Rear Admiral Alfred T. Mahan, U.S.N.

Title: Mahan on naval warfare

Selections from the writing of Rear Admiral Alfred T. Mahan

Author: A. T. Mahan

Editor: Allan F. Westcott

Release date: December 14, 2023 [eBook #72412]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Little, Brown

Credits: Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783.

The Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire, 1793–1812. 2 vols.

Sea Power in Its Relations to the War of 1812. 2 vols.

The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future.

The Life of Nelson, the Embodiment of the Sea Power of Great Britain. 2 vols.

Types of Naval Officers.

Retrospect and Prospect.

Lessons of the War with Spain, and other Articles.

The Problem of Asia, and Its Effect upon International Policies.

Some Neglected Aspects of War.

Naval Administration and Warfare.

The Interest of America in International Conditions.

Naval Strategy.

The Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence.

The Harvest Within.

Rear Admiral Alfred T. Mahan, U.S.N.

![[Logo]](images/i_title.jpg)

In his volume of reminiscences, “From Sail to Steam,” Rear Admiral Mahan gives us his father’s opinion and his own later judgment regarding his choice of the navy as a life work. “My father told me he thought me less fit for a military than for a civil profession, having watched me carefully. I think myself now that he was right; for though I have no cause to complain of unsuccess, I believe I should have done better elsewhere.”[1]

The father, Dennis Hart Mahan, was a graduate of West Point, in later life a distinguished professor of engineering at the Military Academy, and thus well qualified to weigh his son’s character and the requirements of a military career. The verdict of both father and son, moreover, may appear borne out by the fact that, while the name of Mahan is more widely known to-day than that of any other American naval officer, his fame rests, not on his achievements as a ship or fleet commander, but as a great naval historian and student of naval warfare.

Whatever the apparent wisdom of the choice at the time, it was in the event fortunate both for himself and for the naval profession. His long and varied service as an officer afloat and ashore gave him an invaluable background for the study of vinaval history and international affairs. On the other hand, his writings have brought home to every maritime nation the importance of sea power, and have stimulated in his own profession an interest in naval history and naval science which has helped to keep it abreast the progress of the age. This direct bearing of his professional experience upon his writings adds significance to the details of his life in the navy.

Alfred Thayer Mahan entered the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, September 30, 1856. Born at West Point, September 27, 1840, he was at the time of his entrance but three days above sixteen. Like many another candidate for the navy, he solicited his own appointment, obtaining it finally through the influence of Jefferson Davis, who had studied under his father at West Point, and was at this time Secretary of War. Having attended Columbia College for two years preceding, the boy was permitted—by a concession of which this is believed to be the only instance in the annals of the Academy—to omit the first year’s work and enter with the “Youngster” class, or “class of ’55 date,” according to the nomenclature then used. Up to the year 1851 the midshipmen’s course had consisted of five years at sea followed by one at the Academy. Mahan entered in the autumn after the graduation of the last class under the old scheme; and it was to the more mature, “sea-going” character of former classes that he attributes the total absence of hazing in his day. The practice was “not so much reprobated as ignored.” It came in viilater, when the Academy was moved to Newport during the Civil War, and “new ideals were evolved by a mass of schoolboys, severed from those elder associates with the influence of whom no professors nor officers can vie.”[2]

In the dusty files of Academy registers for that period one may read the names of boys famous in later years. George Dewey was a class ahead of Mahan; Schley and Sampson were respectively one class and two classes behind. On graduation, Dewey stood fifth in a class of fifteen; Mahan second in a class of twenty, with a record apparently very close to the leader’s; and Sampson stood first. In his last year the future historian was first in seamanship, physics, political science, and moral science, third in naval tactics and gunnery, fourth in “steam engine,” and fifth in astronomy and navigation. The year before he had excelled in physics, rhetoric, and Spanish. The details are noteworthy chiefly as they show the subjects of the old-time curriculum, in which so-called practical branches were less predominant than they are to-day. Of Mahan’s class, which numbered forty-nine at the time of entrance, twenty-nine had dropped back or resigned before the end of the course.

After a cruise in South American waters in the old frigate Congress, Mahan at once received his commission as lieutenant, August 31, 1861, and soon afterward an appointment as second in command of the steam corvette Pocahontas, then in the Potomac flotilla. It illustrates the rapid promotion viiiof those war-time days that each member of his class received similar advancement in the first year of the war. In the Pocahontas he came under fire in the attack on Port Royal, and afterward spent many weary months in blockade duty, first in the Pocahontas off the south Atlantic coast, and later in the Seminole off Sabine Pass, Texas. This latter station, Mahan remarks, “was a jumping-off place, the end of nowhere.” “Day after day we lay inactive—roll, roll.” The monotony was broken by a pleasant eight months at the Naval Academy in Newport and a “practice cruise” to England in the Macedonian; and in the last year of the war he saw more varied service on the staff of Rear Admiral Dahlgren, again on the Atlantic coast blockade.

Commissioned lieutenant commander in 1865, Mahan passed the ensuing twenty years in the customary routine of alternate sea and shore duty. In 1867–1869, a long cruise in the steam frigate Iroquois to Japan, via Guadeloupe, Rio, Cape Town, Madagascar, Aden, and Bombay, gave opportunity, unusual even in the navy, to see the world, and brought him to Kobe in time to witness the opening of new treaty ports and the last days of medieval Japan.

In 1885, when he had reached the rank of captain and was forty-five years of age, he had yet had little opportunity to display the distinctive talents which were to win him permanent fame. Partly, perhaps, in consequence of a book by his pen entitled “The Gulf and Inland Waters” and published two years before, but more likely as a result of the shrewd ixestimate which naval officers form regarding their fellows in the service, he was requested at this time to give a series of lectures on naval history and tactics at the Naval War College, then just established at Newport, Rhode Island. His acceptance of this duty marks a turning point in his career.

The call reached him in the Wachusett off the west coast of South America. It was nearly two years later, in August, 1886, when he took up his residence at the college, succeeding Rear Admiral Luce as president. A change of political administration in the meantime had brought about a less favorable policy toward this new departure in naval education, with the result that, to quote Mahan again, the college “was reefed close down, looking out for squalls at any moment from any quarter,” for the next four or five years. It bears evidence to his tact and tenacity, and it was not the least of his accomplishments for the navy, that he piloted the institution safely through this crucial period, with scant appropriations or none at all, in the face of a hostile Secretary of the Navy and a lukewarm service.

After seven years devoted chiefly to the War College, Mahan went to sea for the last time as commander of the cruiser Chicago in the European squadron. At this time “The Influence of Sea Power upon History” had already been published, and the volume on the French Revolution and Empire was nearly ready for the press. Upon requesting postponement of sea duty until its completion, he was informed by his superior in the xBureau of Navigation that it was “not the business of a naval officer to write books.” The remark was narrow, for the naval or any other profession would soon stagnate without the stimulus of free discussion and study, which finds its best outlet through the press; and it showed slight recognition of the immense value to the navy and the nation of Mahan’s writings. Still it was well for the author that he made this last cruise—his only experience with a ship of the new fleet. If the importance of his first book was not realized at home—and it is stated that he had great difficulty in finding a publisher—it was fully recognized abroad. His arrival in England was taken as an opportunity to pay a national tribute of appreciation, of which the degrees conferred by both Oxford and Cambridge were but one expression. There is a slightly humorous aspect to the competition of American universities to award similar honors upon his return.

Retiring in 1896 after forty years of service, he was recalled to act as a member of the Naval War Board from May 9, 1898, until the close of the War with Spain. His fellow members were Rear Admiral Montgomery Sicard and Captain A. S. Crowninshield. This board practically controlled the naval strategy of the war. Of its deliberations and the relative influence of its members we have no record; but the naval dispositions were effective, and, aside from the location of the “Flying Squadron” at Hampton Roads as a concession to the fears of coast cities, they are fully approved by Mahan in his writings.

xiHis choice a year later as one of the American delegates to the first Peace Conference at The Hague was eminently fitting in view of his thorough knowledge of international relations and the rules governing naval warfare. In determining the attitude of the American delegation, he took a strong stand against any agreement that would contract our freedom of action with regard to the Monroe Doctrine, and against immunity of private property at sea. The arguments against this latter policy he afterward stated effectively in print[3] and in a memorandum to the Navy Department. With the fulfillment of this duty, his public services, aside from his work as a writer, came to a close.

In the navy, as in other walks of life, an incompatibility is often assumed—and often unjustly—between mastery of theory and skill in practice, between the thoughtful student and the capable man of action; and there is no denying that among his contemporaries this assumption was current with regard to Mahan. While a conclusion is difficult in such a matter, the case may well rest on the following statement by a friend and fellow officer: “Duty, in whatever form it came, was sacred. Invariably he gave to its performance the best that was in him. That he distinguished himself pre-eminently on shipboard cannot be claimed. Luck or circumstances denied him the opportunity of doing things heroic, and his modesty those purely spectacular. As a subordinate or as captain of a single ship, what he did was well done. No further proof of his qualities xiiin this respect is needed than the fact that, at the outbreak of the Civil War, when finishing his midshipman’s cruise, he was asked by a shipmate, an officer who expected a command, to go with him as ‘first lieutenant.’ To his colleagues of the old navy this invitation was the highest form of professional approval. The fates decreed that the wider field should not be his wherein, as commander-in-chief of a fleet in war time, he could have exhibited the mastery he surely possessed of that art with which his name will forever be indissolubly linked.”[4]

From the same source may be taken a passage of more intimate portrayal. “In person Mahan was tall, spare, erect, with blue eyes, fair complexion, hair and beard originally sandy. He respected the body as the temple of his soul, and he paid it the homage of abstemious living, of outdoor games and abundant exercise. In manner he was modest to excess, dignified, courteous. Reticent in speech with people in general, those who enjoyed the rare privilege of his intimacy knew him to be possessed of a keen sense of humor and a fund of delightful anecdotes. To such friends he was a most charming companion, so different from the grave, self-contained philosopher he appeared to the rest and less favored of his acquaintance. His home life was ideal.”

The lectures delivered at the Naval War College were the basis of “The Influence of Sea Power xiiiupon History.” The author tells us how the central idea came to him in the library of the English Club at Lima, Peru, while reading Momsen’s “History of Rome.” “It suddenly struck me ... how different things might have been could Hannibal have invaded Italy by sea, as the Romans often had Africa, instead of by the long land route.” A year later, when he returned to the United States, the plan of the lectures was already formed: “I would investigate coincidently the general history and the naval history of the past two centuries with a view to demonstrating the influence of the events of the one upon the other.” Written between May and September of 1886, and delivered as lectures during the next four years, the book was carefully revised before its publication in the spring of 1890.

This book exerted at the time, and has continued to exert, a widespread influence; and while its author’s reputation has been increased by his later writings, it remains his best known and greatest work. One reason for this is that it states his fundamental teaching, and in a form easy to grasp. The preface and the first chapter, which cover but eighty-nine pages, survey rapidly the rise and decline of great sea powers and the national characteristics affecting maritime development. The rest of the book, treating in detail the period between 1660 and 1783, reinforces the conclusions already stated.

Timeliness also contributed to its success. The book furnished authoritative guidance in a period of transition and new departures in international affairs. For nearly twenty years, under Bismarck, xivGermany had been consolidating the empire established in 1871. When William II ascended the throne in 1888, the ambitions of both ruler and nation were already turned toward colonial expansion and world power. A German Admiralty separate from the War Office was established in 1889; Heligoland was secured a year later; the Kiel Canal was nearing completion. In England, the Naval Defense Act of 1889 provided an increase of seventy ships during the next four years. The rivals against whom she measured her naval strength were still France and Russia. In the United States, Congress in 1890 authorized three battleships, the first vessels of this class to be added to the American navy. During the following ten years the rivalry of nations was chiefly in commercial and colonial aggrandisement, marked by the final downfall of Spain’s colonial empire and a greatly increased importance attached to control of the sea.

For the nations taking part in this expansion, Mahan was a kind of gospel, furnishing texts for every discussion of naval policy. “After his first book,” says a French writer, “and especially from 1895 on, Mahan supplied the sound basis for all thought on naval and maritime affairs; it was seen clearly that sea power was the principle which, adhered to or departed from, would determine whether empires should stand or fall.”[5]

To Great Britain in particular the book came as xva timely analysis of the means by which she had grown in wealth and dominion. This was indeed no discovery. Nearly three centuries earlier Francis Bacon had written, “To be master of the sea is an abridgment [epitome] of monarchy ... he that commands the sea is at great liberty, and may take as much and as little of the war as he will.”[6] Before and after Bacon, England had acted upon this principle. But it remained for Mahan to give the thesis full expression, to demonstrate it by concrete illustration, and to apply it to modern conditions. “For the first time,” writes the British naval historian, Sir Julian Corbett, “naval history was placed on a philosophical basis. From the mass of facts which had hitherto done duty for naval history, broad generalizations were possible. The ears of statesmen and publicists were opened, and a new note began to sound in world politics. Regarded as a political pamphlet in the higher sense—for that is how the famous book is best characterized—it has few equals in the sudden and far-reaching effect it produced on political thought and action.”[7]

Germany was not slow to take to heart this interpretation of the vital dependence of world empire on sea power. The Kaiser read the book, annotated its pages, and placed copies in every ship of the German fleet.[8] It was soon translated not xvionly into German but into French, Japanese, Russian, Italian, and Spanish. This and later works by the same author were perhaps most diligently studied by officers of the Japanese navy, then rising rapidly to the strength manifested in the Russian war. “As far as known to myself,” writes Mahan, “more of my works have been done into Japanese than into any other one tongue.”[9] The debt of all students of naval warfare is well expressed by a noted Italian officer and writer,—“Mahan, who is the great teacher of us all.”[10]

What has been said of “The Influence of Sea Power upon History” applies in varying degrees to the sixteen historical works and collections of essays which appeared in the ensuing twenty-five years. While extending the field covered by the earlier book, they maintained in general its high qualities. The most important of these, “The Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire,” covers the period from 1793 to 1812. This and the studies of the American Revolution and the War of 1812 form with his first book a continuous historical series from 1660 to 1815. The “Life of Nelson” and “Life of Farragut” are standard professional biographies of these two commanders, who, if we accept Mahan’s opinion, rank respectively first and second among naval leaders. The best of his thought on contemporary naval warfare is gathered up in his “Naval Strategy,” published in 1911. Based on lectures xviifirst delivered in 1887, and afterward frequently expanded and modified to meet changing conditions, this book, while invaluable to the professional student, lacks something of the continuity and clearness of structure of the historical works.

The authoritativeness of these writings, it may be repeated, was strengthened by the author’s technical equipment and long years of practical experience. Moreover, as Mr. Roosevelt has said, “Mahan was the only great naval writer who also possessed the mind of a statesman of the first class.”[11] His concern always was not merely with the facts of history but with the “logic of events” and their lessons for to-day.

Following his retirement, Admiral Mahan wrote more frequently and freely on problems of the present and future. Of the subjects treated, some were distinctly professional—the speed and size of battleships, the size, composition, and disposition of fleets, modifications in the international codes affecting naval warfare, naval events in contemporary wars. Others entered the wider field of world politics, voicing the author’s sincere belief in American colonial expansion and active participation in world affairs, in the need of a navy sufficient to make our influence felt, in the limitations as well as the usefulness of arbitration, in the continuance of force as an important factor in international relations.

In such discussions, he wrote without the slightest trace of jingoism or sensation mongering; and it xviiiwould be a fanatic advocate of immediate disarmament and universal arbitration who would deny the steadying and beneficent effect of his opposition, with its grip on realities and steadfast respect for truth. Whatever he wrote was not only backed by firm conviction but inspired by the highest ideals.

His style naturally varied somewhat with the audience and the theme. His historical writings have been justly described as burdened with qualifications, and marked by a laborious fullness of statement, which strains the attention, while it adds weight and dignity to the presentation. This in general is true of the histories; but there are many passages in these where the subject inspires him to genuine eloquence. In the “Life of Nelson” and “Types of Naval Officers” there is little of the defect mentioned, and there are few more entertaining volumes of naval reminiscence than “From Sail to Steam.” “The besetting anxiety of my soul,” writes the author himself, “was to be exact and lucid. I might not succeed, but my wish was indisputable. To be accurate in facts and correct in conclusions, both as to application and expression, dominated all other motives.”[12] One might dispense with reams of “fine writing” for a page of prose guided by these standards.

On December 1, 1914, Rear Admiral Mahan died suddenly of heart failure. A month before, he had left his home at Quogue, Long Island, and come to Washington to pursue investigations for a xixhistory of American expansion and its bearing on sea power. His death, occurring four months after the outbreak of hostilities in Europe, was perhaps hastened by constant study of the diplomatic and military events of the war, the approach of which he had clearly foreseen, as well as America’s vital interest in the Allied cause. It was unfortunate that his political and professional wisdom should have been lost at that time.

His work, however, was largely accomplished. By his influence on both public and professional opinion, by prevision and warm advocacy, he had done much to further the execution of many important naval and national policies. Among such may be mentioned the peace-time concentration of fleets in preparation for war, the abandonment of a strictly defensive naval policy, the systematic study of professional problems, the strengthening of our position in the Caribbean, the fortification of Panama. “His interest,” writes Mr. Roosevelt, “was in the larger side of his subjects; he was more concerned with the strategy than with the tactics of both naval war and statesmanship.” In this larger field his writings will retain a value little affected by the lapse of time.

| PAGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction | v | ||

| PART I | |||

| NAVAL PRINCIPLES | |||

| 1. | The Value of Historical Study | 3 | |

| 2. | “Theoretical” versus “Practical” Training | 8 | |

| A Historical Instance | 8 | ||

| What is Practical? | 10 | ||

| 3. | Elements of Sea Power | 16 | |

| 4. | Definition of Terms: Strategy, Tactics, Logistics | 49 | |

| 5. | Fundamental Principles | 50 | |

| Central Position, Interior Lines, Communications | 50 | ||

| Concentration | 60 | ||

| 6. | Strategic Positions | 68 | |

| I. | Situation | 69 | |

| II. | Military Strength | 70 | |

| III. | Resources | 74 | |

| 7. | Strategic Lines | 75 | |

| Communications | 75 | ||

| Importance of Sea Communications | 76 | ||

| 8. | Offensive Operations | 79 | |

| 9. | The Value of the Defensive | 87 | |

| 10. | Commerce-Destroying and Blockade | 91 | |

| Command of the Sea Decisive | 98 | ||

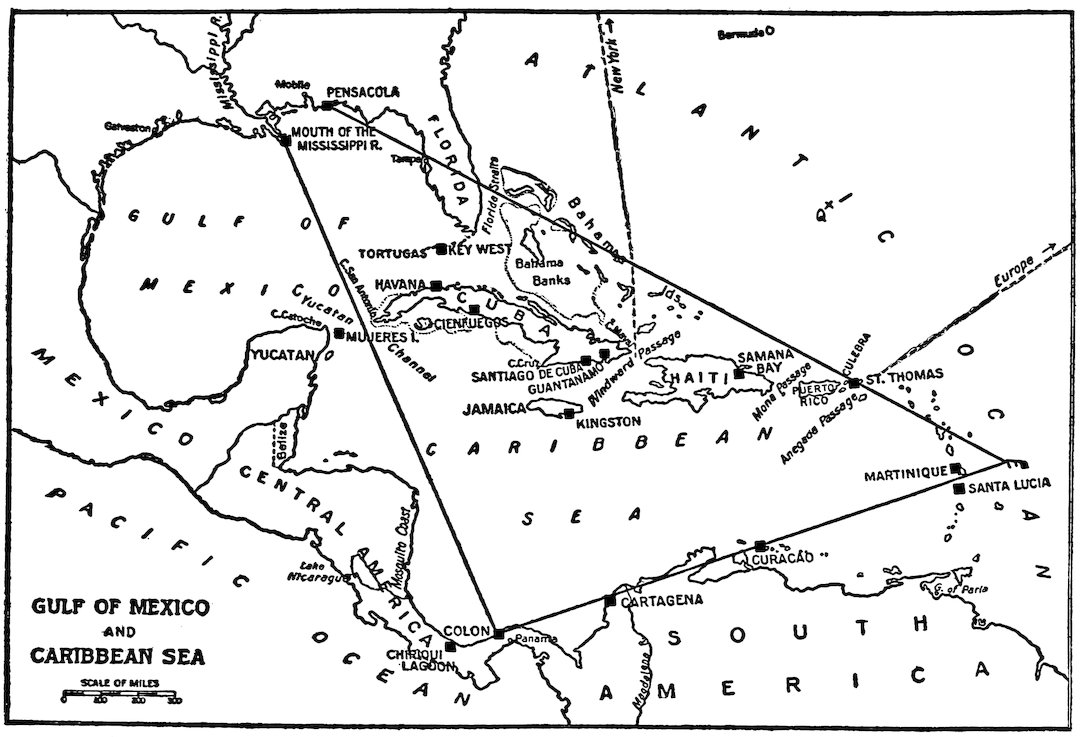

| 11. | Strategic Features of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean | 100 | |

| xxii12. | Principles of Naval Administration | 113 | |

| Opposing Elements | 113 | ||

| The British System | 118 | ||

| The United States System | 122 | ||

| 13. | The Military Rule of Obedience | 125 | |

| 14. | Preparedness for Naval War | 128 | |

| PART II | |||

| SEA POWER IN HISTORY | |||

| 15. | A Nation Exhausted by Isolation | 137 | |

| France under Louis XIV | 137 | ||

| 16. | The Growth of British Sea Power | 141 | |

| England after the Peace of Utrecht, 1715 | 141 | ||

| 17. | Results of the Seven Years’ War | 147 | |

| 18. | Eighteenth Century Formalism in Naval Tactics | 155 | |

| 19. | The New Tactics | 159 | |

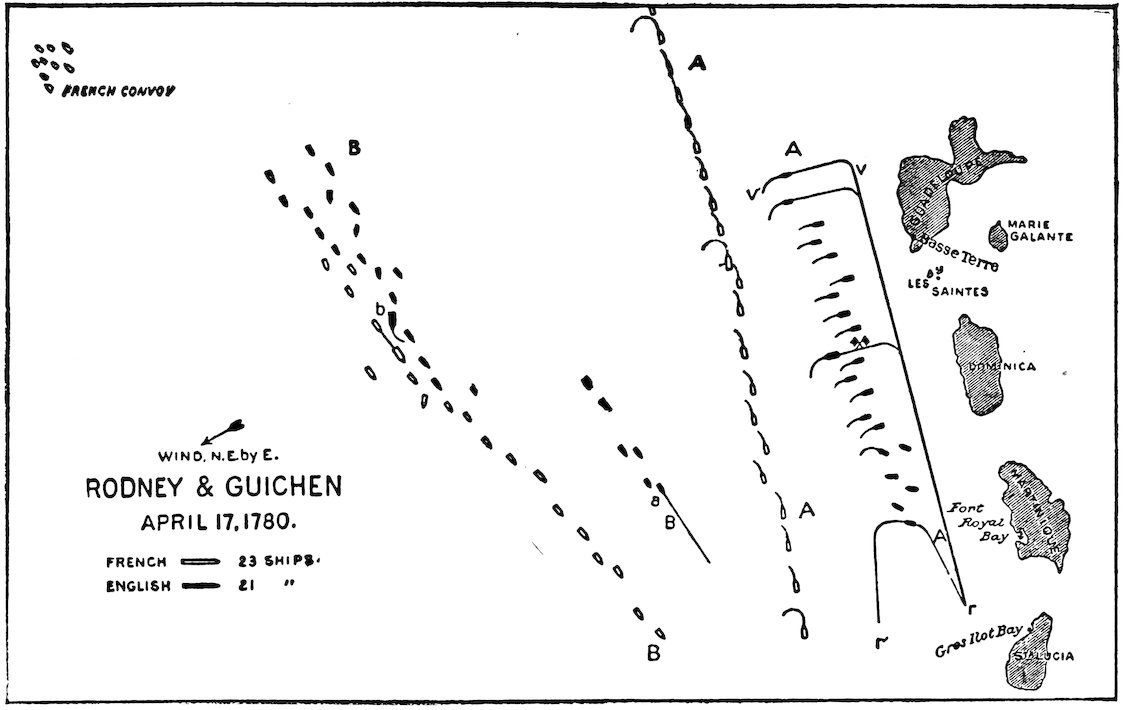

| Rodney and De Guichen, April 17, 1780 | 159 | ||

| 20. | Sea Power in the American Revolution | 164 | |

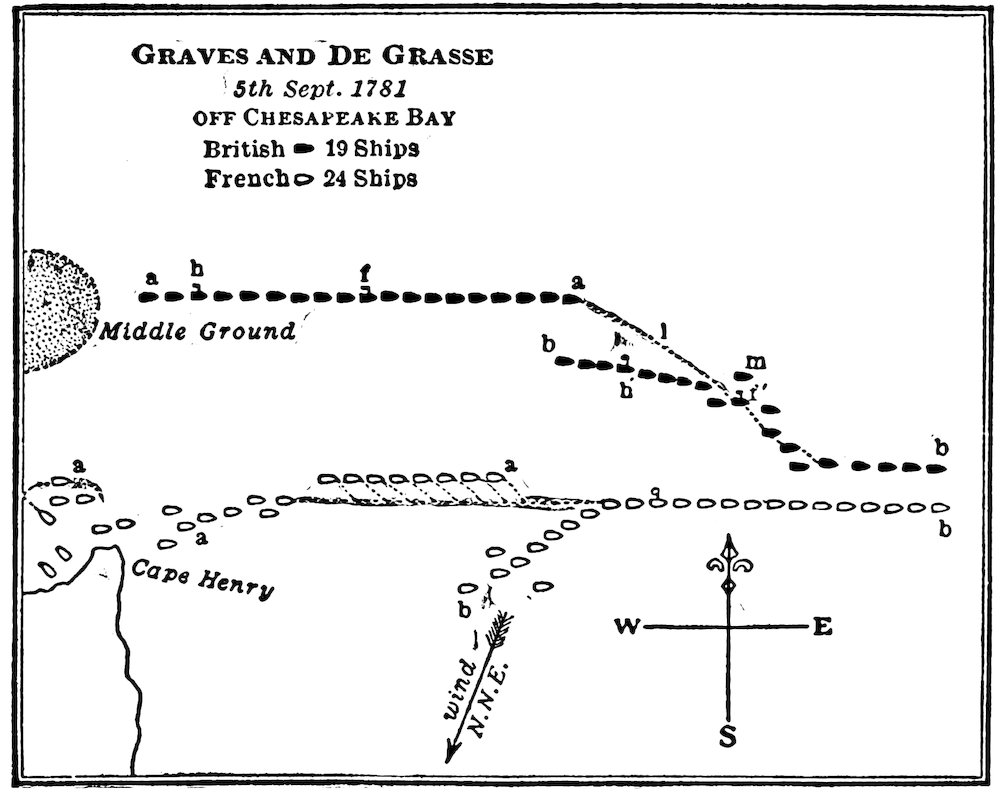

| Graves and De Grasse off the Chesapeake | 164 | ||

| 21. | The French Navy Demoralized by the Revolution | 171 | |

| 22. | Howe’s Victory of June 1, 1794 | 175 | |

| 23. | Nelson’s Strategy at Copenhagen | 184 | |

| 24. | England’s First Line of Defense | 191 | |

| 25. | The Battle of Trafalgar | 196 | |

| “The Nelson Touch” | 200 | ||

| The Battle | 208 | ||

| Commerce Warfare after Trafalgar | 223 | ||

| 26. | General Strategy of the War of 1812 | 229 | |

| Results of the Northern Campaign | 235 | ||

| 27. | Lessons of the War with Spain | 241 | |

| The Possibilities of a “Fleet in Being” | 241 | ||

| xxiii28. | The Santiago Blockade | 250 | |

| 29. | “Fleet in Being” and “Fortress Fleet” | 256 | |

| The Port Arthur Squadron in the Russo-Japanese War | 256 | ||

| Divided Forces | 269 | ||

| 30. | Rozhestvensky at Tsushima | 276 | |

| PART III | |||

| NAVAL AND NATIONAL POLICIES | |||

| 31. | Expansion and Over-Sea Bases | 285 | |

| The Annexation of Hawaii | 285 | ||

| 32. | Application of the Monroe Doctrine | 288 | |

| Anglo-American Community of Interests | 288 | ||

| 33. | Changes in the United States and Japan | 296 | |

| 34. | Our Interests in the Pacific | 299 | |

| 35. | The German State and its Menace | 302 | |

| The Bulwark of British Sea Power | 306 | ||

| 36. | Advantages of Insular Position | 309 | |

| Great Britain and the Continental Powers | 309 | ||

| 37. | Bearing of Political Developments on Naval Policy and Strategy | 317 | |

| 38. | Seizure of Private Property at Sea | 328 | |

| 39. | The Moral Aspect of War | 342 | |

| 40. | The Practical Aspect of War | 348 | |

| 41. | Motives for Naval Power | 355 | |

| APPENDIX | |||

| Chronological Outline | 359 | ||

| Academic Honors | 360 | ||

| Published Works | 361 | ||

| Uncollected Essays | 362 | ||

| References | 362 | ||

| INDEX | 365 | ||

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Diagram Illustrating the Value of the Central Position | 54 |

| Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea | 101 |

| Rodney and Guichen, April 17, 1780 | 161 |

| Graves and De Grasse, September 5, 1781 | 167 |

| The Baltic and Its Approaches | Facing page 185 |

| North Atlantic Ocean | Facing page 197 |

| The Attack at Trafalgar | 214 |

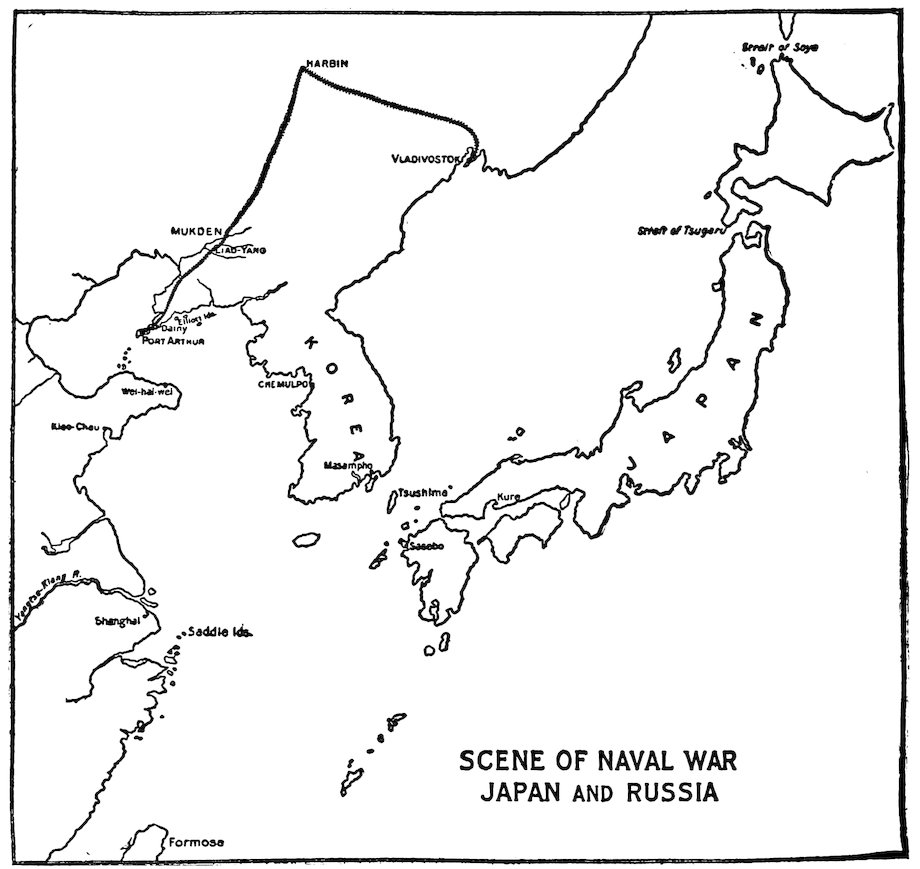

| Scene of Naval War, Japan and Russia | 278 |

The history of Sea Power is largely, though by no means solely, a narrative of contests between nations, of mutual rivalries, of violence frequently culminating in war. The profound influence of sea commerce upon the wealth and strength of countries was clearly seen long before the true principles which governed its growth and prosperity were detected. To secure to one’s own people a disproportionate share of such benefits, every effort was made to exclude others, either by the peaceful legislative methods of monopoly or prohibitory regulations, or, when these failed, by direct violence. The clash of interests, the angry feelings roused by conflicting attempts thus to appropriate the larger share, if not the whole, of the advantages of commerce, and of distant unsettled commercial regions, led to wars. On the other hand, wars arising from other causes have been greatly modified in their conduct and issue by the control of the sea. Therefore the history of sea power, while embracing in its broad sweep all 4that tends to make a people great upon the sea or by the sea, is largely a military history; and it is in this aspect that it will be mainly, though not exclusively, regarded in the following pages.

A study of the military history of the past, such as this, is enjoined by great military leaders as essential to correct ideas and to the skillful conduct of war in the future. Napoleon names among the campaigns to be studied by the aspiring soldier, those of Alexander, Hannibal, and Cæsar, to whom gunpowder was unknown; and there is a substantial agreement among professional writers that, while many of the conditions of war vary from age to age with the progress of weapons, there are certain teachings in the school of history which remain constant, and being, therefore, of universal application, can be elevated to the rank of general principles. For the same reason the study of the sea history of the past will be found instructive, by its illustration of the general principles of maritime war, notwithstanding the great changes that have been brought about in naval weapons by the scientific advances of the past half-century, and by the introduction of steam as the motive power. [The pages omitted point out lessons to be drawn from galley and sailing-ship warfare.—Editor.]

Before hostile armies or fleets are brought into contact (a word which perhaps better than any other indicates the dividing line between tactics and strategy), there are a number of questions to be decided, covering the whole plan of operations throughout the theater of war. Among these are the proper 5function of the navy in the war; its true objective; the point or points upon which it should be concentrated; the establishment of depots of coal and supplies; the maintenance of communications between these depots and the home base; the military value of commerce-destroying as a decisive or a secondary operation of war; the system upon which commerce-destroying can be most efficiently conducted, whether by scattered cruisers or by holding in force some vital center through which commercial shipping must pass. All these are strategic questions, and upon all these history has a great deal to say. There has been of late a valuable discussion in English naval circles as to the comparative merits of the policies of two great English admirals, Lord Howe and Lord St. Vincent, in the disposition of the English navy when at war with France. The question is purely strategic, and is not of mere historical interest; it is of vital importance now, and the principles upon which its decision rests are the same now as then. St. Vincent’s policy saved England from invasion, and in the hands of Nelson and his brother admirals led straight up to Trafalgar.

It is then particularly in the field of naval strategy that the teachings of the past have a value which is in no degree lessened. They are there useful not only as illustrative of principles, but also as precedents, owing to the comparative permanence of the conditions. This is less obviously true as to tactics, when the fleets come into collision at the point to which strategic considerations have brought them. The unresting progress of mankind causes continual 6change in the weapons; and with that must come a continual change in the manner of fighting,—in the handling and disposition of troops or ships on the battlefield. Hence arises a tendency on the part of many connected with maritime matters to think that no advantage is to be gained from the study of former experiences; that time so used is wasted. This view, though natural, not only leaves wholly out of sight those broad strategic considerations which lead nations to put fleets afloat, which direct the sphere of their action, and so have modified and will continue to modify the history of the world, but is one-sided and narrow even as to tactics. The battles of the past succeeded or failed according as they were fought in conformity with the principles of war; and the seaman who carefully studies the causes of success or failure will not only detect and gradually assimilate these principles, but will also acquire increased aptitude in applying them to the tactical use of the ships and weapons of his own day. He will observe also that changes of tactics have not only taken place after changes in weapons, which necessarily is the case, but that the interval between such changes has been unduly long. This doubtless arises from the fact that an improvement of weapons is due to the energy of one or two men, while changes in tactics have to overcome the inertia of a conservative class; but it is a great evil. It can be remedied only by a candid recognition of each change, by careful study of the powers and limitations of the new ship or weapon, and by a consequent adaptation of the method of using it to the qualities it possesses, 7which will constitute its tactics. History shows that it is vain to hope that military men generally will be at the pains to do this, but that the one who does will go into battle with a great advantage,—a lesson in itself of no mean value.

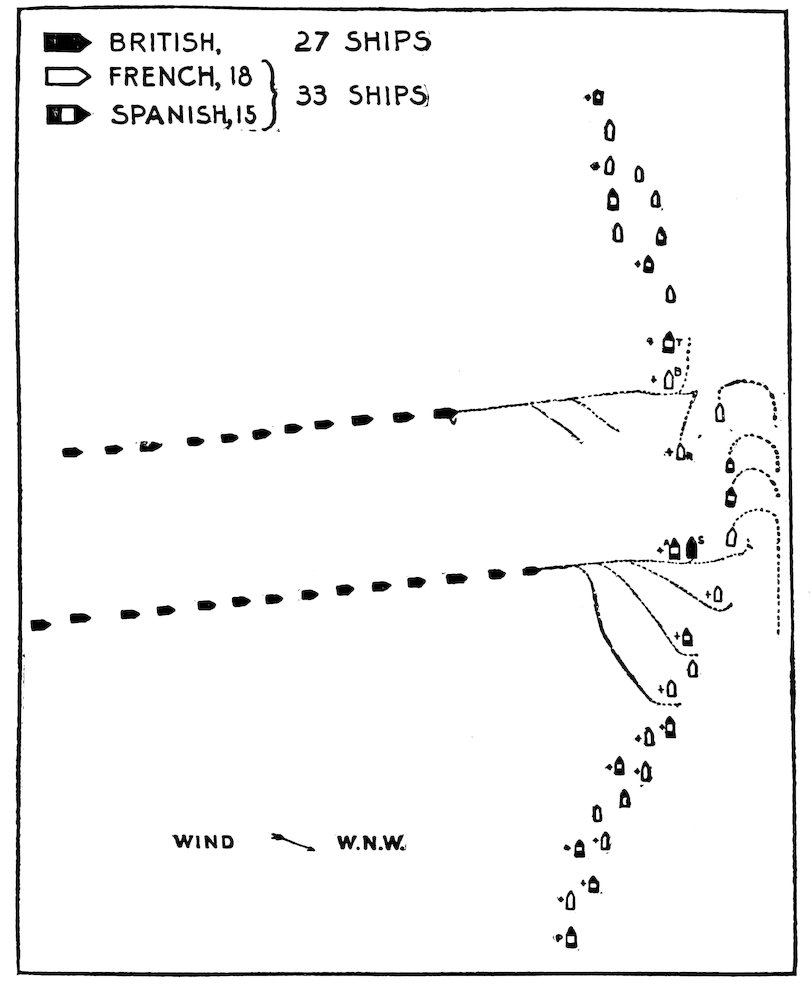

There have long been two conflicting opinions as to the best way to fit naval officers, and indeed all men called to active pursuits, for the discharge of their duties. The one, of the so-called practical man, would find in early beginning and constant remaining afloat all that is requisite; the other will find the best result in study, in elaborate mental preparation. I have no hesitation in avowing that personally I think that the United States Navy is erring on the latter side; but, be that as it may, there seems little doubt that the mental activity which exists so widely is not directed toward the management of ships in battle, to the planning of naval campaigns, to the study of strategic and tactical problems, nor even to the secondary matters connected with the maintenance of warlike operations at sea.[15] Now we have had the results of the two opinions as to the training of naval officers pretty well tested by the experience of two great maritime nations, France and England, each of which, not so much by formulated purpose as by national bias, committed itself unduly to the one or 9the other. The results were manifested in our War of Independence, which gave rise to the only well-contested, widespread maritime war between nearly equal forces that modern history records. There remains in my own mind no doubt, after reading the naval history on both sides, that the English brought to this struggle much superior seamanship, learned by the constant practice of shipboard; while the French officers, most of whom had been debarred from similar experience by the decadence of their navy in the middle of the century, had devoted themselves to the careful study of their profession. In short, what are commonly called the practical and the theoretical man were pitted against each other, and the result showed how mischievous is any plan which neglects either theory or practice, or which ignores the fact that correct theoretical ideas are essential to successful practical work. The practical seamanship and experience of the English were continually foiled by the want of correct tactical conceptions on the part of their own chiefs, and the superior science of the French, acquired mainly by study. It is true that the latter were guided by a false policy on the part of their government and a false professional tradition. The navy, by its mobility, is pre-eminently fitted for offensive war, and the French deliberately and constantly subordinated it to defensive action. But, though the system was faulty, they had a system; they had ideas; they had plans familiar to their officers, while the English usually had none—and a poor system is better than none at all....

It was said to me by some one: “If you want to attract officers to the College, give them something that will help them pass their next examination.” But the test of war, when it comes, will be found a more searching trial of what is in a man than the verdict of several amiable gentlemen, disposed to give the benefit of every doubt. Then you will encounter men straining every faculty and every means to injure you. Shall we then, who prepare so anxiously for an examination, view as a “practical” proceeding, worthy of “practical” men, the postponing to the very moment of imperative action the consideration of how to act, how to do our fighting, either in the broader domain of strategy, or in the more limited field of tactics, whether of the single ship or of the fleet? Navies exist for war; and the question presses for an answer: “Is this neglect to master the experience of the past, to elicit, formulate, and absorb its principles, is it practical?” Is it “practical” to wait till the squall strikes you before shortening sail? If the object and aim of the College is to promote such study, to facilitate such results, to foster and disseminate such ideas, can it be reproached that its purpose is not “practical,” even though at first its methods be tentative and its results imperfect?

The word “practical” has suffered and been debased by a misapprehension of that other word “theoretical,” to which it is accurately and logically 11opposed. Theory is properly defined as a scheme of things which terminates in speculation, or contemplation, without a view to practice. The idea was amusingly expressed in the toast, said to have been drunk at a meeting of mathematicians, “Eternal perdition to the man who would degrade pure mathematics by applying it to any useful purpose.” The word “theoretical,” therefore, is applied rightly and legitimately only to mental processes that end in themselves, that have no result in action; but by a natural, yet most unfortunate, confusion of thought, it has come to be applied to all mental processes whatsoever, whether fruitful or not, and has transferred its stigma to them, while “practical” has walked off with all the honors of a utilitarian age.

If therefore the line of thought, study and reflection, which the War College seeks to promote, is really liable to the reproach that it leads to no useful end, can result in no effective action, it falls justly under the condemnation of being not “practical.” But it must be said frankly and fearlessly that the man who is prepared to apply this stigma to the line of the College effort must also be prepared to class as not “practical” men like Napoleon, like his distinguished opponent, the Austrian Archduke Charles, and like Jomini, the profuse writer on military art and military history, whose works, if somewhat supplanted by newer digests, have lost little or none of their prestige as a profound study and exposition of the principles of warfare.

12Jomini was not merely a military theorist, who saw war from the outside; he was a distinguished and thoughtful soldier, in the prime of life during the Napoleonic wars, and of a contemporary reputation such that, when he deserted the cause of the emperor, he was taken at once into a high position as a confidential adviser of the allied sovereigns. Yet what does he say of strategy? Strategy is to him the queen of military sciences; it underlies the fortunes of every campaign. As in a building, which, however fair and beautiful the superstructure, is radically marred and imperfect if the foundation be insecure—so, if the strategy be wrong, the skill of the general on the battlefield, the valor of the soldier, the brilliancy of victory, however otherwise decisive, fail of their effect. Yet how does he define strategy, the effects of which, if thus far-reaching, must surely be esteemed “practical”? “Strategy,” he said, “is the art of making war upon the map. It precedes the operations of the campaign, the clash of arms on the field. It is done in the cabinet, it is the work of the student, with his dividers in his hand and his information lying beside him.” In other words, it originates in a mental process, but it does not end there; therefore it is practical.

Most of us have heard an anecdote of the great Napoleon, which is nevertheless so apt to my purpose that I must risk the repetition. Having had no time to verify my reference, I must quote from memory, but of substantial accuracy I am sure. A few weeks before one of his early and most decisive 13campaigns, his secretary, Bourrienne, entered the office and found the First Consul, as he then was, stretched on the floor with a large map before him. Pricked over the map, in what to Bourrienne was confusion, were a number of red and black pins. After a short silence the secretary, who was an old friend of school days, asked him what it all meant. The Consul laughed goodnaturedly, called him a fool, and said: “This set of pins represents the Austrians and this the French. On such a day I shall leave Paris. My troops will then be in such positions. On a certain day,” naming it, “I shall be here,” pointing, “and my troops will have moved there. At such a time I shall cross the mountains, a few days later my army will be here, the Austrians will have done thus and so; and at a certain date I will beat them here,” placing a pin. Bourrienne said nothing, perhaps he may have thought the matter not “practical;” but a few weeks later, after the battle (Marengo, I think) had been fought, he was seated with the general in his military traveling carriage. The programme had been carried out, and he recalled the incident to Bonaparte’s mind. The latter himself smiled at the singular accuracy of his predictions in the particular instance.

In the light of such an incident, the question I would like to pose will receive of course but one answer. Was the work on which the general was engaged in his private office, this work of a student, was it “practical”? Or can it by any reasonable method be so divorced from what followed, that 14the word “practical” only applies farther on. Did he only begin to be practical when he got into his carriage to drive from the Tuileries, or did the practical begin when he joined the army, or when the first gun of the campaign was fired? Or, on the other hand, if he had passed that time, given to studying the campaign, in arranging for a new development of the material of war, and so had gone with his plans undeveloped, would he not have done a thing very far from “practical”?

But we must push our inquiry a little farther back to get the full significance of Bourrienne’s story. Whence came the facility and precision with which Bonaparte planned the great campaign of Marengo? Partly, unquestionably, from a native genius rarely paralleled; partly, but not by any means wholly. Hear his own prescription: “If any man will be a great general, let him study.” Study what? “Study history. Study the campaigns of the great generals—Alexander, Hannibal, Cæsar” (who never smelt gunpowder, nor dreamed of ironclads) “as well as those of Turenne, Frederick, and myself, Napoleon.” Had Bonaparte entered his cabinet to plan the campaign of Marengo, with no other preparation than his genius, without the mental equipment and the ripened experience that came from knowledge of the past, acquired by study, he would have come unprepared. Were, then, his previous study and reflection, for which the time of action had not come, were they not “practical,” because they did not result in immediate action? Would they even have been “not 15practical” if the time for action had never come to him?

As the wise man said, “There is a time for everything under the sun,” and the time for one thing cannot be used as the time for another. That there is time for action, all concede; few consider duly that there is also a time for preparation. To use the time of preparation for preparation is practical, whatever the method; to postpone preparation to the time for action is not practical. Our new navy is preparing now; it can scarcely be said, as regards its material, to be yet ready. The day of grace is still with us—or with those who shall be the future captains and admirals. There is time yet for study; there is time to imbibe the experience of the past, to become imbued, steeped, in the eternal principles of war, by the study of its history and of the maxims of its masters. But the time of preparation will pass; some day the time of action will come. Can an admiral then sit down and re-enforce his intellectual grasp of the problem before him by a study of history, which is simply a study of past experience? Not so; the time of action is upon him, and he must trust to his horse sense.

The first and most obvious light in which the sea presents itself from the political and social point of view is that of a great highway; or better, perhaps, of a wide common, over which men may pass in all directions, but on which some well-worn paths show that controlling reasons have led them to choose certain lines of travel rather than others. These lines of travel are called trade routes; and the reasons which have determined them are to be sought in the history of the world.

Notwithstanding all the familiar and unfamiliar dangers of the sea, both travel and traffic by water have always been easier and cheaper than by land. The commercial greatness of Holland was due not only to her shipping at sea, but also to the numerous tranquil water-ways which gave such cheap and easy access to her own interior and to that of Germany. This advantage of carriage by water over that by land was yet more marked in a period when roads were few and very bad, wars frequent and society unsettled, as was the case two hundred years ago. Sea traffic then went in peril of robbers, but was 17nevertheless safer and quicker than that by land. A Dutch writer of that time, estimating the chances of his country in a war with England, notices among other things that the water-ways of England failed to penetrate the country sufficiently; therefore, the roads being bad, goods from one part of the kingdom to the other must go by sea, and be exposed to capture by the way. As regards purely internal trade, this danger has generally disappeared at the present day. In most civilized countries, now, the destruction or disappearance of the coasting-trade would only be an inconvenience, although water transit is still the cheaper. Nevertheless, as late as the wars of the French Republic and the First Empire, those who are familiar with the history of the period, and the light naval literature that has grown up around it, know how constant is the mention of convoys stealing from point to point along the French coast, although the sea swarmed with English cruisers and there were good inland roads.

Under modern conditions, however, home trade is but a part of the business of a country bordering on the sea. Foreign necessaries or luxuries must be brought to its ports, either in its own or in foreign ships, which will return, bearing in exchange the products of the country, whether they be the fruits of the earth or the works of men’s hands; and it is the wish of every nation that this shipping business should be done by its own vessels. The ships that thus sail to and fro must have secure ports to which to return, and must, as far as possible, be followed 18by the protection of their country throughout the voyage.

This protection in time of war must be extended by armed shipping. The necessity of a navy, in the restricted sense of the word, springs, therefore, from the existence of a peaceful shipping, and disappears with it,[17] except in the case of a nation which has aggressive tendencies, and keeps up a navy merely as a branch of the military establishment. As the United States has at present no aggressive purposes, and as its merchant service has disappeared, the dwindling of the armed fleet and general lack of interest in it are strictly logical consequences. When for any reason sea trade is again found to pay, a large enough shipping interest will reappear to compel the revival of the war fleet. It is possible that when a canal route through the Central-American Isthmus is seen to be a near certainty, the aggressive impulse may be strong enough to lead to the same result. This is doubtful, however, because a peaceful, gain-loving nation is not far-sighted, and far-sightedness is needed for adequate military preparation, especially in these days.

As a nation, with its unarmed and armed shipping, launches forth from its own shores, the need is soon felt of points upon which the ships can rely for peaceful trading, for refuge and supplies. In the present day friendly, though foreign, ports are to be found all over the world; and their shelter is 19enough while peace prevails. It was not always so, nor does peace always endure, though the United States have been favored by so long a continuance of it. In earlier times the merchant seaman, seeking for trade in new and unexplored regions, made his gains at risk of life and liberty from suspicious or hostile nations, and was under great delays in collecting a full and profitable freight. He therefore intuitively sought at the far end of his trade route one or more stations, to be given to him by force or favor, where he could fix himself or his agents in reasonable security, where his ships could lie in safety, and where the merchantable products of the land could be continually collecting, awaiting the arrival of the home fleet, which should carry them to the mother-country. As there was immense gain, as well as much risk, in these early voyages, such establishments naturally multiplied and grew until they became colonies; whose ultimate development and success depended upon the genius and policy of the nation from which they sprang, and form a very great part of the history, and particularly of the sea history, of the world. All colonies had not the simple and natural birth and growth above described. Many were more formal, and purely political, in their conception and founding, the act of the rulers of the people rather than of private individuals; but the trading-station with its after expansion, the work simply of the adventurer seeking gain, was in its reasons and essence the same as the elaborately organized and chartered colony. In both cases the mother-country had won a foothold 20in a foreign land, seeking a new outlet for what it had to sell, a new sphere for its shipping, more employment for its people, more comfort and wealth for itself.

The needs of commerce, however, were not all provided for when safety had been secured at the far end of the road. The voyages were long and dangerous, the seas often beset with enemies. In the most active days of colonizing there prevailed on the sea a lawlessness the very memory of which is now almost lost, and the days of settled peace between maritime nations were few and far between. Thus arose the demand for stations along the road, like the Cape of Good Hope, St. Helena, and Mauritius, not primarily for trade, but for defense and war; the demand for the possession of posts like Gibraltar, Malta, Louisburg, at the entrance of the Gulf of St. Lawrence,—posts whose value was chiefly strategic, though not necessarily wholly so. Colonies and colonial posts were sometimes commercial, sometimes military in their character; and it was exceptional that the same position was equally important in both points of view, as New York was.

In these three things—production, with the necessity of exchanging products, shipping, whereby the exchange is carried on, and colonies, which facilitate and enlarge the operations of shipping and tend to protect it by multiplying points of safety—is to be found the key to much of the history, as well as of the policy, of nations bordering upon the sea. The policy has varied both with the spirit of the age and with the character and 21clear-sightedness of the rulers; but the history of the seaboard nations has been less determined by the shrewdness and foresight of governments than by conditions of position, extent, configuration, number and character of their people,—by what are called, in a word, natural conditions. It must however be admitted, and will be seen, that the wise or unwise action of individual men has at certain periods had a great modifying influence upon the growth of sea power in the broad sense, which includes not only the military strength afloat, that rules the sea or any part of it by force of arms, but also the peaceful commerce and shipping from which alone a military fleet naturally and healthfully springs, and on which it securely rests.

The principal conditions affecting the sea power of nations may be enumerated as follows: I. Geographical Position. II. Physical Conformation, including, as connected therewith, natural productions and climate. III. Extent of Territory. IV. Number of Population. V. Character of the People. VI. Character of the Government, including therein the national institutions.

I. Geographical Position.—It may be pointed out, in the first place, that if a nation be so situated that it is neither forced to defend itself by land nor induced to seek extension of its territory by way of the land, it has, by the very unity of its aim directed upon the sea, an advantage as compared with a people one of whose boundaries is continental. This has been a great advantage to England over both 22France and Holland as a sea power. The strength of the latter was early exhausted by the necessity of keeping up a large army and carrying on expensive wars to preserve her independence; while the policy of France was constantly diverted, sometimes wisely and sometimes most foolishly, from the sea to projects of continental extension. These military efforts expended wealth; whereas a wiser and consistent use of her geographical position would have added to it.

The geographical position may be such as of itself to promote a concentration, or to necessitate a dispersion, of the naval forces. Here again the British Islands have an advantage over France. The position of the latter, touching the Mediterranean as well as the ocean, while it has its advantages, is on the whole a source of military weakness at sea. The eastern and western French fleets have only been able to unite after passing through the Straits of Gibraltar, in attempting which they have often risked and sometimes suffered loss. The position of the United States upon the two oceans would be either a source of great weakness or a cause of enormous expense, had it a large sea commerce on both coasts.[18]

England, by her immense colonial empire, has sacrificed much of this advantage of concentration of force around her own shores; but the sacrifice was wisely made, for the gain was greater than the loss, as the event proved. With the growth of her colonial system her war fleets also grew, but her 23merchant shipping and wealth grew yet faster. Still, in the wars of the American Revolution, and of the French Republic and Empire, to use the strong expression of a French author, “England, despite the immense development of her navy, seemed ever, in the midst of riches, to feel all the embarrassment of poverty.” The might of England was sufficient to keep alive the heart and the members; whereas the equally extensive colonial empire of Spain, through her maritime weakness, but offered so many points for insult and injury.

The geographical position of a country may not only favor the concentration of its forces, but give the further strategic advantage of a central position and a good base for hostile operations against its probable enemies. This again is the case with England; on the one hand she faces Holland and the northern powers, on the other France and the Atlantic. When threatened with a coalition between France and the naval powers of the North Sea and the Baltic, as she at times was, her fleets in the Downs and in the Channel, and even that off Brest, occupied interior positions, and thus were readily able to interpose their united force against either one of the enemies which should seek to pass through the Channel to effect a junction with its ally. On either side, also, Nature gave her better ports and a safer coast to approach. Formerly this was a very serious element in the passage through the Channel; but of late, steam and the improvement of her harbors have lessened the disadvantage under which France once labored. In the days of 24sailing-ships, the English fleet operated against Brest, making its base at Torbay and Plymouth. The plan was simply this: in easterly or moderate weather the blockading fleet kept its position without difficulty; but in westerly gales, when too severe, they bore up for English ports, knowing that the French fleet could not get out till the wind shifted, which equally served to bring them back to their station.

The advantage of geographical nearness to an enemy, or to the object of attack, is nowhere more apparent than in that form of warfare which has lately received the name of commerce-destroying, which the French call guerre de course. This operation of war, being directed against peaceful merchant vessels which are usually defenseless, calls for ships of small military force. Such ships, having little power to defend themselves, need a refuge or point of support near at hand; which will be found either in certain parts of the sea controlled by the fighting ships of their country, or in friendly harbors. The latter give the strongest support, because they are always in the same place, and the approaches to them are more familiar to the commerce-destroyer than to his enemy. The nearness of France to England has thus greatly facilitated her guerre de course directed against the latter. Having ports on the North Sea, on the Channel, and on the Atlantic, her cruisers started from points near the focus of English trade, both coming and going. The distance of these ports from each other, disadvantageous for regular military combinations, is an 25advantage for this irregular secondary operation; for the essence of the one is concentration of effort, whereas for commerce-destroying diffusion of effort is the rule. Commerce destroyers scatter, that they may see and seize more prey. These truths receive illustration from the history of the great French privateers, whose bases and scenes of action were largely on the Channel and North Sea, or else were found in distant colonial regions, where islands like Guadeloupe and Martinique afforded similar near refuge. The necessity of renewing coal makes the cruiser of the present day even more dependent than of old on his port. Public opinion in the United States has great faith in war directed against an enemy’s commerce; but it must be remembered that the Republic has no ports very near the great centers of trade abroad. Her geographical position is therefore singularly disadvantageous for carrying on successful commerce-destroying, unless she find bases in the ports of an ally.

If, in addition to facility for offense, Nature has so placed a country that it has easy access to the high sea itself, while at the same time it controls one of the great thoroughfares of the world’s traffic, it is evident that the strategic value of its position is very high. Such again is, and to a greater degree was, the position of England. The trade of Holland, Sweden, Russia, Denmark, and that which went up the great rivers to the interior of Germany, had to pass through the Channel close by her doors; for sailing-ships hugged the English coast. This northern trade had, moreover, a peculiar bearing 26upon sea power; for naval stores, as they are commonly called, were mainly drawn from the Baltic countries.

But for the loss of Gibraltar, the position of Spain would have been closely analogous to that of England. Looking at once upon the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, with Cadiz on the one side and Cartagena on the other, the trade to the Levant must have passed under her hands, and that round the Cape of Good Hope not far from her doors. But Gibraltar not only deprived her of the control of the Straits, it also imposed an obstacle to the easy junction of the two divisions of her fleet.

At the present day, looking only at the geographical position of Italy, and not at the other conditions affecting her sea power, it would seem that with her extensive sea-coast and good ports she is very well placed for exerting a decisive influence on the trade route to the Levant and by the Isthmus of Suez. This is true in a degree, and would be much more so did Italy now hold all the islands naturally Italian; but with Malta in the hands of England, and Corsica in those of France, the advantages of her geographical position are largely neutralized. From race affinities and situation those two islands are as legitimately objects of desire to Italy as Gibraltar is to Spain. If the Adriatic were a great highway of commerce, Italy’s position would be still more influential. These defects in her geographical completeness, combined with other causes injurious to a full and secure development of sea power, make it more than doubtful whether Italy 27can for some time be in the front rank among the sea nations.

As the aim here is not an exhaustive discussion, but merely an attempt to show, by illustration, how vitally the situation of a country may affect its career upon the sea, this division of the subject may be dismissed for the present; the more so as instances which will further bring out its importance will continually recur in the historical treatment. Two remarks, however, are here appropriate.

Circumstances have caused the Mediterranean Sea to play a greater part in the history of the world, both in a commercial and a military point of view, than any other sheet of water of the same size. Nation after nation has striven to control it, and the strife still goes on. Therefore a study of the conditions upon which preponderance in its waters has rested, and now rests, and of the relative military values of different points upon its coasts, will be more instructive than the same amount of effort expended in another field. Furthermore, it has at the present time a very marked analogy in many respects to the Caribbean Sea,—an analogy which will be still closer if a Panama canal route ever be completed. A study of the strategic conditions of the Mediterranean, which have received ample illustration, will be an excellent prelude to a similar study of the Caribbean, which has comparatively little history.

The second remark bears upon the geographical position of the United States relatively to a Central-American canal. If one be made, and fulfil the 28hopes of its builders, the Caribbean will be changed from a terminus, and place of local traffic, or at best a broken and imperfect line of travel, as it now is, into one of the great highways of the world. Along this path a great commerce will travel, bringing the interests of the other great nations, the European nations, close along our shores, as they have never been before. With this it will not be so easy as heretofore to stand aloof from international complications. The position of the United States with reference to this route will resemble that of England to the Channel, and of the Mediterranean countries to the Suez route. As regards influence and control over it, depending upon geographical position, it is of course plain that the center of the national power, the permanent base,[19] is much nearer than that of other great nations. The positions now or hereafter occupied by them on island or mainland, however strong, will be but outposts of their power; while in all the raw materials of military strength no nation is superior to the United States. She is, however, weak in a confessed unpreparedness for war; and her geographical nearness to the point of contention loses some of its value by the character of the Gulf coast, which is deficient in ports combining security from an enemy with facility for repairing warships of the first class, without which ships no country can pretend to control any part of the sea. In case of a contest for supremacy in the 29Caribbean, it seems evident from the depth of the South Pass of the Mississippi, the nearness of New Orleans, and the advantages of the Mississippi Valley for water transit, that the main effort of the country must pour down that valley, and its permanent base of operations be found there. The defense of the entrance to the Mississippi, however, presents peculiar difficulties; while the only two rival ports, Key West and Pensacola, have too little depth of water, and are much less advantageously placed with reference to the resources of the country. To get the full benefit of superior geographical position, these defects must be overcome. Furthermore, as her distance from the Isthmus, though relatively less, is still considerable, the United States will have to obtain in the Caribbean stations fit for contingent, or secondary, bases of operations; which by their natural advantages, susceptibility of defense, and nearness to the central strategic issue, will enable her fleets to remain as near the scene as any opponent. With ingress and egress from the Mississippi sufficiently protected, with such outposts in her hands, and with the communications between them and the home base secured, in short, with proper military preparation, for which she has all necessary means, the preponderance of the United States on this field follows, from her geographical position and her power, with mathematical certainty.

II. Physical Conformation.—The peculiar features of the Gulf coast, alluded to, come properly 30under the head of Physical Conformation of a country, which is placed second for discussion among the conditions which affect the development of sea power.

The seaboard of a country is one of its frontiers; and the easier the access offered by the frontier to the region beyond, in this case the sea, the greater will be the tendency of a people toward intercourse with the rest of the world by it. If a country be imagined having a long seaboard, but entirely without a harbor, such a country can have no sea trade of its own, no shipping, no navy. This was practically the case with Belgium when it was a Spanish and an Austrian province. The Dutch, in 1648, as a condition of peace after a successful war, exacted that the Scheldt should be closed to sea commerce. This closed the harbor of Antwerp and transferred the sea trade of Belgium to Holland. The Spanish Netherlands ceased to be a sea power.

Numerous and deep harbors are a source of strength and wealth, and doubly so if they are the outlets of navigable streams, which facilitate the concentration in them of a country’s internal trade; but by their very accessibility they become a source of weakness in war, if not properly defended. The Dutch in 1667 found little difficulty in ascending the Thames and burning a large fraction of the English navy within sight of London; whereas a few years later the combined fleets of England and France, when attempting a landing in Holland, were foiled by the difficulties of the coast as much as by the valor of the Dutch fleet. In 1778 the harbor of New York, and with it undisputed control of the 31Hudson River, would have been lost to the English, who were caught at disadvantage, but for the hesitancy of the French admiral. With that control, New England would have been restored to close and safe communication with New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania; and this blow, following so closely on Burgoyne’s disaster of the year before, would probably have led the English to make an earlier peace. The Mississippi is a mighty source of wealth and strength to the United States; but the feeble defenses of its mouth and the number of its subsidiary streams penetrating the country made it a weakness and source of disaster to the Southern Confederacy. And lastly, in 1814, the occupation of the Chesapeake and the destruction of Washington gave a sharp lesson of the dangers incurred through the noblest water-ways, if their approaches be undefended; a lesson recent enough to be easily recalled, but which, from the present appearance of the coast defenses, seems to be yet more easily forgotten. Nor should it be thought that conditions have changed; circumstances and details of offense and defense have been modified, in these days as before, but the great conditions remain the same.

Before and during the great Napoleonic wars, France had no port for ships-of-the-line east of Brest. How great the advantage to England, which in the same stretch has two great arsenals, at Plymouth and at Portsmouth, besides other harbors of refuge and supply. This defect of conformation has since been remedied by the works at Cherbourg.

Besides the contour of the coast, involving easy 32access to the sea, there are other physical conditions which lead people to the sea or turn them from it. Although France was deficient in military ports on the Channel, she had both there and on the ocean, as well as in the Mediterranean, excellent harbors, favorably situated for trade abroad, and at the outlet of large rivers, which would foster internal traffic. But when Richelieu had put an end to civil war, Frenchmen did not take to the sea with the eagerness and success of the English and Dutch. A principal reason for this has been plausibly found in the physical conditions which have made France a pleasant land, with a delightful climate, producing within itself more than its people needed. England, on the other hand, received from Nature but little, and, until her manufactures were developed, had little to export. Their many wants, combined with their restless activity and other conditions that favored maritime enterprise, led her people abroad; and they there found lands more pleasant and richer than their own. Their needs and genius made them merchants and colonists, then manufacturers and producers; and between products and colonies shipping is the inevitable link. So their sea power grew. But if England was drawn to the sea, Holland was driven to it; without the sea England languished, but Holland died. In the height of her greatness, when she was one of the chief factors in European politics, a competent native authority estimated that the soil of Holland could not support more than one eighth of her inhabitants. The manufactures of the country were then numerous and important, but they had 33been much later in their growth than the shipping interest. The poverty of the soil and the exposed nature of the coast drove the Dutch first to fishing. Then the discovery of the process of curing the fish gave them material for export as well as home consumption, and so laid the corner-stone of their wealth. Thus they had become traders at the time that the Italian republics, under the pressure of Turkish power and the discovery of the passage round the Cape of Good Hope, were beginning to decline, and they fell heirs to the great Italian trade of the Levant. Further favored by their geographical position, intermediate between the Baltic, France, and the Mediterranean, and at the mouth of the German rivers, they quickly absorbed nearly all the carrying-trade of Europe. The wheat and naval stores of the Baltic, the trade of Spain with her colonies in the New World, the wines of France, and the French coasting-trade were, little more than two hundred years ago, transported in Dutch shipping. Much of the carrying-trade of England, even, was then done in Dutch bottoms. It will not be pretended that all this prosperity proceeded only from the poverty of Holland’s natural resources. Something does not grow from nothing. What is true, is, that by the necessitous condition of her people they were driven to the sea, and were, from their mastery of the shipping business and the size of their fleets, in a position to profit by the sudden expansion of commerce and the spirit of exploration which followed on the discovery of America and of the passage round the Cape. Other causes concurred, 34but their whole prosperity stood on the sea power to which their poverty gave birth. Their food, their clothing, the raw material for their manufactures, the very timber and hemp with which they built and rigged their ships (and they built nearly as many as all Europe besides), were imported; and when a disastrous war with England in 1653 and 1654 had lasted eighteen months, and their shipping business was stopped, it is said “the sources of revenue which had always maintained the riches of the State, such as fisheries and commerce, were almost dry. Workshops were closed, work was suspended. The Zuyder Zee became a forest of masts; the country was full of beggars; grass grew in the streets, and in Amsterdam fifteen hundred houses were untenanted.” A humiliating peace alone saved them from ruin.

This sorrowful result shows the weakness of a country depending wholly upon sources external to itself for the part it is playing in the world. With large deductions, owing to differences of conditions which need not here be spoken of, the case of Holland then has strong points of resemblance to that of Great Britain now; and they are true prophets, though they seem to be having small honor in their own country, who warn her that the continuance of her prosperity at home depends primarily upon maintaining her power abroad. Men may be discontented at the lack of political privilege; they will be yet more uneasy if they come to lack bread. It is of more interest to Americans to note that the result to France, regarded as a power of the sea, 35caused by the extent, delightfulness, and richness of the land, has been reproduced in the United States. In the beginning, their forefathers held a narrow strip of land upon the sea, fertile in parts though little developed, abounding in harbors and near rich fishing grounds. These physical conditions combined with an inborn love of the sea, the pulse of that English blood which still beat in their veins, to keep alive all those tendencies and pursuits upon which a healthy sea power depends. Almost every one of the original colonies was on the sea or on one of its great tributaries. All export and import tended toward one coast. Interest in the sea and an intelligent appreciation of the part it played in the public welfare were easily and widely spread; and a motive more influential than care for the public interest was also active, for the abundance of ship-building materials and a relative fewness of other investments made shipping a profitable private interest. How changed the present condition is, all know. The center of power is no longer on the seaboard. Books and newspapers vie with one another in describing the wonderful growth, and the still undeveloped riches, of the interior. Capital there finds its best investments, labor its largest opportunities. The frontiers are neglected and politically weak; the Gulf and Pacific coasts actually so, the Atlantic coast relatively to the central Mississippi Valley. When the day comes that shipping again pays, when the three sea frontiers find that they are not only militarily weak, but poorer for lack of national shipping, their united efforts may 36avail to lay again the foundations of our sea power. Till then, those who follow the limitations which lack of sea power placed upon the career of France may mourn that their own country is being led, by a like redundancy of home wealth, into the same neglect of that great instrument.

Among modifying physical conditions may be noted a form like that of Italy,—a long peninsula, with a central range of mountains dividing it into two narrow strips, along which the roads connecting the different ports necessarily run. Only an absolute control of the sea can wholly secure such communications, since it is impossible to know at what point an enemy coming from beyond the visible horizon may strike; but still, with an adequate naval force centrally posted, there will be good hope of attacking his fleet, which is at once his base and line of communications, before serious damage has been done. The long, narrow peninsula of Florida, with Key West at its extremity, though flat and thinly populated, presents at first sight conditions like those of Italy. The resemblance may be only superficial, but it seems probable that if the chief scene of a naval war were the Gulf of Mexico, the communications by land to the end of the peninsula might be a matter of consequence, and open to attack.

When the sea not only borders, or surrounds, but also separates a country into two or more parts, the control of it becomes not only desirable, but vitally necessary. Such a physical condition either gives birth and strength to sea power, or makes the country powerless. Such is the condition of the 37present kingdom of Italy, with its islands of Sardinia and Sicily; and hence in its youth and still existing financial weakness it is seen to put forth such vigorous and intelligent efforts to create a military navy. It has even been argued that, with a navy decidedly superior to her enemy’s, Italy could better base her power upon her islands than upon her mainland; for the insecurity of the lines of communication in the peninsula, already pointed out, would most seriously embarrass an invading army surrounded by a hostile people and threatened from the sea.

The Irish Sea, separating the British Islands, rather resembles an estuary than an actual division; but history has shown the danger from it to the United Kingdom. In the days of Louis XIV, when the French navy nearly equalled the combined English and Dutch, the gravest complications existed in Ireland, which passed almost wholly under the control of the natives and the French. Nevertheless, the Irish Sea was rather a danger to the English—a weak point in their communications—than an advantage to the French. The latter did not venture their ships-of-the-line in its narrow waters, and expeditions intending to land were directed upon the ocean ports in the south and west. At the supreme moment the great French fleet was sent upon the south coast of England, where it decisively defeated the allies, and at the same time twenty-five frigates were sent to St. George’s Channel, against the English communications. In the midst of a hostile people, the English army in Ireland was seriously imperiled, but was saved by the battle of the Boyne 38and flight of James II. This movement against the enemy’s communications was strictly strategic, and would be as dangerous to England now as in 1690.