Title: Poisonous Snakes of Kansas

Author: Robert F. Clarke

Release date: March 14, 2019 [eBook #59061]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Robert F. Clarke

Department of Biology

Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia

THE KANSAS SCHOOL NATURALIST

Vol. 5 No. 3 February 1959

Published by

The Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia

Prepared and Issued by

The Department of Biology, with

the cooperation of the Division of Education

Editor: John Breukelman

Department of Biology

Editorial Committee: Ina M. Borman, Robert F. Clarke, Helen M. Douglass, Gilbert A. Leisman, Carl W. Prophet, Dixon Smith

Because of the greatly increased cost, due to the color plates, no free copies of this issue will be available. Extra copies may be obtained for 25 cents each, postpaid. Send orders to The Kansas School Naturalist, Department of Biology, State Teachers College, Emporia, Kansas.

The Kansas School Naturalist is sent upon request, free of charge, to Kansas teachers and others interested in nature education.

The Kansas School Naturalist is published in October, December, February, and April of each year by The Kansas State Teachers College, Twelfth Avenue and Commercial Street, Emporia, Kansas. Second-class mail privileges authorized at Emporia, Kansas.

Many persons either do not know anything at all about the poisonous snakes of our state or have a distorted group of misconceptions concerning them. These misconceptions run from plain misknowledge about the range or identification of poisonous snakes to fancifully elaborate stories in which there may or may not be the barest thread of fact.

The prime reason that every person should know the poisonous snakes of his region by sight and know something about their habits, distribution, and abundance is that it will ease the mind of the average individual in all of his outdoor pursuits. Most persons have heard so many false stories about snakes that they develop a fear of all snakes. This fear is unfounded! A person who knows what poisonous snakes he can expect to encounter in a given area need only learn to identify these and realize that all other snakes, lizards, frogs, toads, salamanders, and turtles do not have a poisonous bite, and, therefore, he need not fear them. With a knowledge of the poisonous snakes, a person can avoid places where these snakes might be found. Another aspect is the conservation of snakes. Too many people kill snakes just because they happen to be snakes. This is uncalled for destruction—a non-poisonous snake should no more be killed than a song bird. In many cases, the harmless snakes are of direct economic value.

In general, all snakes are similar in habits. In Kansas, they retire for the winter in places where the temperature will not get below the freezing point. These may be in rocky ledges, beneath the soil, below the roots of trees, or in protected places of human design, such as grain bins, cisterns, cellars, and silos. With the warm days of spring, the snakes emerge from their winter quarters and set about finding food and mates. After mating, the sexes separate and each individual snake goes its own way to forage for food for the rest of the year. Some snakes lay eggs and others produce the young alive. There is about an even division of these types in Kansas. The king snakes, rat snakes, bull snakes, racers, and many smaller snakes lay eggs in early summer. These eggs are deposited in a spot suitable for hatching, generally beneath a rock or in the soil. When they hatch, the young fend for themselves. In Kansas, water snakes, garter snakes, poisonous snakes, and some smaller snakes give birth to living young in late summer or early fall. Again, the young are on their own after birth. With the coming of cooler weather the snakes leave their summer feeding grounds and travel to places where they will hibernate for the winter.

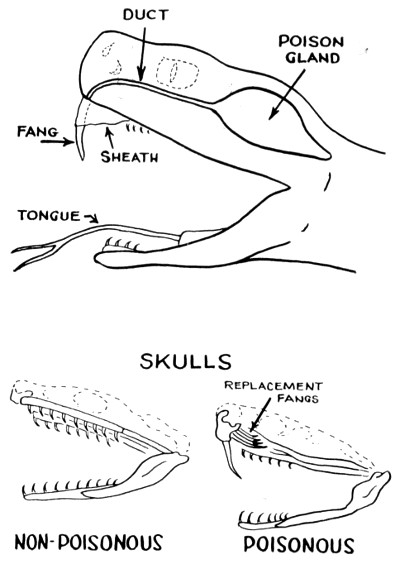

MYTHS: Probably no other group of animals has had the variety and expanse of tall tales credited to them as have the snakes. As the stories go, there are snakes 4 that can put their tails in their mouths and roll downhill hoop-like, snakes that are capable of milking cows dry, snakes that fly into pieces when struck and later reassemble into whole snakes again, snakes that charm their prey, and others too numerous to mention here. Some of these tales deal specifically with the poisonous power of snakes or with snakes that are venomous. There is the “Blow viper,” whose very breath is poisonous! The butt of this fable is the utterly harmless hog-nosed snake, pictured on Page 13. Many persons think that the poisonous “fang” of a snake is the structure which is frequently flicked in and out of the snake’s mouth. This is really its tongue, and is present in all snakes. The “fang” is an enlarged tooth in the upper jaw (see diagram, page 5). Four of the many untruths about poisonous snakes are (1) rattlesnakes cannot cross a horsehair rope—they can! (2) cottonmouth water moccasins cannot bite under water—they can! (3) rattlesnakes always rattle before they strike—not always! (4) the rattles present on the tail of a rattlesnake indicate the snake’s age—no, a new segment is added each time that the skin is shed, which may occur several times during a year.

FOOD: Most of the adult poisonous snakes of Kansas consume only warm-blooded prey, consisting primarily of small rodents: white-footed mice, shrews, voles, and cotton rats in the fields, and house mice and rats about human habitations. Small birds and young rabbits may be taken, as well as occasional lizards and insects. The copperhead is more insectivorous than the rattlesnakes, and the cottonmouth feeds upon other creatures that inhabit the edges of waterways.

The poison of venomous snakes is not only a defensive mechanism, but also a highly efficient food-getting device. Whereas some of the snakes strike and hold the prey within their jaws until the poison has rendered it helpless, others only strike and follow the trail to where the victim falls.

In feeding, the snake does not chew its food, but swallows it whole. The jaws are wonderfully adapted for this purpose, having the bones on each side of the jaws attached to their mates on the other side by an elastic ligament, and the upper and lower jaws also joined by such an attachment. This allows the jaws to be spread apart and lowered, making an opening capable of taking in a food item actually larger in diameter than the snake! The teeth of both the upper and lower jaws are recurved, pointing inward, and as each section of the jaw can work independently, one side secures its grip while the other side moves forward. Thus, the snake actually crawls around its food.

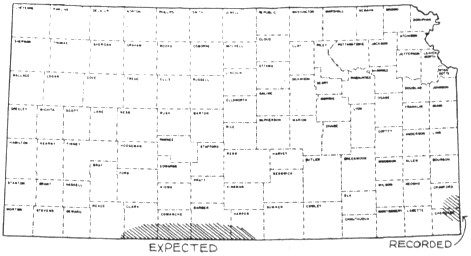

ABUNDANCE: The non-poisonous snakes far outnumber the poisonous kinds, both in number of species and individuals. In the United States, there are approximately 95 species of non-poisonous snakes and only 19 species of poisonous ones, including 15 rattlesnakes, one copperhead, one cottonmouth, and two coral snakes. In Kansas, there are six species of poisonous snakes (two should hardly be counted) and 34 species of non-poisonous snakes. Many of the non-poisonous species are common and widespread. It is far more probable that any snake seen is non-poisonous than poisonous.

SNAKE BITE: Venom is secreted from glands within the head, on each side behind the eyes, causing the swollen appearance of the head in this region. The venom travels through ducts to each of the two fangs. The fangs are enlarged teeth in the front of the upper jaw. They are hollow, with one end connected to the poison duct and the other end having an opening on the front edge near the tip. The fangs are also fastened to a moveable bone, which enables the fangs to be 5 folded back against the upper jaw when the mouth is shut and erected and directed forward when the mouth is opened to strike. The power of a strike imbeds the fangs into the skin of the victim, and muscles force venom from the glands through the duct and hollow fang and out of the opening at the tip. The venom causes a breakdown of the red blood corpuscles and walls of blood vessels. It also has an effect upon the nervous system. Some snakes have venom which is much more destructive to the nervous system. The pit vipers have venom which is more hemotoxic (destructive to blood), whereas the coral snake, which belongs to the cobra group, has a venom which is neurotoxic (destructive to nerves).

The venom is yellowish and somewhat “thicker” than water. The amount of poison ejected at any one strike varies from a part of a drop to 2 cubic centimeters, depending upon size and kind of snake, and time elapsed since last venom ejection. Various factors influence the amount of venom which is injected into the victim, i.e., smaller snakes have smaller fangs and less venom; strikes through clothing or footwear are less effective.

It has been estimated that there are fewer than 50 deaths due to snake bite in the United States in a year; most of these bites result from imprudent handling of venomous serpents. There has been no survey of snakebite in Kansas, but few deaths are reported annually. At times several years have elapsed without any deaths being reported. Most victims are less than 20 years of age and most bites occur on the hands, feet, arms, or legs.

It should be stressed that poisonous snakes cannot be made harmless by removing the fangs. The poison glands and ducts remain and other teeth can still scratch the skin, allowing entrance of the venom. Also, “reserve” fangs are normally present. These are immature fangs lying along the upper jaw bone. At intervals a reserve fang grows down beside a fang which has been used for some time. The old fang is shed and a new sharp “hypodermic needle” is in position. Thus, snakes are sometimes found with three or four fangs.

Snake venom is used to manufacture antivenin, which is injected into snakebite victims to help counteract the effects of the poison. The venom is injected in graduated doses into horses, which build up an immunity to the venom. Blood is withdrawn from the horse and the serum is processed to produce antivenin.

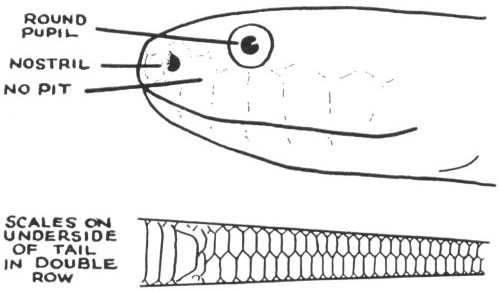

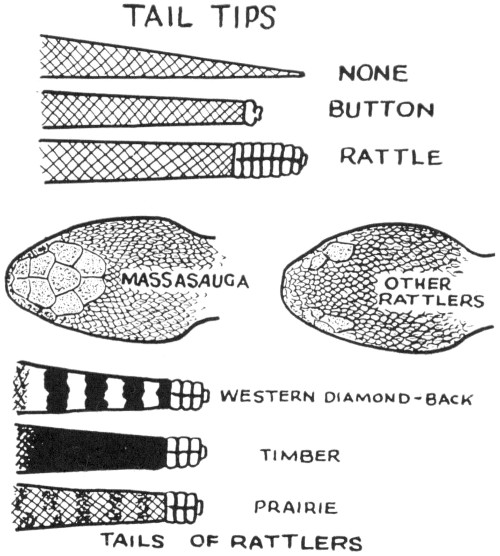

The features given here apply only to Kansas snakes and may not be applicable elsewhere. Even in Kansas, there are some non-poisonous snakes which exhibit either the tail or eye characteristics given for poisonous snakes, but none have the pit. It probably need not be pointed out that these features can be seen only when 6 the snake can be examined closely. Certainly, every snake should not be picked up to look for these characteristics! A warning is necessary at this point—reflex action can cause an apparently “dead” snake to bite, so do not handle “dead” snakes with the hands; use a stick. The best way to be able to identify a poisonous snake is to know all of the venomous snakes of your region by sight. Color and pattern are distinctive and are easily learned.

POISONOUS

NON-POISONOUS

TAIL TIPS

COPPERHEAD (Agkistrodon contortrix). Length usually 2-3 feet. Common where it occurs, the copperhead is probably the most abundant poisonous snake in eastern Kansas. It is most frequently found in the vicinity of rocky ledges in oak-hickory-walnut woods, but it ranges widely, so that individuals may be found in almost any habitat during summer months. Although generally nocturnal during most of its active season, its habit of lying in the open during the daytime among dried leaves in patches of sunlight and shadow causes the pattern to blend perfectly with the background. Any hiker through this habitat should be alert. Because of the rather small size, usually inoffensive disposition, and the low toxicity of its venom this snake should be placed on the non-fatal list for adults. Elderly persons, those in poor health, or small children could find the copperhead bite fatal, however.

A subspecies of the copperhead occurs along the southern border of Kansas. In this form, the crossbands are wider along the mid-line than the more northern variety.

Young copperheads have a sulfur-yellow tail. This color is lost as the snake matures. It is thought that this contrasting tail color is used as a lure to bring prey within striking distance of the small snake. The young are born in August or September. There may be from two to ten in a litter.

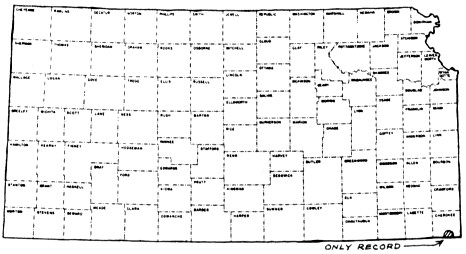

COTTONMOUTH (Agkistrodon piscivorus). Length 3-4 feet. The poisonous water moccasin has been taken only once in Kansas. This was on the Neosho River in Labette County at the Cherokee County line. It is on the basis of this single specimen that it is counted as one of the snakes of Kansas! The many general reports of water moccasins in Kansas refer to the mistaken identification of the harmless water snakes that are common throughout most of the state (see page 12). Young cottonmonths are patterned quite like a wide-banded copperhead, but the colors are not so reddish. These snakes are always found in the vicinity of water. When approached they quite often hold their ground and open their mouths widely, revealing the white lining of the mouth, a habit which gives them their common name. This heavy-bodied snake is dangerously poisonous and, contrary to popular belief, can bite underwater.

Whereas the copperhead is a rather mild-mannered snake, the cottonmouth has a vicious disposition. Although nocturnal, it likes to sun-bathe, and it is frequently seen basking along shorelines, stretched out on low branches or upon the bank. Where this snake occurs, it is usually common.

Generally, eight or nine young are born in August or September, although the number of young may range from five to fifteen. Like the copperhead, the young have a yellow tail tip.

COPPERHEAD

COTTONMOUTH

MASSASAUGA

WESTERN DIAMOND-BACK

TIMBER RATTLER

PRAIRIE RATTLER

Clarke

MASSASAUGA (Sistrurus catenatus). Length 24-27 inches. This snake belongs to a group of small rattlesnakes called “ground” or “pygmy” rattlers, which are differentiated from the larger rattlers by having paired scales on top of the head, as have the copperhead, cottonmouth, and non-poisonous snakes. The massasauga occurs in open fields and rocky outcroppings. It is particularly common in the Flint Hills. This is the “prairie rattler” of eastern Kansas, often found under hay bales in fields. Its food consists primarily of small rodents. The small size and usually docile disposition of this snake tend to place it upon the non-dangerous list, but its venom is extremely toxic, and any bite from a poisonous snake is dangerous. When aroused, these small snakes strike with a fury not seen in the larger snakes. The rattling of this small snake is hardly louder than the buzz of a grasshopper.

The name “massasauga” is an Indian term, meaning “swamp dweller,” a habitat preference which is evidenced more in the states to the northeast of Kansas.

Two subspecies occur in Kansas. In the eastern part of the state is the form that occurs eastward of Kansas, characterized by the dark belly; the lighter-bellied form extends westward from eastern Kansas into states to the southwest.

About eight or nine young are born, usually in August or September.

WESTERN DIAMOND-BACKED RATTLESNAKE (Crotalus atrox). Length 4-5 feet, although some are larger. In the United States, probably more deaths are caused by this snake than by any other. A combination of large size, wide distribution, abundance, and touchy temperament give this distinction to this snake. It is hardly a member of the Kansas snake fauna, having been found only twice in the state, both times in the southeastern corner. It should occur, although presently unrecorded, in south-central Kansas along the Oklahoma line. It is rather common in Oklahoma, just south of this region. The diamond-back prefers dry open plains and canyons, where it feeds upon small rodents, young rabbits, and occasionally, birds. The ground color varies somewhat from buff to gray; the snake generally has a faded appearance. The black and white tail bands are distinctive.

About ten young are born in late summer or early fall. Larger litters have been recorded. The young are fully capable of inflicting a dangerous bite as soon as they are born—and quite willing to do so!

In northern Oklahoma, an annual rattlesnake roundup is held, in which several hundred diamond-backs are captured. These are processed for their venom, from which antitoxin is made. Some of the rattlesnakes are cooked and their steaks used in a banquet. The meat is firm and quite tasty!

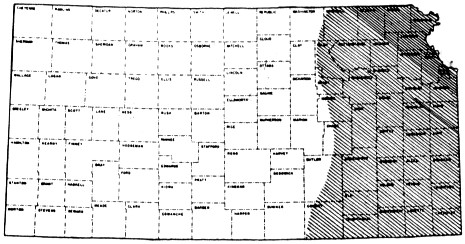

TIMBER RATTLESNAKE (Crotalus horridus). Length 3-4 feet, occasionally longer. The timber rattler occurs only in eastern Kansas and is only locally common, at scattered localities. It prefers the deciduous forest where limestone rock outcrops as ledges, but may wander into cultivated fields and open areas during late spring and summer. The food consists primarily of small rodents and young rabbits. Ordinarily, it is a mild-mannered snake, one which will seek to escape direct contact with man, but its size and habit of living close to human habitations necessitate considering this rattler dangerous. Ground color may vary from a light gray to yellow, with the black chevron-shaped blotches of the back uniting with lateral blotches to form crossbands. Another common name for the timber rattler is banded rattlesnake. Some individuals may be almost all black. The tail is characteristically velvet black in adults; banded in young.

During late spring and summer the timber rattler is quite often encountered crossing roads, where its large size and slow movement often make it a victim of modern transportation.

The timber rattler has a habit of frequently spending daylight time just beneath the edge of overhanging rocks. A hiker should always look beneath any rocks of this sort before using the rock as a resting place.

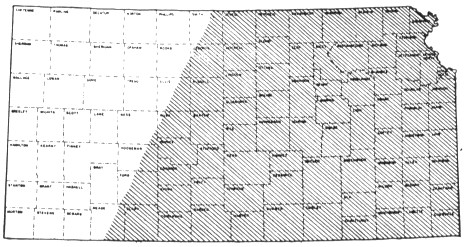

PRAIRIE RATTLESNAKE (Crotalus viridis). Length 3-4 feet. This rattlesnake is common in western Kansas, where it frequents rocky open regions, grassy prairies, and agricultural areas. In eastern Kansas it has been found only in the Pittsburg vicinity, and any “prairie rattler” east of Wichita or Manhattan is usually the massasauga. The habit of denning in large groups is well-known. Several hundred have been found in hibernation in a single den. The food of the prairie rattler is warm-blooded, mostly rodents and small rabbits. It appears to be active in the daytime, whereas the other poisonous snakes are mainly nocturnal. The ground color varies from a light gray to green, and the pattern of dorsal blotches with alternating rows of lateral blotches may cause it to be confused with the smaller massasauga, but the scales on top of the head are all small on the prairie rattler, whereas paired plates are present on the massasauga (see diagram, page 6).

Young are born in late summer or early fall. Usually nine to twelve constitute a litter. As few as five and as many as seventeen have been recorded, however.

It has been found that any one female prairie rattler gives birth to a litter of young every other year. These young are generally about twelve inches in length.

This snake has a wide range over western United States, where it is probably the most common rattlesnake. It is frequently found in prairie dog villages. The burrows of these animals are utilized as shelter and the young are used as food items.

The following six snakes are representative of the harmless snakes commonly and incorrectly thought to be poisonous by the general public.

1. HOG-NOSED SNAKE. Length 2-2½ feet. This is the “blow viper,” “spreadhead viper,” “spreading adder,” or other equally ill-named snake usually found in dry sandy areas. It has a threatening defensive bluff which consists of spreading the fore part of the body cobra-like, hissing and striking (but with mouth closed). Failing to intimidate its opponent, the snake will contort its body convulsively and roll onto its back—apparently dead. It will remain inert unless rolled over onto its stomach; then it will roll onto its back again—the only proper attitude for a dead snake!

2. BLUE RACER. Length 3-4 feet. Many stories are told about this snake attacking persons. It is doubted that most are true interpretations of fact. These rapid-moving snakes may come at a person who is in line with the snake’s preconceived idea of an escape route. Upon capture, most blue racers will bite, but they are definitely non-poisonous. These snakes feed mostly upon small rodents. The color varies in individuals from blue-green to olive or olive-brown; underside is yellow.

3. COMMON WATER SNAKE. Length 2-3 feet. This snake and the yellow-bellied water snake, of very similar appearance, are the most often noted snakes along creeks, rivers, lakes, and ponds. These are usually the “moccasins” that frighten persons near water. Entirely harmless, but with a vicious disposition, these snakes feed upon small fish, frogs, and other creatures that inhabit their neighborhood.

4. DIAMOND-BACKED WATER SNAKE. Length 3 feet. Heavy body, dark appearance, and mean disposition give this particular snake a bad reputation. More than any other Kansas snake, this one gives rise to stories of the poisonous cottonmouth being distributed throughout eastern and southern portions of the state. It is always found in the vicinity of water and feeds upon creatures it finds there.

5. PILOT BLACK SNAKE. Length 5-6 feet. Also more properly called the black rat snake, a descriptive title which is particularly apt. Occasionally, this large snake may find where hen eggs are available and become a nuisance in the hen house, but the wise farmer who allows one of these snakes to stay around the barn and corncrib will reap dividends from the destruction wrought upon the rodent population. This snake is a much better mouser than any cat!

6. RED MILK SNAKE. Length 2-3 feet. A beautiful jewel of a snake, this small creature has been credited with the ability to milk a cow dry! Such a feat is impossible for a number of reasons. This reputation was acquired because this snake was frequently found in barns, where it had gone in search of mice, a favorite food item. The color pattern might be confused with that of the poisonous coral snake (not found in Kansas). In the coral snake, however, the red and yellow rings are adjacent.

HOG-NOSED SNAKE

BLUE RACER

PILOT BLACKSNAKE

COMMON WATER SNAKE

DIAMOND-BACKED WATER SNAKE

RED MILK SNAKE

Clarke

If possible, determine definitely if the snake is poisonous. If it is not, no treatment is necessary other than application of an antiseptic. If the snake is poisonous, typical symptoms will appear rapidly: bruised appearance at bite, noticeable swelling, and intense pain. Later, the victim may become nauseated and may even faint. The important thing to do is to get to a doctor or a hospital as soon as possible. In the meantime, the following measures should be taken to retard the spread of the venom.

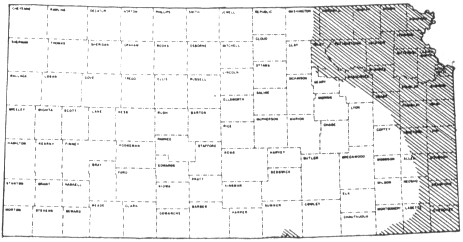

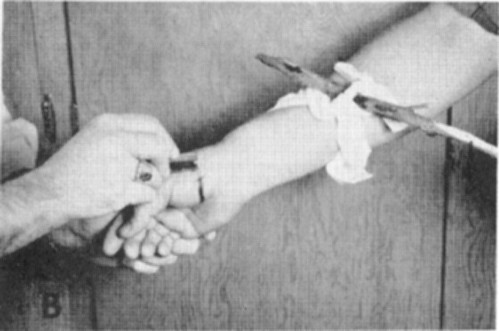

1. Place tourniquet between bite and body. Use handkerchief, tie, or any other handy cloth. Tie loosely around arm, place stick in slack part and twist. (Fig. A) Tourniquet should not be too tight. Should be able to push finger under it. Loosen for a minute every 15 minutes. If bitten on hand or lower arm, be sure to remove any rings, bracelets, or watches.

A

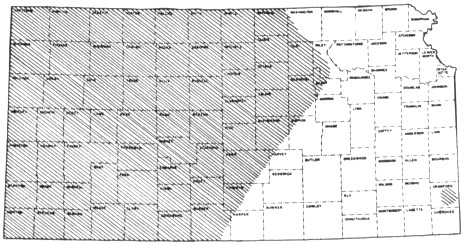

2. Sterilize a knife or razor blade, using a match, and make a cut through each fang puncture ¼ inch deep and ½ inch long, parallel to limb. (Fig. B).

B

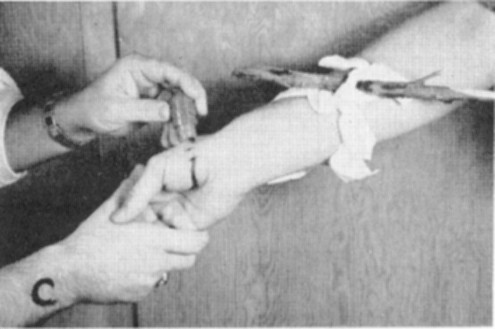

3. Apply suction to cuts, using either the cup from a snake-bite kit or the mouth, if there are no sores, cracked lips, or bleeding gums. Continue suction for several minutes. (Fig. C).

C

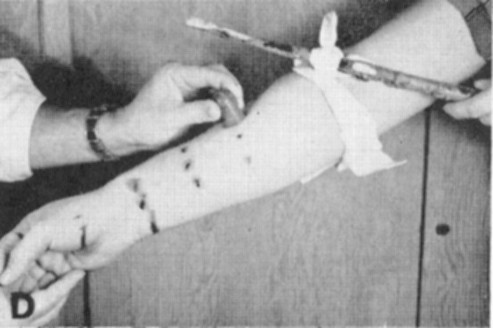

4. As swelling progresses up limb, tourniquet should be moved ahead of swelling and additional cuts and suction should be made at edge of swelling. (Fig. D).

D

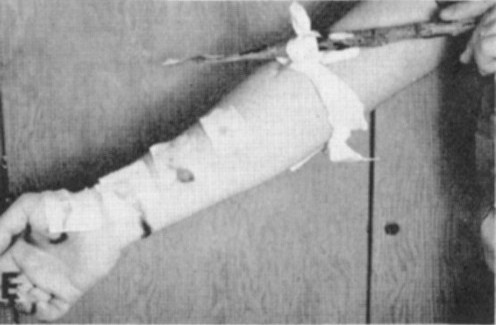

5. A wet compress should be applied over all cuts to encourage bleeding. (Fig. E).

E

Upon arrival at doctor’s or hospital, antivenom may be injected after the determination for serum sensitivity. Antivenin may be administered by a person other than a doctor, but this is recommended only in cases where a doctor or hospital is not readily accessible.

Snake bite kits are available at most drug stores and should be carried by persons or groups going into areas inhabited by poisonous snakes.

Conant, Roger. 1958. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians. 366 pages. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. $3.95.

Klauber, Lawrence M. 1956. Rattlesnakes: their habits, life histories, and influences on mankind. 2 vols. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Minton, Sherman A. Snake-bite in the midwestern region. Quarterly Bulletin, Indiana University Medical Center, Vol. 14, No. 2.

Minton, Sherman A. Snakebite. Scientific American, January 1957, Vol. 196, No. 1.

Oliver, James A. 1955. The Natural History of North American Amphibians and Reptiles. 359 pages. D. Van Nostrand Co., Princeton, N. J.

Pope, Clifford H. 1955. The Reptile World. 325 pages. Alfred A. Knopf, N.Y.

Pope, Clifford H. 1952. Snakes Alive and How They Live. 238 pages. The Viking Press, N. Y.

Schmidt, Karl P. and D. Dwight Davis. 1941. Field Book of Snakes of the United States and Canada. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York.

Smith, Hobart M. 1956. Handbook of Amphibians and Reptiles of Kansas. 356 pages. University of Kansas, Museum of Natural History, $1.50.

Werler, John E. 1950. The poisonous snakes of Texas and the first aid treatment of their bites. Texas Fish and Game, February, 1950.

Wyeth, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa. Antivenin (North American Antisnakebite Serum). 15 pages.

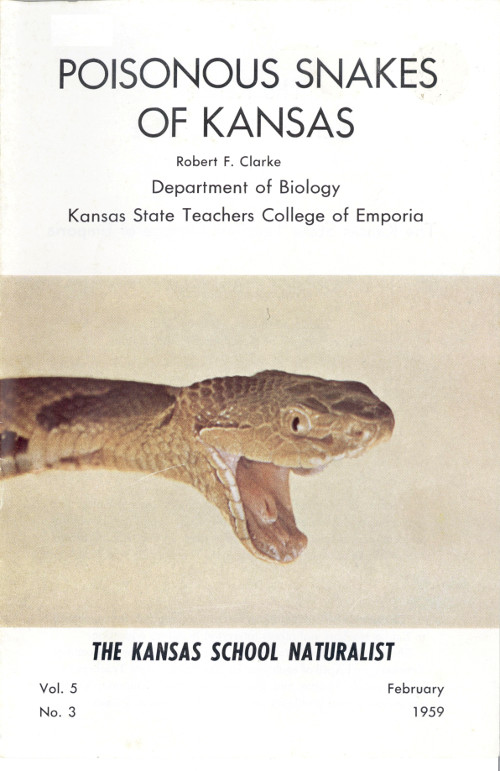

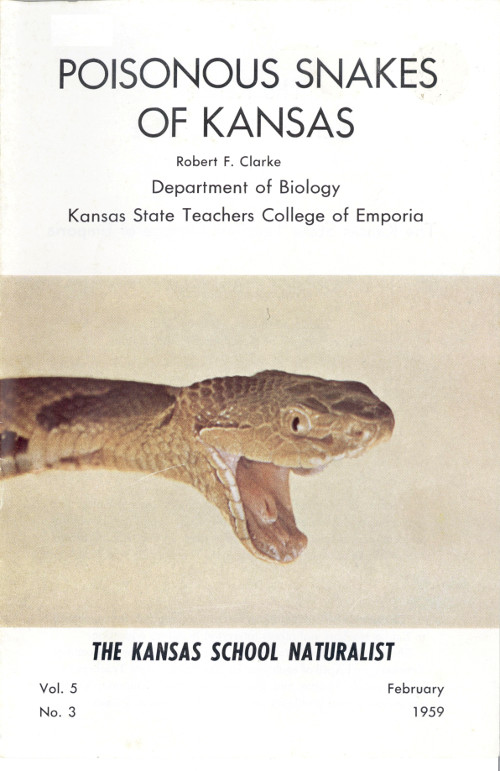

The cover picture is a copperhead. This snake was photographed alive, but somewhat anesthetized with ether, by Dr. John Breukelman and the author, using a single-lens reflex 35 mm. camera, type A Kodachrome film and two photofloods. The illustrations on page 14 were taken by these same two, using a Polaroid Land camera, photofloods, and graduate student George Ratzlafl as victim. The line drawings and color illustrations were made by the author. The color plates of non-poisonous and poisonous snakes were painted in water colors, using live and preserved snakes as models. The original paintings have been reduced one-half in this publication.

Poisonous snakes are only one aspect of the study of herpetology, which includes other reptiles, as well as amphibians. These together may be referred to as herptiles. There are 97 species of herptiles in Kansas: 9 salamanders, 20 frogs and toads, 15 lizards, 40 snakes, and 13 turtles. The turtles of Kansas have been described in a past issue of The Kansas School Naturalist (April, 1956), and an issue on the lizards of the state is in preparation.

Oct. 1954, Window Nature Study; Dec. 1954, Wildlife in Winter; Feb. 1955, Children’s Books for Nature Study (First in a series): April 1955, Let’s Go Outdoors; Oct. 1955, Fall Wildflowers; Dec. 1955, Snow; Feb. 1956, Spring Wildflowers; April 1956, Turtles in Kansas; Oct. 1956, Hawks in Kansas; Dec. 1956, Children’s Books for Nature Study (Second in the series); Feb. 1957, Life in a Pond; April 1957, Spiders; Oct. 1957, Along the Roadside; Dec. 1957, An Outline for Conservation Teaching in Kansas; Feb. 1958, Trees; April 1958, Summer Wildflowers; Oct. 1958, Watersheds in Kansas; Dec. 1958, Let’s Build Equipment.

Those printed in boldface type are still available upon request. The others are out of print, but may be found in many school and public libraries in Kansas.

The Biology Department of the Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia is sponsoring its second Audubon Screen Tour Series during the current school year. This series consists of five all-color motion pictures of wildlife, scenics, plant science, and conservation, personally narrated by leading naturalists. Three of the five programs have been presented; the other two will be given in Albert Taylor Hall at 8:00 p.m. on the dates listed below.

OLIN SEWALL PETTINGILL, JR., Penguin Summer, Monday, April 13.

WILLIAM FERGUSON, This Curious World in Nature, Friday, May 15.

Plan to attend with some of your students. Family and single admission tickets are available. For additional information write to Carl Prophet, Biology Department, KSTC, Emporia.

Plan now to attend the 1959 Workshop in Conservation, which will be a part of the 1959 Summer Session of the Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia, June 2 to 19, and June 22 to July 10, 1959.

As in the past several years, the Workshop will cover water, soil, grassland, and wildlife conservation teaching. Such topics as geography and climate of Kansas, water resources, soil erosion problems and control, grass as a resource, bird banding, wildflowers, conservation clubs, and conservation teaching in various grades will be discussed. There will be lectures, demonstrations, discussion groups, films, slides, field trips, projects, and individual and group reports. You may enroll for undergraduate or graduate credit.

Any interested person may enroll in the first section, enrollment in the second section is limited to those who have an established interest in conservation and some teaching experience.

Fee for first section (3 hours credit): Residents of Kansas, $22.95; non-resident, $42.45

Fee for second section (1, 2, or 3 hours credit): Residents of Kansas, $7.65 per hour; non-resident, $14.15 per hour

For other information about the Workshop write Robert F. Clarke, Department of Biology, KSTC, Emporia, Kansas.

The Kansas School Naturalist

The Kansas State Teachers College

Twelfth Avenue and Commercial Street

Emporia, Kansas

Second-class mail privileges

authorized at Emporia, Kansas