No. 108.—Vol. III.

Price 1½d.

SATURDAY, JANUARY 23, 1886.

Title: Chambers's Journal of Popular Literature, Science, and Art, Fifth Series, No. 108, Vol. III, January 23, 1886

Author: Various

Release date: December 25, 2021 [eBook #67008]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: William and Robert Chambers

Credits: Susan Skinner, Eric Hutton and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

{49}

AN ANGLER’S IDYLL.

IN ALL SHADES.

OUR DOMESTICATED OTTER.

A GOLDEN ARGOSY.

SNOW-BLOSSOM.

OCCASIONAL NOTES.

AT WAKING.

No. 108.—Vol. III.

Price 1½d.

SATURDAY, JANUARY 23, 1886.

I am once more at the water’s edge. It is the Tweed, silver-voiced, musical, its ripples breaking into liquid crystals as the rushing stream leaps into the breast of the softly-circling pool. Here, in its upper reaches, amid the pastoral hills of Peeblesshire, its volume of fair water is untainted by pollution. It has miles and miles yet to run ere it comes up with the floating scum and dismal discoloration of ‘mill-races’ and the refuse of the dye-house. And, there!—is not that Drummelzier Castle on the opposite bank above, its gray walls powdered with the yellows and browns of spreading lichens, and its shattered bastions waving here and there a crest of summer’s greenest grass? The fierce old chieftains who wrangled Border-fashion in its halls are silent to-day; the wild Tweedies and Hays and Veitches have had their rough voices smothered in the churchyard dust. From the shady angle of the old tower steps out a great brindled bull, leading his following of milky dames to where the pasture is juicy in the haughs below. I am thankful the broad deep stream is between us, for as he lifts his head and sees me where I stand, he announces his displeasure in a short angry snort and a sudden lashing of his ponderous tail. Perhaps it is only the flies tormenting him. In any case, it is well to be beyond his reach.

Above me and around are the great brown hills of Tweed-dale. They have this morning a dreamy look. The soft west wind plays about them, and the sunlight weaves a web of mingled glory and gloom over their broad summits and down their furrowed sides. The trees wave green branches in the soft warm air; but I hear them not—only the swish and tinkle of the waters. The sheep that feed upon the long gray slopes move about in a kind of spectral stillness; I almost fancy I hear them bleat, but may be mistaken, so far-off and dream-like is the sound. A distant shot is heard, and a flock of white pigeons rise with swift wing from the summit of the battered old keep, and wheel quick circles round the tower, then settle down as still and unseen as before. And something else is moving on the farther side. It is a milkmaid, tripping down the bank towards the river, her pitchers creaking as she goes. She pauses ere dipping them in the stream, and looks with level hand above her eyes across the meadows now aflame with the morning sun. Perhaps she expects to see some gallant Patie returning from the ‘wauking o’ the fauld,’ or some bashful Roger hiding mouse-like behind the willows. Her light hair has been bleached to a still lighter hue by the suns and showers of many a summer day, but these, though they have bronzed her broad brow and shapely neck, have left undimmed the rosy lustre of her cheek. Light-handed, red-cheeked Peggy, go thy way in sweet expectation! When the westering sun flings purple shadows over the hills, he whose rustic image stirs thy glowing pulses shall steal to meet thee here.

And I?—what have I to do? There is the tempting stream; the pliant rod, with its gossamer line and daintily busked lures, is ready to hand. Deft fingers have mounted it for me without ostentation or display. There has been no struggling with hanked line or tangled cast; I have been served like a prince among anglers, and am ready-equipped to step into the stream. And yet at the moment I am all alone; for round me only are the silent hills, and beneath me the broadly-flowing Tweed.

I have never fished so before. I feel as light as if the normal fifteen pounds to the square inch of atmospheric pressure no longer existed for me. Ah, with what delight I feel the cool water lapping round my limbs, as I fling the light line far across the rippling stream, and watch the ‘flies’ as they drop and float downwards with the current. The broad brown hills, the dewy woods, the gray tower, are forgotten now. The brindled bull and his milky following have gone, with the rosy milkmaid, out of sight and out of mind. The pigeons{50} high on the shattered keep may wheel fleet circles as they choose, and spread white wings in the orient sun, but they cannot draw my eyes from the charmed spot. Down there, in the haugh beneath, near to where Powsail Burn joins the Tweed, the thorn-tree is shading the wizard’s grave; but gray Merlin, sleeping or waking, living or dead, is nothing to me. Yonder, up the river, is Mossfennan Yett, and the Scottish king, for all I know, may once more be riding round the Merecleugh-head, ‘booted and spurred, as we a’ did see,’ to alight him down, as in days of old, and ‘dine wi’ the lass o’ the Logan Lea;’ but to me that old royal lover is at this moment a thing of nought. Border story and Border song, tale of love and deed of valour—what are they now to me, with the soft wind sighing round my head and the swift river rushing at my feet?

A splendid stream, indeed! For a hundred yards it sweeps with broken and jagged surface, from the broad shallow above to the deep dark pool below. In the strong rush of its current, it is not easy keeping your feet. The bottom is of small pebbles, smooth and round, gleaming yellow and brown through the clear water, and they have an awkward knack of slipping cleverly from beneath your feet, giving you every now and then a queer sensation of standing upon nothing. But this is only for a moment, or ever so much less than a moment. For if it were longer than the quickest thought, it might bring you a bad five minutes. To lose your footing in this swift-hurrying stream, might be to have a fleet passage into the great pool that hugs its black waters beneath the shadow of yonder gloomy rock over which the pine-trees wave their sunless boughs. But really, after all, one has no fear of that. Usage gives security. The railway train in which you sit quietly reading the morning paper, might at any moment leave the rails, or break an axle, or collide with the stone bridge ahead; but you do not think of that, or anticipate it—or, if you did, life would not be worth living. So is it here in the broad Tweed. With the faculties engrossed in the work of the moment, foot and hand are equally and instinctively alert. Slowly and securely you move over the shining pebbles, making cast after cast—wondering if ever you are to have a rise.

I must work here with cautious hand and shortened line. For a belt of trees borders the river on the farther side, and a long-armed ash is pushing his boughs far out over the stream, as if seeking to dip his leaf-tips in the cool-flowing water. To hank one’s line on these quivering boughs would lead to a loss of time and probably of temper, and this morning everything is too beautiful and bright for any angry mood. As yet I have no success. Not a fin is on the rise; not a single silvery scale has glittered. Still, what beauties I know to be lurking there. You see that point, where the ground juts out a little into the stream, and a ragged alder hangs with loosened roots from the crumbling bank? It is being slowly undermined by the stream, and one day will slip down and be carried away. But as yet, it affords a rare sheltering-place for the finny tritons. It was but last season I hooked one at that very spot, and after a long and stubborn fight got my net beneath him, and went victor home.

And I know that others are there still, as brave and as beautiful as he. In fancy’s eye I can see them even now, lying with head up-stream, and motionless but for now and then a quick jerk of the tail sideways, their yellow flanks gleaming in speckled radiance when a sunbeam reaches them through the fret-work of the overhanging leaves. That sharp jerk of the tail sideways means that they are keeping their weather-eye open. Being, among other things, insectivorous, they know if they would secure their prey they must be quick about it, hence they are ever on the alert. And yet, the flies which I am offering must have passed close by them a dozen times, but still they have stirred not, except in that knowing way which indicates they are not to be taken in. They have learned a thing or two, these Tweed trout, since the time of the Cæsars. Speak about animals not having reasoning powers? Let any one who deludes himself with this vain fallacy, purchase the best angling apparatus going, and then try his hand upon Tweed trout. Three hours afterwards he will not feel quite so satisfied as to the immeasurable superiority of man over the lower creatures. He may even have some half-defined suspicion that it is himself, and not the other party, that has been taken in. And not without cause. These Tweed trout can pick you out an artificial fly as skilfully as a tackle-maker.

The thought disheartens me for a moment, as I stand here, lashing away, middle-deep in the stream. But it is only for a moment. The wind is soft; the air is bright, but not too bright, with sunshine; a luminous haze is gathering between me and the distant mountains, and the skies have now more of gray than of blue in their airy texture. Everything is beautiful, from the soft contour of the rounded hills to the glitter and sparkle of the silvery stream.—But, there! My reel is whirring off with a sound that seals the senses against everything else. He is on! I saw him rise, and as he turned to descend I struck—and there he is! It was all quicker than thought. He has rushed up-stream a dozen yards, but is turning now. As I reel in, I begin mentally to calculate the ratio of his weight to his strength of pull. This is a useful thing to do; because if you should happen to lose your fish, you are then in a position to assure your friend Jones, who is higher up the water, and very likely has done nothing, that you had one ‘on’ which was two pounds if it was an ounce. Jones will of course believe it, and condole with you upon your loss—perhaps with a secret chuckle.

But this is digressive. I have other work than to talk about Jones at present. Master Fario is not taking kindly to the bridle which I have put in his mouth, and is having another run for it. There he goes, swish out of the water a couple of feet. What an exhilarating moment! Another leap and whirl, and off he goes careering towards the pool below in a way you never saw. But the line is running out after him, and still he is fast. The fight is keen, but he is worth fighting for. With the point of the rod well up, and a considerable strain upon the line, he must soon either yield—or break off. The alternative{51} is dreadful to contemplate. So I renew my caution, and play him gently. By-and-by I feel he is yielding. Reeling in once more, I soon draw him within range of eyesight. What a beauty he is! Plump and fat, the very pink of trouts! Moving uneasily from side to side—boring occasionally as if he would make his way down to catch hold of something, but with a swinging and swaying motion about him indicative of failing power—he comes nearer and nearer to me where I stand, breathless with excitement, dreading lest, even at this last stage of the struggle, I may yet lose him. The supreme moment is at hand! He is almost at my feet. I hold the rod with one hand, and with the other undo the landing-net. He circles round me at as great a distance as the shortened line will allow, and though I have tried once or twice to pass the net beneath him, he has hitherto managed to baffle me. But now, at last, the net is under him—and, there——

Tap, tap!—‘Come in!’—And enter two or three little ones to hid papa good-night. Ah, little sweethearts, what a vision you have undone! The flowing stream, the overhanging trees, the old gray tower, the silent hills, have all, at the touch of your tiny fingers, vanished!

I was not dreaming—no, nor yet asleep. My hook lies turned face down on my knee, and my pipe, extinguished, is still between my lips. It is towards the end of December; the Christmas bells have already rung out their message, and the New Year is waiting, in a few days to be ushered in. Outside, the wind is blowing in loud noisy gusts through the darkness, scattering the snow-flakes before it in a level drift. Here, in my bookroom, as I sat with foot on fender, watching the glowing embers in the grate, thoughts of summer days had stolen over me. I was once more by silvery Tweed, under sunny skies, plying ‘the well-dissembled fly’—the storm and the snow-drift without, being as if they were not. To you, reader, I have uttered aloud the reverie of those brief five minutes of swift fancy; to you, brother anglers, may that phantasmal expedition be the harbinger of coming sport; and with each and all of you I now will part, bidding you reverently, as I bid my little ones, Good-night!

The letter from Edward that had so greatly perturbed old Mr Hawthorn had been written, of course, some twenty days before he received it, for the mail takes about that time, as a rule, in going from Southampton across the Atlantic to the port of Trinidad. Edward had already told his father of his long-standing engagement to Marian; but the announcement and acceptance of the district judgeship had been so hurried, and the date fixed for his departure was so extremely early, that he had only just had time by the first mail to let his father know of his approaching marriage, and his determination to proceed at once to the West Indies by the succeeding steamer. Three weeks was all the interval allowed him by the inexorable red-tape department of the Colonial Office for completing his hasty preparations for his marriage, and setting sail to undertake his newly acquired judicial functions.

‘Three weeks, my dear,’ Nora cried in despair to Marian; ‘why, you know, it can’t possibly be done! It’s simply impracticable. Do those horrid government-office people really imagine a girl can get together a trousseau, and have all the bridesmaids’ dresses made, and see about the house and the breakfast and all that sort of thing, and get herself comfortably married, all within a single fortnight? They’re just like all men; they think you can do things in less than no time. It’s absolutely preposterous.’

‘Perhaps,’ Marian answered, ‘the government-office people would say they engaged Edward to take a district judgeship, and didn’t stipulate anything about his getting married before he went out to Trinidad to take it.’

‘Oh, well, you know, if you choose to look at it in that way, of course one can’t reasonably grumble at them for their absurd hurrying. But still the horrid creatures ought to have a little consideration for a girl’s convenience. Why, we shall have to make up our minds at once, without the least proper deliberation, what the bridesmaids’ dresses are to be, and begin having them cut out and the trimmings settled this very morning. A wedding at a fortnight’s notice! I never in my life heard of such a thing. I wonder, for my part, your mamma consents to it.—Well, well, I shall have you to take charge of me going out, that’s one comfort; and I shall have my bridesmaid’s dress made so that I can wear it a little altered, and cut square in the bodice, when I get to Trinidad, for a best dinner dress. But it’s really awfully horrid having to make all one’s preparations for the wedding and for going out in such a terrible unexpected hurry.’ However, in spite of Nora, the preparations for the wedding were duly made within the appointed fortnight, even that important item of the bridesmaids’ dresses being quickly settled to everybody’s satisfaction.

Strange that when two human beings propose entering into a solemn contract together for the future governance of their entire joint existence, the thoughts of one of them, and that the one to whom the change is most infinitely important, should be largely taken up for some weeks beforehand with the particular clothes she is to wear on the morning when the contract is publicly ratified! Fancy the ambassador who signs the treaty being mainly occupied for the ten days of the preliminary negotiations with deciding what sort of uniform and how many orders he shall put on upon the eventful day of the final signature!

At the end of that short hurry-scurrying fortnight, the wedding actually took place; and an advertisement in the Times next morning duly announced among the list of marriages, ‘At Holy Trinity, Brompton, by the Venerable Archdeacon Ord, uncle of the bride, assisted by the Rev. Augustus Savile, B.D., Edward Beresford Hawthorn, M.A., Barrister-at-law, of the Inner Temple, late Fellow of St Catherine’s College, Cambridge, and District Judge of the Westmoreland District, Trinidad, to Marian Arbuthnot, only daughter of General C. S. Ord, C.I.E.,{52} formerly of the Bengal Infantry.’ ‘The bride’s toilet,’ said the newspapers, ‘consisted of white broché satin de Lyon, draped with deep lace flounces, caught up with orange blossoms. The veil was of tulle, secured to the hair with a pearl crescent and stars. The bouquet was composed of rare exotics.’ In fact, to the coarse and undiscriminating male intelligence, the whole attire, on which so much pains and thought had been hurriedly bestowed, does not appear to have differed in any respect whatsoever from that of all the other brides one has ever looked at during the entire course of a reasonably long and varied lifetime.

After the wedding, however, Marian and Edward could only afford a single week by way of a honeymoon, in that most overrun by brides and bridegrooms of all English districts, the Isle of Wight, as being nearest within call of Southampton, whence they had to start on their long ocean voyage. The aunt in charge was to send down Nora to meet them at the hotel the day before the steamer sailed; and the general and Mrs Ord were to see them off, and say a long good-bye to them on the morning of sailing.

Harry Noel, too, who had been best-man at the wedding, for some reason most fully known to himself, professed a vast desire to ‘see the last of poor Hawthorn,’ before he left for parts unknown in the Caribbean; and with that intent, duly presented himself at a Southampton hotel on the day before their final departure. It was not purely by accident, however, either on his own part or on Marian Hawthorn’s, that when they took a quiet walk that evening in some fields behind the battery, he found himself a little in front with Nora Dupuy, while the newly married pair, as was only proper, brought up the rear in a conjugal tête-à-tête.

‘Miss Dupuy,’ Harry said suddenly, as they reached an open space in the fields, with a clear view uninterrupted before them, ‘there’s something I wish to say to you before you leave to-morrow for Trinidad—something a little premature, perhaps, but under the circumstances—as you’re leaving so soon—I can’t delay it. I’ve seen very little of you, as yet, Miss Dupuy, and you’ve seen very little of me, so I daresay I owe you some apology for this strange precipitancy; but—— Well, you’re going away at once from England; and I may not see you again for—for some months; and if I allow you to go without having spoken to you, why’——

Nora’s heart throbbed violently. She didn’t care very much for Harry Noel at first sight, to be sure; but still, she had never till now had a regular offer of marriage made to her; and every woman’s heart beats naturally—I believe—when she finds herself within measurable distance of her first offer. Besides, Harry was the heir to a baronetcy, and a great catch, as most girls counted; and even if you don’t want to marry a baronet, it’s something at least to be able to say to yourself in future, ‘I refused an offer to be Lady Noel.’ Mind you, as women go, the heir to an old baronetcy and twelve thousand a year is not to be despised, though you may not care a single pin about his mere personal attractions. A great many girls who would refuse, the man upon his own merits, would willingly say ‘Yes’ at once to the title and the income. So Nora Dupuy, who was, after all, quite as human as most other girls—if not rather more so—merely held her breath hard and tried her best to still the beating of her wayward heart, as she answered back with childish innocence: ‘Well, Mr Noel; in that case, what would happen?’

‘In that case, Miss Dupuy,’ Harry replied, looking at her pretty little pursed-up guileless mouth with a hungry desire to kiss it incontinently then and there—‘why, in that case, I’m afraid some other man—some handsome young Trinidad planter or other—might carry off the prize on his own account before I had ventured to put in my humble claim for it.—Miss Dupuy, what’s the use of beating about the bush, when I see by your eyes you know what I mean! From the moment I first saw you, I said to myself: “She’s the one woman I have ever seen whom I feel instinctively I could worship for a lifetime.” Answer me yes. I’m no speaker. But I love you. Will you take me?’

Nora twisted the tassel of her parasol nervously between her finger and thumb for a few seconds; then she looked back at him full in the face with her pretty girlish open eyes, and answered with charming naïveté—just as if he had merely asked her whether she would take another cup of tea:—‘Thank you, no, Mr Noel; I don’t think so.’

Harry Noel smiled with amusement—in spite of this curt and simple rejection—at the oddity of such a reply to such a question. ‘Of course,’ he said, glancing down at her pretty little feet to hide his confusion, ‘I didn’t expect you to answer me Yes at once on so very short an acquaintance as ours has been. I acknowledge it’s dreadfully presumptuous in me to have dared to put you a question like that, when I know you can have seen so very little in me to make me worth the honour you’d be bestowing upon me.’

‘Quite so,’ Nora murmured mischievously, in a parenthetical undertone. It wasn’t kind; I daresay it wasn’t even lady-like; but then you see she was really, after all, only a school-girl.

Harry paused, half abashed for a second at this very literal acceptance of his conventional expression of self-depreciation. He hardly knew whether it was worth while continuing his suit in the face of such exceedingly outspoken discouragement. Still, he had something to say, and he determined to say it. He was really very much in love with Nora, and he wasn’t going to lose his chance outright just for the sake of what might be nothing more than a pretty girl’s provoking coyness.

‘Yes,’ he went on quietly, without seeming to notice her little interruption, ‘though you haven’t yet seen anything in me to care for, I’m going to ask you, not whether you’ll give me any definite promise—it was foolish of me to expect one on so brief an acquaintance—but whether you’ll kindly bear in mind that I’ve told you I love you—yes, I said love you’—for Nora had clashed her little hand aside impatiently at the word. ‘And remember, I shall still hope, until I see you again, you may yet in future{53} reconsider the question.—Don’t make me any promise, Miss Dupuy; and don’t repeat the answer you’ve already given me; but when you go to Trinidad, and are admired and courted as you needs must be, don’t wholly forget that some one in England once told you he loved you—loved you passionately.’

‘I’m not likely to forget it, Mr Noel,’ Nora answered with malicious calmness; ‘because nobody ever proposed to me before, you know; and one’s sure not to forget one’s first offer.’

‘Miss Dupuy, you are making game of me! It isn’t right of you—it isn’t generous.’

Nora paused and looked at him again. He was dark, but very handsome. He looked handsomer still when he bridled up a little. It was a very nice thing to look forward to being Lady Noel. How all the other girls at school would have just jumped at it! But no; he was too dark by half to meet her fancy. She couldn’t give him the slightest encouragement. ‘Mr Noel,’ she said, far more seriously this time, with a little sigh of impatience, ‘believe me, I didn’t really mean to offend you. I—I like you very much; and I’m sure I’m very much flattered indeed by what you’ve just been kind enough to say to me. I know it’s a great honour for you to ask me to—to ask me what you have asked me. But—you know, I don’t think of you in that light, exactly. You will understand what I mean when I say I can’t even leave the question open. I—I have nothing to reconsider.’

Harry waited a moment in internal reflection. He liked her all the better because she said no to him. He was man of the world enough to know that ninety-nine girls out of a hundred would have jumped at once at such an eligible offer. ‘In a few months,’ he said quietly, in an abstracted fashion, ‘I shall be paying a visit out in Trinidad.’

‘Oh, don’t, pray, don’t,’ Nora cried hastily. ‘It’ll be no use, Mr Noel, no use in any way. I’ve quite made up my mind; and I never change it. Don’t come out to Trinidad, I beg of you.’

‘I see,’ Harry said, smiling a little bitterly. ‘Some one else has been beforehand with me already. No wonder. I’m not at all surprised at him. How could he possibly see you and help it?’ And he looked with unmistakable admiration at Nora’s face, all the prettier now for its deep blushes.

‘No, Mr Noel,’ Nora answered simply. ‘There you are mistaken. There’s nobody—absolutely nobody. I’ve only just left school, you know, and I’ve seen no one so far that I care for in any way.’

‘In that case,’ Harry Noel said, in his decided manner, ‘the quest will still be worth pursuing. No matter what you say, Miss Dupuy, we shall meet again—before long—in Trinidad. A young lady who has just left school has plenty of time still to reconsider her determinations.’

‘Mr Noel! Please, don’t! It’ll be quite useless.’

‘I must, Miss Dupuy; I can’t help myself. You will draw me after you, even if I tried to prevent it. I believe I have had one real passion in my life, and that passion will act upon me like a magnet on a needle for ever after. I shall go to Trinidad.’

‘At anyrate, then, you’ll remember that I gave you no encouragement, and that for me, at least, my answer is final.’

‘I will remember, Miss Dupuy—and I won’t believe it.’

That evening, as Marian kissed Nora good-night in her own bedroom at the Southampton hotel, she asked archly: ‘Well, Nora, what did you answer him?’

‘Answer who? what?’ Nora repeated hastily, trying to look as if she didn’t understand the suppressed antecedent of the personal pronoun.

‘My dear girl, it isn’t the least use your pretending you don’t know what I mean by it. I saw in your face, Nora, when Edward and I caught you up, what it was Mr Noel had been saying to you. And how did you answer him? Tell me, Nora!’

‘I told him no, Marian, quite positively.’

‘O Nora!’

‘Yes, I did. And he said he’d follow me out to Trinidad; and I told him he really needn’t take the trouble, because in any case I could never care for him.’

‘O dear, I am so sorry. You wicked girl! And, Nora, he’s such a nice fellow too! and so dreadfully in love with you! You ought to have taken him.’

‘My dear Marian! He’s so awfully black, you know. I really believe he must positively be—be coloured.’

One fine day in early autumn, while straying along the banks of one of the sparkling little trout streams which appear to be at once the cause and the purpose of those lovely winding valleys so numerous in Northern Devon, our attention was drawn, by a faint distressed chirping sound, to a small dark object stirring in the grass at some distance from the stream. We hurried to the spot, and there saw, to our great surprise, wet, muddy, and uneasily squirming at our feet, a baby otter! Poor infant! how came it there? By what concatenation of untoward circumstances did the helpless innocent find itself in a position so foreign to the habits of its kind? Its appearance under conditions so utterly at variance with our experience of the customs and manners of otter society, was so amazing, that we could scarcely believe our eyes. However, there the little creature undoubtedly was; and congratulating ourselves on this unlooked-for and valuable addition to our home menagerie—for these animals are rare in Devon, and to light upon a young scion of the race in evident need of a home and education was quite a piece of good luck—the forlorn bantling was promptly deposited in a coat-pocket and proudly borne homewards.

Introduced to the family circle, ‘Tim’—as he was afterwards duly christened—became at once the centre of domestic interest and unceasing care. To feed him was necessarily our first consideration. A feline or canine mother deprived{54} of her young was suggested as a suitable foster-mother; but, unfortunately, no such animal was at hand, and meantime the creature must be fed. We therefore procured an ordinary infant’s feeding-bottle, and filling it with lukewarm cow’s milk, essayed thus to make good the absence of mamma-otter. At first the little stranger absolutely declined even to consider this arrangement, and in consequence pined somewhat; but in the end the pangs of hunger wrought a change in his feelings, and after several energetic though unscientific attempts, he overcame the difficulties of his new feeding apparatus, and was soon vigorously sucking. For a time, all went well. Tim, with commendable regularity, alternately filled himself with milk and slept peacefully in his basket of sweet hay. But at the close of the second day, a change came over our interesting charge; he was restless and uneasy during the night, and in the morning, refused to feed, and appeared to be suffering pain. Finally, his respiration became laboured and difficult, and for a whole day and night our hopes of rearing him were at the lowest ebb. But at the end of that time, to our great satisfaction, the distressing symptoms began to abate, and in a few hours had disappeared, and the convalescent returned con amore to his bottle. Believing his attack was attributable to over-feeding, we henceforth diluted the cow’s milk with warm water, and removed his bottle at the first sign of approaching satiety, nor did we again administer it until his demands for sustenance became vociferous and imperative. On this system we were successful in rearing him in the face of many prophecies of failure.

At this early stage of his existence, being exhibited to admiring friends, he crawled laboriously and flatly about on the carpet, with a decided preference for backward motion; but if he encountered a perpendicular surface, such as the sides of his hamper or a trouser-leg, he would, with the aid of his claws, climb up it with considerable agility. He distinctly showed a love of warmth, and gave us to understand that he appreciated caresses, by nestling down in feminine laps, and ceasing his plaintive cry while our hands were about him. On awakening from sleep, he would begin, as do ducklings and chickens, with a gentle reminder of his existence and requirements. If no notice were taken of this, the note—which was something between the magnified chirp of a chicken and the very earliest bark of a puppy—would steadily increase in power and insistence, until it became an absolute clamour. When his bottle was given to him, he would seize on the leather teat and tug at it, and plunge about with a violence and impatience which defeated its own end, and woe to the unwary or awkward fingers which came in the way of the tiny fine white teeth at this moment!

Obstacles overcome and success attained, Tim settled down to steady sober enjoyment; the webbed paws were alternately spread and closed like a cat’s when thoroughly content, and the tail curled and uncurled and wagged to and fro, as does a lamb’s when happily feeding. After the lapse of a few days, our new pet showed decided signs of intelligence and a sense of fun: he would run round after one’s finger in a clumsy-lively way, and a jocular poke in the ribs would rouse him to an awkwardly playful attempt to seize the offending digit. In less than three weeks he knew his name, and scuttled across the room when called, followed us about the garden, and endeavoured to establish friendly relations with a pet wild rabbit, which was furiously jealous of the new favourite, and administered sly scratches, and ‘hustled’ him on every possible occasion.

About this time, he also acquired a charming habit of beginning, the moment the sun rose, a clamour which deprived half the household of further sleep, and which was only to be quieted by his being taken into some one’s bed, where he would at once ‘snuggle’ down and lie motionless for hours. At first we resisted this importunity on the part of Tim, partly because an otter is not exactly the animal one would select as a bedfellow, and partly because we could not think it a desirable or wholesome habit for the creature itself. But Master Tim was too much for us. ‘If you won’t let me sleep with you, you shan’t sleep at all!’ he declared in unmistakable language, and by dint of sticking to his point he carried it.

At the end of the first month of his civilised life, some one gave him a scrap of raw meat; and after that, though he ate bread and milk very contentedly between times, he made us understand that his constitution required the support of animal food, and was never satisfied without his daily ration of uncooked flesh. Fish, strange to say, he seemed to prefer cooked. When we were seated at meals, a hand held down would bring Tim quickly to one’s side with an eager look in the small yellow eyes; his cold nose sniffed at one’s fingers with rapid closing and unclosing of the curiously formed nostrils; the softly furred head would be thrust into the palm in search of the expected dainty morsel. If none were to be found, his temper would be sadly ruffled, sometimes to the extent of inflicting with his teeth a sharp reminder that not even an otter’s feelings should be trifled with!

As he grew older, he developed an amount of intelligence scarcely to be expected from the small brain contained in the flat and somewhat snake-like head; he showed decided preferences for some members of the family over others; if permitted, he would follow everywhere at our heels like a dog, and played with the children after the manner of one, but with awkward springs and jumps that put us in mind of a particularly ungraceful lamb. He occasionally made quite energetic assaults on the ankles of some of the ladies of the family; and if he perceived that the owner of unprotected ankles went in fear of him, showed a malicious pleasure in renewing the attack at every favourable opportunity.

When the children went for a country ramble, Tim frequently accompanied them, taking the greatest delight in these excursions. He would be carried until beyond danger from wandering{55} dogs, and then being set at liberty, the fun would begin. Master Tim, all eagerness, trotting on before in search of interesting facts, the children take advantage of a moment when all his faculties are engaged with some novelty attractive to the otter mind, to vanish through a neighbouring gate or behind a haystack. The unusual quiet soon arouses Tim’s suspicions; he looks round, and finds himself alone. The situation, from its strangeness, is appalling to him; he utters a shriek of despair, and scurries back as fast as his legs can take him, squeaking loudly all the time. If he should chance, in his fright, to pass by the hiding-place of his young protectors without discovering them, great is their delight. One little face after another peers out and watches, with mischievous glee, poor Tim’s plump and anxious form trundling along as fast as is possible to it in the wrong direction! But very soon the humour of the situation is too much for some young spirit, and a smothered laugh or a half-suppressed giggle reaches the tiny sharp ears, and Tim quickly turns, and with another shriek of mingled satisfaction and indignation, gives chase to his playful tormentors. Once arrived in the open meadows, where this novel game of hide-and-seek is not possible, it is Tim’s turn. Still, he follows obediently enough, frisking and gamboling in the fresh soft grass, until one of the innumerable small streams is approached. As soon as he catches sight of the water, he is off. At a rapid trot he hurries to the brink, and with swift and noiseless dart, in a flash he has disappeared in the current, and in another reappeared some yards away. Rolling over, turning, twisting, diving, he revels in his cold bath, and it is sometimes a matter of no small difficulty to get him out of the water. A cordon of children is formed—the two biggest with bare feet and legs, to cut off his retreat up and down stream—which, gradually closing in on him, seizes him at last; and reluctantly he is compelled to dry himself in the grass preparatory to returning to the forms and ceremonies of civilised life.

A NOVELETTE.

‘How do you feel now, Margaret?’

‘Nearly over, Miss Nelly. I shall die with the morning.’

A week later, and the patient had got gradually worse. The constant exposure, the hard life, and the weeks of semi-starvation, had told its tale on the weak womanly frame. The exposure in the rain and cold on that eventful night had hastened on the consumption which had long settled in the delicate chest. All signs of mental exhaustion had passed away, and the calm hopeful waiting frame of mind had succeeded. She was waiting for death; not with any feeling of terror, but with hopefulness and expectation.

Up to the present, Eleanor had not the heart to ask for any memento or remembrance of the old life; but had nursed her patient with an unceasing watchful care, which only a true woman is capable of. All that day she had sat beside the bed, never moving, but noting, as hour after hour passed steadily away, the gradual change from feverish restlessness to quiet content, never speaking, or causing her patient to speak, though she was longing for some word or sign.

‘You have been very good to me, Miss Nelly. Had it not been for you, where should I have been now!’

‘Hush, Margaret; don’t speak like that. Remember, everything is forgiven now. Where there is great temptation, there is much forgiveness.’

‘I hope so, miss—I hope so. Some day, we shall all know.’

‘Don’t try to talk too much.’

For a while she lay back, her face, with its bright hectic flush, marked out in painful contrast to the white pillow. Eleanor watched her with a look of infinite pity and tenderness. The distant hum of busy Holborn came with dull force into the room, and the heavy rain beat upon the windows like a mournful dirge. The little American clock on the mantel-shelf was the only sound, save the dry painful cough, which ever and anon proceeded from the dying woman’s lips. The night sped on; the sullen roar of the distant traffic grew less and less; the wind dropped, and the girl’s hard breathing could be heard painfully and distinctly. Presently, a change came over her face—a kind of bright, almost unearthly intelligence.

‘Are you in any pain, Madge?’ Eleanor asked with pitying air.

‘How much lighter it is!’ said the dying girl. ‘My head is quite clear now, miss, and all the pain has gone.—Miss Nelly, I have been dreaming of the old home. Do you remember how we used to sit by the old fountain under the weeping-ash, and wonder what our fortunes would be? I little thought it would come to this.—Tell me, miss, are you in—in want?’

‘Not exactly, Madge; but the struggle is hard sometimes.’

‘I thought so,’ the dying girl continued. ‘I would have helped you after she came; but you know the power she had over your poor uncle, a power that increased daily. She used to frighten me. I tremble now when I think of her.’

‘Don’t think of her,’ said Eleanor soothingly. ‘Try and rest a little, and not talk. It cannot be good for you.’

The sufferer smiled painfully, and a terrible fit of coughing shook her frame. When she recovered, she continued: ‘It is no use, Miss Nelly: all the rest and all your kind nursing cannot save me now. I used to wonder, when you left Eastwood so suddenly, why you did not take me; but now I know it is all for the best. Until the very last, I stayed in the house.’

‘And did not my uncle give you any message, any letter for me?’ asked Eleanor, with an eagerness she could not conceal.

‘I am coming to that. The day he died, I was in his room, for she was away, and he asked me if I ever heard from you. I knew you had written letters to him which he never got; and so I told him. Then he gave me a paper for{56} you, which he made me swear to deliver to you by my own hand; and I promised to find you. You know how I found you,’ she continued brokenly, burying her face in her hands.

‘Don’t think of that now, Margaret,’ said Eleanor, taking one wasted hand in her own. ‘That is past and forgiven.’

‘I hope so, miss. Please, bring me that dress, and I will discharge my trust before it is too late. Take a pair of scissors and unpick the seams inside the bosom on the left side.’

The speaker watched Eleanor with feverish impatience, whilst, with trembling fingers, she followed the instructions. Not until she had drawn out a flat parcel, wrapped securely in oiled paper, did the look of impatience transform to an air of relief.

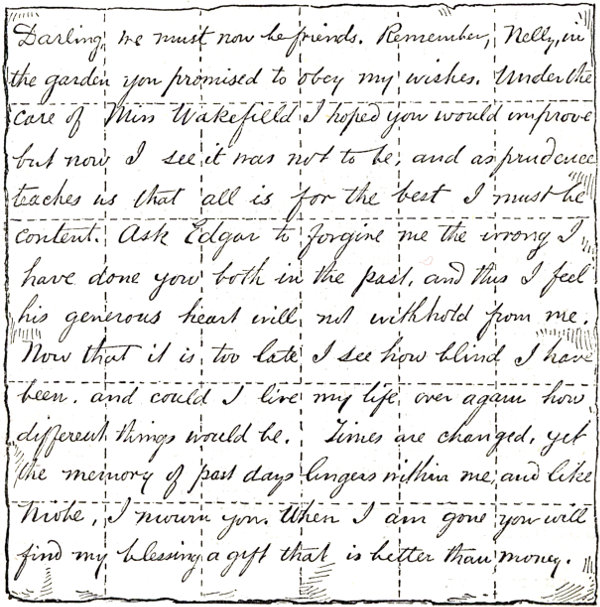

‘Yes, that is it,’ said Margaret, as Eleanor tore off the covering. ‘I have seen the letter, and have a strange feeling that it contains some secret, it is so vague and rambling, and those dotted lines across it are so strange. Your uncle was so terribly in earnest, that I cannot but think the paper has some hidden meaning. Please, read it to me. Perhaps I can make something of it.’

‘It certainly does appear strange,’ observed Eleanor, with suppressed excitement.

Turning towards the light, Eleanor read as follows:

Darling, we must now be friends. Remember, Nelly, in the garden you promised to obey my wishes. Under the care of Miss Wakefield I hoped you would improve but now I see it was not to be, and as prudence teaches us that all is for the best I must be content. Ask Edgar to forgive me the wrong I have done you both in the past, and this I feel his generous heart will not withhold from me. Now that it is too late I see how blind I have been, and could I live my life over again how different things would be. Times are changed, yet the memory of past days lingers within me, and like Niobe, I mourn you. When I am gone you will find my blessing a gift that is better than money.

The paper was half a sheet of ordinary foolscap, and the words were written without a single break or margin. It was divided perpendicularly by five dotted lines, and by four lines horizontally, and displayed nothing to the casual eye but an ordinary letter in a feeble handwriting.

The tiny threads of fate had begun to gather. All yet was dark and misty; but in the gloom, faint and transient, was one small ray of light.

Eleanor gazed at the paper abstractedly for a few moments, vaguely trying to find some hidden clue to the mystery.

‘You must take care of that paper, Miss Nelly. Something tells me it contains a secret.’

‘And have you been searching for me two long years, for the sole purpose of giving me this?’ Eleanor asked.

‘Yes, miss,’ the sufferer replied simply. ‘I promised, you know. Indeed, I could not look at your uncle and break a vow like mine.’

‘And you came to London on purpose?’

‘Yes. No one knew where I was gone. I have no friends that I remember, and so I came to London. It is an old tale, miss. Trying day by day to get employment, and as regularly failing. I have tried many things the last two bitter years. I have existed—I cannot call it living—in the vilest parts of London, and tried to keep myself by my needle; but that only means dying by inches. God alone knows the struggle it is for a friendless woman here to keep honest and virtuous. The temptation is awful; and as I have been so sorely tried, I hope it will count in my favour hereafter. I have seen sights that the wealthy world knows nothing of. I have lived{57} where a well-dressed man or woman dare not set foot. Oh, the wealth and the misery of this place they call London!’

‘And you have suffered like this for me?’ Eleanor said, the tears now streaming down her face. ‘You have gone through all this simply for my sake? Do you know, Madge, what a thoroughly good woman you really are?’

‘I, miss?’ the dying girl exclaimed in surprise. ‘How can I possibly be that, when you know what you do of me! O no; I am a miserable sinner by the side of you. Do you think, Miss Nelly, I shall be forgiven?’

‘I do not doubt it,’ said Eleanor softly; ‘I cannot doubt it. How many in your situation could have withstood your temptation?’

‘I am so glad you think so, miss; it is comfort to me to hear you say that. You were always so good to me,’ she continued gratefully. ‘Do you know, Miss Nelly dear, whenever I thought of death, I always pictured you as being by my side?’

‘Do you feel any pain or restlessness now, Margaret?’

‘No, miss; thank you. I feel quite peaceful and contented. I have done my task, though it has been a hard one at times. I don’t think I could have rested in my grave if I had not seen you.—Lift me up a little higher, please, and come a little closer. I can scarcely see you now. My eyes are quite misty. I wonder if all dying people think about their younger days, Miss Nelly? I do. I can see it all distinctly: the old broken fountain under the tree, where we used to sit and talk about the days to come; and how happy we all were there before she came. Your uncle was a different man then, when he sat with us and listened to your singing hymns. Sing me one of the old hymns now, please.’

In a subdued key, Eleanor sang Abide with me, the listener moving her pallid lips to the words. Presently, the singer finished, and the dying girl lay quiet for a moment.

‘Abide with me. How sweet it sounds! “Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day.” I am glad you chose my favourite hymn, Miss Nelly. I shall die repeating these words: “The darkness deepens; Lord, with me abide.” Now it is darker still; but I can feel your hand in mine, and I am safe. I did not think death was so blessed and peaceful as this. I am going, going—floating away.’

‘Margaret, speak to me!’

‘Just one word more. How light it is getting! Is it morning? I can see. I think I am forgiven. I feel better, better! quite forgiven. Light, light, light! everywhere. I can see at last.’

It was all over. The weary aching heart was at rest. Only a woman, done to death in the flower of youth by starvation and exposure; but not before her task was done, her work accomplished. No lofty ambition to stir her pulses, no great goal to point to for its end. Only a woman, who had given her life to carry out a dying trust; only a woman, who had preserved virtue and honesty amid the direst temptation. What an epitaph for a gravestone! A eulogy that needs no glittering marble to point the way up to the Great White Throne.

Mr Carver sat in his private office a few days later, with Margaret’s legacy before him. A hundred times he had turned the paper over. He had held it to the light; he had looked at it upside down, and he had looked at it sideways and longways; in fact, every way that his ingenuity could devise. He had even held it to the fire, in faint hopes of sympathetic ink; but his labour had met with no reward. The secret was not discovered.

The astute legal gentleman consulted his diary, where he had carefully noted down all the facts of the extraordinary case; and the more he studied the matter, the more convinced he became that there was a mystery concealed somewhere; and, moreover, that the key was in his hands, only, unfortunately, the key was a complicated one. Indeed, to such absurd lengths had he gone in the matter, that Edgar Allan Poe’s romances of The Gold Bug and The Purloined Letter lay before him, and his study of those ingenious narratives had permeated his brain to such an extent lately, that he had begun to discover mystery in everything. The tales of the American genius convinced him that the solution was a simple one—provokingly simple, only, like all simple things, the hardest of attainment. He was quite aware of the methodical habits of his late client, Mr Morton, and felt that such a man could not have written such a letter, even on his dying bed, unless he had a powerful motive in so doing. Despite the uneasy consciousness that the affair was a ludicrous one to engage the attention of a sober business man like himself, he could not shake off the fascination which held him.

‘Pretty sort of thing this for a man at my time of life to get mixed up in,’ he muttered to himself. ‘What would the profession say if they knew Richard Carver had taken to read detective romances in business hours? I shall find myself writing poetry some day, if I don’t take care, and coming to the office in a billy-cock hat and turn-down collar. I feel like the heavy father in the transpontine drama; but when I look in that girl’s eyes, I feel fit for any lunacy. Pshaw!—Bates!’

Mr Bates entered the apartment at his superior’s bidding. ‘Well, sir?’ he said. The estimable Bates was a man of few words.

‘I can not make this thing out,’ exclaimed Mr Carver, rubbing his head in irritating perplexity. ‘The more I look at it the worse it seems. Yet I am convinced’——

‘That there is some mystery about it!’

‘Precisely what I was going to remark. Now, Bates, we must—we really must—unravel this complication. I feel convinced that there is something hidden here. You must lend me your aid in the matter. There is a lot at stake. For instance, if’——

‘We get it out properly, I get my partnership; if not, I shall have to—whistle for it, sir!’

‘You are a very wonderful fellow, Bates—very. That is precisely what I was going to say,’ Mr Carver exclaimed admiringly. ‘Now, I have been reading a book—a standard work, I may say.’

{58}

‘Williams’s Executors, sir, or——?’

‘No,’ said Mr Carver shortly, and not without some confusion; ‘it is not that admirable volume—it is, in fact, a—a romance.’

Mr Bates coughed dryly, but respectfully, behind his hand. ‘I beg your pardon, sir; I don’t quite understand. Do you mean you have been reading a—novel?’

‘Well, not exactly,’ replied Mr Carver blushing faintly. ‘It is, as I have said, a romance—a romance,’ he continued with an emphasis upon the substantive, to mark the difference between that and an ordinary work of fiction. ‘It is a book treating upon hidden things, and explaining, in a light and pleasant way, the method of logically working out a problem by common-sense. Now, for instance, in the passage I have marked, an allusion is made, by way of example.—Did you ever—ha, ha! play at marbles, Bates?’

‘Well, sir, many years ago, I might have indulged in that little amusement,’ Mr Bates admitted with professional caution; ‘but really, sir, it is such a long time ago, that I hardly remember.’

‘Very good, Bates. Now, in the course of your experience upon the subject of marbles, do you ever remember playing a game called “Odd and Even?”’

Bates looked at his principal in utter amazement, and Mr Carver, catching the expression of his face, burst into a hearty laugh, faintly echoed by the bewildered clerk. The notion of two gray-headed men solemnly discussing a game of marbles in business hours, suddenly struck him as being particularly ludicrous.

‘Well, sir,’ Bates said with a look of relief, ‘I don’t remember the fascinating amusement you speak of, and I was wondering what it could possibly have to do with the case in point.’

‘Well, I won’t go into it now; but if you should like to read it for yourself, there it is,’ said Mr Carver, pushing over the yellow-bound volume to his subordinate.

Mr Bates eyed the volume suspiciously, and touched it gingerly with his forefinger. ‘As a matter of professional duty, sir, if you desire it, I will read the matter you refer to; but if it is a question of recreation, then, sir, with your permission, I would rather not.’

‘That is a hint for me, I suppose, Bates,’ said Mr Carver with much good-humour, ‘not to occupy my time with frivolous literature.’

‘Well, sir, I do not consider these the sort of books for a place on a solicitor’s table; but I suppose you know best.’

‘I don’t think such a thing has happened before, Bates,’ Mr Carver answered with humility. ‘You see, this is an exceptional case, and I take great interest in the parties.’

‘Well, there is something in that,’ said Mr Bates severely, ‘so I suppose we must admit it on this occasion.—But don’t you think, sir, there is some way of getting to the bottom of this affair, without wasting valuable time on such stuff as that?’ and he pointed contemptuously at the book before him.

‘Perhaps so, Bates—perhaps so. I think the best thing we can do is to consult an expert. Not a man who is versed in writings, but one of those clever gentlemen who make a study of ciphers. For all we know, there may be a common form of cipher in this paper.’

‘That is my opinion, sir. Depend upon it, marbles have nothing to do with this mystery.’

‘Mr Seaton wishes to see you, sir,’ said a clerk at this moment.

‘Indeed! Ask him to come in.—Good-morning, my dear sir,’ as Seaton entered. ‘We have just been discussing your little affair, Bates and I; but we can make nothing of it—positively nothing.’

‘No; I suppose not,’ Edgar replied lightly. ‘I, for my part, cannot understand your making so much of a common scrap of paper. Depend upon it, the precious document is only an ordinary valedictory letter after all. Take my advice—throw it in the fire, and think no more about it.’

‘Certainly not, sir,’ Mr Carver replied indignantly. ‘I don’t for one moment believe it to be anything but an important cipher.—What are you smiling at?’

Edgar had caught sight of the yellow volume on the table, and could not repress a smile. ‘Have you read those tales?’ he said.

‘Yes, I have; and they are particularly interesting.’

‘Then I won’t say any more,’ Edgar replied. ‘When a man is fresh from these romances, he is incapable of regarding ordinary life for a time. But the disease cures itself. In the course of a month or so, you will begin to forget these complications, and probably burn that fatal paper.’

‘I intend to do nothing of the sort; I am going to submit it to an expert this afternoon, and get his opinion.’

‘Yes. And he will keep it for a fortnight, after reading it over once, and then you will get an elaborate report, covering some sheets of paper, stating that it is an ordinary letter. Who was the enemy who lent you Poe’s works?’

‘I read those books before you were born, young man; and I may tell you—apart from them—that I am fully convinced that there is a mystery somewhere. ’Pon my word, you take the matter very coolly, considering all things. But let us put aside the mystery for a time, and tell me something of yourself.’

‘I am looking up now, thanks to you and Felix,’ Edgar replied gratefully. ‘I have an appointment at last.’

‘I am sure I am heartily glad to hear it. What is it?’

‘It was the doing of Felix, of course. The editor of Mayfair was rather taken by my descriptive style in a paper which Felix showed him, and made me an offer of doing the principal continental gambling-houses in London.’

‘Um,’ said Mr Carver doubtfully. ‘And the pay?’

‘Is particularly good, besides which, I have the entrée of these places—the golden key, you know.’

‘Have you told your wife about it?’

‘Well, not altogether; she might imagine it was dangerous for me. She knows partly what I am doing; but I must not frighten her. I have had two nights of it, and apart from the excitement and the heat, it is certainly not dangerous.’

{59}

‘I am glad of that,’ said Mr Carver; ‘and am heartily pleased to hear of your success—providing it lasts.’

‘Oh, it is sure to last, for I have hundreds of places to go to. To-night I am going to a foreign place in Leicester Square. I go about midnight, and think I may generally be able to get home about two. I have to go alone always.’

‘Well, I hope now you have started, you will continue as well,’ Mr Carver said heartily; ‘at anyrate, you can continue until I unravel the mystery, and place you in possession of your fortune. Until then, it will do very well.’

‘I am not going to count on that,’ Edgar replied; ‘and if it is a failure, I shall not be so disappointed as you, I fancy.’

It wanted a few minutes to eleven o’clock, the same night when Seaton turned into Long Acre on his peculiar business. A sharp walk soon brought him to the Alhambra, whence the people were pouring out into the square. Turning down —— Street, he soon reached his destination—a long narrow house, in total darkness—a sombre contrast to the neighbouring buildings, which were mostly a blaze of light, and busy with the occupations of life. A quiet double rap for some time produced no impression; and just as he had stood upon the doorstep long enough to acquire considerable impatience, a sliding panel in the door was pushed back, and a face, in the dim gas-light, was obtruded. A short but somewhat enigmatical conversation ensued, at the end of which the door was grudgingly opened, and Edgar found himself in black darkness. The truculent attendant having barricaded the exit, gave a peculiar whistle, and immediately the light in the hall was turned up. It was a perfectly bare place; but the carpet underfoot was of the heaviest texture, and apparently—as an extra precaution—had been covered with india-rubber matting, so that the footsteps were perfectly deadened; indeed, not the slightest footfall could be heard. Following his guide in the direction of the rear of the house, and ascending a short flight of steps, Edgar was thrust unceremoniously into a dark room, the door of which was immediately closed behind him and locked. For a few seconds, Edgar stood quite at a loss to understand his position, till the peculiar whistle was again repeated, and immediately, as if by magic, the room was brilliantly lighted. When Edgar recovered from the glare, he looked curiously around. It was a large room, without windows, save a long skylight, and furnished with an evident aim at culture; but though the furniture was handsome, it was too gaudy to please a tasteful eye. The principal component parts consisted of glass gilt and crimson velvet; quite the sort of apartment that the boy-hero discovers, when he is led with dauntless mien and defiant eye into the presence of the Pirate king; and indeed some of the faces of the men seated around the green board would have done perfectly well for that bloodthirsty favourite of our juvenile fiction.

There were some thirty men in the room, two-thirds of them playing rouge-et-noir; nor did they cease their rapt attention to the game for one moment to survey the new-comer, that office being perfectly filled by the Argus-eyed proprietor, who was moving unceasingly about the room. ‘Will you play, sare?’ he said insinuatingly to Edgar, who was leisurely surveying the group and making little mental notes for his guidance.

‘Thanks! Presently, when I have finished my cigar,’ he replied.

‘Ver good, sare, ver good. Will not m’sieu take some refreshment—a leetle champein or eau-de-vie?’

‘Anything,’ Edgar replied carelessly, as the polite proprietor proceeded to get the desired refreshment.

For a few minutes, Edgar sat watching his incongruous companions, as he drank sparingly of the champagne before him. The gathering was of the usual run of such places, mostly foreigners, as befitted the neighbourhood, and not particularly desirable foreigners at that. On the green table the stakes were apparently small, for Edgar could see nothing but silver, with here and there a piece of gold. At a smaller table four men were playing the game called poker for small stakes; but what particularly interested Edgar was a young man deep in the fascination of écarté with a man who to him was evidently a stranger. The younger man—quite a boy, in fact—was losing heavily, and the money on the table here was gold alone, with some bank-notes. Directly Edgar saw the older man, who was winning steadily, he knew him at once; only two nights before he had seen him in a gambling-house at the West End playing the same game, with the same result. Standing behind the winner was a sinister-looking scoundrel, backing the winner’s luck with the unfortunate youngster, and occasionally winning a half-crown from a tall raw-looking American, who was apparently simple enough to risk his money on the loser. Attracted by some impulse he could not understand, Edgar quitted his seat and took his stand alongside the stranger, who was losing his money with such simple good-nature.

‘Stranger, you have all the luck, and that’s a fact. There goes another piece of my family plate. Your business is better’n gold-mining, and I want you to believe it,’ drawled the American, passing another half-crown across the table.

‘You are a bit unlucky,’ replied the stranger, with a flash of his white teeth; ‘but your turn will come, particularly as the young gentleman is really the better player. I should back him myself, only I believe in a man’s luck.’

‘Wall, now, I shouldn’t wonder if the younker is the best player,’ the American replied, with an emphasis on the last word. ‘So I fancy I shall give him another trial. He’s a bit like a young hoss, he is—but he’s honest.’

‘You don’t mean to insinuate we’re not on the square, eh?’ said the lucky player sullenly; ‘because, if that is so’——

‘Now, don’t you get riled, don’t,’ said the American soothingly. ‘I’m a peaceable individual, and apt to get easily frightened. I’m a-goin’ to back the young un again.’

The game proceeded: the younger man lost.{60} Another game followed, the American backing him again, and gradually, in his excitement, bending further and further over the table. The players, deep in his movements, scarcely noticed him.

‘My game!’ said the elder man triumphantly. ‘Did you ever see such luck in your life? Here is the king again.’

The American, quick as thought, picked up the pack of cards and turned them leisurely over in his hand. ‘Wall, now, stranger,’ he said, with great distinctness, ‘I don’t know much about cards, and that’s a fact. I’ve seen some strange things in my time, but I never—no, never—seed a pack of cards before with two kings of the same suit.’

‘It must be a mistake,’ exclaimed the stranger, jumping to his feet with an oath. ‘Perhaps the cards have got mixed.’

‘Wall, it’s not a nice mistake, I reckon. Out to Frisco, I seed a gentleman of your persuasion dance at his own funeral for a mistake like that. He didn’t dance long, and the exertion killed him; at least that’s what the crowner’s jury said.’

‘Do you mean to insinuate that I’m a swindler, sir? Do you mean to infer that I cheated this gentleman?’ blustered the detected sharper, approaching the speaker with a menacing air.

‘That is about the longitude of it,’ replied the American cheerfully.

Without another word and without the slightest warning, the swindler rushed at the American; but he had evidently reckoned without his host, for he was met by a crashing blow full in the face, which sent him reeling across the room. His colleague deeming discretion the better part of valour, and warned by a menacing glance from Edgar, desisted from his evident intention of aiding in the attack.

By this time the sinister proprietor and the players from the other tables had gathered round, evidently, from the expression of their eyes, ripe for any sort of mischief and plunder. Clearly, the little group were in a desperate strait.

‘Have it out,’ whispered Edgar eagerly to his gaunt companion. ‘I’m quite with you. They certainly mean mischief.’

‘All right, Britisher,’ replied the American coolly. ‘I’ll pull through it somehow. Keep your back to mine.’

The proprietor was the first to speak. ‘I understand, sare, you accuse one of my customer of the cheat. Cheat yourself—pah!’ he said, snapping his fingers in the American’s face. ‘Who are you, sare, that comes here to accuse of the cheat?’

‘Look here,’ said the American grimly. ‘My name is Æneas B. Slimm, generally known as Long Ben. I don’t easily rile, you grinning little monkey; but when I do rile, I rile hard, and that’s a fact. I ain’t been in the mines for ten years without knowing a scoundrel when I meet him, and I never had the privilege of seein’ such a fine sample as I see around me to-night. Now you open that door right away; you hear me say it.’

The Frenchman clenched his teeth determinedly, but did not speak, and the crowd gathered more closely around the trio.

‘Stand back!’ shouted Mr Slimm—‘stand back, or some of ye will suffer. Will you open that door?’

The only answer was a rush by some one in the crowd, a movement which that some one bitterly repented, for the iron-clamped toe of the American’s boot struck him prone to the floor, sick and faint with the pain. At this moment the peculiar whistle was heard, and the room was instantly in darkness. Before the crowd could collect themselves for a rush, Mr Slimm passed his hand beneath his long coat-tails and produced a flat lantern, which was fastened round his waist like a policeman’s, and which gave sufficient light to guard against any attack; certainly enough light to show the hungry swindlers the cold gleam of a revolver barrel covering the assembly. The American passed a second weapon to Edgar, and stood calmly waiting for the next move.

‘Now,’ he said, sullenly and distinctly, ‘I think we are quits. We air going to leave this pleasant company right away, but first we propose to do justice. Where is the artist who plays cards with two kings of one suit? He’d better come forward, because this weapon has a bad way of going off. He need not fancy I can’t see him, because I can. He is skulking behind the brigand with the earrings.’

The detected swindler came forward sullenly.

‘Young man,’ said Mr Slimm, turning towards the boy who had been losing so heavily, ‘how much have you lost?’

The youngster thought a moment, and said about twenty pounds.

‘Twenty pounds. Very good.—Now, my friend, I’m going to trouble you for the loan of twenty pounds. I don’t expect to be in a position to pay you back just at present; but until I do, you can console yourself by remembering that virtue is its own reward. Come, no sulking; shell out that money, or’——

With great reluctance, the sharper produced the money and handed it over to the youth. The American watched the transaction with grave satisfaction, and then turned to the landlord. ‘Mr Frenchman, we wish you a very good-night. We have not been very profitable customers, nor have we trespassed upon your hospitality. If you want payment badly, you can get it out of the thief who won my half-crowns.—Good-night, gentlemen; we may meet again. If we do, and I am on the jury, I’ll give you the benefit of the doubt.’

A moment later, they were in the street, and walking away at a brisk pace, the ungrateful youth disappearing with all speed.

‘I am much obliged to you,’ Edgar said admiringly; ‘I would give something to have your pluck and coolness.’

‘Practice,’ replied the American dryly. ‘That isn’t what I call a scrape—that’s only a little amusement. But I was rather glad you were with me. I like the look of your face; there’s plenty of character there. As to that pesky young snip, if I’d known he was going to slip off like that, do you think I should have bothered about his money for him? No, sir.’

{61}

‘I fancy he was too frightened to say or do much.’

‘Perhaps so.—Have a cigar?—I daresay he’s some worn-out roué of eighteen, all his nerves destroyed by late hours and dissipation, at a time when he ought to be still at his books.’

‘Do you always get over a thing as calmly as this affair?’ asked Edgar, at the same time manipulating one of his companion’s huge cigars. ‘I don’t think dissipation has had much effect on your nerves.’

‘Well, it don’t, and that’s a fact,’ Mr Slimm admitted candidly; ‘and I’ve had my fling too.—I tell you what it is, Mr—Mr’——

‘Seaton—Edgar Seaton is my name.’

‘Well, Mr Seaton, I’ve looked death in the face too often to be put out by a little thing like that. When a man has slept, as I have, in the mines with a matter of one thousand ounces of gold in his tent for six weeks, among the most awful blackguards in the world, and plucky blackguards too, his nerves are fit for most anything afterwards. That’s what I done, ay, and had to fight for it more than once.’

‘But that does not seem so bad as some dangers.’

‘Isn’t it?’ replied the American with a shudder. ‘When you wake up and find yourself in bed with a rattlesnake, you’ve got a chance then; when you are on the ground with a panther over you, there is just a squeak then; but to go to sleep expecting to wake up with a knife in your ribs, is quite another apple.—Well, I must say good-night. Here is Covent Garden. I am staying at the Bedford. Come and breakfast with me to-morrow, and don’t forget to ask for Æneas Slimm.’

‘I will come,’ said Edgar, with a hearty handshake.—‘Good-night.’

Under the above title, Professor Wittrock, in Nordenskjöld’s Studies and Researches in the Far North, has given us a wonderful and exhaustive account of the lowest order of plants—those which have their existence on the surface of the snow and ice, and colour the monotonous white or dirty gray of the everlasting snowfields with the warmest and most lovely rosy red and crimson, vivid green, and soft brown, until it almost appears as if these frigid zones have also their time of spring and blossom.

Late researches go to show that the snow and ice flora is far greater and richer than was at one time supposed. Formerly, people had only heard of ‘red snow’—which Agardh poetically calls ‘snow-blossoms’—and ‘green snow,’ first discovered by the botanist Unger—specimens of which were brought from Spitzbergen by Dr Kjellmann, and from Greenland by Dr Berlin. But a closer examination has discovered in the ‘green snow’ about a dozen different kinds of plants, and these not merely comprising the lowest order, but also including some mosses. The latter, however, were only in their germinating state, looking like the green threads of algæ, and therefore showing a much inferior degree of development to that which they would have if growing on a warmer substratum. The flora of the loose snow, too, is generally far richer than that of the solid ice; already forty different varieties of plants having been found, which number will no doubt be greatly increased by every fresh expedition to the arctic zone. On the solid ice, only ten different kinds have been observed.

There is a great difference between the real ice and snow plants which grow exclusively on the snow-line and those hardened children of the sun which only grow on the snow. The latter all belong to the one-celled microscopic algæ of the lowest order, which increase by partition, possessing no generic character, and generally appearing in large horizontal masses of vegetable matter. They are also distinguished by seldom having the pure green chlorophyll colour of other plants, but instead display shades of red, brown, and sap green, whence they have been named coloured algæ.

Some botanists suppose that the chief and most numerous of all the algæ, the red snow, only represents a lower state of a higher class of algæ which has never attained to full development in the region of perpetual snow; and this supposition is the more remarkable, as the brilliant red granules of this species—about the four-thousandth part of an inch in diameter—probably surpass in reproductive powers every other plant. They cover enormous tracts of snow in such dense masses that it sometimes appears as if the snow was coloured blood-red to the depth of several feet. Ever since it was first found, red snow has greatly exercised the minds of the learned. It is often mentioned in old writings, though whether the red snow referred to took its colour from the red algæ or from the meteor-dust which contains iron, is not certain. But there is no doubt that it was the real red-snow algæ which De Saussure found in his Alpine expeditions. He mentions this phenomenon several times in 1760, and states that he had found the most beautiful species on Mont St Bernard, but had thought it must be pollen, wafted thither by the wind, although he knew of no plant that had that kind of red pollen.

The knowledge that the red snow of the polar regions and mountains owes its colour to a living plant, only dates from the year 1818, when Ross and Parry made their celebrated polar expedition, and Ross discovered the ‘crimson cliffs’ of the coast of Greenland, six hundred feet above the level of the sea. Here the red snow coloured the rocky walls of Baffin’s Bay a rich glowing crimson, reaching in some parts to a depth of nine or ten feet, and close to Cape York extending over a distance of eight nautical miles. Various were the surmises and conjectures as to the origin and nature of the phenomenon. Bauer was the first to examine it under a microscope, and he fancied the organic red granules represented a species of fungus. The same year, Charpentier, the great Alpine explorer, started the idea that the red appearance was caused by some meteoric matter, which, falling from the sky, spread over the immense tracts of snow. Hooker was the first who recognised the true nature of this new plant, and compared it to the red slime algæ which are found floating in blood-red masses in water or damp places; while Wrangel declared the granules had apparently no organic substratum, and they must therefore be of the lichen{62} tribe, suggesting also that the germs were generated by the electricity in the air, for he had once seen a rock split in two by lightning, the sides of which were thickly covered with a red dust similar in nature to the ‘red snow.’ Two more botanists agreed that the red granules were ‘red powder that had become organic matter in the oxidised snow;’ the stern hard rock as it decayed had defied death, and come to life again in a new form. It remained for Agardh to put an end to these various fancies by proving the undoubted algal nature of the plant, and to give it, besides, its poetical name of ‘snow-blossom,’ the scientific one of crimson primitive snow-germ (Protococcus Kermesina nivalis). In 1838, Ehrenberg watched the development of this new species by sowing some specimens he had brought with him from the Swiss Alps, on snow, and noting how they developed first into green and then into red granules, joined together like a chain; he called it snow granulæ (Sphærella nivalis), which name it still bears.

Even now, the wild theories about the red snow were not yet ended. Seeing that the young spores of the algæ moved incessantly backwards and forwards in the water, the idea arose that they were animalcula, and ‘red snow’ only the lowest form of animal life. By degrees, however, it came to be an accepted fact that this voluntary motion does not belong exclusively to animal life, and that the young spores of the lower plants, although they move freely about in the water, and are plentifully provided with fine hair-like threads like the real infusoria, still remain plants, and never turn into animals. And thus the plant-nature of the ‘snow-blossom’ was finally settled.

The red-snow alga found on the Alps, Pyrenees, and Carpathians, and also on the summits of the North American mountains as far down as California, is not, however, such a determined enemy to heat as its having its home in the ice-region would imply. In the arctic circle, as well as on our own mountains of perpetual snow, especially on Monte Rosa, the red snow is seen in summer like a light rose-coloured film, which gradually deepens in colour, particularly in the track of human footsteps, till at length it turns almost black. In this state, however, it is not a rotten mass, but consists principally of carefully capsuled ‘quiescent spores,’ in which state these microscopic atoms pass the winter, bearing in this form the greatest extremes of temperature. Some have been exposed to a dry heat of a hundred degrees, and were found still to retain life-bearing properties; while others, again, were exposed with impunity to the greatest cold known in science. This proves that the reproductive organs in a capsuled state can hear vast extremes of temperature without injury; a significant fact, in which lies the secret of the indestructibility of those germs which are recognised as promoters of so many diseases.

Time, too, that great destroyer of most things, seems to pass harmlessly over this capsuled life. If the spores find no favourable outlet for their development, they do not die, no matter how long a time they may remain thus; and so the dried remains of red snow brought home from various polar expeditions have, even after the lapse of several years, fructified. During the uninterrupted light of the arctic summers, the ‘snow-blossom’ develops itself so rapidly, that at last it covers vast and endless tracts of snow. Although the sun does not rise very high above the horizon even at midsummer, yet, owing to the great clearness and dryness of the atmosphere in those high regions, it has a considerable degree of warmth at noon, and Nordenskjöld observed that one day in July, at mid-day, the temperature just above the snow was between twenty-five and thirty degrees centigrade. But it must not be supposed that the red alga vegetates in the pure snow; this would not be possible, as, according to chemical analysis, its body contains numerous mineral substances. The outer skin or membrane, particularly, in which the granulæ are stored seems to hold a quantity of silicon; but chalk, iron, and other mineral substances peculiar to the vegetable world, are also not found wanting in the ashes of the red snow. In fact, the upper surface of the snow and ice always shows, whenever it has lain long enough, a thin coating of inorganic dust, which brings to the snow alga the mineral constituent parts it requires.