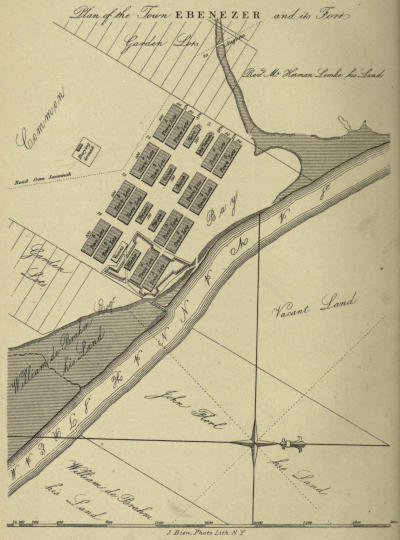

Plan of the Town EBENEZER and its Fort

J. Bien, Photo. Lith. N. Y.

Title: The dead towns of Georgia

Author: Jr. Charles C. Jones

Release date: May 10, 2023 [eBook #70735]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Morning News Steam Printing House

Credits: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BY

CHARLES C. JONES, Jr.

FOR HERE HAVE WE NO CONTINUING CITY.

Heb: xiii. 14

SAVANNAH:

MORNING NEWS STEAM PRINTING HOUSE.

1878.

TO

GEORGE WYMBERLEY-JONES DeRENNE, esq.,

OF SAVANNAH,

WHOSE INTELLIGENT RESEARCH, CULTIVATED TASTE, AND AMPLE FORTUNE HAVE BEEN

SO GENEROUSLY ENLISTED IN RESCUING FROM OBLIVION

THE EARLY MEMORIES OF GEORGIA,

THESE SKETCHES ARE RESPECTFULLY AND CORDIALLY INSCRIBED.

If it be praiseworthy in their descendants to erect monuments in honor of the illustrious dead, and to perpetuate in history the lives and acts of those who gave shape to the past and encouragement to the future, surely it will not be deemed inappropriate to gather up the fragmentary memories of towns once vital and influential within our borders, but now covered with the mantle of decay, without succession, and wholly silent amid the voices of the present.

Against the miasmatic influences of the swamps, Spanish perils, the hostility of the Aborigines, and the poverty and sometimes narrow mindedness of the Trust, did the Colonists grievously struggle in asserting their dominion over the untamed lands from the Savannah to the Alatamaha. Nothing indicates so surely the vicissitudes and the mistakes encountered during that primal period of development, as the Dead Towns of Georgia. From each comes in turn the whisper of hope, the sound of the battle with nature for life and comfort, the sad strain of disappointment, and then the silence of nothingness.

Of the chosen seats and characteristics of the primitive peoples who inhabited this territory prior to the advent of the European we have elsewhere spoken.[1]

Of the indications of a foreign occupancy antedating the colonization under Oglethorpe, such, for example, as those observed by DeBrahm[2] on Demetrius’ island, and a few others which might be mentioned,—we refrain from writing, because the theories explanatory of their origin, possession, and abandonment, are so nebulous as to seem incapable of satisfactory solution.

In narrating the traditions and grouping the almost obsolete memories of these deserted villages we have endeavored to revive them, as far as practicable, in the language of those to whom we are indebted for their transmission.

Charles C. Jones, Jr.

Augusta, Georgia, February 1st, 1878.

| PAGE. | ||

| I. | OLD AND NEW EBENEZER, | 11 |

| II. | FREDERICA, | 45 |

| III. | ABERCORN, | 137 |

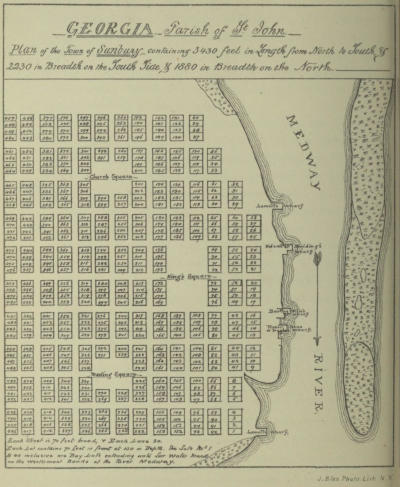

| IV. | SUNBURY, | 141 |

| V. | HARDWICK, | 224 |

| VI. | PETERSBURG, JACKSONBOROUGH, &C., | 233 |

| VII. | MISCELLANEOUS TOWNS, PLANTATIONS, &C., | 245 |

| 1. | PLAN OF NEW EBENEZER. |

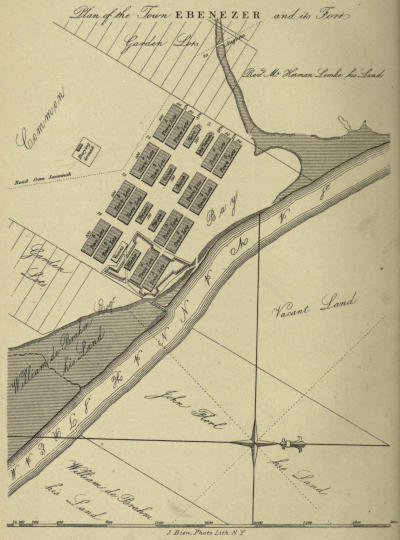

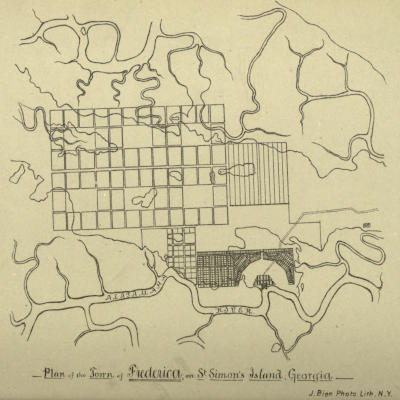

| 2. | PLAN OF FREDERICA. |

| 3. | PLAN OF SUNBURY. |

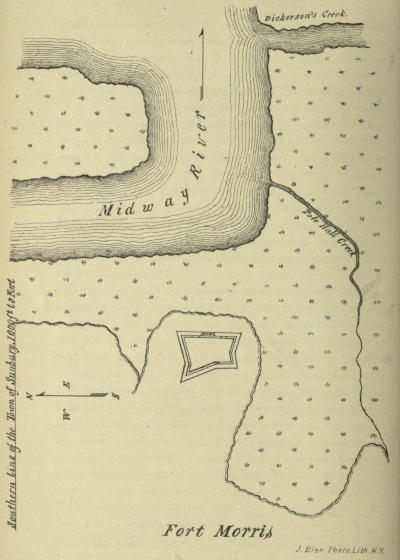

| 4. | PLAN OF FORT MORRIS. |

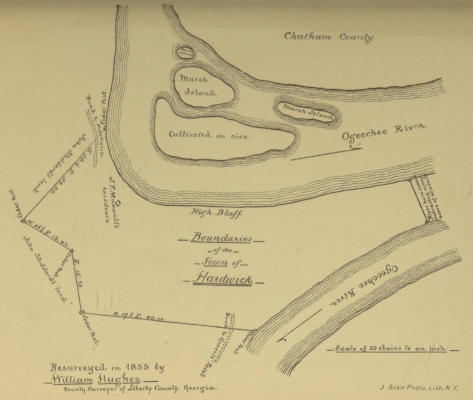

| 5. | OUTLINE OF HARDWICK. |

Plan of the Town EBENEZER and its Fort

J. Bien, Photo. Lith. N. Y.

During the four years commencing in 1729 and ending in 1732, more than thirty thousand Saltzburgers, impelled by the fierce persecutions of Leopold, abandoned their homes in the broad valley of the Salza and sought refuge in Prussia, Holland, and England, where their past sufferings and present wants enlisted substantial sympathy and relief from Protestant communities. Persuaded by the “Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge,” and acting upon the invitation of the Trustees of the Colony of Georgia,—who engaged not only to advance the funds necessary to defray the expenses of the journey and purchase the requisite sea-stores, but also to allot to each emigrant on his arrival in Georgia fifty acres of land in fee, and provisions sufficient to maintain himself and family until such land could be made available for support,—forty-two Saltzburgers, with their wives and children,—numbering in all seventy-eight souls,—set out from the town of Berchtolsgaden and its vicinity for Rotterdam, whence they were to be transported free of charge to Dover, England. At Rotterdam they were joined by their chosen religious teachers, the Reverend John Martin Bolzius and the Reverend Israel Christian Gronau. The oath of loyalty having been administered to them at Dover by the Trustees, these pious, industrious, and honest emigrants,[12] on the 28th of December, 1733, set sail in the ship Purisburg and, after a tedious and perilous passage, reached Charlestown, South Carolina, in safety. Mr. Oglethorpe, chancing to be there at the time, arranged that the Saltzburgers should proceed without delay to Savannah. The Savannah river was entered by them on the 10th of March, 1734. It was Reminiscere Sunday, according to the Lutheran calendar;—the gospel of the day being “Our Blessed Saviour came to the Borders of the Heathen after He had been persecuted in His own Country.” “Lying in fine and calm weather, under the Shore of our beloved Georgia, where we heard the Birds sing melodiously, every Body in the ship was joyful.” So wrote the Reverend Mr. Bolzius, the faithful attendant and spiritual guide of this Protestant band. He tells us also, that two days afterwards, when the ship arrived at the place of landing, “almost all the Inhabitants of the Town of Savannah were gather’d together; they fired off some Cannons, and cried Huzzah! which was answer’d by our Sailors, and other English People in our Ship in the same manner. Some of us were immediately fetch’d on Shore in a Boat, and carried about the City, into the woods, and the new Garden belonging to the Trustees. In the meantime a very good Dinner was prepared for us: And the Saltzburgers, who had yet fresh Meat in the Ship, when they came on shore, they got very good and wholesome English strong Beer. And besides the Inhabitants shewing them a great deal of Kindness, and the Country pleasing them, they were full of Joy and praised God for it.”[3]

Leaving his people comfortably located in tents, and in the hospitable care of the Colonists at Savannah, Mr. VonReck[13] set out on horseback with Mr. Oglethorpe to take a view of the country and select a spot where the Saltzburgers might form their settlement. At nine o’clock on the morning of the 17th of March they reached the place designated as the future home of the emigrants. It was about four miles below the present town of Springfield, in Effingham County, sterile and unattractive. To the eye of the Commissary, however, tired of the sea and weary of persecutions, it appeared a blessed spot, redolent of sweet hope, bright promise, and charming repose. Hear his description: “The Lands are inclosed between two Rivers, which fall into the Savannah. The Saltzburg Town is to be built near the largest, which is called Ebenezer,[4] in Remembrance that God has brought us hither; and is navigable, being twelve Foot deep. A little Rivulet, whose Water is as clear as Crystal, glides by the Town; another runs through it, and both fall into the Ebenezer. The Woods here are not so thick as in other Places. The sweet Zephyrs preserve a delicious coolness notwithstanding the scorching Beams of the Sun. There are very fine Meadows, in which a great Quantity of Hay might be made with very little Pains: there are also Hillocks, very fit for Vines. The Cedar, Walnut, Pine, Cypress and Oak make the greatest part of the Woods. There is found in them a great Quantity of Myrtle Trees out of which they extract, by boiling the Berries, a green Wax, very proper to make Candles with. There is much Sassafras, and a great Quantity of those Herbs of which Indigo is made, and Abundance of China Roots. The Earth is so fertile that it will bring forth anything that can be sown or planted in it; whether Fruits, Herbs, or Trees. There are wild Vines, which run up to[14] the Tops of the tallest Trees; and the Country is so good that one may ride full gallop 20 or 30 miles an end. As to Game, here are Eagles, Wild-Turkies, Roe-Bucks, Wild-Goats, Stags, Wild-Cows, Horses, Hares, Partridges, and Buffaloes.”[5] Upon the return of Mr. Oglethorpe and the Commissary to Savannah, nine able bodied Saltzburgers were immediately dispatched, by the way of Abercorn, to Ebenezer, to cut down trees and erect shelters for the Colonists. On the 7th of April the rest of the emigrants arrived, and, with the blessing of the good Mr. Bolzius, entered at once upon the task of clearing land, constructing bridges, building shanties, and preparing a road-way to Abercorn. Wild honey found in a hollow tree greatly refreshed them, and parrots and partridges made them “a very good dish.” Upon the sandy soil they fixed their hopes for a generous yield of peas and potatoes. To the “black, fat, and heavy” land they looked for all sorts of corn; and from the clayey soil they purposed manufacturing bricks and earthen ware. On the 1st of May lots were drawn upon which houses were to be erected in the town of Ebenezer. The day following, the hearts of the people were rejoiced by the coming of ten cows and calves,—sent as a present from the Magistrates of Savannah in obedience to Mr. Oglethorpe’s order. Ten casks “full of all Sorts of Seeds” arriving from Savannah, set these pious peoples to praising God for all His loving kindnesses. Commiserating their poverty, the Indians gave them deer, and their English neighbors taught them how to brew a sort of beer made of molasses, sassafras, and pine tops. Poor Lackner dying, by common consent the little money he left was made the “Beginning of a Box for the Poor.” The repeated thunderstorms[15] and hard rains penetrated through the rude huts and greatly incommoded the settlers. The water disagreed with them, causing serious affections of the bowels, until they found a brook, springing from a little hill, which proved both palatable and wholesome. By appointment, Monday the 13th of May was observed by the congregation as a season of Thanksgiving.

Depending entirely upon the charity of the Trustees for supplies of sorts, and having but few mechanics among them, these Saltzburgers labored under great disadvantages in building their little town in the depths of the woods, and surrounding themselves with fields and gardens. Patient of toil, however, and accustomed to work, they cut and delved away, day by day, rejoicing in their freedom, blessing the Giver of all good for His mercies, and observing the rules of honesty, morality, and piety, for which their sect had been so long distinguished. Communication with Savannah was maintained by way of Abercorn; to which place supplies were transported by water.

Early in 1735 the settlement was materially strengthened and encouraged by the arrival of fifty-seven more emigrants under the conduct of Mr. Vatt. Among the new-comers were several mechanics whose knowledge, industry, and skill were at once applied to hewing timber, splitting shingles, and sawing boards, to the manifest improvement of the dwellings in Ebenezer.

About a year afterwards occurred what is known as the great embarcation. Including some eighty Germans from the city of Ratisbon, under the control of Baron VonReck and Captain Hermsdorf, twenty-seven Moravians under the care of the Rev’d David Nitschman, the Rev’d John and Charles Wesley, and the Rev’d Mr. Ingham,—Missionaries to[16] the Indians,—and a number of poor English families, this accession to the Colony of Georgia aggregated some two hundred and twenty-seven persons, of whom two hundred and two were conveyed upon the Trust’s account. Francis Moore was appointed keeper of the stores. Oglethorpe in person accompanied the Colonists, and exercised a fatherly care over them during the voyage. They were transported in the Symond of 220 tons,—Capt. Joseph Cornish,—and the London Merchant, of like burthen,—Capt. John Thomas.[6] During the voyage the German Dissenters “sung psalms and served God in their own way.” Turnips, carrots, potatoes, and onions, issued with the salt provisions, prevented scurvy. In order to promote comfort and good order, the ships had been divided into cabins, with gangways between them, in which the emigrants were disposed according to families. The single men were located by themselves. Weather permitting, the vessels were cleaned between decks and washed with vinegar to keep them sweet. Constables were appointed “to prevent any disorders,” and so admirably was discipline preserved, that there was no occasion for punishment except in the case of a boy, “who was whipped for stealing of turnips.” The men were exercised with small arms, and instructed by Mr. Oglethorpe in the duties which would devolve upon them as free-holders in the new settlement. To the women were given thread, worsted, and knitting needles; and they were required to employ “their leisure time in making Stockings and Caps for their Family, or in mending their Cloaths and Linnen.” In this sensible way were matters ordered on these emigrant ships, and the colonists, during a protracted voyage, prepared for lives of industry in their new homes.

On the 5th of February, 1736, these ships, with the first of the flood, were carried over Tybee bar and found safe anchorage within. The emigrants were temporarily landed on Peeper island, where they dug a well and washed their clothes. It was Mr. Oglethorpe’s purpose to send most of these Saltzburgers to Frederica that they might assist in the development of that town and the construction of its fortifications. Desiring the benefit of their ministers, not wishing to divide their congregation, and being reluctant to go to the Southward where “they apprehended blows,”—fighting being “against their religion,”—they persuaded Mr. Oglethorpe to permit them to join their countrymen at Ebenezer, whither they accordingly went some days afterwards and were heartily welcomed. It will be remembered, however, that Captain Hermsdorf, with his little company, assured Mr. Oglethorpe “that he would never forsake him, but serve with the English to the last.” His offer was accepted, and on the 16th he set out with Mr. Oglethorpe for Frederica.

By this second accession the population of Ebenezer was increased so that it numbered in all some two hundred souls. Contentment and prosperity did not obtain in the town. In the fertility of the soil the inhabitants had encountered disappointment. Much sickness prevailed, and they were oppressed with the isolated character of their location. The creek upon which the town was situated was uncertain in volume, serpentine, and difficult of navigation. Although the distance from Old Ebenezer to the Savannah river by land did not exceed six miles, by following this, the only outlet by water, twenty-five miles must be passed before its confluence could be reached.[7]

Moved by these and other depressing considerations, the[18] Reverend Messrs. Bolzius and Gronau visited Savannah at the instance of their flock, and conferred with Mr. Oglethorpe as to the propriety of changing the location of the town. Moore says the Saltzburgers at Ebenezer were so discontented that they “demanded to leave their old Town, and to settle upon the Lands which the Indians had reserved for their own Use.”[8]

Having patiently listened to the request, Mr. Oglethorpe, on the 9th of February, 1736, set out with the Saltzburger ministers and several gentlemen for Ebenezer, to make a personal inspection of the situation and satisfy himself with regard to the expediency of the removal. He was received with every mark of consideration, and proceeded at once to consider the causes which induced the inhabitants to desire a change. Admitting that the existing “dissatisfaction was not groundless, and that there were many embarrassments connected with their situation,” he nevertheless endeavored to dissuade them from their purpose by reminding them that the labor already expended in clearing their lands, building houses, and constructing roads would, upon removal, be almost wholly lost. The hardships incident upon forming an entirely new settlement were urged upon their serious consideration. He also assured them that in clearing the forests, and in bringing the lands on the bank of the Savannah river under cultivation they would encounter the same diseases which afflicted them in their present location. He concluded, however, by assuring them that if they were resolved upon making the change he would not forbid it, but would assist them, as far as practicable, in compassing their design.

After this conference, and upon Mr. Oglethorpe’s return to Savannah, the question of a change of location was again considered by the Saltzburgers, who resolved among themselves that a removal was essential to the prosperity of their colony.[9] Acting upon this determination the community, without delay, set about migrating to the site selected for the new town. This was on a high ridge, near the Savannah river, called “Red Bluff” from the peculiar color of the soil. It received the name of New Ebenezer; and, to the simple-minded Germans, oppressed by poverty and saddened by the disappointments of the past, seemed to offer future happiness and much coveted prosperity. The labor of removal appears to have been compassed within less than two years. In June, 1738, Old Ebenezer[10] had degenerated into a cow-pen, where Joseph Barker resided and “had the care of the Trust’s Cattle.” William Stephens gives us a pitiable view of the abandoned spot when he visited[20] it on the 26th of that month:—Indian traders, returning from Savannah, lodging for the night with Barker, who was unable to give due account of the cattle under his charge, and a servant, Sommers, moving about with “the Small-Pox out full upon him.”[11] Thus early did “Old Ebenezer” take its silent place among the lost towns of Georgia. Its life of trials and sorrow, of ill-founded hope and sure disappointment, was measured by scarcely more than two years, and its frail memories were speedily lost amid the sighs and the shadows of the monotonous pines which environed the place.

The situation of the new Town, Mr. Strobel says, was quite romantic. “On the east lay the Savannah with its broad, smooth surface and its every varying and beautiful scenery. On the south was a stream, then called Little Creek, but now known as Lockner’s Creek, and a large lake called ‘Neidlinger’s Sea;’ while to the north, not very distant from the town, was to be seen their old acquaintance, Ebenezer Creek, sluggishly winding its way to mingle with the waters of the Savannah. The surrounding country was gently undulating and covered with a fine growth of forest trees, while the jessamine, the woodbine and the beautiful azalia, with its variety of gaudy colors, added a peculiar richness to the picturesque scene. But unfortunately for the permanent prosperity of the town, it was surrounded on[21] three sides by low swamps which were subject to periodical inundation, and consequently generated a poisonous miasma prejudicial to the health of the inhabitants.”[12]

The plan adopted in laying out the town was prescribed by General Oglethorpe, and closely resembles that of Savannah;—the size of the lots and the width of the streets and lanes being in each case quite similar. To John Gerar, William DeBrahm, his Majesty’s Surveyor General for the Southern District of North America, who in 1757 erected a fort at Ebenezer, are we indebted for an accurate plan of that town.[13] As the village increased, this plan was extended;—its distinctive characteristics being retained. From contemporaneous notices we learn that New Ebenezer, within a short time after its settlement, gave manifest token of substantial growth and prosperity. The houses there erected were larger and more comfortable than those which had been built in the old town. Gardens and farms were cleared, enclosed, and brought under creditable cultivation, and the sedate, religious inhabitants enjoyed the fruits of their industry and economy.

Funds received from Germany for that purpose were employed in the erection of an Orphan House, in which, for lack of a Church, the community worshipped for several years.

We presume the account of the condition of Ebenezer in 1738-9, furnished by Benjamin Martyn,[14] is as interesting and reliable as any that can be suggested. It is as follows: “Fifteen miles from Purysburg on the Georgia side, is Ebenezer, where the Saltzburghers are situated; their Houses are[22] neat, and regularly set out in Streets, and the whole Œconomy of their town, under the Influence of their Ministers, Mess. Bolzius and Gronau, is very exemplary. For the Benefit of their Milch Cattle, a Herdsman is appointed to attend them in the Woods all the Day, and bring them Home in the Evening. Their Stock of out-lying Cattle is also under the Care of two other Herdsmen, who attend them in their Feeding in the Day, and drive them into Cow-Pens at night. This secures the Owners from any Loss, and the Herdsmen are paid by a small Contribution among the People. These are very industrious, and subsist comfortably by their Labour. Though there is no regular Court of Justice, as they live in Sobriety, they maintain great Order and Decency. In case of any Differences, the Minister calls three or four of the most prudent Elders together, who in a summary Way hear and determine as they think just, and the Parties always acquiesce with Content in their Judgment. They are very regular in their public Worship, which is on Week-Days in the Evening[23] after their Work; and in the Forenoon and Evening on Sundays. They have built a large and convenient House for the Reception of Orphans, and other poor Children, who are maintained by Benefactions among the People, are well taken Care of and taught to work according as their Age and Ability will permit. The Number computed by Mr. Bolzius in June, 1738, whereof his Congregation consisted, was one hundred forty-six, and some more have since been settled among them. They are all in general so well pleased with their condition, that not one of their People has abandoned the Settlement.”

General Oglethorpe received a letter, dated Ebenezer, March 13, 1739, signed by forty-nine men of the Saltzburgers and verified by their Ministers, in which they assured him that they were well settled and pleased with the climate and condition of the country; that although the season was hotter than that of their native land, having become accustomed to it, they found it tolerable and convenient for working people; and that their custom was to commence their out-door labor early in the morning and continue it until ten o’clock; resuming it again from three in the afternoon until sun-set. During the heated term of mid-day, matters within their houses engaged their attention. The General was also informed that they had practically demonstrated the falsity of the tale told them on their arrival that rice could be cultivated only by negroes. “We laugh at such a Talking,”—so they wrote, “seeing that several People of us have had, in last Harvest, a greater Crop of Rice than they wanted for their own Consumption. Of Corn, Pease, Potatoes, Pumpkins, Cabbage, &c., we had such a good Quantity that many Bushels are sold, and much was spent in feeding Cows, Calves and Hogs.” The letter[24] concludes with an earnest petition that negroes should be excluded from their town and neighborhood, alleging as a reason that their houses and gardens would be robbed by them, and that, “besides other great inconveniences, white people were in danger of life from them.”[15]

Of humble origin and moderate education, of primitive habits, accustomed to labor, free from covetousness and ambition, temperate, industrious, frugal and orderly, solicitous for the education of their children and the maintenance of the needy and the orphan, meddling not in the affairs of their neighbors, acknowledging allegiance to the Trustees and the King of England, maintaining direct connection with the Lutheran Church in Germany, and submitting without question to the decisions of their ministers and elders in all matters, whether of a civil or ecclesiastical nature, engaging in no pursuits save of an agricultural or a mechanical character, and little given either to excitement or wandering, these Saltzburgers for years preserved the integrity of their community and their religion, and secured for themselves a comfortable existence. As early as 1738 the Saltzburgers at Ebenezer made some limited experiment in growing cotton and were much encouraged;—the yield being abundant, and of an excellent quality. The Trustees, however, having fixed their hopes upon silk and wine, the cultivation of this plant was not countenanced.[16]

It was estimated by Mr. Benjamin Martyn, Secretary of the Trustees, that up to the year 1741, not less than twelve[25] hundred German Protestants had arrived in the Colony. Their principal settlements were at Ebenezer, Bethany, Savannah, Frederica, Goshen, and along the road leading from Savannah to Ebenezer. They were all characterized by industry, sobriety, and thrift.

About the year 1744 the Saltzburgers at Ebenezer and along the line of the public road running from that town to Savannah, through the assistance of friends in Germany, were enabled to build two comfortable and substantial houses for public worship,—one at New Ebenezer, called Jerusalem Church, and the other about four miles below, named Zion Church. The joy experienced upon the dedication of these sacred buildings was soon turned to grief by the death of one of their faithful pastors,—the Reverend Israel C. Gronau,—who, in the supreme moments of a lingering fever, desiring a friend to support his hands uplifted in praise of the Great Master whom he had so long and so truthfully served, exclaimed “Come, Lord Jesus! Amen!! Amen!!!” and with these words,—the last upon his lips,—entered into peace.[17]

Reverend Mr. Bolzius continued to be the principal pastor and, as an assistant, the Reverend Mr. Lembke was associated with him.

As early as January 31, 1732, Sir Thomas Lombe[18] certified to the Trustees of the Colony that silk produced in Carolina possessed “as much natural Strength and Beauty as the Silk of Italy.” In his “New and Accurate Account of the Provinces of South Carolina and Georgia,”[19] Mr. Oglethorpe enumerated among the chief revenues which[26] might be anticipated from the settlement of Georgia, profits to arise from the manufacture of silk. His opinion was that between forty and fifty thousand people might be advantageously employed in this business. In view of the encouragement which might reasonably be expected from Parliament, and the cheapness of the labor and land, he estimated that the cost of production would be at least twenty-five per cent. lower than that then current in Piedmont. Sharing in this belief, the Trustees sent to Italy for silk-worm eggs, and engaged the services of several Piedmontese to go to Georgia and instruct the Colonists in the production of silk.[20] In the grants of land to parties emigrating to Georgia either at their own expense or at the charge of the Charity, may be found covenants on the part of the grantees to “keep a sufficient number of white mulberry trees standing on every acre,” or else to “plant them where they were wanted.” A special plea is entered by Benjamin Martyn in behalf of silk-culture in Georgia and the manifest benefits to be expected.[21]

The early accounts all agree in representing the production of silk as one of the most important matters to be considered and fostered in connection with the establishment and development of the Colony of Georgia.

In 1735, Queen Caroline, upon the King’s birth-day, appeared in a full robe of Georgia silk; and in 1739 a parcel of raw silk, brought from Georgia by Samuel Augspourguer, was exhibited at the Trustees’ office in London to “Mr. John Zachary,—an eminent raw-silk merchant,—and to Mr. Booth,—one of the greatest silk-weavers in England,”—both[27] of whom “declared it to be as fine as any Italian silk, and worth at least twenty shillings a pound.”[22]

With that industry and patience so characteristic of them as a people, the inhabitants of New Ebenezer were among the earliest and the most persevering in their efforts to carry into practical operation Mr. Oglethorpe’s wishes in regard to the production of silk. In 1736 each Saltzburger there was presented with a mulberry tree, and two of the congregation were instructed by Mrs. Camuse in the art of reeling.

Under date of May 11th, 1741, Mr. Bolzius, in his journal, records the fact that within the preceding two months twenty girls succeeded in making seventeen pounds of cocoons which were sold at Savannah for £3, 8s. The same year £5 were advanced by General Oglethorpe to this Clergyman for the purchase of trees. With this sum he procured twelve hundred, and distributed them among the families of his parish.

On the 4th of December, 1742, five hundred trees were sent by General Oglethorpe to Ebenezer, with a promise of more should they be needed. Near Mr. Bolzius’ house a machine for the manufacture of raw-silk was erected, and the construction of a public Filature was contemplated. Of the eight hundred and forty-seven pounds of cocoons raised in the Colony of Georgia in 1747, about one-half was produced by the Saltzburgers at Ebenezer. Two years afterwards this yield was increased to seven hundred and sixty-two pounds of cocoons, and fifty pounds thirteen ounces of spun silk. Two machines were in operation in Mr. Bolzius’ yard, capable of reeling twenty-four ounces per day. It was[28] apparent, however, that while, by ordinary labor, about two shillings could be earned, scarcely a shilling per diem could be expected by one engaged in the manufacture of silk. This fact proved so discouraging to the Colonists that, except at Ebenezer, silk culture was generally relinquished. The Germans persevered, and as the result of their energy, over a thousand pounds of cocoons and seventy-four pounds, two ounces of raw-silk were raised at Ebenezer in 1750, and sold for £110 sterling. The community was now pretty well supplied with copper basins and reeling machines. Considerable effort was made in England to attract the notice of the Home Government to this production of silk in Georgia, and to enlist in its behalf fostering influences at the hands of those in authority. In 1755 a paper was laid before the Lords of Trade and Plantations, signed by about forty eminent silk throwsters and weavers, declaring that “having examined about 300 wt. of Georgia raw-silk they found it as good as the Piedmontese, and better than the common Italian silks.” Assurance was given that there was the utmost reason to afford “all possible encouragement for the raising of so valuable a commodity.”[23]

In 1764 fifteen thousand two hundred and twelve pounds of cocoons were delivered at the Filature in Savannah, then under the charge of Mr. Ottolenghe, of which eight thousand six hundred and ninety-five pounds were contributed by the Saltzburgers. In 1766 the production of silk in Georgia reached its acme, and from that time, despite the encouragement extended by Parliament, continued to decline until it was practically abandoned a few years before the inception of the Revolution. Operations at the Filature[29] in Savannah were discontinued in 1771; and Sir James Wright, in his message to the Commons House of Assembly, under date 19th of January, 1774, alludes to the fact that the Filature buildings were falling into decay, and suggests that they be put to some other use.

Despite the disinclination existing in other portions of the Colony to devote much time and labor to the growing of trees and the manufacture of silk, the Saltzburgers,—incited by their worthy magistrate, Mr. Wertsch,—redoubled their efforts, and in 1770, as the result of their industry, shipped two hundred and ninety-one pounds of raw-silk. At the suggestion of the Earl of Hillsborough, who warmly commended the zeal of these Germans and interested himself in procuring from Parliament a small sum to be expended in aid of the more indigent of the community, Mr. Habersham distributed among them the basins and reels then being in the unused public Filature in Savannah.

“So popular had the silk business become at Ebenezer that Mr. Habersham, in a letter dated the 30th of March, 1772, says: ‘Some persons in almost every family there understand its process from the beginning to the end.’ In 1771 the Germans sent four hundred and thirty-eight pounds of raw silk to England, and in 1772 four hundred and eighty-five pounds:—all of their own raising. They made their own reels, which were so much esteemed that one was sent to England as a model, and another taken to the East Indies by Pickering Robinson.”[24]

In the face of the distractions encountered upon the commencement of hostilities between the Colonies and the Mother Country, silk culture languished even among these[30] Germans, and was never afterwards revived to any considerable degree. The unfriendliness of climate, the high price of labor, the withdrawal of all bounty—which had been the chief stimulus to exertion,—and the larger profits to be derived from the cultivation of rice and cotton combined to interrupt silk-raising, and, in the end, caused its total abandonment.

The construction of a bridge over Ebenezer creek materially promoted the interests and the convenience of those residing at Ebenezer; and the erection of Churches at Bethany and Goshen,—the former about five miles northwest of Ebenezer, and the latter some ten miles below and near the road leading to Savannah,—indicated the growth of the German plantations along the line of the Savannah river.

The settlement at Bethany was effected in 1751 by John Gerar William DeBrahm, who there located one hundred and sixty Germans. Eleven months afterwards these Colonists were joined by an equal number,—“the Relations and Acquaintance of the former.” The Saltzburgers then numbered about fifteen hundred souls.[25] Alluding to the location and growth of these plantations, and the agricultural pursuits of their cultivators, Surveyor-General DeBrahm says: “The German Settlements have since Streatched S: Eastwardly about 32 miles N: W-ward from the Sea upon Savannah Stream, from whence they extend up the same Stream through the whole Salt Air Zona. They cultivate European and American Grains to Perfection; as Wheat, Rye, Barley, Oats; also Flax, Hemp, Tobacco and Rice, Indigo, Maize, Peas, Pompions, Melons—they plant Mulberry, Apple, Peach, Nectorins, Plumbs and Quince Trees,[31] besides all manner of European Garden Herbs, but, in particular, they Chose the Culture of silk their principal Object, in which Culture they made such a Progress, that the Filature, which is erected in the City of Savannah could afford to send in 1768 to London 1,084 Pounds of raw Silk, equal in Goodness to that manufactured in Piemont; but the Bounties to encourage that Manufactory being taken off, they discouraged, dropt their hands from that Culture from year to year in a manner, that in 1771 its Product was only 290 Pounds in lieu of 1,464, which must have been that year’s Produce, had this Manufactory been encouraged to increase at a 16 years rate. In lieu of Silk they have taken under more Consideration the Culture of Maize, Rice, Indigo, Hemp & Tobacco: But the Vines have not as yet become an Object of their Attention, altho’ in the Country especially over the German Settlements, Nature makes all the Promises, yea gives yearly full Assurances of her Assistance by her own Endeavours producing Clusture Grapes in Abundance on its uncultivated Vines; yet there is no Person, who will listen to her Addresses, and give her the least Assistance, notwithstanding many of the Inhabitants are refreshed from the Sweetness of her wild Productions. The Culture of Indigo is brought to the same Perfection here, as in South Carolina, and is manufactured through all the Settlements from the Sea Coast, to the Extent of the interior Country.”[26]

On the 19th of November, 1765, the Ebenezer congregation was called upon to mourn the loss of its venerable Spiritual Guide, the Reverend Mr. Bolzius, who had been at once teacher and magistrate, counsellor and friend during the thirty years of poverty and privation, labor and sorrow, hope and joy, passed in the wilds of Georgia. He was[32] interred, amid the lamentations of his people, in the cemetery near Jerusalem Church, and no stone marks his grave.

After his demise the conduct of the Society devolved upon Messrs. Lembke and Rabenhorst. This involved not only the spiritual care of this people, but also the preservation and proper management of the mill-establishments and public property belonging to the Ebenezer Congregation. “These two faithful men,” writes the Reverend P. A. Strobel,[27] “labored harmoniously and successfully in the discharge of their heavy civil and religious obligations, and gave entire satisfaction to those with whose interests they were intrusted.” During their administration the large brick house of worship, known as Jerusalem Church, was built at Ebenezer. The materials used in its construction were, for the most part, supplied by the Saltzburgers, while the funds necessary to defray the cost of erection were contributed by friends in Germany.

Upon the death of Mr. Lembke, the Reverend Christopher F. Triebner “was sent over by the reverend fathers in Germany as an adjunct to Mr. Rabenhorst. Being a young man of talents, but of an impetuous and ambitious disposition, he soon raised such a tumult in the quiet community that all the efforts of the famous Mr. Muhlenburg, who was ordered on a special mission to Ebenezer in 1774 to heal the disturbances which had arisen, scarce saved the congregation from disintegration. The schism was, however, finally cured, and peace was restored.” For the better government of the Society, articles of discipline were prepared by Dr. Muhlenburg, which were formally subscribed by one hundred and twenty-four male members. This occurred at Jerusalem Church on the 16th of January, 1775,[33] and affords substantial evidence of the strength of the congregation.

The property belonging to the Church, according to an inventory made by Dr. Muhlenburg in 1775, consisted of the following:

“1. In the hands of Pastor Rabenhorst a capital of £300. 16s. 5d.

2. In the hands of John Casper Wertsch, for the store, £300.

3. In the mill treasury, notes and money, £229. 16s. 2d.

4. Pastor Triebner has some money in hands, (£400) the application of which has not been determined by our Reverend Fathers.

5. Belonging to the Church is a Negro Boy at Mr. John Flöerl’s, and a Negro Girl at Mr. David Steiner’s.

6. A town-lot and an out-lot, of which Mr. John Triebner has the grant in his hands.

7. An inventory of personal goods in the mills belonging to the estate.

8. And, finally, real estate, with the mills, 925 acres of land.”

Including certain legacies from private individuals, and donations from patrons of the Colony in Germany, which were received within a short time, it is conjectured that this church property was then worth not much less than twenty thousand dollars.

So long as the congregation at Ebenezer preserved its integrity, direct allegiance to the parent Church in Germany was acknowledged, its precepts, orders and deliverances were obeyed, its teachers welcomed and respected, and accounts of all receipts, disbursements, and important transactions regularly rendered. Its pastors continued to be charged with the administration of affairs, both spiritual and temporal, and were the duly constituted custodians[34] of all church funds and property. Upon their arrival in Georgia these Saltzburgers, wearied with persecutions and stripped of the small possessions which were once theirs, were at first quite dependent upon public and private charity for bare subsistence. They were then unable, by voluntary contributions, to sustain their pastors and teachers, and build churches. Foreign aid arrived, however, from time to time, and this was supplemented in a small, yet generous way, by the labor of the parishioners and such sums and articles as could be spared from their slow accumulations. With a view to providing for the future, all means thus derived were carefully invested for the benefit of church and pastor. This system was maintained for more than fifty years, so that in the course of time not only were churches built, but reasonable provision was made for clergyman, teacher, and orphan, aside from the yearly voluntary contributions of the members of the Society. The education of youths was not neglected; and DeBrahm assures us that in his day a library had been accumulated at Ebenezer in which “could be had Books wrote in the Caldaic, Hebrew, Arabec, Siriac, Coptic, Malabar, Greek, Latin, French, German, Dutch and Spanish, beside the English, viz: in thirteen Languages.”[28]

In the division of the Province of Georgia into eight Parishes, which occurred on the 15th of March, 1758, “the district of Abercorn and Goshen, and the district of Ebenezer—extending from the northwest boundaries of the parish of Christ Church up the river Savannah as far as the Beaver Dam, and southwest as far as the mouth of Horse-Creek on the river Great Ogechee”—were declared a Parish under[35] the name of “The Parish of St. Matthew.”[29] The parish just below, on the line of the Savannah river, and embracing the town of Savannah, was known as “Christ Church Parish.”

The Parish of St. Matthew, and the upper part of St. Philip lying above the Canouchee river, were, by the Constitution of Georgia adopted at Savannah on the 5th of February, 1777, consolidated into a county called Effingham.[30]

In the opinion of the Reverend Mr. Strobel, to whose valuable sketch of the Saltzburgers and their descendants we are indebted for much of the information contained in these pages, Ebenezer attained the height of its importance about 1774. The population of the town proper was not less than five hundred, embracing agriculturists, mechanics, and shop-keepers, who pursued their respective avocations with energy and thrift. Trade with Savannah and Charleston was carried on by means of sloops and schooners. In a contemporaneous picture, representing the general appearance of the town, may be seen two schooners riding at anchor near the Ebenezer landing.[31]

Although there arose a sharp division of sentiment when the question of direct opposition to the acts of Parliament was discussed at Ebenezer in 1774, and although quite a number of the inhabitants favored “passive obedience and non-resistance,” the response of the majority was: “We have experienced the evils of tyranny in our own land;[36] for the sake of liberty we have left home, lands, houses, estates, and have taken refuge in the wilds of Georgia; shall we now submit again to bondage? No, never.” Among the delegates from the Parish of St. Matthew to the Provincial Congress which assembled in Savannah on the 4th of July, 1775, were the following Saltzburgers: John Stirk, John Adam Treutlen, Jacob Waldhauer, John Flöerl, and Christopher Craemer. Despite the fact that as a community the Saltzburgers espoused the cause of the Revolutionists, a considerable faction, headed by Mr. Triebner, maintained an open and a strenuous adherence to the Crown. Between these parties sprang up an angry controversy, replete with the bitterest feelings, and very prejudicial to the peace and prosperity of the congregation. In the midst of the discussion the Reverend Mr. Rabenhorst, who exerted his utmost influence to curb the dominant passions and inculcate mutual forbearance, crowned his long and useful life with a saintly death.

Three days after the capture of Savannah by Colonel Campbell, a strong force was advanced, under the command of Lieut. Col. Maitland, to Cherokee Hill. The following day [January 2, 1779,] Ebenezer was occupied by the British troops. Upon their arrival they threw up a redoubt within a few hundred yards of Jerusalem Church and fortified the position.[32] The remains of this work are said to be still visible. The moment he learned that Savannah had fallen before Colonel Campbell’s column, Mr. Triebner hastened to that place, proclaimed his loyalty, and took the oath of allegiance. The intimation is that he counselled the immediate occupation of Ebenezer, and in person accompanied[37] the detachment which compassed the capture of his own town and people. He was a violent, uncompromising man,—at all times intent upon the success of his peculiar views and wishes. Influenced by his advice and example, not a few of the Saltzburgers subscribed oaths of allegiance to the British Crown, and received certificates guaranteeing Royal protection to person and property. Prominent among those who maintained their adherence to the Rebel cause were Governor John Adam Trentlen, William Holsendorf, Colonel John Stirk, Secretary Samuel Stirk, John Schnider, Rudolph Strohaker, Jonathan Schnider, J. Gotlieb Schnider, Jonathan Rahn, Ernest Zittrauer, and Joshua and Jacob Helfenstein.

“The citizens at Ebenezer and the surrounding country,” says Mr. Strobel, “were made to feel very severely the effects of the war. The property of those who did not take the oath of allegiance was confiscated, and they were constantly exposed to every species of insult and wrong from a hired and profligate soldiery. Besides this, some of the Saltzburgers who espoused the cause of the Crown became very inveterate in their hostility to the Whigs in the settlement, and pillaged and then burnt their dwellings. The residence on the farm of the pious Rabenhorst was among the first given to the flames. Among those who distinguished themselves for their cruelty was one Eichel,—who has been properly termed an ‘inhuman miscreant,’—whose residence was at Goshen, and Martin Dasher, who kept a public house five miles below Ebenezer. These men placed themselves at the head of marauding parties, composed of British and Tories, and laid waste every plantation or farm whose occupant was even suspected of favoring the Republican cause. In these predatory excursions the most revolting[38] cruelty and unbridled licentiousness were indulged, and the whole country was overrun and devastated.... The Salzburgers, nevertheless, were to experience great annoyances from other sources.... A line of British posts had been established all along the western bank of the Savannah river to check the demonstrations of the Rebel forces in Carolina. Under these circumstances, Ebenezer, from its somewhat central position, became a kind of thoroughfare for the British troops in passing through the country from Augusta to Savannah. To the inhabitants of Ebenezer, particularly, this was a source of perpetual annoyance. British troops were constantly quartered among them, and to avoid the rudeness of the soldiers and the heavy tax upon their resources, many of the best citizens were forced to abandon their homes and settle in the country, thus leaving their houses to the mercy of their cruel invaders.

“Besides all this, they were forced to witness almost daily acts of cruelty practised by the British and Tories toward those Americans who happened to fall into their hands as prisoners of war; for it will be remembered that Ebenezer, while in the hands of the British, was the point to which all prisoners taken in the surrounding country were brought and from thence sent to Savannah. It was from this post that the prisoners were carried who were rescued by Sergeant Jasper and his comrade, Newton, at the Jasper Spring, a few miles above Savannah.

“There was one act performed by the British commander which was peculiarly trying and revolting to the Salzburgers. Their fine brick church was converted into a hospital for the accommodation of the sick and wounded, and subsequently it was desecrated by being used as a stable for their[39] horses. To this latter use it was devoted until the close of the war and the removal of the British troops from Georgia. To show their contempt for the church and their disregard for the religious sentiments of the people, the church records were nearly all destroyed, and the soldiers would discharge their guns at different objects on the church; and even to this day the metal “Swan” (Luther’s coat of arms) which surmounts the spire on the steeple, bears the mark of a musket ball which was fired through it by a reckless soldier. Often, too, cannon were discharged at the houses; and there is a log-house now standing not far from Ebenezer, which was perforated by several cannon shot.... The Salzburgers endured all these hardships and indignities with becoming fortitude; and though a few were overcome by these severe measures, yet the great mass of them remained firm in their attachment to the principles of liberty.”[33]

It is suggested that the establishment of tippling houses in Ebenezer, during its occupancy by the British, and constant intercourse with a licentious soldiery, corrupted the lives of not a few of the once sober and orderly Germans. That the protracted presence of the enemy, the confiscation of estates, the interruption of regular pursuits, the expulsion of such as clave to the Confederate cause, and the general demoralization consequent upon a state of war, tended to the manifest injury and depopulation of the town, cannot, for a moment, be questioned. Indications of decay and ruin were patent in Ebenezer before the cessation of hostilities. From the time of its occupation by Maitland, shortly after the capture of Savannah by Colonel Campbell in December, 1778,—with the exception of the limited period when its garrison was called in to assist in the[40] defense of Savannah against the operations of the allied army under the command of Count D’Estaing and General Lincoln in the fall of 1779,—Ebenezer continued in the possession of the British until a short time prior to the evacuation of Savannah in July, 1783. In his advance toward Savannah, General Anthony Wayne established his head quarters at this town. The Tory pastor, Triebner, who, during the struggle had sided with the Royalists and remained unmoved amid the sufferings and oppressions of his people, betook himself to flight so soon as the English forces were withdrawn, and found a refuge in England, where he ended his days in seclusion.

Upon the evacuation of Savannah, many of the Saltzburgers returned to Ebenezer. Its aspect was sadly changed. Not a few of the abandoned dwellings had been burned. Others had fallen into decay. Smiling gardens had been trampled into desert places, and the impress of stagnation, neglect, and desolation was upon everything. Jerusalem Church was a mass of filth, and very dilapidated. Notwithstanding this sad condition of affairs, much energy was displayed in the purification and renovation of this temple of worship, and in the rehabilitation of the town.

The arrival of the Reverend John Ernest Bergman,—a clergyman of decided talents and of considerable literary attainments,—and the revival of the parochial school greatly encouraged the depressed inhabitants and promoted the general improvement of the place. The population began to increase. It assumed an apparently permanent character, and countenanced the hope that the ante-bellum quiet, good order, thrift, and prosperity would be regained. This expectation, however, was not fully realized. The former trade never revived. The mills were never again put in[41] motion. Silk-culture was renewed only to a limited degree. Having for twenty-five years more remained about stationary, New Ebenezer commenced visibly to decline; and, when scarcely more than a century old, took its place, in silence and nothingness, among the dead towns of Georgia.[34]

The act of February 26th, 1784,[35] provided for the erection of the “Court House and Gaol” and for holding public elections in Effingham County at Tuckasee-King, near the present line of Scriven County. The situation proving inconvenient, three years afterwards the county-seat was removed to Elberton, near Indian Bluff, on the north side of the Great Ogeechee river.

On the 18th of February, 1796, the Legislature of Georgia[36] appointed Jeremiah Cuyler, John G. Neidlinger, Jonathan Rawhn, Elias Hodges, and John Martin Dasher “commissioners for the town and common of Ebenezer,” with instructions to have the town “surveyed and laid out as nearly as possible in conformity to the original plan thereof, to sell all vacant lots, and such as had become vested in the State, [reserving such only as were necessary for public uses,] and appropriate the proceeds to the erection of a County Court House and Jail.” Any over-plus was to be applied to building a public Academy. For three years only did Ebenezer remain the County Town of Effingham County. In 1799, its public buildings were sold, and the village of Springfield was designated by the Legislature as “the permanent seat for the public buildings of the County of[42] Effingham.”[37] David Hall, Joshua Loper, Samuel Ryals, Godhelf Smith, and Drurias Garrison were appointed commissioners to carry this change into effect.

In 1808 the Ebenezer Congregation received legislative permission to sell the glebe lands which it owned. By degrees all the real estate held by the society was disposed of. The proceeds arising from these sales were invested in lands, mortgages, and securities;—the interest accruing being applied to the payment of the pastor’s salary and the current expenses of the church.[38]

Until about the year 1803 all the religious services observed by the Saltzburgers were conducted in the German language; and, in the church at Ebenezer, for a long time subsequent to that date, the religious exercises continued in that tongue. Methodist and Baptist Churches springing up in the neighborhood drew away many of the younger members of the congregation. The introduction of the English language into all the Saltzburger Churches was effected in 1824 through the instrumentality of the Reverend Christopher F. Bergman.

Year by year Ebenezer became more sparsely populated. Many of its citizens removed into the interior and upper parts of the county. Quite a number formed settlements in Scriven County, while others went to Savannah, and to Lowndes, Liberty, and Thomas counties. Others still,—more enterprizing than their fellows,—sought new homes in South Carolina, Alabama, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.

We close this sketch with a picture of Ebenezer painted by one of the late Pastors[39] of Jerusalem Church,—a gentleman[43] of cultivation and of piety, who saw the last waves of oblivion as they closed over the town and obliterated its decayed traces from the grass covered bluff of the Savannah.

“To one visiting the ancient town of Ebenezer, in the present day [1855] the prospect which presents itself is anything but attractive; and the stranger who is unacquainted with its history would perhaps discover very little to excite his curiosity or awaken his sympathies. The town has gone almost entirely to ruins. Only two residences are now remaining, and one of these is untenanted. The old church, however, stands in bold relief upon an open lawn, and by its somewhat antique appearance seems silently, yet forcibly, to call up the reminiscences of former years. Not far distant from the church is the cemetery, in which are sleeping the remains of the venerable men who founded the colony and the church, and many of their descendants who, one by one, have gone down to the grave to mingle their ashes with those of their illustrious ancestors.

“Except upon the Sabbath, when the descendants of the Saltzburgers go up to their temple to worship the God of their fathers, the stillness which reigns around Ebenezer is seldom broken, save by the warbling of birds, the occasional transit of a steamer, or the murmurs of the Savannah as it flows on to lose itself in the ocean. The sighing winds chant melancholy dirges as they sweep through the lofty pines and cedars which cast their sombre shades over this ‘deserted village.’ Desolation seems to have spread over this once-favored spot its withering wing, and here, where generation after generation grew up and flourished, where the persecuted and exiled Saltzburgers reared their offspring in the hope that they would leave a numerous progeny of[44] pious, useful, and prosperous citizens, and where everything seemed to betoken the establishment of a thrifty and permanent colony, scarcely anything is to be seen, except the sad evidences of decay and death.”

Plan of the Town of Frederica, on St. Simon’s Island, Georgia

J. Bien, Photo. Lith. N. Y.

“As the Mind of Man cannot form a more exalted Pleasure than what arises from the Reflexion of having relieved the Distressed; let the Man of Benevolence, whose Substance enables him to contribute towards this Undertaking, give a Loose for a little to his Imagination, pass over a few Years of his Life, and think himself in a Visit to Georgia. Let him see those, who are now a Prey to all the Calamities of Want, who are starving with Hunger, and seeing their Wives and Children in the same Distress; expecting likewise every Moment to be thrown into a Dungeon, with the cutting Anguish that they leave their Families expos’d to the utmost Necessity and Despair: Let him, I say, see these living under a sober and orderly Government, settled in Towns, which are rising at Distances along navigable Rivers: Flocks and Herds in the neighbouring Pastures, and adjoining to them Plantations of regular Rows of Mulberry-Trees, entwin’d with Vines, the Branches of which are loaded with Grapes; let him see Orchards of Oranges, Pomegranates, and Olives; in other Places extended Fields of Corn, or Flax and Hemp. In short, the whole Face of the Country chang’d by Agriculture, and Plenty in every Part of it. Let him see the People all in Employment of various Kinds, Women and Children feeding and nursing[46] the Silkworms, winding off the Silk, or gathering the Olives; the Men ploughing and planting their Lands, tending their Cattle, or felling the Forest, which they burn for Potashes, or square for the Builder; let him see these in Content and Affluence, and Masters of little Possessions which they can leave to their Children; and then let him think if they are not happier than those supported by Charity in Idleness. Let him reflect that the Produce of their Labour will be so much new Wealth for his Country, and then let him ask himself, Whether he would exchange the Satisfaction of having contributed to this, for all the trifling Pleasures the Money, which he has given, would have purchas’d.

“Of all publick-spirited Actions, perhaps none can claim a Preference to the Settling of Colonies, as none are in the End more useful.... Whoever then is a Lover of Liberty will be pleas’d with an Attempt to recover his fellow Subjects from a State of Misery and Oppression, and fix them in Happiness and Freedom.

“Whoever is a Lover of his Country will approve of a Method for the Employment of her Poor, and the Increase of her People and her Trade. Whoever is a Lover of Mankind will join his wishes to the Success of a Design so plainly calculated for their Good: Undertaken, and conducted with so much Disinterestedness.”

By such suggestions did Benjamin Martyn[40] seek to enlist the public sympathy in behalf of the then projected but not established Colony of Georgia.

Mr. Oglethorpe, in a contemporaneous publication,[41] had[47] assigned, among the weightiest reasons for founding the Colony, the ample opportunity which would be afforded in Georgia for persons reduced to poverty at home and constituting a positive charge upon the Nation, to be made happy and prosperous abroad and profitable to England. The conversion of the Indians, the confirmation of the development and security of Carolina, and a lucrative trade in silk, rice, cotton, wine, indigo, grain, and lumber, were enumerated as additional inducements to the enterprize.

On the 9th of June, 1732, his Majesty, George the Second, by Charter, granted to the Trustees for establishing the Colony of Georgia in America and their successors, all the Lands and Territories from the most northern stream of the Savannah river along the sea-coast to the southward unto the most southern stream of the Alatamaha river, and westward from the heads of the said rivers respectively in direct lines to the south seas. Not only the lands lying within these boundaries, but also all islands within twenty leagues of the coast were, by this Royal feoffment, conveyed “for the better support of the Colony.”[42]

During the first year of the foundation of the Colony, Mr. Oglethorpe’s attention was directed to providing for the emigrants suitable homes at Savannah, Joseph’s Town, Abercorn, and Old Ebenezer, to concluding necessary treaties of cession and amity with the Natives, and the erection of a fort on the Great Ogeechee river to command the main passes by which the Indians had invaded Carolina during the late wars, and afford the settlers some security against anticipated incursions from the Spaniards. This fortified post,—as a compliment to his honored patron John, Duke of[48] Argyle,—was called Fort Argyle, and was garrisoned by Captain McPherson and his detachment of Rangers. At this time no English plantations had been established south of the Great Ogeechee river. Having confirmed the Colonists in their occupation of the right bank of the Savannah, and engaged the friendship of the venerable Indian Chief, Tomo-chi-chi, and the neighboring Lower Creeks and Uchees, in January, 1734, Mr. Oglethorpe set out to explore the coast, and determine upon such settlement as appeared most advantageous for the protection of the southern confines of the Colony. During a heavy rain on the 26th of that month, he and his party landed “on the first Albany bluff of St. Simon’s island” and “lay all night under the shelter of a large live-oak-tree and kept themselves dry.” This reconnoissance, which was continued as far as the sea-point of St. Simon’s island, and Jekyll island, convinced Mr. Oglethorpe it was expedient and necessary for the proper defence of the Colony that a military station and settlement should be formed, at the earliest practicable moment, near the mouth of the Alatamaha river; and that, as an outpost, a strong fort should be built on St. Simon’s island.

This plan was in part compassed in January, 1735, when one hundred and thirty Highlanders, and fifty women and children, who had been enrolled for emigration at Inverness and its vicinity, arrived at Savannah, and, a few days afterwards, were conveyed in periaguas to the southward. Ascending the Alatamaha river to a point about sixteen miles above St. Simon’s island, they there landed and entered upon a permanent settlement, which they called New Inverness. Here they erected a fort,—mounting four pieces of cannon,—built a guard-house, a store, and a chapel, and constructed huts for temporary accommodation preparatory to putting[49] up more substantial structures. These Scots were a brave, hardy people,—just the men to occupy this advanced position. In their plaids, and with their broad-swords, targets, and firearms, Oglethorpe says they presented “a most manly appearance.”

Upon their arrival in Savannah some of the Carolinians endeavored to dissuade them from going to the southward by telling them that the Spaniards, from the houses in their fort, would shoot them upon the spot selected by the Trustees for their future home. Nothing daunted, these doughty countrymen of Bruce and Wallace responded[43] “we will beat them out of their fort and shall have houses ready built to live in.” This valiant spirit found subsequent expression in the effective military service rendered by these Highlanders during the wars between the Colonists and the Spaniards, and by their descendants in the primal struggle for independence. To John Moore McIntosh, Captain Hugh MacKay, Ensign Charles MacKay, Colonel John McIntosh, General Lachlan McIntosh, and their gallant followers, Georgia, both as a Colony and a State, owes a special debt of gratitude.

On the 5th of February, 1735,[44] two hundred and two persons, upon the Trust’s account, conveyed in the Symond and the London Merchant, and conducted by Oglethorpe in person, arrived at the mouth of the Savannah river. It was his intention to locate all these emigrants at St. Simon’s island, but, in compliance with their earnest entreaty, such of them as were German Lutherans were permitted to join[50] their friends at Ebenezer. Upon leaving London it was contemplated that the Symond and the London Merchant should sail directly for Jekyll sound, and land their passengers at the point where it was proposed that the new town should be located. The timidity of the captains, however, who, in the absence of experienced pilots, feared the dangers of an unknown entrance, caused this deviation in the voyage.

Having engaged the services of fifty Rangers and one hundred workmen, and having dispatched Captain McPherson with a part of his command to march by land to the support of the Highlanders on the Alatamaha, Mr. Oglethorpe who, since his arrival, had been busily occupied in arranging matters at Savannah and Old Ebenezer, returned to the ships which were still lying in Tybee roads. Finding their captains unwilling to risk their ships without having previously acquired a knowledge of the entrance into Jekyll sound, he bought the cargo of the sloop Midnight, which had just arrived, on condition that it should be at once delivered at Frederica, and with the understanding that captains Cornish and Thomas should go on board of her, acquaint themselves with the coast and entrance, and then return and conduct their vessels to Frederica. During their absence these ships,—the Symond and the London Merchant,—their cargoes still on board,—were to remain at anchor at Tybee roads in charge of Francis Moore, who was appointed keeper of the stores. Mr. Horton and Mr. Tanner, with thirty single men of the Colony, and cannon, arms, ammunition and entrenching tools, were ordered to proceed to the southward with the sloop Midnight. The workmen who had been engaged at Savannah, and Tomo-chi-chi’s Indians were directed to rendezvous at convenient points whence they might be transported as occasion required. The sloop sailed[51] for St. Simon’s island on the morning of the 16th, and at evening of the same day Mr. Oglethorpe set out in the scout boat to meet the sloop at Jekyll sound. Captain Hermsdorf, two of the Colony, and some Indians went with him, and Captain Dunbar accompanied him with his boat. They passed through the inland channels lying between the outer islands and the main. “Mr. Oglethorpe being in haste,” says one of the party, “the Men rowed Night and Day, and had no other Rest than what they got when a Snatch of Wind favoured us. They were all very willing, though we met with very boisterous Weather.... The Men vied with each other who should be forwardest to please Mr. Oglethorpe. Indeed he lightened their Fatigue by giving them Refreshments, which he rather spared from himself than let them want. The Indians seeing the Men hard laboured, desired to take the Oars, and rowed as well as any I ever saw, only differing from the others by taking a short and long Stroke alternately, which they called the Yamasee Stroke.” On the morning of the 18th they reached St. Simon’s island and found that the sloop had come in ahead of, and was waiting for them. Mr. Oglethorpe at once set all hands to work. The tall grass growing upon the bluff at Frederica was burnt off, a booth was marked out “to hold the stores,—digging the ground three Foot deep, and throwing up the Earth on each Side by way of Bank,—and a roof raised upon Crutches with Ridge-pole and Rafters, nailing small Poles across, and thatching the whole with Palmetto-leaves. Mr. Oglethorpe afterwards laid out several Booths without digging under Ground, which were also covered with Palmetto Leaves, to lodge the Families of the Colony in when they should come up; each of these Booths was between thirty and forty Foot[52] long, and upwards of twenty Foot wide.... We all made merry that Evening, having a plentiful Meal of Game brought in by the Indians.

“On the 19th, in the Morning, Mr. Oglethorpe began to mark out a Fort with four Bastions, and taught the Men how to dig the Ditch, and raise and turf the Rampart. This Day and the following Day were spent in finishing the Houses, and tracing out the Fort.”[45]

Such was the simple beginning of Frederica.[46] Near the town Mr. Oglethorpe fixed the only home he ever owned in the Province. In its defence were enlisted his best energies, military skill, and valor. Brave are the memories of St. Simon’s island. None prouder belong to the colonial history of Georgia.

Three days afterwards arrived from Savannah a periagua with workmen, provisions, and cannon, for the new settlement. Captains Cornish and Thomas returned from the southward to Tybee roads on the 26th and, although assured of the fact that there was ample water for the conveyance of their vessels to Frederica, still refused to conduct the Symond and the London Merchant to the southward. Mr. Oglethorpe was consequently compelled to consent that their cargoes should be unloaded into the “Peter and James,” which could not carry above one hundred tons, and the rest transferred in sloops to Savannah for safe storage until such time as opportunity offered for conveying it to its destination. He was also put to the great inconvenience of collecting periaguas[47] sufficient for the transportation of the Colonists.

Much incensed at the conduct of the Captains of the transports, and inconvenienced by the demurrage consequent upon their timidity, he was also indignant at the delay thus caused in the consummation of his plans, annoyed at the additional charges for transfer of passengers and cargo, and solicitous for the health of the colonists who would be exposed in open boats, at an inclement season, during the passage from Tybee roads to Jekyll sound.

It was not until the 2nd of March that the fleet of periaguas and boats, with the families of the Colonists on board, set out from the mouth of the Savannah river. Spare oars had been rigged for each boat. With their assistance,—the men of the Colony rowing with a will,—the voyage to Frederica was accomplished in five days. Mr. Oglethorpe accompanied them in his scout-boat, keeping the fleet together, and taking the hindermost craft in tow. As an incentive to unity of movement, he placed all the strong beer on board one boat. The rest labored diligently to keep up; for, if they were not all at the place of rendezvous each night, the tardy crew lost their ration. Frederica was reached on the 8th, and there was general joy among the colonists.

So diligently did they labor in building their town and its fortifications, that by the 23rd of March a battery of cannon, commanding the river, had been mounted, and the fort was almost finished. Its ditches had been dug, although not to the required depth or width, and a rampart raised and covered with sod. A store-house, having a front of sixty feet, and intended to be three stories in height, was completed as to its cellar and first story. The necessary streets were all laid out. “The Main Street that went from the Front into the Country was 25 yards wide. Each Free-holder had 60 Foot in Front by 90 Foot in Depth, upon the high Street,[54] for their House and Garden; but those which fronted the River had but 30 Foot in Front, by 60 Foot in Depth. Each Family had a Bower of Palmetto Leaves, finished upon the back Street in their own Lands: The Side towards the front Street was set out for their Houses: These Palmetto Bowers were very convenient Shelters, being tight in the hardest Rains; they were about 20 Foot long and 14 Foot wide, and, in regular Rows, looked very pretty, the Palmetto Leaves lying smooth and handsome, and of a good Colour. The whole appeared something like a Camp; for the Bowers looked liked Tents, only being larger and covered with Palmetto Leaves instead of Canvas. There were 3 large Tents, two belonging to Mr. Oglethorpe, and one to Mr. Horton, pitched upon the Parade near the River.”

Such is the description of the town in its infancy as furnished by Mr. Moore, whose “Voyage to Georgia” is one of the most interesting and valuable tracts we have descriptive of the colonization.

That there might be no confusion in their constructive labors, Mr. Oglethorpe divided the Colonists into working parties. To some was assigned the duty of cutting forks, poles, and laths for building the bowers. Others set them up. Others still gathered palmetto leaves, while a fourth gang,—under the superintendence of a Jew workman, bred in Brazil and skilled in the matter,—thatched the roofs “nimbly and in a neat manner.”

Men accustomed to the agriculture of the region, instructed the Colonists in hoeing and planting. Potatoes, Indian corn, flax, hempseed, barley, turnips, lucern-grass, pumpkins, and water-melons were planted. The labor was common and enured to the benefit of the entire community. As it was rather too late in the season to prepare the ground[55] fully and get in such a crop as would promise a yield sufficient to subsist the settlement for the coming year, many of the men were put upon pay and set to work upon the fortifications and the public buildings.

Mr. Hugh MacKay, about this time, arrived in Frederica and reported, that with the assistance of Messrs. Augustine and Tolme, and the guides furnished by Tomo-chi-chi, he had surveyed and located a road, practicable for horses, between Savannah and Darien. This information was very gratifying to the Colonists on St. Simons, assuring them, as it did, that their situation was not so isolated as they at first supposed.

Frederica was located in the midst of an Indian field[48] containing between thirty and forty acres of cleared land. The grass in this field yielded an excellent turf which was freely used in sodding the parapet of the fort. The bluff upon which it stood rose about ten feet above high-water mark, was dry and sandy, and exhibited a level expanse of about a mile into the interior of the island. The position of the fort was such that it fully commanded the reaches in the river both above and below. With their situation the Colonists were delighted. The harbor was land-locked,[49] having[56] a depth of twenty-two feet of water at the bar, and capable of affording safe anchorage to a large number of ships of considerable burden. Surrounded by beautiful forests of live-oak, water oaks, laurel, bay, cedar, sweet-gum, sassafras, and pines, festooned with luxuriant vines, [among which those bearing the Fox-grape and the Muscadine were peculiarly pleasing to the Colonists,] and abounding in deer, rabbits, raccoons, squirrels, wild-turkeys, turtle-doves, red-birds, mocking birds, and rice birds,[50] with wide extended marshes frequented by wild geese, ducks, herons, curlews, cranes, plovers, and marsh-hens,—the adjacent waters teeming with fishes, crabs, shrimps, and oysters, and the island fanned by South-East breezes prevailing with the regularity of the trade winds—the strangers were charmed with their new home. Within their fort were enclosed and preserved several of those grand old live-oaks which for centuries had crowned the bluff, and whose shade was refreshing beyond any shelter the hand of man could devise. The town sprang into being as a military post. It was ordered and grew day by day under the immediate supervision of Oglethorpe. The soil of the island was fertile, and its health unquestioned. Lieutenant George Dunbar, on the 20th of January, 1739, made oath before Francis Moore, Recorder of the Town of Frederica, that since his arrival with the first detachment of Colonel Oglethorpe’s regiment the preceding June, all the carpenters and many of the soldiers had been continuously occupied in building clap-board huts, carrying lumber and bricks, unloading vessels, [often working up to their necks in water,] in clearing the parade, burning wood and rubbish, making lime, and in other out-door exercises,—the hours of labor being from daylight until[57] eleven or twelve M. and from two or three o’clock in the afternoon until dark. Despite these exposures, continues the Affiant, “All the time the men kept so healthy that often no man in the camp ailed in the least, and none died except one man who came sick on board and never worked at all; nor did I hear that any of the men ever made the heat a pretence for not working.”[51]

Beyond question Frederica was the healthiest of all the early settlements in Georgia, and St. Simon’s island has always enjoyed an enviable reputation for salubrity. Until marred by the desolations of the late war, this island was a favorite summer resort, and the homes of the planters were the abodes of beauty, comfort, and refinement. A mean temperature of about fifty degrees in winter, and not above eighty-two degrees in summer, gardens adorned with choice flowers, and orchards enriched with plums, peaches, nectarines, figs, melons, pomegranates, dates, oranges and limes,—forests rendered majestic by the live-oak, the pine, and the magnolia grandiflora, and redolent with the perfumes of the bay, the cedar and the myrtle,—the air fresh and buoyant with the South-East breezes, and vocal with the notes of song-birds,—the adjacent sea, sound, and inlets, replete with fishes,—the shell roads and broad beach affording every facility for driving and riding,—the woods and fields abounding with game in their season, and the culture and generous hospitality of the inhabitants, impressed all visitors with the delights of this favored spot. Sir Charles Lyell, among others, alludes with marked satisfaction to the pleasures he there experienced.

Among the reptiles which not only attracted the notice of, but, to a considerable degree, upon first acquaintance, disquieted the early Colonists, the alligators were the most noted. Listen to this description furnished by an eyewitness[52] in 1736: “They are terrible to look at, stretching open an horrible large Mouth, big enough to swallow a Man, with Rows of dreadful large sharp Teeth, and Feet like Draggons, armed with great Claws, and a long Tail which they throw about with great Strength, and which seems their best Weapon, for their Claws are feebly set on, and the Stiffness of their Necks hinders them from turning nimbly to bite.” In order that the public mind might be disabused of the terror which pervaded it with respect to these reptiles, Mr. Oglethorpe, having wounded and caught one, had it brought to Savannah and made the boys bait it with sticks and finally pelt and beat it to death.

The rattle snakes, too, were objects of special dread.