Title: Kwasa the cliff dweller

Author: Katharine Atherton Grimes

Illustrator: L. J. Wilson

Release date: January 10, 2023 [eBook #69763]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: F. A. Owen Publishing Company

Credits: Demian Katz, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University.)

Instructor Literature Series—No. 257

Kwasa the Cliff

Dweller

By Katherine Atherton Grimes

F. A. OWEN PUBLISHING COMPANY,

DANSVILLE, N. Y.

The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

INSTRUCTOR LITERATURE SERIES

BY

Katherine Atherton Grimes

ILLUSTRATED BY L. J. WILSON

F. A. OWEN PUBLISHING COMPANY,

DANSVILLE, N. Y.

Copyright, 1916, by F. A. Owen Publishing Co.

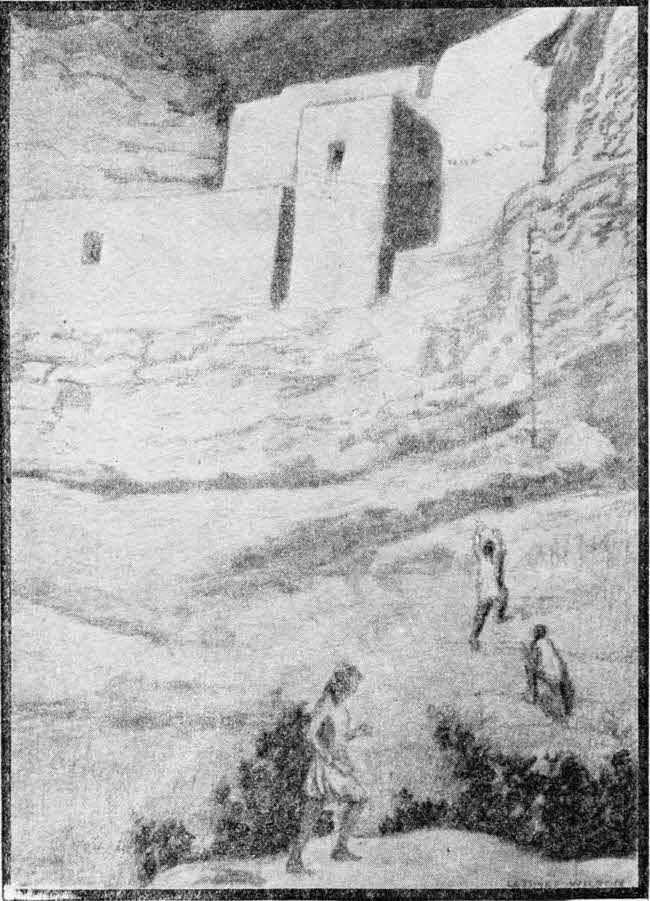

“It was one that few boys would care to attempt”—Chapter 2

Kwasa the Cliff Dweller

“It did,” said Kwasa.

“It didn’t,” said Wiki.

“But I say there were three reds up,” insisted Kwasa.

“And I say one of the dice came up white,” argued Wiki.

“Well,” returned Kwasa good-humoredly, “we will not quarrel about a game. I will throw again.”

Catching up the three small sticks of cane, painted red on the hollowed inner side and white on the upper part, Kwasa tossed them deftly into the air. They came down all together, landing on the stone pavement with the white sides up.

Kwasa gave a cluck of triumph.

“Three whites; better yet.” Reaching across the stone slab covered with a pattern of circles and lines which served as a game board, he carefully moved a white pebble from the mark where it stood to one two spaces nearer the center of the slab.

Wiki seized the dice eagerly. “Well done! Now it is my turn.”

[4]

Into the air spun the three sticks again, but as they came down Wiki saw with disappointment that one showed the white side while the other two had fallen with the red uppermost.

“No play,” cried Kwasa.

“But I have one more throw,” said Wiki, and this time three reds gleamed against the gray rock floor.

“One space, anyway,” said Wiki, and this time a red pebble on the farther side of the slab was set one space nearer the center.

Kwasa laughed.

“When I have beaten you I will show you how to hold the dice,” he boasted playfully. “Old Honau showed me the trick. He can bring down the white every time.”

“I am thirsty,” said Wiki, laying down the dice and jumping up.

“So am I,” said Kwasa, “but it is too far down to the spring. Let us go to the reservoir.”

The lads ran lightly across the long, narrow court and climbed a niche staircase hewn in the rock wall at the back of the cliff. A dozen steps brought them to the top of the wall, from which they looked down into a huge hollow in the rock, which appeared to be partly natural and partly the result of human labor. It was nearly full of water, which fed slowly into it from a small stream trickling down from the higher side of the bluff.

On top of the wall stood a graceful olla, or vase-shaped jar of pottery, strikingly ornamented with red and black. About the neck was a short, twisted rope of yucca fiber, long enough to let the jar down to the water. The boys[5] dropped it down and brought it up full, holding it carefully that it might not strike the side of the wall.

“Bah,” said Wiki, tasting it, “it is too warm to drink, now that the sun is on it. I would rather have gone to the spring.”

“Come, then,” cried Kwasa, jumping down from the wall. “If we go to the spring perhaps we may see something of the hunters. It is time they were returning, my grandmother says.”

Kwasa told the truth when he said it was a long way to the spring. For the great rock-built house, or rather cluster of houses, in whose inner court the boys had been playing, was placed three hundred feet from the bottom of a canyon in a huge cavern which Nature had left in the face of the precipitous cliff. Along the outer edge of the cavern, following the outline of the opening, was a high wall of masonry pierced with numerous openings that served as doors and windows. So exactly had the builders matched the color of the rocky cliff face, and so skilfully was the great structure placed in its lofty niche, that a traveler in the canyon below could hardly have told it was there at all.

This outer wall was in some places four stories high. Back of it the building was terraced down to the floor of the cave, each story projecting beyond the one above it so that its roof made a sort of porch for the upper rooms. Rude ladders were everywhere, leading from each story to the next, for the people who lived in this peculiar dwelling liked to go up and down from the outside. Each story was divided into many rooms, most of them rather[6] small, but several near the center of the structure being of good size. In some of these were stone fireplaces for cooking, and one, larger than any of the others, was set apart for ceremonial use.

Back of the great house, or rather village, for it was the home of many families, was a long and narrow court running well back under the sheltering slope of the cavern roof. Here the children could play and the women could weave and grind and make pottery and mats in well-guarded safety, for back of them and overhead rose the mighty arch of the cavern, and between them and the cliff’s edge stood the solid sandstone structure.

Where the cave roof slanted down to meet the floor there were other rooms, built close in under the rock. These were storerooms where food was kept. In them were great piles of beans and corn, rolls of piki or paper bread which the women were forever baking over the fireplaces, and immense quantities of buffalo meat, dried and pounded fine and laid away between layers of tallow. In one of these rooms was kept the colored corn and beans used in the sacred rites which were held at certain times in the ceremonial hall, or in the queer, underground chamber in the center of the court.

Above the cavern the cliff rose sheer and unbroken for hundreds of feet, but below it the rocky wall fell more unevenly to the valley far below. The vivid brown and yellow and red of the upper expanse was varied only here and there by clumps of cedar or pinon or scrub oak, with scattering bunches of yucca and cactus between, but on the lower slope the vegetation was somewhat more dense.[7] All had the same reddish-brown tinge, for it had been a long time since the rains of the last spring had washed away the wind-blown dust which whirled down in clouds from the bare and forbidding surfaces above.

Across the canyon rose another bluff, but this was unbroken from top to bottom by ledge or cavern. To the southwest the canyon swept away majestically, broadening in the distance to a stretch of comparatively level land through which, in the rainy season, a small river ran. At the head of the canyon, some distance to the northeast, was a large spring of sweet, cold water, which, supplemented by the reservoir at the back of the cavern, furnished an ample supply for the village.

Down the steep stairway leading from the village to the valley Kwasa and Wiki went quickly. A stranger would have had a hard time finding the half-hidden niches cut in the face of the cliff, but the boys, sure-footed as mountain goats, were soon in the valley, running eagerly toward the spring.

“Hush,” warned Kwasa, suddenly crouching behind a tuft of brown yucca.

Looking where he pointed, Wiki saw the slender figure of a young man bending over the spring. He drank eagerly, then taking his cupped hands, poured the cool water over his dusty limbs as if seeking relief in its freshness. His face, the boys saw as he turned it toward them, was weary and seared with the hot, reddish-brown dust, but young and pleasant, and he did not appear to be much older than themselves.

“He is none of our people,” whispered Wiki.

[8]

“No, but I like him,” exclaimed the impulsive Kwasa.

“How do you know?” asked Wiki sharply. “He may be a spy of the Utes for all we know.”

“No,” said Kwasa, “for if he were—”

“Here are the hunters,” cried Wiki joyfully, forgetting all caution and jumping up as a band of men turned into the canyon from the lower side.

“They are well laden,” observed Kwasa. “The men of the Snakes never hunt in vain.”

The young man at the spring, hearing their voices, suddenly straightened himself and looked eagerly about. Seeing the boys running toward the hunting band, he followed slowly, his hand resting cautiously upon his spear shaft, but his frank, brown face expressing nothing but friendliness.

[9]

The long line of hunters, laden with the game secured by a week’s vigorous chase, was at the niche stairway before the boys reached them. Impatient to be in the court when they should arrive, to partake in the welcoming ceremony, the boys could not wait until the last of the procession had filed up the dizzy rock steps. Long before, in their explorations about the canyon, they had discovered another way to reach the cavern, steeper and more perilous, but entirely passable for boys whose lives had been spent in scaling cliffs and finding footholds in all sorts of precarious places.

Running around a projecting spur and diving through a thicket of scrub oaks, Kwasa and Wiki were at the second stairway in a moment. It was one that few boys of to-day would care to attempt. It ran almost straight up the side of the cliff, and in many places they had to pull themselves from ledge to ledge by straggling tufts of wiry grass or by the tough, well-rooted clumps of grease-wood brush. At one spot, to bridge a particularly smooth and difficult part of the ascent, a pole with sticks bound upon it at intervals to make a sort of rude ladder had been swung down from a rocky ledge above.

Up this dangerous ascent Kwasa led the way nimbly, Wiki following close behind him. The young stranger,[10] after looking doubtfully for a moment from the hunting band to the boys, finally plunged through the thicket and took the steeper path, reaching the top only a moment after Kwasa and Wiki had landed with a final active spring upon the safe ledge at the rim of the cavern.

“I must speak to your chief quickly,” he said gravely, as Kwasa, who in the excitement had forgotten all about the stranger at the spring, looked at him in surprise.

“But,” began Kwasa, “this is no time—”

“All times are alike when danger threatens,” said the youth impatiently. “Tell me with whom I should speak.”

Kwasa pointed to a little group of men who stood a little apart from the rest, waiting to greet the hunters as they came up, one by one, over the edge of the cliff.

“Mosu is a priest,” he said, indicating a tall old man with a band of flat red and black beads bound about his forehead. “Honau is very wise, too, and then there is Bimba—”

But the young stranger had hurried away and was accosting Mosu, the tall priest, respectfully. Before he had spoken many words the whole group was listening intently, and in a few minutes the court was hushed and all came crowding about to see what this unusual interruption might mean.

Presently the lad stopped speaking and Mosu held up his hand for attention.

“This young man is Sado. He comes from the Seven Cities to bring us tidings to which it were well to listen, for the Utes are again on the warpath, and the Buffalo and Fox clans have sent out runners to warn all to the[11] southward. They reached Walpi yesterday, and from there this messenger brings us word, that we, too, may be in readiness for an attack.”

“But surely we are safe—”

“They can not reach our village—”

“We could hold the cliff against a thousand, even—”

A babel of voices broke out anxiously. Mosu held up his hand again.

“All you say is true,” he said. “When our fathers came here from the Great Mesa, driven out by the savages from the far north, they sought a place where they might rest secure from attack. And here they found it.” He waved his hand toward the great walls of rock rising protectingly all about them.

“But we must eat, and planting time is near. Those who stay in the village are indeed secure, but what of the men who must plant the seeds and care for the grain in the far fields? We must say farewell to Waka (the sun) with full storehouses, and with heaped fuel for the cold days of winter. And if the thieving Utes swarm down upon our fields and carry off our corn and beans and squashes, what then? Then there is the danger while we plant and harvest. The Watcher in the High Tower must indeed be keen of eye to guard every path that leads to the fields. It is of these things we must think. And in the meantime,” he broke off abruptly, “this lad is weary and hungry. See that he has refreshment and rest. We must not send him back to the Seven Cities to tell of our ingratitude for a friendly deed.”

But Sado shook his head.

[12]

“There are many others to warn,” he said earnestly. “I must not stay, though the thought of rest is tempting. But first I will eat—”

“Has the Snake Clan no runners?” interrupted Mosu proudly.

Old Honau stepped out from the group.

“I am not fleet of foot as when I was young,” he began, “but rather than suffer this brave lad to go farther without rest, I myself will take the warning to the farthest clan.”

But a dozen lads were already pressing forward, Kwasa and Wiki among them. Motioning Honau kindly aside, four of the tallest and strongest were quickly chosen, and Mosu, drawing them to one side, had Sado repeat carefully the message he had brought.

“The Rainbow people are yonder,” he said, pointing southwestward down the open canyon. “And the Bear Clan is not far from them. It is a three days’ journey—”

“They must take plenty of meat and piki,” called one of the women, hurrying forward. “We will fill the food-bags well. It is a long way, but, praise to Waka, the new springs are filling and they cannot suffer from thirst.”

Immediately there was a great bustle in the court. Women ran here and there, bringing new sandals of tough fiber for the feet of the messengers, and thick woolen blankets for the cool nights in the canyons. The skin food-bags were quickly filled and strapped over the slender young shoulders, and Kwasa, as leader, was given a heavy new spear in addition to the bows and arrows which they all carried.

[13]

At last all was ready, and the lads stood forth to be sprinkled with the sacred meal from the handsome red and black bowl in Mosu’s hands.

“The Old Ones be with you,” muttered the priest, as he strewed the meal in a circle about them, and upon the boys’ bowed heads.

“Come back quickly,” called many anxious voices as, one by one, the lads dropped down the niche stairway. Kwasa, the last one to descend, stooped as he left the court and picked up the three red and white dice with which he and Wiki had been playing so short a time before.

“For luck,” he laughed, as he dropped them into the deerskin pouch that hung at his belt.

“Luck is in the hands of the Old Ones, not in painted sticks,” muttered Tcua, the old grandmother of Kwasa, watching the lads with anxious eyes as they filed down the canyon and out of sight. “May they bring back my son’s son safely—a good lad—a good lad.”

And then she went down to grind corn for piki, for waiting in idleness is hard.

[14]

“The door of the Sun-House is open!”

From mouth to mouth flew the word, brought at sunrise from the High Tower far up the cliff where Bimba, the Watcher, kept anxious count of the days till the planting season should begin.

As if by magic the court was filled with busy men, women and children. Waka had come back once more to bring them plenty. It had not been in vain that every morning and evening they had thrown sacred meal toward the rising and the setting Sun, beseeching him to return quickly from his long journey to the south. And now the glad news had come that he had at last touched the peak far away to the east that marked his final favor, and they might get the seeds ready.

Nor was that their only cause of rejoicing. For Kwasa and his companions had returned the night before, worn and weary from their long, swift race to the far-off neighbors at the southwest, but triumphant and proud. They brought word that the Rainbow people and their near kinsmen, the Bear Clan, were ready at a moment’s notice to join them against the dreaded common foe, whether Ute or Apache. Moreover, in the nine days[15] since Sado had left them word had come that in a terrible battle between the Utes and the Pueblo people of the Seven Cities the foe had been repulsed with great slaughter, and had fled, broken and disabled, to their northern mountain fastnesses to nurse their wounds. For the time the danger of attack was over.

So, though the older men of the village still felt some anxiety, the planting was at last to be begun under much more favorable circumstances than they had feared. The women chatted gayly as they brought out the precious seeds to be sorted, sharpened new planting sticks, and baked great sheets of piki to pack in the big food-baskets that were to go with the planters to the distant fields. The children tumbled about on the terraces or played games in the angles of the gray walls, even they noticing the relief in the air which had been so full of dire rumors.

But Kwasa and Wiki, with their two companions, were more excited than any of the rest. For their service as messengers they were to be “adopted,” or consecrated, into the rank of men, and henceforth would take a dignified place in the Clan, though they were some years younger than usual for such an honor. For the first time they were to witness the invocation of the mysterious deities of the cloud and the sun, which took place in the kiva, the sacred underground chamber whose hatchway opened into the court. Mosu, who as head priest was the person of supreme authority on such occasions, had even promised them that they might act as novices at the annual ceremony of the Blessing of the Seeds.

[16]

When the boys were not following Mosu about they lingered in fascinated anticipation about the sloping entrance to the kiva, through which protruded the long ends of the ladder leading to the depths below. They had many times descended through the trap-door on the surface to the great, dusky chamber of the kiva, but never had they been allowed to witness any of the sacred rites, except such as were held in the court and were open to women and children. And now that they were to be admitted as men to the significant symbolism of the ancient service, they felt awed and excited by turns.

Kwasa’s grandmother, old Tcua, had long ago told him the mystic tradition of the Creation, whose sacred story was perpetuated by the solemn ceremonies in the dimly lighted chamber. And now, in awed tones, Kwasa repeated it to Wiki and the others as they sat huddled in an angle of the lower terrace near the opening to the kiva.

“There were no people then—there were only animals. They lived far under the ground in dark caves. But the Old Ones heard them moaning and crying in the dark. They heard the fox, and the bear, and the duck, and the wolf, all crying, crying in the dark. And they were sorry.”

Old as the tale was, the boys listened with breathless interest.

“So the Old Ones dropped a seed through sipapuh[1] and immediately up sprang a wonderful stalk of corn. It grew up, and up, and up, until at last its head rose into the sunlight of the Upper World. Then, one at a time, the fox, and the wolf, and the duck, and all the other[17] animals and birds, came up the great stalk and stood in the light of Waka, the Sun. And they were no longer animals, but men and women. We must never forget this, or the Old Ones will forget us, and we would once more be animals, back in the middle of the earth, crying and moaning for the light.”

“But what of the snakes?” whispered Wiki. “My father says there are more than a hundred in the kisi.” He nodded toward a brush-covered shelter near the kiva.

“Hush,” replied Kwasa, looking furtively about. “They are the prayer-bearers, and carry to the Old Ones the prayers of the Snake Clan for rain, that the crop may thrive. But we must not speak of that now; it is not well to talk too much of the gods so near the place where they dwell.”

[1] A cavity in the floor of the kiva represented the lower world. Over this was placed a stone slab with a round hole in the middle, which was called sipapuh, and represented the outlet through which the ancestral beings emerged.

[18]

For an hour Kwasa had been sitting stiffly on the stone ledge that ran around the outer wall of the kiva, trying to get used to the smothering mask Mosu had put over his head. This mask was a gorgeously painted affair representing the head of a duck. Feathers of green and black were fastened to the crest, and a huge bill of yellow cane projected from the mouthpiece. In it Kwasa became for the time a Katcina, or one of the supernatural beings which mediate between gods and men. As a Katcina he represented one of the ancestral forms which had emerged from the Lower World upon the day of Creation.

[19]

A tunic of cotton cloth reached to his knees. It was brown, and upon it were painted zigzag white lines representing lightning. Over one shoulder was a yellow scarf upon which the same design was repeated, and on his feet were beautifully beaded moccasins, over which his grandmother had bent for weeks, that they might be ready when the time should come for her favorite’s adoption into the ranks of the men. Around his neck, securely tied in a little buckskin bag, hung a charm, an exquisite turquoise, blue as the spring skies and half as large as a swallow’s egg. Old Tcua had fastened this on with trembling fingers as Kwasa left her to descend to the kiva, saying as she did so:

“It is for luck. My father had it from an Antelope priest far to the south. It is yours from this day.”

But Tcua did not know that Kwasa had another charm which to his boyish imagination was more potent than the turquoise. Fastened in a fold of his belt were three red and white sticks of cane, and as the lad sat waiting on the ledge in the kiva he said to himself:

“I am glad I kept the dice: they have brought me much of good.”

He felt something thrust into his hand, and looking at it as closely as he could through the eye-slits in his mask, he saw it was a prayer-plume, or a short stick to which were fastened four feathers, white for the north, red for the east, yellow for the west and green for the south. This he knew he was to carry in the solemn ceremonies to follow, as an invocation to the deities who dwell at the four quarters of the earth.

[20]

“Come,” said the masked figure that had brought the prayer-plume, “the gods wait for us.”

At the word, Kwasa slipped down from his seat and took his place in a long line of youths and men which was being formed at one end of the kiva. He saw Wiki, also carrying a prayer-plume, and wearing a beaver’s mask. In the weird, flickering light from the fire at one end of the chamber he could not distinguish many that he knew, and this, together with the strangeness of the sacred mysteries in which he was about to play a part, awed and half frightened him.

As the line formed the participants stamped softly upon the ground with their moccasined feet, not advancing, but marking time to a wild and monotonous chant which was accentuated by the rattling of small gourds in the hands of the priests and their throaty “hi-yi-yi” as they moved with cat-like tread about the sipapuh in the middle of the kiva.

At last the line began to move forward. Mosu took his place at the head and led it around the outer edge of the kiva, close to the ledge. Round and round they marched, each time drawing a little closer to the sipapuh. At last they formed a compact row about the sacred opening, and in this way encircled it four times more, each in passing stamping his foot on the stone slab as a hint to the listening gods that their attention was asked. At last, at a sign from Mosu, the line halted.

And now came the supreme moment. The participant who was to be most highly honored was to be chosen to hold the sacred bowl above the sipapuh while from the[21] mouth of the great snake effigy which was suspended from above should drop the Kawa-blessed seeds for planting. Everyone in the circle fixed his eyes upon Mosu, each secretly hoping that some deed of his own might be thought worthy such honored recognition.

Kwasa held his breath with the rest, wondering which one of all the line should be adjudged the most worthy. And for a moment the tumultuous beating of his heart made him faint and dizzy as Mosu, beckoning to him and speaking his name, put the great red and black bowl in his hands.

Trembling till he could hardly stand, Kwasa, at a sign from the priest, extended his arms until the bowl was directly above the opening in the slab and under the swinging head of the hollow effigy above. Then through the tube came the seeds, first the yellow and white corn, then the beans, the squash and melons, greenish cotton seeds and rich-smelling brown grains of wheat. At last, when the bowl was nearly full, there was poured down the colored corn for the sacred meal, rounding and covering the rest.

Then Mosu motioned Kwasa to stand to one side, while Wiki was called forward and given a similar bowl. Delighted at his friend’s good fortune, Kwasa hardly heard the muttered congratulations that greeted him as he stepped back into the circle. But stealthily fingering his belt he patted the three red and white canes, telling himself that his own luck and Wiki’s had been unchangeably entwined since the day they had tossed the dice in the court.

But he had not time for more than a fleeting thought[22] even for such momentous things, for something else was happening above the sipapuh. This time the attendant at the hatchway of the kiva poured through the snake effigy into the sacred bowl a small stream of water, signifying that thus would the snake deities of the clouds bless the planted seeds.

At another sign from Mosu, Wiki stepped back into the circle, and Kwasa came forward to distribute to each person a handful of the Kawa-blessed seeds. Then, taking a short stick tipped with stiff turkey feathers, Mosu sprinkled the water from Wiki’s bowl to the six cardinal points, north, east, south, west, the zenith and the nadir.

And the ceremony of the Blessing of Seeds was over.

Kwasa was glad to get out of the stifling air of the kiva and follow the rest up the ladder into the court above, where the final great rain-prayer rite was to be performed. In this he had no part, though he still retained his mask and personated the pawik (duck) katcina in the great circle that made the background for the principal actors.

Into this circle marched the long line of Snake and Antelope priests, participants in this supreme drama of the year. Very awe-inspiring they looked, their bodies rubbed with red paint, their blackened chins rimmed with a broad line of white and their bare arms glittering with barbaric ornaments. To a sort of hissing chant they marched about an improvised sipapuh which had been located in the broadest part of the court, shaking their rattles and stamping their feet upon the slab as they passed. Four times they made the circuit, as in the[23] ceremony in the kiva, then suddenly breaking into groups of three they rushed to the bush-covered kisi near the end of the circle. A group stopped for a moment before this shrine, and in a moment proceeded, the foremost priest, one of the Snake Clan, carrying in his mouth a squirming snake. The Antelope priest who followed him, in an apparent frenzy of excitement, waved a feathered prayer-stick to and fro to attract the reptile’s attention, but the snake only coiled the more tightly about the head and shoulders of the carrier. One after another each group paused at the kisi and secured one of the wriggling reptiles.

Round and round they marched, and then, at a sign from Mosu, an attendant suddenly darted forward and outlined a circle on the floor with sacred meal. Into this the snakes were dropped, to be sprinkled with meal as they fell. A wild scramble ensued, and in a few minutes the snakes were recaptured by the third priests of the groups, who darted across the court and down the niche stairway to replace the reptiles in their native dens. From there they would carry the prayers for rain to the deities of the clouds, the lightning and the thunder, who would thus be brought to bless the crops and insure abundance for the coming year.

“And now we are done with games,” said Wiki softly, as he and Kwasa descended the ladder into the kiva to remove their masks and deposit their prayer-plumes before the sanded altar at the end of the chamber.

“Yes,” returned Kwasa soberly, “but I shall keep the dice. They have brought us good luck.”

[24]

Spring in the canyons! How good the warm, moist air felt after the rains, and how bright and fresh the young grass looked along the little river so far below the cliff village. The rusty red of the pinons and oaks, and of the dull little cedars, too, had been turned to deep, rich green, and the yucca tufts which clambered bravely almost to the top of the gorge were sending up new lances of vivid color. Life was in the air, and it stirred even the oldest people of the cliff village to a keen interest in the year’s greatest event.

[25]

There was a great stir in the court. On every terrace, too, were girls and women at work, tying the sharp new ironwood planting sticks into bundles and shelling the sacred colored corn which was to be planted in a specially prepared corner of the field. Great baskets and bags were filled with food: piki, and pounded acorns baked in sheets with meal, and strips of hard, dry meat. There were cakes of buffalo meat, too, pounded fine, and bags of dried peaches, and beans for eating as well as planting. For from now on until the crop was ready for harvest men must stay in the far-away fields to guard as well as work.

For the first time Kwasa and Wiki were to go with the men. They strutted about the plaza importantly, one minute imitating the stately manners of Honau and the other men, the next strongly tempted to join in the games of leap-frog and hunt-the-deer that were being carried on in the crannies of the great building. Strong as the temptation was, however, they would not have yielded to it for the world, lest in the eyes of the other lads they should lose some of their newly acquired dignity.

The great field lay far away to the south of the village, beyond where the canyon opened out into the wider valley. For many years the same ground had been cultivated by the Clan, and on every side were evidences of the painstaking and careful work that had made possible the abundance of grain the Cliff people had enjoyed from year to year. On a gentle slope beyond the field was a scattering orchard of peach trees, each carefully placed in some particularly fertile spot. From a great rock[26] reservoir on the hill above, a ditch ran down to the fields, separating as it reached the edge into many small passways for water, which could thus be turned upon the growing crop should the gods, whose aid had been so earnestly invoked, neglect to send rain enough. Along the lower edge of the field ran a long, low clay wall or ledge, designed to keep the water thus led into the planted land from wasting by running too far down the slope.

How good the brown earth smelled as the sharp planting sticks turned up the moist soil to make fine, soft beds for the precious seeds. Where the soil was heavy and came up in clods, old Honau, the master of the planting, showed Kwasa and Wiki how to follow behind the seed scatterers and smash the lumps with stone mauls tied to the ends of long sticks. They were instructed, too, how to clean the winter’s wash of mud out of the waterways, and how to repair the lower wall where it had washed away.

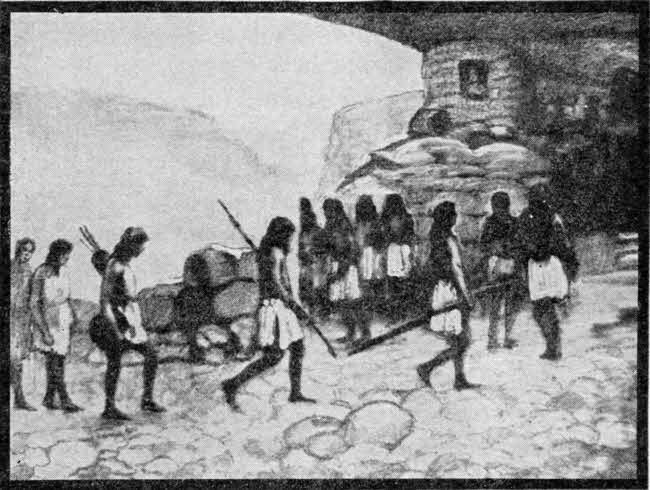

Cliff men going down to work in the fields. The watch tower is seen in the background.

A round tower built of sandstone blocks stood on a jutting point of rock far above the fertile valley. Adjoining it was a low, oblong room fitted with two small openings. This was both guard and shelter. From the tower a watcher kept constant lookout, for the men were far from home and unprotected by natural walls, as they were in the cliff village, and a sudden rush of enemies from any of the many intersecting canyons might result in a terrible loss of life. The watcher was not Bimba, however, who could not be spared from the watch tower above the village, where long usage had made him familiar with every crack and crevice of the hills and valleys[27] within the sweep of his sharp eyes, until not even a rabbit could cross an open spot undiscovered. Now that the men were gone it was more important than ever to have a trusted and experienced watcher to guard the women and children. So the guardian in the tower above the great field was not Bimba, but Haida, who, next after the veteran himself, had the sharpest eyes in the clan.

No alarm came, however, to mar the joy of the planting time. Day after day the men worked on, cleaning away every weed and bush as they went, and seeing that every one of the treasured seeds had its proper chance to grow and thrive. For upon the crop must depend the lives of all the next winter. Though they went on occasional long hunts, the Cliff men were not, like their neighbors and enemies, the Utes and Apaches, dependent upon game for the greater part of their living. Corn was the main food of the people of the cliffs, and whether parched to be eaten whole, or ground in three-parted stone metates to be made into the great thin sheets of piki, or paper bread, it formed the staff of life for them. Hence the great importance of every seed-grain, for the winters in the canyons were long and there were many mouths to feed.

There were long days of work, and weary nights when the men lay down in the stone shelter adjoining the watch tower with aching muscles but hopeful hearts; but at last every seed was in. The irrigating channels were straight and clean, and the reservoir, as they had ascertained, was two-thirds full of water. Even so soon the favor of the gods seemed sure, for twice since the[28] planting had begun good rains had fallen, leaving the earth dark and mellow and rich with promise.

There must be one more thing done, however, before they could return to the village for the short stay possible between the planting and the working of the crop. Two days before a messenger had been sent to tell Mosu that the planting was nearly done, and hardly was the last row finished when they saw him coming. In his hands he carried a bowl of sacred meal, and upon his forehead was the mystic raincloud symbol, colored, like the feathers in the prayer-plume an attendant carried behind him, with red, green, yellow, and white pigments. His tunic of beautifully-dressed deerskin was also decorated with the symbols of the cloud and the sun, while the snake-like lightning symbols were painted in white upon his powerful brown arms. A second attendant bore a great bundle of prayer-plumes, and a third a bowl of water and a short, stiff brush of turkey feathers.

Solemnly the planters met Mosu as he came toward them. Falling into line behind him they marched solemnly around the field, and back to the center where a hole had been dug and a stone slab placed over it in imitation of the sipapuh in the kiva. Here they formed into a hollow square, each side facing a point of the compass. The attendant distributed the prayer-plumes, which each man held high in his left hand as Mosu scattered the sacred meal to north, east, south and west, the zenith and the nadir. Then into the bowl of water he dipped the turkey-feather brush, sprinkling the earth toward the cardinal points. Marching about the improvised sipapuh[29] each man stamped upon it in passing. Then, stooping reverently, they laid the prayer-plumes underneath the slab that covered the excavation, and the ceremony was over.

“I wonder where Sado is,” said Wiki suddenly, as the boys passed the spring at the head of the canyon on their way home.

“I hope we may see him again some time,” returned Kwasa. “Do you suppose he has danced in the kiva yet?”

“Sometimes I wish we had not been ‘adopted,’” said Wiki almost regretfully, “for I would like to throw the dice again.”

“Well, why not?” laughed Kwasa. “The men play at that game, and I have never shown you old Honau’s trick. Besides, here are the dice. Let us hurry home.”

[30]

The summer passed pleasantly in the village of the Cliff. When the men went to the field to work the women often accompanied them, helping in the cultivation of the crop and gathering the wild berries and edible plants that grew in profusion in the fertile valley. In baskets swung from their heads by woven and padded bands they carried the ripened peaches up the steep stairs, spreading them out along the stone ledges to dry.

There was other work, too, that must be done while the weather was warm and pleasant. New earthenware bowls must be made while they could be baked in the summer sun. Garments of soft, exquisitely wrought feather-cloth, and of fur strips wound on heavy cords and woven into fabric, must be made ready for cold weather. There were new rooms to be built, too, for the rapidly increasing population of the village made the old quarters too crowded for winter comfort. So the men brought great gray and brown rocks from the slopes of the canyon, carrying them suspended from head bands as the women carried their baskets. These were carefully chipped and dressed with the great stone mauls, and set evenly and squarely into place, held there by layers of mortar which no one except old Honau knew how to mix.[31] Then the women made a thin, plaster-like cement from colored earths and spread it on with their hands, smoothing it down with many careful pats which left the prints of slender brown fingers in many places on the wet wall. Sometimes the rooms were brightened by wavy red and yellow lines running bandwise just below the ceiling; sometimes they were decorated with sacred symbols such as might bring a peculiar blessing to the household living in them. But always, whatever the inside might be, the outside was cunningly wrought to look like the forbidding walls of the cliff, gray, and dull yellow and brown, with here and there mottled patches of subdued red, so that an enemy might have hard work to spy them out in passing through the canyon below.

It was nearly harvest time, and the corn was already ripening. Day after day the watcher in the field tower, keen-eyed Haida, had reported everything well, until the last lurking fears of even the old men were almost forgotten. The storerooms were being repaired and made ready for the new crop, and the men were working on a larger granary, or storage cist, some distance below the level of the cavern, where the heavy baskets of corn might be emptied without carrying them up the last steep third of the ascent.

Then, early one morning, a wild-eyed messenger from the field tower came hurtling up the niche stairs in the gray light to report evil tidings. A band of savages, of what race he could not say, had ridden their fleet ponies down through the canyons that night, carrying off and trampling down a considerable part of the precious crop.[32] And what was worse, they had raided the very tower itself and had left Haida, whose practised eyes had failed to see them in the moon-blinded lower trail, silent on his face with an arrow between his shoulders. The messenger himself had escaped only by dropping quickly into the farthest shadow of the adjoining shelter-room and lying motionless against the darkest wall until the last sound of the ponies’ drumming feet had died away in the distance.

Mosu quieted the panic-stricken people who crowded about him in the early light as well as he could. One thing was sure, if the people of the Cliff were not to starve when the cold days came, the rest of the crop must be saved. Wisely seeing in vigorous action the best remedy for fear, he hastily organized men and women into bands for taking care of what was left of the grain, giving to the women the actual work of gathering that the men might be left free to protect them.

So, leaving the old men and smaller boys to look after the village, and with many cautions to Bimba to keep speedy messengers always ready to carry news of danger, the harvest bands went silently down the steep stairs and passed swiftly through the canyons to the great field. Once there, no time was lost in stripping the ears from the stalks and piling them into the wide-mouthed baskets which the women carried on their backs, and in cutting down the stalks with keen-edged flint knives to be carried home in bundles on the shoulders of the big boys. The wheat-heads were hastily snatched from their stems, to be shelled out by busy fingers in the leisure hours of[33] winter. They worked in nervous haste, casting fearful glances up and down the canyon at every turn. From the tower the new watchman who had taken dead Haida’s place strained his eyes anxiously into vague distances, intent upon guarding, even to his own death, those lives so dependent upon his vigilance.

Swiftly as they worked, and quickly as the many trips to and from the village were made, it was many days before all the crop was safe and the people could breathe more easily in their well-guarded cavern home. But the old air of careless gayety was gone, and in its place was a constant atmosphere of apprehension. No one knew when the bold savages, encouraged by their success in the valley, might not undertake even so difficult a task as the storming of the cliff fastness. Rumors, too, were constantly afloat of murderous attacks on smaller outlying cliff dwellings, and once a small party that had been down the canyon to look for wild gourds came upon the body of a Cliffman, apparently from one of those distant houses, lying stiff with a Ute arrow in his breast.

In a consultation of the old men it was at last decided that the best thing to be done was to send messengers to the Rainbow and Bear Clans on the south, which were probably so far free from attack, and to the Seven Cities on the North, asking them to be ready to send aid should the threatened danger fall. Mosu, standing stern and tall in the middle of the court, told the people of this decision and asked for messengers.

“The Walpi road is a dangerous one,” he said, “to be undertaken by no one who is afraid to lose his life. He[34] must go alone, for one is as safe as ten, and we have no lives to risk without great reason. I would not willingly send any forth to such chance of death, but if one will offer himself—”

Before he could finish the sentence fifty men and youths had stepped forward. Mosu looked at them with proud sadness.

“Your lives are precious to us,” he said, his eyes kindling, “and there are many among you who cannot be spared. Let those who have wives and children step back, for them we cannot lose.”

Reluctantly more than half of those who had come forth drew back again. There remained only the young men, straight, supple, earnest-eyed lads who were the very flower of the village. In their brown faces was no sign of fear. Mosu scanned them, one by one, his lips set in a thin line, his eyes tenderly kind.

“It is danger we offer you,” he said slowly, “but it is also the greatest honor we can give. Choose among yourselves who shall be sent, for you know your own worth.”

Kwasa stepped forward eagerly.

“Let us toss the dice,” he begged, “and hang our fortunes on the first who shall throw the whites.”

Mosu thought a moment. The idea appealed to him in two ways; for one thing, it removed from anyone the responsibility of sending a comrade forth to possible death, and for another he knew the gambling spirit was strong in every Cliffman’s breast and the decision of the dice would never be disputed.

[35]

“Who has dice?” asked Mosu, turning to the onlookers.

Kwasa undid a fold of his belt and gave the priest the three sticks of cane he had carried so long.

Mosu handed them to the boy who stood nearest. He tossed them nervously, amid a breathless silence. As they came down showing two reds and one white, a woman on the lower terrace gave a sobbing cry. Turning toward her, his lip quivering with disappointment, the lad saw his mother, and bounded across the court to where she sat.

“The gods be praised—they have not taken my son from me,” she said, throwing her arms about his neck.

“But I would have served them well,” he cried, trying hard to keep back unmanly tears.

One after another the youths came forward to try their fortunes with the dice. But no one threw the whites together. Wiki, trembling with eagerness, found them at his feet with all the red sides up, and gave place to Kwasa, who came next.

Carefully placing the sticks in his fingers, and with a quick glance at old Honau, who stood watching with much interest, Kwasa spun the dice high in the air. And when they came down every one knew that the danger and the honor had fallen to Kwasa by the favor of the gods. Tcua, his old grandmother, scorning the weakness that fought its way to her moist eyes, called him proudly to her side and touched the turquoise at his throat.

“You will come back safe—it is a charm,” she said confidently.

But once more Kwasa hid the cane strips carefully in his belt.

[36]

“Yes, I will come back safe—for I have a charm,” he said, smiling.

So Kwasa took the long trail toward the Seven Cities alone and in the dark, for so it was thought best, since he knew the first part of the way well and would need daylight more after coming to the unknown country. And because he had thrown the chance of next value, Wiki was given the place of lesser honor, because of lesser danger, that of messenger to the Clans of the Rainbow and the Bear.

[37]

If Kwasa had not felt so proud of the honor that had been shown him, he might have feared to go down the long, dark canyons alone. But, boylike, his thoughts were not so much on the danger of his task as they were upon the rewards he might hope for when it was done, for he knew the people of the Cliffs would pay royal honors where they were due. And he never thought of failure, for surely one so high in favor with the gods could not fail, however great the task.

So Kwasa picked his way with a light heart along the first well-known part of the journey. He wanted to be far from home by daybreak, and ready to undertake the[38] unknown paths where he would need all his sharpness of sight to keep the right direction. He had received many and definite instructions from the old men, who knew the Walpi road well, and he felt confident of his ability to reach the Seven Cities without loss of time.

The sun came up, hot and strong, just as he emerged from the shadows of the last wooded canyon and stepped forth upon the wide-spaced plateau that stretched away toward Walpi. There was no chance for cover now, he realized, a little startled at the thought, for he had not before considered this difference between a trail on the plateau and one through the canyons. If he had not been afraid both of delay and of losing the trail if he should attempt to follow it by night he would have liked to lie down in a hidden nook and wait for dusk again rather than to run the risk of a race across such open and dangerous country by day. But he knew no time should be lost, so, eating his breakfast from his food-bag as he went along, he swung forward with the long, easy strides of one who is accustomed to travel much by foot.

It was the middle of the forenoon when a fitful gust of wind brought a strange, regular, pounding sound to his ears. He could not think what it was. Again it came, louder than before, a sharp, ringing “clickety-clicket,” that brought him to a standstill. Then, too late for flight or any chance of concealment, he recognized the sound as one that he had never heard more than once or twice in his life—the beating of hard-ridden ponies’ hoofs.

In another minute he saw them coming, a cloud of dark, terrible riders in fantastic head-dress, with their almost[39] naked bodies horribly striped and scarred. At a glance he knew them, though his only idea of them had been formed from the tales he had heard the men tell, and in the same moment gave himself up for lost. For they were the hated enemies whose awful deeds made the blood run cold at the barest thought of them—the Utes of the northeastern mountains.

Kwasa knew they had seen him, so, giving up the hope of hiding which had flitted momentarily through his mind, he determined to stand his ground and sell his life as dearly as he could. He ran a few steps from the trail and placed his back against a jutting ledge of rock, at the same time drawing his bow and setting one of his sharpest arrows. Hardly had he time to make even this scanty preparation when they were upon him, a yelling, death-dealing whirlwind of fiendish faces and quick-footed, fiery-eyed ponies.

With an agonized thought of home, of the trust in which he now must fail, and of the terrible danger which was sweeping down upon the Cliff people, he drew his arrow back to the head. Excited as he was, he took steady aim, and a painted warrior slid limply from his pony’s neck and rolled over in the dust. As he hastily fitted another arrow he felt a stinging pain in his throat, his hand lost its strength, the sky reeled about him and turned dark—and then he knew no more.

When he came to himself again he lay where he had fallen on his face in the red dust of the plateau. How sick and dizzy he felt! His first thought was to wonder how he came there; the next to remember that the Utes[40] were headed straight for the canyons, on what awful errand he did not dare to think. He knew the Cliff village could be held for some time, but would not these fiendish foes at last be able to overcome the peaceful, unwarlike men of the Cliffs, no matter what their advantages might be? Help must be brought, and brought quickly. A glance at the sun assured him that he had not long lain unconscious, even though he knew he must have been left for dead. With a great effort he pulled himself to his feet. How black the sunlight grew! And what was that queer, choking thing that seemed to be gripping him by the throat? Putting up his hand, he felt the shaft of an arrow which had pierced his neck, running through until the point projected above his shoulders. With a shudder he tried to pull it out, but the pain turned him sick again. Then, too, even through the turmoil of his thoughts he realized that to remove the arrow would mean a great and weakening loss of blood. So, blinded and choking as he was, the brave lad stumbled along as fast as he could, imploring the gods to give him strength to reach Walpi and send aid to his people before he should die.

It seemed ages before he saw the dark outlines of the pueblo of Walpi rising above the rounded crest of the mesa. But it was not so far from where he fell after all, for he had been nearer than he believed when the attack occurred. He could never quite remember how things happened after that. He had a vague memory of Sado’s voice calling out in sharp surprise, of telling his story quickly between the gasps of his failing breath, and of[41] a sudden great bustle in the court of the pueblo. Only one thing he remembered distinctly, the sudden idea that flashed through his mind at sight of Sado.

“The hidden path,” he gasped, “tell them to take the hidden path. It will bring them up from the back. No one knows it except—except—” and here in spite of himself his voice trailed off into silence and the blindness that was worse than midnight came over his eyes again.

As in a dream he heard Sado’s excited reply:

“I know—I know—I will lead them. Have no fear, for we will save your people yet!”

And then gentle hands laid him down, and he thought no more except that it was very good to rest.

The terrible Battle of the Cliffs had been fought and done for many weeks before Kwasa was strong enough to hear about it. For the arrow in his throat had come very near indeed to causing his death, and only the tender nursing of careful and practised hands could have brought him back to life and strength again. There was one pair of slim, soft hands that he always knew, even through his delirium, so gentle and capable were they, and so soothingly did they place upon his poor, torn throat the cooling poultices of pounded herbs. After he grew able to think again he fell to wondering what the face would be like that belonged with such dear, gentle fingers; but so weary and listless was he that even after the thought came it was a long time before he opened his eyes to see. But when he did look up into the beautiful young face that bent so anxiously above him, he[42] knew that one of two things would surely happen—either he would stay at Walpi forever, or he would not go back to the canyons alone.

And that day Kwasa heard the story of the Battle of the Cliffs. It was Sado who told it, helping the words with vivid gestures of his long, brown fingers. He told how bravely the men of the village had held their own for many long and fearful hours, even against the death-bearing poisoned arrows of their foes; and how, hard pressed as they were and overwhelmed by numbers, as the Utes swarmed up the niche stairway, the men who stood along the ledge sold their lives at a heavy price. And then, just as the Utes were sounding their wild whoop of final victory, and were pressing upward unchecked over the narrow stair, so slippery with the horrible slime of blood, the fresh band of fighters which Sado had led secretly up the hidden path sounded their battle cry from the back of the long court into which they had come unseen. At this the savages had wavered a moment in surprise, and then, seeing the lithe brown bodies of the men of Walpi, whose prowess they knew of old, had broken and fled, many of them losing their foothold and falling down the face of the cliff to a horrible death on the rocks below. And just then had come up from the south the bands from the Rainbow and Bear Clans, summoned by Wiki, and before the sun had set upon the narrow valley the grass was stained with a deeper red than that of the red dust. Only two Ute horsemen were able to break through the terrible ring of death that shut them in and get away on their fleet ponies.[43] And that, said Sado, was just as it should be, for with the story of that disastrous fight as a warning it would be long before the northern tribes would attempt to take revenge.

The day came at last when Kwasa was strong enough to go back to his people. Glad as he was at the thought of seeing them all again, a greater gladness lay at his heart—a joy even greater than all the honor that his grateful people were waiting to give could bring. For Ani, the gentle sister of Sado, who had nursed the stricken messenger so faithfully and well, was easily persuaded that her services might still be needed by her brave young patient. So she decided to go back across the mesas and down the cool, dusky canyon paths with him, lest evil should again befall him.

So it happened that when the rejoicing people of the Cliffs came down the niche stairway to welcome their honored hero, they took also to their grateful hearts the dark-eyed girl who had saved him from death for them. And not the less did they love her because she was the sister of Sado, who had brought them help in their hour of greatest need.

“But what of Wiki?” said Kwasa, when they would have overwhelmed him with loving honors.

“He has had his share,” answered Wiki himself, pressing the hand of his old playfellow affectionately. “Besides, my little deed needed no honor, since it did not require a particularly stout heart to run an errand where there was no danger. Yet Mosu has promised me no less a gift than that I should lead the dance of the priests[44] in his own place at the next Blessing of Seeds. And he says he will make a priest of me when the time comes. Besides—” he paused in some confusion, and beckoned to a pretty brown maiden who stood not far away.

“Besides?” prompted Kwasa with a smile.

“Not all the maidens in the world dwell on the mesa of the Seven Cities,” blurted out Wiki, taking the girl’s slender fingers in his own.

Kwasa laughed, then his face grew grave.

“Yet it was well for me that one maid dwelt there,” he said softly, looking up into Ani’s sweet face with adoring eyes.

INSTRUCTOR LITERATURE SERIES

7c—Supplementary Readers and Classics for all Grades—7c

☞ This list is constantly being added to. If a substantial number of books are to be ordered, or if other titles than those shown here are desired, send for latest list.

FIRST GRADE

Fables and Myths

*6 Fairy Stories of the Moon—Maguire

*27 Eleven Fables from Æsop—Reiter

*28 More Fables from Æsop—Reiter

*29 Indian Myths—Bush

*140 Nursery Tales—Taylor

*288 Primer from Fableland—Maguire

Nature

*1 Little Plant People—Part I—Chase

*2 Little Plant People—Part II—Chase

*30 Story of a Sunbeam—Miller

*31 Kitty Mittens and Her Friends—Chase

History

*32 Patriotic Stories—Reiter

Literature

*104 Mother Goose Reader—Faxon

*228 First Term Primer—Maguire

*230 Rhyme and Jingle Reader for Beginners

*245 Three Billy Goats Gruff and Other Stories

SECOND GRADE

Fables and Myths

*33 Stories from Andersen—Taylor

*34 Stories from Grimm—Taylor

*36 Little Red Riding Hood—Reiter

*37 Jack and the Beanstalk—Reiter

*38 Adventures of a Brownie—Reiter

Nature and Industry

*3 Little Workers (Animal Stories)—Chase

*39 Little Wood Friends—Mayne

*40 Wings and Stings—Halifax

*41 Story of Wool—Mayne

*42 Bird Stories from the Poets—Jollie

History and Biography

*43 Story of the Mayflower—McCabe

*45 Boyhood of Washington—Reiter

*204 Boyhood of Lincoln—Reiter

Literature

*72 Bow-Wow and Mew-Mew—Craik

*152 Child’s Garden of Verses—Stevenson

*206 Picture Study Stories for Little Children

*220 Story of the Christ Child—Hushower

*262 Four Little Cotton Tails—Smith

*268 Four Little Cotton Tails in Winter—Smith

*269 Four Little Cotton Tails at Play—Smith

*270 Four Little Cotton Tails in Vacation—Smith

*290 Fuzz in Japan—A Child Life Reader

*300 Four Little Bushy Tails—Smith

*301 Patriotic Bushy Tails—Smith

*302 Tinkle Bell and Other Stories—Smith

*303 The Rainbow Fairy—Smith

*308 Story of Peter Rabbit—Potter

THIRD GRADE

Fables and Myths

*46 Puss in Boots and Cinderella—Reiter

*47 Greek Myths—Klingensmith

*48 Nature Myths—Metcalfe

*50 Reynard the Fox—Best

*102 Thumbelina and Dream Stories—Reiter

*146 Sleeping Beauty and Other Stories

174 Sun Myths—Reiter

175 Norse Legends, I—Reiter

176 Norse Legends, II—Reiter

*177 Legends of the Rhineland—McCabe

*282 Siegfried and Other Rhine Legends

*289 The Snow Man and Other Stories

*292 East of the Sun and West of the Moon

Nature and Industry

*49 Buds, Stems and Fruits—Mayne

*51 Story of Flax—Mayne

*52 Story of Glass—Hanson

*53 Story of a Little Water Drop—Mayne

*133 Aunt Martha’s Corner Cupboard—Part I. Story of Tea and the Teacup

*135 Little People of the Hills—Chase

*137 Aunt Martha’s Corner Cupboard—Part II. Story of Sugar, Coffee and Salt

*138 Aunt Martha’s Corner Cupboard—Part III. Story of Rice, Currants and Honey

*203 Little Plant People of the Waterways—Chase

History and Biography

*4 Story of Washington—Reiter

*7 Story of Longfellow—McCabe

*21 Story of the Pilgrims—Powers

*44 Famous Early Americans (Smith, Standish, Penn)—Bush

*54 Story of Columbus—McCabe

55 Story of Whittier—McCabe

57 Story of Louisa M. Alcott—Bush

*59 Story of the Boston Tea Party—McCabe

*60 Children of the Northland—Bush

*62 Children of the South Lands—I (Florida, Cuba, Puerto Rico)—McFee

*63 Children of the South Lands—II (Africa, Hawaii, The Philippines)—McFee

*64 Child Life in the Colonies—I (New Amsterdam)—Baker

*65 Child Life in the Colonies—II (Pennsylvania)—Baker

*66 Child Life in the Colonies—III (Virginia)

*68 Stories of the Revolution—I (Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys)—McCabe

*69 Stories of the Revolution—II (Around Philadelphia)—McCabe

*70 Stories of the Revolution—III (Marion, the Swamp Fox)—McCabe

*132 Story of Franklin—Faris

*164 The Little Brown Baby and Other Babies

*165 Gemila, the Child of the Desert

*166 Louise on the Rhine and in Her New Home (Nos. 164, 165, 166 are the stories from “Seven Little Sisters” by Jane Andrews)

*167 Famous Artists—I—(Landseer and Bonheur)

Literature

*35 Little Goody Two Shoes

58 Selections from Alice and Phoebe Cary

*67 The Story of Robinson Crusoe—Bush

*71 Selections from Hiawatha (Five Grades)

*227 Our Animal Friends: How to Treat Them

*233 Poems Worth Knowing—Book I—Primary

FOURTH GRADE

Nature and Industry

*75 Story of Coal—McKane

*76 Story of Wheat—Halifax

*77 Story of Cotton—Brown

*134 Conquests of Little Plant People—Chase

*136 Peeps into Bird Nooks—I—McFee

*181 Stories of the Stars—McFee

*205 Eyes and No Eyes and The Three Giants

History and Biography

*5 Story of Lincoln—Reiter

*56 Indian Children Tales—Bush

*78 Stories of the Backwoods—Reiter

*79 A Little New England Viking—Baker

*81 Story of De Soto—Hatfield

*82 Story of Daniel Boone—Reiter

*83 Story of Printing—McCabe

*84 Story of David Crockett—Reiter

*85 Story of Patrick Henry—Littlefield

*86 American Inventors—I (Whitney, Fulton)

*87 American Inventors—II (Morse, Edison)

*88 American Naval Heroes (Jones, Perry, Farragut)—Bush

*89 Fremont and Kit Carson—Judd

*91 Story of Eugene Field—McCabe

*178 Story of Lexington and Bunker Hill—Baker

*182 Story of Joan of Arc—McFee

*207 Famous Artists—II—Reynolds and Murillo

*243 Famous Artists—III—Millet

*248 Makers of European History—White

Literature

*90 Fifteen Selections from Longfellow—(Village Blacksmith, Children’s Hour, etc.)

*95 Japanese Myths and Legends—McFee

*103 Stories from the Old Testament—McFee

*111 Water Babies (Abridged)—Kingsley

*159 Little Lame Prince (Cond.)—Mulock

*171 Tolmi of the Tree-Tops—Grimes

*172 Labu the Little Lake Dweller—Grimes

*173 Tara of the Tents—Grimes

*195 Night before Christmas and Other Christmas Poems and Stories (Any Grade)

*201 Alice’s First Adventures in Wonderland

*202 Alice’s Further Adventures in Wonderland

*256 Bolo the Cave Boy—Grimes

*257 Kwasa the Cliff Dweller—Grimes

*291 Voyage to Lilliput (Abridged)—Swift

*293 Hansel and Grettel, and Pretty Goldilocks

*304 Story Lessons in Everyday Manners—Bailey

*312 Legends from Many Lands—Bailey

*314 The Enchanted Bugle and Other Stories

FIFTH GRADE

Nature and Industry

*92 Animal Life in the Sea—Reiter

*93 Story of Silk—Brown

*94 Story of Sugar—Reiter

*96 What We Drink (Tea, Coffee and Cocoa)

*139 Peeps into Bird Nooks—II

210 Snowdrops and Crocuses

263 The Sky Family—Denton

*280 Making of the World—Herndon

*281 Builders of the World—Herndon

*283 Stories of Time—Bush

*290 Story of King Corn—Cooley

History and Biography

*16 Explorations of the Northwest

*80 Story of the Cabots—McBride

*97 Stories of the Norsemen—Hanson

*98 Story of Nathan Hale—McCabe

*99 Story of Jefferson—McCabe

100 Story of Bryant—McFee

*101 Story of Robert E. Lee—McKane

105 Story of Canada—McCabe

*106 Story of Mexico—McCabe

*107 Story of Robert Louis Stevenson—Bush

110 Story of Hawthorne—McFee

112 Biographical Stories—Hawthorne

*141 Story of Grant—McKane

*144 Story of Steam—McCabe

*145 Story of McKinley—McBride

157 Story of Dickens—Smith

*179 Story of the Flag—Baker

*185 Story of the First Crusade—Mead

190 Story of Father Hennepin—McBride

191 Story of La Salle—McBride

*217 Story of Florence Nightingale—McFee

*218 Story of Peter Cooper—McFee

*219 Little Stories of Discovery—Halsey

232 Story of Shakespeare—Grames

*265 Four Little Discoverers in Panama—Bush

274 Stories from Grandfather’s Chair—Hawthorne

*275 When Plymouth Colony Was Young

*287 Life in Colonial Days—Tillinghast

Literature

*8 King of the Golden River—Ruskin

*9 The Golden Touch—Hawthorne

*61 Story of Sindbad the Sailor

*108 History in Verse

*113 Little Daffydowndilly and Other Stories

*180 Story of Aladdin and of Ali Baba—Lewis

*183 A Dog of Flanders—De La Ramee

*184 The Nurnberg Stove—De La Ramee

*186 Heroes from King Arthur—Grames

194 Whittier’s Poems—Selected

*199 Jackanapes—Ewing

*200 The Child of Urbino—De La Ramee

208 Heroes of Asgard—Selections—Keary

*212 Stories of Robin Hood—Bush

*234 Poems Worth Knowing—Book II—Inter.

*244 What Happened at the Zoo—Bailey

*250 At the Back of the North Wind, Selection from—Macdonald

255 Chinese Fables and Stories—Feltges

*309 Moni the Goat Boy—Spyri

*313 In Nature’s Fairyland—Bailey

SIXTH GRADE

Nature and Industry

*109 Gifts of the Forests (Rubber, Cinchona, Resins, etc.)—McFee

249 Flowers and Birds of Illinois—Patterson

*298 Story of Leather—Peirce

*299 Story of Iron—Ogden

Agricultural

*271 Animal Husbandry, I—Horses and Cattle

*272 Animal Husbandry, II—Sheep and Swine

Geography

*114 Great European Cities—I (London-Paris)

*115 Great European Cities—II (Rome-Berlin)

*168 Great European Cities—III (St. Petersburg-Constantinople)—Bush

*246 What I Saw in Japan—Griffis

*247 The Chinese and Their Country—Paulson

*285 Story of Panama and the Canal—Nida

History and Biography

*73 Four Great Musicians—Bush

*74 Four More Great Musicians—Bush

*116 Old English Heroes (Alfred, Richard the Lion-Hearted, The Black Prince)—Bush

*117 Later English Heroes (Cromwell, Wellington, Gladstone)—Bush

*160 Heroes of the Revolution—Tristram

*163 Stories of Courage—Bush

187 Lives of Webster and Clay—Tristram

*188 Story of Napoleon—Bush

*189 Stories of Heroism—Bush

*197 Story of Lafayette—Bush

198 Story of Roger Williams—Leighton

*209 Lewis and Clark Expedition—Herndon

*224 Story of William Tell—Hallock

*253 Story of the Aeroplane—Galbreath

*266 Story of Belgium—Griffis

*267 Story of Wheels—Bush

*286 Story of Slavery—Booker T. Washington

*310 Story of Frances E. Willard—Babcock

Stories of the States

508 Story of Florida—Bauskett

509 Story of Georgia—Derry

511 Story of Illinois—Smith

512 Story of Indiana—Clem

513 Story of Iowa—McFee

515 Story of Kentucky—Eubank

520 Story of Michigan—Skinner

521 Story of Minnesota—Skinner

523 Story of Missouri—Pierce

*525 Story of Nebraska—Mears

*528 Story of New Jersey—Hutchinson

533 Story of Ohio—Galbreath

*536 Story of Pennsylvania—March

*540 Story of Tennessee—Overall

542 Story of Utah—Young

546 Story of West Virginia—Shawkey

547 Story of Wisconsin—Skinner

Literature

*10 The Snow Image—Hawthorne

*11 Rip Van Winkle—Irving

*12 Legend of Sleepy Hollow—Irving

*22 Rab and His Friends—Brown

*24 Three Golden Apples—Hawthorne[2]

*25 The Miraculous Pitcher—Hawthorne[2]

*26 The Minotaur—Hawthorne

*118 A Tale of the White Hills and Other Stories—Hawthorne

*119 Bryant’s Thanatopsis, and Other Poems

*120 Ten Selections from Longfellow—(Paul Revere’s Ride, The Skeleton in Armor, etc.)

*121 Selections from Holmes (The Wonderful One Hoss Shay, Old Ironsides, and Others)

*122 The Pied Piper of Hamelin—Browning

161 The Great Carbuncle, Mr. Higginbotham’s Catastrophe, Snowflakes—Hawthorne

162 The Pygmies—Hawthorne

*211 The Golden Fleece—Hawthorne

*222 Kingsley’s Greek Heroes—I. The Story of Perseus

*223 Kingsley’s Greek Heroes—II. The Story of Theseus

*225 Tennyson’s Poems—Selected (Any grade)

226 A Child’s Dream of a Star, and Other Stories

229 Responsive Bible Readings—Zeller

*258 The Pilgrim’s Progress (Abridged)—Simons

*264 The Story of Don Quixote—Bush

277 Thrift Stories—Benj. Franklin and Others

*284 Story of Little Nell (Dickens)—Smith

294 The Dragon’s Teeth—Hawthorne

*295 The Gentle Boy—Hawthorne

SEVENTH GRADE

*13 Courtship of Miles Standish—Longfellow

*14 Evangeline—Longfellow[2]

*15 Snowbound—Whittier[2]

*20 The Great Stone Face—Hawthorne

123 Selections from Wordsworth (Ode on Immortality, We are Seven, To the Cuckoo, and other poems)

124 Selections from Shelley and Keats

125 Selections from The Merchant of Venice

*147 Story of King Arthur, as told by Tennyson

*149 The Man Without a Country—Hale[2]

*192 Story of Jean Valjean—Grames

*193 Selections from the Sketch Book—Irving

196 The Gray Champion—Hawthorne

213 Poems of Thomas Moore—(Selected)

214 More Selections from the Sketch Book

*216 Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare—Selected

*231 The Oregon Trail (Condensed)—Parkman

*235 Poems Worth Knowing—Book III—Grammar—Faxon

*238 Lamb’s Adventures of Ulysses—Part I

*239 Lamb’s Adventures of Ulysses—Part II

*241 Story of the Iliad—Church (Cond.)

*242 Story of the Æneid—Church (Cond.)

*251 Story of Language and Literature—Heilig

*252 The Battle of Waterloo—Hugo

*254 Story of “The Talisman” (Scott)—Weekes

*259 The Last of the Mohicans (Abridged)

*260 Oliver Twist (abridged)—Dickens

*261 Selected Tales of a Wayside Inn—Longfellow

*296 Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Condensed)

*297 Story of David Copperfield (Condensed)

*307 The Chariot Race—Wallace

*311 Story of Jerusalem—Heilig

*315 The Story of Armenia—Heilig

Nature

*278 Mars and Its Mysteries—Wilson

*279 True Story of the Man in the Moon—Wilson

EIGHTH GRADE

*17 Enoch Arden—Tennyson[2]

*18 Vision of Sir Launfal—Lowell[2]

*19 Cotter’s Saturday Night—Burns[2]

*23 The Deserted Village—Goldsmith

*126 Rime of the Ancient Mariner—Coleridge[2]

*127 Gray’s Elegy and Other Poems

*128 Speeches of Lincoln

*129 Julius Cæsar—Selections—Shakespeare

130 Henry the VIII—Selections—Shakespeare

131 Macbeth—Selections—Shakespeare

*142 Scott’s Lady of the Lake—Canto I[2]

*154 Scott’s Lady of the Lake—Canto II[2]

143 Building of the Ship and Other Poems—Longfellow

148 Horatius, Ivry, The Armada—Macaulay

*150 Bunker Hill Address—Selections from Adams and Jefferson Oration—Webster[2]

*151 Gold Bug, The—Poe

153 Prisoner of Chillon and Other Poems—Byron[2]

155 Rhoecus and Other Poems—Lowell[2]

156 Edgar Allan Poe—Biography and Selected Poems—Link

*158 Washington’s Farewell Address

169 Abram Joseph Ryan—Biography and Selected Poems—Smith

170 Paul H. Hayne—Biography and Selected Poems—Link

215 Life of Samuel Johnson—Macaulay[2]

*221 Sir Roger de Coverley Papers—Addison[2]

*236 Poems Worth Knowing—Book IV Adv.

237 Lay of the Last Minstrel—Canto I—Scott[2]

276 Landing of the Pilgrims (Orations)—Webster

*305 Wee Willie Winkie—Kipling

*306 Howe’s Masquerade—Hawthorne

[2] These have biographical sketch of author, with introduction or explanatory notes.

Price 7 Cents Each. Postage, 1 cent per copy extra on orders of less than twelve.

The titles indicated by (*) are supplied also in Limp Cloth Binding at 12 cents per copy.

EXCELSIOR LITERATURE SERIES

1 Evangeline. Biography, introduction, oral and written exercises and notes. 18c

3 Courtship of Miles Standish. Longfellow. With introduction and notes. 18c

5 Vision of Sir Launfal. Lowell. Biography, introduction, notes, outlines. 12c

7 Enoch Arden. Tennyson. Biography, introduction, notes, outlines, questions. 12c

9 Great Stone Face. Hawthorne. Biography, introduction, notes, outlines. 12c

11 Browning’s Poems. Selected poems with notes and outlines for study. 12c

13 Wordsworth’s Poems. Selected poems with introduction, notes and outlines. 12c

15 Sohrab and Rustum. Arnold. With introduction, notes and outlines. 12c

17 Longfellow for Boys and Girls. Study of Longfellow’s poetry for children. 12c

19 A Christmas Carol. Charles Dickens. Complete with notes. 18c

21 Cricket on the Hearth. Chas. Dickens. Complete with notes. 18c

23 Familiar Legends. McFee. 18c

25 Some Water Birds. McFee. Description and stories of, Fourth to Sixth grades. 12c

27 Hiawatha. Introduction and notes. 30c

29 Milton’s Minor Poems. Biography, introduction, notes, questions, critical comments and pronouncing vocabulary. 18c

31 Idylls of the King. (Coming of Arthur, Gareth and Lynette, Lancelot and Elaine, Passing of Arthur.) Biography, introduction, notes, questions, comments, pronouncing vocab. 24c

33 Silas Marner. Eliot. Biography, notes, questions, critical comments. 238 pages. 30c

35 Lady of the Lake. Scott. Biography, introduction, pronouncing vocabulary. 30c

37 Literature of the Bible. Heilig. 18c

39 The Sketch Book. (Selected) Irving. Biography, introduction and notes. 30c

41 Julius Cæsar. Edited by Thomas C. Blaisdell, Ph.D., LL.D. Notes and questions. 24c

43 Macbeth. Edited by Thomas C. Blaisdell. Notes and questions. 24c

45 Merchant of Venice. Edited by Thomas C. Blaisdell. Notes and questions. 24c

47 As You Like It. Edited by Thomas C. Blaisdell. Introduction, notes, questions. 24c

49 Hamlet. Edited by Thomas C. Blaisdell. Notes and questions. 24c

59 Poe’s Tales. (Selected) Biography, introduction and notes. 24c

61 Message to Garcia and Other Inspirational Stories. Introduction and notes. 12c

63 Lincoln-Douglas Debates. Edited by Edwin Erle Sparks, Pres. Pa. State College. 24c

65 The Man Without a Country. With introduction and notes by Horace G. Brown. 12c

67 Democracy and the War. Seventeen Addresses of President Wilson, with others. 24c

September—1920

Illustrations have been moved to paragraph breaks near where they are mentioned, except for the front illustration.

Punctuation has been made consistent.

Variations in spelling and hyphenation were retained as they appear in the original publication, except that obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

The book catalog that was split between the beginning and end of the original book has been consolidated at the end.