Title: The Bushman — Life in a New Country

Author: Edward Wilson Landor

Release date: December 1, 2004 [eBook #7181]

Most recently updated: August 10, 2012

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sue Asscher

The British Colonies now form so prominent a portion of the Empire, that the Public will be compelled to acknowledge some interest in their welfare, and the Government to yield some attention to their wants. It is a necessity which both the Government and the Public will obey with reluctance.

Too remote for sympathy, too powerless for respect, the Colonies, during ages of existence, have but rarely occupied a passing thought in the mind of the Nation; as though their insignificance entitled them only to neglect. But the weakness of childhood is passing away: the Infant is fast growing into the possession and the consciousness of strength, whilst the Parent is obliged to acknowledge the increasing usefulness of her offspring.

The long-existing and fundamental errors of Government, under which the Colonies have hitherto groaned in helpless subjection, will soon become generally known and understood—and then they will be remedied.

In the remarks which will be found scattered through this work on the subject of Colonial Government, it must be observed, that the system only is assailed, and not individuals. That it is the system and not The Men who are in fault, is sufficiently proved by the fact that the most illustrious statesmen and the brightest talents of the Age, have ever failed to distinguish themselves by good works, whilst directing the fortunes of the Colonies. Lord John Russell, Lord Stanley, Mr. Gladstone—all of them high-minded, scrupulous, and patriotic statesmen—all of them men of brilliant genius, extensive knowledge, and profound thought—have all of them been but slightly appreciated as Colonial rulers.

Their principal success has been in perpetuating a noxious system. They have all of them conscientiously believed their first duty to be, in the words of Lord Stanley, to keep the Colonies dependent upon the Mother Country; and occupied with this belief, they have legislated for the Mother Country and not for the Colonies. Vain, selfish, fear-inspired policy! that keeps the Colonies down in the dust at the feet of the Parent State, and yet is of no value or advantage to her. To make her Colonies useful to England, they must be cherished in their infancy, and carefully encouraged to put forth all the strength of their secret energies.

It is not whilst held in leading-strings that they can be useful, or aught but burthensome: rear them kindly to maturity, and allow them the free exercise of their vast natural strength, and they would be to the parent country her truest and most valuable friends.

The colonies of the Empire are the only lasting and inalienable markets for its produce; and the first aim of the political economist should be to develop to their utmost extent the vast resources possessed by Great Britain in these her own peculiar fields of national wealth. But the policy displayed throughout the history of her Colonial possessions, has ever been the reverse of this. It was that grasping and ungenerous policy that called forth a Washington, and cost her an empire. It is that same miserable and low-born policy that still recoils upon herself, depriving her of vast increase of wealth and power in order to keep the chain upon her hapless children, those ambitious Titans whom she trembles to unbind.

And yet poor Old England considers herself an excellent parent, and moans and murmurs over the ingratitude of her troublesome offspring! Like many other parents, she means to do well and act kindly, but unhappily the principles on which she proceeds are radically wrong. Hence, on the one side, heart-burning, irritation, and resentment; on the other, disappointment, revulsion, and alarm.

Is she too deeply prejudiced, or too old in error, to attempt a new system of policy?

In what single respect has she ever proved herself a good parent to any of her Colonies? Whilst supplying them with Government Officers, she has fettered them with unwholesome laws; whilst giving them a trifling preference over foreign states in their commerce, she has laid her grasp upon their soil; whilst allowing them to legislate in a small degree for themselves, she has reserved the prerogative of annulling all enactments that interfere with her own selfish or mistaken views; whilst permitting their inhabitants to live under a lightened pressure of taxation, she has debarred them from wealth, rank, honours, rewards, hopes—all those incentives to action that lead men forward to glory, and stamp nations with greatness.

What has she done for her Colonies—this careful and beneficent parent? She has permitted them to exist, but bound them down in serf-like dependence; and so she keeps them—feeble, helpless, and hopeless. She grants them the sanction of her flag, and the privilege of boasting of her baneful protection.

Years—ages have gone by, and her policy has been the same— darkening the heart and crushing the energies of Man in climes where Nature sparkles with hope and teems with plenty.

Time, however, too powerful for statesmen, continues his silent but steady advance in the great work of amelioration. The condition of the Colonies must be elevated to that of the counties of England. Absolute rule must cease to prevail in them. Men must be allowed to win there, as at home, honours and rank. Time, the grand minister of correction—Time the Avenger, already has his foot on the threshold of the COLONIAL OFFICE.

CHAPTER.

PLATES.

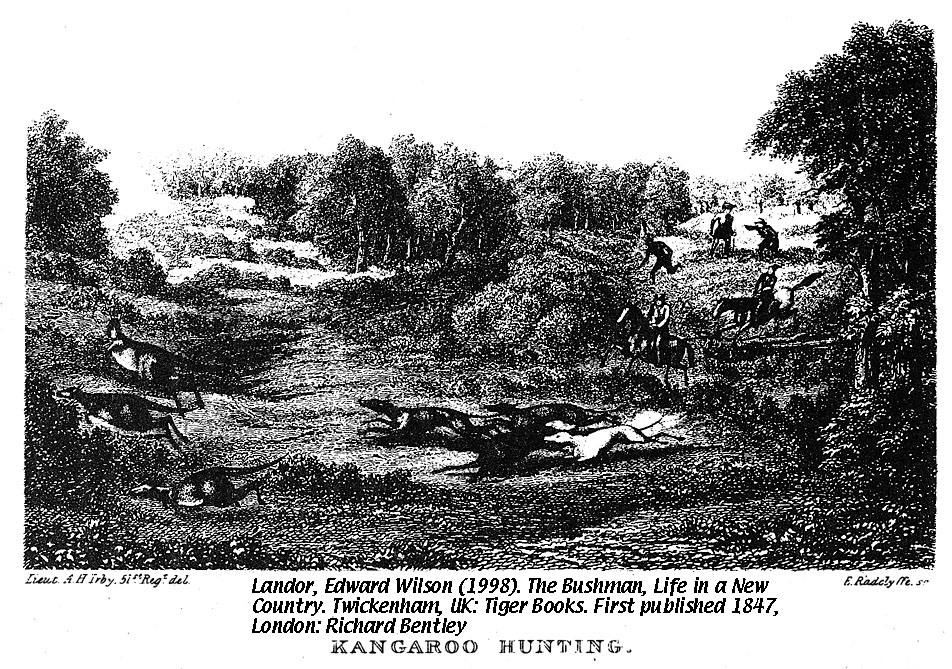

KANGAROO HUNTING (Frontispiece).

THE BIVOUAC.

SPEARING KANGAROO

DEATH OF THE KANGAROO.

EMU HUNT (woodcut).

THE BUSHMAN; OR, LIFE IN A NEW COUNTRY.

The Spirit of Adventure is the most animating impulse in the human breast. Man naturally detests inaction; he thirsts after change and novelty, and the prospect of excitement makes him prefer even danger to continued repose.

The love of adventure! how strongly it urges forward the Young! The Young, who are ever discontented with the Present, and sigh for opportunities of action which they know not where to seek. Old men mourn over the folly and recklessness of the Young, who, in the fresh and balmy spring-time of life, recoil from the confinement of the desk or the study, and long for active occupation, in which all their beating energies may find employment. Subjection is the consequence of civilized life; and self-sacrifice is necessary in those who are born to toil, before they may partake of its enjoyments. But though the Young are conscious that this is so, they repine not the less; they feel that the freshness and verdure of life must first die away; that the promised recompense will probably come too late to the exhausted frame; that the blessings which would now be received with prostrate gratitude will cease to be felt as boons; and that although the wishes and wants of the heart will take new directions in the progress of years, the consciousness that the spring-time of life— that peculiar season of happiness which can never be known again— has been consumed in futile desires and aspirations, in vain hopes and bitter experiences, must ever remain deepening the gloom of Memory.

Anxious to possess immediate independence, young men, full of adventurous spirit, proceed in search of new fields of labour, where they may reap at once the enjoyments of domestic life, whilst they industriously work out the curse that hangs over the Sons of Adam.

They who thus become emigrants from the ardent spirit of adventure, and from a desire to experience a simpler and less artificial manner of living than that which has become the essential characteristic of European civilization, form a large and useful body of colonists. These men, notwithstanding the pity which will be bestowed upon them by those whose limited experience of life leads to the belief that happiness or contentment can only be found in the atmosphere of England, are entitled to some consideration and respect.

To have dared to deviate from the beaten track which was before them in the outset of life; to have perceived at so vast a distance advantages which others, if they had seen, would have shrunk from aiming at; to have persevered in their resolution, notwithstanding the expostulations of Age, the regrets of Friendship, and the sighs of Affection—all this betokens originality and strength of character.

Does it also betoken indifference to the wishes of others? Perhaps it does; and it marks one of the broadest and least amiable features in the character of a colonist.

The next class of emigrants are those who depart from their native shores with reluctance and tears. Children of misfortune and sorrow, they would yet remain to weep on the bosom from which they have drawn no sustenance. But the strong blasts of necessity drive them from the homes which even Grief has not rendered less dear. Their future has never yet responded to the voice of Hope, and now, worn and broken in spirit, imagination paints nothing cheering in another land. They go solely because they may not remain—because they know not where else to look for a resting place; and Necessity, with her iron whip, drives them forth to some distant colony.

But there is still a third class, the most numerous perhaps of all, that helps to compose the population of a colony. This is made up of young men who are the wasterels of the World; who have never done, and never will do themselves any good, and are a curse instead of a benefit to others. These are they who think themselves fine, jovial, spirited fellows, who disdain to work, and bear themselves as if life were merely a game which ought to be played out amid coarse laughter and wild riot.

These go to a colony because their relatives will not support them in idleness at home. They feel no despair at the circumstance, for their pockets have been refilled, though (they are assured) for the last time; and they rejoice at the prospect of spending their capital far from the observation of intrusive guardians.

Disgusted at authority which has never proved sufficient to restrain or improve them, they become enamoured with the idea of absolute license, and are far too high-spirited to entertain any apprehensions of future poverty. These gallant-minded and truly enviable fellows betake themselves, on their arrival, to the zealous cultivation of field-sports instead of field produce. They leave with disdain the exercise of the useful arts to low-bred and beggarly-minded people, who have not spirit enough for anything better; whilst they themselves enthusiastically strive to realize again those glorious times,—

"When wild in woods the noble savage ran."

In the intervals of relaxation from these fatigues, when they return to a town life, they endeavour to prove the activity of their energies and the benevolence of their characters, by getting up balls and pic-nics, solely to promote the happiness of the ladies. But notwithstanding this appearance of devotion to the fair sex, their best affections are never withdrawn from the companion of their hearts—the brandy flask. They evince their generous hospitality by hailing every one who passes their door, with "How are you, old fellow? Come in, and take a nip." Somehow or other they are always liked, even by those who pity and despise them.

The women only laugh at their irregularities—they are such "good-hearted creatures!" And so they go easily and rapidly down that sloping path which leads to ruin and despair. What is their end? Many of them literally kill themselves by drinking; and those who get through the seasoning, which is the fatal period, are either compelled to become labourers in the fields for any one who will provide them with food; or else succeed in exciting the compassion of their friends at home, by their dismal accounts of the impossibility of earning a livelihood in a ruined and worthless colony; and having thus obtained money enough to enable them to return to England, they hasten to throw themselves and their sorrows into the arms of their sympathizing relatives.

Nothing can be more absurd than to imagine that a fortune may be made in a colony by those who have neither in them nor about them any of the elements or qualities by which fortunes are gained at home.

There are, unfortunately, few sources of wealth peculiar to a colony. The only advantage which the emigrant may reasonably calculate upon enjoying, is the diminution of competition. In England the crowd is so dense that men smother one another.

It is only by opening up the same channels of wealth under more favourable circumstances, that the emigrant has any right to calculate upon success. Without a profession, without any legitimate calling in which his early years have been properly instructed; without any knowledge or any habits of business, a man has no better prospect of making a fortune in a colony than at home. None, however, so circumstanced, entertains this belief; on the contrary, he enters upon his new career without any misgivings, and with the courage and enthusiasm of a newly enlisted recruit.

Alas! the disappointment which so soon and so inevitably succeeds, brings a crowd of vices and miseries in its train.

The reader may naturally expect to be informed of the reasons that have induced me thus to seek his acquaintance. In one word—I am a colonist. In England, a great deal is said every day about colonies and colonists, but very little is known about them. A great deal is projected; but whatever is done, is unfortunately to their prejudice. Secretaries of State know much more about the distant settlements of Great Britain than the inhabitants themselves; and, consequently, the latter are seldom able to appreciate the ordinances which (for their own good) they are compelled to submit to.

My own experience is chiefly confined to one of the most insignificant of our colonies,—insignificant in point of population, but extremely important as to its geographical position, and its prospects of future greatness,—but the same principle of government applies to all the British settlements.

A few years ago, I was the victim of medical skill; and being sentenced to death in my own country by three eminent physicians, was comparatively happy in having that sentence commuted to banishment. A wealthy man would have gone to Naples, to Malta, or to Madeira; but a poor one has no resource save in a colony, unless he will condescend to live upon others, rather than support himself by his own exertions.

The climate of Western Australia was recommended; and I may be grateful for the alternative allowed me.

As I shall have occasion hereafter to allude to them incidentally, I may mention that my two brothers accompanied me on this distant voyage.

The elder, a disciple of Aesculapius, was not only anxious to gratify his fraternal solicitude and his professional tastes by watching my case, but was desirous of realizing the pleasures of rural life in Australia.

My younger brother (whose pursuits entitle him to be called Meliboeus) was a youth not eighteen, originally designed for the Church, and intended to cut a figure at Oxford; but modestly conceiving that the figure he was likely to cut would not tend to the advancement of his worldly interests, and moreover, having no admiration for Virgil beyond the Bucolics, he fitted himself out with a Lowland plaid and a set of Pandaean pipes, and solemnly dedicated himself to the duties of a shepherd.

Thus it was that we were all embarked in the same boat; or rather, we found ourselves in the month of April, 1841, on board of a certain ill-appointed barque bound for Western Australia.

We had with us a couple of servants, four rams with curling horns— a purchase from the late Lord Western; a noble blood-hound, the gift of a noble Lord famous for the breed; a real old English mastiff-bitch, from the stock at Lyme Park; and a handsome spaniel cocker. Besides this collection of quadrupeds, we had a vast assortment of useless lumber, which had cost us many hundred pounds. Being most darkly ignorant of every thing relating to the country to which we were going, but having a notion that it was very much of the same character with that so long inhabited by Robinson Crusoe, we had prudently provided ourselves with all the necessaries and even non-necessaries of life in such a region. Our tool chests would have suited an army of pioneers; several distinguished ironmongers of the city of London had cleared their warehouses in our favour of all the rubbish which had lain on hand during the last quarter of a century; we had hinges, bolts, screws, door-latches, staples, nails of all dimensions—from the tenpenny, downwards—and every other requisite to have completely built a modern village of reasonable extent. We had tents, Macintosh bags, swimming-belts, several sets of sauce-pans in graduated scale, (we had here a distant eye to kangaroo and cockatoo stews,) cleavers, meat-saws, iron skewers, and a general apparatus of kitchen utensils that would have satisfied the desires of Monsieur Soyer himself. Then we had double and single-barrelled guns, rifles, pistols, six barrels of Pigou and Wilkes' gunpowder; an immense assortment of shot, and two hundred weight of lead for bullets.

Besides the several articles already enumerated, we had provided ourselves with eighteen months' provisions, in pork and flour, calculating that by the time this quantity was consumed, we should have raised enough to support our establishment out of the soil by the sweat of our brows. And thus from sheer ignorance of colonial life, we had laid out a considerable portion of our capital in the purchase of useless articles, and of things which might have been procured more cheaply in the colony itself. Nor were we the only green-horns that have gone out as colonists: on the contrary, nine-tenths of those who emigrate, do so in perfect ignorance of the country they are about to visit and the life they are destined to lead. The fact is, Englishmen, as a body know nothing and care nothing about colonies. My own was merely the national ignorance. An Englishman's idea of a colony (he classes them altogether) is, that it is some miserable place—the Black-hole of the British empire—where no one would live if he were allowed a choice; and where the exiled spirits of the nation are incessantly sighing for a glimpse of the white cliffs of Albion, and a taste of the old familiar green-and-yellow fog of the capital of the world. Experience alone can convince him that there are in other regions of the world climes as delightful, suns as beneficent, and creditors as confiding, as those of Old England.

The voyage, of course, was tedious enough; but some portion of it was spent very pleasantly in calculating the annual profits which our flocks were likely to produce.

The four noble rams, with their curly horns, grew daily more valuable in our estimation. By the sailors, no doubt, they were rated no higher than the miserable tenants of the long-boat, that formed part of the cuddy provisions. But with us it was very different. As we looked, every bright and balmy morning, into the pen which they occupied, we were enabled to picture more vividly those Arcadian prospects which seemed now brought almost within reach. In these grave and respectable animals we recognised the patriarchs of a vast and invaluable progeny; and it was impossible to help feeling a kind of veneration for the sires of that fleecy multitude which was to prove the means of justifying our modest expectations of happiness and wealth.

Our dogs also afforded us the most pleasing subjects for speculation. With the blood-hound we were to track the footsteps of the midnight marauder, who should invade the sanctity of our fold. The spaniel was to aid in procuring a supply of game for the table; and I bestowed so much pains upon his education during the voyage, that before we landed he was perfectly au fait in the article of "down-charge!" and used to flush the cat in the steward's pantry with the greatest certainty and satisfaction.

Jezebel, the mastiff-birch, was expected to assist in guarding our castle,—an honourable duty which her courage and fidelity amply warranted us in confiding to her. Of the former quality, I shall mention an instance that occurred during the voyage. We had one day caught a shark, twelve feet long; and no sooner was he hauled on deck than Jezebel, wild with fury, rushed through the circle of eager sailors and spectators, and flew directly at the nose of the struggling monster. It was with difficulty that she was dragged away by the admiring seamen, who were compelled to admit that there was a creature on board more reckless and daring than themselves.

We were now approaching the Cape Verd Islands. I daresay it has been frequently mentioned, that there is in these latitudes a vast bed of loose sea-weed, floating about, which has existed there from time immemorial, and which is only found in this one spot of the ocean; as though it were here compelled to remain under the influence of some magic spell. Some navigators are of opinion that it grows on the rocks at the bottom of the sea, beneath the surface on which it floats. Others maintain that it has been drifted across the Atlantic, having issued from the Gulf of Mexico. Here, however, it is doomed to drift about hopelessly, for ever lost in the wilderness of waters; on the surface of which it now vegetates, affording shelter to small crabs, and many curious kinds of fishes.

One of the latter which we caught, about an inch in length, had a spike on his back, and four legs, with which he crawled about the sea-weed.

We approached the Island of St. Jago, sailing unconsciously close to a sunken rock, on which (as we afterwards learnt) the "Charlotte" had struck about six weeks before whilst under full sail, and had gone down in a few minutes, barely allowing time for the crew to escape in their boat.

Notwithstanding we had been five weeks at sea when we dropped anchor in Porto Praya roads, the appearance of the land was by no means inviting to the eyes. A high and extremely barren hill, or large heap of dry earth, with a good many stones about it, seemed to compose the Island. Close to us was the town, a collection of white houses that looked very dazzling in the summer sun. Beside, and running behind it, was a greenish valley, containing a clump of cocoa-nut trees. This was the spot we longed to visit; so, getting into the captain's boat, we approached the shore, where a number of nearly naked negroes rushing into the sea (there being no pier or jetty) presented their slimy backs at the gun-wale, and carried us in triumph to the beach. The town boasted of one hotel, in the only sitting-room of which we found some Portuguese officers smoking pipes as dirty as themselves, and drinking a beverage which had much the appearance of rum and water. There was no one who could speak a word of English; but at length a French waiter appeared, who seemed ravished with delight at the jargon with which we feebly reminded him of his own lively language "when at home." Having ordered dinner, we wandered off in search of the coca-nut valley, and purchased bananas for the first time in our lives, and oranges, the finest in the world.

Those who have been long at sea know how pleasant it is to walk once more upon the land. It is one of the brightest of the Everlasting flowers in the garland of Memory.

We walked along the sea-beach, as people so circumstanced must ever do, full of gladsome fancies. There was delight for us in the varied shells at our feet; in the curious skeletons of small fishes, untimely deceased; in the fantastic forms of the drifted sea-weed; in the gentle ripple of the companionable waves by our side. And little Fig, the spaniel, was no less pleased then ourselves. He ran before us rejoicing in his fleetness; and he ran back again in a moment to tell us how glad he was. Then as a wave more incursive than its predecessor unexpectedly wetted his feet, he would droop his tail and run faster with alarm, until the sight of some bush or bough, left high and dry by the last tide, awakened his nervous suspicions, and dreading an ambuscade, he would stop suddenly and bark at the dreadful object, until we arrived at his side, when, wagging his tail and looking slyly up with his joyous eyes, he would scamper away again as though he would have us believe he had been all the time only in fun.

What profound satisfaction is there in the freedom of land after so long a confinement! The sunshine that makes joyous every object around us finds its way into the deeps of the heart.

And now we determined to bathe. So we crossed over a jutting rock, on the other side of which was a beautiful and secluded little bay, so sheltered that the waves scarcely rippled as they came to kiss the shell-covered beach. Here we soon unrobed; and I was the first to rush at full speed into the inviting waters. Before I got up to my middle, however, I saw something before me that looked like a dark rock just below the surface. I made towards it, intending to get upon it, and dive off on the other side; but lo! as I approached, it stirred; then it darted like a flash of lightning towards one side of the bay, whilst I, after standing motionless for a moment, retreated with the utmost expedition.

It was a ground-shark, of which there are numbers on that coast.

We lost no time in putting on our clothes again, and returned in rather a fluttered state to the inn.

We remained a week at St. Jago, the captain being busily engaged in taking in water, and quarrelling with his crew. One day, at the instigation of our friend, the French waiter, we made a trip of seven miles into the interior of the island, to visit a beautiful valley called Trinidad. Mounted on donkeys, and attended by two ragged, copper-coloured youths, we proceeded in gallant style up the main street, and, leaving the town, crossed the valley beyond it, and emerged into the open country. It was a rough, stony, and hilly road, through a barren waste, where there scarcely appeared a stray blade of grass for the goats which rambled over it in anxious search of herbage.

At length, after a wearisome ride of several hours, we descended suddenly into the most fertile and luxuriant valley I ever beheld, and which seemed to extend a distance of some miles. A mountain brook flowed down the midst, on the banks of which numerous scattered and picturesque cottages appeared. On either side the ground was covered with the green carpet of Nature in the spring of the year. Everywhere, except in this smiling valley, we saw nothing but the aridity of summer, and the desolation caused by a scorching tropical sun. But here—how very different! How sudden, how magical was the change! Every species of vegetable grew here in finest luxuriance. Melons of every variety, pine-apples, sweet potatoes, plantains, and bananas, with their broad and drooping leaves of freshest green and rich purple flower, and ripe yellow fruit. Orange-trees, cocoa-nut trees, limes—the fig, the vine, the citron, the pomegranate, and numerous others, grateful to the weary sight, and bearing precious stores amid their branches, combined to give the appearance of wealth and plenty to this happy valley. It was not, however, destined to be entered by us without a fierce combat for precedence between two of our steeds. The animal whom it was the evil lot of Meliboeus to bestride, suddenly threw back its ears, and darted madly upon the doctor's quadruped, which, on its side, manifested no reluctance to the fight.

Dreadful was the scene; the furious donkeys nearing and striking with their fore-feet, and biting each other about the head and neck without the smallest feeling of compunction or remorse; the two guides shrieking and swearing in Portuguese at the donkeys and each other, and striking right and left with their long staves, perfectly indifferent as to whom they hit; the unhappy riders, furious with fright and chagrin, shouting in English to the belligerents of both classes to "keep off!" The screams of two women, who were carrying water in the neighbourhood, enhanced by the barking of a terrified cur, that ran blindly hither and thither with its tail between its legs, in a state of frantic excitement—altogether produced a tableau of the most spirited description. Peace was at length restored, and we all dismounted from our saddles with fully as much satisfaction as we had experienced when vaulting into them.

There is little more to say about the valley of Trinidad. The cottagers who supply the town of Porto Praya with fruits and vegetables are extremely poor, and very uncleanly and untidy in their houses and habits. We had intended to spend the night with them, but the appearance of the accommodations determined us to return to our inn, in spite of the friendly and disinterested advice of our guides.

St. Jago abounds with soldiers and priests; the former of whom are chiefly convicts from Lisbon, condemned to serve here in the ranks.

The day for sailing arrived, and we were all on board and ready. Our barque was a temperance ship; that is, she belonged to owners who refused to allow their sailors the old measure of a wine-glass of rum in the morning, and another in the afternoon, but liberally substituted an extra pint of water instead.

There is always one thing remarkable about these temperance ships, that when they arrive in harbour, their crews, excited to madness by long abstinence from their favourite liquor, and suffering in consequence all the excruciating torments of thirst, run into violent excesses the moment they get on shore. St. Jago is famous for a kind of liquid fire, called aguadente, which is smuggled on board ship in the shape of pumpkins and watermelons. These are sold to the sailors for shirts and clothing; there being nothing so eagerly sought for by the inhabitants of St. Jago as linen and calico.

Our crew, being thoroughly disgusted with their captain, as indeed they had some reason to be, and their valour being wondrously excited by their passionate fondness for water-melons, came to a stern resolution of spending the remainder of their lives on this agreeable island; at any rate, they determined to sail no farther in our company. The captain was ashore, settling his accounts and receiving his papers; the chief-mate had given orders to loose the fore-topsail and weigh anchor; and we were all in the cuddy, quietly sipping our wine, when we heard three cheers and a violent scuffling on deck. In a few moments down rushed the mate in a state of delirious excitement, vociferating that the men were in open mutiny, and calling upon us, in the name of the Queen, to assist the officers of the ship in bringing them to order. Starting up at the call of our Sovereign, we rushed to our cabins in a state of nervous bewilderment, and loading our pistols in a manner that ensured their not going off, we valiantly hurried on deck in the rear of the exasperated officer. On reaching the raised quarter-deck of the vessel, we found the crew clustered together near the mainmast, armed with hand-spikes, boat-oars, crow-bars, and a miscellaneous assortment of other weapons, and listening to an harangue which the carpenter was in the act of delivering to them. They were all intoxicated; but the carpenter, a ferocious, determined villain, was the least so.

At one of the quarter-deck gangways stood the captain's lady, a lean and wizened Hecate, as famous for her love of rum as any of the crew, but more openly rejoicing in the no less objectionable spirit of ultra-methodism. Screaming at the top of her voice, whilst her unshawled and dusky shoulders, as well as the soiled ribands of her dirty cap, were gently fanned by the sea-breeze, she commanded the men to return to their duty, in a volume of vociferation that seemed perfectly inexhaustible. Fearing that the quarter-deck would be carried by storm, we divided our party, consisting of the two mates, three passengers with their servants, and Mungo the black servant, into two divisions, each occupying one of the gang-ways.

In a few moments the carpenter ceased his oration; the men cheered and danced about the deck, brandishing their weapons, and urging one another to "come on." Then with a rush, or rather a stagger, they assailed our position, hoping to carry it in an instant by storm. The mate shouted to us to fire, and pick out three or four of the most desperate; but perceiving the intoxicated state of the men we refused to shed blood, except in the last extremity of self-defence; and determined to maintain our post, if possible, by means of our pistol-butts, or our fists alone. In the general melee which ensued, the captain's lady, who fought in the van, and looked like a lean Helen MacGregor, or the mythological Ate, was captured by the assailants, and dragged to the deck below. Then it was that combining our forces, and inspired with all the ardour which is naturally excited by the appearance of beauty in distress, we made a desperate sally, and after a fearful skirmish, succeeded in rescuing the lady, and replacing her on the quarter-deck, with the loss only of her cap and gown, and a few handfuls of hair.

After this exploit, both parties seemed inclined to pause and take breath, and in the interval we made an harangue to the sailors, expressive of our regret that they should act in so disgraceful a manner.

The gallant (or rather ungallant) fellows replied that they were determined to be no longer commanded by a she-captain, as they called the lady, and therefore would sail no farther in such company.

I really believe that most of them had no serious intention whatever in their proceedings, but the officers of the ship were firmly convinced that the carpenter and one or two others had resolved to get possession of the vessel, dispose of the passengers and mates somehow or other, and then slip the cable, and wreck and sell the ship and cargo on the coast of South America.

Whilst the truce lasted, the second mate had been busily engaged making signals of distress, by repeatedly hoisting and lowering the ensign reversed, from the mizen-peak. This was soon observed from the deck of a small Portuguese schooner of war, which lay at anchor about half a mile from us, having arrived a few hours previously, bringing the Bishop of some-where-or-other on a visitation to the island. The attention of the officer of the watch had been previously attracted towards us by the noise we had made, and the violent scuffle which he had been observing through his glass. No sooner, therefore, was the flag reversed, than a boat was lowered from the quarter-davits, filled with marines, and pulled towards our vessel with the utmost rapidity. The mutineers, whose attention was directed entirely to the quarter-deck, did not perceive this manoeuvre, which, however, was evident enough to us, who exerted ourselves to the utmost to prolong the parley until our allies should arrive.

The carpenter now decided upon renewing the assault, having laid aside his handspike and armed himself with an axe; but just at this moment the man-of-war's boat ran alongside, and several files of marines, with fixed bayonets, clambering on to the deck, effected a speedy change in the aspect of affairs. Perceiving at once how matters stood, the officer in command, without asking a single question, ordered a charge against the astonished sailors, who, after a short resistance, and a few violent blows given and received, were captured and disarmed.

There was a boy among the party called Shiny Bill, some fifteen years of age, who managed to escape to the fore-shrouds, and giving the marine who pursued him a violent kick in the face, succeeded in reaching the fore-top, where he coiled himself up like a ball. Two or three marines, exasperated by the scuffle, and by several smart raps on the head which they had received, hastened up the shrouds after the fugitive, who, however, ascended to the fore-top-mast cross-trees, whither his enemies, after some hesitation, pursued. Finding this post also untenable, he proceeded to swarm up the fore-top-gallant-mast shrouds, and at last seated himself on the royal yard, where he calmly awaited the approach of the enemy. These, however, feeling that the position was too strong to be successfully assailed by marines, deliberately commenced their retreat, and arrived on deck, whilst their officer was hailing the immovable Bill in Portuguese, and swearing he would shoot him unless he instantly descended.

Disdaining, however, to pay the least attention to these threats, Shiny William continued to occupy his post with the greatest tranquillity; and the officer, giving up the attempt in despair, proceeded to inquire from us in Portuguese-French the history of this outbreak. The scene concluded with the removal of the mutineers in one of the ship's boats to the man-of-war, where, in a few moments, several dozen lashes were administered to every man in detail, and the whole party were then sent on shore, and committed to a dungeon darker and dirtier than the worst among them had ever before been acquainted with. But before all this was done, and when the boats had pulled about a hundred yards from the vessel, Shiny Bill began to descend from his post. He slipped down unobserved by any one, and the first notice we had of his intentions was from perceiving him run across the deck to the starboard bow, whence he threw himself, without hesitation, into the sea, and began to swim lustily after his captive friends. Our shouts—for, remembering the abundance of sharks, we were very much alarmed for the poor fellow—attracted the attention of the officer in the boat, to whom we pointed out the figure of Bill, who seemed as eager now to make a voluntary surrender, and share the fate of his comrades, as he had previously been opposed to a violent seizure. The swimmer was soon picked up, and, to our regret, received in due season the same number of stripes as fell to the lot of his friends captured in battle.

The prisoners remained several days in their dungeon, where they were hospitably regaled with bread and water by the Portuguese Government; and at the end of this period (so unworthy did they prove of the handsome treatment they received) the British spirit was humbled within them, and they entreated with tears to be allowed to return to their duty. The mates, however, refused to sail in the same vessel with the carpenter, and it was accordingly settled that he should remain in custody until the arrival of a British man-of-war, and then be returned to his country, passage free.

It was nearly the end of August when we approached the conclusion of our voyage. The wind was fair, the sun shone brightly, and every heart was gay with the hope of once more being upon land. We drew nigh to the Island of Rottnest, about sixteen miles from the mouth of the river Swan, and anchored to the north of it, waiting for a pilot from Fremantle.

And there we had the first view of our future home. Beyond that low line of sand-hills, which stretched away north and south, far as the eye could reach, we were to begin life again, and earn for ourselves a fortune and an honourable name. No friendly voice would welcome us on landing, but numberless sharpers, eager to prey upon the inexperienced Griffin, and take advantage of his unavoidable ignorance and confiding innocence. There was nothing very cheering in the prospect; but supported by the confidence and ambition of youth, we experienced no feelings of dismay.

In order to wile away the time, we landed on the island, and, passing through a thick wood of cypresses, came to a goodly-sized and comfortable-looking dwelling-house, with numerous out-buildings about it, all built of marine lime-stone.

As the particulars which I then learned respecting this island were afterwards confirmed by experience and more extended information, I may as well enter upon its history at once.

The gentleman who was then Governor of Western Australia, was Mr. John Hutt, a man of enlightened mind, firm, sagacious, and benevolent. From the first, he adopted an admirable policy with regard to the native inhabitants.

Exhibiting on all occasions a friendly interest in their welfare, he yet maintained a strict authority over them, which they soon learned to respect and fear. The Aborigines were easily brought to feel that their surest protection lay in the Government; that every act of violence committed upon them by individual settlers was sure to be avenged by the whites themselves; and that, as certainly, any aggression on the part of the natives would call down the utmost severity of punishment upon the offenders. By this firm administration of equal justice the Aboriginal population, instead of being, as formerly, a hostile, treacherous, and troublesome race, had become harmless, docile, and in some degree useful to the settlers.

But it was not the policy of Mr. Hutt merely to punish the natives for offences committed against the whites; he was anxious to substitute the milder spirit of the British law in lieu of their own barbarous code; and to make them feel, in process of time, that it was for their own interest to appeal for protection on all occasions to the dominant power of Government, rather than trust to their own courage and spears. This was no easy task, and could only be accomplished by firmness, discrimination, and patience; but in the course of a few years, considerable progress had been made in subduing the prejudices and the barbarous customs of the Aborigines. Although it had been declared by Royal Proclamation that the native inhabitants were in every respect subjects of the British throne, and as such entitled to equal privileges with ourselves, and to be judged on all occasions by the common and statute laws, it proved to be no easy matter to carry into practice these views of the Home Government. People in England, who derive their knowledge of savages from the orations delivered at Exeter Hall, are apt to conceive that nothing more is requisite than to ensure them protection from imaginary oppression, and a regular supply of spiritual comforts. They do not consider that whilst they insist upon these unfortunate creatures being treated exactly as British subjects, they are placing a yoke on their own necks too heavy for them to bear in their present condition. Primitive and simple laws are necessary to a primitive state of society; and the cumbrous machinery of civilized life is entirely unsuited to those who in their daily habits and their intellectual endowments are little superior to the beasts that perish. By declaring the savages to be in every respect British subjects, it becomes illegal to treat them otherwise than such. If a settler surprise a native in the act of stealing a pound of flour, he of course delivers him over to a constable, by whom he is conveyed before the nearest magistrate. Now this magistrate, who is an old settler, and well acquainted with the habits of the natives, is also a man of humanity; and if he were allowed to exercise a judicious discretion, would order the culprit to be well flogged and dismissed to his expectant family. But thanks to Her Majesty's well-meaning Secretaries of State for the Colonies, who have all successively judged alike on this point, it is declared most unadvisable to allow a local magistrate the smallest modicum of discretion. He has only one course to pursue, and that is, to commit the offender for trial at the next Quarter Sessions, to be held in the capital of the colony. Accordingly the poor native, who would rather have been flayed alive than sent into confinement for two months previous to trial, whilst his wives are left to their own resources, is heavily ironed, lest he should escape, and marched down some sixty or seventy miles to Fremantle gaol, where the denizen of the forest has to endure those horrors of confinement which only the untamed and hitherto unfettered savage can possibly know.

Among savages, the 'Lex talionis'—the law of retaliation—is the law of nature and of right; to abstain from avenging the death of a relative would be considered, by the tribe of the deceased, an act of unpardonable neglect. Their own customs, which are to them as laws, point out the mode of vengeance. The nearest relative of the deceased must spear his slayer. Nothing is more common among these people than to steal one another's wives; and this propensity affords a prolific source of bloodshed.

They have also a general law, which is never deviated from, and which requires that whenever a member of a tribe dies, whether from violence or otherwise, a life must be taken from some other tribe. This practice may have originated in a desire to preserve the balance of power; or from a belief, which is very general among them, that a man never dies a natural death. If he die of some disorder, and not of a spear-wound, they say he is "quibble gidgied," or speared by some person a long distance off. The native doctor, or wise man of the tribe, frequently pretends to know who has caused the death of the deceased; and the supposed murderer is of course pursued and murdered in turn. This custom necessarily induces a constant state of warfare. Now it is very right that all these barbarous and unchristian practices should be put an end to; but, whilst endeavouring to suppress them, we ought to remember that they are part and parcel of the long-established laws of this rude people, and that it is not possible all at once to make them forego their ancient institutions and customs. The settlers would gladly see punished all acts of violence committed among the natives in their neighbourhood. Were they permitted to inflict such punishments as are best suited to the limited ideas and moral thraldom of the Aborigines, these, without cruelty or injustice, might gradually be brought within the pale of civilization; but when the law declares it to be inevitable that every British subject who is tried and found guilty of having speared his enemy shall be hanged without benefit of clergy, the colonists out of sheer humanity and pity for the ignorance of the culprit, refrain from bringing him to trial and punishment—a proceeding which, by the way, would cost the colony some fifteen or twenty pounds—and thus he goes on in his errors, unreproved by the wisdom or the piety of the whites. Sometimes, however, it happens that the officers who exercise the calling of Protectors of the Aborigines, anxious to prove that their post is no sinecure, make a point of hunting up an occasional law-breaker, who, being brought to trial, is usually found guilty upon his own evidence—the unfortunate culprit, conscious of no guilt in having followed the customs of his ancestors, generally making a candid statement of his offence. The sentence decreed by the English law is then passed upon him, and he would, of course, be duly subjected to the penalty which justice is supposed to demand, did not the compassionate Governor, in the exercise of the highest privilege of the Crown, think proper to step in and commute the sentence to perpetual imprisonment. As it would have entailed a serious expense upon the colony to have had to maintain these prisoners in a gaol in the capital, his Excellency determined to establish a penal settlement at Rottnest; and this he accordingly accomplished, with very good effect.

At the time we visited the island, there were about twenty native prisoners in charge of a superintendent and a few soldiers.

The prisoners were employed in cultivating a sufficient quantity of ground to produce their own food. It was they also who had built the superintendent's residence; and whenever there was nothing else to do, they were exercised in carrying stone to the top of a high hill, on which a lighthouse was proposed to be built.

The Governor has certainly shown very good judgment in the formation of this penal establishment. It is the dread of the natives throughout the colony; and those prisoners who are released inspire among their fellows the greatest horror and dismay by their tales of the hardships they have suffered. No punishment can be more dreadful to these savages—the most indolent race in the world—than being compelled to work; and as their idleness brings them occasionally in contact with the superintendent's lash, their recollections and accounts of Rottnest are of the most fearful description. Certain, however, it is, that nothing has tended so much to keep the Aborigines in good order as the establishment of this place of punishment. It is maintained at very little expense to the colony, as the prisoners grow their own vegetables, and might easily be made to produce flour enough for their own consumption.

It was a clear, beautiful, sparkling day, and there was a sense of enjoyment attached to the green foliage, the waving crops, and the gently heaving sea, that threw over this new world of ours a charm which filled our hearts with gladness.

Having returned to our ship, we saw the pilot-boat rapidly approaching. As it came alongside, and we were hailed by the steersman, we felt a sensation of wonder at hearing ourselves addressed in English and by Englishmen, so far, so very far from the shores of England. With this feeling, too, was mingled something like pity; we could not help looking upon these poor boatmen, in their neat costume of blue woollen shirts, canvass trousers, and straw hats, as fellow-countrymen who had been long exiled from their native land, and who must now regard us with eyes of interest and affection, as having only recently left its shores.

No sooner was the pilot on board than the anchor was weighed, the sails were set, and we began to beat up into the anchorage off Fremantle. Night closed upon us ere we reached the spot proposed, and we passed the interval in walking the deck and noting the stars come forth upon their watch. The only signs of life and of human habitation were in the few twinkling lights of the town of Fremantle: all beside, on the whole length of the coast, seemed to be a desert of sand, the back-ground of which was occupied with the dark outline of an illimitable forest.

It was into this vast solitude that we were destined to penetrate. It was a picture full of sombre beauty, and it filled us with solemn thoughts.

The next morning we were up at daybreak. Certainly it was a beautiful sight, to watch the sun rise without a cloud from out of the depths of that dark forest, rapidly dispersing the cold gray gloom, and giving life, as it seemed, to the sparkling waves, which just before had been unconsciously heaved by some internal power, and suffered to fall back helplessly into their graves.

How differently now they looked, dancing joyously forward towards the shore! And the sun, that seems to bring happiness to inanimate things, brought hope and confidence back to the hearts of those who watched him rise.

Flights of sea-birds of the cormorant tribe, but generally known as Shags, were directing their course landward from the rocky islands on which they had roosted during the night. What long files they form! —the solitary leader winging his rapid and undeviating way just above the level of the waves, whilst his followers, keeping their regular distances, blindly pursue the course he takes. See! he enters the mouth of the river; some distant object to his practised eye betokens danger, and though still maintaining his onward course, he inclines upwards into the air, and the whole line, as though actuated by the same impulse, follow his flight. And now they descend again within a few feet of the river's surface, and now are lost behind projecting rocks. All day long they fish in the retired bays and sheltered nooks of the river, happy in the midst of plenty.

The river Swan issues forth into the sea over a bar of rocks, affording only a dangerous passage for boats, or vessels drawing from four to five feet water. Upon the left bank of the river is the town of Fremantle. The most prominent object from the sea is a circular building of white limestone, placed on the summit of a black rock at the mouth of the Swan. This building is the gaol.

On the other side of the roadstead, about ten or twelve miles distant from the main, is a chain of islands, of which Rottnest is the most northern. Then come some large rocks, called the Stragglers, leaving a passage out from the roadstead by the south of Rottnest; after these is Carnac, an island abounding with rabbits and mutton-birds; and still farther south is Garden island.

Fremantle, the principal port of the colony, is unfortunately situated, as vessels of any burthen are obliged to anchor at a considerable distance from the shore. Lower down the coast is a fine harbour, called Mangles Bay, containing a splendid anchorage, and it is much to be lamented that this was not originally fixed upon as the site for the capital of the colony.

The first impression which the visitor to this settlement receives is not favourable. The whole country between Fremantle and Perth, a distance of ten miles, is composed of granitic sand, with which is mixed a small proportion of vegetable mould. This unfavourable description of soil is covered with a coarse scrub, and an immense forest of banksia trees, red gums, and several varieties of the eucalyptus. The banksia is a paltry tree, about the size of an apple-tree in an English or French orchard, perfectly useless as timber, but affording an inexhaustible supply of firewood. Besides the trees I have mentioned, there is the xanthorea, or grass-tree, a plant which cannot be intelligibly described to those who have never seen it. The stem consists of a tough pithy substance, round which the leaves are formed. These, long and tapering like the rush, are four-sided, and extremely brittle; the base from which they shoot is broad and flat, about the size of a thumb-nail, and very resinous in substance. As the leaves decay annually, others are put forth above the bases of the old ones, which are thus pressed down by the new shoots, and a fresh circle is added every year to the growing plant. Thousands of acres are covered with this singular vegetable production; and the traveller at his night bivouac is always sure of a glorious fire from the resinous stem of the grass-tree, and a comfortable bed from its leaves.

We landed in a little bay on the southern bank of the river. The houses appeared to be generally two-storied, and were built of hard marine limestone. Notwithstanding the sandy character of the soil, the gardens produced vegetables of every variety, and no part of the world could boast of finer potatoes or cabbages. Anxious to begin the primitive life of a settler as speedily as possible, we consulted a merchant to whom we had brought letters of introduction as to the best mode of proceeding. He advised us to fix our head-quarters for a time near to Fremantle, and thence traverse the colony until we should decide upon a permanent place of abode. In the meantime we dined and slept at Francisco's Hotel, where we were served with French dishes in first-rate style, and drank good luck to ourselves in excellent claret.

In the early days of the colony, Sir James Stirling, the first Governor, had fixed upon Fremantle as the seat of government; and the settlers had begun to build themselves country-houses and elegant villa residences upon the banks of the river. These, however, were not completed before it was determined to fix the capital at Perth, some dozen miles up the river, where the soil was rather better, and where a communication with the proposed farms in the interior would be more readily kept up.

The government officers had now to abandon their half-built stone villas, and construct new habitations of wood, as there was no stone to be found in the neighbourhood of Perth, and brick clay had not then been discovered.

It was in one of these abandoned houses (called the Cantonment), situate on the banks of the Swan, about half a mile from Fremantle, that, by the advice of our friend, we resolved to take up our quarters. The building was enclosed on three sides by a rough stone wall, and by a wooden fence, forming a paddock of about three quarters of an acre in extent. It comprised one large room, of some forty feet by eighteen, which had a roof of thatch in tolerable repair. The north side, protected by a verandah, had a door and two windows, in which a few panes of glass remained, and looked upon the broad river, from which it was separated by a bank of some twenty feet in descent, covered with a variety of shrubs, just then bursting into flower. A few scattered red-gum trees, of the size of a well-grown ash, gave a park-like appearance to our paddock, of which we immediately felt extremely proud, and had no doubt of being very comfortable in our new domain. Besides the large room I have mentioned, there were two others at the back of it, which, unfortunately, were in rather a dilapidated condition; and below these apartments (which were built on the slope of a hill) were two more, which we immediately allotted to the dogs and sheep. This side of the building was enclosed by a wall, which formed a small court-yard. Here was an oven, which only wanted a little repair to be made ready for immediate use.

For several days we were occupied in superintending the landing of our stores, and housing them in a building which we rented in the town at no trifling sum per week. A light dog-cart, which I had brought out, being unpacked, proved extremely useful in conveying to our intended residence such articles as we were likely to be in immediate want of.

The two men had already taken up their abode there, together with the rams and dogs; and at last, leaving our comfortable quarters at the hotel with something like regret and a feeling of doubt and bewilderment, we all three marched in state, with our double-barrels on our shoulders, to take possession of our rural habitation.

We had providently dined before we took possession; and now, at sunset, we stood on the bank before our house, looking down upon the placid river. The blood-hound was chained to one of the posts of the verandah; Jezebel, the noble mastiff-bitch, lay basking before the door, perfectly contented with her situation and prospects; and little Fig was busily hunting among the shrubs, and barking at the small birds which he disturbed as they were preparing to roost.

One of the men was sitting on an upturned box beside the fire, waiting for the gently-humming kettle to boil; whilst the other was chipping wood outside the house, and from time to time carrying the logs into the room, and piling them upon the hearth. As we looked around we felt that we had now indeed commenced a new life. For some months, at any rate, we were to do without those comforts and luxuries which Englishmen at home, of every rank above the entirely destitute, deem so essential to bodily ease and happiness.

We were to sleep on the floor, to cook our own victuals, and make our own beds. This was to be our mode of acquiring a settlement in this land of promise. Still there was an air of independence about it, and we felt a confidence in our own energies and resources that made the novelty of our position rather agreeable than otherwise.

There was something exhilarating in the fresh sea-breeze; there was something very pleasing in the gay appearance of the shrubs that surrounded us—in the broad expanse of the river, with its occasional sail, and its numerous birds passing rapidly over it on their way to the islands where they roosted, or soaring leisurely to and fro, with constant eyes piercing its depths, and then suddenly darting downwards like streams of light into the flood, and emerging instantly afterwards with their finny prey. The opposite bank of the river displayed a sandy country covered with dark scrub; and beyond this was the sea, with a view of Rottnest and the Straggler rocks. A few white cottages relieved the sombre and death-like appearance of that opposite shore. Unpromising as was the aspect of the country, it yet afforded sufficient verdure to support in good condition a large herd of cattle, which supplied Fremantle with milk and food.

Here, then, the reader may behold us for the first time in our character of settlers. He may behold three individuals in light shooting coats and cloth caps, standing upon the bank before their picturesque and half-ruinous house, their dogs at their side, and their gaze fixed upon the river that rolled beneath them. The same thoughts probably occupied them all: they were now left in a land which looked much like a desert, with Heaven for their aid, and no other resources than a small capital, and their own energies and truth. The great game of life was now to begin in earnest, and the question was, how it should be played with success? Individual activity and exertion were absolutely necessary to ensure good fortune; and warmly impressed with the consciousness of this, we turned with one impulse in search of employment.

Aesculapius began to prepare their supper for the dogs, and Meliboeus looked after his sheep, which were grazing in the paddock in front of the dwelling. As for myself, with the ardent mind of a young settler, I seized upon the axe, and began to chop firewood—an exercise, by the way, which I almost immediately renounced.

And now for supper!

Our most necessary articles were buried somewhere beneath the heaps of rubbish with which we had filled the store-room at Fremantle. Our plates, cups and saucers, etc., were in a crate which was not to be unpacked until we had removed our property and abode to the inland station which we designed for our permanent residence. There were, however, at hand for present use eight or nine pewter plates, and a goodly sized pannikin a-piece. In one corner of the room was a bag of flour, in another a bag of sugar, in a third a barrel of pork, and on the table, composed of a plank upon two empty casks, were a couple of loaves which Simon had purchased in the town, and a large tea-pot which he had fortunately discovered in the same cask with the pannikins.

The kettle fizzed upon the fire, impatient to be poured out; the company began to draw round the hospitable board, seating themselves upon their bedding, or upon empty packing-cases; and, in a word, tea time had arrived. Hannibal, as we called the younger of our attendants, from his valiant disposition, had filled one of the pewter plates with brown sugar from the bag; the doctor made the tea, and we wanted nothing but spoons to make our equipage complete. However, every man had his pocket-knife, and so we fell to work.

Butter being at that time half-a-crown a pound, Simon (our head man) had prudently refrained from buying any; and as he had forgotten to boil a piece of the salt pork, we had to sup upon dry bread, which we did without repining, determined, however, to manage better on the morrow.

In the meantime we were nearly driven desperate by most violent attacks upon our legs, committed by myriads of fleas. They were so plentiful that we could see them crawling upon the floor; the dogs almost howled with anguish, and the most sedate among us could not refrain from bitter and deep execrations. We had none of us ever before experienced such torment; and really feared that in the course of the night we should be eaten up entirely. These creatures are hatched in the sand, and during the rains of winter they take refuge in empty houses; but they infest every place throughout the country, during all seasons, more or less, and are only kept down by constant sweeping from becoming a most tremendous and overwhelming plague, before which every created being, not indigenous to the soil, would soon disappear, or be reduced to a bundle of polished bones. The natives themselves never sleep twice under the same wigwam.

After tea, the sheep and dogs being carefully disposed of for the night, we turned out before the house, and comforted ourselves with cigars; and having whiled away as much time as possible, we spread out our mattresses on the floor, and in a state of desperation attempted to find rest. We escaped with our lives, and were thankful in the morning for so much mercy vouchsafed to us, but we could not conscientiously return thanks for a night's refreshing rest.

At the first dawn of day we rolled up our beds, lighted the fire, swept out the room, let the dogs loose, and drove the rams to pasture on the margin of the river. After breakfast, which was but a sorry meal, we determined to make our first attempt at baking. Simon, a man of dauntless resolution, undertook the task, using a piece of stale bread as leaven. It was a serious business, and we all helped or looked on; but the result, notwithstanding the multitude of councillors, was a lamentable failure. Better success, fortunately, attended the labours of Hannibal, who boiled a piece of salt pork with the greatest skill.

Mutton at this period, 1841, was selling at sixteen-pence per pound (it is now two-pence), and we therefore resolved to depend upon our guns for fresh meat. We had brought with us a fishing-net, which we determined to put in requisition the following day.

The most prominent idea in the imagination of a settler on his first arrival at an Australian colony, is on the subject of the natives. Whilst in England he was, like the rest of his generous-minded countrymen, sensibly alive to the wrongs of these unhappy beings— wrongs which, originating in a great measure in the eloquence of Exeter Hall, have awakened the sympathies of a humane and unselfish people throughout the length and breadth of the kingdom. Full of these noble and ennobling sentiments, the emigrant approaches the scene of British-colonial cruelty; but no sooner does he land, than a considerable change takes place in his feelings. He begins to think that he is about to place his valuable person and property in the very midst of a nation of savages, who are entirely unrestrained by any moral or human laws, or any religious scruples, from taking the most disagreeable liberties with these precious things.

The refined and amiable philanthropist gradually sinks into the coarse-minded and selfish settler, who is determined to protect himself, his family, and effects, by every means in his power—even at the risk of outraging the amiable feelings of his brother philanthropists at home. In Western Australia, the natives generally are in very good order; they behave peaceably towards the settlers, eat their flour, and in return occasionally herd or hunt up their cattle, and keep their larders supplied with kangaroo.

It is very rarely—I have never indeed heard of a single well-authenticated instance—that any amount of benefits, or the most unvarying kindness, can awaken the smallest spark of gratitude in the breasts of these degraded savages. Those who derive their chief support from the flour and broken meat daily bestowed upon them by the farm settlers, would send a spear through their benefactors with as little remorse as through the breast of a stranger. The fear of punishment alone has any influence over them; and although in this colony they are never treated with anything like cruelty or oppression, it is absolutely necessary to personal safety to maintain a firm and prompt authority over them.

When we first arrived, we were philanthropists, in the usual sense of that term, and thought a good deal about the moral and general destitution of this unfortunate people; but when we first encountered on the road a party of coffee-coloured savages, with spears in their hands, and loose kangaroo-skin cloaks (their only garments) on their shoulders, accompanied by their women similarly clad, and each carrying in a bag at her back her black-haired offspring, with a face as filthy as its mother's—we by no means felt inclined to step forward and embrace them as brethren.

I question, indeed, whether the most ardent philanthropist in the world would not have hesitated before he even held forth his hand to creatures whose heads and countenances were darkened over with a compound of grease and red clay, whose persons had never been submitted to ablution from the hour of their birth, and whose approach was always heralded by a perfume that would stagger the most enthusiastic lover of his species.

But it was not merely disgust that kept us at arm's length. We must confess we were somewhat appalled at this first view of savage life, as we looked upon the sharp-pointed spears, wild eyes, and well-polished teeth of our new acquaintance. Although, in truth, they were perfectly harmless in their intentions, we could not help feeling a little nervous as they drew nigh, and saluted us with shrill cries and exclamations, and childish bursts of wild laughter. Their principal question was, whether we were "cabra-man?" or seamen, as we afterwards discovered their meaning to be. After a good deal of screaming and laughing, they passed on their way, leaving us much relieved by their absence. They seemed to be, and experience has proved to us that they are, the most light-hearted, careless, and happy people in the world. Subsisting upon the wild roots of the earth, opossums, lizards, snakes, kangaroos, or anything else that is eatable which happens to fall in their way, they obtain an easy livelihood, and never trouble themselves with thoughts of the morrow. They build a new house for themselves every evening; that is, each family, erects a slight shelter of sticks covered over with bark, or the tops of the xanthorea, that just keeps off the wind; and with a small fire at their feet, the master of the family, his wife, or wives, and children, lie huddled together like a cluster of snakes— happier than the tenants of downy beds. Far happier, certainly, than we had lately been in ours. We had, however, devised a new plan for the next night. Having each of us a hammock, we suspended them from the rafters; and thus, after the first difficulty and danger of getting into bed was overcome, we lay beyond the reach of our formidable enemies, and contrived to sleep soundly and comfortably.

The next morning we breakfasted early. My brothers resolved to try the effect of the fishing-net, and I myself arranged a shooting excursion with a lad, whose parents rented a house situated about a quarter of a mile from our own. We were to go to some lakes a few miles distant, which abounded with wild ducks and other water-fowl. Preceded by Fig, and more soberly accompanied by Jezebel, we set out upon our expedition.

It was the close of the Australian winter, and the temperature was that of a bright, clear day in England at the end of September. The air was mild, but elastic and dry; the peppermint and wattle-trees were gay with white and yellow blossoms; an infinite variety of flowering shrubs gave to the country the appearance of English grounds about a goodly mansion; whilst the earth was carpeted with the liveliest flowers. It was impossible to help being in good spirits.

We passed up a valley of white gum-trees, which somewhat resemble the ash, but are of a much lighter hue. They belong to the eucalyptus species.

I shot several beautiful parroquets, the plumage of which was chiefly green; the heads were black, and some of the pinion feathers yellow. The country presented very little appearance of grass, though abounding with green scrub; and frequently we passed over denuded hills of limestone-rock, from which we beheld the sea on one side, and on the other the vast forest of banksias and eucalypti, that overspreads the entire country. The river winding among this mass of foliage, relieved the eye.

After a walk of two hours we approached the lakes of which we were in search. situated in a flat country, and their margins covered with tall sedges, it was difficult to obtain a view of the water. Now, then, we prepared for action. Behind those tall sedges was probably a brood of water-fowl, either sleeping in the heat of the day, or carefully feeding in the full security of desert solitude. "Fig! you villain! what are you about? are you going to rush into the water, and ruin me by your senseless conduct? I have got you now, and here you must please to remain quiet. No, you rascal! you need not look up to me with such a beseeching countenance, whilst you tremble with impatience, eager to have a share in the sport. You must wait till you hear my gun. I am now shooting for my dinner, and perhaps for yours also, if you will condescend to eat duck, and I dare not allow you the pleasure of putting up the game. You understand all this well enough, and therefore please to be silent;—or, observe! I'll murder you."

Leaving the boy with the dogs, I began to steal towards the lake, when I heard his muttered exclamation, and turning round, saw him crouching to the earth and pointing to the sky. Imitating his caution, I looked in the direction he pointed out, and beheld three large birds leisurely making towards the spot we occupied. They were larger than geese, black, with white wings, and sailed heavily along, whilst I lay breathlessly awaiting their approach. The dogs were held down by the boy, and we all seemed equally to feel the awfulness of the moment. The birds came slowly towards us, and then slanted away to the right; and then wheeling round and round, they alighted upon the lake.

Creeping to the sedges, I pushed cautiously through, up to the ankles in mud and water. How those provoking reeds, three feet higher than my head, rustled as I gently put them aside! And now I could see plainly across a lake of several acres in extent. There on the opposite side, were three black swans sailing about, and occasionally burying their long necks in the still waters. With gaze riveted upon that exciting spectacle, I over-looked a myriad of ducks that were reposing within a few yards of me, and which, having discovered the lurking danger, began to rise en masse from the lake.

Never before had I seen such a multitude. Struck with amazement, I stood idly gaping as they rose before me; and after sweeping round the lake, with a few quacks of alarm, whirled over the trees and disappeared.

The swans seemed for a moment to catch the general apprehension, and one of them actually rose out of the water, but after skimming along the surface for a few yards, he sank down again, and his companions swam to rejoin him. Gently retreating, I got back upon the dry land, and motioning the boy to remain quiet, hastened round the lake to its opposite bank. More cautiously than before I entered the grove of sedges, and soon beheld two of the swans busily fishing at some distance from the shore. What had become of the third? There he is, close to the border of the lake, and only about fifty yards from my position! My first shot at a swan!—Now then—present! fire!— bang! What a splutter! The shots pepper the water around him. He tries to rise, He cannot! his wing is broken! Hurrah! hurrah! "Here Jonathan! Toby! what's your name? here! bring the dogs—I've hit him—I've done for him!

"Fig, Fig!—O! here you are; good little dog—good little fellow! now then, in with you! there he is!"

With a cry of delight, little Fig dashed through the reeds. The water rushed down his open throat and half-choked him; but he did not care. Shaking the water out of his nose as he swam, he whimpered with pleasure, and hurried after the swan which was now slowly making towards the middle of the lake. Its companions had left it to its fate. We stood in the water watching the chase. Jezebel, excited out of all propriety, though she could see nothing of what was going on, gallopped up and down the bank, with her tail stiff out, tumbling over the broken boughs which lay there, and uttering every now and then deep barks that awoke the astonished echoes of the woods. Sometimes she would make a plunge into the water, splashing us all over, and then she quickly scrambled out again, her ardour considerably cooled.

"Well done, Fig! good little dog! at him again! never mind that rap on the head from his wing."

Away swam the swan, and Fig after him, incessantly barking.

Had not the noble bird been grievously wounded he would have defied the utmost exertions of the little spaniel, but as it was, he could only get for a moment out of the reach of his pursuer by a violent effort, which only left him more exhausted. And now they approached the shore; and the swan, hard pressed, turns round and aims a blow with its bill at the dog.

This Fig managed to elude, and in return made a snap at his enemy's wing, and obtained a mouthful of feathers; but in revenge he received on his nose a rap from the strong pinion of the bird that made him turn tail and fairly yelp with anguish. "Never mind, brave Fig! good dog! at him again! Bravo—bravo! good little fellow!" There he is, once more upon him. And now, master Fig, taught a lesson by the smart blows he had received, endeavours to assail only the wounded wing of the swan. It was a very fierce combat, but the swan would probably have had the best of it had not loss of blood rendered him faint and weak.

He still fought bravely, but now whenever he missed his adversary, his bill would remain a moment in the water, as though he had scarcely strength to raise his head; and as he grew momentarily weaker and weaker, so Fig waxed more daring and energetic in his assaults; until at length he fairly seized his exhausted foe by the neck, and notwithstanding his struggles, and the violent flapping of his long unwounded wing, began to draw him towards the shore. We hurried to meet and help him. Jezebel was the first that dashed breast-high into the water; and seizing a pinion in her strong jaws, she soon drew both the swan and Fig, who would have died rather than let go, through the yielding sedges to the land.

The swan was soon dead; and Fig lay panting on the sand, with his moth open, and looking up to his master as he wagged his tail, clearly implying, "Did not I do it well, master?" "Yes, my little dog, you did it nobly. And now you shall have some of this bread, of Simon's own baking, which I cannot eat myself; and Jonathan and I will finish this flask of brandy and water."

And now we set out on our return home, anxious to display our trophy to envious eyes.

As we approached the Cantonment, I discharged my unloaded barrel at a bird like a thrush in appearance, called a Wattle-bird, from having two little wattles which project from either side of its head.