Title: The Geology of Groton State Forest

Author: Robert A. Christman

Release date: November 16, 2019 [eBook #60710]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Lisa Corcoran and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

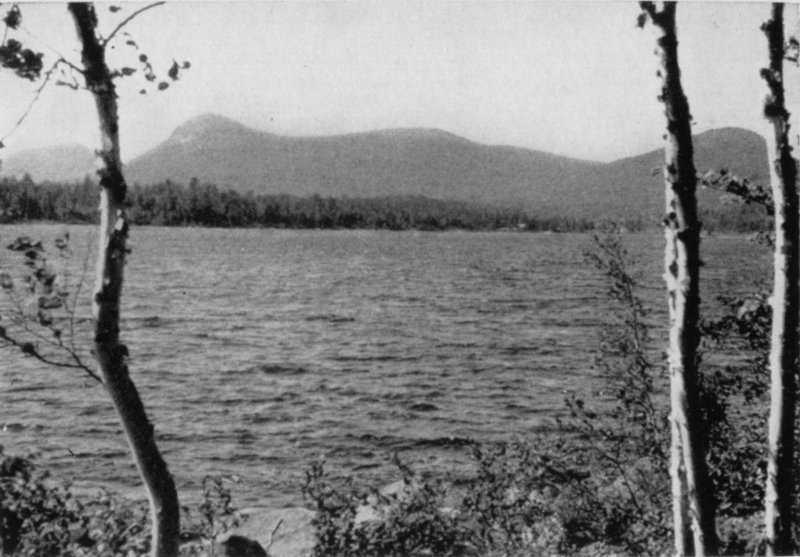

Cover: Looking southward along Groton Pond from near Stillwater Brook.

By

ROBERT A. CHRISTMAN

DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS AND PARKS

Perry H. Merrill, Director

VERMONT DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION

VERMONT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

Charles G. Doll, State Geologist

1956

By

ROBERT A. CHRISTMAN

Geology is the study of the history of the earth as recorded in its rocks. This study explains why certain types of rocks and minerals occur at one place and not another, why the forms of the land differ from one region to another, and why particular animal and plant remains are sometimes preserved as fossils in certain kinds of rocks. The professional geologist makes these studies his business; the amateur finds these studies a fascinating hobby; but the uninitiated person misses much of the pleasure of travel. Anyone who notices the difference between rocks or terrains and wonders “why?”, has a potential for geology. Many fall into this class and it is for them that this booklet has been written. It is hoped that with its aid, the traveler or vacationer may come to know something about the geology of Groton State Forest. The author is confident that those who come into the habit of observing nature and the world around them will find more meaning in life itself. In any case, those traveling with children may find answers to some of their questions about minerals, rocks and mountains.

Groton State Forest is not a geologist’s paradise—as compared to Yellowstone Park or the Grand Canyon—but it does contain interesting rocks and land forms which can be explained geologically. In keeping with the calm, subdued and mature atmosphere of the Vermont countryside, the geology is unobtrusive. There are few jutting cliffs or bare rock exposures; all is mantled with vegetation. If this vegetation could be stripped away—admittedly, a postulation that would destroy the wilderness and charm that belongs to Groton—boulders and gravelly glacial deposits would be seen to fill the valleys. If in turn these boulders and the soil could be stripped away, a continuous floor of rock would be exposed. This would be a geologist’s paradise—square miles of bare rock would be available for study. However, lacking the magic wand to perform this feat, we must be satisfied to glean what information we can from the existing rock exposures.

To use a pun, it can be said that almost all the rocks found at Groton State Forest can be taken for granite. As well as has been determined, 4 all the underlying rock is granite[1] and most of the boulders deposited by glaciers of the last ice age are the same type of granite. To avoid confusion in describing these rocks, the discussion has been divided into two parts: the first deals with the granite of the bedrock, and the second deals with the glaciation of the area and the deposits resulting from it. A third section describes the geology in some of the nearby areas.

Ledges of light-colored granite occur at the summits of most of the mountains and hills in the State Forest area and are found occasionally at lower elevations. They are conspicuous on Owlshead, Silver Ledge, Little Deer, Big Deer, Niggerhead and Spicer Mountains; smaller ledges also occur on Kettle, and Little Spruce mountains, Hardwood Ridge and the low hills east of Groton Pond. At lower elevations, granite is found at the outlet of Groton Pond, along the railroad tracks west of Groton Pond and at Stillwater Brook, along Osmore brook and at several other minor locations. These locations are shown diagrammatically on the map by a black dot. These dots indicate where the granite occurs but nothing about the extent of the exposure. If every location of exposed rock were marked with a dot, certain parts of the map, for instance, the west side of Niggerhead, would be solid black and the contour lines which show the elevation would be obscured completely.

All these rocks are presumably part of one large mass of granite which extends deep below the surface of the earth. Most of this body of granite is hidden by the soil and bouldery glacial deposits, so that its exact areal extent is not known. It appears likely that it extends to the southwest to the vicinity of East Barre.

The granite found at Groton State Forest is a gray to white, medium-grained rock with the mineral grains all about the same size. Surfaces exposed to weathering are generally darker in color and frequently are 5 covered with scales of dark colored lichen. If the rock is broken to reveal an unaltered surface close examination will disclose individual mineral grains of mica, feldspar and quartz. Mica occurs as very small plates which appear either white or colorless, called muscovite, or as black shiny plates called biotite. The feldspar, which is the most abundant mineral in the granite, has a chalky white appearance and may occur as tabular grains which reflect light from their flat surfaces when held in the proper position. Quartz, which contains only silicon and oxygen, the two most common elements in the earth’s crust, is a transparent, glassy mineral which has no flat surfaces. It may appear gray because one can look down into the glassy mineral where there is no light source.

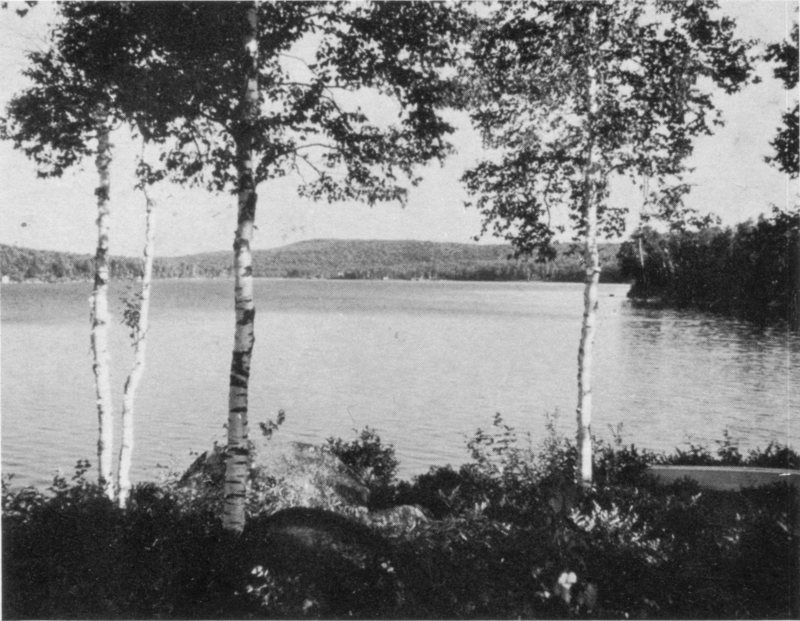

A specimen of granite from Owlshead was studied with a microscope after it had been cut and ground to a thickness of only 0.03 millimeters. Many minerals, which ordinarily appear to be opaque, are transparent when ground this thin. By their various optical properties, the different minerals can be identified and the composition of the rock can be determined. Figure 1 shows a photograph, taken through a microscope, of one of these thin sections of granite. By careful examination of the thin section and by measuring the areal extent of the different minerals present, the rock was determined to contain, by volume, 35 percent quartz, 60 percent feldspar (in proportions of 25 percent microcline feldspar, KAlSi₃O₈ and 35 percent plagioclase feldspar, NaAlSi₃O₈) and 5 percent mica (in proportions of 4 percent biotite and 1 percent muscovite). Although it is a member of the granite family, this rock should, in strict terminology, be called a quartz monzonite rather than a granite to indicate more precisely the mineral composition. Because of slight differences in composition, granite from the same body may elsewhere be correctly called granodiorite, quartz diorite or granite proper, depending on the relative amounts of the two feldspars and quartz. In this report these close distinctions have not been made and the rock is simply called granite.

Two kinds of natural breaks, or cracks, occur in the granite in the State Forest area. Joints are breaks which occur along plane surfaces and exfoliation is the name given to the breakage along curved surfaces related to the exposure of the rock. Granite, as contrasted with other rocks, is characterized by its uniformity of texture and massiveness, so that any cracks present are conspicuous.

Figure 1. Photomicrograph of a thin section of granite from Owlshead Mountain. The mineral with the grid pattern (upper left) is a feldspar named microcline which has the composition of KAlSi₃O₈. The one with the indistinct striped pattern (lower center) is a feldspar named plagioclase, variety oligoclase, which has the composition of approximately NaAlSi₃O₈. The patterns for these minerals result from different portions of the same mineral grain having different orientations, called twinning, so as to give a different optical appearance. The clear white mineral (right center) is quartz. The dark gray mineral with the fine lines (upper center) is biotite and the smaller, lighter-colored, elongate mineral to the right of the biotite is muscovite. The other minerals are feldspar and quartz in different orientations. The actual diameter of the clear white quartz grain (right center) is about four-tenths of a millimeter so that the photograph is a magnification of about one hundred.

Joints are more conspicuous of the two types, and typically belong to a general system so that at a given location they tend to be parallel. On top of Owlshead, for example, the most prominent joints trend N.25°W. (read: North twenty-five degrees to the west) with dips[2] that are vertical or dipping steeply to the southwest. Another set of joints trends N.10°E. with dips that are vertical or dipping steeply to the southwest. Joints represent the breakage of the rock due to stress and strain. Some joints result from tensional forces set up within the rock itself by contraction due to cooling of the originally hot solidified rock. Other 7 joints result from larger-scale forces within the earth’s crust which cause earthquakes and general movement of land masses. An exhaustive study of all the rocks in a large area would be required to determine conclusively the origin of the joints on Owlshead.

In addition to the nearly vertical joints, a third set of nearly horizontal joints may be observed on cliffs. These joints are called sheeting and apparently are related to the depth from a former topographic surface which existed at the time the sheeting originated. The vertical joints and sheeting are important qualities of a rock to be considered in choosing a rock for commercial quarrying. Not only do these factors effect the ease of quarrying, but they also determine the amount of waste material which would have to be removed and discarded because of poor size and shape.

Exfoliation is the term for breakage due to the disintegration caused by decomposition of the rock on surfaces exposed to the weather. It is characterized by the scaling off of concentric shells of altered rock to produce a convex surface. Rocks showing exfoliation surfaces are not common at Groton. One of the best developed exfoliation surfaces, illustrated in Figure 2, occurs at the base of the cliffs on the south side of Owlshead Mountain.

Once joints have formed, they are enlarged by weathering. In particular, rocks are pushed apart by a “frost wedging.” When water freezes it expands by about one-tenth of its volume. If it is confined it may exert a pressure of as much as 138 tons per square foot. In this manner, huge blocks may be pushed apart. If they are at the edge of a cliff, or part of the cliff itself, they may eventually break off and fall to the slope below. The accumulation of broken rock at the base of a cliff is called talus.

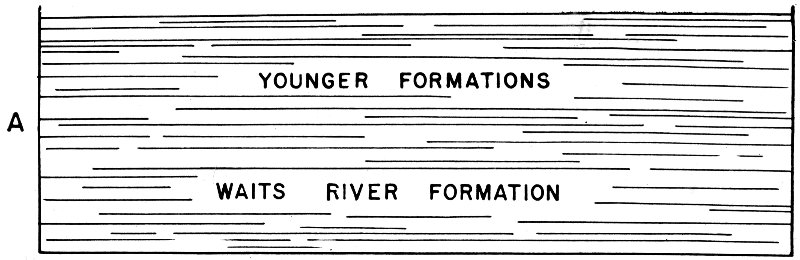

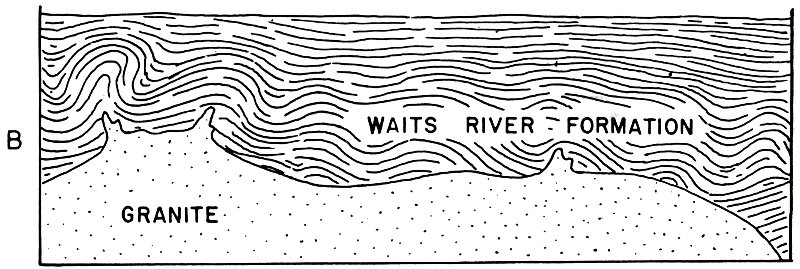

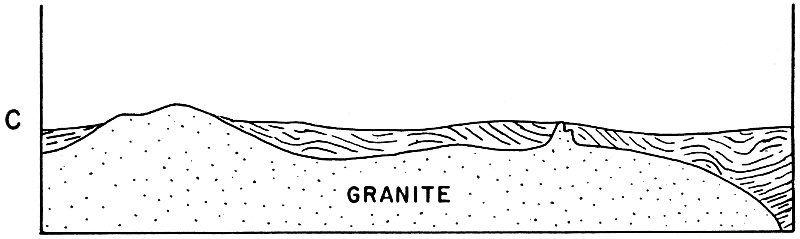

The granite originated in the interior of the earth many million years ago as a molten mass, called magma. This magma moved upward through the earth’s crust by a process of melting the pre-existing rock or by forcefully pushing it aside. When it reached its present position it became cooler and minerals began to crystallize out. However, as is shown in Figure 3, it is important to understand that the surface of the land was not in its present position and that the magma actually cooled beneath a considerable thickness of other rocks. These overlying rocks, now gone, acted as an insulator and prevented the magma from cooling too quickly. If the magma had risen through these rocks and reached 8 their upper surface, it would have formed a lava flow similar to those of present-day volcanoes and would have cooled much more rapidly. Rocks formed near the surface are characterized either by being fine-grained without visible crystals or by having a few large crystals in a fine-grained matrix; they never have a uniformly, medium-to-coarse-grained texture. Thus, the texture of the granite at Groton State Forest proves that it cooled slowly and indicates that, at the time of cooling, the granite was not at the surface. This is a reasonable postulation because studies of the regional geology indicate that a large amount of rock has been removed from this area by erosion through the long periods of geologic time.

Figure 2. Exfoliation surface on the south side of Owlshead Mountain. Joints, of the sheeting type, are visible in the granite cliff. The decomposition of the granite by weathering in the niches has resulted in small patches of soil. The boy in the upper right gives the scale.

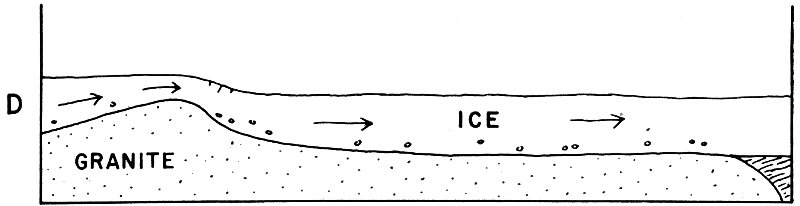

Figure 3. Sequence of events at Groton State Forest shown diagrammatically.

A. The Waits River Formation and other younger formations are deposited from a shallow sea during Ordovician time.

B. The sedimentary rocks are folded and metamorphosed and the granite is intruded into the older rocks and crystallizes during Devonian time.

C. Erosion removes much of the rock from the area.

D. During the ice age, continental glaciers move over the land and erosion by the ice forms Owlshead Mountain and the basin for Groton Pond.

E. Present topography, exaggerated.

Evidence that the granite was emplaced into the older rocks of the earth’s crust can be seen at certain locations outside of the State Forest. At Ricker Mills, for example, narrow bodies of granite can be seen cross cutting the older rocks. A fuller description of the geology at Ricker Mills is given in a later section of this report. Another type of evidence showing that the granite came into older rocks is found in the occurrence of fragments of older rock incorporated into the granite. These are called inclusions and represent broken pieces of older rock which were enveloped by the granite. Inclusions are like peach slices in jello in that the surrounding material solidified after they were dropped in. Inclusions were observed in rocks on top of Kettle and Jerry Lund Mountains.

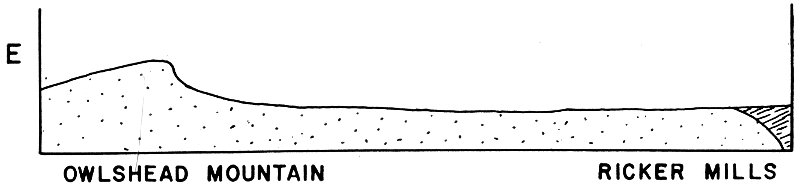

Near the covered picnic shelter at Ricker Pond, one of the large granite boulders deposited by the glacier contains inclusions. Although this boulder has been moved from its original occurrence, it probably has not moved far as it is composed of the white granite which is typical of the area. It is cut by several pegmatitic dikes. The most interesting feature is the occurrence of inclusions of elongate, layered bands of older rocks of gray to dark gray schist.[3] These relations are shown in the sketch of this boulder in Figure 4. A careful examination of the schist inclusions reveals that they contain small plates of biotite in a fine matrix of quartz and more mica. The contact between the schist and granite is gradational at places because when the rock was formed the hot molten granite was in the process of melting the solid schist. The schist resembles the rock which occurred in this area before the granite was intruded and which occurs in nearby areas where no granite is exposed. Older rocks of somewhat similar appearance can be seen at Ricker Mills and on top of Jerry Lund Mountain.

The composition of the granite at Groton State Forest is nearly the same as that which occurs throughout this region of Vermont. Incomplete mapping suggests that the granite at Groton is part of a large mass which extends to the southwest to the vicinity of East Barre. Undoubtedly all the granitic rocks of this region are related although they 11 are not continuous at the surface. They were all emplaced at about the same time following a mountain-building episode in which the older rocks were folded and metamorphosed. On the geologic time scale, the granites were emplaced near the end of the Devonian period which is estimated to be more than 300 million years ago.

Figure 4. Sketch of boulder of granite containing pegmatite band and schist inclusions at picnic area at Ricker Pond.

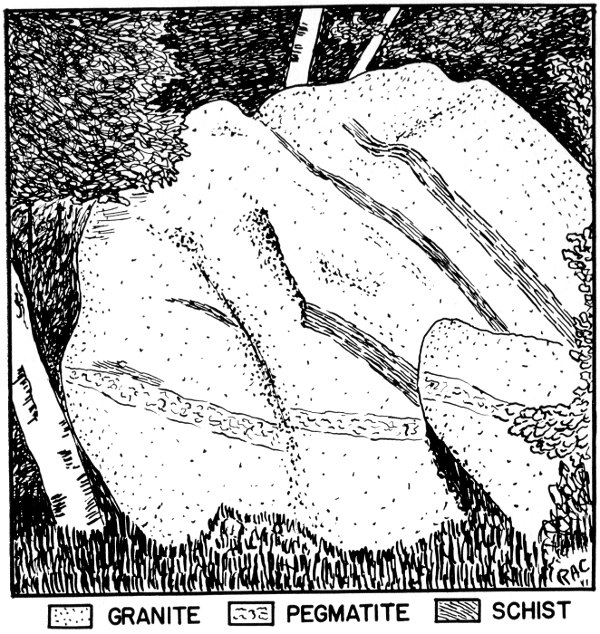

Two other types of igneous rocks called aplite and pegmatite occur sparingly in Groton State Forest. Both of these are productions of crystallization of residual fluids or late stage magma related to the granite. These were emplaced along cracks or planes of weakness in the granite after the granite had solidified. When viewed from the surface the aplite or pegmatite generally appear as bands cutting through the granite. However, when the third-dimension is considered it is easily realized that they are tabular or sheet-like in shape. Igneous rock masses having these dimensions are called dikes. At Groton most of the dikes are nearly vertical with a thickness ranging from less than an inch to more than several feet and extending for considerable distances. On Owlshead, one of these dikes is nearly three feet thick. The extent of these dikes is not known because they are only partly exposed, in that they extend beyond the limited areas of rock exposure.

The pegmatite dikes are coarse-grained, in some cases consisting of individual mineral grains as much as two to four inches in diameter. The mineral composition of the pegmatites is nearly the same as the granite, except that biotite is usually absent. Because of their larger grain size, the minerals can be recognized more easily in pegmatites than in either granite or aplite. Quartz is glassy and breaks with smooth curved fractures. Feldspar is chalky white, or pink, and may occur as tabular crystals with straight-line contacts. It tends to break along definite intersecting planes which can be seen in their reflecting position. Muscovite occurs as “books” of semi-transparent leaves. The large “books” of muscovite are particularly interesting because of the fascinating fact that a mineral sheet can be split along a given planar direction into thinner and thinner sheets until they are too thin to handle. Theoretically the mineral might be split into sheets only as thick as one layer of atoms. The ability of a mineral to break along definite planes is related to its atomic structure and is called cleavage. The cleavage in mica is perfect, whereas the cleavage in feldspar is only poorly developed, and quartz does not possess cleavage at all.

The aplite dikes are composed of nearly the same minerals as granite except that the average grain size is smaller. They are characterized by the absence of dark minerals and muscovite and by a high quartz content which gives the rock a “sugary” appearance. Most of the aplite dikes are less than six inches thick.

Inasmuch as the pegmatite and aplite dikes both cut through the granite, they both must be younger in age than the granite. As is shown by the relations between these two types on Owlshead (reproduced in Figure 5), the pegmatite dike is younger because it cuts across the aplite dike. This is the general age relationship for these dikes in this age.

Figure 5. Sketch showing aplite and pegmatite dikes in the granite on Owlshead Mountain. The cross cutting relations show that the pegmatite is youngest and that aplite is younger than the granite but older than the pegmatite. In the distance is Kettle Pond and Kettle Mountain.

Although the causes of the ice ages remain a matter for conjecture, the fact is established that the northern part of North America was covered by a thick sheet of moving ice several different times beginning about a million years ago. As the effect of the last glaciation erased much of the evidence of previous glaciations, the present topography can be related to that last one. Rather accurate dating by measuring the radioactive decay of Carbon 14, indicates that the ice of the last glaciation retreated from the area about 12,000 years ago. Because the climates between the four glaciations were as warm, if not warmer, than our present-day climate, geologists have speculated that the world may now be in a warm period and that another ice age is scheduled to occur some time in the distant future.

The effect of continental glaciation upon a land mass is twofold. First, the glaciation acts as an erosive agent which tends to scoop out the areas of softer rock and wear down the areas of more resistant rock. Secondly, when the glacier begins to melt, it drops large quantities of gravel and boulders which had become incorporated within the glacier. Most of this material is picked up by the glacier as it moves over the land; some falls onto the glacier where it occupies a valley. Some of the sand, gravel and boulder deposits left by the glacier are distinctive in form and composition and others are characterized by their complete lack of distinctive shapes, and the utterly chaotic nature of the material deposited. The deposits at Groton State Forest seem to be the latter type.

The shape of Spicer, Owlshead, Little Deer and Big Deer mountains are primarily the result of the erosive action of the glacier as it continually moved southward over the land for a great number of years during the last glaciation. When a continental glacier encounters a hill or mountain of resistant rock, it tends to scour the rock on the up-ice side of the hill and to “pluck out” the rocks on the leeward side. For this reason these mountains have broad gentle slopes on the side from which the glacier came and they drop off sharply on the side from which material was removed by plucking action. The last part of Figure 3 illustrates how these mountains may have been formed. Such prominent rock exposures which have been subjected to glacial erosion originally showed deep scratches, called glacial striae, cut by cobbles dragged along the bottom of the glacier. Unfortunately, on most prominences in Groton 17 State Forest exfoliation of the rock has erased these markings; but it is possible that striae may be found on recently uncovered rock exposures.

The depressions in which Groton and Osmore ponds are located probably represent areas in which the glacier scooped out material to a greater depth than elsewhere either because of channeling of bottom flow between topographically prominent features, or because of subtle differences in rock hardness.

When the glacier retreated, that is when it was melting faster than it was advancing, it dropped material in a helter-skelter manner. End moraines, which are ridges of gravel formed where the front of the glacier was stationary because of a close balance between rates of movement and melting, are not evident in Groton State Forest. As far as can be determined, the material was deposited irregularly over the entire area, so that boulders dropped by the glacier are found everywhere. These are particularly noticeable around the lakes where the fine material has been removed and the soil and forest cover does not hide the boulders.

Almost all of the boulders deposited by the glacier are composed of white granite similar to the rock which underlies the entire area. This indicates that most of the boulders have not been transported very far. However, occasionally boulders are found which are not characteristic of the area and represent rocks brought in from the north. Such boulders which are foreign to the area in which they are found are called erratics. Most erratics in this area are dark-colored metamorphosed rocks in which the minerals are oriented to give the rock a layered pattern. These are called either gneisses or schists depending on whether the layering is coarse or fine. Deposits of the glacier are exposed in two gravel or sand pits near the Stillwater Camp site. These deposits are composed principally of sand but contain scattered boulders of different sizes. A few erratics are found in these deposits—particularly a variety of rock which weathers to a soft, brown porous mass resembling decayed wood. These sandy deposits probably were plastered onto the ground from the sole of the creeping glacier or were simply let down as the glacier wasted away.

Because of the irregular manner in which the glacier may deposit its load of sand and gravel, the topography in such areas is uneven and characterized by poor drainage. At a number of places in Groton swampy areas occur at higher elevation which might normally be expected to be well-drained. Some of these areas have become the sites of beaver dams because they are ideal for damming up the water.

Just south of the park at Ricker Mills some of the oldest rocks in the area are exposed in the railroad cut just north of the highway crossing. These rocks belong to a thick sequence of similar rocks which are collectively called the Waits River formation. Studies in other areas indicate that these rocks belong to the portion of geologic time called the Ordovician period which was more than 350 million years ago.

The Waits River formation represents a series of sediments which accumulated at the bottom of a shallow sea during Ordovician time. These sediments included both limy and sandy beds, and fossils may originally have been preserved in some of the beds. Sediments of other types later accumulated over the Waits River formation during a long period of geologic time, so that eventually the formation became deeply buried. (See Figure 3.) The sea retreated and the rocks were subjected to high pressure and temperatures during a period of mountain-building. The rocks which had been sedimentary were folded and converted to metamorphic rocks by partial melting and recrystallization of the components. As a result the rocks became schists or marbles. Any fossils which may have been present were destroyed or badly altered in the process. This is unfortunate because valuable geologic information as the age of the rocks can be determined from the type of fossils present.

The rocks of the Waits River formation at Ricker Mills are dominantly mica schists with layers containing limy material. These are too impure to be considered marble but enough lime is present so that they react strongly with acid, a test for detecting the presence of lime. The schists principally contain quartz, biotite, calcite (lime) with lesser amounts of muscovite, feldspar and impurities. The rocks weather to dark colors; the gray limy beds are particularly susceptible to weathering and turn dark brown to black on the surface. When more lime is present, the rock weathers to a deep brown porous rock which resembles decayed wood. Some boulders of these altered limestones are found in the glacial deposits in the State Forest.

An additional factor which makes the rocks in the railroad cut at Ricker Mills look “messy” is the iron and manganese staining and the formation of mineral crusts on the surface of the rocks through the action of ground water. Rain water falling on the hills above passes through the soils, dissolving minerals, and precipitating them where the water seeps out and evaporates at the lower level of the railroad tracks.

The schists trend about N.80°W. and dip about 30° to the northeast. Along the length of the rock exposures it can be seen that this dip is not constant but varies from 10 to 30°. The variation in dip gives the schists a wavy appearance.

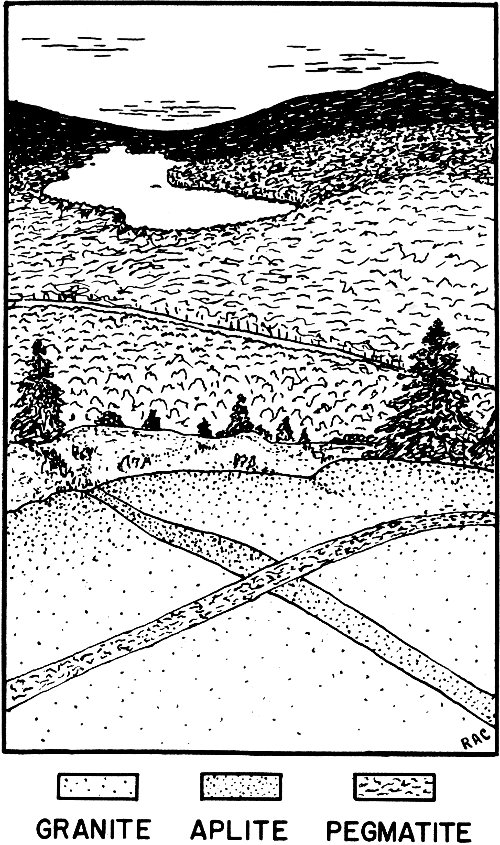

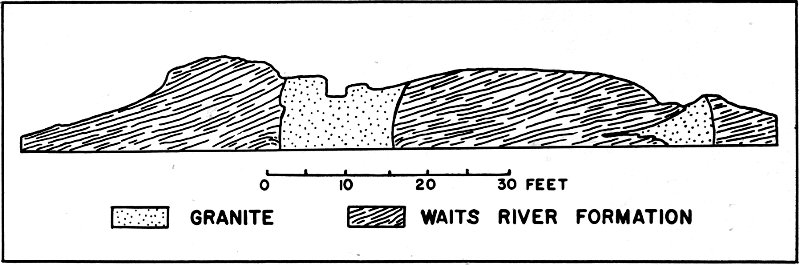

At two places along the railroad cut, the schist has been intruded by granite. As is shown in Figure 6, which is a sketch of the rocks exposed on the east side of the railroad, the granite forms vertical dikes. As the schist ends abruptly at the contact of the granite, this indicates that the granite formed after the schist. The granite is nearly the same as the granite in Groton State Forest except that the mica is muscovite rather than biotite. For this reason the granite is lighter in color on fresh surfaces. In general the exterior is dark in color due to the staining of iron from weathering of the mineral pyrite, an iron sulfide, which occurs in small amounts in the granite.

On top of Jerry Lund Mountain occur other outcrops of the Waits River formation and granite. Their exact relationships cannot be seen easily because of the thick vegetation. The Waits River formation on Jerry Lund Mountain is composed principally of quartz mica schist.

The hike from the end of the road to the top of Owlshead Mountain takes only ten to fifteen minutes. A splendid view of the surrounding area, particularly Groton and Kettle ponds, is obtained from here. If possible, everyone who visits the park should take this short walk. The granite is well-exposed at the summit and dikes of aplite and pegmatite may be seen.

The more venturesome park visitor will want to make other trips away from the “beaten path” into the wilderness of the Vermont woods. The principal difficulty arises in that the wilderness is so real a person may well become lost if he strays too far from the trails. Some of the trails have become overgrown so that they are difficult to follow and portions of others have been destroyed by the damming up of brooks by the beavers. It is suggested that in planning hikes information be obtained from the park superintendent about the condition of the various trails.

Figure 6. Diagrammatic sketch showing the relations between the schist of the Waits River formation and the granite on the east side of the railroad cut, at Ricker Mills.

An interesting hike can be made from Osmore Pond to Deer Mountain but as the trail is poorly marked, one must maintain a sense of direction. From the Osmore picnic area walk south near the shore of the pond to its outlet into Osmore Brook. At this point turn left to the northeast and follow the trail which parallels a wire marking the edge of the game preserve. About three-fourths of a mile from Osmore Brook the trail meets another trail at right angles. To the left the trail follows the game preserve boundary northwestward. The trail to the right leads directly to the top of Deer Mountain where a view may be obtained on the south side of the summit. As an alternate route for returning, follow the trail along the game preserve to the northwest. Some distance beyond a shelter-lean-to the trail divides several times with the main trail leading to Blake Hill and other trails to the left leading to the Osmore Pond road.

A hike along the trail on the north side of Kettle Pond to the shelter-lean-tos makes a pleasant trip along the water. Also, the trail from Owlshead Mountain to Osmore Pond is convenient for a short hike through the woods, if the trail can be found.

The granite quarries at East Barre are in nearly the same type of rock as that which occurs at Groton State Forest. The quarry operations are interesting and educational and the quarries afford a good opportunity of seeing fresh, unaltered specimens of granite. Guide service is offered at some of the quarries.

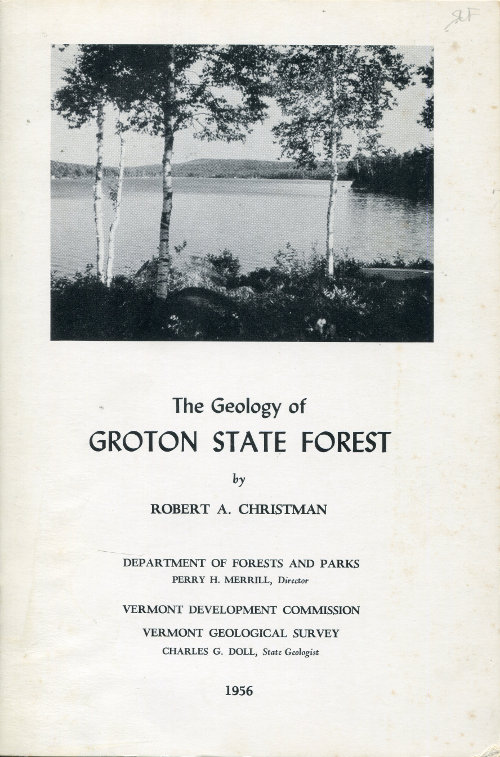

Looking northwest over Groton Pond toward Owlshead Mountain

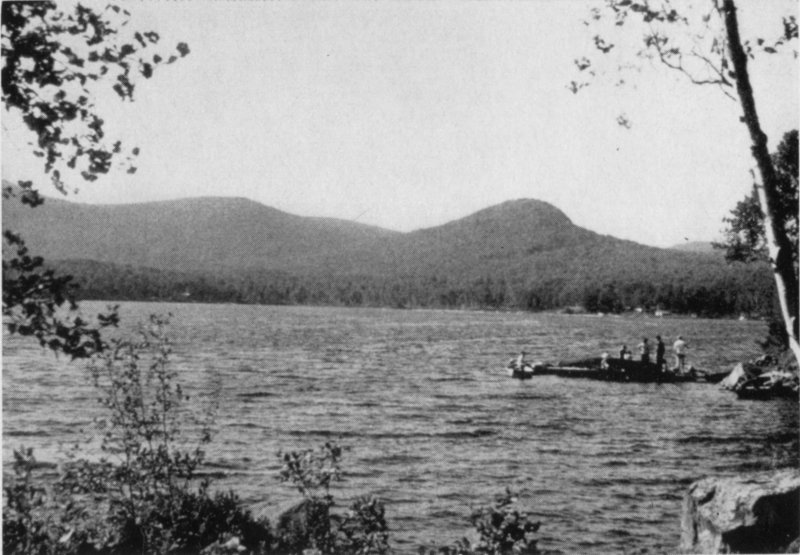

Looking north over Groton Pond toward Little Deer Mountain