Title: Rules for a Dictionary Catalogue

Author: Charles A. Cutter

Release date: April 8, 2019 [eBook #59215]

Most recently updated: June 25, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by MWS, RichardW, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/rulesfordictiona00cuttuoft |

There are plenty of treatises on classification, of which accounts may be found in Edwards’s Memoirs of Libraries and Petzholdt’s Bibliotheca Bibliographica. The classification of the St. Louis Public School Library Catalogue is briefly defended by W. T. Harris in the preface (which is reprinted, with some additions, from the Journal of Speculative Philosophy for 1870). Professor Abbot’s plan is explained in a pamphlet printed and in use at Harvard College Library, also in his “Statement respecting the New Catalogue” (part of the report of the examining committee of the library for 1863), and in the North American Review for January, 1869. The plan of Mr. Schwartz, librarian of the Apprentices’ Library, New York, is partially set forth in the preface to his catalogue; and a fuller explanation is preparing for publication. For an author-catalogue there are the famous 91 rules of the British Museum [1] (prefixed to the Catalogue of Printed Books, Vol. 1, 1841, or conveniently arranged in alphabetical order by Th. Nichols in his Handbook for Readers at the British Museum, 1866); Professor Jewett’s modification of them (Smithsonian Report on the Construction of Catalogues, 1852); Mr. F. B. Perkins’s further modification (in the American Publisher for 1869), and a chapter in the second volume of Edwards. [2] But for a dictionary-catalogue as a whole, and for most of its parts, there is no manual whatever. Nor have any of the above-mentioned works attempted to set forth the rules in a systematic way or to investigate what might be called the first principles of cataloguing. It is to be expected that a first attempt will be incomplete, and I shall be obliged to librarians for criticisms, objections, or new problems, with or without solutions. {4} With such assistance perhaps a second edition of these hints would deserve the title—Rules. [3]

[1] Compiled by a committee of five, Panizzi, Th. Watts, J. Winter Jones, J. H. Parry, and E. Edwards, in several months of hard labor.

[2] To these may now be added: Condensed rules for an author and title catalogue, prepared by the co-operation committee, A. L. A. (printed in the Appendix of the present Rules); F: B. Perkins’s San Francisco cataloguing (1884); C: Dziatzko’s Instruction für die Ordnung der Titel im alphabetischen Zettelkatalog der Univ. Bibliothek zu Breslau (1886), of which an adaptation by Mr. K. A: Linderfelt will shortly be published; Melvil Dewey’s Condensed rules for a card catalogue, with 36 sample cards (published in the Library notes, v. 1, no. 2, 1886, and reprinted as “Rules for author and classed catalogs;” with changes, additions, and a “Bibliography of catalog rules” by Mary Salome Cutler, Boston, 1888, and again as “Library School rules,” Boston, 1889); G. Fumagalli’s Cataloghi di biblioteche (1887); H: B. Wheatley’s How to catalogue a library (1889); and various discussions in the Library journal, the Neuer Anzeiger, and the Centralblatt für Bibliothekswesen.

[3] In this second edition I have retained the discussions of principles of the first edition and added others, because it seems to me to be quite as important to teach cataloguers the theory, so that they can catalogue independently of rules, as to accustom them to refer constantly to hard and fast rules. The index, which will be published separately, has been enlarged so as to form an alphabetical or “dictionary” arrangement of the rules.

No code of cataloguing could be adopted in all points by every one, because the libraries for study and the libraries for reading have different objects, and those which combine the two do so in different proportions. Again, the preparation of a catalogue must vary as it is to be manuscript or printed, and, if the latter, as it is to be merely an index to the library, giving in the shortest possible compass clues by which the public can find books, or is to attempt to furnish more information on various points, or finally is to be made with a certain regard to what may be called style. Without pretending to exactness, we may divide dictionary catalogues into short-title, medium-title, and full-title or bibliographic; typical examples of the three being, 1º, the Boston Mercantile (1869) or the Cincinnati Public (1871); 2º, the Boston Public (1861 and 1866), the Boston Athenæum (1874–82); 3º, the author-part of the Congress (1869) and the Surgeon-General’s (1872–74) or least abridged of any, the present card catalogue of the Boston Public Library. To avoid the constant repetition of such phrases as “the full catalogue of a large library” and “a concise finding list,” I shall use the three words Short, Medium, and Full as proper names, with the preliminary caution that the Short family are not all of the same size, that there is more than one Medium, and that Full may be Fuller and Fullest. Short, if single-columned, is generally a title-a-liner; if printed in double columns, it allows the title occasionally to exceed one line, but not, if possible, two; Medium does not limit itself in this way, but it seldom exceeds four lines, and gets many titles into a single line. Full usually fills three or four lines and often takes six or seven for a title.

The number of the following rules is not owing to any complexity of system, but to the number of cases to which a few simple principles have to be applied. They are especially designed for Medium, but may easily be adapted to Short by excision and marginal notes. The almost universal practice of printing the shelf-numbers or the class-numbers renders some of them unnecessary for town and city libraries.

[4] Note to second edition. This statement of Objects and Means has been criticized; but as it has also been frequently quoted, usually without change or credit, in the prefaces of catalogues and elsewhere, I suppose it has on the whole been approved.

[5] Here the whole is designated by its most important member. The full name would be form-and-language entry. Kind-entry would not suggest the right idea.

among the several possible methods of attaining the OBJECTS.

Other things being equal, choose that entry

This applies very slightly to entries under first words, because it is easy and sufficient to arrange them by the alphabet.

There is such confusion in the use of terms in the various prefaces to catalogues—a confusion that at once springs from and leads to confusion of thought and practice—that it is worth while to propose a systematic nomenclature.

Strictly a book is not anonymous if the author’s name appears anywhere in it, but it is safest to treat it as anonymous if the author’s name does not appear in the title.

Note that the words are “in the title,” not “on the title-page.” Sometimes in Government publications the author’s name and the title of his work do not appear on the title-page but on a page immediately following. Such works are not anonymous.

Books are classified by bringing together those which have the same characteristics. [6] Of course any characteristics might be taken, as size, or binding, or publisher. But as nobody wants to know what books there are in the library in folio, or what quartos, or what books bound in russia or calf, or what published by John Smith, or by Brown, Jones, and Robinson, these bases of classification are left to the booksellers and auctioneers and trade sales. Still, in case of certain unusual or noted bindings, as human skin or Grolier’s, or early or famous publishers, as Aldus and Elzevir, a partial class-list is sometimes very properly made. But books are most commonly brought together in catalogues because they have the same authors, or the same subjects, or the same literary form, or are written in the same language, or were given by the same donor, or are designed for the same class of readers. When brought together because they are by the same author, they are not usually thought of as classified; they form the author-catalogue, and need no further mention here except in regard to arrangement. The classes, i. e., in this case the authors, might of course be further classified according to their nations, or their professions (as the subjects are in national or professional biographies), or by any other set of common characteristics, but for library purposes an alphabetical arrangement according to the spelling of their names is universally acknowledged to be the best.

The classification by language is not generally used in full. There are catalogues in which all the English books are separated from all the foreign; in others there are separate lists of French books or German books. The needs of each library must determine whether it is worth while to prepare such lists. It is undeniably useful in almost any library to make lists of the belles lettres in the different languages; which, though nominally a classification by language, is really a classification by literary form, the object being to bring together all the works with a certain national flavor—the French flavor, the German flavor, or it may be a classing by readers, the German books being catalogued together for a German population, the French for the French, and so on. Again, it is useful to give lists not of the belles lettres alone, but of all the works in the rarer languages, as the Bodleian and the British Museum have published separate lists of their Hebrew books. Here too the circumstances of each library must determine where it shall draw the line between those literatures which it will put by themselves and those which it will include and hide in the mass of its general catalogue. Note, however, that some of the difficulties of transliterating {10} names of modern Greek, Russian authors, etc., are removed by putting their original works in a separate catalogue, though translations still remain to puzzle us.

The catalogue by donors or original owners is usually partial (as those of the Dowse, Barton, Prince, and Ticknor libraries). The catalogues by classes of readers are also partial, hardly extending beyond Juvenile literature and Sunday-school books. Of course many subject classes amount to the same thing, the class Medicine being especially useful to medical men, Theology to the theologians, and so on.

Classification by subject and classification by form are the most common. An example will best show the distinction between them. Theology, which is itself a subject, is also a class, that is, it is extensive enough to have its parts, its chapters, so to speak (as Future Life, Holy Spirit, Regeneration, Sin, Trinity), treated separately, each when so treated (whether in books or only in thought) being itself a subject; all these together, inasmuch as they possess this in common, that they have to do with some part of the relations of God to man, form the class of subjects Theology. Class, however, is applied to Poetry in a different sense. It then signifies not a collection of similar subjects, but a collection of books resembling one another in being composed in that form and with that spirit, whatever it is, which is called poetical. In the subject-catalogue class it is used in the first sense—collection of similar subjects; in the form-catalogue it is used in the second—list of similar books.

Most systems of classification are mixed, as the following analysis of one in actual use in a small library will show:

| Art, science, and natural history. | Subj. |

| History and biography. | Subj. |

| Poetry. | Form (literary). |

| Encyclopædias and books of reference. | Form (practical). |

| Travels and adventures. | Subj. (Has some similarity to a Form-class.) |

| Railroads. | Subj. |

| Fiction. | Form. (Novels, a subdivision of Fiction, is properly a Form-class; but the differentia of the more extensive class Fiction is not its form, but its untruth; imaginary voyages and the like of course imitate the form of the works which they parody.) |

| Relating to the rebellion. | Subj. |

| Magazines. | Form (practical). |

| General literature, essays, and religious works. | A mixture: 1. Hardly a class; that is to say, it probably is a collection of books having only this in common, that they will not fit into any of the other classes; 2. Form; 3. Subj. |

Confining ourselves now to classification by subjects, the word can be used in three senses:

1. Bringing books together which treat of the same subject specifically.

That is, books which each treat of the whole of the subject and not of a part only.

2. Bringing books together which treat of similar subjects.

Or, to express the same thing differently:

Bringing subjects together so as to form a class.

A catalogue so made is called a classed catalogue.

3. Bringing classes together so as to form a system.

A catalogue so made should be called a systematic catalogue.

The three steps are then

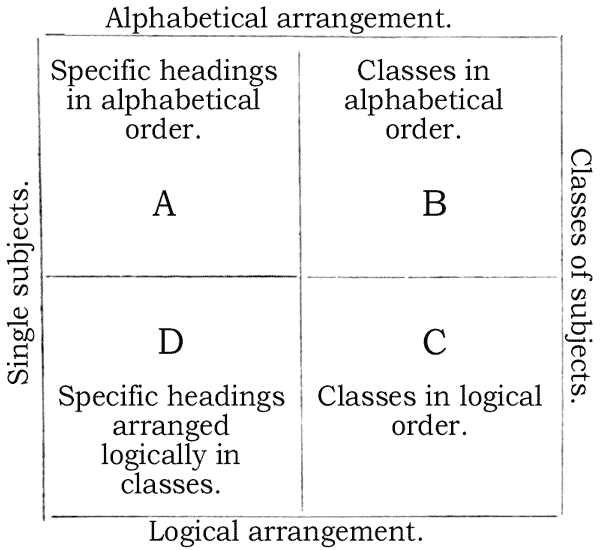

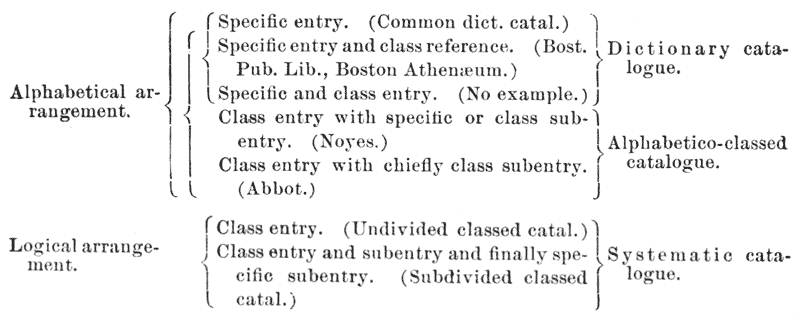

The dictionary stops in its entries at the first stage, in its cross-references at the second.

The alphabetico-classed catalogue stops at the second stage.

The systematic alone advances to the third.

Classification in the first sense, it is plain, is the same as “entry;” in the second {11} sense it is the same as “class-entry;” and in the third sense it is the same as the “logical arrangement” of the table on p. 12, under “Classed catalogue.”

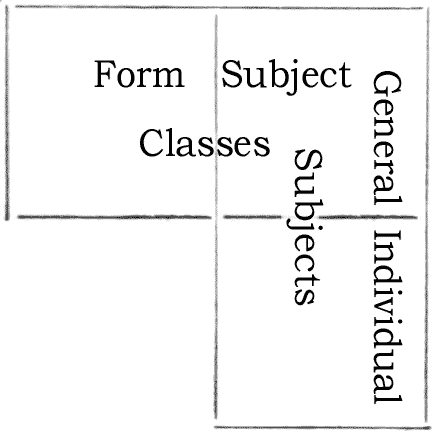

It is worth while to ascertain the relation of subject and class in the subject-catalogue. Subject is the matter on which the author is seeking to give or the reader to obtain information; Class is, as said above, a grouping of subjects which have characteristics in common. A little reflection will show that the words so used partially overlap, [7] the general subjects being classes [8] and the classes being subjects, [9] but the individual subjects [10] never being classes.

[6] This note has little direct bearing on practice, but by its insertion here some one interested in the theory of cataloguing may be saved the trouble of going over the same ground.

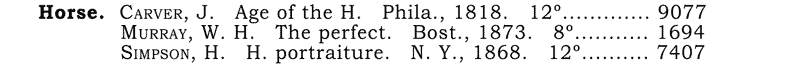

[8] The subjects Animals, Horses, Plants are classes, a fact which is perhaps more evident to the eye if we use the terms Zoology, Hippology, Botany. The subdivisions of Botany and Zoology are obvious enough; the subdivisions of Hippology may be themselves classes, as Shetland ponies, Arabian coursers, Barbs, or individual horses, as Lady Suffolk, Justin Morgan.

[9] Not merely the concrete classes, Natural history, Geography, Herpetology, History, Ichthyology, Mineralogy, but the abstract ones, Mathematics, Philosophy, are plainly subjects. The fact that some books treat of the subject Philosophy and others of philosophical subjects, and that others treat in a philosophical manner subjects not usually considered philosophical, introduces confusion into the matter, and single examples may be brought up in which it seems as if the classification expressed the form (Crestadoro’s “nature”) or something which a friend calls the “essence” of the book and not its subject, so that we ought to speak of an “essence catalogue” which might require some special treatment; but the distinction can not be maintained. It might be said, for example, that “Geology a proof of revelation” would have for its subject-matter Geology but for its class Theology—which is true, not because class and subject are incompatible but because this book has two subjects, the first Geology, the second one of the evidences of revealed religion, wherefore, as the Evidences are a subdivision of Theology, the book belongs under that as a subject-class.

[10] It is plain enough that Mt. Jefferson, John Milton, the Warrior Iron-clad are not classes. Countries, however, which for most purposes it is convenient to consider as individual, are in certain aspects classes; when by the word “England” we mean “the English” it is the name of a class.

E. g., a book on repentance has class entry under Theology; its specific entry would be under Repentance.

A dictionary catalogue contains class-headings, inasmuch as it contains the headings of extensive subjects, but under them there is no class entry, only specific entry. The syndetic dictionary catalogue, however, recognizes their nature by its cross-references, which constitute it in a certain degree an alphabetico-classed (not a systematic) catalogue. Moreover, the dictionary catalogue, without ceasing to be one, might, if it were thought worth while (which it certainly is not), not merely give titles under specific headings but repeat them under certain classes or under all classes in ascending series, e. g., not merely have such headings as Rose, Geranium, Fungi, Liliaceæ, Phænogamia, Cryptogamia, but also under Botany include all the titles which appeared under Rose, Geranium, etc.; provided the headings Botany, Cryptogamia, Fungi, etc., were arranged alphabetically. The matter may be tabulated thus:

The specific entries of A and the classes of B, though brought together in the same catalogues (the class-dictionary and the alphabetico-classed), simply stand side by side and do not unite, each preserving its own nature, because the principle which brings them together—the alphabet—is external, mechanical. But in D the specific entries and the classes become intimately united to form a homogeneous whole, because the principle which brings them together—the relations of the subjects to one another—is internal, chemical, so to speak.

Even the classed catalogues often have specific entry. Whenever a book treats of the whole subject of a class, it is specifically entered under that class. A theological encyclopædia is specifically entered under Theology, and theology is an unsubordinated class in many systems. The alphabetico-classed catalogues have specific entry in many more cases, because they have many more classes. Professor Abbot has such headings as Ink, Jute, Lace, Leather, Life-savers, Locks, Mortars, Perfumery, Safes, Salt, Smoke, Snow, Varnish, Vitriol. Mr. Noyes has scores of similar headings; but neither of them permits individual entry, which the dictionary-catalogue requires. The alphabetico-classed catalogue enters a life of Napoleon and a history of England under Biography and History; the dictionary enters them under Napoleon and England. This is the invariable and chief distinction between the two.

A cataloguer who should put “The insect,” by Michelet, under Entomology would be making a subject-entry; Duncan’s “Introduction to entomology” entered under the same head would be at once a subject-entry and a subject-word-entry.

Will the convenience of this word excuse the twist given to the meaning of τόπος in its formation? Polygraphic might serve, as the French use polygraphe for a miscellaneous writer; but it will be well to have both words,—polygraphic denoting (as now) collections of several works by one or many authors, polytopical denoting works on many subjects.

E. g., registering “The art of painting” under Painting, or a description of the cactus under Cactus. Putting them under Fine arts and Botany would be class-entry. “Specific entry,” by the way, has nothing to do with “species.”

It is worth noting that subjects are of two sorts: (1) the individual, as Goethe, Shakespeare, England, the Middle Ages, the ship Alexandra, the dog Tray, the French Revolution, all of which are concrete; and (2) general, as Man, History, Horse, Philosophy, which may be either concrete or abstract. Every general subject is a class more or less extensive. (See note on Class.) Some mistakes have also arisen from not noting that certain words, Poetry, Fiction, Drama, etc., are subject-headings for the books written about Poetry, Fiction, etc., and form-headings for poems, novels, plays, etc.

A title may be either the book’s name (as “&c.”) or its description (as “A collection of occasional sermons”), or it may state its subject (as “Synonyms of the New {15} Testament”), or it may be any two or all three of these combined (as description and subject, “Brief account of a journey through Europe;” name and description, “Happy thoughts;” name and subject, “Men’s wives;” all three, “Index of dates”).

Bibliographers have established a cult of the title-page; its slightest peculiarities are noted; it is followed religiously, with dots for omissions, brackets for insertions, and uprights to mark the end of lines; it is even imitated by the fac-simile type or photographic copying. These things may concern the cataloguer of the Lenox Library or the Prince collection. The ordinary librarian has in general nothing to do with them; but it does not follow that even he is to lose all respect for the title. It is the book’s name and should not be changed but by act of legislature. Our necessities oblige us to abbreviate it, but nothing obliges us to make additions to it or to change it without giving notice to the reader that we have done so. Moreover, it must influence the entry of a book more or less; it determines the title-entry entirely; it affects the author-entry (see § 3) and the subject-entry (see § 104). But to let it have more power than this is to pay it a superstitious veneration.

This is the bibliographic use of the word, sanctioned by the British Museum rules. That is, it is in this sense only that it applies to all the copies of an edition as it comes from the printer. But there is also a bibliopegic and bibliopolic use, to denote a number of pages bound together, which pages may be several volumes in the other sense, or a part of a volume or parts of several volumes. To avoid confusion I use “volume” in the present treatise as defined in the Rules of the British Museum catalogue, and I recommend this as the sole use in library catalogues, except in such phrases as 2 v. bd. in 1. which means 2 volumes in the bibliographical sense united by binding so as to form one piece of matter.

In the present treatise I am regarding the dictionary catalogue as consisting of an author-catalogue, a subject-catalogue, a more or less complete title-catalogue, and a more or less complete form-catalogue, all interwoven in one alphabetical order. The greater part, however, of the rules here given would apply equally to these catalogues when kept separate.

These rules are written primarily for a printed catalogue; almost all of them would apply equally to a card catalogue.

1. Make the author-entry under (A) the name of the author whether personal or corporate, or (B) some substitute for it.

In regard to the author-entry it must be remembered that the object is not merely to facilitate the finding of a given book by an author’s name. If this were all, it might have been better to make the entry under the professed name (pseudonym), or under the form of name mentioned in the title (Bulwer in one book, Lytton in another, Bulwer Lytton in a third; Sherlock, Th., in that divine’s earlier works; Bangor, Th. [Sherlock], Bp. of, in later ones; Salisbury, Th. [Sherlock], Bp. of, in the next issues; London, Th. [Sherlock], Bp. of, in his last works; Milnes, R. Monckton, for “Good night and good morning,” and the nine other works published before 1863, and Houghton, Rich. M. M., Baron, for the 1870 edition of “Good night and good morning,” and for other books published since his ennoblement), or under the name of editor or translator when the author’s name is not given, as proposed by Mr. Crestadoro. This might have been best with object A; but we have also object D to provide for—the finding of all the books of a given author—and this can most conveniently be done if they are all collected in one place.

2. Anonymous books are to be entered under the name of the author whenever it is known.

If it is not known with certainty the entry may be made under the person to whom the work is attributed, with an explanatory note and a reference from the first word, or the book may be treated as anonymous and entered under the first word, with a note “Attributed to ——,” and a reference from the supposed author. The degree of doubt will determine which method is best. {17}

3. Enter works written conjointly by several authors under the name of the one first mentioned on the title-page, with references from the others.

The writers of a correspondence and the participants in a debate are to be considered as joint authors.

Ex.

Schiller, J: Christoph F: v. Briefwechsel zwischen S. und Cotta; herausg. von Vollmar.

— Briefwechsel zw. S. und Goethe. Stuttg., 1829. 6 v. S.

— Briefwechsel zw. S. und W: v. Humboldt. Stuttg., 1830. S.

Cotta. Briefwechsel. See Schiller, J: C. F: v.

Goethe, J: W. v. Briefwechsel. See Schiller, J: C. F: v.

Humboldt, K: W:, Freiherr v. Briefwechsel. See Schiller, J: C. F: v.

Many catalogues adopt the form of heading

Schiller, J: Christoph F: v., and Humboldt, K: W:, Freiherr v. Briefwechsel. Stuttg., 1830. S.

Humboldt, K: W:, Freiherr v. Briefwechsel. See Schiller, J: C. F: v., and Humboldt, K: W: v. But see § 240.

When countries are joint authors it is better to make full entries under each and arrange them as if the country under consideration were the only one. Each country puts its own name first in its own edition of a joint work; and the arrangement proposed avoids an additional complexity under countries, which are confusing enough at the best.

Whether the joint authorship appears in the title or not should make no difference in the mode of entry; if one name appears on the title, that should be chosen for the entry; if none, take the most important.

4. When double headings are used distinguish between joint authors of one work and two authors of separate works joined in one volume. In the latter case, if there is no collective title, the heading should be the name of the first author alone and an analytical reference should be made from the second. (See § 58 b.)

Ex. “The works of Shelley and Keats” would be entered in full under Shelley (both names being mentioned in the title, but Shelley alone in the heading), and analytically (§ 127) under Keats. In such cases a double heading would often mislead.

5. For university theses or dissertations Dziatzko gives the following rules:

For universities where the old custom was kept up beyond 1750, as the Swedish, Rule I applies till the change was made. {18}

Where there are two respondents, neither specified as author, enter under the first, without reference from the second.

6. Enter pseudonymous works generally under the author’s real name, when it is known, with a reference from the pseudonym; but make the entry under the pseudonym, with a reference from the real name, when the writer is better known by the false name.

In the first edition this rule was without limitation, and I added the following note “One is strongly tempted to deviate from this rule in the case of writers like George Eliot and George Sand, Gavarni and Grandville, who appear in literature only under their pseudonyms. It would apparently be much more convenient to enter their works under the name by which alone they are known and under which everybody but a professed cataloguer would assuredly look first. For an author-catalogue this might be the best plan, but in a dictionary catalogue we have to deal with such people not merely as writers of books, but as subjects of biographies or parties in trials, and in such cases it seems proper to use their legal names. Besides, if one attempts to exempt a few noted writers from the rule given above, where is the line to be drawn? No definite principle of exception can be laid down which will guide either the cataloguer or the reader; and probably the confusion would in the end produce greater inconvenience than the present rule. Moreover, the entries made by using the pseudonym as a heading would often have to be altered. For a long time it would have been proper to enter the works of Dickens under Boz; the Dutch annual bibliography uniformly uses Boz-Dickens as a heading. No one would think of looking under Boz now. Mark Twain is in a transition state. The public mind is divided between Twain and Clemens. The tendency is always toward the use of the real name; and that tendency will be much helped in the reading public if the real name is always preferred in catalogues. Some pseudonyms persistently adopted by authors have come to be considered as the only names, as Voltaire (see § 23), and the translation Melanchthon. Perhaps George Sand and George Eliot will in time be adjudged to belong to the same company. It would be well if cataloguers could appoint some permanent committee with authority to decide this and similar points as from time to time they occur.”

I am now in favor of frequent entry under the pseudonym, with reference from the real name. I should recommend the pseudonym as heading in the case of any popular writer who has not written under his own name, provided he is known to the public chiefly by his pseudonym, and in the subject catalogue for any person who is so known. Examples are George Eliot, George Sand, Gavarni, Grandville, Cagliostro, Cham, Pierre Loti, Daniel Stern, in some doubtful cases a card catalogue might profitably make entry both under the real and the false name. This elastic practice will give a little more trouble to the cataloguer than a rigid rule of entry under the real name, but it will save trouble to those who use the catalogue, which is more important.

But entry should not be made under a pseudonym which is used only once or a few times; if the author writes also under his real name, if he is known to the contemporary public or in literary history under his real name, that is to be used for entry. It may sometimes happen that an author is well known under a pseudonym and afterwards is better known by his real name. In that case change the entries from the false to the real name. If any author uses two different pseudonyms enter under each the works written under it, with references both ways, and from the real name, until the real name becomes better known.

It is plain that this practice of entering under the best known name, whether real or false, puts an end to uniformity of entry between different catalogues, leads to inconsistency of entry in the same catalogue, and will often throw the cataloguer into perplexity to decide which name is best known; but for the last objection it must be remembered that the catalogue is made for the reader, not for the cataloguer, and {19} for the first two that references will prevent any serious difficulty; and in the few cases of nearly equal notoriety, double entry is an easy way out of the difficulty.

7. When the illustrations form a very important part of a work, consider both the author of the text and the designer—or in certain cases the engraver—of the plates to be author, and make a full entry under each. Under the author mention the designer’s name in the title, and vice versa.

Such works are: Walton’s Welsh scenery, with text by Bonney; Wolf’s “Wild animals,” with text by Elliot. Which shall be taken as author in the subject or form entry depends upon the work and the subject. Under Water-color drawings it would be Walton; under Wood-engravings, Wolf; under Wales and Zoölogy, the cataloguer must decide which illustrates the subject most, the writer or the artist. E. g., under Gothic Architecture Pugin is undoubtedly to be considered the author of his “Examples,” though “the literary part” is by E. J. Willson; for the illustrator was really the author and the text was subsidiary to the plates. It was to carry out Pugin’s ideas, not Willson’s, that the work was published.

8. The designer or painter copied is the author of engravings; the cartographer is the author of maps; the engraver in general is to be considered as no more the author than the printer. But in a special catalogue of engravings the engraver would be considered as author; in any full catalogue references should be made from the names of famous engravers, as Raimondi, Müller, Steinla, Wolle. An architect is the author of his designs and plans.

9. Enter musical works doubly, under the author of the words and also the composer of the music.

Short and Medium will generally enter only under the composer; Don Giovanni, for example, only under Mozart and not under Da Ponte. This economy especially applies to songs.

10. Booksellers and auctioneers are to be considered as the authors of their catalogues, unless the contrary is expressly asserted.

Entering these only under the form-heading Catalogues belongs to the dark ages of cataloguing. Put the catalogue of a library under the library’s name. (§ 56.)

11. Put the auctioneer’s catalogue of a public library under the name of the library, of a private library under the name of the owner, unless there is reason to believe that another person made it. In the latter case it would appear in the author catalogue under the maker’s name, and in the subject catalogue under the owner’s name.

12. Enter commentaries with the text complete under the author of the text and also under the author of the commentary, provided that is entitled “Commentary on * * *” and not “* * * with commentary.”

In a majority of cases this difference in the title will correspond to a difference in the character of the works and in the expectation of the public; if in any particular case the commentary preponderates in a title of the second of the forms above, a reference can be made from the commentator’s name. {20}

13. Enter a continuation or an index, when not written by the author of the original work but printed with it, under the same heading, with an analytical reference from its own author (§§ 164, 194); when printed separately, enter it under each author.

14. An epitome should be entered under the original author, with a reference from the epitomator.

Ex. “The boy’s King Arthur” under Sir Thomas Malory, with a reference from Sidney Lanier.

15. A revision should be entered under the name of the original author unless it becomes substantially a new work.

There will often be doubt on this point. To determine it, notice whether the revision is counted as one of the editions of the original work, and whether it is described on the title-page as the work of the original author or the reviser, and read and weigh the prefaces. Refer in all doubtful cases.

16. Excerpts and chrestomathies from a single author go under that author, with a reference from the excerptor if his introduction and annotations are extensive, or he has added a lexicon of importance.

Ex. Urlichs’ Chrestomathia Pliniana goes under Plinius, with a reference from Urlichs.

17. Enter concordances both under their own author and the author concorded. The latter entry, however, is to be regarded as a subject-entry.

Ex. Cleveland’s Concordance to the poetical works of Milton, Brightwell’s Concordance to Tennyson, Mrs. Furness’s Concordance to Shakespeare’s poems.

18. Reporters are usually treated as authors of reports of trials, etc. [11] Translators and editors are not to be considered as authors. [12] (But see References, § 60.)

[11] A stenographic reporter is hardly more an author than the printer is; but it is not well to attempt to make fine distinctions.

[12] A collection of works should be entered under the translator if he is also the collector (see § 59); but again if he translates another man’s collection it should be put under the name of the original collector; as Dasent’s “Tales from the North” is really a version of part of Asbjörnsen and Moe’s “Norske Folkeventyr” and belongs under their names as joint collectors, with a reference from Dasent.

19. Put under the Christian or forename:

a. Sovereigns or princes of sovereign houses. [13] Use the English form of the name except for Greeks and Romans. {21}

b. Persons canonized.

Ex. Thomas [a Becket], Saint.

c. Friars who by the constitution of their order drop their surname. Add the name of the family in parentheses and refer from it.

Ex. Paolino da S. Bartolomeo [J. P. Wesdin].

d. Persons known under their first name only, whether or not they add that of their native place or profession or rank.

Ex. Paulus Diaconus, Thomas Heisterbacensis.

Similarly are to be treated a few persons known almost entirely by the forename, as Michelangelo Buonarroti, Raffaello Santi (refer from Raphael), Rembrandt van Rhijn. Refer always from the family name.

e. Oriental authors, including Jewish rabbis whose works were published before 1700.

Ex. Abu Bakr ibn Badr. This rule has exceptions. Some Oriental writers are known and should be entered under other parts of their name than the first, as “Abu-l-Kasim, Khalaf ibn Abbas,” or under some appellation as “al-Masudi,” “at-Tabari.” Grässe’s “Lehrbuch einer allgemeinen Literärgeschichte” is a convenient guide in this matter; he prints that part of the name by which Arabic writers are commonly known in a heavier type than the rest.

In Arabic names the words of relationship Abu (father), Umm (mother), Ibn, Bin (son), Ahu (brother), though not to be treated as names by themselves, are yet not to be disregarded, as proposed by Dr. Dziatzko. They form a name in conjunction with the word following (e. g., Abu Bakr) and determine the alphabetical place of the entry. But the article al (changed by assonance to ad-, ar-, as-, at-, az-, according to the letter it precedes) is neglected (al-Masudi).

In all Oriental names the cataloguer must be careful not to take titles, as Emir, Bey, Pasha, Sri, Babu, Pundit, for names.

In regard to East Indian names, Dr. Feigl (Centralbl. f. Bibl., 4: 120) gives the rule: If there are two names, enter under the first, which is the individual name, with a reference from the second; if there are three, enter under the third, which is the family name, with a reference under the second.

[13] This must include Popes even before the acquisition and after the loss of the temporal power.

The direction “Use the English form of the name” was a concession to ignorance; when it was given, that form was almost alone employed in English books; since then the tone of literature has changed; the desire for local coloring has led to the use of foreign forms, and we have become familiarized with Louis, Henri, Marguerite, Carlos, Karl, Wilhelm, Gustaf. If the present tendency continues we shall be able to treat princes’ names like any other foreign names; perhaps the next generation of cataloguers will no more tolerate the headings William Emperor of Germany, Lewis XIV than they will tolerate Virgil, Horace, Pliny. The change, to be sure, would give rise to some difficult questions of nationality, but it would diminish the number of the titles now accumulated under the more common royal names.

20. Put under the surname:

a. In general, all persons not included under § 19.

In a few cases, chiefly of artists, a universally-used sobriquet is to be taken in place of the family or forename, as Tintoretto (whose real name was Giacomo Robusti). Similar cases are Canaletto (Antonio Canale and also B. Belotto), Correggio (Ant. Allegri), Garofalo (Benvenuto Piero Tisi), Il Sodoma (Giov. Ant. Bazzi), Spagnoletto (José Ribera), Uccello (Paolo Doni). Always refer from the family name.

b. In particular, ecclesiastical dignitaries. Refer.

Ex.

Kaye, John, Bishop of Lincoln.

Lincoln, John, Bishop of. See Kaye.

Bishops usually omit their family name, canons their forename, on their title-pages, as “by Canon Liddon,” “by the Bishop of Ripon,” “by Henry Edward, archbishop of Westminster,” i. e., H: E: Manning. Care must be taken not to treat Canon as a forename or Edward as a family name. {22}

c. Married women, using the last well-known form. Refer.

Wives often continue writing, and are known in literature, only under their maiden names (as Miss Freer or Fanny Lewald), or after a second marriage retain for literary purposes the first husband’s name. The cataloguer should not hurry to make a change in the name as soon as he learns of a marriage. Let him rather follow than lead the public.

21. Put under the title:

British [14] and foreign [15] noblemen, referring from earlier titles by which they have been known, and, in the case of British noblemen, from the family name.

Ex.

Chesterfield, Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of. Refer from Stanhope.

Saint-Simon, Louis de Rouvroi, duc de.

[14] The British Museum and Mr. Jewett enter British noblemen under the family name; Mr. Perkins prefers entry under titles for British noblemen, in which I agree with him, although the opposite practice is now so well established. The reasons for entry under the title are that British noblemen are always so spoken of, always sign by their titles only, and seldom put the family name upon the title-pages of their books, so that ninety-nine in a hundred readers must look under the title first. The reasons against it are that the founders of noble families are often as well known—sometimes even better—by their family name as by their titles (as Charles Jenkinson afterwards Lord Liverpool, Sir Robert Walpole afterwards Earl of Orford); that the same man bears different titles in different parts of his life (thus P. Stanhope published his “History of England from the peace of Utrecht” as Lord Mahon, and his “Reign of Queen Anne” as Earl Stanhope); that it separates members of the same family (Lord Chancellor Eldon would be under Eldon and his father and all his brothers and sisters under the family name Scott), and brings together members of different families (thus the earldom of Bath has been held by members of the families of Shaunde, Bourchier, Granville, and Pulteney, and the family name of the present Marquis of Bath is Thymne), which last argument would be more to the point in planning a family history. The same objections apply to the entry of French noblemen under their titles, about which there can be no hesitation. The strongest argument in favor of the Museum rule is that it is well-established and that it is desirable that there should be some uniform rule. Ecclesiastical dignitaries stand on an entirely different footing. There is much more use of the family name and much more change of title. In the first edition I followed the British Museum rules, but I am now in favor of the more popular method of entry of noblemen, namely, under their titles, except when the family name is decidedly better known (Francis Bacon, Baron Verulam, Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford). In such cases enter under the family name and refer from the title. This rule was adopted by the committee of the American Library Association (Lib. jnl., 3: 12–19; 8: 251–254). The reasons pro and con were discussed in Lib. jnl., 3: 13, 14. The gist of them is: “Authors should be put under their names. The definition of a name is ‘that by which a person or thing is known.’ British noblemen are known by their titles, not by their family names.”

[15] Put the military nobles and princes of the French Empire under their family names, with references from their titles, e. g., Lucien Bonaparte, Prince de Canino, MacMahon, duc de Magenta.

22. Put the works of authors who change their name under the latest form, provided the new name be legally and permanently adopted.

Do not worry about the proper form of changed and transliterated names, nor spend much time in hunting up facts and deciding. If the necessary references are made, it is of little importance which form is chosen for the main entry, provided, of course, that the library always chooses the same heading.

If the change consist in the addition of a name the new name is to be treated by the next rule. {23}

23. Put compound names:

a. If English, under the last part of the name, when the first has not been used alone by the author.

Ex. Gould, Sabine Baring-; but Halliwell (afterwards Halliwell-Phillipps), J. O., because the author wrote much under the first name.

This rule secures uniformity; but, like all rules, it sometimes leads to entries under headings where nobody would look for them. Refer.

b. If foreign, under the first part.

Both such compound names as Gentil-Bernard and such as Gentil de Chavagnac. There are various exceptions, when a name has been more known under the last part, as Fénelon, not Salignac de Lamothe Fénelon; Voltaire, not Arouet de Voltaire; Sternberg, not Ungern-Sternberg. Moreover, it is not always easy to determine what is a compound surname in French. A convenient rule would be to follow the authority of Hœfer (Biog. gén.) and Quérard, in such cases, if they always agreed; unfortunately, they often differ. References are necessary whichever way one decides each case, especially when the second part of a foreign compound name has been used alone, as Merle d’Aubigné (enter under Merle with a reference from Aubigné).

In French a forename is sometimes joined to a surname by a hyphen. In such cases make the entry under the family name with a reference from the forename, e. g., entry, Rochette, Désiré Raoul; reference, Raoul-Rochette. See Rochette.

c. In foreign compound names of women also, although the first part is generally the maiden name and the second the husband’s name, the entry should generally be under the first, with a reference from the second. (See 20, c.)

Ex. Rivé-King, with cross-reference from King, born Rivé.

24. Put surnames preceded by prefixes:

a. In French, under the prefix when it is or contains an article, Le, La, L’, Du, Des; under the word following when the prefix is a preposition, de, d’.

When the name is printed by the author as one word the entry is made under the preposition, as Debucourt, Decamps.

b. In English, under the prefix, no matter from what language the name is derived, as De Quincey, Van Buren, with references when necessary.

c. In all other languages, under the name following the prefix, as Gama, Vasco da. with references whenever the name has been commonly used in English with the prefix, as Del Rio, Vandyck, Van Ess.

But when the author prints his name as one word entry is made under the prefix, as Vanderhaeghen.

d. Naturalized names are to be treated by the rules of the nation adopting them.

Thus German names preceded by von when belonging to Russians are to be entered under Von. E. g., Фонь Визин is to be entered as Von Vizin (not Vizin, von), as this is the Russian custom. So when Dutch names compounded with van are adopted into French or English (as Van Laun) the Van is treated as part of the family name.

Prefixes are d’, de, de La (the name goes under La not de), Des, Du, L’, La, Le, Les, St., Ste. (to be arranged as if written Saint, Sainte), Van, A’, Ap, O’, Fitz, Mac (which is to be printed as it is in the title, whether M’, or Mc, or Mac, but to be arranged as if written Mac). {24}

25. Put names of Latin authors under that part of the name chosen in Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography, unless there is some good reason for not doing so.

26. Put names of capes, lakes, mountains, rivers, forts, etc., beginning with Cape, Lake, Mt., etc., under the word following the prefix, but when the name is itself used as a prefix, do not transpose Cape, etc., nor in such names as Isle of the Woods, Isles of Shoals.

Ex. Cod, Cape; George, Lake; Washington, Mt.; Moultrie, Fort; but Cape Breton Island. When the name of a fort becomes the name of a city, of course the inversion must be abandoned, as Fort Wayne.

27. Give the names, both family and Christian, in the vernacular form, [16] if any instance occurs of the use of that form in the printed publications of the author. [17]

[16] The vernacular form of most Christian names may be found in Michaelis’s “Wörterbuch der Taufnamen” (Berlin, 1856). There are also meagre lists in foreign dictionaries. For the forms of mediæval names much assistance can be had from A. Potthast’s “Bibliotheca historica medii aevi, Berlin, Weber, 1862,” O, and “Supplement, 1868,” O; also from Alfred Franklin’s “Dictionnaire des noms, surnoms, et pseudonymes latins de l’histoire littéraire du Moyen Age (1100 à 1530), Paris, 1876,” O. (On the names of sovereigns, see § 19; on the Latin names of Greek authors, see § 36; on the names of Greek gods, see § 100.)

[17] This is the British Museum rule. It will obviously be sometimes impossible and often difficult to determine this point in a library of less extent than the Museum, and the cataloguer must make up his mind to some inconsistency in his treatment of mediæval names, and be consoled by the knowledge that if proper references are made no harm will be done. Against a too great preference for the vernacular Professor De Morgan writes in the preface to his “Arithmetical books:” “I have not attempted to translate the names of those who wrote in Latin at a time when that language was the universal medium of communication. I consider that the Latin name is that which the author has left to posterity, and that the practice of retaining it is convenient, as marking, to a certain extent, the epoch of his writings, and as being the appellation by which his contemporaries and successors cite him. It is well to know that Copernicus, Dasypodius, Xylander, Regiomontanus, and Clavius were Zepernik, Rauchfuss, Holtzmann, Müller, and Schlüssel. But as the butchers’ bills of these eminent men are all lost, and their writings only remain, it is best to designate them by the name they bear on the latter rather than the former.”

The same may be said of Camerarius (Kämmerer), Capito (Kopflein), Mercator (Kramer), Œcolampadius (Hausschein), where it would be useless to employ the vernacular name; if both forms are in use, as in the case of Pomeranius = Bugenhagen, the vernacular should have the preference. Reuchlin is much more common than its equivalent, Capnio.

Before the Reformation the presumption is in favor of the Latin form; after it in favor of the vernacular.

Short will consult the convenience of his readers if he uses the English forms of names like Homer, Horace, Virgil, in place of Homerus, Horatius, Vergilius.

The vernacular names of the Middle Ages often appear in various forms. The form which has survived to the present time is to be preferred (as Jean to Jehan), unless a name is commonly used in the old form, as in the romances Jehan de Lançon. Refer from the one not chosen.

28. If an author has written in several modern languages, choose that in which he has written most.

29. In languages which use a masculine and a feminine form of family names (as Modjeski and Modjeska), use that which the authoress herself chiefly employs.

30. When an author’s name is variously spelled, select the best authorized form as heading, add the variants in parentheses, and make references from them to the form adopted.

Of course, great care must be taken not to enter separately works in which an author spells his name differently, as Briant and Bryant, Easterbrookes and Estabrook, Erdmann and Erdtmann. On the other hand, different people who spell their names differently should be separated, as Hofmann and Hoffmann, Maier, Mair, Majer, Mayer, Mayr, Meier, Meir, Mejer, Meyer, Meyr, Schmid, Schmidt, Schmied, Schmiedt, Schmit, Schmitt. (On the arrangement of such names in a card catalogue see § 218.)

In German Christian names there is a want of uniformity in the use of C and K (Carl, Conrad, Karl, Konrad) and f and ph (Adolf, Adolph). Occasionally an author uses both forms in different books, or writing only in Latin (Carolus, Rudolphus), does not show which form he prefers. Where the author thus leaves the point undecided, K and f should be preferred to C and ph (except in Christoph). Swedish f is to be preferred to v, as Gustaf, not Gustav.

31. When family names are written differently by different persons, follow the spelling adopted by each, even though it should separate father and son.

32. Forenames are to be used in the form employed by their owners, however unusual, as Will Carleton, Sally (Pratt) McLean, Hans Droysen, Fritz Reuter.

33. Give names of places in the English form.

Munich not Muenchen or München, Vienna not Wien, Austria not Oesterreich.

34. But if both the English and the foreign forms are used by English writers, prefer the foreign form.

35. Use the modern name of a city and refer to it from the ancient, provided its existence has been continuous and there is no doubt as to the identity.

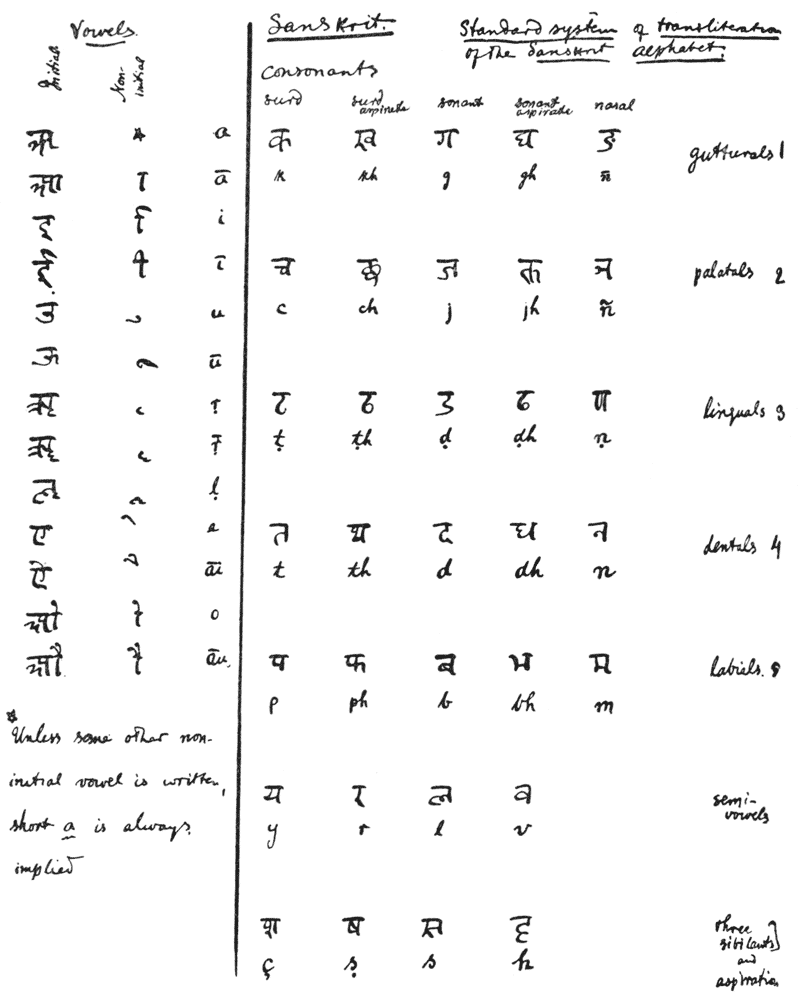

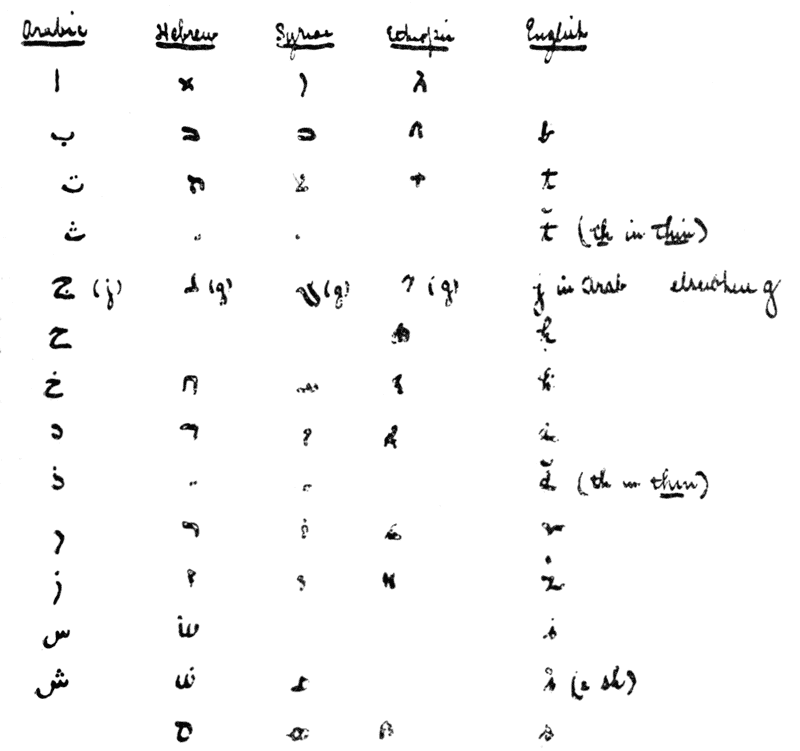

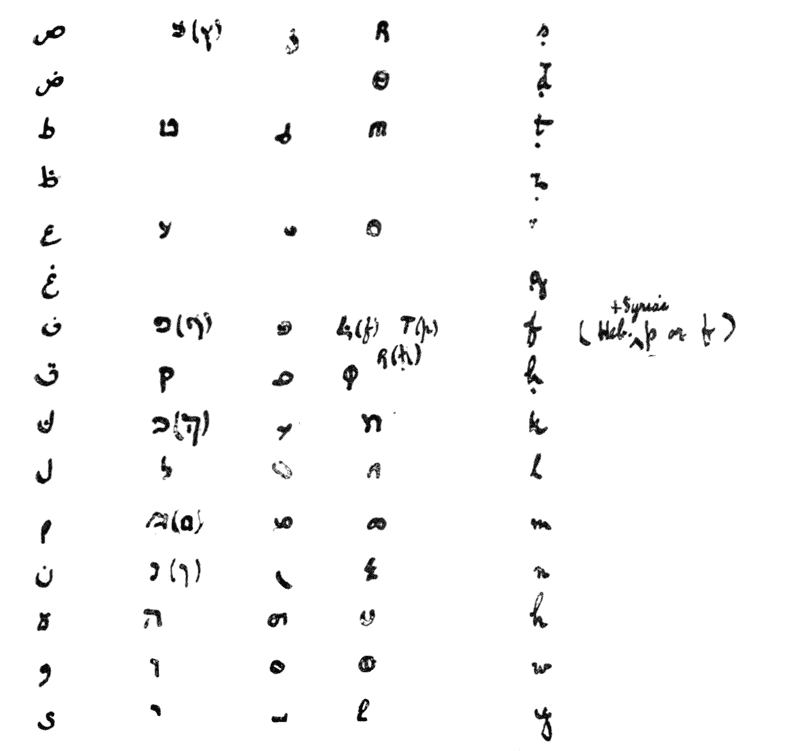

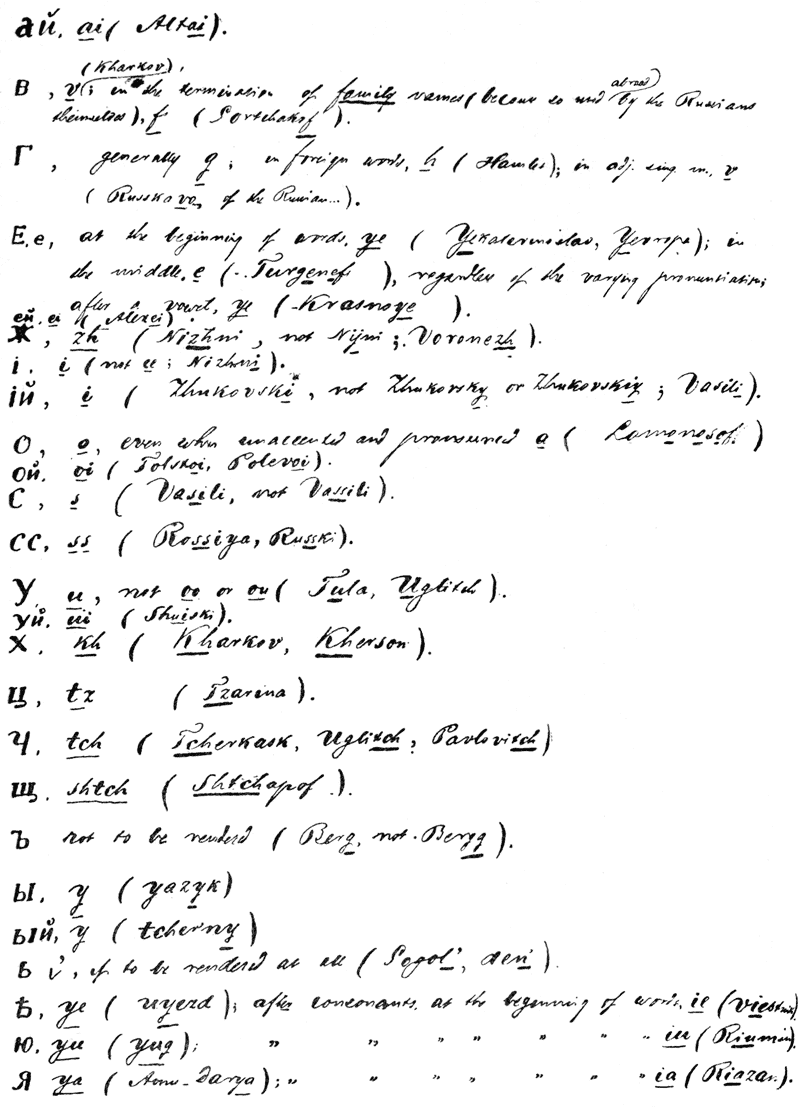

36. In transliteration of names from alphabets of differently formed letters, use the vowels according to their German sounds. (See Appendix II for the report of the Transliteration Committee of the American Library Association.)

I. e., a (not ah) for the sound of a in father, e (not a) for the sound of e in heir or of a in hate, i (not e) for the sound of i in mien, u (not oo nor ou) for the sound of u in true or of oo in moon. This practice makes transliterations that are likely to be pronounced in the main correctly by anyone who knows any language but his own (who would naturally give foreign vowel sounds to foreign names), and will give transliterations agreeing at least in part with those of other nations. In some points, however, we must be careful not to be misled by the practice of foreigners, and when we take a name from Russian, for instance, through the French or German, must see to it that the necessities of their alphabet have not led them to use letters that do not suit our system. A Frenchman writes for Turgenief Tourguénef, and for Golovin {26} Golovine, and uses ou for u, ch for sh, dj for j, j for zh, gu for g, and qu for k. A German for Dershavin writes Derschawin, and, worse than that, is obliged to use the clumsy dsch where an Englishman can use j, as Dschellaleddin for Jalal-ad-Din, and uses tsch for ch or tch, j for y or i (Turgenjew), w for v or f in the ending of Russian names.

In Arabic names I am advised by good scholars to uniformly write a where our ordinary Anglicized names have e, except for Ebn and Ben, which become Ibn and Bin; also i for ee, and u where o has been commonly used; in other words, to uniformly represent the vowel fatha by a, kasra by i, and dhamma by u. Thus Mohammed becomes Muhammad, Abou ed-Deen becomes Abu ad-Din. Of course references must be made from the corrupt forms under which various Arabic authors have become known in the West, unless it is thought that the altered form has been so commonly used that it must be taken for the entry, as perhaps Avicenna from Ibn Sina, Averroes from Ibn Roshd.

In Danish names if the type å is not to be had, use its older equivalent aa; in a manuscript catalogue the modern orthography, å, should be employed. Whichever is chosen should be uniformly used, however the names may appear in the books. The diphthong æ should not be written ae, nor should ö be written oe; ö, not œ, should be used for ø.

In old Dutch names write y for the modern ij and arrange so.

In German names used as headings, use ä, ö, ü, not ae, oe, ue, and arrange accordingly.

For ancient Greek names use the Latinized form, as Democritus not Demokritos, Longinus not Logginos. This holds good of translated works as well as of the originals. It will not do to enter an Italian version of the Odyssey under Omero, or of the Euterpe under Erodoto, or a French version of the Noctes Atticæ under Aulu-Gelle. A college literary catalogue may safely use the more nearly transliterated forms which are coming into use, like Aiskulos, Homeros, but used in a town-library catalogue they would only puzzle and mislead its readers. For that I should prefer the English forms, as Homer, Horace.

For modern Greek names Professor Abbot proposes the following plan: Works in Romaic to be entered in a supplement, the names not transliterated but printed in the Greek type. Translations of works of modern Greek authors to be put under their Greek names in the supplement, with references in the main catalogue under the forms (whatever they may be) which their names assume in the translation. Original works written in French, German, English, etc., by modern Greek authors may be treated in the same way if their authors have not become French, German, or English by residence and literary labors, in which case they should be entered under the French, German, or English forms which they have chosen for their names, with cross-references, if necessary, from the Greek supplement to these names. If, however, transliteration is attempted the following table of equivalents may be used:

| αι | æ |

| αυ | av |

| ει | ei |

| ευ | ev |

| η | i |

| ηυ | iv |

| οι | œ |

| υ | y |

| υι | yi |

| β | v |

| γ | gh |

| γ before κ, γ, χ, ξ | n |

| δ | dh |

| κ after γ | g |

| ξ | x |

| ου | u |

| ρ | r |

| χ | kh |

When Hindus themselves transliterate their names, use their form, whether or not according to our rules. (Appendix II.)

In Hungarian names write ö, ü, with the diæresis (not oe, ue), and arrange like the English o, u.

In Spanish names use the modern orthography i and j rather than the ancient y and x.

In Swedish names ä, å, ö, should be so written (not ae, oe), and arranged as the English a, o.

Ballhorn’s Grammatography (London, 1861) will be found very useful on such points. {27}

37. When an author living in a foreign country has transliterated his name according to the practice of that country and always uses it in that form, take that as the heading, referring from the form which the name would have under § 36; but if he has written much in his own language, use the English transliterated form.

Ex. Bikelas, Demetrius, with reference from Vikelas, Dmitri.

38. If a name which would properly be spelled by the English alphabet has been transliterated into a foreign alphabet, refer from the foreign form.

Ex. Šifner. See Schiefner.

39. Bodies of men are to be considered as authors of works published in their name or by their authority.

The chief difficulty with regard to bodies of men is to determine (1) what their names are, and (2) whether the name or some other word shall be the heading. In regard to (2) the catalogues hitherto published may be regarded as a series of experiments. No satisfactory usage has as yet been established. Local names have always very strong claims to be headings; but to enter the publications of all bodies of men under the places with which the bodies are connected is to push a convenient practice so far that it becomes inconvenient and leads to many rules entirely out of harmony with the rest of the catalogue.

40. Enter under places (countries, or parts of countries, cities, towns, ecclesiastical, military, or judicial districts) the works published officially by their rulers (kings, [18] governors, mayors, prelates, generals commanding, courts, [19] etc.). Refer from the name of the ruler.

[18] Of course this does not affect works written privately by kings, etc., as K. James’s “Counterblast.”

[19] The relation of courts to judicial districts is a little different from the others, but it is convenient to treat them alike. The opinion of a single judge should be entered under his name.

Ex.

UNITED STATES. Supreme Court. Opinions of the judges in the case of Smith vs. Turner, etc.

TANEY, Roger Brooke. Decision in the Merryman case.

41. Similarly Congress, Parliament, and other governmental bodies are authors of their journals, acts, minutes, laws, etc.; and other departments of government of their reports, and of the works published by them or under their auspices.

These are to be entered under the name of the country, city, or town, and not in the main alphabet under the word Congress, Parliament, City Council, or the like.

42. Laws on one or more particular subjects, whether digested or merely collected, must have author-entries both under the name of the country and under the name of the collector or digester.

Ex. Tilsley’s “Digest of the stamp acts” would appear both under Great Britain and Tilsley. {28}

43. Calendars of documents, regesta, etc., are to be entered under their maker, with a series-entry under the department which orders the publication.

Ex. Green, Mrs. M.. Anne Everett (Wood). Calendar of state papers, domestic, Charles II. The series-entry is under Great Britain. Master of the Rolls.

44. Works written officially are to be entered under the name of the department of government or society (see § 56) or ecclesiastical district with a reference from the name of the official, if it is thought worth making.

Some libraries may refer always; most will refer only when the report has exceptional importance (1) from its subject, (2) from the treatment of its subject, (3) from its literary merits, (4) from the fame of its author, or (5) from having been separately published. Horace Mann’s reports, for example, should be catalogued under Massachusetts. Board of Education, to which heading a reference should be made from Mann. Presidents’ messages should appear under United States. President. Proclamations and all other official writings of kings should appear under the name of the country (division King or Crown), arranged by reigns, as,

| Great

Britain. Crown. |

United

States. President. |

| Charles I. | Buchanan. |

| Charles II. | Lincoln. |

| James II. | Johnson. |

| William and Mary. | Grant. |

45. In the entry of Government publications, use for a subdivision the name of the office rather than the title of the officer, i. e., Ministère de la Marine, not Ministre de la Marine, Registry of Deeds, not Register of Deeds. [20] The individual name of the occupant of the office for the time being may be added in parenthesis to the name of the office; [21] and it should be so added when the publication has an individual character.

[20] There are cases, however, where the title of the officer is the only name of the office, as Illinois. State Entomologist.

[21] Great Britain. Crown, 1377–99 (Richard II). A roll, etc.

46. Messages of a superior executive officer (as President or Governor) transmitting to a legislative body or to some higher executive officer the report of some inferior officer should be entered as the report of the inferior officer, provided the message is merely introductory and contains no independent matter; provided, also, there are not three or more reports; if there are, the higher officer is to be regarded as the collecting editor (§ 59, d); in this case refer analytically to the superior officer’s official title from all the inferior officers whose reports are so transmitted.

47. “Articles to be inquired of” in ecclesiastical districts should go under the name of the district; but episcopal charges are not to go under the name of the bishopric unless they relate especially to its affairs, in which case they will have a subject-entry.

Ex. York, Archdeaconry of. Articles to be enquired of within the A. of Y. {29}

48. Reports made to a department, but not by an official, are to be entered under the department, with either an entry, reference, or analytical under the author as circumstances require.

Gould’s “Mollusca and shells” and Cassin’s “Mammalogy and ornithology of the United States Exploring Expedition under Wilkes” are of this nature; so is “Memorial ceremonies at the graves of our soldiers, collected under authority of Congress, by Frank Moore.” (Compare § 43.)

49. Enter congresses of several nations under the name of the place of meeting (as that usually gives them their name), with references from the nations taking part in them and from any name by which they are popularly known.

Ex. The Congress of London, of Paris, of Verona.

50. Enter treaties under the name of each of the contracting parties, with a reference from the name of the place, when the treaty is commonly called by that name, and from any other usual appellation.

Ex. Treaty of Versailles, Barrier treaty, Jay’s treaty.

51. Enter the official publications of any political party [22] or religious denomination or order, [23] or military order, under the name of the party, or denomination, or order. [24]

[22] Platforms, manifestoes, addresses, etc., under Democratic Party, Republican Party, etc.

[23] Confessions of faith, creeds, catechisms, liturgies, breviaries, missals, hours, offices, prayer books, etc., under Baptists, Benedictines, Catholic Church, Church of England, etc.

[24] That part of a body which belongs to any place should be entered under the name of the body, not the place; e. g., Congregationalists in New England, Congregationalists in Massachusetts, not New England Congregationalists, Massachusetts Congregationalists. But references must be made from the place (indeed in cases like Massachusetts Convention, Essex Conference, it may be doubted whether those well-known names should not be the headings). It is to be noticed this rule is just the reverse of the one given under Subjects, § 97. Single churches have usually been entered under the place, a practice which arose in American catalogues from our way of naming churches “The First Church in ——,” “The Second Church in ——,” etc., and applies very well to a majority of English churches, whose name generally includes the name of the parish. It is more in accordance with dictionary principles to limit the local entry of churches to First Church, etc., and those which have only the name of the town or parish, and to put all others (as St. Sepulchre’s, St. Mary Aldermansbury) under their names, as they read, and to treat convents and monasteries in the same way. (See § 56, Rule 2.) Of course the parishes of London (as Kensington, Marylebone, Southwark), like the parts of Boston (Dorchester, Roxbury, etc.), or of any other composite city, will be put under their own names, not under the name of the city.

52. Enter reports, journals, minutes, etc., of conventions, conferences, etc., under the names of the bodies holding the conferences, etc. When the body has no exact name [25] enter under the name of the place of meeting. [26]

[25] Some conventions are held by bodies which have no existence beyond the convention. If, however, they have a definite name, use that; ex., 4th National Quarantine {30} and Sanitary Convention. Often the name is given in different forms. Select that which appears to be the most authentic, and make references from the others.

[26] In any case it is well to refer from the name of the place, and in the case of Presidential conventions it is indispensable.

Put the convention of a county or other named district under the name of the district, with a reference from the town in which it is held, when it is named in the title-page.

53. Enter ecclesiastical councils, both general and special, under the name of the place of meeting. (The Vatican Council under Vatican, not Rome.) Refer from the name of the ecclesiastical body.

54. Enter reports of committees under the name of the body to which they belong; but reports of “a committee of citizens,” etc., not belonging to any named body should be put under the name of the writer, if known, if not, of the chairman, or if that is not given, of the first signer, or if not signed, under the name of the place.

55. Put the anonymous publications of any class (not organized) of citizens of a place under the place.

Ex. “Application to Parliament by the merchants of

London” should go under

London.

Merchants.

56. Societies are authors of their journals, memoirs, proceedings, transactions, publications. (On publishing-societies, see B. Substitutes, § 59, e.)

The chief practices in regard to societies have been to enter them (1. British Museum) under a special heading—Academies—with a geographical arrangement; (2. Boston Public Library, printed catalogue) under the name of the place where they have their headquarters; (3. Harvard College Library and Bost. Pub. Lib., present system) under the name of the place, if it enters into the legal name of the society, otherwise under the first word of that name not an article; (4. Boston Athenæum) English societies under the first word of the society’s name not an article, foreign societies under the name of the place. Both 3 and 4 put under the place all purely local societies, those whose membership or objects are confined to the place. The 1st does not deserve a moment’s consideration; such a heading is out of place in an author-catalogue, and the geographical arrangement only serves to complicate matters and render it more difficult to find any particular academy. [27] The 2d is utterly unsuited to American and English societies. The 3d practice is simple; but it is difficult to see the advantage of the exception which it makes to its general rule of entry under the society’s name; the exception does not help the cataloguer, for it is just as hard to determine whether the place enters into the legal name as it is to ascertain the name; it does not help the reader, for he has no means of knowing whether the place is part of the legal name or not. The 4th is simple and intelligible; it is usually easy for both cataloguer and reader to determine whether a society is English or foreign. I shall mention two other possible plans, well aware that there are strong objections to both.

5TH PLAN. Rule 1. Enter academies, [28] associations, institutes, universities, societies, libraries, galleries, museums, colleges, and all similar bodies, and churches that {31} have an individual name, both English and foreign, according to their corporate name, neglecting an initial article when there is one.

Exception 1. Enter the universities and the royal academies of Berlin, Göttingen, Leipzig, Lisbon, Madrid, Munich, St. Petersburg, Vienna, etc., and the “Institut” of Paris, under those cities. An exception is an evil. This one is adopted because the universities and academies are almost universally known by the names of the cities, and are hardly ever referred to by the name Königliche, Real, etc.

Exception 2. Enter London guilds under the name of the trade; e. g., “Stationers’ Company,” not “Master and Keepers or Wardens and Commonalty of the Mystery and Art of Stationers of the City of London,” which is the corporate title. This exception is adopted because (1) it gives a heading easier to find, and (2) it would be difficult in many cases to ascertain the real names of the London companies.

Exception 3. Enter bodies whose legal name begins with such words as Board, Corporation, Trustees under that part of the name by which they are usually known.

E. g. Trustees of the Eastern Dispensary. Corporation of the Chamber of Commerce in the City of New York. Proprietors of the Boston Athenæum. Contributors to the Asylum for the Relief of Persons deprived of their Reason. Refer from the first word of the legal name.

Exception 4. Enter orders of knighthood under the significant word of the English title; as, Garter, Order of the; Malta, Knights of; Templars, Knights; Teutonic Order.

Exception 5. Enter American State historical and agricultural societies under the name of the State.

Rule 2. a. Enter churches which have no individual name and all purely local benevolent or moral or similar societies under the name of the place.

b. Young men’s Christian associations, mercantile library associations, and the like are to be considered local.

c. Business firms or corporations (except national banks numbered as First National Bank, etc.), libraries, galleries, museums, are not to be considered local, nor are private schools local, but go under their corporate name, or, if they are not corporate, under the name of the proprietor.

d. National libraries museums, and galleries and libraries, museums, and galleries instituted or supported by a city go under the name of the city provided they have not a name of their own. (E. g., the Boston Public Library goes under Boston; but the Reuben Hoar Library of Littleton goes under Hoar.) American public schools should in any case go under the name of the city. (Rule 2, h.)

e. If college societies limited to one college are considered local, they would be entered not under the name of the place but of the college; if they are treated by rule 1, as all general college societies must be, reference (6) must be made. College libraries go under the name of the college. The colleges of an English university and the schools of an American university go under the name of the university.

Refer

f. Universities, galleries, etc., called merely Imperial, Royal, National and the like are not to be considered as having individual names, except the National Gallery of London.

g. Buildings are for the most part provided for in the above rules as museums, galleries, libraries, churches, etc. Any others should be entered under their names, with a reference from the city.

h. If a firm’s name is in the form Raphael Friedlander und Sohn it might be put as it reads, i. e., under R, or reversed, i. e., Friedlander und Sohn, Raphael. I prefer the latter, because the consulter is much more likely to remember the family than the Christian name. Whether the Christian name is written at the end or thus, Town (John) and Bowers (Henry), all firms should be arranged after all the other entries of the first family name, i. e., Friedlander und Sohn after all the Friedlanders. The same reason applies to other bodies whose legal name begins with a forename.

The plan might be tabulated thus:

| Under name. | Under place. |

|---|---|

| Churches not numbered and not named from the place. | Churches numbered or otherwise named from the place. |

| Societies not local. | Societies purely local. |

| English and American academies. | Academies and universities of the European Continent and of South America. |

| Colleges, universities, libraries, galleries, museums, having an individual name. | National or municipal colleges, libraries, galleries, museums, not having an individual name. |

| Private schools. | Public schools. |

| Business firms and corporations. | Municipal corporations. |

| London guilds (name of trade). | State historical societies and State agricultural societies (name of state). |

Ex.

Amiens. Académie des Sciences, Agriculture, Commerce, Belles-Lettres, et Arts du Départment de la Somme. (Rule 1, exc. 1.)

Association Scientifique Algérienne, Algiers. (Rule 1.)

Athenée de Vaucluse, Avignon. (Rule 1.)

Barbers and Surgeons of London (Mystery and Commonalty of), afterwards Royal College of Surgeons. See Royal College of Surgeons.

Boston (Mass.) Public Library. (Rule 2, d.)

Boston. Wells School. (Rule 2, d.)

Boston Athenæum. (Rule 1, exc. 3, Rule 2, c.)

Boston, First Church of. (Rule 2, d.)

British Museum. (Rule 2, d.)

Cambridge (Mass.), First Church of. (Rule 2.)

Chauncy Hall School, Boston, Mass. (Rule 2 c.)

Chemins de Fer de Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée, Comp. des. (Rule 2, c.)

Christiania. Videnskabs-Selskab. (Rule 1, exc. 1.)

Clarke (W. B.), & Co. (Rule 2, c.)

Congrès International des Américanistes. (Rule 1.)

Firenze. Galleria Imperiale. (Rule 2, f.)

Freemasons in Iowa. (§ 513.)

Genootschap “Oefening kweekt Kunst,” Amsterdam. (Rule 1, and ref. 4.)

Geschichts- und Alterthumsforschende Gesellschaft des Osterlandes, Altenburg. (Rule 1.)

Göttingen. K. Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften. (Rule 1, exc. 1.)

Great Britain. Parliament. (§ 41.)

Harvard College. (Rule 1.)

Harvard College. Lawrence Scientific School. (Rule 1, 2, e.)

Harvard College. Library. (Rule 1, 2, e.) {33}

Hermitage, Gallerie de l’, St. Petersburg. (Rule 2, d.)

Houghton & Mifflin. (Rule 2, c.)

L’Internationale. (Rule 1.)

Intime Club, Paris. (Rule 1.)

London. Merchants. (§ 55.)

Louvre, Gallerie du, Paris. (Rule 2, d.)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Mass. (Rule 2, c.)

Madrid. R. Academia de la Historia. (Rule 1, exc. 1.)

National Gallery, London. (Rule 2, f.)

3d National Quarantine and Sanitary Convention. (§ 521.)

New England Trust Co., Boston, Mass. (Rule 2, c.)

New York. Chamber of Commerce. (Rule 1, exc. 3, Rule 2, c.)

New York. First National Bank. (Rule 2, c.)

New York. Young Men’s Christian Association. (Rule 2, b.)

Or San Michele, Chiesa di, Florence. (Rule 1.)

Paris. Bibliothèque Nationale. (Rule 2, d, f.)

ΦΒΚ. A of Harvard. (Rule 2, e.)

Prado, Museo del, Madrid. (Rule 2, d.)

Pratt (Enoch) Free Library, Balt., Md. (Rule 2, d, h.)

San Francisco. Mercantile Library Assoc. (Rule 2, b.)

Société de l’Agriculture de l’Orne, Alençon. (Rule 1.)

Stationers’ Company, London. (Rule 1, exc. 2.)

Templars, Knights. (Rule 2, exc. 4.)

Tübingen. Eberhard-Karls Universität. (Rule 1, exc. 1.)

L’Union Générale, Paris. (Rule 2, c.)

United States. Library of Congress. (§ 40.)

Vatican Council. (§ 53.)

Verona, Congress of. (§ 49.)

Versailles, Treaty of. See ——. (§ 50.)

Wisconsin, State Historical Society of. (Rule 1, exc. 5.)

The 6TH PLAN has the same rules as the 5TH, and no exceptions. It may be preferred by those who think the advantage of having a single uniform rule greater than the inconvenience of unusual headings.

Perhaps from habit I prefer the 4TH PLAN. Of the other plans experience confirms me in the belief that the 5TH PLAN is the best. The A. L. A. adopted the 6TH PLAN. I have used it ever since in the Library journal, and I do not think it works well.

Substitutes for the author’s name (to be chosen in the following order) are—

57. Part of the author’s name when only a part is known.