Title: Harper's Round Table, December 1, 1896

Author: Various

Release date: August 1, 2019 [eBook #60027]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 1, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xviii.—no. 892. | two dollars a year. |

The fault that most people will find with this story is that it is unconvincing. Its scheme is improbable, its atmosphere artificial. To confess that the thing really happened—not as I am about to set it down, for the pen of the professional writer cannot but adorn and embroider, even to the detriment of his material—is, I am well aware, only an aggravation of my offence; for the facts of life are the impossibilities of fiction. A truer artist would have left this story alone, or at most have kept it for the irritation of his private circle. My lower instinct is to make use of it. A very old man told me the tale; he was landlord of the Cromlech Arms, the only inn of a small, rock-sheltered village on the northeast coast of Cornwall, and had been so for nine-and-forty years. It is called the Cromlech Hotel now, and is under new management, and during the season some four coach-loads of tourists sit down each day to table d'hôte lunch in the low-ceilinged parlor. But I am speaking of some time ago when the place was a mere fishing-harbor, undiscovered by the guide-books.

The old landlord talked, and I harkened, the while we[Pg 106] both sat drinking thin ale from earthen-ware mugs late one summer's evening, on the bench that runs along the wall just beneath the latticed windows; and during the many pauses when the old landlord stopped to puff his pipe in silence and lay in a new stock of breath, there came to us the deep voices of the Atlantic, and often, mingled with the pompous roar of the big breakers further out, we would hear the rippling laugh of some small wave that, maybe, had crept in to listen to the tale the landlord told.

The mistake that Charles Seabohn, junior partner of the firm of Seabohn & Son, civil engineers, of London and Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and Mivanway Evans, youngest daughter of the Rev. Thomas Evans, pastor of the Presbyterian church at Bristol, made originally was in marrying too young. Charles Seabohn could hardly have been twenty years of age, and Mivanway could have been little more than seventeen, when they first met upon the cliffs two miles above the Cromlech Arms. Young Charles Seabohn, coming upon the village in the course of a walking-tour, had decided to spend a day or two exploring the picturesque coast; and Mivanway's father had hired a neighboring farm-house wherein to spend his summer vacation. Early one morning—for, at twenty, one takes exercise before breakfast—as young Charles Seabohn lay upon the cliffs, watching the white waters come and go upon the black rocks beneath him, he became aware of a form rising from the waves. The figure was too far off for him to see it clearly, but, judging from the costume, it was a female figure, and promptly the mind of Charles, poetically inclined, turned to thoughts of Venus or Aphrodite, as he, being a gentleman of delicate taste, would have preferred to term her. He saw the figure disappear behind a headland, but still waited. In about ten minutes or a quarter of an hour it reappeared clothed in the garments of the eighteen-sixties, and came towards him. Hidden from sight himself behind a group of rocks, he could watch it at his leisure ascending the steep path from the beach; and an exceedingly sweet and dainty figure it would have appeared even to eyes less susceptible than those of twenty. Sea-water—I stand open to correction—is not, I believe, considered anything of a substitute for curling-tongs, but to the hair of the youngest Miss Evans it had given an additional and most fascinating wave. Nature's red and white had been most cunningly laid on, and the large childish eyes seemed to be searching the world for laughter with which to feed a pair of delicious, pouting lips. Charles's upturned face, petrified into admiration, appeared to be just the sort of thing for which they were on the lookout. A startled "Oh!" came from the slightly parted lips, followed by the merriest of laughs, which in its turn was suddenly stopped by a deep blush. Then the youngest Miss Evans looked offended, as though the whole affair had been Charles's fault, which is the way of women. And Charles, feeling himself guilty under that stern gaze of indignation, rose awkwardly and apologized meekly, whether for being on the cliffs at all or for having got up too early he would have been unable to explain.

The youngest Miss Evans graciously accepted the apology thus tendered with a bow, and passed on, and Charles stood staring after her till the valley gathered her into its spreading arms and hid her from his view.

That was the beginning of all things—I am speaking of the universe as viewed from the stand-point of Charles and Mivanway.

Six months later they were man and wife; or perhaps it would be more correct to say boy and wifelet. Seabohn senior counselled delay, but was overruled by his junior partner. The Rev. Mr. Evans, in common with most theologians, possessed a goodly supply of unmarried daughters and a limited income. Personally he saw no necessity for postponement of the marriage.

The month's honeymoon was spent in the New Forest. That was a mistake to begin with. The New Forest in February is depressing, and they had chosen the loneliest spot they could find. A fortnight in Paris or Rome would have been more helpful. As yet they had nothing to talk about except love, and that they had been talking and writing about steadily all through the winter. On the tenth morning Charles yawned, and Mivanway had a quiet half-hour's cry about it in her own room. On the sixteenth evening Mivanway, feeling irritable, and wondering why (as though fifteen damp, chilly days in the New Forest were not sufficient to make any woman irritable), requested Charles not to disarrange her hair; and Charles, speechless with astonishment, went out into the garden and swore before all the stars that he would never caress Mivanway's hair again as long as he lived.

One supreme folly they had conspired to commit even before the commencement of the honeymoon. Charles, after the manner of very young lovers, had earnestly requested Mivanway to impose upon him some task. He desired to do something great and noble to show his devotion. Dragons were the things he had in his mind, though he may not have been aware of it. Dragons also, no doubt, flitted through Mivanway's brain; but unfortunately for lovers, the supply of dragons has lapsed. Mivanway, liking the conceit, however, thought over it, and then decided that Charles must give up smoking. She had discussed the matter with her favorite sister, and that was the only thing the girls could think of. Charles's face fell. He suggested some more herculean labor, some sacrifice more worthy to lay at Mivanway's feet. But Mivanway had spoken. She might think of some other task, but the smoking prohibition would in any case remain. She dismissed the subject with a pretty hauteur that would have graced Marie Antoinette.

Thus tobacco, the good angel of all men, no longer came each day to teach Charles patience and amiability, and he fell into the ways of short temper and selfishness.

They took up their residence in a suburb of Newcastle, and this was also unfortunate for them, because there the society was scanty and middle-aged, and in consequence they had still to depend much upon their own resources. They knew little of life, less of each other, and nothing at all of themselves. Of course they quarrelled, and each quarrel left the wound a little deeper than before. No kindly experienced friend was at hand to laugh at them. Mivanway would write down all her sorrows in a bulky diary, which made her feel worse; so that before she had written for ten minutes her pretty unwise head would drop upon her dimpled arm, and the book, the proper place for which was behind the fire, would become damp with her tears; and Charles, his day's work done and the clerks gone, would linger in his dingy office and hatch trifles into troubles.

The end came one evening after dinner, when in the heat of a silly squabble Charles boxed Mivanway's ears. That was very ungentlemanly conduct, and he was most heartily ashamed of himself the moment he had done it, which was right and proper for him to be. The only excuse to be urged on his behalf is that girls sufficiently pretty to have been spoiled from childhood by every one about them can at times be intensely irritating. Mivanway rushed up to her room and locked herself in; Charles flew after her to apologize, but only arrived in time to have the door slammed in his face.

It had only been the merest touch; a boy's muscles move quicker than his thoughts. But to Mivanway it was a blow. This is what it had come to! This was the end of a man's love!

She spent half the night writing in the precious diary, with the result that in the morning she came down feeling more bitter than when she had gone up. Charles had walked the streets of Newcastle all night, and that had not done him any good. He met her with an apology combined with an excuse, which was bad policy. Mivanway, of course, fastened upon the excuse, and the quarrel recommenced. She mentioned that she hated him, he hinted that she had never loved him, and she retorted that he had never loved her. Had there been anybody by to knock their heads together and suggest breakfast, the thing might have blown over; but the combined effect of a sleepless night and an empty stomach upon each proved disastrous. Their words came poisoned from their brains, and they believed[Pg 107] they meant what they said. That afternoon Charles sailed from Hull on a ship bound for the Cape, and that evening Mivanway arrived at the paternal home in Bristol with two trunks and the curt information that she and Charles had separated forever. The next morning both thought of a soft speech to say to the other, but the next morning was just twenty-four hours too late.

Eight days afterward Charles's ship was run down in a fog near the coast of Portugal, and every soul on board was supposed to have perished. Mivanway read his name among the list of lost.

By good luck, however, Charles and one other man were rescued by a small trading-vessel, and landed in Algiers. There Charles learned of his supposed death, and the idea occurred to him to leave the report uncontradicted. For one thing, it solved a problem that had been troubling him. He could trust his father to see to it that his own small fortune, with possibly something added, was handed over to Mivanway, and she would be free, if she wished, to marry again. He was convinced that she did not care for him, and that she had read of his death with a sense of relief. He would make a new life for himself and forget her.

He continued his journey to the Cape, and once there he soon gained for himself an excellent position. The colony was young, engineers were welcome, and Charles knew his business. He found the life interesting and exciting. The rough, dangerous up-country work suited him, and the time passed swiftly.

But in thinking he would forget Mivanway, he had not taken into consideration his own character, which at bottom was a very gentlemanly character. Out on the lonely veldt he found himself dreaming of her. The memory of her pretty face and merry laugh came back to him at all hours. Occasionally he would rate her roundly, but that only meant that he was sore because of the thought of her; what he was really rating was himself and his own folly. Softened by the distance, her quick temper, her very petulance became mere added graces; and if we consider women as human beings, and not as angels, it was certainly a fact that he had lost a very sweet and lovable woman.

Ah! if only she were by his side now—now that he was a man, capable of appreciating her, and not a foolish, selfish boy. This thought would come to him as he sat smoking at the door of his tent, and then he would regret that the stars looking down upon him were not the same stars that were watching her; it would have made him feel nearer to her. For, though young people may not credit it, one grows more sentimental as one grows older—at least some of us do, and they, perhaps, not the least wise.

One night he had a vivid dream of her. She came to him and held out her hand, and he took it, and they said good-by to one another. They were standing on the cliff where he had first met her, and one of them was going upon a long journey, though he was not sure which.

In the towns men laugh at dreams, but away from civilization we listen more readily to the strange tales that Nature whispers to us. Charles Seabohn recollected this dream when he awoke in the morning.

"She is dying," he said, "and she has come to wish me good-by."

He made up his mind to return to England at once; perhaps if he made haste he would be in time to kiss her. But he could not start that day, for work was to be done, and Charles Seabohn, lover though he still was, had grown to be a man, and knew that work must not be neglected even though the heart may be calling. So for a day or two he staid, and on the third night he dreamed of Mivanway again, and this time she lay within the little chapel at Bristol where, on Sunday mornings, he had often sat with her. He heard her father's voice reading the burial service over her, and the sister she had loved best was sitting beside him, crying softly! Then Charles knew that there was no need for him to hasten. So he remained to finish his work. That done, he would return to England. He would like again to stand upon the cliffs above the little Cornish village where they had first met.

Thus, a few months later, Charles Seabohn—or Charles Denning, as he called himself—aged and bronzed, not easily recognizable by those who had not known him well, walked into the Cromlech Arms, as six years before he had walked in with his knapsack on his back, and asked for a room, saying he would be stopping in the village for a short while.

In the evening he strolled out and made his way to the cliffs. It was twilight when he reached the place of rocks to which the fancy-loving Cornish folk had given the name of the Witches' Caldron. It was from this spot that he had first watched Mivanway coming to him from the sea.

He took the pipe from his mouth, and leaning against a rock whose rugged outline seemed fashioned into the face of an old friend, gazed down the narrow pathway now growing indistinct in the dim light. And as he gazed, the figure of Mivanway came slowly up the pathway from the sea and paused before him.

He felt no fear. He had half expected it. Her coming was the complement of his dreams. She looked older and graver than he remembered her, but for that the face was the sweeter.

He wondered if she would speak to him, but she only looked at him with sad eyes; and he stood there in the shadow of the rocks without moving, and she passed on into the twilight.

Had he, on his return, cared to discuss the subject with his landlord, had he even shown himself a ready listener—for the old man loved to gossip—he might have learned that a young widow-lady named Mrs. Charles Seabohn, accompanied by an unmarried sister, had lately come to reside in the neighborhood, having, upon the death of the former tenant, taken the lease of a small farm-house sheltered in the valley a mile beyond the village; and that her favorite evening's walk was to the sea and back by the steep footway leading past the Witches' Caldron.

Had he followed the figure of Mivanway into the valley, he would have known that out of sight of the Witches' Caldron it took to running fast till it reached a welcome door, and fell panting into the arms of another figure that had hastened out to meet it.

"My dear," said the older woman, "you are trembling like a leaf. What has happened?"

"I have seen him!" answered Mivanway.

"Seen whom?"

"Charles."

"Charles!" repeated the other, looking at Mivanway as though she thought her mad.

"His spirit, I mean," explained Mivanway, in an awed voice. "It was standing in the shadow of the rocks, in the exact spot where we first met. It looked older and more careworn; but oh! Margaret, so sad and reproachful."

"My dear," said her sister, leading her in, "you are over-wrought. I wish we had never come back to this house."

"Oh, but I was not frightened," answered Mivanway. "I have been expecting it every evening. I am so glad it came. Perhaps it will come again, and I can ask it to forgive me."

So next night Mivanway, though much against her sister's wishes and advice, persisted in her usual walk, and Charles, at the same twilight hour, started from the inn.

Again Mivanway saw him standing in the shadow of the rocks. Charles had made up his mind that if the thing happened again he would speak; but when the silent figure of Mivanway, clothed in the fading light, stopped and gazed at him, his will failed him.

That it was the spirit of Mivanway standing before him he had not the faintest doubt. One may dismiss other people's ghosts as the fantasies of a weak brain, but one knows one's own to be realities; and Charles for the last five years had mingled with a people whose dead dwelt about them. Once, drawing his courage around him, he made to speak, but as he did so, the figure of Mivanway shrank from him, and only a sigh escaped his lips; and hearing that, the figure of Mivanway turned, and again passed down the path into the valley, leaving Charles gazing after it.

But the third night both arrived at the trysting-spot[Pg 108] with determination screwed up to the sticking-point. Charles was the first to speak. As the figure of Mivanway came towards him with its eyes fixed sadly on him, he moved from the shadow of the rocks, and stood before it.

"Mivanway!" he said.

"Charles," replied the figure of Mivanway. Both spoke in an awed whisper suitable to the circumstances, and each stood gazing sorrowfully upon the other. "Are you happy?" asked Mivanway.

The question strikes one as somewhat farcical, but it must be remembered that Mivanway was the daughter of a gospeller of the old school, and had been brought up to beliefs that were not then out of date.

"As happy as I deserve to be," was the sad reply; and the answer—the inference was not complimentary to Charles's deserts—struck a chill to Mivanway's heart. "How could I be happy, having lost you?" went on the voice of Charles.

Now this speech fell very pleasantly upon Mivanway's ears. In the first place it relieved her of her despair regarding Charles's future. No doubt his present suffering was keen, but there was hope for him. Secondly, it was a decidedly "pretty" speech for a ghost, and I am not at all sure that Mivanway was the kind of woman to be averse to a little mild flirtation with the spirit of Charles.

"Can you forgive me?" asked Mivanway.

"Forgive you?" replied Charles, in a tone of awed astonishment. "Can you forgive me? I was a brute—a fool—I was not worthy to love you." A most gentlemanly spirit it seemed to be. Mivanway forgot to be afraid of it.

"We were both to blame," answered Mivanway. But this time there was less submission in her tones. "But I was the most at fault. I was a petulant child. I did not know how deeply I loved you."

"You loved me?" repeated the voice of Charles, and the voice lingered over the words.

"Surely you never doubted it," answered the voice of Mivanway. "I shall love you always and ever."

The figure of Charles sprang forward as though it would clasp the ghost of Mivanway in its arms, but halted a step or two off. "Bless me before you go," he said; and with uncovered head the figure of Charles knelt to the figure of Mivanway.

Really ghosts could be exceedingly nice when they liked. Mivanway bent graciously towards her shadowy suppliant, and as she did so, her eye caught sight of something on the grass beside it; that something was a well-colored meerschaum pipe. There was no mistaking it for anything else even in that treacherous night; it lay glistening where Charles, in falling upon his knees, had jerked it from his breast pocket.

Charles, following Mivanway's eyes, saw it also, and the memory of the prohibition against smoking came back.

Without stopping to consider the futility of the action—nay, the direct confession implied thereby—he instinctively grabbed at the pipe, and rammed it back into his pocket; and then an avalanche of mingled understanding and bewilderment, fear and joy, swept Mivanway's brain before it. She felt she must do one of two things—laugh or scream, and go on screaming; and she laughed. Peal after peal of laughter she sent echoing among the rocks, and Charles, springing to his feet, was just in time to catch her as she fell forward, a dead weight into his arms.

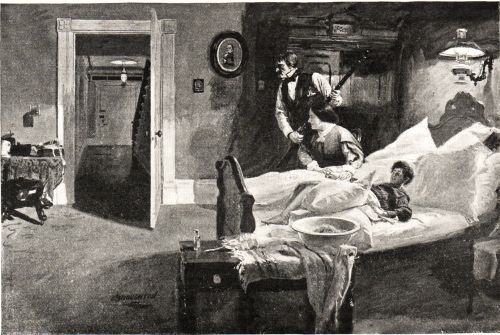

Ten minutes later the eldest Miss Evans, hearing heavy footsteps, went to the door. She saw what she took to be the spirit of Charles Seabohn staggering under the weight of the lifeless body of Mivanway, and the sight not unnaturally alarmed her. Charles's suggestion of a stimulant, however, sounded human, and the urgent need of attending to Mivanway kept her mind from dwelling upon problems tending towards insanity.

Charles carried Mivanway to her room and laid her upon the bed. "I'll leave her with you," he whispered to the eldest Miss Evans. "It will be better for her not to see me until she is quite recovered. She has had a shock."

Charles waited in the dark parlor for what seemed to him an exceedingly long time. But at last the eldest Miss Evans returned.

"She's all right now," were the welcome words he heard.

"I'll go and see her," he said.

And the eldest Miss Evans, left alone, sat down and wrestled with the conviction that she was dreaming.

The boy or girl on whom nature has bestowed the natural talent and liking for art and art-work, will find clay-modelling a fascinating and pleasing branch to follow.

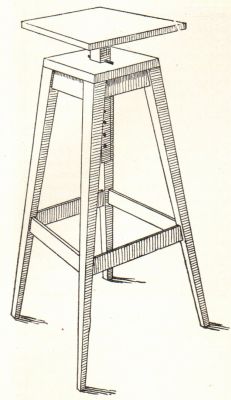

FIG. 1.

FIG. 1.

To become a perfect modeller, and finally a sculptor, requires years of patience and perseverance to accomplish the highest degree that can be aimed at; and to successfully carry out the most minute detail accurately, necessitates a great deal of patient study and close application to the work.

To copy simple objects in clay, carrying out the detail and general line in quite a satisfactory manner, is not a difficult matter, and with some clay, a few tools, and the skeletons or supports, the amateur should not meet with any great obstacle if the following descriptions and instructions are accepted and practised.

It is not possible to give the young modeller the complete demonstration, but the primary helps can be suggested, so that, if carried out in the right manner and by the worker with brains, minute features in the detail can be accomplished that only the inventive brain of the young artist would grasp and use to good advantage.

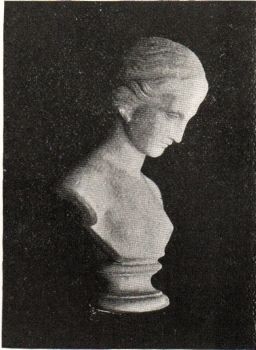

FIG. 2.

FIG. 2.

Very few tools are necessary at the beginning, and those shown in Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, Fig. 5, are a full complement for any beginner. The first four are wire tools, made of spring steel or brass wire, about which fine wire is wrapped; the ends of the wires are securely bound to the end of a round wooden handle, and sometimes for convenience two ends are made fast to a single handle; and these tools are called double-enders, and are used in roughing out the clay in the first stages of the work. No. 5 is a boxwood tool with one serrated edge, and is used for finishing. The tools shown in Nos. 6 and 7 are of steel, and are of use on plaster, where others would not be sufficiently durable. Any of these tools can be purchased at an art-material store for a few cents each, except the steel tools, which are more expensive.

A stand or pedestal will be necessary on which to place the clay model, unless perhaps it should be a medallion, which may be worked over on a table.

FIG. 3.

FIG. 3.

Fig. 6 is a stand that can be made by any boy from a few pieces of pine two inches square, and a top board one[Pg 109] inch and a half in thickness, and arranged with a central shaft that may be raised or lowered, and to the top of which a platform is securely attached.

The movable shaft can have some holes bored through it from side to side, through which a small iron pin may be adjusted to hold the platform at a desired height. Clay can be purchased at the art stores by the pound, or in the country a very good quality of light slate-colored clay may sometimes be found along the edges of brooks, or in swampy places where running water has washed away the dirt and gravel, leaving the clear deposit of clay in the consistency of putty.

FIG. 4.

FIG. 4.

Supports which the clay models are built upon can be made of wood and wire, as the requirements necessitate. That for the head is shown in Fig. 1. Nearly every clay model of any size will need some support, as clay is heavy and settles, and if not properly supported will soon become distorted, and the composition spoiled. Add to the paraphernalia some old soft cloths that can be applied wet to the clay, a pair of calipers, and a small trowel or spatula.

To model well, the art of drawing is constantly used, the idea of form is continually brought into play, so the knowledge of drawing is essential to the good modeller. To begin with, choose some simple object to copy, such as a vase or some small ornament, then when a satisfactory result has been obtained, select something a trifle more difficult, such as a hand or foot.

Plaster heads, hands, feet, and all parts of the human body, as well as animals and flower pieces, can be purchased at the art stores, but if they are not available something that may be at hand in which artistic merit is evident may be chosen as a model.

When copying a head obtain a bust support on which to work the clay, and a very simple and strong one can be made from a piece of board, two sticks, and a short piece of pipe wired to the top end of the upright stick, Fig. 1.

To carry out the proportions of a bust similar to Fig. 4, the clay can be packed about the support much after the manner shown in Fig. 2. This will be the support for the clay.

With a lump of clay and the fingers form the general outline as shown in Fig. 2 for the head, then with the wire tools begin to work away the clay in places so as to follow the lines of the model. With the calipers measurements can be taken from the plaster head and used advantageously in carrying out the accuracy of the clay model. Turn the plaster model and clay copy occasionally, so that all sides may be presented and closely followed in line and detail.

Modelling differs from drawing and painting in that every side of the model is visible, while only the face of the painting is presented to the eye, where the impression of form and outline is worked out on a flat surface.

The contour of proportion is the most difficult part of modelling, and for this reason it is to the student and amateur one of the most beneficial branches of the fine arts. Having successfully mastered the head, next attempt a foot from a plaster cast. Select a simple foot, and afterwards a more elaborate subject, such as a whole figure, can be tried.

FIG. 5.

FIG. 5.

With the wire modelling-tools and the fingers begin to work away the clay to obtain the general outline and form; continue this in a rough manner, until a perfect composition is obtained that compares favorably with the original model; the finishing-touches may then be applied, and the detail worked up more carefully.

Never complete one part and leave the remaining ones until later; always work up the model uniformly, adding a little here and there, or taking away, as may be necessary, and so developing the total composition gradually.

Always turn both model and copy frequently, that comparison may be frequently made, and thus training the eye[Pg 110] to detect any little miscalculation in proportions and lines, and by the addition or removal of small masses the clay will finally take the form and accurate outline and detail of the original.

Moisten the clay occasionally with water sprayed on with a small watering-pot or a green-house sprinkler, to keep it soft and ductile, and when not being worked upon it should be covered with wet cloths to keep it moist.

FIG. 6.

FIG. 6.

As the work progresses the clay may be allowed to harden and consolidate, but not to dry; if allowed to dry entirely the model may be considered ruined, as the shrinkage of the clay around the support results in fissures and fractures that cannot be repaired.

By the time the amateur has acquired the knowledge to attempt a full-size figure he will invent the devices to support it.

The support or skeleton must of course be adapted to line with the pose of the figure, and should be of pipe and heavy wire or rods securely anchored to the base-plate.

The composition of flowers, fruit, foliage, animal life, and landscape is an inexhaustible one, and some beautiful effects can be had in flat-work. Good examples of this character of work can be found on all sides, and to the genius the field of modelling is a broad one, without limit.

For the help and assistance of those who desire to make a deeper study there are many hand-books and treatises on the subject by masters and sculptors, but the boy or girl adopting the work as a pleasant pastime will find this description very beneficial in the selection of tools and materials, as well as the primary steps to the great art of sculpture.

When casting from hands, feet, or ornaments where undercut predominates, the most successful mode is in the use of gelatine or glue.

To cast a head similar to the one shown in Fig. 4, it will be necessary to make a box frame large enough to place the head in.

The cast is to be well oiled, and down the front and back, running around under and back over the base block, strong linen threads are to be stuck on with oil. Warm glue or gelatine is then poured in the box, and left to chill and solidify.

When sufficiently cold the frame may be removed, leaving the solid block of glue like hard jelly; the ends of the threads are to be grasped and torn through the gelatine, thus separating it in two or three parts. The plaster head may then be removed, and the mould put together again and surrounded by the frame to hold it in place.

To make a plaster head this plaster of Paris may be poured into the mould and left for a while, when, on removing the frame and taking the glue mould away, a perfect reproduction of the original head will be found.

When very large objects that would require a great deal of plaster are cast, they are generally made hollow in the following manner:

Obtain the glue mould by the process described, and into it pour a quantity of thin plaster, having first oiled the surfaces that come in contact with it. Turn the mould about and upside down, so the plaster will enter every part and adhere to the glue form. Allow it to "set," and again pour some plaster into the mould, which will adhere to the first coating, and after this has set repeat the operation several times, until a deposit or coating an inch or more in thickness has been made.

The glue mould on being removed will reveal a perfect plaster casting that, instead of being solid, is hollow, and in consequence is much lighter.

"I am not one of those fellows who 'can fight and run away, and live to fight some other day,'" one of the bravest Lieutenant-Commanders in the United States navy said one evening to a party of friends, who were making him feel uncomfortable by discussing his brilliant war record. "My bad leg won't let me run, so I always have to stand and fight it out."

"Why, Commander," one of his friends exclaimed, "I did not know that you had a bad leg. You do not limp."

"No," he answered, "not ordinarily. But when I tire myself I limp a little, and if I were to undertake to run I should come to grief."

"Where did you receive your injury?" another asked.

"In action at Apalachicola," the Commander replied; "the severest action I ever saw."

There was a twinkle in his eye as he spoke, and he looked about the table to see what effect the words had upon his friends. Two of them merely muttered their sympathy, and the third asked for the story of the fight; but the fourth man looked up with a comical expression that told the Commander he was understood in one quarter at least.

"You will certainly have to tell us about that," this fourth man laughed, seeing that the Commander was waiting for a question; "for I have always understood that Apalachicola, being an out-of-the-way place, was one of the few Southern towns that escaped without a scratch in the war. I never heard of any battle there."

"No, there was no battle there," the Commander replied, "and you would hardly hear of the action, because there were so few engaged in it. In fact, I was the only one on the Federal side, and there were no Confederates. When I was a boy there I fell out of a pine-tree and broke my thigh; so it was my own action, and one that I still have reason to remember."

This was the Commander's modest way of describing an accident that brought out all the manliness he had in him, and made him an officer in the United States navy, and he seldom gives any other account of it; but some of the grown-up boys of Apalachicola tell the story in a very different way—the same "boys," some of them, who used to set out in parties of three or four and chase young Jack Radway and make life miserable for him.

Jack had a strange habit, when he was between fifteen and sixteen (this is the way they tell the story in Apalachicola), of going down to the wharf and sitting by the half-hour on the end of a spile, looking out over the bay. That was in 1862. His name was not Jack Radway, but that is a fairly good sort of name, and on account of the Commander's modesty it will have to answer for the present. While he sat in this way it was necessary for him to keep the corner of one eye on the wharf and the adjacent street, watching for enemies. Oddly enough, every white boy in the town was Jack's enemy, generous as he was, and brave and good-hearted; and when one came alone, or even two, if they were not too big, he was always ready to stay and defend himself. But when three or four came together he was forced to retire to his father's big brick warehouse, across the street. They would not follow him there, because it was well known that the rifle standing beside the desk was always kept loaded.

This enmity with the other boys, for no fault of his own, was Jack's great sorrow. A year or two before he had been a favorite with all the boys and girls, and now he was hungry for a single friend of his own age. The reason of it was that his father was the only Union man in Apalachicola. Every white man, woman, and child in the town sympathized with the Confederacy, except John Radway and his wife and their son Jack. The elder Radway had thought it over when the trouble began, and had made up his mind that his allegiance belonged to the old government that his grandfather had fought for.

Near the mouth of the river lay the United States gunboat Alleghany, guarding the harbor, with the stars and stripes floating bravely at her stern.

"Look at that flag," Jack's father told him. "Your great-grandfather fought for it, and I want you always to honor it. It is the grandest flag in the whole world. It is my flag and yours, and you must never desert it."

By the side of Mr. Radway's house stood a tall pine-tree, much higher than the top of the house, with no limbs growing out of the trunk except at the very top, after the manner of Southern pines. Jack was a great climber, and nearly every day, when he did not go down town, he "shinned" up this tall tree to make sure that the gunboat was still in the harbor. And one day, the day of what the Commander calls "the action at Apalachicola," he lost his hold in some way, or a limb broke, and he fell from the top to the ground.

For some time he lay there unconscious, and when he came to his senses he could not get up. There was a terrible pain in his left hip, and he called for help, and his mother and some of the colored women ran out and carried him into the house, and when they laid him on a bed he fainted again from the pain.

Mr. Radway was sent for, and after he had examined the leg as well as he could, he looked very solemn, for there was no doubt that the bone was badly broken. Even Jack, young as he was, could tell that; but with all his pain he made no complaint.

"This is serious business," he said to his wife when they were out of Jack's hearing. "The bone is badly fractured at the thigh, and there is not a doctor left in Apalachicola to set it. Every one of them is away in the army, and I don't know of a doctor within a hundred miles."

"Except on the gunboat," Mrs. Radway interrupted; "there must be a surgeon on the gunboat."

"I have thought of that," Mr. Radway answered; "but if he should come ashore he would almost certainly be killed, so I could not ask him to come. And if I should take Jack out to the boat, we would very likely be attacked on the way. I must take time to think."

Medicines were scarce in Apalachicola in those days, but they gave Jack a few drops of laudanum to ease the pain, and made a cushion of pillows for his leg. For all his terrible suffering, and the doubt about getting the bone set, he did not utter a word of complaint. But he turned white as the pillows, and the great heat of midsummer on the shore of the Gulf added to his misery.

For hours Mr. Radway walked the floor, trying to make up his mind what to do. Jack's suffering was agony to him, and the uncertainty of getting help increased it. Late in the evening, when all the household were in bed but Mr. and Mrs. Radway, they heard the sound of many feet coming up the walk, then a shuffling of feet on the piazza, and a heavy knock at the front door.

"COULD THEY COME TO ATTACK US WHEN THEY KNOW WHAT TROUBLE

WE ARE IN?"

"COULD THEY COME TO ATTACK US WHEN THEY KNOW WHAT TROUBLE

WE ARE IN?"

"Have they the heart for that?" Mr. Radway exclaimed. "Could they come to attack us when they know what trouble we are in? Some of them shall pay dearly for it if they have."

The knock was repeated, louder than before, and Mr. Radway took up a rifle and started for the door. Standing the rifle in the corner of the wall, and with a cocked revolver in one hand, he turned the key and opened the door a crack, keeping one foot well braced against it.

"You don't need your gun, neighbor," said the spokesman of the party without; "it's a peaceable errand we are on this time."

"What is it?" Mr. Radway asked, still suspicious.

"We know the trouble you are in," the man continued, "and we are sorry for you. It's not John Radway we are down on; it's his principles; but we want to forget them till we get you out of this scrape. There are twenty of us here, all your neighbors and former friends. We know there is no doctor in Apalachicola, and we have come to say that if you can get the surgeon of the gunboat to come ashore and mend up the sick lad, he shall have safe-conduct both ways. We will guard him ourselves, and we pledge our word that not a hair of his head shall be touched."

This friendly act came nearer to breaking down John Radway's bold front than all the persecutions he had been subjected to. He threw the door wide open, put the revolver in his pocket, and grasped the spokesman's hand.

"I need not try to thank you," he said; "you know what I would say if I could. My poor Jack is in great pain, and I shall make up my mind between this and daylight what had better be done."

The knowledge that he was surrounded by friends instead of enemies made Jack feel better in a few minutes; but the pain was too great to be relieved permanently in such a way, and all night long he lay with his teeth shut tight, determined to make no complaint.

By daylight he was in such a high fever that his father had no further doubts about what to do. He must have medical attendance at once; and the quickest way was to take him out to the gunboat, rather than risk the delay of getting the surgeon ashore. So a cot-bed was converted into a stretcher by lashing handles to the sides. Colored men were sent for to carry it, and another was sent down to the shore to make Mr. Radway's little boat ready.

The morning sun was just beginning to gild the smooth water of Apalachicola Bay, when the after-watchman on the gunboat's deck, who for some time had been watching a little sail-boat with half a table-cloth flying at the mast-head, called out,

"Small flag-of-truce boat on the port quarter!"

Jack Radway, lying on the stretcher in the bottom of the boat, heard the words repeated in a lower tone, evidently at the door of the Captain's cabin: "Small flag-of-truce boat on the port quarter, sir."

An instant later a young officer appeared at the rail with a marine glass in his hand.

"Ahoy there in the boat!" he called. "Put up your helm! Sheer off!"

The Alleghany lay in an enemy's waters, and she was not to be caught napping. Nothing was allowed to approach without giving a good reason for it.

Then Jack's father stood up in the boat. "I have a boy here with a broken thigh," he said. "I want your surgeon to set it."

"Who are you?" the officer asked.

"John Radway—a loyal man," was the answer.

The name was as good as a passport, for the gunboat people had heard of John Radway.

"Come alongside," the officer called; and five minutes later a big sailor had Jack in his arms, carrying him up the gangway, and he was taken into the boat's hospital and laid on another cot. It was an unusual thing on a naval vessel, and when the big bluff surgeon came the Captain was with him, and several more of the officers.

The examination gave Jack more pain than he had had before, but still he kept his teeth clinched, and refused even to moan.

"It is a bad fracture, and should have been attended to sooner," the surgeon said at length. "There is nothing to be done for it now but to take off the leg."

"Oh, I hope not!" Mr. Radway exclaimed. "Is there no other way?"

"He knows best, father," Jack said; "he will do the best he can for me."

"He is too weak now for an operation," the surgeon continued; "but you can leave him with me, and I think by to-morrow he will be able to stand it."

If Jack had made the least fuss at the prospect of having his leg cut off, or had let a single groan escape, there is hardly any doubt that he would be limping through life on[Pg 112] one leg. But the brave way that he bore the pain and the doctor's verdict made him a powerful friend.

The Captain of a naval vessel cannot control his surgeon's treatment of a case; but the Captain's wishes naturally go a long way, even with the surgeon. So it was a great point for Jack when the Captain interceded for him.

"There's the making of an Admiral in that lad in the hospital," the Captain told the doctor later in the day. "I never saw a boy bear pain better. I wish you would save his leg if you possibly can."

"He'd be well much quicker to take it off," the surgeon retorted. "But I'll give him every chance I can. There is a bare possibility that I may be able to save it."

There was joy in the Radway family when it became known that there was a chance of saving Jack's leg; but all that Jack himself would say was, "Leave it all to the doctor; he will do what he can."

Three weeks afterward Jack still lay in the Alleghany's hospital with two legs to his body, but one half hidden in splints and plaster. Mr. and Mrs. Radway visited him every day, and the broken bone was healing so nicely that the doctor thought that in three or four weeks more Jack might be able to hobble about the deck on crutches, when more trouble came. A new gunboat steamed into the harbor to take the Alleghany's place, bringing orders for the Alleghany to go at once to the Brooklyn Navy-Yard. This was particularly unfortunate for Jack, for his broken bone was just in that state where the motion of taking him ashore would be likely to displace it. But that unwelcome order from Washington proved to be a long step toward making Jack one of our American naval heroes.

"It would be a great risk to take him ashore," the surgeon said to Mr. Radway. "The least movement of the leg would set him back to where we began. You had much better let him go north with us. The voyage will do him good; and even if we are not sent back here, he can easily make his way home when he is able to travel."

Nothing could have suited Jack better than this, for he had become attached to the gunboat and her officers; so it was soon settled that he was to lie still on his bed and be carried to Brooklyn. For more than a month he lay there without seeing anything of the great city on either side of him; and the Alleghany was already under orders to sail for Key West before he was able to venture on deck with a crutch under each arm. There were delays in getting away, so by the time the gunboat was steaming down the coast Jack was walking slowly about her deck with a cane, and the color was in his cheeks again, and the old sparkle in his eyes. He was in hopes of finding a schooner at Key West that would carry him to Apalachicola; but he was not to see the old town again for many a day.

The Alleghany was a little below Hatteras, when she sighted a Confederate blockade-runner, and she immediately gave chase. But, much to the surprise of the officers, this blockade-runner did not run away, as they generally did. She was much larger than the Alleghany, and well manned and armed, and she preferred to stay and fight. Almost before he knew it Jack was in the midst of a hot naval battle. The two vessels were soon close together, and there was such a thunder of guns and such a smother of smoke that he does not pretend to remember exactly what happened. But after it was all over, and the blockade-runner was a prize, with the stars and stripes flying from her stern, Jack walked as straight as anybody down to the little hospital where he had spent so many weeks.

His mother would hardly have known him as he stepped into the hospital and waited till the surgeon had time to take a big splinter from his left arm.

"Where's your cane, young man?" the surgeon asked, when Jack's turn came.

"I don't know, sir!" Jack replied, surprised to find himself standing without it. "I must have forgotten all about it. I saw one of the gunners fall, and I took his place, and that's all I remember, sir, except seeing the enemy strike her colors."

That action made Jack a Midshipman in the United States navy, and gave him a share in the prize-money, and a year later he was an Ensign. For special gallantry in action in Mobile Bay he was made a Lieutenant before the close of the war, and in the long years since then he has risen more slowly to the rank of Lieutenant-Commander.

As soon as breakfast had been finished I bade farewell to Captain Morrison, and to the mate and all of the crew, with whom I had somehow gained popularity, and then I was set on shore.

When I felt the solid ground beneath me and smelt the familiar odors of a seaport town, my fears almost gained the upper hand, and I was tempted to stay by the brig and return to Maryland in her. But finding that the town of Miller's Falls was distant only some thirty miles up in the country, and getting the right direction from the first person I asked, a blacksmith standing at the entrance to his forge, I set out bravely on foot with my belongings on a stick over my back, the way I had seen sailors start on a land voyage from Baltimore.

Hill country was new to me, and the stone walls and fences and neat white houses gave me much to wonder at, as I plodded along the road that was deep in dry dust, and such hard travelling that after I had made twelve miles, or such a matter of distance, I grew very tired, and determined to rest.

Although it was November the day was quite warm, and I sat down by the edge of a little brook and bathed my feet, that had blistered badly. The cold water felt very comforting, and I took my ease.

While drawing on my shoes I heard a strange sound, and saw coming down the road a two-wheeled cart drawn by a team of swaying oxen. Climbing up to the roadway and hailing the man who was walking at their heads, (calling out "Gee," "Haw," every other minute), I asked my whereabouts and the hour.

The farmer, even before he replied to my questionings, began to subject me to many of his own: "Where was I bound?" "Where did I come from?" and, "Who did I know in the parts?" To these I replied as best I could, and with a directness that seemed rather to disconcert him.

But he was a kindly man, and noticing that I limped, and that I was in no condition to travel, he proposed my stopping the night with him, and he would carry me part way on my journey on the morrow. To this I agreed, as I found I had wandered somewhat out of my way.

At supper that evening I tasted for the first time the delightful cakes made out of buckwheat, and had to relate again, for the benefit of my host and his wife (a tall, sharp-featured woman who spoke with a whining drawl), the story of my adventures and the eventful voyage of the Minetta.

When I told of the affair of the severed hand, and the action of the English, the woman quoted a passage from the Bible that was quite as much as a curse on the heads of the offenders, it breathed so of vengeance. But we had not burned half a candle before we all were yawning. Well, to be short, I slept in a great feather bed that night, and the next morning I started northward, mounted astride, behind Farmer Lyman on a jolting gray nag.

When my friend put me down he bade me a farewell,[Pg 114] and told me I had but five miles before me to the town of Miller's Falls.

It was up and down hill, slow going, and noon, I should judge by the shadows, before I saw the village, nestling at the bend of a small valley. On the wind came to me the shrieking and clanking of machinery and the jarring of a waterfall.

I sat down on the top rail of a fence, and surveyed the village for some time before I descended the hill. As I walked along I saw in a steep gorge, a sheer descent of some fifty feet to one side of the roadway, a rushing brook, and almost in the centre of the town itself a pond that spread back into the hills.

The mill that was raising such a clatter stood at one side of a dam built of stone and timber that had backed the water of the pond; and I walked up close to the building and looked with wonder at everything. A huge over-shot wheel was turning and plashing busily, and the water was roaring over the dam and breaking on the brown slippery rocks below. It fascinated me, and I stood for some time leaning over the rail watching it. I grew so interested, in fact, that I almost forgot my mission or where I was, and was recalled to myself by a voice hailing me from only a few feet above my head.

"Well, sonny," said a drawling voice, "be ye wondering where all that water is goin' to?"

A thin cadaverous face with a very pointed nose and chin was thrust out of a little window, and two long hands on either side gave the man the effect of holding himself in his position by the exercise of sheer strength.

"I suppose it goes into the sea," I replied, perceiving that he wished to chaff me.

"Correct," he answered. "Go to the head."

"May I come into the mill?" I asked, for I had never seen one, and the varied noises excited my curiosity.

"Why, certainly," the man said. "Pull the latch-string in the door yonder and come in."

The mill not only sawed the long pine trunks into planks and squared timbers, of which there was a profusion about, but also ground most of the grain for the neighborhood. As I entered, the stones were grumbling and the air was full of dust.

"What is it you're making?" I shouted into the tall man's ear. He had greeted me at the doorway.

"Buckwheat cakes," he replied, thrusting his hand into the top of an open sack. "Ye're a stranger here, ain't ye?"

I knew what to expect by this time, and that probably my appearance had determined the miller to find out all he could about me merely for his own satisfaction. So, half shouting in his ear, I related (by the answering of questions) part of my story—at least I told him where I had come from and the why and wherefore of my trip. When it came to the asking for my uncle's place of residence I ran against trouble, and my heart sank.

"What is the name?" asked the thin man when I had first mentioned it.

"Monsieur Henri Amedee Lavalle de Brienne."

"Eh?"

I had to repeat it.

"No such person in these parts," the man answered, shaking his head positively. "And I ought to know," he added. (I dare say he did, and most people's private business besides.)

But here was an uncomfortable position. What was I to do? Somehow the hum and groaning and rumbling of the mill appeared to prevent my thinking, and I stepped to the door.

The village of Miller's Falls stretched down one wide road that curved about the edge of the mill-pond. It was not a cheerful-looking place taking it altogether, but it had a certain air of prosperity; there was some movement, and a number of horses and carts were on the streets.

All at once the chatter of voices and the familiarly shrill cries of boys at some rough merriment came up from the road at the right. I looked about the corner of the mill and saw that a half-dozen youngsters of about my own age were coming down the hill, and before them rode an odd figure on a small brown horse. It was a little man, who sat very erect, and who had a semi-military hat set aslant his gray hair, which was gathered in a long queue behind. His coat was of a very old fashion, made of velvet, and heavy riding-gaiters encased his thin legs.

The horse he was riding was by no means a bad one, and it was apparently all the old man could do to keep him from breaking into a run; and to accomplish this last was the evident intention of the crowd of small boys, for they were tickling the horse's heels, or giving him a cut now and then with some long switches; they varied this by pelting small pebbles at the rider. The latter, however, kept his seat and controlled the horse exceedingly well, although it was apparent that he was both angry and frightened, for he would stop and scold at the boys, and often turn his horse's head threateningly in their direction. This would excite a scattering and shouts of derision and laughter.

Some one spoke over my head at this moment, and I saw that the tall man and one of the mill hands, attracted by the noise, had perceived the approach of the old man and his tormentors.

"Why, it's old Debrin, from Mountain Brook," said the miller. "Come down to get his wheat ground, I reckon."

Slung across his saddle were two bags, and the rider was now headed toward the mill and restraining the horse with difficulty. When he drew up at the little platform it was all he could do to throw off the bags, and when he had lifted his legs from the stirrups and slid to ground I thought he would have fallen, and for the first time I perceived how old a man he was. Moved by some impulse, I jumped down from the door-sill and helped him tie the rope halter of the little horse fast to a post. The old man's hands were trembling so that I doubt if he could have accomplished it unaided.

My action had so surprised the boys that they had gathered in a circle about us in silence and astonishment. When I had finished, the old gentleman looked at me with his black beadlike eyes and raised his hat.

"Thank you, thank you very much," he said, in broken English, in which I recognized at once the manner in which my mother had spoken. The trace of the French tongue was there beyond all doubt. So I lifted my own cap, and answered in what I may well call my native tongue, and told him in French that I was very glad to have been able to help him.

His astonishment at hearing me address him thus was so great that for a minute it deprived him of the power of answering, but then he burst forth into such rapid speech and into so many violent gesticulations that it was all I could do to follow. The little crowd pressed us so close that I became embarrassed, and the old man, who had been complaining of the conduct of the boys and the temper of his horse, and at the same time stating how welcome it was to hear his own tongue again, suddenly saw that he was creating a great deal of amusement for the gaping, snickering circle about us. He drew himself up and his lip curled with contempt. I now, for the first time, had an opportunity to ask a question that had been forming itself in my mind.

"Are you Monsieur de Brienne?" I ventured.

"I am, and you?" he replied.

"Am Jean Hurdiss, your nephew, who has come all the way from Baltimore to see you."

Instantly his manner changed. I thought he was going to fling his arms about me. But if such was his intention he controlled himself.

"We will not talk before this canaille," he said, quietly, "and I cannot here express my delight at seeing you."

This must have appeared very strange to the on-lookers, who, of course, understood no word of what we were saying, and what happened afterwards must have been stranger still; and I can now readily see why I was regarded as a mystery by the inhabitants of Miller's Falls during the whole course of my stopping there.

The old man with a great deal of dignity laid hold of the sack of corn, and seeing that nobody volunteered to help him, I took up the other end, and we carried it into the mill. There he flung it on the floor, and M. de Brienne pointed at it with his finger.

"Grind me this," he said, in a commanding tone, despite the broken and twisted accents. "I will pay for it when I return."

The surprise occasioned by our actions at the meeting had evidently struck the crowd of youngsters dumb, but they were soon started again in their shouts of laughter by the difficulty that my uncle and I immediately had with the little brown horse. How so feeble a man as he appeared to be could ever manage the restive beast at all was more than I could see. Full half a dozen times he failed to make the saddle, even with my assistance, and this started the boys in their shouts of derision, and even drew laughter from the windows in which some of the mill-crew had gathered.

At last, however, I succeeded in getting the old gentleman into the saddle, and, obeying him, I crawled up behind him and placed my arms about his waist. But between my lack of knowledge, the horse's scampering, and the old man's weakness, we almost came to grief more than once.

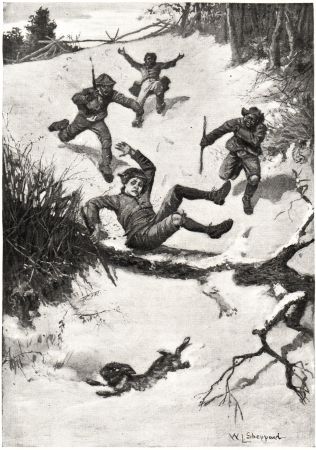

Three of the little rapscallions, who of course could not follow us, for we had started on a run down the road, cut across the meadow by a path, as if intending to head us off for some reason.

They reached the main roadway first, and were waiting in an orchard at the end of a stone wall for us to go by. I noticed that they had gathered some apples, which they held in the hollows of their arms, much as boys carry snow-balls in an attack. I had been angry before, but now my one desire was to get at them. I often fear that I must be a vindictive person indeed.

As we approached they let fly, of course, and one of the apples caught my uncle squarely in the forehead. He would have fallen, I believe, had I not held him for an instant, and reaching forward I caught the reins and brought the little horse to a sudden halt. Then I slipped from my seat to the ground, and with no weapons but my closed fist I charged the enemy.

It is not bragging to say that from some ancestor I have inherited immense strength, and even at the age of thirteen I believe I should have been a match and more for some lads four or five years older. (Since I have been sixteen years old even I have never met a grown man who could force down my arms or twist a finger with me.) But to return: I caught the first boy a jolt with my closed fist on the side of the head, and seizing the second, who came to his rescue, I fairly believe I threw him over the fence without so much as touching it. He landed on some loose stones on the other side, and set up a tremendous bawling. The third lad did not stop to get a chance, but legged it as fast as he could across the meadow. I was so angry now that I believe murder was in my heart, and I picked up the broken branch of a tree and stood over the first boy whom I had struck. He looked up at me and began to beg for mercy.

"Bravo!" called my uncle from the horse, that for a wonder was standing still. "Bravo, mon enfant!"

He was wiping the juice of the apple from his eyes, but catching my glance he threw me a kiss from his finger-tips, and laughed a laugh of congratulation and sympathetic triumph.

I covered my fallen antagonist with added chagrin by scooping up with a sideway stroke of the foot some dust out of the road on top of him, and, walking to the horse, I clambered up behind again. Then, digging my heels into the nag's side, we started on a gallop up the hill and entered the woods that lined the crest.

I had been so angry that I dare say I had shed tears even at the moment of my victory (what varieties of weeping there are, to be sure), and I had such a lump in my throat that I waited for my uncle to begin any conversation he might wish, but he did not speak until after we had progressed some distance in among the trees. Then he pulled the horse up with a jerk (that caused me almost to break my nose on the back of his head), and he ordered me to dismount. I did so. Monsieur de Brienne leaned from the saddle and turned me around by the shoulder, much as I have seen a planter look at a negro before purchasing.

"Very like indeed," he muttered. "A true De Brienne."

Then he leaned further over and told me to embrace him. I complied, and he kissed me on each cheek and between the eyes. This quite embarrassed me, and I dropped my glance to the ground and shuffled uneasily; but the old man had begun to talk, and I dare say it was an hour that we stood there, for I had to tell him, of course, of my mother's death and of the burning of Marshwood. When I came to relate of the loss of the strong-box and its contents, the old gentleman grew quite pale, then he drew a long breath, and ripped out into a frightful burst of temper. For some reason I could not help but feel that it was directed against me, and I waited until he had calmed before I went on. Then I remembered the letter which had given me the only clew that had led to this meeting, and I thrust my hand into my coat pocket. It was not there? Fruitlessly I searched with a growing fear upon me, and I saw that my uncle's little black eyes were following my every movement; I could see that there was a certain suspicion in his look, but the letter was not forth-coming, and was not to be found in my bundle, although I undid it from the strap of the saddle-bag where I had tied it, and spread its few contents on the road-side.

"Where is the miniature that you spoke of finding?" inquired Monsieur de Brienne, in a cold harsh voice.

I told him what I imagined had become of it.

"Ah, bah!" he cried at this, and raised his hand as if he would have struck me. Had he done so I believe I should have pulled him from the saddle. He was scarcely larger than myself, and I was growing angry at his unnecessary and unjust words.

"What have you done?" he cried, restraining himself. "You have lost all the proofs—all the papers, you fool! Now we can prove nothing. A curse on such stupidity! What use are you without them? Why did you come?"

I had gathered up my possessions, and was tying together the corners of the handkerchief, making up my mind to burden him no longer with my presence, and to return whence I had started (for I still had a number of the gold pieces sewed in the lining of my cap, where Mr. Edgerton's maiden sister had placed them), but suddenly M. de Brienne spoke in rather an eager tone, and asked me to come closer to him. I did so, wondering. He leaned forward and caught one of the buttons of my coat between his thumb and forefinger and looked at it closely. Then he heaved a sigh.

"All there is left," he said. "Ah, my child, my child, you do not know what you have lost. Pardon my rough speech of a moment since, but what you told, and what has happened, appeared to turn into ashes what little hope I had left in life."

I was softened by the sadness of his tone and the real grief that showed itself in his small pinched features. So I looked up at him, and tried to smile.

"What is your name?" he questioned of me, eagerly, in a whisper, as if to extract a secret that I might not care to disclose aloud.

"John Hurdiss," I replied. "That's all I know."

The old man drew a long sigh. "Was your mother's name Hortense or Hélène?" he questioned again, suddenly and hoarsely.

"I don't know," I said. "I have no idea."

"So be it," he replied, as if accepting a decision against which there was no use railing. "Come, son; up with you, and we will ride on to my château."

We followed the well-worn road, and then turned off through the woods, and came to some pasture bars at the edge of a clearing. I slid to the ground and opened them at a command from my uncle, and replaced them after he had gone through. The field that we entered had been sheep-grazed, and was poor pasturage. Here and there crumbling hoof-worn patches of rock showed through the wiry close-cropped turf; clusters of rank fern and hard-back bushes were dotted about, and we threaded them, following a narrow path, until we came to another gate, which I opened in the way I had the first. A half-mile of travelling through an expanse of soft swampy ground, grown with alders and dogwood, and I heard the sound of running water. Soon we came to a clear brook that gurgled[Pg 116] under overhanging banks, and purled about gleaming time-smoothed stones; crossing it, and clambering up the steep bank, we came to a second clearing, hardly five acres in extent. A half-score of large apple-trees and a diminutive garden were to the left, and at the upper edge of the clearing was a small unpainted house, and behind it a little barn, whose foundations extended into the hill-side.

"Gaston! Gaston!" called Monsieur de Brienne, at top voice. "Where are you hiding?"

In answer a head was thrust from the doorway, and the oddest-looking figure that I had ever seen came into view. It was an old man, whose frame when covered with flesh or muscles must have been enormous, but now so scantily cushioned were the bones that the quaint clothes hung on him much in the way that a coat hangs on a fence post. But the man moved with incredible swiftness. He gave a strange look at me, and took Monsieur de Brienne's stirrup-leather in his hand and assisted him to dismount. I pushed myself backwards over the horse's hind quarters.

"A guest, Gaston, to Belair. My nephew, Monsieur Jean Hurdiss. This is Gaston, my valet, chef, major-domo, and standing army."

My uncle had smiled as he said this, but the other's face was most serious. As I eyed him closely his countenance looked more like a ball of tightly wound twine with ears and features than anything else I could imagine. I had never seen such a mesh of wrinkles, or imagined that age could stamp itself so wonderfully. That the old man was not decrepit, however, was evident from the deft way in which he unsaddled the little horse and threw the trappings over his shoulder.

Now my uncle turned to me again. "Welcome, my son," he said. "Consider all here as yours entirely."

He ushered me through the doorway. I could scarce control an expression of my astonishment as I looked about. Immediately facing the light I saw something that caused me to start suddenly. It was the figure of a man in flowing satins and velvets; great heavy curls fell over his shoulders, and torrents of lace poured at his wristbands and knees. He had on high red-heeled shoes, fronted by wide bows, and his slender bejewelled hand rested on the top of a tall walking-stick.

It took me a second glance to perceive that it was but a portrait that extended from the floor to ceiling, and was merely nailed, without framing, against the wall. A rough table made of pine boards but covered with a handsome cloth was in the centre of the room. It was heaped high with books in embossed leather covers. Tacked about the walls were many portraits of times long since. One especially, before which I drew a long breath, dumfounded me (it was so like my mother). But Monsieur de Brienne had gathered me by the elbow, as it were, and marched me around.

The portrait whose resemblance had struck me so vividly he told me was my grandmother, and then went on, stopping before each, "Your great-grandfather, your great-uncle, your aunt," and so forth and so forth.

One might have thought that I was being introduced in person to all my ancestors and past family. In fact, I found myself bowing as if it were expected of me.

After a few minutes I had a chance to look about me. There were but four rooms on the ground-floor of the little house and three above; and if the furniture of Marshwood had been an odd assortment, that of Belair was odder still. I had noticed, as I have said, that the portraits were not in frames. They had evidently been brought from their former residence rolled in some shape or other for convenience. Many of them showed traces of rough handling, and were much cracked and soiled.

My uncle slept on the first floor in a great four-poster bed hung about with heavy curtains of embroidered silk, but the rest of the ameublement, was made up of clumsy wooden benches and stools, not the workmanship of a joiner, but clearly made by unskilled hands.

The room upstairs to which I was shown contained nothing but a mattress stuffed with cornhusks, and a beautiful painted landscape (which comparing with some that I have since seen must have been nothing less than a Claude, I dare say). A bench on which stood an ebony cross, and a large brass blunderbuss that hung from a nail over the door, were all the other things in the room.

At dinner that night we were waited upon by the great wizzened-faced servant, and my uncle, who was taken with a sleepy, tongue-tied mood, had attired himself in such a brilliantly faded costume that he resembled nothing less than one of the pictures that looked down at us.

Before the meal was half finished, however (it was exceedingly well cooked and toothsome), I received a shock.

Monsieur de Brienne suddenly and without a warning gave a little cry and fell back in his arm-chair (a home-made affair, cut from a barrel of some sort), and I, frightened, ran to his side.

But the old servant appeared quite used to this, and together we got my uncle into his bed, where we rubbed and chafed his limbs until I grew so tired I could hardly move. The next day I thought he was like to die. He would not let me leave him, and talked so incoherently that I could make no sense out of his maunderings at all.

Now begins such a strange existence that if it were told to me by any one who claimed to have led it I should be most doubtful. It would make a volume in itself, maybe, but I intend to hasten over this period, and to get quickly into that from which has developed the present, and which is leading up to whatever future there is before me.

To this end I shall do my best to resist any temptation to dwell at too great length on the life I led at the lonely farm-house on Mountain Brook.

Two men were once boasting of their wonderful physical powers, and a story told by one would be immediately capped by the other by the relation of a capability far more marvellous. Suddenly one of them pointed to a church spire which could be seen across the valley, and said,

"Do you see that church spire yonder?"

"I do," replied the other.

"Well, I can see a fly crawling on it! Can you?"

His companion looked at it attentively a moment, and said, slowly,

"No, I can't see it, but," placing his hand behind his ear and leaning forward, "I can hear it walk!"

Something quite as remarkable as the hearing the foot-step of a fly on a church steeple a mile distant was accomplished a few weeks ago, when, by means of a slender wire attached to an ordinary telephone, the sound of the "voice of many waters," situated 500 miles away, was distinctly heard in New York city.

The National Electric Light Association held its last[Pg 117] annual meeting in New York, and in the Industrial Arts Building were exhibited the latest appliances of electricity; but of all the wonderful demonstrations of that strange power which slips so swiftly and silently along a slender wire, the most novel, if not the most wonderful, was the transmitting the roar of the Falls of Niagara through the long-distance telephone by means of the power generated by the cataract itself.

The meaning of the Indian name Niagara is "thunder of the waters," and it certainly was a most original idea to place this thunder on exhibition—"thunder on tap," a humorist might call it. The point chosen for collecting the sound was near the Cave of the Winds, where at the foot of the cliff one can get nearer to the waterfall than at any other point. The Cave of the Winds is between Goat and Luna islands, and is reached by the Biddle Stairway, a frail-looking structure built on the face of the cliff, and the adventurous tourist who ventures down this winding stair is almost deafened by the noise of the water as it strikes the great rocks that lie just below him.

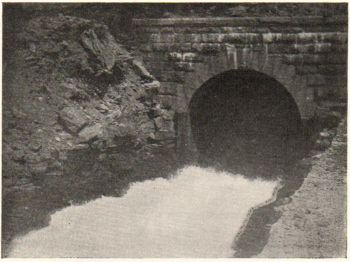

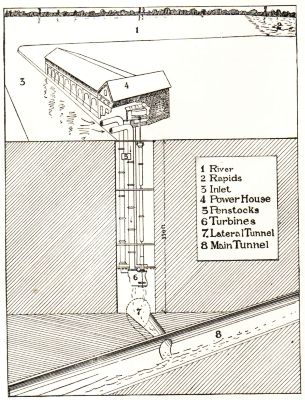

MOUTH OF THE TUNNEL.

MOUTH OF THE TUNNEL.

The mechanical arrangements for sending the sound were very simple. An ordinary telephone, with the necessary apparatus, was placed in a tight wooden box, so that the instrument might be protected from the spray. Wires connected with the long-distance telephone were carried down the side of the cliff and attached to the telephone in the box. From one side of the box projected an immense tin funnel. This was the sound-collector. The rest of the operation was very easy. The current was turned on, and in a few seconds the sound was heard at the extreme end of the line. In the centre of the hall where the electric exposition was held was a working model of the Niagara Falls electric plant; around this model were twenty-four telephone transmitters, and the visitor could not only see the machinery moved by the power generated at the Falls, but hear the ceaseless roar of the great waters.

The greatest distance that electric power had ever before been transmitted was from the Falls of Neckar, in Germany, to a point 110 miles distant. Power for the exposition was to come nearly five times that length, and the occasion was so momentous a one that the gold key which President Cleveland used to set in motion the machinery for the World's Fair was used by Governor Morton to turn on the electric current generated by the Falls. As soon as the exposition was declared open, Governor Morton, according to a previously arranged plan, turned on a current from the Falls power which discharged a piece of government artillery simultaneously in the public squares of Augusta, Maine; St. Paul, Minnesota; San Francisco, California; and New Orleans, Louisiana.

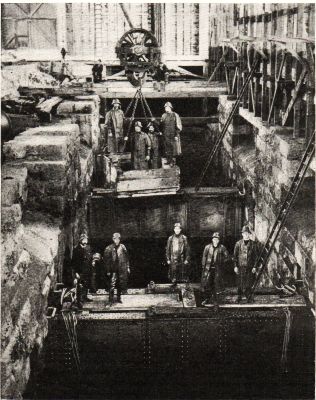

TURBINE READY TO BE LOWERED TO THE BOTTOM OF THE

WHEEL-PIT.

TURBINE READY TO BE LOWERED TO THE BOTTOM OF THE

WHEEL-PIT.

The capturing of Niagara and setting it to work is one of the greatest feats of modern engineering. For years engineers have watched the power going to waste down the great cataract, and studied how it could be made available for mechanical purposes. The only device for using it was the building of a hydraulic canal opening out of the river above the Falls, and emptying into it at the edge of the bluff a mile or two below the Falls. Power was thus carried to several mills built on the bank, but it was a mere cipher compared to the great force daily poured over the great precipice, a force which has been scientifically estimated to equal nearly 6,000,000 horse-power, enough to drive all the machinery on the American continent.

Many plans for using this power were made, only to be abandoned, till Mr. Thomas Evershed, a division engineer on the Erie Canal, devised the scheme of digging wheel-pits above the Falls, placing turbine-wheels at the bottom of the pits, conveying water from the river to turn the wheels—which should be used to furnish the power to generate electricity—and carrying off the waste water through a large tunnel and emptying it into the river. The plan was found feasible, and in 1886 the Niagara Falls Power Company was incorporated by the Legislature of New York. Millions of dollars and the service of the most skilful engineers in the world were employed in carrying out the plan. Work was begun[Pg 118] in 1887, and in January, 1894, the first great turbine-wheel was set at work.

THE WHEEL-PIT IN COURSE OF CONSTRUCTION.

THE WHEEL-PIT IN COURSE OF CONSTRUCTION.