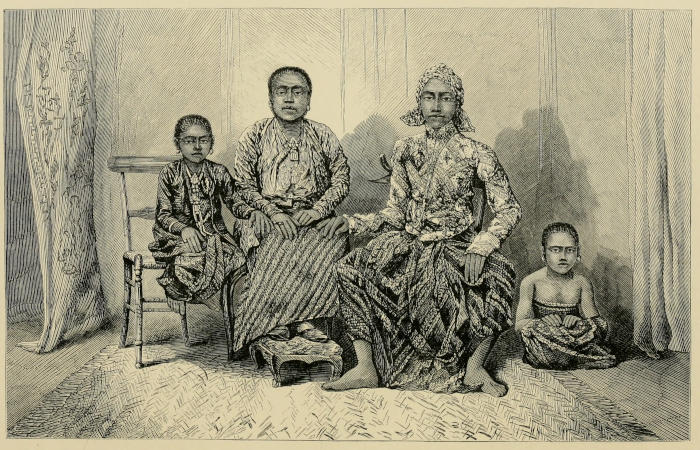

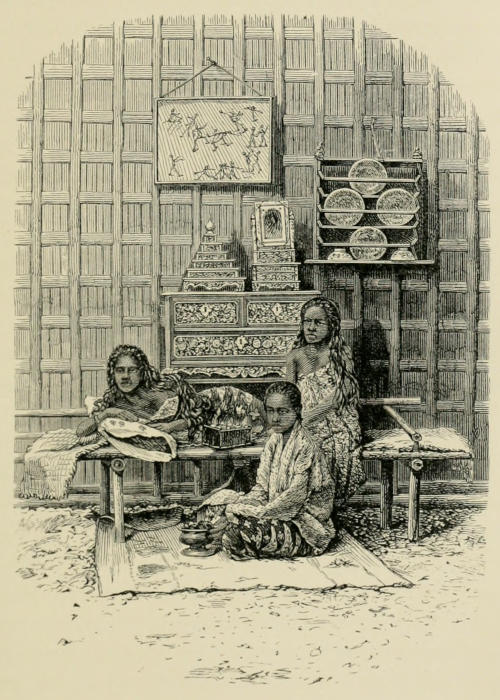

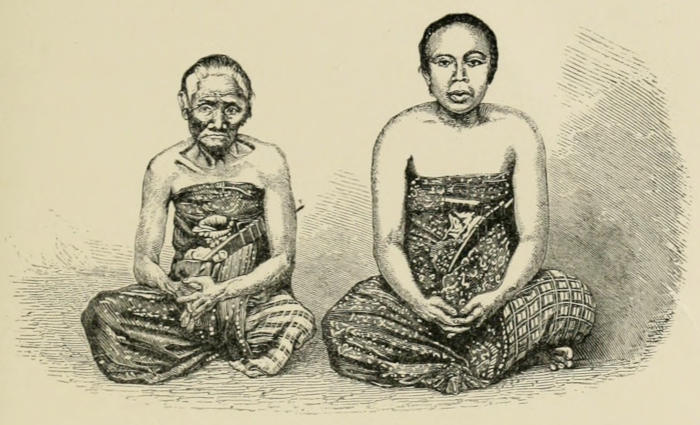

WIVES OF ONE OF THE TWO HIGHEST PRINCES IN JAVA.

Title: Travels in the East Indian archipelago

Author: Albert S. Bickmore

Release date: April 14, 2024 [eBook #73398]

Language: English

Original publication: London: John Murray

Credits: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

WIVES OF ONE OF THE TWO HIGHEST PRINCES IN JAVA.

TRAVELS

IN THE

EAST INDIAN ARCHIPELAGO.

By ALBERT S. BICKMORE, M.A.,

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON,

CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN AND LONDON ETHNOLOGICAL SOCIETIES,

NEW YORK LYCEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, MEMBER OF THE BOSTON SOCIETY

OF NATURAL HISTORY AND AMERICAN ORIENTAL SOCIETY, AND

PROFESSOR OF NATURAL HISTORY IN MADISON

UNIVERSITY, HAMILTON, N. Y.

WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

1868.

The right of Translation is reserved.

LONDON: PRINTED BY W. CLOWES AND SONS, DUKE STREET, STAMFORD STREET,

AND CHARING CROSS.

TO

THE GENEROUS FRIENDS OF SCIENCE

IN

BOSTON AND CAMBRIDGE,

THROUGH WHOSE LIBERALITY THE TRAVELS

HEREIN DESCRIBED WERE MADE,

THIS VOLUME

Is Respectfully Dedicated.

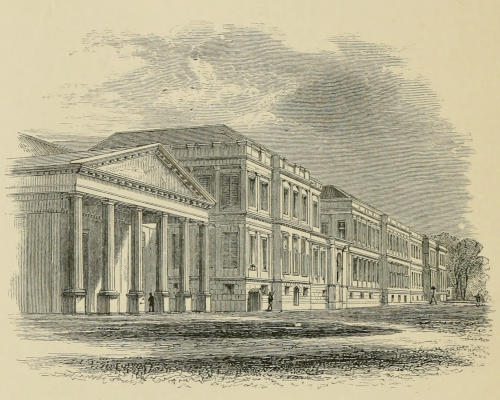

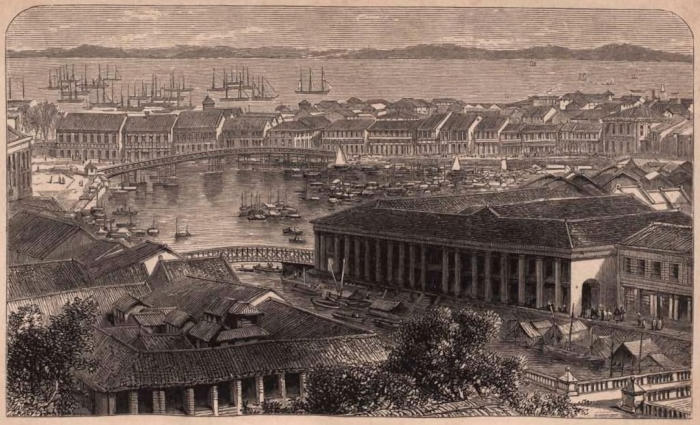

GOVERNMENT BUILDINGS AT BATAVIA.

The object of my voyage to Amboina was simply to re-collect the shells figured in Rumphius’s “Rariteit Kamer,” and the idea of writing a volume of travels was not seriously entertained until I arrived at Batavia, and, instead of being forbidden by the Dutch Government to proceed to the Spice Islands, as some of my warmest friends feared, I was honored by His Excellency, the Governor-General of “the Netherlands India,” with the order given on page 40.

Having fully accomplished that object, I availed myself of the unexampled facilities to travel afforded me in every part of the archipelago, and all except the first six chapters describe the regions thus visited.

The narrative given has been taken almost entirely from my journal, which was kept day by day with scrupulous care. Accuracy, even at any sacrifice[6] of elegance, has been aimed at throughout; and first impressions are presented as modified by subsequent observation.

My sincerest thanks are herein expressed to the liberal gentlemen to whom this volume is dedicated; to Baron Sloet van de Beele, formerly Governor-General of the Netherlands India; to Mr. N. A. T. Arriens, formerly Governor of the Moluccas; to Mr. J. F. R. S. van den Bosche, formerly Governor of the West Coast of Sumatra; to the many officers of the Netherlands Government, and to the Dutch and American merchants who entertained me with the most cordial hospitality, and aided me in every possible way throughout the East Indian Archipelago.

Cambridge, Mass., U. S. A., Sept. 1, 1868.

| CHAPTER I. THE STRAIT OF SUNDA AND BATAVIA. |

|

| Object of the Travels described in this volume—Nearing the coast of Java—Balmy breezes of the Eastern Isles—King Æolus’s favorite seat—A veil of rain—First view of Malays—Entering the Java Sea—The Malay language—Early history of Java—Marco Polo—Hinduism in Java—History of Batavia—The roadstead of Batavia—The city of Batavia—Houses of Europeans—Mode of cooking—Characteristics of the Malays—Collecting butterflies—Visit Rahden Saleh—Attacked with a fever—Receive a letter from the Governor-General | 13-41 |

| CHAPTER II. SAMARANG AND SURABAYA. |

|

| Sail from Batavia for the Moluccas—My companions—Mount Slamat—The north coast of Java—Mount Prau—Temples at Boro Bodo and Brambanan—Samarang—Mohammedan mosque—History of Mohammedanism—Mount Japara—The Guevo Upas, or Valley of Poison—Gresik—Novel mode of navigating mud-flats—Surabaya—Government dock-yard and machine-shops—Zoological gardens—History of Hinduism—The Klings—Excursion to a sugar plantation—Roads and telegraphic routes in Java—Malay mode of gathering rice—The kinds of sugar-cane | 42-70 |

| CHAPTER III. THE FLORA AND FAUNA OF THE TROPICAL EAST. |

|

| Leave Surabaya for Macassar—Madura—The Sapi—Manufacture of salt—The Tenger Mountains—The Sandy Sea—Eruptions of Mount Papandayang and Mount Galunggong—Java and Cuba compared—The forests of Java—Fauna of Java—The cocoa-nut palm—The Pandanus—The banana—Tropical fruits—The mangostin—The rambutan—mango—duku—durian—bread-fruit—Bali—Javanese[8] traditions—Limit between the fauna of Asia and that of Australia—A plateau beneath the sea—Caste and suttee practices on Bali | 71-96 |

| CHAPTER IV. CELEBES AND TIMUR. |

|

| History of Celebes—De Barros—Diogo de Cauto—Head-hunters of Celebes—The harbor of Macassar—Voyages of the Bugis—Skilful diving—Fort Rotterdam—The Societeit, or Club—A drive into the country—The tomb of a native merchant—Tombs of ancient princes—Sail for Kupang, in Timur—Flying-fish—The Gunong Api in Sapi Strait—Gillibanta—Sumbawa—Eruption of Mount Tomboro—The Eye of the Devil—Floris and Sandal-wood Island—Kupang—Fruits on Timur—Its barrenness and the cause of it—Different kinds of people seen at Kupang—Human sacrifice—Purchasing shells—Geology of the vicinity of Kupang—Sail for Dilli—Village of Dilli—Islands north of Timur—The Bandas—Monsoons in the Java and China Seas | 97-129 |

| CHAPTER V. AMBOINA. |

|

| Description of the island and city of Amboina—Dutch mode of governing the natives—A pleasant home—A living nautilus is secured—Excursion to Hitu—Hassar steering—History of the cocoa-tree—Indian corn—Hunting in the tropics—Butterflies—Excursion along the shores of Hitu for shells—Mode of travelling in the Spice Islands—The pine-apple—Covered bridges—Hitu-lama—Purchasing specimens—History of the Spice Islands—Enormous hermit-crabs—An exodus—Assilulu—Babirusa shells from Buru—Great curiosities—Jewels in the brains of snakes and wild boars—Description of the clove-tree—History of the clove-trade—Watched by the rajah’s wives—Lariki and Wakasihu—A storm in the height of the southeast monsoon—Variety of native dialects—Dangerous voyage by night—An earthquake—Excursion to Tulahu | 130-176 |

| CHAPTER VI. THE ULIASSERS AND CERAM. |

|

| The arrival of the mail at Amboina—The Uliassers—Chewing the betel-nut and siri—Haruku—We strike on a reef—Saparua Island, village, and bay—Nusalaut—Strange reception—An Eastern banquet—Examining the native schools—Different classes of natives—Yield of cloves in the Uliassers—Nullahia, Amet, and Abobo—Breaking of the surf on the coral reefs—Tanjong O—Travel by night—Ceram—Elpaputi Bay and Amahai—Alfura, or head-hunters,[9] come down from the mountains and dance before us—Land on the south coast of Ceram—Fiendish revels of the natives—Return to Saparua and Amboina | 177-212 |

| CHAPTER VII. BANDA. |

|

| Governor Arriens invites me to accompany him to Banda—The Gunong Api—Road of the Bandas—Banda Neira and its forts—Geology of Lontar—The Bandas and the crater in the Tenger Mountains compared—The groves of nutmeg-trees—The canari-tree—Orang Datang—We ascend the volcano—In imminent peril—The crater—Perilous descent—Eruptions of Gunong Api—Earthquakes at Neira—Great extent of the Residency of Banda—The Ki and Arru Islands—Return to Amboina—Geology of the island of Amboina—Trade of Amboina—The grave of Rumphius—His history | 213-252 |

| CHAPTER VIII. BURU. |

|

| Adieu to Amboina—North coast of Ceram—Wahai—Buru—Kayéli—Excursions to various parts of the bay—A home in the forests—Malay cuisine—Tobacco and maize—Flocks of parrots—Beautiful birds—History of Buru—The religion and laws of the Alfura—Shaving the head of a young child—A wedding-feast—Marriage laws in Mohammedan countries—A Malay marriage—Opium, its effects and its history—Kayu-puti oil—Gardens beneath the sea—Roban—Skinning birds—Tropical pests—A deer-hunt—Dinding—A threatening fleet—A page of romance—A last glance at Buru | 253-297 |

| CHAPTER IX. TERNATE, TIDORE, AND GILOLO. |

|

| Seasons in Ceram and Buru—Bachian and Makian—Eruptions of Ternate—Magellan—Former monopolies—The bloodhounds of Gilolo—Migrations—A birth-mark—The Molucca Passage—Malay pirates—They challenge the Dutch | 298-322 |

| CHAPTER X. THE NORTHERN PENINSULA OF CELEBES. |

|

| Mount Klabat—Kema—A hunt for babirusa—A camp by the sea—Enormous snakes—From Kema to Menado—Eruption of Mount Kemaas—Population of the Minahassa—Thrown from a horse—The Bantiks—A living death—History of the coffee-tree—In the jaws of a crocodile—The bay of Menado—Lake Linu—A grove by moonlight | 323-355[10] |

| CHAPTER XI. THE MINAHASSA. |

|

| The waterfall of Tinchep—A mud-well—A boiling pool—The ancient appearance of our earth—Lake Tondano—One of the finest views in the world—Palm-wine—Graves of the natives—Christianity and education—Tanjong Fiasco—Gold-mines in Celebes—The island of Buton—Macassar—A raving maniac | 356-383 |

| CHAPTER XII. SUMATRA. |

|

| Padang—Beautiful drives—Crossing the streams—The cleft—Crescent-shaped roofs—Distending the lobe of the ear—Cañons—The great crater of Manindyu—Immense amphitheatres—Ophir—Gold-mines | 384-406 |

| CHAPTER XIII. TO THE LAND OF THE CANNIBALS. |

|

| Valley of Bondyol—Monkeys—The orang-utan—Lubu Siképing—Tigers and buffaloes—The Valley of Rau—A Batta grave—Riding along the edge of a precipice—Twilight and evening—Padang Sidempuan—Among the cannibals—Descent from the Barizan—The suspension bridge of rattan—Ornaments of gold—The camphor-tree | 407-434 |

| CHAPTER XIV. RETURN TO PADANG. |

|

| Bay of Tapanuli—The Devil’s Dwelling—Dangerous fording—Among the Battas—Missionaries and their brides—The feasts of the cannibals—The pepper trade—The English appear in the East—Struck by a heavy squall—Ayar Bangis and Natal—The king’s birthday—Malay ideas of greatness | 435-457 |

| CHAPTER XV. THE PADANG PLATEAU. |

|

| Thunder and lightning in the tropics—Paya Kombo and the Bua Valley—The Bua cave—Up the valley to Suka Rajah—Ancient capitals of Menangkabau—The reformers of Korinchi—Malay mode of making matchlocks—A simple meal—Geological history of the plateau—The Thirteen Confederate Towns—The flanks of the Mérapi—Natives of the Pagi Islands—Where the basin of the Indian Ocean begins | 458-485[11] |

| CHAPTER XVI. CROSSING SUMATRA. |

|

| Bay of Bencoolen—Rat Island—Loss of Governor Raffles’s collection—A trap for tigers—Blood-suckers—Pits for the rhinoceros—virgin children—Plateau of the Musi—From Kopaiyong to Kaban Agong—Natives destroyed by tigers—Sumatra’s wealth—The Anak gadis—Troops of monkeys—From Tebing Tingi to Bunga Mas—We come upon an elephant—Among tigers—The Pasuma people—Horseback travel over—The land of game | 486-520 |

| CHAPTER XVII. PALEMBANG, BANCA, AND SINGAPORE. |

|

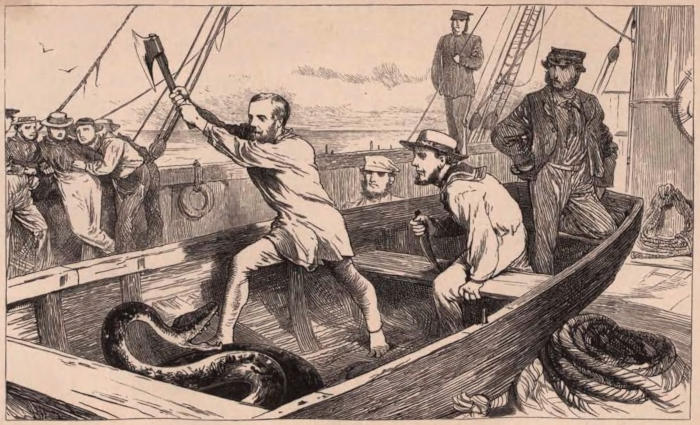

| Mount Dempo—Rafts of cocoa-nuts—Floating down the Limatang—Cotton—From Purgatory to Paradise—Palembang—The Kubus—Banca—Presented with a python—The python escapes—A struggle for life—Sail for China | 521-542 |

| Appendix A. Area of the principal islands, according to Baron van Carnbée | 543 |

| ” B. Population of the Netherlands India, 1865 | 543 |

| ” C. A table of heights of the principal mountains in the archipelago | 544 |

| ” D. Coffee sold by the government at Padang | 545 |

| ” E. Trade of Java and Madura during 1864 | 546 |

| ” F. A list of the birds collected by the author on the island of Buru | 547 |

| Index | 549 |

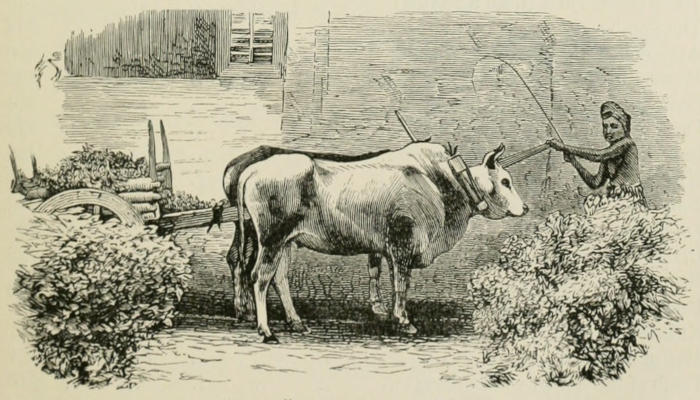

“SAPIE” OXEN FROM MADURA.

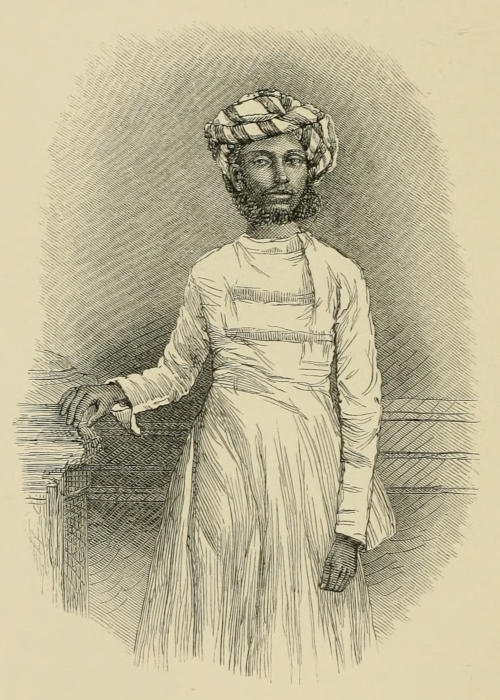

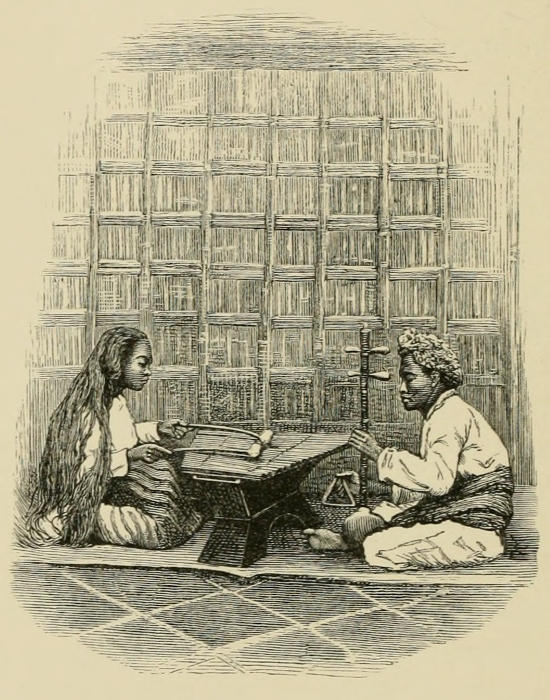

| Wives of one of the great Princes of Java | (from a Photograph) | Frontispiece |

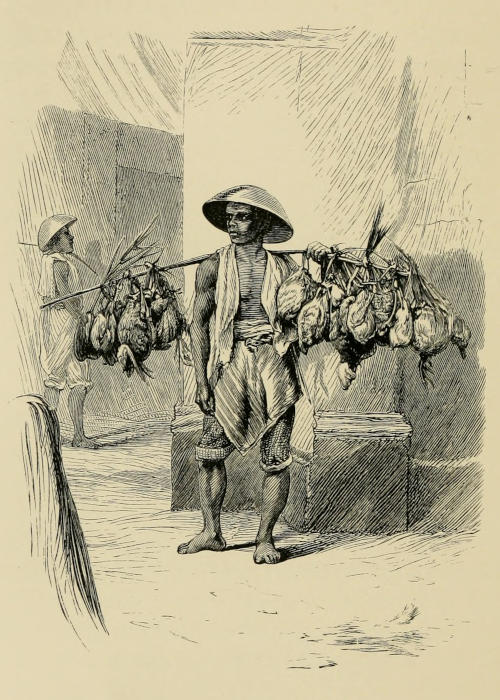

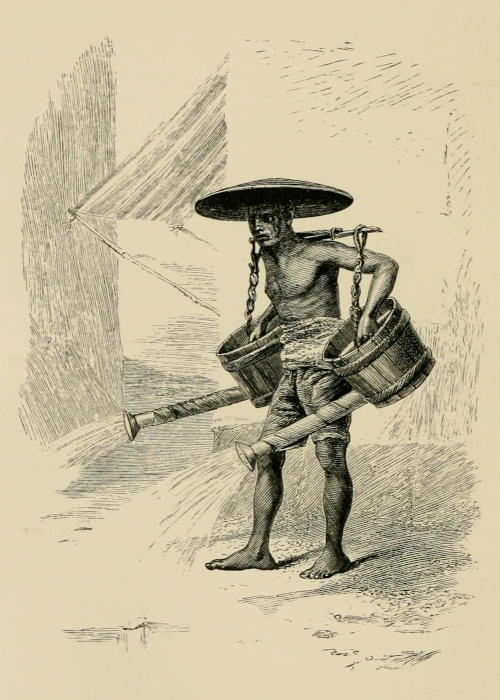

| Poultry Vender, Batavia | ” | Page 27 |

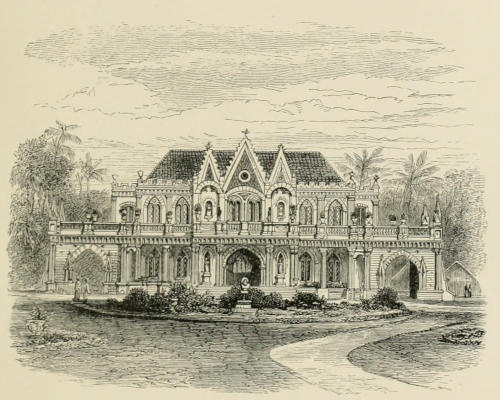

| Government Buildings in Batavia | ” | 4 |

| Sapis, or oxen from Madura | ” | 11 |

| Javanese and family | ” | 33 |

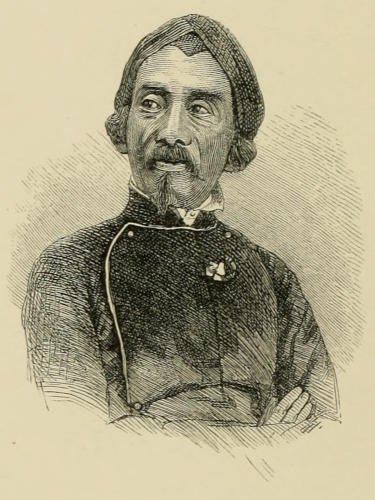

| Rahden Saleh | ” | 37 |

| Rahden Saleh’s Palace | ” | 37 |

| Watering the streets, Java | ” | 49 |

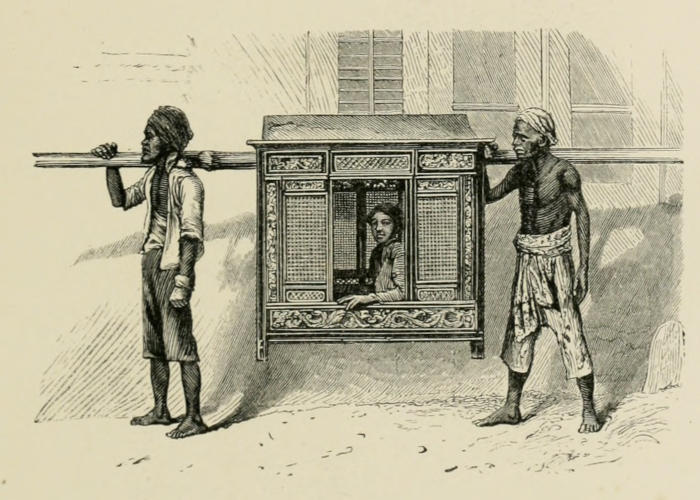

| A Tandu | ” | 49 |

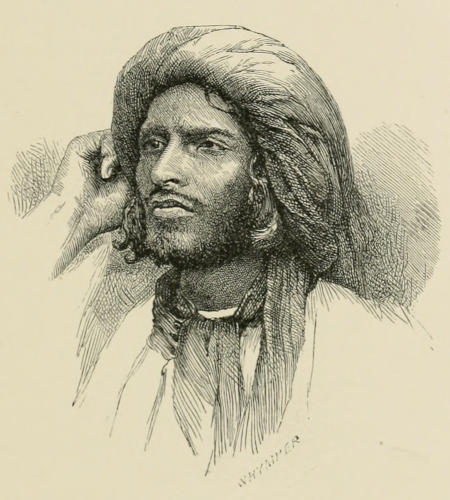

| A Kling | 63 | |

| A Native of Beloochistan | (from a Photograph) | 63 |

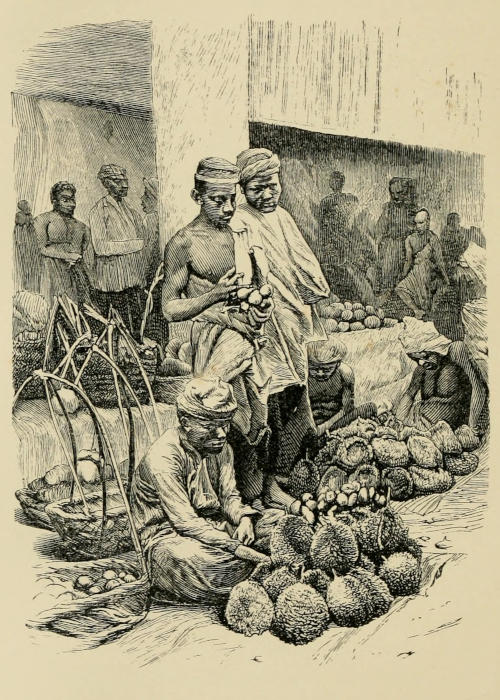

| Fruit-Market | ” | 89 |

| The Pinang, or Betel-nut Palm (from a Drawing by Rahden Saleh) | 180 | |

| After the bath | (from a Photograph) | 182 |

| Musical Instruments of the Malays (Batavia) | 191 | |

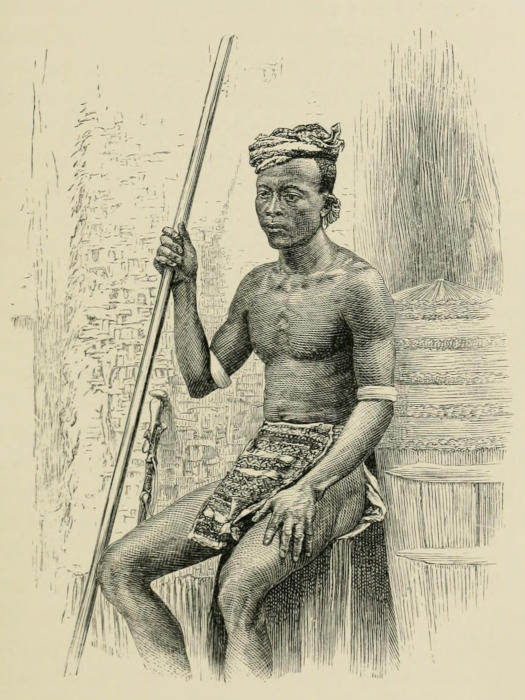

| Dyak, or Head-hunter of Borneo | (from a Photograph) | 206 |

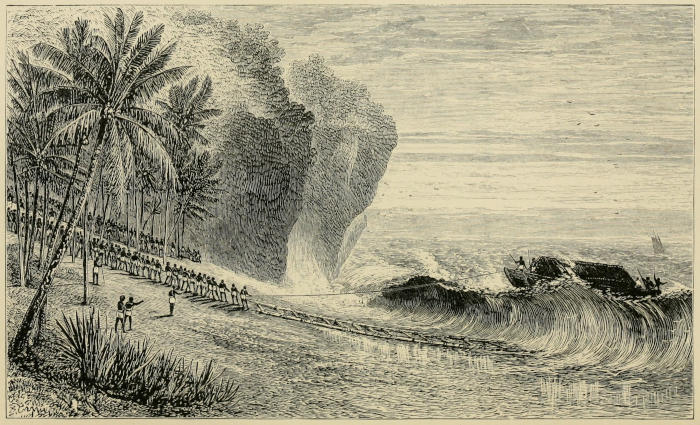

| Landing through the Surf on the south coast of Ceram | (from a Sketch) | 209 |

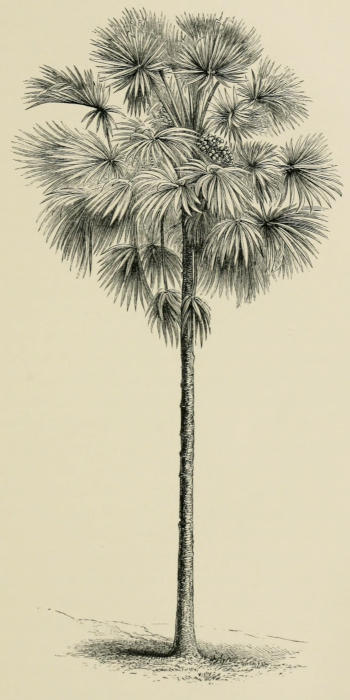

| The Lontar Palm | 220 | |

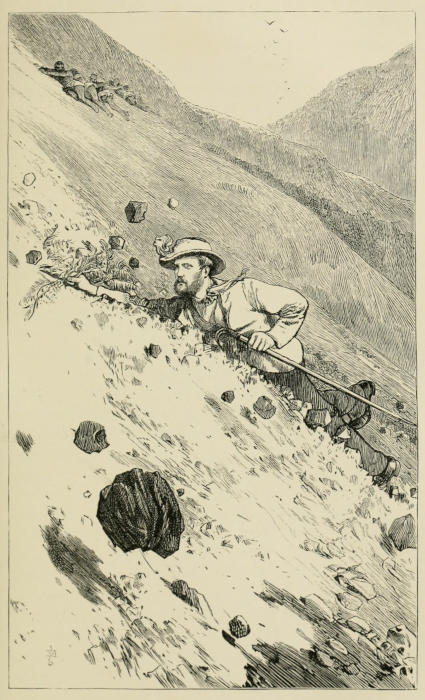

| Ascent of the Volcano of Banda—saved by a fern | (from a Sketch) | 234 |

| A Jungle | 261 | |

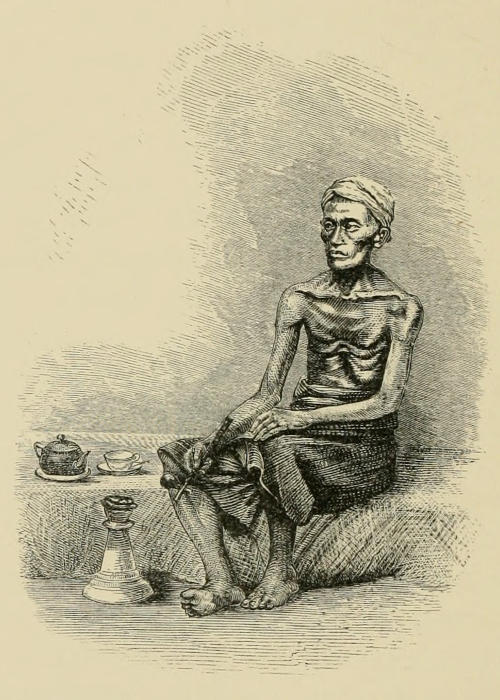

| A Malay Opium-smoker | (from a Photograph) | 281 |

| The Gomuti Palm | (from a Sketch) | 370 |

| The Bamboo | 374 | |

| Approach to the Cleft near Padang | 390 | |

| Women of Menangkaban | 395 | |

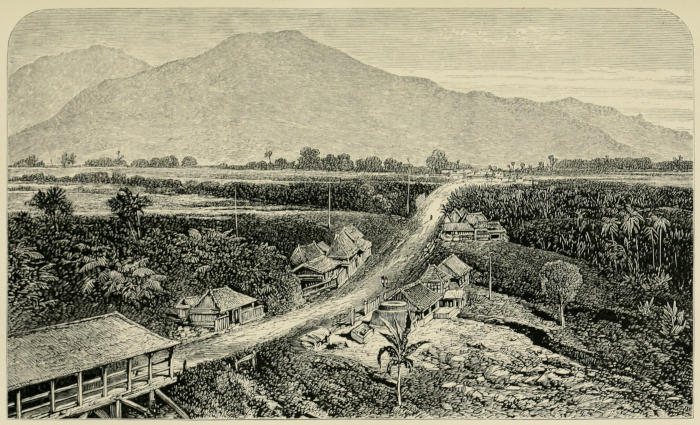

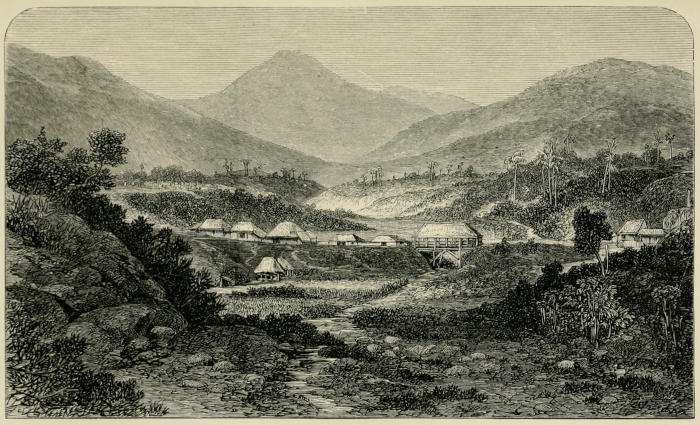

| Scene in the interior of Sumatra | 404 | |

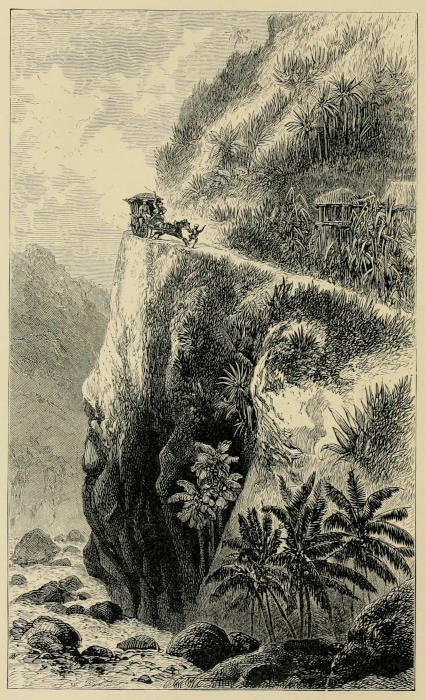

| Driving round a dangerous Bluff | 419 | |

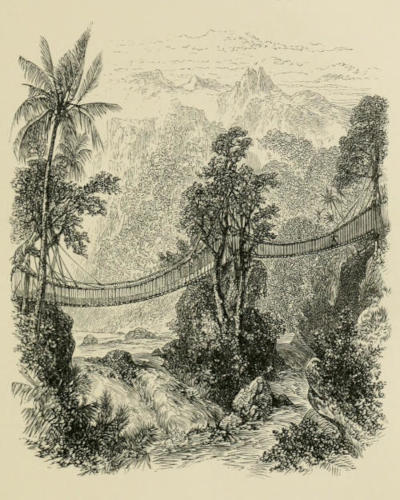

| Suspension Bridge of rattan | 428 | |

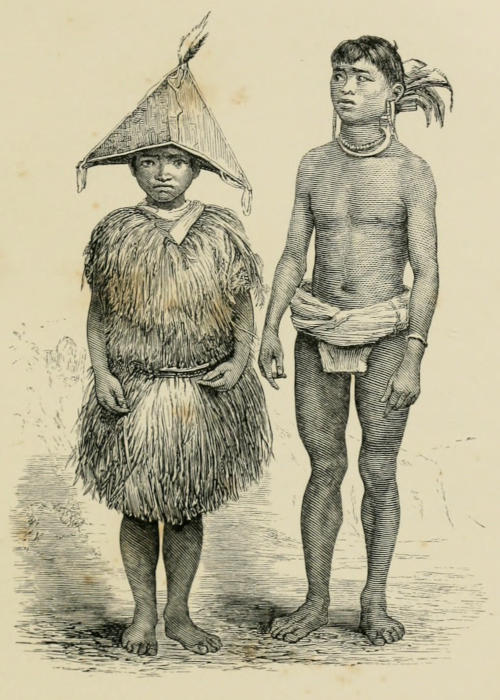

| Native of Nias | 445 | |

| Natives of the Pagi Islands | 482 | |

| Singapore | 521 | |

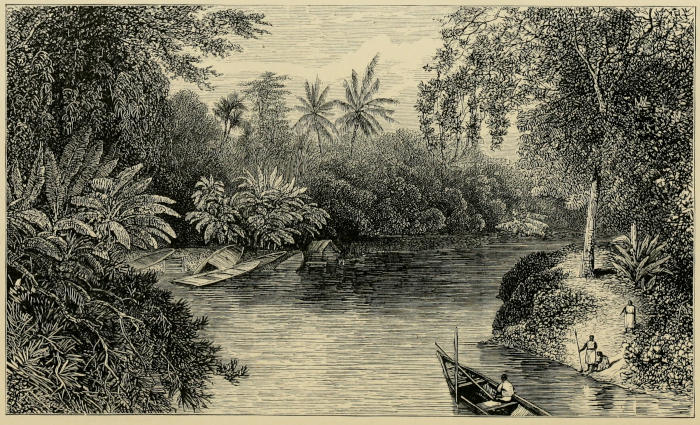

| River Scene in Sumatra, on the Limatang | 525 | |

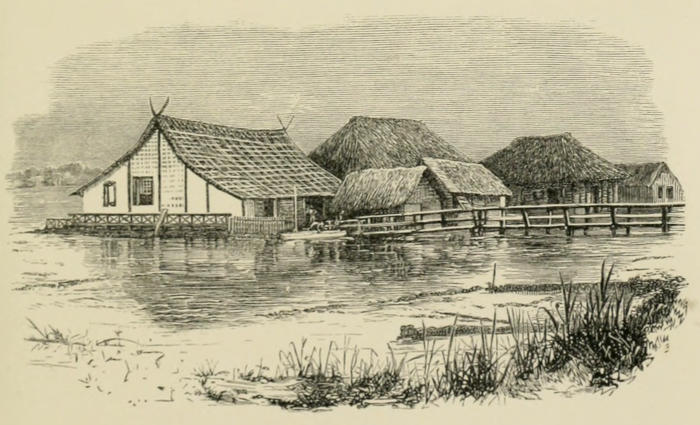

| Natives of Palembang | } | 530 |

| Palembang—high water | } | |

| Killing a Python | 541 | |

| Map of Sumatra | To face page 384 | |

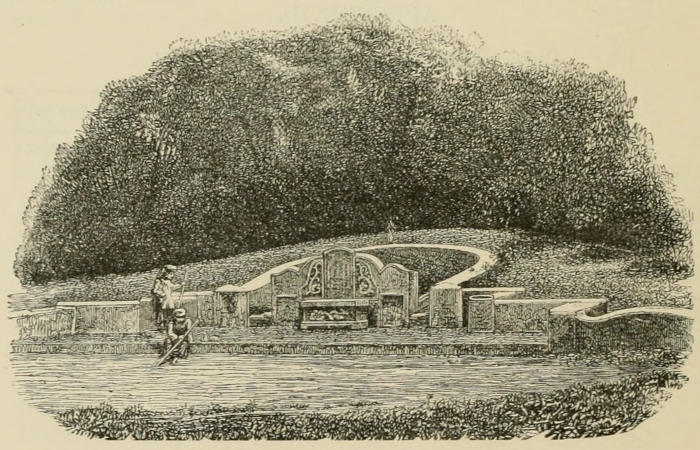

| Tomb of the Sultan—Palembang | 546 | |

| Map of the Eastern Archipelago | at the end | |

On the 19th of April, 1865, I was fifty miles east of Christmas Island, floating on the good ship “Memnon” toward the Strait of Sunda.

I was going to Batavia, to sail thence to the Spice Islands, which lie east of Celebes, for the purpose of collecting the beautiful shells of those seas.

I had chosen that in preference to any other part of the world, because the first collection of shells from the East that was ever described and figured with sufficient accuracy to be of any scientific value was made by Rumphius, a doctor who lived many years at Amboina, the capital of those islands. His great work, the “Rariteit Kamer,” or Chamber of Curiosities, was published in 1705, more than sixty years before the twelfth edition of the “Systema Naturæ” was issued by Linnæus, “the Father of Natural History,” who referred to the figures in that work[14] to illustrate a part of his own writings. When Holland became a province of France, in 1811, and it was designed to make Paris the centre of science and literature in Europe, it is said that this collection was taken from Leyden to that city, and afterward returned, and that during these two transfers a large proportion of the specimens disappeared; and that, finally, what was left of this valuable collection was scattered through the great museum at Leyden. It was partly to restore Rumphius’s specimens, and partly to bring into our own country such a standard collection, that I was going to search myself for the shells figured in the “Rariteit Kamer,” on the very points and headlands, and in the very bays, where Rumphius’s specimens were found.

As we neared the coast of Java, cocoa-nuts and fragments of sea-washed palms, drifting by, indicated our approach to a land very different at least from the temperate shores we had left behind; and we could in some degree experience Columbus’s pleasure, when he first saw the new branch and its vermilion berries. Strange, indeed, must be this land to which we are coming, for here we see snakes swimming on the water, and occasionally fragments of rock drifting over the sea. New birds also appear, now sailing singly through the sky, and now hovering in flocks over certain places, hoping to satisfy their hungry maws on the small fishes that follow the floating driftwood. Here it must be that the old Dutch sailors fabled could be seen the tree—then unknown—that bore that strange fruit, the double cocoa-nut. They always represented it as rising up from a great depth[15] and spreading out its uppermost leaves on the surface of the sea. It was guarded by a bird, that was not bird but half beast; and when a ship came near, she was always drawn irresistibly toward this spot, and not one of her ill-fated crew ever escaped the beak and formidable talons of this insatiable harpy.

But such wonders unfortunately fade away before the light of advancing knowledge; and the prince of Ceylon, who is said to have given a whole vessel laden with spice for a single specimen, could have satisfied his heart’s fullest desire if he had only known it was not rare on the Seychelles, north of Mauritius.

The trades soon became light and baffling. Heavy rain-squalls, with thunder and lightning, were frequent; and three days after, as one of these cleared away, the high mountain near Java Head appeared full a quarter of a degree above the horizon, its black shoulders rising out of a beautiful mantle of the ermine-white, fleecy clouds, called cumuli.

Although we were thirty-five miles from the shore, yet large numbers of dragon-flies came round the ship, and I quickly improvised a net and captured a goodly number of them.

After sunset, there was a light air off-shore, which carried us to within a few miles of the land, and at midnight the captain called me on deck to enjoy “the balmy breezes of the Eastern isles;” and certainly to myself, as well as to the others, the air seemed to have the rich fragrance of new-mown clover, but far more spicy. At that hour it was quite clear, but at sunrise a thick haze rose up from the ocean,[16] and this phenomenon was repeated each morning that we were trying to enter the Strait of Sunda. As we had arrived during the changing of the monsoons, calms were so continuous that for six days we tried in vain to gain fifty miles. When a breeze would take us up near the mouth of the channel, it would then die away and let a strong current sweep us away to the east, and one time we were carried most unpleasantly near the high, threatening crags at Palembang Point, near Java Head. Those who have passed Sunda at this time of the year, or Ombay Strait in the beginning of the opposite monsoon, will readily recall the many weary hours they have passed waiting for a favorable breeze to take them only a few miles farther on their long voyage.

During those six days, at noon the sun poured down his hottest rays, the thermometer ranging from 88° to 90° Fahr. in the shade, and not the slightest air moving to afford a momentary relief. Although constantly for a year I was almost under the equator, these six days were the most tedious and oppressive I ever experienced.

The mountain back of Java Head seemed to be King Eolus’s favorite seat. Clouds would come from every quarter of the heavens and gather round its summit, while the sun was reaching the zenith; but soon after he began to pass down the western sky, lightnings would be seen darting their forked tongues around the mountain-crest: and then, as if the winds had broken from the grasp of their king, thick cloud-masses would suddenly roll down the mountain-sides, lightnings dart hither and thither, and again and[17] again the thunders would crash and roar enough to shake the very firmament.

We are not alone. Six or eight vessels are also detained here—for this Strait of Sunda is the great gate through which pass out most of the valuable teas and costly silks of China and Japan, and these ships are carrying cotton goods to those lands to exchange in part for such luxuries. On the evening of the sixth day a more favorable breeze took us slowly up the channel past a group of large rocks, where the unceasing swell of the ocean was breaking, and making them sound in the quiet night like the howling and snarling of some fierce monster set to guard the way and unable to prevent his expected prey from escaping.

With the morning came a fine breeze, and, as we sailed up the strait, several small showers passed over the mountains, parallel to the shore, on the Java side; and once a long cloud rested its ends on two mountains, and unfolded from its dark mass a thin veil of sparkling rain, through which we could see quite distinctly all the outlines and the bright-green foliage of the valley behind it. The highly-cultivated lands near the water, and on the lower declivities of the mountains, whose tops were one dense mass of perennial green, made the whole view most enchanting to me; but our captain (who was a Cape Cod man) declared that the sand-hills on the outer side of Cape Cod were vastly more charming to him. On the shallows, near the shore, the clear sea-water took a beautiful tint of emerald green in the bright sunlight, and here we passed[18] long lines of cuttle-fish bones and parts of mysterious fruits where the tides met, that were setting in different directions.

Nearly all the islands in the strait are steep, volcanic cones, with their bases beneath the sea; the bright-green foliage on their sides forming an agreeable contrast with the blue ocean at their feet when the waves roll away before a strong breeze; but when it is calm, and the water reflects the light, as from a polished mirror, they appear like gigantic emeralds set in a sea of silver.

As we approached Angir, where ships bound to and from China frequently stop for fresh provisions, we saw, to our great alarm, a steamship! Was it the pirate Shenandoah, and was our ship to be taken and burnt there, almost at the end of our long voyage? I must confess that was what we all feared till we came near enough to see the “Stars and Stripes” of the loyal flag of our native land.

Here many Malays paddled off in their canoes to sell us fruit. We watch the approach of the first boat with a peculiar, indescribable interest. It contains two young men, who row. They are dressed in trousers and jackets of calico, with cotton handkerchiefs tied round their heads. This is the usual dress throughout the archipelago, except that, instead of the trousers or over them, is worn the sarong, which is a piece of cotton cloth, two yards long by a yard wide, with the two shorter sides sewn together, so as to make a bag open at the top and bottom. The men draw this on over the body, and gather it on the right hip; the loose part is then twisted, and[19] tucked under the part passing around the body, so as to form a rude knot. There is a man in the stern, sitting with his feet under him, steering the canoe, and at the same time helping it onward with his paddle. He is dressed in a close-fitting red shirt? No! He is not encumbered with any clothing except what Nature has provided for him, save a narrow cloth about his loins, the usual working-costume of the coolies, or poorer classes. He brings several kinds of bananas, green cocoa-nuts, and the “pompelmus,” which is a gigantic orange, from six to eight inches in diameter. He seems perfectly happy, and talks with the most surprising rapidity. From an occasional word that may be half English, we suppose, like traders in the Western world, he is speaking in no moderate manner of the value of what he has to sell.

Mount Karang, back of Angir, now comes into view, raising its crest of green foliage to a height of five thousand feet; a light breeze takes us round Cape St. Nicholas, the northwest extremity of Java. It is a high land, with sharp ridges coming down to the water, thus forming a series of little rocky headlands, separated by small sandy bays. These, as we sail along, come up, and open to our view with a most charming panoramic effect. Near the shore a few Malays are seen on their praus, or large boats, while others appear in groups on the beaches, around their canoes, and only now and then do we catch glimpses of their rude houses under the feathery leaves of the cocoa-nut palm.

We are in the Java Sea. It seems very strange[20] after being pitched and tossed about constantly for more than a hundred days, thus to feel our ship glide along so steadily; and after scanning the horizon by the hour, day after day, hoping to be able to discern one vessel, and so feel that we had at least one companion on “the wide waste of waters,” now to see land on every side, and small boats scattered in all directions over the quiet sea. That night we anchored near Babi Island, on a bottom of very soft, sticky clay, largely composed of fragments of shells and coral. A boat came off from the shore, and, as the coxswain could speak a little English, I took my first lesson in Malay, the common language, or lingua franca, of the whole archipelago. As it was necessary, at least, that I should be able to talk with these natives if I would live among them, and purchase shells of them, it was my first and most imperative task, on reaching the East, to acquire this language. The Malay spoken at Batavia, and at all the Dutch ports and posts in the islands to the east, differs very much from the high or pure Malay spoken in the Menangkabau country, in the interior of Sumatra, north of Padang, whence the Malays originally came: after passing from island to island, they have spread over all Malaysia, that is, the great archipelago between Asia, Australia, and New Guinea. Perhaps of all languages in the world, the low or common Malay is the one most readily acquired. It contains no harsh gutturals or other consonants that are difficult to pronounce. It is soft and musical, and somewhat resembles the Italian in its liquid sounds; and one who has learned it can never fail[21] to be charmed by the nice blending of vowels and consonants whenever a word is pronounced in his presence. The only difficult thing in this language is, that words of widely different meaning sometimes are so similar that, at first, one may be mistaken for another. Every European in all the Netherlands India speaks Malay. It is the only language used in addressing servants; and all the European children born on these islands learn it from their Malay nurses long before they are able to speak the language of their parents. Such children generally find it difficult to make the harsh, guttural sounds of the Dutch language, and the Malays themselves are never able to speak it well; and, for the same reason, Dutchmen seldom speak Malay as correctly as Englishmen and Frenchmen.

We are now off the ancient city of Bantam, and we naturally here review the voyages of the earliest European navigators in these seas, and the principal events in the ancient history of this rich island of Java.

The word Java, or, more correctly, “Jawa,” is the name of the people who originally lived only in the eastern part of the island, but, in more modern times, they have spread over the whole island, and given it their name. The Chinese claim to have known it in ancient times, and call it Chi-po or Cha-po, which is as near Jawa as their pronunciation of most foreign names at the present day.

It was first made known to the Western world by that great traveller, Marco Polo, in his description of the lands he saw or passed while on his voyage[22] from China to the Persian Gulf, in the latter part of the thirteenth century. He did not see it himself, but only gathered accounts in regard to it from others. He calls it Giaua, and says it produces cloves and nutmegs, though we know now that they were all brought to Java from the Spice Islands, farther to the east. In regard to gold, he says it yielded a quantity “exceeding all calculation and belief.” This was also probably brought from other islands, chiefly from Sumatra, Borneo, and Celebes.

In 1493, one year after the discovery of America by Columbus, Bartholomew Dias, a Portuguese, discovered the southern extremity of Africa, which he called the Cape of Storms, but which his king said should be named the Cape of Good Hope, because it gave a good hope that, at last, they had discovered a way to India by sea. Accordingly, the next year, this king[1] sent Pedro da Covilham and Alfonso de Payva directly to the east to settle this important question. From Genoa they came to Alexandria in the guise of travelling merchants, thence to Cairo, and down the Red Sea to Aden. Here they separated—Payva to search for “Prester John,” a Christian prince, said to be reigning in Abyssinia over a people of high cultivation; and Covilham to visit the Indies, it having been arranged that they should meet again at Cairo or Memphis. Payva died before reaching the principal city of Abyssinia, but Covilham had a prosperous journey to India, where he made drawings of the cities and harbors, especially of Goa and Calicut (Calcutta), and marked their[23] positions on a map given him by King John of Portugal. Thence he returned along the coast of Persia to Cape Guardafui, and continued south to Mozambique and “Zofala,” where he ascertained that that land joined the Cape of Good Hope, and thus was the first man who knew that it was possible to sail from Europe to India. From Zofala he returned to Abyssinia, and sent his diary, charts, and drawings to Genoa by some Portuguese merchants who were trading at Memphis.

On receiving this news, King Emanuel, who had succeeded King John, sent out, during the following year, 1495, four ships under Vasco di Gama, who visited Natal and Mozambique; in 1498 he was at Calcutta, and in 1499 back at Lisbon.

In 1509 the Portuguese, under Sequiera, first came into the archipelago. During the next year Alfonso Albuquerque visited Sumatra, and in 1511 took the Malay city Malacca, and established a military post from which he sent out Antonio d’Abreu to search for the Spice Islands. On his way eastward, D’Abreu touched at Agasai (Gresik) on Java.

In 1511 the Portuguese visited Bantam, and two years later Alvrin was sent from Malacca with four vessels to bring away a cargo of spices from a ship wrecked on the Java coast while on her way back from the Spice Islands.

Ludovico Barthema was the first European who described Java from personal observation. He remained on it fourteen days, but his descriptions are questionable in part, for he represents parents as selling their children, to be eaten by their purchasers,[24] and himself as quitting the island in haste for fear of being made a meal of.

In 1596 the Dutch, under Houtman, first arrived off Bantam, and, finding the native king at war with the Portuguese, readily furnished him with assistance against their rivals, on his offering to give them a place where they could establish themselves and commence purchasing pepper, which at that time was almost the only export.

The English, following the example of the Portuguese and the Dutch, sent out a fleet in 1602, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth. These ships touched at Achin, on the western end of Sumatra, and thence sailed to Bantam.

In 1610 the Dutch built a fort at a native village called Jacatra, “the work of victory,” but which they named Batavia. This was destroyed in 1619, and the first Dutch governor-general, Bolt, decided to rebuild it and remove his settlement from Bantam to that place, which was done on the 4th of March of that year. This was the foundation of the present city of Batavia. The English, who had meantime maintained an establishment at Bantam, withdrew in 1683.

In 1811, when Holland became subject to France, the French flag was hoisted at Batavia, but that same year it was captured by the English. On the 19th of August, 1816, they restored it to the Dutch, who have held it uninterruptedly down to the present time.

In glancing at the internal history of Java, we find that, for many centuries previous to A. D. 1250,[25] Hinduism, that is, a mixture of Buddhism and Brahminism, had been the prevailing religion. At that time an attempt was made to convert the reigning prince to Mohammedanism. This proved unsuccessful; but so soon afterward did this new religion gain a foothold, and so rapidly did it spread, that in 1475, at the overthrow of the great empire of Majapahit, who ruled over the whole of Java and the eastern parts of Sumatra, a Mohammedan prince took the throne. Up to this time the people in the western part of Java, as far east as Cheribon (about Long. 109°), spoke a language called Sundanese, and only the people in the remaining eastern part of the island spoke Javanese; but in 1811 nine-tenths of the whole population of Java spoke Javanese, and the Sundanese was already confined to the mountainous parts of the south and west, and to a small colony near Bantam.

Soon after founding Batavia, the Dutch made an alliance offensive and defensive with the chief prince, who resided near Surakarta. Various chiefs rebelled from time to time against his authority, and the Dutch, in return for the assistance they rendered him, obtained the site of the present city of Samarang; and in this way they continued to increase their area until 1749, when the prince then reigning signed an official deed “to abdicate for himself and for his heirs the sovereignty of the country, conferring the same on the Dutch East India Company, and leaving them to dispose of it, in future, to any person they might think competent to govern it for the benefit of the company and of Java.” Seven years[26] before this time the empire had been nominally divided, the hereditary prince being styled Susunan, or “object of adoration,” whose descendants now reside at Surakarta, near Solo; and a second prince, who was styled Sultan, and whose descendants reside at Jokyokarta. Each receives a large annuity from the Dutch Government, and keeps a great number of servants. Their wives are chosen from all the native beauties in the land, and the engraving we give from a photograph represents those of one of the highest dignitaries in full costume, but barefoot, just as they dress themselves on festive occasions to dance before their lord and his assembled guests.

The next day when the sea-breeze came, about one o’clock, we sailed up through the many islands of this part of the coast of Java. They are all very low and flat, and covered with a short, dense shrubbery, out of which rise the tall cocoa-nut palm and the waringin or Indian fig. This green foliage is only separated from the sea by a narrow beach of ivory-white coral sand, which reflects the bright light of the noonday sun until it becomes positively dazzling. Where the banks are muddy, mangrove-trees are seen below high-water level, holding on to the soft earth with hundreds of branching rootlets, as if trying to claim as land what really is the dominion of the sea.

POULTRY VENDER.

This dense vegetation is one of the great characteristics of these tropical islands; and the constantly varied grouping of the palms, mangroves, and other trees, and the irregular contour and relief of the shores, afford an endless series of exquisite views.[27] As we passed one of the outer islands, its trees were quite covered with kites, gulls, and other sea-birds.

The next evening we came to the Batavia road, a shallow bay where ships lie at anchor partially sheltered from the sea by the many islands scattered about its entrance. The shores of this bay form a low, muddy morass, but high mountains appear in the distance. Through this morass a canal has been cut. Its sides are well walled in, and extend out some distance toward the shipping, on account of the shallowness of the water along the shore. At the end of one of these moles, or walls, stands a small white light-house, indicating the way of approaching the city, which cannot be fully seen from the anchorage.

When a ship arrives from a foreign port, no one can leave her before she is boarded by an officer from the guardship, a list of her passengers and crew obtained, and it is ascertained that there is no sickness on board. Having observed this regulation, we rowed up the canal to the “boom” or tree, where an officer of the customs looks into every boat that passes. This word “boom” came into use, as an officer informed me, when it was the custom to let a tree fall across the canal at night, in order to prevent any boat from landing or going out to the shipping.

Here were crowds of Malay boatmen, engaged in gambling, by pitching coins. This seemed also the headquarters of poultry-venders, who were carrying round living fowls, ducks, and geese, whose feet had been tied together and fastened to a stick, so that they had to hang with their heads downward—the very ideal of cruelty.

Before we could land, we were asked several times in Dutch, French, and English, to take a carriage, for cabmen seem to have the same persistent habits in every corner of the earth. Meanwhile the Malay drivers kept shouting out, “Crétur tuan! crétur tuan!” So we took a “crétur,” that is, a low, covered, four-wheeled carriage, drawn by two miniature ponies. The driver sits up on a seat in front, in a neat baju or jacket of red or scarlet calico, and an enormous hemispherical hat, so gilded or bronzed as to dazzle your eyes when the sun shines.

Though these ponies are small, they go at a quick canter, and we were rapidly whirled along between a row of shade-trees to the city gate, almost the only part of the old walls of the city that is now standing. The other parts were torn down by Marshal Daendals, to allow a freer circulation of air. Then we passed through another row of shade-trees, and over a bridge, to the office of the American consul, a graduate of Harvard; and, as Cambridge had been my home for four years, we at once considered ourselves as old friends.

Before I left America, Senator Sumner, as chairman of our Committee on Foreign Relations, kindly gave me a note of warm commendation to the representatives of foreign powers; and Mr. J. G. S. van Breda, the secretary of the Society of Sciences in Holland, with whom I had been in correspondence while at the Museum of Comparative Zoology in Cambridge, gave me a kind note to Baron Sloet van de Beele, the governor-general of the Netherlands India. I immediately addressed a note to His Excellency, enclosing[29] these credentials, and explaining my plan to visit the Spice Islands for the purpose of collecting the shells figured in Rumphius’s “Rariteit Kamer,” and expressing the hope that he would do what he could to aid me in my humble attempts to develop more fully the natural history of that interesting region. These papers our consul kindly forwarded, adding a note endorsing them himself.

As the governor-general administers both the civil and military departments of all the Dutch possessions in the East, I could not expect an immediate reply. I therefore found a quiet place in a Dutch family, with two other boarders who spoke English and could assist me in learning their difficult language, and, bidding Captain Freeman and the other good officers of the Memnon farewell, took up my abode on shore.

Batavia at present is more properly the name of a district or “residency,” than of a city. Formerly it was compact and enclosed by walls, but these were destroyed by Marshal Daendals, in 1811. The foreigners then moved out and built their residences at various places in the vicinity, and these localities still retain their old Malay names. In this part of the city there are several fine hotels, a large opera-house, and a club-house. There are two scientific societies, which publish many valuable papers on the natural history, antiquities, geography, and geology, of all parts of the Netherlands India. These societies have valuable collections in Batavia, and at Buitenzorg there is a large collection of minerals and geological specimens. The “King’s Plain” is a very large open[30] square, surrounded by rows of shade-trees and the residences of the wealthier merchants. Near this is the “Waterloo Plain.” On one of its sides is the largest building in Batavia, containing the offices of the various government bureaus, and the “throne-room,” where the governor-general receives, in the name of the king, congratulations from the higher officials in that vicinity.

The governor-general has a palace near by, but he resides most of the time at Buitenzorg, forty miles in the interior, where the land rises to about a thousand feet above the level of the sea, and the climate is much more temperate.

A river, that rises in the mountains to the south, flows through the city and canal, and empties into the bay. Many bridges are thrown over this river and its branches, and beautiful shade-trees are planted along its banks.

All the houses in these Eastern lands are low, rarely more than one story, for fear of earthquakes, which, however, occur in this part of the island at long intervals. The walls are of bricks, or fragments of coral rock covered with layers of plaster. The roof is of tiles, or atap, a kind of thatching of palm-leaves. A common plan is, a house part parallel to the street, and behind this and at right angles to it an L or porch, the whole building being nearly in the form of a cross.

In front is a broad veranda, where the inmates sit in the cool evening and receive the calls of their friends. This opens into a front parlor, which, with a few sleeping-rooms, occupies the whole house part.[31] The L, when there is one, usually has only a low wall around it, and a roof resting on pillars. It is therefore open on three sides to the air, unless shutters are placed between the pillars. This is usually the dining-room. Back of the house is a square, open area, enclosed on the remaining three sides by a row of low, shed-roofed houses. Here are extra bedrooms, servants’ quarters, cook-rooms, bath-rooms, and stables. Within this area is usually a well, surrounded with shade-trees. The water from this well is poured into a thick urn-shaped vessel of coral rock, and slowly filters through into an earthen pot beneath; it is then cooled with ice from our own New-England ponds. Thus the cold of our temperate zone is made to allay the heat of the tropics. Several shiploads of ice come from Boston to this port every year. At Surabaya and Singapore large quantities are manufactured, but it is as soft as ice in ice-cream. When one is accustomed to drinking ice-water, there is no danger of any ill effect; but, on returning from the eastern part of the archipelago where they never have ice, to Surabaya, I suffered severely for a time, and, as I believe, from no other cause. In the frequent cases of fever in the East it is a luxury, and indeed a medicine, which can only be appreciated by one who has himself endured that indescribable burning.

The cook-room, as already noticed, is some distance from the dining-room, but this inconvenience is of little importance in those hot lands. The Malays are the only cooks, and I do not think that cooking as an art is carried to the highest perfection in that[32] part of the world, though I must add, that I soon became quite partial to many of their dishes, which are especially adapted for that climate. The kitchen is not provided with stoves or cooking-ranges, as in the Western world, but on one side of the room there is a raised platform, and on this is a series of small arches, which answer the same purpose. Fires are made in these arches with small pieces of wood, and the food is therefore more commonly fried or boiled, than baked. There is no chimney, and the smoke, after filling the room, finally escapes through a place in the roof which is slightly raised above the parts around it.

As I am often questioned about the mode of living in the East, I may add that always once a day, and generally for dinner, rice and curry appear, and to these are added, for dinner, potatoes, fried and boiled; steak, fried and broiled; fried bananas (the choicest of all delicacies), various kinds of greens, and many sorts of pickles and sambal, or vegetables mixed with red peppers. The next course is salad, and then are brought on bananas of three or four kinds, at all seasons; and, at certain times, oranges, pompelmuses, mangoes, mangostins, and rambutans; and as this is but such a bill of fare as every man of moderate means expects to provide, the people of the West can see that their friends in the East, as well as themselves, believe in the motto, “Carpe diem.” A cigar, or pipe, and a small glass of gin, are generally regarded as indispensable things to perfect happiness by my good Dutch friends, and they all seemed to wonder that[33] I could be a traveller and never touch either. It is generally supposed, in Europe and America, that housekeepers here, in the East, have little care or vexation, where every family employs so many servants; but, on the contrary, their troubles seem to multiply in direct ratio to the number of servants employed. No servant there will do more than one thing. If engaged as a nurse, it is only to care for one child; if as a groom, it is only to care for one horse, or, at most, one span of horses; and as all these Malays are bent on doing every thing in the easiest way, it is almost as much trouble to watch them as to do their work.

JAVANESE AND FAMILY.

The total population of the Residency of Batavia is 517,762. Of these, 5,576 are Europeans; 47,570 Chinese; 463,591 native; 684 Arabs; and 341 of other Eastern nations.

All the natives are remarkably short in stature, the male sex averaging not more than five feet three inches in height, or four inches less than that of Europeans. The face is somewhat lozenge-shaped, the cheekbones high and prominent, the mouth wide, and the nose short—not flat as in the negroes, or prominent as in Europeans. They are generally of a mild disposition, except the wild tribes in the mountainous parts of Sumatra, Borneo, Celebes, Timor, Ceram, and a few other large islands. The coast people are invariably hospitable and trustworthy. They are usually quiet, and extremely indolent. They all have an insatiable passion for gambling, which no restrictive or prohibitory laws can eradicate.

They are nominally Mohammedans, but have[34] none of the fanaticism of that sect in Arabia. They still retain many of their previous Hindu notions, and their belief may be properly defined as a mixture of Hinduism and Mohammedanism. A few are “Christians,” that is, they attend the service of the Dutch Church, and do not shave their heads or file their teeth. They are cleanly in their habits, and scores of all ages may be seen in the rivers and canals of every city and village, especially in the morning and evening. The sarong, their universal dress, is peculiarly fitted for this habit. When they have finished their baths, a dry one is drawn on over the head, and the wet one is slipped off beneath without exposing the person in the least. The females wear the sarong long, and generally twist it tightly round the body, just under the arms. Occasionally it is made with sleeves, like a loose gown. A close-fitting jacket or baju is worn with it.

The men have but a few straggling hairs for beards, and these they generally pull out with a pair of iron tweezers. The hair of the head in both sexes is lank, coarse, and worn long. Each sex, therefore, resembles the other so closely that nearly every foreigner will, at first, find himself puzzled in many cases to know whether he is looking at a man or a woman. This want of differentiation in the sexes possibly indicates their low rank in the human family, if the law may be applied here that obtains among most other animals.

Every day I went out to collect the peculiar birds and beautiful butterflies of that region, my favorite place for this pleasure being in an old[35] Chinese cemetery just outside the city, where, as the land was level, the earth had been thrown up into mounds to keep the bones of their inmates from “the wet unfortunate places,” just as in China, when far from any mountain or hill. A Malay servant followed, carrying my ammunition and collecting-boxes. At first I supposed he would have many superstitious objections to wandering to and fro with me over the relics of the Celestials, but, to my surprise, I found his people cultivating the spaces between the graves, as if they, at least, did not consider it sacred soil; yet, several times, when we came to the graves of his own ancestors, he was careful to approach with every manifestation of awe and respect.

A small piece of land, a bamboo hut, and a buffalo, comprise all the worldly possessions of most coolies, and yet with these they always seem most enviably contented.

They generally use but a single buffalo in their ploughs and carts. A string passing through his nostrils is tied to his horns, and to this is attached another for a rein, by which he is guided or urged to hasten on his slow motions. This useful animal is distributed over all the large islands of the archipelago, including the Philippines, over India and Ceylon; and during the middle ages was introduced into Egypt, Greece, and Italy. It thrives well only in warm climates. From its peculiar habit of wallowing in pools and mires, and burying itself until only its nose and eyes can be seen, it has been named the “water-ox.” This[36] appears to be its mode of resting, as well as escaping the scorching rays of the sun, and the swarms of annoying flies; and in the higher lands the natives make artificial ponds by the roadside, where these animals may stop when on a journey. They are generally of a dark slate-color, and occasionally of a light flesh-color, but rarely or never white. They are so sparsely covered with hair as to be nearly naked. They are larger than our oxen, but less capable of continued labor. They are usually so docile that even the Malay children can drive them, but they dislike the appearance of a European, and have a peculiar mode of manifesting this aversion by breathing heavily through the nose. At such times they become restive and unmanageable, and their owners have frequently requested me to walk away, for fear I should be attacked. When the females are suckling their young, they are specially dangerous. A large male has been found to be more than a match for a full-grown royal tiger.

On most of the islands where the tame buffalo is seen, wild ones are also found among the mountains; but naturalists generally suppose the original home of the species was on the continent, and that the wild ones are merely the descendants of those that have escaped to the forests. The Spaniards found them on the Philippines when they first visited that archipelago.

RAHDEN SALEH.

RAHDEN SALEH’S PALACE.

The plough generally used has both sides alike, and a single handle, which the coolie holds in his right hand while he guides the buffalo with the left.[37] The lower part of the share is of iron, the other parts of wood. It only scratches the ground to the depth of six or eight inches—a strange contrast to our deep subsoil ploughing. In these shallow furrows are dropped kernels of our own Indian maize and seeds of the sugar-cane. Sometimes the fields are planted with cocoa-nut palms about twenty yards apart, more for their shade, it appears, than for their fruit, which is now hanging in great green and yellow clusters, and will be ripe in a month. Beneath these trees are blighted nuts, and in many places large heaps of them are seen, gathered by the natives for the sake of the husk, from which they make a coarse rope.

Among these trees I was surprised to hear the noise, or more properly words, “Tokay! tokay!” and my servant at once explained that that was the way a kind of lizard “talked” in his land. So snugly do these animals hide away among the green leaves that it was several days before I could satisfy myself that I had secured a specimen of this speaking quadruped.

During my hunting I enjoyed some charming views of the high, dark-blue mountains to the south. One excursion is worthy of especial mention. It was to the palace of Rahden Saleh, a native prince. This palace consisted of a central part and two wings, with broad verandas on all sides. On entering the main building we found ourselves in a spacious hall, with a gallery above. In the centre of the floor rose a sort of table, and around the sides of the room were chairs of an antique pattern. Side-doors opened out[38] of this hall into smaller rooms, each of which was furnished with a straw carpet, and in the centre a small, square Brussels carpet, on which was a table ornamented with carved-work, and surrounded with a row of richly-cushioned chairs. Along the sides were similar chairs and small, gilded tables. On the walls hung large steel engravings, among which I noticed two frequently seen in our own land: “The Mohammedan’s Paradise,” and one of two female figures personifying the past and the future. In front of the palace the grounds were tastefully laid out as small lawns and flower-plats, bordered with a shrub filled with red leaves. An accurate idea of the harmonious proportions of this beautiful palace is given in the accompanying cut. It is the richest residence owned by any native prince in the whole East Indian Archipelago.

The Rahden at the time was in the adjoining grounds, which he is now forming into large zoological gardens for the government at Batavia. When a youth, he was sent to Holland, and educated at the expense of the Dutch Government. While there, he acquired a good command of the German and French languages, was received as a distinguished guest at all the courts, and associated with the leading literati. In this manner he became acquainted with Eugene Sue, who was then at work on his “Wandering Jew,” and—as is generally believed—at once chose the Rahden as a model for his “Eastern prince,” one of the most prominent characters in that book. But it is chiefly as a landscape-painter that the Rahden is most famous. A few years ago[39] there was a great flood here at Batavia, which proved a fit subject for his pencil; and the painting was so greatly admired, that he presented it to the King of Holland. When I was introduced to him, he at once, with all a courtier’s art, inquired whether I was from the North or the South; and on hearing that I was not only from the North, but had served for a time in the Union army, he insisted on shaking hands again, remarking that he trusted that it would not be long before all the slaves in our land would be free.

I had not been out many times collecting before I found myself seized one night with a severe pain in the back of the neck and small of the back—a sure sign of an approaching fever. The next day found me worse, then I became somewhat better, and then worse again. The sensation was as if some one were repeatedly thrusting a handful of red-hot knitting-needles into the top of my head, which, as they passed in, diverged till they touched the base of the brain. Then came chills, and then again those indescribable darting pains. It seemed as if I could not long retain the command of my mind under such severe torture. At last, after seven days of this suffering, I decided to go to the military hospital, which is open to citizens of all nations on their paying the same price per day as in the best hotels. The hospital consisted of a series of long, low, one-story buildings placed at right angles to each other, and on both sides facing open squares and wide walks or gardens, which were all bordered with large trees and contained some fine flowers. In each of the buildings were two rows of rooms or chambers of convenient size, which[40] opened out on to a wide piazza, where the sick could enjoy all the breezes and yet be sheltered from the sun. Every morning the chief doctor came round to each room with assistants and servants, who carefully noted his directions and prescriptions. He was a German, and appeared very kindly in his manner; but when the time arrived to take medicine, I found he had not only assigned for me huge doses of that most bitter of all bitter things—quinine—but also copious draughts of some fluid villanously sour. The ultimate result of these allopathic doses was, however, decidedly beneficial; and after keeping perfectly quiet for a week, I was well enough to return to my boarding-house, but yet was so weak for some time that I could scarcely walk.

Our consul, who had been kindly visiting me all the while, now came with a letter from His Excellency the governor-general that was amply sufficient to make me wholly forget my unfavorable initiation into tropical life. It was addressed to the “Heads of the Provincial Governments in and out of Java,” and read thus: “I have the honor to ask Your Excellency to render to the bearer, Mr. Albert S. Bickmore, who may come into the district under your command in the interest of science, all the assistance in your power, without causing a charge to the public funds or a burden to the native people.”

Besides honoring me with this kind letter, His Excellency generously wrote the consul that he would be happy to offer me “post-horses free over all Java,” if I should like to travel in the interior. But it was with the hope of reaching the Spice Islands that I[41] had come to the East, and, after thanking the governor-general for such great consideration and kindness, I began making preparations for a voyage through the eastern part of the archipelago. I had brought with me a good supply of large copper cans with screw covers. These were filled with arrack, a kind of rum made of molasses and rice. Dip-nets, hooks, lines, and all such other paraphernalia, I had fully provided myself with before I left America. Yet one paper, besides a ticket, was needed before I could go on board the mail-boat, and that was a “permission to travel in the Netherlands India.” This paper ought to have been renewed, according to law, once every month; but the governor-general’s letter was such an ample passport, that I never troubled myself about the matter again during the year I was journeying in the Dutch possessions.

On the 7th of June, as the twilight was brightening in the eastern sky, I left my new Batavia home, and was hurriedly driven to the “boom.” A small steamer was waiting to take passengers off to the mail-boat that goes to Celebes, Timor, and Amboina, the capital of the Spice Islands.

My baggage all on board, I had time to rest, and realize that once more I was a wanderer; but lonesome thoughts were quickly banished when I began to observe who were to be my companions, there on the eastern side of the world, so far from the centre of civilization and fashion; and just then a real exquisite stepped on board. He was tall, but appeared much taller from wearing a high fur hat, the most uncomfortable covering for the head imaginable in that hot climate. Then his neckcloth! It was spotlessly white, and evidently tied with the greatest care; but what especially attracted my attention were his long, thin hands, carefully protected by white kid gloves. However, we had not been a long time on the steamer, where every place was covered with a thick layer of coal-dust, before Mr. Exquisite changed his elegant apparel for a matter-of-fact suit, and made[43] his second appearance as a littérateur, with a copy of the Cornhill Magazine. As he evidently did not intend to read, I borrowed it, and found it was already three years old, and the leaves still uncut. It contained a graphic description of the grounds about Isaac Walton’s retired home—probably the most like the garden of Eden of any place seen on our earth since man’s fall.

The other passengers were mostly officials and merchants going to Samarang, Surabaya, or Macassar, and I found that I was the only one travelling to Amboina. The general commanding the Dutch army in the East was on board. He was a very polite, unassuming gentleman, and manifested much interest in a Sharpe’s breech-loader I had brought from America, and regarded it the most effective army rifle of any he had seen up to that time. He was going to the headquarters of the army, which is a strongly-fortified place back of Samarang. It was described to me as located on a mountain or high plateau with steep sides—a perfect Gibraltar, which they boasted a small army could maintain for an indefinite length of time against any force that might be brought against it. About five months later, however, it was nearly destroyed by a violent earthquake, but has since been completely rebuilt.

One genial acquaintance I soon found in a young man who had just come from Sumatra. He had travelled far among the high mountains and deep gorges in the interior of that almost unexplored island, and his vivid descriptions gave me an indescribable longing to behold such magnificent scenery—a[44] pleasure I did not fancy at that time it would be my good fortune to enjoy before I left the archipelago.

All day the sky was very hazy, but we obtained several grand views of high volcanoes, especially two steep cones that can be seen in the west from the road at Batavia. A light, but steady breeze came from the east, for it was as yet only the early part of the eastern monsoon. When the sun sank in the west, the full moon rose in the east, and spread out a broad band of silver over the sea. The air was so soft and balmy, and the whole sky and sea so enchanting, that to recall it this day seems like fancying anew a part of some fascinating dream.

This word monsoon is only a corruption of the Arabic word musim, “season,” which the Portuguese learned from the Arabians and their descendants, who were then navigating these seas. It first occurs in the writings of De Barros, where he speaks of a famine that occurred at Malacca, because the usual quantity of rice had not been brought from Java; and “the mução” being adverse, it was not possible to obtain a sufficient supply. The Malays have a peculiar manner of always speaking of any region to the west as being “above the wind,” and any region to the east as being “below the wind.”

June 8th.—Went on deck early this morning to look at the mountains which we might be passing; and, while I was absorbed in viewing a fine headland, the captain asked me if I had seen that gigantic peak, pointing upward, as he spoke, to a mountain-top, rising out of such high clouds that I had not[45] noticed it. It was Mount Slamat, which attains an elevation of eleven thousand three hundred and thirty English feet above the sea—the highest peak but one among the many lofty mountains on Java, and, like most of them, an active volcano. The upper limit of vegetation on it is three thousand feet below its crest. The northern coast of Java is so low here that this mountain, instead of appearing to rise up, as it does, from the interior of the island, seemed close by the shore—an effect which occurs in viewing nearly all these lofty peaks while the observer is sailing on the Java Sea. M. Zollinger, a Swiss, says that at sunrise the tops of these loftiest peaks are brightened with the same rose-red glow that is seen on Monte Rosa and Mont Blanc when the sun is setting, and once or twice I thought I observed the same charming phenomenon. The lowlands and the lower declivities of all the mountains seen to-day are under the highest state of cultivation. Indeed, this part of Java may be correctly described as one magnificent garden, divided into small lots by lines of thick evergreens, and tall, feathery palm-trees. This afternoon we steamed into the open roadstead of Samarang during a heavy rain-squall; for though the “western monsoon,” or “rainy season,” is past, yet nearly every afternoon we have a heavy shower, and every one is speaking of the great damage it is likely to do to the rice and sugar crops which are just now ripening. The heavy rain-squall cleared away the thick haze that filled the sky, and the next morning I went on shore to see the city. A few miles directly back of it rises the sharp peak of Ungarung to a[46] height of some five thousand feet, its flanks highly cultivated in fields, and its upper region devoted to coffee-trees. Somewhat west of this, near the shore, I noticed a small naked cone, apparently of brown, volcanic ashes, and of so recent an origin that the vigorous vegetation of these tropical lands had not had time to spread over its surface. Back of Ungarung rise three lofty peaks in a line northwest and southeast. The northernmost and nearest is Mount Prau; the central, Mount Sumbing; and the southern one, Mount Sindoro.

Mount Prau receives its name from its shape, which has been fancied to be like that of a “prau,” or native boat, turned upside down. It was the supposed residence of the gods and demigods of the Javanese in ancient times, and now it abounds in the ruins of many temples; some partially covered with lava, showing that earthquakes and eruptions have done their share in causing this destruction. Many images of these ancient gods in metal have been found on this mountain. Ruins of enormous temples of those olden times are yet to be seen at Boro Bodo, in the province of Kedu, and at Brambanan, in the province of Matarem. At Boro Bodo a hill-top has been changed into a low pyramid, one hundred feet high, and having a base of six hundred and twenty feet on a side. Its sides are formed into five terraces, and the perpendicular faces of these terraces contain many niches, in each of which was once an image of Buddha. On the level area at the summit of the pyramid is a large dome-shaped building, surrounded by seventy-two[47] smaller ones of the same general form. According to the chronology of the Javanese, it was built in A. D. 1344.

At Brambanan are seen extensive ruins of several groups of temples, built of huge blocks of trachyte, carefully hewn and put together without any kind of cement. The most wonderful of those groups is that of “The Thousand Temples.” They actually number two hundred and ninety-six, and are situated on a low, rectangular terrace, measuring five hundred and forty by five hundred and ten feet, in five rows, one within another; a large central building, on a second terrace, overlooks the whole. This was elaborately ornamented, and, before it began to decay, probably formed, with those around it, one of the most imposing temples ever reared in all the East. According to the traditions of the Javanese, these buildings were erected between A. D. 1266 and 1296.

These structures were doubtless planned and superintended by natives of India. They were dedicated to Hindu worship, and here the Brahmins and Buddhists appear to have forgotten their bitter hostility, and in some cases to have even worshipped in the same temple. The Indian origin of these works is further proved by images of the zebu, or humped ox, which have been found here and elsewhere in Java, but it does not now exist, and probably never did, in any part of the archipelago.

As two Malays rowed me rapidly along in a narrow, canoe-like boat, I watched the clouds gather and embrace the high head of Mount Prau. Only[48] thin and fibrous cumuli covered the other lofty peaks, but a thick cloud wrapped itself around the crest of this mountain and many small ones gathered on its dark sides, which occasionally could be seen through the partings in its white fleecy shroud. The form of the whole was just that of the mountain, except at its top, where for a time the clouds rose like a gigantic, circular castle, the square openings in their dense mass exactly resembling the windows in such thick walls.

Eastward of Ungarung are seen the lofty summits of Merbabu and Mérapi, and east from the anchorage rises Mount Japara, forming, with the low lands at its feet, almost an island, on Java’s north coast.

Like Batavia, Samarang is situated on both sides of a small river, in a low morass. The river was much swollen by late rains, and in the short time I passed along it, I saw dead horses, cats, dogs, and monkeys borne on its muddy waters out to the bay, there perhaps to sink and be covered with layers of mud, and, if after long ages those strata should be elevated above the level of the sea and fall under a geologist’s eye, to become the subject of some prolix disquisition. This is, in fact, exactly the way that most of the land animals in the marine deposits of former times have come down to us—an extremely fragmentary history at best, yet sufficient to give us some idea of the strange denizens of the earth when few or none of the highest mountains had yet been formed.

WATERING THE STREETS, BATAVIA.

A TANDU.

Through this low morass they are now digging a canal out to the roads, so that the city may be approached from the anchorage by the canal and the[49] river. This canal is firmly walled in, as at Batavia. From the landing-place to the city proper the road was a stream of mud, and the houses are small and occupied only by Malays and the poorer classes of Chinese. In such streets two coolies are occasionally seen carrying one of the native belles in a tandu. The city itself is more compact than Batavia, and the shops are remarkably fine. It was pleasant to look again on some of the same engravings exposed for sale in our own shops. The finest building in the city, and the best of the kind that I have seen in the East, is a large one containing the custom and other bureaus. It is two stories high, and occupies three sides of a rectangle. I was told that they were fifteen years in building it, though in our country a private firm would have put it up in half as many months. There are several very fine hotels, and I saw one most richly furnished. Near the river stands a high watch-tower, where a constant lookout is kept for all ships approaching the road. From its top a wide view is obtained over the anchorage, the lowlands, and the city. Toward the interior rich fields are seen stretching away to the province of Kedu, “the garden of Java.” A railroad has been begun here, which will extend to Surakarta and Jokyokarta, on the east side of Mount Mérapi, and will open this rich region more fully to the world.[2]

The church of the city, which is chiefly sustained[50] here as elsewhere by the Dutch Government, is a large cathedral-like building, finished in the interior in an octagonal form. One side is occupied by the pulpit, another by the organ, and the others are for the congregation. At the time I entered, the pastor was lecturing in a conversational but earnest manner to some twenty Malays and Chinese, gathered around him. At the close of his exhortation he shook hands with each in the most cordial manner.

From this church I went to the Mohammedan mosque, a square pagoda-like structure, with three roofs, one above the other, and each being a little smaller than the one beneath it. It was Friday, the Mohammedan Sabbath, and large numbers were coming to pay their devotions to the false prophet, for his is the prevailing religion in this land. By the gate in the wall enclosing the mosque were a well and a huge stone tank, where all the faithful performed the most scrupulous ablutions before proceeding to repeat the required parts of the Koran. It was pleasant to see that at least they believed and practised the maxim that “cleanliness is next to godliness.” From the gate I walked up an inclined terrace to the large doorway, and at once saw, from the troubled expression on the faces of those who were kneeling on their straw mats outside the building, that I had committed some impropriety; and one answered my look of inquiry by pointing to my feet. I had forgotten that I was treading on “holy ground,” and had therefore neglected “to put off my shoes.” Opposite the entrance is usually a niche, and on one side of this a kind of throne, but what[51] was the origin or signification of either I never could learn, and believe the common people are as ignorant as myself in this respect. Their whole ceremony is to kneel, facing this niche, and repeat in a low, mumbling, nasal tone some parts of the writings of their prophet. Their priests are always Arabs, or their mestizo descendants, the same class of people as those who introduced this faith. Any one who has been to Mecca is regarded as next to a saint, and many go to Singapore or Penang, where they remain a year or two, and then return and declare they have seen the holy city. The first conversions to Mohammedanism in any part of the archipelago occurred at Achin, the western end of Sumatra, in 1204. It was not taught by pure Arabs, but by those descendants of Arabs and Persians who came from the Persian Gulf to Achin to trade. Thence it spread slowly eastward to Java, Celebes, and the Moluccas, and northward to the Philippines, where it was just gaining a foothold when the Spanish arrived. Under their rule it was soon eradicated, and supplanted by Catholic Christianity. Bali is almost the only island where the people can read and write their native tongue, and have not partially adopted this religion. On the continent it spread so rapidly that, within one hundred years after the Hegira, it was established from Persia to Spain; but, as its promulgators were not a maritime people, it did not reach Achin until five hundred and seventy-two years after the Hegira, and then its followers had so little of the fanaticism and energy of the Arabs, that it was more than three hundred years in reaching Celebes, and fully establishing[52] itself on that island. The Malay name for this religion is always “Islam.”

On our way back to the mail-boat we passed quite a fleet of fishing-boats, at the mouth of the river. They are generally made alike at both ends, and look like huge canoes. Some have high lantern-shaped houses perched on the stern, as if to make them more unsightly. Here they all have decks, but those at Batavia are merely open boats.

The next day we continued on our course to the eastward, around the promontory formed by Mount Japara, whose sides are so completely scored by deep ravines that little or none of the original surface of the mountain can be seen. Dr. Junghuhn, who has spent many years studying in detail the mountains of Java, finds that above a height of ten thousand feet but very few ravines exist. This height is the common cloud-level, and the rains that they pour out, of course, only affect the mountain-sides below that elevation, hence the flanks of a mountain are sometimes deeply scored while its top remains entire. The substances of which these great cones are chiefly composed are mostly volcanic ashes, sand, and small fragments of basalt or lava, just the kind of materials that swift torrents would rapidly carry away.

The volcanoes of Java are mostly in two lines: one, commencing near Cape St. Nicholas, its northwestern extremity, passes diagonally across the island to its southeastern headland on the Strait of Bali. The other is parallel to this, and extends from the middle of the Strait of Sunda to the south coast in the longitude of Cheribon. They stand along two immense[53] fissures in the earth’s crust, but the elevating power appears only to have found vent at certain separate points along these fissures. At these points sub-aërial eruptions of volcanic ashes, sand, and scoriæ have occurred, and occasionally streams of basaltic and trachytic lava have poured out, until no less than thirty-eight cones, some of immense size, have been formed on this island. Their peculiar character is, that they are distinct and separate mountains, and not peaks in a continuous chain.

The second characteristic of these mountains is the great quantity of sulphur they produce. White clouds of sulphurous acid gas continually wreath the crests of these high peaks, and betoken the unceasing activity within their gigantic masses. This gas is the one that is formed when a friction-match is lighted, and is, of course, extremely destructive to all animal and vegetable life.

At various localities in the vicinity of active volcanoes and in old craters this gas still escapes, and the famous “Guevo Upas” or Valley of Poison, on the flanks of the volcano Papandayang, is one of these areas of noxious vapors. It is situated at the head of a valley on the outer declivity of the mountain, five hundred or seven hundred feet below the rim of the old crater which contains the “Telaga Bodas” or White Lake. It is a small, bare place, of a pale gray or yellowish color, containing many crevices and openings from which carbonic acid gas pours out from time to time. Here both Mr. Reinwardt and Dr. Junghuhn saw a great number of dead animals of various kinds, as dogs, cats, tigers, rhinoceroses, squirrels, and other rodents,[54] many birds, and even snakes, who had lost their lives in this fatal place. Besides carbonic acid gas, sulphurous acid gas also escapes. This was the only gas present at the time of Dr. Junghuhn’s visit, and is probably the one that causes such certain destruction to all the animals that wander into this valley of death. The soft parts of these animals, as the skin, the muscles, and the hair or feathers, were found by both observers quite entire, while the bones had crumbled and mostly disappeared. The reason that so many dead animals are found on this spot, while none exist in the surrounding forests, is because beasts of prey not only cannot consume them, but even they lose their lives in the midst of these poisonous gases.

It was in such a place that the deadly upas was fabled to be found. The first account of this wonderful tree was given by Mr. N. P. Foersch, a surgeon in the service of the Dutch East India Company. His original article was published in the fourth volume of Pennant’s “Outlines of the Globe,” and repeated in the London Magazine for September, 1785. He states that he saw it himself, and describes it as “the sole individual of its species, standing alone, in a scene of solitary horror, on the middle of a naked, blasted plain, surrounded by a circle of mountains, the whole area of which is covered with the skeletons of birds, beasts, and men. Not a vestige of vegetable life is to be seen within the contaminated atmosphere, and even the fishes die in the water!” This, like most fables, has some foundation in fact; and a large forest-tree exists in Java, the Antiaris toxicaria of botanists, that has a poisonous sap. When its[55] bark is cut, a sap flows out much resembling milk, but thicker and more viscid. A native prepared some poison from this kind of sap for Dr. Horsfield. He mingled with it about half a drachm of the sap of the following vegetables—arum, kempferia galanga, anomum, a kind of zerumbed, common onion or garlic, and a drachm and a half of black pepper. This poison proved mortal to a dog in one hour; a mouse in ten minutes; a monkey in seven; a cat in fifteen; and a large buffalo died in two hours and ten minutes from the effects of it. A similar poison is prepared from the sap of the chetek, a climbing vine.

The deadly anchar is thus pictured in Darwin’s “Botanic Garden:”

All the north coast of Java is very low, often forming a morass, except here and there where some mountain sends out a spur to form a low headland. As we neared Madura this low land spread out beneath the shallow sea and we were obliged to keep[56] eight or ten miles from land. On both sides of the Madura Strait the land is also low, and on the left hand we passed many villages of native fishermen who tend bamboo weirs that extend out a long way from the shore.