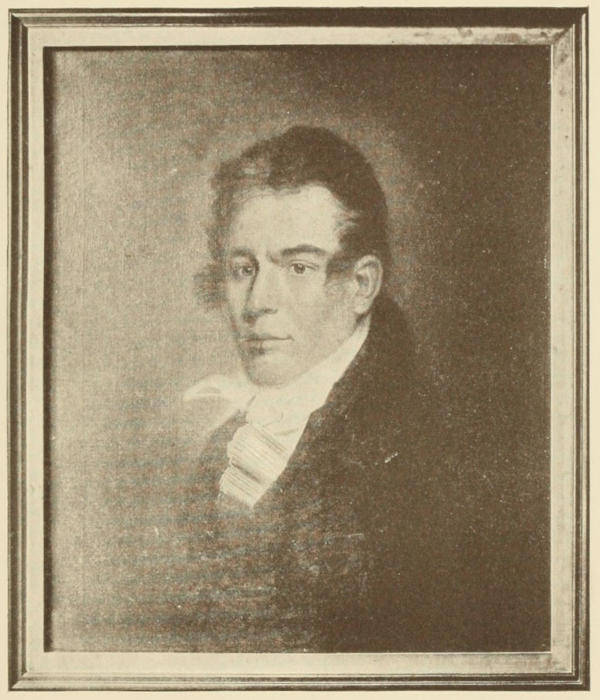

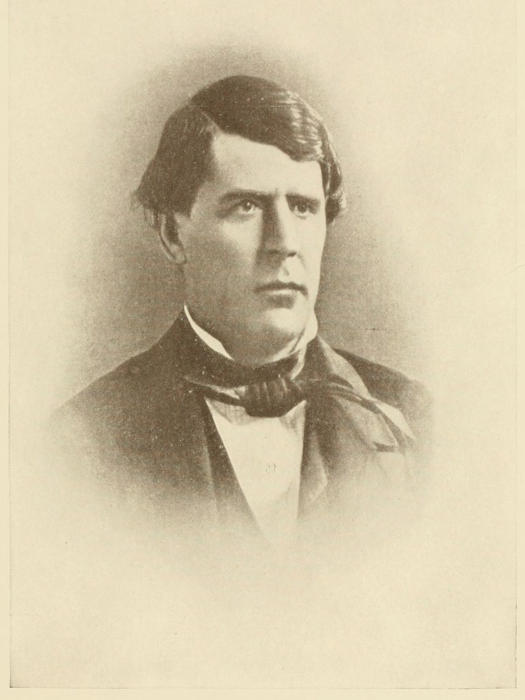

The Author at Twenty-two

Painted by Moïse

Title: Social life in old New Orleans

Being recollections of my girlhood

Author: Eliza Ripley

Release date: December 6, 2023 [eBook #72346]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: D. Appleton and Company

Credits: Emmanuel Ackerman and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

SOCIAL LIFE IN

OLD NEW ORLEANS

The Author at Twenty-two

Painted by Moïse

SOCIAL LIFE IN

OLD NEW ORLEANS

Being Recollections of my Girlhood

BY

ELIZA RIPLEY

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK AND LONDON

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

MCMXII

Copyright, 1912, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

To

MY CHILDREN

and

MY CHILDREN’S CHILDREN

and to

THEIR CHILDREN TO COME

Far more vivid than the twilight of the days in which I dwell, there rises before my inner eye the vision, aglow in Southern sunshine, of the days that are gone, never to return, but which formed the early chapters of a life that has been lived, that can never be lived again.

Many of the following stories are oft-told tales at my fireside—others were written to record phases of the patriarchal existence before the war which has so utterly passed away.

They have been printed from time to time in the pages of the New Orleans Times-Democrat, the editor of which has very kindly consented to their publication in this form.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | New Orleans Children of 1840 | 1 |

| II. | New Orleans Schools and Teachers in the Forties | 7 |

| III. | Boarding School in the Forties | 14 |

| IV. | Picayune Days | 23 |

| V. | Domestic Science Seventy Years Ago | 31 |

| VI. | A Fashionable Function in 1842 | 42 |

| VII. | New Year’s of Old | 50 |

| VIII. | New Orleans Shops and Shopping in the Forties | 58 |

| IX. | The Old French Opera House | 65 |

| X. | Mural Decorations and Portraits of the Past | 71 |

| XI. | Thoughts of Old | 80 |

| XII. | Wedding Customs Then and Now | 87 |

| XIII. | A Country Wedding in 1846 | 94 |

| XIV. | The Belles and Beaux of Forty | 101 |

| XV. | As It Was in My Day | 107 |

| XVI. | Fancy Dress Ball at the Mint in 1850 | 116 |

| XVII. | Dr. Clapp’s Church | 120 |

| XVIII. | Old Daguerreotypes | 125 |

| XIX. | Steamboat and Stage Seventy Years Ago | 130 |

| XX. | Hotel at Pass Christian in 1849 | 140 |

| XXI. | Old Music Books | 146 |

| XXII. | The Songs of Long Ago | 153 |

| XXIII. | A Ramble Through the Old City | 159 |

| XXIV. | “Old Creole Days” and Ways | 173 |

| XXV. | A Visit to Valcour Aime Plantation | 182 |

| XXVI. | The Old Plantation Life | 191 |

| XXVII. | People I Have Entertained | 200 |

| XXVIII. | A Monument to Mammies | 209 |

| XXIX. | Mary Ann and Martha Ann | 216 |

| XXX. | When Lexington Won the Race | 245 |

| XXXI. | Louisiana State Fair Fifty Years Ago | 250 |

| XXXII. | The Last Christmas | 256 |

| XXXIII. | A Wedding in War Time | 264 |

| XXXIV. | Substitutes | 273 |

| XXXV. | An Unrecorded Bit of New Orleans History | 280 |

| XXXVI. | Cuban Days in War Times | 287 |

| XXXVII. | “We Shall Know Each Other There” | 295 |

| XXXVIII. | A Ramble Through New Orleans With Brush and Easel | 303 |

| XXXIX. | A Visit of Tender Memories | 320 |

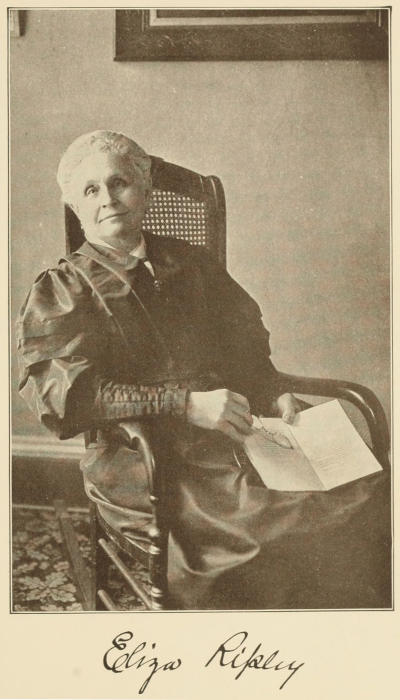

| Biographical Note | 331 |

| PAGE | |

| The Author at Twenty-two | Frontispiece |

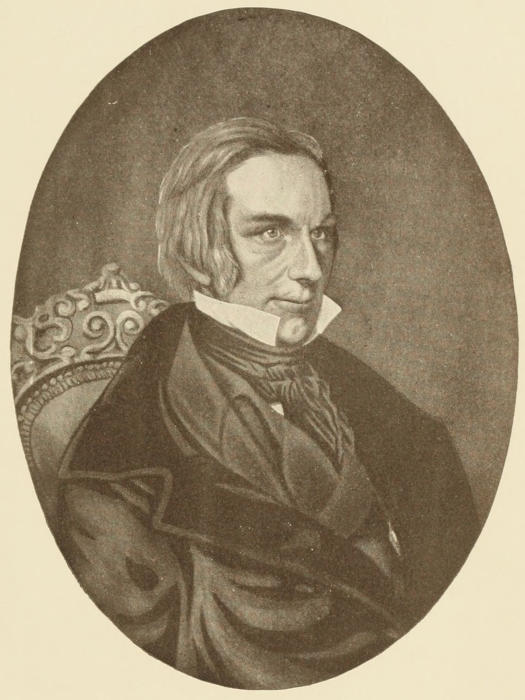

| Richard Henry Chinn | Facing 10 |

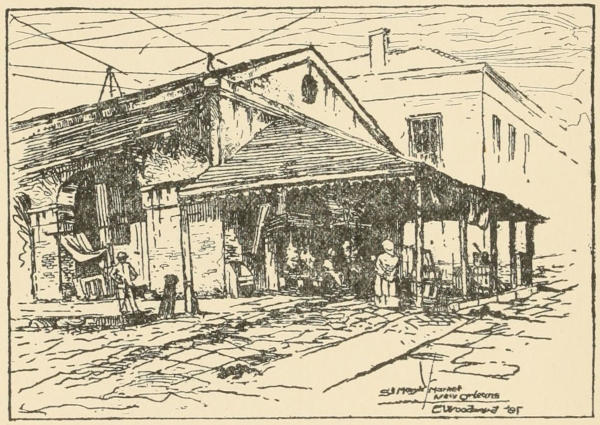

| Market Doorway | 24 |

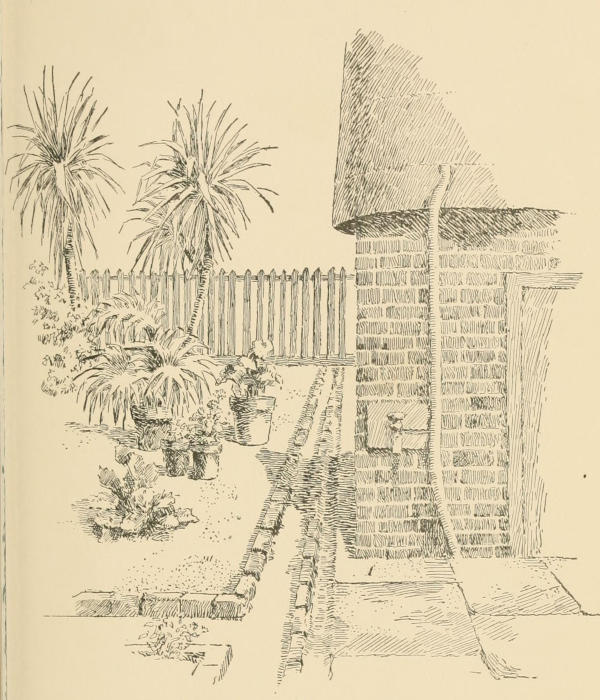

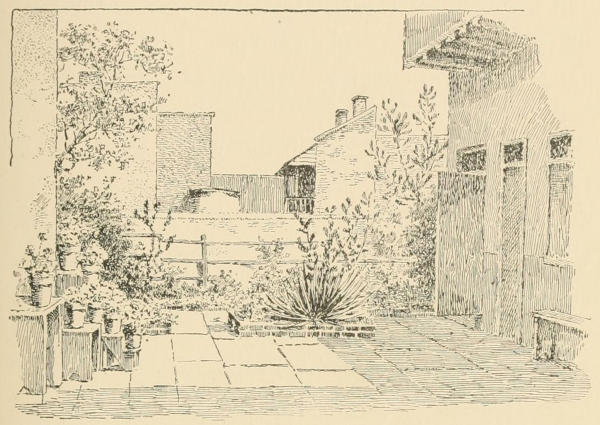

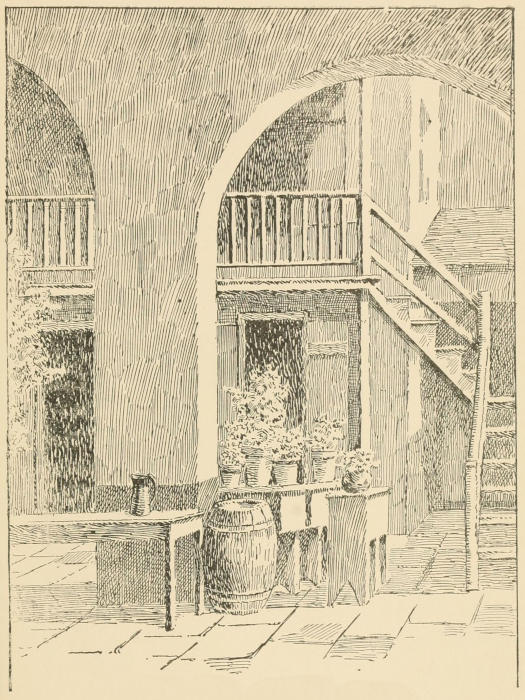

| A New Orleans Yard and Cistern | 33 |

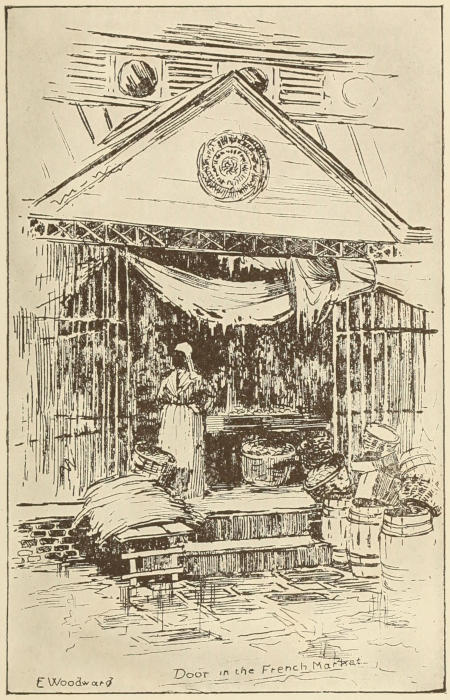

| Door in the French Market | Facing 38 |

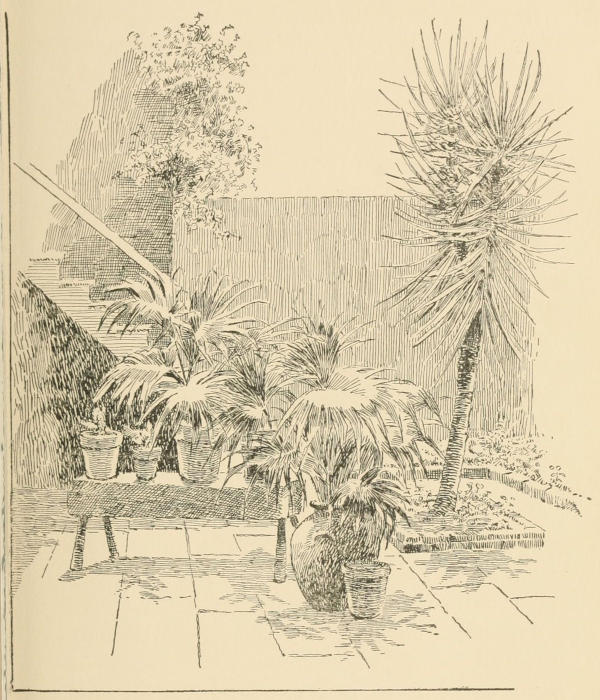

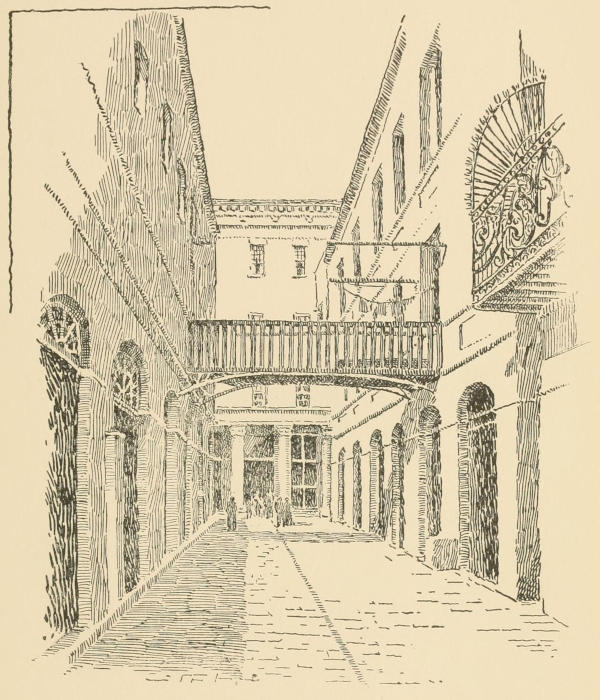

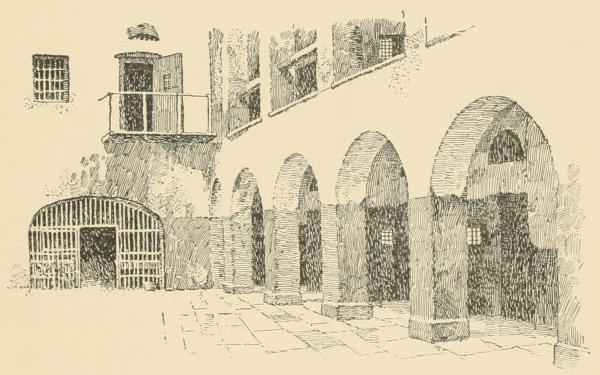

| Courtyard on Carondelet Street | 45 |

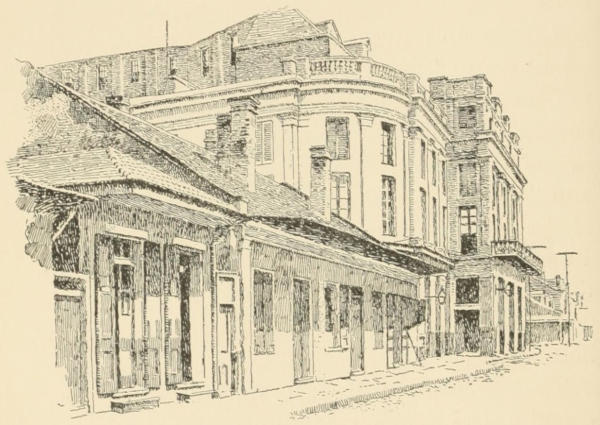

| The Old French Opera House | 66 |

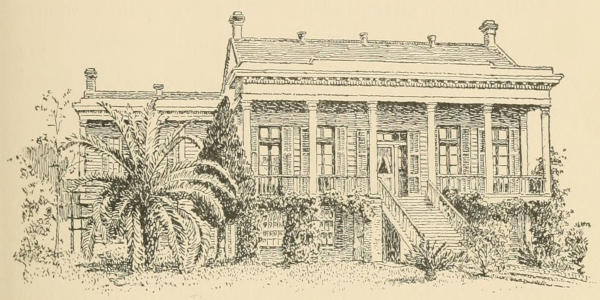

| Typical Old New Orleans Dwelling | 73 |

| A Creole Parterre | 81 |

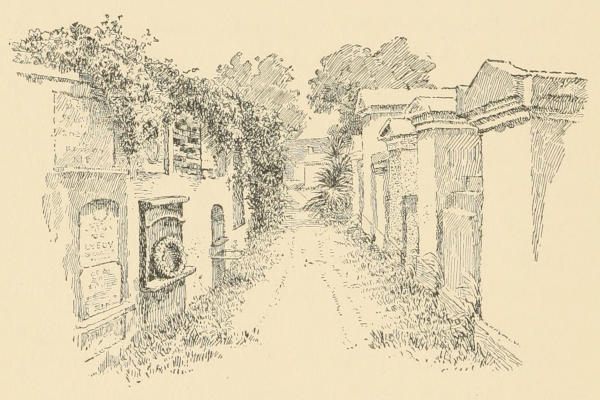

| St. Louis Cemetery, New Orleans | 111 |

| Augusta Slocomb Urquhart | Facing 118 |

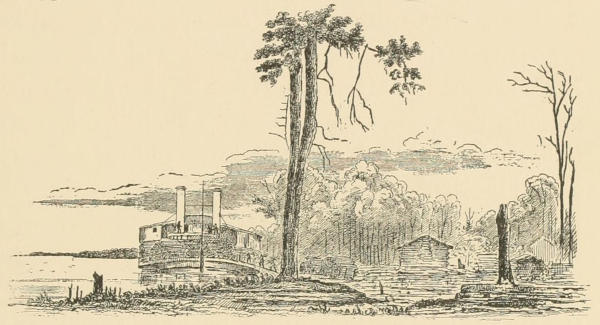

| Steamboat on the Mississippi | 131 |

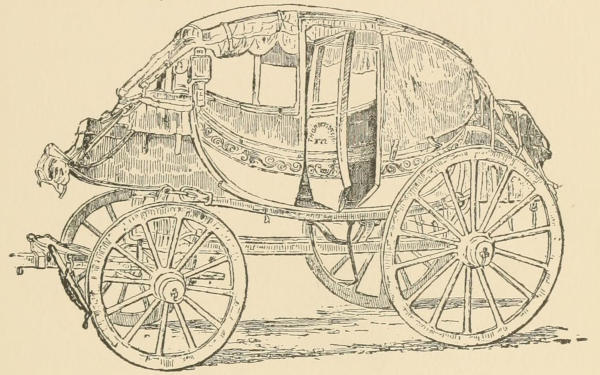

| American Stagecoach | 137 |

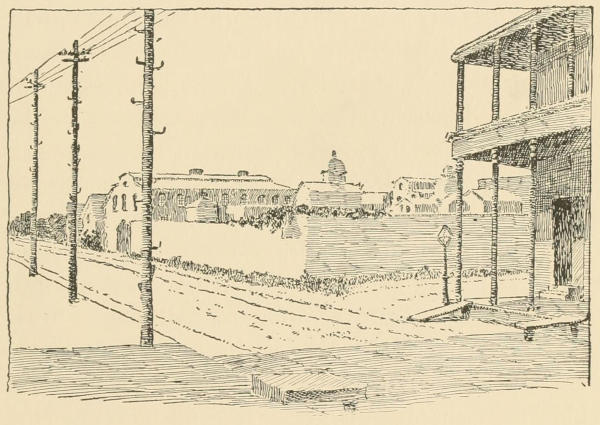

| Seal of the City of New Orleans | 160 |

| Exchange Alley | 163 |

| Henry Clay | Facing 168 |

| Arlington Plantation on the Mississippi | Facing 192 |

| James Alexander McHatton | Facing 258 |

| The Calaboose | 281 |

| A Courtyard in the French Quarter | 305 |

| “Behold a Wrecked Fountain” | 308 |

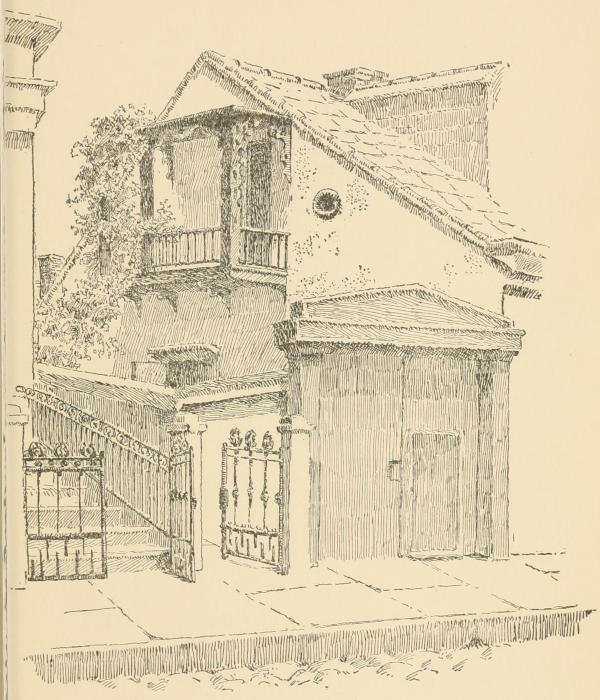

| “A Queer House Opposite” | 311 |

| St. Roch | 316 |

| The Author | Facing 324 |

| A New Orleans Cemetery | 326 |

“Children should be seen and not heard.” Children were neither seen nor heard in the days of which I write, the days of 1840. They led the simple life, going and coming in their own unobtrusive way, making no stir in fashionable circles, with laces and flounces and feathered hats. There were no ready-made garments then for grown-ups, much less for children. It was before California gold mines, before the Mexican war, before money was so abundant that we children could turn up our little noses at a picayune. I recall the time when Alfred Munroe descended from Boston upon the mercantile world of New Orleans, and opened on Camp Street a “one price” clothing store for men. Nobody had ever heard of one price, and no deviation, for anything, from a chicken to a plantation. The fun[2] of hectoring over price, and feeling, no matter how the trade ended, you had a bargain after all, was denied the customers of Mr. Alfred Munroe. The innovation was startling, but Munroe retired with a fortune in course of time.

Children’s clothes were home-made. A little wool shawl for the shoulders did duty for common use. A pelisse made out of an old one of mother’s, or some remnant found in the house, was fine for Sunday wear. Pantalettes of linen, straight and narrow and untrimmed, fell over our modest little legs to our very shoetops. Our dresses were equally simple and equally “cut down and made over.” Pantalettes were white, but I recall, with a dismal smile, that when I was put into what might be called unmitigated mourning for a brother, my pantalettes matched my dresses, black bombazine or black alpaca.

Our amusements were of the simplest. My father’s house on Canal Street had a flat roof, well protected by parapets, so it furnished a grand playground for the children of the neighborhood. Judge Story lived next door and Sid and Ben Story enjoyed to the full the advantages of that roof, where all could romp and jump rope to their heart’s content. The neutral ground, that is now a center for innumerable lines of street cars, was at that[3] time an open, ungarnished, untrimmed, untended strip of waste land. An Italian banana and orange man cleared a space among the bushes and rank weeds and erected a rude fruit stall where later Clay’s statue stood. A quadroon woman had a coffee stand, in the early mornings, at the next corner, opposite my father’s house. It could not have been much beyond Claiborne Street that we children went crawfishing in the ditches that bounded each side of that neutral ground, for we walked, and it was not considered far.

The Farmers’ and Traders’ Bank was on Canal Street, and the family of Mr. Bell, the cashier, lived over the bank. There were children there and a governess, who went fishing with us. We rarely caught anything and had no use for it when we did.

Sometimes I was permitted to go to market with John, way down to the old French Market. We had to start early, before the shops on Chartres Street were open, and the boys busy with scoops watered the roadway from brimming gutters. John and I hurried past. Once at market we rushed from stall to stall, filling our basket, John forgetting nothing that had been ordered, and always carefully remembering one most important item, the saving of at least a picayune out of the market money for a cup of coffee at Manette’s stall. I[4] drank half the coffee and took one of the little cakes. John finished the repast and “dreened” the cup, and with the remark, “We won’t say anything about this,” we started toward home. We had to stop, though, at a bird store, on the square above the Cathedral, look at the birds, chaff the noisy parrots, watch the antics of the monkeys, and see the man hang up his strings of corals and fix his shells in the window, ready for the day’s business. We could scarcely tear ourselves away, it was so interesting; but a reminder that the wax head at Dr. De Leon’s dentist’s door would be “put out by this time,” hurried me to see that wonderful bit of mechanism open and shut its mouth, first with a row of teeth, then revealing an empty cavern. How I watched, wondered and admired that awfully artificial wax face! These occasional market trips—and walks with older members of the family—were the sum of my or any other child’s recreation.

Once, and only once, there was a party! The little Maybins had a party and every child I knew was invited. The Maybins lived somewhere back of Poydras Market. I recall we had to walk down Poydras Street, beyond the market, and turn to the right onto a street that perhaps had a name, but I never heard it.

The home was detached, and surrounded by[5] ample grounds; quantities of fig trees, thickets of running roses and in damp places clusters of palmetto and blooming flags. We little invited guests were promptly on the spot at 4 P. M., and as promptly off the spot at early candlelight. I am sure no débutantes ever had a better time than did we little girls in pantalettes and pigtails. We danced; Miss Sarah Strawbridge played for us, and we all knew how to dance. Didn’t we belong to Mme. Arraline Brooks’ dancing school?

The corner of Camp and Julia Streets, diagonally across from the then fashionable 13 Buildings, was occupied by Mme. Arraline Brooks, a teacher of dancing. Her school (studio or parlor it would be called now) was on the second floor of Armory Hall, and there we children—she had an immense class, too—learned all the fancy whirls and “heel and toe” steps of the intricate polka, which was danced in sets of eight, like old-time quadrilles. Mme. Arraline wore in the classroom short skirts and pantalettes, so we had a good sight of her feet as she pirouetted about, as agile as a ballet dancer.

By and by, at a signal from Miss Sarah, who had been having a confidential and persuasive interview with a little miss, we were all placed with our backs to the wall and a space cleared. Miss Sarah[6] struck a few notes, and little Tenie Slocomb danced the “Highland fling.” Very beautiful was the little sylph in white muslin, her short sleeves tied with blue ribbons, and she so graceful and lovely. It comes to me to-day with a thrill, when I compare the companion picture—of a pale, delicate, dainty old lady, with silvered hair and tottering step, on the bank of a foreign river. It is not easy to bridge the seventy years (such a short span, too, it is) between the two. Then the march from “Norma” started us to the room for refreshments. It is full forty years since I have heard that old familiar air, but for thirty years after that date I did not hear it that the impulse to march to lemonade and sponge cake did not seize me.

Alack-a-day! Almost all of us have marched away.

Of course, seventy years ago, as in the ages past and to come, convents were the places for educating young girls in a Catholic community. Nevertheless, there have always been schools and schools, for those whom it was not expedient or convenient to board in a convent. In New Orleans the Ursuline Convent was too remote from the majority of homes for these day scholars, so there were a few schools among the many that come to my mind to-day, not that I ever entered one of them, but I had girl friends in all. In the thirties St. Angelo had a school on Customhouse Street, next door to the home of the Zacharies. His method of teaching may have been all right, but his discipline was objectionable; he had the delinquent pupils kneel on brickdust and tacks and there study aloud the neglected lesson. Now, brickdust isn’t so very bad, and tacks only a trifle worse, when one’s knees are protected by stockings or even pantalettes,[8] but stockings in those days did not extend over the knee, and old St. Angelo was sure to see that the pantalettes were well rolled up. This method of discipline was not acceptable to parents whose children came home with bruises and wounds. That dominie retired from business before the forties.

Mme. Granet had a school for girls in the French municipality. Elinor Longer, one of my most intimate friends, attended it, and she used to tell us stories that convulsed us with laughter about Madame’s daughter. Lina had some eye trouble, and was forbidden to “exercise the tear glands,” but her tears flowed copiously when Madame refused to submit to her freaks. Thus Lina managed, in a way, to run the school, having half holidays and other indulgences so dear to the schoolgirl, at her own sweet will.

At the haunted house (I wonder if it is still standing and still haunted?) on Royal Street, Mme. Delarouelle had a school for demoiselles. Rosa, daughter of Judge John M. Duncan, was a scholar there. I don’t think the madame had any boarders, though the house was large and commodious, even if it was haunted by ghosts of maltreated negroes. The school could not under those circumstances have continued many years, for every child knew it was dangerous to cross its portals. Our John told[9] me he “seed a skel’ton hand” clutching the grated front door once, and he never walked on that side of the street thereafter. He even knew a man “dat seen eyes widout sockets or sockets widout eyes, he dun know which, but dey could see, all de same, and they was a looken out’en one of the upstairs winders.” With such gruesome talk many a child was put to bed in my young days.

Doctor, afterward Bishop Hawks, when he was rector of Christ Church, then on Canal Street, had a school on Girod Street. It was a temporary affair and did not continue over a season or two. It was entirely conducted by Mrs. Hawks and her daughters, so far as I know, for, as before mentioned, I attended none of the schools.

In 1842 there was a class in Spanish at Mr. Hennen’s house, on Royal Street, near Canal. Señor Marino Cubi y Soler was the teacher of that class; a very prosaic and painstaking teacher he was, too, notwithstanding his startlingly high flown cognomen. Miss Anna Maria and young Alfred Hennen and a Dr. Rhodes, from the Belize, as the mouth of the Mississippi is called, with a few other grown-ups, formed the señor’s class. I was ten years old, but was allowed to join with some other members of my family, though my mother protested it was nonsense for a child like me and a waste of money.[10] Father did not agree with her, and after over sixty years to think it over, I don’t either. When the señor’s class dispersed I imagine the text-books, of which, by the way, he was author, were laid aside. But years and years thereafter, during the war, while traveling in Mexico, some of the señor’s teaching came miraculously back to me, bringing with it enough Spanish to be of material help in that stranger country.

Another teacher wandered from house to house with his “Telemaque” and “colloquial phrases,” giving lessons in French. Gimarchi, from the name, may have been partly, at least, Italian, but he was a fine teacher of the sister language. Por supuésto, his itinerary was confined to the American district of the city.

Is it any surprise that the miscellaneous education we girls of seventy years ago in New Orleans had access to, culminated by fitting us for housewives and mothers, instead of writers and platform speakers, doctors and lawyers—suffragettes? Everybody was musical; every girl had music lessons and every mother superintended the study and practice of the one branch deemed absolutely indispensable to the education of a demoiselle. The city was dotted all over with music teachers, but Mme. Boyer was, par excellence, the most popular. She did not wander[11] from house to house, but the demoiselles, music roll in hand, repaired to her domicile, and received instruction in a music room barely large enough to contain a piano, a scholar and a madame who was, to say the least, immense in bulk, the style of Creole who appears best in a black silk blouse volante.

Richard Henry Chinn

Painted by Hardin

Art was not taught, art was not studied, art was not appreciated. I mean by art the pencil and the brush, so busily wielded in every school now. No doubt there were stifled geniuses whose dormant talent was never suspected, so utterly ignored were the brush and the palette of the lover of art. I call to mind the ability evinced by Miss Celestine Eustis in the use of the pencil. She occasionally gave a friend a glimpse of some of her work, of which, I regret to say, she was almost ashamed, not of the work, but of the doing it. I recall a sketch taken of Judge Eustis’ balcony, and a group of young society men; the likenesses, unmistakably those of George Eustis and of Destour Foucher, were striking.

M. Devoti, with his violin in a green baize bag, was a professor of deportment and dancing. He undertook to train two gawky girls of the most awkward age in my father’s parlor. M. Devoti wore corsets! and laced, as the saying is, “within an inch of his life.” He wore a long-tail coat, very full[12] at the spider waist-line, that hung all round him, almost to the knees, so he used it like a woman’s skirt, and could demonstrate to the awkward girls the art of holding out their skirts with thumb and forefinger, and all the other fingers sticking out stiff and straight. Then curtsey! throw out the right foot, draw up the left.

Another important branch of deportment was to seat the awkwards stiffly on the extreme edge of a chair, fold the hands on the very precarious lap, droop the eyes in a pensive way. Then Devoti would flourish up and present, with an astonishing salaam, a book from the center table. The young miss was instructed how to rise, bow and receive the book, in the most affected and mechanical style. Another exercise was to curtsey, accept old Devoti’s arm and majestically parade round and round the center table. The violin emerged from the baize bag, Devoti made it screech a few notes while the trio balanced up and down, changed partners and promenaded, till the awkwards were completely bewildered and tired out. He then replaced the violin, made a profound bow to extended skirts and curtseys, admonished the pupils to practice for next lesson, and vanished. Thus ended the first lesson. Dear me! Pock-marked, spider-waist Devoti is as plain to my eye to-day as he was in the flesh, bowing,[13] smiling, dancing with flourishing steps as in the days of long ago.

Were those shy girls benefited by that artificial training? I opine not. This seems to modern eyes, mayhap, a whimsical exaggeration; nevertheless, it is a true picture. Devoti’s style was indeed the “end of an era”; he had no successor. Turveydrop, the immortal Turveydrop himself, was not even an imitator. These old schools and teachers march before my mind’s eye to-day; very vivid it all is to me, though the last of them, and perhaps all those they tried to teach, have passed away. Children who went to Mme. Granet and Mme. Delarouelle and Dr. Hawks and all the other schools of that day, sent their daughters, a decade or two later, to Mme. Desrayoux. Now she is gone and many of the daughters gone also. And it is left to one old lady to dig out the past, and recall, possibly to no one but herself, New Orleans schools, teachers and scholars of seventy years ago.

I wonder if the parents of the present do not sometimes contrast the fashionable schools in which their daughters are being educated with the fashionable schools to which their aged mothers, mayhap grandmothers, were sent sixty and more years ago? Among my possessions that I keep—according to the dictum of my grandchildren—“for sentimental sake,” is a much-worn “Scholar’s Companion,” which they scorn to look at when I bring it forth, and explain it to be the best speller that ever was; and a bent, much overworked crochet needle of my schooldays, for we worked with our hands as well as with our brains. The boarding school to which I refer was not unique, but a typical New England seminary of the forties. It was both fashionable and popular, but the young ladies were not, as now, expected to appear at a 6 o’clock dinner in a low neck (oh, my!) gown.

Lately, passing through the now much expanded city to which I was sent, such a young girl, on a[15] sailing ship from New Orleans to New York in the early spring of 1847, I spent a half hour walking on Crown Street looking for No. 111. It was not there, not a trace of the building of my day left; nor was one, so far as I know, of the girls, my old schoolmates, left; all three of the dear, painstaking teachers sleeping in the old cemetery, at rest at last were they. Every blessed one lives in my memory, bright and young, patient and middle-aged—all are here to beguile my twilight hours....

The school routine was simple and precise, especially the latter. We had duties outside the schoolroom, the performance of which was made pleasant and acceptable, as when the freshly laundered clothes were stacked in neat little piles on the long table of the yellow room on Thursdays, ready for each girl to carry to her own room. There were also neat little stacks on each girl’s desk, of personal articles requiring repairs, buttons to replace, holes to patch, stockings to darn, and in the schoolroom on Thursday afternoons—how some of us hated the work!—it was examined and passed upon before we were dismissed. The long winter evenings we were assembled in the library and one of the teachers read to us. I remember one winter we had “Guy Mannering” and “Quentin Durward,” Sir Walter Scott’s lovely stories. We girls were expected[16] to bring some work to occupy our fingers while listening to the readings, with the comments and explanations that illuminated obscure portions we might not comprehend.

There was an old-fashioned “high boy” (haut bois) in the library, in the capacious drawers of which were unmade garments for the missionary box. Woe unto the young lady who had no knitting, crocheting or hemstitching of her own to do! She could sew on red flannel for the little Hottentots! After hymn singing Sunday afternoons there was reading from some suitably saintly book. We had “Keith’s Evidences of Prophecy” (I have not seen a copy of that much-read and laboriously explained volume for more than sixty years). The tension of our minds produced by “prophecy” was mitigated once in a while by two goody-goody books, “Lamton Parsonage” and “Amy Herbert,” both, no doubt, long out of print.

There also were stately walks to be taken twice a day for recreation; walks down on the “Strand,” or some back street that led away from college campus and flirtatious students. Our school happened to be too near the college green, by the way. We marched in couples, a teacher to lead who had eyes both before and behind, and a teacher similarly equipped to follow. With all these precautions[17] we—some of us were pretty—were often convulsed beyond bounds when “we met by chance, the only way,” on the very backest street, a procession of college fellows on mischief bent, marching two and two, just like us. In bad weather we were shod with what were called “gums” and wrapped in coats long and shaggy and weighing a ton. Waterproofs were a later invention. Wet or dry, cold or warm, those exercises had to be taken to keep us in good physical condition. I must mention in this connection that no matter what ailed us, in stomach or back, head or foot, we were dosed with hot ginger tea. I do not remember ever seeing a doctor in the house, or knowing of one being summoned. The girls hated that ginger tea, so no doubt many an incipient headache was not reported.

With the four spinsters (we irreverently called No. 111 Old Maids’ Hall) who lived in the house, there were scraggly, baldheaded, spectacled teachers from outside—a monsieur who read Racine and Molière with us and taught us j’aime, tu aime, which he could safely do, the snuffy old man; a fatherly sort of Turveydrop dancing master, who cracked our feet with his fiddle bow; a drawing master, who, because he sometimes led his class on sketching trips up Hillhouse Avenue, was immensely popular, and every one of us wanted[18] to take drawing lessons. We did some water colors, too; some of us had not one particle of artistic talent. I was one of that sort, but I achieved a Baltimore oriole, which, years after, my admiring husband, who also had no artistic taste, had framed and “hung on the line” in our hall. Perhaps some Yankee may own it now, for during the war they took everything else we had, and surely a brilliant Baltimore oriole did not escape their rapacity!

Solid English branches were taught by the dear spinsters. We did not skin cats and dissect them. There was no class in anatomy, but there was a botany class, and we dissected wild flowers, which is a trifle more ladylike. Our drilling in chirography was something to marvel at in these days when the young people affect such complicated and involved handwriting that is not easily decipherable. And grammar! I now slip up in both grammar and rhetoric, but I have arrived at the failing age. We spent the greater part of a session parsing Pope’s “Essay on Man,” and at the closing of that book I think we knew the whole thing by heart. Discipline was, so to say, honorary. There were rules as to study and practice hours, and various other things. Saturday morning, after the “Collect of the day” and prayers, when we were presumed to be in a celestial frame of mind, each girl reported[19] her infringement of rules—if she was delinquent, and she generally was. That system served to make us more truthful and conscientious than some of us might have been under a different training.

It was expressly stipulated that no money be furnished the pupils. A teacher accompanied us to do necessary shopping and used her discretion in the selection. If one of us expressed the need of new shoes her entire stock was inspected, and if a pair could be repaired it was done and the purchase postponed. Now, bear in mind, this was not a cheap, second rate school, but one of the best known and most fashionable. There were several young ladies from the South among the twenty or so boarders. The Northern girls were from the prominent New York families—Shermans, Kirbys, Phalens, Pumpellys and Thorns. This was before the fashionables of to-day came to the fore.

Speaking of reporting our delinquencies, we knew quite well that it was against the custom, at least, to bring reading matter into the school. There was a grand, large library of standard works of merit at our free disposal. In some way “Jane Eyre” (just published) was smuggled in and we were secretly reading it by turns. How the spinsters found it out we never knew, but they always found[20] out everything, so we were scarcely surprised one Saturday morning to receive a lecture on the pernicious character of the book “Jane Eyre,” so unlike (and alas! so much more interesting than) Amy Herbert, with her missionary basket, her coals and her flannel petticoats. We were questioned, not by wholesale, but individually, if we had the book? If we had read the book? The first two or three in the row could reply in the negative, but as interrogations ran down the line toward the guilty ones they were all greatly relieved when one brave girl replied, “Yes, ma’am, I am almost through, please let me finish it.” Then “Jane” vanished from our possession.

When the Church Sewing Society met at our house, certain girls who were sufficiently advanced in music to afford entertainment to the guests were summoned to the parlor to play and sing, and incidentally have a lemonade and a jumble. I was the star performer (had I not been a pupil of Cripps, Dr. Clapp’s organist, since I was able to reach the pedal with my foot?). My overture of “La Dame Blanche” was quite a masterpiece, but my “Battle of Prague” was simply stunning. The “advance,” the “rattle of musketry,” the “beating of drums” (did you ever see the music score?) I could render with such force that the dear, busy ladies almost[21] jumped from their seats. There were two Kentucky girls with fine voices also invited to entertain the guests. Alas! our fun came to an end. On one occasion when I ended the “Battle of Prague” with a terrific bang, there was an awful moment of silence, when one of the ladies sneezed with such unexpected force that her false teeth careered clear across the room! Not one of the guests saw it, or was aware that she quietly walked over and replaced them, but we naughty girls were so brimful of fun that we exploded with laughter. Nothing was said to us of the unfortunate contretemps, but the musical programmes were discontinued.

College boys helped to make things lively for us, though we did not have bowing acquaintance with one of them. Valentines poured in to us; under doors and over fences they rained. The dear spinsters laughed over them with us. Thanksgiving morning, when the front door was opened for the first time, and we were assembled in the hall ready to march to 11 o’clock church service, a gaunt, skinny, starved-to-death turkey was found suspended to the door knob, conspicuously tied by a broad red ribbon, with a Thanksgiving greeting painted on, so “one who ran could read.” No doubt a good many had read and run, for there had been hours allowed them. The dear spinsters were so mortified[22] and shocked that we girls had not the courage to laugh.

By reason of my distance from home, reached by a long voyage on a sailing ship—the first steamer service between New York and New Orleans was in the autumn of 1848, and the Crescent City was the pioneer steamer—I spent the vacations under the benign influence of the teachers, always the only girl left, but busy and happy, enjoying all the privileges of a parlor boarder. I still have a book full of written directions for knitting and crocheting, and making all sorts of old-timey needle books and pincushions, the initial directions dated 1846, largely the collection and record of more than one long summer vacation at that New England school. What girl of to-day would submit to such training and routine? What boarding school, seminary or college is to-day conducted on such lines? Not one that you or I know. The changes in everything, in every walk of life, from the simple in my day and generation to the complicated of the present, sets me to moralizing. Like all old people who are not able to take an active interest in the present, I live in the past, where the disappointments and heartaches, for surely we must have had our share, are forgotten. We old people live in the atmosphere of a day dead—and gone—and glorified!

The first time I ever saw a penny was at school in Yankeeland in 1847. It was given me to pay the man for bringing me a letter from the postoffice—10 cents postage, 1 cent delivery, in those days. People had to get their mail at the office. There was no free delivery. Certain neighborhoods of spinsters, however—the college town was full of such—secured the services of a lame, halt or blind man to bring their letters from the office to their door once a day for the stipend of a penny each.

There was no coin in circulation of less value than a picayune where was my home. A picayune, which represented so little value that a miser was called picayunish, at the same time represented such a big value that we children felt rich when we had one tied in the corner of our handkerchief. At the corner of Chartres and Canal Streets was a tiny soda fountain, where one could get a glass of soda for a picayune—or mead. We children liked mead. I[24] never see it now, but, as I recall, it was a thick, honey, creamy drink. We must have preferred it because it seemed so much more for a picayune than the frothy, effervescent, palish soda water. It was a great lark to go with Pa and take my glass of mead, while he ordered ginger syrup (of all things!) with his soda. The changing years bring gold mines, greenbacks, tariffs, labor exactions and nouveaux riches, and a penny now buys about what a picayune did in my day. One pays a penny for ever so big a newspaper to-day. A picayune was the price of a small sheet in my time.

Market Doorway.

Many of us must remember the colored marchandes[25] who walked the street with trays, deftly balanced on their heads, arms akimbo, calling out their dainties, which were in picayune piles on the trays—six small celesto figs, or five large blue ones, nestling on fig leaves; lovely popcorn tic tac balls made with that luscious “open kettle” sugar, that dear, fragrant brown sugar no one sees now. Pralines with the same sugar; why, we used it in our coffee. A few years ago, visiting dear Mrs. Ida Richardson, I reveled in our breakfast coffee. “I hope you preserve your taste for brown sugar coffee?” she said. I fairly jumped at the treat.

But a marchande is passing up the street, and if I am a little girl, I beg a picayune for a praline; if I am an old lady, I invest a picayune in a leaf with six figues célestes. Mme. Chose—I don’t give any more definite name, for it is a sub rosa venture on her part—had a soirée last night. Madame buys her chapeaux of Olympe, and her toilettes from Pluche or Ferret, and if her home is way down, even below Esplanade Street, where many Creoles live, she is thrifty and frugal. So this morning a chocolate-colored marchande, who usually vends picayune bouquets of violets from madame’s parterre, has her tray filled with picayune stacks of broken nougat pyramid and candied orange and macaroons very daintily arranged on bits of tissue paper. I vividly[26] recall encountering way down Royal Street, where no one was loitering to see me, this chocolate marchande, and recognizing the delicacies of a ball the previous night. I was on my way to call on Mrs. Garnet Duncan, the dear, delightful woman who was such a gourmande, and I knew how delicious were those sweets; no one could excel a Creole madame in this confection. So I invested a few picayunes in some of the most attractive, carrying off to my sweet friend what I conveniently could. How she did enjoy them! And how she complained I had not brought more! The mesdames of that date are gone; gone also, no doubt, are the marchandes they sent forth. It was a very picayunish sort of business, but labor did not count, for one was not paying $20 a month for the reluctant services of a chocolate lady.

Then again, in the early morning, when one, en papilottes, came down to breakfast, listless and “out of sorts,” the chant of the cream cheese woman would be heard. A rush to the door with a saucer for a cheese, a tiny, heart-shaped cheese, a dash of cream poured from a claret bottle over it—all this for a picayune! How nice and refreshing it was. What a glorious addition to the breakfast that promised to pall on one’s appetite.

Picayune was the standard coin at the market. I[27] wonder what is now? Soup bone was un escalin (two picayunes), but one paid for the soup vegetables, a bit of cabbage, a leek, a sprig of parsley, a tiny carrot, a still tinier turnip, all tied in a slender package. A cornet of fresh gumbo filé, a bunch of horse-radish roots, a little sage, parsley, herbs of every sort in packages and piles, a string of dried grasshoppers for the mocking bird, “un picayun,” the Indian or black woman squatting on the banquette at the old French Market would tell you.

A picayune was the smallest coin the richly appareled madame or the poor market negro could put in the collection box as she paused on her way at the Cathedral to tell her beads. There was no occasion for the priest to rebuke his flock for niggardliness. They may have been picayunish, but not to the extent of the congregation of one of the largest Catholic churches I wot of to-day, where the fathers were so tired counting pennies that it was announced from the pulpit: “No more pennies must be put in the box. We spend hours every week counting and stacking pennies, and it is a shocking waste of time. If you are so destitute that you can’t afford at least a nickel to your church, come to the vestry, after mass, and we will look into your needs and give you the relief the church always extends to her poor.”

The shabby old negro, with her heavy market basket, returning home, no doubt needing the prayers of her patron saint or some other churchly office, filched the picayune from the carefully counted market money. I know, no matter how carefully my mother doled the market fund to John, he always contrived to secure a picayune out of it, and for no saint, either, but for old Coffee-stand Palmyre.

Do not we old ladies remember the picayune dolls of our childhood? The wooden jointed dolls, the funny little things we had to play with, every feature, even hair and yellow earrings, painted on little, smooth bullet heads. They could be made to sit down and to crook their arms, but no ingenuity could make them stand a-loney. How we loved those little wooden dolls! We do not see a pauper child, not even a poor little blackie, with a picayune doll nowadays. I really believe we—I am talking of old ladies now—were happier, and had more fun with our picayune family than the little girls of the present day have with their $10 dolls, with glass eyes that are sure to fall out and long curls that are sure to tangle. We had no fears about the eyes and hair of our picayunes.

The picayune, whose memory I invoke, was a Spanish coin, generally worn pretty thin and often having a small hole in it. I remember my ambition[29] was to accumulate enough picayunes to string on a thread for an ornament. It is unnecessary to say that in those thrifty days my ambition was not gratified. It is more than fifty years since I have seen one of those old 6¼ cent picayunes. I have a stiff, wooden corset board that I sometimes take out to show to my granddaughter when I find her “stooping,” that she may see the instrument that made grandma so straight. I would like to have a picayune to add to my very limited collection of relics. They flourished at the same era and have together vanished from our homes and shops.

We all must have known some “picayune people.” There was a family living near us who owned and occupied a large, fine home on St. Joseph Street, while we and the Grimshaws and Beins lived in rented houses near by. They had, besides, a summer home “over the lake” (and none of us had!). Often, on Mondays, a fish, or a quart of shrimp, or something else in the “over the lake” line, was sent to one of us, for sale. We used to laugh over the littleness of the thing. A quart of shrimp for a picayune was cheap and tempting, but none of us cared to buy of our rich neighbor. The climax came when an umbrella went the rounds for inspection. It was for raffle! Now, umbrellas, like pocket handkerchiefs, are always useful and never go out[30] of fashion. With one accord, we declined chances in the umbrella.

I feel I am, for the fun of the thing, dragging forth a few skeletons from closets, but I do not ticket them, so no harm is done. In fact, if I ever knew, I have long since forgotten the name to tack onto the umbrella skeleton. And the fashionable madame who sent out on the streets what a lady we knew called the “perquisites” of her soirée supper has left too many well-known descendants. I would scorn to ticket the skeleton of that frugal and thrifty madame. There are no more umbrellas for a picayunish skeleton to raffle, no more such delicious sweets for the madame to stack into picayune piles, and, alack-a-day! no more picayunes, either.

Housekeeping is vastly simplified since the days when my mother washed her teacups and spoons every morning. I love the old way; however, I do not practise it. If my grandchildren were to see the little wooden piggin brought me on a tray after breakfast, and see me wash the silver and glass they would think grandma has surely lost her mind. That purely domestic housewifely habit lasted long after my mother had passed away. It still is the vogue in many a New England household, but no doubt is among the lost virtues South. When I was a young lady and occasionally (oh, happy times!) spent a few days with the Slocombs, I always saw Mrs. Slocomb and her aged mother, dear old Mrs. Cox, who tremblingly loved to help, pass the tea things through their own delicate hands every morning. So it was at Mrs. Leonard Matthews’, and so it was in scores of wealthy homes.

Though we had ever so many servants, our family[32] being a large one, my semi-invalid mother, who rarely left her home and never made visits, did a thousand little household duties that are now, even in families where only one or two servants are kept, entirely ignored by the ladies of the house. After a dinner party or an evening entertainment, and my father was hospitably inclined—much beyond his means—my mother passed all the silver, glass and china through her own delicate fingers, and we did not, as I recall after all this lapse of years, have anything of superlative value. It was not a matter of thrift or economy on her part, but a matter of course; everybody did the same.

After a visit to a New England family several years ago I was telling a Creole friend of the lovely old India china that had been in daily use over three generations. The reply was: “Oh, but they did not have a Christophe.” No doubt they had had several Christophes, but they never had a chance to wash those valuable cups. In the days of long ago housewives did not have negligées with floating ribbons and smart laces. They had calico gowns that a splash of water could not ruin.

A New Orleans Yard and Cistern.

Household furniture—I go back full seventy years—was simple and easily cared for. Carpets were generally what was known as “three-ply.” I don’t see them now, but in places, on humble[35] floors, I see imitation Brussels or some other counterfeit. The first carpet I ever saw woven in one piece, like all the rugs so plentiful now (and that was at a much later date) was on the parlor floor of the Goodman house, on Toulouse Street, the home so full of bright young girls I so loved to visit. There was no concern to take away carpets to be cleaned and stored in the summer. Carpets were taken to some vacant lot and well beaten. The neutral green on Canal Street, green and weedy it was, too, was a grand place to shake carpets; no offense given if one carried them beyond Claiborne Street where were no pretentious houses. Then those carpets were thickly strewn with tobacco leaves, rolled up and stored in the garret, if you had one. Every house did not boast of that convenience.

Curtains were not satin damask. At the Mint when Joe Kennedy was superintendent, and his family were fashionable people, their parlor curtains were some red cotton stuff, probably what is known as turkey red; there was a white and red-figured border; they were looped over gilt rods meant to look like spears and muskets, in deference, I suppose, to the military side of that government building, for there were sentinels and guards stationed around about that[36] gave the whole concern a most imposing and military air.

I remember at the Breedloves’ home there were net curtains (probably mosquito net), with a red border. They were thought rather novel and stylish. There were no madras, no Irish point, no Nottingham curtains even, so one did not have a large variety to choose from.

People had candelabras, and some elaborate affairs—they called them girandoles—to hold candles; they had heavy crystal drops that tinkled and scintillated and were prismatic and on the whole were rather fine. The candles in those gorgeous stands and an oil lamp on the inevitable center-table were supposed to furnish abundance of light for any occasion. When my sister dressed for a function she had two candles to dress by (so did I ten years later!), and two dusky maids to follow her all about, and hold them at proper points so the process of the toilet could be satisfactorily accomplished. Two candles without shades—nobody had heard of shades—were sufficient for an ordinary tea table. I was a grown girl, fresh from school, when I saw the first gaslight in a private house, at Mrs. Slocomb’s, on St. Charles Street. People sewed, embroidered, read and wrote and played chess evenings by candlelight, and except a few[37] near-sighted people and the aged no one used glasses. There was not an oculist (a specialist, I mean) in the whole city.

Every woman had to sew. There were well-trained seamstresses in every house; no “ready-mades,” no machines. Imagine the fine hand-sewing on shirt bosoms, collars and cuffs. I can hear my mother’s voice now, “Be careful in the stitching of that bosom; take up two and skip four,” which I early learned meant the threads of the linen. What a time there was when the boys grew to tailor-cut pantaloons! Cut by a tailor, sewed at home, what a to-do there was when Charley had his first tail-coat; he could not sit on the tails, they were too short, so he made an uproar.

I recall also how I cried when sister’s old red and black “shot silk” dress was made over for me, and I thought I was going to be so fine (I was nine years old then and was beginning to “take notice”). The goods fell short, and I had to have a black, low neck, short-sleeve waist. In vain I was told it was velvet and ever so stylish and becoming. I knew better. However, that abbreviated dress and those abbreviated tails did duty at the dancing school.

But we have wandered from house furnishings to children’s clothes. We will go upstairs now and[38] take a look at the ponderous four-poster bed, with its awful tester top, that covered it like a flat roof. That tester was ornamented with a wall paper stuff, a wreath of impossible red and yellow roses, big as saucers, stamped on it, and four strands of same roses reaching to the four corners of the monstrosity. The idea of lying, with a raging fever or a splitting headache, under such a canopy! However, there were “swells” (there always are “swells”) who had testers covered with silk.

I hear a rumor that furniture covered with horse-hair cloth is about to come to the fore again. Everybody in my early day had black haircloth furniture; maybe that was one reason red curtains were preferred, for furniture covered with black haircloth was fearfully funereal. However, as no moth devoured it, dust did not rest on its slick, shiny surface, and it lasted forever, it had its advantages. Every household possessed a haircloth sofa, with a couple of hard, round pillows of the same, the one too slippery to nap on and the others regular break-necks.

Door in the French Market.

Butler’s pantry! My stars! Who ever heard of a butler’s pantry, and sinks, and running water, and faucets inside houses? The only running water was a hydrant in the yard; the only sink was the gutter in the yard; the sewer was the gutter in the[39] street, so why a butler’s pantry? To be sure there was a cistern for rainwater, and jars like those Ali Baba’s forty thieves hid themselves in. Those earthen jars were replenished from the hydrant, and the muddy river water “settled” by the aid of almond hulls or alum.

Of course, every house had a storeroom, called pantry, to hold supplies. It was lined with shelves, but the only light and air was afforded by a half-moon aperture cut into a heavy batten door. We had wire safes on the back porch and a zinc-lined box for the ice—nothing else—wrapped in a gray blanket, gray, I presume, on the same principle we children preferred pink cocoanut cakes—they kept clean longer than the white! Ice was in general use but very expensive. It was brought by ship from the North, in hogsheads.

For the kitchen there were open fireplaces with a pot hanging from a crane, skillets and spiders. We don’t even hear the names of those utensils now. By and by an enterprising housewife ventured on a cook stove. I have a letter written by one such, dated in New Orleans in 1840, in which she descants on the wonders achieved by her stove. “Why, Susan, we baked three large cakes in it at one time.” In the old way it required a spider for each cake.

There were no plated knives, but steel, and they[40] had to be daily scoured with “plenty brickdust on your knife board,” but those knives cut like razors. There was no bric-a-brac, few pictures, nothing ornamental in the parlors. One house I remember well had a Bunker Hill monument, made, I guess, of stucco, and stuck all over with gay seashells; it was perhaps 25 or 30 inches high; it made a most commanding appearance on the center-table. When my sister made a tiresomely long call at that house it amused me to try to count the shells.

An old gentleman, called “Old Jimmie Dick” when I remember him, a rich cotton broker (the firm was Dick & Hill), made a voyage to Europe, and brought home some Apollos, and Cupids, and Mercuries, statues in the “altogether,” for his parlor. Jimmie Dick was a bachelor, and lived on Canal Street, near Carondelet or Baronne, and had a charming spinster niece keeping house for him, who was so shocked when she saw the figures mounted on pedestals (they were glaring white marble and only a trifle under life size) that she immediately made slips of brown holland and enveloped them, leaving only the heads exposed! I never went to that house but the one time when we surprised her in the act of robing her visitors!

I speak of houses that I visited with my grown sister. It was not comme il faut for a young[41] lady to be seen too frequently on the street or to make calls alone. Mother was an invalid and made no visits. Father accompanied sister on ceremonious occasions. I was pressed into service when no one else was available. I feel I am going way back beyond the recollection of my readers, but some of the grandmothers, too old, mayhap, to do their own reading, can recall just such a life, a life that will never be lived again.

It is hard to realize while we are surrounded by so many housekeeping conveniences what an amount of time, energy, and, above all, knowledge of the craft were necessary to the giving of a reception seventy years ago, when every preparation had to be made in the house and under the watchful supervision of the chatelaine.

There were no chefs to be hired, nor caterers to be summoned, not even a postman to deliver invitations. All that was done “by hand.” A darky was sent forth with a basket of nicely “tied up with white ribbons” notes of invitation, and he went from house to house, sending the basket to the occupant, where she not only subtracted her special note, but had the privilege of seeing “who else was invited.” And if the darky was bewildered as to his next stopping-place she could enlighten him. This complicated mode of delivering invitations prevailed into the fifties.

The preparations for the supper involved so much[43] labor that many hosts offered only eau sucrée or gumbo. There was no cut nor granulated nor pulverized sugar, to be turned from the grocer’s bag onto the scales. All sugar except the crude brown, direct from plantations, was in cone-shaped loaves as hard as a stone and weighing several pounds each. These well-wrapped loaves were kept hung (like hams in a smokehouse) from the closet ceiling. They had to be cut into chips by aid of carving knife and hammer, then pounded and rolled until reduced to powder, before that necessary ingredient was ready for use.

There were no fruit extracts, no essences for seasoning, no baking powder to make a half-beaten cake rise, no ground spices, no seedless raisins, no washed (?) currants, no isinglass or gelatine, and to wind up this imperfect list, no egg-beater! Still the thrifty housewife made and served cakes fit for the gods, with only Miss Leslie’s cook book to refer to, and that was published in the twenties. Ice cream was seasoned by boiling a whole vanilla bean in the milk; it was frozen in a huge cylinder without any inside fixtures to stir the mixture; it was whirled in the ice tub by hand—and a stout one at that—and required at least one hour, constant labor, to freeze the cream.

For jelly, calves’ feet were secured days in[44] advance, and Madame superintended the making of gelatine. Pink jelly was colored with a drop or two of cochineal, yellow, doctored with lemon, and a beautiful pale green, colored with the strained juice of scalded spinach. These varieties were served in various attractive shapes; and all, even the green, were delicious. These preparations were also complicated by the necessity of procuring all supplies from the early morning market often a mile or more away, and which, besides, closed at 10 o’clock. No stepping to the corner grocery for eggs or butter in an unforeseen emergency, and to the credit of the community the “borrowing habit” was entirely unknown.

I remember a Mrs. Swiler, chiefly because when I went to see her, with an older sister, she “passed around” bananas. Cuban fruits were scarce in those days, and highly prized.

There were no awnings to be used in bad weather; no camp chairs for the invited guests if all came, and all wanted to sit down at the same time; no waterproofs for them to come in; no rubbers to protect feet from rain-soaked sidewalks; no street cars; no public conveyances that people ever hired for such occasions; no private carriages to bump you over rough cobblestones. So, there you are!

Courtyard on Carondelet Street

Arrived after all these tiresome preparations and your own discomfort at my father’s house, on Canal Street, to a reception given almost seventy years ago, in honor of Commodore Moore of the Texas navy, who brought to my father letters of introduction from President Mirabeau B. Lamar, of the Republic of Texas, and Gen. Sam Houston of the Texas army!

I have reason to think at this late date, not hearing to the contrary at the time, that the commodore’s visit was quite amicable and friendly. If he was escorted by Texas warships! or even arrived in his own flagship! I never knew. With his imposing uniform and a huge gilt star on his breast, a sword at his side, and a rather fierce mustache (mustaches were little worn then), he looked as if he were capable of doing mighty deeds of daring, for the enterprising new republic on our border. He was accompanied by his aide, a callow youth, also in resplendent attire, a sword so long and unwieldy he was continually tripping, and therefore too embarrassingly incommoded to circulate among the ladies. I met that “aide,” a real fighter in Texas during the late war. He proudly wore a lone star under the lapel of his coat of Confederate gray, and we had a merry laugh over his naval début. He was Lieut. Fairfax Grey. His sister was the[48] wife of Temple Doswell, and many of her descendants are identified with New Orleans to-day.

Mr. Clay, grand, serene, homely and affable; also Gen. Gaines in his inevitable uniform. The two military and naval officers commanded my admiration, as I sat quietly and unobtrusively in a corner in a way “becoming to a child of nine”—“a chiel amang ye, takin’ notes”—but no one took note of the chiel. We had also a jolly itinerant Irish preacher, I think of the Methodist persuasion, whom my father had met at country camp meetings. His call was to travel, and incidentally preach where the harvest was ripe. I remember how, laughingly, he remarked to my father, anent the commodore’s visit, that the chief inhabitants of Western Texas were mesquite grass and buffaloes. He was father of John L. Moffitt of Confederate fame, and a very attractive daughter became the wife of President Lamar.

There was dance music—a piano only—but the room was too crowded for more than one attempt at a quadrille. The notabilities, army, navy and State, did not indulge in such frivolity. Life was too serious with them.

These functions generally began at 8 and terminated before the proverbial small hours. So by midnight the last petticoat had fluttered away; and[49] then there followed the clearing up, and, as the old lady said, the “reinstating of affairs,” which kept the hostess and her sleepy helpers busy long after the rest of the family had fluttered away also—to the land of Nod.

Here it is New Year’s Day again. It seems only yesterday when we had such a dull, stupid New Year’s Day. Everybody who was anybody was out of town, at country mansions to flourish with the rich, or to old homesteads to see their folks. Nobody walking the streets, no shops were open. Those of us who had no rich friends with country mansions, or no old homesteads to welcome us, remained gloomily at home, with shades down, servants off for the day, not even a basket for cards tied to the doorknob.

Nobody calls now at New Year’s. It is out of fashion, or, rather, the fashion has descended from parlor to kitchen. When Bridget and Mary don their finery and repair to Bridget’s cousin’s to “receive,” and Sambo puts on a high shirt collar and a stovepipe hat, and sallies out on his round of calls,[51] we have a pick-up dinner, and grandma tries to enliven the family with reminiscences of the New Year’s Days of seventy years ago, when her mother and sister “received” in state, and father and brother donned their “stovepipes” and proceeded to fill the society rôle for the year.

In the forties and for years thereafter, New Year’s Day was the visiting day for the men, and receiving day for the ladies. All the fathers and grandfathers, in their newest rig, stick in hand, trotted or hobbled around, making the only calls they made from year to year. Before noon, ladies were in their parlors, prinked up, pomatumed up, powdered up, to “receive.” Calling began as early as 11, for it was a short winter day, and much to be accomplished. A small stand in the hall held a card receiver, into which a few cards left from last year’s stock were placed, so the first caller might not be embarrassed with the fact that he was the first. No one cared to be the very first then, any more than now.

A table of generous dimensions occupied a conspicuous position in the parlor (we never said “drawing room”), with silver tray, an immense and elaborately decorated cake and a grand bowl of foaming eggnog. That was chiefly designed for the beaux. On the dining room sideboard (we did[52] not say “buffet,” either) a brandy straight or whisky straight was to be found for those walking-stick ones whose bones were stiff and whose digestion could not brook the fifty different concoctions of eggnog they were liable to find in the fifty different houses. Those varied refreshments, which every caller was expected to at least taste, often worked havoc on the young and spry, to say nothing of the halt and lame.

There were no flower decorations. It was the dead season for plants, and Boston greenhouses were not shipping carloads of roses and carnations to New Orleans in the ’40s. Rooms were not darkened, either, to be illuminated with gas or electricity, but windows were thrown wide open to the blessed light of a New Year’s Day. Little cornets of bonbons and dragées were carelessly scattered about. Those cornucopias, very slim and pointed, containing about a spoonful of French confections, were made of stiff, shiny paper, gaudily colored miniatures of impossible French damsels ornamenting them. I have not seen one of those pretty trifles for sixty years. It was quite the style for a swain to send his Dulcinea a cornet in the early morning. If the Dulcinea did not happen to receive as many as she wanted, she could buy a few more. One liked to be a Belle!

Living in Canal Street, a little girl was unconsciously taking notes that blossom now in a chronicle of the doings and sayings of those New Year’s Days of the early ’40s. She enjoyed looking through the open window, onto the broad, unshaded street, watching an endless procession of callers. There were rows of fashionable residences in Canal Street to be visited, and the darting in and out of open doors, as though on earnest business bent, was a sight. The men of that day wore skin-tight pantaloons (we did not call them trousers), often made of light-colored materials. I clearly remember a pea green pair that my brother wore, flickering like a chameleon in and out of open street doors. Those tight-fitting pantaloons were drawn taut over the shoe, a strong leather strap extending under the foot buckled the garment down good and tight, giving the wearer as mincing a gait as the girl in the present-day hobble skirt. The narrow clawhammer coat with tails that hung almost to the knees behind and were scarcely visible in front, had to have the corner of a white handkerchief flutter from the tail pocket.

Military men like Gen. E. P. Gaines (he was in his zenith at that date) and all such who could sport a military record wore stiff stocks about their long necks. Those stocks made the necks appear[54] abnormally long. They were made of buckram (or sheet iron?), so broad that three straps were required to buckle them at the back, covered with black satin, tiny satin bows in front which were utterly superfluous, for they tied nothing and were not large enough to be ornamental. The stocks must have been very trying to the wearers, for they could not turn their heads when they were buckled up, and, like the little boy with the broad collar, could not spit over them. However, they did impart a military air of rigidity and stiffness, as though on dress parade all the time.

I remember Major Waters had a bald spot on the top of his head and two long strands of sandy hair on each side which he carefully gathered up over the bald spot and secured in place by the aid of a side comb! I used to wish the comb would fall out, to see what the major would do, for I was convinced he could not bend his head over that stiff, formidable stock. The major won his title at the battle of River Rasin (if you know where that is, I don’t). My father was in the same battle, but being only seventeen he did not win a title. I don’t suppose that River Rasin engagement amounted to much anyway, for dear pa did not wear a stock, nor a military bearing, either. Gen. Persifor Smith was another stock man who called always at New Year’s[55] and at no other time. And Major Messiah! Dear me, how many of us remember him in the flesh, or can forget the cockaded, epauletted portrait he left behind when he fought his last life’s battle?

All the men wore tall silk hats that shone like patent leather. Those hats have not been banished so long ago that all of us have forgotten their monstrosity, still to be seen now and then in old daguerreotypes or cartes de visite. They flocked in pairs to do their visiting. It would be a Mardi Gras nowadays to see one of those old-time processions. Men of business, men of prominence, no longer society men, fulfilled their social duty once each year, stepped into the dining room at a nod from mother, who was as rarely in the parlor to “receive,” as the men who, at the sideboard, with a flourish of the hand and a cordial toast to the New Year, took a brandy straight. They are long gone. Their sons, the beaux of that day, quietly graduated from the eggnog to the sideboard, become even older men than their fathers, are gone, too.

I remember a very original, entertaining beau of those days saying eggnog was good enough for him, and when he felt he was arriving at the brandy-straight age he meant to kill himself. How would he know when the time for hari-kari came? “When my nose gets spongy.” He had a very pronounced[56] Hebrew nose, by the way. Not so many years ago I heard of him hobbling on crutches. Not only his nose, but his legs were spongy, but he gave no indication that life was not as dear to him as in his salad days.

The younger element, beaux of my grown-up sister, rambled in all day long, hat in hand, with “A happy New Year,” a quaff of eggnog, “No cake, thanks,” and away like a flash, to go into house after house, do and say the same things, till night would find they had finished their list of calls and eggnog had about finished them. So the great day of the year wore on.

After the house doors were closed at the flirt of the last clawhammer coat tail, cards were counted and comments made as to who had called and who had failed to put in appearance, the wreck of glasses, cake and tray removed, and it was as tired a set of ladies to go to bed as of men to be put into bed.

As the beautiful custom of hospitality spread from the centers of fashion to the outskirts of society the demi mondaines, then the small tradesman, then the negroes became infected with the fashion of “receiving” at New Year’s, in their various shady abodes. The bon tons gradually relinquished the hospitable and friendly custom of years. Ladies suspended tiny card receivers on the doorknob, and retired behind[57] closed blinds. Those of the old friends of tottering steps and walking sticks, always the last to relinquish a loved habit, wearily dropped cards into the little basket and passed on to the next closed door. Now the anniversary, instead of being one of pleasant greetings, is as stupid and dull as any day in the calendar, unless, as I have said, one has a friend with a “cottage by the sea” or a château on the hilltop and is also endowed with the spirit of hospitality to ask one to spend the week-end and take an eggnog or a brandy straight.

The shopping region of New Orleans was confined to Chartres and Royal Streets seventy years ago. It was late in the fifties when the first movement was made to more commodious and less crowded locations on Canal Street, and Olympe, the fashionable modiste, was the venturesome pioneer.

Woodlief’s was the leading store on Chartres Street and Barrière’s on Royal, where could be found all the French nouveautés of the day, beautiful barèges, Marcelines and chiné silks, organdies stamped in gorgeous designs, to be made up with wreathed and bouquet flounces, but, above and beyond all for utility and beauty, were the imported French calicoes, fine texture, fast colors. It was before the day of aniline and diamond dyes; blues were indigo, reds were cochineal pure and unadulterated; so those lovely goods, printed in rich designs—often the graceful palm-leaf pattern—could[59] be “made over,” turned upside down and hindpart before, indefinitely, for they never wore out or lost color, and were cheap at fifty cents a yard. None but those in mourning wore black; even the men wore blue or bottle green coats, gay flowered vests and tan-colored pantaloons. I call to mind one ultra-fashionable beau who delighted in a pair of sage green “pants.”

The ladies’ toilets were still more gay; even the elderly ones wore bright colors. The first black silk dress worn on the street, and that was in ’49, was proudly displayed by Miss Mathilde Eustis, who had relatives in France who kept her en rapport with the latest Parisian style. Hers was a soft Marceline silk; even the name, much less the article, is as extinct as the barège and crêpe lisse of those far away days. It was at Woodlief’s or Barrière’s these goods were displayed on shelves and counters. There were no show windows, no dressed and draped wax figures to tempt the passerby.

Mme. Pluche’s shop, on the corner of Royal and Conti, had one window where a few trifles were occasionally displayed on the sill or hung, carefully draped on the side, so as not to intercept the light. Madame was all French and dealt only in French importations. Mme. Frey was on Chartres Street. Her specialty (all had specialties; there was no shop[60] room for a miscellaneous stock of goods) was mantillas, visites, cardinals and other confections to envelop the graceful mesdames en flânant. I call to mind a visite of thinnest muslin, heavily embroidered (no Hamburg or machine embroidery in those days), lined with blue silk, blue cords and tassels for a finish. It was worn by a belle of the forties, and Mme. Frey claimed to have imported it. The madame was not French. She had a figure no French woman would have submitted to, a fog-horn voice and a well-defined mustache, but her taste was the best and her dictum in her specialty was final.

The fashionable milliner was Olympe. Her specialty was imported chapeaux. She did not—ostensibly, at least—make or even trim chapeaux. Olympe’s ways were persuasive beyond resistance. She met her customer at the door with “Ah, madame”—she had brought from Paris the very bonnet for you! No one had seen it; it was yours! And Mam’zelle Adèle was told to bring Mme. X’s chapeau. It fit to a merveille! It was an inspiration! And so Mme. X had her special bonnet sent home in a fancy box by the hand of a dainty grisette. Olympe was the first of her class to make a specialty of delivering the goods. And Monsieur X, though he may have called her “Old Imp,” paid the bill with all the extras of specialty and delivery included,[61] though not itemized. Those were bonnets to shade the face—a light blue satin shirred lengthwise; crêpe lisse, same color, shirred crosswise over it, forming indistinct blocks; and a tout aller, of raspberry silk, shirred “every which way,” are two that I recall.

Madame a-shopping went followed by a servant to bring home the packages. Gloves, one button only, were light colored, pink, lavender, lemon, rarely white; and for ordinary wear bottle green gloves were considered very comme il faut. They harmonized with the green barège veil that every lady had for shopping.

Our shopping trip would be incomplete if we failed to call on an old Scotch couple who had a lace store under Col. Winthrop’s residence on Royal Street. The store had a door and a window, and the nice old parties who had such a prodigious Scotch brogue one would scarcely understand them, could, by a little skill, entertain three customers at one and the same time. If one extra shopper appeared, Mr. Syme disappeared, leaving the old lady to attend to business. She was almost blind from cataract, a canny old soul and not anyways blind to business advantages. I am pleased to add they retired after a few busy years quite well-to-do. There was Seibricht, on Royal Street, a furniture[62] dealer, and still further down Royal Seignoret, in the same lucrative business, for I do not recall they had any competitors. Memory does not go beyond the time when Hyde and Goodrich were not the jewelers; and Loveille, on the corner of Customhouse and Royal, the grocer, for all foreign wines, cheeses, etc. Never do I see such Parmesan as we got from Loveille in my early days.

William McKean had a bookshop on Camp Street, a few doors above Canal. Billy McKean, as the irreverent called him, was a picture of Pickwick, and a clever, kindly old man was he. There was a round table in the rear of his shop, where one found a comfortable chair and a few books to browse over. In my childhood I was always a welcome visitor to that round table, for I always “sat quiet and just read,” as dear old Mr. McKean told me. As I turn the pages of my book of memories not only the names but the very faces of these shopkeepers of seventy years ago come to me, all smiles and winning ways, and way back I fly to my pantalette and pigtail days, so happy in these dreams that will never be reality to any place or people.

There were no restaurants, no lunch counters, no tea rooms, and (bless their dear hearts, who started it!) no woman’s exchange, no place in the whole city where a lady could drop in, after all this[63] round of shopping, take a comfortable seat and order even a sandwich, or any kind of refreshment. One could take an éclair at Vincent’s, corner of Royal and Orleans, but éclairs have no satisfying quality.

There was a large hotel (there may be still—it is sixty years since I saw it), mostly consisting of spacious verandas, up and down and all around, at the lake end of the shellroad, where parties could have a fish dinner and enjoy the salt breezes, but a dinner at “Lake End” was an occasion, not a climax to a shopping trip. The old shellroad was a long drive, Bayou St. John on one side, swamps on the other, green with rushes and palmetto, clothed with gay flowers of the swamp flag. The road terminated at Lake Pontchartrain, and there the restful piazza and well-served dinner refreshed the inner woman.

I am speaking of the gentler sex. No doubt there were myriads of cabarets and eating places for men on pleasure or business bent. Three o’clock was the universal dinner hour, so the discreet mesdames were able to return to the city and be ready by early candlelight for the inevitable “hand round” tea.

Then there was Carrollton Garden (I think it is dead and buried now). There was a short railroad leading to Carrollton; one could see open fields and[64] grazing cattle from the car windows as one crept along. Except a still shorter railroad to the Lake, connecting with the Lake boats, I think the rural road to Carrollton was the only one leading out of the city. The Carrollton hotel, like the Lake one, was all verandas. I never knew of any guest staying there, even one night, but there was a dear little garden and lots of summer houses and pagodas, covered with jasmines and honeysuckle vines. One could get lemonade or orgeat or orange flower syrup, and return to the city with a great bouquet of monthly roses, to show one had been on an excursion. A great monthly rose hedge, true to its name, always in bloom, surrounded the premises. To see a monthly rose now is to see old Carrollton gardens in the forties.

It was on Orleans Street, near Royal—I don’t have to “shut my eyes and think very hard,” as the Marchioness said to Dick Swiveller, to see the old Opera House and all the dear people in it, and hear its entrancing music. We had “Norma” and “Lucia di Lammermoor” and “Robert le Diable” and “La Dame Blanche,” “Huguenots,” “Le Prophète,” just those dear old melodious operas, the music so thrillingly catchy that half the young men hummed or whistled snatches of it on their way home.

There were no single seats for ladies, only four-seated boxes. The pit, to all appearances, was for elderly, bald gentlemen only, for the beaux, the fashionable eligibles, wandered around in the intermissions or “stood at attention” in the narrow lobbies behind the boxes during the performances. Except the two stage boxes, which were more ample, and also afforded sly glimpses towards the wings and flies, all were planned for four occupants. Also,[66] all were subscribed for by the season. There was also a row of latticed boxes in the rear of the dress circle, usually occupied by persons in mourning, or the dear old messieurs et mesdames, who were not chaperoning a mademoiselle. One stage box belonged, by right of long-continued possession, to Mr. and Mrs. Cuthbert Bullitt. The opposite box was la loge des lions, and no less than a dozen lions wandered in and out of it during an evening. Some were blasé and looked dreadfully bored, a few were young and frisky, but every mortal one of them possessed a pompous and self-important mien.

The Old French Opera House.

If weather permitted (we had to consider the[67] weather, as everybody walked) and the opera a favorite, every seat would be occupied at 8 o’clock, and everybody quiet to enjoy the very first notes of the overture. All the fashionable young folks, even if they could not play or whistle “Yankee Doodle,” felt the opera was absolutely necessary to their social success and happiness. The box was only five dollars a night, and pater-familias certainly could afford that!

Think of five dollars for four seats at the most fashionable Opera House in the land then, and compare it with five dollars for one seat in the topmost gallery of the most fashionable house in the land to-day. Can one wonder we old people who sit by our fire and pay the bills wag our heads and talk of the degenerate times?

Toilets in our day were simple, too. French muslins trimmed with real lace, pink and blue barèges with ribbons. Who sees a barège now? No need of jeweled stomachers, ropes of priceless pearls or diamond tiaras to embellish those Creole ladies, many of whom were direct descendants of French nobles; not a few could claim a drop of even royal blood.

Who were the beaux? And where are they now? If any are living they are too old to hobble into the pit and sit beside the old, bald men.

It was quite the vogue to saunter into Vincent’s, at the corner, on the way home. Vincent’s was a great place and he treated his customers with so much “confidence.” One could browse about the glass cases of pâtés, brioches, éclairs, meringues, and all such toothsome delicacies, peck at this and peck at that, lay a dime on the counter and walk out. A large Broadway firm in New York attempted that way of conducting a lunch counter and had such a tremendous patronage that it promptly failed. Men went for breakfast and shopping parties for lunch, instead of dropping in en passant for an éclair.

As I said, we walked. There were no street cars, no ’buses and precious few people had carriages to ride in. So we gaily walked from Vincent’s to our respective homes, where a cup of hot coffee put us in condition for bed and slumber.

Monday morning Mme. Casimir or Mam’zelle Victorine comes to sew all day like wild for seventy-five cents, and tells how splendidly Rosa de Vries (the prima donna) sang “Robert, toi que j’aime” last night. She always goes, “Oui, madame, toujours,” to the opera Sunday. Later, dusky Henriette Blondeau comes, with her tignon stuck full of pins and the deep pockets of her apron bulging with sticks of bandoline, pots of pomade, hairpins and a[69] bandeau comb, to dress the hair of mademoiselle. She also had to tell how fine was “Robert,” but she prefers De Vries in “Norma,” “moi.” The Casimirs lived in a kind of cubby-hole way down Ste. Anne Street. M. Casimir was assistant in a barber shop near the French Market, but such were the gallery gods Sunday nights, and no mean critics were they. Our nights were Tuesday and Saturday.