Cover art

Title: Trail-Tales of Western Canada

Author: F. A. Robinson

Author of introduction, etc.: Ralph Connor

Release date: April 7, 2019 [eBook #59220]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

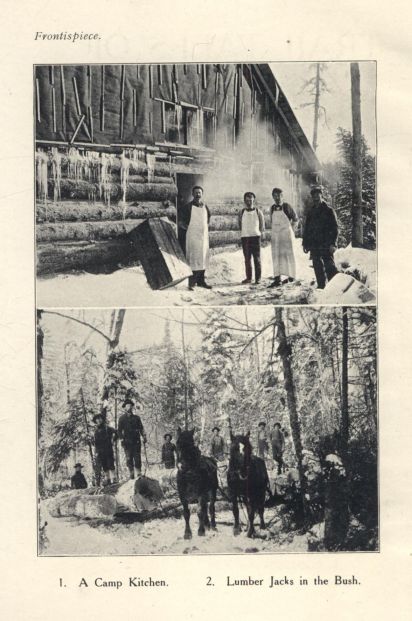

1. A Camp Kitchen. 2. Lumber Jacks in the Bush.

BY

F. A. ROBINSON, B.A.

MARSHALL BROTHERS, LTD.,

LONDON, EDINBURGH & NEW YORK

TO THE REVEREND ROBERT JOHNSTON, D.D.,

MINISTER OF THE AMERICAN PRESBYTERIAN

CHURCH, MONTREAL, AND TO FRIENDS IN

HIS CONGREGATION WHOSE UNFAILING

INTEREST AND KINDNESS HAVE FOR YEARS

BEEN AN INSPIRATION IN THE WRITER'S

LIFE-WORK.

This book has this virtue among others, that it is a true rescript of events that have happened in the author's personal experience. It is made up of human documents that deal with matters of surpassing interest. The book tells in simple and vivid style the story, always fascinating and thrilling, of the triumph of the Gospel in the souls of men. It is a heartening book and a moving. It will bring courage and hope to those who read it, and awaken in their hearts a deeper passion to share in God's great mission to men.

The new west is full of the broken driftwood of humanity, showing the marks of the attrition of time and conflict and defeat—good stuff it is, but waste and lost. This book tells of its salvage to the infinite joy of men, and to the glory of God.

The author has the further distinction of having seen himself a large part of the events he describes.

The book will do good wherever it goes.

CHARLES W. GORDON.

("Ralph Connor.")

WINNIPEG, CANADA.

October 5th, 1914.

CONTENTS

"Thy Touch has still its Ancient Power"

The Regeneration of Bill Sanders

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

FRONTISPIECE.

A camp kitchen. Lower half, Lumber Jacks in the Bush.

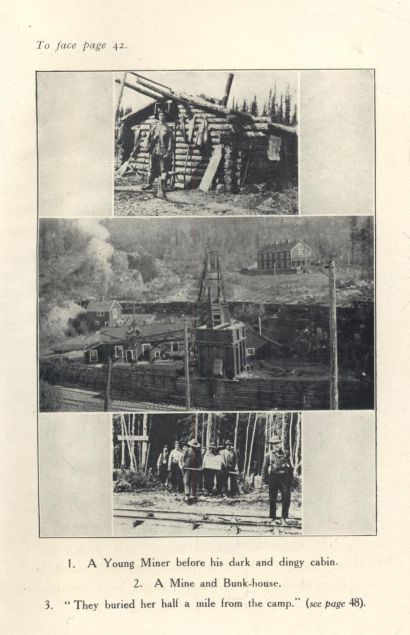

FACING PAGE 42.

1. A young miner before his dark and dingy cabin.

2. A mine and bunk-house. 3. "They buried her

half a mile from the camp" (see page 48).

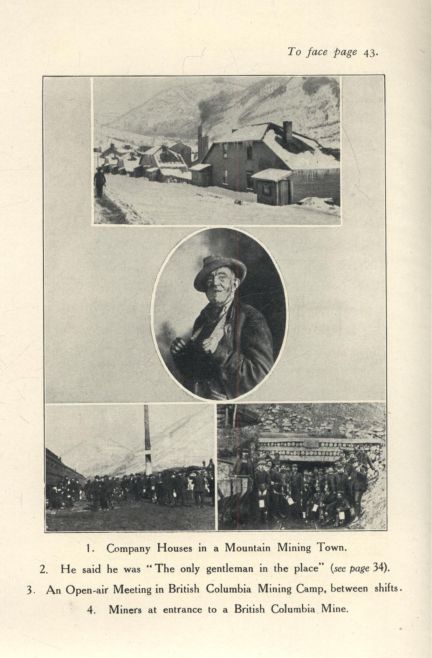

FACING PAGE 43.

1. Company house in a mountain mining town. 2. He

said he was "The only gentleman in the place"

(see page 34). 3. An open-air meeting in British

Columbia mining camp, between shifts. 4. Miners

at entrance to a British Columbia mine.

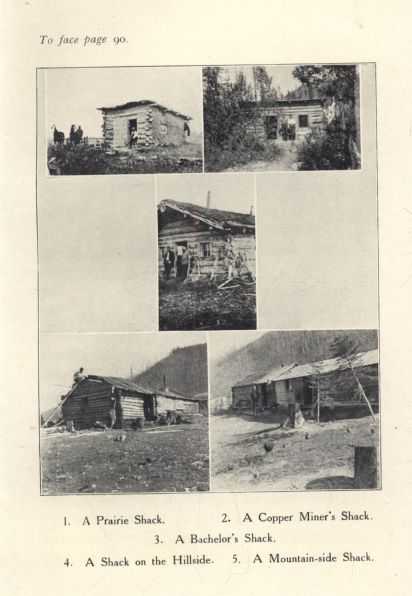

FACING PAGE 90.

1. A prairie shack. 2. A copper miner's shack.

3. A bachelor's shack. 4. A shack on the hillside.

5. A mountain-side shack.

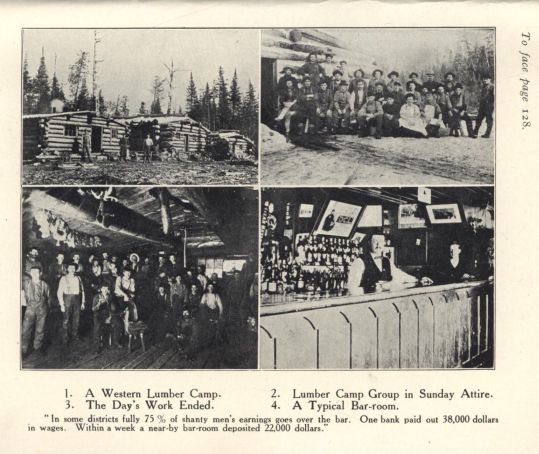

FACING PAGE 128.

1. A western lumber camp. 2. Lumber camp

group in Sunday attire. 3. The day's work ended.

4. A typical bar-room.

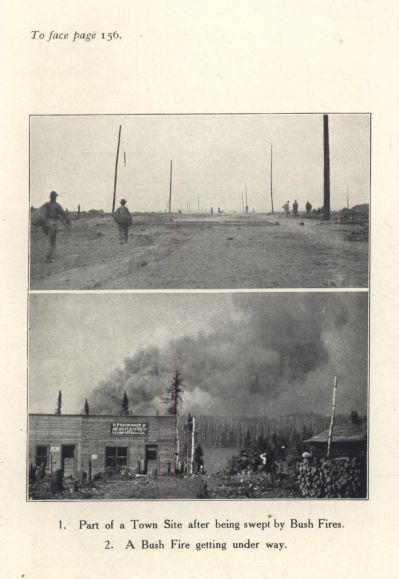

FACING PAGE 156.

1. Part of a town site after being swept by bush fires.

2. A bush fire getting under way.

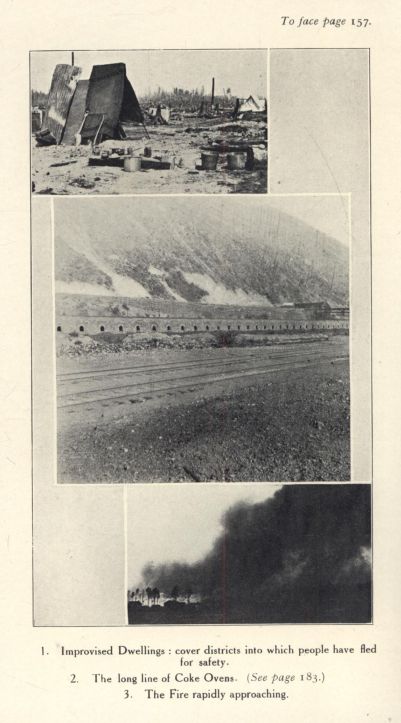

FACING PAGE 157.

1. Improvised dwellings; cover districts into which

people have fled for safety. 2. The long line of coke

ovens (see page 183). 3. The fire rapidly approaching.

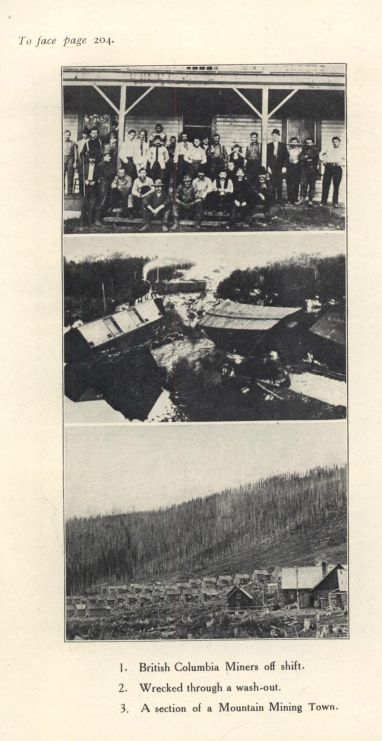

FACING PAGE 204.

1. British Columbia miners off shift. 2. Wrecked

through a wash-out. 3. A section of a mountain

mining town.

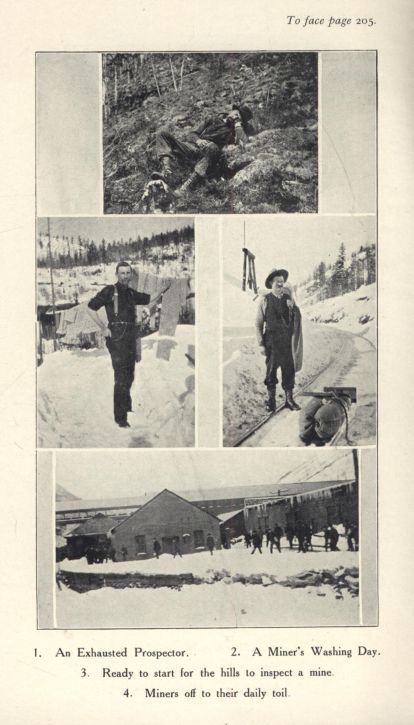

FACING PAGE 205.

1. An exhausted prospector. 2. A miner's washing

day. 3. Ready to start for the hills to inspect a

mine. 4. Miners off to their daily toil.

Old Ken was "down on his luck." For well-nigh fifty years he had "gone the pace" in a district where certain men say glibly, "there's no God west of the Rockies." The old prospector had been, according to those who knew him best, in one of three conditions for some years. He was either "getting drunk, drunk, or sobering up." And yet in spite of his weakness and sin, and in spite of the curses he got, there was no more popular man in the whole camp than Old Ken, although likely he was not conscious of it. One of the miners had once expressed a conviction about Ken that was dangerously popular. It was at the time Frank Stacey's mother died, in the East, and Frank had not "two bits" to his credit. As might have been expected, it was Old Ken who started the hat to wire that Frank was leaving on the next train, and to see that he had "enough of the needful to do the decent thing." "It's his last chance, boys," said Ken, as he made the rounds during the noon hour. "I got twenty-two dollars since eleven o'clock, so I guess, with what you fellers is a-going to do, the old camp's on the job, as usual, when a chap like Frank wants to pay his last respects." There was some mystery about those twenty-two dollars until Andy the bar-tender told how Old Ken had "got it out of the boss" on the solemn promise that for two weeks he would "work like a Texas steer" without touching a cent until the debt of thirty dollars, minus eight for board, was discharged. Then it was that one of the boys expressed himself thus about Ken: "By gosh, fellers, he's white clear through, that same old soak is, when there's any trouble on. He's a pile decenter than his thirsty old carcase 'll let him be."

On a particular morning some months ago the old prospector stood at the little station a mile or so away from the camp centre. The "mixed" was winding her way slowly around the curves of the summit of the Rockies. From the windows of the solitary passenger car a young man looked somewhat anxiously across the valley below. A few shacks nestled among the poplar brush, and in the distance an unpainted building stood, with distinct outline, towering against the dark background of the mountain range opposite. The young man knew well enough, from his work among the miners and loggers, that yonder building was as a moral cancer eating out the best life of the community. The outlook was not bright, but he was on the King's Business, and he knew that he had in his care the mightiest thing, and the greatest remedy, the world knows of.

Alone he stepped off the train, and being the only arrival he received the entire benefit of Old Ken's curious but not unfriendly gaze. The new-comer, who was conducting special services at selected mining and lumbering camps that were considered especially needy, looked around for a district missionary who was expected to act as his pilot for a few days. No one but Old Ken and the station agent were in sight, so after friendly greetings to the former the young preacher made known the purpose of his visit. Old Ken listened courteously. "Well, stranger, you've hit the right spot alright; we kin stand the gospel in big doses here for sure; most of us is whiskey soaks or bums, and some of us is both. I wish you luck, partner, but I'm feared most of us is incurable. Yes, partner, I'm feared you've come too late, too late."

The Frenchman who was hotel-keeper, professional gambler, lumberman and mine-owner, was not enthusiastic about allowing the sky-pilot to board in his notorious hotel and gambling den, but eventually accommodation was secured.

The dance-hall was procured for the services, and Ken volunteered the information that the preacher wouldn't likely be disturbed, because there were only four women left in the camp, and he added, "two of 'em can dance like elephants and one's got ingrowing toenails or something else, so there's only one on duty, and that ain't enough variety for a good hop."

A few days after the services commenced, Old Ken managed to replenish his treasury by the fortunate desire on the part of two men to get a haircut. The old man boasted that he knew how to do most things. "I'm never idle, preacher," he said with a wink; "when I ain't doing something I'm a-doing nothin', so I'm always a-doing something you see."

No sooner were the locks shorn than the old man made his way to the bar-room. He was emerging from his favourite haunt when the preacher met him. "'Taint no use pretending I'm what I ain't, preacher," he said after a few minutes' conversation. "I'm an old fool and I know it, but what does it matter? Who cares?"

"It matters a good deal to you, Ken," the preacher replied quietly, "and there are some of us who care. Ken, if you would give God as big a place in your life as you've given whiskey there wouldn't be room for the things that have made you call yourself an old fool. I know He could make a mighty good man of you, Ken."

"Thank you kindly, preacher, but you don't know me: I'm the hardest old guy in this country; the fellers around here think they can go it some, but let 'em all get as full as they kin hold and I'll take as much as any one of 'em and then put twelve glasses more on top of that to keep it kind of settled, and then pile the whole gang under the table and walk out like a gentleman. Yes, sir, I kin do it; and if a feller's as big as a house I'll whittle him down to my size and lick him. Yer intentions are good, partner, but you're about fifty years late on this job."

The days allotted to the mission were rapidly passing away, and while not a few had given evidence of seeing "the vision splendid," there were some after whom "the little preacher," as he had come to be generally spoken of in the camp, greatly longed.

Coming down the stairs one day he saw Old Ken standing with his back to the stair rail. Putting his hand on the old man's shoulder he entered into conversation.

"Ken, you haven't been to one of the services yet, and I want you to come to-night."

"Lord bless you, preacher, if I went to a religious meeting the roof 'ud fall in for sure, and I don't want to bust up the dance-hall."

But the little preacher was not in a mood to be "jollied" that day. "Ken," he continued, "I'd like you to give God a chance. Do you know, I like the look of you, and——"

The old prospector cut the sentence short, straightened up, and gazed appreciatively into the speaker's eyes. "What's that you said, preacher? What's that you said? You like the look o' me! Well, siree, that's the decentest thing that's been said to me in thirty years! Yes, sir, it is: I'm treated like a yaller dog around here; but you speak decently to a yaller dog, he'll wag his tail. He likes it, you know. Say, preacher, when you need me just you whistle and I'm on the job!"

"I take your offer, old man," said the preacher. "I've been here for some time and I've heard a good deal that I didn't want to hear. Some of you fellows have been cursing pretty nearly day and night since I came. I didn't want to hear it, but I couldn't get away from it. I've heard the boys; it's only fair they should hear me. Ken, you round them up and bring them to the dance-hall."

Ken's hand was extended. "Here's my hand on it, preacher; I'm yer man. If the boys ain't there you'll see my head in a sling in the morning."

At 7.30 Ken organized himself into an Invitation Committee. There were rumours that he even brushed his coat. At any rate, at 7.45 he stood at the door of the gambling den, and with an air of unusual importance he succeeded in getting silence long enough to tell "the boys" that there was "a religious show on in the dance-hall." "The procession will form in ten minutes," he continued, "and every —— man in this place has got to be in it." A few laughed; some cursed at the interruption, and others were so engrossed in their game that they appeared not to have heard.

In a few minutes Ken entered the barroom and started his round-up. After telling one or two quietly that it was "up to him" to get the boys to the religious show, he made his proclamation. "Come out of this, you —— fellers, and come up to the —— dance-hall and give the —— little preacher a fair show, or I'll kick the —— hide off you." The writer has no apology to make for blasphemy either in the East or West, but like classical music, to some ears, Old Ken's blasphemous language was not so bad as it sounded.

After the old man had brought into use all his remarkable reserve of Western mining camp vocabulary, there was only one man besides the bar-tender who failed to join the procession.

The services had become well advertised throughout the entire district by this time, so that when Old Ken arrived with his company the little hall was fairly well filled. But the old man was "going to see this thing through," and so, despite the protestations that almost upset the gravity of the preacher conducting the preliminary song service, the gang was coaxed and forced to the front seats. Ken directed the seating operations in a way that suggested his ownership of the entire place. In a stage whisper he instructed the boys to "get a squint at the preacher's hair." With pride he continued, "mighty good cut that, I performed the operation this afternoon."

At the close of the service he came to the platform. "Say, preacher, that was a great bunch. There ain't a —— (excuse me, preacher, I forgot you don't swear), but say, there ain't a man of 'em but's done time. I'll tell you, preacher, we'll run this show together. I'll round 'em up and you hit 'em;" then with a swing of his big arm he added, "and hit 'em hard. See here, preacher, you take a tip from me; us old sinners don't want to listen to none of yer stroke-'em-down-easy preachers; we wants a feller what 'll tell us we're d—— fools to be hoodwinked by hitting the pace, and what'll help us to get up after he shows us we're down."

A few nights later the preacher had Ken's "bunch" particularly in view as he delivered his message. Near the close he asked during one of those times of reverent silence that may be felt but not described: "Are not some of you men tired of going the pace? You know it doesn't pay. Many a time you curse yourselves for being fools, and yet you go back to the old ways that blast your life. Men! God knows how some of you are tempted, and He is ready to help. His Son came into the world to save sinners. He stood in the face of the fiercest temptations, and with the command of a conqueror He said, 'Get thee behind Me.' And, Men! He is ready to stand alongside of every passion-torn man to-day and to help him to overcome. Isn't there some man here to-night who wants to do the decent thing, and who will accept His offer of help in the biggest fight any man has?"

The words were simple and commonplace enough, but the One who uses stumbling lips was present that night. Unexpectedly one man arose, pulling himself up by the back of the seat in front of him—a sin-marred man, trembling as a result of daily dissipation—and said in a muffled voice, "I want to do the decent." A confirmed gambler not far away stood up and merely said, "Me too, Bob." Another, in a tone of despair, cried, "God and me knows there's nothing in this kind of life! Oh the d——, d—— whiskey, it's ruined me." Late into the night the preacher walked along the trail with one of these sin-wrecked men; but the transformation of that life and other lives must constitute a separate story.

A few days before the mission closed Old Ken came to the preacher and announced his intended departure from the camp. "You see, stranger, the camp's pretty quiet, and I ain't a-making enough money to buy a dress for a humming-bird. I ain't got the wherewithal for a ticket, but if I strike the right kind of conductor I guess I'll make the grade. You see they can't put a feller off between stations in this country. So I'll get one station along anyway, and if they chuck me off I'll wait for the next train, and a few chucks and I'll get to N—— anyway."

The following morning prospector and preacher walked together down the railway track to the little station. A farewell word was spoken, and a farewell token slipped into the big hard hand. Old Ken stood a moment or two on the steps of the car. There was a far-away look in the old man's eyes as he gazed in the direction of the distant Cascade range. "Good-bye, preacher. Yes, maybe, maybe we'll strike the main trail that leads home. I hope so—God knows—maybe it ain't too late for me yet. I kinder think lately that God wants Old Ken. Good-bye, preacher; God bless you."

Three months later "the little preacher" received a letter from a British Columbia miner. One paragraph may be quoted here: "Poor Old Ken was burned to death in a hotel fire in S—— three weeks ago. He was the kindest old man I ever met, and as long as I live I shall thank God for the night he rounded us up and brought us to your meeting in the dance-hall."

When Charlie Rayson passed out of the dance-hall in the little mountain mining town a few nights after Old Ken's round-up, he was on the border-line between despair and hope. Was there any chance? For years he had apparently worked with the logging gang only that he might give full rein to the lusts that devoured him; and if he remained in the bush the whole winter it was with an impatience for the days to pass so that the spring might bring him to the bar-rooms and dens of vice, where the awful monotony might be relieved in a spring-long spree. Nobody had any particular interest in Charlie, and no one knew from whence he came.

And yet there seemed to be some slight ray of hope to-night. He had listened for the first time since boyhood to the pearl of the parables, and then Old Ken had asked the preacher to "sing that there Wandering Boy piece." Charlie knew not if his mother still lived, but the words, "Oh! could I see you now, my boy, as fair as in olden times," came like his mother's call through the sin-stained past. For thirteen years he had cut himself entirely off, so far as his whereabouts was concerned, from that one who had never ceased to love him.

In a few minutes after the close of the service Charlie and the preacher were alone on the mountain trail. Suddenly Charlie stopped and said, "Good God, preacher, you can't, you don't understand what I'm up against. For nineteen years I've been in the hands of the doctor or the policeman—my passions rip me to pieces—men can't help me; I wonder if God can? I want to believe what you said to-night is true, but I've always wanted to do the thing that damns me, worse than I have wanted to do anything else, and yet I never do it without something saying 'don't.'"

In the silence of the lonely hills the two men stood, while one asked Him who is the Help of the helpless to be the Refuge of the passion-pursued man. Poor Charlie could utter but few words: "God, oh, God," he sobbed, "I'm like that prodigal, and I'm sick of it all. Oh, God, can you help me? I want to see my old mother." With the mention of the word mother the man burst into a passion of weeping. For several minutes no word was uttered, as the preacher steadied the trembling man. It was no easy task for Charlie to do what he was counselled to do after he had made the Great Decision. But that night he read, from the Testament given him, a portion of the third chapter of St. John's Gospel, and knelt by his bunk and asked for strength sufficient. To kneel down and pray in certain Western mining camp bunk-houses is a man's job, but Charlie had realized that only One was able to deliver from the passions that rend, and to that One he appealed.

A fortnight later an old woman in a far-away Ontario village received a letter bearing a British Columbia postmark. She was a poor, lonely, half-crippled individual, but the message of that letter enriched and cheered her and quickened her footsteps as nothing had done in years. To everybody she knew, and to a good many people she did not know, she told of her new joy. In her trembling old hands she held the precious letter. "Do you know, I've got a letter from my Charl. I thought he was dead. I haven't heard from him in thirteen years, but he's in British Columbia, and he says he's a Christian man now, and he wants to see his mother—and he's going to save up so's he can come home, and till he comes he's going to write every week—and he sent me some money. Oh, how good God is to give me back my Charl!" The poor old soul seemed raised as if by a miracle from her invalidism.

Charlie toiled on in the logging gang, and when pay-day came the hotel-keeper reaped the usual harvest from most of the men, and was hoping that Charlie and Bill Davis, two of his best customers, would be coaxed back to their old habits. Bill had been known as the "little devil" of Primeau's gang, and his professed change of heart was a thing incredible to the entire community. But Charlie and Bill had been a good deal together of late, and the latter had told Charlie all he purposed to do and be with God's help, and so the two men became mutually helpful.

Five months passed, and besides having purchased new clothes, Charlie Rayson had one hundred and fifty dollars in the savings bank at Brandon Falls.

And so at last the home journey was to be made. It would be hard to say who was the more excited, Charlie or his loyal friend Bill Davis. For some time Bill thought he would "pull out" when Charlie went, but later he decided to stay on his job a few months longer. Nothing would do but that Charlie should take "just a little remembrance" of $25 from Bill to the aged mother.

On Saturday afternoon the final arrangements were made, and Bill did a score of things to make Charlie's get-away easier and pleasanter. While Bill was purchasing a few little necessities at the company store, Charlie stepped across the threshold of the bar-room for the first time in months. He wanted to say good-bye to Andy the bar-tender. A number of Charlie's old pals were sitting or lounging around, some of them well on the way to their terrible monthly debauch. Numerous hands were extended and not a few glasses offered to Charlie. "Not for me, boys—I've cut it out for good, thanks all the same," was Charlie's firm response.

"Oh, come off," cried one, "you ain't a-going back on your old pals just 'cause you've got a new suit o' clothes."

Numerous sallies followed this, but to each one Charlie gave a similar reply, and backed towards the door. It has always been supposed that it was Primeau himself who tripped Charlie, but be that as it may, somehow Charlie stumbled backwards to the bar-room floor; and when Bill Davis was returning through the hall some of the men were holding Charlie while others were pouring whiskey through his lips, "just to give him a lesson in sociability." Bill Davis could scarcely believe that the boys had tried to make Charlie drink, but when he realized what had happened, his indignation prompted the profanity that had become a life habit. He checked the words, however, and shouted at the scoffing group to leave Charlie alone or somebody would get a headache. There was a laugh from one and a muttered "mind your own d—— business" from another. And then Bill took a hand in the affair.

The following day the affray was being generally discussed. One or two men who were participants in it were careful to keep out of the public gaze. Bill had not selected places where they should fall when he was defending Charlie. To a little group in the bar-room Andy gave the information that "There was something doing alright, when Bill started in to look after Charlie. Say! the feathers was a-flying. Bill ain't such a blamed good Christian that he's forgot how to fight."

The taste of whiskey had aroused the old craving in Charlie, and long after the east-bound train had pulled out he was fighting his battle with Bill by his side.

Never had the two men felt more alone, and never had they more needed a friend than now. All Charlie's confidence in his ability to stand firm seemed to be shaken. "Bill!" he said, "I swallowed some, and it seems like it was running all through me to find some more to keep it company. Bill! for God's sake don't leave me. I feel as if I was going to lose the game."

Bill hardly knew what to say or do. The fight in Charlie's behalf and the disappointment over the delayed journey had left a great depression. Neither of the men went down to the evening meal. To pass the bar-room door and to face the men again seemed more than Charlie dare undertake.

The next train for the East passed through at 3 a.m., and after thinking over the events of the afternoon, Bill made up his mind that they would flag Number 56, and that he would journey a hundred miles or so with his sorely-tempted chum. In the darkness of midnight, the two men passed quietly out of the building and along the trail to the railway station. At last they were really on the train, and having found an empty double seat the men made themselves as comfortable as possible, and were soon, like their fellow-passengers, getting such fitful sleep as one may obtain on the average "local."

It was the season of the year when "washouts" make journeying dangerous, and frequently in Western Canada trains are delayed many hours, and sometimes days, by the swelling of the mountain streams which in their onward rush sometimes carry culverts and ballast from beneath ties and track.

The train had pulled out of Sinclair, and was making her usual time through the eastern section of the Pass, when passengers were suddenly thrown from their seats by a terrific jolt. Lamp glasses crashed to the aisle, and baggage was dislodged from the racks. Charlie pulled himself to his feet almost instantaneously, despite the knocks he had received. The lamps were flickering and smoking, but fortunately there appeared no danger of fire. The brakeman, hatless and with a bleeding face, came rushing through the cars seeking to allay the fears. "Stay in the cars, please—there's no danger of fire. You're better here than outside. Doctors will be here soon."

Bill had not escaped serious injury. He found it impossible to rise, and as tenderly as he knew how, Charlie pillowed his head and stooped beside him as he lay in the aisle. "I'm feared I'm pretty badly hurted, pardner," groaned Bill. "There was something kind o' crushed inside. Guess I'll just lie here for a bit."

The engine had plunged through an undermined piece of track, and engineer and fireman were terribly cut and scalded, while the baggage-man had been pinned beneath some heavy trunks that had shot forward and downward when the engine crashed into the washout.

"It's the hospital for you, my man," said the doctor kindly, after a hurried examination of Bill's injuries. "We'll make you as comfortable as we can before the 'special' pulls out, but you need a little attention that you can't get in the camp even if you were able to stand the journey."

Charlie got permission to accompany his pal, and for Bill's sake he kept a brave heart, although the events of the past twenty-four hours robbed him of the lightheartedness that had been his in anticipation of the home-going.

Two days later Charlie decided to continue his journey eastward. The doctors were still anxious about Bill, but there was nothing Charlie could do, and he knew the old mother was waiting for her boy.

It was a touching farewell as the sick man's hand was clasped. A score of times Charlie had expressed his sorrow that he had ever let Bill accompany him, and yet each time in his own way he thanked Bill for standing by him when he was "near bowled out."

Bill tried to say that he was glad Charlie was going home, but his tone and look revealed his sense of loss and loneliness at the prospect of his pal's departure, and Charlie's eyes needed a good deal of attention, which they received surreptitiously.

Motioning for Charlie to come nearer, the sick man whispered: "You're a brick, old pard, to stay by me this long. I guess she's getting anxious for yer. Say, Charlie, when yer away down there I'll be kind er lonely; how would it be if yer made a bit of a prayer once in a while for me?" Then with a last pressure on the still clasped hand, he added, "Good-bye, old pal, God bless yer; maybe we'll hit the trail together again some day, but say, Charlie!" (the voice was throbbing with emotion, and the eyes reflected well-nigh a mother's tenderness)—"say, Charlie! we'll stay by it, won't we? If the whole world goes back on Jesus Christ we two'll stick to him, 'cause we know what He can do; don't we, Charlie?"

Thus they parted. Inside of three days the one was clasped in a mother's arms and there was great joy in the little village home; and almost at the same hour the other reached his Father's Home, and there, too, was great joy.

Charlie Rayson was the man who first suggested the holding of special services at the "Banner." "Oh! boys, but it's a hard spot. I mind when Old Ken hit the trail to get a job there. Somebody brought word they was paying six bits an hour for rough carpentering, and next morning Ken took over the mountain with his pack. He never stopped even long enough to get on a spree. In about a week he was back at the old spot. That night he was in the bar-room telling the boys about his trip. I mind he told 'em they could judge what it was like when he was 'the only gentleman in the place.'" Those who knew Ken needed no further report of conditions at the Banner Mines.

When the District Superintendent heard that the men were planning to go to the "Banner," he wrote to tell them not to be too much discouraged if it took a week's hard work to get half a dozen hearers. "The spot is known to many as the 'hell-hole of the Province,' and the Church does not begin to figure in importance with the corner grocery, but with two special workers and the amount of earnest prayer that is everywhere being offered. I am hopeful that the heartrending indifference may be overcome."

And so on a certain Monday morning the missioners made their way to the Junction, and then took the dirty work-train up the gulch to the camp. In a community where men have for years read anti-church, anti-religious literature, and where "parasite" is hissed under the breath every time a minister of the Gospel is seen, it could scarcely be expected that anything approaching a welcome would be given the new-comers.

Inside of an hour the work of getting acquainted was commenced. On the trail, along the railway track, at the tipple, at the entrance to the mines, in the washroom, wherever men could be met, the missioners sought to enter into conversation with the miners. Some answered civilly, a few were almost cordial, many were surly, and many others either absolutely indifferent and silent, or openly antagonistic. Dave Clements, a disabled miner, who looked after the wash-room, expressed himself thus: "Religion ain't no good here; most of the mine-owners is supposed to hev got it, and so the rest of us don't want it. Look at the houses what they make us live in—my missus has been sick most all winter—jest frozen, that's why! We pays eighteen dollars a month for the —— places. The company owns everything around here: land, houses, stores, train—even the air belongs to 'em, 'cause it's full of their coal-dust. We has to pay about three times the proper price for things; but, then, that's what helps 'em to be religious; that's what gives 'em the front seats in the synagogue, you bet; we fellers sweat to buy church organs and plush cushions, and then the parasite parsons pat the mine-owners on the pate and give thanks for such generous brethren. If anybody needs revivalling, stranger, it's that gang of hypocrites back yonder what makes us poor devils raise the wind to blow their glory trumpets." Yet even Dave was compelled to say of Him whom the missioners sought to exalt, "I find no fault in this man."

In response to an invitation to attend an evening service one miner replied: "Meeting, eh? Any booze going? No? Any dance after? Something better than that? Gee! it must be swell!" Then the tone was contemptuous: "No, siree; you couldn't get me into a religious meeting with a couple of C.P.R. engines."

Yet the daily conversations and invitations were not all in vain, for when there is a real concern on the part of Christians for non-Christians, that concern is likely to be imparted to those whom they seek to win.

Moses Evans, a Welsh miner, listened somewhat impatiently to the missioner's words, as he stood leaning against a telephone pole. Then with apparent weariness he answered, "Look here, young fellow, there ain't a —— man in this country can live a Christian life in this camp. I've tried it; you ain't. I know; you don't. I used to be a Christian in Wales—leastwise, I think I was—but you can't be here." The interview ended, however, with a promise on Moses' part to be present on the following night. Three nights later he knelt, at the close of the service, behind the old piano, and brokenly asked God to make him "different again." "Forgive my sins," he continued, "and help me like You did in Wales."

Near the end of the week the missioners planned to hold an open-air service a mile and a half down the gulch, at a spot called "Spanish Camp," where nearly two hundred miners lived. It was hoped that by arranging the meeting between "shifts" a number might hear the Gospel message, who had not previously been reached. Every tent and shack was visited twice preceding the meeting, and hand-printed signs were posted wherever likely to arrest attention. At the time for the meeting to commence there were five children and eight dogs present. It was not a "dignified" course to pursue, and probably merited the disapproval of the "church fathers," but one of the missioners, yearning to get a hearing for his message, got possession of a large tin can from a nearby rubbish heap, and with the aid of a club succeeded in getting considerable noise from its emptiness. The people may have appreciated his advertising ability, or it may be they preferred to hear the Gospel rather than the noise that was coming from the tin can; but, at any rate, in a few minutes a circle of thirty or forty gathered around the speakers.

A few minutes after the meeting had commenced the limping figure of Moses Evans might have been seen on the mountain-side near No. 3 Mine. Hurrying down the trail he crossed the rustic bridge over the little mountain stream, and came to where the crowd had gathered. Without any hesitation he pushed through the circle and stood in the centre. Reverently removing his miner's cap, he said, "I'd like to pray." A few faces expressed a sneer, but Moses clasped his hands and uttered his petition, which was written down immediately thereafter. "Oh, God, you know as how the devil has been at me all day, saying as I dasn't stand out in the public air and confess Thee. You know, oh, my God! that I want to be a good man again. You know I can't read nor write in English, but You've put words in my mouth; put them into my heart, and keep it clean, for Jesus' sake. Amen."

Moses Evans and other men, who with him made open confession of Jesus Christ, were again and again spat upon and cursed, as they passed along the "entry" at their daily toil in the mine. "But it's a great thing," wrote the school-teacher, "that these men can be by tongue damned higher and damned lower than anything else in this world, and yet stand firm. Increase the number of such men, and you have a leaven of righteousness that will eventually permeate this whole mining community. This is our only hope of rescue from the mire of sensuality and vice into which many of our miners have sunk. Moses says to please tell you that the words of the hymn you used to sing are true in his own experience:—

'Through days of toil, when heart doth fail

God will take care of you;

When dangers fierce your path assail,

God will take care of you.'"

It was the acceptance of the challenge to attend the "Hop" at the Bonanza Camp that popularized the services at the Banner Mines.

1. A Young Miner before his dark and dingy cabin.

2. A Mine and Bunk-house.

3. "They buried her half a mile from the camp." (see page 48).

After the open-air meeting a number of men lounged around one of the shacks discussing the question of religion. When one of the preachers approached the group to invite them to the meeting in the Hall, "Smut" Ludlow at once began to air his grievances against the Church, and to inform the preacher that there were "more —— rascals in the Church than in any other organization on earth." Then Frank Stacy contributed his bit of condemnation: "See here, preacher! The last time I was back East, I thought I'd see what sort of a show they was still running in yer House o' God, and so I went in. Just over the archway inside was a fine piece of writing, something about 'the rich and the poor meeting together, and going snooks.' I thought it sounded pretty good, so I made myself as comfortable as I could in one of them soft seats. After a while some dude started to play the organ, and folks dressed up fit to kill strutted into their seats and bobbed their heads down and pretended to say their prayers. Then I watched an old guy trying to get his overcoat off: I mind how his other coat well-nigh come off with it; he sure was scared when he saw his shirt sleeve, and he hustled both his coats on again like he'd been caught stealing. Just then somebody tapped me on the shoulder, and a coon with a silk tile in his hand told me to sit at the back where the seats weren't rented. I went back looking like a fool, but you bet I didn't stop for a back seat: I decided I'd take an outside berth, and it'll be a few hundred years before this chicken gets caught again. Rich and poor meet together, and go snooks! It looked like it, didn't it? See here, preacher, ain't it about time you fellers stopped talking one thing and serving up another? The whole thing is tommy-rot, that's what I say."

1. Company Houses in a Mountain Mining Town.

2. He said he was "The only gentleman in the place" (see page 34).

3. An Open-air Meeting in British Columbia Mining Camp, between shifts.

4. Miners at entrance to a British Columbia Mine.

Hal Rinnell was not antagonistic, but objected to an illustration that the preacher had used. "Say, preacher, warn't that there story about the Bishop and the silver candlesticks a bit fishy? You mind you said about the feller swiping 'em after the Bishop had give him a bed, and then he got away with 'em through the night; and when the p'liceman saw him with 'em next morning, and know'd they belonged to the Bishop, they jest nabbed him and brought him back. And you mind you said the Bishop told 'em the man didn't swipe the candlesticks, but got 'em from him as a present. Then when the p'lice was gone, the Bishop called the thief 'brother,' and made him keep his haul and promise to be square from that on. Now that ain't reasonable: it ain't human nature. I'd like to see the pumpkin-head what would swipe my candlesticks, if I had any, arter I'd give him a decent bed. He'd hev his next breakfast in Hades, you bet. Some o' you preachers ain't reasonable; you kinder get yer wires crossed."

The cross-firing ended by a proposition from "Smut." "There's going to be a hot old time to-morrow night at the Bonanza, preacher. I'll make a deal with you. You don't like our style; we don't like your hot air. You attend the ball at Bonanza, we'll attend your show, providing you start when we start, and leave when we leave, and get home as soon as we do. How's that, boys?" The "boys" trusted Smut's judgment, and knew by his wink that the proposition was safe, hence their unanimity to make it a "go." None of them dreamed that the proposal would be accepted, but after a moment's conference with his fellow-worker the preacher agreed; and in order that there should be no misunderstanding, he repeated Smut's proposition.

The following evening the six-mile walk to the Bonanza was commenced, and the second party to the contract followed the leaders. The first mile of trail was familiar to the preacher, then the way led over rarely-travelled paths. Carefully he took his bearings when that was possible, for few landmarks existed. He observed the whisperings and smiles when the way was wide enough for two or three of the men to walk together, and surmised that he was the subject of the conversation.

At last the Bonanza was reached, and already the gaudily-decorated dining-room of the boarding-house resounded with laughter and shouting from well-nigh a hundred guests. From all corners of the district they had gathered, for where social opportunities are so rare the camp ball is a great event.

The "band" consisted of violin, cornet, and horn, accompanied by the rhythmic pounding of the performers' feet.

Women were scarce in the district, and most of the men desired to dance with every woman present, so that the periods of rest were few and short.

Liquor was dispensed freely, and some of the dancers became hilarious and others quarrelsome.

Only once was there anything approaching a fight. "Nell" Webster, a notorious character, who was once well known in the crime colony of an American city because of her more than ordinary attractiveness, had passed through many degrading experiences, and had eventually taken up her abode at the Bonanza. Excessive use of drugs and liquor had wrecked her attractiveness, but a dance was considered incomplete without her, and when excited by intoxicants she could "hold the floor with any of them." It was through one miner attempting to monopolize Nell's dances that the quarrel arose. Heated words, then curses and threats, created an ugly situation, until a few of the more sober managed to separate the angered ones. It was the last night they would quarrel over Nell. Her mad race was ended. The girl of beauty had let sin become her taskmaster, and now for years her cup of pleasure had contained only the dregs. Step by step the progress had been downward. Once, "respectable" men with refined brutality had made her think she was their valued companion, and then, like an orange from which the sweetness had been extracted, they had cast her off. For a time she gained notoriety by being the wife of Len Walsh, counterfeiter, burglar, confidence-man, and all-round crook. At that time she was known as "Len Walsh's woman," but when Len lapsed from clever crime to simple drunkenness, she left him and took another name. And now for years her associates had been drunks and crooks.

Once during the revelry, as an opportunity presented itself, the preacher spoke a few words to her about her terrible mode of living. He thought there was a shadow of remorse as, with a forced smile, she replied, "I don't give a d—— now; better try it on somebody younger."

Two days later the preacher was asked to return to the Bonanza and "make a last prayer over Nell." They had found her lifeless body the morning following the camp ball. Her grimy shack was littered with bottles and glasses, and there were evidences of a fracas—sin-marred, sin-mauled Nell lay on the filthy floor in the dress she had worn at the dance. They buried her half a mile from the camp, and one of the boys crudely carved the word "Nell" on a cedar post, and placed it at the head of the solitary grave amid the lonely mountains. Few sadder moments has the preacher ever spent than the ones occupied in the burial of Nell. Again and again were her last words to him recalled—words that have since become an appeal in behalf of the wandering: "I don't give a d—— now; better try it on somebody younger."

But to return to the dance. It was long past midnight when the "Banner" contingent started for home. There was something of interest that Smut had to confidentially communicate to each man. Then there was a hurried shout, "All right, boys," and the crowd immediately disappeared in the darkness. Thus far the preacher had kept his part in the agreement, but Smut Ludlow was planning that on the homeward journey the rest of the contract must be made impossible.

The miners struck a furious pace, and the preacher was for a few minutes unable to see the winding way, but he stumbled along as rapidly as the hindmost of his fellow-travellers. Very soon he realized that many of the men could not maintain that pace for long, and so, refraining from conversation, he held himself well in reserve, being content to take his pace from the slowest in the line. For half an hour no change in position took place. The foremost men were chuckling to themselves over "shaking" the preacher, and were wondering how far back on the trail he was, and whether he would spend the next few hours in the woods waiting for daylight. But their mirth was short-lived. The preacher decided that it was his move next. He could hear the panting of the men immediately ahead of him, and at a favourable opportunity he increased the length and speed of his stride, and passed two of the boys. At each widening of the trail he performed the same feat, until only Smut remained ahead.

Smut was mightily amazed when he discovered who was his nearest fellow-traveller, and an oath escaped him. With vigorously swinging arms he made every effort to keep the lead, trying for a while to do a "jog-trot," but his feet began to drag heavily, and once or twice he stumbled. No word was exchanged, for Smut was being pressed to the utmost expenditure of his strength, and the other contestant had never more longed for victory. More than once he had received the cheers of the thousands when he was the favourite on McGill's field-day, but somehow he felt to-night larger issues were at stake than the athletic glory of a college. He was still comparatively fresh, for he had been only an onlooker at the dance, and had no alcohol in his system. Narrating his final contest to his fellow-worker, he said, "If ever I prayed Samson's prayer with all my heart it was right then: 'Strengthen me, I pray Thee, only this once, O God.'"

At last the two men were side by side, but only for a few seconds. With the enthusiasm of a victor the preacher quickly lengthened the distance, and managed to spare enough breath to call back, "Come on, boys; it's no use hanging around here all night." At the first winding of the trail he broke into a run, and kept it up until he reached the bunk-house. With all possible speed he unlaced his boots, threw off his coat, made himself as comfortable as possible, and when the boys filed in he was sitting alongside of the dining-table with his feet on a box and a book in his hand, looking as though he had been having a quiet night of reading.

Poor Smut! If ever a man had it rubbed in, it was Smut Ludlow. Even before the camp was reached the attack commenced. "Smut, you're a —— fool, and you've made —— fools of every —— man in the camp," started Frank Stacey.

But with characteristic Western fair-play the preacher's stock went up rapidly. "That sky pilot ain't no slouch." "Gee! whiz! you should have seen him give Smut the go-by when he was plunging around like a whale in shallow water, and puffing like the 'dummy' when she's trying to make the grade with too big a haul." Many similar expressions went the round the next day, and the preacher was no longer regarded as the under-dog.

"Say, pilot," said Frank at the noon hour, "where d'you learn that gait you struck last night?" With a smile came the quiet reply, "I was brought up on the farm, and used to drive the calves to the water." As Frank walked away he remarked, "Yer guv'nor must have raised blamed good calves."

The most annoying result of the whole incident, so far as the men were concerned, lay in the fact that they were in honour bound to attend the evangelistic meeting. To some it was so exasperating that they suggested the violation of the contract. But that was not to be thought of in the opinion of the majority. "We was licked, and we'll take our medicine, though it's —— hard to swaller," said Hal Rinnell.

For the meeting that night the hand-printed signs gave the information that a series of lantern slides would be exhibited at the commencement of the service.

A few minutes after the opening, and while a popular Gospel hymn was being sung, about a dozen men availed themselves of the mercifulness of the semi-darkness, and slipped into back seats. By the time the lights were turned up they had become accustomed to their surroundings, and bore with fair grace the suggestive glances that were directed towards them.

The appeal was based on the words: "I find no fault in this Man." All the controversial weaknesses of the Church were dismissed, and the great problems of heart and life were dealt with in a manly, sympathetic manner, and men's thoughts were directed to that One whose name still occupies its splendid solitary pre-eminence. Before any person left the building, the speaker was in his accustomed place at the door to speak a personal word and give a handshake. Frank Stacey clasped the proffered hand with genuine cordiality, and in a voice that was heard by all, said, "You're playing a bully good game, preacher. You hit as good a pace to-night as last night, and if you keep it up you'll lick us to a finish before your innings is out."

Smut Ludlow was not in good humour, and as the boys sat around the bunk-house stove having their last smoke for the day, he was clearly disgusted and maddened at the changed attitude of the camp toward the preacher. Once he expressed himself after Frank had praised the preacher for his "grit." "You're a —— lot of turncoats; things are in a —— of a mess if you fellows can be bamboozled by one of these —— parasites."

"Well! we ain't the only ones what were bamboozled, Smut. He sure put it all over you last night, and if you had enough brains to fill a thimble you'd keep your fool mouth shut." Never in their long acquaintance had Frank opposed Smut to the extent of this deliverance, but there was no question but that the preacher had overcome Frank's opposition and aroused his admiration. "Anyhow," he continued, "that chap's a different brand to most of 'em, and I kinder think he can put up the genuine goods."

Frank threw his clothes over the line and clambered into his untidy bunk, and long after the heavy breathing of wearied men had become general he lay with strangely new thoughts. He agreed with the preacher that it wasn't a square deal to "find no fault in this Man," and then to deliver Him to be crucified. And that night the preacher had, by numerous illustrations, compelled the worst of men to pay their tribute to Him who was the highest that humanity has known; and yet were they any "squarer" to Him than Pilate was? Had they not much more evidence than Pilate had, and yet, in the face of an absolutely unanimous verdict of "not guilty," they pronounced what was equal to the death penalty. Again and again Frank said to himself "That ain't square."

There was not a seat to spare in the dance-hall during the subsequent nights. Frank Stacey missed no service, and when, at the mission's close, a meeting was called of those interested in the organization of a Church and the erection of a building, he was one of the little company.

When six months later they were ready to occupy the new church, Frank was insistent that Mr. ——, "the man who showed Smut where to get off," should be the preacher for the day. "Impossible," said a number; "it would cost over thirty dollars for railway fare alone." "Impossible nothing!" was Frank's response; and twenty-four hours later he handed fifty dollars to the Treasurer for railway fare and pulpit supply, and after two weeks of correspondence the announcement was made that the desired speaker was coming.

No one enjoyed the day of the opening more than Frank. The building of the church had absorbed all his interest, and now the effort was crowned with success. For several nights a dozen Welsh and English miners had practised the hymns "to give the thing a good send-off." They sat in the corner near the reading-desk, and led the music with increasing confidence as the day's services progressed.

"I guess the devil over-reached himself when he tried to make a fool of the preacher the night of the dance," said Frank, as a group stood outside at the close of the afternoon's Communion service. "'Tain't often he gets as hard hit in the neck by his friends as he was that night."

The Church at the "Banner" has had its ups and downs during the past three years. One of the mines has closed, and many shacks are now unoccupied. Frank Stacey has gone over to Vancouver Island, and some of the "charter members" have ceased their earthly labours; but each Sabbath-day a few faithful ones, "the salt of the earth," gather for worship in the Church that Smut Ludlow unwittingly caused to be built.

Jack Roande was on one of his periodical sprees. For eight years he had been going the pace. They had been long, weary years to the one whom Jack had vowed to love and cherish. Night after night, through these long years, she had listened for the awful home-coming. There were few in the little mining town but had often seen her eyes reddened by weeping, and all knew of the Eastern home she had left. Among those who had joined in the "send-off," nearly fifteen years ago, were two men whose names are still honoured household words throughout the Dominion. There was no note of sadness that day, for Jack was a "model young man," and every one agreed that there was "no finer girl than Nell."

Jack blamed his downfall to dabbling in politics. "Politics are rotten in this province," said he, as he endeavoured to excuse his condition; but perhaps, as a chum of Jack's said, he only blamed politics "'cause a fellow generally tries to find a soft place to fall." Whatever the cause, at least the fact was plain to all in the town that Jack was "down and out."

The business men said so, and agreed with the authorities that Jack was a nuisance to the town. Some of those who had assisted in his downfall spoke of him as a "dirty loafer," and even the bar-rooms, where he had "spent all," tolerated his presence only when the cruel pity of some patron called him in for a treat, or when he could exhibit some coin.

It was through the "tender mercies of the wicked" to Jack that there were three empty stockings in the Roande home on the recent Christmas Eve. "For the children's sake," there had been a tearful plea that the husband would be home Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. With glad expectancy the meagre resources of the pantry were combined by loving hands to give the nearest possible approach to a feast. From the near-by woods the children had brought cedar and pine for decorative purposes, and these, with stray bits of brightly-coloured tissue paper, had done much to give the home a Christmas appearance. The usual notes had been written to Santa Claus, and the mother-heart had lovingly suggested a curtailment of such requests as Santa might find it difficult to grant. The little ones had thrown their letters into the fire, and watched some of the gauzy ashes carried up the chimney to the mysterious but generous friend of the children, who would soon be loading his sleigh somewhere in the far north.

Jack appeared to respond to his wife's pleadings, and so on account of her many home duties she confided to him some of the requests the children had made, and how the much-coveted toys were parcelled and waiting to be called for at one of the down-town stores. No word was spoken of the sacrifice the purchases had involved, nor of the sting love had endured when for the children's sake she began to take in sewing. It was therefore agreed that Jack should bring the parcel home shortly before tea on Christmas Eve, and in the darkness it could be hidden away until the little ones were asleep.

Jack was true to his word, and started for home with the precious toys under his arm, in ample time for the evening meal.

"Merry Christmas, Jack," called a voice as Jack was rounding the saloon corner; "come on in and have one."

"Guess I'd better get home," was the hesitating reply. It needed little persuasion, however, to get Jack inside, and after a second treat he lost all anxiety to reach home, and was ready for a night's debauch.

During the tea-hour the bar patrons became fewer, and Jack's chances for further drinks were far apart. In response to a request to "chalk up a couple of whiskeys," he received an emphatic "not on your life" from the bar-tender.

There was a momentary conflict within Jack, and then the beast became lord over the man. Going to the corner he brought his parcel from the bench and placed it on the bar. "How much can I draw on for that?" There was a wild determination in the voice. Unwrapping the parcel beneath the bar, the bar-tender at once knew what the contents meant.

"I don't want 'em, Jack: you better get home to your kids." But Jack was insistent, and gradually the other weakened. "Well, it's your property, and if you're going to sell 'em I guess I may as well buy 'em as anybody else. I'll chalk you fifty cents." The articles were worth three times the amount offered, but Jack was being consumed with that hellish thirst that he had developed through many years, and he at once started to use up his credit.

A mile away an anxious wife awaited Jack's return. Cheerfully she had gone about her work until the hour for the evening meal, but with the passing moments the husband's absence caused her fears to increase.

With forced smiles she did her best to bring into the home the gladness that belongs to Christmas Eve, but the heart was heavy, and the little ones saw now and again the tears that could not be suppressed.

Bedtime was prolonged to two hours beyond the customary time, but still there was no sign of the father. Once the mother expressed the fears that were in her heart when she suggested that sometimes Santa Claus did not get to homes when the father was away, at which suggestion there were tearful little eyes and oft-expressed wishes that "daddy" would come home. Bravely the mother gathered the three children around her chair for their good-night sing. Favourite hymns of the Sabbath School were sung, and all the time four pairs of ears were alert for the sound of Jack's return.

It was while Grace's favourite hymn, "I am so glad that our Father in Heaven," was being sung, that footsteps were heard at the door. Instantly the little ones ceased their singing, as Grace joyously shouted, "It's daddy; Santa Claus will come now, won't he, mother?"

For a minute or two before Grace's glad shout two men had stood an the darkness outside the Roande home. After he had been turned out of the "Kelby House," Jack had staggered and stumbled around the streets for some time, and at last lay prostrate in the snow not far from the home of one who had often befriended him. A woman hurrying along the street suddenly saw the dark form on the snow, and with a cry of fear ran to the near-by house. The minister who resided there, at once recognizing poor Jack, dragged him into the house, and after securing a neighbour's sleigh and a driver, started for Jack's home.

From the sleigh to the house he managed to conduct Jack safely, but when the strains of "I am so glad" from childish voices reached his ears, he stood still for a moment. How could he take such a father home at such a time! Yet it was impossible for him to remain long outside with Jack as he was, and so he guided the poor drunken father onward. Jack stumbled and fell heavily against the door just as Grace's glad shout silenced the hymn-singing. The minister was dragged almost to the floor as the door sprang open and Jack lurched into the room.

Few words were spoken, for all hearts were sad as the stupefied man almost immediately fell asleep on the floor of the sitting-room, and filled the air with the drunkard's stench. The little ones were tenderly told to go to their beds.

"Had he a parcel when you found him?" whispered the mother as soon as she could control her voice. Then followed the narration of her plans to fill the three stockings that had already been hung up at the back of the stove. And now it was too late to find out what had happened to the parcel. The minister looked into the mother's face, and then at the three empty stockings with their mute appeal for a visit from Santa Claus.

"I could bear this, hard as it is," she continued, glancing at the drunken sleeper, "but the poor children——." The head dropped on her arms which were resting on the table, and quietly she wept over the bitter disappointment the little ones must bear on Christmas morning.

"Mrs. Roande"—a hand touched her shoulder lightly—"if you are not too wearied to wait up I'll do my best to locate the parcel." The look from the grateful mother was all that was needed to send the minister forth on his errand of love.

The store from which the toys were secured was closed, but the proprietor had not yet retired, and was able to reassure the midnight visitor that Jack had procured the parcel shortly before supper-time. It was not long before the clue led the minister to the home of the bar-tender. Wearied, but with mingled sorrow and anger, he rang the door bell. The man he was looking for came downstairs partly disrobed, and was manifestly surprised at a pastoral call, especially at such an hour. The minister stepped unasked into the hall. "Mr. Klint, I apologize for disturbing you, but Mr. Roande left a parcel somewhere that I must find to-night, and I understand he was in your bar-room. Do you know anything about it?"

The answer not being satisfactory, a further question was put.

"No, sir, he left nothing; we had a square deal, but that's nobody's business but mine and his."

"May I then ask if a parcel containing toys had any place in that deal?" No answer being given, the minister said with quiet firmness, "I must have an answer to that question before I leave this house. Mr. Klint, this is Christmas Eve! There are three empty stockings hanging in the room where Jack Roande lies drunk, and the things intended for those stockings must be there before morning."

"I'm not obliged to tell you or anybody else anything about my business," answered Klint surlily; "but if you are so anxious to know, then I can tell you that I bought that parcel to oblige Jack, and it was his deal, not yours."

"This is not the time for much talking. Be good enough to tell me where the parcel is now, and what you paid for it." Again there was hesitancy, and again there was pressure. At last the information was elicited that the toys were beneath the roof that sheltered them, and that the price paid was fifty cents.

"Be good enough for the children's sake, if not for your own, to take back your fifty cents and let me take the parcel."

Eventually the deal was consummated. When the toys were safely in his possession the minister said, "Mr. Klint, if you were dealt with as you deserve, you would spend Christmas day, not in your own comfortable home, but in the hospital or in jail: I only hope you are not as contemptible as your deed. I shall see you again, some other day."

The hand-clasp from the thankful mother was ample repayment for the midnight search, and in the early morning the exclamations of delight from her little ones in turn lifted something of the burden from her trouble-worn life.

Thus had it been, sorrow after sorrow, for poor Nell Roande for over eight years, and at times she felt there was little hope of any change, but the new day was soon to come, and the night of weeping was to be turned into the morn of song.

On the Tuesday night following the commencement of special services, as a little group of young men were leaving the Pool-room adjoining the Opera House, Jack Roande came stumbling along. It was a great joke, so Bill Thornton thought, to "jolly" Jack into believing that there was a "free show in the Opera House, with pretty girls and swell dancing." Within a few minutes Jack was sitting with eyes as wide open as he could get them, ready to take in the "swell dancing." He quickly realized that he had been fooled, and catching the word "religion" he shook his fist as he departed saying, "Religion! it's all d——d rot. There's nothing in it." The missioner was down the aisle in a few seconds, and as Jack was passing through the swinging doors a kindly hand was laid upon his shoulder, and a voice, made tender by acquaintance with the Friend of sinners, said "Good-night, friend; you have the marks of a gentleman although you have made a slip to-night. I hope you will come again."

Returning to the platform he continued his message, but it was easy to see that the speaker's heart was out in the night whereever Jack was. Was it that yearning that brought Jack back again in less than half an hour? Be that as it may, the man who had left with a curse, staggered in again before the closing hymn, and made not the slightest disturbance after he reached a seat. At the close he conversed in as intelligent a way as his intoxication permitted. The conversation need not be recorded. It was one of several. Five nights later, twenty minutes after the clock had made its lengthiest strike, a subdued knock was heard at the door of the home in which the missioner was being entertained. The burner of midnight oil hurried downstairs. Jack stood in the doorway. "Mr. Williams, I've got to settle it, and I've got to do it now." Two souls tarried in the upper room, and while they tarried He came. At last the broken cry ascended, "My Father, I want to get back to Thee. Help me to walk in the paths of righteousness, for Jesus' sake. Amen."

It was a great night for the fisher of men. Like the wearied disciples of old, he said "It is the Lord."

The following night, Jack Jr., Mamie and Grace accompanied their father to the service, and happily united their voices in the service of praise.

Grace—they called her "Gay," for that was the best pronunciation wee Jean, now departed, could once give—told several of her schoolmates confidentially in her mother's words, that she had a "new daddy." And the subsequent days have proven the truth of her assertion.

The closing night arrived. The Opera House was crowded, and from the opening words, "Our Father," until the "And now I commend you to God," every one present seemed to feel that this was no ordinary religious gathering. An opportunity was given for a word from new converts. Tenderly, prayerfully, these were urged to in some way publicly confess their new-found Lord. There was a hush as Jack stood erect. In a low, clear voice he addressed himself particularly to the half-hundred young men at the back. "I do not need to tell you what I was. Two weeks ago it would have been inconceivable to you and to me that the change I have experienced could take place. There is only One who could do it, and He has done it. I cannot say more now, but if you want to know all about it, come to me at the close of this service, or come to my home."

The eyes of the wife at his side were red again, but the tears were tears of joy. "It is very wonderful: we are all so happy. Oh, how glad I am that these services have been held," were her farewell words.

Jack's hand was the last one the missioner clasped. "Jack, you will be God's man. I go, but He remains. This change is all His doing, and He will hold you fast if you only trust Him. Many a day I'll pray for you, Jack. Remember that your feelings may change, but your purposes must endure. Good-bye."

"Good-bye, Mr. Williams; God helping me I won't fail. It'll be no easy business, but I'm not in the fight alone; God's in it too. Good-bye."

And the years that have passed since these words were spoken have shown clearly enough that Jack is not fighting alone. Once again prayerful hearts are returning thanks for the touch that "has still its ancient power."

George fell—all the people knew that was what would happen. When he told in the church that he was going, with God's help, to be a Christian and "act the square," there was only one at the close of the meeting to say an encouraging word to him; the rest left him alone. On the whole, they did not believe in "results" from Special Services, and, despite the Pastor's frequent appeals for their unprejudiced and whole-hearted support, none were enthusiastic over the effort being put forth, and many were antagonistic. In the opinion of the majority the regular, "well-ordered" Sabbath services gave ample opportunity for those who wanted to lead different lives, and so far as reaching the outsiders was concerned, the endeavour to invite personally the non-churchgoers was quite unnecessary—all such knew they were welcome, because the fact had been on the announcement board outside the church for over ten years.

The missioner was told on all sides what a notoriously untrustworthy man George was: "You see, we know his past, and you have been here only two weeks, or you'd know better than to put any faith in what he did and said last night. It was just a passing emotion, and it won't mean anything." So George fulfilled their expectations when he returned from the city uproariously drunk one night three weeks after the mission closed.

The morning following the outbreak the minister's wife made a special trip down street. The door of the carpenter's shop was fortunately open, and George was leaning against his bench looking, as he felt, far from happy. Pleasantly the little woman greeted him, and passed on. Then, with an exquisite piece of deception, she appeared to have a sudden after-thought, and turning quickly, she said, "Oh, George, the doors in the pantry cupboard are so swollen that I cannot close them. Could you fix them for me?"

The carpenter looked wearily at her. "I ain't feeling much like fixing anything, Mrs. Lamb, but I'd try to do most anything for you."

"Thank you, George," was the reply, "I believe you would; come as soon as you can."

George had said what was true; he believed in Mrs. Lamb, and what was still better, he felt that she believed in him. When, on the night of his confession, she took his hand and said, "I'm so glad, George," he valued her word and tone, and look and hand-clasp, as only the friendless man can.

But George was thoroughly disheartened to-day. Everybody knew what he had said in the meeting, and by now they would know that he had failed. Yet no one would blame him more than he blamed himself. He called himself a fool for going to the city. The business could have been done equally well by correspondence. From the time he decided to go he feared that he would return home intoxicated. He was quite aware of a terrible craving, that he knew only too well made it dangerous for him to frequent the old haunts so soon, but in spite of inner warnings he made up his mind to go, so that the battle was lost before the temptation was actually met.

Twice that afternoon George took up a few tools to go to the Manse in response to Mrs. Lamb's request, and twice he put them down again. The prison cell would have been entered with less fear than the Manse that day. He felt he had betrayed one of the best friends he ever had. And so night came, and the pantry doors were untouched.

Family prayers were about to be conducted at the Manse. Baby Jean was on mother's knee, and Harold's chair was close to father's. Just before kneeling the good wife said quietly: "Please remember George, papa." There were tears in her eyes when the petition was offered "for those who have failed," and a whispered "Amen" followed each clause that was uttered in behalf of George.

The following morning George made his way to the Manse and attended to the pantry doors. When the work was finished, Mrs. Lamb led the way through the dining-room to the front door. Her hand rested on the door-knob, and she seemed in no hurry to let George out. It was evident she wanted to say something, but the words did not easily come.

At last George broke the silence, and his voice quivered with penitence as he looked for a moment into Mrs. Lamb's sympathetic eyes. "I suppose you've heard all about it, Mrs. Lamb, and the mess I've made of things?"

"Yes, George, I know, and I'm so sorry; but you are going to win yet: God's going to help you win. Perhaps, George, you trusted too much in your own strength, and you forget how weak we all are when we stand alone. You know the hymn that says—'Christ will hold me fast'? You cannot get along without Him, George. Tell Him all about it, when you and He are alone, and ask forgiveness, and, George, I know God can and will make you a good, strong, true man; He loves you, and we love you."

"You are going to win yet," and "He loves you, and we love you," were sentences that gave the man, overtaken in a fault, new hope. Deep yearnings were in his heart as he walked back to the shop. He believed his better moments were his truest moments, and yet it seemed to him that no one except Mrs. Lamb credited him with noble aspirations. He knew very well that there were Christian people who were suspicious and unsympathetic toward him, and so his better nature seemed to retire in their presence.

Later on he told how he used to feel like saying, "Why won't you believe in me, and stand by me, and give me a fighting chance?" Often he felt like a man who had been injured, and who needed support until he could reach a place of safety; and yet few did more than look with disgust on him, and think it unlikely that he could make the journey without falling. But, despite his weakness and his sin, George believed there were possibilities of noble living even for him.

The following Sabbath he was back in his place in church, a humble, penitent man. The sermon that day was different from the ones the people were used to hearing; not that it was better, for all Mr. Lamb's sermons were of a high order, but it had an element that was unusual, an element of great tenderness. The text was: "Go, tell His disciples and Peter." Peter's past, traitorous conduct was graphically pointed out, but so also was his weeping. "We cannot think too harshly of our sins," said the preacher, "but we may think too exclusively of them. Peter thought of his sins, but he also thought of His Saviour, and when he saw his Risen Lord, the erring but penitent disciple said: 'Thou knowest that I love Thee,' and the Master forgave all and sent him out to service."

The God whom the Minister was accustomed to preach about was a splendid, strong, but rather pitiless Being; now they heard of a loving, pitiful Father who was ever seeking those who had turned from Him, and who was more than ready to receive them as they turned again home. All He wanted was to hear from their own lips, "Father, I have sinned." That confession opened Heaven's wardrobe for the man made disreputable by wandering.

At the close of the evening service George accepted Mrs. Lamb's invitation to "slip in and have a cup of cocoa." "Just the three of us," she added. "You know the way; walk right in." Hurriedly she passed on to give kindly greetings to a few strangers she had noticed.

For nearly two hours George and the Minister sat in the glow of the firelight. It was a great relief to the disheartened man to be with those who knew all, and who yet loved him, and who, by their faith in him, gave him a little more faith in himself and in God.

Referring to his drinking habit, he said, "Sometimes I feel I'd rather drop dead in my tracks than touch it again; and then there are other days when it seems as if some slumbering devil had awakened within me, and I'm so crazy for it that I'd give the whole of Canada, if I had it, for another drink." Then, after a pause, he continued, "I suppose a man shouldn't try to blame his sin on others, but one of the earliest things I can remember, Mr. Lamb, is being held in my mother's arms and putting my hands around the beer jug while she gave me a drink. Many a night, when I was 'knee-high to a grasshopper' as we say, I have clung to her skirt, as she dragged me from bar to bar, around High Street and George Street in old Glasgow. I guess my father and mother were drunk every Saturday night for five years. One night I can remember as clear as if it was only yesterday. It was the time of the Glasgow Fair, and I was wishing they'd go home. I must have been about six years old, and my sister Janet was two years younger, and then there was a baby they called Bobbie. Mother had Bobbie fastened around her with an old shawl. She and father had been on a spree all the evening. Father was leaning against a lamp-post, just drunk enough to say the fool things that amuse some of them folks who don't think anything about the big price somebody is paying for that kind of fun. Maybe you think it's queer of me to talk that way, when God knows I've been guilty enough myself. Well! let me finish my story, anyway. My mother was dead drunk, sitting on the curbstone near him, and maybe Bobbie was stupefied with liquor like I had been many a time. Once in a while she'd rouse up, and press her hands against her maddened head and shriek all kinds of curses. Police! why, Mr. Lamb, the Glasgow police couldn't have handled the crowds that was drunk them days. I've seen hundreds of drunken men and women in one night around Rotten Row and Shuffle Lane, and other streets near the corner of George and High Streets: so long as they didn't get too awful bad the police let them alone. Mother was a very devil when she got fighting. I've heard father brag about what she could do in that line. When she used to roll up her sleeves for a fight, she was like a maddened beast. I tell you, there isn't much in the fighting line I haven't seen; but it makes me kind of shudder yet when I think of how she'd punch, and kick, and scratch, and all the time she'd be using language that would make a decent man's blood run cold. You were saying something about 'sacred memories around the word "mother"' in one of your sermons, but that was the kind of mother I had, Mr. Lamb.