Title: Commentaries on the Surgery of the War in Portugal, Spain, France, and the Netherlands

Author: G. J. Guthrie

Release date: June 15, 2021 [eBook #65622]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Brian Coe, SF2001, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

IN PORTUGAL, SPAIN, FRANCE, AND

THE NETHERLANDS,

FROM THE BATTLE OF ROLIÇA, IN 1808, TO THAT OF

WATERLOO, IN 1815;

WITH ADDITIONS RELATING TO THOSE IN THE CRIMEA IN

1854-1855.

SHOWING

THE IMPROVEMENTS MADE DURING AND SINCE THAT PERIOD IN THE

GREAT ART AND SCIENCE OF SURGERY ON ALL THE

SUBJECTS TO WHICH THEY RELATE.

REVISED TO OCTOBER, 1855.

BY G. J. GUTHRIE, F.R.S.

SIXTH EDITION.

PHILADELPHIA:

J. B. LIPPINCOTT & CO.

1862.

TO

The Right Honorable

The Lord Panmure,

SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE WAR DEPARTMENT,

ETC. ETC. ETC.,

THESE COMMENTARIES

ARE, BY PERMISSION,

INSCRIBED,

BY HIS LORDSHIP’S VERY OBEDIENT

AND FAITHFUL SERVANT,

G. J. GUTHRIE.

Twenty months have elapsed since the Introductory Lecture was published in The Lancet; fifteen others succeeded at intervals, and fifteen have been printed separately to complete the number of which the present work is composed. Divested of the historical and argumentative, as well as of much of the illustrative part, contained in the records whence it is derived, it nevertheless occupies 585 pages—the essential points therein being numbered from 1 to 423.

Sir De Lacy Evans, in some observations lately made in the House of Commons on the subject of a Professorship of Military Surgery in London, alluded to these Lectures in the most gratifying manner; he could not, however, state their origin, scope, or object, being unacquainted with them.

On the termination of the war in 1814, I expressed in print my regret that we had not had another battle in the south of France, to enable me to decide two or three points in surgery which were doubtful. I was called an enthusiast, and laughed at accordingly. The battle of Waterloo afforded the desired opportunity. Sir James M’Grigor, then first appointed Director-General, offered to [6] place me on full pay for six months. This would have been destructive to my prospects in London; I therefore offered to serve for three, which he was afraid would be called a job, although the difference between half-pay and full was under sixty pounds; and our amicable discussion ended by my going to Brussels and Antwerp for five weeks as an amateur. The officers in both places received me in a manner to which I cannot do justice. They placed themselves and their patients at my entire disposal, and carried into effect every suggestion. The doubts on the points alluded to were dissipated, and the principles wanting were established. Three of the most important cases, which had never before been seen in London nor in Paris, were sent to the York Military Hospital, then at Chelsea. The rank I held as a Deputy Inspector-General precluded my being employed. It was again a matter of money. I offered to do the duty of a staff-surgeon without pay, provided two wards were assigned to me in which the worst cases from Brussels and Antwerp might be collected. The offer was accepted; and for two years I did this duty, until the hospital was broken up, and the men transferred to Chatham. In the first year a Course of Lectures on Military Surgery was given. The inefficiency of such a Course alone was soon seen, for Surgery admits of no such distinctions. Injuries of the head, for instance, in warfare, usually take place on the sides and vertex; in civil life, more frequently at the base. They implicate each other so inseparably, although all the symptoms are not alike or always present, that they cannot be disconnected with propriety. This equally obtains in other [7] parts; and my second and extended Course was recognized by the Council of the Royal College of Surgeons as one of General Surgery.

When the Court of Examiners of the Royal College of Surgeons of England—of which body I have been for more than twenty years a humble member—confer their diploma after examination on a student, they do not consider him to have done more than laid the foundation for that knowledge which is to be afterward acquired by long and patient observation. When a student in law is called to the bar, he is not supposed to be therefore qualified to be a Queen’s counsel, much less a judge or a chancellor. The young theologian, admitted into deacon’s orders, is not supposed to be fitted for a bishopric. When the young surgeon is sent, in the execution of his duties, to distant climes, where he has few and sometimes no opportunities of adding to the knowledge he had previously acquired, it is apt to be impaired; and he may return to England, after an absence of several years, less qualified, perhaps, than when he left it. To such persons a course of instruction is invaluable. It should be open to them as public servants gratuitously, and should be conveyed by a person appointed and paid by the Crown. He should be styled, in my opinion, the Military Professor of Surgery, and be capable, from his previous experience and his civil opportunities, of teaching all things in the principles and practice of surgery connected with his office, although he may and should annually select his subjects. Leave of absence for three months might be advantageously granted to officers in turn for the purpose of at[8]tending these lectures, and the Professor should certify as to their time having been well employed. For thirty years I endeavored to render this service to the Army, the Navy, and the East India Company, from the knowledge I had acquired of its importance. To the Officers of these services my two hospitals, together with Lectures and Demonstrations, were always open gratuitously, as a mark of the estimation in which I held them. By the end of that period the enthusiasm of the enthusiast who wished for another battle in 1814 had oozed out, like the courage of Bob Acres in “The Rivals,” at the ends of his fingers. The course of instruction was discontinued, but not until such parts were printed, under the title of “Records of the Surgery of the War,” as were not before the public, in order that teachers of civil or systematic surgery should be acquainted with them.

4 Berkeley Street, Berkeley Square,

June 21, 1853.

The rapid sale of the fifth, and the demand for a sixth edition of this work, enable me to say that the precepts inculcated in it have been fully borne out and confirmed by the practice of the Surgeons of the Army now in the Crimea in almost every particular. To several of these gentlemen I desire to offer my warmest thanks for the assistance they have afforded. Their names are given with the cases and observations they have been so good as to send me, and a fuller “Addenda” shall be made from time to time, as I receive further information from them, and others who will, I hope, follow the example they have thus set. More, however, has been done; they have performed operations of the gravest importance at my suggestion, that had not been done before, with a judgment and ability beyond all praise; and they have modified others to the great advantage of those who may hereafter suffer from similar injuries. They have thus proved that if the Administrative duties of the Medical Department of the Army have not been free from public animadversion, that its practical and scientific duties have merited public approbation; which I am satisfied, from what they have already done, they will continue to deserve.

[10] The precepts laid down are the result of the experience acquired in the war in the Peninsula, from the first battle of Roliça in 1808, to the last in Belgium, of Waterloo in 1815, which altered, nay overturned, nearly all those which existed previously to that period, on all points to which they relate. Points as essential in the Surgery of domestic as in military life. They have been the means of saving the lives, and of relieving, if not even of preventing, the miseries of thousands of our fellow-creatures throughout the civilized world.

I would willingly imitate the example lately indulged in, by many of the best Parisian surgeons, of detailing circumstantially the improvements they have made in practical and scientific surgery; the manner in which they were at first contested, and the universal adoption of them which has succeeded, were it not that I might run the risk of being accused of gratifying some personal vanity, while only desirous of drawing the attention of the public to the merits of the men who so ably served them in the last war, nearly all of whom are no more; and who have passed away, as I trust their successors will not, with scarcely a single acknowledgment of their services, except the humble tribute now offered by their companion and friend.

4 Berkeley Street, Berkeley Square,

October 7, 1855.

ON GUNSHOT WOUNDS, ETC.

1. A wound made by a musket-ball is essentially contused, and attended by more or less pain, according to the sensibility of the sufferer, and the manner in which he may be engaged at the moment of injury. A musket-ball will often pass through a fleshy part, causing only the sensation of a sudden and severe, although sometimes of a trifling blow. If it merely strike the same part without rupturing the skin, the pain is often great. Major King, of the Fusiliers, was killed at New Orleans by a musket-ball, which struck him on the pit of the stomach, leaving only the mark of a contusion.

2. Wounds from musket-balls, particularly of the face, sometimes bleed considerably at the moment of injury, and for some little time afterward, although no large vessel shall be injured to render the bleeding inconvenient or dangerous. The application of a tourniquet is then seldom if ever necessary, unless a vessel of some magnitude should be partially torn or divided.

3. When a limb is carried away by a cannon-shot, any destructive bleeding usually ceases with the faintness and failure of strength subsequent on the shock, and a hemorrhage thus spontaneously suppressed does not generally return; it is the effort of nature to save life. The application of a tourniquet is rarely necessary, unless as a precau[26]tionary measure, when it should be applied loosely, and the patient, or some one else, shown how to tighten it if necessary. A musket-ball will often pass so close to a large artery, without injuring it, as to lead to the belief that the vessel must have receded from the ball by its elasticity. A ball passed between the femoral artery and vein of a soldier at Toulouse without doing more injury than a contusion, but it gave rise to inflammation and closure of the vessels, followed by gangrene of the extremity. General Sir Lowry Cole was shot through the body at Salamanca, immediately below the left clavicle; a part of the first rib came away, and the artery at the wrist became, and remained, much diminished in size. General Sir Edward Packenham was shot through the neck on two different occasions, the track of each wound being apparently through the great vessels. The first wound gave him a curve in his neck, the second made it straight. His last unfortunate wound, at New Orleans, was directly through the common iliac artery, and killed him on the spot. Colonel Duckworth, of the 48th Regiment, received a ball through the edge of his leather stock, at Albuhera, which divided the carotid artery, and killed him almost instantaneously.

4. Secondary hemorrhage of any importance from small vessels does not often occur. On the separation of the contused parts, or sloughs, a little blood may be occasionally lost; but it is then generally caused by the impatience of the surgeon, or the irregularity of the patient, and seldom requires attention.

5. A large artery does sometimes give way by ulceration between the eighth and the twentieth days; but the proportion is not more than four cases in a thousand, requiring the application of a ligature; exclusive of those formidable injuries caused by broken bones, or the inordinate sloughing caused by hospital gangrene, when not properly treated.

6. A certain constitutional alarm or shock follows every serious wound, the continuance of which excites a suspicion of its dangerous nature, which nothing but its subsidence, and the absence of symptoms peculiar to the internal part presumed to be injured, should remove. The opinion given under such circumstances should be very guarded; for if this symptom of alarm should continue, great fears may be entertained of hidden mischief. Colonel Sir W. Myers was shot, at Albuhera, at the head of the Fusilier Brigade, at [27] the moment of victory, by a musket-ball, which broke his thigh, and lodged. The continuance of the alarm and anxiety satisfied me it had done other mischief. He died next morning, of mortification of the intestines. General Sir Robert Crawford was wounded at the foot of the smaller breach at the storming of Ciudad Rodrigo, by a musket-ball, which entered the outer and back part of the shoulder, and came out at the axilla. There was a third wound, a small slit in the side, apparently too small to admit a ball. The continuance of the anxiety and alarm pointed out some hidden mischief, which I declared had taken place; and when he died his surgeon found the ball loose in his chest. It had been rolling about on his diaphragm. Surgery was not sufficiently advanced in those days to point out the situation, or to authorize an attempt for the removal of the ball. It must in future be done.

This constitutional alarm and derangement are not always present to so marked an extent. A soldier at Talavera was struck on the head by a twelve-pound shot, which drove some bone into, and some brain out of his head: he was walking about, complaining but little, immediately after the accident, although he died subsequently.

7. It is not always possible, from their appearance, to decide which opening is the entrance, which the exit of an ordinary sized round ball; or when two holes are distant from each other, to ascertain whether they have been caused by one, or by two distinct balls. When a ball is not impinging with much impetus, it may become a penetrating, without being much of a contused wound, which will close in and heal with little suppuration. If the ball do not press upon, or interfere with some important part, the slight degree of irritation which follows may give rise to the formation of a sac, which adheres to it and possibly keeps it quiet for years, if not for life.

8. The wound made by the entrance of an ordinary musket-ball is usually circular, depressed, of a livid color, and capable of admitting the little finger, the exit being more ragged, and not depressed. It is sometimes little more than a small slit or rent, although at others, as in the face or in the back of the hand, it may be much torn, giving to an otherwise simple wound a more frightful appearance, such as is not usually seen in the thigh, or other equally firm fleshy part.

[28] 9. Wounds from flattened or irregular-shaped musket-balls, pieces of shells, or other sharp-edged destructive instruments, are often very much lacerated, and their entrance is less marked. The part thus torn can generally be preserved, and the wound healed with comparatively little loss of substance.

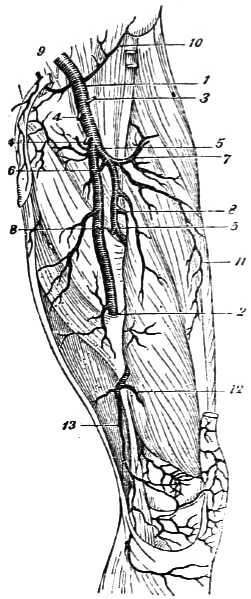

10. When it is desirable to ascertain the exact course of a ball, and, if possible, the internal part injured by it, the sufferer should be placed in the position he was in when he received the injury, with especial reference to the probable situation of the enemy, when that will often become very intelligible which was before indistinct. My attention was directed, after the battle of Toulouse, to a soldier, whose foot was gangrenous without an apparent cause, he having received merely a flesh wound in the thigh, not in the exact course of the main artery, which, nevertheless, I said was injured. On placing the man in the same position with regard to us, that he supposed himself to have been in toward the enemy when wounded, the possibility of such an injury was seen; and dissection after death proved the correctness of the opinion.

11. When one opening only can be seen, it is presumed the ball has lodged; but this does not follow, although the finger of the surgeon may pass into the wound for some distance. At the battle of Vimiera, I pulled a piece of shirt, with a ball at the bottom of it, out of the thigh of an officer of the 40th Regiment, into which it had gone for at least three inches. After the battle of Toulouse, a ball, which penetrated the surface of the chest, and passed under the pectoral muscle for two inches, was ejected by the elasticity of the rib against which it struck. Scarcely any inconvenience followed, and the officer rapidly recovered. After the battle of Waterloo, I was requested to decide whether a young officer should be allowed to die in a few days, or to have a chance for his life by losing his leg above the knee. The joint was open, the suppuration profuse. A large or grape-shot was supposed to be lodged in the head of the tibia. The limb was amputated, and he is now alive, forty years afterward, but no shot was found in his limb. It had dropped out after doing the injury.

12. The treatment of simple gunshot or flesh wounds should be, under ordinary circumstances, as simple as themselves. Nothing should be applied but a piece of linen or [29] lint, wetted with cold water; this may be retained by a strip of sticking-plaster, or any other thing applicable for the purpose of keeping the injured part covered. A compress of linen, or other similar substance, moistened with cold or iced water when procurable, will be useful; and a few inches of a linen bandage may be sewed on, to prevent the compress from changing its position during sleep. When the wound becomes tender, a little oil, lard, or simple ointment may be placed over it. A roller, as a surgical application, is useless, if not injurious. At the first and second battles in Portugal, every wound had a roller applied over it; it soon became stiff, bloody, and dirty. They did no good, were for the most part cut off with scissors, and thus rendered useless. When really wanted, at a later period, they were not forthcoming. An advancing army cannot, and ought not to carry casks full of rollers into the field; and the apothecary-general had better have instead, two casks or boxes full of good wax candles; for, although every regimental surgeon ought to have four in his panniers, kept as carefully for emergencies as his capital instruments, they will require from time to time to be replaced. No roller should be more than two inches and a quarter wide, and made of good, strong, coarse linen, very much, in fact, the reverse of the rollers which have until lately been supplied to the army.

13. Cold or iced water may be used as long as cold is grateful to the sufferer. When it ceases to be so, it should be exchanged for warm, applied in any convenient way which modern improvements have suggested, whether by piline, gutta-percha, oiled silk, etc. An evaporating poultice may be used in private life, but no poultices should be permitted in a military hospital, until the principal surgeon is satisfied they are necessary. They are generally cloaks for negligence, and sure precursors of amputation in all serious injuries of bones and joints. They are properly used to alleviate pain, stiffness, swelling, the uneasiness arising from cold, and to encourage the commencing or impeded action of the vessels toward the formation of matter. As soon as the effect intended has been obtained, the poultice should be abandoned, and recourse again had to water, hot or cold, with compress and bandage. I was in the habit of calling a poultice when misapplied a cover-slut.

14. Many simple flesh wounds are cured in four weeks; the greater part in six. Fresh air and cold water are essen[30]tial. Purgatives may be occasionally given, and abstinence is an excellent remedy. Emetics, bleeding, and something approaching to starvation as to solids, are of great importance if the sufferers should be irregular in their habits, or the inflammatory symptoms run high. In weakly persons, a generous diet with tonic remedies will be necessary.

15. In wounds of muscular parts inflammation usually occurs from twelve to twenty-four hours after the injury, and the vicinity of the wound becomes more sensible to the touch, with a little swelling and increase of discoloration. A reddish serous fluid is discharged, and the limb becomes stiff and nearly incapable of motion, from its causing an increase of pain. These symptoms are gradually augmented on or about the third day; the inflammation surrounding the wound is more marked; the discharge is altered, being thicker; the action of the absorbents on the edges of the wound may be observed; and, on the fourth or fifth, the line of separation between the dead and living parts will be very evident. The wound will now discharge purulent matter mixed with other fluids, which gradually diminish as the naturally healthy actions take place. The inside of the wound, as the process of separation proceeds, changes from a blackish-red color to a brownish yellow, moistened by a little good pus. On the fifth and sixth days, the outer edge of the separating slough is distinctly marked, and begins to be displaced; the surrounding inflammation extends to some distance, the parts are more painful and sensible to the touch; the discharge is more purulent, but not great in quantity. On the eighth or ninth day, the slough is, in most cases, separated from the edges of the track of the ball, and hanging in the mouth of the wound, although it cannot yet be disengaged; the discharge increases, and the wound becomes less painful to the patient, although frequently more sensible when touched.

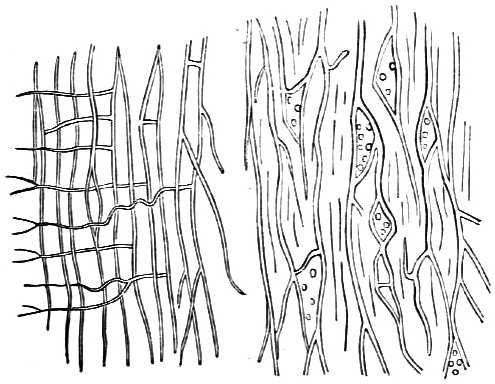

If there be two openings, the exit of the ball, or the counter-opening, is in general much the cleaner, being often in a fair granulating state before the entrance of the ball is free from slough. If the inflammation have been smart, the limb is at this time a little swollen and discolored for some distance around; fibrin and serum are thrown out into the cellular membrane, or areolar tissue, as it is now termed; the redness diminishes; the sloughs are discharged, together with any little extraneous substances which may be in the [31] wound; and there is frequently a slight bleeding, if the irritable granulations are roughly treated. The limb on the twelfth, and even fifteenth day, retains the appearance of yellowness and discoloration which ensues from a bruise, and which continues a few days longer. The sloughs do not, sometimes, separate until this period, and, in persons slow to action, not even until a later one. The wound now contracts; the middle portion of the track first closes, and is no longer pervious; the lower opening soon heals, while the upper, or that usually made by the entrance of the ball, continues to discharge for some time, and toward the end of six weeks, or sometimes two months, finally heals with a depression and cicatrix, marking distinctly the nature of the injury that has been received.

16. The state of constitution, the difficulties and distresses of military warfare, exposure to the inclemency of the weather, the season of the year, or the imprudence of individuals, will sometimes bring on a train of serious symptoms, in wounds apparently of the same nature as others in which no such evils occur. After the first two or three days, the symptoms gradually increase, the swelling is much augmented, the redness extends, and the pain is more severe and constant. The wound becomes dry, stiff, with glistening edges, the general sensibility is increased, the system sympathizes, the skin becomes hot and dry, the tongue loaded, the head aches, the patient is restless and uneasy, the pulse full and quick; there is fever of the inflammatory kind. The swelling of the part increases from deposition in the areolar tissue to a considerable extent above and below the wound, and the inflammation, instead of being entirely superficial or confined to the immediate track of the ball, spreads widely. The wound itself the sufferer can hardly bear to be touched; it discharges but little, and the sloughs separate slowly. Pus soon begins to be secreted more copiously, not only in the track of the wound, but in the surrounding parts; sinuses may form in the course of the muscles, or under the fascia, and considerable surgical treatment be necessary, while the cure is protracted from three to four, and even to six months; and is often attended for a longer period with lameness, from contraction of the muscles or adhesions of the areolar tissue. The parts, from having been so long in a state of inflammation, are much weaker, and if the injury have been in the lower extremity, the leg [32] and foot swell on any exertion, which cannot be performed without pain and inconvenience for a considerable time. The treatment should be active; the patient, if robust, ought to be bled if no endemic disease prevail, vomited, purged, kept in the recumbent position, and cold applied so long as it shall be found agreeable to his feelings; when that ceases to be the case, warm fomentations ought to be resorted to, but they are to be abandoned the instant the inflammation is subdued and suppuration well established. The feelings of the patient will determine the period, and it is better to begin a day too soon than one too late. If the inflammation be superficial, leeches will not be of the same utility as when it is deep seated; but then they must be applied in much greater numbers than are usually recommended. The roller and graduated compresses, or pressure made by slips of adhesive plaster under them, are the best means of cure in the subsequent stages, with change of air, and friction to the whole extremity, which alone, when early and well applied, will often save months of tedious treatment. If the limb become contracted and the cellular membrane thickened, it is principally by friction (shampooing) that it can be restored to its natural motion.

17. If the ball should have penetrated without making an exit, or have carried in with it any extraneous substances, the surgeon must, if possible, ascertain its exact situation, and remove it and any foreign bodies which may be lodged; indeed, if there be time, every wound should be examined so strictly as to enable the surgeon to satisfy himself that nothing has lodged. This is less necessary where there are two corresponding openings evidently belonging to one shot; but it is imperiously demanded of the surgeon, where there is one opening only, even if that be so much lacerated as to lead to the suspicion of its being a rent from a piece of shell; for it is by no means uncommon for such missiles, or a grape-shot, to lodge wholly unknown to the patient, and to be discovered by the surgeon at a subsequent period, when much time has been lost and misery endured. A soldier during the siege of Badajoz had the misfortune to be near a shell at the moment of its bursting, and was so much mangled as to render it necessary to remove one leg, an arm, and a testicle, (a part of the penis and scrotum being lost.) In one of the flesh wounds in the back part of the thigh and buttock a large [33] piece of shell was lodged, and kept op considerable irritation until it was removed. The man recovered.

18. In examining a wound, a finger should be gently introduced, if possible, in the course of the ball, to its utmost extent; in parts connected with life, or liable to be seriously injured, it is the only sound usually admissible. While this examination is taking place, the hand of the surgeon should be carefully pressed upon the part opposite where the ball may be expected to lie, by which means it may perhaps be brought within reach of the finger, and for want of which precaution, it may be missed by a very trifling distance. While the finger is in the wound the limb may be thrown as nearly as possible into that action which was about to be performed on the receipt of the injury, when the contraction of the muscles and the relative change of the parts will more readily allow the course of the ball to be followed. If this should fail, attention should be paid to the various actions of the limb, the attendant symptoms arising from parts affected, and what may be called the general anatomy of the whole circle of injury. A muscle, in the act of contraction, may oppose an obstacle to the passage of an instrument in the direction the ball has taken, especially if it should have passed between tendons or surfaces loosely connected by cellular membrane; as by the side of, or between the great blood-vessels, which by their elasticity may make way for the ball, and yet impede the progress of a sound. When the ball is ascertained to have passed beyond the reach of the finger, a blunt silver sound or elastic bougie may be used, and the opposite side of the limb should be carefully examined, and pressure made on the wounded side, when it will probably be found more or less deeply seated. If the ball should not be discoverable by these means, the surgeon should consider every symptom, and every part of anatomy connected with the wound, before he decides on leaving the ball to the operations of nature.

19. It is unnecessary to dilate a wound without a precise object in view, which might render an additional opening requisite. This dilatation or opening, when made, should always be carried through the fascia of the limb. A wound ought not to be dilated because such operation may at a more distant period become necessary. The necessity should first be seen, when the operation follows of course.

Suppose a man be brought for assistance with a wound [34] through the thigh, in the immediate vicinity of the femoral artery, which he says bled considerably at the moment of injury, but the hemorrhage had ceased. Is the surgeon warranted in cutting down upon the artery, and putting ligatures upon it on suspicion? Every man in his senses ought to answer, No. The surgeon should take the precaution of applying a tourniquet loosely on the limb, and of placing the man in a situation where he can receive constant attention in case of need; but he is not authorized to proceed to any operation, unless another bleeding should demonstrate the injury and the necessity for suppressing it. By the same reasoning, incisions are not to be made into the thigh on the speculation that they may be hereafter required. If the confusion which has enveloped this subject be removed, and bleeding arteries, broken bones, and the lodgment of extraneous substances be admitted to be the only legitimate causes for dilating wounds in the first instance, the arguments in favor of primary dilatation in other cases must fall to the ground.

When the inflammation, pain, and fever run high, the tension of the part being great, an incision should be made by introducing the knife into the wound, and cutting for the space of two or three inches, according to circumstances, in the course of the muscles, carefully avoiding any other parts of importance. The same should be done at the inferior or opposite opening, if mischief be seriously impending, not so much on the principle of loosening the fascia as on that of taking away blood from the part immediately affected, and of making a free opening for the evacuation of the fluids about to be effused.

It is no less an advantageous practice in the subsequent stages of gunshot wounds, where sinuses form and are tardy in healing. A free incision is also very often serviceable when parts are unhealthy, although there may not be any considerable sinus. Upon the necessity of it where bones are splintered, there is no occasion in this place to insist.

20. In making incisions for the removal of balls in the vicinity of large vessels, particularly in the neck, the hand should always be unsupported, in order to prevent an accident from any sudden movement of the patient. This caution is the more necessary on the field of battle, where many things may give rise to sudden alarm. At the affair [35] of Saca Parte, near Alfaiates, in Portugal, I stationed myself behind a small watch-tower, and the wounded were first brought to this spot for assistance. A howitzer had also been placed upon it, being rising ground, and at the moment I was extracting a ball situated immediately over the carotid artery, the gun was fired, to the inexpressible alarm of surgeon, patient, and orderly, who bolted in all directions. From my hand being unsupported, no mischief ensued, and the operation was completed as soon as all had recovered their usual serenity. When a ball is discovered on the opposite side of a limb, through which it has nearly penetrated, but has not had sufficient power to overcome the resistance and elasticity of the skin, it should be removed by incision. An opening is thus obtained for the evacuation of any matter which may be formed in the long track of such a wound, and any other extraneous bodies are more readily extracted. When a ball has penetrated half through the thick part of the thigh, in such a direction that it cannot readily be removed by the opening at which it entered; or, from the vicinity of the great vessels, it may be considered unadvisable to cut for it in that direction; or if the ball cannot be distinctly felt by the finger through the soft parts, it ought not to be sought for at the moment, for an incision of considerable extent will be required to enable the surgeon to extract it. Much pain will be caused, and higher inflammation may follow than would ensue if the wound were left to the efforts of nature alone, by which, in time, the ball would in all probability be brought much nearer to the surface, and might be more safely extracted. It frequently happens, that after a few days or weeks, a ball will be distinctly felt in a spot where the surgeon had before searched for it in vain. A wound will frequently close without further trouble, the ball remaining without inconvenience in its new situation; and the patient not being annoyed by it, does not feel disposed to submit to pain or inconvenience for its removal. A very strong reason for the extraction of balls during the first period of treatment, if it can be safely accomplished, is, that they do not always remain harmless, but frequently give rise to distressing or harassing pains in or about the part, which often oblige the sufferer to submit to their extraction at a later period, when their removal is infinitely more difficult; and may be more distressing than at the moment of injury.

[36] Nothing appears more simple than to cut out a ball which can be felt at the distance of an inch, or even half an inch below the skin, but the young surgeon often finds it more difficult than he expected, because he makes his incision too small; and cannot at all times oppose sufficient resistance to prevent the ball from retreating before the effort he makes for its expulsion with the forceps or other instrument. The ball also requires to be cleared from the surrounding cellular substance, to a greater extent than might at first be imagined; for all that seems to be required is, that a simple incision be made down to the surface of it, when it will slip out, which is not usually the case. When a ball has been lodged for years, a membranous kind of sac is formed around it, which shuts it in as it were from all communication with the surrounding parts. If it should become necessary to extract a ball which has been lodged in this manner, the membranous sac will often be found to adhere so strongly to the ball that it cannot be got out without great difficulty, and sometimes not without cutting out a portion of the adhering sac.

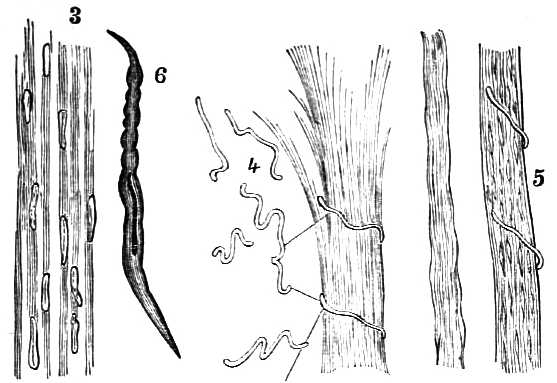

It often occurs that a ball lodges and cannot be found, especially where it has struck against a bone, and slanted off in a different direction. If the ball should lodge in the cellular tissue between two muscles, it often descends by its gravity to a considerable distance, and excites a low degree of irritation, which slowly brings it to the surface, or terminates in abscess. Colonel Ross, of the Rifle Brigade, was wounded at the battle of Waterloo by a musket-ball, which entered at the upper part of the arm and injured the bone. More than one surgeon had pointed out the way by which it had passed under the scapula and lodged itself in some of the muscles of the back. About a year afterward I extracted it close to the elbow, the ball lying at the bottom of an abscess, which was only brought near the surface by time, by the use of flannel, and by desisting from all emollient applications.[1]

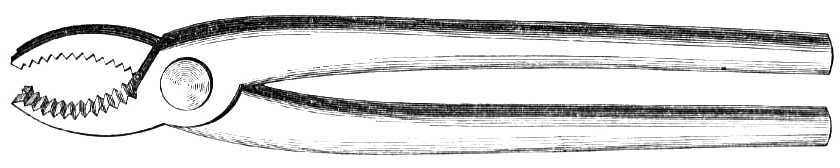

[1] Various instruments have been invented for the removal of balls which have been deeply lodged in soft parts; but little assistance has been derived from them hitherto, although many of them are very ingenious.

21. A ball will frequently strike a bone, and lodge, without causing a fracture, although it will a fissure. It will even go through the lower part of the thigh-bone, between [37] or a little above the condyles, merely splitting without separating it, and some balls have lodged in bones for years, with little inconvenience. It should nevertheless be a general rule not to allow a ball to remain in a bone, if it can be removed by any reasonable operation. The rule is not entirely devoid of exception. Lieutenant-Colonel Dumaresq, aid-de-camp to the present Lord Strafford, was wounded at Waterloo by a ball which penetrated the right scapula, and lodged in a rib in the axilla. The thoracic inflammation nearly cost him his life, but he ultimately quite recovered, and died many years afterward of apoplexy, the ball remaining enveloped in bone.

22. When a bayonet is thrust into the body it is a punctured wound made by direct pressure; when of little depth, much inconvenience rarely ensues, and the part heals slowly, but surely, under the precaution of daily pressure. A punctured wound, extending to considerable depth, labors under disadvantages in proportion to the smallness of the instrument, and the differences of texture through which it passes. When the instrument is large, the opening made is in proportion, and does not afford so great an obstacle to the discharge of the fluids poured out or secreted as when the opening is small. Lance wounds are therefore less dangerous than those inflicted by the bayonet. When a small instrument passes deep through a fascia, it makes an opening in it which is not increased by the natural retraction of parts, inasmuch as it is not sufficiently large to admit of it; and which opening, small as it is, may be filled or closed up by the soft cellular tissue below, which rises into it, and forms a barrier to the discharge of any matter which may be secreted beneath. If the instrument should have passed into a muscle, it is evident that if that muscle were in a state of contraction at the moment of injury, the punctured part must be removed to a certain distance from the direct line of the wound when in a state of relaxation, and vice versa. The matter, secreted, and more or less in almost every instance will be secreted, cannot in either case make its escape, and all the symptoms occur of a spontaneous abscess deeply seated below a fascia. That inflammation should spread in a continuous texture is not uncommon; that matter, when confined, should give rise to great constitutional disturbance is, if possible, less so; but that this disturbance takes place without the occurrence of inflamma[38]tion, or the formation of matter, may be doubted; and it may be concluded that there is no peculiarity in punctured wounds that may not be accounted for in a satisfactory manner. Serious effects have been attributed to injuries of nerves, but without sufficient reason; nevertheless, those who have seen locked-jaw follow a very simple scratch of the leg from a musket-ball, more frequently than from a greater injury, are not surprised at any symptoms of nervous agitation that may occur after punctured wounds. As many bayonet wounds through muscular parts heal with little trouble, it is time enough to dilate them when assistance seems to be required. Cold water should be used at first; care should be taken not to apply a roller or compress of any kind over the wound; matter, when formed, should be frequently pressed out, and, if necessary, a free exit should be made for it.

23. A great delusion is cherished in Great Britain on the subject of the bayonet—a sort of monomania very gratifying to the national vanity, but not quite in accordance with matter of fact. Opposing regiments, when formed in line, and charging with fixed bayonets, never meet and struggle hand to hand and foot to foot, and this for the very best possible reason, that one side turns round and runs away as soon as the other comes close enough to do mischief; doubtless considering that discretion is the better part of valor. Small parties of men may have personal conflicts after an affair has been decided, or in the subsequent scuffle if they cannot get out of the way fast enough. The battle of Maida is usually referred to as a remarkable instance of a bayonet fight; nevertheless, the sufferers, whether killed or wounded, French or English, suffered from bullets, not bayonets. The late Sir James Kempt commanded the brigade supposed to have done this feat, but he has assured me that no charge with the bayonet took place, the French being killed in line by the fire of musketry; a fact which has of late received a remarkable confirmation in the published correspondence of King Joseph Bonaparte, in which General Regnier, writing to him on the subject, says: “The 1st and 42d Regiments charged with the bayonet until they came within fifteen paces of the enemy, when they turned, et prirent la fuite. The second line, composed of Polish troops, had already done the same.” Wounds from bayonets were not less rare in the Peninsular war. It may be that all those who were [39] bayoneted were killed, yet their bodies were seldom found. A certain fighting regiment had the misfortune one very misty morning to have a large number of men carried off by a charge of Polish lancers, many being also killed. The commanding officer concluded they must be all killed, for his men possessed exactly the same spirit as a part of the French Imperial guard at Waterloo. “They might be killed, but they could not by any possibility be taken prisoners.” He returned them all dead accordingly. A few days afterward they reappeared, to the astonishment of everybody, having been swept off by the cavalry, and had made their escape in the retreat of the French army through the woods. The regiment from that day obtained the ludicrous name of the “Resurrection men.”

The siege of Sebastopol has furnished many opportunities for partial hand to hand bayonet contests, in which many have been killed and wounded on all sides, but I do not learn that in any engagements which have taken place regiments advanced against each other in line and really crossed bayonets as a body; although the individual bravery of smaller parties was frequently manifested there, as well as in the war in the Peninsula.

ON INFLAMMATION, MORTIFICATION, ETC.

24. In some very rare cases, an intense, deep-seated inflammation supervenes after some days, almost suddenly and without any obvious cause. The skin is scarcely affected, although the limb—and this complaint has hitherto been observed only in the thigh—is swollen, and exceedingly painful. If relief be not given, these persons die soon, and the parts beneath the fascia lata appear after death softened, stuffed, and gorged with blood, indicating the occurrence of an intense degree of inflammation, only to be overcome by general blood-letting; and especially by incisions made through the fascia from the wound, deep into the parts, so as to relieve them by a considerable loss of blood, and by the removal of any pressure which the fascia might cause on the swollen parts beneath.

[40] 25. Erysipelatous inflammation is marked by a rose or yellowish redness, tending in bad constitutions to brown or even to purple, but in all cases terminating by a defined edge on the white surrounding skin. It frequently spreads with great rapidity, so that the limb, and even the whole skin of the body, may be in time affected by it, the redness subsiding and even disappearing in one part, while it extends in another direction. When this inflammation attacks young and otherwise healthful persons of apparently good constitution, it should be treated by emetics, purgatives, and diaphoretics, in the first instance, with, perhaps, in some cases, bleeding. When the habit of body is not supposed to be healthy, bleeding is inadmissible, and stimulating diaphoretics, combined with camphor and ammonia, will be found more beneficial after emetics and purgatives; these remedies may in turn be followed by quinine and the mineral acids, with the infusion and tincture of bark. Little reliance can be placed on large doses of cinchona in powder; they nauseate and therefore distress.

When the inflammation extends deeper than the skin, into the areolar or cellular tissue, it partakes more of the nature of the healthy suppurative inflammation, commonly called phlegmonous, is accompanied by the formation of matter, and tends to the sloughing or death of this tissue at an early period. The redness in this case is of a brighter color, although equally diffuse, and with a determined edge; the limb is more swollen and tense, and soon becomes quagmiry to the touch. The skin is then undermined, and soon loses its life, becomes ash colored and gangrenous in spots, and separates, giving exit to the slough and matter which now pervade the whole extremity affected. If the patient survive, it will probably be with the loss of the whole of the skin and the cellular substance of the limb.

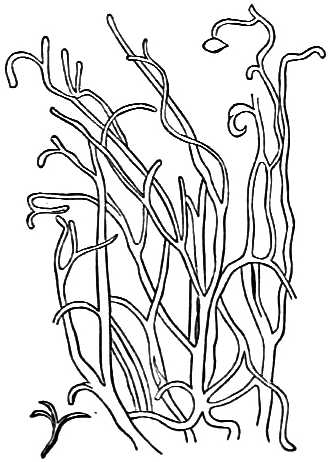

As soon as the inflamed part communicates the springy, fluctuating sensation approaching, but not yet arrived at the quagmiry feel alluded to, an incision should be made into it, when the areolæ or cells of the cellular tissue will be seen of a bright leaden color, and of a gelatinous appearance, arising from the fluid secreted into them, being now nearly in the act of being converted into pus. The septa, dividing the tissue into cells, have not at this period lost their life, and the fluid hardly exudes, as it will be found to do a few hours later, when the matter deposited has become purulent. [41] When this change has taken place, the patient is in danger, and if relief be not given, he will often sink under the most marked symptoms of irritative fever of a typhoid type. Nature herself sometimes gives the required relief by the destruction of the superincumbent skin; but this part is tough, offers considerable resistance, and does not readily yield until the deep-seated fascia is implicated, and the muscular parts are about to be laid bare.

An incision made into the inflamed part through the cellular tissue, down to the deep-seated fascia, which should not be divided in the first instance, gives relief. One of four inches in length usually admits of a separation of its edges to the amount of two inches, by which the tension of the skin, which principally causes the mischief which follows the inflammation, is removed. As many incisions are required as will relieve this tension, according to the extent of the inflammation, which is also relieved by the flow of blood, but that requires attention, as it is often considerable, particularly if the deep fascia be divided on which the larger vessels are found to lie. If the necessary incisions be delayed until the quagmiry feeling is fully established, the skin above it is generally undermined and dies. The following case is given as the first known in London, in which long incisions were made for the cure of this disease, and their effect in relieving the constitutional irritation is so strongly marked as to need no further explanation:—

Thomas Key, aged forty, a hard drinker, was admitted into the Westminster Hospital, under my care, on the 21st of October, 1823, having fallen and injured his left arm against a stool, four days previously. On the 30th, the skin being very tense, the part springy, and yielding the boggy feel described, pulse 120, mind wandering, I proposed, in consultation with my colleagues, to make incisions into the part, but which were considered to be unusual and improper. On the 31st, the pulse being 140, and everything indicating a fatal termination, I refrained from any further consultation, although directed by the rules of the hospital; and, after my old Peninsular fashion, made an incision eight inches long into the back of the arm, and another of five on the under edge, in the line of the ulna, down to the fascia, which was in part divided; one vessel bled freely. The next day, November 1, the pulse was 90; the man had slept, and said he had had a good night. The [42] incision on the back of the arm was augmented to eleven inches; and from that time he gradually recovered, being snatched as it were from the jaws of death.

This case, published at the time, has been the exemplar on which this most successful practice has been followed throughout the civilized world—a practice entirely due to the war in the Peninsula.

When this kind of inflammation attacks the scrotum, which it sometimes, although rarely, does, as a sporadic disease, independent of any urinary affection, incisions into it should be made with great caution, not extending beyond the discolored spots, in consequence of the loss of blood which would ensue from the great vascularity of the part. They should be confined to, and not extend beyond, the parts obviously falling into a state of slough or of mortification.

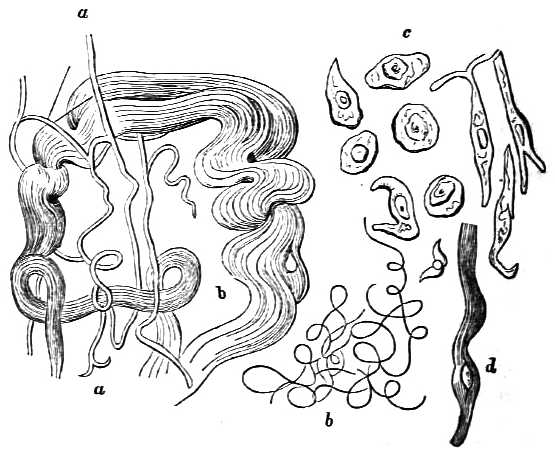

26. Mortification is the last and most fatal result of inflammation, although it may occur as a precursor of it in the neighboring parts, and not as a consequence. The essential distinction is, between that which is idiopathic or constitutional and that which is local; and has not existed long enough to implicate the system at large, or to become constitutional. Idiopathic or constitutional mortification, sphacelus or gangrene, may be humid or dry. Humid, when the death of the part has been preceded by inflammation and a great deposition of fluid in it, followed by putrefaction and decomposition, as after an attack of erysipelas following an injury. It may then be said to be acute. Dry, when preceded by little or no deposition of fluid in it, and followed by a drying, shriveling, and hardening of the part, nearly in its natural form and shape, unless exposed to external causes usually leading to putrefaction. The most remarkable instances have occurred in persons suffering from typhus fever, and exposed to cold, without sufficient covering or care. When it occurs in old persons, or in those who have lived on diseased rye or other food, it may be called chronic. The gangrene which follows wounds has been termed traumatic, which explains nothing but the fact of its following an injury.

Local mortification may be the effect of great injury applied direct to the part, or of an injury to the great vessels of the limb. It may occur from intense cold freezing the part, or from intense heat burning or destroying it.

[43] 27. It sometimes happens that a cannon-ball strikes a limb, and without apparently doing much injury to the skin, so completely destroys the internal textures that gangrene takes place almost without an effort on the part of nature to prevent it. This kind of injury was formerly attributed to the wind of a ball; but no one who has seen noses, ears, etc. injured or carried away, and all parts of the body grazed, without such mischief following, can believe that either the wind, or the electricity collected by it, can produce such effect.

The patient is aware of having received a severe blow on the part affected, which does not show much external sign of injury, the skin being often apparently unhurt or only grazed; the power of moving the part is lost, and it is insensible. The bone or bones may or may not be broken, but in either case the sufferer, if the injury be in the leg, is incapable of putting it to the ground. After a short time the limb changes color in the same manner as when severely bruised, and the necessary changes rapidly go on to gangrene. The limb swells, but not to any extent, and more from extravasation between the muscles and the bones than from inflammation, which, although it is attempted to be set up, never attains to any height. The mortification which ensues tends to a state between the humid and the dry, and rather more to the latter than the former. These cases are not of frequent occurrence, and are not commonly observed until after the blackness of the skin, and the want of sensibility and motion attract attention; for the patient is generally stupefied at first by the blow, and the part or parts about the injury feel benumbed. I made these cases an object of particular research after the battle of Waterloo, but could find only one among the British wounded. The man stated that he had received a blow on the back part of the leg, he believed from a cannon-shot, which brought him to the ground, and stunned him considerably. On endeavoring to move, he found himself incapable of stirring, and the sensibility and power of motion in the limb were lost. The leg gradually changed to a black color, in which state he was carried to Brussels. When I saw it, the limb was black, apparently mortified, and cold to the touch; the skin was not abraded; the leg was not so much swollen as in cases of humid gangrene; the mortification had extended nearly as high as the knee; there was no appearance of a line of separation; and [44] the signs of inflammation were so slight that amputation was performed immediately above the knee. On dissecting the limb, I found that a considerable extravasation of bloody fluid had taken place below the calf of the leg, and in the cavity thus formed some ineffectual attempts at suppuration had commenced. The periosteum was separated from the tibia and fibula; the popliteal artery was, on examination, found closed in the lower part of the ham by coagulated lymph, proceeding from a rupture of the internal coat of the vessel. Two inches below this the posterior tibial and fibular arteries were completely torn across, and gave rise, in all probability, to the extravasation. The operation was successful. The proper surgical practice in such cases is to amputate as soon as the extent of the injury can be ascertained, in order that a joint may not be lost, as the knee was in this instance. It is hardly necessary to give a caution not to mistake a simple bruise or ecchymosis for mortification. To prevent such an error leading to amputation, Baron Larrey has directed an incision to be previously made into the part, and to this there can be no objection.

When a large shot or other solid substance has injured a limb to such an extent only as admits of the hope of its being possible to save it, this hope is sometimes found to be futile, at the end of three or four days, from a failure of power, in the part below the injury, to maintain its life for a longer time: mortification is obviously impending. In military warfare, uncontrollable events often render amputation unavoidable in such a case. Under more favorable circumstances, the surgeon should be guided by the principle laid down of constitutional and local mortification; and, although the line cannot perhaps be distinctly drawn between them at the end of three, four, or more days, it will be better to err on the side of amputation than of delay. If the limb should be swollen or inflamed to any distance, with some constitutional symptoms, in a doubtful habit of body, the termination will in general be unfavorable, whichever course be adopted, more particularly if the amputation must be done above the knee. The consideration of the circumstances in which the patient is placed, his age, and habit of body, should have great weight in forming a decision in the first instance, as to the propriety of attempting to save the limb, which ought only to be done in persons of good constitution and apparent strength.

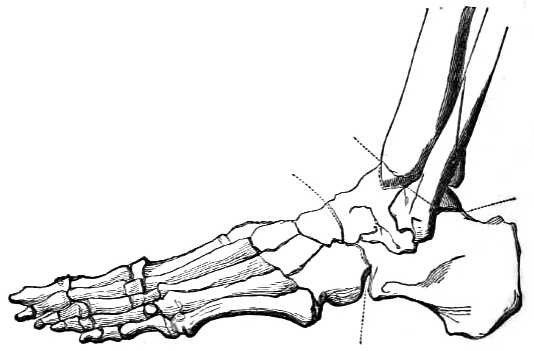

[45] 28. Whenever the main artery of a limb is injured by a musket-ball, mortification of the extremity will frequently be the result, particularly if it be the femoral artery; it will be of certain occurrence if both artery and vein are injured, although they may not be either torn or divided. There may not then be such a sudden loss of blood, in considerable quantity, as to lead to the suspicion of the vessel being injured. The fact is known from the patient’s soon complaining of coldness in the toes and foot, accompanied by pain, felt especially in the back part or calf of the leg, or in the heel, or across the instep, together with an alteration of the appearance of the skin of the toes and instep, which, when once seen, can never be mistaken. It assumes the color of a tallow candle, and soon the appearance of mottled soap. Although there may be little loss of temperature under ordinary circumstances of comfort, there is a feeling of numbness, but it is only at a later period that the foot becomes insensible. This change marks the extent of present mischief. The temperature of the limb above is somewhat higher than natural, and some slight indications of inflammatory action may be observed as high as the ham, and the upper part of the tibia in front; it is at these parts that the mortification usually stops when it is arrested. The general state of the patient, during the first three or four days, is but little affected, and there is not that appearance of countenance which usually accompanies mortification from constitutional causes. In a day or two more, the gangrene will frequently extend, when the limb swells, becomes painful, and more streaked or mottled in color; the swelling passes the knee, the thigh becomes œdematous, the patient more feverish and anxious, then delirious, and dies.

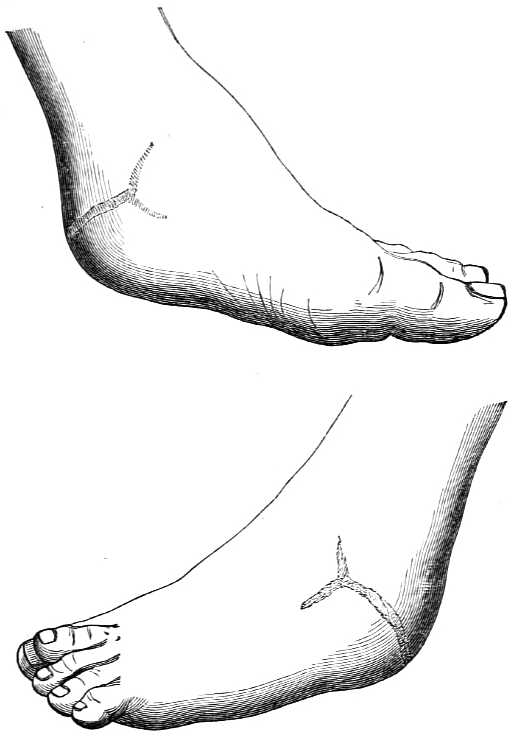

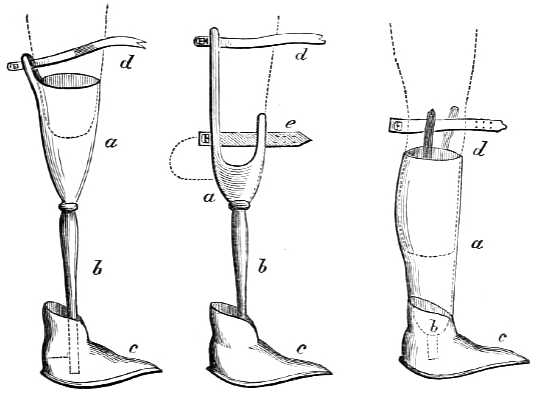

An extreme case will best exemplify the practice to be pursued. A soldier is wounded by a musket-ball at the upper part of the middle third of the thigh, and on the third day the great toe has become of a tallowy color and has lost its life. What is to be done? Wait with the hope that the mortification will not extend. Suppose that the approaching mortification has not been observed until it has invaded the instep. What is to be done? Wait, provided there are no constitutional symptoms; but if they should present themselves, or the discoloration of the skin should appear to spread, amputation should be performed forthwith, for such cases rarely escape with life if it be not [46] done. Where in such a case should the amputation be performed? I formerly recommended that it should be done at the part injured in the thigh. I do not now advise it to be done there at an early period, when the foot only is implicated; but immediately below the knee, at that part where, if mortification ever stops and the patient survives, it is usually arrested; for the knee is by this means saved, and the great danger attendant on an amputation at the upper third of the thigh is avoided. The upper part of the femoral artery, if divided, rarely offers a secondary hemorrhage. The lower part, thus deprived by the amputation of its reflex blood, can scarcely do so; and if it should, the bleeding may be suppressed by a compress. The blood will be dark colored. If the upper end should bleed, the blood will be arterial, and by jets, and the vessel must be secured by ligature.

29. When from some cause or other amputation has not been performed, and the mortification has stopped below the knee, it is recommended to amputate above the knee after a line of separation has formed between the dead and the living parts. This should not be done. The amputation should be performed in the dead parts, just below the line of separation, in the most cautious and gentle manner possible, the mortified parts which remain being allowed to separate by the efforts of nature. A joint will be saved, and the patient have a much better chance for life.

30. A wound of the axillary artery rarely leads to mortification of the fingers or hand. If it should do so, the principle of treatment should be similar, although the saving of the elbow is not so important as that of the knee: neither is the amputation in the axilla, below the tuberosities of the humerus, as dangerous as that above the knee.

31. Mortification after the sudden application of intense cold or heat is to be treated on similar principles.

32. When a nerve or plexus of nerves conveying sensation and motion, and going to a part, or an extremity of the body, is divided, the part or limb is deprived of three great qualities: motion, sensation, and the power of resisting with effect the application of a degree of heat or of cold, which is innocuous when applied in a similar manner to the opposite or sound extremity. In other words, it will be scalded by hot water and frost-bitten by iced or even cold water, [47] which are harmless when applied to another and a healthy part.

An officer received, at the battle of Salamanca, two balls, one under the left clavicle, which was supposed to have divided the brachial plexus of nerves, as the arm dropped motionless and without sensation to the side. The other ball passed through the knee-joint, which suppurated. The left side of the chest became affected; he suffered from severe cough, followed by hectic fever, and was evidently about to sink. As a last chance, I amputated his leg above the knee, after which he slowly recovered. Fourteen years afterward he showed me his arm in the same state, and told me he had been indicted for a rape, but that the magistrates, seeing the wooden leg and the useless arm, while admitting the attempt, would not assent to the committal of the offence.

33. When one nerve only of several going to an extremity such as the arm and hand, is divided, the loss sustained is confined to the extreme part more immediately supplied by the injured nerve. Thus, if the ulnar nerve only be divided, the little finger and the adjacent side of the ring finger suffer, perhaps in some degree the inner side of the thumb and the adjoining fingers; if the median nerve, the thumb and other fingers; if the radial, the back of the hand next the thumb. In some instances there seems to be a kind of collateral communication by which a degree of sensibility is after a time recovered.

34. If any foreign substance should lodge in and continue to irritate the nerve, the wounded part often becomes so extremely painful as not to be borne; the nerve at that part forms a tumor of a most painful character, requiring removal, or in extreme cases even the amputation of the extremity.

35. After an ordinary amputation, the extremity of a nerve enlarges so as to resemble a leek, and if this should adhere to the cicatrix of the wound, painful symptoms, referred to the toes and other parts of the removed leg, are experienced often to an almost unbearable degree; the end of the nerve should be removed. The pain apparently felt in and referred to the toes is merely the effect of irritation of the extremity of the nerve.

36. Wounds or injuries of nerves, which do not entirely divide the trunk, or a principal branch given off from a [48] plexus of nerves, may give rise to general as well as to local symptoms; that is, by sympathy, connection, or continuity of disease, other nerves and organs of the body are affected. This applies also to the spinal marrow, when the injury does not destroy at once. General Sir James Kempt was wounded at the storming of the castle of Badajoz, on the inside of the left great toe, by a musket-ball which, from the appearance of a slit-like opening, was supposed to have rebounded from the bone, but was discovered a fortnight afterward flattened and lying between it and the next toe. Inflammation had ensued, followed by great irritability and numerous spasmodic attacks, appearing to render locked-jaw probable. The spasms soon became general, extending from the foot to the head, but tetanus did not take place. On his return to England, they gradually subsided, but he did not sleep at night for a year. After the battle of Waterloo the spasms became more frequent and troublesome, attacking the muscles at the back of the neck and throat, causing considerable anxiety. The attack was often traced to exposing the foot to cold or to undue pressure, and frequently to derangement of stomach, although he was most regular in diet. After the lapse of six or seven years these severe symptoms subsided; but during the last forty years of his life he suffered occasionally from them.

Admiral Sir Philip Broke received a cut with a sword on boarding the Chesapeake, on the left side of the back of the head, which went through his skull, rendering the brain visible; the wound healed in six months, although splinters of bone came away for a year. A second cut on the right side did not penetrate the bone. After a temporary paralysis of the right side, he recovered, with a loss of power and a disordered sensation in the second, third, and little fingers of the right hand, aggravated by cold weather and by mental anxiety.

Seven years afterward, he fell from his horse, and suffered from concussion of the brain, which added to his former sensations by rendering the left half of his whole person incapable of resisting cold, or of evolving heat. In a still atmosphere abroad, at 68° Fahr., he said, “the left side requires four coatings of stout flannel, which are augmented as the thermometer descends every two degrees and a half, to prevent a painful sense of cold; so that when it stands at the freezing point the quantity of clothing of the affected [49] side becomes extremely burdensome. When exposed to a breeze, or even in moving against the air, one or even two oilskin coverings are necessary in addition, to prevent a sensation of piercing cold driving through the whole frame. Moderate horse exercise and generous diet improved the general health; the warm bath caused a distressing effect; the shower bath, cold or tepid, increased the paralytic affection. Frictions, with remedies of all kinds, increased it also, and so did sponging with vinegar and water, as well as any violent, stimulating, quick excitement, or earnest attention to any particular subject. The Admiral died unrelieved, twenty-six years after the receipt of the injury, of disease of the bladder.”

37. Brigade-Major Bissett was wounded on horseback, in the Kaffir war, by a musket-ball, which entered on the outside of the lower part of the left thigh, passed upward across the perineum, wounding the rectum within the anus—from which part he lost a quantity of blood—and came out through the pelvis on the opposite side. The course of this ball was accounted for by the fact that he saw the Kaffir who shot him standing some yards below him when he fired. The ball, in its passage upward and across the thigh, injured the great sciatic nerve, and the consequence is continued pain in the toes, instep, and foot, with contraction of the muscles, and lameness, together with the usual incapability of bearing heat or cold, particularly the latter, against which he is peculiarly obliged to guard. The skin shows no sign of discoloration or derangement. Position gives the explanation why the ball took such a peculiar course; the symptoms show the nature of the injury. From other effects he has perfectly recovered, but his leg is comparatively useless, while it is a constant source of suffering.

38. The cases related in the Lectures on wounds of arteries, of mortification taking place in the foot and leg, after the division of the principal artery in the thigh, show that the maintenance of the life of a part depends on the blood. The cases now related show that neither an injury nor the division of the principal nerve, nor, perhaps, of all the nerves going to a part, will destroy that life. The complete failure of the circulation, in a part such as the foot, impairs, but does not totally destroy, the sensibility imparted by the nerves, until after the loss of life has taken [50] place, or until decomposition is about to occur. An injury then to the nerve causes great pain, not usually at the part injured, but in the extreme parts supplied by it; some loss of the power of motion; some deprivation of its ordinary sensibility, as shown by a feeling of numbness, and an incapability, to a certain extent, of resisting heat or cold. When all the nerves have been divided, the power of moving the limb is lost, as well as its sensibility in a general sense. The temperature remains at a natural standard under ordinary circumstances, but no extra evolution of heat can take place by which cold is resisted, nor any absorption of it, which perhaps renders the application of a high temperature, particularly when combined with moisture, dangerous. The circulation is capable of maintaining the ordinary heat of a part, although it is deprived of the influence of the special nerves of sensation and of motion; but a greater evolution of heat appears to depend on something communicated by the nerves in a state of integrity. In the case of Sir P. Broke, this something appeared to be derived from the brain, on which part the wound was inflicted, and the transmission of which was interrupted by the injury. The evolution of animal heat has of late been supposed to be dependent on electricity, from the resemblance which exists between it and the nervous power, although the attempts to identify them have not been successful. That the evolution of heat is the result of nervous power, appears to be indisputable; in what that power consists, physiologists have yet to ascertain.

39. The best means of mitigating the pain, independently of the application of warmth—and cold rarely does good, as the sufferer soon finds out—is by the application of stimulants to the whole of the extremity affected, followed by narcotics. The tinctures of iodine and lytta, the oleum terebinthinæ, the oleum tiglii or cajeputi, the liquor ammoniæ or veratria, may be used in the form of an embrocation, of such strength as to cause some irritation on the skin, short, however, of producing any serious eruption. After the parts have been well rubbed, opium, belladonna, or henbane may be applied in the form of ointment; or the tincture of opium, henbane, or aconite may in turn be applied on linen. Great advantage has been derived in many neuralgic pains from the application of an ointment of aconitine, carefully prepared, in the proportion of one grain to a [51] drachm of lard, at which strength it will sometimes irritate almost to vesication, as well as allay pain.

When the pains return from exposure to cold, particularly in the lower extremity, great advantage has been derived from cupping on the loins, from purgatives, opiates, and the warm bath. Benefit has been obtained occasionally from quinine, and from belladonna, aconite, and stramonium, administered internally in small doses frequently repeated, but not suffered to accumulate without purgation; as the accumulated effects are sometimes dangerous.

AMPUTATIONS, ETC.

40. When the wound of an extremity is of so serious a nature as to preclude all hope of saving the limb by scientific treatment, it should be amputated as soon as possible.

41. An amputation of the upper extremity may almost always be done from the shoulder-joint downward, without much risk to life. When necessary, the sooner it is done the better.

42. An amputation of any part of the lower extremity below the knee may be done forthwith, with nearly an equal chance of freedom from any immediate danger, as of the upper extremity at or near the shoulder-joint.

43. It is otherwise with amputations above the middle of the thigh, and up to the hip-joint. They are always attended with considerable danger.

44. There can be no doubt that if the knife of the surgeon could in all cases follow the ball of the enemy or the wheel of a railway carriage, and make a clean good stump, instead of leaving a contused and ragged wound, it would be greatly to the advantage of the sufferer; but as this cannot be, and an approach to it even can rarely take place, the question naturally recurs,—At what distance of time, after the receipt of the injury or accident, can the operation be performed most advantageously for the patient?

45. In order to answer this question distinctly, it should be considered with reference to distinct places of injury:—

1st. When injuries require amputation of the arm below [52] the shoulder-joint, or of the leg below the knee, these operations may be done at any time from the moment of infliction until after the expiration of twelve or twenty-four hours, without any detriment being sustained by the sufferer with regard to his recovery; although every one, under such circumstances, must be desirous to have the operation over. The surgeon having several equally serious cases of injury of the head or trunk brought to him at the same time as two requiring amputation of the upper extremity, may defer the latter more safely perhaps than the assistance he is also called upon to give to the other cases, the postponement of which may be attended with greater danger.

2d. This state embraces those great injuries in which the shoulder is carried away with some injury to the trunk; or the thigh is torn off at or above its middle, rendering an amputation of the upper third, or at the hip-joint, necessary. It is this or nearly this state which alone implies a doubt as to the propriety of immediate amputation, and demands further investigation. It is the state to which attention is earnestly drawn for future observation.

46. It has been implied, if not actually maintained, that a man could have his thigh carried away by a cannon-shot without being fully aware of it, or, if aware of it, that it did not cause much alarm—in fact, that it did not materially signify as to his apprehension, whether the ball took off his limb or the tail of his coat, or only grazed his breeches. An instance of this kind has not fallen under my observation.

47. A surgeon on the field of battle can rarely have a patient brought to him, requiring amputation, under less time than from a quarter to half an hour; a surgeon in a ship may see his patient in less than five minutes after the receipt of the injury; and to the surgeons of the navy we must hereafter defer for their testimony as to the absence or presence of the constitutional alarm and shock to which I have alluded, and to what degree they follow, immediately after the receipt of such injury. The question must not be encumbered and mystified by a reference to all sorts of amputations after all sorts of injuries, but to the one especial injury, viz., that of the upper third of the thigh.

48. My experience, which may be erroneous, like everything human, has taught me, that when a thigh is torn, or nearly torn off, by a cannon-shot, there is always more or less loss of blood, suddenly discharged, which soon ceases in [53] death, or in a state approaching to syncope. When the great artery has been torn, this fainting saves life, for an artery of the magnitude of the common femoral does not close its canal by retracting and contracting in the same manner as a smaller vessel; it can only diminish it; and the formation of an external coagulum is necessary to preserve life, which the shock, alarm, and fainting, by taking off the force of the circulation, aid in forming; and without which the patient would bleed to death. An amputation, in this state of extreme depression, might destroy life, although aided by the exhibition of chloroform.

49. If the cannon-shot, or other instrument capable of crushing the upper part of a thigh, should not divide the principal artery, and the sufferer should not bleed, it is possible he may be somewhat in the state alluded to in which the patient, for he may not be called sufferer, is said to be just as composed as if he had only lost a portion of his breeches. Nevertheless few have seen a man lose even a piece of his skin and of his breeches by a cannon-shot, without perceiving that he was indisputably frightened. Dr. Beith, surgeon of the Belleisle, hospital ship, in the Baltic, informs me that Mr. Wrottesley, of the Engineers, was struck by a cannon-shot, at Bomarsund, on the upper part of his right thigh, which shattered it and his hand, which was resting upon it. His leg was also broken by a splinter from the gun which the ball had previously struck. The femoral artery was not injured, and it was said he lost but little blood. He, however, never rallied from the blow, but sank in twenty minutes after he was brought to Dr. Beith. The constitutional shock and alarm were great; countenance sunk and pallid, pulse scarcely perceptible.

“An East Indian, twenty-two years of age, of healthy aspect, in the month of October, 1854, when proceeding on a shooting excursion, at Moulmein, in Burmah, was most severely wounded by the accidental explosion of his gun, the entire charge of large shot lodging in the center of the left thigh, and causing a bad compound fracture, with fearful laceration of the soft parts. I was asked to see the patient by Dr. Reynolds, the staff-surgeon of the station, at half-past seven A.M., an hour after the injury had been inflicted, and found him laboring under most urgent collapse and great nervous depression. It was of course impossible to save the limb, but I suggested delay for some hours, and the moderate [54] use of stimulants, till the system had in some degree recovered its equilibrium. Such was the case at five P.M., and the flap operation was done while the man was under the full influence of chloroform, (three drachms being required for that purpose.) When placed in bed, he became conscious, but never rallied, and died in half an hour.

“Very little blood was lost during the operation, and the impression on my mind was, that it would have been wiser to have steadily but carefully continued the use of stimulants during the operation, and thus have counteracted the shock of the latter following on that of the injury, from which the system had only partially recovered.”—Case by Dr. Dane, Surgeon to the Forces.