J. Card. Mezzofanti

Perugini, del. H. Adlard, sc.

Title: The life of Cardinal Mezzofanti

Author: Charles William Russell

Release date: December 4, 2022 [eBook #69473]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Longman, Brown, & Co

Credits: Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

J. Card. Mezzofanti

Perugini, del. H. Adlard, sc.

THE LIFE

OF

CARDINAL MEZZOFANTI;

WITH

AN INTRODUCTORY MEMOIR

OF

EMINENT LINGUISTS, ANCIENT AND MODERN.

BY

C. W. RUSSELL, D.D.

PRESIDENT OF ST. PATRICK’S COLLEGE, MAYNOOTH.

LONDON:

LONGMAN, BROWN, AND CO.

PATERNOSTER-ROW.

1858.

[The Right of Translation is reserved.]

The following Memoir had its origin in an article on Cardinal Mezzofanti, contributed to the Edinburgh Review in the year 1855. The subject appeared at that time to excite considerable interest. The article was translated into French, and, in an abridged form, into Italian; and I received through the editor, from persons entirely unknown to me, more than one suggestion that I should complete the biography, accompanied by offers of additional information for the purpose.

Nevertheless, the notices of the Cardinal on which that article was founded, and which at that time comprised all the existing materials for a biography, appeared to me, with all their interest, to want the precision and the completeness which are essential to a just estimate of his attainments. I felt that to judge satisfactorily his acquaintance with a range of languages so vast as that which fame ascribed to him, neither sweeping statements founded on popular reports, however confident, nor general assertions from individuals, however distinguished and trustworthy, could safely be regarded as sufficient. The proof of his familiarity with any particular language, in order to be satisfactory, ought to be specific, and ought to rest on the testimony[vi] either of a native, or at least of one whose skill in the language was beyond suspicion.

At the same time the interest with which the subject seemed to be generally regarded, led me to hope that, by collecting, while they were yet recent, the reminiscences of persons of various countries and tongues, who had known and spoken with the Cardinal, it might be possible to lay the foundation of a much more exact judgment regarding him than had hitherto been attainable.

A short inquiry satisfied me that, although scattered over every part of the globe, there were still to be found living representatives of most of the languages ascribed to the Cardinal, who would be able, from their own personal knowledge, to declare whether, and in what degree, he was acquainted with each; and I resolved to try whether it might not be possible to collect their opinions.

The experiment has involved an extensive and tedious correspondence; many of the persons whom I have had to consult being ex-pupils of the Propaganda, residing in very distant countries; more than one beyond the range of regular postal communication, and only accessible by a chance message transmitted through a consul, or through the friendly offices of a brother missionary.

For the spirit in which my inquiries have been met, I am deeply grateful. I have recorded in the course of the narrative the names of many to whom I am indebted for valuable assistance and information. Other valued friends whom I have not named, will kindly accept this general acknowledgment.

There is one, however, to whom I owe a most special and grateful expression of thanks—his Eminence the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster. From him, at the very outset of my task, I received a mass of anecdotes, recollections, and suggestions, which, besides their great intrinsic interest, most materially assisted me in my further inquiries; and the grace of the contribution was enhanced by the fact, that it was generously withdrawn from that delightful store of Personal Recollections which his Eminence has since given to the public; and in which his brilliant pen would have made it one of the most attractive episodes.

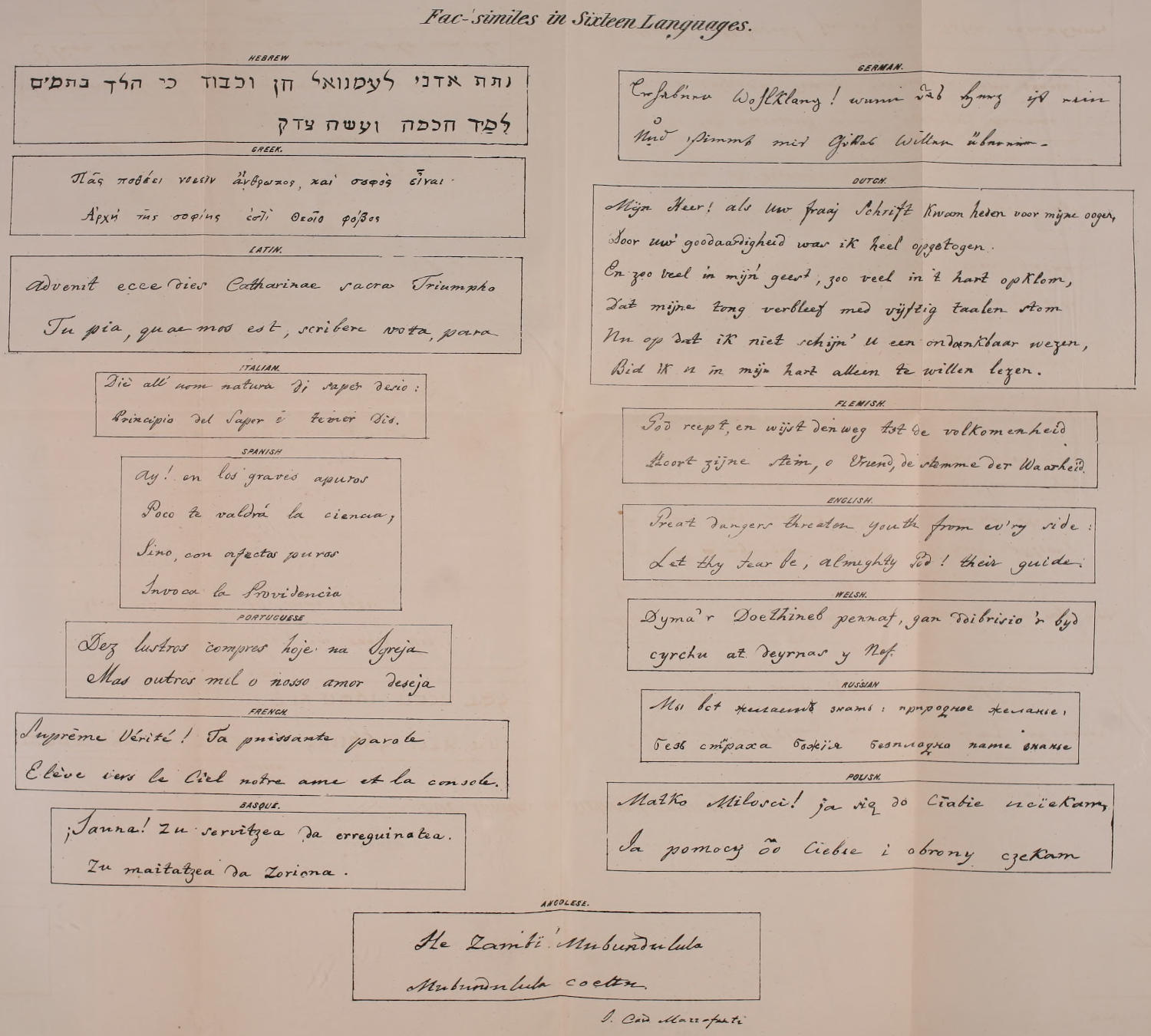

Several of the autographs, also, which appear in the sheet of fac-similes, I owe to his Eminence. Others I have received from friends who are named in the Memoir.

| PREFACE, | pp. v-vii. |

| INTRODUCTORY MEMOIR. | |

| Ancient period:— | |

| History of Linguists little known—Legendary Linguists—The Jews—The Asiatics—The Greeks—Mithridates—Cleopatra—The Romans—Prevalence of Greek under the Empire—The Early Christians—Decline of the Study—Separation of the two Empires—The Crusaders—Frederic II—The Moorish Schools in Spain—Council of Vienne—Roderigo Ximenes—Venetian travellers—Fall of Constantinople—Greeks in Italy—Complutensian Polyglot, | pp. 5-18. |

| Modern period:— | |

| I. Linguists of the East. Dragomans—Genus Bey—Jonadab Alhanar—Interpreters in the Levant—Ciceroni at Mecca—Syrian Linguists—The Assemani—Greeks—Armenians—The Mechitarists, | pp. 18-24. |

| II. Italian Linguists. Pico della Mirandola—Teseo Ambrosio—Pigafetta—Linguistic Missionary Colleges—The Propaganda—Schools of the Religious Orders—Giggei—Galani—Ubicini—Maracci—Podestà—Piromalli—Giorgi—De Magistris—Finetti—Valperga de Galuso—The De Rossis, | pp. 25-34. |

| III. Spanish and Portuguese Linguists. Fernando di Cordova—Covilham—Libertas Cominetus—Arias Montanus—Del Rio—Lope de Vega—Missionaries—Antonio Fernandez—Carabantes—Pedro Paez—Hervas-y-Pandura, | pp. 34-41. |

| IV. French Linguists. Postel—Polyglot-Pater-Nosters—Scaliger—Le Cluse—Peiresc—Chasteuil—Duret—Bochart—Picquet—Le Jay—De la Croze—Renaudot—Fourmont—Deshauterayes—De Guignes—Diplomatic affairs in the Levant—De Paradis, Langlés—Abel Remusat—Modern School, Julien, Bournouf, Renan, Fresnel, the d’Abbadies, | pp. 41-58. |

| V. German, Dutch, Flemish, and Hungarian Linguists. Müller—(Regiomontanus)—Bibliander—Gesner—Christmann—Drusius—Schultens—Maes—Haecx—Gramaye—Erpen—The Goliuses—Hottinger—Kircher—Ludolf—Rothenacker—Andrew[x] Müller—Witzen—Wilkins—Leibnitz—Gerard Müller—Schlötzer—Buttner—Michaelis—Catholic Missionaries—Richter, Fritz, Widmann, Grebmer, Dobritzhofer, Werdin—Berchtold, Adelung, Vater, Pallas, Klaproth, Niebuhr, Humboldt and his School—Castrén, Rask, Bunsen, Biblical Linguists—Hungarian Linguists—Csoma de Körös, | pp. 59-81. |

| VI. British and Irish Linguists. Crichton—Andrews—Gregory—Castell, Walton, Pocock, Ockley, Sale, Clarke, Wilkins, Toland, “Orator” Henley, Carteret, Jones, Marsden, Colebrooke, Craufurd, Lumsden, Leyden, Vans Kennedy, Adam Clarke, Roberts Jones, Young, Pritchard, Cardinal Wiseman, Browning, Lee, Burritt, | pp. 81-99. |

| VII. Slavonian Linguists. Russians—Scantiness of Materials—Early Period—Jaroslav, Boris—The Romanoffs—Beründa Pameva, Peter the Great, Catherine I., Mentschikoff, Timkoffsky, Bitchourin, Igumnoff, Giganoff, Tchubinoff, Goulianoff, Senkowsky, Gretsch, Kazem-Beg—Poles—Meninski, Groddek, Bobrowski, Albertrandy, Rzewuski, Italinski—Bohemians—Komnensky, Dobrowsky, Hanka, | pp. 99-110. |

| Miraculous gift of tongues—Royal Linguists—Lady-Linguists—Infant Phenomena—Uneducated Linguists, | pp. 110-121. |

| LIFE OF CARDINAL MEZZOFANTI. | |

| CHAPTER I. (1774-98.) | |

| Birth and family history—Legendary tales—Early education—First masters—School friends—Ecclesiastical studies—Illness and interruption of studies—Study of languages—Anecdote—Ordination—Appointment as Professor of Arabic—Deprivation of professorship, | pp. 125-147. |

| CHAPTER II. (1798-1802.) | |

| Straitened circumstances—Private tuition—The Marescalchi family—The military hospitals—Manner of study—The Magyar, Czechish, Polish, Russian, and Flemish languages—Foreigners—The Confessional—Intense application—Examples of literary labour, | pp. 148-161. |

| CHAPTER III. (1803-1806.) | |

| Appointed as Assistant Librarian of the Istituto di Bologna—Catalogue Raisonné—Professorship of Oriental Languages—Paper on Egyptian obelisks—De Rossi—Correspondence with him—Polyglot translations—Caronni’s account of him—Visit to Parma, Pezzana,[xi] Bodoni—Persian—Illness—Invitation to settle at Paris—Domestic relations—Correspondence—Translations, | pp. 162-190. |

| CHAPTER IV. (1807-14.) | |

| Labour of compiling Catalogue—His skill as linguist tested by the Russian Embassy—Deprivation of Professorship—Death of his mother—Visit to Modena and Parma—Literary friends—Giordani’s account—Greek scholarship—Bucheron’s trial of his Latinity—Deputy Librarianship of University—Visitors—Lord Guildford—Learned societies—Academy of Institute—Paper on Mexican symbolic Paintings, | pp. 191-204. |

| CHAPTER V. (1814-17.) | |

| Restoration of the Papal Government—Pius VII. at Bologna—Invites Mezzofanti to Rome—Re-appointment as Professor of Oriental languages—Death of his father—Notices of Mezzofanti by Tourists—Kephalides—Appointed head librarian—Pupils—Angelelli—Papers read at Academy, | pp. 205-18. |

| CHAPTER VI. (1817-20.) | |

| Tourists’ Notices of Mezzofanti—Society in Bologna—Mr. Harford—Stewart Rose—Byron—The Opuscoli Letterarj di Bologna—Panegyric of F. Aponte—Emperor Francis I. at Bologna—Clotilda Tambroni—Lady Morgan’s account of Mezzofanti—Inaccuracies—The Bologna dialect—M. Molbech, | pp. 219-40. |

| CHAPTER VII. (1820-28.) | |

| Illness—Visit to Mantua, Modena, Pisa, and Leghorn—Solar Eclipse—Baron Von Zach—Bohemian—Admiral Smyth—The Gipsy language—Blume—Armenian—Georgian—Flemish—Pupils—Cavedoni, Veggetti, Rosellini—Foreigners—Daily duties—Correspondence—Death of Pius VII.—Appointment as member of Collegio dei Consultori—Jacobs’ account of him—Personal appearance—Cardinal Cappellari—Translation of Oriental Liturgy—Mezzofanti’s disinterestedness—Birmese, | pp. 241-70. |

| CHAPTER VIII. (1828-30.) | |

| Visit of Crown Prince of Prussia—Trial of skill in languages—Crown Prince of Sweden—M. Braunerhjelm—Countess of Blessington—Irish Students—Lady Bellew—Dr. Tholuck—Persian couplet—Swedish—Cornish Dialect—Frisian—Abate Fabiani—Letters—Academy of the Filopieri, | pp. 271-86.[xii] |

| CHAPTER IX. (1831.) | |

| Political parties at Bologna—M. Libri’s account of Mezzofanti—Hindoo Algebra—Indian literature and history—Indian languages—Manner of study—Revolution of Bologna—Delegates to Rome—Mezzofanti at Rome—Reception by Gregory XVI.—Visit to the Propaganda—Dr. Cullen—Polyglot conversation—Renewed Invitation to settle at Rome—Consents—Calumnies of revolutionary party—Dr. Wordsworth—Mr. Milnes—Removal to Rome, | pp. 287-300. |

| CHAPTER X. (1831-33.) | |

| Rome a centre of many languages—Mezzofanti’s pretensions fully tested—Appointments at Rome—Visit to the Chinese College at Naples—History of the College—Study of Chinese—Its difficulties—Illness—Return to Rome—Polyglot society of Rome—The Propaganda—Amusing trials of skill—Gregory XVI.—Library of Propaganda rich in rare books on languages—Appointed First Keeper of the Vatican Library—Letters, | pp. 301-17. |

| CHAPTER XI. (1834.) | |

| The Welsh language—Dr. Forster—Dr. Baines—Dr. Edwards—Mr. Rhys Powell—Flemish—Mgr. Malou—Mgr. Wilde—Canon Aerts—Pere van Calven—Pere Legrelle—Dutch—M. Leon—Dr. Wap—Mezzofanti’s extempore Dutch verses—Bohemian—The poet Frankl—Conversations on German and Magyar Poetry—Maltese—Padre Schembri—Canonico Falzou—Portuguese—Count de Lavradio, | pp. 318-37. |

| CHAPTER XII. (1834-36.) | |

| The Vatican Library—Mezzofanti’s colleagues—College of St. Peter’s—Mezzofanti made Rector—His literary friends in Rome—Angelo Mai—Accademia della Cattolica Religione—He reads papers in this Academy—Gregory XVI.’s kindness—Cardinal Giustiniani—Albani—Pacca—Zurla—Polyglot party at Cardinal Zurla’s in his honour—Opinions regarding him—Number of his languages—Mr. Mazzinghi—Dr. Cox—Dr. Wiseman—Herr Fleck—Greek Epigram—Herr Fleck’s criticisms—Mezzofanti’s Latinity—His English—Dr. Baines—Cardinal Wiseman—Mr. Monckton Milnes—Mezzofanti’s style formed on books—Lady Morgan’s opinion of his English—Swedish Literature—Professor Carlson—Count Oxenstjerna—Armenian Literature—Mgr. Hurmuz—Padre Angiarakian Arabic of Syria—Greek Literature—Mgr. Missir—Romaic—Abate Matranga—Polish Literature—Sicilian—The poet Meli, | pp. 338-54.[xiii] |

| CHAPTER XIII. (1836-38.) | |

| Californian students in Propaganda—Californian language—Mezzofanti’s success in it—Nigger Dutch of Curaçoa—American Indians in Propaganda—Augustine Hamelin—“The Blackbird”—Mezzofanti’s knowledge of Indian languages—Dr. Kip—Algonquin—Chippewa Delaware—Father Thavenet—His studies in the Propaganda—Arabic—Albanese—Mr. Fernando’s notice of him—Cingalese—East Indian languages—Hindostani—Mahratta—Guzarattee—Dr. M’Auliffe—Count Lackersteen—M. Eyoob—Chinese, difficulty of—Chinese students—Testimony of Abate Umpierres—Cardinal Wiseman—West African languages—Father Brunner—Angolese—Oriental languages—Paul Alkushi—“Shalom”—Letter, | pp. 355-72. |

| CHAPTER XIV. (1838-41.) | |

| Created Cardinal—The Cardinalate—Its history, duties, emoluments, congregations, offices—Mezzofanti’s poverty—Kindness of Gregory XVI.—Congratulations of his Bolognese friends—The Filopieri—Polyglot congratulations of the Propaganda—Friends among the Cardinals—His life as Cardinal—Still continues to acquire new languages—Abyssinian—M. d’Abbadie—His visit to Mezzofanti—Basque—Amarinna—Arabic—Ilmorma—Mezzofanti’s failure—Studies Amarinna—Abyssinian Embassy to Rome—Their account of the Cardinal—The Basque language—M. d’Abbadie—Prince L.L. Bonaparte—M. Dassance—Strictures on Mezzofanti—Mrs. Paget—Baron Glucky de Stenitzer—Guido Görres—Modesty of Mezzofanti—Mr. Kip—Görres—Cardinal Wiseman—Mezzofanti among the pupils of the Propaganda, | pp. 373-97. |

| CHAPTER XV. (1841-43.) | |

| Author’s recollections of Mezzofanti in 1841—His personal appearance and manner; his attractive simplicity—Languages in which the author heard him speak—His English conversation—Various opinions regarding it—Impressions of the author—Anecdotes—Cardinal Wiseman—Rev. John Smyth—Father Kelleher—His knowledge of English literature—Mr. Harford—Dr. Cox—Cardinal Wiseman—Mr. Grattan—Mr. Badeley—Hudibras—Author’s own conversation with the Cardinal—The Tractarian movement—Mr. Grattan—Baron Bunsen—Author’s second visit to Rome—The Polyglot Academy of the Propaganda—Playful trial of Mezzofanti’s powers by the students—His wonderful versatility of language—Analogous examples of this faculty—Description of it by visitors—His own illustration—The Irish language—Mezzofanti’s admission regarding it—The Etruria Celtica—The Eugubian Tables—Amusing experiment[xiv] suggested by Mezzofanti—Dr. Murphy—The Gælic language—Mezzofanti’s extempore Metrical compositions—Specimens—Rapidity with which he wrote them—Power of accommodating his pronunciation of Latin to that of the various countries—National interjectional sounds—Playfulness—Puns, | pp. 398-431. |

| CHAPTER XVI. (1843-49.) | |

| Death of his nephew Mgr. Minarelli—His sister Teresa—Letter—Visitors—Rev. Ingraham Kip—English conversation—English literature—American literature—The American Indian languages—Scottish dialect—Burns and Walter Scott—Rev. John Gray—Mezzofanti as a philologer—Baron Bunsen—The Abbé Gaume—French patois—Spanish—Father Burrueco—Mexican—Peruvian—New Zealand language—Armenian and Turkish—Father Trenz—Russian—M. Mouravieff—The Emperor Nicholas—Polish—Klementyna z Tanskich Hoffmanowa—Makrena, Abbess of Minsk—Her history—Her account of Mezzofanti—His occupations—House of Catechumens—First communion—Fervorini—The confessional—Death of Gregory XVI.—Election of Pius IX.—Mezzofanti’s epigrams on the occasion—His relations with the new Pope—Father Bresciani’s account of him—The revolution of 1848—Its effect on Cardinal Mezzofanti—His illness—Death and funeral, | pp. 432-56. |

| CHAPTER XVII. (Recapitulation.) | |

| Plan pursued in preparing this Biography—Points of inquiry—Number of languages known to Mezzofanti—What is meant by knowledge of a language—Popular notion of it—Mezzofanti’s number of languages progressive—Dr. Minarelli’s list of languages known by him—Classification of languages according to the degrees of his knowledge—Languages spoken by him with great perfection—Languages spoken less perfectly—Languages in which he could initiate a conversation—Languages known from books—Dialects—Southern and central American languages—Total number known to him in various degrees—His speaking of languages not literally faultless, but perfect to a degree rare in foreigners—Comparison with other linguists—His plan of studying languages—Various systems of study—Mezzofanti’s method involved much labour—Habit of thinking in foreign languages—His success a special gift of nature—In what this consisted—Quickness of perception—Analysis—Memory—Peculiarity of his memory—His enthusiasm and simplicity—Mezzofanti as a philologer, as a critic, a historian, a man of science—Piety and charity, liberal and tolerant spirit—Social virtues, | pp. 457-493. |

| APPENDIX, | pp. 495-502. |

| Page | 35, | Line | 5, for “yards” read “feet.” |

| 52, | last, after “(1704),” supply “who.” | ||

| 57, | 21, for “Bourmouf,” read “Bournouf.” | ||

| 59, | 8, for “John and,” read “and John.” | ||

| 76, | 2nd last, for “Boehthingk,” read “Boehtlingk.” | ||

| 117, | 4th last, (and three other places,) for “marvelous,” read “marvellous.” | ||

| 119, | 2nd last, for “months,” read “years.” | ||

| 121, | 2nd last, for “Hall,” read “Hill.” | ||

| 281, | 22, for “Grüner,” read “Grüder.” | ||

| 283, | 17, for “Rabinical,” read “Rabbinical.” | ||

| 312, | 10, for “unable,” read “able.” | ||

| 426, | 4th last, for “seneeta,” read “senecta;” also interchange ; and ! |

Fac-similes in Sixteen Languages.

In the Life of Cardinal Mezzofanti I have attempted to ascertain, by direct evidence, the exact number of languages with which that great linguist was acquainted, and the degree of his familiarity with each.

Eminence in any pursuit, however, is necessarily relative. We are easily deceived about a man’s stature until we have seen him by the side of other men; nor shall we be able to form a just notion of the linguistic accomplishments of Cardinal Mezzofanti, or at least to bring them before our minds as a practical reality, until we shall have first considered what had been effected before him by other men who attained to distinction in the same department.

I have thought it desirable, therefore, to prefix to his Life a summary history of the most eminent linguists of ancient and modern times. There is no branch of scholarship which has left fewer traces in literature, or has received a more scanty measure of justice from history. Viewed in the light of a curious but unpractical pursuit, skill in languages is admired for a time, perhaps indeed enjoys an exaggerated popularity; but it passes away like a nine days’ wonder, and seldom finds an exact or permanent record. Hence, while the literature of every country abounds with memoirs of distinguished poets, philosophers, and historians, few, even among professed antiquarians, have directed their attention to the history of eminent linguists, whether in ancient or in modern times. In all the ordinary repositories of curious learning—Pliny, Aulus Gellius, and Athenæus, among the ancients; Bayle, Gibbon, Feyjoo, Disraeli, and Vulpius, among the moderns—this interesting chapter is entirely overlooked; nor does it appear to have engaged the attention even of linguists or philologers themselves.

The following Memoir, therefore, must claim the indulgence due to a first essay in a new and difficult subject. No one can be more sensible than the writer of its many imperfections;—of the probable omission of names which should have been recorded;—of the undue prominence of others with inferior pretensions; and perhaps of still more serious inaccuracies of a different kind. It is only offered in the absence of something better and more complete; and with the hope of directing to what is certainly a curious and interesting subject, the attention of others who enjoy more leisure and opportunity for its investigation.

The diversity of languages which prevails among the various branches of the human family, has proved, almost equally with their local dispersion, a barrier to that free intercommunion which is one of the main instruments of civilization. “The confusion of tongues, the first great judgment of God upon the ambition of man,” says Bacon, in the Introductory Book of his “Advancement of Learning,” “hath chiefly imbarred the open trade and intercourse of learning and knowledge.”[1] Perhaps it would be more correct to say that these two great impediments to intercourse have mutually assisted each other. The divergency of languages seems to keep pace with the dispersion of the population. Adelung lays it down as the result of the most careful philological investigations, that where the difficulties of intercourse are such as existed among the ancients and as still prevail among the less civilized populations, no language can maintain itself unchanged over a space of more than one hundred and fifty thousand square miles.[2]

It might naturally be expected, therefore, that one of the earliest efforts of the human intellect would have been directed towards the removal of this barrier, and that one of the first sciences to invite the attention of men would have been the knowledge of languages. Few sciences, nevertheless, were more neglected by the ancients.

It is true that the early literatures of many of the ancient nations contain legends on this head which might almost throw into the shade the greatest marvels related of Mezzofanti. In one of the Chinese stories regarding the youth of Buddha,[7] translated by Klaproth, it is related that, when he was ten years old, he asked his preceptor, Babourenou, to teach him all the languages of the earth, seeing that he was to be an apostle to all men; and that when Babourenou confessed his ignorance of all except the Indian dialects, the child himself taught his master “fifty foreign tongues with their respective characters.”[3] A still more marvellous tale is told by one of the Rabbinical historians, Rabbi Eliezer, who relates that Mordechai, (one of the great heroes of Talmudic legend), was acquainted with seventy languages; and that it was by means of this gift he understood the conversation of the two eunuchs who were plotting in a foreign tongue the death of the king.[4] Nor is the Koran without its corresponding prodigy. When the Prophet was carried up to Heaven, before the throne of the Most High, “God promised that he should have the knowledge of all languages.”[5]

But when we turn to the genuine records of antiquity, we find no ground for the belief that such legends as these have even that ordinary substructure of truth which commonly underlies the fables of mythology. Neither the Sacred Narratives, nor those of the early profane authors, contain a single example of remarkable proficiency in languages.

It is true that in the later days of the Jewish people, interpreters were appointed in the synagogues to explain the lessons read from the Hebrew Scriptures for the benefit of their foreign brethren; that in all the courts of the Eastern monarchs interpreters were found, through whom they communicated with foreign envoys, or with the motley tribes of their own empire; and that professional interpreters were at the service of foreigners in the great centres of commerce or travel,[6] who, it may be presumed, were masters of[8] several languages. The philosophers, too, who traversed remote countries in pursuit of wisdom, can hardly be supposed to have returned without some acquaintance with the languages of the nations among whom they had voyaged. Solon and Pythagoras are known to have visited Egypt and the East; the latter also sojourned for a considerable time in Italy and the islands; the wanderings of Plato are said to have been even more extensive. Nay, in some instances these pilgrims of knowledge extended their researches beyond the limits of their own ethnographical region. Thus, on the one hand, the Scythian sages, Anacharsis and Zamolxis, themselves most probably of the Mongol or Tartar tongue, sojourned for a long time in countries where the Indo-European family of languages alone prevailed; on the other, the merchants of Tyre were in familiar and habitual intercourse with the Italo-Pelasgic race; and the Phœnician explorers, in their well-known circumnavigation of Africa described by Herodotus, must have come in contact with still more numerous varieties both of race and of tongue. Nevertheless it may fairly be doubted whether these or similar opportunities among the ancients, resulted in any very remarkable attainments in the department of languages. The absence of all record furnishes a strong presumption to the contrary; and there is one example, that of Herodotus, which would almost be in itself conclusive. This acute and industrious explorer devoted many years to foreign travel. He visited every city of note in Greece and Asia Minor, and every site of the great battles between the Greeks and Barbarians. He explored the whole line of the route of Xerxes in his disastrous expedition. He visited in succession all the chief islands of the Egean, as well as those of the western coast of Greece. His landward wanderings extended far into the interior. He reached Babylon, Ecbatana, and Susa, and spent some time among the Scythian tribes on the shores of the Black Sea. He resided long in Egypt, from which he passed southwards as far as Elephantine, eastwards into Arabia, and westwards through Lybia, at least as far as Cyrene. And yet Dahlmann is of opinion that, with all his industry, and all the spirit of inquiry which was his great characteristic, Herodotus never became acquainted even with the language of Egypt, but contented himself with the service of an interpreter.[7]

In like manner, it would be difficult to shew, either from the Cyropædia, or the Expedition of Cyrus, that Xenophon, during his foreign travel, became master of Persian or any kindred Eastern tongue. Nor am I aware that there has ever been discovered in the writings of Plato any evidence of familiarity with the language of those Eastern philosophers from whose science he is believed to have drawn so largely.

It is strange that the two notable exceptions to this barrenness of eminent linguists which characterizes the classic times, Mithridates and Cleopatra, should both have been of royal rank. The former, the celebrated king of Pontus, long one of the most formidable enemies of the Roman name, is alleged to have spoken fluently the languages of all the subjects of his empire; an empire so vast, and comprising so many different nationalities as to throw an air of improbability over the story. According to Aulus Gellius,[8] he “was thoroughly conversant” (percalluit) with the languages of all the nations (twenty-five in number) over which his rule extended.[9] The other writers who relate the circumstance—Valerius Maximus,[10] Pliny,[11] and Solinus—make the number only twenty-two. Some commentators have regarded the story as a gross exaggeration; and others have sought to diminish its marvellousness by explaining it of different dialects, rather than of distinct languages. But there does not appear in the narrative of the original writers any reason whether for the doubt or for the restriction. Pliny declares that “it is quite certain;” and the matter-of-fact tone in which they all relate it, makes it clear that they wished to be understood literally. It was the king’s invariable practice, they tell us, to communicate with all the subjects of his polyglot empire directly and in person, and “never through an interpreter;” and Gellius roundly affirms that he was able to[10] converse in each and every one of these tongues “with as much correctness as if it were his native dialect.”

The attainments of Cleopatra, although far short of what is reported of Mithridates, are nevertheless described by Plutarch[12] as very extraordinary. He says that she “spoke most languages, and that there were but few of the foreign ambassadors to whom she gave audience through an interpreter.” The languages which he specifies are those of the Ethiopians, of the Troglodytes (probably a dialect of Coptic), of the Hebrews, of the Arabs, the Syrians, the Medes, and the Persians; but he adds that this list does not comprise all the languages which this extraordinary woman understood.

Now the very prominence assigned to these examples, and the absence of all allusion to any other which might be supposed to approximate to them, may afford a presumption that they are almost solitary. Valerius Maximus, in his well-known chapter De Studio et Industria, cites the case of Mithridates as a very remarkable example “of study and industry.” It is highly probable therefore, that, if he knew any other eminent linguists, he would have added their names. Yet the only cases which he instances are those of Cato learning Greek in his old age, of Themistocles acquiring Persian during his exile, and of Publius mastering all the five dialects of Greece during the time of his Prætorship. In like manner, Aulus Gellius has no more notable linguist to produce, in contrast with Mithridates, than the old poet Ennius, who used to boast that he had three hearts,[13] because he could speak Greek, Latin, and his rude native dialect, Oscan. And Pliny, with all his love of parallels, is even more meagre:—he does not recite a single name in comparison with that of Mithridates.

The Romans, especially under the early Republic, appear to have been singularly indifferent or unsuccessful in cultivating languages; and the bad Greek of the Roman ambassadors to Tarentum, for their ridicule of which the Tarentines paid so dearly, is almost an average specimen of the accomplishments of the earlier Romans as linguists. Nor can this circumstance fail to appear strange, when it is remembered over how many different races and tongues the wide domain of Rome extended. The very multiplicity of languages submitted to her government[11] would seem to have imposed upon her public men the necessity of familiarizing themselves, even for the discharge of their public office, with at least the principal ones among them. But, on the contrary, for a long time they steadily pursued the policy of imposing, as far as practicable, upon the conquered nationalities the Latin language, at least in public and official transactions.[14]

And, so far as regards the Eastern and Northern languages, this exclusion was successfully and permanently enforced at Rome. The slave population of the city comprised almost every variety of race within the limits of the Empire. The very names of the slaves who are introduced in the plays of Plautus and Terence—Syra, Phœnicium, Afer, Geta, Dorias, &c. (which are but their respective gentile appellatives)—embrace a very large circle of the languages of Asia, Africa, and Northern Europe. And yet, with the exception of a single scene in the Pænulus of Plautus, in which the well-known Punic speech of Hanno the Carthaginian is introduced,[15] there is nothing in either of these dramatists from which we could infer that any of the manifold languages of the slave population of Rome effected an entrance among their haughty masters. They were all as completely ignored by the Romans, as is the vernacular Celtic of the Irish agricultural servant in the midland counties of England.

But it was not so for Greek. From the Augustan age onwards, this polished language began to dispute the mastery with Latin, even in Rome itself.

applies to the language, even more than to the arts. In the days of the Rhetorician, Molon, (Cicero’s master in eloquence,) Greek had obtained the entrée of the Senate. In the time of Tiberius, its use was permitted even in forensic pleadings. With the emperors who succeeded,[16] the triumph of Greek was still more complete. From Pliny downwards, there is hardly an author of eminence in the Roman Empire who did[12] not write in that language;—Pausanias, Dion, Galen, even the Emperor Marcus Aurelius himself, with all the traditionary Roman associations of his name.

It was so also with the Christian population and the Christian literature of Rome. Almost all the Christian writings of the first two centuries are in Greek. The early Roman liturgy was Greek. The population of Rome was in great part a Greek-speaking race. A large proportion of the inscriptions in the Roman Catacombs are Greek, and some even of the Latin ones are engraved in Greek characters. Nay, the early Christian churches in Gaul, Vienne, Lyons, and Marseilles, and the few remains of their literature which have reached us, are equally Greek.[17]

In a word, during the first two centuries of the Christian era, making due allowance for the difference of the periods, Greek and Latin held towards each other in Rome the same relation which we find between Norman-French and Saxon in England after the Conquest; and we may safely say that, during those centuries, a knowledge of both languages was the ordinary accomplishment of all educated men, and was shared by many of the lowest of the population.

Beyond this limit, however, we read of no remarkable linguists even among the accomplished scholars of the Augustan age. No one will doubt that the two Varros may fairly be taken as, in this respect, the most favourable specimens of the class. Now neither of them seems to have gone further than a knowledge of Greek. Out of the four hundred and ninety books which Marcus Terentius Varro wrote, there is not one named which would indicate familiarity with any other foreign language.

The Neo-Platonists of the second and third centuries, whose researches in Oriental Philosophy must have brought them into contact with some of the Eastern languages, may possibly form an exception to this general statement; but, on the whole, in the absence of positive and exact information on the subject, it may not unreasonably be conjectured that, among the Christian scholars of the second, third, and fourth centuries, we might find a wider range of linguistic attainments than among their gentile contemporaries. The critical study of the Bible itself involved the necessity of familiarity, not only with Greek and Hebrew, but with more than one cognate oriental dialect besides. St. Jerome, besides the classic languages and[13] his native Illyrian, is known to have been familiar with several of the Eastern tongues; and it is not improbable that some of the earlier commentators and expositors of the Bible may be taken as equally favourable specimens of the Christian linguists.[18] Origen’s Hexapla is a monument of his scholarship in Hebrew, and probably in Syriac and Samaritan. St. Clement of Alexandria was perhaps even a more accomplished linguist; for he tells that of the masters under whom he studied, one was from Greece, one from Magna Græcia, a third from Cœle-Syria, a fourth from Egypt, a fifth an Assyrian, and a sixth a Hebrew.[19] And St. Gregory Nazianzen expressly relates of his friend St. Basil, that, even before he came to Athens to commence his rhetorical studies, he was already well-versed in many languages.[20]

From the death of Constantine, however, the study began rapidly to decline, even among ecclesiastics. The disruption of the Empire naturally tended to diminish the intercourse between East and West, and by consequence the interchange of their languages. It would appear, too, as if the barbarian conquerors adopted, in favour of their own languages, the same policy which the Romans had pursued for Latin. Attila is said to have passed a law prohibiting the use of the Latin language in his newly conquered kingdom,[21] and to have taken pains, by importing native teachers, to procure the substitution of Gothic in its stead. At all events, in whatever way the change was brought about, a knowledge of both Greek and Latin, which in the classic times of the Empire had been the ordinary accomplishment of every educated man, became uncommon and almost exceptional. Pope Gregory the Great, who, bitterly as he has been assailed as an[14] enemy of letters, must be confessed to have been the most eminent Western scholar of his day, spoke Greek very imperfectly; he complains that it was difficult, even at Constantinople, to find any one who could translate Greek satisfactorily into Latin;[22] and a still earlier instance is recorded, in which a pope, in other respects a man of undoubted ability, was unable to translate the letter of the Greek patriarch, much less to communicate with the Greek ambassadors, except through an interpreter.[23]

More than one, indeed, of the early theological controversies was embittered through the misunderstandings caused between the East and West by mutual ignorance of each other’s language. Pelagius succeeded in obtaining a favourable decision from the Council of Jerusalem in 415, chiefly because, while his Western adversary, Orosius, was unable to speak Greek, the fathers of the Council were ignorant of Latin. The protracted controversy on the Three Chapters owed much of its inveteracy to the ignorance of the Westerns[24] of the original language of the works whose orthodoxy was impugned; and it is well known that the condemnation of the decree of the sixth council on the use of sacred images issued by the fathers of Francfort, was based exclusively on a strangely erroneous Latin translation of the acts of the council, through which translation alone they were known in Germany and Gaul.[25]

The foundation of the Empire of Charlemagne consummated the separation between the Greek and Latin races and their languages. The venerated names of Bede and of Alcuin in the Western Church, and the more questionable celebrity of the Patriarch Photius in the Eastern, constitute a passing exception. But it need hardly be added that they stand almost[15] entirely alone; and it will readily be believed that, amid the Barbarian irruptions from without, and the fierce intestine revolutions, of which Europe was the theatre during the rest of the earlier mediæval period, even that familiarity with the Greek and oriental languages which we have described, entirely disappeared in the West.

The wars of the Crusades, and the reviving intellectual activity in which this and other great events of the second mediæval period originated, gave a new impulse to the study of languages. Frederic II., a remarkable example of the union of great intellectual gifts with deep moral perversity, spoke fluently six languages, Latin, Greek, Italian, German, Hebrew, and even Arabic.[26] The Moorish schools in Spain began to be visited by Christian students. In this manner Arabic found its way into the West; and the intermixture of learned Jews in the European kingdoms afforded similar opportunities for the cultivation of Hebrew, which were turned to account by many, especially among biblical scholars. On the other hand, notwithstanding the contempt for profane learning which breathes through the Koran, the Saracen scholars began to direct their attention to the learning of other creeds, and the languages of other races. Ibn Wasil, who came into Italy in 1250 as ambassador to Manfred, the son of Frederic II., was reported to be familiar with the Western tongues. The Spanish Moors, too, began sedulously to cultivate Greek. The works of Aristotle, of Galen, of Dioscorides, and many other Greek writers, chiefly philosophical, were translated into Arabic by Averroes, Ibn Djoldjol and Avicenna. And the Jewish scholars of that age were equally assiduous in the cultivation of Greek. The learned Rabbi Maimonides, born in Cordova in the early part of the 12th century, was not only master of many Eastern tongues, but was also thoroughly familiar with the Greek language.

It would be a mistake, however, to imagine that it was among the Moors or the Hebrews that the revival of the study of languages first commenced. Alcuin, in addition to the modern languages with which his sojourn in various kingdoms must have made him acquainted, was also familiar with Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Hermann, the Dalmatian, the first translator of the Koran, was well acquainted with Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic. The celebrated Raymond Lully, who was a native of Majorca, was able to lecture in Latin[16] Greek, Arabic, and perhaps Hebrew;—an accomplishment especially wonderful in one who was among the most laborious and prolific writers of his age, and who left after him, according to some authorities, (though this, no doubt, is a great exaggeration), not less than a thousand[27] works on the most diversified subjects. At the instance of this eminent orientalist, the council of Vienne directed that professorships should be founded in all the great Universities, for the Hebrew, Chaldee, and Arabic languages.[28]

An example of, for the period, very remarkable proficiency in modern languages is recorded in the history of the Fourth Lateran Council, 1215. Roderigo Ximenes,[29] Archbishop of Toledo in the early part of the thirteenth century, a native of Navarre, but a scholar of the University of Paris, was one of the representatives of the Spanish Church at that Council. A controversy regarding the Primacy of Spain had arisen between the Sees of Toledo and Compostella, which was referred for adjudication to the bishops there assembled. Ximenes addressed to the council a long Latin oration in defence of the claim of Toledo; and, as many of his auditory, which consisted both of the clergy and the laity, were ignorant of that language, he repeated the same argument in a series of discourses addressed to the natives of each country in succession; to the Romans, Germans, French, English, Navarrese, and Spaniards,[30] each in their respective tongues. Thus the number of languages in which he spoke was at least seven, and it is highly probable that he had others at his disposal, if his auditory had been of such a nature as to render them necessary.

The taste for the languages and literature of the East received a further stimulus from the foundation of the Christian principalities at Antioch and Jerusalem, from the establishment of the Latin Empire at Constantinople, and in general from the long wars in the East, to which the enthusiasm of the age attracted the most enterprising spirits of European[17] chivalry. The pious pilgrimages, too, contributed to the same result. Many of the knights or palmers, on their return from the East, brought with them the knowledge, not only of Greek, but of more than one of the oriental languages besides. The long imprisonments to which, during the holy wars, and the Latin campaigns against the Turks, they were often subjected, supplied another occasion of familiarity with Arabic, Syriac, Turkish, or Persian.

The commercial enterprise of the Western Nations, and especially of the Venetians and Genoese, was a still more powerful instrument of the interchange of languages. Few modern voyagers have possessed more of that spirit of travel which is the best aid towards the acquisition of foreign tongues, than the celebrated Marco Polo. It is hard to suppose that he can have returned from his extensive wanderings in Persia, in Tartary, in the Indian Archipelago, and in China and Tibet, without some tincture of their languages. Still less can this be supposed of his countryman, Josaphat Barbaro, who sojourned for sixteen years among the Tartar tribes.[31] It was in the commercial settlements of the Venetians in the Levant that the profession of interpreters, of which I shall have to speak hereafter, and which has since become hereditary in certain families, was originated or brought to perfection.[32]

It is only, however, from the revival of letters, properly so called, that the history of linguistic studies can be truly said to commence.

The attention of Scholars, in the first instance, was chiefly directed towards the classical languages and the languages of the Bible. The Greek scholars who were driven to the West by the Moslem occupation of Constantinople brought their language, in its best and most attractive form, to the Universities[18] of Italy. In the Council of Florence, in 1438, more than one Italian divine, especially Ambrogio Traversari, was found capable of holding discussions with the Greek representatives in their native tongue. In like manner, the Jews and Moors, who were exiled from Spain by the harsh and impolitic measures of Ferdinand and Isabella, deposited through all the schools of Europe the seeds of a solid and critical knowledge of Hebrew and Arabic and their cognate languages. The fruits of their teaching may be discerned at a comparatively early period in the biblical studies of the time. Antonio de Lebrixa published, in 1481, a grammar of the Latin, Castilian and Hebrew languages: and I need only allude to the mature and various oriental learning which Cardinal Ximenes found ready to his hand, in the very first years of the sixteenth century, for the compilation of the Complutensian Polyglot. Although some of the scholars whom he engaged, as for instance, Demetrius Ducas, were Greeks; and others, as Alfonzo Zamora or Pablo Coronell,[33] were converted Jews; yet, the names of Lopez de Zuniga, Nunez de Guzman, and Vergara[34] are a sufficient evidence of the success with which the co-operation of native scholars was enlisted in the undertaking.[35]

From this period the number of scholars eminent in the department of languages becomes so great, and the history of many among them presents so frequent points of resemblance, that it may conduce to the greater distinctness of the narrative to classify separately the most distinguished linguists of each among the principal nations.

Although the inquiry must of course commence with the East, the cradle of human language, unfortunately the materials for this portion of the subject are more meagre and imperfectly preserved than any other.

In the East indeed, the faculty of language appears, for the most part, in a form quite different from what we shall find among the scholars of the West. The Eastern linguists, with a few exceptions, have been eminent as mere speakers of languages, rather than scholars even in the loosest sense of the word.

As it is in the East that the office of Dragoman or “interpreter” first rose to the dignity of a profession, so all the most notable Oriental linguists have belonged to that profession.

A very remarkable specimen of this class occurs in the reign of Soliman the Magnificent, and flourished in the early part of the sixteenth century. A most interesting account is given of him, under his Turkish name of Genus Bey, by Thevet, in that curious repertory—his Cosmographie Universelle.[36] He was the son of a poor fisherman, of the Island of Corfu; and while yet a boy, was carried away by pirates and sold as a slave at Constantinople. Thence he was carried into Egypt, Syria, and other Eastern countries; and he would also seem to have visited most of the European kingdoms, or at least to have enjoyed the opportunity of intercourse with natives of them all. His proficiency in the languages both of the East and West, drew upon him the notice of the Sultan, who appointed him his First Dragoman, with the rank of Pasha. Thevet (who would seem to have known him personally during his wanderings,) describes him in his quaint old French, as “the first man of his day for speaking divers sorts of languages, and of the happiest memory under the Heavens.” He adds, that this extraordinary man “knew perfectly no fewer than sixteen languages, viz: Greek, both ancient and modern, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Moorish, Tartar, Armenian, Russian, Hungarian, Polish, Italian, Spanish, German, and French.” Genus Bey, was, of course, a renegade; but, from a circumstance related by Thevet, he appears to have retained a reverence for his old faith, though not sufficiently strong to be proof against temptation. He was solicited by some bigoted Moslems to remove a bell, which the Christians had been permitted to erect in their little church. For a time he refused to permit its removal; but at last he was induced by a large bribe, to accede to the demand. Thevet relates that, in punishment of his sacrilegious weakness, he was struck with that loathsome disease which smote King Herod, and perished miserably in nine days from the date of this inauspicious act.

In Naima’s “Annals of the Turkish Empire,” another renegade, a Hungarian by birth, is mentioned, who spoke fourteen languages, and who, in consequence of this accomplishment, was employed during a siege to carry a message through the lines of the blockading army.[37]

A still more marvellous example of the gift of languages is mentioned by Duret, in his Trésor des Langues (p. 964)—that of Jonadab, a Jew of Morocco, who lived about the same period. He was sold as a slave by the Moors, and lived for twenty-six years in captivity in different parts of the world. With more constancy to his creed, however, than the Corfu Christian, he withstood every attempt to undermine his faith or to compel its abjuration; and, from the obduracy of his resistance, received from his masters the opprobrious name Alhanar, “the serpent” or “viper.” Duret says that Jonadab spoke and wrote twenty-eight different languages. He does not specify their names, however, nor have I been able to find any other allusion to the man.

It would be interesting, if materials could be found for the inquiry, to pursue this extremely curious subject through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and especially in the military and commercial establishments of the Venetians in the Morea and the islands. The race of Dragomans has never ceased to flourish in the Levant. M. Antoine d’Abbadie informed me that there are many families in which this office, and sometimes the consular appointment for which it is an indispensable qualification, have been hereditary for the last two or three centuries; and that it is very common to find among them men and women who, sufficiently for all the ordinary purposes of conversation, speak Arabic, Turkish, Greek, Italian, Spanish, English, German, and French, with little or no accent. This accomplishment is not confined to one single nation. Mr. Burton, in his “Pilgrimage to Medinah and Meccah,” mentions an Afghan who “spoke five or six languages.”[38] He speaks of another, a Koord settled at Medinah, who “spoke five languages in perfection.” The traveller, he assures us, “may hear the Cairene donkey-boys shouting three or four European dialects with an accent as good as his own;” and he “has frequently known Armenians (to whom, among all the Easterns, he assigns the first place as linguists) speak, besides their mother tongue, Turkish, Arabic, Persian, and Hindostanee, and at the same time display an equal aptitude for the Occidental languages.”[39]

But of all the Eastern linguists of the present day the most notable seem to be the ciceroni who take charge of the pilgrims at Mecca, many of whom speak fluently every one of the numerous languages which prevail over the vast region of the Moslem. Mr. Burton fell in at Mecca with a one-eyed Hadji,[21] who spoke fluently and with good accent Turkish, Persian, Hindostani, Pushtu, Armenian, English, French, and Italian.[40] In the “Turkish Annals” of Naima, already cited, the learned Vankuli Mohammed Effendi, a contemporary of Sultan Murad Khan, is described as “a perfect linguist.”[41] Many similar instances might, without much difficulty, be collected; nor can it be doubted that, among the numerous generations which have thus flourished and passed away in the East, there may have been rivals for Genus Bey, or even for “the Serpent” himself. But unhappily their fame has been local and transitory. They were admired during their brief day of success, but are long since forgotten; nor is it possible any longer to recover a trace of their history. They are unknown,

It would be a great injustice, however, to represent this as the universal character of the Eastern linguists. On the contrary, it has only needed intercourse with the scholars of the West in order to draw out what appears to be the very remarkable aptitude of the native Orientals for the scientific study of languages. Thus the learned Portuguese Jew, Rabbi Menasseh Ben Israel (1604-1657), was not only a thorough master of the Oriental languages, but was able to write with ease and exactness several of the languages of the West, and published almost indifferently in Hebrew, Latin, Spanish, and English.[43] I allude more particularly, however, to those bodies of Eastern Christians, which, from their community of creed with the Roman Church, have, for several centuries, possessed ecclesiastical establishments in Rome and other cities of Europe.

The Syrians had been remarkable, even from the classic times,[44] for the patient industry with which they devoted themselves to the labour of translation from foreign languages into their own. Many of the modern Syrians, however, have deserved the still higher fame of original scholarship.

The Maronite community of Syrian Christians has produced several scholars of unquestioned eminence. Abraham Echellensis was one of the chief assistants of Le Jay, at Paris, in the preparation of his Polyglot. His services in a somewhat similar capacity at Rome are familiar to all Oriental scholars. But it is to the name of Assemani that the Maronite body owes most of its reputation. For a time, indeed, literature would seem to have been almost an inheritance in the family of Assemani. It has contributed to the catalogue of Oriental scholars no less than five of its members—Joseph Simon, who died in 1768; his nephews, Stephen Evodius and Joseph Lewis; Joseph Aloysius, who died at Rome in 1782; and Simon, who died at Padua in 1821. The first of them is the well-known editor of the works of St. Ephrem, and author of the great repertory of Oriental ecclesiastical erudition, the Bibliotheca Orientalis.

The Greeks, with greater resources, and under circumstances more favourable, are less distinguished as linguists. John Matthew Caryophilos, a native of Corfu, who was archbishop of Iconium and resided at Rome in the early part of the seventeenth century, was a learned Orientalist, and, besides several literary works of higher pretension, published some elementary books on the Chaldee, Syriac, and Coptic languages. But he has few imitators among his countrymen. Leo Allatius (Allazzi), although a profound scholar, and familiar with every department of the literature of the West, whether sacred or profane,[45] can hardly be considered a linguist in the ordinary[23] sense of the word. The same may be said of the many Greek students, as, for instance, Metaxa, Meletius Syrius, and others, who, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, repaired to the universities of Italy, France, and even England.[46] It can hardly be doubted, of course, that many of them acquired a certain familiarity with the languages of the countries in which they sojourned, but no traces of this knowledge appear to be now discoverable. By far the most notable of them, Cyrillus Lucaris, the well-known Calvinistic Patriarch of Constantinople, spoke and wrote fluently Arabic, Greek, Latin, and Italian; but, if his latinity be a fair sample of his skill in the other languages, his place as a linguist must be held low indeed.[47] It should be added, however, that as polyglot speakers, the Greeks have long enjoyed a considerable reputation. The celebrated Panagiotes Nicusius[48] (better known by his Italianized name Panagiotti) obtained, despite all the prejudices of race, the post of First Dragoman of the Porte, about the middle of[24] the seventeenth century; and, from his time forward, the office was commonly held by a Greek, until the separation of Greece from the Ottoman Empire.

Mr. Burton’s observation that no natives of the East seem to possess the faculty of language in a higher degree than the Armenians, is confirmed by the experience of all other travellers; and the commercial activity which has long distinguished them, and has led to their establishing themselves in almost all the great European centres of commerce, has tended very much to develope this national characteristic. A far higher spirit of enterprise has led to the foundation of many religious establishments of the Armenians in different parts of Europe, which have rendered invaluable services, not only to their own native language and literature, but to Oriental studies generally. Among these the fathers of the celebrated Mechitarist order have earned for themselves, by their manifold contributions to sacred literature, the title of the Benedictines of the East. The publications of this learned order (especially at their principal press in the convent of San Lazzaro, Venice,) are too well known to require any particular notice. Most of their publications regard historical or theological subjects; but many also are on the subject of language,[49] as grammars, dictionaries, and philological treatises. A little series of versions, the Prayers of St. Nerses in twenty-four languages, printed at their press, is one of the most beautiful specimens of polyglot typography with which I am acquainted. Among the scholars of the order the names of Somal, Rhedeston, Ingigean, Avedichian, Minaos, and, above all, of the two Auchers, are the most prominent. One of the latter is best known to English readers as the friend of Byron, his instructor in Armenian, and his partner in the compilation of an Anglo-Armenian grammar. The fathers of this order generally, however, both in Vienna and in Italy, have long enjoyed the reputation of being excellent linguists. Visitors of the Armenian convent of St. Lazzaro at Venice cannot fail to be struck by this accomplishment among its inmates. Besides[25] the ordinary Oriental languages, most of them speak Italian, French, and often German. I have heard from M. Antoine d’Abbadie that, in 1837, Dr. Pascal Aucher spoke no less than twelve languages.

The most prominent among the nations of the West at the period immediately succeeding the Revival of Letters, is of course Italy.

The first in order, dating from this period, among the linguists of Italy, is also in many respects the most remarkable of them all;—at least as illustrating the possibility of uniting in a single individual the most diversified intellectual attainments, each in the highest degree of perfection;—the celebrated Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, son of the Duke John Francis of that name.[50] He was born in 1463, and from his childhood was regarded as one of the wonders of his age. Before he had completed his tenth year, he delivered lectures in civil and canon law, not less remarkable for eloquence than for learning. While yet a boy he was familiar with all the principal Greek and Latin classics. He next applied himself to Hebrew; and, while he was engaged in that study, a large collection of cabalistic manuscripts, which were represented to him as genuine works of Esdras, turned his attention to the other Eastern languages, and especially the Chaldee, the Rabbinical dialect of Hebrew, and the Arabic. Unfortunately, the strange and fantastic learning with which he was thus thrown into contact gave a tinge to his mind, which appears to have affected all his later studies. His progress in languages, however, cannot but be regarded as prodigious, when we consider the poverty of the linguistic resources of his age. At the age of eighteen he had the reputation of knowing no fewer than twenty-two languages, a considerable number of which he spoke with fluency. And while he thus successfully cultivated the department of languages, he was, at the same time, an extraordinary proficient in all the other knowledge of his day. His memory was so wonderful as to be reckoned among the[26] marvellous examples of that gift which are enumerated by the writers upon this faculty of the human mind. Cancellieri states that he was able, after a single reading, not only to recite the contents of any book which was offered to him, but to repeat the very words of the author, and even in an inverted order.[51] In 1486 he maintained a thesis in Rome, De omni Re Scibili. Much of the learning which it displayed was certainly of a very idle and puerile character; much of it, too, was the merest pedantry; but nevertheless it is undeniable that the nine hundred propositions of which it consisted, comprised every department of knowledge cultivated at that period. And it is impossible to doubt that, if Pico’s career had been prolonged to the usual term of human life, his reputation would have equalled that of the greatest scholars, whether of the ancient or the contemporary world. He was cut off, however, at the early age of thirty-one.

It is not unnatural to suppose that this circumstance, as well as the rank of Pico, and the singular precocity of his talents, may have led to a false or exaggerated estimate of his acquirements. But, even allowing every reasonable deduction on this score, his claim must be freely admitted to the character of one of the greatest wonders of his own or any other age, whether he be considered as a linguist or as a general scholar.

Marvellous, however, as is the reputation of Pico della Mirandola, perhaps the science of language owes more to a less brilliant but more practical scholar of the same period, Teseo Ambrosio, of the family of the Albonesi. He was born at Pavia, in 1469. His admirers have not failed to chronicle such precocious indications of genius as his composing Italian, Latin, and even Greek poetry, before he was fifteen; but he himself confesses that his proficiency in these studies dates from a considerably later time. He entered the order of Canons Regular of St. Augustine, and fixed his residence at Rome, where he devoted himself with great assiduity to Oriental studies, and acquired such a reputation, that when, in the Lateran Council of 1512, the united Ethiopic and Maronite Christians solicited the privilege of using their own peculiar liturgies while they maintained the communion of the Roman church, it was to him the task of examining those liturgies, and of ascertaining how far their teaching was in accordance with the doctrines of the Church, was entrusted by the Holy See. Teseo assures us that, at the time when he received this[27] commission, he knew little more than the elements of Hebrew, Chaldee, and Arabic. He set to work with the assistance of a native Syrian (who, however, was entirely ignorant of Latin); and, carrying on their communication by mutual instruction, he was soon able not only to master the difficulties of these languages, but to set on foot what may be regarded as (at least conjointly with the Complutensian Polyglot) one of the earliest systematic schemes for the promotion of Oriental studies. He had types cast expressly for his projects; and he himself prepared the Chaldee Psalter for the press, and repaired to his native city of Pavia for the purpose of having it printed. He died (1539) before it was completed;[52] but his types were turned to account by other scholars. It was with Teseo’s types that William Postel printed two out of the five Pater Nosters contained in his collection—the Chaldee and the Armenian.[53] And to him we owe a still greater boon—the first regular attempt at a Polyglot Grammar; which, however imperfectly, comprises the elements of Chaldee, Syriac, Armenian, and ten other languages.

The scholarship of Ambrogio was derived almost entirely from books. His countryman, Antonio Pigafetta, enjoyed among his contemporaries a different reputation, that of considerable skill as a speaker of foreign languages, acquired during his extensive and protracted wanderings. Pigafetta was born at Vicenza, towards the end of the fifteenth century. In the expedition undertaken, under the patronage of Charles V., for the conquest of the Moluccas, by the celebrated Fernando Magellan, the first circumnavigator of the globe, one of the literary staff was Pigafetta, who acted as historiographer of the expedition, and to whose narrative we are indebted for all the particulars of it, which have been preserved.

Marzari describes Pigafetta as a prodigy of learning; and, although this has been questioned by later inquirers,[54] there is no reason to doubt his acquirements in modern languages at[28] least, and particularly his skill and success in obtaining information as to the languages of the countries which he visited. It is to him[55] we are indebted for the first vocabularies of the language of the Philippine and Molucca islands, the merit of which is recognized even by recent philologers.[56]

It may be permitted to class with the linguists of Italy, a Corsican scholar of the same period, Augustine, bishop of Nebia. It is difficult to pronounce definitively as to the extent of his attainments; but his skill in the ancient languages, at least, is sufficiently attested by the polyglot Bible which he published, (containing the Hebrew, Greek, Chaldee, and Arabic texts,) of which Sixtus of Sienna speaks in the highest terms; and if we could receive without qualification the statement of the same writer, we should conclude that Augustine’s familiarity with modern languages was even more extensive. Sixtus of Sienna describes him as “deeply versed in the languages of all the nations which are scattered over the face of the earth.”

Towards the close of the sixteenth century the study of languages in Italy assumed that practical character in relation to the actual exigencies of missionary life by which it has ever since been mainly characterized in that country. The Oriental press established at Florence by the Cardinal Ferdinand de Medici, under the superintendence of the great orientalist Giambattista Raimondi;[57] the opening at Rome of the College De Propaganda Fide; the foundation of the College of San Pancrazio, for the Carmelite Oriental Missions in 1662; the opening of similar Oriental schools in the Dominican, the Franciscan, Augustinian, and other orders, for the training of candidates for their respective missions in the East; and above all, the constant intercourse with the Eastern missions which began to be maintained, gave an impulse to Oriental studies,[29] the more powerful and the more permanent, because it was founded on motives of religion; and although we do not meet among the missionary linguists that marvellous variety of languages which excites our wonder, yet we find in them abundant evidences of a solid and practical scholarship, whose fruits, if less attractive, are more useful and more enduring. Nearly all the linguists of Italy from the close of the sixteenth century, appear to have been either actually missionaries, or connected with the colleges of the foreign mission.

Thus, Antonio Giggei, one of the “Oblates of Mary,” taught Persian in a missionary college, at Milan, and, at a later period, taught Arabic in Florence. Giggei’s Thesaurus Linguæ Arabicæ,[58] is still much esteemed. He wrote besides, a Grammar of Chaldee and of Rabbinical Hebrew, which is still preserved in manuscript in the Ambrosian Library at Milan; and his translation of a Rabbinical commentary on the Proverbs of Solomon, published at Milan in 1620, is an evidence of his familiarity, not only with Biblical Hebrew, but with the language of the Talmud in all its successive phases.

In like manner, Clemente Galani, the eminent Armenian scholar, spent no less than twelve years as a missionary in Armenia. On his return to Rome, in 1650, he was such a proficient in the language that he was able, not only to write both in Armenian and Latin his well-known work on the conformity of the creeds of the Armenian and Roman Churches,[59] but also to deliver theological lectures to the Armenian students in Rome in their native tongue.[60]

Tommaso Ubicini was a Franciscan missionary in the Levant.[61] He was born at Novara, and entered young into the order of Friar-minors. He was named guardian of the Franciscan convent in Jerusalem; and, during a residence of many years, made himself master, in addition to Hebrew and Chaldee,[30] of the Syriac, Arabic, and Coptic languages. The latter years of his life were spent in the convent of San Pietro in Montorio at Rome; where, besides publishing several works upon these languages, be taught them to the students of his order. His great work, Thesaurus Arabico-Syro-Latinus was not published till 1636, several years after his death.[62]

Ludovico Maracci, best known to English readers by the copious use to which Gibbon has turned his translation and annotations of the Koran, was one of the missionary “Clerks of the Mother of God.” He was born at Lucca in 1612, and first obtained notice by the share which he had in the Roman edition of the Arabic Bible, published in 1671. He taught Arabic for many years with great distinction in the University of the Sapienza at Rome. But his best celebrity is due to his critical edition of the Koran, and the admirable translation which accompanies it.[63] From this repertory of Arabic learning, Sale has borrowed, almost without acknowledgment, or rather with occasional depreciatory allusions, all that is most valuable in his translation and notes.

One of Maracci’s pupils, John Baptist Podestà, (born at Fazana early in the 17th century), is another exception to the general rule. Having perfected his Oriental studies in Constantinople, he was appointed Oriental Secretary of the Emperor Leopold at Vienna, and attained considerable reputation as Professor of Arabic in that university. He published a Grammar of Arabic, Persian, and Turkish; which, however, was severely, and, indeed, ferociously, criticised by his contemporary and rival, Meninski.

But Podestà’s contemporary, Paolo Piromalli, was trained in the school of the Mission. He was a native of Calabria, and became a member of the Dominican order. Piromalli was for many years attached to the Mission of his order in Armenia, and was eminently successful in reconciling the separated Armenians to the Roman Church, having even the happiness to number among his converts the schismatical patriarch himself. From Armenia, Piromalli passed into the Missions of Georgia and Persia. He afterwards went, in the capacity of Apostolic Nuncio, to Poland, with a commission of much importance to the Emperor from the Pope, Urban VIII.[31] In the course of one of his voyages he was made prisoner by the Algerine corsairs, and carried as a slave to Tunis; but he was soon after redeemed and called to Rome, whence, after he had been entrusted with the revision of an Armenian Bible, he was sent back to the East, as Bishop of Nachkivan in 1655. He remained in this charge for nine years, and was called home as Bishop of Bisignano, where he died in 1667. Piromalli published two dictionaries, Persian and Armenian, and several other works upon these languages.[64]

The Augustinian order in Italy, also, produced a linguist, not inferior in solidity, and certainly superior in range of attainments, to any of those hitherto enumerated—Antonio Agostino Giorgi.[65] He was born at San Mauro, near Rimini, in 1711, and entered the Augustinian order at Bologna; but Benedict XIV., who, during his occupancy of the see of Bologna, had become acquainted with his merit, invited him to Rome after his elevation to the Papacy, and appointed him to a professorship in the Sapienza. Father Giorgi occupied this post with much distinction for twenty-two years, till his death, in 1797. His acquirements as a linguist were more various than those of any of the scholars hitherto named. Besides modern languages, he knew not only Greek, Hebrew, Chaldee, Samaritan, and Syriac, but also Coptic and (what was at that period a much more rare accomplishment) Tibetan. On the last named language he compiled an elementary work for the use of missionaries, which, although it is not free from inaccuracies, deserves, nevertheless, the highest praise as a first essay in that till then untried language.

Simon De Magistris, one of the priests of the Oratory, (born at Ferrara in 1728) was for many years at the head of the Congregation of the Oriental Liturgies in Rome. He was not only deeply versed in the written languages of the East, but spoke the greater number of them with the same ease and fluency as his native Italian.[66]

Of the learned Dominican, Finetti, I am unable to offer any particulars. His treatise “On the Hebrew and its cognate Languages” is a sufficient evidence of his ability as an Orientalist; but it contains no indication of anything beyond the learning which is acquired from books.

The same may be said of the Oratorian, Valperga de Galuso. He was born at Turin in 1737, but lived chiefly in the convents of his order at Naples, Malta, and Rome. In addition, however, to his accomplishments as an Orientalist, Padre de Galuso had the reputation of being one of the most skilful mathematicians of his day. He died in 1815.

Our information regarding the two De Rossi’s, Ignazio, author of the Etymologicum Copticum, and Giambernardo, of Parma, is more detailed and more satisfactory.

Ignazio de Rossi was born at Viterbo in 1740, and entered the Jesuit society at a very early age. In the schools of Macerata, Spoleto, and Florence, he was employed in teaching the Humanities and Rhetoric until the suppression of the order in 1773; after which event he repaired to Rome, and received an appointment as professor of Hebrew in the University, which he held for thirty years, rejoining his brethren, however, at the first moment of their restoration under Pius VII.

As a general scholar, Father De Rossi was one of the first men of his day. His memory may be ranked among the most prodigious of which any record has been preserved. On one occasion, during the villeggiatura at Frascati, it was tried by a test in some respects the most wonderful which has ever been applied in such cases. A line being selected at pleasure from any part of any one of the four great Italian classics, Dante, Petrarca, Tasso, and Ariosto, De Rossi immediately repeated the hundred lines which followed next in order after that which had been chosen; and, on his companions expressing their surprise at this extraordinary feat (which he repeated several times), he placed the climax to their amazement by reciting in the reverse order the hundred lines immediately preceding any line taken at random from any one of the above-named poets.[67] His reputation as an Orientalist was founded chiefly upon his familiarity with Hebrew and the cognate languages. But he was also a profound Coptic scholar; and it is a subject of regret to many students of that language that his numerous MSS. connected therewith have been suffered to remain so long unpublished. He died in 1824.

Giovanni Bernardo de Rossi was a linguist of wider range.[33] He was born at Castel Nuovo, in Piedmont, in 1742, and in his youth was destined for the ecclesiastical state. He began his collegiate studies at Turin, and manifested very early that taste for Oriental literature which distinguished his after life. Within six months after he commenced his Hebrew studies, he produced a long Hebrew poem. In addition to the Biblical Hebrew, he was soon master of the Rabbinical language, of Chaldee, Syriac, and Arabic. He learned besides, by private study, most of the languages of modern Europe;—his plan being to draw up in each a compendious grammar for his own use. In this way he prepared grammars of the German, English, and Russian languages. In 1769, he obtained an appointment in the Royal Museum at Turin; but, being invited at the same time to undertake the much more congenial office of Professor of Oriental Languages in the new University of Parma, he gladly transferred himself to that city, where he continued to reside, as Professor of Oriental Literature, for more than forty years. During the latter half of this period, De Rossi maintained a frequent correspondence with Mezzofanti, upon the subject of their common studies.[68] From the terms in which such a scholar as Mezzofanti speaks of De Rossi, and the deference with which he appeals to his judgment, we may infer what his acquirements must have been. On occasion of the marriage of the Infante of Parma, Charles Emanuel, he published a polyglot epithalamium,[69]—a Collection of Hymeneal Odes in various languages—which even still is regarded as the most extraordinary of that class of compositions[70] ever produced by a single individual. It does not belong to my present plan to allude to the works of De Rossi, or to offer any estimate of his learning; but without entering into any such particulars, or attempting to specify the languages with which he was acquainted, it may safely be said that no Italian linguist[34] from the days of Pico della Mirandola can be compared with him, either in the solidity or the extent of his linguistic attainments. De Rossi died in 1831.[71]

The fame of the linguists of Italy during the nineteenth century has been so completely eclipsed by that of Mezzofanti, that I shall not venture upon any enumeration of them, though the list would embrace such names as Rossellini, Luzatto, Molza, Laureani, &c. There are few of whom it can be said with so much truth as of Mezzofanti:—