Title: No-Time-Land: A Story for Girls and Boys

Author: M. J. C. Fulton

Release date: September 7, 2021 [eBook #66237]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: Australia: The Examiner

Credits: Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from scans of public domain works at The National Library of Australia.)

A STORY

FOR . . .

GIRLS AND BOYS.

. BY .

Tasmania:

Printed at The Examiner Office, Launceston.

1901.

To all my dear little Nephews, Nieces, and other little boys and girls, this Story is dedicated, trusting they will derive both amusement and profit from its pages.

Wishing them all a “Happy New Century.”

From their affectionate Aunt and Friend,

MARY J. C. FULTON.

Leith,

Tasmania,

December, 1900.

“Guy, come and play with me.”

“Oh! I can’t, Tina, I have no time; I am going fishing soon with Urie Cass.”

“Oh, dear!” said the little voice; “you never get time, Guy, to have a game.”

“Cannot you have one game with her, sonny!” said his mother; “the wee girlie is dull playing by herself all day.”

“But mother, dear, I have no time now,” and so saying, Guy shouldered his fishing rod and walked off.

But his mother’s sad, grieved expression seemed to haunt him all day, and his little sister’s voice echoed so in his ears, that the fishing was not altogether such an enjoyable[6] time as he expected. He got back tired and hungry, and soon after tea he was glad to go to bed.

He was just dropping off to sleep, when his eyes seemed to wander to the open window, where the moonbeams were dancing in, as if they had come to see what sort of a room it was, and what the inmate was like. They are inquisitive little things, you know; both moonbeams and sunbeams. They like to get into all the odd dark corners, and if people are dirty and slovenly in their work, they show up the dust, and dirt, as much as to say: “Oh, fie, for shame, you slovenly creatures!”

Just as Guy’s eyes alighted on the windows he saw two ladies come floating in on the moonbeams. “There he is,” one of them whispered, “that is the little boy who has no time. Let us carry him off to No-Time-Land.”

Guy was fascinated at the beauty of his visitors; so much so that he never thought of hiding under the bed-clothes; but it would have been little use if he had done so, for these kind of ladies see everything, like the fairies of fairyland. They lifted him up; it was no use his struggling, for he seemed quite powerless and unable to move a limb. While they were carrying him, Guy noticed they were very pretty. Gueldine, as her companion called her, had golden hair and large brown eyes, with golden brown lashes and eyebrows, the other had chestnut brown hair, and large blue eyes, with dark brown lashes and eyebrows; her name was Crystal.

They ought to have changed eyes, he thought: but perhaps they would not have looked so nice? His eyes next went to their dresses. Gueldine’s dress was pure white, with a gold thread interwoven through it, and a gold sash with long ends. It gave her[8] a very dazzling appearance. On her hair she wore a crescent moon of diamonds and rubies. Crystal’s dress was white, with silver interwoven, a silver sash with long ends; in her hair were stars made of diamonds and sapphires.

Away they went, over hills and water, then he caught sight of dim grey hills in the distance, as they drew nearer to them the two ladies exclaimed—“Here we are in No-Time-Land.”

They floated across to the nearest town, and placed him on a bench in the middle of one of the parks, as it was getting daylight, and said, “Good-by, little boy, we have no time to stop,” and away they went. Guy watched them till he could see them no longer, and as it was fast getting daylight, and things were becoming clearer every minute, he roused himself, as he found now he could move, and looked around. Dear[9] me! What a dreadful untidy-looking place; and so it was, for papers were lying about everywhere. In the centre of the square was a fountain, but it was broken; the wall round the basin was crumbling and falling to pieces; the water seemed stagnant, the flower beds, and grass lawns were overgrown with weeds, and everything looked sadly neglected and forlorn. A boy came sauntering along, so Guy said to him—“Boy; why does your park look so neglected and untidy?” The boy stared at him.

“Are you a stranger?” he asked at last.

“Yes,” said Guy.

“Well,” said the other; “no one has time here to put it right.”

“Are they so busy,” asked Guy.

“Too busy to answer your questions,” replied the other, and walked off.

“No time either for manners,” shouted Guy; but the boy was out of earshot, so did not hear.

“I will go into the town,” he thought, “and see what it is like,” so got up and strolled about; but everywhere he went the same neglect met his eyes. He became very hungry after a while, and seeing a young woman hurrying along, went up to her.

“Is there any place here where I can get something to eat, please ma’am,” asked Guy.

“Oh! I have no time to talk to little boys,” she said.

Again and again he asked the same question, and received the same reply. He at last saw a pastry cook’s shop, and went in. People kept coming in and ordering things, and, eating them, went out, saying, “I have no time to pay, put it down.” A little girl came in and asked for two penny buns.

“Why don’t you pay for them?” asked Guy.

“No one pays here,” she said, “we have no time.”

How dreadfully dishonest, he thought.

“Please ma’am,” said Guy, “I am so hungry, can you give me some bread and butter and milk? but I have no money to pay for it.”

She handed him a couple of rolls and some butter on a plate, also a large tumbler of hot milk.

“Never mind about money,” she said; “I have no time to take it. I will just put it down,” and she immediately started to eat a cake.

Guy began to laugh, saying—“That’s a funny way to put it down.”

“No time for anything else,” she replied.

Guy sighed. I am getting quite tired hearing those words, he thought to himself, “No time, no time,” always dinned into one’s ears. As he had finished his meal he went out.

Seeing a number of children going to school, he followed them in, and sat down with them.

They all started as the schoolmaster came in to sing—

“I suppose Paul is the schoolmaster,” said Guy to the girl sitting next to him.

“What is your name?” she asked.

“Guy,” he answered.

Then they all began to sing again—

Guy became very angry upon hearing this, and began himself to sing—

“School is dismissed,” said the schoolmaster, “I have no time to-day to hear lessons.”

Guy went down a narrow lane, or passage, it seemed, as it was carpeted; he saw a little boy crying.

“What’s the matter?” said Guy.

“I have no time to tell you,” he said.

“Oh, rubbish,” said Guy; “make time.”

The boy looked up in surprise.

“Why that is what they used to say to me before I came down here. But I am not clever, and I cannot make anything, not even time.”

Guy was disgusted.

“No;” he said, “stupids like you want a good beating, and I would like to give you one, only I think it would be a waste of time to give you even that.”

“I did not know time had a waist,” said the boy. “I thought it was only people.”

“You thickhead,” said Guy, and walked off.

“What funny words he uses,” said the boy “I wonder where he comes from? But, oh dear; I have no time to think.”

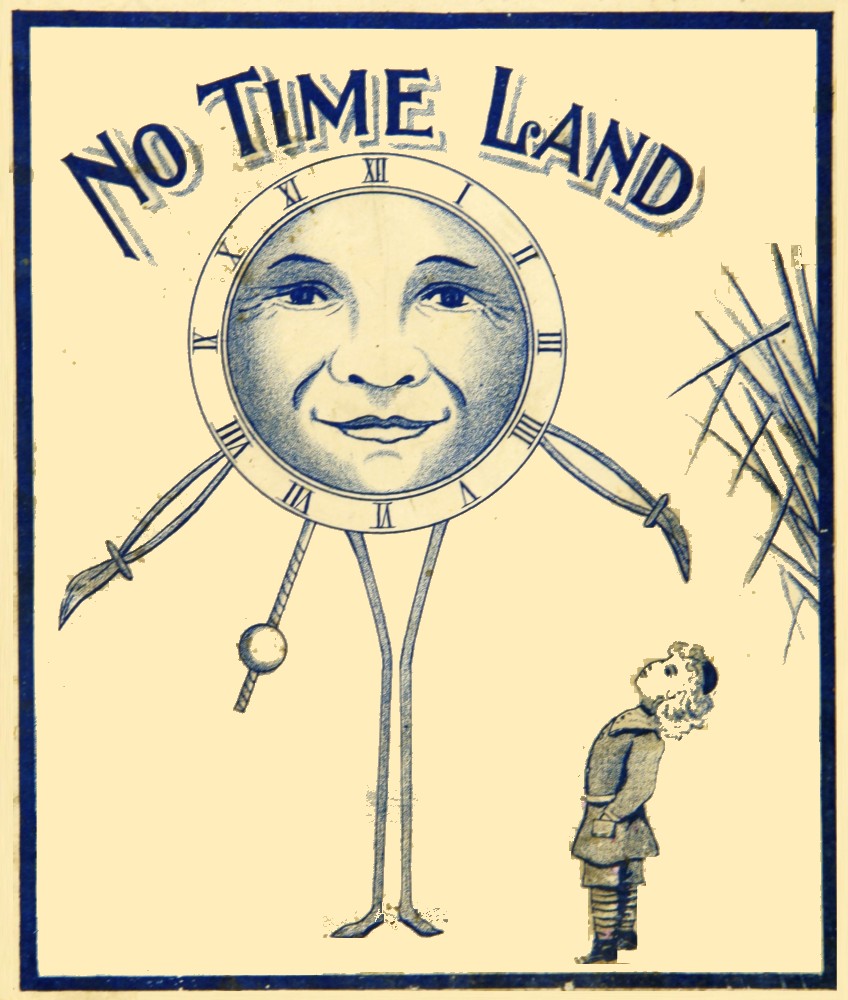

Almost at the end of the passage Guy came to a large eight-day clock; he stood and gazed at it with surprise; and well he might. For the clock was fixed upon a long stick; in the centre of the clock the eyes and lips moved as if it was alive. Outside the face it had figures all round, in order to tell the time of day. The arms and hands protruded from the sides of the clock like numerous arms and hands; which gave it[15] rather an odd look. The pendulum hung below, swinging backwards and forwards. Just as Guy was looking at him, the clock opened his mouth, rolled up his eyes, and began to sing—

“Dear me,” said Guy; “I’ve heard something like that before; but it sounds all wrong?”

“Everything is wrong in this land,” said the clock.

“How is that?” asked Guy.

“No time,” said the clock.

“Did you ever study?” again asked Guy.

“Study?” questioned the clock, in a tone of surprise. “I have heard of a person being in a brown study, if that is what you mean.”

“No, no! Study the time,” said Guy. “If you studied time you might manage to get along better, you know.”

“Oh! I get along alright,” said the clock; “only if there is no time, how can you study it?” He gave such a loud tick, and pulled such a funny grimace that it frightened Guy, so he began to run; and, as he turned the corner, seeing no one was after him, he stopped to take breath, and there right in front of him was a large open piece of ground, in the centre of which was a summer house, and roads branching all ways from it, and sign-posts saying where each road led to.

Guy read some of the signs. One was to the land Selfishness, another to Forgetfulness. To the land of Put-off, and By-and-by. Another was I Can’t and I Won’t.

“Oh, dear! They are all as bad as the one I am in, and I’ve no time to read any more. Dear! Dear! I am always saying no time myself now;” and, feeling very miserable, he entered the arbour, sat down on one of the cane chairs, and, putting his arms on the table, rested his head on them.

“What a dreadful muddle things have got into.”

“Perhaps you have stirred up the mud,” said a voice.

Guy started! “The only sensible thing I have heard yet,” he thought; and, looking[18] up, saw on the mantelpiece—he never noticed a fireplace in the arbour before—a little old man holding a scroll.

“May I ask your name, please sir?” said Guy.

“Mr. Memory-Pricker,” replied the little man; “but I am called M.P. for short.”

“Why, that stands for member of Parliament too,” said Guy.

“Well, it is the same thing,” answered the little man. “You see, ‘Parle’ in French means to speak. So it is meant, that I, an active member, speak to, and prick up, people’s memories; it is what people would call a play upon words; only you have a way of putting it backwards.”

“Please, sir, can you tell me why this is called No-Time-Land; at least, how it got its name?”

“Well, I think I can,” said the M.P. “You must have noticed people hurrying along[19] bent on some great purpose, but they never seem to attain that purpose; or to put it still plainer, they want to do some great thing, or even little things, but they never get time, they say, to do them, so all their great and little ideas end in simple talk. Consequently, and in fact, all lazy people who say they have no time, are sent to No-Time-Land.”

“Do they ever leave here? Mr. M.P.”

“Sometimes,” said the little man, “when they stray into my arbour, I prick up their memories; they occasionally turn over a new leaf then, if they wish to overcome their bad habits; but it is not often,” sighed he, “not often!”

“May I ask what you use the scroll for, please sir?”

“Yes; this is my scrap book. I am a collector of poetry, wise sayings, and various other things of interest. Here is a piece—you may like to read.”

Guy got up and went close to the scroll, and read these lines—

“I like that,” said Guy. “I think I will have a try, too.”

“Small beginnings may lead to great endings,” said the Memory Pricker.

Ting, ting, went a bell. A great noise arose. Guy hurried out to see what it was all about. People were hurrying along, shouting “Kill him! Kill him! Kill him!”

“Kill who?” cried Guy, running up to a small boy.

“Time, of course;” said the boy.

“But why kill him,” cried Guy. “What has he done?”

“You simpleton,” said the other, “have you never heard of ‘People killing time’ or ‘Murdering the time’?”

“Yes I have,” remarked Guy; “but instead of ‘Killing’ him, suppose you try and ‘Keep’ time my boy?” so saying, Guy stuck out his leg and tripped him up. Guy heard Mr. Time laugh and shout out—

But Guy heard no more, for he had to run, as the little boy was chasing him. He ran and ran till he was nearly out of breath, and thought the boy would soon catch him, as he was gaining on him fast.

When he heard someone shaking him, and saying, “Guy, dear! Guy, wake up! the breakfast bell has rung, and you will be late for school.”

“Oh! Mother,” said Guy, “can it all be only a dream?”

“Yes, sonny; you have been very fast asleep; but hurry, now, and you can tell me your dream as soon as you are dressed.”

While he was eating his breakfast, he told his mother his dream.

“Was it not a strange dream, Mother?”

“Yes, dearie; but strange dreams are often sent us for some wise purpose, if we have only the wisdom to understand the meaning of them.”

“You mean, Mother, it was sent to break me of my fault of always saying ‘I have no time.’”

His mother smiled, and said “Just that, sonny!”

In after years, Guy used to say that dream of his was at the bottom of all his success in life, as he mastered a bad fault, and at last quite gave up saying “I have no time,” but[23] always “found time” for everything, not only in doing his own work, but also in helping others, so that his life became a truly happy and useful one.

And now, dear little readers, will you also try and overcome your faults? Not in your own strength, for then you will surely fail; but in the strength of Him, who said “Be ye perfect, even as your Father in Heaven is perfect.” Then you, too, can claim the promise, which is this:—“He that overcometh shall inherit all things, and I will be his God, and he shall be my son.”—Rev. xxi. 7.

Printed at The Examiner Office,

Launceston, Tasmania.

Transcriber’s Note:

Punctuation and spelling inaccuracies were silently corrected.