Title: The Art of Ballet

Author: Mark Edward Perugini

Release date: October 25, 2020 [eBook #63550]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by deaurider, Susan Carr, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Art of Ballet, by Mark Edward Perugini

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/artofballet00peru |

THE

ART OF BALLET

BY MARK E. PERUGINI

LONDON: MARTIN SECKER

NUMBER FIVE JOHN STREET ADELPHI

First published 1915

TO

MY WIFE

Some may possibly wonder to find here no record of Ballet in Italy, or at the Opera Houses of Madrid, Lisbon, Vienna, Buda-Pest, Berlin, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Warsaw, or Petrograd (formerly St. Petersburg), not to speak of the United States and South America. This, however, would be to miss somewhat the author’s purpose, which is not to trace the growth of Ballet in every capital where it has been seen. To do so effectively were hardly possible in a single volume. A whole book might well be devoted to the history of the art in Italy alone, herein only touched upon as it came to have vital influence on France and England in the nineteenth century. We have already had numerous volumes dealing with Russian Ballet; and since the ground has been extensively enough surveyed in that direction there could be no particular advantage in devoting more space to the subject than is already given to it in this work, the purpose of which only is to present—as far as possible from contemporary sources—some leading phases of the history of the modern Art of Ballet as seen more particularly in France and England.

A brief series of biographical essays “Cameos of the Dance,” by the same writer, was published in The Whitehall Review in 1909; various articles on the subject also being contributed to The Evening News, Lady’s Pictorial, Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, Pall Mall Gazette and other London journals during 1910 and 1911; and a series of “Sketches of the Dance and Ballet,” coming from the same hand, appeared in The Dancing Times, 1912, 1913 and[8] 1914. They were based on portions of the manuscript of the present work which, begun some years ago by way of pastime, and written during the scant leisure of a crowded business life, was completed at the publisher’s request, and was—save for a few brief insertions in the proofs—ready, and announced for publication before the Great War began in August 1914.

The preparation of this book has involved the marshalling of a vast array of facts and dates, the delving into and comparison of some three hundred or more ancient and modern volumes on dancing and on theatrical and operatic history, the study of scores of old newspaper-files and long-forgotten theatrical “repositories” and souvenirs. Error is always possible in spite of care, and if it should have happened here the writer will be grateful for correction. In covering so wide a field a full bibliography becomes impossible from limits of space; but to those interested the following list of leading authorities—supplemented by those referred to in the text—may be of service. “La Danse Grecque Antique,” by M. Emmanuel; “Roman Life and Manners under the Early Empire,” by L. Friedländer; “Dramatic Traditions of the Dark Ages,” by Joseph S. Tunison (University of Chicago Press); “Orchésographie,” by Thoinot Arbeau (1588); “Des Ballets Anciens et Modernes,” by Père Menestrier (1682); “La Danse Antique et Moderne,” by De Cahuzac (1754); “The Code of Terpsichore,” by Carlo Blasis (1823); “Dictionnaire de la Danse,” by G. Desrat (1895); “Dancing in all Ages,” by Edward Scott (1899); “Histoire de la Danse,” by F. de Menil (1905); and “The Dance: Its Place in Art and Life,” by T. and M. W. Kinney (1914).

| BOOK I. THE FIRST ERA | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| OVERTURE: ON THE ART OF BALLET | 15 | |

| I. | A DISTINCTION, AND SOME DIFFERENCES | 21 |

| II. | EGYPT | 25 |

| III. | GREECE | 32 |

| IV. | MIME AND PANTOMIME: ROME, HIPPODROME—OBSCURITY | 41 |

| V. | CHURCH THUNDER AND CHURCH COMPLAISANCE | 47 |

| VI. | A BANQUET-BALL OF 1489: AND THE BALLET COMIQUE DE LA REINE, 1581 | 53 |

| VII. | THOINOT ARBEAU’s “ORCHÉSOGRAPHIE,” 1588 | 61 |

| VIII. | SCENIC EFFECT: THE ENGLISH MASQUE AS BALLET, 1585-1609 | 71 |

| IX. | BALLET ON THE MOVE | 83 |

| X. | COURT BALLETS ABROAD: 1609-1650 | 88 |

| XI. | THE TURNING POINT: “LE ROI SOLEIL AND HIS ACADEMY OF DANCING,” 1651-1675 | 99 |

| BOOK II. THE SECOND ERA | ||

| XII. | SOME EARLY STARS AND BALLETS | 109 |

| XIII. | “PANTOMIME” AT SCEAUX, AND MLLE. PRÉVÔT | 113 |

| XIV. | ITALIAN COMEDY, AND THE “THEATRES OF THE FAIR” | 119 |

| XV. | WATTEAU’S DEBT TO THE STAGE | 130 |

| XVI. | [10]“THE SPECTATOR” AND MR. WEAVER | 142 |

| XVII. | A FRENCH DANCER IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY LONDON | 149 |

| XVIII. | LA BELLE CAMARGO, 1710-1770 | 156 |

| XIX. | “THE HOUSE OF VESTRIS” | 163 |

| XX. | JEAN GEORGES NOVERRE | 171 |

| XXI. | GUIMARD THE GRAND | 179 |

| XXII. | DESPRÉAUX, POET, “MAÎTRE,” AND “HUSBAND OF GUIMARD” | 195 |

| XXIII. | A CENTURY’S CLOSE | 201 |

| BOOK III. THE MODERN ERA | ||

| XXIV. | THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY | 207 |

| XXV. | CARLO BLASIS, A LEADER OF THE MODERN SCHOOL | 213 |

| XXVI. | THE “PAS DE QUATRE”: I. MARIE TAGLIONI. (“SYLPHIDE”) | 223 |

| XXVII. | THE “PAS DE QUATRE” II. CARLOTTA GRISI. (“GISELLE”) | 235 |

| XXVIII. | THE “PAS DE QUATRE”: III. FANNY CERITO. (“ONDINE”) | 240 |

| XXIX. | THE “PAS DE QUATRE”: IV. LUCILE GRAHN. (“EOLINE”) | 244 |

| XXX. | THE DECLINE AND REVIVAL | 249 |

| XXXI. | THE ALHAMBRA 1854 TO 1903 | 252 |

| XXXII. | THE ALHAMBRA 1904 TO 1913 | 269 |

| XXXIII. | THE EMPIRE THEATRE 1884 TO 1906 | 276 |

| XXXIV. | THE EMPIRE THEATRE 1907 TO 1914 | 294 |

| XXXV. | FINALE, THE RUSSIANS AND—THE FUTURE | 309 |

| INDEX | 327 | |

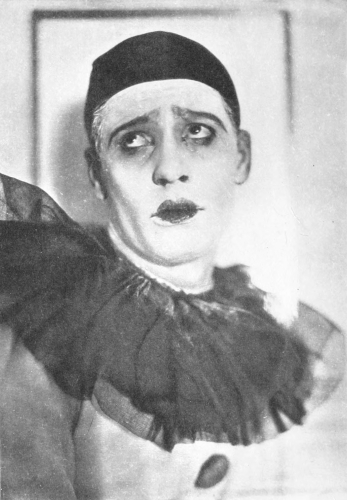

| ADOLF BOLM IN “CARNIVAL” | Frontispiece | |

| From a photograph | ||

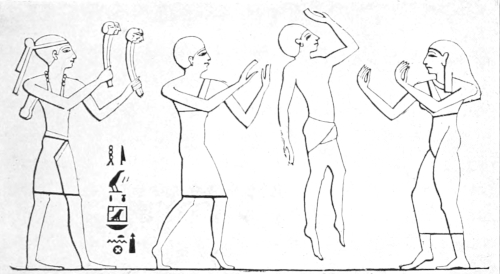

| AN EGYPTIAN MALE DANCER | Facing page | 30 |

| From a Theban fresco | ||

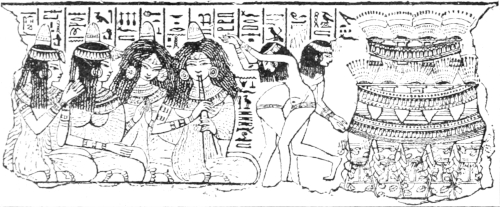

| EGYPTIAN DANCING GIRLS | ” | 30 |

| From a mural painting in the British Museum | ||

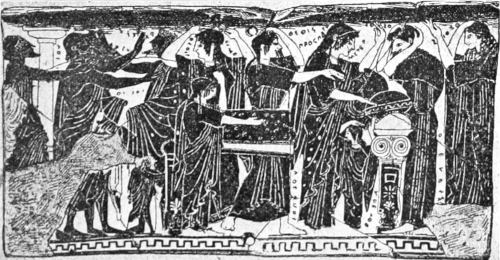

| A GREEK FUNERAL DANCE | ” | 30 |

| From a coloured plaque in the Louvre | ||

| STAGE EFFECT IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY | ” | 56 |

| A scene from, the “Ballet Comique de la Royne,” by Baltasar de Beaujoyeux, 1581 | ||

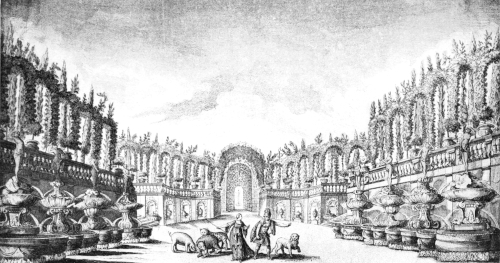

| STAGE EFFECT IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY | ” | 88 |

| From a coloured engraving of a scene from “Circe,” 1694 | ||

| THE DUCHESSE DU MAINE | ” | 114 |

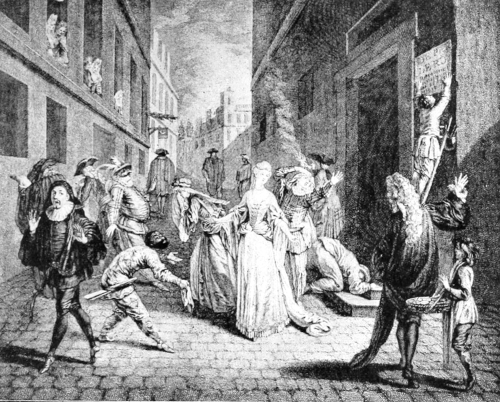

| THE DEPARTURE OF THE ITALIAN COMEDIANS, 1697 | ” | 128 |

| From an engraving by L. Jacob of Watteau’s picture | ||

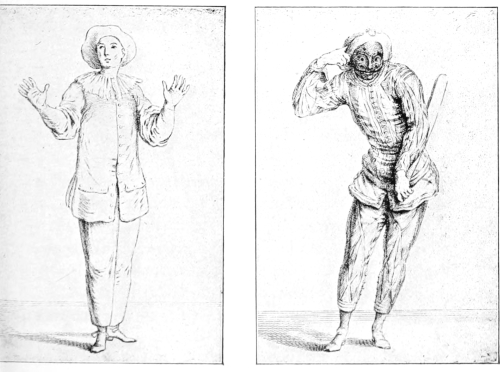

| PIERROT AND ARLEQUIN, IN THE EARLY EIGHTEENTH CENTURY | ” | 128 |

| From Riccoboni’s “Histoire du Théâtre Italien” | ||

| L’AMOUR AU THÉÂTRE ITALIEN | ” | 132 |

| From the Julienne engravings from Watteau, British Museum | ||

| L’AMOUR AU THÉÂTRE FRANÇAIS | ” | 132 |

| From the Julienne engravings from Watteau, British Museum | ||

| LE CONCERT | ” | 136 |

| From the painting by Watteau, Wallace Collection | ||

| LA LEÇON DE MUSIQUE | ” | 136 |

| From the painting by Watteau, Wallace Collection | ||

| LES PLAISIRS DU BAL | ” | 138 |

| From the Julienne engravings from Watteau, British Museum | ||

| MLLE. DESMARES EN HABIT DE PÈLERINE | ” | 140 |

| From the Julienne engravings from Watteau, British Museum | ||

| L’EMBARQUEMENT POUR L’ILE DE CYTHÈRE | ” | 140 |

| From a photograph by E. Alinari of Watteau’s painting in the Louvre | ||

| MARIE SALLÉ | ” | 150 |

| From an engraving by Petit, after a picture by Fenouil | ||

| [12]M. BALLON AND MLLE. PRÉVÔT | ” | 160 |

| From an old print | ||

| CAMARGO | ” | 160 |

| From the painting by Lancret in the Wallace Collection | ||

| GAETAN VESTRIS | ” | 166 |

| From an old print | ||

| JEAN GEORGES NOVERRE | ” | 174 |

| From an old engraving | ||

| MADELEINE GUIMARD | ” | 192 |

| From the painting by Fragonard | ||

| FANNY ELSSLER | ” | 210 |

| From an old engraving | ||

| CARLOTTA GRISI | ” | 210 |

| From a coloured lithograph | ||

| CARLO BLASIS | ” | 218 |

| From a lithograph | ||

| MARIE TAGLIONI | ” | 228 |

| From a lithograph dated 1833 | ||

| THE PAS DE QUATRE OF 1845 | ” | 228 |

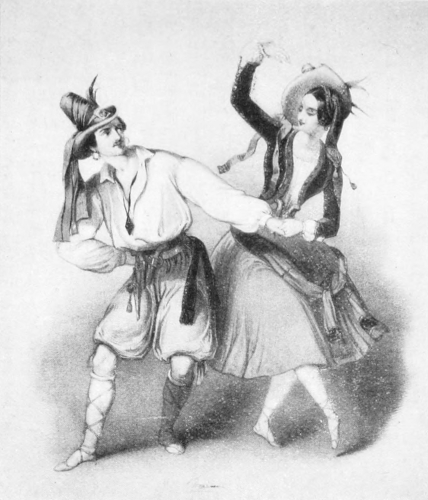

| FANNY CERITO AND ST. LEON | ” | 242 |

| LUCILLE GRAHN AND PERROT | ” | 242 |

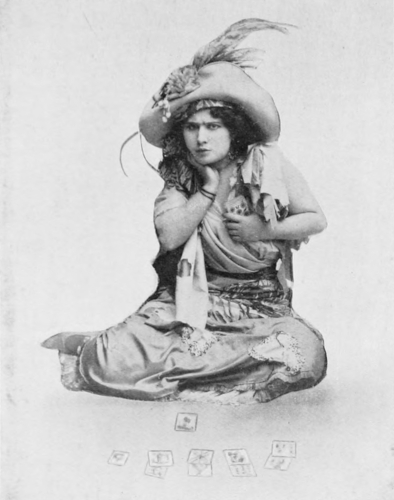

| MLLE. PALLADINO IN “NINA” AT THE ALHAMBRA | ” | 266 |

| From a photograph | ||

| MLLE. BRITTA | ” | 266 |

| From a photograph | ||

| MME. GUERRERO | ” | 274 |

| From a photograph | ||

| MLLE. LEONORA | ” | 274 |

| From a photograph | ||

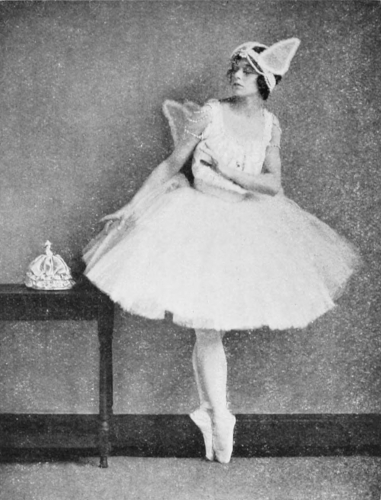

| MLLE. ADELINE GÉNÉE | ” | 292 |

| From a photograph | ||

| MME. LYDIA KYASHT | ” | 304 |

| From a photograph | ||

| MISS PHYLLIS BEDELLS | ” | 304 |

| From a photograph | ||

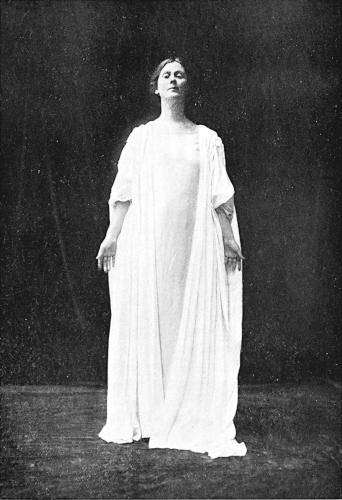

| MISS ISADORA DUNCAN | ” | 314 |

| From a photograph | ||

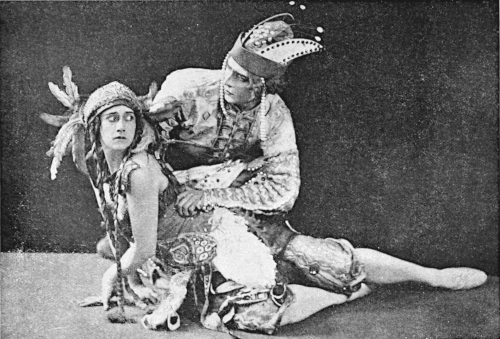

| MME. KARSAVINA AND M. ADOLF BOLM IN “L’OISEAU DE FEU” | ” | 322 |

| From a photograph |

There may be some who could not agree that Ballet is an “art,” or even that it has, or ever had, any special charm or historic interest. The charm—as in the case of any other art—will probably always remain rather a matter of individual opinion; the historic interest is merely a matter of fact.

No man can hope for agreement with his fellows in all things. The world were flat if it could be so. He may hector, and not convince; he may cajole and not convert; he may tell the simple truth in simple speech and still be misunderstood. So many of his partners in the dance of life speak in different tongues; or, speaking the same, use words and phrases more familiar to them than to himself.

In going to a foreign land we change our currency; but it is hardly to be accounted spurious because it is not as ours. There may be something to be said for the variety; and, also, there may be some common basis of value which can be accepted readily by both. A world-currency has not yet arrived. In opinion it is much the same.

But the sense of “fair play” is so admirable, and so truly British a characteristic, that one may usually rely on it for a considerate hearing. Possible dissentients may be the more[16] inclined to grant this if they are informed at the outset that this book has no specially persuasive purpose, and that I am content that it should be mainly accounted a record of fact.

One of the facts which it chronicles is that Ballet, whether an “art” or not, has existed, in some form or another, for about two thousand years. An interest which can show so long a record may yet not be of such surpassing importance, let us say, as Statecraft or Religion; but one which has thus long and widely appealed to the æsthetic sense of mankind can hardly be considered worthless. It were a vast and complex matter to decide the relative values of the various “arts,” and, certainly this book is no endeavour to pronounce thereon, nor to persuade any that Ballet is the greatest, though it is unquestionably one of the oldest of the arts. But it will suffice to offer the opinion that, whether it has reached its highest level or not as yet Ballet is an art in itself; one that in the past has had so many judicious and sympathetic exponents, and has so long a record of existence, that there is really some justification for the expenditure of casual leisure by any who cares to play the chronicler or to read such chronicle.

This much said, before setting out to travel the road of the past, let us for a moment reconsider another fact, namely, that we have in London two theatres where for about a quarter of a century Ballet was the main attraction. The fact is unique in the annals of the British stage.

Ballets have been produced elsewhere occasionally. We have seen operas, pantomimes, burlesques, of which they formed a part. At earlier periods—as in the ’forties of last century—they have also been seen as separate items in the programme of an operatic season; and there has been a quite remarkable revival of interest during the past few years. But in all the history of the stage there was never before a time when it could be said that for such a period not one[17] but two theatrical houses in London continuously offered this kind of entertainment as their chief attraction.

It has to be remembered that this sustained existence of Ballet in England has been, as in the case of all “legitimate drama,” without State aid such as it has received in Milan, Rome, Naples, Paris, Vienna, Petrograd, Copenhagen, and elsewhere on the Continent, where the physical advantages of dancing and the artistic value of Ballet are fully appreciated. The arts must flourish haphazard here! We have no national conservatoire in which this art of Ballet is taught as it is abroad. Consequently it has been less generally understood; and, being so, has had to exist in face of considerable prejudice.

Some critics profess to despise it because it ignores the spoken word. Some have decried it because of the presence of dancing. Some will not admit that it is worthy to be called an art at all, and there are possibly still some primly primitive people who pretend to view with moral pain the existence of any such entertainment. They may patronise a theatre or tolerate an actor or actress—but a Ballet or a Ballet-Dancer!

The misunderstanding of the aims and possibilities of the Art of Ballet, as seen at its best, is to be regretted.

Not for such critics are the music of moving lines, the modulating harmonies of colour, the subtleties of mimic expression, nor all the wealth of historic associations and romantic charm which a knowledge of its past recalls.

Austere critics would do well, when deprecating Ballet, to remember that many others have found it, as Colley Cibber regretfully admitted it was found in his time: “a pleasing and rational entertainment.”

That it is “pleasing” many know from witnessing some of the best of modern examples. As to whether it can be considered “rational” depends so much on the kind of meaning that may be given to that word. All rational people speak in prose; constantly to speak in verse might be considered quite[18] irrational. But are we to banish poetry from the world because it is not the common form of speech?

Some people might find it quite irrational to sit in a theatre and laugh or weep at the imaginary joys or woes of imaginary characters impersonated by people who are not seriously concerned therewith, and with whom, personally, we are not at all concerned.

It might be well considered irrational to be moved by any “concord of sweet sounds,” at least in the shape of “opera”; or to be enspelled by the charm of a statue or a painting, or by the wizardry of any form of art; for once it is questioned whether it be “rational,” there need be no end to dispute; and one remembers how poor Tolstoy fared in essaying to decide: “What is Art?”

That of Ballet surely is no less rational than Poetry, than Drama, than Music, Sculpture, Painting—all of which exist by their conventions, all of which in principle it employs; to all of which it is akin. It is not less an art; and when looking at a modern ballet we can hardly fail to consider the long train of reasoned thought and of artistic tradition that lie beyond the entertainment that we see to-day.

What is it that we see? An orchestra of dancers who are also mimes, who represent—one should rather say, realise—the imaginative creations of an author, or a number of authors working harmoniously together, in terms of rhythmic movement and dramatic expression, with the aid also of colour and music and sound.

Every one of these dancers has had to undergo a special and arduous training, the traditions of which reach back through centuries till lost in time’s obscurity.

Each has an allotted place at any given moment in the general scheme. Every grouping and dispersal of a group—like the formation and modulation of chords in music—is part of an ordered plan.

Every step of every dancer, every gesture, every phrase of music, is composed or selected to express particular ideas or series of ideas; every colour and each change of tone in the whole symphony of hues has been appraised. Not a thing that happens is haphazard.

It is probably by reason of the number of people that must be employed, and the labour entailed before a successful result can be achieved, and on account of the difficulties and risks attendant on its production, that we have had so few theatres devoted to an art so thoroughly appreciated abroad, not only as one of ancient institution, but as one that still offers wide scope for the creative genius of poet, artist and musician, apart from the interpretative abilities of dancer and of mime.

The chief elements of Ballet as seen to-day are—dancing, miming, music and scenic effect, including of course in this last the costumes and colour-schemes, as well as the actual “scenery” and lighting.

It is in the proper harmonising of these elements that the true art of Ballet-composition, or, as it is called, “choreography,” consists. Each has its individual history, and all have been combined in varying proportions at various periods. But it is only in the past hundred and fifty years or so that they have been harmoniously blended in the increasing richness of their development to give us this separate, protean and beautiful art—the Ballet of the Theatre.

These four elements are the material of which Ballet is composed, and the result may be judged by their balance.

We are to think not of the worst examples that have been, but of the best, and of those that yet might be.

Most of the older writers on dancing speak of almost all concerted dances as ballets and refer to the “ballets” of the Egyptians, the Greeks and the Romans. The Abbé Menestrier, however, writing in the seventeenth century, wisely observed the distinction between dances that are only “dances,” and those that approximate to “ballet.”

It should be borne in mind that it is possible to dance and not represent an idea save that of dancing, as when a child[22] dances for joy, not in order to represent the joy of another. That is the province of the Mime. It is equally possible to mimic without dancing.

The best ballet-dancer is one who has intelligence and training to do both, whose dancing and mimicry are interpretative.

Speaking of certain Egyptian and Greek figure-dances and the approach of some of them to the Ballet as he knew it towards the end of the seventeenth century, Menestrier wrote: “J’appelle ces Danses Ballets parce qu’elles n’etoient pas de simples Danses comme les autres, mais des Representations ingenieuses, des mouvements du Ciel et des Planétes, et des evolutions du labyrinthe dont Thésée sortit.” That is a distinction to be remembered by any who may look on the Art of Ballet as simply—dancing.

It is necessary to-day to make another distinction, that between “ballet,” and “the ballet of the theatre.” In a sense the Hindus, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, indeed all peoples in past ages have had ballets; that is, dances which were “representations ingenieuses,” which represented an idea or told a story.

There have been entertainments, too, of which dancing formed a considerable part—such as our English “masques,” which, contemporaneously, were often spoken of as “ballets.”

But though they may for convenience have been so called, they were never more than partly akin with the ballet of the theatre as we see it to-day. They never exhibited that balance of subordinated and developed arts which the best examples of later times have shown; and were not seen in the public theatre, as a form of dramatic entertainment apart from others.

One has only to consider for an instant what were the musical and scenic resources of the Greek and Roman stage, and compare them with the resources of modern orchestration[23] and scenic effect to realise the difference between antique “ballet” and that of to-day.

Setting aside this difference, which arises from the development of the several elements through the centuries, one may find many an ancient definition of “ballet” that appears apt enough to-day, for the difference is not so much one of principle as this of resources.

Athenæus, a second-century Greek critic, declared: “Ballet is an imitation of things said and sung,” and Lucian, that—“It is by the gesture, movements and cadences that this imitation or representation is made up, as the song is made up by the inflections of the voice.” This is a happy illustration. Inflections might well be described as “gestures” of the voice.

Menestrier (who, besides writing an exceedingly entertaining history of Ballet, also wrote extensively on Heraldry, and was author of several solid historical works as well as numerous poems and libretti) has said: “Ballet is an imitation like the other arts, and that much has in common with them. The difference is, that while the other arts only imitate certain things, as painting, which expresses the shape, colour, arrangement and disposition of things, Ballet expresses the movement which Painting and Sculpture could not express, and by these movements can represent the nature of things, and those characteristics of the soul which only can find expression by such movements. This imitation is achieved by the movements of the body, which are the interpreters of the passions and of the inmost feelings. And even as the body has various parts composing a whole and making a beautiful harmony, one uses instruments and their accord, to regulate those movements which express the effect of the passions of the soul.”

These definitions have decided value, but hardly quite meet the case of modern Ballet.

Noverre, Blasis, Gardel, and other of the older maîtres de ballet[24], have told us in several charming books, essays, letters, dialogues and libretti, much as to what Ballet can and should be, but yet leave something to seek in the matter of brief yet comprehensive definition.

It is with some hesitancy, therefore, that I venture, before talking of its history, to suggest as a simple definition that: “a ballet is a series of solo and concerted dances with mimetic actions, accompanied by music and scenic accessories, telling a story.”

It is by reason of this definition that I propose to pass somewhat lightly over the early dawn of Ballet, or rather of its earliest elements, the dance and miming; and that I propose to deal more fully with the period after the advent of Louis Quatorze—in France and in England—which saw the development of the Ballet du Théâtre.

There have, of course, been modern ballets that did not tell a story. But the true Ballet of the theatre should.

Such have been the best of those of Noverre, of Blasis, of Perrot, Nuittier, Théophile Gautier, and of later composers of ballet like Taglioni, Manzotti, Coppi, Mme. Lanner, Wilhelm, Curti, Fokine, and, indeed, all the best ballets of later years; and such will the best always be.

The origin of the drama is hardly to be reckoned among the historic mysteries. By serious triflers debate might be held as to what should be considered the first dramatic representation and when it actually took place.

Some five centuries before the Christian era the first plays of which scholarship has taken note were performed at Athens, those of Thespis, forerunner of the first great dramatists of the world—Æschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides.

For convenience the origin of Western drama may be dated from Thespis because it seems first to have assumed then a definite form. That is not its actual origin any more than the origin of any human being is to be dated from its birth. As a possibility it may be said to have existed always. Even Chronology has its limitations, and preceding any given event there must have existed principles or tendencies.

When it is said, therefore, that the origin of the Drama is not an historic mystery it is because we are not very much in the dark as to when it began to assume a somewhat definite form; and, moreover, we can be fairly clear as to what must have preceded it. There seems rather more than a probability that the Drama derived its existence from the Poet, in his capacity as a Narrator.

For some hundreds of years the Drama has been chiefly a representation of character and events, whether real or fictitious. In its earliest forms it was mainly descriptive. It[26] would seem to be the natural order of things that from mere description there should arise in time—possibly from a half-conscious feeling of the need of emphasis, of a desire to impress the hearers—the attempt to illustrate or to represent the scenes or actions described. The mere repetition of any story seems to tend towards that. Have we not observed that no “fish” story is ever quite complete—if not convincing—without histrionic illustrations?

Though in India and China, with their more ancient civilisation, the chronologic origin of the Drama might be more remotely placed, it is probable that in the Homeric bard and the Homeric audience, should be sought the true beginning of the Western theatre; while, all the world over, the evolution of the dramatic form has probably been much the same—namely, a gradual transition from poetic narration to imitative representation. Thus at the back of the Drama is probably the Poet. Beside the Poet, too, is often the Priest.

Greek tragedy is usually said to have had a purely “religious” origin, and certainly it was from early times employed for the purposes of, or in the service of, Religion; but it would, one feels, be rather truer to presume its actual origin to be purely secular, and to be found in the Poet making his appeal to an ordinary audience, in a word, to the People, while sometimes under the patronage of priestly and ruling classes.

When, however, we come to consider the origin of the Dance—first and most important of the “four elements” of Ballet—we are forced to the conclusion that, even though we are on more uncertain ground, it must, nevertheless, be far older than the Drama. Why this should be so, even though we have no approximate date to go upon as in the case of the Thespian theatre, is not difficult to see.

The Drama evolved from, and has always depended on, the faculty of speech, and on the growth of a language. A copious vocabulary and flexibility of verbal expression are not[27] exactly characteristics of the primitive races; and, without both, the Drama, as we have known it for some centuries, could not have existed.

But the Dance (with mimicry, which has always followed close upon its heels) has no need of words, and is itself a kind of speech, in which the whole body is used as a means of expression.

We are none of us old enough to remember, and there is consequently no need to be dogmatic and assert that the Dance actually did precede speech; but it is far from improbable that it could have done; and while one shudders to think of the ardent danse tourbillon our Mother Earth must have danced from the moment of her birth, it is perhaps more amusing—and yet not wholly frivolous—to contemplate a possible origin of the Dance in the sport some Simian ancestors may have found in rhythmically swaying on the flexile branches of some primeval tree, before they had acquired a vocabulary sufficiently copious for the analysis of their sensations.

Seriously, however, and just because it has a rhythmic basis, dancing in some form is among the earliest instincts of mankind, even as it is of children. In all climes, at all periods, men and women have danced; and its origin is lost in the mists of prehistoric years. Non-civilised races still existent may offer evidence as to stages in its evolution; but even among the more primitive races, dancing seems to have some definiteness of form, marking a heritage of long practice.

From some earliest, uncouth leapings and gestures of savage or half savage tribes (the effect of mere exuberant physical energy) may have grown the idea of thus expressing joy and thankfulness; for joy, not sorrow, one feels must surely have been always the first inspirer of the Dance; and possibly a victory over an enemy, or gratitude for a full harvest may have[28] come to be first the inspiration, and then the excuse for repeating such manifestations.

Repetition of an act tends to create a habit, and what may be at first apparently a spontaneous experiment grows by repetition into a cult, with set form and ritual.

The ritual of the Dance seems to be as ancient as the stars, in representing the movements of which, it is supposed by some to have had its origin in Egypt over two thousand years ago. Nowhere is it found without form. All must be done in a certain way, according to the traditions of the locality in which the dance is seen, or according to some wider tradition. Always it has a ritual of its own, but also with religious ritual the origin of the Dance—as also of the Drama—appears in some mysterious manner to be upbound.

Of all the records that we have of dancing, the earliest are, apparently, those of Egypt. Its origin is not there; it must be older; but we know at least that the Egyptians were among the first people with a civilisation that encouraged dancing.

One of the finest among modern historians of the art, divides dancing, for convenience in tracing its evolution, into “sacred” and “profane”; that is, the Dance forming, as so often it did in ancient times, part of a religious ceremonial, and that which in any other of its forms was merely a pleasure of the people. For our purpose in tracing the growth of Ballet, however, it would seem advisable to divide the Dance yet further, into “sacred,” “secular,” and “theatrical.”

The Egyptians had no Ballet of the theatre, because they had no theatre. They had dances which seem to have been “representations ingenieuses,” and to that extent, as mimetic dances, partook of the nature of Ballet; but they were not organised as theatrical spectacles for private or public entertainment.

The Greeks had no Ballet of the theatre because, though[29] they had the theatre, they, like the Egyptians, had merely mimetic dances, not Ballet.

But if Egypt had no popular theatre in which dancing was seen, it appears to have existed, nevertheless, in three distinct forms—as a pleasure of “the man in the street”—just as we see children dance to a barrel-organ in the London streets to-day; again, as an entertainment for the wealthy, just as a popular singer, dancer or other entertainer of to-day is engaged for an “at home” or dinner-party; and, finally, as an element of the elaborate and somewhat theatrical Egyptian religious ceremonial.

Monuments from Thebes and Beni Hassan show pictures of Egyptian dancers performing steps very similar to some we can see to-day. They appear to be performing them for the pleasure of onlookers as well as their own. This acquiring of an audience has, after all, been always of first importance, and without it the Drama could hardly have come into existence.

Most people are interested in seeing others do something they are unable to do themselves, and when they can see it well done, in a manner, that is, suggesting a difficult feat accomplished with ease, they will even pay for the exhibition. That is the popular (with managers the extremely popular) side of the theatrical arts, of which dancing is one. When there arises the desire to see the exhibition repeated frequently, then must follow the special place with special facilities and accessories for the performance, and the theatre, or something like it, thus comes into existence as an institution sustained by popular support. There is first the thing done for pleasure—which is art; then the exploitation of it for profit—which is commerce; that is the brief epitaph of any art as a fruit of civilisation.

The Egyptians did not reach the “theatre” stage. But dancing, essentially a popular art, received encouragement as[30] an element in religious festivals and as an entertainment of the wealthy classes.

Considerable difference of opinion exists as to the “religious” dances of Egypt. Enthusiastic historians of dancing seem rather too prone to expand the little store of fact we possess, and some go to the length of speaking of the religious and popular “ballets” of the Egyptians. But it is certain that they had no regular theatrical spectacles in which dancing was of prime importance; and their popular dances, to any such extent as they could be described as “representations ingenieuses,” were primitive in comparison with any of later times.

Solo-dances and pas de deux were general enough, but the dancing of massed groups, and the dramatic representation of a story, appear to have been unknown, or have passed unrecorded if they were known. The nearest approach to them, though not of course performed as a theatrical spectacle, would seem to have been an “astronomical dance,” which was done by or under the direction of the priests of Apis, and is said to have been—appropriately enough!—a representation of the movements of the stars. It is probable that it was employed mainly as a means of education.

Holy Church in mediæval times took advantage of the popular craving for theatrical shows, and sought by the aid of “mystery plays,” and “moralities” to extend the knowledge of religious truths. It may be conjectured that the Egyptian hierarchy similarly had some such end in view, and that the priestly caste sought to utilise the popular taste for dancing as a means of influence, and that the actual performance of the dance served to fix more lastingly in the minds of novices the religious and astronomical truths it embodied.

In addition to the star-dance, the Egyptians are said to have had a “funeral” dance, but it is doubtful if this, the “Maneros”—of which Herodotus speaks—was a solemn[31] dance. The fact is, however, that information both as to the religious and ceremonial uses of dancing among the Egyptians is very scant, and what little record we have of their dancing is mainly on its popular side and is to be gleaned from monuments.

One of the frescoes in the British Museum shows two girls performing, apparently before a select audience of women, one of whom is seen to be applauding, or perhaps marking the time with syncopated clapping, as negroes do to-day.

Another representation of dancing is on a fresco from Thebes showing three figures, the centre of whom is apparently performing an entrechat, as seen to-day, the step in which the dancer crosses feet in mid-air; while a fourth acts as orchestra with a couple of the curious curved maces which were beaten together to mark the rhythm in sonorous fashion.

Other Egyptian monuments also show dancers, one from Beni Hassan depicting several couples, apparently boys, performing a dance that obviously had certain set steps, and suggests that it was used mainly as a rhythmic athletic exercise, as were many of the Greek dances. And yet another monument shows men apparently in the act of performing a pirouette. About them all there is the air of decision, a suggestion of trained performance that in itself, remembering that these monuments are some four thousand years old, and depict steps similar to some performed to-day, is testimony to the antiquity of the art of dancing.

There is no lack of testimony, pictorial and literary, to the ancient Greek love of the Dance.

Among the various arts of war and peace that Vulcan engraved upon that wondrous shield which he fashioned at the entreaty of sad Thetis for her son Achilles, the Dance was not forgotten; and the Homeric singer must have been a lover of the art to limn as clear a picture as is given in the eighteenth book of the Iliad.

The “two tumblers” is an interesting detail, but it does not necessarily refer to the sort of acrobatic “tumbling”[33] we are familiar with to-day. There have always been two phases of the Dance which can best be understood by noting the distinction marked by the use of two words in French—at least by their use among the masters and writers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—namely, danser and sauter. The former means to dance, “terre-à-terre,” that is, always with the feet, or one foot at least, on or close to the ground; sauter, means invariably to leap into the air, or even to perform steps while both feet are in the air.

We usually speak of “a somersault,” a “double somersault,” and so forth. The word is a corruption from the old French soubresault, from the Latin supra, over, and saltus, leap.

Early historians of the Dance frequently speak of “saltation,” without any reference to the “somersault” as we know it, but to what we should call simply dancing.

The Homeric picture must have been repeated innumerable times since it was first limned, whenever and wherever there has been a gathering of men and maids on a village green, dancing in a circle, with a couple of high-leaping lads in the centre inciting all to quicken the rhythm of the whirling dance. Many an Elizabethan village must have realised such a scene; and for all the artifice of the stage, with its paint and footlights, does it not hold something of the antique tradition in the picture often seen, of a circle of dancing girls enclosing two wildly turning “stars”? Is it impossibly un-Hellenic to presume that the “Two tumblers, in the midst, were whirling round” in pirouettes? At least it may be considered—a presumption!

Far later in Hellenic days we have a gracious picture of the Dance in Theocritus’ eighteenth Idyll, “The Bridal of Helen,” which reads delightfully in Calverley’s translation:

The Greek dance, it should be noted, was almost invariably accompanied by singing; and the poet probably was often indebted to the dance for the rhythm of his verse. The bridal dance was of very ancient institution. Indeed, there were few occasions which were not celebrated with dancing, and the Greeks even followed the Egyptian custom of having “dancers” at their funerals! It is not to be thought, however, that the steps were exactly gay; nor need there have been anything incongruous, for we can be sure the instinctive taste of the people would not have admitted such a thing, and, moreover, a dance and a dancer as they saw it, were rather different from the vision we have recalled by such words.

To the ancient Greeks the Dance was a cult, an element in the religious and physical well-being of the individual and the State: and the dance that was taught to the child became an important and lasting factor in the physical growth and culture of the man.

We who, most of us, are only too apt to look on dancing as a mere trivial pastime, may wonder that it was so seriously considered by the Greeks, and that it should have so earnestly engaged the attentions of such philosophers as Plato and Lucian. But perhaps that is only because we have not considered it sufficiently ourselves and have associated it too closely with theatrical display.

In any form in which it is at its best the theatre is one of the noblest and most influential institutions of civilisation; as dancing, at its best, is one of the finest, because most[35] comprehensive, of the theatrical arts. But there is a vast difference between the dance which was a means of physical and mental development, pursued amid the health-giving surroundings of sunshine and fresh air, and, let us say, some such degradation of art as some examples of the “classic” dance we have seen of recent years, performed in the glare of footlights, amid the smoke-laden atmosphere of a music-hall.

The contrast is an obvious one, but the thing to consider is that we in England have allowed an art which held an important place in Greek national life, and which should be of the greatest educational value to ourselves, to become mainly a spectacle of the theatre, where more often than not it is seen at its best, not necessarily because it is the result of the best system, but because it is the fruit of the greatest practice.

It is obviously impossible to deal very fully with the Hellenic dance in the space of a chapter in a volume which is not intended to trace the evolution of the Dance but of Ballet. An entire book were needed to treat the subject adequately—and we have not such a book in English, as yet. But Emmanuel’s masterly technical review of Hellenic dancing in his volume La Danse Grecque, is invaluable, and is testimony to the sound and catholic scholarship which in France scorns no subject as “trivial” merely because those ignorant of its history dismiss it as such; and which finds sympathetic students in a country where all the arts are treated with a respect that is at least as great as that offered to commercialism.

The Greeks are said to have derived their earlier dances from Egypt. This may be questionable, because it is equally likely that there was a traditional, indigenous dance in Greece. But it was through the Greeks, certainly, that dancing first assumed that variety and perfection of form[36] and style which all the arts seemed destined to attain under their quickening, purifying, and inspiring influence; and it was the Greeks, too, who first began to develop the art of mimicry.

First, as already suggested, there would probably have been some occasion for joy, tending to express itself by dancing; and a victory over an enemy, or gratitude for a full harvest (the more exalted when the harvest was of the grape!) would have been such occasions. Later must have come the idea of representing the victory celebrated, or the imagined characteristics of the being or beings who were supposed to be the cause of the earth’s fruition, and who, if propitiated by this tumultuous acknowledgment of gratitude, perhaps might renew their favours.

Thus, in time, out of the ritual of the Dance would have grown the ritual of representation—Mimicry, miming, or “acting,” as we call it; and little by little, from the wild exuberance of recurring poetic festivals, such as those in honour of Dionysus, would have grown the ordered sense of Drama, the representation of thanksgiving, of feelings, events and things by Mimicry, the actor’s art; either allied with, or separate from, dancing.

The Greeks, improving on the Egyptians, invented and developed the idea of the Theatre. But though the Greeks in their Drama utilised the arts of dancing and mimicry, it would seem that they were quite subordinated to the literary and dramatic art of the all-inspiring Poet, and that words, with a meaning behind them, words representing, as far as words can, thoughts, passions, emotions, actions, things, were the essential medium of Greek Drama, not the art of the Dancer or the Mime.

It should be noted that the Greek orcheisthai (ὀρχεῖσθαι), to dance, implied more than mere steps with the feet. It included much that goes to make a really good ballet-dancer[37] of to-day—interpretative dancing and mimetic gesture. The Greeks in fact had some of the material, if they did not have as we know it—the Ballet.

The earliest dramatic poets, Thespis, Phrynichus, were called “dancers” because in addition to providing the drama as poets, their function was to train their choruses in the dances which, accompanied by singing, were introduced in the play.

One of the most celebrated of the actors in the plays of Æschylus, Telestes, was said not merely to indicate feelings but to “describe” events with his hands; and this, which was really miming, was considered as part of dancing, which Aristotle defined as “the representation of actions, characters and passions by means of postures and rhythmic movements.”

Plutarch analyses dancing as “Motions, Postures and Indications,” a “posture” being the attitude of the dancer at the moment of arrested movement, and an “indication,” the gesture which indicated an external object referred to in a poet’s lines, such as the sky; or such as an orator would use when raising his hand heavenward invoking the gods.

The chief dances used in the Greek drama were the Emmeleia, a stately measure; Hyporchemata, lively dances; the Kordax, a very coarse and rough comic dance; and finally the Sikinnis, which was attached especially to satyric comedies and parodied as a rule the measure of the Emmeleia.

These were all a part, though a subordinate part, of the classic drama, and, according to some authorities, had their foundation in the rhythm of the poet’s verse as it was sung by the chorus or declaimed by the chief actors.

But apart from these there were mimetic dances. One, in which we may perhaps even see a hint of the origin of dancing itself, is found in Longus’ novel, Daphnis and Chloe, in which Dryas performs a vintage-dance, “pretending to[38] gather grapes, to carry them in panniers, to tread them in a vat and pour the flowing juice into jars, and then to drink of the wine thus newly made”; and all done so cleverly that the spectators were deceived for the time and thought they really saw the grapes, the vats, and the wine the actor made pretence of drinking. This, probably an incident drawn from life, was indeed a “representation ingenieuse,” and even suggests yet another of the many possibilities as to the origin of the Dance, namely—that dancing itself may have originated from the treading of grapes.

The famous Pyrrhic dance was of course mimetic and represented a series of war-like incidents, all of which had an educational purpose, as by their means the youthful soldier was taught how to advance and retreat, how to aim a blow or hurl a javelin and to dodge them; and how to leap and vault, in event of meeting ditches and walls. Apart from military dances in which physical culture and grace were the chief aims, there were many dances of a purely festival character taken part in by young men and girls, and by girls alone.

The close association between religion and the Dance in ancient Hellenic days is seen in the number of festivals in honour of the gods, at which special dances were performed, apart from those which formed part of the classic drama and others which were merely by way of joyous pastime. Certain dances were performed annually in honour of Jupiter; others, such as the Procharysteriæ, were in honour of Minerva; then there was the Pæonian dance in honour of Apollo; the Ionic, and the Kalabis and the famous Dance of Innocence, instituted by Lycurgus, and executed to the glory of Diana, by young Lacedæmonian girls before the altar of the goddess. The Delian dance, special to the isle of Delos, was much the same in character and closed with the offering of floral garlands on the altar of Aphrodite.[39] One of the most solemn incidents of the Eleusinian mysteries was the mystical dance-drama representing the search of Ceres for her daughter Proserpine—practically a “ballet,” in the older acceptance of the word.

The secular dance of the Greeks was essentially an individualistic form. Men and women only rarely danced together, and when they did, the joining of hands, or anything like chain-dancing was exceptional. One of these exceptions was the Hormos, or Collar-dance as it was called, which Lucian describes as being danced by youths and maidens advancing one by one in the form of a collar, made up of the alternating jewels of feminine grace and manly strength, the dance being led by a youth. Most of the Greek dances had a leader, and the favour in which the art was held is shown by the fact that they termed their Chief Magistrate Pro-orchestris, or Leader of the Dance. As a rule, chain-dances were performed by one or the other sex.

In another sense also the Hellenic dance was individualistic. We are accustomed to see entire groups, eight, sixteen, or even thirty-two or more dancers all performing the same step simultaneously. It is one of the conventions of Ballet, like the chorus in “musical comedy.” But the Greeks had not that convention.

Although their dance was based on strict rhythm and was governed by rigid rules, they governed the dance of the individual, not of groups. He, or she, was adjudged a good dancer by the grace of line displayed and rhythmic balance of movement, and many a vase painting exhibits groups of dancers who, though dancing in the mass, are each doing different steps; and equally the gestures and mimetic expression of each differed.

The system unquestionably had its advantages, for while the rhythm of the song or poetic verse which accompanied the performers was the common basis of the dance for all,[40] the individuality of expression undoubtedly gave a vitality to the group which accounts for the vividness and charm of their representation on many an antique vase.

Numerous indeed were the various forms of the Hellenic dance, sacred, dramatic, secular—Meursius catalogues some two hundred—but further description would detain us too long en route towards the culmination of all these earlier types of mimetic and other dances in the Ballet of to-day, and we have next to trace the growth of Latin Mime and Pantomime.

If to Greece modern Ballet owes much for the encouragement of the Dance, to Rome it is even more indebted for the development of the art of Pantomime.

By many the word Pantomime is associated solely with that time-honoured entertainment which children, home for the Christmas holidays, are supposed to be too blasé to care for, but which they go to by way of obliging parents who feel it their duty to take them.

The Christmas pantomime has long been one of our cherished institutions, though, like the British Constitution, it has undergone many changes. It is still given at Christmas. That much of tradition remains. But most of its original features have all but disappeared. Time was, two hundred years ago, when it was mainly “Harlequinade,” and Harlequin and his gay comrades of Italian comedy were the heroes of the play. Then classical plots and allusions, with an elaboration of scenic effect and “machines,” brought about a gradual change. In the early nineteenth century a “topical” and “patriotic” element had crept in; but the Harlequinade, although shortened, and, shall we say, broadened, still remained.

Then a craze for “transformation” scenes set in because the extreme gorgeousness of the tinsel productions of Kemble and Macready—the archæological and historic “accuracy” of which was always emphasised!—forced the pantomime producers in self-defence to go one better.

And then came Grimaldi to give a new life to the whimsies of that Clown whose prototype dates back to ancient Rome; and for half a century or more the Christmas pantomime continued much the same—a familiar nursery-story played out to the accompaniment of fairy-like and glittering scenic accessories, concluding with a rough-and-tumble Harlequinade, until in recent years the introduction of the Music-hall performer gave us the entertainment we have to-day.

Not thus, however, was the antique “pantomime,” which, evolving from the more ancient and spoken “Mimes,” became, because it took all nature for its province—pan-mimicry, or pantomime; the stage representation, without the spoken word, of all that eye could see or mind of man conceive.

Now, it is a far step from narrative to impersonation—marking an advance in the technique of acting; and it was some time before the Greek Drama had achieved this. But it was not so much the impressive and noble side of the Greek Drama that taught the actors, not merely to declaim situations but to act them; it must have been the popular, the comic side; and it was probably the Doric farce, and later the early Latin comedy derived therefrom, that really brought to perfection under the Roman Empire the art of Miming apart from the art of Dancing.

The comic is so much nearer to life as we see it every day than the tragic; and it was this ability to see the more familiar comic side of life, and the desire to travesty the serious—whether in Greece or Rome—that first gave flexibility and variety to the art of miming, or “acting,” as we call it nowadays.

It is because of this nearness to the life of the time, because of the travesty of contemporary types and public affairs, that the Latin actors made their wide appeal.

From public encouragement would come the increasing[43] endeavour of popular actors to outshine each other in technical tours de force; and from playing the familiar types of Latin Comedy, such as Maccus, with his double hump, prototype of our Punch; Pappus, forerunner of Pantaloon, and other characters (some from the early Mimi, some from the Atellanæ and Togatæ of tradition), the Latin Actors of the first and second centuries A.D. ultimately aspired to the wordless representation of the gods and heroes of myth and legend.

According to one authority, “the Latin Pantomime grew out of the custom at this period—the first century of the Christian era—of having lyrical solos, such as interludes to flute accompaniment, between the acts of the Latin comedies.” According to that admirable historian of the stage, Mr. Charles Hastings, “this new mode (Pantomime) was a kind of mime, in which poses and gestures constituted the fundamental portion of the play. Words occupied a secondary place, and eventually disappeared altogether. Only the music was preserved, and in order that the audience might understand the gestures of the actors, little books were distributed in Greek text, intelligible only to the learned and to the upper classes. Later on the mask—rejected by the mime—was adopted, and a chorus was employed to accompany the comedian with their voices, and to explain the multiple gestures by which the actors created the different characters in turn. Moreover, there was a company of mute players. The libretti left almost unlimited liberty of detail. Sometimes the music broke off to enable the actor to finish his fioritura and variations. Sometimes, on the other hand, the comedian paused, or left the stage, while the story was taken up by the recitative and the instruments.”

All this reads much like a description of a modern “mimodrame,” such as “L’Enfant Prodigue,” or “Sumurun.” Again it reads not unlike a description of a modern ballet,[44] for with these do we not often have printed synopses distributed, though not in Greek text? But we have to remember that the music was primitive, the scenic effect, though often remarkable, was different from that of our modern stage, with its greater mechanical resources; and, finally, that all this was an innovation of the Roman stage, for we are talking of the period that saw the dawn of the Christian era.

Among the more famous of the Latin pantomimists were Pylades, who was the inventor of tragic pantomimes; and Bathyllus, who was the composer of livelier episodes. For some time they joined forces and had a theatre of their own, where they staged comedies and tragedies composed by themselves without words or any other aid in telling the story of the play than dancing, pantomime and music.

The innovation struck the popular fancy, and all Rome flocked to support the new venture. The two actors were received at the Emperor’s Court, and became the spoilt darlings of the Roman “smart” set. The inevitable happened. They began to intrigue at Court, and were made the centre of intrigue; they became as jealous of each other as rival opera singers, and in time a financially happy partnership was dissolved, and there were two theatres devoted to pantomimes instead of one.

But as this form of drama was a novelty, and pleased the “connoisseurs,” who were numerous and increasing in numbers, both theatres were equally successful, perhaps the more so in that the public is always specially interested in ventures that appear to be in rivalry. The taste for existing stage-productions slackened in favour of those offered by Pylades and Bathyllus. Their “ballets” whether tragic, comic or satiric were looked on as the very perfection of tragedy, comedy or satire.

It was no longer a matter of declamatory style to enjoy[45] or to criticise, it was a matter of steps, movements, gestures, attitudes, figures or positions that were discussed by wise connoisseurs of “the new thing,” who in Rome, as elsewhere to-day, had much to say on what they presumed to understand because—it was new! And such, it is said, was the genius of the “producers” of this novel form of entertainment; the effect was so natural, the stage-pictures were so convincing, the pathos was so moving or the gaiety so free and infectious, that the audiences forgot they had ears while using enchanted eyes; and expressive gestures took the place of vocal inflections, of the power of words and the magic of poetic verse.

Pylades before long found a rival star arise in the person of Hylas, whose greatest performance was said to be in Œdipus. If Pylades and Bathyllus had quarrelled, there was evidently no love lost between Pylades and Hylas.

Hylas on one occasion was giving a representation of Agamemnon and, at a particular line referring to that historic personage as “the great,” he rose up on tip-toe. “That,” said Pylades scornfully, “is being tall, not ‘great’”; a criticism not only just, but giving an excellent insight into the methods and ideas of the famous Latin pantomimist.

It is somewhat uncertain whether it was the Court intrigues of Bathyllus or of Hylas or of both which ultimately secured from the Emperor the sentence of banishment for Pylades, or whether it was the daring, not to say impudence of the actor in representing well-known people, or whether again it may not have been the increasing danger of the constant brawls which were taking place daily in the streets of Rome between the rival factions—the Pyladians and the Bathyllians.

But whatsoever the reason, the probability is that the perpetual strife between the parties supporting the adored actors (worse than ever was that between the Piccinists and[46] Gluckists of the eighteenth century), with the constant blood-shed it involved, was made the excuse for the convenient removal of one of the principal factors in the disorder, and that the influence of Bathyllus, possibly backed up by that of Hylas, was able to secure the removal of the tragic actor.

Pylades, however, had his revenge, for such was the uproar in Rome on his banishment that the Emperor was practically forced to recall him, and he returned in triumph.

It is time, however, to leave the affairs of popular actors of the ancient world, since it is less the details of their personal history we need to consider than their importance as the virtual inventors of the second element of Ballet, the art of the mime, or, to use for a moment the more comprehensive word—pantomime. Thus we can see that it is largely due to the perfecting by the Italians of that art which seems to have been even more natural to them than to the Greeks—miming, that we have the Ballet of to-day.

From the dawn of the Christian era, comedy gave place to a perfect craze, first for the mime, and then for its offspring, pure pantomime. But, finally, the mimetic art as a standing entertainment of the Roman public, came to suffer neglect in favour of circuses; then, together with the circuses, it was opposed by the Churches. There were spasmodic revivals in the fourth and fifth centuries, but from the fifth century mime and pantomime practically ceased to exist in Constantinople, to which the seat of the Roman Empire had by that time been removed; and the arts both of the dancer and the mime fell upon a period of obscurity, though they went into retirement with all the reluctance of a modern “star.”

It is a truism of history that opposition towards the amusements of a people only increases the desire for them, and that the undue pressure of a law, or of a too rigid majority, only stimulates the invention of evasions. In dramatic history there is ample proof of this.

In England during the seventeenth century the force of Puritan opinion and of law did not crush the Drama, but led to unseemly licence.

When, in the early eighteenth century, Paris was enlivened by the spectacle of the majestic Royal Opera, endeavouring by legal thunder to suppress the lively vaudeville performances of the too popular Paris Fairs, and even going to the length of obtaining decrees forbidding the Fair theatres to perform musical plays in which words were sung, were the managers of the little theatres downhearted?

No! they merely evaded the law and made a mockery of pompous interference by having the music of their songs played, while the meaning was acted in dumb-show, and—the actual words, printed very large, were displayed on a screen let down to the stage from above! Their audiences, catching the spirit of the thing, enjoyed the wit of the evasion and supported the performances all the more.

There are many people who can only relish that which they have been told is wrong.

Much the same spirit was abroad about sixteen hundred years ago, when the growing power of the Christian Church began to be a calculable factor in “practical politics,” and the embarrassment of successive Roman emperors in trying to rule an unwieldy and decaying Empire was increased by the moral warfare between the more rigid sects of the new Church and the pleasures of the people.

It should, however, be said in justice to the early Churchmen that many of the pleasures of the people had become entirely scandalous, and detrimental to the manhood of the Empire, at least as seen in the Empire’s capital. Over such let us draw a veil!

While, in these “democratic” days, it may be doubted if there are any of the English-speaking race who “dearly love a lord” (though there is really no reason why they should not!), there were certainly some thousands of the Byzantine populace in the third and fourth centuries to whom a successful circus-rider or gladiator, actor or dancer, was of far more interest than any peer of their period.

The histrionic favourites lacked, of course, the advantages of picture-postcard fame, and had to be content with immortality in verse. But as for the now hackneyed “stage romance” of the marriage of a youthful scion of a noble house with some resplendent star of the theatrical firmament, did not a Byzantine Emperor, Justinian, marry Theodora, once a popular dancer at the Hippodrome!

Yet he it was who made one of the more effective moves to suppress some of his people’s excessive opportunities for amusement, by abolishing the laws under which the expense of the performances in the Hippodrome, and some of the less important theatres had been met by the Imperial treasury. This, however, was mainly due to his beautiful wife, who had seen all the vilest side of theatrical life in a[49] time when the older dramatic culture had given place to banal and vulgar entertainments involving a horrible servitude of those engaged in providing them.

Before this, however, the Church’s thunder had been launched at the grosser theatrical spectacles, and the Theatre had retaliated by mocking the adherents of the then new religion. Where fulmination failed, control by influence was essayed. But for all the attacks of the more advanced and severer leaders of the early Church, there must have been something of confusion for at least the first five centuries of the Christian era. Indeed, in the endeavour of the Church to transmute the popular love of theatrical spectacles into something higher, and to awaken the public interest in the service of the Church, what with the introduction of choral song, with strophe and antistrophe, and of solemn processionals, even it is said of ceremonial dances performed by the choir—such as the Easter dances still seen in Spain to-day—the Church itself must have come at times to seem perilously sympathetic towards the very things it was professing to condemn.

Did not Gregory Nazianzen implore Julian, before he became “the Apostate,” to be more discreet, saying in effect: “If you must dance, and if you must take part in these fêtes, for which you seem to have such a passion, then dance, if you must; but why revive the dissolute dances of the daughter of Herodias, and of the pagans? Dance rather as King David did before the Ark; dance to the glory of God. Such exercises of peace and of piety are worthy of an Emperor and a Christian.”

In short, wise cleric as he was, he found no fault with the healthy exercise of the dance itself, but only with such dance and other Byzantine entertainment as had tended, or might tend, to become merely an exhibition of depraved taste.

Indeed, how could he have inveighed against the dance as an expression of clean rejoicing when it had been recorded: “And Miriam the prophetess, the sister of Aaron, took a timbrel in her hand; and all the women went out after her with timbrels and with dances”?[1] Had not the servants of Achish said: “Is not this David the king of the land? did not they sing one to another of him in dances, saying, Saul hath slain his thousands, and David his ten thousands?”[2] Had it not, too, been written: “And David danced before the Lord with all his might.”[3]

No, the Church thunder had been directed against the licence by which the arts of dancing and miming had been corrupted, and against, not wholesome athleticism and healthy sport, but the hysterical brutalities and “professionalism” of the arena.

And if further proof were required of ecclesiastical interest in and practice of the thing it only attacked when seen in degraded form, it is to be found in the fact that in 744, the Pope Zacharias promulgated a Bull suppressing all so-called “religious dances,” or “baladoires” as he called them, which were showing signs of becoming “degenerate.”

These were dances which were performed in, or within the precincts of cathedrals and churches at certain festivals such as Easter, Midsummer and Christmas; and of which the old English bonfire dances of St. John’s Eve, were (and the modern carnival, and the Eastertide ceremonial seen in Seville to-day, are) probably survivals, though, to be sure, they should be accounted originally as survivals of earlier pagan dances in honour of the sun, and of the harvest, and not as originating with the Christian Church.

It may seem a far cry from the date of Pope Zacharias’ edict of 744, to 1462, when the first of the ballets ambulatoires [51]is recorded, but it must not be supposed that dancing, if not miming, is entirely lacking in history during those seven hundred odd years. Any history of dancing would aid us in at least partly bridging such a gap; but it will be convenient in a chapter dealing more especially with early ecclesiastical influence on the evolution of Ballet, to deal now with a form of entertainment or of religious festival which was essentially a creation of the earlier Church.

The famous procession of the Fête Dieu which King René d’Anjou, Count of Provence, established at Aix in 1462, was, as an old historian tells us, an “ambulatory” ballet, “composed of a number of allegorical scenes, called entremets.” This word entremets, which was later replaced by “interludes,” designated a miming spectacle in which men and animals represented the action. Sometimes jugglers and mountebanks showed their tricks and danced to the sound of their instruments. These entertainments were called entremets because they were instituted to occupy the guests agreeably at a great feast, during the intervals between the courses. “The entre-actes of our first tragedies,” the writer adds, “were arranged in this manner, as one sees in the works of Baif, the interludes in the tragedy of Sophonisbie. More than five hundred mountebanks, Merry Andrews, comedians and buffoons, exhibited their tricks and prowess at the full Court which was held at Rimini to arm the knights and nobles of the house of Malatesta and others.”

As the fêtes and tournaments, given on these occasions, were accompanied by acts of devotion, the festivals of the Church often displayed also something of the gallant pomp of the tournaments.

These ballets ambulatoires, however, with all their richer pageantry, were yet to be outshone by the two secular entertainments to which we must devote our next chapter—the[52] banquet-dance of Bergonzio di Botta, of 1489, and the still more famous “Ballet Comique de la Reine,” of 1581, the last of which, there can be little doubt, had important effect in the development if not creation of our English masque, which, in turn, had an immense influence on the evolution of modern Ballet.

A superb and ingenious festivity was that arranged by Bergonzio di Botta, a gentleman of Tortona, in honour of the wedding of Galeazzo, Duke of Milan, with Isabella of Aragon.

The good Bergonzio was a lover of all the best things of life, but especially of dining and of dancing. That historic gourmet, Brillat Savarin, commends him for his taste in the former matter, as may we for the bright idea of combining a dinner with a dance, one of somewhat nobler plan than any modern example!

The dinner was of many courses and each was introduced by the servers and waiters with a dance in character, the whole constituting a sort of dinner-ballet. In the centre of a stately salon, which was surrounded by a gallery where various musicians were distributed, there was a large table.

As the Duke and his lady entered the salon by one door, from another approached Jason and the Argonauts who, stepping proudly forth to the sound of martial music and by dance and gestures expressing their admiration of so handsome a bride and bridegroom, covered the table with the Golden Fleece which they were carrying.

This group then gave place to Mercury who, in recitative,[54] described the cunning which he had used in stealing from Apollo, who guarded the flocks of Admetus, a fat calf, with which he came to pay homage to the newly married pair. While he placed it on the table three “quadrilles” who followed him executed a graceful entrée.

Diana and her nymphs then succeeded Mercury. The Goddess was followed by a kind of litter on which was a hart. This, she explained, was Actæon, who, although no longer alive, was happy in that he was to be offered to so amiable and fair a nymph as Isabella of Aragon. At this moment a melodious symphony attracted the attention of the guests. It announced the singer of Thrace, who was seen playing on his lyre while chanting the praises of the young duchess.

“I mourned,” he sang, “on Mount Apennine the death of tender Eurydice. Now, hearing of the union of two lovers worthy to live for one another, I have felt, for the first time since my sorrow, an impulse of joy. My songs have changed with the feelings of my heart. A flock of birds has flown to hear my song. I offer them to the fairest princess on earth, since the charming Eurydice is no more.”

A sudden clamour interrupted his song as Atalanta and Theseus, heading a nimble and brilliant troupe, represented by lively dances the glories of the chase. The mimic hunt was terminated by the death of the wild boar of Calydon, which was offered to the young Duke, with triumphal “ballets.”

A magnificent spectacle then succeeded this picturesque entrance. On one side was Iris, seated on a car drawn by peacocks and followed by several nymphs, covered in light gauze and carrying dishes of superb birds. The youthful Hebe appeared on the other side, carrying the nectar which she poured for the gods. She was accompanied by Arcadian shepherds, laden with all kinds of food and by Vertumnus and[55] Pomona who offered all manner of fruits. At the same time the shade of that famous gourmet Apicius rose from the earth, presenting to this superb feast all the delicacies he had invented and which had given him the reputation of the most voluptuous among ancient Romans. This spectacle disappeared and then there was a wondrous ballet of all the gods of the sea and rivers of Lombardy; who carried the most exquisite fish and served them while executing dances of different characters.

This extraordinary repast was followed by a yet more singular spectacle opened by Orpheus, who headed a procession of Hymen and a troop of Loves, followed by the Graces who surrounded Conjugal Faith, whom they presented to the Princess, while offering, themselves, to serve her.

At this moment, Semiramis, Helen, Medea and Cleopatra interrupted a recitative by Conjugal Faith to sing of the delights of Passion. Then a Vestal, indignant that the recital of pure and true marriages should be sullied by such guilty songs, ordered the notorious queens to withdraw. At her voice, the Loves, who accompanied her, joined in a lively dance, pursuing the wicked queens with lighted torches and setting fire to the gauze veils of their headdress! Lucretia, Penelope, Thomiris, Porcia and Sulpicia replaced them and presented to the young Princess that palm for chastity which they had merited during their lives. Their “modest and noble” dance, however, was interrupted by Bacchus, with a troop of revellers who came to celebrate so illustrious a bridal, and the festival terminated in a manner as gay as it was ingenious.

The fête achieved a prodigious fame throughout Italy. It was the talk of every city and a full description of its glories was published, while crowds of “society hostesses” of the period endeavoured to emulate the ingenuity[56] of its originators, and the vogue of the dinner-ballet “arrived.”

One effect of its fame was that for a century it set the fashion for the Royal and Ducal Courts throughout Europe. Every Court had its “ballets,” in which lords and ladies of highest degree took part; and the movement was greatly fostered by Catherine de Medici, who sought to divert the attention of her son, Henry III, from political affairs towards the more congenial ways of social amusement, of which Court-ballets formed considerable part.

The culmination of these sumptuous entertainments came, however, in 1581, when in celebration of the betrothal of the Duc de Joyeuse and Marguerite of Lorraine, sister of the Queen of France, a spectacle was arranged, the splendour of which had never been seen in the world before. This was Beaujoyeux’s famous “Ballet Comique de la Royne”—or de la Reine in modern spelling—which set all cultured Europe aglow with praise of its designer. A special account of it, with many charming engravings, was printed by order of the King to send to foreign Courts. So much did it set a fashion that the elaborate masked balls and the numerous Court-masques and entertainments which followed in the reigns of Henry VIII, Elizabeth and James were directly inspired by the success of Beaujoyeux’s ballet, even as they in turn influenced the subsequent productions of Louis XIV in France.

The author and designer was an Italian, by name Baltasarini, famous as a violinist. He was introduced by the Duc de Brissac to the notice of Catherine de Medici, who appointed him a valet de chambre, and subsequently he became official organiser of the Court fêtes, ballets and concerts, assuming the name of Baltasar de Beaujoyeux.

The account of the ballet was sumptuously published. The title-page read as follows:

BALET COMIQUE

After a courtly dedication “Au Roy de France, et de Pologne,” full of praise for his prowess in arms and his taste in art, full of graceful compliment by classic implications, he follows with an address:

AU LECTEUR.

Povravtant, amy Lecteur, que le tiltre et inscription de ce livre est sans example, et que lon n’a point veu par cy deuant aucun Balet auoir esté imprimé, ny ce mot de Comique y estre adapté: ie vous prieray ne trouver ny l’un ny l’autre estrange. Car quant au Balet, encores que ci soit vne inuention moderne, ou pour le moins, repétée si long de l’antiquité, que l’on la puisse nommer telle: n’estant à la verité que des meslanges geometriques de plusieurs personnes dansans ensemble sous vne diuerse harmonie de plusieurs instruments: ie vous confesse que simplement representé par l’impression, cela eust eu beaucoup de nouveauté, et peu de beauté, de reciter vne simple Comedie: aussi cela n’eust pas esté ny bien excellent, ny digne d’vne si grande Royne,[58] qui vouloit faire quelque chose de bien magnifique et triomphant. Sur ce ie me suis advisé qu’il ne seroit point indecent de mesler l’un et l’autre ensemblement, et diversifier la musique de poesie, et entrelacer la poesie de musique et le plus souvent les côfrondre toutes deux ensemble: ansi que l’antiquité ne recitoit point ses vers sans musique, et Orphée ne sonnoit jamais sans vers, i’ay toutes fois donné le premier tiltre et honneur à la danse, et le second à la substâce, que i’ay inscrite Comique, plus pour la belle, tranquille et heureuse conclusion, ou elle se termine, que pour la qualité des personnages, qui sont presque tous dieux et déesses, ou autres personnes heroiques. Ainsi i’ay animé et fait parler le Balet, et chanter et resonner la Comedie: et y adjoustant plusieurs rares et riches représentations et ornements, ie puis dise avoir contenté en un corps bien proportionné, l’œil, l’oreille, et l’entendement. Vous priant que la nouveauté, ou intitulation ne vous en face mal juger; car estant l’invention principalement. Composée de ces deux parties, ie ne pouvois tout attribuer au Balet, sans faite tout à la Comedie, distinctement representée par ses scènes et actes: ny à la Comedie sans prejudicier au Balet, qui honore, esgaye et rempli d’harmonieux recits le beau sens de la Comedie. Ce que m’estant bien advis vous avoir deu abondamment instruire de mon intention, ie vous prie aussi ne vous effaroucher de ce nom et prendre le tout en aussi bonne par, comme i’ay desire vous satisfaire pour mon regard.

Although the quaint spelling of the old French may offer a passing difficulty to some readers, I have felt it advisable to give the address as it stands, for it presents several points of extraordinary interest.

First and foremost is the fact that it claims Beaujoyeux’s ballet to be the first ever printed!