Title: The salon and English letters

Chapters on the interrelations of literature and society in the age of Johnson

Author: Chauncey Brewster Tinker

Release date: October 20, 2023 [eBook #71916]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: The Macmillan Company

Credits: MWS, John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dashed blue underline.

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO · DALLAS

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

THE SALON

AND ENGLISH LETTERS

CHAPTERS ON THE INTERRELATIONS

OF LITERATURE AND SOCIETY

IN THE AGE OF JOHNSON

BY

CHAUNCEY BREWSTER TINKER

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE

IN YALE UNIVERSITY

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1915

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1915,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published April, 1915.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

TO

C. E. A.

SAPIENTIS PATRIS FILIO

SAPIENTIORI

| PART I. THE FRENCH BACKGROUND | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 3 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Origin and Characteristics of the Salon | 16 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Eighteenth Century Salon | 30 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| English Authors in Parisian Salons | 42 |

| PART II. THE ENGLISH SALON | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Earlier English Salon | 83 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Conversation Parties and Literary Assemblies | 102 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Bluestocking Club | 123 |

| CHAPTER VIII[viii] | |

| The London Salon | 134 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Bluestockings as Authors | 166 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Mrs. Montagu as a Patron of the Arts | 189 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Results | 209 |

| PART III. THE SOCIAL SPIRIT IN ENGLISH LETTERS | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Johnson and the Art of Conversation | 217 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Walpole and the Art of Familiar Correspondence | 236 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Fanny Burney and the Art of the Diarist | 254 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Boswell and the Art of Intimate Biography | 268 |

| INDEX | 285 |

| The Conversazione | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| The Levee | 102 |

| Hannah More | 157 |

| Johnson pointing out Mrs. Montagu as a Patron of the Arts | 199 |

| Samuel Johnson | 217 |

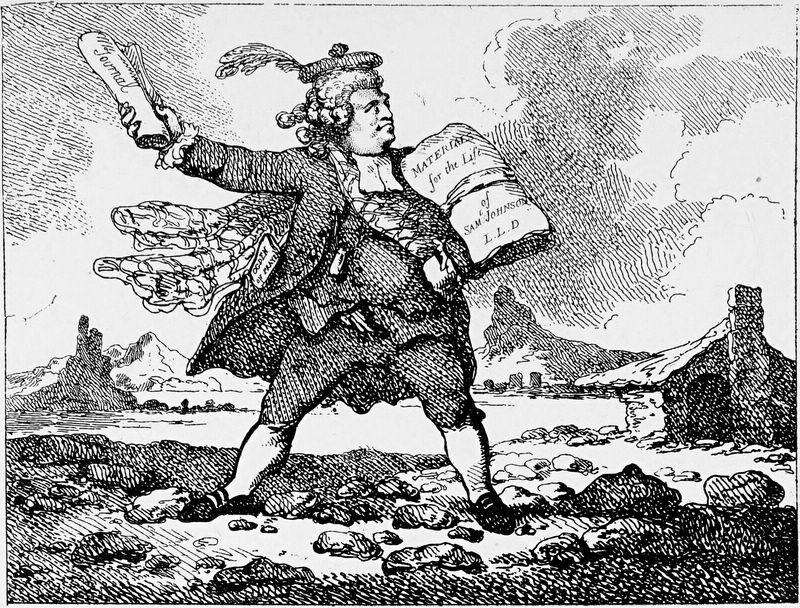

| Boswell the Journalist | 268 |

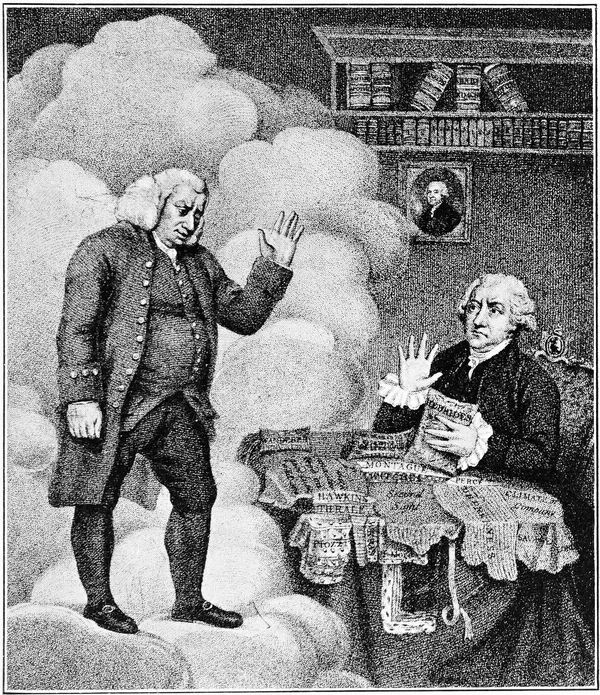

| Boswell Haunted by the Ghost of Johnson | 277 |

It is one of the venerable commonplaces of criticism that ‘manners,’ as distinct from romance and the idealistic interpretation of life, make the bulk of eighteenth century literature. Comment has often begun and more often ended with this platitude. But that large body of work vaguely termed ‘literature of manners’ can no more be dismissed with a truism than can the life that it depicts, but demands a critical method as varied as the matter which is treated. In so far as this prevailing interest of the century manifested itself in belles lettres, in novel, drama, satire, and descriptive verse, it offers no unusual problem to the literary historian; but side by side with such types we have forms no less characteristic of the age, but much less susceptible of adequate criticism: intimate biography, autobiography, memoirs, diaries, and familiar correspondence. These must of necessity be rather summarily passed over by the literary historian as not exclusively belletristic in appeal. And below these, in turn, there are certain expressions of the social spirit so anomalous that they can at most detain the critic but a moment, and must often be[4] dismissed with no consideration at all. Among these, intangible and evanescent by nature, yet of the first importance in bringing certain kinds of literature to birth, are conversation, the salon, the authors’ club, and in general those forms of social activity which exist to stimulate the production or diffuse the appreciation of literature. These, which are in themselves no more literature than are painting and politics, come at times so close to it that dividing lines are blurred. A mere record of conversation, such as gives the pages of Boswell’s Johnson or Fanny Burney’s Diary their unique value, brings us to a borderland between society and letters where a distinction between them is merely formal. What is a critic to do with works which hardly sue for recognition as literature (though the world has so acclaimed them), but avowedly exist to record the delights of social intercourse? To treat them as ‘mere literature,’ neglecting the social life in which they sprang up and to which they are a tribute, is, to say the least, inadequate.

It is with this borderland, this territory where literature and society meet in mutual respect, and presumably to their mutual advantage, that I propose to deal in this volume. I shall trace as well as I can the attempt made in England between 1760 and 1790 to emulate the literary world of Paris by bringing men of letters and men of the world into closer relations, and by making the things of the mind an avocation of the drawing-room; and thereafter I shall endeavour[5] to show the results of this movement as they appear in the improved artistry of three or four types of writing.

So long as letters and society retained this intimate relation and men and manners were deemed the all-sufficient study of poets, it was natural that authors should gather in the metropolis. The city was to them ‘the true scene for a man of letters’; ‘the fountain of intelligence and pleasure,’ the place for ‘splendid society,’ and the place where ‘a man stored his mind better than anywhere else.’[1] When the old ideal of letters was displaced by a wider and perhaps nobler, the supremacy of the metropolis as a literary centre fell with it; but in the Age of Johnson London was still the land of promise, at once a workshop and a club, a discipline and an opportunity. ‘A great city is, to be sure,’ said Johnson, ‘the school for studying life.’ Johnson, Goldsmith, Burke, Fielding, Smollett, Sterne, Sheridan, Beattie, Chatterton, Crabbe, Boswell, and many another went up thither, as their predecessors for generations had done, to seek their literary fortune or to enjoy their new-established fame.

The authors’ clubs, hardly less popular than in the days of Anne, indicate an even closer centralization. A theory of literature squarely based on reason and the tradition of the classics produced a solidarity of sentiment[6] among men of letters which was of great use in making their aims intelligible to society at large. Books were not meant to be caviare to the general. Poets did not strive to be nebulous. The ever growing democracy of readers honoured what it felt that it understood. King, Church, women of society, women of no society, painters, actors, and universities joined in paying respect to a literature that had not yet shattered into the confusion of individualism. The world of letters was, in a word, still a kingdom.

As in Paris, an alliance could, accordingly, be effected. The salon was the natural outgrowth of the intelligent interest of the reading world; it exhibited the same community of sentiment in readers that we have noticed in writers, and writers accordingly honoured it. In London, as in Paris, it became possible to find the men of light and leading gathered in a few places of favourite resort, in drawing-room or club. ‘I will venture to say,’ remarked Johnson[2] to a group of friends, ‘there is more learning and science within the circumference of ten miles from where we now sit than in all the rest of the Kingdom;’ and once, when the boasting fit was on him, he asserted that the company sitting with him round the table was superior to any that could be got together even in Paris.

It was no mean ideal of society that was held by groups such as these. Mere repartee, a display of rhetorical agility, was not its principal aim. The[7] desire to be sound mingled with the desire to be clever, and produced that wisdom which the eighteenth century loved to call wit. Wit was aphoristically pretentious to truth. It was of course important to talk in the mondaine manner, but the mondaine ideal was to talk sense. There was a general willingness to give and to receive information in the ordinary social relations of life. Never to ‘diffuse information,’ to have ‘nothing conclusive’ in one’s talk, was to fail. Johnson once contended that Goldsmith was not ‘a social man’: ‘he never exchanged mind with you.’[3] Burke’s conversation, on the other hand, delighted him because it was the ebullition of a full mind.[4] ‘The man who talks to unburthen his mind is the man to delight you,’ said he.[5] Cheerful familiarity was not the social ideal: true sociability was a communion of minds. Madame du Deffand summed up her criticism of a dinner at Madame Necker’s in the words, ‘I learned nothing there.’[6]

It was to an ideal thus frankly educational that the salon and the club responded. The passion for such society was like that which many serious souls to-day feel for the society of a university. To breathe the air of it was to grow in the grace of wisdom. In such an idealization of the social life, we may find the explanation of many so-called ‘deficiencies’ of the age, its indifference to Nature (whatever that may mean),[8] its preference for city life, its common sense, its dread of the romantic and the imaginary, and of all that seems to repudiate the intellectual life and its social expression.

Such was the delight in society felt by Hannah More and Fanny Burney in their younger days. Such was Boswell’s delight. The greatness of the latter, so ridiculously aspersed, reposes entirely upon his realization of the importance of the social instinct. Boswell was not merely a social ‘climber.’ He was a man who had the sense to see a short-cut to education. To call him toad and tuft-hunter may be an ingenious display of one’s vituperative gifts, but evinces a surprising ignorance of the fact that a man may educate himself by living contact with great minds.

It would be a simple explanation of all this respect for the salon and its discussions to observe that England was now enjoying an age of free speech. It is even simpler to point out that there was much discussion because there was much to discuss. There were problems confronting the public which were no less important than novel. This is all true, but somewhat lacking in subtlety. The peculiar adaptability of these problems to conversation was due to the fact that they were, in general, still problems of a remote and idealistic kind. They did not yet demand instant solution, for better or for worse. Exception must of course be made of questions purely political, but the rest of them—the theory of equality and the republican form of[9] government, the development of machinery, the education of the masses, humanitarianism, the problem of the dormant, self-satisfied, aristocratic Church, romanticism, and the whole swarm of theories popularized by Rousseau—had been stated and widely discussed, but they had not yet shaken society to its foundations. They were still largely theoretical. Men’s thoughts were engaged, and their tongues were busy, but their hearts were not yet failing them for fear.

We may cite as a significant example the position of the lower classes. There had been as yet no serious disturbance of what Boswell loved to call ‘the grand scheme of subordination.’ Now Boswell was no fool. He was, in truth, singularly broad-minded; yet in such a matter as this his notions hardly rose above a benevolent feudalism. Despite his interest in Rousseau, despite his sympathy with Corsica and with America, he could record with bland approval Johnson’s denunciation[7] of a young lady who had married with ‘her inferior in rank,’ and the Great Moralist’s wish that such dereliction ‘should be punished, so as to deter others from the same perversion.’ Democracy could be little more than a theory to Johnson when he asserted[8] that ‘if he were a gentleman of landed property he would turn out all his tenants who did not vote for the candidate whom he supported,’ contending that ‘the law does not mean that the privilege of voting should be independent of old family interest.’ Again, when he explained[10] to Mrs. Macaulay ‘the absurdity of the levelling doctrine’ by requesting her footman to sit down and dine with them,[9] he conceived of himself as smashing a delusion with a single blow. Such ‘levelling’ notions being, for the moment, doctrinaire, might no doubt be put down by a sally of wit. With the fall of the Bastille they took on a different aspect.

Nor was the case widely different with writers less passionately conservative than Johnson. Horace Walpole had a dim perception that the trend of affairs was destructive of the old order, but he never suspected that the theories discussed in the salons were to have immediate practical results. His attitude is well shown by his account of certain Parisian savants who talked scepticism in the presence of their lacqueys. ‘The conversation,’ he writes, ‘was much more unrestrained, even on the Old Testament, than I would suffer at my own table in England, if a single footman was present.’[10] Walpole was certainly no ardent defender of the orthodox faith, but sceptic as he was, he was not ready to meet all the issues involved in the spread of the doctrine. Religion, it seems, will still do very well for menials.

Even Hume and Gibbon, the darlings of the Parisian salon, conceived of the problems they themselves had helped to raise as largely speculative. Gibbon, for example, plumes himself on having vanquished the Abbé Mably in a discussion of the republican form of[11] government[11]—and this but a few years before the foundation of the two great republics of modern times. The irony of his triumph must, presently, have been clear to him, for on September 9, 1789, he wrote to Sheffield: ‘What a scene is France! While the assembly is voting abstract propositions, Paris is an independent republic.’ In the previous August he had expressed his amazement ‘at the French Revolution.’ We may perhaps reserve a portion of our amazement for the historian who had failed to realize that the theories with which he had been long familiar in the salons would one day cease to be mere matters of discussion.

This failure of English authors to come into full sympathy with the French doctrines of the hour is the more remarkable because Frenchmen had long regarded England as the home of reason and of liberty.[12] Indeed France had turned to England for that ‘freedom of thought’ denied to herself; but having adopted it, she had pushed it to extremes of which her teachers, conservative at heart, could never have conceived. D’Alembert, than whom the salons contained no more splendid figure, acknowledged in his Essay on Men of Letters that it was the works of English authors which had communicated to Frenchmen their precious liberty of thought.[13] So common is the praise of England that[12] he now feels compelled to protest against the further progress of Anglicism.[14] But in vain. The decades passed by with no diminution of the respect for England. In 1763 Gibbon[15] still found English opinions, fashions, and games popular in Paris, every Englishman treated as patriot and philosopher, and the very name of England ‘clarum et venerabile gentibus.’ In the next year Voltaire, who had done so much by judicious praise and injudicious blame to spread the knowledge of English literature and philosophy, addressed to the Gazette Littéraire a letter[16] containing a defence of the current Anglomania. In this he laughed at those who thought it a ‘crime’ to study, observe, and philosophize as do the English. A year later, Saurin’s play, l’Anglomanie,[17] had appeared, and though its success on the stage was not great, Walpole thought it[13] worth while to send Lady Hervey a copy of it as an example of a reigning fad. The leading character, Éraste, who affects a preference for Hogarth to all other painters, who quotes Locke and Newton, and drinks tea for breakfast, sums up his views in these verses:

All this of course is farcical; but the author, a member of the French Academy, had a serious purpose. He was attacking an attitude which was expressed in Voltaire’s well-known eulogy,

Le soleil des Anglais, c’est le feu du génie.

Saurin, in his preface, announces his esteem for England and her authors, but declares that the popularity of the ‘cult’ is due to the jealous dislike by Frenchmen of their own authors—a conclusion not quite obvious. In any case, the academician felt that he had a duty to the nation. In 1772 he revised his comedy, and it was again performed.

But Anglomania lived on. English authors were still graciously received in the salons. Madame du Deffand dared to assert that they were completely superior to the French in all matters of reasoning.[18][14] The English language was increasingly studied, and English novelists and philosophers continued popular. Madame Necker records[19] an anecdote of a lady who went to England ‘pour renouveler ses idées.’ The lady was perhaps fulfilling Montesquieu’s famous advice, to travel in Germany, sojourn in Italy, and think in England.

Anglomania was thus more than a passing fashion; it was but the superficial evidence of a respect for English philosophy of life which Frenchmen had taken more seriously than had the English themselves. It happened, as it has happened more than once, that English literature was more highly esteemed abroad than at home. ‘Nous avons augmenté,’ said Madame Necker to Gibbon,[20] ‘jusque chez vous la célébrité de vos propres auteurs.’ English novels were read in France for the new ideals of life which they were supposed to embody, and much that in England was a mere pastime—Clarissa, for example—became in France a philosophy of conduct. A philosopher like Hume, and a philosophical historian like Gibbon, found that Paris delighted to honour the prophets whom England was too careless to stone.

The pupil had thus outrun his master, and had indeed become the master. In the earlier decades of the century, Voltaire and Montesquieu had gone to England to enjoy the privilege of thought: in the later decades[15] Englishmen visited Paris for a precisely similar purpose. From the middle of the century until the outbreak of war in 1778, Englishmen could discover in the conversations of the salons what a nation, always radical at heart, had made of the theories of free thought, liberty, and equality before the law, which they had, through Voltaire and Montesquieu, derived long since from England. English authors were received with a cordiality and a deference which had never been shown them in their own country. They found in Paris a social system conducted in honour of authors and of the philosophies which they were disseminating. It was the salon, the forcing-bed of the new ideas.

The one unfailing characteristic of the salon, in all ages and in all countries, is the dominant position which it gives to woman. It is woman who creates the peculiar atmosphere and the peculiar influence of salons; it is she, with her instinct for society and for literature, who is most likely to succeed in the attempt to fuse two ideals of life apparently opposed, the social and the literary. The salon is not a mere drawing-room and not a lonely study, but mediates between the promiscuous chatter of the one and the remote silence of the other. The aims of the salon are well shown by the ridicule of those enemies who accuse the hostess of attempting to transform a school of pedants and hacks into a group of courtiers. The social world is likely to laugh at the salon because it suggests the lecture-hall, and scholars sneer at it because it pretends to the distinction of a literary court.

The first salons were indeed courts—the courts of the Italian Renaissance. We find in the Parisian salons of later centuries the disjecta membra of this earlier Italian society, whose true relationship is understood only when we trace them back to this remote[17] original. In the light of that Italian dawn, all leaps into a consistent scheme. Much that seems odd and unrelated in salon life is brought into perspective: the authoritative position of the scholar, the unique influence of woman, and the tendency to set up ‘Platonic’ relations between the sexes. Humanism, Platonism, and gallantry were aspects of the Renaissance and of the Italian Court, and in their lesser manifestations as learning, philosophism, and ‘Platonic love,’ they remain characteristic of salons. Again, the courts of the fifteenth century brought into focus many movements: they carried on the mediæval system of patronage; they adopted many of the gallantries of the old ‘courts of love’; and they brought the new humanism into vital contact with society, so that the expression of serious thought was no less possible in conversation than in the study or the lecture-hall. Each of these lives on in the salon.

The Renaissance court may be studied in any one of a numerous group. We may find the ideal set forth in the group of artists and men of letters who surrounded the youthful Beatrice d’Este, patroness of Leonardo and many another; we may see it in the court of her sister, Isabella, Marchioness of Mantua; we may see it in the coterie of Caterina Cornaro, once Queen of Cyprus, and in her later days mistress of a little court[21][18] at Asolo. We may study it at its grandest in the somewhat earlier court of Lorenzo the Magnificent, with its conscious imitation of the Greek symposium. The court which held Politian, Pulci, Ficino the Platonist, Alberti, and, later, Michelangelo, might well have boasted itself ‘the little academe’ of Love’s Labour’s Lost. But perhaps the most useful example is the delightful court of Urbino, described by Castiglione in his Cortegiano.

If it be objected that Castiglione’s description of court life is too radiant to be quite true to fact, if it be a society fairer than any whose existence can be demonstrated, I reply that it is so much the better suited to our purpose. It is ideals that we would be at. We are spared the attempt to reconstruct them for ourselves. There is nothing to be gained by reminding ourselves that courts attracted the parasite, the flatterer, and the opportunist; it is the finer aims of the men of genius and of the noble women who patronized them that will reward our attention. Castiglione knew these aims, and we cannot do better than quote his words as they were given to Elizabethan England in Hoby’s beautiful translation.[22] The first quotation refers to Frederick, first Duke of Urbino:

This man emong his other deedes praisworthy, in the hard and sharpe situation of Urbin buylt a Palaice, to the opinion of many men, the fayrest that was to be founde in all Italy, and so fornished it with everye necessary implement belonging thereto, that it appeared not a palaice, but a Citye in fourme of a palaice, and that not onlye with ordinarie matters, as Silver plate, hanginges for chambers of verye riche cloth of golde, of silke and other like, but also for sightlynesse: and to decke it out withall, placed there a wonderous number of auncyent ymages of marble and mettall, verye excellente peinctinges and instrumentes of musycke of all sortes, and nothinge would he have there but what was moste rare and excellent. To this with verye great charges he gathered together a great number of most excellent and rare bookes, in Greke, Latin and Hebrue, the which all he garnished wyth golde and sylver, esteaming this to be the chieffest ornament of his great palaice....

We turn now to the court of his son Guidobaldo, who carried on the traditions of his father:

He sett hys delyte above all thynges to have hys house furnished with most noble and valyaunte Gentylmen, wyth whom he lyved very famylyarly, enjoying theyr conversation wherein the pleasure whyche he gave unto other menne was no lesse, then that he receyved of other, because he was verye wel seene in both tunges, and together with a lovynge behavyour and plesauntnesse he had also accompanied the knowleage of infinite thinges.... Because the Duke used continuallye by reason of his infirmytye, soon after supper to go to his rest, everye man ordinarelye, at that houre drewe where the Dutchesse was, the Lady Elizabeth Gonzaga. Where also continuallye was the Lady Emilia Pia, who for that she was endowed with so livelye a wytt and judgement as you knowe, seemed the maistresse and ringe leader of all the companye,[20] and that everye manne at her receyved understandinge and courage.[23] There was then to be hearde pleasaunte communication and merye conceytes, and in every mannes countenaunce a manne myght perceyve peyncted a lovynge jocundenesse. So that thys house truelye myght well be called the verye mansion place of Myrth and Joye. And I beleave it was never so tasted in other place, what maner a thynge the sweete conversation is that is occasioned of an amyable and lovynge companye, as it was once there.... But such was the respect which we bore to the Dutchesse wyll, that the selfe same libertye was a verye great bridle. Neither was there anye that thought it not the greatest pleasure he could have in the worlde, to please her, and the greatest griefe to offende her. For this respecte were there most honest condicions coupled with wonderous greate libertye, and devises of pastimes and laughinge matters tempred in her sight.... The maner of all the Gentilmen in the house was immedyatelye after supper to assemble together where the dutchesse was. Where emonge other recreations, musicke, and dauncynge, whiche they used contynuallye, sometyme they propounded feate questions, otherwhyle they invented certayne wytty sportes and pastimes, at the devyse sometyme of one sometyme of an other, in the whych under sundrye covertes,[24] often tymes the standers bye opened subtylly theyr imaginations unto whom they thought beste. At other tymes there arrose other disputations of divers matters, or els jestinges with prompt inventions. Manye times they fell into purposes,[25] as we now a dayes terme them, where in thys kynde of talke and debating of matters, there was wonderous great pleasure on all sydes: because (as I have sayde) the house was replenyshed wyth most noble wyttes.

Such conversational ‘pastimes’ were enjoyed almost every night:

And the order thereof was such, that assoone as they were assembled where the Dutches was, every man satt him downe at his will, or as it fell to his lot, in a circle together, and in sittinge were devyded a man and a woman, as longe as there were women, for alwayes (lightlye) the number of men was farr the greater. Then were they governed as the Dutchesse thought best, whiche manye times gave this charge unto the L. Emilia.

Il Cortegiano is the tribute paid to this group and the conversation which passed in it. The spirit of the book is not to be shown by a few quotations, but a reading of it will reveal the following facts: that men and women meet on a plane of equality, that it is the presence of women (though fewer in number than the men), that gives the peculiar tone of lightness and gallantry; that the author looks to the court not only for reward, but for inspiration; that the conversation at its noblest (as in Bembo’s discourse at the end) passes over into poetry; that the conversation is of a classical and philosophic cast, often Platonic, but that this high seriousness does not exclude mirth and wit.[26][22] Now these aims are no other than the aims of the salon.

This ideal, diffused over Europe, had a long and brilliant history. We shall encounter it again in the courtly salons of Elizabethan England, and even in the comedies of Shakespeare. The tradition passed over into France and there became the formative influence in the great type and parent of the Parisian salon, the Hôtel de Rambouillet.

In tracing the Hôtel de Rambouillet back to the earlier Italian court, two facts stand out as of first importance. In the first place, that salon was established by a woman who was herself half Italian, had passed many years in Italy, and knew the traditions of the old nobility. In the second place, the Hôtel de Rambouillet originated in protest against the crudities of the Gascon court at Paris, and represented an attempt to realize a worthier society.

When, in the second decade of the seventeenth century, Cathérine de Vivonne opened her famous house in the Rue Saint Thomas du Louvre and initiated the reign of good taste in France, her salon displayed almost immediately certain aspects which had distinguished the Italian courts and which were to become, in varying degrees, permanent features of the Parisian salon and of its London counterpart. The Marquise de Rambouillet became the type and exemplar of all the later hostesses. Even the English bluestockings were aware that they were in the line of descent from her. In her[23] poem Bas Bleu,[27] Hannah More compares the English group with that which met in the Hôtel de Rambouillet, and Wraxall[28] later took up the comparison and developed the parallel between the drawing-rooms of London and those of Paris. The Hôtel de Rambouillet, therefore, is the type of the salon. It enables us to distinguish what is permanent and common to all salons, from what is merely transitory. For the sake of convenience, I shall make a fivefold grouping of these features. It will of course be understood that this analysis does not afford a complete characterization of the Hôtel de Rambouillet; for that society had certain important aims—such as the attempt to purify the language—which were not destined to remain permanent marks of the succeeding salons, and are therefore passed over in silence. Nor must it be assumed that the fivefold analysis describes each and every later salon. A given salon may be entirely lacking in one of the features—though never, I think, in a majority of them—without losing its character; and in proportion as a given salon satisfies these five conditions, we may say that it approaches the ideal.

(1) In the first place, then, the house, the very[24] room, in which the company gathers, is influential in forming its spirit and establishing its reputation. We have just examined Castiglione’s description of the magnificence of Urbino: something of that royal splendour is demanded of the salon. It was Madame de Rambouillet’s sense for architectural arrangement and decoration that contributed to her social success. Indeed the name by which her salon is known plainly implies it. As is well known, she began by breaking up the great reception-hall with its vast, unsocial coldness into a series of smaller rooms and alcoves, thus providing for the intimacies of conversation as distinct from the hubbub and the crowd. Her own favourite room, the chambre bleu d’Arthénice,[29] where a privileged few—at most eighteen—sat by her couch, was the centre and soul of the house. It was the perfumed temple of the Graces, where the year was always at spring, the haunt of Flora, and the throne of Athena herself. This room reproduced itself in countless ‘alcoves,’ ‘blue rooms,’ and ruelles throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Madame de Boufflers was famous for her apartments hung with rose-coloured damask, and Madame Geoffrin for her house, which was crammed with rare china and bronzes, portraits by Boucher, and easel-pictures by Van Loo.

(2) The salon must retain an aristocratic tone, but without submitting to the unyielding formality of the[25] aristocracy. It sets up a standard of recognition based on talent,[30] and neither courts nor rejects the nobility. It was even possible for the bourgeois to obtain admission to the Hôtel de Rambouillet and to have a career there. Vincent Voiture, known as ‘Chiquito,’ the son of a wine-merchant, became the leading spirit in all the amusements. His position reminds us now of the mediæval jester, now of Beau Nash, the King of Bath.

In the eighteenth century the salons are proud to represent a democracy of genius. Madame Geoffrin was the daughter of a valet de chambre and the wife of a manufacturer; Madame Necker was the daughter of a Swiss parson; and Mlle. de Lespinasse, a foundling, who had been ‘humble companion’ to Madame du Deffand, and who had not means sufficient to entertain her guests at dinner. Wit, intellect, and personality, rather than noble birth, became the key to social success.

(3) The chief staple of entertainment offered by the salons is conversation, literary or philosophical in character. Other amusements, such as Castiglione describes at Urbino, are not necessarily excluded, and, in France, dancing, excursions, card-playing, and gaming were popular in various salons and at various times. But conversation always reasserted itself in[26] the end. Discussion was stimulated by the reading of original poems, essays, sermons, and plays. The criticism of these, especially of the plays, was of no mean importance in forming the spirit of French literature. In particular the salon gives birth to certain minor forms of literature, epistles, epigrams, extempore verses of all kinds, ‘thoughts,’ maxims, bons mots, ‘portraits,’ and éloges;[31] but of more importance than these is its unconscious formative influence on such arts as letter-writing, biography, and all manner of anecdotal writing.

(4) The friendships of the salon are of peculiar depth and warmth, developing occasionally into passion, but always Platonic rather than domestic in their expression. Thus the salon, in which woman assumes the throne, and queens it over a coterie (chiefly men) is perhaps the last phase of the Italian court with its gallantries and lady-worship. It passed on to the French salon that note of sentiment and Platonic love which is found in Il Cortegiano, and which becomes characteristic of Sappho Scudéry and the later seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century this sentimental friendship united with the more practical system of patronage, and resulted in a type of relationship which eludes definition, for, on the one hand, it is at times so utilitarian as to savour of philanthropy,[27] and, on the other, it may develop into a grande passion, and compare itself to Abelard and Héloïse. Examples of it are the various relations existing between Madame Geoffrin and Marmontel, Madame du Deffand and d’Alembert, Madame du Deffand and Horace Walpole, Madame de Boufflers and David Hume, Mlle. de Lespinasse and d’Alembert, Mlle. de Lespinasse and Guibert, Madame Necker and Edward Gibbon.

(5) The hostess of the salon is invariably the subject of ideal descriptions, ‘tributes’ which recite her charm as a hostess, her merits as a patron, and her general superiority to the Muses. From Castiglione’s eulogy of Elizabeth Gonzaga, through the Hôtel de Rambouillet (where Malherbe was a kind of poet laureate), down to the death of Mlle. de Lespinasse, whose genius was celebrated by d’Alembert in the Tombeau de Mlle. de Lespinasse, this is an almost unfailing result of salon life.

Such are, then, the permanent marks by which we may detect that interplay of the social and the literary life in what, for want of a better term, we call the salon. There are two features of the life manifested only at certain times which it is not proper to include, though they are more generally attributed to the salons than any that have been mentioned. They are transitory phases; but they must be briefly considered, if only by way of avoiding false assumptions.

The women of the salons are usually thought of as[28] femmes savantes, or ‘learned ladies,’ who affect a learning which has no basis in fact. Such female pedants were common figures in the salons of a certain period. The depiction of them by Molière is no more exaggerated than the purposes of comic art demand. It must be further admitted that such women may appear now and again in the salons of any period; we shall meet with a few in the pages of this volume. But they are not common in the best salons of the best periods. Neither in the beginning, nor in the eighteenth century, were the hostesses of the salon what we ordinarily mean by the phrase femmes savantes. Of Madame de Rambouillet, for example, M. Vourciez writes:[32] ‘Ce sont les aliments les plus solides qu’elle digérait sans prétention à devenir une “femme savante,” car Balzac eût pu lui adresser à elle aussi le compliment qu’il fit à Madame des Loges: “Vous savez une infinité de choses rares, mais vous n’en faites pas la savante, et ne les avez pas apprises pour tenir école.”’ As for the women of the next century, they assisted their friends chiefly by qualities which have little to do with book-learning, by superb intelligence, wit, sympathy, and good taste. They made no pretence to erudition. Indeed they rather piqued themselves on their ignorance of it. To mistake Madame Geoffrin, who said she could not spell, and Madame du Deffand, who was bored by a savant, for a woman like Armande[29] or Bélise is to have done with all distinctions at once. It is to confound Prospero with Polonius.

It is no less true that the women of the salons were not permanently précieuses ridicules. Preciosity had its day; it did its work (which was by no means contemptible); and it was laughed out of existence. There were no précieuses in 1750. Indeed the caustic penetration of Madame du Deffand,[33] the homely wit of Madame Geoffrin, and the romantic ardour of Mlle. de Lespinasse are at equal removes from the conceits and the mincing niceties of the earlier salons. ‘Il n’y a que le premier pas qui coûte,’ said Madame du Deffand of Saint Denis walking with his severed head in his hands; ‘Je suis une poule qui ai couvé des œufs de canard,’ said Madame Geoffrin of herself and her daughter; ‘Presque personne n’a besoin d’être aimé,’ said Mlle. de Lespinasse to her faithless lover. Is this the language of preciosity?

A salon is not a mere literary club. It is something other than a group of men and women gathered in a drawing-room to discuss literature or meet a poet. It aims to exert a creative influence in the literary world. It does not concern itself with literature as a finished product to be studied, but with literature as a growing thing that may be trained. Hence it gets behind the product to the producer, and seeks to influence the characters and ideas out of which books are formed. It is an informal academy. Its aim is private in that it is directly concerned with improving the condition of authors, and public in that it attempts to mould public opinion.

Thus it is, at bottom, a system of patronage. It offers to the author that aid, advertisement, and protection which he had once sought from a patron. Patronage of literature was, as we have seen, an essential feature of the court life of the Renaissance. It had lived on through the seventeenth century at courts and in noble houses. During its rapid decline in the eighteenth century, many of its duties were taken over by the salons. In the person of the hostess, the salon[31] made gifts of money, granted unofficial pensions, paid printers’ bills, and even gave authors a home. Walpole was amused at the number of authors who were ‘planted’ in the homes of French ladies. Madame Geoffrin in Paris, like Mrs. Montagu in London, was recognized as a patron of all the arts, and both gave of their wealth to the support of indigent or improvident authors.

But the salon bestowed a yet more valuable favour in its recognition of literary merit. Like the patron, it vouched for new authors. It gave its support to their new ideas. And in this subtler form of patronage, in the discharge of the duties of a literary jury or academy, it anticipated the modern press, for it had similar influence and fell into similar errors. Like the modern critical review, it was at once feared and courted by authors who affected at times to despise its pronouncements but never ignored them. The salon mediated between the author and the public. It aimed, like a true critic, to correct both the conceit of the author and the indifference of the world. It responded to a genuine critical demand created by the disappearance of the outworn system of patronage and by the rapid growth of a reading democracy. The salon sprang into renewed activity during a period of transition. It served a peculiar need during changing conditions, and passed away with the dawn of a new century which had its own system of criticism by which to dispense fame and to create opinion.

The growing spirit of independence in the author had already caused grave dissatisfaction with the old order of things, as the increasing tendency to enjoy the society of his fellows in clubs and taverns had prepared the author for the new order of social patronage. D’Alembert, in his Essay on Men of Letters, speaks of the old system in terms of strong disgust. The rôle of courtier is the most despicable that can be acted by a man of letters. Authors and peers should meet on a plane of equality. ‘Les seuls grands Seigneurs dont un homme de lettres doive désirer le commerce, sont ceux qu’il peut traiter et regarder en toute sûreté comme ses égaux et ses amis.’[34] Here is a man who will not lightly expose himself to feel the sting of charity, for whom a new system not wanting in grace and true appreciation must be devised. The Essay was translated into English in 1764. The original must have been written about the time when Johnson was penning his immortal definition of patron, ‘a wretch who supports with insolence and is paid with flattery.’

Was it possible for the reading world to render assistance to men of this temper? Could a way be found to make grants of money or to draw attention to worthy writings without an offensive display of philanthropy? Was it not possible to assist an author, yet cause him to feel that any favour was conferred[33] by himself? The salon was the answer. It summoned authors out of their seclusion and segregation, and confidently bade them show the world that genius might express itself elsewhere than in the study or the coffee-house. Let them try an appeal to a ‘select public.’ Let them, by the charm of their conversation in a congenial company, break down the barriers of indifference and prejudice. It was a call to men of letters to treat with the world. The drawing-room in which they were received, not as a dependent or tool, but as chief guests doing honour to the company by their presence, was a new field of arbitration between authors and the world.

In the successful execution of any plan for the social recognition of letters, woman must have a prominent place. If the drawing-room is to replace the tavern as a favourite resort of authors, the presence of woman is as truly implied in the one as her absence is from the other. The shift from the coffee-house to the drawing-room was indeed a plain tribute to woman, the new critic and the new patron. As she was already displaying her power in the world of readers by bringing a new tone of refinement into literature, she was exerting the same power to draw the men of letters into her salon.[35]

It was the peculiar fortune of France to produce women to discharge this social and literary duty whose personality is at once so brilliant and so influential that it rises to the level of genius. These women are not merely persons gifted with an instinct for social leadership; they are, like Cleopatra and Elizabeth, types of their sex and a revelation of its power. They are the very symbols of the century, ‘the abstract and brief chronicles of the time.’ In the amazing career of Madame de Tencin may be read the abandoned profligacy with which the seventeenth century closed, and which, in sheer disillusion, turned with the new century to decency and to letters. In Madame Geoffrin we see the surpassing common sense of the period, its force, its humour, its kindliness, and perhaps something of its hardness. As the best of the bourgeois is typified in Madame Geoffrin, the aristocracy of the ancien régime is expressed in Madame du Deffand. Its merciless clarity, its wit, which is wisdom in masquerade, its hardness of heart and contempt of spiritual things, and, one is tempted to say, even its blindness, are they not found in her? And the desolation of her last years, with their appealing cry for love, are they not, as Lanson has said,[36] the hunger of the heart which turns at last to the gift of love and the sweetness of tears? But it is Mlle. de Lespinasse who reveals[35] romanticism in its full blow. In the history of that movement the tornado of passions which convulsed her spirit and at length destroyed her are no less typical than the sorrows of Werther, or the pageant of Byron’s bleeding heart.[37]

It was by force of personality and by their attitude towards life that these women succeeded in influencing literary movements. It is not by learning or authorship that they hold a place in the history of French literature. Not one of them was known to her own circle as an author or as ambitious to become one. Madame de Tencin was, to be sure, a novelist, but she concealed the fact from all her friends save Montesquieu and Fontenelle, allowed her works to be attributed to others, and kept her secret as long as she lived. Madame du Deffand and Mlle. de Lespinasse have attained fame as letter-writers, but through no conscious effort on their part. Their dread of authorship is easily explained. A successful hostess must avoid giving the impression that she is forming a coterie in order to have readers for her books. Madame du Bocage found her authorship of no assistance in her career as hostess: she was laughed at as a femme savante, and her guests were said to be invited for the purpose of praising her poems.

As personality is of more consequence to the hostess[36] than authorship, so maturity of experience is of more value to her than youth and beauty. None of these women, except Madame du Bocage (‘forma Venus, arte Minerva’) pretended to the fascinations of youth. Madame de Tencin was forty-six when her salon became famous; Madame Geoffrin was fifty when she succeeded Madame de Tencin as the chief hostess in Paris, and she was sixty-seven when, as ‘queen-mother,’ she made her triumphal visit to the King of Poland. Madame du Deffand was sixty-eight when, in the eyes of Walpole, she eclipsed all the other hostesses in Paris; when she was eighty, Edward Gibbon still found in her salon, ‘the best company in Paris.’ Julie de Lespinasse, the youngest of them all, died—and died of love—at forty-four. It is not surprising that Walpole found in Paris the ‘fountain of age.’[38] ‘One is never old here,’ he writes, ‘or never thought so’; and elsewhere,[39] ‘The first step towards being in fashion is to lose an eye or a tooth. Young people I conclude there are, but where they exist I don’t guess: not that I complain; it is charming to totter into vogue.’ Ten years later he finds no change:[40] ‘It is so English to grow old! The French are Struldbrugs improved. After ninety they have no more caducity or distempers, but set out on a new career.’

Laurence Sterne goes into greater detail. Of the[37] second period in the life of a French woman of fashion, he says:[41] ‘When thirty-five years and more have unpeopled her dominions of the slaves of love, she repeoples it with the slaves of infidelity.’ Here of course is a glance at the atheism of the philosophes. In morals, politics, and philosophy, the Parisian salon is frankly on the radical side. It not only welcomes new ideas, but goes in search of them. Radicalism becomes its measure of success. The prevailing hostility to the Church and the contempt for anything savouring of dogma caused those who might hold orthodox or conservative views to conceal them, lest they be taken as evidence of a cowardly spirit or a feeble mind. Adherents of the Church, priests, Jesuits, the whole tribe of dévots, and at last even the deists, were condemned as pharisees and time-servers. Voltaire himself was too cautious. ‘Il est bigot,’ said a woman to Walpole,[42] ‘c’est un déiste.’ When Hume was admitted to Madame Geoffrin’s, he found no deists there, for all had, presumably, passed on to atheism. Madame Geoffrin herself retained an odd sort of formal relation with the Church which amazed her friends who whispered about it as though it were some scandalous liaison.

Thus the salons developed a looseness of morals and[38] a so-called freedom of thought which their exponents were fain to regard as a splendid audacity. Such ideals are still dear to a certain class of writers chiefly composed of minor poets. But the wits of the eighteenth century promulgated their doctrines without the aid of that slovenliness which is indispensable to our free-thinking Bohemians. They adopted a manner approved of the world in order that they might win the world. They avoided anything that might make themselves or their speculations ridiculous, for they wished to recommend their theories to men, to challenge their intelligence, and to capture their interest. There is an odd simile used by Madame Necker[43] to account for Shakespeare’s fame in England, which is of no use whatever as explaining Shakespeare, but of great significance because of its obvious reference to the salons. She attributes the renown of the poet to the acting of Garrick who, for three hours daily, captures the hearts as well as the ears of the English people, and so has the same effect that is produced in Paris by conversation. The aim of the salon is, obviously, to create interest, to capture hearts. In the same letter, when urging Gibbon to come to Paris and enjoy the fruits of his fame, she says, ‘C’est là seulement ... qu’on fait passer ses sentiments dans l’âme des autres.’ There is the express aim of the salon:—to bring ideas out of the realm of the abstract down to the business[39] and bosoms of men. In such a process it is the function of the hostess to give unity and solidity to the divergent views of her coterie, and frequently to be the channel by which they reach the world.[44] Thus the salon became a source for the dissemination of ideas and of a new and radical philosophy.

But what of the influence of the salon upon the authors who composed it? That it produced an effect upon them the least sympathetic was obliged to acknowledge: ‘At worst,’ says Walpole,[45] ‘I have filled my mind with a new set of ideas.’ There men corrected as well as expanded their personal views. There they might ‘clarify their notions by filtrating them through other minds.’[46] The salon gave an opportunity for the development of ideas in a new medium—the liveliness of conversation. At such time, when the formulation of opinion is stimulated by contact with other minds, when all barriers are down, all dread of critics forgotten, a man may give free rein to his doctrines and borrow all the brilliancy that lives in exaggeration.[47] The pomposity of the platform[40] and the solemn pedantry of the study disappear, and a man talks for the joy of talking. He makes up in vivacity what he loses in dignity. When an author deserted the salons, as did Rousseau, it frequently indicated a state of self-absorption which was not always advantageous; and, on the other hand, when an author made his submission to them, the result was frequently evident in a note of urbanity and in a piquancy of illustration which he could hardly have attained elsewhere.[48] Thus the function of the salon was to preserve the sanity and clarity of literature, to keep authors abreast of the times and in touch with one another and with the world. But in this alliance of authors with the world, in this exchange of solitude for society, of the study for the drawing-room, there were dangers which threatened the very life of literature; for it was an attempt to serve two masters. Far from removing the petty faults of a literary life, it brought with it a host of new ones—flattery, the overestimation of the works of a clique, the attempt to direct public opinion by force, and above all, the cultivation of the graces at the expense of the imagination. There was actually a tendency towards the dangers of democracy—the surrender to majority, the descent to a common level—but without a saving reliance upon the elemental instincts of mankind.[41] The whole prophetic side of literature, the vision of the poet, the glory and the folly of the ideal, priest and lyrist, Wordsworth and Shelley, de Vigny and de Musset—these are all beyond the ken of salons. But they had their office. It was their function to teach the observation of life, to lend clearness and vivacity to style, and so to add a charm to learning, to win the ignorant and to elevate the frivolous by showing that dulness could be overcome with wit and pedantry with grace.

The English visitor was a familiar figure in the Parisian salon. In an age when travellers were studying manners rather than mountains, and preferred the society of philosophers to the finest galleries in Europe, no visit to Paris was complete without a conversation with good Madame Geoffrin or an hour with the ‘blind sibyl,’ du Deffand of the bitter tongue. A stream of Englishmen from Prior to Gibbon poured through their drawing-rooms[49] and listened with interest or with alarm to the philosophes who were, to use Walpole’s words,[50] busily pulling down God and the King. Sometimes a returning traveller proved his acquaintance with this society by sacrificing his veracity. Thus Goldsmith asserted[51] that he was present ‘in a select company of wits of both sexes at[43] Paris’ when Diderot, Fontenelle, and Voltaire disputed about the merits of English taste and learning. The interview, it has been repeatedly shown, could hardly have taken place, inasmuch as during the months when Goldsmith must have been in Paris, Voltaire was never once there. But the very lie is eloquent, for it shows the kind of experience in Paris which English authors sought and prized.

The cosmopolitan tone was contributed to the salon by the eighteenth century. It begins with Madame de Tencin. This brilliant woman, somewhat promiscuous in all her tastes, expanded the influence of her drawing-room, and thereby that of later salons, by welcoming distinguished men without respect of nationality; nor were foreigners slow to improve the opportunity of meeting a woman who was no less renowned for her social prestige than for the picturesque iniquity of her past. Her salon was in truth the atonement which she offered the world for the sins of her youth.

She had begun her career by running away from the convent where she had taken the veil. She used her secularized charms to win lovers, and used her lovers to advance her brother in the Church. She became mistress of the Regent, who snubbed her because she wished to talk business when his mind ran on love. The royal harlot then sank into a cheap adventuress; she gave birth to a son, destined to become famous as d’Alembert, and ‘exposed’ him on the steps of Saint[44] Jean le Rond in the hope of making an end of him. At length when a maddened lover shot himself to death under her own roof, she was imprisoned in the Bastille, where she languished for some months. And then, after her release, as if to show that she had a head if not a heart, she abandoned her career of profligacy as lightly as she had formerly abandoned a lover or a child, and opened a drawing-room which, with the death of Madame de Lambert in 1733, became the most brilliant and influential in Paris. Here for twenty years she reigned over such retainers as Montesquieu and Fontenelle. Her success is easier to understand than her motives. Certain it is, however, as Professor Brunel has suggested,[52] that she attracted the men of letters because she gave them to understand that their respect was the one thing in the world for which she cared.

Madame de Tencin had become intimate with Englishmen even before the days of her fame. She was that ‘eloped nun who has supplanted the nut-brown maid’[53] in the affections of Matthew Prior, during his diplomatic service in Paris in the winter[45] of 1712-13. She used him to bring the needs of her brother (whom Prior did not consider to be ‘worth hanging’[54]) before Lord Bolingbroke. He himself was presently avowing her his Queen, and himself her faithful and devoted subject ‘dans tous ses états.’[55] Leslie Stephen[56] considers that Bolingbroke made use of Madame de Tencin in his intrigues with the Regent; but however this may be, his intrigues with the Regent’s mistress became common gossip, and were published abroad by the ballad-singer in the streets.[57]

But Bolingbroke was not the only English peer who paid court to the ‘nonne défroquée.’ Lord Chesterfield was introduced to her by Montesquieu, and, in 1741, passed some time in her salon, during its later glory. Here he enjoyed the society of authors whom he was always pleased to regard as superior to those of his own country and whose works, particularly Montesquieu’s Esprit des Lois, Fontenelle’s Pluralité des Mondes, and the productions of Crébillon and Marivaux, he never tired of recommending to his son. Fontenelle, the placid death’s-head who had never laughed and who could lead a minuet at the age of ninety-seven, must have seemed to Chesterfield the [46]pattern of a man. And yet he could assert, a few years later, that Fontenelle had sacrificed somewhat too much to the Graces.[58]

But what did he think of Madame? What did the great exemplar of the bel air, himself a patron of letters, think of the life and aims of the salon? It is not easy to say. He flattered Madame de Tencin outrageously, according to his professed theories; he praised the good taste of Frenchmen (of which Madame was at once ‘le soutien et l’ornement’), and denounced the brusqueness of his countrymen according to his wont. He boasted himself[59] the ‘ami, favori, et enfant de la maison’ of Madame de Tencin. But when he had occasion to describe the literary life of Paris to his son, he declared that the salons were filled with gossips who talked nonsense and philosophes whose works were metaphysical fustian, verba et voces et praeterea nihil.[60] It was an institution which young Stanhope must visit, where he was to talk epigrams, false sentiments, and philosophical nonsense, but to which he was to maintain a large superiority. Yet, in spite of this show of indifference, I cannot but feel that Chesterfield liked the salon. What else in heaven or earth was there for such a man to like? What could have been more to his taste than its courtly union of intrigue and[47] elegance, of literature and wit, of free thought and easy morals? The salon certainly liked Chesterfield. ‘Let him come back to us,’ cried Montesquieu and the rest of them when Madame de Tencin had read his letter to the circle, and read it more than once. ‘He writes French better than we do,’ exclaimed Fontenelle, ‘qu’il se contente, s’il lui plaît, d’être le premier homme de sa nation, d’avoir les lumières et la profondeur de génie qui la caractérisent; et qu’il ne vienne point encore s’emparer de nos grâces et de nos gentillesses.’[61] When Madame de Tencin despatched this mass of flattery to Chesterfield, Fontenelle added a note begging the English lord not to draw down upon himself too much French jealousy.[62] Unless Chesterfield was, like Fontenelle, incapable of all human emotions, he was pleased by that. The Frenchmen had studied him well. They touched his vulnerable point, and posterity will not easily be persuaded that it was in vain.

‘In future, then,’ said Fontenelle, after the death of Madame de Tencin, ‘I shall go to Madame Geoffrin’s.’ The change must have supplied the aged wit with many observations on the diversity of the female[48] character; for though ‘la Geoffrin’ had studied the methods of her predecessor, there was no resemblance in character between the two. There is no suggestion of Madame de Tencin’s subtlety in the amiable bourgeoise who became a queen of society at fifty, but rather a rich simplicity of nature that is very winning. Her faults as well as her virtues are quite obvious. Her humour is for ever expressing itself in homely maxims[63] which suggest the lore of peasants. She made her way by the simplest means, a warm heart, abiding common sense, and a persistent will. Her keen intelligence, the gift of nature, not of books, enabled her to understand the philosophers at least as well as they understood themselves, to advise—almost lead—them, to be their ‘Mother,’ and to push them into the Academy. It is, at first blush, amazing that a woman without education, who, indeed, found grammar a mystery, could thus have become the empress of the wits. But living as she did in an ‘age of reason’ when the imagination was turning back to contemplate man in a ‘state of nature,’ unspoiled by the arts of a luxurious civilization, such a defect was not fatal. Shrewd, placid yet alert, simple and with[49] the sweep of vision that is given only to the simple, she looked out fearlessly upon the society of her time, with all its elaborate systems and new philosophies—and understood. As she was without fear, so she was without contempt. She saw what was good in the new order and encouraged it, but without becoming its slave. Like Johnson (whom she would have understood), she contrived to ‘worship in the age of Voltaire,’ but this was with no surrender of her interest in Voltaire. She was intolerant of pretence. She adopted a manner of treating her friends which, in its combination of brusqueness and affection, is thoroughly parental. She scolds and pushes, punishes and rewards. She decides disputes with a word. She spends with open hand. Her great desire is to be of help to her children. D’Alembert writes[64] of her, ‘“Vous croyez,” disait elle à un des hommes qu’elle aimait le plus, “que c’est pour moi que je vois des grands et des ministres? Détrompez-vous; je les vois pour vous et pour vos semblables, qui pouvez en avoir besoin: si tous ceux que j’aime étaient heureux et sages, ma porte serait tous les jours fermée a neuf heures, excepté pour eux.”’ But she never forgot that, in her own house, she alone was mistress. Her charity, which she conducted on a heroic scale, implied a certain obedience in the recipients of it; but both charity and obedience were only devices for promoting their interests. ‘Elle ne respirait que pour faire le bien,’ said[50] d’Alembert.[65] He and the other writers for the Cyclopædia profited by her charity, for without her patronage that great work could hardly have been carried to publication.

In the salon of Madame Geoffrin and her free-thinking friends, David Hume found, in 1763, a natural abiding-place. It had, indeed, a dual attraction for him in the person of its hostess and the character of her coterie. Madame Geoffrin must have found the Scotch philosopher a man after her own heart. She understood the broad-featured, simple man, whom she presently took to calling[66] her ‘coquin,’ her ‘gros drôle.’ Like her, he enjoyed the society of rationalists. He writes naïvely in his Autobiography: ‘Those who have not seen the strange effects of modes, will never imagine the strange reception I met with at Paris, from men and women of all ranks and stations. The more I resiled from their excessive civilities, the more I was loaded with them. There is, however, a real satisfaction in living at Paris from the great number of sensible, knowing, and polite company with which the city abounds above all places in the universe. I thought once of settling there for life.’ But he kept his head under the pelting flattery. He neither despised his social success nor exalted it as the summum bonum. Like Madame Geoffrin, he made no apologies for himself, and pretended to no social graces which he could not easily acquire. His French was[51] wretched. Walpole protested[67] that it was ‘almost as unintelligible as his English.’ He had no bons mots. He did not even talk much. Grimm found[68] him heavy, and Madame du Deffand dubbed him ‘the peasant.’[69]

But to more serious souls he was even as the Spirit of the Age. He had voiced the new scepticism. He had given the death-blow to miracles. Before his coming to Paris, all his better-known work had been done, and the fame of it preceded him. Alexander Street wrote from Paris to Sir William Johnstone, on December 16, 1762: ‘When you have occasion to see our friend, David Hume, tell him that he is so much worshipped here that he must be void of all passions, if he does not immediately take post for Paris. In most houses where I am acquainted here, one of the first questions is, “Do you know M. Hume whom we all admire so much?” I dined yesterday at Helvétius’s, where this same M. Hume interrupted our conversation very much.’[70]

His influence was, in truth, greater in France than in England; for the temper of English literature never became openly rationalistic. Deism itself was living a subterranean existence; for the authority of such powerful men as Johnson and Burke ran directly[52] counter to it. But in France all sails were set, and men’s faces turned towards ‘unpath’d waters, undreamed shores.’ To the ‘free’ thought that was becoming ever freer and now drifting towards all manner of negation, Hume came as a high priest, an acknowledged pontiff. He was the man whom the King delighted to honour, whose praises were lisped by the King’s children, who was approved by Voltaire, petted by all the women and revered by all the men. In less than two years, Walpole finds him[71] ‘the mode,’ ‘fashion itself’; he is ‘treated with perfect veneration,’ and his works held to be the ‘standards of writing.’ Hume himself writes to Fergusson[72] that he overheard an elderly gentleman, ‘esteemed one of the cleverest and most sensible’ of men, boasting that he had caught sight of Hume that day at court.[73] At last they pay him the compliment (Madame Geoffrin leading off, no doubt) of ‘bantering’ him and telling droll stories of him. He begins to fear that the great ladies are taking him too much from the society of d’Alembert, Buffon, Marmontel, Diderot, and the rest.[74]

Among the distinguished women in Paris who wooed him were Mlle. de Lespinasse, Madame du Bocage,[53] who sent him her works, and the Marquise de Boufflers, who made no secret of her fondness for the British. This lady once cherished a ‘petite flamme’[75] for Beauclerk, Johnson’s gay friend, and even crossed the path of the Lexicographer himself; for it was she whom Johnson, like a squire of dames, gallantly escorted to her coach, and afterwards honoured with a letter. The sentimental homage which she paid to Hume incurred the contempt of Madame du Deffand, who sneered at her worship of false gods, and made her miserable by leading others to denounce her idol.[76]

Madame de Boufflers played a prominent part in the great quarrel between Hume and Rousseau, which involved many of the most prominent persons mentioned in this chapter. The story, which has been frequently told, may be briefly dismissed.[77] The union by which the sentimentalist gave himself in charge to the rationalist, might well have furnished a Hogarth with a subject for an allegorical group representing Scotch solidity and Gallic perversity. Hume, through Madame de Boufflers, had assured Rousseau that he could find in England appreciation, friends, and a true[54] home; and the ill-assorted pair accordingly departed from Paris early in 1776. It was not long before wild letters reached the salons.[78] The two philosophers were hurling epithets at each other, scélérat! traître!

The most immediate cause of their rupture was a letter, written by Walpole, to amuse Madame Geoffrin’s coterie. It purported to be by the King of Prussia, and invited Rousseau to come to court and enjoy his fill of persecution. A brief extract will show the character of this sprightly epistle:

Si vous persistez à vous creuser l’esprit pour trouver de nouveaux malheurs, choisissez-les tels que vous voudrez. Je suis roi, je puis vous en procurer augré de vos souhaits: et ce qui sûrement ne vous arrivera pas vis-à-vis de vos ennemis, je cesserai de vous persécuter quand vous cesserez de mettre votre gloire à l’être.[79]

This letter, which had been touched up by Helvétius and the Duc de Nivernois, circulated in the salons, and at last found its way to England, where it was printed by various newspapers in April 1766. The quarrel between Rousseau and Hume, which had been threatening for some weeks, now burst in fury; for Rousseau believed that Hume was in league with Walpole to disgrace him.

Every one now plunged into controversy and correspondence. Mlle. de Lespinasse attempts to soothe feelings. D’Alembert outlines Hume’s campaign. Baron d’Holbach condoles. Walpole explains. Madame de Boufflers fears for the renown of philosophy. Madame du Deffand, who hated everybody concerned, except Walpole, and whom d’Alembert accused of having stirred up all the trouble, finally did as much as any one to put an end to it.[80] Nothing having been accomplished, and the vanity of all having been fully displayed, the matter subsided, leaving a general conviction in the mind of each that all the others had conducted themselves very foolishly.

Hume never returned to the salons, though Mlle. de Lespinasse implored and Madame de Boufflers protested. It was to the latter that he wrote the tranquil letter from his death-bed ‘without any anxiety or regret’[81] which elicited the admiration even of Madame du Deffand[82] and delighted the salons by showing that their favourite could die like a philosopher.[83]

Hume’s acceptance of the salon and its ideals is in[56] striking contrast to the fussy dissatisfaction of Horace Walpole. ‘I was expressing my aversion,’ he writes, ‘to disputes: Mr. Hume, who very gratefully admires the tone of Paris, having never known any other tone, said with great surprise, “Why, what do you like if you hate both disputes and whisk?”’ Walpole’s reply is not recorded. Certainly he did not like les philosophes and their conversation which he found ‘solemn, pedantic, and seldom animated but by a dispute.’[84] He hated authors by profession. He hated political talk (having practical knowledge and experience of politics). He hated savants, free thinkers, and beaux esprits, with their eternal dissertations on religion and government.[85] ‘I have never yet,’ he wrote[86] to Montagu, ‘seen or heard anything serious that was not ridiculous. Jesuits, Methodists, philosophers, politicians, the hypocrite Rousseau, the scoffer Voltaire, the encyclopedistes, the Humes, the Lytteltons, the Grenvilles, the atheist tyrant of Russia, and the mountebank of history Mr. Pitt, all are to me but impostors in their various ways.’ He is ‘sick of visions and systems that shove one another aside and come over again like the figures in a moving picture.’ Yet like all scoffers, he has nothing to set up in the place of all this. He could not give his heart to the new system, but he was equally incapable of being loyal to the old.[57] Dissatisfied with both, he laughed at both, and was nettled because he could find none in Paris to laugh with him. Laughing was not fashionable in the salons.[87] He despised the prevalent devotion to cards. He was scornfully amused at the popularity of the English in Paris—and even at his own popularity. ‘Vous n’observez,’ said Madame du Deffand, ‘que pour vous moquer; vous ne tenez à rien, vous vous passez de tout; enfin, enfin, rien ne vous est nécessaire.’[88] But there was one thing necessary to Walpole, and it was the thing he professed to despise—the salon. Without knowing the salons he could not ridicule them. No satirist can be a hermit. So Walpole frequented the salons, and vastly enjoyed, not the salons themselves, but his own superiority to them. It was at Madame Geoffrin’s that his career began. He brought a note of introduction from Lady Hervey, met Madame Geoffrin, and discovered to his surprise—and the reader’s—that he liked her. She had sense, ‘more common sense than he almost ever met with.’[89] He notes her quickness in penetrating character, her protection of artists, her services to them, and her ‘thousand little arts and offices of friendship,’ of which[58] latter she was presently to give him a specimen. When he had an attack of gout, she took him under her care. On October 13, 1765, he writes of her to Lady Hervey:

Madame Geoffrin came and sat two hours last night by my bedside:[90] I could have sworn it had been my lady Hervey, she was so good to me. It was with so much sense, information, instruction, and correction! The manner of the latter charms me. I never saw anybody in my days that catches one’s faults and vanities and impositions so quick, that explains them to one so clearly, and convinces one so easily. I never liked to be set right before! You cannot imagine how I taste it! I make her both my confessor and director, and begin to think I shall be a reasonable creature at last, which I had never intended to be. The next time I see her, I believe I shall say, ‘Oh! Common Sense,[91] sit down: I have been thinking so and so; is it not absurd?’—for t’other sense and wisdom, I never liked them; I shall now hate them for her sake. If it was worth her while, I assure your Ladyship she might govern me like a child.

The attention which he received was not without its effect, and at last he was obliged to admit himself pleased.[92] He does not know when he will return to England; and he dwells with delight on the honours and distinctions he receives.

He became one of the most prominent men in Parisian society, and for a time eclipsed the reputation of Hume[59] himself. The latter had been worshipped as a philosopher; Walpole reigned as a wit. The letter to Rousseau, which has been described above, captivated the salons, and probably even made them laugh. The jeu d’esprit, which had first occurred to him at Madame Geoffrin’s, so pleased him that he cast it into more elaborate form, displayed the forged letter in the salons, and became famous at once. ‘The copies,’ he writes to Conway, ‘have spread like wildfire; et me voici à la mode.’[93] It was long before Walpole heard the last of his jest; for, as we have seen, it involved him in the controversy between Hume and Rousseau, and Walpole hated controversy as much as he loved wit. But for the moment it served to draw the eyes of the French world upon him.

Meanwhile, he had become intimate with Madame Geoffrin’s great rival, the blind Madame du Deffand, now in her sixty-ninth year, who rapidly displaced Madame Geoffrin in his affections. By December 1765, he was supping with her twice a week, and in January he wrote Gray his famous description of her:[94]

Madame du Deffand was for a short time mistress of the Regent, is now very old and stone-blind, but retains all her vivacity, wit, memory, judgement, passions, and agreeableness. She goes to operas, plays, suppers, and Versailles; gives suppers twice a week; has everything new read to her; makes new songs and epigrams, ay, admirably, and remembers every one[60] that has been made these fourscore years. She corresponds with Voltaire, dictates charming letters to him, contradicts him, is no bigot to him or anybody, and laughs both at the clergy and the philosophers. In a dispute, into which she easily falls, she is very warm, and yet scarce ever in the wrong: her judgement on every subject is as just as possible; on every point of conduct as wrong as possible: for she is all love and hatred, passionate for her friends to enthusiasm, still anxious to be loved, I don’t mean by lovers, and a vehement enemy, but openly. As she can have no amusement but conversation, the least solitude and ennui are insupportable to her, and put her into the power of several worthless people, who eat her suppers when they can eat nobody’s of higher rank; wink to one another, and laugh at her; hate her because she has forty times more parts—and venture to hate her because she is not rich.[95]

It was natural that Walpole should prefer her society to Madame Geoffrin’s. Being Horace Walpole, it was inevitable that he should come to regard Madame Geoffrin’s coterie with disdain, to complain that it was made up of ‘pretended beaux esprits’ and faux savants, and that they were ‘very impertinent and dogmatic.’[96] Madame herself had offended him by calling him[97] ‘the new Richelieu’ in reference to his numerous conquests. Walpole grew suddenly afraid of the Geoffrin’s intimacy, and feared that he was becoming an object of ridicule. But in Madame du Deffand[61] he found one of his own sort, a woman used to the society of the great but with no illusions about it, a woman who ruled her circle by despising almost every one who came into it, who had no faith in any one, and least of all in the authors and diplomats who surrounded her, and whose society she endured only because she found it less intolerable than her dark solitude.

In a beautiful letter to her on her blindness, which had become total about a dozen years before the period when we encounter her, Montesquieu reminded[98] her that they were both ‘small rebel spirits condemned to darkness.’ There is in truth something suggestive of the powers of darkness in Madame du Deffand’s pride and perversity. She was of a will never to submit or yield. Pride in the reputation she had made, a passionate delight in conversation, and, above all, the horror of her lonely hours of introspection determined her to continue her salon in spite of all. She did not fail. But a blow hardly less grievous had yet to fall. Mlle. de Lespinasse, on whose assistance she had leaned, had caught the secret of her success, and was forming a coterie of her own, an inner circle within Madame du Deffand’s. When the blind woman learned of her assistant’s treachery, she broke with her, and Mlle. de Lespinasse departed, carrying with her d’Alembert, adored of Madame du Deffand, and his friends, the flower of the flock.

Even then the dauntless old woman would not give up. The aged sibyl in her ‘tonneau’[99] at the Convent Saint Joseph could still attract the curious and the clever. Blind as she was, her ‘portraits’ of character were better than Madame Geoffrin’s,—who excelled in portraits,—and the clarity of her vision was surpassed only by the crispness of her phrasing. At sixty-eight, she had an eager curiosity about her own times[100] that was a stimulus to youth. To speak with her was to witness the triumph of mind.