Title: The Poet Assassinated

Author: Guillaume Apollinaire

Illustrator: André Derain

André Rouveyre

Translator: Matthew Josephson

Release date: November 23, 2019 [eBook #60771]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Laura Natal Rodrigues at Free Literature (Images

generously made available by Hathi Trust.)

CONTENTS

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTICE

I. RENOWN

II. PROCREATION

III. GESTATION

IV. NOBILITY

V. PAPACY

VI. GAMBRINUS

VII. CONFINEMENT

VIII. MAMMON

IX. PEDAGOGY

X. POETRY

XI. DRAMATURGY

XII. LOVE

XIII. MODES

XIV. ENCOUNTERS

XV. VOYAGE

XVI. PERSECUTION

XVII. ASSASSINATION

XVIII. APOTHEOSIS

NOTES

André Rouveyre (May 1916)

There are men who cannot bring themselves to conform with the rest of human society, who cannot conceive of a secure and honorable career even at the hands of a tolerant age. They flee, they are eternally escaping from the fold by some particularly outrageous or suicidal action. Rimbaud having mastered the art of poetry in his twenties, deserted literature to lead caravans through the African desert. Apollinaire at almost as early an age had also mastered the traditional forms of his art, but with Rimbaud's example before him could not become "an explorer, a trapper, a robber, a hunter, a miner."

Possessed of great energy, curiosity, and disrespect, he was from the start thrown upon the side of those who flout authority, court disorder and embrace the glitter and profusion of an intensely mundane existence.

To regard the spectacle of modern life and to sense the cleavage with the past and with the art or humanities of the previous day, is to be "modern". For many the word is hateful; and yet Apollinaire set out deliberately to be modern: to revalue the contributions of the past in terms of the phenomenal changes which the twentieth century and the Great War had brought in.

The barbarous new age he courted, adopting much of its method, the character of its institutions and its cruel philosophy. Perhaps he has interpreted his age best in his own personality, that is to say his life, a large and daring conception in itself.

"Vain to be astonished at his continual feast-making," says his friend the painter, Rouveyre, "at the rash exploits he undertook, at the crown of thorns he inflicted upon himself... He was a prodigious creator and all of his literary and social games, were of the most brilliant and lavish character, far more so than their objects. Like God, who could make man out of nothing, Apollinaire made many, with the same poverty of material." (Souvenirs de mon Commerce—A. Rouveyre, Paris, 1919, Mercure de France.)

Apollinaire was born in Monte Carlo in 1880. It is still a delicate matter to approach the facts of his life, to some extent, because of his confusing boasts and pretensions. We do know that his mother was Mme de Kostrovitzka, a lady of Polish descent who lived in France, and that Apollinaire (i. e., Wilhelm de Kostrovitzki) was baptized in Rome on September 29, 1880.

He received an extensive and preciose education. He lived with his mother in a chateau outside of Paris, a huge mansion that had a billiard room, music parlors, salons, and animals of all kinds: monkeys, dogs, snakes, parrots, canaries. Apollinaire travelled much when he was quite young, chiefly in Germany, Italy and Eastern Europe; he lived and studied in the Rhineland. Then he came back to Paris, with "all the poems he had been collecting in a cigar-box."

A literary career in Paris, is perfectly conventional by now. You run after the editors of newspapers, and finally you are allowed to contribute "feuilletons" to them. Then the magazines, the publishers, and you have "arrived." Apollinaire became a journalist and lived for a time by the veriest pot-boiling, some of which included translations of Aretino, an edition of the Marquis de Sade, introductions to pornographical classics, and even a great bibliographical work, called, "The Inferno of the National Library." But he soon became notorious in Paris. He gathered a motley horde of writers, painters and types (i. e., idiots, or freaks), and paraded from the right bank to the left, from the Montmartre to Montparnasse. His associates are now the most distinguished names of France, Henri-Matisse, Picasso, Dérain, Braque, Rousseau (the old man whom he "discovered" near the fortifications of Paris), and André Salmon, Marie Laurencin, Max Jacob, Pierre Reverdy, "baron" Mollet, his secretary.

He was intensely conscious of the time-spirit. An original and rugged intellect, he disquieted those who were repelled by his lavish and heedless manner. For him the French literature of the Symbolist era, which de Gourmont still presided over, was dead, and he became, during that whole period from 1905 to the end of the Great War, the only living force in France. He predicted the sterile close of the literature of de Regnier and Paul Fort, "Prince of Poets" (!), heralding an age of boundless expansion and experiment, with new zones of experience, new forms, and a yet more complex and rich civilization.

Such ideas were in the air of Europe: there was Marinetti, in Italy: Cézanne had nearly brought his stupendous work to a close; and a group of painters, Picasso, Duchamps, Picabia, Braque, Dérain (the Cubists), launched their work upon a frightened world. The abstract investigations of the Cubists appealed to him powerfully. Apollinaire became their ringleader. His book, "The Cubist Painters," is an authoritative apology for this movement. But not content with this, he conceived little movements of his own, invented names for them, wrote up programs, and precipitated bad painters into careers. It was not all buffoonery. He may have placed silly, vacuous individuals at the head of the reviews he organized, "Les Soirées de Paris", Nord Sud (named after the new subway); but some of the best modern writing of the time, by Max Jacob, Pierre Reverdy, André Salmon, Paul Valéry, Apollinaire himself, and some extremely youthful poets who are now Dadaists, were included in them. His great charm in conversation, his uproarious wit, his complete shamelessness, made him idol of all who were drawn to him.

Alcools, his first collection of poems, appeared in 1913. It was the escape of a personality from the "eternal recurrence." The Symbolists had sought a kind of exalted, objective state; this false mysticism was accompanied by an attitude of fatigue, and preciose resignation. Even the language, in their hands had become crystallized, or static. Apollinaire's attitude was the complete reverse. A wonderfully happy man, his verse was lustier and sturdier. He had learned much from the reawakened interest in the "primitive" Italian painters. There was no false shading in his work. Every line was as direct as in a child's drawing. No one could use clichés or write of the most common diurnal experiences as freshly as he. His verse had also a certain heroic character, an air of prophecy.

It has always been the good fortune of France that Paris draws gifted strangers from other lands, who bring real gold to her. Apollinaire, a weird mixture of what Slavic and Latin strains, laid rough hands on the language. His aberrations are superb. He could never resist the foreigner's impulse toward jeux des mots; and none are quicker than the French themselves to accept and enjoy the new puns and double-entendres. For the French have gone farther, their language has been more pawed over and revivified through foreign usage than ours. Apollinaire's exoticisms were not bizarre; they had the air of being conceived in conversation.

In the summer of 1914, Apollinaire was in Deauville, surrounded by a cosmopolitan horde of Poles, Germans, Hungarians, Czechs and Russians when the Great War began. He embraced the superb irony of these events with the utmost ardour; his attitude was precisely that which Pascal epitomizes:

"Why do you wish to kill brother?"

"Do I not live on the other side of the river?"

He went into the artillery, and was stationed at Nîmes. He became Second Lieutenant Guillaume Apollinaire. There were dull months upon months in the barracks. There was also active fighting. He was three times wounded in the head, and trepanned. In the Fall of 1915, he lay in a hospital in Paris, recovering from a successful operation. It was at this time that he assembled the fragments of a novel over which he had been working for a period of years, The Poet Assassinated.

The poet, Croniamantal, is one of the few frankly epic figures of modern literature. Apollinaire had never really outlived the poet's age of twenty-five, and the preposterous life of his hero is drawn against the artistic and social foibles of his age. By no means mere satire in the 18th century sense. Apollinaire grows positively hilarious and intoxicated over his characters so that at times he is beside himself with sheer fun. Results: humor of extraordinary eloquence and sonority, and a form that is complete unrepresentative, with perpetual digressions and asides.

There have been so many tired men in France who wrote like flagellants. Flaubert made his waking hours a nightmare; Gautier was much too corseted; to Stendhal writing was a torturesome but resistless destiny; Villiers was a devout artisan; Mallarmé goaded himself into obscuracy and speechlessness.

We must go back to Stendhal to find such extreme opposition to naturalism. It is enemy of all that was Ibsen. Distortion or under-emphasis are employed to fantastic ends; when a puppet is uninteresting or wrung dry he is dismissed or killed. Here is the destructive side of it: Apollinaire runs all the risks, obeys no rules, and writes for fun.

In the following year he was dismissed from the army and pronounced unfit for anything but censorship service.

Discharged from the hospital, he bought himself the most immaculate officer's uniform, somewhat constricting for his already corpulent form and his double chin, and in a victoria rode up to the editorial offices of the Mercure de France. His manner was perfectly that of "a Marseillaise tenor in an opera comique." His friends were in an uproar over him. The art life of Paris, flared up again, under the guns. He broke loose again upon his maddest tours de forces. A great welcoming ball was given him, an orgy attended by a howling, cursing, fighting throng, in which men and women tore about like Chaplin in the films. There had never been such an outlandish and heterogeneous bazaar. Apollinaire was ravished at being the orchestra-leader of such disorders and follies. To stupefy them he gave a production of his preposterous play, Les Mammelles de Tiresias. From the point of view of "action," of living, these were his greatest moments. Even before the war, these carryings on had passed all boundaries and were a source of scandal all over the world. Apollinaire was the man of the day, for this desperate crowd. He made poets and painters. "He made men and women seem much madder than they really were." While they understood little his interior laughter, his rebellious imagination.

I have stressed Apollinaire's social adventures, regarding them as an aspect of his creative expression. Wholly absorbed in art, he was completely wanting in the false reverence and dignity which some affect. Believing in the new painting of Picasso, Braque, Dérain, he could as well hold a street demonstration, parading his friends as sandwich-men bearing cubist paintings.

In the last days of 1918 he was stricken with influenza and was taken off very quickly. All the fools and freaks stopped pirouetting.

Calligrammes, his book of war poems had just appeared, and it is agreed that his strongest and most singular expressions lie in these reactions to the war. All other artists were involuntarily baffled by their moral sentiments. Only Apollinaire, with his completely negative philosophy, his un-morality, his shame in all of the common virtues, could retort to this war with his gorgeous buffoonery and his ringing apostrophes. He seized the new meanings of the modern era, from the phallic zeppelins in the sky, the labels on his tobacco tins, the pages of newspapers, or the walls of old cities. If these things are unworthy, if the age is damnable, then Apollinaire is damned.

"Is there nothing new under the sun?" he asks. "Nothing—for the sun, perhaps. But for man, everything." He calls upon artists to be at least as forward as the mechanical genius of the time. The artist is to stop at nothing in his quest for novelty of form and material; to seize upon all the infinite possibilities afforded by the new instruments and opportunities, creating thereby the myths and fables of the future.

MATTHEW JOSEPHSON

À René Dalize

The glory of Croniamantal is now universal. One hundred and twenty-three towns in seven countries on four continents dispute the honor of this notable hero's birth. I shall attempt, further on, to elucidate this important question.

All of these people have more or less modified the sonorous name of Croniamantal. The Arabs, the Turks and other races who read from right to left have never failed to pronounce it Latnamainorc, but the Turks call him, bizarrely enough, Pata, which signifies goose or genital organ. The Russians surname him Viperdoc, that is, born of a fart, the reason for this soubriquet will be seen later on. The Scandinavians, or at least, the Dalecarlians, call him at will, quoniam, in Latin, which means, because, but often serves to indicate the noble passages in popular accounts of the middle ages. It is to be noted that the Saxons and the Turks manifest with regard to Croniamantal, a similar sentiment, since they refer to him by an identical surname, whose origin, however, is still scarcely explained. It is believed that this is an euphemistic allusion to the fact stressed in the medical report of the Marseilles doctor, Ratiboul, on the death of Croniamantal. According to this official document, all the organs of Croniamantal were sound, and the lawyer-physician added in Latin, as did Napoleon's aide Major Henry: partes viriles exiguitatis insignis, sicut pueri.

For the rest, there are countries where the notion of the Croniamantalian virility has entirely disappeared. Thus, the negroes in Moriana call him Tsatsa or Dzadza or Rsoussour, all feminine names, for they have feminized Croniamantal as the Byzantines feminized Holy Friday in making it Saint Parascevia.[1]

Two leagues from Spa, on the road bordered by gnarled trees and bushes, Vierselin Tigoboth, an ambulant musician who was coming on foot from Liège, struck his flint to light his pipe. A woman's voice cried:

He lifted his head, and a wild laugh burst out: "Hahaba! Hohoho! Hihihi! thine eyelids are the color of Egyptian lentils! My name is Macarée. I want a tom-cat."

Vierselin Tigoboth perceived by the roadside a young woman, brunette and formed of nice curves. How charming she seemed in her short bicyclist's skirt! And holding her bicycle with one hand, while gathering sloes with the other, she ardently fixed her great golden eyes on the Flemish musician.

"Vs'estez one belle bâcelle," said Vierselin Tigoboth, smacking his tongue. "But, my God, if you eat all those sloes, you will have the colic tonight, I'm sure."

"I want a tom-cat," repeated Macarée and unclasping her bodice she showed Vierselin Tigoboth her breasts, sweet as the buttocks of the angels, and whose aureole was the tender color of the rose clouds of sunset.

"Oh! oh!" cried Vierselin Tigoboth, "As pretty as the pearls of Amblevia, give them to me. I shall gather a big bouquet of ferns for you and of irises, color of the moon."

Vierselin Tigoboth approached to seize this miraculous flesh which was being offered to him for nothing, like the holy bread at Mass; but then he restrained himself.

"You're a sweet lass, by God, you're nicer than the fair of Liège. You're a nicer little girl than Donnaye, than Tatenne, than Victoire, whose gallant I have been, and nicer than Rénier's daughters, whom old Rénier always has for sale. Mind you, if you want to be my love, 'ware o' the crablouse, by God."

MACARÉE

They are the color of the moon

And round as the wheel of Fortune.

VIERSELIN TIGOBOTH

If you fear not to catch the louse

Then I should love to be your spouse.

And Vierselin Tigoboth approached, his lips full of kisses: "I love you! It is pooh! O beloved!"

Soon there were nothing but sighs, the songs of birds and of russet and horned little hares, like elves, fleet as the seven-league boots, passing by Vierselin Tigoboth and Macarée, prone under the power of love behind the plumtrees.

Then Macarée was off on the old contraption.

And sad unto death, Vierselin Tigoboth cursed the instrument of velocity which rolled away and vanished behind the terraced rotunda, at the same moment that the musician began to make water while humming a jingle...

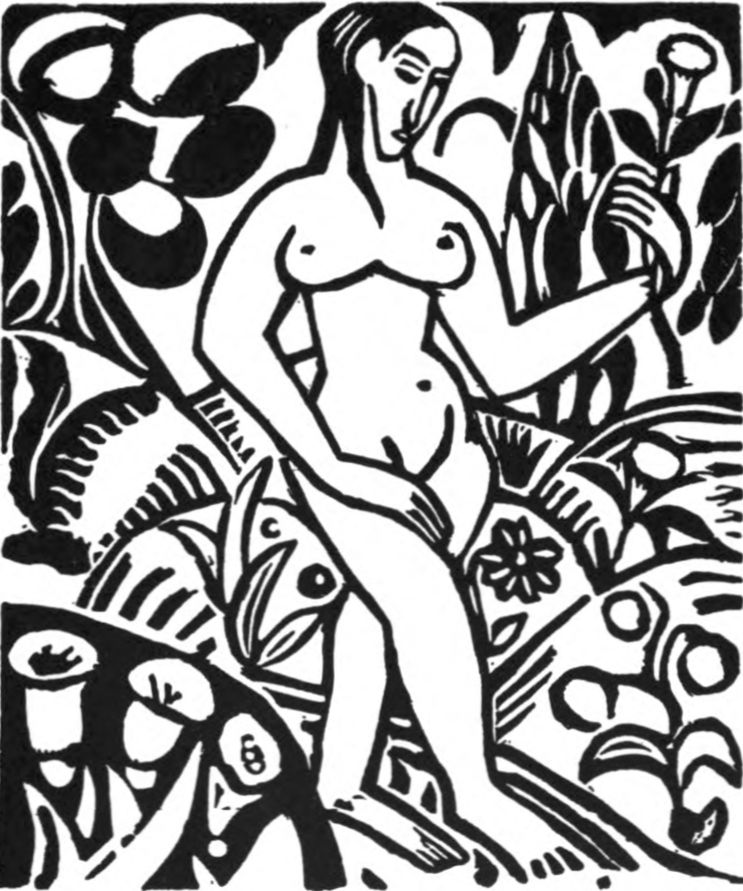

André Dérain

Macarée soon became aware that she had conceived by Vierselin Tigoboth.

"How annoying!" she thought at first, "But medicine has made much progress lately. I shall get rid of it when I want. Ah! that Walloon! He will have toiled in vain. Can Macarée bring up the son of a vagabond? No, no, I condemn this embryo to death. I should never even preserve this foetus in alcohol. And thou, my belly, if thou knewest how much I love thee since knowing thy goodness. What, wouldst stoop to carry such baggage as thou findest along the road? O too innocent belly, thou art unworthy of my selfish soul.

"What shall I say, o belly? thou'rt cruel, thou partest children from their parents. No! I love thee no longer. Thou'rt naught but a full bag, at this moment, o my belly, smiling at the nombril, o elastic belly, downy, polished, convex, sorrowful, round, silky, which ennobles me. For thou makest noble, o my belly, more beautiful than the sunlight. Thou shalt ennoble also the child of the Flemish vagabond and thou art worthy of the loins of Jupiter. What a misfortune! a moment ago I was about to destroy a child of noble race, my child who already lives in my beloved belly."

She opened the door suddenly and cried:

"Madame Dehan! Mademoiselle Baba!"

There was a rattling of doors and bolts and then the proprietors of Macarée's lodging came running out.

"I am pregnant," cried Macarée, "I am pregnant!"

She was sitting up in bed, her legs spread apart. Her skin looked very delicate. Macarée was narrow at the waist and broad-hipped.

"Poor little one," said Madame Dehan, who had but one eye, no waistline, a moustache, and limped. "After confinement women are just like crushed snail-shells. After confinement women are simply prey to disease (look at me!) an egg-shell full of all sorts of rubbish, incantations and other witch-spells. Ah! Ah! You have done very well."

"All foolishness," said Macarée. "The duty of women is to have children, and I am sure that their health is generally improved thereby, both physically and morally."

"Where are you sick?" asked Mademoiselle Baba.

"Shut up! I say," exclaimed Madame Dehan. "Better go and look for my flask of Spa elixir and bring some little glasses."

Mademoiselle Baba brought the elixir. They drank of it.

"I feel better now," said Madame Dehan, "After so much emotion, I need to refresh myself."

She poured out another little glass of the elixir for herself, drank it and licked the last few drops up with her tongue.

"Think of it," she said finally, "think of it, Madame Macarée ... I swear by all that I hold sacred, Mademoiselle Baba can be my witness, this is the first time that such a thing has happened to one of my tenants. And how many I have had! My Lord! Louise Bernier, whom they nicknamed Wrinkle, because she was so skinny; Marcelle la Carabinière (the freshest thing you ever saw!); Josuette, who died of a sunstroke in Christiania, the sun wishing thus to have his revenge of Joshua; Lili de Mercœur, a grand name, mind you, (not hers of course) and then vile enough for a chic woman, as Mercœur put it: 'You must pronounce it Mercure,' screwing up her mouth like a chicken's hole. Well she got hers, all right, they filled her as full of mercury as a thermometer. She would ask me in the morning; What sort of weather do you think we'll have today?' But I would always answer: 'You ought to know better than I...' Never, never in the world would any of those have become enceinte in my house."

"Oh well, it isn't as bad as that," said Macarée, "I also never had it happen to me before. Give me some advice, but make it short."

At this moment she arose.

"Oh!" cried Madame Dehan, "what a well-shaped behind you have! how sweet! how white! what embonpoint! Baba, Madame Macarée is going to put on her dressing-gown. Serve coffee and bring the bilberry tart."

Macarée put on a chemise and then a dressing gown whose belt was made of a Scotch shawl.

Mademoiselle Baba came back; she brought a big platter with cups, a coffee pot, milk-pitcher, jar of honey, butter cakes and the bilberry tart.

"If you want some good advice," said Madame Dehan, wiping away with the back of her hand the coffee that dribbled down her chin, "You had better go and baptize your child."

"I shall make sure and do that," said Macarée.

"And I even think," said Mademoiselle Baba, "that it would be best to do it on the day he is born."

"In fact," Madam Dehan mumbled, her mouth full of food, "you can never tell what may happen. Then you will nurse him yourself, and if I were you, if I had money like you, I should try to go to Rome before the confinement and get the Pope to bless me. Your child will never know either the paternal caress or blow, he will never utter the sweet name of papa. May the blessing of the Holy Papa at least follow him all his life."

And Madame Dehan began to sob like a kettle boiling over, while Macarée burst into tears as abundant as a spouting whale. But what of Mademoiselle Baba? Her lips blue with berries, she wept so hard that from her throat the sobs flooded down to her hymen and nearly choked her.

After having won a great deal of money at baccarat, and already rich, thanks to Love, Macarée, whose corpulency nothing could conceal, came to Paris, where above all, she ran after the most fashionable modistes.

How chic she was, how chic she was!

* * *

One night when she went to the Théâtre Français a play with a moral was presented. In the first act, a young woman whom surgery had rendered sterile lamented the fatness of her husband who had the dropsy and was very jealous. The doctor went out saying:

"Only a great miracle and great devotion can save your husband."

In the second act, the young woman said to the young doctor:

"I offer myself up for my husband. I want to become dropsical in his stead."

"Let us love each other, Madame. And if you are not unfaithful to the principle of maternity your wish will be granted. And what sweet glory I shall have thereof!"

"Alas!" murmured the lady, "I no longer have any ovaries."

"Love," cried the doctor at this, "Love, madame, is capable of working the greatest miracles."

In the third act, the husband, thin as an I, and the lady, eight months gone, felicitated each other on the exchange they had made. The doctor communicated to the Academy of Medicine the results of his experiments in the fecundation of women become sterile as a result of surgical operations.

* * *

Toward the end of the third act, someone shouted "Fire!" in the hall. The frightened spectators rushed from the hall howling. In fleeing, Macarée possessed herself of the arm of the first man she encountered. He was well dressed and fair of feature, and as Macarée was charming, he seemed flattered that she had chosen him as her protector. They made each other's acquaintance at a café and from there went to sup in the Montmartre. But it appeared that François des Ygrées had negligently forgotten to take his purse with him. Macarée gladly paid the bill. And François des Ygrées pushed gallantry so far as not to allow Macarée to spend the night alone, the incident at the theatre having rendered her nervous.

* * *

François, baron des Ygrées (a doubtful baronetcy belonging to whoever claimed it) called himself the last offshoot of a noble house of Provence and pursued a career in heraldry on the sixth floor of an apartment in the rue Charles V.

"But," he said, "the revolutions and the demagogues have changed things so that arms are no longer studied except by ill-born archaeologists, and the nobility is no longer tutored in this art."

The baron des Ygrées, whose coat of arms was of azur à trois pairies d'argent posés en pal, was able to inspire enough sympathy in Macarée for her to want to take lessons in heraldry out of gratitude for that night at the Théâtre Français.

Macarée showed herself, it is true, little given to learning the terminology of heraldry, and one might even say that she did not interest herself seriously in anything but the arms of the Pignatelli who had furnished popes for the Church and whose coat-of-arms was adorned with kettles.

However, these lessons were wasted time to neither Macarée nor François des Ygrées, for they ended by marrying. Macarée brought as her dot, her money, her beauty and her fatness. François des Ygrées offered to Macarée a great name and his noble bearing.

Neither complained of the bargain and they found themselves very happy.

"Macarée, my dear wife," said François des Ygrées a few days after their marriage, "Why have you ordered so many robes? It seems to me that hardly a day passes without some modiste brings new costumes. They do, true enough, honor to your taste and to their skill."

Macarée hesitated for a moment and then replied:

"It is to our honeymoon that you refer, François!"

"Our honeymoon, yes, I have thought of it. But where do you want to go?"

"To Rome," said Macarée.

"To Rome, like the bells of Easter?"

"I want to see the Pope," said Macarée.

"Very fine, but what for?"

"That he may bless the child who lies under my heart," said Macarée.

"Phew-ew-ew!"

"It will be your son," said Macarée.

"You are quite right, Macarée. We shall go to Rome like the bells of Easter. You will order a new robe of black velvet; and the dressmaker must not neglect to embroider our arms at the bottom of the skirt: of azur à trois pairies d'argent posés en pal."

Per carita, baroness, (I had almost called you Mademoiselle!) Ah! Ah! Ah! But the baron, your husband, he would protest. Ah! ah! quite true, you have a little belly which commences to become arrogant. They do their work well, I see, in France. Ah! if that fine country would only become religious again, the population decimated by anti-clericalism would at once, (yes, baroness) the population would increase considerably. Ah! dear Christ! how well she listens, the arrogantine, when one talks seriously, yes, baroness, you have the air of an arrogantine. Ah! ah! ah! so, you want to see the Pope. Ah! ah! ah! the benediction of a mere cardinal like me will not do. Ah! ah! tut-tut, I understand quite well. Ah! ah! I shall try to obtain an audience for you. Oh! no need to thank me, you can let my hand go. How well she kisses, the arrogantine, oh! Come here, again, I want you to carry away with you a little souvenir of me.

"There! a chain, with the medal of the holy house of Lorette. Let me put it about your neck... Now that you have the medal you must promise me never to part with it. There, there, there! Come here so that I can kiss you on the forehead. Come, come, can she be afraid of me, the little arrogantine? Done! Now tell me why you laugh?... Nothing! Well! Now, one bit of advice! When you go to the Vatican, I warn you not to use so much odour, I mean so much perfume. Goodbye, arrogantine. Come and see me again. My compliments to the baron."

* * *

It was thus, that, thanks to Cardinal Ricottino, who had been to Paris as nuncio, Macarée obtained an audience with the Pope.

She went to the Vatican dressed in her beautiful armorial robe. The baron des Ygrées, in full dress, accompanied her. He admired much the bearing of the royal guards, and the Swiss mercenaries, inclined to drunkenness and brawling, seemed fine devils to him. He found occasion to whisper into his wife's ear something about one of his ancestors who was a cardinal under Louis XIII...

* * *

The couple returned to the hotel deeply moved and almost prostrated by the benediction of the Pope. They undressed chastely, and in bed, they spoke for a long time about the pontiff, the whitened head of the old church, a pressed lily, the snow which Catholics think eternal.

"My dear wife," said François des Ygrées finally, "I esteem you to adoration, and I love the child whom the Pope has blessed with all my heart. May he come, the blessed infant, but I want him to be born in France."

"François," said Macarée, "I have never yet been to Monte-Carlo. Let us go there! I needn't lose our whole pile. We are not millionaires, but I am sure that we shall be lucky in Monte-Carlo."

"Damn! damn! damn!" swore François, "Macarée, you make me see red."

"Ho, there," cried Macarée, "you gave me a kick, you——"

"I note with pleasure, Macarée," said François des Ygrées waggishly, recovering his good humor, "that you do not forget that I am your husband."

"Come, then, li'l nobs, let's go to Monaco."

"Yes, but you must have your confinement in France, for Monaco is an independent state."

"Agreed," said Macarée.

On the morrow the baron des Ygrées and the baroness, all swollen by mosquito bites, took tickets at the station for Monaco. In the coach they laid charming plans.

The baron and the baroness des Ygrées in taking tickets for Monaco had thought to arrive at the station which is the fifth on the way from Italy to France and the second in the little principality of Monaco.

The name of Monaco is properly the Italian name of this principality, although it is widely used nowadays in French, the French terms Mourgues and Monéghe having fallen into desuetude.

However the Italians call Monaco, not only the principality which bears that name but also the capital of Bavaria which the French call Munich. The messenger accordingly gave the baron tickets for Monaco-Munich instead of Monaco-principality. Before the baron and the baroness had noticed their error they were already at the Swiss frontier, and after having recovered from their astonishment, they decided to finish the voyage to Munich in order to see at close hand all that the anti-artistic spirit of modern Germany could conceive of ugliness in architecture, sculpture, painting and the decorative arts...

* * *

The cold winds of March made the couple shiver in this stone-box Athens.

"Beer," the baron des Ygrées had said, "is excellent for women who are enceinte."

And so he led his wife to the royal brewery of Pschorr, to the Augustinerbräu, to the Münchnerkindl and other great breweries. They penetrated to the Nockerberg where there is a great garden. They drank there, as long as it held out, the famous March beer, Salvator, and it didn't last very long, for the Munich people are great drunkards.

* * *

When the baron and his wife entered the garden they found it thronged with a mob of drinkers, who were already under-the-weather and sang head to head and danced dizzily, breaking all the empty steins.

Peddlers sold roast fowl, grilled herrings, pretzels, rolls, sausages, sweets, souvenirs, post-cards. And there was also Hans Irlbeck, the King of Drinkers. Since Perkeo, the midget drunkard of the great cask of Heidelberg, no such boozer had ever been seen. At the time of the March beer, and in May, Bock-time, Hans Irlbeck drank his forty quarts of beer a day. Ordinarily he did not have occasion to drink more than twenty-five.

Just as the gracious Ygrées pair passed by, Hans placed his colossal buttocks on a bench which, bearing already the weight of some twenty huge men and women, cracked disconsolately. The drinkers fell, their legs in the air. Some bare thighs could be seen because Munich ladies never wear their stockings above their knees. Bursts of laughter everywhere. Hans Irlbeck who had also been floored, but had not let go of his stein, spilled its contents over the belly of a girl who had rolled near him, and the beer bubbling under her resembled that which she did when she got to her feet after swallowing a quart at one gulp in order to recover her composure.

But the proprietor of the garden cried:

"Donnerkeil! damned swine ... a bench broken."

And he started off with his towel under his arm, calling loudly for the waiters:

"Franz! Jacob! Ludwig! Martin!" while the patrons called for the proprietor:

"Ober! Ober!"

However the Oberkellner and the waiters did not come back. The drinkers crowded about the counters and took their steins themselves, but the kegs were no longer emptied, and no more were heard the sonorous blows of another cask being put under the hammer. The singing ceased, the drinkers, angered, proffered oaths at the brewers and at the March beer itself. Some profited by the lull to vomit with violent efforts, their eyes almost popping out of their heads; their neighbors encouraged them with imperturbable seriousness. Hans Irlbeck who had picked himself up, not without difficulty, grumbled with a great snort:

"There is no more beer in Munich!"

And he repeated, with the accent of his native city:

"Minchen! Minchen! Minchen!"

After raising his eyes toward heaven, he fell upon a vendor of fowls, and having ordered him to roast a goose for him, began to formulate his desires:

"No more beer in Munich... if there were only some white radishes!"

And he repeated many times the Munich expression:

"Raadi, raadi, raadi..."

Suddenly he stopped. The crowd of drinkers, beside themselves, gave a cry of exultation. The four waiters had just appeared at the door of the brewery. With dignity they were carrying a sort of canopy under which the Oberkellner marched proud and erect, like a negro king dethroned. Behind him came fresh kegs of beer which were put under the hammer at the sound of the bell, while shouts of laughter rang out, and cries and songs rose above this teeming butte, hard and agitated as the Adam's apple of Gambrinus himself, when, burlesqued in the costume of a monk, a white radish in one hand, he tossed off with the other the jug which rejoiced his gullet.

And the unborn child found himself right shaken by the laughter of Macarée who, greatly amused by the spectacle of this colossal gluttony, drank and drank in company with her spouse.

But then, the vivacity of the mother exerted a happy influence on the character of the offspring who acquired therefrom much common sense, before his birth, and some of the real common sense, of course, which great poets are made of.

Baron François des Ygrées left Munich when the baroness knew that the hour of delivery was approaching. Monsieur des Ygrées did not want to have a child born in Bavaria; he was sure that that country was overrun with syphilis.

They arrived in the springtime, in the little port of Napoule, which in an excellently turned verse the baron baptised for eternity:

Napoule of the golden skies.

It was there that the delivery of Macarée's child took place.

* * *

"Ah! Ah! Aie! Aie! Aie! Ouh! Ouh! Whee-ee-ee!"

The three local midwives took to improvising pleasantly:

FIRST MIDWIFE

I dream of war.

O my friends, the stars, the bright stars, have you ever counted them?

O my friends, do you even remember the titles of all the books you have read and the names of their authors?

O my friends, have you ever thought of the poor men who tread the broad highways?

The herdsmen of the golden age led their herds to pasture without fear that the cattle would flee, they feared only the jungle beasts.

O my friends, what do you think of all these cannons?

SECOND MIDWIFE

What do I think of these cannons? They are vigorous phalli.

O my beautiful nights! I am happy because of a sinister horn which enchanted me last night, 'tis a good augury. My hair is perfumed with abelmosch.

O! the beautiful and rigid phalli that these cannons are! If women had to do military service they would all go into the artillery. The sight of the cannons in battle would be strange for them.

Lights are born on the sea far off.

Reply, o Zelotide, reply with thy sweet voice.

THIRD MIDWIFE

I love his eyes at night, he knows my hair well and its odour. In the streets of Marseilles an officer pursued me for a long time. He was well dressed and of fair colour, there was gold on his costume and his mouth tempted me, but I fled his kisses and took refuge in my "bedroom" of the "family-house" where I was stopping.[2]

FIRST MIDWIFE

O Zelotide, spare the sad men as thou sparest this beau. Zelotide what thinkest thou of the cannons.

SECOND MIDWIFE

Alas! Alas! I want to be loved.

THIRD MIDWIFE

They are the tools of the ignoble love of the people. O Sodom! Sodom. O sterile love!

FIRST MIDWIFE

But we are women, why dost thou speak of Sodom?

THIRD MIDWIFE

The fire of heaven devoured her.

THE CONFINED

When you have finished your monkey-tricks, if it please you, will you not forget to give a little attention to the baroness des Ygrées.

* * *

The baron slept in a corner of the room on several travelling blankets. He made a fart which caused his better half to laugh until the tears came. Macarée wept, cried, laughed and a few moments later brought into the world a sturdy child of the male sex. Then, exhausted by these efforts, she rendered up her soul, with a scream that was like the ululation of the eternal first wife of Adam, when she crossed the Red Sea.

In reporting the above, I believe that I have elucidated the important question of the birthplace of Croniamantal. Let the 123 towns in 7 countries dispute the honor of his birth.[3]

We know now, and the state records bear testimony that he was born of the paternal fart at Napoule of the golden skies, on the 25th of August, 1889, but not announced at the mayoralty until the following morning.[4]

It was the year of the Universal Exposition, and the Eiffel Tower, which was just born, saluted the heroic birth of Croniamantal with a beautiful erection.

The baron des Ygrées made another fart which woke him by the macabre bed where the corpse of Macarée reclined. The child cried, the midwives croaked, the father sobbed, and declaimed:

"Ah, Napoule with the golden skies, I have killed my hen with the golden eyes!"

Then he bathed the new-born calling him by a name which he invented forthwith and which did not belong to any saint in Paradise: CRONIAMANTAL. He left on the following day, having arranged for the funeral of his spouse, written the necessary letters assuring his inheritance, and announced the child under the names of Gaëtan—Francis—Etienne—Jack—Amélie—Alonso des Ygrées. And with this nursling whose putative father he was, he took the train for the Principality of Monaco.[5]

A widower, François des Ygrées established himself near the principality; on the grounds of Roquebrune; he took pension with a family, which included a pretty brunette called Mia. There he reared the bearer of his own name with the baby-bottle.

Often he would go out at dawn for a walk at the sea shore. The road was fringed with amaryllis which he would always compare involuntarily with packages of dried cod. Sometimes, because of the contrary winds, he would turn to light an Egyptian cigarette whose smoke rose in spirals like the bluish mountains emerging far off in Italy.

* * *

The family in whose bosom he had installed himself was composed of the father, the mother and Mia. M. Cecchi, a Corsican, was a croupier at the casino. He had previously been croupier at Baden-Baden and had married a German woman there. Of this union Mia was born; her carnation tint and black hair bespoke her Corsican blood. She was always dressed in buoyant colors. Her walk was balanced, her figure arched; she was smaller at the breast than at the buttocks, and a touch of strabism lent her dark eyes a somewhat distraught look, which only rendered her more tempting.

Her speech was lazy, soft, guttural, but pleasant nevertheless. It was the accent of the Monegascans whose syntax Mia followed. After having seen the young girl gather roses, François des Ygrées began to take notice of her and was much amused by her syntax for whose rules he enjoyed making research... First of all, he noticed the italianisms in her vocabulary, and especially the habit of conjugating the verb "to be" with the wrong auxiliary. For example, Mia would say: "Je suis étée," instead of "J'ai été." He also noted her bizarre way of repeating the verb in her principal clause: "I was at the Moulins, while you went to Menton, I was;" or better: "This year I am going to the gingerbread fair at Nice, I am."

One time before sunrise, François des Ygrées went down to the garden. He abandoned himself to sweet reveries, during which he caught cold. All of a sudden he began to sneeze about twenty times in succession.

Sneezing aroused him. He saw that the sky had whitened and the horizon cleared with the first light of dawn. Then the first shafts of sunlight enflamed the sky along the Italian coast. Before him spread the still sorrowful sea, and on the horizon, like little clouds above the film of sea, could be seen the curving peaks of Corsica, which always disappeared after the rising of the sun. The baron des Ygrées shivered, then he yawned and stretched himself. He kept on regarding the sea to the east where one might have said there glittered a royal navy in sight of a seaport with white houses, Bodighère, which furnished palms for the festivities of the Vatican. He turned toward the immobile guardian of the garden, a great cypress, begirt with a full-blown rose bush which clambered up almost to its top. François des Ygrées breathed of the sumptuous roses of nonpareil fragrance whose petals, as yet closed, were of flesh.

And just then Mia called him to have his breakfast.

With her braid hanging down her back, she had just come to pick some figs and she was letting a few creamy drops flow into a pitcher of milk. She smiled at François des Ygrées, saying:

"Have you slept well?"

"No, there are too many mosquitoes."

"Don't you know that when you are stung you should rub the place with lemon and in order not to be stung by them you should put vaseline on your face before going to sleep. They never bite me."

"That would be too bad. For you are very pretty, and ought to be told so oftener."

"There are those who tell me so and others who think so without telling. Those who tell it to me make me neither hot nor cold, as for the others, so much the worse for them..."

And François des Ygrées conceived at once a little fable for the timid:

FABLE OF THE OYSTER AND THE HERRING

An oyster dwelt, beautiful and wise, on a rock. She never dreamed of love but during fine weather simply bayed beatifically at the sun. A herring saw her and it was as a spark of powder. He tumbled hopelessly in love with her without daring to avow it.

One summer day, happy and coy, the oyster yawned. Smuggled behind a rock the herring looked on, but all at once the desire to imprint a kiss upon his beloved became so overpowering that he could no longer restrain himself.

And so he threw himself between the open shells of the oyster who in her surprise shut them with a snap, decapitating the wretched herring, whose headless body floats aimlessly upon the ocean.

"'Twas so much the worse for the herring," said Mia laughing, "He was much too foolish. I too want people to tell me that I am pretty, not for fun, but so as we can marry..."

And François des Ygrées noted for future consideration her curious peculiarities of syntax: "so as we can marry." ...And he thought further: "She doesn't love me. Macarée dead. Mia indifferent. Alas I am unhappy in love."

* * *

One day he found himself in the valley of Gaumates on a little knoll covered with skinny little pines. The shore trimmed by the white-blue of the waves stretched far out before him. The Casino emerged from the bank of splendid trees in its gardens. This palace looked like a man squatting and lifting his arms toward heaven. Near it, François des Ygrées hearkened to an invisible Mammon:

"Regard this palace, François, it is made in the image of man. It is sociable like him. It loves those who come to it and especially, those who are unhappy in love. Go there and thou wilt win, for thou canst not lose in play, since thou hast lost all in love."

Since it was six o'clock, the angelus tinkled from the different churches in the neighborhood. The voice of the bells prevailed against the voice of the invisible Mammon, who became silent, while François des Ygrées searched for him.

* * *

On the next day, François took the road to the temple of Mammon. It was Palm Sunday. The streets were littered with children, young girls and women carrying palms and olive-branches. The palms were either very simple or woven in a peculiar fashion. At each corner of the street, the weavers of palms were sitting against the wall, working. Under their deft hands the palm fibers bent, circled bizarrely and charmingly. The children were playing about already with hard eggs. On a square a troop of urchins were pummelling a red-headed kid whom they had found trying to consume a marble egg. Very small girls were going to mass, well dressed and carrying like candles the woven palms in which their mothers had hung sweet-meats.

François des Ygrées thought:

"The sight of these palms brings good luck and today, which is gay Easter, I shall break the bank."

* * *

In the game hall, he regarded at first the diverse throng which pressed about the tables...

François des Ygrées approached a table and played. He lost. The invisible Mammon had come back and spoke sharply each time they erased a deal:

"Thou hast lost!"

And François saw the crowd no more, his head was turning, he placed louis, packages of bills, on one square, diagonally, transversally. He played a long time losing as much as he wanted to.

He turned away at last and saw the whole brilliant hall where the players still pressed about the tables as before. Noticing a young man whose chagrined face revealed that he had had no luck, François smiled at him and asked whether he had lost.

The young man replied angrily:

"You too? A Russian just won more than two hundred thousand francs by my side. Ah! if I only had a hundred francs more, I would make up what I have lost twenty or thirty times over. But Oh, I have beastly luck, I am hoodooed, done for. Imagine..."

And taking François by the arm, he led him toward a divan on which they sat down.

"Imagine," he continued, "I have lost everything. I am almost a thief. The money I have lost did not belong to me. I am not rich, I had a position of trust. My employer sent me to recover claims in Marseilles. I got them. I took the train to come here and try my luck. I lost. What is there left? They will arrest me. They will say that I am a dishonest man, even though I haven't ever profited of the money I took. I have lost all. If I had won, no one would have reproached me. What luck I have! There is nothing for me to do but to kill myself."

And suddenly rising the young man put a revolver to his mouth and fired. The corpse was carried away. Several players turned their heads a moment, but none of them bothered at all, and most of them took no notice of the incident which, however, made a profound impression on the mind of the baron des Ygrées. He had lost all that Macarée had left him and the child. As he went out François felt the whole universe contract about him like a tiny cell, and then like a coffin. He got back to the villa where he lived. At the door he passed Mia who was chatting with a stranger who carried a valise.

"I am a Hollander," said the man, "but I live in Provence and I would like to hire a room for several days; I have come here to make some mathematical observations."

At this moment the baron des Ygrées sent a kiss with his left hand to Mia, while with a revolver in his right he blew his brains out and rolled in the dust.

"We have only one room to rent," said Mia, "but it has just become free."

And she quickly closed the eyelids of the baron des Ygrées, gave cries of grief, and aroused the neighborhood.

* * *

As to the young child, whom his father had in such a characteristic burst of lyricism named for aye Croniamantal, he was gathered up by the Dutch traveller who soon carried him off to bring him up as his own son.

On the day they left, Mia sold her virginity to a millionaire trap-shooting-champion, and it was the thirty-fifth time that she had lent herself to this little commercial transaction.

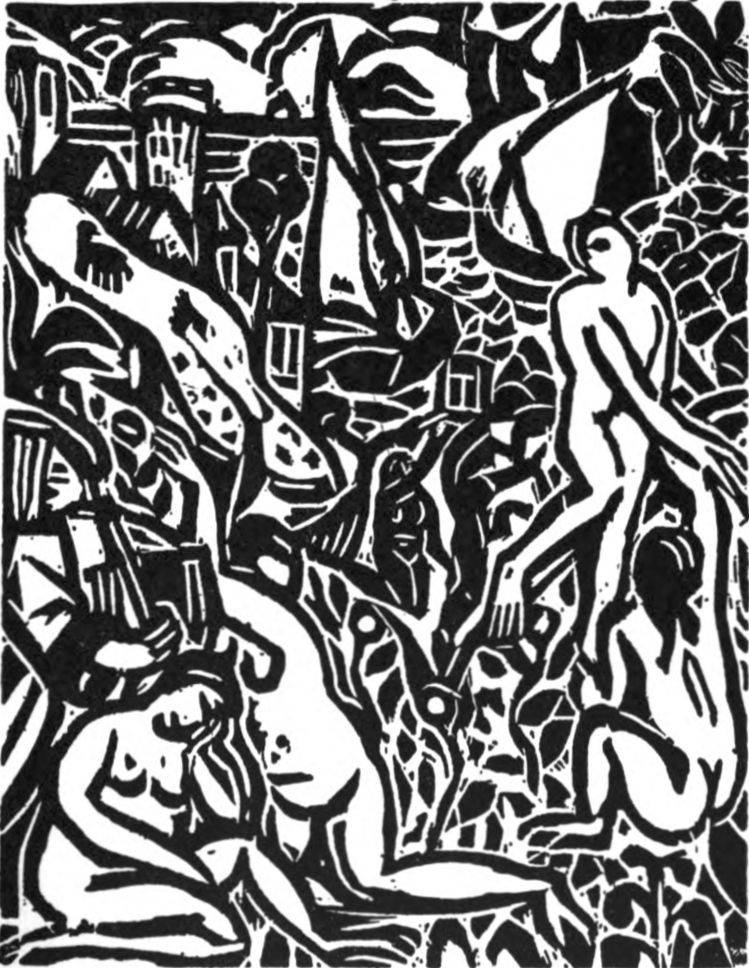

André Dérain

The Dutchman, named Janssen, led Croniamantal to the region of Aix, where there was a house which the people of the neighborhood called le Chateau. Le Chateau had nothing lordly about it other than its name and was nothing but a vast domicile having a dairy and a stable.

Mr. Janssen possessed a modest income and lived alone in this dwelling which he had bought in order to live in solitude, a suddenly broken off betrothal having rendered him rather hypochondriac. He devoted all his energies now to the education of the son of Macarée and Vierselin Tigoboth: Croniamantal, heir of the old name of des Ygrées.

The Dutchman, Janssen, had travelled much. He spoke all the languages of Europe, Arabian, and Turkish, not to mention Hebrew and other dead languages. His speech was as clear as his blue eyes. He soon made the friendship of several scholars of Aix whom he would visit from time to time and he corresponded with many foreign scientists.

When Croniamantal was six years of age, Mr. Janssen would often take him to the country. Croniamantal came to love these lessons along the paths of wooded hills. Mr. Janssen would often stop and show Croniamantal the birds hopping about or butterflies pursuing each other and fluttering together among the wild rose-bushes. He would say that love reigned over all of Nature. They would also go out on moonlit nights and the master would explain to his pupil the hidden destinies of the heavenly bodies, their regular course, and their effects upon the life of man.

Croniamantal never forgot how one moonlit night his master led him to a field at the edge of a forest; the grass bubbled with milky light. Fireflies fluttered around them; their phosphorescent and jagged lights gave the site a strange aspect. The master called the attention of his disciple to the sweetness of this May night.

"Learn," he said, "learn to know all of Nature and to love her. Let her be your veritable nurse, whose salutary mammals are the moon and the hills."

Croniamantal was thirteen years of age at this time and his mind was quite ripe. He listened attentively to Mr. Janssen's words.

"I have always lived in her, but I must say, lived badly, for one should not live without human love as companion. Do not forget that all is a sign of love in Nature. I, alas! am damned for not having observed this law whose demands nothing can withstand."

"What," said Croniamantal, "you, my teacher, who know so many sciences did not recognize this law which every country lout and even the animals, the vegetables, and inert matter observe?"

"Happy child who at your age can put such questions!" said Mr. Janssen. "I have always known that law, from which no human being should rebel. But there are some luckless men destined never to know the joys of love. That often happens to poets and scientists. Their souls are vagabond; I am always conscious of existences preceding my own. This knowledge has never stirred any but the sterile bodies of scientists. (You should not be astonished in the least at what I say.) Whole races respect animals and proclaim the principle of metempsychosis, a most worthy belief, self-evident but fantastical, since it takes no account of lost forms and of their inevitable dispersion. Their worship should have extended to the vegetable kingdom and to minerals. For what is the dust of roads but the ashes of the dead? It is true that the Ancients did not concede life to inert matter. But rabbis believed that the same soul inhabited the body of Adam, Moses and David. In fact, the name, Adam, is composed in Hebrew of the letters Aleph, Daleth and Mem, the first letters of the three names. Your soul like mine, inhabited other human forms, other animals, or was dispersed and will continue so after your death, since all things must serve again. For perhaps there is nothing new any more, and creation has ceased, perhaps... I affirm that I have not desired love, but I swear that I would not begin such a life over again. I have mortified my flesh and suffered severe punishment. I should like your life to be happy."

Croniamantal's master made him devote most of his time to the sciences, keeping him au courant with all recent inventions. He also instructed the boy in Latin and Greek. They often read the Eclogues of Virgil or translated Theocritus in an olive grove. Croniamantal had learned a very pure French, but his master taught him in Latin. He also taught him Italian, and at an early age Croniamantal received the poems of Petrarch, who became one of his favorite poets. Mr. Janssen also taught Croniamantal English, and made him familiar with Shakespeare. Above all he gave the boy a taste for old French authors. Among the French poets he admired chiefly Villon, Ronsard and his pléiade, Racine and La Fontaine. He also made him read translations of Cervantes and of Goethe. On his advice, Croniamantal read the romances of chivalry which might have made part of the library of Don Quixote. They developed in Croniamantal an unquenchable thirst for experiment and perilous love adventures; he devoted himself to fencing and to horseback riding; at the age of fifteen he declared to anyone who came to visit them that he had decided to become a celebrated and peerless cavalier, and already he dreamed of a mistress.

Croniamantal was, at this time, a handsome youth, thin and straight. The girls at the village fêtes, when he touched them lightly, would stifle little bursts of laughter and redden, lowering their eyes under his regard. Habituated to poetic forms, his mind thought of love as a conquest. Thoughts of Boccacio, his natural daring, his education, everything disposed him to take the final step.

One May day, he went out for a long ride. It was morning, everything was still fresh. The dew hung from the flowers of the hedges, and on either side of the road stretched the fields of olive trees whose gray leaves trembled gently in the sea breeze and compared agreeably with the blue sky. He arrived at a place where the road was being mended. The road menders, handsome boys in bright colored caps, worked lazily, singing the while, and stopping occasionally to drink from their flasks. Croniamantal thought that these handsome fellows had sweethearts. It is thus that they call a lover in that country. The boys say "my sweetheart," the girls, "my sweetheart," and in fact they are both sweet in that lovely country. Croniamantal's heart leaped and his whole being, exalted by the springtime and the riding, cried for love.

At a turn in the road, an apparition increased his trouble. He arrived close to a little bridge thrown across a river which cut the road. The place was isolated, and across the hedges and the trunks of poplars, he saw two beautiful girls bathing, quite naked. One was in the water and held herself up by a branch. He admired her brown arms and abundant beauties, hardly concealed by the water. The other, standing on the bank, dried herself after her bath and exposed ravishing lines and graces which inflamed the heart of Croniamantal; he decided to join them and mingle in their pleasures. Unluckily, he perceived in the branches of a neighboring tree two youths spying on this prey. Holding their breath and watching the least movements of the bathers, they did not see the equestrian, who, laughing uproariously, threw his horse into a gallop and cried aloud as he crossed the little bridge.

The sun had risen almost to its zenith and was now darting its dreadful rays. An ardent thirst added itself to the amorous inquietudes of Croniamantal. The sight of a farm along the road brought him unspeakable joy. He arrived at a little orchard whose blossoming trees made a lovely sight. It was a little wood, rose and white with the cherry and peach blossoms. On the fence linen was drying and he had the pleasure of seeing a charming peasant girl of about sixteen, at work washing clothes in a vat in the shadow of a fig-tree that had just begun to bloom. Not having noticed his arrival, she continued to accomplish her domestic function which he found noble; for, his imagination full of memories of antiquity, he compared her to Nausica. Descending from his horse he approached and contemplated the young girl with ravishment. He looked at her back. Her folded up skirt discovered a well made leg in a very white stocking. Her body moved in a manner that was pleasantly exciting because of the efforts occasioned by the soaping. Her sleeves were rolled up and he observed her pretty brown plump arms, which enchanted him.

I have always loved beautiful arms particularly. There are people who attach great importance to the perfection of the foot. I admit that they touch me too, but the arm is to my mind that which should be most perfect in woman. It is always in motion, one always has one's eye upon it. One might say that it is the veritable organ of the graces, and that by its deft movements, it is the veritable arm of Love, since when curved, this delicate arm resembles a bow, and when extended, the arrow thereof.

This was also Croniamantal's point of view. He was thinking of this, when his horse, who suddenly remembered that it was the habitual hour for being fed, began to whinny. At once the young girl turned and showed surprise at seeing a stranger regarding her from above the fence. She blushed and only seemed the more charming. Her dusky skin attested to the Moorish blood that flowed in her veins. Croniamantal asked her for food and drink. With much good grace this sweet girl did have him enter the house and served him a rude repast. With some milk, eggs, and black bread, his thirst and his hunger were soon sated. In the meantime, he questioned his young hostess, in the hope of finding an opportunity for paying her gallant compliments. He learned that her name was Mariette, and that her parents had gone to the neighboring town to sell vegetables; her brother was working on the road. This family lived happily on the products of the orchard and the barnyard.

At this moment, her parents, fine looking peasants, returned, and there was Croniamantal already in love with Mariette, quite disappointed. He paid the mother for the meal, and went off, after having given Mariette a long look which she did not return, but he had the satisfaction of seeing her blush as she turned away.

He mounted his horse and took the road to his house. Being for the first time in his life, sad for love, he found extreme melancholy in this same countryside which he had previously traversed. The sun had dropped low over the horizon. The grey leaves of the olive trees seemed as sad as himself. The shadows stretched out like waves. The river where he had seen the bathers was abandoned. The lapping of the water became unbearable for him, like a mockery. He threw his horse into a gallop. Then there was the dusk, lights appearing in the distance. Then night came; he slowed up his horse and abandoned himself to a disordered revelry. The sloping road was bordered with cypresses, and it was thus, somnolent with the night and with love, that Croniamantal pursued his melancholy way.

* * *

His master soon noticed in the days that followed that he gave no more attention to the studies to which he had been wont to apply himself with such diligence. He divined that this disgust came of love.

His respect was mingled with a little scorn because Mariette was nothing but a simple peasant girl.

The end of September had been reached, and one day Mr. Janssen led Croniamantal out under the laden olive trees in the orchard and censured his disciple for his passion, the latter hearkening to his reproaches with ruddy embarrassment. The first winds of autumn complained in the fields and Croniamantal, very sad and much ashamed, lost forever his desire to see again the pretty Mariette and kept nothing but the memory of her.

* * *

And so Croniamantal attained his majority.

A disease of the heart which was discovered in him led to his dismissal by the military authorities. Soon after, his guardian died suddenly, leaving him by will the little which he possessed. And after having sold the house called le Chateau, Croniamantal went to Paris to give himself freely to his taste for literature; he had been for some time past composing poems secretly and accumulating them in an old cigar-box.

In the early days of the year 1911, a young man who was very badly dressed went running up the rue Houdon. His extremely mobile countenance seemed to be filled with joy and anxiety by turns. His eyes devoured all that they saw and when his eyelids snapped shut quickly like jaws, they gulped in the universe, which renewed itself incessantly by the mere operation of him who ran. He imagined to the tiniest details the enormous worlds pastured in himself. The clamour and the thunder of Paris burst from afar and about the young man, who stopped, and panted like some criminal who has been too long pursued and is ready to surrender himself. This clamour, this noise indicated clearly that his enemies were about to track him like a thief. His mouth and his gaze expressed the ruse he was employing, and walking slowly now, he took refuge in his memory, and went forward, while all the forces of his destiny and of his consciousness retarded the time when the truth should appear of that which is, that which was, and of that which is to be.

The young man entered a one story house. On the open door was a placard:

Entrance to the Studios

He followed a corridor where it was so dark and so cold that he had the feeling of having died, and with all his will, clenching his fists and gritting his teeth he began to take eternity to bits. Then suddenly he was conscious again of the motion of time whose seconds, hammered by a clock, fell like pieces of broken glass, while life flowed in him again with the renewed passage of time. But as he stopped to rap at a door, his heart beat more strongly again, for fear of finding no one home.

He rapped at the door and cried:

"It is I, Croniamantal!"

And behind the door the heavy steps of a man who seemed tired, or carried too weighty a burden, came slowly, and as the door opened there took place in the sudden light the creation of two beings and their instant marriage.

In the studio, which looked like a barn, an innumerable herd flowed in dispersion: they were the sleeping pictures, and the herdsman who tended them smiled at his friend. Upon a carpenter's table piles of yellow books could be likened to mounds of butter. And pushing back the ill-joined door, the wind brought in unknown beings who complained with little cries in the name of all the sorrows. All the wolves of distress howled behind the door ready to devour the flock, the herdsman and his friend, in order to prepare in their place the foundations for the NEW CITY. But in the studio there were joys of all colours. A great window opened the whole north side and nothing could be seen but the whole blue sky, the song of a woman. Croniamantal took off his coat which fell to the floor like the corpse of a drowned man, and sitting on the divan he gazed for a long time at the new canvas placed on the support. Dressed in a blue wrap, barefooted, the painter also regarded the picture in which two women remembered themselves in a glacial mist.

The studio contained another fatal object, a large piece of broken mirror hooked to the wall. It was a dead and soundless sea, standing on end, and at the bottom of which a false life animated what did not exist. Thus, confronting Art, there is the appearance of Art, against which men are not sufficiently on their guard, and which pulls them to earth when Art has raised them to the heights. Croniamantal bent over in a sitting posture, leaned his fore-arms on his knees, and turned his eyes from the painting to a placard thrown on the floor on which was painted the following announcement:

I AM AT THE BAR—The Bird of Benin

He read and re-read this sentence while the Bird of Benin contemplated his picture, approaching it and withdrawing from it, his head at all angles. Finally he turned towards Croniamantal and said:

"I saw the woman for you last night."

"Who is she?" asked Croniamantal.

"I do not know, I saw her but I do not know her. She is a really young girl, as you like them. She has the sombre and child-like face of those who are destined to cause suffering. And despite all the grace of her hands that straighten in order to repel, she lacks that nobility which poets could not love because it would prevent their being miserable. I have seen the woman for you, I tell you. She is both beauty and ugliness; she is like everything that we love nowadays. And she must have the taste of the laurel leaf."

But Croniamantal, who was not listening to him, interrupted at this point to say:

"Yesterday I wrote my last poem in regular verses:

Well,

Hell![6]

and my last poem in irregular verses (take care that in the second stanza the word wench is taken in its less reputable meaning):

PROSPECTUS FOR A NEW MEDICINE

Why did Hjalmar return

The tankard of beaten silver lay void,

The stars of the evening

Became the stars of the morning

Reciprocally

The sorceress of the forest of Hruloë

Prepared her repast

She was an eater of horse-flesh

But he was not

Mai Mai ramaho nia nia.

Then the stars of the morning

Became again the stars of the evening

And reciprocally

They cried—In the name of Maröe

Wench of Arnamoer

And of his favorite zoöphyte

Prepare the drink of the gods

—Certainly noble warrior

Mai Mai ramaho nia nia.

She took the sun

And plunged him into the sea

As housewives

Dip a ham in gravy

But alas! the salmons voracious

Have devoured the drowned sun

And have made themselves wigs

With his beams

Mai Mai ramaho nia nia.

She took the moon and did her all with bands

As they do with the illustrious dead

And with little children

And then in the light of the only stars

The eternal ones

She made a concoction of sea-brine

The euphorbiaceans of Norwegian resin

And the mucous of Alfes

To make a drink for the gods

Mai Mai ramaho nia nia.

He died like the sun

And the sorceress perched at the top of a fir pine

Heard until evening

The rumours of the great winds engulfed in the phial

And the lying scaldas swear to this

Mai Mai ramaho nia nia.

Croniamantal was silent for an instant and then added:

"I shall from now on write only poetry free from all restrictions even that of language.[7]

"Listen, old man!"

MAHEVIDANOMI

RENANOCALIPNODITOC

EXTARTINAP # v.s.

A. Z.

Telephone: 33-122 Pan : Pan

OeaoiiiioKTin

iiiiiiiiiiii

"Your last line, my poor Croniamantal," said the Bird of Benin, "is a simple plagiarism from Fr.nc.s J.mm.s."

"That is not true," said Croniamantal. "But I shall compose no more pure poetry. That is what I have come to, through your fault. I want to write plays."

"You had better go to see the young woman of whom I spoke to you. She knows you and seems to be crazy about you. You will find her in the Meudon woods next Thursday at a place that I shall designate. You will recognize her by the skipping rope that she will hold in her hand. Her name is Tristouse Ballerinette."

"Very well," said Croniamantal, "I shall go to see Ballerinette and shall sleep with her, but above all I want to go to the theatres to offer my play, Ieximal Jelimite, which I wrote in your studio last year while eating lemons."

"Do what you want, my friend," said the Bird of Benin, "but do not forget Tristouse Ballerinette, the woman of your future."

"Well said," said Croniamantal. "But I want to roar to you once more the plot of Ieximal Jelimite. Listen:

"A man buys a newspaper on the seashore. From the garden of a house at one side emerges a soldier whose hands are electric bulbs. A giant 10 feet tall descends from a tree. He shakes the newspaper vendor, who is of plaster and who in falling breaks to bits. At this moment a judge arrives. With strokes of a razor he kills everybody, while a leg which passes hopping crushes the judge with a kick in the nose, and sings a pretty little song."

"How wonderful!" said the Bird of Benin. "I shall paint the decoration, you have promised me that."

"That goes without saying," answered Croniamantal.[8]

On the following day Croniamantal went to The Theatre, which was meeting at Monsieur Pingu's, the financier. Croniamantal succeeded in gaining entry by bribing the doorman and the butler. He entered boldly the hall where The Theatre, its satellites, its stool-pigeons and its hired thugs were gathered.

CRONIAMANTAL

Ladies and Gentlemen of THE THEATRE, I have come to read you my play entitled Ieximal Jelimite.

THE THEATRE

Good gracious, wait a minute, young man, until you have been informed about our methods of procedure. You are here in the midst of our actors, our authors, our critics and our spectators. Listen attentively and don't even speak.

CRONIAMANTAL

Gentlemen, I thank you for the cordial reception that you give me and I shall profit, I am sure, of all that I hear.

THE ACTOR

My rôles have slowly withered like the roses

But mother, I love my metempsychoses

O seats of proteus and their metamorphoses

AN OLD STAGE MANAGER

Do you remember, Madame! One snowy night of 1832, a lost stranger knocked at the door of a villa situated on the road leading from Chanteboun to Sorrento...

THE CRITIC

Nowadays, for a play to be successful it is important that it should not be signed by its author.

THE TRAINER TO HIS BEAR

Roll about in the sweet peas

Play dead... suckle...

Dance the polka... now the mazurka...

CHORUS OF DRINKERS

Juice o' the grape

Ruddy liquor

Let us drink drink

If we may

CHORUS OF EATERS

Horde of gluttons

There's no more

A crumb left

In the plate

DRINKERS

Bloated heads

Drink o drink

The juice o' the grape

R.D.RD K.PL.NG, THE ACTOR, THE ACTRESS,

THE AUTHORS

(To the spectators)

Pay! Pay! Pay! Pay! Pay! Pay! Pay!

THE PROMPTER

The theatre, my dear brothers, is a school for scandal, it is a place of perdition for the soul and the body. According to the testimony of the stage carpenters everything is faked in the theatre. Witches older than Morgane come there to pose as little girls of fifteen years.

How much blood is spilt in a melodrama! I say truthfully, though it be false, this blood will be upon the heads of the children of the authors, the actors, the directors, and the spectators, unto the seventh generation. Ne mater suam, the little girls used to say to their mothers. Nowadays they ask: "Are we going to the theatre tonight?"

I tell you frankly my friends. There are few shows which do not endanger the soul. Outside of the spectacle of nature I know of nothing that one may witness without fear. This last spectacle is Gallic and healthy, my dear friends. The sound dilates the glands, chases Satan from the stinking shades where he lies and thus the Fathers come in from the desert to exorcise themselves.

THE MOTHER OF AN ACTRESS

Are you p..., Charlotte?

THE ACTRESS

No, mama, I am roasting.

M. MAURICE BOISSARD

We have with us today the entrails of a mother!

AN AUTHOR WHO HAS A PLAY ACCEPTED BY THE COMEDIE-FRANÇAISE

My friend, you do not look very confident today. I am going to explain the meaning of several words from the theatrical vocabulary. Listen attentively and remember them if you can.

Acheron (ch hard)—A river of Hades, not of hell.

Artists (two types)—Is never used except in speaking of a comedian or a comedienne.

Brother—Avoid using this substantive together with "little." The adjective "young" is more proper.

NOTA BENE—This phrase does not apply to operettas.

"High Life"—This very French expression is translated in English as "fashionable people."

Liaisons—They are always dangerous in the theatre.

Papa—Two negatives are equal to an affirmative.

Cooked Potatoes—(never used in the singular)—A crudity that is deleterious to the stomach.

Tut-tut—This worn expression...

Would you like to have some titles for plays also? They are very important in order to succeed. Here are some sure ones:

THE CONTOUR; The Circumference; THE CONDOR; Hurry up Harry; THE TOWER; Louise, your shirt is coming out; STEP ALONG; The Mysterious Bar; HUNDREDTH TO THE RIGHT; The Magician; THE GUELF; I am going to kill you; MY PRINCE; The Artichoke; THE SCHOOL FOR LAWYERS; The Torch-bearer!

Good-bye, sir, don't thank me.

A GREAT CRITIC

Gentlemen, I have come to give you a report of the triumph, last night. Are you ready? I begin:

GRIT AND GRIP

A play in three acts by Messrs. Julien Tandis, Jean de la Fente, Prosper Mordus and Mmes Nathalie de l'Angoumois, Jane Fontaine and the countess M. Des Etangs, etc. Sets by Messrs. Alfred Mone, Leon Minie, Al. de Lemere. Costumes by Jeanette, hats by Wilhelmine, properties by the MacTead Company, phonographs by Hernstein and Company, sanitary napkins by Van Feuler Brothers.

I recall the captive who dared to p... before Sesostris. I never saw a more poignant scene than this from the play of Messrs, and Mmes etc. I must speak of the scene which made such a great hit at the opening night and in which the financier Prominoff bursts into a fit of rage against the coroner.

The play, which was very good, otherwise, did not accomplish all that was expected of it. The courtesan wife who feathers her nest out of the green old age of a vulgar brewer, remains, however, an unforgettable and touching figure which leaves in the shadow that of Cleopatra and Mme de Pompadour. M. Layol is an excellent comedian. He acted the father of a family in every sense of the expression. Mlle Jeannine Letrou, a young star of tomorrow, has very pretty legs. But the real revelation was Mme Perdreau whose sensitive nature we know so well. She acted the scene of the reconciliation with the most perfect naturalism. In short a great evening and prospects for a hundred night run.[9]

THE THEATRE

Young man we are going to give some subjects for plays. If they were signed by famous names we would play them, but they are masterpieces by unknowns which were given to us and which we are generously turning over to you because of your nice face.

PLAY WITH A THESIS—The prince of San Meco finds a louse on his wife's head and makes a scene. The princess has not slept with the viscount of Dendelope for the past six months. The couple make a scene before the viscount, who, not having slept with anyone but the princess and Mme Lafoulue, wife of a Secretary of State, causes the ministry to fall and overwhelms Mme Lafoulue with his scorn.

Mme Lafoulue makes a scene with her husband. Everything becomes clear, however, when Monsieur Bibier, the Deputy, arrives. He scratches his head. He is stripped. He accuses his electors of being lousy. Finally everything is in order once more. Title: Parliamentarism.

COMEDY OF MANNERS—Isabelle Lefaucheux promises her husband that she will be faithful to him. Then she remembers that she has promised the same thing to Jules, the boy who works in their store. She suffers from not being able to grant her faith and her love.

However, Lefaucheux fires Jules. This event precipitates a dramatic triumph of love, and we soon find Isabelle cashier in a department store where Jules is salesman. Title: Isabelle Lefaucheux.

HISTORICAL PLAY—The famous novelist Stendhal is the ringleader of a Bonapartist plot which ends in the heroic death of a young singer during a presentation of Don Juan at the Scala Theatre in Milan. Since Stendhal had hidden his identity under a pseudonym, he withdraws from the affair admirably. Grand marches, procession of historical personages.

OPERA—Buridan's ass hesitates to satisfy his hunger and his thirst. The she-ass of Balaam prophesies that the ass will die. The golden ass comes, eats and drinks. The Wild-Ass's-Skin comes and displays his nudity to this asinine herd. Passing by, Sancho's ass thinks that he can prove his robustness by carrying off the child, but the traitor, Melo, warns the Genius of la Fontaine. He proclaims his jealousy and beats the golden ass. Metamorphoses. The Prince and the Infant make their entrance on horseback. The King abdicates in their favor.

PATRIOTIC PLAY—The Swedish government lays suit against the French Government for manufacturing an imitation of "Swedish matches." In the last act they exhume the remains of an alchemist of the XIVth Century who invented these matches, at La Ferté-Gaucher, a village in France, not far from Paris.

COMEDY——

The handsome chauffeur

Cried to his neighbor

If you will show me your salon

I wilt show you my kitchen.

Here is enough to nourish a whole career of playwriting, sir.

M. LACOUFF, SCHOLAR

Young man, it is also important to know theatrical anecdotes; they help to fill out the conversation of a young dramatic author; here are a few: