Title: Gloria at Boarding School

Author: Lilian Garis

Release date: May 6, 2021 [eBook #65271]

Language: English

Credits: Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

GLORIA

AT BOARDING SCHOOL

By

LILIAN GARIS

Author of “Gloria: A Girl and Her Dad,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1923, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Mixed Baggage | 1 |

| II | Telling Trixy | 15 |

| III | Meet Maggie | 25 |

| IV | The Talisman | 36 |

| V | Jack’s Sudden Departure | 48 |

| VI | Smoldering Fires | 57 |

| VII | Broncho Billy | 70 |

| VIII | Almost a Tragedy | 81 |

| IX | From Icy Waters | 97 |

| X | Jack’s Story | 109 |

| XI | A New Angle | 124 |

| XII | A Tribute | 136 |

| XIII | Serious School Work | 147 |

| XIV | Balked Ambition | 159 |

| XV | Steppy and the Clue | 171 |

| XVI | At the Rookery Tea Room | 186 |

| XVII | The Sacrifice | 198 |

| XVIII | Say It with Popcorn | 210 |

| XIX | Gems and Moss Agate | 223 |

| XX | The Lure of Boarding School | 233 |

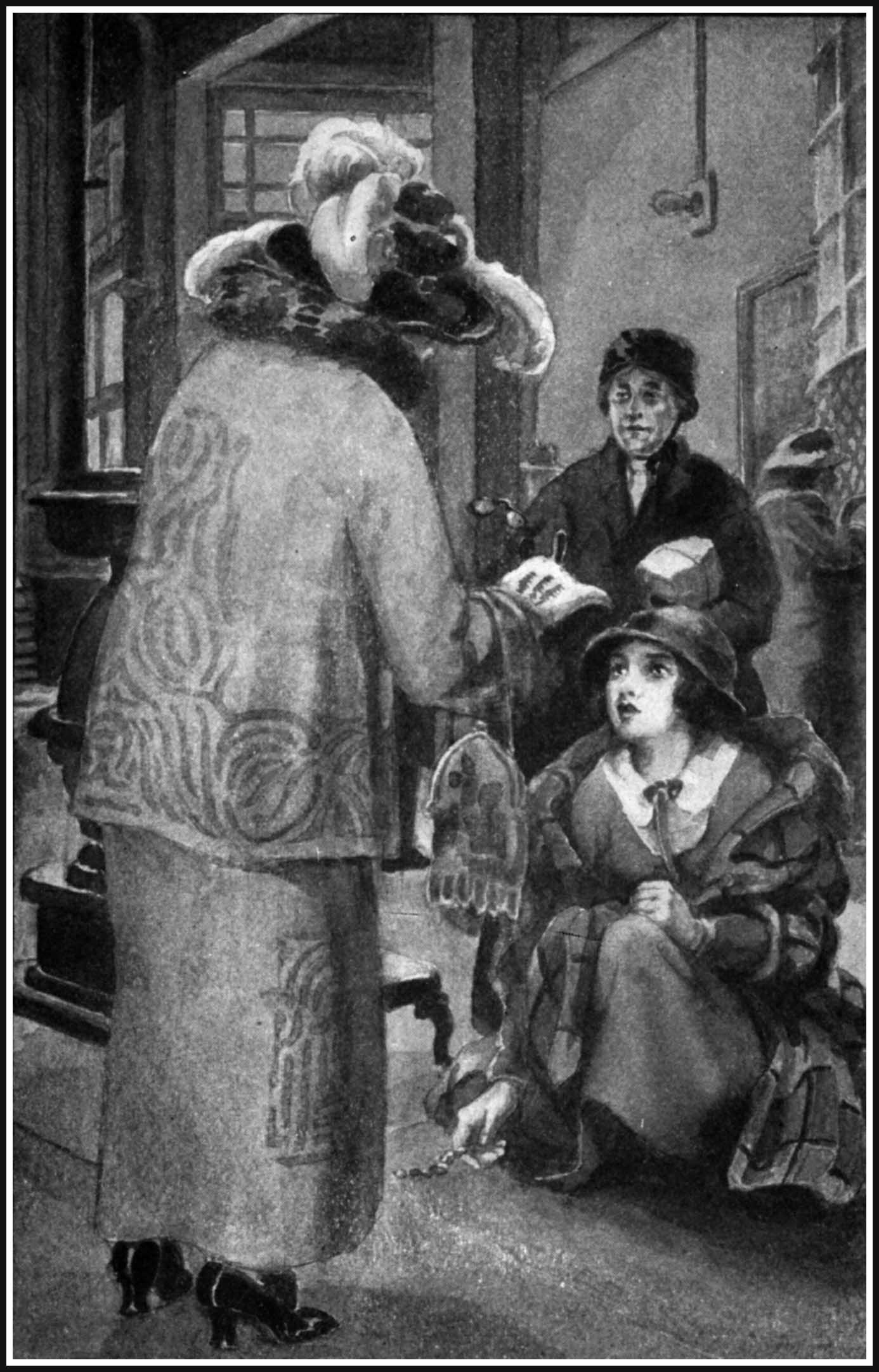

The dark haired girl, sitting on the cretonne couch, chuckled.

“So this is boarding school!”

No one heard her, the little clock on the corner shelf ticked away and never “let on,” for new girls coming to that room were no novelty to the clock. They came and went yearly, sometimes oftener, and what difference did it make that this one chuckled? Those who sighed, or even those who wept, always got over it in time. No doubt the dark haired girl would get over her rather cynical defiance of Miss Alton’s rules for lady-like deportment. Also, she might in time learn to sit on a chair properly.

Gloria Doane really felt defiant. Boarding2 school always represented restrictions to her inexperienced reasoning, and restrictions were never a part of her chosen schedule. A sense of freedom was necessary to her happiness.

At her Barbend home she scarcely respected the wildest coast storm, and often thought it a lark to help life guards shoot out their boats or rig up a buoy. But last year Gloria was “due” to go to this exclusive school and she had not done so. In fact, circumstances wove such a net about her that the meshes represented a most unusual story, told in the first volume of this series called, “Gloria: A Girl and Her Dad.” But now the net was flattened out, stretched to dry on regulation lines, and Gloria had emerged like a fairy mermaid, changed back to an earth maiden, and was doing such ordinary things as going to boarding school.

All this she pondered as voices roused her and a step near her door threatened invasion.

“Trixy!” she called lightly. The step halted.

“Did you get your trunk? It’s downstairs and you will want to change your dress before dinner, or maybe it’s supper,” surmised Trixy Travers, the girl from Sandford, who decided to come to Altmount because Gloria begged her to3 do so. Trixy was quite as fond of freedom as was Gloria, so, ultimately, they both decided “it wouldn’t kill them to try it for a year.” And there they were, ready to put the test to their resolve.

“Trunks,” murmured Gloria, indifferently. “I saw one that looked like mine——”

“In the first hall? Get that bean pole they call Sam, to lug it up for you before the others come in. Then we can dress in our prettiest and flabbergast the crowd.” A pulled face, quite unlike Trixy’s usual countenance, put a period to this threat.

“Brilliant idea. I’ll go straight for the bean pole. Just hook up that gorgeous drapery and our rooms will constitute a suite. So glad we are together. If you were down the hall I’d surely sit on your door mat like a faithful poodle. I just couldn’t risk trying out this exciting life without the protection and guidance of your wisdom. I noticed Miss Alton herself paused in a speech as you towered over her.”

“Glo, get your duds; you’ll feel better when you are out of those dusty things,” interrupted Trixy. “I’ll go down to that cute little room where Miss Alton holds court, and see about a4 telephone to mother. She will want to know we got here safely.”

The next item of note was the entrance of the bean pole, Sam, bearing a shiny new trunk.

“Just here,” directed Gloria. “I suppose I can keep it in my room——”

“With a cover. Miss Alton she always likes pretty covers over trunks.” Sam shifted the little table to give more space. “There, I guess that’ll be all right——”

“Oh, yes; thanks.” A half dollar was pressed into his convenient hand, and Gloria did not hide her impatience to be rid of the voluble Sam. He went. Girls were calling for him and there might be more tips.

Quickly Gloria fell to her trunk task but it did not readily give in to her key.

“Queer, but I suppose it’s stiff, being new,” she reasoned.

The rose colored dress, that which Jane insisted was most becoming to Gloria’s dark hair and dark eyes, would be found in the top tray of the new trunk, and this was to be the “irresistible gown” Trixy suggested as a flabbergaster for the first evening’s appearance.

“There!” exclaimed Gloria, as a spring of the5 lock indicated surrender. “Now I’ve got it.”

But raising the cover did not disclose the expected rose voile dress.

“Of all things!” gasped Gloria. “Whatever is—this?”

She was staring at a mass of glittering beads, or spangles, that seemed to fill the trunk tray. Just a hint of some material very green showed beneath the glistening surface, but whatever the article might be, it never had belonged to the girl looking at it.

She picked up an end of the material and found it heavy with spangles. Then she noticed an envelope pinned to an edge. Scrutinizing this she found the word “Precious” written across it, also “with care,” was plainly inscribed upon the little square. Realizing now that the trunk was not hers, Gloria attempted to replace the glittering stuff, but as she did so something red and sparkling fell from the envelope into her hand.

“Gems!” she exclaimed, gazing spellbound at the deep red glow that seemed to absorb all the light about it. The stone was about the size of a small bean and was cut in facets.

Frightened lest she be found in possession of6 another’s valuables, Gloria quickly dropped the end of the spangled goods back into the trunk tray, then slipped the big, red gem into the envelope through the corner hole it had cut its way out of. She had forgotten all about the rose colored costume, and even that Trixy was due back to dress for the first meeting with the girls of Altmount.

“How ever could I have mistaken that trunk?” Gloria worried. “Of course, it’s exactly like mine, but where’s the tag?”

With the lid closed and the lock snapped back she looked closer but found no tag to identify the strange piece of baggage.

Then, shuffling in the hall and Sam’s characteristic groaning indicated the coming of more baggage, and quickly as the door was opened Gloria welcomed her own special new trunk, which had been purchased amid much discussion, for Jane, the faithful, was insistent that a new trunk be at once beautiful and useful, a combination seemingly realized in the black enamelled article, so easily mistaken for another. The “popular trunk for young ladies” was, apparently, very popular at Altmount.

“Made a mistake,” wheezed Sam. “T’other7 girl had yourn. Jest a mite more work, but that’s all right,” hinted the hopeful handy man.

“I’m in such a hurry,” retorted Gloria meaningly.

“Oh, yes, of course. But ’t warn’t my fault exactly.”

“That’s perfectly all right. See, here’s my name on this trunk. I hadn’t noticed the other.”

“They’re all the same to me,” chuckled Sam, shuffling off without further reward.

When Trixy returned, Gloria was already aglow in her rose colored gown.

“Lovely!” pronounced the admiring Trixy. “If we don’t make an impression to-night it won’t be the fault of clothes. Just look at this. Isn’t it stunning?”

“Perfectly. Trix, you have such a modish way about you——”

“Oh, I don’t know. You are no dowdy yourself. You always look to me like Molly Dawn, or Betty Bangle, or some other quaint character, bound to smile and look darling.” An affectionate little squeeze illustrated this compliment, and presently both girls were being introduced to their fellow students. Gloria in rose color that heightened her sparkling dark beauty, and Trixy8 in French blue that beckoned the glints of her eyes.

It was a small school and boasted of the fact. Also, that its clientele would stand the “Social test,” whatever that uncertain measure is supposed to be, was conspicuously stated in the prospectus.

Gloria was secretly happy to be sponsored by the impressive Trixy. As a matter of fact, no one could doubt the latter’s standing. She was tall, a mellow blonde, the type softened with a tawny brown glow, and her mannerisms! It must have taken generations, thought Gloria humbly, to develop that smooth, irresistible ease and languid indifference toward irritating trifles.

But as a type Gloria, herself, was decidedly more pronounced. She was dark, with eyes that seemed to shoot sparks, with one dimple that always apologized for any pout the rather boyish mouth might affect, and withal Gloria had an air of independence sometimes mistaken for defiance.

As various as the characters they represented were the forms of greetings offered the new girls by those familiar with Altmount. Some9 “gushed,” impulsively generous in their squeezing handshakes and ebullient chatter, others were “stand off,” formal and “frozen,” as Gloria secretly classed the most conservative.

Pat Halliday explained her name as coming from the same Greek word Harriet was taken from.

“Only Patricia is so much nicer and Pat is perfectly jolly,” declared the Grecian descendant. “I should abhor Harriet; though Harry isn’t so bad.”

Gloria quickly found interest in Pat. She was almost red headed and almost blue eyed, losing out by a mere shade in each instance. She talked a lot and laughed a lot, but plainly was no poser. Taking a place beside Gloria at table, Pat kept up a running fire of talk that saved the new girl from any possible self consciousness. At another table Trixy was trying to be pleasant with a girl of very different personality. She (the other girl) raised her eyebrows instead of uttering replies, she shrugged her shoulders haughtily and seemed insipidly affected.

“The girl without a smile,” Gloria was promptly dubbing the ashen blonde. Trixy, sitting near enough, was flashing secret messages10 back to Gloria agreeing with the above. She was not having a very good time with the smileless girl, that was obvious.

Miss Alton sat at the head of the table, radiating good will. It was so important that her girls all become acquainted auspiciously. Although a small school, Altmount claimed the distinction of “finishing,” so that a sprinkling of high school graduates, and a few who failed to win the honor, were to be found among those present.

Both Trixy and Gloria were covertly taking notice of as many girls as politeness afforded glances at. There was, of course, a bevy of “Gabbies” who scarcely paused to swallow, also, like the girl without a smile, there were those who held off, looked important and posed for impressions. This might have been their honest prerogative, but somehow it seemed to natural, naïve Gloria, a bit affected.

“I do hope you’ll like it,” bubbled Pat. “We need a few good sports and I’m sure you’re one. There’s room for more fun here if we only have the workers.”

“I like fun,” admitted Gloria. “And yes, I guess I am used to it.” Her brown eyes sent out a sparkling guarantee.

11 After tea the girls paired off and strolled about the grounds. Pat “grabbed” Gloria, and both being of the younger set their romping went unscrutinized. Trixy, the imperturbable, seemed determined to provoke something like a smile from the reserved Mary Mears, but her good natured and tactful attempts were far from being successful. Mary Mears was wise, any one could see that. Her experience stood out like a wall, neither to be climbed over nor broken through. She was pretty but her skin betrayed traces of the applied arts, while her really wonderful violet eyes worked like magnetos. All this attracted Trixy. Any one so totally different offered her a working problem, something to find out, to analyze and, mayhap, to conquer.

The September evening was quickening into shadows when the students turned back to the broad verandahs and cozy porch corners.

“Hear that?” Pat asked Gloria. “That’s Jack Corday. She never stops talking and never says a sensible thing. Flashy,” criticised the jolly one. “Just notice her get up. But she’s a dear.”

It was impossible not to notice it. The girl called Jack (Gloria later heard Miss Alton give12 her Jacquinot) did talk incessantly in a voice that intruded everywhere, and as she promenaded up and down, dragging along a timid new girl called Ethel, the “get up” Pat mentioned was equally intrusive. A glaring, tiger-lily red baronet skirt, a black silk sweater and colorful bobbed hair. Dangling from her neck was a string of varied colored wooden beads with which she toyed constantly.

The string of beads reminded Gloria of the mistaken trunk.

“Is she a—stranger?” she asked Pat.

“Somewhat. That is, she comes and goes. I wonder Miss Alton admits her. Jack never settles down to anything serious. She makes me think of a big butterfly.”

“The black and yellow kind.”

“Uh-huh!” conceded Pat.

A call to the opening chorus within the assembly room was reluctantly obeyed. “Hail, Altmount,” composed by a brilliant but unpopular girl of the graduating class two years back, was murmured, mumbled and otherwise abused. The faculty chimed in with more enthusiasm than voice, and eventually the wail ended.

13 “Oh, let’s sing the regular college songs,” proposed Jack, slamming a yellow book on the piano rack in front of demure Miss Taylor.

But the majority of the girls, the great majority, deserted, and left few with Jack and timid Ethel to “try” the regular college songs. No one seemed to have a voice or there was something seriously wrong with the tunes, for one after the other they were “tried,” until the long suffering Miss Taylor proposed a truce.

“Jack doesn’t seem to be very popular,” ventured Gloria to the giggling Pat, when the trials were all over.

“She isn’t exactly, but somehow she seems to love opposition. I don’t know her well. This is only my second term, I came last Spring, but Jack Corday could climb a flag pole if she wanted to. She’s a wiz at gym, but books! She has about as much use for a book as an Indian has,” declared the accommodating Pat. “Just the same I love her.”

“My friend Trixy seems to have struck an iceberg,” further commented Gloria. The “iceberg” being the ashen blonde called Mary Mears.

“Oh, I don’t know her, she’s new,” replied Pat.14 “But even icebergs melt finally. She’s rather pretty, isn’t she?”

“Rather,” agreed Gloria just as Trixy joined her group on the corner bench.

By the merest chance Gloria did not tell Trixy of the trunk incident. Not that she had any intention of keeping from her friend such an interesting possibility, but because—well, each time she thought of it something intervened, until after days and then more than a week passed, the tale seemed too stale to be revived.

Pat proved delightfully amusing, Mary Mears was mysterious and Jacquinot Corday so spectacular that the first month at Altmount went by without a dull day or even a lonely night for Gloria.

Trixy Travers was at the finishing school chiefly because Gloria Doane had inveigled her into coming. As the fashionable and popular girl at Sandford, where her father was an important manufacturer, Trixy had enjoyed good times unlimited, but as Gloria was due to attend16 boarding school and she reasonably decided there would be much more security from either boredom or loneliness with Trixy to lean upon.

Few letters and fewer home visits were advised by this, as by most boarding schools, during the students’ first month or two, so that those away from home for the first time might more promptly become inured to their new surroundings; so it happened Gloria had only received and written two letters from and to Jane. Now, Jane, the faithful, had for years stood sponsor for Gloria, whose mother had died when Gloria was but a tiny child. Jane kept house at Barbend, the original home of Gloria and her father, and when the young girl came into Sandford to remain with her Aunt Harriet while her father took a foreign commission from his firm, Jane Morgan went to visit her own sister, she who had so many children that the snapshot pictures frequently sent Jane were apt to be misleading in personalities. They all looked alike and seemed too many for the camera.

Mr. Doane, Gloria’s father, had returned from abroad during the previous late winter, only to enter upon a longer trip to the Philippines. His homecoming the Christmas before added the17 final happy chapter to Gloria’s adventure as a real estate expert, for with Mr. Doane had come the young engineer, Sherry Graves, whose venture in Echo Park proved disastrous, ruined his hopes, and all but sent him adrift in despair. Then, the natural enemy of the pretty little park, an underground river vein, was accidentally discovered by Gloria and promptly turned into a harmless course by Sherry and his friend, Ben Hardy.

The result was a boomerang credited to Gloria. These home conditions explain the dearth of letters coming or not coming to her just now, at the new boarding school.

There had been one, however, from her father, remailed at San Francisco, and also a characteristic scrawl from Tommy Whitely, her childhood friend at Barbend. Aunt Harriet had written, of course, telling of her daughter Hazel’s wonderful progress in voice culture. Hazel had spent the previous year at Altmount, while Gloria submitted meekly to a confused, if not unjust plan, of giving this preference to the “artistic cousin.”

Trixy’s letters were not quite so restricted, as she was in the finishing class. Among the most18 interesting was one from Sherry, who told of a “perfectly thrilling plan” for the further development of Gloria’s Echo Park.

“You’ll be rich, Glo, if Sherry keeps on. He writes of perfectly fairy like castles on your property.”

“I don’t want to be rich,” replied Gloria evenly, “but I am glad that the poor mason and his family, the one who at first lost so much in the work there, are finally made happy and comfortable. Of course it was Ben’s genius in engineering that did it all.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” drawled Trixy. “It was rather queer the genius couldn’t find that sneaky little river vein, that almost turned the pretty park on end. A mere girl, one Gloria Doane, managed that.”

The two chums were spending the evening in their connecting rooms, discussing the home news. A letter to Trixy received on the late mail added zest to the discussion.

“Really, how do you like it here, Glo?” asked Trixy. She shot her feet out in front of her with the question, and kicked over a useless little stool in the process.

“Much better than I expected,” admitted19 Gloria. “Pat’s always so jolly, then there’s the haughty Mary Mears and the breezy Jack Corday for variety. Who could complain with all that?”

“Isn’t Pat a lark? She just bubbles over everything and, as the boys say, gets away with it,” replied Trixy. “But Mary really seems mysterious. I haven’t been able to pry open the reserve crust. Yet, it doesn’t seem at all natural to me.”

“How about Jack?”

“The human pinwheel?”

“Pat says she is just about that.”

“How?”

“A wiz at gym.”

“Oh. Perhaps that accounts for her circus clothes.”

“That reminds me, Trixy. I have been wanting to tell you so often——”

“Whew! Sounds guilty!”

“Not quite. But I really have wanted to tell you,” floundered Gloria.

“Go ahead!”

“Then please listen.”

“All ears.”

Gloria tossed her head up defiantly. “One20 doesn’t peg confidences at another’s head,” she pouted.

“Now, Glo, darling,” cooed Trixy. “I does truly want to hear. Be a lamb and tell me.”

Settling anew Gloria began:

“It’s about trunks——”

“The portable, or athletic?”

“Now, Trixy!”

“But you do offer such bait for little fishes, pet, I just can’t resist. I had trunks on my mind. The basket ball squad is considering something like them to pad out for rough play. But tell me, like a pet, what about your trunks?”

Trixy was irresistible. She wore the simple uniform of Altmount, the white shirtwaist and dark blue skirt used by the older girls, and its very simplicity set off more effectively her almost faultless personality. With an arm around the pouting Gloria, and lips in close proximity to a left ear, she again cooed her request for the secret.

Gloria’s own lips lost their pout in a real surrendering smile, as she again attempted the tale.

“You see, that afternoon we came here there was so much confusion with baggage and so little time to dress——”

“And I warned you to fix up your finest.”

21 “Exactly. Well, I tackled, what I took for my own new, shiny, black trunk, and found it too hard to unlock——”

“You called in the Bean Pole?”

“No. I struggled and conquered.”

“Being you, you would.”

“But when the lid finally decided to come up I found the belongings within not mine.”

“Oh!” Trixy fell back a little and waited. Her exclamation was merely a polite acquiescence.

“Yes,” continued Gloria, “the top of that trunk was covered if not filled with the queerest materials——”

“Oh! Whoozy-boozy! How mysterious! No skeletons?”

“Quite the opposite. A perfect glitter of gems——”

“Gloria Doane! And you have never told me we are harboring a pirate’s daughter! Gems!”

“At least they looked like gems,” went on the imperturbable Gloria. “Of course, I was all a-flutter and couldn’t possibly inspect,” (this with an air of real importance) “but I did manage to lay hold of an envelope.”

“Glo! An envelope! With the pirate’s address!”

22 “Are they so careless as to leave addresses lying around loose like that? I thought they always used secret codes, made with pieces of string and rusty nails scattered in a long, long trail.”

“Of course. How stupid of me. The envelope was full of rusty spikes.”

Gloria twisted herself away with an air of finality until Trixy seized her. “Go ahead,” she implored. “Go right straight ahead. This suspense is killing me. What was the glitter and what did the envelope say about the secret?”

“You know, Trix, I really was a bit scared. You were off gallivanting, and there I was all alone, with a strange trunk full of mysteriously glittering stuff. How did I know who might rush in and accuse me.”

“Exactly! How did you know?” Trixy’s banter now toned down to real interest. “The envelope, dear, what about that?”

“I had begun to realize I was trespassing, you know, and I just glanced at the envelope. On it was written the word ‘Precious.’”

“Precious?”

“Yes. That and ‘With Care.’ But just as I attempted to put it back, I had taken it in my23 hands of course, just as I went to put it back, a stone fell out.”

“A gem?”

“It looked like one. A great red garnet or some sort of stone that seemed bursting with imprisoned glow.”

“How perfectly wonderful!”

“Yes, honestly, Trix, it made me creepy. I got the fire-drop back in that envelope as quickly as I could, you can believe me. It made me think of an animal’s eye, not a serpent’s eye, they’re green, but the eye of some sneaky little beast——”

“Beastie, Glo. You must call the small ones, beasties. But you are so, so graphic, you give me the shivers. Are you sure there are none of the beasties crawling around here now?”

“But I haven’t told you about the spangly things,” persisted Gloria, ignoring the frivolity. “They didn’t seem to be on gowns. I couldn’t, in the moment, make out what the article was. All I saw was glitter and sparkle.”

“What color was it?”

“Many colors, I thought; but red shone through. You see, Sam came back just as I got the trunk shut. I wouldn’t want to have been24 discovered snooping into another girl’s stuff,” declared Gloria.

“But whom could it have belonged to?”

“That’s an interesting question, don’t you think so? Just imagine what sort of girl would bring that here?”

“Exactly. But you watch little Trixy solve the mystery of the trunk full of gems!”

“I’m quite willing to,” agreed Gloria, with a weary little sigh.

Two days later Maggie, who swept rooms and talked a lot, also counted hairpins, picked from the dust, and bewailed her own constant loss insinuating a present need, this Maggie, with a season’s new broom and last year’s dust pan, a basket of dusters, brushes, and in the bottom such articles as the girls donated on her rounds, well, anyhow, she came in to clear up Gloria’s room.

“This bein’ a double,” analyzed Maggie, “I’ll have to have it free.”

“Free?” repeated Gloria.

“Yes. I could do it whilst you’re in class, but I like to keep these new curtains well shook and that makes considerable flare around. Ain’t they pretty?”

“Very.”

“Then, jest pick up your precious stuff, I allus26 calls the little things precious, and whilst you’re out this afternoon—you will be out?”

“Yes.”

“Whilst you’re both out I clean. I allus thinks this is the prettiest ‘sweet’ in the house. Ain’t it now?”

Gloria was hurrying before the wavering broom. Her “precious stuff” would be easily gathered and then she might escape from Maggie’s gossip.

“About the hairpins now, where shall I put them?”

“Oh, keep them,” smiled Gloria. “You see I never use any.”

“That’s so. Ain’t I stupid. Since the bobbs came in it seems to me that hairpins is harder to get. Stores even, don’t allus carry them.” She retrieved a brown lock of hair that was trying to get down her back. “And my hair’s such a nuisance. You don’t wear nets either?”

“No.”

“What a comfort. I’ll put any baby pins and such right—where should I put them?”

“You won’t be apt to find any,” said Gloria, wondering what next Maggie might hint for.

“Well, I’m honest as the sun, Miss Alton says,27 and what’s on the floor goes on the bureau, every time.” The basket and contents were inadvertently tipped over just then, and Maggie dove after the things that flew.

“There, ain’t that a pretty waist? Miss Davis, she’s the rich girl that has number ten, she’s been here, land know how long, and I asked her yesterday if this was her last year and she didn’t know. She’s the loveliest girl, and so good-natured. I jest said I loved blue and she gave me the waist. I think it’ll fit me.” It was held aloft midway between chin and waistline, and Gloria said it looked all right.

Then she escaped.

And Maggie ostensibly swept the room, aired the pillows and shook the curtains. Trixy’s room had an unusually large mirror hung from the wall, between two windows, and whether Maggie posed in borrowed finery or merely spent time in profitable meditation, is not relevant, for it was her own time as well as her own work, and Maggie managed to finish on schedule in spite of all interruptions.

When Gloria ventured back, after first peeking in from behind Trixy’s curtains, she found things nicely slicked up.

28 “Good old Maggie!” she thought. “I am sure she is quite as honest as she claims to be.”

Addressing the well dusted bureau with a few more appropriate remarks, Gloria’s gaze fell upon a strange object.

“What’s this?” she asked aloud, for a small, glittering, bead-like stone instantly recalled the other. That one she had replaced in the torn envelope and put back in the strange trunk.

“A gem! A real garnet—or ruby——”

There was no question as to where it came from. Maggie had found it upon the floor, perhaps under the edge of the rug, and it must have fallen there from the envelope marked “Precious.”

Gloria turned the stone over on her open palm. She knew little of precious stones, but she easily guessed that this was valuable.

“What shall I do with it?”

The thought that its owner would resent her knowledge of so secret an affair as the opening of a trunk, and the handling of its contents, was disturbing.

“Oh, bother!” complained Gloria. “What am I going to do about a thing like this, anyway?”

29 Trixy’s return was welcomed. And the discovered treasure promptly and adequately discussed.

“Suppose you keep it for a day or two——”

“No indeed,” objected Gloria. “I have no wish to be throttled by the pirate’s daughter.”

“But it has been here for days——”

“That’s why my head ached. This thing is charmed. Maybe a drop of some one’s blood is sealed within the crystal,” she flippantly suggested, turning the stone over and over, smiling fondly upon it and otherwise showing neither fear nor distaste for the frozen “drop of blood.”

“I think it’s a garnet,” suggested Trixy.

“Why should a boarding school girl want to lug such stuff around with her?”

“Why?” repeated Trixy. “No custom officers to dodge.”

“But in that trunk! And not even in a strong little box,” argued Gloria.

“Some girls are careless. Also some grown ups. You know how very often real diamonds are hidden in old shoes and retrieved by honest cobblers, who become socialists after receiving the dollar ninety-eight cents reward,” philosophised Trixy. “Still, the girl who dropped them30 in her trunk must have been in an awful hurry.”

“But why hasn’t the owner advertised on the bulletin?” reasoned Gloria further.

“It is queer. Do you suppose Maggie knows——”

“That’s so. I’ll have to give Maggie something.”

“Better thank her for finding your bead and give her ten cents,” suggested the practical Trixy. “Otherwise, you may not be able to make a satisfactory accounting. Don’t let her suspect what you suspect.”

“A good idea. Listen! I hear her plaintive voice. Let’s have done with it. Lend me exactly a dime.”

“First, put the pirate’s treasure in my jewel box. I’ll be responsible for it and defy its evil eye—until you find the owner,” agreed Trixy affably. Gloria borrowed the dime and thrust it upon the inarticulate Maggie. Money, it seemed, always surprised her into speechlessness.

“And now,” decided Gloria, “I’ll take the ‘evil eye’ down to the office——”

“Suppose it is a real secret, that the owner has some worthy motive in hiding it.”

“Trix, you’re a regular Portia. I do hope31 you decide to study law. How would you suggest I get rid of the thing?”

“Post a notice, asking the loser of a small red stone to call at this room. We might excite less comment if we said ‘trinket’ instead of ‘stone.’”

“And have every one who lost a hair net, a hairpin, or a barrette, calling,” objected Gloria.

“That’s so. But Maggie may see the notice and recognize her find.”

“She won’t have time to read bulletins today.”

“No, I suppose not. Then just write a simple, unsuspicious notice, and say small red stone.”

“Peachy!” exclaimed Gloria. “Then we’ll have a chance to learn who really is the Pirate’s Daughter.”

Trixy wrapped the vagrant stone in a piece of tissue paper and then in a piece of tin foil from her film package, meanwhile moaning weird incantations. Then, after waving it in the air to break the spell, she very gingerly dropped the paper and tin foil packet into her little jewel case.

Gloria wrote the “found notice” with directions for reclaiming the “red stone” and was off instantly to post it upon the bulletin.

32 “Thir-rill-ling!” she chanted. “Suppose it’s Pat’s!”

“Or Jack’s?”

“Or just a red bead from the ten cent store?”

“I’d like to get a couple of dozen,” declared Trixy.

“Well, here’s for the bill board. Better watch out. Some one might kidnap me.”

With a parting laugh Gloria raced off and it seemed she was back, out of breath, and out of speech, before Trixy could close the drawer on the jewel box.

“I feel like a thief!” she gasped. “Isn’t it horrid to find a thing so long after?”

“As if you had been waiting for an offered reward?” laughed Trixy. “We aren’t likely to be suspected of anything like that, so don’t worry, lamb. I’m just all a-quiver of anticipation.”

But after lunch the little note was missing from its hook on the bulletin and in its place was found a message sealed and addressed to “Finder.” The girls read it in their own room behind closed doors.

The note read: “Please drop into old brass vase on teakwood stand in alcove of west sitting room.” That was all.

33 “Oh,” moaned Gloria, in disappointment. “Not even to say drop what.”

“How perfectly mean,” growled Trixy.

“Suppose we don’t. We might say that it ‘must be called for,’” suggested Gloria.

“But then,” mused Trixy, “there may be a real reason.”

“Again, noble Portia, I salute thee,” mocked Gloria. “In other words, just as you say. But I’d hate to be fooled again. That old trunk seems destined to add to my misery. Not that there’s much more room for addition,” (another groan and wild, agonizing rolling of eyes) “but I suppose we may as well drop the ‘jool’ in the vaase.”

“May as better,” amended Trixy.

“You do it and I’ll watch.”

“Foxy. Suppose some of the eagles see you. How do we know this isn’t sort of an initiation?”

“We don’t. I never thought of that, little Brightness. As you say, we had better follow directions, and not be compelled to wear our waists inside out, or parade two different colored stockings. Here, give me the pesky thing. I’ll hie me to the dump with it and so cast off the spell.”

Almost as quickly as she had posted the letter34 did she “dump the thing and beat it,” in her own inelegant language. She now stood before Trixy making foolish faces.

“Ugh!” she exclaimed, brushing her hands to shed the imagined pollution, “now it’s all over. And we’ve lost trace of the Pirate’s Daughter.”

“There’s no telling,” presaged Trixy. “She may remember you in her will.”

“And again she may not. Well, may all our ill health go with it, as dear old Jane would say. Trixy, when do we go out to see our anxious friends?” (This meant the home folks.)

“I dunno. But let’s stick it out for a while and then, when we do take a little trip to Sandford, we won’t feel like a couple of hookey kids. Not that I wouldn’t love to see my mommer right now——”

“And my—da-da!”

Reflection brought gloom. Forgotten was the frozen blood stone and the old brass vase. Two girls sat glum, with heads down and knees up, with chins pushed up into pouting lips, and naught but an occasional groan or grunt giving sign of articulation.

“I dunno,” said Gloria finally. “But there’s Pat! Mum’s the word, dearie, about the pirate’s35 watch guard or collar button or—paper weight. Don’t let us whisper——”

“Not a whisper,” agreed Trixy.

So Pat never knew what she had missed, and didn’t even guess that she had missed anything.

“What was that?”

“What?”

“I heard something. I felt the door open.”

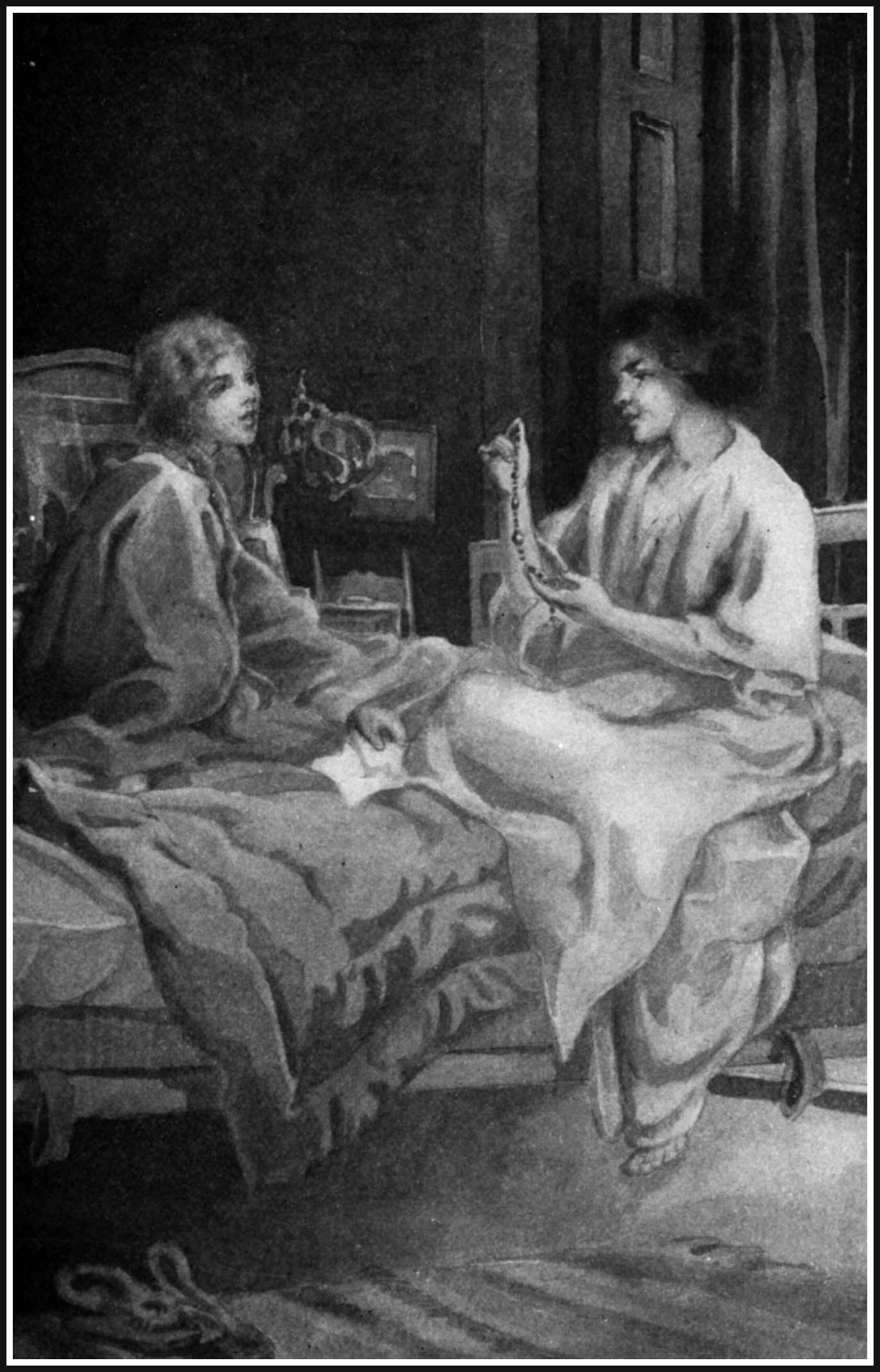

“You’re dreaming. It isn’t daylight yet. Turn over and try the other side.”

“Honest, Trixy,” Gloria raised her voice a trifle, “I did hear something. I am going to get up and look around.”

She did. It was daylight but not yet very bright, as the late fall morning was tardy in asserting itself.

“The door is open!” exclaimed Gloria. “I am sure I shut it.”

“I have always told you to lock it,” Trixy reminded her.

“But I hate bolted doors. They make me feel I’m being locked in a jail.” Gloria shut the37 door almost noiselessly, and then turned on the light.

“Nothing missing, that I can see——”

“Then, please, go back to bed,” begged Trixy from the other side of the curtains. “I do hate to lose the last half hour.”

“Sorry,” Gloria went to the window and looked out at the early lights and shadows. Then she quietly stole back to turn off the light that hung over her dresser.

As she raised her hand her eye fell upon a strange object. There was something, a small, white paper packet on the pin tray.

“Trix!” she exclaimed excitedly. “There’s something here——”

“What?”

“Get up. Let’s look. It has been slipped in the door and left on the tray.”

There was no mistaking the seriousness of her voice. Gloria meant what she was saying, so Trixy tumbled out of bed and joined her before the dresser.

“It’s heavy,” she said.

“Open it. You’re not afraid of it?”

“Of course not, but I am surprised. I hope it’s no more blood stones——”

38 “Just that. From the Pirate’s Daughter, I’ll bet! Hurry and let’s see! I’m quivering with——”

“Come over on the bed and spread out something,” suggested Gloria. “I don’t want the jools to roll under the rug this time.”

They both sat under a carefully spread pink coverlet, and then, very gingerly, Gloria opened the little package.

“Maybe some trick,” she guessed, still delaying inspection. “I hate to spoil our fun by finding some pop-corn, maybe.”

“Oh, do give it to me,” begged Trixy impatiently. “If it’s pop-corn I’m not going to waste any more time over it.”

“A’w right,” agreed Gloria affably. “Half the responsibility is yours, don’t forget that.”

The white tissue paper was carefully unfolded, and then there was disclosed a little necklace, made of some dark, queer beads.

“Oh-oo-ho!” squealed Gloria. “More queer stones! And look! Here’s a note!”

Eagerly scanning what was written in back-hand on a piece of plain white note paper, the girls found this:

They read it again. Gloria coiled the necklace around on the palm of her hand until it looked like a little black snake. Then she gave it to Trixy.

Held up to the light Trixy thought it looked like agate. Her father, she said, had a ring, his grandfather gave every boy in the family a moss agate stone each cut from the parent specimen, and this little necklace had one stone at least that looked like agate.

“But these,” pointed out Gloria, “they just look like Egyptian beads I bought at our fair. Don’t you know those you always liked? Black pearls, or some imitation?”

“But these are each different?”

“Yes. Sort of home-made affair. Who ever could have wished it on me?”

Both girls sat there thinking. Each turned40 her head, this way and that, cocking ears up as if some myth in the air might explain the mystery, the necklace was passed back and forth automatically, but neither offered to try it on. It was about big enough to slip over the head, and the more they scrutinized it the better they liked it.

“It’s so odd,” conceded Gloria.

“Not as odd as its circumstances,” said Trixy. “Why in the world would a girl want to be so mysterious? Seems to me sort of sensational.”

“And so wounds your social soul,” teased Gloria. “Never mind, dearie, when I drag in the Pirate’s Daughter from her den, it may be in the attic here, you know, and when I tame her so that she’ll eat out of my hands, I fix it up to include you in our trip to her father’s cave. He must be richer than old Captain Kidd to raise such a crop of gems or illuminated spangles, as I glimpsed in that trunk. Now, why couldn’t In Cog have sent me a little jewelled apron or a bedizened girdle to wear to the dingus? You know we are invited?”

“Yes.” The “dingus” or regular social affair exclusively for the pupils of Altmount, did not, at the moment, offer distraction.

“It seems to me we ought to detect a queer41 girl, easily. She is queer, of course, or she couldn’t think this way. She had to follow her own line of reasoning, and you’ve got to admit that’s queer,” said Trixy, philosophically. “Therefore she must be queer. Now, who is the queerest?”

“Impossible to select,” joked Gloria, “they’re all so queer. Pat’s funny, Jack’s funny, Jean’s snippy, little Helen is just the kind of girl to get an awful crush on one. She goes about with her eyes and mouth at half mast, ready to weep or laugh at the crack of a whip; but even at that she’d never have sense enough to plan all this. Well, Ixy-love, you may wear my jools whenever thou wisheth, and be sure to note the effect. They may give you chills or you might get a fever, or even that black, squarish little stone may exert a beneficent influence on the snippy Jean and make her perlite, for once in her sour life,” Gloria’s manner is not transferable to words but it was flippantly funny. “Perhaps we better start a new diary, the diary of the hoodooed necklace,” she suggested, and would have turned a somersault right then and there, had not Trixy grabbed her left leg ‘on the wing.’

“And I guess we may as well crawl out and42 get into a shower,” she continued, “before the infants rub their sleepy little eyes into the early sunlight. Though it looks like rain. I couldn’t say anything pretty without sunlight. There’s the seven-thirty bell. Would you ever believe it was more than five A. M.?”

The necklace lay on the pink coverlet while the two girls locked arms and swung back and forth like a pair of solemn Arabs. Anent nothing, they embraced always in that fashion, and the signal to halt was usually the realization of urgent duty. It was now time to dress.

“Scrum-bunctuous, anyhow,” decided Gloria. “Just think of all that’s happened a-ready. I cracked open a trunk, had a precious stone hid under my rug for nearly a month, returned it by way of a moldy old vase, got a note from an In Cog and was the recipient of a coal miner’s souvenir, the last strike settlement maybe; all this and nothing more at Altmount, quoth the raven. Never-more! There! When it’s first worn by either of us I fully expect a sensation.”

“Why don’t you put it right on and go down to breakfast? If a girl should notice it you might have just cause for suspicion.”

“You put it on, if you want to,” retorted Gloria.43 “This isn’t my day for necklaces. I have already decided to wear the ugly and uncomfortable sailor’s noose, prescribed.”

But all the day and for sometime thereafter both girls were ever on the alert to detect a clue to the original owner of the little talisman. Many strings of beads were significantly fingered and admired, but without provoking a tell-tale flush of admission, and as often as the opportunity could be made, Gloria or Trixy talked about foreign stones, especially dark ones with little light streaks running through. But at the end of a week both girls were forced to admit “no progress.”

“Tell you what we’ll do,” proposed Gloria. “Just let’s forget it. Put it away and wait. Some day the culprit will betray herself. Then, if we are not parties to some dark plot that includes hiding the queen’s jools, we’ll be lucky kids.”

“Just as you say,” agreed Trixy. “But don’t forget to-night is the night we are supposed to celebrate. I hope you can express a note of interest in this here Altmount without straining your conscience. Me—I’m beginning to like it.”

44 “It is picking up,” admitted Gloria. Both were assuming facetiousness.

There was, however, plenty of interest, “without straining consciences” at the dance. The fine old assembly room was gay with colors of many classes no longer otherwise represented, there was a very creditable orchestra composed of seniors and girls in the finishing classes, but more than these mere details, the personalities of all those present came out for the “acid test” according to Trixy.

Friends paired off, and groups assembled. Pretty gowns were praised with wordless glances of approval, new dances were demonstrated and various local peculiarities shown, even Pat declaring that the new position was quite like the “old fashioned way her mother had always insisted was the only correct way,” and so on passed a happy evening, at the boy-less dance, after which, like the spreading of a map, the personalities of students stood revealed.

No silly stunts nor traditional initiations were countenanced at Altmount, not since that rather disastrous event, still talked of, but no longer risked. It was the night one girl got locked in a45 closet and another climbed from the third floor window on a rope of bed sheets. Both were “laid up for repairs,” and a stringent rule against all rough play or initiations was the outcome.

But there were even now some secret affairs held in junior or soph quarters, usually followed the next day by pronounced fits of absentmindedness in class. Neither Gloria nor Trixy had been invited to any of these. First years usually were not, quite contrary to the regulation college customs.

“That’s because they want a chance to find out Who’s Who before taking one into their exclusive circles, I suppose,” Gloria remarked to Trixy, after listening for the best part of an hour to a report given by Janice. She had been asked by Jean’s contingent. She had the advantage of belonging to a family whose ancestral trees were knotted by colonial ties.

“But so far as I could gather,” scoffed Gloria, “it was an amateur fudge party, and the fudge got badly scorched, so I guess we didn’t miss much.”

“And, whereas it is against the rules to light little stoves in rooms, and the perpetrators are46 apt to be censured, I guess we are well out of it,” also scoffed Trixy.

“But they have to break rules, that’s the main idea,” Gloria explained. “Yet, it must have been pathetic to see the dear things trying to get fun out of the wicked pastime of making fudge on pin trays. I’d love to have had a view from a convenient distance.”

“We’ll see if we can’t hire the real kitchen, some evening,” suggested Trixy. “We’ll ask the faculty, invite them, I mean.”

“And all the kitchen staff,” added Gloria. “That would be fun. And the fudge will run a far greater chance of being fit to eat.”

This was held to be a brilliant idea and worth working out. So it happened that the domestic science class took on a new group of pupils unawares, and not only did Gloria and Trixy hold a fudge party in the kitchen a few afternoons later, as their part in the new year’s activity but the idea spread, until pop-corn drills and taffy pulls in the kitchen became almost common. Then it was that entertaining afterwards, in rooms, while despoiled of the precious rule breaking, offered real opportunities, and as a hostess Trixy became47 decidedly popular, while Gloria and Pat achieved marked success as floaters.

But such ordinary school happenings were mere calendar incidents, and like the calendar, interesting only to those who mark the days.

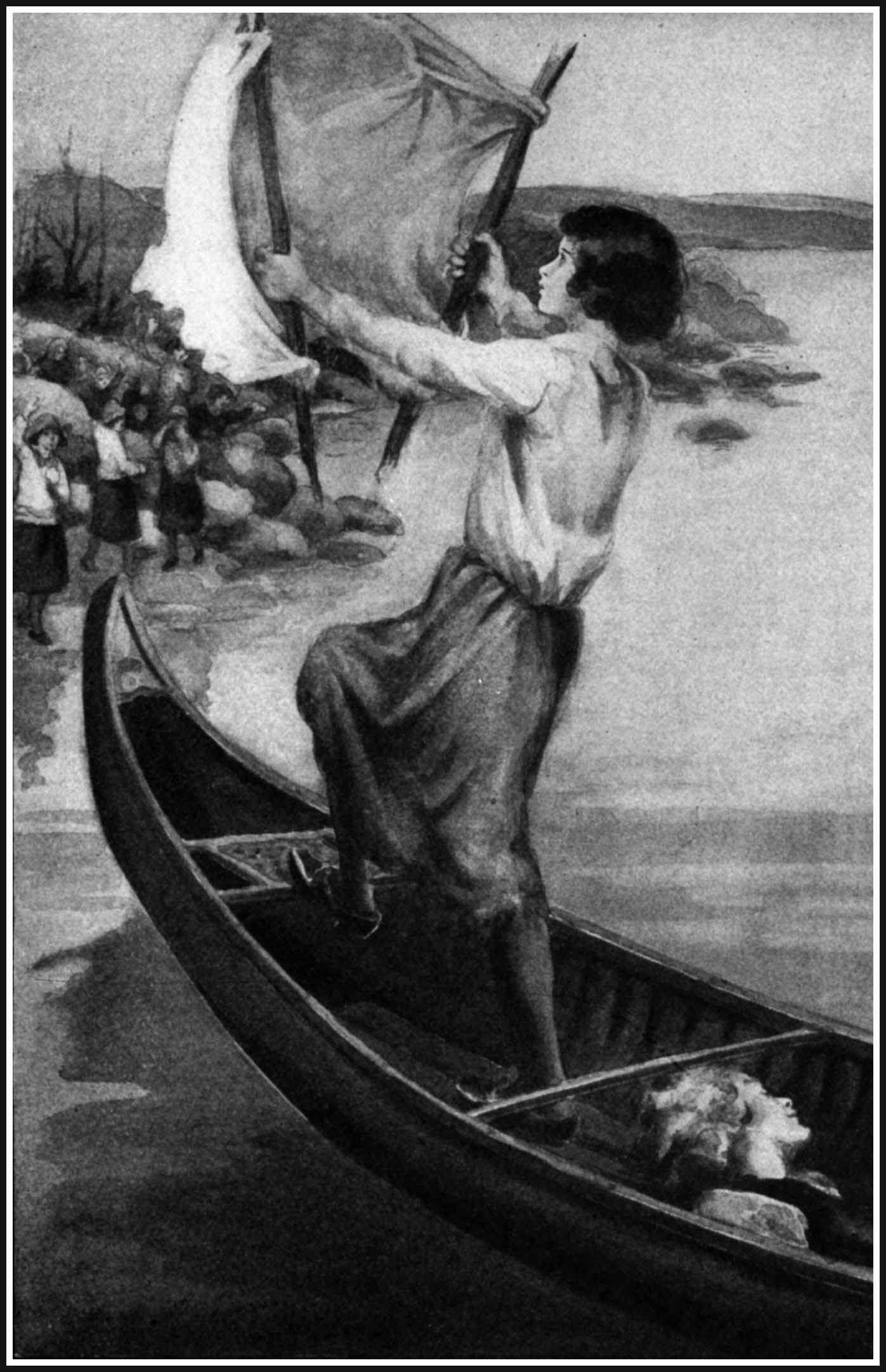

It was Pat who spread the news. A messenger boy had come late in the night with a telegram for Jack, and now, today, the day after the night alarm, Jack was gone!

“Some one sick or a sudden death?” hazarded Gloria. It was about time for a class and the conversation was necessarily snatchy.

“Jack doesn’t seem to have folks, at least, no one comes to see her,” explained the entertaining Pat, catching her blue barrette in a clump of hair much beyond its capacity.

“We’ll miss her,” spoke up Trixy. “I like Jack; she’s a positive cure for the blues.”

“Isn’t she? Jack is a lark, even if she does dress like—a fire sale.”

Gloria didn’t smile. Pat should not be encouraged in such criticism, especially now that Jack was gone and could not defend herself.

49 But after the morning classes and just before lunch, it was impossible for either Gloria or Trixy not to overhear a little stronger criticism than Pat’s harmless remark was intended to convey.

A group of girls behind a screen in the lavatory were even more critical and less considerate.

“Did you hear the row?” asked one.

“Did I? Thought the house was afire,” from another.

“Such a voice! That woman must be a perfect tyrant. The way she shouted at poor Alty.”

Gloria coughed loudly and meaningly, but the girls in the wash room rattled on.

“Couldn’t a’been her mother?”

“No—a Steppy, Jack calls her.”

“But why drag her away like that? In the middle of the night.”

“Family affairs,” tittered a new voice. “Wasn’t it dramatic?”

“Can’t say I think so, in an open hall and at midnight,” some one grumbled.

“But she wired first.”

“She should have sent the fire department first. Poor Alty was almost choked with indignation.”

Trixy slammed down the shoes she was attempting50 to clean, but her warning was altogether misinterpreted, for Jean Engle popped from behind the screen and claimed both Trixy and Gloria as additional debaters.

“We’re just talking about poor Jack,” gurgled Jean. “Isn’t it a shame she had to go away? She must perfectly dread her old ‘Steppy’—stepmother, and now she’s dragged her off again.” An uncertain sigh ended the pretended sympathy.

“Too bad she isn’t long distance eared,” joked Trixy, with a shade of subtility. “I’m sure she would be flattered with such championship.”

“I don’t care,” persisted Jean, not to be quelled in her efforts at a little excitement. “Jack never gets a chance to become interested in her work, and I suppose if she flunks at exams there’ll be no more mercy shown her than——”

“Hear! Hear!” broke in Arline Spragg. “Can any one imagine our Jean casting such precious bread upon the waters——”

Arline paused. A step outside gave warning and all eyes turned toward the opening curtains that divided the “lav” from a small rest room. Mary Mears’ form was now framed in the shadow. Her face was white, her deep set, violet eyes seemed almost black, and there was51 no mistaking her whole attitude as one of consternation.

Trixy was the first to find speech.

“Hello, Mary,” she said quite casually. “We are enjoying the most popular indoor sport, backbiting.”

“Yes!” Eyebrows lifted and shoulders shrugged.

“You know poor Jack is gone,” chimed in Jean Engle. “Dragged away in the night by a horrid Steppy——”

“Steppy!”

“Uh-huh. That’s what Jack calls her. We’ve never, any of us, seen her, but have all heard her. She’s that sort, vulgarly noisy——”

Poor Mary’s blonde head had gone higher and the white face seemed a shade more pallid as Jean gabbled on. Disgust, nothing less, except perhaps a hidden fear, was expressed in her haughty attitude, and somehow she reminded Gloria of a handsome animal trapped by refined cruelty.

“I hate gossip,” Mary said, crisply.

“You do!” retorted Pat. “Well, it’s a necessary evil here. We have to do something, why not gossip?”

“When a girl’s back is turned?” Mary qualified.

52 “But it isn’t about Jack, it’s the old lady. She must be a shrew. Can’t we say that about her when she wakes us up in the dead of the night?” Pat retorted.

“And we are really defending Jack.” This from Jean.

Gloria, being a newcomer and also in the “freshie” class, held back from the discussion. Exchanging glances with Trixy, both had plainly shown surprise that Mary should have appeared so haggard. Even her usual studied calmness was replaced by nervous little jerks, one of which caused her to drop and shatter the drinking glass.

“Oh!” she gasped. “How stupid of me!”

“Let me pick it up,” offered Gloria kindly. “Trixy says I can walk on glass, just because she saw me walk over clam shells at home. Anybody here ever bathe from a shelly beach? I have one at my native dock.”

This sally mercifully changed the subject, and beaches sandy, beaches rocky, or beaches shelly, were soon being discussed from as many view points as there were persons expressing them.

Mary beamed gratitude upon Gloria. It was her first unbending, and perhaps because the approval was not easy to obtain, Gloria appreciated53 it more fully. She twinkled understandingly.

“I hate to be a nuisance,” Mary said rather humbly, “but my hand must have been wet and the glass slipped. Do you report damages to the office?”

“Don’t you dare!” thundered Pat. She was now all primped and pretty and ready for the walk or hike, as she termed the proposed exercise scheduled for the afternoon. “If you start anything so honest as paying for a broken drinking glass, I would feel absolutely bound to tell who broke the glass dish——”

“Hush, Pat. You perpetual gabber. We all hated the dish. It was too small for cookies——”

“All right, Becky dear. Don’t get excited. I’m not on my way to the office.”

Gloria had gathered up the splints of glass and skillfully dropped them into the marshmallow box Mary held to receive them.

“You’re a dear,” murmured the pale girl. “But I shouldn’t have let you do it.”

“You couldn’t have stopped me,” retorted Gloria. “Don’t you know how stubborn I am? When I take a notion——”

“Come along,” interrupted Trixy in an undertone. “Going to hike, Mary?”

“Oh, do,” begged Gloria. “There’s nothing like it for nerves, and you have a headache, haven’t you?”

“A little. I didn’t sleep well. Guess I’m not quite fit for this quiet life——” she smiled quizzically.

“Isn’t it awful?” interrupted Trixy. “I don’t know whether to bless or blame Gloria for dragging me here. But not being a quitter I suppose I’ll stay.”

“If you don’t, I don’t,” declared Gloria. All three had separated themselves from the others and were now on the porch ready for the hike and awaiting the leader.

“Really, don’t you like it here?” pressed Mary gently. She might not have seemed so pale but for her black satin dress. She always wore such dark colors when the uniform was not required, whereas then the other girls just melted into color glory.

“We are rather spoiled, I’m afraid,” admitted Trixy. “Little Glo has lately distinguished herself as an engineer; that is, she discovered a river the engineers had overlooked, and what hasn’t happened in the way of good fortune since55 that eventful day!” Trixy intoned reminiscently.

“How interesting!” Mary said politely.

“Since you’re telling tales, Trixy, I might add——” drawled Gloria, “that the engineer, the young, handsome and all that sort of thing young fellow, is a special friend of yours. There is the barest possibility she misses him——”

“Glo!”

“And he’s gone off again following my dear dad! Way out Philippine way——”

“Just for that you shan’t see my letter!”

“A letter! From Sherry?”

“Sherwood, please. He has outgrown Sherry. Want to see his stationery?”

The inscribed envelope (from Trixy’s pocket) was passed around. Gloria read it backwards and forwards, made fun of it and approved in the same breath. Then it was handed over to Mary.

“Why!” she exclaimed, “that name seems familiar. Was he abroad last year?”

“Yes. Were you?” asked Trixy simply.

“Yes, that is—yes,” floundered Mary, and a hint of confused color touched up the pale cheeks.

“How jolly! Did you really know our noble Sherry?” demanded Gloria quite enthused.

“Oh, I wouldn’t just say that,” Mary answered56 with a return of her usual restraint. “One meets others while travelling, and sometimes we see names on the hotel lists——”

“But we must tell Sherry,” Gloria rattled on. “Trixy, do you mind if I write?”

“I’ll put in a little censored note——”

“I’m sure he has never heard of me, of Mary Mears,” declared Mary, just as Miss Alton, otherwise “Alty” and little Miss Taylor, otherwise “Whisper” appeared and marshalled forces for the four mile hike.

There was opportunity for confidences along the way, and Mary’s attitude was seriously discussed by the two girls from Sandford.

“She’s high-spirited,” declared Trixy.

“And touchy,” added Gloria.

“I can’t just see why she acts so offish.”

“Seems to keep the brake on every minute.”

“Afraid of hills—sliding, I mean.”

“Into reality. I’ve thought of that.”

“She’s a splendid contrast to Jack, isn’t she?” concluded Gloria, as the hikers halted at Van Winkle’s Spring. Then Old Rip entertained most royally.

“Altmount” was so named from the fact that the Alton family had settled, built and managed the mount for more than four generations. The original homestead was now the smallest of the three imposing structures that clung to the hillsides, and was used to house the youngest pupils of the select school, while in a splendid stone and shingle structure recently built, and unquestionably an important executive building for the seminary proper, were domiciled Gloria and Trixy.

Gloria might have been relegated to No. 2 known as the Wigwam, from a curious Indian legend attached to it, but somehow the influential Trixy succeeded in keeping her friend with her. Not quite sixteen, country life and natural fondness for healthy exercise had developed Gloria into the attractive personality termed “wholesome,” but comparing this with the uncertain ages58 and equally uncertain types about her, very often the “sweet sixteen” was mistaken for seventeen or even greater “teens.”

Now, Pat was seventeen, and she might have been classed among the “little ones.” She was small, round, dimplely and “bubblely.” It would be hard to imagine Pat ever supporting with dignity her real title, Patricia Halliday. Jean Engle was tall and willowy, and wore brown braids in a coronet about her head. She had rather a sharp tongue, and unfortunately her friends laughed at “her cuts.” The comparative isolation of boarding school naturally drew out and magnified each girl’s peculiar traits, so that what might have seemed rude in Jean at home was hailed as “good fun” at Altmount.

It was she who suddenly checked Gloria’s laughter. The departure of Jack had not yet ceased to be a subject for gossip, when a group of the girls were squatted around the Sentinel Pine, the only one tree upon the spacious grounds allowed to foster from year to year the carpet of pine needles about its roots. These were not raked up because they formed so splendid a little rest ground for the fortunate girls who “got there first.”

59 “You’re not a bit like your cousin,” announced Jean out of a clear sky, favoring Gloria with a critical look at the same moment.

“You mean Hazel?” floundered Gloria, sensing objection in Jean’s pert remark.

“Of course. Hazel seems so—oh, so sort of—well——”

“Do say it, Jean. Glo will forgive you,” broke in Pat characteristically.

“Oh, you see,” interfered Trixy, “Hazel is temperamental. She has a voice. See how short a time she stayed here. Just a brief year——”

“Where is Hazel now?” asked Blanche Baldwin.

“She is at home when not at the conservatory,” replied Gloria. “Hazel really has a promising voice.”

“Ye-ah,” drawled Pat, with an uncertain smile and an impolite gulp.

“But I meant that, somehow, you don’t seem a bit like Hazel—in your ways,” came back Jean without so much consideration as a direct address with Gloria’s name to soften it.

Gloria bit her lip. Pat bit hers so hard it dragged the dimple out of her chin. Trixy, as usual, knew just what to say and she said it.

60 “Hazel has rather sophisticated ways for a girl brought up in Sandford. But then, it has always seemed to me, that big town folks are apt to overdo it; like strangers trying on the Boston accent.”

Gloria smiled at Trixy’s adroitness. She had deliberately turned the interests from Gloria’s possible mannerisms to Hazel’s. Still, a suppressed little twinge tugged at her consciousness. Was she different from the other girls? Were her tom-boyish, country ways rude or even rough?

More than once she had noticed surprised eyes staring at her when impulsively she had said or done something as she might have done at her old Barbend home, when Tommy Whitely would have shouted with glee or Mildred Graham chuckled delightedly. But no such result was achieved at Altmount. The girls there, with the exception of Pat and perhaps one or two others, all seemed bent upon outdoing their companions in correct social behavior.

A sort of pairing off followed the discussion of Hazel’s ways. That she had a wonderful voice all were willing to concede, but just what Jean meant by her comparison with Gloria was not61 clear, at least not satisfactorily clear to Gloria, or her special friends, including Pat.

The school cliques, inevitable, were again being set in motion. Clubs or Sororities were forbidden, as they had been the cause of more than one bitter quarrel among the girls in past years, when the faculty had tolerated the Bluejays, or the Social Sixes or even the Gabfesters, but a girl like Jean is sure to lead in a subtle way. Her pronounced opinions are always easier to accept than to combat, and just now she was “making up” something quite “clicquey.”

“The deceitful thing,” murmured Pat, when girl after girl slipped away from the pine needle carpet to follow Jean’s unspoken suggestion. “And she ate more of our pop-corn than any other three eaters added up.”

“Was she a great friend of Hazel’s?” asked Gloria. Her dark eyes were glinting under rather fluttering lids, and a “set expression,” as good old Jane would have described it, seemed to have suddenly burned out Gloria’s happiness fuse.

“Jean is always pals with the airified ones,” said Pat, answering Gloria’s question. “The way she eats them up makes me—suspicious.”

62 Trixy broke into a genuine laugh. Pat could say the wisest things in the queerest way.

“But I notice she didn’t gobble you up,” went on Pat to Trixy. “How come?”

“Do you suppose I am in the way?” Gloria had not yet found a smile and was plainly pouting.

“Silly baby!” chided Trixy. “If you really have saved me from anything like that——” sweeping a hand toward the departing contingent, “then indeed, I am more than grateful.”

“Oh, I have it,” exploded Pat. “Let’s get up an opposition!”

“To what?” inquired Trixy.

“To—to Jean, of course.”

“I wouldn’t satisfy her to do anything of the sort,” sniffed Gloria.

“But don’t you see they are planning something?” asked Pat.

“Who cares?” retorted Gloria. “I’m getting sort of homesick, I guess, but I just would like a whole day away from—all this.” A suspicion of tears dimmed her eyes.

“You have been a perfect lamb, Glo,” declared Trixy, winding her arm about the younger girl’s shoulders in sympathy. “Never made a mite of trouble.”

63 “But you are sort of used to—to changing about, aren’t you, Glo?” asked Pat, quite innocently.

“Why, Pat, what do you mean?” demanded Gloria, sensing an undercurrent to the last remark.

“Oh, I don’t mean you have been to other schools, or that sort of thing,” returned Pat, brightening up in alarm at Gloria’s tone, “but you see, Hazel was—talkative, and she told everybody how you lived at her house, and about—your mother being dead and all that.” There was no mistaking Pat’s own sincerity.

“So that’s it!” A wave of understanding flooded over Gloria. “They think I lived on Hazel’s folks! Poor relation——” bitterly.

“Gloria Doane, I won’t have you getting such foolish notions in your pretty head,” interrupted Trixy. “If folks don’t know what you and your dad have done for Hazel and her folks, it is only because you are both too high principled to let it be known.” Trix’s eyes were now flashing and her open defense of Gloria was just what any one knowing Beatrix Travers would have expected.

Gloria smiled cynically. “Just the same, Trix, those girls have no use for the cousin Hazel has64 told them all about. Not that I mind, really, for I have all I care for, but somehow—Oh, what’s the use?” she broke off sullenly.

“Rudeness is the meanest sort of cut, always,” took up a new voice just as quiet Mary Mears glided up to the little party, from behind the hedge that outlined the path.

“Oh, hello, Mary!” greeted Pat. “Come along and join the wake. You’re welcome,” and she made a place on the big low cut stump.

“I always thought boarding school was composed of sets, little clicques, you know,” continued Mary, “now I’m sure of it. Of course, I’m on the very outer rim——”

“Nothing of the sort,” spoke up Trixy with spirit. “If we care to we may, very easily, have a better, if not bigger, crowd than Jean Engle has. I hate to start things, but as Pat says, there’s no use standing still and applauding their efforts. What do you say, Mary? Shall we organize?”

“I’d love to, but——”

“Now forget the ‘buts’ and let’s!” exclaimed Pat joyfully. “I’ve been in the dumps since Jack went. Never knew how much I depended upon Jack for amusement,” her voice trailed off. “Poor old Jack! I wonder where she is and—why?”

65 Gloria had not raised her head and therefore could not see the swift change that swept over Mary’s pale face. Trixy again intervened.

“If we organize what is to be our object?” she asked.

“Fun,” snapped Pat.

“Of what sort?” persisted Trixy.

“Oh, every kind. We can’t exactly effect riots in this retreat,” mocked Pat, “but we might get up some highly interesting rows. There’s nothing like a real, tip-top scrap to set the feathers flying.” An anticipatory chuckle gave warning of Pat’s active intentions.

“But really, Trix,” spoke up Gloria, “I have no idea of making a martyr of you on my account. You don’t belong in our baby class and we all know perfectly well that the other girls are crazy to get you in their set, but well, I don’t blame them really, for not wanting to bother with me.”

A ripple of delicious laughter was Trixy’s reply.

“Oh, if you feel that way about it——” began Pat merrily.

All this time Mary appeared to be listening abstractedly. Gloria’s face was serious, with quite an unusual expression for her, but Mary always serious, now seemed actually depressed.66 The late November day was warm and glowing as any in October, and shadows shot through the giant pine, making murky haloes about the heads beneath. Altogether conditions conspired toward plots and intrigue. It had taken just that long for the usual hikes, lake pleasures, tennis and such sports to lose their interest, and now with the brisk, crisp air of winter’s foreshadow, the pupils at Altmount, naturally, swung to more original forms of recreations.

Pat had been doing most of the talking since Jean so pointedly gathered her chums to other stamping grounds. Of course, Trixy did her best to banish Gloria’s ill humor, the result of that remark from Jean concerning Hazel’s and Gloria’s mannerisms, but the cloud was still there, just as Mary’s moody aloofness was more pronounced as she attempted to hide it.

“Then we’re to have a clan,” repeated Pat. “We’ll ask all the girls who are not manacled to Jean’s ankles.”

“Really, Pat, it wouldn’t be fair to take Trixy from the seniors,” interrupted Gloria.

“Say, Glo!” in quick succession interrupted Pat. “Whatever has come over you? Why the martyr’s crown?”

67 Gloria swung her chin around and up high in mock contempt. “I was never sure I’d like boarding school,” she remarked evenly. “Now I know I don’t,” she declared emphatically.

“Just because catty Jean Engle digs——”

“No, Pat, that isn’t it. It’s because I’m not the sort that fits in.”

“You’re not the sort that follows the crowd,” broke in Trixy, “but you do fit in, Gloria. Any one can follow the band wagon,” declared Trixy with unmistakable scorn.

“What made you jump so, Mary?” asked the outspoken little Pat. “Do you hate band wagons worse than ‘pizen’?”

“Yes,” said Mary quite helplessly, and even Gloria stared in surprise.

“Seems to me we better adjourn, as the lawyers say ‘sine die.’ We are having such a deplorable time,” concluded Trixy. Even her good nature could be tried too far.

Gloria got to her feet first and looked resolutely at the big building on the hill top.

“Don’t go hating it,” cautioned Trixy, kindly sensing her emotion.

“No, indeed. I’ll have to—conquer it now,” replied Gloria bravely.

68 “I wish I could feel as you do,” remarked Mary. She was the gloomiest of all.

“How do you feel?” demanded Pat.

“Like running away,” admitted Mary, her lips drawn tight.

“But you wouldn’t! Mary, have you had a sorrow?” asked Trixy impulsively in an undertone.

A quivering lip left words unnecessary.

Trixy linked her arm into Mary’s and the long delayed confidence was under way.

“She’ll cut you out, first thing you know,” warned Pat in Gloria’s nearest ear.

“For Trixy’s sake I hope she does,” declared the sullen girl who even turned aside from Pat’s good-natured arm.

This was the stage of boarding school life usually classified as “the reaction,” and upon just what course the girls would now take depended much of the year’s pleasures or disappointments.

That Gloria and Mary were alike disappointed was very evident, but the cause!

Gloria’s highly sensitive nature was feeling keenly the slights aimed at her by Jean’s contingent, but why Mary Mears should go from the quiet stage to the actual melancholy was puzzling every one.

69 Would she confide in Trixy?

Would Trixy ever choose any one in Gloria’s place?

And above all, what was the reason that Jacquinot Corday left school several times during the term?

Inquisitive, carefree, little Pat seemed to thrive on the possible replies to such questions, but Gloria’s own heart was too heavy for speculation. She longed for the freedom that lent personal activity, she hated doing things because they should be done, and she was unconsciously preparing for an attack. The smoldering fire is sure to blaze up sometime.

“But it isn’t like you to mope, Gloria,” reasoned Trixy, with a suspicion of reproof.

“I know, Trix, but I just feel I am—country!”

“If you mean natural, I’ll agree. The city has a knack of artifice. But why you should let a word from that feather brain, Jean, so affect you?”

“It wasn’t that alone. I’ve felt ever since I came that Hazel had branded me as the poor relation, the little orphan Annie——”

“Oh, Hazel isn’t really mean——”

“No, but she’s so high and mighty that her very compliments sting,” argued the miserable Gloria. “Truly, Trix, I don’t care a rap for myself, but I’ve been selfish about you. They didn’t ask you to ride yesterday, I noticed.”

“I had a glorious canter before their old horses were out of the stalls,” flung back Trixy. “I71 hate riding in a crowd. It’s like travelling with a party. Every move is subject to the schedule, prearranged. Besides, I made a discovery while out on my run, and if you are a good girl I’ll disclose it to you.”

“Be a lamb and tell me the glad tidings,” coaxed Gloria. “I’m just dying for something new. Don’t you hate the rules and regulations that put us asleep, wake us up, feed us, think for us——”

“Gloria Doane! You little wild oriole, with your black head and new sweater!” laughed Trixy. “I’m afraid you really do need the Altmount discipline. You have been such a free little creature all your life.” Trixy looked absently out the window over the wavering trees, some already leafless, others gorgeously colorful. She was remembering Gloria Doane at her seaside, Barbend home, and again recalling the heroic Gloria, who a few months ago, had fought her way out of a flooded house, where with the little boy, Marty, she had become imprisoned. This was the great adventure related in “Gloria” and comparing the girl of such adventures with the one Trixy now confronted, it was not unreasonable indeed to find her rebelling, straining at the72 silken cords of Altmount’s restrictions. But Trixy’s life had been very different. The child of wealth is born to responsibilities, and they scarcely ever include escapes from flooded cellars, or the rescue of frightened children surrounding helplessly sick mothers.

“You know, Gloria,” spoke Trixy again, “there really is a lot to learn here. We couldn’t expect to find everything rosy, that would mean deadly monotony.”

“Oh, I know I’m horrid to grumble,” promptly admitted Gloria, “but I do like to do things. There seems so little to do here except follow rules.”

“Why don’t you put on the charmed necklace? That might precipitate an adventure,” suggested Trixy.

“Put it on! No, indeedy. I’m glad it’s on your side of the curtain,” declared Gloria, “for I do get strange fancies concerning the thing. The more I try to solve the mystery of the original owner, the further I get from it. Do you suppose there is some one here not really a pupil——”

“Maggie?” mocked Trixy.

“No. Of course not Maggie. But there are73 rather queer folks sauntering around. There’s the official mender, for instance. That one who wears a wig to hide her shaved head, according to Pat. Now, she might really own a trunk, and those home-made beads look rather like her. Just imagine me wearing a gift from her.”

Trixy laughed uproariously at the possibility, and she finally decided with Gloria, that the necklace had better be kept in seclusion.

“But I had an adventure this morning,” again promised Trixy.

“Tell me about it,” begged Gloria. “Was there a nice woozy old tramp in it or, mayhap, a plumed knight?”

“Neither. But let’s take our constitutional. These walls—might have ears,” cautioned Trixy.

“So secret as that! Goody!” Gloria executed a little skip over to the curtained closet, snatched her cap off a hook and clapped it on her head. “Every one seems late this morning,” she remarked. “We can have the birch lane all to ourselves. Hurry and give me the thrill. I’m famished for it.”

But as they tried to slip out, more than one hail from peekers in doorways demanded to know whence and why, and evading the rebound of Pat,74 who dashed into the “lav” and intended to dash out again, was not altogether a simple matter. In fact, the tower stairs were finally used as a means of escape.

“Hurry!” whispered Trixy. “The side door is open.”

“Tell me!” begged Gloria. “I’m fairly quivering with expectancy.”

“It’s about Jack,” began Trixy, catching her breath.

“Is she back?”

“She must be. I saw her before breakfast.”

“Where?”

“That’s my story, but you’re spoiling it all with your unromantic questions. Please, as the witnesses say, let me tell it in my own way.”

“Proceed,” ordered Gloria, with a flourish of her free arm.

“You know I went out very early——”

“I do.”

“But I didn’t waken you. I heard you breathing awake long before.”

“Yes, I was awake. Really, Trix, I’m afraid I was a bit homesick. But never mind me. Can’t you feel me tr-r-r-em-bell, awaiting your story?”

75 “Walking at this pace is an absorbing occupation,” objected Trixy. “Let’s sit down and talk like civilized folks.”

A squat on the big rustic bench under the Twin Oaks didn’t look very civilized, but it was better for confidence than was racing.

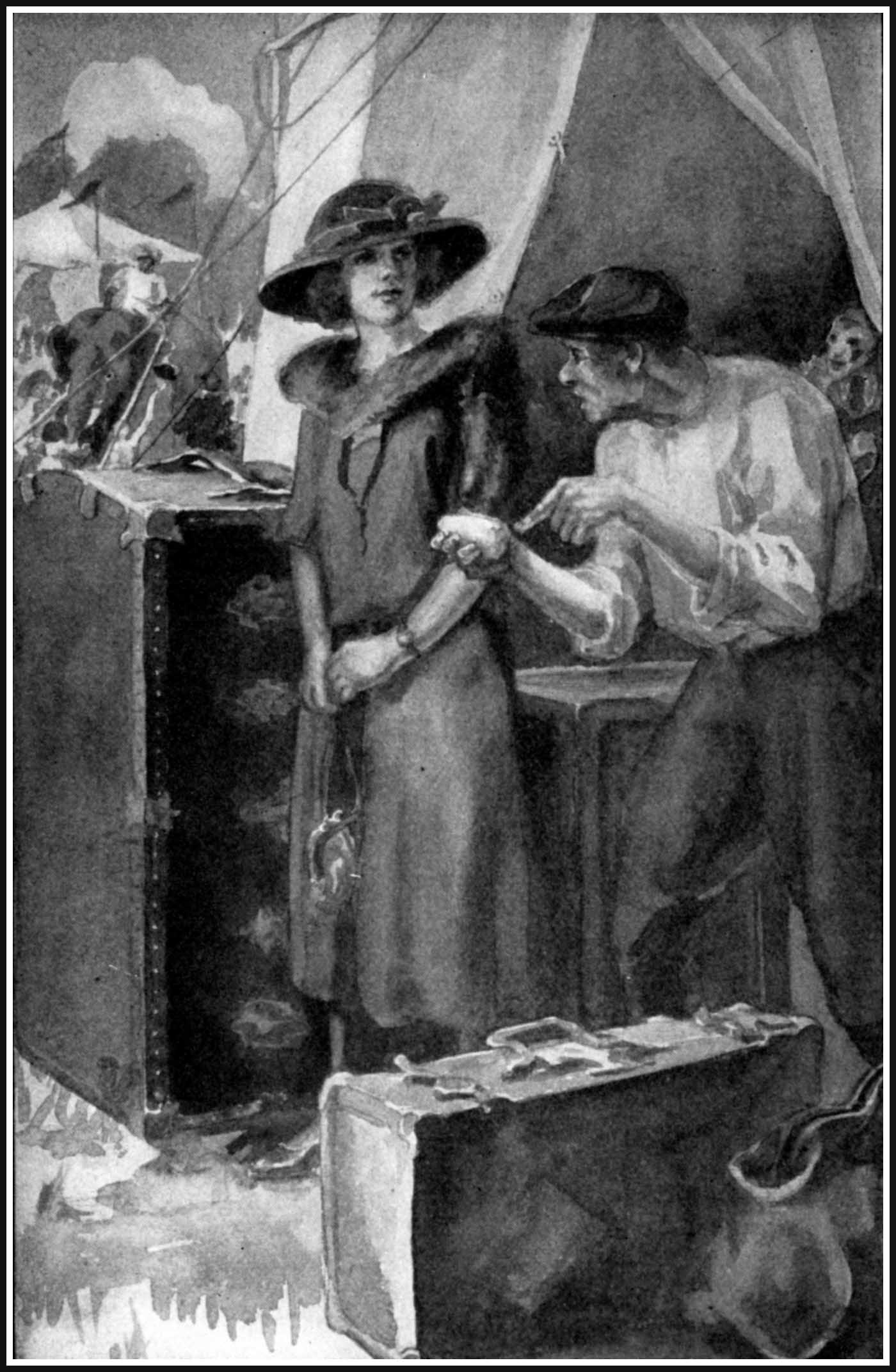

“I was just turning in with ‘Whirlwind’ (he’s a lovely little horse,) when I saw or rather heard a party trotting along from the Sound Road,” began Trixy. “They were on a regular trot and coming like the wind. I pulled to one side to let them pass, and that put me behind the line of low cedars. They couldn’t see me but I faced them——”

“Who?”

“I only recognized one. Jack. You should have seen her! She looked like a poster girl.”

“Jack!”

“Yes. Her hair was loose, it must have fallen from under her hat, a brown felt, and her habit! It wasn’t a habit at all, but shirt and trousers like a regular little Broncho Billy!”

“Our Jack——”

“Yes, indeed. I might not have believed my eyes if my ears hadn’t helped. Just as her horse swung into the lane she called to him. It was76 certainly Jack’s voice,” declared Trixy, still mildly excited over the unusual encounter.

“And who was with her? You said others——” prompted Gloria, foreseeing an interesting escapade in Jack’s assuming the rôle of a Broncho Billy.

“Yes, there was a woman and she also was an expert rider, besides—now get a good long breath, Glo, you’ll need it,” warned Trixy. “The other member of the wild rider’s troupe was a perfectly stunning looking young fellow.”

“Oh, how delightful! Oh, how exciting,” sighed Gloria. “How ever has Jack kept such a plot all to herself?”

“Perhaps she hasn’t. You forget we are comparative strangers.”

“And out of the confidence club,” a hint of yesterday’s bitterness flashed through that remark.

“But what particularly struck me,” resumed Trixy, ignoring the cynicism, “was the wonderful mounts, the absolute expertness of those three riders. They certainly are professionals,” she insisted.

“Oh, I have it!” exclaimed Gloria. “My trunk mystery! Jack belongs to—to a troupe!”

77 “A troupe!” For a moment Trixy was mystified.

“You know,” insisted Gloria, “the strange trunk I opened? And all the—glittering stuff?”

“Oh, yes. Of course. You—we have never solved that mystery——”

“And Jack is always so sort of spectacular! Oh Trix, do you really think she might belong to a circus?”

“A circus! How ever could a circus performer get into Altmount?”

“That’s so. This is rather an exclusive place. I recall that your mother had to vouch for me.”

“Gloria Doane! You are a perfect little simpleton! No one had to vouch for you. Your own mother attended one of the Alton schools and her name was an excellent voucher. All my mater had to do was to——”

“Say she knew me, and my dad, and all the rest of the family!” Scorn mocked the words.

Trixy tossed her head back impatiently. Gloria’s humility was plainly far from genuine, but she swung quickly to her friend’s side and threw an affectionate arm around her.

“Darling Trix,” she whispered. “I am getting to be a horrid prig, I know it. Just plain78 vanity, of course. But for mercy sakes, tell me about Jack’s chariot race. We’ll have to go indoors directly and I haven’t heard half.”

“There really isn’t any more to tell,” replied Trixy. She smiled forgiveness into Gloria’s eyes, however. “They had ridden a long distance, that was evident, and I just wish you could have seen what a raving beauty Jack looked.”

“War paint.”

“Strange I never thought of that, I do believe she might have had some queer color on her face——”

“What fun!” cried Gloria, springing to her feet and threatening to dance. “Do you suppose we’ll see her in all her togs? Which way did she go? Didn’t you even shout at her?”