PITTA STREPITANS: Temm.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

Title: The Birds of Australia, Vol. 4 of 7

Author: John Gould

Release date: December 2, 2019 [eBook #60833]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, MWS, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

| Pitta strepitans, Temm. | Noisy Pitta | 1 |

| —— Vigorsii, Gould | Vigors’ Pitta | 2 |

| —— Iris, Gould | Rainbow Pitta | 3 |

| Cinclosoma punctatum, Vig. & Horsf. | Spotted Ground-Thrush | 4 |

| —— castanotus, Gould | Chestnut-backed Ground-Thrush | 5 |

| —— cinnamomeus, Gould | Cinnamon-coloured Cinclosoma | 6 |

| Oreocincla lunulata | Mountain Thrush | 7 |

| Chlamydera maculata, Gould | Spotted Bower-Bird | 8 |

| —— nuchalis | Great Bower-Bird | 9 |

| Ptilonorhynchus holosericeus, Kuhl | Satin Bower-Bird | 10 |

| —— Smithii, Vig. & Horsf. | Cat Bird | 11 |

| Sericulus chrysocephalus | Regent Bird | 12 |

| Oriolus viridis | New South Wales Oriole | 13 |

| —— flavo-cinctus | Crescent-marked Oriole | 14 |

| Sphecotheres Australis, Swains. | Australian Sphecotheres | 15 |

| Corcorax leucopterus | White-winged Chough | 16 |

| Struthidea cinerea, Gould | Grey Struthidea | 17 |

| Corvus Coronoïdes, Vig. & Horsf. | White-eyed Crow | 18 |

| Neomorpha Gouldii, G. R. Gray | Gould’s Neomorpha | 19 |

| Pomatorhinus temporalis | Temporal Pomatorhinus | 20 |

| —— rubeculus, Gould | Red-breasted Pomatorhinus | 21 |

| —— superciliosus, Vig. & Horsf. | White-eyebrowed Pomatorhinus | 22 |

| Meliphaga Novæ-Hollandiæ | New Holland Honey-eater | 23 |

| —— longirostris, Gould | Long-billed Honey-eater | 24 |

| —— sericea, Gould | White-cheeked Honey-eater | 25 |

| —— mystacalis, Gould | Moustached Honey-eater | 26 |

| —— Australasiana | Tasmanian Honey-eater | 27 |

| Glyciphila fulvifrons | Fulvous-fronted Honey-eater | 28 |

| —— albifrons, Gould | White-fronted Honey-eater | 29 |

| —— fasciata, Gould | Fasciated Honey-eater | 30 |

| —— ocularis, Gould | Brown Honey-eater | 31 |

| Ptilotis chrysotis | Yellow-eared Honey-eater | 32 |

| —— sonorus, Gould | Singing Honey-eater | 33 |

| —— versicolor, Gould | Varied Honey-eater | 34 |

| —— flavigula, Gould | Yellow-throated Honey-eater | 35 |

| —— leucotis | White-eared Honey-eater | 36 |

| —— auricomis | Yellow-tufted Honey-eater | 37 |

| —— cratitius, Gould | Wattle-cheeked Honey-eater | 38 |

| —— ornatus, Gould | Graceful Honey-eater | 39 |

| —— plumulus, Gould | Plumed Honey-eater | 40 |

| —— flavescens, Gould | Yellow-tinted Honey-eater | 41 |

| —— flava, Gould | Yellow Honey-eater | 42 |

| —— penicillatus, Gould | White-plumed Honey-eater | 43 |

| —— fusca, Gould | Fuscous Honey-eater | 44 |

| —— chrysops | Yellow-faced Honey-eater | 45 |

| —— unicolor, Gould | Uniform Honey-eater | 46 |

| Plectorhyncha lanceolata, Gould | Lanceolate Honey-eater | 47 |

| Zanthomyza Phrygia | Warty-faced Honey-eater | 48 |

| Melicophila picata, Gould | Pied Honey-eater | 49 |

| Entomophila picta, Gould | Painted Honey-eater | 50 |

| —— albogularis, Gould | White-throated Honey-eater | 51 |

| —— rufogularis, Gould | Red-throated Honey-eater | 52 |

| Acanthogenys rufogularis, Gould | Spiny-cheeked Honey-eater | 53 |

| Anthochæra inauris, Gould | Great Wattled Honey-eater | 54 |

| —— carunculata | Wattled Honey-eater | 55 |

| —— mellivora | Brush Wattle-Bird | 56 |

| —— lunulata, Gould | Lunulated Wattle-Bird | 57 |

| Tropidorhynchus corniculatus | Friar-Bird | 58 |

| —— argenticeps, Gould | Silvery-crowned Friar-Bird | 59 |

| —— citreogularis, Gould | Yellow-throated Friar-Bird | 60 |

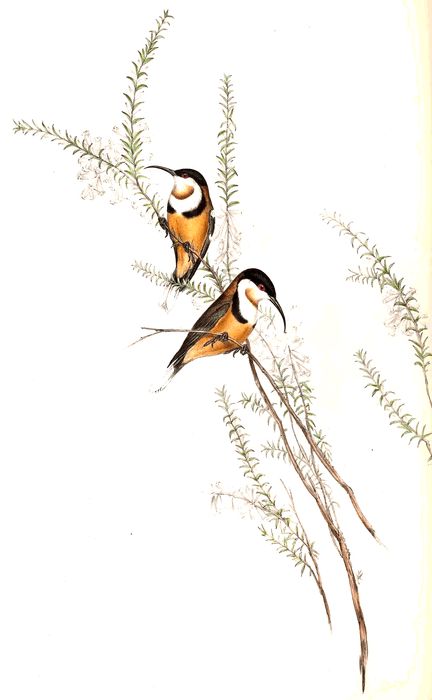

| Acanthorhynchus tenuirostris | Slender-billed Spine-bill | 61 |

| —— superciliosus | White-eyebrowed Spine-bill | 62 |

| Myzomela sanguineolenta | Sanguineous Honey-eater | 63 |

| —— erythrocephala, Gould | Red-headed Honey-eater | 64 |

| —— pectoralis, Gould | Banded Honey-eater | 65 |

| —— nigra, Gould | Black Honey-eater | 66 |

| —— obscura, Gould | Obscure Honey-eater | 67 |

| Entomyza cyanotis | Blue-faced Entomyza | 68 |

| —— albipennis, Gould | White-pinioned Honey-eater | 69 |

| Melithreptus validirostris, Gould | Strong-billed Honey-eater | 70 |

| —— gularis, Gould | Black-throated Honey-eater | 71 |

| —— lunulatus | Lunulated Honey-eater | 72 |

| —— chloropsis, Gould | Swan River Honey-eater | 73 |

| —— albogularis, Gould | White-throated Honey-eater | 74 |

| —— melanocephalus, Gould | Black-headed Honey-eater | 75 |

| Myzantha garrula | Garrulous Honey-eater | 76 |

| —— obscura, Gould | Sombre Honey-eater | 77 |

| —— lutea, Gould | Luteous Honey-eater | 78 |

| —— flavigula, Gould | Yellow-throated Miner | 79 |

| —— melanophrys | Australian Bell-Bird | 80 |

| Zosterops dorsalis, Vig. & Horsf. | Grey-backed Zosterops | 81 |

| —— chloronotus, Gould | Green-backed Zosterops | 82 |

| —— luteus, Gould | Yellow Zosterops | 83 |

| Cuculus optatus, Gould | Australian Cuckoo | 84 |

| —— inornatus, Vig. & Horsf. | Unadorned Cuckoo | 85 |

| —— cineraceus, Vig. & Horsf. | Ash-coloured Cuckoo | 86 |

| —— insperatus, Gould | Brush Cuckoo | 87 |

| Chalcites osculans, Gould | Black-eared Cuckoo | 88 |

| Chrysococcyx lucidus | Shining Cuckoo | 89 |

| Scythrops Novæ-Hollandiæ, Lath. | Channel-Bill | 90 |

| Eudynamys Flindersii | Flinders’s Cuckoo | 91 |

| Centropus Phasianus | Pheasant Cuckoo | 92 |

| Climacteris scandens, Temm. | Brown Tree-Creeper | 93 |

| —— rufa, Gould | Rufous Tree-Creeper | 94 |

| —— erythrops, Gould | Red-eyebrowed Tree-Creeper | 95 |

| —— melanotus, Gould | Black-backed Tree-Creeper | 96 |

| —— melanura, Gould | Black-tailed Tree-Creeper | 97 |

| —— picumnus, Temm. | White-throated Tree-Creeper | 98 |

| Orthonyx spinicaudus, Temm. | Spine-tailed Orthonyx | 99 |

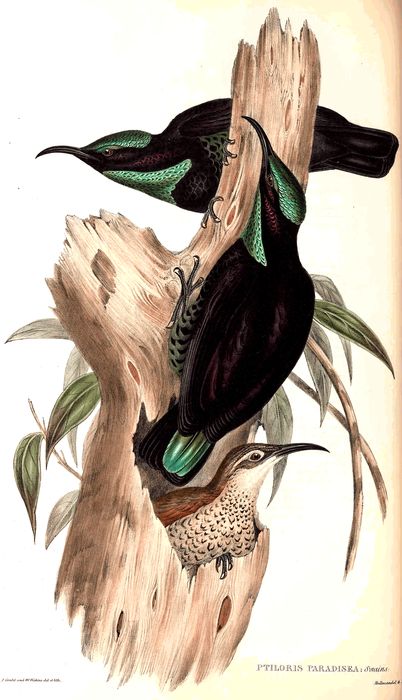

| Ptiloris paradiseus, Swains. | Rifle Bird | 100 |

| Sittella chrysoptera | Orange-winged Sittella | 101 |

| —— leucocephala, Gould | White-headed Sittella | 102 |

| —— leucoptera, Gould | White-winged Sittella | 103 |

| —— pileata, Gould | Black-capped Sittella | 104 |

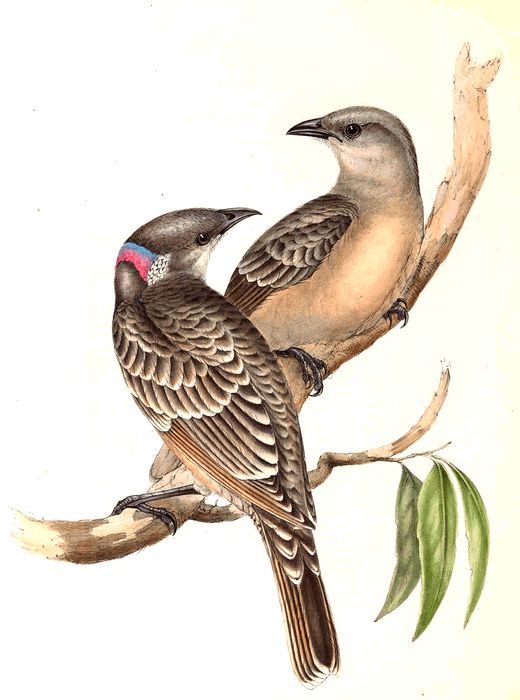

PITTA STREPITANS: Temm.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

Pitta strepitans, Temm. Pl. Col. 333.—Jard. and Selb. Ill. Orn., vol. ii. pl. 77.

Pitta versicolor, Swains. in Zool. Journ., vol. i. p. 468.

The description of Pitta versicolor given by Mr. Swainson in the “Zoological Journal” agrees so accurately with the description and figure of Pitta strepitans in the “Planches Coloriées,” that not the slightest doubt exists in my mind as to their identity; but which of these names has the priority is a point I have been unable satisfactorily to determine, in consequence of the latter work having been published in parts at irregular periods. Mr. Swainson, it is true, refers to the “Planches Coloriées,” and institutes a comparison between his bird and the Pitta cyanoptera, beautifully figured in Pl. 218; the Pitta strepitans, on the other hand, forms the subject of Pl. 333, which we may reasonably suppose must have appeared at a much later period, although it may still have been prior to the publication of P. versicolor; the numbers of foreign works being frequently much in arrear in this country. In support of the priority of M. Temminck’s name, I may quote a passage from the “Illustrations of Ornithology” of Messrs. Jardine and Selby:—“This species seems to have been unnoticed until the figure of M. Temminck, who received his specimen from Mr. Leadbeater. It then appeared to be the only individual of this form known to belong to New Holland; and it is only lately that Mr. Swainson has added a second species, in his P. versicolor, to the interesting ornithology of that country.”

Never having seen this bird alive, I am unable to give any account of its habits and manners from my own observation. It is said to dwell in those almost impenetrable brushes of the eastern coast of Australia, and is tolerably abundant in all such localities between the river Macquarrie and Moreton Bay; it is also said to be very thrush-like in its disposition, and, as its long legs would lead us to suppose, resorts much to the ground, although it readily takes to the branches of trees when its haunts are intruded upon. Its food consists of insects, and probably berries and fruits.

The two young figured in the accompanying Plate with an adult were collected in the brushes bordering the river Clarence on the east coast, which must consequently be enumerated among its breeding-places. The circumstance of the young, like those of the Kingfishers, assuming the characteristic plumage of the adult from the time they leave the nest is very singular, and the knowledge of this fact is very important, inasmuch as it may lead to some valuable results in classification.

The sexes appear to present but little differences either in colour or size; some specimens, which I take to be males, however, differ in having the tail-feathers more largely tipped with green than others.

Crown deep ferruginous with a narrow stripe of black down the centre; on the chin a large spot of black terminating in a point on the front of the neck, and uniting to a broad band on each side of the head, encircles the crown and terminates in a point at the back of the neck; back and wings pure olive-green; shoulders and lesser wing-coverts bright metallic cærulean blue; across the rump a band of the same colour; upper tail-coverts and tail black, the latter tipped with olive-green; primaries black, becoming paler at the tips; at the base of the fourth, fifth and sixth a small white spot; sides of the neck, throat, breast and flanks buff; in the centre of the abdomen a patch of black; vent and under tail-coverts scarlet; irides dark brown; bill brown; feet flesh-colour.

The figures are of the natural size.

PITTA VIGORSII; (Gould).

Drawn from Nature & on Stone by J. & E. Gould. Printed by C. Hullmandel.

Pitta brachyura, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 218.

A single specimen of this beautiful species of Pitta forms part of the collection of the Linnean Society of London, where it has always been considered as identical with the Pitta brachyura, but from which it differs in many important characters, among the most conspicuous of which may be noticed its larger size, and the narrow streak of light greenish grey which passes from the nostrils over each eye, and nearly surrounds the occiput.

I have not been able to obtain any decided information respecting the portion of Australia from which this bird was obtained, but the eastern and northern coasts may be regarded as its most likely habitat; and I am unable to render any account of its habits, or the situations it frequents: several of the members of the group, however, particularly the other Australian species (Pitta strepitans), are known to prefer the thick brushes near the coast, where it hops about and scratches up the leaves, etc., in search of food. The Pitta brachyura is also said to perch on the topmost branches of decayed trees, and to resort to the sides of inland streams and waters, where it sports among the shallows, frequently wading up to its knees, which aquatic habits are indicated by the general character of its plumage; and as the present bird is very nearly allied to that species, it has doubtless similar habits.

Messrs. Vigors and Horsfield having omitted to notice the distinctive characters of this species, while engaged upon their elaborate Catalogue of the Australian Birds in the Linnean Society’s collection, I have much pleasure in dedicating it to the memory of the late Mr. Vigors, whose high scientific attainments, especially in Ornithology, are so well known that my testimony is unnecessary.

Crown of the head, ear-coverts, and back of the neck jet-black; a narrow stripe of greenish grey commences at the nostrils, passes over each eye, surrounds the crown, and nearly unites at the occiput; back, scapularies, outer edges of the secondaries, and the greater wing-coverts bronzy green; shoulders, rump, and upper tail-coverts fine lazuline blue; throat white; chest, flanks, and thighs tawny buff; centre of the abdomen dark blood-red, passing into scarlet on the under tail-coverts; primaries black, with a white bar across the centre of the third, fourth, fifth and sixth; tail black, tipped with green; bill dark brown; legs flesh-colour.

The figure is of the natural size.

PITTA IRIS: Gould.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

Pitta Iris, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., February 8, 1842.

Two specimens of this new and beautiful Pitta, both killed on the north coast of Australia, have already come under my notice. One of these is in the collection of Dr. Bankier, Acting Surgeon of H.M.S. Pelorus, and the other, apparently a female, is in the British Museum, having been lately presented to the national collection with many other fine birds, by Captain Chambers, R.N., of the same vessel.

The Rainbow Pitta differs so much from all other known species of this lovely tribe of birds, as to render a comparison quite unnecessary. By its discovery we can now enumerate three species from Australia. How rapidly is this fine country unfolding her rich treasures, of which, indeed, sufficient have been seen to rank her second to none in the interest of her productions!

Both the specimens above-mentioned are from the Cobourg Peninsula, where the species is not uncommon, and it will doubtless, hereafter, be found to range over a great portion of the north coast. No further account of the habits of this fine bird have been received than that it inhabits the thick “cane-beds” near the coast, through which it runs with great facility; the boldness and richness of its markings render it a most attractive object in the bush.

Head, neck, breast, abdomen, flanks and thighs deep velvety black; over the eye, extending to the occiput, a band of ferruginous brown; upper surface and wings golden green; shoulders bright metallic cærulean blue, bordered below with lazuline blue; primaries black, passing into olive-brown at their tips, the third, fourth, fifth and sixth having a spot about the centre of the feather; tail black at the base, green at the tip, the former colour running on the inner web nearly to the tip; rump-feathers tinged with cærulean blue; lower part of the abdomen and under tail-coverts bright scarlet, separated from the black of the abdomen by yellowish brown; irides dark brown; bill black; feet flesh-colour.

The figures are of the natural size.

CINCLOSOMA PUNCTATUM: Vig. & Horsf.

J. & E. Gould del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

Turdus Punctatus, Lath. Ind. Orn. Supp., p. xliv.

Punctated Thrush, Lath. Gen. Syn. Supp., vol. ii. p. 187.—Ib. Gen. Hist., vol. v. p. 130.—Shaw, Zool. New Holl., p. 25.—Ib. Gen. Zool., vol. x. p. 202.

Cinclosoma Punctatum, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 220.—Griff. An. King., vol. vi. p. 529. pl. 29.

This species has been long known to ornithologists, being one of the birds earliest described from Australia; still little or no information has hitherto been acquired respecting its habits and economy, which, however, are extremely interesting.

It is everywhere a stationary species, and enjoys an extensive range of habitat, being distributed over the whole of Van Diemen’s Land and the eastern portion of Australia, from Moreton Bay to Spencer’s Gulf, to the westward of which I have never been able to trace it, and I have therefore reason to believe that this is the limit of its range in that direction; its place appearing to be supplied in Western Australia by the species represented in the succeeding Plate. During my researches in South Australia, I found both species sparingly dispersed over the country, in such localities as are suitable to their habits, between the great bend of the Murray and Lake Alexandrina; this, therefore, would seem to be the border-line of their range on either hand; how far these species are spread to the northward, is yet to be determined.

The Spotted Ground-Thrush gives a decided preference to the summits of low stony hills and rocky gullies, particularly those covered with scrubs and grasses. Its flight is very limited, and this power is rarely employed, except for the purpose of crossing a gully or passing to a neighbouring scrub; it readily eludes pursuit by the facility with which it runs over the stony surface and conceals itself among the underwood. When suddenly flushed it rises with a loud burring noise, like the Quail or Partridge. Its short flight is performed by a succession of undulations, and is terminated by the bird pitching abruptly to the ground almost at right angles.

It seldom perches on the smaller branches of trees, but may be frequently seen to run along the fallen trunks so common in the Australian forests.

Unlike many others of the Thrush family which are celebrated for their song, the note of this species merely consists of a low piping whistle, frequently repeated while among the underwood, and by which its presence is often indicated.

In Hobart Town it is frequently exposed for sale in the markets with Bronzewing Pigeons and Wattle-birds, where it is known by the name of Ground-Dove, an appellation which has doubtless been given both from its habit of running and feeding upon the ground like the Pigeons, and the circumstance of its flesh being very delicate eating; to its excellence in this respect I can bear testimony. The pectoral muscles are very largely developed, and the body, when plucked, has much the contour of a Quail.

The duty of incubation is performed in October and the three following months, during which period two and often three broods are produced. The nest is a slight and rather careless structure, composed of leaves and the inner bark of trees, and is of a round open form; it is always placed on the ground, under the shelter of a large stone, stump of a tree, or a tuft of grass. The eggs are two, and sometimes three, in number, one inch and three lines long, and are white, blotched with large marks of olive-brown, particularly at the larger end, some of the spots appearing as if on the inner surface of the shell. The young, which at two days old are thickly clothed with long black down, like the young of the genus Rallus, soon acquire the power of running, and at an early age assume the plumage of the adult, after which they are subject to no periodical change in their appearance. The stomach is very muscular, and in those dissected were found the remains of seeds and caterpillars mingled with sand.

Adult males have the forehead and chest ash-grey; crown of the head, back, rump, and the middle tail-feathers rufous brown, each feather of the back having a broad longitudinal stripe of black down the centre; shoulders and wing-coverts steel-black, each feather having a spot of white at the extreme tip; primaries blackish brown, margined on their outer edges with lighter brown; throat and a narrow band across the chest steel-black; stripe over the eye, a nearly circular spot on the side of the neck, and the centre of the abdomen white; flanks and under tail-coverts reddish buff, with a large oblong stripe of black down the centre of each feather; lateral tail-feathers black, broadly margined with grey on their inner webs, and largely tipped with white; bill black; legs fleshy-white; feet darker; eyes very dark lead-colour, with a naked blackish brown eyelash. The female differs from the male in having all the upper surface of a lighter hue; the throat greyish white instead of black; the spot on the neck rufous instead of white, and in being destitute of the black pectoral band.

The figures are of the natural size.

CINCLOSOMA CASTANOTUS: Gould.

J. & E. Gould del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

Cinclosoma castanotus, Gould, Proc. of Zool. Soc., September 8, 1840.

Boȍne-Yung, Aborigines of the mountain districts of Western Australia.

This new species of Cinclosoma appears to be as much confined to the southern and western portions of Australia as the preceding species is to the eastern. It inhabits various parts of the great scrub bordering the Murray above Lake Alexandrina, and I have ascertained that it is also found in the neighbourhood of Swan River.

The economy of the present bird closely resembles that of the Spotted Ground-Thrush, as the similarity of their form would naturally lead us to expect; but the more level plains, particularly those that are studded with clumps of dwarf trees and scrubs, would appear to be the situations for which it is more peculiarly adapted, at least such was the character of the country in the Belts of the Murray where I discovered it. On the other hand, it is stated in the notes accompanying specimens received from Swan River, that “it is rarely seen in any but the most barren and rocky places. The white-gum forests, here and there studded with small patches of scrub, are its favourite haunts. It is only found in the interior; the part nearest to the coast, where it has been observed, being Bank’s Hutts on the York Road about fifty-three miles from Fremantle.”

Its disposition is naturally shy and wary, a circumstance which cannot be attributed to any dread of man as an enemy, since it inhabits parts scarcely ever visited either by the natives or Europeans. Few persons, I may safely say, had ever discharged a gun in that rich arboretum, the Belts of the Murray, before the period of my being there; still the bird was so difficult of approach, that it required the utmost exertion to procure any number of specimens. They were generally observed in small troops of four or six in number, running through the scrub one after another in a line, and resorting to a short low flight, when crossing the small intervening plains. The facility with which it runs over the surface of the ground is even greater than in its near ally, and on examination the toes will be found shorter than in that species, and admirably suited to its terrestrial habits: although it doubtless possesses the power of perching, I do not recollect having ever seen it on a tree.

In its mode of flight and nidification it assimilates so closely to the Spotted Ground-Thrush, as to render a separate description superfluous.

The stomach is extremely muscular, and the food consists of seeds and the smaller kind of Coleoptera.

The male has the crown of the head, ear-coverts, back of the neck, upper part of the back, upper tail-coverts and two central tail-feathers brown; stripe over the eye, and another from the base of the lower mandible down the side of the neck white; scapularies and lower part of the back rich chestnut; shoulders and wing-coverts black, each feather having a spot of white at the tip; primaries and secondaries dark brown, margined with lighter brown; lateral tail-feathers black, largely tipped with white; chin, throat and centre of the breast steel-black; sides of the chest and flanks brownish grey, the latter blotched with black; centre of the abdomen and under tail-coverts white; bill black; base of the under mandible lead-colour; irides reddish hazel; legs blackish brown. The female differs in having the whole of the plumage much lighter, and with only a slight tinge of chestnut on the rump; the stripes of white over the eye and down the sides of the neck less distinctly marked; the chin, throat and breast grey instead of black; the irides hazel, and the feet leaden brown.

The figures are of the natural size.

CINCLOSOMA CINNAMOMEUS: Gould.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

Cinclosoma cinnamomeus, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., Part XIV. p. 68.

We are indebted to the researches of that enterprising traveller Captain Sturt for our knowledge of this new Cinclosoma, which is the more interesting as forming an additional species of a singular group of Ground-Thrushes peculiar to Australia, of which only two were previously known. The specimen from which my figure is taken now forms part of the collection at the British Museum, and we learn from Captain Sturt that it was the only one procured during his lengthened sojourn at the Depôt in that sterile and inhospitable country, the interior of Australia.

It is considerably smaller than either of its congeners, the C. castanotus and C. punctatum, and, moreover, differs from them in the cinnamon colouring of the greater portion of its plumage.

The whole of the upper surface, scapularies, two central tail-feathers, sides of the breast and flanks cinnamon-brown; wing-coverts jet-black, each feather largely tipped with white; above the eye a faint stripe of white; lores and throat glossy black, with a large oval patch of white seated within the black, beneath the eye; under surface white, with a large arrow-shaped patch of glossy black on the breast; feathers on the sides of the abdomen with a broad stripe of black down the centre; lateral tail-feathers jet-black, largely tipped with pure white; under tail-coverts black for four-fifths of their length on the outer web, their inner webs and tips white; eyes brown; tarsi olive; toes black.

The accompanying Plate represents the bird in two positions of the natural size.

OREOCINCLA LUNULATA.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

Turdus lunulatus, Lath. Ind. Orn. Supp., p. xlii.

Philedon, Temm. Man. d’Orn., 2nd Edit. tom. i. p. lxxxvii.

Lunulated Thrush, Lath. Gen. Syn. Supp., vol. ii. p. 184.

—— Honey-eater, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. iv. p. 180.

Turdus varius, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 218.

Oreocincla Novæ-Hollandiæ et O. macrorhyncha, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., Part V. p. 145; and in Syn. Birds of Australia, Part IV.

Mountain Thrush, Colonists of Van Diemen’s Land.

In all localities suitable to its habits and mode of life this species is tolerably abundant, both in Van Diemen’s Land and in New South Wales; it has also been observed in South Australia, where however it is rare. From what I saw of it personally, I am led to infer that it gives a decided preference to thick mountain forests, where large boulder stones frequently occur covered with green moss and lichens, particularly if there be much humidity; rocky gulleys and the sides of water-courses are also among its favourite places of resort. In Van Diemen’s Land, the slopes of Mount Wellington and other similar bold elevations are situations in which it may always be seen if closely looked for. During the summer it ascends high up the mountain sides, but in winter it descends to the lower districts, the outskirts of the forests, and occasionally visits the gardens of the settlers. In New South Wales, the Cedar Brushes of the Liverpool range and all similar situations are frequented by it; I also observed it on the islands at the mouth of the Hunter; and I possess specimens from the north shore near Sydney and the banks of the Clarence. Its chief food is Helices and other mollusks, to which insects of many kinds are added; most likely fruits and berries occasionally form a part of its diet. It is a solitary species, more than two being rarely observed together, and frequently a single individual only is to be seen, noiselessly hopping over the rugged ground in search of food. Its powers of flight are seldom exercised, and so far as I am aware it has no song. Considerable variation exists in the size and in the colouring of individuals from different districts. The Van Diemen’s Land specimens are larger, and have the bill more robust, than those from New South Wales; considerable difference also exists in the lunations at the tip of the feathers, some being much darker and more distinctly defined than others. The young assume the plumage of the adults from the nest, but have the lunations paler and the centre of the feathers of the back bright tawny instead of olive-brown.

The Mountain Thrush breeds in all the localities above-mentioned during the months of August, September and October, the nest being placed on the low branches of the trees, often within reach of the hand; those I saw were outwardly formed of green moss and lined with fine crooked black fibrous roots, and were about seven inches in diameter by three inches in depth; the eggs, which are two in number, are of a buffy white or stone-colour, minutely freckled all over with reddish brown, about one inch and three-eighths long by seven-eighths broad.

The sexes are alike in plumage, and may be thus described:—

The whole of the upper surface olive-brown, each feather with a lunar-shaped mark of black at the tip; wings and tail olive-brown, the former fringed with yellowish olive and the outer feather of the latter tipped with white; under surface white, stained with buff on the breast and flanks, each feather, with the exception of those of the centre of the abdomen and the under tail-coverts, with a lunar-shaped mark of black at the tip, narrow on the breast and abdomen and broad on the sides and flanks; irides very dark brown; bill horn-colour, becoming yellow on the base of the lower mandible; feet horn-colour.

The figures are of the natural size.

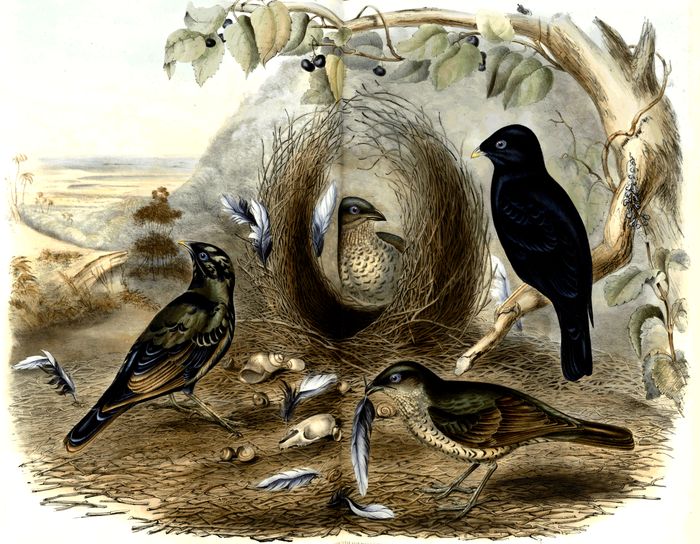

CHLAMYDERA MACULATA: Gould.

J. & E. Gould del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

Calodera maculata, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., Part IV. p. 106, and Syn. Birds of Australia, Part I.

Chlamydera maculata, Gould, Birds of Australia, 1837, Part I. cancelled.

This species, which is nearly allied to the Satin Bower-bird, is especially interesting, as being the constructor of a bower even more extraordinary than that of the latter, and in which the decorative propensity is carried to a far greater extent. It is as exclusively an inhabitant of the interior of the country as the Satin Bower-bird is of the brushes between the mountain ranges and the coast; and though in all probability it has a wide range over the central portions of the Australian continent, the only parts in which I have observed it, or from which I have ever seen specimens, are the districts immediately to the north of the colony of New South Wales. During my journey into the interior I observed it to be tolerably abundant at Brezi on the river Mokai to the northward of the Liverpool Plains: it is also equally numerous in all the low scrubby ranges in the neighbourhood of the Namoi, as well as in the open brushes which intersect the plains on its borders; still, from the extreme shyness of its disposition, the bird is seldom seen by ordinary travellers, and it must be under very peculiar circumstances that it can be approached sufficiently close to observe its colours. It has a harsh, grating, scolding note, which is generally uttered when its haunts are intruded on, and by which means its presence is detected when it would otherwise escape observation: when disturbed it takes to the topmost branches of the loftiest trees, and frequently flies off to another neighbourhood. I found the readiest way of obtaining specimens was by watching at the water-holes where they come to drink; and on one occasion, near the termination of a long drought, I was guided by a native to a deep basin in a rock, which still held water from the rains of many months before, and where numbers of these birds, as well as Honey-suckers and Parrots, were constantly assembling throughout the day. This natural reservoir had probably been but seldom, if ever, visited by the white man, being situated in a remote mountain, and presenting no attraction to any person but a naturalist. My presence was evidently regarded with suspicion by the visitants to the spot; but while I remained lying on the ground perfectly motionless, though close to the water, their thirst overpowering their fear, they would dash down past me and eagerly take their fill, although an enormous black snake was lying coiled upon a piece of wood near the edge of the pool. Of the numerous assemblage here congregated the Spotted Bower-birds were by far the shyest of the whole, yet six or eight of these, displaying their beautiful necks, were often perched within a few feet of me. The scanty supply of water remaining in the cavity must soon have been exhausted by the thousands of birds that daily resorted to it, had not the rains, so long withheld, soon afterwards descended in torrents, filling every water-course and overflowing the banks of the largest rivers: I remained at this, to me, interesting spot for three days.

In many of its actions and in the greater part of its economy much similarity exists between this species and the Satin Bower-bird, particularly in the curious habit of constructing an artificial bower or playing-ground. I was so far fortunate as to discover several of these bowers during my journey to the interior, the finest of which I succeeded in bringing to England, and it is now in the British Museum. The situations of these runs or bowers are much varied: I found them both on the plains studded with Myalls (Acacia pendula) and other small trees, and in the brushes clothing the lower hills. They are considerably longer and more avenue-like than those of the Satin Bower-bird, being in many instances three feet in length, They are outwardly built of twigs, and beautifully lined with tall grasses, so disposed that their heads nearly meet; the decorations are very profuse, and consist of bivalve shells, crania of small mammalia and other bones. Evident and beautiful indications of design are manifest throughout the whole of the bower and decorations formed by this species, particularly in the manner in which the stones are placed within the bower, apparently to keep the grasses with which it is lined fixed firmly in their places: these stones diverge from the mouth of the run on each side so as to form little paths, while the immense collection of decorative materials, bones, shells, &c., are placed in a heap before the entrance of the avenue, this arrangement being the same at both ends. In some of the larger bowers, which had evidently been resorted to for many years, I have seen nearly half a bushel of bones, shells, &c., at each of the entrances. In some instances small bowers, composed almost entirely of grasses, apparently the commencement of a new place of rendezvous, were observable. I frequently found these structures at a considerable distance from the rivers, from the borders of which they could alone have procured the shells and small round pebbly stones; their collection and transportation must therefore be a task of great labour and difficulty. As these birds feed almost entirely upon seeds and fruits, the shells and bones cannot have been collected for any other purpose than ornament; besides, it is only those that have been bleached perfectly white in the sun, or such as have been roasted by the natives, and by this means whitened, that attract their attention. I fully ascertained that these runs, like those of the Satin Bower-bird, formed the rendezvous of many individuals; for, after secreting myself for a short space of time near one of them, I killed two males which I had previously seen running through the avenue.

Crown of the head, ear-coverts and throat rich brown, each feather surrounded with a narrow line of black; feathers on the crown small, and tipped with silvery grey; a beautiful band of elongated feathers of light rose-pink crosses the back of the neck, forming a broad, fan-like, occipital crest; all the upper surface, wings and tail of a deep brown; every feather of the back, rump, scapularies and secondaries tipped with a large round spot of rich buff; primaries slightly tipped with white; all the tail-feathers terminated with buffy white; under surface greyish white; feathers of the flanks marked with faint, transverse, zigzag lines of light brown; bill and feet dusky brown; irides dark brown; bare skin at the corner of the mouth thick, fleshy, prominent, and of a pinky flesh-colour.

Both sexes, when fully adult, are adorned with the rose-coloured frill; but the young birds of the year, both male and female, are without it.

The Plate represents the bower, with two birds, a male and a female, all of the natural size.

CHLAMYDERA NUCHALIS.

J. & E. Gould del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

Ptilonorhynchus nuchalis, Jard. and Selb. Ill. Orn., vol. ii. pl. 103.

Calodera nuchalis, Gould, Syn. Birds of Australia, Part I.

Chlamydera nuchalis, Gould, Birds of Australia, 1837, Part I. cancelled.—G. R. Gray, List of Gen. of Birds, p. 40.

This fine species was first described and figured in the “Illustrations of Ornithology,” by Sir William Jardine and Mr. Selby, from the then unique specimens in the collection of the Linnean Society; but neither the part of Australia of which it is a native or any particulars relative to its habits were known to those gentlemen, nor have I myself had an opportunity of observing it in a state of nature, the bird being an inhabitant of the north-west coast, a portion of the Australian continent that has, as yet, been but little visited. I am indebted for individuals of both sexes of this bird to two of the officers of the “Beagle,” Messrs. Bynoe and Dring; but neither of these gentlemen furnished me with any account of its economy. Captain Grey, however, on his return from his expedition to those regions, informed me that he frequently found during his rambles a most singular bower, made in every way like that of the Chlamydera maculata, and which was always an object of great interest to him, being unable to satisfy himself as to what animal had constructed it, or even whether it was the work of a bird or of a quadruped: he was inclined to suppose the latter, but I think there need not be the slightest hesitation in ascribing its formation to the Chlamydera nuchalis; for we may reasonably expect that a species so very closely allied to that of the southern and eastern portions of the continent would partake of its peculiar habits and economy. The following notes were written on the spot, and were kindly given to me by Captain Grey:—

“These bowers were formed of dead grass and parts of bushes, sunk a slight depth into two parallel furrows, in sandy soil, and were nicely arched above; but the most remarkable fact connected with them was, that they were always full of broken sea-shells, large heaps of which also protruded from each extremity of the bower. In one of these bowers, the most remote from the sea that we discovered, were found a heap of the stones of some fruit which had evidently been rolled in the sea. I never saw any animal in or near to these bowers, but the dung of a small species of Kangaroo was always abundant close to them, which induced me to suppose them to be the work of some kind of quadruped.”

The circumstance of Captain Grey, never having perceived the birds near the runs, serves to show that it exhibits the same shyness of disposition as the other species.

Head and all the upper surface greyish brown, the feathers of the former with a shining or satiny lustre; the feathers of the back, wing-coverts, scapulars, quills and tail tipped with greyish white; on the nape of the neck a beautiful rose-pink fascia, consisting of narrow feathers, partly encircled by a ruff of satin-like plumes, the tips distinct, rounded, and turning inwards; under surface yellowish grey, the flanks tinged with brown; irides, bill and legs brownish black.

In one of the specimens I possess, and which formed the subject of the upper figure in the Plate, no trace of the nuchal ornament is observable, a circumstance I conceive to be indicative of youth rather than a distinguishing characteristic of the sexes, since in the other species I find the mark common to both, but the young bird of the year without any trace of it.

The Plate represents a male and a young bird, of the natural size.

PTILONORHYNCHUS HOLOSERICEUS: Kuhl

J. & E. Gould del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

Ptilonorhynchus holosericeus, Kuhl, Beytr. zur Zool. S. 150.—Wagl. Syst. Av. sp. 1.—G. R. Gray, Gen. of Birds, p. 40.—Swains. Class. of Birds, vol. ii. p. 271.

Pyrrhocorax violaceus, Vieill. Nouv. Diet. d’Hist. Nat., tom. vi. p. 569.—Ib. Ency. Méth. 1823, p. 896.

Kitta holosericea, Temm. Pl. Col. 395 and 422.—Less. Traité d’Orn., p. 350, pl. 46. fig. 1.

Satin Grakle, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. iii. p. 171.

Ptilonorhynchus MacLeayii, Lath. MSS., Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 263.

Corvus squamulosus, Ill., female or young?

Ptilonorhynchus squamulosus, Wagl. Syst. Av. sp. 2, female or young?

Satin Bird, of the Colonists of New South Wales.

Cowry, of the Aborigines of the coast of New South Wales.

Although this species has been long known to ornithologists, and is familiar to the colonists of New South Wales, its habits, which in many respects are most extraordinary, have hitherto escaped attention; or if not entirely so, have never been brought before the scientific world. It is, therefore, a source of high gratification to myself to be the first to place them on record.

One point to which I more particularly allude,—a point of no ordinary interest, both to the naturalist and the general admirer of nature,—is the formation of a bower-like structure by this bird for the purpose of a playing-ground or hall of assembly, a circumstance in its economy which adds another to the many anomalies connected with the Fauna of Australia.

The localities favourable to the habits of the Satin Bower-bird are the luxuriant and thickly-foliaged brushes stretching along the coast from Port Philip to Moreton Bay, the cedar brushes of the Liverpool range, and most of the gullies of the great mountain-chain separating the colony from the interior. So far as is at present known, it is restricted to New South Wales; certainly it is not found so far to the westward as South Australia, and I am not aware of its having been seen on the north coast; but its range in that direction can only be determined by future research.

It is a stationary species, but appears to range from one part of a district to another, either for the purpose of varying the nature, or of obtaining a more abundant supply of food. Judging from the contents of the stomachs of the many specimens I dissected, it would seem that it is altogether granivorous and frugivorous, or if not exclusively so, that insects form but a small portion of its diet. Independently of numerous berry-bearing plants and shrubs, the brushes it inhabits are studded with enormous fig-trees, some of them towering to the height of two hundred feet; among the lofty branches of these giants of the forest, the Satin Bower-bird and several species of Pigeons find in the small wild fig, with which the branches are loaded, an abundant supply of a favourite food: this species also commits considerable depredation on any ripening corn near the localities it frequents. It appears to have particular times in the day for feeding, and when thus engaged among the low shrub-like trees, I have approached within a few feet without creating alarm; but at other times I have found this bird extremely shy and watchful, especially the old males, which not unfrequently perch on the topmost branch or dead limb of the loftiest tree in the forest, whence they can survey all round, and watch the movements of the females and young in the brush below.

In the autumn they associate in small flocks, and may often be seen on the ground near the sides of rivers, particularly where the brush descends in a steep bank to the water’s edge.

Besides the loud liquid call peculiar to the male, both sexes frequently utter a harsh, unpleasant, guttural note indicative of surprise or displeasure. The old black males are exceedingly few in number, as compared with the females and young male birds in the green dress, from which and other circumstances I am led to believe that at least two, if not three years, elapse before they attain the rich satin-like plumage, which, when once perfectly assumed, is, I believe, never again thrown off.

I regret to state, that although I used my utmost endeavours, I could never discover the nest and eggs of this species, neither could I obtain any authentic information respecting them, either from the natives or the colonists, of whom I made frequent inquiries.

The extraordinary bower-like structure, alluded to above, first came under my notice at Sydney, to the Museum of which place an example had been presented by Mr. Charles Coxen, as the work of the Satin Bower-bird. I at once determined to leave no means untried for ascertaining every particular relating to this peculiar feature in the bird’s economy, and on visiting the cedar brushes of the Liverpool range I discovered several of these bowers or playing-places; and a glance at the accompanying illustration will, I presume, give a more correct idea of the nature of these erections than the most minute description. They are usually placed under the shelter of the branches of some overhanging tree in the most retired part of the forest: they differ considerably in size, some being a third larger than the one here represented, while others are much smaller. The base consists of an extensive and rather convex platform of sticks firmly interwoven, on the centre of which the bower itself is built: this, like the platform on which it is placed and with which it is interwoven, is formed of sticks and twigs, but of a more slender and flexible description, the tips of the twigs being so arranged as to curve inwards and nearly meet at the top: in the interior of the bower the materials are so placed that the forks of the twigs are always presented outwards, by which arrangement not the slightest obstruction is offered to the passage of the birds. The interest of this curious bower is much enhanced by the manner in which it is decorated at and near the entrance with the most gaily-coloured articles that can be collected, such as the blue tail-feathers of the Rose-hill and Pennantian Parrots, bleached bones, the shells of snails, &c.; some of the feathers are stuck in among the twigs, while others with the bones and shells are strewed about near the entrances. The propensity of these birds to pick up and fly off with any attractive object, is so well known to the natives, that they always search the runs for any small missing article, as the bowl of a pipe, &c., that may have been accidentally dropped in the brush. I myself found at the entrance of one of them a small neatly-worked stone tomahawk, of an inch and a half in length, together with some slips of blue cotton rags, which the birds had doubtless picked up at a deserted encampment of the natives.

For what purpose these curious bowers are made, is not yet, perhaps, fully understood; they are certainly not used as a nest, but as a place of resort for many individuals of both sexes, which, when there assembled, run through and around the bower in a sportive and playful manner, and that so frequently that it is seldom entirely deserted.

The proceedings of these birds have not been sufficiently watched, to render it certain whether the runs are frequented throughout the whole year or not; but it is highly probable that they are merely resorted to as a rendezvous, or playing-ground, at the pairing time and during the period of incubation. It was at this season, as I judged from the state of the plumage and from the internal indications of those I dissected, that I visited these localities; the bowers I found had been recently renewed; it was however evident, from the appearance of a portion of the accumulated mass of sticks, &c., that the same spot had been used as a place of resort for many years. Mr. Charles Coxen informed me, that, after having destroyed one of these bowers and secreted himself, he had the satisfaction of seeing it partially reconstructed; the birds engaged in this task, be added, were females. With much care and trouble I succeeded in bringing to England two fine specimens of these bowers, one of which I presented to the British Museum, and the other to the collection at Leyden, where they may be seen by all those who take an interest in the subject.

It will be observed, that the two following nearly allied species, Chlamydera maculata and Chlam. nuchalis, also build similar erections, and that in them the decorative propensity is carried to a much greater extent than in the Satin Bower-bird.

The adult male has the whole of the plumage of a deep shining blue-black, closely resembling satin, with the exception of the primary wing-feathers, which are of a deep velvety black, and the wing-coverts, secondaries and tail-feathers, which are also of a velvety black, tipped with the shining blue-black lustre; irides beautiful light blue with a circle of red round the pupil; bill bluish horn, passing into yellow at the tip; legs and feet yellowish white.

The female has the head and all the upper surface greyish green; wings and tail dark sulphur-brown, the inner webs of the primaries being the darkest; under surface containing the same tints as the upper, but very much lighter, and with a wash of yellow; each feather of the under surface also has a crescent-shaped mark of dark brown near the extremity, giving the whole a scaly appearance; irides of a deeper blue than in the male, and with only an indication of the red ring; bill dark horn-colour; feet yellowish white tinged with olive.

Young males closely resemble the females, but differ in having the under surface of a more greenish yellow hue, and the crescent-shaped markings more numerous; irides dark blue; feet olive-brown; bill blackish olive.

The Plate represents the bower, an old male, female, and two young males; one in the green dress and the other in a state of change, all about a fifth less than the natural size.

PTILONORHYNCHUS SMITHII: Vig. & Horsf.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

Varied Roller, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. iii. p. 86.

Ptilonorhynchus Smithii, Lath. MSS. Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 264.

—— viridis, Wagl. Syst. Av., sp. 3.

Kitta virescens, Temm. Pl. Col., 396.

Cat Bird of the Colonists of New South Wales.

So far as our knowledge extends, this fine species is only found in New South Wales, where it inhabits all those luxuriant forests that extend along the eastern coast between the mountain ranges and the sea; those of Illawarra, the Hunter, the MacLeay, and the Clarence and the cedar brushes of the Liverpool range being, among many others, localities in which it may always be found: situations suitable to the Regent and Satin Birds are equally adapted to the habits of the Cat Bird, and I have not unfrequently seen them all three feeding together on the same tree, when the branches bore a thick crop of berries and fruits. The wild fig, and the native cherry, when in season, afford it an abundant supply. So rarely do they take insects, that I do not recollect ever finding any remains in the stomachs of those specimens I dissected. In its disposition it is neither a shy nor a wary bird, little caution being required to approach it, either when feeding or while quietly perched upon the lofty branches of the trees. It is at such times that its loud, harsh and extraordinary note is heard; a note which differs so much from that of all other birds, that having been once heard it can never be mistaken. In comparing it to the nightly concerts of the domestic cat, I conceive that I am conveying to my readers a more perfect idea of the note of this species than could be given by pages of description. This concert, like that of the animal whose name it bears, is performed either by a pair or several individuals, and nothing more is required than for the hearer to shut his eyes from the neighbouring foliage to fancy himself surrounded by London grimalkins of house-top celebrity.

While in the district in which this bird is found, my almost undivided attention was directed to the acquisition of all the information I could obtain respecting its habits, as I considered it very probable that it might construct a bower similar to that of the Satin Bird; but I could not satisfy myself that it does, nor could I discover its nest, or the situation in which it breeds; it is doubtless, however, among the branches of the trees of the forest in which it lives. It certainly is not a migratory bird, although it may range from one portion of the brushes to another, according as the supply of food may be more or less abundant.

The sexes do not offer the slightest difference in plumage, or any external character by which the male may be distinguished from the female; she is, however, rather less brilliant in her markings, and somewhat smaller in size.

Head and back of the neck olive-green, with a narrow line of white down each of the feathers of the latter; back, wings and tail grass-green, with a tinge of blue on the margins of the back-feathers; the wing-coverts and secondaries with a spot of white at the extremity of their outer web; primaries black, their external webs grass-green at the base and bluish green for the remainder of their length; all but the two central tail-feathers tipped with white; all the under surface yellowish green, with a spatulate mark of yellowish white down the centre of each feather; bill light horn-colour; irides brownish red; feet whitish.

The Plate represents the two sexes of the natural size.

SERICULUS CHRYSOCEPHALUS.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. Hallmandel & Walton Imp.

Meliphaga chrysocephala, Lewin, Birds of New Holl., pl. 1.

Golden-crowned Honey-eater, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. iv. p. 184.

Oriolus regens, Temm. Pl. Col., 320.—Quoy et Gaim. Zool. de l’Uranie, pl. 22.—Less. Zool. de Coquille, pl. 20 (female).

Sericulus chrysocephalus, Swains. in Zool. Journ., vol. i. p. 478.—Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 326.—Jard. and Selb. Ill. Orn., vol. i. pls. 18, 19, 20.—G. R. Gray, List of Gen. of Birds, 2nd edit., p. 38.—Swains. Class. of Birds, vol. ii. p. 237.—Less. Traité d’Orn., p. 340.—Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiv. p. 266.

Sericulus regens, Less. Man. d’Orn., tom. i. p. 256.

This beautiful species, one of the finest birds of the Australian Fauna, is, I believe, exclusively confined to the eastern portion of the country; it is occasionally seen in the neighbourhood of Sydney, which appears to be the extent of its range to the southward and westward. I met with it in the brushes at Maitland in company and feeding on the same trees with the Satin and Cat Birds and the Oriolus viridis; it is still more abundant on the Manning, at Port Macquarrie, and at Moreton Bay; I sought for and made every inquiry respecting it at Illawarra, but did not encounter it, and was informed that it is never seen there, yet the district is precisely similar in character to those in which it is abundant about two degrees to the eastward: while encamped on Mosquito Island, near the mouth of the river Hunter, I shot several, and observed it to be numerous on the neighbouring islands, particularly Baker’s Island, where there is a fine garden, and where it is one of the greatest pests the proprietor has to contend with; for during the summer months, when the peaches and other fruits are ripening, it commits serious injury to the crops and their owner.

Although I have spoken of this bird as abundant in the various localities referred to, I must mention that at least fifty out of colour may be observed to one fully-plumaged male, which when adorned in its gorgeous livery of golden yellow and deep velvety black exhibits an extreme shyness of disposition, as if conscious that its beauty, rendering it a conspicuous object, might lead to its destruction; it is usually therefore very quiet in its actions, and mostly resorts to the topmost branches of the trees; but when two gay-coloured males encounter each other, frequent conflicts take place. To obtain specimens in their full dress, considerable caution is necessary; on the other hand, females and immature males are very tame, and when feeding among the foliage, appear to be so intent upon their occupation as not to heed the approach of an intruder; and I have occasionally stood beneath a low tree, not more than fifteen feet high, with at least ten feeding voraciously above me. The stomachs of those dissected contained the remains of wild figs, berries and seeds, but no trace of insects.

I did not succeed in discovering the nest, or in obtaining any information respecting it.

I believe that the fine plumage represented in the Plate is not assumed until the second or third year, and when once acquired is not afterwards thrown off; it may be thus described:—

Head and back of the neck, running in a rounded point towards the breast, rich bright gamboge-yellow tinged with orange, particularly on the centre of the forehead; the remainder of the plumage, with the exception of the secondaries and inner webs of all but the first primary, deep velvety black; the secondaries bright gamboge-yellow, with a narrow edging of black along the inner webs; the first primary is entirely black, the next have the tips and outer webs black—the half of the inner web and that part of the shaft not running through the black tip are yellow; as the primaries approach the secondaries the yellow of the inner web extends across the shaft, leaving only a black edge on the outer web, which gradually narrows until the tips only of both webs remain black; bill yellow; irides pale yellow; legs and feet black.

The female has the head and throat dull brownish white, with a large patch of deep black on the crown; all the upper surface, wings and tail pale olive-brown, the feathers of the back with a triangular-shaped mark of brownish white near the tip; the under surface is similar, but here, except on the breast, the white markings increase so much in size as to become the predominant hue; irides brown; bill and feet black.

The young males at first resemble the females, but their hues are continually changing until they gain the livery of the adult.

The Plate represents a male and a female on a branch of one of the wild figs of the brushes of New South Wales, all the size of life.

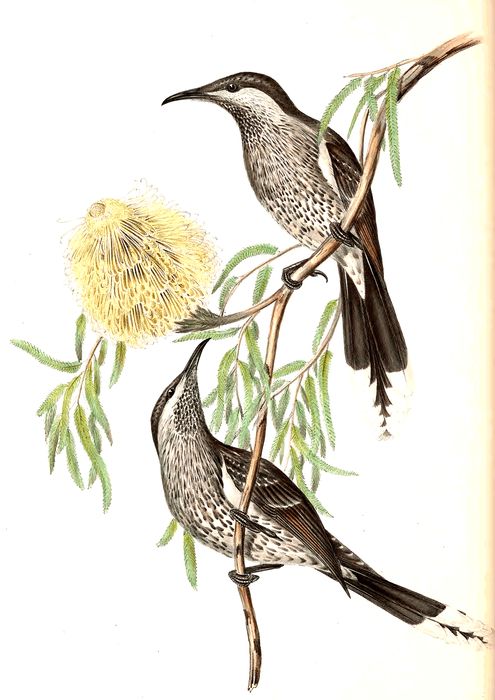

ORIOLUS VIRIDIS.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

Gracula viridis, Lath. Ind. Orn. Supp., p. xxviii.—Shaw, Gen. Zool., vol. vii. p. 473.

Loriot, Temm. Man. d’Orn., 2nd Edit. p. liv.

Green Grakle, Lath. Gen. Syn. Supp., vol. ii. p. 129.—Ib. Gen. Hist., vol. iii. p. 168.

Coracias sagittata, Lath. Ind. Orn. Supp., p. xxvi.—Shaw, Gen. Zool., vol. viii. p. 400.

Striated Roller, Lath. Gen. Syn. Supp., vol. ii. p. 122.—Ib. Gen. Hist., vol. iii. p. 83.

Streaked Roller, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. iii. p. 84, young.

Mimetes viridis, King, Survey of Intertropical Coast of Australia, vol. ii. p. 419.

Mimeta viridis, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 326.—Jard. and Selb. Ill. Orn., vol. ii. pl. 61.—G. R. Gray, List of Gen. of Birds, 2nd Edit. p. 38.

—— Merulöides, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 327, young.

Oriolus viridis, Vieill., 2nd Edit. du Nouv. Dict. d’Hist. Nat., tom. xviii. p. 197.—Ib. Ency. Méth. Orn., part ii. p. 697.

—— variegatus, Vieill., 2nd Edit. du Nouv. Dict. d’Hist. Nat., tom. xviii. p. 196.—Ib. Ency. Méth. Orn., part ii. p. 696.

This bird was first described by Latham, by whom it was placed in the genus Gracula, but it agrees in no respect with the members of that genus, and “in fact,” says Captain King, “the genus Oriolus is that to which it bears the closest resemblance in its general appearance. I would at once refer it to that genus, but that I have some reason to think that it belongs to the meliphagous birds.... Of the tongue or mode of feeding I can myself say nothing decisively; but general opinion places this bird among the groups that feed by suction, and as I have a second species hitherto undescribed which is closely allied to it, I prefer forming both provisionally into a new genus” (Mimetes) “to referring them to one, from which, although they agree with it in external appearance, they may be totally remote in consequence of their internal anatomy and habits of life. If the tongue be found to accord with that of the Orioles and not of the Honey-suckers, my group of course must fall.” Messrs. Jardine and Selby took the same view of the subject when describing and figuring the bird in their “Illustrations of Ornithology,” and have given a description of the structure of the tongue, which certainly offers a slight resemblance to that of the true meliphagous birds; but my own observations of the bird in a state of nature enable me to affirm that in appearance, habits, economy, and in the nature of its food it is truly an Oriole, to which group of birds it was correctly assigned by M. Vieillot in the second edition of the “Dictionnaire d’Histoire Naturelle,” and that consequently Captain King’s generic term Mimetes must sink into a synonym of Oriolus.

The true and probably the restricted habitat of this species is New South Wales, where in the months of summer it is tolerably plentiful in every part of the colony. I frequently observed it in the Botanic Garden at Sydney, and in all the gardens of the settlers where there were trees of sufficient size to afford it shelter; the brushes of the country, the sides of brooks and all similar situations are equally inhabited by it. I did not find it in South Australia, neither has it been observed to the westward of that part of the country. That its range extends pretty far to the northward I have no doubt, as its numbers rather increased than diminished in the neighbourhood of the rivers Peel and Namoi; and many persons would, I feel assured, assign to it a much more extended range by considering it identical with the bird of the same form found at Port Essington,—an opinion in which I cannot myself coincide, believing as I do that the latter bird is a distinct species, although at a hasty glance it would appear to be one and the same; the general colouring of the two birds is, it is true, very similar, but the following differences exist and are found to be constant:—The Port Essington bird (for which the specific term affinis would be an appropriate appellation) is smaller in the body, has a shorter wing, a much larger bill, and the white spots at the tip of the lateral tail-feathers considerably smaller than the bird inhabiting New South Wales; in other respects they are so precisely alike that it will not be necessary to figure both.

The following notes descriptive of their habits and economy are equally applicable to the one and the other.

The bird observed by me in New South Wales was bold and active, and was often seen in company with the Regent, Satin and Cat Birds, feeding in the same trees and on similar berries and fruits, particularly the small wild fig. It possesses a loud pleasing whistling note, which is poured forth while the bird is perched on a lofty branch. I often observed it capturing insects on the wing and flying very high, frequently above the tops of the loftiest trees.

Mr. Gilbert states that the Port Essington bird is “abundant in every part of the peninsula and the adjacent islands in every possible variety of situation.” Its native name is Mur-re-a-̏rwoo. It possesses a very loud and distinct note, unlike that of every other bird I have yet heard; the sound most commonly uttered is a loud clear whistle terminating in a singular guttural harsh catch, but in the cool of the evening, when perched on and sheltered in the thick foliage of one of the topmost branches of a Eucalyptus, it pours forth a regular succession of very pleasing notes.

A nest taken on the 4th of December contained two nearly hatched eggs; it was attached by the rim to a drooping branch of the swamp Melaleuca, about five feet from the ground; was very deep and large, and formed of very narrow strips of the paper bark mixed with a few small twigs, the bottom of the interior lined with very fine wiry twigs.

The eggs, which are large for the size of the bird, are of a beautiful bluish white, sparingly spotted all over with deep umber-brown and bluish grey, the latter appearing as if beneath the surface of the shell; their medium length is one inch and three lines long by eleven lines broad.

The sexes when fully adult differ so little in colour that they can scarcely be distinguished; the male is however of a more uniform tint about the head, neck and throat, and has the yellowish olive of the upper surface of a deeper tint than the female.

Head and all the upper surface yellowish olive; wings and tail-feathers dark brown; the outer webs of the coverts and secondaries grey, margined and broadly tipped with white; all but the two centre tail-feathers with a large oval-shaped spot of white on the inner, and the extremity of the outer web white, the white mark gradually increasing in size as the feathers recede from the centre until it becomes an inch long on the external one; under surface white, washed with olive-yellow on the sides of the chest, each feather with an elongated pear-shaped mark of black down the centre; bill dull flesh-red; irides scarlet; feet lead-colour.

The young bird during the first year has the bill blackish brown instead of dull flesh-red; the upper surface olive-brown, each feather strongly streaked down the centre with dark brown; wings brown; under surface of the shoulder and all the wing-feathers except the primaries margined with sandy red; the black streaks on the breast more decided, and the white spot at the tip of the lateral tail-feathers much smaller than in the adult.

The figures represent the two sexes of the natural size on a plant gathered in the brushes of New South Wales, the name of which I have not been able to ascertain.

ORIOLUS FLAVOCINCTUS.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

Mimetes flavo-cinctus, King, Survey of Intertropical Coasts of Australia, vol. ii. p. 419.—Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiv. p. 351.

Mimeta flavo-cincta, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 327.

This species was discovered on the north coast of Australia by Captain Philip Parker King, R.N., who described it in his “Survey of the Intertropical Coasts of Australia,” referred to above; Mr. Gilbert procured two specimens at Port Essington, and Lieut. Ince, R.N., subsequently obtained an additional example in the same locality. All the information that has reached me respecting its habits and economy is contained in a short note sent to me by Mr. Gilbert, which merely states that his specimens were obtained in the forests of mangroves bordering the coast.

Like the O. viridis it is in every respect a true Oriole, although neither of them are so gaily attired as the other members of the genus.

The male has the head, neck and all the upper surface dull greenish yellow, with a stripe of black, broad at the base and tapering to a point, down the centre of each feather; under surface greenish yellow, passing into pure yellow on the under tail-coverts; wings black, all the feathers margined externally with greenish yellow and broadly tipped with pale yellow; tail black, washed on the margins with greenish yellow and largely tipped, except the two middle feathers, with bright yellow, which increases in extent as the feathers recede from the centre; irides reddish orange; bill dull red; feet lead-colour.

The female differs in being of smaller size, in having the under surface striated with black, and the markings of the wings straw-white instead of yellow.

The Plate represents the two sexes of the size of life.

SPHECOTHERES AUSTRALIS Swains.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

Sphecotheres viridis, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 215.

—— virescens, Jard. and Selb. Ill. Orn., vol. ii. pl. 79.

—— Australis, Swains.

—— canicollis, Swains. Anim. in Menag., p. 320.

I killed a fine specimen of this bird on Mosquito Island, at the mouth of the river Hunter, in September 1839; it was perched on a dead branch which towered above the green foliage of one of the high trees of the forest, and my attention was drawn to it by its loud and singular note: this was the only example that came under my observation: I am informed that it is more plentiful in the neighbourhood of the river Clarence, and abundant at Moreton Bay, and that it enjoys a wide range is proved by Mr. Bynoe having procured an adult male on the north coast. It appears to be a bird peculiar to the brushes, and its food doubtless consists of the berries and fruits which abound in those districts.

The sexes differ very widely from each other in the colouring of their plumage; that of the male being in masses, while that of the female is of a striated character.

The male has the crown of the head and the cheeks glossy black; orbits and a narrow space leading to the nostrils naked and of a light buffy yellow; throat, chest and collar at the back of the neck dark slate-grey; all the upper surface, greater wing-coverts, outer webs of the secondaries, abdomen and flanks yellowish green; lesser wing-coverts, primaries, and inner webs of the secondaries slaty black, fringed with grey; vent and under tail-coverts white; tail black, the apical half and the outer web of the external feather pure white; the apical half of the second feather on each side white, the next on each side with a large spot of white at the extremity, and the six central feathers slightly fringed with white at the tip; bill black; irides very dark brown in some, red in others; feet flesh-colour.

The female has the upper surface brown washed with olive, each feather with a darker centre, assuming on the head the form of striæ, the brown hue passing into yellowish green on the rump and upper tail-coverts; wings dark brown, the coverts and secondaries conspicuously, and the primaries narrowly, edged with greenish grey; under surface buffy white, each feather with a broad and conspicuous stripe of brown down the centre; flanks washed with yellowish green; under tail-coverts white, with a narrow stripe of brown down the centre; tail brown, each feather narrowly edged on the inner web with white, and all but the two lateral ones on each side washed with yellowish green; bill and feet lighter than in the male.

The figures represent a male and a female of the natural size.

CORCORAX LEUCOPTERUS.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

Pyrrhocorax leucopterus, Temm. Man. d’Orn., tom. i. p. 121.—Less. Man. d’Orn., tom. i. p. 384.

Fregilus leucopterus, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 265.—Less. Man. d’Orn., tom. i. p. 384.

Corcorax Australis, Less. Traité d’Orn., p. 325.

—— leucopterus, G. R. Gray, List of Gen. of Birds, 2nd Edit., p. 52.

Waybung, Aborigines of New South Wales.

This bird is a stationary species, and appears to be distributed over all parts of New South Wales and South Australia; it is very abundant in the whole of the Upper Hunter district, and I have also killed it in the interior of South Australia; it is usually met with in small troops of from six to ten in number, feeding upon the ground, over which it runs with considerable rapidity; the entire troop keeping together, but one bird running before the other and searching for food with the most scrutinizing care. In disposition it is one of the tamest of the larger birds I ever encountered, readily admitting of a very close approach, and then merely flying off to the low branch of some neighbouring tree. During flight the white marking of the wing shows very conspicuously, and on alighting the bird displays many curious actions, leaping from branch to branch with surprising quickness, at the same time spreading the tail and moving it up and down in a very singular manner; on being disturbed it peeps and pries down upon the intruder below, and generally utters a harsh, grating, disagreeable and tart note; at other times, while perched among the branches of the trees, it makes the woods ring with its peculiar hollow mournful pipe.

During the pairing-season the male becomes very animated, and his manners so remarkable, that it would be necessary for my readers to witness the bird in its native wilds to form a just conception of them: while sitting on the same branch close to the female, he spreads out his wings and tail to the fullest extent, lowers his head, puffs out his feathers and displays himself to the utmost advantage, and when two or more are engaged in these evolutions, the exhibition cannot fail to amuse and delight the spectator. A winged specimen gave me more trouble to catch than any other bird I ever chased; its power of passing over the ground being so great, that it bounded on before me and cleared every obstacle, hillocks and fallen trees, with the utmost facility.

The White-winged Chough is a very early breeder, and generally rears more than one brood in a year, the breeding-season extending over the months of August, September, October and November. The nest is a most conspicuous fabric, composed of mud and straw, resembling a bason, and is usually placed on the horizontal branch of a tree near to or overhanging a brook. The eggs vary from four to seven in number, and are of a yellowish white, boldly blotched all over with olive and purplish brown, the latter tint appearing as if beneath the surface of the shell; they are one inch and a half long by one inch and one line broad.

It has often struck me that more than one female deposited her eggs in the same nest, as four or five females may be frequently seen either on the same or the neighbouring trees, while only one nest is to be found.

The bird generally evinces a preference for open forest land, but during the breeding-season affects the neighbourhood of brooks and lagoons, which may be accounted for by the fact of such situations being necessary to enable it to procure the mud wherewith to build its nest, besides which they also afford it an abundance of insect food.

The whole of the plumage black, with glossy green reflections, with the exception of the inner webs of the primaries, which are white for three parts of their length from the base; irides scarlet; bill and feet black.

The figure is that of a male somewhat less than the natural size.

STRUTHIDEA CINEREA: Gould.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

Struthidea cinerea, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., Part IV. p. 143; and in Syn. Birds of Australia, Part I.—G. R. Gray, List of Gen. of Birds, 2nd Edit., p. 51.

Brachystoma cinerea, Swains. An. in Menag., and Two Cent. and a Quarter of New Birds, No. 51.—Class. of Birds, vol. ii. p. 266.

So little information has been obtained respecting this highly curious bird, that my account of it must necessarily be very meagre. From what I have personally observed, it would seem to be a species peculiar to the interior, and so far as is yet known, confined to the south-eastern portion of the Australian continent. I found it inhabiting the pine ridges, as they are termed by the colonists, bordering the extensive plains of the Upper and Lower Namoi, and giving a decided preference to the Callitris pyramidalis, a fine fir-like tree peculiar to the district. Those I observed were always in small companies of three or four together, on the topmost branches of the trees, and were extremely quick and restless, the whole company leaping from branch to branch in rapid succession, at the same time throwing up and expanding their tails and wings; these actions were generally accompanied with a harsh unpleasant note; their manners, in fact, closely resembled those of the White-winged Chough and the Pomatorhini: a knowledge of its nidification and the number and colour of its eggs would throw considerable light upon the affinities of this curious form. I would, therefore, particularly impress upon those who may reside in, or visit the localities it inhabits, to pay especial attention to, and to make known their observations upon, these points.

The food, as ascertained by dissection, was insects; the stomachs of those examined were tolerably hard and muscular, and contained the remains of coleoptera.

The sexes assimilate so closely in size and in the colouring of their plumage, that they are to be distinguished only by dissection.

Head, neck, back, and under surface grey, each feather tipped with lighter grey; wings brown; tail black, the middle feathers glossed with deep rich metallic green; irides pearly white; bill and legs black.

The figures are of the natural size.

CORVUS CORONOÏDES: Vig. & Horsf.

J. Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

Corvus Australis, Lath. Ind. Orn., vol. i. p. 151.?—Gmel. Syst. Nat., vol. i. p. 365.?—Daud. Orn., tom. ii. p. 226.?

South Sea Raven, Lath. Gen. Syn., vol. i. p. 363.?—Cook’s Last Voy., vol. i. p. 109.?—Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. iii. p. 7.?

Corvus Coronoïdes, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 261.

W̏ur-dang, Aborigines of Western Australia.

Ȍm-bo-lak, Aborigines of Port Essington.

Crow of the Colonists.