LANDSEER’S FANCY

Title: Trotwood's Monthly, Vol. I, No. 2, November 1905

Author: Various

Editor: John Trotwood Moore

Release date: April 28, 2022 [eBook #67946]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: The Trotwood Publishing Co

Credits: hekula03 and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

LANDSEER’S FANCY

| VOL. 1. | NASHVILLE, TENN., NOVEMBER, 1905. | NO. 2 |

By John Trotwood Moore

(Author of “Ole Mistis,” “Songs and Stories From Tennessee,” “A Summer Hymnal,” etc.)

Chickamauga Creek had no place on the map until September, ’63. Then it ran blood and became history. For it takes blood to make history.

When Bragg went to pieces two months later, after the shambles of Missionary Ridge, Hooker’s Corps was the pack turned loose to harry him out of the valley. They rushed thoughtlessly—Hooker’s hounds always did—and the foremost quickly paid the tax which Rashness pays to Reason. Cleburne, the rebel general, who brought up the rear of Bragg’s army, turned, wolf-like, at a gap in the mountains and cut to pieces the hound that had outstripped the pack in its zeal to snap at harried haunches. The hound whimpered and fell back, but not before Cleburne had shingled the sides of the mountain with the dead of the Yankee army.

The General who claimed the cut-up regiment was mad, and as he rode, with his staff, to the front, he was swearing in a deep, jerky, guttural voice. He stopped to look at the bloody gap, the lusty, voiceless, blue-coated forms, lying so weirdly unnatural—as trees when the hurricane has passed: “Mountain gaps—they are little traps of hell,” he kept repeating, and he spurred on for a guide—to a cracker cabin higher up on the mountain side.

The General rode a clean-limbed, loosely-ribbed, long-back thoroughbred, fresh from a blue grass paddock in Middle Tennessee. For he was weak on horse-flesh, and had impressed this scion of a Derby winner before Rosecrans went North.

Two mountaineers stood in the cabin yard. One was middle-aged, sullen-eyed and stooped, but standing six feet with the stoop. He leaned on an unmounted axe-helm, and as he stood slouching, long armed, bowed in the legs, his hairy chest gleaming through open shirt front, he looked not unlike a great gorilla, brought to bay with uprooted club in his hands.

The other man was not much more than a boy, except in size. He was larger, bigger chested, bigger fisted, and his wonder-haunted, kindly face wore a smile instead of a scowl. Never before had he seen the flag which one of the officers carried. Never such a horse as the one ridden by the man in front—never such a horse, and how he did love horses!

But the thoroughbred shied at the sight of the bearded man and sprang sideways, snorting, and wheeled to run. The boy’s face broke over in a quizzical, familiar grin, and he drawled exultantly:

“Say, Mister, whut yo ridin’ there?” The man turned sullenly and knocked him down with the axe-helm. He went down helplessly and with a subdued surprise in his blue eyes. The man did not turn his body, but stood indifferently, watching him slowly arising, wiping the blood from his forehead and whimpering like a struck cub:

“Ef mammy hadn’t tuck an’ went an’ died—I promised mammy I’d nurver strike ye, dad.” He blew the blood from his nose and stood scratching one leg with the bare foot of the other, whimpering still, and dazed.

“Solomon Hosea Hanks, ye’re a blatherin’ yearlin’ an’ ’ll allers be one. Ain’t I knocked ye down often fur buttin’ in ye horns befo’ ye’re axed up to the trough?”

He was talking to the boy, but saying it for the men in front: “Gentlemen, ’light an’ look at yer saddles. I’m jes teachin’ the lad some manners—you hafter teach ’em to some folks with a club.”

The boy suddenly straightened up. Half defiantly, and with quick eagerness, he leaped across the path where sat the color-bearer. He stopped beneath the flag and began to fondle it as a child would—the pretty stars, the gold cord that fell from the eagle above: “Ye’ll nurver knock me down ag’in, Dad. Ye’re a g’erriller an’ ye know it, an’ ye wanter[63] make me one, but I’ve seen my country’s colors to-day an’ I’m goin’ ter jine.”

He turned to the group: “I know whut you want, Mister-men, an’ I’ll lead you over the mount’in ef you’ll let me jine. ’Taint uverbody I’ll let knock me down”—he wagged his head at the man with whimpering apology—“promised mammy afo’ she tuck an’ went an’ died I’d nurver strike him”—

A rattling volley of shots rang out across the mountain, down in the next valley. They were echoed back, then shouts, and when the General wheeled, the boy had struck out toward the firing, his tough, bare feet crounching the gravel as he strode on in his shambling way. They followed him, but could not overtake the long, swinging trot in the crooked path amid the boulders and clay roots. On a projection beyond the ridge he stopped, calling back to the man:

“Far’well, Dad—you’ll nurver see me aga’in onless I hear you’ve beat little Dinah Mariah—then I’ll come back an’ forgit I urver had a mammy.” He shook his great fist at the man still standing immovable, then: “Come on, Mister-men—Bragg’s a good dog, but Holdfas’ is better.”

And that is how Solomon came into the camp of the Tenth.

He led them to the firing line, where the General suddenly found plenty to do. So much that he forgot Solomon until the brigade went into camp five miles further, on the trail of the retreating enemy. Then Solomon staggered in through the darkness to the camp fire carrying a half dead Confederate on his back. He laid the man down on a bed of leaves near the mess tent of the Tenth. He lifted the helpless head very tenderly and gave him water while the stricken one kept whispering, “Water—more water—for God’s sake—and death!”

The staff had been laughing and swearing before, with tin cups full of mountain whisky. For they were tired, and death had sprung up so often and so suddenly that day from batteries and trenches and mountain gorges; and from still, restful copses of silent woods, peaceful and inviting, until—Spit! Spit!—and the rattlesnake of sharp-shooting rifles spat out the virus which had put comrades and mess-mates to sleep. But now the silence and the night fell from the deep treetops together. That dying man in the camp, that strange, solemn giant of the woods—

The General, his tin cup half emptied, spoke first, in a voice strangely soft, the staff thought, for the old fighter:

“Any kin to you, Solomon—the man there?”

“He’s mighty nigh to me—mighty nigh.”

“Ah—sorry—sorry. And who is he?”

“Jes’ my brother, that’s all.”

“Oh, too bad—sorry—sorry”—and the staff muttered the echo.

Then the General put down his cup, went over and glanced at the man. He stepped back quickly and hastily drained the tin cup: “Nasty fix, Solomon—sorry—but we’ll do what we can for him. When did you see him last?”

“Nurver seed him befo’—but thar’s hund’erds of ’em—all our brothers, ’specially when we’ve shot ’em an’ they’re helpless an’ dyin’.”

The General winced and turned quickly to the fire. The staff went after another drink. Solomon’s eye fell on the mess table—the supper set forth and waiting; then Solomon fell on the supper. Between mouthfuls he growled out:

“You fellers orter be ashamed o’ yerselves to shoot a man’s innards out like that. I found him three miles beyant the mount’in whar you-uns fit thar this mornin’ an’ I fetch’t him over on my back.”

That reminded him. He picked up some hardtack and bacon and started toward the groaning man. Then he stopped, disappointed: “Whut’s the use—he’s got no whur to put it. You-uns done shot his innards out. The fust lickin’ Dad gin me was fur shootin’ a b’ar in ther innards.”

He sat down again and ate everything in sight. The General and staff got busy at something else. Solomon gave the dying man another drink and began looking around like a huge bear-dog for a spot to roll up on, and sleep. He found it in the General’s blanket, his huge feet sticking out, bunion covered and black. They thought he was asleep and coming quietly back one by one, sat down, and[64] were eating in silence when a shock of hair blurred up out of the blanket:

“Say, Mister-men, but ain’t war hell sho’ nuff? But tell the boys not to shoot ther Innards out—’taint fair.” Then he slept.

The General waited till he heard him snoring: “Major, if you happen to lose him to-morrow in the first skirmish—really, I don’t think we need him, Major?” The Major was sure they did not—so were the others.

They made the dying man as comfortable as they could, the General sparing his own warm rain-coat for the limbs now rapidly chilling. But his groans kept them awake: “Water—water—oh, God—water and death—kill me, somebody!”

The cry fell out of the silence with the starlight, mingling strangely with the shivering wail of a screech owl—so uncannily mingling that they seemed as one.

It was nearly midnight when the General saw the foot withdrawn, the big form arise and slouch over to the dying man: “Water—water—and, oh, for God’s sake—have mercy and kill me.”

Solomon tenderly lifted the gasping lips to the canteen: “Do yo’ means it—want me to kill ye sho’ nuff, brother?”

The man’s eyes were beseeching as he gasped: “I——can’t——live——death every——minute——put me——out of misery—God will——reward you.”

Solomon’s eyes were wet with tears. His great pitying heart thumped loudly: “How, brother? Whut with?”

The dying man nodded at a bayonetted rifle near by: “That——push that——through my heart——quick!”

The General arose just in time. Solomon, with a strange sob in his throat, stood over the man, the gun poised, the bayonet’s point—

“My God, Solomon!”—and he grasped the descending gun by the barrel. “This is murder—I’ll have you shot!” The giant turned on him astonished: “He cyant live—you-uns shot him to pieces. That’s war. I put him out o’ his misery—that’s murder. Strange—strange! Brother,” he stooped and whispered regretfully to the man, who beseeched him with fixed, unwinking eyes, “Brother, I’d do it—God knows I’d like ter ’commodate yer, but ye heurn yo’self.” Still lower: “But say, brother, ef you fin’ ye cyant stan’ it no longer—when they sleep—call Solomon—an’ I’ll sho’ ’commodate you in this. God bless ye.”

Later there was a rigid stiffening and gasps among the leaves and Solomon knew there was no need for his bayonet.

The next morning when the General arose, Solomon had fed and rubbed down Ajax, the thoroughbred. He stood talking to himself—he had forgotten the war: “Whut a hoss—whut legs—whut muscles, like bees a swarming! I’ve allers dreamed o’ keerin’ fur sech!” He turned to the General: “I’ll take keer o’ him from now on.” The General was touched and when he shook Solomon’s hand the bond was sealed.

“How long have you been up, Solomon?”

“Two hours b’ day—Gen’l.” It was the first time he had used the word and the old fighter inwardly scored one more point for the horse—that could prune the pride of the mountaineer—he who knew no titles, no superior.

“Ye see, Gen’l, forgot yistiddy to kiss Dinah Mariah good-bye. She’s the little deef-mute mammy lef’ befo’ she tuck an’ went an’ died. I raised her—gi’n her urver rappin she had ’cep the milk she drunk, an’ wish’t I c’ud er gi’n her that. Dad’s been so tarnel mean to her. D’ye know I had an idee that he wanted ter put her out o’ the way? So I steps back over the mount’in an into the cabin whur they all sleeps—all ’leven on ’em. But ye know I couldn’t kiss ’er good-bye, seein’ ’er sleepin’ thar so sweet?” He struck savagely at his eyes with his big-knuckled fist. “But I fetched this—I’ve jined fur the war an’ I wants my own gun—don’t like ther blunderbusses you-uns shoots. This un’s a Deckerd—been thro’ ther Revolushun, an’ with Ole Hickory at New ’leans. It’s fittin’ fur it to fit ag’in fur the Union. Thar—see!” and he pointed the gun high up at the limb of a big oak.

The General saw nothing until the great flint and steel snapped together like the jaws of an alligator, and he had a tender but headless fox squirrel for his breakfast, cooked, later, by Solomon’s[65] own hand. “An’ I don’t shoot ther innards out, nurther,” he growled.

“You needn’t lose him, Major,” chuckled the general, as he pulled off a succulent hind limb, roasted on a green stick-spittle over a pit of coals. The Major having the mate of it in his own mouth, could not speak, but nodded vigorously.

A hard winter and deadly fighting between Missionary Ridge and Atlanta: but Solomon enlivened it for the Tenth. For he was their brother and his quaint sayings became their intellectual stock in trade. For instance: “The —— Iowa flickered at Dug’s Creek. Then they sulked.” They had done it before. “What shall I do with them?” snarled the General that night in camp. Solomon drawled in:

“’Pint ’em ter bury ther dead—they’re nat’ul born pallbearers. I’ve seed lots o’ folks that was.”

When old Tecumseh Sherman heard of this he offered to promote Solomon to a corporalcy:

“Nun—no,” said Solomon, “then I’d hafter wear boots an’ a unerform. An’ say, them thar unerforms you-uns wear meks you-uns look jes lak them little flyin’ stink-ants that swarms out in the spring. God didn’t inten’ no two fol’ks ter be alike. Es fur boots, they fus’ jes make yer feet tender an’ then wears out. I’ve got on a pa’r thet nurver wears out.”

He figured next in a horse race with a Kentucky regiment which was first unwise enough to cast aspersions on the speed of Ajax and then bold enough to back them with the long green. It was a great race run between two lines of howling blue. “Nurver bet agin natur’,” said Solomon dryly, as he pocketed all the money of the Republic which the unwise Kentuckians had. “Ajax is by natur’ a horse an’ your’n ain’t.”

For a week after that the Tenth indulged in vain and effeminate luxuries.

Spring brought the fighting and the tragedy—of the latter, Solomon was the ink.

They made him color-bearer—he was so strong, and it was so easy to see him in his coon-skin cap, his Deckerd strapped to his back. For he would not lay it down even while carrying the flag. At Resaca he took the colors through balls which came thick enough to stop a bluebird. Mines cut the tail from his cap, a buck-and-ball cleared one foot of bunions, and canister carried his canteen bodily from his body; but in the thick of it he yelled out savagely at the General: “Say, thar, Gen’l, get out o’ thar on that hoss! You mout get ’im hurt!”

He spent the next week nursing the wounded enemy: “For ain’t they our brothers?” he asked, and the scoffers in blue were silent.

A beautiful valley beyond Resaca and Solomon had never seen such rich land. A grand mansion in the valley and Solomon had never seen such a house. The General had pitched his camp near by. A thousand other camps dotted the valleys and hills. A hundred battle flags fluttered from their staffs. There was planning, priming; trenches crept across the hills in the night, like mole-paths in a garden, and the valleys were billowed with them, cannon crowned and picketed with steel. They would give little Joe his death blow.

Solomon stood sentinel that night by the big house on the lawn. It was never the color-bearer’s duty to stand sentinel—but “Yer see, Gen’l, Ajax is stalled right over thar beyant, an’ them brothers o’ our’n from Kentucky loves a good hoss.”

It was past midnight and the army was asleep. There was a light suspiciously faint in the window of the big house. Solomon slipped up and peeped in through a blind slat, awry. He stepped back blushing, ashamed that he had peeped. He picked up his Deckerd. The light went out and the door opened silently and a handsome man dressed in citizens’ clothes kissed a Beautiful One good-bye. Then he slipped out into the dark and mounted a horse hid so securely as to surprise Solomon, with his keen mountain eyes.

“Halt, thar, brother, an’ gin the countersign.”

Pistol shots buzzing from the cylinder of Colt, and that quick grapple of horse hoofs in the gravel which tells of a rowel driven in suddenly; then[66] the sound of a flying horse through the lane.

Silence, then quaintly as if talking to himself: “A cyclone spiked with hell-fire! Solomon, yer nurver had so narrow a shave—yer’ll be keerful ther nex’ time yer brother a gatlin’-gun buckled to a thoroughbred.”

The girl clutched the window—white and with eyes lit with flashes of the weird starlight. It seemed a half hour to Solomon before he heard her give a rippling, cut-off laugh, and the dawn sprang to her cheeks as the starlight went out of her eyes. High up on the mountain she had seen what Solomon had not—a splinter of light leap out of the heart of the mountain beyond the picket lines. Solomon was still watching her—so strangely fascinated that he had not noticed the blood running down his arm. She closed the window with a happy laugh, and Solomon felt that it was now night—all around him.

And so the spell of the big house was upon Solomon and he begged to stand guard next day. It was early and he stood silent before the splendor of the house, the marble steps, the big, hooded gables, then—

“God! she’s comin’!”

He turned—no, he was a sentinel—he could not run. She wore white—fluffy and airy in the warm June morning. Above—

“Molasses candy hair,” said Solomon, licking his mouth, “an’, oh, Lord, Black-Eyed-Susan eyes!”

He thought again of running. Then of the wild fawn that once ran to meet him, off in the mountain woods, so innocent that it knew not that death dwelt with man.

He slipped behind a tree. Never before had he been ashamed of his bare feet. He peeped out—she was still coming—no, she had come, and he turned pale and his knees trembled, for there she stood smiling as only an angel could, and holding something out to him:

“I know you must be hungry, and it is so good of you to guard our house. Now, please let me serve you your breakfast.”

Off came his coon-skin cap. Her smile, her eyes made him homesick. He saw the summer lightning playing at midnight around the peaks of Tiger Head. Then tears welled which made him hate himself—him a soldier of the Tenth—and he slipped farther around the tree. She was serious instantly, and her beautiful eyes had sized him up—gratitude, homesickness, all—and when she peeped around the tree again—after awhile, and he had had time to brace himself, she laughed a musical, comrady laugh, and—

“Now, please don’t be offended, for I should love so much to be your friend.”

Again the homesickness. That laugh, that voice—it was the silver ripple of Telulah Falls under the white stars of the mountain. That meant home and Dinah Mariah. Trembling, dazed and choking with the swelling that made him wish to do something—to do something grand for once in his life, he tried to speak, but ended in bringing his Deckerd to present arms. She laughed, saluting him in turn with a saucy military flash of her pretty hand.

“Miss—Miss”—

“Nellie,” she said, sympathetically, helping him out.

“Do they—breed ’em—all like you-uns down here?”

She laughed and handed him the plate. Solomon knew the ham, but did not know what the rolls and the orange were. His hand touched hers—he fumbled and dropped the plate: “God, but I thort I—I teched fire!”

“Oh!” and the hurt look made Solomon wish to fight something for her sake—“but I’ll soon be back with more.” She turned with a pretty gesture.

“Don’t—don’t,” he called, “send it by a nigger. Who can eat with a angel lookin’?” She laughed so heartily at this that Solomon was soon himself. When she brought him another plate he forgot everything except he had seen her, that at last into his life something had come. He wished very much to impress her—to say something grand, but everything he tried to say ended in a brag—so unusual for Solomon:

“I was heah las’ night a-guardin’ you-uns, an’ I come mighty nigh killin’ a man.”

“Oh!”—and the fun went out of her[67] eyes. “I am so grateful to you. Did—did—he hurt you when he fired?”

All the brag went out of him. Not for the world would he have her know that.

“No—but—it was a narrow shave.”

“I am so glad—you see he—was—my brother.”

“Sho’ nuff?” and Solomon guffawed. Somehow it relieved him so to know he was only a brother. “Wal, now, how strange! But the Gen’l was tellin’ us ’bout a Johnny Scout in here, a tall feller in citizens’ clothes. Oh, he’s played the devil with us. He knows our plans better’n we do. We ’low we s’prise little Joe at Dug’s Gap, but little Joe s’prises us. Then we ’low we’ll trap him at Resaca an’ swing round on his flank. But he come nigh trappin’ us. We laid for him mighty keerful at New Hope an’ saunt Howard to turn his flank. He turned our’n. It’s all that’r scout, and so the Gen’l sed when he saunt me out las’ night: “Solomon, shoot anything in citizens’ clothes that tries to buck our lines. Kill him fust an’ ax him whur he’s goin’ after’uds.” So when he steps out las’ night—that brother er your’n—I was right thar watchin’, an’ I flung up my old Deckerd an’ I drawed a bead on him—it was all so plain, him outlined in the starlight. But he looked so han’sum a-settin a hoss so lak Ajax thet I sed: ”No, I’ll not shoot him—he’s somebody’s brother. An’ sho’ nuff he was your’n!”

The girl turned white, then pink. Tears came to her eyes, the sight of which made Solomon’s jaws set in stern decision. He pitied her, thinking of Dinah Mariah—his sister. He swelled savagely: “Say, but don’t you cry. I’ll lick arry man that ’ud hurt yo’ brother!”

“That is so sweet of you,” she said softly.

“Then I fetched my piece down an’ axed him fur the countersign an’—wal,” he nodded his head up and down meaningly—“I got it!” He rolled up his sleeve and showed the red furrow of another across his arm.

“Oh, I am so sorry—do—do come in and let mamma and me dress it.”

Solomon laughed: “Now, don’t bother ’bout it, Miss—yo’ bein’ sorry has already cured it. I’d have it dressed but Gen’l ’ud find out an’ say I was a fool fur not shootin’.”

But she dressed it—she and a stately White-haired one, bringing the salve and bandages out to his beat; and when they had finished and the smarting pain had ceased, Solomon belonged to them.

Then came the strange change in Solomon. He did not know what it meant. Why he put on the uniform, the cavalry boots and the big spurs. Why he wanted to strut and swell in the pride of his six feet three, when the old General blurted out:

“Solomon, damned if you ain’t real handsome—what’s come over you?”

“Gen’l—Gen’l, I dunno—but I finds myse’f struttin’ jes like a wood-cock in the spring.”

“Oho,” laughed the General, “look out, Solomon.”

That was all open—seen of all men. But secretly, silently, painfully—in the depths of his great soul something stirred within him that he told to no man, for he knew not what it was. What it did he knew: “God, it lifts me out o’ the clay o’ myse’f!”

Never had he been so happy. Ride? He could ride Ajax over a whole regiment. He could lick Johnston’s whole army. “An’ the cu’is part, Solomon—yer fool—you are wantin’ to fight outwardly, but in’ardly you are cryin’ all the time.”

It hurt him when he saw her. He was sorry when she brought him his meals; he got behind a tree and wept when she left, and in this state he stopped one day and turned white: “God, mebbe it’s that thar blin’ staggers I’ve got—that I heur’n so o’ fo’ks havin’ in the rich valleys.” The dreadful blind staggers he had heard of all his life—that never came to those high up in the pure air of the mountain! He was sure they had him.

It was the third day and twilight, and when she came out, bringing his supper, the red ribbon in the white of her gown, her dark eyes above, made him think of the tiger lilies that grew by Telulah. He pretended not to see her and when[68] she blocked his path with a pretty smile and salute, he feigned astonishment:

“Law, but I thort the moon had riz!”

“Oh, you are a poet, Solomon, and a dreadful flatterer,” but she laughed in so pleased a way that Solomon swelled up in his great chest and blew deep and long, snorting it out, to loosen the great hurting feeling that was there. Then, too, he had seen Ajax do it with the thunder of battle in his nostrils.

She sat on the stump before him, kicking her slippered heels against the rough bark and watching him so keenly with measuring, wistful eyes.

“Solomon, I have been thinking, and mother and I want you to come in the house and hear my music. You have been so good to us and we are so fond of you.” She jumped down, took his hand and led him. It burned him—it made him gasp for breath, yet all he could do was to follow.

And the house—never before had he seen splendor. They had trouble persuading him to step on the rugs and to walk on the carpets. But the sweet-faced, white-haired lady came graciously forward and shook his hand which made him feel better. Then the Angel sat down before something Solomon had never seen and—

They both stood over him ten minutes afterwards, for he was sitting on a sofa weeping:

“’Scuse me—no—no, ’taint my wounded arm—it’s that’r thing over thar that’s waked up the cat birds in the roderdendrums at home, an’ I heurd the water failin’ over Telulah an’ the wind at midnight in Devil’s Gorge, an’ I nurver knowed befo’ whut little Dinah Mariah had missed bein’ a deef-mute an’—so—it sot me ter bellerin’ this away.”

They were very gentle with him after that, and more gracious, and when the Angel played another piece full of dash and jig and rosened-bow and thunder, he stood it until the blood began to boil under his hair and they found him again in the middle of the floor shouting:

“Hurrah, boys! Lord, but can’t he run? Come home, Ajax!” “’Scuse me—’scuse me—Mrs.—Mrs.—Angul—” after he came to himself—“but—but—she plays that thing ’zactly like Ajax runs.”

It was the greatest day that had ever come into his life, and when he left to go back to his beat he proclaimed exultingly to the White-haired one that it was “Christmas, an’ hog-killin’ an’ heav’n all rolled into one.”

It was twilight when she came out on the lawn, dressed in white with ribbons in her hair. When he turned she had perched herself on her favorite stump and was beckoning him to sit by her. Trembling, weak he obeyed, his great arm touching hers, which thrilled him so that pains shot into his wounds. She was silent, looking at him with the same wistful, doubting eyes of the morning. He had seen them before, in camp, when the boys gambled and their month’s pay was at stake, holding a card aloft uncertain whether to cast or not. And how they held him—those eyes of hers with the tragedy in them!

“Solomon, you know how we love you, mamma and I.” He sat mute with bowed head. “And Solomon, if I trust you—if I tell you—will you never betray?”

“Whut—like that’r Judas I onct heurn of the time I went to meetin’?” She nodded. It hurt him. “I can’t betray—It ain’t in me,” he said simply.

“Forgive me, Solomon. I knew it,” and she put her hand in his just as Dinah Mariah had so often done, except that this made his heart beat so it bothered his breathing and unlike Dinah Mariah’s he could not—she being an angel—clasp it in turn. “Now, Solomon, my brother is coming to-night—he will slip in yonder,” and she pointed to a by road leading through shrubbery to a side gate. “You are not to see him, Solomon, and you are to let him out the same way after we have fed him. For he is hungry, Solomon, and in great danger—been surrounded and hiding for days—they are on his trail. Your men, you know, have killed his horse”—(Solomon winced—it hurt him to hear of a horse being killed)—“and, Solomon, this is the only way he can get out—can save his life—for—for, Solomon, they are to take him dead or alive.” She had ceased to smile. Tears were in her eyes and[69] Solomon’s great hand closed over her little one.

“So he’p me God, I’ll nurver pester him!”

“And when he is ready to go—to try to escape, oh, Solomon, you will stand by us—with Ajax ready?”

He started—he jumped from his seat. “Not Ajax—any critter we got but Ajax.”

“Oh, Solomon, they cannot run—it’s—it’s—Ajax or death for him.”

She was weeping, her head on his great shoulder, clinging to his arm, the perfume of her hair going into the soul of him like the odor of wild grape blossoms after the spring rains in Dingley Dell. “Will you—will you, Solomon; oh, save him for me!”

“So he’p me God, I will—he bein’ yo’ brother—my brother.”

“You are my brother, Solomon—the Brother of Nobility.”

Silence. He sat holding her hand as he would Dinah Mariah’s. “Will you—er—kiss yo’ brother—when he gits here?”

She blushed. “Don’t we always kiss our brothers, Solomon?”

He scratched his head thoughtfully. “Awhile ago you made a remark cal’k’lated ter sorter sot me to ’sposin’ thet mebbe I mou’t also be yo’ brother—”

There was a ripple from Telulah Falls, the pressure of lips on his cheek, a whiff of wild grape blossoms in the Dell, a rustle of skirts up the path, and Solomon sat breathing hard in silence.

“Wal, ef lightnin’ ’ud only give us notice when an’ whur it’s goin’ ter strike!”

In camp he heard news—strange news. The whole army would strike next day, for they had Johnston with his flank wide open; would bag him if that scout didn’t get back through the lines—Captain Coleman, the daring rebel scout. They had him surrounded now in a thicket by the creek, the man they would give a brigade for—he was theirs if the pickets were careful.

Then it all came over Solomon and with it a blow that brought the great strange man to dumbness. “I swore not to betray her—not to be her Judas—oh, God, enny body but thet white-livered, snivelin’—” He heard the flag rustling in the night air. He walked over, crept under the folds, pressing it to his hot cheeks, kissing and fondling it. “Judas! Judas!—oh, my country’s colors.” He looked across the night to the hills where a thousand camp-fires twinkled in unbroken lines of starry sentinels.

“Ye’ve got so menny to defen’ ye,” he said to the flag, “so menny twixt you an’ death. An’ she—jes’ me—jes’ me!” He sang low the song that had taken the camp.

He stopped and looks at the living scene before him—it was all so true. Then lower still:

He sprang up with a pain in his heart. “Siftin’ out the Judases, an’, oh God, I’m a Judas arry way you fix it! Why did you fling me in this heah pit among the wolves o’ war—away from my mount’in home—from little Dinah Mariah?”

When Solomon went back to his beat he had slipped out Ajax, saddled, and held him in the clump of orchard trees, near the sweet window where the faint light came out, that he knew shone also over her and her brother. He held his Deckerd proudly, for was he not all that stood between her and death? He swelled with the pride of it and that queer sullen feeling that came over him at times—that savage feeling he could not understand—that made him willing to kill—kill if—

“They’d better not pester her,” he growled as he heard the pickets go out for their night’s duty.

He heard them moving in the room. Her brother was preparing to go. He peeped and turned away his head. “Somehow it riles me to see her brother kiss her that away.” He tapped on the blind saying softly: “Ready—ready.”

“O, Solomon,” joyfully in a whisper, “bless you; bless you!”

“No Judas in mine, Angul.”

He turned, for Ajax had thrust his head over his keeper’s shoulder and the man laid his cheek against it and his lips had parted for the pet words which he never uttered; for there was a noise[70] in the dark behind him and two soldiers tried to rush by to the door of the room.

Solomon stopped them with his great Deckerd at port. “Halt fus’ an’ give the countersign,” he said, and he heard the scream of a woman, the hurrying of feet within.

“Stand back, you fool, we are men of the Tenth and we’ve got Coleman in there.”

“Stan’ back yerse’f—he’s her brother—my brother.”

There was a rush at him, into arms which made them think of a mountain bear, for he gathered them to his heart, and the breath of them went out. In the glare of the wide open door a girl stood white-faced with tragedy. A man leaped to the back of a horse and the swaying, struggling group were baptized in a shower of flying gravel. Shots and shouts behind and the scud of a flying horse into the night.

“You damned traitor!” Solomon dropped the two men in the paralysis of the bayonet thrust that sank into his back.

He quivered to the death stroke and turned beseechingly to the man: “Shoot me, quick, brother—in the heart—in the breast—I’m no traitor, no Judas—she’ll say I ain’t.” The man cocked his rifle but the great head with the shock of long hair had gone down and the girl stood between them.

“No—no—not Judas—she’ll swear I ain’t.”

She did not seem to notice them—her beautiful head was turned side-wise listening to the vanishing rhythm of flying hoof beats. “O, Solomon, Solomon; will they catch him?”

“Whut—an’ him on Ajax? Ho-ho-oh,” and the great chest, schooled to the mountain halloo, echoed it for the last time, like the sound of thunder among the hollow gorges of the hills.

Then joy, great, radiant joy in her face, and with the returning glory of it all—tenderness—tenderness and sorrow for him. “Can I—O, Solomon—can I do anything for you?” She sat by him, her hand on the sweat-damp brow.

“You mou’t—kiss—me ag’in—an’ ef—you—happen to see—little Dinah Mariah—”

By H. D. Ruhm

Mr. Ruhm is one of the pioneers in the phosphate field and his paper on this subject is the work of an expert.—Ed.

The phosphates of Tennessee occur chiefly, in fact, almost entirely, in the strata representing the Silurian and Devonian geological ages, or, more properly, in the former, and in a transition period between the two.

The Silurian age was essentially the age of shell fish, animals with their skeletons entirely on the outside of their bodies. The deposits of countless millions of these shell fish and their remains form the immense beds of limestone representing the Silurian age. The composition of these shell fish was carbonate of calcium, or “lime,” and hence our common limestones are calcium carbonate.

The Devonian age was the age of fishes or vertebrates, and owing to the need of greater elasticity of their bones and smaller weight, they are composed of phosphate of calcium, or “lime.” Far back in the Silurian age the “Hand that fashioned all things well” began to change some of these shell fish to provide for the future order of things, so that their outside skeletons, or shells, were composed of phosphate of lime instead of carbonate. These two commingling, the resultant beds of rock became somewhat phosphatic and formed the “phosphatic limestones” of the Silurian age. In some places the phosphate shells were in considerable proportion, and subsequent erosion, proper underground drainage and leaching, dissolved out the carbonate of lime to greater or less extent and left the “brown phosphate” of the middle basin, varying in grade according to the preponderance of phosphate shells in the original deposit and the extent of the subsequent leaching. Meantime the transition stage between the two ages had been reached and the resulting deposit spread over the central basin and the highland rim in the form of a thin blanket of varying thickness and quality of the so-called blue rock, which is blue, brown, gray and black, according to the coloring matter present or absent, composed of a preponderance of microscopic shell fish with skeleton composed of phosphate of lime, but mixed with enough carbonate to make the resulting mass vary from sixty-five per cent to as high as eighty per cent calcium phosphate.

The subsequent depression and deposit of Devonian shales and subcarboniferous beds and subsequent great pressure hardened all these into rock, and about the middle of the subcarboniferous age all these were elevated above the surrounding[72] country, and while the rest of the land was taking its turn in being formed under the seas, this old central basin was undergoing the wear and tear of erosion that finally produced the “Dimple of the Universe,” surrounded by its chain of hills and ridges and flatwoods of the highland rim.

In the central basin where conditions were favorable the intervening strata between the blue rock and the phosphatic limestones that were being converted into “brown rock” were sometimes partly and sometimes entirely washed away, and the blanket of the blue rock, cracked and broken into plates of the hardest and most durable parts, settled down on the brown rock, sometimes resting directly on it and sometimes with a clay seam left to represent the former intervening strata.

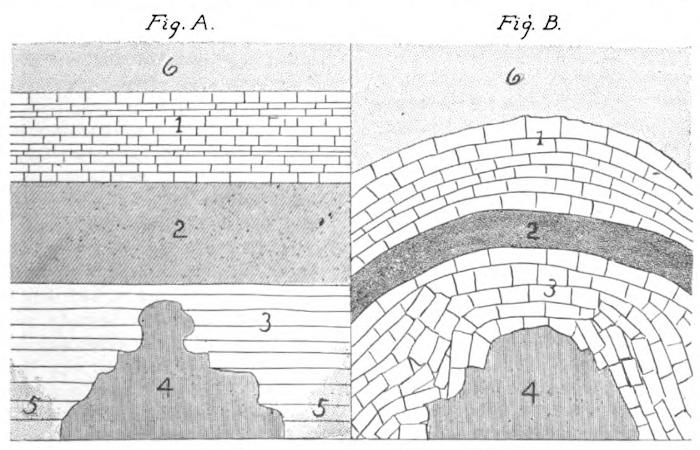

A glance at the illustrations will show the process. Let Figure A represent the deposit as it originally was before the erosion and leaching started in.

No. 1 represents the layer of blue rock in its original position; 2 the layers of limestone underneath; 3 the layers of highly phosphatic limestone in suitable condition for leaching; 4 the hard, insoluble portions of the limestone, and 5 the soluble portions of the limestone, nonphosphatic.

In Figure B, No. 5 has dissolved out and disappeared. In No. 3, the carbonate has leached out and it has separated into laminations and falling into the places left by No. 5, has assumed the jumbled condition found in the dips between lime boulders; No. 2 has dissolved down to the clay seam so generally found, varying in thickness from one or two inches to two or three feet, and No. 1 has settled down conforming to the general bottom of 3 or top of 4, forming the top rock generally prevalent in the brown rock field.

If the analysis of the original phosphatic limestone was, say, 50 per cent phosphate of lime, 38 per cent carbonate and 12 per cent insoluble, and other matters, and the leaching took out all the soluble carbonate, the resulting mass would be 80 per cent phosphate, which is generally the analysis of the bottom rock at Mt. Pleasant, or the “export,” as it is termed. The top rock varies in analysis from 65 to 80, just as the original blue rock did.

In the highland rim this process took place only on the slopes of the narrow creek valleys and occasionally in projecting points, instead of over large areas of country as in the central basin.

In the portion of the highland rim left intact the blue rock remains in place as a general thing with its varying quality and thickness, retaining its original compact form and density.

Occasionally, however, is found the layer of blue rock resting immediately on the layer of phosphatic limestone, and where this is the case numerous faults and dips occur, showing a similar structure to the Mt. Pleasant formation typified.

Again, in the central basin or brown rock region, the top erosion first disintegrated and then partially took off the upper layers of shale or flint, sometimes entirely, sometimes leaving it from one to forty feet thick, which accounts for the varying overburden.

In some places the limestone layers were entirely soluble or reduced to clay and some acid condition of soil water dissolved the upper layers of phosphate and redeposited it in the boulder and stalagmite forms of the “white rock” found in Perry and Decatur counties and near Godwin, in Maury County, and the “boulder rock” found everywhere to greater or less extent but in especially heavy deposits near Nashville on the McGavock Place. These latter redeposit varieties vary in analysis from 50 per cent to as high as 90 per cent phosphate, and are uncertain as far as the general variety goes, though individual deposits varying in extent from one to twenty or thirty acres, are found of very uniform quality.

The first phosphate rock discovered in Tennessee was the kidney formation that almost always attends the blue rock and black shale deposit. The eminent physician, naturalist, botanist and geologist, Dr. Gattinger, of Nashville, of revered and beloved memory, was first to recognize these as phosphate rock, but being much more interested in determining the family and pedigree of some new[73] beetle or plant than in the commercial aspect of any mineral proposition, he never gave his discovery to the world, and only by his casual mention of the fact one day to Will Shirley and Maj. W. J. Whitthorne, of Columbia, are we able to give him credit for the knowledge. Dr. Safford, in his “Geology of Tennessee,” describes in detail both the blue and brown rocks geologically, referring to the blue rock as a blue fossiliferous limestone nearly always occurring under the Devonian shale; but no chemical investigations being provided for, he did not find out that it was a phosphate rock. Major Whitthorne and Mr. Shirley kept up a systematic hunt for a deposit of commercial value and finally the former located one on upper Swan Creek simultaneously with the discovery made lower down the same creek by Messrs. Bates and Childs. These latter gentlemen were insistent that the black shale, commonly called slate rock, so abundant in the highland rim country, was a form of, or indicative of the proximity of, coal, and at regularly recurring intervals they would send in particularly promising looking samples to Professor Wharton, of Nashville, for analysis. One day they dropped into their bag of samples a piece of blue rock which they informed Professor Wharton was nearly always present under the “slate,” and seemed to be a “bloom.” What was their astonishment to receive from Professor Wharton the report that their coal was still worthless, but that their bloom was phosphate rock, analyzing over 70 per cent. This was in December, 1893, and like the news of William Tell in Switzerland, of old, “From hill to hill the summons flew,” and the whole country went phosphate and option mad.

Lack of transportation and timidity of capital, coupled with the large amount of territory occupied by the deposit and the numerous parties holding properties caused the development to be spasmodic and comparatively small and scattered, and in consequence the price soon fell from $4.25 per ton f. o. b. Aetna, which was the first sale, made by the old Southwestern Phosphate Co., to $2.25 per ton, which was the price at which blue rock guaranteed 65 per cent was sold in 1896, being just a small margin over the cost of production and hauling to the railroad.

In January, 1896, at a time when negotiations were on foot for the sale of a large tract of blue rock land on Swan Creek, Mr. S. Q. Weatherly, former county judge, and prior to that county surveyor of Lewis County, while on a trip to Mt. Pleasant, noticed the peculiar brown rock in the ditch at the roadside on the W. S. Jennings’ farm west of Mt. Pleasant, and being interested in minerals, picked up a piece of it. Noticing the analagous appearance to the weathered blue rock, which is generally brown on the surface, he dropped it in his buggy. On his return to Swan Creek, he showed it to Mr. Harry Arnold and Col. D. B. Cooper, who were interested in the negotiations above mentioned. These gentlemen had it analyzed and finding it to be 75 per cent phosphate rock, induced Mr. Weatherly to say nothing about it until after their deal was consummated. Associated with these gentlemen was also Mr. W. J. Webster, and during the time from January to July, 1896, when the negotiations for the sale of the blue rock properties were finally closed, they ascertained partially the extent of the Mt. Pleasant brown rock field.

When their “big trade” was made they formed the firm of H. I. Arnold & Co., bought two and one-half acres of land from Mr. Mumford Smith, ostensibly for a calf lot for Mt. Pleasant’s present genial mayor, Mr. W. D. Cooper, leased at a royalty of ten cents per ton a few acres from Mr. Cooper and a few from a darky named Tom Smith, got an option from Mrs. M. G. Frierson on the present Columbian & Blue Grass Hills, and commenced mining rock and putting it on the cars at a cost of about eighty-five cents per ton. This rock, without preparation, ran 75 per cent instead of 65 per cent, but whereas the blue rock had never run higher than 3 per cent I. & A., this rock ran, in the state they shipped it, from 4½ to 6 per cent I. & A.

Of course the manufacturers had bought blue rock for $2.25, and knew they were getting it at very nearly the cost of production, and when they saw the “snap” the miner had, they took the[74] stick this excess of I. & A. gave them and proceeded to beat the price down with it until $1.25 and eventually $1.00 per ton were common prices.

Capitalists were rendered more timid than ever before, and even astute phosphate man that he was Col. D. B. Cooper threw up both hands and quit. He said, “Boys, if that is phosphate, the whole basin of Middle Tennessee is full of it, and it will never be worth mining, as every farmer will pick it up off the ground and haul it to the railroad.”

Mr. John S. O’Neal, in a paper presented to the Engineering Association of the South, as late as 1897, said, “the owner of a bed of phosphate rock, is not as well off as the owner of a sand bank, given the same proximity to market.”

The poor fellows in the phosphate business, however, couldn’t get out, and kept digging away, until gradually capital decided it was worth buying the lands after all, and as a result nearly $2,000,000 has been paid for property in the Mt. Pleasant field, about $500,000 in other portions of Maury County, and over $1,000,000 for property in the counties of Decatur, Perry, Lewis, Hickman, Giles, Williamson, Davidson and Sumner. Rock has gradually advanced in price until now 65 per cent blue rock sells at from $2.60 to $2.80 per ton, 75 per cent brown rock at from $3.10 to $3.60 per ton and 78 per cent domestic (4½ I. & A.) at $3.75 to $4.00, while 78 per cent export rock with 3 to 4 per cent I. & A. sells for from $4.00 to $4.25 per ton.

As the prices have increased the cost of production has increased for one reason and another, until now each ton of phosphate rock put on board the cars represents an average cost in labor and salaries of $2.00 per ton. The production for 1904 having been 540,000 tons, the wage earners of Tennessee have profited by this industry to the extent of $1,080,000 during last year alone. On the other hand, fertilizer factories have sprung up all through the interior of the country like magic, and as they now get 75 per cent rock at their factory for less than the freight they used to pay on 62 per cent rock from South Carolina, acid phosphate is cheaper than ever before, and consequently the farmer gets cheaper fertilizer or else better fertilizer for the same money.

The first thing which impresses itself on the mind of almost any visitor to the phosphate fields is the almost universal dependence on hand labor of the simplest pick and shovel kind. This is partially due to the fact that they “just started that way,” and hence the most “experienced laborers” have always done that way; and partially to the fact that after sufficient capital was at hand for the purpose, the varying conditions met with in the deposit made it very difficult to devise appliances suitable for one portion of a mine that would answer the requirements in the closely adjacent portions.

For instance, it is possible in the same open face of a mine to find the overburden varying from two feet to twenty and the rock from a few inches thick, sticking tight to the top of a lime boulder, to fifteen feet in the “dip between two boulders,” while the rock itself will vary from the shaly, partially disintegrated top rock through various sizes to heavy blocks six to eight inches thick and often ten or twelve feet long.

It will therefore be seen how difficult it is to design a machine that will accommodate itself to the handling of this material. The removal of the overburden has been generally accomplished with wheel scrapers. Two companies have used the New Era or Western machine plow with elevator belt loading the dirt into dump bottom wagons alongside. Two steam shovels are now in use, being of the traction type, and occasionally these have been used in digging the rock, though apparently with not sufficient success to justify its continuance. Cableways have never been used to transport the material and this is done largely by wagon and team, though many tram roads with cars propelled either by mules or dinky engines are in use.

The bulk of the rock, however, is dug by the miner with pick and fork, loaded into wagons, hauled out and dumped in windrows on the ground, stirred with a potato plow and harrows, allowed to dry in the sun, taken up again into wagons and hauled either direct to cars for shipping[75] or put under sheds for storage. When an extra good quality of rock is wanted, as for export, a few layers of cordwood are put down and the sun-dried rock put on that. Then, when ready to ship, the wood is fired, and after the rock is cool, it is broken and loaded with forks, when most of the dirt sloughs off, leaving the rock almost perfectly clean.

Some rock can be put from the mines immediately on the wood and burned for export, but generally this will only be a safe domestic rock. Some companies who have water accessible, pick out the large pieces and send them direct to the dry kilns and then the small pieces with the dirt, known as “muck,” are passed through washers, the rock coming out clean, and being deposited on cordwood and burned as above described.

The resulting rock, after being crushed, is passed through screens which separate it in three sizes, from one and one-half inch up going for export, between that and one-fourth inch for domestic, and the dust and one-fourth inch pieces being ground up and sold for direct use or to small factories.

The Century Phosphate Co. has installed a system of dryers and do not wash the rock, but dry it thoroughly in mechanical dryers and then screen and separate it as above.

The reason the larger pieces are as a rule of higher grade than the smaller, is that the dirt and impurity is mostly on the surface of the rock and the greater the proportion of surface to volume the lower the grade in B. P. L. and the higher in iron and alumina.

Owners and operators of mines are gradually turning their attention to labor-saving devices for primary operations, and for systems of reclaiming the immense amount of waste that has heretofore gone on, both in the mining and the preparation of the rock.

One marked step forward in the business is the establishment of a small mixing plant for making complete fertilizers, and the commencing of operations on a large acid phosphate factory, with prospects for additional ones later on.

At least ten per cent of the present output is thrown away to prepare the high grade rock necessary, and this waste will make good 13 per cent acid phosphate, so that every year 50,000 tons of valuable material is absolutely thrown away. This is more phosphate rock than is annually used by any one fertilizer factory in the world, so far as known to the writer. This waste product could easily be transported to a local factory for an average cost of less than 50 cents per ton. Sulphuric acid can be bought laid down at Mt. Pleasant for $7 per ton. The mixing and other preparation will not exceed $2 per ton, so that using half acid and half rock the cost of the acid phosphate will not be more than $4.75 per ton, while it will probably sell for at least $8 per ton. From these figures we appear to be throwing into the waste pile at present material that should represent a profit of not less than $162,500 per annum. That this will be allowed to continue does not appear likely. The question might arise, however, “What will you do with the acid phosphate thus manufactured to keep from overcrowding or at least injuring the market?” I should answer this by calling attention to the immense area of land in Maury, Lawrence, Lewis and Hickman counties, known as “The Barrens,” which are gradually being denuded of their timber for cordwood that is shipped to Mt. Pleasant for use in drying the phosphate rock. There are at least 250,000 acres of this land, which is now readily purchasable at $3 per acre, with the cord wood on it. The wood alone will yield in value more than this price, thus leaving the land clear. Now, it has been demonstrated at Lawrenceburg, Summertown, Loretto, St. Joseph, Hohenwald and numerous other places that systematic and intelligent farming, even with the meager supply of fertilizer (almost entirely in the shape of bone meal) that has been used, will bring these lands up to a point where they will bring from fifteen to twenty bushels of wheat or from twenty-five to thirty bushels of corn per acre. Such lands that have been so brought up readily sell for from $10 to $40 per acre, according to location.

From experiments it has been ascertained[76] that the principal element of plant food lacking in these soils is phosphoric acid. The application of 275 pounds of acid phosphate per acre each year on these lands would consume right at our doors the entire output of the proposed acid factory, even if none were sold elsewhere. This appears chimerical to the casual observer, I must confess, but a careful investigation will demonstrate the soundness of the position taken.

A feature throwing some light on the development of the business at Mt. Pleasant is shown by the following table:

The lengths of track built in each year are as follows:

| Year. | L. & N. R. R. | Private Parties. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feet. | Miles. | Feet. | Miles. | |

| 1896 | 200 | .04 | ||

| 1897 | 1,106 | .21 | 10,343 | 1.96 |

| 1898 | 4,403 | .83 | 2,386 | .45 |

| 1899 | 4,857 | .92 | 30,965 | 5.86 |

| 1900 | 23,835 | 4.51 | 33,152 | 6.28 |

| 1901 | 250 | .05 | 1,364 | .26 |

| 1903 | 29,040 | 5.50 | ||

| Totals | 34,651 | 6.56 | 107,250 | 20.31 |

In addition to these tracks, there are about six miles of narrow gauge tracks and about eight or nine sidings and spurs have been built in Lawrence County for loading cordwood for shipment to Mt. Pleasant.

In Hickman County, the N. C. & St. L. Ry. has built and acquired by purchase from private owners about seven miles of track, which it is now engaged in extending three miles farther up Swan and Blue Buck creeks, and some five or six miles of private tracks have been built.

The following table shows the production of phosphate rock in Tennessee, 1894-1904:

| Year. | Quantity (Long tons). |

Value. |

|---|---|---|

| 1894 | 19,188 | $ 67,158 |

| 1895 | 38,515 | 82,160 |

| 1896 | 26,157 | 57,370 |

| 1897 | 128,723 | 193,115 |

| 1898 | 308,107 | 498,392 |

| 1899 | 462,561 | 1,272,022 |

| 1900 | 450,856 | 1,352,568 |

| 1901 | 394,139 | 1,186,033 |

| 1902 | 454,078 | 1,341,161 |

| 1903 | 445,510 | 1,434,660 |

| 1904 | 540,000 | 1,944,000 |

| Total | 3,267,834 | $9,428,639 |

With more or less frequency, according to whether the news supply is sufficiently good to enable them to get “their per column,” correspondents fire into the several papers of the State some sensational head-liny article about the new “discovery of phosphate rock at Crossroadsville, 5 to 40 feet thick, analyzing from 60 to 90 per cent bone phosphate of lime.” For fear of being behindhand with the news all the papers copy it, and before the report can be corrected to its proper reality of from 6 to 9 per cent, it has been heralded to the four corners of the earth and its effect on future and pending sales can better be imagined than estimated.

If one will take the reports of the geological survey he will find that every possible deposit of phosphate rock in the State is absolutely and positively located. There will be no new discoveries. Of course there will be much new development, but the location of such development will have been discovered long before.

The principal localities in the State where operations are now in progress, are: Mt. Pleasant, Kleburn, Jameson and Century, in Maury County; Lower Swan Creek, Twomey and Totty’s Bend, in Hickman County; near Gallatin, in Sumner County; Wales Station, in Giles County, and near Nashville, in Davidson County.

The principal localities where developments will gradually take place as the demands of the business require are: Southport, Estes Bend, Bear Creek, Neeley’s Valley, Little Bigby, West Fork, *Baptist Branch and *Leiper’s Creek, in Maury County; Richland Creek, in Giles County; Station Camp Creek, in Sumner County; north and west of Franklin, in Williamson County; Brentwood and Bellevue, in Davidson County; Beech River, in Decatur County; Tom’s Creek, Buffalo River, *Hurricane Creek and Cane Creek, in Perry County; *Forty-eight Mile Creek, in Wayne County; *Upper Swan and *Indian Creek, in Lewis County; *Lower Swan, *Indian Creek, Ship’s Bend, Gray’s Bend, Persimmon, Haleys and *Leatherwood creeks, in Hickman County.

* Blue rock.

Anything exploited outside of these[77] known and designated deposits is very apt to prove either a flash in the pan or will be found to be only worked by the newspaper correspondents at so much per column.

Of the present working localities the principal one is Mt. Pleasant, and while the property owners there are beginning to figure a little on how much they have left, still the prevailing impression that Mt. Pleasant is about through mining is an exceedingly mistaken one. With the present rate of output, the visible supply of the Mt. Pleasant field proper will last for seven years longer, without taking into consideration the Southport field, which is practically part of the Mt. Pleasant field. With the Southport field mining will last here at the present rate of output for eleven years. It is very easy to understand that as work progresses at Mt. Pleasant and the end comes more nearly in sight, some miners drop out by selling, some by working out their small deposits and these naturally go to the other fields above referred to. In none of the other fields is found the persistently uniform high grade brown rock of Mt. Pleasant except Southport, Century and Kleburn, in the two latter of which operations are now in progress, and in the former the extension of the Mt. Pleasant Southern Railway will soon cause development work there.

As these deposits afford practically the same grade of rock as Mt. Pleasant proper, they will be worked out simultaneously with it and will cater to the same market.

With their knowledge that the visible supply of this character of rock is comparatively limited, producers are gradually increasing their prices, and by reason of such increase they are slowly reducing their output and giving opportunity for the marketing of the lower grades in the other fields, notably the Swan Creek and Indian Creek deposits in Hickman County.

This, of course, means that the producers at Mt. Pleasant will make more money from their product, and that it will last a considerably longer time, so that it is safe to say that mining in force will be carried on at Mt. Pleasant and kindred localities for at least twenty years.

During the next decade, to supply the diminution of Mt. Pleasant’s output, will come the gradual development of the vast blue rock field of Maury, Hickman and Lewis counties, and the white rock of Perry and Decatur counties, which form the backbone of the phosphate industry in Tennessee, and whose millions of tons will cause these counties to be considered the phosphate reservoir of the world for the next seventy-five or one hundred years.

The change of base will be gradual and easy, and the trade will have ample opportunity and time to adjust its operations so as to utilize the lower grade blue rock as it becomes advisable and necessary to do so. Its many points of superiority for acidulation and for direct use without acidulation will largely make up for its lower grade, and as a mining proposition it more nearly approaches a technical field of operation.

The blue rock field proper covers a territory bounded approximately by a trapezoid having as its four corners Centreville, in Hickman County; Kinderhook and Mt. Joy, in Maury County, and Lewis Monument, in Lewis County. Traversing this territory are Duck River, Indian, Swan, Blue Buck and Cathey’s creeks, and their tributaries, and outcropping along these valleys and underlying the ridges between them are deposits of blue rock running in bone phosphate from 60 per cent to 78 per cent, with less than 3 per cent iron and alumina, that will aggregate in the neighborhood of 40,000,000 tons.

This field will soon be developed by the extension of the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis branch up Swan Creek and the Louisville & Nashville branch down Swan Creek, with side lines and spurs leading off each, surveys for which have been made, and work on construction will soon be under way.

If, however, the Florence Northern Railroad should ever be built from Florence to Nashville it will run through the heart of this territory as well as the magnificent iron deposits of Wayne and Lewis.

With the above road and a road from[78] Huntsville on the southeast to Milan on the northwest all of the phosphate territory would be fully developed, and this section of Maury, Hickman, Lewis, Perry, Giles, Davidson and Williamson counties would be the site of more fertilizer factories than will be found elsewhere in the world in the same space.

Contributary to such prospective development is the present opening up of pyrites deposits at Pyriton, near Talladega, Ala., with ore running two to four units higher than the Virginia ores, and while from four to six units lower than the best Spanish ores, it is much more free burning than the latter, and with its advantage in freight rates, will likely give manufacturers equally as good a product at a lower price.

The vein of pyrites is about one and one-half miles long and from four to fifteen feet thick and has been exploited to a depth of 430 feet, the ore improving in quality with the depth. It is reported by manufacturers who have used it to be the freest burning pyrites ore known, leaving only about ½ of 1 per cent of the sulphur in the cinder and containing no deleterious ingredients. The deposits are controlled by the Alabama Pyrites Company and the Southern Sulphur Ore Company, the latter owned by Messrs. Carpenter & Howard, of Columbia, their vein running from eight to fifteen feet thick. The railroad into this deposit has been built from the Louisville & Nashville, at Talladega, a distance of twenty miles, at a cost of nearly $400,000.

The consumption of fertilizers has increased 200 per cent in the United States in the past twelve years, and while the visible supply of phosphate rock is rapidly decreasing, the consumption of fertilizers is almost as rapidly increasing, and with this fact in view, the large fertilizer companies are and have been for several years gradually buying up phosphate lands to provide themselves for the future. This tendency has put a large amount of phosphate property in such strong hands that little or no danger is possible of the old scramble to sell, with its attendant low prices. At the same time, a considerable amount of land valuable for its phosphate deposits is still uncontrolled by manufacturers, so that a healthy competition in the business is still open.

The amount of fertilizer used in Middle Tennessee is almost a minus quantity, but this state of things cannot long exist. The horse worked continuously without feeding soon dies, and so it will be, nay already is, with much of our land in the “dimple of the universe.”

Farmers know that the crops of ten years ago cannot be raised to-day and are all waking up to the fact that something is needed. The large stock-raiser, who husbands his stable manure, can partially take care of the thin spots on his land. But the small farmer, the backbone of the country, whose acres do not afford him land sufficient to till and still have the rich pastures necessary to raise much stock, contents himself with simply wearing out his farm, selling it at a low price, generally with the mediation of the sheriff, and moving elsewhere for better or more probably for worse. To this class the use of fertilizer in Tennessee is practically unknown, but their successors of the next few decades will form, as is the case in other States, the bulk of the fertilizer consumers, and when this comes to pass Tennessee will indeed have come into her own.

The use of fertilizer in the cotton States has enabled the planters to continue year after year to raise the enormous crops of cotton and has also enabled them to diversify their crops by being able to produce the same yield of cotton on a less number of acres.

So fertilizers will enable the Middle Tennessee farmers to raise the same amount of feed on fewer acres, leaving more land to grow up to blue grass, and our present greatly depreciated live stock interests will come up by leaps and bounds until we will rival the famous blue grass section of Kentucky, if we do not far outstrip it.

When one stops to consider (1) that the wheat crop alone annually removes from the soil of the United States more phosphoric acid than is the equivalent of twice the amount of phosphate rock produced in the country; and (2) that over half of the amount mined is exported so that the fertilizers used in the United States return to the soil only[79] one-fourth of the phosphoric acid that is taken away by the wheat crop alone, without considering the other crops, we can readily see that the consumption of fertilizer and phosphate rock not only will, but of right ought to, enormously increase, and that the industry is a permanent one that will last without cessation or danger of serious interruption as long as the world eats bread. That it has been and still is being developed almost entirely by outside capital is one of the features that seems to attend the development of practically all the industries of the State.

A complete analysis of a dry sample of average “brown rock,” which the writer had made several years ago, may be of interest, and is as follows:

| Moisture | .87 |

| Combined water and organic matter | 1.53 |

| Sand and insoluble matter | 2.76 |

| Peroxide of iron | 2.40 |

| Alumina | 1.99 |

| Lime | 49.07 |

| Magnesia | .24 |

| Carbonic acid | 1.08 |

| Equals carbonate of lime, 2.41. | |

| Fluorine | 2.98 |

| Sulphuric acid | 1.03 |

| Phosphoric acid | 35.62 |

| Equals bone phosphate of lime, 77.78. | |

| Total | 99.57 |

The rock which is exported from Tennessee goes to England, Scotland, Ireland, Belgium, Holland, France, Spain, Italy, Austria and Japan. The domestic rock is consumed by the various fertilizer factories all over that part of the United States east of the Mississippi River, some of the principal points being Philadelphia, Pa.; Buffalo, N. Y.; Cleveland and Columbus, Ohio; Chicago, Ill.; Indianapolis, Ind.; Lynchburg, Staunton, Norfolk and Richmond, Va.; Memphis, Nashville and Chattanooga, Tenn.; Greenville, Columbia and Charleston, S. C.; Charlotte and Winston, N. C.; Macon and Atlanta, Ga.; Meridian, Miss.; Birmingham, Montgomery and Mobile, Ala.

In conclusion, a word might be appropriate on the subject of the direct use of raw ground phosphate rock as a fertilizer, without acidulation.

The experiment stations of the great States of Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Maryland and New Jersey have made exhaustive experiments with this material, and their bulletins may be had by any farmer desiring them, showing that this material has given results that prove it to be more valuable for many soils than the acidulated phosphate. The great State of Tennessee, on the other hand, without any practical experiments to back it up, in the face of the opinions of some of its most eminent chemists and experts, continues on its statute book an absolute prohibition against the sale of this material within its borders.

Mr. Cyril Hopkins, of the Illinois Experiment Station, says that the discovery of the Tennessee phosphate deposits is the greatest thing that ever happened for the farmers of Illinois.

Each year many carloads of this material are shipped into other States and wherever it has been used its use is spreading, yet these people have to pay more in freight alone than it would cost the average Tennessee farmer at his farm.

Immense deposits of this rock exist in Tennessee high enough in grade to meet the requirements for direct use, and if this prohibition were removed, almost every county seat in the sixth and seventh congressional districts would have phosphate mills to supply the local trade, just as they have flour mills.

The next Legislature should certainly correct the errors of the past by allowing the Tennessee farmer to exercise the same amount of free agency, common sense judgment as his fellows of the other States.

The principal mines in Tennessee are shown in the table on the following page:

| County. | Operators. | Name of Tract or Mine | Holdings. | Character of mining: Underground or surface. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Post Office | How Held | No. of Acres | |||

| Davidson | Charleston, S. C., Mining and Mfg. Co. | Charleston, S. C. | Caldwell | Fee | 65 | Surface. |

| Hickman | American Cotton Oil Co. | New York | Gregory | Fee | 125 | Both. |

| Hickman | Jarecki Chemical Co. | Cincinnati, O. | Ratliff | Fee | 300 | Both. |

| Hickman | Meridian Fertilizer Fac. | Meridian, Miss. | Laverick | Fee | 2,280 | Under’gr’d. |

| Hickman | Rich & Hays Phos. Co. | Twomey | Brown | Fee | 50 | Surface. |

| Hickman | Rich & Hays Phos. Co. | Twomey | Wiss | Lease | 40 | Both. |

| Hickman | Swift & Co. | Chicago | Eason | Fee | 60 | Both. |

| Hickman | Tenn. Blue Rock Phos. Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Fogg | Lease | 200 | Under’gr’d. |

| Hickman | S. M. Ward Mining Co. | Centerville | McGill | Lease | 500 | Both. |

| Maury | H. F. Alexander | Columbia | Jameson | Surface. | ||

| Maury | H. F. Alexander & Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Mt. Pleasant | Surface. | ||

| Maury | Blue Grass Phos. Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Blue Grass | Lease | 1,000 | Surface. |

| Maury | Central Phosphate Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Dawson | Surface. | ||

| Maury | Central Phosphate Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Kittrell | Lease | 125 | Surface. |

| Maury | Central Phosphate Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Harris | Surface. | ||

| Maury | Central Phosphate Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Long | Fee | 140 | Surface. |

| Maury | Charleston, S. C., Mining and Mfg. Co. | Charleston, S. C. | Arrow | Fee | 690 | Surface. |

| Maury | ” ” ” | Charleston, S. C. | Howard | Fee | 182 | Surface. |

| Maury | ” ” ” | Charleston, S. C. | McMeen | Fee | 540 | Surface. |

| Maury | ” ” ” | Charleston, S. C. | Ridley | Fee | 319 | Surface. |

| Maury | Columbian Phos. Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Columbian | Fee | 60 | Surface. |

| Maury | H. B. Battle | Winston, N. C. | Battle | Fee | 84 | Surface. |

| Maury | Federal Chemical Co. | Louisville, Ky. | Tenn. Phos. Co. | Fee | 1,200 | Surface. |

| Maury | International Phos. Co. | Columbia | Solita | Fee | 110 | Surface. |

| Maury | International Phos. Co. | Columbia | Satterfield | Fee | 275 | Surface. |

| Maury | Maury Phos. Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Moore | Fee | 264 | Surface. |

| Maury | Petrified Bone Min. Co | Mt. Pleasant | Petrified | Fee | 220 | Surface. |

| Maury | Swift & Co. | Chicago, Ill. | Bailey | Lease | 361 | Surface. |

| Maury | Tenn. Chemical Co. | Nashville | Douglass | Fee | 250 | Surface. |

| Sumner | Buffalo Fertilizer Co. | Buffalo, N. Y. | Watkins | Fee | 250 | Surface. |

| Sumner | Smith Agr. Chem. Co. | Columbus, O. | Sumner Phos. Co. | Fee | 1,500 | Surface. |

| Sumner | Swift & Co. | Chicago, Ill. | Guthrie | Fee | 321 | Surface. |

| Maury | France & Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Goodloe | Fee | 40 | Surface. |

| Maury | Ruhm & Barrow | Mt. Pleasant | Sedberry | Fee | 130 | Surface. |

| Hickman | N. Y. & St. L. Min. & Mfg. Co. | Aetna, Tenn | Peery | Fee | 7,000 | Under’gr’d. |

| Maury | Globe Phos. Co. | Mt. Pleasant | American | Fee | 2,500 | Surface. |

| Maury | Century Phos. Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Harlan | Lease & Fee | 1,000 | Surface. |

| Maury | Southport Phos. Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Southport | Fee | 943 | Surface. |

| Hickman | Amer. Cot. Oil Co. | New York | Gilmer | Fee | 200 | Both. |

| Lewis | Big Swan Phos. Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Walker | Fee | 600 | Under’gr’d. |

| Hickman | Ruhm & Wheeler | Mt. Pleasant | Harvill | Fee | 736 | Under’gr’d. |

| Hickman | Killebrew, Ruhm & Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Rochell | Fee | 541 | Both. |

| Perry | Perry Phos. Co. | Columbia | Tom’s Creek | Fee | 500 | Under’gr’d. |

| Decatur | Beech River Phos. Co. | Nashville | Parsons | Fee | 1,000 | Surface. |

| Lewis | Charleston M. & Mfg. Co. | Mt. Pleasant | Mayfield | Fee | 500 | Under’gr’d. |

The achievements and development of the pacer in the past ten or fifteen years, since the advent of the Hals, and the swift tribe of trotting-bred pacers, has been so marked and so great that a special chapter is needed for its explanation. The old “side-wheeler” has gone—the new, beautifully gaited, true striding pacing race horse has taken his place. No other feature of a race meeting brings out the crowd and the enthusiasm equal to the free-for-all pace. Never before had such races been witnessed as those first seen in the days of the Big Four—the queen of which was Mattie Hunter 2:12½, the first great Hal mare to attract the attention of the world. She was the star of the Big Four, the others being Blind Tom, Lucy and Rowdy Boy. Later, some of the great free-for-allers were Little Brown Jug, Brown Hal, Hal Pointer, Robert J, Direct, Joe Patchen, John R Gentry and many others whose names will be readily remembered by every horseman. The very mention of these names brings a thrill to the heart as, toward the last of the century, Robert J, John R. Gentry and Joe Patchen and Star Pointer began to bring the pacing record to the two-minute mark. This was first done by Star Pointer, an inbred Hal, crossed again and again in the thoroughbred blood which, undoubtedly, gave to the Hals the staying power so characteristic of the family. And so, looking back, the following article, written by Trotwood December 29, 1892, seems prophetic—that is, if there were such a thing as prophecy. But, alas, there is not, for prophecy is merely another name for the cause of the future as foreseen in the present’s effect. And though this was written thirteen years ago, it is embodied into this history, as fitting so well the present:

“There can no longer be any doubt that the pacer, as a future product on the light harness race course, will be a still stronger factor than he is to-day. Even if desired, it is now not possible to eliminate him from the light harness breeding world. He has come to stay. It matters not to us whether the honest, but sturdy, rascal can trace his ancestors to Marsh’s five-toed orohippos, weighing about forty pounds, and which had all he could do to keep out of the way of Darwin’s “missing link,” and thus save himself from drudgery, even before the days of the Silurian serpents, or whether he was developed in Trojan wars as carved on the frieze of Grecian temples; the fact remains the same, that to-day he is here by a large majority, and though snubbed by his more aristocratic brother, he persistently refuses to stay behind in the procession, and is never happier than when he can get up a good,[82] rattling fight in a five-heat race, or stick his common, but inquisitive, nose a few seconds beyond the trotting record securely placarded on the front of old Father Time. Flung into the world without prestige, friends or influence; his coming regarded as the epitome of a breeder’s ill luck; condemned before he was born, and damned before he could walk; a little too good to kill, yet hardly good enough to be allowed a square meal once a week that he might grow up like any other horse; toe-weighted and hobbled and banged about, and forced to trot in spite of the laws of nature herself, yet the game and honest little fellow, when relieved of his owner’s prejudices and hobbles, has flown to the front with the ease of a swallow through the air and the grace of a game fish in the lake, and now holds the first record for speed and the chief place on the program in the eye of a grand stand that paid its way to see an honest horse race.

“It is the old story of the rejected stone, and he now holds up with surprising popularity his corner of the race horse structure. And yet twenty years ago a pacer was scarcely allowed on a fashionable race course; his pedigree, they said, took to the woods on the first cross; he was regarded by the trotting world as a camel-backed, cat-hammed, narrow-chested, curby-legged beast who paced because he couldn’t trot, and was alive because nobody cared to buy powder enough to kill all of them in the woods of Tennessee and Kentucky. He was allowed to exist on the race course very much on the same idea that a slave is allowed to breathe the same air and view the same heaven his master does. He began his career because he was a good kind of an animal to have around to do the race act at the pumpkin show and come in along with the fat woman and the five-legged calf. His coming to the front was his own work; and to use a classical phrase, he was purely the architect of his own fortune. The American people are a long time finding out merit, but nothing helps them to see it as quickly as the image of the American eagle stamped on the back of a silver dollar—and this the pacer has shown them.