Title: The Girl's Own Paper, Vol. VIII, No. 362, December 4, 1886

Author: Various

Release date: May 16, 2021 [eBook #65358]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Susan Skinner and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

{145}

Vol. VIII.—No. 362.

Price One Penny.

DECEMBER 4, 1886.

[Transcriber’s Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

MERLE’S CRUSADE.

CHRISTMAS GIFTS.

THE AMATEUR CHOIR TEACHER.

“SHE COULDN’T BOIL A POTATO.”

“NO.”

THE SHEPHERD’S FAIRY.

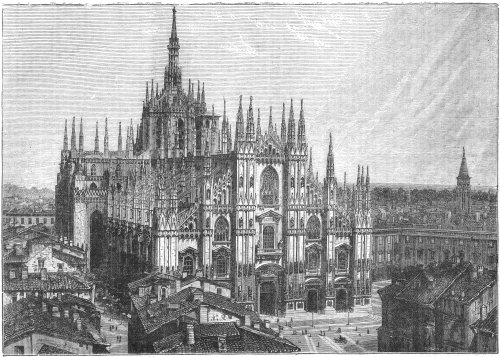

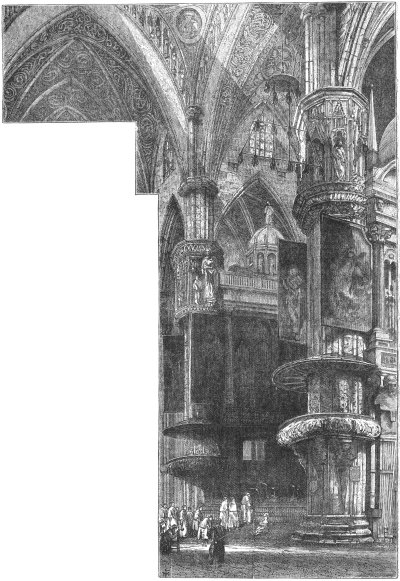

OUR TOUR IN NORTH ITALY.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

By ROSA NOUCHETTE CAREY, Author of “Aunt Diana,” “For Lilias,” etc.

“‘OH, MERLE!’ SHE WHISPERED, IN A VOICE OF AGONY.”

All rights reserved.]

{146}

BERENGARIA.

he bright spring days found me a close prisoner to the house. The end of April had been unusually chilly, and one cold rainy night Reggie was taken with an attack of croup.

It was a very severe attack, and for an hour or two my alarm was excessive. Mrs. Morton was at a fancy ball, and Mr. Morton was attending a late debate, and, to add to my trouble, Mrs. Garnett, who would at once have come to my assistance, was confined to her bed with a slight illness.

Travers had no experience in these cases, and her presence was perfectly useless. Hannah, frightened and half awake as she was, was far more helpful. Happily Anderson was still up, and he undertook at once to go for the doctor, adding, of his own accord, that he would go round to the stables on his return, and send the carriage off for his mistress. “She is not expected home until three, and it is only half-past one, but she would never forgive us if she were not fetched as quickly as possible.”

I thanked Anderson, and begged Hannah to replenish the bath with hot water. Happily, I knew what remedies to use; my former experience in my schoolfellow’s nursery proved useful to me now. I remembered how the doctor had approved of what I had done, and I resolved to do exactly the same for Reggie. Frightened as I was, I am thankful to know my fears did not impede my usefulness; I did all I could to relieve my darling, and Hannah seconded my efforts. I am sure Travers wished with all her heart to help us, but she had no nerve, and her lamentable voice made me a trifle impatient.

It was a great relief when Anderson appeared with Dr. Myrtle. He waited for a few minutes to hear from the doctor that all dangers had been averted by the prompt remedies, and then he went in search of Stephenson. It was some time before we heard the sound of carriage wheels.

Reggie was still wrapped in a blanket on my lap, and had just fallen asleep, worn out by the violence of the remedies still more than by the attack. Dr. Myrtle whispered to me not to move, as he would speak to Mrs. Morton downstairs, and enforce on her the need of quiet. It would have been grievous to wake the exhausted little creature, and I was quite content to sit holding him in my lap until morning, if Dr. Myrtle thought it well for me to do so.

I had forgotten all about the fancy ball, and my start when I saw Mrs. Morton standing in the doorway almost woke Reggie. I really thought for a moment that I was dreaming. I learnt afterwards that she had taken the character of Berengaria, wife of the lion-hearted Richard, but for the moment I was too confused to identify her. She was dressed in dark blue velvet, and her gown and mantle were trimmed with ermine; she wore a glittering belt that looked as though it were studded with brilliants, and her brown hair hung in loose braids and plaits under a gold coronet. As she swept noiselessly towards us, I could see the tears were running down her cheeks, and her bosom was heaving under her ermine.

“Oh, Merle!” she whispered, in a voice of agony, as she knelt down beside us, “to think my boy was in danger, and his mother was decked out in this fool’s garb; it makes me sick only to remember it; oh, my baby, my baby!” and she leant her head against my arm and sobbed, not loudly, but with the utmost bitterness.

“Dear Mrs. Morton,” I returned, gently, “it was not your fault; no one could have foreseen this. Reggie had a little cold, but I thought it was nothing. Oh, what are you doing!” for she had actually kissed me, not once, but twice.

“Let me do it, Merle,” returned my sweet mistress; “I am so grateful to you, and so will my husband be when he knows all. Dr. Myrtle says he never saw a nurse who understood her duties so well; everything had been done for the child before he came.”

“Oh, Aunt Agatha, if only you and Uncle Keith had heard that!”

We had talked in whispers, but nothing seemed to disturb Reggie. A moment after Mr. Morton came hurriedly into the nursery; he was very pale and discomposed, and a sort of shock seemed to pass over him as he saw his wife.

“Violet,” he whispered, as she clung to him in a passion of weeping, “this has unnerved you, but, indeed, Dr. Myrtle says our boy will do well. My darling, will you not try to comfort yourself?”

“I was at Lady S.’s ball when Muriel, our precious baby—oh, you remember, Alick”—for she seemed unable to go on. Poor woman, no wonder her tears flowed at such a memory. Mrs. Garnett told me reluctantly, when I questioned her the next day, that baby Muriel had been taken with a fit when Mrs. Morton and her husband were at a ball, and the mother had only arrived in time to see the infant breathe its last.

“Yes, yes,” he said, soothing her, “but nothing could have saved her, you know. Dr. Myrtle told you so; and you were only spared the pain of seeing her suffer. Try to be sensible about it, my dearest; our baby has been ill, but everything has been done for him; and now he is relieved, poor little fellow. We have to thank you for that, Miss Fenton. How nicely you are holding him! he looks as comfortable as possible,” touching the boy’s cheek with his forefinger. “Now, my love, let me relieve you of this cumbrous thing,” taking off her coronet; “this mantle will unfasten, too, I see. Now, suppose you put on your dressing-gown, and ask Travers to make you and Miss Fenton some tea. I will not be so cruel as to tell you to go to bed”—as she looked at him, pleadingly. “If you were a wise woman you would go, but I suppose I must humour you; but you must get rid of all this frippery.”

“Oh, Alick, how good you are!” she said, gratefully, and in a few minutes more she returned in her warm, quilted dressing gown, with her hair simply braided; she looked even more beautiful than she had done as Berengaria.

Mr. Morton soon left us after placing his wife in my charge. The night passed very quickly away after that. When Reggie stirred I put him in his cot, and begged Mrs. Morton to lie down on the bed beside him. She did not refuse; emotion had exhausted her, but her eyes never closed. She told me long afterwards she dared not sleep, lest the old dream should torment her of the dead baby’s hand, that she could never warm with all her efforts.

“I can feel it quite icy cold in mine, and sometimes there is a little cold face on my bosom, but nothing ever warms them, and when I wake up I am shivering too.”

I could not tell what was passing through the poor mother’s mind, but I did not like the feverish look in her wide, distended eyes. Mr. Morton was right, and the shock of her boy’s illness had utterly unnerved her. I thought, perhaps she was blaming herself needlessly, and yet never was there a human being more utterly devoid of vanity and selfishness; she was simply sacrificing her maternal duties to her husband’s ambition; of her own accord she would never have entered a ball-room; I am sure of that.

I longed to soothe her, and yet I hardly knew what to say. Presently she shivered, and I covered her up carefully with all the wraps I could find, and then knelt down and chafed her hands.

“You cannot sleep, Mrs. Morton; I am so sorry, and yet you are tired out.”

“I do not want to sleep,” she answered. “I dream badly sometimes, and I would rather lie awake and listen to my boy’s breathing; he is sleeping nicely, Merle.”

“Yes, indeed; there is no need for anxiety now, and I am watching him carefully.”

“Oh, I can trust you,” with a faint smile; “I trusted you from the first moment. But, my poor girl, I am afraid you are very tired, and I have taken your bed from you.”

“I would rather see you resting there, Mrs. Morton.”

“Do you think you could read to me a little? My husband often reads to me when I am nervous and cannot sleep. Anything will do, the simplest child’s story; it is just the sound of the voice that soothes me. What is that book? Oh, the Bible! I am afraid I do not read that enough, I have so little time to myself, and then I am often too tired.”

“It is just the book for tired people,” I returned; “if you want a story. I think the history of Ruth is one of the most touching, she has always seemed to me one of the sweetest characters in the Bible; it is a perfect idyll of Oriental life.”

“It is so long since I have read it,” she returned, apologetically, “you shall read it to me if you like.” And I read{147} the whole book throughout to her, only pausing now and then to look at Reggie.

She listened to it without interrupting me once, but I was rejoiced to see that the strained expression had passed out of her eyes; they looked more natural.

“You are right, Merle,” she observed, when I had finished, “it is very beautiful and touching; that was something like love, ‘where thou goest, I will go.’ Now you may read me a psalm, if you are not tired. I like your voice, it is so clear and quiet.”

I read to her until she bade me stop; and then we talked a little. I told her an incident or two in my school-days about our nutting expeditions in the Luttrell woods, and how one of our party had strayed and had encountered a gipsy caravan. I was just in the middle of Rose Mervyn’s recital, when I heard measured breathing. She had fallen asleep.

I saw a great deal of Mrs. Morton during the next few days. She was very unwell, and Dr. Myrtle insisted on her giving up all her engagements for a week. He spoke very decidedly, and Mr. Morton was obliged to yield to his opinion; but he seemed a little put out.

“It is such a pity all those people should be disappointed,” he observed, in a grumbling voice. “Mrs. Granville had quite set her heart on having us both on Thursday. I knew how it would be when you fretted yourself ill last night.”

“I could not help it,” she pleaded. “Anderson gave me such a fright; of course, he thought his coming for me was the best, but when I saw his face I thought I should have died with fear.”

“Nonsense, Violet, you ought to learn more self-control; you know I dislike to see you give way so entirely. Well, we must abide by Dr. Myrtle’s orders and treat you as an invalid.”

“But, Alick,” detaining him as he was turning away, not in the best of humours, as I could see from the night nursery, “I can write for you all the same; the library is quite warm.”

“How absurd!” was the reply. “Do you think I should let you tire yourself for me? I hope I am not quite so selfish, my dear child,” for she was still holding his arm beseechingly; “you must really let me go, for I am dreadfully busy; rest yourself and get well, that is all I ask of you,” and he kissed her and left the room. He was not often hasty with her, but he was overworked and irritable.

We made the most of that week between us. Reggie soon recovered, and as long as he was kept in a certain temperature, and carefully watched, gave us no further anxiety.

His mother took entire charge of him during that week; she came up to the nursery as soon as she was dressed, and stayed with us until Reggie was in bed and Travers came to summon her. She even took her meals with us. Dr. Myrtle thought she was suffering from a chill, and the warm nursery was just the right temperature for her. It was a lovely sight to watch her with her children. I think even Mr. Morton was struck by the beauty of the scene when he came up one afternoon and found her sitting in her easy chair with Reggie on her lap and Joyce standing beside her.

“You seem all very happy together,” he said, as he took up his position on the rug. I had retreated with my work into the other room, but I could hear her answer distinctly.

“Oh, Alick, it has been such a happy week—a real holiday; it was worth being ill to see so much of the children; Reggie has such pretty ways; I knew so little about him before. He can say ‘fada,’ quite plainly.”

“Indeed, my boy, then suppose you say your new words.”

“Do you know what I have been wishing all this week?” she continued, when Reggie had finished his vocabulary, and had been taken into his father’s arms.

“No, my dear,” sitting down beside her, “unless you wished for me to be a Cabinet Minister.”

“Oh no, Alick,” and there was pain in her voice, “not unless you wish it very much too; I had a very different desire from that.”

“Perhaps you were longing for a house in the country; well, that may come by-and-by.”

“Wrong again, Alick. I was wishing that you were a poor man—not a very poor man, I should not like that—and that we lived in a small house with a pretty garden where there would be a lawn for the children to play on, and plenty of flowers for them to pick.”

“Indeed! this is a strange wish of yours, you discontented woman.”

“No, not discontented, but very, very happy, dear, so you need not frown over my poor little wish; everyone builds castles, only mine is not a castle, but a cottage.”

“I should not care to live in your cottage, Violet; I am an ambitious man. The Cabinet would be more to my taste.”

“Yes, dear,” with a sigh, “it was only make believe nonsense,” and she did not say another word about that fancy of hers, but began questioning him about last night’s debate. That was just her way to forget herself and follow his bent. No wonder he could not do without her, and was restless and ill at ease if she were unavoidably absent.

I wonder he understood in the least what she meant by wishing him to be poor. No doubt her innocent fancy had constructed a home where no uncongenial anxieties or ambition should sever her from her children, where she should be all in all to them as well as to her husband.

I daresay she imagined herself no longer burthened with wearisome receptions, but sitting working in the shade of the little porch while her children made daisy chains on the lawn of that humble abode. The mother would undress her children and hear them say their little prayers. Hark! was not that a click of the gate? Father has come home. How late you are, Alick; the children are asleep; you must kiss them without waking them. Hush, what nonsense, she is dreaming. Alick would be in the Cabinet; people were prophesying that already. She must take up her burthen again and follow him up the steep hill of fame. What if her woman’s heart fainted sometimes, women must do their work in life, as she would do hers.

The next day the mother’s place was empty in the nursery. “Mrs. Morton was with her husband in the library,” Travers told us. Later on we heard she was driving. Just as I was putting Reggie, half asleep, in his cot, she came up to wish the children good-night, but she did not stay with us ten minutes. I remarked that she looked very ill and exhausted.

“Oh, I am only a little tired,” she returned, hurriedly; “I have been paying calls all the afternoon, trying to make up for my idle week, and the talking has tired me. Never mind, it is all in the day’s work.” And she nodded to me kindly and left the room.

(To be continued.)

{148}

ith the approach of Christmas and Christmas gifts, the cares of the girl members of a large family may be said to arrive at a crisis. There is no girl so friendless or so heartless that there is no one she loves or wishes to remind of that love at this season, while there are many surrounded by affectionate relations and true friends, whose love they warmly return, and whom they wish to please with a gift, and yet have but a small sum at command, and must think carefully over its division.

How many anxious calculations have to be made, what knitting of smooth brows, what hasty arithmetic on stray scraps of paper, what self-denial in personal matters to increase the little store, and then, when the materials are bought, what secret work is carried on behind father’s chair, should he happen to be awake, and in this and that out-of-the-way nook of the house, so that the all-important, and generally extremely apparent, secret is not divulged until the Christmas or New Year’s morning!

All honour to this secrecy, this planning and patient work! It is the true spirit of present-giving; and let not any of our readers despise it as childish; rather let them remember that that which costs no time, no thought, no self-sacrifice is but of little value in the eyes of affection, and pleases only where the gift is valued for itself, and not for the giver. The girl who can walk into a shop and select the first handsome article in it for mamma, and pay for it from an amply-supplied purse, neither awakens in herself or her mother the same holy feelings that are excited when baby works an impossible kettle-holder “all by herself,” and which she “bided” out of the pennies given her for sweeties.

Admiring and sympathising as we do with girls who are generous-minded and do not count labour and time when anxious to please, we have brought together in this paper, with the idea of helping them, several useful and pretty articles that can be made without any great expense.

For a small present, costing at the utmost one shilling, the fashionable little “hold-all bags” are good. These bags are four in number, and are connected together only at the top; they are filled with odds and ends, such as buttons and silks, until they stand upright and all of a row, and they find a conspicuous place among drawing-room nick-nacks.

To make them, purchase one yard of good satin ribbon, in colour either ruby, navy blue, or chestnut brown, with the reverse side of a pale blue or old gold shade. The ribbon should be from two and a half to three inches wide. Divide the yard into four equal portions, sew over the sides, and hem the tops of two bags without decorating them, but work on one of the other bags a handsome and legible monogram containing the initials of the person for whom the present is intended. Work this with fine gold-coloured purse silk, and surround the chief outlines with Japanese gold thread. On the other bag work a small spray of flowers, either a branch of wild rose, a bit of heather, forget-me-not, or jessamine. Sew up these two bags, and hem them round like the others; then make sixteen eyelet-holes, four on each bag; make these round and not very big, and place them opposite to each other, and at the extreme corners of the opening. Sew the bags together by overcasting the first bag with its monogram turned outwards on the inner side of its opening to the outer side of the opening of one of the undecorated bags. Attach the second plain bag to the inner side of the first plain bag, and sew the fourth bag, with its decorated side turned outwards, to the inner side of the third bag. By this arrangement both the decorated bags are outside, and every bag at its base is separate. Finally, take a silk dress lace, the colour of the satin ribbon, and run that through the eyelet-holes to make a draw-string. Fill the bags, plant them out on the table, and draw their openings slightly together.

These “hold-all bags,” instead of being filled with odds and ends, are sometimes turned into flower-vases. The smallest-sized penny tumblers are inserted into each bag and filled with cut flowers, or the smallest size flowerpot, filled with a tiny fern, is used. In the latter case, a piece of American cloth is fastened round the pot to prevent any moisture soiling the satin bag.

The present method for concealing flower-pots when required for drawing room decoration makes another simple but acceptable present. This is a bag of plush, into which the pot is put. To make this bag of plush, cut a round of millboard or stiff cardboard the size of the bottom of an ordinary flower-pot. Take a piece of plush, in width twice the circumference of the centre part of the pot, and in height the height of the pot; sew the two ends of the plush together, and make a hem an inch and a half wide. As a finish to the upper part, just below this hem, on the wrong side of the bag, run on a narrow piece of black tape to hold a draw-string, which make by running in a piece of strong elastic, that will draw in the fulness of the plush until it fits the upper part of the flower-pot tightly. Gather the lower ends of the plush, arrange evenly round the piece of millboard, and sew to the latter with the edges concealed, using strong thread for the securing stitches. When the plush cover is used, its millboard foundation keeps the bottom of the pot (which may be damp) from doing any damage to the furniture, and the wide hem beyond the draw-string stands out as a frilling a little below the edge of the pot. Half a yard of plush, which costs two shillings, will make a pair of flower-pot covers.

From America comes to us a novelty in bedroom decoration, and one very suitable as a present to a young lady who uses her bedroom as a sitting-room and likes it prettily decorated. This is known as a “pillow sham,” and is a long strip of linen or cambric ornamented with lace and ribbons, and laid over the top part of the bed in the daytime only. It fits the width of the bed whatever size that is, and does not fall down the sides. If the worker is an adept at drawn-thread work, the pillow sham can be made very inexpensively and of material that will last through much wear, but when drawn-thread work is not used, Torchon and other strongly made lace is required. An easy way for making a pillow sham is to buy four new hem-stitched-bordered handkerchiefs, and upon the corner of one of the handkerchiefs to embroider the first letter of the owner’s Christian name, making it four inches high and slanting it from the corner to the middle of the handkerchief. Join these handkerchiefs together, inserting between each an inch and a half wide strip of Torchon lace insertion, and bordering the handkerchiefs lengthways with a line of the same, so that each square of cambric is surrounded by insertion lace. Finish with a frill of Torchon lace edging, which carefully whip to the insertion lace. A careless bow of ribbon or one of Liberty’s silk scarves tied in a bow is sewn to the corner of the pillow sham, just above the embroidered corner.

When using drawn-work instead of lace insertion, a piece of linen the length and width of the sham is taken, and the threads from this are drawn out as strips down the width, leaving five squares of plain linen between them. After working the strips over with linen thread into a pattern, narrow coloured ribbon is run down the centres of the drawn-work, and the linen squares embroidered with washing cotton of the same colour as the ribbon. An edging of lace finishes the border, and into this lace a line of narrow ribbon is threaded.

Another variety of pillow sham is made by sewing together five or eight pocket handkerchiefs with coloured borders, and ornamenting the same with a large knot of narrow ribbons of various shades of colour. The handkerchief borders in this case need not be alike, but should blend together, and their colours should be used as some of the colours in the knot of ribbons.

Palm-leaf fans still find favour as drawing-room fans, but are no longer left undecorated. The two newest ways of decorating them are as follows:—Take a well shaped and strong fan and paint it with oil-colours, with which a very little varnish has been mixed, either a very bright yellow or a brilliant scarlet. Give two coats of colour, and let the fan dry. Buy some ribbon half an inch in width; in colours, black, vivid green, sky-blue, and yellow-pink. Make a wide vandyke running down one of the lengths of ribbon by taking the running thread in diagonal lines across the ribbon from edge to edge. Draw the ribbon up so that it forms a number of pointed vandykes, sew the strips down the ribs of the fan at equal distances apart, and use black ribbon more than the other colours. Sew on a line of red gold tinsel between each strip of ribbon, and finish the handle with a knot of coloured ribbons.

The second make of fan requires a piece of plush, some narrow coloured silk cords, and various shades of tinsel. The cords are obtained by buying a yard of a twisted silk cord made up of various shades, and using the strands of this separately. Cut the piece of the plush the size of half the fan, so that it covers the fan on one side from the tip of leaf to the handle. Fasten this round the edge to the back of the fan, and ornament its straight edge on the fan with a line of tinsel on the uncovered side of the fan. Sew down each rib alternate lines of coloured silk cord and double lines of tinsel, using as many varieties of tinsel as possible, and arranging the cords with due regard to effect. Take three long peacocks’ feathers, and fasten these across the piece of plush and sew their ends together close to the handle of the fan. Cover the handle with a piece of plush, and arrange a bow and ends of ribbon round the handle and to conceal the peacock feather ends. Line the back of the fan with thin silk or dark twill.

Blotting-book covers of velveteen are always acceptable presents. The foundation for these is a sixpenny blotter, size ten inches by eight inches, while three quarters of a yard of velveteen (price three shillings the yard) will make two covers, with a piece of brown holland or blue twill for the inside lining. The decoration for these covers is embroidery,{149} but this is only worked on the upper side of the blotter, the underside being left plain, so as not to interfere with its usefulness. The embroidery can be of any description of silk embroidery, either oriental embroidery with its quaintly-formed but impossible flowers and foliage, or sprays of naturally-tinted flowers worked in crewel silks, and both worked directly on to the velveteen foundation; or silk embroidery finished with a gold thread outline and worked upon a coloured rep silk foundation, and sewn on as an ornamental corner to the blotter; in fact there are many ways of ornamenting the cover, and the embroidery the worker is most proficient in should be selected. If church embroidery is within her capabilities, we advise the initials or coat of arms of the owner being worked in a frame on linen, cut out and couched down to the velveteen foundation with gold thread or gold cord; but such elaborate embroidery is not often obtainable. The way to make up the blotter is to cut the holland lining exactly the size of the sixpenny blotter, and the velveteen a little larger. Turn in the edges of both, and overcast them together, enclosing the stiff cover of the blotter between them, and sewing the blotting paper sheets in when the cover is made. Bradshaw covers are made like blotters, but naturally take less material, and are only embroidered in one corner.

Large photograph-holders can be easily made at home. These are used for the display of a number of cabinet photos, and are fitted with bands, into which the photograph is slipped and easily taken out. The size of such a stand is usually seventeen inches long by thirteen inches high, but they can be made of any size desired. The foundation is of millboard, to which a millboard support is fastened by its being glued to stout tape and the tape glued to the millboard, with sufficient width of tape left between the two pieces of millboard to allow the support to work. The upper side of the millboard is covered with quilted satin. The satin is selected of some bright colour, and the quilting lines are run as diagonal lines, not as making diamonds. Three tight bands of satin are sewn across the quilting; these are two inches in width, and require a lining of stiff net when made up. They are embroidered with coloured silks, either forming a running design, such as a spray of jessamine or celandine, or with some geometrical pattern constantly repeated. When finished and lined, the bands are placed as diagonal lines across the satin, not as horizontal lines.

For a photograph-holder the size given, the first band will be eleven inches in length, and will cross from the top of the holder to the left-hand side; the second band will be nineteen inches in length, and will cross from the extreme top corner of the frame on the right side to the bottom of the frame on the left; the third band will be twelve inches in length, and will be arranged beneath the last-mentioned, crossing from the right side to the bottom of the frame. Into these bands the photographs are stuck; therefore, they must be sewn firmly down at the sides where they end and commence, and stretch tightly across the quilted frame. On the right-hand bottom corner of the foundation, which is never covered with photographs, the owner’s initials are sometimes worked in black silk over the quilting lines. This makes a good finish, but is not essential.

Bachelors’ wall pincushions are useful presents for gentlemen. They are made of plush, and are ornamented with the perforated brass ornament used about the harness of cart-horses. These brass rounds are sold by all harness and saddle makers, and cost from sixpence to a shilling, and for the latter price the small brass handle by which they hang will be removed by the shopman, as it is not required for the pincushion. A quarter of a yard of plush, a quarter of a yard of house-flannel, and one yard of narrow satin ribbon are required for these cushions. To make them, tear up the house-flannel into an inch and a quarter wide widths. Roll these strips very tightly one over the other as a wide narrow wheel, and keep the strips firm by sticking pins through the wheel. When a round as large as the perforated brass is made, cut the plush into two rounds of the same size and a long strip an inch and a half wide. Cover one plush round with the perforated brass, and sew them both on the face of the wheel and well through to the back; turn the edges of the round of plush over the side, and sew on the round for the back of the cushion; conceal the edges of both pieces of plush with the narrow band, which turn in at its edges and secure tightly round the sides of the cushion. Make a loop of the ribbon to hang up the pincushion by, and sew the ends to the sides of the cushion, and with the remaining ribbon make a pretty bow, which fasten to the top of the loop.

The newest decoration for white wooden articles is the poker or burnt-wood work. This consists of burning down the background of any design so that the design itself is in relief. The fumes of the burning wood slightly colour the parts left untouched, and give an extremely soft and ivory-like appearance to the work, which, if carried out with the new apparatus introduced by Mr. Barnard, is quickly and easily accomplished.

The articles decorated with burnt wood work are all kinds of white wood photo frames, small wooden table screens, all kinds of boxes, bookslides, book cutters, drawing-room bellows, salt boxes, milking stools, tubs, paste rollers, etc. The best designs are those of large, single-petalled flowers, with their leaves, such as daffodils, daisies, and dog-roses. The design is drawn upon the wood, outlined with a burnt-in line, and its chief lines, such as divisions of flower petals, centres of flowers, veins of leaves indicated, and then the background burnt until it is depressed, and is of a warm brown deepening to black in colour. Mr. Barnard’s apparatus consists of a platinum point connected by an indiarubber tube to a bottle of benzine, which is connected with another indiarubber tube to a small air pump. The latter held in the left hand is pressed, forcing air over the benzine to the platinum point and keeping that always red hot. The right hand holds the point and uses it like a broad pencil, keeping it steadily pressed on the wood until that is deeply burnt in. This apparatus costs twenty-five shillings, but if several girls join together to purchase it, there is no further outlay. Small pokers are used if the apparatus is not procurable. These are about eight inches long and an inch in circumference; they are sunk in wooden handles, and kept hot in a fire; four to six are required at once, as they soon become cold. The parts of the wood not burnt, such as the back of a screen, the legs of a stool, require to be stained, sized, and varnished, and the burnt wood is also varnished (not stained) as a finish. The paste rollers are used for holding whips, keys, etc. They are hung to the wall with coloured ribbons, and have a row of hooks screwed into them to hang keys, etc., to.

B. C. Saward.

By the Hon. VICTORIA GROSVENOR.

n a former article we made some suggestions as to the possibility of improving a moderate gift for music with the view of learning to play the organ and qualifying for the noblest of service, that of leading God’s praise in His church.

We propose now to take up the subject of training choirs for the same excellent service, on the understanding that the future teacher has taken the advice already given as to her own musical improvement. Personal fitness for this branch of instruction is most necessary; as if once the taught discover they know anything of which the teacher has not more perfect knowledge, that teacher’s task will be a hard one. Therefore, there should be familiar acquaintance with every description of musical notation. Alto and tenor clefs should be well understood to be clearly explained when met with. On this subject we should like to recommend the careful study of “A Short Treatise on the Stave,” by the late Dr. John Hullah, published by Parker, where the whole matter is admirably set forth and illustrated on its own technical grounds. The often-heard, but somewhat slipshod explanation, “Oh! you must read a note higher or a note lower,” which leaves the puzzled learner very much where he was before, will thus be avoided. Even supposing the alto and tenor clefs are never met with, the study will repay the intending teacher by opening her mind and giving clearness to her musical ideas.

It will be seen, by what has been said, that we consider our amateur teacher’s first qualification should be thorough knowledge of her subject. The second should decidedly be untiring patience, which will bear with stupidity, carelessness, want of zeal, deficient ear, bad pronunciation, and all the thousand and one difficulties which beset choirs. These consist generally of volunteers who join with but little idea of giving of their best to God, and an impatient teacher would soon find herself in the lonely position of the last player in Haydn’s “Good-bye” symphony.

We would next place hopefulness in the teacher’s catalogue of moral furniture. The learners will soon find out if they are being taught without hope of their improvement; listless work will be the result, and the shy, anxious members will give it up in despair. The power of encouraging effort, of detecting and commending the slightest sign of improvement, of persuading the members mentioned above that the work is within their grasp, if persevered in, is most necessary, and a kindly sunny disposition ever ready to look at the brightest side is simply invaluable.

Next we should place regularity and perseverance.{150} Without these the teacher can do nothing. If she works in the best spirit she will feel that, like David, she cannot offer to God of that which doth cost her nothing, and she will be ready to forego little pleasures in order that the practice may not be interfered with, or the evening of the week changed. This last is a most important point; as the lives of working people, from whose ranks most members of choirs are recruited, do not adapt themselves to change, they seldom receive in its integrity a hasty message sent round to put off, and of all things, a walk for nothing after a day’s work is to be avoided. Of course rules must be elastic and not unbending as iron, but experience shows that the above advice is really needful. Regularity in the teacher is sure to be imitated by the learners, and steady work must tell in the end.

The next point should be firmness tempered with wisdom. The teacher must be supreme, or no choir will prosper. Infallible she cannot be while here below; but even so, one will must rule or anarchy will be the result. Twenty (or whatever number may compose the choir) views of doing the same thing cannot conduce to harmony, moral or musical, and this fact must be impressed. At the same time there are local prejudices and fancies in most places, which a clever tactful teacher will soon discover and understand, so as to know when she had better give way.

Enough has been said to show that we do not consider the task of teaching a choir an easy one, nor will it always repay with success those who have given it much trouble. The teacher must sometimes find herself grappling with the effort of making the proverbial “sow’s ear into a silk purse.” She has impossible materials to weld, such as, e.g., excellent, but roaring basses, trebles possessing no high notes, tenors out of tune, and leaning to amalgamation with treble, altos none! What is she to do? Courage! Go on, do your best, teach, exhort, scold, coax, never lose hope, and if you get no credit, try not to mind. Man does not know, but God does, what work you do for His sake, only be sure that you are so doing it. If the music be really the unattainable “silk purse,” how much may be done in teaching the inharmonious little choir to phrase well, to throw out by judicious accent the sense of canticle and hymn, and so lead the congregation to think of the lesson it contains! How much zeal may be kindled by the teacher’s energy! How speedily the broad dialect peculiar to the place will disappear before a little good-natured chaff and imitation from one in whose lips it is seen, even by its votaries, to be ridiculous! How the ill-used letter “H” may be helped and restored with the advice of breathing over it.

The reader will not, perhaps, think us very encouraging; but it is obvious that where excellent voices are to be had, forming them into a choir only needs intelligence and a firm hand from one who is equal in knowledge to the task undertaken. We have, therefore, tried to suit our advice to the needs of the many, who must perforce work under difficulty, being obliged to take, not the materials they desire to have, but only the heterogeneous ones at hand.

A few practical suggestions and we have done! Do not attempt too much in public. Congregations are very critical. One piece of music badly done will be more noticed than several faultless ones. On the other hand, keep on learning some music above the power of the choir for improvement and interest. In cold weather, when possible, choose music which does not try the voices too much by giving them sustained high notes to sing.

Lastly, work according to the views of the vicar of the parish, who is responsible for everything in it; try to carry out in the best possible manner whatever form of musical worship he desires to have in his parish church. You may not be of the same opinion; but you will gain nothing but good by putting your own views in the background and thus learning to obey as well as to teach. And may we not hope that the loving Father will acknowledge such work, even if imperfect in its results, as done by His child to His Glory?

By DORA HOPE.

Mrs. Wilson’s recovery was slow and tedious, even more trying to herself, perhaps, than to her nurses. She had always been particularly brisk and active, and had scorned to consider, or, as she said, “coddle,” herself in any way, and it was a great trial to her energetic, self-reliant nature to be waited on hand and foot, and watched over “like a baby.”

Ella, entirely unaccustomed as she was to illness of any sort, save her mother’s occasional attacks of asthma, thought the nurse was unnecessarily checking her aunt’s attempts to help herself, till Mrs. Mobberly explained to her what different treatment is necessary for different people, and how impossible it would be, with Mrs. Wilson’s active temperament, to prevent her from getting excited and over-tired if she once began to take any part in what was going on around her, although a little exertion might have been actually beneficial to one of a calmer and more indolent nature.

It seemed a long time before Mrs. Wilson was allowed any food more substantial than beef-tea, of which she wearied greatly in spite of the nurse’s many devices for varying it. She showed Ella how to alter the nature of it altogether by making it with half the quantity of mutton, or veal, instead of entirely beef; or with all three together. This not only made a pleasant change, but the doctor told them it was often found more easily digestible than when made of beef alone. Then again, both flavour and consistency were varied by adding cream, or an egg well beaten up, or thickening with corn flour, tapioca, wheaten flour, or rice, while at other times it was served clear, without either flavouring or thickening, or in the form of a jelly turned out of a tiny mould not larger than a teacup.

Gradually, however, Mrs. Wilson began to take more solid food, and then Ella’s great difficulties began. By the end of her first week’s experience of providing real meals for her aunt, she wrote to her mother that she had come to the conclusion that it was quite impossible to arrange dishes suitable in every respect for a sick room.

“Do pity the sorrows of a poor young housekeeper,” she wrote, “with three people to please, the doctor, the nurse, and the patient, and they all want something different. First comes the doctor, and tells me I must now devote my attention to making the dishes as nourishing as possible, as it is time aunt was picking up her strength again; so I crowd in all the strengthening things I can think of, and flatter myself I have made a mixture strong enough to restore the weakest invalid; and the consequence is that next day nurse tells me she has been up all night with her patient, whose supper was too concentrated to digest. Next time, inspired by nurse’s tale of sufferings, I make the simplest dish imaginable, which could not disagree with a baby, and it comes down almost untouched, with a sarcastic remark from Aunt Mary that when she is well she does not mind how plain her food is, but that in her present state of health she needs something to tempt the appetite a little. And yet——but I will draw a veil over the doctor’s reproaches when I ventured to make her a spicy little dish.”

But on the whole, in spite of her poor opinion of her own performances, Ella managed to supply the needs of the sick-room very satisfactorily; and she was much comforted on hearing from her mother that even the most experienced housekeepers find it a hard task to tempt the capricious appetite of an invalid, especially when it is necessary also that the food should be very nourishing, and at the same time so light as not to overtax the most feeble digestion, Mrs. Hastings sent her daughter a list of suggestions for little dishes for the sick-room, and added, at the close of her letter—

“At any rate, my child, if your task is difficult, as I know it must be, it is also satisfactory, for you can watch your patient each day able to take a little more nourishment, or a little more substantial food than the day before. You are saved the terribly sad duty of vainly trying to tempt an appetite which daily gets a little poorer, or of watching a dear one getting each day a little weaker, proving only too clearly that all your efforts are in vain.”

Happily Mrs. Wilson liked oysters, and, though she soon tired of them, as of everything else, they formed the basis of a number of tempting little dishes. The favourite of these, a suggestion of the doctor’s, was called “Angels on Horseback.” Ella was very anxious to know what the ridiculous name meant, but could get no information from the doctor, who said he had often wondered himself, but all he knew was that it was a favourite dish with invalids, and that was the name it had always gone by. Each oyster was taken from the shell, and the beard cut off, and was then rolled up in a very thin slice of bacon, tied round with cotton, and fried. Usually three of these little rolls were enough for a dish.

At first Ella’s generous nature led her into the mistake of sending up too large quantities of everything for the patient, but she soon learnt that a dish which would tempt an invalid if offered in small quantities, would be pushed aside in disgust if large and substantial-looking.

Next to “Angels on Horseback,” the favourite dishes were scalloped or stewed oysters; while for a little additional nourishment between meals, the nurse would often suggest a “Prairie Oyster.” This exceedingly{151} simple dish is not an oyster at all, but merely the raw yolk of an egg, served like an oyster on a small shell, with the smallest possible sprinkling of salt and pepper over it. The white must be very carefully strained off, so as to preserve the yolk unbroken, and it can then be slipped into the mouth and swallowed without any trouble to the patient.

Two other favourite dishes which the cook was particularly clever in making were jellied veal and faggots. For the former a small knuckle of veal was boiled till the meat slipped easily off the bones, which were then taken out. The meat was cut into very small pieces, and pepper, salt, mace, and thyme added to taste, with a small shalot chopped very fine. This was all put back into the liquor, and boiled again till it was thick, and then turned into a mould. When cold it formed a stiff jelly. Ella always found the flavouring a difficulty, for Mrs. Wilson’s taste as an invalid was of course very different from what it was when in health, and her digestion was very easily upset; but the cook obstinately declared that she knew her mistress’s tastes better than Ella, and in spite of all orders persisted in putting in flavouring according to her own fancy; so that many dishes which might have been simple and nourishing enough to be frequently asked for, had to be altogether prohibited, as being too spicy for the invalid’s delicate digestion.

For the faggots, a rump steak was cut into thin strips of about three inches by two, and on these was spread a little butter, with pepper, salt, and the smallest atom of minced shalot, or sometimes a few herbs. The strips were then rolled up, tied with string, and fried in butter or clarified dripping, and served up in gravy.

Then there were the different kinds of panada, made of slices of chicken or game cut off the bones, and scraped and pounded, and gently simmered in milk; not to mention the numberless ways of cooking eggs, buttered, scrambled, poached, and boiled, besides omelettes, custards, and milk puddings of all descriptions.

At last, Mrs. Wilson began to show signs of real improvement, and as her strength returned she was allowed to spend part of every day on her comfortable, old-fashioned sofa, while a few visitors were admitted to see her. The nurse kept a very watchful eye over these visitors, and after their departure sometimes expressed herself in very strong language to Ella, saying that, “They ought to know better than to tire out an invalid with stopping such a long time, and as for some of them, why, they don’t never seem to care how high they send Mrs. Wilson’s temperature up, with their worriting talk, and exciting the poor creature so.”

The nurse would have soon taken the matter into her own hands, and requested the visitors to retire when her patient began to look tired, but that Mrs. Wilson preferred Ella’s attendance in the room to that of the nurse when visitors came, and she was not sufficiently experienced to know when her aunt was beginning to get tired. The nurse hit upon a plan, at last, which afforded Ella a good deal of secret amusement. Mrs. Wilson’s spectacle-case was always placed on a little table by the side of her sofa, and the nurse arranged that, whenever she began to feel a little tired, and wished to be relieved of her visitors, she should take up this spectacle-case and lay it beside her on the sofa, which should be the signal for Ella, or the nurse, to suggest to the caller that Mrs. Wilson had talked as much as was good for her.

Every morning Ella had to bring an account of all the pets to her aunt, and under her searching questions revealed an amount of ignorance that quite appalled the old lady.

“You should not feed the ducks and hens together,” she said, one day, in answer to a remark of Ella’s. “Of course, the ducks eat more than their share, with their great flat bills. Where are your brains, child?”

Ella had a good deal of trouble with the fowls’ food at first. Their morning meal was soft food, consisting of “sharps” (the outer part of wheat, which is separated in grinding the corn for white flour) and barley meal, mixed in equal parts, and added to any kitchen scraps there might be. This was wetted with boiling water, and should have been made into a stiff, dryish paste—a point Mrs. Wilson had been most particular about. The cook, however, objected to any extra trouble; as it was much easier to pour in water enough at once to make the mixture wet and sloppy, she always did so; while, as for the kettle really boiling—well, that was only one of her mistress’s many fads.

Then there was the Indian meal, which ought not to have been used, except in the cold weather, and then only occasionally mixed with the other meal, but this had all been used up, and no fresh had been ordered, so the fowls had been fed on Indian meal alone, till that, too, was finished.

Again, with her liberal ideas, Ella gave them far more food than they could eat, and the wet, sour mess lay about all day; so that it was not at all to be wondered at that the fowls drooped, seemed out of order, and did not lay their proper quantity of eggs, and Ella, afraid of exciting her aunt by telling her they were ailing, only increased the evil by increasing the quantity of food.

This state of things had lasted some time, when the nurse took pity on Ella’s difficulties, and told her it would do her aunt no harm to be asked for advice about the fowls; so, to Ella’s great relief, they talked the matter over together, and a change was instituted in the feeding. Fresh meal of all kinds was ordered, and Ella had a practical lessons in mixing it.

Mrs. Wilson had all the materials brought into her room, and directed the process, while Ella, arrayed in a large apron, and with her sleeves turned up carefully, followed her instructions.

Some potato peelings and kitchen scraps had previously been boiled together till they were quite soft, and now Ella cut these up small, with an old knife, and then mixed the meal in equal parts, while waiting for the kettle to boil.

As soon as it boiled, the scraps were mixed in with the dry flour, and Ella, seizing the big wooden spoon, began to stir vigorously, while the nurse poured in the boiling water.

“Enough water,” Mrs. Wilson cried, in spite of the incredulity of the two operators, who had intended to put in twice as much. “Don’t stop beating it up, child,” and Ella continued till she was hot and breathless.

“Now take up a handful and squeeze it.”

Ella did so, and it fell from her hand a stiff lump, leaving her palm quite clean.

“That is quite right,” said Mrs. Wilson, encouragingly, after slowly arranging her gold spectacles, and peering at the mass in the basin. “See that it is always stiff like that; and never give them more than they will run after when you throw it for them. If you find any is left, do not give them so much next time. At night give them each as much grain as you can take up in your hand, but no more. You may give the ducks a little more, but stop at once when their hunger is not keen. Now go and feed them, child; I am tired.”

Under this treatment the fowls soon revived, and Ella was happy about them again, at any rate till she discovered that she had made other mistakes. She found the eggs she got now were much better and richer than those bought in shops, or even than those she got when the fowls were being carelessly fed, and that in consequence fewer of them were necessary in cooking.

One day, before she had began to take solid food, to the great delight of her nurses, Mrs. Wilson declared she was hungry, and had taken a fancy for a boiled egg. There were not many eggs from the hens now, but the ducks laid regularly; so Ella picked out a fine large duck egg, and carried in the prettily arranged tray herself; but what was her disappointment when, on breaking the shell, the egg was found not to be fresh. Her aunt pushed the tray away in disgust, the sight of the bad egg had quite turned off her appetite, and she refused to eat anything at all.

The nurse was very much vexed, and Ella herself was greatly distressed, and went off with the tray, more convinced than ever that housekeeping was not her vocation, and that she never would succeed in it.

The next time she was alone in the sick-room her aunt told her that she was evidently very careless about the eggs, and must begin to manage them differently. To begin with, she must use up all in the house as quickly as possible for cooking, and every fresh one that came in must be dated with lead pencil, and placed in order, with the large end downward, in a board pierced with round holes for the purpose, and which was kept in the cool larder. They were to be used in the order in which they were brought in, and, Mrs. Wilson added, severely, she hoped they would not soon disgrace themselves again by serving up a musty egg.

At the beginning of January, Mrs. Wilson directed Ella to bring a certain note-book and the writing materials.

“Now,” she began, as soon as Ella was ready, “you will find a list, at the beginning, of all subscriptions that are due. I want you to write to all the people, and enclose the amounts. I will write cheques for the large sums, but for the others you must get postal orders. Make a list of all you will want, and then you can get them when you go out.”

“But they have not applied for the subscriptions yet, auntie. I have brought you every application that has come. Would it not be better to leave them till they are asked for?”

But this did not suit Aunt Mary’s views at all. She pointed out to Ella that she kept a note herself of the date when her subscriptions were due, and therefore knew the time as well as the recipients; and so she did not see the good of making the charities expend a penny postage, in addition to the cost of paper and envelope and clerk’s salary, in merely reminding her of the fact.

“And be sure,” she continued, “that you put a stamped envelope in with each subscription. I want them to get the benefit of the whole amount, without having to spend part of it in reminding and thanking me.”

“There is another notice under the ‘January’ heading, auntie, about paying the dog tax. Ought that to be attended to?”

“Oh, yes, to be sure. Now you see the good of keeping a memorandum book, for I had quite forgotten that January was the month for renewing the licence. That will be seven and sixpence. Two dogs, did you say? Dear, dear, child, how ignorant you are, to be sure! Don’t you know that dogs are not taxed till they are six months old, and the puppy is not nearly that yet?”

Ella looked rather crestfallen at this rebuke, which her aunt perceiving, hastened to comfort her by saying—

“Well, it can’t be helped. You are a good girl, and do your best, my dear; but things were different when I was young, and girls were expected to know all the ways of a house. Ah, yes! girls were very useful, in the old days, when I was young.”

(To be continued.)

{152}

By MARY E. HULLAH.

Embrance Clemon sat writing in a snug room on the second floor of a house in an old-fashioned London street. A geranium stood on a flower-stand near the window; the walls were painted brown, and the carpet had faded into a comfortable insignificance.

Embrance was just twenty-four. She had come to London three years ago, on the strength of a promise of two pupils, and, behold! the pupils had multiplied rapidly, and she now had as many lessons as she could manage. She had been brought up by an aunt in the west of England; she had been educated at a high school, where she had successfully passed all the examinations that were open to her, and she was thoroughly happy in her present work. In very truth, she stood alone in the world. A few months ago, Mrs. Clemon (the aunt who had bestowed upon her such good care) had set sail for New Zealand, to join her only son, who was a farmer. She would fain have taken Embrance with her, but there were two insurmountable difficulties in the way: a lack of funds, and the young farmer’s desire to marry his cousin, as soon as he should be in a position to support a wife. Embrance liked him, but she did not like him well enough to consent to this arrangement; she therefore decided to remain in London, and Mrs. Clemon, after some fretting, had been induced to look upon the plan with approval.

The years of work in the smoke and fog had not done more than tone down the roses in Embrance’s cheeks; her hair, simply drawn back and plaited to her head, was that shade of brown that most people call black; she had kindly brown eyes, a large mouth, and a smile that won the hearts of her pupils at once, and caused their elder sisters to say that, after all, Miss Clemon was not so plain when you came to talk to her. Certainly, Miss Clemon was very little given to thinking about her appearance. It was, as Mrs. Clemon had always maintained, a pity. The grey gown that she wore, with a stiff collar, was singularly unbecoming to her; it was, indeed, warm and scrupulously neat, but when you had said that, you had come to an end of its praises. It was hideous.

At last, Embrance put down her pen and looked at the clock; it was getting late, and the tea-things were still uncleared from one end of the table. The street was very quiet, and she heard the postman’s knock next door.

“I wish somebody would write to me,” she said, aloud.

It was not the mail day, but there were friends in the country who corresponded with her from time to time, and to-night she would have rejoiced over the arrival of any letter. “I almost think,” she said, looking round her little domain with a half-stifled sigh, “that it was a pity that I refused to go to that concert, but if I had gone”—with a glance at a thick book—“I shouldn’t have got through{153} my reading. By-and-by, when I’m an old lady, perhaps I shall have time to enjoy myself!” The gratification that she derived from this reflection was considerably damped by the after-thought, “and then I shan’t care about it!”

Her meditations were interrupted at this stage by a sound of stumbling footsteps on the staircase. It was Annie, the maid, panting and out of breath; there was a lady just come, who wanted to see Miss Clemon.

“A lady!” repeated Embrance. “What is her name?”

“She didn’t say, miss; she is coming up.”

A sharp ring of a bell sent Annie hurrying down stairs again; the lady, whoever she was, would have to find her way unassisted.

Embrance went out on to the landing. “The stairs are very steep,” she said, “please take care.”

“Embrance, oh, dear Embrance! is that you at last?” said a voice from below. “I thought I should never find you in this horrible dark place; how can you bear it?”

“Hush! Come up; I am glad to see you, Joan. Come into my room.”

The new-comer ran up the last few steps, and flung her arms vehemently round Embrance, who led her into her sitting-room, and then drew back to look at her.

“Oh, Embrance,” gasped Joan, fairly breaking down now that the door was shut behind her, “do be glad to see me! I have taken you by surprise, haven’t I? But you said you would always help me, so I’ve come.”

She took off her hat, and sat down on the sofa, dragging Embrance with her. She was a young, fair girl, graceful in every movement, with a small, delicate face, surrounded by masses of yellow hair. Her blue eyes were full of tears, and her pretty lips quivered.

“My darling,” said Embrance, tenderly, holding her by both hands, “of course you came if you wanted me; but you are so tired and cold, I will ring for some hot water and make you fresh tea, and when you are rested you shall tell me all about it.”

“Let me tell you now,” said Joan, excitedly. “Oh, Embrance! it is so dull at home now that you are gone, and Mrs. Clemon is gone, and everybody I care for! And I don’t get on with my painting, and they cracked my best plate just when I wanted to send it to the Exhibition at Exeter.”

“Well, never mind. You must begin another one,” said Embrance, coaxingly, almost as if she had been speaking to a child, while she cut thin slices of bread-and-butter, and produced cake from the recesses of a cupboard. “Tell me, is your grandfather in London?”

“No; he’s at home, and Emily, too. I said that I should like to come to you, and they said very well—I must write and ask you if it would be convenient. And then I packed a bag, and just came up by the next train.”

“My dear Joan, they will think that you are lost.”

“No they won’t. I wrote a letter to grandpapa before I came away, and he had given his consent, you know. Are you shocked, Embrance?”

“Not in the least.” Embrance’s dark eyes rested on her friend with a look that showed how completely she meant what she said. “But I should like to hear the rest of the story, Joan. There is something more than a cracked plate.”

“You are a real conjuror. I believe you know all about it without my telling you.” Joan hung her head, and went on pathetically, “Alfred Brownhill has been tiresome again, and grandpapa is bent upon my accepting him, and Emily keeps on trying to persuade me. She says that it is ridiculous for a girl in my position to throw away such a good chance. I am tired of being told so often that I’m dependent; so——”

“You came to me to learn to do for your self, you poor child! You know how glad I shall be to help you, if I can.”

“Embrance, you’re the kindest person in the world!” was all Joan said; but she slipped her hand into her friend’s slim fingers caressingly.

They had been friends from childhood. Embrance had often helped little Joan Fulloch with her lessons, or coaxed her grandfather into overlooking some escapade that was against his notions of propriety. She knew well that it was a dreary home for an imaginative girl down at Doveton, and that Emily (another granddaughter of the old man’s) was as unsympathetic as she could be, looking upon Joan’s wish to become an artist as the wildest of wild schemes. Embrance had vague recollections of Mr. Brownhill (a flourishing county town solicitor) as a dull man, who played lawn tennis. She did not believe that Joan liked him, and as the child was harshly treated at home, she was doubly welcome here. At any rate, if the worst came to the worst, there was a small sum in the savings bank that would pay extra expenses for a year to come—and a year was a long time to look forward in Embrance’s eyes.

Joan soon regained her spirits, and forgot her fatigue in the novelty of the situation. It was like a fairy tale, living up here at the top of that corkscrew staircase; and what a pretty flower! and might she paint here when Embrance was out? She had her own notions, though they were somewhat erratic, about making money.

To-morrow she would write to her cousin, Horace Meade, and he would help her to get something to do; and she began making calculations as to the number of people who required dinner services in the course of a year. If Horace could once get orders for her, her fortune was made, and in her spare time, she would paint landscapes for exhibitions. “Then, you must give up these rooms,” exclaimed Joan, eagerly, “and we can go and live somewhere where there is a garden. And, dear Embrance, you’ll let me buy you another dress. You ought really never to wear that cold colour.”

Joan’s own dress was of a delicate blue shade, hanging in artistic folds about her pretty figure.

Embrance heaved a little sigh; she was accustomed of old to her friend’s castle-building, but she would not say a word to damp her ardour on this first night. She arranged her books and papers ready for the morning’s work (her special reading must, of course, be put aside now), then she came and sat by Joan, and listened to her long account of home troubles, till the clock struck eleven, and the lamp began to burn low.

The days passed on; the winter was at hand. In spite of Joan Fulloch’s good resolutions, in spite of her hostess’s kindness, she was far from content in her new surroundings. Her grandfather had sent a box containing clothes and painting materials; he had enclosed a brief note in which he foretold that she would soon wish to return to Doveton. Perhaps, if it had not been for this note, Joan would have said good-bye to Embrance and the second floor parlour some weeks ago. As it was she stayed on, always looking out for commissions that never came, and making plans to paint pictures that she never began. Either the light was too bad, or she had a headache; there was always an excuse, and Embrance returned night after night, to find her visitor plunged in the depths of despair. She would straightway set to work to cheer her up, and before tea was over, Joan was invariably sure of success—to-morrow or the next day. At last she heard of a pupil, but, unfortunately, she did not take kindly to teaching; she was very unpunctual, and it did not seem likely that her connection would increase with rapidity. In the meantime, Embrance had begun to draw upon her savings, for the expenses had increased marvellously since the autumn. There were so many little luxuries that Joan, poor child, could not possibly do without.

“Embrance,” said Joan, one evening. She was sitting over the fire with a novel, her face was flushed, and her hair was disordered; “I do want so many things. I wish I could earn some money.”

“You have got your pupil,” said Embrance, looking up from her book. She was translating Schiller, and it was the third time that Joan had interrupted her.

“Five shillings an hour!” exclaimed Joan, kicking the fireirons down with a clatter. “It’s so little; I shan’t have earned enough by Christmas to buy a winter jacket, and besides, I owe you so much, Embrance!”

“Never mind about that, Joanie; I have enough for the present, if we are careful.”

“It is so tiresome of Horace to be away just when I want him most,” continued Joan, “but he’ll come to-morrow; he has enough to do; he ought to be able to help me. Do try and be in early to-morrow.”

Embrance shook her head. “I can’t be home till seven o’clock.”

“Put off that stupid lesson.”

“I’m afraid it is impossible.”

“I want you to see Horace. You never do anything I ask you!”

“I am very sorry, Joan.”

“What’s the good of being sorry?” asked Joan, pettishly. “No, no! I don’t mean it!” She turned round sharply and saw that her friend’s eyes were full of tears. In a second, she had flung down her book and was kneeling at Embrance’s chair: “Do forgive me, it isn’t true. You are the only person in the world who has real patience with me. Don’t mind what I said; I didn’t mean it.”

It took some time to calm Joan down after her fit of penitence, but at last she went back to her novel.

Embrance sat with both arms on the table; the translation got no farther. Her heart was full of love for her friend, and yet—she had her fair share of common sense—she could not but see that Joan was thoroughly unfit for her present mode of life. She was just one of those girls who would be happiest in a home of her own. Here, for once, Embrance found herself cordially agreeing with Emily Fulloch, who was as old-fashioned in her notions as it was possible for a narrow-minded spinster to be.

Perhaps a “brain-wave” of sympathy passed from one friend to another at that moment, for Joan looked up from her book:

“Darling, I think you will like Horace better than Mr. Brownhill, though he is not so good-looking. I hope you will!”

“I will try,” said Embrance, jumping up to kiss Joan; “I will try my hardest, for your sake.”

Joan blushed, and Embrance began talking of other matters.

A week later, Mrs. Rakely (a friend of the Fullochs) came to London. She stayed at an hotel close by, and was glad of Joan’s company, as she wished to get through as much sight-seeing as she conveniently—or inconveniently—could in the space of a fortnight.

One Saturday afternoon Embrance had come home early (Joan had gone to luncheon with Mrs. Rakely); she was tired, it had been a warm, rainy day; her boots were muddy and her dress was damp. The armchair by the fire looked very tempting; she sat down, and{154} in a few seconds was fast asleep, dreaming of a magnificent abode in New Zealand, where Joan, in a white satin gown and a diamond necklace, was blissfully wedded to an emperor with flowing ringlets and bright grey eyes. The emperor had very bright eyes, indeed, and a habit of knocking on the ground with his sceptre; he was also afflicted with a curious kind of cough that did not sound natural—and yet it was natural, appallingly so. With a start and a jerk, Embrance sat up in her chair wide awake, and met the gaze of a real pair of grey eyes (brimming over with fun) that belonged to a gentleman, who stood, hat in hand, at the open door.

“I really apologise humbly,” he said, without venturing to approach; “but I was told to walk up, and I knocked several times, and someone said ‘Come in.’”

Embrance had recovered her presence of mind. “Please do come in,” she said. “I am very sorry that I was asleep; but I was so tired. I think you are Mr. Meade?”

“That is my name,” said the visitor, looking across the room from the smoky fire to the rows of books with a quick glance; “and I have the pleasure of speaking to Miss Clemon.”

“Yes,” said Embrance, holding out her hand. “Joan will be so disappointed to miss you. She is not in.”

The recollection of her plans for Joan’s future happiness brought the blood to her cheeks. She stooped over the fire to hide her confusion. Yes, she liked the look of him. He had a clever, kindly face, much bronzed by the sun; he wore a short beard and a turned-down collar; he had no gloves, and his hands were long and thin.

“Do let me do that for you,” said Mr. Meade, putting down his hat and umbrella. “I am exceedingly skilful at managing fires and chimneys; in fact, I have occasionally regretted not having been brought up to it professionally.”

“As a chimney-sweep?” inquired Embrance.

“No, I think not,” said Mr. Meade, gravely, as he inserted the poker between the bars, “but there might have been an opening as stoker or master of the bellows in some grand family. There, now, if you will allow me to have a sheet of newspaper, I think I shall succeed to perfection.”

Embrance fetched the newspaper, and in a few minutes the crimson flames were leaping up the chimney.

(To be continued.)

A PASTORALE.

By DARLEY DALE, Author of “Fair Katherine,” etc.

The following Saturday turned out to be a misty November morning. Towards noon the fog lifted, and at half-past one, when Dame Hursey prepared to start to keep her appointment with her son, it was tolerably clear, but the old wool-gatherer, who was as weather-wise as John Shelley himself, shook her head as she scanned the horizon from the door of her miserable cottage, and muttered to herself she doubted the fog would come on worse than ever at sunset.

As this was the first time she had seen her son for twelve or thirteen years, and would probably be the last, seeing that he was going back to Australia, probably never to return, at least in her lifetime, Dame Hursey regarded the occasion as a festive one, and had taken a holiday in honour of it. Her morning had been spent in cleaning her miserable cottage, in the faint hope that her son might be persuaded to come home and spend the evening with her. In this hope all her wool-gatherings had been taken upstairs instead of lying about the floor and corners of the kitchen, as they usually did; the floor had been scrubbed, a fire was lighted, two rickety armchairs drawn up to it, and a cup and saucer, a mug, and two or three plates—Dame Hursey’s stock of crockery—placed on the table. She dispensed with dinner, and contenting herself with a piece of bread and cheese, reserved two red herrings for her tea on her return with her son.

Then she dressed herself in her Sunday dress, not without some qualms lest the fog should turn to rain. Even if it did, on such an occasion as this she must wear her best things, so she put on her black stuff dress, a black and white plaid shawl, and a bonnet that might have come out of the ark, judging from its antique shape, and which, to Dame Hursey’s pride, was ornamented with some dirty old artificial flowers. Thus attired, and having made up the fire and left the kettle on the hob, she locked up her hut, put the key in her pocket, and providing herself with a gigantic cotton umbrella, to answer the purpose of a walking-stick as well as in case of rain, she set out for Mount Harry.

Though Dame Hursey knew all the short cuts, it was more than an hour’s walk from her house to the top of Mount Harry, but the old woman was longing to see her son again, so she started in good time, and reached the spot a quarter of an hour before he did, though he was punctual. The fog was rolling up again, as the old wool-gatherer had predicted, and, accustomed as her black eyes were to piercing the mists which so often wrap those rounded hills like a damp clinging garment, her son was close upon her before she saw his form, looming like a gigantic grey figure close beside her. It was twelve years and a half since they had met, and George Hursey was very much altered in appearance since, in the character of John Smith, carpenter on board the French yacht Hirondelle, he had laid the baron’s little daughter on John Shelley’s doorstep; but for all that his mother declared she would have recognised him in a crowd.

“You’ll come home and have a cup of tea and a chat, George, after all these years, won’t you?” said the old dame, gazing with pride and affection on her ne’er-do-well son.

“No, mother, no; I might be recognised, and I don’t want to be arrested for making off with a child, before I go back to my own wife and children.”

“The child is safe enough, if you mean the child you left on John Shelley’s doorstep thirteen years ago come next June.”

George Hursey gave a sigh of relief, for many a nightmare had that innocent baby, which, for aught he knew to the contrary, might have perished from cold or exposure through his fault, given him.

“John Shelley took it in then, as I thought he would?”

“Yes, and a beauty she is, and no mistake. George, tell me who the child is, will you, honey?” said Dame Hursey, in a wheedling tone.

“That’s what I have come here for chiefly, that and to see you once again, for when I say good-bye to England to-morrow it will be for good this time; I am going to give up the sea, and live at home now.”

“Well, you know your own affairs best; but about the lassie, George; whose child is she? No poor person’s, I’ll be bound,” said Dame Hursey, whose curiosity about Fairy exceeded even her interest in her son’s family affairs.

“She is the niece of my late master, a French gentleman, and it was by his wish I took her to John Shelley, only instead of going in as I pretended I had done, I left her on the doorstep, and went off with the purse; and if ever I cursed in my life I have cursed that money, which, for aught I knew till a few minutes ago, had made me a murderer, though for that matter I may be one still, for the baroness may have fretted herself into her grave for her baby.”

“The baroness, did you say, George? Sure, I was right, she is no common child, no fit wife even for gentleman Jack,” exclaimed the old woman, opening her umbrella, partly to keep the fog off, partly as a sort of screen to shut in the secret she had yearned so long to learn. But George was following up his own train of thought, and went on, heedless of her interruption—

“Though, as true as I stand here, I never knew till last week that Monsieur Léon was drowned, and the Hirondelle lost a day or two after I left her. Likely as not the baron thinks the child was drowned too, since they have never found her. I might never have known, only I happened to ask at Yarmouth if they had ever had a French yacht named Hirondelle over there, and some of the fishermen remembered all about the wreck. When I heard that I determined{155} to come and see if the child was safe, and now I know it is, I want to do the rest, mother.”

“Yes, honey, what is it? You may trust me. I guessed the night I met you you knew all about the fairies’ child, and I have kept your secret and watched the child ever since, for your sake, George.”

“Well, I want you to go to John Shelley, or to the parson if you like, or both, and tell them the child belongs to the Baron de Thorens, of Château de Thorens, near Carolles, in Normandy. Shall I write it down for you?”

“No, no, I can’t read it if you do; I shall remember fast enough—Baron de Thorens, Château de Thorens, near Carolles, Normandy. I shall think of Christmas carols, De Thorens, Château de Thorens,” repeated Dame Hursey.

“Never mind château, it only means castle, but don’t forget the name, De Thorens. Here, I’ll cut that word on your umbrella handle with my knife in printed letters. You can read print, I know.”

“All right; and what else am I to tell them?”

“Why, that my master and the baron gave me the child twelve years and a half ago to put out to nurse with an Englishwoman. I went ashore at Brighton in a little boat with Pierre Legros, one of the sailors, and I walked across the downs with the child, and left it on John Shelley’s doorstep; then I told Monsieur Léon John had taken it in and promised to look after it. He took the address, and the only person I thought I had robbed was John Shelley, though I knew the baron would make it up to him when he heard of it.”