Title: Survey of London, Volume 05 (of 14), the parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, part 2

Author: William Edward Riley

George Laurence Gomme

Release date: November 16, 2023 [eBook #72144]

Language: English

Original publication: London: London County Council

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Bryan Ness, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

iiiTHE PARISH OF ST. GILES-IN-THE-FIELDS (PART II.), BEING THE FIFTH VOLUME OF THE SURVEY OF LONDON, WITH DRAWINGS, ILLUSTRATIONS AND ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTIONS, BY W. EDWARD RILEY, ARCHITECT TO THE COUNCIL. EDITED, WITH HISTORICAL NOTES, BY SIR LAURENCE GOMME, CLERK OF THE COUNCIL.

The Rt. Hon. EARL CURZON OF KEDLESTON, G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E., F.R.S.

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| GENERAL TITLE PAGE | i | |

| SPECIAL TITLE PAGE | iii | |

| MEMBERS OF THE JOINT PUBLISHING COMMITTEE | iv | |

| MEMBERS OF THE SURVEY COMMITTEE | v | |

| DESCRIPTION OF THE PLATES | ix | |

| PREFACE | xv | |

| THE SURVEY OF ST. GILES-IN-THE-FIELDS:— | ||

| Boundary of the Parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields | 1 | |

| High Holborn, from the Parish Boundary to Little Turnstile | 3 | |

| Nos. 3 and 4, Gate Street | 10 | |

| High Holborn, between Little Turnstile and Kingsway | 13 | |

| No. 211, High Holborn | 16 | |

| Smart’s Buildings and Goldsmith Street | 18 | |

| Nos. 181 and 172, High Holborn | 23 | |

| Site of Rose Field (Macklin Street, Shelton Street, Newton Street (part) and Parker Street (part)) | 27 | |

| No. 18, Parker Street | 33 | |

| Great Queen Street (general) | 34 | |

| No. 2, Great Queen Street | 38 | |

| Nos. 26 to 28, Great Queen Street | 40 | |

| Nos. 55 and 56, Great Queen Street | 42 | |

| Freemasons’ Hall | 59 | |

| Markmasons’ Hall | 84 | |

| Great Queen Street Chapel | 86 | |

| Site of Weld House | 93 | |

| Nos. 6 and 7, Wild Court | 98 | |

| No. 16, Little Wild Street | 99 | |

| No. 1, Sardinia Street | 100 | |

| Site of Lennox House | 101 | |

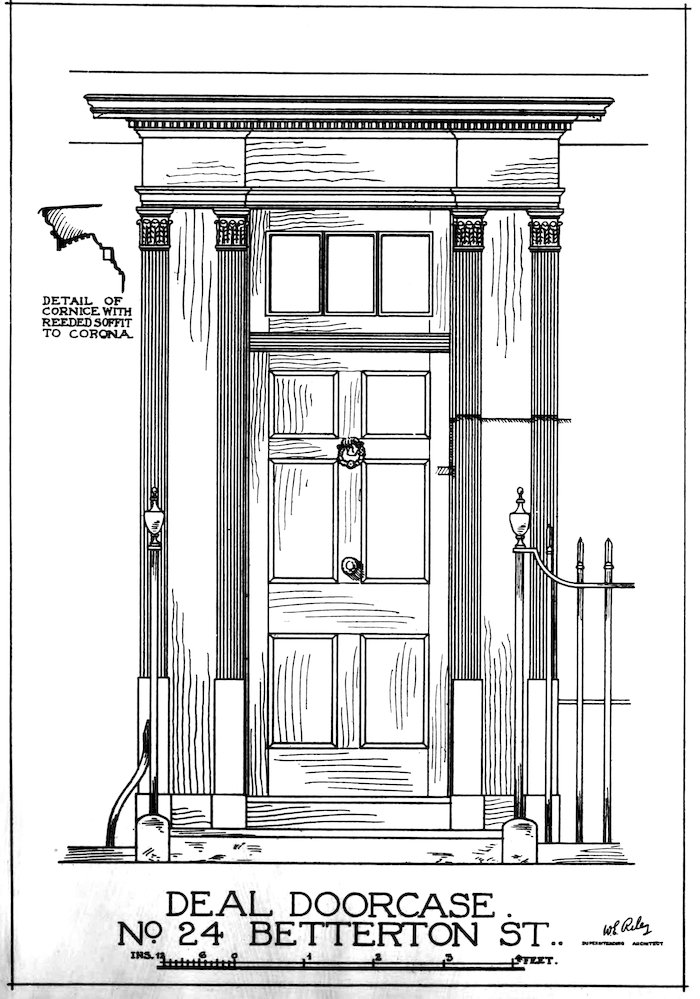

| Nos. 24 and 32, Betterton Street | 104 | |

| No. 25, Endell Street | 105 | |

| North of Short’s Gardens | 106 | |

| Site of Marshland (Seven Dials) | 112 | |

| The Church of All Saints, West Street | 115 | |

| Site of the Hospital of St. Giles | 117 | |

| Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields | 127 | |

| Nos. 14 to 16, Compton Street | 141 | |

| Nos. 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 and 11, Denmark Street | 142 | |

| viii | North of Denmark Place | 144 |

| Site of The Rookery | 145 | |

| Nos. 100, 101 and 102, Great Russell Street | 147 | |

| Bedford Square (General) | 150 | |

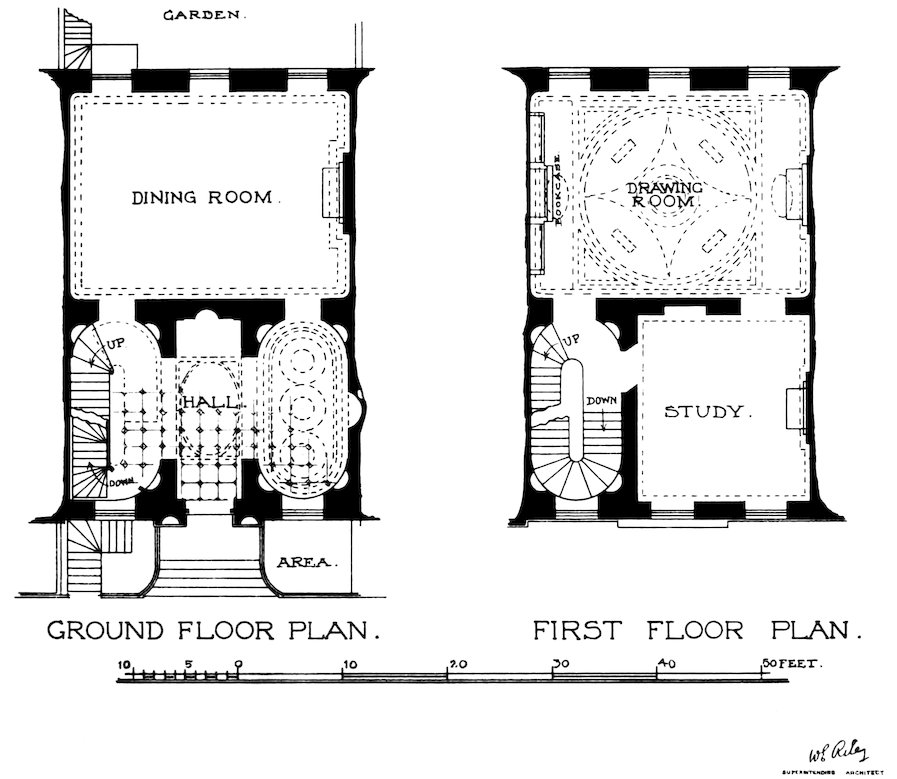

| No. 1, Bedford Square | 152 | |

| Nos. 6 and 6A, Bedford Square | 154 | |

| No. 9, Bedford Square | 157 | |

| No. 10, Bedford Square | 158 | |

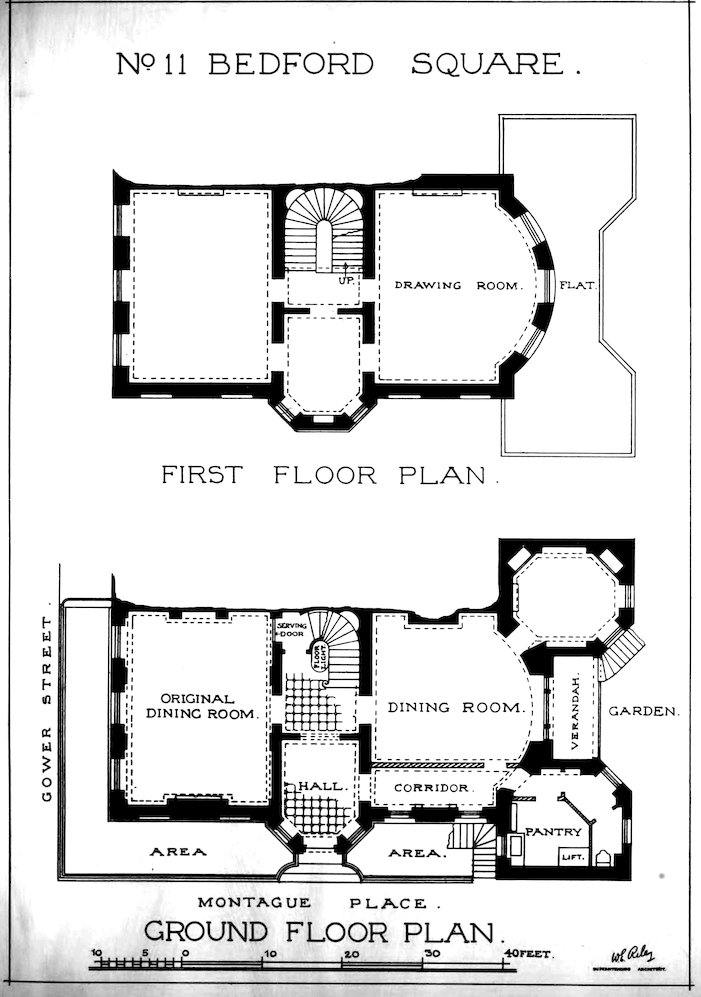

| No. 11, Bedford Square | 161 | |

| No. 13, Bedford Square | 163 | |

| No. 14, Bedford Square | 164 | |

| No. 15, Bedford Square | 165 | |

| No. 18, Bedford Square | 166 | |

| No. 23, Bedford Square | 167 | |

| No. 25, Bedford Square | 168 | |

| No. 28, Bedford Square | 170 | |

| No. 30, Bedford Square | 171 | |

| No. 31, Bedford Square | 172 | |

| No. 32, Bedford Square | 174 | |

| No. 40, Bedford Square | 176 | |

| No. 41, Bedford Square | 177 | |

| No. 44, Bedford Square | 178 | |

| No. 46, Bedford Square | 179 | |

| No. 47, Bedford Square | 180 | |

| No. 48, Bedford Square | 181 | |

| No. 50, Bedford Square | 183 | |

| No. 51, Bedford Square | 184 | |

| Nos. 68 and 84, Gower Street | 185 | |

| North and South Crescents and Alfred Place | 186 | |

| House in rear of No. 196, Tottenham Court Road | 188 | |

| INDEX | ||

| PLATES Nos. 1 to 107 | ||

| MAP OF THE PARISH | ||

| PLATE. | ||

|---|---|---|

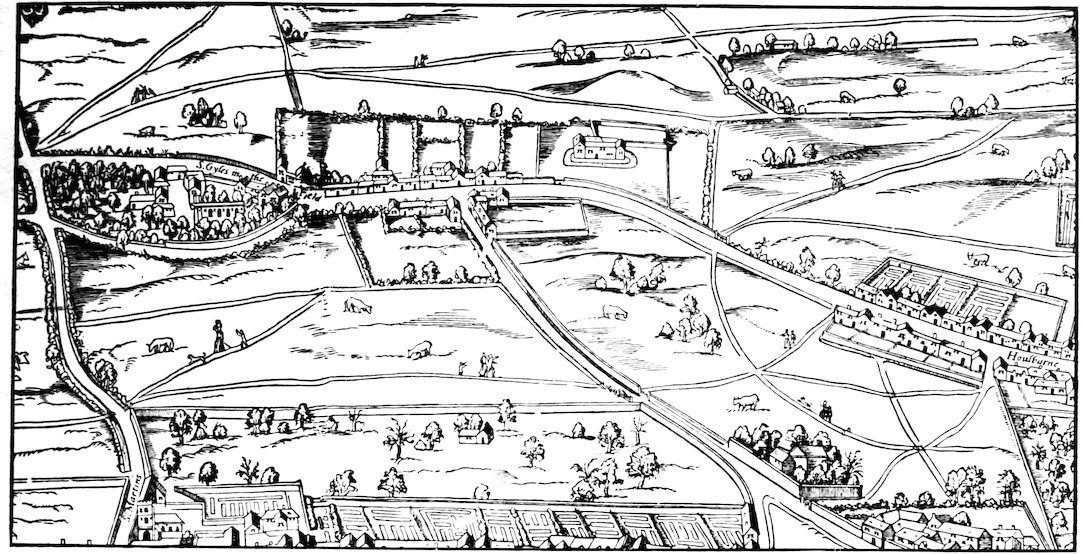

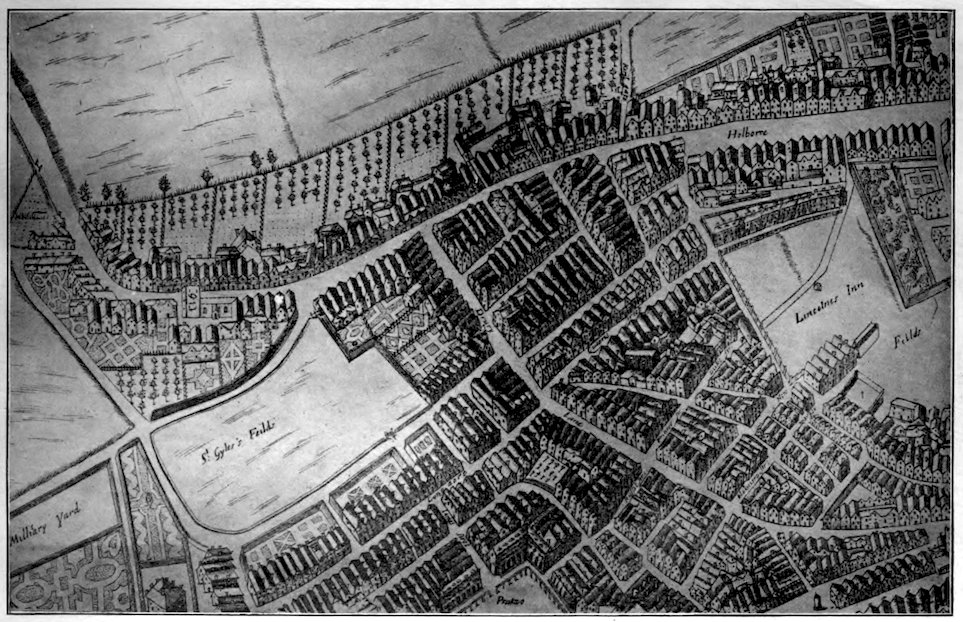

| 1. | Extract from Agas’s Civitas Londinum, showing the neighbourhood of St. Giles-in-the-Fields circ. 1560–70. | |

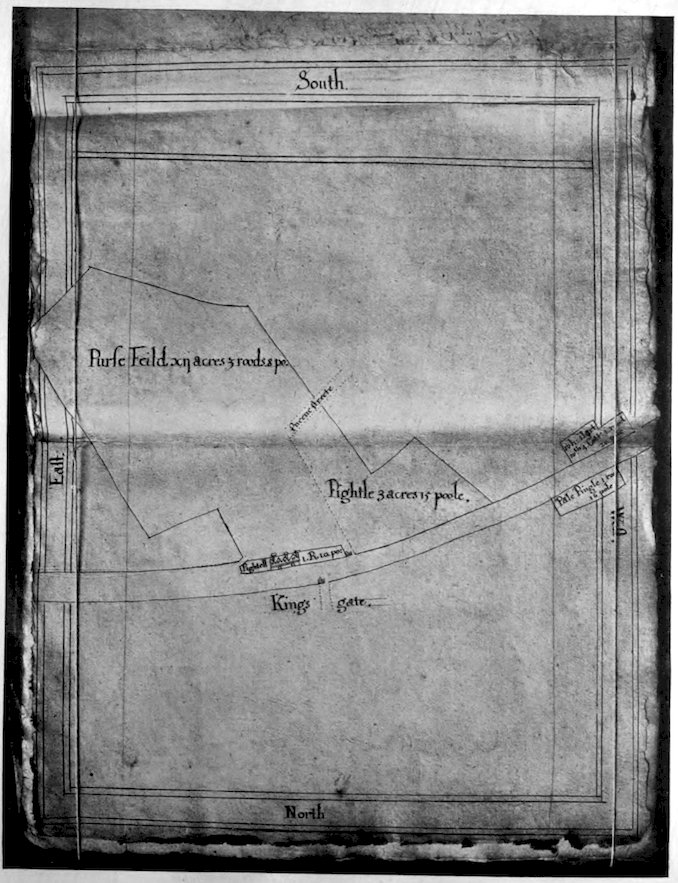

| 2. | Purse Field circ. 1609, from a deed dated 1650 in the Public Record Office. | |

| 3. | Extract from Map by Hollar of the area now forming the West Central District of London, showing the neighbourhood of St. Giles-in-the-Fields circ. 1658. | |

| 4. | Extract from Map by Fairthorne and Newcourt showing the neighbourhood of St. Giles-in-the-Fields in 1658. | |

| 5. | Map of the Parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields circ. 1720 from Strype’s edition of Stow. | |

| 6. | Plan of the Parishes of St. Giles-in-the-Fields and St. George Bloomsbury by Hewett, 1815. | |

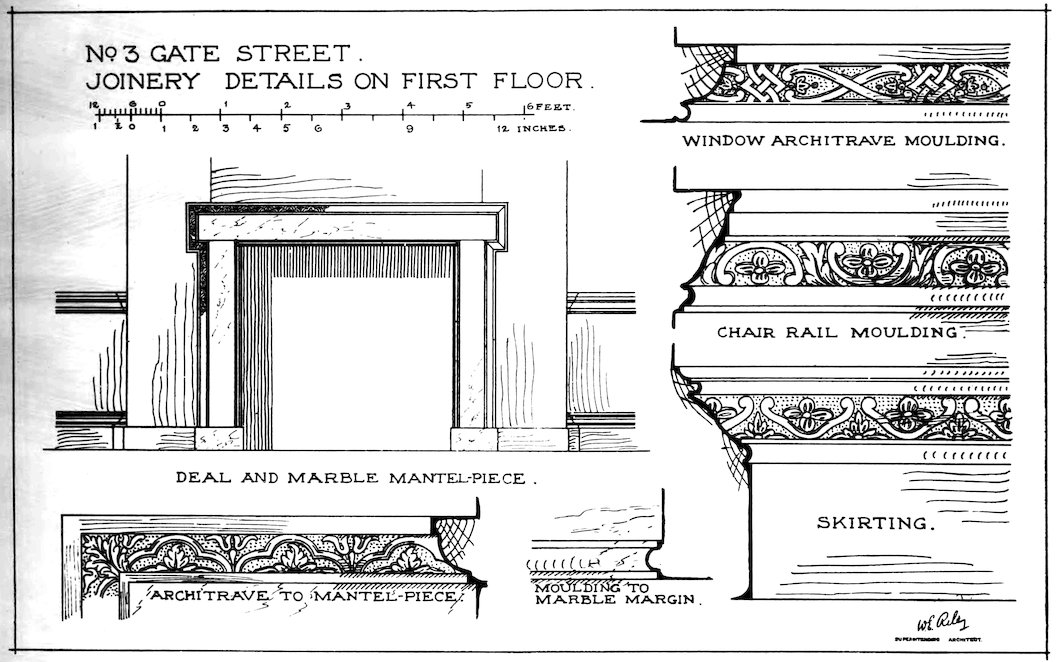

| 7. | No. 3, Gate Street, Joinery Details on First Floor | Measured Drawing. |

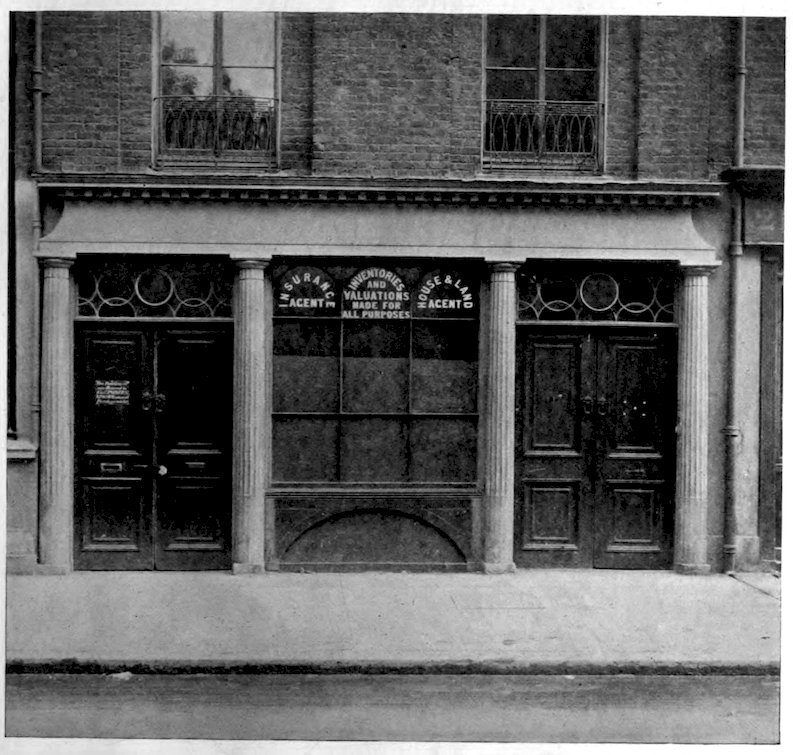

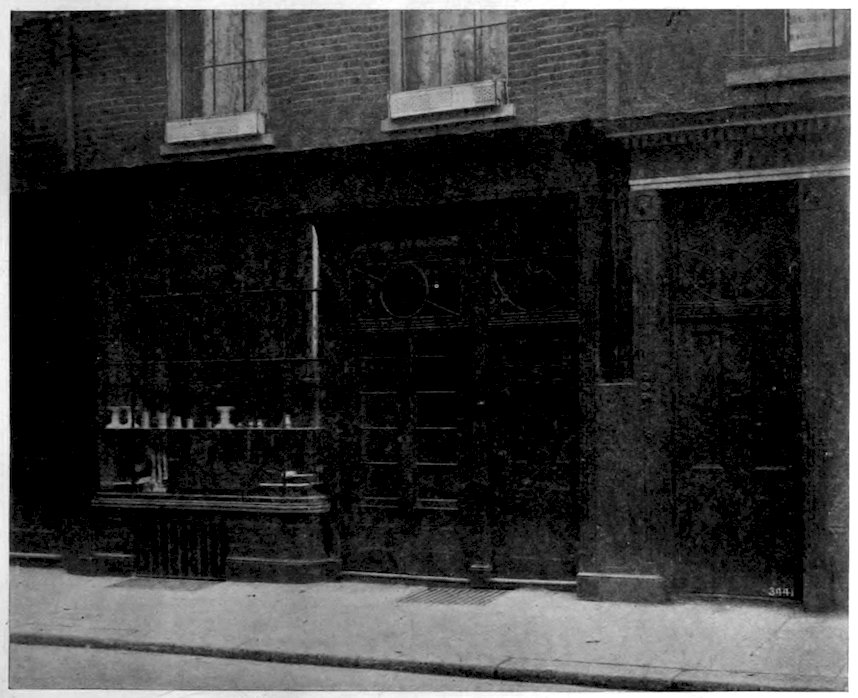

| 8. | No. 211, High Holborn, Shop Front | Photograph. |

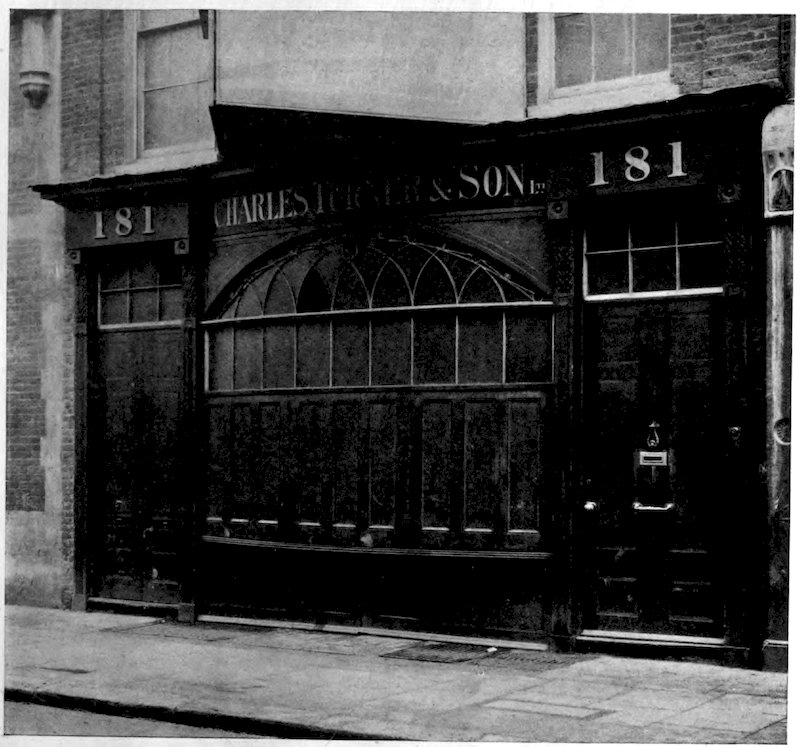

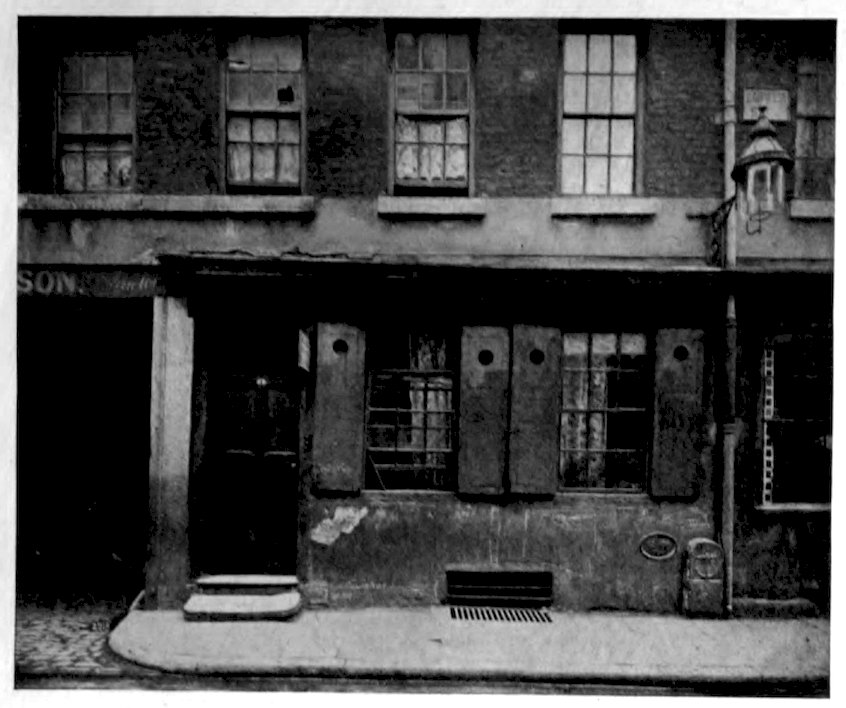

| 9. | No. 181, High Holborn, Shop Front | Photograph. |

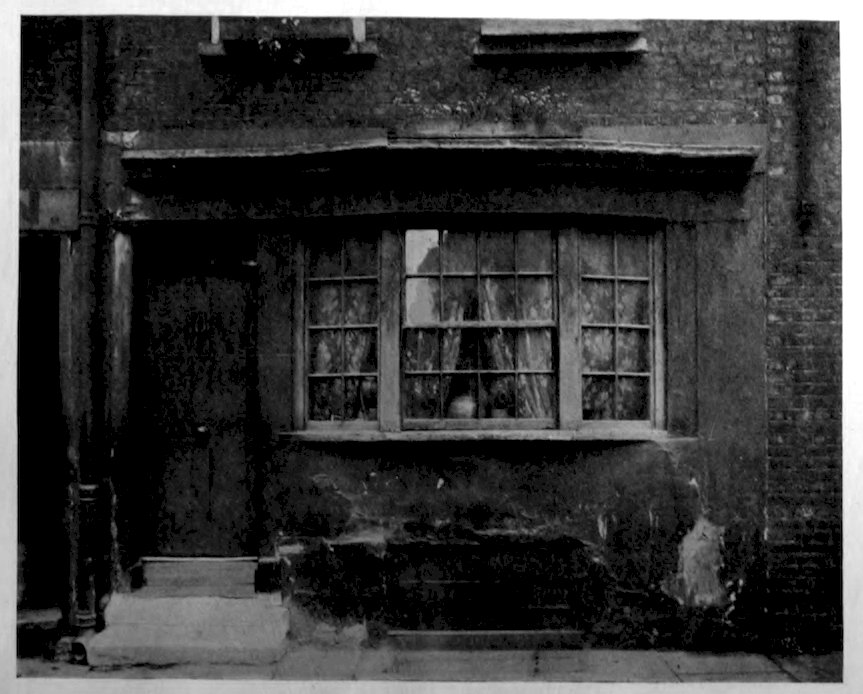

| 10. | No. 172, High Holborn, Shop Front | Photograph. |

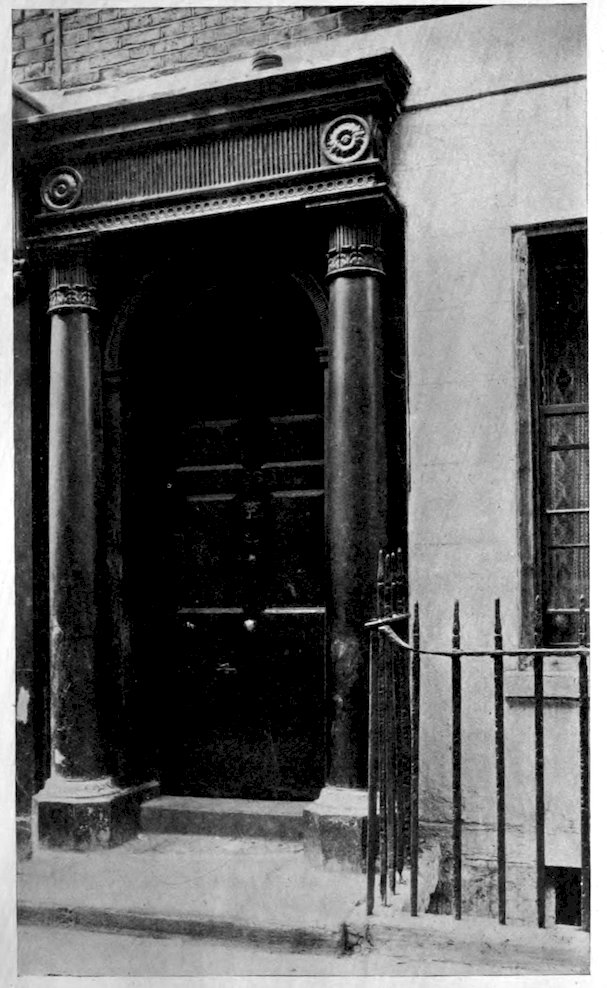

| 11. | No. 1, Sardinia Street | Photograph. |

| No. 18, Parker Street | Photograph. | |

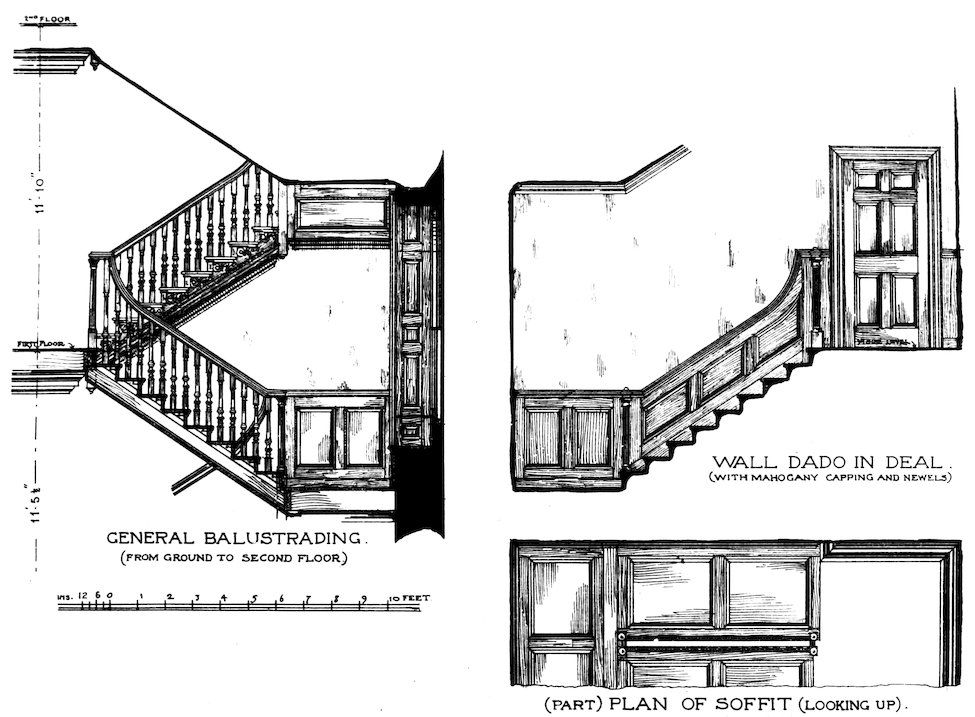

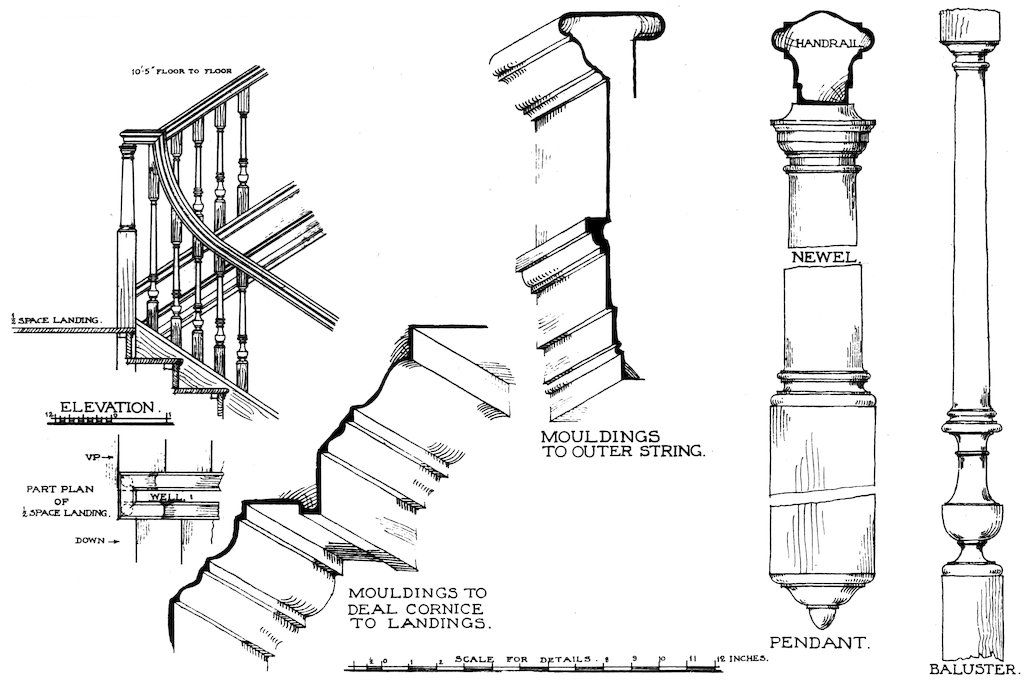

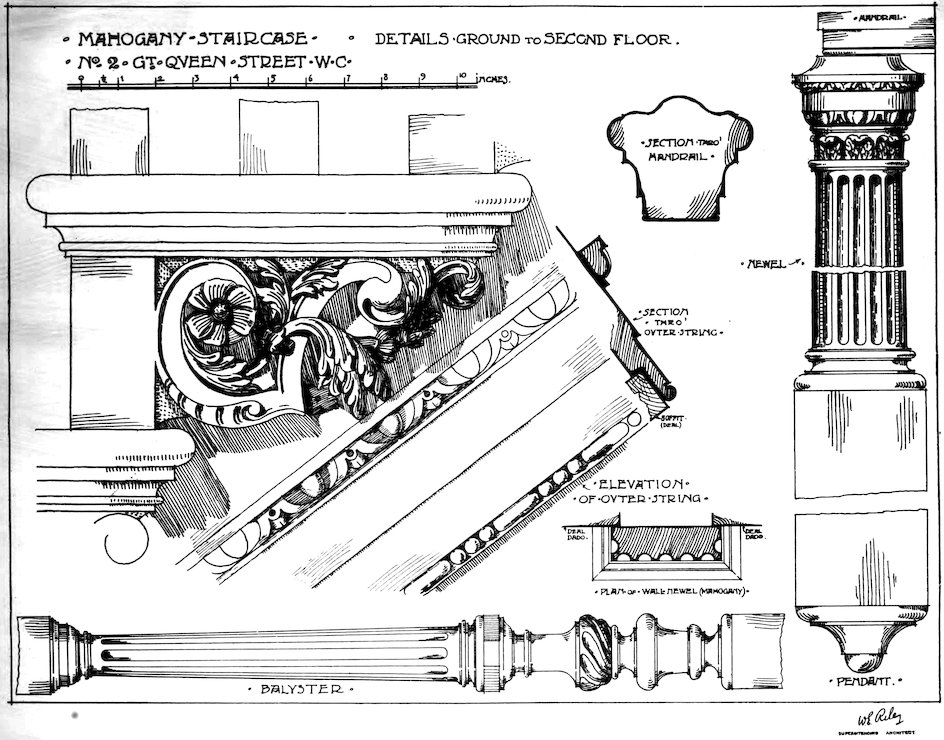

| 12. | No. 2, Great Queen Street, Mahogany Staircase | Measured Drawing. |

| 13. | No. 2, Great Queen Street, Details of Staircase | Measured Drawing. |

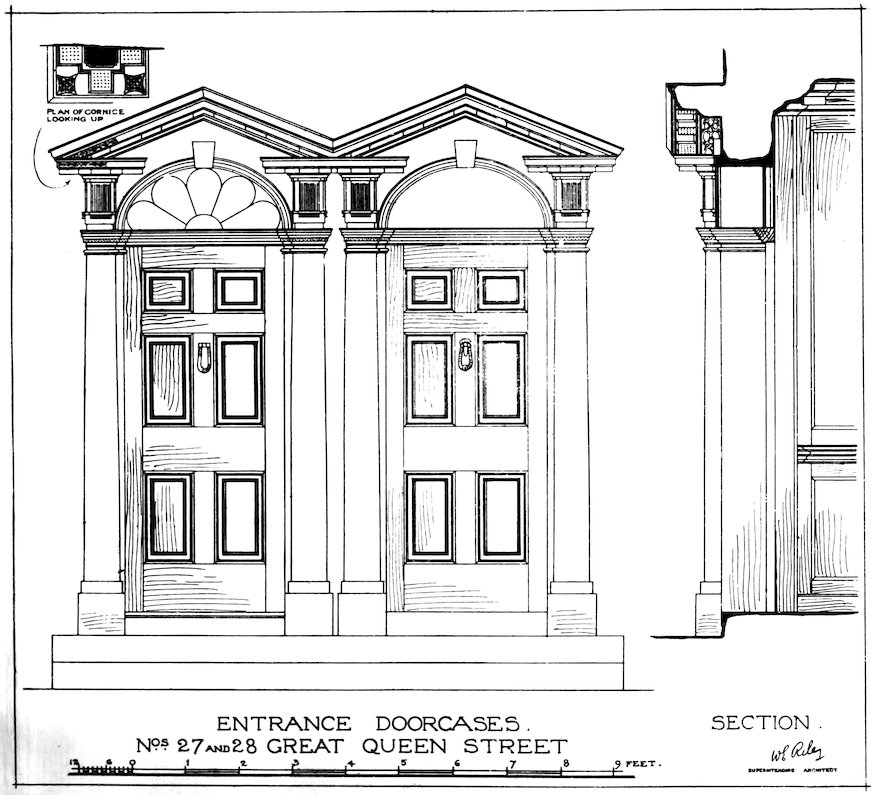

| 14. | Nos. 27 and 28, Great Queen Street, Entrance Doorcases | Measured Drawing. |

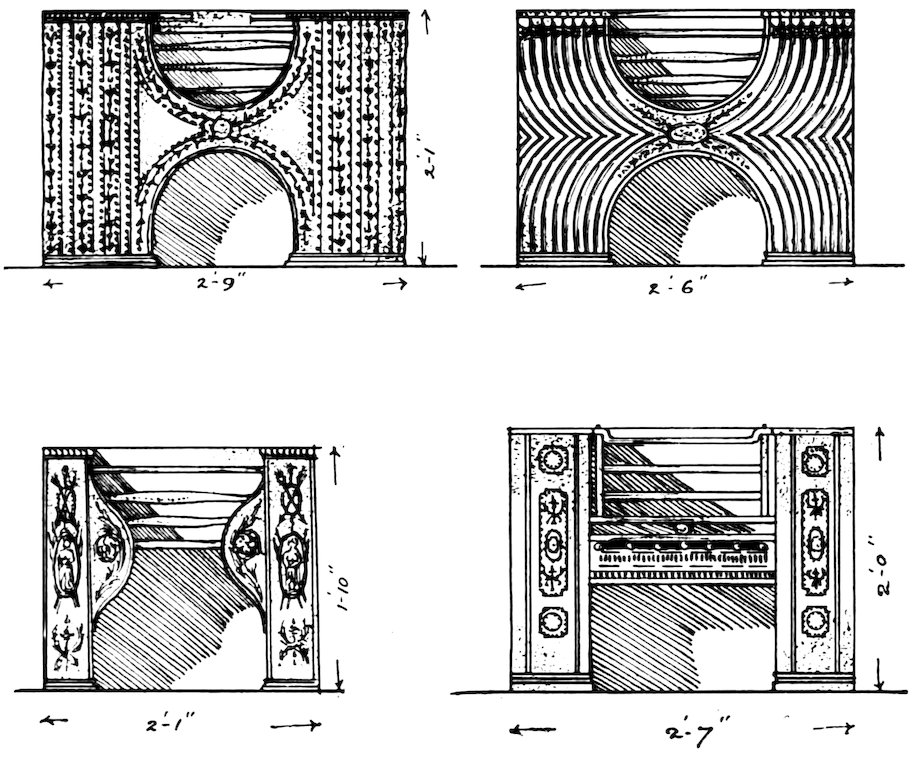

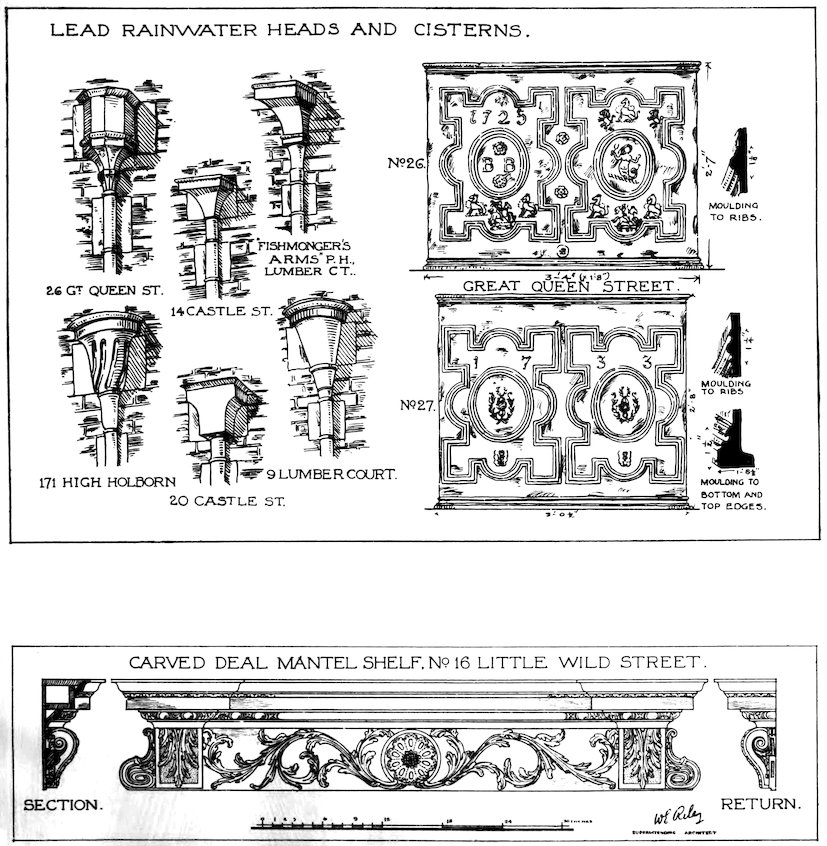

| 15. | Lead Rainwater Heads and Cisterns | Measured Drawing. |

| No. 16, Little Wild Street, Carved Deal Mantel Shelf | Measured Drawing. | |

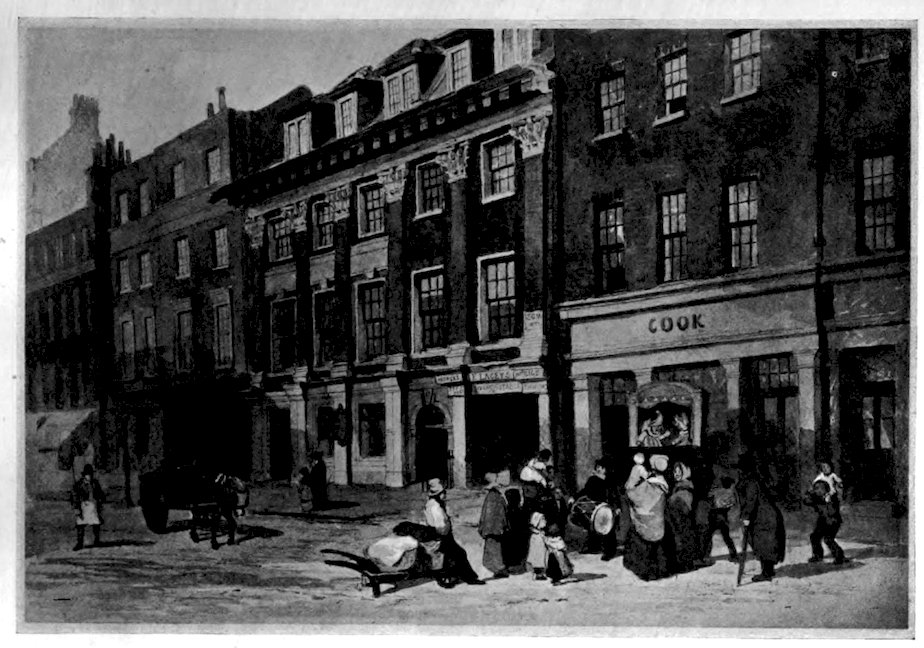

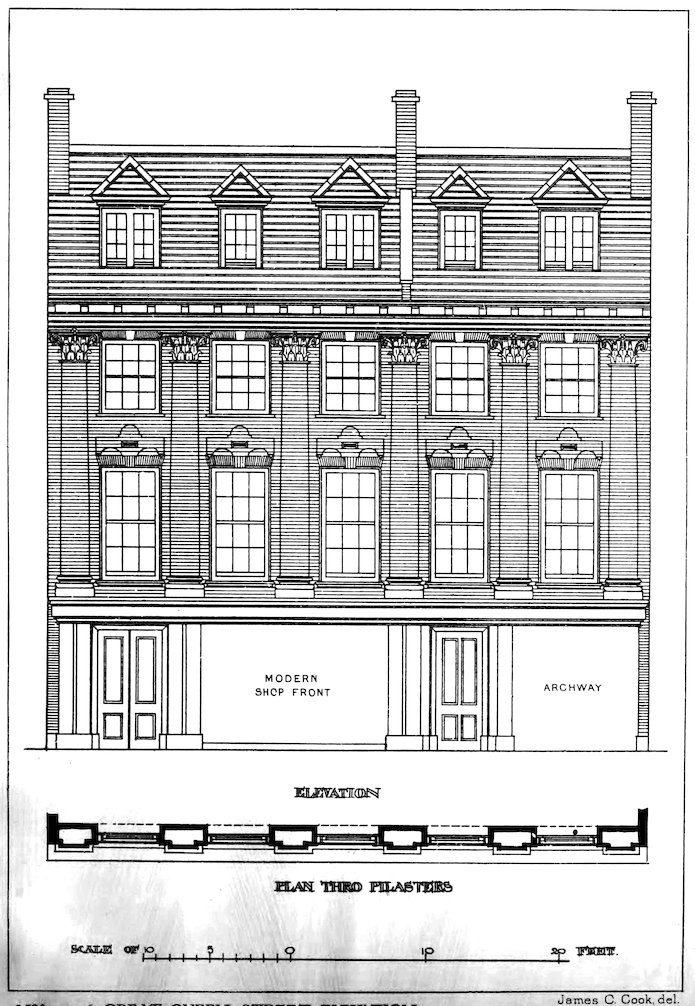

| 16. | Nos. 55 and 56, Great Queen Street in 1846, from a watercolour by J. W. Archer, “House called Queen Anne’s Wardrobe,” preserved in the British Museum | Photograph. |

| “House of the Sardinia Ambassador, Lincoln’s Inn Fields,” from a watercolour (1858) by J. W. Archer, preserved in the British Museum | Photograph. | |

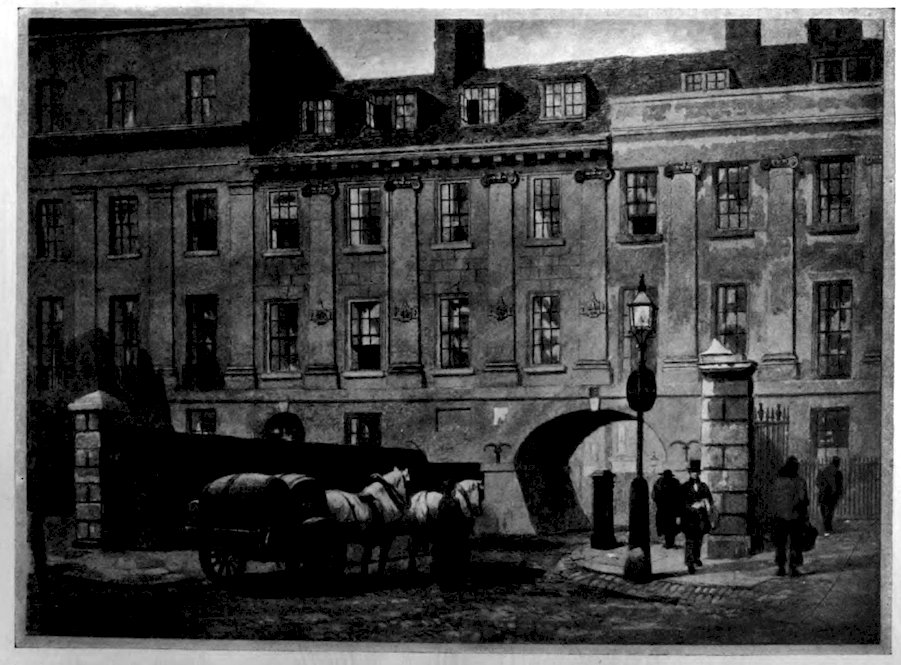

| 17. | Nos. 55 and 56, Great Queen Street, Ground, First and Second Floor Plans | Measured Drawing. |

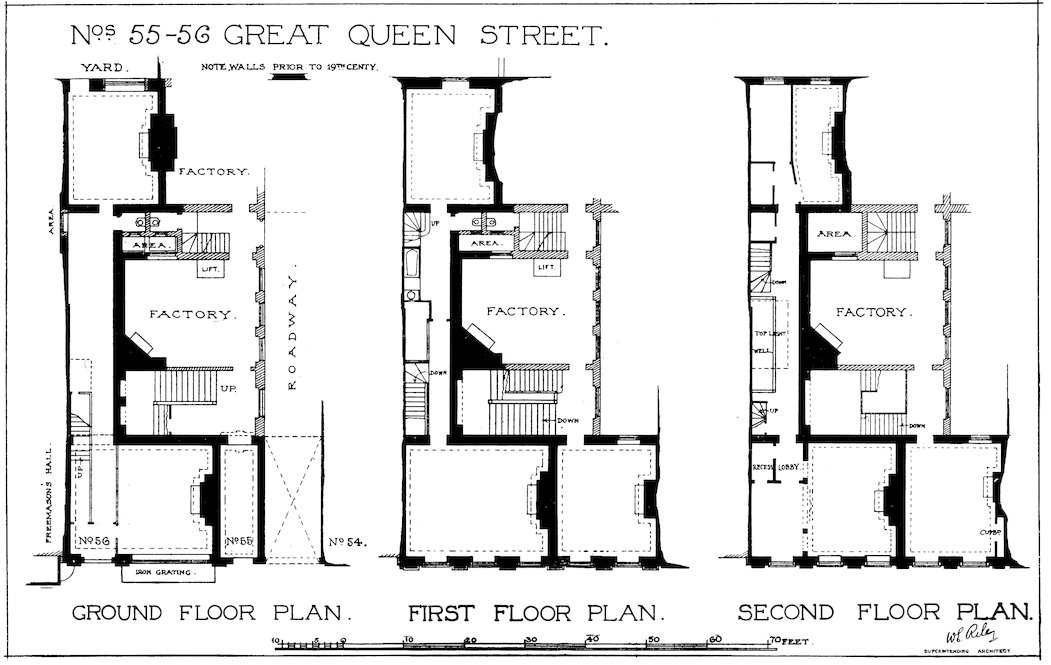

| 18. | Nos. 55 and 56, Great Queen Street, Elevation. Reproduced by kind permission of B. T. Batsford, Ltd., from Later Renaissance Architecture in England by John Belcher and Mervyn E. Macartney. | Measured Drawing by James C. Cook. |

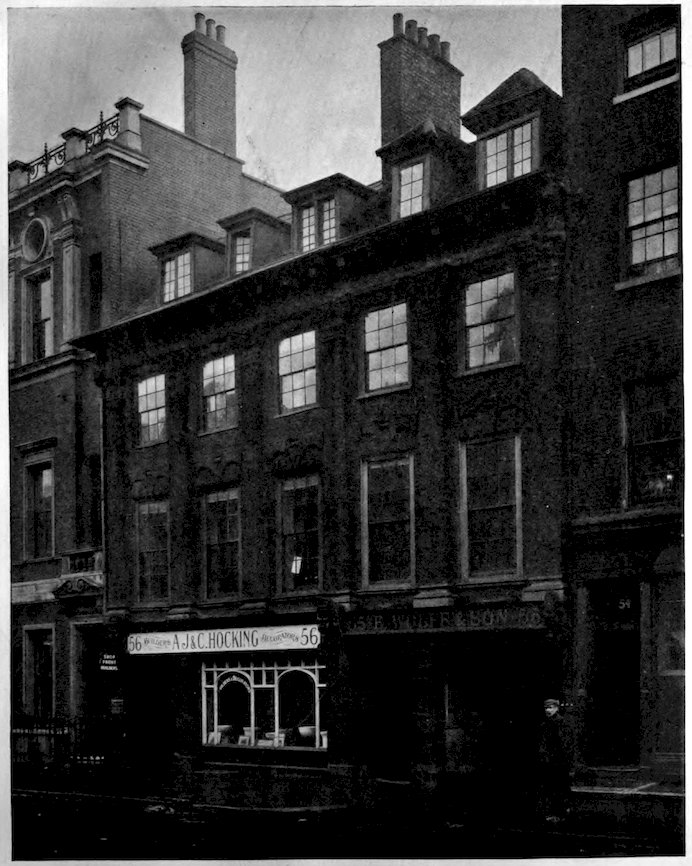

| 19. | Nos. 55 and 56, Great Queen Street (May 1906) | Photograph. |

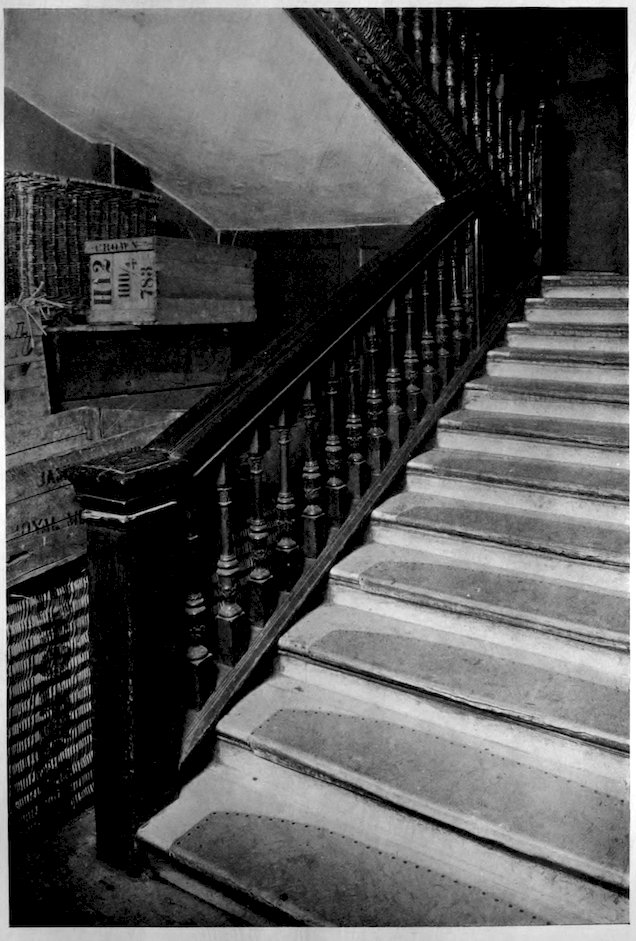

| 20. | No. 55, Great Queen Street, Staircase | Photograph. |

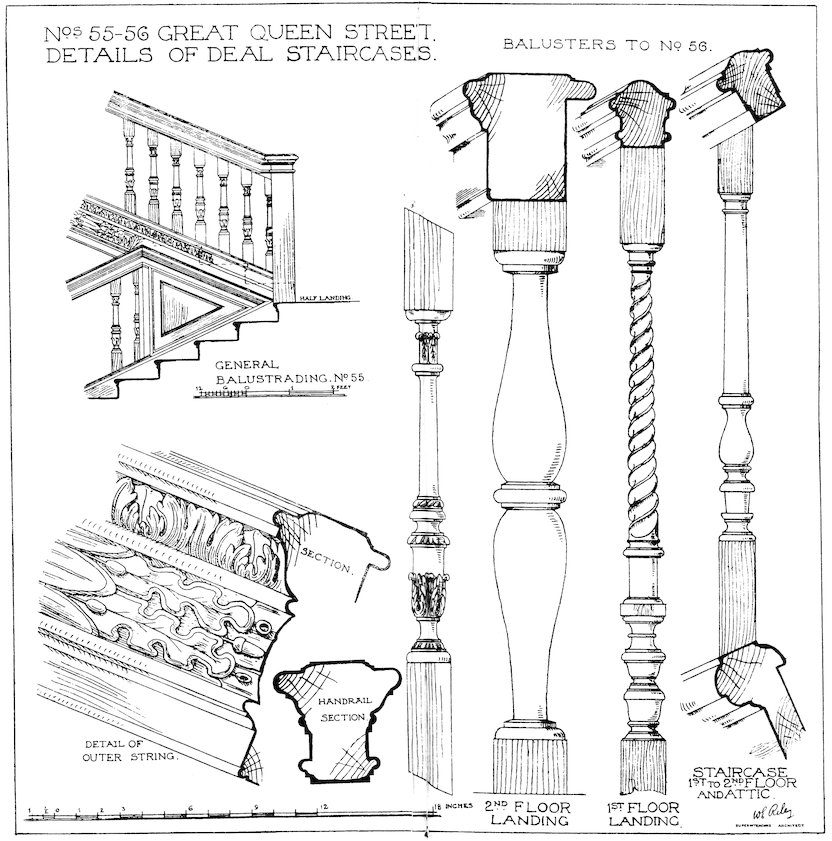

| 21. | Nos. 55 and 56, Great Queen Street, Details of Staircases | Measured Drawing. |

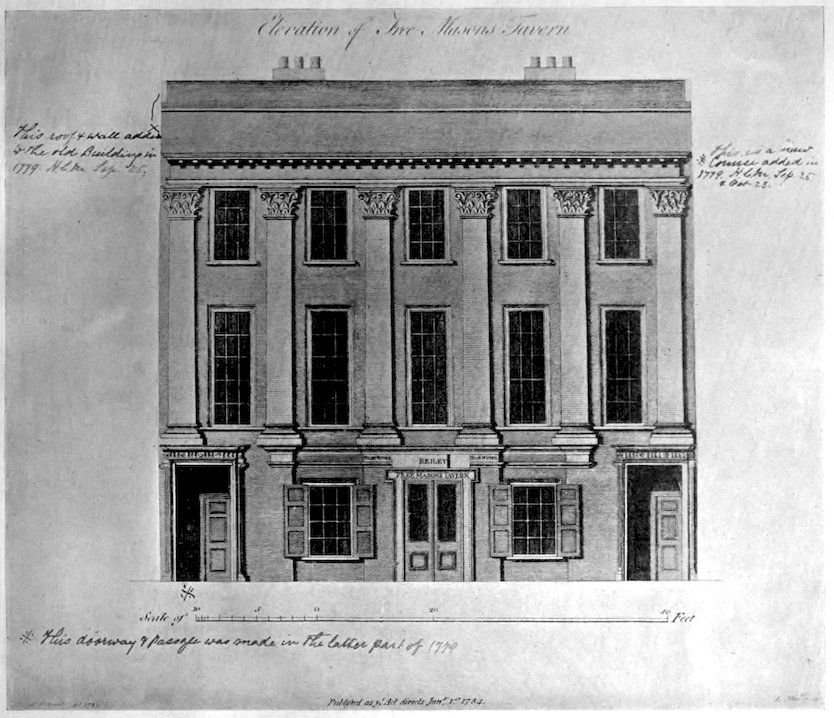

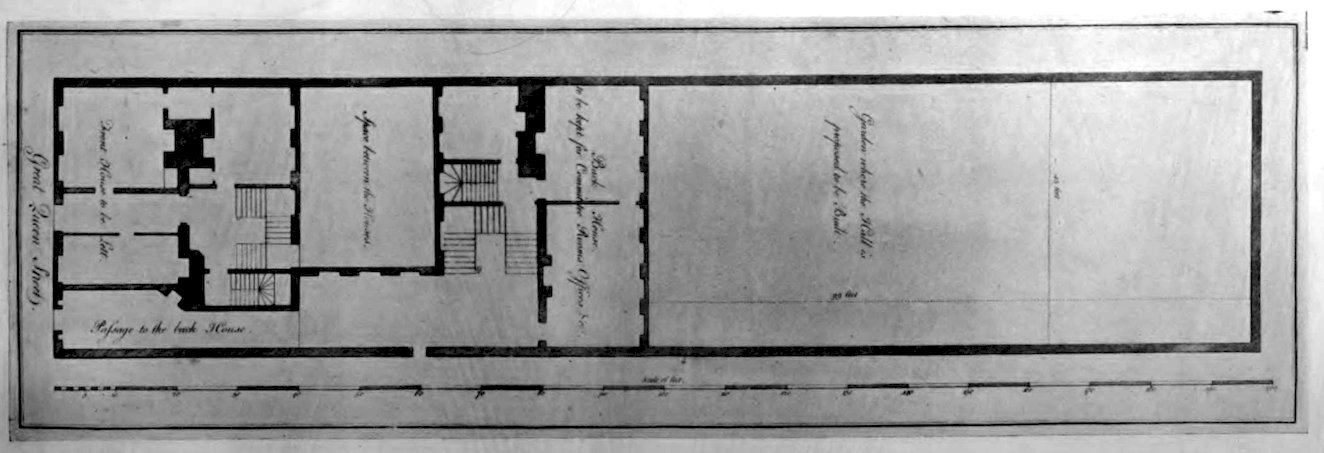

| 22. | Freemasons’ Hall, Elevation in 1779 | Photograph. |

| Freemasons’ Hall, Plan of Premises before 1779 | Photograph. | |

| (Both are reproduced by kind permission of the Grand Lodge from engravings in their possession.) | ||

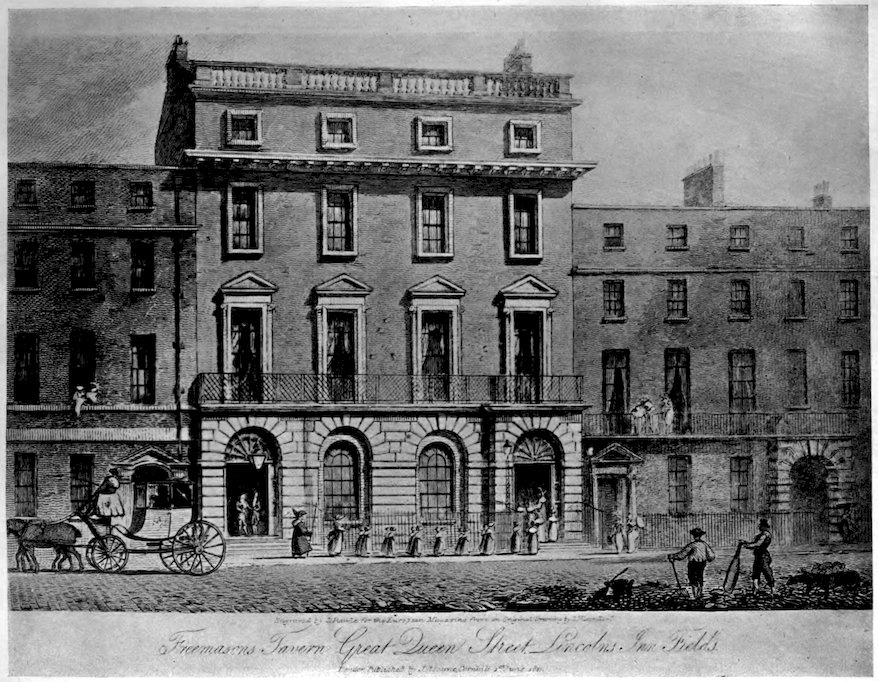

| x23. | Freemasons’ Hall in 1811 (Façade designed by W. Tyler in 1785), from an Engraving by S. Rawle after I. Nixon | Photograph. |

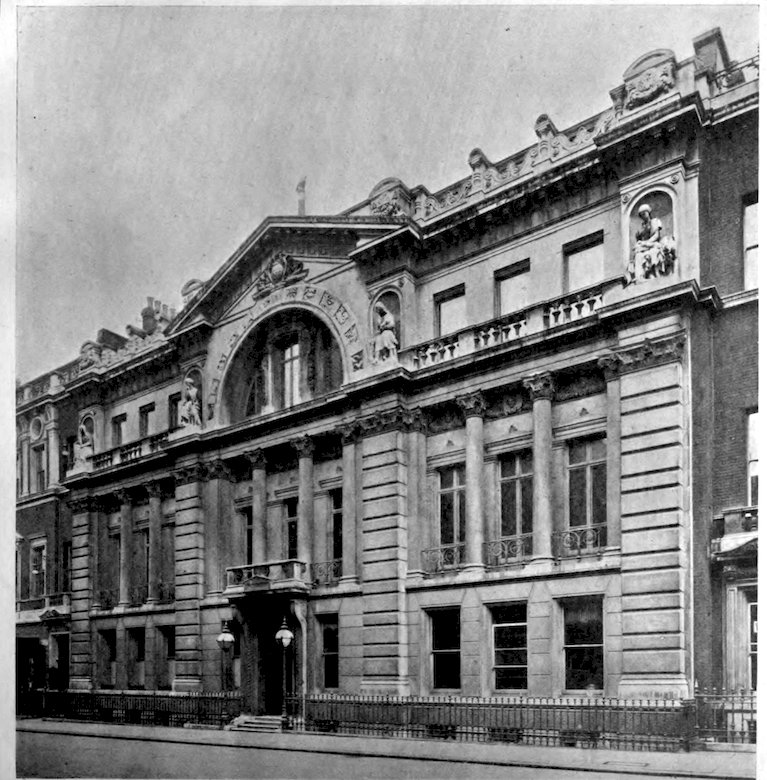

| 24. | Freemasons’ Hall, Façade (designed by F. P. Cockerell, 1866) | Photograph. |

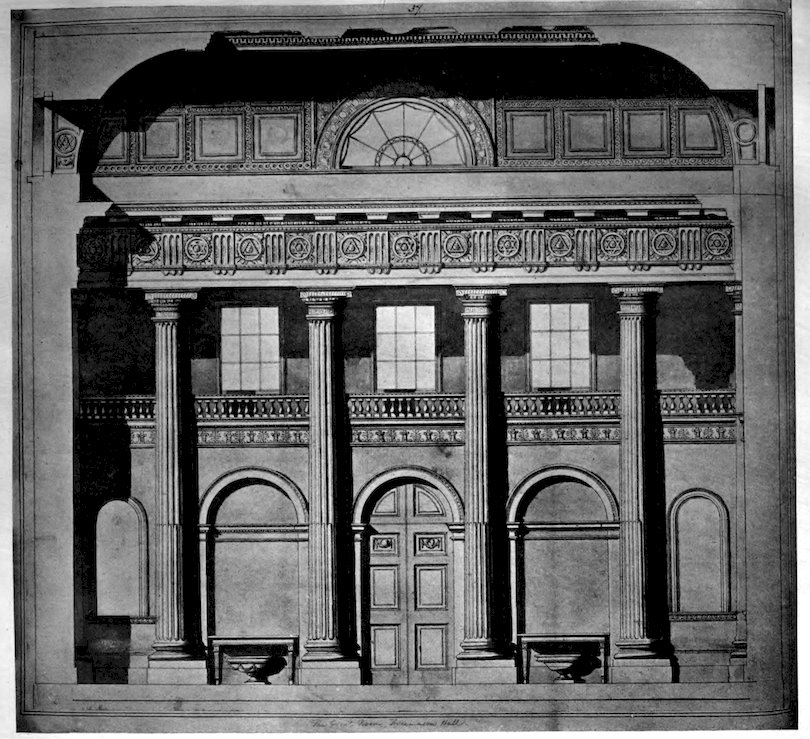

| 25. | Freemasons’ Hall, Elevation of North end of Temple in 1775 (designed by Thos. Sandby), from an original drawing preserved in the British Museum | Photograph. |

| 26. | Freemasons’ Hall, the Temple looking South | Photograph. |

| 27. | Freemasons’ Hall, “View of the new Masonic Hall, looking South,” from an original pen sketch design by Sir J. Soane, 1828, preserved in the Soane Museum | Photograph. |

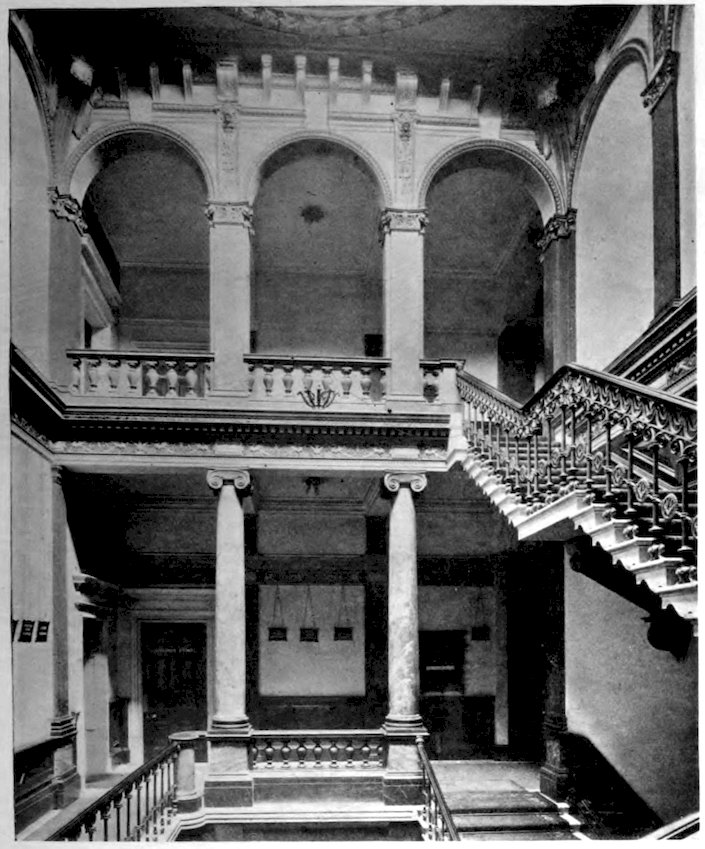

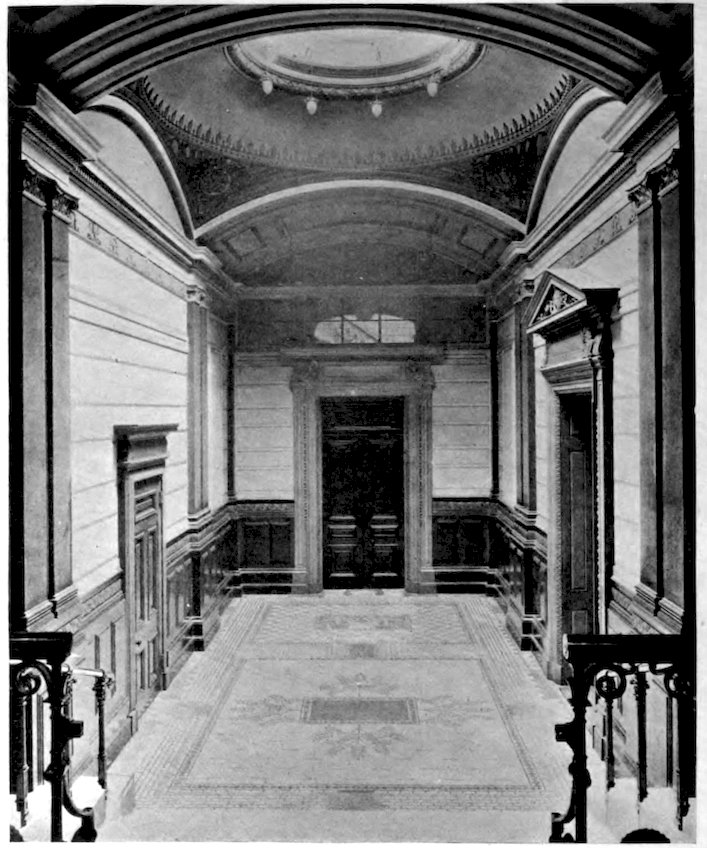

| 28. | Freemasons’ Hall, Grand Staircase | Photograph. |

| Freemasons’ Hall, Vestibule to Temple | Photograph. | |

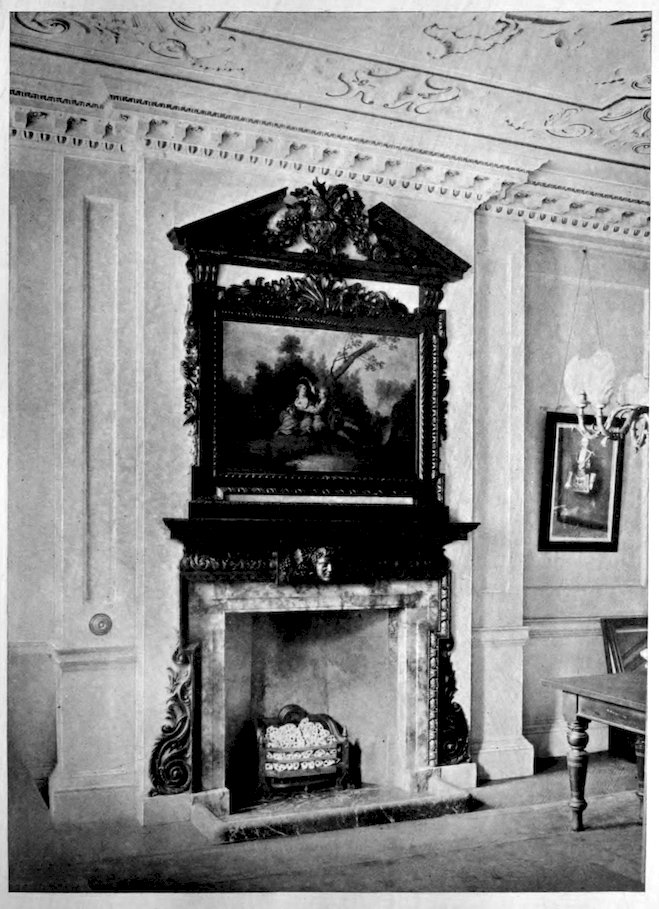

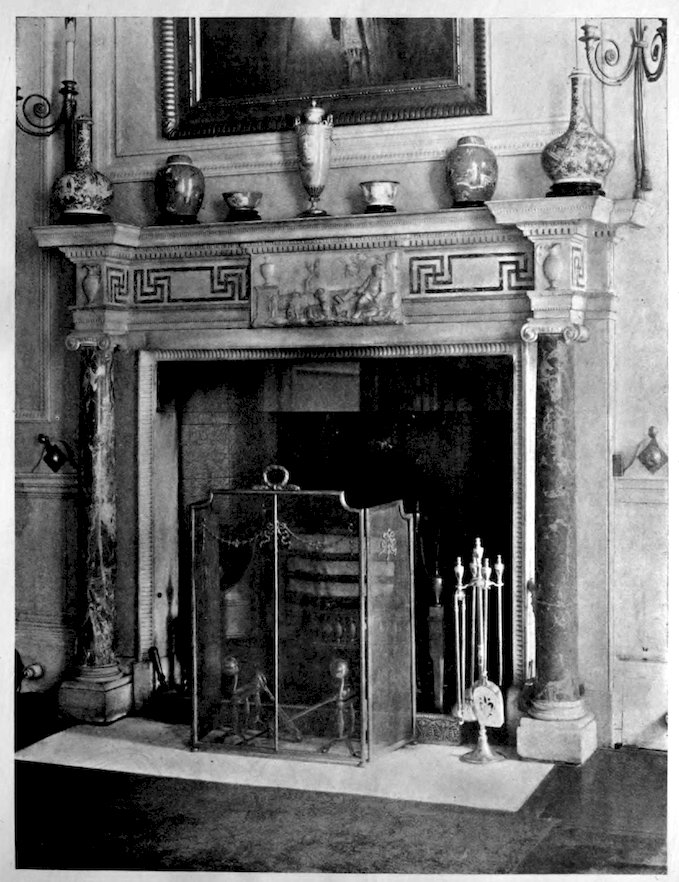

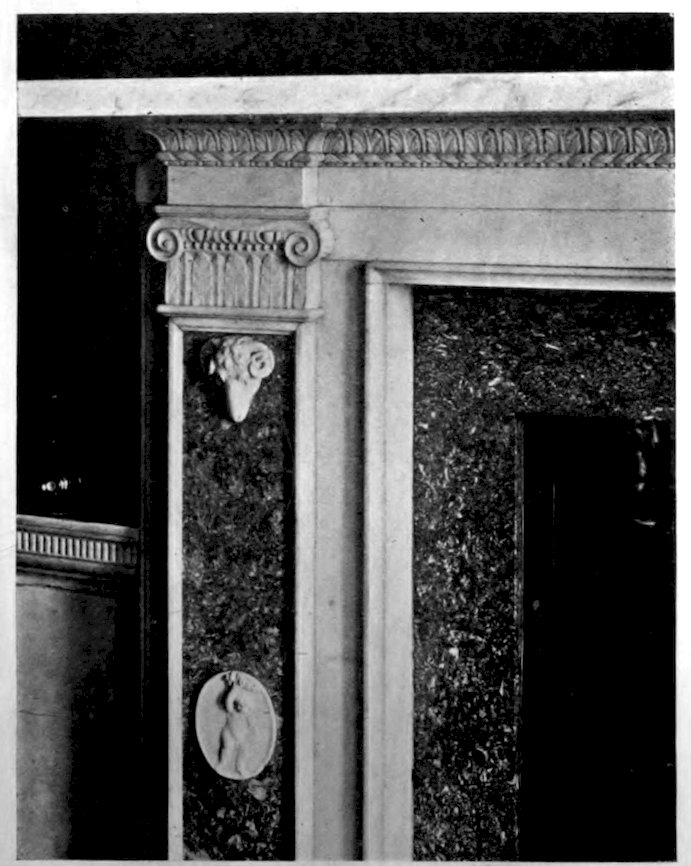

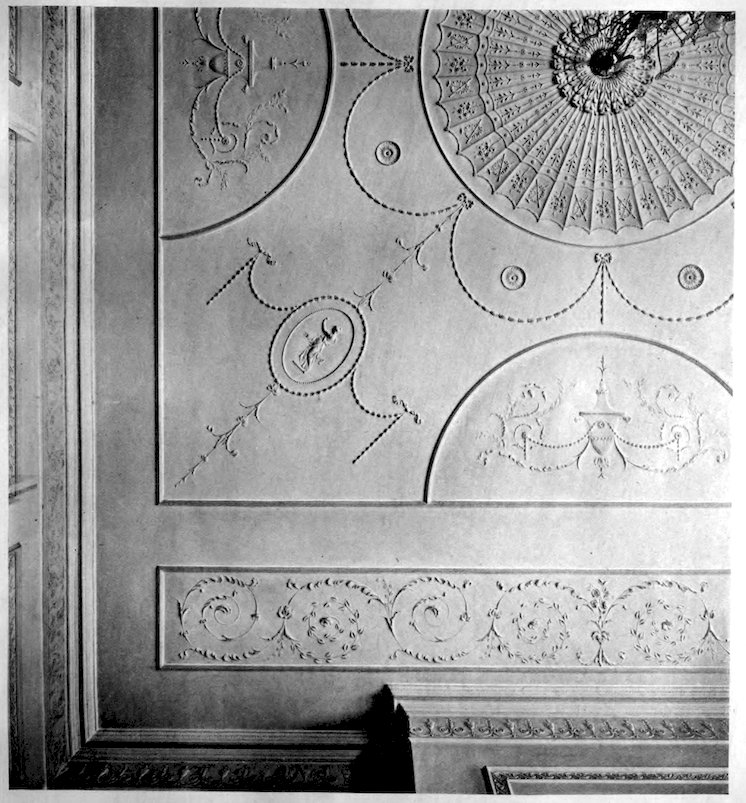

| 29. | Markmasons’ Hall, Chimneypiece in Boardroom | Photograph. |

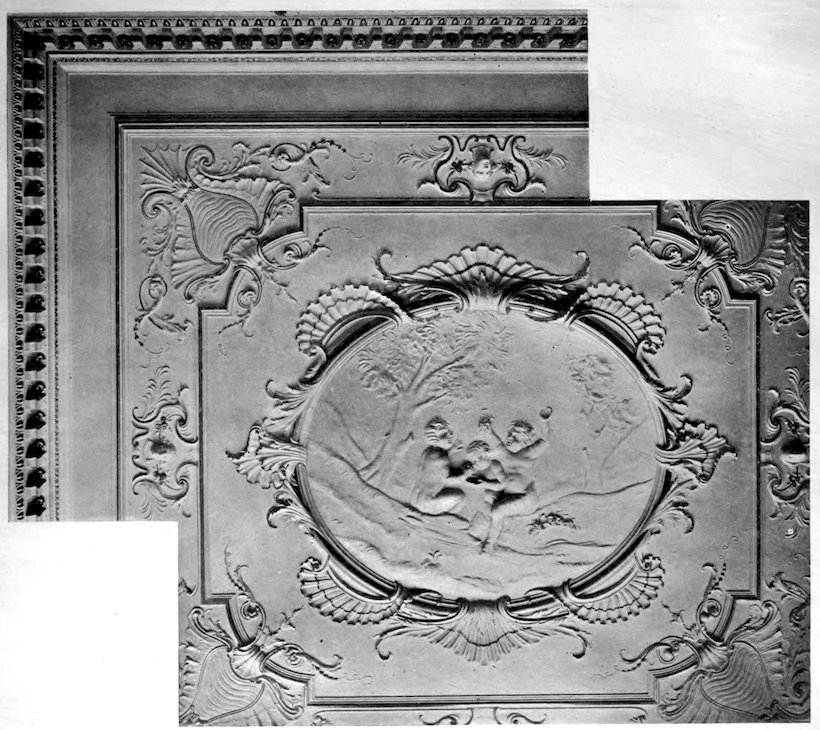

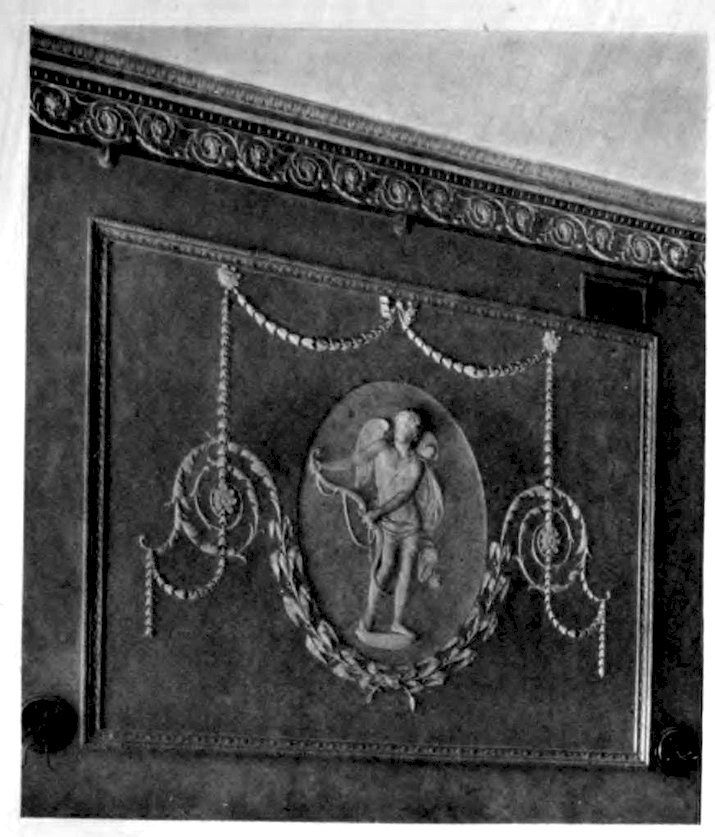

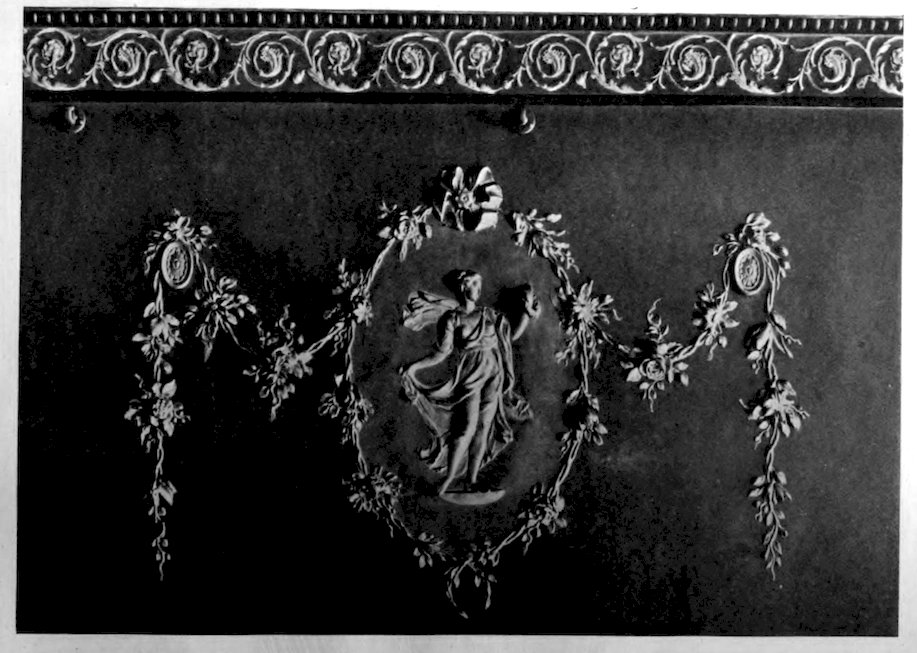

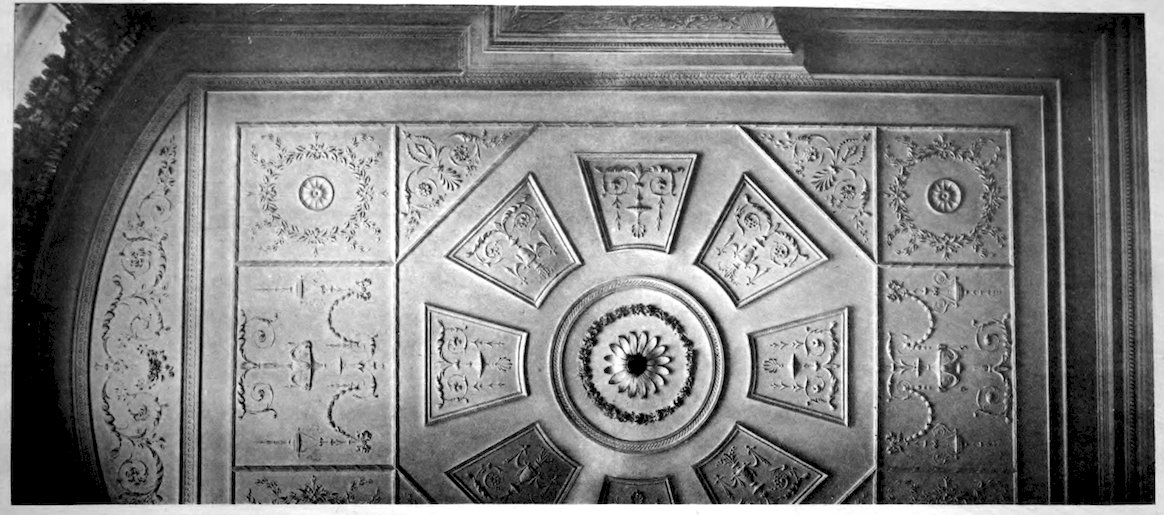

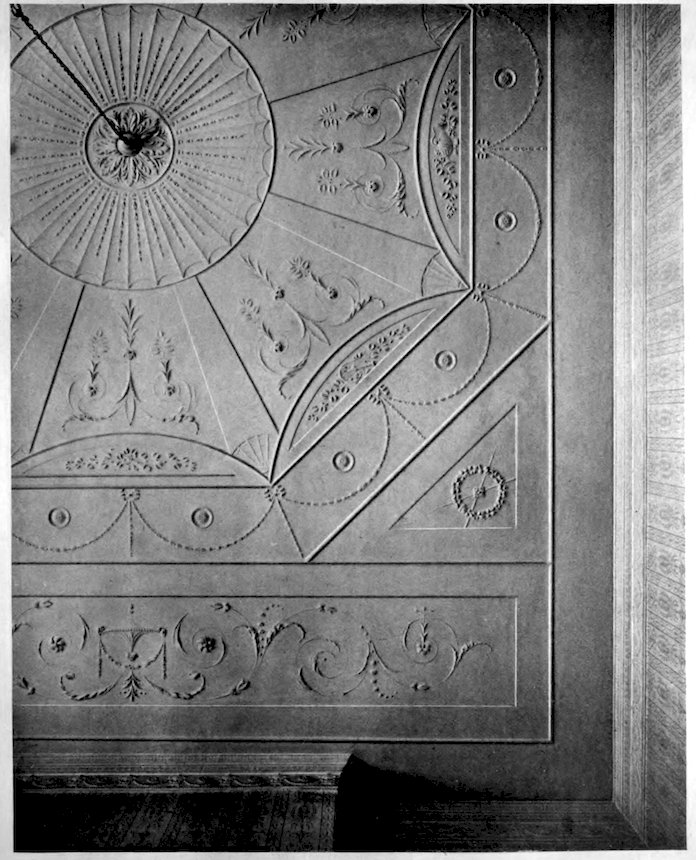

| 30. | Markmasons’ Hall, Ceiling in Boardroom | Photograph. |

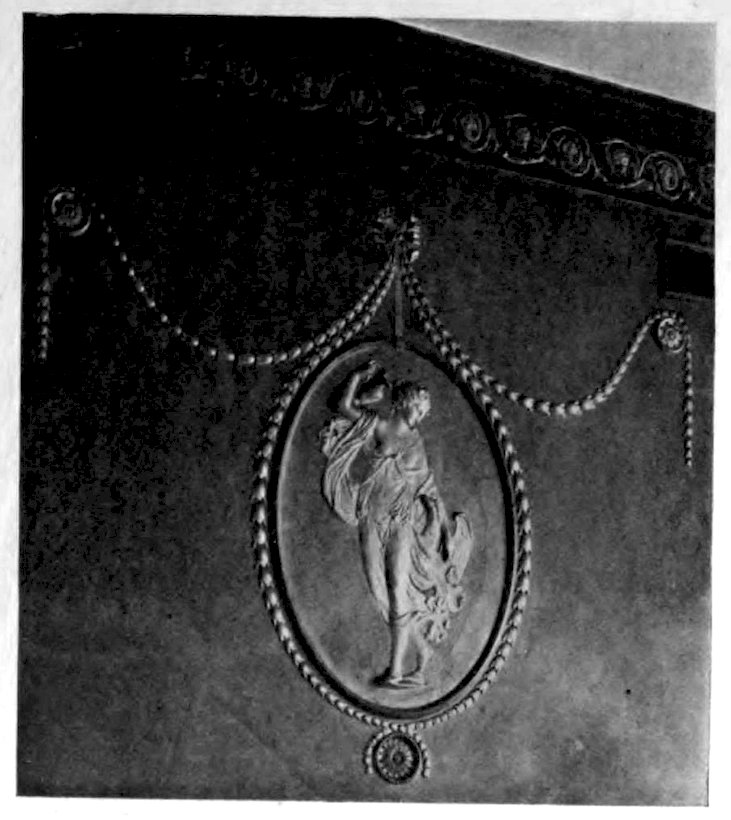

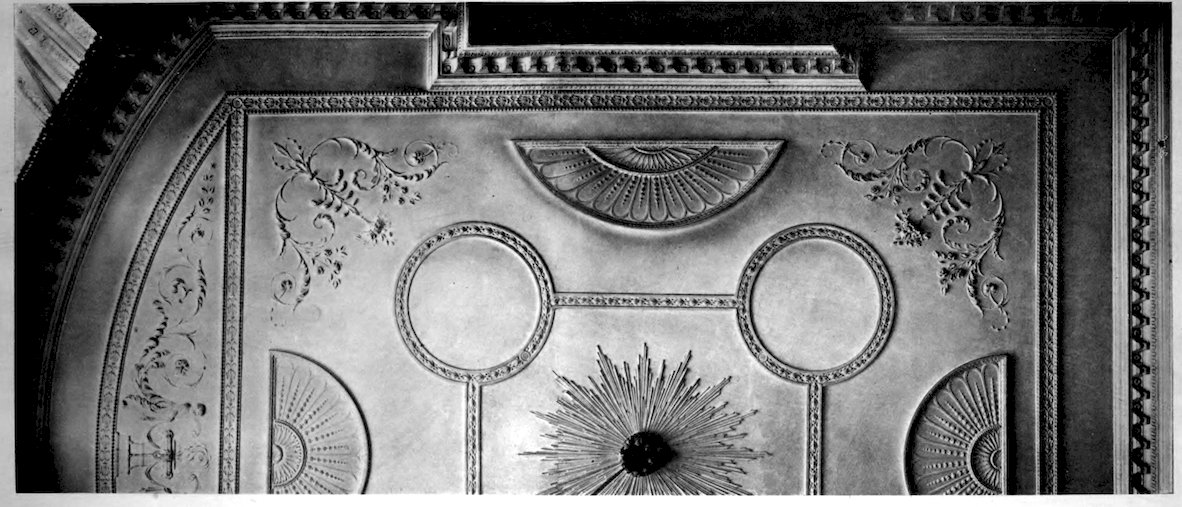

| 31. | Markmasons’ Hall, Ceiling in Grand Secretary’s Room | Photograph. |

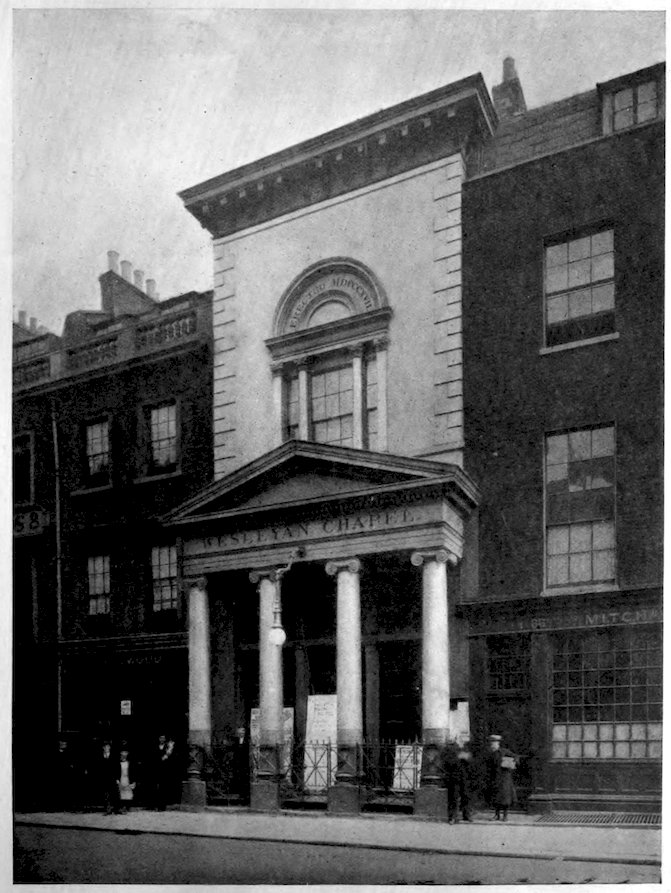

| 32. | Great Queen Street Chapel, Exterior | Photograph. |

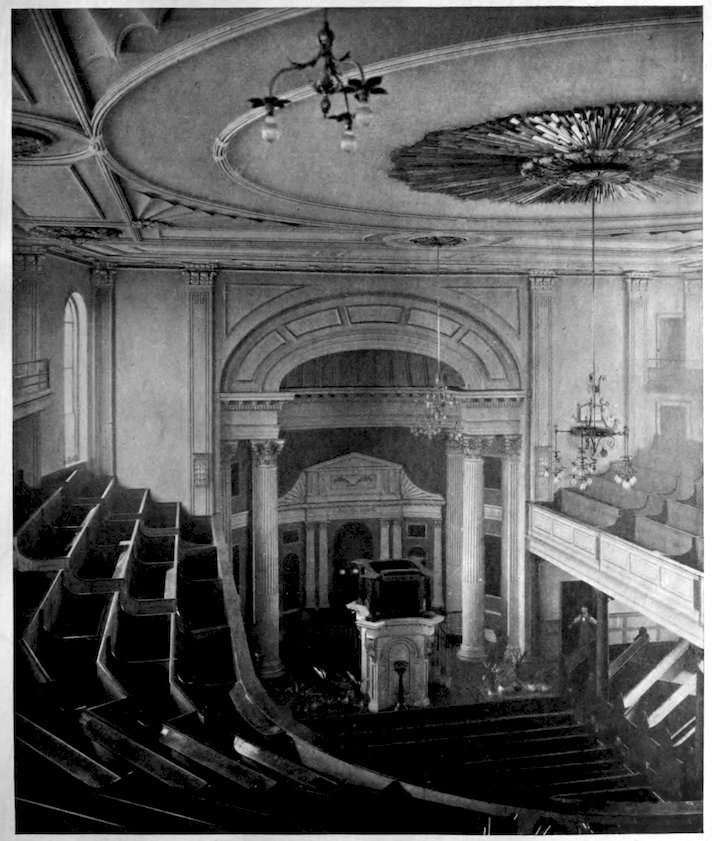

| 33. | Great Queen Street Chapel, Interior from the Gallery | Photograph. |

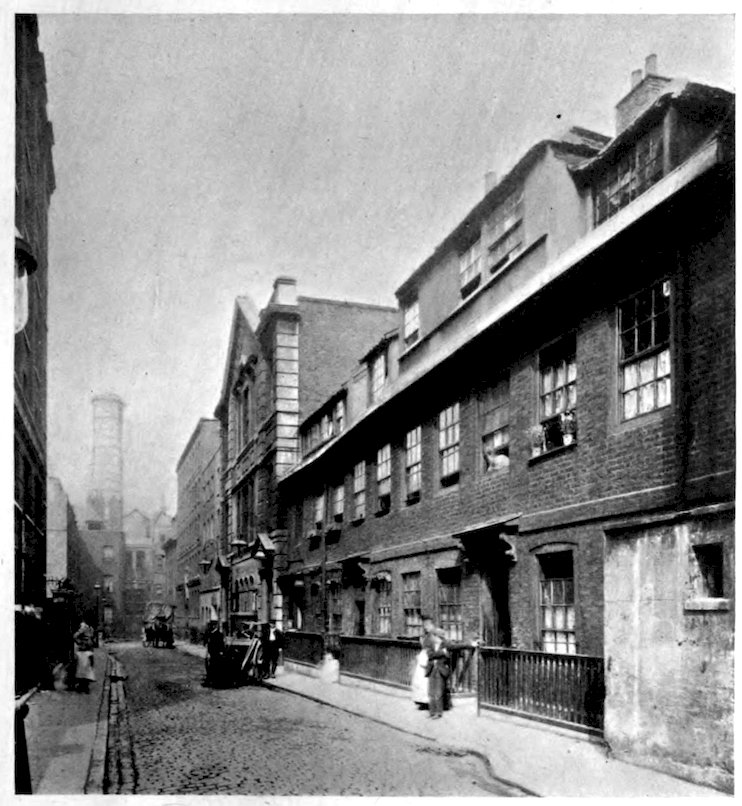

| 34. | Little Wild Street, View looking North-east (1906) | Photograph. |

| 35. | No. 24, Betterton Street, Entrance Doorcase | Measured Drawing. |

| 36. | No. 32, Betterton Street, Entrance Doorcase | Photograph. |

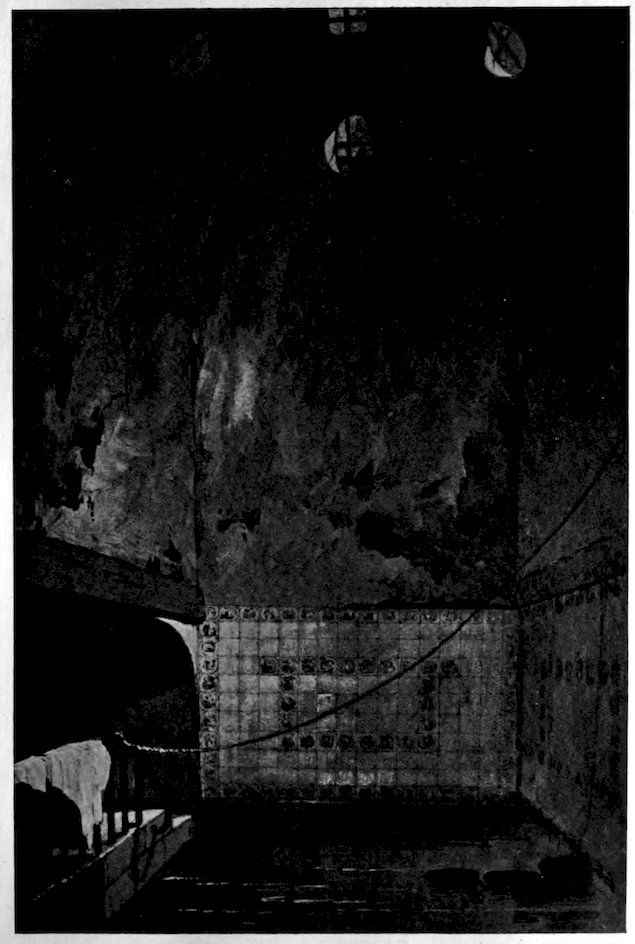

| 37. | “Queen Anne’s Bath,” No. 25, Endell Street, from a watercolour drawing by J. W. Archer (1844), preserved in the British Museum | Photograph. |

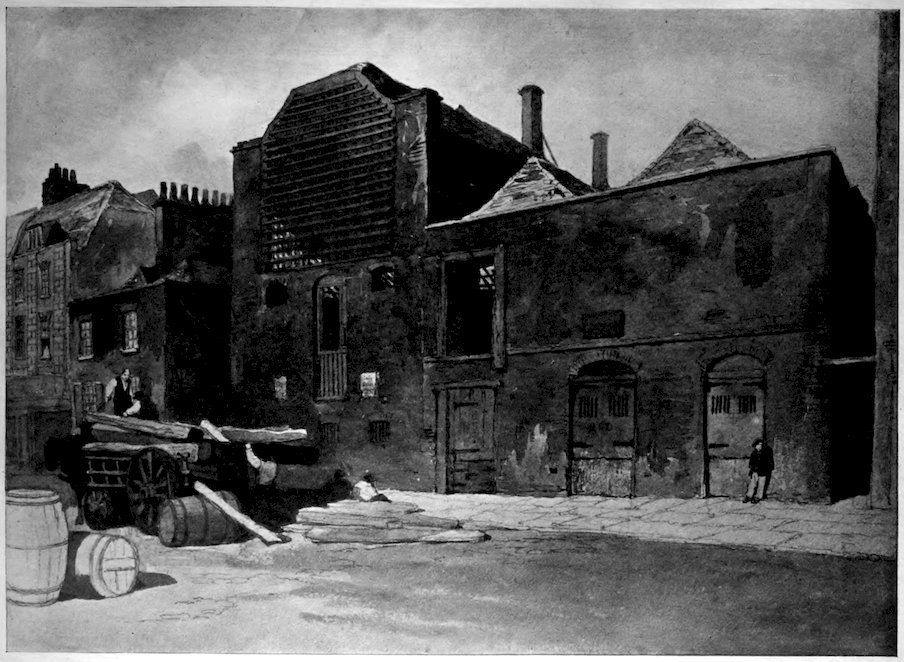

| 38. | “The Bowl Brewery,” from a watercolour drawing by J. W. Archer (1846), preserved in the British Museum | Photograph. |

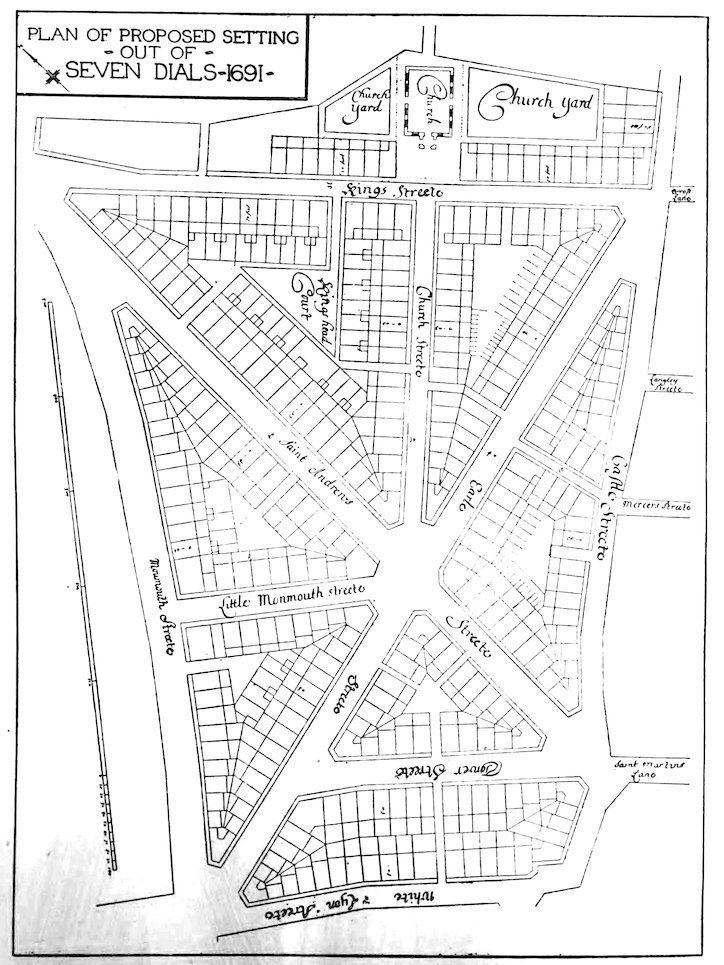

| 39. | Plan of proposed setting out of Seven Dials, from a drawing on parchment preserved in the Holborn Public Library | Drawing. |

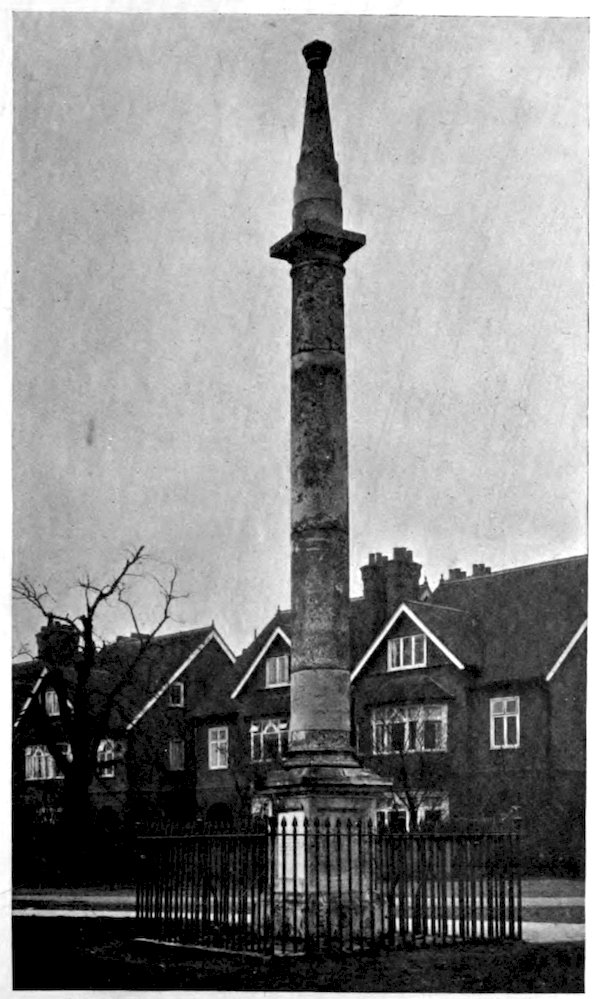

| 40. | Seven Dials Column at Weybridge | Photograph. |

| 41. | Little Earl Street looking East | Photograph. |

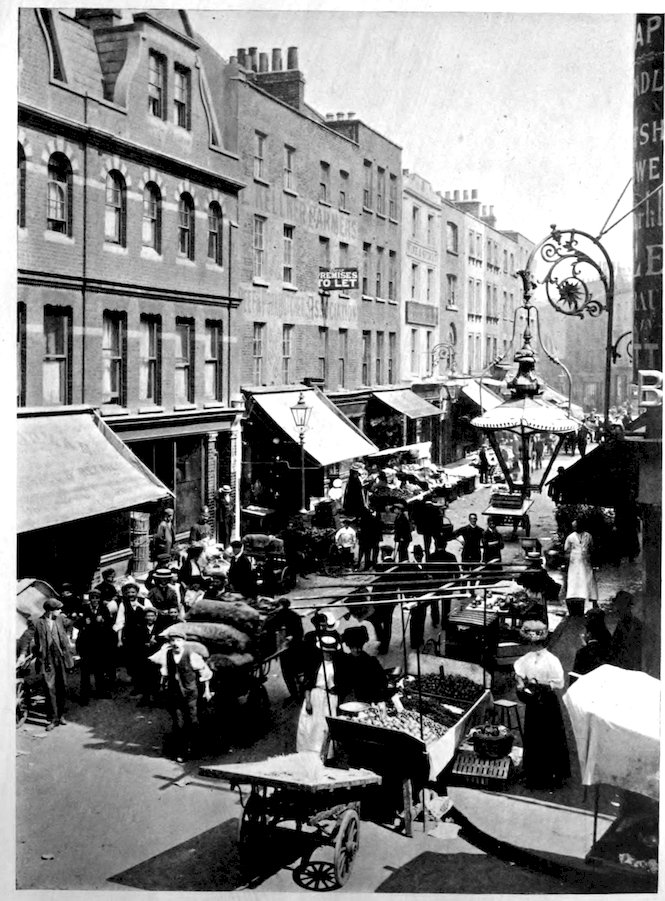

| 42. | Nos. 14 to 16, New Compton Street, Shop Fronts | Photographs. |

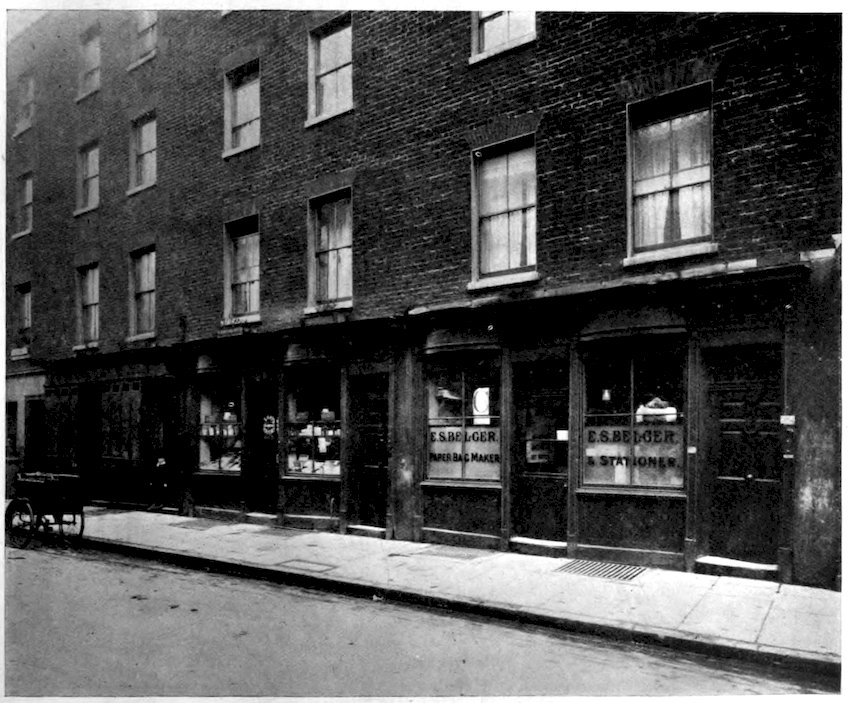

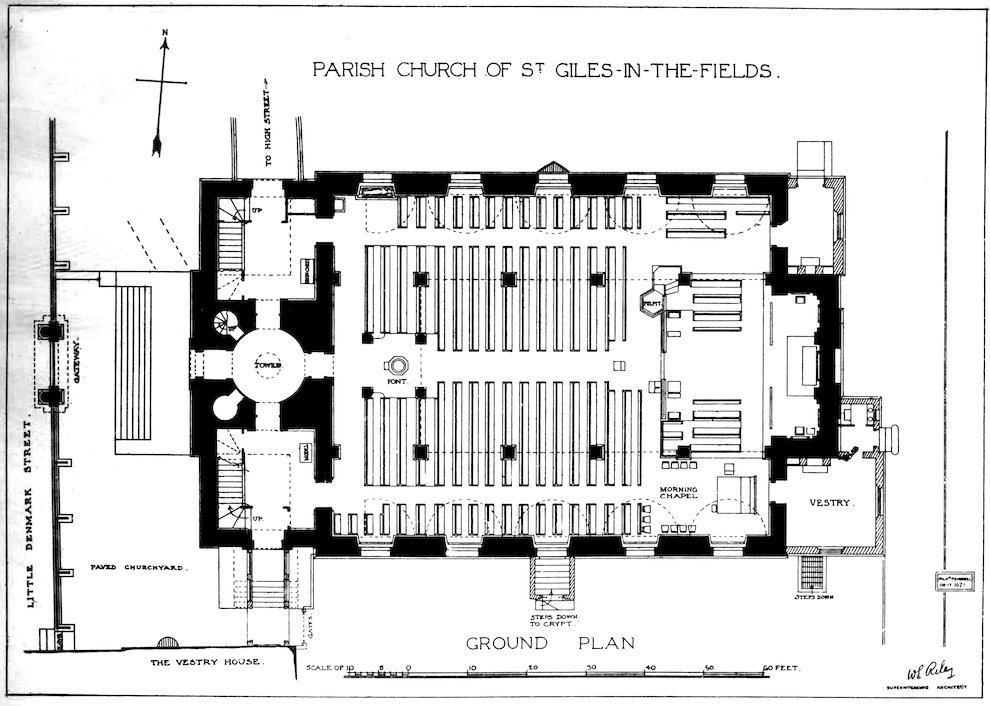

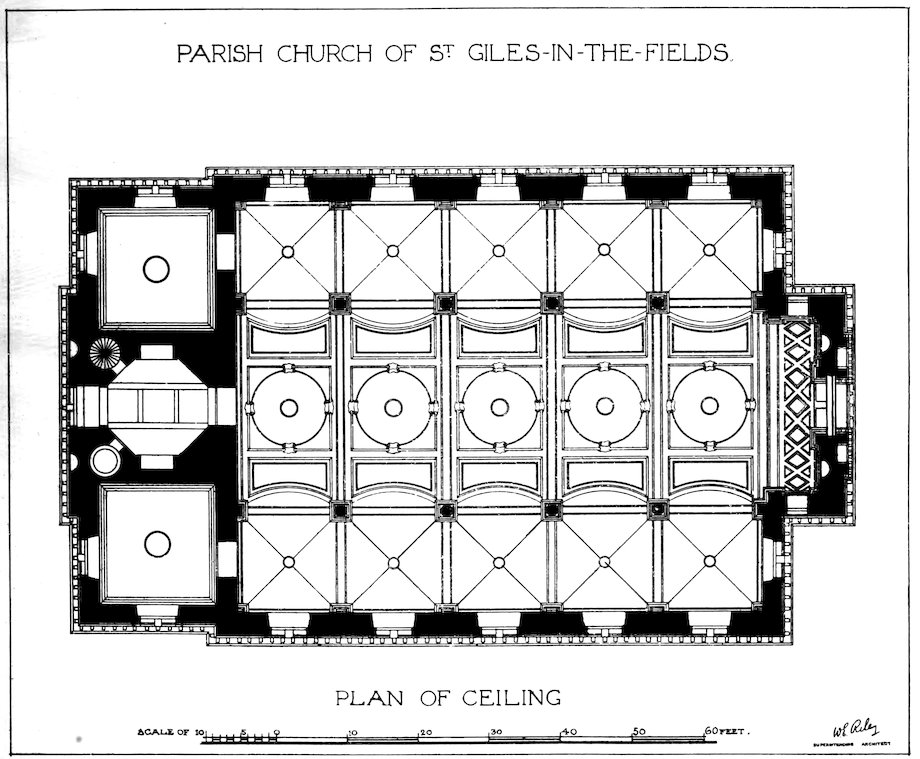

| 43. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Ground Plan | Measured Drawing. |

| 44. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Plan of Ceiling | Measured Drawing. |

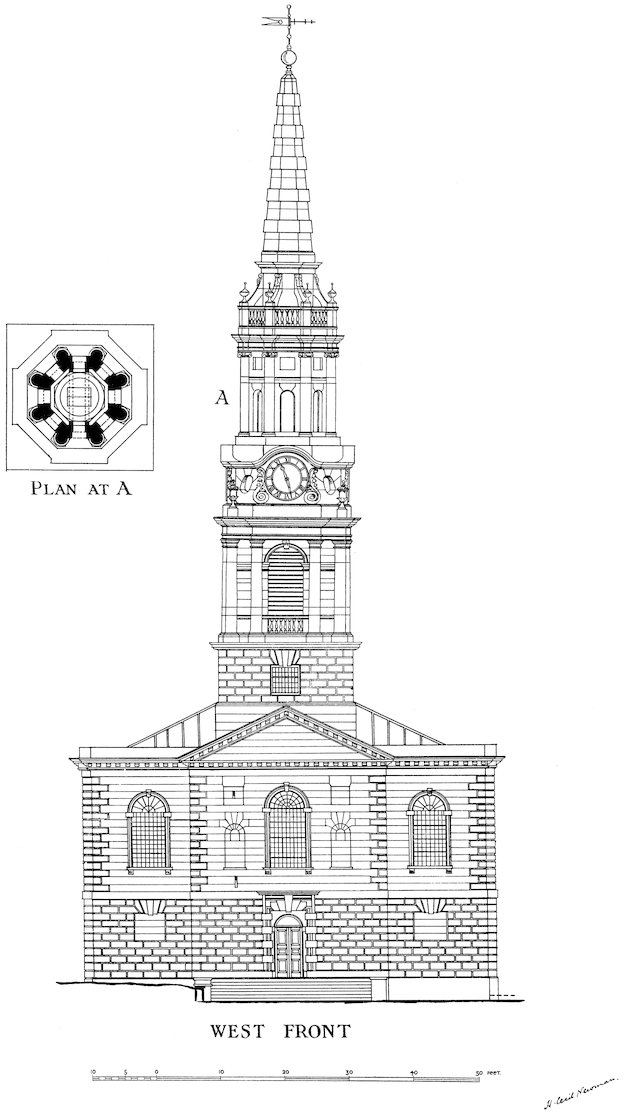

| 45. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, West Front, reproduced by kind permission of H. Cecil Newman | Measured Drawing by H. Cecil Newman. |

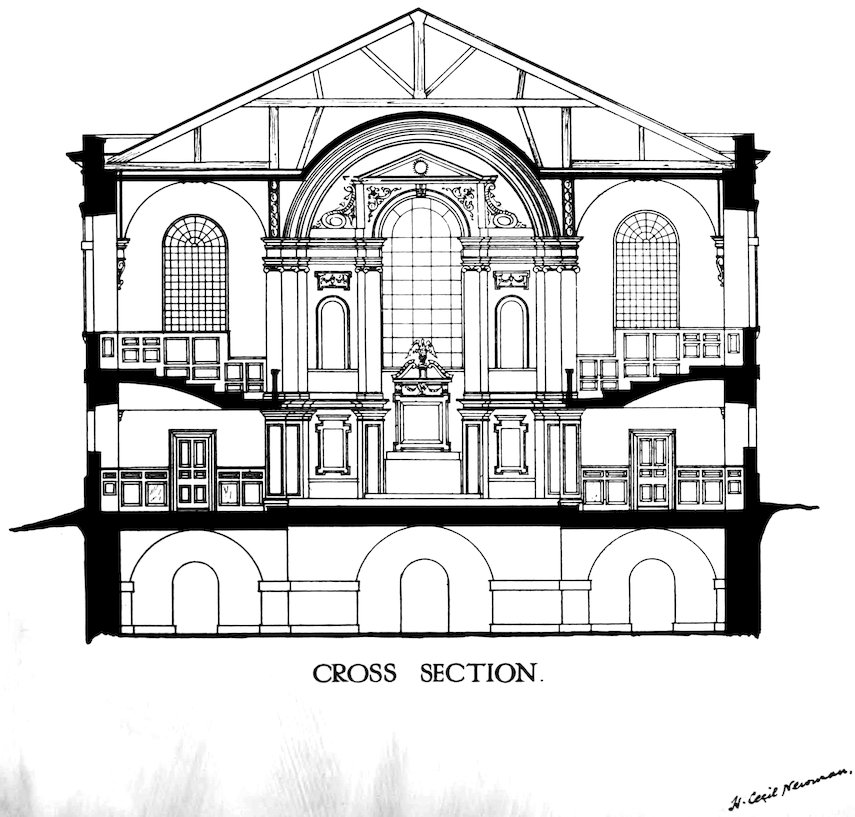

| 46. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Cross Section, reproduced by kind permission of H. Cecil Newman | Measured Drawing by H. Cecil Newman. |

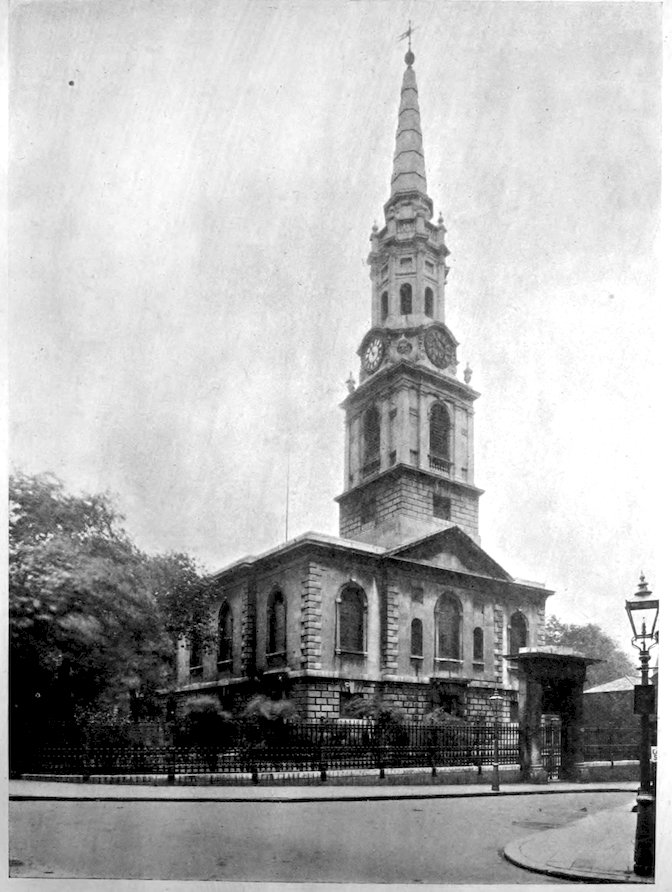

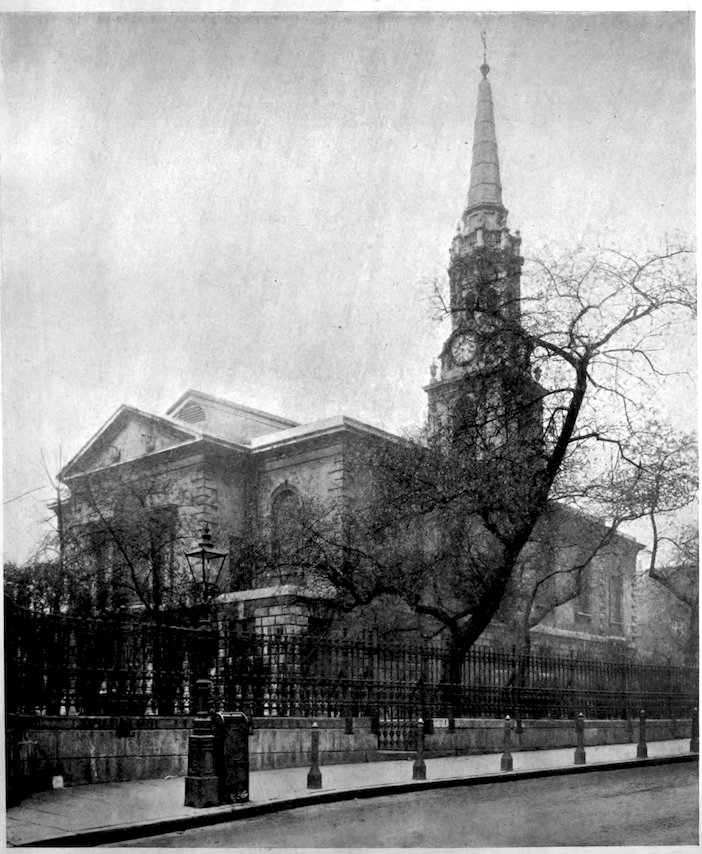

| 47. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Exterior from the North-west | Photograph. |

| 48. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Exterior from the North-east | Photograph. |

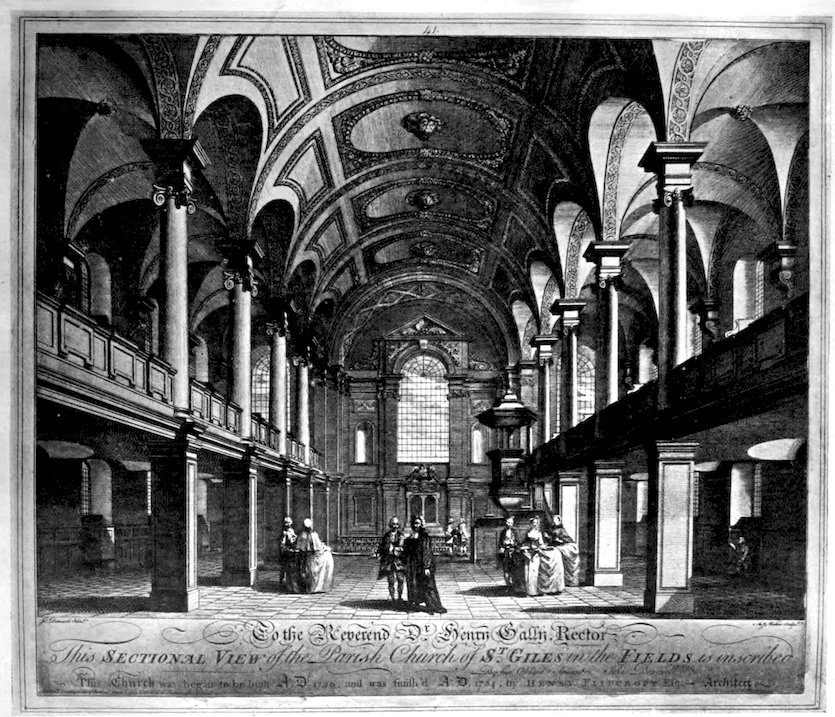

| 49. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Interior, looking East, 1753. From an engraving by A. Walker after J. Donowell | Photograph. |

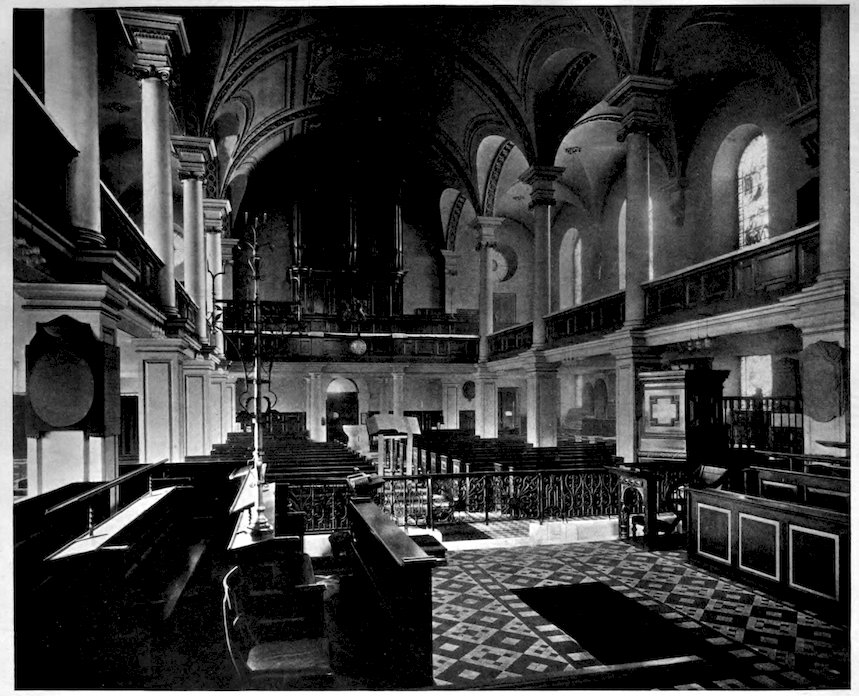

| 50. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Interior, looking West | Photograph. |

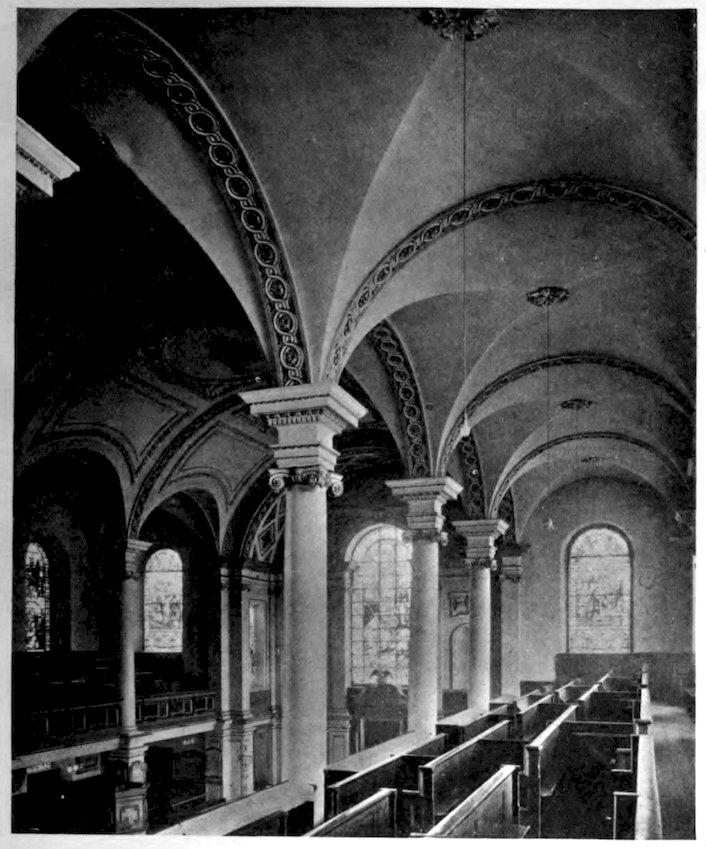

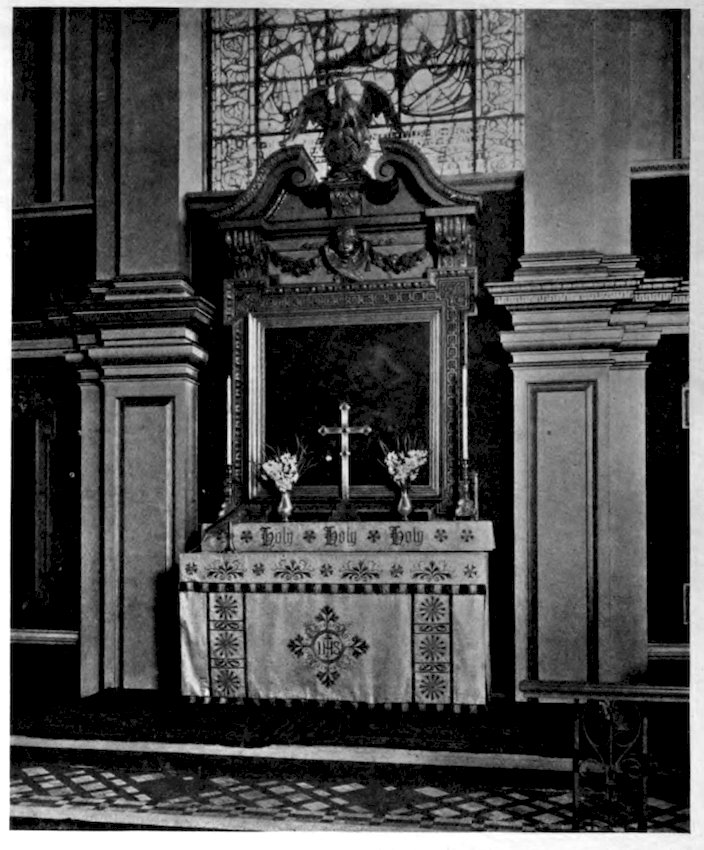

| xi51. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields: (a) Columns and Ceiling, (b) Altarpiece | Photographs. |

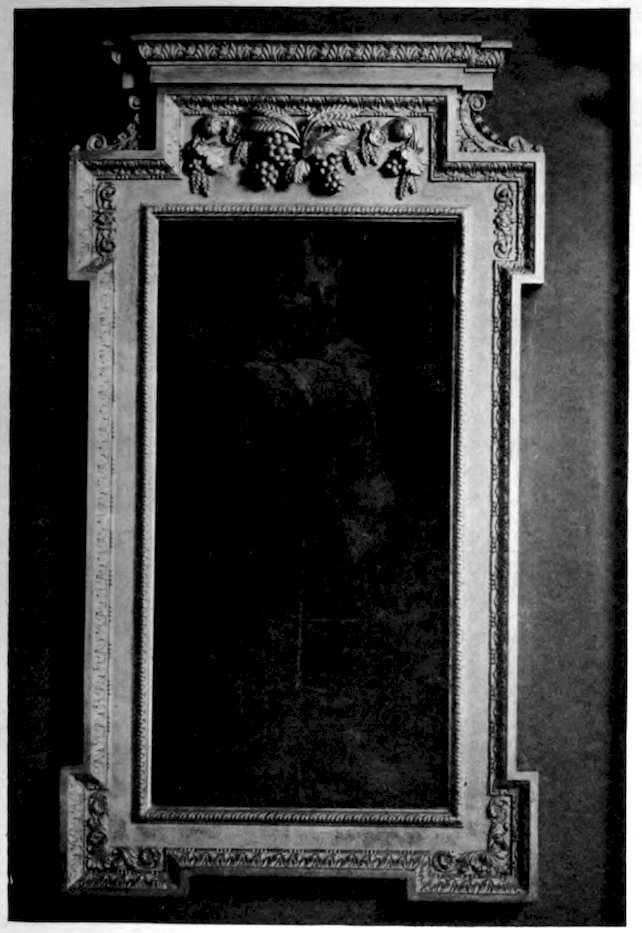

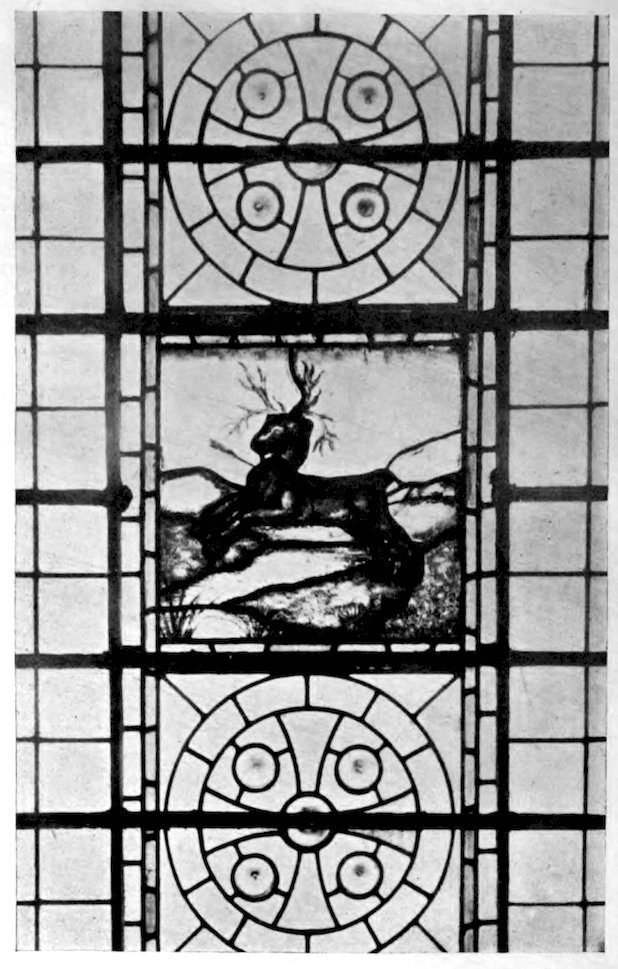

| 52. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields: (a) Carved Oak Frame with Picture of Moses, (b) Painted Glass Panel, probably from former Church | Photographs. |

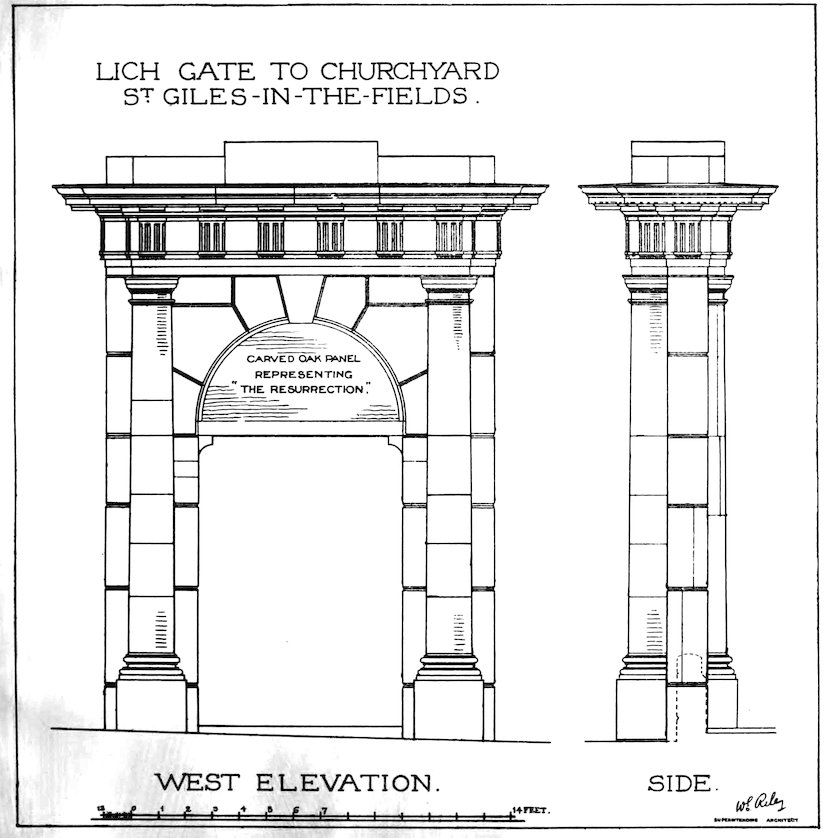

| 53. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Lich Gate to Churchyard | Measured Drawing. |

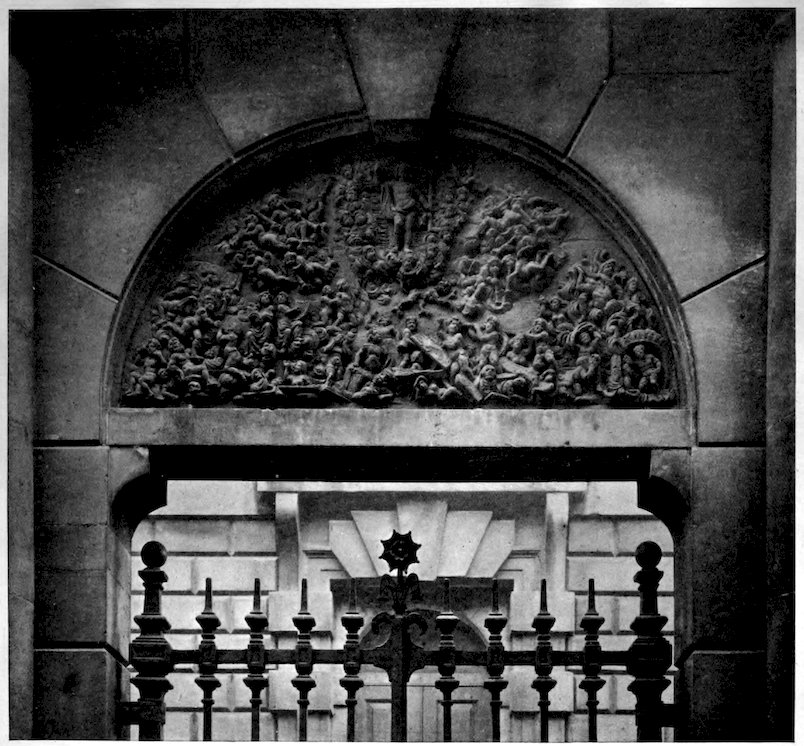

| 54. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Oak Panel (“Resurrection”) in lich gate | Photograph. |

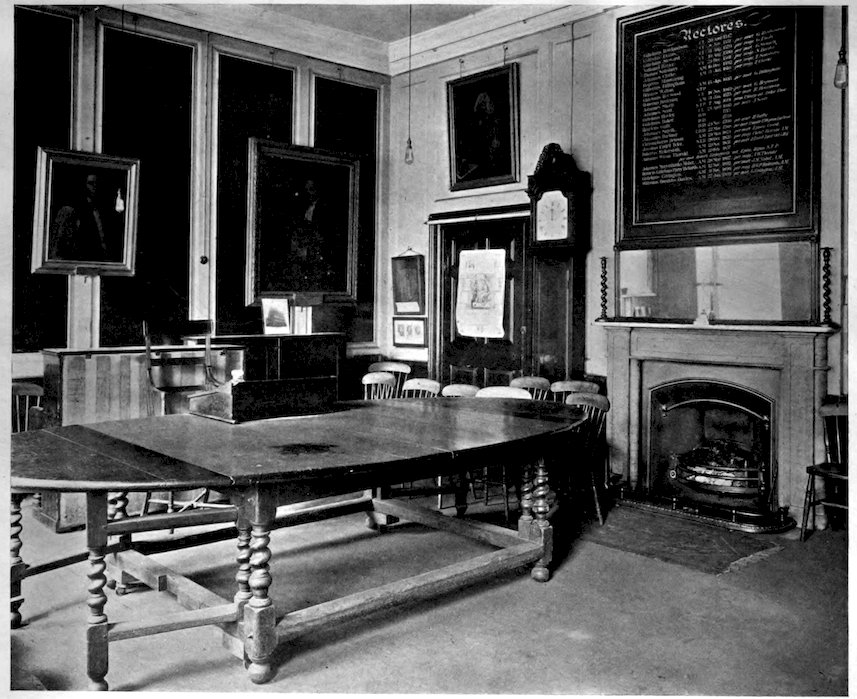

| 55. | Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, Vestry | Photograph. |

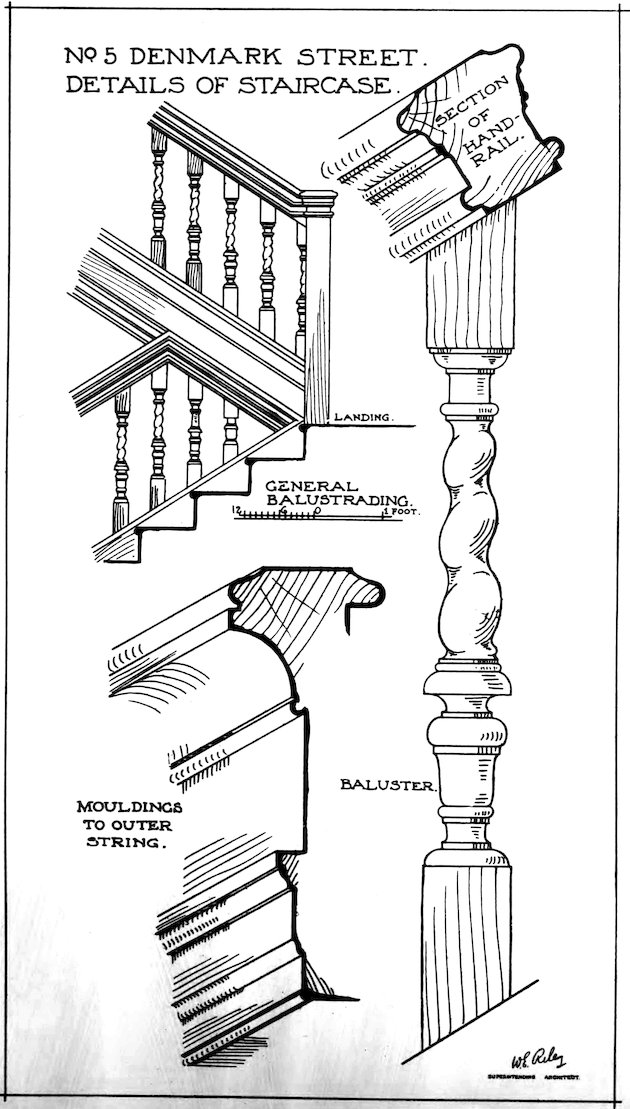

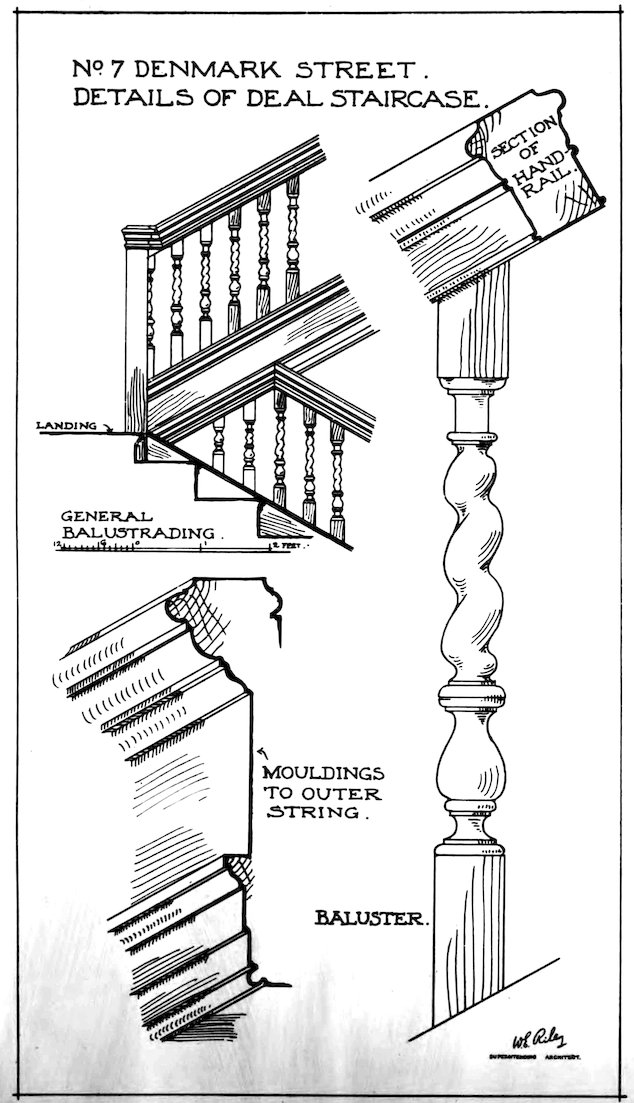

| 56. | No. 5, Denmark Street, Details of Staircase | Measured Drawing. |

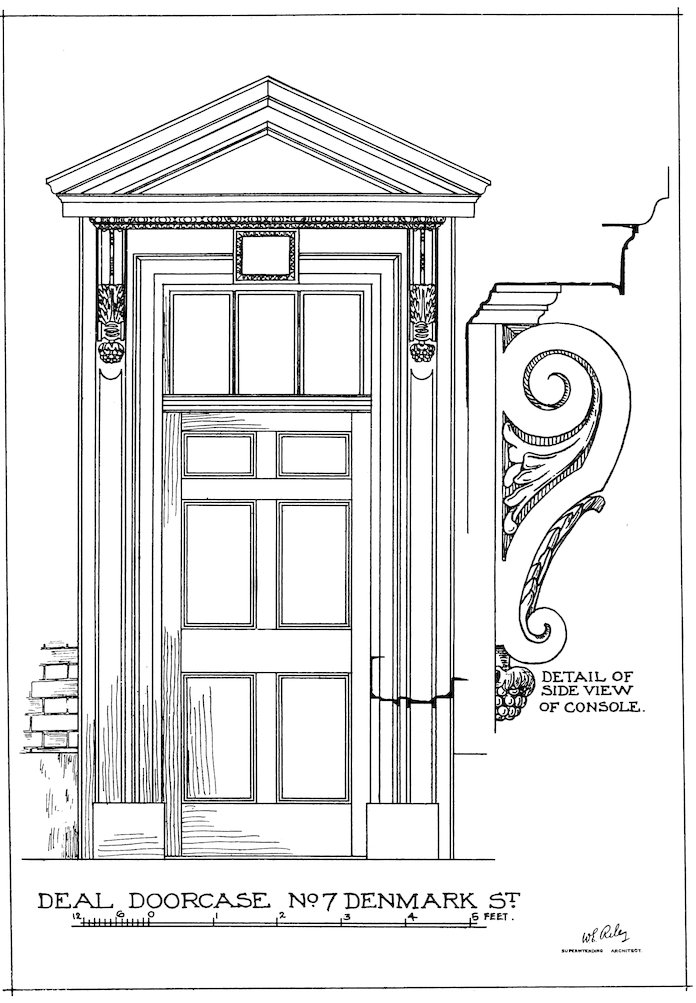

| 57. | No. 7, Denmark Street, Doorcase | Measured Drawing. |

| 58. | No. 7, Denmark Street, Details of Staircase | Measured Drawing. |

| 59. | Nos. 10 and 11, Denmark Street | Photograph. |

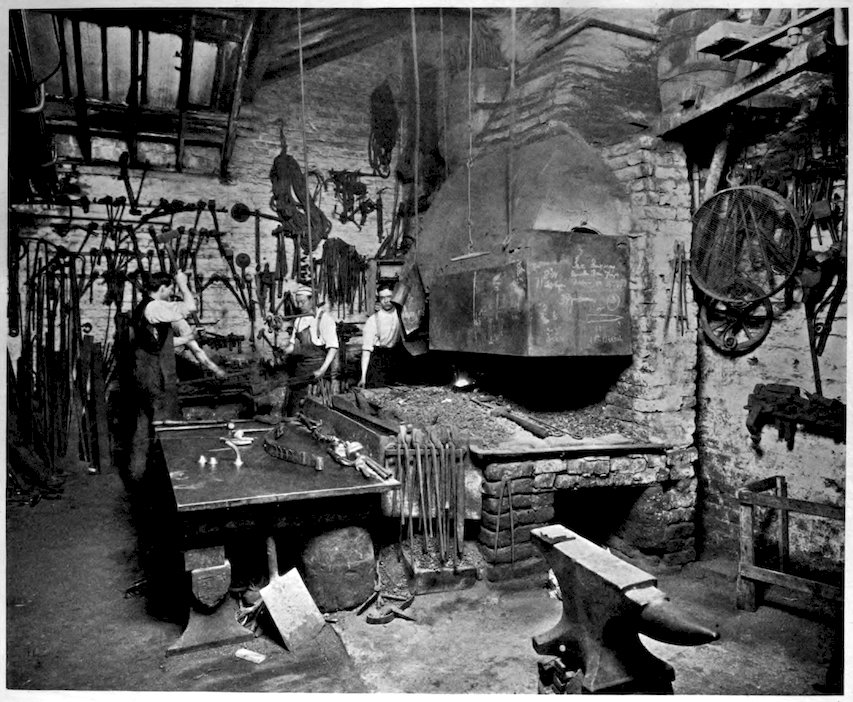

| 60. | Denmark Passage, Blacksmith’s Forge | Photograph. |

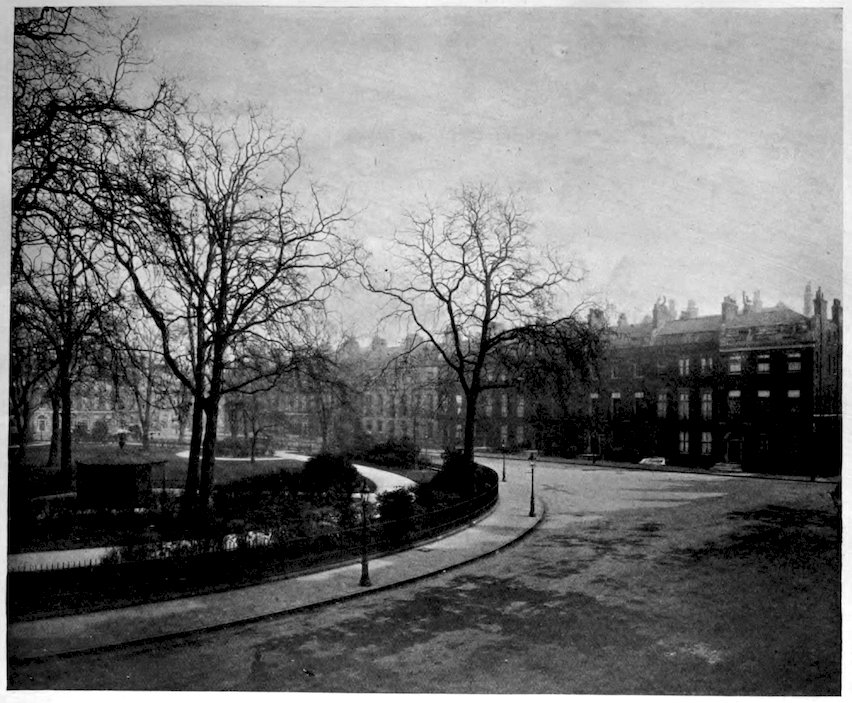

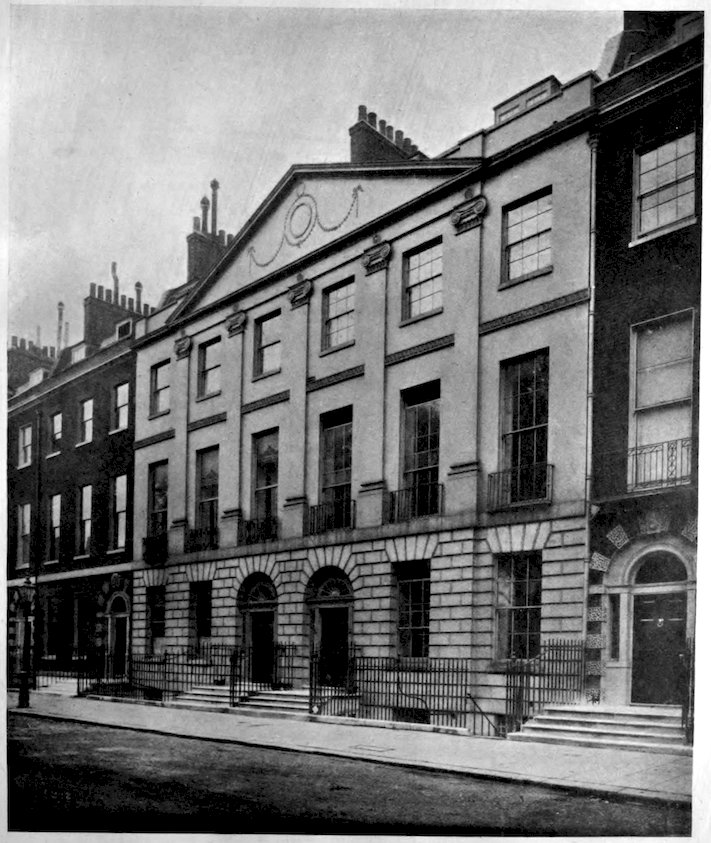

| 61. | Bedford Square, South Side | Photograph. |

| 62. | No. 1, Bedford Square, Ground and First Floor Plans | Measured Drawing. |

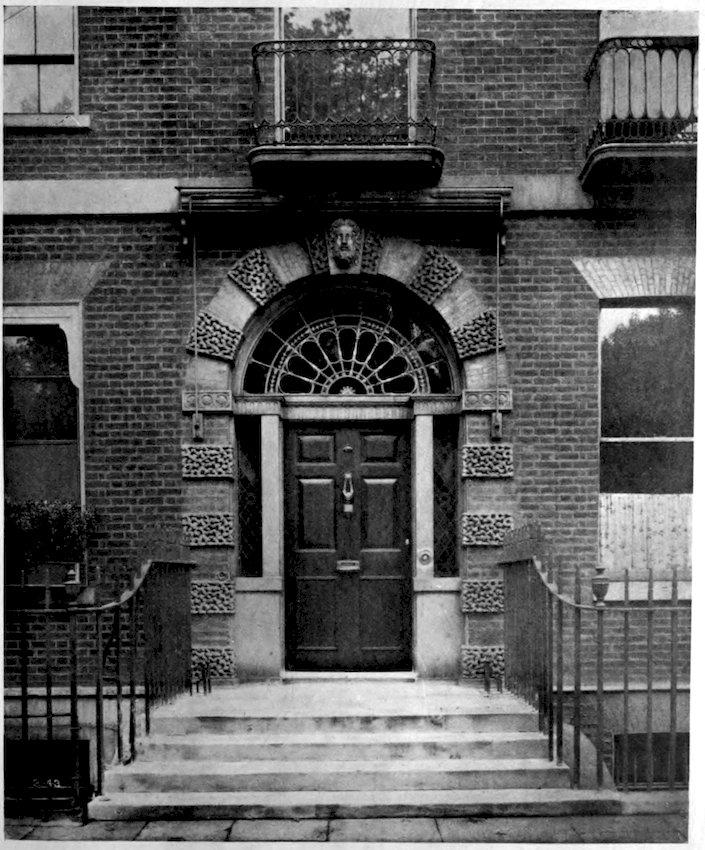

| 63. | No. 1, Bedford Square, Front View | Photograph. |

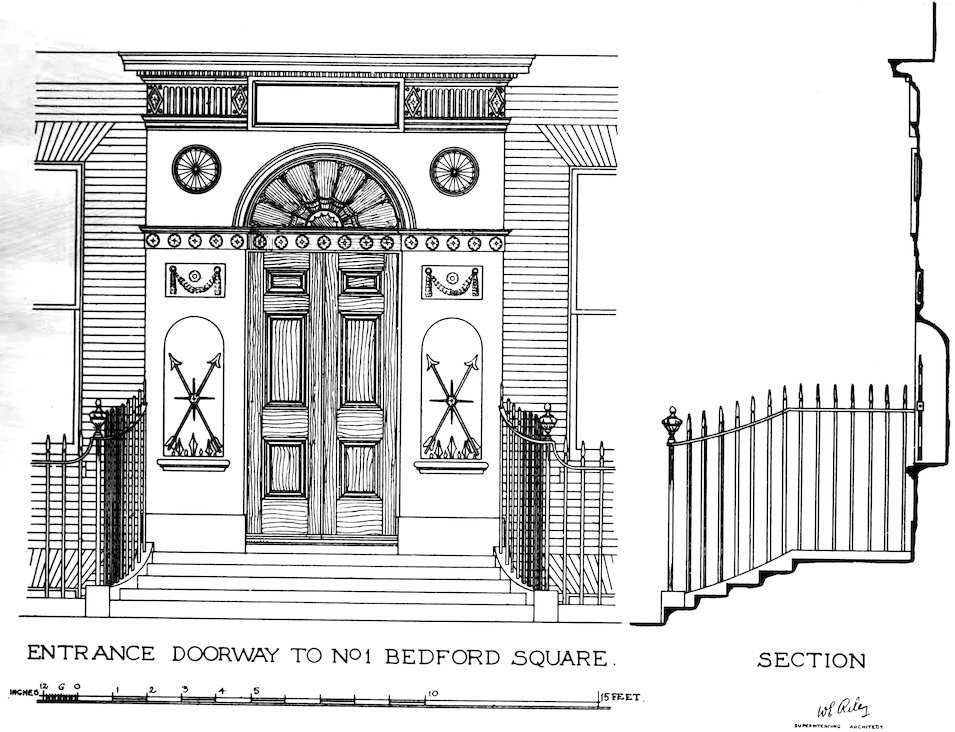

| 64. | No. 1, Bedford Square, Entrance Doorway | Measured Drawing. |

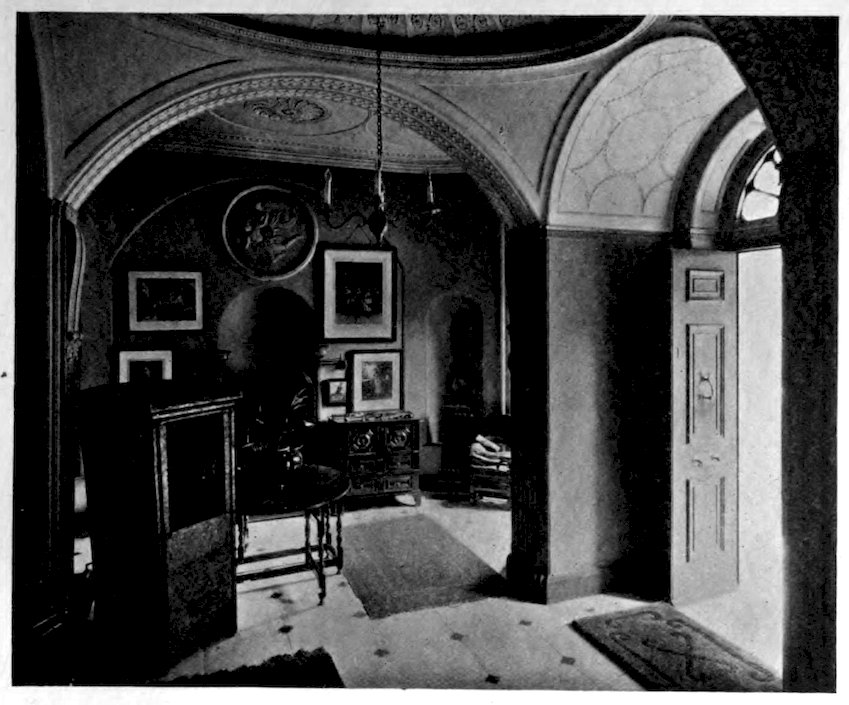

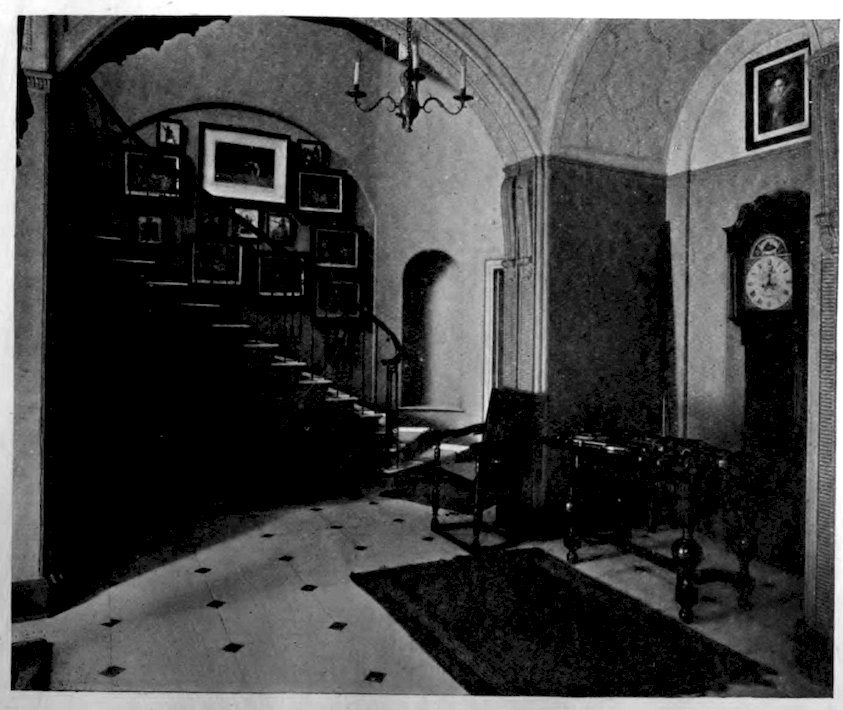

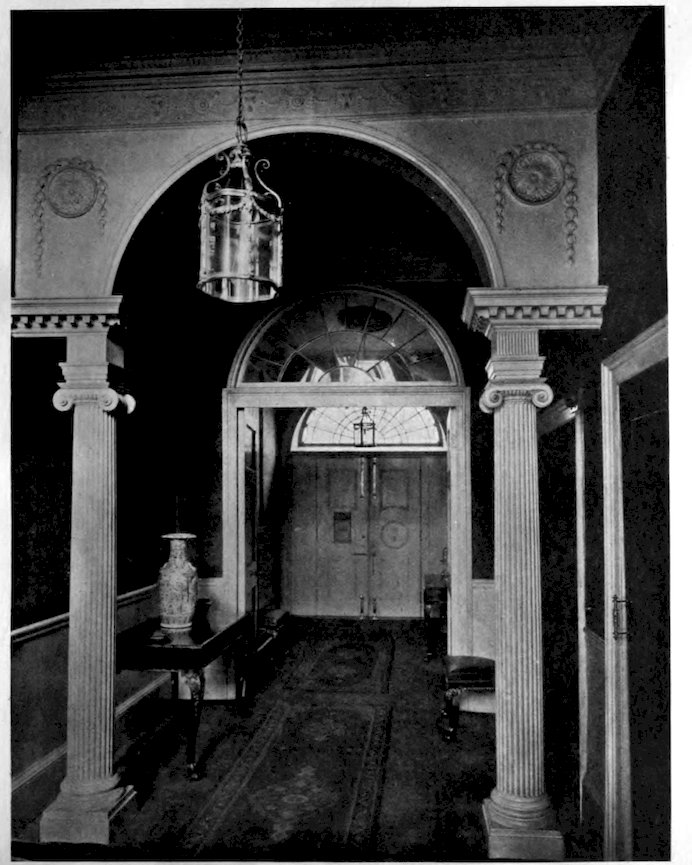

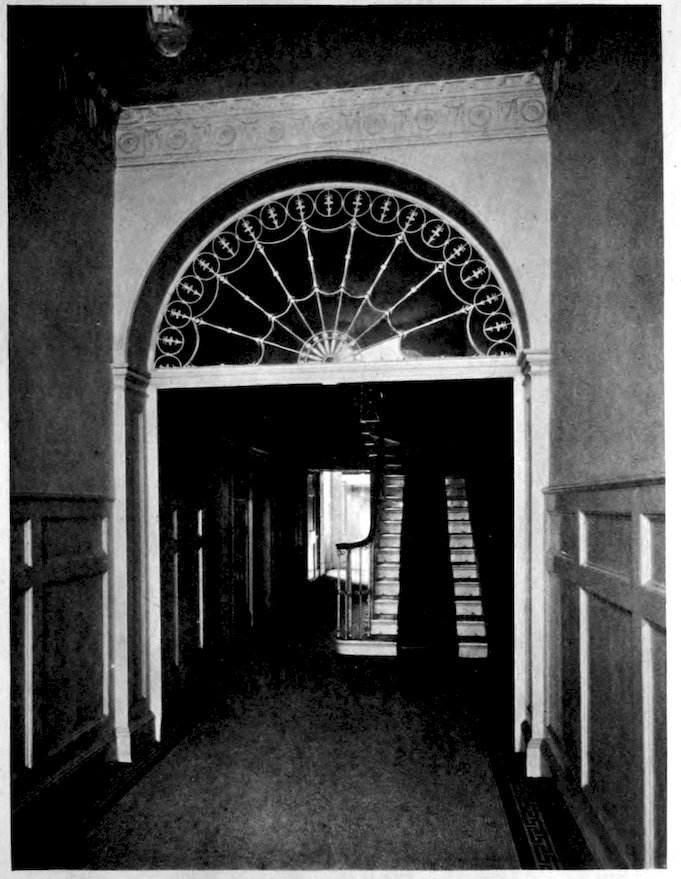

| 65. | No. 1, Bedford Square: Entrance Hall (a) looking South, (b) showing Staircase | Photographs. |

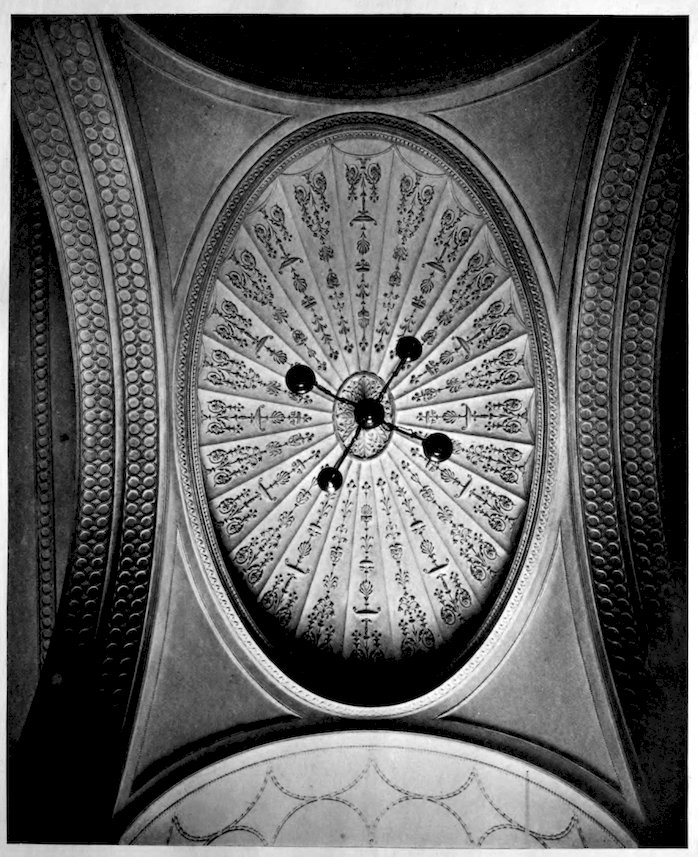

| 66. | No. 1, Bedford Square, Ceiling in Entrance Hall | Photograph. |

| 67. | No. 1, Bedford Square, Chimney Breast, Rear Room, Ground Floor | Photograph. |

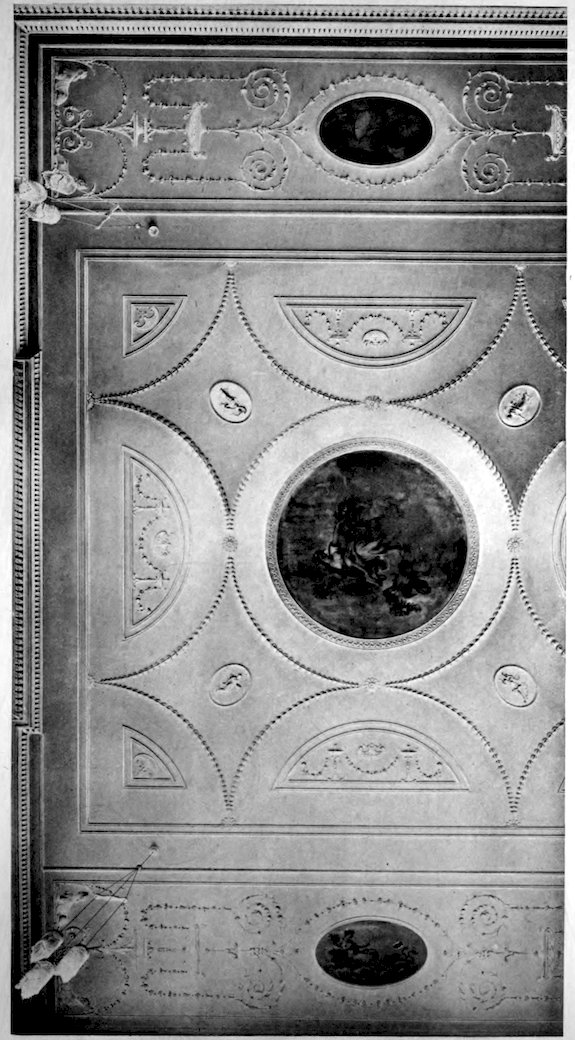

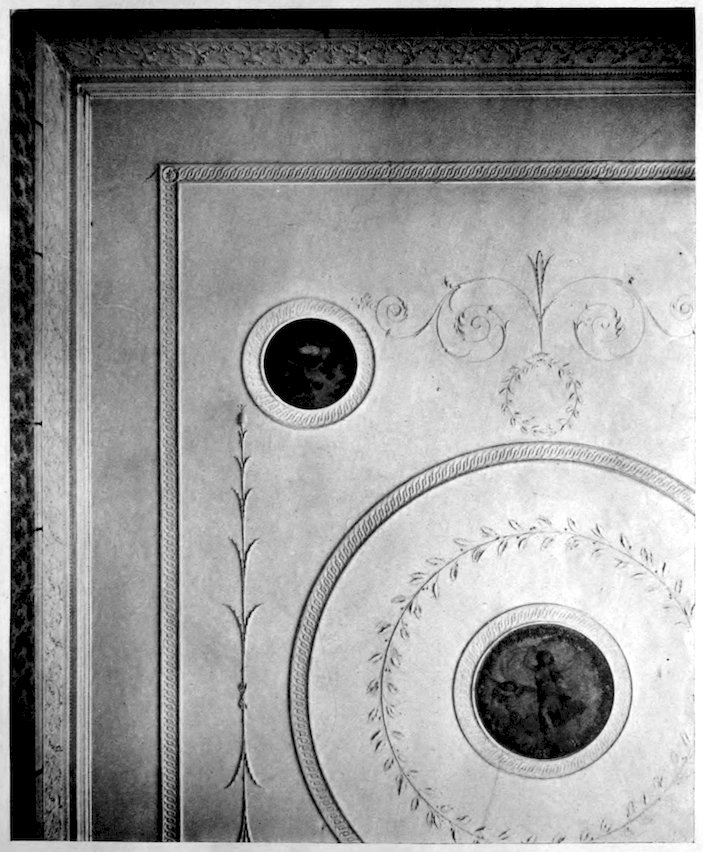

| 68. | No. 1, Bedford Square, Plaster Ceiling, with Painted Panels, Rear Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

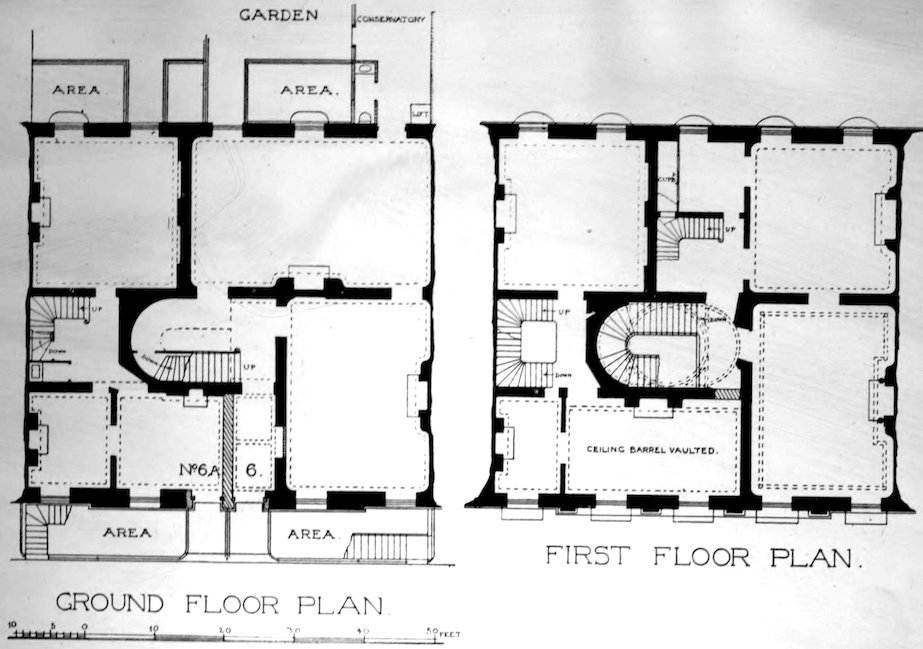

| 69. | No. 6, Bedford Square, Ground and First Floor Plans | Measured Drawing. |

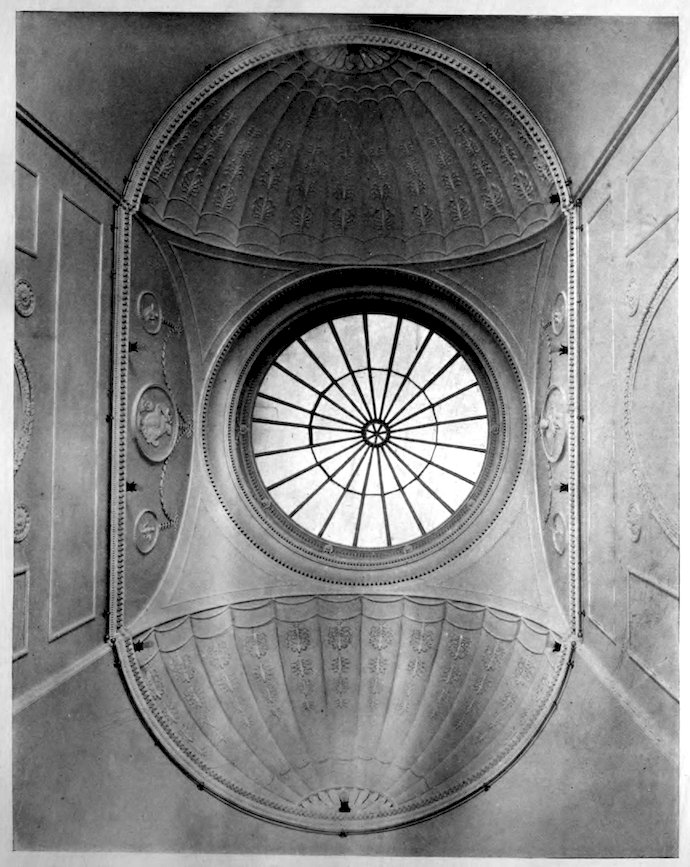

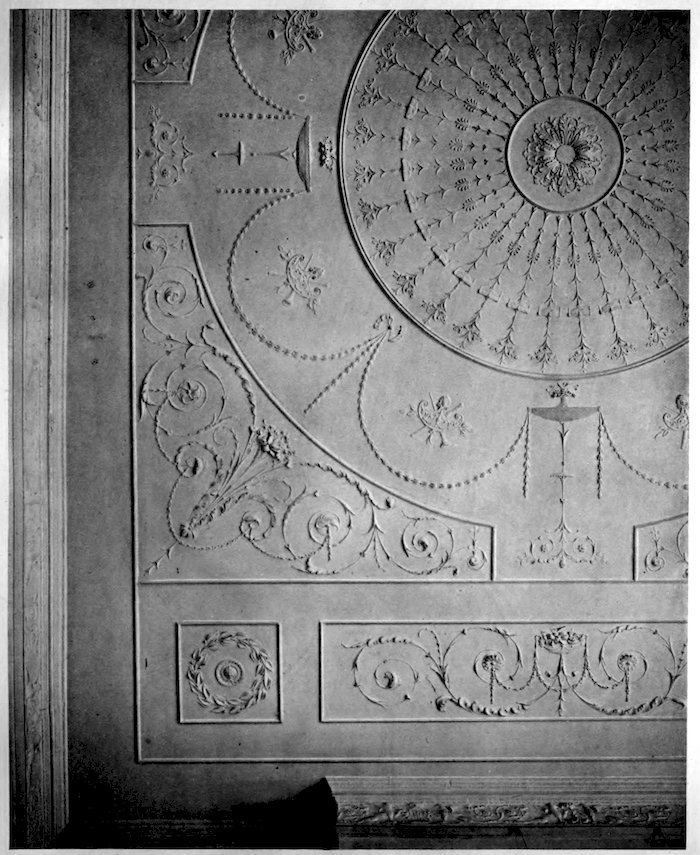

| 70. | No. 6, Bedford Square, Lantern over Staircase | Photograph. |

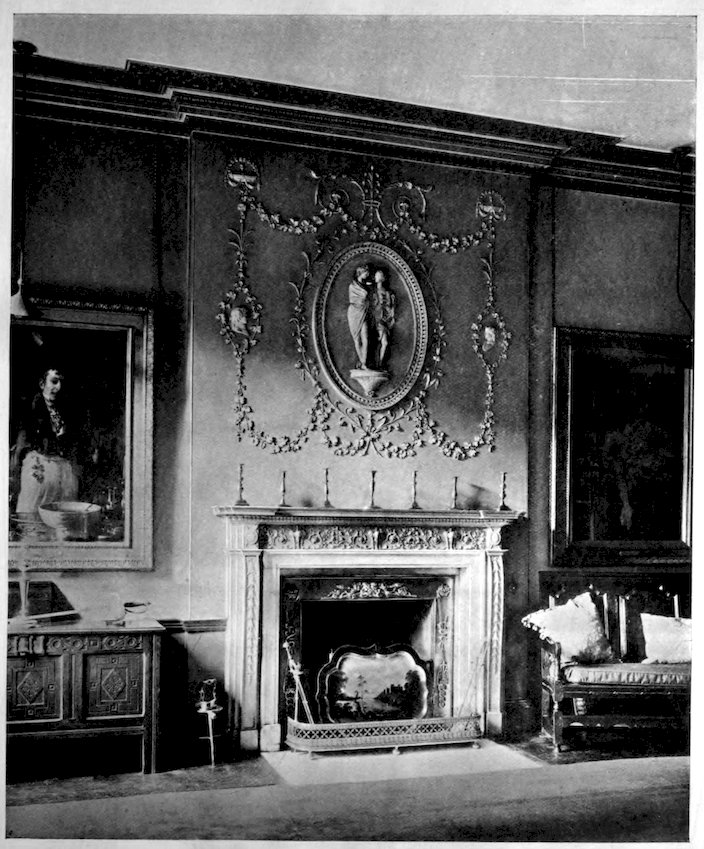

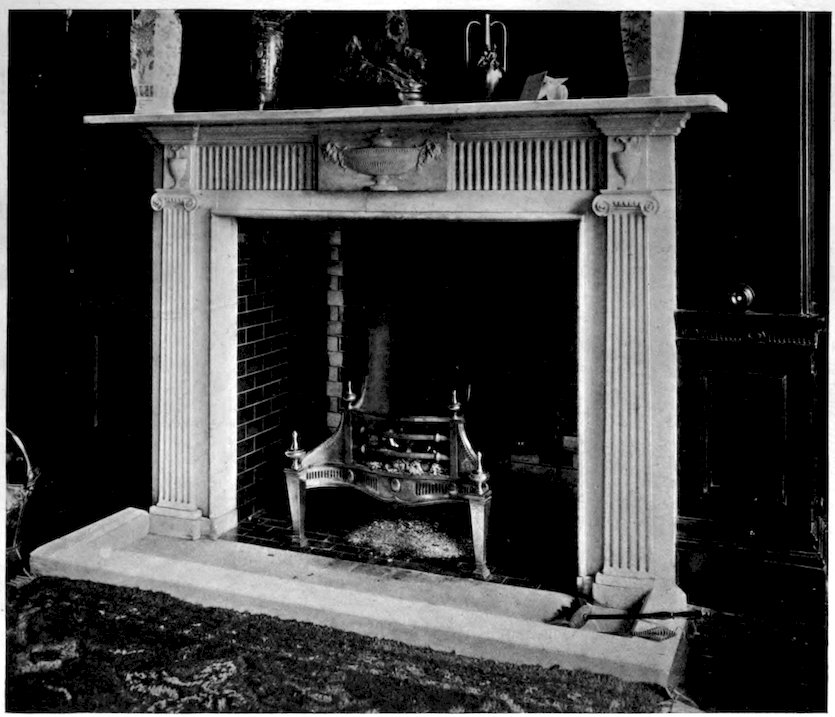

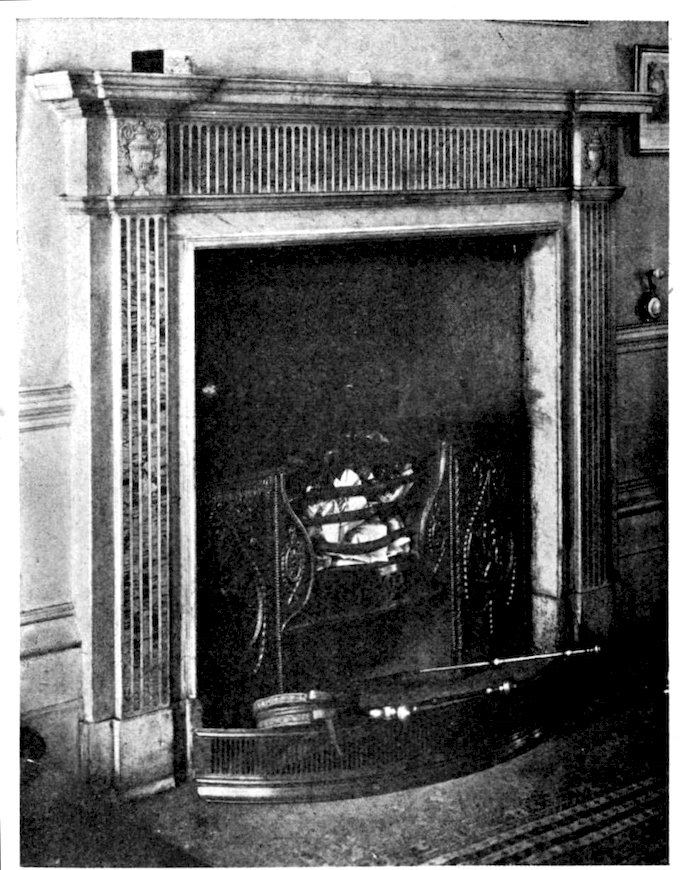

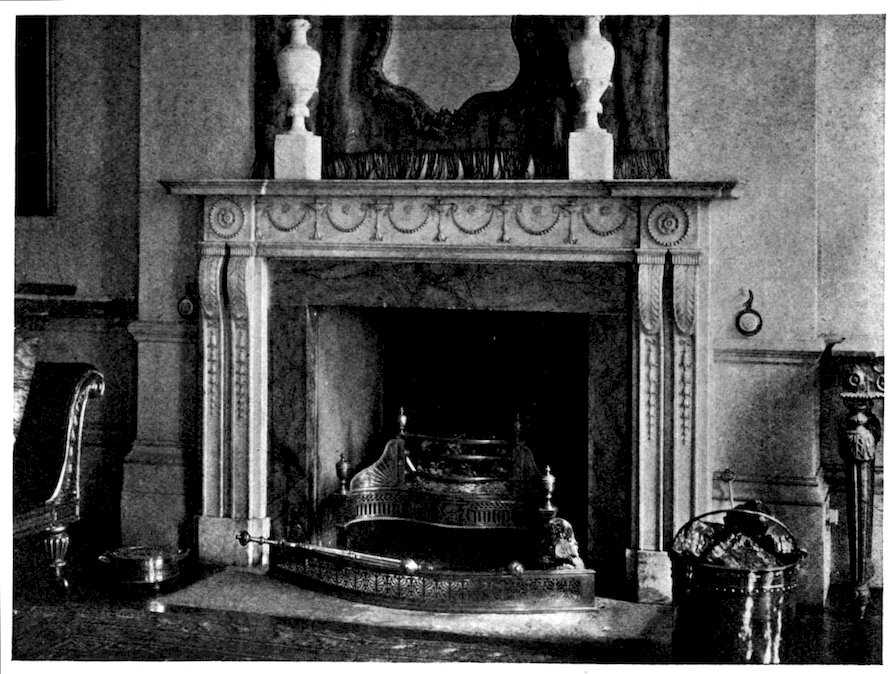

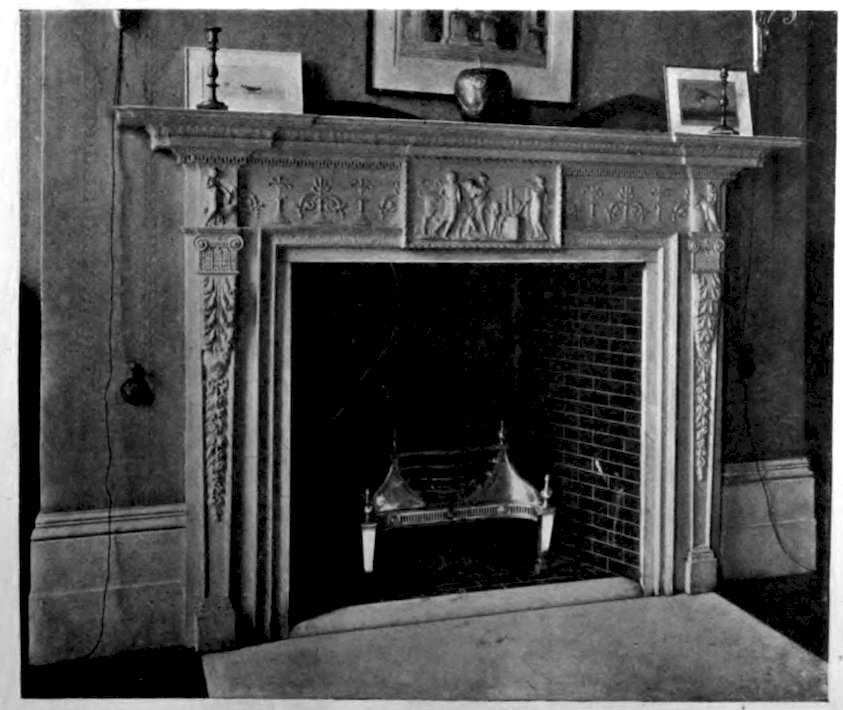

| 71. | No. 6, Bedford Square, Chimneypiece, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

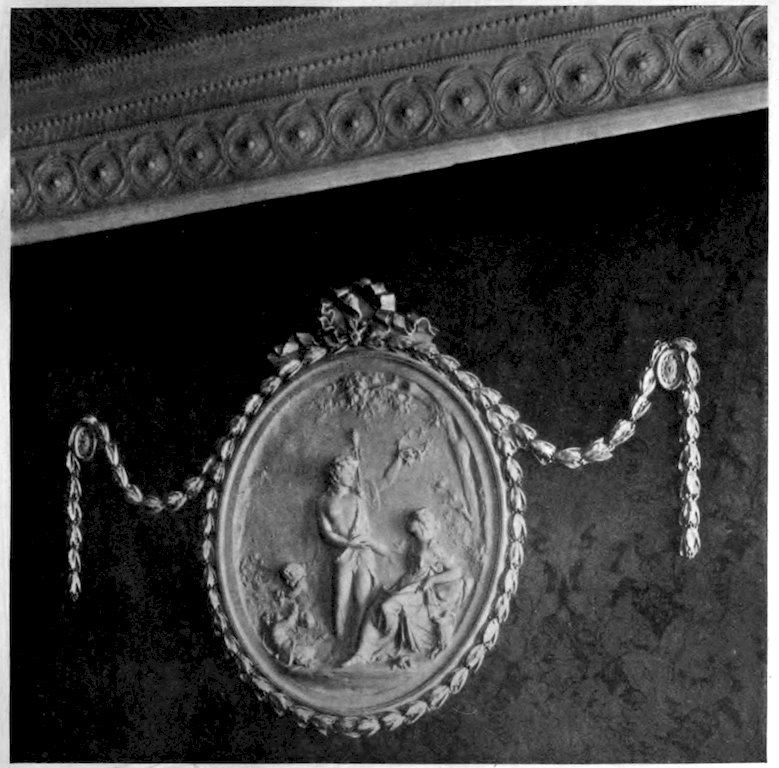

| 72. | No. 9, Bedford Square, Plaster Plaques: (a) On Chimney Breast, Front Room, Ground Floor; (b) On Chimney Breast, Rear Room, Ground Floor; (c) Over Door, Front Room, Ground Floor | Photographs. |

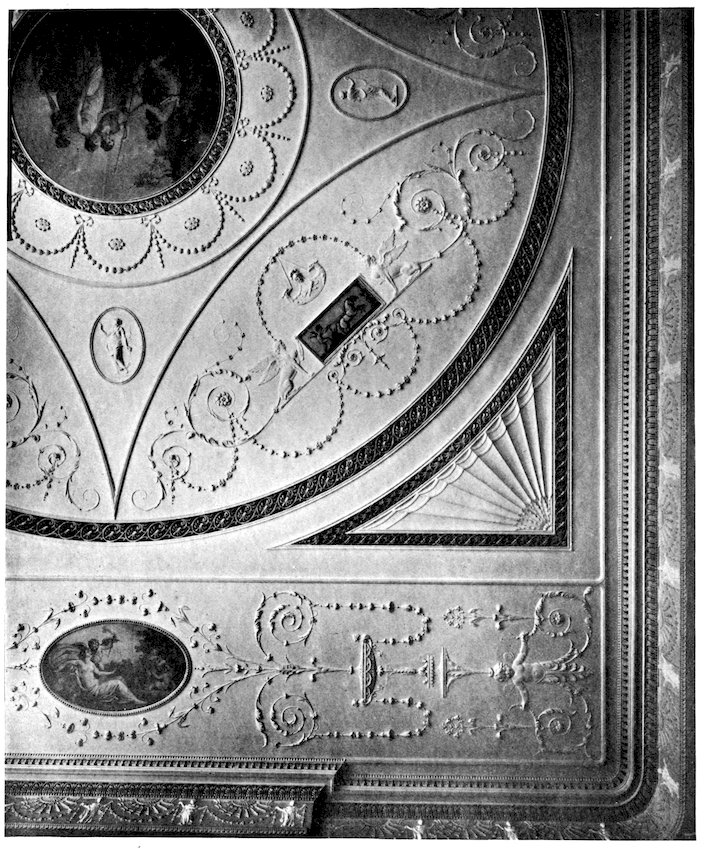

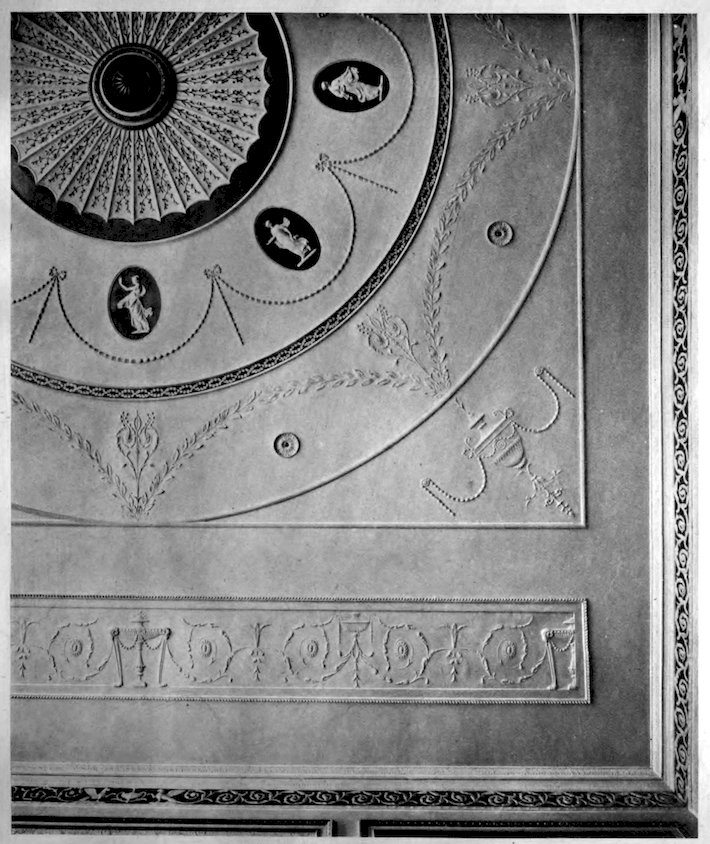

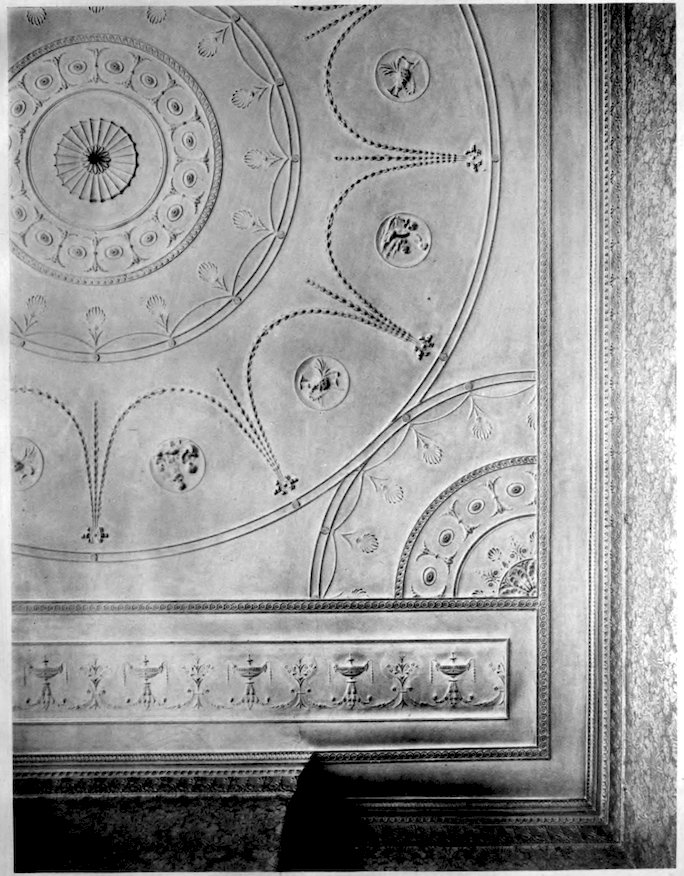

| 73. | No. 9, Bedford Square, Plaster Ceiling, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

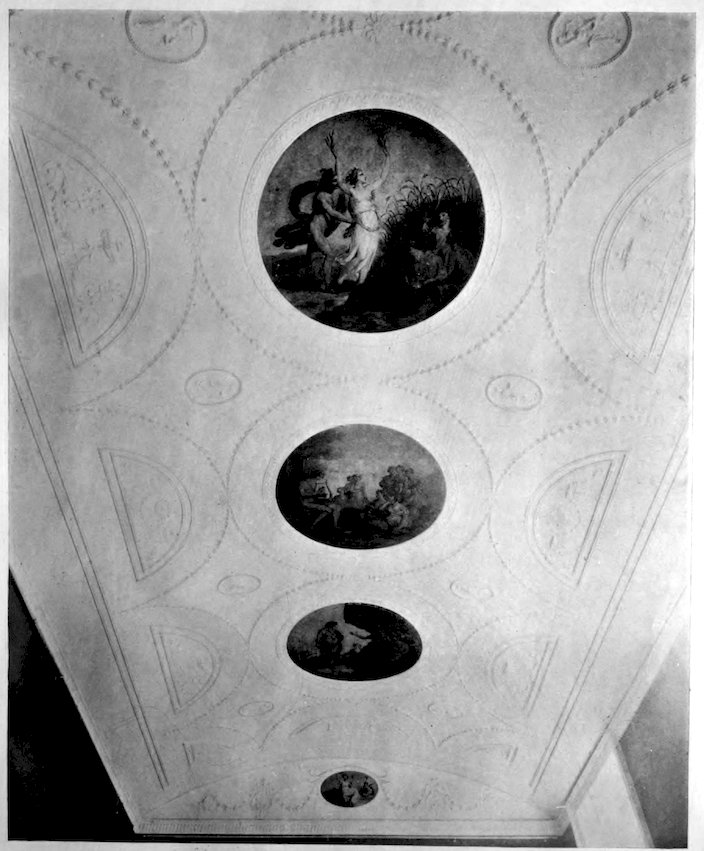

| 74. | No. 10, Bedford Square, Plaster Ceiling with Painted Panels, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

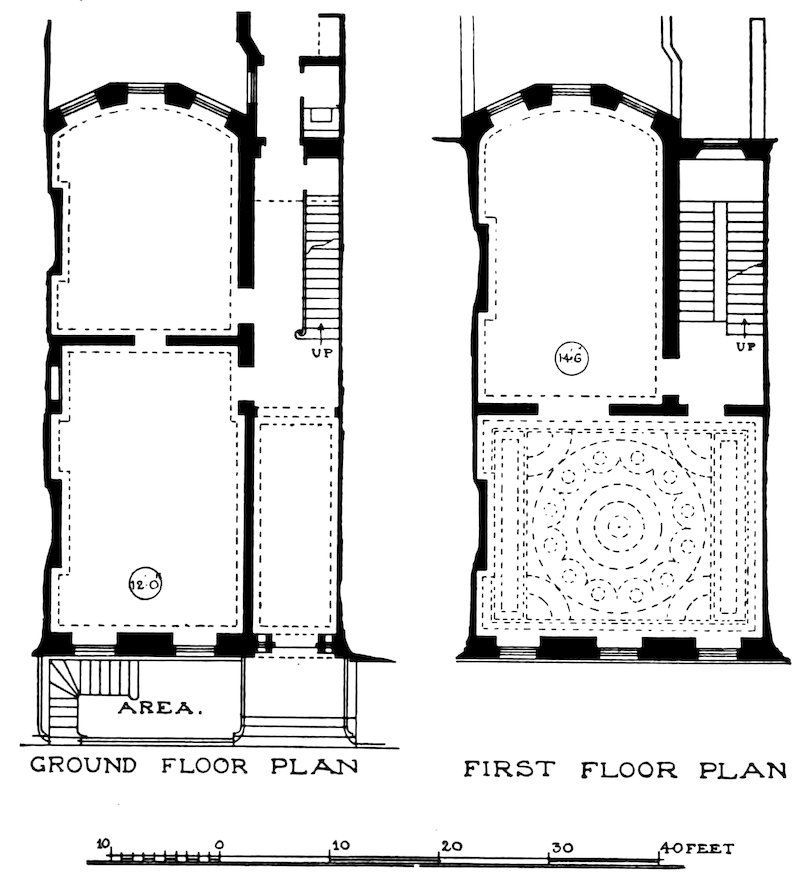

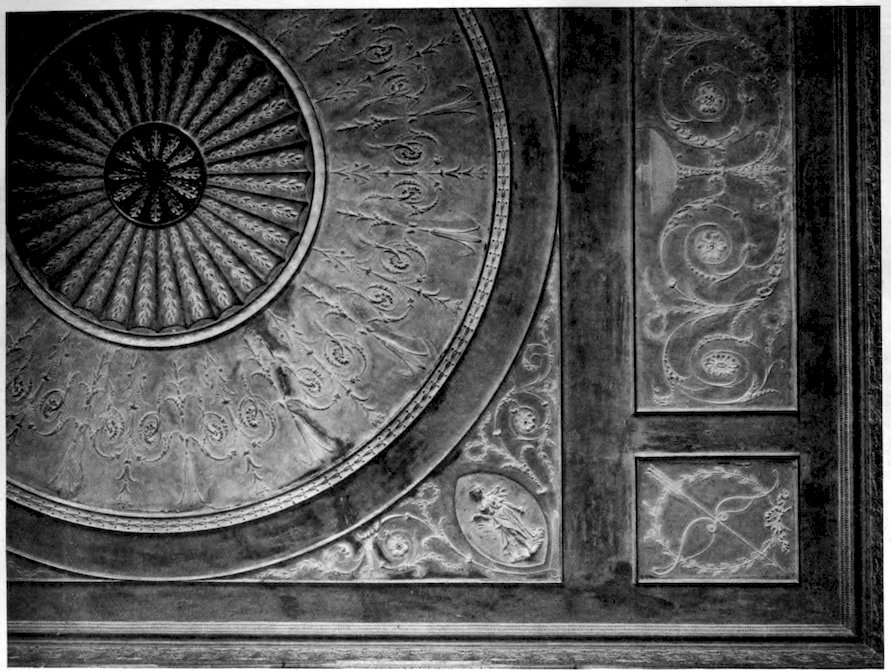

| 75. | No. 11, Bedford Square, Ground and First Floor Plans | Measured Drawing. |

| 76. | No. 11, Bedford Square, Exterior | Photograph. |

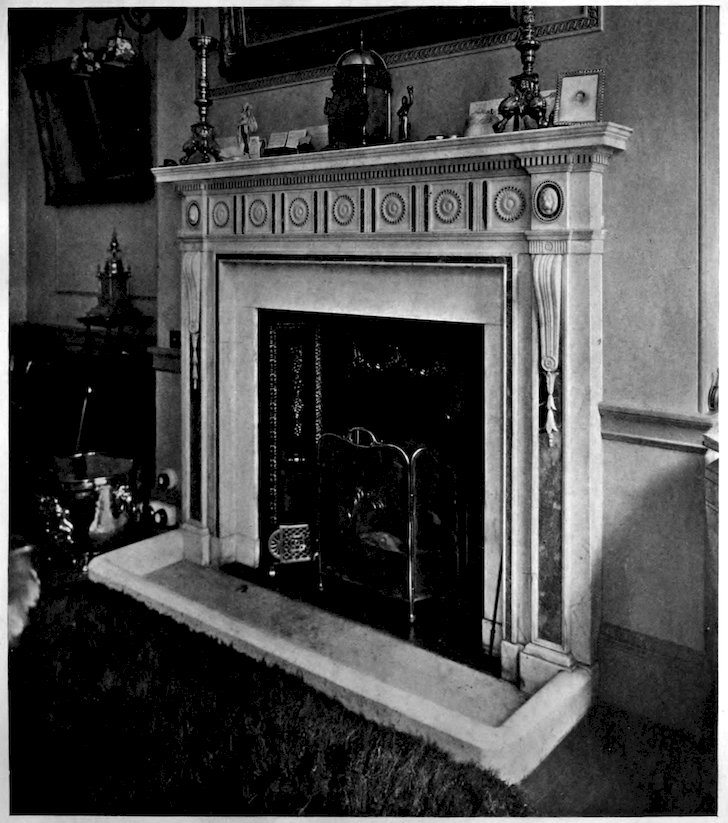

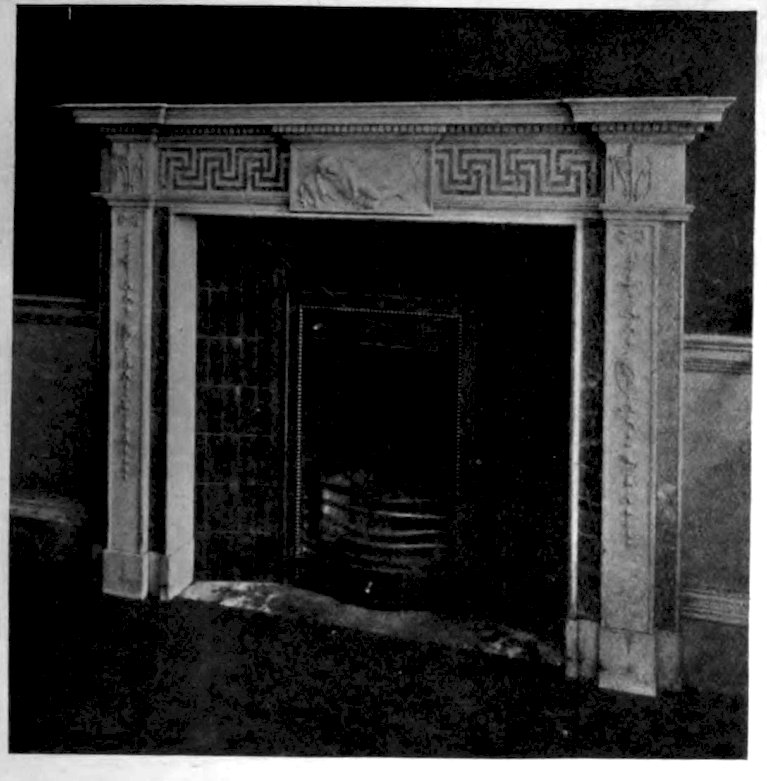

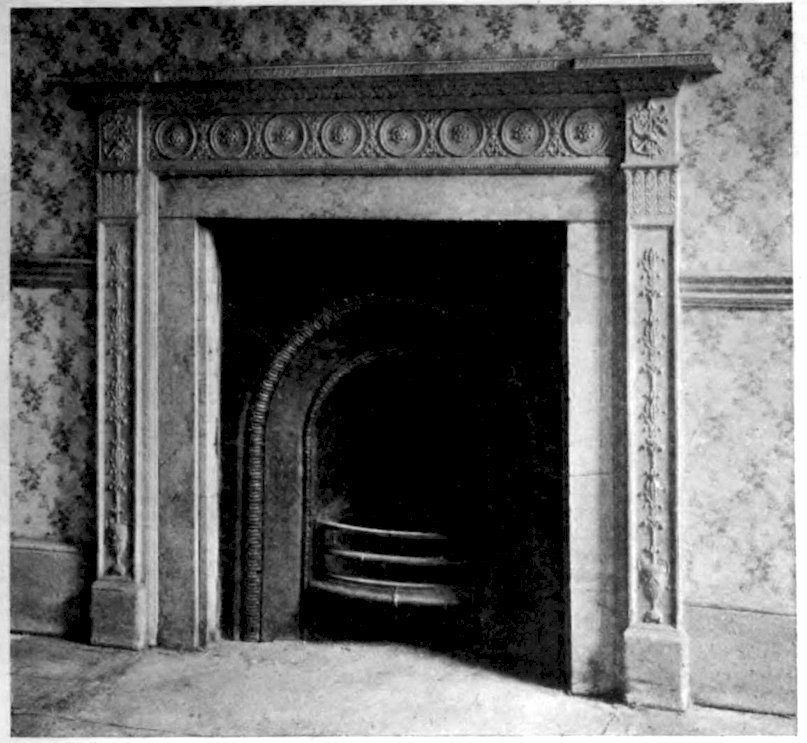

| 77. | No. 11, Bedford Square, Chimneypiece, Front Room, Ground Floor | Photograph. |

| 78. | No. 13, Bedford Square, Plaster Ceiling with Painted Panels, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

| 79. | No. 14, Bedford Square, Ceiling, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

| 80. | No. 15, Bedford Square, Entrance Doorway | Photograph. |

| 81. | No. 18, Bedford Square, Chimneypiece, Front Room, Ground Floor | Photograph. |

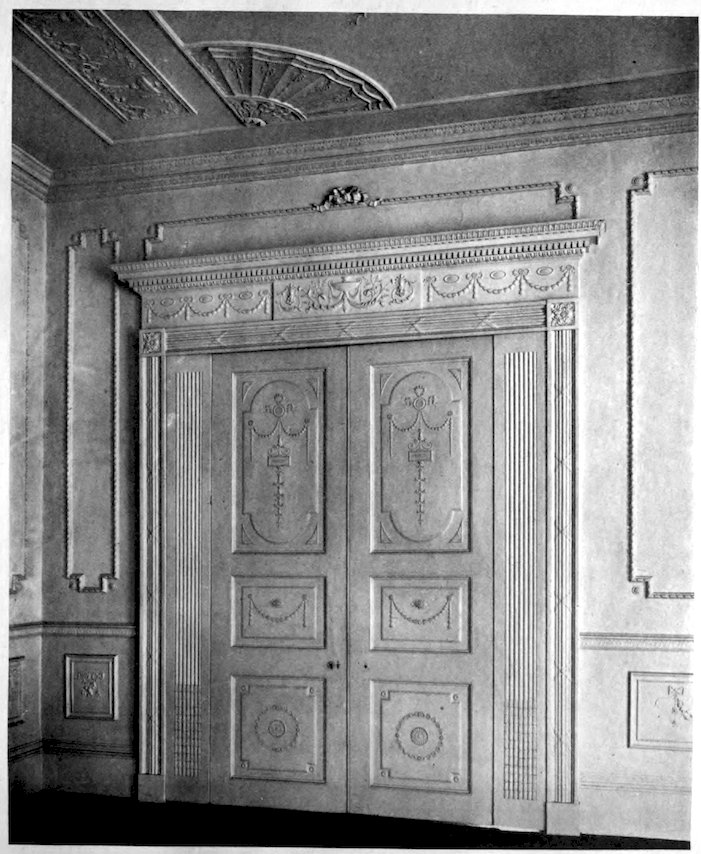

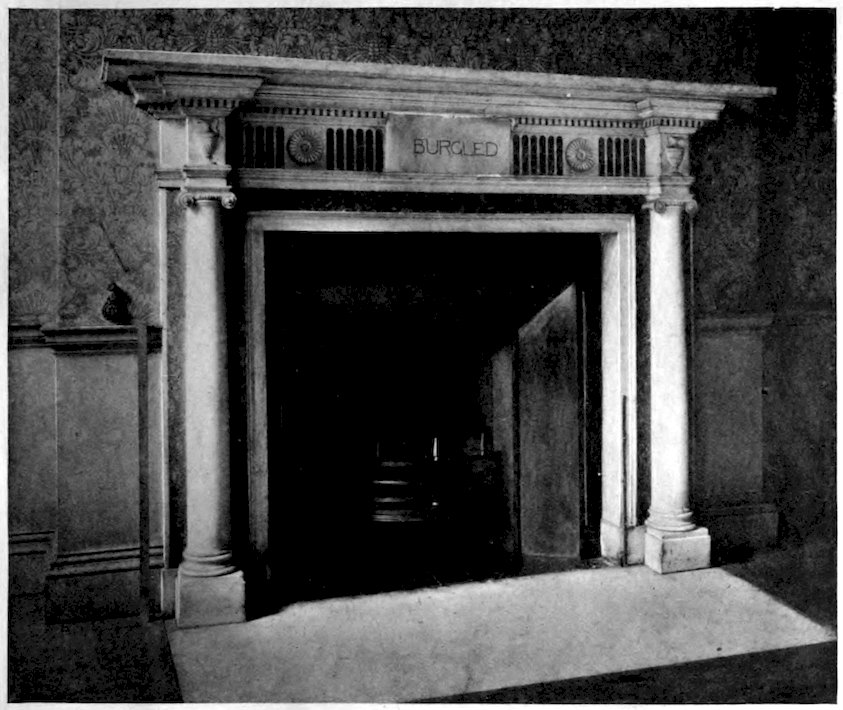

| xii82. | No. 23, Bedford Square, Doors and Doorcase, Front Room, Ground Floor | Photograph. |

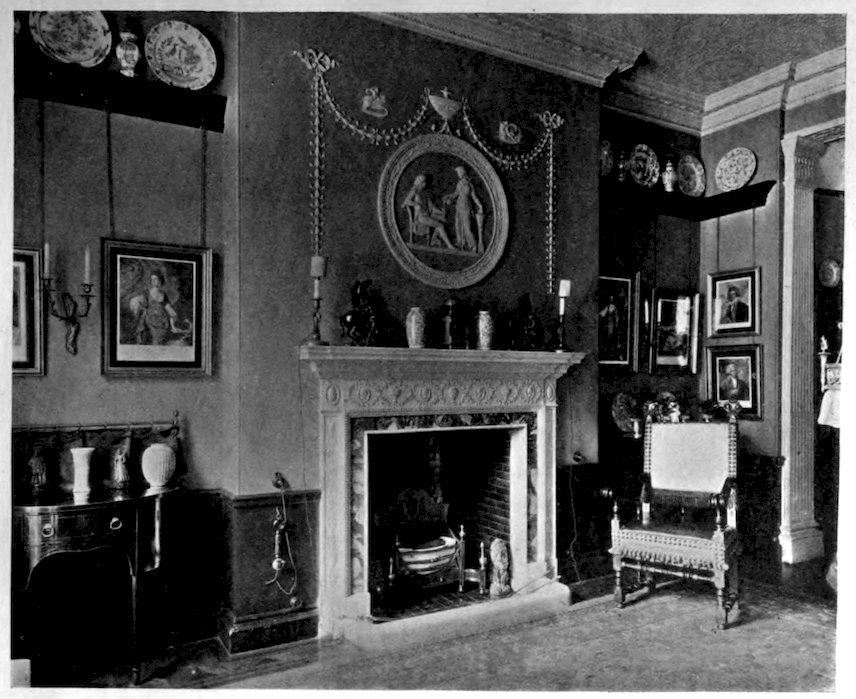

| 83. | No. 25, Bedford Square: (a) Chimney Breast, (b) Alcove, Front Room, Ground Floor | Photographs. |

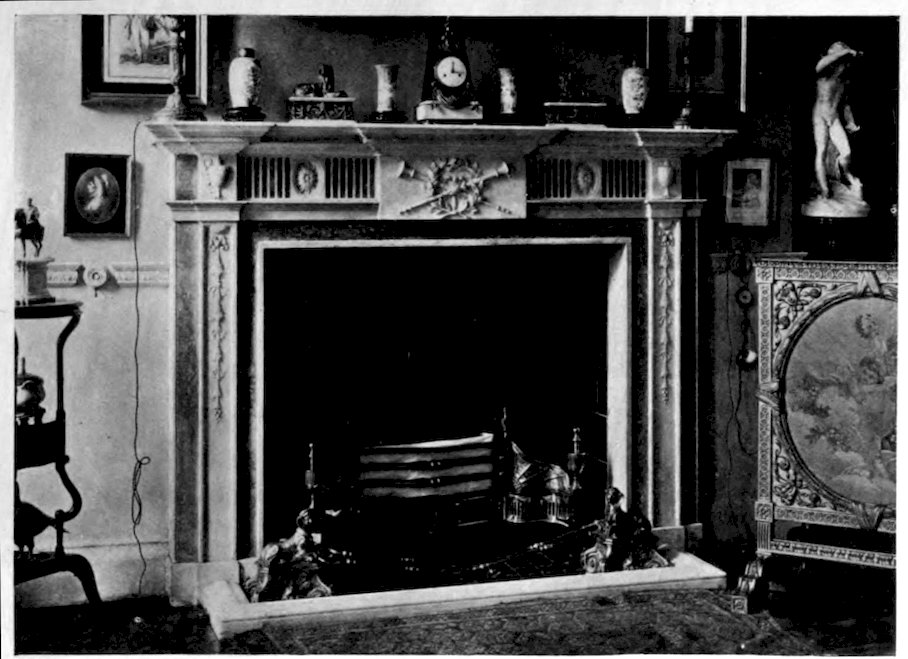

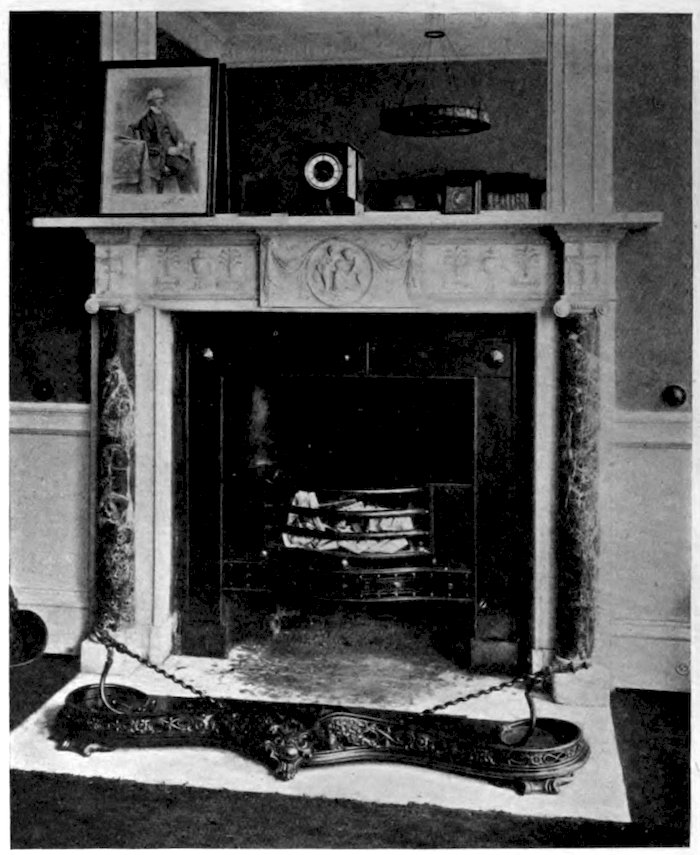

| 84. | No. 25, Bedford Square, Chimneypieces: (a) Front Room, First Floor; (b) Rear Room, First Floor | Photographs. |

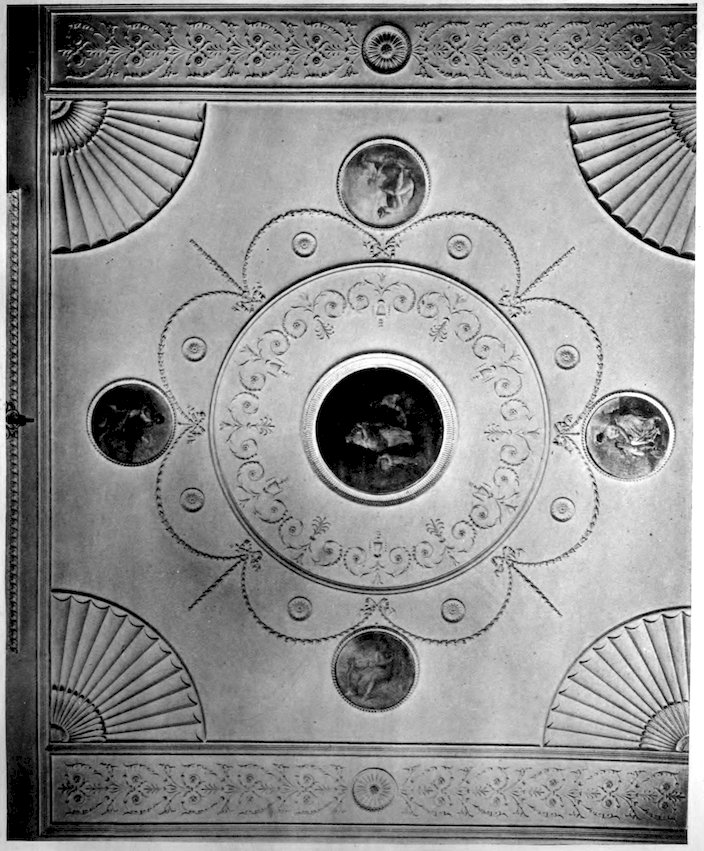

| 85. | No. 25, Bedford Square, Plaster Ceiling with Painted Panels, Rear Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

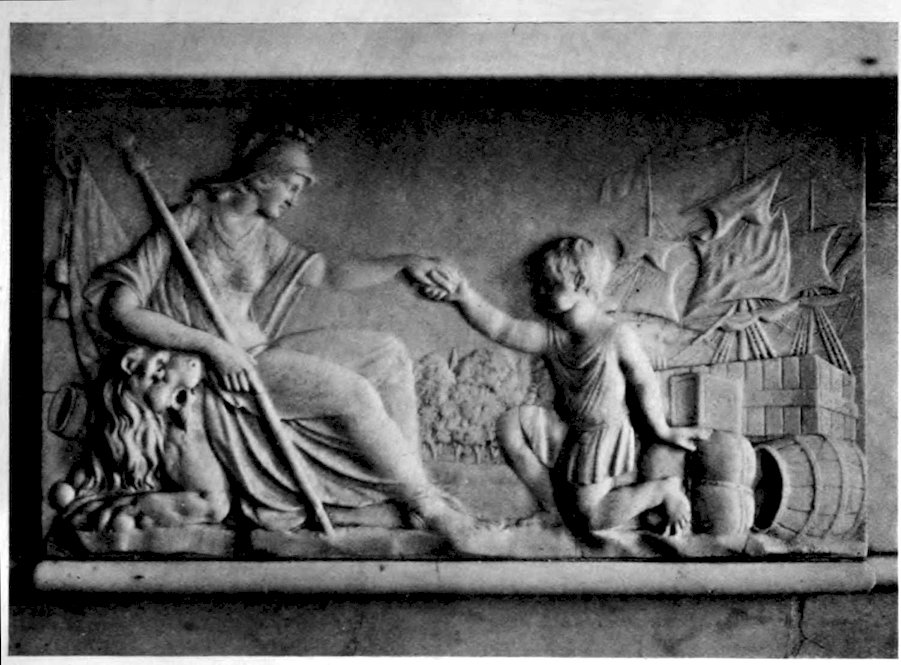

| 86. | No. 28, Bedford Square: (a) Chimneypiece; (b) Detail of Central Panel; Front Room, Ground Floor | Photographs. |

| 87. | No. 30, Bedford Square, Ceiling, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

| 88. | No. 31, Bedford Square, Ceiling, Rear Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

| 89. | No. 32, Bedford Square, Front Elevation | Measured Drawing. |

| 90. | No. 32, Bedford Square, Screen in Hall | Photograph. |

| 91. | No. 32, Bedford Square: (a) Panel of Chimneypiece, Rear Room, First Floor; (b) Detail of Chimneypiece, Rear Room, Ground Floor | Photographs. |

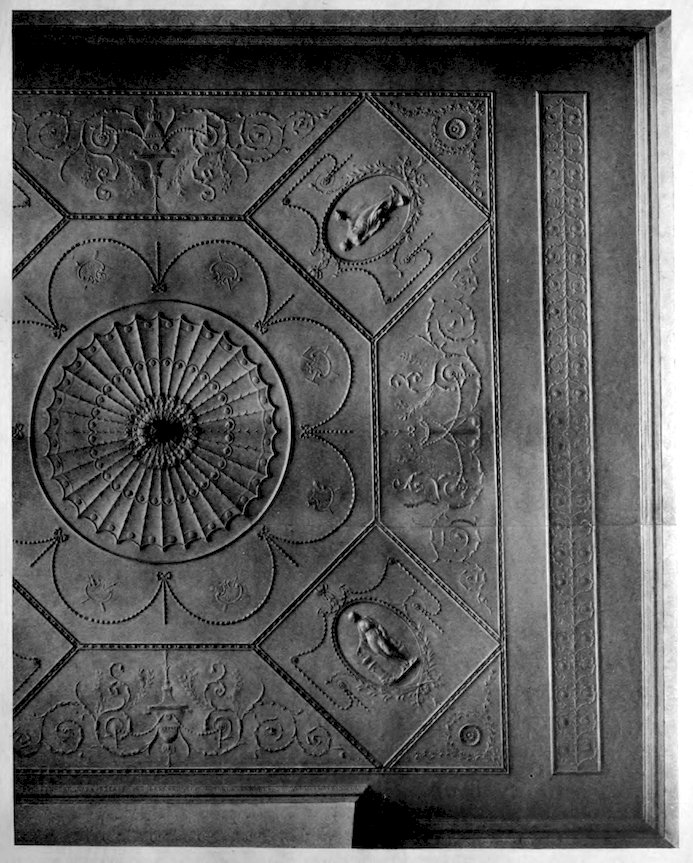

| 92. | No. 32, Bedford Square, Ceilings: (a) Rear Room, Ground Floor; (b) Rear Room, First Floor | Photographs. |

| 93. | No. 40, Bedford Square, Plaster Plaque, Front Room, Ground Floor | Photograph. |

| 94. | No. 40, Bedford Square, Plaster Ceiling with Painted Panels, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

| 95. | No. 41, Bedford Square, Chimneypieces: (a) Rear Room, First Floor; (b) Front Room, First Floor | Photographs. |

| 96. | No. 44, Bedford Square, Ceiling, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

| 97. | Nos. 46–47, Bedford Square, Exterior | Photograph. |

| 98. | No. 46, Bedford Square, Chimneypieces: (a) Front Room, Ground Floor; (b) Front Room, First Floor | Photographs. |

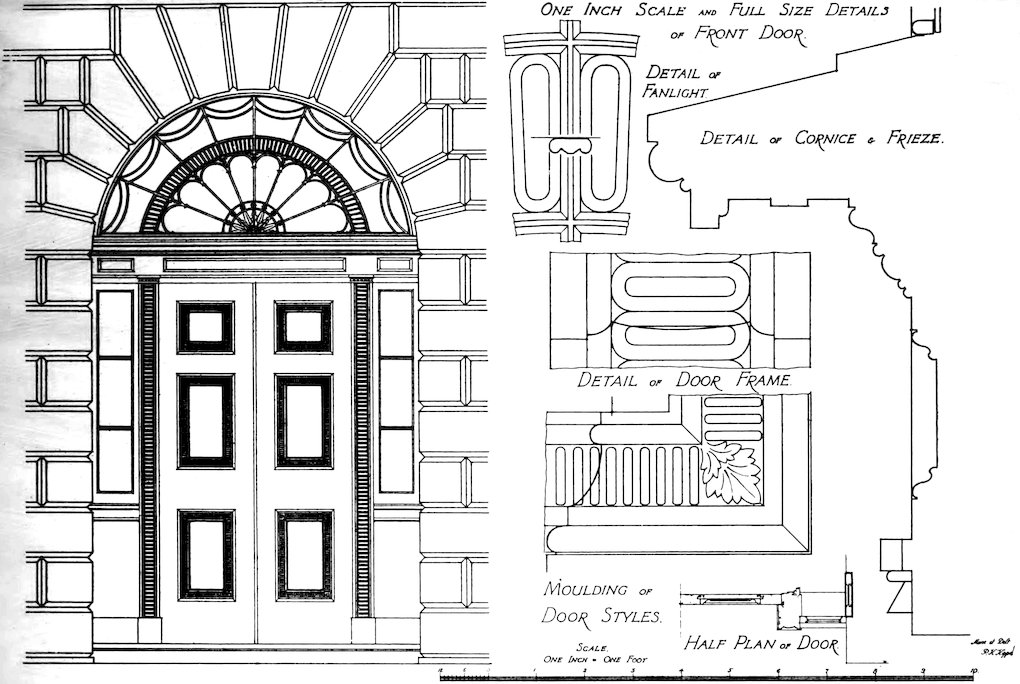

| 99. | No. 47, Bedford Square, Entrance Doorcase | Measured and Drawn by P. K. Kipps. |

| 100. | No. 47, Bedford Square: (a) Ceiling over Staircase; (b) Chimneypiece, Front Room, First Floor | Photographs. |

| 101. | No. 47, Bedford Square, Ceiling, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

| 102. | No. 48, Bedford Square, Chimneypiece, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

| 103. | No. 48, Bedford Square, Ceiling, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

| 104. | No. 50, Bedford Square, Fanlight in Entrance Hall | Photograph. |

| 105. | No. 51, Bedford Square, Ceiling, Front Room, First Floor | Photograph. |

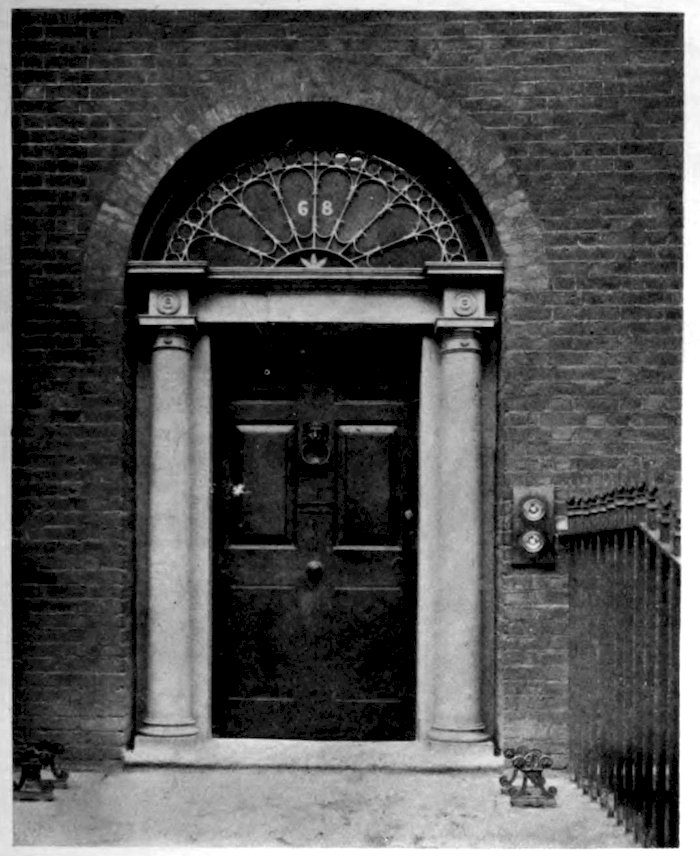

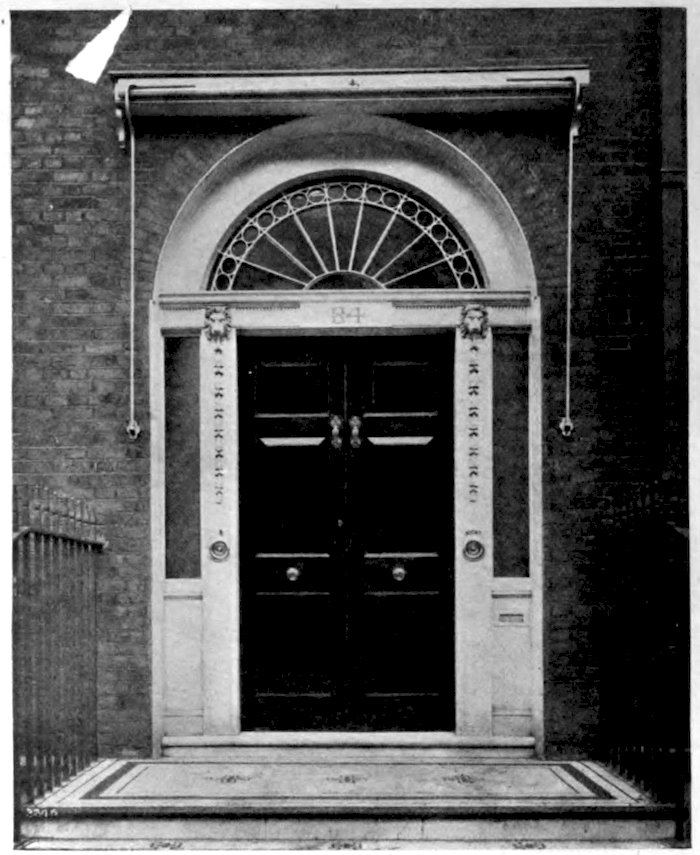

| 106. | (a) No. 68, Gower Street; (b) No. 84, Gower Street, Doorcases | Photographs. |

| 107. | House in rear of No. 196, Tottenham Court Road: (a) Exterior; (b) Chimneypiece, Front Room, First Floor | Photographs. |

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Stone Boundary Tablet (1691) from No. 2, Sheffield Street | 2 |

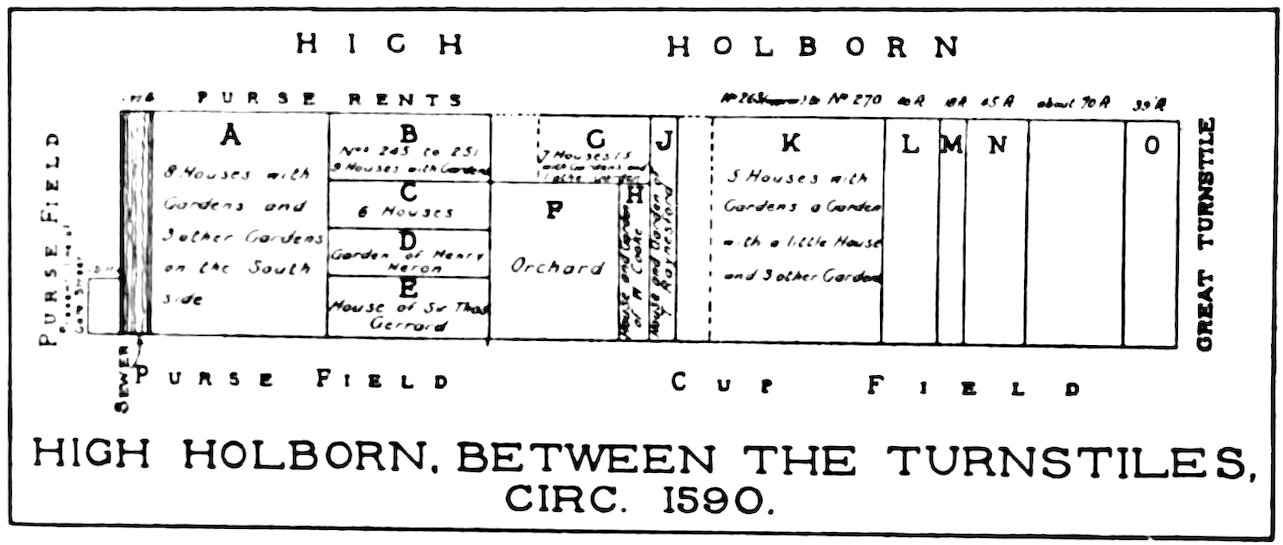

| 2. | Rough Plan of High Holborn between the Turnstiles, circ. 1590 | 4 |

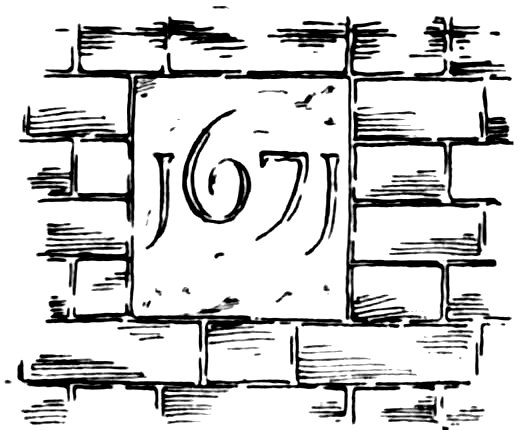

| 3. | Stone Tablet (1671), formerly on No. 27, Goldsmith Street | 21 |

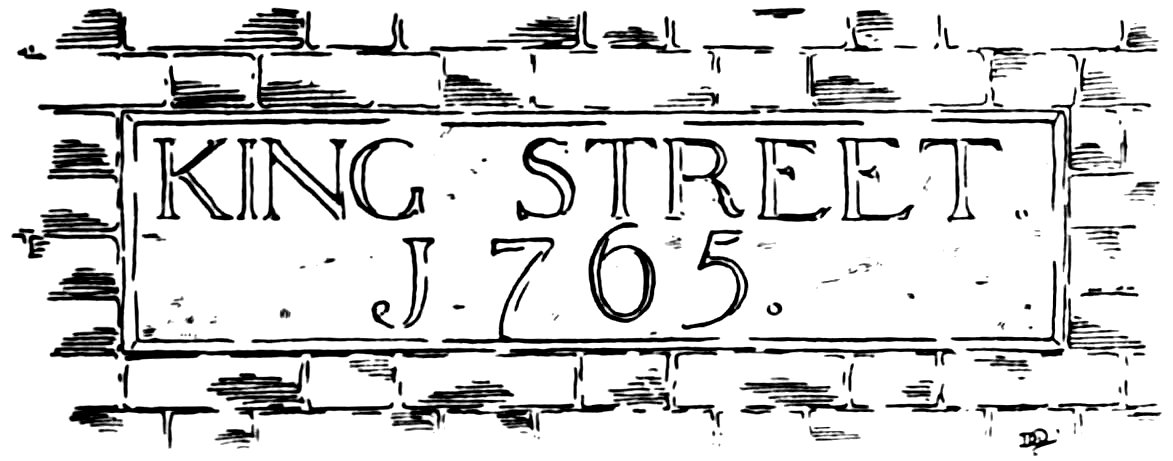

| 4. | Stone Tablet (1765), formerly on flank wall of No. 166, Drury Lane | 31 |

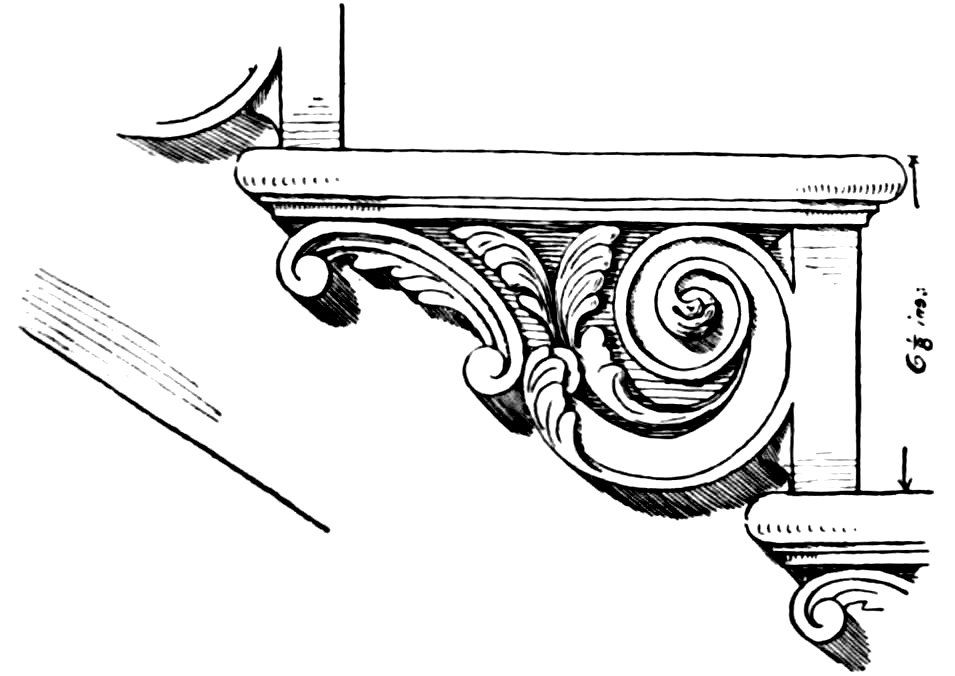

| 5. | Deal Stair Bracket to Outer String to No. 27, Great Queen Street | 41 |

| 6. | Signature of Wm. Newton | 43 |

| 7. | Nos. 55–58, Great Queen Street. Sketch by J. Nash (1840), reproduced from The Growth of the English House, by J. Alfred Gotch, by kind permission of B. T. Batsford, Ltd. | 48 |

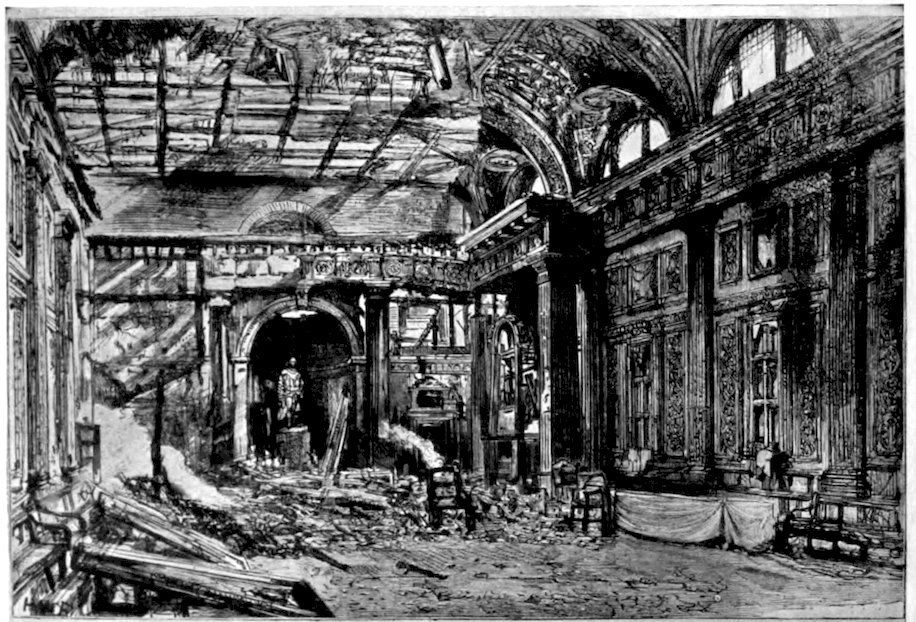

| 8. | The Disastrous Fire at Freemasons’ Hall, Great Queen Street—the scene of the conflagration (1883), from a woodcut in the Illustrated London News | 62 |

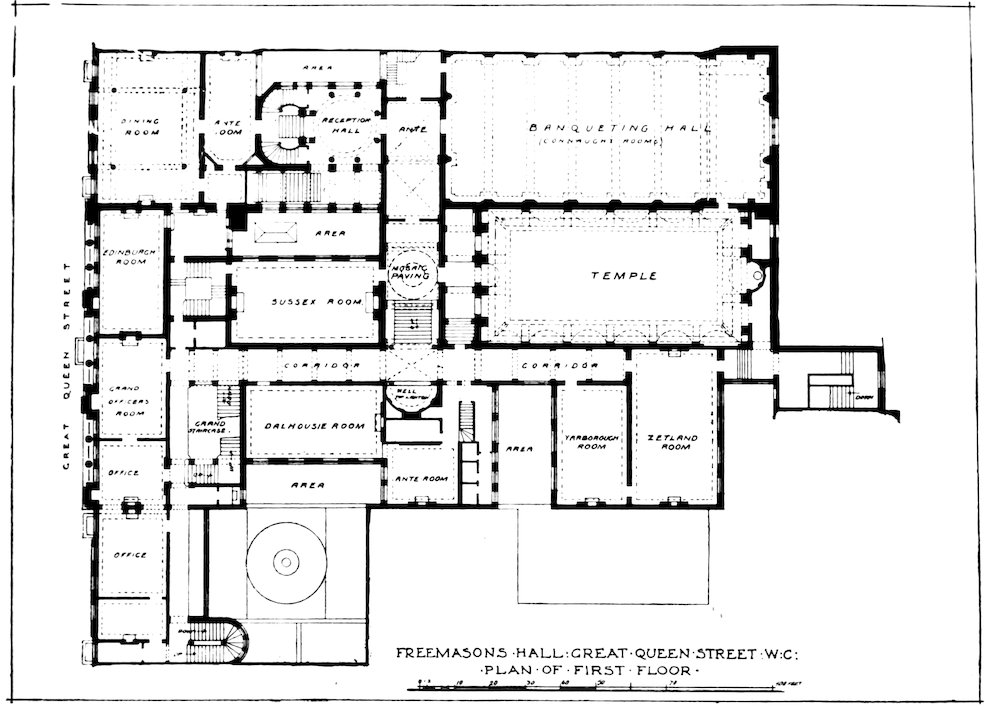

| 9. | Freemasons’ Hall, Plan of Principal Floor before the alterations of 1899 | 64 |

| 10. | Cast-iron Hob Grates from Nos. 6 and 7, Wild Court | 99 |

| 11. | Wooden Key at No. 56, Castle Street | 114 |

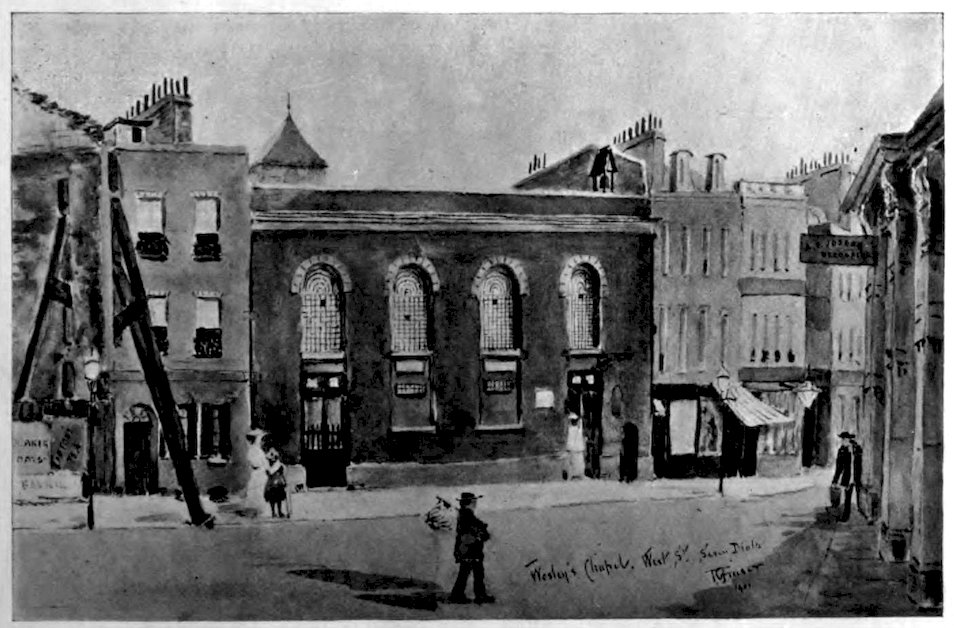

| 12. | All Saints’ Church, West Street, Exterior. From a watercolour drawing by T. G. Fraser, reproduced by kind permission of the Rev. C. W. M. Steffens | 115 |

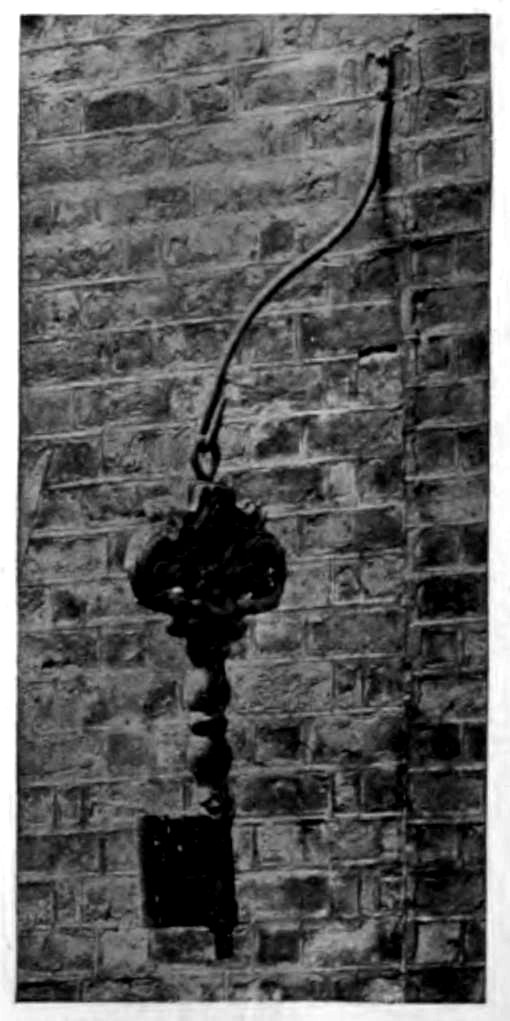

| 13. | The Top Part of Wesley’s Pulpit | 116 |

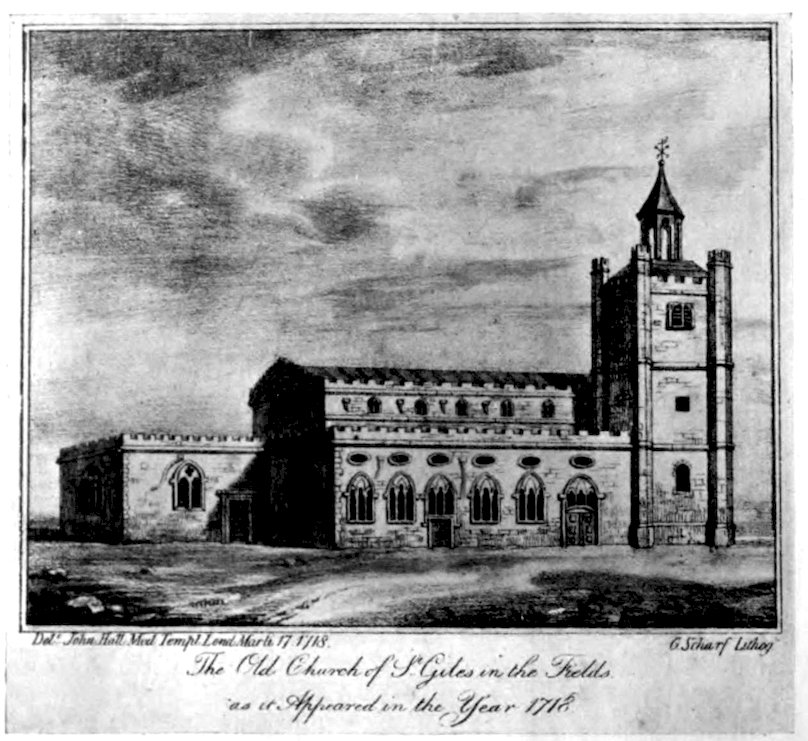

| 14. | The Old Church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields as it appeared in the year 1718, from a lithograph of G. Scharf after John Hall | 128 |

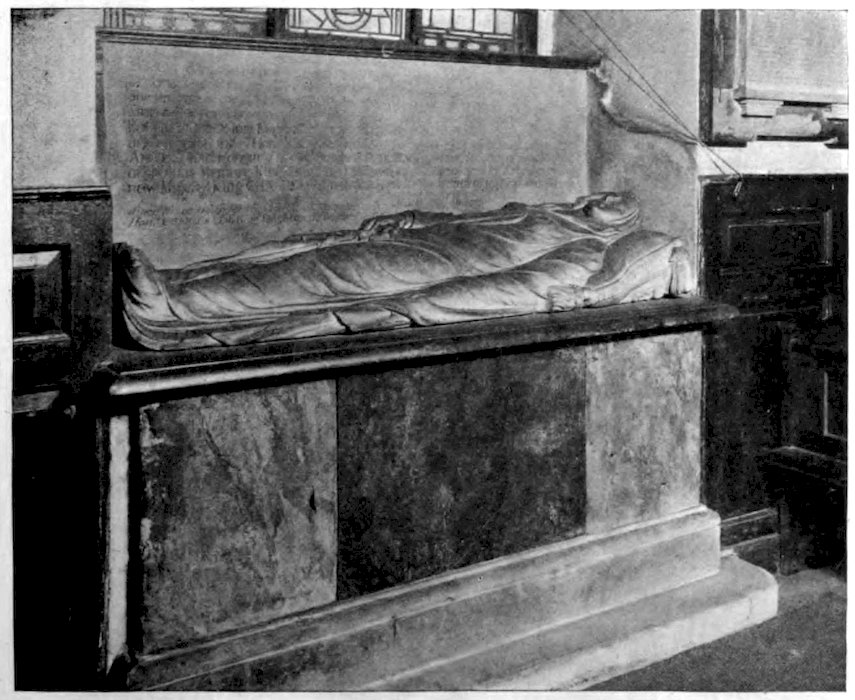

| 15. | Recumbent Effigy of Lady Frances Kniveton | 135 |

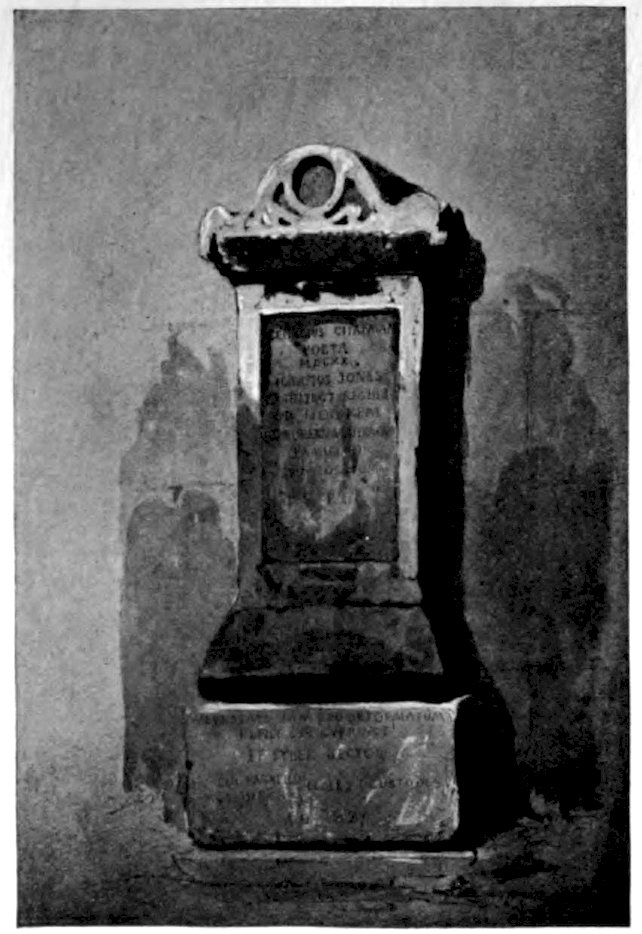

| 16. | Tombstone of George Chapman, from a watercolour drawing by J. W. Archer (1844), preserved in the British Museum | 136 |

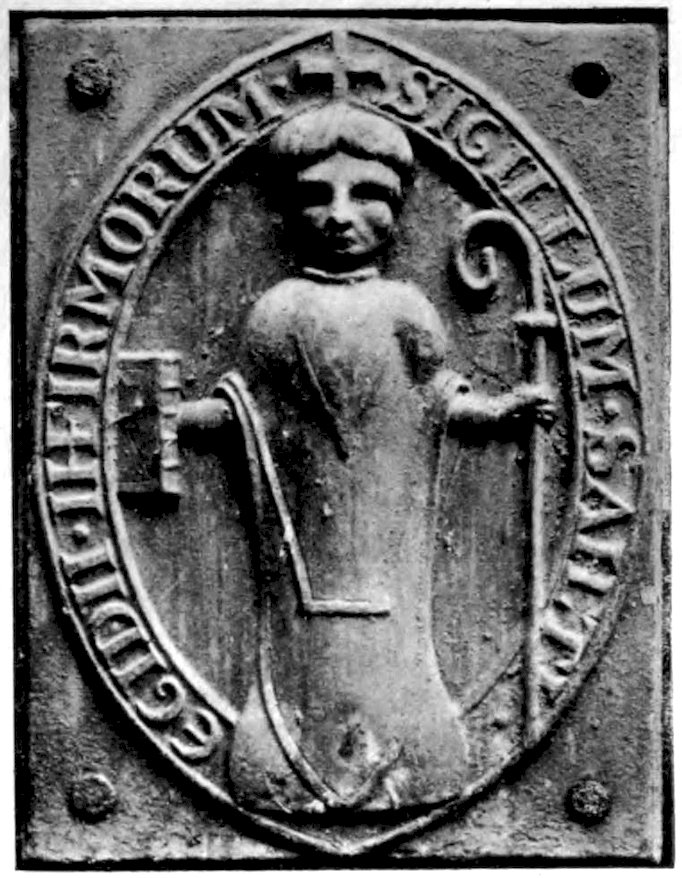

| 17. | Cast-iron Enlargement of Seal of the Hospital of St. Giles | 139 |

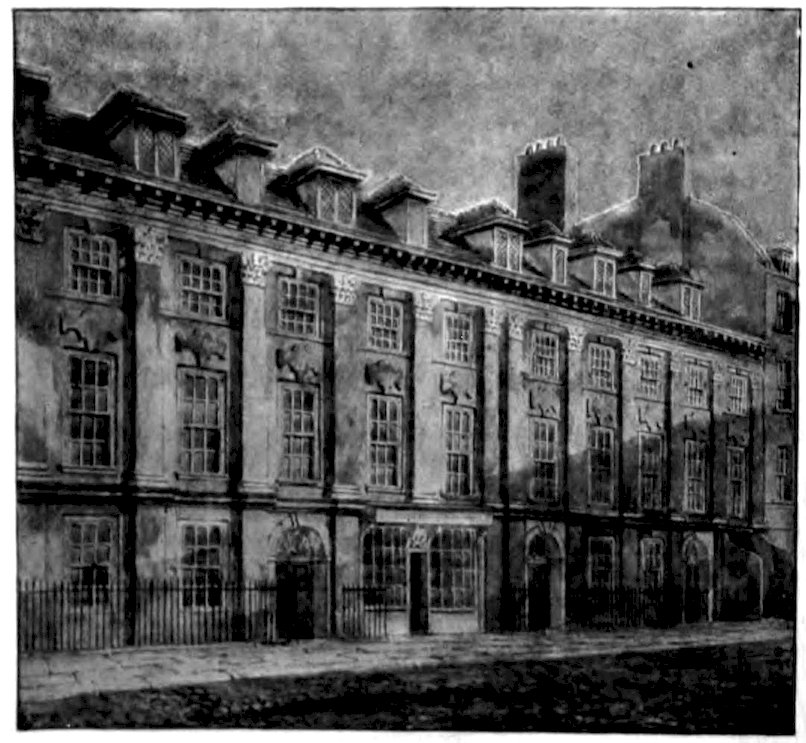

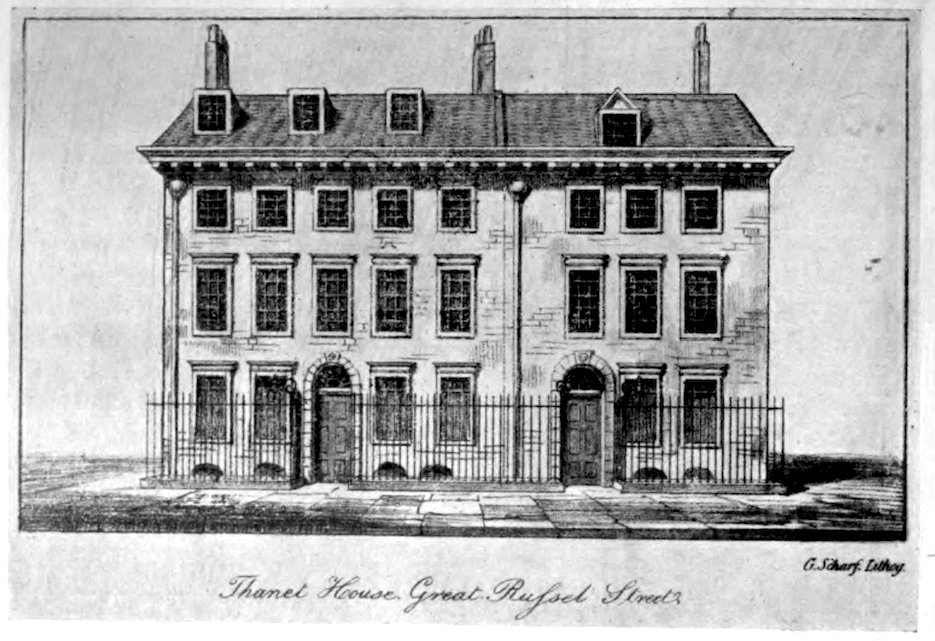

| 18. | Thanet House, Great Russell Street, from a lithograph by G. Scharf | 148 |

| 19. | No. 1, Bedford Square, Ornamental Plaster Frieze, Rear Room, First Floor | 153 |

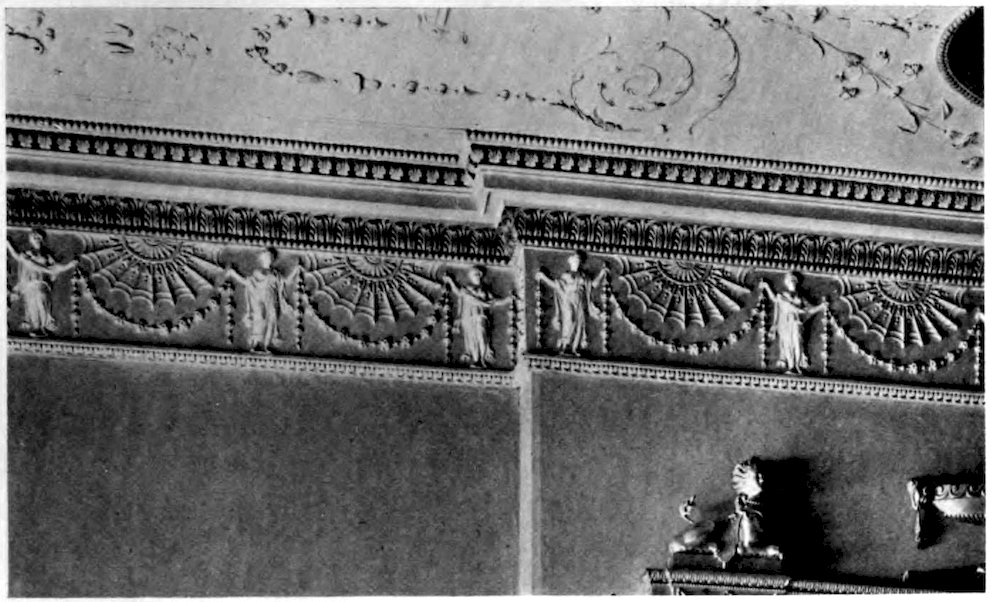

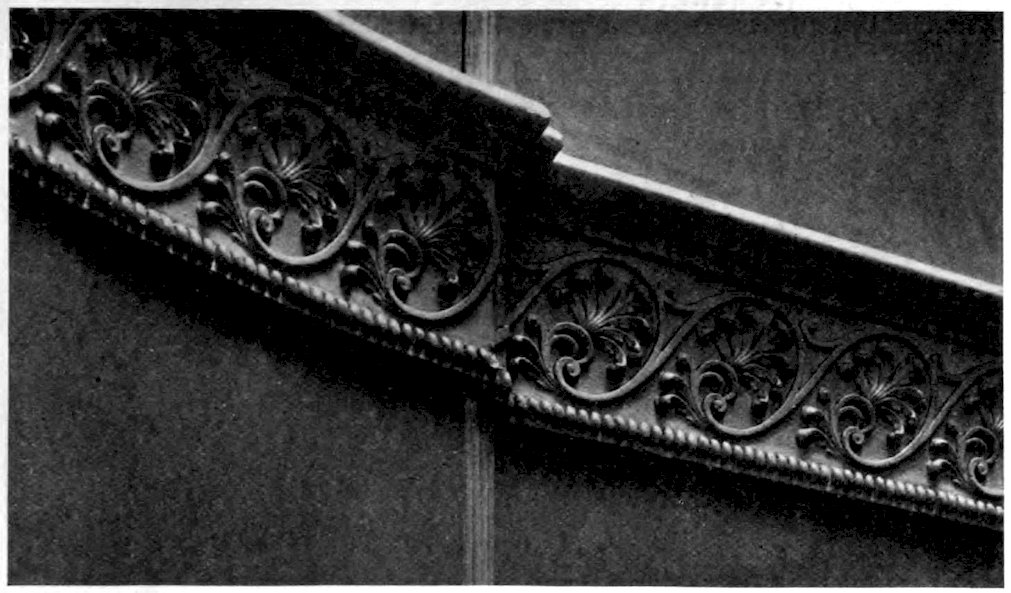

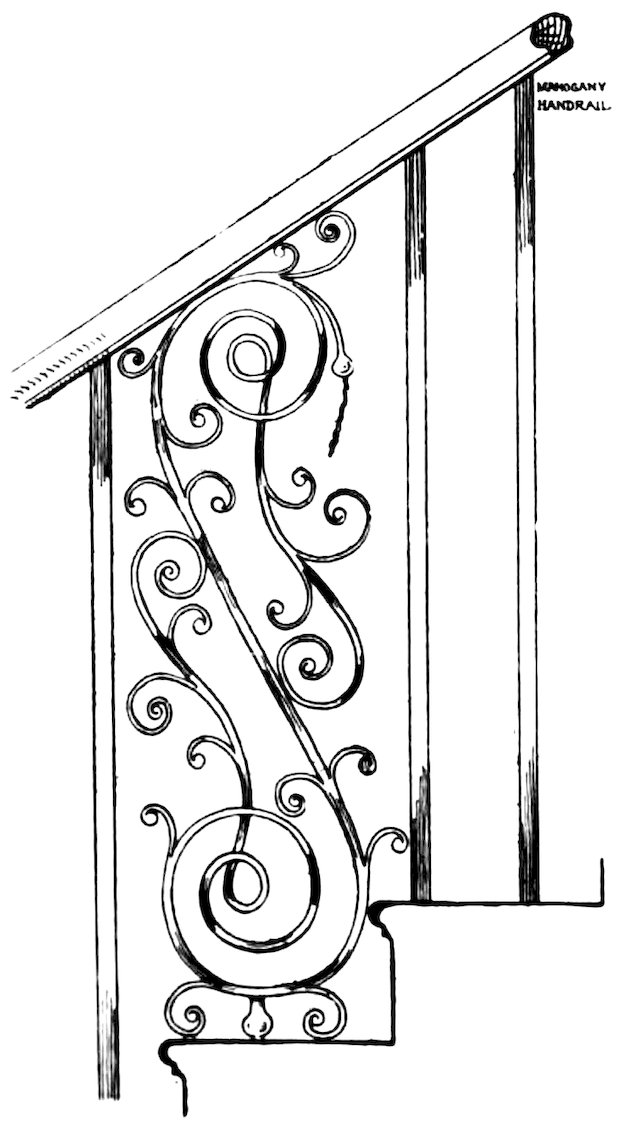

| 20. | No. 6, Bedford Square, Iron Stair Balusters | 154 |

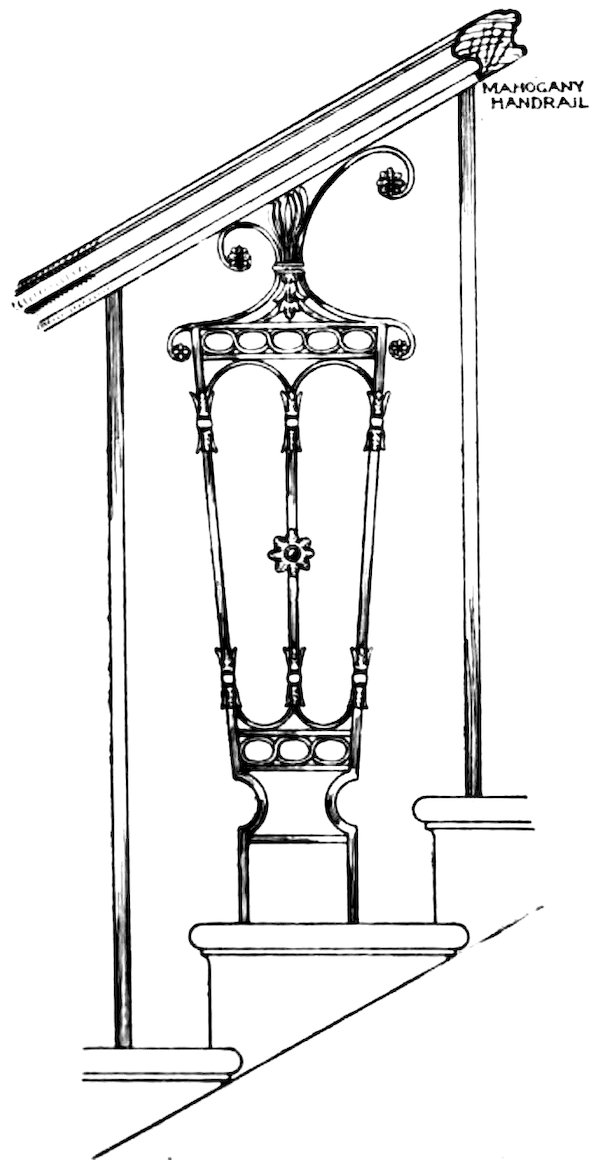

| 21. | No. 6, Bedford Square, Detail of Plaster Decoration to Staircase | 155 |

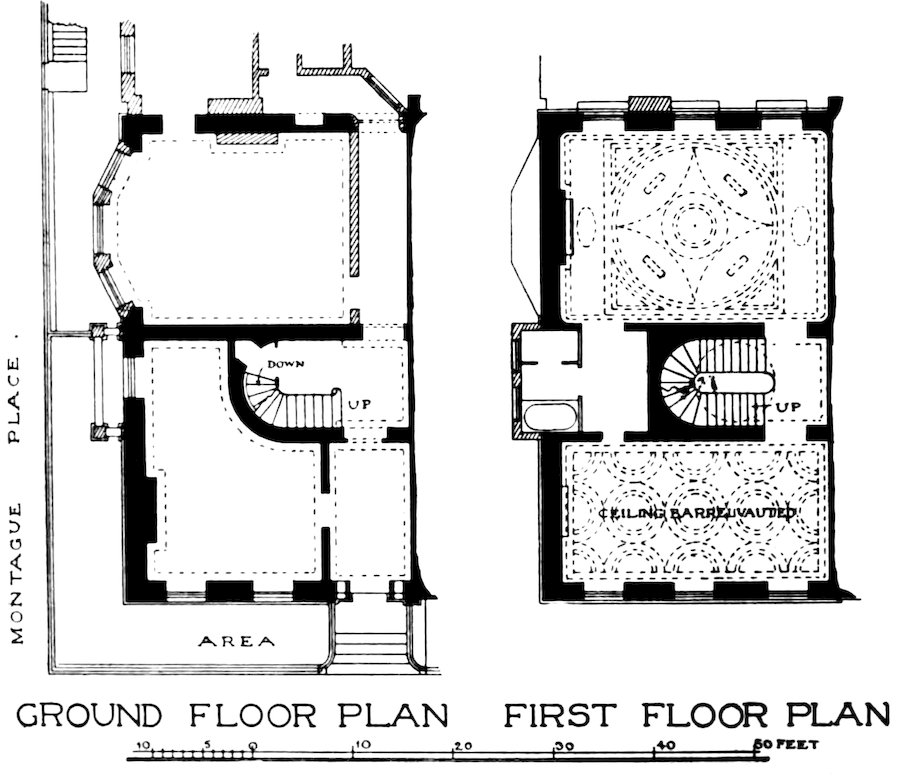

| 22. | No. 10, Bedford Square, Ground and First Floor Plans | 158 |

| 23. | No. 10, Bedford Square, Painted Panel in Ceiling, Rear Room, First Floor | 159 |

| 24. | No. 11, Bedford Square, Frieze and Cornice in Drawing Room | 161 |

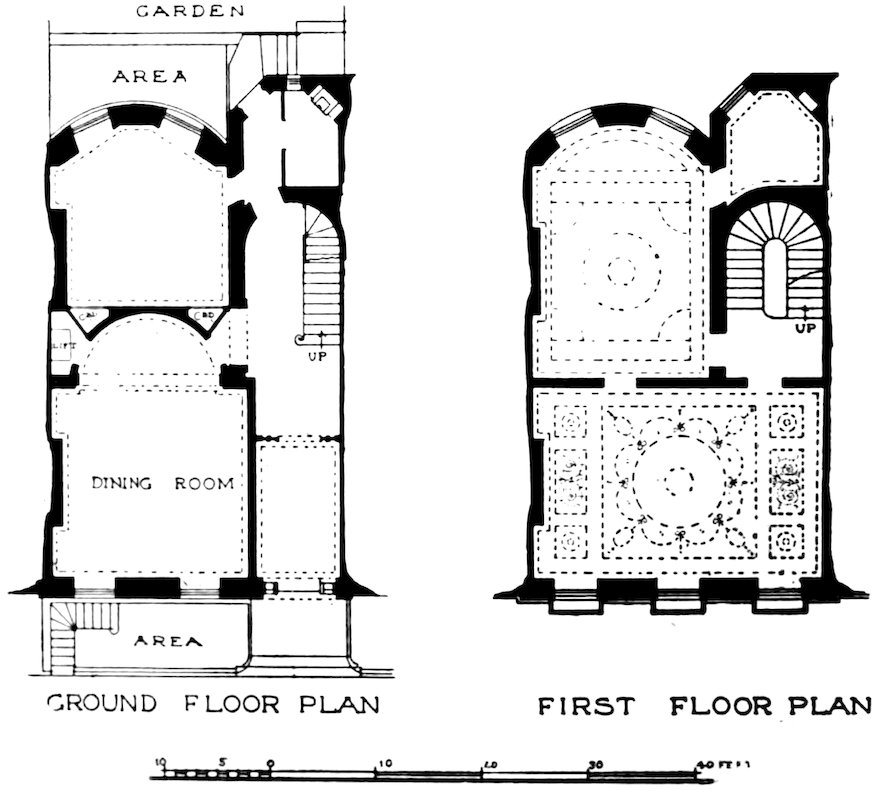

| 25. | No. 25, Bedford Square, Ground and First Floor Plans | 168 |

| 26. | No. 32, Bedford Square, Wrought-iron Stair Balusters | 174 |

| 27. | No. 48, Bedford Square, Ground and First Floor Plans | 181 |

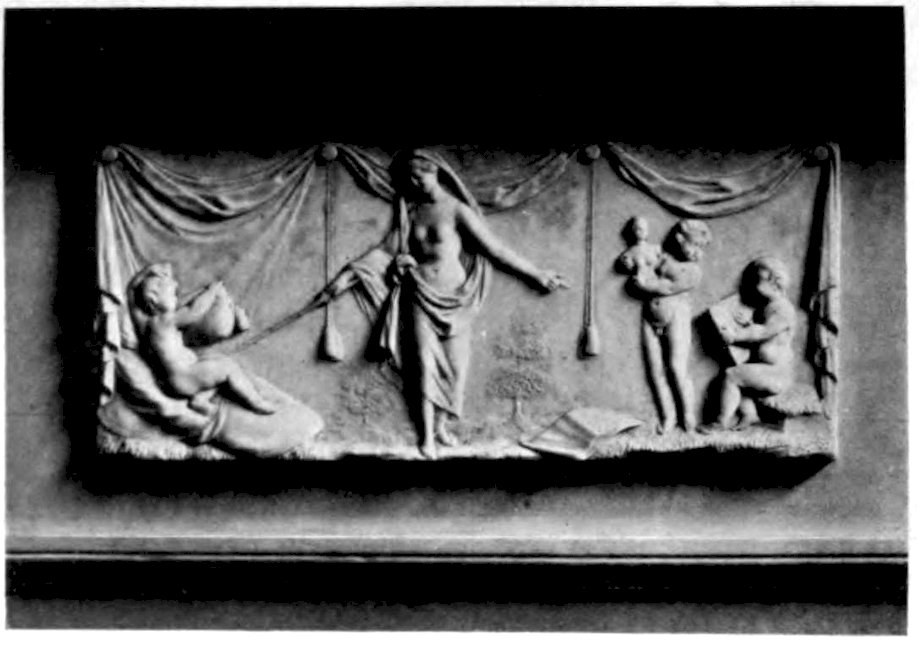

| 28. | No. 51, Bedford Square, Sculptured Panel on Chimneypiece in Entrance Hall | 184 |

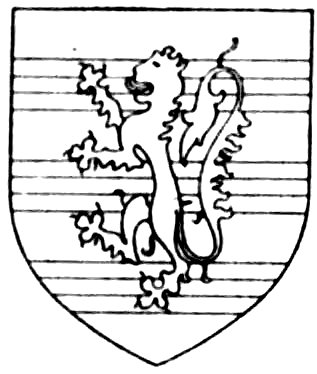

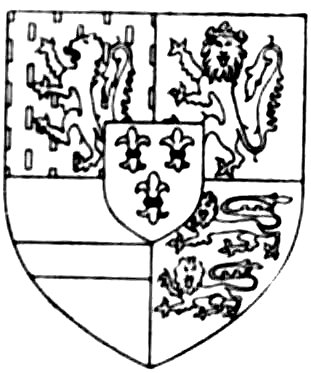

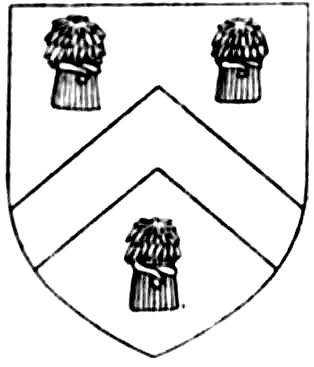

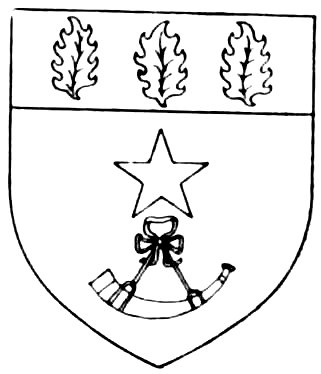

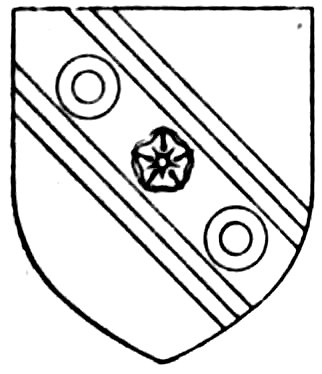

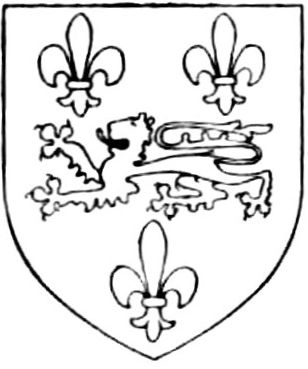

| 1. | DE BURGH | Or, a cross Gules, in the dexter canton a lion rampant Sable. |

| 2. | DIGBY | Azure, a fleur-de-lis Argent, with a molet for difference. |

| 3. | FAIRFAX | Argent, three bars gemelles Gules, surmounted by a lion rampant Sable. |

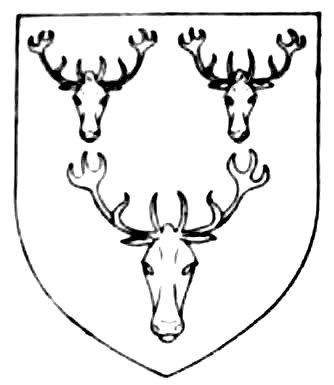

| 4. | CAVENDISH | Sable, three bucks’ heads caboched Argent. |

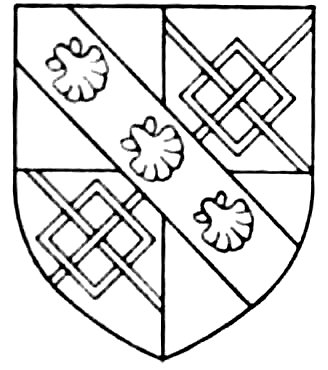

| xiv5. | SPENCER | Quarterly Argent and Gules, in the 2nd and 3rd quarters a fret Or, over all, on a bend Sable, three escallops of the 1st. |

| 6. | GREY | Barry of six Argent and Azure. |

| 7. | BROWNE | Sable, three lions passant in bend between two double cotisses Argent. |

| 8. | ELIZABETH, COUNTESS RIVERS. | Argent, six lions rampant, three, two and one, Sable. |

| 9. | O’BRIEN | Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale per pale Or and Argent. |

| 10. | FREDERICK NASSAU DE ZUYLESTEIN, EARL OF ROCHFORD. | Quarterly, 1st, Azure semée of billets Or, a lion rampant of the 2nd for Nassau; 2nd, Or a lion rampant guardant Gules, ducally crowned Azure for Dietz; 3rd, Gules, a fesse Argent for Vianden; 4th, Gules, two lions passant guardant in pale Or for Catznellogen; over all, in an escutcheon Gules three zules Argent, two and one, for Zuylestein. |

| 11. | SHEFFIELD | Argent, a chevron between three garbs Gules. |

| 12. | BURNET | Argent, three holly leaves in chief Vert, and a hunting horn in base Sable, garnished and stringed Gules, with a molet Azure in the fess point for difference. |

| 13. | CONWAY | Sable, on a bend cotised Argent, a rose between two amulets Gules. |

| 14. | FINCH | Argent, a chevron between three griffins passant Sable. |

| 15. | NORTH | Azure, a lion passant Or, between three fleurs-de-lis Argent. |

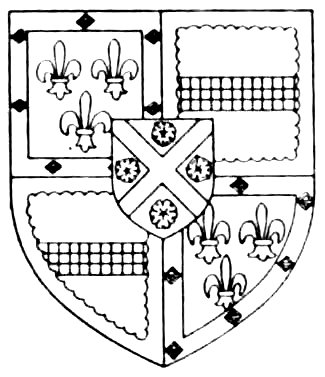

| 16. | ESMÉ STUART, SEIGNEUR D’AUBIGNY, DUKE OF LENNOX. | Quarterly, 1st and 4th Azure, three fleurs-de-lis Or within a bordure Gules charged with seven buckles of the second, for Aubigny; 2nd and 3rd, Or, a fess chequy Azure and Argent within a bordure Gules engrailed for Stuart of Darnley; over all on an escutcheon Argent a saltire Gules between four roses of the same, for Lennox. |

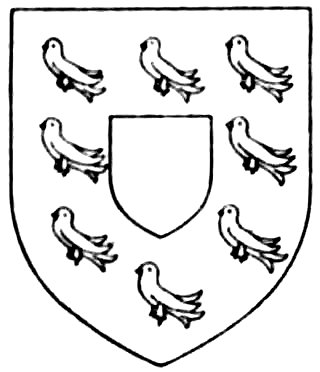

| 17. | BROWNLOW | Or, an escutcheon, with an orle of eight martlets Sable. |

| 18. | DUDLEY | Or, a lion rampant Azure, double queued Vert. |

| 19. | BLOUNT | Barry nebulée of six Or and Sable. |

| 20. | RUSSELL | Argent, a lion rampant Gules, on a chief Sable three escallops of the first. |

The present volume—the fifth in the Survey of London—completes the record of the Parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields. As in the case of the other volumes issued, the important part of the book, from the survey point of view, is to be found in the photographs and drawings, to which the letterpress is strictly subservient, but which form only a portion of the actual collection in the hands of the Council. Nevertheless, considerable attention has been devoted to history, the more particularly because existing books on the parish, notably, Parton’s Hospital and Parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields and Blott’s Blemundsbury, are incomplete, and in many cases actually misleading. An attempt has been made to retrace the history of each plot of land to the time before the erection of buildings, that is, practically to the reign of Elizabeth. No doubt, had time permitted, it would have been possible to do this adequately in many instances where the investigation has had to remain incomplete, though it is doubtful whether in all cases the necessary records are in existence.

The materials for the history have been gathered from diverse sources, and the lists of occupiers of the various houses dealt with have been obtained principally from the parish and sewer ratebooks, supplemented by the Hearth Tax Rolls and information given in deeds. The four Hearth Tax Rolls used were described in the previous volume[1] dealing with St. Giles. The sewer ratebooks have not proved of so great assistance in supplementing the parish books (which begin only in 1730) as was the case in the previous volume, since, with the important exception of those containing Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Great Queen Street, there are very few relating to this parish which date from the 17th century.

It is desired to take this opportunity of thanking those owners and occupiers of houses who have kindly granted permission to the Council to make surveys of the interior of their premises, and take photographs for reproduction in this volume. The thanks of the Council are especially due to His Grace the Duke of Bedford, K.G., for information most willingly imparted with reference to those premises which are in the Manor of Bloomsbury, and to the Holborn Metropolitan Borough Council for the facilities given to the Council’s officers for the examination of the parish ratebooks and other records.

I gladly repeat the acknowledgment, made in Vol. III. of this series, of the great assistance rendered in connection with the preparation of this volume by Mr. W. W. Braines, B.A. (Lond.), the officer in charge of the Records, Publications and Museums Branch of my department.

The earliest mention of the parish boundary of St. Giles-in-the-Fields occurs in a decree of 1222, terminating the dispute between the Abbey of Westminster and the See of London respecting the ecclesiastical franchise of the conventual church of St. Peter. According to this the boundary of the Parish of St. Margaret, Westminster, began at the watercourse of Tyburn and stretched towards London as far as the garden of the Hospital of St. Giles, “thence as the way beyond the same garden extends as far as the boundaries dividing Marshland and the parish of St. Giles.”[2] This is pretty clear evidence that in those early days the southern portion of the western boundary of St. Giles passed along the thoroughfare bounding the Precinct and Marshland on the west, thus agreeing precisely with the limits at the present day.

Although, however, there does not seem to have been any change in that comparatively small part of the parish boundary, in many other respects the limits of the parish have undergone serious modification. The first considerable alteration took place in 1731, when the Parish of St. George, Bloomsbury, was formed out of the old parish, and made to include all that part which lay to the north of High Holborn and east of Dyot Street and of a line drawn northwards from the latter’s termination in Great Russell Street (see Plate 6). This northward line was afterwards slightly modified. Again, quite recently, the parish was further curtailed as a result of Orders made under the London Government Act, 1899. The south side of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and the area lying between Wild Street and Drury Lane, were thereby taken from St. Giles, a give-and-take line was adopted between the west side of Lincoln’s Inn Fields and the junction of Kemble Street and Wild Street, and certain small additions to the parish were made at Francis Street on the north and Broker’s Alley on the south.

The stone tablet, illustrated on the next page, is a relic of the old boundary line of the parish. It was built into the wall of No. 2, Sheffield Street, which premises were demolished in 1903 in connection with the formation of Kingsway. The stone was preserved by the London County Council and has been lent to the London Museum.

2The boundary between the parishes of St. Giles-in-the-Fields and St. George, Bloomsbury, cuts through Bedford Square in such a way that although the greater part of the square is in the former, all the houses on the east side and a few on the south side are in the parish of St. George. As it was felt that there were advantages in dealing with the square as a whole, it was decided that, as had been done in the case of Lincoln’s Inn Fields,[3] the entire square should be treated in one volume.

The whole of the space between the parish boundary and Great Turnstile was occupied by houses at least as early as, and probably long before, the reign of Henry VIII. In 1545, Edward Stockwood sold to Thomas Dyxson, 5 messuages and 5 gardens in the parishes of St. Andrew, Holborn, and St. Giles-in-the-Fields,[4] and when, in the following year, Dyxson transferred the property to Richard Clyff, the western and eastern boundaries are described[5] as the tenement of John Coke and the inn called The Antelope, respectively. In the course of the next century, the five houses seem to have been divided or rebuilt as seven houses, four of which were in St. Giles, the remaining three being in St. Andrew’s.[6]

Between the westernmost of these and Great Turnstile there were, in 1545, three houses in the possession of John Coke.[7] These had belonged to the Priory of St. John of Jerusalem before the dissolution of that monastery.[8]

Great Turnstile is mentioned as early as 1522, under the name “Turngatlane”[9]; it was also known as “Turnpiklane.”[10] It is quite certain that in 1545 no houses had been built along the sides of Great Turnstile, and none probably were erected there until many years later. The earliest records so far obtained of such houses on the eastern and western sides of the lane are dated respectively 1632 and 1630[11], and probably these dates are not far removed from the actual time of building.

Reference was made in a previous volume[12] to the ten houses belonging to the Priory of St. John of Jerusalem, which, in the reign of Henry VIII., occupied the frontage of High Holborn, between Great Turnstile and certain property belonging to the Hospital of St. Giles, and it was 4then suggested that their western limit practically corresponded with the boundary between Cup Field and Purse Field. Definite proof of this has not been obtained, but it will be shown that the St. John’s property must have extended to within a little of this, thus occupying the site of about thirty numbers. Obviously, the houses must have been very scattered. It is also possible that certain buildings were in existence further to the west, towards Little Turnstile, as early as the reign of Edward II.,[13] and certainly the whole of this part of the frontage to High Holborn was covered in the early part of Elizabeth’s reign.

Agas’s map (Plate 1) shows a single line of buildings extending between the two turnstiles, but this is not an adequate representation of the state of affairs in the closing years of the sixteenth century. In order to describe this, so far as the records which have come to light in the course of the investigation for this volume will allow, it will be necessary to go into some detail, but as the point has never before been dealt with, it has been thought desirable to do so. Although the results in some cases fall short of certainty, it is hoped that thereby an idea may be gained of the somewhat complex system of houses, gardens and orchards that existed between High Holborn and the site of Whetstone Park. The accompanying plan will render the description of the properties more easy to follow. It should be understood that the plan is quite a rough one, and intended merely to give a general idea of the situation about the year 1590. The discovery of further records would, no doubt, modify it in certain details.

HIGH HOLBORN, BETWEEN THE TURNSTILES, CIRC. 1590.

Where now is the entrance to Little Turnstile, there then existed an open ditch or sewer. In the Survey of Crown Lands[14] taken in 1650, reference is made to a certain property “scituate and adjoyninge to Lincolnes Inn Fields alias Pursefeild,” being 214 feet long from Purse Field south, to Mr. Lane’s 5houses on the north, and 22 feet wide, which ground was “heertofore a ditch or comon sewer and filled upp to bee part of the Pursefeild.” Lane’s houses were on the projecting north side of Little Turnstile, and the sewer lay 21 feet to the east of the present line of Gate Street.[15]

In 1560, Lord and Lady Mountjoy sold[16] to Thomas Doughty and Henry Heron “syxtene meses, mesuages or tenementes adioyninge nere together ... scytuate and being in Holborne,” called by the name of Purse Rents, together with six additional gardens. From the inquisition[17] held on the death of Doughty in 1568 it appears that he held eight of the houses and three of the gardens.

Eight years later (1576) Thomas Doughty, junior, sold[18] that part of the property to “Buckharte Cranighe,[19] doctor of physyke.” In the same year Queen Elizabeth granted[20] to John Farnham, one of her gentlemen pensioners, the whole of the combined Doughty and Heron property, increased on the Heron side by two houses, five cottages, three stables and an orchard, none of which are mentioned in the previous deeds. Farnham immediately sold the property afresh to Doughty[21] and Heron.[22] The latter in 1589 sold to [23]Rowland Watson and Thomas Owen, nine houses, which, by the names of the occupiers, can be identified as nine of the ten sold by Farnham, and which are stated to contain in length together on the street side 35½ yards. In 1669 the same property, then consisting of seven houses, was sold[24] by William Watson to Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and is obviously to be identified with the six houses in High Holborn leased by the college in 1800,[25] and described as Nos. 246 to 251, High Holborn. The length of the Holborn frontage of Nos. 246 to 251 accords well with the dimension required (35½ yards), and the identification of these houses with the property sold by Heron to Watson (B on accompanying plan) may be regarded as fairly certain.

In 1592 Heron sold a further portion of his property[26], the purchaser 6this time being Anne Carew.[27] This consisted of (i.) six messuages (C on plan) abutting north upon the lands and tenements of Master Watson (i.e. B), and south upon Heron’s garden; (ii.) a messuage in the occupation of Sir Thomas Gerrard,[28] abutting north on Heron’s garden and south on “the White Hart feilde”, (i.e., Purse Field, which was held with The White Hart); (iii.) the said garden and an orchard[29] lying together and containing three roods, the garden adjoining west on “the lands late Burcharde Crainck,” and the orchard towards the east, abutting on the messuage and garden of William Cook; and (iv.) the messuage and garden of Cook (H on plan) abutting south on Cup Field, on the north on a tenement of Mistress Buck, widow, and east on a garden late of Thomas Raynesford. In the light of (iii.) it is now possible to assign the Doughty property (afterwards Burrard Cranigh) to position A.

Plots A to F are thus roughly settled, but before leaving them it is necessary to trace further the history of F until its development by building. On the death of Anne Carew the property seems to have passed[30] to her son George, afterwards Baron Carew of Clopton and Earl of Totnes, and by him to have been bequeathed to Peter Apsley, grandson of his brother Peter. In 1640, John Apsley sold[31] to Daniel Thelwall and William Byerly, together with other adjacent property, a messuage with an orchard containing half an acre, “scituate over against the said messuage and extending from the way or path there to the feild side,” all formerly in the occupation of John Waldron. Of this William Whetstone held a lease, which he had obtained certainly before 1646[32], and in 1653 reference is made[33] to “all the newe buildings thereon erected.” It is most probable, therefore, that this was the scene of the building operations described in the Earl of Dorset’s report to the Privy Council on 11th December, 1636, when he complained that “one William Whetstone,” having lately erected five brick houses in 7Lincoln’s Inn Fields, without proper permission, had “for the better countenanceing of himselfe therein, and for the finishinge and mayntayneing the said buildings, counterfeited his Lopps hand, as also the hand of his Secre, frameing a false lycence,” etc. It having been decided that this was “a presumption of a high nature, and a fraud and offence not fitt to be passed by wthout exemplary punishment,” instructions were given for the demolition of the houses,[34] but it is not known whether this was actually done.

At any rate, Whetstone succeeded in stamping his name on the new thoroughfare which parted the property in High Holborn from that in the adjoining fields, though the western part was at first known as Phillips Rents. The Phillips in question was perhaps the John Phillips mentioned in a document[35] of 1672, as having lately been in occupation of a piece of land in the rear of Purse Rents, “being southward upon a way [i.e., Whetstone Park] leading from Partridge Alley towarde Great Queene Street.”

Notice must now be taken of another property of Heron, “parcell of the lands of the late dissolved Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem.” In 1586 he sold to John Buck[36] eight houses (seven with gardens attached) and one garden plot, the first house being described as “all that messuage or tenement with a garden and backsyde, now in the tenure, farme or occupacion of one Thomas Raynesford or his assignes.” The position of Raynesford’s messuage and garden is obviously J (see above) and as H is distinctly stated to be bounded on the north by a tenement of Mistress Buck,[37] the Buck property may be assigned to position G.

In October 1583, Heron had sold[38] to Anne Carew five houses with gardens, a garden with a little house, and three other gardens. The only information given as to the position of the property is that it was situated in St. Giles-in-the-Fields. It is, however, possible to locate it approximately. In 1634, Peter Apsley sold[39] to Sir John Banks, the attorney general, “all that messuage or tenement with appurtenances, scituate in High Holborne, in St. Giles, together with the court or yard lying on the south part of the said messuage, and the garden beyond the said court, extending to the feildes lying on the south of the said messuage, as the same is enclosed with a brick wall, and as the said premises were lately heretofore in the occupation of Sir John Cowper, Knt. and Bart. deceased, and formerly in the occupation of Sir Anthony Asheley, Knt. and Bart. deceased.” In 1661 Sir Ralph Banks sold[40] the house to William Goldsborough, and in 1716 Edward Goldsborough assigned[41] the remainder of a lease of 500 years 8granted in January, 1692, by Grace and Robert Goldsborough in respect of premises described as “all that messuage, tenement or inn, with appurtenances, scituate in High Holborne in St. Giles-in-the-Fields, known by the name of The George, together with a courtyard or backside lying on the south part thereof, and the peice of vacant ground or garden beyond the said court and belonging to the said messuage and extending to a certain street or place there called Whetstones Park, lying on the south side of the said messuage or inn.” There can be little doubt that the premises are identical with those described in the deed of 1634, and it may therefore be assumed that the Carew property included the site of The George, which a reference to Horwood’s Map of 1819 will show is now occupied by the eastern portion (No. 270) of the Inns of Court Hotel.

This identification is confirmed by the following. Sir Ralph Banks owned two other houses, one behind the other, adjoining Goldsborough’s house on the east, and these Goldsborough bought at the same time as he purchased his own house. In 1663, he sold them to Edmond Newcombe, and in the indenture[42] embodying the transaction they are described as being 40 feet broad and 160 feet long, and bounded on the east by “the house in which Firman now dwelleth.” In June, 1716, a mortgage was effected by Prescott Pennyston and Thomasin, his wife, of two messuages in High Holborn, adjoining the inn called The Unicorn. Thomasin was the daughter and heir of Elizabeth Hollinghurst, formerly Tompson, cousin and devisee of William Firmin. Now Unicorn Yard occupied a position corresponding approximately to the western half of the present No. 274 (the position is well shown on Horwood’s Map, though the numbering does not quite accord with that of the present day), and distant about 58 feet from No. 270. Assuming the two houses to be one behind the other, as was the case in Newcombe’s property, this leaves the 40 feet required for Newcombe’s house, and 18 feet for Firmin’s house, corresponding almost exactly with the old No. 274 shown by Horwood. The Carew property may therefore be assigned definitely to position K with a fixed eastern limit at No. 270. It has not proved possible to determine its frontage towards the west, and perhaps it did not extend as far as Raynesford’s house (J). It is, however, known that it included a tavern called The Three Feathers.[43] It seems a reasonable assumption that this was in the neighbourhood of Feathers Court, shown in Horwood’s Map as occupying much the same position as the present Holborn Place, but entering High Holborn somewhat further east. The Three Feathers would therefore correspond approximately to the present No. 263.

The adjoining properties (L and M) have already been referred to. The house (M) next to The Unicorn was in Elizabeth’s reign in the possession of John Miller, and in 1607 was described as “all that messuage, cottage, 9tenement or house with a forge,” in High Holborn, “reaching to a certeyne pasture adjoyninge to Lincolnes Inne on the south syde,” and bounded on the west by the house and land of John Thornton.[44] Beatrice Thornton, widow, is shown in the Subsidy Rolls as far back as 1588 as resident at or near this spot, and this circumstance is undoubtedly to be connected with the name of Thornton’s Alley, which was hereabouts.[45]

The premises (N), which in the early part of the seventeenth century comprised a single inn, The Unicorn, had in 1574 been purchased by Francis Johnson from John and Margaret Cowper, as three messuages and three gardens,[46] and are described in 1626[47] as having been “now longe since converted into one messuage or inn commonly called The Unicorne.” Apparently its use as an inn was of recent date, for in the description of (M), dated 1607, the eastern boundary of that property is said to be “a tenement in the occupation of John Larchin, baker,” and in 1629, when the premises had been re-divided into two, one is said to be[48] “now in the tenure of Mary Larchin, widdowe, and is now used by her as a common inne, and is called by the name or signe of The Unycorne.” The dimensions of the premises are given as 45 feet wide on the north, 40 feet on the south on Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and 156 feet long.

No records of the time of Elizabeth relating to property between The Unicorn and the house at the corner of Great Turnstile have, so far, been discovered. The latter (O), having a frontage to High Holborn of 39 feet, was certainly at the time in the possession of the same John Miller[49] who held the property (M).

The ground landlord of No. 3 is the London County Council.

The area lying between Great Queen Street, Little Queen Street and Gate Street (the east to west portion of which street was formerly known as Princes Street) was originally a portion of Purse Field, the early history of which has already been detailed.[50]

On 27th May, 1639, William Newton sold to John Fortescue[51] “all that peece or parcell of ground, being part of Pursefeild and the pightells, designed for two messuages to be built thereon by the said John Fortescue, the foundations whereof be now laid.” The ground is described as measuring 50 feet 3 inches from north to south, and 127 feet from east to west. Between the ground and Princes Street (“a way leading upon a backgate of an Inn lately called The Falcon and Greyhound”) lay the houses (or their sites) of Lewis Richard and John Giffard, and a slip of ground afterwards bought by Arthur Newman, having widths of 25 feet, 25 feet and 8½ feet respectively[52]. From these measurements it can be shown that the ground sold to Fortescue was the site of what afterwards became Nos. 3 and 4, Gate Street. The indenture contained, in common with those relating to Richard’s and Giffard’s houses, a provision “that there doth and soe perpetually shall lye open from the front of the said messuage eastward, three score foote of assize, wherein there shall be noe building erected or builded by the said William Newton, his heirs ... or any other person or persons whatsoever, it being the principall motive of the said John Fortescue to purchase the estate and interest aforesaid, to have the said 60 foote in front to lye open for an open place from the front of the building, except 11 foote to be inclosed in before the house, and that there shal be noe buildinges erected at the south-east end of the said open place by the space of 30 foote, to take away the prospect of the greate fielde, otherwise than a fence wall, whether he, the said William Newton or his assignes, keepe the same in his or their owne hands, or doth or doe depart with it to any other.” It was also agreed “that there shall not at any tyme or tymes hereafter be erected or built any manner of building 11whatsoever” in the gardens of any of the four messuages[53] in question. These conditions, as will be seen, have been more than observed.

From the above it is clear that the foundations of the two houses had already been laid by 27th May, 1639, and the premises were accordingly probably completed by the end of the year. No exact date can be assigned to the rebuilding of the houses, but it seems probable that this took place about the middle of the 18th century. The carved mouldings of the joinery on the first floor of No. 3 are interesting, and details are given in Plate 7.

No. 4 was demolished about 1905. No. 3 has been much cut about, and is now used as a workshop.

The occupants of these two houses[54], up to the year 1800, so far as it has been possible to ascertain them, were as follows:—

| No. 3. | No. 4. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1667. | Richd. Sherbourne. | 1659 until after 1675. | Thomas Povey. |

| 1675. | Judge Twisden. | ||

| 1683. | Sir John Markham. | 1683. | “Jervas Perepont.” |

| Before 1708. | Thomas Broomwhoerwood. | 1708. | John Partington. |

| 1708–1732. | Phineas Cheek. | 1715. | Mrs. Ann Partington. |

| 1732–1735. | J. Winstanley. | 1723. | William Thomson. |

| 1735–1753. | Phineas Cheek. | From before 1730 until 1732. | Mrs. Anne Thomson. |

| 1755–1763. | Wm. Mackworth Praed. | ||

| 1763–1767. | Dr. Jas. Walker. | ||

| 1768–1772. | William Hamilton. | 1732–1736. | Elizabeth Partington. |

| 1773. | Wm. Everard. | 1736–1743. | [55]Henry Perrin. |

| 1774–1786. | The Rev. Chas. Everard. | 1744–1746. | Thomas Smith. |

| 1786–1792. | The Rev. Chas. Booth. | 1746–1748. | R. Symonds. |

| 1794–1800. | Robert Kekewitch. | 1749–1753. | Joseph Martin. |

| 1753–1755. | Thomas Western. | ||

| 1760–1794. | Charles Catton. | ||

| 1795–1797. | Messrs. Burton and Co. | ||

| 1798– | Thomas Burton. |

Sir Thomas Twisden, second son of Sir William Twisden, was born at East Peckham in 1602. In 1617 he was admitted to the Inner Temple, and called to the Bar in 1626. Although a staunch royalist, he prospered during the Commonwealth, and in 1653 was made serjeant at law. At the Restoration he was confirmed in this 12dignity, advanced to a puisne judgeship in the King’s Bench, and knighted. In 1664 he was created a baronet. He died in 1683.

Thomas Povey was the son of Justinian Povey, auditor of the exchequer and accountant general to Anne of Denmark. At the outbreak of the civil war he at first joined neither party, and published a treatise called The Moderator: expecting sudden Peace or certaine Ruine. In 1647, however, he entered the Long Parliament, and was subsequently appointed a member of the council for the colonies. At the Restoration he was taken into favour, and many lucrative appointments were bestowed on him. The dates of his birth and death are unknown. His residence in Gate Street, then known as Lincoln’s Inn Fields, seems to date from the latter part of 1658 or the very commencement of 1659. A letter from him is extant written from Lincoln’s Inn Fields, dated 9th February, 1658–9, while one dated 20th July, 1658 is written from “Graies Inn.”[56] Apparently he took the house on the occasion of his marriage, as in an undated letter, after mentioning certain family bereavements, he proceeds: “I was [thus] driven to meditat on a settlement of myself; and did therefore accept of such an oportunitie, as it pleased God about that time to offer mee, of adventuringe upon marriage, wch I have donn upon such grounds as you have all waies heretofore proposed to myself, my wife being a widdowe, about my own yeares, never having had a child; of a fortune capable of giving a reasonable assistance to mine, and of a humour privat and retired. Soe that I am now become a settled person in a house of my own in Lincolnes Inn Fields.”[57] His house was famous, and both Evelyn and Pepys have, in their diaries, left a description of it. The former thus records a visit paid by him on 1st July, 1664. “Went to see Mr. Povey’s elegant house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where the perspective in his court, painted by Streeter, is indeed excellent, with the vases in imitation of porphyry, and fountains; the inlaying of his closet; above all, his pretty cellar and ranging of his wine-bottles.” Pepys had been there a few weeks before, and under date of 29–30th May, 1664, writes: “Thence with Mr. Povy home to dinner; where extraordinary cheer. And after dinner up and down to see his house. And in a word, methinks, for his perspective upon his wall in his garden, and the springs rising up with the perspective in the little closet; his room floored above with woods of several colours, like but above the best cabinetwork I ever saw; his grotto and vault, with his bottles of wine, and a well therein to keep them cool; his furniture of all sorts; his bath at the top of his house, good pictures, and his manner of eating and drinking; do surpass all that ever I did see of one man in all my life.”

Charles Catton, the elder, was born in Norwich in 1728. He was apprenticed to a London coach painter, and attained eminence, not only in this branch of the profession, but as a painter of landscapes, cattle and subject pictures. He was appointed the king’s coach painter, and was one of the foundation members of the Royal Academy. He died in Judd Place, in 1798.

For a number of years (1776–1781) his son, Charles Catton, the younger, is shown in the Royal Academy Catalogues as residing at his father’s house in Gate Street. He was born in London in 1756, and acquired a certain reputation as a scene-painter and topographical draughtsman. He died in the United States in 1819.

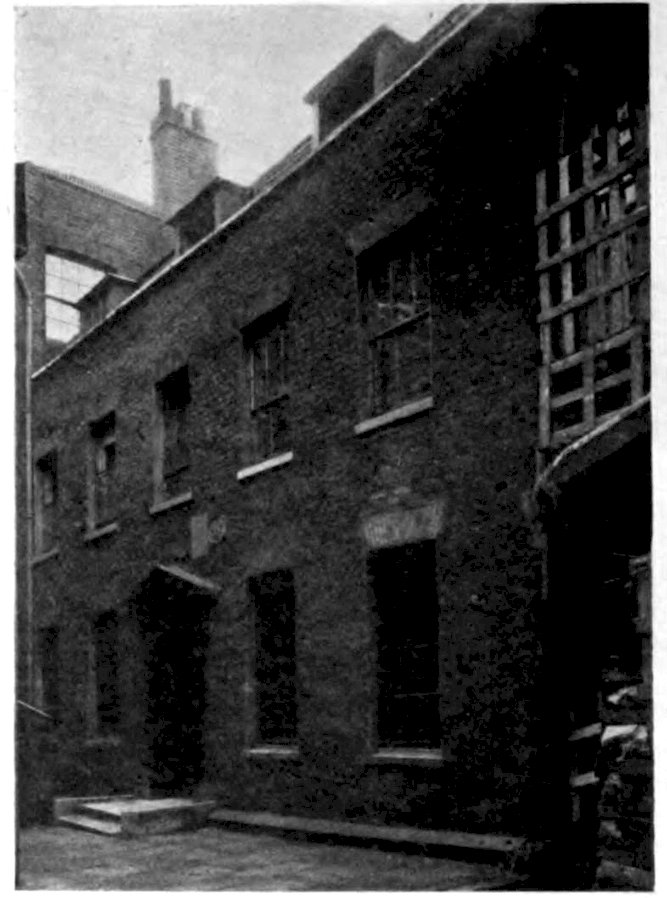

Exterior of No. 3 and cross to the memory of Mr. Booker, 1837 (photograph).

[58]Joinery details on first floor of No. 3 (measured drawing).

The Ship Tavern, Gate Street—exterior, showing Little Turnstile (photograph).

Twyford Buildings—View of court in 1906 (photograph).

In 1592 a Commission on Incroached Lands reported[59] the existence of certain property in St. Giles, held without any grant, state, or demise from the sovereign. On 29th August, 1609, James I. granted the whole of this to Robert Angell and John Walker. As the point is of importance, the description of the premises included in the grant is here given in some detail.[60]

“All that one messuage of ours with appurtenances in the tenure of Thomas Greene, and one cottage with appurtenances, with garden, in the tenure of Thomas Roberts, situated in the parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields ... and all those four cottages with appurtenances lying and being on the south side of the public way leading from the said town called St. Giles-in-the-Fields towards Holborne ... and all those small cottages built within the small pightell called Pale Pingle, lying and being within the parish of St. Giles opposite the aforesaid cottages, namely, on the north side of the royal way between the town of St. Giles aforesaid ... and Holborne.”

In 1650 a survey[61] was made of certain property “late belonginge to Charles Stuart, late king of England,” and included therein were a number of premises, which extended along the south side of High Holborn for a distance of 234½ feet eastwards from Little Queen Street, and the easternmost house of which was The Falcon.

To the reversion in fee farm of this property a Mr. Gibbert laid claim, basing his pretensions on the identification of the property with certain of that included in the grant of James I. above referred to, and the surveyors reviewed at length his title, annexing a “plott of ye ground” (Plate 2). The conclusion to which they came was, that it was “clere and aparent” that Green’s messuage and Roberts’ cottage and garden, together with the four cottages opposite the Pale Pingle, were the tenements granted to Gibbert, and that these were “at the least 40tie pole” distant from the houses which he claimed. “Soe yt his clayme in those aforesaid houses is very unreasonable, false, imperfect and untrue. And wee, whose names are heerunto subscribed, shall (if Gibbert should bee so uncivell or shameles heereafter to lay clayme to them before yor honors) make it clerely appeare to the contrary if at any tyme required.”

In spite of this emphatic condemnation of the unfortunate Mr. Gibbert, there can be no doubt that the surveyors were wrong. They 14seem entirely to have overlooked the possibility that the houses of Green and Roberts were not adjacent to the four cottages opposite the Pale Pingle; in fact, a perusal of the royal grant is sufficient to make it reasonably certain that they were quite distinct. The matter is, however, capable of definite proof.

A fortnight after the grant by James I., Angell and Walker conveyed the whole of the property to Richard Reade and Henry Huddleston,[62] and they in turn, on 23rd November, 1610, sold it to John Lee.[63] In the indenture accompanying this sale the two first mentioned houses are described as “all that messuage or tenement with appurtenances, late in the tenure of one Thomas Greene ... now called the signe of The Falcon, also one messuage or tenement or cottage there late in the tenure of one Thomas Roberts.”

It is quite clear therefore that Gibbert was right in his contention, and that the premises extending from Little Queen Street up to and including The Falcon had had their origin in the house of Green and the cottage of Roberts, which had first been officially noticed in 1592. There is also evidence (see below) that the land included in the grant reached as far east as Little Turnstile.

With the above information it is possible to date the interesting plan (Plate 2) appended by the surveyors to their report. It will be apparent that this has almost exclusive reference to the property granted to Angell and Walker in 1609. Thus, there are shown the four cottages by the White Hart, opposite the Pale Pingle, the Pale Pingle itself, and the land extending from Little Turnstile to Little Queen Street, including Green’s premises, the only building which in the royal grant is dignified with the name of “house.” It is therefore suggested with confidence that the plan in question is a copy of the one appended to the grant of 1609. With this assumption the title “Queene streete,” given to the still unformed thoroughfare entering Purse Field is in entire accord.[64]

Immediately after or shortly before Lee’s purchase, additional buildings were erected, for on 11th December, 1610, he and Nicholas Hawley sold The Falcon to William Woodward,[65] “with all yards, wayes, waste groundes, stables and appurtenances,” excepting, however, from the sale “four little houses, cottages or tenements latelie builded on the west side of the Falcon yarde.” Moreover, in 1612–13, the same vendors sold to William Lane, junior, one messuage, two cottages, two gardens, and a rood of land with appurtenances in the parish of St. Giles.[66] As in 1661 the property immediately to the west of Little Turnstile is described 15as “now or late” in the possession of Mistress Lane,[67] it is practically certain that the land sold in 1612 was identical therewith, and Hollar’s plan of 1658 (Plate 3), which shows the area fully built on, indicates the development which had taken place in the course of the half century.

Building on the remaining portion of the land had also greatly increased.[68] The survey of 1650 contains a detailed description of the property, giving much interesting information as to the building materials, arrangement of the rooms, outhouses, etc. The following is a list of the premises. In most cases there were garrets in addition to the storeys mentioned.

The Falcon (2 storeys), and a house (3 storeys) in the rear. Frontage 15 feet. (Present No. 233.)

A house of three storeys. Frontage 33 feet. (Present No. 232 and site of New Turnstile.)

The King’s Head Inn (3 storeys), with an addition (2 storeys), a gateway, a smith’s shop with room, stables, sadler’s house, tenement of 2 storeys, shed and coachhouses, houses of office. Frontage 54 feet. (Present Nos. 229–231.)

Two small tenements lying in front of The King’s Head (3 storeys), a house (3 storeys), with small back addition. Frontage 19 feet.

A house (3 storeys), a garden with coach house and stable. Frontage 26 feet. (The site of these last two houses is now occupied by the Holborn Station of the Piccadilly tube railway.)

The Gate Tavern (3 storeys.) Special mention is made of the “very faire and spacious dyneinge room, 38 feet in length,” on the first floor. A bowling alley and gardens were in the rear. Frontage 38 feet. The site is occupied partly by the Holborn station and partly by Kingsway.

A house of 3 storeys, with a garden containing a small tenement of 2 storeys. Frontage 16 feet.

A similar house, with a garden containing a “small decayed tenement.” Frontage 16 feet.

A tenement of 2 storeys, with a shop on the ground floor, a back addition of 2 storeys. In the garden behind were two small tenements of 2 storeys. Frontage 17½ feet. The site of the three last mentioned houses is now covered by Kingsway.

It will be seen from the above that New Turnstile was not included in the original scheme for building. It is not shown in Morden and Lea’s Map of 1682, nor in the map accompanying Hatton’s New Guide to London of 1708, but appears in the sewer rate book for 1723.

It is very difficult to say when the south side of High Holborn, between the sites of Kingsway and the Holborn Public Library, was first built upon. Perhaps, even in Elizabeth’s reign, there were some scattered buildings here, but certainly nothing like a continuous line of houses. There seem to have been no building operations on a large scale, until after the acquisition of the lease of Purse Field by Sir Charles Cornwallis, in 1613.[69] Cornwallis sub-leased certain portions of the Holborn frontage, extending south to the site of Parker Street, and on these portions houses had been erected before 1650. No records of the sub-leases have been found, but a part at least of the frontage to Holborn had been sub-leased before 1634. Two years previously Charles I. had confirmed a grant, made by his father to Trinity College, of six markets and twelve fairs for the building of their hall. The college sold to Henry Darell two markets and three fairs, and in August, 1634, the latter petitioned to be allowed to set these up in St. Giles on His Majesty’s inheritance.[70] This was granted on 15th December, 1634, a writ of Ad Quod Damnum issued, and on 10th March, 1634–5, an inquisition by a jury was held, from which it appears that the proposal was to hold the markets and fairs “in locis vocatis le pightells et Pursfeild.”[71] The project aroused keen opposition on the part of the Corporation of the City of London,[72] and in spite of its revival in 1637,[73] was eventually abandoned.

It is possible to identify the site of the proposed market, inasmuch as in 1650 the frontage to Holborn between Little Queen Street and Newton Street consisted of two “ranges” of buildings known as Shenton’s tenements and Dayrell’s buildings, and it is clear that the latter represent Henry Darell’s proposed market. Darell no doubt had already obtained his lease before applying for a grant for a market, but no houses would have been erected until after the failure of his scheme. It is known[74] that one of his plots were let on a building lease on 23rd November, 1639. The erection of buildings on this part of the Holborn frontage may therefore be assigned provisionally to the year 1640.

Shenton’s tenements consisted of six houses in High Holborn and five in Little Queen Street, extending 100 feet along the former and 115½ feet along the latter thoroughfare. Their site is therefore wholly covered by the Holborn Restaurant.

17The largest house, then in occupation of Mrs. Shenton herself, was the next but one to the corner, and is described in the survey of 1650 as “all that tenement built as aforesaid[75] ... consistinge of one kitchen, one hall, and one small larder, and adjoyninge one backside and one garden, with severall necessary houses therein built and standinge. And above stayres in the first story, one dyneinge roome with a balcony there, and one chamber and a closett there. And above stayres in the second story, two chambers with a closett there and two handsome garret roomes over the same.”

Dayrell’s buildings consisted of twelve houses in High Holborn, and five in Newton Street, and covered an area of 186 feet by 122 feet. They were, on the whole, much superior to Shenton’s tenements. The westernmost and largest house is described as “All yt spacious brick buildinge ... built with brick in a comely shape and very reguler, and consistinge of 5 stepps in ascent leadinge into an entry leadinge into a faire hall and parlour wth sellers underneath the same, divided very comodiously into a kitchen, a buttery and a larder. And above staires in the first story a very faire dyneinge roome well floored, seeled and lighted wth a belcony there on the streete side alsoe, wth said roome is very well adorned and set fourth wth a faire chimney peice and frames all of black marble, and on the same floore backwards one other faire chamber. And in the second story two faire chambers and a closett in one of them. And in the 3rd story two more faire chambers and a closett there, and over the same two faire garretes. Alsoe adjoyninge to the same one garden.”

The houses appear to have been of different sizes, for their rentals varied greatly, and this, combined with the fact that in subsequent rebuilding nine houses took the place of the original twelve in High Holborn, makes it impossible to identify the house which originally occupied the site of No. 211.

The house was perhaps rebuilt in the latter part of the 17th century.[76] A further rebuilding (perhaps the third) seems to have taken place in 1815, when the premises were re-leased by the Crown.[77]

Plate 8 shows an interesting shop front. The ornamental iron guards to the first floor windows are good specimens of wrought iron work.

The house was demolished in 1910.

[78]Shop front (photograph).

At the time of the survey of 1650 Newton Street (i.e., the old Newton Street, north of the stream which crossed it where Macklin Street now joins, and separated it from Cross Lane), was fully built, and the remaining frontage of Purse Field to Holborn, between Newton Street and the site of the Holborn Public Library, was apparently occupied by nine houses, held by Thomas Farmer and Henry Alsopp, to whom Francis Cornwallis had assigned his lease so far as concerned that part of the field.

The yard, formerly Green Dragon Yard, at the side of the Holborn Public Library, marks the site of the ancient stream which formed the western boundary of Purse Field. The stream seems to have remained open in this part of its course until about 1650, as a deed dated 7th November in that year,[79] in view of the fact that Thomas Vaughan and his wife Elinor “are to be att greate cost and charges in the arching or otherwise covering over the sewer or wydraught under mencioned, by meanes whereof the inhabitants there adjacent shall not be annoyed as formerly they were thereby, as for divers other good considerations them hereunto moving,” provides that the said sewer “as the same is now severed, sett out and fenced, scituate ... on the backside of a messuage of the said Thomas Vaughan commonly called ... by the name or signe of The Greene Dragon” shall be demised to the Vaughans.

The land immediately to the west of the yard in question originally formed part of Rose Field, and was probably developed at the same time as the rest of that estate. In 1650, William Short, the owner of Rose Field, in conjunction with John De La Chambre, sold to Thomas Grover 4 messuages, 12 cottages, 12 gardens and one rood of land with appurtenances, in St. Giles.[80] The precise position of this property is not mentioned, but there does not seem to be much doubt that the premises are identical with, or a portion of, those which Grover sold to Edmond Medlicott in 1666,[81] and which consisted of 16 houses in Holborn, including the “messuage commonly known by the name or signe of The Harrow,” and also the “lane or alley called Wild boare Alley alias Harrow Alley, with all the severall messuages, tenements, edifices and void peice or plot of ground in the said alley.” The property is said to front upon Holborn on the north, and to have for its eastern boundary a way or passage leading from Holborn to the house and garden of Mr. Braithwait. The dimensions are given as: 19“In depth from north to south at the west end, one hundred fourscore and ten foote, and throughout the whole range and pile of buildings besides from north to south fower score and seven foote, and in breadth from east to west sixty and three foote.” The last figure is certainly wrong, for even if half of the sixteen houses in Holborn were lying behind the rest (as indeed was probably the case) this would only admit of an average frontage of 8 feet to a house. A probable emendation is “six score and three” which gives a 15 feet frontage to each house.

The land behind these premises, reached by the path along, and afterwards over, the stream, was leased by William Short in 1632 to Jeremiah Turpin for the remainder (20 years) of a term of 36 years,[82] and then consisted of garden ground upon which Turpin had recently built a house. It seems most probable that this[83] is the place referred to in the petition,[84] dated 17th June, 1630, of the inhabitants of High Holborn, calling attention to the fact that there was a dangerous and noisome passage between High Holborn and St. Giles Fields, by reason of a dead mud wall and certain old “housing,” which lately stood close to the same, where divers people had been murdered and robbed, and praying for leave for building to be erected thereon. In their report[85] on this petition, the Earls of Dorset and Carlisle refer to it as “concerning the building of Jeremy Turpin,” and recommend the granting of leave to build.

It may therefore be concluded that the house was built between 1630 and 1632. A full description[86] of the property as it was in 1640 is extant, and is interesting as giving an idea of the private gardens of that time. Reference is made, among other things, to the arbour formed of eight pine trees, the “sessamore” tree under the parlour window, 13 cherry trees against the brick wall on the east of the garden, 14 more round the grass plot, rows of gooseberry bushes, rose trees and “curran trees,” another arbour “set round about with sweete brier,” more cherry trees, pear, quince, plum and apple trees, a box plot planted with French and English flowers, six rosemary trees, one “apricock” tree and a mulberry tree.

The ground on which Smart’s Buildings and Goldsmith Street were erected at one time formed part of Bear Croft or Bear Close, so called, no doubt, because it was used as pasture land in connection with The Bear inn, on the south side of Broad Street, St. Giles.[87]

At about 1570 there were, immediately to the south of the White Hart property at the corner of Drury Lane, eight houses. The three most northerly abutted on the east upon “a close of grounde called the Bere 20Close, late belonging to Robert Wise, gentilman”[88]; while the five others, with the close itself (of 2½ acres) are described as “adjoynynge to the Quenes highe waye ... leadinge from Strande ... to thest end of the said towne of Saint Giles on the west parte, and abuttinge upon the close nowe our said soveraigne ladye the Quenes Majesties, called the Rose feilde, on thest and south partes, and abuttinge upon the messuage or tenemente nowe or late in the tenure of one William Braynsgrave,[89] and the tenement called The White Harte, late in the tenure ... of one Matthewe Bucke, and nowe in that of one Richarde Cockshoote, and the Quenes highe waye leadinge from Holborne towardes the est end of the said towne of Saint Gyles on the north part.”[90]

The boundary line between Bear Close and Rose Field is nowhere described. It is known, however,[91] that Rose Field reached as far north as the line bounding the rear of the buildings in Macklin Street, and there is reason to believe that this line marks the actual division between the two fields. As regards the eastern boundary a line starting from High Holborn between No. 191 and No. 192[92] and running along the western side of the southerly spur of Goldsmith Street, seems to fulfil all the conditions. It is not known what was the depth of the eight houses and gardens fringing Bear Close on the west, but allowing 60 feet, the area of Bear Close, defined as above, amounts to two acres. It is hardly possible, therefore, to limit its boundaries any further. It seems probable that the quadrangle shown in Agas’s map (Plate 1) at the north-east corner of Drury Lane was Bear Close, and it will be observed that, according to the map, the houses south of The White Hart stretched along the whole of the Drury Lane frontage of the close.

Bear Close formed a part of that portion of the property of the Hospital of St. Giles which, after the dissolution, came into the hands of Katherine Legh, afterwards Lady Mountjoy. With the five southernmost of the houses separating Bear Close from Drury Lane, and other property, it was purchased of the Mountjoys by George Harrison, from whom by various stages it came into the possession of James Mascall.[90] The latter died on 11th May, 1585,[93] leaving the whole of his property to his wife, Anne, who subsequently married John Vavasour. From her the whole of the property above mentioned[94] seems to have 21come into the hands of Olive Godman, younger daughter of James and Anne. A portion of this, including “all the ground or land lying on the backside of [certain] messuages towards the east, contayning two acres, now or late in the occupation of ... Thomas Burrage” was settled on her daughter, Frances, on the marriage of the latter with Francis Gerard in 1634.[95] There seems little doubt that the land in question was Bear Close.

It was apparently soon after this that the close was laid out for building, the planning taking the form of a cross, the long and cross beams being represented respectively by the present Goldsmith Street and Smart’s Buildings. The former street was, up to 1883, known as The Coal Yard, in consequence it is said, “of the place being used for the storage of fuel.”[96] The tale has a somewhat suspicious look. The fact, too, that “Mr. Francis Gerard,” the owner of Bear Close, and “Bassitt Cole, Esq.,” are found living in two adjoining houses in Drury Lane close by in 1646 rather suggests that “Cole Yard” is so called because of the name of its builder.[97]

The date at which Bear Close seems to have been built upon favours the above suggestion. The Hearth Tax Roll for 1666 gives 41 names which are apparently to be referred to Coal Yard, while Hollar’s Plan of 1658 shows the area by no means covered. The Subsidy Roll for 1646 gives only five names definitely in respect of “Cole Yard,” but there are 15 more which probably must be assigned thereto.

At some time before 1666 the eight houses fronting Drury Lane had given way to the present number of twelve. In the case of the four northernmost, this happened shortly after 1636, when a building lease of the sites of the houses was granted to Richard Brett.[98]

Built in the brick wall of an 18th-century tenement (No. 27, Goldsmith Street) was a stone tablet, dated 1671. The premises have lately been demolished, and at present the site is vacant.

Smart’s Buildings is a comparatively modern name for that part of Coal Yard which runs north into High Holborn. Hatton’s New View of London (1708) does not mention Smart’s Buildings, but refers to “Cole Yard” as “on the N.E. side of Drury Lane, near St. Giles’s, a passage into High Holbourn in 2 places”; Strype 22(1720) states that “the Coal Yard ... hath a turning passage into Holborn”; and Rocque’s Map of 1746 definitely names it “Cole Yard.”

In a deed of 1756[99] it is referred to as “the passage leading into the Coal Yard called Smart’s Buildings.” Which of the three Smarts, grandfather, father and son (William, Lewis and John), mentioned in the same deed, it was who gave his name to the street, there is nothing to show. No record of the purchase of the property by any person of the name has, so far, been discovered, but the deed of 1756 certainly suggests that the ownership of the houses on the eastern side of the passage originated with William, who is, moreover, described as “carpenter,”[100] and in that case would date from the beginning of the 18th century.

[101]No. 27, Goldsmith Street. Stone tablet in front wall (drawing).

Smart’s Buildings. General view of exterior (photograph).

The land at the eastern corner of Drury Lane and High Holborn may perhaps be, either wholly or in part, identified with certain land held of the Hospital of St. Giles by William Christmas in the reign of Henry III. “with the houses and appurtenances thereon, situate at the Cross by Aldewych.”[102] Aldewych was Drury Lane,[103] and the Cross by Aldewych would almost certainly be situated at the junction of the two roads. The identification of the western corner as the site of Christmas’s land seems to be excluded by the fact that this was occupied by property of John de Cruce,[104] who was certainly a contemporary of William Christmas.[105] It is possible that the land in question was situated on the north side of Broad Street, but as it is known that Christmas owned land on the south side of the way, some of which may even possibly be the actual land referred to, the identification suggested above seems reasonable. Whether in Christmas’s time there was at this spot an inn, the forerunner of the later White Hart, is unknown.[106] Blott’s suggestion that the sign of the White Hart was adopted in honour of Richard II., whose badge it was, even if correct, does not necessitate the assumption that no inn was there 24before that king’s reign (1377–1399). The sign might possibly have been changed in Richard’s honour.

The first mention of The White Hart does not, however, occur until a century and a half later. In 1537 Henry VIII. effected an exchange of property with the Master of Burton Lazars, as a result of which there passed into the royal hands “one messuage called The Whyte Harte, and eighteen acres of pasture [Purse Field] to the same messuage belonging.”[107] In 1524 “Katherine Smyth alias Katherine Clerke” was living in The White Hart.[108] She was apparently succeeded as tenant by William Hosyer,[109] but there is no evidence whether he actually resided in the inn.[110] In 1567 the occupant of the inn is said to be Matthew Buck, and in 1582 it was Richard Cockshott.[111] In 1623 Hugh Jones is mentioned as barber and victualler, at Holborn end, next Drury Lane.[112] The survey of Crown Lands taken in 1650 describes the premises as follows:—

“All that inn, messuage or tenement commonly called ... The White Harte scituate ... in St. Gyles in the feildes ... consistinge of one small hall, one parlour and one kitchen, one larder and a seller underneath the same, and above stayres in the same range, and over the gatehouse, 9 chambers. Alsoe over against the said halle and parlour is now settinge upp one bricke buildinge consistinge of 6 roomes, alsoe one stable strongly built with brick and fflemish walle, contayninge 44 feete in length and 37 feete in breadth, lofted over and covered with Dutch tyle; and two other stables next adjoyninge, built as aforesaid, and 2 tenements or dwelling houses over the same. Alsoe one large yard contayninge 110 feete in length and in breadth 46 feete. Now in the occupation of one Anthony Ives, and is worth per annum

“All yt tenement adjoyninge to ye north side of the abovesaid house, being a corner shopp, consisting of one seller and a faire shopp 25over the same; alsoe one kitchin, and above stayres two chambers. Nowe in the occupation of Richard Raynbowe, a grocer, and is worth per annum

It would seem that at the time of the transfer of The White Hart to Henry VIII. there were no buildings to the east of the inn. The fact that no such premises are mentioned in connection with the exchange is not, indeed, conclusive, and it is more to the point to observe that no mention of the buildings is contained in any of the grants of the property, during the 16th century, which have been examined. Moreover, on 13th November, 1592, a certificate was returned by the Commission for Incroached Lands, etc.,[113] to the effect that four cottages, with appurtenances, on the south side of the highway leading from St. Giles towards Holborn, opposite certain small cottages built on the Pale Pingle,[114] were possessed without any grant, state or demise from the sovereign. Plate 2 shows the cottages in question, occupying the site of the buildings to the east of The White Hart.

It may be taken therefore that these four cottages were the earliest buildings on the site, and that they were erected probably not long before 1592, when their existence was first officially noticed.

By 1650 they had grown to a long range of buildings. In that year they were described as follows:—

“All that range of buildinge adjoyninge to thaforesaid inn called The White Hart, abuttinge on the high way on the north, with two tenements on the south side of The White Hart, lyenge uppon the way leadinge into Drury Lane, all which said buildings are now divided into xxj severall habitacions in the occupation of severall tenants, and are worth per annum £24.”

The whole property, including The White Hart, the courtyards and gardens, is said to “contayne in length from Drury Lane downe to the first [tenement] 96 feete, and in breadth 76 feete; the other length backward from the stables to the lower side of the garden 125 feete and 93 feete in breadth, bounded with the highway leadinge from St. Gyles into Holburne on the north and Drury Lane on the west.” The entire site therefore had a length of 221 feet, and a width of 76 feet along Drury Lane, increasing to 93 feet behind the inn. Allowing for the subsequent widening of High Holborn at this point, it is clear that the area is represented at the present day by the sites of the houses from the corner as far as and including No. 181, High Holborn, while the southern boundary runs to the north of Nos. 190–191, Drury Lane, then turns to the south a little beyond the eastern boundary of those premises, and thence runs in a slightly curved line as far as the eastern boundary of No. 181, High Holborn.[115]

26A reference to the map in Strype’s edition of Stow (Plate 5) will show that in the 18th century both High Holborn and Drury Lane were very narrow at this spot. Moreover, in course of time, the large courtyard of the inn became used as a public way, and grew crowded with small tenements. In 1807 the leases of the property expired, and an arrangement was come to between the Vestry of St. Giles and the Crown, by which the latter and its lessees gave up sufficient land to enable the frontage line both to High Holborn and Drury Lane to be amended, with the result that the west end of the former and the north end of the latter were widened by 15 feet and 7 feet respectively. On its part the Vestry consented to the stopping up of White Hart yard and the building thereon of the Crown lessees’ new premises.[116]

Two of the houses, Nos. 181 and 172, erected in accordance with the arrangement, are illustrated in this volume.

Plate 9 shows the distinctive early 19th-century shop front, which was attached to No. 181. The design embodied a large, slightly bowed window with segmental head, flanked by two doorways. The window was fitted with small panes of glass, having bars forming interlacing segmental panes above the transom. The doors were of quiet and refined design, with excellently treated side posts, having brackets, carved with acanthus ornament, supporting the entablature. The whole exhibits a distinctly Greek feeling.