Title: Harper's Young People, August 29, 1882

Author: Various

Release date: May 20, 2019 [eBook #59557]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| vol. iii.—no. 148. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, August 29, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

Luckily the water was only four feet deep, as Charley found when he tried to touch bottom; so he stopped swimming, and with the water nearly up to his shoulders, stood still and began to think what to do next.

The canoes—including the sunken Midnight—were a good mile from the shore, and although the sandy shoal on which Charley was standing was firm and hard, it was of small extent, and the water all around it was too deep to be waded.

"You'll have to get into one of our canoes," said Harry.

"How am I going to do it without capsizing her?" replied Charley.

"I don't believe it can be done," said Harry, as he looked first at the Sunshine and then at the Twilight;[Pg 690] "but then you've got to do it somehow. You can't swim a whole mile, can you?"

"Of course I can't, but then it won't do me any good to spill one of you fellows by trying to climb out of the water into a canoe that's as full now as she ought to be. Besides, I'm not going to desert the Midnight."

"I thought the Midnight had deserted you," said Joe. "If my canoe should go to the bottom of the lake without giving me any warning, I shouldn't think it a bit rude to leave her there."

"Don't talk nonsense!" exclaimed Charley; "but come here and help me get my canoe afloat again. We can do it, I think, if we go to work the right way."

Charley found no difficulty in getting hold of the painter of his canoe with the help of his paddle. Giving the end of the painter to Joe, he took the Dawn's painter, and by ducking down under the water succeeded after two or three attempts in reeving it through the stern-post of the sunken canoe, and giving one end to Harry and the other to Tom. Then, taking the bow painter from Joe, he grasped it firmly with both hands, and at a given signal all the boys, except Joe, made a desperate effort to bring the wreck to the surface.

They could not do it. They managed to lift her off the bottom, but Harry and Tom in their canoes could not lift to any advantage, and so were forced to let her settle down again.

"I've got to unload her," said Charley, gloomily. "I think we can get her up if there is nothing in her except water. Anyhow we've got to try."

It was tiresome work to get the water-soaked stores and canned provisions out of the canoe, and Charley had to duck his head under the water at least a dozen times before the heaviest part of the Midnight's cargo could be brought up and passed into the other canoes. His comrades wanted to jump overboard and help him, but he convinced them that they would have great difficulty in climbing back into their canoes, and that in all probability they would capsize themselves in so doing. "He's right!" cried Joe. "Commodore, please make an order that hereafter only one canoe shall be wrecked at a time. We must keep some dry stores in the fleet."

When the Midnight was partly unloaded, a new and successful effort was made to raise her. As soon as she reached the surface Charley rolled her over, bottom upward, and in this position the small amount of air imprisoned under her kept her afloat.

The cause of the leak was quickly discovered. There was a hole through her canvas bottom nearly an inch in diameter, made by some blow she had received while on the way to the lake. The wonder was, not that she sank when she did, but that she had floated long enough to be paddled a mile. It is probable that the ballast-bag, which was close by the hole, had partly stopped the leak at first, but had afterward been slightly moved, thus permitting the water to rush freely in.

The surface of painted canvas dries very quickly in the hot sun, and it was not long before the bottom of the Midnight was dry enough to be temporarily patched. Harry lighted his spirit-lamp and melted a little of the lump of resin and tallow which had been provided for mending leaks. This was spread over a patch of new canvas; the patch was then placed over the hole, and more of the melted resin and tallow smeared over it. In about fifteen minutes the patch was dry enough to be serviceable, and Charley righted the canoe, bailed her out, and by throwing himself across the cockpit, and then carefully turning himself so as to get his legs into it, found himself once more afloat and ready to paddle.

The canoe still leaked, but the leak could be kept under without difficulty by occasional bailing, and in the course of half an hour the sand-spit for which the fleet had started was reached. It was part of a large island with steep, rocky shores and a beautiful little sandy beach. It was just the place for a camp; and though the boys had expected to camp some miles farther north, the sinking of Charley's canoe had so delayed them that it was already nearly six o'clock, and they therefore decided to paddle no farther that day.

The canoes were hauled out on the beach and unloaded, and shored up with their rudders, back-boards, and a few pieces of drift-wood so as to stand on an even keel. Then came the work of rigging shelters over them for the night. Harry's canoe tent was supported by four small upright sticks resting on the deck and fitting into cross-pieces sewed into the roof of the tent. The sides and ends buttoned down to the gunwale and deck of the canoe, and two curtains, one on each side, which could be rolled up like carriage curtains in fair weather and buttoned down in rainy weather, served both as the doors and windows of the tent. The shelters rigged by the other boys were much less complete. The two masts of each canoe were stepped, the paddle was lashed between them, and a rubber blanket was hung over the paddle, with its edges reaching nearly to the ground. The blankets and the bags which served as pillows were then arranged, and the canoes were ready for the night.

It was a warm and clear night, and a breeze which came up from the south at sunset blew the mosquitoes away. Harry found his tent, with the curtains rolled up, cool and pleasant; but his fellow-canoeists found themselves fairly suffocating under their rubber blankets, and were compelled to throw them aside.

Toward morning, when the day was just beginning to dawn, the canoeists were suddenly awakened by a rush of many heavy, trampling feet which shook the ground. It was enough to startle any one, and the boys sprang up in such a hurry that Harry struck his head against the roof of his tent, knocked it down, upset the canoe, and could not at first decide whether he was taking part in a railway collision, or whether an earthquake of the very best quality had happened. The cause of the disturbance was a herd of horses trotting down to the water's edge to drink. There were at least twenty of them, and had the canoes happened to be in their path, they might have stumbled over them in the faint morning light; in which case the boys would have had the experience of being shipwrecked on dry land.

A gentle southerly breeze wrinkled the water while breakfast was cooking, and the Commodore ordered that the masts and sails should be got ready for use. It was impossible to make an early start, for Charley's blankets had to be dried in the sun, and the hole in his canoe had to be repaired with a new patch in a thorough and workmanlike way. It was therefore ten o'clock before the canoes were ready to be launched; and in the mean time the wind had increased so much that the boys decided to use only their mainsails.

The moment the sails drew, the canoes shot off at a pace which filled the young canoeists with delight. The canoes were in good trim for sailing, as they were not overloaded; and while they were skirting the west shore of the island the water was quite smooth. Each canoe carried a bag partly filled with sand for ballast, and every one except Joe had lashed his ballast-bag to the keelson. This was a precaution which Joe had forgotten to take, and before long he had good reason to regret his error.

As soon as the northern end of the island was passed, the canoes came to a part of the lake where there was quite a heavy sea. The Dawn and the Twilight were steered by the paddle, which passed through a row-lock provided for the purpose; and Joe and Tom found little difficulty in keeping their canoes directly before the wind. The two other canoes were steered with rudders, and occasionally, when their bows dipped, their rudders were thrown nearly out of the water, in consequence of which they steered[Pg 691] wildly. All the canoes showed a tendency to roll a good deal, and now and then a little water would wash over the deck. It was fine sport running down the lake with such a breeze, and the boys enjoyed it immensely.

The wind continued to rise, and the lake became covered with white caps. "Commodore," said Charley Smith, "I don't mean to show any disrespect to my commanding officer, but it seems to me this is getting a little risky."

"How is it risky?" asked Harry. "You're a sailor, and know twice as much about boats as I do, if I am Commodore."

"It's risky in two or three ways. For instance, if the wind blows like this much longer, a following sea will swamp some one of us."

"Oh, we're going fast enough to keep out of the way of the sea," cried Joe.

"Just notice how your canoe comes almost to a dead stop every time she sinks between two seas, and you won't feel quite so sure that you're running faster than the sea is."

The boys saw that Charley was right. The canoes were so light that they lost their headway between the seas, and it was evident that they were in danger of being overtaken by a following sea.

"Tell us two or three more dangers, just to cheer us up, won't you?" asked Joe, who was in high spirits with the excitement of the sail.

"There's the danger of rolling our booms under, and there is a great deal of danger that Harry's canoe and mine will broach to when our rudders are out of water."

"What will happen if they do broach to?"

"They'll capsize, that's all," replied Charley.

"What had we better do?" asked Harry. "There's no use in capsizing ourselves in the middle of the lake."

"My advice is that we haul on the port tack, and run over to the west shore. The moment we get this wind and sea on the quarter, we shall be all right—though, to be sure, we've got more sail up than we ought to have."

The canoes were quite near together, with the exception of the Twilight, which was outsailing the others; but even she was still near enough to be hailed. Harry hailed her, and ordered the fleet to steer for a cove on the west shore. As soon as the wind was brought on the port quarter, the canoes increased their speed; and although the Twilight made more leeway than the others, she drew ahead of them very fast. The wind was now precisely what the canoes wanted to bring out their sailing qualities. The Sunshine soon showed that she was the most weatherly, as the Twilight was the least weatherly, of the fleet. The Midnight kept up very fairly with the Sunshine; and the Dawn, with her small lateen-sail, skimmed over the water so fast that it was evident that if she could have carried the big balance-lug of the Sunshine she would easily have beaten her.

The canoes were no longer in danger of being swamped; but the wind continuing to rise, the boys found that they were carrying more sail than was safe. They did not want to take in their sails and paddle, and though all of the sails except the Dawn's lateen could be reefed, nobody wanted to be the first to propose to reef; and Harry in his excitement forgot all about reefing. The wind, which had been blowing very steadily, now began to blow in gusts, and the boys had to lean far out to windward to keep their canoes right side up.

"We can't keep on this way much longer without coming to grief," Charley cried at the top of his lungs, so that Harry, who was some distance to windward, could hear him.

"What do you say?" replied Harry.

"We've got too much sail on," yelled Charley.

"Of course we'll sail on. This is perfectly gorgeous," was Harry's answer.

"He don't hear," said Charley. "I say, Joe, you'd better take in your mainsail, and set the dandy in its place. You'll spill yourself presently."

"The dandy's stowed down, below, where I can't get at it. I guess I can hold her up till we get across."

Tom was by this time far out of hailing distance, and was apparently getting on very well. Charley did not doubt that he could manage his own canoe well enough, but he was very uneasy about Harry and Joe, who did not seem to realize that they were carrying sail altogether too recklessly. The fleet was nearly two miles from the shore, and a capsize in the heavy sea that was running would have been no joke.

Charley turned part-way around in his canoe to see if his life-belt was in handy reach. As he did so he saw that the water a quarter of a mile to windward was black with a fierce squall that was approaching. He instantly brought his canoe up to the wind, so that the squall would strike him on the port bow, and called out to Harry and Joe to follow his example. Harry did not hear him, and Joe, instead of promptly following Charley's advice, stopped to wonder what he was trying to do. The squall explained the matter almost immediately. It struck the Sunshine and the Dawn, and instantly capsized them, and then rushed on to overtake Tom, and to convince him that Lake Memphremagog is not a good place for inexperienced canoeists who want to carry sail recklessly in squally weather.

The postman in our Western lands is a common sight to city children; they meet him at every corner, jostle against him on their way to school, and spring for the messages which he brings from far-off friends and distant relatives. No child but has a welcome for the postman.

THE MAIL-RIDER OF THE DESERT.

THE MAIL-RIDER OF THE DESERT.

But the carrier whose strange and picturesque figure is shown in the illustration on the following page has but little resemblance to our daily visitor on his hurrying round through our crowded cities. His route is the desert—a dangerous, solitary, and fatiguing journey. Borne by his lithe dromedary over its arid wastes, he paces the desert track, with no pause in the nine days' travel, save when at some oasis he stops to drink the cool water and to refresh his tired camel. At the edge of the desert he leaves his precious load, taking in exchange the return mail. He seldom penetrates into the cities' depths and crowded bazars, or rests in the fragrant gardens of Damascus, but jogs backward and forward over the dreary waste, loaded with messages from the outer world, and yet indifferent to them all, except to deliver each one in safety.

I wonder if he never wearies of his monotonous existence, or sighs for some excitement in his silent journey, and for some companionship besides that of his enduring steed?

I could never see this express-courier start forth on his desert journey without being reminded of some lone mariner setting sail on a wide sea for some distant port. The desert is so much like the ocean, with its boundless expanse, the same unbroken curve of the horizon, the same tracklessness and solitude. So the camel is often called "the ship of the desert." Yet monotonous as the journey of this postman seems, he has to be continually on the alert. It is not always silent meditation under the burning sky and changeless heavens. There are hidden dangers lurking on every side—plundering Arabs and terrible sand-storms. Many a traveller is buried under the fierce drifts, suffocated by the driving sand sleet.

As this singular postman swings on his way under the coppery sky, his Syrian song fills the silence of the desert noon; the high shrill notes tremble and ring in the air in a dreary strain, harmonizing with the sultry, unchanging landscape. The camel steps more quickly to the music, but the rider seems lost in a deep reverie.

No monk in his cell is more isolated than this old letter-carrier, so shut out from the world, so separated from all human kind, yet carrying messages of such lively interest.

"Mamma," said Willie Beetham, "may I go down to the beach this morning?"

"No, my boy; you know I don't like your going down there by yourself, and nurse is too busy to take you and Lucy out just yet. You can go there with her after luncheon."

Willie looked very much disappointed. "There's no fun going out with nurse," he said; "she won't let me do anything. It is always: 'Now, Master Willie, don't go there; you'll soil your shoes. Master Willie, come back; you'll tumble into the water.' Going with her is all very well for girls and babies; but I am a big boy now. You said so yourself to papa the other day. I can take care of myself quite well."

The "big boy" was a bonny little fellow of six years' old, with golden hair, and a sunny smile that won every one's heart. He was a bold, thoughtless boy, always getting into mischief, but of such an affectionate disposition, so sorry for having done anything to vex those he loved, that no one was ever angry with him long. This made him less careful, perhaps, in being obedient than he ought to have been.

"No, my boy, you can't be trusted to go by yourself just yet. You can go into the garden and play with Lucy for a little. When nurse is ready, she will take you both out for a walk on the beach."

Willie was very fond of his little sister, who cared for nobody so much as for him. So he drew her about for a while in his little cart, ran races, and pulled daisies with her in the field. But all would not do. He wanted to go down to the shore. Where he stood he could see the bright waves rolling in to land. He forgot all that had been said to him, and resolved to go. He would not stay long.

"Lucy, I am going down to the beach for a little while. Wait here till I come back, and don't tell any one where I have gone. I'll be back in a quarter of an hour."

Off he ran without waiting for a reply. Lucy remained quietly sitting, pulling the daisies, and plaiting them into a long chain, thinking how it would please her brother. The quarter of an hour passed, half an hour, an hour. Willie did not appear. Lucy was too faithful to leave her post; but time was beginning to hang heavy on her hands, and, besides, she was growing frightened at his absence. Lucy began to cry.

What was Willie about meanwhile? On reaching the shore, which was only about five minutes' walk from the house, his delight knew no bounds at being able to scamper about everywhere without being perpetually called to order. He ran races with the waves that were rolling in, clear and shining, and breaking in white foam on the yellow sands, and shouted with glee when he just saved his distance, and escaped without even wetting the toes of his boots. Then he tossed about the great heaps of brown weed and tangle, and searched for the lovely crimson sea-weed his elder sister used to gather and set so prettily on white paper when she came home for the holidays. Then, as the tide was low, he scrambled in among the rocks, and in the clear pools he found crabs and cockles and beautiful red and striped sea-anemones. Willie was very fond of natural history, which his papa used to teach him occasionally, and he became so absorbed in examining these pretty things that he not only forgot what his mamma had said, but also his promise to his little sister of returning in a quarter of an hour.

He was still busy poking about in the clear water of the pool, when he suddenly felt a cold plash on his foot. Starting up, he saw, to his dismay, that the water had been gradually creeping up and surrounding the low rock on which he was standing looking into the pool. At first he could not think how that had come about, as the sands had been quite dry toward the land side when he first went on to it. Suddenly it dawned on him that the tide must be rising. He did not know very well what the rising and falling tide meant, as his parents had not lived very long by the sea, but he remembered hearing his papa speak of people having been caught by the high tide and drowned. If he had started at once, he might still have got safely to shore by wading. But he was too much terrified to think of trying it. Looking about him, he saw a large flat rock near, and with some difficulty he succeeded in scrambling on to it. He thought it must be high enough to shelter him, until the tide should fall again. Had he not heard papa say that the tide fell as well as rose?

Placed thus, as he thought, in a position of safety, Willie's spirits began to rise again. All his fear had vanished, and he began to pretend to himself that he was a shipwrecked sailor cast away on a desert island; and he could not help laughing with glee when the merry little waves, dashing against the rock he was standing on, sent up sparkling showers of spray that seemed trying to reach him, but couldn't.

"Aha!" he thought, "you'll be clever if you catch me here on this big rock. I wish you'd be quick and go lower, though. I want to go home to mamma and Lucy."

Instead of going lower, however, the water kept rising higher and higher, until at length a wave, in breaking on the rock, sent a shower of spray in Willie's face.

The tide had been rising so fast that the shore seemed a long distance away now. The rock where he had been standing looking into the pool was now completely covered with water.

Oh, how he wished himself now sitting with Lucy plucking daisies in the field! How he repented of having been so disobedient to his kind mamma, who, he remembered now when it was too late, never forbade him anything except for his own good! How he resolved that he would never, never more be disobedient if he should ever again reach the land! But still the water kept rising.

In the mean time poor little Lucy sat crying on the lawn with her lap full of daisies.

"Miss Lucy! Miss Lucy! come in and get on a clean pinafore before luncheon."

"Lucy tan't tome in yet, nursie; Lucy p'omised to wait here for Willie."

"Why, I thought Master Willie was here with you. Where is he gone to?"

"Lucy no tell oo where Willie is don to. Lucy p'omised no tell 'at Willie is don to de beach."

"Gone down to the beach, indeed? Well, his mamma will be real angry, and his papa too."

Lucy began to cry again at the thought of papa and mamma being angry with Willie; but nurse carried her off to get her clean pinafore on before luncheon.

"Are the children ready, nurse?" called papa from the dining-room. Papa liked to have his little people about him at meal-times.

"Miss Lucy is a-coming, sir; but she says Master Willie has gone down to the shore."

"To the shore! impossible!" says mamma. "I told him this morning he was not to go alone."

"Well, ma'am, all I know is that Miss Lucy says so; and, as I can't find him nowhere, I think it must be so."

"Run down to the beach and see if he is there," says papa. "If he is disobedient like this, we must be more severe with him in future."

They began luncheon.

Suddenly, in the midst of carving a fowl, Mr. Beetham dropped the carving knife and fork.

"My dear," he said to his wife. "I hope it is not a spring-tide to-day. If it be, and that boy has got among the rocks, it might be a bad business."

The almanac was consulted, and announced a high spring-tide for that day. Any little boy or girl who had seen the dismay on Mr. and Mrs. Beetham's faces on learning this would have resolved never to be disobedient again so as to grieve such kind parents.

Mr. Beetham was starting up to go himself in search of the naughty little truant, when nurse rushed in to the room.

"Oh, sir!" she cried, "Master Willie is standing on a rock far out in the sea. He is waving his handkerchief and shouting, but there is no getting to him."

"Run for Fisherman Ralph," said Mr. Beetham.

"My dear," to his wife, "don't be afraid. Ralph's boat will soon get him ashore. Mind little Lucy while I run down and help to get it out."

But he was very much afraid, for all that, when, on reaching the beach, he saw his little boy standing on a point of rock that threatened every instant to be covered with the rising water.

"Ralph," he cried, as the fisherman—a tall, stalwart figure in a blue cap and corduroys—came up, "where is your boat?"

"Jack's gone a-fishing in it," said Ralph.

"Heavens! what shall we do?" cried Mr. Beetham. "My boy will be drowned before my very eyes."

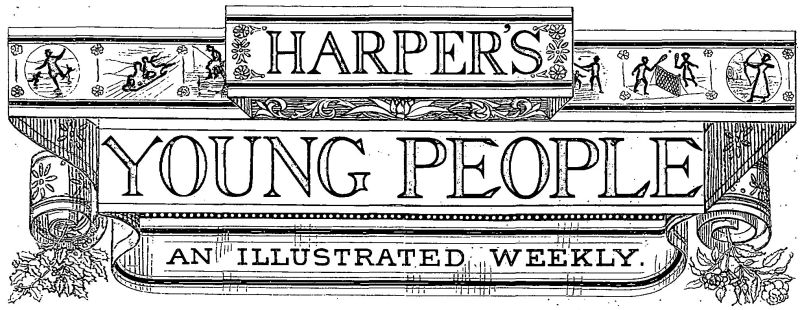

"Not if I can help it, sir," said Ralph, throwing off his jacket. "I'm big enough. I'll see if I can't wade to him."

"He'll never reach him," cried Mr. Beetham, running up and down the beach in an agony of anxiety, which was shared by all the by-standers, as the strong man strode on with the water above his waist, and the rock still not reached. It was nearly up to his shoulders before he got to where Willie stood.

"STEADY! STEADY! YOUNG MASTER! I'VE GOT YOU SAFE ENOUGH

NOW."

"STEADY! STEADY! YOUNG MASTER! I'VE GOT YOU SAFE ENOUGH

NOW."

"Steady, steady, young master. Don't be afraid of a wetting, and don't hold on so fast. I've got you safe enough now." And so, half wading, half swimming, the gallant fellow, battling with the great waves that were now rolling in heavily, brought poor Willie, drenched and cold, to land, and laid him in his glad father's arms.

Another minute and the rock had disappeared.

Willie learned a lesson that day which he has never forgotten, and after papa, mamma, and little Lucy, there is no one he loves so much as big Fisherman Ralph, who saved his life on the day of the high tide.

It is not seldom, in the melancholy records of shipwreck, that the "noble savage" maintains the character with which writers of romance have invested him. He is generally cruel, pitiless, greedy of gain, and more to be feared by the helpless mariner than the reef or the storm. There have been, however, one or two exceptions to this general rule, and the British sailor Captain Philip Austin had reason to speak well of the Caribs of Tobago.

In 1756 he sailed from Barbadoes, in a brig of eighty tons, to the Dutch settlement of Surinam. These people were so much in need of horses that at that time no vessel was permitted to trade with them of whose lading horses did not form a part, and, as well may be imagined, they were not the safest kind of cargo. So rigidly was this strange rule enforced that masters of ships were compelled to preserve the ears and hoofs of horses dying on the passage, and to make oath that they had embarked them alive for the colony.

On the night of the 10th of August, of the year mentioned, when near their journey's end, and while Austin and his mate were keeping watch together, "sitting on hen-coops" and "telling stories to one another, in order to while away the time, according to the customs of mariners of all countries," the broadside of the brig suddenly turned to windward, through the fouling of the tiller, and there being a heavy sea on, she filled at once, so that five out of the nine men who formed her crew "were drowned in their hammocks without a groan." The vessel then upset, going completely over, with her masts and sails in the water, "the horses rolling out above each other, and the whole together exhibiting a most distressing sight."

The coast was of sand, and the sea comparatively shallow, so that some portions of the brig were above water. To these the survivors clung, and at once stripped themselves of their clothes, except one who could not swim, and who was therefore without hope of saving himself by that means. There was one small boat, twelve feet long, fortunately unsecured by lashings, and this floated out, and was seized upon by the mate, but it was bottom upward.

Austin swam out to him, and the two endeavored to right her. This, after many efforts, was accomplished, "the mate contriving to put his feet against the gunwale and to seize the keel with his hands," while Austin "tilted her up from the opposite side with his shoulders." She was still, however, full of water. This was got rid of in a very ingenious manner, for the enormous hat which Austin wore, "after the fashion of the dwellers in the West Indies," was useless to bail her. The mast of the brig rose and fell some twenty feet, and the captain fastened a rope to its top, and held on to it from the boat. Whenever the vessel rose, it lifted up him and the boat, by which three-fourths of the water was emptied; but "having no means of disengaging her from the masts and shrouds, they fell down, driving him and the boat under the surface, and nearly breaking his thigh."

Despite his wound, which, however, rendered any further attempt without assistance hopeless, Austin threw himself into the water, and with the rope in his mouth swam to the men on board the brig, who, by their united strength, hauled the boat over the brig's stern, and emptied it. A hole, however, was knocked in it by this rough treatment, which was repaired by being stuffed with the shirt of the man who could not swim, and had therefore retained that garment. They had no oar, no sail, and except a dog belonging to the captain, "which was gladly taken in case of necessity," no provisions.

The brig remained longer above water than might have been expected, for she had casks of flour and butter on board, "the former of which slowly imbibes water, and the latter always swims," but none of these things could be got at. When she sank, the boat being still kept near her, a chest containing clothes and linen, with chocolate and sugar, floated out of her, and for these poor sailors it contained more than the riches of the Indies. It was too large, however, to be lifted into the boat, which, indeed, it would have sunk; and though they exhausted every means to open it, they found this impossible, and had to let it go. They picked up thirteen floating onions, and that was all.

They had no fresh-water; they were without any kind of implement except a knife, which was in the pocket of the sailor who could not swim, and they calculated that at the very nearest they were one hundred and fifty miles from land. Surely never were human creatures in a worse position.

Not a moment, however, was lost in vain regrets. By patient perseverance they loosened one of the planks with which the boat was lined, and formed it into a kind of mast, which they tied to the foremost thwart; another piece of plank served as a yard, and to this they fixed their only pair of trousers for a sail. Two of the men had always to lie along the gunwale with their backs to the waves, which would otherwise have swamped the boat, and, even so, another had constantly to bail it by means of the Dutch hat.

Thus they ran before the wind all night at the rate of about a league an hour. At daylight they ate half an onion each, which "wonderfully revived them," but they were tormented with agonies of thirst. Their naked limbs, too, were so scorched with the sun that from head to foot they were red and blistered as from fire. On the third day the captain killed his dog. He "afterward reflected on it with regret, but at that time no such sentiment affected him."

At last the exhausted men gave themselves up to despair, and refused to make any more exertions for their own deliverance, nor would he who had to bail the boat continue to do so, though Austin fell "on his knees to entreat him."

On the fifth day an enormous shark followed the boat—an omen the dark meaning of which was only too well known to them; and this depressed them still further. The dog had long been eaten, and they caught but one flying-fish, which was little indeed among so many. There were several heavy showers, but there was nothing to catch the rain in but the hat and the trousers, which had become so impregnated by salt-water that they were almost useless for that purpose. "Their only resource was endeavoring to catch a few drops as they fell into their open mouths to cool the heat of their tongues."

The two seamen drank sea-water and became delirious, but the captain and mate resisted that temptation; they each kept a nail in his mouth, and sprinkled his head with water, which afforded but slight relief to their sufferings. On the eighth day the two men died, but in the evening the boat reached land, and the two survivors, "forsaking the bodies of their companions, crept out of the boat and crawled on all fours" along the sand. The cliffs that walled it they were quite unable to climb up.

At eight in the morning a young Carib discovered them, "whose eyes, upon beholding their forlorn appearance, filled with tears." He understood a few French words, and informed them that they were on the island of Tobago. He brought them fresh-water, which they drank with passionate eagerness, and cakes of cassava and broiled fish, which they could not swallow.

Other natives showed them similar kindness, removing the two corpses out of the boat "with signs of the utmost compassion," and following in all respects the example of the good Samaritan. They brought soup, which seemed[Pg 695] to Austin the most delicious food he had ever tasted, but his stomach was in so weak a state that it refused to retain it. Herbs and broth were prepared for him by the women, and his wound was bathed with a lotion made of tobacco. Every morning the men lifted these unfortunates from their hammocks, and carried them in their arms under the shade of a lemon-tree while they anointed their blistered skin with a healing oil pressed from the tails of crabs.

In consequence of this friendly care and attention Austin was able in three weeks to go about on crutches, and receive Carib visitors from all parts of the island, "none of whom came empty handed." He gave boards with his name cut on them, to be shown to any ship captains who might chance to touch on the island, and after many weeks this plan met with success. A sloop, bound for Martinique, laden with mules, touched at Sandy Point, the western extremity of Tobago, and its master at once sent the intelligence to Messrs. Roscoe & Nyles at Barbadoes, the owners of Captain Austin's bark, who promptly sent a small vessel to fetch him.

When about to depart, the friendly Caribs loaded him down with presents of poultry and fruit, especially oranges and lemons, which they thought useful for his recovery. He had absolutely nothing to give them in return, save the boat in which he had arrived, and which they might have taken without his leave. More than thirty of them accompanied him to the beach, where, at parting from them, "neither Austin nor the mate could refrain from tears."

The effects of the poor captain's privations were lasting. His digestion was so impaired that he could hardly speak or walk, and had to give up his calling and return to England. His case excited much public attention. A Bath physician, Dr. Russell, who had resided in the East, and was accustomed to deal with cases arising from long-protracted thirst in the Arabian deserts, came to London to prescribe for him. By means of constant bathing, and asses' milk for his only diet, Austin regained his health in six months, and survived his disaster two-and-twenty years.

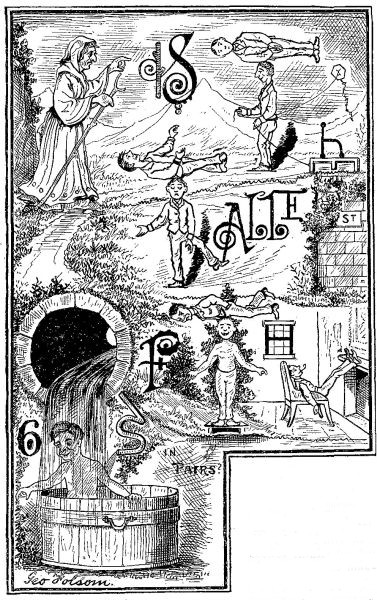

This is the story of a boy who had red hair, a good appetite, and much else in common with other boys; one who rose very high in the world, who came down and rose again, not so high, but in a better way. He was not a genius, or I should not tell his story; for there are so many boy geniuses nowadays in books that the record of a common red-haired child may be more interesting, as a change.

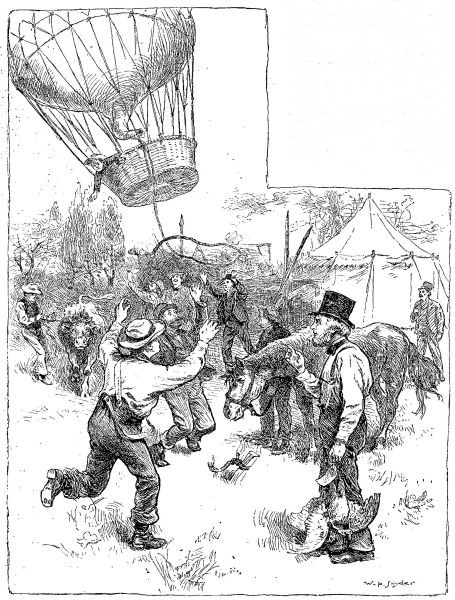

One day fifteen years ago there had been a county fair in Langham. The grounds were full of people even at six o'clock in the afternoon. But under the tent the gay bed-spreads, the oil-paintings, the hair flowers, and the wax-works were being taken down, while the farmers' wives were exchanging compliments, sample biscuit, and currant jelly. Outside the canvas the men were taking away the cattle—the great oxen with prize tickets on their horns, or sheep, or swine, or poultry. Everywhere there was bellowing, grunting, shouting, scolding, and some grumbling. This last was chiefly done by a noisy party who came to the fair, not to bring the grain or cattle raised by their industry, but to stare at the two-headed calf never raised by anybody, to bet on horses, to steal water-melons, and to join at last the crowd that was elbowing around a man with a balloon, in which he was to go up when ready. This balloon, already inflated, was fastened by a rope to a well-driven stake, and floated a little way above the ground. Among the lookers-on, some who pretended to know declared that it was not a very good balloon, and must surely come to grief.

After a while the man drew down the car low enough to get into it, and cried out: "Does anybody wish to accompany us in our grand aerial flight?" He said "us," as sounding fine; but he immediately explained that he would take a light gentleman only.

In a moment there shot from the crowd a long-legged, keen-eyed boy about fourteen years old, who nimbly stowed himself into the car, amid great laughter and shouts of "There goes Billy Knox!" "Good-night, Billy!" "Bring us down a star, Billy!" and like efforts at wit.

"Did you ever see a chap so ready and willing to risk his life for nothing?" asked somebody; and another man answered, coolly, "'Tain't no loss if he does break his neck; nobody owns him, and the world will be well rid of him."

Billy heard the heartless words, and turned to look at the speaker, while the owner of the machine arranged the ropes before getting into the car.

BILLY'S FIRST RISE IN THE WORLD.

BILLY'S FIRST RISE IN THE WORLD.

Suddenly, like a bubble from a pipe bowl, up rose the balloon, Billy in and the man out! The crowd gave a gasp of surprise, the man stared stupidly, and then, just too late, leaped up like an acrobat, and clutched—only air. Billy, moving slowly up, sat like a statue; but loud and clear came down from the car a cry, not of terror, almost one of triumph.

"He'll be killed, sure," said the former speaker, emphatically, and his companion echoed, "Don't seem to care a bit about it either, just as you said."

Some of the people thought it a trick of the owner of the balloon, but his frantic denial and his evident distress at the loss of his property proved it to have been a mishap. Meanwhile the news flew like the wind over the field, and in a moment hundreds of faces were upturned toward the vanishing balloon. Everybody hoped the boy would not meet a dreadful death, though a goodly number said it might better be Billy than any one else; and all alike watched, not sorry, if such a thing must happen, that they were there to see it.

Up, up, went the car, and "nobody's boy" was rising far above the earth. The sunset light smote his red hair, and made it glitter like gold. But Billy was soon too far away for the crowd to jeer at him, even if the roughest could have done so while the boy was in such terrible peril.

Billy looked down once and shouted. Then he began to wish that his conveyance would travel sideways, instead of rising so steadily.

It occurred to him at last that if the man who owned the balloon were in the car, he would probably turn some "stop-cock" or other, and let himself down. However, Billy was not sure that he wanted to go down even if he could.

As he rose higher and higher, the people on the ground below him began to look like small things crawling, and the great white tent almost like a card-board house. He questioned whether or not he should meddle with any mysterious part of the balloon. He remembered, not unpleasantly, having heard some one early in the day say it would certainly collapse of itself. If collapse meant to come down, to meddle with it might be to turn on steam and send him beyond the sun and moon, where he had no desire to go. He sailed across a forest, over a river, lost sight of the fair ground, and then began to come nearer earth, slowly nearer, then faster, the car rocking in a way that threatened to dump him out.

"We are surely 'collapsing,'" thought Billy. He grew a little dizzy, the earth seemed coming to meet him, and all the houses, barns, and hay-stacks were inflated, in their turn, and getting bigger. At last a gnarled old tree that had been charging straight on the balloon ran into it, upset, tore it, and after entangling Billy in ropes and branches, tearing his clothes, scratching his hands and switching[Pg 696] him like an old-time school-marm, let him fall roughly down to earth. He was glad to lie quiet, thinking first of the torn balloon, then of himself.

While he was thinking, the words that he had heard that afternoon as he entered the car came back to him: "Nobody owns him, and the world will be well rid of him."

Heretofore he had been proud of the fact that nobody owned him. He had never thought of himself as a nuisance to the community. Billy had not much sentiment, but to-night his heart ached as well as his limbs. He thought of all his past life as intently as a boy could think. He had begun to take care of himself when he was only eight years old. He dimly remembered his poor mother as always enveloped in the steam from hot soap suds, a practical kind of a halo, the result of her efforts to feed him with honestly earned bread. She died and left him to the care of a drunken father, who two years later followed her to the grave.

The town gave Billy a home in the poor-house, but he staid there only three days. At the end of it he resolved to start out into the world and earn his own bread. He ran away to the nearest city, where he blacked boots, sold papers, learned a certain amount of evil in the streets, and some good, in a night school. Finally he tired of city life, and started for California, but after getting ten miles on the way, his money gave out, and his courage too. He found himself in the town of Langham, and there he staid, doing odd jobs when he could get them, and at other times amusing himself as best he could.

There never was a fire that Billy was not close behind the hose-cart, or a circus that he did not ride the kicking donkey, or a county fair where he was not present looking out for anything in the way of fun that offered. His last undertaking was going up in a balloon. Now here he was, down again, and the question was, what should he do next?

A boy in a book would have decided to become a judge, or a merchant, or an artist; but Billy had another ambition. He desired to become a negro-minstrel. He knew one, a man who wore fine clothes and had plenty of money. He earned it by being funny—oh, so extremely funny.

While Billy was considering the matter, he heard a voice, and looking up saw a man following a cow. Naturally enough, the balloon, attracted the man's attention, and he came near enough to discover the boy.

A conversation followed, in which the whole story was told.

"Well," said Billy's new friend, who proved to be a tailor in a very small way of business, "how do you feel now?"

"Lonesome and sort of empty."

"Do you mean hungry?"

"Perhaps that's it," said Billy.

"Then you may come home with me to-night," said the man, "and after supper I'll see if the balloon is spoiled.'

"It is only collapsed," said Billy, very pompously; but when on getting up to walk he found his clothing reduced to about half what he had before, he assumed a meeker tone, and followed his new friend thankfully. The cow going first, turned down a lane bordered with sunflowers, and stopped by the door of a wee red house. A moment after, a small figure with a tin pail came out of the house, and sat down to milk the cow.

"This is my son Ben," said the host.

At first Billy had taken the child for a girl, for the little boy's checked apron came down to his copper-toed shoes, and he wore a green sun-bonnet, under which Billy saw soft white hair, and a very sweet face. They entered a kitchen, small, bare, but very clean, where a table was spread with blue dishes, brown-bread, baked apples, and cold pork. In the chimney-corner sat a little old woman, who sang as she rocked. She was very deaf, but she smiled on Billy, on the tailor, and on her little grandson. She would have smiled on anybody, as to that. But a grandmother's kind face being new to Billy, he thought it beautiful. He found the supper exceedingly good, if[Pg 697] not very abundant, and he was interested in watching Ben. The child soberly washed the dishes, and neatly swept up the crumbs, saying very little. The reason for his silence was after a while apparent to Billy: little Ben stuttered.

After supper, the room being warm, and Billy being tired, he dozed in a corner of the old lounge. While he slept the tailor went to see about the balloon, and staid a long time.

Later in the evening Billy was awakened by a voice. Ben was reading to his grandmother. She had her cap off, and her hair was as white as snow. She was warming her feet over the last coals, while Ben held a candle in one hand, and bent over an old book.

"'He shall call upon me, and I will answer him,'" read the boy, in his awkward, stuttering tones. "'I will be with him in trouble. I will deliver him, and honor him. With long life will I satisfy him, and show him my salvation.'"

Billy did not catch the last word, for the child could scarcely pronounce it, but he asked, abruptly, "Who will do it?"

The old grandmother heard the boy's voice, and answered: "God will do it all for those who love Him."

"Folks like you, old and good, I suppose," added Billy, as she tottered away to bed.

Once she would have stopped to teach him some holy lesson, but now she had crept in her feebleness so close to the door of heaven that she was forgetful of all darkness that might be behind her for younger travellers. Billy fell asleep again, then waked up blinking. The outer door was open, and Ben was pulling, bracing, and otherwise guiding his[Pg 698] father into the house.

When the tailor was safely dumped into a wooden chair, he began to jabber about the "b'loon, you know—scientif'—experiment. If I got a chance—like to own b'loon myself—always was scientific."

"Humph! that's it, is it?" said Billy, stretching out again for the night. He had seen too much of life to be either shocked or surprised. Doubtless Ben could get his drunken father to bed alone; and the child did indeed do it, as he often had done it before.

THE RABBIT HUTCH.

THE RABBIT HUTCH.

"But you can't expect Hatty to put off her birthday, can you?" and Ralph Wicksley shied a small pebble against the hand of his friend by way of emphasizing the absurdity of the idea.

"Oh, pshaw! of course not," replied the other boy, with a half-smile; "but ten chances to one it rains at a picnic anyway, and on a Friday, and the 13th of the month, there's no knowing what may not happen."

"Why, George Hendon, how long since you've turned a superstitious pagan?" exclaimed a voice behind the two, who were taking a "sun bath" on the beach at Seamere.

"Hello, Graham!" cried Ralph, springing to his feet. "We'll leave the matter to you. You know about the picnic we're to give your sister on her thirteenth birthday? Well, we've just discovered that it occurs not only on the 13th of the month, but on a Friday besides, and George here thinks we ought to postpone it on that account. It's all nonsense, isn't it?"

"I don't believe any of the girls will go on that day," put in George, by way of influencing Graham Burd's answer.

"And I don't believe one of them has thought of the coincidence," returned the latter; "and probably never will, unless you put it into their heads. You're not afraid to go yourself, are you?"

"Well, no, I'm not exactly afraid, but I think we'd feel more comfortable all around if we should choose some other day. You know sailors are terribly superstitious, and if, while we are in the boat, some one should mention the three queer facts (although I give you my word it won't be me), all the pleasure for some of the girls would be spoiled."

"Oh, don't you believe it!" cried Graham. "I'm sure Hatty, for one, has too much sense to make herself miserable because of a mere silly old wives' tale, so don't put it off on her account. Besides, there'll be more than thirteen in the party, which fact of itself ought to calm the fears of the most timid."

George said no more on the subject; everybody went on making preparations for the long-anticipated expedition to Forest Island; and when the day arrived, no more beautiful one could have dawned. By ten o'clock the Burds' tiny wharf was crowded with the young summer residents of Seamere, who were transferred, amid much laughter, chatter, and playful shrieks, to Ralph Wicksley's handsome Whitehall row-boat.

"It's too bad the Maxtons can't go, isn't it?" remarked Hatty, as the boys pushed off, and good-byes were waved to fathers and mothers on the lawn. "Their cousin Jack arrived from South America last night, and as he can only stay with them one day, of course they didn't like to leave him."

"Yes, I had the other boat all ready to bring along," added Ralph; "but as the party was thus reduced by four, I thought it would be pleasanter for us all to keep together."

"Why, I do declare," exclaimed Albertina Brown, a few moments later, "there are just thirteen of us! It's lucky we're to eat on the grass and not at a table."

"And to-day's Friday!" cried Fanny Ray.

"And the 13th of the month!" added her sister Helen.

"And my thirteenth birthday!" finished Hatty, whereupon a chorus of dismal "Oh! oh! ohs!" arose from all the girls, while Ralph cast a despairing glance toward Graham, and George Hendon smiled the least bit triumphantly at them both.

"Let's go back," proposed a faint girlish voice, after the first excitement had subsided; but such a "cowardly course" was at once vetoed by a deep-toned "Forward!" from the boys, who bent to their oars with curved backs in their determination to prove how splendidly everything could be made to go off in spite of the series of ill omens.

The girls, however, could think of nothing else but the wonderful inauspicious coincidences, and although not one of them, when questioned individually, would acknowledge to being really superstitious, still the numberless stories told in which unlucky days and figures were shown at their worst were almost sufficient, one would think, to sink the boat of themselves.

Among others was the tale of the matter-of-fact ship-owner, who put no faith in any of the sailors' silly beliefs, and who, to prove their absurdity, laid the keel of a vessel on Friday, named it Friday, launched it on a Friday, at length succeeded in finding a crew for it commanded by a Captain Friday, set sail on that day, and—was never heard of afterward.

To offset the depressing effects of this tragic albeit somewhat doubtful narrative, Ralph told about the Thirteen Club which had been recently organized in the city, the membership of which was restricted to thirteen, and which met for dinner on the 13th of each month at a hotel the name of which was spelled with thirteen letters. "And nothing 'perfectly awful' has befallen any one of the members so far as heard from," concluded Ralph, exultingly.

There were certainly several grains of comfort to be extracted from this fact, and cheerfulness began to diffuse itself once more over the party, when Fanny Ray, who[Pg 699] was steering, suddenly declared that the sight of salt-water on every side of her always made her thirsty for a drink of fresh, and a search was at once instituted for the water jug.

"I saw Graham put it somewhere in the stern here," continued Fanny; "but don't any of you boys try to get at it, for you'll be sure to put your foot into the basket of cake or the jar of jelly. Here, Hatty, I think I feel it right down here; but Ralph says I mustn't let go of the ropes; so will you please stoop down and lift it out for me?"

Now, as may be imagined, with a party of thirteen aboard, there was not much spare room in the boat, so when anything was wanted from the bottom of it, it had to be felt, not looked for.

"I've got hold of the cork, at any rate," she presently announced, "but the jug seems to be wedged in some way. There, now! I've pulled the cork out. Oh dear! why didn't I find the handle?"

"Let me try," proposed George, giving his oar to Phil Hallibey, and making his way aft.

"Here's the glass!" exclaimed Albertina; "and I'm thirsty too."

"Oh, George Hendon, right on my foot!" cried Helen.

"Careful now," commanded Fanny. "I'm awfully sorry to make all this trouble, and—"

"O—h—h! we're sinking! we're sinking! Help! help!"

And the next moment it became known to them all that Hatty had mistaken the boat plug for the cork of the water bottle, had pulled it out, and that now the river was pouring in with appalling swiftness.

"Pull for the flats, fellows!" shouted Ralph, tearing off his jacket as he spoke. "Here, George, see if you can stuff this coat into the hole; and, girls, keep perfectly quiet, or you'll overturn the boat. Don't mind if you do get wet, but sit still."

Ralph spoke in loud, commanding tones that were at once obeyed; but the danger was by no means over. The boat was settling rapidly, the water being already half-way up to the thwarts, but ruined skirts and soaked shoes were never thought of as all sat watching breathlessly, now George's efforts to stop the leak, now the light streak on the river that marked the edge of the flats, and which was still several yards distant.

"Pull! pull!" cried Ralph, working himself with all his strength. "Can't you stop it, George? We're nearly there, girls."

Higher and higher rose the water in the boat; again and again was George baffled in his attempts to stem the incoming floods, as in the crowded condition of the stern he could not see what he was doing, and to ask any one to move would be to endanger capsizing the whole party. And all the while the sun shone brightly down on the sparkling river; the village, too, was still in sight, and not far off was the shady island where the picnic was to be held. It seemed terrible to think of going down, down amid such—

"Saved!" suddenly shouted Ralph, as the boat shot out from the channel and in among the eel-grass. "Somebody's sure to see and take us off very soon, and meanwhile you needn't mind sitting in the water, as long as it isn't up to your eyes. It's salt, so you won't catch cold."

Nevertheless the situation of the party was anything but a pleasant one, for the boat settled until it touched bottom, and then careened over, throwing both Graham Burd and Phil Hallibey into the river.

"Here comes a boat!" suddenly exclaimed Albertina.

"And it's the Maxtons out rowing with their cousin Jack," added Hatty.

The young cousin from South America proved to be an old sailor, and under his superintendence the girls were soon carried ashore in detachments to the nearest point, after which he returned to help "raise the wreck."

The thirteen having been dried and lunched at their several homes, they all met to spend the afternoon at the Maxtons', where the same useful cousin proved himself likewise a master-hand at entertaining, so what with games, stories, music, and ice-cream, the lost excursion was lavishly atoned for; and when a terrible thunder-storm about three o'clock caused them all to feel glad that they were not on Forest Island, even George Hendon acknowledged that in spite of coincidences and the boat plug, their Friday picnic was a lucky one after all.

Travelling in our country is both comfortable and agreeable, if the traveller will pay attention to a few directions. I suppose, dear little friends, that you have seen fussy and fidgety people on the road, who made themselves and other people unhappy by their behavior. The cars were too warm or too cold, the locomotive was going too fast or too slow, they feared the baby in the next seat had the whooping-cough, or they were sure there would be a collision. If on the water, they were in terror lest the engineer was racing, and the uneasiness they felt made them wretched.

Now, my dears, listen to me. When you go on a journey you are a passenger; your ticket is paid for; and as you are neither captain, pilot, conductor, nor engineer, give yourself no trouble about the way car or boat is being managed. Never take responsibility that does not belong to you.

The old Romans used to call baggage impedimenta. They tried to have as little of it as they could when on a march. Unless you are going to stay a long time, take no more luggage than is necessary. A little hand-bag or a shawl-strap, with perhaps an umbrella, is all that a young traveller should have to care for on a journey.

When you purchase your ticket, if no older friend is with you to attend to the checking of your trunk, you must see to it yourself. This is very simple. Go with your ticket to the place to which the expressman has taken your trunk, show your ticket to the baggage-master, and he will attach a check to your goods, and give you one precisely like it. You must put this away in a place where you can get at it conveniently, as you must return it to the steamer or railway company when you claim your property.

Never tuck your ticket out of sight or into some out-of-the-way pocket. Have it ready to show the conductor whenever it is called for.

A little girl is sometimes uncertain what to do about her money if she is travelling with a gentleman. For instance, Eda is going to visit Angeline, and at the station in New York she is met by Angeline's brother Dick. She does not wish him to purchase her ticket, but she feels awkward about offering him the money to pay for it.

The proper thing for Eda is to hand her pocket-book to Mr. Dick, and request him to take from it the amount of her fare. The pleasantest way, if the journey be a long one, would be for Eda's papa to give her escort a sufficient sum to pay all her expenses.

People on a journey should not be selfish. Nobody should take two seats when only entitled to one. Two or three merry boys and girls travelling together should be careful not to laugh and talk so loudly that they annoy others. Ladies and gentlemen never do this. You can have a great deal of fun without being conspicuous.

Never neglect a chance to do a kindness to an aged or feeble person. Nothing is more beautiful on the road than courtesy from the young to those who are old or in trouble.

How often has it happened that on reaching a camping ground, hotel, or boarding-house near river or lake, where pickerel, bass, and large perch abounded, I have found no provision for the angler's sport but a boat; no lines, sinkers, or floats; no nets for catching live bait, and no bait but worms! For sunfish, cat-fish, and small perch, worms are very fair bait; but for pickerel, bass, and large perch, live bait is best. Under such trying circumstances, I have learned to get up at short notice and at small expense many make-shifts and aids that may be of great assistance and consolation to other young anglers when placed in a similar position.

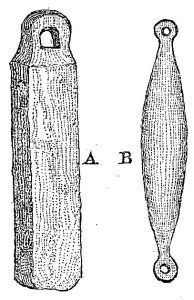

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

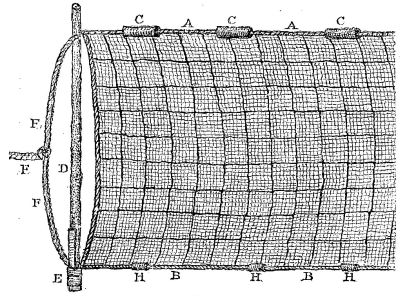

Fig. 1 is an end section of a mosquito-net seine for taking live bait. The length of the seine is thirty-eight feet; depth, five feet. The "cork line" (A A) consists of a small-sized clothes-line. Corks not always being obtainable, I have used pieces of thoroughly seasoned white pine three inches in length and one inch in diameter (C C C). Through these rounded pieces of wood holes are bored, through which the clothes-line passes. These floats are placed eight inches apart, and are kept in position by the clothes-line fitting tightly in the holes. At the bottom of the seine another clothes-line is sewed to the netting; (B B). This is called the "lead line," and is for the purpose of keeping the lower part of the seine close to the bottom of the water. On the "lead line" pieces of sheet-lead one inch in length are fastened (H H H) twenty-eight inches apart. The "staff" (D) is a well-seasoned piece of hickory six feet long, to the lower end of which sheet-lead is also fastened (at E) to keep it down. To the staff is attached the staff line (F F F), thirty feet long, which is for the purpose of drawing in the seine after it has been cast.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

A seine of this size is generally worked by two persons and two boats. Each person takes one of the staff lines in his boat, and rowing toward the shore with the extended seine, describes a semicircle between the boats. As the shore is approached, each boat closes in, thereby causing the two staffs to meet, and imprison, all the fish that have come within the bounds of the seine. When one person works the seine, one of the staff lines is tied to a rock or stake on the shore, and the other line is taken into a boat, or the operator wades out, and causes his end of the seine to describe a circle until the two staffs meet. Great care must be taken to keep the lead line close to the bottom, otherwise the fish will escape. In the selection of the seining ground always avoid stony bottoms, snags, and brush, which will cause the seine to "roll up" and tear.

The cost of the above-described seine ranges from three to four dollars, and is capable of lasting two seasons if carefully handled and spread out on the grass to dry after using it. A much superior article to mosquito net is bobinet, which will last several seasons.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

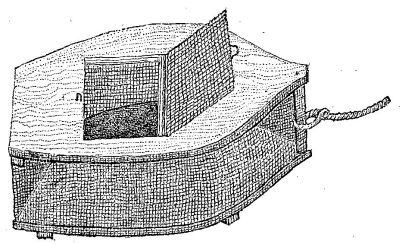

Fig. 2 is a bait boat, for keeping the bait alive. It is towed behind or kept by the side when fishing. The top and bottom pieces consist of half-inch pine "stuff"; in the centre of each piece square openings are cut; that on the top is protected by a door made of wire-cloth of quarter-inch mesh, fastened to two small staples, which answer the purpose of hinges; over the opening in the bottom piece wire-cloth is nailed, to admit of a free circulation of water. Under the back end of the top piece a cleet is nailed, also two cleets on the bottom piece, as shown in the figure. At[Pg 701] the bow of the boat an upright piece of wood is fastened to the top and bottom of the bait boat by means of screws. The sides of the boat consist of one piece of wire-cloth, the ends of which meet at the upright piece of wood at the bow, and are nailed with broad-headed galvanized nails. The top and bottom edges of the wire-cloth are also fastened with nails to the edges of the top and bottom of the boat, as shown in the figure. A tow-line is fastened to the bow, and the boat is complete.

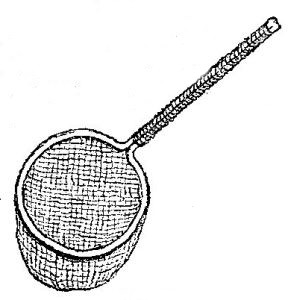

When handling the bait a small hand-net (Fig. 3) is used, consisting of a stout piece of wire bent as shown in the figure; the straight parts of the wire are bound together with fishing-line, and constitute the handle; to this frame netting is sewed to form the net bag.

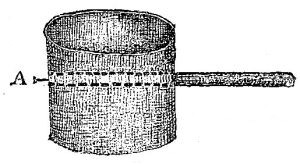

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

When fish are caught, they ought to be kept in water to keep the scales soft, otherwise they become dry and set, and are troublesome to clean.

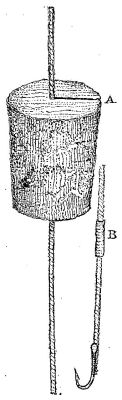

For a make-shift float I have found nothing better than a good-sized bottle cork, into which a cut has been made with a sharp knife or razor, extending from the side to the centre of the cork. Into this cut the line is drawn as shown in Fig. 4, A.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Sheet-lead is always a useful aid in make-shift fishing-tackle, and for light lines makes excellent sinkers when bent and compressed around the line, as shown at Fig. 4, B.

For a pole nothing is nicer than a light and straight piece of the aromatic sweet-birch. I am not a convert to hundred-dollar fishing-poles with polished mountings, but have reasons to still believe there is much virtue in birch.

For cleaning out a boat a stiff whisk-broom made of fine birch twigs bound together with wire or fishing-line, as shown at Fig. 5, will be found very useful.

Fig. 6, A and B are hand-made sinkers beaten and carved out of old lead pipe. The carved one, B, is first roughed out with a jackknife and finished up with fine emery or sand paper. A is beaten into shape with a railroad spike on an anvil or smooth stone. This beating and carving of lead is very pleasant work, the lead being of such an easy and good-natured temper.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

For a cheap and easily obtainable bailer I have made use of an empty tomato or corned beef can, as shown in Fig. 7. A hole sufficiently large to admit of the handle is punched in the side of the can, the inside end of the handle is champered off so as to fit close to the inner side of the can; through the can and into the end of the handle a stout nail is driven, as at A.

A good bait for large fish is a strip cut from the under side of a small pickerel, perch, or sunfish, which is placed on the hook as shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

For black bass I have found the black field and house crickets most excellent bait. Within the last two weeks I have taken good messes of horned pouts (cat-fish) with set night lines baited with "cat-worms" (so named by the inhabitants of the lake where I am camping). These "cat-worms" are those elderly, corpulent, and well-to-do angle-worms, that pay their respects to one another on dewy, moonlight nights. When using angle-worms I place them in damp moss for three days, to rid them of all earthy matter; this toughens them so that they may be run on the hook with more certainty and less bother; and, besides, they have more squirm in them, which is a decided gain.

See! This Italian boy,

Much to the children's joy.

Has taught his goat

With the furry coat

To caper and prance

To the tune of a dance,

While he will play

All a summer's day

On his mandolin

His bread to win.

At night he'll lie

'Neath the open sky,

With the grass for bed,

And beneath his head

For pillow the goat

With the furry coat,

And sleep till day,

When again he'll play

On his mandolin

His bread to win.

What fun it is to pack a trunk! Is it not, little travellers? And how much more troublesome the packing is when you are coming home than it was when you were going away! So many pretty things collected during the summer are to be carried safely, so that the dear ones at home may see them, and that they may adorn brackets and corners, and make rooms beautiful the whole winter long. I hope the children who are going back to school with brown faces and rosy cheeks are all ready to pack away plenty of learning in the little minds, which are not precisely like trunks. You may get a trunk so full that it can hold no more; but a healthy boy and girl can never fill his or her mind so full of useful knowledge that there will not be room for something else.

So, little folks, trip merrily to school, and show how much you have enjoyed your play by working like beavers, bees, and birds, building character, gathering honey, and singing cheerily all the while.

Amherst, Massachusetts.

I am a boy eight years old, and I want to write you a letter about my little kitten Daisy. I made a little house out of a box, and I made steps for her to go in the house, and I put it out in the wood-shed. I put her in front of the steps, and she walked right in and went to sleep, and now she sleeps there always. Last Sunday evening she caught her first mouse, and she played with it for a long time, and when it was dead she tried to make it alive again by tossing it up in the air. This is all I have to say this time, but if you like I will write to you again.

Rufus Tyler L.

You were a clever boy to make a house for your kitty. A friend of mine took pity one cold winter on a wandering cat that had no home. As the ladies of the family did not want to take so forlorn and wild a thing in-doors, this kind man set a box in the yard, put some straw in it for a bed, and every day placed a saucer of milk or a plate of food beside it for the poor hungry puss. Like your kitty, this one learned to know her own house, and grew quite plump and handsome, as well as tame, under the gentle treatment.

Cottage City, Martha's Vineyard.

My mother, father, brother, and myself are spending the summer at Cottage City. Last Saturday we joined an excursion to Gay Head. Gay Head is on the other end of the island. We enjoyed the steamboat ride through Vineyard Sound, although the scenery was not very pretty. We were obliged to land in row-boats, which were managed by natives. These natives are a cross between the negro and American Indian; they are generally very homely, with the exception of the children, who soon lose their prettiness, judging by the looks of their elders. We walked some distance along the beach before we came to the cliffs. These cliffs extend about half a mile along the shore, and are formed entirely of different-colored clay—green, yellow, red, blue, white, and brown. The red resembled sunburned rocks, only much brighter; the yellow looked from a distance as if a load of sand had been dumped there, and rolled half-way down the cliffs; the white was very pure and dazzling, and with the dark green bayberry growing on it, the effect was very fine. We went into the light-house and saw the light, which belongs to the first class. The keeper said it flashed in ten seconds, and revolved in four minutes. He has to wind it up every hour. While in the light-house the steamer began to whistle, so we had to hurry back, as we did not wish to get left. We found the sail home rather tiresome, and were glad enough when the Seaview wharf hove in sight. I am afraid that the Postmistress will think this too long to print. If she does not, I will write again, and tell about my excursion to Nantucket. Good-by.

A. B.

Yes, dear, write again. Letters which describe what you see, and tell where you go, are very welcome.

Oswego, New York.

I wish some of the boys and girls who write to you could see my room. The ceiling is papered with nursery papers; then there is a border of Japanese pictures, and the rest of the wall is entirely covered with advertisement cards, some of which I bought and some of which were given me. I have a large cupboard in my room, and that is covered with the same cards. I have over two thousand cards on the wall. I have been to New York this summer, and visited on Governor's Island. I saw Generals Hancock and Sherman, and the former gave me an orange. I am seven years old, and although I have never been to school or studied much at home, I have learned to read. I have been reading Boys of '76 and Old Times in the Colonies, and like both very much. I went to Coney Island in June, and came very near being lost or stolen. I have over two hundred little soldiers, and have fun having battles with them. I hope you will publish this very soon, and excuse me for writing such a long letter.

L. W. M.

Your room must be very beautiful, dear. It is what we call unique, and I think it must be quite gay and rainbow-like. I am glad you were neither lost nor stolen at Coney Island.

Waco, Texas.

I am a resident of St. Louis, and am spending my school vacation in Texas, where I am visiting a brother. I have taken Young People since its first number, and have often wanted to write a letter to the other boys. I left St. Louis July 5, coming through the State of Missouri, and down through the Indian Nation, the prettiest country I ever saw. I came the entire distance alone. I like Texas very much, and will probably stay here until Christmas. The Brazos River runs through the town, dividing it into East and West Waco. It is spanned by one suspension-bridge and two railroad bridges. This is one of the prettiest places in the State.

Lewis M. H.

I like to hear from a self-reliant and manly little fellow who is able to take care of himself on a journey.

Hudson, New York.

I'm going to send a letter to you, but I don't know exactly what I'm going to say until I think of it as I go. I live on the banks of the Hudson River. The mowing-machine is just cutting down the grass. The view is beautiful from here, but still more beautiful from Mr. Church's, who lives on the hill. I haven't many pets to tell you about, except two canary-birds, and a lamb that is hardly a lamb now, but a full-grown sheep.

Nelly G. E. (not yet six years old.)

I suppose little Nelly sometimes climbs the hill to gaze with her own bright eyes at the golden sunsets which Mr. Church looks at from his pleasant home, and then paints so beautifully for the rest of us to enjoy. Do you know, dear, that the best letters ever written are written in your way—just by thinking what to say as you go on?

Hillsdale.

I thought I would write you a letter to let you know how much I like to read Young People. I think it is a very good paper, and I watch every week for the number to come. The first piece I read is "Mr. Stubbs's Brother." I think a good deal of a good circus. Jimmy Brown's stories are very interesting. We have a pet crow; he is very tame. He flies all over the farm, and goes wherever he pleases. He is afraid of other crows. When they come too close, he flies to the house if he is not too far away. He likes to follow along in the corn field, and pick up the bugs and worms. Good-by.

John S. R.

Is your crow afraid of a scarecrow? I suppose you will be surprised, but I once had a pet crow of my own. He was as black as black could be, and oh! such a mischief, and so fond of stealing things and hiding them. His favorite perch was on the sewing-machine. I was very, very glad when one day Mr. Crow flew over the hills and far away, and never came back. In which State is your Hillsdale, John? You forgot to tell me.

Baltimore, Maryland.

My grandpa has moved his house down near to ours. First they put great beams under the house, and wooden rollers under them, and then they built a platform in front of it to roll it on. Then they fastened a chain to the house, and a rope to the chain, and then a horse pulled it round a block and tackle. My grandma came out here to-day and took me to ride. When my birthday comes I am going to have a little party, and give the children presents instead of having people give me things, and I am making some balls for some of the boys. My papa has taken Harper's Young People for me ever since its beginning. I like Toby Tyler very much, and I hope his circus will not come to an end. I wish that lady who wrote the letter about the hospital for little children would write another one. I have a bird and a cat. When I give my cat anything to eat, he tries to get it before I can put the plate on the ground. I went to Luray this summer and took my doll, and it took me a long time to get her ready. The next time I write I will tell you about the cave I went into. I guess I am getting sleepy now, and I want to go to bed, and I will end off my letter by saying, "Won't you please print this in Harper's Young People?"

I send you a picture of my bird and cat. I am seven years old, but I can only write printing letters, so mamma wrote this for me.

Evalina Carroll S.

Thank you for the pretty picture. I like your idea of making others happy on your birthday. A sweet Bible verse tells us that it is more blessed to give than to receive. How much you must have enjoyed watching the moving of grandpa's house! Were you frightened when you explored the Luray Cave?

Charlotte, New York.

We are spending the summer at Lake Ontario, and see a great number of butterflies fluttering along the road-side, and over the fields. Reading the article in No. 142 of Young People on butterflies, my brother and I started a collection. We have caught several specimens of Papilio turnus and Papilio asterias. We also caught a beautiful butterfly which is not described in Young People. Its wings are velvety black, and the hind-wings are tailed. The fore-wings are marked with rows of greenish-yellow spots on the margin, and the hind-wings with rows of spots of a peculiar green (called gas green, I believe), and above the spots is a large irregular spot covering two-thirds of the wing. We have only one specimen of those yellow butterflies spoken of. They are very plentiful, but I find them hard to catch, as they take alarm very quickly. About four o'clock in the hot afternoons we go over to the edge of the woods, where there is a break in the trees, and the grass is deep, and find quantities of tawny orange butterflies marked with black on the upper side and silver on the under. The black and green butterfly that we caught was prettier on the under side than it was on the upper. Its hind-wings were marked underneath with light blue, silver, and orange. I hope that my letter is not too long.

Winifred J. B.

Macon Station, Alabama.

I like the stories written by Jimmy Brown very much. I am very much interested in "Mr. Stubbs's Brother." We have three kittens, and their names are Toby, Abner, and Mr. Stubbs. While my sister and brother were out driving one evening they heard a kitten crying behind them, and brother got out, picked it up, and brought it home. Mr. Stubbs is very playful. I have a pet lamb and a pet chicken. The lamb's mother died when it was very young, so I took it, and it is a large lamb now. I raised the chicken myself too. I had a calf, but it died. I was twelve years old the third day of June. I have three brothers and two sisters. All of us read Young People except the two youngest.

Susie B. R.

"A snow-white mountain lamb, with a maiden by its side." Do you say, "Drink, pretty creature, drink," to your lamb, as Barbara Lethwaite does in Wordsworth's poem?

Jersey City, New Jersey.

We are a little brother and sister seven and five years old. Papa buys Harper's Young People for us, and mamma reads the stories first, and then tells us what she thinks we can understand. We had a pair of rabbits sent to us from Indianapolis last year, but they were so much trouble we gave them away; we had a little turtle no larger than a twenty-cent piece, but that is dead; it lived two years. The sweetest pet we ever had was our dear little brother Arthur. He died last November, and we all miss him very much. He was so cunning! He was one year and a half old. We have never written to Young People before, and hope this will be published.

Harry and Emily F.