“The Battle of the Blood”

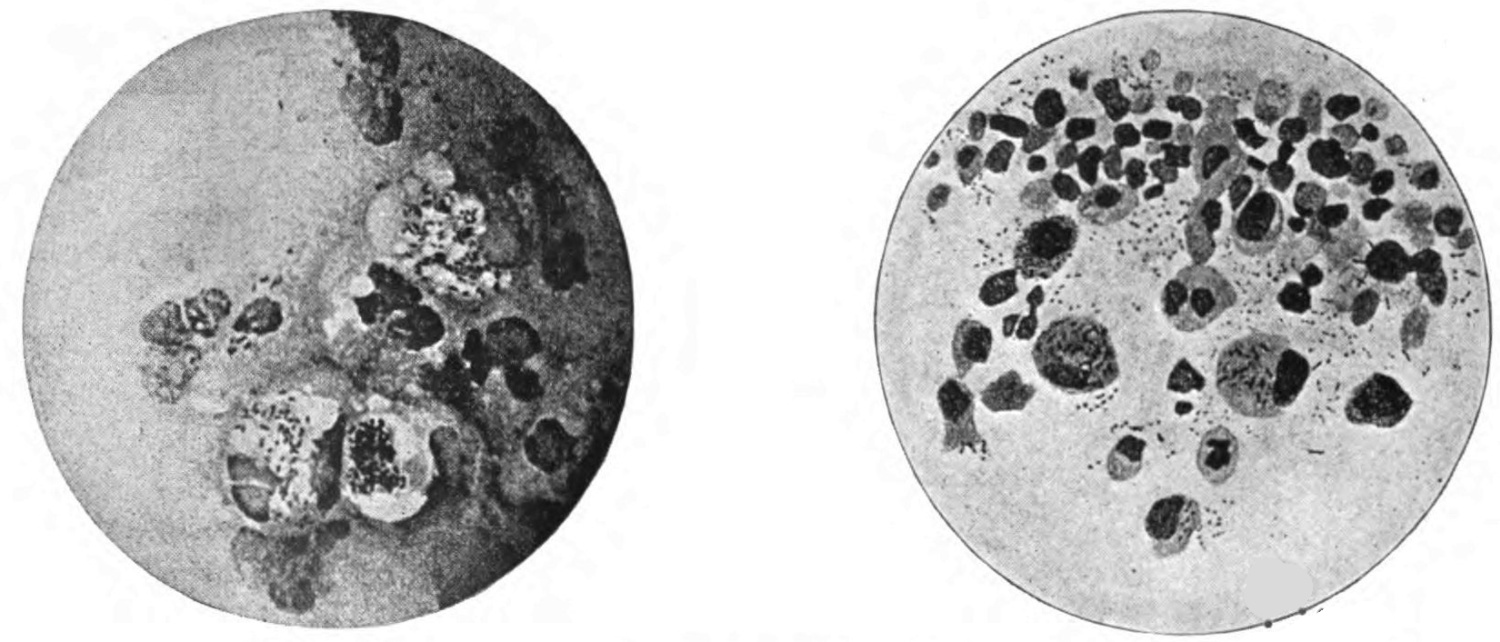

Micro-photograph of leucocytes (white and grayish bodies) in conflict with Germs (black dots and bodies). In Fig. A the germ is that of influenza, in Fig. B that of plague.

Title: Good Health and How We Won It, With an Account of the New Hygiene

Author: Upton Sinclair

Michael Williams

Release date: August 17, 2021 [eBook #66077]

Language: English

Credits: Tim Lindell, Les Galloway and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected. Variations in hyphenation have been standardised but all other spelling and punctuation remains unchanged.

The cover was prepared by the transciber and is placed in the public domain.

GOOD HEALTH AND

HOW WE WON IT

WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE NEW HYGIENE

BY

UPTON SINCLAIR

AND

MICHAEL WILLIAMS

WITH SIXTEEN FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

NEW YORK

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1909,

By FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

All rights reserved

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

| I. | The Battle of the Blood | 21 |

| II. | How to Eat: The Gospel of Dietetics According to Horace Fletcher | 41 |

| III. | The Yale Experiments | 69 |

| IV. | How Digestion Is Accomplished | 95 |

| V. | How Foods Poison the Body | 113 |

| VI. | Some Important Food Facts | 127 |

| VII. | How Often Should We Eat | 145 |

| VIII. | Health and the Mind | 159 |

| IX. | The Case as to Meat | 173 |

| X. | The Case Against Stimulants | 193 |

| XI. | Diet Reform in the Family | 203 |

| XII. | Breathing and Exercise | 219 |

| XIII. | Bathing and Cleanliness | 239 |

| XIV. | A University of Health | 258 |

| XV. | Health Reform and the Committee of One Hundred | 274 |

| Appendix | 287 |

| “The Battle of the Blood” | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

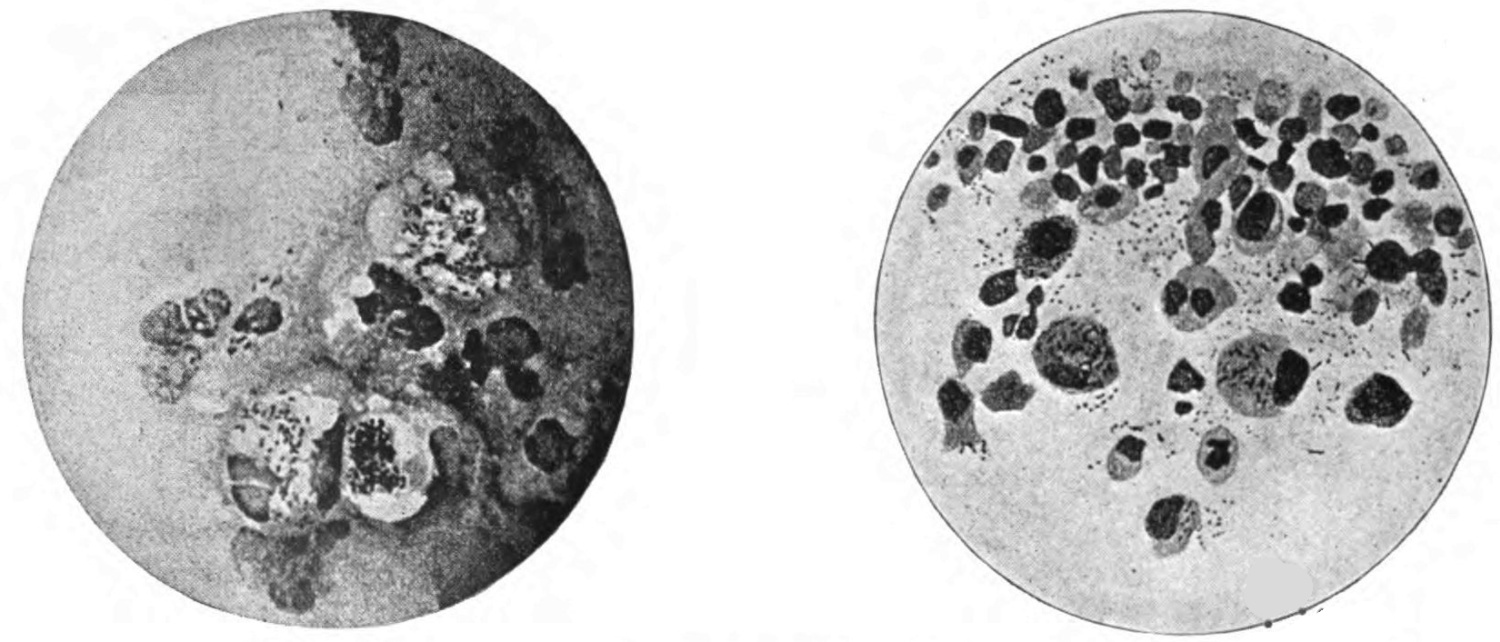

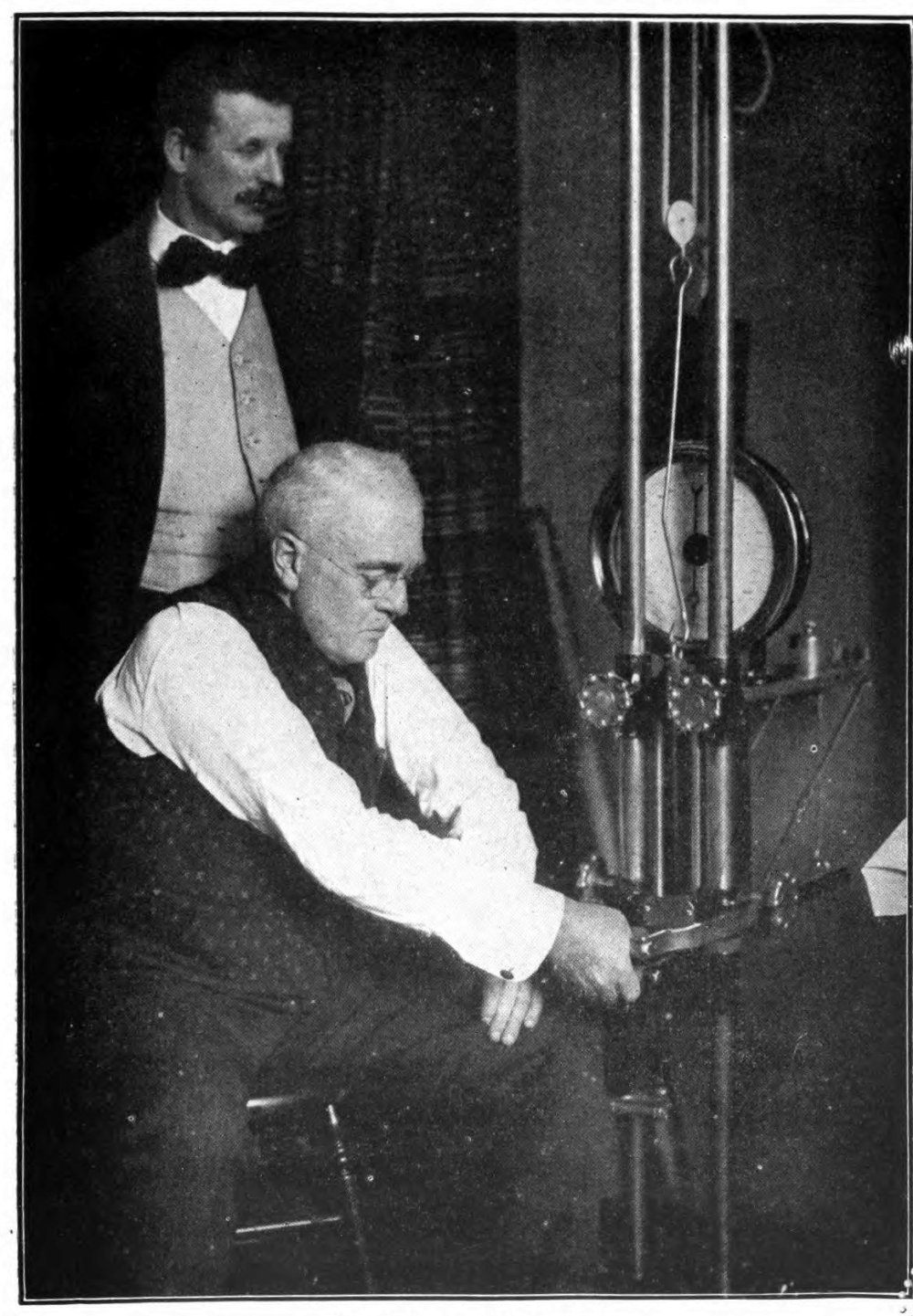

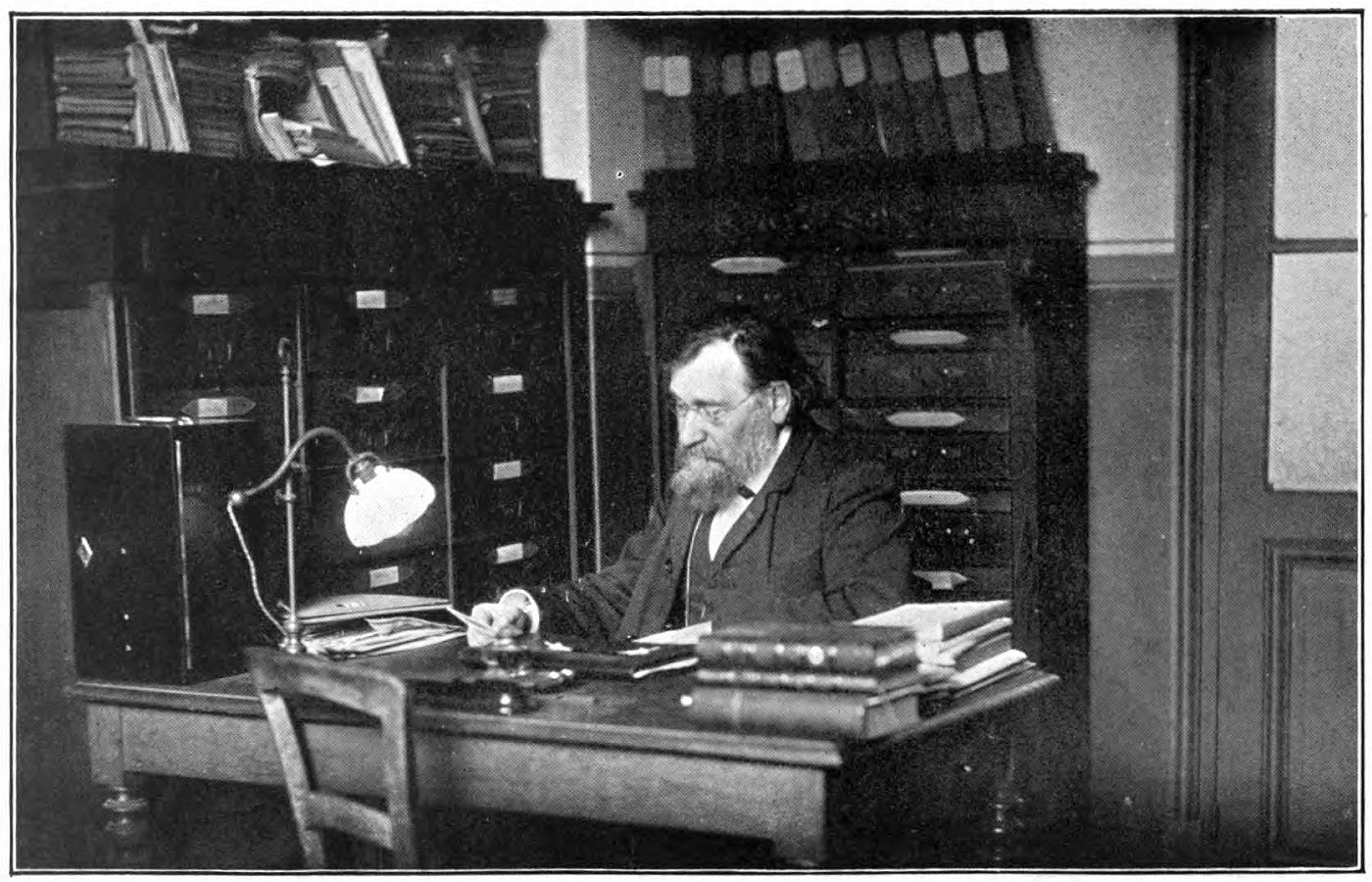

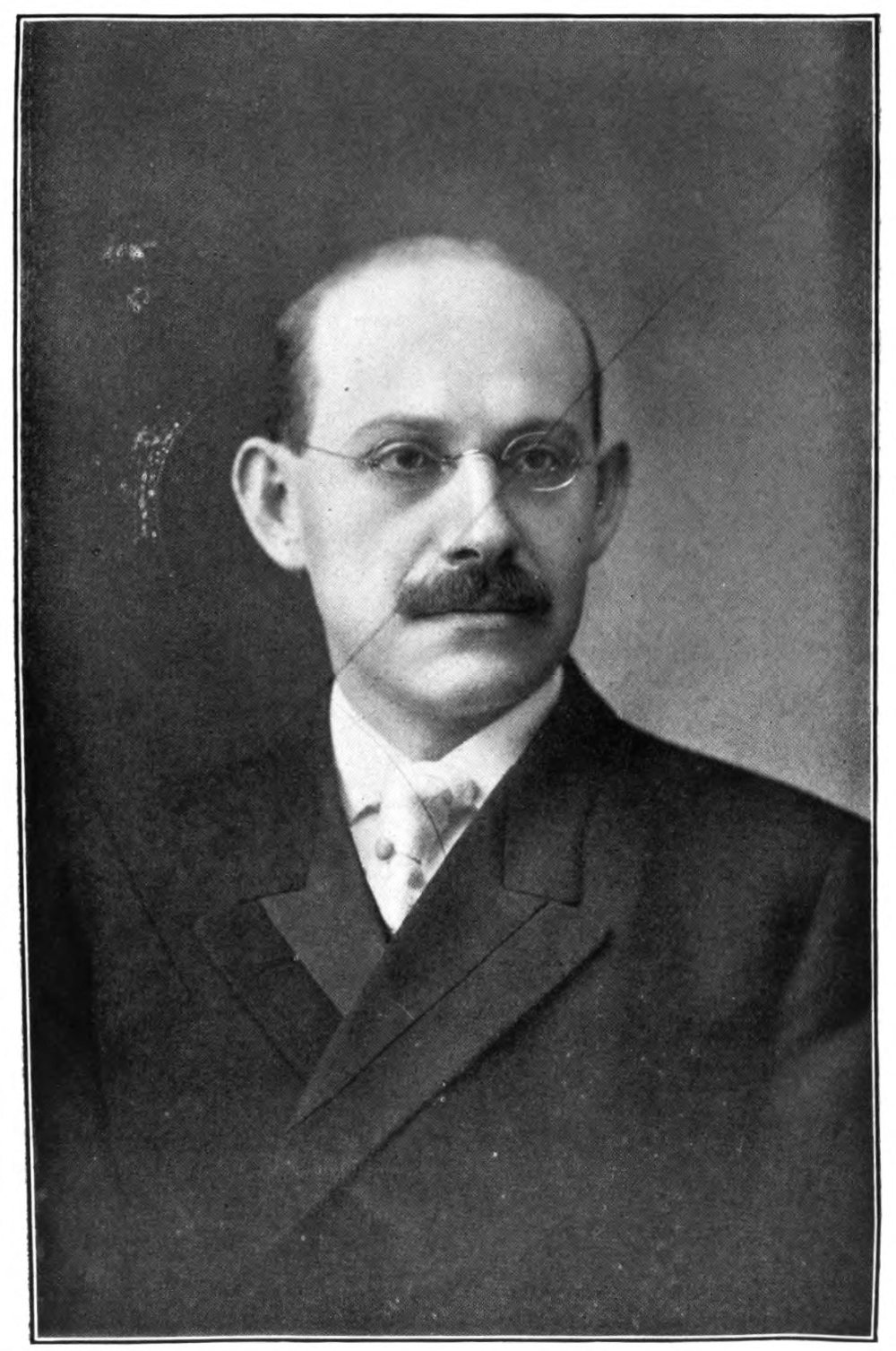

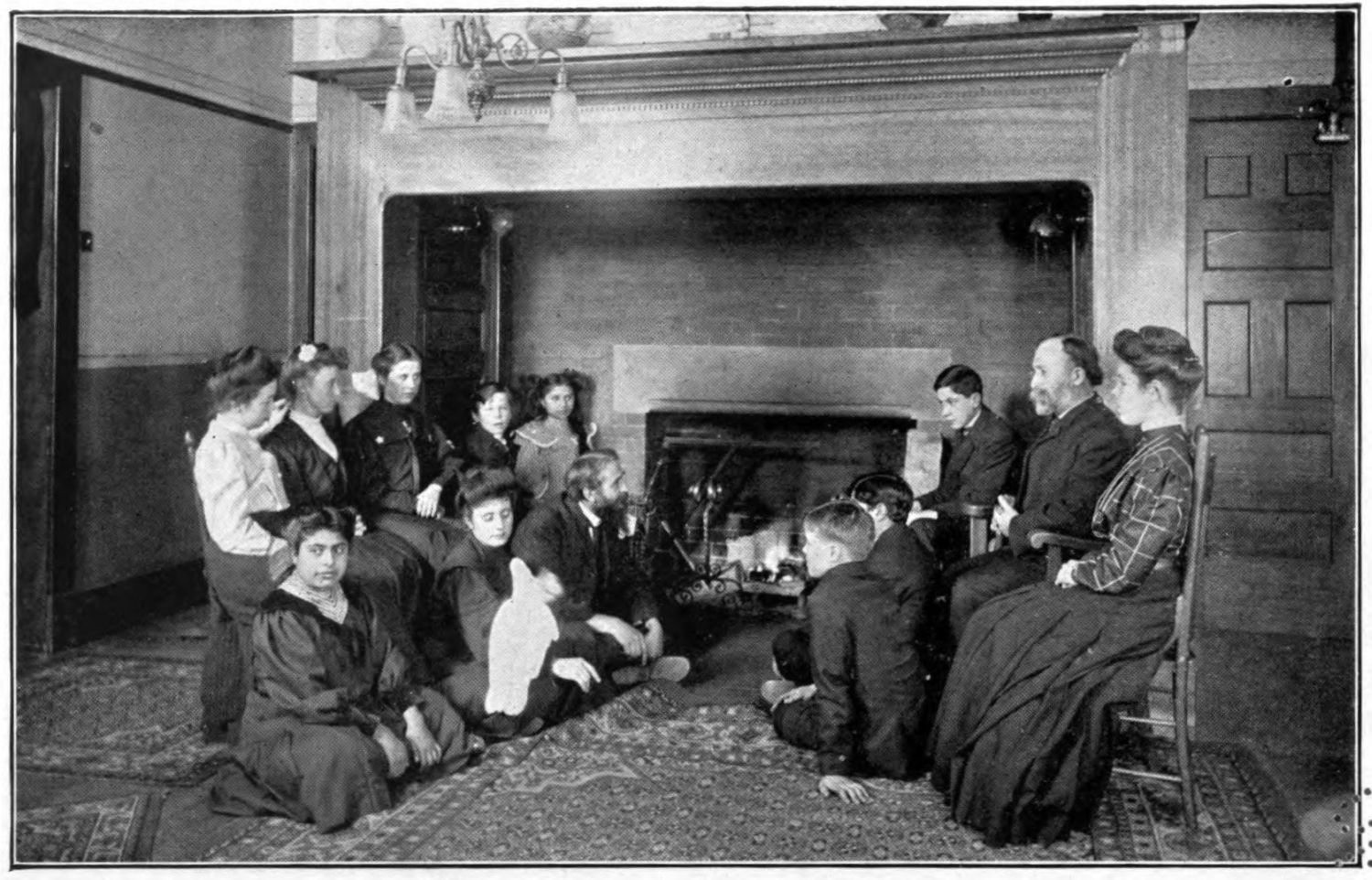

| Mr. Upton Sinclair and Mr. Michael Williams | 16 |

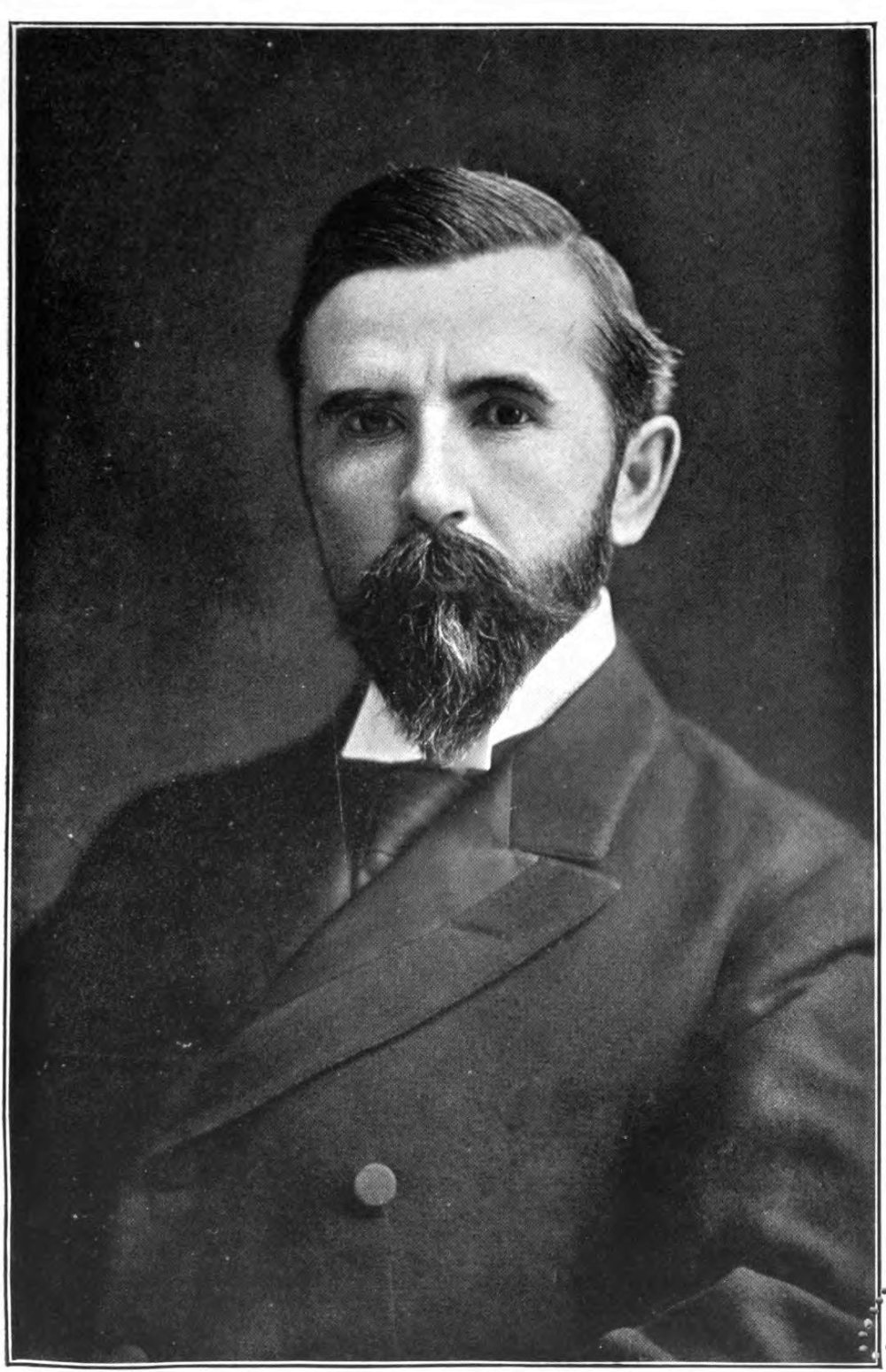

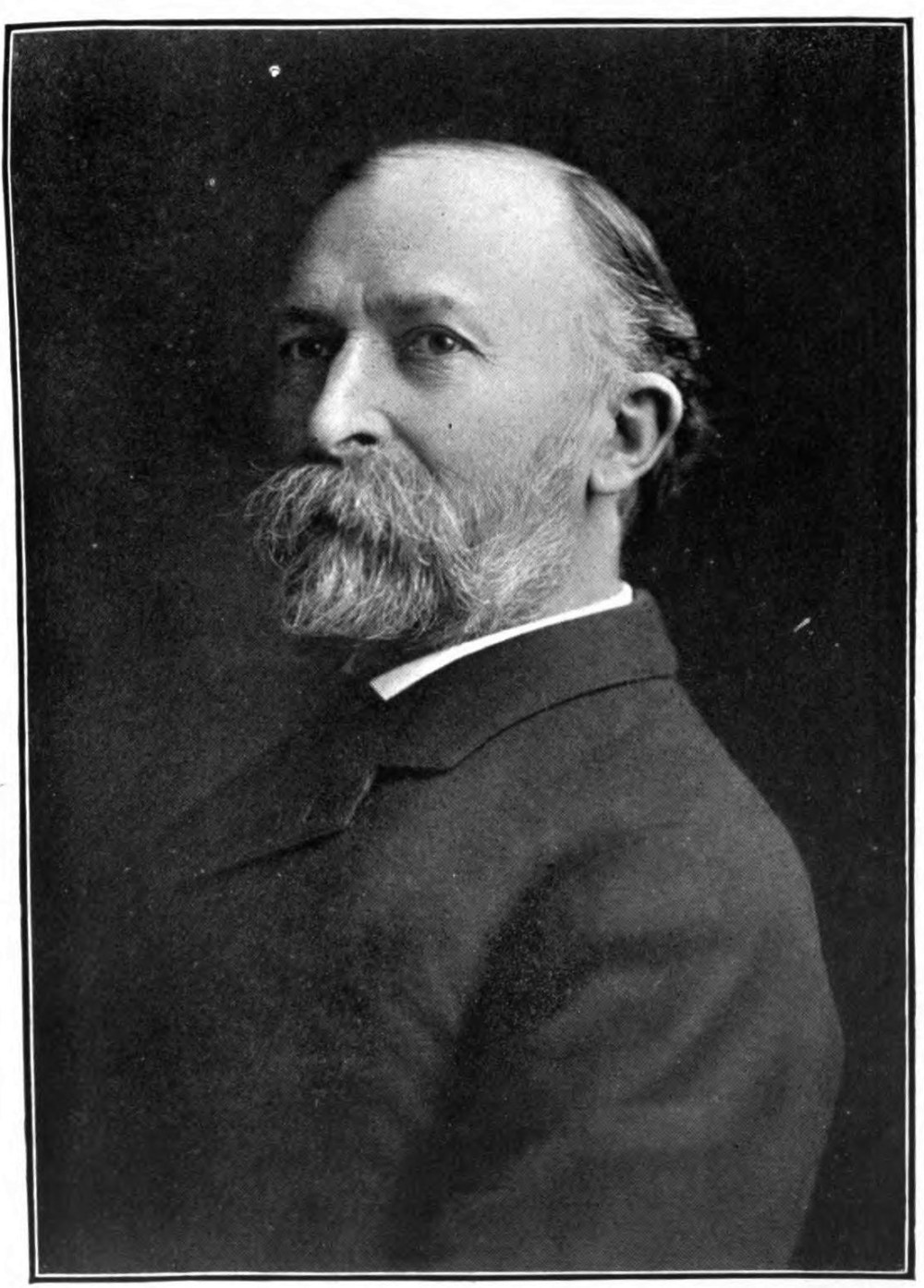

| Mr. Horace Fletcher | 42 |

| Mr. Horace Fletcher Making a World’s Record | 52 |

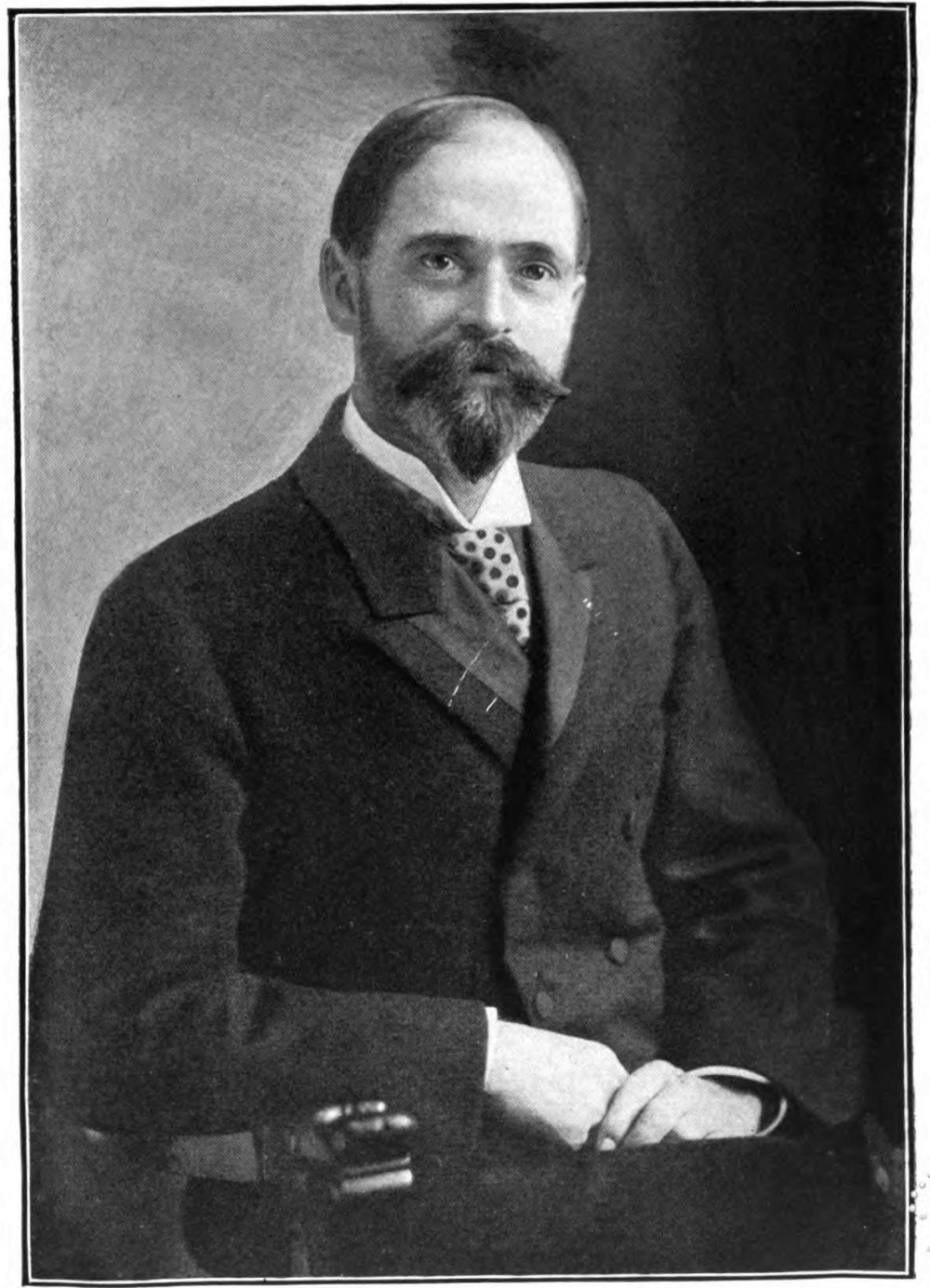

| Professor Russell H. Chittenden, Ph. D., LL.D., Sc. D. | 70 |

| Professor Irving Fisher, Ph. D. | 82 |

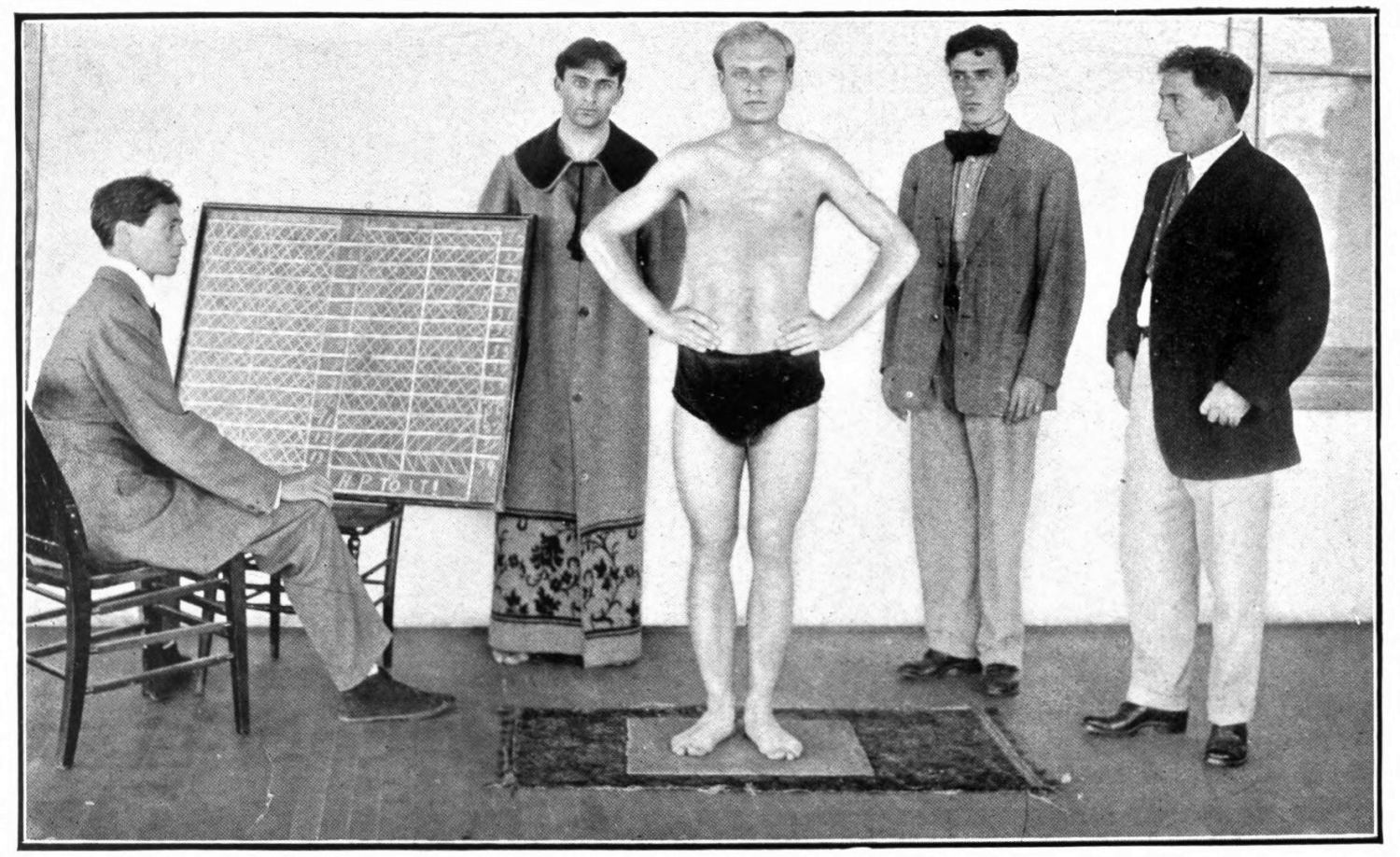

| Mr. John E. Granger Breaking the World’s Record for Deep-Knee Bending | 88 |

| M. Elie Metchnikoff | 114 |

| Professor Lafayette B. Mendel, Ph. D. | 138 |

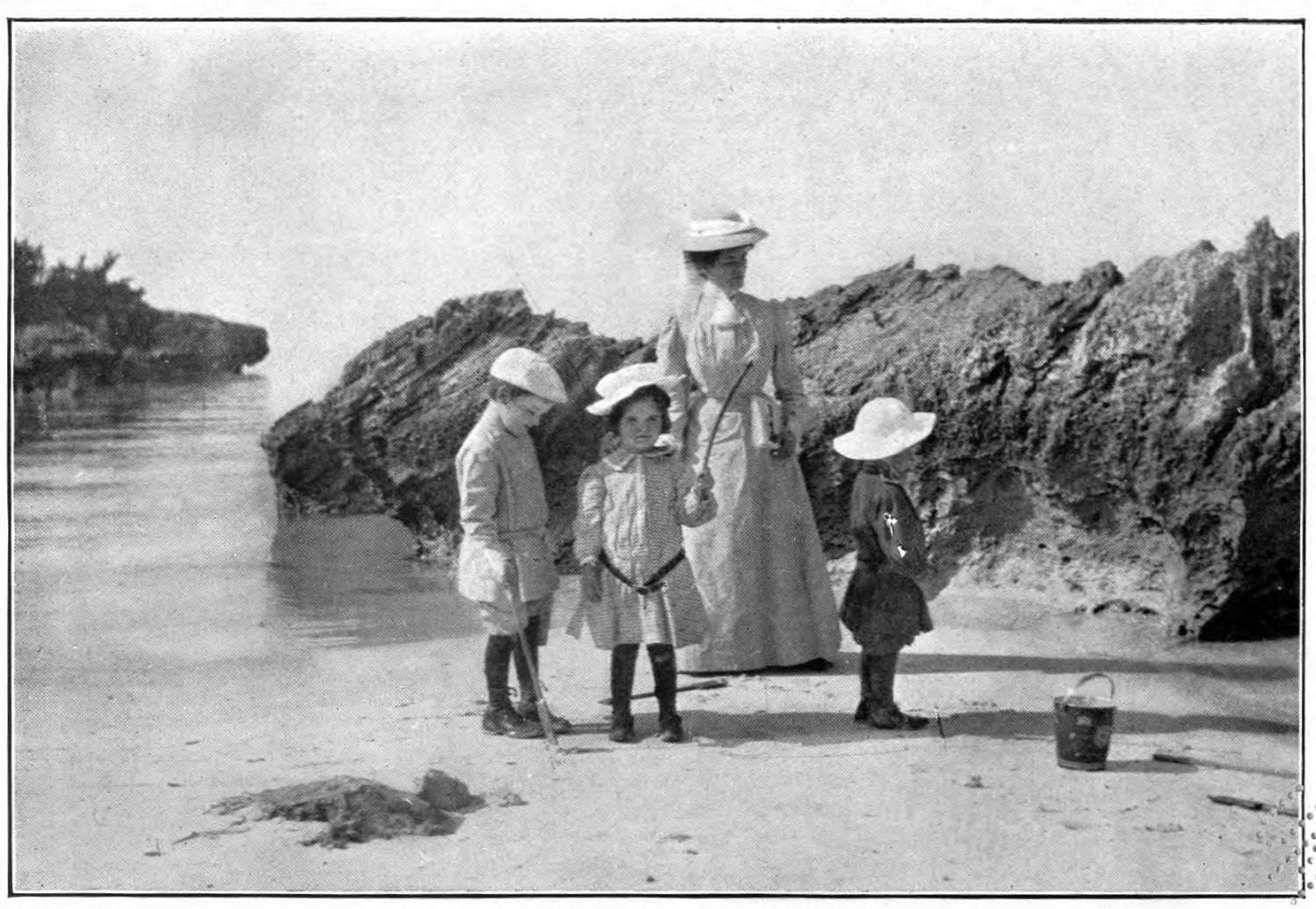

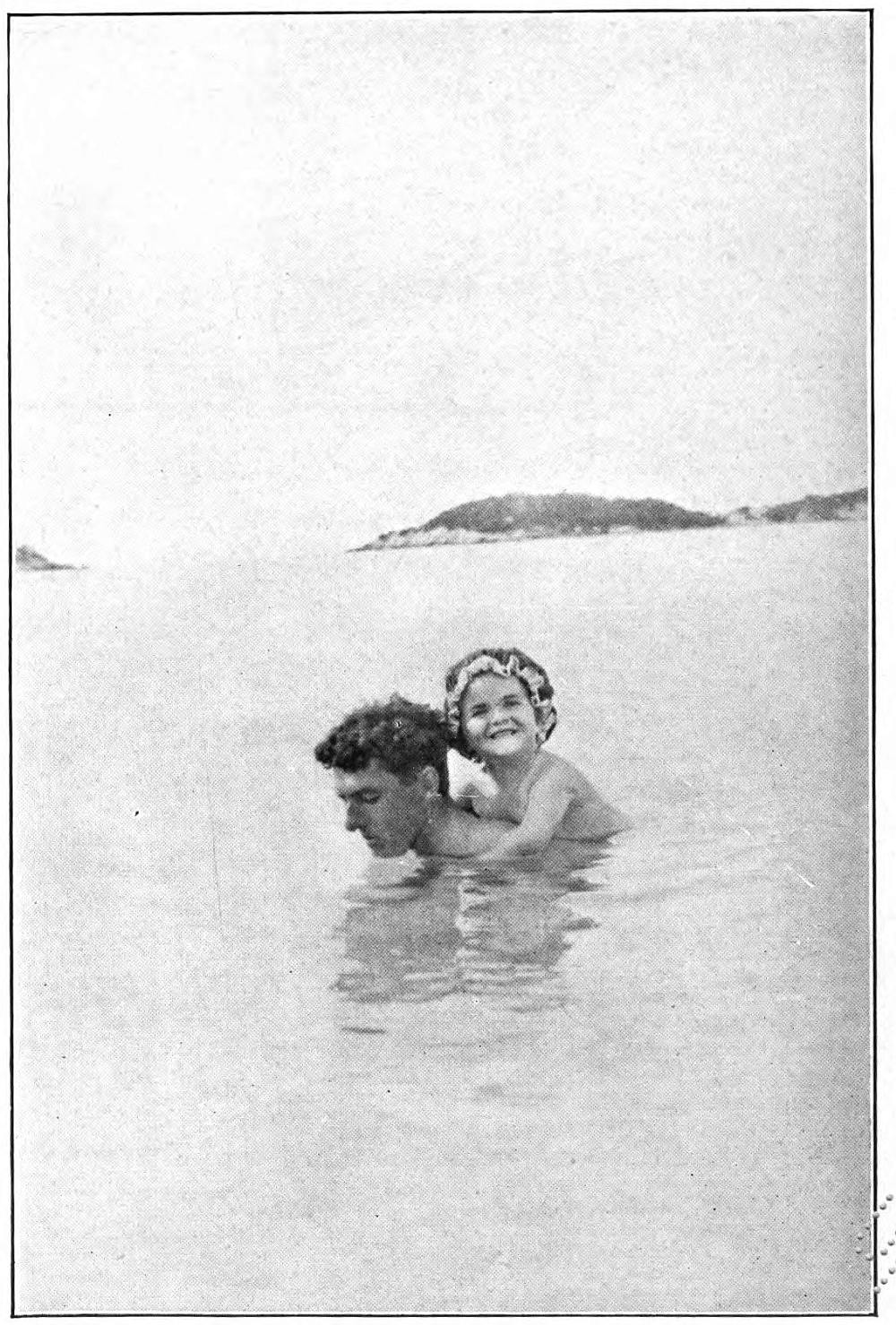

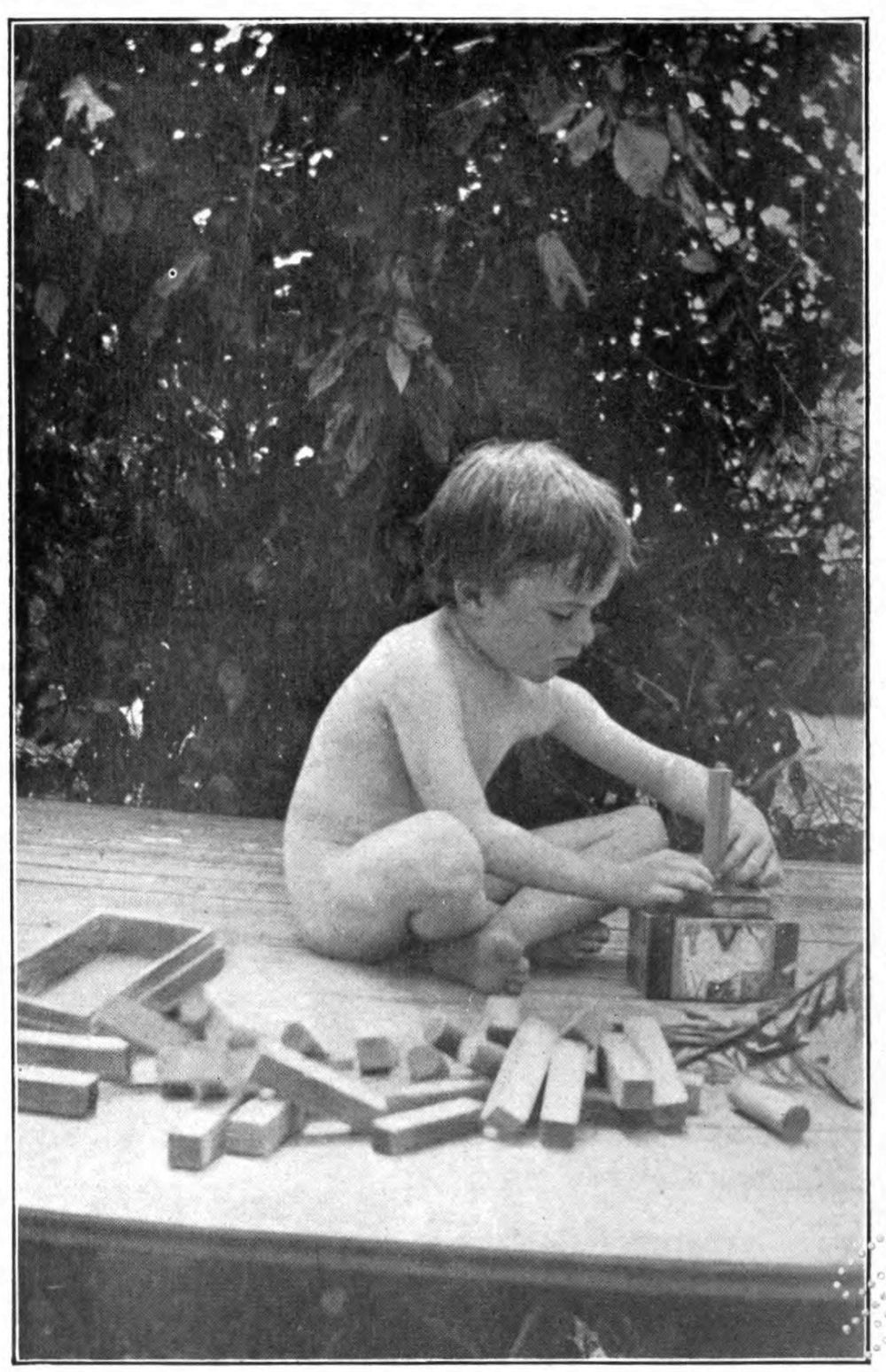

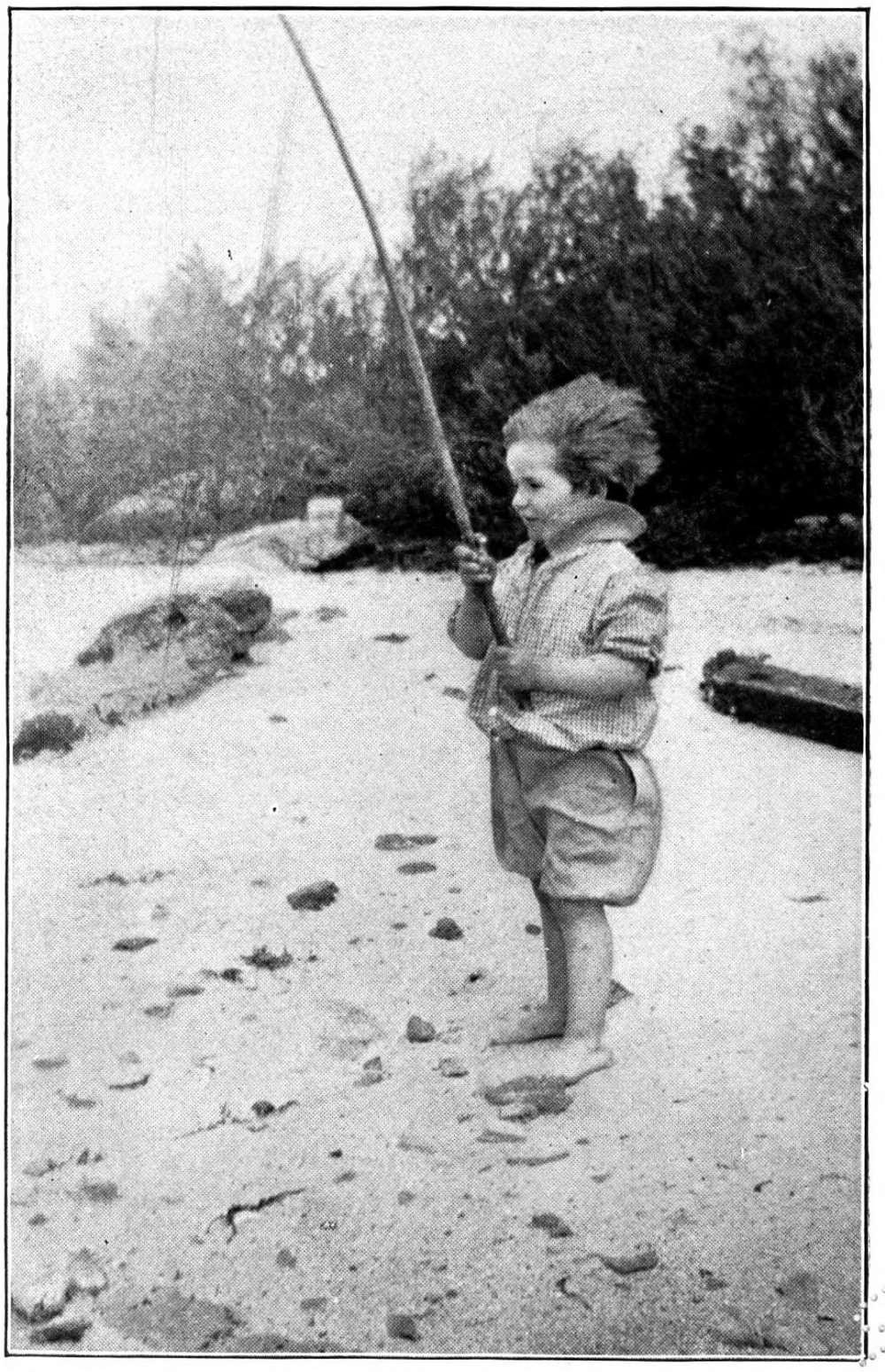

| Mr. Upton Sinclair’s Children | 146 |

| Mr. Sinclair’s Children | 176 |

| The Daily Swim | 206 |

| Fresh Air in Bermuda | 220 |

| Outdoor Exercise | 236 |

| Dr. J. H. Kellogg | 2580 |

| A Group at the Battle Creek Sanitarium | 27 |

[Pg 1]

Ten years ago, when I was a student at college, I fell a victim to a new and fashionable ailment called “la grippe.” I recollect the date very well, because it was the first time I had been sick in fourteen years—the last difficulty having been the whooping-cough.

I have many times had occasion to recall the interview with the last physician I went to see. I made a proposition, which might have changed the whole course of my future life, had he only been capable of understanding it. I said: “Doctor, it has occurred to me that I would like to have someone who knows about the body examine me thoroughly and tell me how to live.”

I can recollect his look of perplexity. “Was there anything the matter with you before this attack?” he asked.

“Nothing that I know of,” I answered;[Pg 2] “but I have often reflected that the way I am living cannot be perfect; and I want to get as much out of my body and mind as I can. I should like to know, for instance, just what are proper things for me to eat——”

“Nonsense,” he interrupted. “You go right on and live as you have been living, and don’t get to thinking about your health.”

And so I went away and dismissed the idea. It was one that I had broached with a great deal of diffidence; so far as I knew, it was entirely original, and I was not sure how a doctor would receive it. All doctors that I had ever heard of were people who cured you when you were sick; to ask one to take you when you were well and help you to stay well, was to take an unfair advantage of the profession.

So I went on to “live as I had been living.” I ate my food in cheap restaurants and boarding-houses, or in hall bedrooms, as students will. I invariably took a book to the table, and ate very rapidly, even then; frequently I forgot to eat at all in the ardor of my work. I[Pg 3] was a worshiper of the ideal of health, and never used any sort of stimulant; but I made it a practice to work sixteen hours a day, and quite often I worked for long periods under very great nervous strain. And four years later I went back to my friend the physician.

“You have indigestion,” he said, when I had told him my troubles. “I will give you some medicine.”

So every day after meals I took a teaspoonful of some red liquor which magically relieved the distressing symptoms incidental to doing hard brain-work after eating. But only for a year or two more, for then I found that the artificially digested food was not being eliminated from my system as regularly as necessary, and I had to visit the doctor again. He gave my ailment another name, and gave me another kind of medicine; and I went on, working harder than ever—being just then at an important crisis in my life.

Gradually, however, to my great annoyance, I was forced to realize that I was losing that fine robustness which enabled me to say that[Pg 4] I had not had a day’s sickness in fourteen years. I found that I caught cold very easily—though I always attributed it to some unwonted draught or exposure. I found that I was in for tonsilitis once or twice every winter. And now and then, after some particularly exhausting labor, I would find it hard to get to sleep. Also I had to visit the dentist more frequently, and I noticed, to my great perplexity, that my hair was falling out. So I went on, until at last I was on the verge of a nervous breakdown, and had to drop everything and go away and try to rest.

That was my situation when I stumbled upon an article in the Contemporary Review, telling about the experiments of a gentleman named Horace Fletcher. Mr. Fletcher’s idea was, in brief, that by thorough and careful chewing of the food, one extracted from it the maximum of nutriment, and could get along upon a much smaller quantity, thus saving a great strain upon the bodily processes.

This article came to me as one of the great discoveries of my life. Here was a man who[Pg 5] was doing for himself exactly what I had asked my physician to do for me so many years previously; who was working, not to cure disease, but to live so that disease would be powerless to attack him.

I went at the new problem in a fine glow of enthusiasm, but blindly, and without guidance. I lived upon a few handfuls of rice and fruit—with the result that I lost fourteen pounds in as many days. At the same time I met a young writer, Michael Williams, and passed the Fletcher books on to him—and with precisely the same results. He, like myself, came near killing himself with the new weapon of health.

But in spite of discouragements and failures, we went on with our experiments. We met Mr. Fletcher himself, and talked over our problems with him. We followed the course of the experiments at Yale, in which the soundness of his thorough mastication and “low proteid” arguments were definitely proven. We read the books of Metchnikoff, Chittenden, Haig and Kellogg, and followed[Pg 6] the work of Pawlow of St. Petersburg, Masson of Geneva, Fisher of Yale, and others of the pioneers of the new hygiene. We went to Battle Creek, Michigan, where we found a million-dollar institution, equipped with every resource of modern science, and with more than a thousand nurses, physicians and helpers, all devoting their time to the teaching of the new art of keeping well. And thus, little by little, with backslidings, mistakes, and many disappointments, we worked out our problems, and found the road to permanent health. We do not say that we have entirely got over the ill effects of a lifetime of bad living; but we do say that we are getting rid of them very rapidly; we say that we have positive knowledge of the principles of right living, and of the causes of our former ailments, where before we had only ignorance.

In the beginning, all this was simply a matter of our own digestions, and of the weal and woe of our immediate families. But as time went on we began to realize the meaning of this new knowledge to all mankind. We[Pg 7] had found in our own persons freedom from pain and worry; we had noticeably increased our powers of working, and our mastery over all the circumstances of our lives. It seemed to us that we had come upon the discovery of a new virtue—the virtue of good eating—fully as important as any which moralists and prophets have ever preached. And so our interest in these reforms became part of our dream of the new humanity. It was not enough for us to have found the way to health for ourselves and our families; it seemed to us that we ought not to drop the subject until we had put into print the results of our experiments, so that others might avoid our mistakes and profit by our successes.

Historians agree that all known civilizations, empire after empire, republic after republic, from the dawn of recorded time down to the present age, have decayed and died, through causes generated by civilization itself. In each such case the current of human progress has been restored by a fresh influx of savage peoples from beyond the frontiers of[Pg 8] civilization. So it was with Assyria, Egypt and Persia; so Greece became the wellspring of art and the graces of life, and then died out; so Rome conquered the world, built up a marvellous structure of law, and then died out. As Edward Carpenter and others have shown us, history can paint pictures of many races that have attained the luxuries and seeming securities of civilization, but history has yet to record for us the tale of a nation passing safely through civilization, of a nation which has not been eventually destroyed by the civilization it so arduously won.

And why? Because when ancient races emerged out of barbarism into civilization, they changed all the habits of living of the human race. They adopted new customs of eating; they clothed themselves; they lived under roofs; they came together in towns; they devised ways of avoiding exposure to the sun and wind and rain—but they never succeeded in devising ways of living that would keep them in health in their new environment.

The old struggle against the forces of nature[Pg 9] once relaxed, men grew effeminate and women weak; diseases increased; physical fibre softened and atrophied and withered away; moral fibre went the same path to destruction; dry rot attacked the foundations of society, and eventually the whole fabric toppled over, or was swept aside, to be built up again by some conquering horde of barbarians, which in its turn grew civilized, and in its turn succumbed to the virulent poison that seemed inherent in the very nature of civilization, and for which there seemed to be no antidote.

So much for the past. As to the present, there do not lack learned and authoritative observers and thinkers who declare that our own civilization is also dying out. They point out that while in many directions we have bettered our physical condition, improved our surroundings, and stamped out many virulent diseases (smallpox, the plague and yellow fever, for instance), and have reduced average mortality, nevertheless we have but exchanged one set of evils for another and perhaps more serious, because more debilitating and degener[Pg 10]ating set: namely, those manifold and race-destroying evils known as nervous troubles, and those other evils resulting from malnutrition, which are lumped together vaguely under the name of dyspepsia, or indigestion—the peculiar curse of America, the land of the frying-pan.

It is also plain, say the critics of our civilization, that society to-day cannot be regenerated by barbarians. To-day the whole world is practically one great civilization, with a scattering of degraded and dying little tribes here and there. Modern civilization seems to have foreseen the danger of being overrun some day as the ancient civilizations were, and to have forestalled the danger by the inventions of gunpowder and rum, syphilis and tuberculosis.

Are these critics right? I believe that they are, as far as they go; I believe that to-day our civilization is rapidly degenerating; but also I believe that it contains within itself two forces of regeneration which were lacking in old societies, and which are destined ultimately to[Pg 11] prevail in our own. The first of these forces is democracy, and the second is science.

To whatever department of human activity one turns at the present day, he finds men engaged in combating the age-long evils of human life with the new weapon of exact knowledge; and their discoveries no longer remain the secrets of a few—by the agencies of the public school and the press they are spreading throughout the whole world. Thus, a new science of economics having been worked out, and the causes of poverty and exploitation set forth, we see a world-wide and universal movement for the abolition of these evils. And hand in hand with this goes a movement of moral regeneration, manifesting itself in a thousand different forms, but all having for their aim the teaching of self-mastery—the replacing of the old natural process of the elimination of the unfit by a conscious effort on the part of each individual to eliminate his own unfitness. We see this movement in literature and art; we see it in the new religions which are springing up—in Christian Science,[Pg 12] and the so-called “New Thought” movements; we see it in the great health movement which is the theme of this book, and which claims for its leaders some of the finest spirits of our times.

In the state of nature man had to hunt his own food, so he was hungry when he sat down to eat. But having conquered nature, and accumulated goods, he is able to think of enjoyments, and invents cooks and the art of cookery—which is simply the tickling of his palate with all kinds of stomach-destroying concoctions. And now the time has come when he wishes to escape from the miseries thus brought upon him; and, as before, the weapon is that of exact science. He must ascertain what food elements his body needs, and in what form he may best take them; and in accordance with this new knowledge he must shape his habits of life. In the same way he has to examine and correct his habits of sleeping and dressing and bathing and exercising, in accordance with the real necessities of his body.

This is the work which the leaders of the[Pg 13] new movement are engaged upon. To quote a single instance: while I was “living as I had been living” and eating the preparations of ignorant cooks in boarding-houses and restaurants, Dr. Kellogg of Battle Creek was bringing all the resources of modern chemistry and bacteriology to bear upon the problem of the nutrition of man; taking all the foods used by human beings, and analyzing them and testing them in elaborate experiments; determining the amount of their available nutriment and their actual effect upon the system in all stages of sickness and health; the various ways of preparing them and combining them, and the effect of these processes upon their palatability and ease of digestion. Every day for nine years, so Kellogg told me, he sat down to an experimental meal designed by himself and prepared by his wife; and the result is a new dietary—that in use at the Battle Creek Sanitarium—which awaits only the spread of knowledge to change the ways of eating of civilized man.

This new health knowledge has been amassed[Pg 14] by many workers and, as in all cases of new knowledge, there is much chaff with the grain. There are faddists as well as scientists; there are traders as well as humanitarians. It seemed to us that there was urgently needed a book which should gather this new knowledge, and present it in a form in which it could be used by the average man. There have been many books written upon this; but they are either the work of propagandists with one idea—containing, as we have proved to our cost, much dangerous error; or else the work of physicians and specialists, whose vocabulary is not easily to be comprehended by the average man or woman. What we have tried to write is a book which sets forth what has been proved by investigators in many and widely-scattered fields; which is simple, so that a person of ordinary intelligence can comprehend it; which is brief, so that a busy person may quickly get the gist of it; and which is practical, giving its information from the point of view of the man who wishes to apply these new ideas to his own case.

[Pg 15]

Michael Williams was recently persuaded to give a semi-public talk on the subject before an audience of several hundred professional and business people. He was compelled to spend the rest of the evening in answering the questions of his audience; and listening to these questions, I was made to realize the tremendous interest of the public in the practical demonstration which Mr. Horace Fletcher has given of the idea of Metchnikoff, that men and women to-day grow old before they ought to do so, and that the prime of life should be from the age of fifty to eighty. A broken-down invalid at forty-five, Mr. Fletcher was at fifty-four a marvel of strength—and at fifty-eight he showed an improvement of one hundred per cent. over his tests at the age of fifty-four; thus proving that progressive recuperation in the so-called “decline of life” might be effected by followers of the new art of health.

As a result of this address, Williams was invited by the president of one of the largest industrial concerns in the country to lecture to[Pg 16] his many thousands of employees on the new hygiene; his idea being to place at their disposal the knowledge of this new method of increasing their physical and mental efficiency.

For business men and women, indeed, for workers of all kinds, good health is capital; and the story of the new hygiene is the story of the throwing open of hitherto unsuspected reserve-stores of energy and endurance for the use of all.

In writing upon this subject, the experiences most prominent in our minds have naturally been those of ourselves, of our wives and children, and of friends who have followed in our path. As the setting forth of an actual case is always more convincing than a general statement, we have frequently referred to these experiences, and what they have taught us. We have done this frankly and simply, and we trust that the reader will not misinterpret the spirit in which we have done it. Mr. Horace Fletcher has set the noble example in this matter, and has been the means of helping tens of thousands of his fellow men and women.

[Pg 17]

I have sketched the path by which I was led into these studies; there remains to outline the story of my collaborator. Williams is the son of a line of sailors, and inherited a robust constitution; but as a boy and youth he was employed in warehouses and department stores, and when he was twenty he went to North Carolina as a tuberculosis patient. Returning after two years, much benefited by outdoor life, he entered newspaper work in Boston, New York, and elsewhere, and kept at it until four years ago, when again he fled South to do battle with tuberculosis, which had attacked a new place in his lungs. After a second partial recuperation, he went to San Francisco. At the time of the earthquake he held a responsible executive position, and his health suffered from the worry and the labors of that period. A year later there came the shock and exposure consequent upon the burning of Helicon Hall. Williams found himself hovering upon the brink of another break[Pg 18]down, this time in nervous energy as well as in lung power. A trip to sea failed to bring much benefit; and matters were seeming pretty black to him, when it chanced that a leading magazine sent him to New Haven to study the diet experiments being conducted at Yale University by Professors Chittenden, Mendel and Fisher. He found that these experiments were based upon the case of Horace Fletcher, and had resulted in supporting his claims. This circumstance interested him, suggesting as it did that he himself might have been to blame for his failure with Mr. Fletcher’s system. So he renewed the study of Fletcherism, and later on the same magazine sent him to Dr. Kellogg’s institution at Battle Creek, with the result that he became a complete convert to the new ideas. Like a great many newspaper men, he had been a free user of coffee, and also of alcohol. As one of the results of his adoption of the “low proteid” diet, and of the open-air life, he was able to break off the use of all these things without grave difficulty. A bacteriological examination re[Pg 19]cently disclosed the fact that his lungs had entirely healed; while tests on the spirometer showed that his breathing capacity was far beyond that of the average man of his weight and size. In less than three months, while at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, tests showed a great gain in the cell count of his blood, and in its general quality. Also, his general physical strength was increased from 4635 units to 5025, which latter figure is well above the average for his height, 68.2 inches.

In conclusion, we wish jointly to express our obligation to Mr. Horace Fletcher, to Dr. J. H. Kellogg, to Professor Russell H. Chittenden, to Professor Lafayette B. Mendel, and to Professor Irving Fisher for advice, criticism and generous help afforded in the preparation of some of the chapters of this book. The authority of these scientists, physicians and investigators, and of others like Metchnikoff, Pawlow, Cannon, Curtis, Sager, Higgins and Gulick, whose works we have studied, is the foundation upon which we rest on all questions of fact or scientific state[Pg 20]ment. They are the pathbreakers and the roadbuilders,—we claim to be simply guides and companions along the journey to the fair land of health. The journey is not long, and the road is a highway open to all.

[Pg 21]

The new ideas of living which are the subject of this book have proceeded from investigation of the human body with the high-power microscope. The discoveries made, which have to do, not so much with the body itself as with the countless billions of minute organisms which inhabit the body, may be best set forth by a description of the blood. “The blood is the life,” says Exodus, and modern science has confirmed this statement. From the blood proceeds the life of all the body, and in its health is the body’s health.

If you should prick your finger and extract a drop of your own blood, and examine it under a microscope, you would make the fascinating discovery that it is the home of living creatures, each having a separate and independent existence of its own. In a single ounce of blood there are more of these organ[Pg 22]isms than there are human beings upon the face of the globe. These organisms are of many kinds, but they divide themselves into two main groups, known as the red corpuscles and the white.

The red corpuscles are the smaller of the two. The body of an average man contains something like thirty million of millions of these corpuscles; a number exceeding the population of New York and London are born in the body every second. They are the oxygen conveyers of the body; the process of life is one of chemical combustion, and these corpuscles feed the fire. No remotest portion of the body escapes their visitation. They carry oxygen from the lungs and they bring back the carbon dioxide and other waste products of the body’s activities. They have been compared to men who carry into a laundry buckets of pure water, and carry out the dirty water resulting from the washing process.

The other variety of organisms are the white cells or leucocytes, and it is concerning them that the most important discoveries of modern[Pg 23] investigators have been made. The leucocytes vary in number according to the physical condition of the individual, and according to their locality in the body. Their function is to defend the body against the encroachments of hostile organisms.

We shall take it for granted that the reader does not require to have proven to him the so-called “germ theory” of disease. The phrase, which was once accurate, is now misleading, for the germ “theory” is part of the definite achievement of science. Not only have we succeeded in isolating the specific germ whose introduction into the body is responsible for different diseases, but in many cases, by studying the history and behavior of the germ, we have been able to find methods of checking its inroads, and so have delivered men from scourges like yellow fever and the bubonic plague.

An experiment that is often tried in operating rooms furnishes a vivid illustration of the omnipresence of these invisible, yet potent,[Pg 24] foes of life. In order to impress upon young surgeons the importance of maintaining antiseptic conditions, they are instructed to thoroughly wash their hands and arms in antiseptic soap and water; then they are told to leave their arms exposed for a few minutes, after which a microscopic examination of the bared skin will result in exposing the presence of myriads of germs. Many of these are, of course, harmless; some are even “friendly”—since they make war upon the dangerous kinds. But others are the deadly organisms which find lodgment in the lungs and cause pneumonia and tuberculosis; or the thirty odd varieties of bacilli which cause the various kinds of grippe and influenza and “colds,” which plague the civilized man; or others which, finding entrance into the digestive tract, are the cause of typhoid and other deadly fevers.

So it appears that we live within our bodies somewhat in the same fashion as isolated barons lived in their castles in the Dark Ages, beleaguered constantly by hordes of enemies[Pg 25] that are bent upon our destruction—these being billions upon billions of disease germs. Every portion of the body has its defenses to protect it against these swarms. The skin is germ-tight in health; and each of the gateways to the interior of the body has its own peculiar guard—tears, wax, mucous membrane, etc. As Dr. Edward A. Ayers points out,—“Many of these entrances are lined with out-sweeping brooms—fine hairs similar to the ‘nap’ or ‘pile’ of carpet or plush—which constantly sweep back and forth like wheat stalks waving in the breeze. You cannot see them with the low-powered eye, but neither can you see the germs. They sweep the mucous from lungs and throat, and try to keep the ventilators free from dust and germs. Behind the scurf wall and the broom brigade of the mucous membranes, the soldier corpuscles of the blood march around the entire fortress every twenty-eight seconds” (the time occupied by the blood in its circulation through the body).

[Pg 26]

And again (to quote another authority, Dr. Sadler), “All the fluids and secretions of the body are more or less germicidal. The saliva, being alkaline, discourages the growth of germs requiring an acid medium. The normal gastric juice of a healthy stomach is a sure germ-killer. In the early part of digestion, lactic acid is present, and there soon appears the powerful hydrochloric acid, which is a most efficient germicide....

“The living, healthy tissues of the body are all more or less germicidal; that is, they are endowed with certain protective properties against germs and disease. This is true of many of the other special secretions, like those found in the eye and elsewhere in the body, when they are normal. The blood and lymph, the two great circulating fluids of the body, are likewise germicidal. In some conditions of disease, there may be found various substances in the blood which can destroy germs.”

[Pg 27]

And this definitely brings us to the other kind of inhabitants of the human blood, the leucocytes, or white blood corpuscles,—and so to the germ theory of health, which science is showing to be no less true than the germ theory of disease. In their natural state these cells are transparent, spherical forms of the consistency of jelly drops, which float in the bloodstreams or creep along the inner surface of the vessel. Their function was for a long time not understood; the discovery of the real facts, perhaps the most epoch-making discovery ever made concerning the human body, the world owes to the genius of Metchnikoff, the head of the Pasteur Institute of Paris. These cells are the last reserves of the body in its defense against the assault of disease. Whenever, in spite of all opposition, the hostile germs find access either to the blood or to the tissue, the white cells rush to the spot, and fall upon them and devour them.

In their fight against the hordes of evil bacteria that invade the blood, where the battles[Pg 28] are waged, the body’s defenders have four main ways of battling. Again we quote from Dr. Ayers: “The blood covers some germs with a sticky paste, and makes them adhere to one another, thereby anchoring them so that they become as helpless as flies on fly paper. The paste comes from the liquid of the blood, the plasma. Another blood-weapon (the ‘lysins’) dissolves the germs as lye does. A third means of defense is the ability of the white blood corpuscles to envelop and digest the living germs. One white cell can digest dozens of germs, but it may mean death to the devouring cells.

The fourth and recently discovered weapon, or ammunition, of the blood is the opsonins. Wright and Douglas in London in 1903 coined the word, which comes from the Latin opsono: “I cook for the table,” “I prepare pabulum for.” This is precisely what the opsonins do in the blood. They manifest this beneficial activity when invading disease germs appear. They attract white blood cells to the germs and make the bacteria more eatable for the[Pg 29] cells. They are appetizers for the white blood cells; or sauces, which help the white blood cells to eat more of the bacteria than they could do without this spur to their hunger. Wright and Douglas demonstrated beyond peradventure the ability of the white blood cells to eat a larger number of bacteria when the latter are soaked in opsonins. They also showed that this opsonic sauce, or appetizer, which stimulates the blessed hunger of the white blood cells for disease bacteria, could be artificially produced, and hypodermically introduced into a patient’s blood, thus increasing that blood’s power of defense by raising the quantity of opsonins. They also worked out a practical laboratory technique by means of which the opsonins can be measured, or counted, with a considerable degree of exactitude, thereby making it possible to estimate within limits of accuracy any one’s ability to resist bacterial invasions. If the blood is rich in opsonins, its power to fight disease is strong. Opsonins are now inoculated into the blood at several institutions, notably McGill University[Pg 30] in Montreal, and at the Battle Creek Sanitarium.

The process by which the white cells fight for us may be watched in the transparent tissue of a frog’s foot or the wing of a bat. If a few disease germs are introduced into this tissue, the white cells may be seen to accumulate on the wall of the blood vessel just opposite where the germs have entered. “Each cell begins to push out a minute thread of its tissue,” writes Dr. Kellogg, in describing the process, “thrusting it through the wall of its own blood vessel. Little by little the farther end of this delicate filament which has been pushed through the wall grows larger and larger, while the portion of the cell within the vessel lessens, and after a little time each cell is found outside the vessel, and yet no openings are left behind. Just how they accomplish this without leaving a gap behind them is one of the mysteries for which Science has for many years in vain sought a solution. The[Pg 31] vessel wall remains as perfect as it was before. Apparently, each cell has made a minute opening and has then tucked itself through, as one might tuck a pocket handkerchief through a ring, invisibly closing up behind itself the opening made. Once outside the vessel, these wonderful body-defenders, moving here and there, quickly discover the germs and proceed at once to swallow them. If the germs are few in number, they may be in this way destroyed, for the white cells not only swallow germs, but digest them. If the number is very great, however, the cells sacrifice themselves in the effort to destroy the germs, taking in a larger number than they are able to digest and destroy. When this occurs, the germs continue to grow; more white cells make their way out of the blood vessels, and a fierce and often long-continued battle is waged between the living blood cells and the invading germs.”

Now, it must be understood that this description is not the product of any one’s imagination, but is a definitely established fact which[Pg 32] has been studied by scientists all over the world. Because of the importance of the discovery, and of the new views of health to which it leads, we have placed a picture of this “battle of the blood” at the front of this book. It shows the leucocytes of the human body in conflict with the germs of influenza: the black dots being the germs, and the larger grayish bodies the leucocytes. We have chosen a photograph rather than a drawing, so that the reader may realize that he is seeing something which actually has existence. We request him to study the picture and fix it upon his mind, for it is not too much to say that from it is derived every principle of health which is set forth in the course of this book.

The human body is a complex and intricate organism, in some wonderful and entirely incomprehensible way integrating the activities of all these billions of other living organisms. Each and every one of these latter has its function to fulfill, and the life of the indi[Pg 33]vidual body is a life of health so long as the unity of all its organisms is maintained. Outside of the body are millions of hostile organisms assaulting it continuously; and the problem of health is the problem of enabling it to make headway against its enemies for as long a period as possible. Every act of a human being has its effect upon this battle; at every moment of your life you are either strengthening the power of your own organism or strengthening your enemies. Once the organism is unable to beat back its enemies, health begins to fail and death and complete disintegration is the ultimate result.

It must be understood that the peril of these hostile germs is not merely that they devour the substance upon which the body’s own organisms have to be nourished. If that were all, they might remain in the body as parasites, and by taking additional nourishment a man might sustain life in spite of them. Nor is it even that they multiply with such enormous rapidity; the peril is that they throw off as the products of their own activity a number of[Pg 34] poisons, which are as deadly to the human body as any known. These poisons are produced much more rapidly than they can be eliminated from the system, and so they fill the blood, and death ensues.

Thus the problem becomes clear. In the first place, what can we do to keep disease germs from securing entrance to the body; and second, what can we do to strengthen the body’s army of defense so that the fate of any which do find entrance may be immediate destruction?

In actual practice it is found that the second problem is by far the more important one. Some germs we can avoid. If we boil all the water that we drink we will not be very apt to have typhoid. If we exterminate rats and mosquitoes and flies and fleas, we will not have yellow fever, or malaria, or plague. But we cannot hope to do this at present in the case of such diseases as, for instance, consumption, grippe, and influenza. If we live in a city, we[Pg 35] take into our lungs and throat millions of the germs of these diseases every day. Therefore the one hope that is left is to keep ourselves in such a condition of health that the army of our bodies shall be able to destroy these germs. When the blood is in a healthy condition, the white cells are numerous, powerful, and active, but when the blood flows stagnantly, or when it is impoverished, then the white cells are few and the forces of disease obtain a foothold.

Healthy men can go through many epidemics with impunity. Because the Japanese army was an army of healthy men, its death rate from those diseases which usually follow in the wake of all armies was lower than the world had ever known before. Robert Ingersoll once said that if he had been God and had made the world, he would have made health “catching,” and not disease. As a matter of fact, health is catching. It abounds in the very air we breathe, in the water we drink, in the movements of every muscle and the play of every fibre and nerve of the body; it comes[Pg 36] from and is nourished by each and every one of the bodily actions and functions; while disease is only secured by persistent transgressions of the proper way of living, and by injurious habits and customs that result in lowering the “vital resistance.”

This vital resistance is the innate power of the body to keep itself strong; its very lifeforce. This is what we mean when we say that this or that person has “a good constitution,” or has “a weak constitution.” This is the capital in the bank of each individual life, placed there by Nature at the birth of that life, and increased or diminished by each and every action of our bodies, and also of our minds. As Rokitansky, the eminent German scientist, said, “Nature heals. This is the first and greatest law of therapeutics—one which we must never forget. Nature creates and maintains, therefore she must be able to heal.”

Many of the most notable discoveries and experiments of modern science concur in demonstrating that the natural and innate healing power of the body is man’s greatest re[Pg 37]source in combating disease and maintaining health. It is the body itself which cures the sick man; his own vitality, and not the drug or medicants which he may take. These may assist the healing process, but they do not set going the healing processes themselves. More often, indeed, they are distinct detriments. They stamp out or banish the distressing symptoms of ailments, and thus in effect they silence the signal bells of danger which the body rings at the approach of disease.

Modern science has turned its forces upon this question of maintaining at its highest potentiality the ability of the body to resist disease. All the habits of the human race have been investigated in the light of this idea, and some have been found to be wise and others to be unwise. These conclusions, with the evidence therefor, are the subjects of our book.

It has been found that the most important problems connected with health are those of nutrition—the questions of what and when[Pg 38] and how and how much food we ought to eat.

Every language under the sun contains a prayer somewhat similar to that which we have in the Anglo-Saxon tongue, “Give us this day our daily bread.” If we stop to think for a moment, we realize that next to the air we breathe, and the water we drink, our food is the most important consideration in the maintenance of life. All this is the veriest commonplace; yet the fact remains that it is very rarely indeed that we do stop to think upon the subject of our food. It is something that we take for granted, like life itself. In the regular routine of our days our meals become fixed habits, and the taking of food an almost involuntary custom. It requires some extraordinary event to arouse us to a just appreciation of the importance of knowledge on this subject. Or else the coming of one of the myriad forms of digestive diseases will serve the purpose of introducing the subject to our notice.

Our blood is made directly from what we[Pg 39] eat, and that old Saxon proverb is true which says that every man has lain in his own trencher. Man is his food. Each human body is made by chemical action from its food. All our actions and all our thoughts come from what we eat, even as the movements of machinery proceed from the coal fed into the boilers of the engine which operate the machine. If we eat the right food, namely, the food which contains the elements our bodies require in the proper proportions, we repair all waste, replace broken down tissue and supply ourselves with physical and mental energy for our toils and joys in life; while if we eat the wrong foods we quickly injure our delicate though powerful physical and mental machinery.

All this would seem to be obvious; yet most people would grant that they have still much to learn concerning what really constitutes the best foods, and about the best ways of preparing, or making, or using those foods. Few of us possess anything more definite to guide us in our eating than the habits we acquired as[Pg 40] children, or habits picked up in later life from following the example of our friends, or the food fashions of the day—for there are such things as fashions in foods and in the eating of foods, even as there are fashions in clothes and the making and wearing thereof. In this place it is proposed to study the subject of food from one standpoint, namely, its effect upon the Battle of the Blood; its relation to the vital resistance of the body whereby health is maintained.

[Pg 41]

We shall first of all see what modern science has to tell us concerning the question of how we ought to eat.

It may not seem possible that anything essential remains to be said at this late day on the subject of one of the commonest and decidedly most necessary of all human acts. That there should be knowledge of the utmost importance to learn regarding the actions and movements of the tongue, the teeth, and the jaws, may come with as much surprise to the majority of our readers as it did to us when we first hit upon this disturbing, but illuminating, fact.

The act of eating is the starting point of the long series of processes whereby our bodies are nourished. It is the only act of them all which lies within our control. We[Pg 42] can directly supervise the work of our mouths; we can watch over the action of the teeth, and tongue, and palate; but we can not supervise the work of the stomach, or of the intestinal tube. Once we have swallowed our food, our mastery over it has ceased—except for some hit-or-miss participation in the further processes of its digestion by means of pills or potions. Realizing this, we come to recognize the basic importance of knowing the right way of eating.

This knowledge the world owes to Horace Fletcher, the American business man who has made many of the greatest physiologists of our times embark upon years-long series of experiments and inquiries into the problems of man’s nutrition. As a result, the text-books of physiology are now being rewritten; and as a further result, tens of thousands of men and women, among them some of the best known authors, physicians, clergymen, military men, and business men of both Europe and America, have been restored to health by the knowledge of how to eat their food.

[Pg 43]

This knowledge Mr. Fletcher gained at the very door of death, and in no more interesting and striking fashion could the importance of it be shown than by the relation of his remarkable case.

At the age of forty-five, after a varied and adventurous career, as miner, and explorer, and sailor, and hunter, Mr. Fletcher had won wealth, and retired from his business in order to devote himself to long-cherished interests in art and philosophy. He was still comparatively young, he was a member of many clubs, he had warm friends in all the capitals and countrysides of the world (Mr. Fletcher being one of the most untiring of globe-trotters), and in all ways except one he was equipped and ready for a long life of ease and enjoyment.

The one way in which he was not equipped was—in health.

[Pg 44]

Once he had been a man of robust physique, a champion gymnast and athlete; he had been president of the far-famed Olympic Club in San Francisco (which he founded, and where the pugilist Corbett was discovered), and had won plaudits even from famous professionals for his prowess with the gloves.

But he had overdrawn his account at the bank of life. He had expended more vital resistance than he had stored up; to such an extent, indeed, that when Mr. Fletcher went to the insurance companies at the time he retired from business he was rejected by them all; he was obese; he was suffering from three chronic diseases, and he was dying fast. Such was the verdict given by the skilled and experienced medical examiners of the life insurance companies. And instead of entering upon a long life of ease and enjoyment, he was thus condemned, seemingly, to a short life of invalidism and suffering.

[Pg 45]

But Mr. Fletcher declined to accept any such decision as that. He decided that he would regain his health—not that he would try to regain his health, but that he would regain his health.

He first turned to the physicians. Possessed of wealth, he was able to secure the services of many of the most able specialists of the world. He visited the most celebrated “cures” and “springs” and sanitariums of Europe and America. Nothing availed. He found passing relief now and then, but no permanent good. He gained no health, in other words, but obtained merely temporary abatement of this or of that disease.

Then he turned to himself. He began the study of his own case. As he attributed most of his bodily woes to faulty habits of eating, the subject of nutrition became uppermost in his studies. He was, coincidentally, deeply immersed and interested in the study of practical philosophy; and in a very remarkable[Pg 46] fashion these two subjects, these two interests, nutrition and practical philosophy, became fused into one subject, supplementing and completing each other and jointly forming the burden of the message of Hope, of the tidings of great joy, which it became the mission of Horace Fletcher to deliver to mankind.

He discovered, or rather rediscovered, and applied, two great and simple truths:

First, that the complete chewing of all food, both liquid and solid, whereby a process of involuntary swallowing is established, foods being selected in accordance with individual tastes, is by far the most important and most necessary part of human nutrition. It is the key that unlocks the door of health, and opens the way to the real hygienic life.

Second, that nothing poisons the body, and aids the forces of disease, more than worry—which Mr. Fletcher has named Fearthought. It is our nature to look forward, to anticipate. We can anticipate in two ways—anticipate[Pg 47] evil, or anticipate good. The first way is to use fearthought; the second way is to use forethought. Forethought will produce cheerfulness and health, even as unspoiled rose seeds will produce roses. Fearthought will produce disease and trouble, even as the germs of putrefaction will produce sickness and death.

So great an authority in philosophy and psychology as William James has given the sanction of his use to Mr. Fletcher’s phrases; and has also named him as a shining example of those exceptional men who find in some mental idea a key to unlock reservoirs of hidden and unsuspected energy. While there is no doubting the fact that Horace Fletcher is decidedly an exceptional man, yet the records prove that his key is not merely for the use of exceptional people, but that it is one susceptible of being used by everybody possessing willpower enough to enable them to say “yes” when offered something good.

Like other great discoveries, Mr. Fletcher’s discovery of the right way to eat came partly as an accident. Happening to be in Chicago[Pg 48] at a time when his friends were all away, and being forced to stay in the city, he took to lingering over his meals in order to pass away the time. He began to taste every spoonful of soup, to sip every mouthful of anything liquid, with great deliberation, noting the different tastes and searching out new flavors.

He chewed each morsel of meat or bread or fruit or vegetable until, instead of being gulped down, it was drawn in easily by the throat. And in this manner did he stumble upon his pathway to deliverance. He had not been “toying” with his food—as he then considered he was doing—for more than a few weeks before he noticed that he was losing a great deal of superfluous fat, that he was eating less, but with far greater enjoyment, than ever before in his life, that his taste for simpler foods increased as his taste for highly seasoned and complex dishes decreased, and that he was feeling better both physically and mentally than he had felt in many years.

[Pg 49]

What did these things mean? Some hidden virtue in the food he was eating? Some hitherto quite unsuspected tonic in the smoke of Chicago? Or a lesson in health furnished by the “how” of his eating? At this point there flashed through Mr. Fletcher’s memory the story of Gladstone’s advice to his children to chew each morsel of food thirty-two times (once for each tooth in their heads) if they would preserve their health. In that moment, Mr. Fletcher began his investigation of the many processes that go to make up the simple act of mastication, an investigation which has now been going on for more than ten years, and which has resulted in directing public attention to the supremely important subject of nutrition with more emphasis, and in the arousing of more general interest and the production of more telling effect than any other circumstance or event has done in the history of physiologic science. The word “Fletcherizing” was first applied by Dr. J. H. Kellogg,[Pg 50] of Battle Creek, after the analogy of “pasteurizing,” in describing the act of mastication as recommended by Mr. Fletcher. “Fletcherism,” as Mr. Fletcher’s system of mental science and of physical culture through mastication has come to be known, after first being for years a stock jest of the newspaper funnyman, has now been recognized, even by those scientists who detest all “isms,” as a most valuable bridge from the land of bad food habits and disease to the land of good food habits and health.

The bridge certainly afforded its builder a passage from one region to the other. Following a constant improvement in his general condition, beginning almost simultaneously with the adoption of his new way of life, Mr. Fletcher is to-day one of the strongest and most enduring men alive. Tests of his strength and endurance made at the Yale gymnasium at different times prove beyond a doubt that this is so. The following is a quotation from the report of Dr. William G. Anderson, director of the Yale Gymnasium:

[Pg 51]

“In February, 1903, I gave to Mr. Horace Fletcher the exercises used by the ‘Varsity’ crew. He went through these movements with ease and showed no ill effects afterwards. At that time Mr. Fletcher weighed 157½ pounds, and was in his fifty-fifth year. On June 11, 1907, Mr. Fletcher again visited the Yale Gymnasium and underwent a test on Professor Fisher’s dynamometer. This device is made to test the endurance of the calf muscles.

“The subject makes a dead lift of a prescribed weight as many times as possible. In order to select a definite weight, the subject first ascertains his strength on the Kellogg mercurial dynamometer by one strong, steady contraction of the muscles named—and then he finds his endurance by lifting three-fourths of this weight on the Fisher dynamometer as many times as possible at two or three second intervals. One leg only is used in the lift, and as indicated, the right is usually chosen.

“Mr. Fletcher’s actual strength as indi[Pg 52]cated on the Kellogg machine was not quite four hundred pounds, ascertained by three trials. In his endurance test on the Fisher machine he raised three hundred pounds three hundred and fifty times and then did not reach the limit of his power.

“Previous to this time, Dr. Frank Born, the medical assistant at the Gymnasium, had collected data from eighteen Yale students, most of whom were trained athletes or gymnasts. The average record of these men was 87.4 lifts, the extremes being 33 and 175 lifts.

“You will notice that Mr. Fletcher doubled the best record made previous to his feat, and numerous subsequent tests failed to increase the average of Mr. Fletcher’s competitors. Mr. Fletcher informs me that he had done no training nor had he taken any strenuous exercise since February, 1907. On two occasions only during the past year he reports having done hard work in emergencies; once while following Major-General Wood in the Philippines in climbing a volcanic mountain through a tropi[Pg 53]cal jungle on an island near Mindanao for nine hours; and once wading through deep snow in the Himalayan Mountains, some three miles one day and seven miles the next day, in about as many hours. This last emergency experience came through being caught in a blizzard near Murree, in Northern India, at 8500 feet elevation, on the way to the vale of Kashmir. These two trials represented climatic extremes, and Mr. Fletcher states that neither the heat nor the cold gave him discomfort, a significant fact in estimating physical condition.

“Before the trial on the Fisher machine, the subject’s pulse was normal (about 72); afterwards it ran 120 beats to the minute. Five minutes later it had fallen to 112. No later reading was taken that day.

“The hands did not tremble more than usual under resting conditions, as Mr. Fletcher was able to hold in either hand immediately after the test a glass brimming with water without spilling a drop. The face was flushed, per[Pg 54]spiration moderate, heart action regular and control of the right foot and leg used in the test normal immediately following the feat. I consider this a remarkable showing for a man in his fifty-ninth year; 5 feet, 6½ inches in height, weighing 177½ pounds and not in training.”

In order to make a more thorough test of Mr. Fletcher’s power of endurance under varying degrees of physical strain, he underwent on the 17th, 18th, 19th, 21st and 22nd of June, 1907, a number of other exceedingly severe tests, of which Dr. Anderson says: “After each test the respiration and heart action, while active, were healthy, and, under such conditions, normal.

“There was not the slightest evidence of soreness, stiffness or muscular fatigue either during or after the six days of the trials. Mr. Fletcher made no apparent effort to conceal any evidence of strain or overwork and did not show any. He informs me that he felt no distress whatever at any time. Should any one wish to become more familiar with the[Pg 55] strenuousness of the movements selected, let him try them. The effort will be more convincing than any report.

“During the thirty-five years of my own experience in physical training and teaching, I have never tested a man who equalled Mr. Fletcher’s record.

“The later tests, given in June, 1907, were more taxing than those given in 1903, but Mr. Fletcher underwent the trials with more apparent ease than he did four years ago.

“What seems to me to be the most remarkable feature of Mr. Fletcher’s test is that a man nearing sixty years of age should show progressive improvement of muscular quality merely as the result of dietetic care and with no systematic physical training. The method of dietetic care, too, as given by Mr. Fletcher, is so unusual that the results seem all the more extraordinary. He tells me that during the four and a half years intervening between the first and the recent examinations he has been guided in his choice of foods and in the quality also, entirely by his appetite, avoiding as much[Pg 56] as possible any preconceived ideas as to the values of different foods or the proportions of the chemical constituents of the nourishment taken.

“During this four year period he has more than ever catered to his body nourishment in subservience to instinctive demand. He has especially avoided eating until appetite has strongly demanded food, and has abstained from eating whenever he could not do so in comfort and enjoyment. Mastication of solid food and sipping of liquids having taste to the point of involuntary swallowing, according to his well-known theory of thoroughness in this regard, has also been faithfully followed.

“There is a pretty good evidence that taking food as Mr. Fletcher practices and recommends limits the amount ingested to the bodily need of the moment and of the day, leaving little or no excess material to be disposed of by bacterial agency. This might account for the absence of toxic products in the circulation to depress the tissue.

“The possible immunity from lasting[Pg 57] fatigue and from any muscular soreness, resulting from the unaccustomed use, and even the severe use, of untrained muscles is of utmost importance to physical efficiency.

“My own personal observance and trial of Mr. Fletcher’s method of attaining his surprising efficiency, strengthened by my observation of the test-subjects of Professors Chittenden and Fisher who have come under my care meantime, lead me to endorse the method as not only practical but agreeable. As Mr. Fletcher states, both the mental and mechanical factors in selecting and ingesting food are important, the natural result of the care being a wealth of energy for expression in physical exercise.”

So much for Horace Fletcher’s own case.

Yet when he first announced his discovery, his own family laughed at him, and the medical world called him crank. But by quiet, sane, persistent work—by applying to the propaganda of his idea the same methods that had brought him success in business, he suc[Pg 58]ceeded in impressing the scientific world with the value of his method.

An extensive literature has grown up around Mr. Fletcher’s own books. The most important medical bodies in Europe and America have invited him to lecture before them. Hospitals in larger cities have printed his own code of the rules of mastication for distribution. And no large sheet of paper was required, for the whole system could be printed on a postal card, and room would be left for a picture of its author.

Why is complete mastication the best way of eating? Why does its practice lead to recovery of lost health, or increase of health; to increase of strength, to increase of endurance. Is it not a very tedious method, and thus of more trouble than its promised benefits are worth? Does it not waste time? Does it not lead to loss of enjoyment of food?

These are a few of the questions which a discussion of Fletcherism invariably arouses. We speak with a deep conviction of truth when we say that Fletcherism leads to saving of[Pg 59] time, instead of loss of time; that it brings increase of sensuous enjoyment of food instead of decrease of it; and that if it is tedious or a bore, then it is not Fletcherizing. The very essence of Fletcherism is the dropping of worry, the elimination of stress and strain. If you do as Fletcher says, instead of doing as somebody says that Fletcher says, you will chew for taste, and not for time; you will take a crust of bread, or a morsel of potato, for instance, into your mouth and roll it with your tongue, and press it against the roof of your mouth, and pass it to and fro, and crunch it, and crush it; and all the while you will not be counting the chews, nor even thinking about chewing, but on the contrary you will be thinking of the taste of the morsel, and seeking that taste—and finding it.

Yes, finding it, even in a crust of bread or in a morsel of potato, in those humble foods which the most of us seem to take more as matters of habit; for by giving the saliva in the mouth a chance to fulfill the work for which it is put in our mouths by nature, we[Pg 60] find that the starch in the bread and in the potato is turned into a sweet, toothsome and partly digested morsel of sugar.

Here is a point that answers another of the questions which arose a paragraph or so back. This turning of the starch in bread into sugar by the action of saliva is only one of the numerous acts of digestion which is accomplished in the mouth by the teeth, the tongue, the palate, and the various kinds of juices, or saliva, which are in the mouth. Horace Fletcher pointed out, and medical science now confirms his assertions, that many of the most important parts of the digestive process are meant by nature to be carried out in the first three inches of the alimentary canal. And this is the only place in all the thirty feet or so of the alimentary canal where digestion is in our own control. If we bolt or insufficiently masticate our food, these mouth processes of digestion are simply not accomplished; and for this the whole system suffers sooner or later. The stomach and the intestines are called on to do a great deal of extra work, and much of[Pg 61] this extra work is of a kind which they are unable to do. Consequently, what food can not be digested must decompose in the intestines, with the consequent production of poisonous fluids and gases which permeate the body. The whole machinery of digestion is thrown out of gear. All the various germs of disease race to be first to enter the disarranged mechanism, as criminals rush to a city that is in disorder. The blood not being as well nourished as it should be, the white army of the soldiers of the body begin to weaken and to die, and the forces of disease penetrate through their warding lines and attack the fort of life from many sides, or else concentrate their strength in the form of some virulent sickness.

Thorough mastication, on the other hand, means the reverse of these conditions. Almost incredible seem the hundreds of stories which we personally know to be true of men and women who have used Mr. Fletcher’s method as a means to enter the land of good health. In the opinion of Dr. Kellogg of Battle Creek,[Pg 62] “There is no doubt that thorough mastication of food solves more therapeutic problems than any other thing that can be mentioned. It solves the whole question of the right combination of foods; solves the question of the quantity of foods, and the quality of foods, after one has got his appetite trained, his natural instinct trained; and when it comes to certain diseases like acidity of the stomach, hyper-acidity or hypo-acidity, dilation of the stomach or cirrhosis of the liver, or any other trouble with the digestive organs, if it does not effect a radical cure it makes it possible to tolerate a condition which otherwise would be deadly in a short time. It makes it possible for a patient to live a long time, enjoying comfortable health, where otherwise he would be crippled so that he could not live long at all.”

Although we insist upon the fact that Fletcherism is simple, and easy, too, once you have really begun its proper use, yet we also know that there are many difficulties which the average man or woman has to face at the outset. Professor Fisher encountered these diffi[Pg 63]culties when experimenting with his students at Yale, and we are indebted to him for enumerating some of them. And these difficulties, like the habit of hasty eating itself, are products of our civilization.

We mean such difficulties as, first, conventionality, or the desire to eat what others eat, and the unwillingness to appear different; politeness, the desire to please one’s host, or hostess, and eat “what’s set before you,” or to eat something which you know you don’t want or which you know is bad for you, because you fear to offend somebody or other who has cooked it, or bought it for you; food notions, or the opinion that certain foods are “wholesome,” and that certain foods should be avoided as injurious even if delicious to the taste; narrowness of choice, as at a boarding house table (and a great number of home tables!) which often supplies what is not wanted and withholds what is; and, lastly, habit, by which the particular kinds and amounts of food which have become customary through the action and interaction of the[Pg 64] causes previously named, are repeated day after day, without thought.

“Habit hunger” is another of our handicaps. Habit hunger is said by Mr. Fletcher to be responsible for a vast deal of overeating. He refers to the fact that when we are children we eat at least one-third more proteid or tissue-building foods, in proportion to our size, than we require as adults, for the reason that our growing frames must then be nourished and upbuilt; but when we reach the adult stage we are apt to maintain this excessive consumption of proteid food—and proteid, as we shall see later on, is the chief source of dietary ills.

These are some of the difficulties to be encountered by the person who sets out upon the road to health. But they are very slight barriers, indeed, to the person possessed of willpower, and when the benefits and pleasures to be gained are so enormously in excess of the few initiatory troubles, it is not to be wondered at that more than a million persons in England and America are already following Horace Fletcher’s system in whole or in part.

[Pg 65]

Certain remarkable experiments conducted by Rogers, Metchnikoff, and Pawlow in Europe, and by Cannon and Kellogg in America, have thrown a new and interesting light upon the ideas of Fletcher; proving that the act of chewing the food gives to the nerves that control the digestive fluids an opportunity to assay the food, to test it and select for it the particular kind of digestive fluid which that particular kind of food requires. It appears that there are many different kinds of saliva, and each one of these kinds has a particular kind of work to do, which no other kind is able to do. Metchnikoff has shown that if one takes cane sugar into the mouth with or without other food, there is manufactured by the salivary glands a certain peculiar fluid which digests cane sugar. If the cane sugar is not taken into the mouth, then that substance is not made. The saliva that flows into the mouth when there is food there but no cane sugar with the food, will not digest cane sugar.[Pg 66] So it readily can be seen that if cane sugar should be hastily swallowed, it is much less likely to be properly digested. And this holds good with nearly all other kinds of food.

“But how is a person to know when he has chewed a mouthful long enough?” the reader asks. Mr. Fletcher answers that nature has provided us with a food filter—an automatic safety device. Professor Hubert Higgins, formerly demonstrator of anatomy at Cambridge University in England, and Professor Hasheby of Brussels, Belgium, have lately conducted a series of experiments which throw light on this question on its scientific side. At the back of the tongue there are a number of little knobs, which are really taste buds, or apparatus for the tasting of food. During the time that mastication is going on, the mouth is closed and is completely air tight, and germproof. This fact one can readily demonstrate by filling out the lips with air. The mouth is full of air, yet one can breathe behind this[Pg 67] curtain of air, showing that the mouth is thoroughly cut off. This is what happens during mastication, for of course one should masticate with the lips closed. Now, when the food has become sufficiently ensalivated, or mixed up, the circumvallate papillæ at the back of the throat, where the taste buds are, relax, and behind that the soft palate forms a negative pressure. This soft palate is muscled just as it is in the horse—which is an animal that masticates, but is not found in the dog, which is an animal that bolts its food. Whenever the food is ready for the body, the soft palate relaxes, and is sucked back, and the swallowing of a mouthful of the prepared food takes place involuntarily.

The body is thus supplied with as perfect a protection as could be devised, and perfectly automatic; all that is necessary being that one should masticate the food until it naturally disappears. One must not attempt to keep the food too long in the mouth, but let it have its own course. There are some sorts of food which, when one has chewed them three or four[Pg 68] times, are sucked up, showing that they have received all the mouth treatment that nature requires they should. With other foods one can masticate up to one hundred and fifty times, and still they are not sucked up.

This food filter is a perfectly instinctive apparatus; but as people have acquired the habit of flavoring foods with artificial sauces and relishes, most of them have spoiled this protective device. In the words of Mr. Fletcher himself: “This is a gift of Nature to man which we have been neglecting. It is not a gift which has been given to me and a few others alone. I think everybody could acquire the use of it if they would give Nature a chance by eating slowly, by eating with a sense of enjoyment, and by never eating save when they are really hungry and in a mood to enjoy the food.”

[Pg 69]

At Yale University, Professor Russell H. Chittenden, Director of the Sheffield Scientific School, Lafayette B. Mendel, Professor of Physiological Chemistry, and Irving Fisher, Professor of Political Economy, have carried on a long series of experiments, begun six years ago as a test of the claims made by Fletcher. The net results of these experiments up to date (for they are still in progress) may be put into a nutshell. The following statement was drawn up by one of the writers of this book and submitted to Professors Chittenden and Fisher, who have accepted it as a summary of their present views:

“The commonly accepted standards which claim to tell the quantity of food needed each day by the average man are based upon many careful observations of what men actually do eat.

“We challenge these standards, however, as[Pg 70] the exact science of to-day cannot accept as authority common customs and habits in any attempt to ascertain the right principles of man’s nutrition, since experiments have demonstrated how readily one set of habits may be substituted for another and how easily wrong habits become hardened into laws. The evidence presented by observers of common customs, while they must be duly considered, cannot, therefore, be taken as proof that these habits and customs are in accord with the true physiological needs of the body.

“We believe that the following propositions have been demonstrated as truths by the experiments we have made at Yale.

“People in general eat and drink too much.

“Especially do they eat too much meat, fish and eggs.

“This is so because meat, fish and eggs are the principal proteid-containing foodstuffs.

[Pg 71]

“Proteid is an essential food element, absolutely necessary for the upbuilding of tissue, for the maintenance of life. It is one of three main elements into which all foodstuffs may be divided—the others being Carbohydrates (the sugars and starches) and Fat. While it is indispensable, it is also the element which the body machinery finds most difficult to dispose of. Proteid is ‘nitrogenous.’ Nitrogen is never wholly consumed in the body furnace as fats, sugars and starches are. There is always solid matter left unconsumed, like clinkers in a furnace; which clinkers the kidneys and liver have to labor to dispose of. If the clinkers are produced in excess of the ability of these organs to handle them without undue wear and tear, damage of a serious, and sometimes permanent, nature follows. The ideal amount of proteid is the amount which will give the body all of that substance which it needs without entailing excessive work upon the body machinery.

“Excessive consumption of proteid foodstuffs—like meat, fish and eggs—is the greatest evil affecting man’s nutrition. The excess of proteid not only remains unburned in the bodily furnace, but this waste matter very often decays in the body, forming a culture[Pg 72] bed for germs which effect the whole system, a condition scientifically known as autointoxication, or self-poisoning of the body through the action of the germs of putrefaction, and of other germs, which are bred in the colon, or large intestine. The researches of Metchnikoff, Bouchard, Tissier, Combe, and other eminent scientists, have shown that autointoxication is the source of a great number of the most serious chronic diseases which afflict mankind.

“We say, then, that the existing dietary standards place in all cases the minimum of proteid necessary for the average man’s daily consumption at far too high a figure. It may be safely said that it is placed twice as high as careful and repeated experiments show to be really necessary.

“There can be little doubt that the habit of excessive eating and drinking, combined with the habit of too hasty eating and drinking, especially of meat, fish and eggs, are probably the most prolific sources of many bodily disabilities affecting men and women, and are[Pg 73] consequently the greatest deterrents to the attaining by men and women of a high grade of efficiency in work, of better health, of greater happiness, and of longer life.

“We believe that it has been demonstrated as a fact that health can be bettered, endurance increased, and life lengthened, by cutting down the commonly accepted standards of how much meat, eggs, fish and other proteid food we should eat and drink by about one-half.”

After Horace Fletcher had attracted the notice of the scientific world in 1902, Professor Chittenden invited him to become the subject of a series of experiments at Yale, where the Sheffield Scientific School possessed an equipment suitable for an elaborate inquiry of this kind much superior to any to be found in Europe.

Professor Chittenden first made certain, by experiments which precluded any chance of error, that Horace Fletcher’s claims were[Pg 74] justified so far as Horace Fletcher himself was concerned. But this, of course, by no means solved the problem. Mr. Fletcher might simply be a physiological curiosity—a digestive freak—of whom there are many known cases. He lived and thrived on an amount of proteid food startlingly less than was deemed necessary by all existing standards, but this could not be taken as proof that people in general could do likewise. Only an exhaustive series of tests on a large number of people of varying ages and conditions of life could prove this. Professor Chittenden resolved to make these tests.

At the very outset, however, he faced this difficulty. If Mr. Fletcher’s was merely a freak case, there would be a grave danger in putting other men upon his dietary. Mr. Fletcher was flourishing on a daily consumption of proteid foodstuffs amounting to an average of only 45 grams, and the fat, sugar and starch consumed by him were in quantities only sufficient to bring the total food value of the daily food up to a little more than 1600[Pg 75] “calories,” or units of fuel energy. The Voit standard—which is the typical one, the one most commonly accepted, and which is based upon thousands of studies of what men and women actually eat—demands that the average man shall eat at least 118 grams of proteid, with a total fuel value of 3000 large “calories” for the daily ration.

To make clear to the non-scientific reader just what quantity of foodstuffs is represented by 50 grams of proteid, which is 5 grams more than that consumed daily by Mr. Fletcher in his tests, and is approximately the amount consumed daily by other men in the Yale experiments, it may be said that 50 grams is about equal to 772 grains, which are equal to about 1¾ ounces. This quantity would be represented by the proteid contents of 9½ ounces of lean meat, or 7 eggs, or 27 ounces of white bread. Nine and one-half ounces of meat (using comparisons furnished by Dr. Edward Curtis) is about the weight of a slice measuring 7 by 3 inches and cut ¼ of an inch thick. Twenty-seven ounces of bread represent[Pg 76] somewhat less than two loaves, the standard loaf weighing one pound (16 ounces). Of course, few people ever eat 7 eggs, or 2 loaves of bread in a day; but the vast majority of people in America do eat a great deal more proteid than would be represented by 7 eggs, or 2 loaves of bread or a slice of meat of the size named, since proteid is found in a great number of other foodstuffs besides those mentioned.

Professor Chittenden realized that to ask a number of men to subsist on a ration similar to that which nourished Mr. Fletcher might possibly result in seriously weakening their constitutions. This is the problem which has often confronted other scientists, and Professor Chittenden solved it in a way characteristic of the true scientist—the devoted warrior in humanity’s cause who wages warfare against the forces of evil. He began his experiments upon himself.

The result rewarded his self-sacrificing[Pg 77] spirit; for within a few months a severe case of muscular rheumatism (which had plagued him for years, refusing to yield to treatment) disappeared; and with it went a recurrent bilious headache. And it may be stated that these have never returned. Professor Chittenden has adopted as a habit of life the dietary which he began as an experiment five years ago. At that time he was a hearty eater of three meals a day, meals rich in meat and other proteid foodstuffs.

Professor Chittenden then began experiments with a group of university professors and instructors, with a group of thirteen enlisted men of the army, and a group of eight college athletes in training. All three of these groups of men were subjected to careful laboratory observations for continuous periods of many months, during which the proteid ration was reduced from one-half to one-third what had been customary. The professors and athletes followed their customary voca[Pg 78]tions during the period of observations, while to the ordinary drills of the soldiers were added severe gymnasium work under the supervision of Dr. Anderson.