Preface.

Contents.

Dictionary of Flowers,

The Calendar of Flowers.

The Dial of Flowers.

{1}

{2}

{3}

{4}

THE LANGUAGE OF FLOWERS.

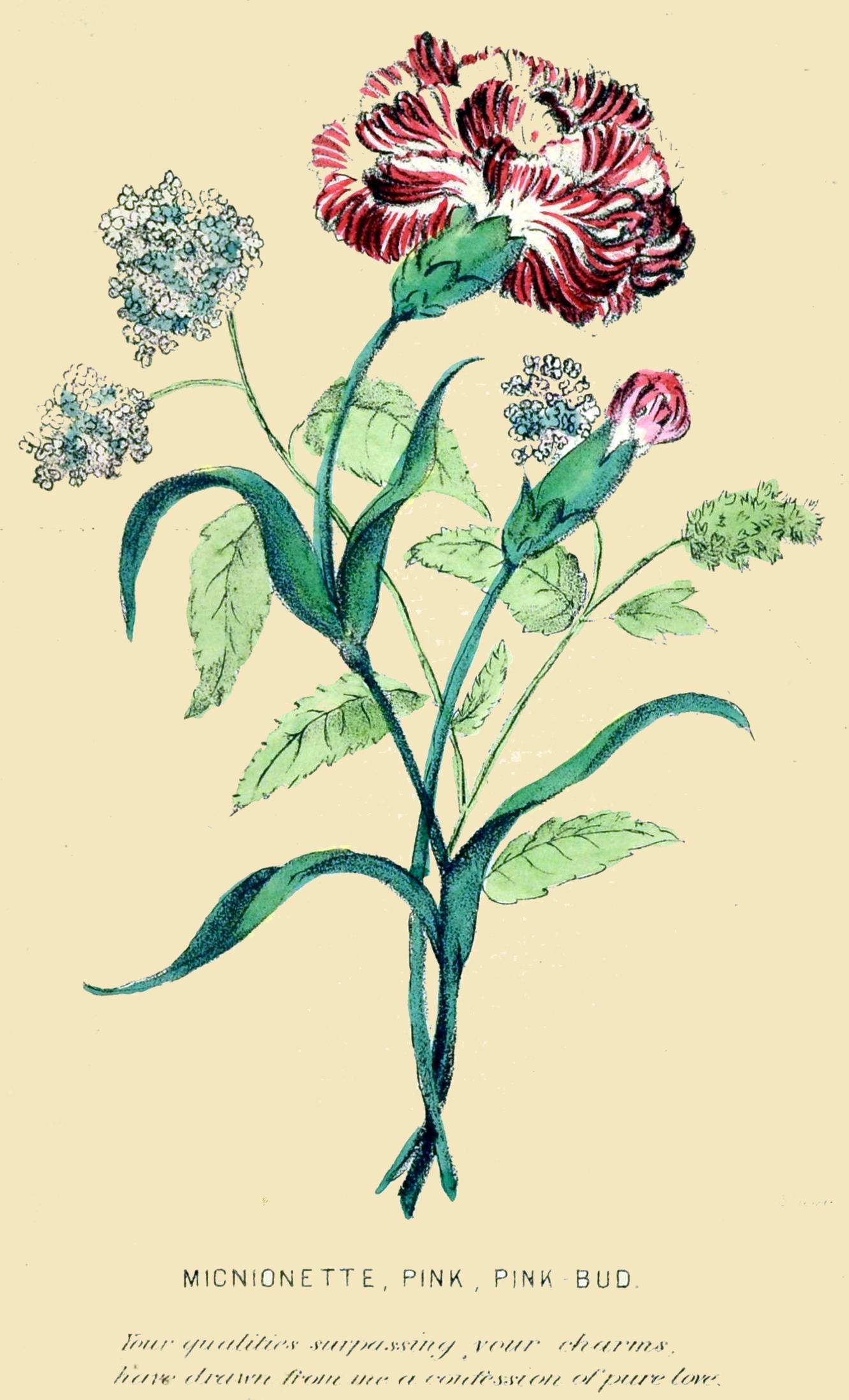

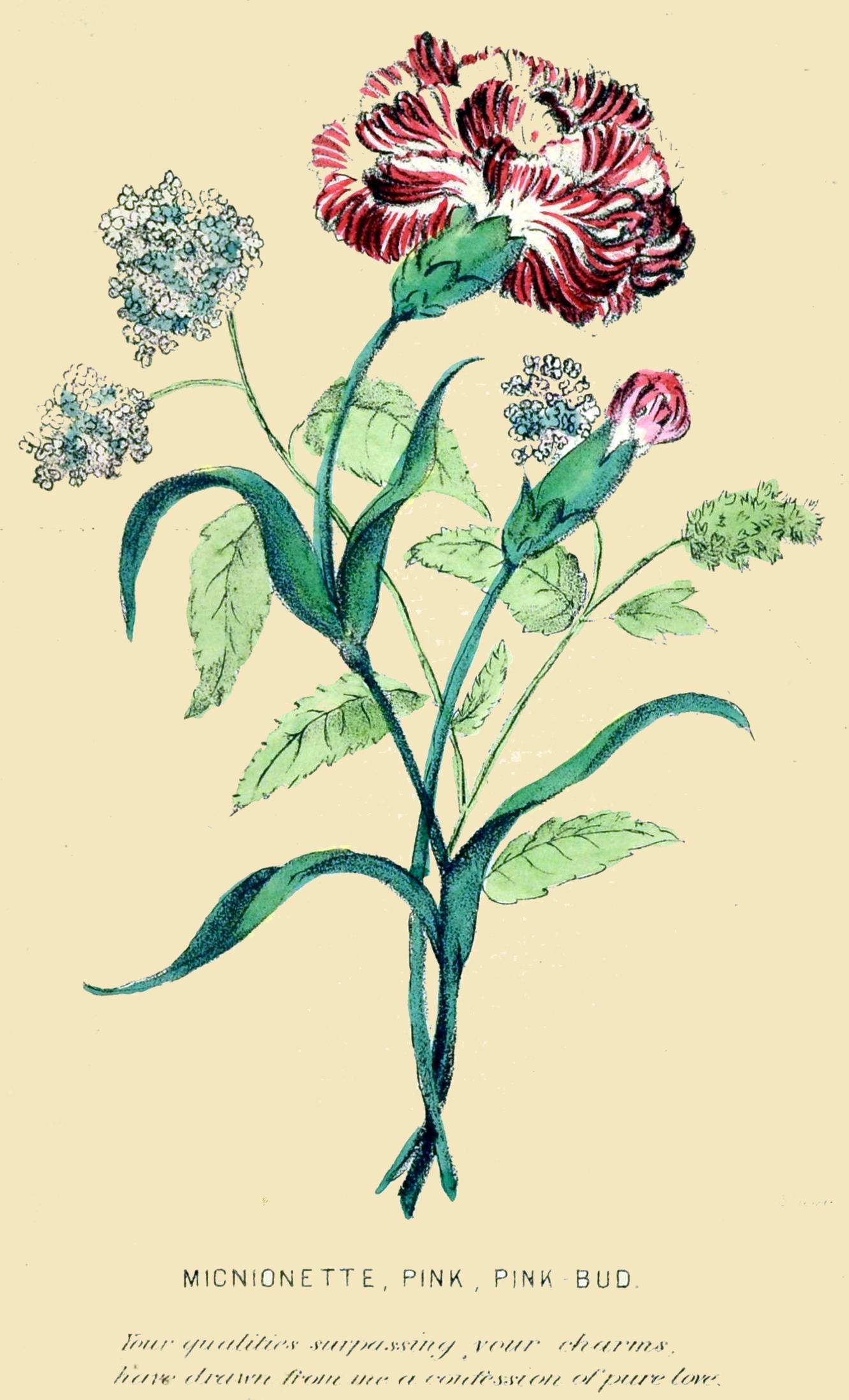

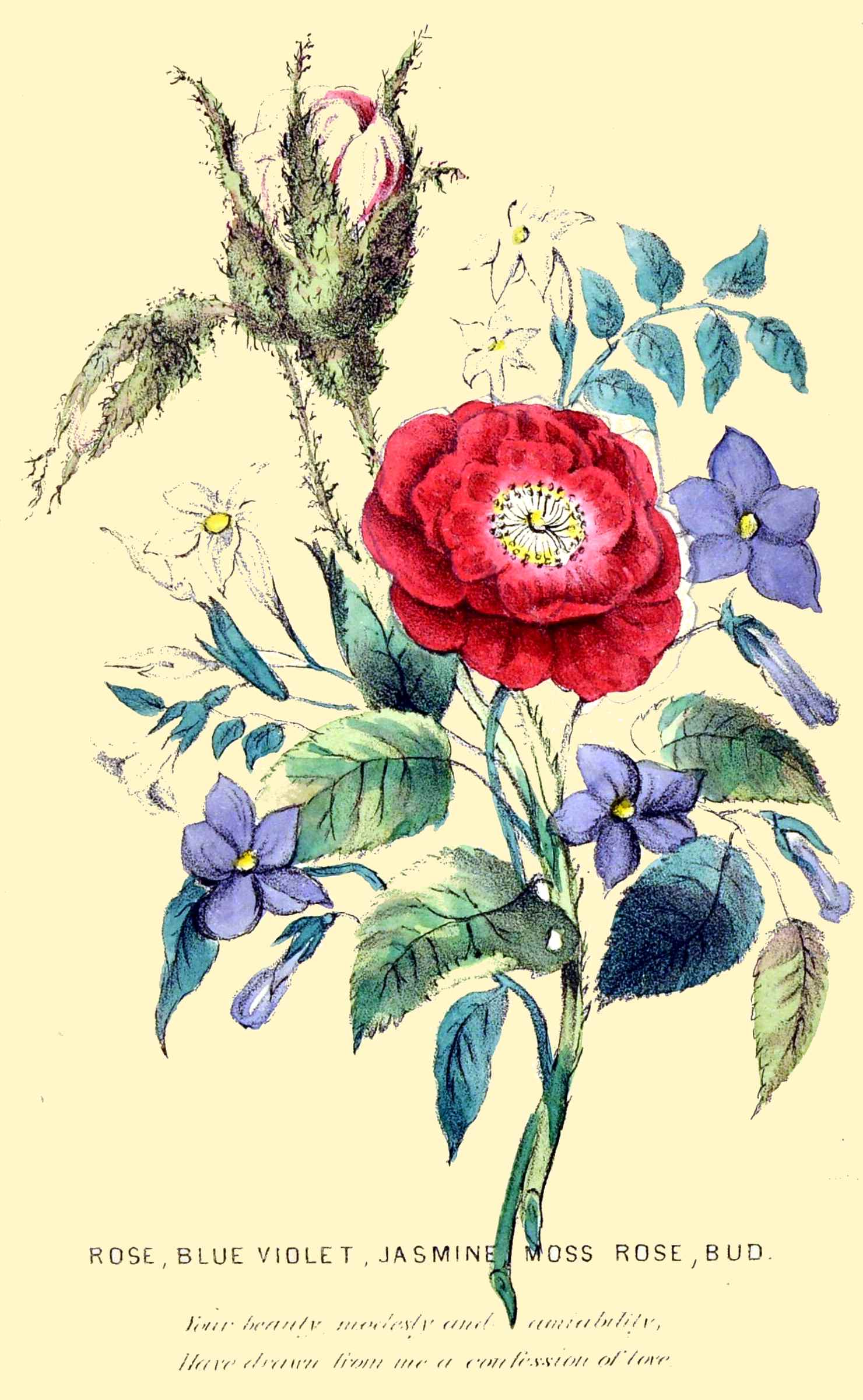

ROSE, BLUE VIOLET, JASMINE MOSS ROSE, BUD.

ROSE, BLUE VIOLET, JASMINE MOSS ROSE, BUD.

Your beauty, modesty and amiability,

Have drawn from me a confession of love.

THE

FLORAL OFFERING:

A

TOKEN OF AFFECTION AND ESTEEM;

COMPRISING

WITH COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS, FROM ORIGINAL DRAWINGS.

————

By HENRIETTA DUMONT.

————

PHILADELPHIA:

H. C. PECK & THEO. BLISS.

1851.

{6}

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1851, by

H. C. PECK & THEO. BLISS,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the Eastern District of

Pennsylvania.

STEREOTYPED BY L. JOHNSON AND CO.

PHILADELPHIA.

{5}

Preface.

Why has the beneficent Creator scattered over the face of the earth such

a profusion of beautiful flowers—flowers by the thousand and million,

in every land—from the tiny snowdrop that gladdens the chill spring of

the north, to the gorgeous magnolia that flaunts in the sultry regions

of the tropics? Why is it that every landscape has its appropriate

flowers, every nation its national flowers, every rural home its home

flowers? Why do flowers enter and shed their perfume over every scene of

life, from the cradle to the grave? Why are flowers made to utter all

voices of joy and sorrow in all varying scenes, from the chaplet that

adorns the bride to the votive wreath that blooms over the tomb?

It is for no other reason than that flowers have in themselves a real

and natural significance. They have a positive relation to man, his

sentiments, passions, and feelings. They correspond to actual emotions.

They have their mission—a mission of love and mercy. They have their

language, and from the remotest ages this language has found its

interpreters.

In the East the language of flowers has been universally understood and

applied “time out of mind.” Its meaning finds a place in their poetry

and in all their literature, and it is familiarly known among the

people. In Europe it has existed and been recognised for long ages among

the people, although scarcely noticed by the literati until a

comparatively recent period. Shakspeare, however, whom nothing escaped

which was known to the people, exhibits his intimate acquaintance with

the language of flowers in his masterly delineation of the madness of

Ophelia.

Recent writers in all languages recognise the beauty and propriety of

this language to such an extent, that an acquaintance with it has now

{7}become indispensable as a part of a polished education.

Our little volume is devoted to the explanation of this beautiful

language. We have made it as complete as our materials and limits would

permit. We present it to our readers in the humble hope that we shall

increase the means of elegant and innocent enjoyment by our “Floral

{9}{8}Offering.”

Contents.

| | PAGE |

| Acacia, (Friendship) | 123 |

| Acanthus, (The arts) | 140 |

| Almond Blossom, (Indiscretion) | 22 |

| Aloe, (Grief) | 28 |

| Althea, (Consumed by love) | 162 |

| Amaranth, (Immortality) | 100 |

| Anemone, (Forsaken) | 122 |

| Ash Tree, (Grandeur) | 222 |

| Box, (Stoicism) | 63 |

| Broom, (Humility) | 179 |

| Cactus, (Ardent love) | 26 |

| Camellia Japonica, (Modest merit) | 156 |

| Chamomile, (Energy in adversity) | 225 |

| China Aster, (Variety) | 200 |

| Citron, (Estrangement) | 227 |

| Columbine, (Desertion) | 87 |

| Common Thistle, (Misanthropy) | 243 |

| Corn, (Riches) | 186 |

| Cowslip, (Pensiveness) | 113 |

| Coxcomb, (Singularity) | 235{12} |

| Cranberry, (Cure for the heartache) | 188 |

| Crocus, (Youth) | 23 |

| Cypress, (Mourning) | 49 |

| Dahlia, (Elegance and dignity) | 154 |

| Daisy, (Innocence) | 39 |

| Dandelion, (The rustic oracle) | 132 |

| Dead Leaves, (Death) | 217 |

| Dew Plant, (Serenade) | 246 |

| Dragon Plant, (You are near a snare) | 229 |

| Dyer’s Weed, (Relief) | 166 |

| Fennel, (Strength) | 233 |

| Fir, (Time) | 238 |

| Forget-me-not | 116 |

| Grass, (Submission) | 236 |

| Hawthorn, (Hope) | 52 |

| Hazel, (Peace, reconciliation) | 204 |

| Heliotrope, (Devoted affection) | 106 |

| Holly, (Foresight) | 195 |

| Hollyhock, (Ambition) | 96 |

| Hyacinth, (Constancy) | 59 |

| Ice Plant, (Frigidity) | 25 |

| Ivy, (Constancy) | 193 |

| Jasmine, (Amiability) | 109 |

| Juniper, (Protection) | 203 |

| Lady’s Slipper, (Capricious beauty) | 160 |

| Larkspur, (Flights of fancy) | 164 |

| Laurel, (Glory) | 98 |

| Lavender, (Distrust) | 36 |

| Lichen, (Solitude) | 254 |

| Lilac, (First emotions of love) | 46 |

| Lily, (Majesty) | 67 |

| Lily of the Valley, (Modesty) | 58 |

| Love-lies-bleeding, (Deserted love) | 55

{13} |

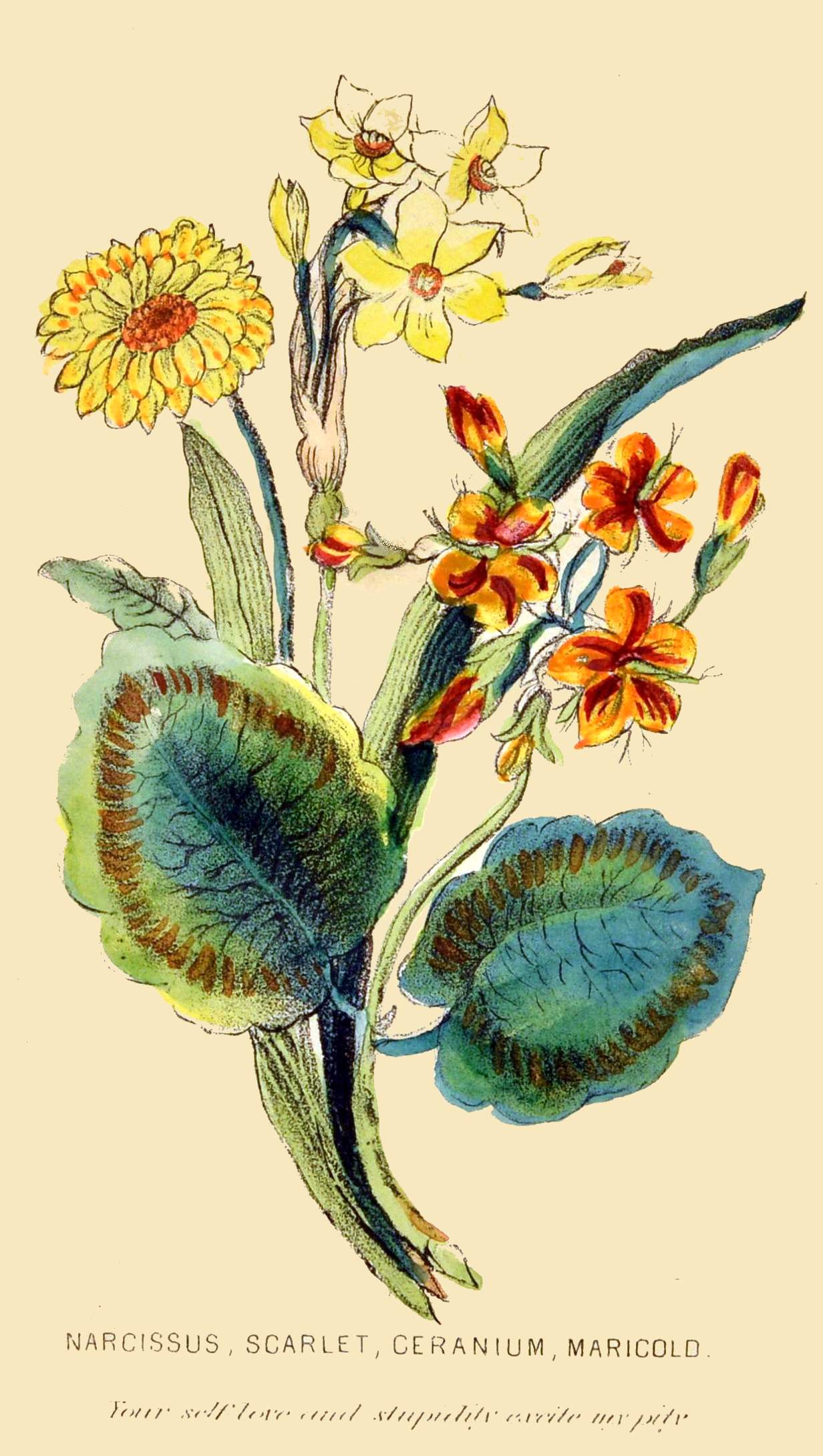

| Marigold, (Grief) | 72 |

| Marvel of Peru, (Timidity) | 143 |

| Meadow Saffron, (My best days are past) | 198 |

| Mezereon, (Coquetry, desire to please) | 13 |

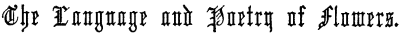

| Mignonette, (Your qualities surpass your charms) | 108 |

| Mistletoe, (I climb to greatness) | 220 |

| Moss, (Maternal love) | 125 |

| Moss Rose, (Confession of love) | 69 |

| Myrtle, (Love) | 56 |

| Narcissus and Daffodil, (Self-love) | 65 |

| Nasturtion, (Patriotism) | 168 |

| Nettles, (Cruelty) | 86 |

| Nightshade, or Bitter-sweet, (Truth) | 170 |

| Oak, (Nobility) | 206 |

| Oak Geranium, (Friendship) | 150 |

| Orchis, (A belle) | 61 |

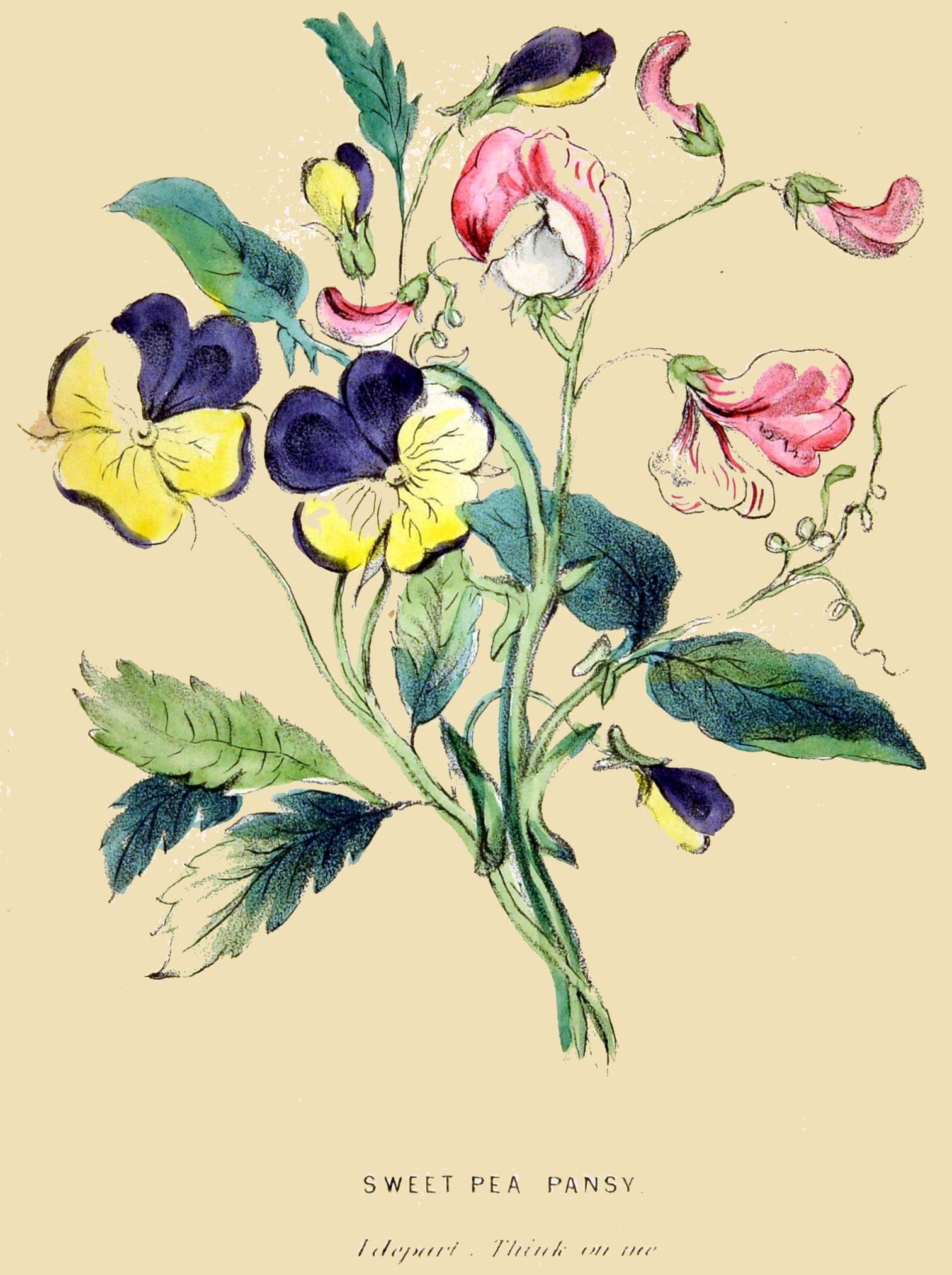

| Pansy, (Think of me) | 37 |

| Passion Flower, (Faith) | 89 |

| Peony, (Anger) | 85 |

| Periwinkle, (Tender recollections) | 43 |

| Pimpernel, (The weather-glass) | 133 |

| Pine, (Pity) | 248 |

| Pink, (Pure love) | 91 |

| Poppy, (Consolation) | 135 |

| Primrose, (Early grief) | 20 |

| Red Rose, (Beauty and love) | 77 |

| Reed, (Single blessedness) | 231 |

| Rosemary, (Remembrance) | 120 |

| Sage, (Domestic virtues) | 251 |

| Scarlet Geranium, (Stupidity) | 147 |

| Sensitive Plant, (Chastity) | 92 |

| Snowdrop, (Hope) | 15 |

| Starwort, American, (Welcome) | 202

{14} |

| St. John’s Wort, (Superstition) | 181 |

| Stock, (Lasting beauty) | 145 |

| Strawberry, (Perfection) | 102 |

| Sweet-Brier, or Eglantine, (Poetry) | 45 |

| Sweet-Flag—Acorus Calamus, (Grace) | 172 |

| Sunflower, (False riches) | 104 |

| Thorn-Apple, (Deceitful charms) | 158 |

| Thyme, (Activity) | 94 |

| Tuberose, (Dangerous love) | 152 |

| Tulip, (Declaration of love) | 48 |

| Valerian, (An accommodating disposition) | 142 |

| Vervain, (Enchantment) | 184 |

| Violet, (Modest worth) | 31 |

| Wall-Flower, (Fidelity in adversity) | 51 |

| White Water-Lily, (Purity) | 70 |

| White Rose, (I would be single) | 74 |

| Woodbine, or Honeysuckle, (Affection) | 111 |

| Wormwood, (Absence) | 30 |

| Yellow Rose, (Jealousy) | 75 |

| Yew, (Sorrow) | 215 |

| Death of the Flowers | 257 |

| Dictionary of Flowers | 259 |

| Calendar of Flowers | 268 |

| Dial of Flowers | 293 |

The Floral Offering.

Mezereon.... Coquetry—Desire to please.

This shrub, clothed in its showy garb, appears amidst the snow, like an

imprudent and coquettish female, who, though shivering with cold, wears

her spring attire in the depth of winter. The stalk of this shrub is

covered with a dry bark, which gives it the appearance of dead wood.

Nature, to hide this deformity, has encircled each of its sprays with a

wreath of red flowers, terminating in a tuft of leaves. These flowers

give out a peculiar and offensive smell.

You oftentimes can mark upon the street

The gilded toy whom fashion idolizes;

Heartless and fickle, swelled with self-conceit,

Avoiding alway what good sense advises.

Who flutters like the butterfly while burns his sun,

Nor afterwards is missed when life is done.

W. H. C.

Clouds turn with every wind about;

They keep us in suspense and doubt;

Yet oft perverse, like woman-kind,

Are seen to scud against the wind.

Is not this lady just the same?

For who can tell what is her aim?

Swift.

Thou delightest the cold world’s gaze,

When crowned with the flower and the gem,

But thy lover’s smile should be dearer praise

Than the incense thou prizest from them.

And gay is the playful tone,

As to the flattering voice thou respondest;

But what is the praise of the cold and unknown

To the tender blame of the fondest?

John Everett.

Know, Celia, (since thou art so proud,)

’Twas I that gave thee thy renown:

Thou hadst, in the forgotten crowd

Of common beauties, lived unknown,

Had not my verse exhaled thy name,

And with it impt the wings of Fame.

That killing power is none of thine,

I gave it to thy voice and eyes:

Thy sweets, thy graces, all are mine;

Thou art my star, shin’st in my skies!

Then dart not from thy borrowed sphere

Lightning on him that fixed thee there.

Snowdrop. ... Hope.

The Snowdrop is looked upon as the herald of the approach of

flower-wreathed Spring. The north winds howl; the naked branches of the

trees are white with frost; the earth is carpeted with the virgin snow;

the feathered musicians are silent; and stern Winter’s icy hand chills

the rivulet till it ceases to murmur. At this season, a tender flower

springs up amid the snow, expands its blossoms, and leads thought to the

verdant hours to come. This beautiful sign of awakening Nature may aptly

be considered as the emblem of Hope.

The Snowdrop, winter’s timid child,

Awakes to life bedewed with tears,

And flings around its fragrance mild;

And, where no rival flowerets bloom,

Amidst the bare and chilling gloom

A beauteous gem appears.

All weak and wan, with head inclined,

Its parent breast the drifted snow,

It trembles, while the ruthless wind

Bends its slim form; the tempest lowers,

Its emerald eye drops crystal showers

On its cold bed below.

Where’er I find thee, gentle flower,

Thou still art sweet and dear to me;

For I have known the cheerless hour,

Have seen the sunbeams cold and pale,

Have felt the chilling wintry gale,

And wept and shrunk, like thee!

No one is so accursed by fate,

No one so utterly desolate,

But some heart, though unknown,

Responds unto his own;

Responds, as if with unseen wings

An angel touched its quivering strings,

And whispers in its song,

“Where hast thou stayed so long?”

Longfellow.

The star of Hope will beam in Sorrow’s night,

And smile the phantoms of Despair to flight.

Anon.

“Why do you call the Snowdrop pale,

Our first of flowerets bright?

For the Christmas Rose came long before,

So did the Aconite.”

I know the yellow Aconite;

I know the Christmas Rose:

But neither one nor other e’er

Within my garden grows.

They seem to me presumptuous things,

That rudely hurry on,

And struggle for the precedence

A fairer flower hath won.

When I was but a wee, wee thing,

A young Snowdrop I nursed,

And I loved it when they told me how

It always blossomed first.

I marked its tiny, trembling stem,

And dainty little bell,{17}

And, oh! so tenderly enjoyed

Its faint, delicious smell.

It was not only fair and sweet,

’Twas the first flower that came;

So said they then, and there is none

I could love now the same.

The Aconite may deck with gold

Its merry little face—

The Christmas Rose at Christmas bloom,

But none can fill her place.

Within my garden’s small domain

The Snowdrop still shall find

Herself the earliest flower. She leads,

The others come behind.

And, lo! above the heaving mould

The clustering bells hang here;

Like foam upon the storm-black wave,

Or pearls in Ethiop’s ear.

And I know where they’re crowding thick,

With none their wealth to note;—

All o’er that woody isle, that lies

Girt by the ancient moat.

There, under tall, dark crested firs,

The Snowdrops spring each year;

And shed about that gloomy place

A lightness pale and clear.

A grand old Manor House once stood

On that dim moated isle;

But long years since have floated by,

And its story died the while.

Yet roses, cultured ones, run wild,

And fruits, grown rough and sour,{18}

That linger still around, tell tales

Of garden and of bower.

And so the Snowdrops may have dwelt

In borders neat and trim,

And gentle beings tended them,

Though now all’s drear and dim.

The brave and beautiful have died,

Not e’en a name is known:—

Time hath laid low the stately house,—

Ye cannot find a stone.

But still there runneth brightly there

The little sedgy stream

Into the moat, that lieth still

And shadowy as a dream.

And still there groweth plenteously

The fragile Snowdrop’s bell:—

Oh, human pride! that thou wouldst list

The tale these small things tell!

Louisa A. Twamley.

As Hope, with bowed head, silent stood,

And on her golden anchor leant,

Watching below the angry flood,

While Winter, mid the dreariment

Half-buried in the drifted snow,

Lay sleeping on the frozen ground,

Not heeding how the wind did blow,

Bitter and bleak on all around:

She gazed on Spring, who at her feet

Was looking on the snow and sleet.

Spring sighed, and through the driving gale

Her warm breath caught the falling snow,{19}

And from the flakes a flower as pale

Did into spotless whiteness blow.

Hope, smiling, saw the blossom fall,

And watched its root strike in the earth:

“I will that flower the Snowdrop call,”

Said Hope, “in memory of its birth:

And through all ages it shall be

In reverence held, for love of me.”

“And ever from my hidden bowers,”

Said Spring, “it first of all shall go,

And be the herald of the flowers,

To warn away the sheeted snow.

Its mission done, then by thy side

All summer long it shall remain.

While other flowers I scatter wide,

O’er every hill, and wood, and plain,

This shall return, and ever be

A sweet companion, Hope, for thee.”

Hope stooped and kissed her sister Spring,

And said, “For hours, when thou art gone,

I’m left alone without a thing

That I can fix my heart upon:

’Twill cheer me many a lonely hour,

And in the future I shall see

Those who would sink raised by that flower;

They’ll look on it, then think of thee:

And many a sadful heart shall sing,

The Snowdrop bringeth Hope and Spring.”

Primrose. ... Early Grief.

The Primrose is one of the earliest flowers of spring. It was anciently

called Paralisos, the name of a beautiful youth, who died of grief for

the loss of his betrothed Melicerta, and was metamorphosed by his

parents into this flower, which has since been a favourite of the poets.

With fairest flowers,

Whilst summer last, and I live here, Fidele,

I’ll sweeten thy sad grave: thou shalt not lack

The flower that’s like thy face, pale Primrose.

Cymbeline.

The Primrose pale is Nature’s meek and modest child.

Balfour.

Nay, weep not while thy sun shines bright,

And cloudless is thy day,

While past and present joys unite

To cheer thee on thy way;

While fond companions round thee move,

To youth and nature true,

And friends whose looks of anxious love

Thy every step pursue.

Common-Place Book of Poetry.

The Primrose, tenant of the glade,

Emblem of virtue in the shade.

Ask me why I send you here

This firstling of the infant year;

Ask me why I send to you

This Primrose all bepearled with dew:

I straight will whisper in your ears,

The sweets of love are washed with tears.

Ask me why this flower doth show

So yellow, green, and sickly too;

Ask me why the stalk is weak

And bending, yet it doth not break:

I must tell you these discover

What doubts and fears are in a lover.

Thomas Carew.

By the soft green light in the woody glade,

On the banks of moss where thy childhood played,

By the household tree through which thine eye

First looked in love to the summer sky;

By the dewy gleam, by the very breath

Of the Primrose-tufts in the grass beneath,

Upon thy heart there is laid a spell,

Holy and precious—oh, guard it well!

Yes! when thy heart in its pride would stray

From the first pure loves of its youth away;

When the sullying breath of the world would come

O’er the flowers it brought from its native home;

Think thou again of the woody glade,

Of the sound by the rustling ivy made;

Think of the tree at thy father’s door,

And the kindly spell shall have power once more.

Almond Blossom. ... Indiscretion.

The Almond tree is the first of the trees to put forth its blossoms,

when spring breathes the breath of life through nature. It has been made

the emblem of indiscretion, from flowering so early that frosts too

often give a death-chill to the precocious germs of its fruit. In

ancient times, the abundance of blossoms upon the Almond tree was

considered to promise a fruitful season. The following is the fabulous

account of the origin of this tree:—Demophoon, son of Theseus and

Phædra, in returning from the siege of Troy, was thrown by a storm on

the shores of Thrace, where then reigned the beautiful Phyllis. The

young queen graciously received the prince, fell in love with him, and

became his wife. When recalled to Athens by his father’s death,

Demophoon promised to return in a month, and fixed the day. The loving

Phyllis counted the hours of his absence, and, at last, the appointed

day arrived. Nine times she repaired to the shore; but, losing all hope

of his return, she died of grief, and was converted into an Almond tree.

Soon afterwards, Demophoon returned. Overwhelmed with sorrow, he offered

a sacrifice at the sea-side, to appease the manes of his bride. The

Almond tree instantly put forth its blossoms, and seemed to sympathize

with his repentance.

Oh! had I nursed when I was young

The lessons of my father’s tongue,

(The deep laborious thoughts he drew

From all he saw, and others knew,){23}

I might have been,—ah, me!

Thrice sager than I e’er shall be.

For what says Time?

Alas! he only shows the truth

Of all that I was told in youth.

Barry Cornwall.

Crocus. ... Youth.

The Crocus is one of the earliest of the spring flowers, and, therefore,

a fit emblem of the spring of life. It is a small flower, of variegated

hues; the principal being purple, yellow, and white. The Crocus

Vernus, or Spring Crocus, is a wild flower now in various parts of

England, though not considered to be really a native of the country. We

learn from the favourite writers, Mr. and Mrs. Howitt, that they are

plentiful about Nottingham, “gleaming at a distance like a perfect flood

of lilac, and tempting very many little hearts, and many graver ones

too, to go out and gather.”

Oh! many a glorious flower there grows

In far and richer lands;

But high in my affection e’er

The beautiful Crocus stands.

I love their faces, when by one

And two they’re looking out;

I love them when the spreading field

Is purple all about.

I loved them in the by-gone years

Of childhood’s thoughtless laughter,

When I marvelled why the flowers came first,

And the leaves the season after.{24}

I loved them then, I love them now—

The gentle and the bright;

I love them for the thoughts they bring

Of spring’s returning light;

When, first-born of the waking earth,

Their kindred gay appear,

And, with the Snowdrop, usher in

The hope-invested year.

Louisa A. Twamley.

You’re glad

Because your little tiny nose,

Turns up so pert and funny;

Because I know you choose your beaux

More for their mirth than money;

Because your eyes are deep and blue,—

Your fingers long and rosy;

Because a little maid like you

Would make one’s home so cozy;

Because, I think, (I’m just so weak,)

That some of these fine morrows

You’ll listen while you hear me speak

My story, and my sorrows!

Anon.

Gay hope is theirs, by fancy fed,

Less pleasing when possest;

The tear forgot as soon as shed,

The sunshine of the breast;

Theirs buxom health, of rosy hue;

Wild wit, invention ever new,

And lively cheer of vigour born;{25}

The thoughtless day, the easy night,

The spirits pure, the slumbers light,

That fly the approach of morn.

Alas, regardless of their doom,

The little victims play!

No sense have they of ills to come,

No care beyond to-day.

Yet see how all around them wait,

The ministers of human fate,

And black misfortune’s baleful train,

Ah! show them where in ambush stand,

To seize their prey, the murderous band!

Ah, tell them they are men!

Gray’s Eton College.

Life went a Maying

With Nature, Hope, and Poesy,

When I was young!

Coleridge.

Ice-Plant.... Frigidity.

Canst thou no kindly ray impart,

Thou strangely beauteous one?

Fairer than fairest work of art,

Yet cold as sculptured stone!

Thou art in Friendship’s bright domain

A flower that yields no fruit;

And Love declares thy beauty vain;—

Of fragrance destitute!

With pellucid studs the Ice-Flower gems

His rimy foliage, and his candied stems.

Darwin.

As water fluid is, till it do grow

Solid and fixed by cold,

So in warm seasons love doth loosely flow;

Frost only can it hold;

Your coldness and disdain

Does the sweet course restrain.

Cowley.

Cactus.... Ardent Love.

The flower of the Cactus is chosen to signify ardent love, because of

the glowing hues of the flower itself, and the heat of the climate in

which the plant grows to the greatest size. The gorgeousness of the

flower of the Cactus needs no eulogy. No fitter emblem could have been

selected to represent the passion of love in its full flame.

I think of thee, when soft and wide

The evening spreads her robes of light,

And, like a young and timid bride,

Sits blushing in the arms of night:

And when the moon’s sweet crescent springs

In light o’er heaven’s deep waveless sea,

And stars are forth like blessed things,

I think of thee—I think of thee.

Thou’rt like a star; for when my way was cheerless and forlorn,

And all was blackness like the sky before a coming storm,

Thy beaming smile and words of love, thy heart of kindness free,

Illumed my path, then cheered my soul, and bade its sorrows flee.

Thou’rt like a star—when sad and lone I wander forth to view

The lamps of night, beneath their rays my spirit’s nerved anew,

And thus I love to gaze on thee, and then I think thou’st power

To mix the cup of joy for me, even in life’s darkest hour.

Thou’rt like a star—whene’er my eye is upward turned to gaze

Upon those orbs, I mark with awe their clear celestial blaze;

And then thou seem’st so pure, so high, so beautifully bright,

I almost feel as if it were an angel met my sight.

American Ladies’ Magazine.

Could genius sink in dull decay,

And wisdom cease to lend her ray;

Should all that I have worshipped change,

Even this could not my heart estrange;

Thou still wouldst be the first, the first

That taught the love sad tears have nursed.

The sick soul

That burns with love’s delusions, ever dreams,

Dreading its losses. It for ever makes

A gloomy shadow gather in the skies,

And clouds the day; and looking far beyond

The glory in its gaze, it sadly sees

Countless privations, and far-coming storms,

Shrinking from what it conjures.

Simms’s Poems.

The rolling wheel, that runneth often round,

The hardest steel in tract of time doth tear;

And drizzling drops, that often do redound,

Firmest flint doth in continuance wear:

Yet cannot I, with many a dropping tear,

And long entreaty, soften her hard heart,

That she will once vouchsafe my plaint to hear,

Or look with pity on my painful smart:

But when I plead, she bids me play my part;

And when I weep, she says tears are but water;

And when I sigh, she says I know the art;

And when I wail, she turns herself to laughter;

So do I weep and wail, and plead in vain,

While she as steel and flint doth still remain.

Spenser.

Aloe.... Grief.

The Aloe is attached to the soil by very feeble roots; it delights to

grow in the wilderness, and its taste is extremely bitter. Thus grief

separates us from earthly things, and fills the heart with bitterness.

These {29}magnificent and monstrous plants are found in barbarous Africa:

they grow upon rocks, in dry sand under a burning atmosphere. Some have

leaves six feet long, and armed with long spires. From the centre of

these leaves shoots up a slender stem covered with flowers.

Sister Sorrow! sit beside me,

Or, if I must wander, guide me:

Let me take thy hand in mine,

Cold alike are mine and thine.

Think not, Sorrow, that I hate thee,—

Think not I am frightened at thee,—

Thou art come for some good end;

I will treat thee as a friend.

R. M. Milnes.

And this is all I have left now,

Silence and solitude and tears;

The memory of a broken vow,

My blighted hopes, my wasted years!

Anon.

It may be that I shall forget my grief;

It may be time has good in store for me;

It may be that my heart will find relief

From sources now unknown. Futurity

May bear within its folds some hidden spring

From which will issue blessed streams; and yet

Whate’er of joy the coming year may bring,

The past—the past—I never can forget.

Of comfort no man speak:

Let’s talk of graves, of worms, of epitaphs:

Make dust our paper, and with rainy eyes

Write sorrow on the bosom of the earth.

Let’s choose executors, and talk of wills;

And yet not so—for what can we bequeath,

Save our deposed bodies in the ground?

Shakspeare.

Wormwood. ... Absence.

Wormwood is the bitterest of plants; and absence, according to La

Fontaine, is the worst of evils. Those in whose anxious breasts the

“flame divine” is burning, will agree with the French author in his

assertion. To be absent from one we love is to carry a vacant chamber in

the heart, which naught else can fill.

When thou shalt yield to memory’s power,

And let her fondly lead thee o’er

The scenes that thou hast past before,

To absent friends and days gone by,—

Then should these meet thy pensive eye,

A true memento may they be

Of one whose bosom owes to thee

So many hours enjoyed in gladness,

That else perhaps had passed in sadness,

And many a golden dream of joy,

Untarnished and without alloy.

Oh, still my fervent prayer will be,

“Heaven’s choicest blessings rest on thee.”

How can the glintin sun shine bright?

How can the wimplin burnie glide?

Or flowers adorn the ingle side?

Or birdies deign

The woods, and streams, and vales to chide?

Eliza’s gane!

J. W. H.

If she be gone, the world, in my esteem,

Is all bare walls; nothing remains in it

But dust and feathers.

John Crown.

Thus absence dies, and dying proves

No absence can subsist with loves

That do partake of fair perfection;

Since, in the darkest night, they may,

By love’s quick motion, find a way

To see each other in reflection.

Suckling.

Violet.... Modest Worth.

The Violet has always been a favourite theme of admiration among

visitors of Parnassus. Its quiet beauty and love of retired spots have

ever made it the emblem of true worth that shrinks from parade. It is

one of the first children of spring, and awakens pleasing emotions in

the breast of the lover of the beautiful, as he strolls through the

meadows in the season of joy. Ion, the Greek name of this flower, is

traced by some etymologists to Ia, the daughter of Midas, who was

be{32}trothed to Atys, and changed by Diana into a Violet, to hide her from

Apollo.

A woman’s love, deep in the heart,

Is like the Violet flower,

That lifts its modest head apart

In some sequestered bower.

Anon.

The maid whose manners are retired,

Who, patient, waits to be admired,

Though overlooked, perhaps, a while

Her modest worth, her modest smile,—

Oh, she will find, or soon, or late,

A noble, fond, and faithful mate,

Who, when the spring of life is gone,

And all its blooming flowers are flown,

Will bless old Time, who left behind

The graces of a virtuous mind.

Paulding.

Pansies, Lilies, Kingcups, Daisies,

Let them live upon their praises;

Long as there’s a sun that sets,

Primroses will have their glory;

Long as there are Violets,

They will have a place in story:

There’s a flower that shall be mine,

’Tis the little Celandine.

Eyes of some men travel far

For the finding of a star;

Up and down the heavens they go,

Men that keep a mighty rout!{33}

I’m as great as they, I trow,

Since the day I found thee out,

Little flower!—I’ll make a stir,

Like a great astronomer.

Modest, yet withal an elf,

Bold, and lavish of thyself,

Since we needs must first have met

I have seen thee, high and low,

Thirty years or more, and yet

’Twas a face I did not know:

Thou hast now, go where I may,

Fifty greetings in a day.

Ere a leaf is on the bush,

In the time before the thrush

Has a thought about its nest,

Thou wilt come with half a call,

Spreading out thy glossy breast

Like a careless prodigal;

Telling tales about the sun,

When there’s little warmth or none.

Wordsworth.

Shakspeare regarded the Violet as the emblem of constancy, as the

following occurs in one of his sonnets:—

Violet is for faithfulness,

Which in me shall abide;

Hoping, likewise, that from your heart

You will not let it slide.

The Violet in her greenwood bower,

Where birchen boughs with hazles mingle,

May boast herself the fairest flower,

In glen, or copse, or forest dingle.

Scott.

Under the hedge all safe and warm,

Sheltered from boisterous wind and storm,

We Violets lie:

With each small eye

Closely shut while the cold goes by.

You look at the bank, mid the biting frost,

And you sigh, and say that we’re dead and lost;

But, Lady stay

For a sunny day,

And you’ll find us again, alive and gay.

On mossy banks, under forest trees,

You’ll find us crowding, in days like these;

Purple and blue,

And white ones too,

Peep at the sun, and wait for you.

By maids and matrons, by old and young,

By rich and poor, our praise is sung;

And the blind man sighs

When his sightless eyes

He turns to the spot where our perfumes rise.

There is not a garden, the country through,

Where they plant not Violets, white and blue;

By princely hall,

And cottage small—

For we’re sought, and cherished, and culled by all.{35}

Yet grand parterres and stiff trimmed beds

But ill become our modest heads;

We’d rather run,

In shadow and sun,

O’er the banks where our merry lives first begun.

There, where the Birken bough’s silvery shine

Gleams over the hawthorn and frail woodbine,

Moss, deep and green,

Lies thick, between

The plots where we Violet-flowers are seen.

And the small gay Celandine’s stars of gold

Rise sparkling beside our purple’s fold:—

Such a regal show

Is rare, I trow,

Save on the banks where Violets grow.

Louisa A. Twamley.

I know where bloom some Violets in a bed

Half hidden in the grass; and crowds go by

And see them not, unless some curious eye

Unto their hiding-place by chance is led.

I often pass that way, and look on them,

And love them more and more. I know not why

My heart doth love such humble things; but I

Esteem them more than robe or diadem

Of haughty kings. A babe, or bird, or flower

Hath o’er the soul a most despotic power.

The tearful eye of infancy oppressed—

A flower down-trodden by the foot of spite—

Awaken sighs of sorrow in the breast,

Or nerve the arm to vindicate their right.

Lavender.... Distrust.

It was anciently believed that the asp, a dangerous species of viper,

made Lavender its habitual place of abode, for which reason that plant

was approached with extreme caution. The Romans used it largely in their

baths, from whence its name is derived.

Our doubts are traitors,

And make us lose the good we oft might win,

By fearing to attempt.

Shakspeare.

Who never doubted never half believed,

Where doubt there truth is—’tis her shadow.

Bailey.

When first, with all a lover’s pride,

I wooed and won thee for my bride,

I little thought that thou couldst be

Estranged as now thou art from me!

Anon.

Thy confidence is held from me,

In fear my love but shows,

Like one, art thou, who fears the bee

May sting thee, through the rose.

Pansy.... Think of me.

The Pansy, or Heart’s-ease, is a beautiful variety of the Violet,

differing from it in the diversity of its colours. In fragrance it is

inferior to the Violet. Pansy is an old English corruption of the French

Pensée.

“And there are Pansies, that’s for thoughts.”

Shakspeare.

CHILDHOOD.

Sister, arise, the sun shines bright,

The bee is humming in the air,

The stream is singing in the light,

The May-buds never looked more fair;

Blue is the sky, no rain to-day:

Get up, it has been light for hours,

And we have not begun to play,

Nor have we gathered any flowers.

Time, who looked on, each accent caught,

And said, “He is too young for thought.”

YOUTH.

To-night, beside the garden-gate?

Oh, what a while the night is coming!

I never saw the sun so late,

No heard the bee at this time humming!

I thought the flowers an hour ago

Had closed their bells and sunk to rest:

How slowly flies that hooded crow!

How light it is along the west!

Said Time, “He yet hath to be taught

That I oft move too quick for thought.{38}”

MANHOOD.

What thoughts wouldst thou in me awaken?

Not love? for that brings only tears—

Nor friendship? no, I was forsaken!

Pleasure I have not known for years:

The future I would not foresee,

I know too much from what is past,

No happiness is there for me,

And troubles ever come too fast.

Said Time, “No comfort have I brought,

The past to him’s one painful thought.”

OLD AGE.

Somehow the flowers seem different now,

The Daisies dimmer than of old;

There’s fewer blossoms on the bough,

The Hawthorn buds look gray and cold;

The Pansies wore another dye

When I was young—when I was young!

There’s not that blue about the sky

Which every way in those days hung.

There’s nothing now looks as it “ought.”

Said Time, “The change is in thy thought.”

Miller.

I think of thee at morn, when glisten

The tearful dew-drops on the grass;

I think of thee at eve, and listen,

When the low, whispering breezes pass.

And thou, so rich in gentle names, appealing

To hearts that own our nature’s common lot;

Thou, styled by sportive Fancy’s better feeling

A Thought, the Heart’s-Ease, and Forget-me-not.

Barton.

Daisy.... Innocence.

Shakspeare speaks of the Daisy as the flower

Whose white investments figure innocence;

and succeeding poets have generally used it as the image of that pure

quality. Fable informs us that the Daisy owes its origin to Belides, one

of the Dryads, who were supposed to preside over meadows and pastures.

While dancing on the turf with Ephigeus, whose suit she encouraged, she

attracted the admiration of Vertumnus, the deity who presided over

orchards; and, to escape from him, she was transformed into the humble

flower, the Latin name of which is Bellis. The ancient English name of

the flower was Day’s Eye, of which Daisy is a corruption. In Ossian’s

poems, the Daisy is called the flower of the new-born—most expressive

of innocence.

When smitten by the morning ray,

I see thee rise alert and gay,

Then, cheerful flower! my spirits play

With kindred gladness:

And when, at dark, by dews opprest,

Thou sink’st, the image of thy rest

Hath often eased my pensive breast

Of careful sadness.

She dwells amid the world’s dark ways,

Pure as in childhood’s hours;

And all her thoughts are poetry,

And all her words are flowers.

Mrs. M. E. Hewitt.

’Twas when the world was in its prime,

When meadows green and woodlands wild

Were strewn with flowers, in sweet spring-time,

And everywhere the Daisies smiled.

When undisturbed the ring-doves cooed,

While lovers sang each other’s praises,

As in embowered lanes they wooed,

Or on some bank white o’er with Daisies:

While Love went by with muffled feet,

Singing, “The Daisies they are sweet.”

Unfettered then he roamed abroad,

And as he willed it past the hours—

Now lingering idly by the road,

Now loitering by the wayside flowers;

For what cared he about the morrow?

Too young to sigh, too old to fear—

No time had he to think of sorrow,

Who found the Daisies everywhere;

Still sang he, through each green retreat,

“The Daisies they are very sweet.”

With many a maiden did he dally,

Like a glad brook that turns away—

Here in, there out, across the valley,

With every pebble stops to play;

Taking no note of space nor time,

Through flowers, the banks adorning,{41}

Still rolling on, with silver chime,

In star-clad night and golden morning.

So went Love on, through cold and heat,

Singing, “The Daisy’s ever sweet.”

’Twas then the flowers were haunted

With fairy forms and lovely things,

Whose beauty elder bards have chanted,

And how they lived in crystal springs,

And swang upon the honied bells;

In meadows danced round dark green mazes,

Strewed flowers around the holy wells,

But never trampled on the Daisies.

They spared the star that lit their feet,

The Daisy was so very sweet.

Miller.

When soothed awhile by milder airs,

Thee Winter in the garland wears

That thinly shades his few gray hairs;

Spring cannot shun thee;

Whole summer fields are thine by right,

And autumn, melancholy wight,

Doth in thy crimson head delight,

When rains are on thee.

In shoals and bands, a morrice train,

Thou greet’st the traveller in the lane;

If welcomed once thou count’st it gain,

Thou art not daunted;

Nor car’st if thou be set at naught:

And oft alone in nooks remote

We meet thee, like a pleasant thought,

When such are wanted.

I cannot gaze on aught that wears

The beauty of the skies,

Or aught that in life’s valley bears

The hues of paradise;

I cannot look upon a star,

Or cloud that seems a seraph’s car,

Or any form of purity—

Unmingled with a dream of thee.

P. Benjamin.

The Daisy scattered on each meade and downe,

A golden tuft within a silver crown;

Faire fell that dainty flower! and may there be

No shepherd graced that doth not honour thee.

Browne.

There is a flower, a little flower

With silver crest and golden eye,

That welcomes every changing hour,

And weathers every sky.

Montgomery.

Heaven may awhile correct the virtuous,

Yet it will wipe their eyes again, and make

Their faces whiter with their tears. Innocence

Concealed is the stolen pleasure of the gods,

Which never ends in shame, as that of men

Doth oftentimes do; but like the sun breaks forth,

When it hath gratified another world;

And to our unexpecting eyes appears

More glorious through its late obscurity.

Periwinkle.... Tender Recollections.

In France, the Periwinkle has been adopted as the emblem of the

pleasures of memory and sincere friendship, probably in allusion to

Rousseau’s recollection of his friend, Madame de Warens, occasioned,

after a lapse of thirty years, by the sight of this flower, which they

together had admired. This plant is deeply rooted in the soil which it

adorns. It throws out its shoots on all sides to clasp the earth, and

covers it with flowers, which reflect the hue of heaven. Thus our first

affections, warm, pure, and artless, seem to be of heavenly origin.

Though the rock of my last hope is shivered,

And its fragments are sunk in the wave,

Though I feel that my soul is delivered

To pain,—it shall not be its slave.

There is many a pang to pursue me:

They may crush, but they shall not contemn;

They may torture, but shall not subdue me,—

’Tis of thee that I think, not of them.

Byron.

’Tis sweet, and yet ’tis sad, that gentle power,

Which throws in winter’s lap the spring-tide flower:

I love to dream of days my childhood knew,

When, with the sister of my heart, time flew

On wings of innocence and hope! dear hours,

When joy sprang up about our path, like flowers!

The lesser Periwinkle’s bloom,

Like carpet of Damascus’ loom,

Pranks with bright blue the tissue wove

Of verdant foliage: and above

With milk-white flowers, whence soon shall swell

Red fruitage, to the taste and smell

Pleasant alike, the Strawberry weaves

Its coronets of three-fold leaves

In mazes through the sloping wood.

Mant.

Where captivates the sky-blue Periwinkle

Under the cottage eaves.

Hurdis.

Remember thee?

Yea, from the table of my memory

I’ll wipe away all trivial fond records,

All saws of books, all forms, all pressures past,

That youth and observation copied there;

And thy commandment all alone shall live

Within the book and volume of my brain,

Unmixed with baser matter.

Shakspeare.

Oh! only those

Whose souls have felt this one idolatry

Can tell how precious is the slightest thing

Affection gives and hallows! A dead flower

Will long be kept, remembrancer of looks

That made each leaf a treasure.

Sweet-Brier, or Eglantine.... Poetry.

The Eglantine is the poet’s flower. In the floral games, it was the

prize for the best composition on the charms of study and eloquence.

Though its flowers are most beautiful in hue, their fragrance is their

more valuable quality. In like manner, the charms of poetry and

eloquence should be considered superior to those of appearance.

And well the poet, at her shrine,

May bend and worship while he woos;

To him she is a thing divine,

The inspiration of his line,

His loved one, and his muse.

If to his song the echo rings

Of fame—’tis woman’s voice he hears;

If ever from his lyre’s proud strings

Flow sounds, like rush of angel wings,

’Tis that she listens, while he sings,

With blended smiles and tears.

Halleck.

Give me the poet’s lyre!

And as the seraph in his orbit sings,

Oh, may I strike the heaven-attuned strings,

With a seraphic fire!

With music fill the mighty dome of mind,

And the rapt souls of men in music brightly bind!

Trace the young poet’s fate;

Fresh from his solitude, the child of dreams,

His heart upon his lips he seeks the world,

To find him fame and fortune, as if life

Were like a fairy tale. His song has led

The way before him; flatteries fill his ear,

His presence courted, and his words are caught;

And he seems happy in so many friends.

What marvel if he somewhat overrate

His talents and his state? These scenes soon change.

The vain, who sought to mix their name with his;

The curious, who but live for some new sight;

The idle—all these have been gratified,

And now neglect stings even more than scorn.

Miss Landon.

Lilac.... First Emotions of Love.

The freshness of the verdure of the Lilac; the flexibility of its

branches; the profusion of its flowers; their transitory beauty and

their soft hues,—all remind us of those emotions which embellish

beauty, and throw such a light around our youthful hours. It is said

that Van Spaendonc himself threw down his pencil on viewing a group of

Lilacs. Nature seems to have delighted in creating its delicate

clusters, which astonish by their beauty and variety. The fragrance of

the flowers is even more gratifying than their beauty.

She had grown,

In her unstained seclusion, bright and pure

As a first opening Lilac, when it spreads

Its clear leaves to the sweetest dawn of May.

When first thou earnest, gentle, shy, and fond,

My purest, first-born love, and dearest treasure,

My heart received thee with a joy beyond

All that it yet had felt of earthly pleasure;

Nor thought that any love again might be

So deep and strong, as that I felt for thee.

Mrs. Norton.

I love thee,—and I live! The moon,

Who sees me from her calm above,

The wind, who weaves her dim, soft tune

About me, know how much I love!

Naught else, save night, and the lonely hour,

E’er heard my passion wild and strong;

Even thou yet deem’st not of thy power,

Unless thou read’st aright my song!

Barry Cornwall.

She loves—but knows not whom she loves,

Nor what his race, nor whence he came;—

Like one who meets, in Indian groves,

Some beauteous bird without a name,

Brought by the last ambrosial breeze,

From isles in the undiscovered seas,

To show his plumage for a day

To wondering eyes, and wing away!

Tulip.... Declaration of Love.

The Tulip is an extraordinary favourite in many parts of Europe and

Asia; and, in Holland and Turkey, the most extravagant prices are paid

for fine specimens. On account of the elegance of its form, the beauty

of its colours, and its want of fragrance and other useful qualities,

this flower has been considered as an appropriate symbol of a female who

possesses no recommendation but a beautiful appearance. In the East, the

Tulip is employed as the emblem by which a lover makes known his passion

to his mistress; as the Tulip expresses the idea that he has a face all

fire and a heart all coal.

Not one of Flora’s brilliant race

A form more perfect can display:

Art could not feign more simple grace,

Nor Nature take a line away.

Yet, rich as morn, of many a hue,

When flushing clouds through darkness strike,

The Tulip’s petals shine in dew,

All beautiful, but none alike.

Montgomery.

My heart is sad and lonely,

With weariness I pine;

Would thou wert here, mine only,—

Would I were wholly thine!

H. J. H.

DAISY WALL FLOWER AND TULIP.

DAISY WALL FLOWER AND TULIP.

Your innocence and fidelity in misfortune

Have caused me to declare my love for you

{49}

If spirits, pure as those who kneel

Around the throne of light above,

The power of beauty’s spell could feel,

And lose a heaven for woman’s love,—

What marvel that a heart like mine

Enraptured by thy charms should be!

Forget to bend at glory’s shrine,

And lose itself—ay, heaven—for thee!

Memorial.

Fain would I speak the thoughts I bear to thee,

But they do choke and flutter in my throat,

And make me like a child.

Joanna Baillie.

Cypress.... Mourning.

The ancients consecrated the Cypress to the Fates, the Furies and Pluto.

They placed it near tombs. The people of the East retain the same custom

in the decoration of their cemeteries. The Turks plant the Cypress at

the head and at the foot of the graves. According to Ovid, the Cypress

derived its name from Cyparissos, an especial friend of Apollo’s, who,

in grief at having inadvertently killed a favourite stag of his, prayed

the gods that his mourning might be made perpetual, and was changed into

a Cypress tree, the branches of which were thenceforward used at

funerals.

Lady dear! this history

Is thy fated lot,

Ever such thy watching

For what cometh not,{50}

Till with anxious waiting dull,

Round thee fades the beautiful;

Still thou seekest on, though weary,

Seeking still in vain.

Miss Landon.

Thou art lost to me for ever,—I have lost thee, Isadore,

Thy head will never rest upon my loyal bosom more.

Thy tender eyes will never more gaze fondly into mine,

Nor thine arms around me lovingly and trustingly entwine.

Thou art dead and gone, loving wife,—thy heart is still and cold,—

And I at one stride have become most comfortless and old;

Of our whole world of love and song, thou wast the only light,

A star, whose setting left behind, ah! me, how dark a night!

Thou art lost to me, for ever, Isadore.

Albert Pike.

The Cypress is the emblem of mourning.

Shakspeare.

Alas, for earthly joy, and hope, and love,

Thus stricken down, e’en in their holiest hour!

What deep, heart-wringing anguish must they prove,

Who live to weep the blasted tree or flower!

Oh, wo, deep wo to earthly love’s fond trust,

When all it once has worshipped lies in dust!

Wall-Flower.... Fidelity in Adversity.

This flower derives its name from the circumstance of its growing upon

old walls, the casements and battlements of ancient castles, and among

the ruins of abbeys. The troubadors were accustomed to wearing a bouquet

of Wall-flowers, as the emblem of an affection which is proof against

time and the frowns of fortune.

Adah.—Alas! thou sinnest now, my Cain; thy words

Sound impious in mine ears.

Cain.—Then leave me!

Adah.—Never,

Though thy God left thee!

Byron.

An emblem true thou art

Of love’s enduring lustre given

To cheer a lonely heart.

Barton.

Flower of the solitary place!

Gray Ruin’s golden crown,

That lendest melancholy grace

To haunts of old renown;

Thou mantlest o’er the battlements

By strife or storm decayed;

And fillest up each envious rent

Time’s canker-tooth hath made.

Though human, thou didst not deceive me;

Though woman, thou didst not forsake;

Though loved, thou forborest to grieve me;

Though slandered, thou never couldst shake;

Though trusted, thou didst not disclaim me;

Though parted, it was not to fly;

Though watchful, ’twas not to defame me;

Nor, mute, that the world might belie.

Byron.

Yes, love! my breast, at sorrow’s call,

Shall tremble like thine own;

If from those eyes the tear-drops fall,

They shall not fall alone.

Our souls, like heaven’s aerial bow,

Blend every light within their glow,

Of joy or sorrow known;

And grief, divided with thy heart,

Were sweeter far than joy apart.

Anon.

Hawthorn.... Hope.

Various significations have been given to the Hawthorn. Among the Turks,

a branch of it expresses the wish of a lover to receive a kiss from the

object of his affection. Among the ancient Greeks, the Hawthorn was a

symbol of conjugal union; its blossomed boughs were carried about at

their wedding festivities, and the newly-married couple were even

lighted to their bridal chamber with torches made of its wood. In

England, the Hawthorn is used in the sports of May-days, and is,

therefore, frequently called May. There is a{53} proverb among the rural

inhabitants of that country, that a “store of haws portend cold

winters.” Though the Hawthorn is quoted as the emblem of Hope, it must

be considered more particularly as the lover’s hope.

HOW MAY WAS FIRST MADE.

As Spring upon a silver cloud

Lay looking on the world below,

Watching the breezes as they bowed

The buds and blossoms to and fro,

She saw the fields with Hawthorns walled:

Said Spring, “New buds I will create.”

She to a Flower-Spirit called,

Who on the month of May did wait,

And bade her fetch a Hawthorn-spray,

That she might make the buds of May.

Said Spring, “The grass looks green and bright,

The Hawthorn-hedges too are green,

I’ll sprinkle them with flowers of light,

Such stars as earth has never seen;

And all through England’s girded vales,

Her steep hill-sides and haunted streams,

Where woodlands dip into the dales,

Where’er the Hawthorn stands and dreams,

Where thick-leaved trees make dark the day,

I’ll light each nook with flowers of May.

Like pearly dew-drops, white and round,

The shut-up buds shall first appear.

And in them be such fragrance found,

As breeze before did never bear;{54}

Such as in Eden only dwelt,

When angels hovered round its bowers,

And long-haired Eve at morning knelt

In innocence amid the flowers:

While the whole air was, every way,

Filled with a perfume sweet as May.

And oft shall groups of children come,

Threading their way through shady places,

From many a peaceful English home,

The sunshine falling on their faces;

Starting with merry voice the thrush,

As through green lanes they wander singing,

To gather the sweet Hawthorn bush;

Which, homeward in the evening bringing

With smiling faces, they shall say,

‘There’s nothing half so sweet as May.’

And many a poet yet unborn

Shall link its name with some sweet lay,

And lovers oft at early morn

Shall gather blossoms of the May;

With eyes bright as the silver dews,

Which on the rounded May-buds sleep,

And lips, whose parted smiles diffuse

A sunshine o’er the watch they keep,

Shall open all their white array

Of pearls, ranged like the buds of May.”

Spring shook the cloud on which she lay,

And silvered o’er the Hawthorn spray,

Then showered down the buds of May.

Miller.

With hope all pleases, nothing comes amiss.

And Hawthorn’s early blooms appear,

Like youthful hope upon life’s year.

Drayton.

Gay was the love of paradise he drew

And pictured in his fancy; he did dwell

Upon it till it had a life; he threw

A tint of heaven athwart it—who can tell

The yearnings of his heart, the charm, the spell,

That bound him to that vision?

Percival.

Love-lies-bleeding.... Deserted Love.

This beautiful emblem of love, wounded and bereaved by fate, is a

species of Amaranthus. The flower is of a reddish-purple hue, which

circumstance suggests its name.

A single rose is shedding

Its lovely lustre meek and pale:

It looks as planted by despair—

So white, so faint—the slightest gale

Might whirl the leaves on high.

Byron.

And on with many a step of pain,

Our weary race is sadly run;

And still, as on we plod our way,

We find, as life’s gay dreams depart,

To close our being’s troubled day,

Naught left us but a broken heart.

Nor would I change my buried love

For any heart of living mould,

No—for I am a hero’s child—

I’ll hunt my quarry in the wild;

And still my home this mansion make,

Of all unheeded and unheeding,

And cherish, for my warrior’s sake,

The flower of Love-lies-bleeding.

Campbell.

Upon her face there was the tint of grief,

The settled shadow of an inward strife,

And an unquiet drooping of the eye,

As if its lid were charged with unshed tears.

Byron.

Myrtle.... Love.

The Myrtle has ever been consecrated to Venus. At Rome, the temple of

the goddess was surrounded by a grove of Myrtles; and in Greece, she was

adorned under the name of Myrtilla. It was observed by the ancients,

that, wherever the Myrtle grew, it excluded all other plants. So love,

wherever it is permitted to grow, excludes all other feelings. The

ladies of modern Rome retain a strong affection for this plant,

preferring its odour to that of the most fragrant essences.

Our love came as the early dew

Comes unto drooping flowers;

Dropping its first sweet freshness on

Our life’s dull, lonely hours.

Love is a celestial harmony

Of likely hearts, composed of stars’ consent,

Which join together in sweet sympathy,

To work each other’s joy and true content,

Which they have harboured since their first descent,

Out of their heavenly bowers, where they did see

And know each other here beloved to be.

Spenser.

I have done penance for contemning love;

Whose high imperious thoughts have punished me

With bitter fasts, with penitential groans,

With nightly tears, and daily heart-sore sighs.

Shakspeare.

The Myrtle on thy breast or brow

Would lively hope and love avow.

J. H. Wiffen.

Comfort cannot soothe

The heart whose life is centred in the thought

Of happy loves, once known, and still in hope,

Living with a consuming energy.

Percival.

As in the sweetest bud

The eating canker dwells, so eating love

Inhabits in the finest wits of all.

Lily of the Valley.... Modesty.

The beautiful Lily of the Valley is the fit emblem of the union of

beauty, simplicity, and love of retirement. It adds an indescribable

charm to the spots where it blooms. Its snowy hues and general delicacy

of appearance excite emotions of a kindred nature to those we experience

in the company of one whose heart is free from guile, and whose manners

are gentle and unpretending.

Lilacs then, and daffodillies,

And the nice-leaved, lesser Lilies,

Shading, like detected light,

Their little green-tipt lamps of white.

Hunt.

I had found out a sweet green spot,

Where a Lily was blooming fair;

The din of the city disturbed it not,

But the spirit that shades the quiet cot

With its wings of love was there.

I found that Lily’s bloom,

When the day was dark and chill;

It smiled like a star in a misty gloom,

And it sent abroad a soft perfume,

Which is floating around me still.

Percival.

The Lily, in whose snow-white bells

Simplicity delights and dwells.

Hyacinth.... Constancy.

The blue Hyacinth is mentioned by several English writers as the emblem

of constancy. There are many varieties found in Europe and America, but

the variety known in Scotland as the “Blue Bell” is the most common and

the most celebrated.

When daisies blush, and wind-flowers wet with dew,

When shady lanes with Hyacinth’s are blue,

When the elm blossoms o’er the brooding bird,

And, wild and wide, the plover’s wail is heard,

Where melts the mist on mountains far away,

Till morn is kindled into brightest day.

Elliott.

Then come the wild weather, come sleet, or come snow,

We will stand by each other however it blow.

Oppression and sickness, and sorrow, and pain,

Shall be to our true love as links to the chain.

Longfellow.

She loves him yet!

The flower the false one gave her

When last he came,

Is still with her wild tears wet.

She’ll ne’er forget,

Howe’er his faith may waver,

Through grief and shame,

Believe it,—she loves him yet!

Over the moorland, over the lea,

Dancing airily, there are we:

Sometimes, mounted on stems aloft,

We wave o’er broom and heather,

To meet the kiss of the zephyr soft;

Sometimes, close together,

Tired of dancing, tired of peeping,

Under the whin you’ll find us sleeping.

Daintily bend we our honied bells,

While the gossipping bee her story tells,

And drowsily hums and murmurs on

Of the wealth to her waxen storehouse gone;

And though she gathers our sweets the while,

We welcome her in with a nod and a smile.

No rock is too high—no vale too low,

For our fragile and tremulous forms to grow.

Sometimes we crown

The castle’s dizziest tower, and look

Laughingly down

On the pigmy men in the world below,

Wearily wandering to and fro.

Sometimes we dwell on the cragged crest

Of mountain high,

And the ruddy sun, from the blue sea’s breast,

Climbing the sky,

Looks from his couch of glory up,

And lights the dew in the bluebell’s cup.

We are crowning the mountain

With azure bells,

Or decking the fountains

In forest dells,

Or wreathing the ruin with clusters gray,{61}

And nodding and laughing the livelong day;

Then chiming our lullaby, tired with play.

Are we not beautiful? Oh! are not we

The darlings of mountain and moorland and lea?

Plunge in the forest—are we not fair?

Go to the high-road—we’ll meet ye there.

Oh! where is the flower that content may tell,

Like the laughing and nodding and dancing bluebell.

Louisa A. Twamley.

The Hyacinth’s for constancy,

Wi’ its unchanging blue.

Burns.

Orchis.... A Belle.

The Butterfly Orchis is rather rare except where there is a chalky soil.

The Spider Orchis has gained its name from the great resemblance it

bears to one of those large, fat-bodied garden spiders, which are often

noticed for the singular beauty of the markings on their backs. Another

is so very like a fly, that it is named the Fly Orchis; another is like

a lizard, or some strange reptile, and the flowers being yellow, green,

and purple, and twisted in and about one another in a very odd way, it

really looks like some horrible group of queer living creatures. One,

from being fancied like a man, is called Man Orchis; another, very gayly

spotted, and ornamented with a helmet-like{62} appendage, is the Military

Orchis; another is called Bee Orchis. Bishop Mant thus alludes to some

of these:

Well boots it the thick-mantled leas

To traverse: if boon nature grant,

To crop the insect-seeming plant,

The vegetable Bee; or nigh

Of kin, the long-horned Butterfly,

White, or his brother purple pale,

Scenting alike the evening gale;

The Satyr flower, the pride of Kent,

Of Lizard form, and goat-like scent.

No wonder that cheek in its beauty transcendent,

Excelleth the beauty of others by far;

No wonder that eye is so richly resplendent,

For your heart is a rose and your soul is a star.

Mrs. Osgood.

What right have you, madam, gazing in your shining mirror daily,

Getting so by heart your beauty, which all others must adore;

While you draw the golden ringlets down your fingers, to vow gayly,

You will wed no man that’s only good to God,—and nothing more.

Box.... Stoicism.

The common Box, of which our hedge is formed, is indigenous in England,

preferring the chalky hills of Surrey and Kent for its residence, but

flourishing well on other soils. It is one of the most useful evergreen

shrubs we possess, and especially as it will grow under the drip and

shadow of other trees, as you know is the case with our hedge. It is

found in most European countries, from Britain southwards, also about

Mount Caucasus, Persia, China, Cochin China, and America. It was

formerly much more common in England than now, having disappeared under

the spread of agriculture. Box-hill, in Surrey, is named from this tree,

and is a conical elevation covered with a wood of Box-trees, some of

large size. Boxley in Kent, and Boxwell in Gloucestershire, are also

named from it. The leaf and general appearance of the tree are too

familiar to require any description. The scent of the spring blossoms is

rather powerful, and to some persons unpleasant. The timber is very

valuable, it is sold by weight, and, being very hard and smooth, and not

apt to warp, is well adapted for many nice and delicate purposes. In the

days of good old Evelyn, it appears to have been as much used as at

present, for he says, “It is good for the turner, engraver, carver,

mathematical instrument maker, comb and pipe, or flute-maker, and the

roots for the inlayer and cabinet-maker. Of box are made wheels,

sheaves, pins, pegs for musical instruments, nut-crackers,

button-moulds, weavers’ shuttles, hollar-sticks, bump-sticks, and

dressers for the shoe{64}maker, rulers, rolling-pins, pestles, mall-balls,

beetles, tops, chessmen, tables, screws, bobbins for bone-lace, spoons,

knife-handles, but especially combs.” Most of those engravings in books,

called wood-cuts, are done upon Box wood, and for that purpose English

Box is superior to any other, though a great portion of what is used in

this country comes from the Levant. The ancients used combs made of

Box-wood, and also instruments to be played on with the mouth. The

Romans used to adorn their gardens with it, clipped into form, as we

find from mention being made of clipped Box-trees by their writers. It

was formerly much cut in this manner here, and was ranked next to the

Yew for its capabilities of taking artificial and grotesque forms; but

except a few ancient hedges of Box, like our own, and those at Castle

Bromwich Hall, where the Yew hedges are also preserved, there are not

many vestiges of its former garden-glory remaining. A dwarf kind is used

for making a neat and firm edging to flower borders, for which nothing

answers so well, or produces so proper an effect.

Though youth be past, and beauty fled,

The constant heart its pledge redeems,

Like Box, that guards the flowerless bed,

And brighter from the contrast seems.

Narcissus and Daffodil.... Self-Love.

There are several species of the Narcissus. The Yellow Narcissus is

better known as the Daffodil, and bears much resemblance to the Yellow

Lily. The Poetic Narcissus is the largest of the species, and may be

distinguished by the crimson border of the very shallow and almost flat

cup of the nectary. Shakspeare, in his Winter’s Tale, speaks of

Daffodils,

That come before the swallow dares, and taste

The winds of March with beauty.

The ancients attributed the origin of the Narcissus to the metamorphosis

of a beautiful youth of that name, who, having slighted the love of the

nymph Echo, became enamoured of his own image, which he beheld in a

fountain, and pined to death in consequence.

I wandered lonely, as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host of golden Daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of the bay;

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.{66}

The waves beside them danced, but they

Outdid the sparkling waves in glee;

A poet could not but be gay

In such a joyful company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth to me the show had brought.

For oft when on my couch I lie,

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude.

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the Daffodils.

Wordsworth.

Nature’s laws must be obeyed,

And this is one she strictly laid

On every soul which she has made,

Down from our earliest mother:

Be self your first and greatest care,

From all reproach the darling spare,

And any blame that she should bear,

Put off upon another.

Miss Gould.

The pale Narcissus

Still feeds upon itself; but, newly blown,

The nymphs will pluck it from its tender stalk,

And say, “Go, fool, and to thy image talk.”

Lily.... Majesty.

The Lily’s height and beauty speak command. The Jews imitated its form

in the decorations of their first magnificent temple; and Christ

described it as more splendid than King Solomon in his most gorgeous

apparel. According to ancient mythology, there was originally but one

species of Lily, and that was orange-coloured; and the white was

produced by the following circumstance:—Jupiter, wishing to render

Hercules immortal, prevailed on Juno to take a deep draught of nectar,

which threw the queen into a profound sleep. Jupiter then placed the

infant Hercules at her breast, so that the divine milk might ensure

immortality. Hercules drew the milk faster than he could swallow it, and

some drops fell to the earth, from which immediately sprang the White

Lily.

Flowers of the fairest,

And gems of the rarest,

I find and I gather in country or town;

But one is still wanting,

Oh! where is it haunting?

The bud and the jewel must make up my crown.

Thou pearl of the deep sea

That flows in my heart free,

Thou rock-planted Lily, come hither, or send;

Mid flowers of the fairest,

And gems of the rarest,

I miss thee, I seek thee, my own parted friend!

Ye well arrayed——

Queen Lilies—and ye painted populace,

Who dwell in fields, and lead ambrosial lives.

Young.

The wand-like Lily, which lifted up,

As a Mœnad, its radiant-coloured cup,

Till the fiery star, which is in its eye,

Gazed through clear dew on the tender sky.

Shelley.

Her glossy hair is clustered o’er a brow

Bright with intelligence, and fair and smooth;

Her eyebrow’s shape is like the aerial bow,

Her cheek all purple with the beam of youth,

Mounting at times to a transparent glow,

As if her veins run lightning; she, in sooth,

Has a proud air, and grace by no means common,

Her stature tall,—I hate a dumpy woman.

Byron.

Oh, he is all made up of love and charms,

Whatever maid could wish or man admire;

Delight of every eye! when he appears,

A secret pleasure gladdens all that see him;

And when he talks, the proudest men will blush

To hear his virtues and his glory!

Moss Rose.... Confession of Love.

The origin of this exquisitely beautiful variety of the Rose is thus

fancifully accounted for:—

The Angel of the Flowers one day,

Beneath a Rose-tree sleeping lay,

That spirit to whose charge is given

To bathe young buds in dews from heaven.

Awaking from his light repose,

The angel whispered to the Rose,

“O fondest object of my care,

Still fairest found where all are fair,

For the sweet shade thou hast given to me,

Ask what thou wilt, ’tis granted thee.”

Then said the Rose, with deepening glow,

“On me another grace bestow.”

The spirit paused in silent thought—

What grace was there that flower had not?

’Twas but a moment—o’er the Rose

A veil of moss the angel throws;

And, robed in nature’s simplest weed,

Could there a flower that Rose exceed?

Anon.

They gather gems with sunbeams bright,

From floating clouds and falling showers;

They rob Aurora’s locks of light,

To grace their own fair queen of flowers.

Thus, thus adorned, the speaking rose

Becomes a token fit to tell{70}

Of things that words can ne’er disclose,

And naught but this reveal so well.

Then take my flower, and let its leaves

Beside thy heart be cherished near,

While that confiding heart receives

The thought it whispers to thine ear.

Token, 1830.

White Water-Lily.... Purity.

The White Water-Lily is the Queen of the Waves, and reigns sole

sovereign over the streams; and it was a species of Water-Lily which the

old Egyptians and ancient Indians worshipped—the most beautiful object

that was held sacred in their superstitious creed, and one which we

cannot look upon even now without feeling a delight mingled with

reverence. No flower looks more lovely than this “Lady of the Lake,”

resting her crowned head on a green throne of velvet, and looking down

into the depths of her own sky-reflecting realms, watching the dance, as

her attendant water-nymphs keep time to the rocking of the ripples, and

the dreamy swaying of the trailing water streams.

Thine is a face to look upon and pray

That a pure spirit keep thee—I would meet

With one so gentle by the streams away,

Living with nature; keeping thy pure feet

For the unfingered moss, and for the grass

Which leaneth where the gentle waters pass.{71}

The autumn leaves should sigh thee to thy sleep;

And the capricious April, coming on,

Awake thee like a flower; and stars should keep

A vigil o’er thee like Endymion;

And thou for very gentleness shouldst weep

As dews of the night’s quietness come down.

Willis.

Oh, come to the river’s rim, come with us there,

For the White Water-Lily is wondrous fair,

With her large broad leaves on the stream afloat,

Each one a capacious fairy-boat.

The swan among flowers! How stately ride

Her snow-white leaves on the glittering tide!

And the Dragon-fly gallantly stays to sip

A kiss of dew from her goblet’s lip.

Anon.

The Lily on the water sleeping,

Enwreathed with pearl, and bossed with gold,

An emblem is, my love, of thee:

But when she like a nymph is peeping,

To watch her sister-buds unfold,

White shouldered on the flowery lea,

Gazing about in sweet amazement,

Thy image, from the vine-clad casement,

Seems looking out, my love, on me.

Miller.

Little streams have flowers a many,

Beautiful and fair as any;

Typha strong, and green bur reed,

Willow herb with cotton seed,{72}

Arrow head with eye of jet,

And the Water-Violet;

There the flowering Rush you meet,

And the plumy meadow sweet,

And in places deep and stilly

Marble-like, the Water-Lily.

Mrs. Howitt.

Marigold.... Grief.

The Marigold is the conventional emblem of distress of mind. It is

distinguished by many singular properties. It blossoms the whole year,

and on that account, the Romans termed it the flower of the calends, or

of all the months. Its flowers are open only from nine in the morning

till three in the afternoon. They always follow the course of the sun,

by turning from east to west as he proceeds upon his daily journey. In

July and August these flowers emit, during the night, small luminous

sparks. Alone, the Marigold expresses grief; interwoven with other