Title: Passed by the censor

The experience of an American newspaper man in France

Author: Wythe Williams

Author of introduction, etc.: Myron T. Herrick

Contributor: Georges Clemenceau

Lafayette Young

Release date: September 11, 2022 [eBook #68970]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2022

Language: English

Original publication: United States: E. P. Dutton & Company

Credits: Graeme Mackreth and The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

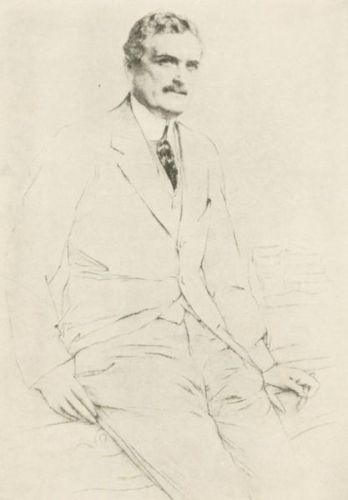

MYRON T. HERRICK

UNITED STATES AMBASSADOR TO FRANCE

From a hitherto unpublished drawing by Royer

PASSED BY THE CENSOR

THE EXPERIENCE OF AN

AMERICAN NEWSPAPER MAN IN FRANCE

BY

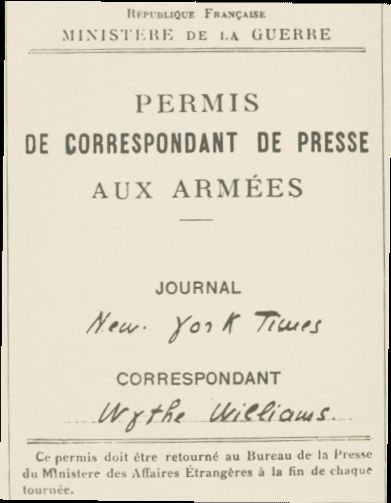

WYTHE WILLIAMS

PARIS CORRESPONDENT OF THE NEW YORK TIMES,

OFFICIALLY ACCREDITED TO THE FRENCH

ARMIES ON THE WESTERN FRONT

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

MYRON T. HERRICK

FORMER UNITED STATES AMBASSADOR TO FRANCE

NEW YORK

E.P. DUTTON & COMPANY

681 FIFTH AVENUE

Copyright, 1916

By E.P. DUTTON & COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO VIOLA

PREFACE

Special correspondents in great numbers have come from America into the European "zone of military activity," and in almost equal numbers have they gone out, to write their impressions, their descriptions, their histories, their romances and songs.

Other correspondents who are not "special," but who by the grace of the military authorities have been permitted to enter the forbidden territory, and by the favor of the censor have been allowed to tell what they saw there, have entered it again and again at regular intervals.

These are the "regular" correspondents, who lived in Europe before war was declared, and who during many idle hours speculated on what they would do with that great arm of their vocation—the cable—when the expected hour of conflict arrived.

Few of their plans worked out, and new ones were formed on the minute—on the second. For the Germans did not cut the cable, as some of the correspondents, in moments of despair, almost hoped they would do, and the great American public clamored insistently for the "news" with its breakfast.

It is a journalist's methods in covering the biggest, the hardest "story" that newspapers were ever compelled to handle, that this book attempts to describe.

Wythe Williams.

Paris, October, 1915.

AN ENDORSEMENT

By Georges Clemenceau

Former Premier of France.

"In the crowded picture which this American journalist has presented we recognize our men as they are. And he pronounces such judgment as to arouse our pride in our friends, our brothers and our children. Such a people are the French of to-day. They must also be the French of to-morrow. Through them France sees herself regenerate.

"Of our army, Mr. Wythe Williams says:

"'It seems to me to be invincible from the standpoints of power, intelligence and humanity.'

"Is there not in that something like a judgment pronounced upon France before the people of the world? Where I am particularly surprised, I admit, is that the eye of a foreigner should have been so penetrating, and that our friendly guest should have coupled the idea of an 'invincible' army with the supreme ethical consideration of its 'humanity.'

"Mr. Wythe Williams is right to proclaim this, even though it is something of a stroke of genius for a non-Frenchman to have discovered it."—(From an editorial in L'Homme Enchainé.)

LETTER TO THE AUTHOR FROM SENATOR LAFAYETTE YOUNG

My Dear Williams:

I am glad to know that you are going to write about the war in book form. In doing this you are discharging a plain duty. You have been in the war from the start. You have studied the soldier in the trench, and out. You have witnessed every phase of battle. The war is in your system. You are full of it. Therefore, you can write concerning it with inspiration and fervor.

I remember our long marches in and near the trenches in Northern France in April and May, last. I know how deeply you are interested; therefore, I know how well you will write.

A thousand historians will write books concerning the present great conflict, but the real historians will be the honest, independent observers such as you have been.

Newspaper reports will be the basis of every battle's history.

Take the battle of the Marne, for instance. Who knows so well concerning it as men like yourself, who were in Paris or near it during the seven days' conflict?

The passing years may bring dignified historians who will compose sentences which shall sound well, but none of them will be so full of real history as your volume if you write your own experiences.

I never knew a man freer from prejudice, and at the same time fuller of enthusiasm than yourself. I want you to write your book with the same free hand you write for the New York Times. Forget for the time that you are writing a book.

I am pleased to know that you have been with the army several times since I parted company with you. This, with your experience as an ambulance driver, when the first hostilities were on, has certainly made you a military writer worth while.

I count you to be one of the three best and most truthful American correspondents who have been in the war from the start.

I am hoping the time will come when these wars shall end, when bright men like yourself shall return to the work of journalism in America.

With greatest affection, I subscribe myself,

Lafayette Young.

| Introduction by Myron T. Herrick | ||

| PART ONE | ||

| THE HECTIC WEEK | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Day | 1 |

| II | The Night | 9 |

| III | Herrick | 19 |

| IV | Les Américains | 31 |

| V | War | 39 |

| PART TWO | ||

| THE GREATEST STORY | ||

| VI | The Actuality | 49 |

| VII | The Field of Glory | 55 |

| PART THREE | ||

| THE ARM OF MILITARY AUTHORITY | ||

| VIII | The Field of Battle | 73 |

| (A) Sentries in the Dark | ||

| (B) The Wounded Who Could Walk | ||

| (C) A Lull in the Bombardment | ||

| IX | "Detained" by the Colonel | 94 |

| X | The Cherche Midi | 110 |

| XI | Under the Croix Rouge | 120 |

| (A) Trevelyan | ||

| (B) The Rue Jeanne d'Arc | ||

| (C) Those from Quesnoy-sur-Somme | ||

| PART FOUR | ||

| WAR-CORRESPONDING DE LUXE | ||

| XII | Out with Captain Blank | 145 |

| XIII | Joffre | 157 |

| XIV | The Man of the Marne and the Yser | 172 |

| XV | The Battle of the Labyrinth | 184 |

| XVI | "With the Honors of War" | 193 |

| XVII | Sister Julie, Chevalier of the Legion of Honor | 209 |

| XVIII | The Silent Cannon | 226 |

| XIX | D'Artagnan and the Soul of France | 230 |

| PART FIVE | ||

| THREE CHAPTERS IN CONCLUSION | ||

| XX | A Rearpost of War | 245 |

| XXI | Myths | 256 |

| XXII | When Chenal Sings the "Marseillaise" | 264 |

By Myron T. Herrick,

Former United States Ambassador to France.

The rigid censorship placed on journalism upon the declaration of war in Europe brought the representatives of the American press into close relationship with the Embassy. The news which they brought to the Embassy and such news as they received there, required unusual discretion, frankness and confidence on the part of all concerned in order that the American public should receive accurate information, while avoiding the commission of any improprieties against the countries involved in the great conflict.

In this supreme test the American newspaper representatives appreciated that they were something more than mere purveyors of news; they arose to the full comprehension of their responsibility, and were of invaluable assistance to the Embassy, and through it to the nation.

While there has been no opportunity to read the advance sheets of this book, my confidence in the character and ability of the author, begotten in those days when real merit, and demerit as well, were revealed, makes it a pleasure to write this foreword, and to commend this volume unseen.

(Signed)

Myron T. Herrick

Cleveland, Ohio, October 19th, 1915.

At the outbreak of the European war, the author, who was then stationed in Paris as the correspondent of the New York Times, was refused, with all other correspondents, any credentials permitting him to enter the fighting area. He entered it later, immediately after the battle of the Marne, with what were in Paris considered sufficient credentials. But he was arrested, returned to Paris as a prisoner of war and lodged in the Cherche Midi prison, the famous military prison, where Dreyfus was confined. He was released upon the intervention of Ambassador Herrick, but still baffled in getting to the front as a war correspondent, he volunteered for service in the Red Cross as an orderly on a motor ambulance. A few of the descriptions in the following pages are written from notes made during the two months he remained in that service.

At the beginning of 1915, the author was officially accredited as a correspondent attached to the French army, and at the beginning of February sent to his paper the longest cable despatch permitted to pass the censor since the beginning of the war, and the first authentic detailed description of the French forces after the battle of the Marne.

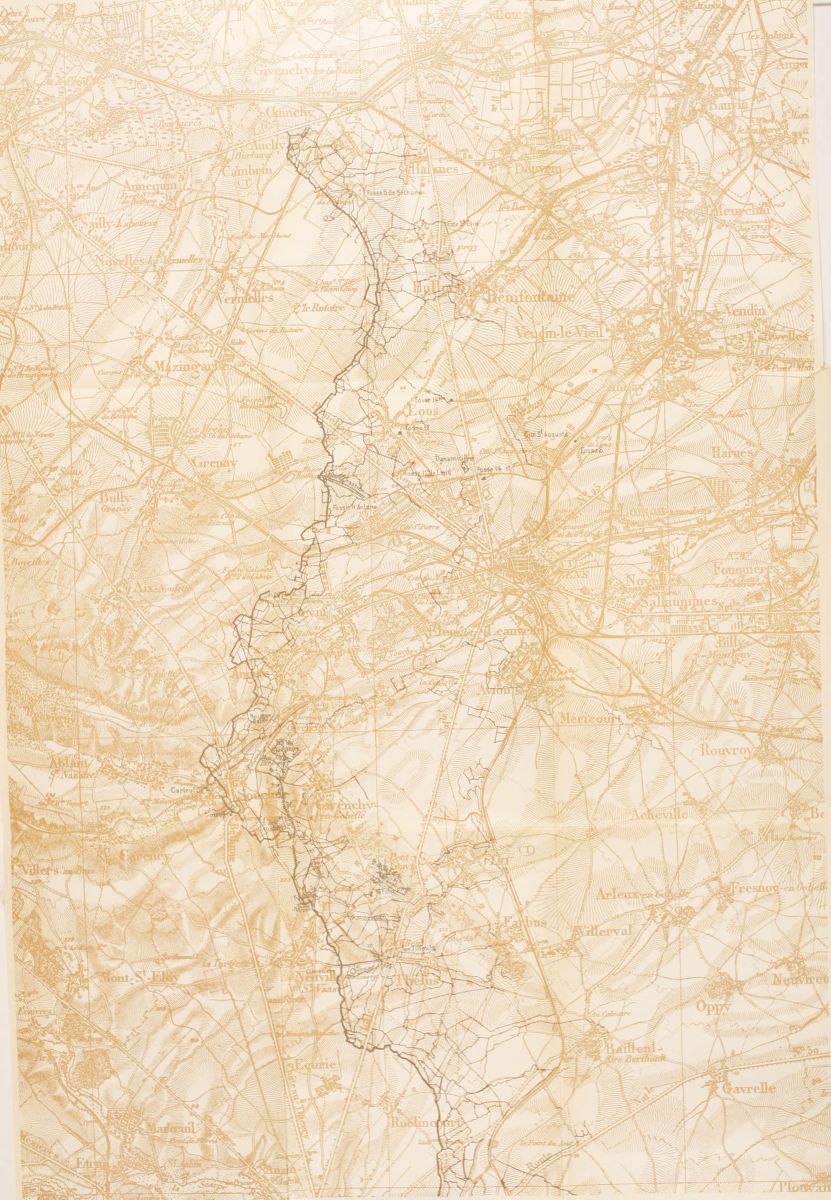

The following spring, at the height of the first great French offensive north of Arras, the famous ground, every yard of which is stained with both French and German blood, the author was selected by the French Ministry of War as the only neutral correspondent permitted there. The first description given to America of the battle of the Labyrinth was the result.

Since then the author has made a number of trips to the front, always under the escort of an officer of the Great General Headquarters Staff, and has seen practically the entire line of the French trenches, up to the moment of the autumn offensive in Champagne. He was the first American correspondent to foreshadow this offensive in a long cable to his paper at the end of August, in which he asserted that the attack would commence "before the leaves are red," that being the only wording of the facts permitted by the censor, but which exactly timed the date of the action. A few of the following chapters have been rewritten from the author's article published in the New York Times, to which acknowledgment is made for permission to use such material. The author however wishes alone to stand sponsor for the sentiments and opinions expressed throughout the volume.

THE HECTIC WEEK

THE DAY

A member of the Garde Republicaine, whose duty was to keep order in the court, was creating great disorder by climbing over the shoulders of the mob in the press section. He ousted friends of the white-faced prisoner in the dock, to make room for a fat reporter from Petit Parisien, who ordinarily did finance but was now relieving a confrère at the lunch hour. The case in court was that of the famous affaire Caillaux and all the world was reading bulletins concerning its progress as fast as special editions could supply them.

I was sitting in the last of the over-crowded rows allotted to the press, but filled with whoever got there first. I was one of the few Americans permitted to cover this important "story" first hand, instead of having to write my nightly cables from reports in the evening papers.

As the Petit Parisien man wheezed and jostled his way to a seat on the bench just in front of me, I caught some words he flung to a friend in passing. Maitre Labori was proclaiming the innocence of the prisoner with all the fervor for which he is celebrated, and I was wondering how soon an adjournment would let us escape from the stifling heat of the room. It was the latter part of July, 1914; and true to French custom all of the windows were shut tight.

The words of the fat reporter pricked my flagging attention, "There is a panic on the Bourse."

The words caused a buzz of comment all around me. One English journalist, monocled and superior, even stopped his writing, and the financial reporter, his fat body half crowded into his seat, paused midway to add: "The Austrian note to Serbia that has got them all scared."

Another French newspaperman some seats away overheard the talk and joined in loudly. It did not matter how much we talked during the proceedings of the affaire Caillaux. Everybody talked. Often everybody talked at the same moment. This journalist prefaced his remarks by a derisive laugh.

"They are crazy on the Bourse," he said. "You may be sure that nothing matters now in[Pg 3] France but this trial. No panic, or Austrian note, or Russian note or anything, will rival it as a newspaper story, I am certain."

The fat reporter again wheezed into speech.

"I do not know very much concerning this affaire Caillaux," he replied, "but I will bet you money that the verdict will not get a top headline."

"Why?" cried some of us, mocking and incredulous.

"Because of what I've told you. There is a panic on the Bourse."

The presiding judge announced the luncheon adjournment; we trooped to the basement restaurant of the Palais de Justice. I found myself sitting at a table with the superior Englishman. We discussed the qualities of French cuisine for a moment; then he said:

"It will be jolly annoying if this Bourse business develops into war, you know."

This was the first mention that I remember of the word "war" in connection with the events that followed so fast for the next few weeks, that now as I look back upon them, they do not seem real at all. One week to the day following this luncheon, I remember saying to a fellow newspaper correspondent, "Is it a week, or is it a year,[Pg 4] since we had Peace in the world?" But at the first mention of the word—the first premonition of the nearness of the tragedy that was descending upon Europe—I remember signaling somewhat abstractedly to a waiter, and giving him an order for food.

Every one of the Americans who covered that session of the Caillaux trial had lived in Europe for years; and the majority were to remain as onlookers of the great war that had been so long predicted. But on this day none of us realized, and none of us knew; and that was the greater part of all our troubles.

I remember a conversation only a few weeks before all this happened, with Mr. Charles R. Miller, the editor of the New York Times, who was passing through Paris on his return to New York from Carlsbad. He asked me when I intended going home, and I replied to him as I had to many others:

"Not until they pull off this war over here. I have been in the newspaper game ever since I left college, but I have never been lucky enough to cover a war. So I do not propose to miss this one."

Then came the invariable question:

"When do you think it will come?"

I had my reply ready. All of us had made it many times.

"Oh, perhaps in a few years. Perhaps it will not be so very long."

The next remark of at least half the persons with whom I discussed the question was, "Pooh, pooh, there'll never be a European war." Mr. Miller only said, "What will you do when it comes?"

Again the reply was pat to hand, but how vague it seems now, in the light of then fast approaching events! It was:

"There will be warning enough to make our plans for beating the censor, I am certain."

It is easy enough to look back now and declare that incidents such as Agadir, the Balkan war and Sarejebo should have been sufficient handwriting on the wall. All those affairs were exactly that, but we simply could not grasp the idea, that actual Armageddon could come without at least months of announcement—time enough for all of us to make our plans. In this I do not think we should be blamed, for we followed so exactly the fatuous beliefs of even foreign ministries. That the great moment should come in a week never entered our imaginations.

We filed back to the court room on that after[Pg 6]noon of the Caillaux trial and fought for the last time the twice daily battle for our seats. I sat beside the superior Englishman. We listened idly to famous politicians and famous doctors and famous lawyers garbling as best they could the dead question of the murder of Gaston Calmette, and the more burning though irrelevant one as to whether Joseph Caillaux was a traitor.

My companion and I discovered that our arrangements for a summer vacation included the same tiny Brittany hamlet by the sea. We passed a portion of the afternoon making mutual plans for the coming month, and at the adjournment drove away from the ancient building on the banks of the Seine in the same fiacre, both trying to align the chief features of the day's sitting, and planning the writing of our night's despatches.

After an hour at my desk that evening, I remember turning to Mr. Walter Duranty, my chief assistant, and saying, "It is about two thousand words to-night. With all the direct testimony that the Associated Press is sending, it ought to lead the paper to-morrow morning. Mark it 'rush.'"

"But about this panic on the Bourse story! Don't you think we should send a special on that?" Mr. Duranty asked.

"Why?" I questioned.

"Because there is an Austrian brokerage firm that has been selling like mad—started all the trouble; it is the identical firm that two years ago—" His voice broke off suddenly. "Listen!" he then shouted. We made a rush to the front windows looking upon the Boulevard des Italiens near the Opera.

The street was seething, which signified exactly nothing, for the Caillaux case had kept the boulevards stirred up for days.

"They are yelling, 'Down with Caillaux!'" I said, as we tore open the window sashes.

"No—it's something else."

We leaned far out. Under the lights moved thousands of heads. Hundreds were reading the latest editions, but in the middle of the road a mob was surging, and we heard a monotonous cry. It was a cry heard that night in Paris for the first time in forty-four years.

The mob was shouting, "To Berlin!"

I slammed shut the window. "Cut that Caillaux cable to a thousand words," I yelled, as I seized my hat, ran down the stairs, and plunged into the crowd, snatching the latest editions as I ran.

The Austro-Serb and Russian news had become[Pg 8] worse within a few hours, and there were already rumors of Franco-German frontier incidents. I hurried along the boulevards, calling at the offices of the Matin and the London Daily Mail, but could get no inside information; nothing but official announcements which would be cabled by the news agencies, and did not interest me, the correspondent of a paper receiving all agency matter.

Later I returned to my office, cabled a story that pictured the scene in the boulevards and gave some details concerning the Austrian brokerage firm that had precipitated the trouble on the Bourse by its selling orders. My paper alone carried the next morning the significant information that this same Austrian house, with high Vienna connections, had made an enormous fortune just two years before, when it had accurate and precise information concerning the hour that the conflict in the Balkans would begin.

This story was a "beat"—probably it was the first "beat" of the European war, but it was almost lost in the mass of heavy despatches that on that night began crowding the cables from every capital in Europe. The next morning probably every newspaper in the world led its columns with the subject of war. Even in Paris the affaire Caillaux was relegated to the second page.

THE NIGHT

A "beat" or a "scoop," otherwise known as exclusive news, is a great matter to a newspaper man. To "put over a beat" gives soul satisfaction, but to be beaten causes poignant feeling of another sort.

There have been some great beats and a multitude of little ones, but up to the beginning of the European war, the greatest beat that was ever put over came from a Paris correspondent.

This was the occasion when Henri de Blowitz, the famous representative of the London Times, gave the full text of the treaty of Berlin before the hour when it was actually signed. That was a real beat, not to be classified with the majority of beats of later years, which were often scandalous, more often paltry, and which often caused us to wonder whether they were worth the cable tolls.

In ante-bellum discussions, the Paris correspondents often opined that the coming conflict would[Pg 10] open a more important field. At least we would no longer chronicle the silly ways of fashion and the crazy ways of society. The turf, the mannequin, the Rue de la Paix, and those who drank tea at the Pré Catalan would give way to real and stirring matters. We all schemed to put over a real beat as soon as the war drums began to roll and the new Paris was revealed. The old Paris, in the minds of American editors, had only been an important place for unimportant things.

Looking back now at the beginnings of Armageddon, and at the particular corner in which I performed a minor rôle, I can say generally that all our schemes went wrong and that there were no "beats" of the slightest importance secured by anybody. Remember, I am only speaking of Paris and France. There were a few great beats elsewhere. There was the famous "scrap of paper" interview given to the Associated Press. There were some exclusive interviews secured in both Germany and England. But France, the real theater of action, where beats were expected, was quite the equal of Japan in her sudden tight sealing of every crevice from which news either big or little might leak.

France had learned several lessons from the year 1870, but this one she learned almost too well.[Pg 11] So far as the neutral opinion of the world was concerned, it was scarcely known that France had an army. Later, but much later, and then very gradually, some real stories were passed by the censor—but even then very few of them were beats.

But during the hectic week when France went to war the censorship was almost overlooked and there were a few precious hours during which the correspondents and their methods of communication were free. The first sign of the censor was the shutting off of the telephone between Paris and London. It had been my custom to talk with our London office nightly in order that the news of the two capitals might be checked, and that we might not duplicate stories.

The second night following the events of the foregoing chapter I talked to our London bureau for the last time. All that day my mind had been busy with one idea: "If war is declared, how can we beat the censor?"

The first answer that probably occurred to every correspondent was: "Code." Alas, events moved too quickly. A secret code was a matter that might have been arranged had we been given our expected months of notice, but there was no time now.

I gave the call for our London office, however, with this idea still uppermost in mind. I waited a quarter of an hour to be put through. Then I heard the voice of my colleague. It sounded harassed. I shall never forget his first remark after the communication was established. I could almost see him pass a hand over a fevered brow; I could almost hear the sigh that I am sure accompanied the words which were:

"My gracious, I never expected to live to see such days as these!"

It was quite natural that he should have said just that, but somehow there did not seem any fitting reply. Also it seemed rather hopeless to talk about codes. So I said:

"I am told that we will not be allowed to telephone after to-night."

He replied: "That's a fact. I guess this is good-by for a while." He paused—then as an afterthought, added: "I think you would better just send everything you can from Paris without paying any heed to whether London does or not."

Inasmuch as a moment had arrived when there was only one possible way to do many things, I quite agreed with him.

The conversation lagged.

"Well, good-by," I shouted.

"Good-by," he replied, "and good luck."

That was the end of the telephone as an adjunct to transatlantic journalism. I have never spoken with our London office from that night.

After hanging up the receiver I had an idea.

It did not and does not now seem a particularly brilliant one; but, again, it was the only possible thing to do. I turned to Mr. Duranty and said:

"We will have a little race with the censor. We will crowd everything possible on the cable before he gets on the job."

All the late editions were on my desk. I clipped and pasted everything of interest on cable forms and sent them to the Bourse. Mr. Duranty took them himself, "just to see if there were any signs of the censor," as he expressed it. Then I began to write, interrupted continually by my dozen extra assistants. I had hired every freelance newspaper man I could find—and I had also a number of volunteers, young American visitors, too interested in events to be in a hurry to get out of the city.

The night was warm and the windows all open. The boulevards were dense with shouting people. There was no mistaking the cries on this night. "À Berlin—À Berlin," echoed above the roar of the traffic and the mob. Cuirassiers frequently[Pg 14] rode through the streets but the crowd immediately surged in behind them.

At ten o'clock the concierge mounted to protest against the street door being open. She was afraid. She was alone in the loge. I told her that the business of the office required the doors kept unlocked. She went away and in a few moments came back with the proprietor of the building, whom she had called by telephone. He insisted on closing the street door. I told him this was a violation of my lease. In view of the circumstances he persisted in his demand. I wheeled my chair about and said to him:

"This office remains open—all night if I desire. It is a newspaper office and we cannot close. If you interfere with me I guarantee that I will keep a man there, but if necessary that man will be a soldier."

"What do you mean?" he asked.

"I mean that I will apply to the American Embassy for the protection of my rights as an American citizen."

He went away and that difficulty ended.

I turned back to my work. I wrote thousands of words that night; when not writing I was dictating, and piecing together the reports of my assistants.

Mr. Duranty returned from the Bourse. His clothes were awry and he was trembling with excitement. He had diverged, in his return trip, to the Gare du Nord, to get a story of the stormy scenes there—thousands, chiefly Americans, fighting for places in the trains for England. He had been arrested, he explained. Oh, yes, he had been surrounded by a mob at the Gare, who spotted him as a foreigner, and the police had rescued him. He explained his identity and was released.

At the end of the story he suddenly leaped across the room to the window. I leaped at the same moment and so did the stenographer. Across the boulevard was a store that dealt in objects of art. The proprietor was a German. During the day he had boarded the place with stout planks. As we reached the window the sound of splitting and tearing planks sounded above even the cries and roars of the angry people. One look and Duranty was out of the office and in the street.

I sat in the window and watched the mob do its work. The torn planks were used as battering rams through the plate glass, through the expensive statuary and costly vases. In five minutes the place was a ruin. Then the cuirassiers came and drove the crowd away. Duranty returned[Pg 16] with the details of the story. I asked him what the police had said to the crowd.

"A man came out holding a marble Adonis by the arm," he replied. "A cop said to him, 'Be good now—be good!' and the chap replied, 'Well, if I can't smash it, you smash it!'—So the cop took it and leaped upon it with both feet."

"Write it," I said; "also the Gare du Nord story."

It was midnight and the uproar was greater than ever. Processions blocks long wended through the middle of the streets singing the "Marseillaise," the "Carmagnole" and other fire-eating songs of the Revolution. Through it all I worked, and steadily sent messenger after messenger to the Bourse with the latest news from the various scenes of action. No signs yet of the censor.

About one o'clock the crowd concentrated just below my window. The cries grew fiercer and louder, with a more terrible note. I went to the window. The faces of the mob were turned to an upper window of the building next door. Some rash voice had shouted from that window a cry that no man might shout that night in Paris with safety. He had cried: "Hurrah for Germany!"

I crawled out on my window ledge and watched.[Pg 17] The crowd filled the street completely. They watched that upper window, they yelled their rage and they battered against a great grilled iron door that baffled their efforts. The police tried to disperse them, but as soon as the street was partly cleared they surged back again. They hung about that door, their faces turned up, the hate showing in their eyes, their mouths open, bellowing forth their rage. They waited as patiently as wolves that have surrounded a quarry that must come out to meet them soon. But the waiting was so long that I crawled back from my window ledge into the office.

I finished a despatch that I had compiled from various documents given out to the morning papers by the Foreign Ministry, and of which I had secured a copy. They were an undisputable proof that Germany meant war on France, for they noted a dozen incidents proving that German mobilization had been under way for days. The dawn was breaking as I pushed my chair from the desk.

I told the stenographer and other assistants to go home and get some sleep—not to report again until late afternoon. Duranty, who, like myself, kept no hours but worked always while there was work to do, sauntered into the private room. He[Pg 18] had counted the words of copy that had been filed that night—nearly twenty thousand.

The yelling of the mob below had given way to low rumbling. We had ceased to think about it. We lighted our pipes and yawned.

"Shall we cut it out for a few hours?" Duranty asked.

"Think so," I replied. "We will hunt a cab and go home until noon."

I stifled another yawn and relighted my pipe.

A scream came from the sidewalk—my pipe dropped to the floor and we were out on the window ledge.

A man was struggling in the middle of the street. He was the man who had so rashly shouted "Vive l'Allemagne" from the window.

He fell and passed out of sight under a mass of bodies. The crowd opened once. The man struggled to his knees. His face was covered with blood. Again we lost sight of him. Then cuirassiers charged down the street. One of them lifted a broken body across his saddle. That story never reached New York. The censor was on the job.

HERRICK

On the morning of September 3, 1914, an "official statement," so called, was inserted by the American Ambassador, Myron T. Herrick, in the Paris edition of the New York Herald. This announcement read:

"The American Ambassador advises, as he has done before, that all Americans who can go, leave Paris, for obvious reasons."

The French Government was then most anxious to get every foreigner possible out of Paris. A siege was imminent and the food question might become very grave. Preparations were made for taking out the British residents. Mr. Herrick arranged with General Galliéni, then the Military Governor, for trains to transport a thousand of them a day, the British Government furnishing the money.

I now have Mr. Herrick's permission to state for the first time, that the American Embassy was then in receipt of a telegram from Mr. Gerard,[Pg 20] our Ambassador in Berlin, in which he said in substance that the German General Staff "advises you and all Americans to leave Paris at once by Rouen and Havre."

For a considerable length of time there was practically no doubt that there would be a siege, and very many believed it would be followed by a German entry into Paris. What happened at Louvain seemed reasonably likely to be repeated at the Louvre; in fact, it was well known to the Government that the German plan was to blow up Paris section by section until the French were forced to capitulate.

When the ministry changed and Delcassé and Millerand came into power, there was a change also in policy, and it was determined that the city should be defended.

On the morning of September second, the President of the Republic summoned Mr. Herrick to the Elysée, to thank him for remaining in Paris. He added that "We propose to defend the city at the outer gates, at the inner gates, and by the valor of our troops, and there will be no surrender."

Under these circumstances the advice to Americans was inserted in the Herald. I called on Mr. Herrick immediately after the notice was written.[Pg 21] He said to me: "What explanation can be made if no such warning is given, and if there is a siege, with many killed and wounded, in face of the situation as it is to-day, and of the warning telegram I have received from Berlin?"

The question has since been asked, sometimes critically, as to why this warning was given, since after all the Germans did not enter Paris. I have therefore given these heretofore unpublished facts at the beginning of this chapter, in order that it shall be known just how faithfully our ex-ambassador guarded his trust to the American people, to give an insight into the character of the man who was easily the most remarkable figure in Paris at the beginning of the war, who was not only the rock upon which the thousands of Americans leaned so heavily, but was also an outstanding favorite of the Paris public.

On one of the nights just preceding mobilization, when the boulevards were at the zenith of their frenzy, I looked out my office window and saw an open carriage, with footmen wearing ambassadorial livery and cockades, driving slowly along the Boulevard des Capucines. Voices snarled in the crowd. Certain ambassadors were not popular in Paris in those days; so just who[Pg 22] might this ambassador be, at that moment straining his eyes to read a paper under the electric arc lights?

He looked up as he heard the hoots directed at himself—then smiled and shouted something at the crowd.

"Ah, l'Ambassadeur Americain!" they passed the word. Then rose cries of "Vive l'Amérique!—Vive Herrick!" Men jumped on the carriage steps and Mr. Herrick shook their hands. Banter was exchanged on all sides, and cheers followed him down the boulevard. The Paris public felt then what they came to know later, that he liked them almost as much as "his Americans." They knew, when the French Government went to Bordeaux, that the American Embassy remained—that the eye of the great neutral republic would see what happened should the Germans enter their city.

The later significant comment made by Mr. Herrick, when a German taube dropped bombs on a spot he had just passed, that "A dead ambassador might be more useful than a live one," has been written in the history of France. And when the war is over I believe that the names of Franklin, Jefferson and Herrick will constitute a triumvirate of American ambassadors to France, that[Pg 23] all French school children of the future will be taught to remember and respect.

I passed much time at the Embassy during the first weeks of war, for it was a real center of news for an American newspaper. And I remember quite distinctly a statement that I made at home during one of the rare moments when I was able to reach it and which I repeated many times afterwards. It was a simple "Thank God that Myron T. Herrick is the American Ambassador." To the mild inquiry "why?" I could only say: "Because he is such an honest-to-God sort of man."

Mr. Herrick was undoubtedly shrewd in his friendships for newspapermen and he was clever in his use of them. But he always knew that we understood his cleverness and he always saw to it that we got value received in the way of "copy" for the praise that was often bestowed upon him as the result of it.

Mr. Herrick often said to us, in a manner quite casual, things that he had thought over carefully before our arrival. He knew just how those cables would look in the newspaper columns, and what the effect would be upon the reader, long before he handed out the subject matter. But if I ever argued to myself that I was receiving a[Pg 24] rather intime portrait of a clever and an astute diplomat, I could always honestly say, especially during the eventful days I am attempting to describe, that he was one man in Paris whose poise was undisturbed by the rapid succession of giant shocks, and that all the things which he did and said were to his everlasting credit and honor.

The American correspondents were sometimes referred to as "journalistic attachés" of the Embassy. We went there regularly, and it was ordered that our cards be taken to "His Excellency" the moment that we arrived.

He sometimes revealed to us "inside information" which, had we been able to print it, would have been, to say the least, sensational. On one occasion when he did not extract the suspicion of a promise that I preserve secrecy, Mr. Herrick told me a story which, if published to-day, would cause one of the biggest sensations of the war. But it is a story that can be printed only when the war is over, and perhaps not then, unless Mr. Herrick himself then gives permission.

Since leaving Paris, however, he has "released for publication" some things that could not for various reasons be printed at that time. For instance, when the French Government moved to Bordeaux, the American banks in Paris were in[Pg 25]clined to follow them and in fact did send considerable amounts of money there. Mr. Herrick told them that he wished them to remain; that their services were necessary to carry on the relief work for the German and Austrian refugees, and other charities of which he was in charge. He told them they might use the Embassy cellar for their money, that there was a row of vaults across the cellar and under the sidewalk. At one time, when the German peril was most extreme those vaults contained more than three million dollars in gold, which was guarded night and day by six marines from the U.S.S. Tennessee.

Also, in order to avoid panic, we could not print at that time, that the Embassy expected any day a rush of refugees; Mrs. Herrick had stocked the Embassy cellars with provisions for a thousand persons for several weeks. Mrs. Herrick, too, proved herself an excellent executive, for not only did she take this entire burden of preparing for the Americans, should the Germans enter Paris, but at the same time she organized a hospital at the American Art Club and vigorously assisted French as well as American charities.

I feel now that a sufficient period has passed for the publication in more detail of some of the[Pg 26] memorable interviews that took place in the private room of the Embassy. At the time some of them were printed in the form of short cable-grams, but more often lost in the rush of events.

I shall never forget a talk that took place just two days before the declaration of war.

Mr. Herrick was sitting at his big, flat-topped desk smoking a cigarette and looking out of the open window. He waved his hand toward the cigarette box as he greeted me and pointed at a chair. He continued looking out of the window, but I knew that he saw nothing. There were no preliminaries; only one subject interested every mind in Paris.

"What do you know?" I asked.

"It's bad," he replied.

"Any fresh developments?"

"None you don't already know—but come again to-night and I'll tell you anything I learn."

"What will you do with the Americans—the town is full of them? What about them if it comes?" I next asked. We always referred to the war as just "it."

"Take care of 'em," he announced briefly—then a pause; and he laughed. "Don't know yet that they'll need it—let's hope it won't come."

"But you expect it?"

He looked me directly in the face as he slowly answered:

"Yes—it's only a question of days—or hours."

We both drew long breaths.

"And—" I began; but he went on talking slowly and heavily.

"It's what the Orient has waited for—waited for all these centuries—the breaking down of Occidental civilization—" He drew himself up with a jerk. "But that's too much like pessimism. Have a cigarette. I've got to keep smiling, you know. That's part of an ambassador's job."

And he did keep smiling. There were few moments during all those days when there was not a smile upon his face and an honest welcome in his manner. But once I saw him angry.

He was furiously angry at certain information I had brought to the Embassy. It was the first day after the military order that all foreigners residing in Paris should register at their local police commissariats within twenty-four hours. The city was no longer a city officially. It was an intrenched camp. Only military law prevailed. The penalty for not obeying orders was severe, and for the thousands of Americans to obey the order in question was manifestly impossible. I myself had no police permit—not even[Pg 28] a passport. I had no time to go near a police station. My wife telephoned that at our commissariat the line of waiting foreigners was about eight hundred. She flatly declined to take her turn—permit or no permit. I suggested that she go home; but later I heard disquieting rumors, that there had been several arrests of foreigners unable to show a permis de séjour. I did not blame the police, for the city was full of spies; but I could see no good reason why the Americans should suffer and I went full speed to the Embassy to put the facts before the Ambassador.

His face changed color. His hands gripped the sides of his chair.

"Say that over again," he said quietly.

I repeated. Suddenly both his hands left the arms of his chair, and doubled into fists, crushed down upon his desk.

"By God," he shouted, half rising, his jaw thrust forward. "By God, they won't arrest any of my people."

He pushed a button on the desk, at the same time calling the name of one of the Embassy secretaries. Rapidly and explosively outlining the situation, the Ambassador finished with the order:

"Now you get to the Foreign Office quick; and[Pg 29] let them know that if one American is arrested for not having his papers, until this rush at the commissariat is over, it means trouble—that they'll answer to me for it."

I believe this incident more correctly illustrates the character of the ex-ambassador than anything one could say or write about him. When he came first to France, with a reputation as a successful Ohio politician, no one knew whether he was a real diplomat or not. I do not believe Mr. Herrick knew himself; but I do not believe that either then or later he ever thought much about it. He had sufficient savoir faire to make him greatly admired and respected by the French people, and his record proves whether or not he was a good diplomat. But there were moments, such as the one I have described, when he did not stop to consider whether or not an ambassador was supposed to be a diplomat.

I can picture other ambassadors I have known going over in their minds the rules of diplomacy and then delicately, oh, how delicately, approaching the subject. Herrick sometimes rode roughshod over all rules of diplomacy. He did it successfully, too—for there were no Americans arrested in France for not having their permis de séjour.

I have seen multi-millionaires standing in line at the Embassy, waiting their turn to get temporary passports; and I have seen powerful politicians and trust magnates waiting in the hall outside that famous private room, while Mr. Herrick talked to a little school teacher from Nebraska who had arrived earlier in the morning and secured a position ahead of them in the line.

I have seen him walk through the salons of his residence, which he kept open night and day to hundreds of Americans who felt safer just to be there, smiling, shaking hands and telling stories, although I knew he had not slept for twenty-four hours. And I have waked him up at midnight to tell him details concerning American refugees and their suffering which only he could alleviate and which he did alleviate without sleeping again until the work was done.

I witnessed many things in company with Mr. Herrick behind the scenes of the mighty drama as it was unfolding; most of them I am sure it would not be good "diplomacy" on my part to repeat. But all of them combined to make more fervent my thanks to the Almighty that in those days Myron T. Herrick was the American Ambassador to France.

LES AMÉRICAINS

My first and most poignant recollection of the thousands of Americans caught in France at the outbreak of war is in connection with a cable containing some five thousand of their names, which was killed by the censor on the ground that it was code. I worked hard on that cable, too. I compiled it in the hope that it would relieve the anxiety of friends and relatives at home. But the censor, after pondering over the Smiths, Jones, Adamses and Wilsons in the list, believed that I had evolved a scheme to outwit the authorities and that important war news would be published if it were allowed to pass.

I have lived long enough in France to know when not to argue. In this case I was meekly and respectfully silent. The censor said it was code—therefore it must be code. He even refused to pass a private message to my editors, who had asked for all the names of Americans that I could get, in which I said that I had tried[Pg 32] to meet their wishes but had failed. This, too, the censor thought had a hidden meaning.

The story of the Americans alone would have been almost the biggest that a newspaper man ever had to handle, had it not been for the fact that after all they were only incidental to a far bigger matter. Naturally they did not consider that they could be of lesser importance than anything. Also, the New York editors thought them almost, if not quite, as important as the declaration of war. Unfortunately newspaper correspondents, even Americans, located in the capital of a belligerent power, had officially to think with the authorities, and let the story of the Americans take what place it could find in the jumble of greater and lesser news. True, their story was covered—after a fashion—and the world knew what a real sort of a man the American Ambassador was in the way he protected his people. But most of the tragedy and nearly all of the comedy—much of it was comedy—was lost in the roll of drums.

In those days Europe was for Europeans. As I recall the Americans now, it seems to me that no nation finding herself in such a position as France, could have treated so patiently, so unselfishly, so kindly, as she, the strangers within[Pg 33] her gates. As for the strangers, alas, many of them felt distinctly aggrieved that war should come to spoil their summer holidays and bitterly resented their predicament. They ignored the fact that France was fighting for her life.

Their predicament, after all, was not so serious. After all, no American died; no American was wounded; no American even starved. Their troubles were really only inconveniences; but none of them would believe that Uhlans would not probably ride down the Champs Elysées the following morning, shouting "hands up" to the population.

I visited one afternoon the office of the White Star Line, jammed as usual with white-faced, anxious-voiced Americans seeking passage home. The veteran Paris manager of the line was behind the counter. He was speaking to a frightened woman in tones sufficiently clear to be heard by everybody.

"I speak from personal experience, madam," he told the woman. "I know that there will be plenty of room for everybody just as soon as mobilization is over. In two weeks the situation will be much easier."

"How do you know?" was the question. "What is your experience?"

His answer should have brought assurance, had assurance been at all possible.

"I was here in eighteen-seventy," he replied.

The prediction was nearly right. It took longer than two weeks to clear the ways; but when the battle of the Marne began, almost the last batch of tourists were at Havre, awaiting their boat.

The American newspaper correspondents who remained were looked upon as fools. The tourists could not understand our point of view that perhaps, after all, Paris instead of Belgium would produce the biggest story of the war.

I was on one amusing occasion the "horrible example" of the man who would not leave town, in a little sidewalk drama whose stellar rôle was played by one of the best known American actors. On one of the first evenings after mobilization I decided to go to our consulate, then in the Avenue de l'Opera, in order to learn the number of people applying for aid and learn if possible the approximate number of American tourists in Paris.

It was late. When I reached the consulate it was closed, but a large crowd remained waiting on the sidewalk. I learned from the concierge that the staff had departed for the night. As I[Pg 35] turned to go I met William H. Crane, the comedian, entering the building. I told him the place was shut, and we stood in the doorway talking.

The benevolent face and gray hair of Mr. Crane marked him with the crowd, and they immediately decided that if he was not the Consul General himself, he was at least a person of highest importance in the affairs of our Government. A group of school teachers timidly approached. I spoke to him quickly in French.

"You can act off the stage, can't you?"

He muttered something about getting away quickly, but I seized his coat lapel, saying: "Look here, there are many persons in this line and they have picked you out to be the big chief. The consulate is closed and if you don't play your part they will stand here all night. They are desperate."

Crane hesitated—then walked down the line, hearing each tale of woe and giving advice. He remained an hour, until the last question was asked and the last tourist satisfied. But he insisted that I remain with him. He told them all that I was so unfortunate as to live in Paris, that I had a house and family there, and that I had no possible chance to get out. And so, he argued, how much better off were they than "this mis[Pg 36]erable person," for they would surely get away in few days or weeks at the latest. As they did.

My last recollection of les Américains with which the word poignant might be used, was the morning before the battle of the Marne. It appeared certain to all of us who remained that the entry of the Germans could be only a question of hours. I, however, was fairly happy that day, for at four o'clock that morning my family had left the city for safety. The American Ambassador had told me confidentially something I already knew—that Paris was no longer a safe place for women and children. I had set forth my own belief for days, but my wife had remained. However, she was a great believer in the American Ambassador. So when I gave her the "confidential information"—and I set it forth strong—she consented to go to England.

I walked the streets that morning feeling a load off my mind. I had been up all night, getting my little family off and inasmuch as the day was too important for sleep, I took a refreshing bath and then strolled along the empty Boulevard des Capucines. I had found a shady nook on a sidewalk terrasse when some one touched me on the arm. I turned and looked into the terrified faces[Pg 37] of an American friend and his wife. "What are you doing here?" they inquired anxiously.

"Why, I live here," I replied. "Won't you sit down and have something?"

"Oh, no," the man answered. "We are on our way to the train; we were in the country when the trouble began. It was awful. They arrested us as spies. We only got here this morning. We have seats in the last train for Marseilles and will sail from there."

"Yes," I said, somewhat uninterestedly I fear, "but you have lots of time—sit down."

My friend grasped my shoulder. "Man, are you crazy?" he cried. "You look as if you were going to play tennis. You come along with us to America."

"Can't do it," I replied. "I've got to stay."

They stared at me silently. The woman took my hand.

"Good-by," she whispered.

The man took my hand in both of his. "Good-by," he quavered. "I'll tell them in New York that I saw you."

"Do," I replied.

I was not at all courageous in remaining in Paris. I did not remain because I so desired. I remained because, as a newspaper man appointed[Pg 38] to cover the news of Paris, I could not run away. Then, also, the biggest news that perhaps Paris would ever know seemed so near. I bought a number of American flags that day and hung them outside my windows.

I felt more fortunate than my fellow Americans who had gone away.

WAR

A night spent sending despatches—a yelling, singing mob beneath the windows making it almost impossible for messengers to cross to the cable office;—a dawn passed in riding from one ministry to another, wherever any portion of the war councils might still be in session;—and a forenoon spent in a Turkish bath, brought me near to the fateful hour on Saturday, August 1st, when France went to war.

I went to the bath establishment for sleep; but insistently I heard the voices of the night before—the yells, the cheers and the "Marseillaise." They were just as audible in that Moorish room, with dim lights and a trickling marble fountain. There was no such thing as sleep.

I went to my office and found a sum of gold awaiting me. I was glad to get that gold. I had sent an urgent letter in order to get it, in which I used such phrases as "difficulty of getting cash," "moratoriums, etc." My debtor wrote back, "What is a moratorium?" but he sent the[Pg 40] cash. It saved the situation for me during the next month, while the financial stringency lasted. I went over to my bank, The Equitable Trust Company, to deposit it. Mr. Laurence Slade, the manager, was in the hall.

"Is it safe to leave this with you," I asked, "or must I go clinking around town with it hung in a leather belt festooned about my person?"

"Leave it," he suggested.

"But the moratorium?" I inquired.

"Won't take advantage of it with any of our customers and we will keep open unless a shell blows the place up."

I thrust it into his hands, thankful that I had always used an American banking institution in Paris. All French banks took advantage of the moratorium the moment it was declared.

On the boulevards the crowds were thinner than the days before. I stood watching them idly. Every one seemed to realize that the declaration of war was hanging just over our heads. There was less excitement, less feeling of all kind. I said to myself, "Well, it's coming, the greatest story in all the world and there isn't a line to be written." It was just too big to be written then—and except the official bulletins of marching events I know of nothing that was sent to any[Pg 41] newspaper on that day either remarkable from the standpoint of writing or facts.

After idling along the boulevard for a few moments, I decided to go to my usual hunting ground for news—the Embassy. I hailed a taxi, and just as I opened the door on one side to enter, a bearded Frenchman opened the door opposite. I stated that the taxi was mine, and he declared emphatically that it belonged to him. The chauffeur evidently saw us both at the same instant and could not make up his mind as to our respective rights. A crowd began to gather, as the Frenchman, recognizing that I was a foreigner, began haranguing the chauffeur.

"What do you mean?" he cried. "Do you propose to let foreigners have taxis in times like this? Taxis are scarce."

The crowd began to mutter "foreigner." In a minute they would have declared that I was a German. But I had an inspiration.

"I want to go to the American Embassy," I told the Frenchman. "If you are going that direction why not come with me? We can share the cab."

I have always maintained that a Frenchman, no matter how excited he is—and when he is excited he is often almost impossible—will always[Pg 42] listen to reason if you can get his attention. My proposition was so entirely unusual that immediately he listened, then smiled and stepped into the cab, motioning me to do the same.

"L'Ambassade Americaine," he bellowed to the chauffeur, and as we drove away he was accepting a cigar from my case.

He explained both his excitement and his hurry. When the mobilization call came it would be necessary for him to join his regiment on the first day. I wanted to tell the chauffeur to drive to his home first, but he would not allow this, and when we arrived at the Embassy it was actually with difficulty that I forced upon him the payment for the taxi up to that point.

I was soon in the famous private room of conference and confidence. The Ambassador, as usual, was sitting with his face to the open window, and smoking a cigarette.

I placed my hat and stick upon the desk and seated myself in silence. We remained quiet for quite a full minute. Finally Mr. Herrick said, with a short laugh:

"Well, there does not seem anything more to talk about, does there?"

"No," I replied, "we seem to be at that point. There isn't anything even to write about."

A door behind us opened quietly, and Mr. Robert Woods Bliss, the first secretary of the Embassy, entered. He walked to the desk. Neither the Ambassador nor I turned. Mr. Bliss stood silent for a moment, then said quietly:

"It's come."

"Ah," breathed Mr. Herrick.

"Yes," replied Mr. Bliss, "the Foreign Office has just telephoned. The news will be on the streets in a minute."

It was the biggest moment, perhaps, the world will ever know. It was so big that it stunned us all.

I rose and took my hat and stick.

"Well," I ejaculated somewhat uncertainly.

"Well," said the Ambassador in much the same manner.

Then we shook hands; and like a person in a trance I walked out of the room and down to the street.

The isolated Rue de Chaillot was quite deserted; I walked down to the Place de l'Alma to find a cab. There the scene was different. Cabs by the dozen whirled along, but none heeded my signals. A human wave was rolling over the city. Fiacres, street cars, taxis filled with men and baggage were sweeping along. Almost every[Pg 44] vehicle was headed for one or another of the railway stations. Already the extra editions had notified the populace of the state of affairs and mobilization was under way.

Finally an empty fiacre came along and I signaled the driver, jumping aboard at the same moment. Just as an hour earlier when I signaled a cab, a Frenchman stepped in at the opposite side. Only, this time, the Frenchman wasted no words concerning his rights to the carriage.

He bowed. "I go to the Place de l'Opera," he said pleasantly.

I bowed. "I go to exactly the same spot," I replied tactfully.

We sat down and he directed the driver. We remained silent as we drove down the Cours la Reine until we came opposite the Esplanade of the Invalides. The sun was setting behind the golden dome over the tomb of Napoleon. Then my companion spoke:

"I will take the subway at the Opera station and go to my home. It will be the last time. I join my regiment to-morrow."

I looked at him for a moment, then asked curiously: "How do you feel about it? Tell me—are you glad—and are you confident?"

He looked me straight in the eye. "I am glad," he answered. "We are all glad—glad that the waiting and the disappointments, the humiliations of forty-four years, are over."

"And will you win—you think?"

"I do not know, but we will fight well—that is all I can say, and this time we are not fighting alone."

We arrived at the Opera. He jumped to the sidewalk and put out his hand. "Good-by," he said, smiling. "May we meet again." I wrung his hand and watched him dive down the stairs to the subway station.

I remained at the office as the afternoon slipped into evening and evening into night, writing my despatches on the actual outbreak of war. As I sat by the window, I suddenly realized that instead of the dazzling illumination of the boulevards I was gazing into the darkness. I investigated this phenomenon and I wrote another despatch upon the new aspect of the city of Paris on the first night of the war. It was a cable describing the death of the old "Ville Lumière" and the birth of the new French spirit. For not only were the boulevards dark, but the voices of the city were hushed. It began to rain—a gentle, warm, summer rain; the gendarmes put on their[Pg 46] rubber capes and hoods and melted into the shadows.

I went out to take my despatches to the cable office. The streets were quiet as death. A forlorn fiacre ambled dismally out of a gloomy side street, the bell on the horse's neck giving forth a hollow-sounding tinkle. I climbed in. The driver turned immediately off the boulevard into a back street, when suddenly the decrepit horse fell to his haunches in the slippery road. At once I felt, for I could scarcely see, four silent figures surrounding us. The night before I would have scented danger; but now I had a different feeling entirely. The four shadowy figures remained silent, at attention, as the driver hauled the kicking and plunging horse to his feet.

"He thinks of the war," said the driver.

A quiet chuckle came from the quartet, and I could now distinguish that they were gendarmes.

"You travel late," one of them said, addressing me.

"La presse," I replied briefly.

"Bien!" was the reply. We drove down the dark street, I astonished at this city that had found itself; this nation that had got quietly and determinately to business, at the very signal of conflict, to the amazement of the entire world.

THE GREATEST STORY

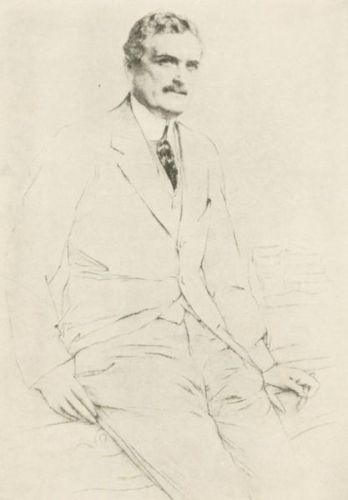

WYTHE WILLIAMS OF THE "NEW YORK TIMES"

THE ACTUALITY

On the sidewalk terrasse of a little café a few doors from the American Embassy I was one of a quartet of newspaper men on one of the final afternoons of August, 1914.

War news, thanks to the censor, had lapsed in volume and intensity; but the troubles of refugee Americans still made our cables bulky, and we continued to pass much time at the Embassy or in its vicinity.

A man wabbled wearily down the street on a bicycle. I recognized him as a "special correspondent" who had called on me ten days before, asking advice as to where he should apply for credentials permitting him to describe battles. He later disappeared into the then vague territory known as the "zone of military activity," without any papers authorizing the trip.

He leaned his bicycle against a tree and joined us. He had little to say as to where he had been, but told us that he had been a prisoner of the British army for several days. He mentioned a[Pg 50] town near the Belgian frontier where, as he described the situation, "the entire army came piling in before he had a chance to pile out."

I do not know what made me suspect that Mr. Special Correspondent was then the possessor of big news, for he gave not the slightest suggestion of the direction in which the British army was traveling. But I suspected him. In a few minutes he left us to call on the Ambassador. Later, when I saw him ride away from the Embassy on his bicycle, I sent in my card.

Mr. Herrick was as bland as usual, but there was a worried look on his face. I wasted no time.

"Mr. —— called on you this afternoon," I said, naming the special correspondent. "He told you some real news."

"Yes, that is so," the Ambassador replied. "How did you guess it?"

I explained that I only had a suspicion, and the Ambassador continued:

"He cannot cable it, you need not worry. He will not attempt it. He has gone now to write an account for the mail. He told me so that I could make some plans."

"Some plans?" I interrupted. "The news is bad then."

Mr. Herrick eyed me keenly for a moment—then he leaned over his desk and spoke in a whisper. He kept the confidences of the "special correspondent," but he gave me information that supplemented it, which he had from his own sources. He told me no names—no details—but he gave me the news appearing in the official communiqués three full days later;—that the British had been forced back at Mons—the French defeated at Charleroi, and that the entire Allied line was retreating. I did not learn where the line was. But as I left the Embassy I realized that France was invaded; I realized that the greatest story in the world was at hand. The fear was upon me, although I failed to grasp it entirely, that this was a story which in its entirety would never be written for a newspaper.

Mr. Special Correspondent passed two days in the seclusion of his hotel writing a splendid chapter for which he received high praise, but he was unable to get it printed until several weeks after the entire story had gone into history. Other correspondents were able to write half and quarter chapters which in a few instances received publication while the story was in progress.

I sat at my desk that night pondering on how to cable some inkling of my information to[Pg 52] America. I confess that I almost wished the cable was cut and the loose ends lost on the bottom of the Atlantic.

I studied the map of Europe facing me on the wall. Sending a courier to England was as useless as cabling direct, for the English censor was equally severe as the French. A code message was under censorial ban. A courier aboard the Sud-express might have filed the news from Spain or Portugal but the mobilization plans of General Joffre had arranged that there would be no Sud-express for some time.

There were undoubtedly other correspondents who knew as much concerning the state of affairs as I. Many British correspondents, without credentials, were dodging about the armies, getting into captivity and out again. Several American correspondents were in Belgium following the Germans as best they could. But none of them was at the end of a cable. Had they been they would have been quite as helpless as I. For had I been able that night to use the cable as I desired, I would have beaten the press of the world by three full days with the story of the danger that threatened Paris.

The next night, although I was completely ignorant whether the news was then known in[Pg 53] America, I tried to beat the censor at his own game. I succeeded to the extent of having my despatch passed, but unfortunately it was not understood in the home office of my newspaper. This was my scheme:

During the day rumors of disaster began to spread; but the Paris papers printed nothing of the truth, and officially the Allied armies continued to hold the Belgian frontier. That night refugees from French cities began entering Paris at the Gare du Nord.

I began an innocent despatch that seemed hardly worth the cable tolls. It ambled along, with cumbrous sentences and involved grammar, describing American war charities. Then without what in cable parlance is known as a "full stop," which indicates a complete break in the sense of the reading matter, I inserted the words "refugees crowding gare du nord to-night from points south of Lille," and continued the despatch with more material of the sort with which it began.

I went home hoping for the best and wondering if I had made myself sufficiently clear to arouse the suspicion of the copy reader on the other side of the ocean who handled my copy. If I had I knew that those eleven words would be printed in the largest display type the following morning.

Two weeks later, when the next batch of newspapers reached Paris, I read those words with interest. They were all there, but carefully buried in the story of war charities exactly where I had placed them.

THE FIELD OF GLORY

The battle of the Marne was fought by the Allies in the direct interest of the city of Paris. The result was the city's salvation. At the time, only a small percentage of the inhabitants knew anything about it. But as all the world knows now, the battlefield of the Marne was the first field of glory for the Allied armies in the great European war. When the war is over, the sight-seeing motors will reach it in two hours, probably starting from the corner of the Avenue de l'Opera and the Rue de la Paix—a street that by now might have a different name had it not been for the thousands who died only a few miles away.

On one of the first days of September, 1914, the few journalists who remained in Paris gathered at the Café Napolitain early in the afternoon, instead of at the apéritif hour. The Café Napolitain, around the corner from the sight-seeing motor stand, is the rendezvous for journalists, and always has been. At the apéritif[Pg 56] hour—just before dinner—you may see all the best-known figures in the French journalistic world, also the correspondents of the London and New York press, seated on its sidewalk terrasse.

I sat on the terrasse on that never to be forgotten afternoon of September. We were mostly Englishmen and Americans. The majority of our French confrères were serving in their regiments. Some of them, with whom we had argued only five weeks before concerning the trial of Madame Caillaux, were now lying on the fields of Charleroi and Mons. Some of the Englishmen had decided, because of the rumored orders of the Kaiser concerning the fate of captured British journalists, that Bordeaux was a better center for news than Paris, and had followed the Government to their new capital, on the anniversary of Sedan. Several of the Americans had also left town, but in order to better follow the movements of the Allied armies. Owing to the vigorous unemotionalism of General Joffre, none of them was any nearer the "field of operations" than we who sat on the Café terrasse.

I doubt if ever a world capital presented such a scene, or ever will again, as Paris on that afternoon. The day itself was perfect—glorious summer, not hot—just pleasantly warm. The sun[Pg 57] hung over the city casting straight shadows of the full leaves, down on the tree lined sidewalk. But there was not an automobile, nor carriage, scarcely even a person in the boulevards. The city was completely still. It had seen in the three days previous probably the greatest exodus in the history of the world. The ordinary population had shrunk over a million. The last of the American tourists left that morning for Havre. The railroad communications to the north were in the hands of the German army. There were no telegraph communications. Even the telephone was rigidly restricted. The censor made the sending of cables almost an impossibility. We were in a city detached—apart from the rest of the world.

That morning, at the headquarters of the military government, we were advised to get out quickly—on that same day in fact—or take our own chances by remaining. Possibly all the bridges and roads leading out of the city might be blown up before next morning. Uhlans had been seen in the forest of Montmorency, only ten miles away. It seemed that Paris, which has supplied so much drama to the world's history, was about to add another chapter, and the odds were that it would be a final one.

So, as I have said, I sat with my fellow jour[Pg 58]nalists on the terrasse of the Café Napolitain that fateful afternoon—and waited. That is why we were there—to wait. Several times we thought our waiting was rewarded, and we strained our ears. For we were waiting to hear the guns—the guns of the German attack. Through that entire afternoon, not one of us, singly or in partnership, would have offered ten cents for the city of Paris. We felt in our souls that it was doomed. It was an afternoon to have lived—even though nothing happened.

Toward nightfall we learned that the German forces had suddenly diverted their march to the southeast. We sat on our terrasse and wondered. That night every auto-taxi in the city was conveying a portion of General Maunoury's army out of the north gates, to fall on the enemy's right flank. The next morning, bright and early, those of us who were astir, heard very faintly—so faintly we could scarcely believe, but we heard nevertheless, the opening guns of the battle of the Marne.

I know only one journalist who actually saw the battle of the Marne. I know several who said they saw it, but I did not believe them, and I know better than to believe them now. Of course there are French journalists who took a military part in the battle, but they have not yet had opportu[Pg 59]nity to chronicle their impressions—those of them who live. This one journalist saw the battle as a prisoner with his own army; he was lugged along with them clear to the Aisne.

The week following the German retreat to the Aisne, I was permitted to visit the field of glory. It was only after skilful maneuvres and great difficulties that I secured a military pass. And then my pass was canceled after I had been out of Paris only three days—and I was sent back under a military escort. But I saw the battlefield before the hand of the restorer reached it.

The trees still lay where they fell, cut down by shells. Broken cannon and aeroplanes were in the ditches and in the fields. Unused German ammunition and food supplies were strewn about, showing where the enemy had been forced to a hasty retreat. Sentries guarded every cross roads. The dead, numbering thousands, lay unburied and dotted the plain as far as the eye could see. It was still the field of glory. It was still wet with blood.

We who took that trip were thrilled by all the silent evidence of the mighty struggle that had taken place there only a few days—only a few hours before. It was easy for us to picture the mammoth combat, the battle of the millions, across[Pg 60] that wonderful, beautifully undulating plain. The war was terrible—true. But it was glorious. The men who died there were heroes. Our emotions were almost too much for us. And in the very near distance the artillery still thundered both night and day.

On the third of February, 1915, five months from the time I sat on the terrasse of the Café Napolitain waiting to hear the guns, I travel for a second time over the battlefield of the Marne.

This time I do not have a military pass. It is no longer necessary. The valley of the Marne is no longer in the zone of operations. I go out openly in an automobile. There are no sentries to block the way. The road is perfectly safe; so safe that I take my wife with me to show her some of the devastations of war. She is probably the first of the visitors to pass across that famous battlefield, perhaps soon to be overrun by thousands.

Our car climbs the steep hill beyond Meaux, which is the extreme edge of the battlefield, about ten in the morning; and during the day circuits about half the area of the fighting, a distance of about seventy-five miles—or a hundred miles.

The "Field of Five Thousand Dead" is what[Pg 61] the majority of the tourists will probably call the battlefield of the Marne, because of the tragic toll of life taken on that one particular rolling bit of meadow.

We stop at this field in the morning soon after leaving Meaux. As we look across it we see none of the signs of conflict that I had witnessed in September. There are none of the ruined accouterments of war. No horses lie on their backs, four legs sticking straight in the air. There are no human forms in huddled and grotesque positions in the ravines and on the flat. True, every tree bears the mark of bullets, every wall has been shattered by shells, but these signs are not overpowering evidences of massive conflict. There is nothing to make vivid the fearful charge of the Zouaves against the flower of Von Kluck's army only five months before.

Yes—there is something. As we look more closely we see far away a cluster of little rude black wood crosses. They are not planted on mounds, they just stick up straight from the level ground. There are other little clusters throughout the field. Each cross marks a grave. Each grave contains from a dozen to fifty bodies. Together the crosses mark the total of five thousand dead.

An old woman hobbles along the main road. She looks at us curiously and stops beside the car. I ask if we can go close to the little black crosses. She replies that we can but that the fields are very muddy. I ask if any of the graves are marked with the names of the fallen soldiers. She shakes her head. No, they are the unknown dead. The regiments that fought across that field are known—that is all. There are both French and German dead. The relatives of course know that their men were in those regiments and they may assume, if they have not received letters from them recently, that they have been buried there—out on that vast, undulating, wind swept plain under one of the little black crosses. But, of course, one can never be sure. They might not be dead at all—only prisoners—or again, they might have died somewhere else. It is all very confusing and vague—what happens to the men who no longer send letters home. It is safe to believe they are just dead—to determine where they died is difficult.

The old woman suggests that we visit the little village graveyard, at the corner of the field. The Zouave officers are buried there—those who were recognized as officers. Some English had also been found and carried there. She is the caretaker[Pg 63] of the little graveyard. She will show it to us. She says that it is much more interesting than the field. The field is much too muddy.

The world is as still as the death all around us when we enter that little country graveyard. It has been trampled by a multitude. The five months that have elapsed and the hard work of the little old woman have not destroyed the signs of conflict there. But the time has taken the glory. The low stone wall that surrounds the place has been used as a barricade by the Zouaves. It is pierced with holes for their rifles. In many places portions of the wall are missing, showing where the shells have struck.