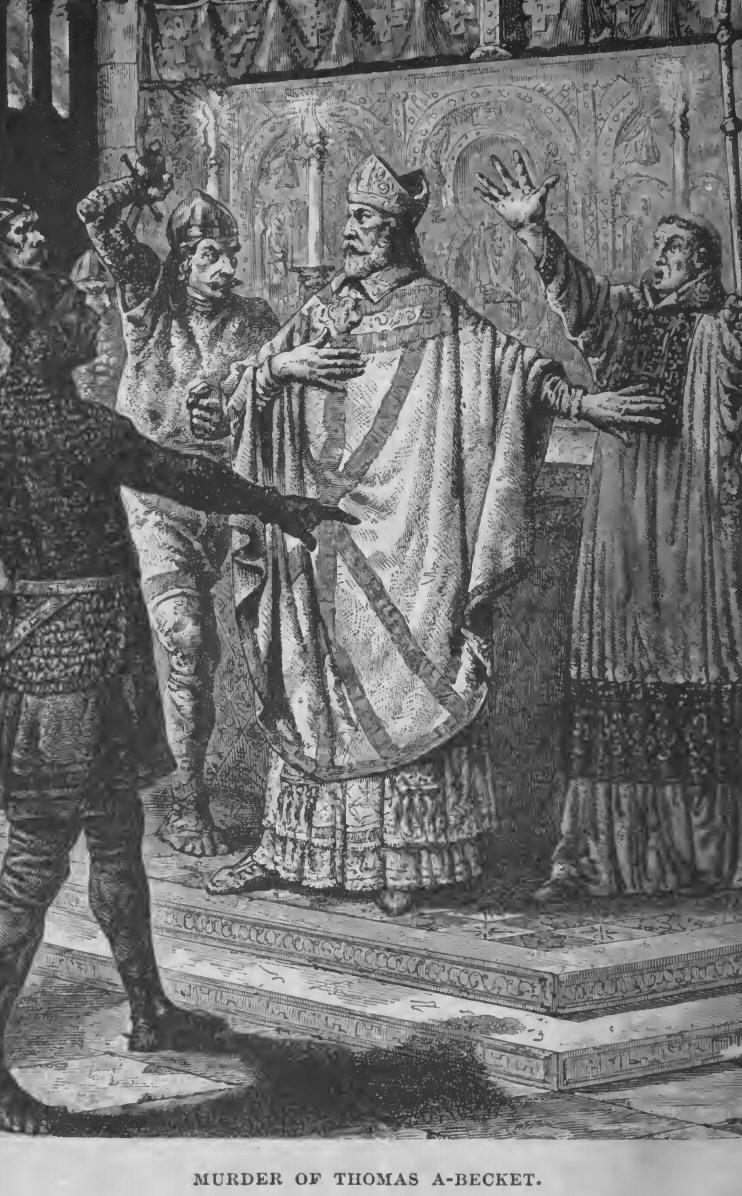

Murder Of Thomas A-Becket.

Title: A Popular History of England, From the Earliest Times to the Reign of Queen Victoria; Vol. I

Author: François Guizot

Editor: Madame de Witt

Release date: March 21, 2020 [eBook #61647]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Don Kostuch

[Transcriber's note: This production is based on http://www.archive.org/details/popularhistoryeng01guiz.

Spoiler alert: If you expect to hear about Cinderella and Prince Charming living in Camelot, here are some of the most frequently used words in this book, ordered by number of occurrences.

war, armies, enemies, soldiers, weapon, prison, attack, defence, conquer, battle, invade, fortifications, dead, suffer, anger, seize, kill, insurrection, threat, fight, traitor, surrender, fear, escape, pursue, opposition, strike, wound, condemn, blood, victor, quarrel, insurgent, punish, capture, rival, pirate, danger, crime, violence, destroy, arrest, trouble, archer, unhappy, murder, disorder, combat, reinforcement, pillage, dying, anxiety, exile, besiege, repulse, executed, captive, hostages, cruel, bitter, conspiracy, insult, revenge, humiliated, imprisoned, ruin, assassin, plunder, barbarian, rampart, jealous, confiscate, avenge, alarmed, usurpation, tyrannical, savage, malcontents, massacre, slaughter, despair, military, misfortunes, unfortunate, widow, detested, succumb, die, dagger, languished, assault, mercenaries, disaster, armor, booty, perjury, drown, repugnance, fatal, slave, armistice, robber, odious, greed, poison, incursion, false, foe, impeached, ambush, capricious, perfidious, scaffold, dungeon, decapitated.]

Murder Of Thomas A-Becket.

| Murder of Thomas A'Becket. | Frontispiece |

| Caractacus and his Wife before Claudius. | 16 |

| Augustine preaching to Ethelbert. | 32 |

| Alfred in the Herdsman's Hut. | 44 |

| Canute by the Seashore. | 72 |

| William the Conqueror reviewing his Troops. | 98 |

| Robert's Encounter with his Father. | 110 |

| Azelin forbidding the burial of William the Conqueror. | 116 |

| Death of William Rufus. | 122 |

| Escape of the Empress Maud from Oxford. | 144 |

| Richard Removing the Archduke's Banner. | 188 |

| Richard's farewell to the Holy Land. | 192 |

| King John's Anger After Signing Magna Charta. | 214 |

| King Henry and his Barons. | 228 |

| That is the Title by which I Hold my Lands. | 242 |

| Bruce warned by Gilbert de Clare. | 262 |

| Robert Bruce Regretting His Battle-Axe. | 274 |

| The Battle of Sluys. | 294 |

| Van Arteveldt at his Door/ | 298 |

| Queen Philippa on her knees before the King. | 314 |

| King John Taken Prisoner by the Black Prince. | 320 |

| The Black Prince Serving the French King. | 322 |

| Death of Wat Tyler. | 346 |

| Chapter I. | Ancient Populations of Britain Roman Dominion (55 B.C. to 411 A.D.) |

9 |

| Chapter II. | The Rule of the Saxons to the Invasion of the Danes (449 -832 | 24 |

| Chapter III. | The Danes. Alfred the Great (836-901) |

37 |

| Chapter IV. | The Saxon and Danish Kings. The Conquest of England by the Normans (901-1066) |

59 |

| Chapter V. | Establishment of the Normans in England (1066-1087) | 103 |

| Chapter VI. | The Norman Kings. (1087-1154) William Rufus Henry I. Stephen |

117 |

| Chapter VII. | Henry II. (1154-1189) | 146 |

| Chapter VIII. | Richard Cœur-de-Lion. John Lackland. Magna Charta (1189-1216) |

182 |

| Chapter IX. | King and Barons. Henry III. (1216-1272) |

218 |

| Chapter X. | Malleus Scotorum Edward I. (1272-1307.) Edward II. (1307-1327) |

238 |

| Chapter XI. | The Hundred Years' War. Edward III. (1327-1377) |

285 |

| Chapter XII. | Bolingbroke. Richard II. (1377-1308). Henry IV. (1398-1413) |

335 |

"The History of France," related to his grandchildren by M. Guizot, is now universally known. It has supplied a want which every one must have felt; it has been welcome both to children and to parents. Our national history enjoyed one indisputable privilege: it had everywhere the right to the first place. But after the "History of France," my father had related for the benefit of his grandchildren the "History of England." He had adopted a plan slightly different from that which he had followed in his previous narratives. He felt that in this case the knowledge which would enable the reader to supply any hiatus is less extended; he was, in consequence, careful to preserve the regular and chronological sequence of events. I have collected these lessons as I collected those of "The History of France." My father foresaw that he would not himself make use of the notes which I preserved. He therefore requested me to edit them, and he took a pleasure in re-perusing my work. I have thus written this "History of England," step by step, as he related, and in great part revised it; and I now publish it in accordance with his desire, and, in the hope of enabling others to share in the useful instruction which we all derived from it, both parents and children. {8} The French have often been charged with ignorance of the history of foreign nations. It is time to remove that reproach. For us the "History of England" is important and interesting above all others. In peaceful times and in times of war it is everywhere connected with our own by a national bond, which all the causes of dissension have not been able to destroy. In studying the History of England we study again the History of France; and we may draw from it useful lessons for the service and the welfare of that country whose trials and sorrows have rendered her a thousand times dearer to us.

Guizot De Witt.

[Henriette Guizot de Witt, daughter of François Guizot.]

The earliest periods of English History are obscure, and even the origin of its inhabitants is still a subject of discussion. The first authentic information which we possess with regard to them is derived from their conqueror. Julius Caesar remarked their resemblance to the Gauls, and modern researches have confirmed his testimony. Every thing seems to show that the inhabitants of Britain were Celts, or Gaels, a name which the population of the highlands of Scotland retain to this day. On the Southern Coasts, an invasion of Cimrys, or Belgians, appears to have mingled with the Celtic population and to have brought with it some elements of civilization. Long before the advent of Cæsar, the Phoenicians and Greeks established at Marseilles, had entered into relations of commerce with the Scilly Isles, which they called the Cassiterides, and also with the extremity of the County of Cornwall, where the tin-mines were situated. {10} Pytheas, who lived at Marseilles at the commencement of the Fourth Century B.C., has related his voyage along the coast of Britain; but it is with the invasion of the Romans that the history of England commences. It is here that we penetrate for the first time into those islands which, though separated from the rest of the world, sent to the Gauls, who were struggling for their independence, succor, which furnished Cæsar with a pretext for the attempt to conquer them. After his fourth campaign in Gaul, about the year 55 B.C., the great Roman general set sail on the 26th of August for Britain. He had brought with him the infantry of two legions,—about twelve thousand men, and he disembarked near the point where the town of Deal is now situated. The Britons had gathered in a mass upon the shore. A great number were on horseback, urging their horses into the waves, and insulting and defying the foreigners. They were almost entirely naked, having cast off the clothing of skins with which they were ordinarily covered, in order to prepare for the combat. Their war chariots were driven rapidly along the shore. For a moment the Roman soldiers hesitated, troubled by the unaccustomed sight, perhaps from a dread of offending the unknown gods of people celebrated among their Gaulish brethren for the devotion with which they surrounded the Druidical faith. The standard-bearer of the tenth legion was the first to precipitate himself into the sea. "Follow me, my fellow-soldiers," said he, "unless you will give up your eagle to the enemy. I at least will do my duty to the Republic and to our general." His comrades followed his example, and the savage inhabitants of Britain retired in disorder, driven back, in spite of their bravery, after a short engagement.

On the morrow, ambassadors from the Britons came to solicit peace. At the first rumor of the projected invasion they had sent emissaries into Gaul to offer their submission to the Romans, in the hope of turning them from their enterprise. {11} Cæsar had listened to them with kindness and had had them conducted by his own envoy Comius, king of the Belgian Atrebates; but he did not relinquish his intentions, and the Britons in their irritation had put the delegate of Cæsar in irons. This was the first matter with which the conqueror reproached them, at the same time demanding hostages for their future good behavior. Some hostages were immediately given. The British chiefs asked for time to send others, and Cæsar entered into separate negotiations with the chiefs who came one after the other to treat with the conqueror.

During these negotiations the sea rendered aid to the Britons. Great part of the Roman fleet was destroyed. The barbarians perceived their advantage and were dilatory in sending the hostages. Meanwhile Cæsar had promptly set his soldiers to the task of repairing the vessels, and making requisitions upon the Gauls for the materials which were required. The vessels were beginning to be in a state to take the sea when the seventh legion, detached on a foraging expedition in the country, was surprised in the only field of grain then standing, by a number of Britons who were lying in ambush concealed by the long stalks of the corn. Horsemen and war chariots issued forth from the surrounding forests. The Romans ran the risk of being crushed, when Cæsar came to their assistance with the remainder of his forces, and defeated the barbarians, who sued for peace. The equinox was approaching. The general did not even wait for the hostages, but set sail for Gaul in the middle of September, sending at the same time news to Rome which induced the Senate to decree twenty days of public thanksgivings to the Immortal Gods. In his Commentaries, however, Caesar modestly describes this first campaign in Britain as a reconnoitring expedition. He cherished the design of returning thither later.

Accordingly in the following year (54 B.C.), Caesar embarked at the same point upon the coast of Gaul, in order to land at the same spot, though with very different forces. He carried with him the infantry of five legions (about thirty thousand men) and two thousand cavalry. Eight hundred transport vessels covered the sea.

From the summits of their cliffs the Britons had perceived this formidable expedition, and had sought refuge in the vast forests which cover their shores. Cæsar marched forward to drive them back into their retreats, when a violent tempest destroyed forty of his ships and drove a great number ashore. The first care of the conqueror was to protect his fleet against the fury of the sea and the hostility of the islanders. He caused all his vessels to be hauled ashore, in order to surround them afterwards by a strong intrenchment. His largest galleys were diminutive in comparison with our vessels of war. His transport ships were hardly more than barges. The Roman soldiers labored without intermission ten days and ten nights before they had rendered their fleet secure.

They then resumed their march against the Britons, whose army was still increasing. All the chiefs had united their forces under the orders of a commander-in-chief, Cassivelanus, king of the Cassii, renowned for his bravery and skill. The Britons avoided a general engagement. Assailing the Romans incessantly with their cavalry and their war-chariots, which they conducted with the ease of habit even along the edge of precipices, they retired again into the forests from the moment that the advantage was no longer on their side. But this barbarian intrepidity was not accompanied by experience. Cæsar's cavalry, supported by three legions, having scoured the country in quest of forage, the enemy had remained concealed all day, when suddenly they issued in a mass from the neighboring forests and swept down upon the Romans who were scattered about the country. {13} Already the Britons imagined themselves victors; but the well-disciplined Roman detachments formed again as if by enchantment, the horsemen rallied, and the Britons, enclosed in a formidable circle, sustained losses so great that on the morrow the allies of Cassivelanus nearly all deserted him and returned into their territories, leaving him to face the Romans unsupported. The king in his turn fell back upon his kingdom, which was situated on the left bank of the Thames.

In their pursuit the Romans had traversed the fertile country which now forms the counties of Kent and Surrey, while this skirmishing species of warfare continued, often with results favorable to the Britons. But the fatal want of union common to barbarous tribes lent aid to the Romans. Cassivelanus was detested by his neighbors the Trinobantes, who sent ambassadors to Cæsar, asking the restoration of their king Mandubratius, a fugitive in Gaul, where he had implored the protection of the Romans against this same Cassivelanus, who had conquered and put to death the father of his rival. On this condition the the Trinobantes offered their submission. Some other tribes followed their example. These seceders acquainted the Romans with the road to Cassivelanus's capital situated on the environs of the spot now occupied by the town of St. Alban's. This was a collection of huts reminding beholders of the dwellings of the Gauls. They rested on a foundation made of stones, from which arose the walls composed of timber, earth, and reeds, and surmounted by a conical roof which served at once to admit daylight and to allow smoke to escape through a hole in the top. Fens and woods surrounded by a ditch and earthworks protected this primitive capital, which soon fell into the hands of the Romans.

Cassivelanus had only one hope left. He had given orders to the four chiefs who had the command in Kent to attack the Roman vessels. They obeyed, but the detachment charged with the protection of the fleet was on its guard. The Britons were repulsed. Cassivelanus, beaten and discouraged, humbled himself so far as to sue for peace. Nevertheless when Cæsar at the commencement of September retired once more to Gaul, he left in Britain neither a soldier nor a fortress. The second campaign, longer and more fortunate than the first, had not produced any greater results.

Ninety-six years elapsed; the Roman Republic had become the Roman Empire; but the Britons had been troubled by no new invasion. The Belgian population of the sea-coast had continued to cultivate their fields, to which they already knew how to apply marl for manure. They had woven in peace their long brogues, or chequered breeches, their square mantles, and their tunics. The Celts, more savage, had seen their flocks multiply around them. Even this, the only kind of wealth among barbarous tribes, did not exist in the northern part of Britain. The rude inhabitants of Scotland depended only on the products of the chase, and found a shelter for their almost naked state in the hollow of rocks or in the obscurity of caverns; but no invader had come to trouble their wild liberty up to the day when the Emperor Claudius, in the year 45 of the Christian Era, conceived the project of marching in the footsteps of Cæsar and subduing the savage land of Britain. One of the most experienced of his generals, Aulus Plautius, sent forward with a force of fifty thousand men, obtained at first some successes, notwithstanding the resistance of the chief of the Silures, Caractacus. {15} When the Emperor arrived, the capital of this people was captured, and several tribes had submitted almost without a struggle. Claudius returned to Rome to enjoy there the honors of an easy triumph.

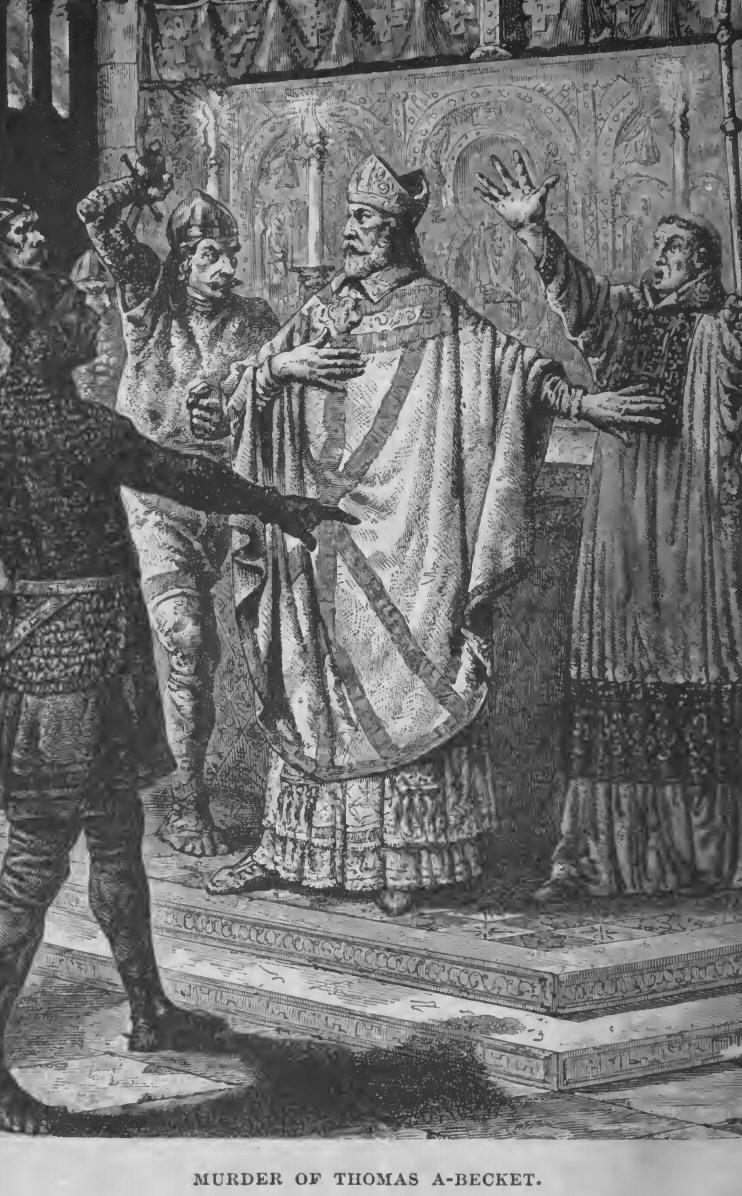

Thirty battles fought by Aulus Plautius were insufficient to reduce Caractacus. Ostorius Scapula was the first to succeed in establishing on the Severn a line of forts separating from the rest of the island the country, now become Roman, which comprised nearly all the Southern tribes. The Britons, who appeared to be subdued, were disarmed. But a new insurrection soon broke forth. The Iceni, who occupied the country now known as the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk, were the first to rise. The Cangi followed their example; and in order to reduce them the Praetor was compelled to pursue them as far as to within one day's march of the sea which separates England from Ireland. From the territory of the Brigantes, which embraced a portion of the present counties of Lancashire and York, Ostorius hastened to invade the Silures, who inhabited the southern portion of Wales, and who were always the most indomitable opponents of a foreign domination. "Behold the day which is to decide the fate of Britain!" exclaimed Caractacus at the sight of the Romans. "To-day begins the era either of liberty or eternal slavery. Remember that your ancestors were able to drive back the great Cæsar, and to save their liberty, their life, and their honor!" He spoke in vain. The naked breasts and bare heads of the Britons could not resist the broad swords of the Roman soldiers. The massacre was horrible. The wife and the daughter of Caractacus were captured, but the chief himself had disappeared. Hoping to renew the struggle, he had taken refuge with his mother-in-law, Cartismandua, queen of the Brigantes. She delivered him up to the Romans. {16} Caractacus was sent to Rome with his family. "How can men who possess such palaces make such efforts to conquer our miserable hovels?" exclaimed the British hero, while traversing the streets of Rome. He appeared before the tribunal of the emperor. Agrippina was there by the side of her husband. The wife of Caractacus threw herself at her feet, imploring her pity; but the conquered chief asked for nothing, and exhibited no sign of fear. This greatness in defeat penetrated to the heart and to the sluggish mind of Claudius. He gave the order to set the captives free. Tradition states that he even restored to his prisoner a portion of his territory, but Tacitus does not mention this; he leaves the story of the vanquished chief at the point where the fetters fall from his hands.

For a moment Nero, who had become emperor, thought of abandoning the conquest of Britain, so difficult to secure. It was not until the year 59 A.D. that Paulinus Suetonius, at that time prætor, resolved to crush the resistance of the Britons in their innermost retreat. The island of Mona (now Anglesey) was consecrated to the Druid worship; the priests had nearly all taken refuge there, and there the defeated chiefs found an asylum. Religion even then exercised a considerable power over the minds of the inhabitants of Britain. In no part were the Druids more numerous and powerful; nowhere had they a greater number of disciples diligently occupied during long years in engraving upon their memory the regulations of their worship, the sacred maxims, the ancient poems, which the priests did not allow to be committed to writing. Great, therefore, was the emotion in Britain when the Romans were seen to attack the holy isle.

Caractacus and his Wife before Claudius.

On the shore a great crowd awaited the advance of the enemy, "savage and diversified" in appearance, says Tacitus. The armed men were assembled in a mass; the women, attired in sombre dress, running about with dishevelled hair, like furies brandishing their torches; and the Druids were standing, clothed in their long white robes, as if about to sacrifice to their gods, their heads shaved, their beards long, their hands raised to heaven, while they pronounced the terrible maledictions of the Celtic races against the enemies of their people and their divinities. The Roman soldiers hesitated; their limbs seemed paralyzed by fear, and they exposed themselves, without resisting, to the blows of their enemies. Their general urged them to advance. At length, each encouraging the other to despise the infuriated cries of a band of priests and women, they rushed upon the Britons, and precipitated them upon the stakes which they had prepared in order to sacrifice the Roman prisoners to their gods. A garrison was placed on the island; the sacred grove was cut down; and the fugitive Druids disappeared, to seek an asylum among the tribes which still offered a resistance.

The number of these tribes had increased in the absence of the prætor. The infamous treatment inflicted upon Boadicea, queen of the Iceni, and her children, by order of the procurator Catus, had aroused the indignation of her neighbors as well as of her own subjects. By secret intrigues the malcontents from all quarters were invited to strike a great blow for the recovery of their liberty. The colony of Camalodunum was first attacked and put to fire and sword. Suetonius hastened from the isle of Mona, and marched first towards London, already an important and populous city. Defence was impossible. The prætor withdrew the garrison to protect the rest of the provinces, and all the citizens who had not been able to retire under the shelter of the Roman eagles were massacred. The Roman colony of Verulam suffered the same fate. {18} It is said that more than 70,000 Romans and their allies had already perished under the blows of the insurgents, when the two armies found themselves confronted. Queen Boadicea rode along the ranks of the Britons, clothed in a robe of various colors, with a golden zone around her waist. She reminded her countrymen that she was not the first woman who had led them to battle, since the custom of the country often called to the throne the widow of a sovereign, passing over his children. She spoke of the irreparable insults which she had undergone, of the misfortunes of the nation, and she exhorted the warriors to immolate all the Romans to Andrasta, the goddess of victory. The Romans remained motionless; they were awaiting the attack of the Britons.

The barbarians, excited by the glowing words of the queen, rushed upon the legions; the Romans bestirred themselves at length, and their broad swords opened for them a passage through the midst of the mass of Britons. The latter fell without flinching; but their enemy advanced to the line of chariots, and put to the sword women and children. It is said, though no doubt, with the usual exaggeration of the time, that 80,000 Britons perished on that day. Boadicea, resolved not to survive her hopes of vengeance, poisoned herself upon the battle-field.

Successive prætors had failed to establish tranquillity in Britain, or to obtain the submission of the people, when Agricola, father-in-law of the celebrated historian Tacitus, arrived in his turn in this indomitable island. His brilliant exploits soon caused him to be respected; but, while pursuing year by year the course of his conquests, he endeavored to found the Roman rule upon the most durable basis. In his hands the civil administration became milder; the Britons governed with justice, became gradually less estranged from their conquerors. {19} A taste for luxury and Roman civilization began to distinguish the chiefs admitted to the prætorian court; the Roman toga took the place of the British mantle; buildings arose upon the model of the Roman constructions; children began to speak Latin; and at the same time the spirit of liberty and resistance diminished among the inhabitants of the south of Britain. "The Britons willingly furnish recruits to our armies," wrote Tacitus; "they pay the taxes without murmuring, and they perform with zeal their duties towards the government, provided they have not to complain of oppression. When they are offended their resentment is prompt and violent; they may be conquered, but not tamed; they may be led to obedience, but not to servitude."

The military progress of the Roman general was no less important than his moral conquests. He had reached the Firth of Forth and the narrow isthmus which separates this river from the mouth of the Clyde. After every new victory he protected the subjected territory with forts. He even constructed a wall, the ruins of which, crossing the north of England from the Solway to the mouth of the Tyne, bear to this day his name. In the eighth and ninth year of his government he passed the line of the forts and penetrated into Scotland, the country of the Caledonians, savage tribes who had not yet beheld the Roman eagles. Scarcely had the conquerors invaded this new territory when the Caledonians, under the command of their chief, Galgacus, descended from the Grampian hills and fell upon the invader. On Ardoch Moor traces of the combat still exist, together with the lines of the Roman encampment. The struggle lasted all day, and the barbarians were defeated; but on the morrow at sunrise they had disappeared, and the Romans found themselves alone in the midst of a wild country. {20} In their flight the Caledonians had set fire to their habitations, and with their own hands had slain their wives and children, to prevent their falling victims to the vengeance of the conqueror. The savage tribes had returned into their mountains, leaving, according to the chronicles, 10,000 dead upon the field of battle. Agricola made no effort to pursue them. Falling back towards the south, he despatched his vessels to make a voyage of exploration all round the island, the northern shores of which had not yet been visited. The mariners returned, reporting that no tongue of land connected Britain with the continent, that they had seen in the distance Thule (Iceland), enveloped in mists and eternal snow, and that the seas which they had traversed were of a sluggish kind, heavy under the oar, and never agitated by wind or storms. Agricola was recalled to Rome through the jealousy of the Emperor Domitian, but his wise government had appeased the passions of the Britons, and for thirty years afterwards the Roman annals contain no mention of British affairs—an evidence that peace reigned in the island.

An invasion of the Caledonians brought the Emperor Hadrian to Britain (120 A.D.). Having driven them back beyond the forts which connected the mouth of the Solway on the west with that of the Tyne on the eastern coast, he caused to be raised behind this rampart an enormous wall, fortified by a wide fosse and provided with towers which received a garrison. This redoubt is still partly in existence, as is the wall of Antoninus, constructed some years later across the isthmus of the Forth, after a fresh invasion of the barbarians.

No rampart, however, could resist the warlike ardor of these savage populations; and the disorganization which had attacked the vast body of the Empire began to make itself felt among the legions established in Britain. The soldiers often murmured; the general, Albinus, after having refused the title of Cæsar from the hands of the Emperor Commodus, accepted it upon the offer of Septimius Severus, and, suddenly rejecting his allegiance, he was proclaimed emperor by his troops. Crossing immediately into Gaul to sustain his pretensions by force of arms, he was defeated near Revoux, and paid for his ambition by the loss of his head; but he had brought with him and had sacrificed the best of the troops in Britain, both Roman and native. The Caledonians took advantage of this opportunity to redouble their efforts, and the case became so grave that the emperor left Rome to oppose them (207 A.D.).

Septimius Severus was old and infirm, but his spirit was still unsubdued. When he entered into Caledonia with his son Caracalla, he brought in his train enormous armaments. His enemies were badly armed; they carried only the short sword and the target, which their descendants in the highlands still employed during the wars of the last century. But they were skilled to take advantage of the natural defences of their country, and without being able to meet the Caledonians in a fixed battle the emperor had lost, it is said, 50,000 men before abandoning his expedition. He had carried the name and arms of the Romans so far that he had no intention of retaining the territory which he had traversed. He left there neither fortress nor garrison, but when he had returned into the subjected territory he separated it from Caledonia by a new rampart, more imposing than all those of his predecessors. For two years the legions were employed in constructing it in stone, fortifying it with towers, and surrounding it with roads. The remains of this gigantic work attest to this day the power of those who raised it. {22} The Caledonians, however, had just attempted another invasion when the emperor, who was marching against them, died at York (211 A.D.), and his son Caracalla, compelled to hasten back to Rome to protect the safety of the empire, hurriedly concluded with the rude tribes a peace which lasted for some years.

It was not until the year 228, under the reign of Diocletian and Maximilian, that the dangers which threatened Britain again disturbed the repose of the Emperors. Her shores were threatened by Saxon and Scandinavian pirates. A commander of Belgian origin named Carausius was sent against them, who crowned his success by causing himself to be proclaimed emperor by his legions. Diocletian conferred on him the title of Cæsar. This new sovereign was assassinated at York, and succeeded in the year 297 by his minister Allectus, who himself fell soon after before the power of Constantius Chlorus. When this prince died at York, his son Constantine, proclaimed emperor by his troops, carried with him on leaving Britain a great number of the young men of the country eager to serve in his armies.

The Roman empire no longer existed. The distant seat of power had been transferred to Constantinople. The province of Britain escaped from the imperial watchfulness. It was at the same time ill defended. The Caledonians at this period had yielded their place, either in fact or in name, to the Picts, so called perhaps by the Romans on account of the colors with which they painted their bodies. Side by side with them, and often driving them back upon their own territory were the Scots, originally from Ireland, from which country they crossed over in so great a number in their little flat-bottomed boats that they finally gave their own name to the country they invaded. Under the Emperor Valentinian we find them pursuing their depredations as far as London, and driven back to their own country with great difficulty by Theodosius, father of Theodosius the Great. Before him and after his death, in the year 393, Britain presented a similar spectacle to that of the other Roman provinces. {23} The generals who were in command there, were proclaimed emperors by their legions, assassinated by their rivals, or decapitated by order of the sovereign rulers of Rome or Constantinople, from the moment that they attempted to leave the island to extend their conquests. Every one of these attempts cost Britain a number of soldiers and contributed to weaken a race already deteriorated by foreign domination. In 420, under the Emperor Honorius, when the Empire was expiring under the attacks of the barbarians, the Britons deposing the Roman magistrates, proclaimed their independence, which was immediately recognized by the emperor. But the Britons were not in a condition to struggle against the invaders who were pressing them on all sides. Like the Roman Empire, their country was fated to fall into the hands of the barbarians.

Like the Roman Empire, however, Britain had already received the principle which was destined to save her from complete desolation. In the midst of political disorganization, and of power distributed among a hundred petty chiefs, all enemies and rivals, she had already heard the only name which has been given to men for their salvation. The gospel of Jesus Christ had been proclaimed upon her shores. At what epoch or by whom is not known. Probably Rome brought with her arms the Christian faith to the British people; the Christians were numerous in the imperial armies, and their zeal often won to Jesus Christ the souls of the vanquished. Up to the reign of Diocletian the progress of Christianity in Britain was not impeded by any severity. At that epoch (303—305) the great persecution which was raging throughout the empire extended itself to Britain. {24} Constantius Chlorus, who was then governor, favorable though he was to the Gospel, was nevertheless unable to avoid calling around him the officers of his household and announcing to them the necessity of either relinquishing their trusts or abjuring the name of Christ. Those who were cowardly enough to prefer earthly greatness to Christian fidelity found themselves disappointed in their ambitious hopes. The general immediately deprived them of office, remarking that men faithless to their God would be equally wanting in fidelity to their emperor. But the moderation of Constantius Chlorus was insufficient to extinguish the persecuting zeal of the inferior magistrates; and the British Church soon counted its martyrs. The Christians took refuge in the forests and the hills. They were able to find brethren among the rude tribes of the north; for Tertullian tells us that, in the portion of Britain where the arms of the Romans had failed to penetrate, Jesus Christ had conquered souls. With the power of Constantine Christianity ascended the throne; the British Church was organized; she had sent three Bishops to the Council of Arles in 314; but Britain was about to undergo a new yoke: and her dawning Christianity was destined to encounter other enemies.

Discord prevailed in Britain. The petty rival chiefs, sometimes triumphant, sometimes defeated, united in vain against the Picts and Scots, whom the Roman walls no longer impeded now that the Roman power had disappeared. {25} In this disorder, the Britons were dwindling in numbers day by day, when Vortigern, chief of Kent, conceived the project of calling to his assistance the Saxons, a famous people who inhabited the northern coasts of Germany and Denmark and extended their power even to a portion of the territory now known as Holland. Several tribes were descended from a common origin. The Jutes, the Angles, the Saxons (properly so called) all led the life of pirates, and many a time had they suddenly appeared upon the coasts of Britain or of Gaul, scattering terror among the inhabitants, whose houses they pillaged and burnt, killing all who resisted them. For a long time they risked their lives and sported with the dangers of the sea in mere skiffs; but in 449, when Vortigern called to his aid two celebrated pirates among the Jutes, named Hengist and Horsa, the Saxon vessels were long, strongly built, and capable of carrying a considerable number of men and of wrestling with the fury of the waves. The pirates responded promptly to the appeal, and for some time they faithfully observed their engagements, driving the Picts and Scots back into their territory and fighting for Vortigern against his British enemies. It is related that the Saxon Hengist, having fortified himself at Thong-Caster, situated in the county of Lincoln, gave there a feast to King Vortigern. Hengist had sent for his daughter, the beautiful Rowena, who, bending the knee before the British sovereign, offered him the cup of welcome. Her beauty enchanted Vortigern, and he could not rest until he had obtained her hand.

Whether from a weakness for the father of his wife, or from gratitude for services, or from the impossibility of ridding himself of the allies whom he had sent for, Vortigern permitted Hengist to establish himself in the isle of Thanet; and gradually fresh vessels arrived bringing reinforcements for the foreign colony. {26} Angles followed Jutes; and the Britons began to be anxious about these powerful neighbors. At the first quarrel swords were drawn from their scabbards. Their blades were equally good and keen; for the Britons had derived their military equipments from the Romans, and the Saxons, passionately fond of iron, attached more importance to their arms than to any other possession. But the Britons had been weakened by their old dissensions; the Saxons allied themselves with the Picts and Scots, against whom they had been originally called to fight, and several indecisive battles ended in a truce. It is even related that the two parties being assembled at a banquet at Stonehenge, on the 1st of May, Hengist cried out to the Saxons, in their language, "Draw your swords!" and, at the same moment, the long knives concealed under the garments of the Saxons were plunged into the hearts of their entertainers. Vortigern alone was spared, no doubt at the intercession of Rowena. The war began; the Britons were defeated, and Eric, son of Hengist, became in 457 the first Saxon king of the county of Kent, the Isle of Wight, and that part of the coast of Hampshire which faces that island.

The success of Hengist and Horsa naturally attracted new hordes. In the year 477 the Saxons, under the command of Ella, founded the kingdom of Sussex (South Sax), which comprised only the present county of Sussex. In the year 519 other Saxons, under the orders of Cerdic, completed the invasion of South Britain, and extended themselves from the county of Surrey, bordering upon Sussex and Kent, to the eastern extremity of England; they occupied also Surrey and all that portion of Hampshire not in the possession of the Jutes, together with Hampshire, Wiltshire, Somersetshire, and Devonshire, not even leaving to the Britons the whole of the county of Cornwall. This new kingdom took the name of Wessex (West Sax).

The invaders grew bolder. In 530 a new body of Saxons, the name of whose leader is not recorded in history, arrived, and established themselves upon the northern border of the kingdoms of Kent and Wessex, founding there the kingdom of Essex (East Sax), the importance of which was due to the Thames and London, since it comprised only the county of Essex, the small territory of Middlesex, and the southern part of the county of Herts.

"Thus," says M. Guillaume Guizot in his History of Alfred the Great, "the Saxons originally rested their power upon the first state founded by the Jutes at the south-eastern extremity of England. They surrounded it by their own settlements, and all established themselves in the southern part of the island." They had scarcely completed their migrations when the Angles, who had then arrived only in small numbers, and were mingled with the Jutes, began on their own account to invade the eastern coast. About the year 527 several bands of Angles arrived under different chiefs, but it was not until some years later that they united to form the kingdom of East Anglia, which comprised the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridge, the isle of Ely, and probably a portion of Bedfordshire. The territories of Norfolk and Suffolk owe even their names to two tribes of Angles, the North folk and the South folk, while the entire race have given their name to England. This new kingdom, still isolated as well as defended by the sea, was fortified by fens and by many rivers. Where natural defences were wanting the Angles raised earthworks, long known as the Giant's Dyke, then as the Devil's Dyke. In spite of the draining of the fen, the line of these works can be traced to this day.

In the year 547, new bands of Angles, led by a chief named Ida, landed upon the north-east coast and founded there the kingdom of Bernicia, which comprised Northumberland and the south of Pentland, between the Tweed and the Firth of Forth. Some years later, in 560, other Angles, no less enterprising than their predecessors, established themselves from the southern limit of Bernicia as far as the Humber, and from one sea to the other, occupying all the territory of the counties of Lancaster, York, Westmoreland, Cumberland, and Durham. This was the kingdom of Deira. These two colonies were united under the same sceptre in 617, and took the name of Northumbria.

The Angles began to advance from the coasts. In the year 586 they occupied all the country bounded on the north by the river Humber and the kingdom of Deira; on the west, by Wales, which alone remained in the hands of the Britons; on the south, by the Saxon kingdoms; and on the south-east, by the Angles of East Anglia. Mercia, as the new kingdom was called, comprised then on the south-east the northern part of the counties of Hertford and Bedford; on the east, all the counties of Northampton, Huntingdon, and Rutland; on the north, the counties of Lincoln, Nottingham, Derby, and Chester; on the west, Staffordshire, Shropshire, Worcestershire, and Herefordshire; in the centre of the island, Warwickshire and Leicestershire; on the south, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, and the county of Buckingham. In this kingdom, the most extensive of all, the British population had not been destroyed or driven back, as they had in the greater portion of other parts; they continued to inhabit their ancient country, mingled with and subject to the Angles.

Such was the division of Britain among the conquerors, and the constitution of the Saxon kingdoms. This is what is known as the Heptarchy, or Octarchy, according to whether we place the denomination before or after the union of the kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia in a single kingdom of Northumbria. Such was the new scene of the wars which were destined to break out again and deluge Britain, now become England, with blood.

A more gentle influence was soon to exercise its effect upon the sanguinary passion of the barbarous races. The British Christians, though vanquished and driven back into the narrow territory of Cambria or Wales, do not seem to have attempted to convert their conquerors. For a moment they had themselves run the risk of falling into the heresies of Pelagius, an Irish monk who denied the doctrine of original sin; but the missionaries from Gaul, Saint Germain and Saint Loup, had succeeded in 429 and 446 in uprooting among them these disastrous tendencies. One day Saint Germain, who had been a soldier before being a bishop, found himself in the presence of a band of Picts and Saxons who were laying waste the coast. Putting himself at the head of his flock, he marched against the enemy amidst loud cries of "Alleluia!" These cries taken up by the neighboring echoes terrified the pirates, who fled; hence this peaceful victory became known by the name of "The Battle of the Alleluias."

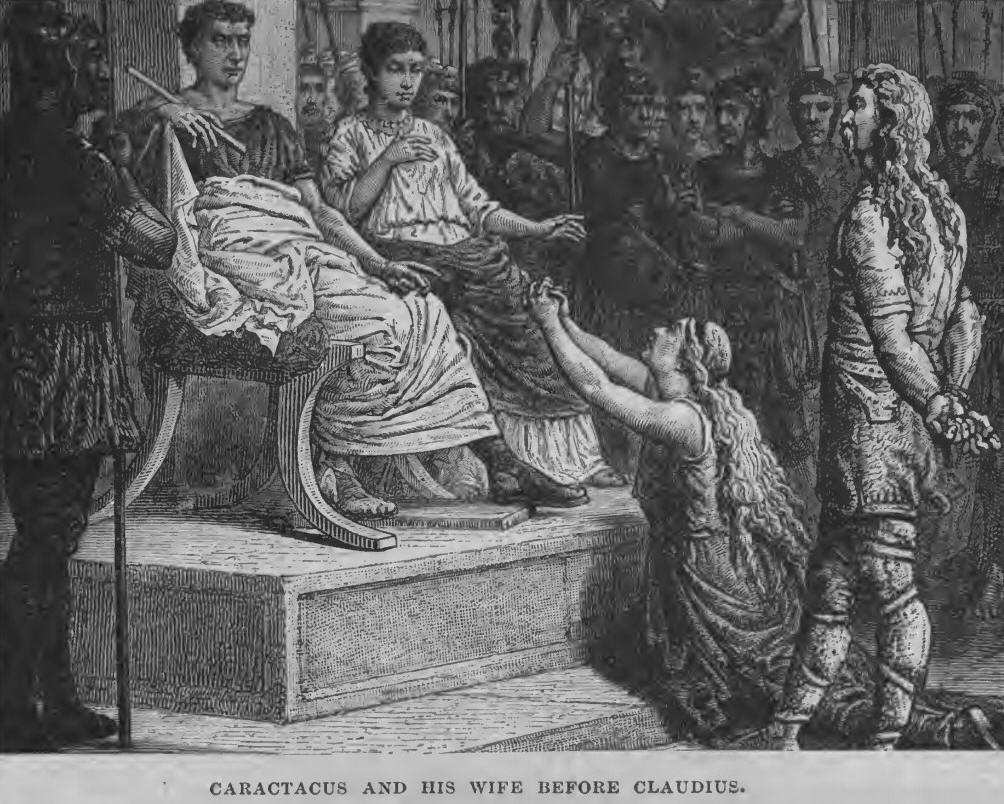

The Britons were not heretics, but with the independence which always characterized their race they differed from Rome and from the Eastern Church upon various points of little importance in themselves, though they had often created divisions in Christendom. {30} For no reason that has come down to us the Britons celebrated Easter in accordance with the customs of the Eastern Church—that is to say, at the fourteenth day of the moon, whatever might be the day on which that event fell, in imitation of the Jews who on that day offered up the Paschal lamb. The Western Church, on the contrary, postponed the celebration of Easter till the Sunday following. Nothing more was needed to breed dissensions between the British bishops and the missionaries despatched from Rome by Pope Gregory the Great. For some years previously, Gregory, not yet become a bishop, and being in fact only a simple priest, passing through the slave-market in Rome, had been struck by the handsome appearance of some young persons offered there for sale. Learning that they belonged to the race of Angles, or Saxons, "They would not be Angles but angels," he exclaimed, "if they were Christians;" and he conceived the project of going himself to preach the faith of Jesus Christ to a people so well endowed by nature. His friends were only able to prevail on him to renounce his intention by inducing the Pope to forbid his departure from Rome. When in his turn he was elevated to the episcopal dignity in the most important see of the Western Church, he did not forget the Saxons whose conversion had previously occupied his thoughts. He endeavored first to inflame with his zeal the young slaves whom he had caused to be placed in convents; but the Saxons were apparently not disposed to become Missionaries, for in the year 595 the Pope despatched to Britain a young monk named Augustine, prior of the Convent of St. Andrew at Rome, accompanied by forty friars. They took the road towards Gaul; but they had scarcely arrived at Aix, when they heard such terrible accounts of the ferocity of the Anglo-Saxons that they were alarmed and wrote to the Pope to ask his leave to retrace their footsteps. Gregory, on the contrary, encouraged them to persevere in their enterprise, and furnished with interpreters by the good offices of Brunehaut, who was reigning over Austrasia in the name of her grandsons, they arrived in 597 in the Isle of Thanet. Augustine sent immediately one of his monks to Ethelbert, king of Kent, announcing his intention of coming to preach Christianity to his court.

The place could not have been better chosen. A powerful prince in his domains, Ethelbert was their Bretwalda, or general chief of all the Heptarchy. This title, which was in no way well defined, but which conferred a certain influence in the counsels of the seven Saxon states, seems to have been accorded to a kind of merit understood by all. Two chiefs had already borne it before Ethelbert— Ella, first king of Sussex, and Ceawlin, king of Wessex. The new Bretwalda was a pagan, but he had married a Christian wife, Bertha, daughter of Charibert, king of Paris: she had reserved to herself the free exercise of her religion; a French bishop had even accompanied her. Ethelbert had no repugnance towards Christianity and he consented to receive the Roman missionaries. "Be careful to grant them an audience in the open air," said the pagan priests, however; "their maledictions will be less powerful there than under a roof." It was therefore in the open field that the Saxon Bretwalda awaited the approach of the Christian priests. They advanced bearing a crucifix and a banner on which was painted the image of the Saviour. They made the air resound with their grave canticles. The imagination of the barbarians was no doubt struck by these ceremonies, and when Augustine by the aid of an interpreter, had explained to the king the leading doctrines of the Christian faith and asked permission to preach to his subjects the religion which they had come to proclaim to him, Ethelbert mildly replied, "I am not disposed to abandon the gods of my fathers for an unknown and uncertain faith; but since your intentions are good and your words full of gentleness, you can speak freely to my people. {32} I will prevent any one interfering with you, and will furnish food to you and your monks." Augustine overjoyed, directed his steps towards the neighboring city of Canterbury, which he entered chanting, "O Eternal Father, we supplicate Thee according to Thy mercy turn Thy anger from this city and from Thy sacred place, for we have sinned. Alleluia!"

The preaching of Augustine and the sanctity of his life exercised a powerful influence over the Saxons. Numerous converts already pressed around him when King Ethelbert decided to embrace the Christian religion. His conversion attracted his subjects in a mass to the new Faith, and Pope Gregory, delighted with the success of the Mission, sent to Augustine the episcopal pallium [Footnote 1] with the title of Archbishop of Canterbury. At the same time Gregory advised the new prelate not to destroy the pagan temples to which the people had been accustomed, but to consecrate them to the worship of Jesus Christ, and to transform the pagan festivals into joyful family meetings at which the Christian Saxons could eat their oxen instead of sacrificing them to false gods.

[Footnote 1: An ornament of woollen texture, sprinkled with black crosses, which the Pope sends to the Archbishops and sometimes to Bishops.]

With these sage counsels Gregory sent a reinforcement of missionaries; but they did not suffice for the zeal or the views of Augustine, who resolved to address himself to the British bishops in Wales asking their assistance in the work of evangelization. The Britons were jealous and anxious. They consulted a hermit of great reputation for sanctity upon the claims of Augustine to their trust and obedience. "If the stranger comes from God, follow him," said the hermit. "But how shall we know if he is from God?" asked the Britons. "By his humility." … The reply still appeared to the envoys to be vague.

Augustine preaching to Ethelbert.

"If he rises at your approach, know that he is the leader sent by God to direct his people," continued the hermit. "If he remains seated reject him because of his pride." Fortified with this precise instruction the British priests, with seven Bishops and the Abbot of Bangor, presented themselves at the conference. Augustine was seated, and did not rise to receive them. The question was already settled in their minds when the Archbishop of Canterbury stated his demands. He desired that the British priests should henceforth celebrate the festival of Easter on the same day as the Western Church; that they should employ the Roman forms in the ceremony of baptism, and that they should join their efforts with his for the conversion of the Saxons. All these proposals were rejected. Then Augustine rose and in a loud voice exclaimed, "You refuse to labor to convert the Saxons! You will perish by the swords of the Saxons." This prediction was remembered some years later when all the monks of Bangor were massacred by the Northumbrians in a Saxon expedition into Cambria.

In spite of the coolness of the British Bishops the work of conversion went on. The zeal of Ethelbert had already engaged his nephew Sebert, king of Essex, to receive baptism. A church had been founded in London which possessed a bishop. Another prelate had his seat at Rochester. Ethelbert had also gained over to the Christian faith the chief of East Anglia, Redwald, who became after him Bretwalda of the Heptarchy. But the wife of Redwald was still a pagan and his subjects were attached to the religion of their ancestors. The king set up two altars in the same temple, one dedicated to Odin and the other to the God of the Christians; but the new faith soon prevailed over its rival, and East Anglia took its place among the Christian kingdoms of the Heptarchy.

Christianity had not yet penetrated into Northumbria when the king Edwin married a daughter of Ethelbert, a Christian like her father. The queen came accompanied by a Roman bishop named Paulinus; but the king remained faithful to the worship of his forefathers in spite of the solicitations of his wife, of Paulinus, and even of the Pope. He had, however, consented to the child of Ethelburga being baptized; and the day was at hand when his scruples were destined to be overcome. In his youth, during a long exile and in the midst of serious perils, there had appeared before him, doubtless in a dream, a person of venerable aspect, who asked him, "What wouldst thou give to one who should deliver thee to-day?" "All that I possess," replied the Saxon. "If he asked thee only to follow his counsels, wouldst thou obey?" "Unto death," was the answer. "It is well," said the apparition, at the same time placing his hand softly upon his head; "when one shall return and make thee this sign, follow him." Edwin had escaped from the dangers which threatened him, and his dream had remained deeply engraved upon his memory.

One day when he was alone, the door of his apartment opened, and Paulinus entering softly placed his hand upon his head. "Dost thou remember?" he asked, and the Saxon, falling on his knees, promised to do whatever he should desire. Still thoughtful and prudent, however, while accepting baptism for himself, he reserved the right of his subjects to act as might seem well to them. The Council of Wise Men or Aldermen was called together, and the king having informed them of his change of faith, as the basis of a new doctrine, asked them what they thought of it. The chief of the priests was there, and spoke first. {35} "Our gods are powerless," he said; "I have served them with more zeal and fidelity than all the people, yet I am neither richer nor more honored. I am weary of the gods."

An ancient warrior near the king rose at this speech. "O king," he said, "thou rememberest perhaps in the winter days when thou art seated with thy captain near a good fire, lighted in a warm apartment, while it is raining and snowing out of doors, that a little bird has entered by one door and gone out by another with fluttering wings. He has passed a moment of happiness, sheltered from the rain and the storm; but the bird vanishes with the quickness of a glance, and from winter he returns again to winter. Such it appears to me is the life of man upon this earth. The unknown time is irksome to us. It perplexes us because we know nothing of it. If thy new faith teaches us something, it is worthy of our adherence."

The whole assembly took the side of the two chiefs; but when Paulinus proposed, as a token of renunciation to false gods, that their idols should be cast down, all hesitated except the high priest. He demanded a horse and a javelin in place of the mare and the white rod which pertained to his old office, and galloping towards the temple he struck the image with his weapon. The people trembling awaited some token of the wrath of the gods; but the heavens and the earth remained silent, and the king was baptized with all the most distinguished of his people, who were accompanied by a crowd of warriors. Edwin soon became Bretwalda, and his reign was an epoch of repose and happiness for his subjects.

During the struggles which recommenced after the death of Edwin, three kingdoms fortified themselves, and took the lead over the others. These were Northumbria, Mercia, and Wessex. {36} These three divisions of the Heptarchy were predominant in the year 800, when Egbert, prince of Wessex, returned to his country after a long exile. He had passed a considerable portion of the time at the court of Charlemagne, and had thus acquired a development of intellect and of knowledge rare at that time among the Saxon princes. The first part of his reign was peaceful; but from the year 809 forward, the sword of Egbert was drawn from the scabbard, and for many years he pursued his conquests from kingdom to kingdom. He had already extended his dominion over the British people of Cornwall, who had consented to pay him tribute, when he subjugated Mercia and the kingdom of Kent, Essex, and East Anglia. He had carried his victorious arms up to the frontiers of Northumbria. The chiefs, anxious and already beaten in anticipation, came to meet him, recognizing him for their sovereign, and promising him obedience. Egbert accepted their homage, and retired without fighting a battle. Nearly the whole Heptarchy had accepted his laws, and the title of Bretwalda had conferred upon him an authority more considerable than in the case of any of his predecessors. He continued, however, to assume the simple title of king of Wessex. He reigned until the year 836, happy and powerful; but the last years of his reign were troubled by the first invasions of the Danes. Egbert repulsed them with glory; but if he had possessed a spark of the almost prophetic foresight of Charlemagne, he would have wept, like the Frankish hero, over the infinite woes with which these men from the North menaced his country.

For nearly four centuries the Saxons had been established in Britain; they had become the sole masters of the country, and had there forgotten the original source of their wealth. But the nation from which they had sprung was still prolific in warriors, vigorous, enterprising, and possessed of nothing in the world but their arms and their ships, for all the property of the family belonged by right to the eldest son: warriors too ardent in conquering and in obtaining wealth at the point of the sword. The peninsula of Jutland and the provinces still further north of Scandinavia sent year by year to the French and English coasts a great number of ships, manned by the "Sea-kings," as they styled themselves: "The tempest is our friend," they would say; "it takes us wherever we wish to go." Repulsed three times from the coast of England by Egbert, these pirates soon reappeared under the reign of his son Ethelwulf; the whole island became surrounded by their light skiffs. The Saxons had been compelled to organize along the shores a continual resistance, and to appoint officers whose duty it was to call out the people in a body to repulse the enemy. Three serious contests took place in 839—at Rochester, at Canterbury, and at London. King Ethelwulf himself was wounded in battle. But shortly after, the internal dissensions which were agitating the whole of France, attracted the pirates as the dead body attracts the vulture. During twelve years the Danish fleets altered their course, and repaired to the French coasts. {38} When they reappeared, in 831, in England, their successes were at first alarming; three hundred and fifty of their vessels ascended the Thames as far as London, and the town was sacked. But the king awaited the enemy at Oakley: they were defeated, and suffered great losses. After having met with severe reverses at several other parts of the Saxon territory, the Danes withdrew from there, and respected the English coasts during the remainder of the reign of Ethelwulf.

It is at this period that there appears in the pages of history the name of the fourth son of Ethelwulf, him whom England was one day to call Alfred the Great, Alfred the Well-beloved. He had first seen the light of day at Wantage, in the heart of the forests of Berkshire, in 849, two years before the departure of the Danes. His mother Osberga, a noble and pious woman, gave herself up entirely to the task of rearing her little son, who soon began to excite the hope and admiration of all who saw him. Doubtless the predilection which his father had for this little child, induced him to give a startling proof of his affection, for Alfred was scarcely four years of age when he was sent to Rome with a numerous suite of nobles and servants, to ask for himself, of Pope Leo IV., the title of king, and the holy unction. The Pope was aware of the piety of the Saxon monarch, and he consecrated with his own hands the little king, and even administered to him the sacrament of confirmation. Alfred returned to England, and it was no doubt the recollection of what he had seen at Rome, which began thenceforward to instil into his soul the desire to gain knowledge, the pursuit of which was probably very rare among the young Saxons. His mother, one day, was holding a pretty manuscript in her hand, a collection of ancient Saxon poems, and was showing it to her four sons, who were playing beside her. "I will give this pretty book," she said, "to whichever of you shall learn it the soonest by heart." {39} Ethelbald, Ethelbert, and Ethelred eyed the book with indifference, and went on with their game; but little Alfred approached his mother: "Really," said he, "will you give this beautiful manuscript to whoever shall learn it by heart the quickest and who shall come and repeat it all to you?" The large, round eyes of the child were fixed upon his mother: she repeated her promise, and even gave up the manuscript into the keeping of the little prince. He quickly hurried away with it to his master, who was able to read aloud to him the verses which it contained, for, alas! Alfred could not read until he was twelve years of age. He soon returned, triumphant, repeated the lines, received the book from his mother, and preserved thenceforth throughout his life a taste for the old Saxon ballads of which he had thus first made the acquaintance.

Alfred was six years old and had lost his mother, when his father, wishing to make the pilgrimage to Rome in his turn, took his youngest son with him: the Saxon king spent a year with the Pope, carrying from church to church his sumptuous devotion. On his return journey, he stopped at the court of Charles the Bold, a court elegant and polite in comparison with the still rude customs of the Saxons; and, attracted by the beauty as well as the arts of Princess Judith, daughter of Charles, Ethelwulf married her, notwithstanding the disparity in their ages, and brought her in triumph into his kingdom. But the two persons whom the old king loved best, his young wife and his youngest son, were distrusted by the rest of his family, as well as by his people; Judith claimed a share of the sovereign power, according to the old custom in Britain and Germany, which had become odious to the Saxons by reason of the crimes of several queens; the elder sons of Ethelwulf feared that their young brother, so dear to their father, might be raised above themselves; the eldest, Ethelbald, revolted, and his father found a general rising against him when he returned to England. {40} The old king did not resist: he ceded to his son the greater portion of his states and died at the end of two years, having shared equally between his sons his kingdom of Wessex, previously enlarged by the addition of Kent and Sussex. The tributary states of Northumbria and Mercia had shaken off the feeble authority of Ethelwulf and had recommenced their internal wars. The Danes profited by these disputes, and had taken up with renewed ardor their terrible incursions upon the English coasts.

In this alarming situation of affairs the sons of Ethelwulf foresaw that the division of Wessex would be their ruin; instead, therefore, of sharing it among themselves they agreed that each should reign over the whole in turn, according to their ages. The reigns of the three eldest were short. Supported successively by their brothers, they fought against the Danes, and all died in the flower of their youth; the last, Ethelred, was still on the throne, when an invasion of the Danes, who penetrated as far as Reading, called all the men of Wessex to arms. The war had a short time before assumed a new aspect; the Danes did not content themselves with descending upon the most fertile portions of the coast with their long ships, or with taking possession of all the horses. Overrunning the country, they ravaged and sacked everything in their passage, and re-embarked in their vessels before the frightened inhabitants had had time to rise up to resist them. From pirates, the Danes had become conquerors, and desired to establish themselves in that England which their predecessors, the Saxons, had formerly snatched from the Britons. Already possessed of East Anglia and a portion of Northumbria, they were threatening Wessex, and had intrenched themselves at Reading. {41} Alfred had recently been married to a princess of Mercia, but his new relations did not give him any support against the Danes, when, having beaten several detached corps of the pirates, Ethelred and Alfred attacked the citadel. The greater number of the Danes sprang outside the walls, "like veritable wolves," says Asser, the historian of Alfred, and the struggle recommenced.

The Danes were nearly all tall men; their wandering and adventurous life favored the development of their muscular powers; they did not fear death, for the Walhalla or Paradise of their god Odin, promised to the brave warriors who fell in battle all the pleasure which they esteemed most on earth. The figure of the raven, the confidant of their god, floated on the red flags of the Danes; if its dark wings fluttered on the long folds of silk, victory was certain; if they remained motionless, the Northmen feared defeat. The wings of the raven were fluttering triumphantly before Reading, for the Saxons were defeated and were obliged to retreat.

They had not lost courage, however, and four days later they returned to give battle once more to their enemies; the Danes had already issued forth from their intrenchments, but Ethelred was still in his tent, attending holy mass, and would not hurry to the scene of battle, in spite of urgent messages from Alfred. The latter, therefore, attacked their opponents single-handed, opposite a little tree which the Danes had chosen as a rallying-spot. The Saxons fought with the fury of despair; Ethelred soon came to support his brother, and the Danes, beaten upon the great plain of Assendon, took to flight; but only to return a fortnight afterwards, their number swelled by the reinforcements which were continually arriving by sea. {42} Wessex alone had sustained eight battles in one year; her resources were becoming exhausted in such an unequal struggle; Ethelred, wounded, had just died, and Alfred found himself alone at the age of twenty-two years (871), subject to a peculiar illness which had succeeded to a slow fever of his boyhood, and of which the attacks would frequently bring him to the very verge of the grave. His men and his resources exhausted, a ninth and unfortunate battle completely disabled him; he was compelled to sue for peace. The Danes willingly consented to his proposal; there were other princes to vanquish, other territories to conquer, less valiantly defended than Wessex, on which they proposed to revenge themselves when it should stand alone in its resistance to them. In 875 they had finished their conquest; Wessex alone still preserved its independence, and three Danish kings who had passed the winter at Cambridge embarked secretly, by night, to attack the coast of Dorset. Vainly did Alfred strive to resist his enemies by sea; his ships were beaten, and soon the long line of incendiarism and murder which always marked the progress of the Danes extended as far as Wareham. This was past endurance, and Alfred, stricken down on a sick-bed, asked for and obtained peace at the price of gold. The Danes retired after having sworn friendship upon some relics brought by the Christian king and on their sacred bracelets steeped in the blood of their victims, exchanging hostages, whose fate they troubled themselves very little about. The very night after peace was concluded, the Saxon horsemen were destroyed and cut up piecemeal by the Danes, who took possession of their horses in order to make a raid into the interior of the country. The remonstrances of Alfred were powerless to stop these disastrous expeditions, so easy for an enemy who threatened the country from all sides.

Alfred took to arms once more; and for awhile the issue of the war seemed to incline in his favor; he had been the first to see the necessity for attacking the Danes on the ocean, which was incessantly bringing them inexhaustible reinforcements, and his vessels having met the pirates during a storm had defeated and dispersed them, thus cutting off all hope of succor to the Danes whom Alfred was besieging in Exeter. This glimmering of success did not last however; in 878 the enemy was once more invading Wessex in two formidable troops; one of them was stopped and even defeated by some faithful retainers of Alfred's, but the second army, which had entered the kingdom by land, was advancing without opposition from town to town. The subjects of Alfred were weary and discouraged. The king, on whom they had founded such great hopes, had lost in their eyes his prestige; brave but uncertain, he had not profited by the advantages which his military genius had sometimes given him, and his people complained of his inflexibility, of his pride, of the severity which he manifested towards offenders; of the indifference which he displayed towards the unfortunate. They did not enter with any spirit into the struggle against the invaders, and the Saxon kings held no power but by the free will of their subjects. The clergy, who were especially hated by the pagan enemy, fled to France, carrying with them from their country its relics and the treasures from the churches. The agricultural population submitted to cultivate the land for the Danes. The latter were seeking Alfred; but the king had suddenly abandoned his post, and left by the struggle sick and wounded to the heart by the defection of his subjects, he had disappeared, his place of concealment being unknown and not even suspected.

The fugitive king did not know where to go. Wandering from forest to forest, from cave to cave, he went his way, trying to conceal his deep disgrace, learning in his cruel wanderings, as his historian and friend Asser says, "that there is one Lord alone, Master of all things and all men, before whom every knee bends, who holds in His hand the hearts of kings, and who sometimes makes His happy servants feel the lash of adversity, to teach them, when they suffer, not to despair of the Divine mercy, and to be without pride when they prosper."

Alfred wanted confidence in God, when he arrived in the island of the Nobles (Ethelingaia), now called Athelney, in order to hide himself there in the hovel of a cowherd. He received him at first as a traveller who had lost his way, and ended by learning in confidence from his guest that he was a Saxon noble of the court of King Alfred, flying from the vengeance of the Danes. The worthy Ulfoath was perfectly satisfied with the explanation, and allowed the fugitive to remain at his house.

His wife was not in the secret, and was annoyed, no doubt, to see her work increased by the presence of this unknown guest. She would ask him at times to perform little services, and would leave him in charge of some household duties. One Sunday, while the husband was gone to lead the beasts to the field and the wife was busy with several little matters, she had left some loaves or thin cakes by the fire, which were baking slowly on the red stone of the hearth. Alfred had been commissioned to watch them, but, absorbed in his sad meditations, he had forgotten that the bread was burning; the smell warned the housewife; she sprang at a bound to the fireplace, and quickly turning her cakes, she called out angrily to the king, "Whoever you may be, are you too proud to turn the loaves? You will not take the slightest heed of them, but you will be very glad to eat some of them presently." Alfred did not lose his temper; he laughed, and helped the woman to finish her task. A few days later the cowherd's wife learnt with dismay the name of the guest whom she had thus scolded.

Alfred in the Herdsman's Hut.

Some of the faithful subjects of Alfred, pursued by the Danes, took refuge also in the island of Nobles, where they discovered to their great astonishment their king. Secretly and by degrees the rumor that Alfred was living spread through his family, who came in search of him. The little band became greater day by day, and the king was beginning to gain courage. In his solitude and humiliation, God had taken charge of this great soul which had hitherto forgotten Him, and which regained through religious faith the necessary energy to struggle against the enemies of his country.

The Danes had not profited by their victory. They had established themselves in the conquered country as plunderers, and not as owners. The inhabitants of Wessex were writhing under their cruel and capricious rule. They had now forgotten the rigorous acts with which they had reproached Alfred, and regretted that the Christian king was no longer at their head. Exasperated by their sufferings, the Saxons were ripe for revolt.

Such were Alfred's prospects when he began with his companions the work of re-establishing himself in his country. A solid bridge, defended by two towers, enabled the king to issue out easily from his retreat in his fortress. He gathered around him all the malcontents before making anybody aware of his identity, and without announcing his great projects; each day he saw his little army swell in numbers, and he defeated the Danes in every skirmish which he chanced to have with them. He then went back to the island of Nobles. It is even said that he went by day, disguised as a minstrel, into the very camp of the Danes, in order to ascertain their numerical strength. {46} In the month of May, 878, he finally decided to attack them openly. Secret messengers were despatched through the neighborhood, who said to the Saxons; "King Alfred is alive. Assemble in the forest of Selwood, at Egbert's field; he will be there, and you shall all march together against the Danes." The Saxons, desperate, were rushing there in crowds, and soon Alfred's standard, bearing the golden dragon, was boldly unfurled before the Danish raven.

The secret had been well kept. The Danish king, Godrun, was vaguely aware that a number of Saxons were assembled in the neighborhood, but he knew neither how many they mustered, nor the name of their chief, when he found himself suddenly attacked on the plain of Ethandune. The Saxons were in high spirits: "It is for your own sakes that you are about to fight," Alfred had said to them. "Show that you are men, and deliver your country from the hands of these strangers." The Danes had not had time to recover from their surprise before Alfred was upon them, his whole army following him. The standard-bearer was pushing to the front, accomplishing prodigies of valor: "It is St. Neots himself," Alfred cried, designating a saint held in great reverence by the Saxons, and an ancestor of his own. His soldiers gained fresh courage at these words; the Danes were beaten, and pursued, and they perished in great numbers. King Godrun, shut up with his court at the fortress of Chippenham, was compelled to surrender after a siege which lasted three weeks. He gave hostages without taking any in exchange, a proceeding very humiliating to the Danes, and Alfred wisely imposed upon him an agreement useful in securing the definitive tranquillity of England, if not consistent with the spiritual welfare of the Danes; the conqueror exacted that the defeated enemy should embrace the Christian religion. {47} Godrun and his son were baptized and settled in the portion of land which Alfred conceded to them. Finding the impossibility of driving from the country the whole of the Danes, who were already masters of the land in Northumbria, in Mercia, and in East Anglia, Alfred hoped to accomplish, by the aid of Christianity and his right over part of the land, a fusion of the Danish and Saxon races, and to secure by that union a kind of rampart against any new Scandinavian invasions.

He was not mistaken. In the year following, a Danish fleet entered the Thames; but in vain did the warriors call for help to Godrun, who was established in the country He remained deaf to their voices, and they, discouraged by his refusal, went away again and pursued their ravages on the coast of Flanders.

For more than thirteen years peace reigned over all England. One or two little isolated invasions served to exercise the energy of Alfred's troops, and each day his forces were augmenting. But Godrun was dead, and a dangerous enemy now threatened the Saxon king: the famous pirate Hastings, already advanced in age, but still passionately fond of the "game of war" was encamped upon the coast of France, at Boulogne, in 892. Wherever he appeared, death and ruin followed in his wake. The black raven always unfurled its wings for him; he was always assured of victory before the fray began. He sailed forth in the spring of 893, and instead of descending upon the lands already held by the Danes, he disembarked in Kent, a country rich and fertile, inhabited entirely by Saxons; and dividing his army into two corps, he lay awaiting Alfred, who was advancing in haste to resist him. {48} The Danish pirate had cleverly organized the attack. Already the Danish population of East Anglia were profiting by his presence to attack the Saxon towns; but Alfred had studied too well the art of war to disperse his army over the country; he led the whole of his available forces against Hastings. There the greater portion of the enemy's army, protected by a forest and a river, were met by the Saxon king, who sent out at the same time several small bodies of men in pursuit of the Danish warriors who were pillaging the country, staying by these means the progress of the invasion, and opposing with exemplary patience the ruses of the barbarians. Hastings appeared to grow weary of this: he asked for peace, and sent his young sons as hostages. Alfred had just returned them to him after having baptized them, when the Danes, caring little for their plighted Word, began to march towards Essex, which they intended to attack, passing by way of the Thames. The king hastened at once in pursuit of them and to the support of his eldest son, Edward, who was defending the frontier. They joined their forces; a great battle was fought near Farnham in the county of Surrey; the Danes were vanquished and driven as far as the isle of Mersey, which they fortified for their defence. The king attacked them at once; but while he had been away recruiting his forces a Danish fleet threatened the coast of Devonshire. Alfred marched against the new invaders, while the forces which he left behind fought against Hastings, and in a sortie got possession of the wife and children of that chief. These were sent to Alfred; but the Christian warrior could not forget that he had presented the young barbarians at the baptismal fount, and sent them back to their father loaded with presents.

The pirate, however, was not overcome by his foe's generosity. He attacked Mercia, sustained by the Danish hordes established in the country. Abandoning all thought of the conquests which he had originally intended, and the kingdom which he had wished to found, he once more took up the irregular invasions by which he had acquired so much wealth, and thought only of plundering the Saxon territory. But the subjects of Alfred had learnt some useful lessons; they rose with one accord against the foreign enemy, and when the king, returning in haste from Devonshire, arrived in the vicinity of the Severn, he found himself at the head of a numerous army which allowed him to completely surround the trenches of Hastings. The Danes had been decimated by hunger: they had even eaten their horses. Making a last desperate effort, they opened up a passage straight through the ranks of their enemies, and took refuge in Chester, where they spent the winter.