Title: Harper's Round Table, December 29, 1896

Author: Various

Release date: September 5, 2019 [eBook #60240]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 29, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xviii.—no. 896. | two dollars a year. |

Augustus Albumblatt, young and new and sleek with the latest book-knowledge of war, reported to his first troop commander at Fort Brown. The ladies had watched for him, because he would increase the number of men, the officers because he would lessen the number of duties; and he joined at a crisis favorable to becoming speedily known by them all. Upon that same day had household servants become an extinct race. The last one, the commanding officer's cook, had told the commanding officer's wife that she was used to living where she could see the cars. She added that there was no society here "fit for man or baste at all." This opinion was formed on the preceding afternoon when Casey, a sergeant of roguish attractions in G troop, had told her he would be a brother to her always. Three hours later she wedded a gambler, and this morning at six they took the stage for Green River, two hundred miles south, the nearest point where the bride could see the cars.

"Frank," said the commanding officer's wife, "send over to H troop for York."

"Catherine," he answered, "my dear, our statesmen at Washington say it's wicked to hire the free American[Pg 210] soldier to cook for you. It's too menial for his manhood."

"Frank, stuff!"

"Hush, my love. Therefore York must be spared the insult of twenty more dollars a month, our statesmen must be re-elected, and you and I, Catherine, being cookless, must join the general mess."

Thus did all separate housekeeping end, and the garrison began unitedly to eat three meals a day what a Chinaman set before them, when the long-expected Albumblatt stepped into their midst, just in time for supper.

This youth was spic-and-span from the Military Academy, with a top-dressing of three months' thoughtful travel in Germany. "I was deeply impressed with the modernity of their scientific attitude," he pleasantly remarked to the commanding officer. For Captain Duane, silent usually, talked at this first meal to make the boy welcome in this forlorn two-company post.

"We're cut off from all that sort of thing here," said he. "I've not been east of the Missouri since '69. But we've got the railroad across, and we've killed some Indians, and we've had some fun, and we're glad we're alive—eh, Mrs. Starr?"

"I should think so," said the lady.

"Especially now we've got a bachelor at the post!" said Mrs. Bainbridge. "That has been the one drawback, Mr. Albumblatt."

"I thank you for the compliment," said Augustus, bending from his hips; and Mrs. Starr looked at him and then at Mrs. Bainbridge.

"We're not over-gay, I fear," the Captain continued; "but the flat's full of antelope, and there's good shooting up both cañons."

"Have you followed the recent target experiments at Metz?" inquired the traveller. "I refer to the flattened trajectory and the obus controversy."

"We have not heard the reports," answered the commandant. "But we own a mountain howitzer."

"The modernity of German ordnance—" began Augustus.

"Do you dance, Mr. Albumblatt?" asked Mrs. Starr.

"For we'll have a hop and all be your partners," Mrs. Bainbridge exclaimed.

"I will be pleased to accommodate you, ladies."

"It's anything for variety's sake with us, you see," said Mrs. Starr, smoothly smiling; and once again Augustus bent blandly from his hips.

But the commanding officer wished leniency. "You see us all," he hastened to say. "Commissioned officers and dancing-men. Pretty shabby—"

"Oh, Captain!" said a lady.

"And pretty old."

"Captain!" said another lady.

"But alive and kicking. Captain Starr, Mr. Bainbridge, the Doctor, and me. We are seven."

Augustus looked accurately about him. "Do I understand seven, Captain?"

"We are seven," the senior officer repeated.

Again Mr. Albumblatt counted heads. "I imagine you include the ladies, Captain? Ha! ha!"

"Seven commissioned males, sir. Our Major is on sick-leave, and two of our Lieutenants have uncles in the Senate. None of us in the churchyard lie—but we are seven."

"Ha! ha, Captain! That's an elegant double-entender on Wordsworth's pome and the War Department. Only, if I may correct your addition—ha! ha!—our total, including myself, is eight."

The commanding officer rolled an intimate eye at his wife.

That lady was sitting big with rage, but her words were cordial still: "Indeed, Mr. Albumblatt, the way officers who have influence in Washington shirk duty here and get details East is something I can't laugh about. At one time the Captain was his own adjutant and quartermaster. There are more officers at this table to-night than I've seen in three years. So we are doubly glad to welcome you at Fort Brown."

"I am fortunate to be on duty where my services are so required, though I could object to calling it Fort Brown." And Augustus exhaled a smile.

"Prefer Smith?" said Captain Starr.

"You misunderstand me. When we say Fort Brown, Fort Russell, Fort Et Coetera, we are inexact. They are not fortified."

"Cantonment Et Coetera would be a trifle lengthy, wouldn't it?" put in the Doctor, his endurance on the wane.

"Perhaps; but technically descriptive of our Western posts. The Germans criticise these military laxities."

Captain Duane now ceased talking, but urbanely listened; and from time to time his eye would scan Augustus, and then a certain sublimated laugh, to his wife well known, would seize him for a single voiceless spasm, and pass. The experienced Albumblatt meanwhile continued, "By-the-way, Doctor, you know the Charité, of course?"

Doctor Guild had visited the great hospital, but being now a goaded man he stuck his nose in his plate, and said, unwisely: "Sharrity? What's that?" For then Augustus told him what and where it was, and that Krankenhaus is German for hospital, and that he had been deeply impressed with the modernity of the ventilation. "Thirty-five cubic metres to a bed in new wards," he stated. "How many do you allow, Doctor?"

"None," answered the surgeon.

"Do I understand none, Doctor?"

"You do, sir. My patients breathe in cubic feet, and swallow their doses in grains, and have their inflation measured in inches."

"Now there again!" exclaimed Augustus, cheerily. "More antiquity to be swept away! And people say we young officers have no work cut out for us!"

"Patients don't die then under the metric system?" said the Doctor.

"No wonder Europe's overcrowded," said Starr.

But the student's mind inhabited heights above such trifling. "Death," he said, "occurs in ratios not differentiated from our statistics." And he told them much more while they looked at him over their plates. He managed to say modernity and differentiate again, for he came from our middle West, where they encounter education too suddenly, and it would take three generations of him to speak clean English. But with all his polysyllabic wallowing, he showed himself keen-minded, pat with authorities, a spruce young graduate among these dingy Rocky Mountain campaigners. They had fought and thirsted and frozen; the books he knew were not written when they went to school; and so far as war is to be mastered on paper, his equipment was full and polished when theirs was meagre and rusty.

And yet, if you know things that other and older men do not, it is as well not to mention them too hastily. These soldiers wished they could have been taught what he knew; but they watched young Augustus unfolding himself with a gaze that might have seemed chill to a less highly abstract thinker. He, however, rose from the table pleasantly edified by himself and hopeful for them. And as he left them, "Good-night, ladies and gentlemen," he said; "we shall meet again."

"Oh, yes," said the Doctor. "Again and again."

"He's given me indigestion," said Bainbridge.

"Take some metric system," said Starr.

"And lie flat on your trajectory," said the Doctor.

"I hate hair parted in the middle for a man," said Mrs. Guild.

"And his superior eye-glasses," said Mrs. Bainbridge.

"His staring conceited teeth," hissed Mrs. Starr.

"I don't like children slopping their knowledge all over me," said the Doctor's wife.

"He's well brushed, though," said Mrs. Duane, seeking the bright side, "He'll wipe his feet on the mat when he comes to call."

"I'd rather have mud on my carpet than that bandbox in any of my chairs," said Mrs. Starr.

"He's no fool," mused the Doctor. "But, kingdom come, what an ass!"

"Well, gentlemen," said the commanding officer (and[Pg 211] they perceived a flavor of the official in his tone), "Mr. Albumblatt is just twenty-one. I don't know about you; but I'll never have that excuse again."

"Very well, Captain, we'll be good," said Mrs. Bainbridge.

"And gr-r-ateful," said Mrs. Starr, rolling her r piously. "I prophecy he'll entertain us."

The Captain's demeanor remained slightly official, but walking home, his Catherine by his side in the dark was twice aware of that laugh of his, twinkling in the recesses of his opinions. And later, going to bed, a little joke took him so unready that it got out before he could suppress it. "My love," said he, "my Second Lieutenant is grievously mislaid in the cavalry. Providence designed him for the artillery."

It was wifely but not right in Catherine to repeat this strict confidence in strictest confidence to her neighbor Mrs. Bainbridge over the fence next morning before breakfast. At breakfast Mrs. Bainbridge spoke of artillery re-enforcing the post, and her husband giggled girlishly and looked at the puzzled Duane; and at dinner Mrs. Starr asked Albumblatt, would not artillery strengthen the garrison?

"Even a light battery," pronounced Augustus, promptly, "would be absurd and useless."

Whereupon the mess rattled knives, sneezed, and became variously disturbed. So they called him Albumbattery, and then Blattery, which is more condensed; and Captain Duane's official tone availed him nothing in this matter. But he made no more little military jokes; he disliked garrison personalities. Civilized by birth and ripe from weather-beaten years of men and observing, he looked his Second Lieutenant over, and remembered to have seen worse than this. He had no quarrel with the metric system (truly the most sensible), and thinking to leaven it with a little rule of thumb, he made Augustus his acting quartermaster. But he presently indulged his wife with the soldier cook she wanted at home; and Mrs. Starr said that showed he dreaded his quartermaster worse than the Secretary of War.

Alas for the Quartermaster's sergeant, Johannes Schmoll, that routined and clock-work German! He found Augustus so much more German than he had ever been that he went speechless for three days. Upon his lists, red ink, and ciphering, Augustus swooped like a bird of prey, and all his fond red-tape devices were shredded to the winds. Augustus set going new quadratic ones of his own, with an index and cross-references. It was then that Schmoll recovered his speech and walked alone, saying, "Mein Gott!" And often thereafter, wandering among the piled stores and apparel, he would fling both arms heavenward and repeat the exclamation. He had rated himself the unique human soul at Fort Brown able to count and arrange under-clothing. Augustus rejected his laborious tally, and together they vigiled after hours, verifying socks and drawers. Next Augustus found more horse-shoes than his papers called for.

"That man gif me der stomach pain efry day," wailed Schmoll to Sergeant Casey. "I tell him, 'Lieutenant, dose horse-shoes is expendable. We don't acgount for efry shoe like they was men's shoes, und oder dings dot is issued.' 'I prefer to dake them oop!' says Baby Bismarck. Und he smile mit his two beaver teeth."

"Baby Bismarck!" cried, joyfully, the rosy-faced Casey. "Yo-hanny, take a drink."

"Und so," continued the outraged Schmoll, "he haf a Board of Soorvey on dree pound horse-shoes, und I haf der stomach pain."

It was buckles the next month. The allowance exceeded the expenditure, Augustus's arithmetic came out wrong, and another board sat on buckles.

"Yo-hanny, you're lookin' jaded under Colonel Safetypin," said Casey. "Have something."

"Safetypin is my treat," said Schmoll; "und very apt."

But Augustus found leisure to pervade the post with his modernity. He set himself military problems, and solved them; he wrote an essay on "The Contact Squadron"; he corrected Bainbridge for saying "throw back" instead of "refuse the left flank"; he had reading-room ideas, canteen ideas, ideas for the Indians and the Agency, and recruit-drill ideas, which he presented to Sergeant Casey. Casey gave him, in exchange, the name of Napoleon Shave-Tail; and had his whiskey again paid for by the sympathetic Schmoll.

"But bless his educated heart," said Casey, "he didn't learn me nothing that'll soil my innercence!"

Thus did the sunny-humored Sergeant take it, but not thus the mess. Had Augustus seen himself as they saw him, could he have heard Mrs. Starr— But he did not; the youth was impervious, and to remove his complacency would require (so Mrs. Starr said) an operation, probably fatal. The commanding officer held always aloof from gibing, yet often when Augustus passed him his gray eye would dwell upon the Lieutenant's back and his voiceless laugh would possess him. That is the picture I retain of these days—the unending golden sun, the wide, gentle-colored plain, the splendid mountains, the Indians ambling through the flat clear distance; and here, close along the parade-ground, eye-glassed Augustus, neatly hastening, with the Captain on his porch, asleep you might suppose.

One early morning the agent, with two Indian chiefs, waited on the commanding officer, and after their departure his wife found him breakfasting in solitary mirth.

"Without me," she chided, sitting down. "And I know you've had some good news."

"The best, my love. Providence has been tempted at last. The wholesome irony of life is about to function."

"Frank, don't tease so! And where are you rushing now before the cakes?"

"To set our Augustus a little military problem, dearest. Plain living for to-day, and high thinking be jolly well—"

"Frank, you're going to swear, and I must know!"

But Frank had sworn and hurried out to the right to the Adjutant's office, while his Catherine flew to the left to the fence.

"Ella!" she cried. "Oh, Ella!"

Mrs. Bainbridge, instantly on the other side of the fence, brought scanty light. A telegram had come, she knew, from the Crow Agency in Montana. Her husband admitted this three nights ago; and Captain Duane (she knew) had given him some orders about something; and could it be the Crows? "Ella, I don't know," said Catherine. "Frank talked all about Providence in his incurable way, and it may be anything." So the two ladies wondered together over the fence, until Mrs. Duane, seeing the Captain return, ran to him and asked, were the Crows on the war-path? Then her Frank told her yes, and that he had detailed Albumblatt to vanquish them and escort them to Carlisle School to learn German and Beethoven's sonatas.

"Stuff, stuff, stuff! Why, there he does go!" cried the unsettled Catherine. "It's something at the agency!" But Captain Duane was gone into the house for a cigar.

Albumblatt with Sergeant Casey and a detail of six men was in truth hastening over that broad mile which opens between Fort Brown and the agency. On either side of them the level plain stretched, gray with its sage, buff with intervening grass, hay-cocked with the smoky, mellow-stained, meerschaumlike canvas tepees of the Indians, quiet as a painting; far eastward lay rose-red long low hills, half dissolved in the trembling mystery of sun and distance; and westward, close at hand and high, lifted the great pale blue serene mountains through the vaster serenity of the air. The sounding hoofs of the troops brought the Indians out of their tepees to see. When Albumblatt reached the agency, there waited the agent and his two chiefs, who pointed to one lodge standing apart some three hundred yards, and said, "He is there." So then Augustus beheld his problem, the military duty fallen to him from Providence and Captain Duane.

It seems elementary for him who has written of "The Contact Squadron." It was to arrest one Indian. This man, Ute Jack, had done a murder among the Crows, and fled south for shelter. The telegram heralded him, but with boundless miles for hiding he had stolen in under the cover of night. No welcome met him. These Fort Brown[Pg 212] Indians were not his friends, and less so when he arrived wild drunk among their families. Hounded out, he sought this empty lodge, and here he was, at bay, his hand against every man's, counting his own life worthless except for destroying others before he must die.

"Is he armed?" Albumblatt inquired, and was told yes.

Augustus considered the peaked cone tent. The opening was this way, but a canvas drop closed it. Not much of a problem—one man inside a sack with eight outside to catch him! But the books gave no rule for this combination, and Augustus had met with nothing of the sort in Germany. He considered at some length. Smoke began to rise through the meeting poles of the tepee, leisurely and natural, and one of the chiefs said:

"Maybe Ute Jack cooking. He hungry."

"This is not a laughing matter," said Augustus to the bystanders, who were swiftly gathering. "Tell him that I command him to surrender," he added to the agent, who shouted this forthwith; and silence followed.

"Tell him I say he must come out at once," said Augustus then; and received further silence.

"He eat now," observed the chief. "Can't talk much."

"Sergeant Casey," bellowed Albumblatt, "go over there and take him out!"

"The Lootenant understands," said Casey, slowly, "that Ute Jack has got the drop on us, and there ain't no getting any drop on him."

"Sergeant, you will execute your orders without further comment."

At this amazing step the silence fell cold indeed; but Augustus was in command.

"Shall I take any men along, sir?" said Casey in his soldier's machine voice.

"Ah—yes. Ah—no. Ah—do as you please."

The six troopers stepped forward to go, for they loved Casey; but he ordered them sharply to fall back. Then, looking in their eyes, he whispered, "Good-by, boys, if it's to be that way," and walked to the lodge, lifted the flap, and fell, shot instantly dead through the heart. "Two bullets into him," muttered a trooper, heavily breathing as the sounds rang. "He's down," another spoke to himself with fixed eyes; and a sigh they did not know of passed among them. The two chiefs looked at Augustus and grunted short talk together; and one, with a sweeping lift of his hand out towards the tepee and the dead man by it, said, "Maybe Ute Jack only got three—four—cartridges—so!" (his fingers counted it). "After he kill three—four—men, you get him pretty good." The Indian took the white man's death so; but the white men could not yet be even saturnine.

"This will require re-enforcement," said Augustus to the audience. "The place must be attacked by a front and flank movement. It must be knocked down. I tell you I must have it knocked down. How are you to see where he is, I'd like to know, if it's not knocked down?" Augustus's voice was getting high. "I want the howitzer," he screeched generally.

A soldier saluted, and Augustus chattered at him.

"The howitzer, the mountain howitzer, I tell you. Don't you hear me? To knock the cursed thing he's in down. Go to Captain Duane and give him my compliments, and—no, I'll go myself. Where's my horse? My horse, I tell you! It's got to be knocked down."

"If you please, Lieutenant," said the trooper, "may we have the Red Cross ambulance?"

"Red Cross? What's that for? What's that?"

"Sergeant Casey, sir. He's a-lyin' there."

"Ambulance? Certainly. The howitzer—perhaps they're only flesh wounds. I hope they are only flesh wounds. I must have more men—you'll come with me."

From his porch Duane viewed Augustus approach and the man stop at the hospital, and having expected a bungle, sat to hear; but at Albumblatt's mottled face he stood up and said, "What's the matter?" And hearing, burst out: "Casey! Why, he was worth fifty of— Go on, Mr. Albumblatt. What next did you achieve, sir?" And as the tale was told he cooled, bitter but official.

"Re-enforcements is it, Mr. Albumblatt?"

"The howitzer, Captain."

"Good. And G troop?"

"For my double flank movement I—"

"Perhaps you'd like H troop as reserve?"

"Not reserve, Captain. I should establish—"

"This is your duty, Mr. Albumblatt. Perform it as you can, with what force you need."

"Thank you, sir. It is not exactly a battle, but with a, so-to-speak, intrenched—"

"Take your troops and go, sir, and report to me when you have arrested your man."

Then Duane went to the hospital, and out with the ambulance, hoping. But the wholesome irony of life reckons beyond our calculations, and the unreproachful, sunny face of his Sergeant evoked marches through long heat and cold, back in the rough, good times.

"Hit twice, I thought they told me," said Duane; and the steward surmised that one had missed.

"Perhaps," mused Duane. "And perhaps it went as intended, too. What's all that fuss?"

He turned sharply, having lost Augustus among his sadder thoughts, and here were the operations going briskly. Powder smoke in three directions at once! Here were pickets far out-lying, and a double line of skirmishers deployed in extended order, and a mounted reserve, and men standing to horse—a command of near a hundred, a pudding of pompous, incompetent, callow bosh, with Augustus by his howitzer, raising and lowering it to bear on the lone white tepee that shone in the plain. Four races were assembled to look on—the mess Chinaman, two black laundresses, all the whites in the place (on horse and foot, some with their hats left behind), and several hundred Indians in blankets. Duane had a thought to go away and leave this humiliation under the eye of Starr, for the officers were at hand also. But his second thought bade him remain, and looking at Augustus and the howitzer, his laugh returned to him.

It was an hour of strategy and cannonade, an hour which Fort Brown tells of to this day; and the tepee lived through it all. For it stood upon fifteen slender poles, not speedily to be chopped down by shooting lead from afar. When low bullets drilled the canvas, the chief suggested to Augustus that Ute Jack had climbed up; and if the bullets flew high, then Ute Jack was doubtless in a hole. Nor did Augustus contrive to drop a shell from the howitzer upon Ute Jack and explode him—a shrewd and deadly conception; the shells went beyond, except one, that ripped through the canvas, somewhat near the ground; and Augustus, dripping, turned at length, and saying "It won't go down," stood vacantly wiping his white face. Then the two chiefs got his leave to stretch a rope between their horses and ride hard against the tepee. It was military neither in essence nor to see, but it prevailed. The tepee sank, a huge umbrella wreck along the earth, and there lay Ute Jack across the fire's slight hollow, his knee-cap gone with the howitzer shell. But no blood had flown from that, because he was already then dead some time. One single other shot had struck him—one through his own heart, that had singed the flesh.

"You see, Mr. Albumblatt," said Duane, in the whole crowd's hearing, "he killed himself directly after killing Casey. But if your manœuvres with his corpse have taught you anything you did not know before, we shall all be gainers."

"Captain," said Mrs. Starr, on a later day, "you and Ute Jack have ended our fun. Since the Court of Inquiry let Mr. Albumblatt off, he has not said Germany once—and that's three months to-morrow."

"The giant I want to look at,"

Said Bobbie, "must be so tall

It'll take me a week and two other days,

To look at him all!"

Sandboys, in his stories of adventure told to Bob and Jack, had so frequently in past years alluded to Indians that it suddenly occurred to Bob to find out if possible just how far Sandboys's experiences with the original owners of the soil had gone. There had been Indians in this section of New Hampshire. The boys knew that well, for the names of many of the hills and rivers attested the fact—Pemigewasset, Ammonoosuc, Moosilauke—all these names were decisive evidence that the red men had once inhabited the region, and dominated it sufficiently to leave their names at least forever impressed upon it. Furthermore, the Great Stone Face that looked stolidly out over the placid surface of the little lake, less than a mile from the hotel, had connected with it many an Indian legend which the boys had from time to time picked up in the course of their stay.

But it was not with the Indian as an idea, a memory, that caught their fancy. They wanted to have something of the Indian of the present, a live Indian and therefore a bad one, and with this end in view they approached Sandboys one evening while waiting for their parents to come down to supper.

"Of course," Sandboys said in reply to their question—"of course there's been Indians around here, but there ain't any now. Civilization's driven 'em all out to Nebrasky an' Honnerlulu and other Western States where they can afford to live. They hung on here as long as they could, but when the hotels began to get built and a new set of prices for things was established in the section, they couldn't afford to stay, so they enervated out West."

"They what?" asked Bob, to whom Sandboys's meaning was not quite obvious.

"Enervated—skipped—moved out. That's the right word, ain't it?" asked Sandboys.

"Emigrated, I guess you mean," suggested Jack.

"That's it—emigrated. I allers gets enervated and emigrated mixed up somehow," Sandboys confessed. "Fact is, when words gets above two syllabuls they kerflummux me. I really oughtn't to try to speak 'em, but once in awhile they drop off my tongue without my thinking, and most generally they gets fractured in the fall. But as I was tellin' you, when it began to git expensive living here in the mountains, the Indians found they was too poor to keep in with the best society, and they energated to Nebrasky and other cheaper spots. I've allers felt that the government ought to remember that point, an' instid of sendin' the army out with cannon and shot to kill the Indians and git kilt itself, they should civilize the section by buildin' a half a dozen swell hotels an' charge people ten dollars a day for breathin' the air. That'll kill an Indian quicker'n anything—or if it don't, instid of goin' about scalpin' soldiers and hullaballoin' in war-paint, after one or two seasons he'll begin to make baskits out of hay an' bulrushes an' sell 'em to guests for eight dollars. From what I know about Indians, they'd rather sell a baskit worth ten cents for eight dollars than kill a man, a fact which the government doesn't seem to take notice of. I'd like to be put in charge of the Indian question for just one administration at Washington. You wouldn't hear about any more Piute or Siouks uprisin's in the West, but you would hear of a great increase in the hay-baskit industry and summer-hotel-buildin' trade."

"It sounds well," said Jack.

"I guess it does," said Sandboys. "It would work too."

"It might be dangerous for two or three seasons for the guests, though," said Bobbie. "I don't think I'd want to go to a place for the summer where the Indians were thick and still wild. I don't want to get scalped."

"Oh, you'd be all right as long as you wasn't a dude!" rejoined Sandboys. "Now that the dudes has taken to wearin' their hair long in the back, no wild Indian's goin' to bother with boys. There's no fun scalpin' a small boy, with football scalps in sight. You've hit on the great trouble about Indians, though," Sandboys added, reflectively. "You can civilize 'em. You can teach 'em Latin, Greek, French, or plumbing. You can teach 'em to dance and sing. You can make 'em wear swaller-tail coats and knickerbockers instead o' paint an' hoss blankets, but you can't entirely kill their taste for takin' hair that don't belong to 'em. It was on just that point that I had my only experience with Indians in this place here, and I tell you what there was lively times that summer. It nearly ruined this hotel, and if it hadn't been for me, I kind o' think it would have been goin' on yet.

"It was back in the eighties somewhere that it happened. I don't remember whether it was '87 or '88. Tennyrate, it was the year Mr. Hicks's boy Jimmie caught a five-pound bass in Echo Lake with his Waterbury watch. Ever hear about that? Funniest thing y' ever heard of. Jimmie Hicks was the liveliest little boy you ever saw. You two rolled into one wouldn't be half as lively. He was everywhere at once, Jimmie was. He's the boy that busted the hole in the roof with the elevator. Set the thing goin' up, couldn't stop it, and bang! first thing he knew the whole thing had smashed up through the roof and toppled over on its side. He had a watch—a Waterbury watch. His father got it for him just because it took an hour to wind it up, and that kept Jimmie busy for an hour a day, anyhow, an' he used to be doin' everything he could with it. I've seen him smash a black fly on the wall with it, usin' it like a sling-shot; but the queerest thing of the lot was his catchin' the bass with it. He was out in a boat, an' nothin' would do but he should trail that watch in the water after him. The bass he see it, thought it was a shiner, snapped at it, swallered it, and Jimmie pulls him in. Weighed five pounds an' three ounces on the office scales. It was that year we had the time with old Rocky Face—I don't remember his Indian name, but Rocky Face was what it meant in English.

"He was a quiet, peaceable, civilized old Indian, and the last of the old tribe that used to live about here. The others had fled to Nebrasky, as I told you, because they couldn't stand the expense of livin' in the White Mountains, but Rocky Face said they couldn't freeze him out. He'd been born here, and he was goin' to die here, if he had to steal a livin'. So he staid on, an' lived in an old pine-bough shanty he built for himself up on the other side of Mount Lafyette. What he fed on nobody knew, but[Pg 214] every once in a while he'd turn up at the hotel and ask what they'd charge to let him look at the clock, and everybody'd laugh, and call him a droll old Indian, and ask him to come back. Finally he got to makin' baskits and birch-bark canoes and bows and arrows, and he'd sell 'em to the guests. They took so many of 'em that Rocky Face soon got to earnin' twenty an' thirty dollars a day, an' when he got to that point he could afford a small back room in the hotel, and so he came here to live.

"He became one of what they call the features of the place, an' they got to puttin' his picture in the hotel perspectacle."

"Prospectus, do you mean?" queried Bob.

"Hyop. That's the thing," said Sandboys. "They put his picture in that as one o' the sights. They called him 'A Rollic of the Past: The last of the Pemmijehosophats.' He used to make a good many people nervous, the way he eyed their hair, for, as I've said, although he'd become more or less civilized, it wasn't in him not to covet other people's hair. About that time there was an awfully pretty girl here from down South somewheres—Conneticut, I think. She was a regular belle, and she had the finest yeller hair you ever see. Every night she'd be out rowin' on the lake with all the legible young men in the place; but all of a sudden she didn't come down to breakfast one morning. She had it sent up, an' her mother looked very anxious when she came down and said her daughter was very sick. Then two other ladies didn't appear any more, and a very well known old lady remarked in my hearin' that there was a thief in the house—she'd lost a switch. Well, that set me to thinkin', but I couldn't come to any conclusion until one night I took a pitcher of ice-water up to the Conneticut young lady's room, and, by Joe, there she sat readin', with scarcely no hair at all on her head."

"Scalped?" cried Bob, in horror.

"Not a bit of it," said Sandboys. "Robbed! An' then it all came to me. That old last of the Pemicans had spoke several times about her hair to me, an' I could see he was kind of thirsty for it, an' I made up my mind to two things. First was, Miss Conneticut's hair was nothin' but a wig; and second, old Rocky Face had it. I stole into his room that night when he was at supper and opened his trunk. Will you believe it, it was full o' false hair, an' in an old hat-box in one corner was the beautiful yeller locks of Miss Conneticut. That feller'd scalped enough bureaus to fill three good-sized mattresses."

"As much as that?" cried Jack.

"Hyop!" said Sandboys. "Most o' the ladies didn't like to mention it, but there was hardly one of 'em that hadn't lost two or three headsful to that old sinner, and I found it out. Of course I told the proprietor, and the hair was restored to its owners. Miss Conneticut appeared again, more popular than ever, and old Rocky Face was sent to jail, and he's never come out as I know of."

"Well, that is a singular story," said Bob.

"Isn't it," said Jack. "I should think Miss Conneticut ought to have been very much obliged to you."

"She was," replied Sandboys. "She gave me twenty-five dollars—five for findin' the wig, and twenty for keepin' quiet about it around the hotel. That's one reason I can't remember her real name."

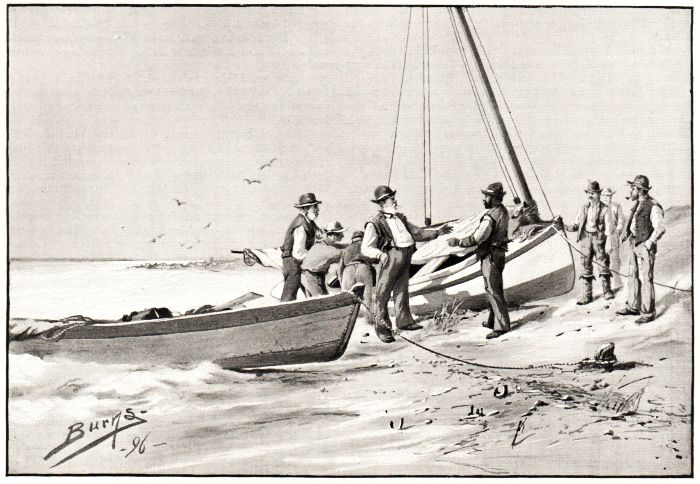

"Whoop! Bully!" That shout came from the wreckers, within fifty yards, just as Pete got the hook of the Captain's "gaff" into the gills of the bass, and Kroom himself hoisted the prize on board. Every ounce of their suspicion was gone in a moment, and the cat-boat tacked away; but just then Sam said, in a very low voice:

"There's that white thing, if it's a life-preserver. It's got stuck again."

In the other boat there was trouble. All the men noticed the Elephant with her extra passenger, now that she was near enough; and suddenly the man at the helm stood up and said:

"Captain Kroom did go to the wreck. I saw that big feller that's with him. He was on the Goshawk when the tug left her. We'd better watch Kroom and see if he's gropplin' on his own account. We can't do or say a thing unless we can pick up what was thrown over."

"Thrue for ye," replied the man next him. "Thin the inlet's the place to wait for thim. We can luk into his boat, sure."

"I'll tell you what, boys," said the steersman, "those fellers threw over more'll we know of. They'll come back for every pound of it, but we can beat 'em."

It looked as if their view of the matter was just as Captain Kroom had said. They had not the slightest idea but what it was entirely honest to do what they were attempting. Does not anything that drifts ashore belong to the land it is stranded on?

It is true that the laws of most countries and the rights of other men are against the wreckers, but they have a strong belief in a kind of "storm law." It is a law that reaches out into the sea sometimes, and covers anything which may be found floating around. It certainly takes in all that can be fished up from the bottom.

That is the general idea of the men who are known as wreckers. The cat-boat with these four men in it ran on into the inlet for quite a distance while they were talking about Kroom and the Goshawk and the tug-boats.

The place at which they had anchored was very near the bay side of the long sandbar island whose front was toward the ocean. Here they were entirely hidden, but at the same time they were unable to keep any watch upon the Elephant and the possible doings of her crew. This was not exactly what they intended, and before long the steersman arose and remarked to his mates:

"This won't do. You'd better put me ashore. I'll go over to the ocean beach and keep an eye on 'em. Glad I brought my glass along. 'Tisn't only old Kroom. Some o' the tug-boat fellers may have come back."

A pretty spirited debate followed, and all the while the weakfish and flounders were biting freely. They therefore were having pretty good luck in their ordinary character of fishermen.

In spite of that, however, they all seemed to feel very much as did their steersman, and the entire four at last decided to go ashore on the bar and walk over to watch Kroom. They left their boat, pulled all the way out of water, at the bay end of the inlet, and there was not another craft of any kind in sight when they began to trudge across the sand.

In the Elephant, slowly sailing along from its place of danger too near the surf, the course of affairs had been very interesting to its crew.

"Pete," said Sam, at the moment when the wrecker boat tacked away and the big sea-bass lay floundering fiercely on the bottom, "that's the largest fish I ever saw caught."

"Biggest kind!" responded Pete. "You or I couldn't have done anything with him. They generally catch 'em off shore, with a bass-rod and a reel. Tire 'em out, you know, before they try to pull 'em in. It's science!"

Sam had heard of such things, and it made a proud boy of him to find himself right in among what seemed to him the greatest fishing in all the world—unless, he thought, it might be fishing for sharks or whales. Captain Kroom himself had been a whaler, and Pete had been out shark-fishing. Sam was beginning to feel a good deal of respect for Pete, and he whispered to him:

"Why don't you try on that blue suit? It's as dry as a bone. See if it fits."

Captain Pickering must have heard him, for he said at once: "That's it, boy; put it on. What you need most is a new rig."

"Sam pulled it up," he said. "It's one of his fish."

"Fisherman's luck," laughed Captain Kroom, with a very deep, hearty laugh. "It's your share. Put it on."

Pete had eyed that suit until he knew every seam and button of it. Hour after hour during the cruise of the Elephant he had grown better and better acquainted with the strange idea that it was to be his own. He had hardly told himself how much more it must have cost than had any clothes he had ever owned before. "Guess I'll wait till I get home," he said.

"No, you don't," thundered Captain Kroom; "I want to see how you look in it. Put it on!"

Pete was pretty well accustomed to obeying the Captain, and not to do so now would have been something like mutiny on shipboard. He turned very red in the face, and he put on the trousers wrong side out the first trial, but then he got them right, and the blue shirt and the jacket followed.

"They fit him!" exclaimed Sam. "Make him look like another fellow."

So they all said, and it made little difference that Pete was still barefooted or that his straw hat turned up in front. It was an out-and-out sailor rig, and it had taken only a twinkling, or perhaps two or three twinklings, to get it on.

Meantime the Elephant had tacked to and fro, and Captain Kroom and Sam had kept their trolling-lines out. As for Captain Pickering, he had again opened his valise, and was now at work with his double-barrelled spy-glass, as Sam called it.

"Kroom," he remarked, "keep on fishing. Those chaps are in the inlet, out of sight, just now. One more tack and we can stretch on across the channel, not far from that buoy."

They all knew that he meant the bit of white float, the life-preserver, that was continually appearing and disappearing among the waves to the eastward.

"Now!" exclaimed Captain Kroom; but at that instant Sam shouted,

"Oh! Guess it's a bluefish!"

"Just the thing!" replied Kroom. "Pull! While you're getting him in we'll try for that float. It isn't a hundred yards away."

At that moment, unknown to the crew of the Elephant, the four wreckers were plodding along across the dry hot sand of the bar-island, eager to reach the seaward beach, from which they might discover what was going on inside of the tossing, foaming lines of the surf.

The life-preserver was nothing but a long India-rubber-cloth bag of wind, bent around in a ring. It was meant to be worn under the arms of a person in the water. There it was, bobbing to and fro on the water, but not getting along very well. The tide was strong, but there was a hitch as of something that dragged on the bottom.

"Got it!" exclaimed Pickering, as the Elephant swung around close to the float. "I'll fetch it up as quick as I can! Oh!"

He had not caught it, for it bobbed away from him as if it were dodging.

"Gaffed!" said Captain Kroom the next instant. "That's it, Pete. Now hold hard. Don't let it get away."

"I won't!" almost gasped Pete, tugging with all his might. "Can't you tack, Captain?"

The Elephant seemed to swing on her own account, so perfectly was she handled by the old sailor, but Pickering now had hold of the handle of the gaff, and it was not likely to get away from him.

"In she comes!" he said, but he was now grasping a rope that was knotted hard to the life-preserver.

"I'll let the boat kite along," said Kroom. "Don't let anybody see you pull that in."

He was keeping the sail of the Elephant full spread toward the bar and the inlet. That was why a man with a spy-glass, who came running down the beach and began to look, shouted back to some other men:

"There she comes! They're only trolling. They haven't stopped for anything. But the sail kind o' hides 'em."

The Elephant had not paused, to speak of, but behind her sail Captain Pickering was lifting something over her gun-wale.

"Conscience!" he exclaimed. "This here is part of my luggage that I thought went on the tug this morning. I saw all the rest of it stowed away safe enough, but I'd ha' lost this."

"Some o' the tug crews are the worst kind o' wreckers," remarked Captain Kroom. "We've beat 'em this time, unless there were some more life-preservers out."

"Guess not," said Pickering. "There isn't much in this that would be hurt by salt water. It's had a soak, that's all."

It was not so large a valise as the other, but it seemed as heavy. It was just the thing to keep a life-preserver under in deep water, and to let a strong current drag it along into shallows.

"Don't open it till you get ashore," suggested Kroom. "I'm heading the boat for the inlet. Cast off the float."

Pickering had already done that; but as the Elephant bowed her head and swung away, the life-preserver, although robbed of its precious drag, seemed to be following her.

"Pete," said Sam, "look! I can see those fellows."

"They've come over the bar to watch what we're doing," growled Kroom. "Pickering, now's our time to run through into the bay. I've an idea in my head. Can't you hide those things?"

Off came Pickering's coat, and down it went over the two valises, side by side. Next to them lay the handsome shapes of the bass and the two bluefish, and one more was added to these by Sam himself before they had sailed a hundred yards.

Only four fish, but they made a pretty good appearance. At all events, there was not a sign of recaptured wreckage on board the Elephant. Her crew and passengers could not hear the wreckers saying to each other: "Kroom's giving it up. He's off for home. We can go back now."

"Boys," it was the steersman, after a long squint through his glass, "I can see our float! She's coming. Let's go for the boat. Now's our time."

Perhaps so; but they had lost a great deal of time, and the Elephant was already in the inlet, running well, when they started back.

"Wish there was more wind," said Pickering, impatiently. "Their boat's over there somewhere."

"That's what I'm after," replied Kroom; "and I reckon we'll get there first."

That might depend a great deal on the strength of the breeze, and even more on the crookedness of the channel. Account had also to be taken of the fact that no man can do his fastest walking in yielding sea-sand.

"There it is!" said Pete. "Captain, they hauled their boat a'most out o' water."

"They can shove it in again quick enough," replied Kroom. "I don't know exactly what to do or say. The fact is, they're a prime good lot of fellows—hard-working, sober, peaceable. All of 'em go to meeting."

"Well, Kroom," said Pickering, "I knew a real partiklar feller once, and they said he'd been a pirate. I didn't quite believe it of him."

"Here we come!" responded Kroom, as the Elephant glided somewhat lazily around a sandy curve. "Jump ashore, Pete! Get there!"

Sam had already noticed how remarkably quick his long-shore comrade could be in his movements, but he was surprised now at the sudden elastic bound which took Pete out of the Elephant as she almost grazed the bank on that side of the inlet. Then away he went toward the wrecker boat, and his bare feet were the correct thing for sand-walking, or wading.

At that very moment the four bay fishermen came in sight, toiling along breathlessly under the hot sun, and the foremost of them shouted: "Hullo, Kroom! Want to see ye!"

"Come on!" roared Kroom. "We'll wait for ye! H'ist yourselves along. Plenty o' time!"

Pete was now at the hauled-out boat and was peering over into her, but he had not uttered a sound. He was thinking very fast indeed. "We've got 'em!" he said to himself. "What rascals they are! Who'd ha' thought it of 'em! This is what it means to be wrecked among wild savages. Take everything you have. But then they murder a fellow, and old Kroom says some of 'em eat him. Now I wonder what they'll say when they find they're caught?"

He did not have to wait long before he found out. Here came the Elephant, her sail slipping down as she ran her nose into the sand. Out stepped Captain Pickering, and at the same moment the four bay fishermen came in a hurry to the opposite side of the cat-boat.

"My quadrant!" shouted Captain Pickering. "Those two English guns of mine, and Captain Sanders's spare chronometer! It beats all!"

"Yours, are they?" loudly responded the steersman of the cat-boat. "Well, if I ain't glad to see ye! And old Kroom, too! I was wonderin' how we'd get 'em back to their owners."

"WHAT?" THUNDERED CAPTAIN KROOM. "JUST SAY THAT OVER

AGAIN!"

"WHAT?" THUNDERED CAPTAIN KROOM. "JUST SAY THAT OVER

AGAIN!"

"What?" thundered Captain Kroom. "Just say that over again!"

"Why, Captain," replied the fisherman, "them there insurance fellers are straight enough, but the tug-boat men are no better than so many river thieves. Reg'lar wreckers! We couldn't do a thing while they were around. Some of the Goshawk's crew were just as bad."

"Ye'd not belave me," put in another of the fishermen, "but it's so. They're all foreigners, ivery mon av thim. Not an American among thim. The dirthy spalpanes! It's bad enough for a mon to foind himself wrecked, widout bein' ploondered. We got away these things from the toog-boat min, but they threw over stuff and buoyed it to coom and get it. We was gropplin' for it the day. I hope ye're no wrecker, Captain Kroom. They say most o' thim owld sailors'll sthrip ony wreck."

The bronzed face of Captain Kroom was furious with indignation for a moment, and then he burst into a very deep-chested roar of laughter.

"Sam," whispered Pete, "think of their taking him and you and me for wreckers."

"They'll have to give up all those things, though," whispered back Sam.

The bay fishermen had no thought of doing anything else. They listened with keen interest to the account of the spar buoy, that had been set adrift without their knowledge. They seemed entirely satisfied with the capture of the life-preserver. In return, they told all they knew of the ways of the tug-boat men, and Pat Malone again and again asserted that "those chaps are all sorts, from iverywhere, and not wan American."

Captain Pickering was ready to pay the four very honest fishermen liberally for the time they had spent in watching the thieves and in grappling. It was quite dark, however, before the Elephant again had her crew on board.

"Biggest day I ever had," said Sam to Pete. "Let's come again, right away."

"Bully!" said Pete. "We'll come out with Captain Kroom."

"Come along, boys," put in the Captain. "We'll fish all summer. Glad there's more breeze to carry us home. Pickering, it's just as I told you. Our bay fishermen are honest. They' wouldn't cheat you in the weight of a flounder."

The moon came up, as if the new fresh breeze had brought it, and the homeward sail across the bay did great credit to the qualities of the Elephant. Nevertheless there was much tacking to and fro, while Pete and Sam listened to the two old sailors. There was really hardly anything for them to do but to exchange yarns about their voyages in the splendid clipper-ships which were now being driven from the seas by that terrible fellow, Steam.

"Pete," said Sam, as they stepped out at last upon the wharf, "ain't I glad I came."

"I'm glad you did," replied Pete; "but the Captain's going to take us out again, any day."

We did not proceed to sea, as it had been expected that we should, but we stretched several new sails, and the Captain marked them for alteration by the ship's sail-maker, much as a tailor changes the cut of a coat to secure a proper fitting. The men were made to take their positions at the guns, and I found that I had been made a second captain of the long 12-pounder, and was expected to work the roller handspike in getting her into position. For three long hours we were kept at this, slewing the guns hither and thither, aiming and gauging distance, and bringing powder and shot from the magazines. Of course we indulged in no firing, but served the pieces in pantomime.

The men appeared eager, and I could see that Captain Temple looked pleased at their performance. The majority were old hands, and needed little schooling. There is no use denying it, they jumped to the best of their ability. But my trial was soon to come. Most of the greenhorns had been enrolled into a company of marines. They were standing in an awkward row arranged in the waist, and keeping out of the way of the more experienced gunners who were indulging in the mimic battle.

"Debrin!" called a voice. "Pass the word for Debrin."

A squint-eyed bowlegged boatswain's mate was bawling about the deck.

For an instant I was so confused that I almost forgot the name I had assumed.

"Here!" I called at last, with my heart giving a wild leap into my throat. I gave over the roller handspike to my friend of the night before, and the boatswain's mate looked at me out of his crooked eyes.

"The old man wishes to speak to you," he said, in a low voice.

I stepped aft and pulled off my cap, as I had seen the other sailors do.

"Take hold of those gawk-legs and lick them into shape," said Captain Temple, apparently counting up my ribs as he looked me through and through. "You say you know the drill. There's a rack of muskets forward on the berth-deck, and a chest of cutlasses at the after-ladder. If any one gives you a sneer or a back word make him sweat his blood."

I hope that the quiver that went over me was not apparent, but I felt a cold sensation from my chest to the end of my spine. Now, as it happened, I had watched closely, as a boy, the drilling of the train-band at Baltimore, where I learned much from my friend the Major, and had once formed a company of my schoolmates at Mr. Thompson's, electing myself their leader. I tried to recall the orders of command and the positions as I marched the men below and armed them at the rack. But when I came back to the deck I was again seized with a fit of trembling that made me keep in movement to conceal it, for I perceived that those under me were watching with some curiosity to see what I should do. Besides this, it appeared to my imagination that all the crew were standing about with popping eyes, ready to laugh at me if I should open my mouth. So I took a long swallow, threw back my head and shoulders[Pg 218] (ah! there is nothing like it to keep up one's courage!) and adopting a terse mode of speech, I began to sift the men into military shape, according to their height.

My uncle had impressed one thing upon my mind as the surest way to obtain authority; it was not to make men hear, but to make them listen; so I did not shout, but endeavored to speak in low firm tones, explaining to the men as I gathered them into line how they should stand and hold themselves. Some were inclined to smile at first, and indeed I cannot blame them; for despite my size, my youth was evident, no matter my air of authority.

To those who appeared amused I kept repeating my instructions until the grin had faded from their faces, and at last I felt that feeling which expands the spirit of the holder of it—the sense of authority over others. So stepping out before them, I picked up a musket and began to drill them according to my recollection of the manual of arms.

If there had been an expert present, he might have found some fault with my method, but I got through without a hitch, and I might claim, without boasting, that I held attention. Over and over again we went through the motions. I was wondering whether there was to be no time limit to the drill, when suddenly some one spoke to me from behind.

"Very good, drill-master," said Mr. Bullard. "Dismiss the landsmen, and take up the boarders with some cutlass-work."

The muskets returned to the racks, I once more came on deck, and found that I had to face a very different ordeal. There, awaiting me, were thirty or forty sailor-men—I could see that at a glance. They regarded the idea of my instructing them as something of a huge joke, for they stood there open-mouthed and nudging one another, half sneering, and all whispering. As soon as I took the position of "on guard," I noticed that some of them fell into it at once involuntarily, but others displayed an awkwardness that I knew must be premeditated. Now was the time for me to stand or fall.

I stepped up to a tall man who topped me by half a head, and bidding him stand out, I gently pushed him into the right position, moulding him, as it were, and paying no attention to the anger which flashed in his eyes and drew the corners of his mouth. The rest were becoming interested, but I saw that they were not grinning at me now, but at their messmate. Satisfied that the man could do what I wished, I again gave the order for them to act together. The tall sailor twisted his cutlass in his hand and held it upside down. Once more, as if believing this came from sheer stupidity, I went through the same performance, trying to speak kindly and firmly, but really on the verge of breaking down. Three times did I do this, and then the man succumbed.

But I had not finished. On the left of the line was a short, thick-set foretopman, with brawny, tattooed arms. Apparently he considered himself beyond all this and an adept with the weapon, for he indulged in side remarks that set those near him tittering, and he exaggerated all my motions. I saw that he was a leader in his way, and that for comfort's sake I should have him with me, so I called the others to a rest, and bade this man step forward. He did so in a careless, jaunty way, although his face had reddened. Placing him before me, I told all hands to observe me closely; that I would show them the bad effect of too open a guard and too lowered a point. It was a dangerous game to play, perhaps, but I called upon the seaman to make the various cuts and thrusts at my head and body. He did so with a vengeance, and it took all my strength to keep him from reaching me.

Captain Temple and the other officers had gathered in a little knot to one side and were watching. My blood was up, and I would rather have died than fail in what I was attempting. So I called upon the man to guard himself, and assured him that I would not harm him. Keeping my wrist well up, I told him to have a care of his left cheek. He grinned in reply. By a quick motion, the secret of which Monsieur de Brienne had taught me (for he was an adept with the broadsword as well as with the rapier), I got inside the man's guard and laid my blade along his throat. I well believe I could have severed his head from his body with a backward draw-stroke. The man paled and clinched his teeth. I resumed my position, with my eyes fixed on his, for I feared mischief. Then using the same movement that I had in my encounter with Captain Temple, I twisted his blade from his grasp and sent it flying. I verily believe it would have gone overboard had it not caught a stay overhead. Picking it up myself before any one could reach it, I returned it to him, and he stepped back into the ranks. I had no more trouble after that.

Now, strange as it may seem, when I got away I went forward and leaned out of an open port, and there, for some strange reason, the strain under which I had been laboring almost overcame me, and it was all I could do to keep from sobbing or to control the shaking of my limbs. While crouched there I felt a hand laid on my shoulder, and looking up I saw it was Edmundson, the Third Lieutenant.

"The Captain wishes to speak to you in the cabin, lad," he said, kindly. "Jump aft."

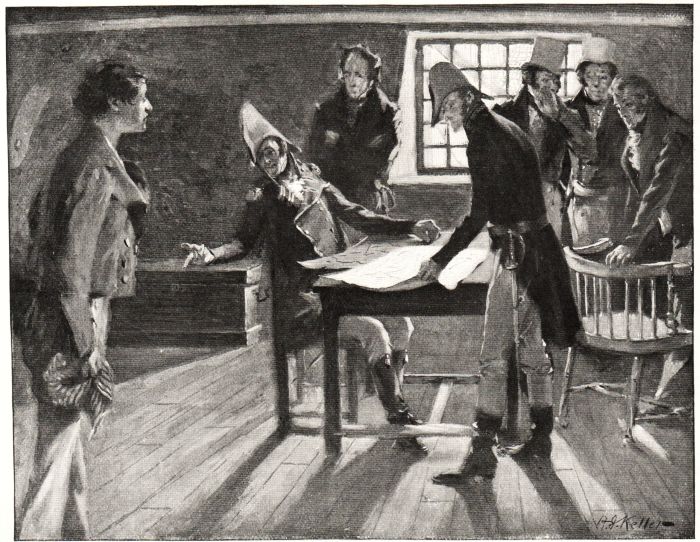

When I entered the plainly furnished little space, for the quarters of the officers were almost as confined as those of the crew, I saw that Captain Temple was sitting at the end of the table, which was covered with open charts. He looked up, and seeing who it was, half smiled.

"IF YOU ARE AS GOOD A SAILOR AS YOU ARE A SWORDSMAN, YOU

WILL END THIS CRUISE AN OFFICER."

"IF YOU ARE AS GOOD A SAILOR AS YOU ARE A SWORDSMAN, YOU

WILL END THIS CRUISE AN OFFICER."

"Debrin," he said, "you have done well. If you are as good a sailor as you are a swordsman, you will end this cruise an officer. This is more than I have ever said in the way of praise or promise to any living man. Forget it, and do your duty."

I could not have replied at this moment, for my wits left me; so I merely touched my forehead in salute, and went forward again. I could see that the men were whispering, and it was all I could do to hide my embarrassment. I believe that I was blushing like a schoolgirl.

The next day was a repetition of this one, albeit the work was quite easy for me, and I grew keen with the interest of it. The Fourth Lieutenant, a Mr. Spencer, arrived in the afternoon; and a sergeant, who had served in the army, was enlisted as a Lieutenant of marines. Apparently he found no fault with whatever they had been taught under my instruction, and Sutton, the man with whom I had had the passage of arms, came to me to learn the disarming stroke. As I met him more than half-way in this overture, we became friendly. In the afternoon I endeavored to get ashore (oh, how I wished to talk to Mary!), and I was delighted at being one of the crew that pulled Captain Temple to the wharf at six o'clock.

Captain Temple's stay on shore, however, had been short, consisting merely of a visit to Mr. McCulough's office (the latter was part owner of the Young Eagle), and I got no chance to run up into the town, as I had intended. My wish, if it were possible, to get another glimpse of Mary Tanner, was frustrated. This fortune was not to be mine. Oh, one thing that I almost came to forgetting: On the pier, standing in the crowd, was Gaston, his outrageous black hat tied about with a streamer and his long cloak flapping about his shanks. I doubt not the people were making fun of him. But he did not recognize me, and I breathed more freely.

As we rowed back to the ship, I heard the Captain say to a caderverous-looking man who had joined him at the dock with a big bundle and an oak chest,

"Well, Mr. Flemming, we sail on the early tide to-morrow."

The new-comer was the ship's surgeon, and one of the bowmen observed to me, as we got the gig up at the davits,

"Well, messmate, how would you like old sawbones there to take a hack at you—eh, Johnny?"

I might state, if I have not done too much bragging in this chapter already, that I had already received a nickname in the forecastle, and was known as "Johnny Cutlass," which, instead of resenting, I felt quite proud of.

The stays and running-gear were tested and made taut before the nightfall, and all sorts of stories went from lips to lips concerning our destination. Some said northward to the Gulf of St. Lawrence; others declared that the Spanish main would be our cruising-ground; while a few[Pg 219] asserted that nothing but the English Channel would please old "Kill Devil."

Now whither we were bound, of a truth I never found out, and of this I will speak at some length, and give a strange accounting. My, but I was tired when at last I got into my hammock!

Although it was very early in the morning when the tide was at the flood, a large crowd had gathered at the shore to watch us set sail. It was a damp, low-clouded day.

A fifer had been discovered among the landsmen, and hardly had I reached the deck, sleepily rubbing my eyes, when he began to pipe a merry jig step; the men fitted the capstan bars to the capstan, and while some scrambled aloft, as many as could lay hold and find foot room began trotting merrily about to the music. In came the cable, a couple of men alongside slushing it with water to keep the black mud off the deck, and slowly the Young Eagle walked up to her anchor. A slight breeze was blowing toward the mouth of the harbor, and the foresail and top-sail fluttered and caught it. A faint cheer sounded from the wharves, and the crew answered. Then the brass swivel on the forecastle cracked out a salute, and the privateer was off for adventures.

A wild exhilaration thrilled me, but I could see that I was not the only one affected in this manner. A double allowance of grog had been served as soon as we were under way. I tasted it, of course, and it burned my throat like fire, so that I handed my allowance to Sutton, thereby cementing the friendship that had sprung up between us, and it was not bad policy.

Soon Fishers Island and the mainland faded out in the blotch of gray fog that, despite the wind, hung all around. And now, as if to test the seamanship of the crew, sails were taken in and spread again, and as the wind increased the brig heeled over until the sea was roaring and tumbling along her rail, and the lower sails were wet with the splash of the spray as it flew across the deck. But there was no stopping the headway of the little vessel as she met the heavy ground-swell of the ocean. There was none of the thumping that I remembered hearing on board the old Minetta.

One great, hairy-chested fellow, as fine a specimen of a sailor as I ever saw, swung his arms about his head and gazed up at the swelling sails.

"Oh, oh! isn't she a beauty?" he exclaimed. "A darling ship! Ay, she's a sweetheart!"

There was an accent of love and of admiration in this that was not to be mistaken; his speech rang with a worshipfulness that was contagious. I caught it and could have shouted.

The last boat to leave the shore had brought off to the ship what appeared to me to be a load of old iron. Apparently short crowbars fastened on rings, and cannon balls welded together by solid bars of iron or attached to each other with short lengths of chain. Fearing to ask what they were, although I knew not, I waited for some landsman less ashamed of his ignorance than I to ask their meaning. My lanky friend who swung with me was the means of my finding out what I wished.

"What are they?" he inquired. "Those things in the boat?"

"Them's Yankee tricks," answered the squint-eyed quartermaster, "and four of them will do more damage in walking through a vessel's rigging than a frigate's broadside. They're British puzzlers."

They were the dreaded star-shot and chain-shot that the English had declared barbarous and inhuman in warfare, for what reason they or no one else could tell you; but they were fearsome things in battle, and this I had afterwards a chance to witness and can subscribe to.

About noon the wind had died away, and the fog thickened, and we drifted, heaving and rearing in the smooth round seas. I had more of a chance to observe the people whom I supposed I was to live with for the next few months. The great majority of them were fine Yankee seamen, men who had served on merchant-vessels or in the Marblehead fishing-fleet, typical Down-Easters, with a scattering of sailors who had seen service on board vessels of the navy. There were a few foreigners, Portuguese or Spaniards, I should judge, quick, active men with black hair and wiry frames. Some rough-looking characters there were, too, whose faces showed instincts not all the best, and, as I have said before, a scattering of countrymen making their first voyage filled out the complement.

The threshing and moving of the vessel seemed to discommode these latter, and many were ill, and wished themselves ashore, I take it, from their looks (one or two desired to die, I am sure). In the little steerage four or five prize-masters bunked together. They were mostly men past middle age, and had the appearance of broken down seafarers, and the majority of them were prone to the bottle habit, unless they belied their appearance. In all there were crowded on board the Young Eagle in the neighborhood of one hundred and thirty souls, perhaps more.

I have never seen any one so careful of detail as Captain Temple. He would permit no slouching in appearance, as well as duty. There was an attempt at uniform; and the forecastle, and in fact the whole vessel, was inspected by him as regularly as if she were a man-of-war.

Odd to relate, the skipper himself was a teetotaler when at sea, no matter what his behavior was when dry ground was beneath him. To show his carefulness and regard for neatness, I heard him rate a man severely for not being clean shaven. His own costume, in which he looked most picturesque, would have attracted attention anywhere. He wore his huge cocked hat set lightly athwartships on his head, his neat blue coat fitted his trim figure to a nicety, and his legs were encased in Hessian boots with gold tassels, like those of a dandy. In fact he was a handsome man to look at, and there were stories about his being a great favorite with the ladies.

Junior officers get their key from their commander, and although our Lieutenants did not present so fine an appearance or wear their clothes so well, they were a good-looking set, and all young men with the exception of Edmundson, who may have turned forty odd.

All night long the fog hung about us. We had been drilled during the day, and never have I seen a crew pick up so much knowledge in such a short space of time.

After breakfast on the second day the fog-bank lifted, and land was made out to the northwest. I heard one of the officers say that it was Montauk Point. A slight wind was stirring, and we sailed on, steering south by west, and by noon we had sunk the headland, and a cry came down from aloft that a sail was in sight to windward. We altered our course, and made in the direction of the stranger. An air of eagerness showed in the faces of the crew. I fairly believe that some of them began to count upon their share of prize-money. As the other vessel was approaching, soon we could see her from the deck.

She was bringing the wind with her, and had all sails set, stu'n'-sails and royals. Mr. Spencer went aloft, and took a squint from the cross-trees, through the glass. All hands were watching him, and the way he hastened down to the deck showed that he had something to communicate. This was evident, for immediately the Young Eagle was hove to, and then put before the wind.

"Old Kill Devil's changed his mind, I reckon," said Sutton, the foretopman, coming up to me. "And he wouldn't without good reason, you can bet a cotton hat. Now to my way of thinking, that vessel's an English frigate, unless it be one of our own, as the Johnnie Bulls generally sail in company."

It soon became evident that it was Temple's intention to give the on-comer as wide a berth as possible, for we spread every stitch we had, and steered a more westerly course. It was thick weather up aloft, and the sunlight barely filtered through it. But it was one of those days when distance is hard to judge, the sea one dead gray-green, with no flash or change in color, and nothing to tell whether the horizon was five miles off or twenty—nothing but the white sails of the approaching vessel, and occasionally a sight of the dark hull lifting underneath the canvas.

We were holding our own quite well, with perhaps a slight gaining on the pursuer, for such she had become,[Pg 220] when the fog began to lower, or better, we ran into it. It thickened, and soon we could see nothing but the heaving water fading into a gray wall at a distance of a few hundred feet.

We took in our kites, and squaring the yards, changed our course to the northward. The interest was less intense now, owing to the other vessel being out of sight, and Captain Temple's evident intention was to give her the slip and let her pass to the southward of us. For two hours we sailed on. It had grown lighter overhead, as if all the clouds had settled down upon us; but occasionally we caught a glimpse of sunlight and blue sky.

I lay on my back against the bowsprit with my hands under my head. I was thinking of the strange life that I had led, and wondering what my uncle thought of my strange disappearance. Why had old Gaston pursued me to Stonington, and what a lugubrious figure he had presented standing there on the dock in that strange head-gear! Of course this brought me to thinking of Mary also, and I put my hand inside the bosom of my shirt. There was the rose that she had given me, and that I had carefully pinned in a wrapping of strong paper. But my thoughts were interrupted by a sudden commotion. A man who had been aloft for some reason or other, disentangling the color halyards, which had fouled the main-truck, if I remember right, suddenly gave a shout.

"Sail, ho, to windward!" he cried. And never have I seen a man get to deck so quickly. He jumped the last twelve feet off the ratlines to the deck, and ran aft. Temple and Mr. Edmundson came forward to meet him. What he said was heard distinctly.

"I can make out the topsails of a vessel above the fog, sir, not much above a mile to windward. She's bearing down upon us."

The way that Captain Temple tripped aloft showed that he was a topman, and one of the best. Edmundson, although a larger man, was not far behind them. And all hands watched them make their way to cross-trees and swarm up higher. Then we could see they were pointing. Quickly they descended to the deck. Mr. Spencer, and Bullard, and the prize-masters had all come on deck. The crew also were gathered amidships.

"It's the English frigate," said Temple, in a whisper. (As I was standing close by I caught the words distinctly.) "She must have us in sight from aloft. Our top-gallant-masts are plain to view. Ecod, we'll fool them, though," he cried, "if this fog holds."

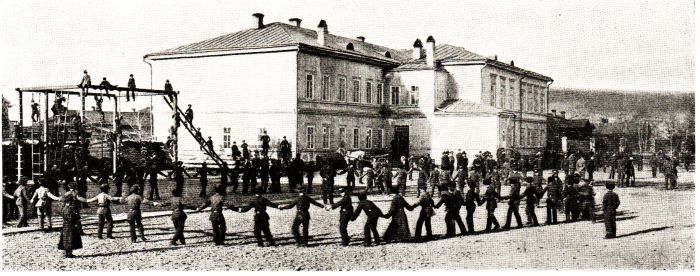

The word Siberia recalls a broad yellow space across the map of northern Asia, with a dot here and there for a town with an unpronounceable name; and that is about all any of us knew of Siberia when your father and I were boys. But we are beginning to learn better, and the person old or young who now speaks of that country as a barren stretch of forests and marshes, where the people wear furs most of the time, and live mainly on seal-blubber, shows himself far behind the times.

STARTING OFF FOR A HOLIDAY.

STARTING OFF FOR A HOLIDAY.

I must confess, however, that the schools of Siberia are a little ahead of what I expected to see when I made a flying trip across the country last year. My journey was from the Pacific coast to Russia, and, in winter, by more than 3000 miles of sledge travel. It extended from Habarofsk, at the junction of the Amoor and Ussuri rivers, northeast of Peking, to the city of Krasnoyarsk, which at that time was the terminus of the railway which the Russian government is rapidly building from Moscow to the Pacific coast. This route led me through the principal cities of Siberia, and I was able to stop in most of them a few days, and thus to see many places and things of interest. Many of these cities are large and handsome towns; and as all lie in the southern part of the country, where the climate and soil are much like those of eastern Canada, they are surrounded[Pg 221] by wide farming tracts, lumbering districts, and mines, and have a trade that reaches to great distances. These are old towns, too, for it must not be forgotten that Siberia has been growing civilized during 250 years, or about as long as the United States itself, and they are often populous also, since Irkootsk, where the Governor-General of Western Siberia lives, has about 80,000 people; Tomsk, the university town, has 30,000; Blagovestschensk, the largest city in Eastern Siberia, 40,000; and half a dozen others 10,000 or 12,000 more. They have water-works, electric lights, police and fire departments, theatres, and all the rest that belongs to a wide-awake town; but they are proudest of their schools and the institutions of religion and public charity.

THE RING GAME AND OPEN-AIR GYMNASIUM.

THE RING GAME AND OPEN-AIR GYMNASIUM.

In every city the central school-house, or gymnasium, as it is called, is one of the largest, most costly buildings, and often is surrounded by fine grounds, while within it are the best appliances that can be had. In many of them, for example, each pupil has a little desk to himself; and these are adjustable, and fitted to him, so that the short-legged youngster may have a low seat, while his next neighbor, who may be tall and thin, enjoys a higher one. This is more than most American schools can show. The walls are covered with blackboards, maps, and pictures, and always, at least in the principal rooms, there is a portrait of the Emperor, whom the Russian people often speak of as their Little Father, meaning he is next in their love and respect to the Great Father in heaven. You will notice these and some other things in the illustrations of one of the school-rooms in Krasnoyarsk, which, as well as the other pictures, has been made from a photograph taken by one of the teachers there.

Several other things are noticeable in that scene. You will observe that the right-hand corner is cut off, as if by a chimney; but this is the stove—the chimney being above it. The Russian stove is a small chamber built up of bricks, in the base of which is a fire-box, whose door in this case is hidden by the blackboard. A rousing wood fire is built in the early morning, then the doors are closed, and the dampers so regulated that the heat from the mass of coals permeates the brick walls, which diffuse a genial warmth throughout the room for the rest of the day.

HOT TEA FROM THE SAMOVAR AT A PICNIC.

HOT TEA FROM THE SAMOVAR AT A PICNIC.

In the left-hand corner is hung the ikon, with its ever-burning lamp, found in every Russian house or public room, great or small, and which usually consists of one or more framed tablets that contain carvings or paintings of the head of Christ, with perhaps other subjects relating to the Saviour. It is the sacred symbol of religion in the Russian (or Greek) Church, like the crucifix in the Roman Church. Their religious duties are never forgotten by the Siberians, and form an important part of the school life. Each school has a chapel—often richly decorated; and to it is attached a chaplain or priest, who holds religious services there every morning and gives instruction in sacred subjects. One of these priests is sitting at the back of this room, as you may see by his robe and his long hair, parted in the middle, and his golden cross; these are the signs of his office. He has a kindly face, and is, no doubt, the friend of every boy in the establishment.

Next to him is seated the principal—a hearty-looking man, dressed, as usual, in military uniform—and other visitors, for this is evidently an examination day. A teacher stands at the blackboard, and perhaps has asked a question which the lad before him has been unable to answer,[Pg 222] for he has turned to another boy, who has risen at his desk as though to give the needed reply. One need not go outside our Yankee school-rooms to make a similar picture any day; but he would never see in this country the abacus, which is used all over Siberia, China, and Japan by pupils and teachers in their arithmetic lessons, and by merchants in their stores, instead of the pencil and paper with which we do sums too large for head-work. It is a very ancient device, and the boys who went to school in Rome before Cæsar wrote that all Gaul was divided into three parts, or Virgil declared "Arma virumque cano," learned their multiplication table by the help of its sliding balls.

THE SKATING-POND.

THE SKATING-POND.