“There you are!” said Gloria.

Title: Gloria: A Girl and Her Dad

Author: Lilian Garis

Release date: April 25, 2019 [eBook #59354]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and Sue Clark from page images

digitized by the Google Books Library Project

(https://books.google.com) and generously made available

by HathiTrust Digital Library (https://www.hathitrust.org/)

“There you are!” said Gloria.

| I | Companions |

| II | Tommy-Lad |

| III | Shadows |

| IV | Nancy Trivett |

| V | The Forecast |

| VI | At Turtle Cove |

| VII | The Hunt |

| VIII | Nanny’s Return |

| IX | Love’s Golden Shadows |

| X | Meet Ben Hardy Junior |

| XI | Part Payment |

| XII | Uncle Charley |

| XIII | The Quest of a Tweed Coat |

| XIV | At Crystal Springs |

| XV | Tommy’s Token |

| XVI | A Revelation |

| XVII | A Serious Predicament |

| XVIII | The Emergency Case |

| XIX | That Crowded Day’s End |

| XX | Misgivings |

| XXI | Echo Park |

| XXII | Trapped |

| XXIII | The Rescue |

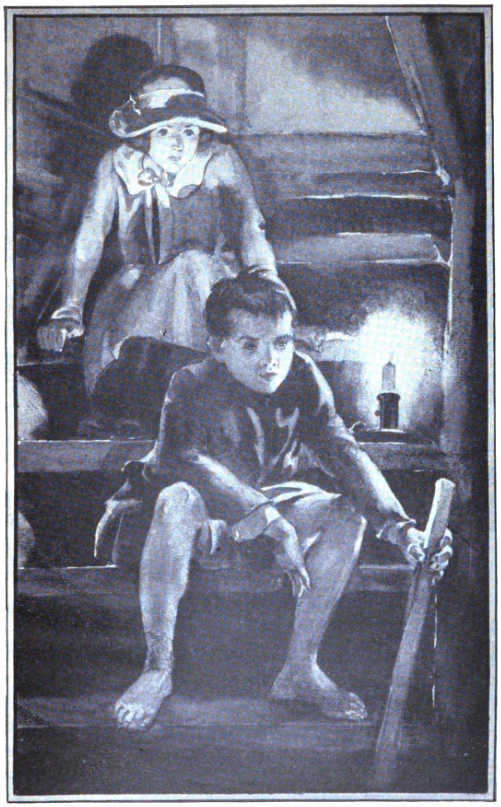

The boy was taller than the girl, this could be noticed from quite a distance, but other marks of difference, such as Gloria’s red cheeks and Tom’s brave freckles, her black eyes flashing while Tom’s were meek, blue and shadowy; these distinct and contrary characteristics were only observable when one looked under Gloria’s floppy white hat, or glimpsed Tom’s quaint, boyish person at a little distance.

There was that about Gloria which compelled a close scrutiny, under the brim of her hat seemed the very point of vantage, while Tom—one would hate to scrutinize Tom. Even the friendliest notice would seem rude if too closely given. He was not bashful, really, nor was he in any way stupid, on the contrary, his alert mind that only flashed out in moments of unchecked enthusiasm was the magnet that held Gloria Doane to his companionship, ever since they had both toddled off to their first battle with learning, in the back room of Miss Mary Drake’s Fancy Store. But few others understood Tom, they were generally too busy condemning Gloria’s lack of discrimination in her selection of such a companion.

Besides those shadowy blue eyes Tom also had freckles—a real saddle of them across his nose; splendid, healthy, ginger brown freckles. They were rather unfair to the nose, however, destroying what might have been an aristocratic outline; but freckles are like that—ruthless when once they get a footing. Being tall, having freckles and possessing a musically liquid voice, gave Tom his chief claim to personality, but his own mother called him Tommy-lad and declared he was a fine, upstanding little youngster.

Just as Gloria Doane had a father and no mother, so Tom Whitely had a mother and no father. This similarity of parental privation may have forged the bond of companionship stronger; at any rate, Gloria and Tom were chums.

All the joys of country life ever piped in poet’s tunes would be flat and monotonous if unshared by a chum. You may talk of the music of the birds and the magic of the running brook, even of the glory of wild daisy fields and the beauty of sovereign sunsets, but to youth, to the eager young and even to childhood, these would be all rather stupid in solitude. There is no solitude in the city—that can be said in its favor. Even a sick boy or girl may be shut up in narrow quarters there, but somehow the hum of companionship will reach in and sometimes cheer. But in the country it is very different.

Without a chum would be like being without a roof, or even without a family dog. That life around a fishing village is not apt, however, to be so solitary as is found inland, and it was in the seaside town of Barbend that our interesting little friends lived.

Vacation had been particularly merry; picnics, lawn parties, launch trips and even city scouting parties filled the days with continual change and thrilling variety. Tom had earned more than ever before in any vacation, and Gloria felt like a pinwheel revolving in golden sprayed breezes of good times and surprise adventures. Only a few weeks remained now, then the new adventure of fresh school days, with brand new programmes and mysterious possibilities in new teachers (two were due at Barbend this year), these delights, in spite of dreaded routine and perhaps hated studies, beckoned every girl and boy in the township; to say nothing of the hurried last stitches being put in new blouses for the boys and into new dresses for the girls, by anxious mothers.

The launch Finnan-Laddie was lapping the dock just after Gloria had stepped ashore, and Tom happened to be passing from the swamp with a great basket of pond lilies for his next day’s sales. Automatically they fell into step, if that could be said of their peculiar motion, Gloria sort of easing into Tom’s shuffle with a queer little grace note trick that kept the tempo going.

No greetings were exchanged. Would one say hello to the sun, or to the moon or even to some familiar star?

“How did you make out?” asked Gloria, eagerly.

“All right,” replied Tom.

“Can it be fixed?”

“Sure.”

“It’s a wonder you weren’t killed.”

Tom grinned. “That wasn’t anything.”

“It wasn’t!” Gloria’s voice boomed. “Well, if it wasn’t, then I don’t ever want to see another bicycle spill.”

“Not even at the races?”

“No. I hate spills anyhow. They make you gulp and you can’t see anything but dust.”

“You saw my basket go, didn’t you?”

“I should say I did. I thought it would never stop bumping over the stones until it went straight into the brook. But, Tom, honest, you ought to be more careful.”

“Oh, listen who’s talking!”

“Just the same, I never ride over that hill with a clothes basket full of pond lilies and an arm full of papers.”

“But you do ride over there with trees full of blossoms—”

“Oh, well. That was only when we had to get the school decorated—”

“And this was only when I had a big order—”

They laughed, gave in and changed the subject.

“What if your mother finds out?” persisted Gloria.

“She won’t.”

“A lot of folks saw you. They were down waiting for the launch.”

“Well, ’twasn’t anything.”

“Tom Whitely! You almost rolled over on the railroad track and Mrs. Trivett nearly had a heart spell.”

“Oh, Mrs. Trivett!”

“But she talks more than half of the town.”

“Who listens to her?”

“Folks can’t help it. She’s so—pesky.” Gloria dropped a spray of golden rod.

“My mother never bothers with her.”

“But you know, Tom, others listen to her, and then—then. Just suppose someone tells your mother you rolled down that hill when the Flyer was whistling—”

“Say, Glo. Who’s been stringing you?”

“Tom Whitely, that’s no way to talk.” Gloria’s nose seemed to sniff her hat brim, and her black eyes flashed at the willows they were passing.

“Oh, I didn’t mean it.” Tom’s voice was caressing now. His eyes blinked and he changed his big basket to the other arm in spite of Gloria’s blue gingham dress and her own armful of sweet-flag roots being on that side. There was plenty of room now, however, for she had edged off toward the stone wall.

The road turned at the creek—Tom would go one way and Gloria the other, but before they separated they had made up the momentary difference. Just as it began it ended. Neither boy nor girl was subject to any nonsensical apologies or explanations over such silly little trifles.

“If I were you, Tom, just the same, I’d tell my mother I had a spill and that your bike is broken. Then—”

“Oh, yes, I know, Gloria. That’s easy enough to say. But you don’t know my mother.”

“I do so.”

“I mean, like I know her.”

“Of course I don’t know her as well as you do.”

“Then you can’t know how she fusses. I don’t want her to know I had that spill, Gloria, and if you hear folks talking about it just hush them up. I didn’t get hurt—”

“You did, too, Tom Whitely!”

“Oh, that!” scoffed Tom. “I don’t call that getting hurt.”

“Just the same, I’ll bet you don’t swim for a week.”

“I don’t have to.”

“All right,” conceded Gloria with a show of impatience. “Of course you don’t have to—”

“Say, Glo!” Again Tom’s voice mellowed. “You know I’m not—not forgetting your kindness. I always count on that,” he said a little awkwardly. “But you see how it is. If mother ever hears I spilled I’ll have the awfullest time getting her to believe that I don’t spill every day just for fun, you know. Mother’s a brick, but gosh! She can stew.”

“I know, Tom, and you’re just a brick, too, trying to save her.” Gloria always talked very slowly when a parent was under discussion. “I know how it is with my dad—”

“Oh, you’re dad is a peach.”

“He sure is. A perfect peach.” Every word was beautifully rounded and just rolled from Gloria’s lips like solid balls of tone. “I often think how your mother has to be father and mother, and my dad has to be both, just the same.” She stopped and almost sighed, but Gloria Doane was not the sighing kind. “Anyhow, Tom, we’ve got a wonderful pair between us,” she boomed.

“That’s right.” Tom shifted the basket again and the effect of the much discussed spill was not completely hidden in the frown that scattered with the effort, his freckles. “That’s why, Glo, I hate to worry mother.”

“Then take my advice.” Gloria laughed that she should indulge in advice. “Tell her about it.” Tom attempted to speak but the girl hurried on. “That is, tell her something about it.”

“Well, maybe.”

“And, Tom,” her sweet-flag roots were shedding their damp grains of earth over her checked gingham, “how are you going to get the bike fixed?”

“Got to wait—till I earn it, extra.”

“Then you’ll have to walk.”

“That’s nothing.”

“It will take twice as long.”

“I know. But the chain’s broke.”

“Where is it?”

“Up at Nash’s.”

“How much will it cost?”

“How much do you think?”

“I couldn’t guess. Millie had hers overhauled and the bill was ten dollars.”

“Gee whiz! Glad mine won’t be that much. But it will be three dollars,” said Tom ruefully.

“I’ll tell you, Tom. I’ve got five dollars—”

“As if I’d borrow money from a girl!”

“It isn’t borrowing. I’m just offering it to you till you earn it,” insisted Gloria. “It doesn’t make one bit of difference to me.”

Tom looked thoughtfully far ahead—clear past the blackberry clump. He needed that wheel. He was earning something worth while. He carried all the orders for the vegetable store in his handle-bar basket. Gloria saw his indecision and eagerly followed it.

“Go ahead, Tom. This is my own money—”

“Oh, I know that. You wouldn’t offer anyone else’s.”

“And I’ve just got it along with me. The folks who had our launch out just paid—”

“Wouldn’t that be your dad’s?”

“No. He owes it to me and said I was to collect it.”

“Of course, I know,” agreed Tom affably.

“But I can earn it—”

“If you don’t take it, Tom, perhaps you will never get another chance to refuse.”

“Why? Going up in the air?”

“No, not up in the air—but perhaps,” Gloria’s face suddenly became a mysterious casket of secrets, “I’ve got a big thing to tell you.”

Tom looked at his companion eagerly. It was as if his boyish sense of alarm had sounded a gong some place around his indefinite heart. “Going away?” he asked very slowly.

“It’s more than that.” Girls love to tease boys. “But I won’t tell you one word now. Are you going to take this money?”

She was holding out her brown hand; on its palm rested two green bills.

Tom set his basket down and looked very serious. He kicked his sneakers into the soft earth, he swung his uninjured arm like a pendulum, he opened and closed his lips a number of times. Then he put out his hand and took the money over.

Just as any boy or girl, or any boy and girl, could deceive a mother about a thing like that! Tom Whitely was painted up like an Indian before he even had his supper, and not satisfied with the iodine and arnica in the house, Mrs. Whitely had asked Pete Duncan to get more from the drug store when he went in to the post-office for the evening mail.

“Tommy-lad, you’re too reckless altogether,” she scolded affectionately. The bandage on the bruised arm was patted gently but fondly, and then the sleeve was slipped over it without so much as brushing the lint.

“’Tisn’t anything, mother,” protested the boy repeatedly.

“Too reckless and anxious for the dollar. Why, son, you don’t have to do all the supporting, you know. Mother is able and quite popular yet with them who didn’t have the chance she had to learn how to sew.” Mrs. Whitely was shaking her brown head with a show of pardonable pride, and anyone could have seen by the shadows that made her blue eyes look gray, just whom Tommy looked like.

“That’s all right, ma, but Summer’s the time, you know,” argued the boy. There was a favorite supper simmering on the stove, its appetizing odor provoking Tommy to impatience.

“And old Sam Powers was here a while ago. Didn’t say what he wanted, but from the way he worked his handsome face,” she chuckled, “it must have been something mighty important.”

“I’ll have to go up—”

“Now, we’ll just see about that, Tommy-lad,” interrupted the well-meaning little mother. How could she know Tommy was anxious to go out and see about that bicycle chain? She couldn’t and he didn’t want her to.

“But there might be a special letter for me to deliver,” argued Tom, slyly.

“There’s more boys than one in Barbend, and besides, you haven’t your wheel.”

“My basket was so full of the lilies—”

“Yes, I know, and it shakes them to a frazzle, the little beauties.” She glanced at the tub which made a nest for the lilies. The fragrant blooms now closing their waxy petals looked so cool, comfortable and happy there, it was easy to see that no root had been cruelly dislodged in their gathering, and to understand that a pond lily can make a home anywhere in water.

As always happens when one tries to tell part of the truth, Tom’s story to his mother, that the slight injuries and serious number of scratches had resulted from a toss into a clump of briar bushes, wove a web of complications which only entangled him more as he tried to escape from it. Sam Powers, the man who ran the general store and helped out Postmaster Johnston by supplying the special delivery boy, would not have called at the Whitely home for anything trifling. Even Tom’s mother suspected trouble and perhaps that was one reason why she tried to keep her son home just now. He was young, and to her, very tender; the only child she had, and he constituted her entire family and likewise the object of her entire heroic devotion. As Tom had told Gloria “she fussed a lot”—but even fussing did not always keep Tommy-lad at the end of her neat apron strings. So, with supper over, the table cleared and his mother installed on the side porch where no vines obscured the late twilight as she read the weekly paper, Tom was slipping off, slowly but surely village-ward.

At the creek he met Sidney Brown, a boy who “dressed up” and wore a hat week days.

“Hey, Tom! Sam’s looking for you,” called out Sidney.

“I’m going there,” answered Tom sharply, his wonder increasing. Why had Sam scattered the news? Couldn’t he wait until Tom had his supper down?

Up at the village, the little triangle composed of a group of stores and including the post-office, Tom found things still closed up for supper. Sam Powers’ store was locked, just a little girl was “minding” the grocery store next door, but there was no sign of life around the post-office. Only the bicycle repair shop showed any activity, and that consisted in Abe Nash, the proprietor, spilling some rubbish into a broken soap box at the side door.

Tom hurried over. “Hello, Abner!” he called. “Got that bike fixed yet?”

The man in the oily duster looked over his specks. Then he kicked the splintered side of the unfortunate soap box. “Fixed!” he repeated, sending the word out with a hiss from the corner of his mouth. “What do you think this is?”

“Oh, I was down to Sam’s and I thought I’d just ask,” put in Tom humbly.

“Did-ju see Sam?”

“No. He’s not around.”

“Well, y’u better wait. He’s a-huntin’ fer y’u.”

“What for? What does he want?” demanded Tom.

Abner Nash stuck his hands deep into the duster pockets. “Somethin’ lost, I guess,” he muttered.

“Oh,” said Tom. He was holding the two green bills Gloria had given him, very tightly in his hand and his hand was in his pocket.

“When do y’u want the wheel?” asked Abner.

“Quick as I can get it.”

“How y’u goin’ to pay for it? Three dollars for that new chain.”

“Oh, I’ve got the money right now,” said Tom, innocently producing the bills.

“You have, eh! Humph! Well, you’re pretty smart. Sell all them lilies since you picked them?” Tom’s shadowy eyes glared. He saw now what Abe Nash meant.

“No, I didn’t,” he retorted. “But I’ve got the money to pay for that wheel when it’s ready.”

“So I see.” The man turned toward the patched netting door. “Well, it’ll be ready by tomorrow noon.”

Tom looked attentively at the money that he had smoothed out on his hand. Then glancing up, he felt a breath almost over his shoulder.

It was Sam Powers!

“Where’d you get that money?” The man’s voice was full of threats.

“Where did I get it?” gasped Tom. “What’s that to you?”

A big hand was settling heavily upon his shoulder.

Indignantly he drew back and confronted the man who was attempting to seize him. Tom wanted to “haul off” but instinctively he dropped his hands and relieved his emotion with full, long, audible breaths.

For a few moments neither spoke. Powers was not usually a bully, and even now something like a smile played around his square mouth.

“Come over here and talk it over, Tommy,” he said. “No need to get excited.”

Boyish indignation choked Tom’s reply. Why do grown folks always accuse children first and investigate later?

Tom finally spoke: “What’s all this about, anyway?”

“It’s about Mrs. Trivett’s money.”

“I don’t know anything about her money.”

“Now wait a minute, Tommy. Wait a minute.” Each word was separated with a provoking sing-song drawl. It mocked every instinct of justice surging over the boy. “You see—well, you know what old Nancy Trivett is—”

“Sure I do,” retorted Tom.

“Now, don’t get excited, son.” He had unlocked the store door and Tom, helpless to do otherwise, followed him inside. “She came in here this mornin’ jest after we packed the first orders. Yes, it was jest after that because—”

“Say, Sam,” interrupted Tom. “I’ve got to get back home. Can’t you hurry some?”

“I could, but I was jest tryin’ to be polite—”

“Don’t bother to be,” growled Tom.

“All right, son,” Sam continued. “We’ll jest cut out the po-lightness and get down to hard tacks. Where’d y’u get that money?”

“Well, I didn’t get it around here—”

“Now, I’m not accusin’ you, Tom.” Again the square smile. “But you see, this ain’t pay day and three dollars—”

“Can’t anybody in Barbend have three dollars ’cept old Nancy Trivett!”

“Not at the same identical time—’cordin’ to Nancy.” The chuckle that followed this was drowned in a noisy shuffle of Tom’s impatient feet.

“I tell you, Sam, I don’t know anything about Trivett’s money. This is mine.”

“But where’d y’u get it?”

“I got it to pay for my bike—it’s broken.”

“Oh, I know it’s broken. Good thing your neck ain’t broke with it. Nancy saw you roll under the car wheels—”

“Is that what gave her a fit? Thought she saw me go under the wheels?”

“No, Tom. No, Tom—son—” a kindness crept into old Sam’s voice, “even her best friend would not be good-natured enough to say she thought she saw you. The fact is—well, you know Nancy.”

It was growing dark. Tom would have hurried off and left Sam to his drawl but he knew better. That would simply have been to invite Sam to go up to Tom’s mother with the same drawl and more mischievous insinuations. So, he said:

“I can’t just tell you exactly where I got this money, Sam, but did you ever find me short a cent?”

“Not a red.”

“Then why do you suspect me?”

“I don’t.”

“All right. That settles it. I’ve got to get home.”

“But you know old Abe Nash. He said you was goin’ to get your wheel fixed and he said, right to Nancy, that you didn’t have any money to pay for it. And now you go and show him a roll.”

“How’d she lose her old money?”

“Says she left it on the basket of tomatoes. You took them over.”

“Yes, and there was no more money on them than there was diamonds.” Tom could be sarcastic. He kicked a peach basket viciously.

“Now I’ll tell you, son. Your best game is to give that money back to your maw—”

“I didn’t get it from mother.”

“You didn’t?” there was just a hint of suspicion in Sam’s voice now.

“No.”

“Weil, if you borrowed it from anyone else—give it back.”

“All right, Sam, guess I will.”

“And let the old Skin-flint Abe wait for his money.”

“Ye-ah.”

“But how about the orders?”

“That’s it. I need the darn wheel.”

Both stopped and fell into deep consideration. It all seemed so simple a matter, but to country folks these simple things are momentous.

“If you was to tell me who you got that from, I might see my way clear to advance you the money on next week’s pay,” suggested Sam, with marked caution.

“I can’t tell you, Sam. I promised not to.” Tom’s blue eyes now went gray as his mother’s. He declined Sam’s confidence reluctantly.

“Well, that’s the best I can do,” said Sam. “But take my advice and put a crick in old Abe Nash’s sour tongue before he meets up with Nancy.”

“All right,” said Tom. And on the way home he wondered how he would manage to put that crick in, wisely and effectively.

When Gloria left Tom, after pressing her three dollars upon him, she met her chum Mildred Graham. Millie had been out in a canoe with the girl visiting old Mrs. Jenkins, and like Mrs. Jenkins, her visitor Katherine Bruen, was a most likable person. She had all the city ways and city graces, she dressed stylishly and looked well in the clothes, in fact the girls whom she had met at Barbend considered Kathy quite the most attractive visitor they had been privileged to entertain in a number of summers. Her light brown hair was bobbed, as so many other heads of hair were that year, and she had blue eyes with heavy lashes, rather too heavy to look real, she was plump and wore dresses that seemed to have been poured upon her—they were so slick and plain. Alongside of her, Millie, who was really quite up-to-date, looked rather quaint in her ginghams and flowered voiles.

“We were looking for you,” Millie told Gloria when the two fell together walking the remainder of the way to their cottages.

“Oh, I’ve been working for dad,” smiled Gloria. “The pleasantest sort of work—collecting launch dues,” she explained.

“We had a wonderful sail. Won’t we miss Katherine? She goes in two more days,” sighed Millie.

“Yes, we will; I think Kathy is a splendid girl. But, Millie, vacation is almost over for all of us,” Gloria reminded her chum.

“I wonder who will be the new teacher and what she will be like?”

“Perhaps I won’t be here to find out,” said Gloria wistfully. She was purposely mysterious.

“Going away, Glo?”

“Perhaps.”

“Where?”

“I may go to boarding school.”

“Oh, how lovely!”

“It isn’t quite settled yet, and, Millie, you know, I’ve told you the very first.”

Millie looked slyly out of her hazel eyes. “Before Tom?” she asked archly.

“Yes. Before Tom.”

“Oh, I know, Glo,” and she squeezed the arm next her. “But I love to tease. Tom and you are such a jolly pair.”

“If I go I shall surely miss you both,” said Gloria, with a solemnity quite new and not exactly natural.

“As if we won’t miss you!” Millie’s tone was equally dramatic.

“Well, Millie, you know how long I have hoped for the chance and I am not perfectly positive it has arrived now. But my Aunt Lottie always promised to educate both me and my cousin Hazel. She, Aunt Lottie, was an invalid, you know, and was afraid to part with any of her money while she lived lest some turn in her ailment might mean very big expenditures. She was lovely, poor little Aunt Lottie!”

The affection and sympathy in Gloria’s voice filled the space of several moments as they walked. The red roof of Gloria’s low house could be seen through the trees in the settling twilight, and the late summer flowers were doing their fragrant best to sweeten the air, while frogs croaked, birds whimpered and every living hidden thing poured out its soul in vesper greeting.

“Your Aunt Lottie died last month, didn’t she?” finally asked Millie.

“Yes, and Hazel’s mother, Aunt Harriet, is settling her affairs. You see, she lived with them.”

“Is Hazel to go to school with you?”

“I’m afraid not. They built a new house and Aunt Lottie gave Hazel’s share to them for that. But dad would never touch mine. You know how he works with this house. He just painted it all himself and, you know, Millie,” Gloria’s voice was affectionate, “you know, dad never did heavy work. He has always hoped to follow his calling, but I have held him here. Now, Millie, I am telling more than I planned, but I know I can depend upon you to keep it secret.”

“Of course you can, Gloria. But I just hope you won’t go.”

“Don’t you want me to grow up stylish, like Kathy?” teased Gloria.

“I don’t want you to go away, and I don’t want you to grow up like anyone but Gloria Doane,” said Mildred fondly. “Now, I’ll have to run. I promised Joe to help weed his garden and I’ve been out all afternoon. So-long, Glo! See you tomorrow.”

“So-long, Millie,” waved Gloria, for her chum was running off with her feet in one direction and her eyes in the other. Now she was looking back at Gloria Doane as she stood for a few moments under the big cedar tree.

Did Gloria want to leave all this? How peaceful and sweet it seemed now! But no idle dreamer was Gloria. With the first temptation to feel sorry for herself she called up the picture of her dad, Edward Doane, working at a bookkeeper’s desk and dreaming of the great adventure. The young man made serious through sudden hardship—the loss of a lovely wife and the care of a darling daughter. This last would not have meant hardship, if only things had been different in Barbend. But here he had come in quest of the hoped-for health of an ailing wife. Here he had set up his humble home, and here he had still remained for Gloria’s sake.

The girl and her dad were inseparable when he could be at home. He taught her more than she had learned from books, and the best of his gifts was a determination to overcome obstacles. When other girls of her age were suffering from the well meant shelter and warning of the home circle, Gloria was absorbing the lessons of courage and determination. And now she was soon to see results. Her dad was going to have his chance. He was to be free from the care of a rather fractious daughter; he was to be unchained from the cottage that always needed a shingle or a daub of paint; he was to go on the trip that would pay its own way and take care of the explorer, while Gloria would be safely imprisoned in a boarding school. She thought of it that way. No love of culture nor hope of new adventure, even such as she had so long and so often read about, presented to her anything like a glowing picture of boarding school life. Kathy Bruen had done something to color up the prospect, but then there was Millie, and Tom, and even her faithful housekeeper and care-taker, Jane Morgan. Jane loved her and she was so faithful! Ever since Gloria could remember it had been Jane.

Jane’s gray head made a second post at the gate just now. Gloria hurried on to answer the unspoken call to supper. Her father would not be home; he only came up the river twice a week in busy season and this was not his night.

“There’s a letter for you, dear,” said Jane, with a smile that betrayed the possibility of good news.

“From Aunt Harriet?”

“Postmark’s Sandford, so I guess it must be,” said Jane, winding an arm around Gloria’s waist as they both moved to the door.

“I’m getting so excited now I can hardly wait,” said Gloria.

Jane threw her head up and turned away slightly, but not too secretly to betray a sigh of regret.

“Of course I hate to leave you, Nanty,” said Gloria, using her pet name coined to be as near “aunty” as no such relationship might imply. “But then—it won’t be for long.”

“I know, Glory. It is going to be just beautiful for you and your dad. As far as I am concerned, I might as well confess, I am aching to get out to sister Mary’s and have a close look at all the children she is constantly sending pictures of. Can’t tell whether they’re white or black, big or little, and as for knowing or guessing which is good or which is a rascal—” Jane stopped as if that were indeed too much even to guess at from the serial snap-shots sister Mary Murdock, of Logan Center, kept sending.

All during supper the two talked of the great prospects ahead, but for once Gloria did not read aloud her letter from Aunt Harriet. She had, however, read it over twice up in her room just before coming down to the table, and what she suspected the veiled references therein might mean, had by no means a pleasant outlook. Aunt Harriet wanted to know if Gloria could go out to her home in Sandford to talk over a matter without her father’s knowledge. She also asked Gloria not to make any new plans until she had talked things over, “because,” the letter stated, “there is something we must consider very seriously, and,” said Aunt Harriet, “I hated to tell you about it before, so I just kept putting it off.” Now that was like Aunt Harriet. She was plainly taking refuge in a foolish excuse, nevertheless that there was really something serious to be considered Gloria had not the slightest, not even the feeblest doubt. She wished she had. The hint was very dark and all black around the edges. Of course, being secret she would not consult the ever faithful Nanty, but without her dad and without her caretaker’s confidence just now, the burden seemed rather heavy. And just when everything was so thrilling! So promising! It couldn’t be that something would prevent her going to boarding school after all her plans were made? And after her father was all ready to take the commission to go abroad on his long hoped-for enterprise?

“Let’s go down to the post office,” suggested Gloria suddenly, with a determined attempt to throw off the impending gloom. “It’s wonderful out, Nanty, and I suppose you have been poking over that hot stove all afternoon.”

Jane agreed. It was a wonderful evening and she always enjoyed a quiet walk after tea, with Gloria.

“Don’t let’s do anything until we get back,” said the girl who was already slipping on a bright red sweater. “We can work after dark but we can’t see the sunset then.”

So it happened they met Tom Whitely coming toward their cottage. He was slicked up as he always was for evening, his very brown hair bubbling up in little curls in spite of all his troubles with it, and his fresh blue blouse showing his brown neck to advantage. The blue garment was sold as a blouse, his mother called it a waist, but Tom insisted that kind were shirts. He scorned anything else.

Seeing Jane, Tom wondered how he was going to get a word alone with Gloria. All three walked amiably along through the locust grove, but Tom did not appear to get much vim into his answers, and made no attempt at anything so positive as a question. He was very glum.

Finally, at Mrs. Mayhew’s, Jane stopped. “Suppose you two go on,” she said, “and I’ll stop and talk to Clara. There she’s alone on the porch, and I want to ask her something about apple jelly.”

This gave Tom his chance.

“Gloria,” he began directly, tugging at her arm and glancing anxiously about, “Gloria, please take this money back.”

“Why! Tom!”

“I’ll tell you all about it when I get a chance.” He was pressing the bills into her surprised hand.

“I just couldn’t keep it. I—” he faltered so miserably that Gloria almost laughed at his discomfiture.

“Is it haunted, Tom?” she teased. “Or is it poisoned?”

“Oh, I got into a row—”

Gloria rippled a laugh that frightened off a little pee-wee. “What ever do you mean, Tom? You got into a—row!”

“Say, Glo,” the boy interrupted, finding her sweater pocket and hurriedly crushing into it the two bills, a two and a one, all folded up into a tiny square. “Listen. Old Nancy Trivett says she lost three dollars in our store this morning, and Sam tipped me off not to give this to Abe Nash—”

“Oh, I see,” said Gloria mercifully. “They are just mean enough to think a thing like that.” She drew her mouth into a line that bulged at the corners. “I don’t know which is the meanest, Abe or Nancy, but they’re a pretty mean pair. I just wonder, Tom, why such folks always love to suspect us. They can’t find enough of fault without making it up.” Indignation was sending the girl’s voice first up and then down until she seemed to be taking a breathing exercise. “I’d just like to fight it out with them for once. Why don’t you do it, Tom?” she asked, excitedly.

“On account of mother. She just hates rows and can’t even stand it when I scrap with the fellows,” said Tom. “But gosh! I was thunderstruck!”

“She didn’t say you took her mouldy old greenbacks!” exclaimed Gloria. “I’ll bet they were mouldy too, just from her squeezing them, hating to part with the precious horde!”

They had walked along slowly but were now almost in the village. Persons were coming along, eagerly scanning such pieces of mail as make up the evening delivery; post card and advertisements composing the best part of it, judging from the stray bits of paper carelessly discarded and sent fluttering about the street.

Emerging from the River Road, Gloria and Tom faced Main Street.

“Gee whiz!” exclaimed Tom. “If there ain’t old Nance! Just let me duck!” and before Gloria could answer, the boy turned a corner and disappeared. But Nancy Trivett came straight for Gloria—head on!

“Where’d that young rowdy go?” demanded the irate woman, her voice as sharp as her unpleasant features.

Gloria did not deign to answer her. She attempted to pass on with her head higher than felt comfortable.

“I saw him!” continued the woman. “And I’ll get him too. He needn’t think he’s goin’ to get away with my hard earned money—”

“Mrs. Trivett, what are you talking about?” asked Gloria angrily. “Do you mean to say you think Tom Whitely took your money?”

“Oh, no; of course he didn’t take it. He just found it—”

“He did not.” If Gloria shrieked this reply she had righteous indignation on her side. “Tom didn’t find a cent.”

“Abe Nash saw him have three dollars!”

The tirade had attracted so much attention that a small crowd was gathering. Anything for excitement in Barbend, but a clash between Nancy Trivett and Gloria Doane was particularly promising. Realizing her conspicuous position, but at the same time summoning her usual clearheaded courage to combat it, Gloria was secretly glad that Tommy escaped. He would never have been able to answer Nancy, and the crowd would be apt to jeer at a boy, at any boy against the spectacular Nancy. Just now she did look too funny! She wore the same hat she always appeared in, a black sailor, or one that had once been black, and this was festooned and decorated with feathers, flowers and ribbons, or bits of stuff that represented such decorations. Her dress was equally a mixture of useless odds and ends, all piled on, or plastered on at intervals from the neck to the jagged hem. It looked black but it should have been brown—that is the alpaca that composed the foundation for all the trimmings. But queerest of all was Nancy’s own personality. She had red hair that “changeth not,” and eyes of no less permanency. They were a sort of hazel, and her complexion was not bad at all where it got a chance to show itself, but the strong sun and the rough weather do things to the complexion that goes with sandy hair and hazel eyes, and they did it unmercifully to Nancy’s.

But her chiefest and most conspicuous feature was her hand bag. She carried it everywhere and never seemed to be without it. The bag was once brown leather but again time had collected its toll, and the bag looked now like something the rummage sale couldn’t get rid of. It was large enough to carry a half dozen of eggs which Nancy often traded with the dealers for other commodities, and it was flat enough to go in her basket, and had a clasp! It was that clasp that fascinated Nancy.

All these details were as familiar to the Barbend folks as was Nancy herself, but while introducing her in her oddities, it is best to take a good look.

Gloria now confronted the woman with something of a scornful smile on her lips. She was so glad that Tommy did not have to answer that foolish accusation! Being a normal girl with a sense of justice ever ready to assert itself, she felt at first very much inclined to tell the old-young lady just what she thought of her, but the small crowd just emerging from the post office were too plainly eager for a lark. Gloria was not quite good natured enough to satisfy them.

All this time Nancy kept talking. What she said did not matter in the least, her voice was so strident it supplied what her words might have lacked in the way of force.

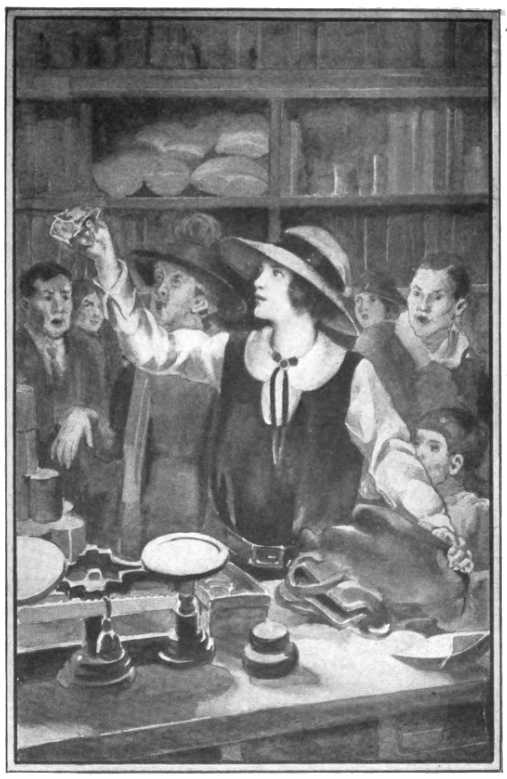

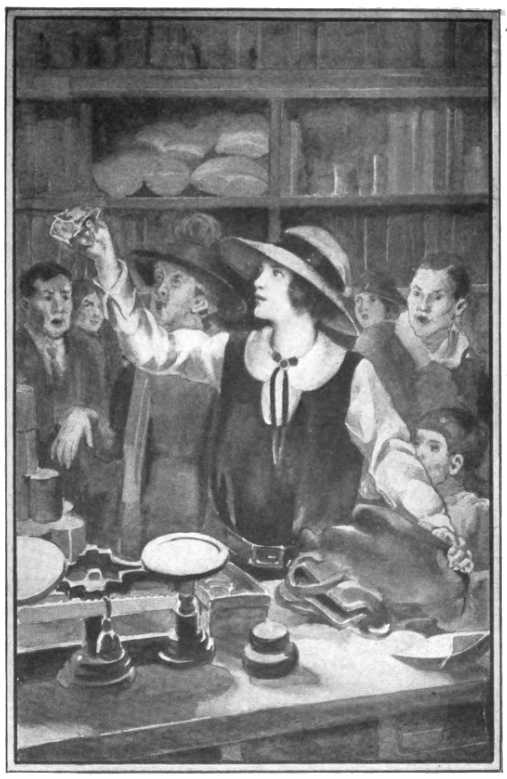

“Say, Mrs. Trivett,” said Gloria after a long wait filled with the other’s cackling, “when and where did you lose that money?”

“Haven’t I told you? I laid it right down on the basket of tomatoes—”

“Come on over to Sam’s,” suggested Gloria.

“It might be stuck around—”

“Haven’t I looked everywheres? Do you suppose I would go all day without that money that I had set aside for the fire insurance, if it was in Sam’s store?”

Nevertheless, she followed Gloria. Only a dim light fell from a center lamp around the dingy place, but the baskets of vegetables were easily shifted. Gloria went to work with a will. Sam looked on indifferently, all he asked was that his stuff be handled carefully. But the money did not come to light.

“What did you carry it in?” asked Gloria, as the next step in her systematic investigation.

“Why, in my bag, of course,” replied Nancy, indignant that such a question should be put to her.

“Let’s see it?” asked Gloria.

“Oh, see here!” and Nancy’s indignation mounted. “Do you suppose I’m such a fool—”

“Never mind about that, Nancy,” said Gloria evenly. “But just remember you have accused a boy of having that money. At least make sure you have searched thoroughly for it.”

This argument was unanswerable, and Nancy opened the bag with the trick catch. She fumbled through a miscellaneous collection of articles and then looked up sharply.

“But just let me have a look,” asked Gloria.

Reluctantly the bag was handed over. Gloria simply dumped the articles out into an empty berry basket, and with the refuse out of the way proceeded to look into the corners of the old hand Satchel.

“You don’t need to look—” interrupted the impatient woman. But Gloria kept right on looking.

Presently she felt a lump between the torn lining and the leather covering, and before Mrs. Nancy Trivett could offer any more protests Gloria held out to her the two crumpled bills.

“There you are,” said Gloria simply, turning away without so much as noticing the other’s gasping astonishment. She left her to return the trash to her bag and also to “fight it out with Sam.”

Those faithful few who had “stuck around to see the finish” gloated over Gloria’s triumph, but she did not so much as deign to answer Fred Ayres’ question, who was really polite enough in putting it.

He just wanted to know where was Tommy Whitely.

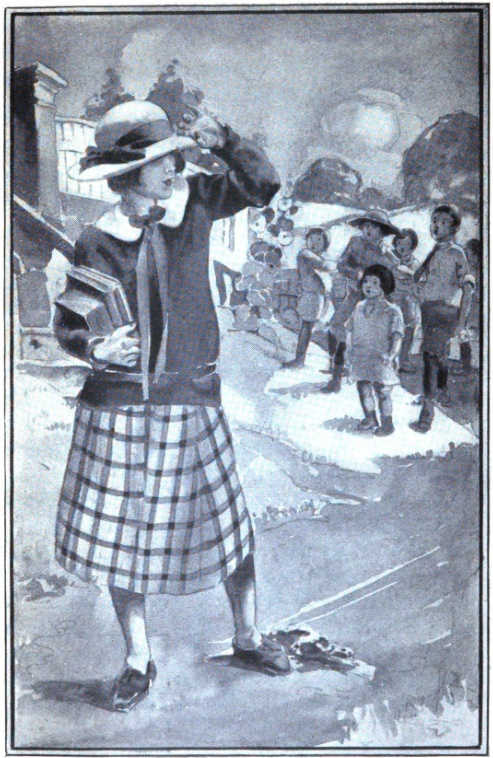

The incident settled, Gloria had much more important matters to concern herself with. She might have a second letter from Aunt Harriet. The post office would close in five minutes and there was no time to lose in crossing the dusty street.

And there she found the second letter in her box. With it were cards and a letter from her dad. She had just time to put the Aunt Harriet letter in her blouse when Jane appeared with others to mail for Mrs. Mayhew.

The flame of indignation lighted in Gloria’s cheeks by Nancy Trivett, was now smoldering to a shadow of anxiety. It was never easy to understand the doings of Aunt Harriet. Gloria was so abstracted on the way home that gentle Jane decided she was sorry to leave Barbend. But the anxiety threatening came from a deeper source than mere girlish sentiment.

The trip out to Sandford in the open trolley was bound to be either very pleasant or horrid. Today it was horrid, for a light drizzle floated in, not heavy enough to demand that curtains be lowered and not light enough to be just damp. Gloria was going out to her Aunt Harriet’s in response to the mysterious summons given in last night’s letter.

There seemed to be many things mysterious lately about her aunt, but Gloria was determined that no unforeseen circumstance should come between her and her father’s commission to the foreign port. From a small beginning Edward Doane had quickly made his worth known to the big firm he was employed by, and now the chance long hoped for had come, right alongside of the opportunity to accept it.

Gloria’s education was to be assured, and with it that special care expected from such circumstances as a first class boarding school afforded. Because of the pronounced peculiarities of Gloria’s Aunt Harriet, her father had not interfered with any matters concerning his wife’s relatives, and even the loved Aunt Lottie had been very gently refused when she had asked him to act as one of the two executors of her estate.

Gloria did not know of the request. She only knew that her Aunt Harriet and some strange man had been put in charge, and she was too delicately sensitive about the whole situation to ask any direct questions.

There had been unexpected delays about the settlement, but these Gloria condoned with the assurance to her father that with Aunt Harriet and Hazel everything would be all right, and so she insisted he was to finish up all his business and leave the details of hers to those just mentioned.

The few passengers on the jerky trolley were taking their leave of each other as the trip to Sandford lengthened, but Gloria had to ride to the Green, then transfer to Oakley. The misty rain was collecting stringy little drops when she alighted behind a rattling old farm wagon, and when it passed and she emerged from her hiding place, she almost ran into the arms of a girl crossing toward her.

“Oh, hello, Gloria!” greeted the girl with the wonderful smile. “Whatever are you doing out here?”

“Hello, Trix,” called back Gloria, succumbing to the ready grasp of her friend’s hand upon her arm. “I’m bound for Aunt Harriet’s—”

“Oh, of course,” interrupted Trix Travers. “Thought maybe you were out for the postponed tennis match. It isn’t. Did you ever see such a mean day?”

The two were upon the sidewalk now, Trix affably abandoning her evident way to the north while she traveled south with Gloria. She was older than Gloria but had that encompassing way about her that always swept folks off their feet and into her graces. Even the tennis racket under her arm had no cause to complain that it was being disappointed in a possible victory, for Trixy held it fondly and found no fault herself. The girls chatted as they walked, Trixy told Gloria of her cousin Hazel’s try “in the tournament” and hinted of her ambitions to make the team at “her school,” but Gloria was prudently impersonal, and only said how fine tennis was, and how she wished the girls at Barbend would get up a club.

“You babes,” teased Trixy, “better be playing bean-bag. It’s safer.” Her sally was a compliment, the smile and tone completely belying her words.

Presently a little roadster swung up to the curb and a young man, after greeting Trixy, asked if he could not give them a lift. It was while driving out to Oakland that Gloria tried to vision herself in these new surroundings permanently. The town was so unlike Barbend—a newly built place with everything glowing and shining and threatening to break out over night in further improvements. There was a hum and a din, but no moan of the water bending over the bar, and no call of the kingfishers’ tallying their catches from the lake or river.

And how would Tommy compare with this artless Hal Caldwell? Of course Hal was older, but would Tommy ever get to be like that? The capable little car buzzed along. Trixy chatted first into Gloria’s ear then over the wheel into Hal’s. Every one on the way bowed, smiled or called out pleasantly, and while the ride was only a short one it seemed to Gloria to typify life in Sandford.

They left her in front of her Aunt Harriet’s new cottage, and Trixy wanted Gloria to promise she would call her up on the ’phone before she left town. Trixy Travers was the sort of girl who makes friends as readily as she smiles, and who keeps them without any more apparent effort.

But whatever happened within the cottage between Gloria and her Aunt Harriet it seemed to take all the glow out of the girl’s face, and to put more gleam into her dark eyes. She did not wait to see Hazel later, instead, she walked away quickly, not even waiting for the little “jigger” that would have taken her to the regular trolley. Had Trixy Travers happened to meet her on the return trip, perhaps even her winning smile might not have been able to penetrate Gloria’s clouds.

The rain had stopped and it was late afternoon. A repressed sunset was apologizing for the other dismal outlines of a jaded world, but none of this diverted the young girl under the linen hat that shaded little wisps of curls making tendrils to border the pretty face. It was pretty even in its sadness.

Tommy happened to be at the square when her car rumbled in. She tried to avoid him but he waited for her, his own face aglow with some good news.

“I made it!” he exclaimed. “I made the extra three dollars.”

“Oh, that’s good.” Gloria jerked her mind back to the disabled bicycle and smiled.

“Yep, I ran the launch all afternoon and Pop Sargeant gave me the dollar he’s been owing me so long.”

“That’s fine,” said Gloria abstractedly.

“And what do you think?” went on Tommy. “Old lady Trivett made mother a present of a horse-shoe geranium, the kind ma always admired.”

“She never!” exclaimed Gloria.

“Sure did,” insisted Tom. “We were awfully surprised.”

“I should think you would be,” agreed Gloria. She and Tom were leaving the village behind them and wending their way homeward.

“I tell you, Tom,” mused Gloria. “I guess poor old Nancy felt sorry for being so—so hasty. You can’t always judge folks, can you?”

“No. Ma said she’d rather have that potted slip all ready for the winter, you know, than most anything else.”

“So, see what your wheel spill did after all.” Gloria laughed lightly—rather too lightly for Gloria. “That geranium’s what they call a conscience gift, I guess,” she continued. “You know how Walter Garrabrant sent a dollar to the trolley company last year?”

“Yes, but that seemed foolish,” replied Tom. “If he stole rides he didn’t use any extra power.”

“Tom Whitely! I’m ashamed of you!” declared Gloria. “Of course the trolley company can’t be robbed any more than other folks. I believe the very meanest feeling must be that of taking and keeping something belonging to someone else.” She shuddered so that Tom looked up queerly.

“What’s the matter, Glo? Did you have any trouble out to your aunt’s?”

“Why no. Of course not,” said Gloria quickly.

“How’s your cousin with the red hair?”

“Look out who you’re calling a red head, Tom Whitely,” charged Gloria, “I can’t see that your own head is exactly black.”

“’Tisn’t as carroty as hers,” retorted Tom. “Well, how is the girl with the golden locks? If you like that better.”

“I didn’t see Hazel,” replied Gloria indifferently. Then hurried to talk of something else. “Tom,” she said suddenly, “I guess I’ll have time to go over and see the peace offering. Jane doesn’t expect me till the six o’clock car.”

“And Mumsey will be glad to see you, Glo,” responded the boy, brightly. “She said this morning you were scarcer than hen’s teeth.”

“I don’t like to be compared with hen’s teeth, but since there isn’t any such thing perhaps I’ll forgive you. How’s all the bruises?”

“Turning green and mother says that’s the last stage. But no fooling, that old arm is stiff.” He demonstrated with a couple of easy exercises and even winced at those.

“Get the wheel?”

“I wouldn’t take it. The chain rattled like a flivver. There’s mother fetching in kindling. I thought I left enough for a week,” and before Gloria had time to reply Tom was off to relieve the mother of her kindling basket.

Amid praise and good wishes for Nancy Trivett the rose geranium was presently exhibited.

“You can’t always tell the difference between a wasp and a bee,” said Mrs. Whitely. “Both buzz a lot but only one poisons.”

“Well, Nancy is more the wasp—”

“Tommy-lad! You hush!” ordered the mother. “Nancy Trivett leads a lonely life—”

“Moth-er!” mocked Tom. “As if any one could be lonesome with those geese, chickens and—”

But the mother shooed the irrepressible Tom clear off the porch before he could further tell of Nancy Trivett’s diversions.

“I heard Sally Hinds say the new teachers were to board at Blains,” said Mrs. Whitely, while Toni remained at a safe distance.

“Yes?” said Gloria.

“What’s the matter, child? You don’t seem a bit like yourself,” remarked Mrs. Whitely, noting Gloria’s abstraction.

“I’m just tired,” replied the girl, avoiding those eyes so like Tom’s in their kind scrutiny. “And you see—I’m not going to Barbend school next term.”

Then in snatches and exclamations, the prospect of Gloria’s change of school, change of home life and change, perhaps, of acquaintance was talked of. But somehow Gloria could not respond to her friend’s sympathetic eagerness.

Tom went for Higgins’ cows while the way to the Doane’s cottage was traversed, but before they had reached the lane where Gloria should have parted with her companion, she suddenly jerked out a queer “S’long!” and raced off leaving Tom with his mouth open wider than his eyes.

This was a new Gloria.

Busy days followed. There was so much to do before Gloria should leave home and before her father should go on his extended trip, that it took the combined energies of Jane and Gloria, to say nothing of help offered by Millie, to get things into order for the important events.

But all preparations were halted when her dad came home, for he at once planned a picnic and ordered his daughter to gather her friends for the festivity.

As a father Edward Doane was disappointing to strangers. He was in no way old, did not have a visible gray hair, he was not fat, nor funny, did not wear glasses, and as a widower he failed utterly to mope and lament. Instead, he was an attractive young man who had more than once been taken for Gloria’s big brother. But in spite of their close companionship, Gloria was the most devoted daughter and the best little business partner one would hope to find in all Barbend. Their companionship was doubly dear, as the loss of her mother left Gloria so much to the care of her young father, and perhaps it was the similarity of dispositions that gave each so complete an understanding of the other.

When he was at home Gloria could do nothing but enjoy his company, and now even the temporary breaking up of her home did not debar her from this coveted pleasure.

Millie and Tom helped distribute the picnic invitations, Mr. Doane insisted that every one who could be piled into the Finnan-Laddie be asked, and when Saturday afternoon came it brought with it exquisite sunshine from a sapphire sky that belongs distinctly to the early autumn.

Jane-the-wonderful did up the lunch. She insisted it be carried in her second sized bread box, as that would surely be impervious to sunshine, engine heat and dampness. The lemon juice was stored in patent topped soda bottles, and because Tom insisted the boys should fetch something, he carried to the launch the most precious prize of all: a packed container of real store ice cream, and Jerry Mack carried the dozen cones to dish it into. Only Mr. Doane knew of this treat, as Tom and Jerry “made it up” and the other four boys chipped in.

When Millie checked up her list of guests it included besides herself and Gloria, Margie Trebold, Grace Ayres, Nettie Leonard and Blanche Richmond. On Tom’s list were besides Jerry and himself, Arthur Williams, George Alton, Ranny Blake, Ralph Dana and little Neddie Mack, Jerry’s irrepressible brother, who had to go or Terry would have had to stay away “to mind him.”

Mr. Doane ran the launch, of course, and on the way over to the cove the children sang, shouted, yelled and did everything that youngsters usually do when turned loose for a good time. Neddie required considerable cautioning about leaning over to trail his very small fingers through the waves left in the boat’s track, but Gloria loved him, she “adored his kinky curls,” and she didn’t mind in the least his irresponsible lolly-pop that now and then would brush her sleeve.

Tom crouched up front with the skipper, and not a turn of the engine but he checked up with a smile, if not with an outright grin. He loved this boat—it was the pride of the lake, and not often did the little ones get a chance to enjoy it. Mr. Doane was plainly very fond of the boys who paid him homage outright—no king on his throne could have received more flagrant tribute.

The girls naturally gave color to the party. They wore their brightest if not their newest, sweaters, and the prospect of romping in the woods suggested skirts not easily affected by brush or briar.

It was a wonderful sail. The lake was lined with jagged trees, and the deep green of cedars and hemlock sent the softest shadows along the water’s edge.

Tom had told Mr. Doane privately that the ice cream cones would have to be served at once or drank from cups, so that the usual planting of a stake to make their landing, was delayed until after the treat had been administered.

“Tom Whitely!” exclaimed Gloria when she beheld with surprise, Tom and his box of cream, and Jerry with the row of cones all set up in the long cover of a paste-board box so that the “dishing” might be exactly even. “However did you manage—”

“Eat, lady, eat,” cautioned Tom. “This isn’t any pie imitation, it’s the real thing. Hey, there, Ranny! hand these out. Jerry’s rack is a bit wobbly.”

“The best I ever tasted!” declared Millie, who ate cream in spite of her fear of fat. “You boys are just—just fine!” she insisted.

Gloria was seeing to it that Neddie got his cone. Her solicitude was really not necessary, Neddie being more apt to get more than his share than to be neglected, but her devotion to the small boy helped her to cover other emotions, and her companions, noticing her strange manner, naturally ascribed it to threatening homesickness.

“Mr. Doane,” called Grace Ayres, she with the lovely, long brown braids and two active dimples, “I think you should have two cones. You are the guest of honor.”

“Count ’em out first,” called back the man who was still doing something to the engine. “I like cones but I could get along with the regular allowance.”

Tom took personal care of this serving, stepping gingerly over the boat’s edge and offering the rather liquid little portion to Mr. Doane.

“Well, I’ll say this is a treat,” declared the boat’s captain, dropping the screw driver and taking his place on Gloria’s cushion—the one she always insisted he make himself comfortable on. Tom had his own cone in the other hand, and with a show of importance rather unlike Tom, he squatted down beside the captain.

“We’re awfully sorry Gloria’s going away,” he said quietly. “She and I’ve been chums ever since we lived in the quarry house.”

“Yes,” said Mr. Doane, “you have, Tom, and I know you will miss Gloria.” He paused with his cone half way to his lips. For a few moments neither spoke, then the father continued: “I hate to think of letting her go, but it was her mother’s wish that she be educated at that seminary. She just couldn’t go—before.”

“Oh, I know,” replied Tom. “It’s the best thing, of course, and it’ll do her a lot of good.” Tom’s words were meaningless to him but he felt he had to say something. As a matter of fact he had not the slightest idea what a boarding school was intended to do for its pupils. He had not even read a story with a boarding school girl mentioned in it. His stories were built upon sterner lines.

Clamoring for their leader, the children upon the shore would have presently re-embarked if Tom and Mr. Doane had not met their demands to “Come ashore.” Every one seemed to have a separate and individual plan for the afternoon’s enjoyment, but that which included a preliminary hike to the top of the hill was decided upon by a majority vote.

“Who’s going to watch the grub can?” asked Jerry Mack. He felt himself to be provision custodian. Didn’t Jane tell him not to let any one take the lid off that box until Gloria said so?

“That’ll be all right,” answered Ranny Blake, quite out of order.

“Nobody’s around here,” chimed in Neddie Mack, sending a searching eye up and down the beach.

“We’ll just cover things up and forget them,” suggested Mr. Doane. “When we come back we’ll be hungry enough to eat the screw driver.”

This brought forth a shout from the boys, but the girls were already starting up the hill in that precise, deliberate way girls have of doing things when boys are in the party.

But there was nothing self conscious about the followers of Mr. Doane. The boys looked up to him as if he were a veritable miracle man; they repeated his words, they openly jostled each other for the coveted place nearest him, and Jerry, being really quite a talker, received a jab from Tom’s bare elbow, at regular intervals.

“When I was a boy I lived in the city,” Mr. Doane would say. Whereat his listeners would know of so many others who “lived in the city” that the proposed story would flutter away on the wings of a hearty laugh.

“But there’s nothing like the great outdoors to give fellows muscle—”

“I’m goin’ to take boxin’ lessons,” put in Jerry eagerly, but the jeers and groans from his companions offered very slight encouragement for such an undertaking.

“I’ve got the gloves,” he declared. “An’ can’t a feller put on weight boxin’, Mr. Doane?”

“Skin—nay!” retorted Ranny Blake.

“You ought to get enough exercise around here without putting on the gloves, Jerry,” said Mr. Doane kindly. As a matter of fact any one would have suggested the rest cure to put flesh on the thinnest boy in the crowd.

But the mention of athletics uncorked the most popular topic for male consideration, and in spite of the great outdoors all around them—the greatest kind of a day and the most perfect piece of rural scenery all the way up the hill, even over the county landmark, a huge boulder that was painted white and shone for miles around—every step and mis-step of the way the boys talked of sports. Boxing, baseball, skating, football and every other line of amateur and professional activity was discussed fully and enthusiastically, Mr. Doane acting as referee and umpiring the “meet” and its distant prospects.

The girls were gathering wild asters, golden rod and sweet fern. They romped about now with little Neddie as an excuse, hiding from him, teasing him with Indian calls and animal imitations, although Neddie was only tolerating their excessive attention.

“Come on and be Peter Pan,” suggested Gloria while she and Millie “boosted” the small boy into a dogwood tree.

This gave the embarrassed youngster his chance. The tree was heavy enough to climb and climb it he did, never pausing until he reached a perfectly safe perch far from the reach of mere girls.

“You’ll fall!” shouted Gloria.

“That limb is bending!” warned Grace.

“Come down, Neddie, the boys are going snake hunting,” tempted Millie.

But Neddie hugged a branch and swung on his limb in such a reckless fashion that Margie suggested making a life net.

How could they know how much a boy hates to be fussed over? Gloria was enough fusser, but when the others all piled in he felt like the prize baby at the Cattle Show—the one that was weighed right before everybody.

Jerry was so glad to be free of the small brother he would not have cared if the climb went still higher, but when Mr. Doane held out his strong arms, down came the little Peter Pan ker-plunk! He had no intention of missing the snake hunt.

“Come along, girls,” called out Mr. Doane when the petulant Peter Pan had been once more disposed of. “If you don’t want to hunt snakes make it b’ars! Big black woolly ones, that old Sam Sykes is always insisting he used to chum with up in this baby mountain. Gloria, you know the worn trail, but don’t get out of speaking distance. We boys will head for the first slant, over toward the big tree, and if we don’t find snakes, or bears—”

“We’ll find deers,” shouted Jerry, ignoring the regular way of making the plural. “Nort Sloane saw a deer up here last week!”

“All right,” laughed Mr. Doane. “Snakes, b’ars or deer, all the same to the hunters. But don’t use sling-shots, now, boys,” as Ralph and George examined a suspicious bit of string. “Sling-shots are not safe in mixed company.”

So the hunt for wild animals began.

“Oh! Come here, quick!” yelled Ranny, in tones that made the others respond promptly.

“What is it?” demanded Tom.

“A wild animal!” shouted back Ranny.

“Whereabouts?” asked Jerry, the fearless.

“He’s—he’s behind that—rock!” panted Ranny, pointing to a huge boulder that in size almost matched the county landmark.

“Got—got anything—to get—him with?” gasped Arthur Williams, creeping up toward the path-finder Ranny, but managing to keep pretty well behind him.

“Don’t make any noise,” cautioned Ranny. “I saw him first near the spring, and when I whistled—! Sh-s-s-h!” came the sibilant warning. “I saw—him—move!”

Two or three steps over the crunching brush and the boys made a sudden plunge to get under cover—of anything. An object had moved! It sounded like a small animal and it moved in bounds and leaps. By this time the remainder of the hiking party realized something new was in prospect. Mr. Doane was with the girls, who had insisted upon obtaining some perilously perched wild columbine, while the remainder of the boys were scattered about near Moon Rock. But now there was a sudden change of base, and the squad presented battle formation at the trunk of the biggest and roundest tree.

There was no need for explanation. The secret signal that shouts danger, was bristling from the red hair of Tommy, and from the black curls of Neddie, and every little gasp of the others fairly echoed to the four ends of the earth, in the silent language of hikers.

“There he goes!” breathed Tom, as something went from the oak to the button-ball tree. But it did not fully come out into view, there was merely a flash of soft color seen to dart among the green.

“Yep! It’s a deer!” confirmed Ralph Dana, although he could not possibly have seen even the flash from his hiding place.

“Don’t make any noise! They’re awfully scared,” said Jerry, while his own cautious movements seemed to make more noise than the combined shifting of all the others.

“Let’s get sticks,” suggested George Alton.

“What for?” demanded the path-finder Ranny.

“To beat the brush down—”

“Think a deer would hide under brush?” came the derisive query of Tom.

“Naw, o’ course he wouldn’t,” scoffed Jerry. “They run like anything if you only—only shake a stick at them.”

“Sure. They’re the scariest animals they is,” said little Neddie, glad to be in the deer hunt in lieu of the snake chase.

“There he goes again!” called out Arthur Williams, now openly defying orders to keep quiet.

Something very nimble, indeed, leaped over a few more stones; but as before succeeded in hiding its real identity.

The boys stood breathless. This creature was surely a rare animal, and it came to the mind of more than one boy that it would be greatly to their credit if they could capture it single handed, without the aid of Mr. Doane.

“Who’s got the rope?” demanded Jerry, sending a scathing look over those companions within his range.

Hands went down into incompetent pockets, and into blouse depths but none fetched up a coil of rope suitable for lassoing.

“Of course, we didn’t bring any,” again growled Jerry.

“Of course not,” echoed Arthur Williams.

“I could lasso him just as easy—”

“Sure we could,” confirmed Tom.

“Sure!” went down the line till Neddie swallowed it.

“Well, we got to do something! Look! There he goes! The son-of-a-gun!” groaned Arthur.

“Into the cave!” gasped Ralph.

“Gone!” sighed Tom, except that the sigh was somewhat like a gasp.

Their concentration had attracted the attention of the columbine hunters, and now the girls, with Mr. Doane, came as quickly through the wood as the deep underbrush would allow.

Signs and wig-wags warned them not to speak, but of course Millie had to giggle. A “Sh-s-s-h!” from Tom brought Gloria up so suddenly that she all but fell headlong into a nest of briars.

“What—is it?” whispered Grace Ayres.

“Somethin’,” admitted Neddie, rebelling against the tight squeeze Ranny was holding him in with.

Mr. Doane somehow took in the situation without any explanation. Perhaps that was because he had been a boy not so very long before, and he could easily guess what hunters are apt to come upon in Turtle Cove Woods.

“He’s in there,” ventured Ranny, pointing to the hole in the rocks which had swallowed up the prize.

“Big?” asked Mr. Doane.

“You bet!” replied Tom. “He looks like a deer.”

“We’ll get him,” boasted the man with such a look of courage and determination that every boy was at once his slave with renewed, if unspoken, allegiance.

“A rope,” suggested Jerry crisply.

“You bet, old man,” agreed Mr. Doane. “We have one in the boat—”

“I’ll get it,” offered Arthur, but perhaps Tom thought of the lunch box, for he turned and ran along with the first messenger.

They had not yet reached the launch when a hail from Jerry brought them both to a standstill.

“Hey, wait!” he yelled, but they paid no heed to the order, for at any moment that animal might dash out of the cave and get away.

Tom climbed into the boat and Arthur followed.

“I saw the rope here—” began Tom, but Jerry was now climbing in and still saying something.

“A sandwich!” he finally managed to exclaim. “They want a sandwich.”

“I guess you won’t have any sandwich,” declared Tom, not in the most amiable tones.

“They want it!”

“What for?” demanded Arthur.

“For the deer,” replied the impatient Jerry.

“A sandwich—for—a deer!” gasped Tom, pausing with a cushion in one hand and a life preserver in the other.

“Sure,” snarled Jerry. “Did you think I wanted it for myself?”

“We didn’t know,” said Tom, “but no one gets anything out of that box—”

“Oh, hey!” snarled Jerry. “Can’t you see anything? Mr. Doane wants to bait the deer with it.” His tone was scornful enough to poison the very atmosphere.

“Well, I’ll get one,” finally condescended Tom. “Glo told me to get it,” insisted the annoyed Jerry, climbing over his two companions and making his way up to the big blanket that covered the bread box.

Both boys stopped in the rope hunt to watch him.

“Be careful,” ordered Tom. “They’re each wrapped in wax paper.”

“I know,” retorted Jerry, who now actually had hold of one of the precious sandwiches and was shutting the box.

“One’s enough,” said Arthur, foolishly.

“You don’t need to think I’m cribbin’.”

“Oh, come along,” called Tom, who had procured the rope and was scrambling out with it. “Think a wild deer is going to wait all day?” They didn’t, evidently, for Jerry held the sandwich in both hands and followed his companions up the hill, there to find the others still waiting anxiously, lined up like a guard of honor on each side of the cave.

More signs and wig-wagging, but few words were used in giving the directions necessary to lay the trap and bait it with one of Jane’s best corn beef sandwiches—it was in the lightest brown paper outside the inside wax paper, so that was sure to be corn beef.

Tom laid the rope in a ring just at the opening of the rocks as Mr. Doane directed, then Jerry very carefully placed the unwrapped sandwich right in the very center, and the two most important actors stepped back in line with the others.

They waited.

Mildred giggled.

Gloria almost choked.

“Your red sweater!” hissed Ranny. “They’re afraid of red.”

Mr. Doane agreed without saying so, but he looked so intelligently at Gloria that she crept back of him to hide her sweater and—her laugh.

“I see—him! Here he comes!” gasped little Neddie, and before any one could even say “So he does!” something sprang out from the rocks!

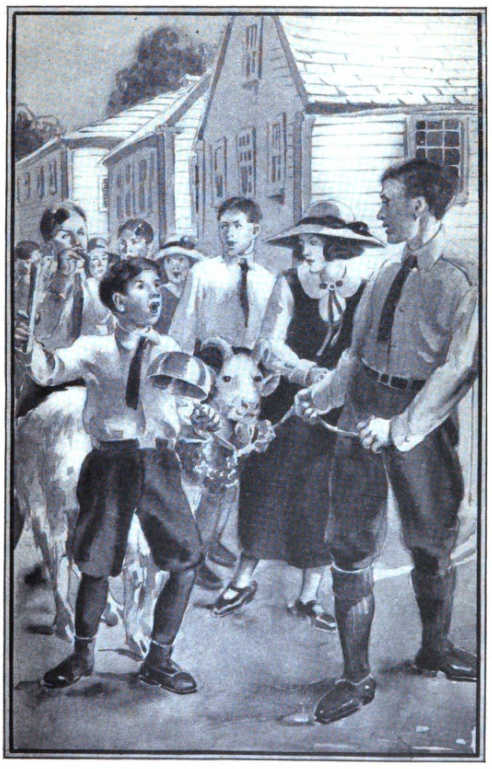

“Mrs. Higgins’ Nanny!”

This was announced by so many that it doesn’t really matter who is credited with the identification, for the pretty deer-like, faun-colored goat deliberately gulped down the corn beef sandwich, while Ranny pulled the rope and captured the “wild animal.”

“Poor Mrs. Higgins has been looking for Nanny for two whole days—” said Gloria ruefully.

“She’ll have her tonight,” replied Mr. Doane. “But go easy with the rope, Ranny, and let the poor creature finish up the paper.”

“They love it,” added Blanche without a trace of disappointment in her voice. What’s a deer or a goat to animal hunters? Besides, Mrs. Higgins sold the goat’s milk to a delicate old lady who believed it had health value—every one knew that.

“We’ll tie her to a tree and eat our lunch,” suggested Mr. Doane, and the way that order was carried out left no suspicion of poor health demanding goat’s milk among any of those present.

But Nanny wasn’t home yet, and it was quite a sail over the tranquil waters, back to Barbend.

Greatly as they enjoyed the feast, and what is greater than a feast on the shores of a lake on a perfect autumn evening—still, the thrill of adventure enshrouded that little goat.

Mr. Doane did not give orders. He was one of those charming men who would not interfere with children’s plans unless he felt obliged to do so through some safety measure, so now, as each planned and the other contradicted as to the best method of getting Nanny across the lake and back to her little shed among Mrs. Higgins’ lima bean poles, Mr. Doane just ate his sandwiches and drank his lemonade as any guest of honor should have done.

“Let me tell you! Hey, listen a minute!” begged Tom. He was copying Mr. Doane’s manner in a sort of aloofness until now. “I know a goat can swim—”

“But not so far,” interrupted Mr. Doane.

“Oh, well, maybe,” acceded Tom. “But anyway, we don’t have to take her in the launch—”

“I should say not!” cried out Gloria, while the other girls gathered in their scant skirts apprehensively.

“’Course you don’t have to take her in the launch,” echoed George Alton, who was the best “echoer” in the party, but never seemed able to send out an original suggestion.

“She could float,” lisped Neddie, trying to take care of his own sandwich, while he ate the one Ranny gave him.

They were too busy thinking to laugh. The goat must be brought back to Barbend, but how?

“A raft!” exclaimed Tom, who had considered and disregarded almost every other craft for the visiting goat.

“That’s it,” replied Mr. Doane, smiling broadly. “I was just waiting to see if any scout would think of that.”

“Sure, that’s it, a raft,” repeated Jerry quite as if he had been waiting to give out the information. “We can make it—easy.”

“How?” asked Ranny. He had not complete faith in Jerry’s ideas.

“We’ve got hammer and nails and that’s heaps more than scouts generally have to start with,” said Mr. Doane.

“It seems to me that this is pretty much a boys’ party,” remarked Gloria. She had sprinkled the flowers with lake water, and refused to let Neddie feed the goat any more of their sweet-flag root. After all, it did seem that boys knew best how to have a good time in the woods.

“Why, Gloria!—” her father exclaimed under his breath. “Haven’t you been having a good time?”

“Oh, of course, daddy, but the boys have climbed trees—”

“I thought I saw you up a tree—”

“Oh, that! That was only a little birch, and Mildred wanted a big branch to chew on,” replied Gloria. She was sunburned from the water’s sun and her hair was flying wildly about her head. Her red sweater “had whiskers on it,” as some one had remarked, for briars and brambles can pull a sweater pretty well apart. Still, she must have enjoyed herself, although there was that far-away look in her dark eyes, and often when the others were too busy to notice, she would gaze steadily at her father and seem to study anew his loved personality.

Now the girls took exception to her complaint of the afternoon’s pleasure, and each tried to outdo the other in declaring they had had simply a wonderful time.

Getting the raft made and putting the surprised goat upon it caused considerable excitement. But it was finally accomplished, and when the last knot was tied as gently as Tom could tie it, and the little animal lay helpless, her full faun-colored length upon the rough woods’ timber, Gloria said it reminded her of the Bible pictures of Abraham’s sacrifice.

“All aboard!” called out Mr. Doane. “I’ve promised to get you youngsters home before supper time, and just look at that sun!”

“Couldn’t I get a couple more white stones?” begged Neddie.

“You’ve got plenty of stones,” scoffed his brother Jerry. “And what won’t mother do to you for stuffin’ them in that good blouse?”

The trophies of the hunt were not as varied as usual, as Mrs. Higgins’ goat had taken up a lot of time, but then, it was a real find, and now as the launch started off, the boys were simply gasping with the excitement of “draggin’ home the prey.”

“We’ll go as smoothly as we can,” announced Mr. Doane, “for poor old Nanny won’t know exactly what to make of her sail.”

“But she isn’t kickin’,” declared Ranny. “I thought she’d kick like a steer.

“Why, Ranny Blake!” scoffed Mildred. “How could she kick with her feet tied?”

“I mean—wiggle them,” corrected Ranny.

“She does take it all right,” remarked Tom, who had given up his seat in the bow to keep a hand on the rope that trailed from the stern.

No hunters from the wilds ever returned with more precious spoils than Nanny constituted, as she lay quite contentedly upon her rugged raft. And in spite of Gloria’s comment, that the party had been mostly for boys, the girls were now as eager and enthusiastic over the capture as were their sterner companions.

Crossing the lake took but a few minutes—less than half an hour really, and once upon the home shore there was an exciting time deciding just who would bring to Mrs. Higgins her errant goat.

A wreath of wild flowers had been woven by the girls on the trip across, and this looked very festive indeed upon the neck of the prodigal.

Besides this, her reins were interwoven with sprays and sprigs of foliage, so that her return was marked with gaiety and glamor, when Neddie drummed on a tin pan and Arthur piped on a squeaky tin whistle, as the march towards home-quarters was finally under way.

“It isn’t far, let’s all go,” proposed Blanche when the escort was discussed, and there being no dissenting vote her plan was unanimously adopted.

Mr. Doane laughed heartily as his little guests started off. He was delighted that Gloria had made so many friends in her home town, and while he may have feared the effects of new surroundings upon his brave, if self-willed, daughter—he was too anxious to get away and make brighter prospects for her, to entertain doubts of the ultimate success of his plan.

The last of the marchers had turned the corner before he covered up the engine of the Finnan-Laddie, and a shout from some of the boys sent back a distant report of the triumphal advance.

Over on the back road the youngsters were leading Nanny. She took it all so indifferently. In fact, the fragrant wreath upon her neck and the nice cool leaves brushing her slender sides seemed to please, rather than to trouble, the queen goat.

Mrs. Higgins, fat and good-natured, was at the gate as they came up the lane.

“My land of the livin’! What’s that!” she exclaimed excitedly.

“Your goat,” yelled a chorus.

“We found her—”

“Nope, we hunted her—”

“Listen, Mrs. Higgins, we trapped her—”

“Oh say! Can’t you tell a story straight?

“Mrs. Higgins, we lassoed her—”

Each of the boys responsible for one of these outbursts now stood wondering why Mrs. Higgins did not respond. She had not taken a single step forward to welcome her retrieved goat.

“What’s the matter, Mrs. Higgins?” asked Gloria. “Aren’t you glad to get her back?” The jovial Irish face wrinkled into a smile of the one piece pattern. “I was always fond of old Nanny,” said the woman, “but I sold her to Tom Sykes and here you fetched her back—”

She broke into a laugh that began at her toes and surged over her generous form like a merry little earthquake.

“Oh!” sighed the children, crestfallen. Nanny bleated expectantly.

“We can never take her back,” began Gloria seriously. “It was some trouble, we’ll say, to get her over here.”

“Sure, you couldn’t take her back,” agreed Mrs. Higgins, advancing now to welcome the wayfarer. “And isn’t she pretty?” She patted the wreath and Nanny kissed her familiar hand.

“I’ll bet old Sykes starved you—”