FRANK DIVED OVERBOARD

Title: The Racer Boys; Or, The Mystery of the Wreck

Author: Clarence Young

Release date: February 29, 2020 [eBook #61534]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and Sue Clark from page images

digitized by the Google Books Library Project and generously

made available by HathiTrust Digital Library

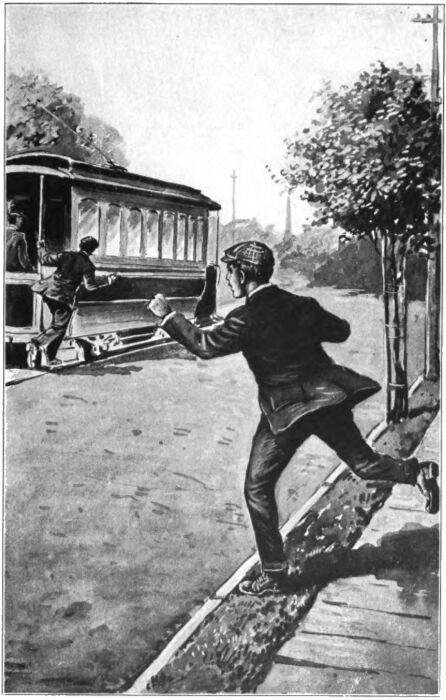

FRANK DIVED OVERBOARD

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I. | Hit by a Whale |

| II. | The Wrecked Motor Boat |

| III. | The Boy’s Rescue |

| IV. | “Who Are You?” |

| V. | Seeking the Wreck |

| VI. | Chet Sedley’s Style |

| VII. | A Lively Cargo |

| VIII. | Andy is Caught |

| IX. | “Thar She Blows!” |

| X. | A Rival Claim |

| XI. | A Fire on Board |

| XII. | The Stranger Again |

| XIII. | A Midnight Scare |

| XIV. | The Wreck Again |

| XV. | Ordered Back |

| XVI. | On the Search |

| XVII. | On Cliff Island |

| XVIII. | “There He Is!” |

| XIX. | In the Cave |

| XX. | The Rising Tide |

| XXI. | Death is Near |

| XXII. | The Storm |

| XXIII. | To the Rescue |

| XXIV. | The Escape |

| XXV. | A Lucky Quarrel |

| XXVI. | The Prisoner |

| XXVII. | Searching the Wreck |

| XXVIII. | Building a Raft |

| XXIX. | “Sail Ho!” |

| XXX. | The Accusation—Conclusion |

“How about a race to the dock, Frank?”

“With whom, Andy?”

“Me, of course. I’ll beat you there—loser to stand treat for the ice cream sodas. It’s a hot day.”

“Yes, almost too warm to do any speeding,” and Frank Racer, a lad of fifteen, with a quiet look of determination on his face, rested on the oars of his skiff, and glanced across the slowly-heaving salt waves toward his brother Andy, a year younger.

“Oh, come on!” called Andy, with a laugh rippling over his tanned face. “You’re afraid I’ll beat you.”

“I am, eh?” and there was a grim tightening of the older lad’s lips. “Well, if you put it that way, here goes! Are you ready?”

“Just a minute,” pleaded Andy, and he moved over slightly on his seat in order better to trim the boat. He took a tighter grip on the oars, and nodded toward his brother, still with that tantalizing smile on his face.

“Let her go!” he called a moment later, adding: “I can taste that chocolate soda now, Frank! Yum-yum!”

“Better save your breath for rowing,” counseled Frank good-naturedly, as he bent to the ashen blades with a will.

The two boats—for each of the Racer lads had his own craft—were on a line, and were headed for a long dock that ran out into the quiet inlet of the Atlantic which washed the shores of the little settlement known as Harbor View, a fishing village about thirty miles from New York.

“Wow! Here’s where I put it all over you by about six lengths!” boasted Andy Racer, paying no attention to his brother’s well-meant advice, and then the two lads got into the swing of the oars, and the skiffs fairly leaped over the waves that rolled in long swells.

Both boys having spent nearly all their summer vacations at the coast resort, which was something of a residence, place for summer colonists, as well as a fishing centre, were expert oarsmen, sturdy and capable of long exertion. They were nearly matched in strength, too, in spite of the difference in their ages. They had taken a long, leisurely row that summer morning and were on their way back when Andy proposed the race.

“Row! Row! Why don’t you put some speed in your strokes, Frank?” called the younger brother.

“That’s all right—you won’t want to do any speeding by the time you get to the dock,” and Frank glanced over his shoulder to where the public dock stretched out into the bay like some long water-snake. “It’s nearly two miles there, and the swell is getting heavier.”

Frank spoke quickly, and then relapsed into silence. It was characteristic of him to do whatever he did with all his might, while his more fun-loving brother sometimes started things and then left off, saying it was “too much trouble.”

For a time Andy’s skiff was in the lead, and then, as he found the exertion too much, he eased up in his strokes, and lessened the number of them.

“I thought you were going it a bit too heavy,” remarked Frank, with a smile.

“Oh, you get out!” laughed Andy. “I’ll beat you yet. But I like your company, that’s why I let you catch up to me.”

“Oh, yes!” answered Frank, half sarcastically. “But why don’t you stop talking? You can’t talk and row, I’ve told you that lots of times. That’s the reason you lost that race with Bob Trent last week—you got all out of breath making fun of him.”

“I was only trying to get him rattled,” protested Andy.

“Well, he got the race just by sticking to it. But go on. I don’t care. I’m going to win, but I don’t want to take an unfair advantage of you.”

“Oh, lobsters! I’m not asking for a handicap. You never can beat me in a thousand years.” And, with a jolly laugh Andy began to sing:

“All right, have your way about it,” assented Frank good-naturedly. “I can stand it if you can,” and with that he increased his strokes by several a minute, until his skiff had shot ahead of his brother’s, and was dancing over the waves that, now and then, brilliantly reflected the sun as it came from behind the fast-gathering clouds.

“Oh, so you are really going to race?” called Andy, somewhat surprised by the sudden advantage secured by his brother. “Well, two can play at that game,” and he, also, hit up the pace until in front of both boats there was a little smother of foam, while the green, salty water swirled and sparkled around the blades of the broad ashen oars, for the boys did not use the spoon style.

For perhaps two minutes both rowed on in silence, and it was so quiet, not a breath of wind stirring, that each one could hear the labored breathing of the other. The pace was beginning to tell, for, though Frank was not over-anxious to make record time to the dock, he was not going to let his brother beat him, if he could prevent it.

“I shouldn’t wonder but what there’d be a storm,” spoke Andy again, after a pause. He couldn’t keep quiet for very long at a time.

“Um,” was all the reply Frank made.

“What’s the matter; lost your tongue overboard?” questioned Andy with a chuckle.

Frank did not reply.

“I’m going to pass you,” called the younger brother a moment later when, by extreme exertion, he had regained the place he had held, with the bow of his craft in line with Frank’s. Then Andy fairly outdid himself, for, though Frank was rowing hard, his brother suddenly shot ahead.

“It’s about time you did some rowing,” was Frank’s quiet remark, and then he showed that he still had some power in reserve, for he caught up to his brother, and held his place there with seeming ease, though Andy did not let up in the furious pace he had set.

“Oh, what’s the use of killing yourself?” at length the younger lad fairly panted. “It’s—it’s farther than I thought.”

He began losing distance, but Frank, too, had no liking for the fast clip, so he, likewise, rowed slower until the two boats were on even terms, bobbing over the long ground swell that seemed to be getting heavier rapidly.

From time to time one brother or the other glanced over his shoulder, not so much to set his course, for they could do that over the stern, having previously taken their range, but in order to note the aspect of the fast-gathering clouds which were behind them.

The wind, which had died out shortly after they had started on their row that morning, now sprang up in fitful gusts, with a rather uncanny, moaning sound, as if it was testing its strength before venturing to develop into a howling storm.

“Don’t you think it’s going to kick up a rumpus?” asked Andy, tired of keeping quiet.

“Um,” spoke Frank again, for his breath was needed to keep up his speed in the swells.

“There you go again—old silent-face!” and Andy laughed to take the sting out of his words. “Your tongue will get so tired being still so long that it won’t know how to wiggle when you want it.”

Frank smiled, and glanced over his shoulder again. He noted that the dock, which was their goal, was now a little more than half a mile distant. He could see several fishing boats and other craft making for the more sheltered part of the harbor. Frank was calculating the space yet to be covered, to decide when he should begin the final spurt, for, though the race was only a friendly one, such as he and his brother often indulged in, yet he wanted to win it none the less. He decided that it would not do to hit up the pace to the limit just yet.

“It’s a heap sight longer than I thought it was,” came from Andy, after a bit. “What say we call it off?”

“Not on your life” exclaimed Frank vigorously. “I’m going to finish whether you do or not—but you have to buy the sodas if I do.”

“I will not. I’ll finish, too, and I’ll beat you.”

Once more came a period of silent rowing. Then, whether it was because he pulled more strongly on one oar than on the other, or because of the drift of the current, and the effect of the wind, the younger lad suddenly found himself close to the boat of his brother.

At that moment Frank had once more turned to look at the dock, and Andy could not resist the chance to play a little trick on him. Skillfully judging the distance, he suddenly swept back his left oar, so that the flat blade caught the crest of a long roller and a salty spray flew in a shower over Frank.

“What’s that—rain?” Frank cried, turning quickly.

He saw the laughing face of his brother, and guessed what had happened.

“I thought this was a rowing race, not a splashing contest!” he cried good-naturedly.

“It’s both,” was the answer. Then, though Frank kept on vigorously swinging the oars, Andy paused, rested on the ashen blades, and, holding the handles of both under his left palm for a moment, he pointed out to sea with his right hand, and cried:

“Look! What’s that out there, Frank?”

“Oh, ho! No you don’t! You don’t catch me that way—pretending to show me a sea serpent!” objected the older lad.

“No, really, there’s something there—something big and humpy—it’s moving, too! Don’t you see it? Look, right in line with the Eastern Spit Lighthouse! See!”

Andy stood up in his boat, skillfully balancing himself against the rolling swell, and pointed out to sea. His manner was so earnest that, in spite of the many times he had joked with his brother, Frank ceased rowing and peered to where the extended finger of the younger lad indicated something unusual.

“Smoked star fish! You’re right!” agreed Frank, forgetting all about the race now, and standing up in his craft, in order to get a better view.

“What is it?” cried Andy. “A floating wreck?”

“That’s no wreck,” declared Frank.

“Then what is it?”

“It’s a whale, if I’m any judge. A whale, and a big one, too!”

“Dead?”

“I guess so. No—by Jupiter! It’s alive Andy, and it’s coming this way!”

“Cracky! If we only had a harpoon or a bomb gun now, that would be the end of Mr. Whale. Let’s row out and meet him!”

“Say, are you crazy?” demanded Frank, with some heat.

“Crazy? No; why?”

“Wanting to tackle a whale in these boats! We’d be swamped in a minute! We’d better pull out to one side. Most likely the whale will keep on a straight course, though he’ll be stranded if he goes much farther in. The tide’s out, and it’s shallow here. Pull to one side, Andy—the race is off. Pull out, I tell you!” and Frank swung his skiff around with sudden energy.

“I am not! I’m going to get a nearer view of the whale!” cried Andy. “Maybe he’s hurt, or perhaps there’s a harpoon with a line fast to it in him. We might get hold of it and—”

“Yes, and go to kingdom come. Nixy! Get out of the way while you’ve got time. Jinks! He’s coming on faster than ever!”

Frank’s manner so impressed his brother that the younger lad now began to swing his craft around. They could both see the whale plainly now, even while sitting down, for the great sea animal was nearer.

Then, whether it was some sudden whim, or because he saw the boats and took them for natural enemies, there was a sudden swirling of water and the whale increased his speed, heading straight for the two skiffs that were now almost touching side by side.

“He’s coming!” yelled Andy.

“I told you he was!” cried Frank. “Row! Row! Get out of the way!”

This was more easily said than done. In vain did the lads pull frantically on their oars. The whale was now coming on with the speed of an express train. He was headed right for the two boats!

“Pull out! Pull out!” shouted Andy. “He may go between us then!”

It was good advice, and Frank, who was a little the better rower, started to follow it.

But it was too late. On came the monster of the deep, his great head throwing up a huge wave in front of him. Andy was rowing as hard as was his brother until he suddenly jumped his left oar out of the oarlock. In another moment it had gone overboard.

This seemed to attract the attention of the whale to the skiff of the younger lad. The monster might have thought that the occupant of the boat was trying to hurl a harpoon.

Suddenly changing his course, the leviathan, which had been headed for Frank’s craft, now turned toward Andy’s.

“Look out!” frantically shouted the older lad.

“I can’t! He’s got me!” screamed Andy.

The next instant there was a splintering, crashing and rending of wood. A shower of spray flew high in the air. Frank’s boat rocked on the heavy swell caused by the flukes of the whale, as they went deep into the water after delivering a glancing blow upon the unfortunate Andy’s skiff.

Frank had a momentary glance of his brother’s boat, with one side smashed down to the water’s edge. He saw the green sea pouring in, and he saw Andy standing up, ready to leap overboard. He saw the maddened monster sheering off out to sea again, and then Frank cried:

“I’m coming, Andy! I’m coming! I’ll save you! Hold on to your boat! Don’t jump!”

The whale disappeared in a smother of foam, as Frank, with desperate energy, bent to his oars and swung his boat in the direction of the sinking one containing his brother.

“Hold on, Andy! Hold on! You’ll float for a while yet!” called Frank, while he threw all his strength upon the oars in the endeavor to reach his brother. He cast anxious eyes about, fearing a return of the whale, but there was no sign of the big creature.

“All right—take your time!” called Andy. “I can keep afloat for quite a while yet. Maybe I won’t sink after all.”

“I’m not taking any chances,” returned Frank, and then he swung his craft up alongside that of his brother. As Andy had said, his skiff was in pretty good condition. This was due to two causes. The blow of the whale’s tail had been a glancing one, and the skiff had an unusually high freeboard, so that though it was splintered down to the water edge, not much of the sea had entered.

“I believe she’ll float when I’m out of it so she’ll ride higher,” declared the younger lad. “Take me into your boat, and maybe we can tow mine in and fix it up. It’s too good to lose.”

“That’s right. Wow! But you had a narrow escape!” and Frank looked very grave as he assisted his brother into the undamaged craft. “I thought it was all up with you.”

“So did I, when I saw that beast coming for me. But he sheered off just in time. Then I felt sure my boat would fill and sink in an instant, when I saw the water pouring in, after he swiped me, so I got ready to jump. I didn’t want to be carried down with it.”

“That’s right. Say, that’s cut through as clean as if done with a knife,” and Frank looked at the slash in the side of his brother’s boat. It was indeed a sharp cut, and showed with what awful force the tail of the monster must have descended.

“As much water came pouring in over the side as there did through the hole,” went on Andy. “That’s what gave me a scare. But did you see the harpoon in that whale?”

“No, was there one?”

“Sure as you’re a foot high. There was a short piece of line fast to it, and the whale had a big hole in his side. He’s been wounded, probably by a steamer’s propeller after he was harpooned up north, or else that’s the wound of a bomb gun. I could see it quite plainly.”

“Yes, you had a nearer view than I’d want,” observed Frank, as he made fast Andy’s boat to the stern of his own. As the younger lad had said, his skiff, now that it was higher in the water, because his weight was out of it, took in very little of the sea.

“I guess we can tow it if we bail out,” observed Frank. “Are you very wet?”

“Not much—only up to my knees. I was just going to jump in and swim for it when you called to me. Well, here goes for bailing.”

“Yes, and if you shift that anchor back to the stern it will raise the bow, and the hole will be so much more out of water. It’ll row easier, too.”

“Right you are, my hearty. Shiver my timbers! But it’s some excitement we’ve been having!” and Andy laughed.

“Say, I believe you’d joke if your boat was all smashed to pieces, and you were floating around on the back of the whale,” observed Frank gravely.

“Of course I would. A miss is as good as a mile and a half. But if I can find my other oar I’ll help you row in your boat. It ought to be somewhere around here,” and Andy ceased his bailing operations to cast anxious looks over the rolling waves.

“Yes, we’ll look for it after we get some of the water out of your craft. I can’t get over what a close call you had,” and, in spite of the fact that he had been in many dangerous places in his life, Frank could not repress a shudder.

“Oh, forget it!” good-naturedly advised Andy, vigorously tossing water out of his boat with a tin can. “Hello! There’s my lost oar out there. Put me over.”

“All right,” agreed Frank. “I think we’ve got enough water out so she’ll ride high. Now for the dock.”

“I guess you’ll win the race,” observed the younger lad, half regretfully, as he recovered his ashen blade.

“Oh, we’ll call it off,” said Frank good-naturedly. “We’ll have something to tell the folks when we get back to the cottage; eh?”

“I guess. But are you going right home?”

“Why not?”

“Oh, I thought we might row in, and take out our sail boat. I’d like to have another try for that whale. We might get him, and there’s money to be made.”

“Say, do you mean to tell me you’d take another chance with that whale?” demanded Frank, as he prepared to row.

“Of course I would! It would be safe enough in our catboat. He’d never attack that. We could take our rifles along and maybe plug him. Think of hunting for whales! Cricky! That would be sport!” and Andy sighed regretfully. He seemed to have forgotten the narrow escape he had just experienced. “Come on, let’s do it, Frank,” he urged. “Don’t go up to our cottage at all. If you do mother will be sure to see me all wet. Then she’ll want to know how it happened, and the whale will be out of the bag, and we can’t go. Let’s start right out in the Gull as soon as we hit the pier. There won’t be any danger, and we might sight the whale. He must be nearly dead by this time.”

“I wonder if we could find him,” mused Frank.

“Sure!” exclaimed his impulsive brother. “It will be great. There’s some grub aboard the Gull and we can stay out until nearly dark. Mother doesn’t expect us home to dinner, as we said we might go to Seabright. Come on!”

“Well, if you feel able, after—”

“Pshaw! I’m as fit as a fiddle. Let’s hit it up, and get to the dock as soon as we can. Think of landing a whale!”

“Or of being lambasted by one,” added Frank grimly. Nevertheless, he fell in with his brother’s plan, as he usually did. The two boys rowed steadily toward the pier, towing the damaged boat. They were very much in earnest.

In fact, though of different characters, the brothers were very much alike in one trait—they always liked to be doing things. Their name fitted them to perfection; they were “Racers” by title and nature, though Andy was the quicker and more impulsive.

They were the sons of Mr. Richard Racer, a wealthy wholesale silk merchant of New York City. Mr. Racer owned a neat cottage at Harbor View, and his summers were spent there. His wife, Olivia, was a lady fond of society, and when she closed her handsome house in New York, to go to the coast resort for the summer, she transferred her activities there.

While in the metropolis Mrs. Racer spent much time at charitable organizations, and at Harbor View she was a moving spirit in the ladies’ tennis and golf clubs.

Mr. Racer traveled back and forth from New York to Harbor View each day during the summer, for his business needed much of his attention. His vacation, however, was an unbroken series of days of pleasure at the coast resort where he and his wife and sons enjoyed life to the utmost.

The two boys had spent so many summers at Harbor View that they were almost as well known there as some of the permanent residents, and they had many friends among the seafaring folk, especially in the lads. They had one or two enemies, as will develop presently, not through any fault of their own, but because certain lads were jealous of our heroes.

“Well, we’re here,” announced Frank at last, as he swung the boat up alongside the landing stage which rose and fell with the tide.

“And it’s a good wind coming up,” observed Andy. “We can make good time out in the Gull.”

“Maybe we’d better beach your boat before we go out, and pull it above high-water mark,” suggested Frank. “Some of the seams may have been opened, as well as this hole being in her, and she might sink.”

“Good idea. We’ll do it.”

As the brothers were ascending the gangway from the float to the pier, preparatory to going out in their sailing craft, they were hailed by an elderly man, whose grizzled, tanned face gave evidence of many days spent on the water under a hot sun.

“Where you boys bound fer now?” the sailor demanded.

“Oh, we’re just going out for a little sail, Captain Trent,” replied Andy.

“Better not,” was the quick advice.

“Why?” Frank wanted to know.

“It’s coming on to blow, and it’s going to blow hard. Hear that wind?” and the captain, whose son Bob was quite a chum of the Racer boys, inclined his grizzled head toward the quarter whence the breeze came.

“Oh, that’s only a cat’s paw,” declared Andy.

“You’ll find it’ll turn out to be a reg’lar tomcat ’fore you’re through with it,” predicted the old salt. “But what happened to your boat, Andy? I see you’ve got a hole stove in her. Did you run on the rocks?”

“No, something ran into us,” replied Frank quickly. “Don’t say anything to him about the whale,” he remarked to his brother in a low voice.

“What’s that about a sail?” demanded the captain, catching some of Frank’s words.

“We’re going for a sail,” spoke Andy quickly. “Come on, Frank.”

“Better not!” again cautioned Captain Trent. But our heroes were no different from other boys, and did not heed the warning. Had they done so perhaps this story would not have been written, for the events following their sail that day were unusual, and had a far-reaching effect.

“Come on!” called Andy sharply to his brother, as he saw the captain making ready to start a discussion about the weather. Mr. Trent might also ask more questions about the damaged boat, and neither Andy nor his brother wanted to answer—just yet.

Five minutes later saw the two brothers sailing away from the pier. The breeze was getting stronger every moment, until the rail of their trim boat was under water part of the time.

“Say, it is blowing!” declared Frank.

“Oh, what of it? The Gull can stand more than this. Besides we’re safe in the harbor, and we may soon sight the whale. Keep a good lookout!”

For some time they sailed on, each one scanning the expanse of the bay, which was now dotted here and there with whitecaps. The boat was heeling over almost too much for comfort.

“Hadn’t we better turn back?” asked Frank, after a period of silence, broken only by the swish of the water.

“Of course not,” declared the more daring Andy. “It was about here that my boat was stove in. The whale may be around these diggings looking for us.”

“Likely—not!” exclaimed Frank decidedly.

There came a fiercer gust of wind, and it fairly howled through the rigging. The waters whitened with spray and foam.

“It’s a squall!” yelled Frank. “Better turn back.”

“We can’t now,” shouted Andy at the top of his voice, to make himself heard above the howling of the wind. “We’d better keep on to Seabright. We can lay over there until this blows by. See anything of the whale?”

“No. It’s useless to look for him. I’m going to take a reef in the sail.”

“That’s right. I guess you’d better shorten some of our canvas. I’ll hold her as steady as I can while you’re doing it. Or shall I lash the helm and help you?”

“No, you stay there. I can manage it.”

The storm increased in sudden fury, and it was no easy task to shorten sail with the pressure of the wind on it. But Frank Racer had considerable skill in handling boats, and with his brother at the helm, to ease off when he gave the word, he managed to cast off the throat and peak lines, lower the gaff and sail, and then take a double reef in the canvas.

Even under the smaller spread the Gull shot along over the foam-crested waves like some speeding motor boat. Andy was so taken up with watching his brother, and in aiding him as much as he could by shifting the helm as was needful, that he did not look ahead for several minutes. He was recalled to this necessary duty by a sudden, frightened cry from Frank.

“The rocks! Look out for the rocks!” shouted the older lad. “We’ll be on ’em in a second! Port your helm! Port!”

Andy desperately threw over the tiller, and with fear-blanched face he looked to where his brother pointed. Amid a smother of white foam, almost dead ahead and scarcely two cable lengths away there showed the black and jagged points of rocks, known locally as the “Shark’s Teeth.” The Gull was headed straight for them.

Anxiously, and with strained eyes, the brothers looked to see if their boat would answer her rudder. For a moment or two she hung in the balance, the howling wind driving her nearer the rocks, to strike upon which meant sure destruction in the now boiling sea.

Then, with a feeling of relief, Andy saw that they were sheering off, but very slowly. Could they make it? They were near to death, for no one—not even the strongest swimmer—could live long unaided in that boiling sea that would pound him upon the sharp rocks.

Suddenly Frank uttered a cry, and pointed to a spot at the left of the rocks, in a space of water comparatively calm.

“There! Look! Look!” he shouted.

“What is it? The whale?” demanded Andy.

“No, a boat—a motor boat! It’s disabled—drifting! It must have been on the rocks. It’s a large one, too. Look out you don’t hit it.”

“It’s on fire!” cried Andy. “See the smoke—the flame! It’s burning up!”

The Gull was now far enough from the Shark’s Teeth to warrant her safety, and the boys could look at the motor craft, that was bobbing helplessly about in the spume and spray, being tossed hither and thither by the heaving waves.

“See anybody on her?” yelled Andy.

“No—not a soul,” answered Frank, who had made his way forward, and was standing up, clinging to the mast.

Suddenly, amid the howling of the storm, there came a sharp explosion. There was a puff of flame, and a cloud of smoke hovered over the hapless motor boat, which, strange to say, still remained intact and afloat.

“She’s blown up! Exploded!” yelled Andy.

“Yes, and there’s a boy in the water! Look!” fairly screamed Frank. “He was on the boat! The explosion must have blown him out! He’s floating! We must save him, Andy!”

“Sure! Jupiter’s lobsters! but things are happening to us to-day! Look out! I’m going to put about!”

Frank scrambled back to join his brother. The big boom with its shortened sail swung over, and, heeling under the force of the shrieking wind, the Gull darted toward the dangerous rocks once more. Toward the wrecked motorboat, toward the figure of the boy floating in the smother of foaming and storm-torn waves she swept.

Could they reach the helpless lad in time? It was the question uppermost in the hearts of Frank and Andy Racer.

“Can we make it, Frank?” questioned Andy desperately.

“We’ve got to,” came the quick answer. “Ease her off a little until I get the lay of things.”

“Is he swimming?” demanded the younger lad.

“Yes, but only with one hand. He must be injured. He can just manage to keep afloat. Put in a little closer. We’ve passed the worst of the Teeth. It’s deep water here, isn’t it?”

“Yes, as near as I can tell. I haven’t been here very often. It’s too dangerous, even in calm weather, to say nothing of a storm.”

The wind was now a gale, but the boys had their sailboat well in hand and were managing her skillfully. They came nearer to the feebly swimming lad.

“There he goes—he’s sunk—he’s under!” yelled Andy, peering beneath the boom.

“Too bad!” muttered Frank. “We’re too late!”

Eagerly he looked into the tumult of waters. Then he uttered a joyful cry.

“There he is again! He’s a plucky one. We must get him, Andy!”

“But how? I daren’t steer in any closer or I’ll have a hole in us and we’ll go down.”

“We’ve got to save the poor fellow. I wonder who he is?”

“It’s tough,” murmured Andy. “See, the fire on the motor boat seems to be out.”

“Yes, probably the explosion blew it out. The boat floats well. Maybe we can save that.”

“Got to get this poor boy first. Oh, if he could only swim out a little farther we could throw him a line. Hey there!” he called to the lad, “we’re coming! Can you make your way over here? We daren’t come in any closer.”

There was no answer, but the desperately struggling lad waved his one good arm to show that he had heard. Then he resumed his battle with the sea—an unequal battle.

“Plucky boy!” murmured Frank. “I’m going to save him. He can never swim out this far.”

Andy had thrown the boat up in the wind, and had lowered the sail so that she was now riding the waves comparatively motionless, for there came a lull in the gale.

Then, even as Frank spoke, the unfortunate lad again disappeared from sight.

“He’s gone—for good this time I guess,” spoke Andy, and there was a solemn note in his faltering voice.

“No! There he is again!” fairly yelled Frank. “I’m going overboard for him.”

“You can’t swim in this sea!” objected his brother. “There’ll be two drowned instead of one.”

“I can do it!” firmly declared the older lad. He began to take off his shoes, and divest himself of his heavier garments.

“You’re crazy!” cried Andy. “You can’t do it!”

“Just you watch,” spoke Frank calmly. “I can’t stand by and see a lad drown like that. Have we a spare line aboard?”

“Yes, plenty. It’s up forward in the port locker under the deck.”

“Good. Now I’m going to tie a line around my waist, and go overboard. I’ll swim to that chap and get a good hold on him. Then it will be up to you to pull us both in, if I can’t swim with him, and I’m afraid I can’t do much in this sea. Can you haul us in, and manage the boat?”

“I’ve just got to!” cried Andy, shutting his teeth in grim determination. “The boat will ride all right out here. The wind isn’t quite so bad now. Take care of yourself.”

“I will. Shake!”

The brothers clasped hands. Frank well knew the peril of his undertaking, no less than did Andy. They stood on the heaving, sloping deck of the Gull, and looked into each other’s eyes. They understood.

“Watch close, and pull when you see me wave to you,” ordered the older lad, as he fastened the rope about his waist.

“All right,” answered Andy, in a low voice.

With a quick glance about him, noting that the wounded lad was still struggling feebly in the water, Frank dived overboard. He disappeared beneath the green waves with their crests of foam, and for a moment Andy anxiously watched for his brother. Then he saw him reappear, and strike out strongly toward the other youth. Frank was an excellent swimmer.

“That’s the way to do it!” murmured Andy admiringly. “If anybody can save him, Frank can.”

The younger lad was braced against the tiller, standing in a slanting position, his feet planted firmly in the cockpit, while he payed out the rope, one end of which was about Frank’s waist, and the other made fast to a deck cleat.

“To the left. To the left!” yelled Andy suddenly, as he saw his brother taking a slightly wrong course. The spume in his eyes, and the bobbing waves which now and then hid the wounded lad from sight, had confused Frank. The latter made no reply, but his hand, raised above the water, and waved to Andy, told that he understood the hail.

Frank changed his course, still swimming strongly. The wind had again begun to blow hard, and the Gull was drifting nearer the rocks, yet Andy dared not send her out for fear of pulling Frank with him. He must stand by until—

Carefully he payed out the line. He could see it slipping through the green water. Then he caught a glimpse of his brother on the crest of a wave. The next moment he saw how close he was to the lad he had so bravely set out to save.

“Tread water! Don’t swim! Tread water and save your strength!” cried Andy to the injured one. The boy heard and obeyed.

In another moment Frank was near enough to clasp the almost exhausted lad in his strong right arm. Andy saw this and there was no need for the signal which his brother gave an instant later. Frank was on his guard lest the youth he was rescuing might clasp him in a death grip. But the latter evidently knew something about life saving, for he placed his uninjured hand on his rescuer’s shoulder and let Frank do as he would.

Andy began to haul in on the rope. It was hard work to do this, and manage the boat at the same time, but he did it somehow—how he never could really tell afterward. But he had something of his brother’s grim determination and that was just what was needed in this emergency.

Slowly the rope came in, pulling the rescuer and the rescued one. Without it that life could never have been saved, for the waves were running high, and there was a current setting in toward the sharp, black rocks.

Foot by foot Frank and his almost unconscious burden were pulled toward the Gull.

“Can you keep up?” asked the elder Racer lad.

“I—I guess—so,” was the faint reply.

“We’ll be there in a minute now. You’ll soon be all right!”

The other did not answer. Valiantly Andy hauled in, until his brother’s head was right under the rail.

“I’ll take him now,” called Andy, as he let go of the tiller, and reached for the lad Frank had saved. With a strong heave Andy got him over the side. He slumped down into the cockpit, unconscious. A moment later Frank clambered on board and quickly untied the rope from his waist.

“Quick, Andy!” he cried. “Mind your helm! We’re drifting on the rocks again!”

“Look out for this lad. I’ll steer clear!” yelled his brother in reply, as he sprang back to the tiller, after hoisting the sail.

Frank lifted the unconscious form in his arms, and moved the wounded lad over to a pile of tarpaulins. With all his strength Andy forced over the tiller, for the wind was strong on the sail, and the waves were running high, their salty crests filling the atmosphere with spume, while a fine spray drenched those aboard the Gull.

Suddenly there was a scraping sound, and the little craft shivered from stem to stern.

“The rocks! The rocks! We’re on the rocks!” cried Frank, as with blanched face he looked up from where he was kneeling over the silent form of the lad he had rescued from the sea and the gale.

For a moment terror held the Racer boys motionless. The danger had come so suddenly that it deprived them of the power to think. Then came the reaction, and they were themselves once more.

“Quick! Throw your helm over! We can just make it!” yelled Frank. “I’ll attend to the sheet—you manage the tiller! Lively now!”

Andy needed no second command. He fairly threw himself at the helm, and with all his strength forced it hard over. The shortened sail rounded out with the pressure of the wind on it, and the Gull heeled over at dangerous angle. Under her keel came that ominous scraping sound that told of her passage over part of the Shark’s Teeth.

“It’s a submerged rock!” shouted Andy. “We may scrape over it!”

“Let’s hope so!” murmured Frank, as he looked hastily down at the unconscious form of the strange lad. Then he gave all his attention to the rope that controlled the end of the swinging boom.

With the same suddenness that it had come upon them, the danger was past. The Gull slid into deep water, and the hearts of the boys beat in glad relief. Rapidly the craft paid off until she was well away from the ugly black points that could be seen, now and then, rearing up amid a smother of foam.

“Round about and beat for home!” yelled Frank. “Whoever this fellow is, he needs a doctor right away. I hope the wind holds out.”

“Did you learn who he was?” asked Andy, as he gave his attention to putting the boat on the proper course.

“No. How could I? He was as weak as a cat when I got to him, but he had sense enough not to grab me. He knows how to swim all right, but something is the matter with his left arm.”

“Think it’s broken?”

“I don’t know. It’s a wonder he wasn’t killed when that boat blew up. He must have been hurt in some way, or he wouldn’t be unconscious.”

“Maybe it’s because he’s nearly drowned. He may be half full of water.”

“That’s so,” agreed Frank. “I’ll see what I can do for him while you steer. Make all you can on each tack.”

They were fast leaving behind them the wrecked motor boat which bobbed about on the waves. It was no longer on fire, and the brothers would liked to have towed it to the pier, but this was impossible in the storm.

Then, as his brother skillfully managed the sailboat, Frank once more bent over the unconscious form. He knew what to do in giving first aid to partly drowned persons, and lost no time in going through the motions designed to rid the lungs of water.

Frank did succeed in getting some fluid from the system of the stranger, but the lad still remained unconscious, with such a pale face, with tightly closed eyes, and showing such apparent weakness, that Andy remarked:

“I guess he’s done for, poor fellow!”

“I’m not so sure of that,” responded Frank. “He’s still breathing, and there’s a spark of life in him yet. We must get him to our house, and have a doctor right away. Oh! now’s the time I wish we had a motor boat!”

“We’re doing pretty well,” declared Andy. And indeed the Gull was skimming along at a rapid rate. She was quartering the wind, until a sudden lull in the gale came. They hung there for a moment or two, and the brothers looked anxiously at each other. Were they to be becalmed when it was so vitally necessary to get the stranger to a doctor immediately?

But once more the sail swelled out, and with joy the Racer boys noticed that the wind was now right astern and that they could run down to the dock on the wings of it, making an almost straight course.

“This is the stuff!” cried Frank, as he made a sort of pillow from some sail cloth for the sufferer’s head.

“It sure is. We’ll be there soon. You’d better get some of your clothes on before we land.”

Frank slipped on his garments over his wet underwear and trusted to the wind to dry him before reaching home.

“I wonder who he can be?” mused Andy. “He wears good clothes, and if he owns that wrecked motor boat he must have money, for it was a big one, and cost a lot.”

“It sure did. Well, we may find out who he is when he comes to, after the doctor has seen him. We’ll take him up to our house.”

“Of course. There’s no other place for him in Harbor View. We’ll be at the dock in five minutes more.”

The rest of the trip was quickly covered, and, a little later, the two brothers had run their craft right up to the float, made her fast and began lifting out the unconscious form of the lad they had saved.

“Avast there! What ye got?” cried the hearty voice of Captain Trent. “Is he dead? Who is he?” He peered down over the pier railing.

“We don’t know,” answered Frank to both questions. “He was in a motor boat—wrecked—it blew up—we saved him.”

“By Davy Jones! Ye don’t mean it! Wa’al, I’ll give you a hand.”

With the old salt’s aid the boy was soon lifted up to the pier. Then Frank asked:

“Where’s your horse and wagon, Captain? We can never carry him to our house without something like that. Where’s the wagon?”

“Bob jest got back from delivering clams in it. I’ll go clean it out—the hoss is hitched to it yet, an’—”

“Don’t bother to clean it!” interrupted Andy. “Just put some sail cloth in the bottom. It doesn’t matter if it’s dirty. Every second counts now. Get the wagon.”

“Right away!” cried the old sailor, who did a general clamming and fish business. He hurried off in the direction of his store and stable, impressed by the words and energetic actions of the Racer boys. “Hi there, Bob!” the captain called to his son, whom he saw approaching. “Bring Dolly an’ the rig here as quick as you can! Frank an’ Andy Racer went out an’ brought back a dead motor boat—leastways I mean a fellow that was nearly killed in one. Bring up the rig jest as she is! Lively!”

“Aye, aye!” answered Bob, seaman fashion.

A minute later a nondescript vehicle, drawn by a big but bony horse rattled up, driven by the captain’s son.

“What’s up?” asked Bob Trent of the lads, with whom he was quite friendly. “Who is he?”

“That’s what we’d like to know,” spoke Frank. “We may find out if he doesn’t die. We’ve no time to spare.”

They lifted the unconscious form into the wagon, on the bottom of which had been spread a number of old sails.

“I’ll drive,” said Bob briefly. “I can get more out of Dolly than most folks. You’ve got to do your best now, old girl,” he called to the horse. The animal pricked up her ears.

“I’ll ride in back and hold his head,” volunteered Frank. “Andy, you go telephone for Dr. Martin. Tell him to get to our house as soon as possible—explain why. Have him there by the time we arrive, if possible.”

“Right!” cried Andy sharply, and he raced off toward the nearest telephone, there being a few of the instruments in Harbor View.

“Wa’al, I’ll be jib-boomed!” exclaimed Captain Trent, as his son drove off, the horse making good time. “Them Racer boys is allers up to suthin’ or other.”

Bob spoke the truth when he said he could do better with Dolly than most drivers, for the steed started out at a fast pace, and kept it up until the rickety vehicle turned into the drive that led to the handsome cottage owned by Mr. Racer. Mrs. Racer hurried to the door as she heard the sound of wheels, and at the sight of Frank sitting in the wagon, holding the head of another lad in his lap, Mrs. Racer cried out:

“Oh, Frank! What has happened? Is—is it—Andy? Is he—is he—?” she could say no more, and began crying.

“It’s all right, mother!” shouted Frank heartily. “We rescued an unknown lad. Andy has gone to telephone for Dr. Martin. He ought to be here now. Tell Mary to get some hot water ready. We may need it. Lay out some blankets. Get a bed ready, mother.”

Frank issued his requests as if he had been used to saving drowned persons every day. His crisp words had the effect of restoring Mrs. Racer to her usual calmness.

“I’ll attend to everything,” she said. “Oh, the poor fellow! Bring him right in here. Can you and Bob lift him?”

“I think so,” answered the captain’s sturdy son.

“Oh, why doesn’t Dr. Martin come?” cried Mrs. Racer.

“That sounds like his auto now!” exclaimed Frank, as he and Bob carried the unknown lad into the house. “Yes,” he added a moment later, “here he comes.”

“And Andy’s with him,” added Bob. “The doctor must have picked him up on the way here.”

It was the work of but a few moments to get most of the unconscious youth’s clothes off and place him in bed. By that time the physician was ready to begin his ministrations.

“I don’t know,” mused Dr. Martin, as he felt of the feeble, flickering pulse, and listened to the scarcely audible breathing. “He’s pretty far gone. Hurt internally, I imagine. But we’ll see if we can save him.”

With the eager and able assistance of the Racer boys, their mother and Bob Trent, Dr. Martin labored hard to restore the lad to consciousness. At first his efforts seemed of no avail. His eyes remained closed, and the pulse and breathing seemed to grow more feeble.

“I think I’ll try the electric battery,” said the doctor finally. “If one of you will bring it in from my auto, I’ll see what effect that has.”

“I’ll get it!” cried Andy, and he fairly ran out and back.

For a time it looked as if even the powerful current would be useless, but when the doctor turned it on full strength there was a convulsive shudder of the body. Then, suddenly the eyes opened, and the voice of the rescued lad murmured:

“It’s cold—the water—Oh! The gasolene tank! It will explode! I can’t get away now! I must jump!”

He raised himself in bed, but the doctor gently pressed him back.

“There, there now,” spoke the physician soothingly. “You are all right. Don’t worry. You’ll be all right.”

“He’s going to live,” said Andy softly.

Once more the tired eyes closed, and then opened again.

“Where—where am I?” asked the lad wildly.

He looked about the room in amazement, and once more tried to get out of bed, but was restrained.

“You’re with friends,” said Mrs. Racer softly. “You will be well taken care of.”

“What—what place is this?” gasped the lad.

“Harbor View,” replied Frank promptly. “Who are you?”

Eagerly they all leaned forward, for they wanted to solve the mystery of the identity of the rescued lad. He gazed at them all in turn. A half smile played about his face. Then he said weakly:

“I am—”

He sank back upon the bed unconscious, his name unspoken.

For a moment there was silence in the room, and something like a disappointed sigh came from Frank and his brother. Andy leaned over the bed.

“Who are you?” he asked, placing his hand on the head of the lad. “Can’t you tell us who you are, or where you live? We want to help you. How did you come to be in the boat alone? How did it get on fire?”

There was no response.

“It is useless to question him,” said Dr. Martin. “I will give him some medicine, now that he is partially restored to consciousness, and perhaps when he is stronger he can tell who he is. In the meanwhile it will be best not to bother him.”

The boys took this as a hint that they had better leave the room, so the three of them filed silently out to permit of the physician and Mrs. Racer continuing their efforts to bring the lad out of the stupor into which he had fallen.

“It’s a queer case,” mused Frank.

“It sure is,” agreed his brother. “I hope he doesn’t die before we find out who he is, or where he belongs.”

“I hope he doesn’t die at all,” put in his brother quickly.

“Oh, of course,” assented Frank. “So do I.”

“Could you make out any name on the motor boat?” inquired Bob.

“Didn’t have a chance,” answered the older Racer lad. “Andy and I had our hands full managing our boat, and, when I went overboard I had to depend on Andy to pull that lad and me back. The sea was fierce and it was blowing great guns. All I know is that it was a fine boat, and it’s a shame it was wrecked on the Shark’s Teeth.”

“She’ll go to pieces if she stays there long,” was Bob’s opinion. “The bottom will be pounded out of her and she’ll go down.”

“Your father was right about the storm coming up,” said Frank, after a pause. “I never saw it blow so hard in such a short time.”

“Oh, dad can generally be depended on for a weather guess,” said the son proudly. “Well, I must be getting back. Got to put on another load of clams before supper. Let me know how that chap makes out, will you?”

“Sure,” assented Frank. “And if you see or hear anything of that motor boat up or down the coast, let us know. Maybe we can save it, and find out something about this boy from it, in case he isn’t able to tell.”

“I’ll do it,” promised the captain’s son.

“And if you see a wounded whale, it belongs to us,” added Andy.

“A wounded whale?” gasped Bob. “Are you stuffing me? This isn’t Thanksgiving.”

“It was a whale all right,” went on Andy, playfully poking his brother in the ribs, “and it stove in my boat. If I could catch the beggar I’d sell his hide or oil or whatever is valuable about him, and get a new boat.”

“Does he mean it?” asked Bob, turning to Frank, for the younger Racer lad was well known for his practical jokes and his fun-loving characteristics.

“Yes, we did get rammed by one just before we went out in the Gull,” said Frank, a bit solemnly, for the events of the past few hours had made quite an impression on him. Then he briefly told the story of the monster’s attack.

“We didn’t say anything to your father about it when we came in,” explained Andy, “as we didn’t want to be delayed. But if you see or hear of that whale, don’t forget he belongs to us.”

“I won’t,” declared Bob. “Now I’ve got to hustle, as it’s almost supper time.”

“Supper!” cried Andy. “That reminds me, we haven’t had dinner yet, Frank.”

“My stomach reminded me of that some time ago,” declared the brother. “We had such a strenuous time that it slipped our minds, I guess. But I’m going to make up for it now. So long, Bob; see you later.”

“So long.”

Then, as the rickety wagon was driven away Frank and Andy went in the house to change their wet garments.

The two brothers were tiptoeing their way to the room where the wounded lad lay, having first ascertained from Mary, the cook, that supper would soon be ready, when they saw Dr. Martin coming from the apartment.

“Is he better?” asked Frank in a whisper.

“Yes,” and the doctor smiled. “I succeeded in fully restoring him to consciousness, and he is now sleeping quietly. I have given him a powder and it will be some time before he awakens. He is worn out, in addition to being injured.”

“Is he badly hurt?” Andy wanted to know. “Is his arm broken?”

“No, only severely sprained. In addition, he has several big bruises and a number of cuts where he must have been tossed against the rocks. His hands are burned slightly, but there is nothing dangerous, and with care he ought soon to recover.”

“He must have gotten burned trying to put out the fire on the boat,” commented Frank. “But, Dr. Martin, did you learn anything about him? What’s his name? Where does he belong? What was he doing near the Shark’s Teeth in a gale?”

“I can’t answer any of your questions,” replied the physician gravely. “I asked the lad who he was, thinking that his people would be worried, and that I might be able to send some word to them. But, though he was fully in his senses, and seemed to realize what he had gone through, I couldn’t get a word out of him about his name.

“When I asked him, as I did several times, and as also did your mother, he would begin, ‘I am—’ Then he would stop, pass his hand across his forehead, and look puzzled. He did this a number of times, and it seemed to pain him to try to think. So I gave it up.”

“How do you account for that?” asked Andy.

“Well, the fright and injuries he received may have caused a temporary loss of memory,” replied the doctor. “Or there may be some injury to the brain. I can’t decide yet. But I’ll look in again this evening. He’ll be much improved by then, I am sure.”

“It’s getting queerer and more queer,” commented Andy, as the physician hastened away in his car. “Think of forgetting who you are, Frank!”

“It sure is too bad. We must try to help him. That motor boat would be a clue, I think. As soon as the weather gets better, and this storm blows over, we’ll have a search for it.”

“Yes, we’re in for a hard blow, I think. It’s a worse gale now than when we were out.”

The wind, which had momentarily died out, had sprung up again with the approach of night, and it began to rain. Out on the bay, a view of which could be had from their house, the boys could see big tumbling billows.

“It’s a good night to be home,” mused Frank. “I’m afraid we’ll never see that wrecked motor boat again. It will pound to pieces on the Shark’s Teeth.”

“Very likely. Well, let’s go in and see how much nearer supper is ready. Dad’s home now.”

It was rather a long and dreary night, with the storm howling outside, and Frank, who had the last watch, was not sorry when the gray daylight came stealing in. The unidentified lad had slept soundly, only arousing slightly once or twice.

“We must have a nurse for him,” Mrs. Racer decided, when she and her husband, together with the boys, had talked the case over at the breakfast table. “Poor lad, he needs care. He looks as if he came from good people—a refined family—don’t you think so, Dick?” and she turned to her husband.

“Oh, yes, he seems like a nice lad. Get a nurse if you can, and have the best of everything. And I don’t want you boys tackling any more whales,” Mr. Racer added decidedly, as he gazed at his sons a bit sternly.

“No, indeed!” their mother hastened to add. “I should have died of nervousness if I had known they went out again, after that dreadful fish smashed Andy’s boat.”

“A whale’s an animal, not a fish, mother,” said the younger lad as he gave her a kiss. “We are going to capture that one and sell its oil.”

“Don’t you dare venture whale-hunting again, or we’ll go straight back to New York, and that will be the end of your vacation,” she threatened.

“That’s right,” added Mr. Racer. “Don’t forget. Well, I must be off or I’ll miss my boat,” and he hurried away to his New York office.

There was quite an improvement in the condition of the mysterious youth that day, and, with the arrival of the nurse, the Racer boys and their mother were relieved from the care of him, though one or the other of them paid frequent visits to the sick room.

“He’s doing nicely,” said Dr. Martin on the third day. “He is out of danger now.”

“And still not a word to tell who he is?” spoke Frank.

“No,” said the doctor musingly, “he talks intelligently on every subject but that. He remembers nothing of his past, however. He doesn’t even seem to know that he was out in a motor boat. All he can recall is that he was in some kind of trouble and danger, and that he was saved. He knows that you boys saved him, and he is very grateful.”

“And he doesn’t know a thing about himself?” asked Andy wonderingly.

“Not a thing. It is as if he was just born, or as if he came to life right after the wreck. He has some dim memory of being in a big city, and of looking for some man, but who this man is seems to be as mysterious as who he himself is. So I have given up questioning him for the present as it distresses him.”

“Will he ever recover his mind?” asked Mrs. Racer anxiously.

“Well, such cases have been known,” replied the doctor. “Perhaps in time, with rest and quietness, it may all come back to him as suddenly as it left him. But what are your plans in regard to him?”

“He is to stay here, of course, until he recalls something of himself,” said Mrs. Racer decidedly. “Then he may be able to tell us who his people are.”

“And if that should take—say all summer?” The doctor looked at her questioningly.

“If we have to take him back to New York with us in the fall, we’ll do it,” went on the mother of Frank and Andy.

“Perhaps the city sights may recall him to himself,” suggested Frank.

“Perhaps,” agreed Dr. Martin. “Well, I’ll stop in again to-morrow.”

The next day, and the next, however, saw very little change. The lad grew much stronger, so that he could sit up in bed, but that was all. The past remained as dark as before. Yet he was intelligent, and could talk on ordinary topics with ease, and with a knowledge that showed he had been well educated. But even his name was lost to him. They looked in the newspapers but saw no mention of a lost boy.

Meanwhile Frank and Andy had made diligent inquiries about the wrecked boat, but had heard nothing. Nor was there any news of the whale.

“Of course I don’t intend to go out after him, when dad and mom don’t want us to,” Andy carefully explained to his brother, “but it does no harm to ask; does it?” and he laughed joyously.

“No, I suppose not,” assented Frank.

It was about a week after the rescue of the mysterious lad, and his physical condition had continued to improve. He would soon be able to get around, the doctor said. Frank and Andy, who never grew tired of discussing the problem, and of wondering when the lad’s mind would come back, were strolling along the beach of Harbor View. The weather had cleared and they were thinking of going for a sail, mainly on pleasure but incidentally to look for the wrecked motor boat.

“It’s queer no one has sighted her, or heard of her,” remarked Andy, gazing off to sea, as if he might pick up the disabled craft on the horizon.

“Yes,” agreed Frank. “I guess she’s sunk all right.”

They walked on in silence, and were about to turn back toward where their boat was moored, when they noticed a man walking rapidly along the sands of the beach toward them.

“He seems to be in a hurry,” observed Frank, in a low voice.

“Yes,” agreed his brother. “He looks as if he wanted to speak to us.”

“He’s a stranger around here,” went on Andy.

A moment later the man hailed them.

“I beg your pardon,” he began, striding up to the two brothers, and shifting his gaze rapidly from one to the other. “But have you seen or heard of a large motor boat going ashore around here? I’m looking for one. There would be a boy in it perhaps—a lad of about your size. Perhaps he put in here to get out of the storm. I’ve inquired all along the coast, but I can’t get any word of him. You haven’t happened to have heard anything, have you?”

Frank and Andy looked at each other quickly. At last they seemed on the track of the mystery.

“Was he a tall, dark lad, with black hair?” asked Frank.

“Yes—yes, that’s the boy I’m looking for!” exclaimed the man quickly.

“And was the motor boat a long one, painted white with a green water line, and with the engines forward under a hood?” added Andy.

“Yes!” eagerly cried the man, in his excitement taking hold of Andy’s coat. “That’s the boat! Where is it? I must have it!”

“She’s wrecked,” said Frank quickly. “We saw her on the Shark’s Teeth, going to pieces, and we’ve been looking for her since, but the boy—”

“Yes—yes! The boy—the boy! What of him? Where is Paul—?”

The man stopped suddenly, and fairly clapped his hand over his own lips to keep back the next word. He seemed strangely confused.

“We rescued the boy, and he is up at our house,” said Frank quickly. “We have been trying to pick up the wreck of the boat and learn who the boy is. He has lost his memory.”

“Lost his memory!” the man exclaimed, and he actually appeared glad of it.

“Yes, he doesn’t remember even his name,” explained the elder Racer lad. “But now we can solve the mystery as you know him. You say his name is Paul. What is his other name? Who are you? Don’t you want to see him? We can take you to him—to Paul.”

The brothers eyed the man eagerly. On his part he seemed to shrink away.

“I—I made a mistake,” he said, biting his nails. “I know no one named Paul. I—I—it was an error. That is not the boy I want. I must hurry on. Perhaps I shall get some news at the next settlement. I am—obliged to you.”

His shifty eyes gazed at the brothers by turns. Then the man suddenly turned away muttering something under his breath.

“But you seemed to know him!” insisted Frank, feeling that the mystery was deepening.

“No—no! I—I made a mistake. His name is not Paul. I am wrong. That is—well, never mind, I’m sorry to have troubled you.”

He was about to hurry away.

“Won’t you come and see him?” urged Frank. “It is not far up to our house. My mother would be glad to meet you. Perhaps, after all, this lad may be the one you seek. His name may be Paul.”

“No—no! I must go! I must go. I—I don’t know any Paul,” and before the Racer boys could have stopped him, had they been so inclined, the man wheeled about and walked rapidly down the beach.

“Well, wouldn’t that frazzle you!” exclaimed Andy.

“It certainly is queer,” agreed his brother.

They stood looking down the beach after the figure of the strange man who had seemed to know the lad whom they had rescued from the sea, but who, on learning of his location, had shown a desire to get away without calling on the unfortunate youth.

Andy set out on a run.

“Here, where you going?” his brother demanded quickly.

“I’m going after that man, and make him tell what he knows!” declared the impulsive youth. “It’s a shame to let him get away in this fashion, just when we were on the verge of learning something,” Andy called back over his shoulder.

“You come right back here!” exclaimed the older lad, sprinting after his brother and catching him by the arm.

“But he’ll get away, and we’ll never solve the mystery!”

“That may be, but we can’t take this means of finding out. We don’t know who that man is. He may be a dangerous chap, who would make trouble if you interfered with him. You stay here.”

“But how are we ever going to find out, Frank?”

“If this boy is the one whom that man wants he’ll show his hand sooner or later. He was taken by surprise when he found that we had him, and he didn’t know what to say. But he won’t disappear altogether—not while the lad is with us. He’ll come around again. Now you stay with me.”

“All right,” assented Andy, but with no very good grace. “I’m going to holler after him, anyhow.”

Then, before Frank could stop him, had he been minded to do so, Andy raised his voice in a shout:

“Hey, where are you going? Don’t you want to send some word to that boy we rescued?”

The man turned half around, and for a moment Andy and Frank hoped he would come back. Instead he shouted something that sounded like:

“Important business—see—later—don’t bother me.”

“Humph!” exclaimed Andy, as the man resumed his rapid walk. “We’re not going to bother you. But we’ll solve that mystery, whether you want us to or not,” he added firmly. “Won’t we, Frank?”

“If it’s possible. I’m almost ready to go out now and have a search for the motor boat, but I think we’d better go back and tell him what happened.”

“Tell who, the doctor?”

“No, this lad—the one who’s at our house. He may know the man when we describe him.”

“That’s so. Paul, the man said his name was. Wonder what the other half was?”

“Guess you’ll have to take it out in wondering. Come on back to the house.”

It was a great disappointment to Frank and Andy when, after detailing their adventure with the queer man, and describing him minutely, to have the rescued lad say:

“I’m sorry, boys, but I can’t recall any such man.”

“Try hard,” suggested Frank.

“I am trying,” and the youth frowned and endeavored hard to concentrate his thoughts. “No, it’s useless,” he added with a sigh. “My memory on that point, if I ever had any, has gone with the rest of the past. It’s too bad. I wish I could remember.”

“Well, don’t try any more now,” said Frank quickly, as he saw that the youth was much distressed. “We’ll do our best to help you out. And the first thing we’ll do will be to look for that motor boat—that is, if she’s still floating.”

“Does the name Paul mean anything to you?” asked Andy. “That’s what the man called you before he thought.”

“Paul—Paul,” mused the lad. “No, it doesn’t seem to be my name. Did he mention any other?”

“No, he cut himself off short. But what’s the matter with us calling you Paul, until we find out your right name? It’s a bit awkward to refer to you as ‘he’ or ‘him’ all the while. How does Paul suit you?”

“Fine! I like it.”

“But what about his other name?” asked Frank.

“Gale!” suddenly shouted Andy.

“Gale?” repeated his brother wonderingly.

“Yes, don’t you see,” and Andy laughed. “We picked him up in a gale. His first name’s Paul, I’m sure, and Paul Gale would be a good name. How about it, Paul?”

“It will do first rate until I can find my real one. Paul Gale—Paul Gale—it sounds good.”

“Then Paul Gale it shall be,” declared Andy, and when he suggested it to his father and mother that night they agreed with him. So the rescued lad became Paul Gale.

As the days passed he gained in health and strength until he was able to walk out. Then the wonderful sea air of Harbor View practically completed the recovery, until Dr. Martin declared that there was no further use for medicine, and only nourishing food was needed.

“But about his mind,” the physician went on, “time alone can heal that. We must be patient. Take him out with you, Andy and Frank, when he is able to go, and let him have a good time. That will help as much as anything.”

In the meanwhile, pending the gaining of complete strength on the part of Paul Gale, as he was now called, the two Racer boys made many trips around the Shark’s Teeth in their sailboat, looking for the wrecked motor craft. But they could not locate it. Nor were their inquiries any more successful. Sailors and fishermen who went far out to sea were questioned but could give no trace of the wreck.

“Guess we’ll have to give it up,” said Andy with a sigh one day.

“It’s like the mysterious man,” added his brother.

Mr. Racer was much interested in the efforts his sons were making to solve the mystery of Paul Gale. He even advertised in a number of papers, giving details of the rescue, and asking any persons who might possibly know the history of such a youth as he described, to call on him at his New York office. But none came.

Paul had not yet ventured far from the house, for he was still rather weak. His arm, too, was very painful, and he could not yet accompany his two friends on any of their rowing or sailing trips.

“But I’ll go soon,” he said one day, when Frank and Andy started off for the beach, with the intention of interviewing some lobstermen who were due to arrive from a long cruise out to sea. “Some time I’ll surprise you by coming along.”

“Glad of it,” called Frank, linking his arm in that of his brother. Together they strolled down on the sands, to await the arrival of the lobstermen. They found Bob Trent there, loading up his wagon with soft clams, which he had just dug.

As Bob tossed in shovelful after shovelful of the bivalves, the two Racer boys saw approaching the vehicle a youth of about their own age but of entirely different appearance. For, whereas the Racer boys dressed well they made no pretense of style, especially when they were away on their vacation. But the lad approaching the wagon was “dressed to kill clams,” as Andy laughingly expressed it.

“Look at Chet Sedley!” exclaimed the younger lad to his brother. “Talk about style!”

“I should boil a lobster; yes!” agreed Frank, laughing.

And well he might, for Chet, who was a native of Harbor View, had donned his “best” that afternoon. He wore an extremely light suit, with new tan ties of a light shade, and his purple and green striped hose could be seen a long distance off.

“You can hear those socks as far as you can get a glimpse of them,” remarked Andy.

“And look at his hat,” observed Frank. It was a straw affair, of rough braid, and the brim was in three thicknesses or “layers” so that it looked not unlike one of those cocoanut custard cakes with the cocoanut put in extremely thick. In addition to this Chet’s tie was of vivid blue with yellowish dots in it, and he carried a little cane, which he swung jauntily.

As Chet passed the clam wagon, manned by Bob, who was dressed in his oldest garments, as befitted his occupation, one of the bivalves slipped from the shovel, and hit on the immaculate tan ties of the Harbor View dude. It left a salt water mark.

“Look here, Bob Trent! What do you mean by that?” demanded Chet indignantly as he took out a handkerchief covered with large green checks and wiped off his shoe. “How dare you do such a thing?”

“What did I do?” asked the clammer innocently, for he had not seen the accident.

“What did you do? I’ll show you! I’ll teach you to spoil a pair of new shoes that cost me two dollars and thirty-five cents! I’ll have you arrested if that spot doesn’t come out, and you’ll have to pay for having them cleaned, too.”

“I—I—” began Bob, who was a lad never looking for trouble, “I’m sorry—I—”

“Say, it’s you who ought to be arrested, Chet!” broke in Andy, coming to the relief of his chum.

“Me? What for, I’d like to know?” asked the dude, as he finished polishing the tan ties with the brilliant handkerchief.

“Why you’re dressed so ‘loud’ that you’re disturbing the peace,” was the laughing reply. “You’d better look out.”

“Such—er—jokes are in very bad taste,” sneered Chet, whose parents were in humble circumstances, not at all in keeping with his dress. In fact, though Chet thought himself very stylish, it was a “style” affected only by the very vain, and was several years behind the season at that.

“You’re a joke yourself,” murmured Frank. “It wasn’t Bob’s fault that the clam fell on you, Chet,” he added in louder tones.

“Why not, I’d like to know?”

“Because you are so brilliant in those togs that you blinded his eyes, and he couldn’t see to shovel straight; eh, Bob?”

“I—I guess that’s it. I didn’t mean to,” murmured Bob.

“Well, you’ll pay for having my shoes shined just the same,” snapped Chet, as he restored his handkerchief to his pocket with a grand flourish.

“Whew! What’s that smell?” cried Andy, pretending to be horrified. “I didn’t know you could smell the fish fertilizer factory when the wind was in this direction.”

“Me either,” added Frank, entering into the joke. “It sure is an awful smell. Whew!”

“I—I don’t smell anything,” said Chet, blankly.

“Maybe it’s your handkerchief,” went on Andy. “Give us a whiff,” and before the dude could stop him the younger Racer boy had snatched it from his pocket. “Whew! Yes, this is it!” he cried, holding his nose as he handed the gaudy linen back. “How did it happen, Chet? Did you drop it somewhere? It’s awful!” and he pretended to stagger back. “Better have it disinfected.”

“That smell! On my handkerchief!” fairly roared Chet. “That’s the best perfumery they have at Davidson’s Emporium. I paid fifteen cents a bottle for it. Give me my handkerchief.”

“Fifteen cents a bottle?” cried Andy. “Say, you got badly stuck all right! Fifteen cents! Whew! Get on the other side, where the wind doesn’t blow, please, Chet.”

“Oh, you fellows think you are mighty funny,” sneered the dude. “I’ll get even with you yet. Are you going to pay for shining my shoes, Bob?”

“I—er—” began the captain’s son.

“Sit down and let’s talk it over,” suggested Andy, as he flopped down on the sand. “Have a chair, Chet. You must be tired standing,” he went on.

“What? Sit there with—with my good clothes on?” demanded the dude in accents of horror. “Never!”

“A clam might bite you, of course. I forgot that,” continued the fun-loving Andy. Then, as Chet continued to face Bob, and make demands on him for the price of having his tan shoes polished, the younger Racer lad conceived another scheme.

In accordance with what he thought were the dictates of “fashion,” Chet wore his trousers very much turned up at the bottoms. They formed a sort of “pockets,” and these pockets Andy industriously proceeded to fill with sand. Soon both trouser legs bulged with the white particles.

“Well, are you going to pay me?” demanded Chet of Bob finally.

“I—I didn’t mean to do it, and I haven’t any change to pay you now,” said the captain’s son.

“Pay him in clams,” suggested Frank.

“No, I want the money,” insisted the dude. He took a step after Bob, who walked around to get on the seat of the wagon. At his first movement Chet was made aware of the sand in the bottoms of his trousers.

The dude looked down, half frightened. Then he made a leap forward. The sand was scattered all about, a good portion of it going into the low shoes Chet wore. This filled them so that they were hard to walk in, and the next moment the stylishly dressed youth lurched, stepped into a hollow, and fell flat on the sand, his slender cane breaking off short at the handle as it caught between his legs.

“Come here and I’ll pick you up!” shouted Andy, who had scrambled away as he saw Chet start out.

“You—you—who did this? Who pushed me?” stammered Chet, as he got up spluttering, for some sand had gotten in his mouth. “I’ll have revenge for this—on some one! Who knocked me down?”

“It was the strong perfumery on your handkerchief,” suggested Andy. “It went to your head, Chet.”

“It was you, Bob Trent; you did it!” yelled the dude, making a rush for the captain’s son. “I’ll give you a thrashing for this!”

“Hold on there, Chet!” cried Andy, as he saw Bob about to suffer for the trick he himself had played. The dude had hauled back his fist to strike the captain’s son, who put himself in a position of defense.

“You can’t stop me!” yelled Chet, making rapid motions with his fists. Bob Trent shrank back.

“Stop, I say!” shouted Andy again, making a rush to get between the prospective combatants.

“Now you see what your fooling did,” spoke Frank, in a low voice to his brother. “Why can’t you cut it out?”

“Can’t seem to,” answered the fun-loving lad. “But I won’t let ’em fight. I’ll own up to Chet, and he can take it out of me if he likes.”

“There!” suddenly cried Chet, as he landed a light blow on Bob’s chest “That’ll teach you to dirty up my shoes, fill my pants full of sand and trip me up. There’s another for you!”

He tried to strike the captain’s son again, but Bob, though he was not a fighting lad, was a manly chap, who would stand up for his rights. Suddenly his fist shot forward and landed with no little force on the nose of the dude.

Once more Chet went down, not so gently as before, measuring his length in the sand. When he arose his face was red with anger, and his former immaculate attire was sadly ruffled.

“I—I—I’ll have you all arrested for this!” he yelled. “I’ll make a complaint against you, Bob Trent, and sue you for damages.”

Chet made another rush for the driver of the clam wagon as soon as he could arise, but this time Andy had stepped in between them and blocked the impending blows.

“That’ll do now!” exclaimed the younger Racer lad with more sternness and determination than he usually employed. “It was all my fault. I filled your pants with sand, Chet. I really couldn’t help it, the bottoms were so wide open. But I didn’t push you when you fell the first time. You tripped in that hollow. Now come on, and I’ll buy you two chocolate sodas to square it up. I’ll treat the crowd. Come along, Bob.”

“No, I can’t,” answered Bob. “Got to get along with these clams. I’m late now. But I want to say that I’m sorry I knocked Chet down. I wouldn’t have done it if he hadn’t struck me first.”

“That’s right,” put in Frank. “I’m sorry it happened.”

“So am I,” added Andy contritely. But it is doubtful if he would remain sorry long. Already a smile was playing over his face.

“Well, who’s coming and have sodas with me?” asked the younger Racer brother, after an awkward pause, during which Bob mounted the seat of his wagon and drove off. “Come on, Chet I’ll have your cane fixed, too. And if you don’t like a chocolate soda you can have vanilla.”

“I wouldn’t drink a soda with you if I never had one!” burst out the dude, as he wiped the sand off his shoes and brushed his light suit. “I’ll get square with you for this, too; see if I don’t.”

“Oh, very well, if you feel that way about it I can’t help it,” said Andy. “I said I was sorry, and all that sort of thing, but I’m not going to get down on my knees to you. Come along, Frank. Let’s go for a sail.”

The clam wagon was heading for the street that led up from the beach. Chet had turned away with an injured air, and Andy linked his arm in that of his brother.

“You see what your fooling led to,” said Frank in a low voice, as the two strolled off. “Why can’t you let up playing jokes when you know they’re going to make trouble?”

“How’d I know it was going to make trouble, just to put sand in Chet’s pants?” demanded Andy, with some truth in his contention. “If I had known it I wouldn’t have done it. But it was great to see him tumble, wasn’t it?”

“Oh, I suppose so,” and in spite of his rather grave manner Frank had to smile. “But you must look ahead a bit, Andy, when you’re planning a joke.”

“Look ahead! The joke would lose half its fun then. It’s not knowing how a thing is going to turn out that makes it worth while.”

“Oh, you’re hopeless!” said Frank, laughing in spite of himself.

“And you’re too sober!” declared his brother. “Wake up! Here, I’ll beat you to the dock this time!” And with that Andy turned a handspring, and darted toward the pier, near which their sailboat was moored. Frank started off on the run, but Andy had too much of a start, and when the elder lad arrived at the goal Andy was there waiting for him.

“Now the sodas are on you!” he announced.

“How’s that?”

“Why, we didn’t finish the rowing race on account of the whale, but this contest will do as well. I’ll have orange for mine.”

“Oh, all right, come on,” and Frank good-naturedly led the way toward the only drug store in Harbor View. “But I thought you were going for a sail, and see if we could get a trace of the mysterious wrecked motor boat,” he added.