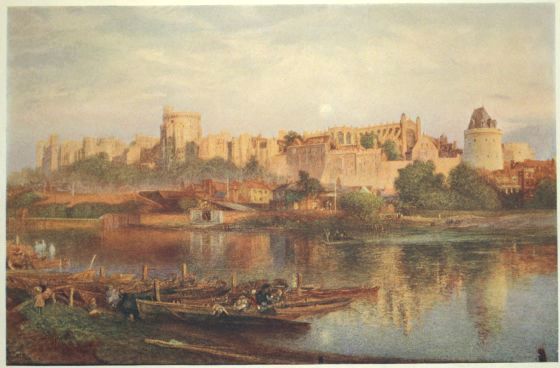

Reproduced by André & Sleigh, Ltd., Bushey, Herts.

WINDSOR CASTLE.

FROM A WATER-COLOUR PAINTING BY ALFRED W. HUNT R.W.S. IN THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF BRITISH ART.

Title: Cassell's History of England, Vol. 6 (of 8)

Author: Anonymous

Release date: February 24, 2020 [eBook #61502]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Jane Robins and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

FROM THE DEATH OF SIR ROBERT PEEL TO

THE ILLNESS OF THE PRINCE OF WALES

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS,

INCLUDING COLOURED

AND REMBRANDT PLATES

VOL. VI

THE KING'S EDITION

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LIMITED

LONDON, NEW YORK, TORONTO AND MELBOURNE

MCMIX

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

PAGE

The Papal Aggressions—The Ecclesiastical Titles Bill—Mr. Locke King's Motion on County Franchise—Resignation of the Government—The Great Exhibition—The President of the French Republic and the Assembly—Preparations for the Coup d'État—The Barricades—The Plébiscite—Weakness of the Russell Administration—Independence of Lord Palmerston—The Queen's Memorandum—Dismissal of Palmerston—The Militia Bill—Russell is turned out—The Derby Ministry—The General Election—Defeat of the Conservatives—Death and Funeral of the Duke of Wellington—The Aberdeen Administration—Mr. Gladstone's Budget—The Eastern Question again—The Diplomatic Wrangle—The Sultan's Firman—Afif Bey's Mission—Difficulties in Montenegro—England and France—The Menschikoff Mission—Lord Stratford de Redcliffe's Instructions—The Czar and Sir Hamilton Seymour—Menschikoff at Constantinople—The English and French Fleets—Arrival of Lord Stratford de Redcliffe—Menschikoff's ulterior Demands—Action of the Powers 1

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Widening of the Question—The Fleets in Besika Bay—Lord Clarendon's Despatch—The Czar and Lord Stratford de Redcliffe—Nesselrode's "Last Effort"—Military Preparations—Blindness of the British Cabinet—Nesselrode's Ultimatum rejected—Occupation of the Principalities—Projects of Settlement—The Vienna Note—Its Rejection by the Porte—-Division of the Powers—Text of the Note—Divisions in the British Cabinet—The Fleets in the Bosphorus—The Conference at Olmütz—The Sultan's Grand Council—Lord Stratford de Redcliffe's last Effort—Patriotism of the Turks—Omar Pasha's Victories—The Turkish Fleet destroyed at Sinope—Indignation in England—The French Suggestion—It is accepted by Lord Clarendon—Russia demands Explanations—Diplomatic Relations suspended—The Letter of Napoleon III.—The Western Powers arm—An Ultimatum to Russia—It is unanswered—The Baltic Fleet—Publication of the Correspondence—Declarations of War 19

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Attitude of the German Powers—The Lines at Boulair—The Campaign on the Danube—The Siege of Silistria—It is raised—Evacuation of the Principalities—The British Fleet in the Black Sea—Arrival of the Allied Armies—A Council of War—The Movement on Varna—Unhealthiness of the Camp—An Attack on the Crimea resolved on—Doubts of the Military Authorities—Despatch to Lord Raglan—Lord Lyndhurst's Speech—Raglan's reluctant Assent—The Expedition sails—Debarkation in the Crimea—Forays of the French Troops—Composition of the Allied Armies—The Start—The first Skirmish—St. Arnaud's Plan—Slowness of the British—Battle of the Alma 35

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

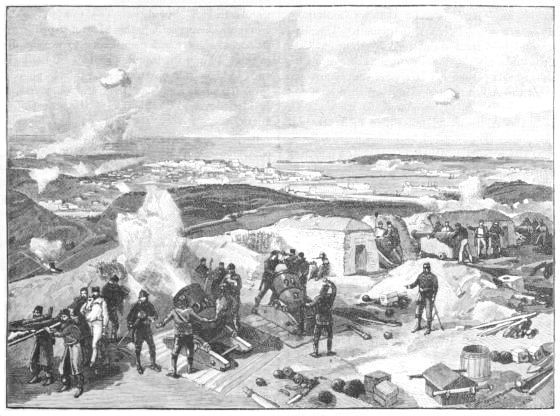

Two Days on the Alma—Retreat of the Russians—Raglan proposes a Flank Movement—Korniloff and Todleben—Death of St. Arnaud—The Allies in Position—Menschikoff reinforces Sebastopol—Todleben's Preparations—The Opposing Batteries—The Sea—Defences of Sebastopol—Doubts of the Admirals—Opening of the Bombardment—The French Fire silenced—Success of the British—Failure of the Fleets—The Bombardment renewed—Menschikoff determines to Raise the Siege—The Attack on Balaclava—Lord Lucan's Warning—Liprandi's Advance—Capture of the Redoubts—The 93rd—Lord Lucan's Advance—Charge of the Heavy Brigade—Raglan, Lucan, and Nolan—Charge of the Light Brigade—The Valley of Death—The Goal—End of the Battle 50

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Effects of Balaclava—Attack on Mount Inkermann—Evans defeats the Russians—Menschikoff is reinforced—The Guards to the Rescue—Arrival of Lord Raglan—Bosquet's Help refused—The Fight at the Sandbag Battery—The Coldstreams—The Guards' Charge—Defeat of Cathcart—Charges of the Zouaves—The Russians slowly retreat—Canrobert hesitates to pursue—Loss of the Allies—Their Plight—The Baltic Fleet—Changed Position of the Allies—Determination of the British Nation—Storm of November 14th—Destruction of the Transports—Sufferings of the Troops—Conduct of the War—-Timidity of the Government—Enlistment of Boys—Autumn Session—The Paper Warfare—Hostile Motions in Parliament—Lord John Russell's Resignation—Palmerston forms a Ministry—Resignation of the Peelites 64

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

State of the Army—Food, Clothing, and Shelter—Absence of a Road—Want of Transport—Numbers of the Sick—State of the Hospitals—Miss Nightingale—Mr. Roebuck's Committee—Military Operations—The French Mistake—Improvement of the Situation—Arrival of General Niel—Attack upon the Malakoff Hill approved—The Russian Redoubt constructed—Death of Nicholas—Todleben's Counter-Approaches—Raglan and Canrobert disagree—The second Bombardment—Egerton's Pit—Night Attack of General de Salles—The Emperor's Interference—Canrobert's Indecision—The Kertch Project—Arrival of the Sardinian Contingent—The Emperor's Visit to Windsor—The Emperor's Plan of Campaign—It is rejected by Raglan and Omar—Resignation of Canrobert 80

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

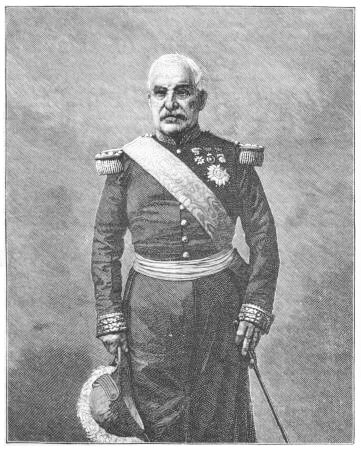

The Course of Diplomacy—Austria's Position—The Four Points—The Czar agrees to negotiate—Russell's Mission to Vienna—Prince Gortschakoff's Declaration—The Third Point broached—Its Rejection by Russia—Count Buol's final Proposition—The War debated in Parliament—Lord John Russell resigns—Strength of the Government—The Sardinian and Turkish Loans—Vote of Censure on the Aberdeen Cabinet—Finance of the War—General Pélissier—The Fight for the Cemetery—Success of the French—Occupation of the Tchernaya—Expedition to Kertch—Description of the Peninsula—Sir George Brown's Force—The Russians blow up their Magazines—Occupation of Kertch and Yenikale—Lyons in the Sea of Azoff—Result of the Expedition—Attack upon Sebastopol decided—Ordnance of the Allies—The Attack—The French occupy the Mamelon—The British in the Quarries—Lord Raglan overruled—New Batteries—Pélissier's Change of Plan—The Fourth Bombardment—Preparations for the Assault—Mayran's Mistake—Brunet and D'Autemarre—The Attack on the Redan fails—Abandonment of the Assault—General Eyre—Losses on both Sides—Death of Lord Raglan 91

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

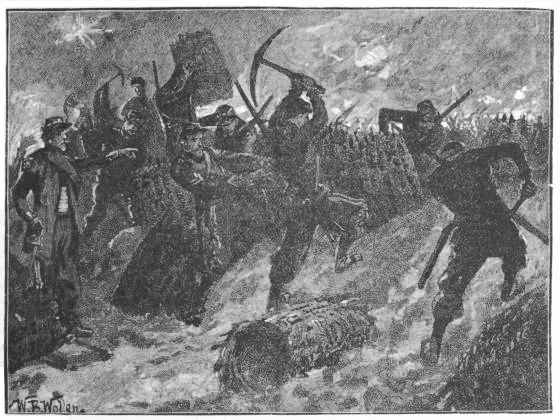

Changes in the Allied Camp—Advance upon the Malakoff and Redan—Prince Gortschakoff determines to Attack—The Allied Camp on the Tchernaya—Gortschakoff's Reinforcements—The Russian Plan—Read's Precipitation—Check of the Russian Attack—The French Counter-stroke—Gortschakoff changes his Front—The Battle is won—Allied Losses—The French sap towards the Malakoff——The British Bombardment—Combats before the Malakoff—Gortschakoff secures his Retreat—Council of September 3rd—Plan of Attack—The Last Bombardment—The Hour of Attack—The Signal—Assault of the Malakoff—MacMahon and Vinoy—Failures upon the Curtain and Little Redan—MacMahon is Impregnable—Failure to take the Redan—Evening—Gortschakoff's Retreat—End of the Siege 113

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

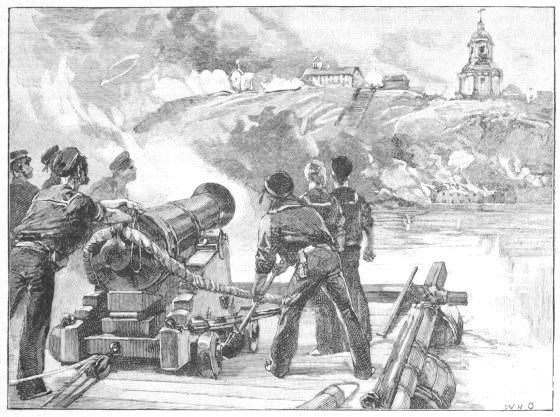

Gortschakoff clings to Sebastopol—Destruction of Taman and Fanagoria—Expedition to Kinburn—Resignation of Sir James Simpson—Explosion of French Powder Magazine—The Fleets in the Baltic—The Hango Massacre—Attack on Sveaborg—What the Baltic Fleet did—Russia on the Pacific Coast—Petropaulovski blown up—The Russian Position in Asia—The Turks left to their Fate—Foreigners in Kars—Defeat of Selim Pasha—Battle of Kuruk-Dereh—Colonel Williams sent to Kars—Mouravieff arrives—His Expeditions towards Erzeroum—The Blockade begins—The Assault of September 29th—Kmety's success—The Tachmasb Redoubt—Attack on the English Lines—Victory of the Turks—Omar's Relief fails—Sufferings of the Garrison—Williams capitulates—Terms of the Surrender 128

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Winter of '55—Visit of the Czar to the Crimea—State of the British Army—Sufferings of the French—Destruction of Sebastopol—The Armistice—Views of Austria and Russia—And of the Emperor Napoleon—Britain acquiesces in Peace—Walewski's Circular—Austria proposes Peace—Buol's Despatch—Nesselrode's Circular—The Austrian Ultimatum—Russia gives way—The Congress fixed at Paris—The Queen's Speech—Speeches of Clarendon and Palmerston—Meeting of the Congress—The Armistice—An Imperial Speech—The Sultan's Firman—Prussia admitted to the Congress—Birth of the Prince Imperial—The Treaty signed—Its Terms—Bessarabia and the Principalities—The Three Conventions—The Treaty of Guarantee—Count Walewski's Four Subjects—The Declaration of Paris—International Arbitration mooted—The Kars Debate—Debates on the Peace—General Rejoicings—Cost of the War—First Presentation of the Victoria Cross 144

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Prorogation of 1853—End of the Kaffir and Burmese Wars—The Wages Movement—The Preston Strike—The Crystal Palace—Marriage of the Emperor of the French—His Visit to England—The Queen's Return Visit—Festivities in Paris—Lord Lyndhurst on Italy—Lord Clarendon's Reply—Similar Debate in the Commons—Withdrawal of the Western Missions from Naples—The Anglo-French Alliance—The Suez Canal—The Arrow Affair—Mr. Cobden's Resolution—Mr. Labouchere's Reply—Lord Palmerston's Speech—The Division—Announcement of a Dissolution—Retirement of Mr. Shaw-Lefevre—Lord Palmerston's Victory at the Polls—Mr. Denison elected Speaker—Betrothal of the Princess Royal—Abolition of "Ministers' Money"—The new Probate Court—The Divorce Bill in the Lords—The Bishop of Oxford's Amendments—Motions of Mr. Henley and Sir W. Heathcote—Major Warburton's Amendment—The Bill becomes Law—The Orsini Plot—Walewski's Despatch—The Conspiracy to Murder Bill—Debate on the Second Reading—Defeat of the Government—The Derby Ministry 160

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Condition of India—The Bengal Army—The Greased Cartridges—The Prudence of Hearsey—The Chupatties—Disarming of the 19th—Inactivity of Anson—The Sepoys at Lucknow—A Scene at Barrackpore—At Meerut—The Rebellion begins—The Rush on Delhi—The City is sacked—The Powder Magazine—It is exploded—The Fall of Delhi—Sir Henry Lawrence—Energetic Measures at Lahore—Mutiny at Ferozepore—Peshawur is saved—Action of the Civil Authorities—The Siege Train—Death of Anson—John Lawrence in the Punjab—Cotton disarms the Sepoys—The Trans-Indus Region is secure—Mutiny supreme elsewhere—Progress of the Rising—Lucknow—Oude ripe for Revolt—The first Outbreak suppressed—The Ranee of Jhansi—The Five Divisions of Oude 182

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

March of the British on Delhi—Battles on the Hindon—Wilson joins Barnard—Hodson reconnoitres Delhi—The Guides arrive—The Delhi Force in Position—An unfulfilled Prophecy—Lord Canning's Inaction—Lord Elphinstone's Discretion—Troops from Madras and Persia—Benares is saved—So is Allahabad—Cawnpore—Nana Sahib and Azimoolah—The Europeans in the Entrenchment—The Mutiny—Sufferings of the Garrison—Valour of the Defence—The Well—The Hospital catches Fire—Incidents of the Siege—Moore's Sortie—Nana Sahib's Letter—The Massacre at the Ghaut—Central India—Lawrence fortifies the Residency at Lucknow—The Death of Lawrence. 203

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Havelock to the Front—Nana Sahib's Position—Cawnpore reoccupied—Nana Sahib's Vengeance—Havelock pushes on for Lucknow—End of Havelock's first Campaign—Lord Canning and Jung Bahadoor—Mutiny at Dinapore—Its Effects—Before Delhi—Attempt to surprise a Convoy—Death of Barnard—Wilson's Discipline—John Lawrence's Perplexities—Disarmament at Rawul Pindee and Jhelum—Mutiny at Sealkote—It is avenged by Nicholson—The Drama at Peshawur—Reinforcements for Delhi—Nicholson arrives—The Crisis in the Siege. 219

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Defect of the Delhi Fortifications—The British Advance—Nicholson's Column—The Cashmere Gate exploded—Nicholson mortally wounded—Failure at the Lahore Gate—The British possess the City—Capture of the King—The Princes shot—Effect of the Fall of Delhi—Greathed's Column—The Relief of Agra—Affairs at Lucknow—The Garrison—Character of the Attack—Explosion of Mines—Inglis's Report—Sir Colin Campbell at Calcutta—Havelock superseded by Outram—Position of Havelock's Army—Eyre's Exploits—Havelock crosses the Ganges—Combat of Mungulwar—Battle at the Alumbagh—The Plan of Attack—The Goal is reached—The Scene that Evening—Havelock's Losses—Outram determines to remain—Energy of the Indian Government—The Force at Cawnpore—Sir Colin to the Front—Kavanagh's daring Deed—Campbell retires on Cawnpore—Death of Havelock. 233

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Windham at Cawnpore—Sir Colin Campbell to the Rescue—Battle of Cawnpore—Seaton advances from Delhi—His Campaign in the Doab—Hodson's Ride—Campbell at Futtehghur—Condition of Central India—Rose at Indore—Oude or Rohilcund?—Plans for the Reduction of Lucknow—Waiting for the Nepaulese—Campbell's final Advance—Outram crosses the Goomtee—Death of Hodson—The Fall of Lucknow—Lord Canning's Proclamation—The Conquest of Rohilcund—Nirput Singh's Resistance—Sir Colin marches on Bareilly—Battle of Bareilly—The Moulvie attacks Shahjehanpore—It is relieved by Brigadier John Jones—Sir Colin returns to Futtehghur—End of the Campaign. 255

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

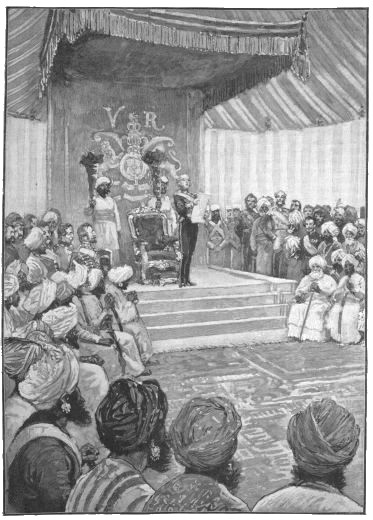

The State of Central India—Objects of Rose's Campaign—The two Columns—Capture of Ratghur—Relief of Saugor—Capture of Gurrakota—Annexation of the Rajah of Shahghur's Territory—Capture of Chandaree—Rose arrives at Jhansi—The Ranee and Tantia Topee—Jhansi is stormed—Battles of Koonch and Calpee—Tantia Topee captures Gwalior—Smith and Rose rescue the Place—Lord Elphinstone's Proceedings—Flight of Tantia Topee—Lawrence in the Punjab—Banishment of the King of Delhi—The Subjugation of Oude—Hope Grant's Flying Column—Transference of the Government to the Crown—The Queen's Proclamation—Clyde enforces the Law—Disappearance of the Begum and Nana Sahib—The Country at Peace—The Last Adventures of Tantia Topee—Settlement of India—The Financial Question—The Indian Army—Increase of European Troops—The Native Levies—Abandonment of Dalhousie's Policy. 270

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

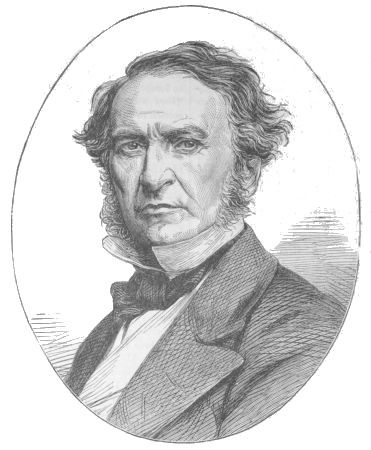

Termination of the Hudson's Bay Monopoly—British Columbia and Vancouver—Mr. Locke King's Bill for the Abolition of the Property Qualification—Attempt to abolish Freedom of Arrest for Debt—Mr. Bright agitates for Reform—The Conservatives propose a Reform Bill—Mr. Disraeli's Speeches—Secession of Mr. Walpole and Mr. Henley—Lord John Russell's Resolution—Seven Nights' Debate—Replies of Lord Stanley and Sir Hugh Cairns—Mr. Bright's Speech—Speeches of Mr. Gladstone and Mr. Disraeli—Defeat of the Government—Lord Derby announces a Dissolution—The General Election—Parliament reassembles—Lord Hartington's Amendment—Defeat of the Government—Lord Malmesbury's Statement in his "Memoirs"—Union of the Liberal Party—Lord Granville's attempt to form a Ministry—Lord Palmerston becomes Premier—His Ministry—The Italian Question in Parliament—State of the Peninsula—Speeches of Napoleon and Victor Emmanuel—Ambiguous Attitude of Napoleon—Lord Malmesbury's Diplomacy—Lord Cowley's Mission—The Austrian Ultimatum—Malmesbury's Protest—"From the Alps to the Adriatic"—The Armies in Position—First Victories of the Allies—Magenta and Milan—Battle of Solferino—The Armistice—Treaty of Villafranca—Lord John Russell's Commentary. 287

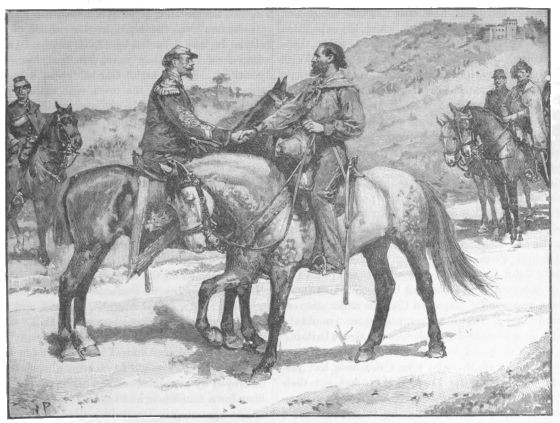

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

The Peace of Zurich—Its Repudiation by Italy—The Idea of a Congress—Garibaldi in Central Italy—The Cession of Nice and Savoy—The Sicilian Expedition—Garibaldi lands at Marsala—Capture of Palermo—The Convention for Evacuation signed—Battle of Milazzo and Evacuation of Messina—Garibaldi master of Sicily—Attempts to prevent the Conquest of Naples—A Landing effected—The victorious March—Flight of the King—Garibaldi occupies Naples—He is warned off Venetia—The Sardinian Troops occupy the Papal States—Battle of the Volturno—Victor Emmanuel's Advance—His Meeting with Garibaldi—Accomplishment of Garibaldi's Programme—Refusal of his Demands—He retires to Caprera—Lord John Russell's Despatch. 303

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

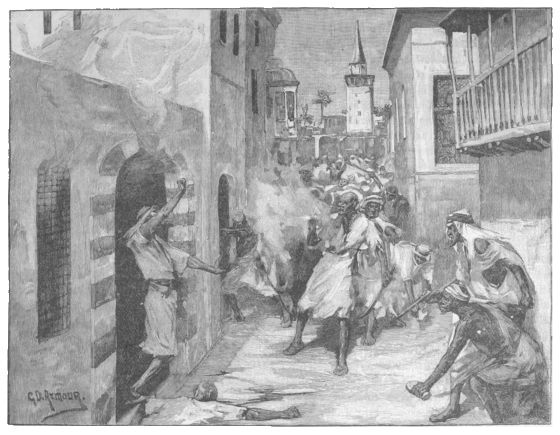

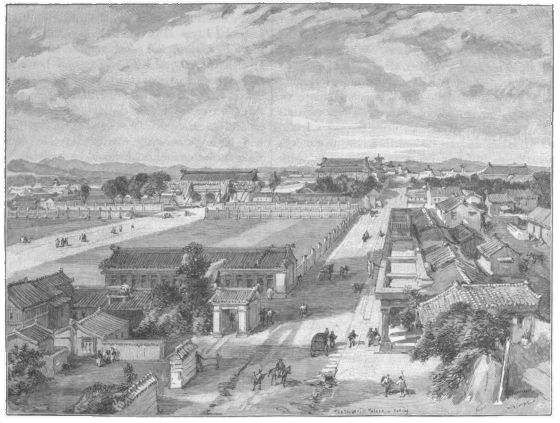

The Session of 1860—Debates on Nice and Savoy—Mr. Gladstone's Budget—The French Commercial Treaty—The Paper Duties Bill—Lord Palmerston's Motion of Inquiry—Mr. Gladstone's Resolution—Lord John Russell's Reform Bill—Mr. James Wilson and Sir Charles Trevelyan—The Defences of India and Great Britain—The Massacre by the Druses—The French Expedition—China once more—Repulse on the Peiho—Lord Elgin and Baron Gros—The Advance on Pekin—Capture of the Taku Forts—The Summer Palace looted—Release of Mr. Parkes—Lord Elgin decrees the Destruction of the Palace—The Treaty of Peace—The Prince of Wales in Canada—Death of the Duchess of Kent—The American Civil War—Election of Lincoln—Secession of South Carolina—The Confederate States—The British Cabinet declares Neutrality—Affair of the Trent—The Paper Duties Bill and the Church Rates Bill—Sidney Herbert and the Volunteers 310

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

The Queen's Visit to Ireland—The Royal Family at Balmoral—Illness and Death of the Prince Consort—The Address in Parliament—The Education Code—The American War in Parliament—The Nashville—The Blockade and the Cotton Famine—The Game Act—Palmerston and Cobden—Prorogation of Parliament—The Garotters—The Alabama—Mr. Adams and Earl Russell—The Alabama sails—Progress of the War in America—Greece and the Ionian Islands—The Society of Arts—The Exhibition of 1862—Jealousy of Prussia and France—The Colonial Exhibition—The Cotton Famine in 1863—Engagement and Marriage of the Prince of Wales—Mr. Gladstone's Budget—"Essays and Reviews"—Obituary of the Year—Russell and Gortschakoff—The Polish Revolution—Russell and Brazil—The Coercion of Japan—The American War in 1863—The Crown of Mexico offered to the Archduke Maximilian—Captain Speke in Central Africa 326

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Peace and Prosperity in 1864—Birth of an Heir to the Prince of Wales—Mr. Gladstone's Budget—Mr. Stansfeld and Mazzini—The Government and the London Conference on the Danish Question—Mr. Gladstone on Parliamentary Reform—Resignation of Mr. Lowe—Lord Westbury on Convocation—Garibaldi's Visit to England—The Shakespeare Tercentenary—"Essays and Reviews" again—The Colenso Controversy—Mr. Disraeli and the Angels—The Fenians in Dublin—Origin of the Belfast Riots—The Ashantee War—The Maori War—Waitara Block and its consequences—Suppression of the Rebellion—Final Defeat of the Taepings—Bombardment of Simonasaki—The Cyclone at Calcutta—Its Ravages. 343

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

The Schleswig-Holstein Question—The Nationalities of Denmark—The Connection between Schleswig and Denmark—The Declaration of 1846—Incorporation of Schleswig with Denmark—The Rebellion and its Suppression—The Protocol of London—Defects of the Arrangement—Danification of the Duchies—A Common Constitution decreed and revoked—The King's Proclamation—Schleswig incorporated in Denmark—Federal Execution voted—Russell's high-handed Diplomacy—Death of Frederick VII.—The Augustenburg Candidate—Austria and Prussia override the Diet—Russell's abortive Conference—The Austrian and Prussian Troops advance—Collapse of the Danes—Russell proposes an Armistice—Russell and M. Bille—France declines to interfere—Possibilities of Swedish and Russian Intervention—The Cabinet divided—An Armistice—A futile Conference—The War resumed—Fate of Denmark is sealed—To whom do the Spoils belong?—Summary of Events in Mexico and North America—Southern Filibusters in Canada—Their Acquittal at Montreal—Excitement in America—The Sentence reversed 353

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

The National Prosperity in 1865—Debate on the Malt Tax—Remission of Fire Insurance Duty—Mr. Gladstone's Budget—The Army and Navy Estimates—Academic Discussions of large Questions—Mr. Lowe on Reform—The Union Changeability Bill—The New Law Courts Bill—Debate on University Tests—The Catholic Oaths Bill—Other Ecclesiastical Discussions—The Edmunds Scandal—Mr. Ward Hunt's Motion—Lord Westbury resigns—The General Election—The Rinderpest—The Fenian Conspiracy—Stephens the Head-Centre—His Arrest and Escape from Richmond Gaol—The Special Commission—Obituary of the Year—Lord Palmerston and Mr. Cobden 363

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

The Quietness of Europe—Debate on Poland—The English Prisoners in Abyssinia—Mr. Newdegate and the Encyclical—Visit of the French Fleet—Conclusion of the American War—The Death of Lincoln—Inflated Prosperity of India—The Canadian Defences—The Maori War continues—Mr. Cardwell's Policy—The Jamaica Rebellion—Gordon is hanged—The total of Deaths—Excitement in England—The Jamaica Committee—Eyre committed for Trial—The Chief Justice's Charge—The Bill thrown out—Recovery of Jamaica—Reform again—The Bill of '66—Mr. Gladstone's Speech—Mr. Lowe and Mr. Horsman—"The Cave"—Lord Grosvenor's Amendment—The Government perseveres—The Redistribution Bill—Its Details—Mr. Bouverie's Amendment—It is accepted—Captain Hayter's Amendment—Mr. Disraeli's Strategy—Lord Stanley's Attack—Mr. Walpole's Amendment—Amendments of Mr. Hunt and Lord Dunkellin—Gross Yearly Rental and Rateable Value—The Debate on the Dunkellin Proposal—Defeat of the Government—Their Resignation—Mr. Gladstone's Statement—Earl Russell and the Queen—Lord Derby's Conservative Ministry—The Refusals—Mr. Disraeli's Election Speech—Peace in Parliament—Indian Finance—The Hyde Park Meeting—The Queen's Speech and the Rinderpest 378

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

The Cholera—Laying of the Atlantic Cable—Reform Demonstrations—Mr. Bright and the Queen—The Government prepares a Bill—"Black Friday"—The Overend and Gurney Failure—Limited Liability—Royal Marriages—Prize-Money—The Loss of the London—A bad Harvest—The Fenian Trials—Lord Wodehouse's Letter—Suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act—Rapid Legislation—Wholesale Arrests—Renewal of the Act—Lord Kimberley's Speech—Sweeny and Stephens—The Niagara Raid—Whewell and Keble 406

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

The Schleswig-Holstein Difficulty—Austria favours a Settlement—Bismarck's Terms rejected—His high-handed Proceedings—Convention of Gastein—Bismarck at Biarritz—The Italian Treaty—Question of Disarmament—Fresh Austrian Proposals—Bismarck advocates Federal Reform—La Marmora's Perplexity—He abides by Prussia—Efforts of the Neutral Powers—Failure of the projected Congress—Rupture of the Gastein Convention—The War begins—The rival Strengths—Distribution of the Prussian Armies—Collapse of the Resistance in North Germany—Occupation of Dresden—The Advance of the Prussian Armies—Battle of Königgratz—Cession of Venetia—Italian Reverses—The South German Campaign—Occupation of Frankfort—The Defence of Vienna—French Mediation—The Preliminaries of Nikolsburg—Treaty of Prague—Conditions awarded to Bavaria and the Southern States—The Secret Treaties—Their Disclosure—Humiliation of the French Emperor—His pretended Indifference 418

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Parliamentary Reform—Mr. Disraeli's Resolutions—Mr. Lowe's Sarcasms—The "Ten Minutes" Bill—Lord John Manners' Letter—Ministerial Resignations—Mr. Disraeli's Statement—The Compound Householder—The Fancy Franchises—Mr. Gladstone's Exposure—Mr. Lowe and Lord Cranborne—The Spirit of Concession—Mr. Gladstone on the Second Reading—Mr. Gathorne Hardy's Speech—Mr. Bright and Mr. Disraeli—The Dual Vote abandoned—Mr. Coleridge's Instruction—The Tea-Room Cabal—Mr. Gladstone's Amendment—His other Amendments withdrawn—Mr. Hodgkinson's Amendment—Mr. Disraeli's coup de théâtre—Mr. Lowe's Philippic—The County Franchise—The Redistribution Bill—Objections to It—The Boundaries—Lord Cranborne and Mr. Lowe—Mr. Disraeli's Audacity—The Bill in the Lords—Four Amendments—Lord Cairns's Minorities Amendment—The Bill becomes Law—The "Leap in the Dark"—Punch on the Situation—The Scottish Reform Bill—Prolongation of the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act—Irish Debates—Oaths and Offices Bill—Mr. Bruce's Education Bill—The "Gang System"—Meetings in Hyde Park—Mr. Walpole's Proclamation and Resignation—Attempted Attack on Chester Castle—Attack on the Police Van at Manchester—Explosion at Clerkenwell Prison—Trades Union Outrages at Sheffield—The Buckinghamshire Labourers—The French Evacuation of Mexico—The Luxemburg Question—The Austrian Compromise—Creation of the Dual Monarchy—The Abyssinian Expedition—A Mislaid Letter 433

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

More Coercion for Ireland—The Scottish Reform Bill—The Church Rates Bill—Mr. Disraeli succeeds Lord Derby—Reunion of the Liberals—The Irish Reform Bill—Mr. Gladstone's Irish Church Resolutions—Maynooth Grant and the Regium Donum—The Suspensory Bill—Lord Stanley's Foreign Policy—General Election—Mr. Gladstone's Ministry—Martin v. Mackonochie—Obituary of the Year—Lord Brougham, Archbishop Longley, and Others—The Abyssinian War—Rise of Theodore—The unanswered Letter—Theodore's Retaliation—Mr. Rassam's Mission—His Interview with Theodore—The King's Charges against Cameron—Dr. Beke's Letter—Rassam's Arrest—Mr. Flad's Journey—The Captives' Treatment—Merewether's Advice—Lord Stanley's Ultimatum—Constitution of Sir R. Napier's Expedition—Friendliness of the Natives—Attitude of the Chiefs—Proceedings of Theodore—Massacre of Prisoners—Advance on Magdala—Destruction of Theodore's Army—Negotiations with Theodore—Release of the Prisoners—A Present of Cows—Bombardment of Magdala—Suicide of Theodore—The Return March—The "Mountains of Rasselas"—Sketch of Continental Affairs 464

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

England in 1869—The Irish Church Difficulty—Mr. Gladstone unfolds his Scheme—Debate on the Second Reading—A Bumper Majority—The Bill passes through the House of Commons—Lord Redesdale and the Coronation Oath—The Opposition in the Lords—Dr. Magee's Speech—Amendments in Committee—Concurrent Endowment—Danger of a Collision between the Houses—The Queen and Archbishop Tait—Conference between Lord Cairns and Lord Granville—Their Compromise—Its Terms accepted by Mr. Gladstone—The Bill becomes Law 493

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Mr Lowe's Budget—The Surplus disappears—Mr. Lowe creates a Surplus and proposes Remissions of Taxes—Cost of the Abyssinian Expedition—Sir Stafford Northcote's Explanation—The Endowed Schools' Bill—Speech of Mr. Forster—The Commissioners—Religious Tests at the Universities—Sir John Coleridge's Bill—Sir Roundell Palmer's Speech—The Bill passes through the Commons—It is rejected by the Lords—The Mayor of Cork—The O'Sullivan Disability Bill—Mr O'Sullivan resigns—The Bill dropped—Life Peerages—Lord Malmesbury's Speech—Fenianism in Ireland—Deaths of Lord Derby and Lord Gough—European Affairs: the Emperor prophesies Peace—The General Election—The Senatus Consultum—Official Candidates—The Revolution in Spain—Wanted a King—General Grant the President of the United States—The Alabama Convention rejected 507

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

Law-making in 1870—The Queen's Speech—The Irish Land Problem—Diversities of Opinions—The Agrarian Agitation—Mr. Gladstone's Land Bill introduced—Its Five Parts—Grievances of the Irish Tenant—Free Contract—The Ulster Custom—Compensation for Eviction—The Landlord's Safeguards—The Irish Labourer—Mr Gladstone's Peroration—Direct and Indirect Opposition—The Second Reading carried—Agrarian Outrages—Mr. Fortescue's Coercion Bill—Mr. Disraeli's Amendment to the Land Bill—A Clever Speech—Mr. Lowe's Reply—Progress of the Debate—The Bill becomes Law 518

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

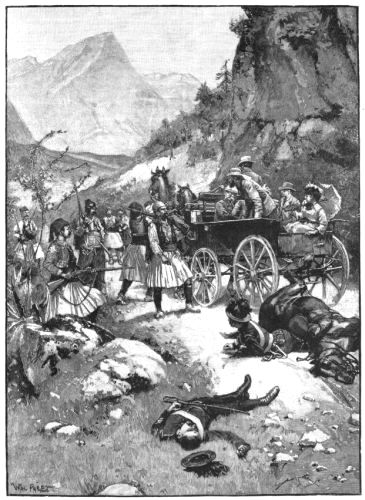

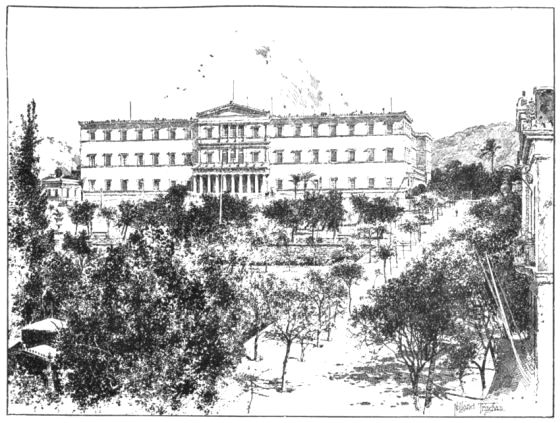

The Elementary Education Bill—Mr. Forster's Speech—Mr. Dixon's Amendment—Mr. Forster's Reply—Mr. Winterbotham's Speech and the Churchmen—Partial Concessions—Changes in the Bill—It becomes Law—Outrage in Greece—Seizure of Tourists by Greek Brigands—Murder of the Prisoners—Army and Navy Estimates—The Budget—Disaster in the Eastern Seas—Obituary of the Year 529

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

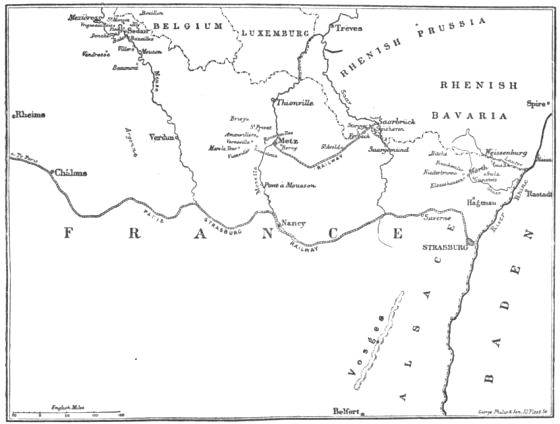

France in 1870—The Ollivier Ministry—Lull in European Affairs—The Hohenzollern Incident—Benedetti at Ems—His Second Interview with King William—War declared at Paris—Efforts of the British Government—Bismarck divulges a supposed Franco-German Treaty—Benedetti's Explanation—Earl Russell's Speech—Belgian Neutrality guaranteed—Unpreparedness of the French Army—The Emperor's Plans—Saarbrück—Weissenburg—The Emperor partially resigns Command—Wörth—MacMahon at Châlons—Spicheren—The Palikao Ministry—Bazaine Generalissimo—Battle of Borny—Mars-la-Tour—Gravelotte—English Associations for the Sick and Wounded—Palikao's Plan—MacMahon's Hesitation—De Failly's Defeat—MacMahon resolves to Fight—Sedan—The Surrender—Napoleon and his Captors—Receipt of the News in Paris—Impetuosity of Jules Favre—A Midnight Sitting—Jules Favre's Plan—Palikao's Alternative—Fall of the Empire—The Government of National Defence—Suppression of the Corps Législatif—The Neutral Powers: Great Britain, Austria, and Italy 548

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

The Vatican Council—The Doctrine of Papal Infallibility—Victor Emmanuel determines on the Occupation of Rome—The Popular Vote—The Papal Guarantees—The Spanish Throne—The Savoy Candidature—Death of Prim—Paris after the Revolution of September—Jules Favre's Circular—Bismarck's Reply—The Negotiations at Ferrières—The Fortifications of Paris—The Investment completed—Thiers and Gambetta—Fall of Strasburg—Bazaine in Metz—Regnier's Intrigue—The Army of Metz capitulates—Thiers negotiates in vain—The Army of the Loire—D'Aurelle de Paladines reoccupies Orleans—Chanzy's Defeat and Recapture of Orleans—The Second Army of the Loire—Garibaldi in the East—The New Year in Paris—Dispositions of the German Armies—Battle of Amiens—Faídherbe's Campaign—Bapaume—St. Quentin—An Unpleasant Incident—Le Mans—The Bombardment of Paris—The Armistice—Termination of the Siege—Bourbaki's Attempt—Action at Villersexel—The Eastern Army crosses the Swiss Frontier—The National Assembly at Bordeaux—Prolongation of the Armistice—Resignation of Gambetta—Preliminaries of Peace—Occupation of Paris—Acceptance of the Preliminaries—The Definitive Treaty—German Unity 571

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

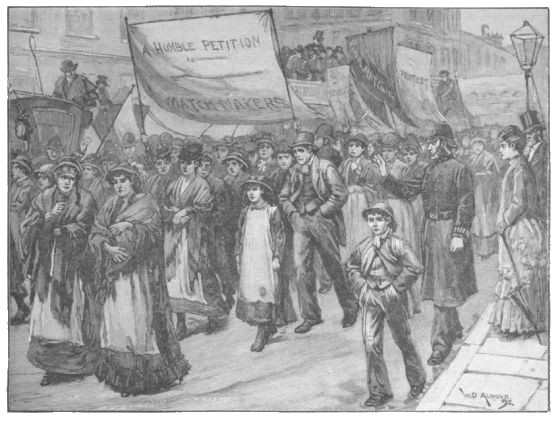

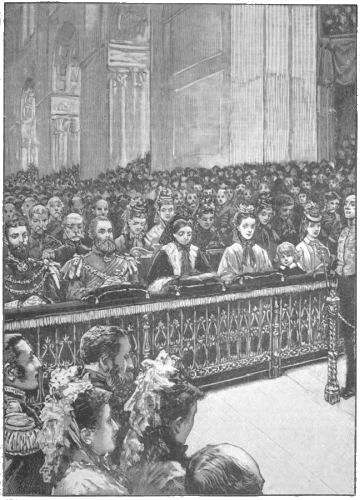

Army Reform—Mr. Trevelyan's Agitation—The Abolition of Purchase—Mr. Cardwell's Bill—History of Purchase—Military Opposition in the Commons—Rejection of the Bill by the House of Lords—Abolition of Purchase by Royal Warrant—Indignation in Parliament—The cost of Compensation—Mr. Lowe's Budget—The Match-Tax—Its withdrawal—Mr. Goschen succeeds Mr. Childers—The Ballot Bill—The Epping Forest Bill—Rejected Measures—The Religious Tests Bill—Marriage of the Princess Louise—Sir Charles Dilke's Lecture—The real State of the Civil List—Illness of the Prince of Wales—Crises of the Disease—The Prayers of the Nation—The Thanksgiving Service—Unpopularity of the Government—The 25th Clause—Landing of the ex-Emperor of the French—Resignation of Speaker Denison—Riot in Dublin—The Home Rule Movement—Mr. Gladstone at Aberdeen—Assassination of Mr. Justice Norman—Australian Federation—Russia repudiates the Black Sea Clauses—Lord Granville's Despatch—Prince Gortschakoff's Reply—A Conference suggested—Meeting of the Plenipotentiaries—Their Deliberations—Settlement of the Difficulty—Obituary of the Year—Sir John Burgoyne, Lord Ellenborough, Grote, Sir William Denison, and others 595

| PAGE | |

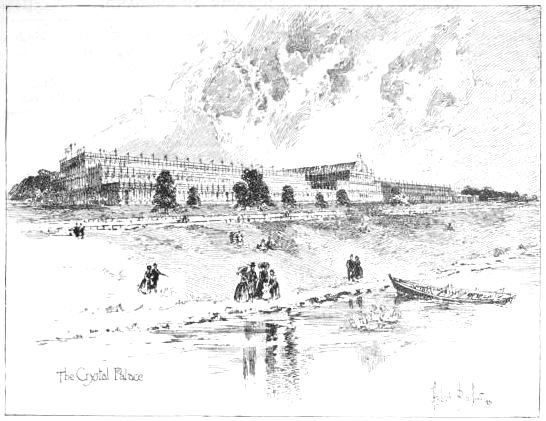

| The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, 1851 | 1 |

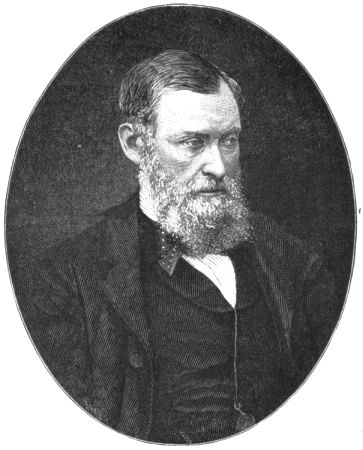

| Prince Albert | 5 |

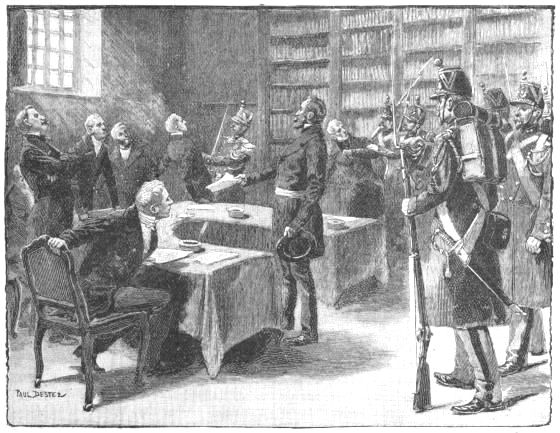

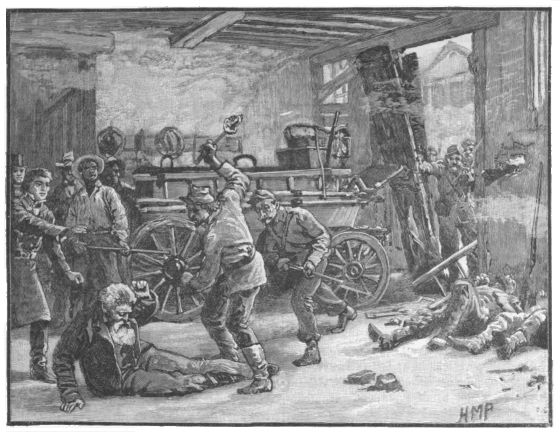

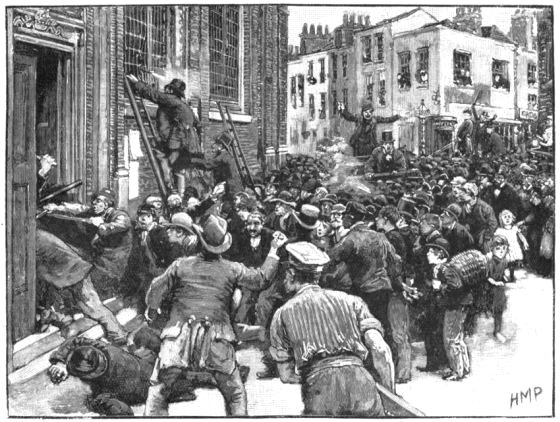

| The Coup d' État: Eviction of the Judges | 9 |

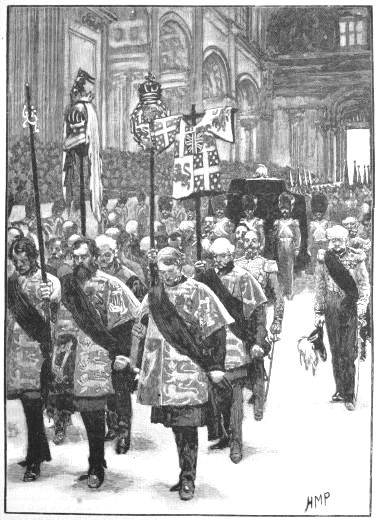

| The Burial of Wellington | 13 |

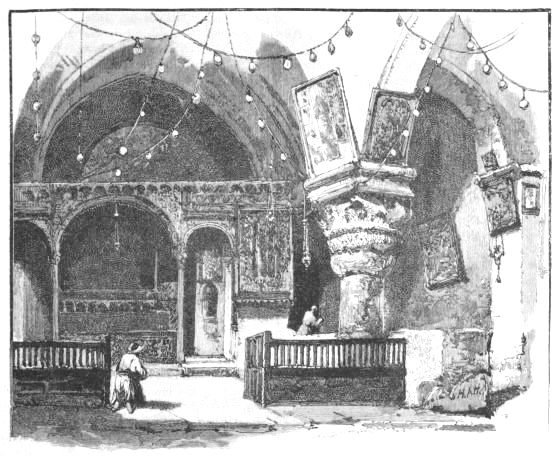

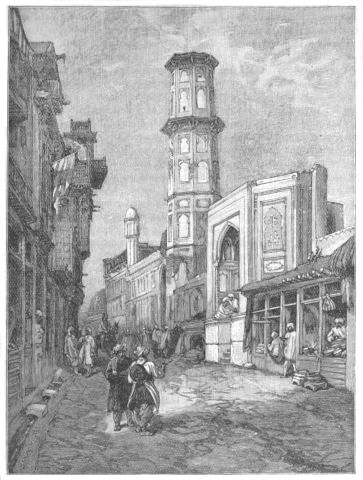

| Chapel of St. Helena, Jerusalem | 17 |

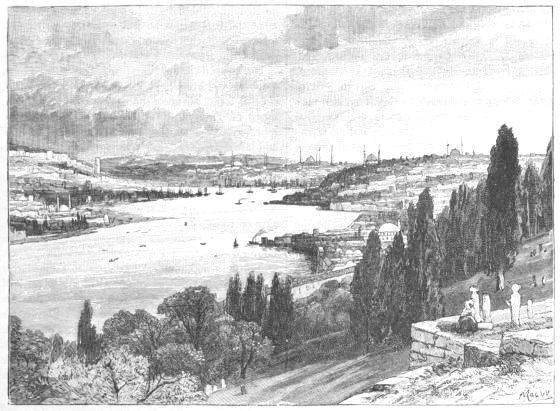

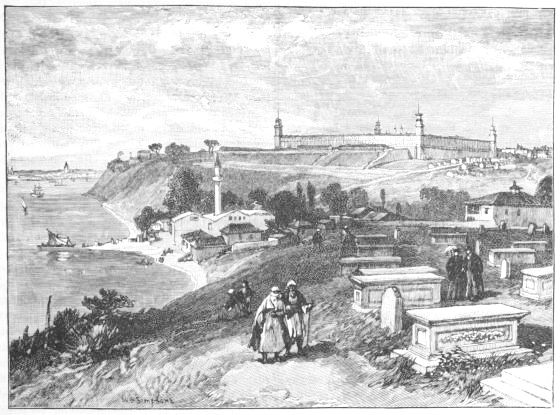

| Constantinople | 21 |

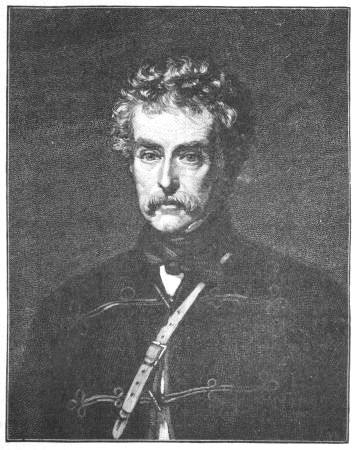

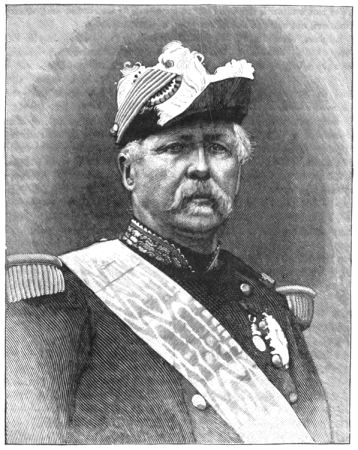

| Omar Pasha | 25 |

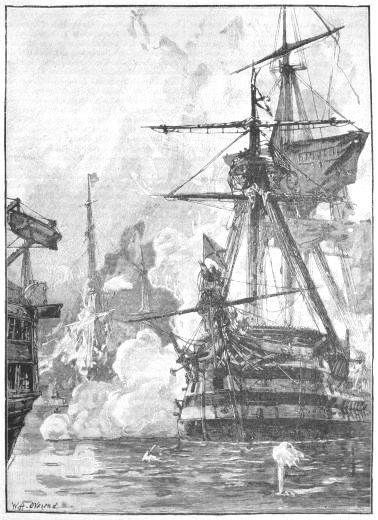

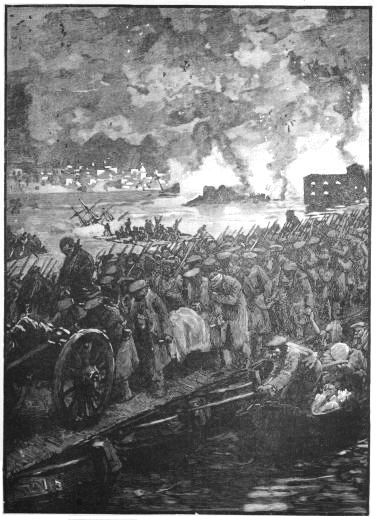

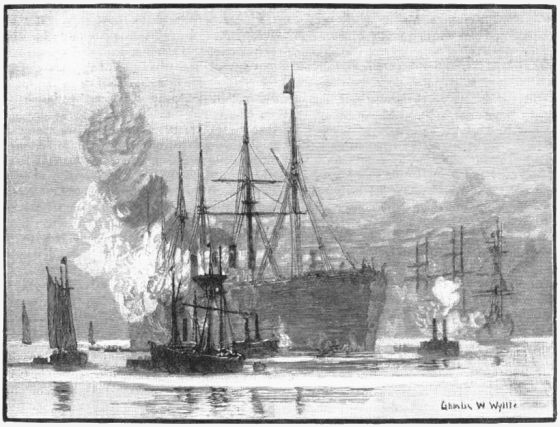

| The Russian Attack on Sinope | 29 |

| Gatchina Palace, St. Petersburg | 32 |

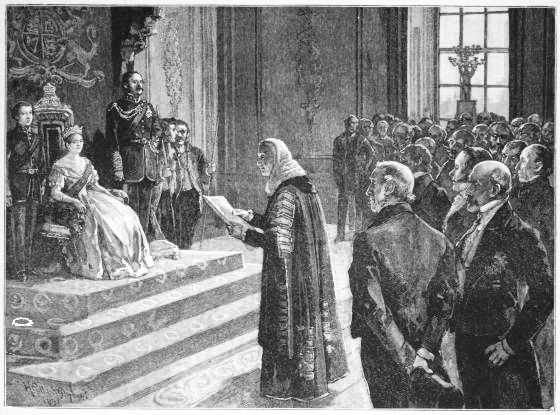

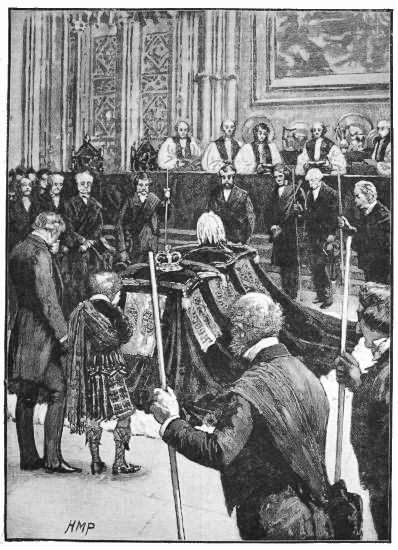

| Peers and Commoners presenting the Patriotic Address to the Queen on the Eve of the Crimean War | 33 |

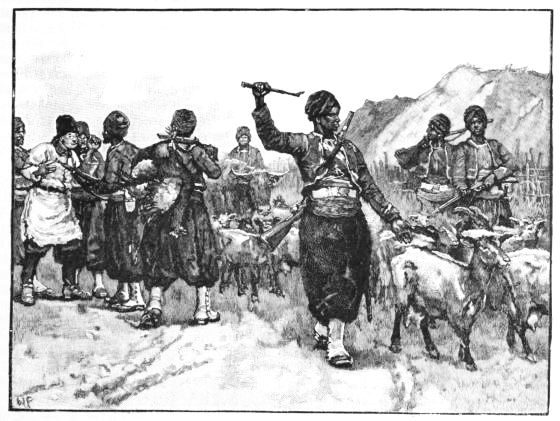

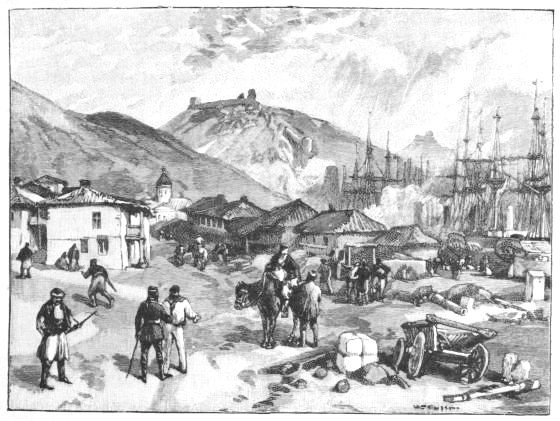

| Zouaves looting a Village in the Crimea | 37 |

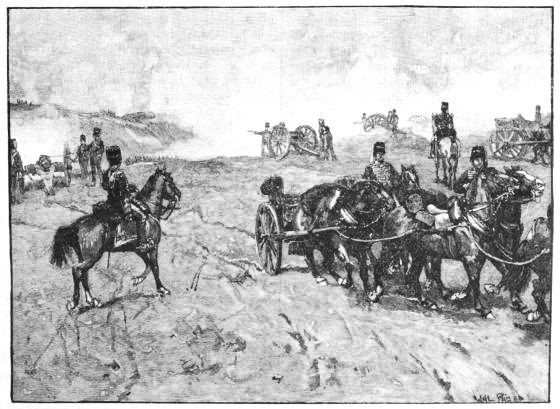

| Skirmish on the Bulganâk: Maude's Battery coming into action | 41 |

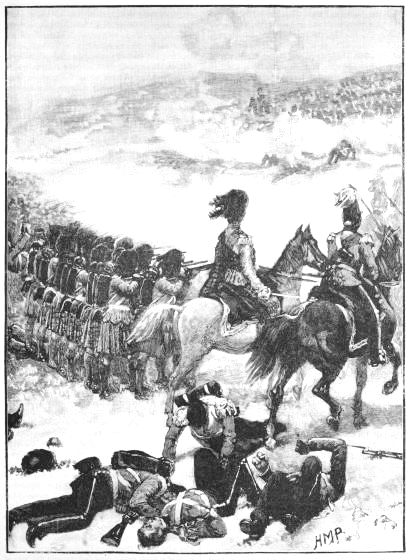

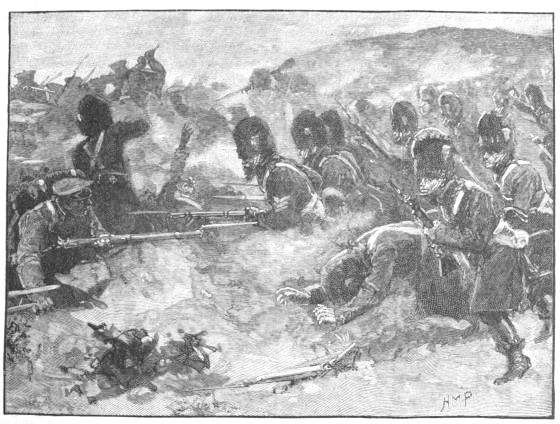

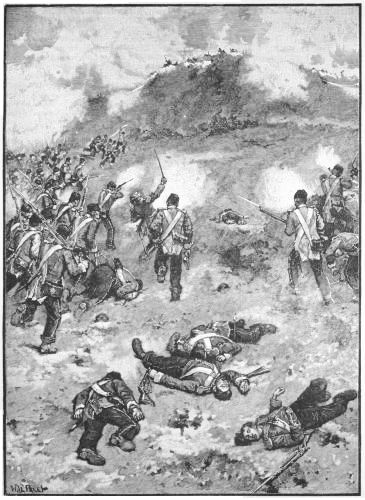

| The Highlanders at the Alma | 45 |

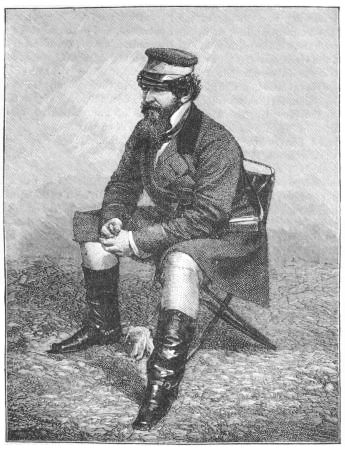

| Lord Raglan | 48 |

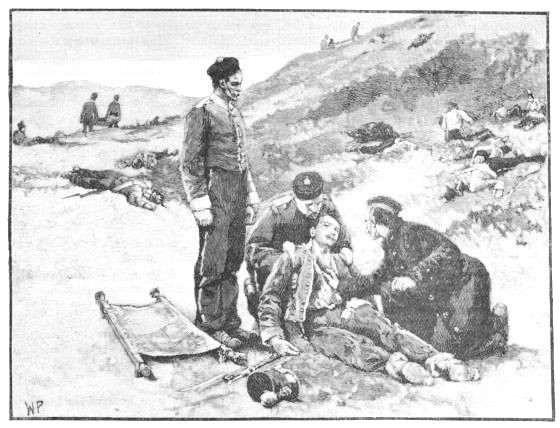

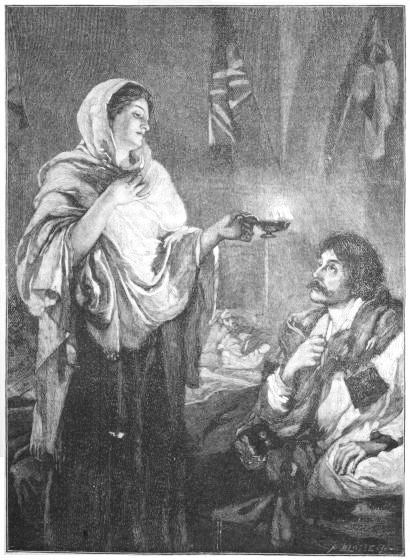

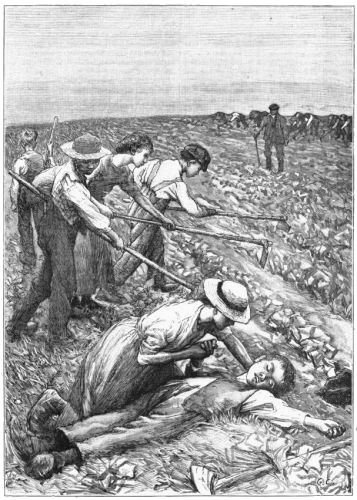

| On the Battle-Field of the Alma: the Mission of Mercy | 49 |

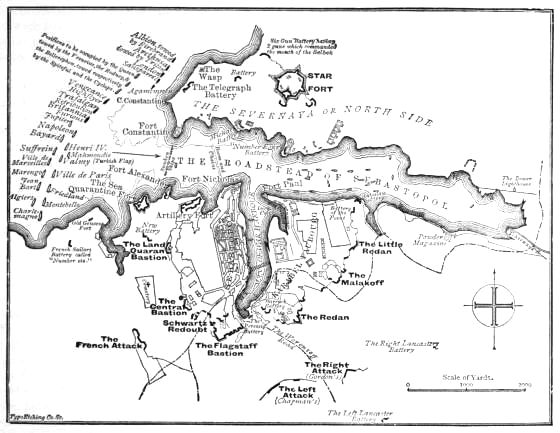

| Plan of Sebastopol, showing the Defence | 53 |

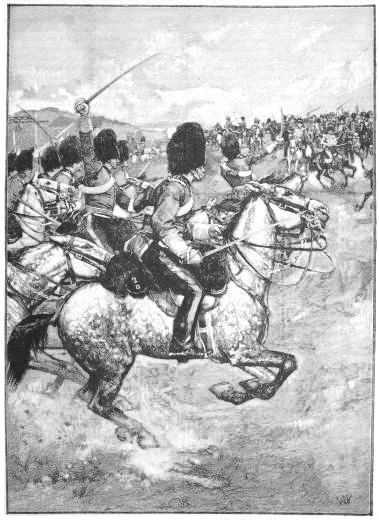

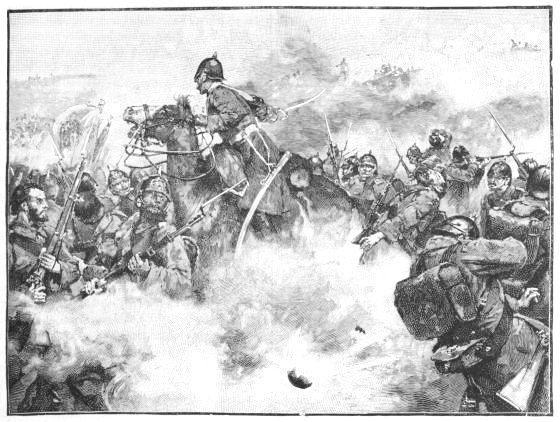

| Charge of the Heavy Brigade | 57 |

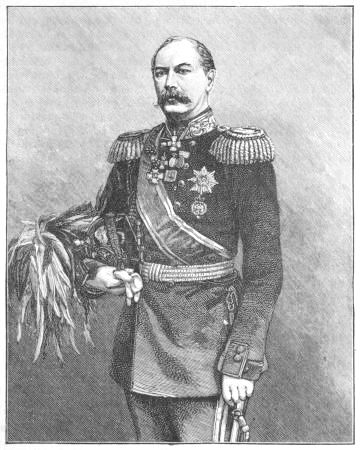

| General Todleben | 61 |

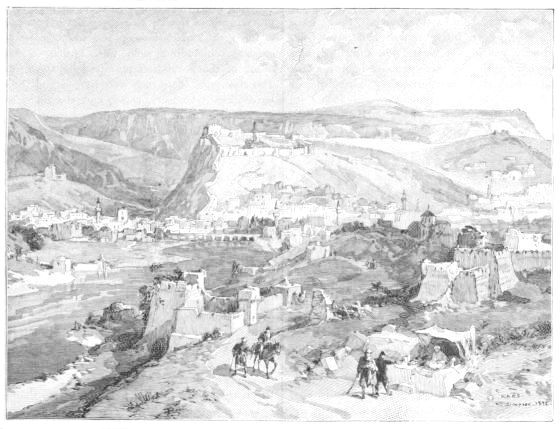

| Balaclava | 65 |

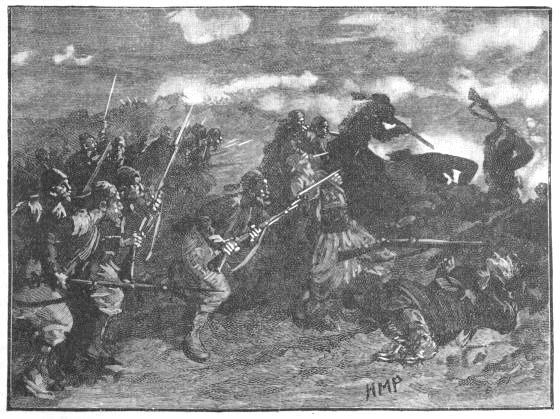

| The Guards recovering the Sandbag Battery | 69 |

| The Hospital and Cemetery at Scutari, with Constantinople in the distance | 73 |

| The Late Sir W. H. Russell, Correspondent of the Times in the Crimea | 77 |

| The Lady with the Lamp: Miss Nightingale in the Hospital at Scutari | 81 |

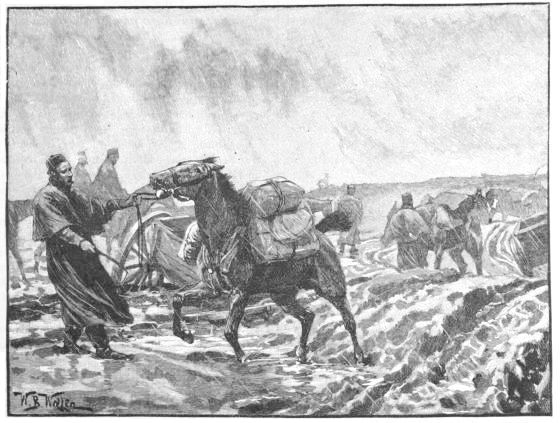

| The "Block" at Balaclava | 85 |

| The Zouaves assaulting the Rifle-pits | 89 |

| Sebastopol from the Right Attack | 93 |

| The Emperor Nicholas | 96 |

| Sappers destroying the Russian Trenches | 97 |

| Volunteers of the Flying Squadron firing the Shipping at Taganrog | 101 |

| Marshal Pélissier | 105 |

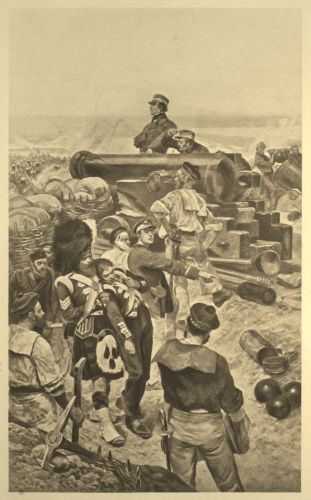

| The Assault on the Redan | 109 |

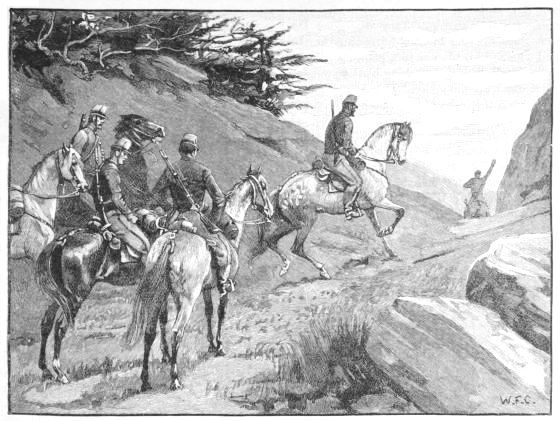

| Reconnaissance of French Cavalry in the Baidar Valley | 113 |

| General Simpson | 117 |

| The French in the Malakoff | 121 |

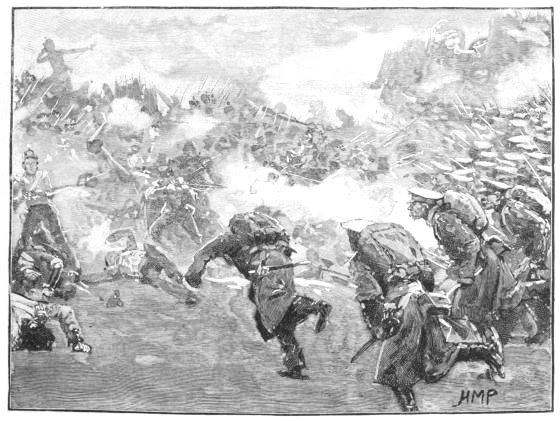

| The Struggle in the Redan | 125 |

| Evacuation of Sebastopol | 129 |

| Sir Colin Campbell | 133 |

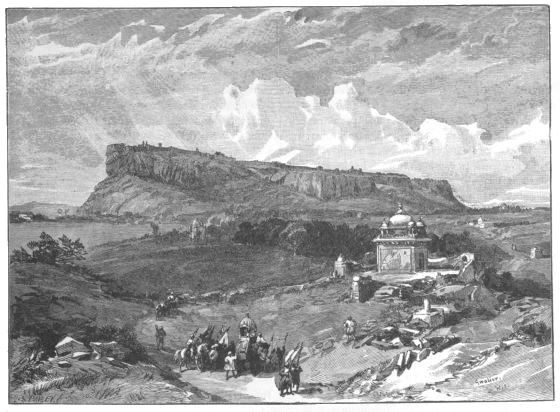

| Kars | 137 |

| The repulse of the Russians at Kars | 141 |

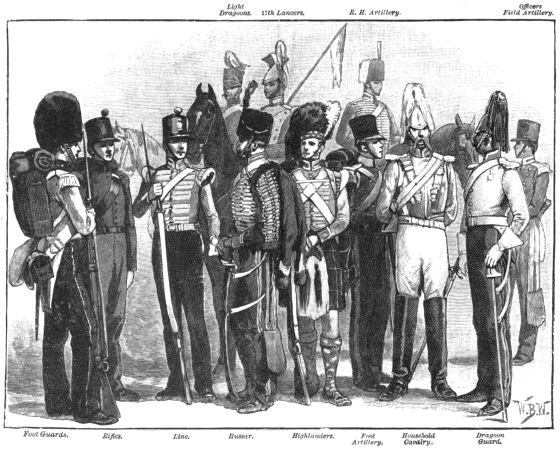

| Uniforms of the British Army in 1855 | 144 |

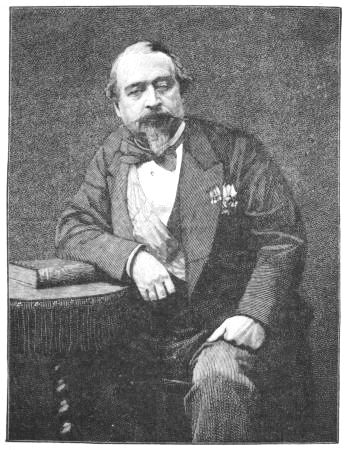

| Napoleon III | 145 |

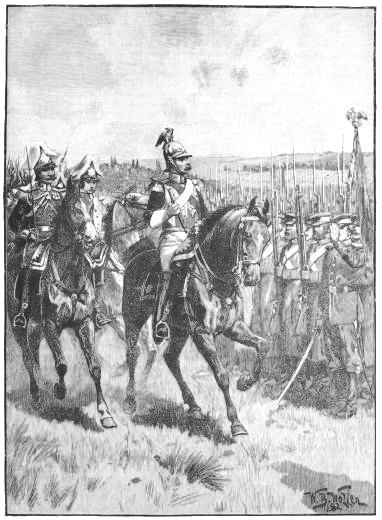

| The Czar renewing his Army at Sebastopol | 149 |

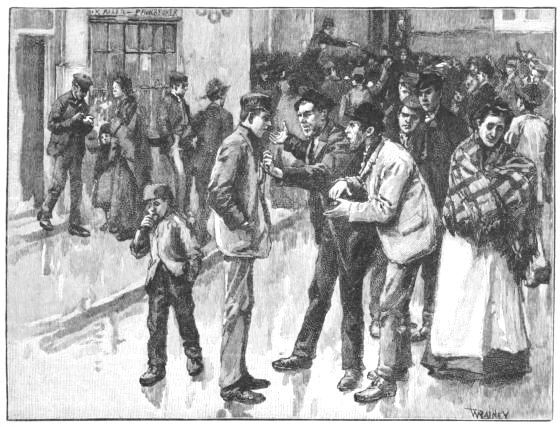

| Scene during the Preston Strike | 157 |

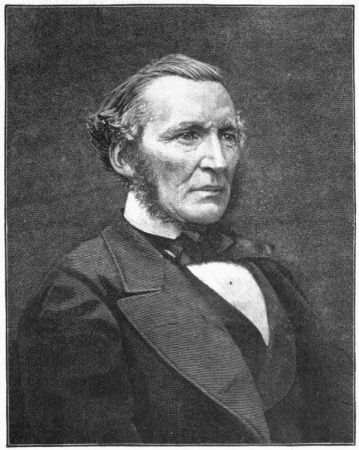

| The Duke of Newcastle | 161 |

| The Queen opening the Crystal Palace | 165 |

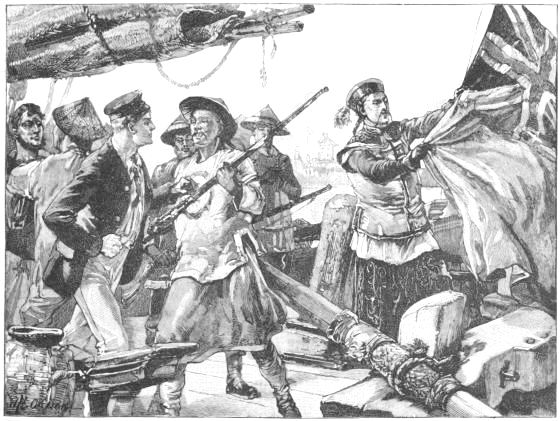

| Chinese Officers hauling down the British Flag on the "Arrow" | 169 |

| Victoria, Hong-Kong, from the Chinese Mainland | 173 |

| Mr. Speaker Denison | 177 |

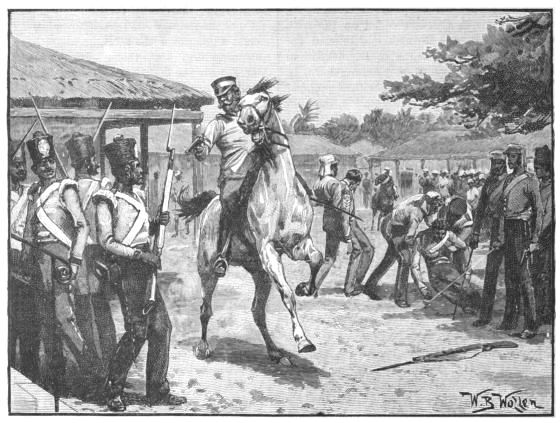

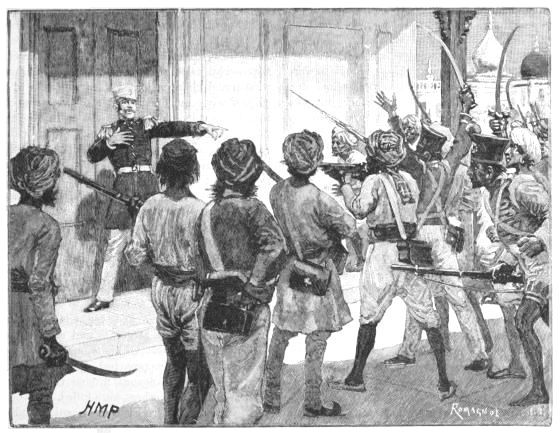

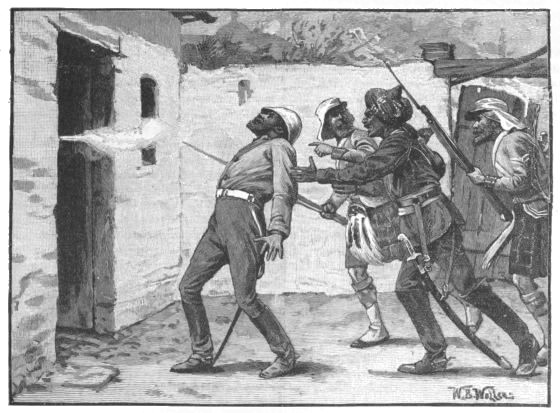

| Outbreak of the Indian Mutiny: High Caste v. Low Caste | 185 |

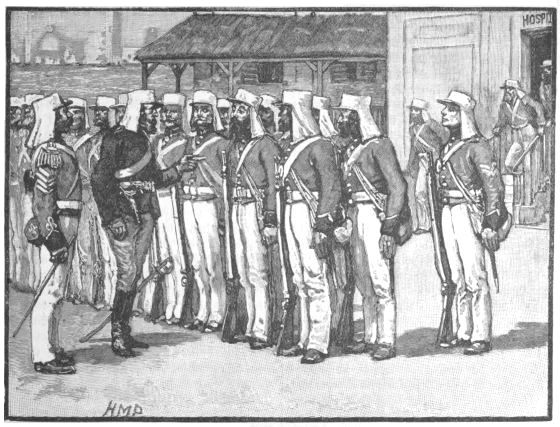

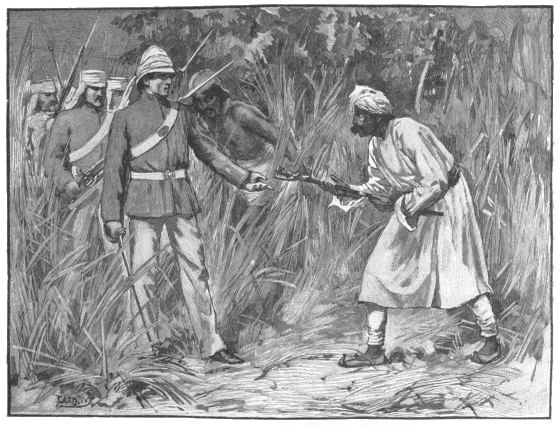

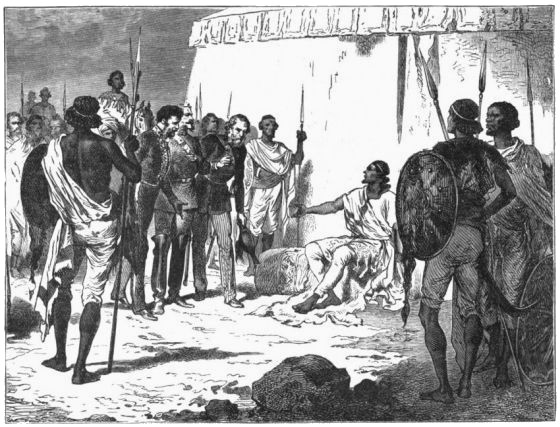

| General Hearsey and the Mutineers | 188 |

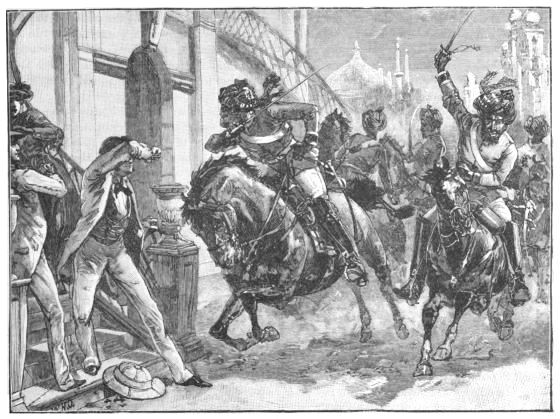

| The Rebel Sepoys at Delhi | 189 |

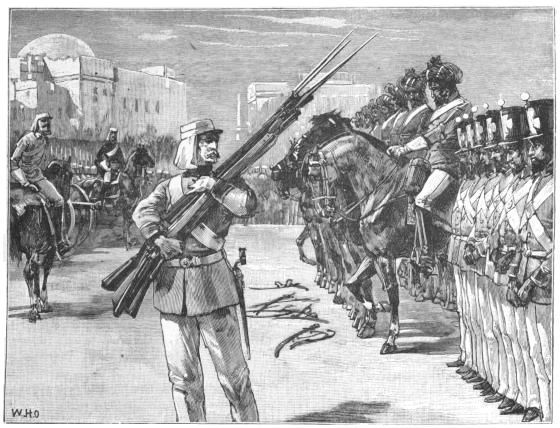

| Disarmament of the 26th at Barrackpore | 193 |

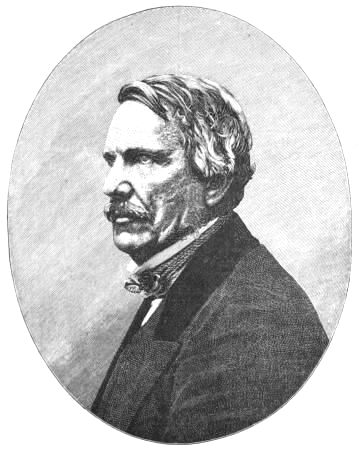

| Sir John Lawrence (afterwards Lord Lawrence) | 197 |

| De Kantzow defending the Treasury at Mynpooree | 201 |

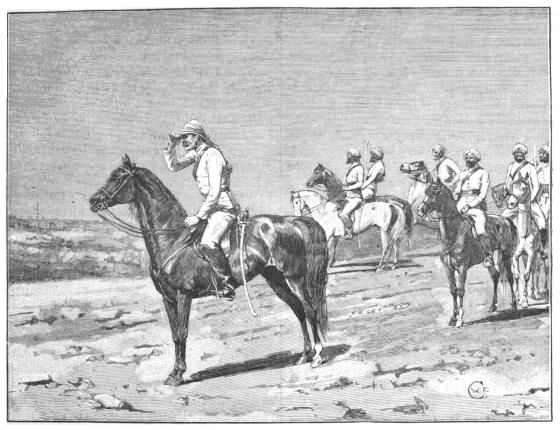

| Hodson reconnoitring before Delhi | 205 |

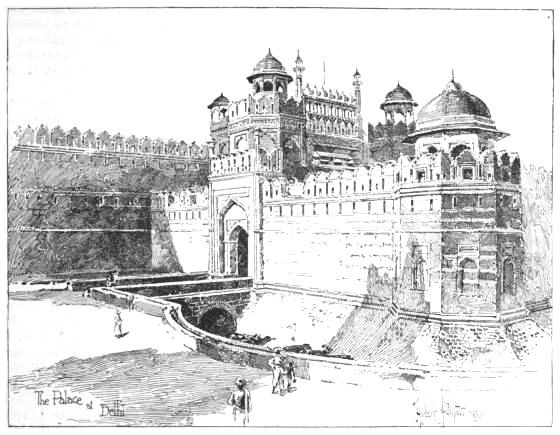

| The Palace, Delhi | 209 |

| Sir Henry Havelock | 213 |

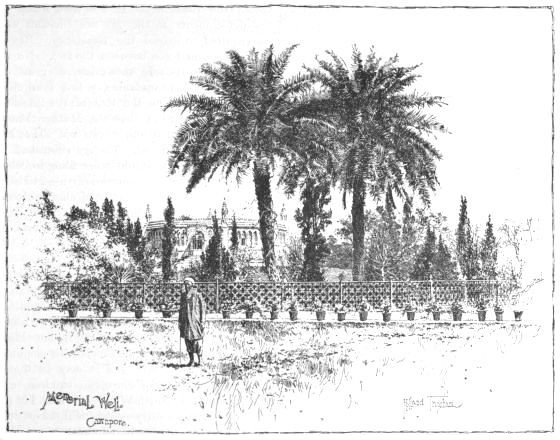

| Memorial at the Well, Cawnpore | 217 |

| The Highlanders capturing the Guns at Cawnpore | 221 |

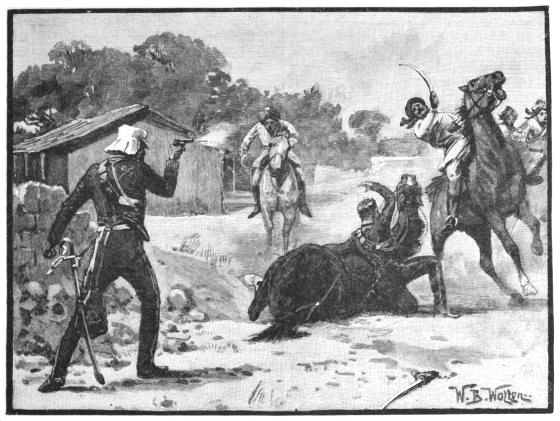

| How Major Tombs won the Victoria Cross | 225 |

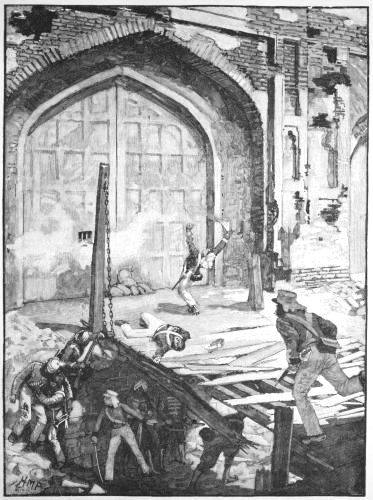

| Blowing up of the Cashmere Gate at Delhi | 229 |

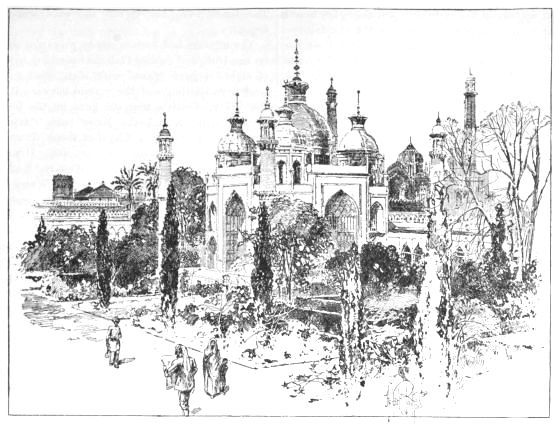

| Hooseinabad Gardens and Tomb of Zana Ali, Lucknow | 233 |

| Sir Hope Grant | 237 |

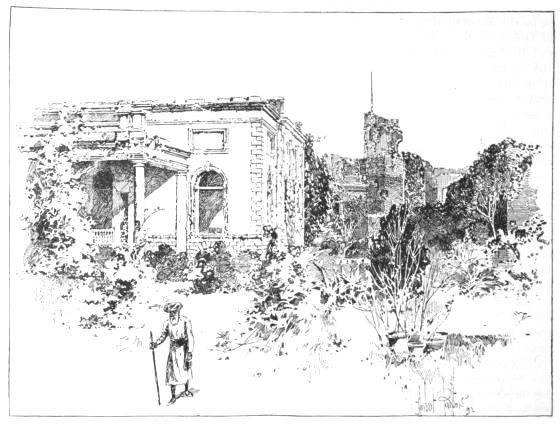

| Ruins of the Residency, Lucknow | 240 |

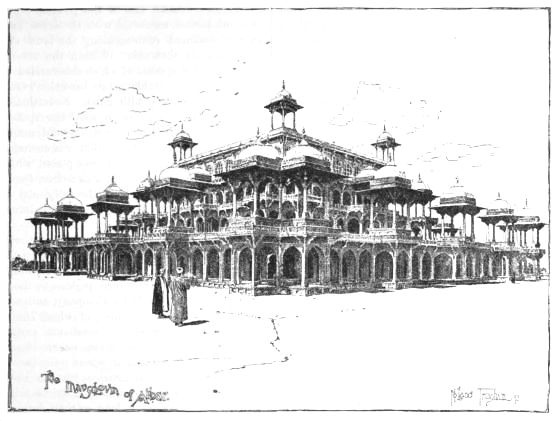

| The Mausoleum at Akbar, Agra | 241 |

| Incident in the Defence of Lucknow | 245 |

| Lieutenant Havelock and the Madras Fusiliers carrying the Charbagh Bridge at Lucknow | 249 |

| Sir James Outram | 253 |

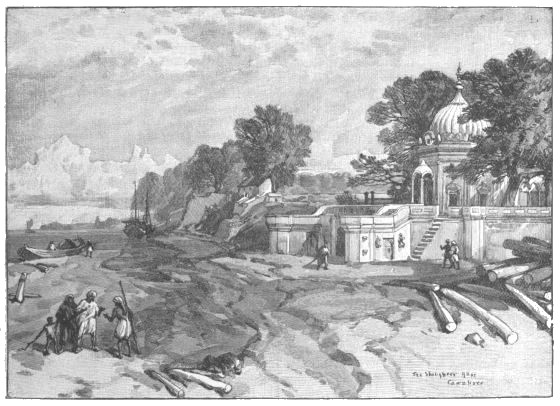

| The Slaughter Ghat, Cawnpore | 257 |

| The Relief of Lucknow | 261 |

| Death of Hodson | 265 |

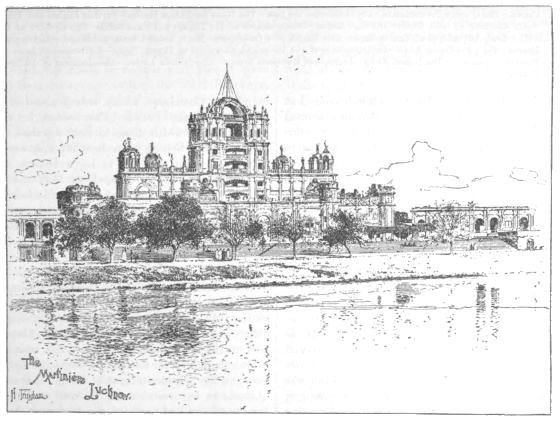

| The Martinière, Lucknow | 269 |

| Sir Hugh Rose (afterwards Lord Strathnairn) | 273 |

| Proclamation of the Queen as Sovereign of India | 277 |

| Gwalior, from the south-east | 281 |

| Capture of Tantia Topee | 285 |

| Lord Canning | 288 |

| Street in Peshawur | 289 |

| Earl Russell | 293 |

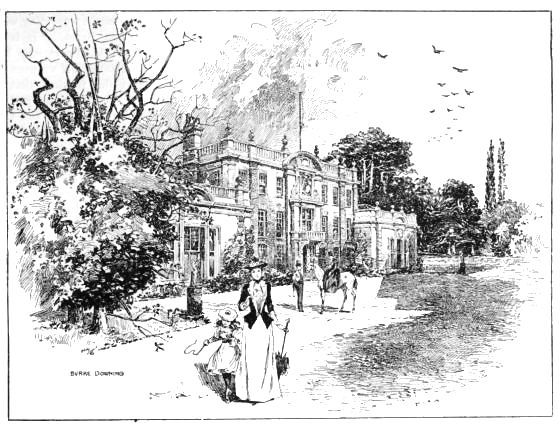

| Office of the First Lord of the Treasury, 10, Downing Street, London | 297 |

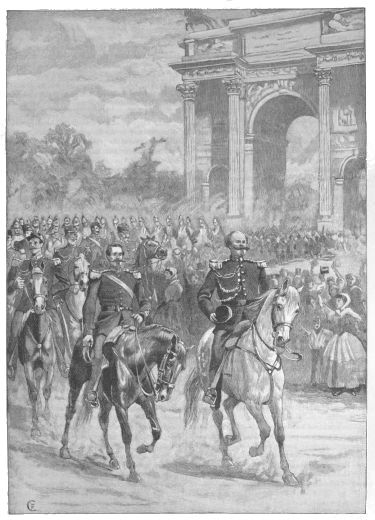

| Entry of Napoleon and Victor Emmanuel into Milan | 301 |

| Meeting of Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel | 305 |

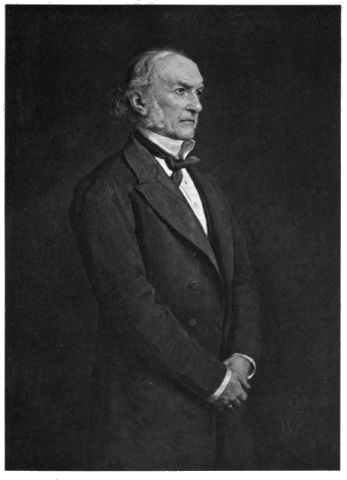

| William Ewart Gladstone (1860) | 312 |

| Demonstration against the Christians in Damascus | 313 |

| The Imperial Palace, Pekin, looking north | 317 |

| Capture of John Brown at Harper's Ferry | 321 |

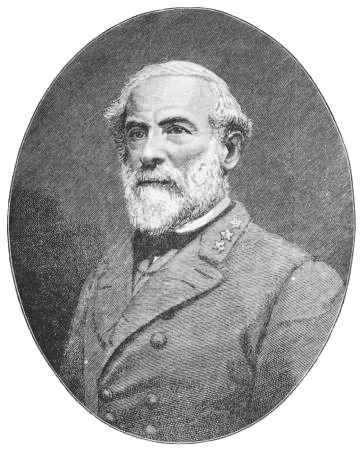

| General Robert Lee | 325 |

| Funeral of the Prince Consort | 329 |

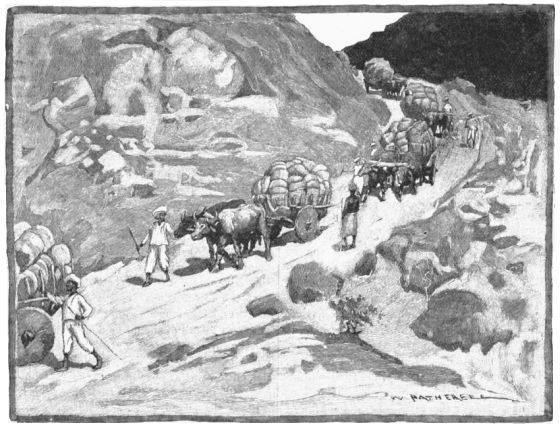

| Hindoos bringing Cotton through the Western Ghauts | 333 |

| Abraham Lincoln | 336 |

| Marriage of the Prince of Wales | 337 |

| Mr. Phelps planting the Shakespeare Oak on Primrose Hill, London | 345 |

| Scene in the Belfast Riots | 349 |

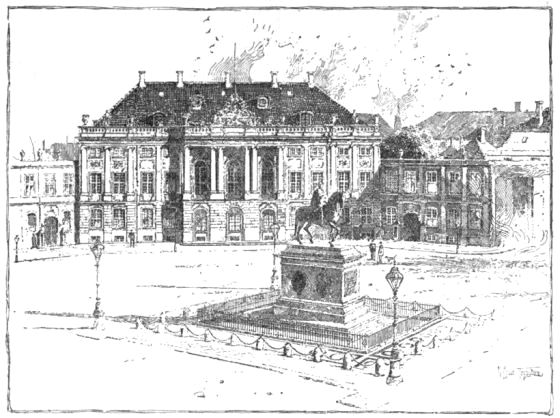

| Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen | 353 |

| Lord Palmerston | 357 |

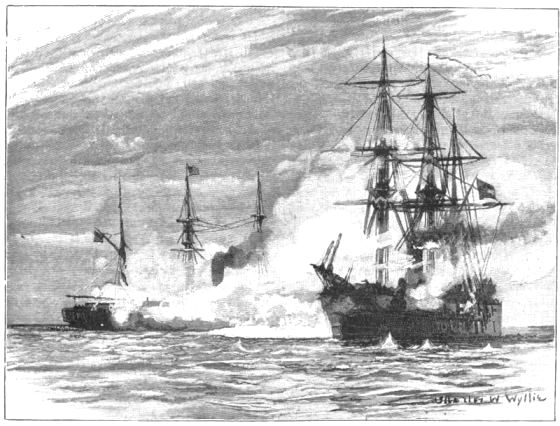

| The Fight between the Alabama and the Kearsarge | 361 |

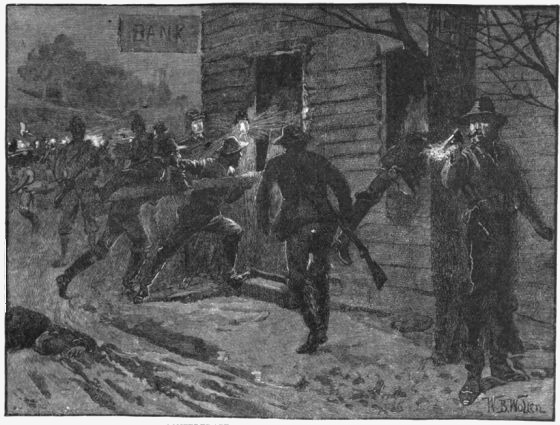

| Confederate Raid into Vermont | 365 |

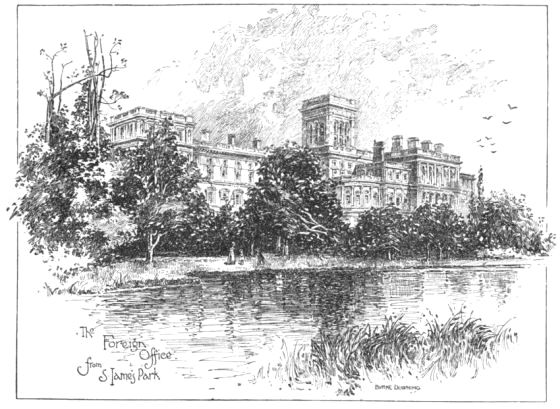

| The Foreign Office, London, from St. James's Park | 369 |

| Arrest of Head-Centre Stephens | 373 |

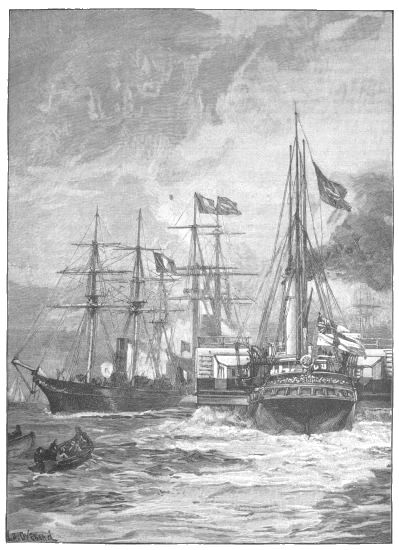

| Reception of the French Fleet at Portsmouth | 377 |

| General Grant | 381 |

| Meeting of Lee and Grant at Appomattox Court-House | 384 |

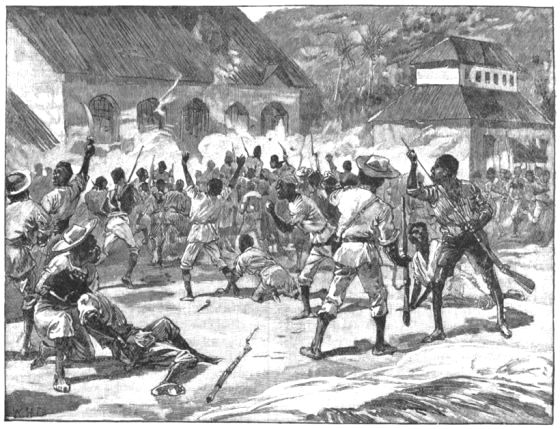

| The Attack on the Court-House, St. Thomas-in-the-East | 385 |

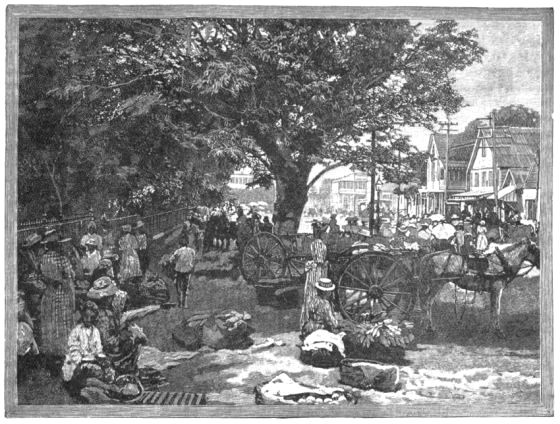

| Street Scene, Kingston, Jamaica | 389 |

| John Stuart Mill | 393 |

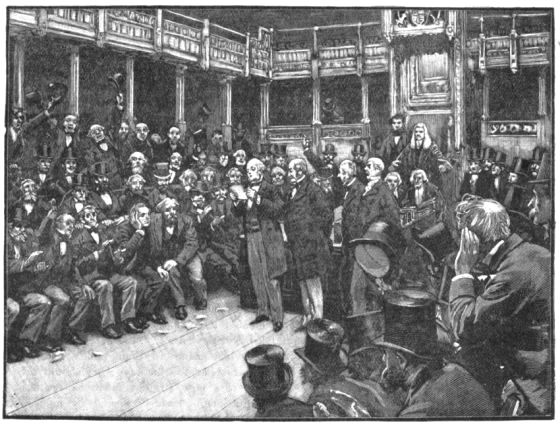

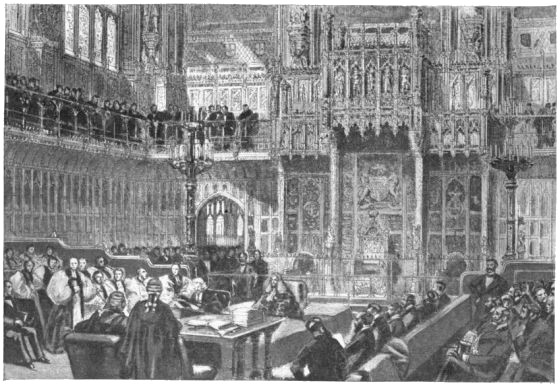

| Scene in the House of Commons: a Narrow Majority | 397[xii] |

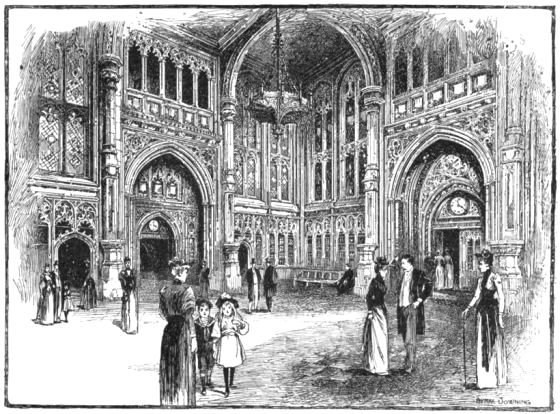

| The Lobby, House of Commons | 401 |

| Reform Leaguers at the Marble Arch | 405 |

| Arrival of the "Great Eastern" at Trinity Bay | 409 |

| Robert Lowe (afterwards Lord Sherbrooke) | 413 |

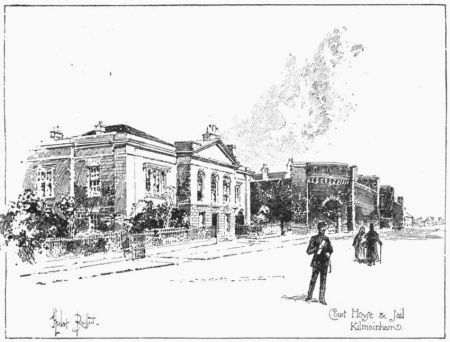

| Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin | 417 |

| The Battle of Koniggrätz | 421 |

| The Battle of Langensalza | 425 |

| Count Von Moltke | 429 |

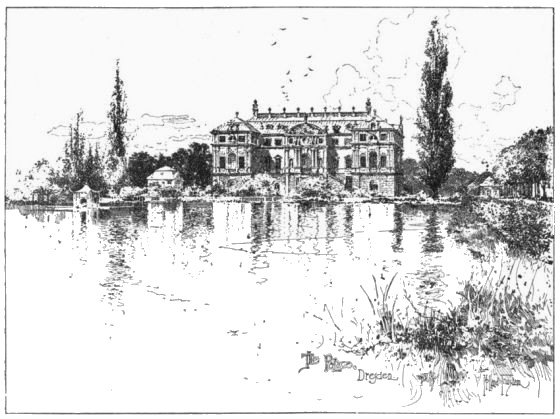

| The Palace, Dresden | 432 |

| The Old War Office, Pall Mall | 433 |

| Lord Malmesbury | 437 |

| Tea-Room, House of Commons | 441 |

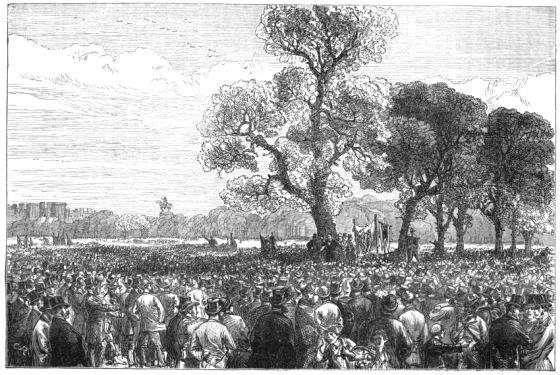

| Meeting at the Reformers' Tree, Hyde Park, London | 445 |

| John Bright | 449 |

| "Gang System" of Farming | 453 |

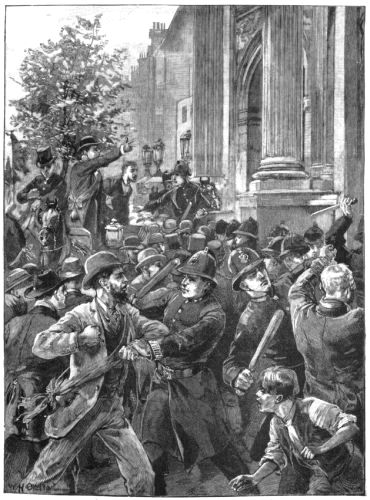

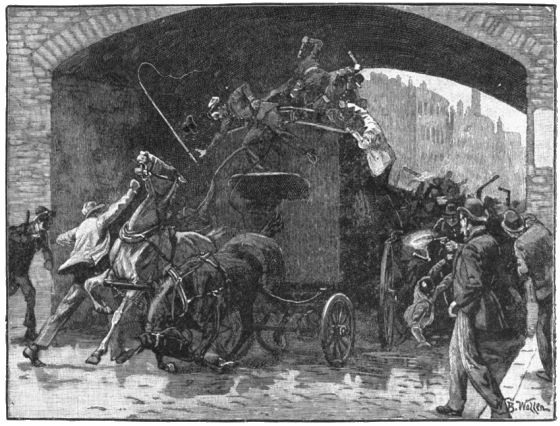

| Fenian Attack on the Police Van in Manchester | 457 |

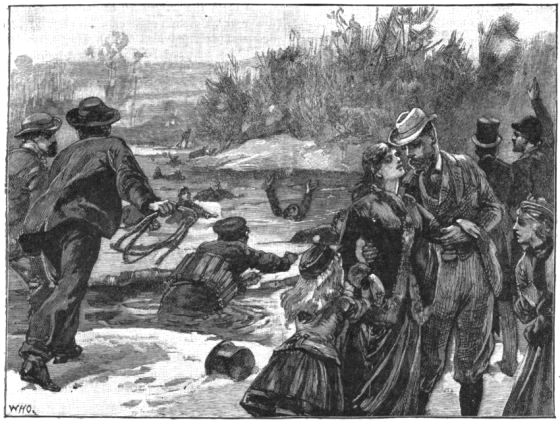

| Skating Disaster in Regent's Park, London | 461 |

| Lord Cairns | 465 |

| Scene in the Birmingham "No Popery" Riots | 469 |

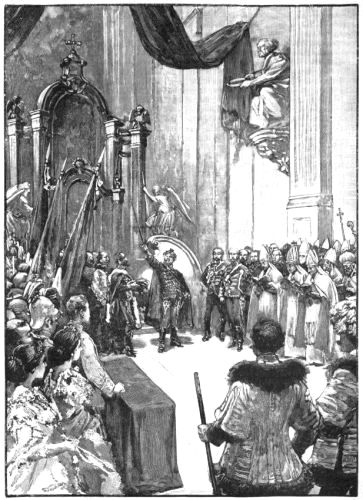

| Coronation of the Emperor of Austria as King of Hungary | 473 |

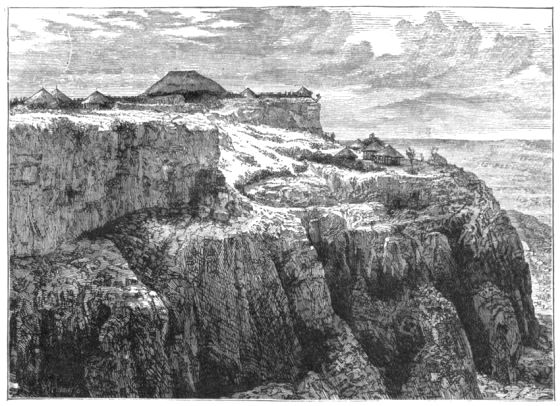

| King Theodore's House, Magdala | 477 |

| Mr. Rassam's Interview with King Theodore | 480 |

| The Emperor Theodore granting an Audience | 481 |

| Sir Robert Napier (afterwards Lord Napier of Magdala) | 485 |

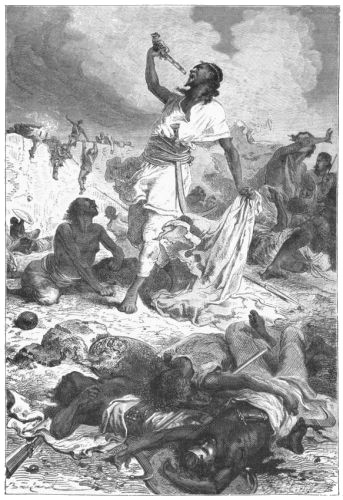

| Death of the Emperor Theodore | 489 |

| St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin | 493 |

| Archbishop Trench | 497 |

| Dr. Magee, Bishop of Peterborough, addressing the House of Lords | 501 |

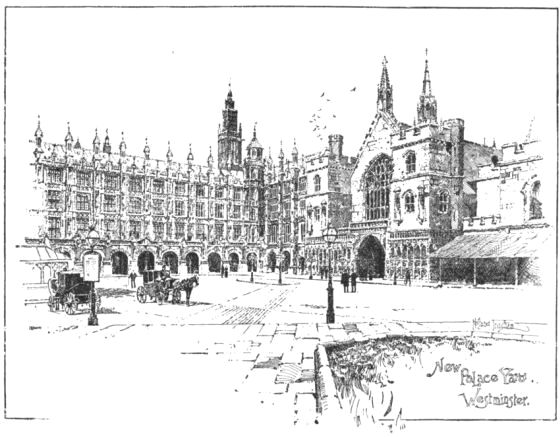

| New Palace Yard, Westminster | 505 |

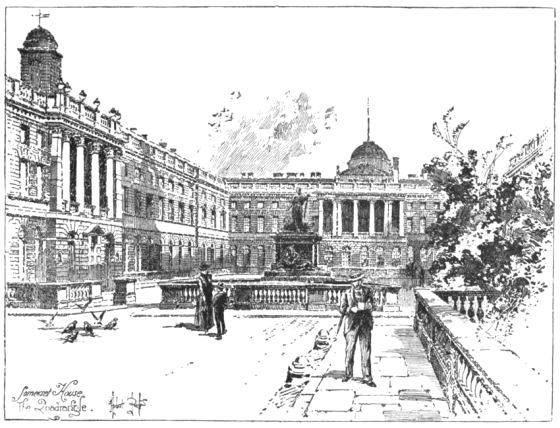

| The Quadrangle, Somerset House | 509 |

| Sir Stafford Northcote (afterwards Earl of Iddesleigh) | 513 |

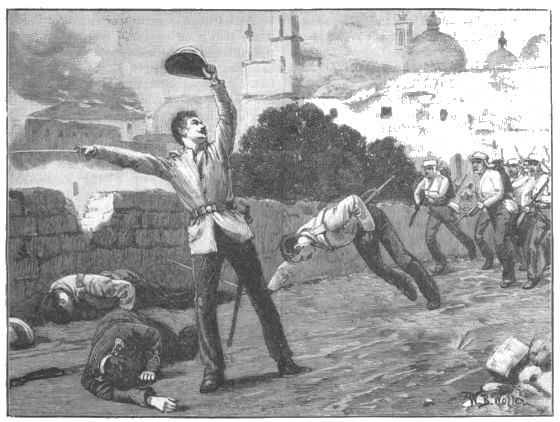

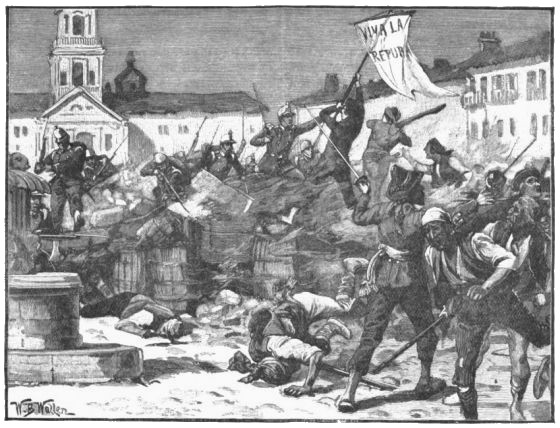

| Street-Fighting in Malaga | 517 |

| Mr. Chichester Fortescue (afterwards Lord Carlingford) | 521 |

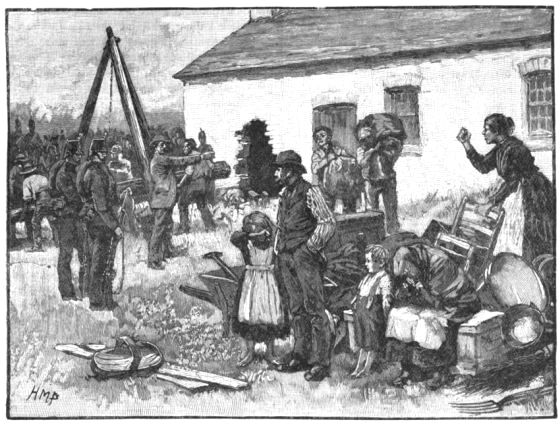

| A Visit from Captain Moonlight | 524 |

| An Eviction in Ireland | 525 |

| The Duke of Richmond and Gordon | 528 |

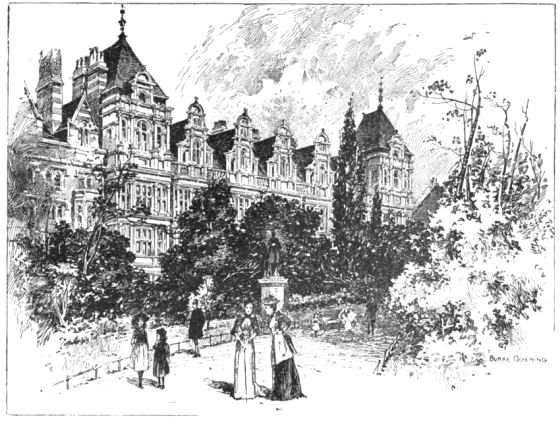

| Office of the London School Board, Thames Embankment | 529 |

| Mr. W. E. Forster | 533 |

| Office of the Education Department, Whitehall | 537 |

| Capture of English Tourists by Greek Brigands | 541 |

| The Royal Palace, Athens | 545 |

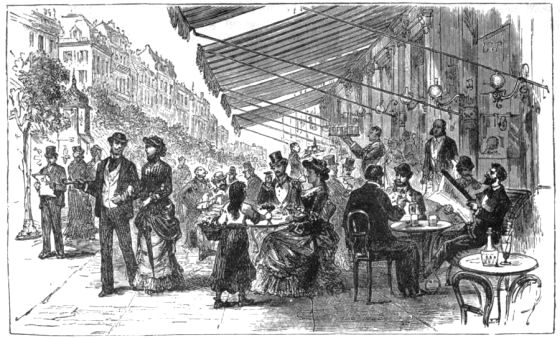

| The Boulevard Montmartre, Paris | 548 |

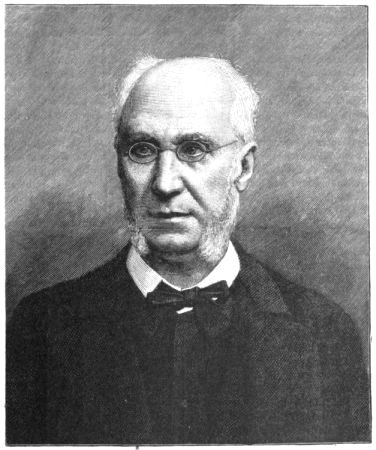

| Émile Ollivier | 549 |

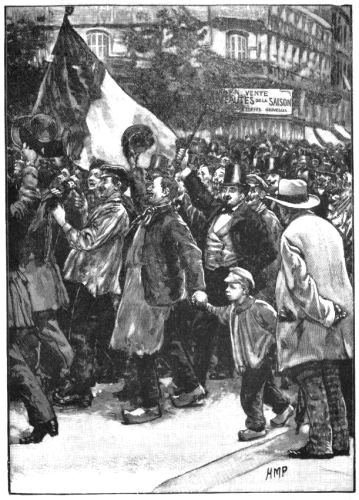

| "À Berlin!" Parisian Crowds declaring for War | 553 |

| Prince Bismarck | 557 |

| Franco-German War, Sketch-Map of the Campaign in the Rhine Country | 561 |

| Sedan | 564 |

| Marshal MacMahon | 565 |

| Camden Place, Chislehurst (Napoleon's Home in England) | 569 |

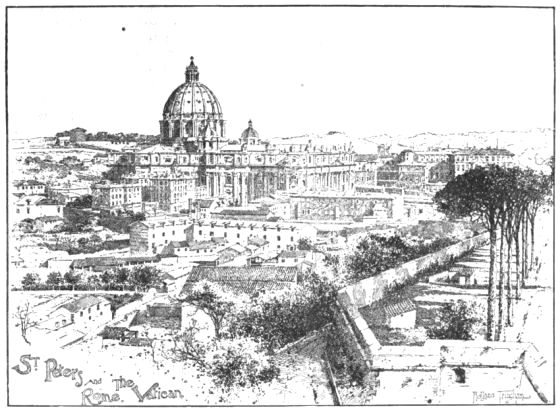

| The Vatican, Rome | 573 |

| Dr. Döllinger | 576 |

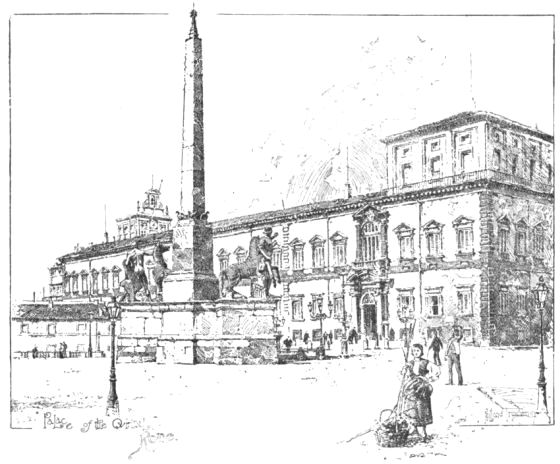

| Palace of the Quirinal, Rome | 577 |

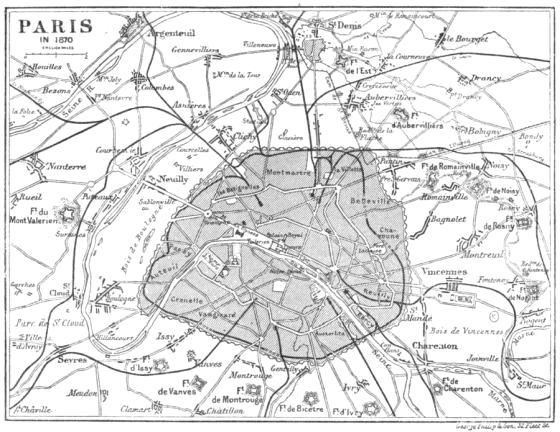

| Siege of Paris: Map of the Fortifications | 580 |

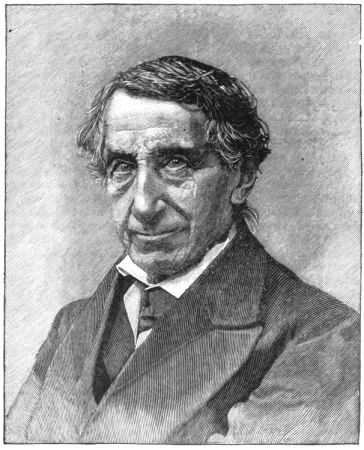

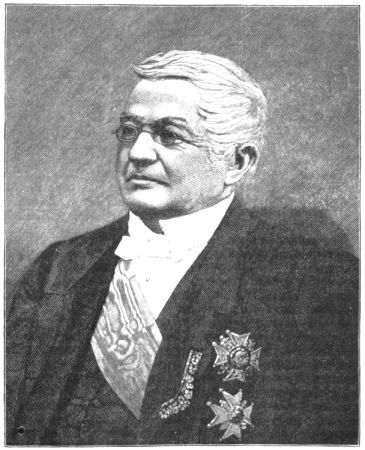

| L. A. Thiers | 581 |

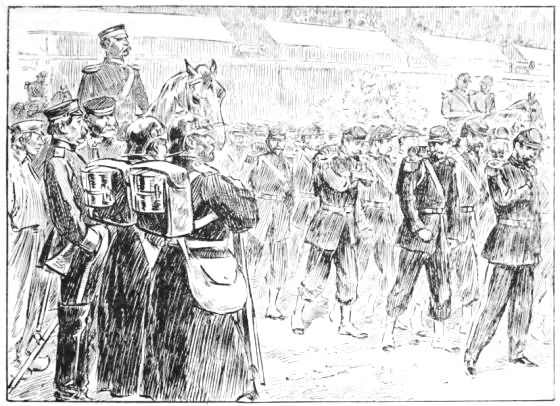

| Evacuation of Metz | 585 |

| Léon Gambetta | 589 |

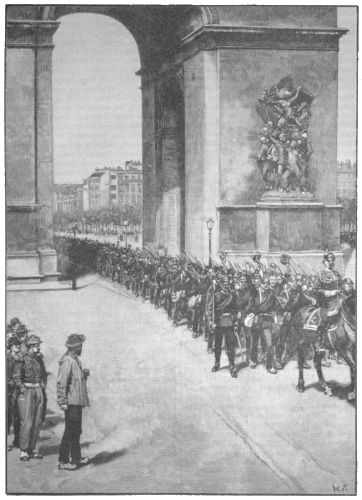

| German Troops passing under the Arc de Triomphe in Paris | 593 |

| Mr. (afterwards Viscount) Cardwell | 597 |

| Procession of Match-Makers to Westminster | 601 |

| The Prince of Wales (afterwards Edward VII.) in his Robes as a Bencher of the Middle Temple | 604 |

| The Thanksgiving Service in St. Paul's Cathedral | 605 |

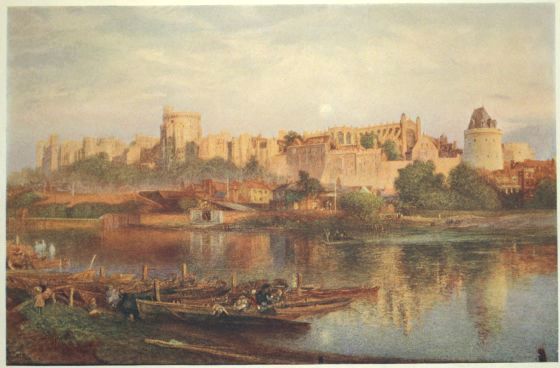

| WINDSOR CASTLE. (By Alfred W. Hunt, R.W.S.) | Frontispiece | |

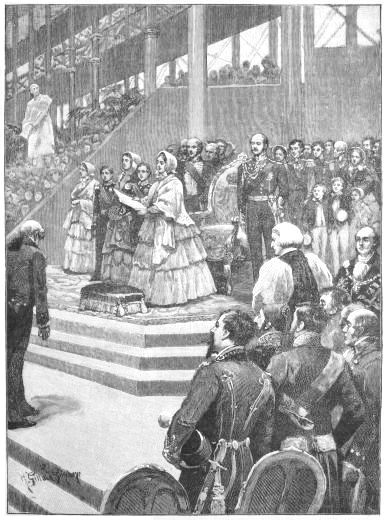

| THE OPENING BY QUEEN VICTORIA OF THE GREAT EXHIBITION IN HYDE PARK. (By H. C. Selous.) | To face p. | 9 |

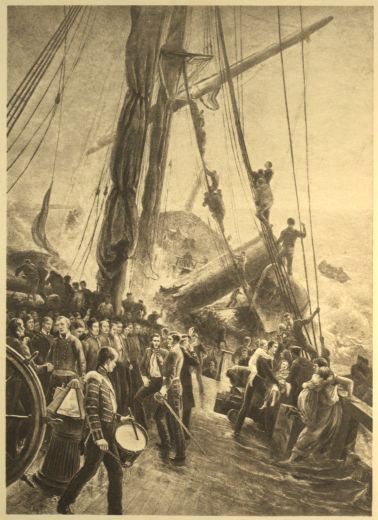

| THE WRECK OF H.M.S. Birkenhead. (By Thomas M. Henry) | " | 14 |

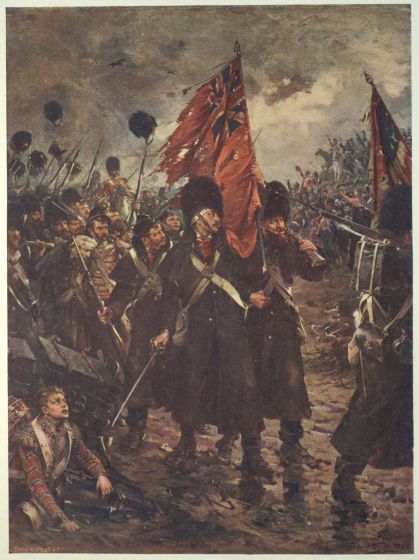

| SAVING THE COLOURS: THE GUARDS AT INKERMAN. (By Robert Gibb, R.S.A.) | " | 41 |

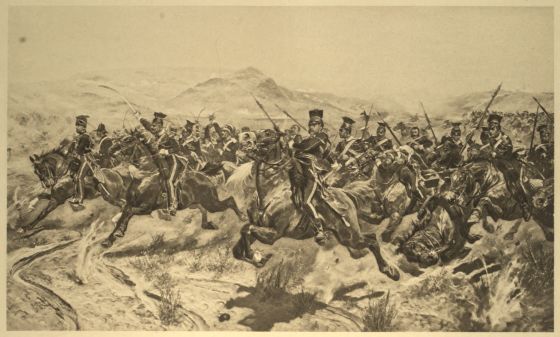

| THE CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE AT BALACLAVA. (By R. Caton Woodville) | " | 62 |

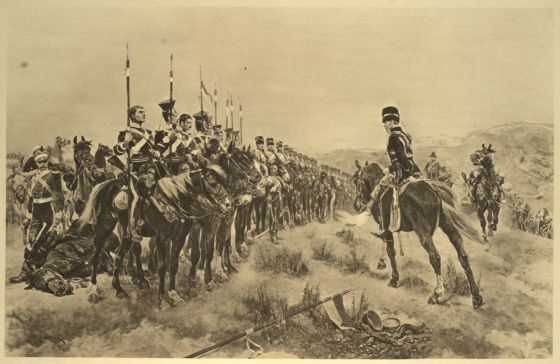

| "ALL THAT WAS LEFT OF THEM, LEFT OF SIX HUNDRED." (By R. Caton Woodville) | " | 86 |

| QUEEN VICTORIA REVIEWING THE CRIMEAN VETERANS (1854). (By Sir John Gilbert, R.A., P.R.W.S.) | " | 90 |

| LORD RAGLAN VIEWING THE STORMING OF THE REDAN AT THE SIEGE OF SEBASTOPOL. (By R. Caton Woodville) | " | 126 |

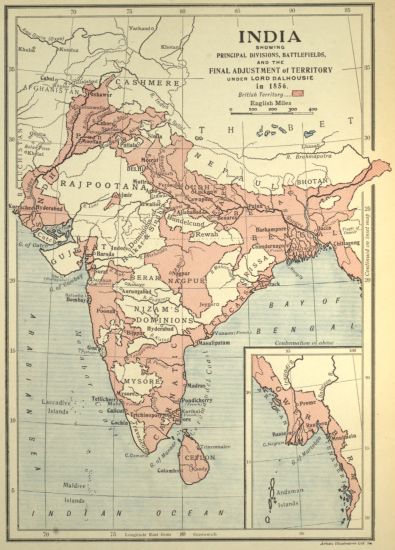

| MAP OF INDIA, 1856. | " | 182 |

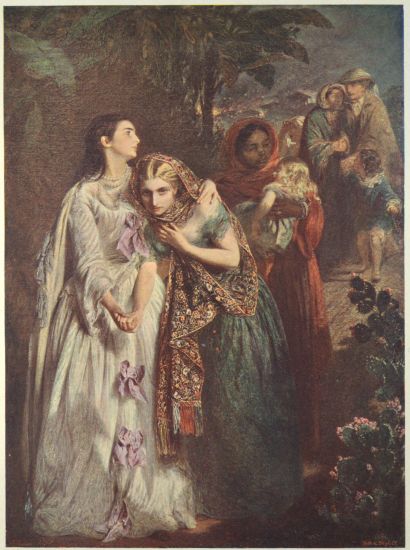

| THE FLIGHT FROM LUCKNOW. (By A. Solomon) | " | 217 |

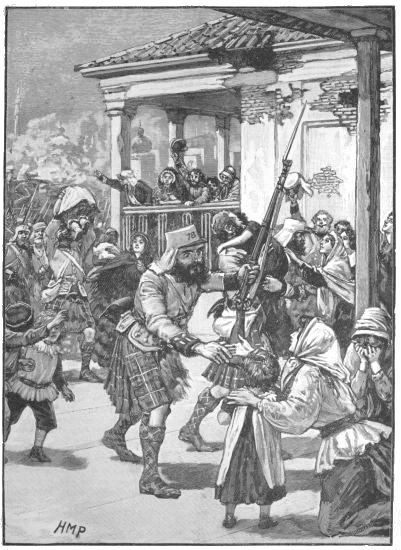

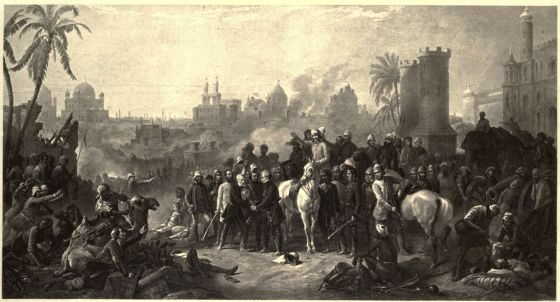

| THE SECOND RELIEF OF LUCKNOW, 1857. (By Thomas J. Barker) | " | 262 |

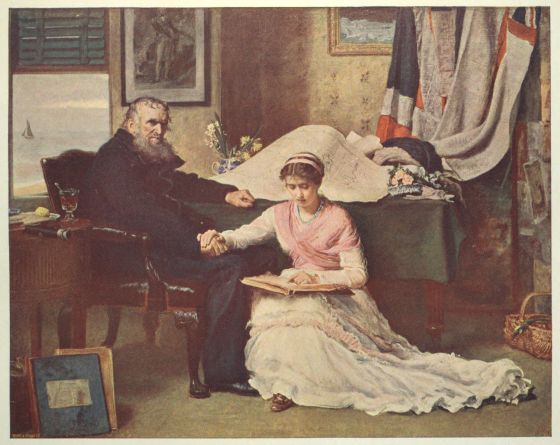

| THE NORTH-WEST PASSAGE. (By Sir J. E. Millais, Bart., P.R.A., D. C.L., etc.) | " | 287 |

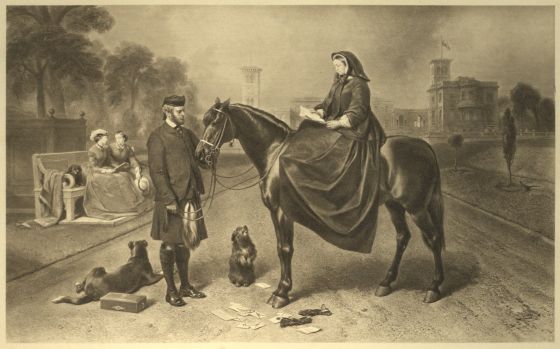

| QUEEN VICTORIA AT OSBORNE. (By Sir Edwin Landseer, R.A.) | " | 326 |

| THE MARRIAGE OF THE PRINCE OF WALES, 1863. (By G. H. Thomas) | " | 338 |

| A COTTAGE BEDSIDE AT OSBORNE. (Gourlay Steell, R.S.A.) | " | 408 |

| MARRIAGE OF PRINCESS HELENA. (By C. Magnussen) | " | 412 |

| THE WHITE TOWER, TOWER OF LONDON. (By H. E. Tidmarsh) | " | 481 |

| W. E. GLADSTONE. (By Sir J. E. Millais, Bart., P.R.A.) | " | 500 |

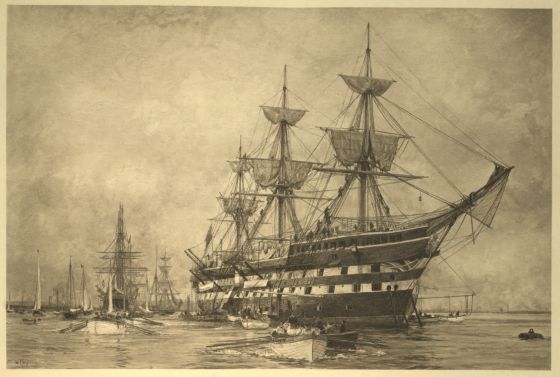

| REARING THE LION'S WHELPS. (By W. L. Wyllie, A.R.A.) | " | 544 |

| THE THANKSGIVING SERVICE, 27TH OF FEBRUARY, 1872: THE PROCESSION AT LUDGATE HILL. (By N. Chevalier) | " | 602 |

Reproduced by André & Sleigh, Ltd., Bushey, Herts.

WINDSOR CASTLE.

FROM A WATER-COLOUR PAINTING BY ALFRED W. HUNT R.W.S. IN THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF BRITISH ART.

THE CRYSTAL PALACE IN HYDE PARK, LONDON, 1851

——♦♦♦——

THE REIGN OF VICTORIA (continued).

The Papal Aggressions—The Durham Letter—Meeting of Parliament—The Ecclesiastical Titles Bill—Debate on the Second Reading—Amendments in Committee—The Bill in the Lords—Mr. Locke King's Motion on County Franchise—Resignation of the Government—The Great Exhibition—Banquet at York—Opening of the Exhibition—Success of the Project—The President of the French Republic and the Assembly—Preparations for the Coup d'État—The Army gained—Dissolution of the Assembly—Expulsion of the Assembly—Their Imprisonment—The High Court of Justice—The Barricades—St. Arnaud and Maupas—The Plébiscite—Weakness of the Russell Administration—Independence of Lord Palmerston—The Queen's Memorandum—Dismissal of Palmerston—The Militia Bill—Russell is turned out—The Derby Ministry—Its Measures—The General Election—An Autumn Session—Defeat of the Conservatives—Death and Funeral of the Duke of Wellington—The Aberdeen Administration—Mr. Gladstone's Budget—The Eastern Question again—The Diplomatic Wrangle—The Sultan's Firman—Afif Bey's Mission—Difficulties in Montenegro—England and France—Attempts to effect direct Negotiations—The Menschikoff Mission—Lord Stratford de Redcliffe's Instructions—The Czar and Sir Hamilton Seymour—Menschikoff at Constantinople—The English and French Fleets—Arrival of Lord Stratford de Redcliffe—The Difficulty settled—Menschikoff's ulterior Demands—Action of the Powers.

FROM the Revolution of 1688, when the Roman Catholic hierarchy was abolished with the arbitrary power of James II., the government of the Roman Catholic clergy was maintained in England by "vicars apostolic." England was divided into four vicariates, and this state of things continued[2] until 1840, when Gregory XVI. ordained a new ecclesiastical division of England, doubling the number of vicariates, which were thenceforward named the London, the Western, the Eastern, the Central, the Welsh, the Lancastrian, the York, and the Northern districts. In consequence of the increase of Roman Catholics in Great Britain, and the removal of their civil disabilities by the Emancipation Act, a desire grew up for the re-organisation of the regular episcopal system of the Church of Rome, and Pius IX. resolved to establish it in 1850. England and Wales were divided by a Papal brief into twelve sees; one of them, Westminster, was erected into an Archbishopric, and Dr. Wiseman, soon afterwards created a Cardinal, was appointed to it.

Perhaps there never was a document published in England that caused so much excitement as this pastoral letter; nor was society ever more violently agitated by any religious question since the Reformation. The pastoral provoked from Lord John Russell a counterblast in the shape of a letter to the Bishop of Durham, in which he gave deep offence to the Roman Catholics by stating that "the Roman Catholic religion confines the intellect and enslaves the soul." The Protestant feeling in the country was excited in the highest degree. The press was full of the "Papal aggressions." Meetings were held upon it in almost every town in the United Kingdom. It was alluded to in the Speech from the Throne, and during the Sessions of 1851 and 1852 it occupied a great portion of the time and attention of Parliament.

In both Houses of Parliament this topic occupied a prominent place in the debates on the Address, and on the 7th of February, 1851, the Prime Minister introduced his Ecclesiastical Titles Bill, which prevented the assumption of such titles in respect of places in the United Kingdom. He referred, in connection with the subject, to recent occurrences in Ireland. Dr. Cullen, who had spent most of his life at Rome, had been appointed Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of all Ireland, though his name had not been returned by the parish priests of the diocese, who were accustomed to elect three of their number to be submitted to the Pope as dignus, dignior, dignissimus. He was afterwards transferred to Dublin as the more influential post, with the powers of legate, which placed him at the head of the hierarchy. Then there was the Synod of Thurles, which condemned the Queen's Colleges, and interfered with the land question, and other temporal matters. He argued from the terms of the Pope's Bull that there was an assumption of territorial power of which our Roman Catholic ancestors were always jealous.

The Bill was vehemently opposed by the Irish Roman Catholic members. Mr. Bright and Mr. Disraeli also opposed the measure, which was supported by the Attorney-General, Lord Ashley, Mr. Page Wood, and Sir George Grey. Several other members having spoken for and against the Bill, its introduction was carried by the overwhelming majority of 395 to 63.

Various alterations were subsequently made in the Bill, to prevent its interfering unnecessarily with the Roman Catholic bishops in Ireland. The second reading was moved on the 14th of March. Mr. Cardwell refused his assent to the second reading, believing that, by supporting the measure, he would affront Protestant England, and do much to render Ireland ungovernable. Lord Palmerston supported the Bill, because churches were like corporate bodies, encroaching; because it would supply an omission in the Act of 1829; and as the Church of Rome obeyed that Act, she would also obey this. Sir James Graham, on the contrary, expressed his conviction that the passing of this Bill would be a repeal of the Emancipation Act, and then the Dissenters must look about them. Mr. Gladstone ably criticised the Bill, and concluded as follows:—"For three hundred years the Roman Catholic laity and secular clergy—the moderate party—had been struggling, with the sanction of the British Government, for this very measure, the appointment of diocesan bishops, which the extreme party—the regulars and cardinals at the Court of Rome—had been all along struggling to resist. The present legislation would drive the Roman Catholics back upon the Pope, and, teasing them with a miniature penal law, would alienate and estrange them. Religious freedom was a principle which had not been adopted in haste, and had not triumphed till after half a century of agonising struggles; and he trusted we were not now going to repeat Penelope's process without her purpose, and undo a great work which had been accomplished with so much difficulty." Mr. Disraeli expressed his sentiments, and those of his party, upon the general question and the particular measure. He denied that the Pope was without power. He was a prince of very great, if not the greatest power, his army being a million of priests; and was such a power to be treated as a Wesleyan Conference, or like an association of Scottish Dissenters? Sir George Grey having replied to the objections of Mr. Gladstone and others, the House divided, when[3] the second reading was carried by a still greater majority than the first, the numbers being—for the bill, 438; against it, 95; majority 343.

Considering that Sir James Graham, Mr. Gladstone, and all the leading Peelites, as well as Mr. Roebuck, Mr. Bright, and the advanced Liberals, joined the Roman Catholics on this occasion, the minority was surprisingly small, showing how deep and wide-spread was the national feeling evoked by the Papal aggressions. Several amendments were moved in committee; but they were nearly all rejected by large majorities. On the 27th of June Sir F. Thesiger proposed certain amendments with a view of rendering the measure more stringent, when about 70 Roman Catholic members retired from the House in a body. Lord John Russell, alluding to this "significant and ostentatious retirement," said it would not save them from the responsibility, as it would cause the passing of the amendments. They were accordingly carried against the Government. On the 4th of July, the day fixed for the third reading, Lord John Russell moved that those amendments should be struck out. One of them was that it should be penal to publish the Pope's Bulls, as well as to assume territorial titles; and another to enable common informers to sue for penalties. There was a division on each of these clauses. The question was then put by the Speaker, "that this Bill do now pass." Another long debate was expected; but no one rising, the division was abruptly taken, with the following result:—For the third reading, 263; against it, 46: majority, 217.

On the 21st of July the Bill was introduced by the Marquis of Lansdowne, into the Upper House. The debate there was chiefly remarkable for the speech of Lord Beaumont, a Roman Catholic peer, who gave his earnest support to the Bill as a great national protest, which the necessity of the case had rendered unavoidable. The Duke of Wellington remarked that "the Pope had appointed an Archbishop of Westminster; had attempted to exercise authority over the very spot on which the English Parliament was assembled. And under the sanction of this proceeding, Cardinal Wiseman made an attack upon the rights of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster. That this was contrary to the true spirit of the laws of England, no man acquainted with them could doubt, for throughout the whole of our statutes affecting religion we had carefully abstained from disturbing the great principles of the Reformation." Lord Lyndhurst supported the Bill in an elaborate and able speech. The second reading was carried in this House also by an overwhelming majority, the numbers being—for the bill, 265; against it, 38. On the 29th of July it was read a third time and passed, and shortly afterwards received the Royal Assent, after occupying nearly the whole of the Session. So far as the assumption of titles and the actual establishment and working of the Roman Catholic hierarchy were concerned, the Act undoubtedly proved a dead letter; but it is not to be inferred from this fact that it did not substantially answer its purpose in materially restraining aggression and keeping our jurisprudence clear of the Roman canon law. Cardinal Wiseman and his suffragans in England, on the whole, pursued a moderate and conciliatory course. But a very different course might have been pursued had not the national feeling been so strongly expressed, and been legally embodied in the Ecclesiastical Titles Act.

Lord John Russell's Administration had been for some time in a tottering state. Early in the Session of 1851 the Government was defeated on a motion by Mr. Locke King, for leave to bring in a Bill to make the franchise in counties in England and Wales the same as in boroughs; that is, the occupation of a tenement of the annual value of £10. The motion was carried against the Government by a majority of forty-eight. The Budget came on shortly afterwards, and gave so much dissatisfaction, that there was a general conviction that the Cabinet could not hold together much longer. It was felt that the times required a strong Government; but this had become gradually one of the weakest. The announcement of its resignation, therefore, excited no surprise; but the anxiety to learn what would be the new Ministerial arrangements was evinced by the crowded state of the House of Commons on Friday, the 21st of February. On the order for going into Committee of Ways and Means being read, the Prime Minister rose and requested that it might be postponed till the 24th. On the 24th both Houses were full. In the Upper House, Lord Lansdowne stated that in consequence of divisions which had recently taken place in the House of Commons, the Ministers had unanimously resigned; that Lord Stanley had been sent for by the Queen, and a proposal was made to him to construct a Government, for which he was not then prepared. Lord Stanley gave an account of his gracious reception by her Majesty, but reserved his reasons for declining to undertake the task. In the Lower House, on the same evening, Lord John Russell stated that her Majesty had sent for Lord Stanley, who had declined to form an[4] Administration, and that her Majesty had then asked him to undertake the task of reconstructing one, which he said he had agreed to do. He asked the House to adjourn to the 28th, and when that day arrived, matters were still in a state of confusion. Lord John Russell had failed to reconstruct his Cabinet; Lord Aberdeen and Sir James Graham had refused to concur in forming an Administration. Lord Stanley had also failed in a similar attempt, owing, according to Lord Malmesbury's "Recollections of an Ex-Minister," to the feeble counsels of Mr. Henley and Mr. Herries. From explanations given by Lord Aberdeen, Lord Stanley, Sir James Graham, and Lord John Russell himself, it appeared that the attempts to reconstruct the Cabinet, or to form a new one, arose from two difficulties in the way of any coalition between the leaders of existing parties—Free Trade, and the Ecclesiastical Titles Bill. There could be no union between the Whigs and the Peelites on account of the latter, nor between the Peelites and the Protectionists on account of the former. Lord Stanley remarked that the Peelites, with all their ability and official aptitude, seemed to exercise their talents solely to render any Ministry impossible. A purely Protectionist Administration was out of the question, as it would have to contend against a large majority in the House of Commons. In this dilemma the Queen sent for the Duke of Wellington, and he advised her Majesty that the best course she could adopt in the circumstances was to recall her late advisers; and Lord John Russell's Cabinet resumed their offices accordingly in exactly the same position that they had been before the resignation.

The year 1851 will be for ever memorable by reason of the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park. The idea is generally said to have originated with Prince Albert, who took a lively interest in everything that tended to promote industrial progress and to improve the public taste. As President of the Society of Arts, his attention had been attracted to the Exposition at Paris, under the guidance of the Minister of the Department of Commerce and Industry; and his Royal Highness thought that a similar exhibition in London, open to competitors from all nations, would be useful in a variety of ways, especially in uniting together the people of various countries by the bonds of mutual interest and sympathy. The proposal, from whatever source it originated, was embraced with alacrity by the British public. On the 21st of March, 1850, the Lord Mayor of London gave a splendid banquet at the Mansion House to the chief magistrates of the cities, towns, and boroughs of the United Kingdom, to stimulate their combined interest in the proposed Exhibition. The banquet over, his Royal Highness addressed the guests in an admirable speech, in which the tendencies of the age, the modern developments of art and science, the rapid intercommunication of thought, all realising the unity of mankind, were strikingly presented. The Ministers, past and present, the foreign ambassadors, prelates, and peers, vied with each other in expressing the high value they attributed to the design for the Exhibition.

A similar banquet was given by the Lord Mayor of York, when the Prince Consort and the Lord Mayor of London, the Prime Minister, the Earl of Carlisle, and many of the nobility were present. The Archbishop of York and the High Sheriff of Yorkshire headed the provincial guests, while the Lord Provost of Edinburgh and the Lord Provost of Glasgow appeared as the chiefs of the municipal magistrates. The ancient capital of the north of England brought forth upon that occasion a gorgeous display of historical memorials. There was a collection of maces, State swords, and various civic insignia belonging to corporate bodies, wreathed with flowers and evergreens through which gleamed the bosses and incrustations of gold on the maces that had been wielded by generations of mayors, with the velvet shields and gaudy mountings of gigantic swords of State. Among the ornaments appeared the jewel-bestudded mace of Norwich, presented by Queen Elizabeth. York, on this occasion, surpassed the City of London in the splendour of the banquet. The Prince, in returning thanks for his health, paid a well-turned tribute to the memory of Sir Robert Peel.

A Royal Commission was appointed to manage the Exhibition. Hyde Park in London was fixed upon as the most appropriate site for the building, and Mr. Paxton, head-gardener to the Duke of Devonshire, though not an architect, furnished the plan of the Crystal Palace, as the Exhibition building was called. It was chiefly composed of iron and glass, being 1,848 feet long, 408 feet broad, and 66 feet high, crossed by a transept 108 feet high and also 408 feet in length, for the purpose of enclosing and encasing a grove of noble elms. Within, the nave presented a clear, unobstructed avenue, from one end of the building to the other, 72 feet in span, and 64 feet in height. On each side were aisles 64 feet wide, horizontally divided into galleries, which ran round the whole of the nave and transept. The wings exterior to the[5] centre or nave on each side had also galleries of the same height, the wings themselves being broken up into a series of courts, each 48 feet wide. The Palace was within 10 feet of being twice the width of St. Paul's and four times the length. The number of columns used in the entire edifice was 3,230. There were 34 miles of gutters for carrying off the rain-water to the columns, which were hollow, and served as water-pipes, 202 miles of sash bars, and 900,000 superficial feet of glass, weighing upwards of 400 tons. The building covered about 18 acres of ground, and with the galleries gave an exhibiting surface of 21 acres, with 8 miles of tables for laying out goods.

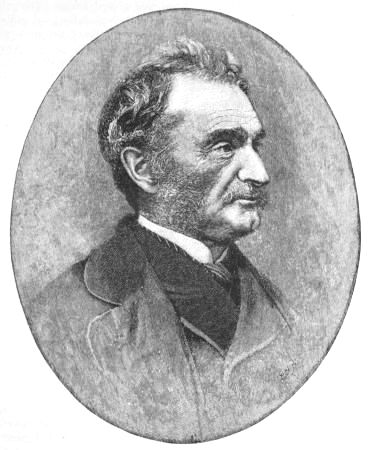

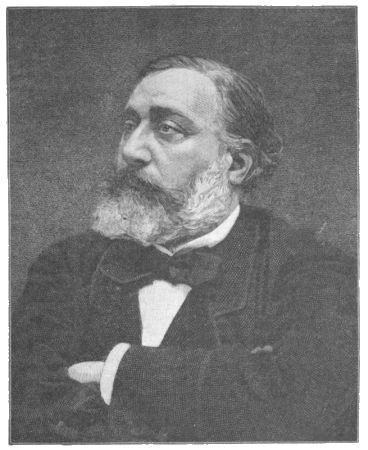

PRINCE ALBERT.

(From a photograph by Mayall and Co., Limited.)

The plan was accepted on the 26th of July, 1850; and Messrs. Fox, Henderson, and Co. became the contractors, for the sum of £79,800, if the materials should remain their property, they being at the expense of removal; or £150,000 if the materials became the property of the Commissioners. It actually cost £176,030. The first column was fixed on the 26th of September, 1850; the contract to deliver over the building complete to the Commissioners on the 31st of December was virtually performed; and on the 1st of January, 1851, the Commissioners occupied the vast space with their carpenters, painters, and various artisans. The Crystal Palace excited universal admiration, from the wonderful combination of vastness and beauty, from its immense magnitude united with lightness, symmetry, and grace, as well as admirable adaptation to its purpose. And when it was fully furnished and open to the public, on the 1st of May, 1851, the visitor felt as if he had entered a fairy-like scene of enchantment, a palace of beauty and delight, such as one might[6] suppose mortal hands could not create. The effect on the beholder far surpassed all that its most sanguine projectors could have anticipated.

The scene was impressive on the opening on that beautiful May morning by the Queen and Prince Albert, followed in procession through the building by a long train of courtiers, Ministers of State, foreign ambassadors, and civic dignitaries; while the sun shone brightly through the glass roof upon trees, flowers, banners, and the picturesque costumes of all nations, the great organ at the same time pealing gloriously through the vast expanse, which was filled by a dense mass of human beings, representing the grandeur, wealth, beauty, intelligence, and enterprise of the civilised world. The number of exhibitors exceeded 17,000, of whom upwards of 3,000 received medals. It continued open from the 1st of May till the 15th of October, altogether 144 days, during which it was visited by 6,170,000 persons, giving an average daily attendance of 42,847. The greatest number in one day (October 8th) was 109,760. The greatest number in the Palace at any one time was 93,000, which surpassed in magnitude any number ever assembled together under one roof in the history of the world. The charges for admission were half-a-crown on particular days, and one shilling on ordinary days. The receipts, including season tickets, amounted to £505,107, leaving a surplus of about £150,000, after paying all expenses; so that the Exhibition was in every sense pre-eminently successful. However, it did not, as was anticipated, inaugurate an era of peace.

We have already seen that Louis Napoleon, when President of the French Republic, solemnly and vehemently vowed to maintain the Constitution. These vows were repeated from time to time in his speeches and declarations, which he was always ready to volunteer. The National Assembly, however, had suspected him for some time to be entertaining treasonable designs, and plotting the ruin of the republic. One of the symptoms of this state of mind was found in the rumours propagated in France about the failure of Parliamentary government, and the designs of the Red Republicans. In this way vague fears were generated that another bloody revolution was impending, and that, in order to save the State, it was necessary to have a strong Government. In fact, the conviction somehow gained ground that a monarchical régime was the best fitted for France. The army was probably inclined the same way. The first thing the President did, of course, was to sound its disposition, and ascertain how far he might be able to wield its irresistible power against the liberties of his country. But however the soldiers might be disposed to aid his designs, it was well known that its generals would not allow a shot to be fired without orders from the Minister of War; and the man who held that post was not a character likely to lend himself as the instrument of a treasonable plot. Louis Napoleon therefore found it necessary to enlist others in his service. The principal of these were daring and needy adventurers, namely—his half-brother M. de Morny, a great speculator in shares; Major Fleury, a young officer who had squandered his fortune in dissipation, entered the army as a common soldier, and risen from the ranks; St. Arnaud, an Algerian officer; M. Maupas, who had been a prefect, and had been guilty of conspiracy to destroy innocent persons by a false accusation of treason; and Persigny, alias Fialin, who had entered the army as a non-commissioned officer. St. Arnaud was made Minister of War, and Maupas Prefect of Police. General Magnan, the Commander-in-Chief of the army at Paris, readily entered into the plot which was originally fixed for September but postponed on the advice of Fleury. On the 27th of November 1851 he invited twenty generals who were under his command to meet at his house. There they matured their plans, and after vows of mutual fidelity, they solemnly embraced one another. In the meantime the common soldiers were pampered with food and wine, stimulated by flattery and exasperated by falsehood against the "Bedouins" of Paris. On Monday night, the 1st of December, the President had an assembly at the Elysée, which included Ministers and others who were totally ignorant of the plot. The company departed at the usual hour, and at eleven o'clock only three of the guests remained—Morny, who had shown himself at one of the theatres, Maupas, and St. Arnaud.

Meanwhile the State printing-office was surrounded by gendarmerie, and the compositors were all made prisoners, and compelled to print a number of documents which had been sent from the President. These were several decrees, which appeared on the walls of Paris at daybreak next morning, to the utter astonishment of the population. They read in them that the National Assembly was dissolved, that the Council of State was dissolved and that universal suffrage was re-established. They read an attack upon the Assembly, in which it was charged with forging arms for civil war, with provocations, calumnies, and outrages against the President. These things[7] were said to be done by the men who had already destroyed two monarchies, and who wanted to overthrow the republic; but he, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, would baffle their perfidious projects. He submitted to them, therefore, a plan of a new Constitution: a responsible chief, named for ten years, Ministers dependent on the executive alone, a Council of State, a Legislative Corps, a Second Chamber. There was also an appeal to the army, which told the soldiers to be proud of their mission, for they were to save their country, and to obey him, the legitimate representative of the national sovereignty.

At half-past six o'clock in the morning M. de Morny took possession of the Ministry of the Interior. The army and the police were distributed through the town and had all received their respective orders. Among these were the arrest of seventy-eight persons, of whom eighteen were representatives and sixty alleged chiefs of secret societies and barricades. All these arrests were effected accordingly. At the appointed minute, and while it was still dark, the designated houses were entered. The most famous generals of France were seized and dragged forth from their beds—Changarnier, Bedeau, Lamoricière, Cavaignac, Leflo—all were placed in carriages, ready at their doors to receive them, and conveyed to prison through the sleeping city. Precisely at the same moment the chief members and officers of the Assembly shared the same fate.

All the trusted chiefs and guides of the people being thus disposed of, De Morny from the Home Office touched the chords of centralisation, and conveyed to every village in France the unbounded enthusiasm with which the still sleeping city had hailed the joyful news of the revolution which had been effected. When the free members of the Assembly heard of the arrest of their brethren, they ran to the Hôtel de Ville, the entrance of which was guarded. Those who had got in by a private passage were rudely expelled, some of them being violently struck by the soldiers. They then reassembled at the Mairie of the 10th Arrondissement, at which they passed a resolution depriving Louis Napoleon of authority, but the Chamber was not long permitted to deliberate in peace. Two commissaries of police soon entered, and summoned the representatives to disperse. "Retire," said the President. After some hesitation the commissaries seized the President by the collar, and dragged him forth. The whole body then rose, 220 in number, and declaring that they yielded to force, walked out, two and two, between files of soldiery. In this way they were marched through the street, into the Quai d'Orsay, where they were shut up in the barracks, without any accommodation for their comfort. During the day eleven more deputies were brought to the barracks, three of whom came for the express purpose of being incarcerated with their brethren. After being left for hours on a winter's evening in the open air, the Assembly were driven into the barrack rooms upstairs, where they were left without fire, almost without food, and were obliged to lie upon the bare boards. At ten o'clock most of the 220 members of Parliament were thrust into large prison vans, like felons, and were carried off, some to the fort of Mont Valérien, some to the fortress of Vincennes, and some to the prison of Mazas. Before dawn on the 3rd of December, all the leading statesmen and great generals of France, all the men who made her name respected abroad, were lying in prison.

The High Court of Justice met on the 2nd of December, and having referred to the placards that had been issued that morning, made provision for the impeachment of Louis Napoleon and his fellow-conspirators. But while the court was sitting, an armed force entered the hall, and drove the judges from the bench. Before they were thrust out, they adjourned the court to "a day to be named hereafter," and they ordered a notice of impeachment to be served upon the President at the Elysée.

These astounding acts did not produce the alarm that might have been expected. Hitherto Louis Napoleon was not regarded with terror, as the inscrutable and the unpitying, but rather with a feeling of contempt and derision by the citizens of Paris. But the citizens had been disarmed; the leaders of the Faubourgs had been carried off by the police. In the absence of such leaders, the members of the Assembly who happened to be at large called upon the people to resist the usurpers. During the night of the 3rd, therefore, barricades were rapidly erected along the streets which lay between the Hôtel de Ville and the Boulevards Montmartre and des Italiens. But the troops were ready for action, 48,000 strong, including cavalry, infantry, artillery, engineers, and gendarmes. They had been supplied with rations, wine, and spirits in abundance. They had been ordered to give no quarter, either to combatants or to bystanders; but to clear the streets at any cost. Magnan's conscience, however, caused him to hesitate long, and was on the point of making a coward of him. There was a small barricade[8] which crossed the boulevard close to the Gymnase Theatre, which was occupied by a small advanced guard of the insurgents; and facing this, fifty yards off, was an immense column of troops, which occupied all the boulevard, and also the whole way to the Madeleine. The windows and balconies along the line were filled with ladies and gentlemen gazing at the grand military spectacle, which seemed only to be a demonstration to overawe the disaffected, there being no visible enemy to contend with.

Suddenly a few musket shots were fired at the head of the column. The troops returned the fire so regularly that it seemed at first a feu-de-joie. The column advanced, still firing, and to the utter consternation of the spectators, the shots were directed at the windows and balconies, shivering the panes of glass, smashing the mirrors, rending the curtains, and rattling against the walls. This continued for a quarter of an hour, the inhabitants endeavouring to save themselves by lying prostrate on the floor and flying to the back apartments. There is no doubt that this fusilade was the result of a panic among the troops, who apprehended an attack from the windows. Many persons were shot down in the streets, some endeavouring to escape into the houses. Next day pools of blood were to be seen round the trees along the boulevard. Fortunately the massacre did not last long. When the barricade of St. Denis had been carried, the insurrection was at an end; but while it did last, it was fearful. Many women and children were victims.

In order to save the conspirators from the effects of the universal horror which these atrocities were calculated to excite, it was necessary to set forth in a public manner the reasons for the usurpation of power by Napoleon. St. Arnaud did not hesitate to say all that was thought needful. There was only one ground on which a shadow of excuse could be offered for the deeds that had been done—that was, that it was necessary to save society from Red Republicanism, and this was the topic of his order of the day. But to give the full appearance of truth to this lying proclamation to the army, it was necessary that the police should play their part. Therefore De Maupas sent forth a circular to the commissaries of police, stating that arms, ammunition, and incendiary writings were concealed to a large extent in lodging-house, cafés, and private dwellings. The National Guard was disbanded on the 7th, as another precautionary measure. There was one order of men, however, which could neither be disbanded nor sent off in prison vans, but which, if conciliated, could be made powerful auxiliaries of despotism; while, if alienated and exasperated, they would be its most dangerous enemies—the Roman Catholic clergy. Therefore Louis Napoleon hastened to announce the restoration of the Panthéon to its original use as the Church of St. Geneviève.

The next step was a proclamation to the French people, stating that he had saved society, that it was madness to oppose the united and patriotic army, and that the intelligent people of Paris were all on his side. Then followed the vote by universal suffrage, which was put in this way:—"For Louis Napoleon and the new Constitution, Yes or No." This was putting before the nation this alternative—a strong Government or anarchy. The result of the voting was, for Louis Napoleon, 7,481,231; against him, 640,737. Thus armed, the President met his consultative commission on the last day of the year, and told them that he understood all the grandeur of his new mission, that he had an upright heart, that he looked for the co-operation of all right-minded men.

On the public mind in England, as the facts were made known through correspondence, the effect produced was a general feeling of alarm. But it had political consequences of a serious nature, for it caused the fall of the Russell Administration. That weak-kneed body had not benefited much by its temporary popularity in the year of the Great Exhibition. The Budget of 1851 contained a most unpopular proposal for the substitution for the window tax of a duty of 1s. in the pound on houses, and 9d. on shops, which had to be considerably reduced, and Mr. Hume, with the assistance of the Conservatives, carried against the Government the limitation of the income-tax to a year. Further, Lord Naas, afterwards Earl of Mayo, placed them in a minority on a resolution connected with the spirit duties. The Cabinet naturally became divided and dispirited, and not the least source of its disunion was the boldness and insubordination of Lord Palmerston. We have already mentioned his rash despatch to Sir Henry Bulwer, which led to that Minister's dismissal from Madrid. This communication was written both without the knowledge and against the express orders of the Prime Minister. The Queen naturally resented this independent action, and Lord Palmerston speedily found himself at variance with the Prince Consort, who was in favour of a German Customs Union, whereas the Foreign Minister resented its[9] formation as injurious to Free Trade. During the revolution of 1848 Palmerston acted with more than his usual contempt for control, and remonstrances from the Queen were frequent and strongly worded. They culminated in a memorandum, which ran as follows follows:—

THE OPENING BY QUEEN VICTORIA OF THE GREAT EXHIBITION IN HYDE PARK, LONDON, 1ST MAY, 1851.

FROM THE PAINTING BY H. C. SELOUS IN THE VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM, SOUTH KENSINGTON.

"The Queen requires, first, that Lord Palmerston will distinctly state what he proposes in a given case, in order that the Queen may know as distinctly to what she has given her royal sanction; secondly, having once given her sanction to a measure, that it be not arbitrarily altered or modified by the Minister. Such an act she must consider as failing in sincerity towards the Crown, and justly to be visited by the exercise of her constitutional right of dismissing that Minister. She expects to be kept informed of what passes between him and the foreign Ministers before important decisions are taken based upon that intercourse; to receive the foreign despatches in good time; and to have the drafts for her approval sent to her in sufficient time to make herself acquainted with their contents before they must be sent off. The Queen thinks it best that Lord John Russell should show this letter to Lord Palmerston."

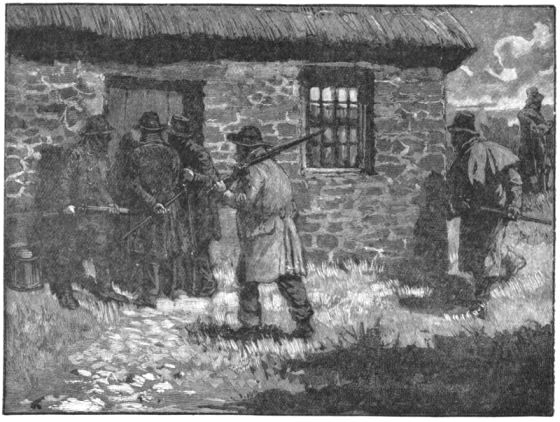

THE COUP D'ÉTAT: EVICTION OF THE JUDGES. (See p. 7.)

This was sent to Lord Palmerston by Lord John Russell, and it was acknowledged by Lord Palmerston as follows:—"I have taken a copy of this memorandum of the Queen's, and will not fail to attend to the directions which it contains." This occurred in August, 1850, more than twelve months before the occurrence of the coup d'état in Paris, and in the interval Palmerston, with difficulty dissuaded from receiving Kossuth who was on a visit to England, accepted an address from the Radicals of Islington in which the Emperors of Russia and Austria were stigmatised as despots, tyrants, and assassins. A few days later he committed a fresh indiscretion in conversation with Count Walewski, the French Ambassador, to whom he expressed a strong approval of the coup d'état. When Palmerston was asked to explain his conduct, he evaded the point by a long defence of the action of Louis Napoleon, and Lord John Russell at last summoned up courage to dismiss him from his office.