed so as to fight off the Indians. They looked like a fort. A lot of cedar bridge-piles and telegraph poles and cottonwood ties were stacked here, brought in by ranchers’ wagons from the places where they had been cut. The road didn’t get much of such stuff, on these bare plains, but once in a while there was a valley or some bottom-land with a little timber growing. Cedar ties and cottonwood ties were no good, though, until they were soaked in zinc, to make them hard and lasting. The best ties came from Missouri, Iowa and Wisconsin.

The next stop was at Plum Creek, also named for the old stage station, opposite; then there was a pause on a side-track, to let another train by; and they were off again. It certainly was fast work.

General Dodge entered his headquarters car.

“How do you like railroading, now?” he asked.

“Fine, sir. We go some, don’t we!”

“Rather beat the stages, or your old yellow mule, that’s a fact,” the general admitted. “But if it wasn’t for you fellows that lay the track in such good shape, we couldn’t go at all.”

“And the men who discover the trail—they count a heap, too, I guess,” Terry added.

“Yes, siree. The surveyors’ job is the most ticklish job, especially out on the desert and in the mountains. Track-layers, graders, and surveyors—they’re all heroes. They do the hard work, but the people who never see them don’t think of them. Well, will you stay aboard into Omaha?”

[48]“Would I be a long time getting back?” Terry queried.

“No, sir; not unless the road is tied up by Indian trouble. I’ll put you on a train and send you right through to North Platte; then you can jump a construction-train, and keep going to end of track again. You’ll have your pass.”

“Where do we stop next, please?” Terry asked.

“At Kearney. We’ll be there in about an hour. You can get off and stretch your legs, and so can the dog.”

“Could I go back from Kearney?” Terry blurted.

“Oh, pshaw!” And the general’s eyes twinkled. “You aren’t homesick already, are you? You might have to wait there until two o’clock in the morning, for the passenger train. You could catch the same train farther down the line. No; you’d better ride on to Omaha, and see the whole system that you’ve helped build.”

“Yes, sir,” agreed Terry—but somehow he felt a little doubtful. If he should be kept at Omaha, on account of Indian trouble—oh, that wouldn’t do at all. His place was at the front.

Kearney had been named for old Fort Kearney, across the river. It wasn’t much of a place, yet: just the station and a store and scattering of small houses. There were several soldiers from the fort standing around. General Dodge and Superintendent Reed had jumped off and seemed to be having business with an officer, while the engine took on water; so Terry and Shep jumped off, too. Then a man came running[49] from the station door, with a piece of yellow paper—a telegram—for the engineer.

He was a lively young man, with a limp. Staring, Terry scarcely could believe his eyes. Now he, too, ran, yelling, and Shep bolted ahead, barking, and they caught the young man, who turned, astonished.

Yes, it was Harry Revere, all right—good old Harry, ex-school teacher, ex-Pike’s Peaker, ex-prospector, ex-Pony Express rider, ex-Overland Stage station-keeper, and a dandy partner.

“For heaven’s sake, what you doing here?” he demanded, as they shook hands.

“Oh, I’m traveling special, inspecting the U. P.,” grinned Terry. “What you doing?”

“I’m the boss lightning-shooter at this shebang,” proclaimed Harry. “You couldn’t travel at all, if it wasn’t for me. See? Wait till I deliver this dispatch.”

In a moment he came back.

“Thought you were somewhere down the line farther; thought you were in Omaha, maybe,” said Terry.

“So I was, but I’m getting promoted out toward the front. That’s where I want to be. I won’t stop till I’m clear through to Salt Lake. But where you going? Thought you had a job at the front, yourself? How’s Jenny? [Jenny really was Harry’s mule, but she was working for the company.] How are your folks?”

“They’re all right. So’s Jenny. Jimmie Muldoon’s brother is riding her and spelling me. I’m going to Omaha. General Dodge invited me.”

[50]“You haven’t quit?”

“No. I’m just on a little trip.”

“What do you want to go on to Omaha for?” scolded Harry. “Shucks! This is no time to take it easy, when we’re trying to make a big year. I want to be at the front, myself. There’s nothing between here and Omaha. Where’s George?”

“He’s on survey, ’way out.”

“Wish I was with him,” asserted Harry. “But I’m getting along, by hops and skips. I don’t savvy why you want to go to Omaha, when you were at the front, yourself, with Jenny.”

“I don’t want to go, Harry,” Terry confessed. “Gee, I’d like to be back already. General Dodge has asked me, though; I guess he thinks it’s a treat for me to ride to Omaha. I’m sick of loafing—I’ve been gone a night and half a day, now, and I ought to be back, in case they need me.”

“Bully for you,” Harry praised. “I’ll tell you: You stop off here with me, for a couple of hours. You can explain to the general that you’d rather stay and visit me than go on to Omaha. You won’t have to wait for the passenger train. No, sir! I’ll fix you out.”

“I’ll ask him,” answered Terry, on the run again.

The general seemed to understand perfectly.

“You see, sir,” Terry finished, “I’d like to be on the job till you come through next time, and then maybe I can get off to go out on that survey trip, if you have room for me. I’d rather find George Stanton than go to Omaha. I like the front, and I’ve seen a whole lot of the road, now.”

[51]“That’s all right,” General Dodge approved. “The front’s the best place. You stay there, and keep your share of the rails moving up. We can’t run trains without rails, and unless we have the rails we can’t get to Salt Lake and beat the Central. So good-by and good luck. I’ll have a wire sent to your father that you’ve turned back.”

“Please tell him to tell Pat Miles that I’ll be there tomorrow morning sure, and I’ll want my mule and truck,” Terry begged.

The general laughed. He and Mr. Reed boarded their train and it pulled out. Terry and Shep found Harry Revere in the operator’s room of the passenger station—which also was the station-agent’s room.

“What do you have to do, Harry?”

“Nothing much. I only sell tickets and check up freight and bill express and send dispatches and read the wire and wrestle baggage and sweep out and answer questions and once in a while tend some woman’s baby while she goes home after something she’s forgotten. When there’s nothing more important, I eat or sleep. But I’m hoping to push on up front, where it’s lively. I aim to get to Salt Lake as soon as the rails and poles do. Were you in that Injun fracas at end o’ track, yesterday?”

“I shore was. How’d you hear?”

“I picked it off the wire. I just sat here and made medicine while you-all fought. Nobody scalped, was there? Did they hurt Jenny? I asked the North Platte operator and he laughed at me. ‘Ha, ha!’ was all he said.”

[52]“Nope; nobody scalped, except a couple of the Sioux. They put a hole through Jenny’s ear, though.”

“The low-down villains!” grumbled Harry. “Abused the beautiful ear of my Jenny, did they? When I come along I’ll bring her an earring. Reckon a little bale of hay would please her most: an earring to represent a little bale of hay. And a cob of corn for the other ear, if she gets a hole through that too. Say,” he asked, “you didn’t see Sol Judy in those parts, did you?”

“No. Is Sol around there?”

“Yep. He’s a scout at Fort McPherson, helping guard the line.” That was good news. Sol Judy was another old friend. He dated away back to the Kansas ranch, where he’d appeared on his way from California. And he’d been with them in the Colorado gold diggin’s, and had driven stage and scouted along the Overland; and now here he was again, still doing his share of work while the country grew.

“Our whole family’s joining in with the U. P., looks like,” Harry added.

“All except my mother and George’s mother and Virgie.” Virgie was George Stanton’s sister. “And I bet you they’ll be on the job some way, before we get done with it.”

“You win,” Harry chuckled. “That’s their style—right up and coming. Well, let’s go to dinner. How’d you like fried ham and saleratus biscuits?”

“Fine.”

“Good. Yesterday I had saleratus biscuits and fried ham, today we’ll have fried ham and saleratus[53] biscuits; tomorrow there’ll be just biscuits and ham. It’s a great system.”

They ate in the section house, at a board table covered with oilcloth. After dinner they swapped yarns and visited, while Harry busied himself dispatching or attending to the people who dropped in. A passenger train from the west came through, and a freight.