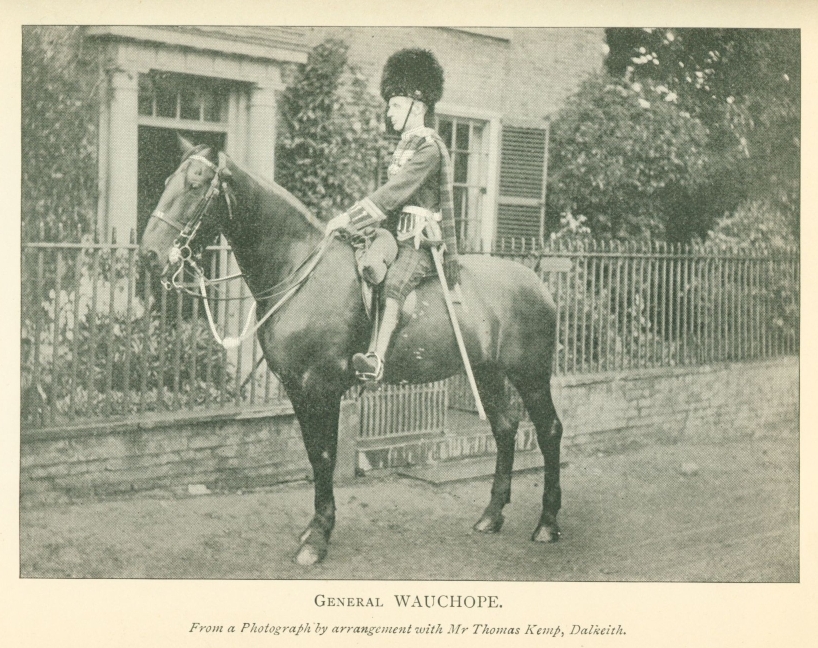

Major-General WAUCHOPE, C.B., C.M.G., LL.D.

From a Photograph by Horsburgh, Edinburgh.

Title: General Wauchope

Author: F.S.A. Scot. William Baird

Release date: June 11, 2021 [eBook #65570]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Al Haines

Major-General WAUCHOPE, C.B., C.M.G., LL.D.

From a Photograph by Horsburgh, Edinburgh.

BY

WILLIAM BAIRD, F.S.A. SCOT.

AUTHOR OF

'JOHN THOMSON OF DUDDINGSTON, PASTOR AND PAINTER'

'ANNALS OF DUDDINGSTON AND PORTOBELLO'

'SIXTY YEARS OF CHURCH LIFE IN AYRE'

ETC.

EDINBURGH AND LONDON

OLIPHANT ANDERSON AND FERRIER

1900

TO THE

OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE HIGHLAND BRIGADE

WHO BRAVELY FOUGHT AT MAGERSFONTEIN

THIS MEMOIR OF THEIR LEADER

IS INSCRIBED

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAP.

I. THE WAUCHOPES OF NIDDRIE MARISCHAL

II. CHILDHOOD—EARLY TENDENCIES—THE 'HOUSEHOLD TROOP'—EDUCATION—NAVAL TRAINING—THE 'BRITANNIA'—THE 'ST. GEORGE'—PRINCE ALFRED

III. ENTERS THE ARMY—THE BLACK WATCH—ASHANTI WAR—RETURN HOME—BANQUET AT PORTOBELLO

IV. DEATH OF WAUCHOPE's FATHER—ORDERED TO MALTA—REMINISCENCES—RELIGIOUS CONVICTIONS—CYPRUS—APPOINTMENT AS CIVIL COMMISSIONER OF PAPHO—REMINISCENCES—SIR ROBERT BIDDULPH—THE SULTAN'S CLAIMS

V. WAR IN SOUTH AFRICA—ARABI PASHA'S REBELLION IN EGYPT—TEL-EL-KEBIR—MARRIAGE—LIFE IN CAIRO

VI. THE EASTERN SOUDAN—BATTLE OF EL-TEB—ATTEMPT TO RELIEVE GENERAL GORDON—ASCENT OF THE NILE—THE WHALE-BOATS—BATTLE OF KIRBEKAN—RETURN TO CAIRO—MALTA—GIBRALTAR

VII. THE MIDLOTHIAN CAMPAIGN

VIII. THE 73RD REGIMENT AT MARYHILL BARRACKS—INCIDENTS OF HOME LIFE—MILITARY LIFE AT YORK—APPOINTMENT TO SOUDAN CAMPAIGN

IX. THE SOUDAN—BATTLES OF ATBARA AND OMDURMAN—ARRIVAL HOME—RECEPTION AT NIDDRIE—DEGREE OF LL.D.—PAROCHIAL DUTIES—PARLIAMENTARY CONTEST FOR SOUTH EDINBURGH

X. OUTBREAK OF HOSTILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA—COMMAND OF THE HIGHLAND BRIGADE—DEPARTURE FOR SOUTH AFRICA—THE SITUATION—BATTLE OF MAGERSFONTEIN—DEATH—FUNERAL—AFTER THE BATTLE

XI. CHARACTERISTICS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PORTRAIT . . . . Frontispiece

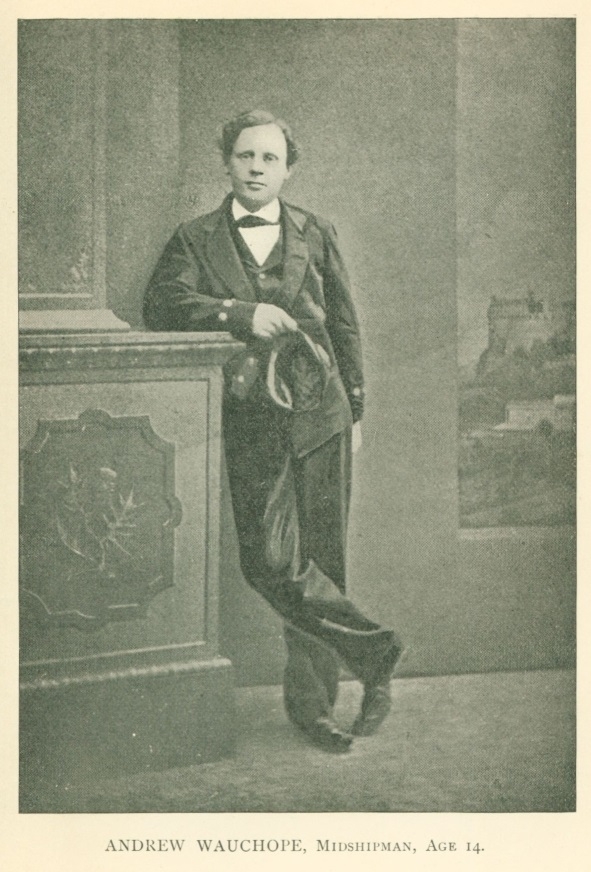

ANDREW WAUCHOPE, MIDSHIPMAN, AGE 14

On the 11th day of December 1899, amid the rattle of rifles, the fierce booming of cannon, and the sharp bang of exploding shells, a British force of Scottish Highlanders found themselves suddenly confronted in the darkness of an early African morning by an unseen enemy. All night they had been on the march, tramping the bare rocky veldt north of the Modder river, to attack, and if possible capture, the fortified and strongly entrenched position held by the Boer army of General Cronje among the rocks and cliffs of Magersfontein. This was full of difficulty and danger. But the relief of the beleaguered garrison of Kimberley was urgent, and if the work were to be done, it demanded the best the British army could achieve. Steadily and determinedly stepped out the men of the Highland Brigade, commanded by him they had long had reason to trust. As lieutenant, as captain, as colonel, they had followed him in many a well-fought battle, and now with Major-General Wauchope leading them in the darkness, no doubt or fear entered their breast.

But suddenly there was a flash of light from the rocks above, followed immediately by a long belching flame of fire from a thousand rifles in front. They had unexpectedly {10} stumbled on the enemy. There was no time for reorganisation, and in the midst of an entanglement of trenches and barbed wire fencing, and exposed the while to a withering fire against which nothing human could stand, the Highland Brigade was mown down. Here it was, but well in front of his men, endeavouring to the last to cheer on his followers, one of the most gallant and daring of modern British generals fought and fell, a martyr for his Queen and country.

General Wauchope's tragic end was no unfitting conclusion to a life of devoted, arduous service. He died as he had lived, ever in the midst of strife, an earnest, brave, and self-denying man, thinking more of others than himself; graced with the dignity that comes from inborn gentleness of spirit, and ever in his conduct exemplifying the faith he professed. No wonder that when such a man fell, there was a wail of lamentation, not merely around his own home in Edinburgh where he was best known and loved, but throughout the whole British Empire.

The story of his life is one of incident and hairbreadth escapes, and it deserves to rank high in the military annals of our country; for among those who have helped to raise Great Britain to the honourable position she holds among the nations of the world, as the vindicator of freedom, as the protector of the weak against the strong, as the pioneer of commerce, and the disseminator of Christianity, there are few who have laboured more zealously or fought more bravely than he whose career we shall in the following pages attempt to sketch.

In biography there is perhaps nothing more alluring than to trace out traits in remote kindred, and to watch them coming forth with new accompaniments in later generations, to work out, as it were, the full story of the race, and probably to mark a climax in some chosen individual. Though we have not space to follow this out in the present case, the distinguishing characteristics of General Wauchope's ancestors may easily be discerned throughout his career; to them he doubtless owed that simple manliness which looked upon every man—whatever his station—as a brother; that unswerving courage in time of danger, that unflinching devotion to duty, that cheerfulness of disposition, which made him a general favourite; all sobered by a sense of the unseen and eternal which entered into the very heart of his life.

The author's efforts to gather the scattered material of so chequered a career have been met on all hands by so willing a response from those who could in any way claim the General's acquaintance, that his task has been a pleasant and a comparatively easy one. For interesting details and incidents coming under their personal observation, his best thanks are due to Admiral Lord Charles W. D. Beresford, C.B.; General Sir Robert Biddulph, G.C.M.G., G.C.B., lately Governor of Gibraltar; Sir John C. M'Leod, G.C.B.; Colonel R. K. Bayly, C.B.; Colonel Brickenden; Colonel Gordon J. C. Money; Major A. G. Duff; Captain Christie, and other of his brother officers who shared with him the dangers and toil of naval and military service, in various parts of the world.

He cannot too gratefully acknowledge the kind assistance heartily given by the Rev. George Wisely, D.D., Malta; the Rev. John Mactaggart, Edinburgh; and the Rev. Alexander Stirling, York, army chaplains. Their contributions have been invaluable.

So fully indeed has material been placed at the author's disposal, that the volume might have been easily extended beyond its present limits. But enough, it may be hoped, has been said in illustration of General Wauchope's career as a soldier, and his character as a man, to enable his fellow-countrymen to realise that in his lamented death the nation has lost one of its bravest and best.

THE WAUCHOPES OF NIDDRIE MARISCHAL

Andrew Gilbert Wauchope came of a long line of ancestry, who have distinguished themselves as soldiers, as churchmen, or in the more commonplace capacity of country gentlemen.

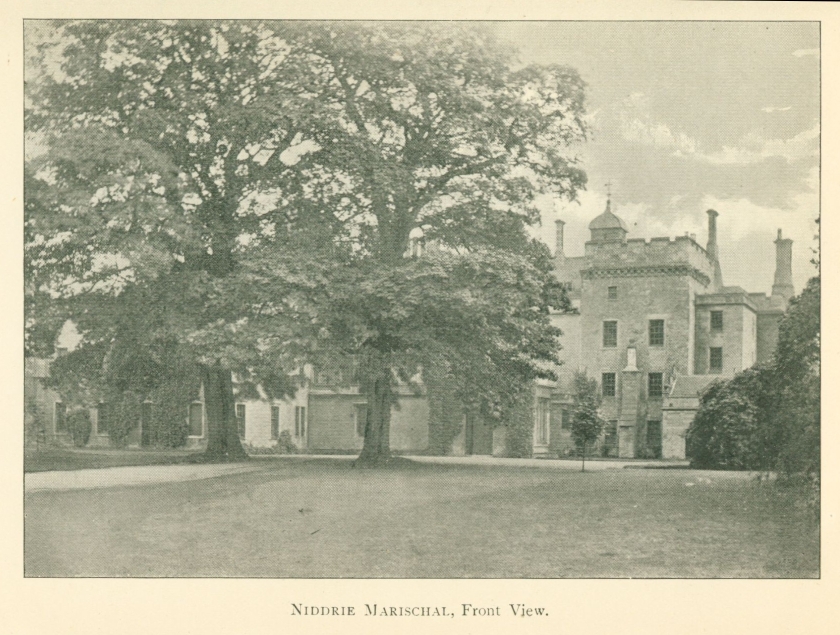

The family history can be traced back for several centuries at least, as occupying in the immediate vicinity of Edinburgh the estate of Niddrie Marischal; and throughout the various troubles in which Scottish history has been involved, the Lairds of Niddrie had their fair share, forfeitures and restorations being an experience not uncommon in their career.

Glancing over their genealogy, one might almost say with truth that the Wauchopes have ever been a fighting race, holding opinions strongly, and as strongly asserting them by word or deed when occasion arose.

The very name of their estate has a smack of the military in it, if it is true, as Celtic scholars say, that 'Niddrie' is derived from the Gaelic Niadh and Ri—signifying, in the British form of Celtic, the king's champion. Then the addition to the word, as distinguishing it from several other Niddries in Scotland, of Marischal, Marishal, or Merschell appears to have been given to the {14} estate from the fact that the Wauchopes of Niddrie were in early times hereditary bailies to Keith Lords Marischal, and later, Marischal-Deputies in Midlothian, in the reign of James v.

Whether it be true, as stated by Mackenzie in his Lives of Eminent Scotsmen, that the Wauchopes had their first rise in the reign of Malcolm Caenmore, and that they came from France, we shall not stay to discuss; but it is generally allowed that the name is a local patronymic, common in the south of Scotland, and that the Wauchopes of Niddrie Marischal belonged originally to Wauchopedale in Roxburghshire, where they were for long vassals of the Earls of Douglas.

The records of the earlier generations of the family having been lost, one cannot with accuracy say who was its founder, or when he lived. In James the Second's reign, for making an inroad into England, and again in Queen Mary's time, for espousing the cause of that unfortunate sovereign, the estate of Niddrie was confiscated and passed for a time into the hands of others, while the feu-charters that remained were afterwards destroyed when the English under Oliver Cromwell came to Scotland. But notwithstanding these misfortunes, there are documents extant which go to show that as far back as the time of Robert III., who began to reign in 1390, there was one Gilbert Wauchope holding the lands of Niddrie from that king, who is supposed to be the grandson of Thomas Wauchope in the county of Edinburgh, mentioned in the Ragman Rolls of 1296.

One scion of the family, born about the year 1500, in the reign of James IV. attained to considerable distinction as an ecclesiastic. This was Robert, the famous Archbishop of Armagh, a younger son of Archibald, the Laird of Niddrie. Defective in his vision almost to blindness, he was, {15} notwithstanding this misfortune, possessed of great natural abilities, and by diligent study attained to high and varied accomplishments. So proficient did he become in the study of the Scriptures, the Fathers, and the Councils, that he was appointed Doctor of Divinity in the University of Paris; and in 1535, having attracted the notice of Pope Paul III., he was called to Rome, and employed by him as legate to the Emperor of Germany and the King of France, in both of which commissions he is said to have exhibited the highest qualifications as an ambassador. Some time after he was promoted to be Archbishop of Armagh, in Ireland. There he laboured with incredible pains to enlighten the ignorant natives, travelling about his diocese, and often preaching to them four or five times a week. Archbishop Wauchope found scope for his great talents at the Council of Trent. This famous council, called together by the Pope to counteract the influence of the Reformation initiated by Luther in Germany, met in March 1544, and continued its sittings till 1551. The archbishop not only took a part in its proceedings, but wrote a full account of them, a labour which, however, proved too much for his strength, for he died at Paris on his way home on 9th November 1551. He appears to have been held by his contemporaries in high admiration. Lesley says: 'Such was his judgment in secular affairs, that few of his age came near him,' and in his capacity as legate 'he acquitted himself so well that every one admired his wit, judgment, and experience.'

Sir James Ware, speaking of him in a similar strain, and alluding, like Lesley, to his having been born blind, says: 'He was sent legate a latere from the Pope to Germany, from whence came the German proverb, "a blind legate to the sharp-sighted Germans."'

Some ancestors

Robert's elder brother, Gilbert Wauchope, was meanwhile Laird of Niddrie, acquiring more property, extending his borders, and getting himself involved in the local feuds peculiar to the time of James V.; that king on one occasion, April 1535, having to grant a letter of protection in favour of him 'and his wife and bairns' against Sir Patrick Hepburn of Wauchtonne and thirty-four others for 'umbesetting the highway for his slaughter.' In this quarrel, even the Pope was called upon to interfere in the interest of peace and safety. In 1539 Paul III. put forth a mandate to the Dean of the Church of Restalrig, stating that a beloved son, a noble man, Gilbert Wauchope, lord in temporals of the place of Niddriffmarschall, within the diocese of St. Andrews, had represented to the Pope that some sons of iniquity, whom he was altogether ignorant of, had wickedly brought many and heavy losses upon the said Gilbert Wauchope by concealing the boundaries and limits or marches of the piece of land or place called Quhitinche, feued to him by the Abbot and Convent of the Monastery of the Holy Cross (Holyrood).... Therefore the Pope intrusted to the discretion of the said Venerable Dean and Commissary to admonish publicly in churches, before the people, ... all holders, etc., and to discover and restore these to the said Gilbert Wauchope or to the Abbot of the Monastery, under a general sentence of excommunication against these persons, till suitable satisfaction was made.

But the Reformation brought many changes, upsetting the laws, customs, and opinions held sacred for centuries. The sons no longer walked in the ways of their fathers, but began to think for themselves. And so we find that Gilbert, the son of the laird who had sought and obtained protection from the Pope, renounced the Pope and took {17} an active part in promoting the Reformation. He was present at Knox's first sermon at St. Andrews in 1547. And at the conference of notables that afterwards was held, where Knox and his preaching were fully discussed, and Wauchope was asked what he thought of the Reformer, 'this answer gave the Laird of Nydre—"a man fervent and uprycht in religioun."' This Gilbert Wauchope of Niddrie was a member of the famous Parliament, held at Edinburgh in August 1560, by which the Reformation was established.

Later on we have a George Wauchope, a celebrated Professor of Civil Law at Caen, in Normandy, who was a grandson of Gilbert, and who in 1595, when he was about twenty-five years of age, wrote A Treatise concerning the Ancient People of Rome.

But the early Wauchopes were a wonderfully varied class of men, who could take their share of fighting when necessary; and towards the close of the sixteenth century their feuds, their 'slauchters,' and political partisanship well-nigh led to their extinction. The feuds with the neighbouring Hepburns and Edmonstons were the occasion of many unhappy conflicts, while their adhesion to the cause of Queen Mary for a time brought ruin on the family. Professor Aytoun, in his poem of 'Bothwell,' referring to Bothwell's attempt to intercept the Queen on her way from Stirling and carry her to Dunbar Castle, says:—

'Hay, bid the trumpets sound the march,

Go, Bolton, to the van;

Young Niddrie follows with the rear;

Set forward every man.'

The estate of Niddrie is quite close to Craigmillar Castle, where Mary frequently resided, and in all {18} probability the fascination of her character brought the Wauchopes into frequent contact with her, and led them to espouse her cause when many of the leaders of the Scottish nobility had declared against her. We find, therefore, that Robert Wauchope and his son Archibald are mentioned in the 'charge agains personis denuncit rebellis' in June 1587. This Archibald appears to have been a youth of wonderful pugnacity, and to have got himself continually involved in trouble with the authorities for breaches of the peace, out of which he as often extricated himself, with no little cleverness. Once, in 1588, for an attempted 'slauchter' of 'umquhile James Giffert, and Johne Edmonston,' the adjoining laird, he was arrested, tried, and warded in the Tolbooth of Edinburgh; but 'no pardoun being granted' by the king, 'and about a thousand persouns in the Tolbuith waiting upon the event, the candles were put furth about ellevin houres at night, and Nidrie and his complices escaped out at the windowes.' It is a curious reflection upon the Wauchopes of this time that their name should be associated with the wild Clan Gregor of Perthshire as disturbers of the peace. King James VI. was married in 1590 to the Princess Anne of Denmark. On the 1st May the king and queen landed at Leith, amid a great concourse of loyal subjects, 'and with volleys of cannon, and orations in their welcome.' James had been absent from Scotland more than six months, and it was remarked at the time, and came to be memorable afterwards, that these months were a time of universal peace and good order in Scotland. 'The only notable exceptions,' according to Spottiswood, 'had been a riot in Edinburgh by Wauchope of Niddry, and an outbreak of the Clan Gregor in Balquhidder.'

In connection with this, we find Wauchope charged {19} by the Privy Council (7th January 1590), 'along with all other keepers of the places and fortalices of Rossyth and Nudry,' to deliver the same to the officer executing these letters, within six hours after charge, under penalty of treason; the said officer to fence the goods and rents belonging to Wauchope, which are ordered to remain under arrest at the instance of the King's Treasurer, 'aye and quhill he be tryit foule or clene of sic crymes quharof he is dilaitet.'

Attack on Holyroodhouse

Not to mention other scrapes of a similar kind, Archibald Wauchope was implicated in the attack on the palace of Holyroodhouse, 27th December 1591, and for this and other misdemeanours he was forfeited, along with the Earl of Bothwell and others, and had to leave the country for a time. He afterwards came to an untimely end by falling from a window in Skinner's Close in Edinburgh, about the year 1596.

It was apparently about this period that the old house or tower of Niddrie Marischal—'so commodious that it could garrison a hundred men'—was destroyed by the enemies of the family.

For some years the estate was in the hands of Sir James Sandilands of Slamannan, until 1608, when, through the good graces of James VI., it was restored to Francis, son of Archibald Wauchope, a restitution which was confirmed by Act of Parliament in 1609. Francis (usually styled Sir Francis Wauchope) appears to have done a good deal for the estate, but his son, Sir John Wauchope, may be regarded as the chief restorer of the house of Niddrie. He was frugal in his living, and he added several adjoining properties to the estate by purchase, and received the honour of knighthood from Charles I. on his visit to Scotland in 1633. He was an intimate friend of the {20} notorious Duke of Lauderdale in their younger days, living with him, and spoken of as 'his bed-fellow.'

Sir John exercised great judgment in the management of his affairs; so much so, that in 1661 he acquired by purchase the border estate of Yetholm or Lochtour, in Roxburghshire, which has remained in the family ever since. He was present in London at the coronation of Charles II.; in 1663 he was elected a member of the Scottish Parliament, and one of the Committee for the Plantation of Kirks; and in 1678 was a member of the Convention of Estates.

Other lairds appear in succession as the years rolled on. There are Williams, Andrews, Gilberts, Roberts, following one another as the leaves succeed in the spring to those that have fallen in the autumn, but it is not our purpose to follow their story. One fought and fell at Killiecrankie with Viscount Dundee in 1689; another fought for the Stuarts at the Revolution, and afterwards rose to high command in the French and Spanish services; and though the Wauchopes took no active part in the Stuart risings of 1715 and 1745, their sympathies were all for the exiled race.

In Niddrie House there are to be seen full-length portraits of Charles I. and his queen; four small half-lengths of the Chevalier and his consort, and their two sons, Prince Charles Edward and the Cardinal York, as boys. These are understood to have been forwarded direct from the Chevalier himself to the Niddrie family as an acknowledgment of their loyalty, and the assistance—pecuniary and otherwise—which the royal line of Stuart had received at their hands.

A 'Minden' hero

To come to more recent times, we find that Andrew Wauchope of Niddrie—the great-grandfather of the subject {21} of our sketch, born about the year 1736—was a captain in the First Regiment of Dragoon Guards, and fought at the battle of Minden in Westphalia, where in 1759 the French were defeated by an army of Anglo-Hanoverian troops. He lived to a good old age, for it was he who was alluded to by Sir Walter Scott in the ballad written on the occasion of the visit of George IV. to Scotland in 1822:—

Come, stately Niddrie, auld and true,

Girt with the sword that Minden knew;

We have owre few sic lairds as you,

Carle, now the King's come.

This Andrew Wauchope married, in 1786, Alicia, daughter of William Baird, Newbyth, and sister of the celebrated Sir David Baird, the hero of Seringapatam, who a few years afterwards—in 1805—commanded the expedition to the Cape of Good Hope which, after a decisive victory over the Dutch, received, on 6th January 1806, the surrender of the colony to Great Britain. There were nine children of this marriage, five boys and four girls. The eldest, Andrew, was killed in 1813 at the battle of the Pyrenees while in command of the 20th Regiment of Foot, and so the second son, William, succeeded to the property, old Andrew Wauchope having resigned it in his favour in 1817, retaining for himself the liferent.

William Wauchope, who had the year before married Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Robert Baird of Newbyth, and niece of the then Marchioness of Breadalbane, was a lieutenant-colonel in the army. Curiously enough, William's younger brother, Admiral Robert Wauchope, was stationed at Cape Town at the beginning of the century, where he resided for many years with his wife. They knew the Dutch well, and were on the most friendly terms with both Dutch and English settlers in the colony.

William Wauchope died in 1826, leaving a family of two, the eldest of whom, Andrew Wauchope, born in 1818, being then a minor, succeeded to the property. His sister, Hersey Susan Sydney, was married in 1842 to George Elliot, captain, Royal Navy, eldest son of the Hon. Admiral Elliot. Andrew Wauchope, the father of the subject of our memoir, was for a time in the army—an officer in the dragoons; but, being of a delicate constitution, he retired after his marriage to reside at Niddrie, where he was long known and respected as a kind and indulgent landlord, ever ready to give a helping hand to his tenants or to religious and philanthropic objects. He did a great deal towards completing the extensive improvements begun by his father on the house and grounds of Niddrie.

The newer part of the house, forming the north-east wing, was erected by William Wauchope about seventy-five years ago. It contains some handsome apartments, and it is interesting to note that the celebrated Hugh Miller, when a lad, was employed (in 1823) as a mason at the work, and is said to have carved a number of the ornamental chimneys which form a distinctive feature of a most picturesque edifice. What the father began, the son ultimately completed. The park was extended, new approaches and avenues were formed, lodges erected, and gardens and vineries laid out—the whole place being transformed into one of the most beautiful country seats to be found in the county of Midlothian. These somewhat extensive works, resumed by the father of the General about the year 1850, were steadily carried on year by year until his death, 22nd November 1874, for he took much pride in the work, and made it his life hobby.

Sir William Wallace

So far this brief genealogy of General Wauchope's family has been traced through the male line, but it would be {23} incomplete and lacking in public interest, did we not also refer to his descent on the female side from the family of Sir William Wallace, the champion of Scottish freedom. This interesting connection is traced to James Wauchope, the grandfather of the 'Minden' hero. In 1710 he married Jane, daughter of Sir William Wallace, Bart, of Craigie, near Ayr, whose eldest son, Andrew, succeeded his cousin in 1726, and in his line the property has remained to the present time.

Niddrie Marishchal, Front View

Over the fireplace of the dining-room of Niddrie House there is a painting on canvas inserted in panelling said to be a portrait of 'Wallace Wight.' It has been in possession of the family for nearly two hundred years, being mentioned in various inventories of the property from the year 1707. An interesting notice of it appeared in James Paterson's Wallace and his Times, and the family tradition is that it is a genuine portrait of the hero, the words inscribed above the likeness, 'Gvl: Wallas: Scotvs: Host: ivm: Terror,' certainly giving colour to the supposition. We are more inclined to think, however, that the portrait represents one of the more immediate ancestors of the Jane Wallace who brought the connection into the family—probably Sir William Wallace of Craigie, who distinguished himself as a loyalist in the civil wars. It certainly came into the family through the marriage of James Wauchope in 1710 with Jane, daughter of Sir William Wallace of Craigie, and if it does not represent the champion of Scottish independence, it is from the same source as a similar portrait preserved at Priory Lodge, Cheltenham, in the hands of a descendant of the Craigie-Wallace family.

It was when he was serving with his regiment at Monaghan, in Ireland, that the father of General Wauchope first met his future wife, Frances Maria, daughter of Henry Lloyd of {24} Lloydsburgh, County Tipperary. They were married on 26th March 1840, and two sons and two daughters were the issue of the marriage. These were—

1. William John Wauchope, born in September 1841.

2. Harriet Elizabeth Frances, afterwards married to Lord Ventry of County Kerry, Ireland, by whom she has issue, five sons and four daughters, of whom her daughter, the Hon Hersey Alice Eveleigh-De-Moleyne, is the present Countess of Hopetoun.

3. Andrew Gilbert, the subject of our story, born at Niddrie on 5th July 1846.

4. Hersey Josephine Frances Mary, now residing in London.

A typical Scotsman, loyal to the backbone to the land of his birth, Andrew Gilbert Wauchope had always a warm corner in his heart for Ireland, and was ever ready to acknowledge, and indeed to boast of, his Irish extraction. Combining as he did much of the canniness of the Scot with that steady-going determination of purpose and fearlessness in danger peculiar to his countrymen, he displayed the Irish side of his character in that generous light-heartedness and impulsive good nature which often led him into self-denying deeds of kindness, and now and again into trouble. General Wauchope was, as we have seen, the heir to no mean family traditions. The record of the Wauchopes is one of patriotic energy through five or six hundred years of stirring Scottish history, many of them years of turmoil and strife; and the warlike spirit of the fathers, as well as their more peaceful characteristics, may be found not infrequently imaged in this last scion of the race.

CHILDHOOD—EARLY TENDENCIES—THE 'HOUSEHOLD TROOP'—EDUCATION—NAVAL TRAINING—THE 'BRITANNIA'—THE 'ST. GEORGE'—PRINCE ALFRED.

General Wauchope's boyhood was spent mostly at Niddrie, with occasional short visits in summer to the other property of the family at Yetholm, among the pastoral Cheviot hills.

A high-spirited, frolicsome boy, delighting in the open air and every kind of outdoor sport, 'Andy,' as he was familiarly called, found scope for his energies in the beautifully wooded park surrounding the house. Bird-nesting, rabbit-catching, and fishing in the burn which meanders through the estate, found him an ardent enthusiast, but often brought him into trouble with his father and mother. His bird-nesting feats, prosecuted with all the zest of a professional poacher, often resulted in the dislocation of his clothes, and shoes and stockings too often betrayed the fact that friendly visits to the burn were more frequent and prolonged than ought to be. Many a time Andy was thus in a sore plight. Drenched and torn, he would go to the kindly gardener's wife, to get the rents in his jacket sewed, his stockings changed, and his shoes dried, before venturing into the family presence. In his adventures over the property, the burn was never a barrier to his {26} progress. It was the same with hedges, ditches, or stone walls. If he wanted to reach a certain point, he made a straight road to it over every obstacle.

Youthful tendencies

But the limits of the park did not always satisfy his roving desires. He soon made himself acquainted with the surroundings of his home. Craigmillar Castle was a favourite resort on the one side; the beach at Portobello gave him a taste for the sea and aquatic exercise; while the neighbouring little village of Niddrie was not long in making his acquaintance. Here he was known to every one, for Andy made himself at home in every cottage; and if the boys stood in some awe of him, and mothers blamed him for sending their sons home with their clothes torn, or their noses bleeding, still, for all that, he was always welcomed among them, sometimes with a 'jeelie' (jelly) piece or a new-baked scone!

Many a frolic he and the boys of the village were engaged in, if all tales were told, and sometimes Andy got credit for more than he deserved. Boys will be boys, but his boyhood early showed the spirit of the man, for to have a number of country boys together, and put them through military drill, was the height of his delight. He was a born leader, and he doubtless imbibed his love of soldiering from the frequent opportunities he had of seeing military manoeuvres in the Queen's Park, or more likely on Portobello sands, where at that time there was a great deal of drilling, both of the regulars and of the yeomanry cavalry. That the military instinct revealed itself early may be gathered from the following:—One day the village dominie, worthy old Mr. Savage, looking out of the school door across the road, saw the youthful form of Andy—then about seven or eight years old—on the top of the high boundary wall of his father's park, which at that place is {27} nearly nine feet high. 'What are you doing up there?' shouted the dominie; 'get down at once, you young rascal, or you'll get killed!' But Andy only waved his hand as he shouted back, 'It's all right, Mr. Savage: I'm only viewing the enemy,' and off he scampered along the top of the wall!

Andy's 'household troop' was not a large one, but it sufficed. With Tom and Jim, the gardener's sons, and their sisters, Jess and Bella, assisted by a few male and female recruits from among the children of the other workers, with his sister Fanny and his cousins Elizabeth and Nina Elliot, now Lady Northesk and Mrs. J. Dacre Butler respectively—one of whom carried the banner, and another the drum—the youthful general managed to make a fair show. He drilled them well, and was naturally very proud of them. One day there happened to be company at the house. Andy, anxious to display his forces, marched them up to the front door, and there, seated on his little black pony 'Donald,' he put them through their facings, to the great entertainment of the visitors. He was not content with this, however. He must needs take the place by storm, and so, putting himself at the head of his troop, he gave the word of command, 'Forward, march!' and actually marched them into the hall, and through the dining-room to the terrace at the back of the house, bravely leading them on his pony!

The ice-house stood in the park not very far from the house. It was a vaulted chamber covered with turf, forming externally a mound which made a capital fort. Many a time was it the scene of mimic warfare, its defence or assault giving splendid scope for the youthful general's military genius,—brilliant attacks being as brilliantly defeated without any great loss of life!

Sometimes 'Andy's' attacks took a wider range, and {28} nocturnal escapades of a frolicking nature are said to have been not infrequent. It is told of him that having gathered a few of the village boys together, they made a raid one night upon the workshop of the village joiner, and took away a number of odd cart-wheels lying about in the yard. These they fastened to the doors of some of the cottages, where they were found next morning, much to the surprise of the inmates, who had some difficulty in getting egress from their houses! Nobody, of course, could tell who was to blame; but, as our informant remarked, 'They a' kent wha did it: it was just some o' Maister Andra's mischief.'

One old woman in the village, whose temper was not very good, and who laboured under the conviction that her hen-house was from time to time robbed of its roosters, had made herself somewhat obnoxious, and it was determined to give her a real fright. So one evening, after all decent folks were supposed to be in bed, Andy and his company slipped quietly round to the hen-house, and presently there was a great commotion and cackling among the feathered occupants. The old lady in her bed heard it all, but was too frightened to come to the rescue. She was certain, however, that some of her favourite hens had been taken, and next day she went up to the laird at the big house to complain, and to ask compensation. Andy was with his father when the old woman was laying off her story, but betrayed no signs of his complicity in the transaction, wisely preferring to keep his own counsel in the matter. Of course the boys had taken none of her property. They only wanted to play a trick upon her.

Andy was, however, not a boy who would perpetrate any wilful mischief, or do anything that would cause pain. He hated cruelty, and once when he was accused of having {29} killed the cat of an old servant of the family, who lived as a pensioner in the village, he heard the accusation with the greatest indignation. Going at once to Mary's house he strongly asserted his innocence, telling her with all earnestness, 'I'd rather shoot myself, as shoot your cat, Mary.'

Very early in life he evinced a strong desire to share in the sport of the hunting-field. His father would not, however, hear of it, and refused to allow him to get a proper rig-out. But Master Andrew was not to be balked in his ambition, for one morning, getting into a pair of his father's top-boots, many sizes too large for him, and securing the biggest horse in the stables, he boldly set off for the hunt. The appearance of such a mite with boots that would scarcely keep on his feet, on the back of a big hunter, created great laughter among the county gentry at the meet.

Early education

During these early years of Wauchope's life, so free from restraint, his education was being carried on at home under a tutor. At the age of eleven he was sent to a school at Worksop, in Nottinghamshire, but he did not remain there very long. He had a hankering for active life, and specially for the sea. It was accordingly resolved to prepare him for entering the navy as a midshipman, and he was sent to Foster's School, Stubbington House, Gosport. His experience here was also a short one, and was marked by an incident characteristic of his spirit of adventure and faithfulness to obligations; though in this case we must say the latter virtue was rather misapplied, and it might well be said 'his faith unfaithful kept him falsely true.' The boys at Foster's, evidently wanting to vary the monotony of school life—perhaps none of the brightest—thought it would be a good lark if one would run away from the school, and they resolved to draw lots who it {30} should be. The lot fell upon young Andy Wauchope, and, like the loyal lad he was, he resolutely stuck to the agreement and ran off from the school, but of course he was promptly brought back by his people, and no doubt received the just reward of his frolic!

He used to say long afterwards that he had only been at two schools when he was a boy. 'At one of them he was said to be the best boy in the school, but at the other he was the very worst!'

With what would now be considered a very inadequate training, young Wauchope was on the 10th September 1859 entered as a naval cadet on board Her Majesty's ship Britannia, there to pick up in the rough school of a sailor's life that knowledge of the world, and particularly of his naval duties, which books and schooling had denied him. At the same time, though deprived of the advantages of Eton or Harrow, or any of the Scottish Universities, he had a much better gift than education—an immense natural shrewdness, and a persevering application, which afterwards made him a good French and German scholar. Among his shipmates on the Britannia he was a general favourite. He was only thirteen years of age, but appears to have been a plucky little fellow, full of life and fun, and quite capable of standing up for himself, or for a friend if need be; and in the thirteen months of his service in the ship he made several lifelong friendships. Admiral Lord Charles Beresford, writing to us of that period, mentions that he and Wauchope joined the navy about the same time. 'I remember,' he says, 'our chests were close together in the Britannia. We separated when we went to sea, but we never lost the friendship we formed in the Britannia. We met often in different parts of the world, and I always {31} found him the same sterling, honest, strong, and chivalrous friend, whose splendid characteristics had so impressed me as a boy. I have always regarded his friendship for me with sentiments of pride. He was very proud of being a Scotsman, and being an Irishman myself, we had many arguments—as boys will have—as to which nation possessed the most interesting personalities. We agreed cordially on every other point, but never once on this. The nation has lost one of its best in poor Andy Wauchope.' There are doubtless others of his Britannia shipmates surviving who could give similar testimony.

Enters the Navy

On the 5th October 1860, Wauchope received his discharge from the Britannia, and was entered as a midshipman on board H.M.S. St. George, and he mentions himself with what pride and satisfaction he found himself on that autumn day walking down the main street of Portsmouth in his new uniform to join the St. George. 'It was one of the happiest days of my life,' he says; 'a day in which I felt myself identified as an officer in Her Majesty's service, more particularly as on the way down to the harbour I was met and saluted by one of the marines.'

The St. George was manned by eight hundred men, and in 1860 was considered a well-equipped vessel, and as compared with the days of Nelson and Collingwood showed a great advance in naval strength and efficiency. At Trafalgar the biggest gun in the whole British fleet was only a fifty-six pounder, but the St. George had in addition to a number of that calibre several sixty-eight pounders, while her speed of ten knots an hour was considered highly satisfactory. Though these equipments would not bear comparison with present-day standards, the young midshipman was proud of his ship and proud of the service, and in after years could with no little exultation {32} honestly say that, 'though armaments had changed, the hearts of oak remained as of yore; while the old red rag, which had withstood the battle and the breeze for a thousand years, was still able to claim the allegiance of its people.'

H.R.H. Prince Alfred

Wauchope's commanding officer on board the St. George was Captain the Hon. Francis Egerton—whose son, Commander Egerton, was killed at Ladysmith in November 1899—and among his brother officers were H.R.H. Prince Alfred, afterwards the Duke of Edinburgh, and latterly known as the Duke of Saxe-Coburg Gotha, and Admiral Sir Robert Harris, now Commander-in-Chief of the Cape of Good Hope station.

The St. George was commissioned at Portsmouth, and was transferred to Devonport early in 1861. She was then one of the noblest and most imposing-looking ships of the service, having the year before been thoroughly overhauled and converted from a one hundred and twenty gun ship to one of ninety guns. As a three-decker sailing ship she was considered one of the finest fighting vessels afloat, and her conversion to a steamship of the line had been attended with the most successful results. She was selected by Prince Albert for his son, the youthful Prince Alfred, who joined her as a midshipman a few months after Wauchope—on the 16th January 1861—as she lay in Plymouth Sound, under orders for a cruise to the British North American Stations and the West India Islands.

The greater part of the year seems to have been spent in and about Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia, which became a centre for cruises in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Canadian ports. We have it on the authority of several of those who were midshipmen with the Prince, that they were a jovial, happy company, all on the most friendly {33} terms with one another. The Prince, who was very fond of 'Andy,' as he was always called, showed him particular friendship, and the affection which as boys and shipmates they formed then continued more or less in later years.

The Prince came back to England in the month of August to spend a short holiday with his parents at Balmoral, but rejoined his ship, which was lying at Halifax, in October. His return was welcomed by his mates and by the citizens of that town; and the Governor, the Earl of Mulgrave, entertained His Royal Highness and the officers of the St. George at a state dinner on the eve of their departure for a cruise to Bermuda. Among the sunny islands of the South the ship and her crew were everywhere received with the utmost enthusiasm, the black and white population alike vying with each other in their demonstrations of loyalty; but the sudden death of the Prince Consort at the end of December compelled the return home for a time of Prince Alfred, who left his ship at Halifax on receipt of the sad news, with every expression of sympathy from his brother officers. In the spring of 1862 Wauchope's ship paid another visit to the West India Islands, taking up her station for some weeks with other six ships of the line at Bermuda, where the young 'middies' were entertained to a continued round of amusements and excursions.

A seafaring life, if often one of risks and toil, has its seasons of enforced idleness. Midshipmen's amusements and practical jokes are proverbial, and the quarter-deck of the St. George was not always free of them. Many pranks were played upon one another in idle hours by these sprightly young officers, leading sometimes to reprimands by their superiors; and young Andy Wauchope did not {34} always escape the suspicion that he was an active leader in such ploys. It has even been hinted that he had on one occasion the pluck—or, shall we say, audacity?—to have a stand-up fight with the Queen's son. We do not vouch for the story; but of this we are certain, that, if he had a just cause of quarrel, he was not the boy to let even the prestige of royalty stand between him and the punishment due to the aggressor, whoever he might be.

Some years afterwards, in the winter of 1863-64, when Prince Alfred resided at Holyrood Palace, and was a student of Edinburgh University, he paid a friendly visit to his old shipmate at Niddrie, spending the day in pigeon-shooting. He and a number of his friends arrived in the forenoon on horseback, and the identity of the party not having been made known to the keeper of the Niddrie toll, through which they had to pass to reach the house, he peremptorily insisted upon payment. But being told that it was the Queen's son going to see the laird, his loyalty so much got the better of him that he would not take a copper.

After luncheon the party adjourned to the park to have some shooting. Mr. Wauchope, 'Andy's' father, was with them, and was persuaded to try a shot, but unfortunately the piece went off in his hand before he could take aim, and one of the footmen in attendance was hit in the arm by the charge. Mr. Wauchope was so distressed over the accident that he vowed he would never again take a gun in his hand.

ANDREW WAUCHOPE, Midshipman, Age 14.

But it was not in the navy that young Wauchope was destined to distinguish himself. It has been said that the severity and even harshness of the naval discipline gave him a distaste of the service, and drove him from it. Possibly some remarks he made on one occasion as to his {35} having been unjustly punished for some petty offence may have given some colour to this supposition. We rather incline to accept the explanation of a brother officer, who asked him afterwards why he left the navy. His reply was, 'for no reason except that his father wished him, and that his father desired that he should have a naval training before he entered the army.'

The St. George

The experience gained at sea was certainly not lost, for his father's wisdom furnished him with a dual equipment which in after years was not infrequently of value. The injustice of the punishment he received when in the St. George, whatever it may have been, certainly impressed itself upon him to this extent, that later in life he made it a rule never to punish a soldier until thoroughly satisfied of his guilt, and he always was inclined to give a man the benefit of a doubt.

The St. George returned home in the beginning of July 1862 from her long cruise in American waters, and with her return young Wauchope closed his naval career. The official Admiralty record simply states that 'on the 3rd of July 1862 Midshipman Wauchope was discharged from the service at his own request, in order that he might qualify for the army.' His whole naval experience, therefore, covered a period of scarcely three years, but it gave him a knowledge of men and things, and a knowledge of the world, better, perhaps, than any study of books could afford.

ENTERS THE ARMY—THE BLACK WATCH—ASHANTI WAR—RETURN HOME—BANQUET AT PORTOBELLO.

Young Wauchope had not long to wait for a commission. At that time positions in the army could only be got by purchase and strong influence, but he was fortunate in being enrolled as ensign, in November 1865, in the 42nd Highlanders, one of the most popular and distinguished of Scottish regiments, and familiarly known as the 'Black Watch.' He was only nineteen years of age at the time when he joined the regiment at Stirling Castle, and is described by one of his superiors as then 'a merry, rollicking lad, full of life and fun.' 'Andy,' as he used to be called by the officers, and 'Red Mick' more frequently by the men, was a general favourite; and, notwithstanding his natural lightness of heart, he had soundness of brain and judgment enough to know that promotion would only come to him by diligent study and close application to his profession. His commanding officer, Sir John M'Leod, appears, at all events, to have been struck with the young man's energy of character and indefatigable 'go,' for he describes him as at that time 'a particularly energetic young lad, who thought nothing of walking from Stirling to Niddrie to see his old father whenever he could get a few days' leave at a week-end.' This, he explains, was not {37} at all from motives of economy, 'but merely to walk off superfluous energy.' Assiduous in the matter of drill, Wauchope soon became as proficient as his instructor, for he took a thorough pleasure in the exercise. The innate smartness and recklessness of the red-polled ensign at once endeared him to a grave old Crimean drill-sergeant, who forthwith charged himself with his training. Concerning this latest accession to the commissioned strength of the Black Watch, the man of stripes was wont to say—'That red-headed Wauchope chap will either gang tae the deil, or he'll dee Commander-in-Chief!'

The Black Watch

Though the worthy sergeant's prediction has in neither case been verified, young Wauchope, though at first inclined to consider his superiors a trifle slow, soon fell into the steady sober ways of the 42nd, then as now noted for the gentlemanly conduct of its officers, and the upright character of its rank and file. 'Step out, shentlemens; step out. You're all shentlemens here; if you're not shentlemens in the Black Watch, you'll not be shentlemens anywhere.' Such was the opinion of their old Highland sergeant as he put them through their drill. We have been told that at that time one might be a year among the officers and never hear an oath uttered, while smoking and drinking were scarcely known. Wauchope was thus fortunate in being, at a critical period of his life, associated with men who shunned what was vulgar, and whose influence over him was for good. In military matters he early manifested the inquiring mind. Points in drill or tactics, which he might not at first understand, set him thinking, and he would not rest till he got an explanation of their meaning and object. Captain Christie, then adjutant of the Black Watch, lately governor of Edinburgh Prison, was early taken into the young ensign's {38} confidence in difficulties of this kind. Having been through the hard fighting and the terrible scenes of the Indian Mutiny, the captain was made frequently to 'fight his battles o'er again,' explaining the methods and tactics by which decisive results were attained in the various engagements. Never what may be called a great reader of books, Wauchope had two, however, placed in his hand by his adjutant when in Stirling Castle, which he studied assiduously. These two books—Macaulay's Essays and Burke's French Revolution—he read and re-read, borrowing them several times, and there is little doubt that the perusal of them made a deep and lasting impression upon his mind, going a long way towards the formation of that strong political sagacity, administrative ability in civil affairs, and military genius which were displayed on many occasions in his after-life.

In 1867 Wauchope went to Hythe, where he passed in the Military School of Instruction first-class in musketry, and in June of that year was promoted to be lieutenant. So proficient was he found in the matter of drill that, in spite of his youth, he was appointed to the important position of adjutant to the regiment in 1870, though still retaining the rank of lieutenant, a position which he held with the utmost credit for the next three years. During this time he served successively with the 42nd in garrison duty at Edinburgh, Aldershot, and Devonport.

Leaving Edinburgh in 1869 by the transport Orontes, from Granton to Portsmouth, the regiment reached Aldershot camp on the 12th November, and was stationed there for two and a half years. After taking a part in the Autumn Manoeuvres at Dartmoor in August 1873, they were stationed for a few months at the Clarence Barracks, Portsmouth. His duties during all these years were of the {39} most arduous and trying description, but his singularly lovable and attractive nature made him so many friends that difficulties disappeared before his cheerful countenance. Speaking of this period in his career, Colonel Bayly, afterwards his commanding officer, says—'It was very early in his subaltern career that Wauchope was voted for the appointment of adjutant, and he made one of the best that had ever been appointed. His charm of disposition enabled him to gain the love of his men, whilst his tact and firmness enabled him to enforce the necessary discipline.'

Ashanti war

On the outbreak of the Ashanti war on the west coast of Africa in the autumn of 1873, young Lieutenant Wauchope found his first opportunity, in active foreign service, of showing the metal of which he was made.

The king of Ashanti—Koffee Kalcallee—the head of a strong warlike kingdom on the north of the Gold Coast, had long asserted his authority over the neighbouring provinces of Akim, Assin, Gaman, and Denkira, down to the very coast where the Dutch and English had settlements. The transfer, in 1872, of the Dutch possessions adjoining Cape Coast Castle to Great Britain for certain commercial privileges, gave King Koffee of Ashanti the opportunity for asserting what he considered his lawful authority over the Fantees or adjoining coast tribe. This, however, was only a covert excuse for striking a blow at British rule on the Gold Coast, and in January 1873 an army of 60,000 warriors—and the Ashantis, though cruel, are brave and warlike—was in full march upon Cape Coast Castle and Elmina. The British force on the spot under Colonel Harley was only a thousand men, mainly West India troops and Haussa police, with a few marines; and though the neighbouring friendly tribes, whose interest it {40} was to remain under the British protectorate, raised a large contingent for their own defence, this was a force that could not be relied on. By the month of April the Ashantis had crossed the river Prah, the southern limit of their kingdom, and were within a few miles of Cape Coast Castle, and matters were looking serious. With the aid of a small reinforcement of marines, the enemy were fortunately kept at bay until the 2nd October, when a strong force arrived from England, which turned the tide against King Koffee, and ultimately swept him and his warriors back upon his capital. This expedition, under Major-General Sir Garnet Wolseley, with his staff and a body of five hundred sailors and marines, not only held their own, but by the end of November, after much hard preliminary work, had forced the king to retreat to Kumasi. Wolseley, finding the expedition a more arduous one than was at first expected, had meantime asked for further reinforcements, and on the 4th December the Black Watch, accompanied by a considerable number of volunteers from the 79th, left Portsmouth, arriving on 4th January 1874 at their destination. Sir Garnet had now at his disposal a force consisting of the 23rd, 42nd, and 2nd Battalion Rifle Brigade, detachments of Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers, and Royal Marines, which, with native levies, formed a small but effective army wherewith to advance into the enemy's country.

This was no light task, more especially when the dangerous nature of the climate is taken into account, and the necessity there was that the enterprise should be accomplished, if at all, before the rainy season, with all its concomitant malaria, set in. To pierce into the heart of a country like Ashanti, with its marshes and matted forests, its pathless jungles and fetid swamps, with a {41} cunning foe ever dogging their steps, was the service imposed on this brave little army of British. As Lord Derby remarked at the time, this was to be 'an engineers' and doctors' war.' Roads had to be made, bridges built, telegraphs set up, and camps formed. But by the energy and skill of General Wolseley, ably supported by such men as Captain (now Sir) Redvers Buller, Colonel (afterwards Sir John) N'Neil, Lieut.-Colonel (afterwards Sir Evelyn) Wood, Colonel (now Sir John) M'Leod, and others who have since risen to distinction in the army, the enterprise was successfully and brilliantly accomplished within a month. The Ashantis were forced back upon their own territory in a number of engagements, until at last their capital was seized and burned to the ground.

Wauchope's black boys

Lieutenant Wauchope's share in this expedition was highly creditable to his bravery and military skill. Accompanying Sir Garnet Wolseley at an early stage of the struggle, as one of the staff, he resigned his adjutantship of the Black Watch, and was afterwards fortunate in obtaining special employment as a commander of one of the native regiments formed at Cape Coast Castle, namely, Russell's regiment of Haussas, the Winnebah Company. To form such crude material into a well-disciplined body of soldiers seemed at first a well-nigh hopeless undertaking. Their fear made cowards of them all. The very sight of a gun terrified them, and for long they held their arms in such superstitious dread, that they would hang them up in the trees and actually worship them. But Wauchope's admirable drilling qualifications stood him in good stead. He took, we are told, a great pride in the training of his 'black boys,' as he called them, and infused into them much of his own daring spirit. This appointment separated him for a time from his own regiment, but on {42} the Black Watch arriving afterwards at the Gold Coast, he had frequent opportunities of fighting by their side.

In the advanced guard, the 42d Regiment and Russell's Haussas, under Colonel M'Leod, having crossed the Adansi hills, reached Prah-su on the 30th January, and occupied a position about two miles from the Ashanti main position at Amoaful. Surmounting innumerable difficulties, and carrying all before them, the Highlanders by their dash and intrepidity were a splendid example to those led by Wauchope, who sometimes had difficulty in inspiring his men with courage enough to face their much-dreaded enemy. In scouting and clearing the ground his men were, however, invaluable, and if we consider the dense undergrowth that covered the country traversed, this was a work of great importance. By one traveller we are told 'the country hereabout (at Amoaful) is one dense mass of brush, penetrated by a few narrow lanes, where the ground, hollowed by rains, is so uneven and steep at the sides as to give scanty footing. A passenger between the two walls of foliage may wander for hours before he finds that he has mistaken the path. To cross the country from one narrow clearing to another, axes and knives must be used at every step. There is no looking over the hedge in this oppressive and bewildering maze.' It was in such a position as this that the battle of Amoaful was fought. The enemy's army was never seen in open order, but its numbers are reported by Ashantis to have been from fifteen to twenty thousand. After a stubborn day's fight in the entanglement of the forest, the Ashantis were finally defeated with great loss.

Attack on Kumasi

On the 1st February, the day following this important engagement, orders were issued for an attack upon Becquah, towards which Captain Buller and Lord Gifford {43} scouted at daybreak. The attack was intrusted to Sir Archibald Alison, who had under his orders the Naval Brigade, one gun and one rocket detachment, Rait's Artillery, detachment of Royal Engineers, with labourers, 23rd Fusiliers, five companies of 42nd Highlanders, and Russell's regiment of Haussas, with scouts. This force was divided into an advanced guard and main body, and Wauchope was again honoured with the post of danger, his regiment of Haussas being in the advanced guard along with the Naval Brigade and Rail's Artillery, all under the command of Colonel M'Leod. After a toilsome march through the bush under a tropical sun, the town of Becquah was reached, and a sharp but decisive engagement took place, the main brunt of which fell upon Lord Gifford's scouts and the Haussas. Still pressing on, the intrepid little army, through many mazy trampings, arrived at Jarbinbah, every inch of the ground being disputed by the enemy. Here Wauchope was wounded in the chest by a slug fired down upon him from one of the tall trees in the swampy ground in front of an ambuscade; but, serious enough though it was, and causing much loss of blood, it did not prevent him sticking to his post and looking after his 'black boys.' After this battle King Koffee sent in a letter to Sir Garnet Wolseley, with vague promises of an indemnity, hoping to prevent the invading army approaching his capital; but his previous prevarications did not admit of his tardy proposals being for a moment entertained. The king, realising this, resolved to dispute the passage of the river Ordah. The stream was about fifty feet wide, and waist-deep, and the enemy, to the number of at least 10,000 men, were posted on the further side. Russell's regiment of Haussas was, on the afternoon of the 3rd February, at once passed to the other side of the stream as a covering party to the Engineers, who {44} were ordered to throw over a bridge. They rapidly made entrenchments, and cleared the ground on the north side, so that the whole advanced guard might successfully cross. In this affair Lieutenant Wauchope acquitted himself with much coolness and bravery, notwithstanding his wounded state, Colonel M'Leod reporting the regiment as 'being in front the whole day, and having behaved with remarkable steadiness under trying circumstances, reserving their fire with remarkable self-control.' This shows a decided improvement in the discipline of Wauchope's 'black boys' from a former despatch, where their firing was characterised as 'wild.' By daybreak on the morning of the 4th February the bridge over the Ordah was completed, amid drenching rain, which had continued all night, and the whole available force was successfully passed over in spite of the vigorous resistance of the Ashantis, who, with drums beating and great shouting, were endeavouring to circle round the British. 'For the first half-mile from the river the path rose tolerably even,' says one report; 'then after a rapid descent it passed along a narrow ridge with a ravine on each side; dipped again deeply, and then finally rose into the village. To the south-west of the village, extending almost to the village itself, and for a considerable distance along the road, the enemy had made a clearing of several acres, by cutting down a plantain-grove. Colonel M'Leod steadily advanced along the main road under cover of a gun, after a few rounds from which the Rifles made a corresponding advance; then the gun was brought up again, and another advance made; and in this manner the village was at last reached and carried.' The Ashantis fought well, and with a vigour and pertinacity which won the praise and admiration of the Highlanders. The soldiers were put to their mettle, and even the Haussas, as if {45} catching the fierce courage of the Scotsmen, laboured with vigour and energy not eclipsed by any in the field. The dislodgment of the enemy was not effected, however, without considerable loss, Lieutenant Eyre being killed, while Wauchope received a second severe wound, this time on the shoulder.

Kumasi captured

The battle virtually decided the fate of Kumasi and King Koffee. On the news of the defeat of his army the king fled, no one knew whither, and the victorious General Wolseley, with his troops, entered the blood-stained capital in the evening. Attempts were made to negotiate with the king. He preferred to keep in hiding, and after two days' stay in his capital in order, if possible, to compel him to come to terms, it was at length resolved to destroy the place and at once retire to Cape Coast Castle. Kumasi was burned to the ground on the 6th February, and the British troops having accomplished their purpose retraced their steps, and notwithstanding the swollen state of the rivers—for the rainy season had just set in—their destination was reached in twelve days. No time was lost in getting the troops out of the influence of the deadly climate, and accordingly by the 4th March the whole expeditionary force was embarked for home.

Wauchope's wounds, thanks to a good constitution, readily healed, and by the time of his arrival at Portsmouth he was fairly convalescent, though every effort made to extract the slug had been unsuccessful. He left his favourite Haussas—his 'black boys'—with every manifestation of regret, at Cape Coast Castle. Nor was the regret only on his side, for we learn from one of his brother officers that 'they looked up to him as a father, and would willingly have followed him through any danger, even to death itself.'

Home again

For his conspicuous bravery in the various engagements in Ashanti, Sir Garnet Wolseley's despatches brought Wauchope under the favourable notice of the Government, and he was awarded the Ashanti medal and clasp. On the return of the troops, they were received with the utmost enthusiasm, commanders and men being fêted and thanked, both at Cape Coast Castle and in England, for their brilliant services. The expedition entered Portsmouth in March 1874, with loud demonstrations of welcome, the Black Watch especially coming in for a large share of popular attention.

Sir Garnet Wolseley had in London and elsewhere a repetition of the extraordinary reception he and his followers had experienced at Cape Coast Castle on their triumphal return from Kumasi.

A civic banquet was given in April by the Lord Mayor of London in the Egyptian Hall, at which nearly three hundred guests sat down, including nearly all the officers of the expedition. Among those present were the Prince of Wales, Prince Arthur, the Duke of Cambridge, and the Duke of Teck, besides a number of members of the Cabinet. But although the bulk of the honours naturally fell to Sir Garnet Wolseley and the senior officers of the expedition, and Wauchope's name scarcely appears in these public demonstrations, his friends in Scotland had their eye upon the young lieutenant who had in a few short months carved out for himself a distinguished reputation, and had added to the laurels of the house of Niddrie. The people of Portobello specially determined to show their appreciation of his gallant services by a public banquet, and though at first the natural modesty of the young soldier shrank from such a recognition of his services, after some persuasion he consented. The {47} banquet took place on the 12th June in the Town Hall. There was a large gathering of the principal inhabitants. Provost Wood presided, and was supported by, among others, Sir James Gardiner Baird, Lord Ventry, and a number of county gentry.

In proposing the toast of the evening, Provost Wood took occasion to say:—'We are met to do honour to a soldier who volunteered to serve on the staff of General Wolseley in the recent war. At that time it was thought that British troops would not be required, but that the friendly natives, commanded and disciplined by British officers, would be able to cope with the savage Ashantis. Lieutenant Wauchope, on his arrival at the Gold Coast, was appointed one of the officers of the Haussas—a body of natives who proved themselves superior in courage and endurance to any of our African allies. Commanded and led by British officers—the chief being the gallant Lord Gifford—these troops did much valuable service. They formed the van of our advancing army, and were frequently engaged in the most severe and wild fighting. Our guest, in his ardour to see active service, had voluntarily separated himself from his own regiment. Yet he was destined to share with them the dangers and glory of the war. The War Office, finding that the Ashantis were more formidable than was at first expected, and that our native allies were less to be relied upon, resolved to send out British troops. This meeting must feel proud, as an assemblage of Scotsmen, that the 42nd Royal Highlanders was one of the chosen regiments, and our guest must have felt gratified when he found he had an opportunity of fighting beside his own regiment at Amoaful; and at that place, while leading on his Haussas, our gallant guest was wounded. He did not, however, fall to the rear, but continued to {48} push forward, and, along with the glorious 42nd, he entered the now famous city of Kumasi. I need scarcely recall the events of the campaign—how a very small British army, with little assistance from native allies, in the course of a few weeks beat and shattered the enormous Ashanti forces, and compelled the hitherto unconquered Ashantis to sue for peace, and give freedom and security to the country round. It has always been the pride and the pleasure of the people of this country to do honour to those who have fought and bled for their country's cause, especially so when that cause is associated, as it was in this instance, with the spread of civilisation and the prevention and prohibition of slavery and cruelty. The newspaper reports showed us that the Lothians had gallant representatives at the Ashanti war, and the people of Portobello felt proud to see the old and honoured name of Wauchope prominently noticed. We also felt a desire to give expression to the sympathy and respect we entertain for the house of Niddrie by a public demonstration in honour of a young scion of that house, who has proved that he has within him a dauntless spirit worthy of his ancient lineage. We desire this evening to congratulate our guest, that a kind Providence has guarded his life, and protected him through the imminent risks of a pestilential climate and the dangers of a wild war; and we hope yet to see Lieutenant Wauchope rise to that high position in the service which his talents and abilities so eminently qualify him to fill.'

Banquet at Portobello

Lieutenant Wauchope's reply was characteristic of the man. He was not quite so much at his ease, or felt he was in his proper place, as if he had been at the head of his Haussas. 'He thanked the Provost for the too flattering words in which he had referred to his services. He had {49} not deserved such great honour at their hands. His services as rendered to the State were poor and insignificant—very much so indeed. But he felt himself standing on firmer ground when he remembered that he was an officer in the 42nd Royal Highlanders. He recognised in the entertainment a desire to mark their appreciation of the conduct of the regiment to which he had the honour to belong. He had no hesitation in saying that the 42nd deserved well of its country, and he thought that it had added honour to its history.

'They were all well aware that the Ashantis had invaded our allies' country, and had perpetrated many horrible cruelties. Our representative on the coast sent remonstrances and threats, but these were all in vain until backed by picked battalions. Two hundred marines were first sent out. They landed at a most unhealthy season, and most of them died. Sir Garnet Wolseley then arrived on the scene, accompanied by British officers, and the result was that the Ashantis were driven back beyond the river Prah, and within fifteen miles of Kumasi. On the 4th February, King Koffee gave instructions to his bodyguard that any man who ran away would have his head cut off. But even King Koffee himself had to run before the British bullets. He did not think that the lives that were lost, or the money that was spent, were given in vain, because it would show those barbarous nations that the glory of old England was not to be trampled upon with impunity—that if people would invade our territory and commit murders and crime, the retribution would be terrible. The British lion took a long time to rise. He was a grand old animal in his way; but when he did rise, the vengeance would be speedy. He believed that the King of Ashanti bitterly regretted the {50} day that he first invaded the British Protectorate.' He thanked the company for the high honour they had done him, and concluded with a few jocular remarks as to his connection with the town and district. He could assure them, he said, that if fortune should smile on him, and if on a future occasion he should return from some campaign as a successful soldier, he should be disappointed if he was not entertained by them in a similar manner. He was proud of the district—of the county which gave him birth. He had often said to himself that he would spend the latter days of his life in Portobello. It might be that yet he would take the position of a town councillor of the Burgh. He had no doubt he would make a most excellent civil magistrate, and be a terror to evil-doers! In afterwards replying to the toast of the House of Niddrie, Lieutenant Wauchope referred to the long connection it had with the district, and 'expressed the hope that as it had never brought dishonour upon its name, it would never do so in the future. So far as in him lay, he would always try to sustain its honour.'

It is perhaps not wise to attach too much importance to after-dinner speeches, but there is a ring of sincerity of purpose in these last words, which in the light of after events gives them an importance they might not otherwise have. Wauchope lived up to his ideal standard of a chivalrous knight, and nobly upheld the honour of his name. What Chaucer five hundred years ago wrote of his imaginary knight, we to-day may say of our real one:

'He nevere yit no vileinye ne sayde

In al his lyf, unto no maner wight,

He was a verray perfight gentil knight.'

Father and son

Wauchope's father was unfortunately unable to be present on so auspicious an occasion on account of the state of his health, but he was much gratified by this public recognition of his son's services. The latter, still in indifferent health, with the slug-wounds in his chest giving him no little trouble, had, however, a long period of rest, and was much of the time at Niddrie. His attention to his father was very marked while at home—father and son being frequently seen arm in arm walking through the grounds.

DEATH OF WAUCHOPE'S FATHER—ORDERED TO MALTA—REMINISCENCES—RELIGIOUS CONVICTIONS—CYPRUS—APPOINTMENT AS CIVIL COMMISSIONER OF PAPHO—REMINISCENCES—SIR ROBERT BIDDULPH—THE SULTAN'S CLAIMS.

In November 1874 Wauchope had the misfortune to lose his father, for whom, especially since the death of his much-loved mother in the summer of 1858, he had the closest affection, never permitting any opportunity to pass without visiting the paternal roof. Though Mr. Andrew Wauchope of Niddrie was only fifty-six when he died, he had for some years been very much of an invalid, and was latterly unable to take any active part in public business. He spent much of his time in and about his house and grounds, taking a considerable interest in their improvement; but outside he was well known for his efforts to improve the position of those dependent upon him, and for his quiet but consistent Christian character.

He attended for several years before his death the Free Church at Portobello, then under the ministry of the Rev. Robert Henderson Ireland. There was no more regular attender of the church than Mr. Wauchope, who was generally accompanied by one of his daughters, and by his son Andrew when he happened to be at home, and {53} to the last the friendship between Mr. Wauchope and his minister was of the most cordial and kindly nature. We believe he often expressed his sense of the benefit he derived from sitting under Mr. Ireland's ministry.

On Mr. Wauchope's death Lieutenant Wauchope's elder brother, William John Wauchope, then a Major in the Enniskilling Dragoons, succeeded to the estates, and in some measure this change altered his relationship to the old home. It could not now be the same to him as formerly, though he was on the most friendly terms with his brother, and not unfrequently spent some of his time at Niddrie and Yetholm.

There is little doubt that his father's death, coupled with his own precarious state of health, brought to his mind a deeper conviction of the seriousness of life, and led to his forming more pronounced views of religious truth. But Lieutenant Wauchope, having creditably won his spurs and fought and bled in his country's service, was not the man to rest upon his laurels. He was ready, notwithstanding former wounds, for further service when the occasion might arise.

Ordered to Malta

In November 1875 he again joined his regiment at Malta, where it had been stationed for nearly a year. His arrival among his old comrades was the occasion of a cordial welcome at the Floriana barracks, and he at once threw himself with spirit into the whole work and drill of the regiment, taking a lively interest in the welfare of the men and also of their wives and children. A brother officer who was then also a subaltern, and had joined the regiment at Malta a few months later, says: 'Wauchope was the "Father of the Subalterns" or senior Lieutenant, and right well he "fathered" newly joined youngsters, always ready to help them in any way—lending {54} them ponies to ride and play polo on. I was always,' he continues, 'associated with him on the mess committee, and served under him, and what struck one most about him was the thoroughness with which he tackled whatever was on hand.'

As regards the rank and file, he was a very brother to many of them, as the following from one of the colour-sergeants will show:—'Lieutenant Wauchope was always a favourite with the men, and in Malta he took a deep interest in them and did much for them, always manifesting a kindly sympathy towards any who were married without leave, or who happened to be involved in any trouble which entailed a deduction from their pay. On pay-day, while the sergeant was paying the men, Wauchope would often sit at the table looking on, and note any who got only a few coppers on account of stoppage for support of wife and family, or for other reasons. He would quietly tell them to wait a little till the company was all paid. Then he would speak to each separately, giving them a word of sympathy or admonition, along with a piece of money, expressing the hope as he dismissed them that they would try to do better in the future. This was so unusual as between officers and men that it had a wonderful effect upon them.' Even in their recreations and amusements he showed an interest, and encouraged them in every possible way. 'He kept a small yacht while at Malta, and he was in the habit of inviting the sergeants to an afternoon's enjoyment in cruising about the harbour for an hour or two.'

Life in Malta

With him, care for his men was his first thought; and in commanding the G company of the 42nd in Floriana barracks, another of his sergeants observes 'that even in the hot summer afternoons, when the men were lying {55} down in their beds, he used regularly to sit on the barrack-room table lecturing them on minor tactics, often, I fear, more to his own satisfaction than to their edification!'