MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA • MADRAS

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO

DALLAS • SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

Title: Kabuki

The popular stage of Japan

Author: Zoë Kincaid

Release date: April 5, 2023 [eBook #70471]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: MacMillan and Co., Limited

Credits: Anonymous

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

KABUKI

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA • MADRAS

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO

DALLAS • SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

BY

ZOË KINCAID

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1925

COPYRIGHT

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

[v]

In my study of Kabuki I am deeply indebted to Mr. Seiseiin Ihara, the author of several volumes on the history of the popular stage of Japan. No progress toward an understanding of the development of Kabuki can be made without extensive reference to this valuable work. I wish particularly to acknowledge Mr. Ihara’s investigations into the mass of chronicles of the theatre, his lives of the actors, his painstaking researches into drama, also his collection of facts relating to the interference of the officials with the theatre and persecution of the actors. His Generations of the Ichikawa Family has also proved a record of great assistance.

Mr. Ihara has not only furnished me with data for study, but has been an indefatigable friend. A true lover of the theatre, he is one of the leading dramatic critics of Tokyo, and has not only given generously of his knowledge as a recognised authority on Kabuki, but acted on my behalf to smooth away a misunderstanding or straighten out a difficulty that sometimes arose concerning my attendance at the theatre.

To the late Mr. E. Motono, brother of the late Viscount Motono, I owe many of the first translations that opened up before me a new theatre world. Mr. Eishiro Hori, Professor of English at Keio University, rendered the greatest assistance in translations that gave me an insight into the history and technique of the Nō and Doll-theatre.

I also acknowledge my indebtedness to Mr. Mokuan Sekine for his Engeki Taizen, or Complete Drama, relating [vi]to the old customs of Kabuki, and to his Fifty Years of Meiji Kabuki. Another fruitful source of information has been Kabuki Sosho, a collection of old Kabuki records.

I take this opportunity to thank the friends who so often accompanied me to the theatre, and who were unfailing in their help, Mrs. Koto-ko Kuroda, Miss Shige Takenaka, Miss Chiyo-ko Hiraiwa, Mr. Hisashi Fujisawa, and Mr. M. Kinai.

Nor can I fail to acknowledge the kindness of the three leading managers of Tokyo who allowed me free access to their theatres, Mr. K. Yamamoto of the Imperial, the late Nariyoshi Tamura of the Ichimura-za, and later his son and successor, and Mr. Otani, head of the Matsutake Company, which now controls the greatest number of playhouses in Japan.

For twelve years I sat among the critics of the Tokyo stage at the regular performances, and cannot forget the unfailing courtesy of my journalistic associates.

To my good friends among the actors, Nakamura Utayemon of the Kabuki-za; Onoe Baiko and Matsumoto Koshiro of the Imperial; Onoe Kikugoro, the sixth, of the Ichimura-za; Nakamura Kichiyemon of the Kabuki-za, and Nakamura Ganjiro of Osaka; to Mr. Y. Ninomiya, stage producer and playwright of the Imperial; Miss Ritsu-ko Mori, leading actress of the Tokyo stage; Mr. Kiyotada Torii, the theatre artist; Mr. Beisai Kubota, stage designer,—to all the friends of long standing in the theatre, I take this opportunity to express my gratitude for the privilege of their friendship and kind assistance.

ZOË KINCAID.

London, March 2, 1925.

[vii]

| PAGE | ||

| Acknowledgement | v | |

| Introduction | xv | |

| KABUKI | ||

|---|---|---|

| CHAPTER I | ||

| Kabuki | 3 | |

| CHAPTER II | ||

| Kabuki Audiences | 9 | |

| CHAPTER III | ||

| Conventions of Kabuki | 17 | |

| CHAPTER IV | ||

| Craftsmanship of Kabuki | 28 | |

| CHAPTER V | ||

| Kabuki’s School of Acting | 35 | |

| CHAPTER VI | ||

| Actor Ceremonials | 40 | |

| [viii]ORIGIN OF KABUKI | ||

| CHAPTER VII | ||

| O-Kuni of Izumo | 49 | |

| CHAPTER VIII | ||

| Onna Kabuki: The Woman’s Stage | 58 | |

| CHAPTER IX | ||

| Wakashu Kabuki: The Young Men’s Stage | 64 | |

| CHAPTER X | ||

| Theatres of the Three Towns | 74 | |

| YAKUSHA | ||

| CHAPTER XI | ||

| Danjuro and Tojuro | 87 | |

| CHAPTER XII | ||

| Yakusha of Genroku | 99 | |

| CHAPTER XIII | ||

| Yakusha of Horeki | 111 | |

| CHAPTER XIV | ||

| Yakusha of Pre-Restoration Period | 121 | |

| CHAPTER XV | ||

| Onnagata | 132 | |

| [ix]CHAPTER XVI | ||

| Yakusha and Marionette | 144 | |

| CHAPTER XVII | ||

| Lives of the Yakusha | 153 | |

| SHIBAI | ||

| CHAPTER XVIII | ||

| Customs of Shibai | 169 | |

| CHAPTER XIX | ||

| Shibai and Outside Influence | 183 | |

| CHAPTER XX | ||

| Music of Shibai | 192 | |

| CHAPTER XXI | ||

| Shibai and Interference | 201 | |

| CHAPTER XXII | ||

| Externals of Shibai | 215 | |

| SAKUSHA | ||

| CHAPTER XXIII | ||

| Customs of the Sakusha | 225 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV | ||

| Representative Sakusha | 232 | |

| [x]PLAYS | ||

| CHAPTER XXV | ||

| Kabuki Play Forms | 253 | |

| CHAPTER XXVI | ||

| Motives of Kabuki Plays | 276 | |

| CHAPTER XXVII | ||

| Kabuki Rôles | 310 | |

| MEIJI KABUKI | ||

| CHAPTER XXVIII | ||

| Meiji Kabuki | 323 | |

| I. | Yakusha of Meiji | 323 |

| II. | The Ninth Ichikawa Danjuro | 330 |

| III. | A Theatre Manager of Meiji | 337 |

| IV. | Rise and Fall of Shimpa | 342 |

| V. | Reforms of Meiji | 347 |

| VI. | Actresses of Meiji | 353 |

| VII. | Playwrights of Meiji and Taisho | 358 |

| KABUKI TO-DAY | ||

| CHAPTER XXIX | ||

| Contemporary Kabuki | 367 | |

| Bibliography | 377 | |

| Index | 379 | |

[xi]

| FACE PAGE | |

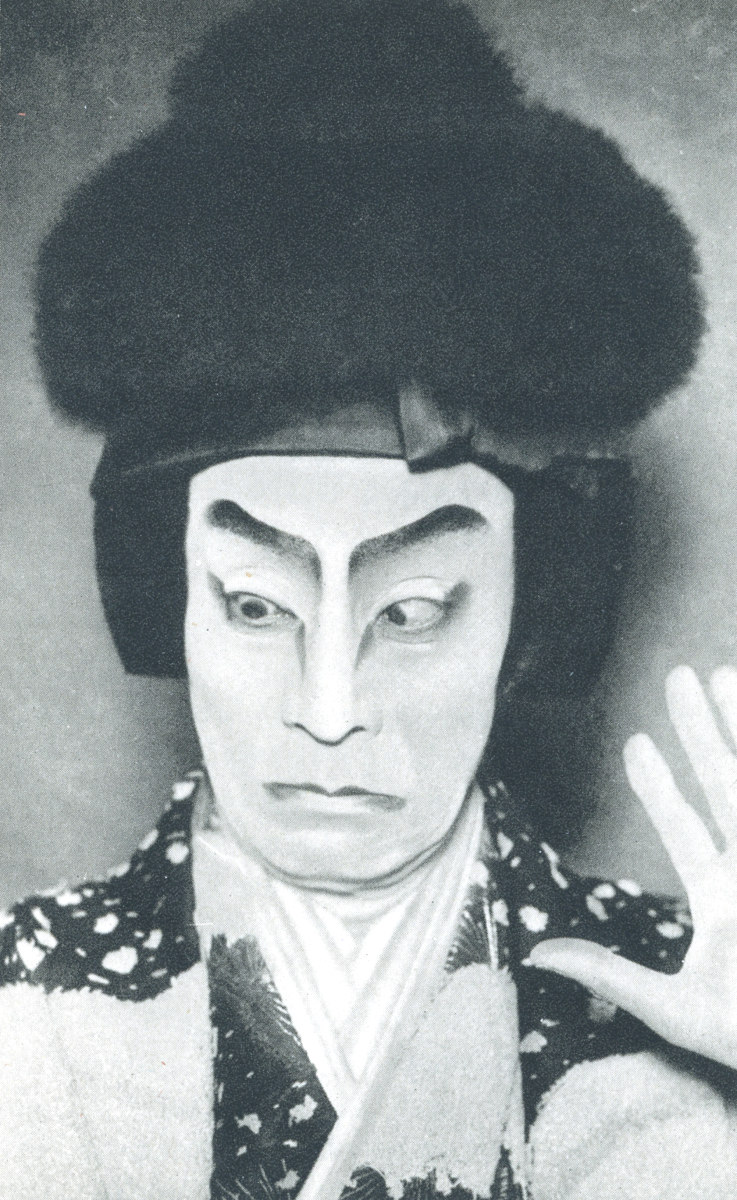

| The character of Kamakura Gongoro, a warrior of Old Japan, as presented in Shibaraku! (lit., Wait-a-Moment). A famous actor improvisation, or aragoto play, one of the hereditary eighteen pieces of the Ichikawa Danjuro family. (From a painting on silk by Torii Kiyotada, the present head of the Torii School) | |

| Frontispiece, in colour | |

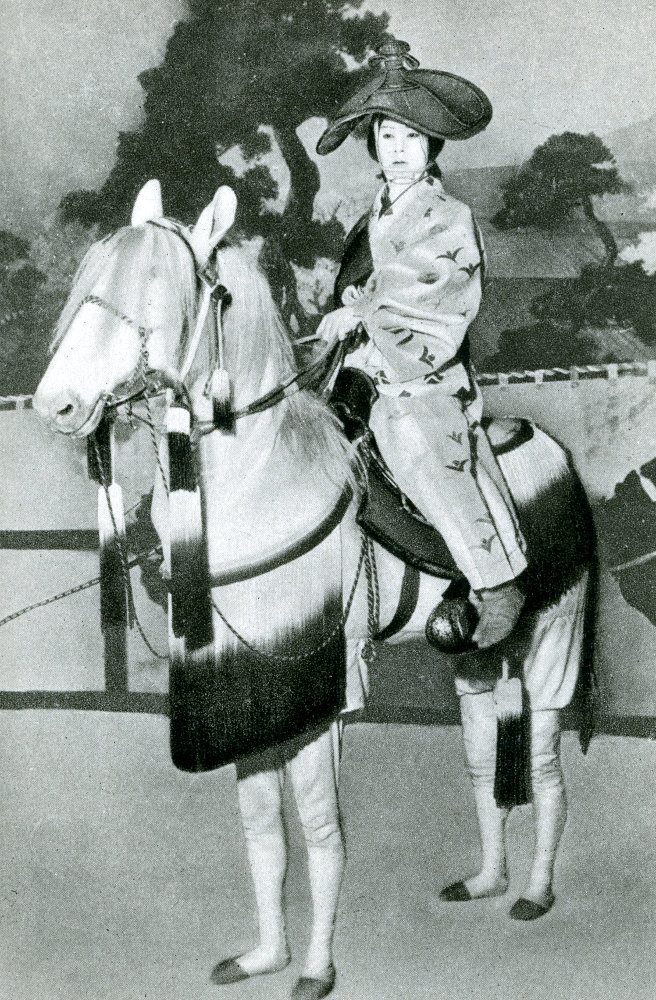

| Onoe Kikugoro as a brave samurai woman mounted on a white velvet stage steed | 22 |

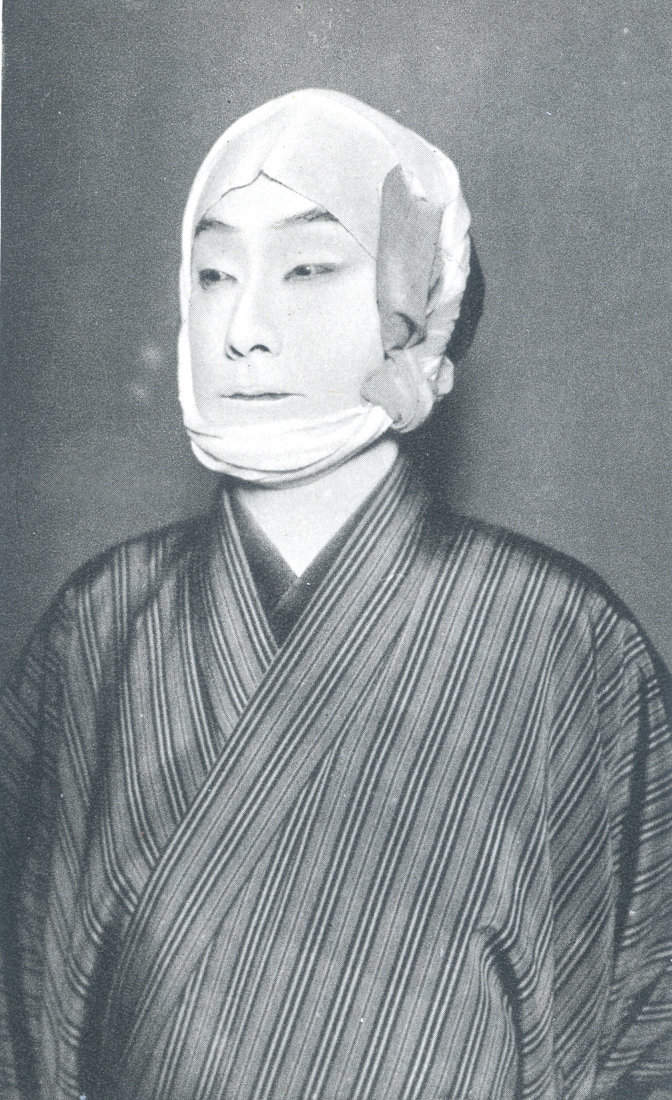

| Nakamura Matagoro, the leading boy-actor of the Tokyo stage in the rôle of a girl-pilgrim, O-Tsuru | 36 |

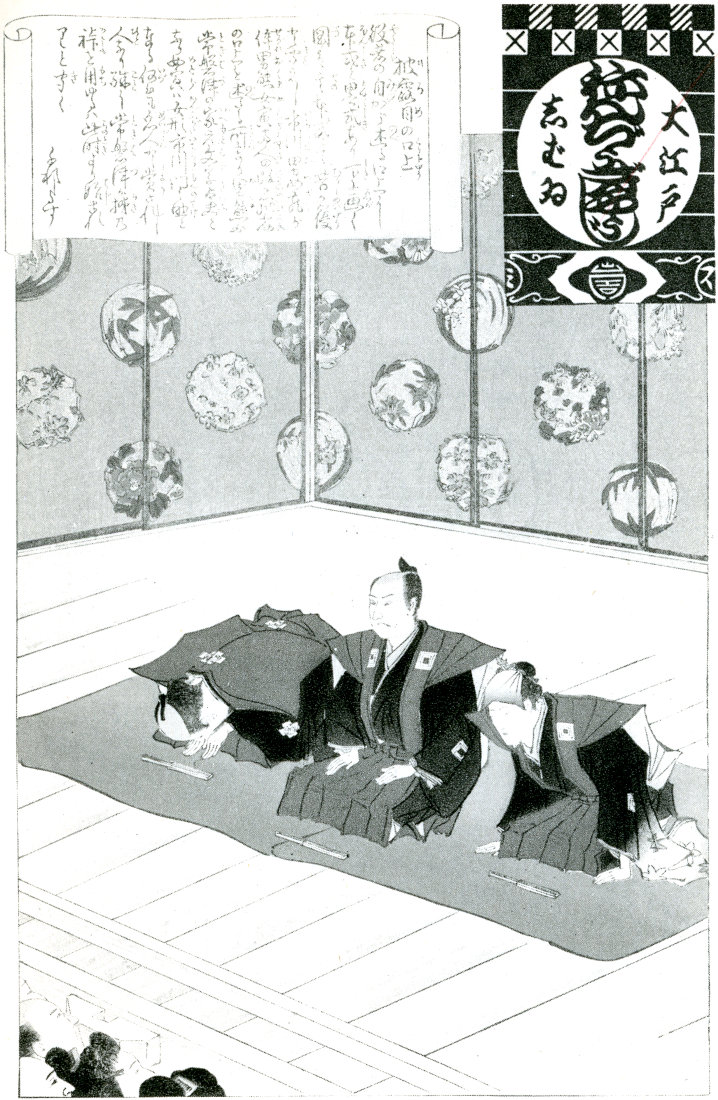

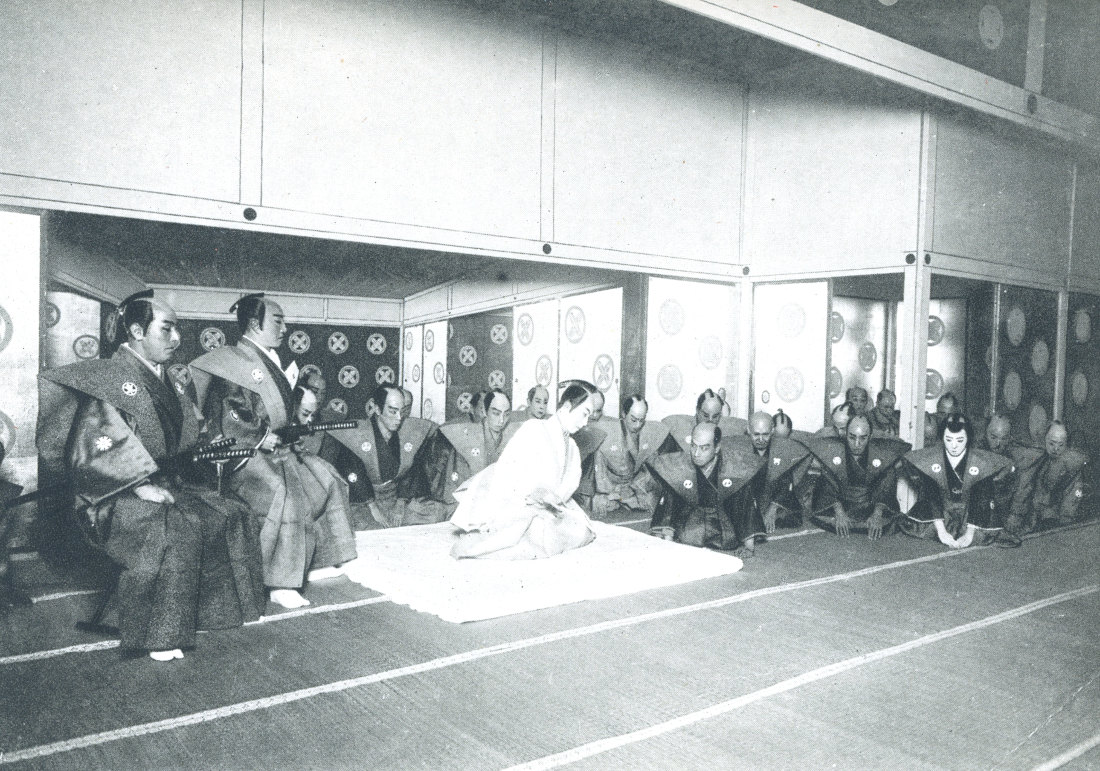

| Announcing Ceremony. Kojo, or announcement ceremony, in which the central figure is Ichikawa Danjuro. The modest actor whose name is to be changed or rank raised bows low, hiding his face from view. (Colour print by Hasegawa Kampei, the fourteenth, and Torii Kiyosada, father of Kiyotada) | 40 |

| The last of the Ichikawa family, the granddaughter of Ichikawa Danjuro, the ninth | 42 |

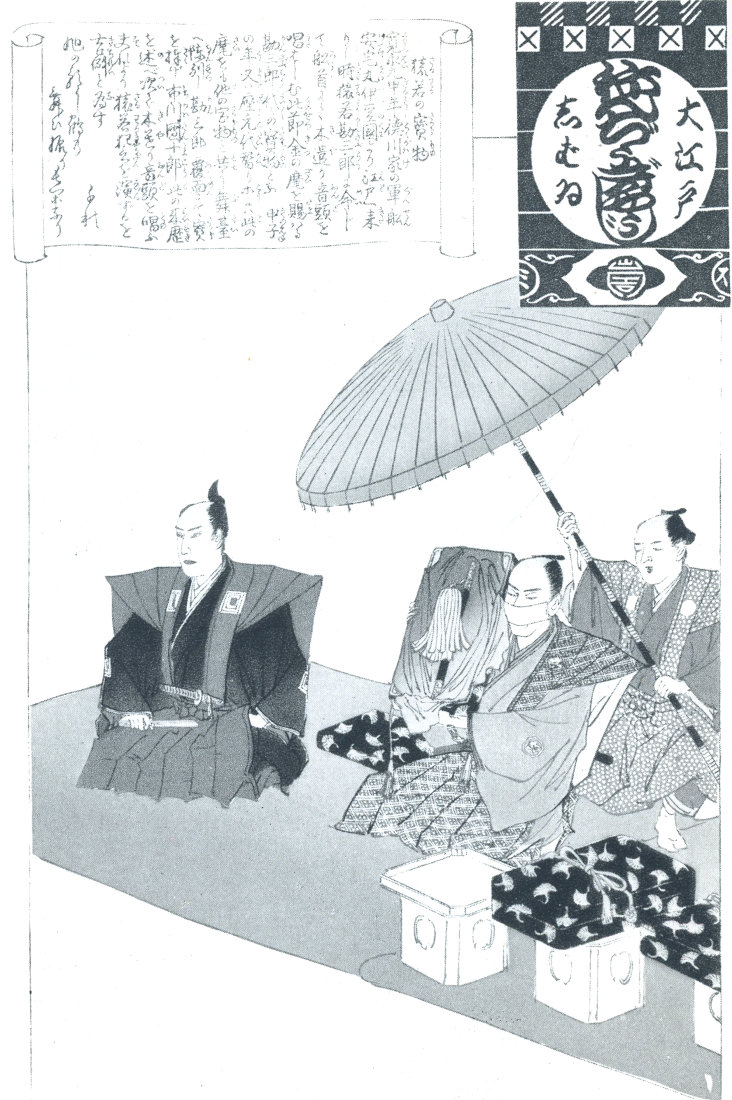

| Theatre Treasures exhibited. At the Nakamura-za, founded by Saruwaka Kansaburo, the gifts given to him by the Shogun were considered as treasures of the theatre and exhibited on certain anniversaries with much respect, the actor holding the gold sai, or battle signal, and covering his mouth with a piece of paper lest his breath soil it. (Colour print by Hasegawa Kampei, the fourteenth, and Torii Kiyosada, father of Kiyotada) | 69 |

| Ichimura Uzaemon, the thirteenth, as Yasuna in a posture dance descriptive of a man who has become demented because of the loss of his wife | 82 |

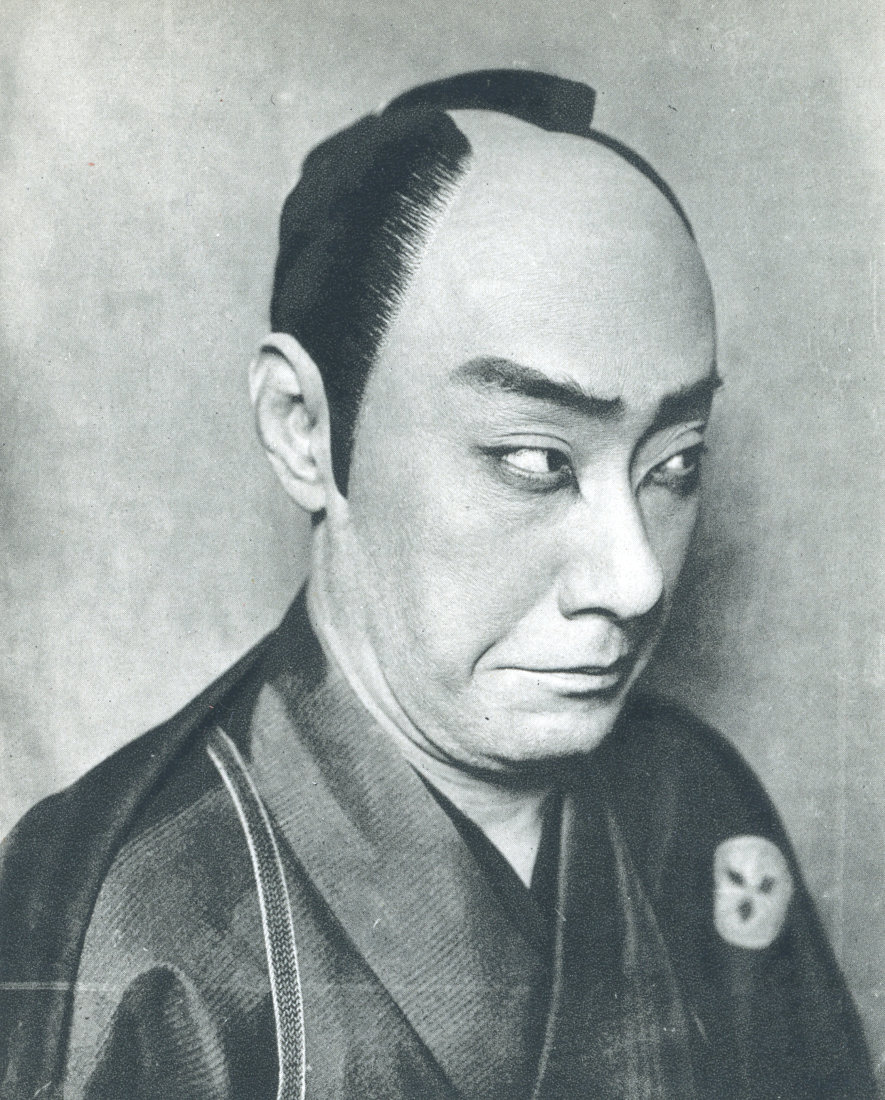

| Onoe Matsusuke as Komori Yasu, or Bat Yasu, so called because of the birth-mark on his cheek which resembles a bat. A bold, bad man of Yedo | 99 |

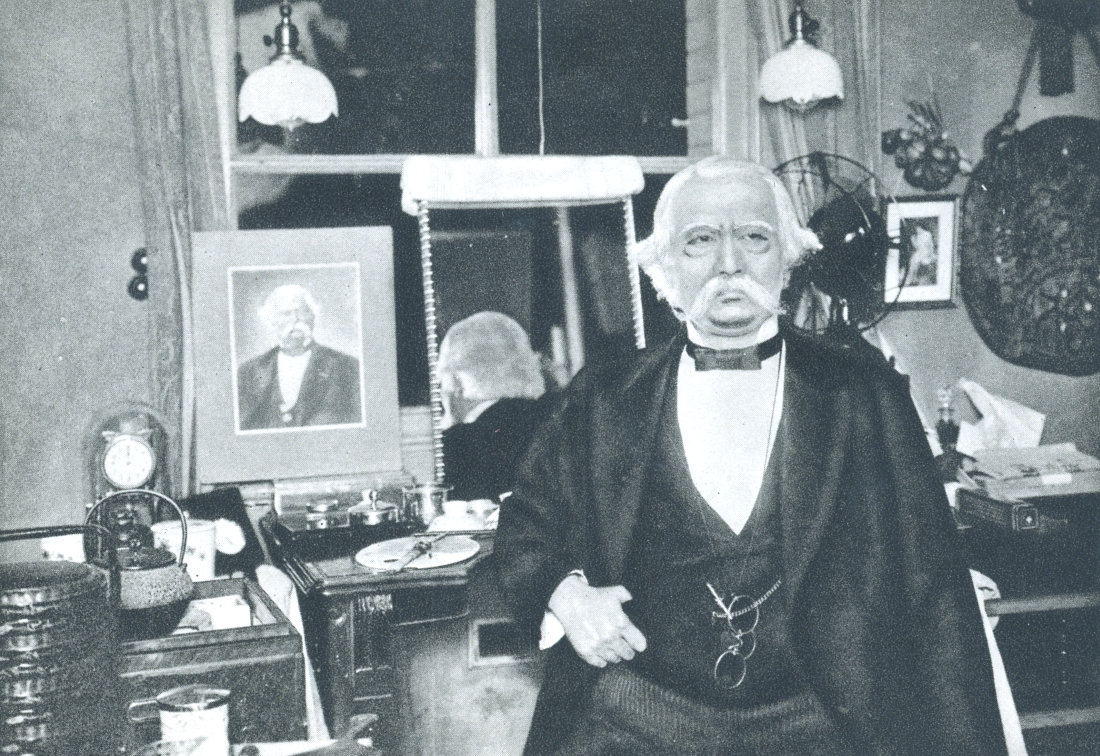

| Matsumoto Koshiro, of the Imperial Theatre, in the character of Townsend Harris, the first American Minister to Japan. A photograph of the intrepid Kentucky Colonel is on the actor’s dressing-table | 111 |

| Nakamura Utayemon, leading actor of the Tokyo stage, in the rôle of Yayegaki-hime, the young princess in the play Nijushiko, or Twenty-four Filial Persons | 132 |

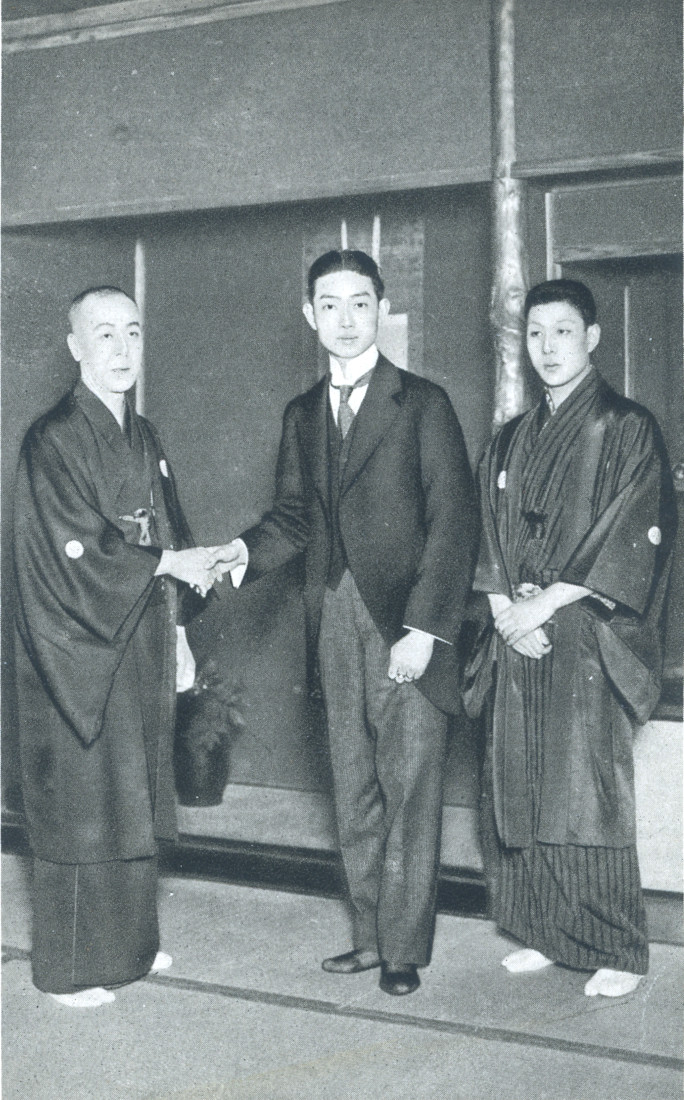

| [xii]Three onnagata of Asia: in the centre Mei Ran-fan of the Peking stage, to the left Nakamura Utayemon, the leading onnagata of Japan, and on the right Nakamura Fukusuke, the son of Utayemon and one of the most fascinating impersonators of women in Tokyo | 136 |

| Nakamura Jakuyemon of Osaka, an onnagata who imitates the acting of the marionettes | 140 |

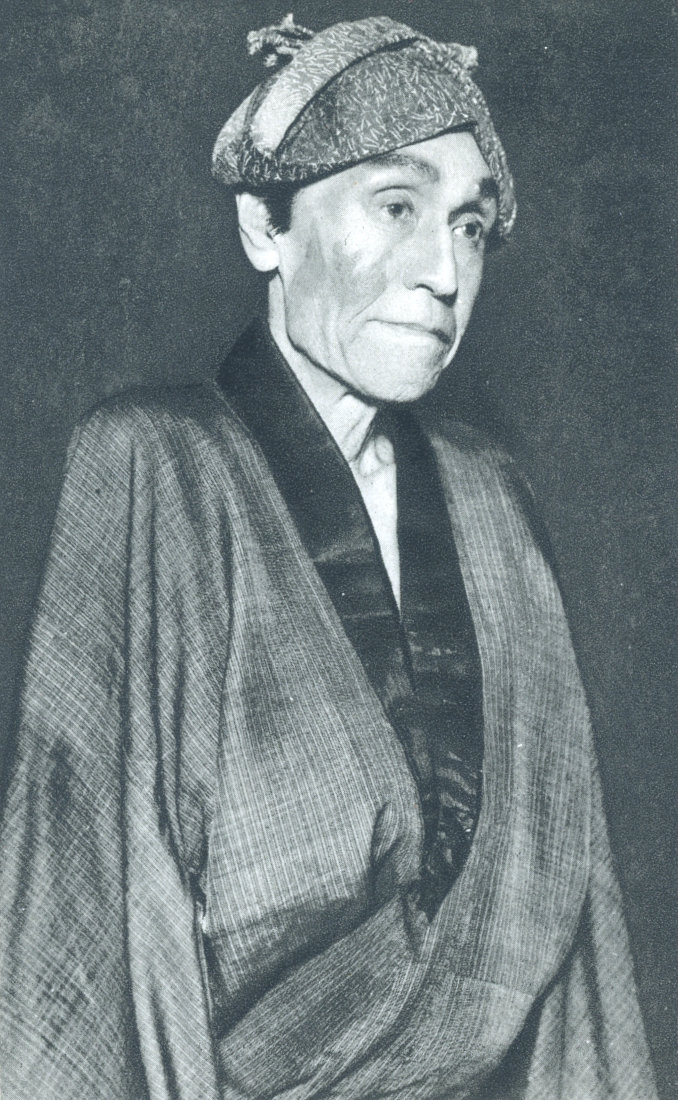

| Yoshida Bungoro, a doll-handler of the Bunraku-za of Osaka, who has devoted his life to the management of female marionettes | 144 |

| A scene from Chushingura, as played by the marionettes in the Bunraku-za of Osaka | 148 |

| O-Sato, heroine of a ballad-drama of the Doll-theatre. Reproduced from an oil painting by an Osaka artist and shown in a Tokyo art exhibition. The doll-handlers are grouped behind like shadows | 150 |

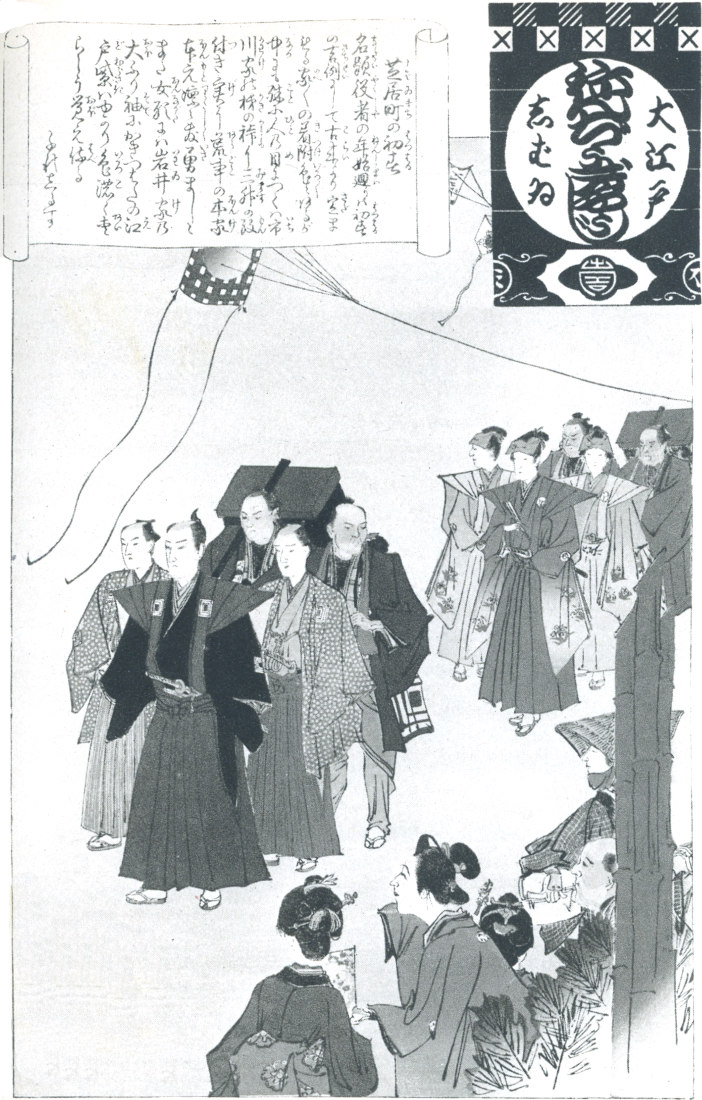

| Yakusha making a round of New Year calls. In the foreground a member of the Ichikawa family, with two pupils and his servants, following behind an onnagata similarly attended. The kites in the picture show the favourite pastime of children during the New Year holidays. (Colour print by Hasegawa Kampei, the fourteenth, and Torii Kiyosada, father of Kiyotada) | 154 |

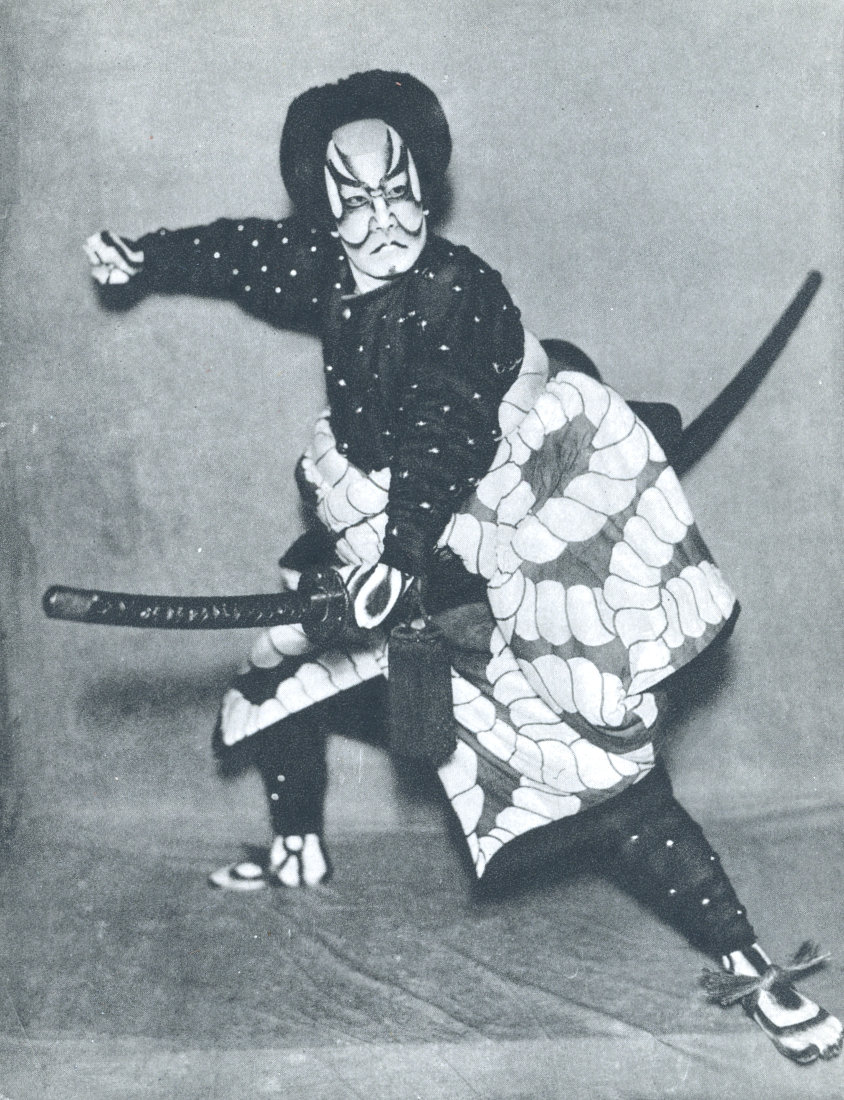

| Matsumoto Koshiro in the rôle of an otokodate, or chivalrous commoner, ready to defend the oppressed lower classes from the blustering two-sworded samurai | 160 |

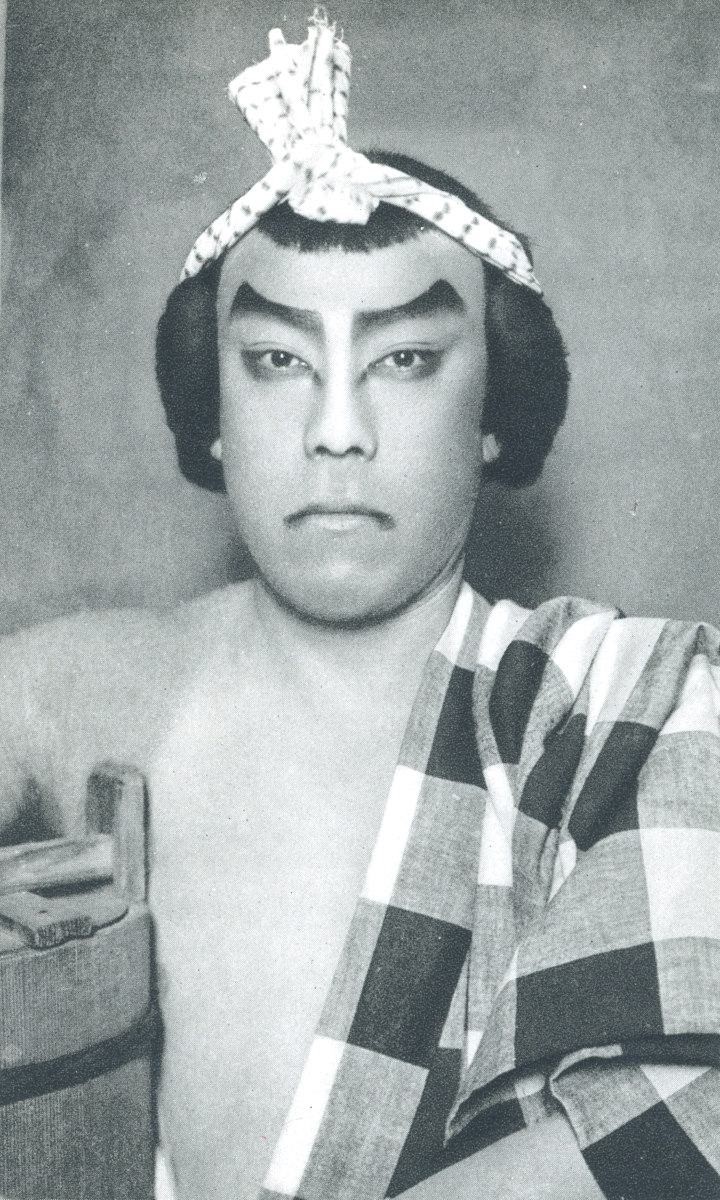

| Nakamura Kichiyemon as Kumagae, a warrior of Old Japan | 166 |

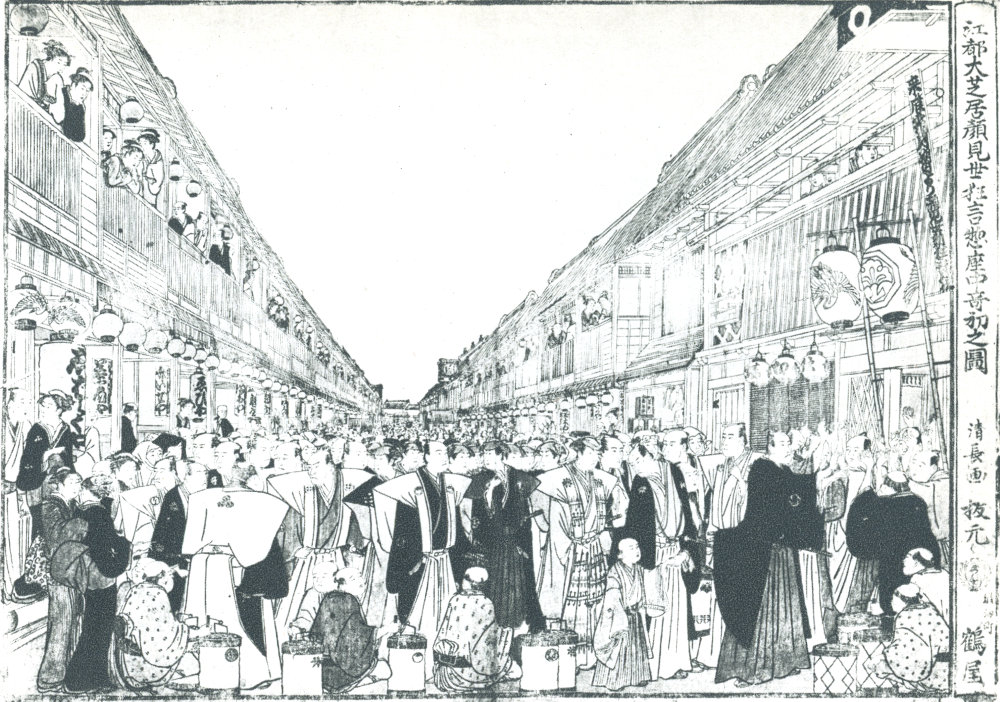

| To mark the opening of the theatre season when actors, playwrights, and musicians were engaged, there was a gathering called Seeing- for-the-First-Time. (Colour print by Torii Kiyonaga) | 175 |

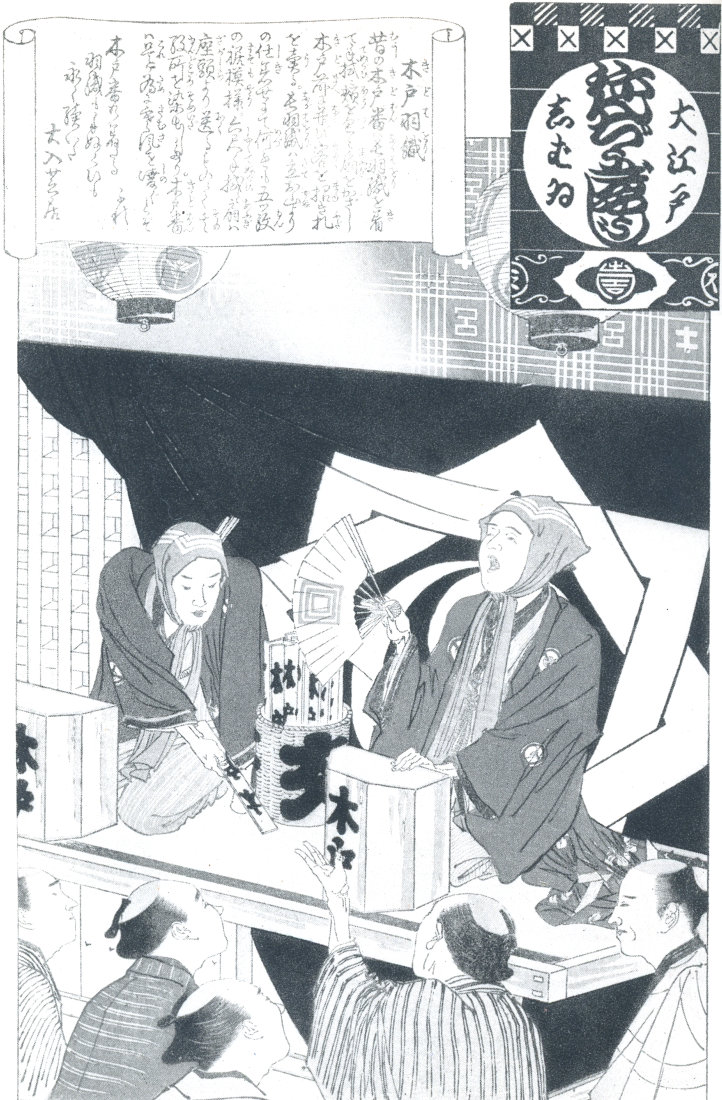

| Advertising the Play. During the performances two men garbed in long trailing feminine attire, their heads covered with cotton towels, attracted the passers-by by their verbal advertisement. One imitated the lines of the actors, and the other handed out wooden tickets. (Colour print by Hasegawa Kampei, the fourteenth, and Torii Kiyosada, father of Kiyotada) | 177 |

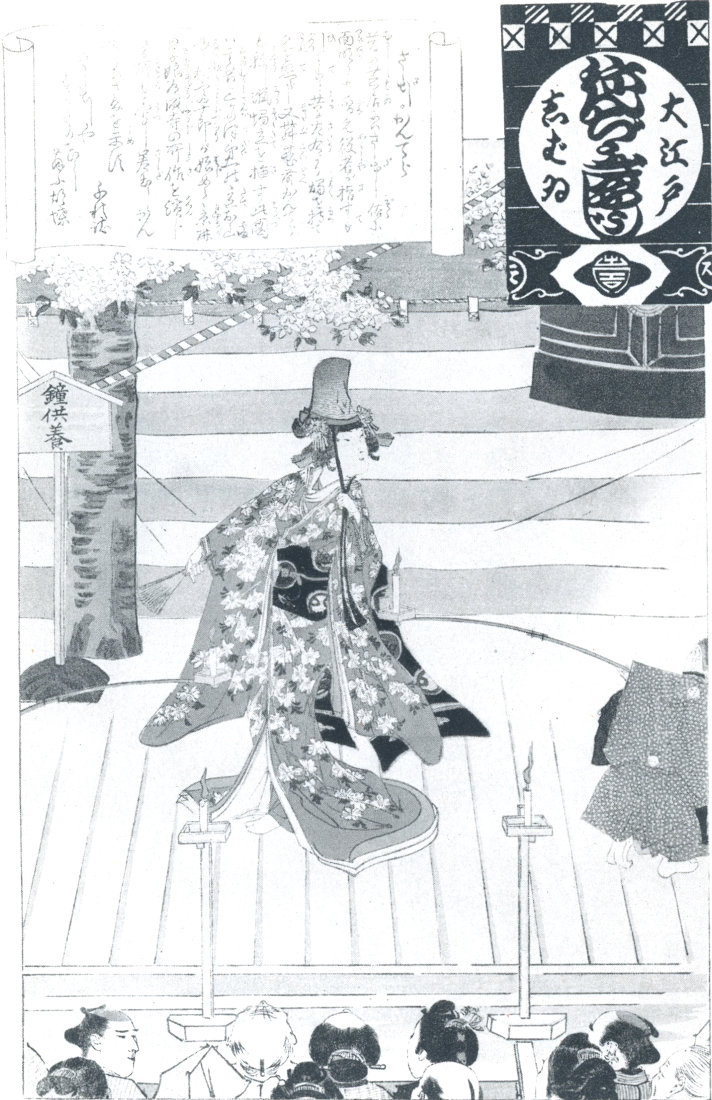

| Face Lights for the Actors. When the theatre became dark it was necessary to illumine the actor’s face with candle-light. Here property men are holding out candles on the ends of pliant rods that the face of the dancer may be seen, and candles form the footlights. The performer is the serpent princess in the disguise of a beautiful dancer in the piece Dojo-ji. (Colour print by Hasegawa Kampei, the fourteenth, and Torii Kiyosada, father of Kiyotada) | 181 |

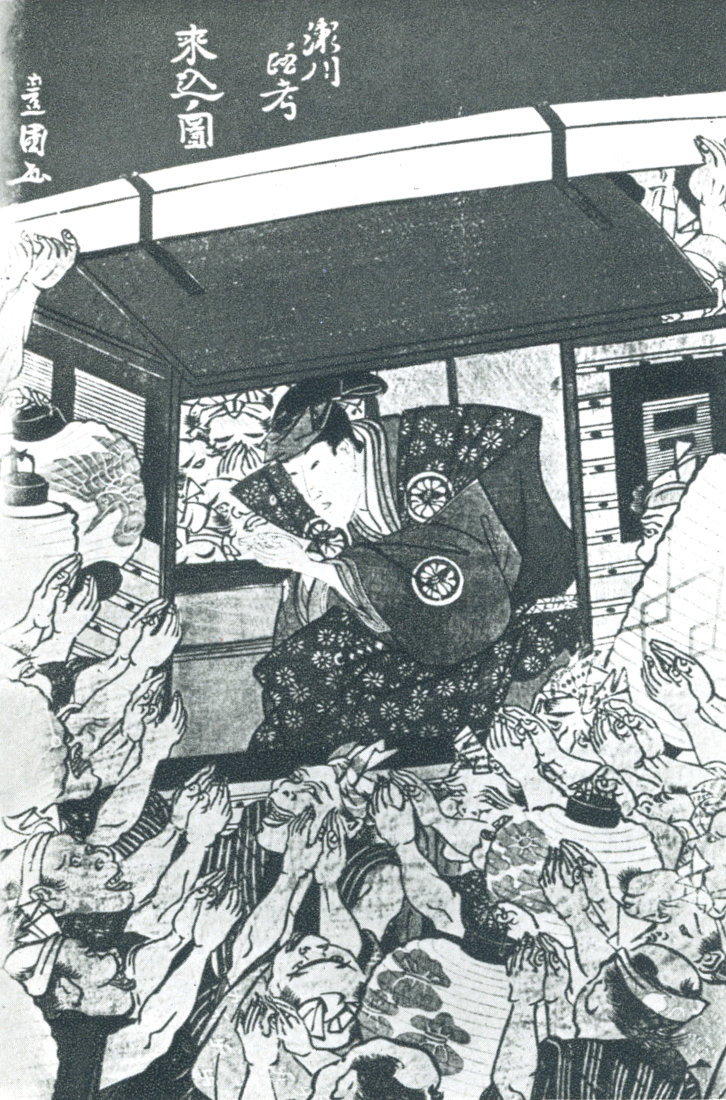

| Ceremony of welcoming an actor. It represents the onnagata, Segawa Kikunojo, returning to the Nakamura-za in Yedo after an absence of two years in Osaka. (From colour print by Utagawa Toyokuni) | 182 |

| [xiii]Nakamura Ganjiro of Osaka as a melancholy lover in a play of the people | 186 |

| Nakamura Fukusuke of Tokyo in an onnagata rôle | 215 |

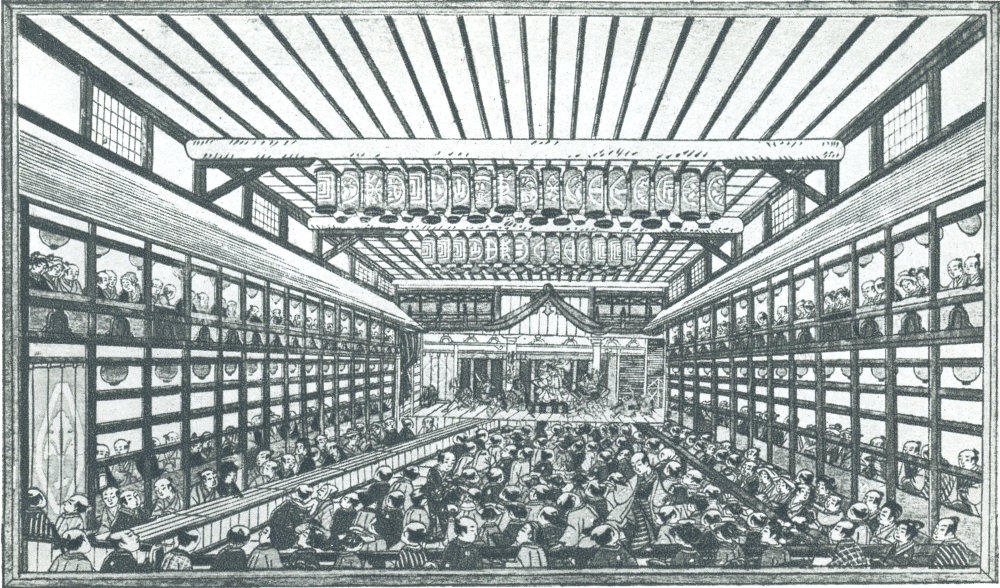

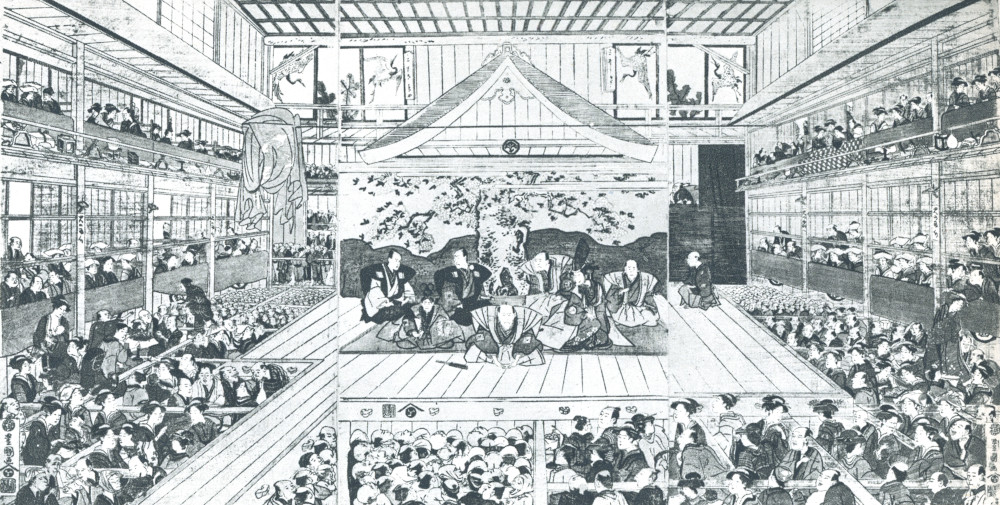

| A Kaomise, or face-showing ceremony at the Nakamura-za in 1772. By this time the roof of the stage had disappeared and only its symbol remained over the front of the stage, which now approached the long narrow style in vogue in the Doll-theatre. (Colour print by Utagawa Toyoharu) | 217 |

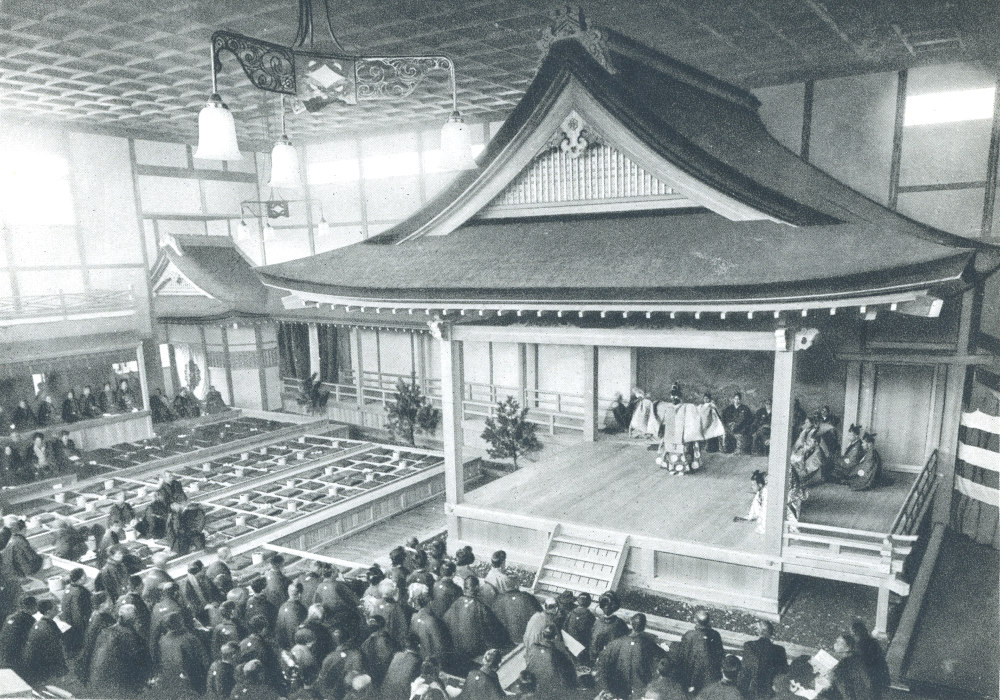

| Interior of the Nakamura-za in 1798 when Ichikawa Danjuro, the sixth, was promoted to the head of the theatre. By this time the roof of the stage had become a decoration overhead. (Colour print by Utagawa Toyokuni) | 218 |

| The largest Nō theatre in Japan, that of Onishi Ryotaro in Osaka, a modern structure combining architectural features representing the different periods of Nō theatre development | 220 |

| Kataoka Nizaemon, the eleventh, as Yuranosuke, the leader of the Forty-seven Ronin, in the play Chushingura | 228 |

| Nakamura Ganjiro of Osaka in his favourite rôle, that of Izaemon, the lover of Chikamatsu Monzaemon’s drama, and played for two centuries by the Kabuki actors | 256 |

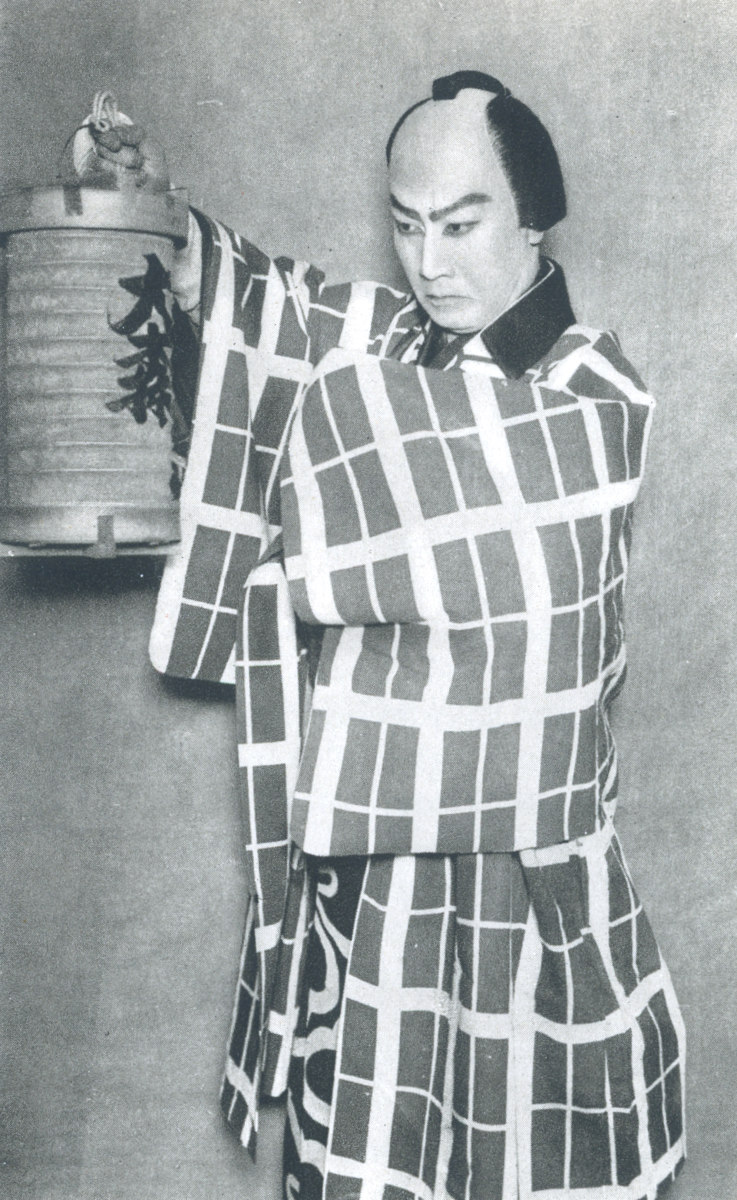

| Matsumoto Koshiro, the seventh, as Watonai, the grotesque hero of Chikamatsu Monzaemon’s drama, Kokusenya Kassen, or the Battle of Kokusenya. The inner garment is bright red studded with brass, the lower purple with a design of twisted white rope | 262 |

| Matsumoto Koshiro, the seventh, as Benkei, the warrior-priest in Kanjincho. He performed in this rôle when the Prince of Wales visited the Imperial Theatre | 264 |

| Sawamura Sojuro, the seventh, of the Imperial Theatre, as Togashi, the keeper of the barrier, in Kanjincho, Kabuki’s music-drama masterpiece | 266 |

| Morita Kanya, the thirteenth, son of the aggressive theatre manager of Meiji, as Yoshitsune, the young hero of the music-drama, Kanjincho | 268 |

| Onoe Baiko as the Wistaria Maiden, in a descriptive dance | 272 |

| Onoe Kikugoro, the sixth, as the transformation of a maid into a white fox, in a descriptive dance, Kagami Shishi, or the Mirror-Lion | 274 |

| Nakamura Ganjiro of Osaka as Genzo, the village schoolmaster in Terakoya, or The Village School, by Takeda Izumo | 278 |

| Ichikawa Chusha as Matsuomaru in Terakoya (The Village School), who sacrifices the life of his son that the Michizane heir may survive | 280 |

| Jitsukawa Enjaku of Osaka as Gonta in the sacrifice play, Sembonzakura, by Takeda Izumo | 282 |

| [xiv]Ichikawa Sadanji as Sadakura, the highwayman, in the play Chushingura | 284 |

| The Harakiri scene from Chushingura | 286 |

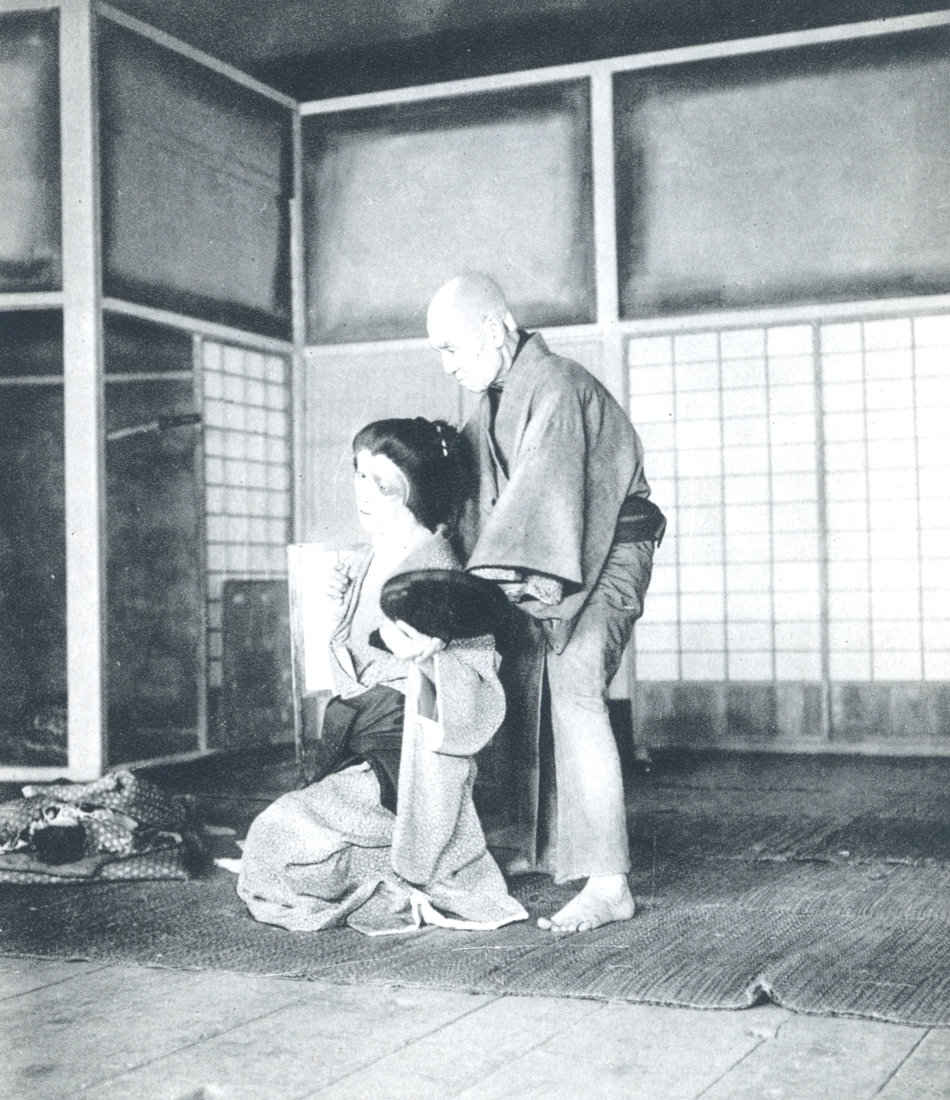

| Scene from Yotsuya Kaidan, or The Ghost of Yotsuya, by Namboku Tsuruya. Onoe Baiko is seen as the disfigured O-Iwa, and Onoe Matsusuke the kind old masseur who holds up the mirror that she may learn the truth | 294 |

| Banzuiin Chobei, a man of the people, rôle by Matsumoto Koshiro | 300 |

| Nakamura Kichiyemon as Sakura Sogoro, the Village Head who sacrificed his life for the good of the people | 302 |

| Nakamura Fukusuke of Osaka as a belle of the gay quarters. Letters are made as long as possible to produce the better effect | 304 |

| Onoe Baiko as the demon woman in Ibaraki, escaping with her severed arm | 306 |

| Matsumoto Koshiro and Onoe Baiko in Seikinoto, the music-drama piece, in which Baiko appeared as the spirit of the cherry tree | 316 |

| Ritsu-Ko Mori, the leading actress of the Tokyo stage | 347 |

| The Imperial Theatre of Tokyo, completed in 1911. The building withstood the earthquake shocks of the great disaster of 1923, but the interior was destroyed by fire. It has now been entirely restored. The Imperial is becoming an international theatre centre, and has welcomed actors, musicians, and dancers from England, America, Russia, Italy, and China | 368 |

| Onoe Baiko, leading actor of the Imperial Theatre in an onnagata rôle | 370 |

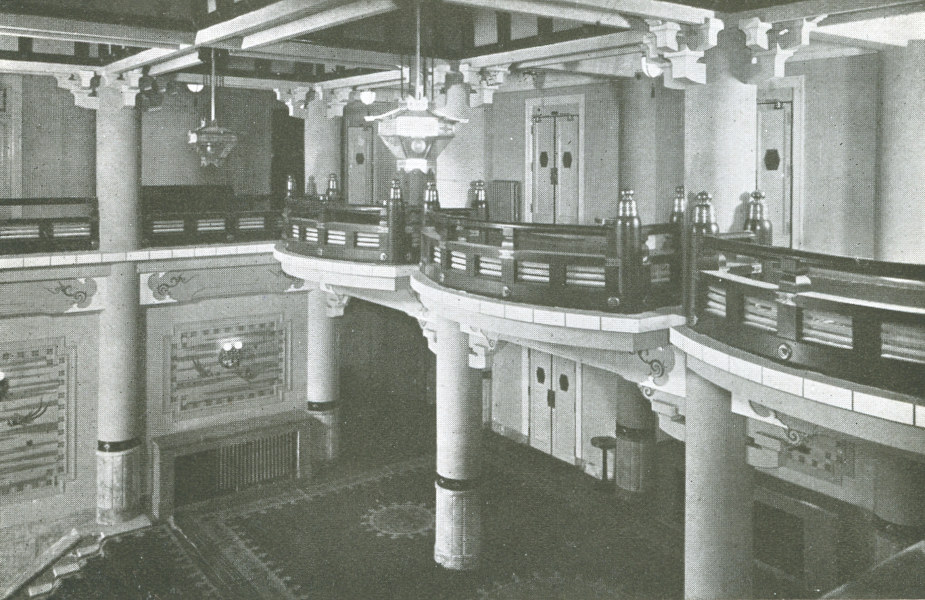

| (1) The new Kabuki-za. (2) Entrance Hall of the new Kabuki-za. The new Kabuki-za, with a seating capacity of 4000, which was opened on January 6, 1925. Under construction at the time of the earthquake disaster, September 1, 1923, the concrete structure remained intact. Japanese architectural features have been used throughout the Kabuki-za, and, rising out of the ruins of the city, it is one of the most imposing buildings in Tokyo | 374 |

[xv]

Interest in the Theatre, and in the arts and crafts which belong to it, is to-day so lively and so general that it is rather surprising how little has been written about the popular theatre in Japan. There have been several books on the Nō, that unique form of drama which rigidly maintains unaltered all the traditions and fine conventions of the medieval period. But this stationary, aristocratic art has never entered into the life of the Japanese people as has the Kabuki theatre, with which the present volume is concerned. In January of this year was opened the new building of the Kabuki-za, rising from the ashes and ruins of the capital. It is a huge building, with a seating capacity of four thousand. The Japanese cannot live without the theatre: it is in a most real sense part of the national life. Through the theatre the least educated become familiar with the heroic past of their country, its legends and its actual history, so abounding in dramatic episodes “where duty and inclination come nobly to the grapple”. It stimulates and sustains their imaginative life; it is a bond of union for all sorts and conditions of men. Such a theatre is worth knowing about; and the art of this theatre is, in all its details, of extraordinary interest. No nation is so thorough as the Japanese in any art they undertake; and the Kabuki theatre exacts the most prolonged and rigorous training from childhood in those who serve it; their art is of the most finished. Technically, also, the devices and conventions of Kabuki scenes—the revolving stage, for instance—offer points of comparison and contrast with the European theatre which we can profitably study, as readers of this book will discover.

The writer of this book has lived for years in Japan, [xvi]has assiduously frequented the theatre (and not the Kabuki theatre only), and has made herself intimately acquainted with its history. Collectors and students of Japanese colour-prints know how entwined with that popular art is the life of the theatre. Some of the finest designers of those beautiful prints devoted their lives to depicting the actors of the day in their most successful scenes. And print-collectors have long been in want of a book which would tell them about the famous actors, whether of masculine or feminine parts (for women, as on the Elizabethan stage, were played by men), and about the plays in which they appeared. Only quite recently has it been discovered that the actor-prints can very often be dated by the help of theatre-records; and thus we are enabled to distinguish between the different actors of stage-families bearing the same name. (The hereditary character of the actor’s calling is another interesting feature of the Japanese stage.) In this book one’s natural curiosity about the lives and personalities of the successive Danjuros and other great actors is in large measure satisfied: and I am sure that print-collectors will welcome this illuminating aid to their study. But it is to those interested in the theatre as theatre that these pages will appeal above all.

Many of us remember the performances of Sada Yacco and her husband, Mr. Kawakami, in London, now many years ago. They gave us just a glimpse of the fascination of Japanese acting: but they represented an experimental effort—Sada Yacco herself was an actress only by accident—and in the West we have never seen any true representation of the national drama of Japan. I cannot but express the hope, which I am sure will be shared by those who read these pages, that before long Tokyo may be persuaded to send a company to Europe, and at last allow us to enjoy and understand something of the scrupulous and intense dramatic art, so rich in tradition yet so alive to the finger-tips, of the Japanese popular theatre.

LAURENCE BINYON.

[1]KABUKI

[3]

Solid attention from the close-set heads of the playgoers kneeling on their cushions in the boxes of the pit to the crowded galleries on three sides, and enthusiasm displayed in the tachimi, or standing-to-see place near the ceiling, where patient people remain on their feet for long hours—the keenest critics as well as the warmest supporters of the actors—such is the scene witnessed daily in the theatre of Japan.

The Occidental cannot long withstand the mass psychology of this audience; that is, if he makes an attempt to share its point of view and appreciate the excellent things provided upon the stage. He feels its subtle unity, its amazing cohesiveness; he is carried away by an unseen stream, engrossed, engulfed, and wakes up with a start to find himself an entity again; or else, detaching himself from the atmosphere in which he has been immersed, wonders at this overflowing expression of Japanese life.

Statesmen, publicists, and editors of the Occident wax eloquent about Japan and her problems, but here is something they quite ignore and leave out of consideration, this manifestation of the pure spirit of the people with minds relaxed enjoying the theatre art that pleased their ancestors.

Seekers after mystery will not find it here, for there is nothing that is inscrutable. Merely the people laughing or crying as the play proceeds, spontaneous in their approval of the triumph of right over wrong, absorbed in the clash of evil and good,—the same theatre material that has served [4]to amuse and attract mankind for the last two thousand years.

Just the people, displaying depths of human nature, undisturbed by the questions that vex the politicians, the propagandists, the militarists, and other dread phantoms that cast their dark shadows over a sunny, smiling world.

The creative spirit belongs to no one land or people, and its expression becomes the treasure of all. Kabuki, the popular stage of Japan, is the result of three hundred years of intensive cultivation. Its genius and successful achievements belong to a common sum total, and are a contribution to the world’s theatre. Its actors are members of the same fraternity as those of the West, and claim kinship with them.

Nothing in the entire realm of Japanese life reveals the characteristics of the people so unerringly as Kabuki. It is a store-house of history, and has exercised a moral force upon the whole people. The crowded audiences in the big theatres of Tokyo, Osaka, Kobe, Kyoto, Yokohama, and the countless minor places of amusement, testify to the enjoyment and relaxation afforded by the performances. There are the achievements of the actors, who may easily be recognised as men of the first ability; the frequent attempts of new stage writers, that are worthy of consideration as evidence of Japan’s modern tendencies; the living traditions of the old masterpieces to witness, and the many interesting ceremonies of the theatre. Kabuki represents a whole world of creativeness both past and present, a sphere of theatre activity that remains a terra incognita to the Occident.

There is something poignant in the endeavours of generations of Kabuki players who obeyed the voice within them, asking no acknowledgement, expecting no return, doing their duty as they knew it without the least idea of the vague western hemisphere—completely unknown to their brothers in other lands.

For more than three hundred years these actors have [5]lived and had their being in their own narrow spheres. True to the best theatre instinct within them, they bequeathed their accumulated treasures of style and taste, the purest and most varied of theatre material, to their successors, the modern actors, who, so far as the West is concerned, remain obscure, unvalued, and unappreciated, even as did their ancestors when Japan was isolated and had no relations with outside countries. Yet their art was good, and will one day gain recognition. They have carried on their traditions unswervingly; they are the custodians of all that pertains to the theatre of the present, and the future looms large with possibilities.

There are three separate and distinct theatres in Japan: the Nō, or classic drama, with its masked figures, perfected five hundred years ago; Ningyo-shibai, or the Doll-theatre, where marionettes interpret complicated ballad-dramas; and Kabuki, the popular theatre, in which male players reign supreme. These are the Japanese theatre arts, interwoven into the very fabric of society, the amusements of the people that reflect their psychology, tastes, and aspirations.

The Nō became crystallised into an art at the time of the Shogun Yoshimitsu (1368–1398). Long before Yoshimitsu held sway, the country had been brimful of song, dance, poetry, minstrelsy, and the three theatres of modern Japan may be said to have inherited the accumulated tendencies of a thousand years.

Deeply rooted in the people was the love of theatrical entertainments which were held in connection with the festivals of shrines and temples. From these performances developed companies of players who formed hereditary actor families, the members of which were regarded as belonging to the common people.

When Yoshimitsu saw a performance at a Kyoto temple that pleased him he gave his patronage to the players, and at one bound they were elevated to a new position. It was at this time that the Nō was brought to a state of perfection, and the support and encouragement given by [6]so highly placed a personage resulted in the monopoly of this theatre by the aristocracy, to be reserved henceforward for their own use and entertainment.

During the long Tokugawa regime, the Nō continued under the protection of the Shogun, and was patronised by the various daimyo. When the shogunate fell, the Nō almost went out of existence, but slowly regained its prestige, and within recent years it has attained unprecedented popularity. It is regarded as a means of culture, and is claimed by increasing numbers of intellectuals. Yet it still retains its aloofness from the common theatre, which it continues to disdain as cheap, vulgar, and sensational. In spite of the fact that it has come to a standstill and lives on the past, its influence is very great.

As an expression of the human spirit by means of inanimate figures, the Doll-theatre of Japan is unique. It is a surprise to find this jewel of art in Osaka, the city of smoke-stacks—an art that has been alive in Japan for more than three hundred years, but is at present practically confined to one small theatre, the Bunraku-za.

Other countries have their doll-theatres in more or less flourishing conditions, but few have reached such a state of completeness as that of Japan. For here is a rare combination—inanimate figures instead of actors of flesh and blood; doll-men trained from childhood to acquire the technique to manage the cold and lifeless forms through which flows the creative genius of the handlers; minstrels and musicians who have devoted their lives to the interpretation of the plays; and the best brains of the dramatist employed in order that the dolls may be triumphant and their use fully justified.

Kabuki, the popular stage, was but the assertion of the people to the right of their own form of entertainment, since the Nō had become the exclusive amusement of the higher classes. All the materials for a theatre of the people were abundantly at hand, and it only needed the impetus to start it flowing in the right direction.

[7]Ningyo-shibai, or the Doll-theatre, and Kabuki rose at the same time, both popular theatre arts. Kabuki was destined to be profoundly influenced by the marionettes, and the music of the Doll-theatre owed its inspiration directly to the Nō.

While Japan’s theatre genius has not developed in the same direction as the intellectual drama of the Occident, her actors are the product of severe discipline. Kabuki is one of the most professional stages of the world. The actors are trained from childhood, and keep their place in the ranks until their steps are tottering. There is no opening for the amateur to gain admittance to this well-regulated world with its set standards.

And of the countless plays, but few are known to the West. There are the dramas rich in human nature, as romantic and sentimental as the West could desire, with a realism that rivals that of the Occident. On the other hand, there is a remarkable excursion into the realm of the unreal, and grotesque characters cut out of the cloth of exaggeration form the characteristics of the many quaint plays that have been handed down to posterity by the nine stars of the Ichikawa family, the actor-line that has contributed more than any other to the development of the Japanese theatre. There are, also, the shosagoto, or music-posture pieces, ethereal, graceful, fairylike creations, and associated with these a whole sphere of descriptive dancing.

To attempt to justify the existence of Kabuki by seeking to explain it in the light of the Occidental theatre means to digress, for comparisons are idle until the whole story of the Japanese stage is made known. No doubt when Kabuki becomes more familiar to the West much of a critical nature will be written as to where the two approach or diverge.

The aim of this book is to lay the essential facts of Kabuki before Occidental readers. For it is believed that the way to judge such an institution is to find out first what [8]it signifies to those who have brought it into existence. After which may be considered the value it holds for the West. When an attempt is made to explain Kabuki in Western terms confusion begins. It becomes a much simpler matter if left to explain itself.

In the Nō the actor and playwright were subservient to interpretation, and art was greater than personality; in the Doll-theatre, playwrights, minstrels, doll-handlers—all worked so enthusiastically that they forgot themselves and were absorbed in the marionette,—a truly unselfish theatre co-operation. Much of Kabuki, however, has been of an ephemeral nature. The actors improvised as they saw fit. It was their world and the playwrights were their servants. The whole art of Kabuki evolved by these players of Japan is unconscious, and should be of the greatest interest to lovers of the theatre in all lands, for the reason that the relation of a people to their theatre, the different use of dramatic materials, the development of characteristic customs and conventions reveal by way of comparison and contrast the virtues or defects of the systems that exist elsewhere.

[9]

An indescribable din, thoroughly characteristic of the atmosphere of shibai,—that forms part of the pleasure of theatre-going,—is composed of a hubbub of voices, the clatter of tea-cups, the twang of the samisen, the thunder of big drums, the cries of the vendors selling pots of hot tea, rice-cakes, or oranges to customers in the back seats of the gallery, and the metallic click-clack of the hyoshigi, or wooden clappers, that signal the beginning or end of the curtain.

Long before the playgoers begin to arrive, heavy, scattered drum-beats echo through the vacant theatre. This is a reminder of the old days when the drummer stationed in the yagura, or drum-tower, beat his tattoo to announce the opening of shibai, and to hasten the people on their way.

By the time the dekata, or ushers, are bustling about showing the people to their places, the great drum sounds with slow, regular rhythms. A flute begins to shrill, weaving an intricate maze about the deep-toned measures. Next the light, staccato beats of a Nō drum are added to the medley of sounds which, becoming faster and faster, seems to anticipate the thrilling and brilliant scenes that are about to be represented on the stage.

The drummers cease their clamour abruptly, and there succeeds a quiet space broken by the noise of the stage carpenter’s hammer, and the calls of stage hands. Soon the pit is densely packed, the people kneeling down on their [10]cushions in the little square boxes that hold no more than four with comfort. The galleries facing the stage, and to right and left, hung with many lanterns and covered with scarlet cloth, begin to fill.

Increasing the animation of the scene are the changing curtains of rich satins or crepes embroidered or dyed with gay designs, presentation gifts to the actor, symbolising his rank, rôles, or ancestry, that are drawn aside one after the other. The many-coloured kimono and gold and silver obi worn by the fair sex heighten the brightness of the picture.

Deluges of rain do not prevent people from crowding to the theatre, for when ordinary pursuits are interfered with the whole day may be given up to seeing the plays and enjoying the hospitality of shibai.

Should a typhoon be raging, the chaya, or tea-house, presents a lively scene; every second a dozen dripping, two-wheeled kuruma arrive, the short oilskin coats of the pullers streaming with water, their bare legs splashed with mud, as they unbutton the flaps of the hooded vehicles that old, fat dowagers, charming wives, white-haired old gentlemen wearing silk skirts, and geisha, immaculate of toilet, may emerge, only to be succeeded by an endless variety of persons bent on relieving the monotony of the day by a visit to shibai.

Within the chaya, the wide cement entrance floor is quickly covered by a mountain of geta, or clogs, and dripping oiled-paper umbrellas, all thrown together in what seems utter confusion, were it not for the wooden identification tags.

Servants add to the pandemonium by running in all directions calling out loudly as they take the honourable guests’ hats and overcoats, or escort them to their places within the theatre, while crowds of apple-cheeked country maids struggle valiantly to fill innumerable blue and white teapots, disputing with each other as to the destination of these indispensables, arranging them on trays, or filling [11]them by dipping up the boiling water from a huge brass kettle over the charcoal fire let down in the floor.

Outside, the red and white paper lanterns decorating the under-eaves of the tea-house blow about wetly, and a fusillade of vertical rain falls unceasingly upon the grey mud of the street.

From street to seat, and a new world appears, the audience kneeling down on the cushions of the small boxes, packed in like sardines in the narrow confines—faces, faces everywhere, from the patient standing people of the highest gallery to the close-set heads of the first row in the pit. Immediately, the piles of clogs and soggy umbrellas that must be sorted out before the dispersal of the audience, the blustering gale without, even the deafening roar of the unceasing rain upon the roof of the theatre are forgotten, as attention is focussed upon the vivid characters of the Kabuki plays.

Or to leave the dusty, traffic-worn city in the yellow glare of noon, and entering the chaya become lost in Kabuki’s dreamland, is a pleasant sensation. The old world wags. Afternoon gives place to evening, and by the time the playgoer issues forth again into the sphere of actualities, a chorus of thanks from the tea-house attendants for his coming sounding in his ears, the stars are bright in the canopy of darkness.

At the time of O-Kuni, the founder of Kabuki, shibai meant to sit on the grass or earth, and something of its out-of-door origin still remains. The buildings never at any time give the impression that the play is being enacted in some stuffy, mouldy subterranean cavern. Especially in hot weather the audience has a sense of airiness and freedom.

Going to the theatre in midsummer is made agreeable and comfortable. White curtains cover the galleries; the audience is clothed for the most part in cool, white cotton kimono, and the entire auditorium is a-flutter with white fans. The playgoer may look away from the stage and rest [12]his eyes by the sight of a moonlit sky, even bats and moths venturing in from their night resting-places, attracted by the bright interior.

Sunlight slants through the audience and falls on the upturned faces in the pit, and is reflected in the well-oiled and perfectly arranged coiffure of the Japanese woman. Patches of brilliant sunshine stray upon the stage, touching a golden screen or sumptuous costume. The wind blows, moving the fragile paper lanterns suspended from the galleries or in rows over the stage, shibai’s most characteristic decoration. The heads of the kneeling people in the galleries are outlined against an open space of blue sky, trees, and roofs. Afternoon fades, and the background behind the playgoers changes to dark blue velvet imperceptibly melting into the blackness of night as the play proceeds.

For summer audiences suggestions of coolness are made. In a certain scene gold screens will be used, on which are painted pine-clad islands, blue water, and white waves. When that mysterious sea of faces upon which the actor plays is one fluttering mass of paper fans, then the taste inclines to realistic typhoons with thunder and lightning and real rain, that splashes all over the stage, or there is shown an under-the-ocean scene in which fish and mermaids disport themselves. Should a piece with the savour of the sea be given, a curtain is suspended from the galleries showing blue waves on white, and creepy ghost plays are a cooling influence when it is necessary to forget the hot clamminess of the streets.

In winter, however, the near-to-nature aspect of shibai is not conducive to comfort. Then it is necessary to sit on the feet to keep them warm, and the chill air blows through chinks and cracks. The only heat provided is a small porcelain vessel filled with charcoal embers placed in a box that has an aperture in the top, while over the whole is placed a wadded covering—a hand-warmer that theatre-goers could not very well do without.

[13]But if there is signal neglect of creature comforts in the winter shibai, there are compensations. There is no lack of warm food and beverages to suit the taste of the most fastidious. During the intervals between plays the people promenade along the corridors and purchase souvenirs at the stalls, where many tempting wares are displayed to view. An air of enjoyment and pleasure pervades the atmosphere.

April is still, as it was in the old days, the gayest and most attractive month for playgoers. Thousands of provincials flock to Tokyo and Osaka, and the theatres vie with each other to provide the most attractive programmes. Artificial cherry blossoms form the decorations outside the theatres, and the stage shows some special arrangement of these flowers.

Following the old custom, November is the most dignified theatre month in the calendar, when the great actors play their finest rôles to mark the opening of the theatre season. The celebration of the New Year is observed in a special manner, the decorations consisting of pine, bamboo, and plum, and lanterns bearing the names and crests of the leading actors. December is the dullest and most uninteresting theatre month, since the year-end settlement of outstanding accounts makes it necessary to retrench in order to meet all obligations, and because the busy household preparations keep many a matron and maid at home.

Not all the plays on a programme, that lasts from noon to near midnight, are calculated to hold the attention—in some scenes the action, if it can be so called, meanders gently on, the audience manifesting a mild interest. There is a deep undercurrent of repose upon the stage, the actors going about their business leisurely, knowing nothing of the hurry with which Western players cram the events of a lifetime into a short two-hours-and-a-half.

People attend shibai not so much to be startled by sensations, as for relaxation. They take their ease, and [14]feel at home. The dekata waits upon them, attending to their personal needs with a courtesy that makes each individual consider himself an honoured guest.

In the midst of a scene that calls for passive interest, the dekata may be seen balancing in one hand a pile of red or black lacquer boxes full of hot rice and tempting viands with which playgoers are accustomed to regale themselves, or laden down with sake bottles or teapots, moving dexterously from one box to another in the pit.

At such times the doctrine of self-realisation of Asia is best revealed. Contented old men send the smoke from their small, metallic pipes floating towards the ceiling; grandmothers drink tea from cups that hold three mouthfuls. Old cronies discuss the play over sips of hot sake; others read the programmes to acquaint themselves with the forthcoming plays; babies are nursed, dressed, or put to sleep; geisha take out their mirrors and industriously preen and powder; children devour sweets and oranges.

But while each person is enjoying himself according to his own ideas, a hush seems to envelop the entire assembly. There is a sense of unity, an undertow of quietness, that holds the diversified units of the audience firmly together.

As a revelation of human nature there is nothing so illuminating in all Japan as the Kabuki audience. Quick to see the humour of a situation, it is tragedy that it likes and which touches it to the quick.

It is a mistaken idea to suppose that all the people of Japan are samurai to the extent that they never show their feelings. Loyal heroes who die for a cause, victims of the conflict between love and duty, sacrifice of self that others may live, these always bring the tears, and handkerchiefs are pressed to brimming feminine eyes in all parts of the theatre. Nor are men above the softer emotions. They may be seen weeping bitterly in such scenes as that in Chushingura when Enya Hangan commits harakiri and his faithful chief retainer, Yuranosuke, comes just in time to catch his last words. Others mop their heads or cough [15]to keep back the tears. Kabuki audiences seem rather to enjoy a good cry. The sorrow of farewell, mother-love, blindness, death, the common human experiences move them deeply. They may be dazzled by a gorgeous spectacle, excited by a combat, absorbed by the movements of a dancer, but when it comes to the sentiments of everyday life the Kabuki audience responds in a wave of sympathy.

Formerly the audience was composed chiefly of middle or lower class people. Nowadays all classes attend, and a member of the Imperial family, the Prince Regent, witnessed Kabuki performances for the first time when he visited the Imperial Theatre in Tokyo with the Prince of Wales. A distinctive feature of theatre-going are the parties of people who attend regularly in a body, patrons of the leading actors. Firemen, wrestlers, and tradespeople may thus be seen, according to the custom of their ancestors. The geisha are the steadiest patrons of the actors. Sometimes they make a brave show gaily apparelled, occupying the best seats in the gallery. They form an interesting element of the audience, smoking, chatting, weeping over the play, and making up with powder puff to obliterate the traces of tears, the young ones in dazzling kimono and obi, the more sedate in sober garments.

When a popular actor in a piece that has withstood the shocks of time is before the audience interest becomes intense. Familiarity with the play adds to the keenness of the enjoyment. Before a favourite character makes a grand entrance by the hanamichi, every head in the pit is turned to see him come. Shouts of welcome are heard as a beloved hero is about to make his appearance on the scene.

Half of the enjoyment to the playgoers in seeing these old plays is expectancy; not so much in the unfoldment of the plot, for they know the story by heart, and have witnessed the play often, but how the actor will interpret it.

One of the privileges of the audience is to make audible remarks, and they are free and unrestrained in [16]the expression of their admiration or criticism of an actor in a well-known rôle.

“You did very well!” shouts a voice after an actor has portrayed a character to the general satisfaction. If an actor is ill, but refuses to disappoint the audience, a sympathiser calls out: “Take care of yourself!” or “Thank you for coming when you are so ill!” Should a young player, rapidly climbing the ladder of fame, display so much skill as to astonish, there is a surge of great pride throughout the audience, and shouts of “Nippon Ichi!” (“Best in Japan!”) are showered upon him.

When the minstrel and the samisen player, who are to furnish the incidental music of a doll-theatre classic, mount their platform to the right of the stage, there are cries of: “Now do your best!”

Glowing memories of the varied scenes in shibai do not soon fade away; the friendliness of the tea-house mistresses who have remained for long years at their posts; the thrilling experience of meeting an actor off the stage in an upper room of a tea-house looking down on the blaze of oblong lanterns that form the street illuminations; the unfailing attentiveness of the dekata, those servitors of shibai who seem to have wandered into the present from old Yedo; an actor on the hanamichi surrounded by the people, all eyes intent on his movements, or the unrestrained applause when an actor reaches a high level of acting.

Many shibai landmarks are passing, giving place to more advanced ideas. In the leading theatre, chairs have now replaced the cushions laid on the matting as in a Japanese dwelling; steam heat ensures a well-warmed interior in winter; maids in black frocks and white bib and tucker are replacing the dignified, faithful dekata; the time given to the performances is steadily being reduced. Shibai must progress. But in their efforts to be up to date the iconoclasts would throw overboard much of the honest and simple regime that has for so long distinguished Kabuki.

[17]

While the development of the popular theatre of Japan has been co-existent with that of England and Europe, and fundamentally it is the same, there are striking differences in the conventions. These are the result of the isolation of Kabuki, due to the seclusion policy of the shogunate which endured for two centuries and a half.

Kabuki conventions appear at first sight so different from our own that it takes time to understand and appreciate them. Familiarity, however, reveals the taste and sincerity of the Kabuki collaborators, who, far from the influence of the theatres of other lands, worked out their own salvation.

One of the most interesting conventions to the Occidental is the hanamichi, or flower-way. It is an extension of the stage proper to form a path through the audience. There are always two hanamichi in a theatre, one on either side of the stage, that on the left being the wider and more important, that on the right smaller and less used.

Some of the most vital principles of Kabuki are at work when the hanamichi is employed. The modern playwrights who ignore it, not only rob the actors of something strongly theatrical, but at the same time take away from the audience the keen delight that comes from close contact with the creations of the stage.

Pageantry and ceremonial claim the hanamichi as their own. Sweeping over it come processions of gay courtesans; priests in stiff brocades chant as they march solemnly to some ornate stage-temple; daimyo trains wind their way [18]with all the pomp of feudal days; the whole theatre becomes a stage and every person in the audience feels his connection with the play and players.

A company of courtesans enter by the hanamichi and fill it with as brilliant a blaze of colour as it is ever possible to see in a theatre that is justly famous in this direction. The grotesque personages of the prints, the taiyu of old Yedo, are reproduced, the glittering robes of gold and bright embroidery, the elaborately decorated headdresses, and heavily padded brocade rolls to their many kimono, making them the most topheavy persons that could ever be imagined, balancing themselves on their stilt-like black geta, or high footgear, as they lean on the shoulders of their male attendants for support. A whole hanamichi of these extraordinary creatures, men bearing large lanterns, and little maids in scarlet, following in the wake, makes a picture that fairly dazzles.

Many priests with an aged abbot at the head pass through the audience in great dignity and enter a golden temple in the gloom of tall trees, the incense, wave on wave, rising into the air and spreading out over the audience. Fighting men in armour suddenly swarm over the two hanamichi, right above the heads of the bewildered people in their small boxes in the pit, and the whole audience is taken by surprise at the number of men rushing towards the stage.

The greatest variety of entrances and exits is made possible by the hanamichi. A hasty messenger chooses this way for entrance; and a slow exit is made by a melancholy lover with downcast head and folded arms, determined to depart this life. There is the splendid, imposing entrance of a shogun, prince or brave warrior, or the striking exit of some masquerading fox or demon, while the actors are fond of slow introductions, standing for a long time in the most conspicuous position on the hanamichi that they may be viewed from every vantage point in the theatre.

Tall autumn grasses on each side of the hanamichi, prepare for the entrance of a hero playing on his flute in [19]the moonlight, an assassin creeping behind him. If the scene upon the stage is that of winter there will be a snowdrift on the hanamichi, and blue and white cotton will transform this narrow audience-path into a stream of water. An umbrella lies carelessly outspread on the hanamichi; it gently moves as though by its own volition, then there is a puff of smoke, and out springs a beautiful maiden, who dances. By the same trap-door issue forth such characters as Nikki Danjo, magician and conspirator, who transforms himself into a rat that he may steal a family document, and then assuming his own form, although still resembling a rat, stands in the midst of the people, and the next moment mysteriously disappears through the hanamichi.

Armour-clad fighters perched high upon velvet stage-horses thrill by their nearness, and long-lost brothers find each other on the hanamichi. With rapture lovers are united; a wounded hero, shot by an arrow in the eye, reels and sinks down with exhaustion, and two comic old females go out talking volubly to the amusement of the audience. Such are the characters, gay or grave, who have been brought into existence by the hanamichi.

As a means to further characters on their way, the hanamichi is most useful. Two actors will leave the stage taking the hanamichi, and cross over by a narrow footpath into the centre of the pit, where they stand and act. Meanwhile a bridge has been pulled off and a red shrine pushed on, and by the time they wander back to the stage proper they have travelled a long way on their journey.

Travellers, servants, court ladies, peasants, and vendors,—they make a motley train as they pass over the hanamichi and are so near the people that they might, if they wished, reach out and touch their garments.

Interpretative music forms part of almost every play. To produce certain moods in the audience, the drummers and samisen players are accustomed to make sounds and rhythms to increase the emotion or picturesque effect of a scene. These men are called hayashikata, or musicians, [20]and perform on a number of instruments, furnishing Kabuki’s incidental music. They are stationed to one side of the stage and concealed from view, but as a concession there is an opening in the painted scenery, or screens, that they may survey the stage and keep in close relation to the action.

To accompany conversation there are irregular notes of the samisen, and when the characters are thus engaged and what they say is of great interest the audience is so hushed that the stray notes of the samisen sound like dripping water in a silent house. At other times this samisen accompaniment to dialogue is more of a hindrance than a help. For people walking or marching the samisen has another rhythm, and certain variations of measures suggest a lonely farm house.

When two noble persons converse together, the flute, sho (an ancient reed instrument), drum, and samisen are played softly. Rippling sounds convey the merriment of a feast, and excited rhythms are heard as a combat takes place.

For battle there is the confusion made of quick beats of the big drum. To increase the sound of the warlike preparations, a metal gong is struck rapidly, there is a clash of cymbals, and the blowing of a conch shell.

To make more solitary a lonely mountain scene, a horse-driver’s song is sung to the jingle of horse-bells, and when an echo is required two small drums answer each other. Gay and lively festival scenes are accompanied by intricate interweaving of light drum-beats. Crazy persons make their appearance to irregular notes of the samisen, while regular rhythms of the big drum suggest wind. Falling snow is made by soft, muffled, regular drum-beats. Waves are suggested by a vigorous stroke on the big drum, and then a quiet tap, in imitation of the ebb and flow of the tide.

At sunset there is the deep boom of a temple-bell, when lovers are parting, or the approach of some tragic dénouement in deserted temple or country cottage. For harakiri [21]scenes the piercingly sad flute and subdued samisen express the regret of the dying, and for tragedy there are sad little ripples of the samisen in a high tone.

Soft samisen measures accompany melancholy moonlit scenes, and the striking of a wooden gong used in Buddhist worship suggests the appearance of something frightful. Light taps of the big drums make known a sinister motive, and the big drum beaten quickly announces impending evil, while the clatter of the geta, or wooden clogs, on the hanamichi, to the thumping of the samisen and the light tattoo of the small drums, conveys an impression of light-heartedness.

Most of the conventions in regard to make-up have been handed down by word of mouth from one Ichikawa Danjuro to the other, and form a complicated subject. Dead white, with broad black eyebrows, and touches of red to eyes and corners of the mouth, has long been the accepted stage mask for samurai, or persons of high degree. White also forms the established make-up for women. Villains are generally made up with red faces, country people are tanned brown by the sun, and comedians paint their faces with red, white, and blue.

In the exaggerated rôles created by the Ichikawa house, the countenances of these imaginative personages give scope for the most daring attempts. This elaborate design for the face is called kumadori (lit., to-make-borders).

Brave men who have fought a good fight and lost, confront their enemies with an expression of retaliation, broad red lines around the eyes, nose, and chin, with red forks over the forehead. Again, such a character is made up with light pink shading out from the red strokes.

Strong and courageous warriors, undismayed although in the hands of their enemies, have chins of grey, red lips bordered by white, broad upward strokes of red from eyes and cheeks to forehead, and raised eyebrows like the antennæ of some black beetle, the whole giving the impression that the hero is bristling with anger; his hair standing on end.

[22]Benkei, the warrior-priest, loyal to his young master, Yoshitsune, is represented with a grey chin, no eyebrows, two curved lines on forehead, outlined in pink.

A villain of wrathful mien is made up according to the Ichikawa convention with the lower part of the face black, a black and white design on the chin for a beard, the upper portion of the face covered with a network of purple veins, and for eyebrows the antlers of a deer in dark blue. A villain of a different description appears with a bright red face, a pink nose and mouth, and thick black elevated eyebrows.

Most of the conventions for the making up of ghosts have been created by the Kikugoro family, their specialty being the weird and ghostly. A Kikugoro ghost has a branching design of blue veins, a red mouth outlined in black, and eyes painted with red and black. Another apparition has an indistinct blue tinge over the face, the features slightly touched with black. The face of a fox in human disguise is white with sharp pink points upward from the bridge of the nose, and slanting black eyebrows. The spirit of a frog has sharp curved lines of dark and light green about eyes, mouth, and forehead.

Not unlike the clown of the Western circus, the Kabuki comedian makes up with a white ground on which lines of red are painted about the nostrils and eyes, while a red circle between the eyes supports a heavy horizontal line intended for eyebrows. The cheeks are decorated with a blue curved design, suggested by a squirming eel, which represents a moustache.

The modern actors are not slaves to the conventions, but depart from them whenever they feel inclined, making up to suit their own ideas of the characters they take. The actor performs this elaborate duty himself, laying on the lines with brush and finger tip. Matsumoto Koshiro, of the Imperial Theatre, is acknowledged the most versatile and original in his making up, always creating something new and astonishing.

[23]One of the most striking conventions of the Japanese theatre is the Kabuki horse, supported underneath by two minor actors who specialise in supplying legs to make-believe steeds. It waves its mane, kicks and steps about to show its mettle, or jogs along, a patient pack animal. But always it forms a necessary part of the action of a play, as well as an important feature of the stage picture.

This remarkable quadruped with the very human legs and knees occupies a distinct place of its own in the old plays, and its prestige is not dimmed even in the latest productions. Its ancestor may be seen on the Doll-stage, prancing about among the puppets, but the velvet mount of Kabuki is much more dignified, and has advanced a great deal since it ceased to associate with the marionettes.

In a music play, Omori Hikoshichi, by Fukuchi, the horse becomes one of the chief characters. The hero, Omori, while assisting a young woman to cross the ford of a river is suddenly attacked by her. He finds that she is trying to recover her father’s sword, and having it with him, he generously gives it up. To hide his act from his men, he pretends to be overcome by uncanny influences, but this excuse does not satisfy the retainers, and when Omori jumps upon his horse, they pull the bridle this way and that, the restive animal rearing and plunging to the strains of the samisen. At length Omori frees himself and appears in the background on a hill, his war-fan upraised in triumphant attitude, the very intelligent stage-horse pawing the ground, apparently sharing its master’s triumphant emotion.

Acting a horse rôle is not so easy as it may appear, since the fore and back legs must by some stage legerdemain perform in harmony. The front legs take the initiative since to this actor is given the position of look-out. There is a window in the throat of the horse that allows the chief interpreter a partial vision of the stage. The hind legs must follow blindly, and moreover this actor is in a stooping position and apparently has little air for breathing purposes. [24]How the two players enter the outward frame, and how they get along inside, remains a mystery to playgoers, who do not inquire about the matter too closely.

When the young hero, Atsumori, in bright armour, makes his entrance upon the hanamichi riding on a white velvet horse, he has attached to the back of his saddle a series of black lacquered hoops, from which is suspended a long, loose covering of thin orange silk, that streams high above his head and floats like the train of a lady at court far behind the horse. Kumagae, a grizzled warrior, is magnificent on a black horse that tosses its head as though it were truly a fiery steed. He wears gold armour, rides on a black velvet mount, and the streaming silk is of purple. They follow one another into the sea, and the two horsemen are seen in the perspective surrounded by conventional blue and white waves, crossing swords amid the surges. The young hero is overcome. Then the riderless horses, like real runaways, dash along the hanamichi, making a grand exit.

There seems no danger that the Kabuki horse will ever become extinct, for it is employed with too good effect in many of the best plays. A samurai escaping from a battle leans with fatigue on his horse. The enemy are upon him and he must say farewell to his dumb friend, which shows affection for its master by rubbing him with its nose, while the actor without words expresses the sorrow he feels at parting from his faithful companion. Again, the central figure of a dance may be a white horse, with gay trappings of red fringe and brass ornaments.

Some day this interesting quadruped may be considered too antiquated in the pitiless glare of the progressive present, and, ashamed of itself for being a hoax so long, slink away into oblivion.

But it cannot be supplanted by a real one, so long as it forms an important part of the pageantry of the hanamichi, when resplendent daimyo ride in state through the audience in the midst of the little boxes crammed with [25]their human occupants craning their necks to see the passing show.

It would be hard to imagine Kabuki without its devoted kurombo, or property man. Concealed from head to foot in black, the face covered by a flap, which he seldom raises except in an emergency, the kurombo (lit., black-man) serves the stage unselfishly, claiming no recognition, pleased to put his own personality completely in the background; withal he is a most important personage. The variety of his tasks gives him an entire familiarity with the stage. He is a super-actor and stage-manager, entrusted with the smooth running of the performance, responsible for a hundred details, and yet remains the humble menial of the theatre.

A queer profession it seems, to flit about the stage so unobtrusively that the audience is not aware of his presence; yet always engaged in making inanimate objects significant. He holds a piece of silver paper on the end of a long pole and a fish jumps before the eyes of the audience. Hiding behind a thicket of bamboo, he causes the long feathery plumes to sway in a wind storm. The pendant branches of the weeping willow are suddenly agitated by the kurombo in anticipation of some ghostly event, or he squats down behind a clump of grass making it shiver to reveal the concealment place of some desperate character about to come forth.

What magic he effects by means of his long pliable rod! At one time butterflies flutter from the end, or a white moth is suspended over the face of a sleeping man near a white paper lantern, awakening him in time that he may protect himself from danger.

It is the kurombo who causes snakes to glide upon the scene and wriggle in the most realistic manner, while cats, rats, and even crabs make their appearance at the psychological moment at his bidding.

Sometimes he remains so quiet that he appears to be nodding or napping, but the next moment bounds away accomplishing his purpose. Always on the alert, he [26]watches for sliding screens that do not open, or gates that are about to topple over, and holds up a curtain that a dead man may disappear since he is no longer needed on the stage. By a dexterous touch behind, he changes the neutral costume of an actor to one all gold and silver, or gives the right tug that brings the long hair of a distraught heroine all dishevelled about her.

His solicitude for the infants of the footlights is touching. Crouching behind a boy actor, he guides his actions and gives him his cue, waiting to escort him on and off. And when the feet of the old actor become feeble the kurombo is close at hand to assist, knowing his least movement from long association.

Silent observer of the great men, the actors, creeping on all fours behind some gorgeous figure in gold brocade, the kurombo is conscious of the sins and omissions of the players, and he is the humourist of the situation. But he never shows that he is human. The audience seldom if ever catch a glimpse of his face, perhaps only in profile as he takes up some partially exposed position, with book in hand, prompting the actors whose memories are not trustworthy.

The boy kurombo begins to learn the mysteries of the stage at an early age. His father brings him to shibai when he is a mere baby, not more than four years of age, and he may be allowed to go upon the scene and take away a pair of sandals, or other small property, in order that he may begin to learn his life’s duties. Small actors and equally diminutive kurombo thus grow up together.

It is customary for the kurombo in his novitiate to sit at each side of the stage unconsciously taking in every detail. These children soon become accustomed to gaze in a detached way at the audience, which must make a vast impression on their minds, and at the same time they evince a lively interest in all that concerns the stage. Their eyes, round with wonderment, look at a play as though it were a fairy tale unfolding before them,—the ghosts and [27]demons, samurai and peasants of Kabuki passing near. It is small wonder that the kurombo, whose taste for the theatre is bred in the bone, stays with it until old age claims him—always a shadow.

The most perplexing convention of the Japanese theatre to the Occidental, long accustomed to mixed players, is the fact that Kabuki is the possession of actors, and that women characters are in consequence in the hands of males. If this seems a strange business for a man, it must be remembered that Shakespeare’s heroines were played by youthful English actors.

Moreover, it is realised that the peaceful atmosphere and orderly regime behind the stage,—the environment in which the actor lives and works, is in many respects like a man’s club in the West. This freedom to work unhindered by the opposite sex gives the Kabuki actor a greater opportunity to be himself, and the remarkable calm that seems to permeate all that takes place on the stage may be one advantage of the pure male theatre.

Masks and marionettes have had a large part in the shaping of Kabuki conventions. Many of these conventions, that seem so strange and very often absurd upon first acquaintance, become more intelligible in the light of the debt the popular theatre owes to the Doll-stage and to the still older form, the Nō.

Stepping in imaginary waves, washing the feet in water that does not exist; cooking food without fire, drinking tea from empty cups; blows that do not touch; cold steel that does not clash,—all these have come to Kabuki out of the inexhaustible suggestiveness of the Nō. Rhythmic movement to express emotions resulting in symbolic gestures, pantomime and postures of the puppets, were the contribution of the Doll-theatre to the development of Kabuki.

Without these two restraining influences there would have been nothing to prevent Kabuki from following the same realistic route as that of the Western stage.

[28]

When it comes to a question of what the Japanese Theatre holds for the West, the craftsmanship of Kabuki should be of first importance.

Characteristic simplicity, taste, and style are shown by the men accustomed to handle material for stage pictures. Above all, these workers are free from a worship of things, and do not overcrowd, but concentrate on essentials. In the management of details the producer displays a finish that is near perfection. Things are not allowed to clutter up the stage for their own sake, but are necessary only as a medium to express the underlying motive of the play. In the manner, also, in which trees, flowers, birds, the sea, mountains, waterfalls, lakes, and the seasons are represented, it is apparent that Kabuki is still near to nature, and a product of a non-commercial age.

During the three hundred years of its history, Kabuki experts have been designing scenery and fashioning furniture and properties, unknown to their contemporaries in England and Europe, who were quite as much alive to the adornment and embellishment of their stage productions.

Hasegawa Kampei, the fifteenth, is the leader among Kabuki craftsmen in Tokyo. He considers himself a simple workman, and is busy designing and executing scenes in all the theatres of Tokyo, showing a surprising versatility and creativeness. He has, however, to compete with the flood of westernisation that would destroy the very foundations of the art his ancestors developed.

[29]The first Kampei, the son of a samurai, was a skilled artisan in wood-carving and the decoration of temples, setting up stone gateways and lanterns, and the beautiful wooden gates of approach. His ability in this direction became so well known that he was called in to help in the production of plays.

In 1644, large furniture began to be used at the Ichimura-za in Yedo. And by the time of Kampei, the eleventh, the development of odogu and kodogu, or great and small furniture, was at its height, and his designs are regarded as models at the present.

The greatest improvement in the Yedo stage took place from 1780 to 1800, and the Hasegawa Kampei who presided over the destiny of the stage at that time invented new contrivances, especially in the management of ghosts; causing buildings to rise into the air, and trap-door disappearances. Finally the fashion for realistic furniture became so great that the interior of one of the great halls of the Imperial Palace, Kyoto, was reproduced on the stage. The authorities protested against the extravagance shown in this beautiful conception, and inferior materials were substituted by order.

Although the members of the Hasegawa family were skilled men, the real source of Yedo’s stage scenery progress was due to the creativeness of the Doll-theatre in Osaka. The collaborators for the dolls were fertile in ideas, and developed new stage settings in bewildering rapidity.

If there is one direction in which Kabuki shows the true craftsman more than another it is the pictorial. It is doubtful if on any other stage in the world can be viewed more charming effects achieved by such simple means. A red lacquered bridge over an iris pond, and the characters in picturesque combinations of colours; the soft greys and whites of a snowy scene, and in the centre an ancient cherry tree in full bloom; the lonely camp fire of a beggar in the mountains, a castle moat in the moonlight; a single fantastic pine by the seashore, are some of the familiar Kabuki scenes.

[30]Brighter and more elaborate is a maple picnic under flaming foliage, the leaves falling, the feast spread on a scarlet rug, all the properties of black and gold lacquer, and the rainbow tints of Asia used plentifully in the costumes.

There is a flash of steel in the moonlight as many assailants rush upon a samurai, and the air is filled with fireflies. After the courageous hero has disposed of his enemies he wipes his sword, and to ascertain that it is quite clean lifts up a cage of imprisoned fireflies, by the glow of which he is able to see. Or again, it is old Nihonbashi, the Bridge of Japan, the centre of Yedo and from which all distances were calculated; Mount Fuji in the distance; a band of firemen returning after a conflagration, singing a characteristic song.

Much more elaborate is a cherry-viewing party, come to enjoy the cloud of pink blossoms, grouped on a hill-side, seated on a red carpet, with a gay silk curtain for background, made of stripes of black, yellow, purple, red, green, the masses of drooping flowers arranged with thick red ropes strung with brass bells, white paper lanterns in the greenery, serving-maids in pink kimono, merry masked dancers entertaining the company.

In a Nagasaki play relating to the visit of a Chinese envoy, there is seen a temple interior that could not be simpler and yet suggests grandeur—the background, a wide expanse of gold screens arranged with sliding doors on which are painted gold and black dragons, and in the foreground the actors, a group of daimyo in grey-blue, the bronze-brocade and gold-clad villain receiving the gifts that are to be presented to the emissary from China.

Not all Kabuki’s scenes are simple and serene, and nothing daunts the superior stage carpenters when once, they try their hands.

In a popular play there is a scene depicting a realistic earthquake, and a mansion collapses under repeated shocks. The building sinks down amid stage, according to some secret of the carpenters, and the hero makes his way out of [31]the roof, ruin and desolation around him. When it comes to sensational snowstorms, typhoons, and conflagrations, Kabuki can hold its own with the Western stage.

It is, however, in architecture that the hand of the Kabuki craftsman is shown unmistakably. He has been free from the thraldom of the picture frame of the Western stage, and in following his own devices has worked with a freedom that has produced some satisfactory results.

The producer has taken the main room of a Japanese dwelling for his model—a straw-matted room, sliding screens for background, a severely plain apartment; for its sole decoration, an alcove containing a hanging picture, before which stands a vase of flowers or object of art. It has not been necessary for him to knock out one side of the house in order to allow the audience a view of what is passing within. The Japanese room being open to the outside, forms an admirable setting for the action of the plays.

To this room, which is in reality a platform for the players, he has added adjoining apartments, corridors, bridge-passages, verandahs, and the sloping roof is always present, either in part or as a whole. Completing the picture are gardens and rustic gates, stone water-basins, stepping-stones, wells, bridges, ponds, fences, and stone lanterns, and he has surrounded his buildings with the favourite flowers of Kabuki, lotus, chrysanthemum, peony, iris, and azalea. With a true love of nature he has placed in his scenes cherry and plum trees in full bloom, and has used pine trees and scarlet maples, drooping willows and feathery bamboo.

With a room as scene of action, the Kabuki carpenters have created types for all classes of dwellings the plays require. The background for a room in a great mansion will show a series of sliding panels on which are painted Chinese castles and pagodas, golden clouds, and green misty hills. Silver screens may be decorated with black waves in motion, or blue water, lotus leaves and flowers. The structures to be represented vary from an elaborately [32]constructed mansion in cream wood to the realistic interior of the middle-class home in which the white-papered windows and doors form a pleasing feature. Temples, a hermitage in the midst of a forest, the thatched cottage of a farmer, are all variations of the one theme, which gives the widest latitude for invention and decoration.

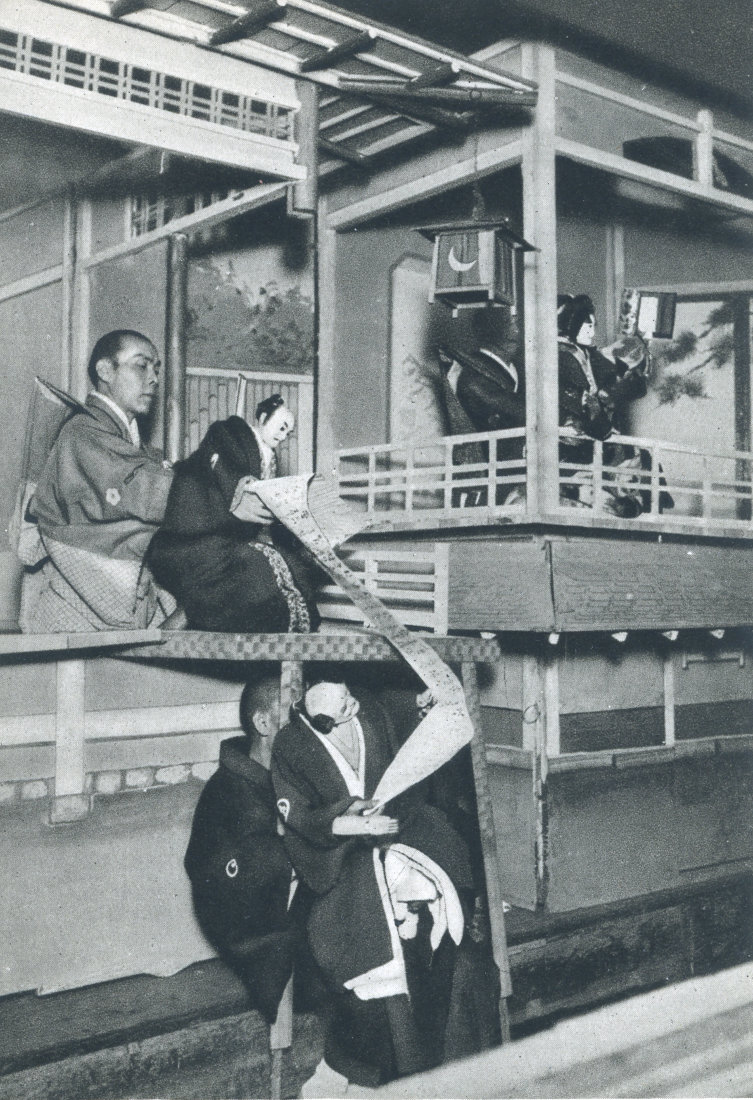

Much of the action in Kabuki plays takes place in this room, with only the screens for background, and standing lanterns at each side. But there are more elaborate architectural triumphs, such as the great red entrance gate of Nanzen-ji, a Kyoto temple, carved, decorated, ornate, two-storied, and produced in detail. The bold robber, Ishikawa Goemon, hides in the second story, and comes forth on the railed balcony to smoke. This portion of the gate is first shown, the wall behind him in gold, painted with many-coloured clouds. As he stands there in his black velvet kimono and great overcoat of gold and black, the gate begins slowly to rise until the lower part is completely in view, the chief temple building in perspective within the arch of the gate, and Goemon looking down from his lofty position at his enemy below.

At another time, the Kabuki craftsmen spare no pains in constructing the Yomei gate of the famous Nikko Shrines, one of the best pieces of architecture in Japan, and so perfectly is it reproduced that the workmanship calls for admiration. But when no longer needed, the entire structure, which towers high, slowly turns over on end, and the bottom represents the background for the following action.

From grey dilapidated temples where apparitions make their appearance, or the nobility partaking of ceremonial tea in some landscape garden, the Kabuki craftsman passes to the fashioning of a red pagoda, the under-eaves showing many brilliant colours. He places two stories of the structure in a snowy scene. Warrior-priests in grey with white head coverings rush on the scene armed with long spears. An old dignitary wearing gold armour, over which there is a thin, black, priest’s robe, stands at one side with a torch [33]in his hand. Another figure, in silver brocade and white, poses on the steps leading to the pagoda. The hero in armour—red, green, and gold—appears on the upper gallery. Then ensues a big fight in the whirling snow, the deep boom of a temple bell sounding through the fray.

The revolving stage that plays such an important part in the scenery of Kabuki has a complicated technique of its own. It allows of three, and sometimes four sets of scenes, that may be in the course of preparation while the actors are engaged in front. But as a general rule the carpenters are busy with but one full set, while the play proceeds.

For an extension of the stage picture, the stage is turned to right and left, or revolves half way for some new scene. In addition to the surprises in store for the playgoer in the changes effected by the revolving stage, there are the strange appearances of characters forced up through a large opening in the floor of the stage, like groups of statuary, and devices for the sudden disappearance of characters through walls and steps, the elaborate apparatus for ghosts that emerge through lanterns or vanish into thin air, and for chunori, or air-riding feats, when a character suspended in mid-air moves across the stage.

The kodogu, or small properties of Kabuki, are a study in themselves,—the lantern in all its shapes and sizes, the oil-paper umbrella, vases, and hanging pictures. The articles in use are not made to look beautiful at a distance, but are genuinely so: tall candle-sticks in brass or lacquer, chests, sword-rests, cups, swords, helmets, lacquered tables, tobacco-boxes, bronze utensils for a temple altar, or Buddhist images, they all represent the arts and crafts of the country.

Keen to adopt and adapt new things, Kabuki is now sensitive to European stage influences, and with a characteristic lack of confidence in its own creations, appears to be opening the door too wide in welcoming the ideas of the West.

[34]The thought can hardly be avoided, however, that the achievements of the Kabuki craftsmen are a contribution to the world’s theatre. But what the place and value of their work in comparison with the stage of the West remain for the judgement of the future.

[35]