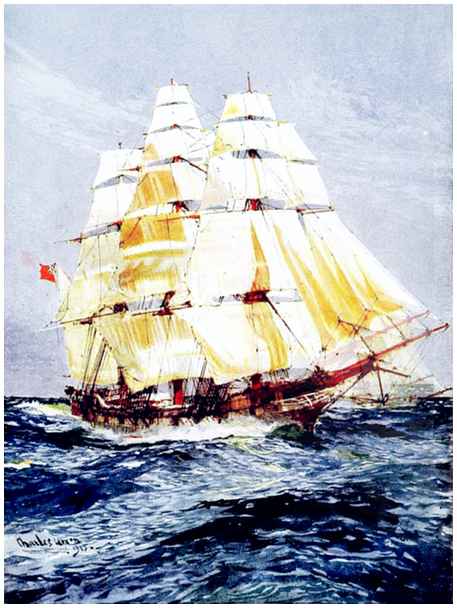

A SHIP OF YESTERDAY

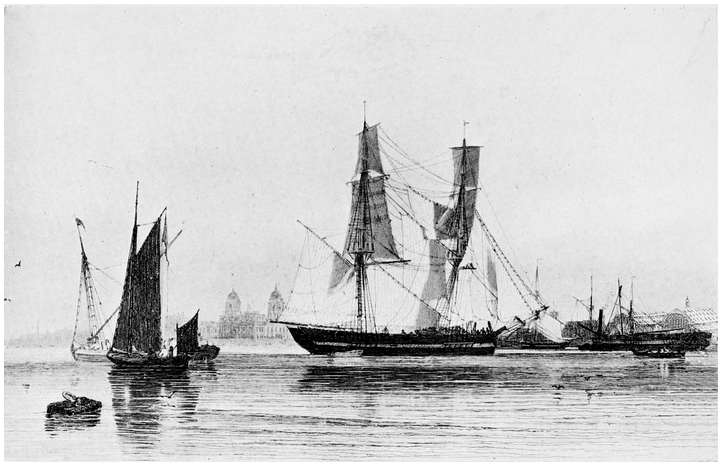

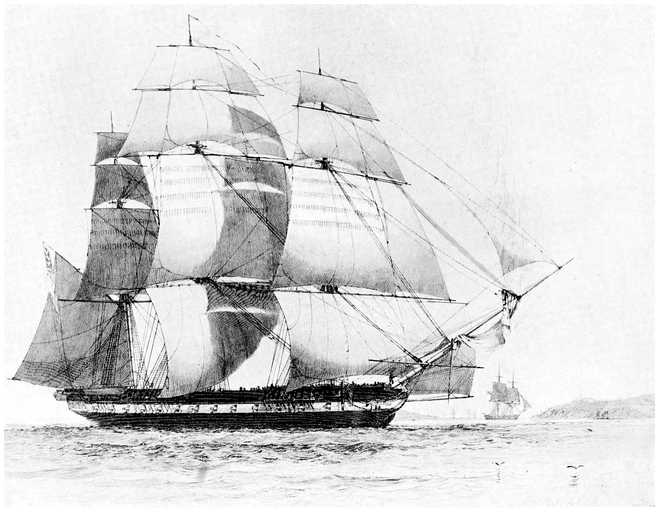

(A Tea-clipper before the Wind)

Title: Ships & Ways of Other Days

Author: E. Keble Chatterton

Release date: September 2, 2019 [eBook #60226]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by deaurider, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

Cover created by Transcriber from pages in the original book. The

result remains in the Public Domain.

A SHIP OF YESTERDAY

(A Tea-clipper before the Wind)

SHIPS & WAYS

OF OTHER DAYS

BY

E. KEBLE CHATTERTON

(Author of “Sailing Ships & Their Story”)

WITH ONE HUNDRED AND

THIRTY ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

SIDGWICK & JACKSON, LTD

3 ADAM STREET, ADELPHI, W.C.

1913

vii

All rights reserved

SHIPS AND WAYS OF OTHER DAYS

PREFACE

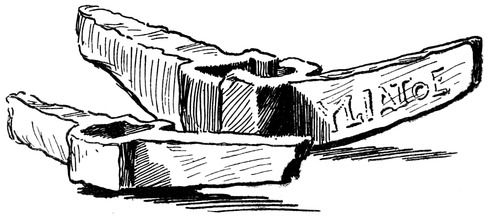

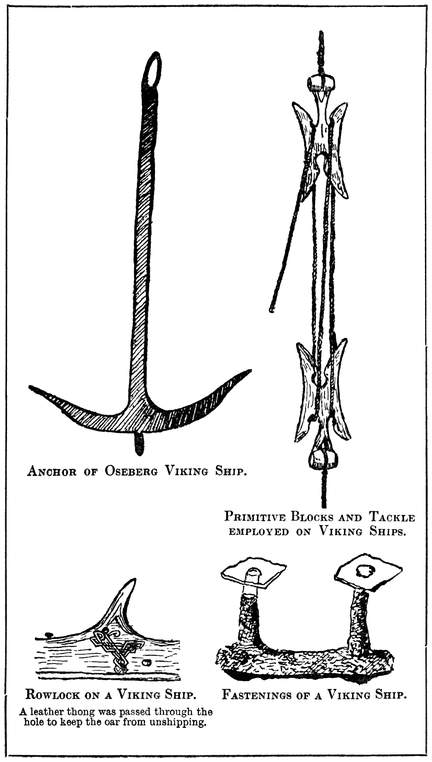

I desire to acknowledge the courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge, for having permitted me to reproduce the three illustrations facing pages 212, 228, and 230. These are from MSS. in the Pepysian Library. The Viking anchor and block tackle are taken from Mr. Gabriel Gustafson’s Norges Oldtid, by permission of Messrs. Alb. Cammermeyer’s, Forlag, Kristiania. The two illustrations on pages 123 and 132 are here reproduced by the kind permission of Commendatore Cesare Agosto Levi from his “Navi Venete.” The Viking rowlock and rivet are taken from Du Chaillu’s “Viking Age,” by the courtesy of Mr. John Murray. To all of the above I would wish to return thanks.

E. Keble Chatterton.

ix

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| List of Illustrations | xi | |

| I. | Introduction | 1 |

| II. | The Birth of the Nautical Arts | 10 |

| III. | The Development of the Marine Instinct | 18 |

| IV. | Mediterranean Progress | 29 |

| V. | Rome and the Sea | 56 |

| VI. | The Viking Mariners | 85 |

| VII. | Seamanship and Navigation in the Middle Ages | 114 |

| VIII. | The Period of Columbus | 150 |

| IX. | The Early Tudor Period | 169 |

| X. | The Elizabethan Age | 186 |

| XI. | The Seventeenth Century | 221 |

| XII. | The Eighteenth Century | 249 |

| XIII. | The Nineteenth Century | 274 |

| Glossary | 291 | |

| Index | 293 |

xi

| PAGE | |||||||||||||||||||||||

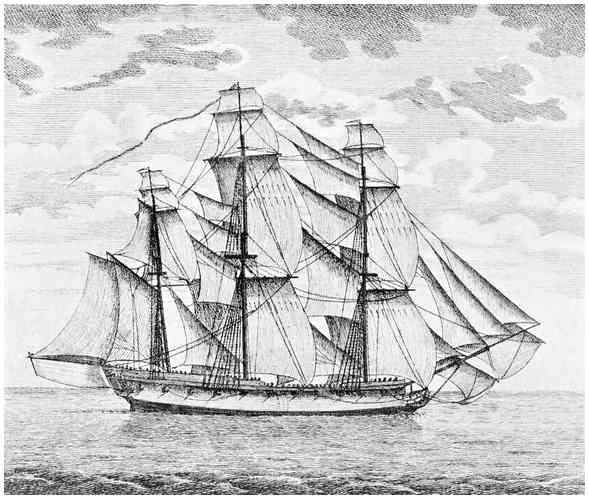

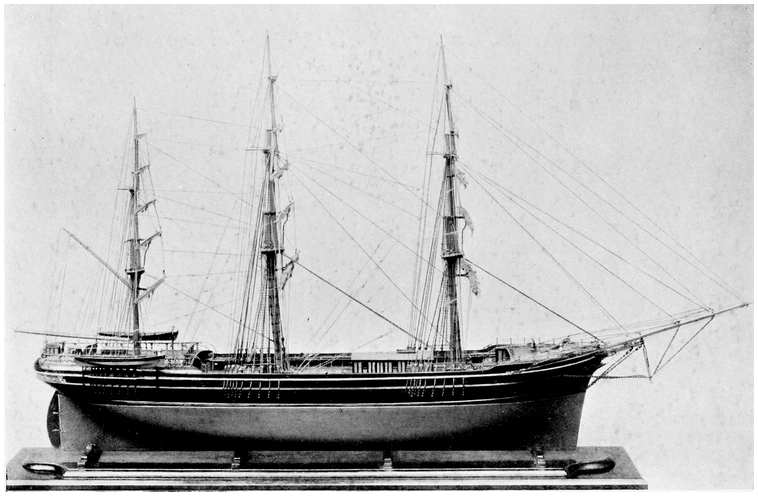

| A Ship of Yesterday (a tea clipper before the wind) To face title-page | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| A Seventeenth-Century Dutch Dockyard Headpiece to Preface | |||||||||||||||||||||||

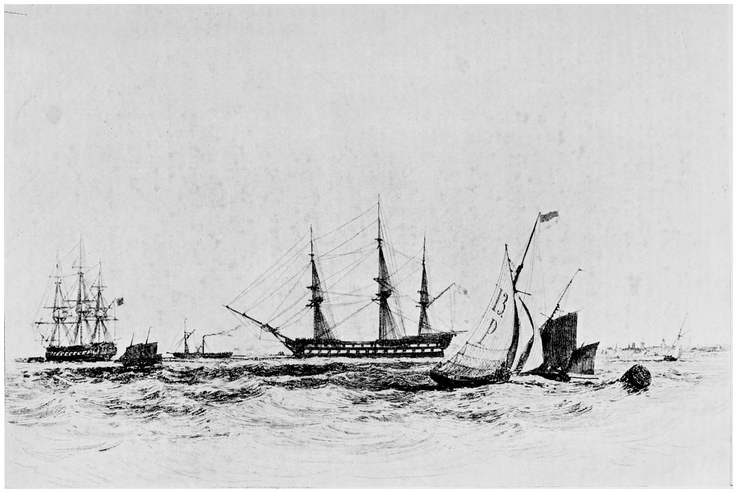

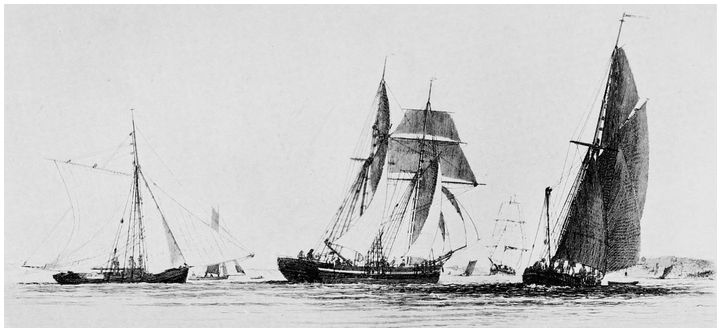

| Spithead in the Early Nineteenth Century | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old-fashioned Topsail Schooner | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| “River sailors rather than blue-water seamen” | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

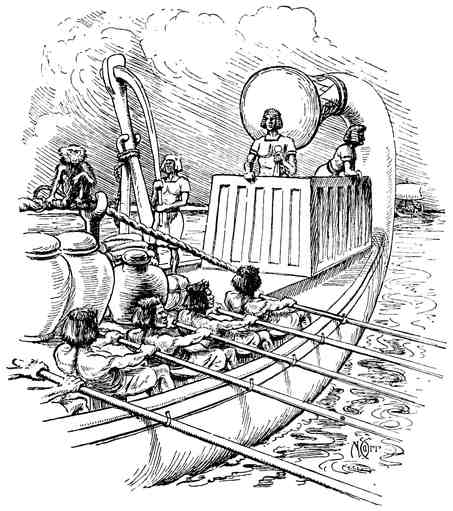

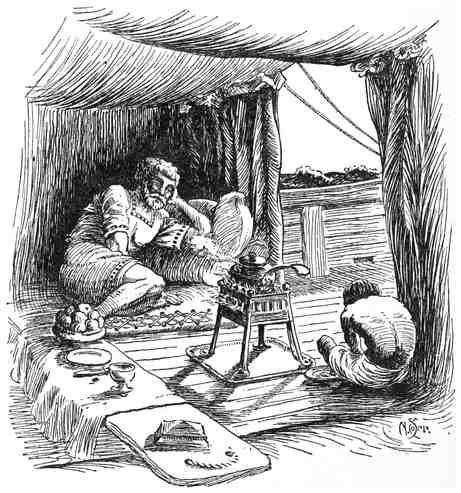

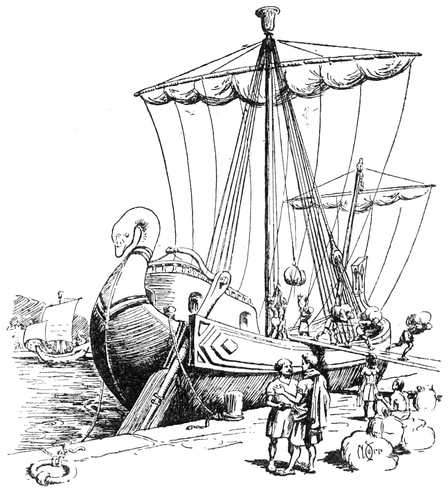

| “Mine be a mattress on the poop” | 34 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cast of a Relief showing Rowers on a Trireme | 38 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vase in the form of a Trireme’s Prow | 42 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

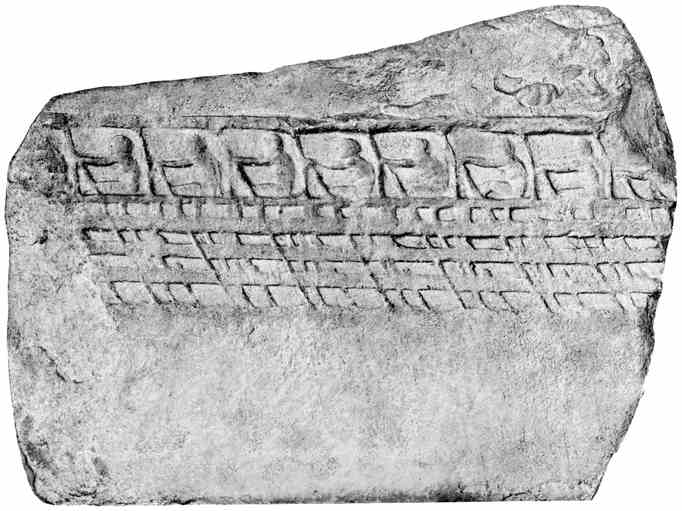

| Portions of Early Mediterranean Anchor | 44 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shield Signalling | 49 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Greek Penteconter from an Ancient Vase | 51 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Egyptian Corn-Ship Goddess Isis | 58 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| The “Korax” or Boarding Bridge in Action | 63 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

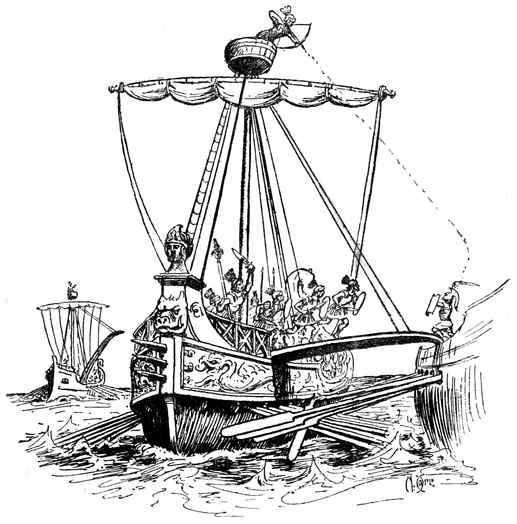

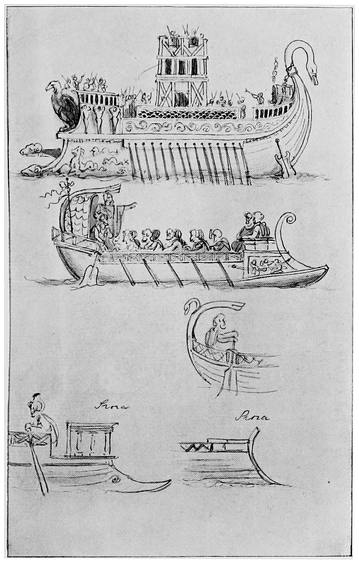

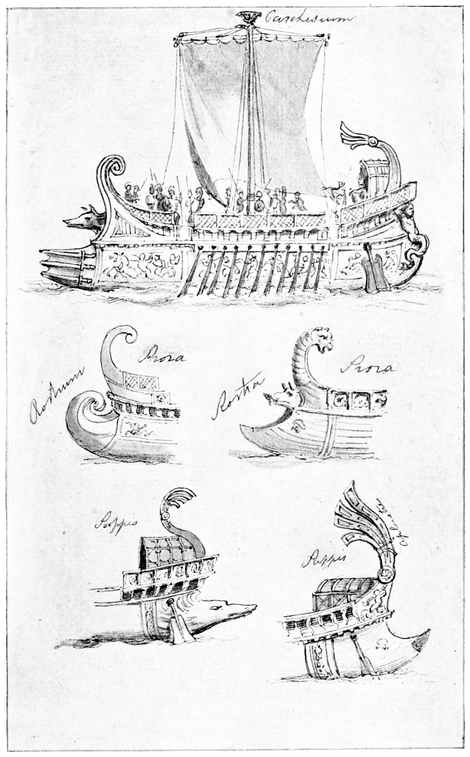

| Sketches of Ancient Ships, by Richard Cook, R.A. | 64 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ancient Coins illustrating Types of Rams | 65 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bronze Figurehead of Roman Ship | 66 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sketches of Ancient Ships, by Richard Cook, R.A. | 66 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

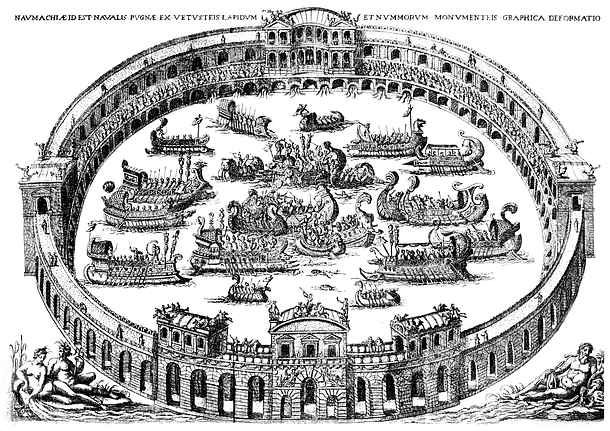

| Two Coins depicting Naumachiæ | 68 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A Roman Naumachia | 68 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

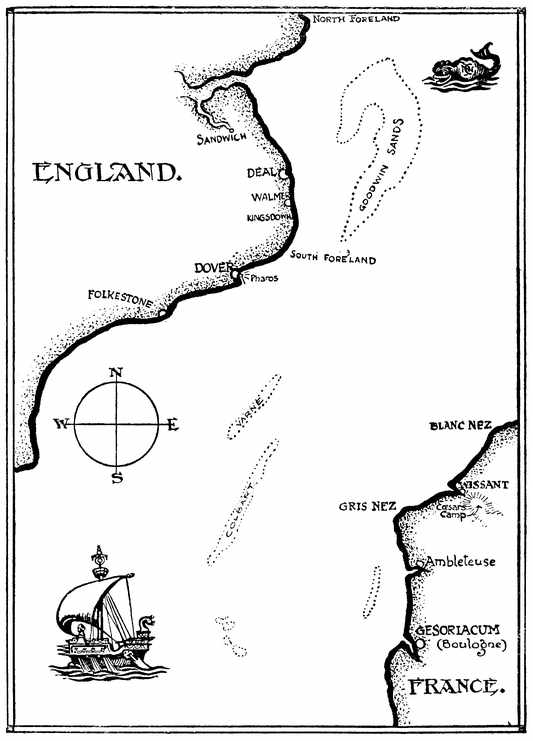

| Chart to illustrate Cæsar’s crossing the English Channel | 71 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

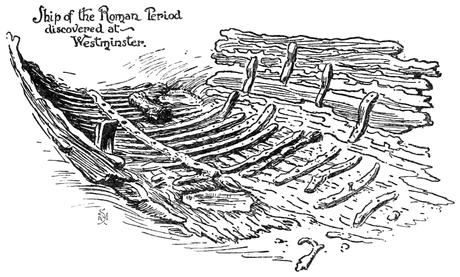

| Hull of Roman Ship found at Westminster | 78 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

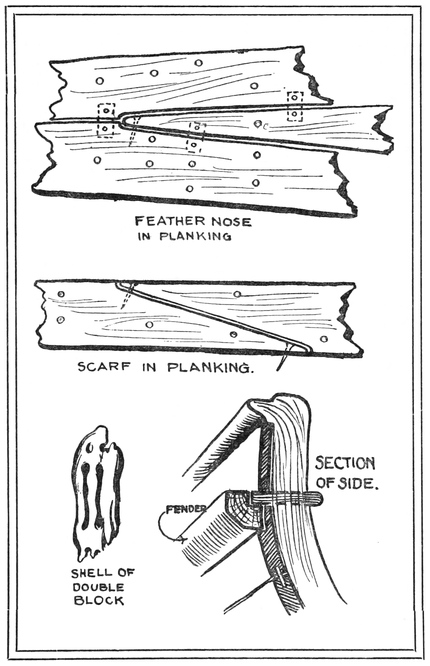

| Details of Roman Ship found at Westminster | 80 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Details of Roman Ship found at Westminster | 82xii | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Primitive Navigation of the Vikings | 89 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

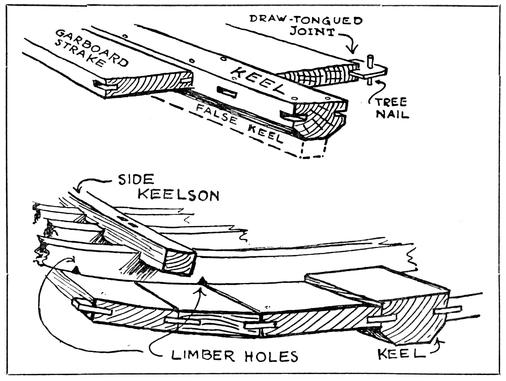

| Details of Viking Ships and Tackle | 99 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vikings boarding an Enemy | 102 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

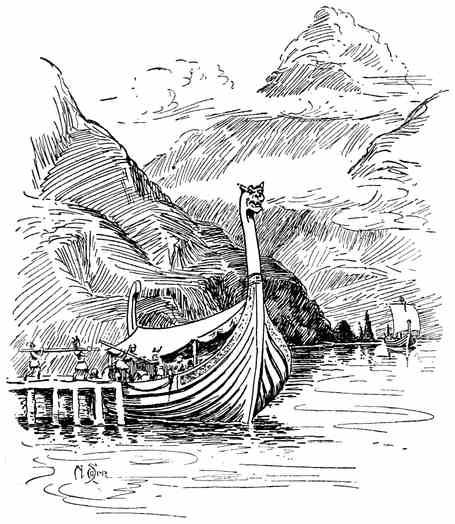

| Viking Ship with Awning up | 111 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

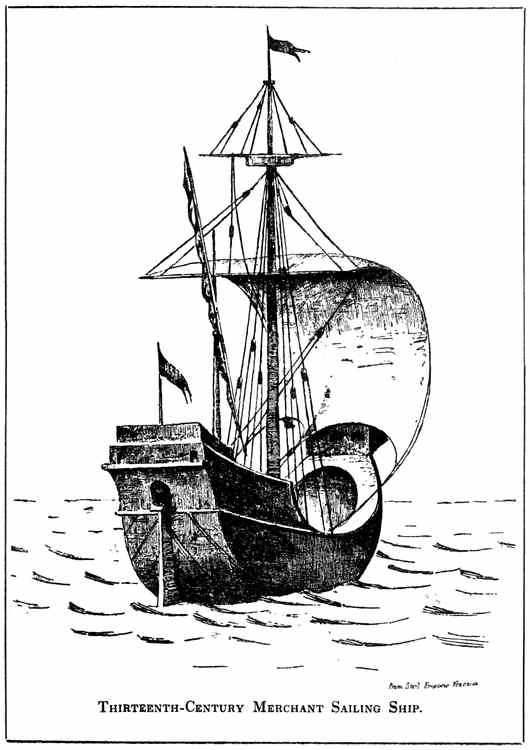

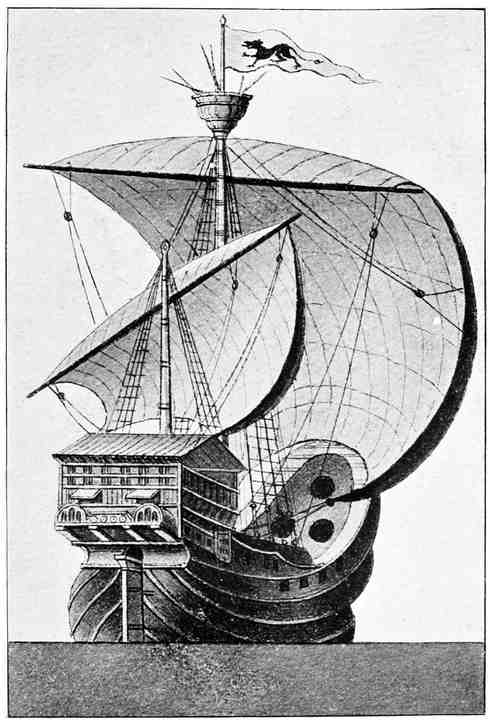

| Thirteenth-Century Merchant Sailing Ship | 123 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

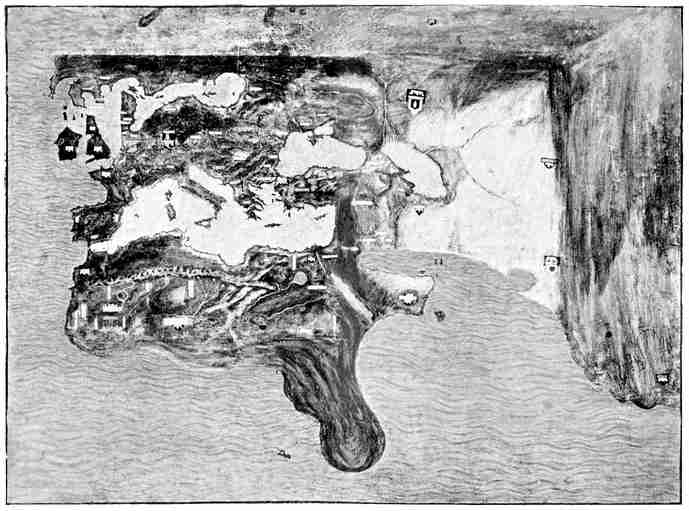

| Fourteenth-Century Portolano of the Mediterranean | 124 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prince Henry the Navigator | 126 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

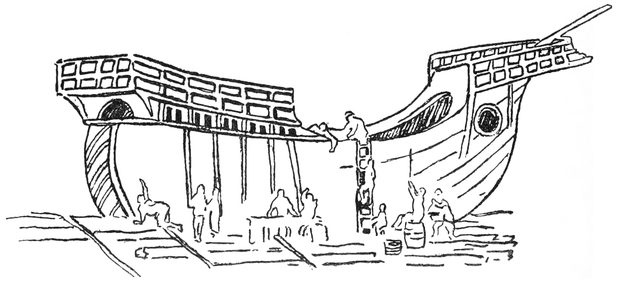

| Fifteenth-Century Shipbuilding Yard | 132 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

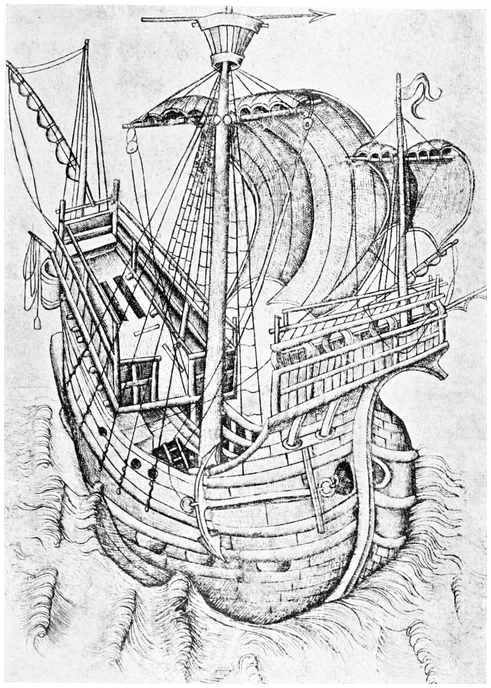

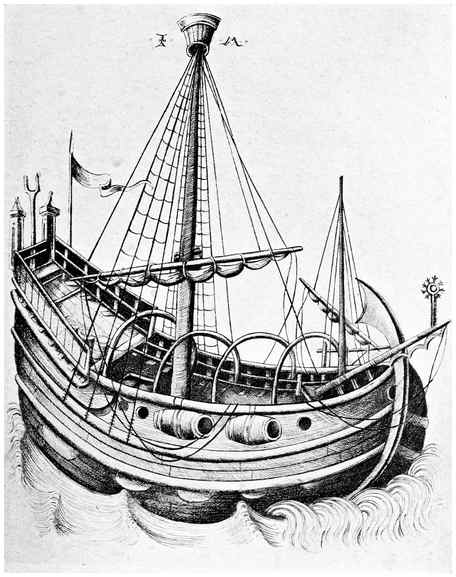

| A Fifteenth-Century Ship | 134 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

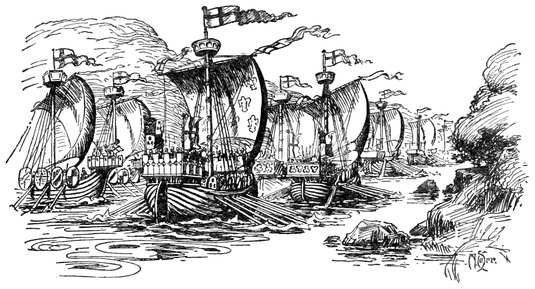

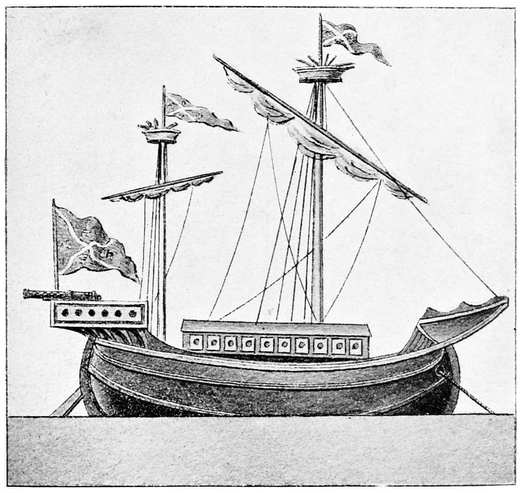

| The Fleet of Richard I setting forth for the Crusades | 139 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A Medieval Sea-going Ship | 146 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

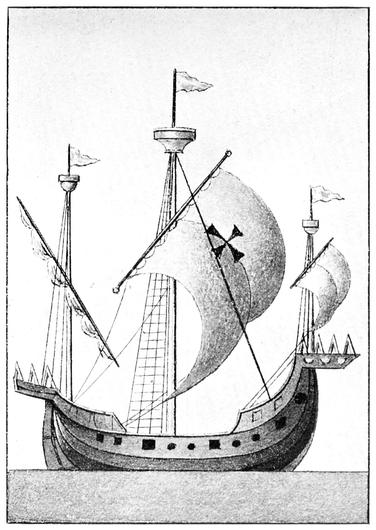

| Fifteenth-Century Caravel, after a Delineation by Columbus | 158 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

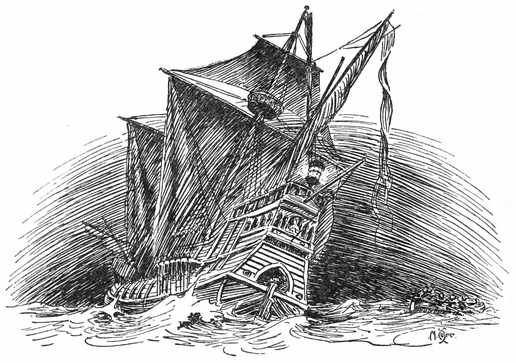

| “Ordered the crew ... to lay out an anchor astern” | 162 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fifteenth-Century Caravel, after a Delineation by Columbus | 164 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

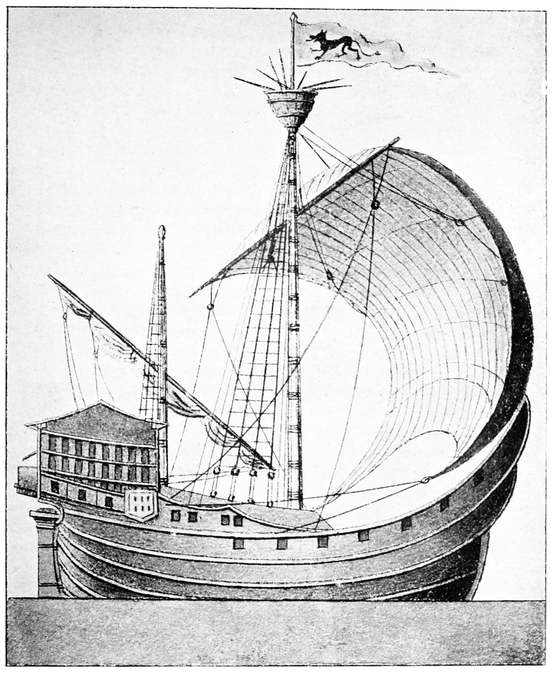

| Three-masted Caravel | 166 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

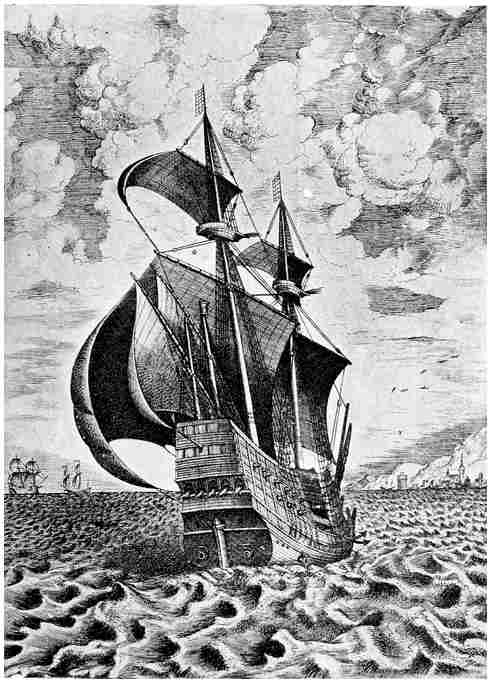

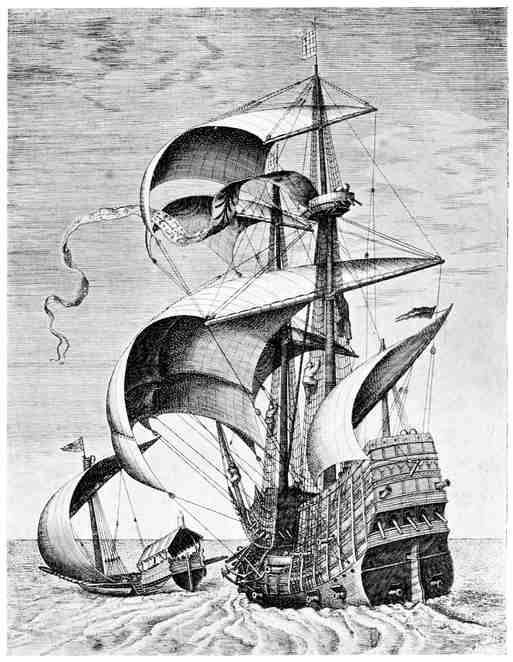

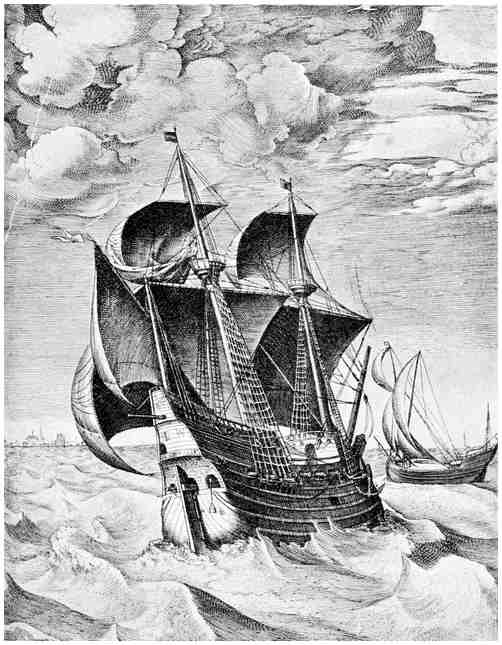

| Sixteenth-Century Caravel at Sea | 166 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

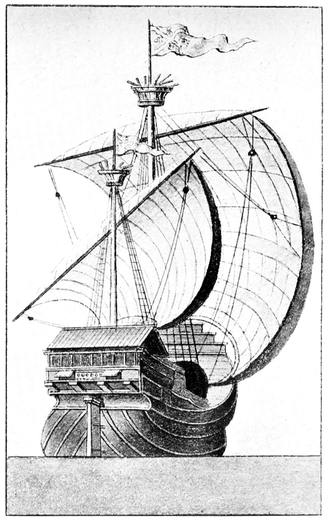

| Sixteenth-Century Caravel at Anchor | 170 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

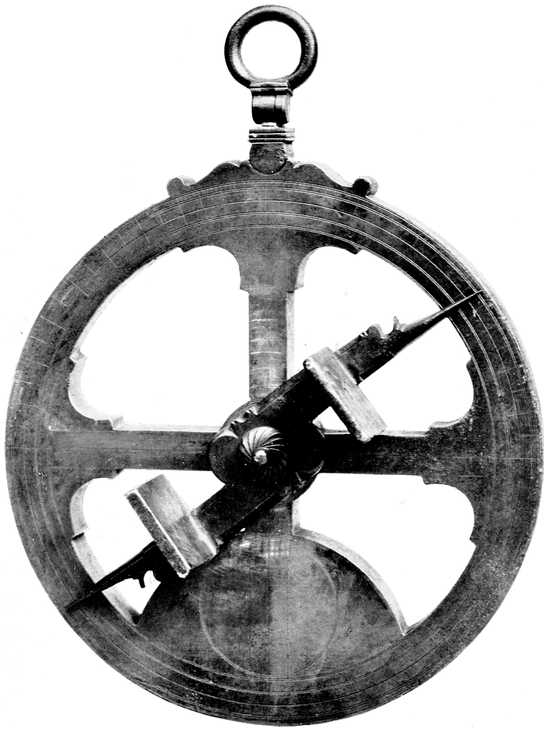

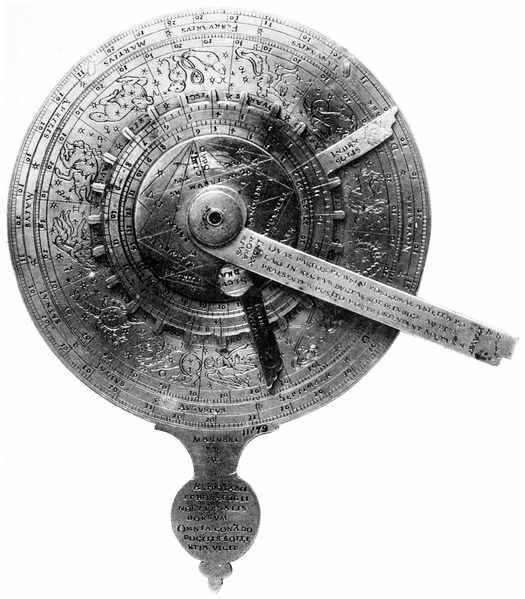

| Sixteenth-Century Astrolabe supposed to have been on board a Ship of the Armada | 172 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

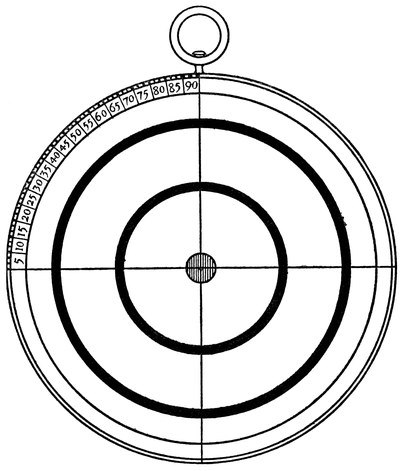

| Astrolabe used by the English Sixteenth-Century Navigators | 173 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

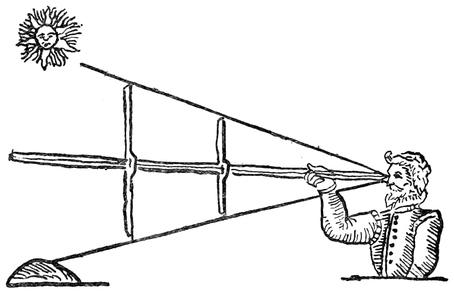

| Sixteenth-Century Navigator using the Cross-staff | 176 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

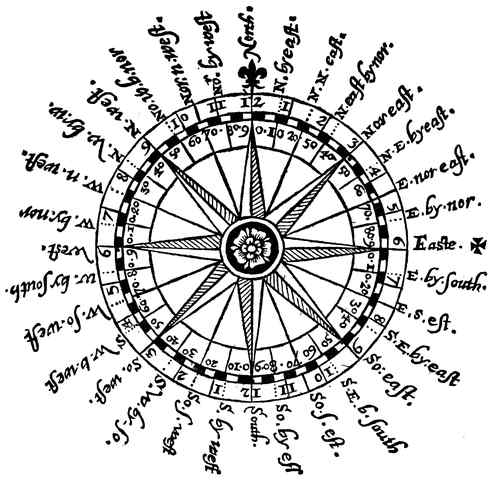

| Sixteenth-Century Compass Card | 177 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| An Old Nocturnal | 178 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sixteenth-Century Four-Masted Ship | 186 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

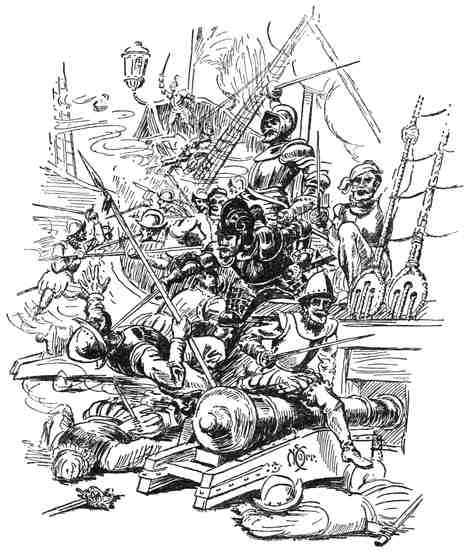

| Elizabethans boarding an Enemy’s Ship | 187 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

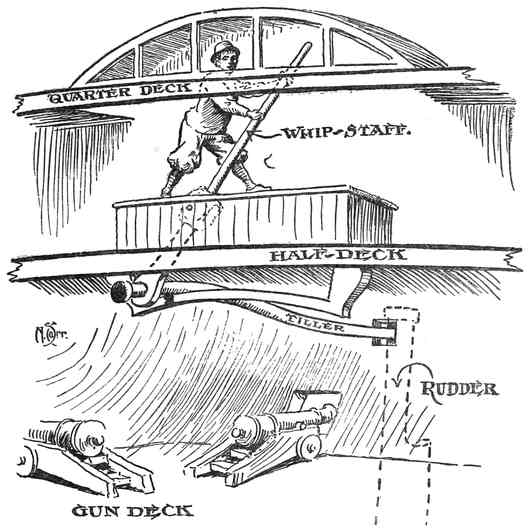

| Elizabethan Steering-Gear | 189xiii | ||||||||||||||||||||||

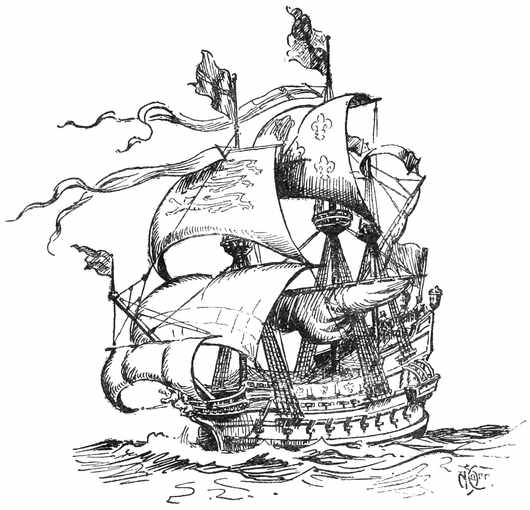

| Sixteenth-Century Ship chasing a Galley | 190 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

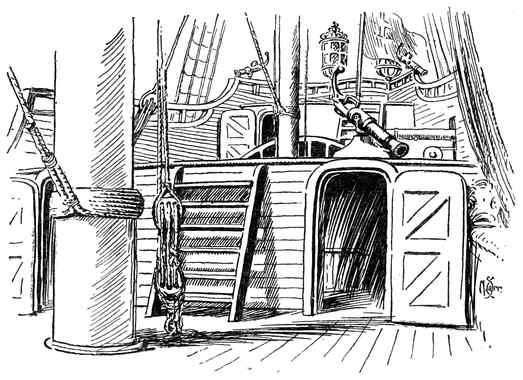

| Waist, Quarter-deck, and Poop of the Revenge | 192 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sixteenth-Century Three-masted Ship | 192 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

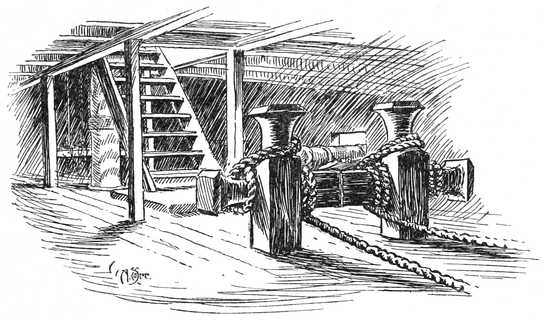

| Riding Bitts on the Gun Deck of the Revenge | 195 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

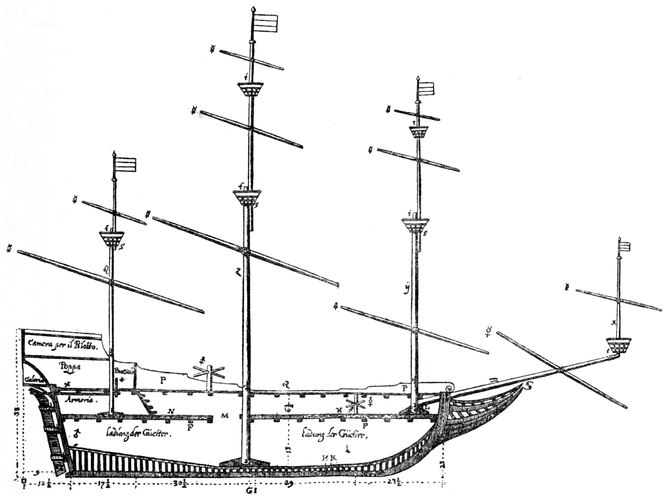

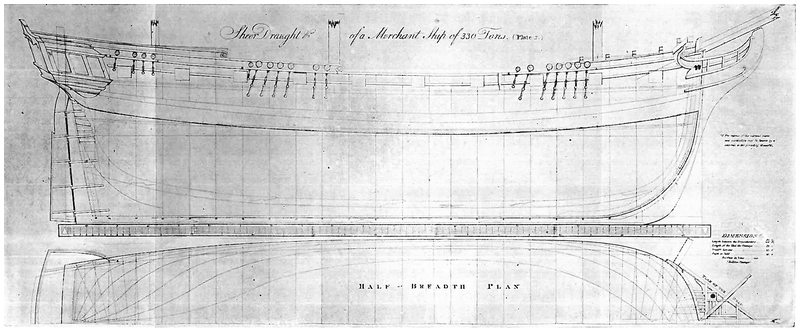

| Plan of Early Seventeenth-Century Ship | 197 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sixteenth-Century Warship at Anchor | 198 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Drake’s Revenge at Sea | 201 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sixteenth-Century Mariners learning Navigation | 206 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

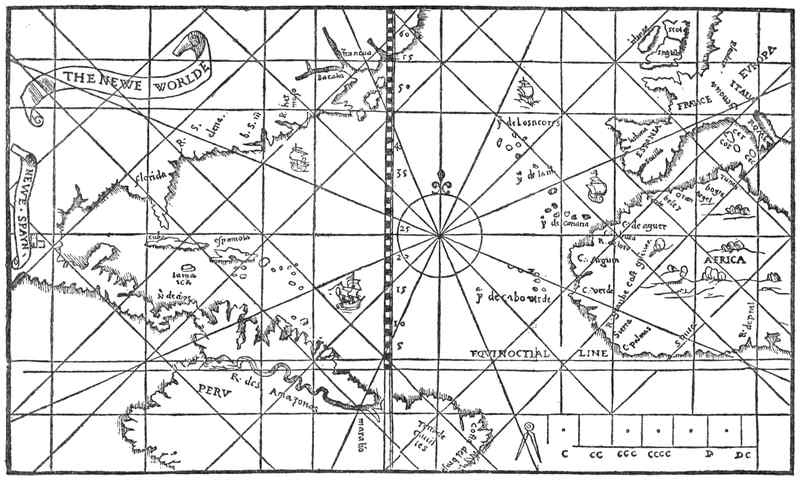

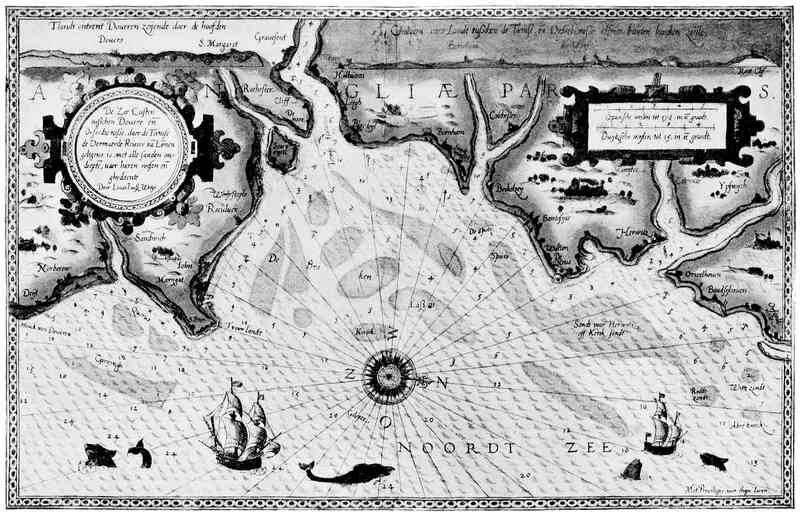

| Chart of A.D. 1589 | 211 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

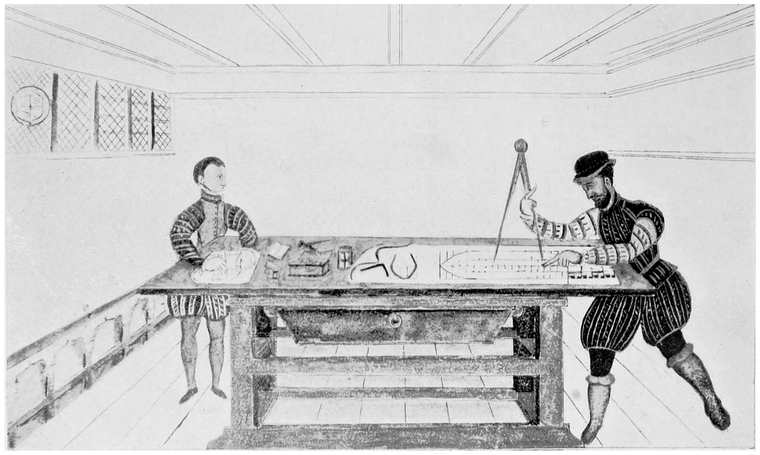

| Ship Designer with his Assistant | 212 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chart of the Thames from the First Published Atlas | 214 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

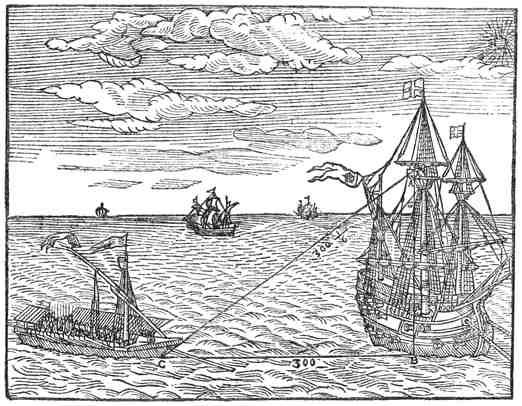

| Diagram illustrating the use of the “Geometricall Square” | 215 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

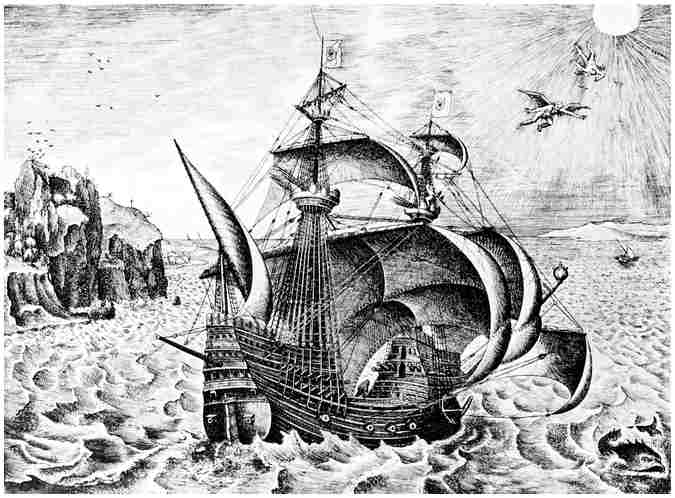

| Sixteenth-Century Ship before the wind | 216 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Early Seventeenth-Century Warship | 218 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

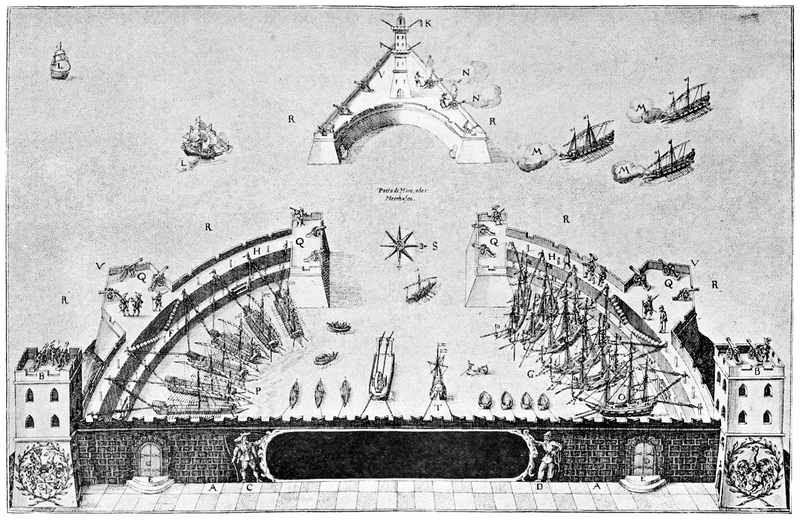

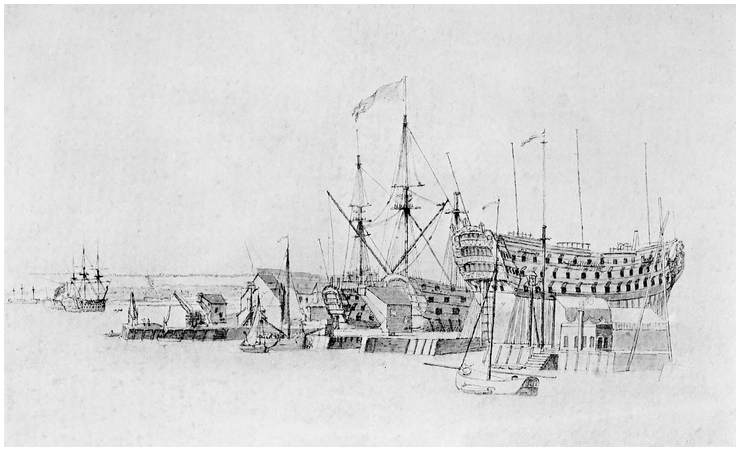

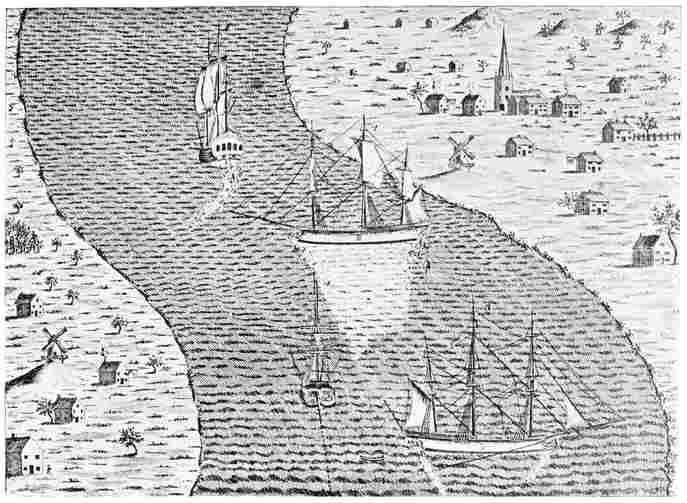

| Early Seventeenth-Century Harbour | 222 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

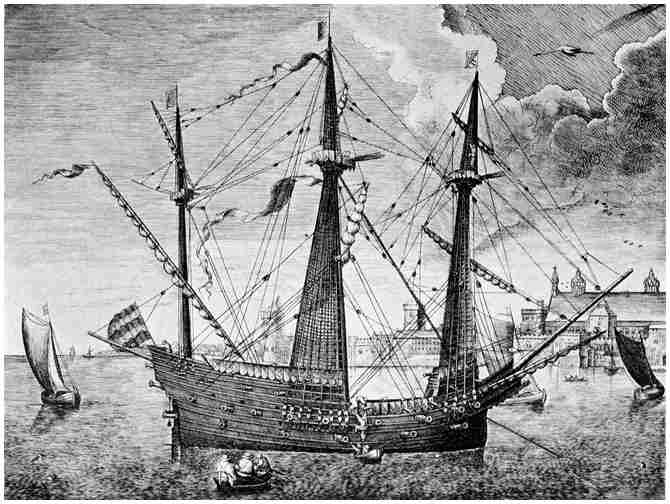

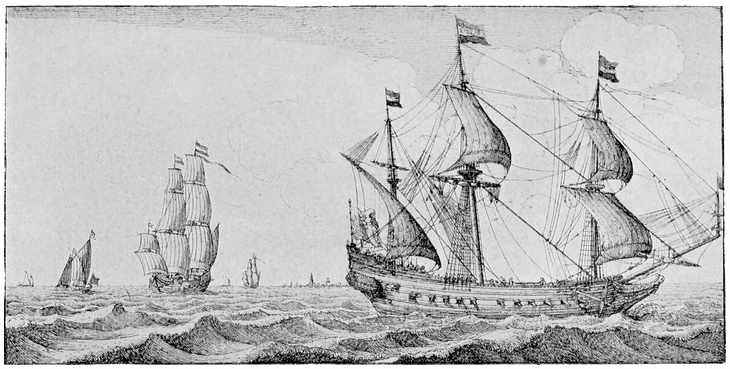

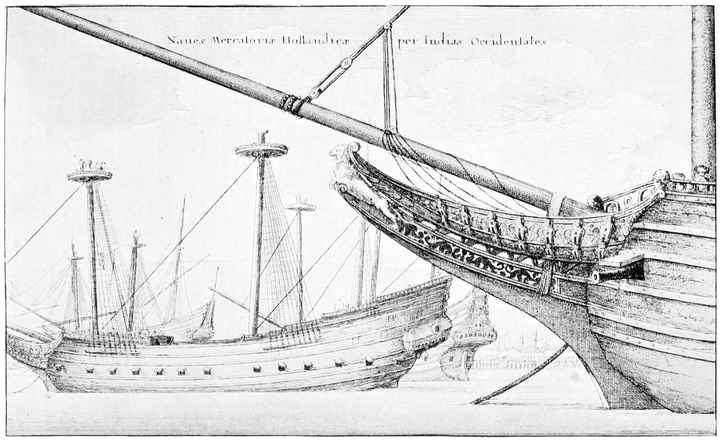

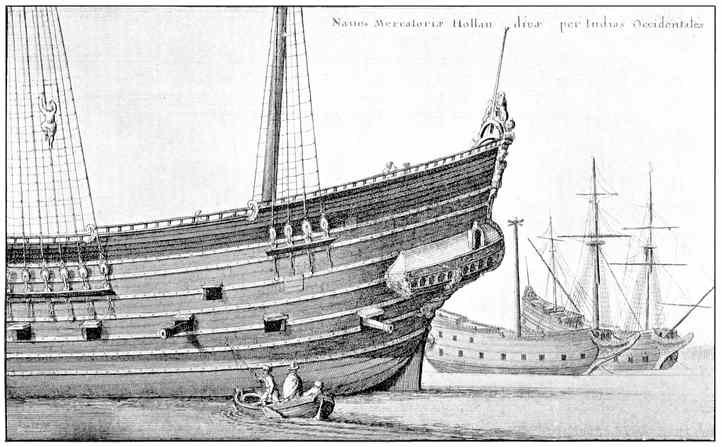

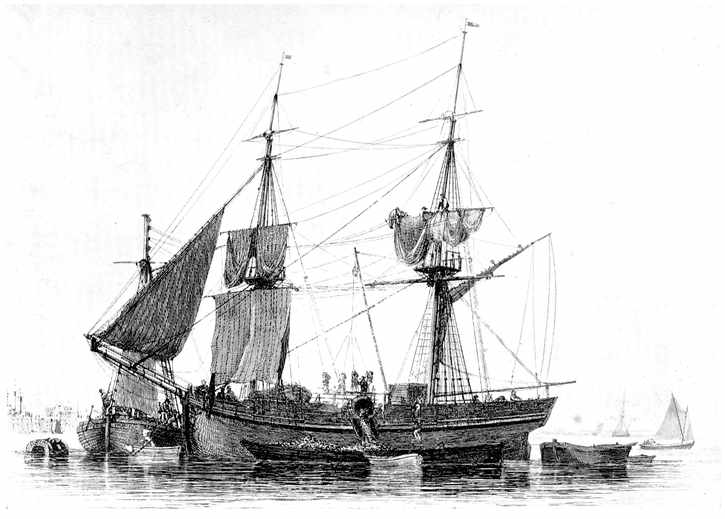

| Early Seventeenth-Century Dutch East Indiamen | 226 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

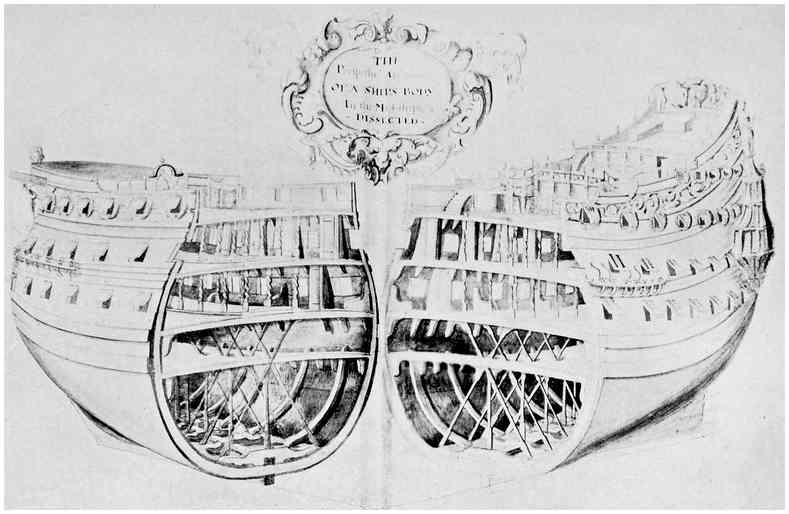

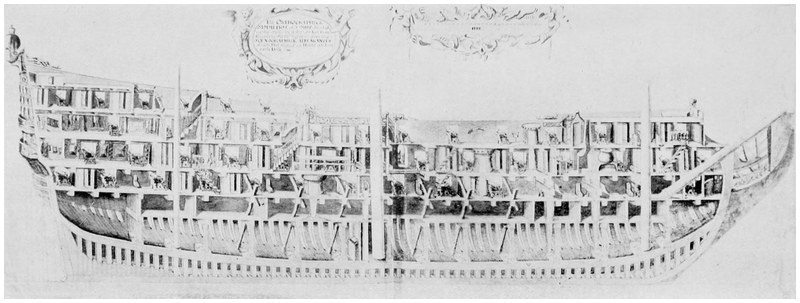

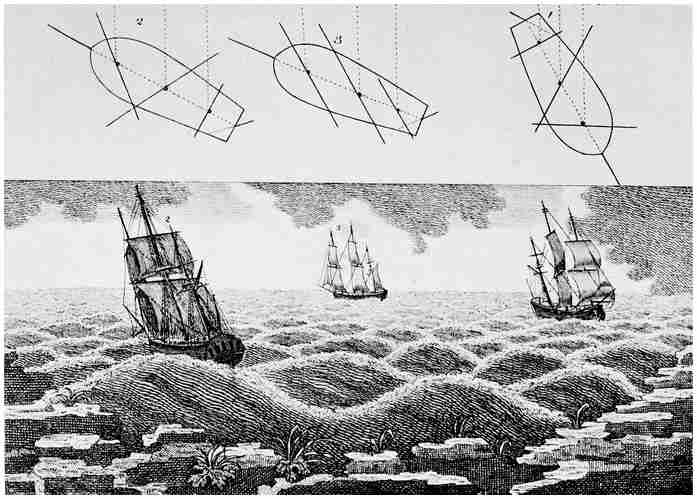

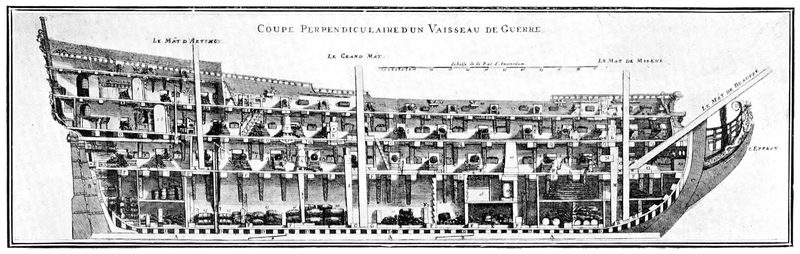

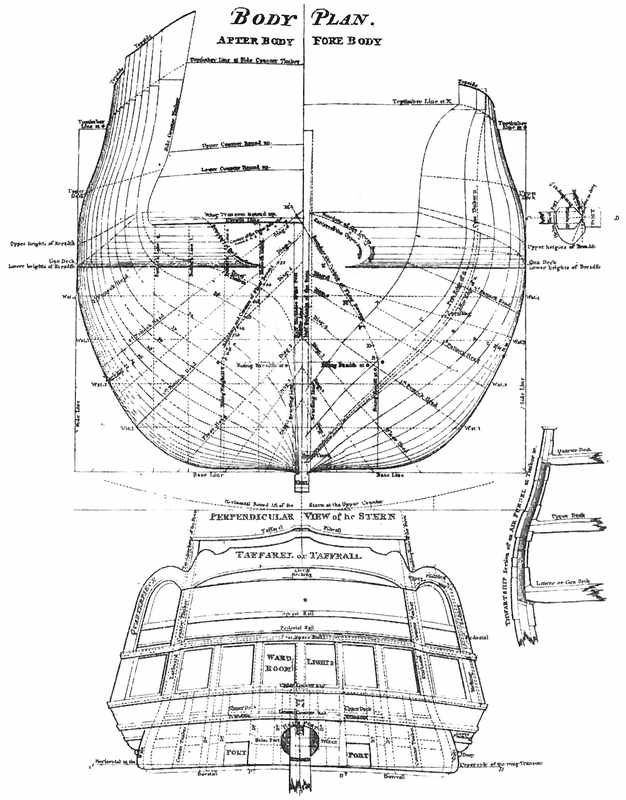

| “The Perspective Appearance of a Ship’s Body” | 228 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| “The Orthographick Simmetrye” of a Seventeenth-Century Ship | 230 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

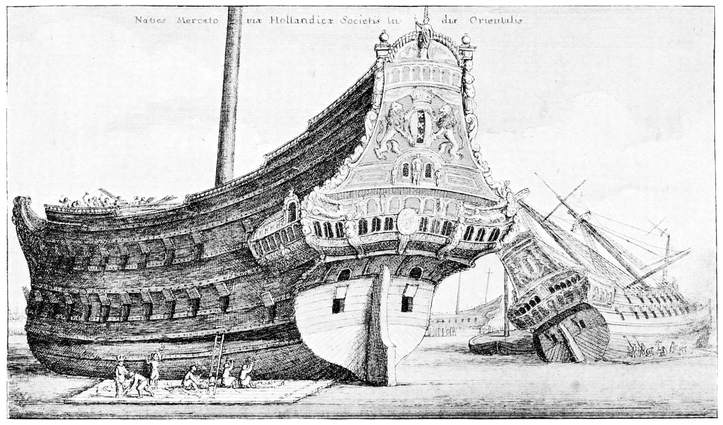

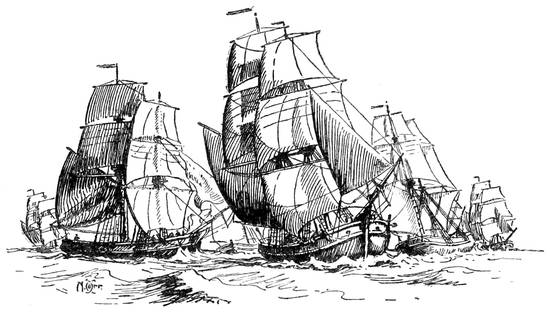

| Early Seventeenth-Century Dutch West Indiamen | 232 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fitting out a Seventeenth-Century Dutch West Indiaman | 236 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Seventeenth-Century Dutch Shipbuilding Yard | 240 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

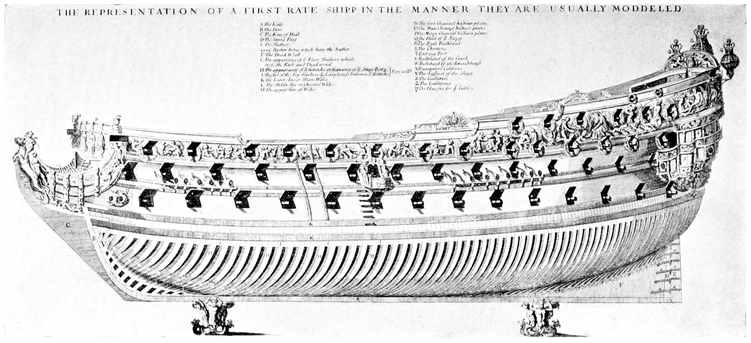

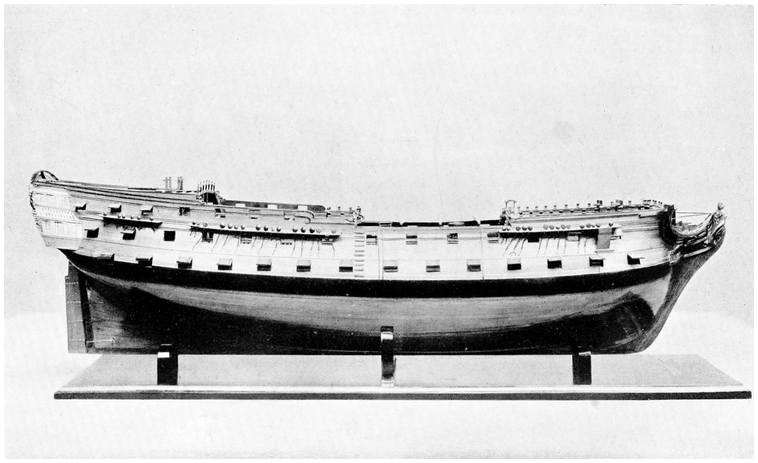

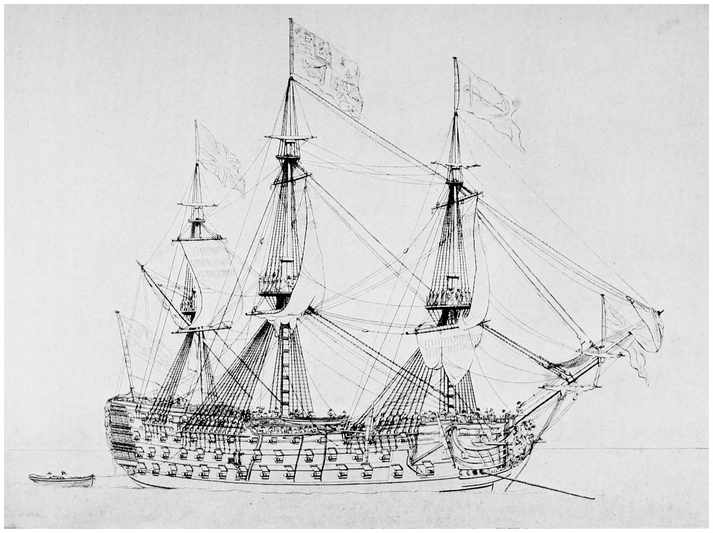

| Seventeenth-Century First-Rate Ship | 244 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

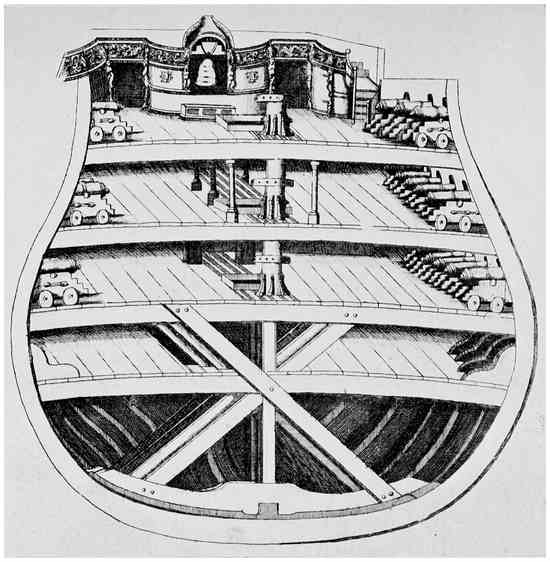

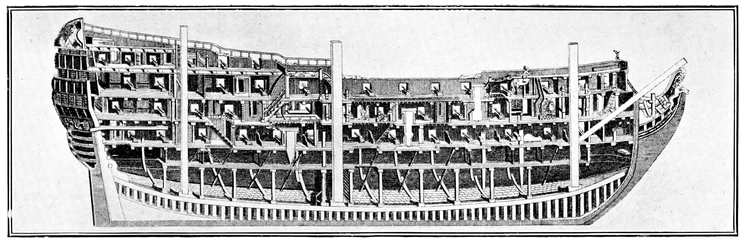

| Section of a Three-Decker | 246 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

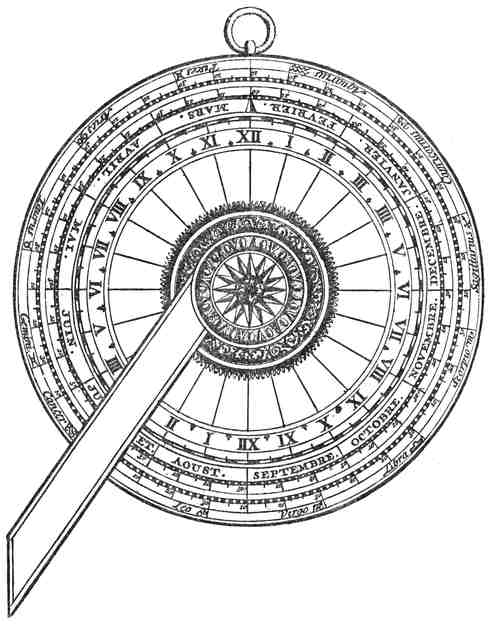

| Nocturnal | 247 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

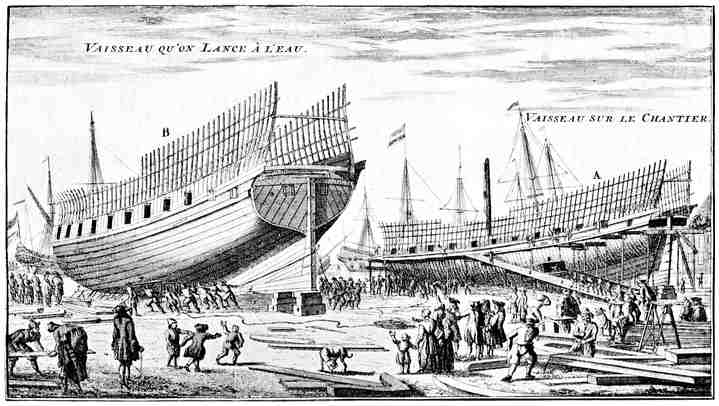

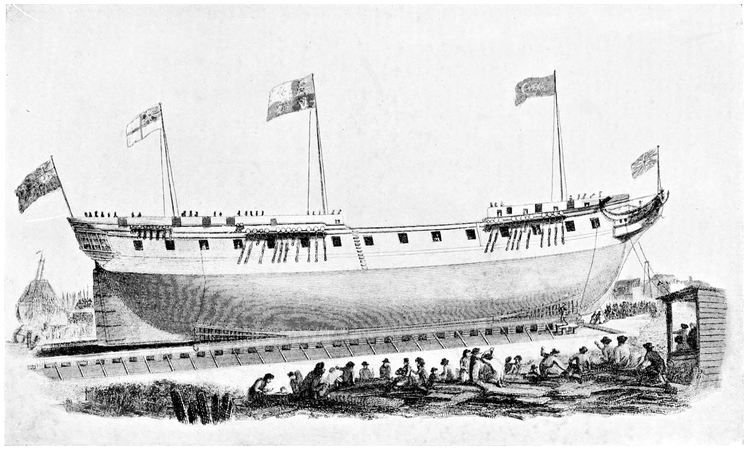

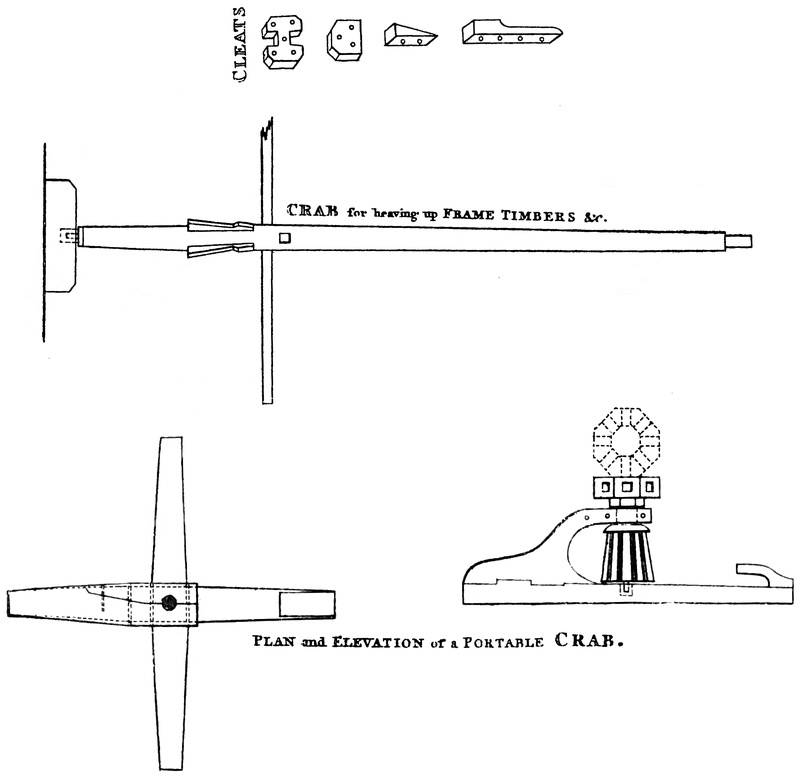

| Building and launching Ships in the Eighteenth Century | 248xiv | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Collier Brig | 250 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boxhauling | 252 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

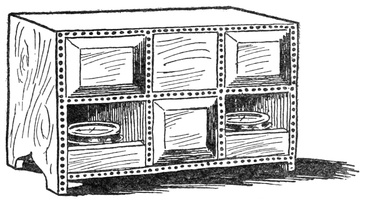

| Eighteenth-Century “Bittacle” | 253 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interiors of Eighteenth-Century Men-of-War | 254 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quarter-deck of an Eighteenth-Century Frigate | 255 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Collier Brig discharging Cargo | 256 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eighteenth-Century Man-of-War | 258 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Collier Brigs beating up the Swin | 259 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

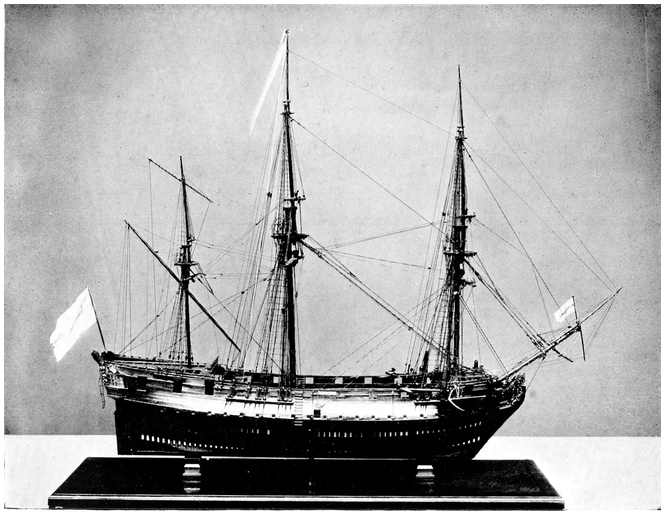

| Model of H.M.S. Triumph | 260 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

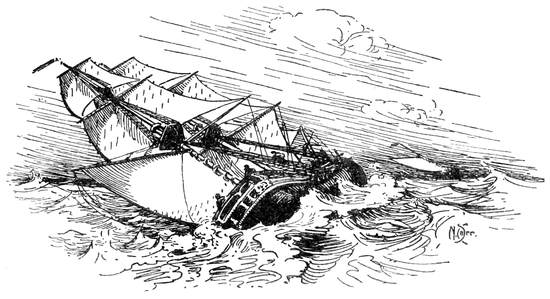

| “Compelled to let the ship lie almost on her beam ends” | 261 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| An interesting bit of Seamanship | 262 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| An ingenious Sail-Spread | 264 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eighteenth-Century Three-Decker | 266 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

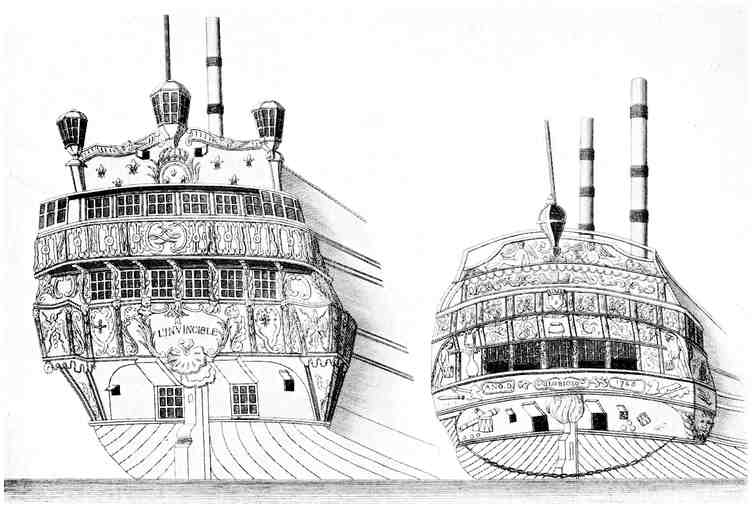

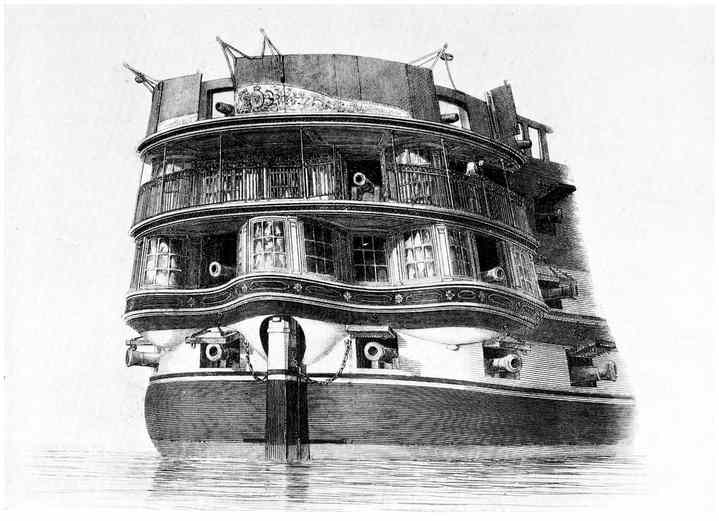

| Sterns of the Invincible and Glorioso | 268 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Model of an English Frigate, 1750 | 270 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

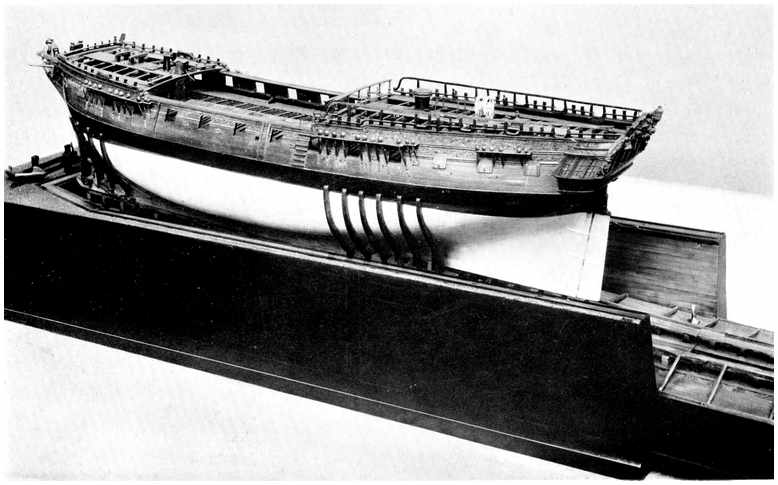

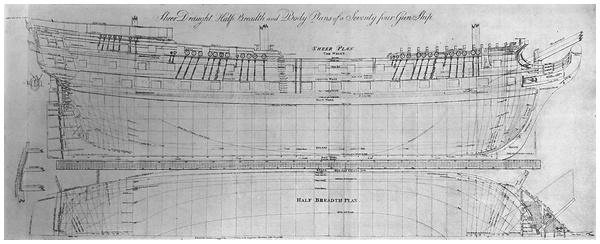

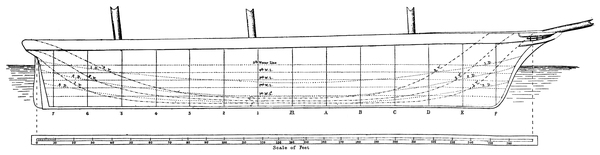

| A 32-gun Frigate ready for Launching | 272 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Launching a Man-of-War in the year 1805 | 274 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

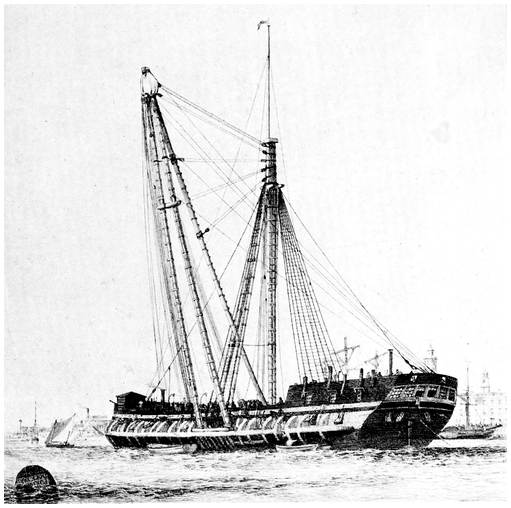

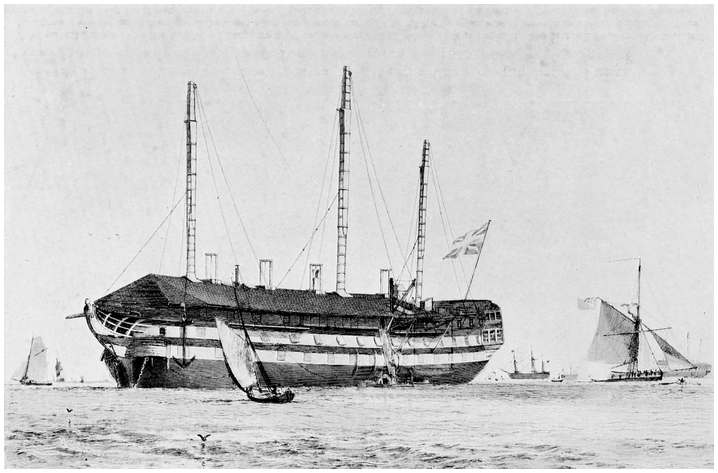

| Sheer-Hulk | 276 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| H.M.S. Prince | 278 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| An Early Nineteenth-Century Design for a Man-of-War’s Stern | 280 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

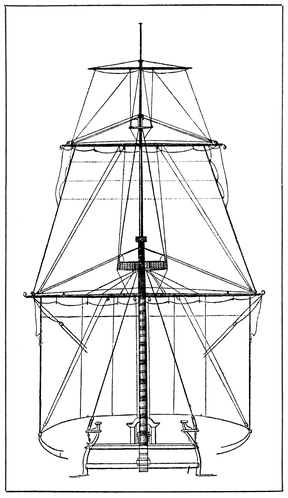

| Course, Topsail, and Topgallant Sail of an Early Nineteenth-Century Ship | 281 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stern of H.M.S. Asia | 282 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

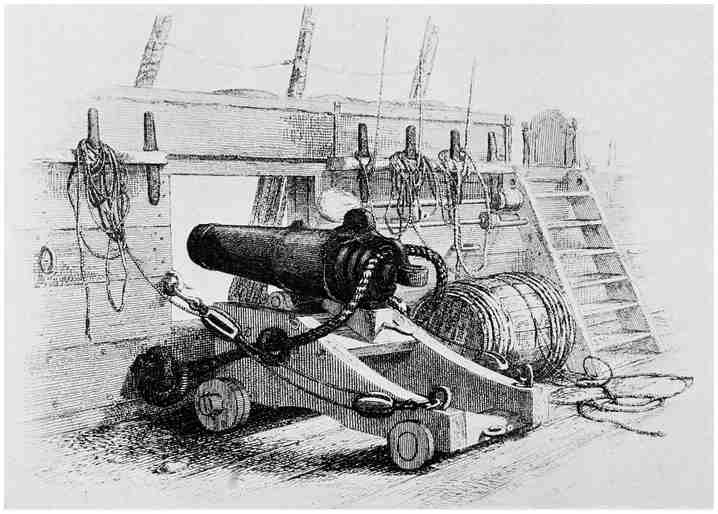

| A Brig of War’s 12-pounder Carronade | 283 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

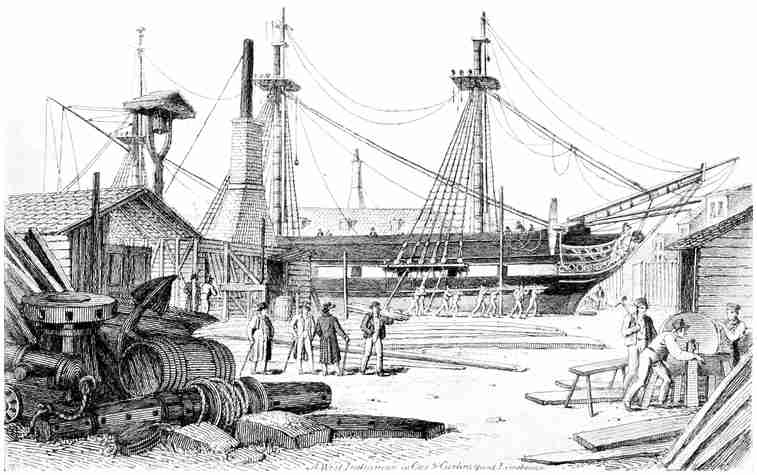

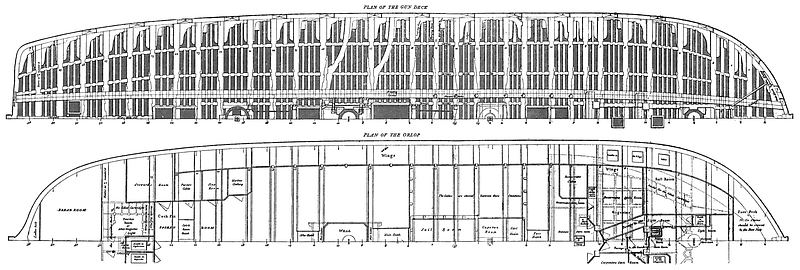

| A West Indiaman in Course of Construction | 284xv | ||||||||||||||||||||||

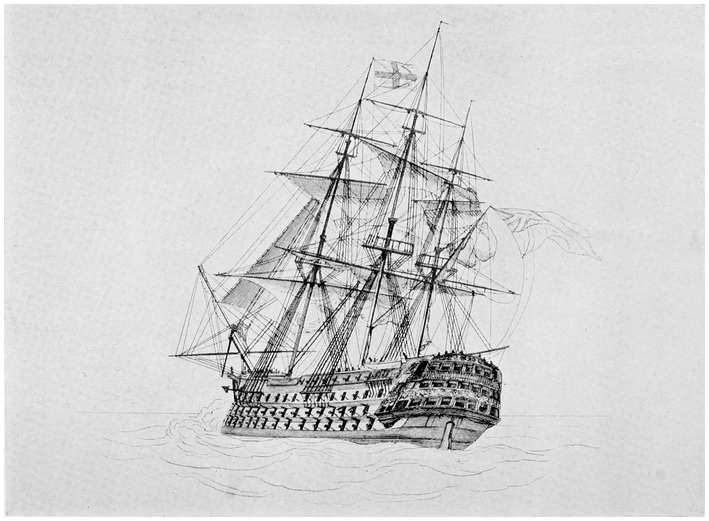

| A Three-Decker on a Wind | 285 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

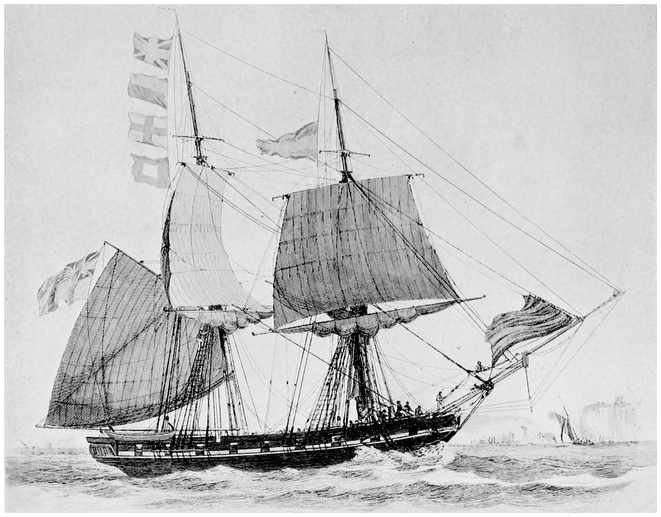

| The Brig Wolf | 286 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A Frigate under all Sail | 287 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Man in the Chains heaving the Lead | 287 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

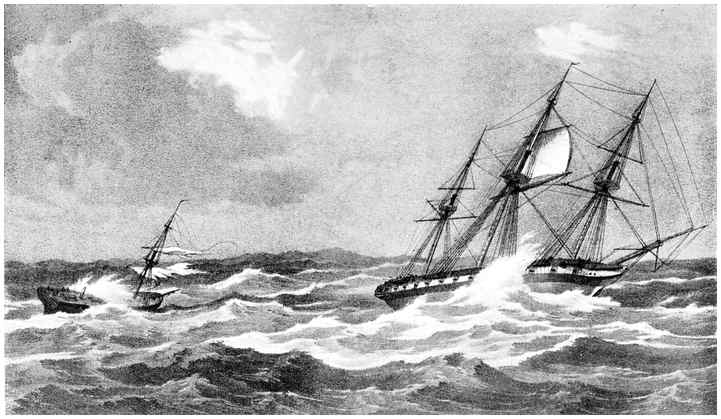

| H.M.S. Cleopatra endeavouring to save the Crew of the Brig Fisher | 288 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| H.M.S. Hastings | 289 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

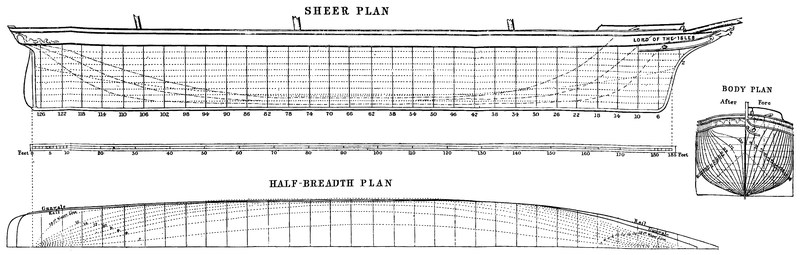

| Model of the Carmarthenshire | 290 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

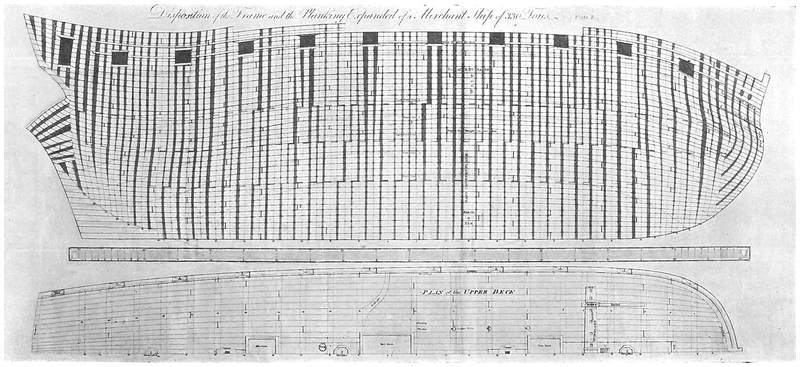

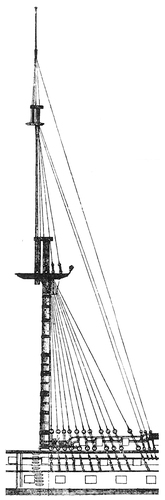

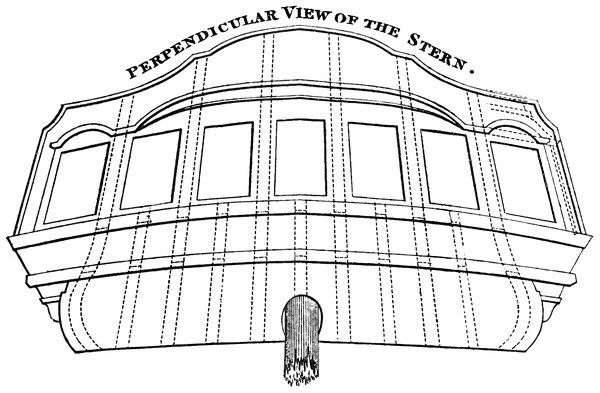

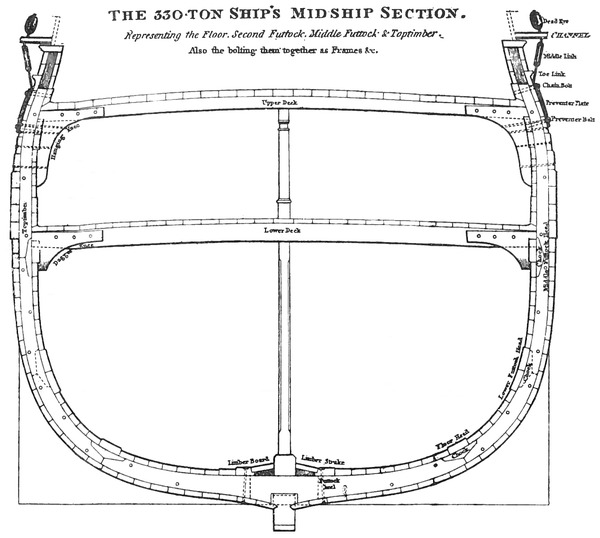

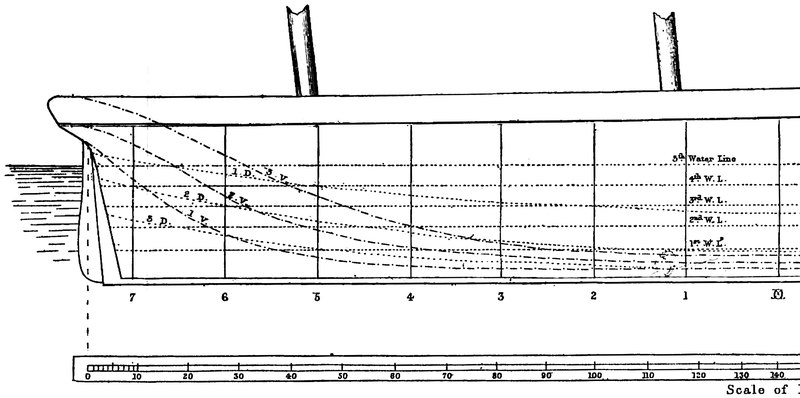

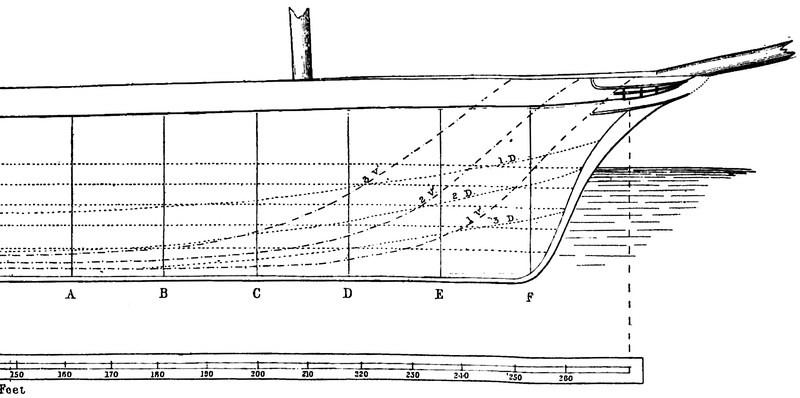

| PLANS | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| (At End of Volume) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

xvi

“The sea language is not soon learned, much less understood, being only proper to him that has served his apprenticeship: besides that, a boisterous sea and stormy weather will make a man not bred on it so sick, that it bereaves him of legs and stomach and courage, so much as to fight with his meat. And in such weather, when he hears the seamen cry starboard, or port, or to bide alooff, or flat a sheet, or haul home a cluling, he thinks he hears a barbarous speech, which he conceives not the meaning of.”

(Sir William Monson’s Naval Tracts.)

1

In “Sailing Ships and their Story” I endeavoured to trace the evolution of the ship from the very earliest times of which we possess any historical data at all down to the canvas-setting craft of to-day. In “Fore and Aft” I confined myself exclusively to vessels which are rigged fore-and-aftwise, and attempted to show the causes and modifications of that rig which has served coasters, pilots, fishermen, and yachtsmen for so many generations.

But, now that we have watched so closely the progress of the sailing ship herself, noting the different stages which exist between the first dug-out and the present-day full-rigged ship or the superb racing yacht, we can turn aside to consider chronologically what is perhaps the most fascinating aspect of all. On the assumption that activity is for the most part more interesting as a study than repose, that human activity is the most of all deserving in its ability to attract, and that from our modern standpoint of knowledge and attainment we are able to look with sympathetic eyes on the efforts and even the mistakes of our forefathers on the sea, we shall be afforded in the following pages a study of singular charm.

2 For, if you will, we are to consider not why the dug-out became in time an ocean carrier, but rather how men managed to build, launch, equip, and fit out different craft in all ages. We shall see the vessels on the shipyards rising higher and higher as they approach completion, until the day comes for them to be sent down into the water. We shall see royalty visiting the yards and the anxious look on the shipwright’s face lest the launching should prove a failure, lest all his carefully wrought plans should after months of work prove of naught. We shall see the ships, at last afloat, having their masts stepped and their rigging set-up, their inventory completed, and then finally, we shall watch them for the first time spread sail, bid farewell to the harbour, and set forth on their long voyages to wage war or to discover, to open up trade routes or to fight a Crusade. And then, when once they have cleared from the shelter of the haven we are free to watch not merely the ship, but the ways of ship and men. We are anxious to note carefully how they handled these various craft in the centuries of history; how they steered them, how they furled and set sail, how these ships behaved in a storm, how they fought the ships of other nations and pirates, how they made their landfalls with such surprising accuracy. As, for instance, seeing that the Norsemen had neither compass nor sextant, by what means were they able in their open ships to sail across the Atlantic and make America? In short, we shall apply ourselves to watching the evolution of seamanship, navigation, and naval strategy down the ages of time.

Frigate.

A 74-Gun Ship.

Portsmouth Pilot Cutter

Spithead in the Early Nineteenth Century.

But we shall not stop at that; for we want to obtain an intimate picture of the life lived on board these many ships. We would, so to speak, walk their decks, fraternise with the officers and men, adventure into their cabins, go aloft with them, join their mess, keep sea3 and watch in their company in fine sunny days and the dark stormy nights of winter. We are minded to watch them prepare for battle, and even accompany them into the fight, noting the activities, the perils, and the hardships of the seamen, the clever tactics, the moves and counter-moves, the customs of the sea and of the ship especially. Over boundless, deep-furrowed oceans not sighting land for weeks; or in short coasting voyages hurrying from headland to headland before impending tempest; or pursued by an all-conquering enemy, we shall follow these ships and men in order to be able to live their lives again, to realise something of the fears and hopes, the disappointments, and the glories of the seaman’s career in the past.

I can promise the reader that if he loves ships, if he has a sympathetic interest in that curious composite creature the seaman—who throughout history has been compelled to endure the greatest hardships and deprivations for the benefit of those whose happy fortune it is to live on shore—he will find in the ensuing pages much that will both surprise him and entertain him. I have drawn on every possible source of information in order to present a full and accurate picture, and wherever possible have given the actual account of an eye-witness. How much would we not give to-day to be allowed to go on board the crack ship of the second century, for instance, and see her as she appeared to an onlooker? Well, Lucian has happily left us in dialogue form exactly the information that we want about the “monster vessel of extraordinary dimensions” which had just put in at the Piræus. On a later page the reader will accompany the visitor up the gangway and go round the ship, and be able to listen to the conversation of these eager enthusiasts, just as he would listen attentively to a party of friends who had just been shown over the latest mammoth steamship.4 What the captain said of his ship, his yarns about gales o’ wind, how great were her dimensions, how much water she drew, what was the average return to the owner from the ship’s cargo—it is all here for those who care to read it. A thousand years hence, how interested the world would be to read the first impressions of one who had been allowed to see over the Mauretania, or Olympic, or their successors! In the same way to-day, how amazingly delightful it is still to possess an intimate picture of a second-century Egyptian corn-ship!

We are less concerned with the evolution of design and build of ships in this present book than with the manner of using these craft. How, for example, on those Viking ships which were scarcely decked at all, did the crew manage to eat and sleep? Did the ancients understand the use of the sounding lead? how did they lay their ships up for the winter? what was the division of labour on board?—and a thousand questions of this sort are answered here, for this is just the kind of information that the reader so often asks for, and so rarely gets, frequently being disappointed at the gaps left in historical works. Believing firmly that a knowledge of the working and fighting of the ships in history is worthy of every consideration, I have for years been collecting data which have taken shape in the following narrative. Seamanship, like the biggest sailing craft, cannot have much longer to live if we are able to read the signs of the times. Steamanship rather than seamanship is what is demanded nowadays; so that before long the latter will become quite a lost art. It is therefore time that we should collect and set forth the ways and customs of a fast-dying race. Seamanship is, of course, a changing quality, but at heart it is less different than one might at first imagine. I venture to suggest that if by any wonderful means you could transfer the men5 of a modern crack 19-metre racing cutter to the more clumsy type of Charles II’s Mary, she would be handled very little differently from the manner in which those Caroline seamen were wont to sail her. Similarly, a crew taken from one of the old clippers of about 1870, and transferred—if it were possible—to one of the Elizabethan galleons, would very soon be able to manage her in just the same manner as Drake and his colleagues. It is largely a matter of sea-bias, of instinct, of a sympathy and adaptability for the work. And in such vastly different craft as the Greek and Roman galley, the Spanish carack, the Viking ship of the north, the bean-shaped craft of medieval England, and so on down to the ships of the present day, you find—quite regardless of country or century—men doing the same things under such vastly different conditions.

The way Cæsar worked his tides crossing the English Channel when about to invade Britain in 55 B.C., or the way William the Conqueror a thousand years later wrestled with the same problem but in different ships—these and like matters cannot but appeal to anyone who is gifted with imagination and a keen desire for knowledge. And then—perhaps some will find it the most interesting of all—there comes that wonderful story of the dawn and rise of the navigational science which to-day enables our biggest ships to make passages across the ocean with the regularity of the train, and to make a landfall with an exactness that is nothing short of marvellous considering that the last land was left weeks ago. It is a story that is irresistible in its appeal for our consideration, firstly because of its ultimate value to the progress of nations, and secondly because no finer example could be afforded us of the persistency of human endeavour to overcome very considerable obstacles. It is a little difficult just at first to place6 oneself in the position of those navigators of the early centuries. To-day we are so accustomed to modern navigational methods, we have been wont so long to rely on them for finding our way across the sea, that it requires a great effort of the imagination to conceive of men crossing the Atlantic and other oceans—not to speak of long coasting voyages—without chart or compass, sextant or log-line. There are many names in history which very rightly have won the unstinted applause of humanity irrespective of national boundaries. These names are held in the highest honour for the wonderful inventions and benefits which have been brought about. But there are two among others which, as it seems to me, the world has not yet honoured in an adequate manner. These two—Pytheas and Prince Henry the Navigator—are separated by thirteen or fourteen hundred years, but their inestimable help consisted in making the ocean less a trackless expanse than a limited space whereon the mariner was not permanently lost, but could find his position along its surface even though the land was not sighted for many a day. Think of the indirect results of this new ability. Think of the subsequent effects on the history of the world—the establishment of new trade routes consequent on the discovery of new continents, the impetus to enterprise, the peopling of new lands, the rise of young nations, the growth of sea-power, the spread of Christianity, the accumulation of fortunes and the consequent encouragement given to the arts and sciences. It is indeed a surprising but unhappy fact that humanity, because normally it has its habitation on land, forgets how much it owes to the sea for almost everything that it possesses. Perhaps this statement may be less applicable to the European continent, but it is in every sense true of all the other parts of the world.

7 Among the decisive battles of the world, among the discoveries of new lands, among the vast trade routes, how many of these do not come under the category of maritime? And yet in many an able-bodied, vigorous man, who owes most of his happiness and prosperity to the sea in some way or another, you find a spirit of antagonism to the sea, a positive hatred of ships, an utter indifference to the progress of maritime affairs. Hence, too, consistently following the same principle, the world always treats the seafaring man of all ranks in the worst possible manner. It matters not that the sailorman pursues a life of hardship in all climes and all weathers away from the comforts of the shore and the enjoyment of his own family. He brings the merchant’s goods through storm and stress of weather across dangerous tracts of sea, but he gets the lowest remuneration and the vilest treatment. He goes off whaling or fishing, perhaps never to come home again, performing work that brings out the finest qualities of manhood, pluck, daring, patience, unselfishness, and cool, quick decision at critical moments. Physically, too, he sacrifices much; but what does he get in return? And then think also of the men on the warships. But it is no new grievance.

Throughout history the world has had but scant consideration for the sons of the sea, whether fighters, adventurers, or freight-carriers. You have only to read the complaints of seamen in bygone times to note this. One may indeed wonder sometimes that throughout the world, and in fact throughout history, men have ever been found knowingly to undertake the seafaring life with all its hardships and all its privations. To people whose ideas are shaped only by the possibilities of loss and gain, who are lacking in imaginative endowment, in romance and the joy of adventure, it is certainly incredible that any man should seriously8 choose the sea as his profession in preference to a life of comfort and financial success on shore. Indeed, the gulf between the two temperaments is so great that it were almost useless to hazard an explanation. The plainest and best answer is to assert that there are two classes of humanity, neither more nor less. Of these the one class is born with the sea-sense; the other does not possess that faculty, never has and never could, no matter what the opportunities and training that might be available. Therefore the former, in spite of his lack of experience, is attracted by the sea-life notwithstanding its essential drawbacks; the latter would not be tempted to that avocation even by the possibility of capturing Spanish treasure-ships, or of discovering an unknown island rich with minerals and precious stones.

From a close study of those records which have been handed down to us of maritime incidents and affairs, I am convinced that the seaman-character has always been much the same. It makes but little difference whether its possessor commanded a Viking ship or a Spanish galleon. To-day in any foreign port, granted that both parties have a working knowledge of each other’s language, you will find that there is a closer bond between shipmen of different nationalities than there is between, say, a British seaman and a British landsman. For seamen, so to speak, belong to a nation of their own, which is ruled not by kings or governments, but by the great forces of nature which have to be respected emphatically. Therefore the crews of every ship are fellow-subjects of the same nationality, no matter whether they be composed of a mingled assemblage of Britishers, Dagoes, “Dutchmen,” and niggers.

Old-fashioned Topsail Schooner.

After E. W. Cooke.

So, as we proceed with our study, we shall look at the doings of different ships and sailors with less regard for the land in which they happened to be born9 than for that amazing republic which never dies, which exists regardless of the rise and fall of governments, which for extent is altogether unrivalled by any nationality that has ever been seen. We shall look into the characteristics, the customs, and the manifold activities of this maritime commonwealth, which is so totally different from any of our land institutions and which has always had to face and wrestle with problems of a kind so totally different from those prevailing on shore.

10

Of all the activities of human nature few are so interesting and so insistent on our sympathy as the eternal combat which goes on between man on the one side and the forces of Nature on the other. Conscious of his own limitations and his own littleness, man has nevertheless throughout the ages striven hard to overcome these forces and to exercise his own freedom. But he has done this not so much by direct opposition as by employing Nature to overcome Nature; and there can be no better instance of this than is found in the art of tacking, whereby the mariner harnesses the wind in order to enable him to go against the wind.

Winds and tides and waves are mightier than all the strength of humanity put together. The statement was as true in pre-Dynastic times as it is to-day. For a long time man was appalled by their superhuman strength and capabilities; he preferred to have nothing to do with them. Those nations which had their habitation inland naturally feared them most. But as familiarity with danger engenders a certain contempt, so those who dwelt by the sea began to lose something of their awe and to venture to wrestle with the great11 trio of wind, wave, and tide. Had they not exercised such courage and independence the history and development of the world would have been entirely different.

It is obvious that the growth of the arts of the sea—by which is meant ship designing and building, seamanship and navigation—can only occur among seafaring people. You cannot expect to find these arts prospering in the centre of a continent, but only along the fringe where land meets sea. And, similarly, where you find very little coast, or a very dangerous coast, or a more convenient land route than the sea, you will not find the people of that country taking to the awe-inspiring sea without absolute necessity. This statement is so obvious in itself, so well borne out by history and so well supported by facts, that it would scarcely seem to need much elucidation. Even to-day, even in an age which has so much to be thankful for in respect of conveniences, we actually hear of landsmen looking forward with positive horror to an hour’s crossing the Channel in a fast and able steamship, with its turbines, its comfortable cabins, and the rest. If it were possible to reach the Continent by land rather than water they would do so and rejoice. So it was in the olden times thousands of years ago; so, no doubt, it will ever be.

Strictly speaking, notwithstanding that the Egyptians did an enormous amount of sailing; notwithstanding that they were great shipbuilders and that their influence is still felt in every full-rigged ship, yet it is an indisputable fact, as Professor Maspero, the distinguished Egyptologist, remarks, that they were not acquainted with the sea even if they did not utterly dislike it. For their country had but little coast, and was for the most part bordered by sand-hills and marshes which made it uninhabitable for those who might otherwise have dwelt by the shore and become seafarers. On the contrary, the Egyptians preferred the land routes to12 the sea. It is true that they had the Mediterranean on their north and the Red Sea on their east, both of which they alluded to as the “very-green.” True, also, it is that there was at least one great sea expedition to the Land of Punt, but this was an exception to their usual mode of life.

At the same time, though they were primarily river sailors rather than blue-water seamen, yet they had used the Nile so thoroughly and so persistently, both for rowing and for sailing, that on the occasions when they took to the sea itself they were bound to come out of the ordeal fairly well, just as a Thames waterman, accustomed all his life to frail craft and smooth waters, would be likely to make a moderately good seaman if his work were suddenly changed from the river to the ocean. From childhood and through generations they had worked their square-sailed craft on the Nile and acquired a thorough knowledge of watermanship, and when the crews of Thebes manned those ships which carried Queen Hatsopsitu’s expedition to Punt and returned in safety back to their homes, they were able to put their lessons learned on the Nile to the best of use on the Red Sea.

So also on the Mediterranean the Egyptian ships were seen. We know that the galleys of Rameses II plied regularly between Tanis and Tyre. This was no smooth-water passage, for the Syrian sea could be very rough, and on a later page we shall give the actual experience of an Egyptian skipper who had a pretty bad time hereabouts in his ship. Even those skilful seamen, the Phœnicians, found it required a good deal of care to avoid the current which flowed along their coasts and brought to them the mud from the mouths of the Nile. Now it was but natural that when the Egyptians took to the sea they should use, for their trading voyages to Syria or their expedition to Punt,13 craft very similar to those which they were wont to sail on the Nile. In fact, it was possible for one and the same ship to be used for river and sea. In my “Sailing Ships and their Story,” the appearance of the Egyptian ships has been so thoroughly discussed that it is hardly necessary to go further into that matter at present. It is enough to state that they were decked both at bow and stern, that short, narrow benches were placed close to the bulwarks, leaving an empty space in the centre14 where the cargo could be stowed, and that there were fifteen rowers a side. There was one mast about 24 feet high setting one squaresail which was about 45 feet along its foot, and in addition to the oarsmen there were four topmen, a couple of helmsmen, and one pilot at the bow, who gave the necessary instructions to the helmsmen as to the course to be taken. Finally, there was an overseer to see that the rowers were kept up to their work and not allowed to slack.

On the whole the Egyptians were a peace-loving nation and not great fighters; but there were times when they had to engage in naval warfare, and on such occasions the ship’s bulwarks were raised by a long mantlet which shielded the bodies of the oarsmen, leaving only their heads exposed. And there were soldiers, too, placed on board these Egyptian ships in time of warfare. Two were stationed on the forecastle, one was in the fighting-top high on the mast, whilst the remainder were disposed on the bridge and quarter-deck, ready to shoot their arrows into the approaching enemy.

The navigation of the Egyptian seamen was but elementary. They coasted for the most part, rarely venturing out of sight of land, fixing their positions by familiar landmarks. This was by day; but at night they lay-to until the dawn returned, when they were enabled to resume their journey. Such methods, of course, demanded a longer time than more able seamen would have required, but the Egyptians were in no hurry, so it mattered not. It is patent enough, from the many representations which we find of craft on the Egyptian monuments which have been unearthed, that ships and boats played a highly important part in the life and habits of the Egyptians; but beyond the funereal customs and the connection which these craft had with their religious ideas, we know but little, if we15 except those models and those representations of their bigger ships seen with sail and mast. It is unquestionable that the shipbuilding industry was one of the most important activities which these Nile-dwellers engaged in; and illustrations still exist which show a shipwright’s yard of the Sixth Dynasty. We can see the men busily at work, whilst the dockyard manager or superintendent is carried in a kind of Sedan-chair to see how the work is progressing. Some are engaged hammering and chipping away at the wood that is to become a boat; some are fixing the different sections in place; whilst others are setting up the truss which was employed for preventing the ship from “hogging.”

But already by the close of the Third Dynasty, Professor Flinders Petrie says, the Egyptian shipbuilders were using quite large supplies of wood for their craft. In one year alone, Senofern constructed sixty ships and imported forty ships of cedar. When we consider that the Nile was the great national highway of Egypt, it was but natural that shipbuilding should be one of the most important trades. There were, first, the light skiffs which could be easily carried from place to place. There were also the larger freight-carriers which sailed the Nile and the open sea; and lastly, there were the houseboats, a kind of modern dahabeeah. The small skiffs were made of reeds for lightness, and coated with pitch. They were punted along the shallows with a pole, or paddled. They could carry only a couple of people, and were practically ferry-boats or dinghies. But the larger boats were built of wood, and probably sometimes of acacia. The masts were of fir which was imported from Syria, the sails being occasionally of papyrus, but probably also of linen.

The lotus plant played a conspicuous part in Egyptian shipbuilding. We see the smaller craft being strengthened16 by the stalks of this plant, bundles of which are depicted being carried down to the yard on the backs of the shipwright’s men. The tail-piece, even of the biggest sea-going craft, is shown to be in the shape of a lotus bud or flower. That they knew how to build ships of great tonnage at these dockyards is evident from the fact that Sesostris had a sacred barge constructed that was 280 cubits long. And it was doubtless owing to the great length of the Nile sailing ships, and their consequent inability to turn quickly, that we find it unusual for the Egyptian ships to have only a single steering oar; very frequently there was one each side at the quarter.

More than this it is difficult to state regarding the manner in which they employed their ships. There is indeed very much that we should like to know, and we cannot be too thankful that modern exploration has actually revealed so many pictorial representations. The Egyptians were not instinctively seamen as the Phœnicians and the Vikings, and if there had been no Nile it is probable that the sea and its coast might have meant even less to them than was actually the case. Nor was it any different with the Assyrians, whose kings feared the sea for a long time. They never ventured on its surface without being absolutely compelled. At a later stage, when their victories brought them to the shores of the Mediterranean, they were constrained to admire its beauty, and presently even took a certain amount of pleasure in sailing on its bosom, but nothing would tempt them far from land or to make a voyage.

But then there came a new precedent when Sennacherib embarked his army on board a fleet and went in search of the exiles of Bit-Iakin. The only ships that were at his disposal were those belonging to the Chaldean States. These craft were in every way unsuitable;17 they were obsolete, clumsy, heavy, bad sea-boats, and slow. During his wars, however, he had seen the famous sailors of Sidon, and noted alike the progress which these seafarers had made in actual shipbuilding, and in the handling of their craft at sea. These were of course Phœnicians, and among his prisoners Sennacherib found a sufficient number of Phœnicians to build for him a fleet, establishing one shipbuilding yard on the Euphrates and another on the Tigris. The result was that they turned out a number of craft of the galley type with a double row of oarsmen. These two divisions of newly built craft met on the Euphrates not far from the sea, the Euphrates being always navigable. The contingent from the Tigris, however, had to come by the canal which united the two rivers. And then, manned with crews from Tyre and Sidon, and Cypriot Greeks, the fleet went forth to its destination; Sennacherib then disembarked his men and rendered his expedition victorious.

Here, then, is just another instance of a non-seafaring people taking to the sea not from choice, not from instinct, but from compulsion—because there was no other alternative; and all the time employing seafaring mercenaries to perform a work that was strange to landsmen, just as in later days at different periods (until they themselves had grown in knowledge and experience), the English had to import sailors from Friesland in the time of Alfred, or Italians in the early Tudor period. The sea was still hardly more than a half-opened book, and few there were who dared to look into its pages.

18

But when we come to the Phœnicians we are in touch with a veritable race of seamen who to the south are in just the same relation as the Vikings are to the north. Whether they took to the sea because they longed to become great merchants, or whether they were seamen first and employed their daring to commercial benefit needs no discussion. They had the true vocation for the sea, and it was inevitable that sooner or later they must become mighty explorers and traders.

They had the real ship-love, which is the foundation of all true seamanship; they were in sympathy with the life and work, and they knew how to build a ship well. They furnished themselves with the finest timber from Lebanon and surpassed the Egyptian inland sailors by making their craft stronger, longer, more seaworthy, and more able to endure the long, daring voyages which it delighted the Phœnicians to undertake. Similarly, their crews were better trained to sea-work, were more daring and skilful than the Nile-dwellers. They minded not to sail out of sight of land, nor lay-to for the darkness to pass away. They were wont to sail the open sea fearlessly direct from19 Tyre or Sidon to Cyprus, and thence to the promontories of Lycia and Rhodes, and so from island to island to the lands of the Acheans, the Daneans, and further yet to Hesperia. How did they do it? What were their means and methods for navigation?

The answer is simply made. They observed the position of the sun by day. They would watch when the sun rose, when it became south, when it set, and then by night there was the Great Bear by which to steer. Their ships they designated “sea-horses,” and the expression is significant as denoting strength, speed, and reliability. By their distant voyages the Phœnicians began to open out the world, and they contributed to geographical knowledge more than all the Egyptian dynasties put together had ever yielded under this category. Their earliest craft were little more than mere open boats which were partially decked. Made of fir or cedar cut into planks, which were fashioned into craft all too soon before the wood had sufficient time to become seasoned, they were caulked probably with bitumen, a poor substitute for vegetable tar. We know from existing illustrations that the Egyptian influence as to design was obvious in their ships. We know also that the thirty or more oarsmen sat not paddling, but rowing facing aft, and that they used the boomless squaresail and shortened sail by means of brails.

“The first considerable improvement in shipbuilding which can be confidently ascribed to the Phœnicians,” says Professor Rawlinson,1 “is the construction of biremes. Phœnician biremes are represented in the Assyrian sculptures as early as the time of Sennacherib (700 B.C.), and had probably then been in use for some considerable period. They were at first comparatively short vessels, but seem to have been decked,20 the rowers working in the hold. They sat at two elevations, one above the other, and worked their oars through holes in the vessel’s side. It was in frail barks of this description, not much better than open boats in the earlier period, that the mariners of Phœnicia, and especially those of Sidon, as far back as the thirteenth or fourteenth century before our era, affronted the perils of the Mediterranean.”

At first the Phœnicians confined their voyages to the limits of the western end of the Mediterranean, but even then, notwithstanding their superiority in seamanship and navigation, they suffered many a disaster at sea. Three hundred ships were lost in a storm off Mt. Athos when they first attempted to invade Greece. And on their second attempt six hundred more ships were lost off Magnesia and Eubœa. In addition to this, it must be presumed that the rocks and shoals of the Ægean Sea, the cruel coasts of Greece, Spain, Italy, Crete, and Asia Minor would account for a good many more losses of ships and men. In those days, too, when one ship on meeting another used to ask in perfect candour if the latter were a pirate, and received an equally candid answer, there was thus a further risk to be undergone by all who used the sea for their living. If the ship were in fact piratical and her commander considered himself the stronger of the two, his crew would waste little time, but promptly board the other ship, confiscate her cargo, bind the seamen and sell them off at the nearest slave market. And be it remembered that a Phœnician ship, inasmuch as she was usually full of goods recently purchased or about to be sold, was something worth capturing. Her cargo of rich merchandise was deserving of a keen struggle and the loss of a number of men.

Nor were the Phœnicians averse from reckoning slaves among their commodities for barter; indeed,21 this was a great and important feature of their trade. Away they went roaming the untracked seas with their powerful oarsmen and single squaresail and their hulls well filled with valuable commodities, “freighting their vessels,” as Herodotus relates, “with the wares of Egypt and Assyria” for the Greek consumer. Year after year the ships sailed forth from Tyre to traverse the whole length of the Mediterranean and out into the Atlantic northwards to the British Isles, through storm and tempest, to embark the cargoes of tin. To be able to perform such a voyage not once but time after time is sufficient proof of the seamanship and navigation of the crews no less than of the seaworthiness of the Phœnician craft. Even that most wonderful circumnavigation of Africa by the Phœnicians as given by Herodotus is regarded by Grote, Rawlinson, and other authorities as having actually occurred and being not a mere figment of imagination. The story may be briefly summed up thus. Neco, King of Egypt, was anxious to have a means of connecting the Red Sea and Mediterranean by water, but had failed in his efforts to make a canal between the Nile and the Gulf of Suez, so he resolved that the circumnavigation of Africa should be attempted. For this he needed the world’s finest seamen and navigators with the best ocean-going ships available. Accordingly he chose the Phœnicians, who, departing from a Red Sea port, coasted round Africa, and after nearly three years arrived safely back in Egypt. The obvious question which the reader will ask is how could such craft possibly carry enough food for three years. The answer is that they did not even attempt such a feat. Instead, they used to make some harbour after part of their voyage was accomplished, land, sow their grain, wait till harvest-time, and then sail off with their food on board all ready for a further instalment of the journey. And22 there is really nothing too wonderful in this long voyage when we remember that in Africa what is to-day called Indian corn can be reaped six weeks after being sown; and that three years is not such an excessively long time for a well-manned craft fitted with mast and squaresail to coast from headland to headland, across all the bays and bights of the African continent. A great achievement it certainly was, not to be attempted (unless history is woefully silent) again until towards the close of the fifteenth century, when Vasco da Gama doubled the Cape of Good Hope.

They had for years been wont in the Mediterranean to make voyages by night. They had steered their course by aid of the Polar star. “They undoubtedly,” remarks Professor Rawlinson, “from an ancient date made themselves charts of the seas which they frequented, calculated distances, and laid down the relative position of place to place. Strabo says that the Sidonians especially cultivated the arts of astronomy and arithmetic as being necessary for reckoning a ship’s course, and particularly needed in sailing by night.” Later on we shall again call attention to the great surprise which confronted the dwellers by the Mediterranean when they voyaged into other seas. The Phœnicians, so long as they cruised only in the former, had no tide to contend with; but when they set forth into the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, the Atlantic, and the English Channel, they found a factor which, hitherto, they had not been compelled to encounter. But by such a seafaring race it was not long before even this new consideration was dealt with and utilised in the proper manner. “They noted,” says Rawlinson, “the occurrence of spring and neap tides, and were aware of the connection with the position of the sun and moon relatively to the earth, but they made the mistake of supposing that the spring tides were highest23 at the summer solstice, whereas they are really highest in December.”

If we omit the Egyptians from our category as being almost exclusively inland navigators, we must regard these Phœnicians as historically the first great seamen of the world, and it is nothing short of remarkable that in an age such as theirs, when there were so few accessories to encourage and develop the marine instinct, they should have essayed so much and succeeded so magnificently in their projects. Remember, too, that they had something of the instinct of the engineer as well as of the seaman in their nature. It was the Phœnicians whom Xerxes employed in 485 B.C. for the purpose of cutting a ship canal through the isthmus which joins Mt. Athos to the mainland. It was they, also, who constructed a double bridge of boats across the Hellespont to form the basis of a solid causeway, and in each of these undertakings they covered themselves with distinction.

They were no amateurs, no mere experimenters. It is certain that, in their own time, they were, even with their primitive ships, very far from primitive in their ideas of seamanship. Read the following exceedingly interesting account of one who went aboard a Phœnician vessel and has left to posterity his impressions of his visit. The descriptive narrative reads so true and seems so perfectly spontaneous and natural that we almost forget the many centuries which have elapsed since it was set down. Here, then, you have the record of no less a person than Xenophon, a man who was far too discriminating to allow any flow of careless words, far too observant, also, to allow anything worth noting to escape his watchful eye. In “The Economist” he makes one of his characters refer to a Phœnician trireme, and he is speaking of that nation’s ships when the Phœnicians were under the Persian system:—

24 “Or2 picture a trireme, crammed choke-ful of mariners; for what reason is she so terror-striking an object to her enemies, and a sight so gladsome to the eyes of friends? Is it not that the gallant ship sails so swiftly? And why is it that, for all their crowding, the ship’s company cause each other no distress? Simply that there, as you see them, they sit in order; in order bend to the oar; in order recover the stroke; in order step on board; in order disembark.”

And again:—

“I must tell you, Socrates, what strikes me as the finest and most accurate arrangement of goods and furniture it was ever my fortune to set eyes on, when I went as a sightseer on board the great Phœnician merchantman and beheld an endless quantity of goods and gear of all sorts, all separately packed and stowed away within the smallest compass. I need scarce remind you (he said, continuing his narrative) what a vast amount of wooden spars and cables a ship depends on in order to get to moorings; or again, in putting out to sea: you know the host of sails and cordage, rigging as they call it, she requires for sailing; the quantity of engines and machinery of all sorts she is armed with in case she should encounter any hostile craft; the infinitude of arms she carries, with her crew of fighting men aboard. Then all the vessels and utensils, such as people use at home on land, required for the different messes, form a portion of the freight; and besides all this, the hold is heavy laden with a mass of merchandise, the cargo proper, which the master carries with him for the sake of traffic. Well, all these different things that I have named lay packed there in a space but little larger than a fair-sized dining-room.25 The several sorts, moreover, as I noticed, lay so well arranged, there could be no entanglement of one with other, nor were searchers needed; and if all were snugly stowed, all were alike get-at-able, much to the avoidance of delay if anything were wanted on the instant. Then the pilot’s mate—the look-out man at the prow, to give him his proper title—was, I found, so well acquainted with the place for everything that, even off the ship, he could tell you where each set of things was laid and how many there were of each, just as well as anyone who knows his alphabet could tell you how many letters there are in Socrates, and the order in which they stand. I saw this same man (continued Ischomachus) examining at leisure everything which could possibly be needful for the service of the ship. His inspection caused me such surprise, I asked him what he was doing, whereupon he answered, ‘I am looking to see, stranger, in case anything should happen, how everything is arranged in the ship, and whether anything is wanting or not lying handy and shipshape. There is no time left, you know, when God makes a tempest in the great deep, to set about searching for what you want or to be giving out anything which is not snug and shipshape in its place.’”

There was something, then, so excellent in arrangement in these Phœnician ships which seemed to Xenophon so superior to the vessels of his own countrymen; and the sailor-like neatness and systematic order were to him so striking that even to his disciplined and orderly mind they were most remarkable. It requires but little imagination to picture from this scant reference the ship’s company doing everything according to drill. The seaman-like care for the running gear on the part of the ship’s husband ready for any emergency is, indeed, highly suggestive.

26 The importance of the Phœnicians is considerable, not merely for their own sake, but because of their permanent influence on the Greeks. But the latter were rather fighters than explorers as compared with the Phœnicians. At a very early date there was the sea communication between the Mediterranean and the North, and we may date this certainly as far back as the year 2000 B.C., suggests Dr. Nansen, himself an explorer and student of the early voyagers. The only places, excluding China, whence tin-ore was known to be procurable in ancient times, he asserts, were North-West Spain, Cornwall, and probably Brittany. It is significant that in the oldest pyramid-graves of Egypt tin is found, and the inference is that the inhabitants of the Mediterranean from at least this epoch voyaged north to fetch this commodity from Western Europe. And with the tin came also supplies of amber as well. Archæological finds, affirms the same authority, prove that as far back as the Scandinavian Bronze Age, or prior to this, there must have been some sort of communication between the Mediterranean and northern lands. One of the earliest trade routes connecting the Mediterranean and the Baltic was from the Black Sea up the Dneiper, then along its tributary the Bug to the Vistula, and down the latter to the coast. By their sea-voyages to distant lands the Phœnicians contributed for the first time a great deal of geographical knowledge of the world, and in many ways influenced Greek geography. Up till then the learned men who applied themselves to such subjects had but the vaguest idea of the North. But just as in subsequent centuries the Spanish kept their explored regions to themselves and continued most cautious lest other nationalities should learn their sources of wealth, so the Phœnicians did their best to keep their trade routes secret lest their rivals, the Greeks, should step in and enrich themselves.27 In the absence, therefore, of anything sufficiently definite, there was for a long period a good deal of wild and inaccurate speculation.

But it is when we come to Pytheas of Massilia that we reach the border-line which separates fact from fable. This eminent astronomer and geographer of Marseilles brought together a knowledge of northern countries which was based not on premonition, not on speculation, not on hearsay, but on actual experience. So original, so accurate, and so far-reaching was his work, that for the next fifteen hundred years he dominated all geographical knowledge. We can fix his time if we remember that he flourished probably about the year 330 B.C. He was the first person in history to introduce astronomical measurements for ascertaining the geographical situation of a place, and thus became the founder of the science of navigation—the science which has enabled seas to be crossed in safety and continents to be discovered; which has given to the ship of all species a freedom to employ her speed without sacrificing safety. Indirectly arising from these may be traced the development and civilising and peopling of the world which have so entirely modified history.

By means of a great gnomon, Pytheas determined “with surprising accuracy” the latitude of Marseilles, and in relation to this laid down the latitude of more northerly places. He observed that the Pole of the heavens did not coincide, as the earlier astronomer Eudoxus had supposed, with any star. What Pytheas did find was that it made an almost regular rectangle with three stars lying near it. (At that time the Pole was some distance from the present Pole-star.) And since Pytheas steered by the stars, the Pole of the heavens was obviously of the highest importance to him. A gnomon, it may be explained, was the pillar of projection which cast the shadow on the various Greek28 forms of dial. In the case under discussion the gnomon was a vertical column raised on a plane.

As to the species of ship in which Pytheas sailed we can but speculate. Most probably it was somewhat similar to the Phœnician type, with oarsmen and one mast with squaresail. But what is known is that he sailed out through the Pillars of Hercules. At that date Cape St. Vincent—then known as the Sacred Promontory—was the furthest of the world’s limit in the minds of the Greeks. He was the first to sail along the coasts of Northern Gaul and Germany. He was the discoverer of at least most of Great Britain, the Shetlands, and Norway as far as the Arctic Circle. And as he voyaged he studied the phenomena of the sea—collected invaluable data as to tides and their origin. Himself a Greek and unaccustomed to tidal movements, he was the first of his race to connect this systematic flowing and ebbing of the sea with the moon. Dr. Nansen, himself the greatest explorer of our times, has not hesitated to describe Pytheas as “one of the most capable and undaunted explorers the world has ever seen.” But as so often happens in the case of a pioneer, Pytheas was ahead of his time, and the description which he brought back of his travels, of the strange lands and unheard-of phenomena, was not believed by his contemporaries. There followed, therefore, a gulf of incredulity for about three hundred years till we come to the time of Julius Cæsar, and from that point we shall, in due course, continue to trace the development of navigational science.

29

But before we proceed further, it is essential that we look carefully into the building, administration, and handling of those fleets of vessels which made history as they scudded across the blue waters of the south of Europe. We want to know, also, something of the composition of their crews, their officers, and the divisions of control, of the tactics employed in naval warfare, of the limitations in manœuvring, the methods of working the oars, of rigging the ships, of steering, and so on.

Greece had accepted the ship as it had evolved in the hands of the Phœnicians with certain modifications. We are no longer anxious to trace that development, but rather to see, in the first place, how the Greeks availed themselves of their inheritance. In the building of their ships the Greeks gave neither sternpost nor stempost. The timbers of the ships were held together by means of wooden pegs (or treenails, as we should call them), and also by metal nails, bronze being chosen in preference to iron nails for the most obvious of reasons. But in those days, as any student of Greek history is aware, not infrequently craft had to be transported. Therefore the fastenings were so30 placed as to allow of the ship being divided into sections for carrying across land to some distant water. The outer framework of the hull was found in the keel and ribs. The ship’s planking, which varied from the somewhat ample 2¼ inches to 5¼ inches thick, was fastened through the ribs to the beams.

The warships had most necessarily to be built of the utmost strength to sustain the terrible shocks in ramming. To prevent the damage incurred being disastrous, cables—called hypozomata—undergirded the ship. The Greek word signifies the diaphragm or midriff in anatomy, but in the plural it is used to designate the braces which were passed either underneath or horizontally around the ship’s hull. The reader may remember that in “Sailing Ships and their Story” I called attention to the Egyptian ships, which used to be strengthened by stretching similar cables not girth-wise, but direct from stem to stern across the deck over wooden forks amidships. Primarily, then, these braces on the Greek ships were to counteract the effects of ramming; incidentally they kept the ship’s hull from “working” when she pounded in heavy seas.

And then when the shipwright had finished his construction of the ship she was coloured with a composition consisting of paint and wax, the latter serving to give these speedy ships the minimum of skin-friction. The colours chosen were purple, two whites, violet, yellow, and blue. Green, for the sake of invisibility, was used for scouts and pirates. The primitive Grecian ships had only patches of colour at the bows, the rest of the hull being covered black with tar. Occasionally neither wax nor tar was employed, but the hull was sheathed with lead outside the planking, layers of tarred sailcloth being placed in between the two materials. They made their sails either of linen, or, sometimes, of papyrus fibre or flax, and there were31 two kinds of sailcloth which the Athenian Navy utilised. The bolt-ropes of the sails were of hide, the skins of the hyena and seal being especially employed. The ropes used for the different purposes of the ship were of two kinds. Some were of strips of hide; more frequently they were from the fibre of papyrus or from flax or hemp. The sails were often coloured—black for mourning, purple or vermilion for an admiral or monarch. Topsails were sometimes coloured, the lower sail remaining uncoloured. The green-hulled scouts also had their sails and ropes dyed to match the colour of the Mediterranean. And sometimes the interesting sight would be seen of sails with inscriptions and devices woven in golden thread into the fabric.

There is a Greek word askos, which signifies a leathern bag or wine-skin, from which the word askoma is derived. The latter was the word given to a leathern bag which was attached to the oar so as to prevent the water from penetrating through into the ship, and yet allowed, with only slight friction, the oar to be brought backward and forward. There is something slightly similar to-day in the leather flap which is found on the Bristol Channel pilot cutters, covering the discharge from the watertight cockpits, the motion of the ship through the water causing the flap to be pressed tightly against the hull, and thus preventing any water from entering. But in the instance of the Grecian craft the flap was much bigger. There were no rowlocks, but the oar was fastened by a leathern loop to a thole-pin against which the rower pulled his oar.

Bear in mind that, whereas the Greek merchant-ship mostly relied on sails, the warship was essentially oar-propelled. And because she must needs carry a large number of rowers they needed supervision. Hence a gangway was placed on either side of the ship, both for that purpose and also for the placing of32 the fighting men. Illustrations on ancient Greek vases clearly show that some warships were fitted with a hurricane-deck above, and this extended down the length of the ship, but not from one side to the other. This hurricane-deck, if we are to give any credence to contemporary illustrations, was a fairly light affair raised on vertical supports of sufficient strength. In addition to the human ballast of the oarsmen, gravel, sand, and stone were used for trimming the ship. For instance, it might be necessary to get the bows deeper into the water so that the ram came into operation; or, after ramming and receiving damage, it might be found advisable to trim the ship by the stern so as to get the bows well out of water. To what extent these craft leaked one cannot say; but one can reasonably suppose that as they were built of unseasoned wood, as the shocks from ramming were very injurious, and as they had to suffer a good deal of wear and tear through frequent beaching, they made a fair amount of water. At any rate, it is certain that they provided against this in arranging an Archimedean screw, worked by a treadmill, or buckets for getting rid of the bilge-water. It is probable, also, that the drinking-water in cisterns or skins would be deposited as low in the hull as possible.

The Greeks, in addition to their technical ability, had inherited a similar sea-instinct to that of the Phœnicians, and this keenness is by no means absent from Greek literature. What, for instance, could be more enthusiastic than the following exquisitely poetic extract from Antipater of Sidon:—

“Now is the season for a ship to run through the gurgling water, and no longer does the sea gloom, fretted with gusty squalls; and now the swallow plasters her globed houses under the rafters, and the soft leafage laughs in the meadows. Therefore wind up your soaked cables, O sailors, and weigh your sunken33 anchors from the harbours, and stretch the forestays to carry your well-woven sails. This I, the son of Bromius, bid you, Priapus of the anchorage.”3

It is an exhortation, at the return of spring, to refit the ships which had been laid up since the winter, tethered to the “soaked cables.” It is an invitation to get the ships properly afloat, to step the masts and set up the forestay in all readiness for getting under way for the sailing season.

Or again, listen to Leonidas of Tarentum in a similar theme.

“Now is the season of sailing,” he says, “for already the chattering swallow is come and the pleasant west wind; the meadows flower, and the sea, tossed up with waves and rough blasts, has sunk to silence. Weigh thine anchors and unloose thine hawsers, O mariner, and sail with all thy canvas set: this I, Priapus of the harbour, bid thee, O man, that thou mayest sail forth to all thy trafficking.”4

“Mine be a mattress on the poop,” sings5 Antiphilus with no less ecstasy of the life on board a Grecian ship, “mine be a mattress on the poop, and the awnings over it sounding with the blows of the spray, and the fire forcing its way out of the hearth-stones, and a pot upon them with empty turmoil of bubbles; and let me see the boy dressing the meat, and my table be a ship’s plank covered with a cloth; and a game of pitch-and-toss, and the boatswain’s whistle: the other day I had such fortune, for I love common life.”

Three thousand years, indeed, before the birth of our Lord there were ships sailing the Ægean Sea, but it was only the progress of time and experience which made these craft and their crews’ ability anything more than primitive. As you look through the poems of34 Homer you find various significant references to craft, and he speaks of the “red-cheeked” ships, referring to the vermilion-coloured bows, where a face was frequently painted, red being the conventional colour in those early times for flesh. The same idea is still seen in the Chinese junks and the Portuguese fishing craft.

The earliest Grecian ships were crescent-shaped, and the stern so resembled the horn of a cow that it was called the korumba or point. There is a reference in35 the Iliad to the high-pointed sterns of ships. From Homer, too, we know that the timber employed in shipbuilding consisted of oak, pine, fir, alder, poplar, and white poplar; that the masts and oars were of fir, that the woodwork of the hull was erected on shipbuilders’ stocks. The word used for the latter was druochoi—meaning the props on which the keel (tropis) was laid. The hull was secured by treenails and dowel-joints, the planking being laid over the ribs. Further, we know also that the ship of Homer had either twenty or fifty oarsmen.

The pre-Homeric Greeks did not use thole-pins, but the oars were fastened to the gunwale by means of leathered hoops. It was not till a later date that the pins already mentioned came into use. It is noticeable, too, that Homer uses the word kleides in referring to the thwarts on which the rowers sat. For the singular of this word means a hook or clasp, and is used in this sense for the thwart or rowing bench which locked the sides of the ship together. Zuga is also used in the Odyssey to signify the same thing. In attempting to piece together these fragmentary details of the Homeric ship, we must bear in mind that below the zuga or rowing thwarts the hold was undecked, but that fore and aft there ran the half-decks—ikria, Homer calls them. The forecastle formed at once a cabin and a look-out post, and helped to keep the forward end protected when butting into a sea. Right aft, of course, sat the helmsman, or kubernetes, and it is supposed that a bench here stretched across the poop on which, as he sat on deck, he could rest his feet and work the oieion or handle of the rudder. A Greek ship usually had two pedalia or steering oars, one being placed on either quarter. These were joined together across the ship by means of cross-bars (zeuglai), to which the tiller or handle was attached. Finally, over36 the poop rose the tail-piece which is so noticeable in some of the vase-illustrations of Grecian ships, and had its counterpart in the lotus-bud seen in the ships of the Egyptians.

Homer speaks of “stepping the mast” (histos), and apparently the step was affixed as low as possible, its heel being supported by a prop and capable of being easily lowered before the galley went into battle under oar-propulsion alone. The forestays, which just now we saw Antipater urging the sailors to stretch, were two in number. The Homeric word for these is protonoi, though the word was used by Euripides in speaking of the braces which controlled the yards. On the yard which stretched at right angles across the mast both merchantmen and warships set the squaresail, and the use by Homer of the word meruomai for drawing up or furling sails is sufficiently indicative that the ancient Greek sailors stowed sail not by lowering it on deck as in a modern fore-and-after, but after the fashion of a modern full-rigged ship.

We find mention also of the halyards—one on each side of the mast is shown in the Greek vase designs—which supported the yard to the top of the mast, the sail being reefed by means of brailing lines. The same word that we have just mentioned, for “drawing up” or “furling” sails, was also employed for drawing up the cables. And here again there is a further connection. The plural kaloi is used to mean (1) cables, (2) reefing ropes (i.e. brails), or even reefs as opposed to the sheets (podes) and braces (huperai). Euripides employs the expression kalōs exienai, meaning to “let out the reefs.” And (3) kaloi also means not merely generally a rope, but also a sounding line, which again is evidence that these ancient seamen found the depth of water as the modern sailor feels his way through shoal seas. The word just given for sheets was applied to the lower37 corners of the sail—clews as we nowadays call them—and thus naturally the ropes attached to the foot (or lowest part) were also called podes. The braces were called huperai, obviously because they were in fact the upper ropes.

As we have just seen from Antipater and Leonidas, the mariner used cables and hawsers for securing his ship, these being sent out from both bow and stern. Instead of anchors the early Greeks used heavy stones for the bow cables, whilst other hawsers were run out from the stern to the shore and hitched on to a big boulder or rock. If the former, then there was a hole therein. An endless rope was rove through this perforated stone, so that thus the ship could be hauled ashore for disembarking, or when wishing to go aboard again, sufficient slack of course having been left at the bow cables. A long pole was used for shoving off, while a ladder, which is seen more than once in Greek vase illustrations, was carried at the stern for convenience in descending to the land from the high-pointed sterns.

There were two sailing seasons. The first was after the rising of the Pleiads, in spring; the second was between midsummer and autumn. When, after the setting of the Pleiads, the ship was hauled up into winter quarters on land, she was supported by props to keep her upright, and then a stone fence was put round her. This afforded her protection against wind and weather. The cheimaros, or plug, was then taken out from the bottom so as to let out all the bilge-water. The ship’s gear, the sails, steering oars, and tiller were then stored at home till the time came once more for the sailors to “stretch” their forestays.

About the year 700 B.C. the Greek warships were manned by fifty rowers; hence these craft were called pentekontoroi. With the existence of a forecastle and a38 raised horned poop, one can understand perfectly well how easy was the transition which caused an upper deck to be added about this century. This gave to the ship greater power, because it allowed two banks of oarsmen, one on each deck. As far as possible these rowers were covered in to avoid the attacks of the enemy. Such shallow-draught vessels as the war-galleys could not possibly be good as sailing craft. They must be looked upon as essentially rowing vessels which occasionally set canvas when cruising and a fair wind was blowing.

The pentekontoroi were single-banked, and for a long time the Greek fleets consisted solely of this type. But then came the additional deck just spoken of which gave two banks, and subsequently the trireme succeeded the bireme. The trireme was very popular till after the close of the Peloponnesian War, when the quadrireme was introduced from Carthage. Dr. Oskar Seyffert6 asserts that before the close of the fourth century B.C. quinquiremes and even six-banked craft, and (later still) even sixteen-banked vessels are supposed by some writers to have been in vogue. But as to the latter this seems highly improbable.

And before we proceed any further, let us endeavour to get a clear idea as to the nature of a trireme. This species of ship had been invented by those great seamen who hailed from the port of Sidon. About the year 700 B.C. this type was adopted by the Greeks, and then began to supersede all other existing types of war-vessels. Themistocles in 483 B.C. inaugurated the excellent practice of maintaining a large permanent navy. As a commencement he built a hundred triremes, and these were used at the battle of Salamis. In the Greek word trieres there is nothing to signify that it was necessarily three-banked, and it is well to realise39 this fact from the start. The word just means “triple-arranged,” neither more nor less. It is when we come to the question as to the details of this triple arrangement that we find a divergence of theory. It will, therefore, be best if we state first the prevailing theory of the trireme’s arrangement, and then pass on to give what is the more modern and the more plausible interpretation.

Cast of a Relief in Athens.

Showing the disposition of rowers in a trireme.

The most general idea, then, is that the trireme was fitted with three tiers of oarsmen. In this case the thalamitai were those who sat and worked on the lowest tier; the zugitai, those who sat on the beams; whilst the thranitai were the men who sat on the highest tier. (Homer refers to the seven-foot bench, or thrēnus, which was the seat of the helmsman or the rowers). Each oarsman, it is thought, sat below and slightly to the rear of the oarsman above him, so that these three sections of men formed an oblique line. This economised space and facilitated their movements. A variation of this same theory suggests that the thalamitai sat close to the vessel’s side, the zugitai who were higher up being distant from the side the breadth of one thwart, whilst the thranitai, higher still, were the breadth of two thwarts away. The oar of each rower would pass over the head of the rower below.

But a better theory of the arrangement of the trireme may be presented as follows, and it has the advantage of satisfying all the evidence found in ancient literature and pictorial representation. Banish, then, from your mind all thought of three superimposed tiers, and instead consider a galley so arranged that the rowers work side by side. Each of the triple set of oarsmen sits pulling his own separate oar. But all three oars emerge through one porthole. In front of each bench was a stretcher, and the rower stood up grasping his oar and pulled back, letting the full weight of his body40 fall on to the stroke till at its end he found himself sitting on the bench. On either side of him, at the same bench, was another rower doing the same exertion. In each porthole there would thus be three thole-pins to fit three oars. In this case, then, the thalamitēs would be he who rowed nearest the porthole. Because he worked the shortest oar and thus had the least exertion he received the least pay. Next to him sat the zugitēs, and next to the latter came the thranitēs, who worked the longest oar, and therefore did the most work, having to stand on a stool (thranos) in order to get greater exertion on to his oar at the beginning of the stroke. It is supposed that the rowers’ benches were not all in the same plane, but that the second would be higher than the first, and the third higher than the second.

The number of oars in an ancient trireme was as many as 170. These oars were necessarily very long, and time was kept sometimes by the music of a flute, or by the stroke set by the keleustes, who was on board for that purpose. This he did either with a hammer of some sort, or his voice. And there is at least one illustration showing such a man using a hammer in an oar-propelled boat for that purpose.7 The inscriptions which were unearthed some years ago, containing the inventories of the Athenian dockyards, belonging to the years between 373 B.C. and 323 B.C., have been collected and published. And it is from them that we obtain such valuable information as the number of oarsmen which the biremes carried. This number was usually 200, and was disposed in the ship as follows: There were 54 thalamitai, 54 zugitai, 62 thranitai, and 30 perineo. The exact meaning of the latter word is supercargoes or passengers, but they were carried perhaps as spare oarsmen in case any became disabled.