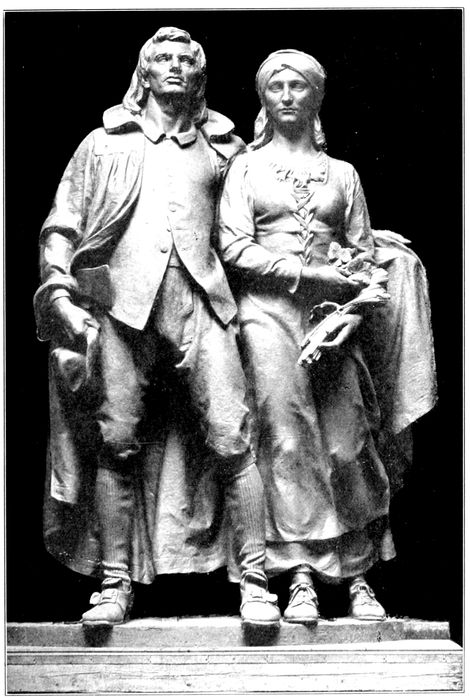

WOMAN TRIUMPHANT

The Story of Her Struggles for Freedom, Education and Political Rights.

Title: Woman Triumphant: The story of her struggles for freedom, education and political rights.

Author: Rudolf Cronau

Release date: October 20, 2019 [eBook #60535]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

America, the History of Its Discovery. 2 vols., with 545 illustrations and 37 maps. (Leipzig 1890–92.) Award World’s Columbian Exposition.

America, historia de su descubrimiento. 3 vols., with several hundred illustrations and maps. (Barcelona 1892.) Award World’s Columbian Exposition.

From Wonderland to Wonderland, Sketches of American Life and Scenery. With 50 heliogravures. (Leipzig 1886.)

Through the Wild West, Journeys of an Artist through the Prairies and Rocky Mountains of America. Illustrated. (Braunschweig 1890.)

Travels in the Land of the Sioux Indians. (Leipzig 1886.)

Our Wasteful Nation; the Story of American Prodigality and the Abuse of Our National Resources. Illustrated. (New York 1908.)

Three Centuries of German Life in the United States, with 210 illustrations. (Berlin 1909.) Award by the University of Chicago.

Illustrative Cloud Forms for the Guidance of Observers in the Classification of Clouds. (U. S. Publication No. 112. Washington, D. C., 1897.)

In the Realm of Clouds and Gods. Illustrated with 25 color-prints.

Three Great Questions in American History Answered. With many maps and illustrations

Are you aware of the fact that you are living in the most important period of human history? Not for the reason that a World’s War has been fought and a “League of Nations” formed, but because all civilized nations are beginning to acknowledge that women, who form the greater part of the human race, are entitled to the same rights and recognition as have heretofore been enjoyed by men only. The entry of woman into industry, the professions, literature, science and art in modern times, her participation in social and political life, mark the beginning of an era of a significance, equal, if not greater, than when by the discovery of America a New World was added to the old.

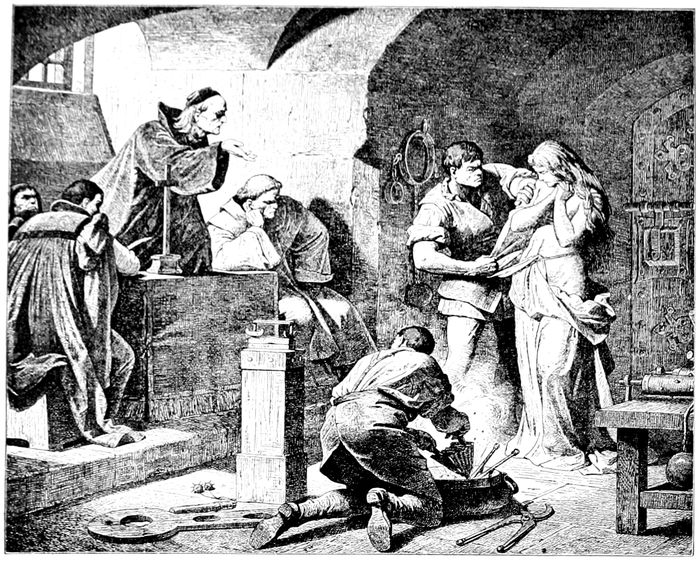

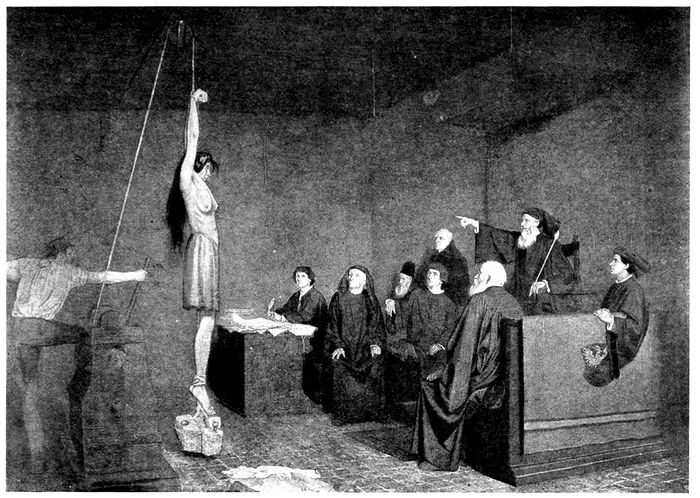

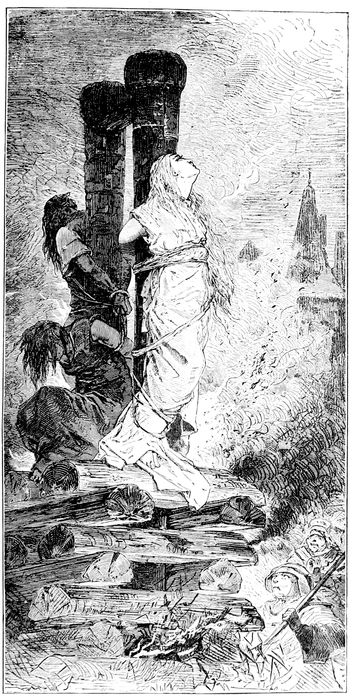

Although it is a fact that man owes innumerable benefits to woman’s care, devotion, and mental initiative, it is also true that through egoism and self-conceit he has never appreciated woman’s work and achievements at their full value. On the contrary: while she was giving all and asking little, while she shared with man all hardships and perils, she was for thousands of years without any rights, not even as regards her own person and property. From ancient times up to the present day she has been an object of rape and barter, and quite often, for sexual purposes, held in the most horrible slavery. During the Middle Ages innumerable women were persecuted for witchcraft, subjected to the most cruel tortures, dragged to the scaffold to be beheaded, or burnt alive at the stake.

Woman’s status to-day is the result of her own energy, efforts and ability. She overcame the prejudice and stubborn opposition of bigoted priests, pedantic scholars and reactionary statesmen, who were unable to see that the advance and emancipation of woman is synonymous with the progress and liberation of the greater part of the entire human race. To short sighted people such as these Tennyson directed his lines:

“The Woman’s Cause is Man’s! They rise or sink together, dwarf’d or godlike, bond or free; if she be small, slight-natured, miserable, how shall men grow!”

The book submitted here gives an account of woman’s evolution, of her enduring and trying struggles for liberty, education, and recognition. While this account will make every woman proud of the achievements of her sex, man, by reading it, will become aware that it is his solemn duty not only to protect woman from injustice, brutality and exploitation, but to give her all possible assistance in her endeavors to attain that position in which she will be man’s ideal consort and friend.

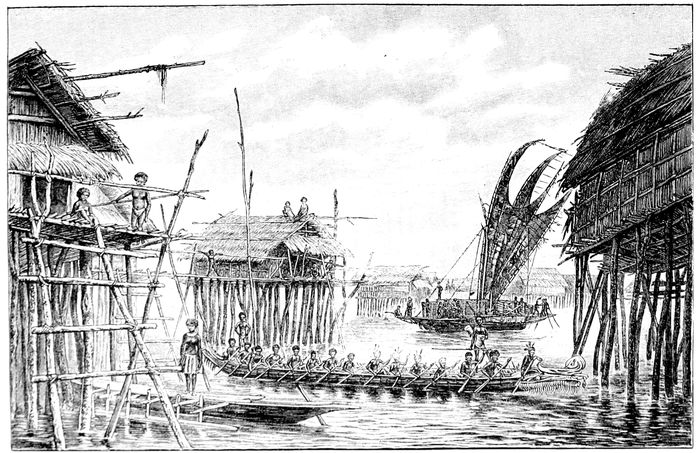

ABORIGINAL HUTS AT THE AMAZON RIVER

While we were young and credulous, black-robed theologians impressed upon our minds their theory of creation, according to which the first man was moulded by the divine author of all things in his own image and placed in an enchanting paradise. Here he enjoyed with his mate, whom the same deity formed from one of man’s ribs, a state of innocence, bliss and happiness, since want, sickness, and death were as yet unknown, and all animals lived together in peace and harmony.

In later years, after we had become inquisitive, we found that this story of creation is merely one of innumerable similar 8myths, invented by aboriginal people when they began to ponder over their origin. We also became acquainted with the theory of evolution, as taught by Lamarck, Darwin, Haeckel, Huxley, Tylor, Lubbock, Osborn, and other eminent anthropologists. And by investigating and comparing fossil facts and living forms we became convinced that man was not specially created, but gradually evolved from far lower animal forms. Furthermore, we recognized that primitive man never enjoyed paradisical peace and happiness, but was constantly compelled to a far more desperate struggle for existence than any human beings had to carry on during later periods.

To realize the innumerable hardships and terrors of this battle is almost beyond the power of imagination. Try to place yourself in the situation of such naked and unarmed beings. Day in and out they were persecuted by wild beasts, which in size as well as in strength and ferocity far surpassed those of to-day.

There were the terrible sabre-toothed tigers, whose enormous fangs hung like daggers from their upper jaws. There were fierce lions and bears, in comparison to which the present species would appear dwarfed. The plains and forests were infested with bloodthirsty hyenas and wolves, that hunted in packs and allowed no creature to escape which they were able to cut off from its retreat. Ugly snakes, quick as lightning, lurked in the underbrush and trees. The lakes and rivers were alive with hideous alligators, that made every attempt to get a drink a hazardous task. Even the skies were full of danger, as sharp-eyed eagles and vultures circled about, ready to swoop on any living thing that might expose itself to view. Awe-inspiring were also the immense mammoths, elephants and rhinoceros, which with heavy tread broke through the dense forests.

In contrast to these powerful beasts man was not protected at all. Indeed, his means of defense were so poor, that his survival strikes us almost as an inconceivable wonder. Neither was he armed with strong teeth, sharp claws, horns or poisonous stings. His body had no covering but a very thin and vulnerable skin. To escape his many pursuers, he was compelled to hide in almost inaccessible places, among the branches of high trees, or in the crags and on top of towering cliffs.

The never-ending struggle increased, when his kin multiplied and began to split into various bands, tribes and races. With this separation quarrels arose over the limits of the hunting grounds. Men began to fight and kill their neighbors. Even worse, they slaughtered the captives and devoured their flesh during cannibal feasts.

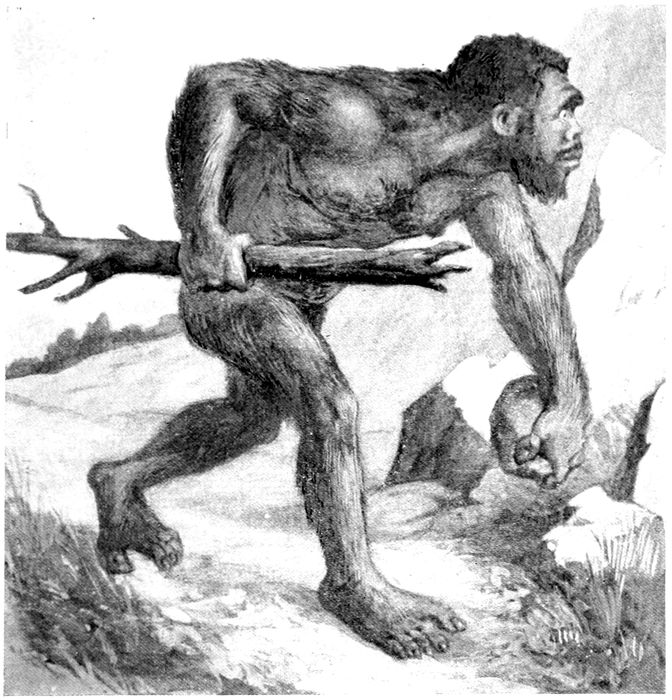

AN APE-MAN

In physical appearance primeval men were far from resembling those ideal figures of Adam and Eve, pictured by mediæval artists who strove to give an idea of the glories of our lost Paradise. While these products of imagination can claim no greater authenticity than the illustrations to other fairy tales, we nevertheless owe to the diligent works of able scientists restorations of the figures of primeval men. These deserve full credit, as they are based on skeletons and bones, found in caves, which some hundred thousand years ago were inhabited by human-like beings. From such remains it appears that our predecessors were near relatives to the so-called man-apes, the orang outang, chimpanzee, gibbon, and gorilla. Ages passed before these ape-men, in the slow course of evolution, developed into man, distinctly human, though still on a far lower level than any savage people of to-day.

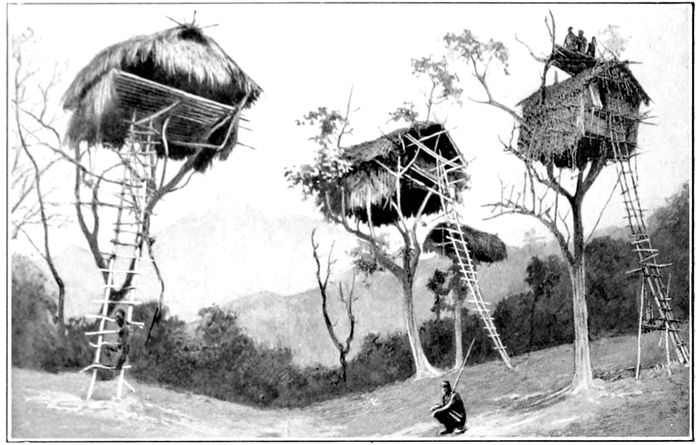

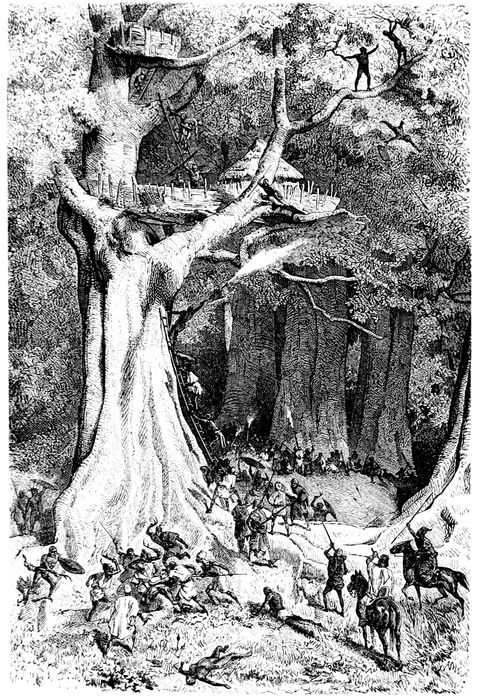

The ape-man probably knew no other shelter than nests of twigs and leaves, similar to those constructed by the orang outang and the gorilla. But with the gradual development of man’s brain and intelligence he improved these nests to 10tree-huts like those still used by certain aborigines of New Guinea, India, and Central Africa. To these huts they retreated at night, to be safe from wild beasts, and also at sudden attacks by superior enemies.

TREE HUTS IN NEW GUINEA

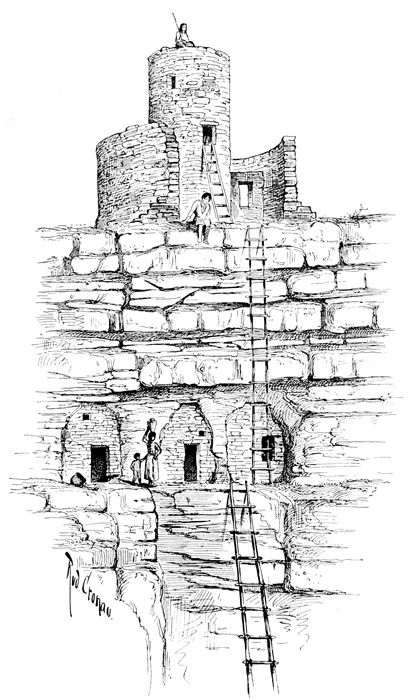

The cliff dwellings, abounding among the steep cañons of Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona were similar retreats. Here we find thousands of stone houses, many hidden at such places and so high above the rivers that they can hardly be detected from below. In the cañon of the Rio Mancos several cliff dwellings are 800 feet above the river. To locate them from below a telescope is needed. How it was possible for human beings to get to some of these places, is a mystery still unsolved.

Other dwellings stand on almost unscalable boulders, or they are placed within the fissures and shallow caverns of perpendicular walls. They can be reached only by descending from the upper rim of the cañon by means of long ropes, or by climbing upwards from below by using hands as well as feet. If one succeeds in getting to these places, one finds them always provided with store rooms for food and water. Constant danger of hostile assaults must have compelled people to live in such difficult retreats, which could be prepared only at enormous expenditure of time and labor.

CLIFF DWELLINGS IN THE CANON OF RIO SAN JUAN, NEW MEXICO

LAKE DWELLINGS IN NEW GUINEA

13Another form of refuge were the lake-dwellings, which were erected far out in the lakes on platforms resting on heavy posts. Traces of such structures have been found in many parts of the world. They are still used by some of the aborigines of New Guinea and India, and also by the Goajiro Indians of Northern Venezuela. Indeed, Venezuela owes its name to the fact, that the Spanish discoverers of these lake-dwellings were reminded of Venice, the queen city of the Adriatic.

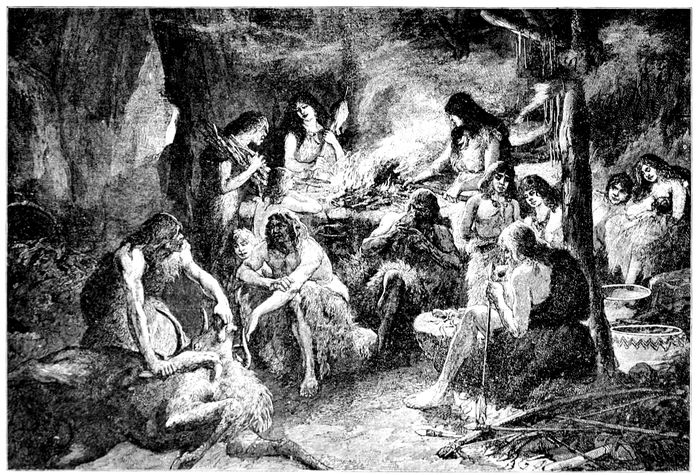

When in time such aboriginal tribes increased, so that their number spelled warning to their neighbors, they created more comfortable camps on the shores. Or they moved into caves, such as abound in all countries where limestone is prevailing.

Nomadic peoples like the Indians of North America and some tribes of Siberia prepare tents of dressed skins, which are sewed together and stretched over a framework of poles. Many aborigines of Southern Africa and Australia are satisfied with bush shelters. Or they construct lodges of willows, which they cover with bark or mud, to afford protection against rain and the fierce rays of the sun.

People, living in cold regions like the Eskimo, seek shelter from the biting winter storms by digging pits five or six feet deep. These holes they cover with dome-shaped roofs of whale-ribs and turf. Where these materials are not at hand the Eskimos rely on hemispherical houses, built of regular blocks of snow laid in spiral courses. The entrance is gained by a long passage-way that shuts off cold as well as penetrating winds.

Having thus summarized the principal kinds of primitive dwellings, we shall now briefly consider the activity of aboriginal peoples.

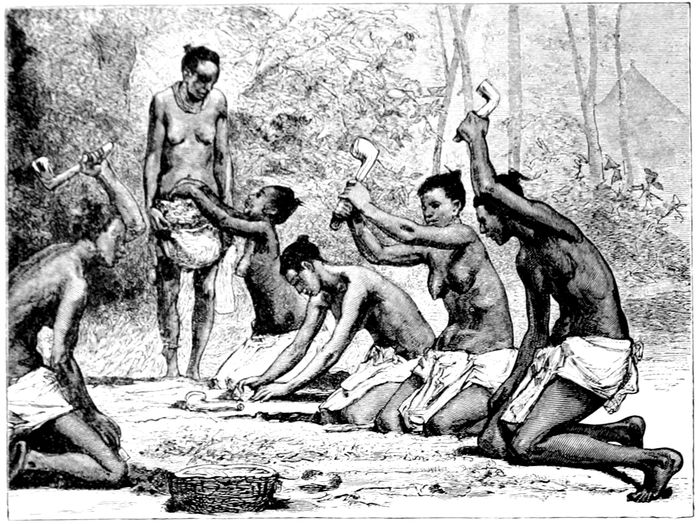

WOMEN OF KAMBALA. CENTRAL AFRICA, CRUSHING GRAIN

Explorers and scientists, who have lived among aboriginal tribes in order to study their manners and customs, have always found, that each sex has its own sphere of duty and work. To the stronger man fell the obligation of protecting his family, which consisted of his wife or wives and their offspring. It was also his share to support them with the products of the chase, and to provide suitable material for the building of the lodge. “These activities,” so states J .N. B. Hewitt in the ‘Handbook of American Indians’ (Vol. II, 969), “required health, strength and skill. The warrior was usually absent from the fireside on the chase, on the warpath, or on the fishing-trip, days, weeks or months, during which he often traveled many miles and was subjected to the hardships and perils of hunting and fighting, and to the inclemency of the weather, often without adequate shelter or food.”

15To the lot of women fell the care of the children, the labor required in the home and in all that directly affected it.

The essential principle governing this division of labor and responsibility between the two sexes lies much deeper than in an apparent tyranny of the man. The ubiquity of danger from human foes as well as from wild beasts, the suddenness of their assaults when least expected, compelled aboriginal men to keep their weapons always at hand. During the day they hardly lay them aside, even for a minute, and at night they are always within reach. This fact explains, why the women and children transport all the loads, while the men carry nothing but their weapons when aborigines move from one place to another.

This division of functions consequently led men to confine their ingenuity and activity chiefly to the improvement and skillful handling of their arms, to the invention of snares for the game and to methods of fighting animal and human foes. It led also to the inclination to regard hunting and warfare as the only occupations worthy of men, and to relegate all domestic work to the women, since such labor would be degrading to the warrior.

But the despised work of the weaker sex has proven of far greater value to the progress of the human race than all heroic acts ever accomplished by fighting men. To woman’s ingenuity we owe our comfortable homes. Women kept the warming hearth-fire burning, prepared the meals, watched faithfully over the children and made the clothes that gave protection against rain and cold. To women’s inventive sense we owe also our most important industries: agriculture, weaving, pottery, tannery, basketry, dyeing, brewing, and many other peaceful arts.—

It has been said that human culture began with man’s knowledge and control of fire, that mysterious, ever consuming, ever brightly flaming element, which was regarded by all aborigines as a thing of life, by some even as an animal. It must have all the more forcibly impressed men’s imagination, inasmuch as it not alone promoted man’s comfort, but even made life endurable, especially in cold climates.

It is certain that the practical knowledge of fire was obtained not at one given spot only but in many different parts of the world and in a variety of ways. In time men discovered also various methods of producing sparks, generally by rubbing two sticks of wood or by knocking two flints together. But as these methods were slow and laborious, it became the custom for each band to maintain a constant fire for the use of all families in order to avoid the troublesome necessity of obtaining it by friction. Generally this constant fire was kept in the centre of the village, to be in reach for everybody. The duty to keep it always burning fell naturally to the women, as they remained always in the village, and especially to those women not burdened with the cares of maternity. As fire later on was regarded as a present of the good spirits or gods to men, these central fires were held sacred, and so the fire worship grew by degrees into a religious cult of great sanctity and importance.

LIFE AMONG PREHISTORIC CAVE-DWELLERS

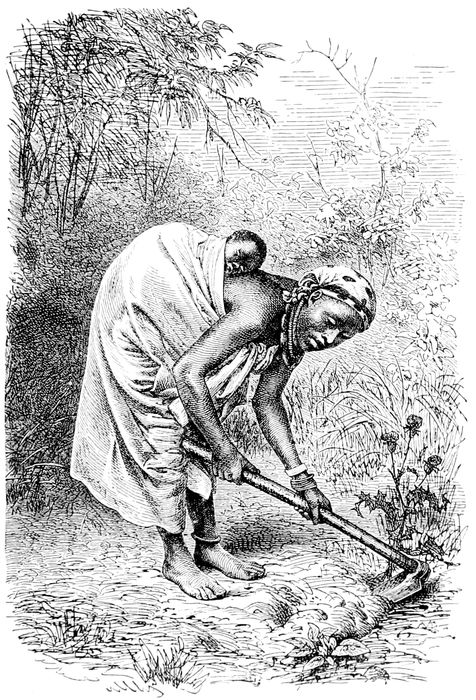

WOMAN OF LOANGO, TILLING THE SOIL

While searching for edible roots and berries, women became aware of the usefulness of many plants. And soon they made attempts to cultivate them in closer proximity to their lodges.

Having cleaned a suitable spot women made with their primitive digging sticks the holes, into which they sunk the 18seeds, from which the plants were expected to develop. Experience, the mother of all wisdom, taught women that these plants needed constant attention. So the ground was kept free from weeds and properly watered. From time to time it was loosened with hoes, which in the beginning were made of bones, shells or stones, and later on of metal.

Such was the origin of our vegetable gardens, orchards, and grain fields. The continuous care, devoted to these plantations, greatly improved the quality of useful plants. Poor and tasteless varieties developed in time into those rich and palatable species, without which our present human race could scarcely exist for a single day. I need only name wheat, corn, barley, rye, peas, lentils, beans, rice, tapioca, potatoes, yams, turnips, bread-fruit, pears, apples, plums, cherries, bananas, dates, figs, nuts, oranges, coffee, cacao, tea, cotton and hemp, to convince the reader of the immense value of women’s activity in agriculture.

As simple as were the tools for the cultivation of the soil, just as simple were the implements for the extraction of flour from the grain. Recent archæological research has disclosed the fact that many thousand years before Christ Egyptian women ground corn between two stones in just the same manner as the women of the Apache and Pueblo Indians and many other aboriginal tribes are doing to this day.

Other aboriginal women crushed the seeds in mortars of wood or stone. In several parts of Asia women succeeded in inventing hand-mills, which proved much more effective.

The necessity of storing provisions for the winter and hard times led to the invention of receptacles in which grain, nuts and dried berries might be kept and be safe from destruction by rain and animals. While pondering over the best methods of accomplishing this, women observed that certain insects and birds moulded their nests from wet clay, and that such nests, after hardening, were rain-proof. By this observation women became induced to use the same material for all kinds of nest-like vessels, in which provisions could be stored successfully. By accident such vessels came in contact with fire. Then it was found that by such baking the hardness of the vessels increased considerably. And so the preliminaries were discovered for the art of pottery, in which many aborigines became masters.

Similar observations led to the art of weaving. The nets, spread out everywhere by spiders for the capture of insects, gave women the first hint to make similar fabrics for the capture of birds and fishes. The spider’s thread was imitated by long hair and the fibres of certain plants. These were twisted together in a manner similar to that used by the weaver-birds in constructing their airy nests.

19For many thousand years weaving was done exclusively by hand. But in time all kinds of apparatus were invented. And so weaving developed into an art that among many aboriginal tribes was improved to the highest degree. At the same time these female weavers created a genuine native art. So for instance the garters, belts, sashes and blankets of the Navajo and Pueblo Indians are, for their splendid quality as well as for their tasteful designs and colors, highly appreciated by all connoisseurs. The same is true in regard to the ponchos of the Mexicans and Peruvians, and the magnificent shawls and carpets, made by the women of Cashmere, Afghanistan, Persia and other countries of the Orient.

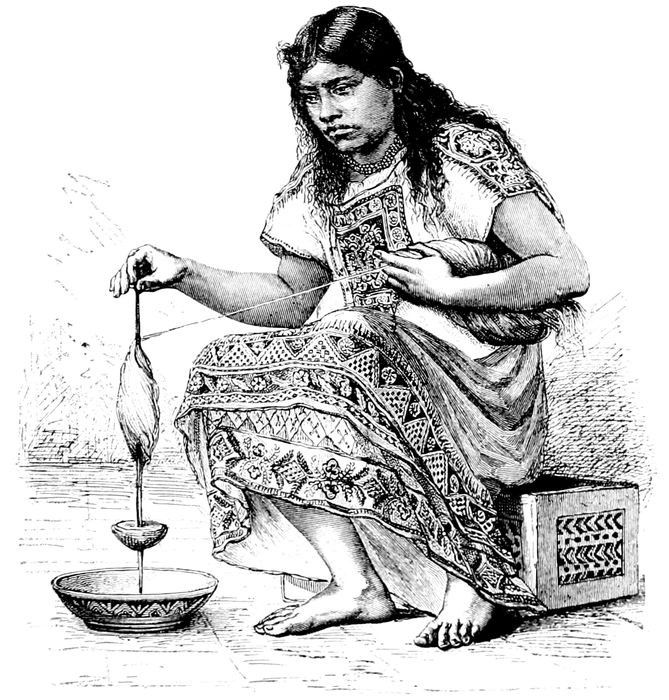

A TOLTEC WOMAN SPINNING COTTON.

Basketry, including matting and bagging, belongs also to the primitive textile arts in which many native women excelled. By using choice materials, or by adding resinous substances, some aboriginal women are able to make baskets water-tight for holding or carrying water for cooking. From crude beginnings basketry developed into an industry, which 20in many countries grew to great importance, as for instance in Morocco, where the markets are always supplied with large quantities of bags and baskets of beautiful design and workmanship.

Aboriginal women also attended to the dressing and tanning of skins of those animals which the men brought home from their hunting expeditions. In the domestic economy of many tribes skins were and are the most valued and useful property, especially in all regions having a severe climate. Every kind of skin, large enough to be stripped from the carcass of beast, bird or fish, is used here in some way.

A painting by George Catlin, the well-known artist, who during the first part of the last century travelled among the various Indian tribes of North America, illustrates the methods by which the skins of buffalo and deer are staked out upon the ground or between poles. We see the women engaged in scraping off the flesh and fat, a process which is followed by several others until the skin is fit to be used for tent covers, beddings, shields, saddles, lassoes, boats, clothes, mocassins, and thousands of other things.

Most skillful tanners and dressmakers are likewise the women of the Eskimo tribes. They make excellent suits from the skins and even the entrails of whales, walrus, seals and other animals.

To the keen sense of women we also owe undoubtedly most of our domestic implements. From the bones of fish and other animals they made needles and pins; from the horns splendid spoons and combs. Gourds, pumpkins and cocoanuts were turned into water bottles. Women also devised the comfortable hammocks. About the cribs, cradles and swings, invented in endless variety by aboriginal mothers for the protection and comfort of their darlings, volumes might be written. And by innumerable pictures and photographs it could be proven that the great care, bestowed nowadays upon our babies, is not the outcome of our advanced culture, but originated many thousand years ago among aboriginal women.

The same is true in regard to the dolls and play-things with which women seek to amuse those little ones, dearest to their hearts. What motherly affection, ever present and everlasting, has done for the welfare and progress of mankind, no one can conceive, nor describe, nor illustrate.

As brief as these remarks about aboriginal woman’s activity are, they indicate, however, sufficiently her share in the founding and evolution of human culture. To appreciate this even more, we must not forget that the life of those women was one of constant care, misery and danger. The 21blissful happiness of aboriginal existence, of which we read sometimes in novels, written by poetical dreamers, was never enjoyed by these women. How full of hardships their share was in reality, we find by investigating their place in the social life of their tribes.

WOMAN OF NORTHERN AFRICA TENDING TO HER BABY

Matrimony is, like all other human institutions, the result of evolution. In the dim past, after the ape-man had evolved to true man, it was not known at all. Most probably all the females were the common property of the males, the strongest of whom took hold of several women, leaving the rest to their inferior chums.

With the evolution of property rights these mates as well as their offspring came to be regarded as the absolute property of the husband and father, who could dispose of them at his pleasure by barter or otherwise. So it was among primitive men a hundred thousand years ago and so it is customary among aboriginal peoples to-day. At the death of the husband his rights generally go to the oldest son or to the person who becomes the head of the family.

Accordingly as girls are not masters of their own bodies, so the barter for women is customary among all aboriginal tribes. If a man sees a girl to his liking he bargains with the head of her family about the price. Among pastoral tribes it is generally paid in cattle; among hunters in skins or other objects of value.

Among the Zulu Kaffres the price for good-looking girls ranges from five to thirty cows. In Uganda it is three or four oxen; among the Samoyedes and Ostiaks of Siberia a number of reindeer; among the Sioux Indians two to twenty horses; among the Bedouins a number of camels; in Samoa pigs or canoes; among the Tatars sheep and several pounds of butter; among the Bongo twenty pounds of iron and twenty spear-heads; among other tribes a certain quantity of gold dust, beads, shells, and so on in endless variety. As soon as the price is paid the girl, without being asked her consent, is obliged to follow her new master.

As among aborigines women have no will of their own, they cannot object if their husbands exchange, trade or loan them to other men. So it is customary among many tribes that if persons of importance come visiting, the daughters or the wives of the host are assigned to comfort them over night.

If among the inhabitants of the Fiji Islands men became tired of their “better halves,” they killed and boiled them and arranged cannibal feasts in which all neighbors participated.

Aboriginal women also must gracefully assent to their husbands’ taking several wives. Their number depends on the man’s means. While poor men satisfy themselves with 23one wife, chiefs generally buy numbers. The despots of Dahomey in West Africa, for instance, filled their houses with hundreds of women, who were obliged not only to amuse these kings during their lifetime, but also to follow them in death. When such an autocrat was assembled to his ancestors, his body was deposited in a large cave. But in order that he should not travel alone through eternity, his wives as well as all the members of his court were led into the cave and provided with food for several days, whereupon the entrance of the cave was closed and the occupants were left to their fate.

CARRYING OFF A WOMAN IN AUSTRALIA

If among the aborigines a man is too poor to buy a wife, he generally tries to steal one. But as he must not do so within his own clan, as he would trespass upon the property rights of his fellow-men, nothing remains but to kidnap a girl of some neighboring tribe. So he lurks around the villages till some day a girl, while gathering berries or edible roots, 24unfortunately happens to come too near his hiding place. In this case the manner of his proposal is sudden, but effective. A blow with his war club makes the damsel unconscious, whereupon he drags her to some secure place. Here he keeps her till she has recovered her senses and is able to follow him to his lodge.

George Gray, who has written about the natives of Australia, states that the life of young and attractive women among those tribes is a continuous chain of capture by different men, terrible wounds and long wanderings to unknown bands. In addition, such unfortunate females must suffer very often extremely bad treatment by other women, to whom they are brought as prisoners by their capturers.

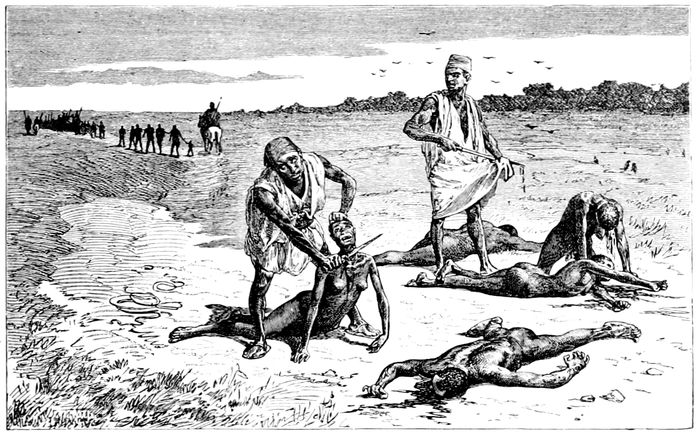

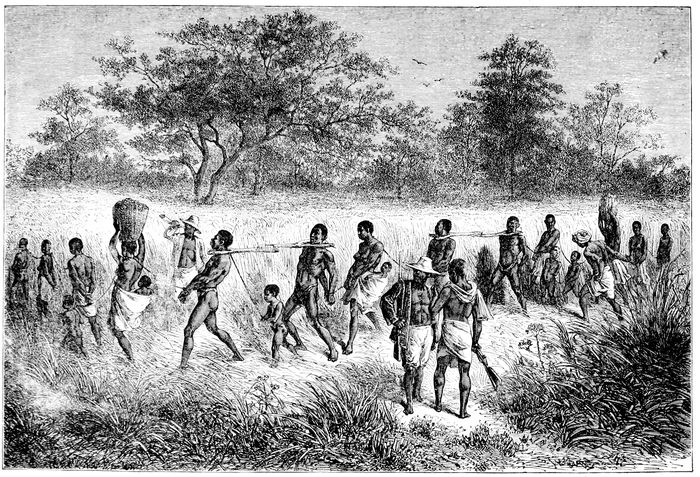

But women have been kidnapped not merely for sexual reasons, but also for their ability to work. Herewith we open the darkest chapter in woman’s history: Slavery, a word which has not lost its terrible meaning for women up to the present day.

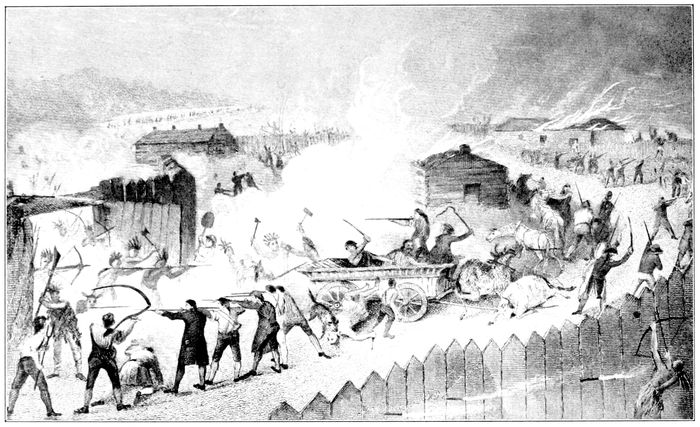

Slavery has been practiced in all parts of the world in some form. But Africa was the continent where it prevailed from time immemorial to the greatest extent and assumed the most cruel forms. Phœnicians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Turks, Spaniards, Portuguese, Italians, Frenchmen, Dutchmen, Englishmen and Americans sailed to its coasts, to capture men as well as women and children, to sell and use them for slaves.

It is impossible for human imagination to conceive the horrors and misery, caused here by heartless pirates for thousands of years.

Imagine a peaceful village, approached stealthily in the night by cruel enemies, who surround it and then set fire to the huts. As the inhabitants rush out in terror, those who resist capture are killed, and those who have escaped the blessing of immediate death are fettered and marched off. Imagine long columns of such unfortunate and often severely wounded men, women and children chained together and driven by ruthless brutes through pathless jungles and arid deserts, to far away markets. No matter how hot the sun burns down, they must move on. Woe to those who break down! They are left where they have dropped, to perish of hunger and thirst, or to be torn by wild beasts. Or, as a warning to the others, they are butchered in cold blood by their drivers. For those who reach their destination, where they are traded like cattle, an existence is waiting that will have fewer moments of joy than there are oases in an endless desert.

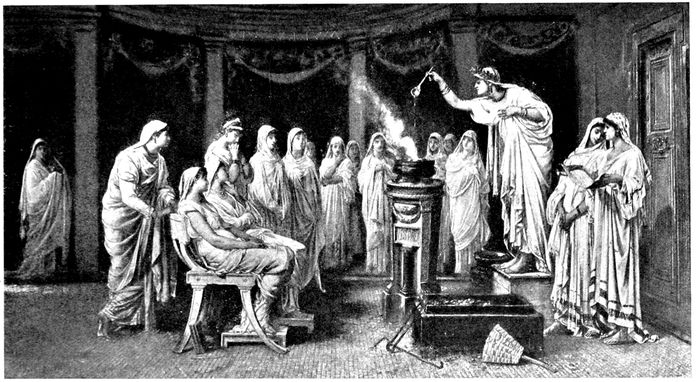

For time immemorial women also fell prey to religious superstition. To keep evil demons in good humor, or to thank some imaginary gods for victories and other blessings, human beings have been sacrificed by thousands. The “Dark Continent” again holds the record in this respect. And again the autocrats of Dahomey were those who, in religious frenzy, spilled the blood of hundreds and thousands of men as well as of women.

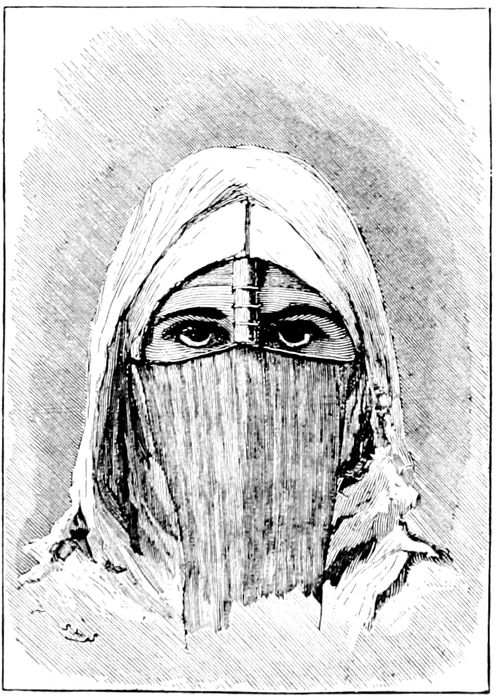

A BRIDE OF THE NILE

After a painting by W. Gentz.

26From their country the so-called Vodoo-service, the worship of the “Great Snake,” has been brought by slaves to the West Indies, where it was handed down from generation to generation. It still prevails in Hayti, “the black man’s republic.” Here it is, that the Vodoo priests and their devout followers meet in silent forests, to pay homage to their ugly god by sacrificing women as well as children.

Herodotus and other historians of classic times relate that every year in Egypt, when the Nile began to rise, to which that country owes its abundance, the priests persuaded a beautiful girl to become the bride of the river-god. Adorned with jewels and flowers, and greeted by all the people, this virgin was led to the flat roof of a temple overlooking the mighty river. After prayers and invocations had been made, she was tossed into the swirling floods, which swiftly carried her away.

Among the early Latin peoples similar sacrifices seem to have been customary, as is indicated by the fact that in Rome on the 15th of May in every year the Vestal virgins, in presence of all the priests, municipal authorities and the people threw twenty-four life-size dolls, the so-called Argeer, into the Tiber.

To calm the rage of the god of fire and earthquake, the priests of ancient Japan also hurled beautiful virgins into the flaming crater of Fuji Yama.

Humanity needed thousands of years to shake off such monstrous illusions and customs, because nothing is so difficult as to eliminate ideas and customs that are rooted in religious superstition, and, through being handed down from generation to generation, become surrounded with a halo of sacredness and solemnity.

To such institutions belonged also, what by some students of human culture has been characterized as “hierarchical or sacred prostitution.” As is generally known, there exist among almost all aboriginal tribes crafty charlatans, who pretend to have influence over those supernatural powers, which are believed to be the distributors of all blessings as well as of all evils. These so-called sorcerers, healers, conjurors, magicians, medicine-men, or shamans, the predecessors of the priests, usurped among many tribes the privilege of deflouring all virgins before their entrance into marriage. With the gradual evolution of priesthood this practice was made a rite, which among various nations of antiquity developed into the most voluptuous orgies known in history.

A NOBLEMAN AND HIS WIFE IN BABYLON

As the cultivated nations of Antiquity sprang from inferior tribes, it is only natural that in their social life many of the habits and customs of prehistorical times survived. Nowhere was this fact more evident than in the status of women. Everywhere we find a strange mixture of the rude conceptions of the dim past and promising prospects for a brighter future. In many places women were still regarded as inferior creatures, subjected to the will of men and with no rights whatever over their own persons. We also note that polygamy, barter, rape, slavery and hierarchical prostitution 30still flourish in all kinds of forms and disguises. But at the same time we are surprised to see that among certain nations the members of the fair sex enjoy already the same respect and almost a similar amount of rights and liberty, as our women possess to-day.

Modern archæologists are inclined to recognize those formerly fertile lands between the Persian Gulf and Asia Minor, and watered by the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, as the “Cradle of Civilization,” or the place, where in misty ages, before history began, the so-called Sumerians, a Semitic people, first attempted to form themselves into organized communities. According to the traditions of the Hebrews here was the original home of the human race, the “Garden of Eden,” and here was, as is told in Genesis XI, “that men said one to another: ‘Go to, let us build a city and a tower whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.’”

This city was called Babylon, and the country Babylonia. Wonderful stories and legends are connected with these two names, but still more astounding are the revelations unearthed by the pick and shovel of modern explorers. By their diligent work it has been discovered that the people, living in this region somewhere about 4,000 to 6,000 years B. C. were already a highly organized and civilized race, skilled in various trades and professions, and living in towns of considerable size and importance. The inhabitants of these cities were by no means awkward in the fine arts. Most important of all, they had already evolved a very complete and highly developed system of writing, which in itself must have taken many centuries to reach the stage at which it was found by the explorers.

As may be read in the elaborate works of Maspero, Hilprecht and other explorers, they discovered in the ruins of the principal cities of Babylonia several ancient libraries and archives containing thousands of tablets of clay, stone and bronze, covered with inscriptions of religious, astrological and magical texts, epics, chronicles and syllabaries. There are also contracts; records of debts; leases of lands, houses and slaves; deeds of transfer of all kinds of property; mortgages; documents granting power of attorney; tablets dealing with bankruptcy and inheritance; in fact, almost every imaginable kind of deed or contract is found among them.

The most precious relic is the famous Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylonia. This collection of laws, engraved on stone 2,250 years B. C. and now preserved in the Louvre, is so elaborate and systematic that it can hardly have been the first one. Back of it there must have been a long period of 31usage and custom. But it is the first great collection of laws that has come down to us. In 282 sections it regulates almost every conceivable incident and relationship of life. Not only are the great crimes dealt with and penalized, but life is regulated down to its most minute details. There are laws on marriage, breach of promise, divorce, desertion, concubinage, rights of women, purchase-money of brides, guardianship of the widow and orphan, adoption of children, etc. Through these laws we gain full information about the position of women in ancient Babylonia. Three classes of women are recognized: wives, concubines, and slaves. From other sources we know that all women of the higher class were cloistered in the harem and never appeared by the side of husbands or brothers in public. The harem system, at least for Western Asia and Europe, most probably originated in Babylonia.

The National Geographic Magazine of February, 1916, gives the text of a love letter, written several thousand years ago and sent by a young man to his sweetheart. It reads as follows: “To Bibea, thus says Gimil Marduk: may the Gods Shamash and Marduk permit thee to live forever for my sake. I write to inquire concerning thy health. Tell me how thou art. I went to Babylon, but did not see thee. I was greatly disappointed. Tell me the reason for thy leaving, that I may be happy. Do come in the month Marchesvan. Keep well always for my sake.”

In the same place we find the following example of a marriage contract:

“Nabu-nadin-akhi, son of Bel-akbe-iddin, grandson of Ardi-Nergal, spoke thus to Shum-ukina, son of Mushallimu: ‘Give me thy Ina-Esagila-banat, the virgin, to wife to Uballitsu-Gula, my son.’ Shum-ukina hearkened unto him and gave Ina-Esagila-banat, his virgin daughter, to Uballitsu-Gula, his son. One mina of silver, three female slaves, Latubashinnu, Inasilli-esabat and Taslimu, besides house furniture, with Ina-Esagila-banat, his daughter, as a marriage-portion he gave to Nabu-nadin-akhi. Nanâ-Gishirst, the slave of Shum-ukina, in lien of two-thirds of a mina of silver, her full price Shum-ukina gave to Nabu-Nadin-akhi out of the one mina of silver for her marriage-portion. One-third of a mina, the balance of the one mina, Shum-ukina will give Nabu-nadin-akhi, and her marriage-portion is paid. Each took a writing (or contract).”

This document, written on a tablet of clay, is signed by six witnesses and the scribe.

As Professor Clay explains “it has been the custom with most peoples in a large part of the ancient as well as the modern Orient to base a betrothal upon an agreement of the 32man or his parents to pay a sum of money to the girl’s father.” In Babylonia this “bride-money,” together with the gift of the father and other gifts, formed the marriage-portion which was given to the bride. There were prudential reasons for this practice. It gave the woman protection against ill-treatment and infidelity on the part of the husband, as well as against divorce; for if she returned to her father’s house she took with her the marriage portion unless she was the offending party. If she died childless, the marriage-portion was divided among them.

In case the girl’s father rejected the suitor after the contract had been made, he was required to return double the amount of the bride price. The betrothals took place usually when the parties were young, and as a rule the engagements were made by the parents. A marriage contract was necessary to make a marriage legal. In some cases peculiar conditions were made, such as the bride’s being required to wait upon the mother-in-law, or even upon another wife. If it was stipulated that the man should not take a second wife, the woman could secure a divorce in case her husband broke the agreement.

Concubinage was indulged in, especially when the wife was childless and she had not given her husband a slave maid that he might have children. The law fully determined the status of the concubine and protected her rights.

At the husband’s death the wife received her marriage-portion and what was deeded to her during the husband’s life. If he had not given her a portion of the estate during his life, she received a son’s share and was permitted to retain her home, but she could marry again. A widow with young children could only marry with the consent of the judge. An inventory of the former husband’s property was made and it was intrusted to the couple for the dead party’s children.

If a man divorced a woman, which he could do by saying to her “Thou art not my wife!” she received her marriage-portion and went back to her father’s home. In case there was no dowry, she received one mina of silver, if the man belonged to the gentry; but only one-third of a mina if he was a commoner.

For infidelity the woman could divorce her husband and take the marriage-portion with her. In case of a woman’s infidelity, the husband could degrade her as a slave; he even could have her drowned or put to death with the sword. In case of disease, the man could take a second wife, but was compelled to maintain his invalid wife in his home. If she preferred to return to her father’s house, she could take the marriage-portion with her.

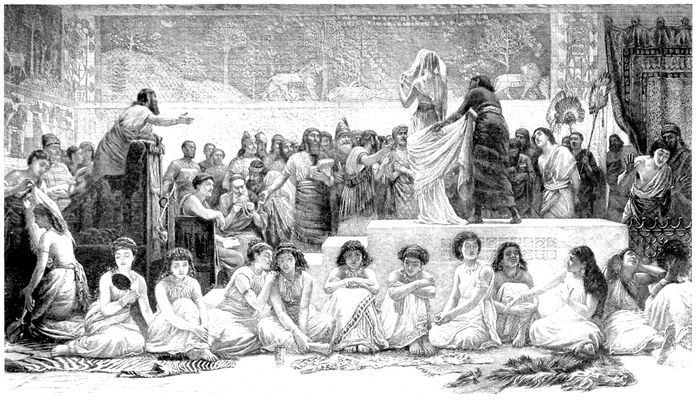

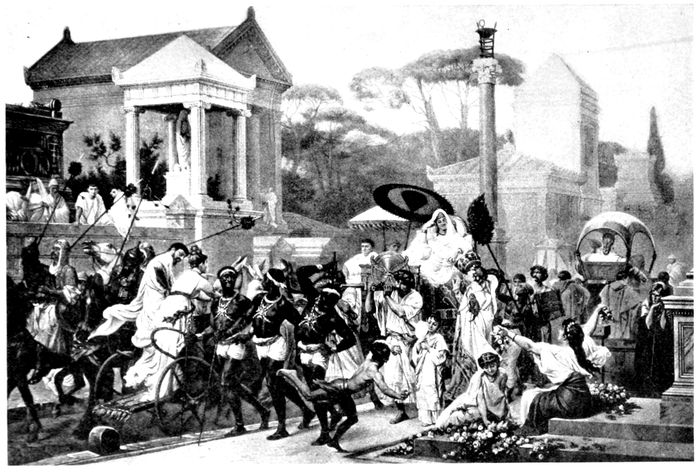

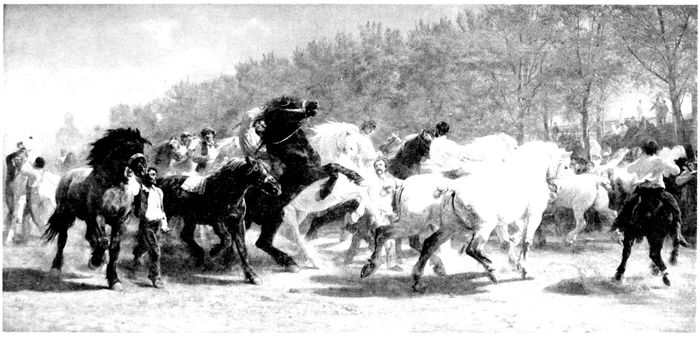

THE MARRIAGE MARKET AT BABYLON

After a painting by Edwin Long.

34From several of these engraved tablets it appears, that a woman received the same pay for the same work when she took a man’s place.

To Herodotus, the so-called “Father of History,” we are indebted for some highly interesting notes about the “marriage market of ancient Babylon.” Its site, uncovered in 1913 by the German Oriental Society, was in close neighborhood of the palaces of Nebuchadnezzar and Belshazzar and occupied a rectangle of 100 by 150 feet. Open to the air on all four sides, it was most probably shielded from the sun by rich awnings devised to shelter the daughters of Babylon and bring out their charms. The marble block upon which they stood while being bid for was in the center of the spectators and richly carved with cherubs, who worshiped and protected the “Tree of Life.” Several inscriptions leave no doubt, that this was the actual market of which Herodotus gave the following description: “Once a year the maidens of age to marry in Babylon were collected at the market, while the men stood around them in a circle. Then a herald called up the damsels one by one and offered them for sale. He began with the most beautiful. When she was sold for no small sum he offered for sale the one who came next to her in beauty. All of them were to be sold as wives. The richest of the Babylonians who wished to wed bid against each other for the loveliest maidens, while the humbler wife seekers, who were indifferent about beauty, took the more homely damsels with marriage-portions. For the custom was that when the herald had gone through the whole number of the fair ones he should then call up the ugliest—a cripple if there chanced to be one—and offer her to the men, asking who would agree to take her with the smallest marriage-portion. And the man who offered to take the smallest sum had her assigned to him. The marriage-portions were furnished by the money paid for the beautiful girls, and thus the fairer maidens portioned out the uglier. No one was allowed to give his daughter to the man of his choice, nor might any one carry away the damsel he had purchased without finding bail really and truly to make her his wife. If, however, it was found that they did not agree the money might be paid back. All who liked might come, even from distant villages, and bid for the women.”

Herodotus as well as the Roman Curtius Rufus have written also about the so-called “hierarchical or sacred prostitution,” as it was connected with the service of Mylitta or Belit, the Babylonian goddess of the producing agencies.[1] Her temple was surrounded by a grove, which, like the temple, became the scene of most voluptuous orgies, about 35which Jeremiah too has given indications in his letter directed to Baruch. (Baruch VI. 42, 43.)

1. About this subject Rev. T. M. Lindsay, Professor of Divinity and Church History, Free Church College, Glasgow, writes in the Encyclopædia Britannica in an essay about Christianity: “All paganism is at bottom a worship of Nature in some form or other, and in all pagan religions the deepest and most awe-inspiring attribute of nature was its power of reproduction. The mystery of birth and becoming was the deepest mystery of Nature; it lay at the root of all thoughtful paganism and appeared in various forms, some of a more innocent, others of a most debasing type. To ancient pagan thinkers, as well as to modern men of science the key to the hidden secret of the origin and preservation of the universe lay in the mystery of sex. Two energies or agents, one an active and generative, the other a feminine, passive, or susceptible one, were everywhere thought to combine for creative purpose, and heaven and earth, sun and moon, day and night, were believed to co-operate to the production of being. Upon some such basis as this rested almost all the polytheistic worship of the old civilization, and to it may be traced back, stage by stage, the separation of divinity into male and female gods, the deification of distinct powers of nature, and the idealization of man’s own faculties, desires, and lusts, where every power of his understanding was embodied as an object of adoration, and every impulse of his will became an incarnation of deity. But in each and every form of polytheism we find the slime-track of the deification of sex; there is not a single one of the ancient religions which has not consecrated by some ceremonial rite even the grossest forms of sensual indulgence, while many of them actually elevated prostitution into a solemn service of religion.”

According to these statements every woman was compelled to visit the temple of Mylitta at least once during her life and give herself over to any stranger, who would throw some money on her lap and with the words: “I appeal to Mylitta!” indicate his desire to possess her. Such an appeal could not be rejected, no matter how small the sum was, as this money was to be offered on the altar of the goddess and thus became sacred.

HEBREW WOMEN DURING THE TIME OF ANTIQUITY.

The early Hebrews or Israelites, being of the same Semitic stock as the Babylonians, but preferring a pastoral life, observed similar habits in their relations to women. Matrimony to them was not a necessity based on mutual love and respect, but a divine order, binding especially the man. While it was his obligation to maintain the human race, especially the Jewish stock, woman was merely the medium to reach this end by her beauty and charm and by giving birth to children.

For the conclusion of a marriage the mutual consent of the two contrahents was necessary. But generally the marriage 37was arranged by the fathers or some other relations, who likewise settled the question as to how much would be the dowry of the son as well as of the daughter. That sometimes even a faithful servant was charged with the negotiation of these delicate questions, is told in Genesis XXIV, where it is said that Abraham, in order to secure for his son Isaac a wife of his kindred, commissioned his eldest servant to make a journey to his former home in Mesopotamia. While resting at a well, he met Rebekah, the beautiful daughter of Bethuel, a son of Nahor, Abraham’s brother. When Rebekah consented to become Isaac’s wife, Abraham’s servant brought forth many jewels of silver and gold and raiment, and gave them to Rebekah. Having given also to her brother and to her mother many precious things, he started for the return journey, taking Rebekah and her maid servants with him.

The story of Jacob and Rachel, as told in Genesis XXIX, proves, that among the early Hebrews the barter for women was customary, but that the wooer might obtain the girl of his longing likewise by serving her father for a certain length of time. As the early Hebrew had an aversion to mingling with the inhabitants of Canaan, Isaac, Jacob’s father, sent him to Mesopotamia, the former habitat of the Hebrews, to select a wife among the daughters of Laban, his mother’s brother.

Meeting Rachel, Laban’s youngest daughter, he became so deeply impressed by her charm, and so eager to gain her, that he offered Laban to serve him for Rachel for seven years. Having fulfilled his contract, Jacob was, however, beguiled by Laban, who at the wedding-night substituted his eldest daughter Leah for Rachel. When in the morning Jacob became aware of the deception, Laban claimed that it was not customary, in his country, to give away a younger daughter before the firstborn. And so he succeeded in persuading Jacob to serve him for Rachel another term of seven years.

While monogamy was the rule among the Hebrews, polygamy was permitted, especially if the first wife was barren. As this was the case with Sarah, the wife of Abraham, she gave her husband Hagar, an Egyptian maid-servant, with whom Abraham begat a son, Ishmael. Of Leah and Rachel, the two wives of Jacob, we may read in Genesis XXX, that they, not having born children to Jacob, likewise introduced to him their maids Bilhah and Zilpah, each of which bore Jacob two sons.—It is certain that some of the patriarchs had a great number of wives, and that not all of these held the same rank, some being inferior to the principal wife. The right of concubinage was practically unlimited. Abraham kept a number of concubines, as appears in Genesis XXV, 6, where it is said that he, when dividing his property, gave 38gifts to the sons of his concubines. Of Solomon the first book of Kings XI, 3, states, that he had 700 wives and 300 concubines.

In the Mosaic law concubinage and divorce was a privilege of the husband only. A wife accused of adultery was compelled to undergo the horrible ordeal of the bitter water, as described in Numbers V. If found guilty, she might be stoned to death.

To continue the male issue of the family was the paramount mission of the wife. That the birth of a male baby was regarded as an event of far greater importance than that of a female, appears from Leviticus XII, where it is said, that a woman, giving birth to a son, was regarded unclean for only seven days and must not touch hallowed things nor come into the sanctuary for a period of thirty-three days. But if unfortunately she became the mother of a girl, she was considered unclean for fourteen days and had to abstain from religious service for sixty-six days. Only after she had made atonement for the sin of motherhood by offering a lamb or a pair of pigeons, was she forgiven.

The prejudice against woman is also confirmed by the fact, that, according to Exodus XXIII, 17, all male Jews were required to appear before the Lord three times in the year, and that they had to repair to Jerusalem once a year, with all their belongings. But the women were not privileged to accompany their husbands.

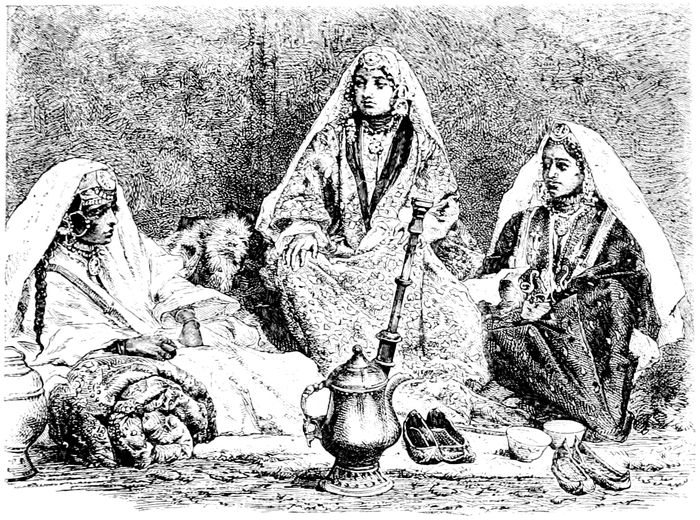

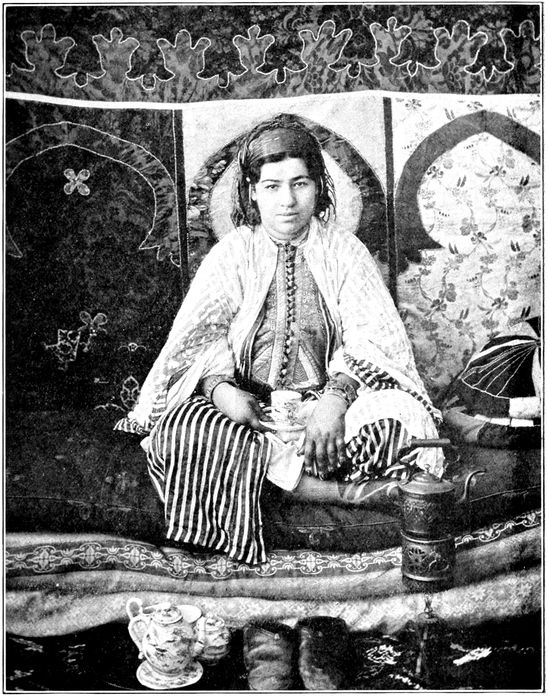

HINDOO WOMEN FROM CASHMERE.

To investigate woman’s position among the other ancient nations of Asia is also of interest.

The Parsee or Parsis, belonging to the great Aryan or Indo-Germanic race, occupied two thousand years before Christ that part of Central Asia known at present as Iran or Persia. Whether this country was the original home of that race, is unknown. Some modern scientists are inclined to seek it in more northern parts of Asia or even of Europe, as the sacred songs of the Parsee contain indications, that the Aryans originally came from countries with a temperate or frigid zone. When for instance the Vedic singers in hot India prayed for long life, they asked for “a hundred winters.”

In their treatment of women these Aryans or Parsee have been much more noble than any other Asiatic race. They believed in marriage for higher purposes than the mere begetting of children. The principal incentive to conclude a marriage was the desire to contribute to the great renovation hereafter, which, according to the sacred book of the Parsee, the Zend-Avesta, is promised to humanity. This renovation 40cannot be carried out in the individual self, but must be gradually worked out through a continuous line of sons, grandsons, and great-grandsons. The motive of marriage was therefore sacred. It was a religious purpose they had in view, when the male and female individuals contributed by marital union their assistance, first, in the propagation of the human race; second, in spreading the Zoroastrian faith; and third, in giving stability to the religious kingdom of God by contributing to the victory of the good cause, which victory will be complete about the time of resurrection. The objects of the marriage bond were, therefore, purely religious, tending to the success of light, piety or virtue in this world. For this reason the Avesta declares that married men are far above those who remain single; that those who have a settled home are far above those who have none; and that those who have children are of far greater value to humanity than those who have no offspring.

While daughters were believed to be less useful than sons for the continuation of the father’s race, they were, however, not disliked, but also objects of love and tenderness. Marriages were not the result of any barter or capture, but of pure selection on the part of the two individuals. If they were still of minor age, the marriage was subject to the confirmation of the parents or guardians.

Infanticide was strictly prohibited. There were also laws against the destruction of the fruit of adultery. Such illegitimate offspring had to be fed and brought up at the expense of the male sinner until they became seven years of age.

Like the valleys of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, and like the highlands of Central Asia, or Ariyana, so the mountains, plains and forests of India were inhabited long before the dawn of history by masses of men of various races and split into many hundreds of tribes. Of these races descendants exist in almost the same conditions as their ancestors did many thousand years ago. In Southern India the Kader are still living in primitive tree-huts. Assam and Bhutan are regions abounding with villages which are the exact counterparts of the prehistorical lake-dwellings of Switzerland.

These vast regions of India were at some unknown time invaded by tribes of Aryan or Indo-Germanic race. While among the aborigines of India women were subjected to all the hardships and bad treatment of primeval times, the women of the Aryans enjoyed, as stated above, a far higher position. Like their husbands they were the “rulers of the house,” had the entire management of household affairs, and were allowed to appear freely in public. Husband and wife also drew near 41to the gods together in prayer. That the education of the females was not neglected is proven by the fact, that some of the most beautiful Vedas or national hymns and lyric poems were composed by ladies and queens.—

With the decline of the Aryan race and culture in India, caused most probably by the hot, enervating climate of the country, the position of women also underwent a change for the worse. Especially the growing despotism of the Brahmanic priests gradually robbed women of all their former rights and liberty. In time they became completely subject to the authority of man. Mothers owed obedience to their own sons, and daughters were absolutely dependent upon the will of their fathers. The system of conventional precepts, known as “Manu’s Code of Laws,” clearly defined the relative position and the duties of the several castes and sexes, and determined the penalties to be inflicted on any transgressors of the limits assigned to each of them. But these laws are conceived with no human or sentimental scruples on the part of their authors. On the contrary, the offenses, committed by Brahmans against other castes, are treated with remarkable clemency, whilst the punishments inflicted for trespasses on the rights of the Brahmans and higher classes are the more severe and inhuman the lower the offender stands in the social scale.

Against the female sex Manu’s laws are full of hostile expressions: “Women are able to lead astray in this world, not only the fools, but even learned men, and to make them slaves of lust and anger.”—

“The cause of all dishonor is woman; the cause of hostility is woman; the cause of our worldly existence is woman; therefore we must turn away from woman.”—“Girls and wives must never do anything of their own will, not even in their own homes.”—“Women are by their nature inclined to seduce men; therefore no man shall sit even with his own relative in lonely places.”—“The wife must be devoted to her husband during her whole life as well as after his death. Even if he is not without blame, even if he is unfaithful and without a good character, she must nevertheless respect him like a god. She must do nothing that might displease him, neither during his life nor after his death.”—“Day and night must women be held in a state of dependence.”—

As the subjection of women was made a cardinal principle of the Brahman priests, they did not shrink from misinterpreting the text of the Vedas accordingly. So the sentence: “You wife, ascend into the realm of life! Come to us! Do your duty toward your husband!” was explained to mean that a widow must not marry again but ought to follow her husband also in death. This led to the voluntary burning of the widows with the corpse of the husband, a practice which assumed 42great dimensions and was observed till the middle of the 19th Century. Mrs. Postans, an English lady, who during the first part of the last century resided many years in Cutch, one of the northern provinces of India, gave the following account of such a ceremony: “News of the widow’s intentions having spread, a great concourse of people of both sexes, the women clad in their gala costumes, assembled round the pyre. In a short time after their arrival the fated victim appeared, accompanied by the Brahmins, her relatives, and the body of the deceased. The spectators showered chaplets of mogree on her head, and greeted her appearance with laudatory exclamations at her constancy and virtue. The women especially pressed forward to touch her garments—an act which is considered meritorious, and highly desirable for absolution and protection from the “evil eye.””

“The widow was a remarkably handsome woman, apparently about thirty, and most superbly attired. Her manner was marked by great apathy to all around her, and by a complete indifference to the preparations which for the first time met her eye. Physical pangs evidently excited no fears in her; her singular creed, the customs of her country, and her sense of confused duty excluded from her mind the natural emotions of personal dread, and never did martyr to a true cause go to the stake with more constancy and firmness, than did this delicate and gentle woman prepare to become the victim of a deliberate sacrifice to the demoniacal tenets of her heathen creed.”

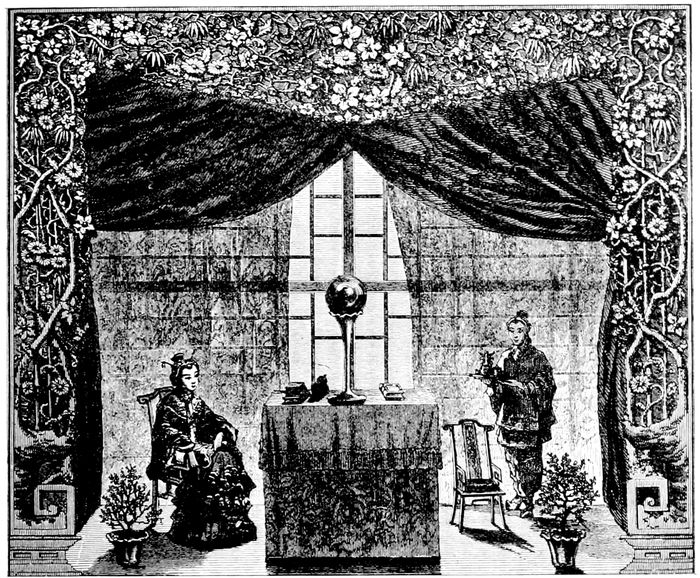

A LADIES’ PARLOR IN CHINA.

While the fate of women in India was shaped by Manu’s Code of Laws, in China it was decided by the orders of Confucius, the famous sage, born in the year 550 B. C. and in popular histories of his life praised in the lines:

In the rules, which this savant gave to his followers, he demanded full subordination of woman to man; also, that the two sexes should have nothing in common and live separated in two different parts of the house. The husband must not mingle in the internal affairs of the home, while the wife must not concern herself in any outside matter. Also women should have no right to make decisions but in everything be guided by the orders of their husbands.

Women have likewise no proper position before the law and cannot be witnesses in any court. The father may 44sell his daughter, and the husband may sell his wife. Concubines are permitted and often are housed under the same roof with the wife. Daughters are not welcomed, but treated with contempt.

To get rid of a superabundance of infant girls which were regarded as a burden and as unwelcome eaters, the Chinese in former times resorted to exposure and infanticide to such an appalling extent that these cruelties became a national calamity and disgrace. Generally the female babies were drowned. In the provinces of Fukian and Kiangsi infanticide was so common, that, according to Douglas, at public canals stones could be seen bearing the inscription: “Infants must not be drowned here!”—

To lessen these abuses one of the emperors of the Sung-dynasty decreed that all persons, willing to adopt exposed children, should be compensated by the government. But this well-meant decree brought evil results, as many people, who adopted such foundlings, raised them for the purpose of making them their own concubines, or to sell them to the keepers of brothels, of which every Chinese city had an abundance. Placed in these brothels when six or seven years old, the unfortunate girls were compelled to serve the older inmates for several years. Later on they assisted in entertaining visitors with song and music. But having reached the age of twelve or thirteen, they were regarded as sufficiently developed to bring profit in the lines of their actual designation.

The final fate of such unfortunate beings was in most cases miserable beyond description. Having been exploited to the utmost by their heartless owners, they were, when withered and no longer desirable, thrown into the streets, to perish in some filthy corner.

Women of the lower classes too had a hard life. In addition to such unfavorable conditions there existed among the aristocrats a strict adherence to ancient manners and customs. Accordingly the life of the whole nation became rigid and ossified. Foreigners, who came in close contact with Chinese aristocrats, speak of their women with greater pity than of the females of the poor, describing them as dull and boring creatures, with no higher interests than dress and gossip.

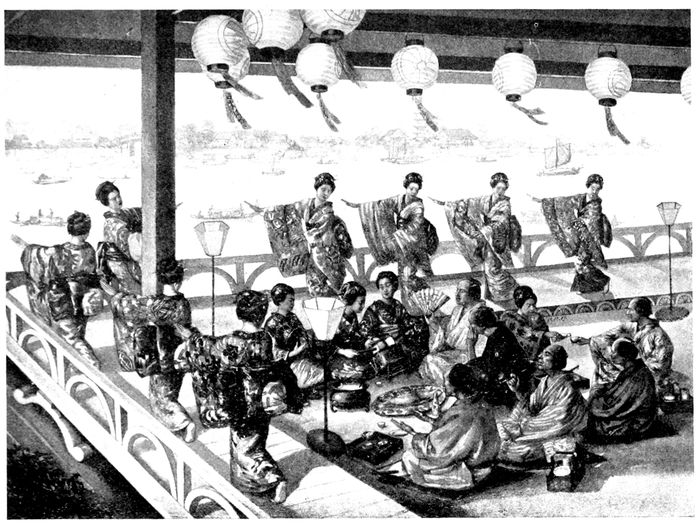

As in Japan the rules of Confucius were likewise in force, the position of woman in “the Land of the Rising Sun” likewise was an inferior one. Obedience was her lifelong duty. As a girl she owed obedience to her father, as a wife to her husband, and as a widow to her oldest son. And in the “Onna Deigaku,” the classic manual for the education of women, she was advised to be constantly aware of the bar between the two sexes.

AN ENTERTAINMENT AMONG THE GEISHAS OF JAPAN.

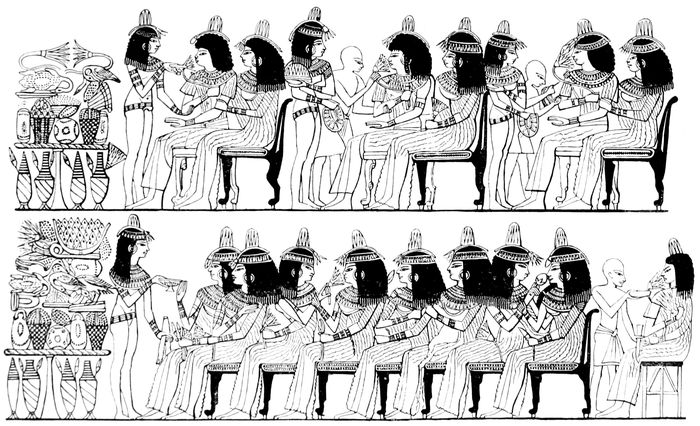

AN EGYPTIAN QUEEN AND HER ATTENDANTS.

Of the many nations that occupy the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, the Egyptians are the oldest. To them one of the foremost scholars, George Ebers, paid the following compliment: “If it is true that the culture of a nation may be judged by the more or less favorable position, held by its women, then the culture of ancient Egypt surpassed that of all other nations of Antiquity.”

Indeed, when we study the innumerable inscriptions, paintings and sculptures of Egyptian tombs, and investigate the many well preserved papyrus rolls, we find this praise fully justified. Not only did the Egyptians generally confine 47themselves to one wife, but they also extended to her more and greater privileges, than she had in any other country. Woman was honored as the source of life, as the mother of all being. Therefore contracts, carefully set up, protected her in her rights and secured her the title Neb-t-em pa, “the mistress of the house.” As such she had, if the authority of Diodorus can be credited, absolute control over all domestic affairs and no objection was made to her commands whatsoever they might be. It is also significant, that where biographical notes appear, on tombs, statues and sarcophagi, the name of the deceased mother is frequently given, while the name of the father is not mentioned. So it reads for instance: “Ani, born by Ptah-sit,” “Seti, brought to life by Ata.” The spirit of true affection and real family life likewise found expression in many poetical names given by sorrowful widowers to their departed wives. There is an inscription, in which a husband praises his lost mate as “the palm of loveliness and charm”; another one extols his spouse as “a faithful lady of the house, who was devoted to her husband in true fondness.”

That the highly developed, culture of the Egyptians was based on strong ethical principles, also appears from the text of the so-called “Papyrus Prisse,” perhaps the oldest book of morals ever written. Its author, Prince Ptah-hotep, who lived about 3350 B. C., gives hints and advice in regard to social intercourse and manners, to be observed among people of refinement. Hear what he says about the treatment of women: “If you are wise, you will take proper care of your house and love your wife in all honor. Nourish, clothe and adorn her, as this is the joy of her limbs. Provide her with pleasing odors; make her glad and happy as long as you live, because she is a gift that shall be worthy of its owner. Don’t be a tyrant. By friendly conduct you will attain much more than by rough force. Then her breath will be merry and her eyes bright. Gladly she will live in your house and will work in it with affection and to her heart’s content.”

Children were regarded as the gifts of the gods, and brought up in good manners and obedience.

In company with their husbands Egyptian women took part in all kinds of social and public festivals. At social affairs the master and mistress of the house presided, sitting close together, while the guests, men and women, frequently mingled, strangers as well as members of the same family. Agreeable conversation was considered the principal charm of polite society, and according to Herodotus it was customary at such gatherings, to bring into the hall a wooden image of Osiris, the Lord of Life and Death, to remind the guests not only of the transitoriness of all earthly things and human pleasures, but also of the duty, to meet all others during the short span of this earthly life with kindness and love.

A LADIES’ PARTY IN ANCIENT EGYPT.

49That ladies’ parties are not an innovation of our times but date back thousands of years before Christ, we learn from many finely executed carvings and frescoes which represent feasts. In long rows we see the fair ones sitting together, in finest attire, with hair carefully dressed and adorned with lotus flowers. Waited upon by handmaids and female slaves, they chat and enjoy the delicious sweets, cakes and fruits, with which the tables are loaded. As the hours passed, fresh bouquets were brought to them, and the guests are shown in the act of burying their noses in the delicate petals, with an air of luxury which even the conventionalities of the draughtsman cannot hide. Wine was also partaken of, and that the ladies were not restricted in its use, is evident from the fact, that the painters have sometimes sacrificed their gallantry to a love of caricature. “We see some ladies call the servants to support them as they sit; others with difficulty prevent themselves from falling on those behind them; a basin is brought too late by a reluctant servant, and the faded flower, which is ready to drop from heated hands, is intended to be characteristic of their own sensations.”[2]

2. Wilkinson, Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, Vol. II, p. 166.

In Egypt women were permitted to practice as physicians. They were likewise admitted into the service of the temple. In most solemn processions they advanced towards the altar with the priests, bearing the sacred sistrum, an instrument emitting jingling sounds when shaken by the dancer. Queens and princesses frequently accompanied the monarchs while they offered their prayers and sacrifices to the deity, holding one or two ceremonial instruments in their hands.

The constitution of Egypt also provided that, when at the death of a king no male successor was at hand, the royal authority and supreme direction of affairs might be entrusted without reserve to one of the princesses, who in such case ascended the throne. History records several Egyptian queens, among them Cleopatra VI, who became famous through her relations to Cæsar and Anthony.

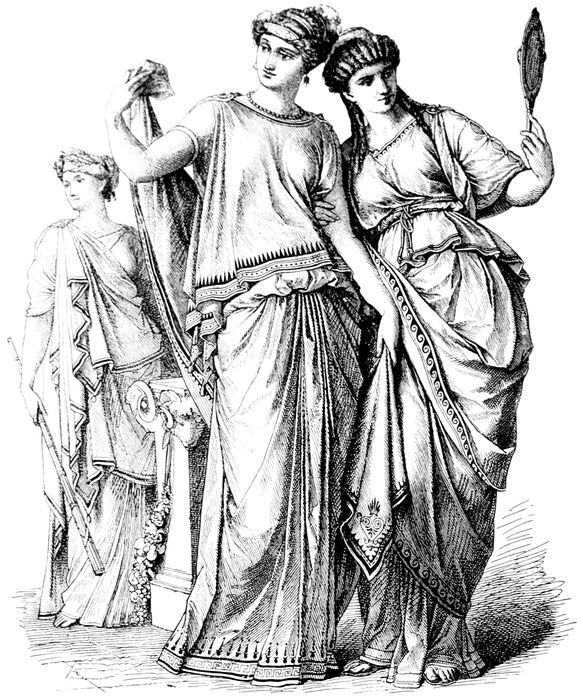

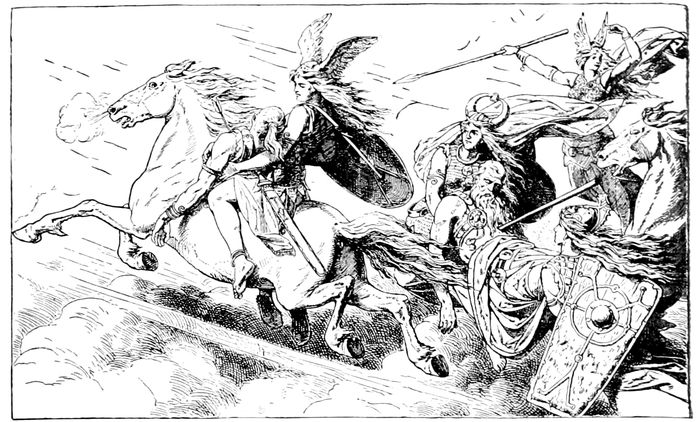

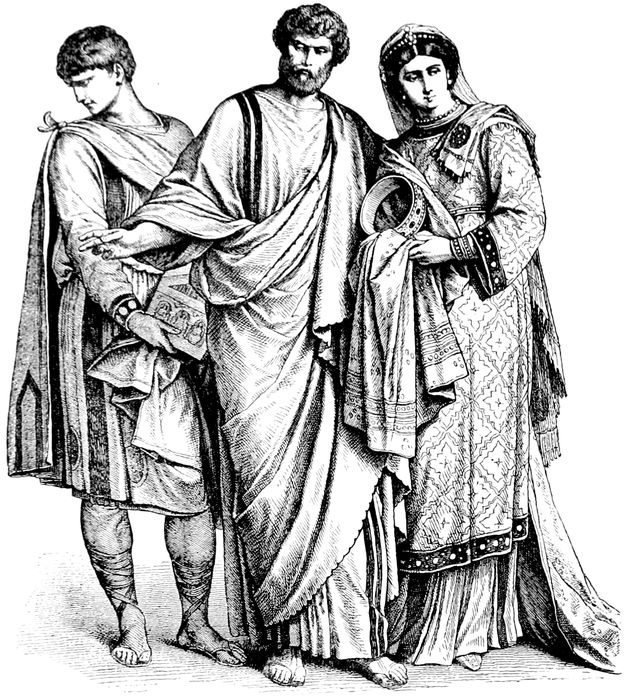

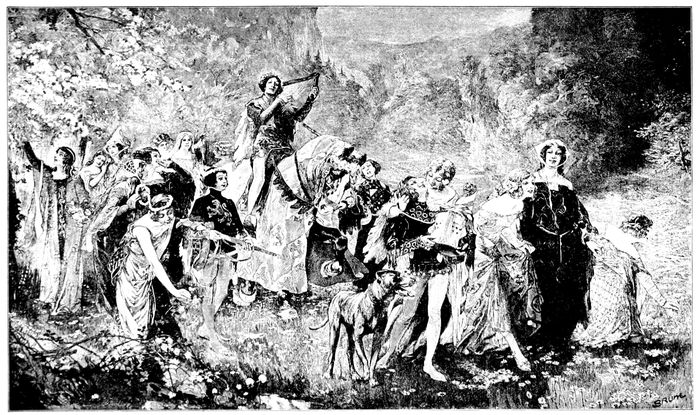

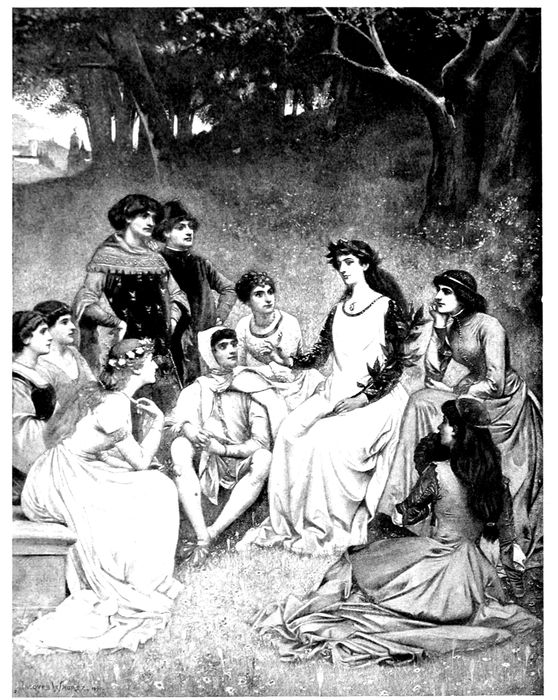

IN THE TIME OF SAPPHO AND ASPASIA.

The great regard extended to women by the Egyptians could not fail to influence to some extent those nations, with whom they came in contact, especially the Greeks and the Romans.

Ancient Greece, or to be more correct, Hellas, was occupied by the Hellenes, belonging to the Aryan or Indo-Germanic race, who had immigrated from Central Asia in prehistoric times. A pastoral rather than an agricultural people, they were divided into several branches, of which the Dorians, Ionians, Aeolians, and Pelasgians were the most prominent.

51No people has ever recognized the charm of women with greater enthusiasm than the Greeks. To them the fair sex was the embodiment of cheerful life, of the joy of being. To this conception we owe many of the most excellent works of art, among them several unsurpassed statues of Venus, the goddess of beauty and love.

In the treatment of their women the various branches of the Hellenes were not alike. But all took deep interest in the harmonious development of the body, of beauty and art. Gymnastic games and prize-fights were the favorite entertainments, especially among the Dorians, one branch of whom, the Spartans, became famous for their strict methods in rearing and educating boys as well as girls.

To secure to the state a race of strong and healthy citizens, the Spartans allowed no sickly infant to live, and girls were required to take part in all gymnastic exercises of the young men. Women were even admitted to co-operate in all public affairs. As great attention was given also to their education, the women of Sparta gained in time such great influence over their men, that the other Hellenes jokingly spoke of “Sparta’s female government,” a remark, which was promptly answered with the reply, that the women of Sparta were also the only ones, who gave birth to real men.

That the Hellenic women were treated with great dignity during the so-called “heroic age,” and that they enjoyed far greater liberty than in later periods, is evident from the poems of Homer. In the Iliad Achilles says: “Every true and sensible man will treat his wife respectfully and take proper care of her.” And in another place Homer declares that “besides beauty good judgment, intellect and skill in all female works are the merits, by which a wife will become a respected consort to her husband.”

In the “Odyssey” Homer gives in Penelope a very attractive example of female faithfulness and dignity. He also makes Odysseus say to Nausikaa: “There is nothing so elevating and beautiful, as when husband and wife live in harmony in their home, to the annoyance of their adversaries, to the rejoicing of their friends, and to their own honor!”

Among the many deities, worshiped by the Greeks, one of the most attractive figures was Hestia, the goddess of the home or hearth fire. As explained in a former chapter, the constant fire, kept by aboriginal bands in the centre of their villages, became in time a sacred symbol of home and family life, and by degrees grew into a religious cult of great sanctity and importance. As women in ancient Hellas too were the guardians of this tribal fire, so its deity was believed to be a goddess, Hestia, whose name means “home—or hearth-fire.” As the tribal fire was always kept burning so the fire 52in the Pytaneion, the temples of Hestia, was to remain alive. If by any mischance it became extinguished, only sacred fire made by friction, or got directly from the Sun, might be used to rekindle it. The Pytaneion was always in the center of the villages and cities. Around its fire the magistrates met, and received foreign guests. From this fire, representing the life of the city, was taken the fire wherewith that on the hearth of new colonies was kindled.

In later times, however, the high conceptions the Greeks had of womanhood underwent considerable change, and the close intimacy between husband and wife, which had hitherto distinguished married life, vanished. When with the extension of navigation and commerce the Greeks came into closer touch with the luxurious life of Asiatic nations, they adopted many of their manners and thoughts. Suspicion and jealousy, conspicuous traits in the character of southern races, now made themselves felt. Besides misogynists like Hipponax, Antiphanes, Eubulos and others began to poison the minds of the people with degrading, insulting remarks about women and matrimony. As did for instance Hipponax by saying: “There are only two pleasant days in married life, the first, when you take your bride in your home, and the second, when you bury her.”—

And Eubulos is responsible for the sentence: “Deuce may take him, who marries a second time! I shall not scold him, that he took his first wife, as he did not know what was in store for him. But later on he knows that this evil is woman.”—

Euripides is responsible for the most degrading comment. He wrote the following lines:

The undermining effect of such remarks was increased by numerous comedies in which married life was turned to ridicule, and husbands were depicted as despicable slaves to women. So bye and bye the high position, formerly held by the female sex, sank to a much lower level. Their liberty was greatly curtailed, and daughters as well as wifes were confined to the strict seclusion of the “Gynäkonitis” or women’s quarters at the back of the house. Here they spent their time 53with spinning, weaving, sewing and other female work, not seeing or hearing much of the outside world. For this reason they were often nicknamed “the locked up,” or “those reared in the shadow.” As they rarely got out into the fresh air, they relied greatly on rouge and cosmetics, to hide their faded complexion. The only interruption in this monotonous life were the festivals of the various deities, during which they joined the solemn processions and carried the ceremonial implements and vessels on their heads.

As the education of the girls was greatly neglected, and as they generally married very early, they had no influence whatever on the male members of the family. They even didn’t appear at table with men, even with their husbands’ guests in their own homes. But the principal cause for the decline of woman’s, position and of family life in Hellas was the rise and growing prevalence of the “heteræ” or courtesans, many of whom became famous for their fascinating beauty and accomplishments. Clever in graceful dances, well educated in song, music and in the art of entertaining, these women, many of whom were natives of foreign countries, in time became constant guests of the symposiums of prominent citizens. Far outshining the housewives and their daughters in gracefulness and wit, they soon won a domineering influence over the all too susceptible men, many of whom became lost to their own neglected families.

The most striking illustration of this is offered by the life of the famous Athenian statesman Pericles, who fell victim to the charms of Aspasia, a courtesan born in Miletus, Asia Minor. Her extraordinary beauty and still more remarkable mental gifts had gained her a wide reputation, which increased after her association with Pericles. Having divorced his wife, with whom he had been unhappy, Pericles attached himself to Aspasia as closely as was possible under the Athenian law, according to which marriage with a “barbarian” or foreigner was illegal and impossible. And after the death of his two sons by his lawful wife he secured the passage of a law, by which the children of irregular marriages might be rendered legitimate. His son by Aspasia was thus allowed to assume his father’s name.

Aspasia enjoyed a high reputation as a teacher of rhetoric. It is said that she instructed Pericles in this art, and that even Socrates admitted to have learned very much from her. The house of Aspasia became the center of the most brilliant intellectual society. Men who were in the advance guard of Hellenic thought, Socrates and his friends included, gathered here.

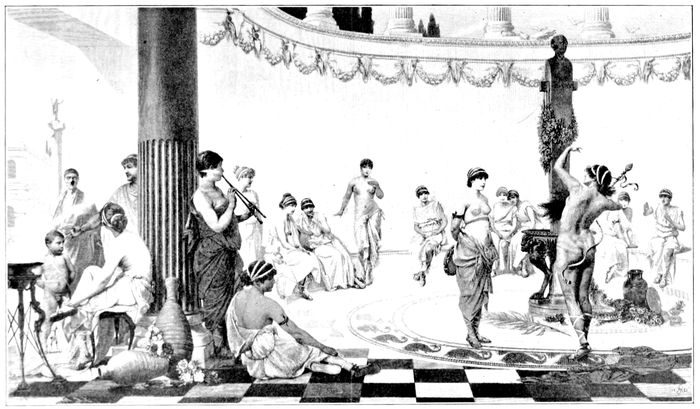

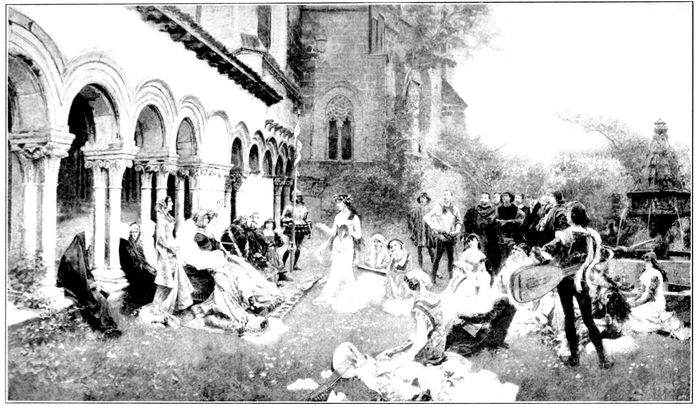

A DANCING LESSON IN THE TEMPLE OF DIONYSOS.

After a painting by H. Schneider.

55Another noted courtesan was Phryne, who by her radiant beauty acquired so much wealth that she could offer to rebuild the walls of Thebes, which had been destroyed by Alexander (335 B. C.), on condition that the restored walls bear the inscription, “Destroyed by Alexander, restored by Phryne, the hetære.” When the festival of Poseidon was held at Eleusis, she laid aside her garments, let down her hair and stepped into the sea in the sight of the people, thus suggesting to Apelles his great painting of “Aphrodite rising from the sea.” The famous sculptor Praxiteles too used her as a model for his statue “the Cnidian Aphrodite,” which Pliny declared to be the most beautiful statue in the world.

Anteia, Isostasion, Korinna, Phonion, Klepsydra, Thalatta, Danae, Mania, Nicarete, Herpyllis, Lamia, Lasthenia, Theis, Bachis and Theodota are the names of other courtesans, who became widely known for their relations with prominent men of Hellas and acquired enormous wealth.

Sappho, the famous poetess, whom Plato dignified with the epithets of “the tenth Muse,” “the flower of the Graces,” and “a miracle,” most probably belonged likewise to this class. It is said that she established in Mytilene a literary association of women of tastes and pursuits similar to her own, and that these women devoted themselves to every species of refined and elegant pleasure, sensual and intellectual. Music and poetry, and the art of love, were taught by Sappho and her older companions to the younger members of the sisterhood.

Hierarchical prostitution prevailed in Hellas. It was connected with the service of Aphrodite, the Greek counterpart of the Babylonian Mylitta. Strabo states, that in her temple of Corinth more than one thousand courtesans were devoted to the service of this goddess. The amount of money, earned by these girls and flowing into the priest’s treasury, was so enormous that Solon, the great statesman and law maker, envying the temples for such rich income, founded the Dikterion, a brothel of great style, the income of which went into the treasury of the state.

Enticed by the luxurious and easy life of such courtesans, thousands of young girls chose the same profession and entered the schools, which were established by many courtesans for the special purpose of giving instruction in all the arts of seduction. As the legislators, bribed by heavy tributes, were most liberal in giving concessions to these institutions as well as to prostitutes and keepers of brothels, public life became in time thoroughly demoralized. In fact these conditions were greatly responsible for the final decay and downfall of the whole Hellenic nation.

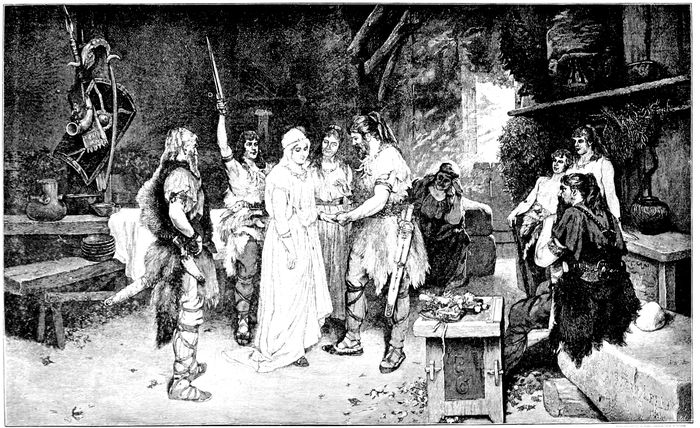

Among the various nations who in early times occupied the Italian peninsula, the Latins, Sabines and Etruscans were the most prominent. That among them barter and the forceful abduction of women was customary, is indicated by the well-known story of the “Rape of the Sabine Women” by the original settlers of Rome.