Title: Audrey

or, Children of light

Author: Mrs. O. F. Walton

Release date: March 22, 2024 [eBook #73229]

Language: English

Original publication: London: The Religious Tract Society

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

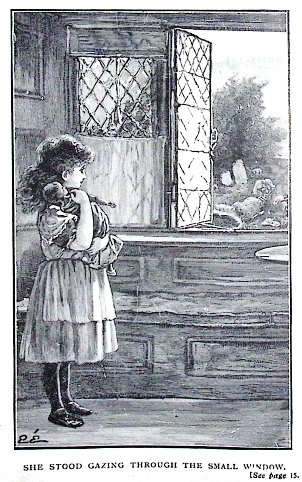

SHE STOOD GAZING THROUGH THE SMALL WINDOW.

OR

Children of Light

By

MRS. O. F. WALTON

AUTHOR OF

"CHRISTIE'S OLD ORGAN," "LITTLE DOT," "OLIVE'S STORY,"

"SAVED AT SEA," "A PEEP BEHIND THE SCENES," ETC.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 Bouverie Street and 65 St. Paul's Churchyard, E.C.

STORIES

BY

MRS. O. F. WALTON.

Christie's Old Organ.

A Peep Behind the Scenes.

Winter's Folly.

Olive's Story.

The Wonderful Door; or, Nemo.

My Little Corner.

My Mates and I.

Audrey; or, Children of Light.

Christie, the King's Servant.

Little Faith.

Nobody Loves Me.

Poppy's Presents.

Saved at Sea.

Taken or Left.

The Mysterious House.

Angel's Christmas.

Little Dot.

Doctor Forester.

The Lost Clue.

Scenes in the Life of an Old Arm-Chair.

Was I Right.

The Religious Tract Society

4, Bouverie Street, & 65, St. Paul's Churchyard

CONTENTS

CHAPTER II. A CURIOUS PLAYGROUND

CHAPTER VII. THE MYSTERIOUS LIGHT

CHAPTER VIII. CHILDREN OF LIGHT

CHAPTER IX. UNDER THE YEW TREE

Audrey

OR

CHILDREN OF LIGHT

The Old House

"NOW, Audrey!"

"Yes, Aunt Cordelia?"

"That's the third clean pinafore that you've had this week," said Aunt Cordelia severely, "and it's only Thursday. Now, Audrey!"

And when Aunt Cordelia said, "Now, Audrey!" The little girl who was addressed knew that something was seriously amiss.

She was a pretty little girl, with fair hair and brown eyes, and the warm summer sun had tanned her as brown as the nuts in the window of Aunt Cordelia's shop. She stood in the corner of the little back parlour looking ruefully at her pinafore, which was almost as black as if she had sent it up the chimney for five minutes' change of air.

"Now, Audrey!" repeated Aunt Cordelia more solemnly than before.

The poor child could not bear up against this last terrible appeal, and bursting into tears, she sobbed—

"I wish there weren't such things as pinafores; I do wish there weren't!"

"No such things as pinafores?" said Aunt Cordelia. "Why, what would become of careless little girls' frocks, if there were no nice pinafores to cover them, I should like to know?"

"I hate pinafores," sobbed the child, taking no notice of her aunt's words; "I wish the Queen would say nobody was ever to wear them again!"

"For shame, Audrey," said Aunt Cordelia, "you should never say you hate anything; it's very wicked indeed! Least of all you should never hate pinafores, that keep you nice and clean and tidy."

"But that's just what they don't do," said Audrey. "They will get black and grimy. I can't ever have a bit of fun because of them."

Then, as she dried her tears, a bright thought struck her, and she said, "Couldn't I have a black pinafore, Aunt Cordelia, and then it wouldn't show the dirt, would it now?"

"Well," said her aunt, laughing in spite of herself, "it will come to that one of these days, I expect. Now go and get a clean pinafore at once; and remember that's four this week," she called after her, as the little girl ran upstairs.

It was a quaint old house in which Audrey and her aunt, Miss Palmer, lived. Miss Palmer loved to boast about it to the customers who came to the shop. It was three hundred years old, she told them, and the wainscot was real oak, and the bannisters on the stairs were carved, and there were curious old cupboards with black oak doors, and there was a chimney so wide that none of the sweep's brushes were large enough to sweep it.

But though Miss Palmer was very proud of her old house, which had been in the family for so many years that the family had quite lost count of their number, yet it caused her a great deal of worry and anxiety. There never was such a place for dust as that old house; it collected in every corner, it lay upon the window-sills, and it settled upon the bright dish-covers and pewter jugs in the kitchen.

With this dust Miss Palmer was always waging war. From morning till night—week in and week out—she fought perseveringly with the ever-gathering dust, and tried to make her house as prim and as neat as her tidy soul longed to see it. But just as Audrey's pinafores would get black, so the old house would get dusty, and the two together brought many a line of care into Miss Palmer's forehead.

Audrey had lived with her aunt since she was a fortnight old. Her father was a baker in a town two hundred miles away. She had never seen him, and he had never seen her since her aunt had carried her off, a tiny, sickly baby, nearly eight years ago. Audrey's mother had died soon after she was born, and her father had sent a piteous letter to his sister Cordelia, telling her he did not know what would become of him and of his nine motherless children, now Alice was gone.

On receipt of that letter, Miss Palmer had at once put up her shop-shutters, packed a small carpetbag, locked up her old house, and had set off for the town, two hundred miles away, where her brother lived. She had only remained one night, for her business could not be neglected; but she had brought the baby back with her, having adopted it as her own.

A curious little thing Audrey looked, as Miss Palmer rolled her in a warm shawl before starting on her homeward journey, for even then she had a quantity of hair, which made her little face look, if possible, smaller and more fragile. But Miss Palmer, although she was an old maid, had had some experience with babies, having at one time been nurse in a respectable family. So the little one had every care and attention bestowed upon her, and had grown up a healthy, hearty child, always untidy, and never clean for half an hour together, but yet with cheeks like roses, and as plump and strong as even Miss Palmer's heart could wish.

She was very fond of the little girl, although she did not often show it. And though she sometimes rebuked her and said, "Now, Audrey!" in a voice which made her tremble, she was not unkind to her, and did not mean to be harsh.

"It was all for Audrey's good," she said to herself.

Thus Audrey, in spite of her pinafores, did not lead at all an unhappy life. She went to a private school in the next street, where an old woman tried to keep order amongst thirty or forty children, and, at such times as she succeeded in making her voice heard, to teach them reading, writing, and a few sums.

Audrey was a quick child, and learnt well all that it was possible to learn in such a place. She could read easily and distinctly, and would have been praised for her writing, had she not covered both herself and her copybook with blots. But the sums were her delight, and she was fast coming to the end of all the arithmetic which Miss Tapper was able to impart.

But there was one thing which Audrey had never been taught, either at school or at home, and that was the power of the love of Jesus. Her aunt made her say a prayer night and morning, but she never talked to her of the dear Lord who died instead of her, and who longed for her to be His loving and obedient child. If Audrey was good she was praised, if she was naughty she was blamed; but no one taught her who alone could make her good, or could teach her not to be naughty.

She was like a little ship beaten about by the waves, driven first one way and then another by the storm of temper on the wind of wilfulness. She had not yet learnt whose hand must be on the helm if she was to sail onward, and to reach the harbour in safety.

When Audrey appeared downstairs in her clean pinafore, she stood at the shop-door watching her aunt, who was weighing out a pound of tea for a customer—a stout, rosy woman with a basket on her arm.

"Aunt Cordelia," began the child; but the customer's tongue was going so fast that her aunt did not hear her.

"Aunt Cordelia," said the child again, as the woman, having finished her long story, took up her parcels, put them in her basket, and departed.

"Well, Audrey?"

"May I go out and play, Aunt Cordelia?"

"Go out and play? No, indeed!" said her aunt indignantly. "Go out and dirty another clean pinafore? Not if I know it! Take your doll and play with it in the window-seat, and keep yourself clean for five minutes, if you can do such a thing."

Audrey obeyed without a word, for she had been taught to do as she was told. She went into the parlour and took up her poor old wooden doll Olivia, who had lost all the colour from her cheeks and all the hair from her head. Audrey did not play with her; she stood with her in her arms gazing through the small square diamond-paned window into her playground outside.

A Curious Playground

AUDREY stood a long time looking out of that window. It opened like a door, and the ground outside was only two feet below it. Audrey could get into her playground in a moment by jumping through the window; and oh, how she longed to be there!

It was a strange place in which to play, for it was a very old and long-disused churchyard. A great tombstone stood close to the window, and shut out much of Audrey's view. A green, moss-grown, dirty old tombstone it looked; but it was only like all the other stones in that melancholy and deserted place.

They had all been put up to the memory of people long since dead—long since forgotten. No loving hands ever brought flowers or wreaths to lay on those old graves, for the ones who loved them and cared for them had themselves been long since numbered with the dead, and were lying in their own quiet resting-places.

Behind the old stones, so black with the smoke of years, so discoloured and weather-stained by the dews of many a summer and the rains of many a winter, Audrey could see the ancient church, which was fully as dismal and deserted as were the graves amongst which it stood. It had been built eight hundred years ago, and at one time large and fashionable congregations had no doubt attended it. Now they had all passed away, and with them had departed the usefulness of the old church. It was shut up and neglected, and was left to the spiders and other creeping things, which had made a happy home there.

That old churchyard was the happiest place in the world to Audrey; she had loved it ever since she was a little child. She knew every corner of it; she felt as if it belonged to her, and as if no one else had a right to be there—no one except little Stephen.

She shared everything with him, and she loved him as if he were her brother. There he was now under the lilac tree, sitting patiently waiting for her to come; and Aunt Cordelia would not let her go out to him. How disappointed Stephen would be! A tear trickled down Audrey's cheek at the thought, and fell on the top of poor Miss Olivia's head.

"What—Audrey crying!" said her aunt, coming briskly into the room. "What is it all about?"

Audrey wiped the tear off Miss Olivia's hair, and made no answer.

"What?" said her aunt. "Because I said you were not to go out? Now, Audrey!"

"Aunt, it isn't that—it isn't that," sobbed Audrey. "It's because Stephen will be disappointed, and it's his birthday. He is five years old to-day, is Stephen."

"Oh, it's his birthday, is it?" said her aunt, relenting. "Well, I did not know that. I suppose I must let you go; but mind your pinafore—that's all!"

"Thank you, aunty!" said Audrey, her face filling with sunshine in a moment, as she climbed on a chair, crept through the small square casement, and jumped to the ground outside.

The little boy gave a cry of joy as he saw her, and came slowly forward to meet her. He could not come quickly, for Stephen was a crippled child, and had never known what it was to run or to jump like other children.

When he was a baby, he was so small that he was quite a curiosity; and the neighbours declared that such a child had never been seen before. But his father had nursed him and watched him as a gardener tends and watches a little sickly plant of which he is very fond. And Stephen had learnt to walk when he was three years old, and could now creep about the churchyard and play quietly with Audrey amongst the old graves. He was his father's only treasure, for Stephen's mother had died when he was a baby; and he loved the little lad with all the love of his heart.

Stephen's father was a cobbler, and his window also opened on the churchyard; and there he sat mending his shoes, and now and then glancing at the children at their play. He was never happy when Stephen was out of his sight, for the child's back was deformed and crooked, and his legs were weak and unsound, and his father always feared some evil might befall him.

And this was Stephen's birthday, and he was five years old.

"Oh, Audrey, I'm glad you've come!" he cried. "I've waited and waited till school should leave, and it did seem so long! I've been looking in at the window of the church and, Audrey, do you know, there's a bird building his nest inside, just over the pulpit. Come and look!"

The two children went round to the other side of the church, and climbing on the top of a large flat tombstone they peered in through the yellow and discoloured panes of the window. What a strange place it was!

The high, rotten old pulpit looked as if it must soon fall; the narrow brown pews, with their high backs, and the large square pews, where the grand people once sat, were all alike gradually slipping into crooked positions, and leaning over on the uneven stone floor.

Audrey and Stephen loved to look into that old church; they peeped in at all times of the day—in the morning, when the church looked bright and almost cheerful, as the sunbeams danced on the old pillars and streamed down the deserted aisles; in the afternoon, when the long shadows fell across the chancel, and the coloured window at the western end threw blue and red lights on the font and on the mouldy pavement below; and again in the evening, just before going to bed, when the old church was weird and ghostly, and the stone figures on the tombs in the chancel looked to the children as if they were alive, and might stand up and call to them as they watched.

Stephen would tremble at such times and cling fast to Audrey; but she was never afraid of the old church by night or by day, and she would have slept as soundly and as happily in one of the square pews as she did in her own bed at home.

This afternoon the church looked very bright, and the sunshine showed the dust and cobwebs which clung to the roof, as Stephen pointed out the nest he had discovered.

It was a swallow's nest, and presently they saw the swallows themselves flying in and out of a broken pane in the east window, and adding finishing touches to their neat little nest.

"Isn't it lovely?" said Audrey. "We will come every day to watch them, and we shall see if any little birds come in the nest."

Then she lifted Stephen down from the stone, and they wandered together through the churchyard. What a forlorn place it was, full of long grass and weeds! All the grave-stones seemed to have fallen out of place, just as all the pews had done. Some were leaning one way and some another.

The names on most of them had long since been worn away, but others were still quite distinct; and Audrey loved to spell them out and to calculate how long it was since those buried in the old graves had died.

In one corner of the churchyard was a swing, which Stephen's father had put up for them; and just underneath the wall of the church was a hutch, where Stephen's white rabbit lived.

It was very, very seldom that any one visited the old church, except the deaf old woman who had the key of the gate; and she only came when some stranger, passing through the old city, happened to discover the whereabouts of the ancient building, and made it worth her while to unlock the door.

A Pair of Robins

THERE were three houses the windows of which looked into the old churchyard. Audrey and her aunt lived in one, Stephen and his father in another, but the third had long been empty. The windows were covered with dust, and the spiders and beetles had taken possession of it, just as they had done of the old church. However, to the children's astonishment, when they came back from watching the swallows on Stephen's birthday, they saw that the window of the empty house had been thrown wide open.

"Who can be inside? Dare you go and look, Audrey?"

"Yes, I'm not afraid," said the child; and leaving Stephen sitting on a flat tombstone, she went up to the window and peeped in.

"Who did you see?" said the little boy, when she came back.

"I saw nobody but a mouse," said Audrey, "a little grey mouse, sitting in the corner and eating a bit of bread; but the floor is all washed and clean, and the cobwebs are gone, and I saw a letter lying on the window-sill."

"Who can be there?" said Stephen. "We must watch and see."

They had not long to wait, for that very afternoon a man's face appeared at the window. He was a tall man, dressed in black, quite a gentleman, Audrey thought him. He was an old man, for his hair was very white, and he stooped a little; but he was very active in spite of his age, and his bright dark eyes seemed to be taking in all he saw at a glance. He only looked out for a minute, but as Audrey and Stephen crept nearer, they saw that he was very busy. He put down a bright-coloured carpet on the floor, and brought in a large, leather easy-chair and a little round table, and placed these close to the window, and he hung a canary in its cage just over the casement. Then he nailed up white muslin curtains, and Audrey and Stephen thought the old house looked very pretty, and were glad that some one had come to live in it.

"Will he live by himself, Stephen, do you think?" said Audrey.

But before Stephen had time to answer, Aunt Cordelia's voice was heard calling—

"Now, Audrey, tea-time! What about your pinafore?"

The pinafore was quite clean this time, and Audrey went in with a light heart; and as a reward for keeping clear of dirt, she was allowed to play with Stephen again after tea. She was eager to get out, that she might catch another glimpse of her old man, as she called him; but she found the shutters closed, and she and Stephen could only watch the flickering of the bright light inside.

"He's got a fire," said Stephen; "look at the smoke coming up out of the chimney."

"And he's got a lamp, too," said Audrey. "Look, you can see it through the crack in this shutter."

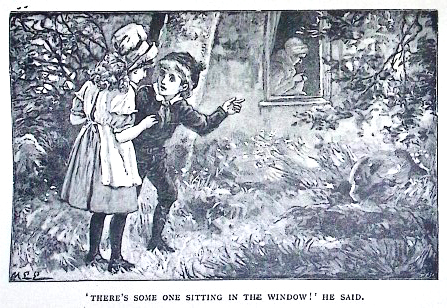

"THERE'S SOME ONE SITTING IN THE WINDOW!" HE SAID.

"Listen—" said Stephen. "What is he doing?"

The sound of hammering came again and again from the room, the window of which looked into the churchyard.

"He's putting up his pictures," said Audrey. "How pretty it will look in the morning!"

There was, however, no time for her to peep at it before school; but when she came home at twelve o'clock, she found Stephen full of excitement.

"There's some one sitting in the window, and I can't make out who it is," he said. "I can see something white, and it moves, but it isn't the old man's head; it's too white for that."

"Why don't you go and look?" said Audrey.

"I daren't," said Stephen; "I waited for you, Audrey."

The little girl went on tip-toe and peeped in.

"It's an old woman, Stephen," she reported, when she came back to him. "Such a pretty old woman, and she is sitting in that arm-chair, knitting, and she is smiling to herself as she knits. I wonder what she is thinking about that makes her smile. Come and look, Stephie."

Very, very quietly the two children crept to the window and peeped in.

"Is any one there?" said a pleasant voice.

But the children were so startled when she spoke, that they ran away and hid behind the bushes, and it was some time before they dared to venture again near the window.

"Is any one there?" said the kindly voice of the old woman. "I am sure I hear some little feet outside."

"Yes, ma'am," said Audrey; "it's me and Stephen."

"You and Stephen, is it?" said the old woman. "And what are you and Stephen like?"

Instead of answering, the two children put their heads in at the window.

How pretty it was inside that room! The walls were covered with pictures and photographs and coloured texts, a fire was burning in the grate, and in front of it lay a tortoiseshell cat fast asleep; the chimney-piece was adorned with stuffed birds and vases filled with grass, and on the round table was a large bunch of wallflowers, which filled the whole room with sweetness.

"Now then, what are you and Stephen like?" said the old woman, smiling again.

"Can't you see us, ma'am?" said Audrey.

"No, I can't see you," said the old woman quietly; "I'm blind."

"Oh dear, what a pity!" said little Stephen.

"No, not a pity," said the old woman, "not a pity, because the good Lord sees best; we must never say it's a pity."

"Can't you see anything?" said Audrey.

"Not a glimmer," said the old woman, "it is all dark now; but I can feel the warm sunshine, thank God, and I can smell these sweet flowers, and I can hear your bonny voices."

"I'm so sorry for you," said little Stephen, "so very, very sorry!"

"God bless you, my dear child!" said the old woman, and a tear rolled down her cheek and fell upon her knitting. "And now tell me who you are, and what you are like."

"I'm Audrey, please, ma'am," said the little girl, "and he's Stephen, and he's as good as my brother, only he isn't my brother—are you, Stephie? And he's got shaky legs, and he can't walk far; but he plays with me among the graves—don't you, Stephie?"

"And now, Stephen, what is Audrey like?" asked the old woman.

"She's got yellow hair," said little Stephen, "and she's nice!" And then he turned shy, and would say no more.

"Now," said the old woman, "you must often come and talk to me as I sit in my window, and you must tell me all you are doing. I know what to call you, but you must know what to call me. My name is Mrs. Robin, and you shall call me Granny Robin. I have some little grandchildren, but they live over the sea in America, so you must take their place."

"Thank you, ma'am," said Audrey. "Thank you, Granny Robin, I mean," she added, laughing.

That was the beginning of a great friendship between the two children and the new-comers. Mr. Robin had been a schoolmaster, and for many years had worked hard and lived carefully, so that in his old age he had saved enough to retire, and to take the old house, and make a comfortable home in it for himself and for his wife.

The rent was low, for few liked to take a house the windows of which looked out upon graves, but the schoolmaster made no objection to the churchyard. There were green trees in it, which would remind him of the pretty village where he had lived so long, and he did not mind the graves: he would soon be lying in one himself, and it was well to be reminded of it, he said. And as for his wife, she could not see the graves, but she could hear the twittering of the swallows that built under the eaves of the deserted church, and she could smell the lilac on the bush close to her window, and it would be a quiet and pleasant home for her until the Lord called her.

The only fear that the schoolmaster had had in choosing his new home had been lest his wife would miss the company to which she had been accustomed in the village where they were so well known. She had a large and loving heart, and there were very few in the village who did not come to her for sympathy both in joy and in sorrow. She knew the history of every one, and, one by one, they dropped in to tell her all that was going on in the village—countless little events which would have been of small interest to others, but which were of great interest to Mrs. Robin.

She sat at her knitting when the neighbours had gone, thinking over what she had heard, and carrying the sorrows of others, as she ever carried her own, to the throne of grace.

But Mr. Robin need not have feared for his wife. She had a happy, contented spirit. It is true she had felt sad at leaving her happy country home, but new interests were already springing up in the one to which she felt the Lord had brought her. Little Stephen with his shaky legs, and Audrey with her motherly care over him, had already won Granny Robin's heart, and the children from that time spent a very large part of their playtime in talking to their new friend, as she sat at her window knitting.

Forgotten Graves

ONE day, as the children stood by Granny Robin's side, they talked about the old graves in the churchyard. It was a bright spring evening, and the golden sunshine was streaming through the branches of the ragged, untidy trees, which nearly hid the old church from sight. Granny Robin could not see the sunshine, but Stephen could see it, and he told her about it, and said he was sure the swallows liked it as much as he did, for they were flying round and round in long circles, twittering as they flew.

It had become quite a regular thing for Stephen to tell the old woman all he saw, and he loved to hear her say that she was now no longer blind, for she had found a pair of new eyes.

One day she called him her "little Hobab," and when he laughed and asked her why she gave him such a funny name, she said it was because, long, long ago, when Moses was travelling through the wilderness with the children of Israel, he said to his brother-in-law, Hobab:

"Thou mayest be to us instead of eyes." And she said that God had sent little Stephen to her, in her old age, that he might be instead of eyes to her.

"I am so sorry for those poor graves," said Stephen on that spring evening, when he had been telling Granny Robin about the sunlight and the swallows.

"Why are you sorry for them?" asked the old woman.

"They look so sad and lonely," said Stephen.

"What are they like?" asked Granny Robin.

"Oh, all green and dirty," said Audrey, "and the trees are fallen against them, and when the wind blows, their branches go beat, beat, beat, against the stones, till Aunt Cordelia says she can't bear to hear them when she's in bed at night."

"Does nobody bring flowers to put on them?" asked the old woman.

"No, never," said little Stephen.

"Nor wreaths?"

"Oh no, never."

"Does no one ever come to look at them?"

"No, never once, Granny Robin," said Audrey.

"And they do look so sad," said Stephen.

"Yes," said the little girl, "I went with Aunt Cordelia to the cemetery one day, and it's lovely there, just like a garden; the flowers are beautiful, and there were heaps of people watering graves, and raking them and pulling off the dead flowers, and some of them were crying."

"But no one cries over these graves," said Granny Robin.

"No, not one person," said Stephen. "My father says all the people that loved them are dead and buried themselves."

"Poor forgotten graves!" said the old woman. "And my grave will be like one of them in fifty years' time—a forgotten grave."

She was talking to herself more than to the children, but little Stephen answered her.

"Will no one remember it, Granny Robin?"

"Yes, some one will," she said brightly; "my Lord will never forget. He will know where it is, and whose body lies inside, and it will be safe in His care till the great Resurrection Day."

"Will the angels know too?" said Stephen.

"I think they will," she said.

"Do they know who are buried in these poor old graves?" asked the child.

"Yes, I believe they do," said the old woman.

"In every one?"

"Yes, in every one."

"Even when the names are worn off?" asked the little boy.

"Yes, I believe they do," said Granny Robin softly.

"I'm so glad," said Stephen. "Then maybe the angels do come and look at them sometimes. I expect they come at night, when Audrey and me are in bed. I'll get out and look some night, Granny Robin; maybe I shall see them; my window looks out this way."

The forgotten graves weighed heavily on Stephen's mind after this talk with the old woman. When Audrey was at school, he used to wander up and down amongst them, pitying them with all the pity of his loving little heart. And he would try to put aside some of the branches that kept blowing against the stones, and which were so fast wearing them away, and he would pull up some of the long grass, which in some places hid the stones completely from sight.

"Audrey—" he said one afternoon when Aunt Cordelia had given her leave to have a long play with him, "Audrey, couldn't we make these poor old graves look nice?"

"We couldn't do them all," said Audrey. "Why, Stephen, there must be a hundred or more!"

"No, we couldn't do them all; we might begin with two—one for you and one for me, Audrey."

"Well, let's choose," said the little girl. "We'll walk round and have a look at them all."

"We'll have one with some reading on," said Stephen, "and then we shall know what to call it."

"Here's a poor old stone against the wall," said Audrey; "I'll read you what it says."

"'SACRED

TO THE MEMORY OF

CHARLES HOLDEN,

WHOSE REMAINS LIE

HERE INTERRED.

HE WAS

OF HUMANE DISPOSITION,

A SOCIAL COMPANION,

A FAITHFUL SERVANT,

AND A SINCERE FRIEND.

HE DEPARTED THIS LIFE

THE 23RD OF DECEMBER, 1781.

AGED 38.'"

"I don't like that one bit," said Stephen; "it has got too many hard words in it."

"Well, here's another."

"'IN MEMORY

OF

JOHN POWELL.

DIED IN 1781.

ALSO MARY, RELICT OF

THE ABOVE, WHO DIED

JANUARY 20, 1827,

AGED 87.

ALSO TWO GRANDCHILDREN,

WHO DIED YOUNG.'"

"That's much nicer," said Stephen. "I like those two grandchildren who died young. I wonder how old they were; do you think they were as old as you and me, Audrey?"

"I don't know," said Audrey; "it doesn't say, and it doesn't tell if they were girls or boys."

"Never mind," said Stephen, "we can guess. I think one was a girl and one was a boy. And are their bodies really down under here, Audrey?"

"Yes, what there is of them," said Audrey; "Aunt Cordelia says they turn to dust."

"Oh," said little Stephen, in an awestruck voice, "I wish we could see the dust of the two grandchildren who died young! I'll have this grave, Audrey, and take care of them. Is there any one else inside it?"

"Yes, there's John Powell, died in 1781; also Mary, relict of the above," read Audrey.

"What does relict mean?" asked Stephen.

"Aunt Cordelia has a relict," said Audrey, "and she keeps it in a box."

"Is it a woman?" asked Stephen.

"No, it's a bit of grey hair; she cut it off her mother's head when she was dead, and she says it's a relict. I don't know what she means, but she keeps it locked up ever so safe."

"I hope John Powell didn't lock Mary up," said Stephen.

"She must have got out if he did," said Audrey, "for she lived a long, long, long time after him. He died in 1781, and she didn't die not until 1827; let me count up, it's quite a long sum. Why, it's forty-six years, Stephen!"

"Oh dear," said Stephen, "that is a long time! Let's tell Granny Robin about it, and I'll ask her if she would have that one if she was me."

Granny Robin quite approved of their plan, and of Stephen's choice of the two grandchildren who died young. She told them that relict meant the wife left behind, and tears came into the old woman's sightless eyes, as she sat at her knitting and thought of the poor widow left behind for forty-six years. She pictured her living on and on, year after year, coming doubtless often to that grave to look at the place where her John lay, but still kept waiting for forty-six years for the glad day when she should see him again.

Granny Robin thought it must have seemed a longs dreary time to poor Mary. And then, maybe, those two grandchildren were a cheer and comfort to her. Yet they were taken, they died young, but old Mary still lived on. Till at last, on that winter's day, January 20, 1827, the call, so long waited for, came, and she and her John were together again. Then, too, the old grandmother saw once more the faces of the two grandchildren who died young.

So Granny Robin mused as she sat at her work; and she wondered whether the waiting-time seemed as long to old Mary, as she looked back to it from the brightness and the joy of the Home above, or did it seem short as a troubled dream seems when we wake from sleep?

"Our light affliction, which is but for a moment."

So long, when we are passing through it; but for a moment, as we look back to it from God's eternity.

The Collection

STEPHEN had now quite settled upon the grave which he was to make his especial care, but he promised not to begin his work until Audrey had chosen hers. She was very undecided for a long time, but at length she chose one, sacred to the memory of another John.

"It will be nice for us each to have a John," she said.

"'BENEATH IS DEPOSITED

ALL THAT WAS MORTAL OF

JOHN HUTTON,

WHO DIED THE 12TH OF APRIL, 1793,

AGED 47.'"

"'Go home, dear wife, and shed no tear,

I must ly here till Christ appear;

And at His coming hope to have

A joyful rising from the grave.'"

"How do you spell lie, Granny Robin?" said Audrey, when she had finished reading it to her.

"L-i-e," said the old woman.

"Well, it's l-y here," said the child.

"That's the old-fashioned way," said Granny Robin.

"Well, now, we'll set to work," said Audrey; "we must wash them first, Stephen. Do you think your father would give us some water in a basin? I daren't ask Aunt Cordelia; she would say I should dirty my pinafore."

"If Stephen's father will give him a basin, I will give you one, Audrey," said Granny Robin.

"And I'll get you both an old sponge," said Mr. Robin, who was smoking his pipe in the window.

What a scrubbing went on after that! Stephen's father, who was always pleased to do anything his poor little boy asked him, brought out soap and two scrubbing brushes, and the children worked away diligently for more than an hour.

At the end of it, they were far from satisfied with their work.

"The two grandchildren who died young won't come clean, Granny Robin," said little Stephen mournfully.

"They're quite as nice as my John is," said Audrey. "Anyhow," she added more hopefully, "they're a deal cleaner than they were before. Now what's the next thing to be done?"

"We must cut the long grass behind them," said Stephen, "and then we must dig up the grave in front of the stone. I'll get father's big scissors and my little spade."

Father's big scissors cut the grass down very successfully, but Stephen's little spade refused to go into the hard ground. It had been trodden underfoot for many years, and it lay hard and dry and stony over the heads of the two grandchildren who died young.

But at this point old Mr. Robin came to the rescue. He brought a large spade out of his house and dug the grave over for little Stephen, and then, after he had rested a little, he did the same for Audrey's John, as she called him.

AT THIS POINT OLD MR. ROBIN CAME TO THE RESCUE.

"Wouldn't the wife be pleased if she saw we were doing it?" she said.

"What wife?" asked Stephen.

"This wife it says about in the hymn—"

"'Go home, dear wife, and shed no tear.'"

"I wonder if she did shed any," said Stephen.

"I expect she did," said Audrey; "I wonder what has become of her. Do you think she will ever come to see how nice we have made her John's grave, Granny Robin?"

"When did John die?" asked the old woman.

"In 1793," said Audrey.

"1793—a hundred years ago!" said Granny Robin. "Why, Audrey, the wife must have been dead long since!"

"And she never sheds any more tears now," said Stephen, "because she's in heaven."

"I hope so," said Granny Robin.

"Does everybody go to heaven when they die?" asked the child.

"No, my dear boy, not every one."

"Shall I go there when I die, Granny Robin? I do hope I shall," said little Stephen.

"I hope so too, my little man. The Lord wants to have you there," she said.

"What is it like, Granny Robin?" asked Stephen.

"We know very little about it, Stephen," said the old woman, "but we can't help thinking about it, and dreaming about it; and I always think of it as a beautiful garden, where the King walks with His friends. I may be wrong, Stephie, but that's what I always see in my mind when I think of it."

"The two grandchildren who died young will like being in the garden," said Stephen. "Do you think they're glad they died young, Granny Robin?"

"I think they are, Stephie," she said; "they did not have to tread far on life's rough ways; their little feet reached the garden long, long years ago."

"And there will be soft grass for them to walk on there," said Stephen, "Maybe I'll see them when I get there. Do you think I'll know them, Granny Robin?"

"I think you will, Stephie; I feel almost sure you will," she said.

"If I see any very dear little children playing under the trees of the garden," said little Stephen, "I might ask them, 'Are you the two grandchildren who died young?' And then they could tell me, couldn't they?"

"God bless you, my dear little lad!" was all the answer Granny Robin gave him.

The next day was Saturday, which was market-day in the old city. It was Audrey's holiday, and the happiest day in the week to Stephen and to herself. Aunt Cordelia was always busy cleaning from morning till night, and sent Audrey into the churchyard, that she might be out of the way of her sweeping-brush and dust-pan.

On this particular Saturday, Audrey and Stephen were whispering together under the lilac tree for a very long time; and about ten minutes afterwards, Mr. Robin, who was smoking his pipe in the window, saw a sight which made him laugh so much, that for a long time he could not tell Granny Robin at what he was laughing.

As he looked across the churchyard, he saw Audrey and Stephen coming towards the window arm in arm. Stephen was dressed in the tall hat which his father wore when he went to chapel on Sunday night, and in an old greatcoat, which was fastened round his neck, and dragged like a long tail behind him, whilst the sleeves were turned up so far that there was far more lining than cloth to be seen. Audrey had a red shawl thrown over her head, and her pinafore was tied round her waist like an apron. Each child carried a tin, on which old Mr. Robin distinctly read the words "Colman's Mustard."

As soon as they came up to the window both children made a low bow, but neither of them spoke.

"Well, what do you want?" said Mr. Robin, as gravely as he could. "Are you going round begging this fine spring morning?"

"Please, sir, we're making a collection," said Audrey.

"Yes, it's a collection," echoed little Stephen.

"What's it for, my little dears?" said Granny Robin, as she laid down her knitting, and began to put her hand into her pocket.

"Mine's for the TWO GRANDCHILDREN WHO DIED YOUNG," said little Stephen.

"And mine's for ALL THAT WAS MORTAL OF JOHN HUTTON," said Audrey.

"Oh, I see," said the old woman; "you want to go and get some roots in the market for your graves—is that it?"

That is it, and Granny Robin's hand must go in the pocket again. It goes in empty, but it comes out well filled. Three pennies for the grandchildren go into Stephen's tin, and three more for John Hutton go rattling to the bottom of Audrey's.

Now it is Mr. Robin's turn, and his pocket seems to be full of pennies too; and the tins make such a noise when they are shaken that Granny Robin pretends to stop her ears, that she may not hear the din.

Then the two children go on to the next window, where Stephen's father sits busy with his work. But the boot is laid down, that the collection may have due attention, and it is silver this time which goes into the tins, two quiet silver threepences, which make no noise, but which the two children admire greatly as they slip in amongst the copper.

"Now for Aunt Cordelia," says Audrey. "You must go first, Stephen; she won't say 'No' to you."

Aunt Cordelia makes a dive at Audrey's pinafore, the bottom of which she declares is collecting all the dust in the churchyard, but she is not angry when she hears why they have come. And when Stephen pleads for something for his two grandchildren, she goes to her till and brings out several pence for each tin, and willingly gives Audrey leave to go that afternoon to the market with Mr. Robin to make her purchases.

Angels' Visits

WHAT an important little person Audrey was, as she set out to do her marketing that afternoon! Stephen was not able to go, for the crowd in the market-place was so great on Saturday afternoon, that his father was afraid he might get hurt. So Audrey and the old man were to do the business between them; Audrey carried the money, and Mr. Robin brought a basket for the flowers.

The market was an open one, and was held in a wide street in the centre of the city. There were stalls for all manner of articles in that market—toys, and kettles, and tins, and slippers, and caps, and all sorts of other things; but the flower-stalls were by far the prettiest, Audrey thought, and these were placed by themselves, all down one side of that long street. The little girl went from stall to stall, admiring all the flowers, and wondering which Stephen would like best.

It was well that Mr. Robin was there to help her to decide, or Stephen's patience would have been exhausted long before she reached home. He was sitting at the window looking out for them the whole time they were away. And oh, what excitement there was when the basket was unpacked, and the contents spread out on Granny Robin's round table!

Then, when all had been duly admired, they were divided into two heaps. One heap was for Stephen's grandchildren, as he called them, and the other was for Audrey's John. There were a yellow and a purple pansy, a red and a white daisy, a yellow musk, a sweet william, a primrose, a violet, a lily of the valley, and two or three beautiful roots of forget-me-nots in each heap.

Then the children went out in great glee to plant their flowers. But what was their surprise to find that, whilst Audrey had been in the market, Stephen's father had been very busy bringing bucketfuls of earth from the garden of a friend of his who lived not far away, and making the two graves as tidy and neat as the daintiest flower-garden. It was easy to plant the roots after this; and oh, how delighted the children were, as they saw the graves growing more and more pretty every moment!

And that evening there was a grand procession. Every one was invited to see and to admire their work. Mr. Robin walked first, with Granny Robin on his arm. The old woman had insisted on climbing out of her window to visit the graves. If she could not see them, she could feel them, she said, and she could smell the flowers.

As for Stephen's father, he had done very little shoe-mending all day, for every few minutes he had come hopping out of his window to see how they were getting on. Yet, although he had helped to choose the place of each plant, the little cobbler still came behind Mr. and Mrs. Robin in the procession which was about to visit the graves, and when he arrived there, he seemed as much surprised and interested as if he had never seen them before.

The difficulty was to get Aunt Cordelia there. Not that she was unwilling to come, for she was anxious to see Granny Robin, of whom the children talked so much; but the trouble was this, she could not make up her mind to climb out of the window. It took Audrey and Stephen nearly an hour to coax her to make the attempt. She even wanted to go down the street to the house of the deaf old woman, that she might get the key of the churchyard gate.

It was only when Audrey told her that if she did so, it would spoil everything—for the old woman would be sure to come with her, and would perhaps be angry with them for doing it without her leave—it was only then that Aunt Cordelia consented to try the undignified descent.

But it was a terribly serious business. A stool was placed outside the window, and Mr. Robin and the cobbler came forward to give her a hand, whilst she gathered her petticoats round her, and at length, slowly and gracefully, managed to alight on the churchyard grass. Then the procession began, and the children's work was duly admired by the whole party. They all had some remark to make about it, and these remarks were very different from each other.

Aunt Cordelia, who was in a very good temper, and who was much gratified by the politeness of Mr. and Mrs. Robin, said, "Well, I declare, it's a very pretty garden, and a deal better play than climbing all day long over those black, filthy old stones, Audrey. You won't dirty half as many pinafores!"

Stephen's father was full of his boy's delight. It would be a pleasure for Stephen every day, he said, and he would buy him a nice little red can with which to water the flowers.

Mr. Robin said it was a real treat to see a bit of flower-bed again; it reminded him of his garden in the country, and was like a bit of home to him.

But Granny Robin, as she knelt on the grass to smell the flowers, repeated softly to herself the words of a verse, which Audrey and Stephen thought very beautiful.

"'Saint after saint on earth

Has lived, and loved, and died,

And as they left us one by one,

We laid them side by side;

We laid them down to sleep,

But not in hope forlorn;

We laid them but to ripen there

Till the last glorious morn.

Come, then, Lord Jesus, come!'"

"Do you think they know what we've been doing?" said little Stephen.

"Who, my dear child?"

"The two grandchildren who died young."

"I don't know," said Granny Robin; "I can't say, Stephen."

"Perhaps the angels will tell them when they go back to-night," said Stephen. "They are sure to notice it when they come to look at the graves, and I think the little children will be glad when they hear."

And that night, long after Stephen's father thought he was fast asleep, the little boy stood at his bedroom window in the moonlight, looking for the angels. The calm, quiet light was streaming through the trees and down upon the desolate graves. It made even the saddest of them look beautiful, little Stephen thought, and he fancied that the moonbeams must be the reflection of the brightness of the angels' wings.

His own grave, as he loved to call it, was lying full in the pure, silvery light. He could see the flowers he had planted distinctly, and he could even distinguish some of the words on the old tombstone. He loved to fancy to himself that the angels were glad to see it looking so beautiful, that they were pleased with what he had done, and that they were lingering round it with bright and happy faces. Some of the other graves were lying in shadow, but the angels, so he thought, had gathered round the one upon which he had bestowed so much care, and were unwilling to leave it behind.

It was not until clouds came drifting across the sky, and one of them was driven over the face of the moon, and the whole churchyard was left in darkness again; it was not until every ray of moonlight had disappeared, that little Stephen crept back to bed. The angels were gone, he said, as he laid his head on the pillow; they had flown away to the King's Garden, and perhaps, even then, they were telling the two grandchildren who died young that the flowers were blooming on their grave, and that it was no longer forsaken and desolate.

The Mysterious Light

"GRANNY ROBIN—" said Stephen, when he and Audrey were leaning on her window-seat on the bright Sunday afternoon which followed that busy Saturday, "Granny Robin, do you think I shall die young?"

"I can't tell, my dear child," said the old woman, as she stroked Stephen's little thin hand; "only the dear Lord above knows that."

"I think I should like to die young," said the child.

"If you go to heaven," said Audrey, "it won't be a good thing if you don't."

"Shall I go to heaven, Granny Robin?" asked the little boy.

"If you have come to Jesus you will, Stephen," she said.

"I would like to come to Jesus, Granny Robin," said Audrey; "but how can I come to Him? If He was in the city, and I knew which house He was in, I would go to Him—wouldn't you, Stephie?"

"Yes," said the child; "we would take hold of hands and go together."

"You have not far to go," said Granny Robin, as she laid down her knitting and put her arms round the two children.

"Tell us just what we must do," said Audrey, "and we'll do it, Stephen and me, both of us, Granny Robin."

"You have a river here, haven't you, somewhere in the city?" asked the old woman.

"Yes," said Audrey; "and it's beautiful in summer-time, it's covered with boats."

"And barges," said Stephen.

"Yes, but the barges are ugly," said Audrey. "But the boats are lovely, and sometimes they have a sail up, and then I like them best of all. One day me and Stephen went down on the new walk by the river, and we sat on one of the seats and watched them."

"Have you ever been over the river?" said Granny Robin.

"Yes, heaps of times," said Audrey.

"Did you swim across?" asked the old woman.

"Oh no, Granny, I should be drowned if I fell in! There's bridges, you know—great big bridges. There's the pay bridge, where you pay a halfpenny to go across, and there's two more; but Aunt Cordelia always goes over the pay bridge."

"Are you afraid of falling in when you're on the bridge, Audrey?"

"Oh no; it's so strong, Granny Robin. Hundreds of folks go over it every day."

"Audrey," said the old woman, "do you know, I once lived in a country which had a very dismal name? It was called the Kingdom of Darkness."

"I shouldn't like to go there," said Stephen. "I don't like to be in the dark."

"I was born there," said Granny Robin, "and I did not notice how dark and gloomy it was. I was used to it, and it did not strike me as being very dismal, not for a long, long time."

"How did you find out it was dark, Granny Robin?"

"I looked across the river to the other side."

"And what did you see there? asked Stephen.

"I saw another kingdom, Stephie, which was full of light; glorious sunshine was streaming on it; there was not a dark corner to be seen in it."

"Had that country a name?" said Audrey.

"Yes, it was named the Kingdom of Light."

"Didn't you want to go there, Granny Robin?"

"Yes, I was not happy in the Kingdom of Darkness any longer," she said. "It looked black as night to me, and I wanted—oh, so much!—to get to the other side."

"Why didn't you go, Granny Robin?"

"I couldn't find the way, Stephie. I tried to get across, but the water was too deep, and I had to turn back."

"Did you ever get over?" asked Audrey.

But just then Aunt Cordelia's voice was heard calling loudly, "Tea, Audrey—tea," and the little girl had to run home without hearing the old woman's answer.

The evening was dark and gloomy. Clouds came driving up and covered the blue sky, and the wind blew mournfully amongst the forlorn trees in the churchyard. Granny Robin's window was closed, and Stephen whispered to Audrey, when she came out, that he heard strange voices inside, and that his father said two people had come to see Mr. Robin from the village where he used to live.

Audrey and Stephen wandered about the churchyard together, but it was very dismal that Sunday evening; even the flowers on the two graves did not look fresh and beautiful, as they had done the night before.

After a time, they climbed on the square tomb and peeped into the church, but it seemed more gloomy there than it did outside. Even the swallow had settled down on his nest, as if he felt too depressed to venture to fly into the churchyard.

"It looks like the Kingdom of Darkness," said Stephen in an awestruck voice. "I wonder if Granny Robin ever got across; don't you, Audrey? Shall we go in now?"

"No, let's stay outside," said the little girl. "Your father's at chapel, and Aunt Cordelia's at church, and it's much darker in than out."

So they wandered about for another half-hour, and then even Audrey owned it would be better to go in.

"Let's have one more look in the church," said Stephen; "I want to see if the swallow has gone to sleep."

They climbed on the stone, but they could see nothing. The old church was quite dark now, and Stephen tried in vain to see the swallow in its nest. They could only distinguish the outline of the chancel window, and Audrey thought she could see the pulpit with its heavy top, but she could not be sure even of that.

"Let's go," said little Stephen, shivering; "it looks more like the Kingdom of Darkness than before."

"LOOK, STEPHEN!" SHE CRIED. "WHAT'S THAT?"

He was climbing quickly down from the gravestone when Audrey called him.

"Look, Stephen," she cried. "What's that?"

The child got on his feet again and pulled himself up to the window. When he had looked into the church a moment before all had been dark, but now a bright light streamed across the chancel. They could see the old, crooked stone pillars standing out clearly against it; they could distinguish the communion table, and the wooden rail in front of it; they could see the high pews and the uneven stone floor; they could even make out the swallow's nest in the arch nearest to the pulpit.

"What can it be?" said Stephen, trembling from head to foot.

"Some one must be inside," said Audrey. "Let's watch."

"It must be old Maria," said Stephen.

"No, it can't be Maria; we should have seen her come," said Audrey. "Why, we've been sitting looking at that little stone path leading from the gate for nearly an hour. I am quite sure it isn't Maria!"

"Who can it be?" said Stephen. "Oh, Audrey, let's fetch father?"

"No, wait a bit," said Audrey; "your father won't be in. Let's watch it; perhaps we shall see some one."

But although they watched for a long time, no one appeared in the church, nor were they able to discover from whence the light came.

It was not a steady light; it flickered up and down, and the shadows on the roof flickered with it. Nothing else moved in the old church; all else was still as death. But Stephen's heart was beating faster and faster as the minutes went on; and Audrey, feeling how much he trembled, was just going to yield to his wish to go home, when quite suddenly, as suddenly as it had appeared a few minutes before, the light went out, and the old church was once more left in darkness.

Children of Light

IT was a little hard on the children, when they went home to tell their tale of the strange light in the church, to find that no one would believe them. Aunt Cordelia was inclined to be angry, and said:

"Whoever heard of a light in the old church? They shouldn't make up such stories!"

Stephen's father only laughed, and told him he must not think of it again; little boys fancied strange things sometimes. Even Granny Robin seemed to imagine that their being out late, and their having felt rather frightened, had something to do with it.

But Stephen and Audrey knew better, and, without saying a word to any one, they would creep out night after night, and would climb upon the fiat tomb that they might look for the sight.

But day after day of that week went by, and they never saw it again.

"Perhaps it only comes on Sunday," said Stephen.

"We must wait and see," said Audrey. "I do hope it will come, and then we will fetch them to see it, and they will all believe it."

Meanwhile the two children had another talk with Granny Robin.

"Did you ever get into the Kingdom of Light?" little Stephen asked her.

"Yes, my child," said the old woman, "I did."

"And how long did you stay there?" said Audrey. "Weren't you sorry to come away, Granny Robin?"

"I never came away," said the old woman; "I'm there now!"

"There now?" repeated Stephen; and he looked round the room, which was fast growing dark, and was full of the shadows of the trees outside. "Did you say you were there now, Granny Robin? I don't think it's very bright now; and then you're blind, you know, and couldn't see it if it was."

"It's always bright in the Kingdom of Light, and I can see that sunshine, Stephen," she said.

"I think Granny Robin means her soul can see," said Audrey.

"Quite right, dear child," said the old woman; "it is my soul, and not my poor old body, that is in the Kingdom of Light."

"I wish I was in the Kingdom of Light," said Audrey.

"You must cross over, Audrey," said Granny Robin.

"How can we cross?" asked little Stephen.

"Just as I did," she said. "You can't walk over or swim over; there is only one way."

"What way is that?" asked Audrey.

"The bridge," said Granny Robin quietly; "you have several bridges over your river—I have only one over mine."

"Is it the pay bridge?" asked Stephen.

"No, it's the free bridge," said Granny Robin, smiling—"'without money and without price.'"

"What is its name, Granny Robin?"

"Christ Jesus," said the old woman reverently. "Did not He say—"

"'I am the way; no man cometh unto the Father but by Me?'"

"Tell me how you got across," asked Audrey.

"I came to Jesus," said the old woman. "I said to myself, 'My Lord is not far away in heaven; He is close beside me in this room, standing by my side, waiting for me to come to Him. I cannot take myself across into the Kingdom of Light, but He can take me. He died on the cross that He might be able to take me. I will trust myself to Him. Hundreds of others have crossed by this bridge, and have crossed safely; I will cross also. I will come to Christ to be saved by Him alone.' And, children, I did cross, and here I am," said the old woman, smiling again.

"I want to go into the Kingdom of Light," said little Stephen, laying his small, thin hand on Granny Robin's.

"Trust yourself to Him this night, Stephen," she said; "you and Audrey, both of you. Tell Him you want to come to Him, just now, that He may be your bridge, and take you safe over from the Kingdom of Satan to the Kingdom of the dear Son, the blessed Kingdom of Light."

And with a child holding each hand, the old woman knelt down and prayed—

"O Lord, Thou art close beside us, and we come to Thee. We want, each one of us, to belong to the Kingdom of Light. Little Audrey and Stephen are coming to Thee now; Thou art the way to God. We trust ourselves to Thee to be saved. Thou hast taken many others out of the darkness and into the light. Lord, we believe Thou wilt take us, just now, just as we are. As we kneel here, hand in hand, we trust ourselves to Thee. Lord, take us now, we do beseech Thee. Amen."

And then, as they sat beside her, and as she went on with her knitting, Granny Robin sang softly—

"Out of my bondage, sorrow, and night,

Jesus, I come—Jesus, I come!

Into Thy freedom, gladness, and light,

Jesus, I come to Thee.

Out of my sickness into Thy health,

Out of my want and into Thy wealth,

Out of my sin and into Thyself,

Jesus, I come to Thee!"

"Now, Audrey and Stephen," said Granny Robin, "if you have come into the Kingdom of the dear Son—the Kingdom of Light—you must remember what you are."

"What are we, Granny Robin?"

"Children of Light," said the old woman, smiling. "Isn't that a beautiful name?"

"It sounds like an angel's name," said little Stephen.

"And the Children of Light must never do the works of darkness," said Granny Robin. "If you are tempted to be cross, or disobedient, or untruthful, you must say to yourself, 'I am a Child of Light; I have crossed over the bridge, and all those deeds of darkness must be left behind in the Kingdom of Darkness.' Will you remember, Audrey and Stephen?"

Just then Aunt Cordelia's voice was heard calling for Audrey to come to her at once. It was an impatient, angry voice, and Audrey said, as she got up reluctantly to go—

"What a bother! There's Aunt Cordelia calling, and she's as cross as two sticks!"

"Children of Light, remember, Audrey," said Granny Robin softly, as she jumped out of the window.

It was Friday, and Aunt Cordelia's baking-day. And if there was one day in the week when Aunt Cordelia was more cross than usual, that day was baking-day. Standing over the large oven and the scorching fire, baking cakes and pies and buns for her shop, with the perspiration streaming down her face, it was no wonder that Aunt Cordelia's temper was tried.

"Come along, Audrey, you lazy child!" she cried, as she took a tray of cakes out of the oven. "Here am I, slaving away this hot day, and you doing nothing but waste your time. There's that shop bell been tinkling as if it was mad this last hour; and how in the world am I to get my baking done, if I'm running backwards and forwards every minute!"

Audrey was just going to say that she had been at school all day, and it was very hard if she couldn't have a bit of play when she came home; but she remembered Granny Robin's words.

"I am a Child of Light," she said to herself; and was quiet.

And when Aunt Cordelia called after her, as she was going into the shop, "Audrey, put a clean pinafore on! Audrey, I never saw such a dirty girl as you are! You're not fit to be seen!"

Audrey went quietly upstairs without a word, changed her pinafore, and came down with a bright and pleasant face to take her place behind the counter.

It was wonderful how happy she felt, even though she knew it was the time when she and Stephen watered the graves, and he would be waiting for her outside. And at tea-time Aunt Cordelia put one of her best cakes on her plate, telling her that she had been a good child, and she might go and play after tea.

That evening Stephen and she talked a great deal about the Children of Light; and Stephen said he wondered if the angel's, when they came to look at the graves to-night, would come and look at them as they lay in their little beds.

"Because you know, Audrey, I think if we are Children of Light, we must be their little brothers and sisters—don't you think so, too?"

When Sunday evening came, the children were very anxious to watch the old church. They sat for a long time keeping a strict look out on the gate, for they fancied that old Maria must have some special business in the church on Sunday, and that they might see her come in.

But though they watched carefully for more than an hour, no one came to turn the rusty lock; and at last, when darkness came on, the children crept somewhat tremblingly to peep into the church.

Yes—there was the light again, flickering as before in the chancel; and yet they could see no sign of any one in the church.

"Now," said Audrey, "we'll make them believe us. You fetch Mr. Robin, Stephen, and I'll fetch Aunt Cordelia; she hasn't gone to church to-night, and we'll show it to them."

Aunt Cordelia refused to come; she was wearing her Sunday dress, and would spoil it, scrambling on those dirty stones, she said.

But Mr. Robin put on his cap, and came with Stephen as quickly as he could.

"Now you will see, Mr. Robin," Audrey whispered to him, as he climbed on the flat stone and looked in at the window. "What do you think it can be?"

"I can't see anything," said Mr. Robin; "it's all dark inside."

The light had entirely vanished—not the faintest glimmer was to be seen; and poor Audrey and Stephen were as far as ever from convincing those at home that it had ever appeared, except in their imaginations.

"It all comes of wandering about amongst those graves," said Aunt Cordelia. "It isn't good for children. But what can we do with them? We can't turn them out into the streets to play."

Under the Yew Tree

IT was wonderful what a difference that talk with Granny Robin had made in Audrey's and Stephen's lives. They never forgot what she had said to them, or that they were the Children of Light. And when Audrey's birthday came, Granny Robin gave her a beautiful text to hang up in her bedroom; and the words of the text were these—

"WALK AS CHILDREN OF LIGHT."

"How ought Children of Light to walk, Granny Robin?" asked Audrey. "What does it mean?"

"It means, behave as Children of Light," said the old woman; "do nothing and say nothing which the Children of Light ought not to do or say."

"I will try, Granny Robin," said Audrey.

And she did try, from that day forward. When Aunt Cordelia was in one of her difficult, fault-finding moods, Audrey would say to herself:

"I am a Child of Light," and would keep back the angry, fretful answer.

When she was tempted to be idle at school, or to join in the disturbance which most of the children were making, she would say again:

"I am a Child of Light," and the thought would make her work with all her might.

When she lay awake at night, and felt lonely in the little top room where she slept, she would creep out of bed and look into the churchyard, and above the old tower to the stars shining overhead, and would say to herself:

"I am a Child of Light."

And then she never felt afraid; for were not the angels watching over all the Children of Light, their little brothers and sisters in the Kingdom?

As for Stephen, he was happier than he had ever been before; it was his one thought night and day.

He was always asking his father, "Father, are you one of the Children of Light? Have you crossed over the bridge?"

And when he received no answer to his question, he would throw his arms round his father's neck, and would say, "Oh, I do hope you are in the Kingdom of Light, father—the Kingdom of the dear Son!"

It must have been about the beginning of May—just at the time when the lilac on the bush near Granny Robin's window was in full bloom—that a very strange thing happened. The children had seen nothing more of the light in the church since the Sunday when they had called Mr. Robin to see it, and they were beginning to despair of ever seeing it again. Yet still, when Sunday evening came, they climbed on the flat tombstone, and looked in through the window, hoping against hope that it might appear, and that they might be able to prove the truth of their story. But as the days grew longer and lighter, it became more and more unlikely that any one who might happen to be in the old church would require a light until long after Audrey's and Stephen's bedtime.

But it so happened that one Sunday night, Aunt Cordelia told Audrey that when she left church, she was going to see a friend of hers who was ill, and who lived on the other side of the river, almost two miles away. This would take her a long time, as the friend might require her help when she arrived, and in that case it would be late before she was home.

Audrey was in alone, for the rain was falling fast, and she and Stephen had not been together all day. The little girl sat for some time by the window, watching the rain which was beating mercilessly on the old tombs, and covering the grave of the two grandchildren who died young with the tiny blue blossoms of the forget-me-not which Stephen had planted there.

It was a long, dreary evening, and it seemed as if it would never come to an end. She would have liked to have gone to church with Aunt Cordelia, but she was not allowed to go in the evening. Once a day was enough for little girls, Aunt Cordelia said.

After a time it grew so dark that Audrey thought she would go to bed, but then she remembered that she had had no supper, and that Aunt Cordelia would not like her to help herself to any. If it had only been fine, and she could have been with Stephen, she would not have minded how long Aunt Cordelia had been away; they would have been so happy together that the time would have seemed short to both of them.

As she was sitting at the window, she suddenly remembered the strange light, and she wondered if it was burning. It was dark enough for any one to need a light, and if it was to be lighted at all that night, she felt sure it would be already burning. It was still raining fast. Audrey could hear it beating against the window, and there was not even light enough for her to see the crooked old tombstone which stood only two yards from the house.

A great longing came over the little girl to run across the churchyard to the other side of the old church, and to peep in at the window. Would Aunt Cordelia be angry if she came home and found her out? She did not think she would be, if she told her how very long the time had seemed to her. Besides, she would not be five minutes away, and she would know for certain whether that strange light was burning or not.

Aunt Cordelia's old mackintosh was hanging behind the kitchen door, and Audrey took it down, and wrapping it round her, she opened the window and crept cautiously out. It was so dark that to any one else, it would have been impossible to cross the churchyard, full as it was of rough, uneven stones, some of which were half buried in the long grass, without either stumbling over them or falling against them. But Audrey knew every inch of the churchyard, and she could find her way about it by night more easily than a stranger could have done so by day.

So the little figure, in her long waterproof cloak, went in and out amongst the old tombstones in safety, and at length reached the wall of the church. Feeling her way by means of it, she passed under the east window on her way to the flat stone on the other side of the church.

But just as Audrey was turning the corner, she stumbled over something which was lying on the ground, and fell forward with her head against the flat tombstone. What could it be? There was no grave close to the wall, and she had felt quite safe in walking there. Audrey sat up and rubbed her head, and wondered more and more what had made her fall. It was very dark at this side of the church, for a thick yew tree overhung the flat tombstone, and Audrey could distinguish nothing whatever.

She thought Stephen must have left something on the ground when he had been playing there the day before; and she was just going to climb upon the stone that she might look for the light, when she heard close beside her a strange noise. It seemed to be a moan, or the cry of some creature in pain; and Audrey thought she must have stumbled over some wounded cat or dog, which must have crept under the church wall to die.

Wrapping her cloak tightly round her, she climbed down from the stone, and felt with her hand on the grass below. To her utter horror and astonishment, a voice spoke to her as she did so.

"Is any one there?" said the voice.

Audrey was trembling so much that she could not answer the question.

"Is any one there?" said the voice again.

"Yes," said Audrey fearfully, "I'm here; Who are you?"

"You needn't be scared," said the voice, "I'm only old Joe." And then he gave another groan, which went straight to Audrey's little heart.

"What's the matter with you?" she said. "Are you ill? Have you hurt yourself?"

"I'm dying, I think," said the voice faintly.

"I'll fetch somebody," said Audrey, getting up from the stone; "I'll bring Mr. Robin."

"Oh no," said the old man in a louder voice, "don't tell of me. I didn't do nobody any harm—don't fetch anybody; don't thee now—they'll lock me up if they come!"

"I'LL FETCH SOMEBODY," SAID AUDREY.

"Mr. Robin won't lock you up," said Audrey; "he's very kind is Mr. Robin."

He made no answer to this, so Audrey did not speak to him again, but at once began to creep past him. She was still trembling so much that she could hardly stand, but she managed to make her way back to the old houses, though not so quickly as she had come.

She stopped at Granny Robin's window, and knocked on the pane. Mr. Robin opened it.

"Why, Audrey," he said, "what are you doing at this time of night—and all wet and dripping, too?"

She could hardly tell him what she wanted, for her heart was beating so fast with the fright she had had; but she begged him to come with her, and to come at once, and to bring a candle with him.

Old Joe

MR. ROBIN climbed out of the window, and taking Audrey's hand in his, he told her to guide him to the place where she had heard the voice. She led him in and out amongst the tombstones; as far as the east window of the church. Then, when they were sheltered from the wind and the rain under the church wall, he lighted his candle, and they went round the corner to the north side of the old building.

There, on the grass under the yew tree, lay an old man, so small, so thin, so shrivelled, that he looked no bigger than a boy twelve years old. His hat had fallen from his head, and his untidy grey hair hung upon his shoulders, and round his neck was a board on which was written the one word—"Blind."

The old man's eyes were closed, and he took no notice of them as they bent over him. Mr. Robin took hold of his hand, and it was cold as ice; then he felt his threadbare clothes, and these were wet through with the rain, and so was his old red scarf, which he had untied, and which was lying beside him on the grass.

"I think he is dying, Audrey," said Mr. Robin gravely.

But just then the old man opened his eyes, and said in a trembling voice—

"Don't tell of me—don't let them lock me up! I didn't do no harm to nobody."

"We'll take him to the fire," said Mr. Robin. "Go and get Stephen's father to help me, Audrey; he'll be in by now."

Very gently the two men carried him through the churchyard, whilst Audrey went before them with the candle. They took him into Mr. Robin's house, and put him in Granny Robin's arm-chair before a blazing fire. Then Audrey went to tell Aunt Cordelia, and to ask her to come and help them.

The kettle was soon boiled, and they gave him some hot tea, and then the colour came back a little into his ashen face, and he said—

"Thank you. I'm better now. You won't tell of me—will you?"

"What is there to tell?" asked Mr. Robin.

"You won't tell of me sleeping in the old church. I don't do no hurt to anybody."

Mr. Robin and Stephen's father looked at each other.

"So you sleep in the old church, do you?" said Mr. Robin.

"Yes," said the old man. "I've slept there about a year now. You won't tell of me, will you? I've nowhere else to go but to the house, and I don't do a bit of harm—not a bit I don't."

"How do you get in?" asked Granny Robin.

"Through the vestry-window," he said. "It hasn't a lock on it. But I couldn't climb up this afternoon; I turned faint and dizzy-like. I fell down quite stupid, and when I came to my senses it was raining fast; I thought I was going to die—I did indeed."

"Then that was the light we saw in the church—me and Stephen!" cried Audrey.

"Did you see it?" said the old man piteously. "Don't tell of me—don't!"

"How do you get your living?" asked Granny Robin.

"I sit under the railway-bridge and play my fiddle," said the old man. "I must have dropped my fiddle, I think," he said, as he felt for it with his trembling hands. "It'll be on the grass outside somewhere; and I get a few coppers—a very few coppers indeed. They buy me a bit of food, but I've none left for lodgings—not a penny, I haven't."

"So you sleep in the old church! Isn't it very damp?" asked Aunt Cordelia.

"Not in the pulpit," said the old man. "I curl away in the pulpit, and put my head on an old cushion—it's snug up in the pulpit. Don't tell of me—now don't, there's good folks!"

"But what do you want a light for?" said Mr. Robin gravely.

"Just to eat my supper by," he said. "It's so dark in there. I feel lonesome when I'm eating my supper. I put it out as soon as ever I've done."

"Then you're not blind!" said Stephen's father, holding up the board which had been hanging round his neck.

"No," he said; "I wear that because they give me more coppers if I do. I haven't very good sight; it's dim-like, but I'm not so blind as all that."

"Oh dear, oh dear!" said Mr. Robin. "This is a very sad story."

"Don't tell of me—" said the old man, whimpering like a child, "don't tell of me!"

"We must think what's to be done," said Granny Robin; "we'll talk it over to-night."

"And you may sleep on this sofa till morning," added Mr. Robin. "We are trusting you very much by letting you stay under our roof; but we can't turn you out in the rain. You won't disappoint our trust, will you?"

"No, I won't, sir," said old Joe; "and thank you kindly, sir!"

He turned so faint after this, that they were obliged to lift him on the sofa and to cover him with a thick shawl. And then, when the others were gone, and Mr. and Mrs. Robin were alone, they talked long and earnestly together about what was to be done with old Joe. He was evidently a poor, ignorant old man, with no idea of right or wrong, and as dark in his soul as a heathen in Africa. Yet perhaps God had sent him to them that they might lead him into the Kingdom of Light, and if so, they ought not to send him away.

So in the morning, after they had given him some breakfast, they talked to him about it.

"We have an empty room at the top of the house," said Mr. Robin, "where you may sleep, and we'll put a mattress for you to lie on, if you'll do two things to please us, and if you'll keep your word about them. First, you must promise me you'll never go into the old church again—if you do, we shall feel it our duty to tell of you; and next, you must let me put that lying board of yours at the back of the fire. If you'll do those two things, old Joe, we'll give you a shelter and welcome."

"And you'll not tell of me?" said the old man.

"Not as long as you keep your word," said Mr. Robin.