Title: The Babees' Book: Medieval Manners for the Young: Done into Modern English

Compiler: Frederick James Furnivall

Editor: Edith Rickert

Translator: L. J. Naylor

Release date: February 28, 2019 [eBook #58985]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Turgut Dincer, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

This book has many links, both to footnotes and to longer notes with more explanation. Clicking on a footnote marker on a page will take you to the text of the footnote.

Sometimes, a footnote will just contain the text “See note.” meaning there is more explanation for that note. Clicking on the highlighted word will take you to the Notes section. If you scroll down through those notes, you’ll find the text for that particular page.

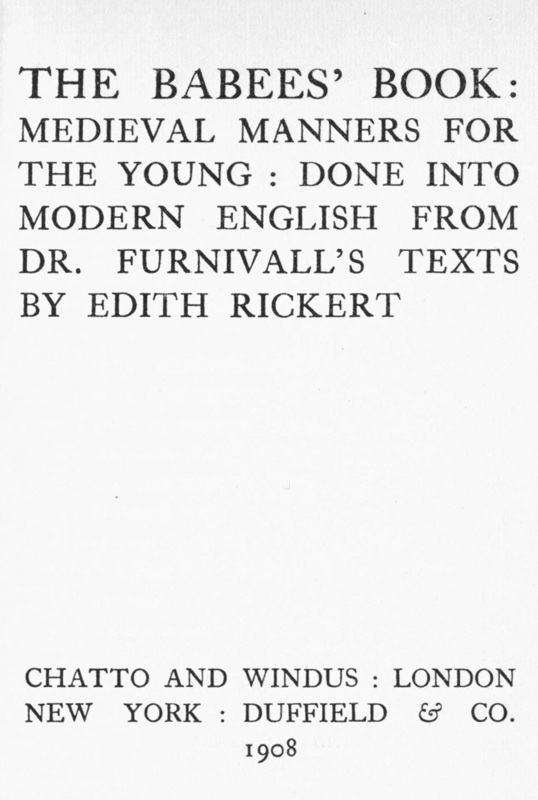

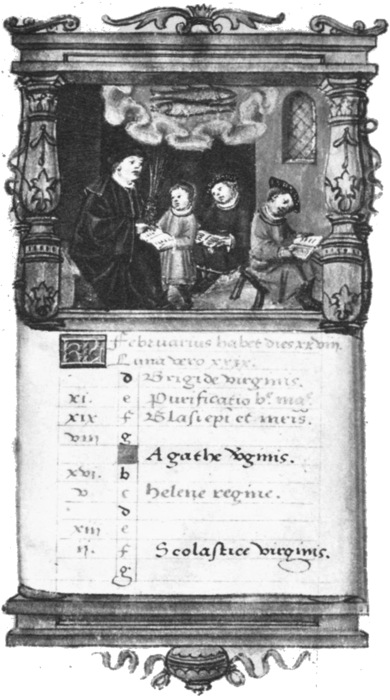

The School of Aristotle.

See page 9.

THE BABEES

BOOK. Mediæval

Manners for the

Young Now first

done into Modern

English from The

Texts of

Dr. F. J. Furnivall:~

Published MCMVIII

| INTRODUCTION | xi |

| THE BABEES’ BOOK | 1 |

| THE A B C OF ARISTOTLE | 9 |

| URBANITATIS | 11 |

| THE LITTLE CHILDREN’S LITTLE BOOK | 16 |

| THE YOUNG CHILDREN’S BOOK | 21 |

| STANS PUER AD MENSAM | 26 |

| HOW THE GOOD WIFE TAUGHT HER DAUGHTER | 31 |

| HOW THE WISE MAN TAUGHT HIS SON | 43 |

| JOHN RUSSELL’S BOOK OF NURTURE | 47 |

| THE BOOK OF COURTESY | 79 |

| SYMON’S LESSON OF WISDOM FOR ALL MANNER CHILDREN | 122 |

| HUGH RHODES’S BOOK OF NURTURE | 126 |

| FRANCIS SEAGER’S SCHOOL OF VIRTUE | 141 |

| RICHARD WESTE’S SCHOOL OF VIRTUE, THE SECOND PART, OR THE YOUNG SCHOLAR’S PARADISE | 157 |

| NOTES | 179 |

| FOOTNOTES | 204 |

| THE SCHOOL OF ARISTOTLE Cotton, MS. Aug. A. 5, fol. 103. | Frontispiece |

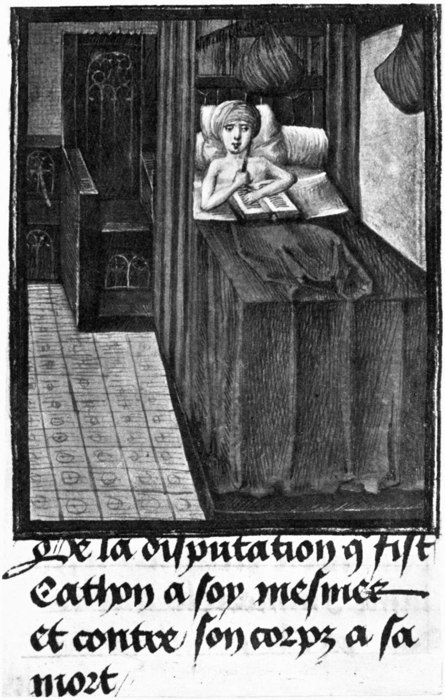

| “DE LA DISPUTATION Q’ FIST CATHON A SOY MESMES ET CONTRE SON CORPZ A SA MORT” Royal MS. 16 G. viii., fol. 324. | 44 |

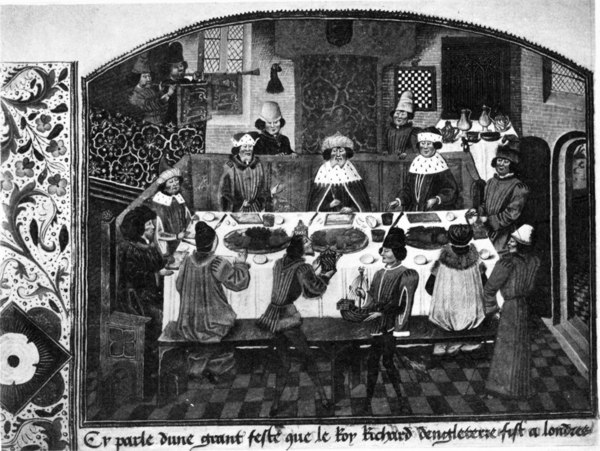

| “CY PARLE DUNE GRANT FESTE QUE LE ROY RICHARD DENGLETERRE FIST A LONDRES” Royal MS. 14 E. iv., fol. 265b. | 54 |

| “IF THOU BE A YOUNG INFANT” Harl. MS. 621, fol. 71. | 85 |

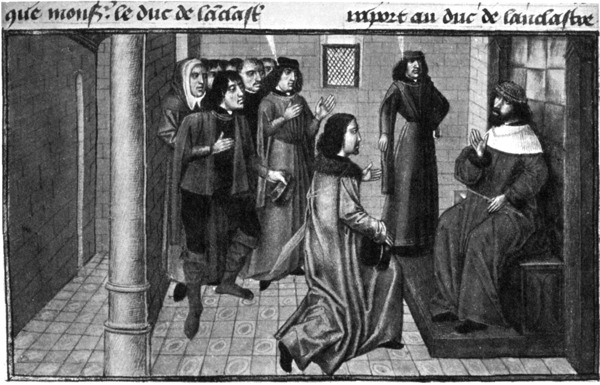

| JOHN OF GAUNT RECEIVES A CIVIC DEPUTATION Royal MS. 14 E. iv., fol. 169b. | 112 |

| “WHO SPARETH THE ROD, THE CHILD HATETH” B.M. Add. MS. 31240, fol. 4. | 126 |

NEARLY forty years ago, Dr. Furnivall collected for the Early English Text Society “divers treatises touching the Manners and Meals of Englishmen in former days.” Some of these were published in 1868, under the title The Babees’ Book,[1] and others, chiefly of later date, in 1869, under the title Queene Elizabethes Achademy.

These two volumes, with their introductions and illustrative matter, to my mind present the most vivid picture of home life in medieval England that we have. Aside from their general human interest, they are valuable to the student of social history, and almost essential to an understanding of the literature of their time. The whole fabric of the romances was based upon the intricate system of “courtesy” as here set forth, and John Russell furnishes an interesting comment xiion Chaucer and his school, as do Rhodes and Seager and Weste on the writers of the sixteenth century. Finally, among these treatises, there is many a plum by the way for the seeker of proverbs, curious lore, superstitions, literary oddities. And as comparatively few people have time or inclination to worry through antiquated English, Dr. Furnivall has long wished that the substance of his collections might be presented in modern form. Therefore this little volume has been undertaken.

Doubtless unwritten codes of behaviour are coeval with society; but the earliest treatises that we possess emphasize morals rather than manners. Even the late Latin author known as Dionysius Cato (fourth century?), whose maxims were constantly quoted, translated, imitated, and finally printed during the late Middle Ages, does not touch upon the niceties of conduct that we call manners; wherefore one John Garland, an Englishman educated at Oxford, who lived much in France during the first half of the thirteenth century, felt bound to supplement Cato on these points. His work, entitled Liber Faceti: docens mores hominum, precipue iuuenum, in supplementum illorum qui xiiia moralissimo Cathone erant omissi iuuenibus utiles,[2] is alluded to as Facet in the first piece in this volume, and serves as basis for part of the Book of Courtesy.

But, earlier than this, Thomasin of Zerklaere, about 1215, wrote in German a detailed treatise on manners called Der Wälsche Gast.[3] And in 1265, Dante’s teacher, Brunetto Latini, published his Tesoretto,[3] which was soon followed by a number of similar treatises in Italian.

While we need not hold with the writer of the Little Children’s Little Book, that courtesy came down from heaven when Gabriel greeted the Virgin, and Mary and Elizabeth met, we must look for its origin somewhere; and inasmuch as, in its medieval form at least, it is closely associated with the practices of chivalry, we may not unreasonably suppose it to have appeared first in France. And although most of the extant French treatises belong to the fourteenth or fifteenth centuries, a lost book of courtesy, translated by Thomasin of xivZerklaere, is sometimes held, on good grounds, to have been derived from French, rather than from Italian.

In any case, such of the English books as were not taken immediately from Latin, came from French sources. To be sure, there is a Saxon poem, based it would seem on Cato, though by no means a translation, called A Father’s Instructions to his Son; but this, although it is greatly exercised about the child’s soul, takes no thought for his finger-nails or his nose.

It is not, therefore, surprising to find that nearly all English words denoting manners are of French origin—courtesy, villainy, nurture, dignity, etiquette, debonaire, gracious, polite, gentilesse, &c., while to balance them I can, at this moment, recall only three of Saxon origin—thew (which belongs rather to the list of moral words in which Old English abounds), churlish and wanton (without breeding), both of which, significantly enough, are negative of good manners.

The reason for the predominance of the French terms is simply that “French use these gentlemen,” as one old writer puts it; that is, from the Conquest until the latter part of the fourteenth century the language of the invaders prevailed almost entirely among the xvupper classes, who, accordingly, learned their politeness out of French or Latin books; and it was only with the growth of citizenship and English together, that these matters came to be discussed in this latter tongue for the profit of middle-class children, as well as of the “bele babees” at Court.

We must suppose, from numerous hints and descriptions, that an elaborate system of manners and customs prevailed long before it was codified. The Bayeux tapestry (eleventh century) shows a feast, with a server kneeling to serve, his napkin about his neck, as John Russell prescribes some four hundred years later.

The romances again, alike in French and in English, describe elaborate ceremonies, and allude constantly to definite laws of courtesy. Now and again we find a passage that sets forth the ideal gentleman. Young Horn, for example, was taught “skill of wood and river” (hunting and hawking), carving, cup-bearing, and harping “with his nails sharp.” Child Florent showed his high birth by his love of horse, hawk, and armour, and by his contempt of gold; but he was not thought ill-mannered to laugh when his foster-father and mother fell down in their attempt to draw a rusty xvisword from its scabbard! Chaucer’s Squire might well have been brought up on a treatise similar to those included in this volume:

But the Prioress outmatched him, having possibly learned her manners in the French of “Stratford-atte-Bowe,” in Les Contenances de la Table, or some such thing:

These maxims were versified that they might be the more easily remembered, as we know from various expressions, notably “Learn or be Lewd” (ignorant), which occurs at the end of several pieces. In 1612 the principle was stated explicitly, “because children will learn that book with most readiness and delight through the running of the metre, as it is found by experience.” And the fact that versified treatises on manners formed part of the schooling of that day, brings up the subject of medieval education.

In the first place, this cannot be understood until we have set aside our modern ideas of master and servant. The old point of view is picturesquely summed up in a pamphlet of 1598, quoted by Dr. Furnivall.

“Amongst what sort of people should then this xviiiserving-man be sought for? Even the duke’s son preferred page to the prince, the earl’s second son attendant upon the duke, the knight’s second son the earl’s servant, the esquire’s son to wear the knight’s livery, and the gentleman’s son the esquire’s serving-man. Yea, I know at this day gentlemen, younger brothers that wear their elder brother’s blue coat and badge, attending him with as reverent regard and dutiful obedience as if he were their prince or sovereign. Where was then in the prime of this profession Goodman Tomson’s Jack, or Robin Rush, my Gaffer Russet-coat’s second son? The one holding the plough, the other whipping the cart-horse, labouring like honest men in their vocation. Trick Tom the tailer was then a tiler for this trade; as strange to find a blue coat on his back, with a badge on his sleeve, as to take Kent Street without a scold, or Newmarket Heath without a highwayman. But now, being lapped in his livery, he thinketh himself as good a man, with the shears at his back, as the Poet Laureate with a pen in his ear.”

From this passage it is clear that at a time not very much earlier, serving was a profession in which every rank, except royalty itself (if indeed this is to be xixomitted, see pp. 1, 179 below), might honourably wear the livery of a man of higher rank. Indeed, under the system of entail, this was, in time of peace, the only possible livelihood for a gentleman’s younger son, unless he had a special aptitude for law or the Church. Debarred from all trade, he could only offer his services to some great man who was compelled by his estate to keep up a large household, and so earn his patronage to provide for the future. It was fully expected that boys so placed would be helped to opportunities at Court or abroad, and girls to good marriages. That these patrons really took an interest in their young servitors, and felt responsible for their welfare, appears in many accounts of help bestowed upon men who afterwards became famous in literature, or scholarship, or state-craft. And as for the girls, Dr. Furnivall quotes an amusing instance of a mistress who, when reproached with dismissing a gentlewoman without due cause, thereby injuring her chances for the future, immediately allowed her forty shillings a year towards her maintenance while she herself lived.

Among rich men it was the custom to receive a number of boys for training in this way. In the household xxof Lord Percy there were nine young “henchmen” who served him as cup-bearers and in various other capacities. To these he allowed servants, one for each two, unless they were “at their friends’ finding,” in which case they might have one apiece. Likewise, in his household, his second son was carver, his third, sewer.

But while in a rich man’s household, younger sons might receive as good a training as if they had been sent elsewhere for the purpose, the case of the younger sons of a poor gentleman might be sufficiently wretched. Orlando, in As You Like It, speaks feelingly on this point. Although his father had left 1000 crowns for his upbringing, he was so neglected that he says: “His (his brother’s) horses are bred better, for, besides that they are fair with their feeding, they are taught their manage, and to that end riders dearly hired;[7] but I, his brother, gain nothing under him but growth ... he lets me feed with his hinds, bars me the place of a xxibrother, and as much as in him lies, mines my gentility with my education.”

The alternative to such a life of hardship was either to enter the Church or depend upon its charity, or to serve in the household of a man of rank. While only a few were fitted for the religious life or cared to undertake it, “many poor gentlemen ... left beggars in consequence of the inheritance devolving to the eldest son,” were supported by the charity of the Church, as we are told by an Italian visitor to England in 1496-7.

The case of an unmarried daughter living at home, though less desperate, was even in well-to-do families sufficiently uncomfortable, as is plainly hinted in a letter written by Margaret Paston to her husband in 1469. She implores him to find his sister “some worshipful place,” and concludes: “I will help to her finding, for we be either of us weary of other.”

The practice of sending children seven or eight years old away from their parents was ostensibly that they “might learn better manners”; but the Italian visitor mentioned above concluded uncharitably that the real reason was, the English had but small affection for their children, and liked to keep all their comforts xxiito themselves, and moreover knew that they would be “better served by strangers than by their own children.” However absurd this may seem at first glance, I incline to think that the foreigner may have touched upon truth here, as is borne out by many instances of Spartan, even brutal, treatment of children by parents in those days. Still, the fact remains that the loss of home life and parental tenderness was balanced by gain in discipline, education, social opportunity, and the opening up of careers.

The education of the various children addressed in these treatises varied according to their social status. As early as the twelfth century certainly, and perhaps earlier, it was customary for “bele babees,” with boys and girls, to have a tutor either at home, or in the household of the great man with whom they were placed. If they went to school, there were at first the monastic and conventual institutions; then later, the universities and grammar-schools. But, in the case of girls like the Good Wife’s daughter, who sold homespun in the market-place, and had to be admonished not to get drunk often, I doubt whether there would be any education beyond her mother’s teaching.

The universities, at first, were frequented chiefly by xxiiipoor men’s sons, and scarcely attended by the upper classes. In Chaucer’s time, the Clerk of Oxenford was lean and threadbare, and had but little gold, and his two Cambridge scholars were in no better case. Nearly two centuries later, Sir Thomas More says: “Then may we yet like poor scholars of Oxford, go a-begging with our bags and wallets, and sing ‘Salve, Regina’” (a carol) “at rich men’s doors.” However, gradually during the sixteenth century, a university education became so fashionable that rich men’s sons crowded in, and “scrooged” (I quote Dr. Furnivall) poor students out of the proceeds of endowments left expressly for them. Still, in 1517, the old ideal of a gentleman as yet held its own, as is amusingly related by Pace in his De Fructu. He tells how “one of those whom we call gentlemen, who always carry some horn hanging at their backs, as though they would hunt during dinner, said: ‘I swear by God’s body I would rather that my son should hang than study letters. For it becomes the sons of gentlemen to blow the horn nicely, and to hunt skilfully, and elegantly carry and train a hawk. But the study of letters should be left to the sons of rustics....’”

But Pace was equal to him. “You do not seem to xxivme to think aright, good man,” said I, “for if any foreigner were to come to the king, such as are ambassadors of princes, and an answer had to be given to him, your son if he were educated as you wish, could only blow his horn, and the learned sons of rustics would be called to answer, and they would be far preferred to your hunter or fowler son,” &c.

The fashion among noblemen of sending their sons abroad to study, either at a university or with a tutor, did not prevail widely until later. In the twelfth century, indeed, the “English nation” was famous at the University of Paris, but was composed largely of poor but earnest students, some of whom became famous men; and even these had ceased to study there before the fifteenth century.

Younger sons of good birth, in the service of a man of rank, were usually taught by a “maistyr” or tutor in the household in which they were placed. It is only in later books like Seager’s that these rules of demeanour were applied extensively to schoolboys. Doubtless gentlemen’s sons went to Winchester (after 1373) and to Eton (after 1440); but of the thirty grammar-schools endowed before 1500, all the others were xxvattended chiefly by the middle classes. The early monastic schools doubtless entertained young noblemen; but the cathedral schools founded by Henry VIII. seem to have been for citizens’ children, such as the boy in Symon’s Lesson of Wisdom, who is urged to learn fast so that when the old bishop dies he may be ready to take his place. However, even earlier we find complaints of the monastic schools which helped each shoemaker to educate his son, and each beggar’s brat to be a writer and finally a bishop, so that lords’ sons must kneel to him.

In general, the system of education implied in the Babees’ Book is that described in the household ordinances of Edward IV. for the young henchmen in charge of a “maistyr,” who should teach them to ride cleanly and surely, to draw them also to jousts, to ... “wear their harness, to have all courtesy in words, deeds, and degrees, diligently to keep them in rules of goings and sittings, after they be of honour.” They learned also “sundry languages,” and harping, piping, singing and dancing. Likewise, their master sat always with them at table in the hall, to see “how mannerly they eat and drink, and to their communication and other forms xxviof court, after the book of Urbanitie[8].” Clearly it would seem that one of the very treatises in this collection was studied by these young pages of Edward IV.

What languages they learned and what else studied we are not told in detail; but in Henry VIII.’s time, young Gregory Cromwell, son of the Earl of Essex, studied French, writing, fencing, “casting accounts,” instrumental music, &c. He was also made to read English aloud for the pronunciation, and was taught the etymology of Latin and French words. His day was as follows: After Mass, he read first the Colloquium on Pietas Puerilis (De Civilitate Morum Puerilium) by Erasmus (written 1530), of which he had to practice the precepts. Now this is nothing more than a collection of maxims similar to the Facet mentioned in the Babees’ Book, together with learned Scholia in Latin and Greek; hence, he had the same kind of thing to learn—only more elaborate—as the boys mentioned a hundred years earlier studied in Urbanitie. Doubtless his master approved the beginning of Erasmus: “Est autem uel prima uirtutis ac honestatis pars, tenere præcepta de moribus.” The xxviispecific nature of these directions appears in the following:

“Cleanliness of teeth must be cared for, but to whiten them with powder does for girls. To rub the gum with salt or alum is injurious.... If anything sticks to the teeth, you must get it out, not with a knife, or with your nails after the manner of dogs and cats, or with your napkin, but with a toothpick, or quill or small bone taken from the tibias of cocks or hens. To wash the mouth in the morning with pure water is both mannerly and healthful; to do it often is foolish.” Indeed, Erasmus’s treatise is only a superior book of courtesy.

His manners attended to, young Gregory wrote for one or two hours, read Fabyan’s Chronicle, and gave the rest of the day to his lute and virginals. When he rode, his master used to tell him stories of the Greeks and Romans, which he had to repeat; and his recreations were hunting, hawking and shooting with the long bow.

A harsher system prevailed with Queen Elizabeth’s wards, according to Sir Nicholas Bacon. They went to church at 6 o’clock, studied Latin until 11, dined xxviiifrom 11 to 12, had music from 12 to 2, French from 2 to 3, Latin and Greek from 3 to 5, then prayers, supper, and “honest pastimes” until 8, then music until 9, and so to bed.

The curricula in these various schools doubtless emphasized the usual Latin subjects (Greek was not taught in England before 1500) of the Middle Ages. Thus we find an account of the “disputations” in a London grammar-school, dating from 1174. But that athletic sports were popular even at that early time, appears from the same narrative, in which we read of football, sham fights, water-quintain, archery, running, leaping, wrestling, stone-casting, flinging bucklers, sliding and skating (on bones), besides the brutal sports of hog-, boar- and cock-fighting, bull- and bear-baiting.

At the other extreme we find the account of a school-day in 1612. Work begins at 6, and those who come first have the best places. At 9 o’clock, there is given 15 minutes for breakfast and recreation; then work continues until 11 or past (to balance the 15 minutes off). Dinner follows, and then work until 3 or 3.30, then 15 minutes off, and work until 5.30, xxixwhen school closes with a piece of a chapter, two staves of a psalm and prayer by the master.

It is probable, however, that these two descriptions are but two sides of the same medal; that Fitzstephen’s holidays were balanced by work days as tedious as those described by Brinsley.[9]

A singular fact to be noted in the English courtesy books is the almost complete absence of allusions to women. Barring the Good Wife and Wise Man, which are distinctly middle class in tone, we have practically nothing to represent the elaborate directions for conduct in some of the foreign treatises. Yet it cannot be doubted that the English system of patronage led to social problems and rules for the demeanour of young men and women together, such as prevailed abroad. Undoubtedly, too, the association of a lord’s pages and a lady’s maidens must have furthered the arrangement of marriages, perhaps not always in the way desired. Take, for example, the case of Anne Boleyn. After seven years’ service with the royal ladies of France, she came home and was placed in the household of Queen Katharine. Meanwhile, there was attendant upon xxxCardinal Wolsey a certain young Lord Percy, who, whenever his master was with the king, would “resort for pastime into the queen’s chamber, and there would fall in dalliance among the queen’s maidens.” In the end, he and Mistress Anne were secretly troth-plight; but Wolsey discovered the arrangement and sent the girl home, whereat she “smoked” (we say fumed) until she was recalled and heard of the great love the king bore her “in the bottom of his stomach”; then she “began to look very hault and stout, having all manner of jewels or rich apparel that might be gotten for money.” And doubtless there are many other similar complications to be found among old records, and more have perished, or were never written down at all.

It is something of a shock to turn from the elaborate rules for carving and serving, as set forth by Russell and others, to the domestic records of the time. The mingled splendour and squalor of the Middle Ages almost passes belief. We read of priceless hangings and costumes that cost each a small fortune, yet Erasmus describes the floors in noblemen’s houses as sometimes encumbered with refuse for twenty years xxxitogether.[10] King Edward IV. was provided with a barber who shaved him once a week, and washed his head, feet, and legs, if he so desired. A proper bath, according to Russell, seems to have been an event to be heralded with flowers and resorted to chiefly as curative. We see to-day the splendid palaces and castles, such as Hampton Court and Windsor, Knole and Penshurst and Warwick, built by kings and noblemen, and yet Henry VIII had to enact a law against the filthy condition of the servants in his own kitchen, and Wolsey, passing through the suitors in Westminster Hall, carried disinfectants concealed in an orange. It is this contrast in manners, doubtless, which will first strike the reader. A young nobleman had to be instructed not only how to hold his carving-knife with a thumb and two fingers, but also not to dip his meat into the salt-cellar, or lick the dust out of dish with his tongue, or wipe his nose on the table-cloth; and other instructions were added too primitive for translation. Undoubtedly, the general impression xxxiithat one derives is, as Dr. Furnivall puts it, of “dirty, ill-mannered, awkward young gawks,” whose “maistyrs” were greatly to be pitied. But, on the whole, it is surprising to note how little the fundamental bases of good manners have altered. Though we are not to-day so plain-spoken, our ideals are similar to those of our ancestors, but theirs was the greater difficulty of attainment. Personal cleanliness, self-respect, reverence to one’s better, and consideration for one’s neighbour seem to have been then as they are now, the foundation-stones.

On the other hand, it is interesting to notice the development of manners with improved conditions of life. One code was altered with the introduction of the handkerchief, another with the use of the fork (apparently first mentioned in 1463, but not common until after 1600, though it had long been in use on the Continent), and so on, so that by degrees social expedients and ceremonies change, while essentials remain.

Of each of the pieces here included I give a brief account in the notes. Needless to say, they form only a small portion of an enormous practical literature, though they are fairly representative of the English xxxiiibranch of it, for the time that they cover. In order to bring even so much within the compass of this small volume, it has been found necessary to condense. The principle of condensation has been as follows: whenever a text is particularly wordy for the matter that it contains, or has been found difficult to reproduce in modern language in the old verse-form, it has been done simply into prose. In cases where the metrical form has been preserved, perhaps both rhythm and rhyme have suffered in the translation; but in no instance has there been any poetic beauty lost, for the plain reason that the literary value of these productions is nil. In addition to a few omissions on grounds of taste, I have put aside various recipes and dietaries, hoping to use them later in a book devoted entirely to that sort of thing; and for the same reason, I have omitted considerable portions of Russell’s work, in which he deals with the dietetic properties and values of different kinds of food, describes various sorts of wines, enters into the details of carving fish, flesh, and fowl, and sets forth numerous recipes and elaborate menus. It is all interesting but has little to do with manners. Likewise, I have omitted Wynkyn de xxxivWorde’s Book of Carving, which seems to be only a prose version of Russell, portions of Rhodes’s work which deal rather with professional serving-men, and of Seager’s and West’s books, which treat of morals rather than manners. Further, I have omitted the various Latin and French poems on the subject, and a number of odds and ends of a generally didactic character, which, it seemed, could be best spared.

In translating, I have tried to keep as much as possible the quaint flavour of the originals, especially in the case of those rendered into modern English in the verse form. To that end I have retained old words and constructions whenever they seemed intelligible, although eccentric and perhaps ungrammatical to-day. When an archaic word alone conveyed the exact meaning, or was especially picturesque, I have left it, with a gloss at the bottom of the page, where also I refer to notes at the end, on points which seem to require special elucidation. My aim throughout has been to make the texts clear with the minimum of alteration. Doubtless I could have improved the metre frequently by merely a change in order of words; but I thought it better to meddle as little as possible, except for the xxxvsake of clearness; and so the verse often bumps along cheerfully, regardless of rhythm, style, and grammar. I think I may claim that in substance the modernised Babees’ Book is as near as possible to its original.

About half of the translations have been made by Miss L. J. Naylor.

MAY He who formed mankind in His image, support me while I turn this treatise out of Latin into my common language, that through this little comment all of tender years may receive instruction in courtesy and virtue.

Facet[11] saith that the Book of Courtesy to teach the practice of virtue is the most helpful thing in the world, so I will not shrink from this labour or refuse it; but for mine own learning will say something that touches upon the matter.

But oh, young babies, whom blood royal hath endowed with grace, comeliness, and high ability, it is on you I call to know this book, for it were great pity but 2that ye added to sovereign beauty virtue and good manners. Therefore I speak to you specially, and not to old men expert in governance, decorum, and honest manners, for what need is to give pangs to Hell, joy to Heaven, water to the sea, or heat to fire already hot?

And so, young babies,[12] my book is only for your instruction; wherefore I pray that no man reprehend it, but amend it where it is at fault, and judge it not, for your own sake. I seek no other reward but that it may please men and give you some ease in learning.[12] Also, sweet children, if there be in it any word that ye ken not, speer[13] while ye may, and when ye know it, bear it in mind; and so by asking you may learn of wise men. Also, think not too strangely that my pen writes in this metre;[12] for such verse is commonly used, therefore take heed.

And first of all, I think to show how you babies who dwell in households, should ’have[14] yourselves when ye be set at meat, and how when men bid you be merry, you should be ready with lovely, sweet and benign words. In this, aid me, O Mary, Mother Revered; and eke, O lady mine, Facetia,[12] guide thou my pen 3and show unto me help. For as A is the first of all letters, so art thou mother of all virtue. Have pity, sweet lady, of my lack of wit, and though untaught I speak of demeanour, support my ignorance with thy goodly aid.

Ah, “bele[15] babees,” hearken now to my lore.

When you enter your lord’s place, say “God speed,” and with humble cheer greet all who are there present. Do not rush in rudely, but enter with head up and at an easy pace, and kneel on one knee only to your lord or sovereign, whichever he be.

If any speak to you at your coming, look straight at them with a steady eye, and give good ear to their words while they be speaking; and see to it with all your might that ye jangle[16] not, nor let your eyes wander about the house, but pay heed to what is said, with blithe visage and diligent spirit. When ye answer, ye shall be ready with what ye shall say, and speak “things fructuous,”[17] and give your reasons smoothly in words that are gentle but compendious,[18] for many 4words are right tedious to the wise man who listens; therefore eschew them with diligence.

Take no seat, but be ready to stand until you are bidden to sit down. Keep your hands and feet at rest; do not claw your flesh or lean against a post, in the presence of your lord, or handle anything belonging to the house.

Make obeisance to your lord always when you answer; otherwise, stand as still as a stone, unless he speak.

Look with one accord that if ye see any person better than yourself come in, ye go backwards anon and give him place, and in nowise turn your face from him, as far forth as you may.

If you see your lord drinking, keep silence, without loud laughter, chattering, whispering, joking or other insolence.

If he command you to sit in his presence, fulfil his wish at once, and strive not with another about your seat.

When you are set down, tell no dishonest tale; eschew also, with all your might, to be scornful; and let your cheer be humble, blithe, and merry, not chiding as if ye were ready for a fight.

5If you perceive that your better is pleased to commend you, rise up anon and thank him heartily.

If you see your lord and lady speaking of household matters, leave them alone, for that is courtesy, and interfere not with their doing; but be ready, without feigning, to do your lord service, and so shall you get a good name.

Also, to fetch him drink, to hold the light when it is time, and to do whatsoever ought to be done, look ye be ready; for so shall ye full soon get a gentle name in nurture. And if you should ask a boon of God, you can desire no better thing than to be well-mannered.

If your lord is pleased to offer you his own cup to drink, rise when you take it, and receive it goodly with both your hands, and when you have done, proffer it to no man else, but render it again to him that brought it, for in nowise should it be used commonly—so wise men teach us.

Now must I tell you shortly what you shall do at noon when your lord goes to his meat. Be ready to fetch him clear water, and some of you hold the towel for him until he has done, and leave not until he be set down, and ye have heard grace said. Stand before 6him until he bids you sit, and be always ready to serve him with clean hands.

When ye be set, keep your own knife clean and sharp, that so ye may carve honestly[19] your own meat.

Let courtesy and silence dwell with you, and tell no foul tales to another.

Cut your bread with your knife and break it not. Lay a clean trencher[20] before you, and when your pottage is brought, take your spoon and eat quietly; and do not leave your spoon in the dish, I pray you.

Look ye be not caught leaning on the table, and keep clear of soiling the cloth.

Do not hang your head over your dish, or in any wise drink with full mouth.

Keep from picking your nose, your teeth, your nails at meal-time—so we are taught.

Advise you against taking so muckle meat into your mouth but that ye may right well answer when men speak to you.

When ye shall drink, wipe your mouth clean with a 7cloth, and your hands also, so that you shall not in any way soil the cup, for then shall none of your companions be loth to drink with you.

Likewise, do not touch the salt in the salt-cellar with any meat; but lay salt honestly on your trencher, for that is courtesy.

Do not carry your knife to your mouth with food, or hold the meat with your hands in any wise; and also if divers good meats are brought to you, look that with all courtesy ye assay of each; and if your dish be taken away with its meat and another brought, courtesy demands that ye shall let it go and not ask for it back again.

And if strangers be set at table with you, and savoury meat be brought or sent to you, make them good cheer with part of it, for certainly it is not polite when others be present at meat with you, to keep all that is brought you, and like churls vouchsafe nothing to others.

Do not cut your meat like field-men who have such an appetite that they reck not in what wise, where or when or how ungoodly they hack at their meat; but, sweet children, have always your delight in courtesy 8and in gentleness, and eschew boisterousness with all your might.

When cheese is brought, have a clean trencher, on which with a clean knife ye may cut it; and in your feeding look ye appear goodly, and keep your tongue from jangling, for so indeed shall ye deserve a name for gentleness and good governance, and always advance yourself in virtue.

When the end of the meal is come, clean your knives, and look you put them up where they ought to be,[21] and keep your seat until you have washed, for so wills honesty.

When ye have done, look then that ye rise up without laughter or joking or boisterous word, and go to your lord’s table, and there stand, and pass not from him until grace be said and brought to an end.

Then some of you should go for water, some hold the cloth, some pour upon his hands.

Other things I might commend you to do, but as my time is brief, I put them not into this little report; but overpass them, praying with a spirit that rejoices in this labour, that no man abuse me; but where too 9little is, let him add more, and where too much, let him take away, for though I would, time forbids that I say more. Therefore I take my leave, and inscribe this book to every wight whom it may please to correct it.

And, sweet children, for love of whom I write, I beseech you, with very loving heart, that you set your delight upon knowing this book; and may Almighty God that suffered bitter pains, make you so expert in courtesy that through your nurture and your governance you may advance yourselves to lasting bliss.

Here endeth the Book of Courtesy that is full necessary unto young children that must needs learn the manner of courtesy.

WHOSO will thrive must be courteous, and learn the virtues in his youth, or in his age he is outcast among men. Clerks who know the Seven Sciences[66] say that Courtesy came from heaven when Gabriel greeted our Lady and Elizabeth met with her; and in it are included all virtues, as all vices in rudeness.

Arise betimes from your bed, cross your breast and your forehead, wash your hands and face, comb your hair, and ask the grace of God to speed you in all your works; then go to Mass and ask mercy for all your trespasses. Say “Good morning” courteously to whomsoever you meet by the way.

When ye have done, break your fast with good meat and drink, but before eating cross your mouth, your diet will be the better for it. Then say your grace—it occupies but little time—and thank the Lord Jesus for your food and drink. Say also a Pater Noster and an Ave Maria for the souls that lie in pain, and then go labour as you are bound to do. Be not idle, for Holy Scripture says to you of Christian faith that if you work, you must eat what you get with your hands.[67] A man’s arms are for working as a bird’s wings for flying.

Look you be true in word and deed, the better shall you prosper; for truth never works a man shame, but rather keeps him out of sin. The ways to Heaven are twain, mercy and truth, say clerks; and he who will come to the life of bliss, must not fail to walk therein.

Make no promise save it be good, and then keep it 23with all your might, for every promise is a debt that must not be remitted through falsehood.

Love God and your neighbour, and thus may ye say without fear or dread that you keep all the law.

Uncalled go to no council, scorn not the poor, nor hurt any man, learn of him that can teach you, be no flatterer or scoffer, oppress not your servants, be not proud, but meek and gentle, and always walk behind your betters.

When your better shows his will, be silent; and in speaking to any man keep your hands and feet quiet, and look up into his face, and be always courteous.

Point not with your finger at anything, nor be lief[68] to tell tidings. If any man speak well of you or of your friends, he must be thanked. Have few words and wisely placed, for so may you win a good name.

Use no swearing or falsehood in buying or selling, else shall you be shamed at the last. Get your money honestly, and keep out of debt and sin. Be eager to please, and so live in peace and quiet.

Advise you well of whom you speak, and when and where and to whom.

24Whenever you come unto a door, say, “God be here,” ere you go further, and speak courteously, wherever you are, to sire or dame or their household.

Stand, and sit not down to meat until you are told by him that rules the hall; and do not change your seat, but sit upright and mannerly where he bids, and eat and drink and be fellowly, and share with him that sits by you—thus teaches Dame Courtesy.

Take your salt with a clean knife.

Be cool of speech and quarrel not, nor backbite a man who is away, but be glad to speak well of all. Hear and see and say nothing, then shall ye not be put to proof.

Hold you pleased with the meat and drink set before you, nor ask for better. Wipe your mouth before you drink lest it foul the edge of the cup; and keep your fingers, your lips and your chin clean, if you would win a good name. When your meat is in your mouth, do not drink or speak or laugh—Dame Courtesy forbids. Praise your fare, wheresoever you be, for whether it be good or bad it must be taken in good part.

Whether you spit near or far, hold your hand before your mouth to hide it.

25Keep your knife clean and sharp, and cleanse it on some cut bread, not on the cloth, I bid you; a courteous man is careful of the cloth. Do not put your spoon in the dish or on the edge of it, as the untaught do, or make a noise when you sup as do boys. Do not put the meat off your trencher into the dish, but get a voider and empty it into that.

When your better hands you a cup, take it with both hands lest it fall, and drink yourself and set it by; and if he speaks to you, doff your cap and bow your knee.

Do not scratch yourself at the table so that men call you a daw,[69] nor wipe your nose or nostrils, else men will say you are come of churls. Make neither the cat nor the dog your fellow at the table. And do not play with the spoon, or your trencher, or your knife; but lead your life in cleanliness and honest manners.

This book is made for young children that bide not long at the school.[70] It may soon be conned and learned, and will make them good if they be bad. God give them grace to be virtuous, for so may they thrive.

LISTEN, lordlings, and ye shall hear how the wise man taught his son. Take good heed to this matter and learn it if ye can, for this song was made with good intent to make men true and steadfast, and a thing well begun makes often a good ending.

There was a wise man taught his son while he was yet a child of tender years, meek and fair to look upon, very eager for learning and with a great desire to all goodness; and his father taught him well and featly by good example and fair words.

He said: “My son, take good heed every morning, ere ye do worldly thing, lift up your heart to God, and pray as devoutly as you can for grace to lead a good life, and to escape sin both night and day, and that heaven’s bliss may be your meed.

“And, my son, wherever you go, be not full of tales; beware what you say, for your own tongue may be your foe. If you say aught, take good heed where and to whom, for a word spoken to-day may be repented seven years after.

44“And, son, whatever manner of man ye be, give yourself not to idleness, but busy yourself every day according to your estate. Beware of rest and ease, which things nourish sloth. Ever to be busy, more or less, is a full good sign of honesty.[110]

“And, son, I warn you also not to desire to bear office, for then can it be no other than that you must either displease and hurt your neighbours, or else forswear yourself and not do as your office demands; and get yourself, maugré,[111] here and there, an hundredfold more than thanks.

“And, son, as far as you may, go on no evil quests, nor bear false witness in any man’s matter. It were better for you to be deaf and dumb than to enter wrongfully into a quest. Think, son, on the dreadful doom that God shall deem[112] us at the last!

“And, son, of another thing I warn you, on my blessing take good heed of tavern-haunting, and of the dice, and flee all lechery, lest you come to an evil end, for it will lead astray all your wits and bring you into great mischief.

“And, son, sit not up too long at even, or have late 45suppers, though ye be strong and hale, for with such outrage your health shall worsen. And of late walking comes debate,[113] and of sitting and drinking out of time, therefore beware and go to bed betimes and wink.

“And, son, if ye would have a wife, take her not for her money, but inquire wisely of all her life, and give good heed that she be meek, courteous and prudent, even though she be poor; and such an one will do you more good service in time of need, than a richer.

“And if your wife be meek and good, and serve you well and pleasantly, look ye be not so mad as to charge her too grievously, but rule her with a fair hand and easy, and cherish her for her good deeds. For a thing unskilfully overdone makes needless grief to grow, and it is better to have a meal’s meat of homely fare with peace and quiet, than an hundred dishes with grudging and much care. And therefore learn this well that if you want a wife to your ease, take her never the more for the riches she may have, though she might endow you with lands.

“And ye shall not displease your wife, nor call her by no villainous names, for it is a shame to you to miscall 46a woman; and in so doing, ye are not wise, for if ye defame your own wife, no wonder that another should do so! Soft and fair will tame alike hart and hind, buck and doe.

“On the other hand, be not too hasty to fight or chide, if thy wife come to you at any time with complaint of man or child; and be not avenged till you know the truth, for you might make a stir in the dark, and afterwards it should rue you both.

“And, son, if you be well at ease, and sit warm among your neighbours, do not get new-fangled ideas, or be hasty to change, or to flit;[114] for if ye do, ye lack wit and are unstable, and men will speak of it and say: ‘This fool can bide nowhere!’

“And, son, the more goods you have, the rather bear you meekly, and be humble, and boast not overmuch; it is wasted, for by their boasting men know fools.

“And look you pay well what you owe, and set no great store by other riches, for death takes both high and low, and then—farewell, all that there is! And therefore do by my counsel, and take example from other men, how little their goods avail them when 47they be dolven[115] in their dens;[116] and one that was not of his kin hath his wife, and all that there is.[117]

“Son, keep you from deadly sin, and assay to enter Paradise. Make amends for your trespasses and deal out of your goods to poor men, make friends of your foes, and strive to gain salvation for your soul, for the world is false and frail, and every day doth worsen. Son, set nought by this world’s weal, for it fares as a ripe cherry. And death is ever, I trow, the most certain thing that is; and nothing is so uncertain as to know the time thereof. Therefore, my son, think on this, on all that I have said, and may Jesus, who for us bare the crown of thorns, bring us to His bliss.”

“IN nomine Patris, God keep me, et Filii, for charity, Et Spiritus Sancti, where that I go by land or else by sea!

An usher I am ye may behold to a prince of high degree, That enjoys to inform and teach all those that would thrive in prosperity.”

48Should I meet with any man who either through inexperience or through negligence knows naught of such things as I shall hereafter diligently show, for my conscience’ sake I will instruct him; for methinks it is charitable to teach virtue and good manners, in which most youths are barren and dull. But if there be any who can nothing good and are not willing to learn, give them a bauble to play with, for they will never thrive.

────────────────

────────────────

Thereupon the young man was glad and loved to 49talk with me; but when I inquired whom he served, he said: “God help me, sir, I serve myself and else no other man.”

“Is thy governance good[118]?” I said. “My son, tell me if thou wilt.”

“I would I were out of this world,” said he; “I reck not how soon when!”

“Say not so, good son, beware! Methinks you mean amiss for God forbids wanhope,[119] which is a horrible sin. Therefore, good son, open your heart to me, peradventure I can relieve you. Remember that when bale[120] is highest, boot[121] is nighest.”

“In truth, sir, I have sought far and near in many a wildsome way to get me a master. But because I knew nothing good, and showed this wherever I went, every man denied me; day by day, wanton[122] and over-nice, reckless, lewd and chattering like a jay, every man refused me.”

“Now, good son, if I will teach, will you learn? Will you be a serving-man, a ploughman, a labourer, a courtier, a clerk, a merchant, a mason or an artificer, a chamberlain, a butler, a panter or a carver?”

50“Teach me, sir, the duties of a butler, a panter or a chamberlain, and especially, the cunning of a carver. If you will make me to know all these, I will pray for your soul that it come never in pain!”

“Son, I will teach you with right good will, so as you will love and fear God as is right and proper, be true to your master, and not waste his goods, but love and fear him, and duly fulfil his commandments.”

“The first year, my son, you shall be panter or butler. In the pantry, you must always keep three sharp knives, one to chop the loaves, another to pare them, and a third, sharp and keen, to smooth and square the trenchers with.[123]

“Always cut your lord’s bread, and see that it be new; and all other bread at the table one day old ere you cut it, all household bread three days old, and trencher-bread four days old.

“Look that your salt be fine, white, fair, and dry; and have your salt-plane of ivory, two inches 51wide and three long; and see to it that the lid of the salt-cellar touch not the salt.

“Good son, look that your napery be sweet and clean, and that your table-cloth, towel, and napkin be folded neatly, your table-knives brightly polished and your spoons fair washed—ye wot well what I mean.

“Look ye have two wine-augers, a greater and a less, some gutters of boxwood that fit them, also a gimlet to pierce with, a tap and a bung, ready to stop the flow when it is time. So when you broach a pipe, good son, do after my teaching: pierce or bore with an auger or gimlet, slanting upward, four fingers’ breadth from the lower rim, so as not to cause the lees to rise—I warn you especially.”

[Here follows a list of fruits and preserves, which presently becomes a mere dietary, ll. 73-108.]

“Take good heed to the wines, red, white, and sweet; look to them every night with a candle, to see that they neither ferment nor leak. Never forget to wash the heads of the pipes with cold water every night; and always carry a gimlet, adze and linen clouts,[124] large and small. If the wine ferment, ye shall know by its singing, 52so keep at hand a pipe of couleur de rose,[125] that has been spent in drinking and add to the fermentation the dregs of this, and it shall be amended. If sweet wine be sick or pallid, put in a Romney to improve it.”

[Then follows a list of the sweet wines, and a long recipe for Hippocras, ll. 117-176.]

“See that your cups and pots be clean, both within and without. Serve no ale till it is five days old, for new ale is wasteful.[125] And look that all things about you be sweet and clean.

“Be fair of answer, ready to serve, and gentle of cheer, and then men will say; ‘There goes a gentle officer.’

“Beware that ye give no person stale drink, for fear that ye bring many a man into disease for many a year.[125]

“My son, it is now the time of day to lay the table. First, wipe it with a cloth ere it be spread, then lay on it a cloth called a cowche.[125] You take one end and your mate the other, and draw it straight; and lay a second 53cloth with its fold on the outer edge of the table.[126] Lift the upper part and let it hang even. And then lay the third cloth with its fold on the inner edge, making a state[126] half a foot wide, with the top. Cover your ewery-cupboard[127] with a diapered-towel, and put a towel round your neck,[126] for that is courtesy, and put one end of it mannerly over your left arm; and on the same arm place your lord’s napkin, and on it lay eight loaves of bread, with three or four trencher-loaves. Take one end of the towel in your left hand, as the manner is, together with the salt-cellar—look you do this—and take the other end of the towel in your right hand with the spoons and knives.

“Set the salt on your lord’s right hand, and to the left of your salt, one or two trenchers, and to the left again, your knife by itself and plain to see, and the white rolls, and beside them a spoon upon a fair folded napkin. Cover your spoon, napkin, trencher and knife, so that they cannot be seen; and at the other end of the table place a salt with two trenchers.

54“If you wish to wrap up your lord’s bread in a stately fashion, first square off the bread sharply and evenly, and see that no bun or loaf be larger in proportion to the others, and so shall ye be able to wrap it up mannerly for your master. Take a towel of Rennes cloth,[128] two and a half yards long, fold it lengthwise[128] and lay it on the table. Roll up a handful from each end tightly and stiffly, then in the middle of the towel place eight loaves or buns, bottom to bottom, and then wrap them wisely and skilfully. To tell you more plainly for your information: take the ends of the towel that lies on the bread, draw them out and twist tightly a handful nearest the bread and smooth the wrapper stiffly. When it is ready, you must open one end all in a moment before your lord.

When your sovereign’s table is dressed in this array, place salts on all the other tables, and lay trenchers and cups; and then set out your cupboard with gay silver and silver-gilt, and your ewery board with basins and ewers, and hot and cold water, each to temper the other. Look that you have ever enough napkins, spoons and cups for your lord’s table; also, for your 55own dignity, that your pots for ale and wine be as clean as possible, and beware ever of flies and motes, for your own sake.

“With lowly courtesy, make the surnape[129] with a cloth under a double of fair napery; fold the two ends of the towel to the outer edge of the cloth, and so hold the three ends together; then fold them all so that there is a pleat at about a foot’s distance, and lay it fair and smooth for your lord to wash after meat, if he will. At the right side of the table, you must guide it along, and the marshal must slip it further—the right side up of all three cloths—and let it be drawn straight and even, both in length and breadth; then raise the upper part of the towel and lay it without wrinkling straight to the other side so that half a yard or an ell hangs down at each end, where the sewer[129] may make a state, and so please his master. When your lord has washed, you must take up the surnape with your two arms, and carry it back to the ewery yourself.

“Carry a towel about your neck when serving your lord, bow to him, uncover your bread and set it by the salt. Look that all have knives, spoons and napkins, 56and always when you pass your lord, see that you bow your knees.

“Go forth to the port-payne[130] and there take eight loaves, and put four at each end of the table, and be sure that each person has a spoon and a napkin.

“Watch the sewer to see how many pottages he covers, and do ye for as many, and serve each according to his degree; and see that none lack bread, ale or wine.

“Be glad of cheer, courteous of knee, soft of speech; have clean hands and nails and be carefully dressed.

“Do not cough or spit or retch too loud, or put your fingers into the cups to seek bits of dust.

“Have an eye to all grumbling and fault-finding, and prevent backbiting of their fellows among the lords at meat, by serving all with bread, ale and wine; and so shall ye have of all men good love and praise.”

“I will that ye eschew forever the ‘simple conditions’ of a person that is not taught.

“Do not claw your head or your back as if you 57were after a flea, or stroke your hair as if you sought a louse.

“Be not glum,[131] nor twinkle with your eyes, nor be heavy of cheer; and keep your eyes free from winking and watering.[132]

“Do not pick your nose or let it drop clear pearls, or sniff, or blow it too loud, lest your lord hear.

“Twist not your neck askew like a jackdaw; wring not your hands with picking or trifling or shrugging, as if ye would saw [wood]; nor puff up your chest, nor pick your ears, nor be slow of hearing.

“Retch not, nor spit too far, nor laugh or speak too loud. Beware of making faces and scorning; and be no liar with your mouth. Nor yet lick your lips or drivel.

“Do not have the habit of squirting or spouting with your mouth, or gape, or yawn, or pout. And do not lick a dish with your tongue to get out dust.

“Be not rash or reckless—that is not worth a clout.

“Do not sigh with your breast, or cough, or breathe hard in the presence of your sovereign, or hiccough, or belch, or groan never the more. Do not trample with 58your feet, or straddle your legs, or scratch your body—there is no sense in showing off. Good son, do not pick your teeth, or grind, or gnash them, or with puffing and blowing cast foul breath upon your lord.... These gallants in their short coats—that is ungoodly guise. Other faults on this matter, I spare not to disapprove in my opinion, when [a servant] is waiting on his master at table. Every sober sovereign must despise all such things.

“A man might find many more conditions than are named here; but let every honest servant avoid them for his own credit.

“Panter, yeoman of the cellar, butler and ewerer, I will that ye obey the marshal, sewer and carver.”

“Good sir, I pray you teach me the skill of carving, and the fair handling of a knife, and all the ways that I shall break open, unlace and penetrate all manner of fowl, flesh and fish—how I shall demean me with each.”

“My son, thy knife must be clean and bright; and it beseems thee to have thy hands fair washed. Hold always thy knife surely, so as not to hurt thyself, and 59have not more than two fingers and the thumb on thy keen knife.

“Midway in thy hand, set the end of thy haft firmly; and unlace and mince with the thumb and two fingers only. In cutting and placing bread, and voiding of crumbs and trencher, look you have skill with two fingers and the thumb. Likewise, never use more for fish, flesh, beast or fowl—that is courtesy.

“Touch no manner of meat with thy right hand, but with thy left, as is proper. Always with thy left hand grasp the loaf with all thy might; and hold thy knife firmly, as I have instructed thee. Ye do not right to soil your table, nor to wipe your knives on that, but on your napkin.

“First take a loaf of trenchers in your left hand, then your table-knife, as I have said before; and with its edge raising your trencher up by you as near the point as you may, lay it before your lord. Right so set four trenchers, one by another, four square, and upon them a single trencher alone. And take your loaf of light bread, as I have told you, and cut with the edge of the knife near your hand; first pare the 60quarters of the loaf round all about, and cut the upper crust[133] for your lord, and bow to him; and suffer the other part to remain still at the bottom, and so nigh spent out,[134] and lay him of the crumbs a quarter of the loaf.

“Touch not the loaf after it is so trimmed; put it on a platter or on the beforenamed alms-dish. Make clean your board that ye be not blamed; and so shall the sewer serve his lord, and neither of you be vexed.”

[Here follows a list of Fumosities, indigestibilities, as Dr. Furnivall calls them, ll. 349-68. The young man then says:]

[He then begs to be taught the art of “carving of fish and flesh[133] after the cook’s care,” and receives detailed instructions for every sort of food, roasted, baked and fried, for the serving of soups, making of sauces and carving of fish, ll. 377-649. He then says:]

“Now since, my son, you wish to learn this science, dread nothing of great difficulty; I will gladly teach you, if you will but listen.

“Take heed when the worshipful head of any household has washed before meat and begins to say grace, then hie you to the kitchen where the servants must attend and take your orders. First ask the panter or officer of the spicery for fruits, such as butter, plums, damsons, grapes and cherries, which are served before dinner according to the season to make men merry, and 62ask if any such are to be served that day. Then commune with the cook and surveyor[137] as to what meats and how many dishes are prepared. When they two have agreed with you, then must the cook dress up all dishes to the surveying-board,[138] and the surveyor must soberly and without turmoil deliver up the dishes to you, that you may convey them to your lord. When you are at the board of service, see that you have courtly and skilful officers to prevent any dish being stolen, which might easily cause a scandal to arise in your service as sewer. See that you have proper servants to carry the dishes, marshals, squires and serjeants-at-arms, if they be there, to bring the dishes without delay or injury from the kitchen, and you need not fear to set them on the table yourself.”[139]

[Then follow various menus, ll. 686-858. The young man answers:]

“The duty of a chamberlain is to be diligent in office, neatly clad, his clothes not torn, hands and face well washed and head well kempt.

“He must be ever careful—not negligent—of fire and candle. And look you[140] give diligent attendance to your master, be courteous, glad of cheer, quick of hearing in every way, and be ever on the lookout for things to do him pleasure; if you will acquire these qualities, it may advance you well.

“See that your lord has a clean shirt and hose, a short coat,[141] a doublet, and a long coat, if he wear such, his hose well brushed, his socks at hand, his shoes or slippers as brown as a water-leech.[140]

“In the morning, against your lord shall rise, take care that his linen be clean, and warm it at a clear fire, not smoky, if [the weather] be cold or freezing.

64“When he rises make ready the foot-sheet, and forget not to place a chair or some other seat with a cushion on it before the fire, with another cushion for the feet. Over the cushion and chair spread this sheet so as to cover them; and see that you have a kerchief and a comb to comb your lord’s head before he is fully dressed.

“Then pray your lord in humble words to come to a good fire and array him thereby, and there to sit or stand pleasantly; and wait with due manners to assist him. First hold out to him his tunic, then his doublet while he puts in his arms, and have his stomacher well aired to keep off harm, as also his vamps[142] and socks, and so shall he go warm all day.

“Then draw on his socks and his hose by the fire, and lace or buckle his shoes, draw his hosen on well and truss them up to the height that suits him, lace his doublet in every hole, and put round his neck and on his shoulders a kerchief; and then gently comb his head with an ivory comb, and give him water wherewith to wash his hands and face.

65“Then kneel down on your knee and say thus: ‘Sir, what robe or gown doth it please you to wear to-day?’ Then get him such as he asks for, and hold it out for him to put on, and do on his girdle, if he wear one, tight or loose, arrange his robe in the proper fashion, give him a hood or hat for his head, a cloak or cappe-de-huse,[143] according as it be fair or foul, or all misty with rain; and so shall ye please him. Before he goes out, brush busily about him, and whether he wear satin, sendal,[144] velvet, scarlet[145] or grain,[146] see that all be clean and nice.

“If he be prince or prelate or other potentate, before he go to church see that all things for the pew be made ready, and forget not cushion, carpet, curtain, beads or book.

“Then return in haste to your lord’s chamber, strip the clothes off the bed and cast them aside, and beat the feather-bed, but not so as to waste any feathers, and see that the blankets and sheets be clean. When you have made the bed mannerly, cover it with a coverlet, spread out the bench-covers,[147] and cushions, set up the 66head-sheet[148] and pillow, and remove the basin. See that carpets[149] be laid round the bed and dress the windows, and the cupboard with carpets[149] and cushions. See there be a good fire conveyed into the chamber, with plenty of wood and fuel to make it up....

“You must attend busily to your lord’s wardrobe, to keep the clothes well, and to brush them cleanly. Use a soft brush, and remember that overmuch brushing easily wears out cloth.

“Never let woollen clothes or furs go a sevennight without being brushed or shaken, for moths be always ready to alight in them and engender; so always keep an eye on drapery and skinnery.

“If your lord take a nap after his meal to digest his stomach, have ready kerchief and comb, pillow and head-sheet; yet be not far from him—take heed what I say—for much sleep is not good in the middle of the 67day, and have ready water and towel so that he may wash after his sleep.

“When he has supped and goes to his chamber, spread forth your foot-sheet, as I have already shown you, take off his gown or whatever garment by the license of his estate he wears,[150] and lay it up in such place as ye best know. Put a mantle on his back to keep his body from cold, set him on the foot-sheet, made ready as I have directed, and pull off his shoes, socks and hosen, and throw these last over your shoulder, or hold them on your arm. Comb his hair, but first kneel down, and put on his kerchief and nightcap wound[150] in seemly fashion. Have the bed, head-sheet and pillow ready; and when he is in bed, there to sleep safe and sound, draw the curtains round about the bed, set there his night-light with wax or Paris-candle,[150] and see that there is enough to last the night, drive out the dog and the cat, giving them a clout, take no leave of your lord, but bow low to him and retire, and thus shall ye have thanks and reward whensoever it fall.”

“If your lord wishes to bathe and wash his body clean, hang sheets round the roof, every one full of flowers and sweet green herbs, and have five or six sponges to sit or lean upon, and see that you have one big sponge to sit upon, and a sheet over so that he may bathe there for a while, and have a sponge also for under his feet, if there be any to spare, and always be careful that the door is shut. Have a basin full of hot fresh herbs and wash his body with a soft sponge, rinse him with fair warm rose-water, and throw it over him; then let him go to bed; but see that the bed be sweet and nice; and first put on his socks and slippers that he may go near the fire and stand on his foot-sheet, wipe him dry with a clean cloth, and take him to bed to cure his troubles.”

“Boil together hollyhock,[151] mallow, wall pellitory and brown fennel, danewort, St. John’s wort, centaury, ribwort and camomile, heyhove, heyriff, herb-benet, 69bresewort, smallage, water speedwell, scabious, bugloss (?), and wild flax which is good for aches—boil withy leaves and green oats together with them, and throw them hot into a vessel and put your lord over it and let him endure for a while as hot as he can, being covered over and closed on every side; and whatever disease, grievance or pain ye be vexed with, this medicine shall surely make you whole, as men say.”

“An usher or marshal, without fail, must know all the estates of the Church, and the excellent estate of a king with his honourable blood. This is a notable nurture, cunning, curious and commendable.

“The estate of the Pope has no peer, an emperor is next him everywhere and a King is correspondent, a high cardinal next in dignity, then a King’s son (ye call him prince), an archbishop his equal; a duke of the blood royal; a bishop, marquis and earl coequal; a viscount, legate, baron, suffragan and mitred abbot; a baron of the exchequer, the three chief justices and the Mayor of London; a cathedral prior, unmitred 70abbot and knight bachelor; a prior, dean, archdeacon, knight and body esquire; the Master of the Rolls (as I reckon aright), and puisne judge; clerk of the crown and the exchequer, and you may pleasantly prefer the Mayor of Calais.[152]

“A provincial,[153] doctor of divinity and prothonotary[154] may dine together; and you may place the pope’s legate or collector with a doctor of both laws. An ex-mayor of London ranks with a serjeant-at-law, next a Mastery of Chancery, and then a worshipful preacher of pardons,[155] masters of arts, and religious orders, parsons and vicars, and parish priests with a cure, the bailiffs of a city, a yeoman of the crown, and serjeant-of-arms with his mace, with him a herald, the King’s herald in the first place, worshipful merchants and rich artificers, gentlemen well-nurtured and of good manners, together with gentlewomen and lords’ foster-mothers[156]—all these may eat with squires.

“Lo, son, I have now told you, after my simple wit, 71the rank of every estate according to his degree, and now I will show you how they should be grouped at table in respect of their dignity, and how they should be served.

“The pope, an emperor, king, cardinal, prince with a golden royal rod,[157] archbishop in his pall—all these for their dignity ought not to dine in the hall.

“A bishop, viscount, marquis, goodly earl may sit at two messes if they be agreeable thereunto.

“The Mayor of London, a baron, a mitred abbot, the three chief justices, the Speaker of Parliament—all these estates are great and honourable, and they may sit together in chamber or hall, two or three at a mess, if it so please them; but in your office you must try to please every man.

“The other estates, three or four to a mess, equal to a knight’s, are: unmitred abbot or prior, dean, archdeacon, Master of the Rolls, all the under judges and barons of the king’s exchequer, a provincial, a doctor of divinity or of both laws, a prothonotary, or the pope’s collector, if he be there, and the Mayor of the Staple.

72“Other ranks you may set four to a mess, of persons equal to a squire in dignity, serjeants-at-law and ex-mayors of London, the masters of Chancery, all preachers, residencers, and parsons, apprentices of the law, merchants and franklins—these may sit properly at a squire’s table.

“Each estate shall sit at meat by itself, not seeing the others, at meal-time or in the field or in the town; and each must sit alone in the chamber or in the pavilion.

“The Bishop of Canterbury shall be served apart from the Archbishop of York, and the Metropolitan shall be served alone. The Bishop of York must not be served in the presence of the Primate of England.[158]

“Now, son, from divers causes, as equally from ignorance, a marshal is often puzzled how to rank lords of royal blood who are poor, and others not of royal blood who are rich, also ladies of royal blood wedded to knights, and poor ladies marrying those of royal blood. The lady of royal blood shall keep her rank, the lady of low blood and degree shall take her husband’s rank. The substance of livelihood[159] is not so 73digne[160] as royal blood, wherefore this prevails in chamber and hall, for some day blood royal might attain to the kingship.

“If the parents of a pope or cardinal be still alive, they must in no wise presume to be equal to their son, either sitting or standing. The estate of their son will not allow them either to sit or stand by him—nor should they desire it; wherefore they should have a separate chamber assigned to them.

“A marshal must look to the birth of each estate, and arrange officers such as chancellor, steward, chamberlain, treasurer, according to their degree.

“He must honour foreign visitors, and strangers to this land, even when they are resident here. A well-trained marshal should think beforehand how to place strangers at the table, for if they show gentle cheer and good manners, he thereby doth honour his lord and bring praise to himself.

“If the king send any messenger to your lord, if he be a knight, squire, yeoman of the crown, groom, page or child, receive him honourably as a baron, knight, squire, yeoman or groom,[161] and so forth, from the 74highest degree to the lowest, for a king’s groom may dine with a knight or a marshal.

“A commendable marshal must also understand the rank of all the worshipful officers of the commonalty of this land, of shires, cities and boroughs—such must be placed in due order, according to their rank.

“The estate of a knight of [good] blood and wealth is not the same as that of a simple and poor knight. Also, the Mayor of Queenborough[162] is not of like dignity with the Mayor of London—nothing like of degree; and they must on no account sit at the same table.

“The Abbot of Westminster is the highest in the land, and the Abbot of Tintern the poorest; both are abbots, yet Tintern shall neither sit nor stand with Westminster.[162] Also, the Prior of Dudley may in no wise sit with the Prior of Canterbury.[162] And remember, as a general rule, that a prior who is a prelate of a cathedral church, shall sit above any abbot or prior of his own diocese, in church, chapel, chamber or hall.

“Reverend doctors of twelve years’ standing shall sit above those of nine years’, although the latter may 75spend more largely of fine red gold. Likewise, the younger aldermen shall sit or stand below their elders, and so in every craft, the master first, and then the ex-warden.

“All these points, with many more, belong to the duty of a marshal; and so before every feast think what estates shall sit in the hall, and reason with yourself before your lord shall call upon you. If you are in any doubt, go either to your lord or to the chief officer, and then shall you do no wrong or prejudice to any state; but set all according to their birth, riches or dignity.

“Now, good son, I have shown you the courtesy of the court, and how to manage in pantry, buttery, cellar or in carving, as a sewer or as a marshal. I suppose ye be sure in these sciences, which in my day I learned with a royal prince, to whom I was usher and also marshal.

“All the officers I have mentioned have to obey me, ever to fulfil my commandment when I call, for our office is the chief in spicery and cellar, whether the cook be lief or loth.[163]

76“All these divers offices may be filled by a single person, but the dignity of a prince requireth each office to have its officer and a servant waiting on him. Moreover, all must know their duties perfectly, for doubt and fear are a hindrance in serving a lord and pleasing his guests.

“Fear not to serve a prince—God be his speed! Take good heed to your duties, and be ever on the watch, and thus doing as ye should, there will be no need to doubt.

“Tasting is done only for those of royal blood, as pope, emperor, empress, cardinal, king, queen, prince, archbishop, duke or earl—none other that I call to remembrance. It is done for fear of poison, so let each man in office keep his room secure and close his safe,[164] chest and storehouse for fear of conspiracy.

“The steward and chamberlain of a prince of the blood must know about homages, services and fewte;[165] and as they have the oversight of all other offices and of the tasting, they must tell the marshal, sewer or carver, how to do it; and he must be in no fear when he tasteth.

“As the evening draws in, and I cannot tarry, I do 77not propose to contrive more of this matter. This treatise that I have entitled, if ye would prove it, I myself assayed in youth, when I was young and lusty; and I enjoyed these aforesaid matters, and took good heed to learn. But crooked age hath now compelled me to leave the court, so assay for yourself, my son, and God speed you!”

“Now, fair befall you, father, and blessings be on you for thus teaching me! I shall dare to do diligent service to divers dignitaries, where before I was afraid for the scantiness of my knowledge; I perceive the whole matter so perfectly that I am ready to try my part, and some good I may learn from practice and exercise. I am bound always to pray God reward you for your gentle teaching of me!”

“Now, good son, thyself and others that shall succeed thee to note, learn and read over this book of nurture, pray for the soul of John Russell, servant to Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. Pray for that peerless prince, and for the souls of my wife and my father and mother, unto Mary, Mother and Maid, that she defend us from our foes, and bring us all to bliss when we go hence. Amen.”

78[The envoi may have been added later[166]]

“If thou be a young Infant”

John of Gaunt receives a civic deputation

“Who spareth the rod, the child hateth”

| S ay well some will | by this my labour, |

| E very man yet | will not say the same. |

| A mong the good | I doubt not favour; |

| G od them forgive | [that] for it me blame. |

| E ach man I wish | [whom] it shall offend, |

| R ead and then judge, | where fault is, amend. |

| First in the morning, | when thou dost awake, |

| To God for His grace, | thy petition then make. |

| This prayer following | use daily to say; |

| Thy heart lifting up, | thus begin to pray. |

| “O God from whom | all good gifts proceed, |

| To thee we repair | in time of our need, |

| That with thy grace | thou would’st us endue, |

| Virtue to follow | and vice to eschew. |

| Hear this our request, | and grant our desire, |

| O Lord, most humbly | we do thee require. |

| This day us defend | that we walking aright |

| May do the thing | acceptable in thy sight; |

| That as we in years | and body do grow, |

| So in good virtues | we may likewise flow |

| To thy honour | and joy of our parents, |

| Learning to live well | and keep thy commandments, |

| In flying from all | vice, sin and crime, |

| Applying our books, | not losing our time, |

| May fructify and go forward | here in good doing, |

| In this vale of misery | unto our lives’ ending; |

| That after this life | here transitory, |

| We may attain | to greater glory.” |

| The Lord’s prayer then | see thou recite, |

| So using to do, | at morning and night. |

| Fly ever sloth | and overmuch sleep; |

| In health the body | thereby thou shalt keep. |

| Much sleep engendereth | diseases and pain, |

| It dulls the wit | and hurteth the brain. |